Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/88/21. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Harding et al. This work was produced by Harding et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Harding et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction (background and objectives)

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Forbes et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific background

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common in adult women, in both the community and the hospital setting. Inoculation of the periurethral tissues, and subsequently the bladder, by bacteria that originate from the lower gastrointestinal tract or vagina may lead to classic symptoms of infective cystitis such as dysuria, frequency, urgency and suprapubic pain. Around 40% of all adult women will experience a UTI in their lifetime, with peak incidences occurring in the third and ninth decades. Annually, 3% of all adult women will be diagnosed with a UTI and almost half of these women will experience a second episode within 1 year. 2,3 With > 300,000 women per year in the UK requiring treatment for recurrent urinary tract infection (rUTI), this represents a significant health problem. 4 Standard preventative treatment of rUTI usually consists of daily low-dose antibiotic therapy, and a previously published meta-analysis from the Cochrane collaboration5 described a reduction in UTI episodes of > 80%. The relationship between antibiotic prescription and the development of antimicrobial resistance is well described, with documented resistance not only confined to the causative micro-organisms but also observed in commensal flora. 6 The judicious prescribing of antibiotic agents, termed ‘antibiotic stewardship’, is an essential component of national and international strategies to halt the progression of global antimicrobial resistance. 7,8 Current cross-specialty guidelines9 have identified that ‘repeated/prolonged treatment with antibiotics’ is a significant contributing factor to this progression. Consequently, interest has focused on non-antibiotic treatments for the prevention of rUTI, which have the potential to improve public health by minimising the development of antimicrobial resistance in bowel reservoirs.

Summary with implications for trial design

The current body of evidence and the contribution of this study

National and international guidelines on the topic of rUTI prevention currently recommend the use of daily low-dose prophylactic antibiotics as the standard of care. 9–12 Level 1a evidence exists to support their use and this is derived from a Cochrane systematic review. 5 That review included data from 19 studies comprising > 1100 women, and described an 85% reduction in symptomatic urinary infections compared with placebo [risk ratio (RR) 0.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.08 to 0.28]. 5 The authors concluded that continuous antibiotic prophylaxis for a 6- to 12-month period was an effective treatment for rUTI. Despite the documented efficacy of daily prophylactic antibiotics, adverse events (AEs) including vaginal and oral candidiasis and gastrointestinal symptoms were more common in the antibiotic-treated groups. In addition, the benefit of daily prophylactic antibiotics did not appear to be sustained following the cessation of this treatment. Data from two studies in the meta-analysis revealed that infection rates returned to pre-treatment levels in the majority of participants. 5

One of the most promising non-antibiotic treatments for the prevention of rUTI is methenamine hippurate. 13 A meta-analysis from the Cochrane group14 included 13 trials with data from > 2000 patients. A 76% reduction in the incidence of UTIs was described (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.89) and is comparable to the data described above for daily prophylactic antibiotics. The quality of the included studies in this meta-analysis was mixed, and there was significant underlying heterogeneity in many of the trials. Despite this, the authors concluded that methenamine hippurate may be an effective preventative treatment for those suffering with rUTI, particularly those patients without underlying renal tract abnormalities. A research recommendation was made for large, well-conducted clinical trials involving this promising treatment, particularly in the prevention of recurrent infection.

According to currently available evidence, daily low-dose prophylactic antibiotics appear to be the most effective intervention for rUTI prevention,5 but a number of well-conducted randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have described the emergence of antimicrobial resistance as an unwanted side effect of this treatment compared with placebo. 5,15,16 The pattern of resistance was not only confined to the prescribed antibiotic but often extended to a range of other agents commonly used to treat symptomatic urinary infections, and some trials have described the emergence of antimicrobial resistance after only a few weeks of prophylactic antibiotic treatment. 2,15,16 The detection of multidrug-resistant bacteria has also been shown to increase significantly following prolonged antibiotic treatment, and in one study this increased from 25% to 80% after such treatment. 6

The obvious theoretical advantages of non-antibiotic preventative treatments for rUTIs are underlined by UK, European and US guideline documents, which describe ‘reducing collateral damage’ of antibiotic use by minimising the risk of resistance development. 7,10,17,18 Current UK health policy advises antibiotic avoidance when possible to reduce the rate of antimicrobial resistance nationally and globally. 17 The wider public health issue of health-care-associated infections (HAIs) with organisms such as meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and, more recently, other types of multiresistant organisms [including those producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs)] is also believed to be, in part, due to antibiotic overprescribing. This is undoubtedly a global issue and must be tackled by international collaborative effort. A recent report19 concerning uropathogenic Escherichia coli speculated that the overuse of non-prescription antibiotics in Asia was a potential causative factor in the development of a new mechanism of ESBL antibiotic resistance detected in the UK. Limiting the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is a key measure in addressing this problem and has been the driver for recent UK guideline updates. 9 The development of antimicrobial stewardship programmes that encourage prudent antibiotic prescribing has already been shown to reduce antibiotic use and, consequently, the incidence of HAIs, which until recently had been increasing. 20,21 The avoidance of antibiotic administration, when possible, is believed to be the single most important factor in the observed decline in HAIs in Scotland. 21

Why this research is needed now

A recent meta-analysis22 reviewed the evidence for non-antibiotic treatments as prophylaxis against rUTI but the results were disappointing, mainly owing to a paucity of evidence. One of the conclusions of this report was that ‘Although sometimes statistically significant, pooled findings for the other (non-antibiotic) interventions should be considered tentative until corroborated by more research’. It would appear that one of the barriers to clinicians recommending non-antibiotic alternatives for the treatment of rUTI is the lack of currently available clinical evidence for these. The campaign for antibiotic stewardship and more prudent prescribing of antibiotic agents can be strengthened only by further work exploring the effectiveness of non-antibiotic alternatives. A further conclusion from this meta-analysis22 was that ‘Large head-to-head trials should be performed to optimally inform clinical decision making’.

One of the most comprehensive guidelines published on the subject of UTI is the 2012 Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) Guideline 88. 9 The literature review carried out prior to the formulation of this document identified much evidence of variations both in practice and when antibiotic treatment is started for UTI. 9 In addition, one of the constant themes in this report is the need to avoid prescribing antibiotics unnecessarily, which is associated with adverse events such as CDI, MRSA and antibiotic-resistant UTIs. 9 The UK antimicrobial resistance strategy and action plan states ‘the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistant micro-organisms is causing international concern’, and identifies that ‘the emergence of resistance represents adaptive selection by micro-organisms which is an inevitable result of therapeutic use of antimicrobial agents’7 (quotations contain public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). This document reflects an urgent need for prudent antibiotic use as one of three key elements of the strategy to control antibiotic resistance. The ALTAR (ALternatives To prophylactic Antibiotics for the treatment of Recurrent urinary tract infection in women) trial aimed to provide high-level contemporary evidence of the relative effectiveness of a non-antibiotic UTI prevention treatment compared with the standard treatment of prolonged low-dose antibiotics in a UK population of women with rUTI in a routine NHS care setting.

Design/methods

The ALTAR trial tests the null hypothesis that the non-antibiotic treatment methenamine hippurate (Hiprex®; Mylan NV, Canonsburg, PA, USA) is inferior to the standard treatment of an extended course of prophylactic antibiotic for the prevention of rUTI in women, and is less cost-effective to the NHS. The alternative hypothesis is that methenamine hippurate is as good at preventing rUTI and is as cost-effective as antibiotic prophylaxis. We have chosen to investigate the possible non-inferiority of methenamine hippurate in order to clarify an alternative treatment choice to antibiotics in treating rUTIs, which, if used more routinely, may prevent increases in antibiotic-resistant strains of infection.

Estimates of prevalence, effectiveness and harms from Cochrane reviews5,14 have informed the power calculation conservatively based on what we, guided by a patient panel, considered to be a minimum threshold difference that would drive patient and clinician acceptability together with change of practice prompted by the inclusion of trial results in future meta-analyses and guidance for management of rUTI in the NHS and internationally.

Aims and objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective is to:

-

Determine the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness for the NHS of two types of licensed preventative treatments for women with recurrent uncomplicated UTI over a 12-month treatment period. Uncomplicated UTI refers to UTIs occurring in patients with no structural or functional urinary tract abnormalities that could contribute to their infective episodes.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives are to determine:

-

the relative impact on the incidence of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI self-reported by patients during the 6-month follow-up period after completion of 12 months of allocated treatment

-

the total number of days spent taking urinary-specific antibiotics (prophylactic or treatment) during the 12-month treatment period and 6 months of follow-up

-

if there is any longitudinal ecological change in terms of phenotype and genotype of bacteria and their resistance patterns in isolates from individual participants’ (1) urine and (2) faecal reservoir during the 12-month treatment period and in the 6 months following completion of treatment

-

the number of microbiologically proven UTIs during the 12-month treatment and 6-month follow-up periods

-

the incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria during the study period

-

the incidence rate of hospitalisation due to UTIs during the study period

-

overall patients satisfaction with antibiotic compared with antiseptic treatment

-

patients’ and clinicians’ views regarding trial processes and participation using an embedded qualitative study

-

the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained at the 18-month time point based on responses to the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)

-

the incremental costs to the NHS and Personal Social Services measured at the end of the 18-month study period

-

the relative health economic efficiency over the patient’s lifetime using a modelling exercise.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Forbes et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter covers general trial methods, statistical analysis and governance; details of methods and findings of the qualitative and health economic analyses are provided in Chapters 3 and 5, respectively.

Summary of study design

The ALTAR trial is a multicentre, pragmatic, open-label randomised non-inferiority trial evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the urinary antiseptic methenamine hippurate, a non-antibiotic treatment for the prevention of rUTI, and comparing it with the current standard treatment of low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis. Outside the trial medication, both arms received usual care and any breakthrough UTIs were treated by discrete courses of antibiotic treatment, as required.

Sites

From June 2016 to June 2017, we established eight research sites comprising NHS organisations across England and Scotland (Table 1). All sites were large, secondary care urology or urogynaecology centres known to have a consistent clinical assessment pathway for women with rUTI. We initially opened six sites: Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust (Wakefield), Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (now known as Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust). In addition, a further two sites, Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust (now known as Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) and Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust (Oldham), were opened to support recruitment to the trial.

| Site | Number of participants randomised |

|---|---|

| Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 84 |

| Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 43 |

| Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (formerly known as Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) | 20 |

| NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde | 24 |

| Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust | 22 |

| Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust | 31 |

| Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (formerly known as Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust) | 8 |

| Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust | 8 |

| Total | 240 |

Trial management

The central trial office was established at the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne. NCTU was responsible for obtaining approvals, trial registration, trial management, provision of the randomisation service, database construction and database management. The trial statistics, health economic evaluation and qualitative research teams were also based at Newcastle University.

Participants

The target population for the ALTAR trial was women (aged ≥ 18 years) with rUTI, for whom, after discussion with their responsible clinician, prophylactic antibiotics were considered as a therapeutic option. The definition of rUTI used was at least three episodes of symptomatic antibiotic-treated urinary infection in the previous 12 months, two episodes of UTI in the last 6 months or a single occurrence of severe UTI requiring hospital admission in the preceding year.

Patients were approached and introduced to the trial by clinical staff at sites during routine clinic visits. If interested, patient eligibility was assessed in accordance with the following eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Women aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Women with rUTI who, in consultation with a clinician, had decided that prophylaxis was an appropriate option (to include women who had suffered at least three episodes of symptomatic UTI within the preceding 12 months or two episodes in the last 6 months or a single severe infection requiring hospitalisation).

-

Women able to take a once-daily oral dose of at least one of nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim or cefalexin.

-

Women able to take methenamine hippurate.

-

Women who agreed to take part in the trial but were already taking methenamine hippurate or antibiotic prophylaxis. These participants were consented for participation and had their preventative therapy stopped for a 3-month washout period. The women were reassessed, and if they were still eligible to take part, then they underwent the baseline assessment and randomisation.

-

Women able to give informed consent for participation in the trial.

-

Women able and willing to adhere to an 18-month trial protocol.

Exclusion criteria

-

Women unable to take methenamine hippurate, for example because they had a known allergy to methenamine hippurate, severe hepatic impairment (Child–Pugh class C, score of ≥ 10 see Appendix 1, Table 26), gout, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of < 10 ml/minute/1.73 m2 and Proteus spp. as consistent proven causative organism for rUTIs.

-

Women who were unable to take any of the trial antibiotics.

-

Women with correctable urinary tract abnormalities that were considered to be contributory to the occurrence of rUTI.

-

Presence of symptomatic UTI; this was treated and symptoms resolved prior to randomisation.

-

Pregnancy or intended pregnancy in the next 12 months.

-

Women who were breastfeeding.

-

Women already taking methenamine hippurate or antibiotic prophylaxis and who declined a 3-month washout period.

Consent procedures

The trial was conducted according to the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. 23 Participants provided informed consent for randomisation, trial participation, telephone interviews and the storage of blood, urine and swabs for future research, and about whether or not they agreed to be contacted about similar research studies. The obtaining of informed consent was undertaken by appropriately trained and delegated staff at each trial site. The consent process involved providing participants with balanced, written information about the need for and overall benefit of the trial, followed by a discussion with a local trial co-ordinator. In relation to the qualitative interviews, the recruiting staff explained why it was important to understand why people do and do not participate, and how an interview study can help to improve the way that trials are conducted. Participants who were willing to be approached were provided with a separate information sheet with details about the study interview. Following receipt of the trial information, participants were given at least 24 hours to decide whether or not they wanted to participate. Written informed consent was obtained prior to randomisation by participants signing and dating the trial consent form. Women who agreed to take part in the trial but who were already taking methenamine hippurate or antibiotic prophylaxis were consented for participation and advised to stop their preventative therapy for a 3-month washout period, but they were not randomised or asked to complete the other baseline measures until the 3-month washout period was complete. Their continued consent and eligibility were reassessed post washout and, if eligible, they were then accepted into the trial.

Randomisation

Participant allocation

Randomisation was administered centrally by the NCTU secure web-based system. Permuted random blocks of variable length (two, four, six or eight) were used to allocate participants on a 1 : 1 basis to the antibiotic prophylaxis and methenamine hippurate arms. An individual not otherwise involved with the trial produced the final randomisation schedule. Stratification by two variables, namely prior frequency of UTI (fewer than four episodes per year, or four or more episodes per year) and menopausal status of participants (pre menopausal or menopausal/post menopausal), was performed prior to randomisation to ensure balanced allocation with regard to these factors. Following randomisation, an appointment was arranged, facilitated by trial staff, with the prescribing clinician to commence allocated treatment and ensure continued supply for the 12-month treatment period, usually through hospital prescription or through the participant’s general practitioner (GP). The antibiotic selected for use as prophylaxis was chosen by both the participant and the clinician while taking into account the individual participant’s characteristics, their previous urine culture results, local guidance and standardised trial information, with preferred agents being, first, nitrofurantoin, second, trimethoprim and, third, cefalexin.

Blinding

This was a pragmatic, open-label trial; therefore, participants, clinicians, local research staff and NCTU staff were not masked to treatment allocation. Central laboratory staff assessing microbiological outcomes were unaware of treatment assignment. Where possible, the clinical research staff conducting the within-trial assessments were blinded to treatment allocation. The trial statistician who performed the final analysis was responsible for preparing unblinded reports to the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and had access to unblinded primary outcome data prior to the final database lock. The senior statistician was responsible for approving the statistical analysis plan (SAP) and remained blind to treatment allocation until after the final database lock. Primary outcome assignment was assessed by the trial statistician following the methods defined in the SAP [see the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Journals Library project web page – URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/138821/#/], with a 10% sample of cases independently assessed by a clinician who was not otherwise involved in the trial.

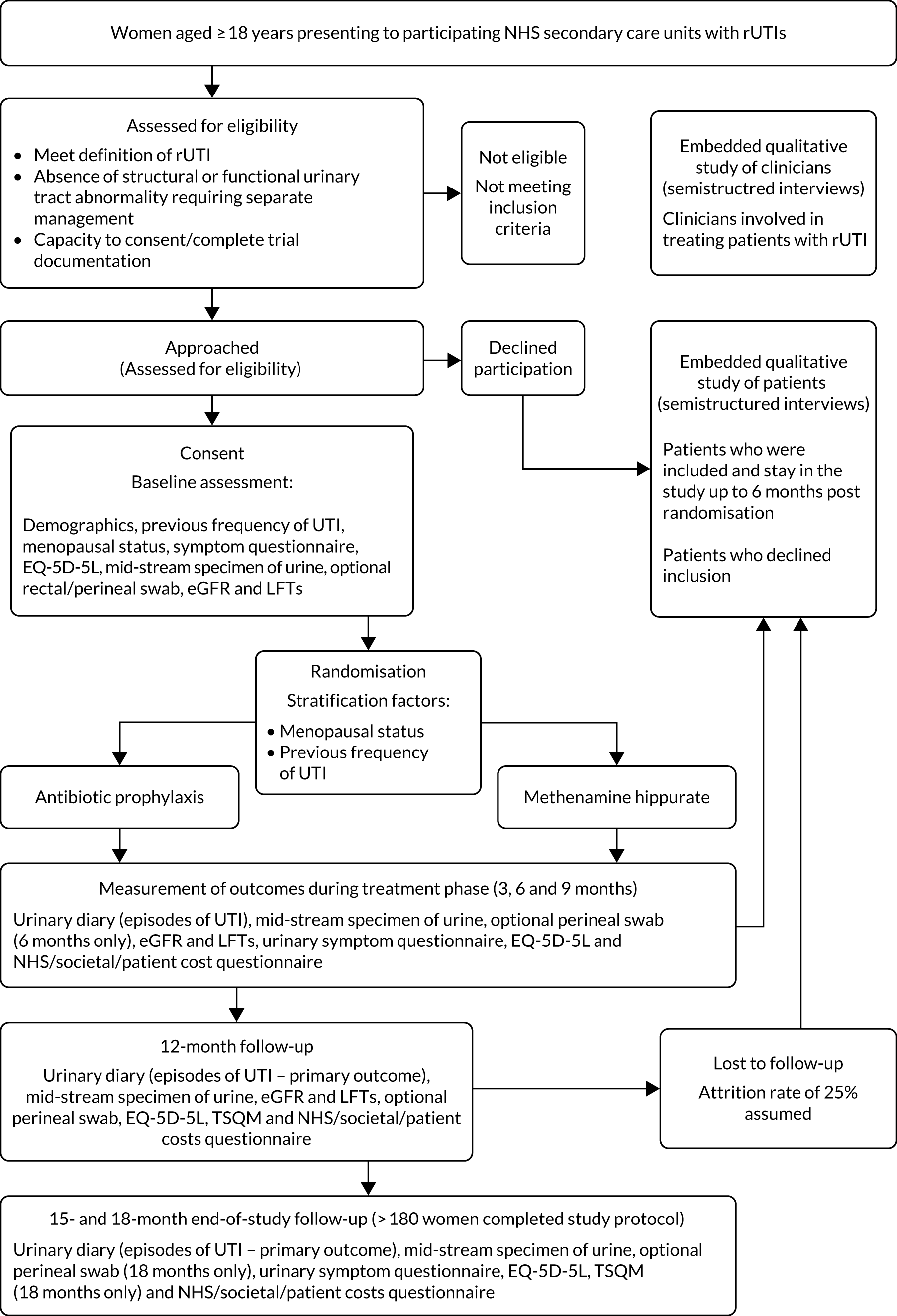

Progress on trial

The trial duration for each participant was 18 months. The patient flow through the trial is shown in Figure 1; for the schedule of events for trial participants, see Table 3.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow. LFT, liver function test; TSQM, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication.

Participant expenses

Participants were reimbursed reasonable travel expenses incurred as a result of taking part in the ALTAR trial. NHS prescription charges for trial medication were reimbursed or managed via hospital prescription or the participant’s GP. Participants were given a £30 thank-you gift voucher when they reached the 3-month time point.

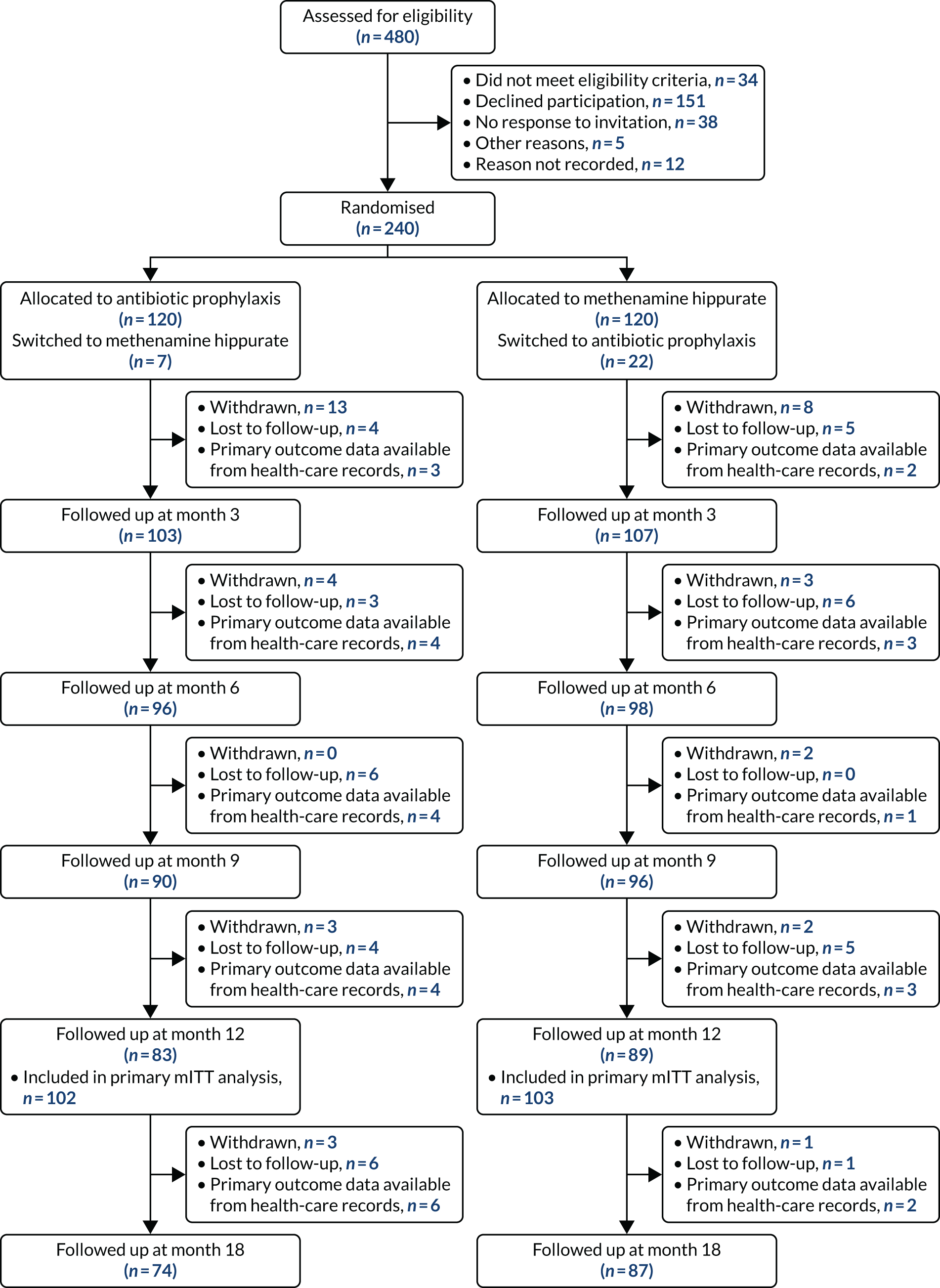

Withdrawal of participants

Participants remained on the trial unless they withdrew their consent, or their participation was deemed inappropriate by trial site staff. Reasons for withdrawal were recorded if agreement was provided by the participant. If a participant chose to withdraw from the trial, their permission was sought to continue to collect primary outcome relevant data through routine health-care records. Participants providing primary outcome data for at least 6 months post randomisation were included in the primary outcome analyses.

Patient and public involvement

The identification and prioritisation of the research topic were directly patient driven. A patient interest group was set up locally at the lead site to help refine the methodology of the trial and, in particular, select an appropriate patient-defined non-inferiority margin. Patient input had previously been central to the development of both the specialist UTI clinic and a standardised protocol in Newcastle for treating recurrent cystitis. Patients highlighted variation in treatment and inequality in the use and availability of non-antibiotic alternatives as drivers for carrying out this research. A significant number of patients expressed a desire not to use antibiotics and asked specifically for alternatives. The alternative treatment (methenamine hippurate) was selected on the basis of this feedback and the existence of level 1 evidence to support its use. This patient group specifically helped to define the strict non-inferiority margin of one single UTI in a year chosen for this trial, which was used in the sample size calculation. This was a stark indication of the morbidity associated with rUTIs from the patients’ perspective. The patient information sheets (PISs) and documentation pro formas were finalised with feedback from patients attending the UTI clinic at the lead site (Newcastle). We also obtained feedback from patient representatives from the Cystitis and Overactive Bladder (COB) Foundation. The COB Foundation previously advised the team on issues relating to the reporting of research, and assisted with the dissemination of research in the national press and in its own publication A Wee Ray of Hope. A member of this patient interest group was invited to join the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Following the conclusion of the trial, our links with patient groups, such as the COB Foundation and Bladder Health UK, will be utilised to ensure widespread dissemination of results.

Details of trial medication

Planned interventions

Both prophylactic antibiotics and methenamine hippurate are licensed and approved for routine NHS use; this was detailed clearly in the trial’s PIS.

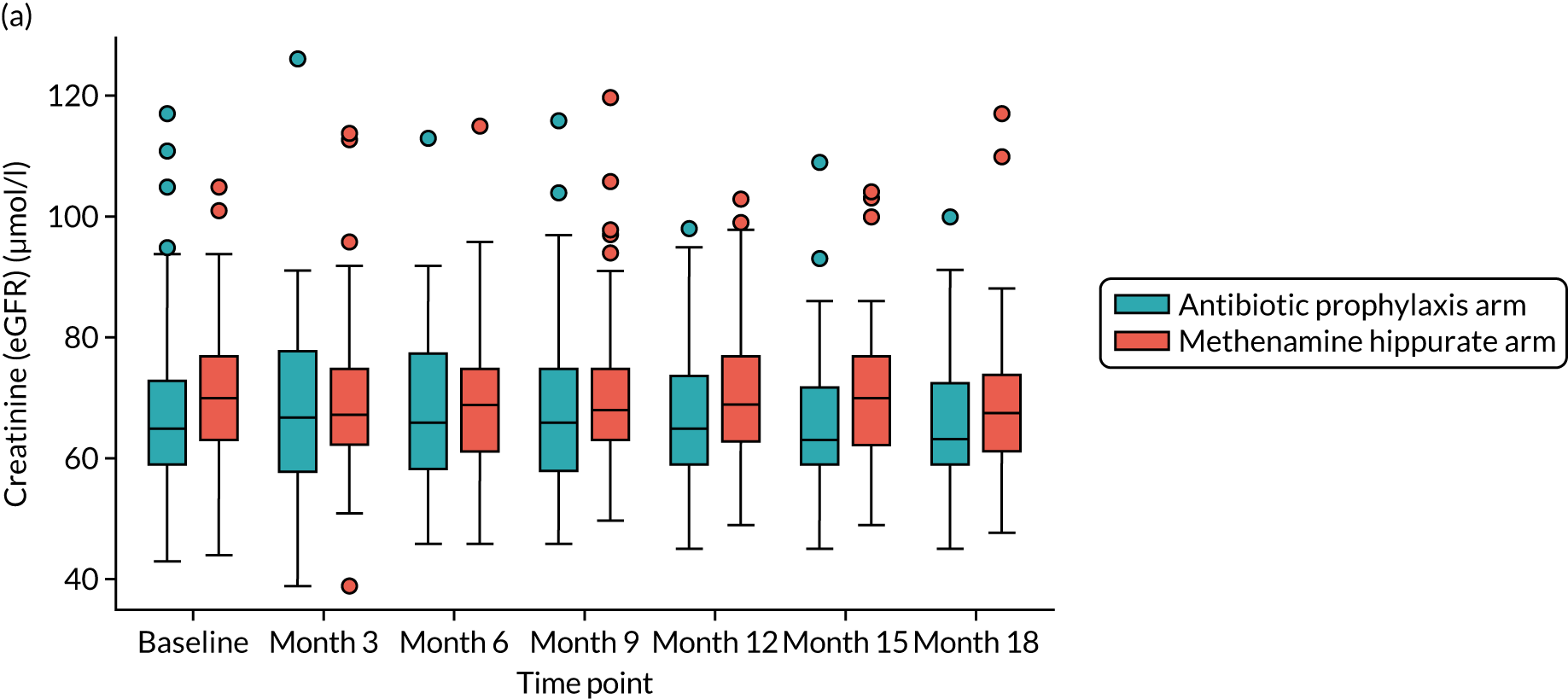

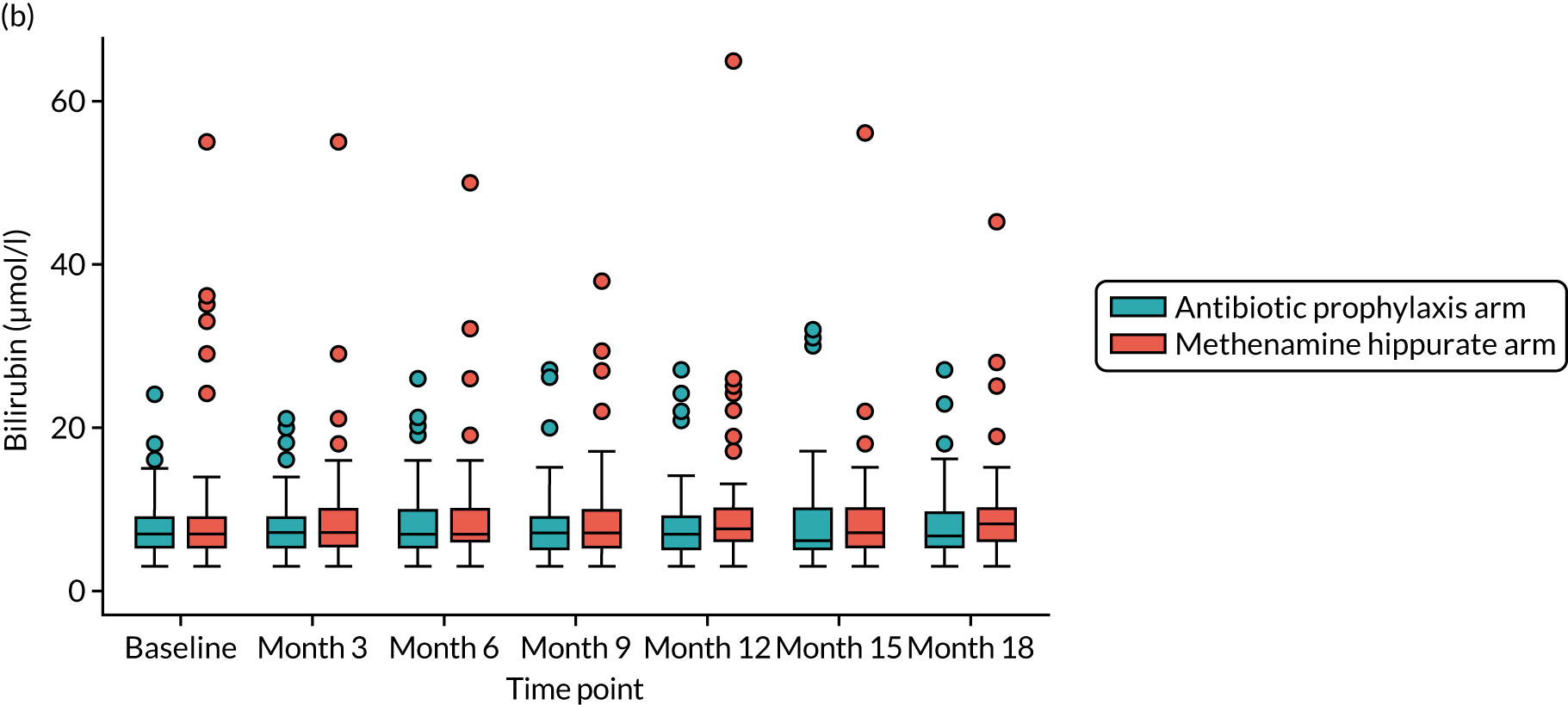

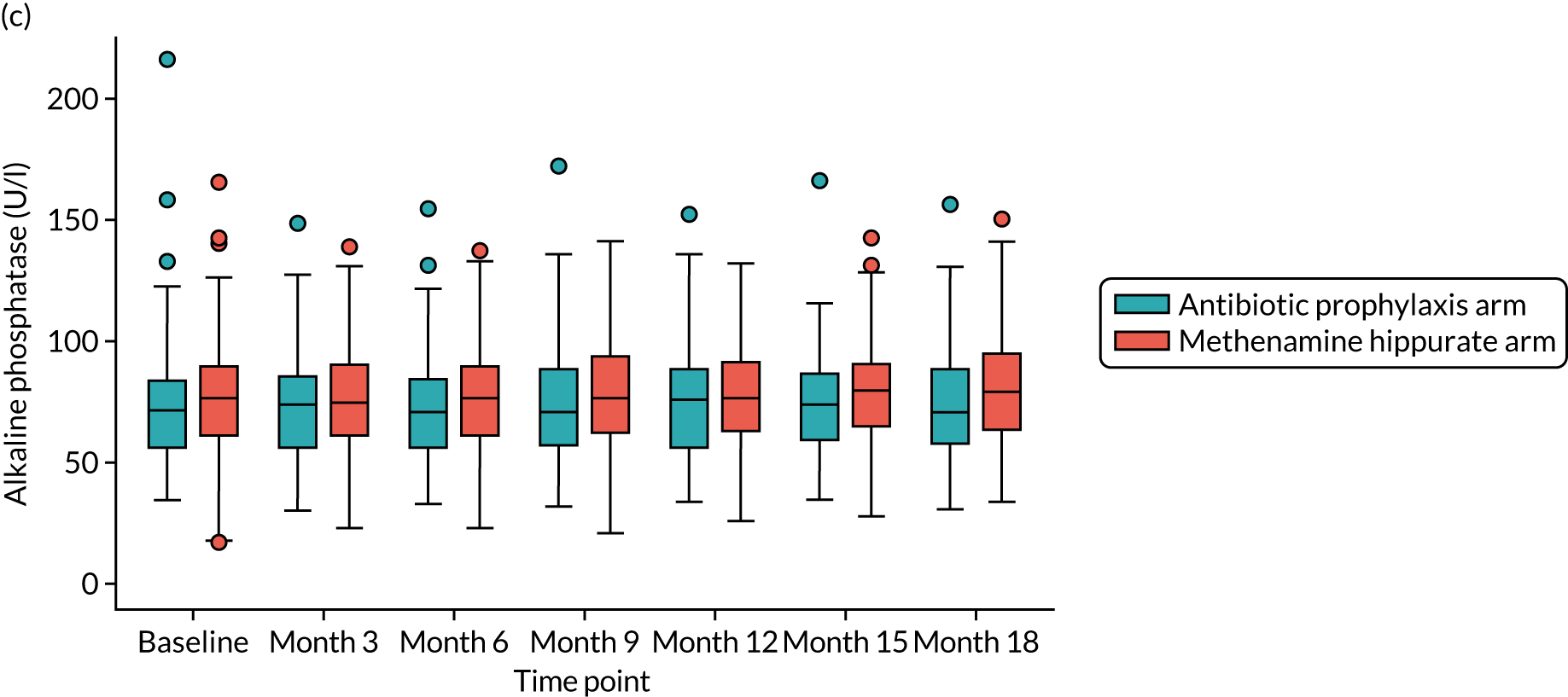

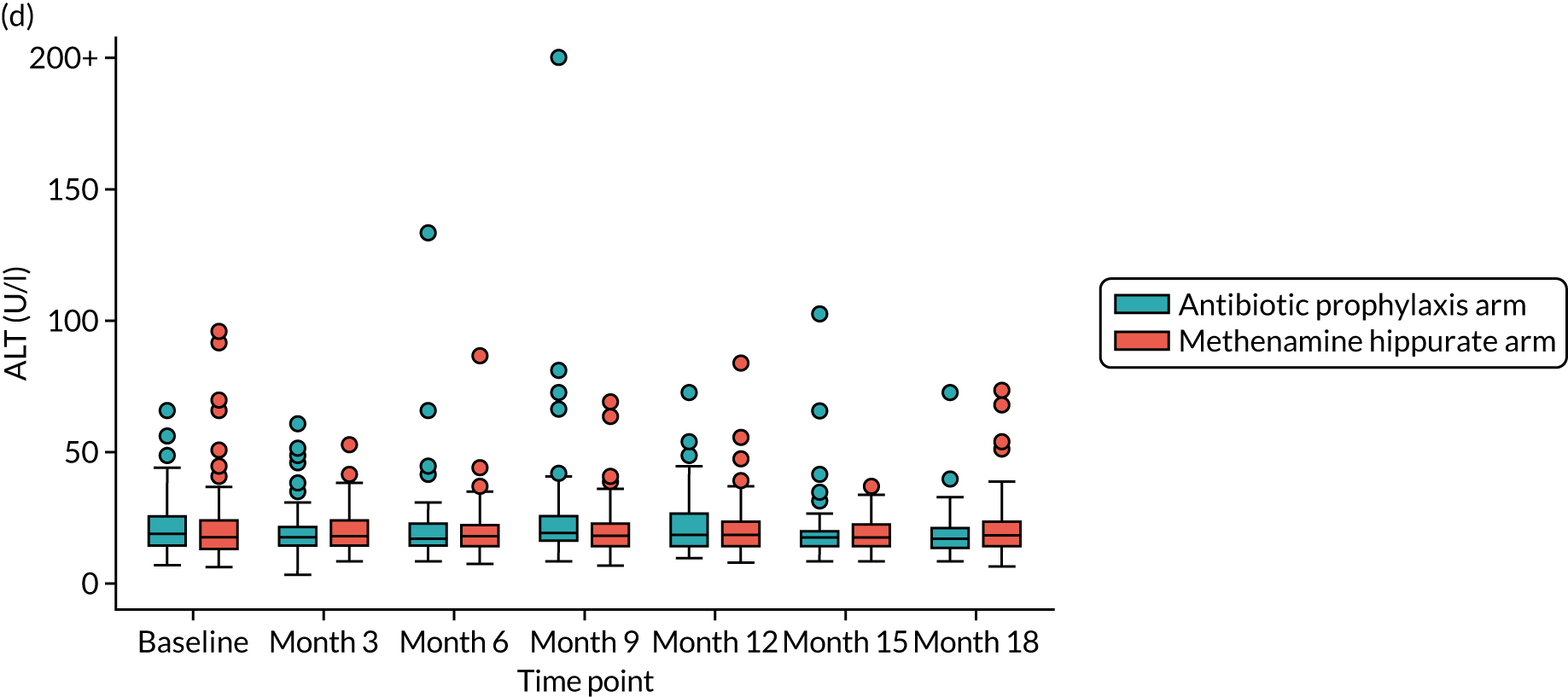

Antibiotic prophylaxis

For those women randomised to receive antibiotics, a once-daily prophylactic low dose was prescribed for 12 months. The agent used was selected by the responsible clinician, with input from the participant, based on patient characteristics such as previous use, allergy, renal function, liver function, prior urine cultures and local guidance. Available evidence suggested the use of 50 mg or 100 mg of nitrofurantoin, 100 mg of trimethoprim or 250 mg of cefalexin, in that order of preference. Renal function was determined by eGFR at baseline, and if this was < 45 ml/minute/1.73 m2 then nitrofurantoin was not used. Participants randomised to receive antibiotic prophylaxis had blood samples taken at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 months to monitor kidney and liver function [eGFR and liver function test (LFT): creatinine, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels]. If there were any abnormalities in these tests during the period of treatment, appropriate action was taken by the responsible clinician. If clinically indicated, the blood tests were taken more frequently. Participants were asked to take once-daily antibiotic prophylaxis as a single dose at bedtime. If there were specific and intolerable adverse effects (e.g. nausea with nitrofurantoin or candidiasis with cefalexin), switching to an alternative antibiotic agent was advised in consultation with the relevant clinician and the reasons for the change were recorded. The aim was to maintain participants on antibiotic prophylaxis using any one of the three agents for as long as possible during the 12-month treatment period within tolerance and safety constraints. Participants intolerant of prophylactic antibiotic despite trying alternative agents had the opportunity to discontinue the medication and were offered an alternative treatment, which may have been a switch to methenamine hippurate. This information was recorded and the participant continued in the trial. If a participant in the antibiotic prophylaxis arm developed symptoms and signs suggestive of breakthrough UTI, they were advised to seek treatment in their usual way mostly by contacting their GP and starting a discrete treatment course of antibiotics. In this scenario, participants were instructed to stop the prophylactic antibiotic while they were taking a treatment course and restart it the day following the last dose of the antibiotic treatment course. Clinicians and participants were advised to use a different agent for treatment from the one taken for prophylaxis. Details of all antibiotic treatment courses were recorded, including the agent used and the number of days participants took the prescribed antibiotic.

Methenamine hippurate

For those women randomised to receive methenamine hippurate, a twice-daily dose of 1 g to be taken 12 hours apart was prescribed for 12 months [as recommended in the British National Formulary (BNF)]. 24 Participants randomised to receive methenamine hippurate had blood samples taken at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 months to monitor kidney and liver function (eGFR and LFT: creatinine, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and ALT). If there were any abnormalities in these tests during the period of treatment, appropriate action was taken by the responsible clinician. If clinically indicated, blood tests were taken more frequently. If there were specific and intolerable side effects, such as nausea, gastrointestinal disturbance, itching or skin rashes, participants were given the opportunity to discontinue treatment and were offered the alternative treatment of prophylactic antibiotics. This information was recorded and the participant continued in the trial. If a participant in the methenamine hippurate arm developed symptoms and signs suggestive of breakthrough UTI then they were advised to seek treatment in their usual way, predominantly by contacting their GP and starting a discrete treatment course of antibiotics. They were instructed to continue taking methenamine hippurate during this antibiotic treatment course. Details of all antibiotic treatment courses were recorded, including the agent used and the number of days participants took the prescribed antibiotic.

Standard care for both arms

The ALTAR trial was pragmatic in design and, apart from random allocation of treatment option and participant completion of questionnaires, participant care followed standard pathways in participating secondary care NHS sites. During the trial, participants had access as desired to the use of other measures to reduce the risk of UTI, such as adequate fluid intake, avoidance of constipation and, for postmenopausal women, vaginally administered oestrogen supplements. Participants were also informed of the possible benefit of other alternative options, including cranberry extract. Participants in both trial arms received on-demand discrete courses of antibiotics for symptomatic UTI, as decided by the responsible clinician. The use of all adjunctive treatments was recorded on the relevant case report forms (CRFs).

Delivery of interventions

Local NHS clinicians at the site of randomisation were responsible for initiating and maintaining the delivery of trial medication.

Funding of trial interventions

The interventions were funded by standard NHS contracting mechanisms, having been sanctioned by local commissioning groups through local trial approval mechanisms. The NHS excess treatment costs were approved by the sponsor and, for primary care, the local Clinical Commissioning Group. Any prescription charges incurred by participants for trial drugs were reimbursed from research costs. The trial interventions were of low cost.

Outcome measurement

Outcomes were collected for each participant over the 12-month treatment period following randomisation and during a follow-up period of 6 months after completion of the planned course of preventative treatment (resulting in a total observation period of 18 months for each participant).

Primary clinical outcome measures

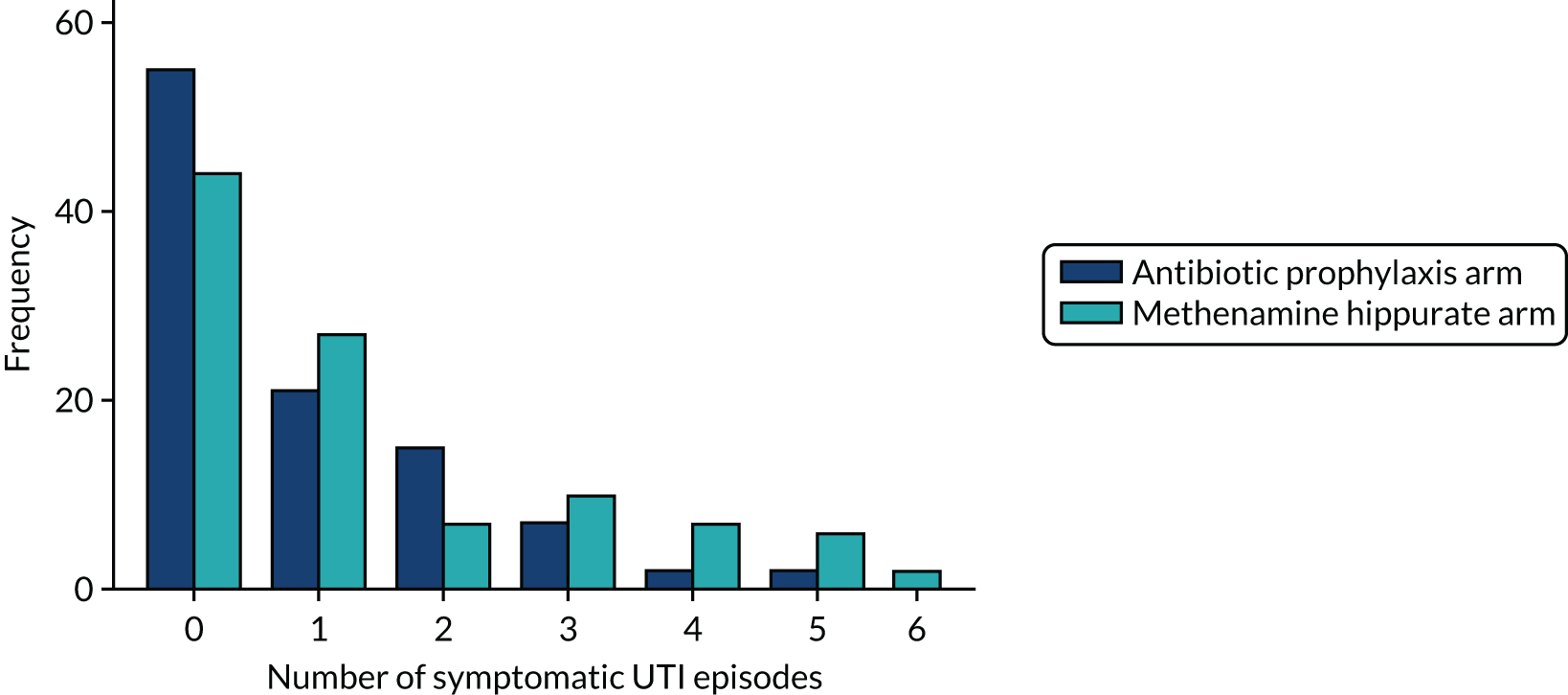

The primary clinical outcome for the trial was incidence of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI self-reported by participants over the 12-month treatment period.

An episode of UTI was defined as the presence of at least one patient-reported or clinician-recorded symptom from a predefined list encompassing the recommendations of the British Infection Association, together with taking a discrete treatment course of antibiotic for UTI prescribed by a clinician or as part of patient-initiated self-start treatment. 25 Symptom diary format conformed to the recommendations of the British Infection Association. 25 The symptoms recorded were fever, shivers, cloudy urine, smelly urine, visible blood in urine, urinary leakage, lower abdominal pain, feeling generally unwell, frequent passing of urine and pain when passing urine. The end of a single episode of UTI was defined as 14 days after the end of the final treatment course of antibiotics. If a further course of antibiotics was prescribed or symptoms restarted before the end of the 14 days this was counted as the same UTI episode.

The primary outcome was determined by the collection of data from multiple sources. At the time of the UTI, participants were asked to record symptoms and antibiotic treatment courses taken on a UTI record form, which was posted to the central trial office for data entry. Participants were also asked to notify local research staff of the occurrence of a UTI using a telephone number with answerphone. Symptoms and antibiotic treatment courses were then recorded on a phone-reported UTI CRF by site staff. Participants were also asked about the occurrence of symptomatic UTI episodes at the time of each 3-monthly participant review with local research staff. Symptoms and antibiotic treatment courses were recorded on the CRF. In addition, antibiotic treatment courses for UTIs were recorded on the 3-monthly participant-completed questionnaires. The occurrence of symptomatic UTI could also be obtained from health-care records, if required.

To ensure consistent attribution and to avoid multiple counting of any UTI episodes reported across different data sources, a hierarchy of evidence was utilised. First, data from health-care records were used as these data should have been the most accurate. Second were UTI record forms and phone-reported UTI CRFs, as these were completed at the time of the UTI. Finally, data from the 3-monthly participant review and participant-completed questionnaires were used. These were deemed the lowest source of evidence because of their retrospective completion, which may have been subject to recall bias.

Episodes of symptomatic UTI were identified by the trial statistician using statistical programming. A clinician not otherwise involved in the trial independently reviewed completed CRFs for a 10% sample of cases, blind to treatment allocation, and was asked to identify symptomatic UTI episodes following the hierarchy of evidence described above. In all cases the number of UTI episodes were found to match that determined by statistical programming when following the predefined criteria. In the event that discrepancies in the number of symptomatic UTI episodes were identified, a second review of the coding algorithm would have been undertaken and a further sample checked; however, this was not required. In the protocol, it was originally anticipated that a randomly selected 10% sample of positive primary outcome episodes would be reported during the first 6 months of the trial and presented as vignettes to the clinical members of the TSC, without details of allocated group, for them to determine whether or not the primary outcome was fulfilled. However, the DMC subsequently advised, as agreed by the TSC, that this role should be fulfilled by an independent clinician not otherwise involved in the trial and that a 10% sample of all cases should be reviewed, not just those observed in the first 6 months of the trial.

The incidence of symptomatic, antibiotic-treated UTI during the 12-month preventative treatment period is primarily defined simply in each group as:

(1)Total number of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI episodes÷Total observational period(in years).

The ‘observational period’ was calculated for each participant as the time from randomisation to the date of the 12-month participant review. If the 12-month review took place more than 1 year from randomisation, the observational period was capped at 1 year. If the participant did not attend their 12-month visit, the observational period was calculated as the time from randomisation to their last attended monthly visit or the date of the last UTI record form or telephone-reported UTI CRF prior to 12 months, whichever was later. For participants who had withdrawn from the trial but allowed continued use of their health-care data, sites were requested to check health-care records for symptomatic UTI episodes once the participant would have reached the 12-month time point. Where this was done, the participant observation time was 1 year.

Subsequent analysis of the primary outcome was based on the incident density rate over the 12-month treatment period. This removed time taking therapeutic antibiotics for UTI from the observational period and was calculated in each group as:(2)Total number of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI episodes÷Total observational period (in years)–Total time taking therapeutic antibiotics for UTI (in years).

For each participant, the time spent taking therapeutic antibiotics for UTI was calculated from antibiotic treatment courses identified following data processing, using the hierarchy of evidence, for the primary outcome measure. Antibiotic treatment courses for UTIs for which no symptoms were reported were included. Where the end date of a treatment course was missing, a period of 5 days was used as a surrogate.

Secondary outcomes

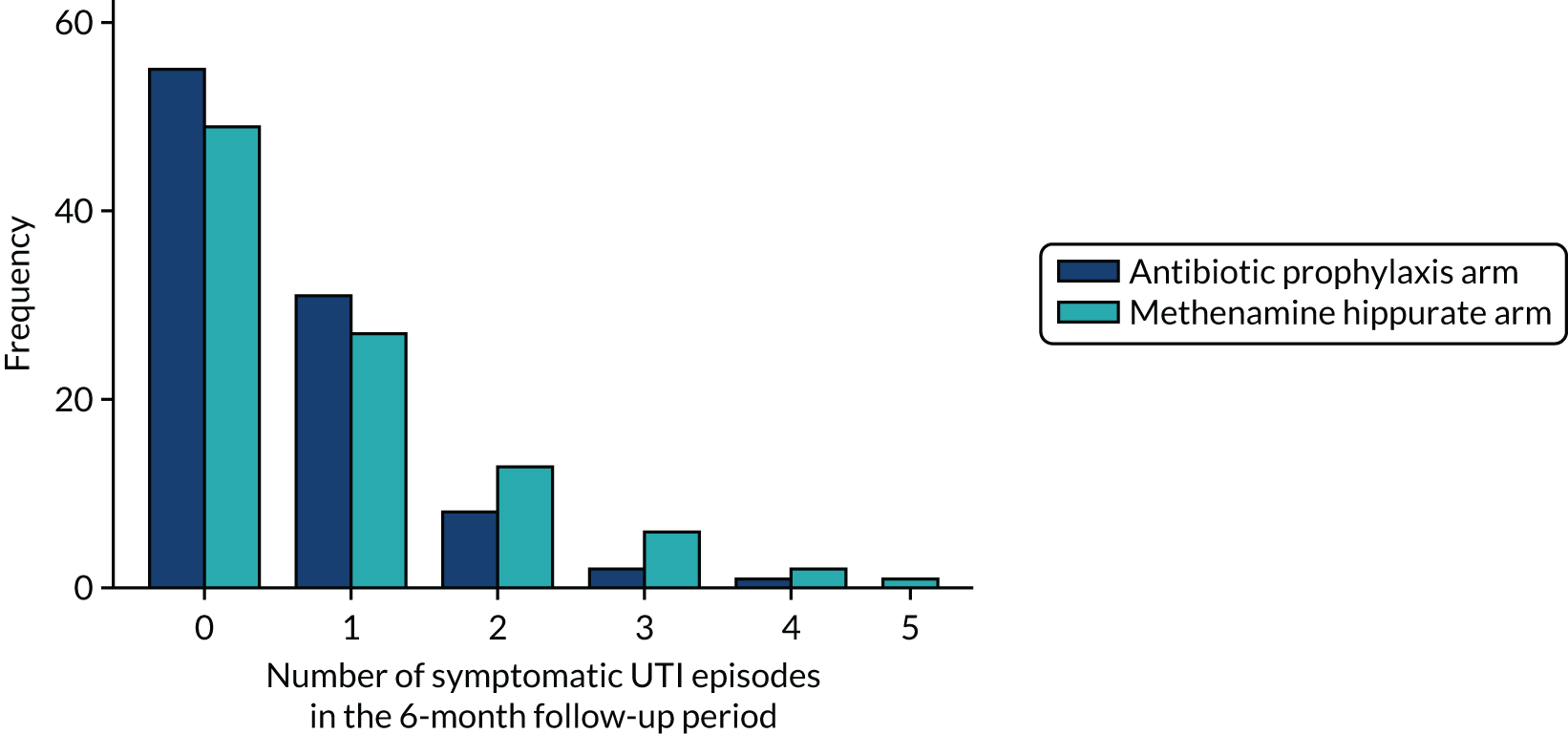

The occurrence of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI in the 6-month follow-up period after stopping the allocated preventative therapy

Episodes of symptomatic UTI occurring between 12 and 18 months post randomisation were defined as for the primary outcome. The observational period was defined as the time (in years) from 1 year post randomisation to the 18-month participant review date. If the 18-month review took place more than 18 months from randomisation, the observational period was capped at 6 months (0.5 years). If the participant did not attend their 18-month visit, the observational period was calculated as the time from 1 year post randomisation to the 15-month visit date or the date of the last UTI record form or phone-reported UTI CRF completed between 12 and 18 months post randomisation, whichever was later. For participants who had withdrawn from the trial but allowed continued use of their health-care data, sites were requested to check health-care records for symptomatic UTI episodes once the participant would have reached the 18-month time point. Where this was done, the participant’s observation time was 6 months (0.5 years).

Antibiotic use

The use of both prophylactic and therapeutic antibiotics was recorded.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

The duration of prophylactic antibiotic use was defined as the number of days for which patients were prescribed antibiotics at a low dose intended for prophylaxis against UTIs. This was measured from the date of first prescription for antibiotic prophylaxis (or the date of randomisation if the first prescription date was unavailable and the participant was randomised to the antibiotic prophylaxis arm) to the patient’s 12-month review, or to the date of stopping treatment, trial withdrawal or switching to the alternative treatment group. For those lost to follow-up during the 12-month treatment period, the last reported treatment compliance assessment date was used. Although for one arm of the trial this was the allocated treatment, measuring this outcome was intended to capture the prophylactic antibiotic use of patients who were initially allocated to the methenamine hippurate arm and needed to change treatment for any reason.

Therapeutic antibiotics

The use of therapeutic antibiotics was defined as the number of days for which patients were prescribed therapeutic (as opposed to prophylactic) doses of antibiotics for breakthrough UTIs during the treatment period of 12 months (following allocation to either the prophylactic antibiotic arm or the methenamine hippurate arm) and, separately, for the 6-month follow-up period (including previous prescription for self-start therapy). Antibiotic treatment courses were those identified following data processing from the primary outcome measure, utilising the hierarchy of evidence to avoid multiple counting of the same treatment course. Antibiotic treatment courses for UTI where there were no associated symptoms reported were included. Where an end date of a treatment course was missing, a period of 5 days was used as a surrogate. The rate of therapeutic antibiotic use was calculated as the total number of days for which therapeutic antibiotics were prescribed divided by the total observational period (in days).

Antibiotics taken for reasons other than UTI were also recorded, given their potential activity against uropathogens. The number of days for which participants were prescribed therapeutic antibiotics for reasons other than UTI was calculated. The rate of therapeutic antibiotic use for reasons other than UTI was calculated as the total number of days for which therapeutic antibiotics were prescribed for reasons other than UTI divided by the total observational period (in days).

Number of microbiologically proven symptomatic antibiotic-treated urinary tract infections

Participants were requested to submit urine samples to the central laboratory in Newcastle when they suspected a UTI, based on symptoms. Symptomatic UTI episodes, identified as per the primary outcome, were considered to be microbiologically proven if a positive urine culture from a urine sample sent to the central laboratory, or, if no sample was received, a positive culture reported by a local laboratory, was available from between 14 days prior to starting antibiotic treatment up to the end of antibiotic treatment. A positive culture was classified according to the current standard Public Health England definitions: the laboratory report of a single isolate at ≥ 104 colony-forming unit (CFU)/ml or two isolates at ≥ 105 CFU/ml. 26

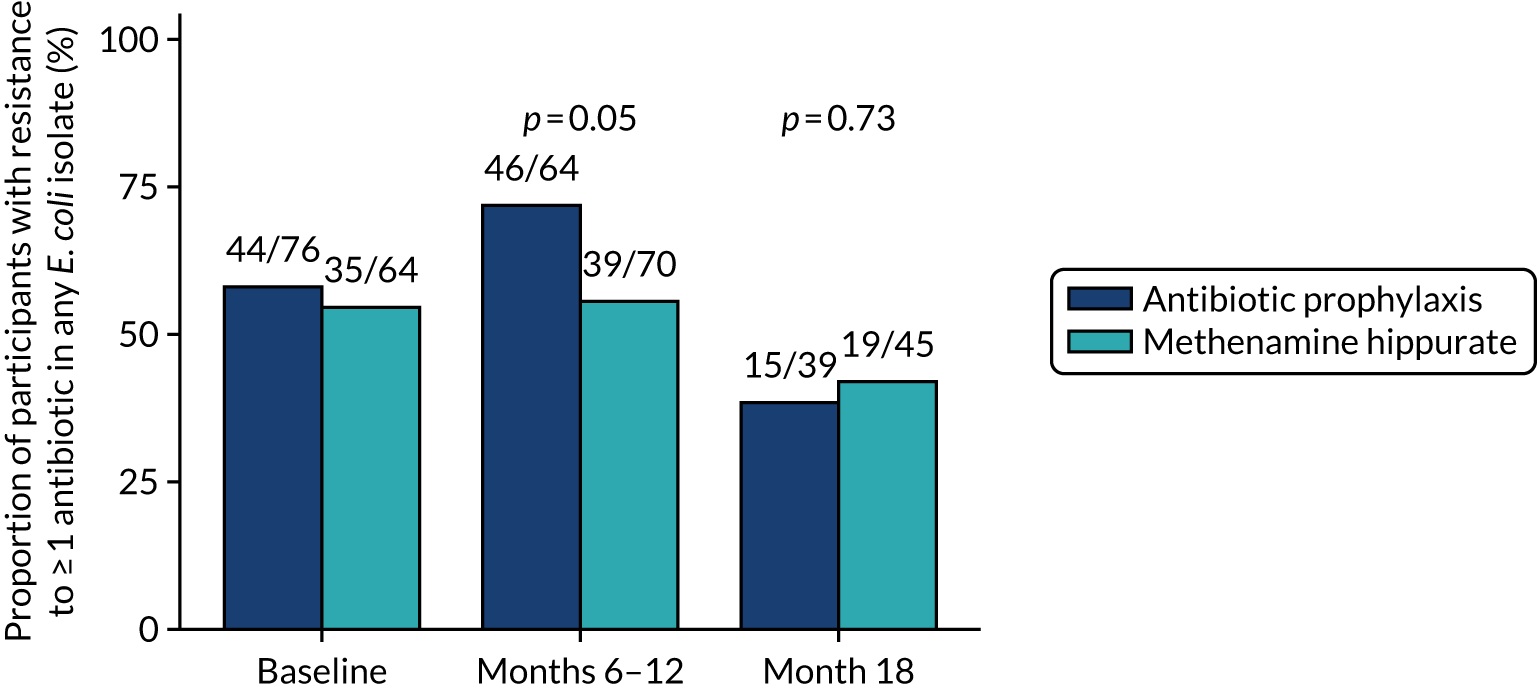

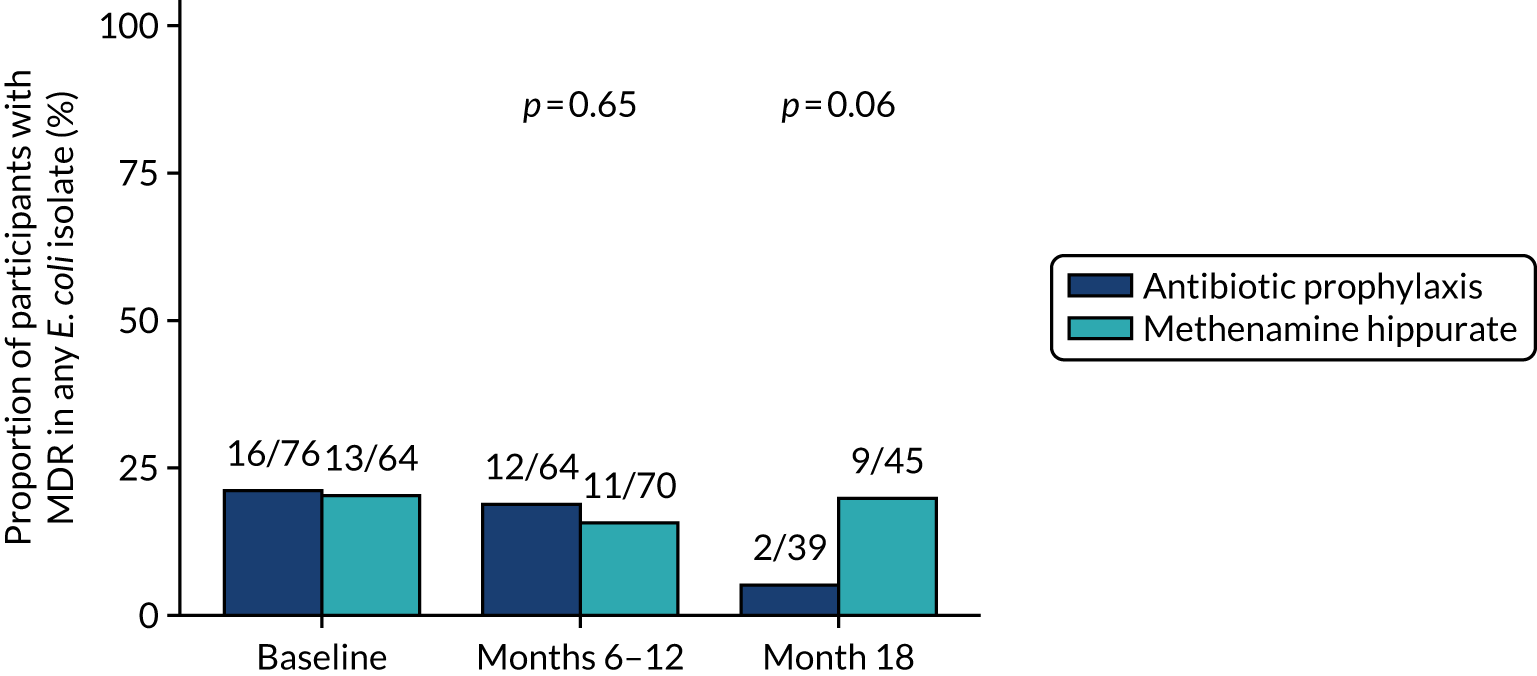

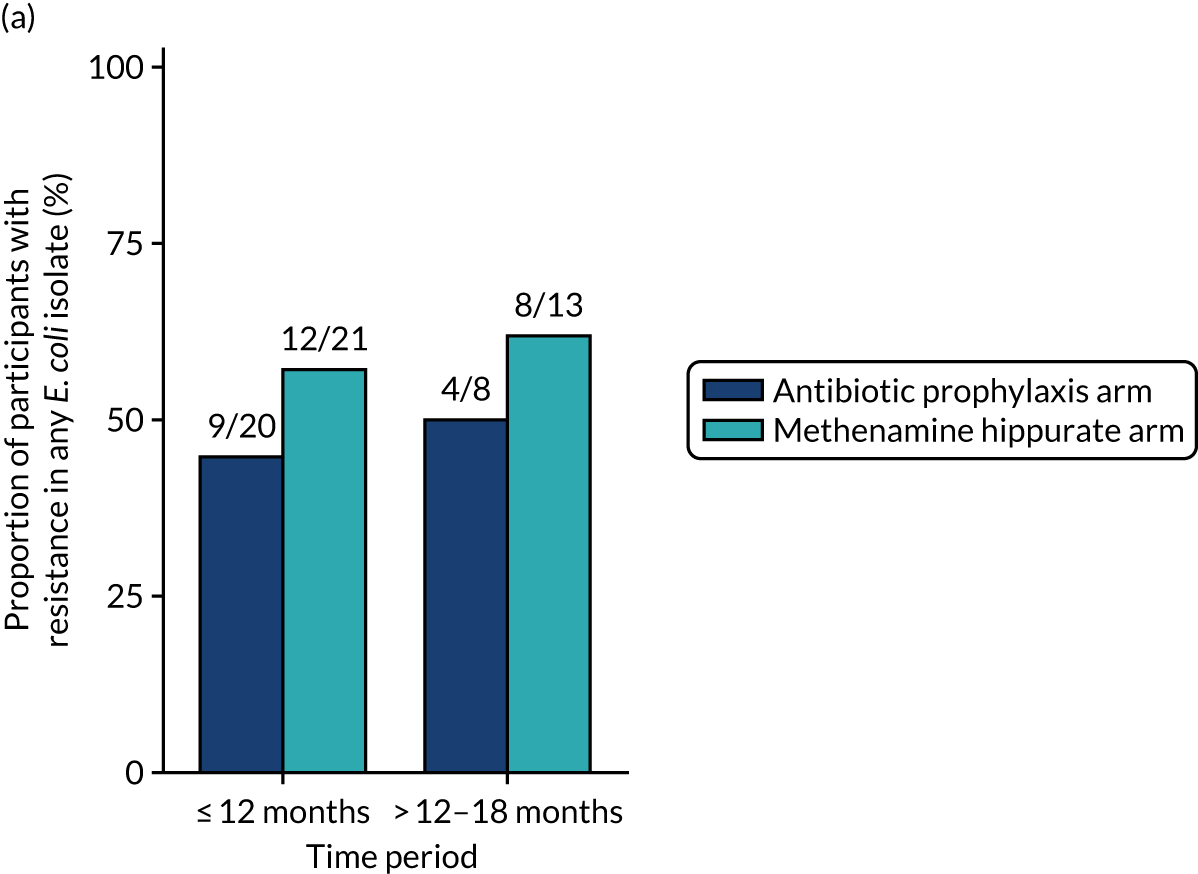

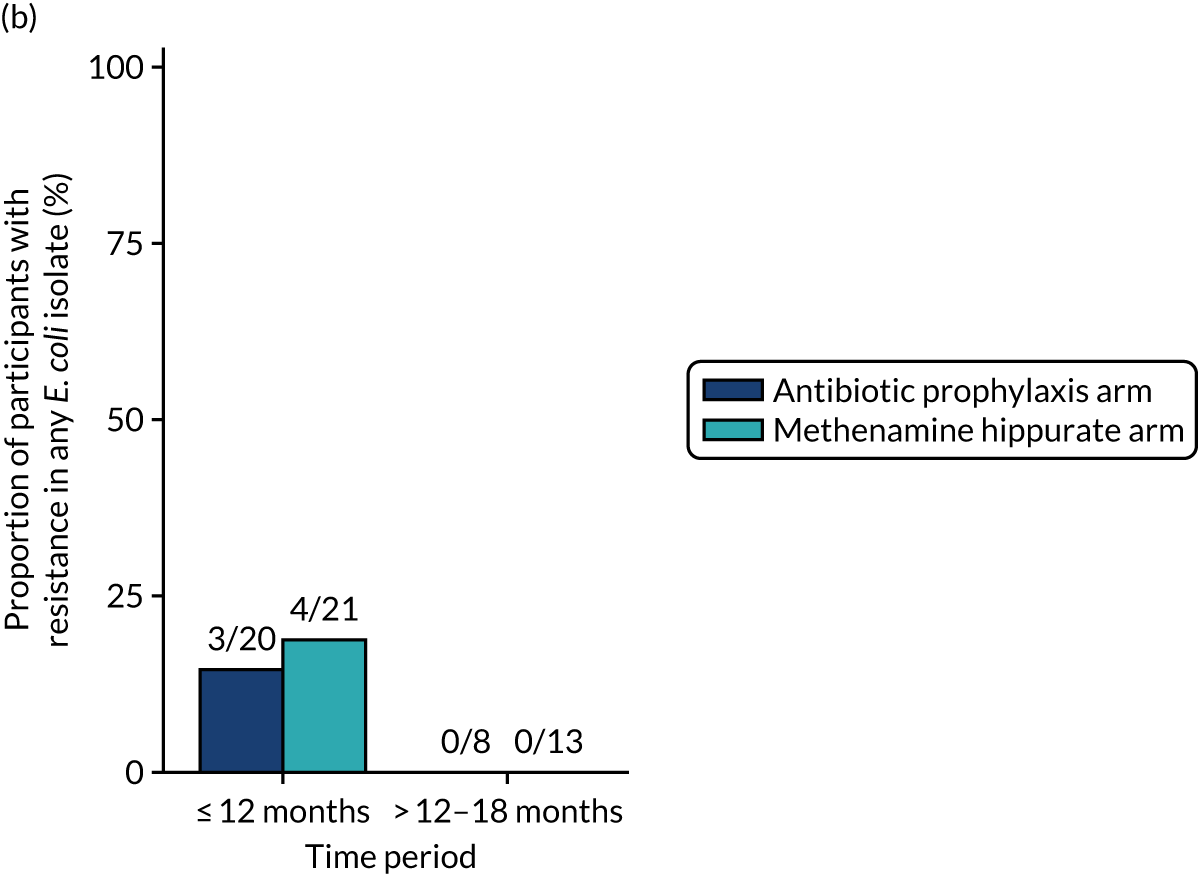

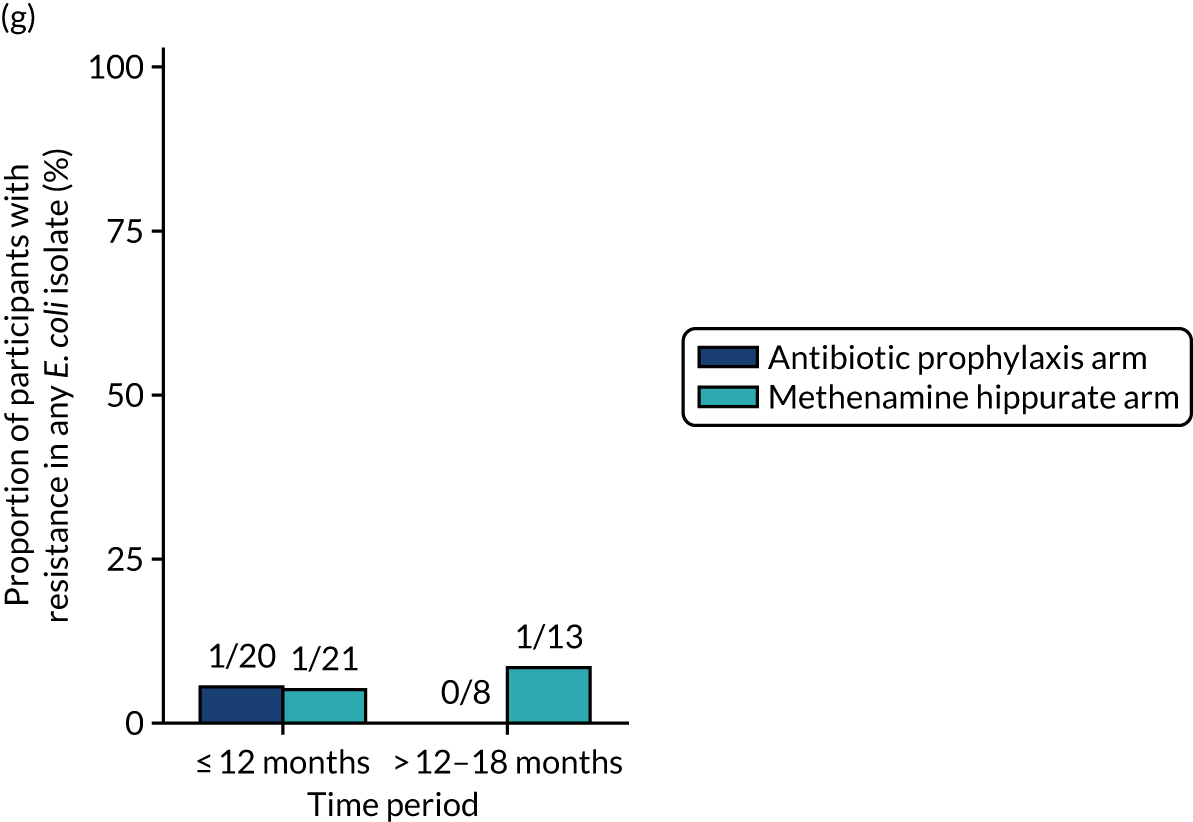

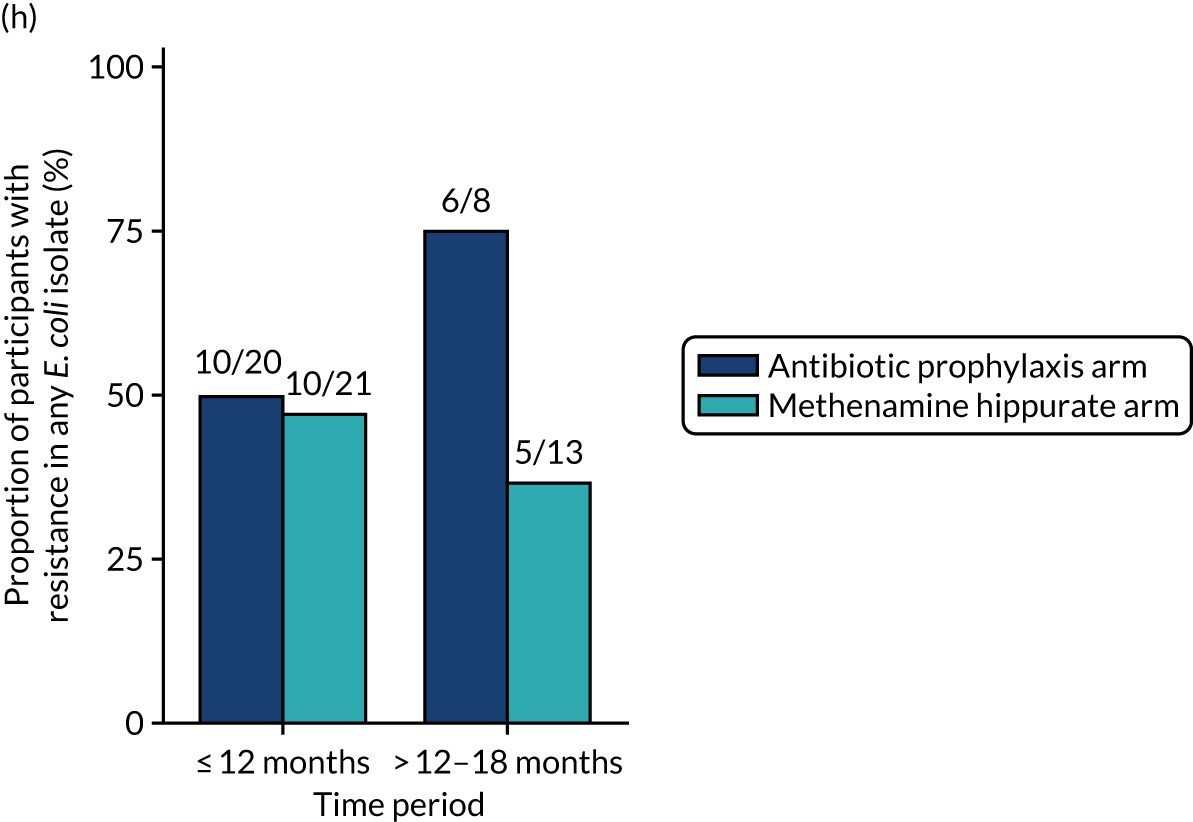

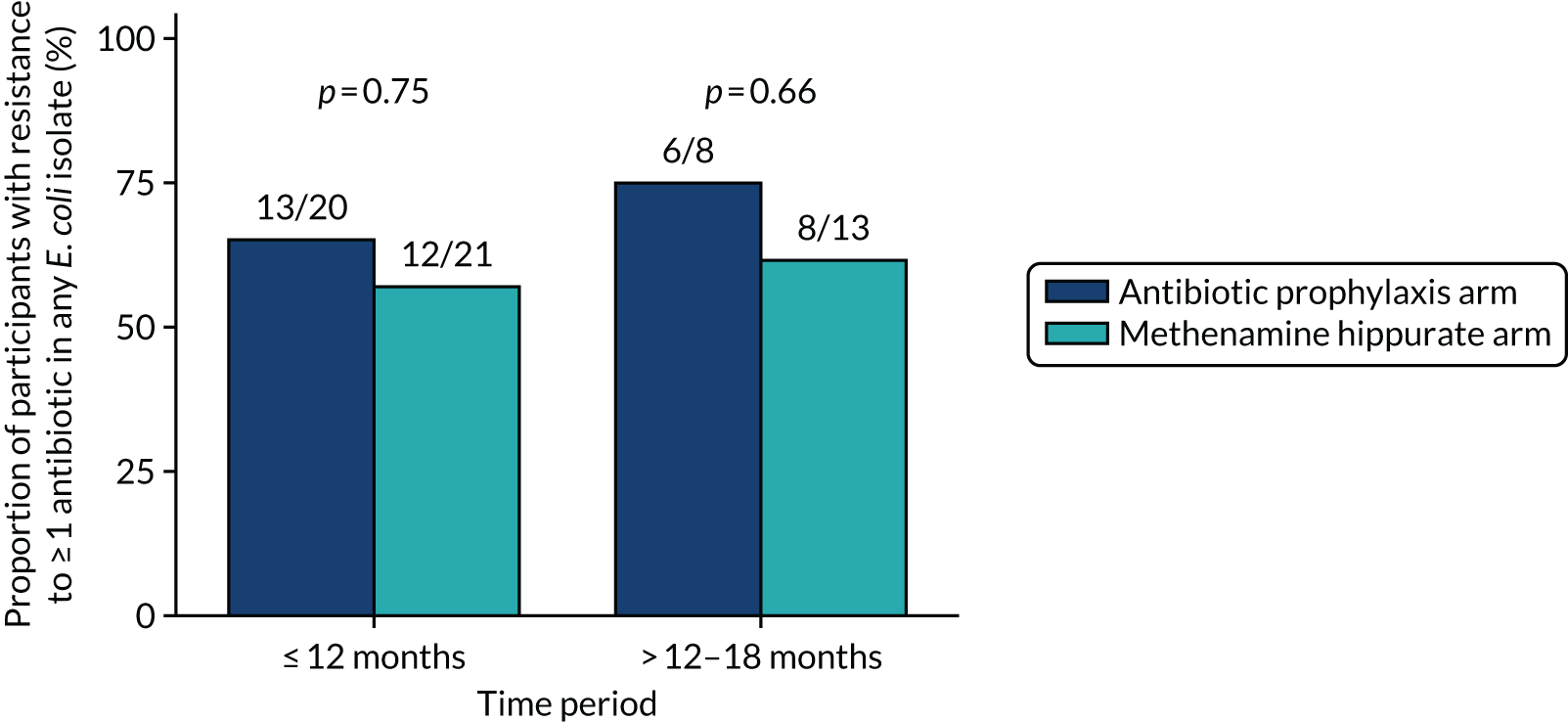

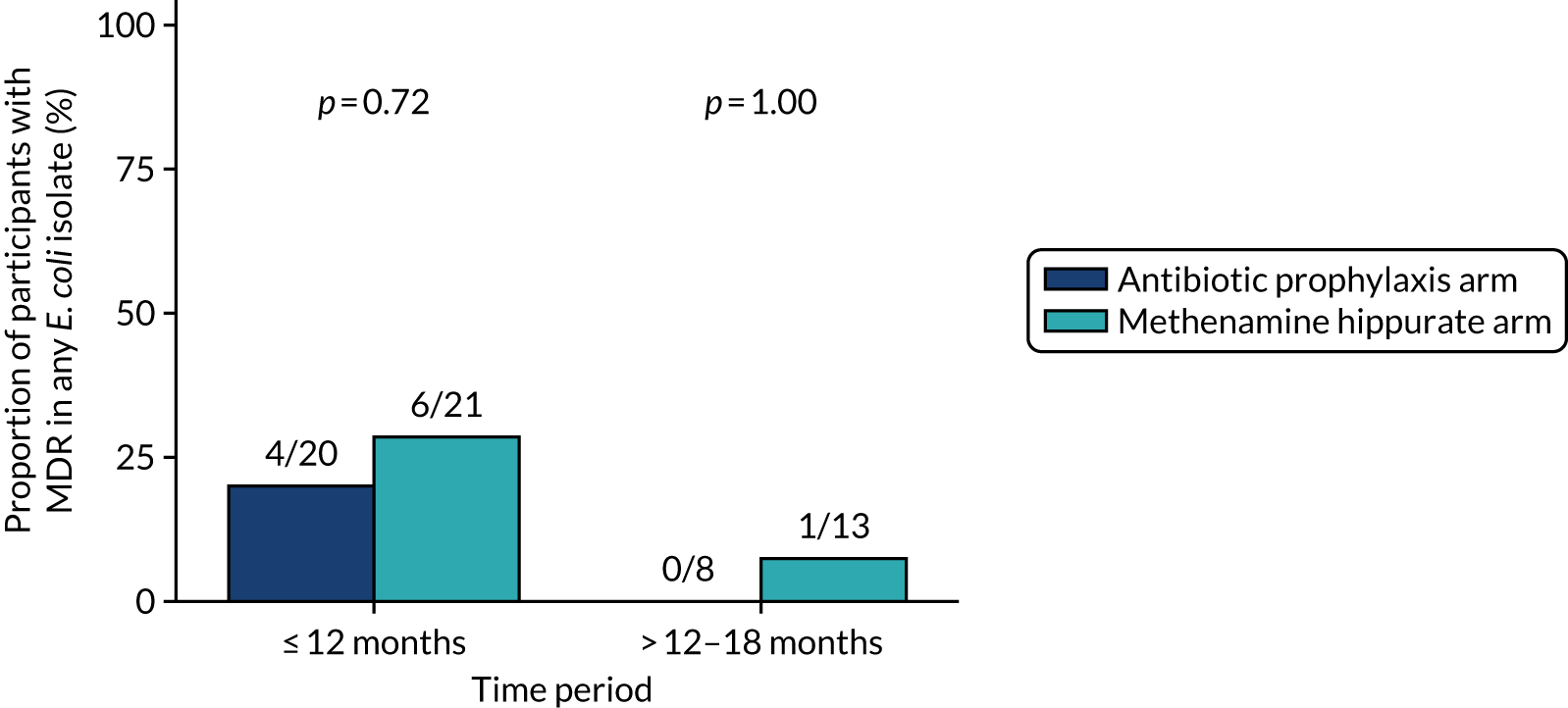

Antimicrobial resistance and multidrug resistance

Ecological change in terms of type of bacteria and their resistance patterns in isolates from (1) mid-stream urine (MSU) samples and (2) the faecal reservoir (via optional perineal swabs) was explored during the 12-month treatment period and in the 6 months following completion of treatment.

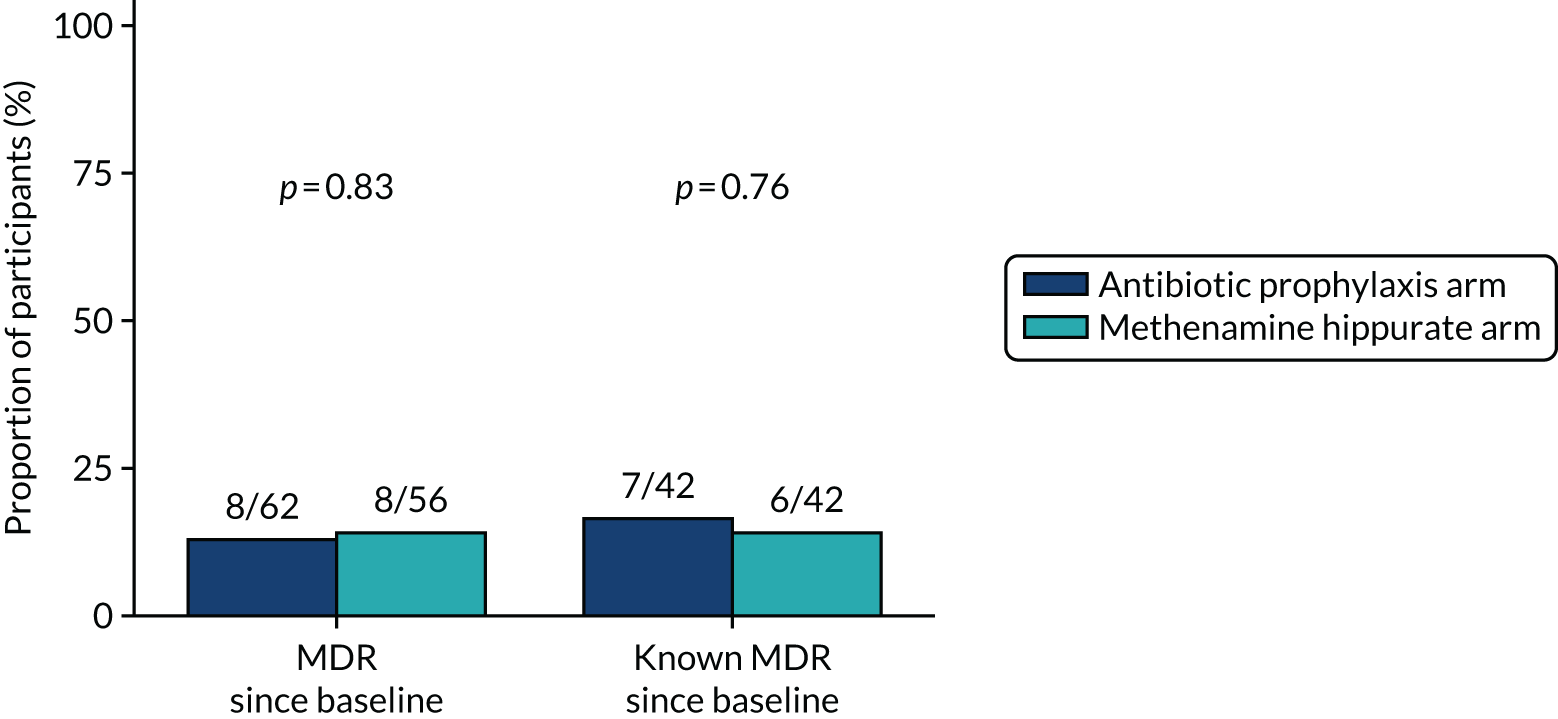

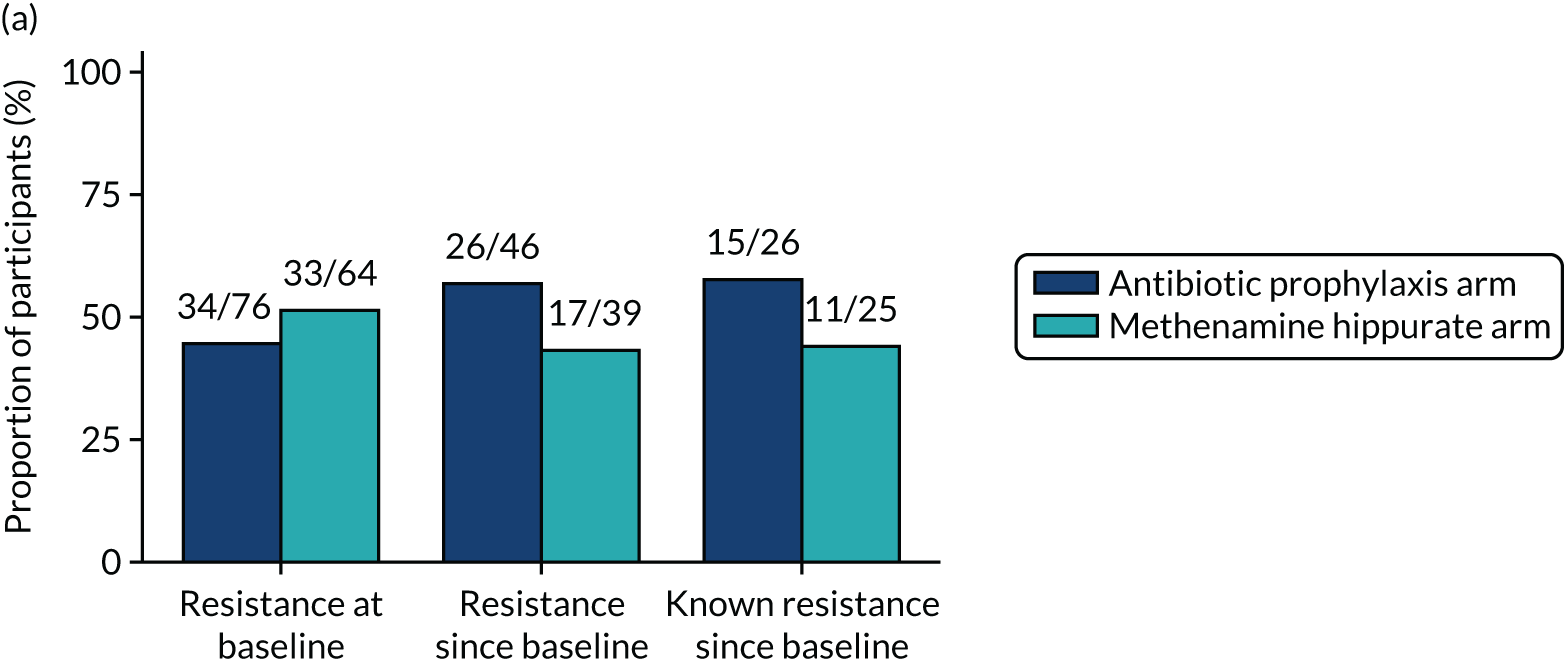

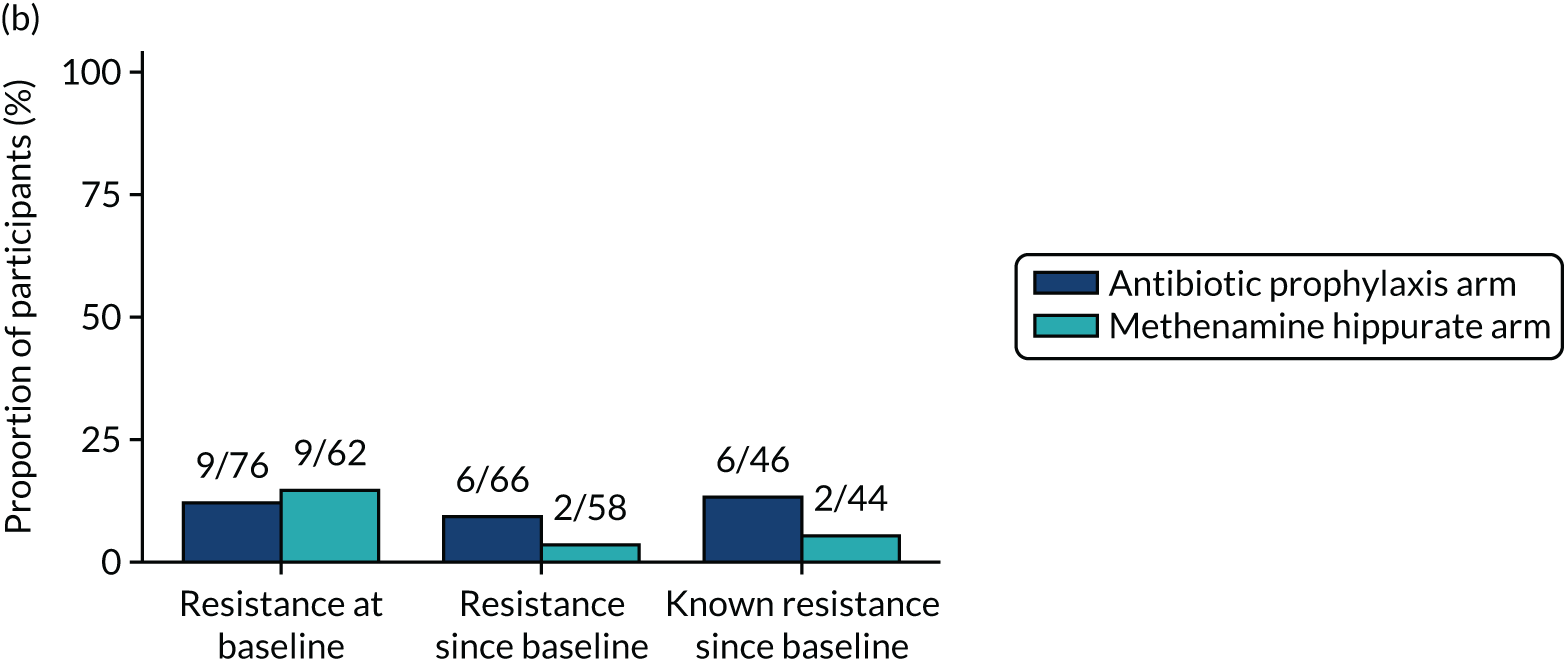

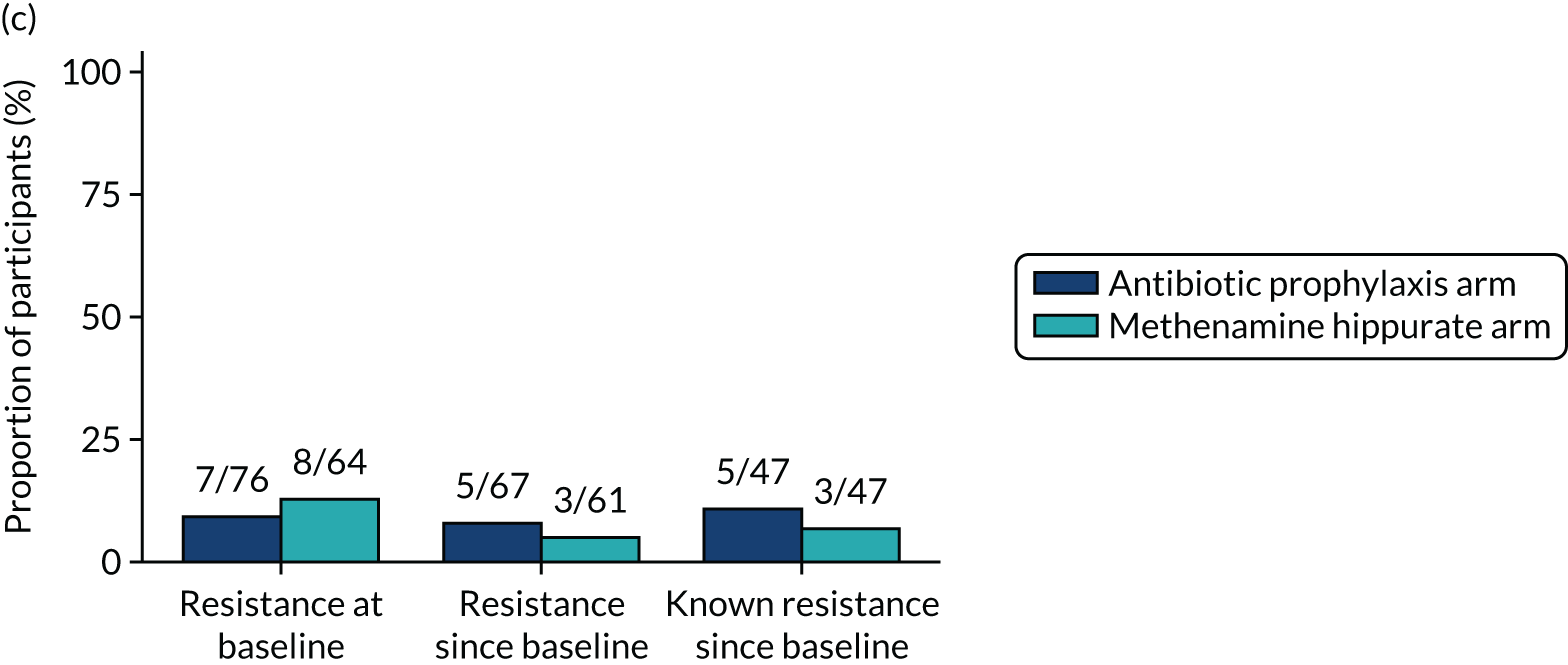

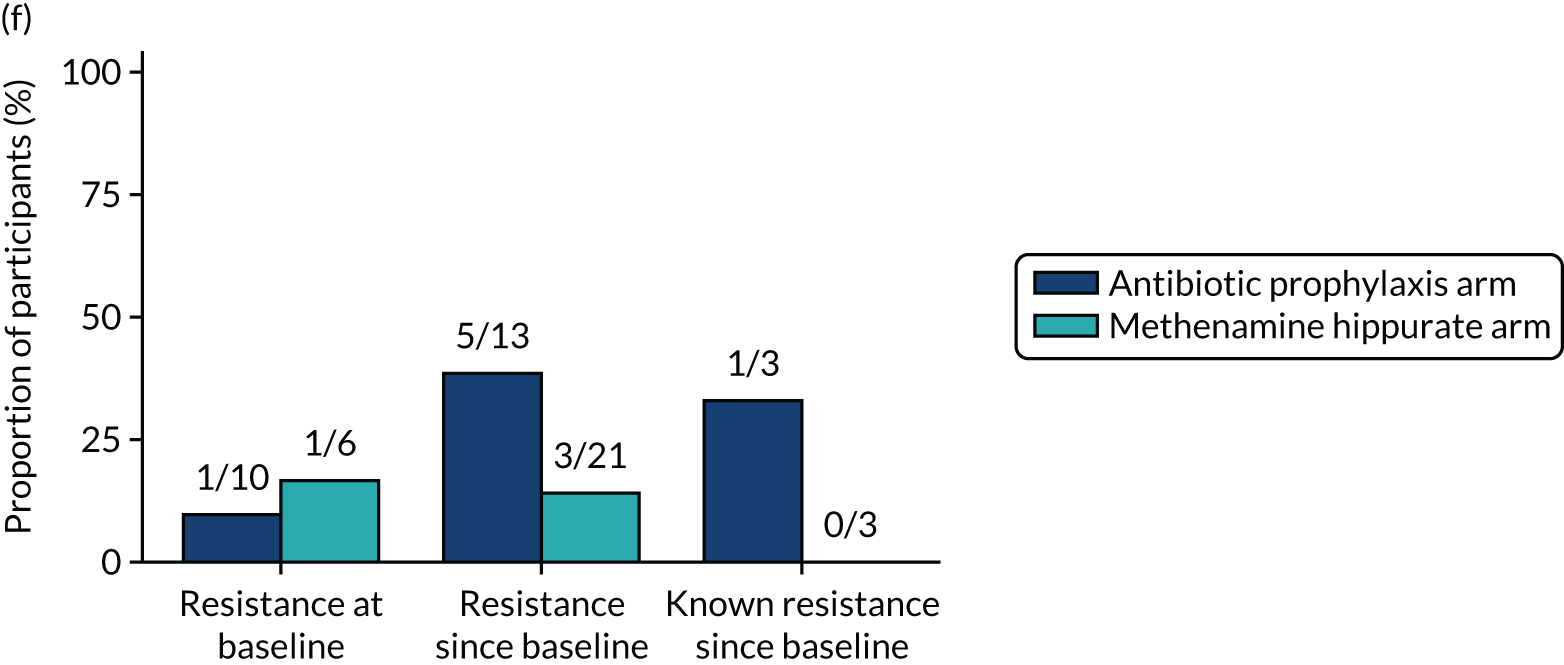

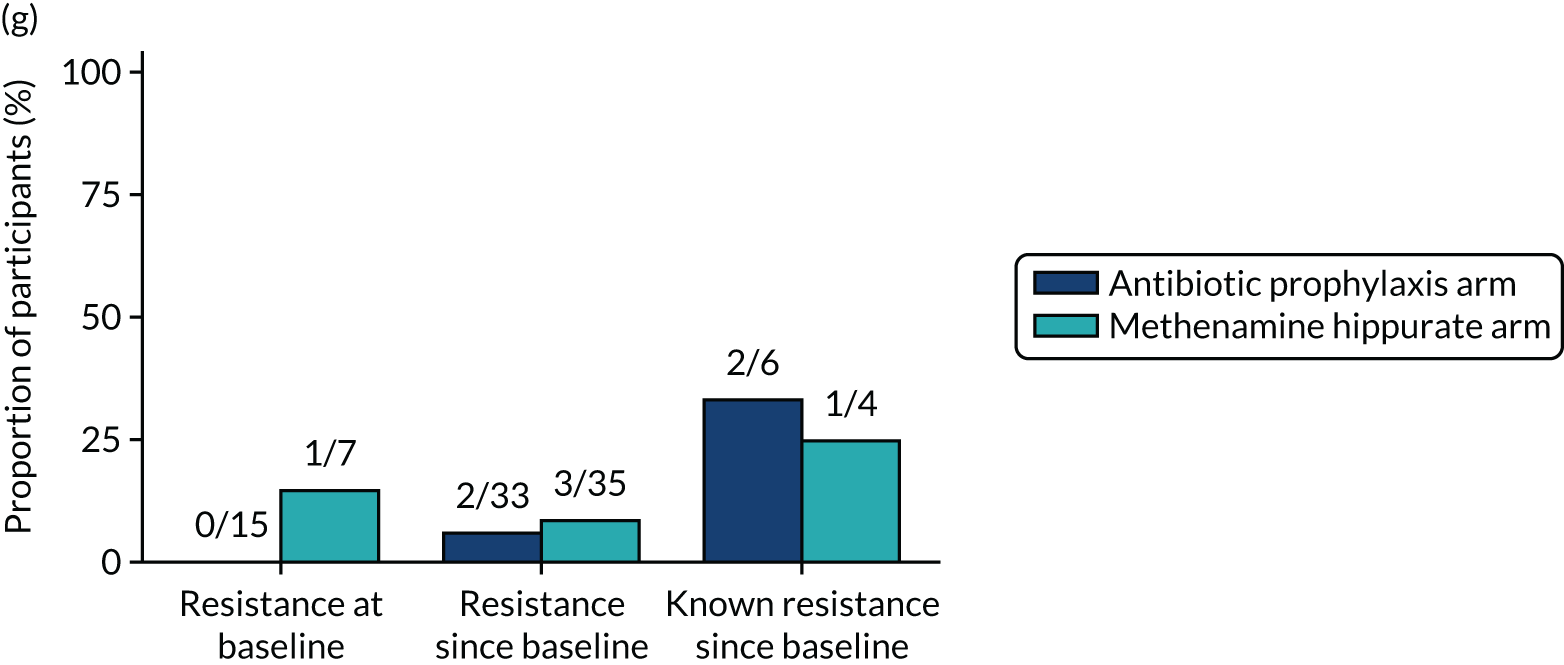

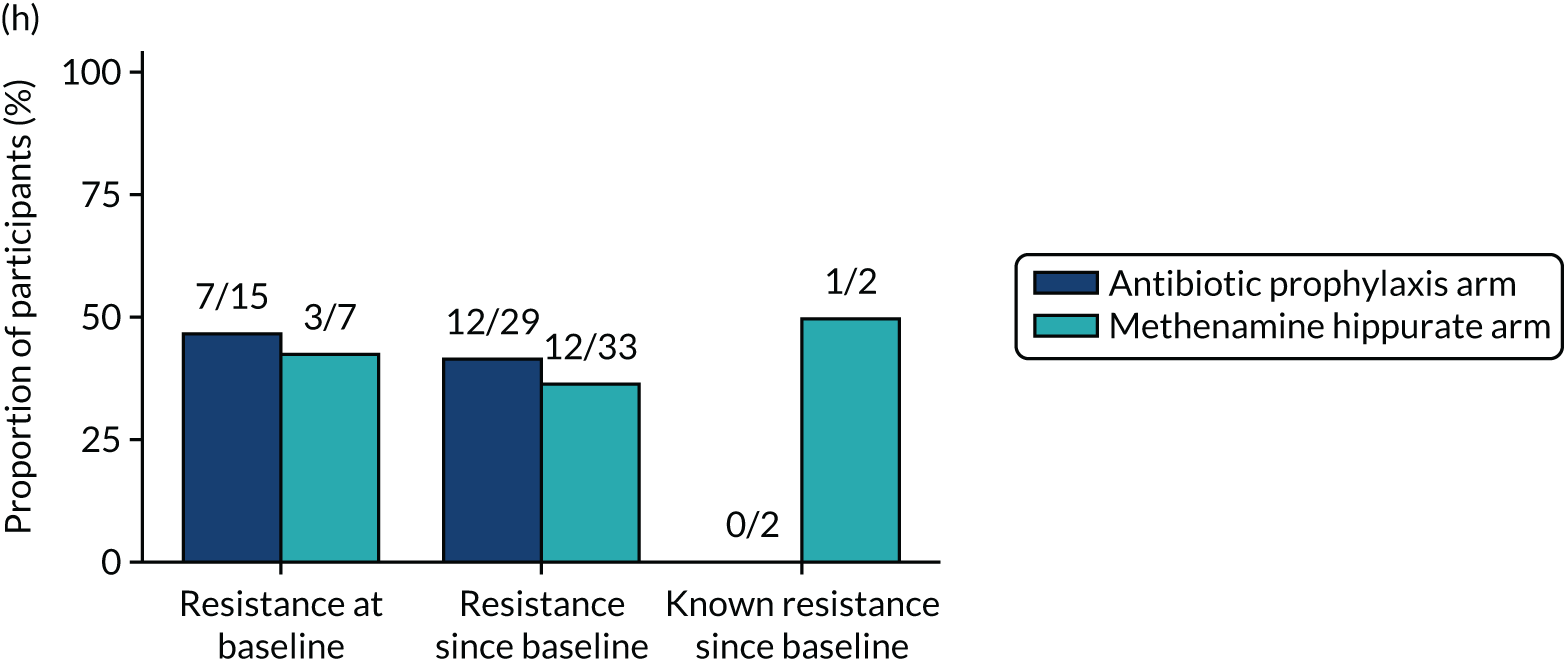

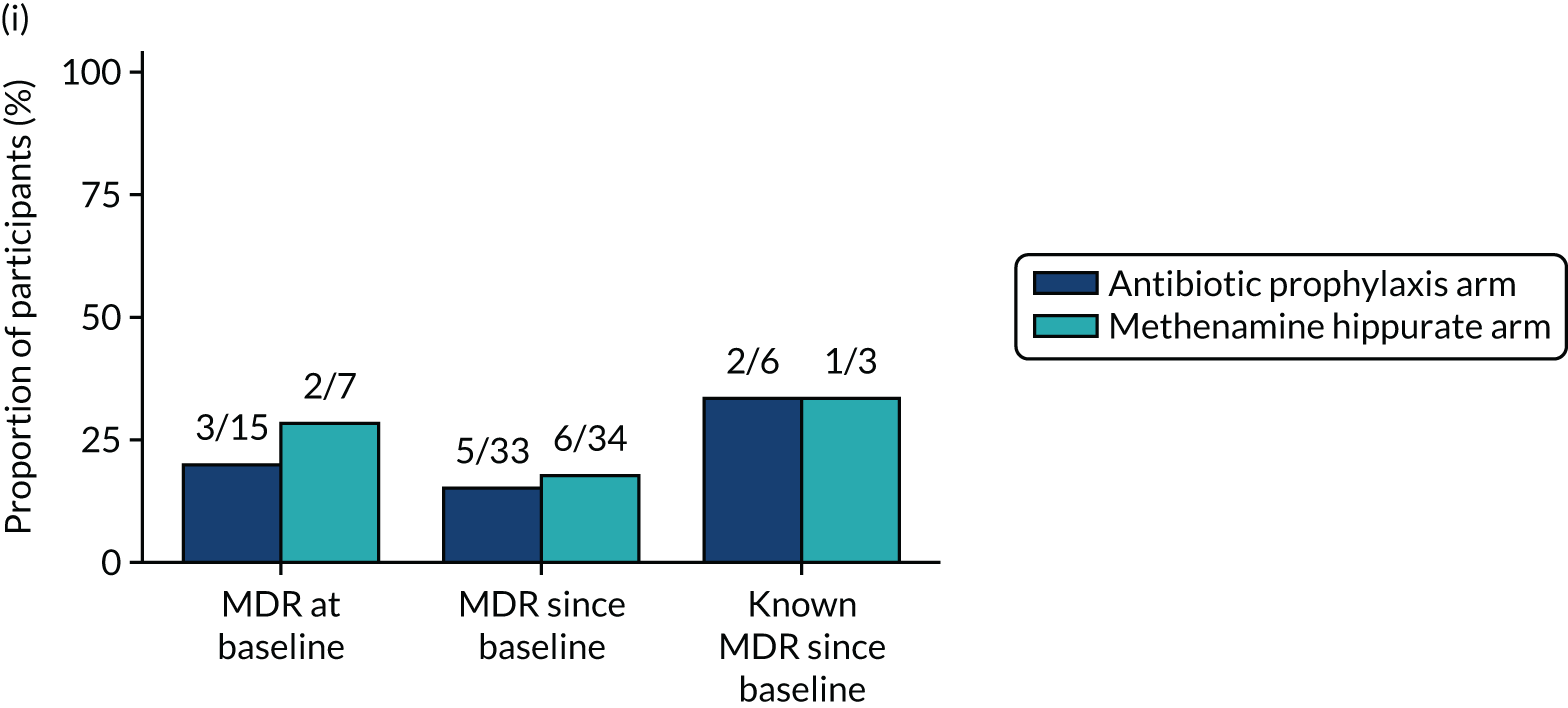

Participants were requested to submit urine samples to the central laboratory when they suspected a UTI based on symptoms, and routinely at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 months. Antimicrobial sensitivity testing against a panel of antibiotics was carried out on all significant urinary isolates (i.e. a single isolate at ≥ 104 CFU/ml or up to two isolates growing at concentrations ≥ 105 CFU/ml). We also assessed antimicrobial resistance in E. coli within the faecal reservoir by obtaining isolates from optional perineal swabs sent to the central laboratory at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months. For the purposes of our study, resistance was defined as resistance to at least one antimicrobial agent. Multidrug resistance (MDR) in E. coli was defined as resistance to at least one antimicrobial agent in at least three antimicrobial categories, following the principles described by Magiorakos et al. 27 For this trial, the antimicrobial agents and categories have been tailored to be specific to uropathogens and are set out in Table 2. For each antibiotic tested, development of ‘(known) resistance’ since baseline was first defined as patients or samples showing resistance post baseline as a proportion of those known to be sensitive at baseline. Owing to the expected low number of positive urine cultures at baseline, we also defined ‘resistance since baseline’ as patients or samples showing resistance post baseline comprising both bacterial isolates confirmed as sensitive at baseline and also those urine samples with no isolates identified in the baseline sample. Development of MDR since baseline was defined similarly.

| Antimicrobial category | Antimicrobial agent |

|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin |

| Antipseudomonal penicillin | Piperacillin/tazobactam |

| Carbapenems | Ertapenem; meropenem |

| Non-extended-spectrum cephalosporins | Cefuroxime; cefalexin |

| Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin |

| Folate pathway inhibitors | Trimethoprim–sulphamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole); trimethoprim |

| Monobactams | Aztreonam |

| Penicillins | Amoxicillin; mecillinam |

| Penicillins + β-lactamase inhibitors | Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav) |

| β-Lactamase-resistant penicillin | Temocillin |

| Phosphonic acids | Fosfomycin |

| Nitrofurans | Nitrofurantoin |

Occurrence of asymptomatic bacteriuria

The occurrence of asymptomatic bacteriuria was defined as a positive urine culture in the absence of symptoms. This was detected from the routine urine samples taken during 3-monthly hospital visits throughout the 18-month trial period where participants confirmed no UTI symptoms. Samples taken within 5 days of the onset of UTI symptoms were not included. A positive culture was classified as the presence of a single isolate at ≥ 104 CFU/ml or two isolates at ≥ 105 CFU/ml.

Hospitalisation due to urinary tract infection

Hospitalisation due to UTI was defined as an unplanned visit to hospital for treatment of a UTI. These data were collected from health-care record review and checked from participant report.

Participant satisfaction with treatment

This was measured using the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) administered at both the end of the 12-month treatment period and then again at 18 months, at the end of follow-up. 28 Four separate subscale scores (effectiveness, side effects, convenience and global satisfaction) were calculated as per the scoring algorithm. Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating increased satisfaction. The effectiveness, convenience and global satisfaction subscales comprised three items and the side effects subscale four. A score was not calculated if more than one item was missing from each subscale.

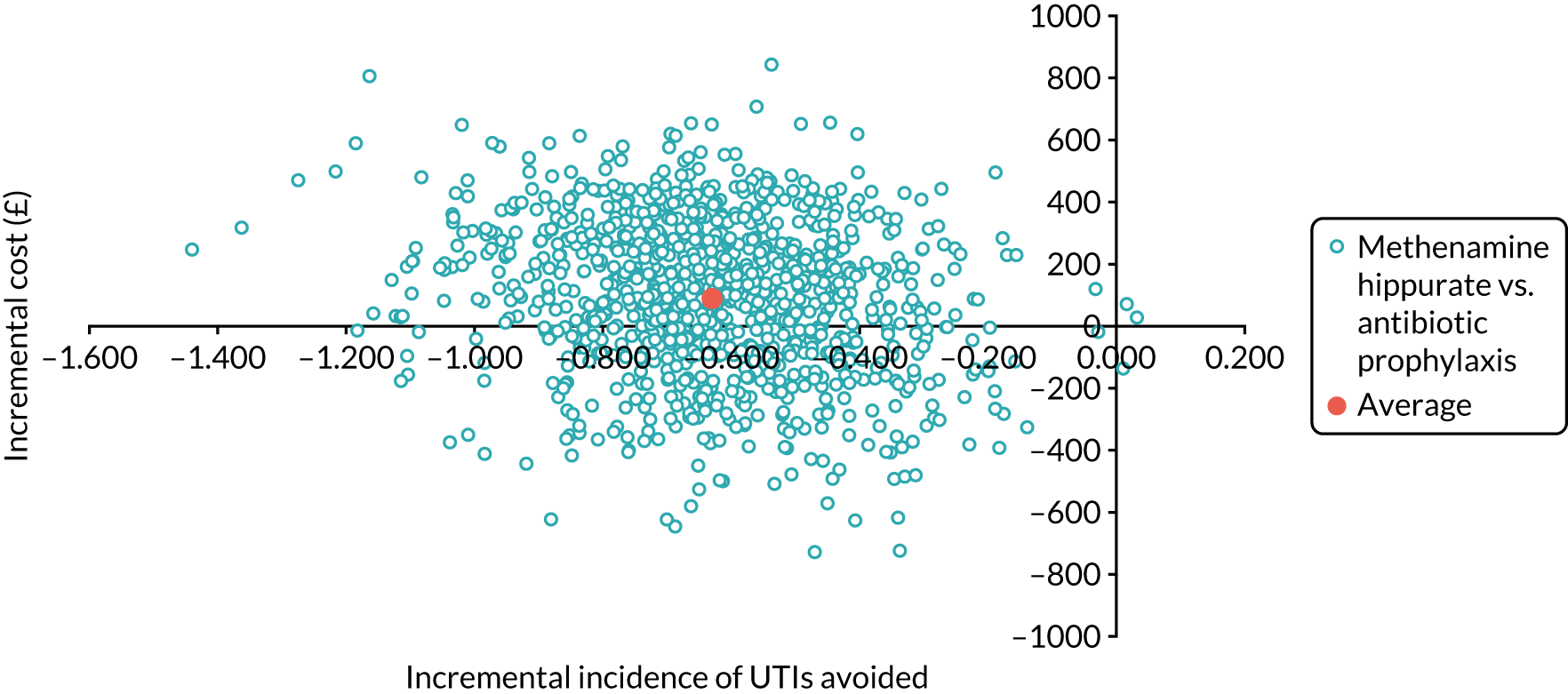

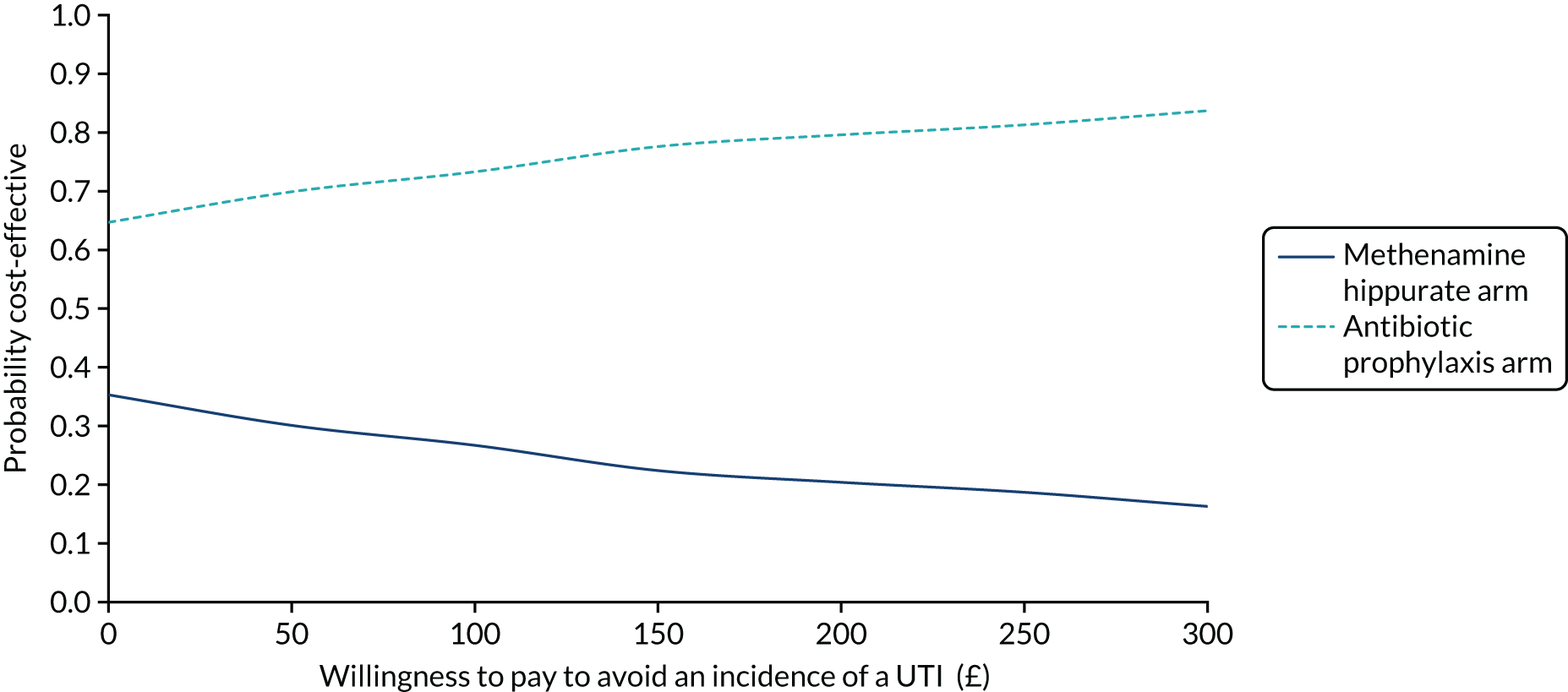

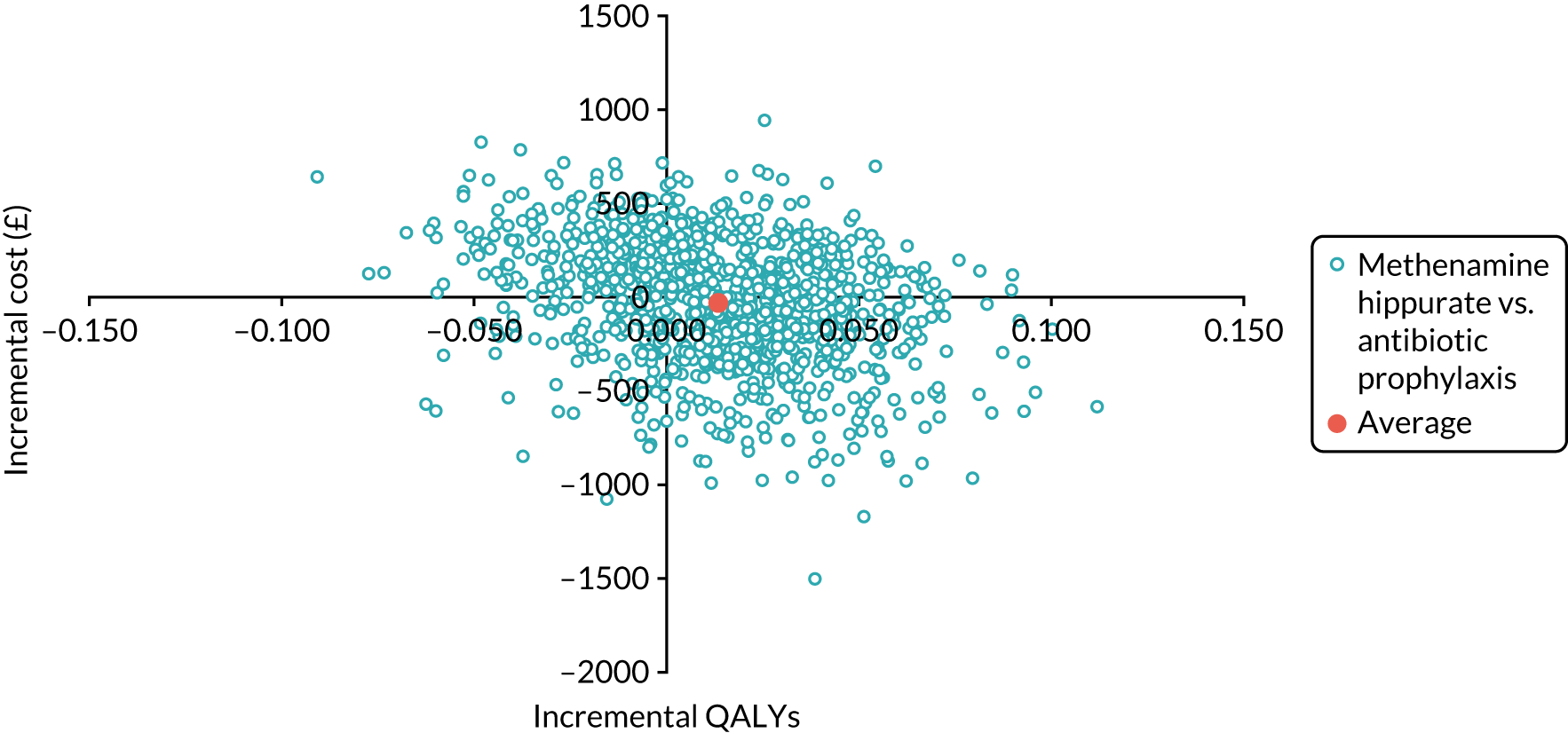

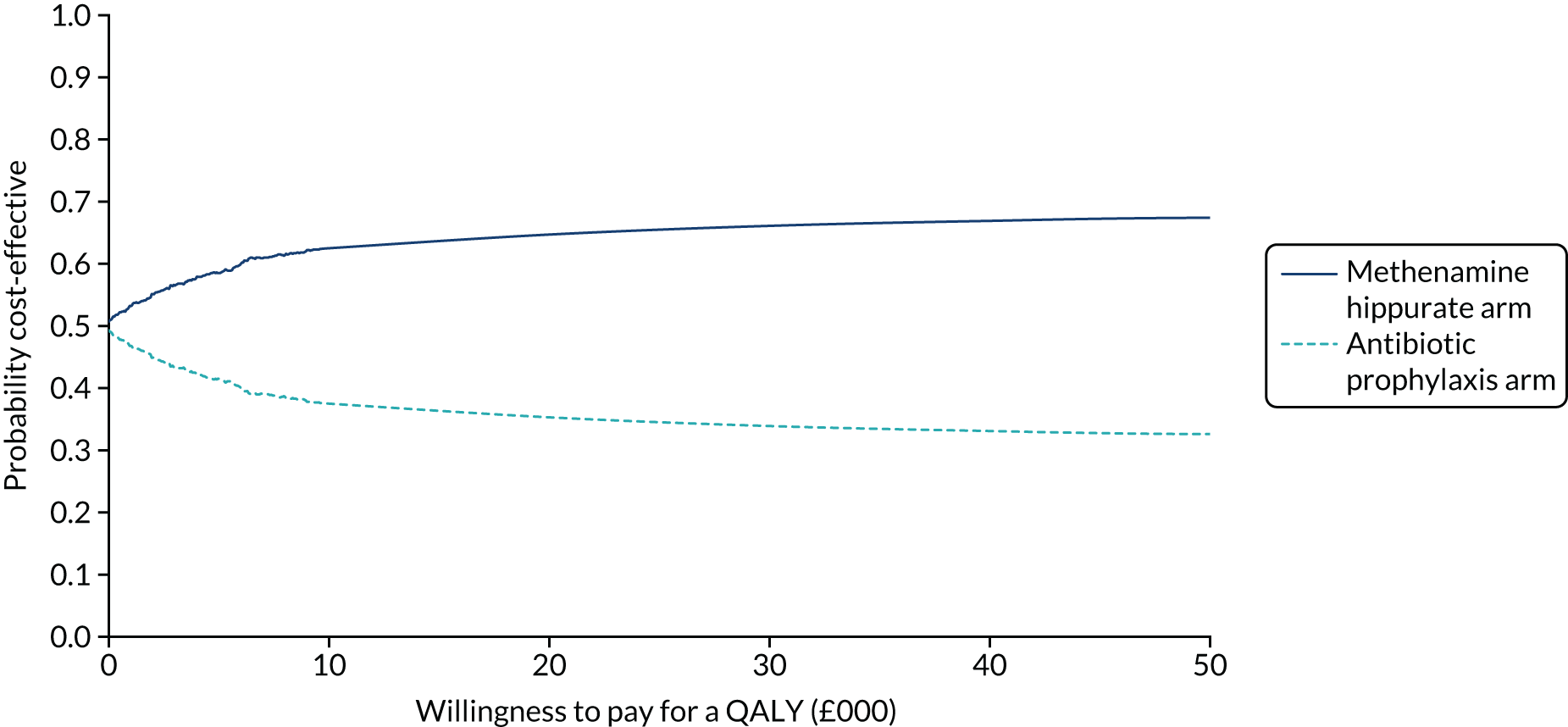

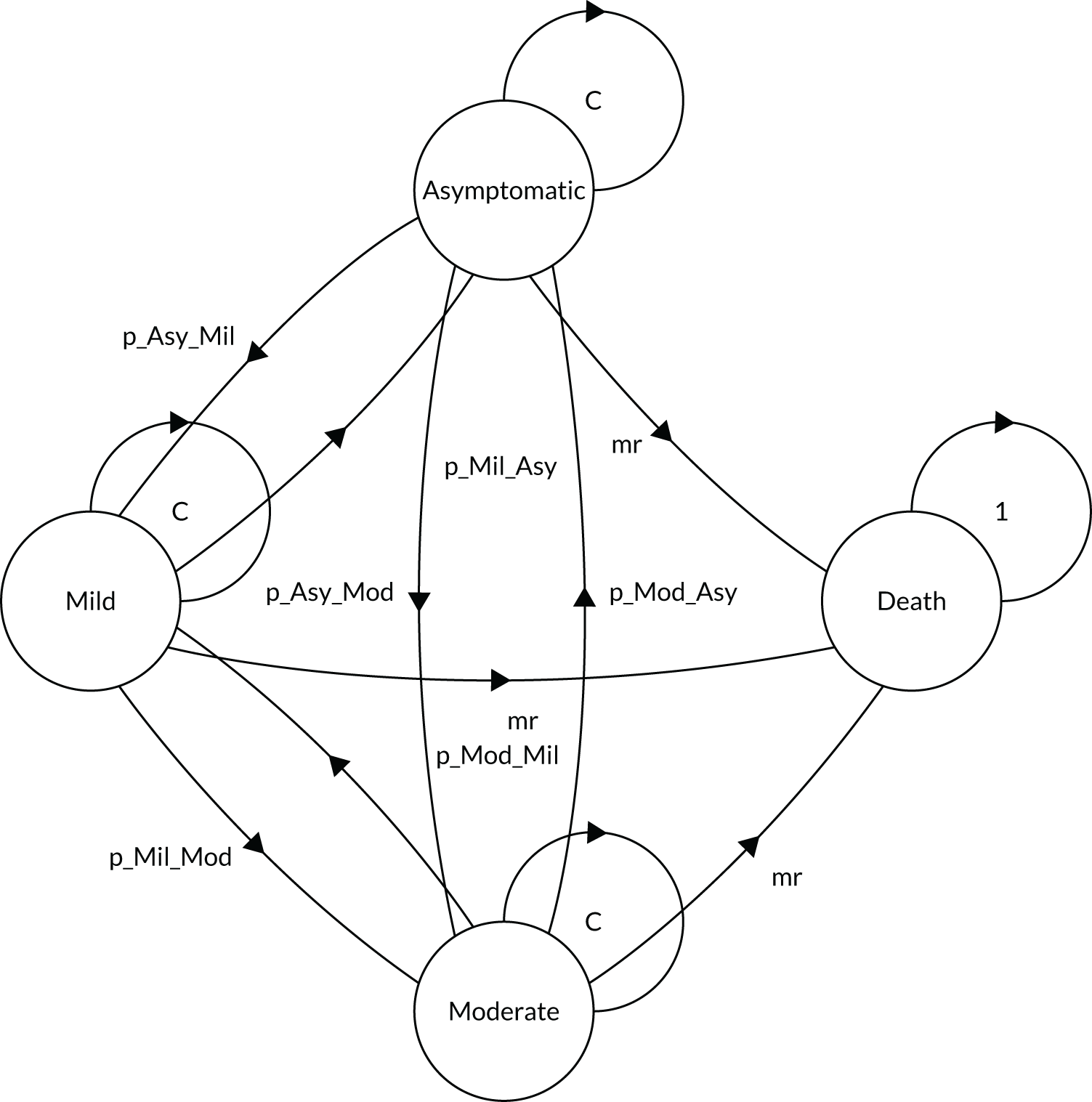

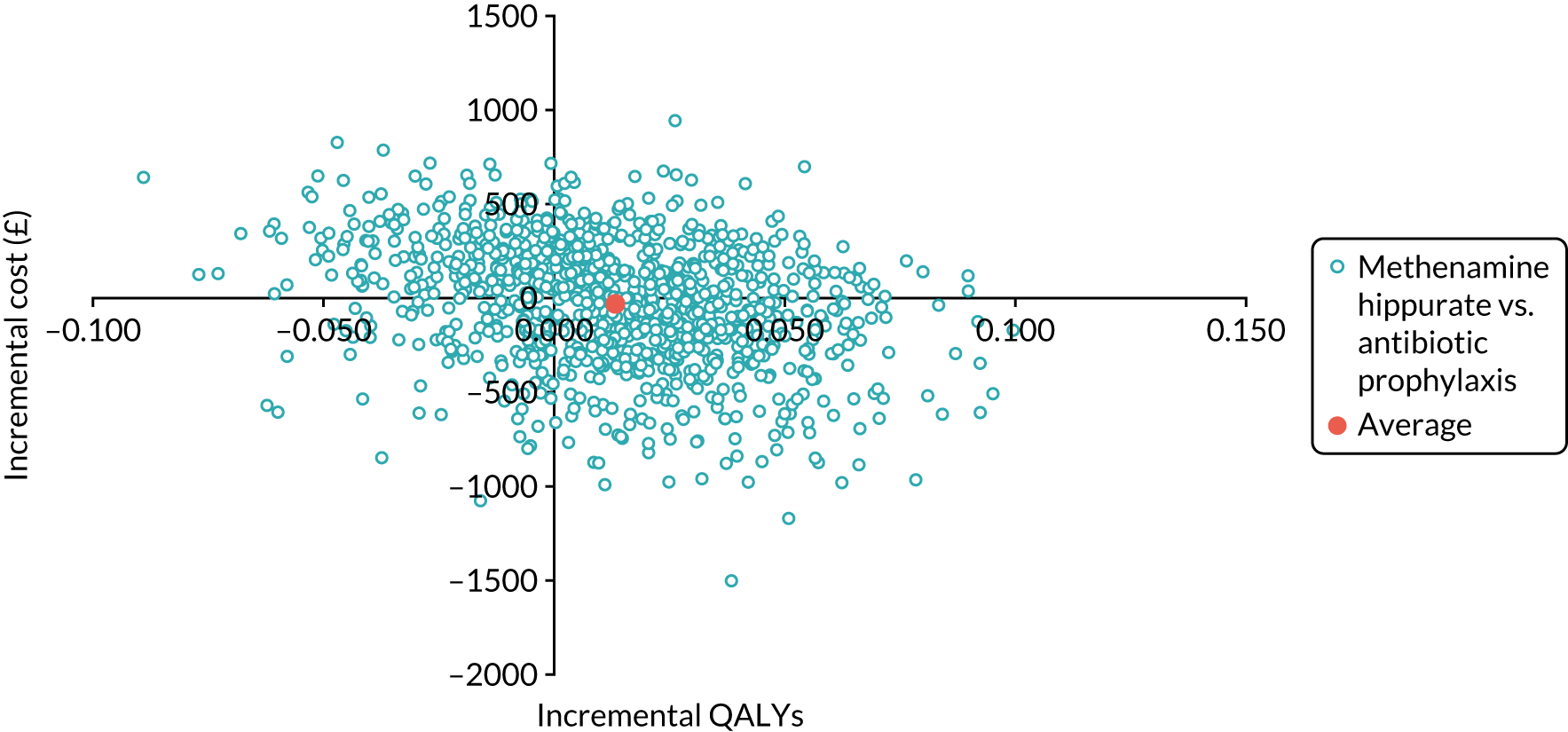

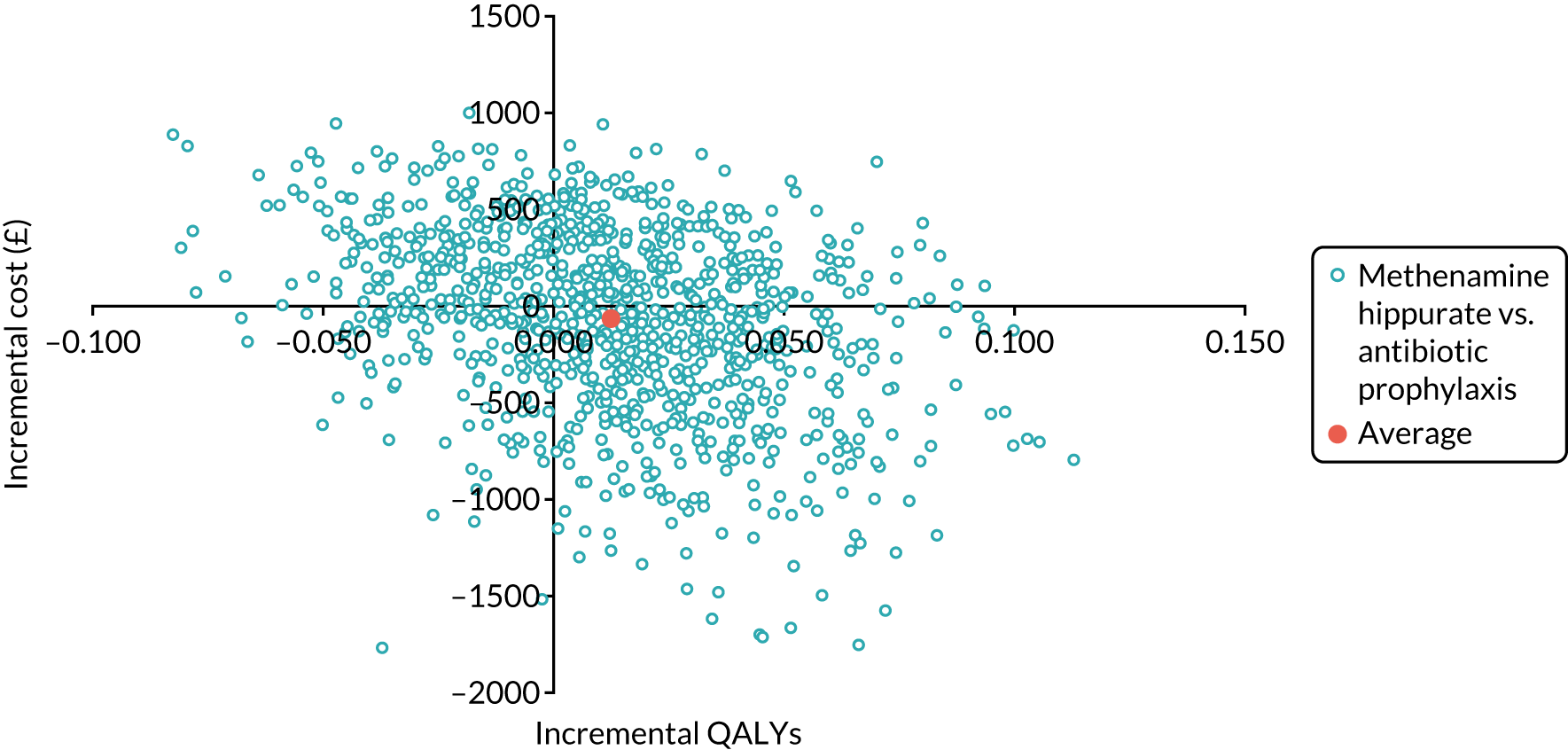

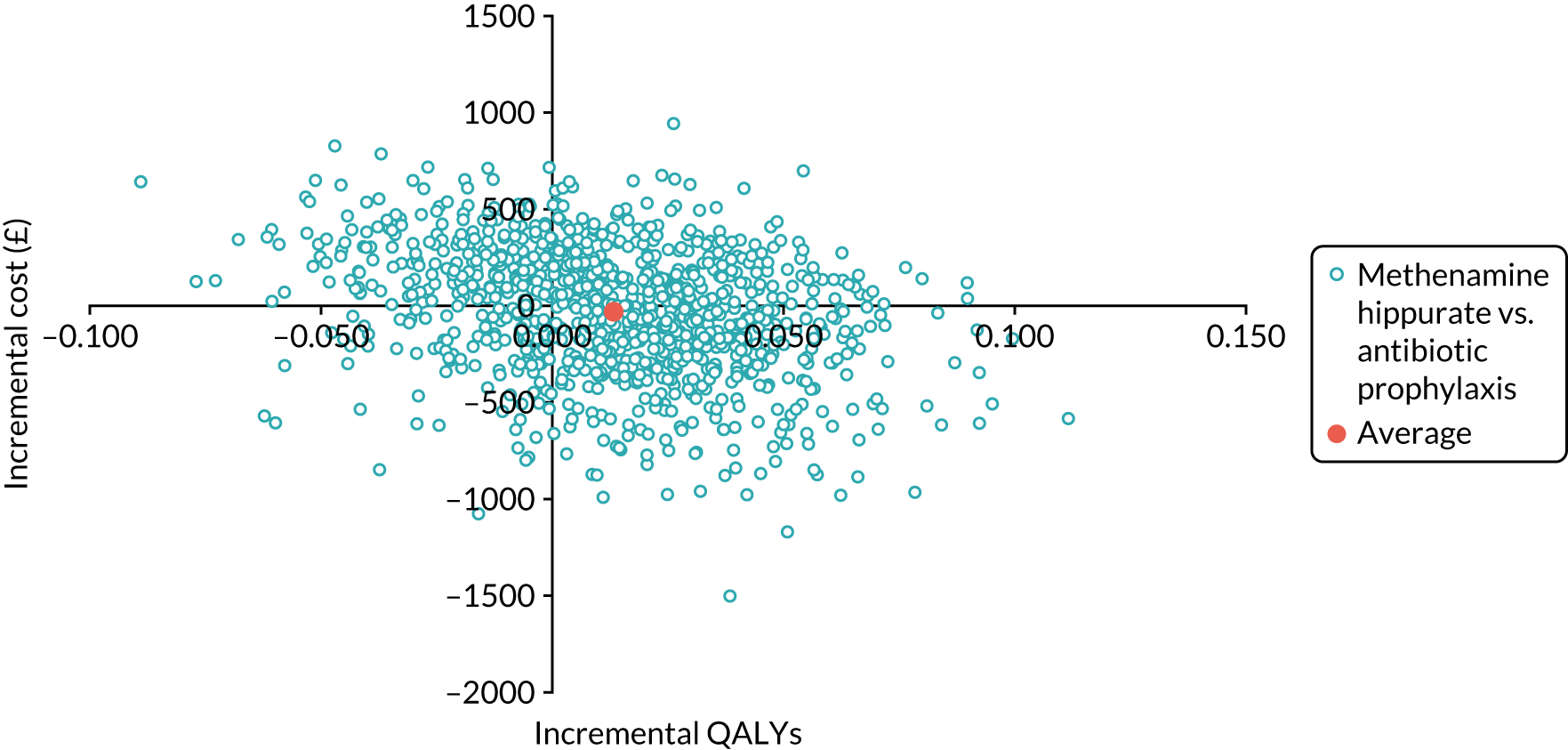

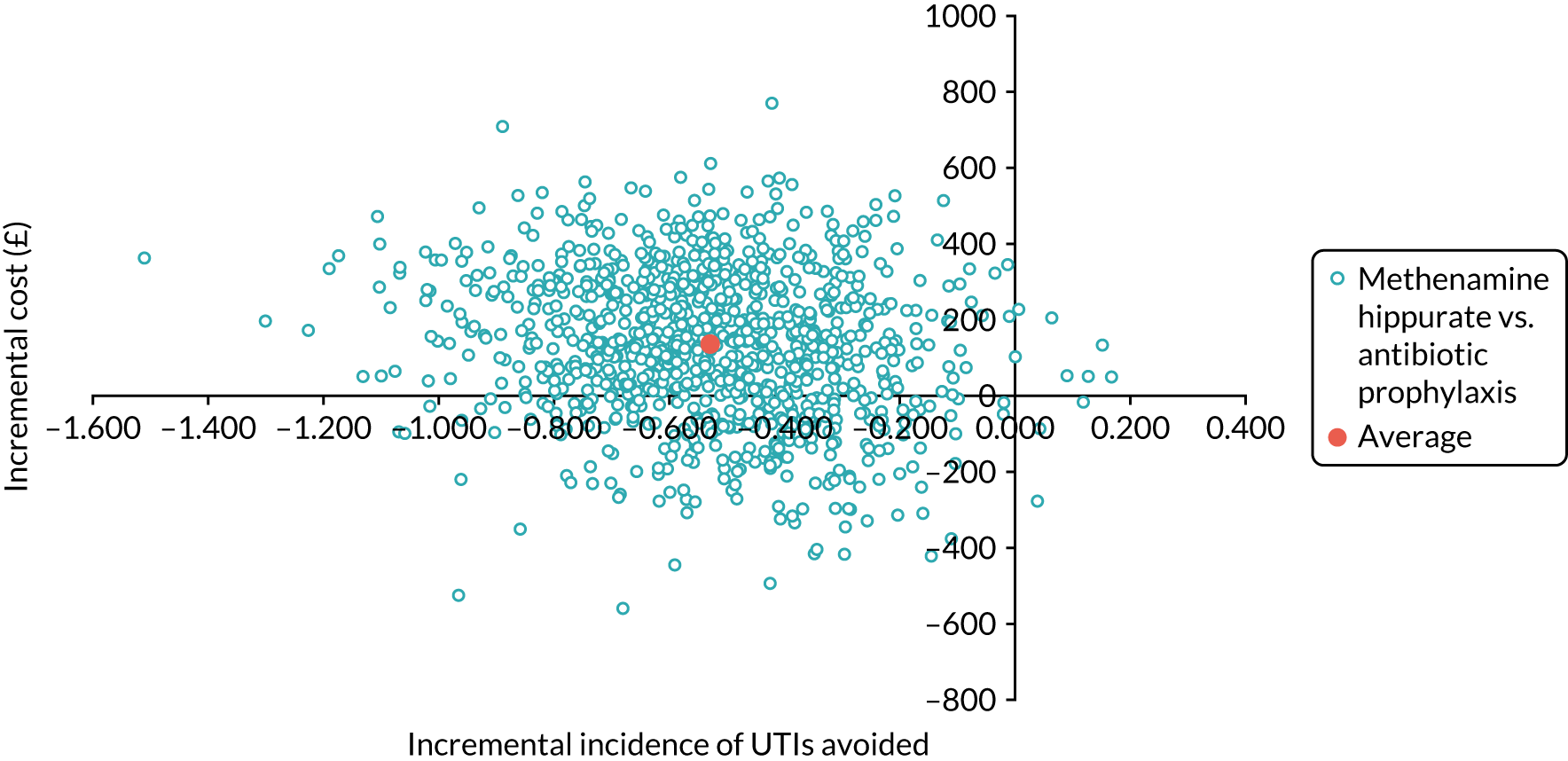

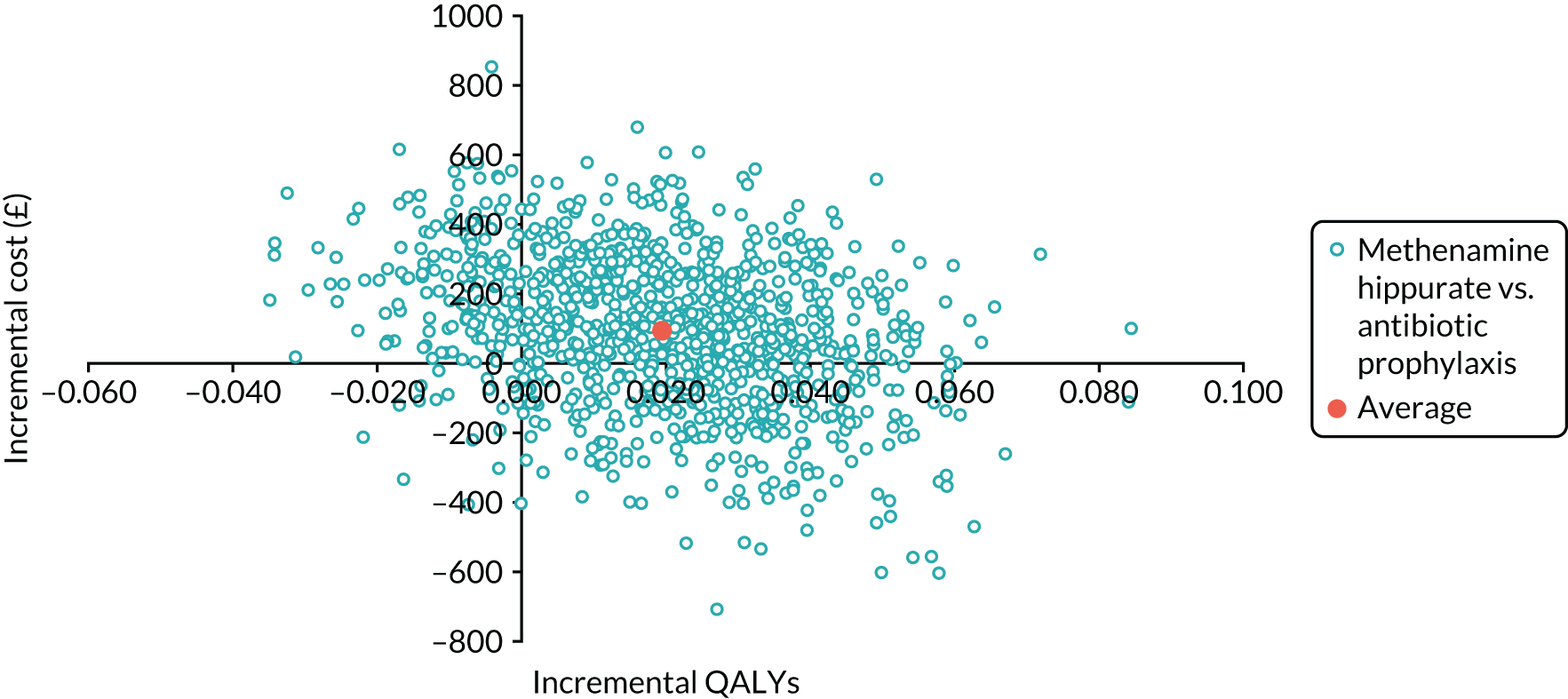

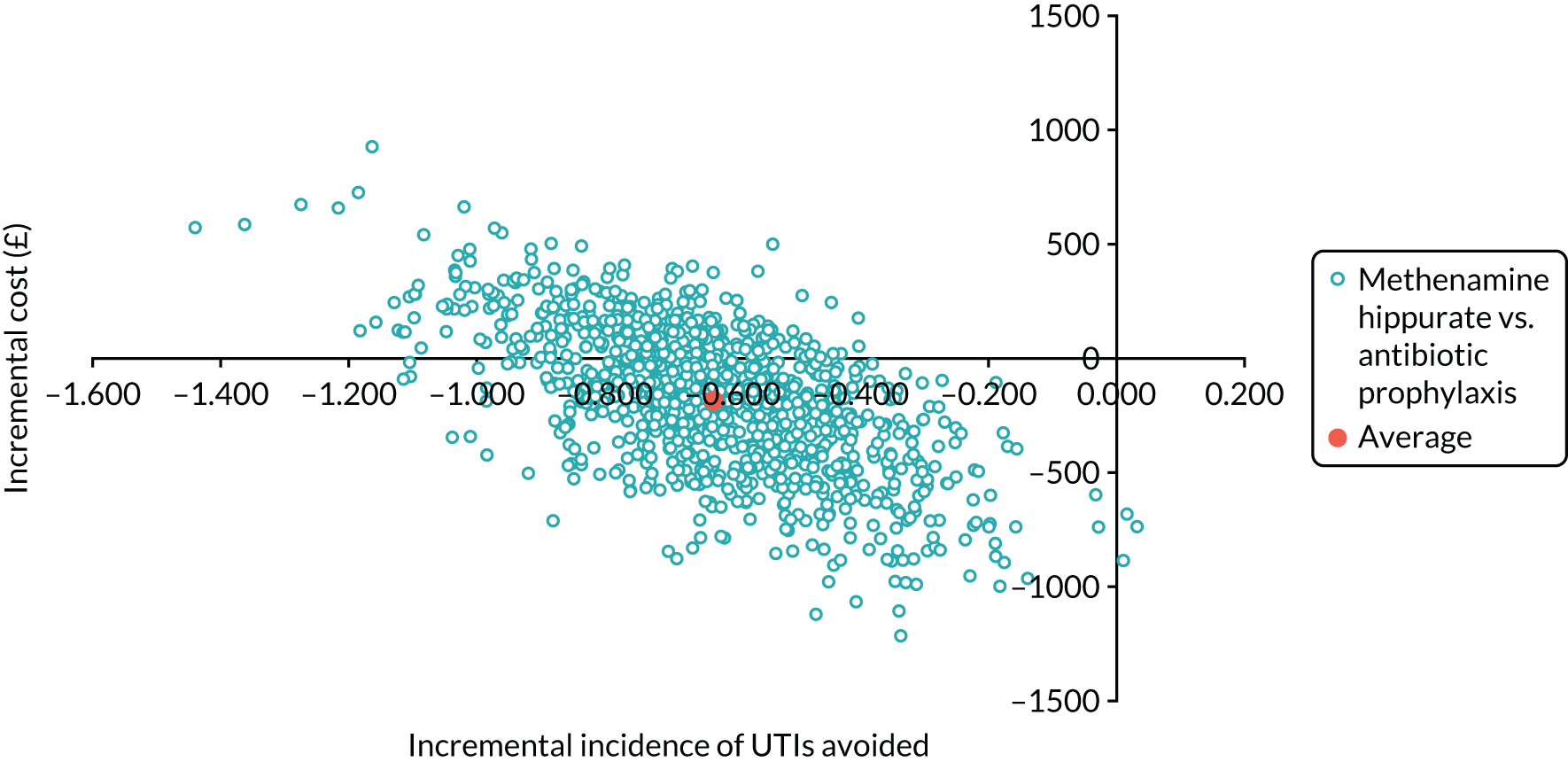

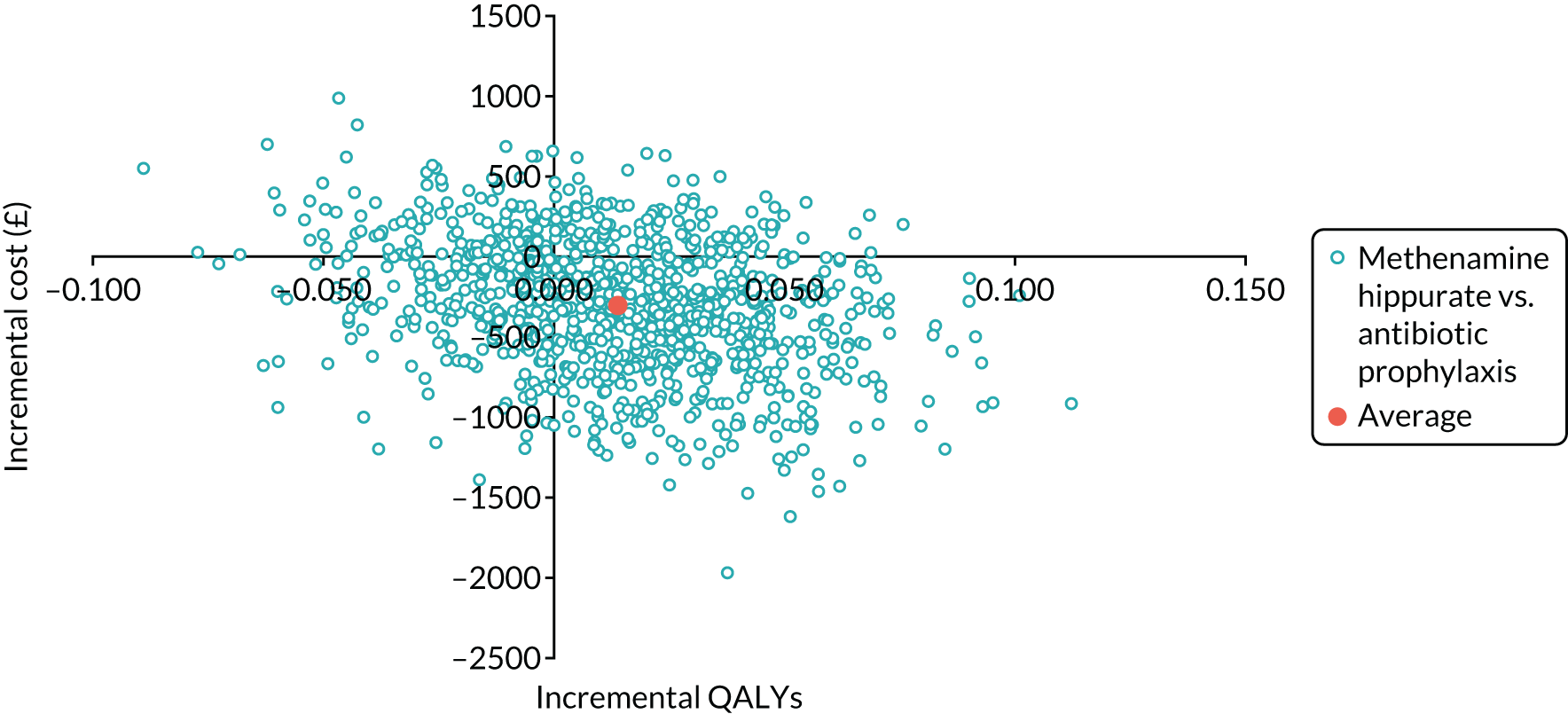

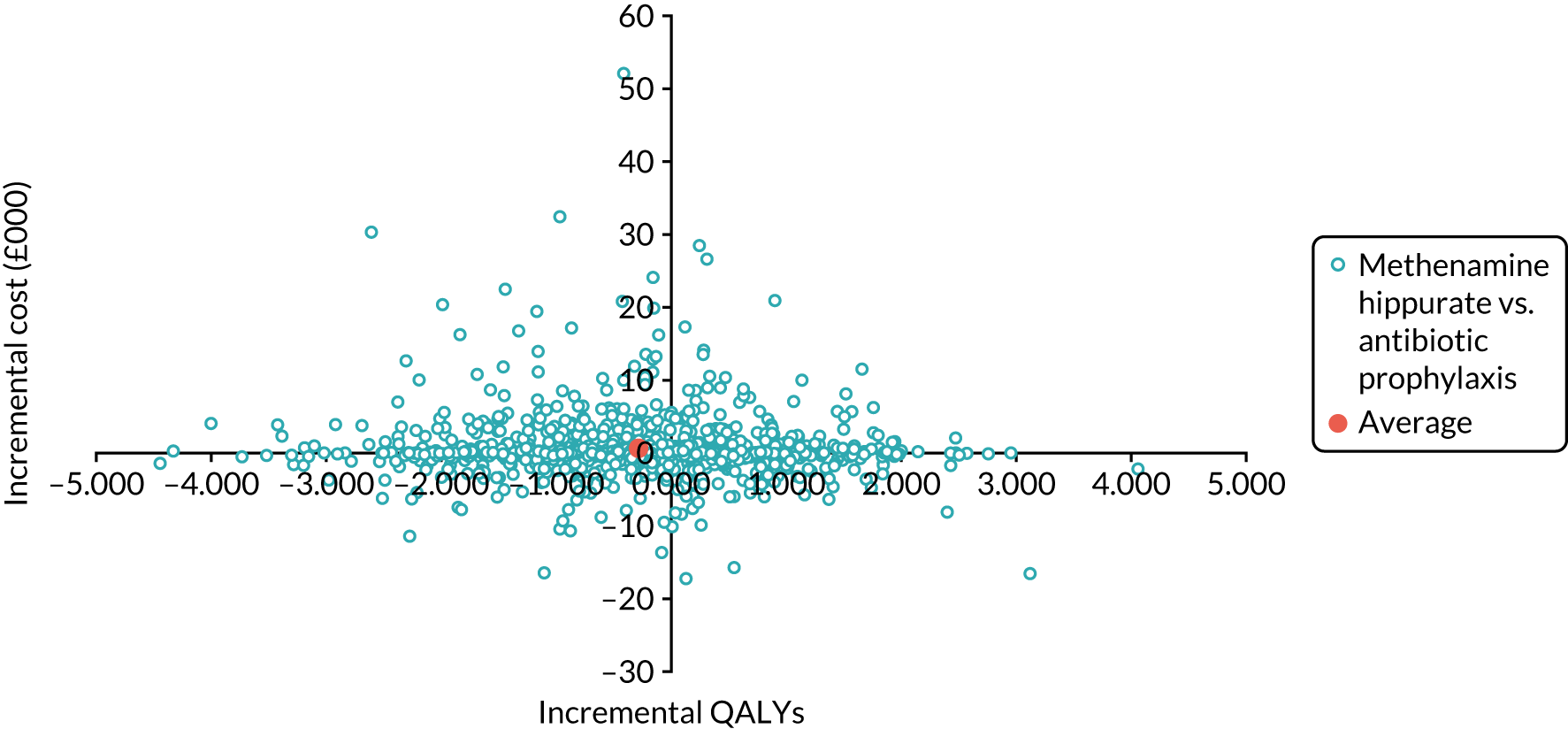

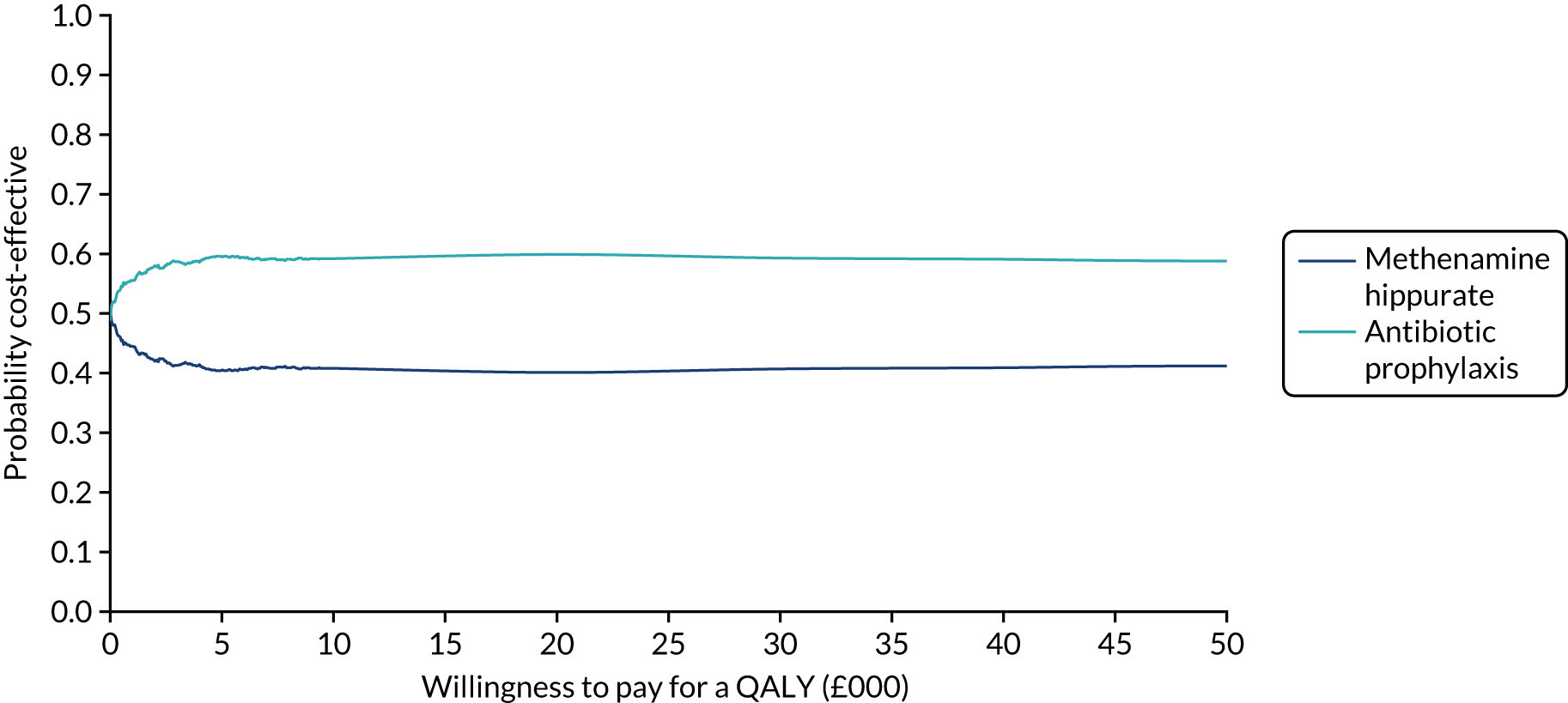

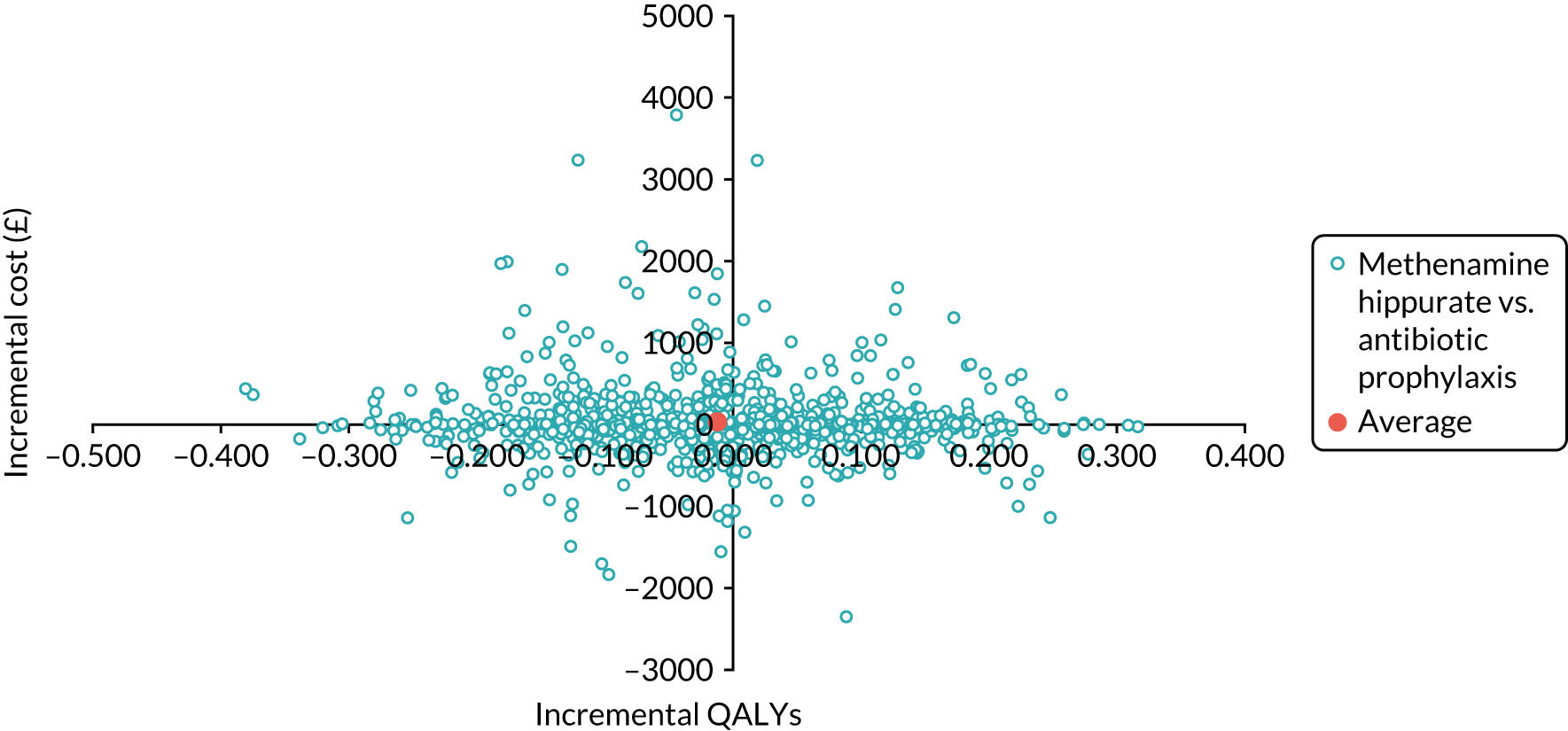

Economic analysis

The objective of the economics analysis in the ALTAR trial was to determine the relative efficiency of methenamine hippurate compared with antibiotic prophylaxis in the management of rUTI. The economic analysis comprised both a within-trial (18-month time horizon) analysis and a model-based analysis (lifetime time horizon). Costs were estimated using trial-specific estimates and unit costs from routine sources. Effectiveness was measured using the primary outcome (incidence of UTIs) and QALYs, which were estimated based on responses to the EQ-5D-5L. The differences in costs were equated to the differences in effectiveness (incidence of UTIs and QALYs) to estimate incremental cost-effectiveness. Stochastic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses determined the probability of methenamine hippurate being considered cost-effective. The inclusion of a within-trial and model-based economic analysis as part of the ALTAR trial was essential to help address uncertainties surrounding the effectiveness and efficiency of each management strategy in the short term (18 months) and over the longer term. For more details of the economic analysis, see Chapter 5.

Data collection

Summary

Outcome data were collected using CRFs, participant-completed questionnaires and UTI records, and information retrieved from participants’ medical notes. Data from the CRFs were entered into the trial-specific database set up using the MACRO clinical data management system (Elsevier BV, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) by delegated research staff at each site. Participant-completed questionnaires and UTI records were returned by post to the central NCTU trial office and entered into the MACRO database by NCTU staff. The results of urine and perineal swab analysis were processed and uploaded into the MACRO database by the database manager from reports produced by the central laboratory. The NCTU trial team worked closely with sites to ensure data completeness and accuracy.

Trial events

Screening

Potentially eligible participants were identified through direct contact or by searches of electronic records held in each participating NHS trust. Participants were provided with trial information via the ALTAR PIS (see the NIHR Journals Library project web page – URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/138821/#/) and consent was taken prior to randomisation (see the NIHR Journals Library project web page – URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/138821/#/). All patients approached were recorded on site-specific screening logs and, where provided, reasons for non-participation were documented.

Participants experiencing symptomatic UTI were treated with standard antibiotic therapy and not randomised until they were symptom free.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed as close as possible to the date of consent (normally this was immediately after). For consented participants who completed a 3-month washout period, eligibility was rechecked prior to randomisation.

Follow-up

The schedule of events for the ALTAR trial is shown in Table 3.

| Procedures | Screening | Baseline | Treatment phase | Follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | At time of UTI | Monthly checks | 15 months | 18 months | |||

| Informed consent | ✓ | |||||||||

| Demographics | ✓ | ✓a | ||||||||

| Medical history | ✓ | |||||||||

| Physical examination | ✓ | |||||||||

| eGFR and LFTs (a sample for DNA analysis will be taken at one of these time points) | ✓ | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| MSU (local lab) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| MSU (central lab) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Perineal swab | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Concomitant medications | ✓ | ✓a | ||||||||

| Eligibility assessment | ✓ | |||||||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | |||||||||

| Dispensing of trial drugs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Compliance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| UTI record | ✓ | |||||||||

| UTI questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Health resource use questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| TSQM | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| AE assessments | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| CRF completion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Data handling and record-keeping

Case report form data were entered by site staff into the trial-specific clinical data management system, MACRO. Participant-completed questionnaires and UTI records, identifiable only by participant identifier, were returned by post to the central NCTU trial office, where they were entered by NCTU staff and stored securely. As per participant consent processes, identifiable data were stored in a separate, password-protected database within NCTU, with access limited to members of the trial team responsible for the preparation and sending of follow-up questionnaires and logging their return. Two reminders, each with an additional copy of the questionnaires, were sent to participants to prompt their return. Central laboratory results of urine and perineal swab analysis were processed and uploaded into the MACRO database by the database manager. Participants were allocated an individual trial number at randomisation and all trial data and laboratory samples were identified by this unique trial number. Essential data will be retained for a period of at least 10 years following close of the trial, in line with the sponsor’s policy and the latest European Directive on GCP (2005/28/EC). 29 Data were handled, digitalised and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 199830 and the General Data Protection Regulation31 (GDPR) from 25 May 2018.

Changes to protocol

Changes made to the protocol during the trial are listed in Table 4.

| Change to protocol | Protocol version | Date |

|---|---|---|

|

1.1 | 7 April 2016 |

|

1.2 | 24 May 2017 |

|

1.3 | 13 Dec 2017 |

|

2.0 | 7 June 2019 |

|

3.0 | 19 Dec 2019 |

Sample size calculation

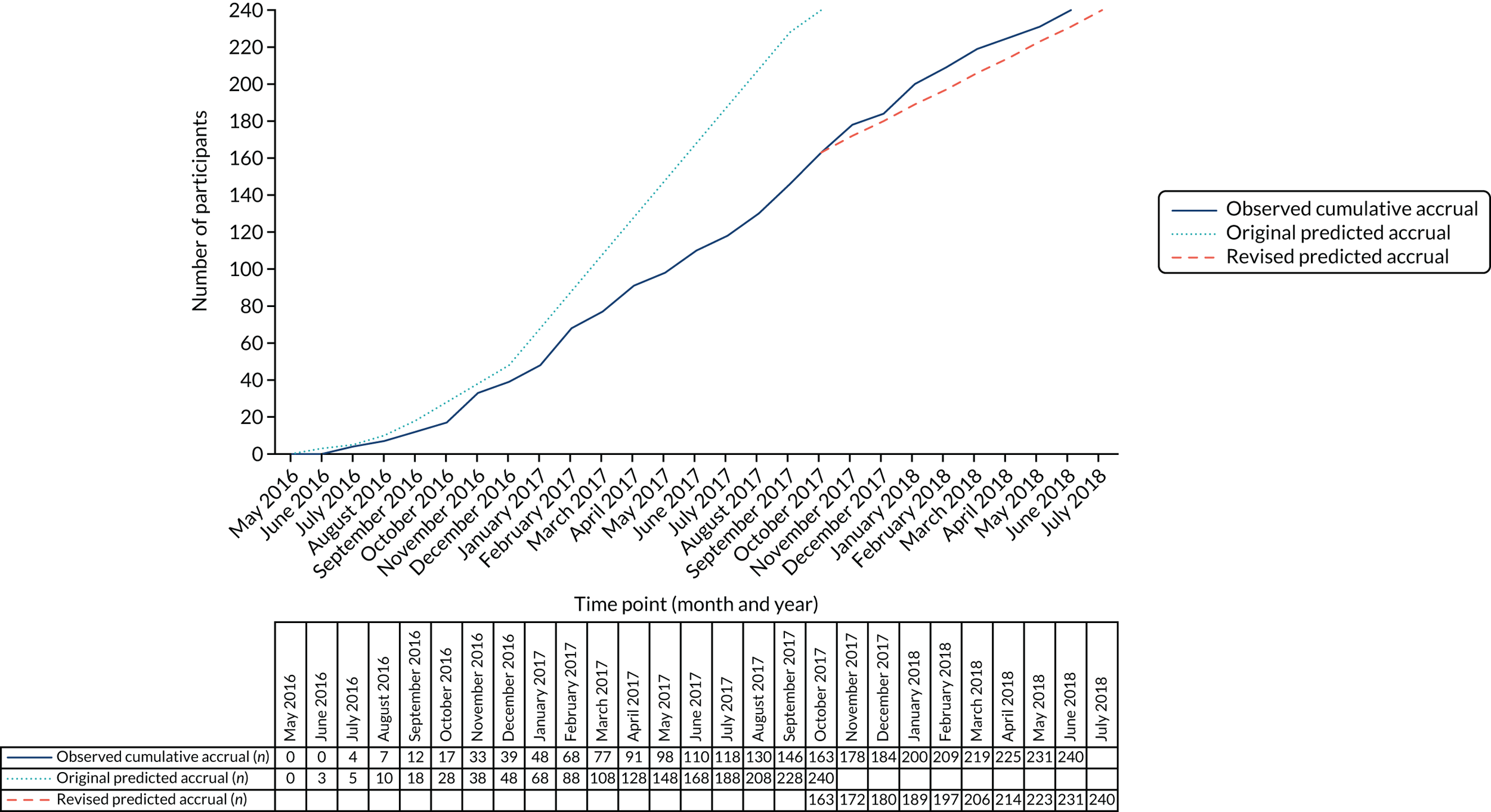

The ALTAR trial had a planned recruitment target of 240 patients, 120 in each of the treatment arms.

A non-inferiority design was chosen, as we believed that an oral urinary antiseptic (methenamine hippurate) would be acceptable to the patient group provided that its effectiveness for UTI prevention was no worse than antibiotic prophylaxis and that the burden of adverse effects was similar or better. There is also the key added potential theoretical benefit of reduced rates of resistant organisms and subsequent collateral harm to the individual and community.

Semistructured interviews with a patient panel of 12 women identified that any reduction in UTI episodes, even one per year, would be deemed worthwhile. Therefore, the minimum clinically important difference between the treatment arms of one UTI per 12 months was set as our strict, non-inferiority margin.

Two existing meta-analyses of studies examining prophylactic antibiotics5 and methenamine hippurate14 both quoted a mean relative risk of UTI compared with placebo of 0.15 and 0.24, respectively. Using these values and data from a local audit (Charlotte Cuff, University of Newcastle, Biomedical Sciences Thesis 2014; n = 200) suggesting that the average number of UTI episodes per year in this patient group is 6.5, we estimated that the average number of UTI episodes per year during preventative treatment would be 0.975 in those randomised to antibiotic prophylaxis and 1.56 in those randomised to methenamine hippurate. This equates to an estimated difference in UTI episodes per year between prophylactic antibiotics and methenamine hippurate of around 0.6 episodes (in favour of antibiotics).

The standard deviation (SD) of UTI episodes per year is taken from the placebo groups in the studies included in the Cochrane meta-analyses and was conservatively estimated at 0.9 episodes per year. 5,14

Using a two-sample t-test and assuming an actual difference of 0.6 UTI episodes per year (in favour of treatment with antibiotics) and a SD of 0.9 UTI episodes per year, then two groups of 87 patients would be required to be 90% sure that the lower limit of a one-sided 95% CI (or equivalently a 90% two-sided CI) was above the non-inferiority limit of one. The attrition rate was conservatively estimated at 25%; therefore, the total sample size required was 232, rounded up to 240.

Statistical analysis

A SAP that includes full details of all statistical analyses was finalised and agreed prior to the final database lock and analysis (see the NIHR Journals Library project web page – URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/138821/#/). The statistician responsible for approving the SAP remained blind to treatment allocation until after the final database lock. The main analysis of the primary outcome measure was performed in the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population and contained all randomised participants with an observational period of at least 6 months. Sensitivity analyses were performed in a strict intention-to-treat (ITT) population and a per-protocol population that included all participants achieving at least 90% compliance with any trial preventative treatment. A post hoc sensitivity analysis in a stricter per-protocol population, including all participants achieving at least 90% compliance with their initial randomised trial treatment, was also performed.

Analyses of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTIs in the 6-month follow-up period (12–18 months) was conducted in all participants in active follow-up at 15 or 18 months plus those with data available from health-care record review.

For all analyses, with the exception of AE data, participants were analysed according to their randomised treatment assignment.

Primary outcome

The simple incidence rate of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI episodes over the 12-month treatment period was calculated in each randomised treatment group and reported with a 95% CI calculated using a resampling (bootstrap) procedure with 5000 replicates. The difference between groups (methenamine hippurate vs. antibiotic) was estimated along with a 90% CI calculated using the same resampling (bootstrap) procedure with 5000 replicates. Provided that the upper 90% confidence limit was lower than the inferiority limit of one, non-inferiority of treatment with antiseptic (methenamine hippurate) compared with antibiotic would be inferred. Analyses were repeated using the incident density rate.

The relative difference between treatment groups in the incidence of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI episodes over the 12-month treatment period was estimated using a negative binomial regression model with differences between centre included as a random effect and prior annual UTI frequency (< four vs. ≥ four episodes) and menopausal status (premenopausal vs. menopausal/postmenopausal) included as fixed effects. Poisson and zero-inflated negative binomial models were also considered, with model fit compared using Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and by graphical examination of the observed and predicted number of events using each model. An estimate of the incidence rate ratio (IRR) was obtained and presented with a 95% CI, calculated using a robust/sandwich estimator of variance. An IRR > 1 would indicate an increased risk of UTI in the methenamine hippurate arm compared with the antibiotic prophylaxis arm.

A binary indicator of at least one episode of symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI was analysed using a logistic regression model, adjusted for centre, prior UTI frequency and menopausal status, as above. The odds ratio (OR) was reported with 95% CI. Note that in all cases mixed-effects logistic regression models were not preferred to the unadjusted model, as assessed using AIC and BIC.

Secondary outcomes

Symptomatic antibiotic-treated urinary tract infection in the 6-month follow-up period

This outcome was analysed using the same approach as for the primary outcome measure but with 95% CI reported for the difference in the incidence rate between groups. For analyses in the 6-month follow-up period a Poisson model was used rather than a negative binomial model, as this provided a better model fit.

Microbiologically confirmed symptomatic antibiotic-treated urinary tract infection

This outcome was analysed using the same approach as for the primary outcome measure but with 95% CI reported for the difference in the incidence rate between groups.

Antibiotic use

The number and proportion of participants receiving prophylactic antibiotic, therapeutic antibiotics for UTI and therapeutic antibiotics for other reasons was reported. Of those receiving treatment, the total duration (in days) was summarised descriptively. The rate of antibiotic use (number of days of treatment over the observational period) was calculated for all participants and summarised descriptively.

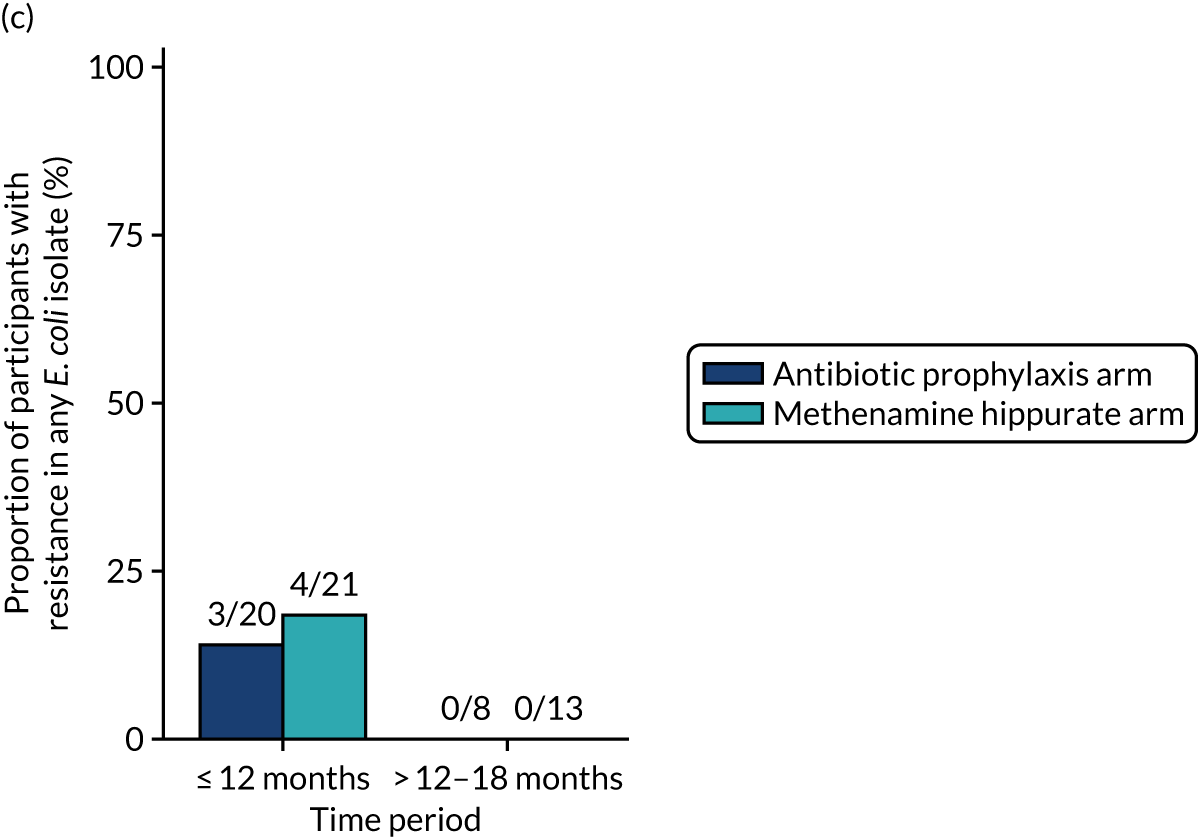

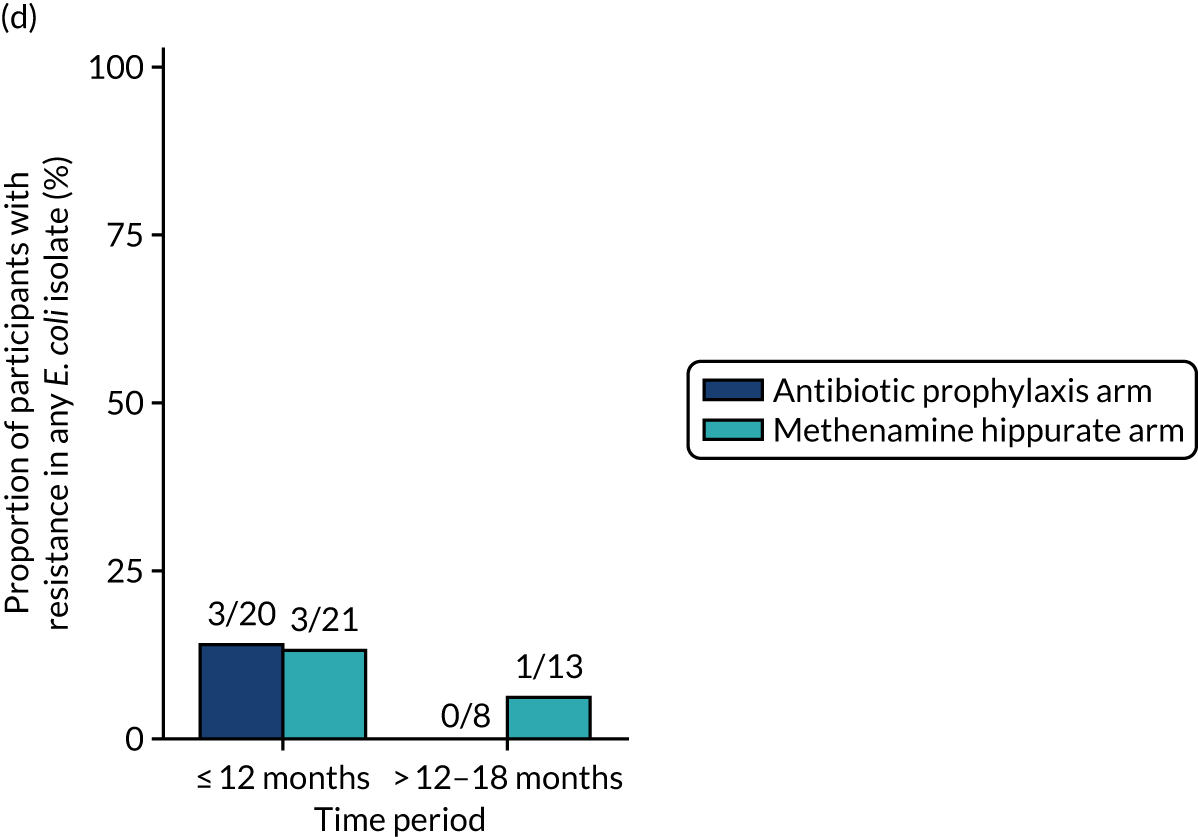

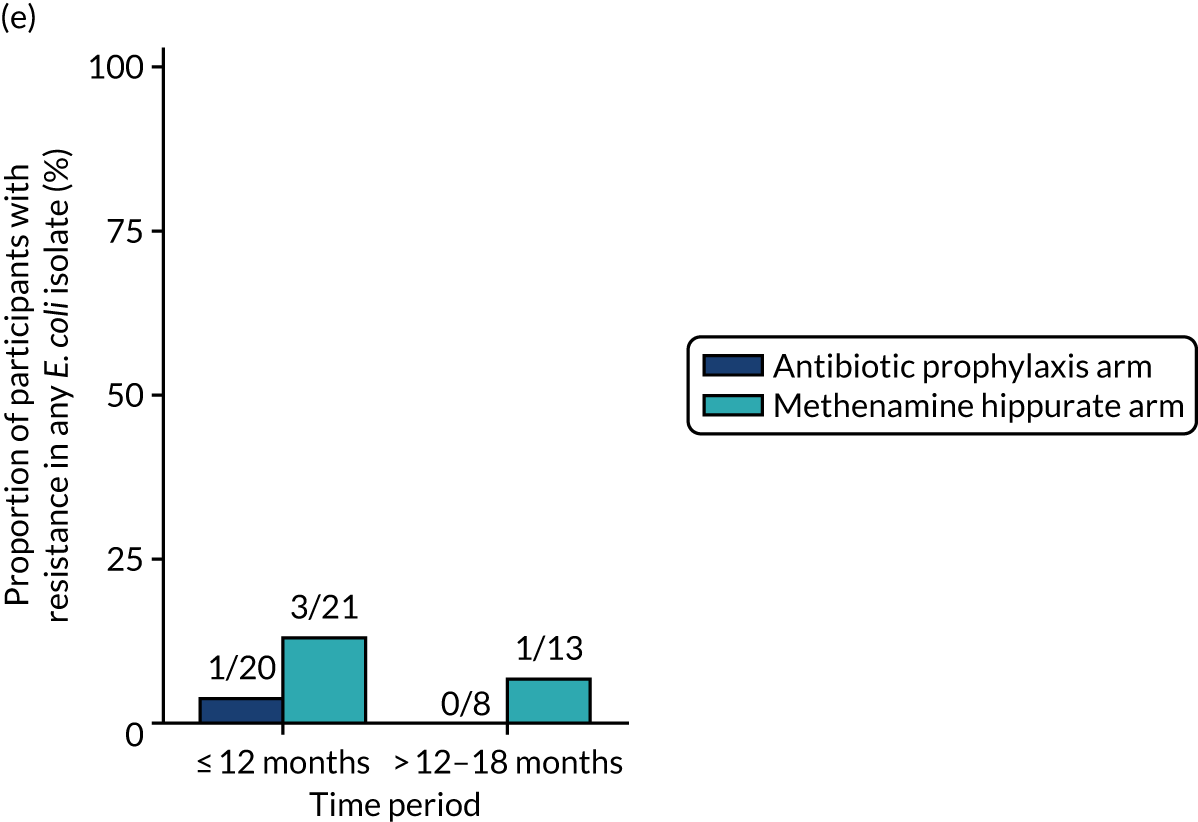

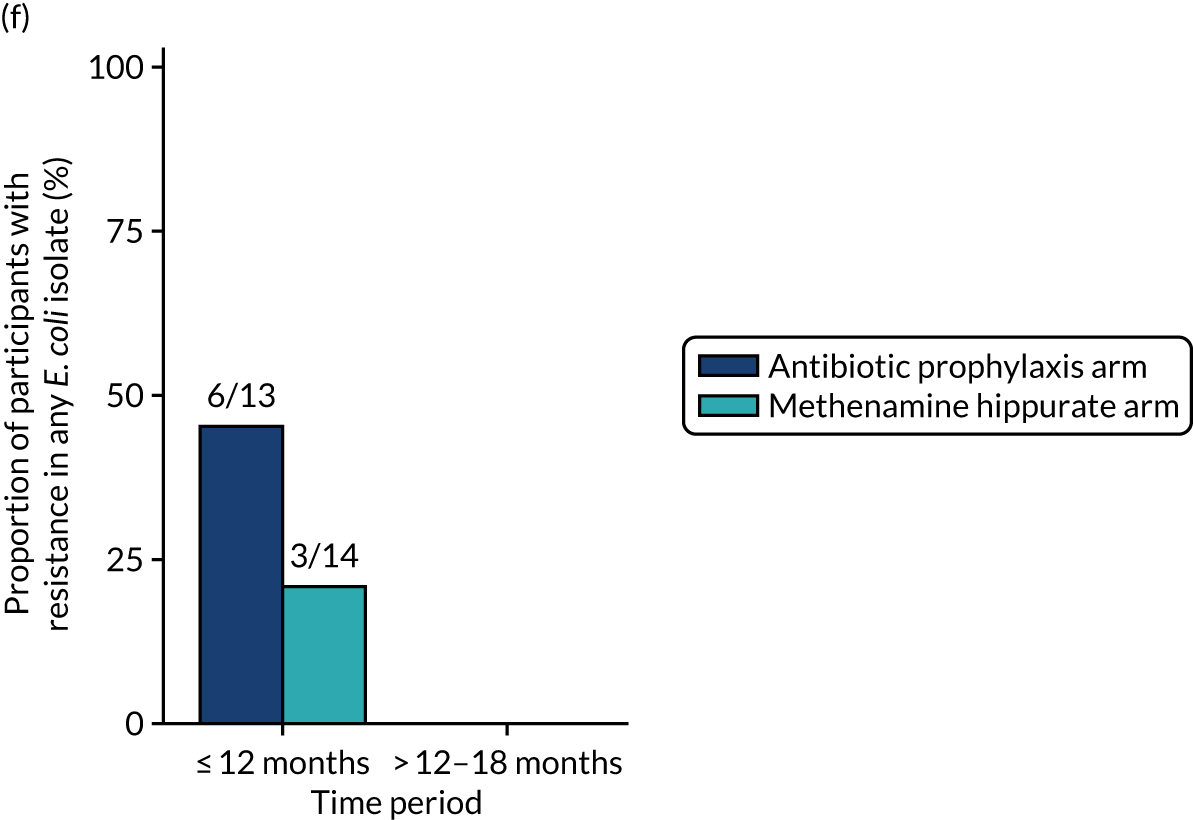

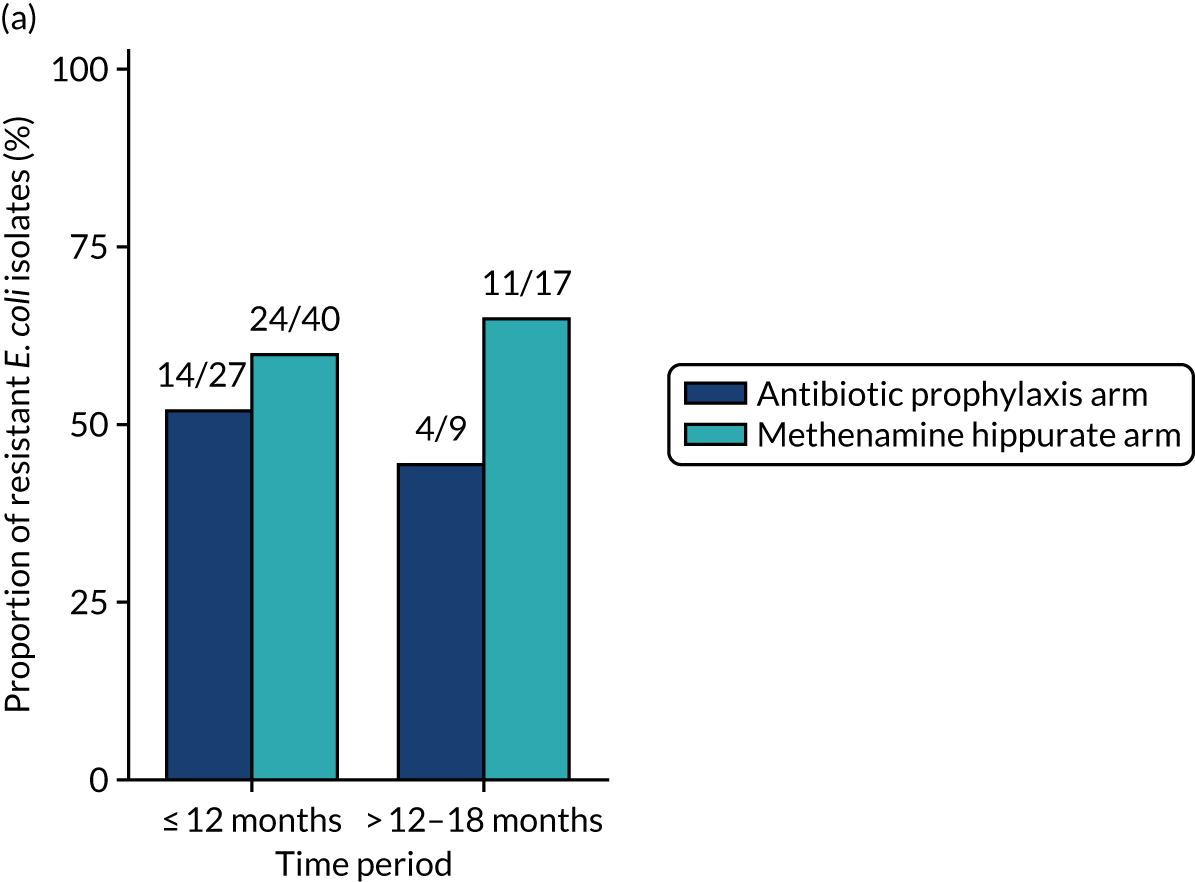

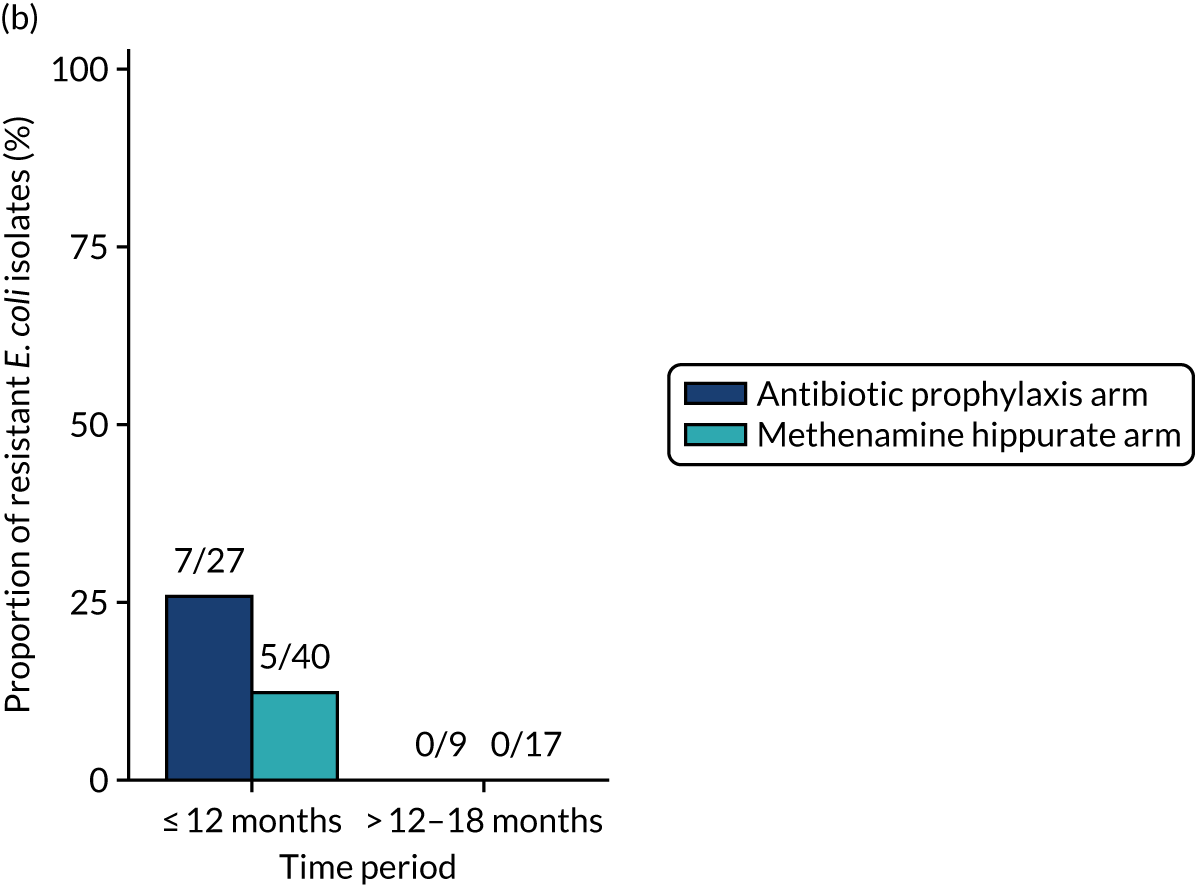

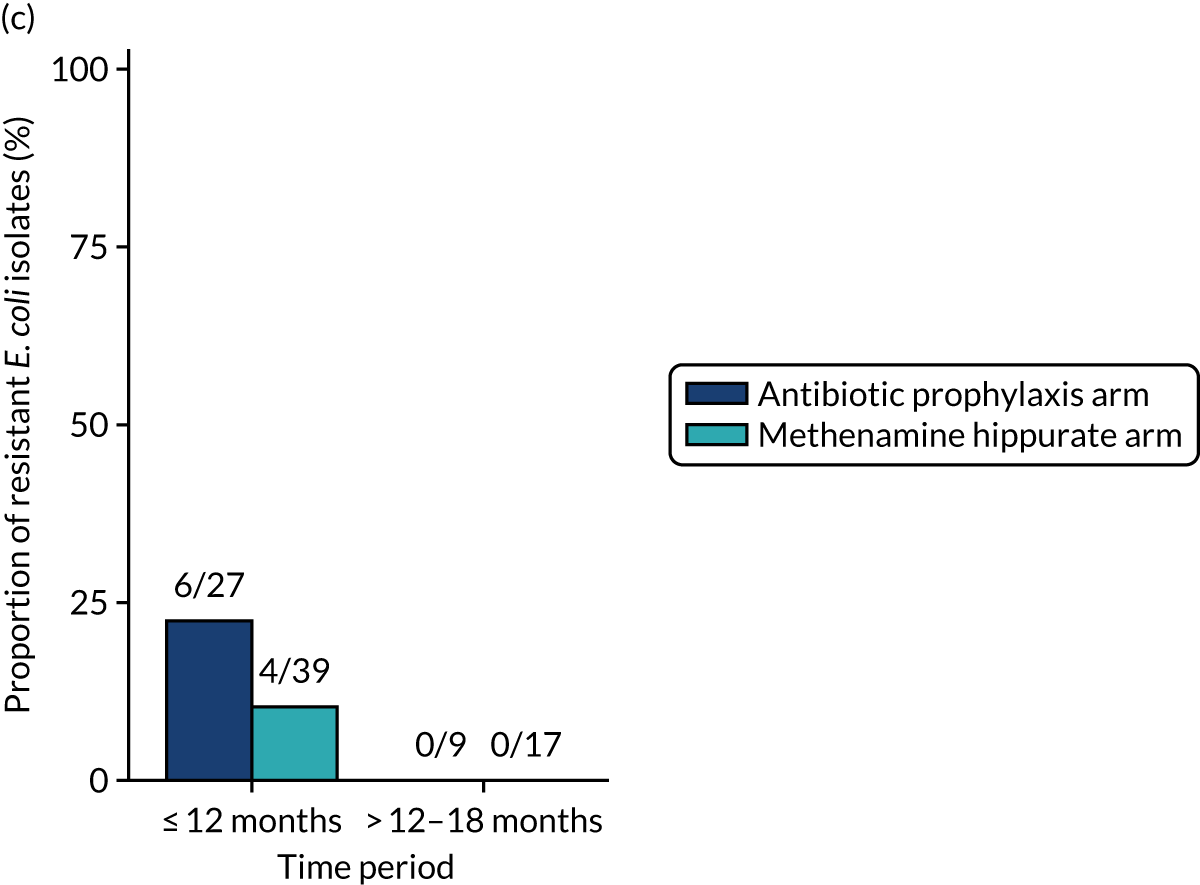

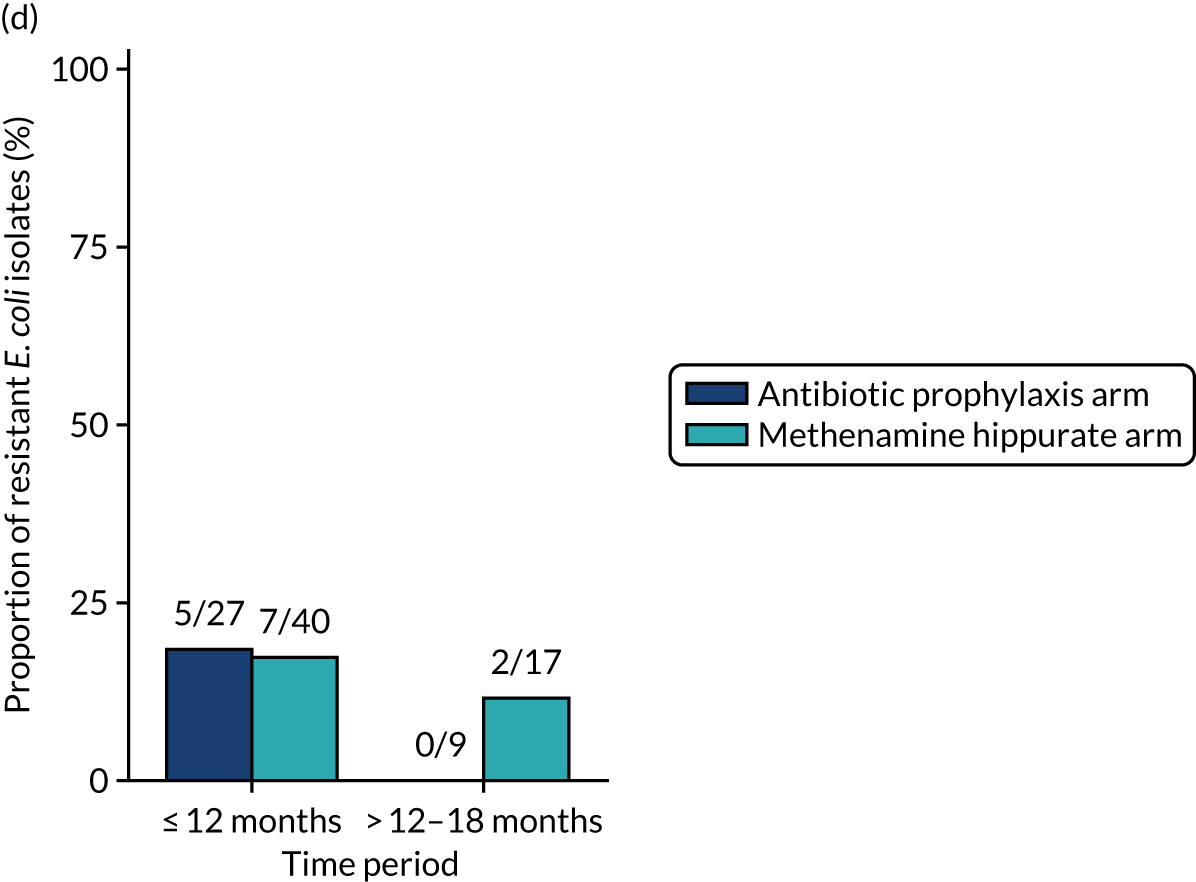

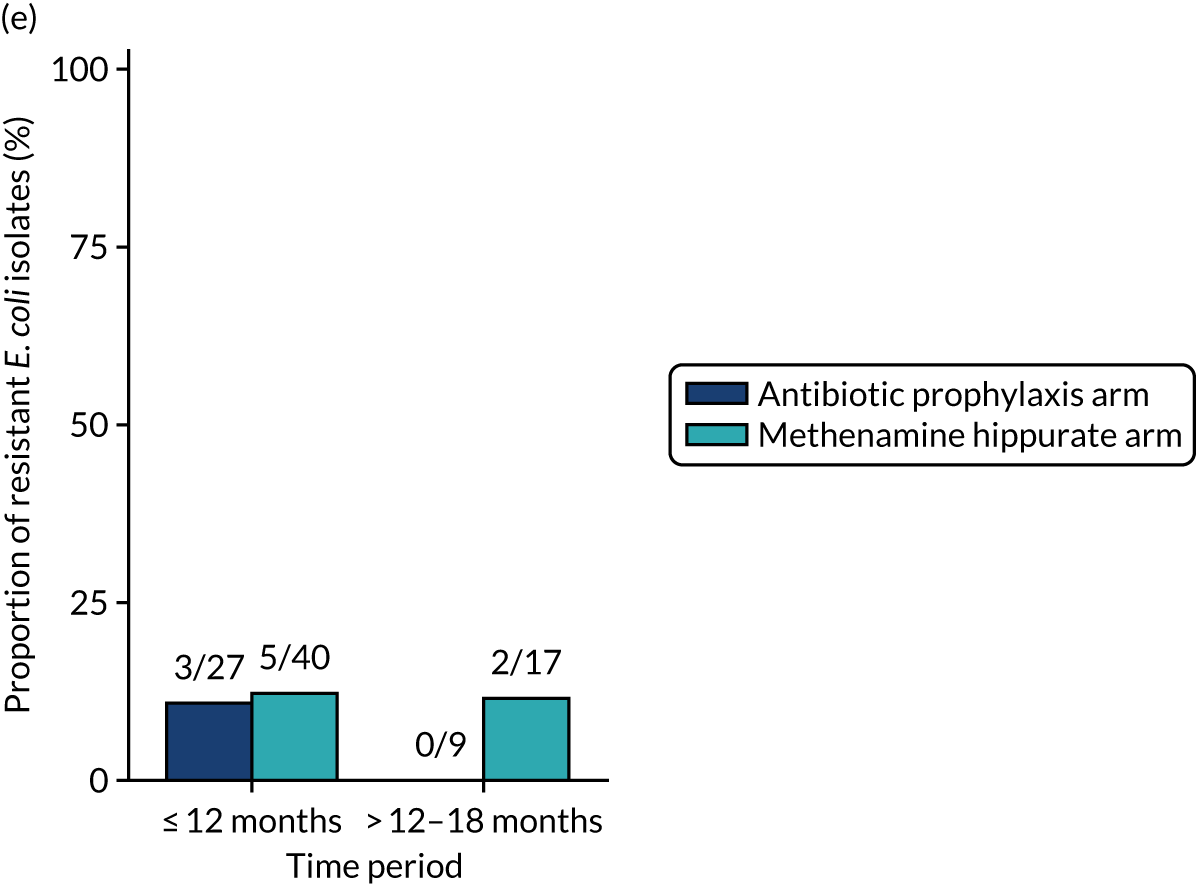

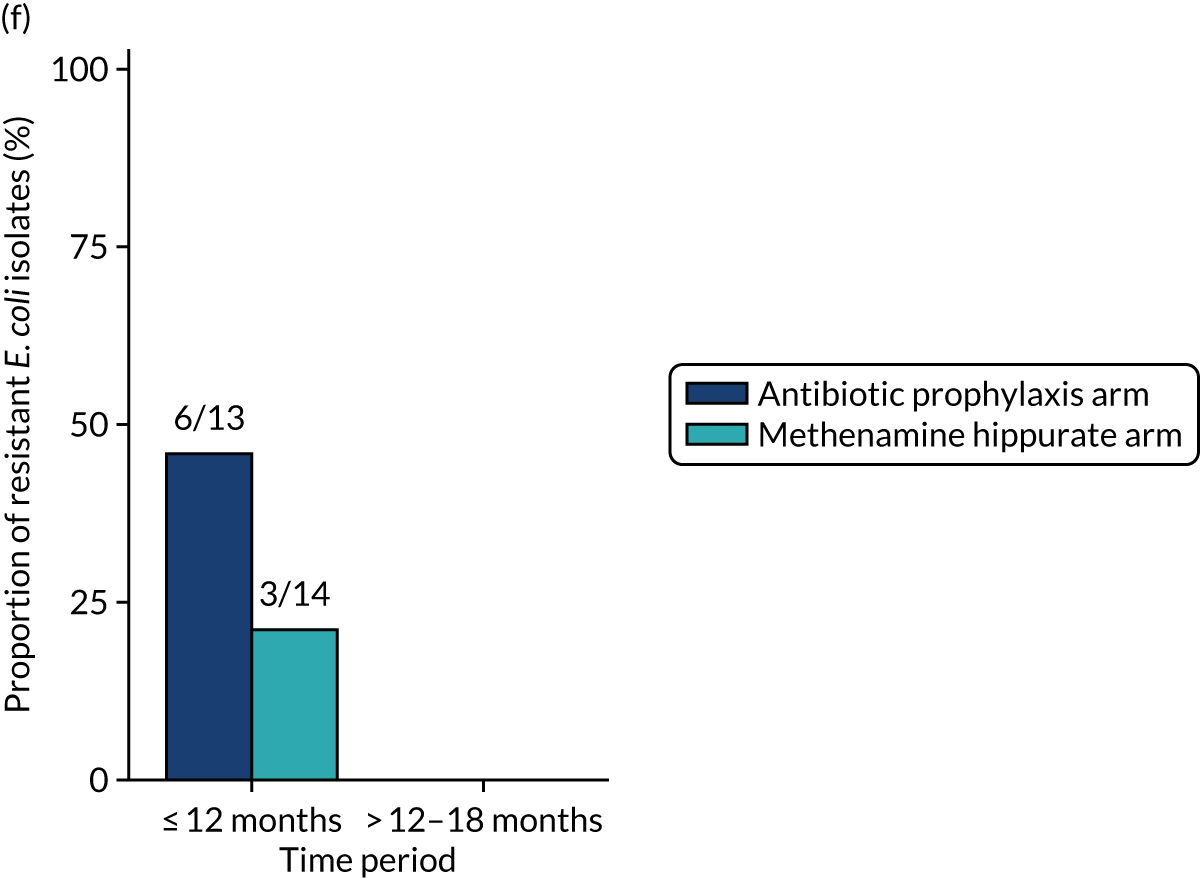

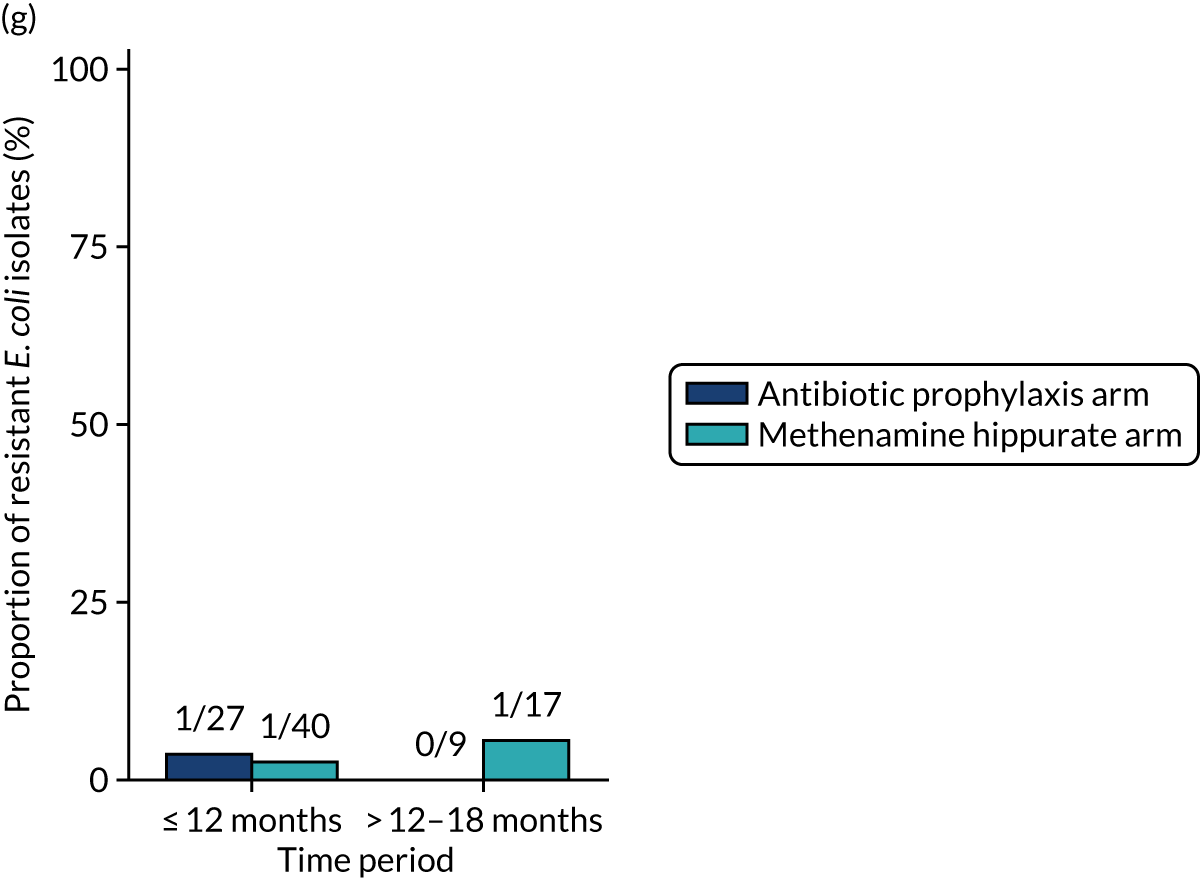

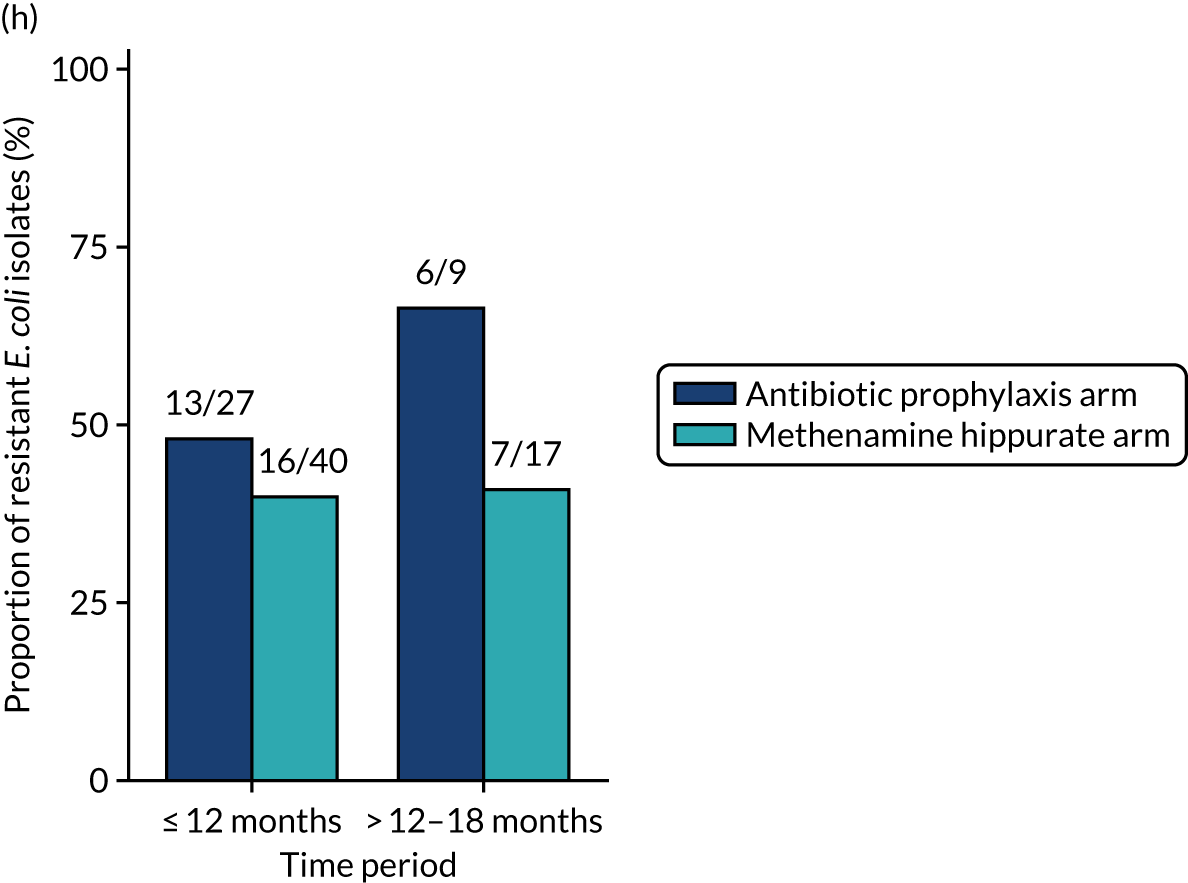

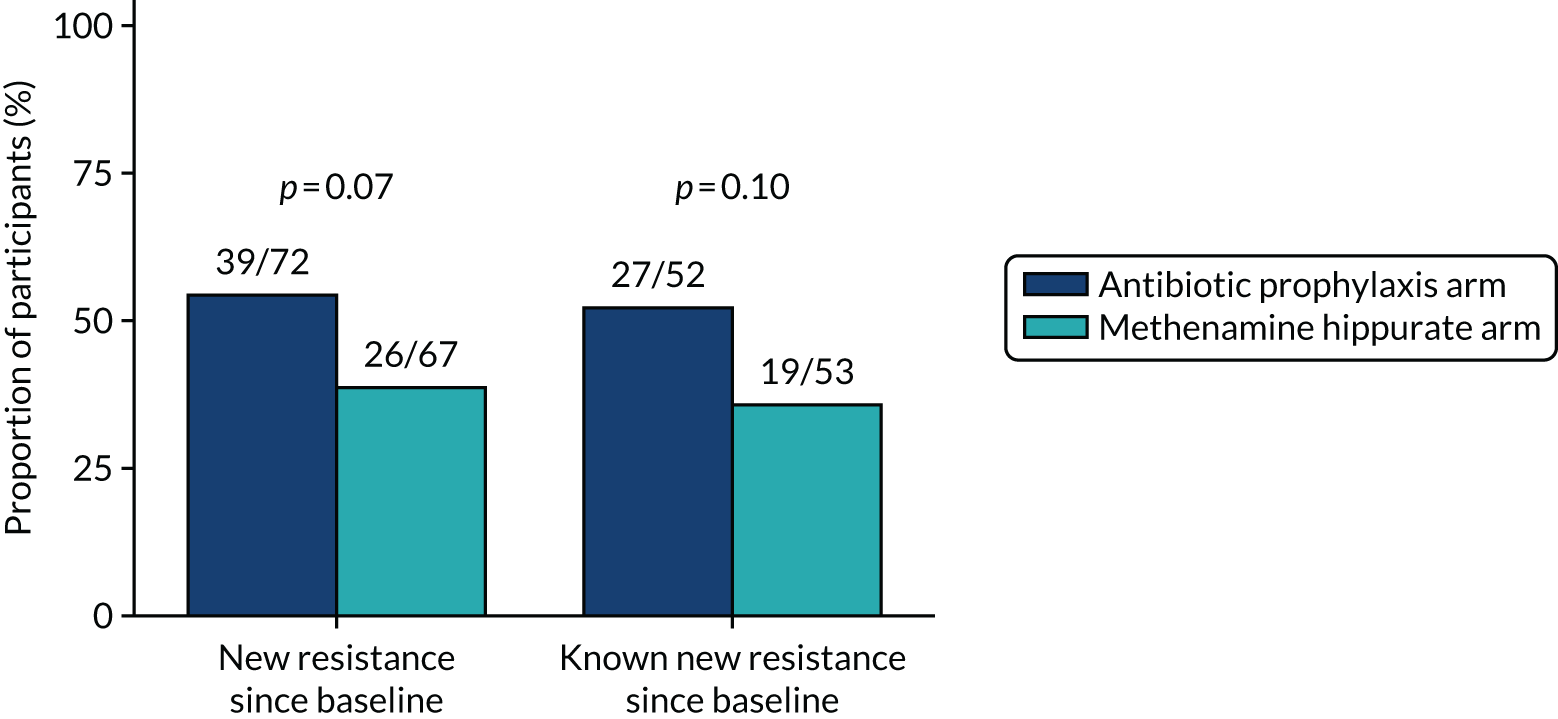

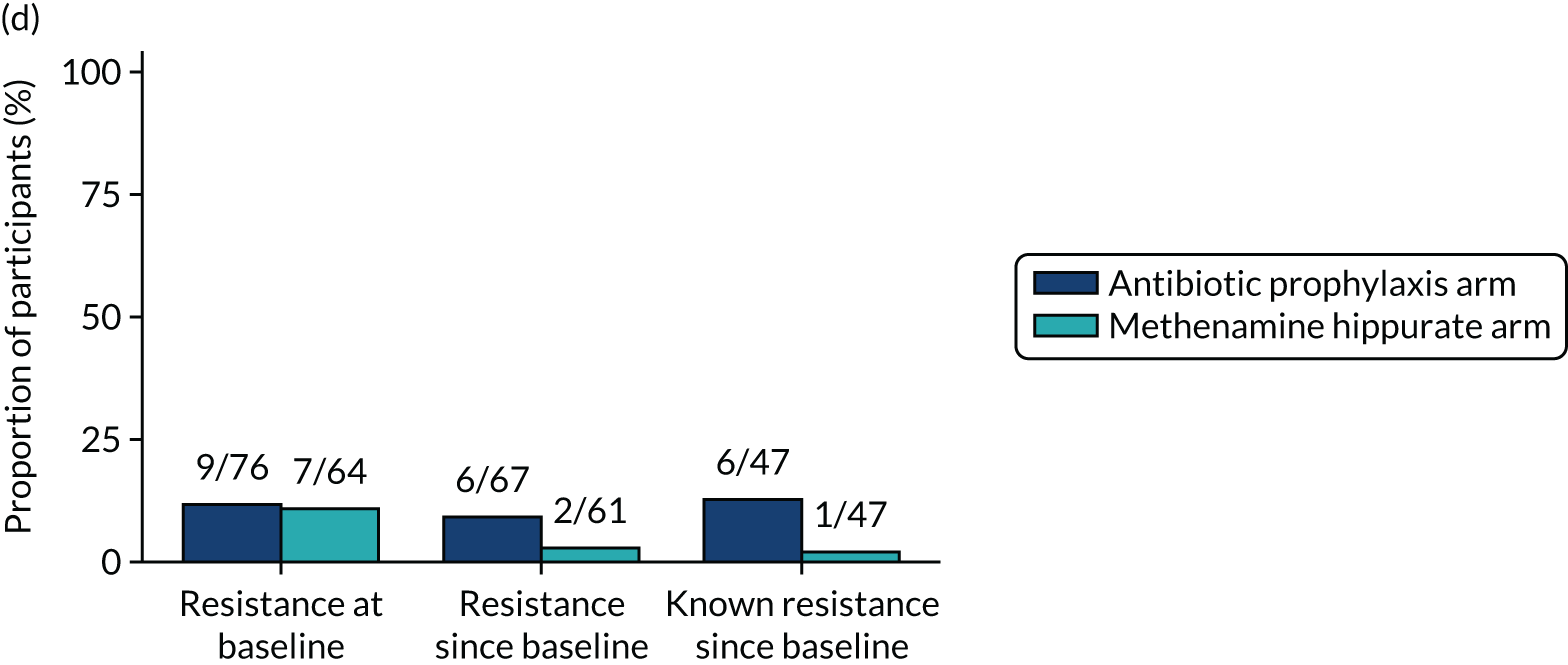

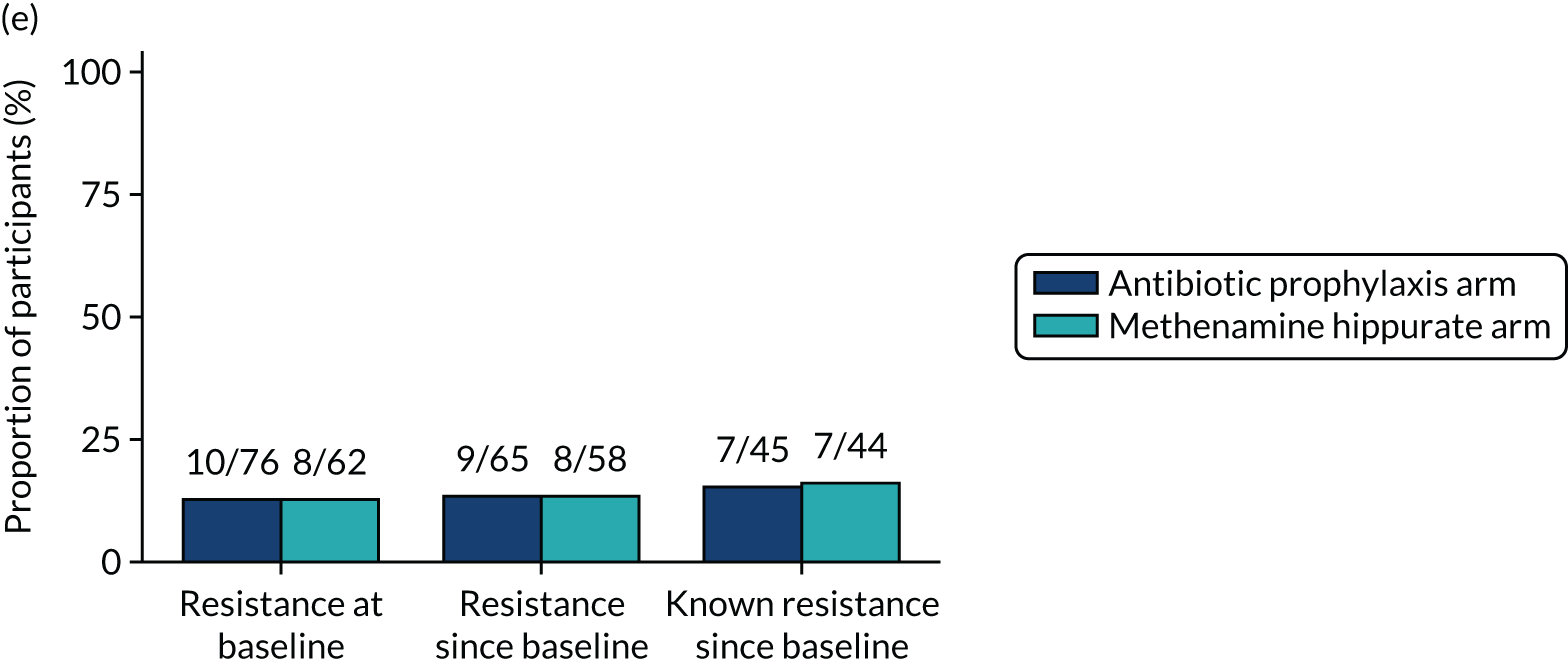

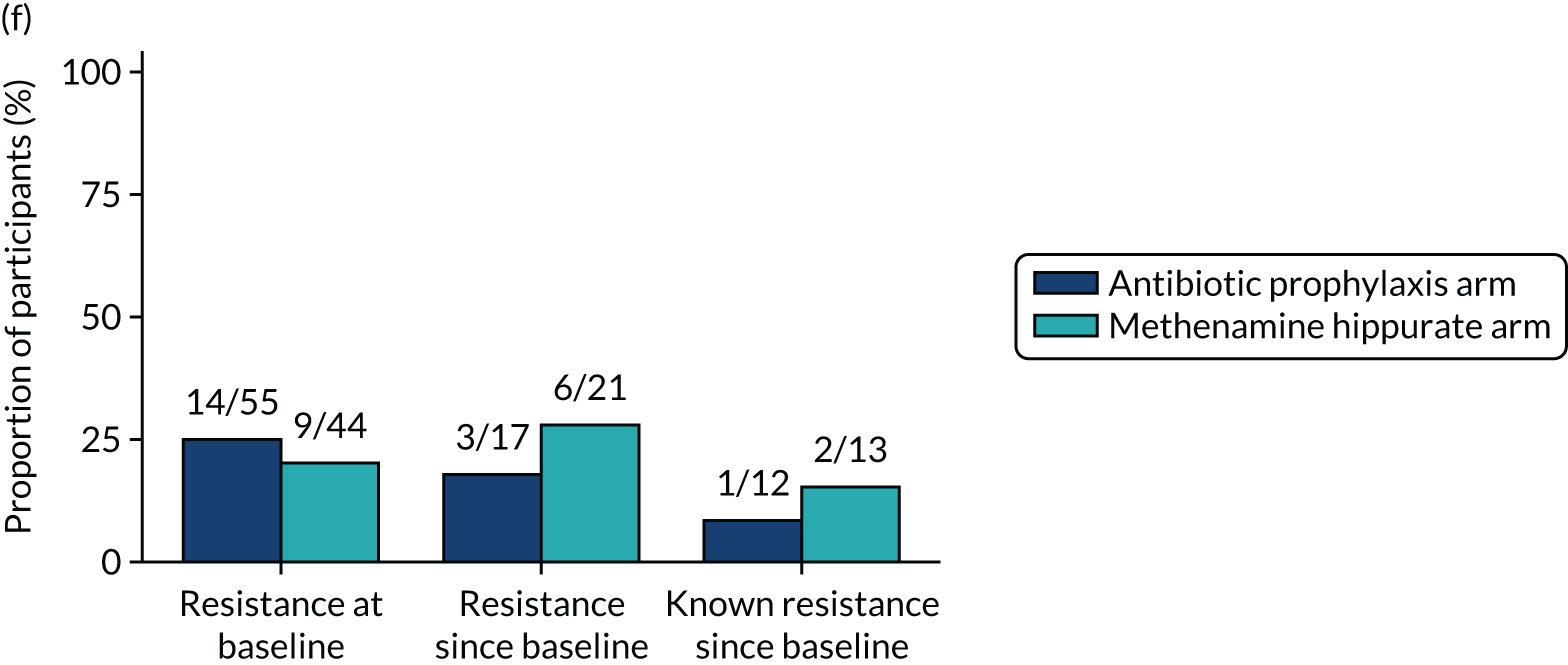

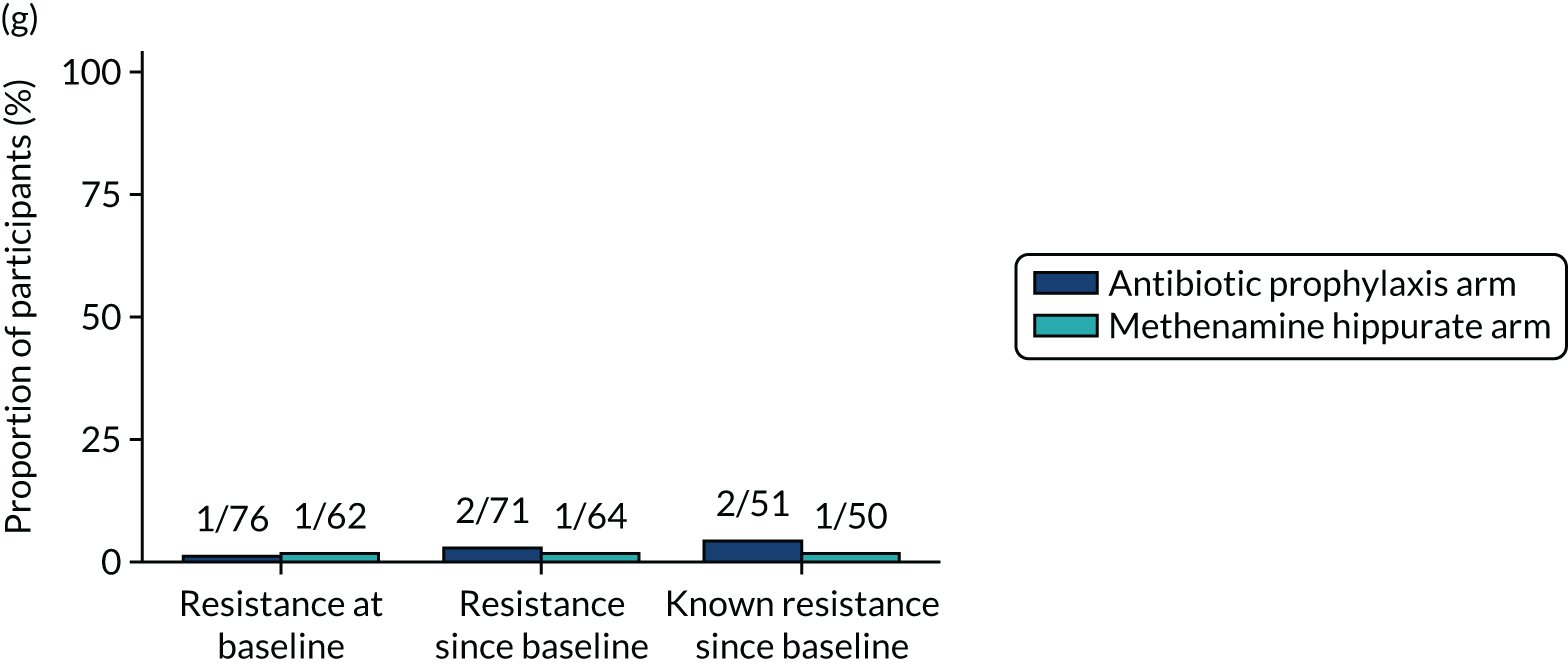

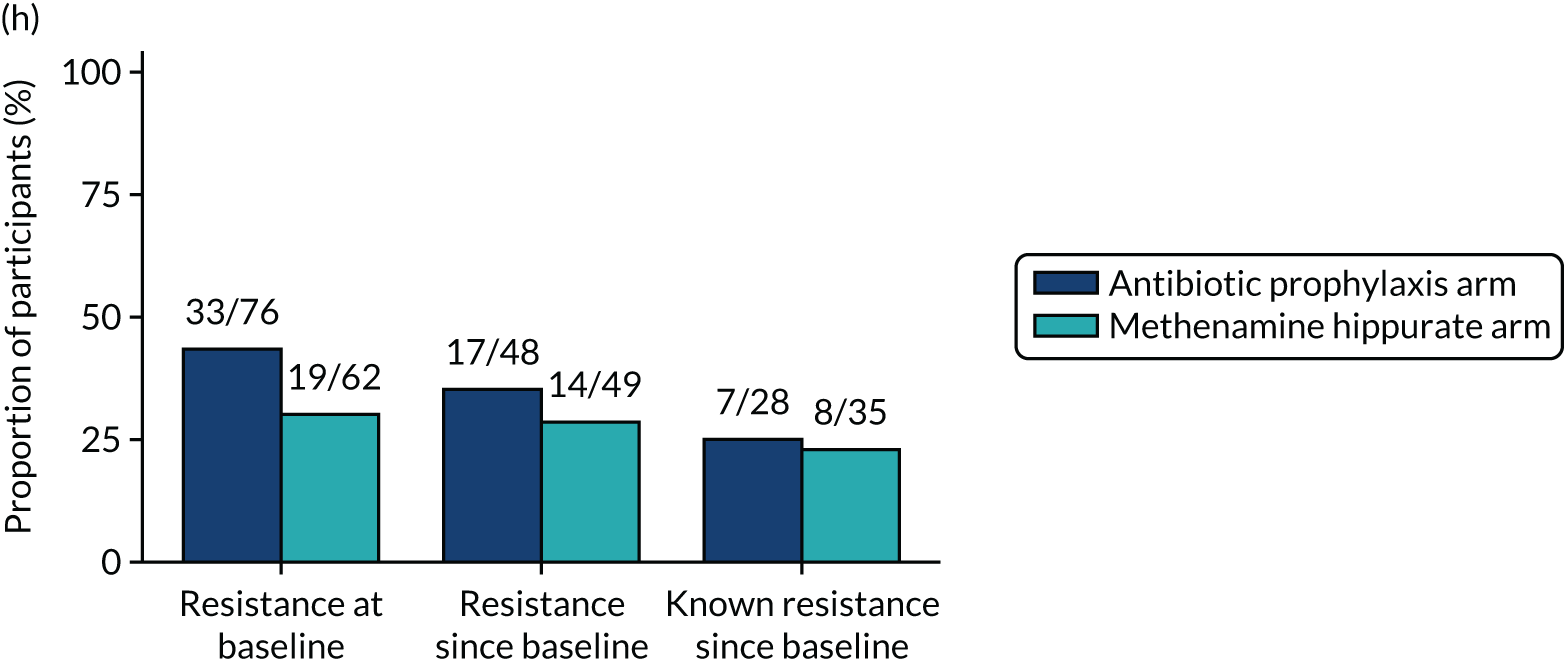

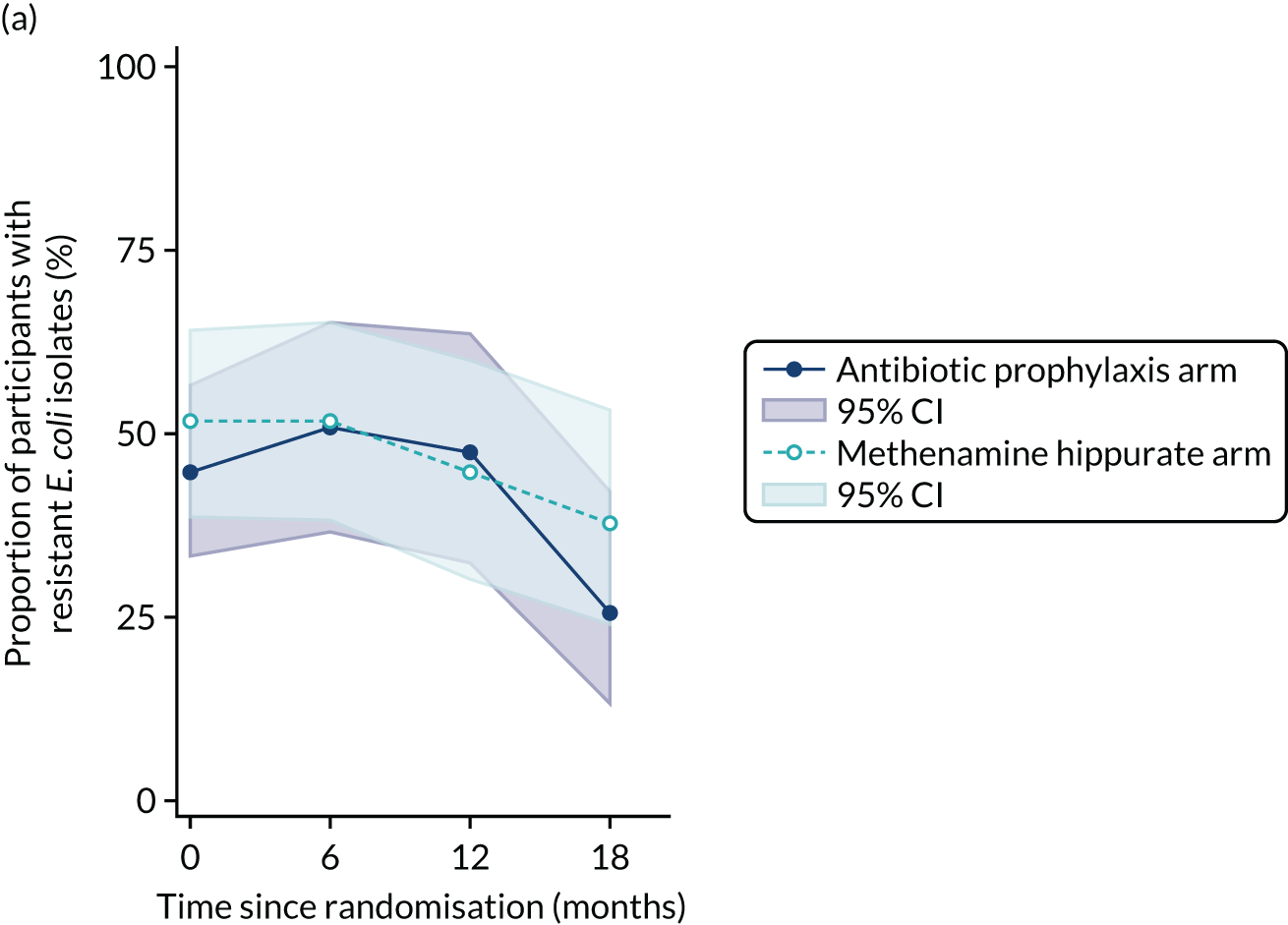

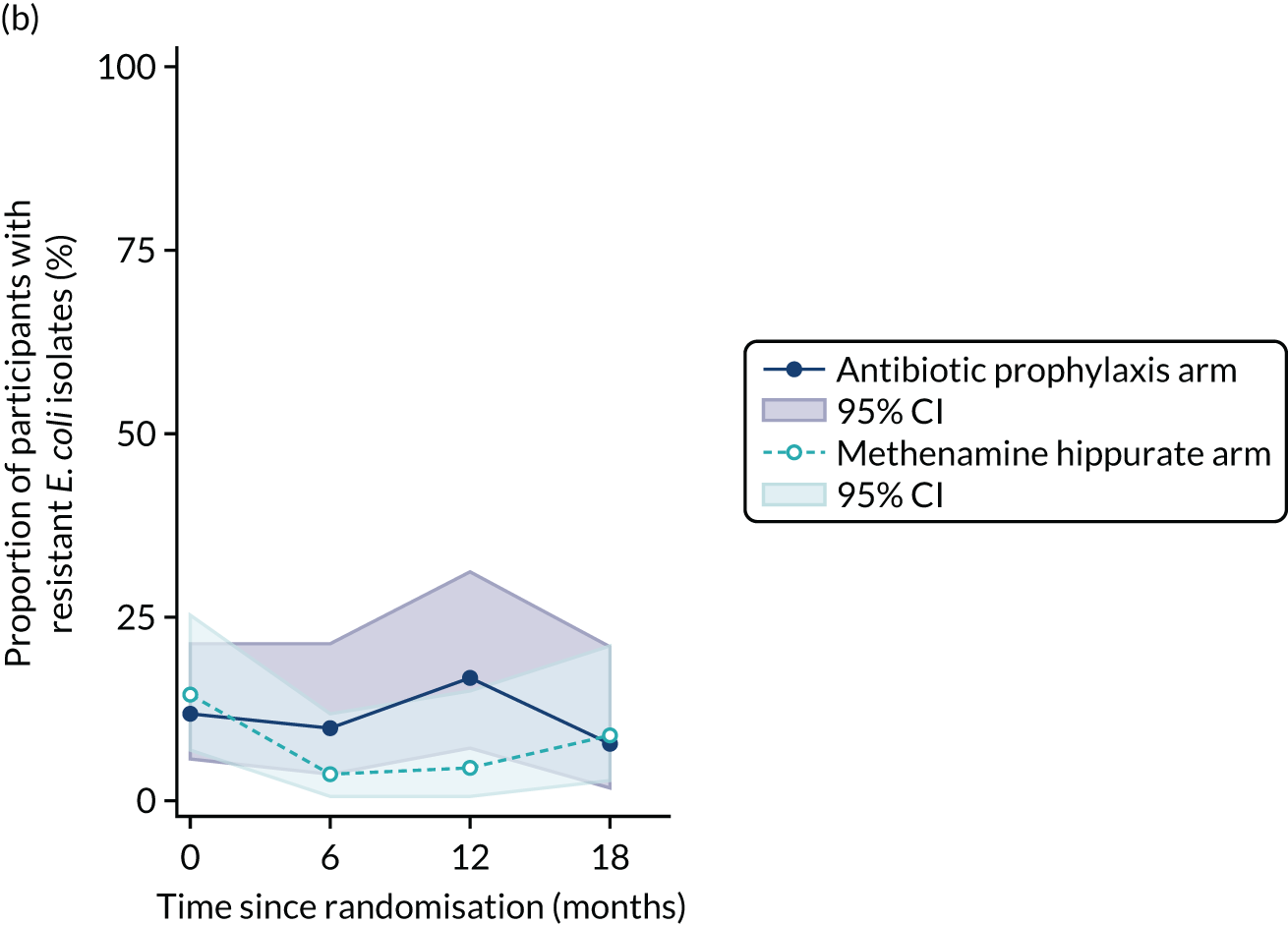

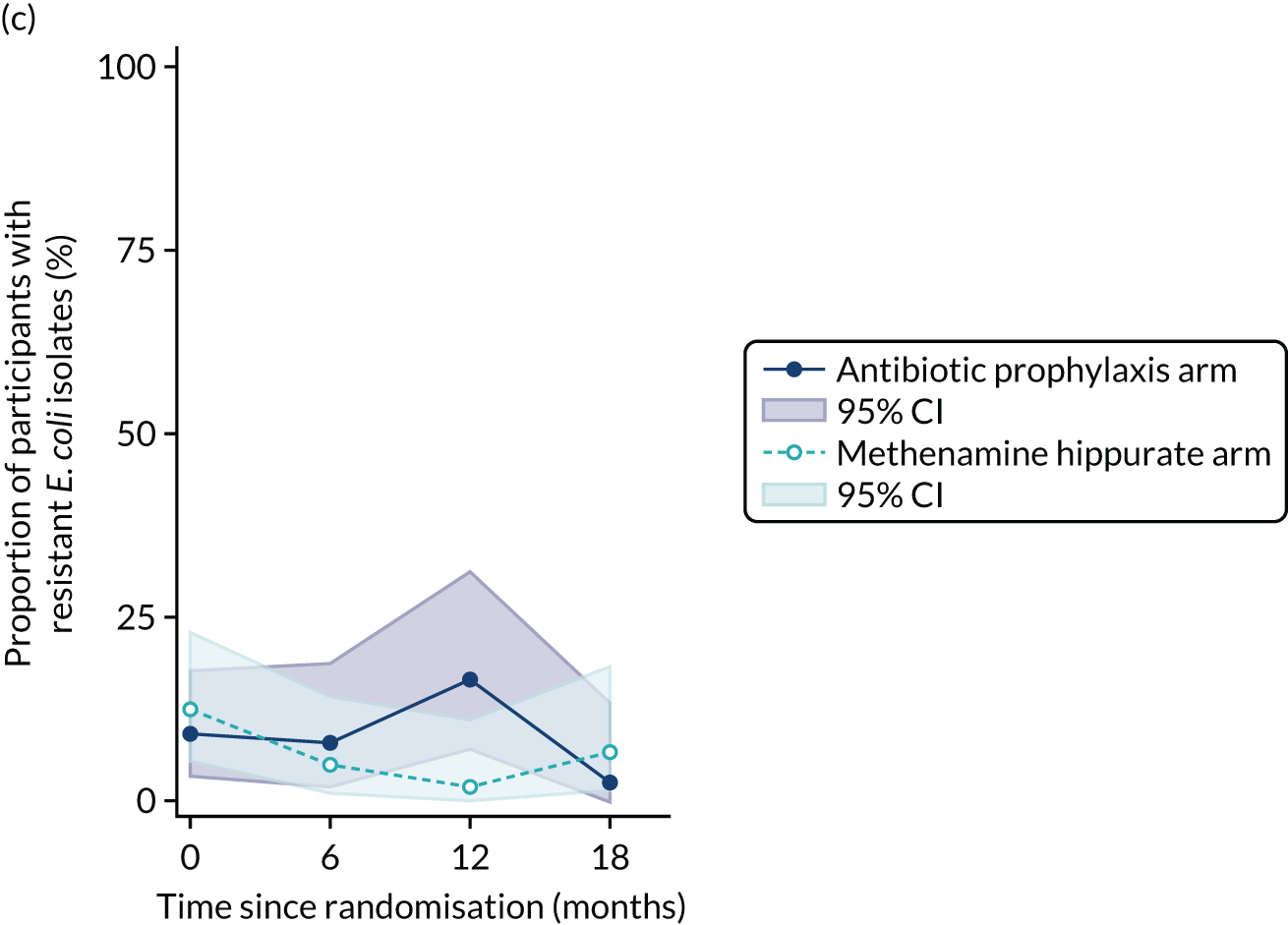

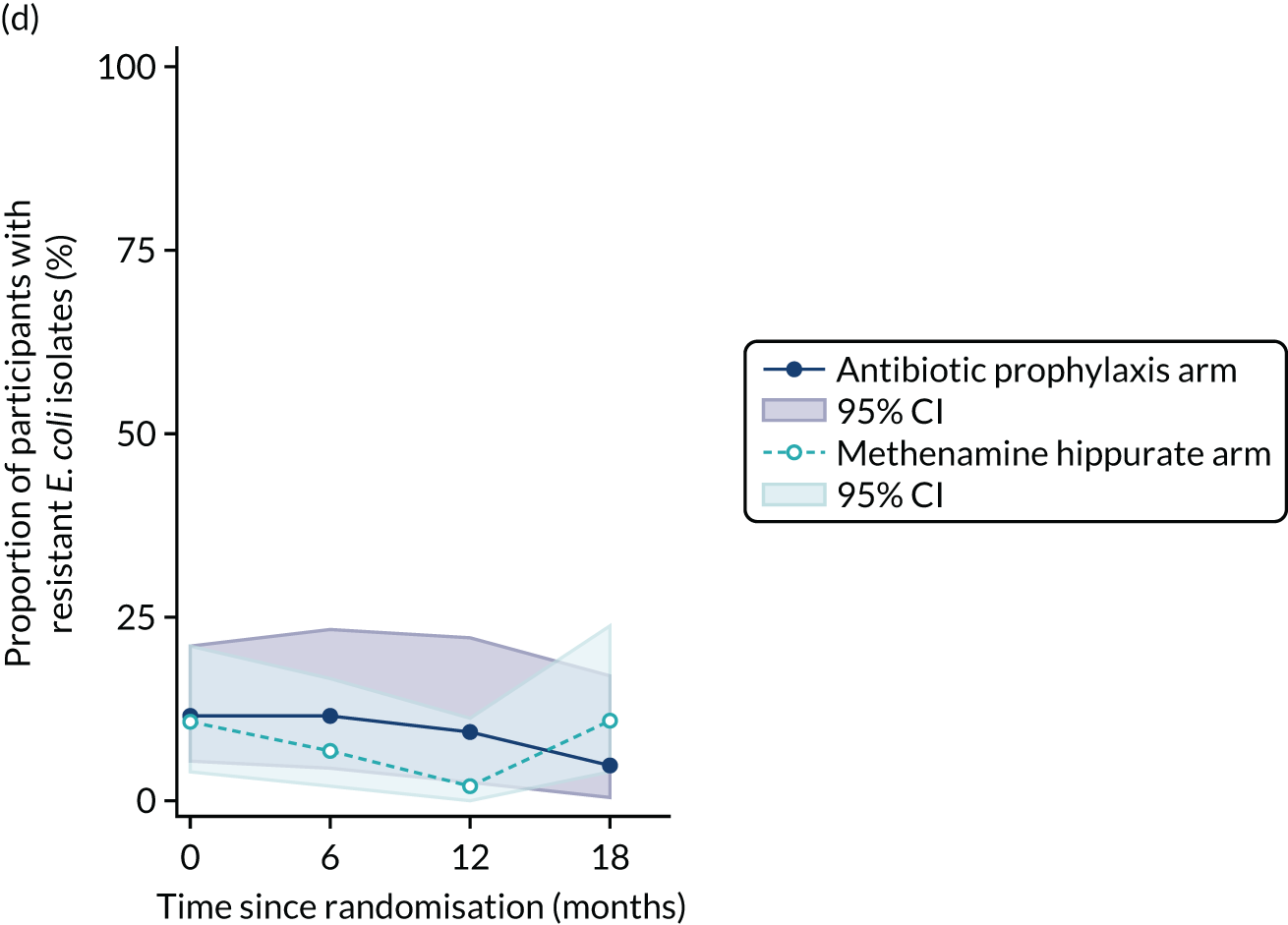

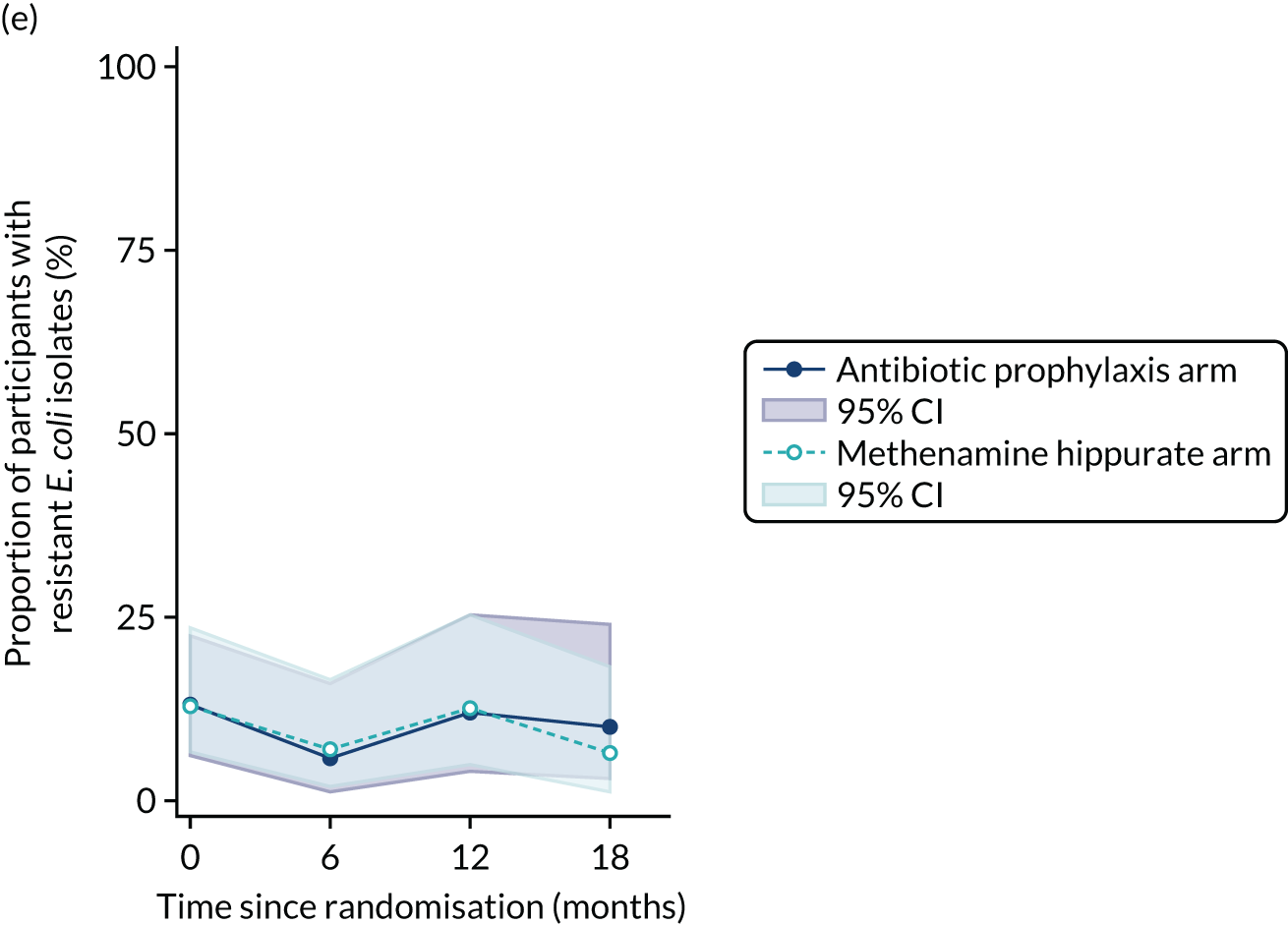

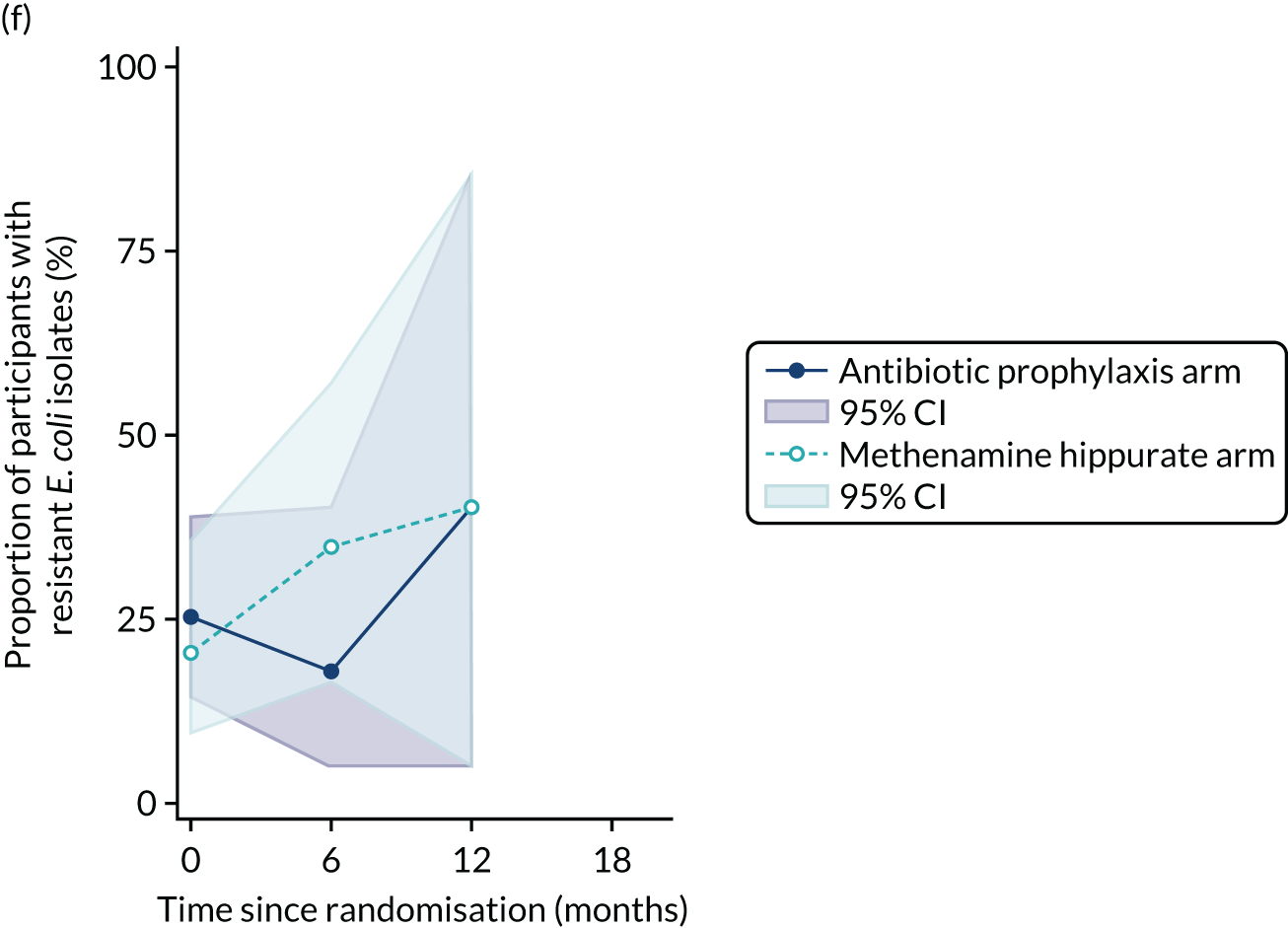

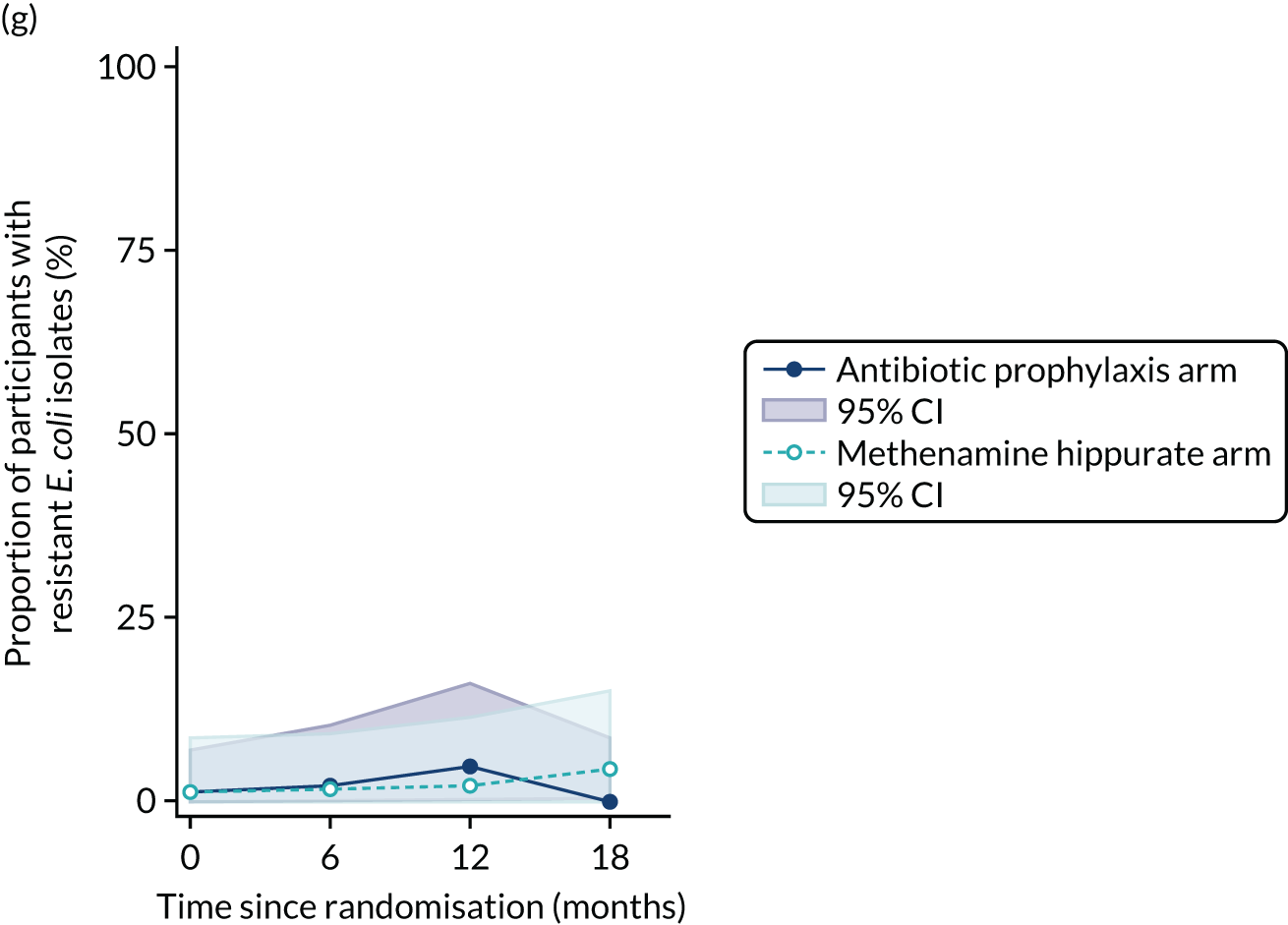

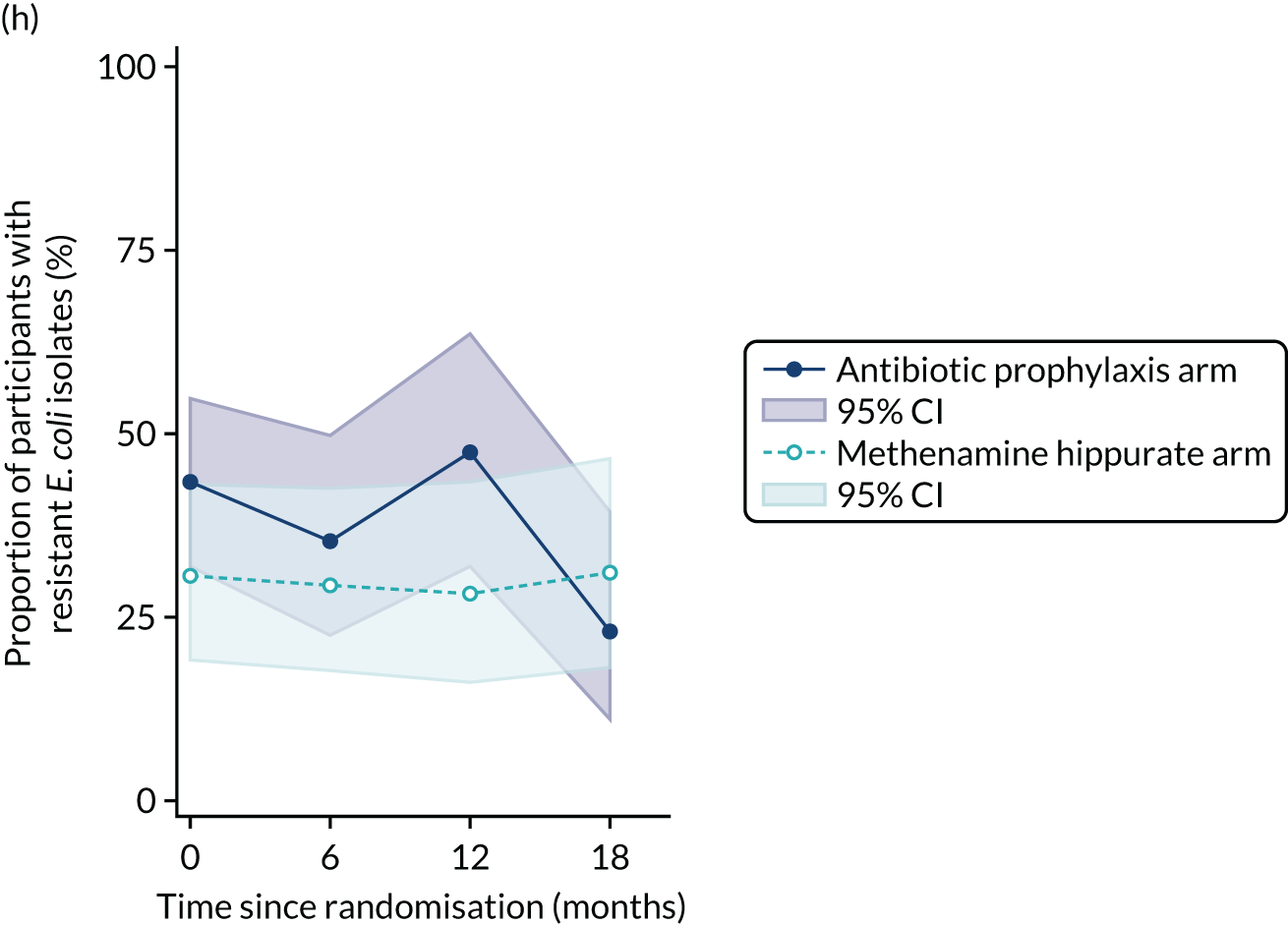

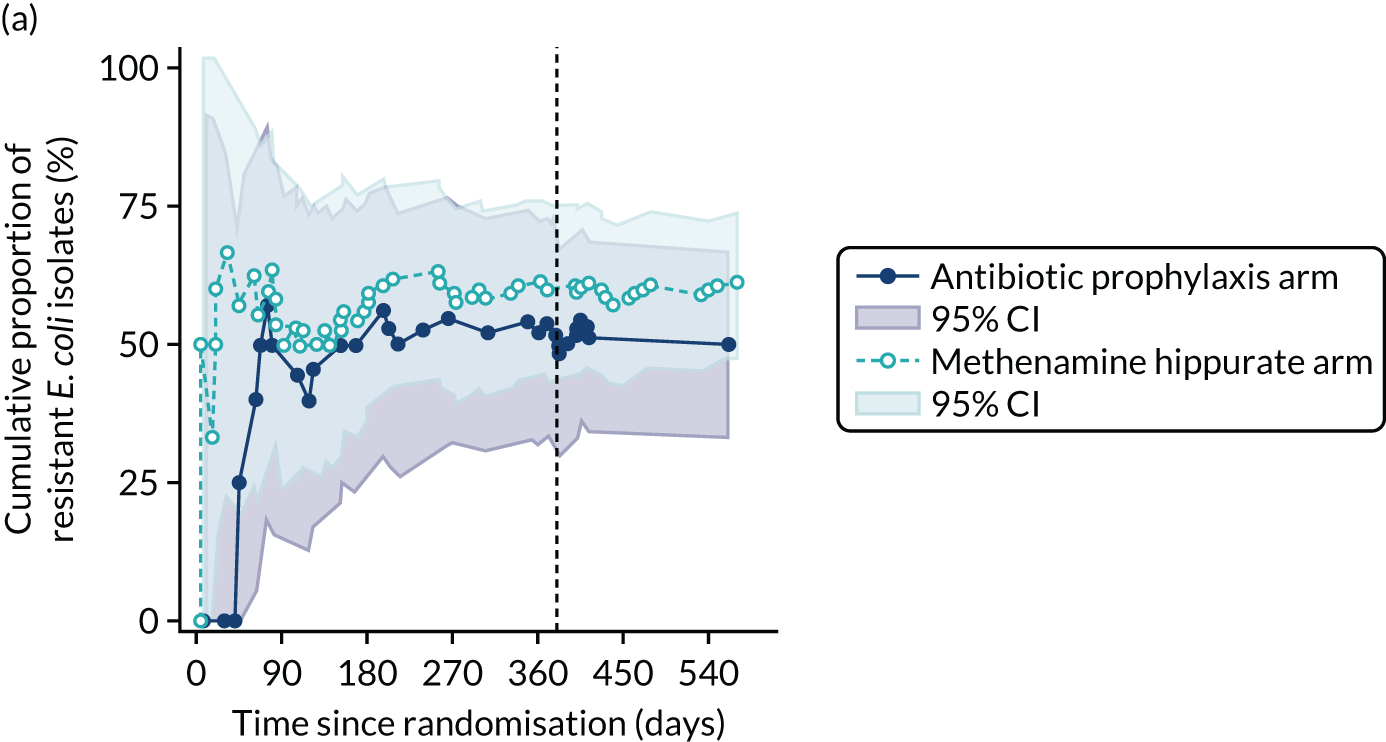

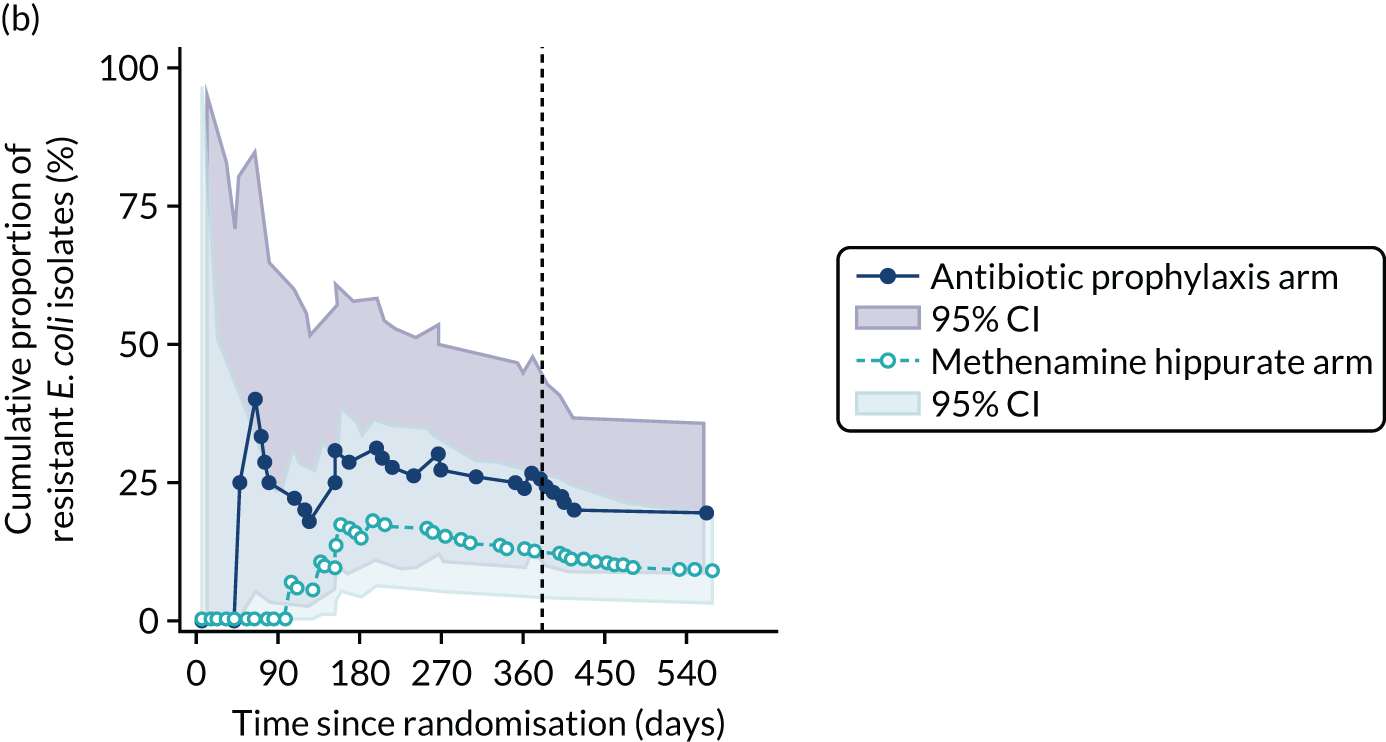

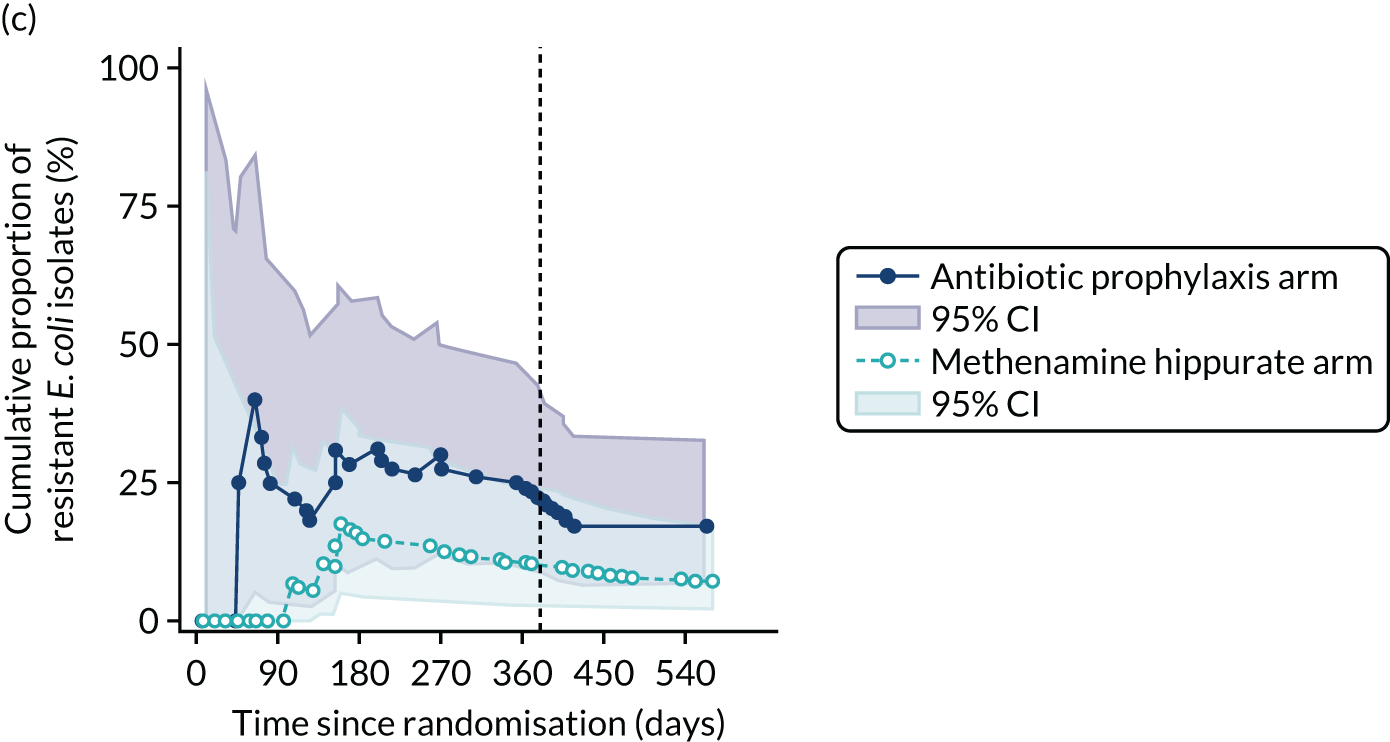

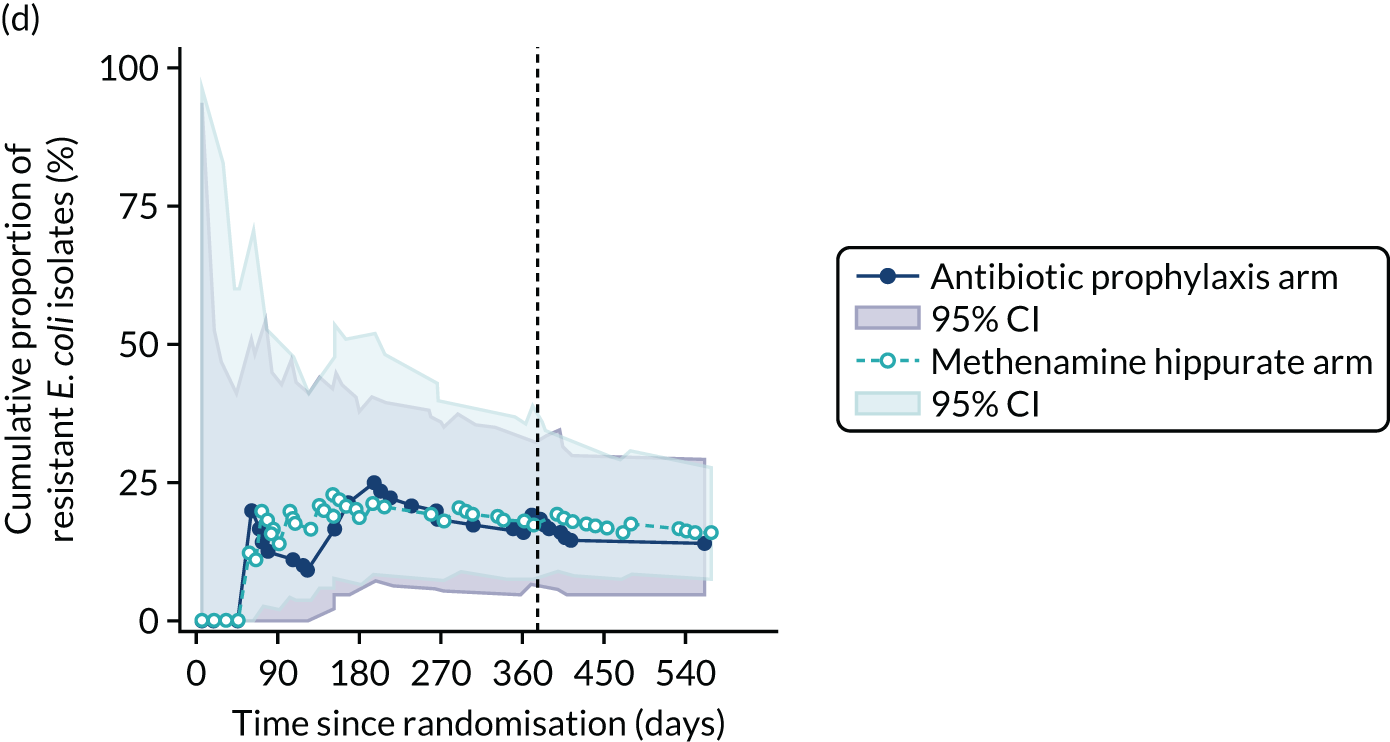

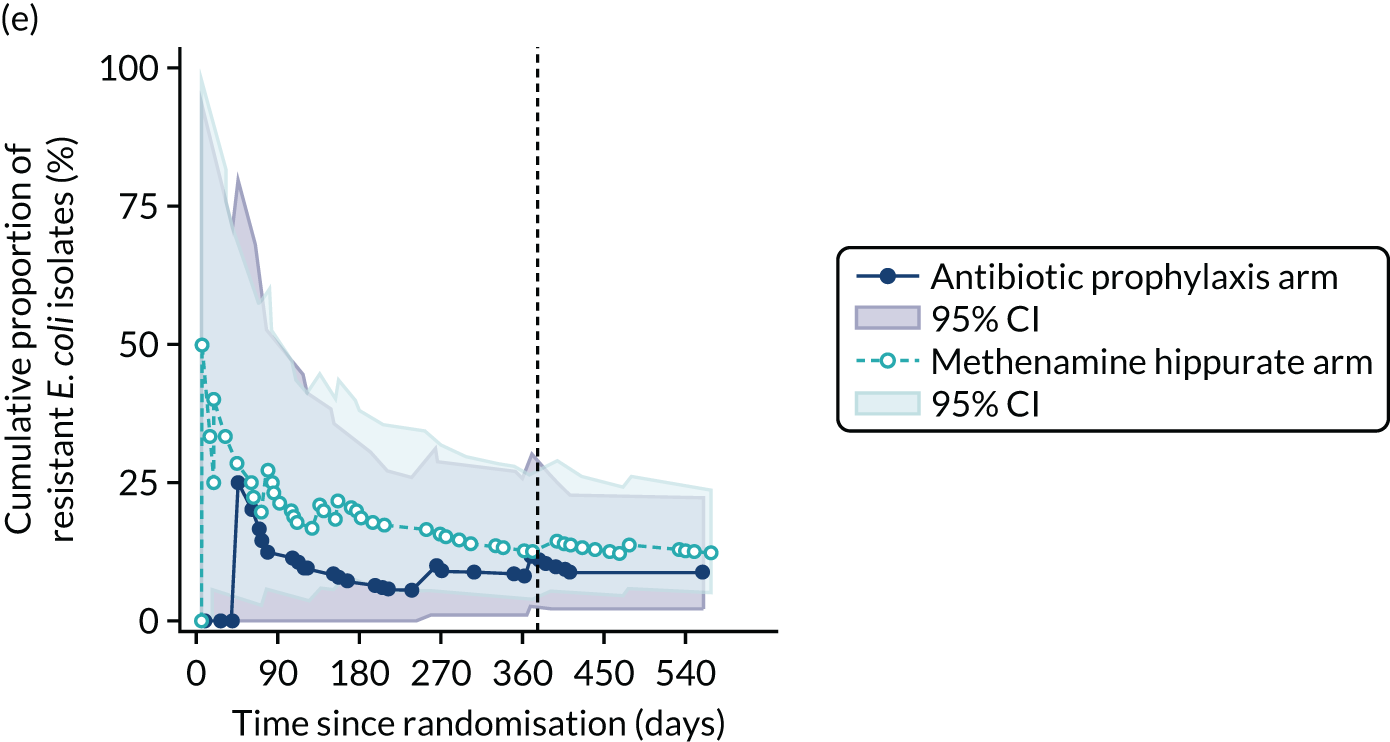

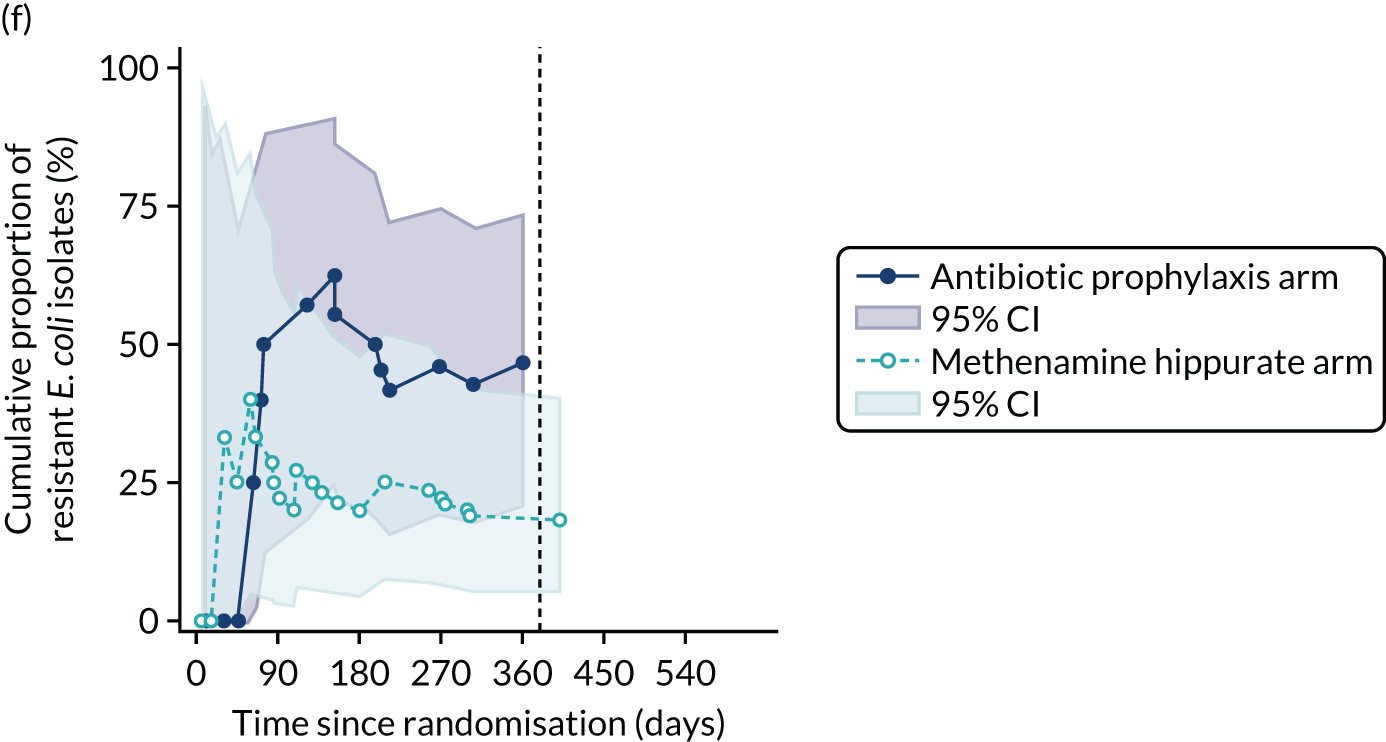

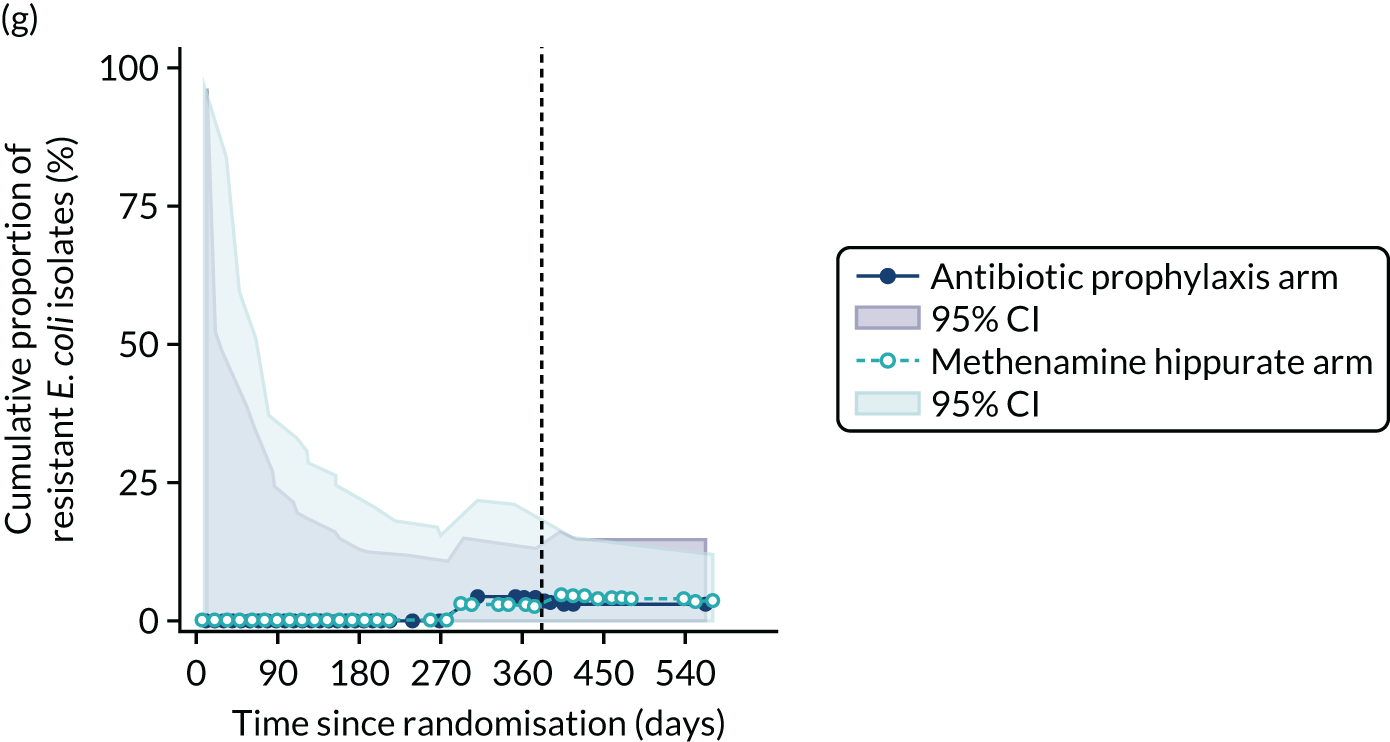

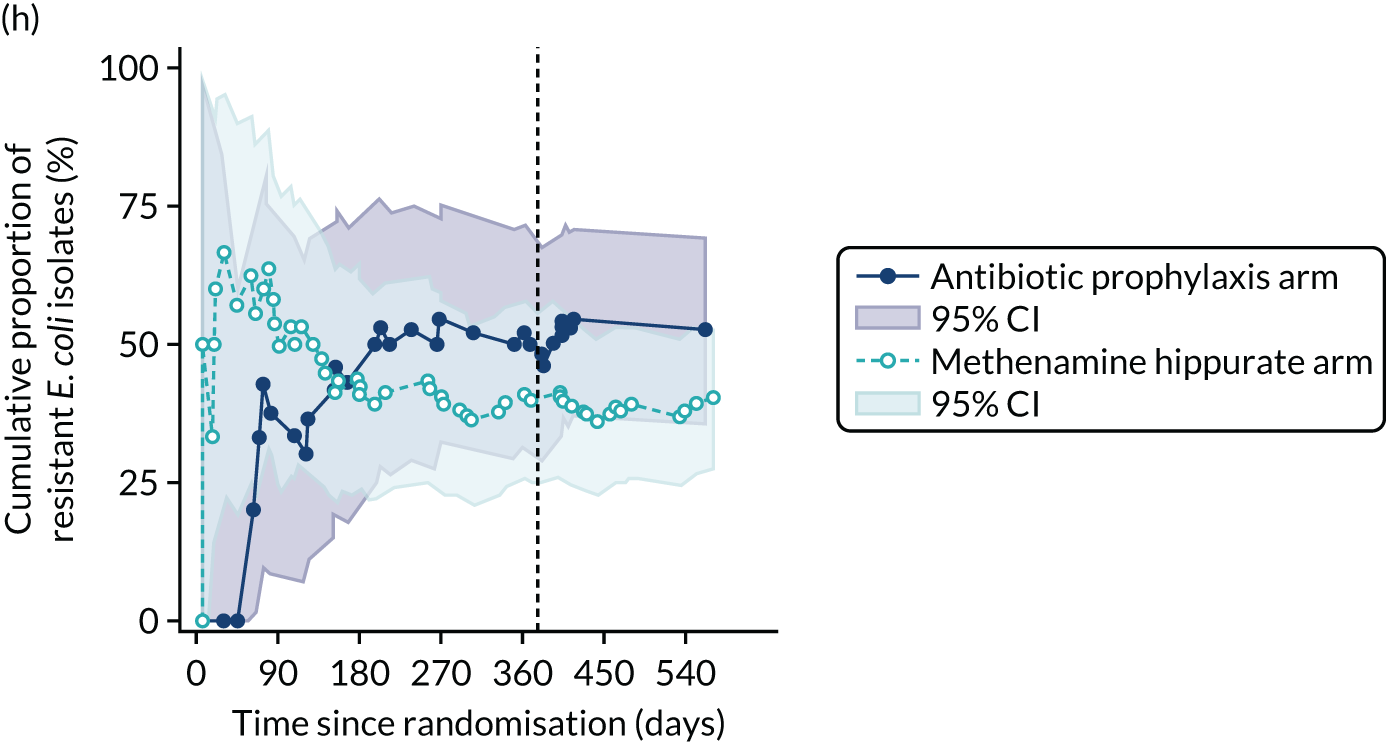

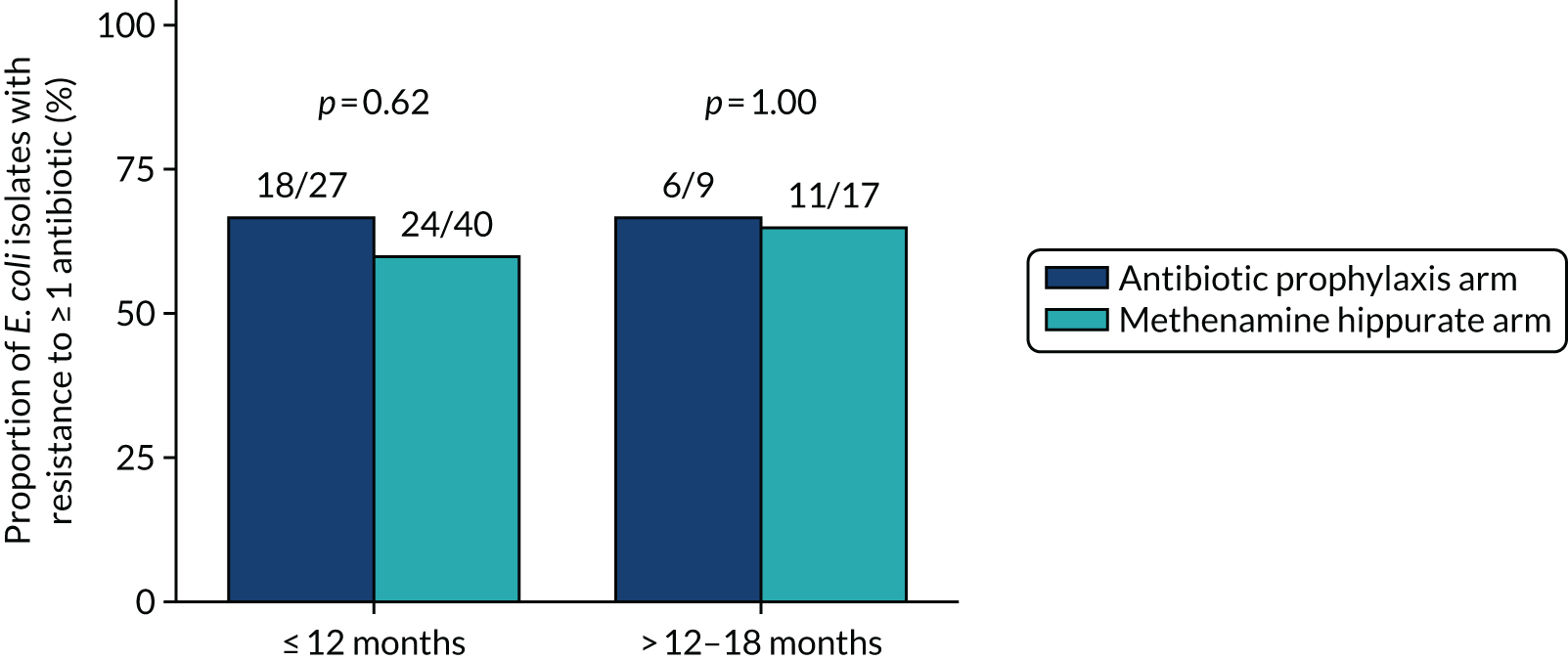

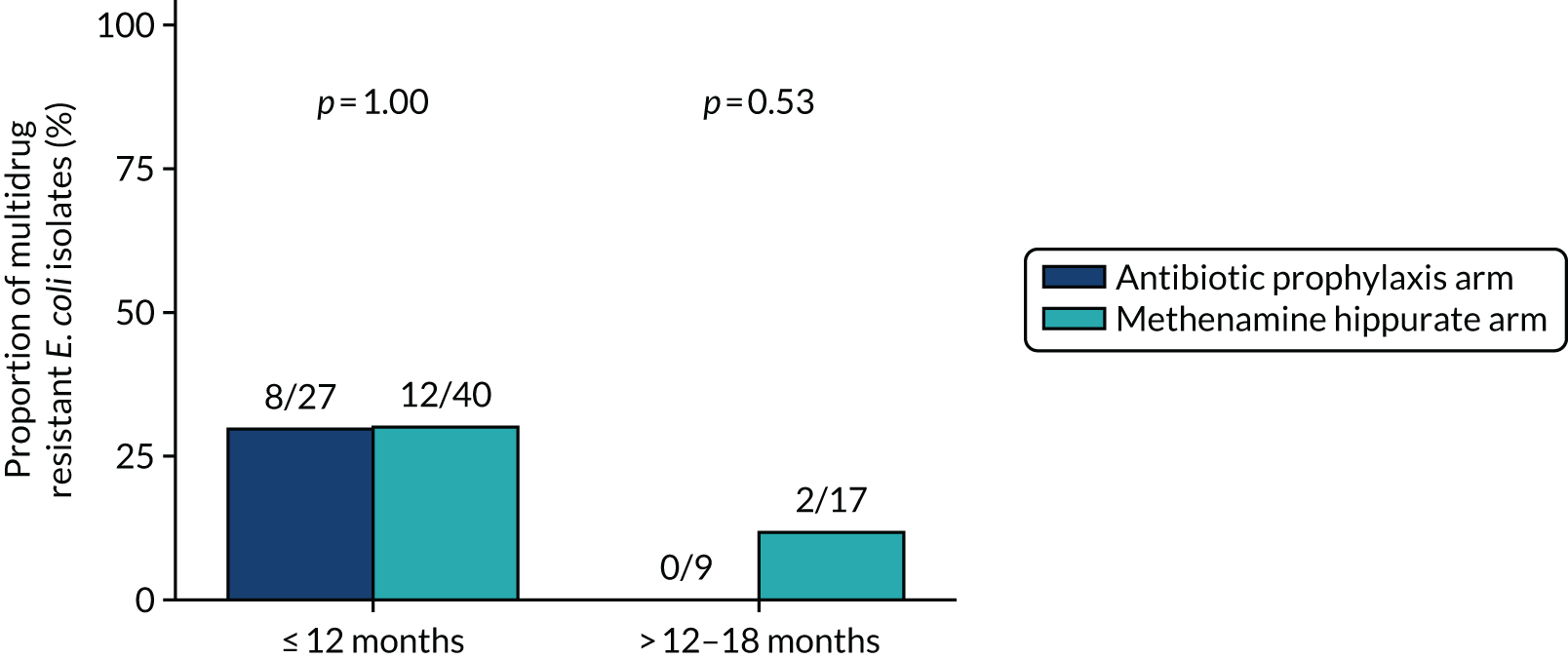

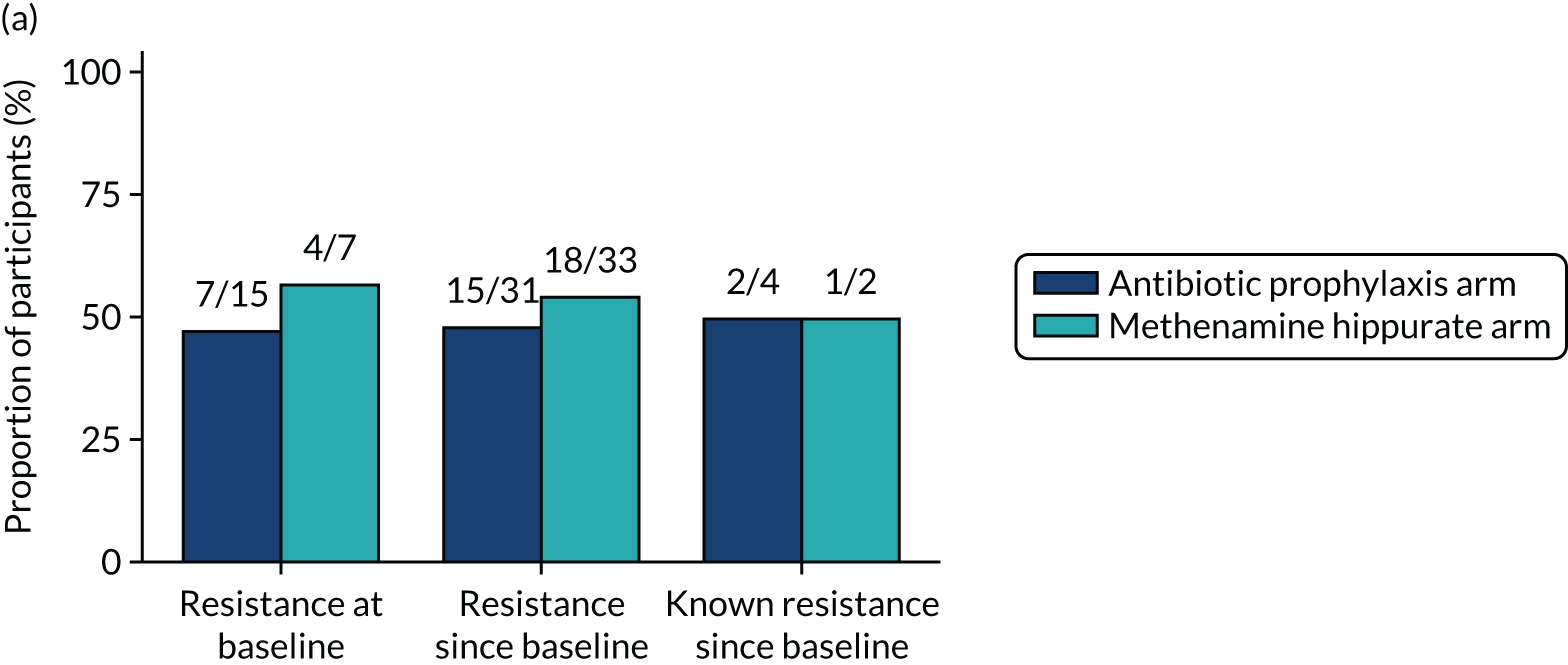

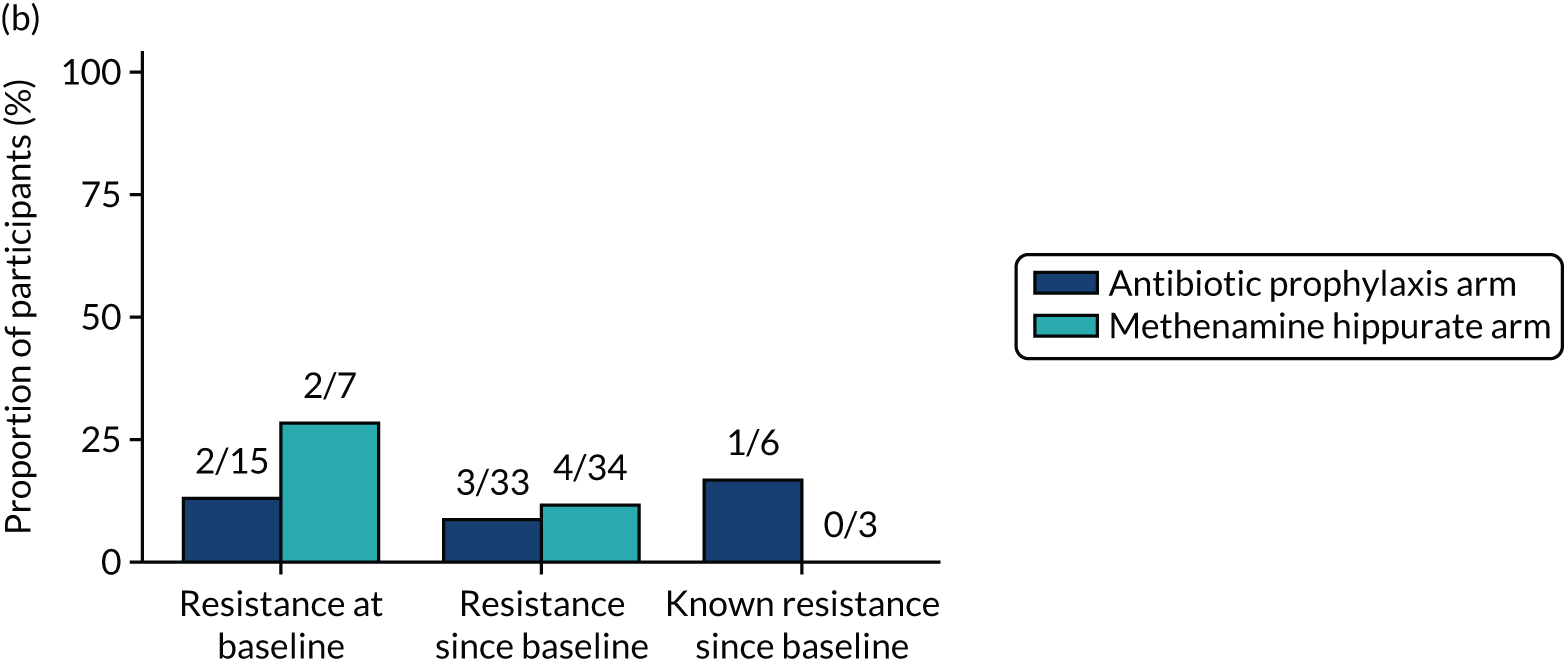

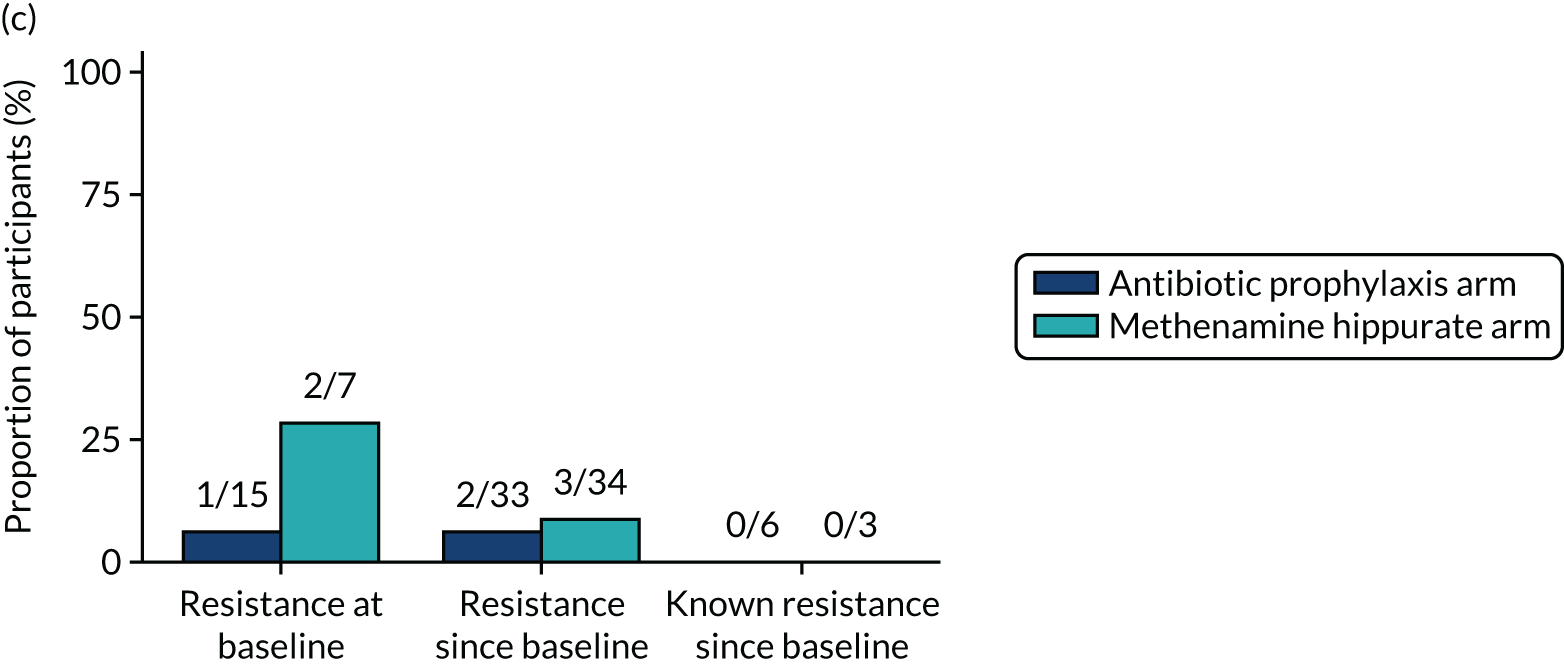

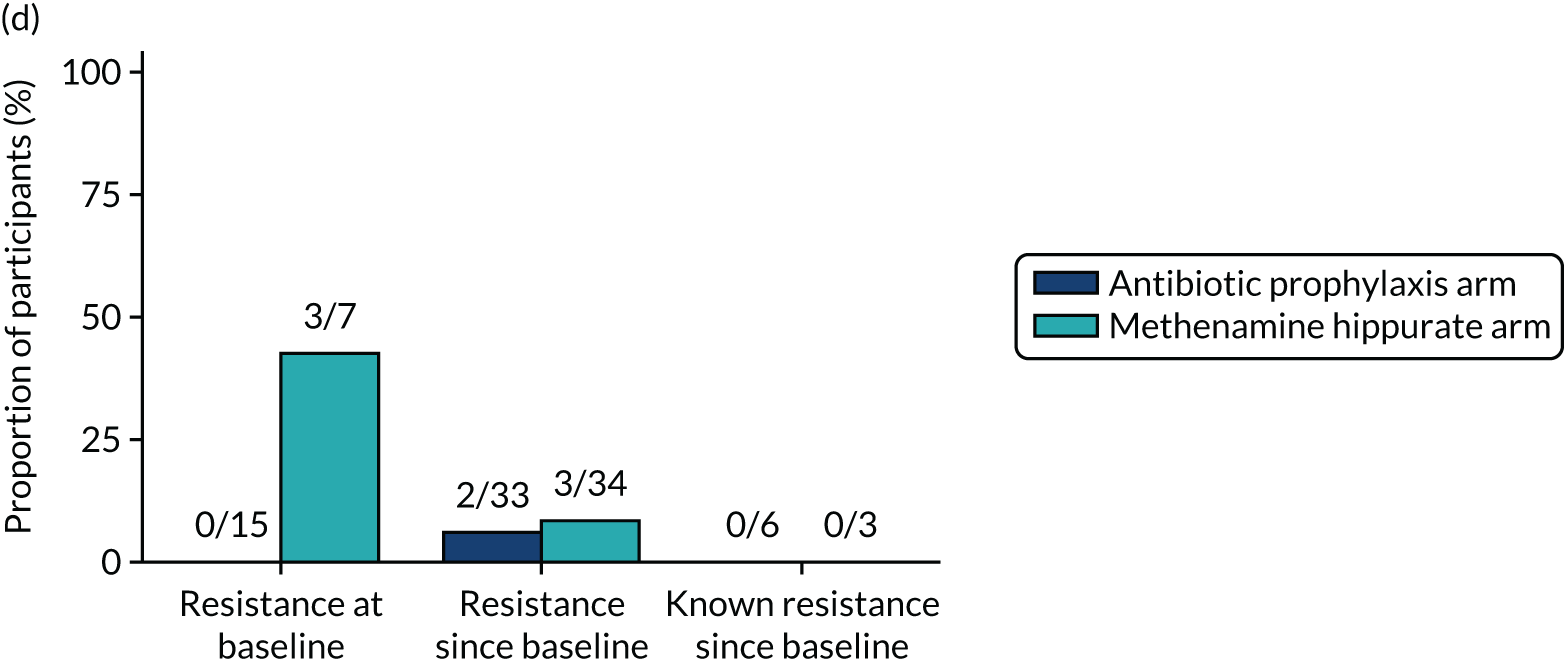

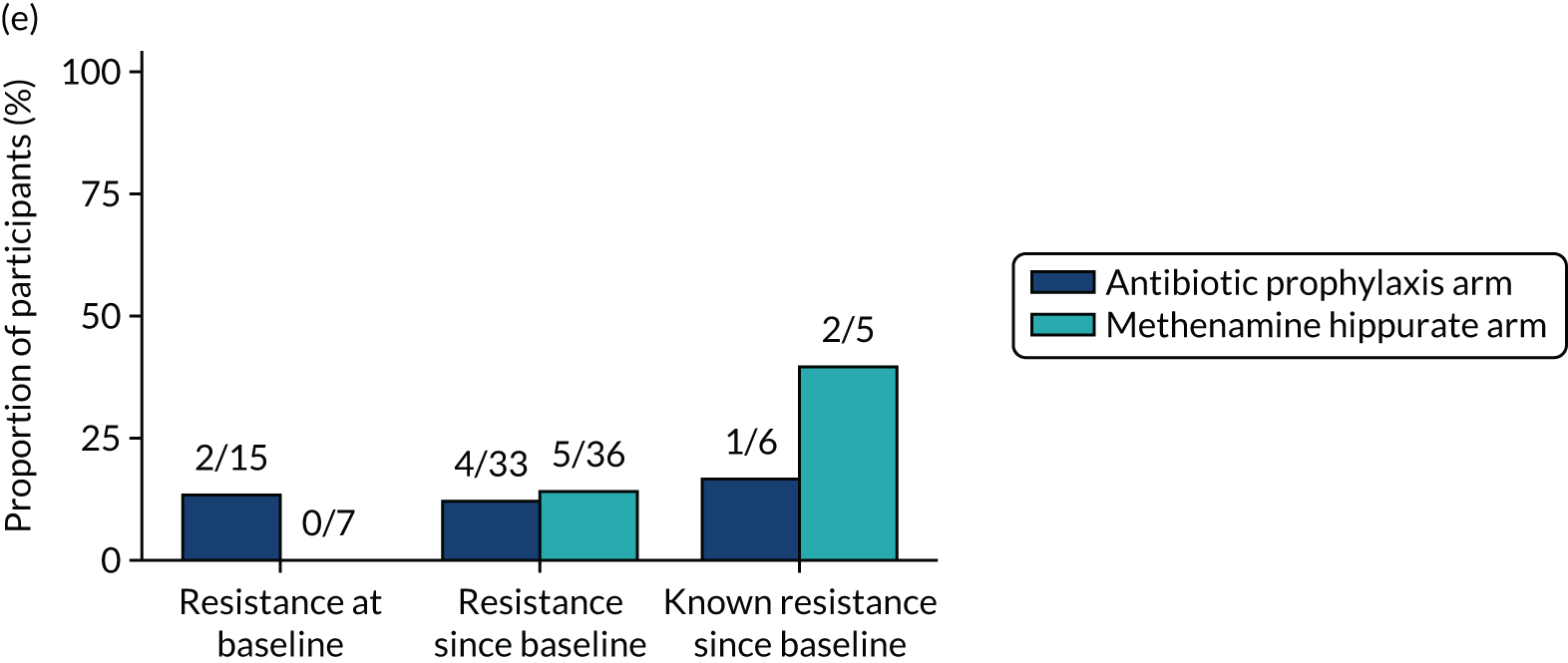

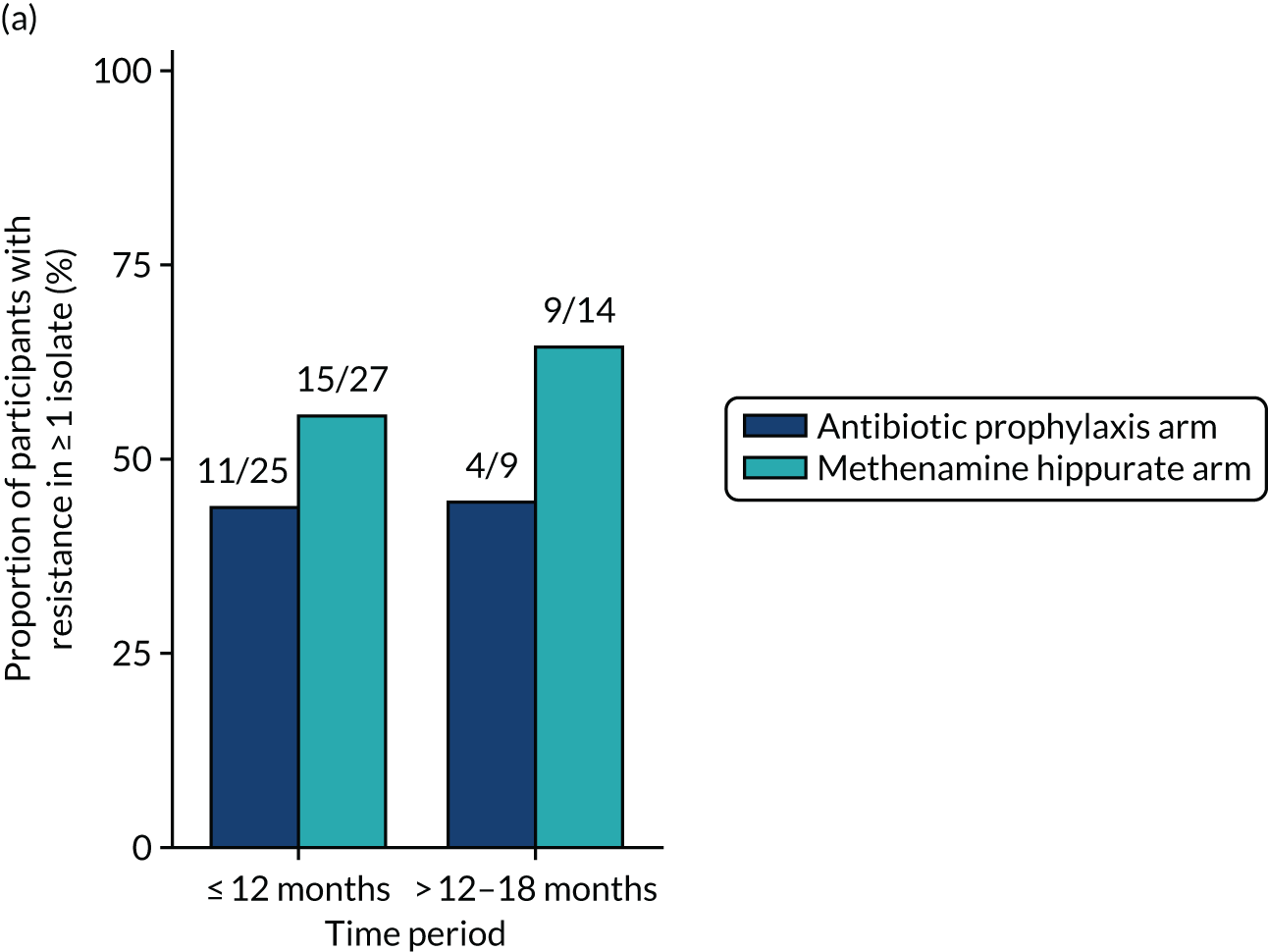

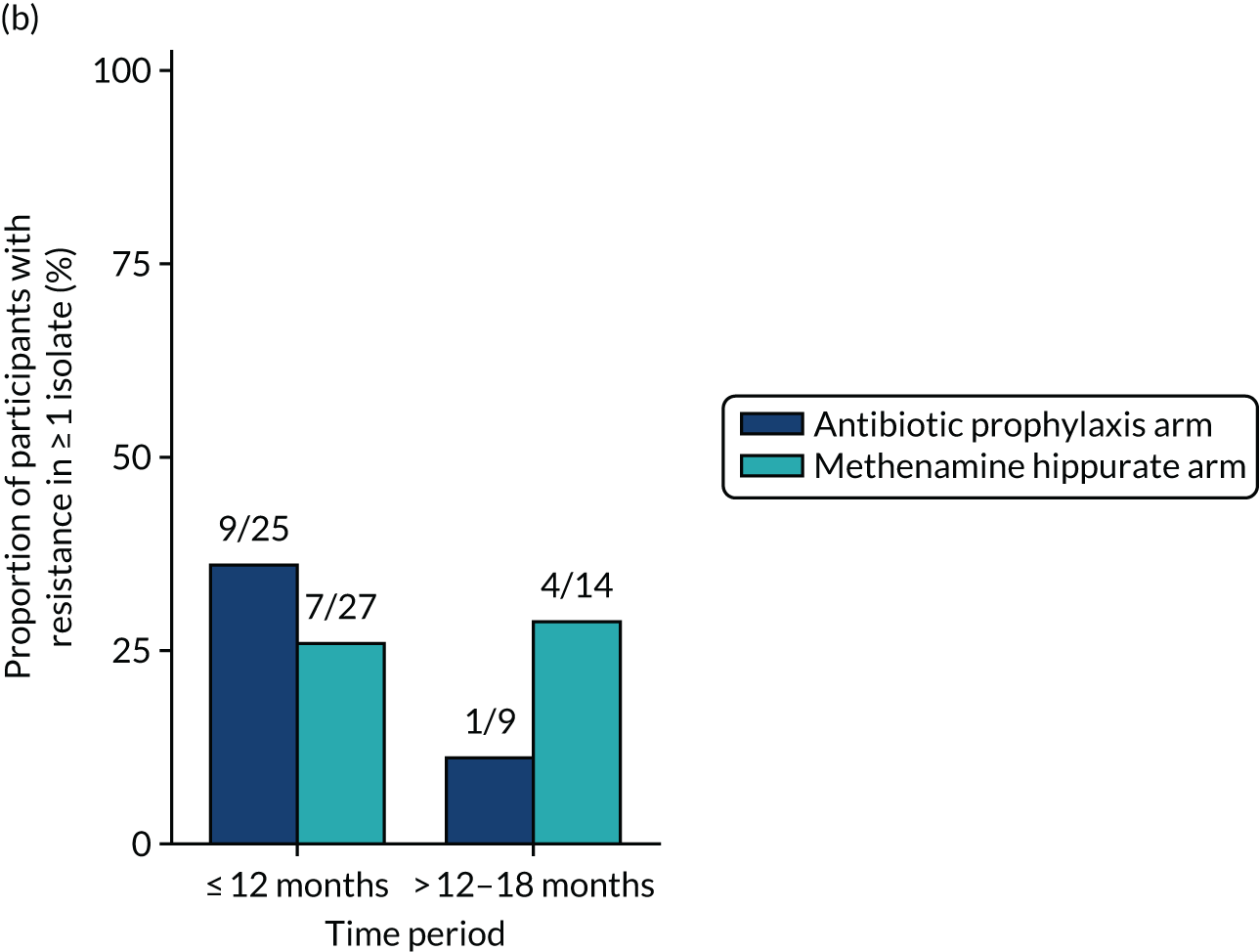

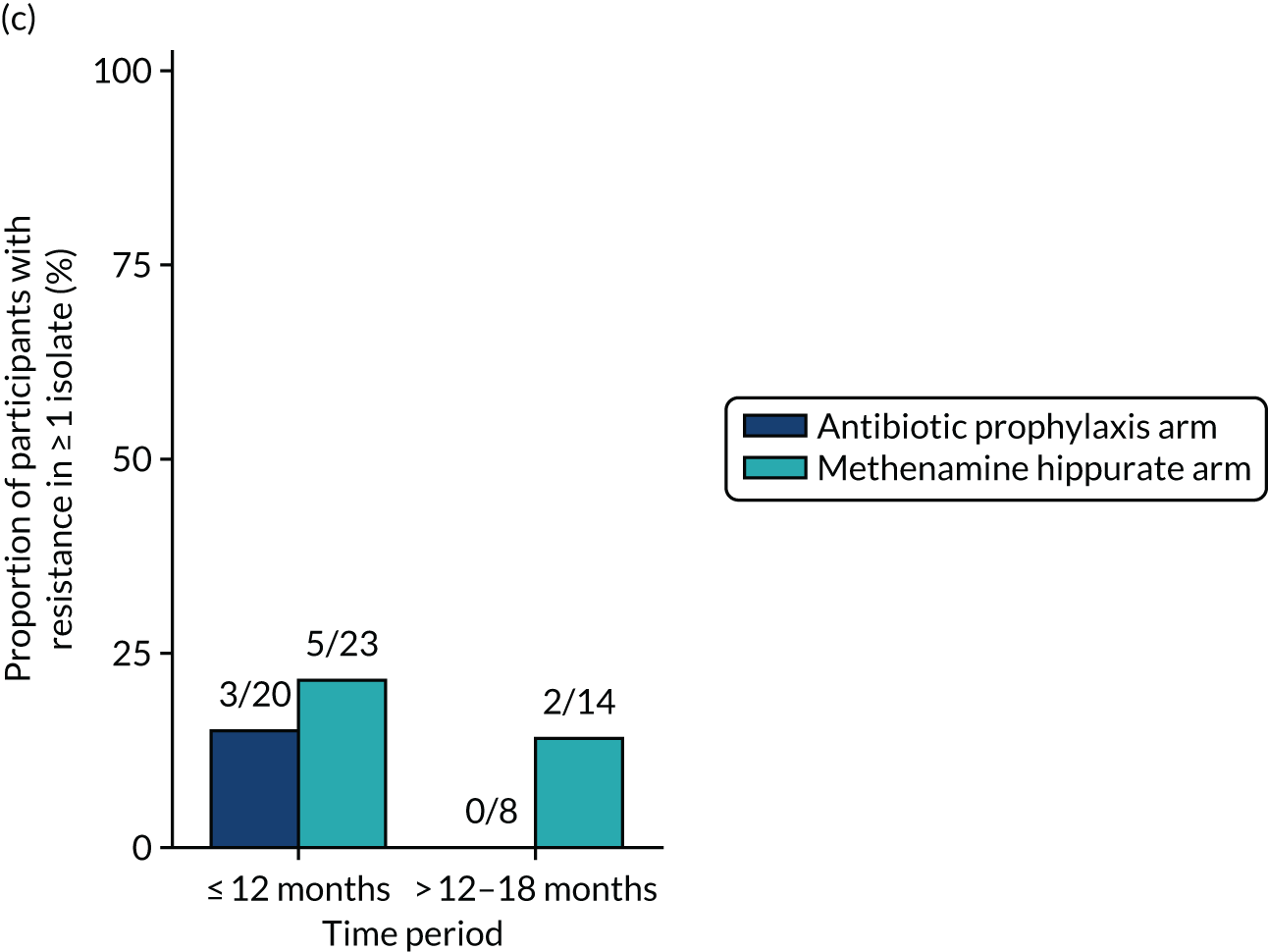

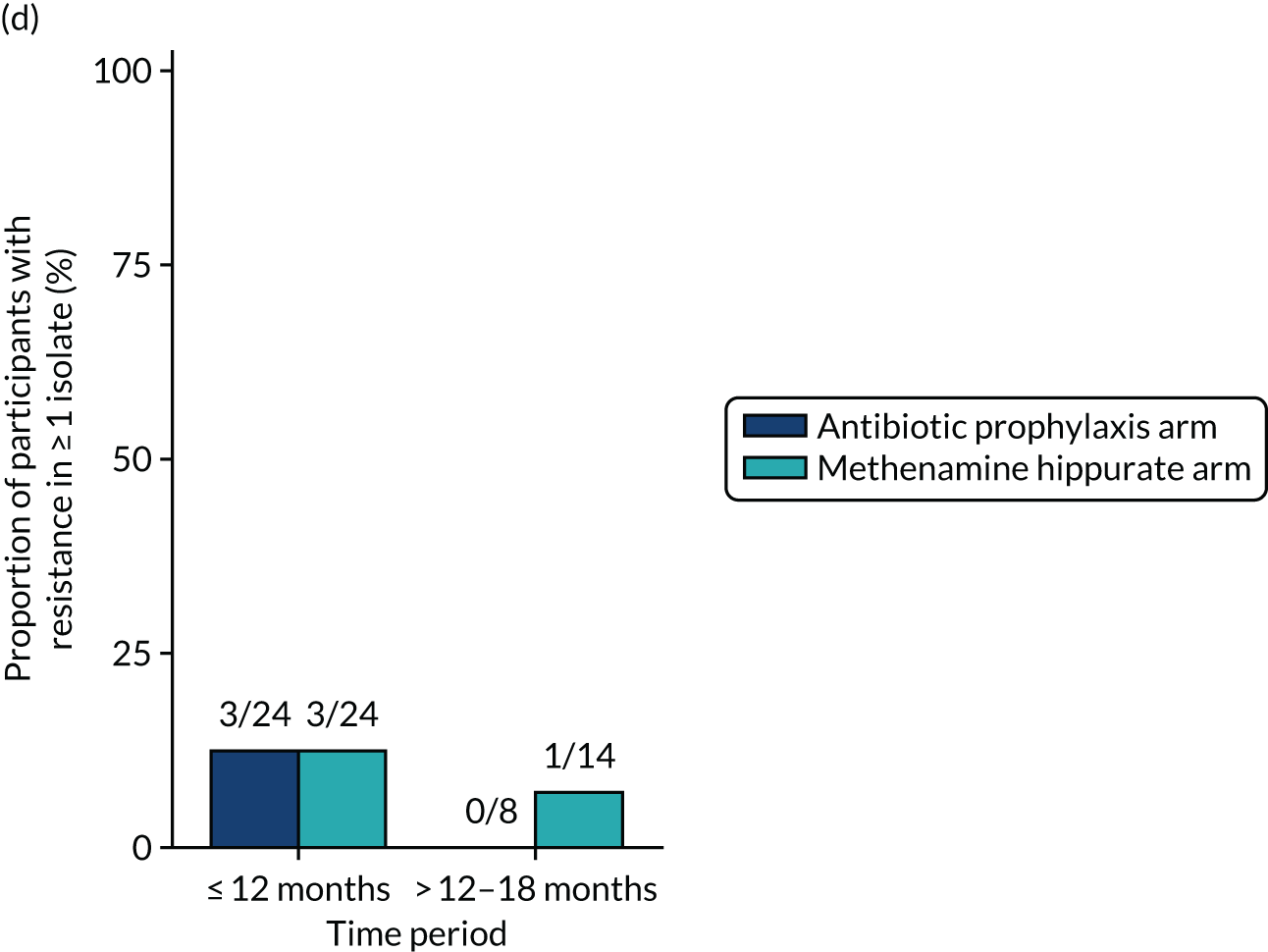

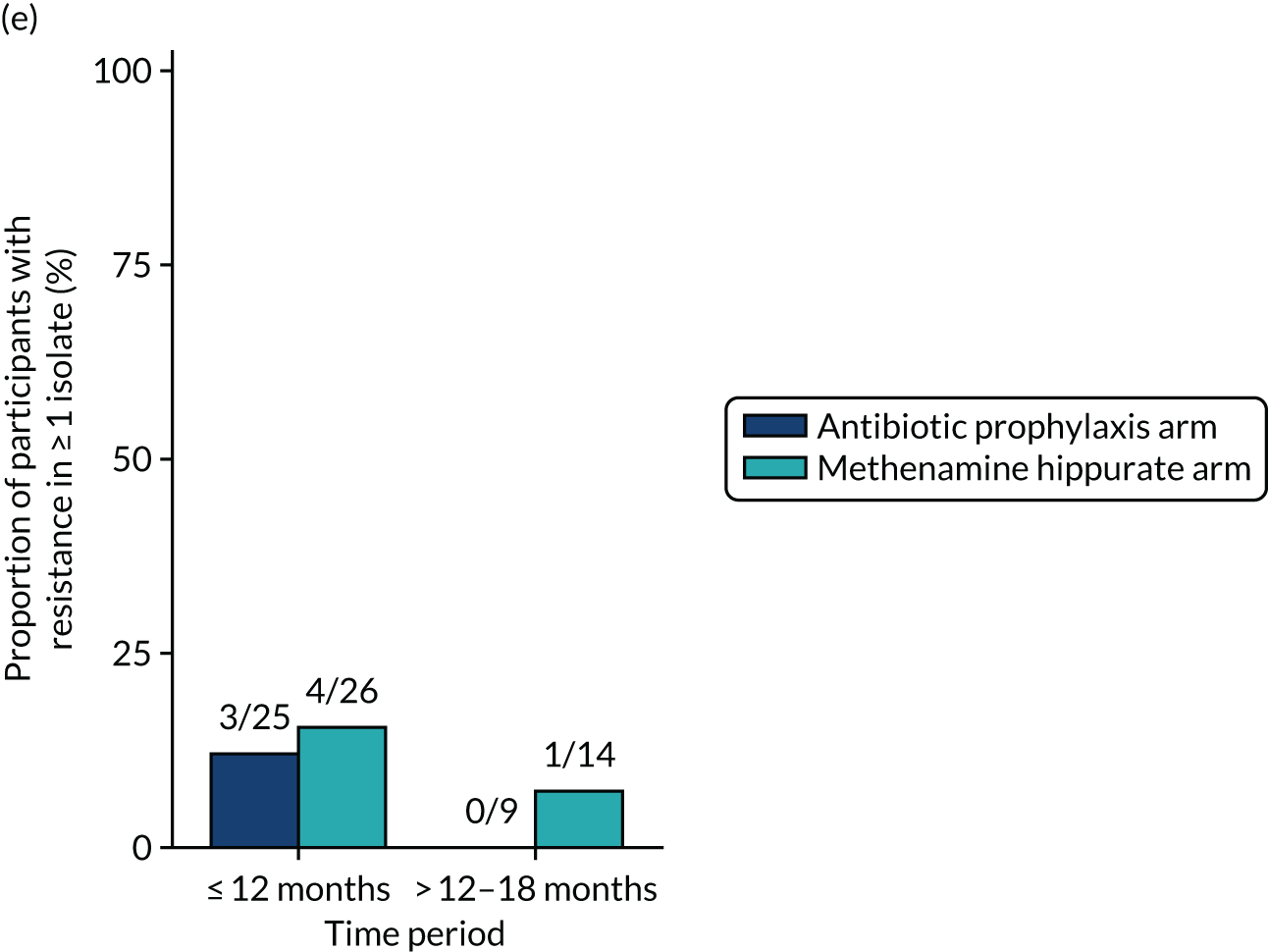

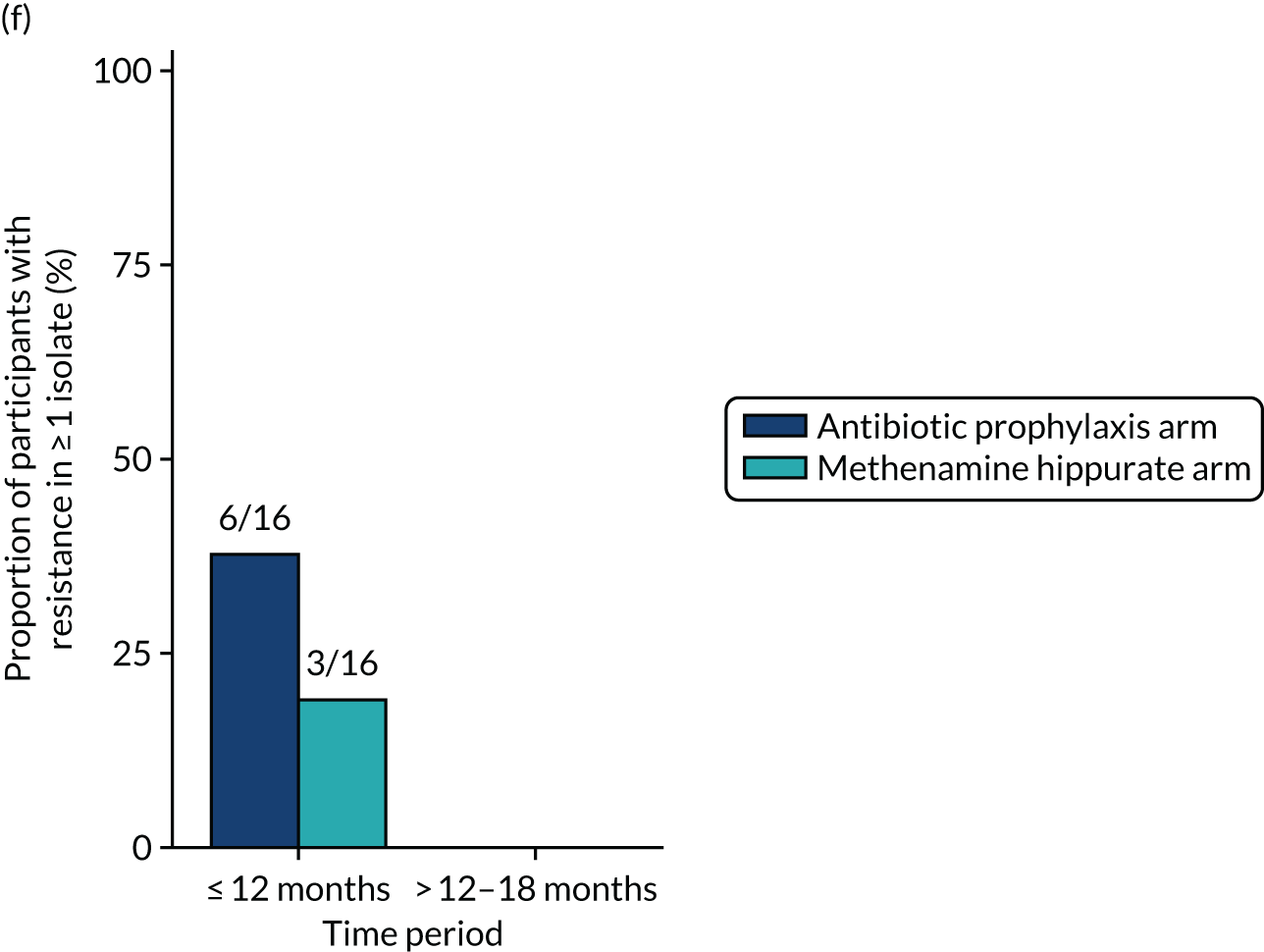

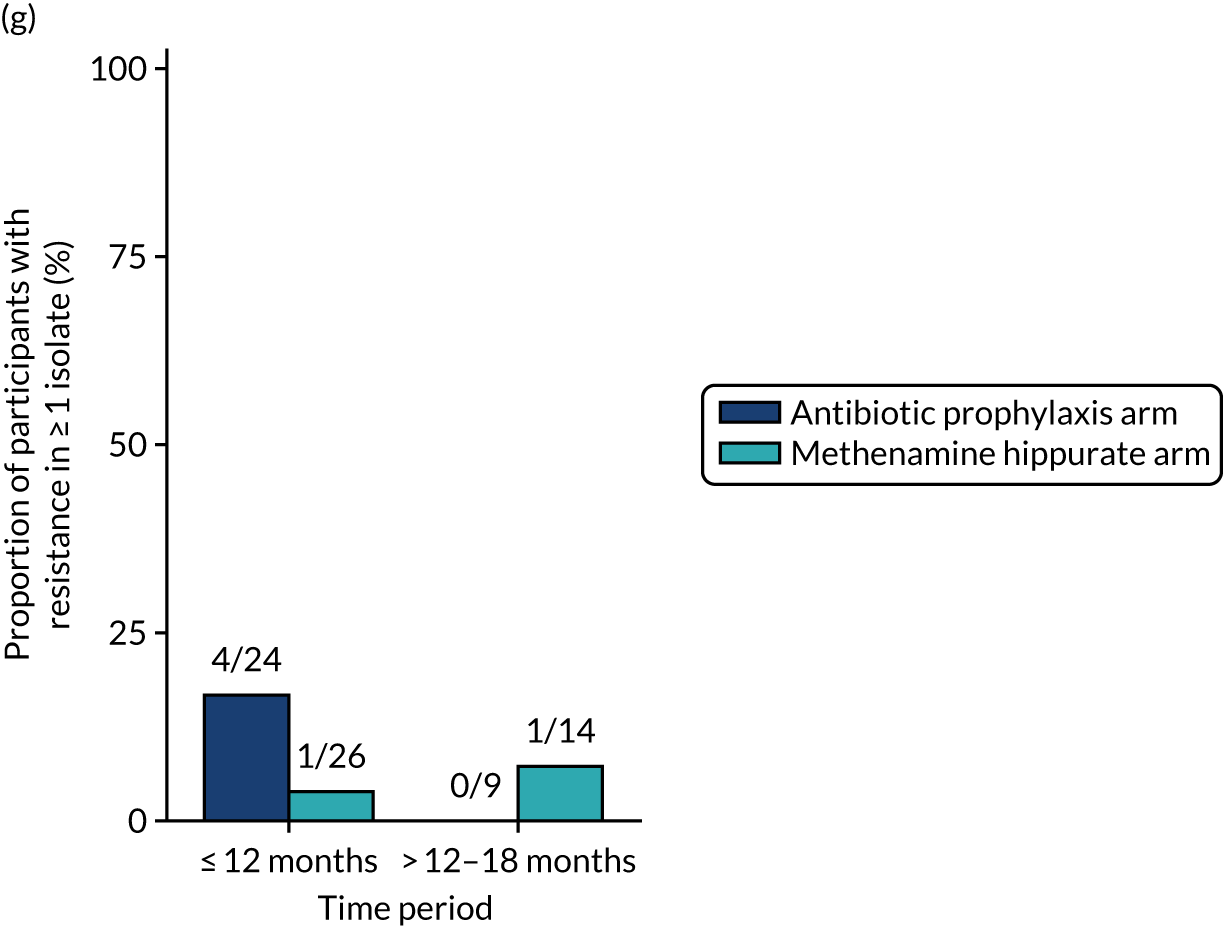

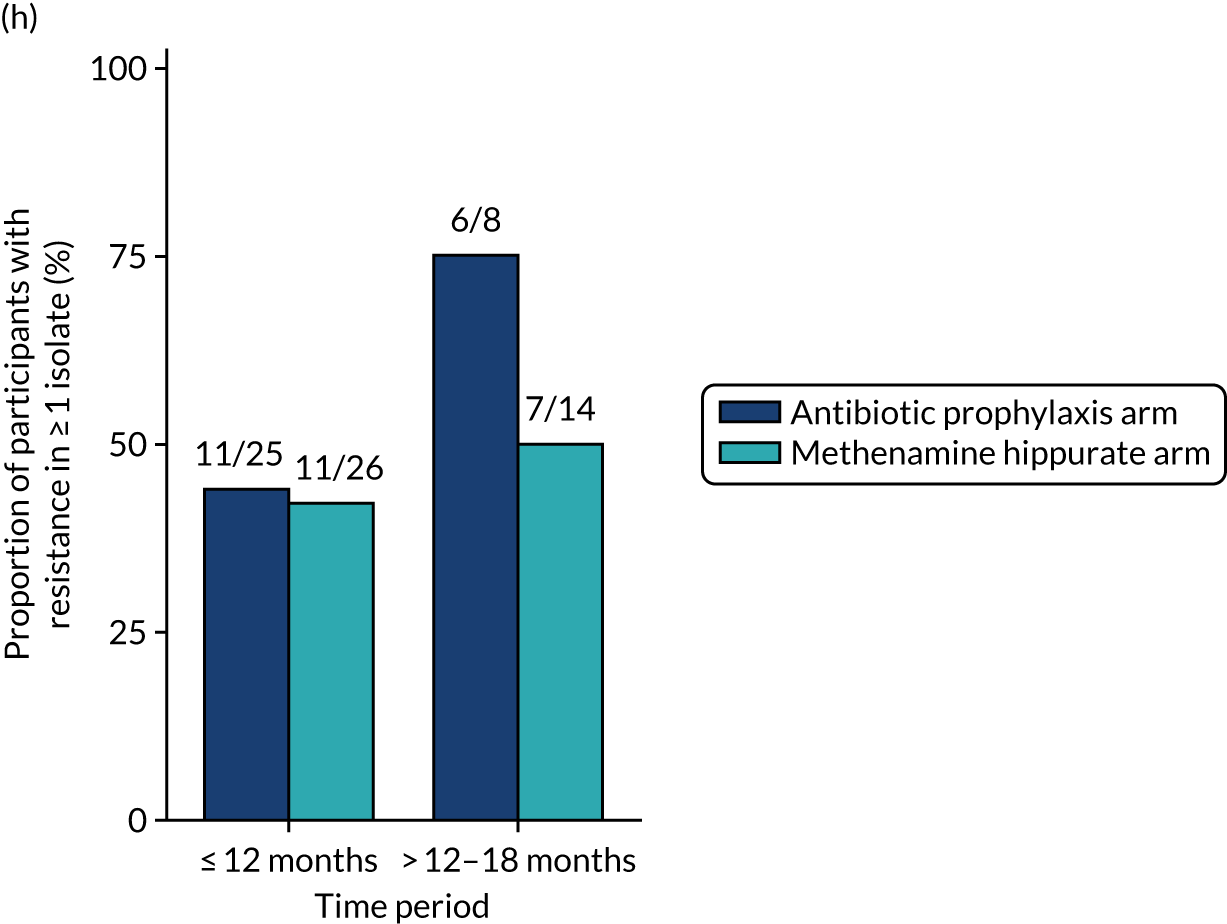

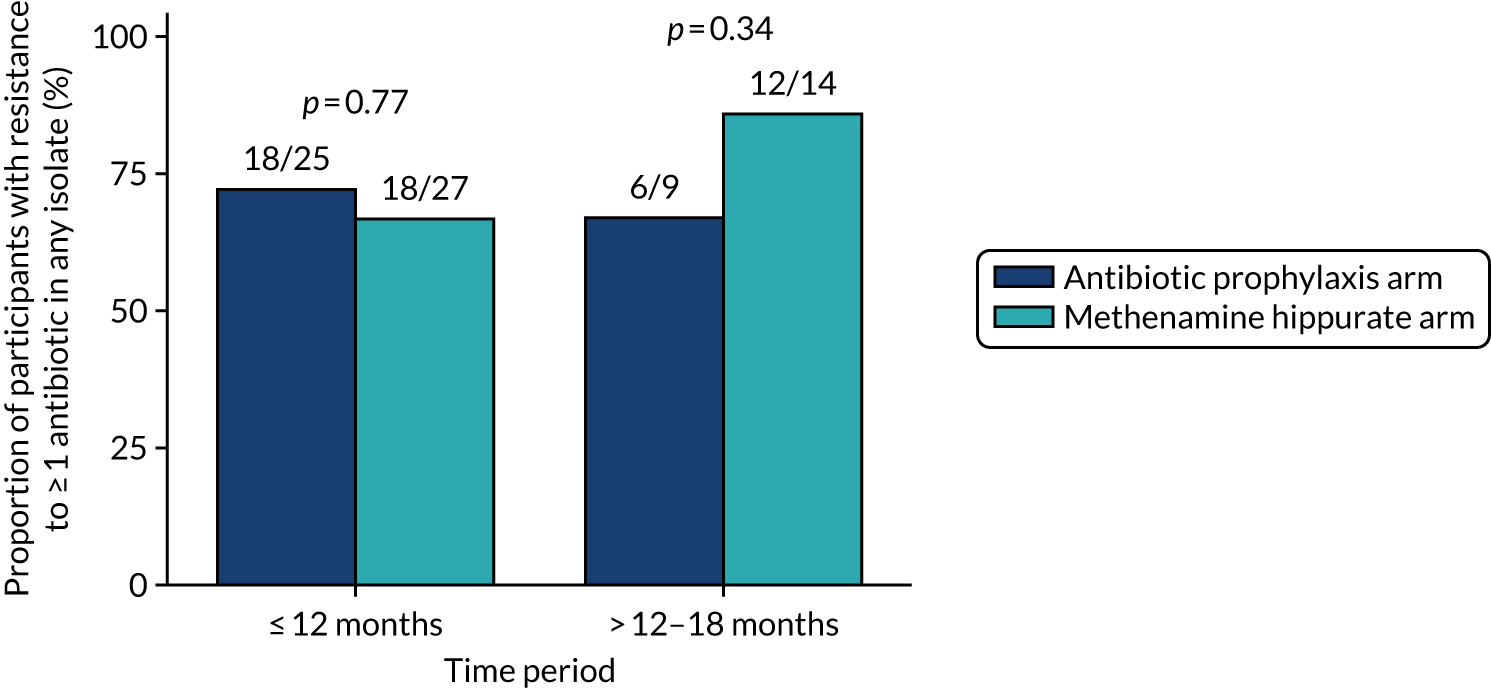

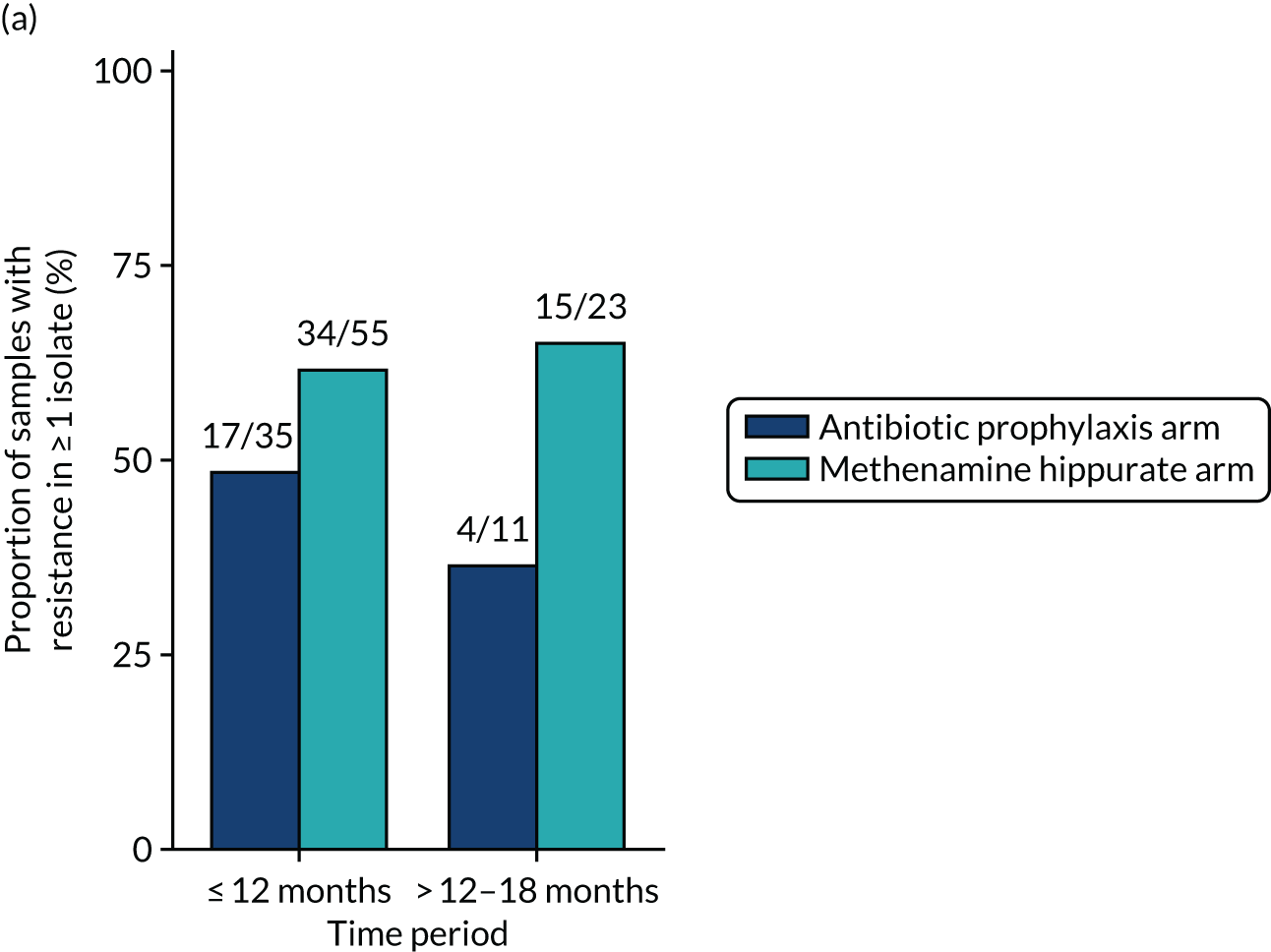

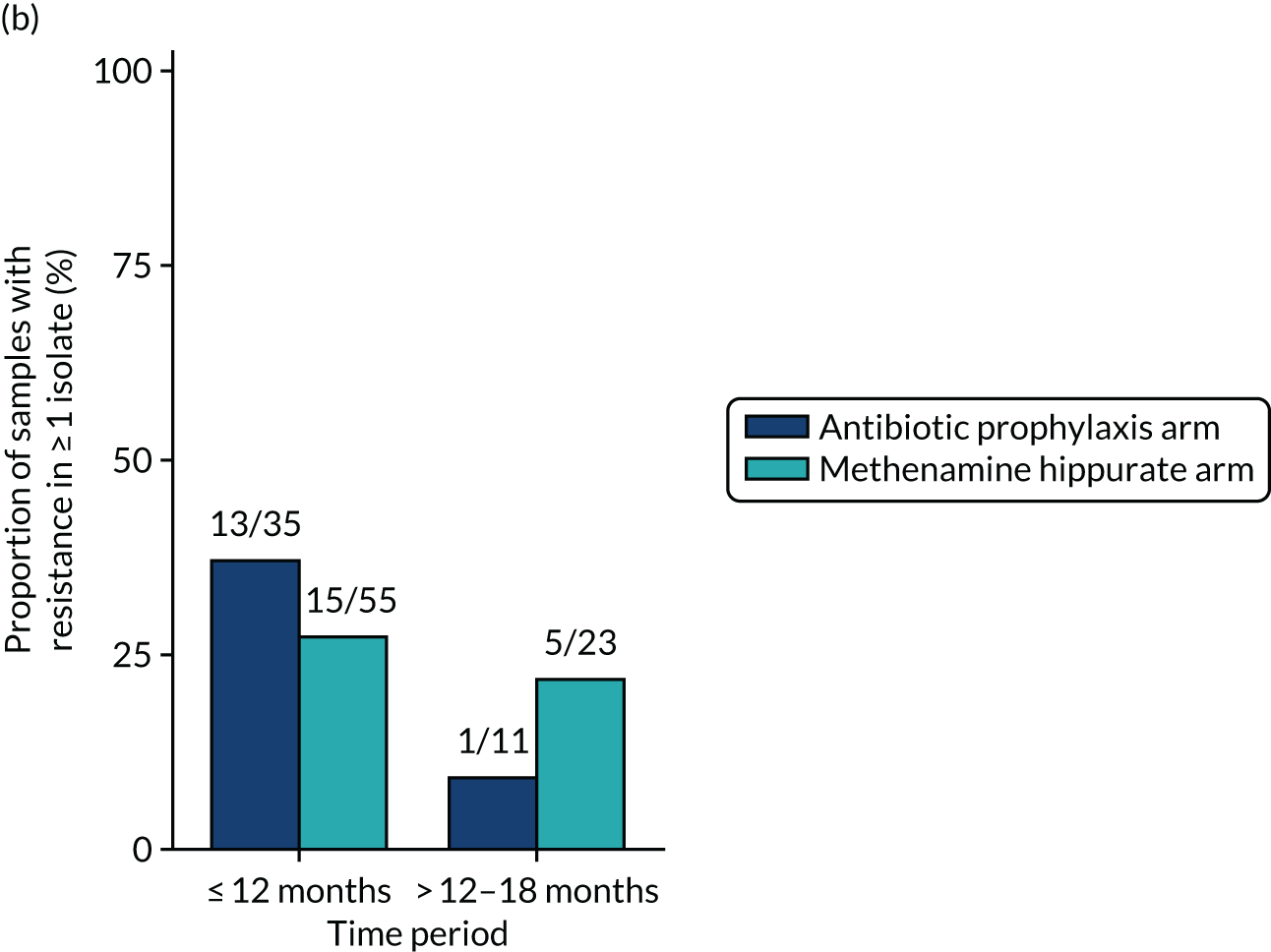

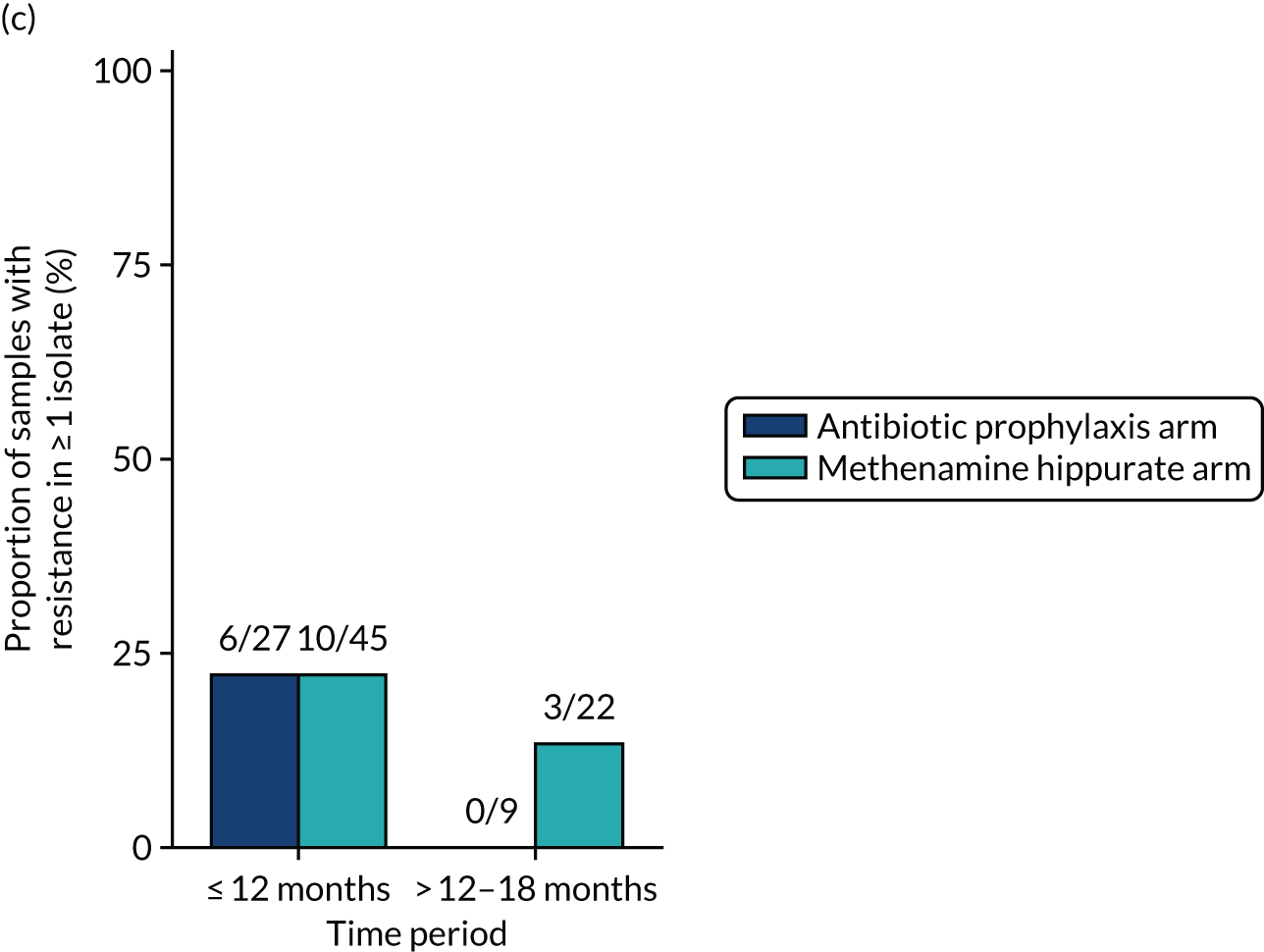

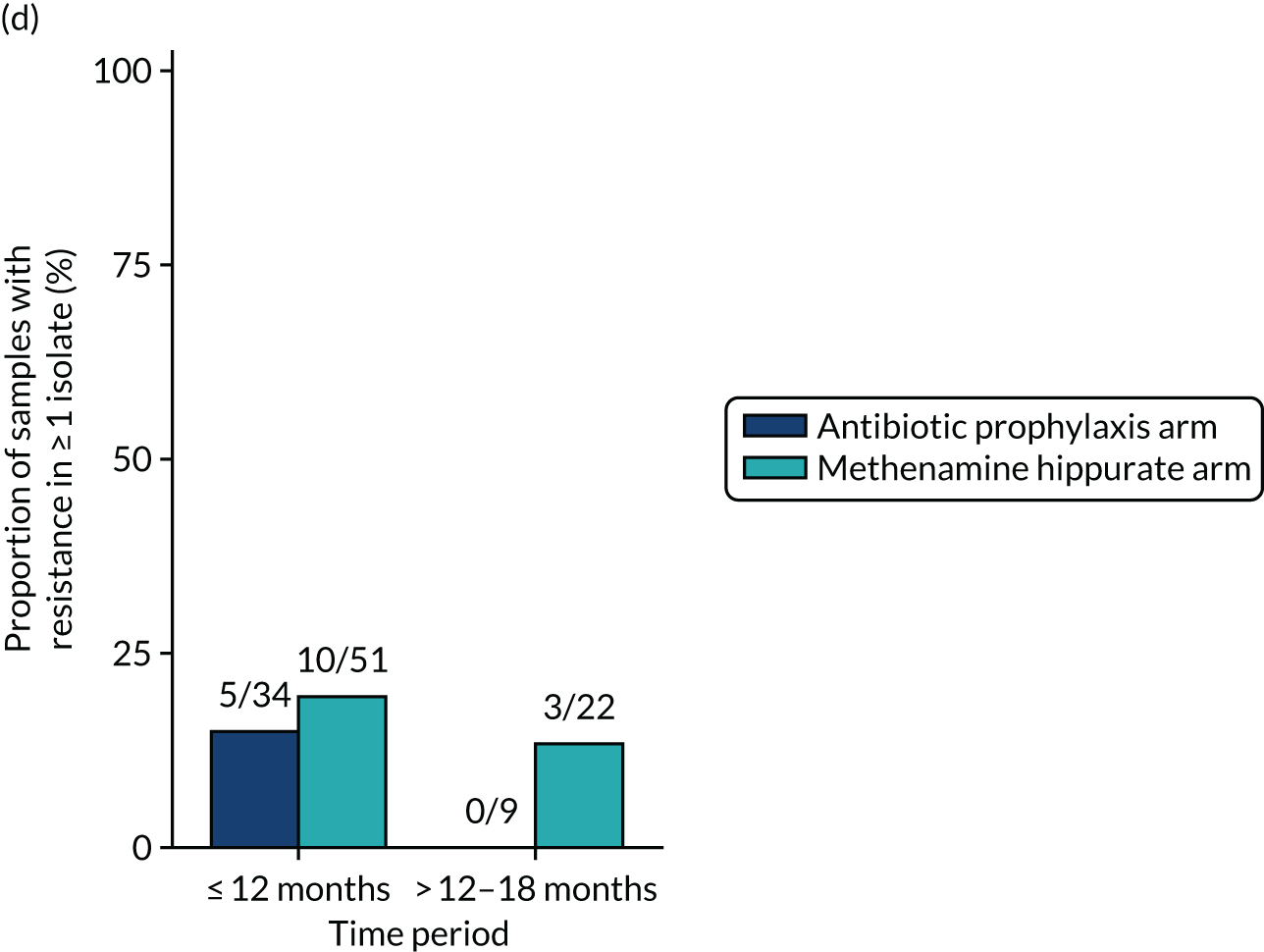

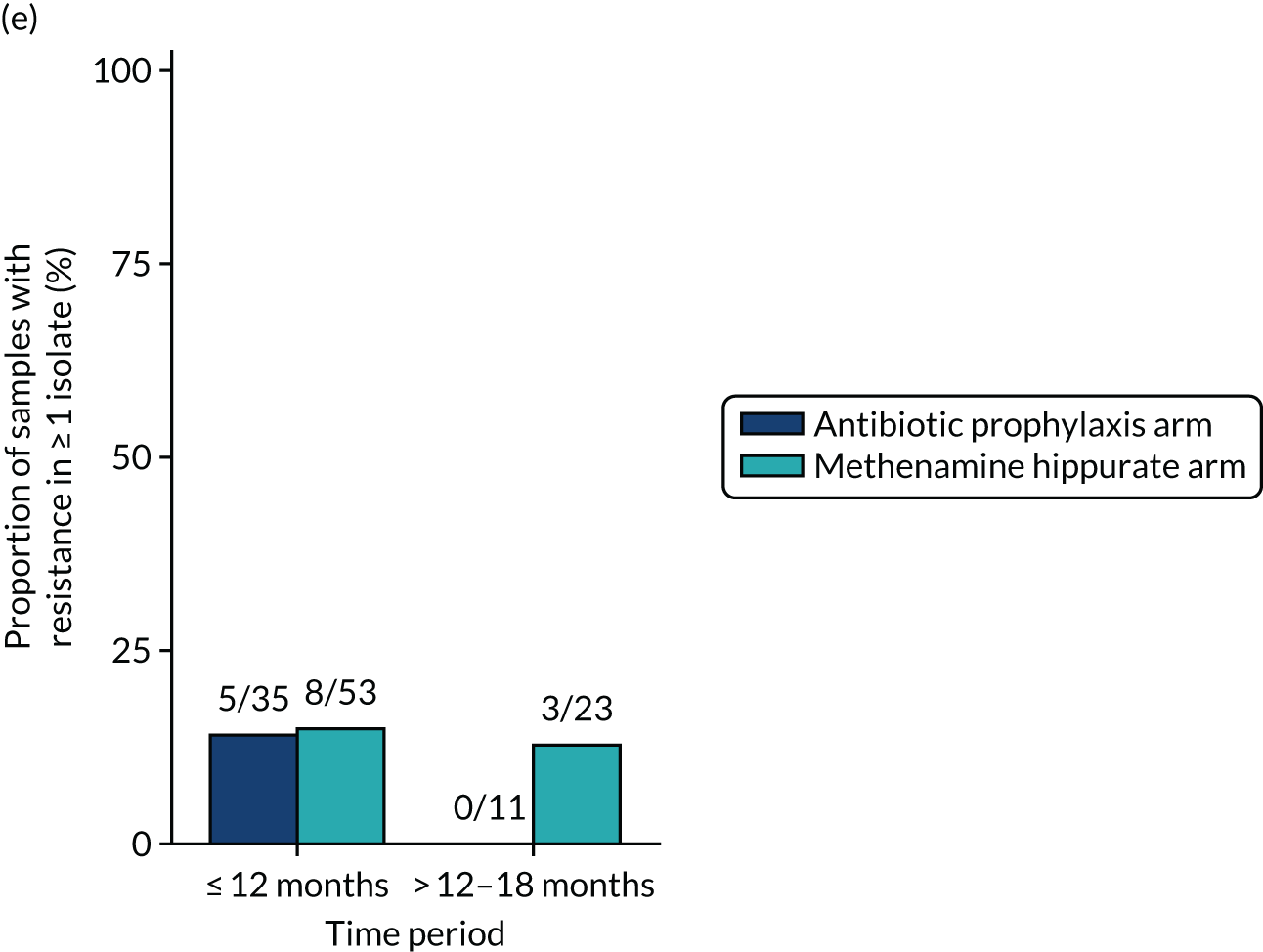

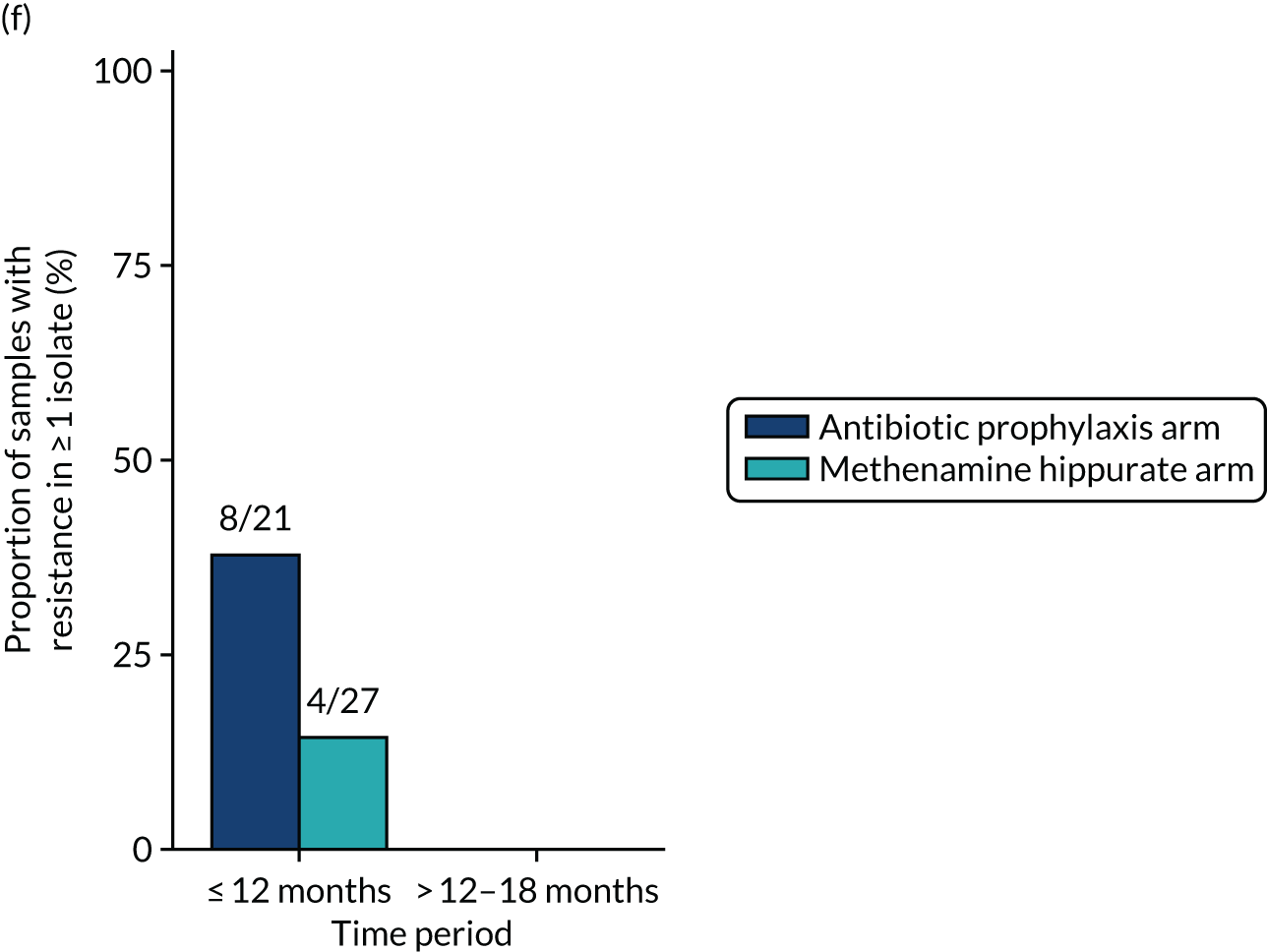

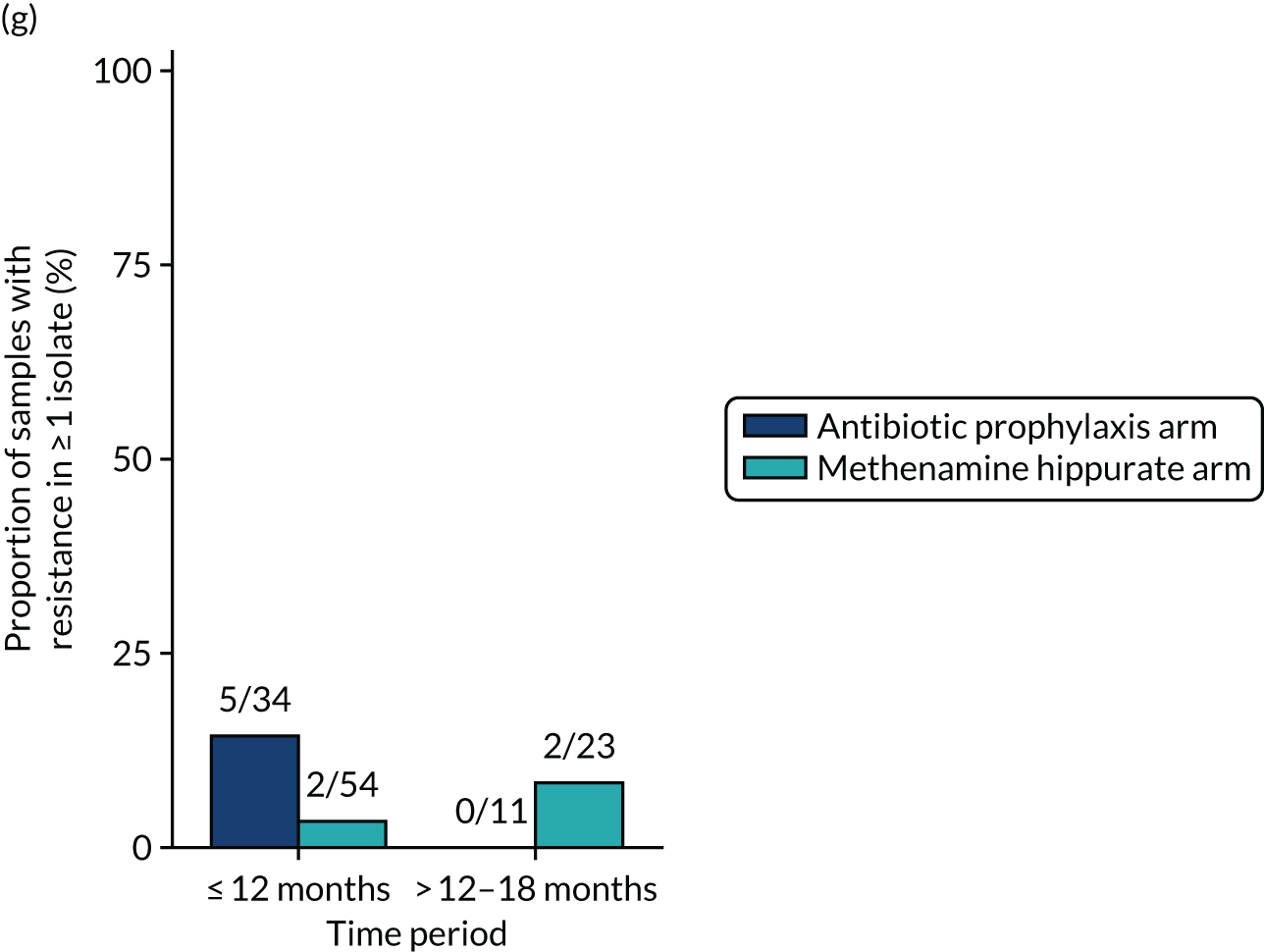

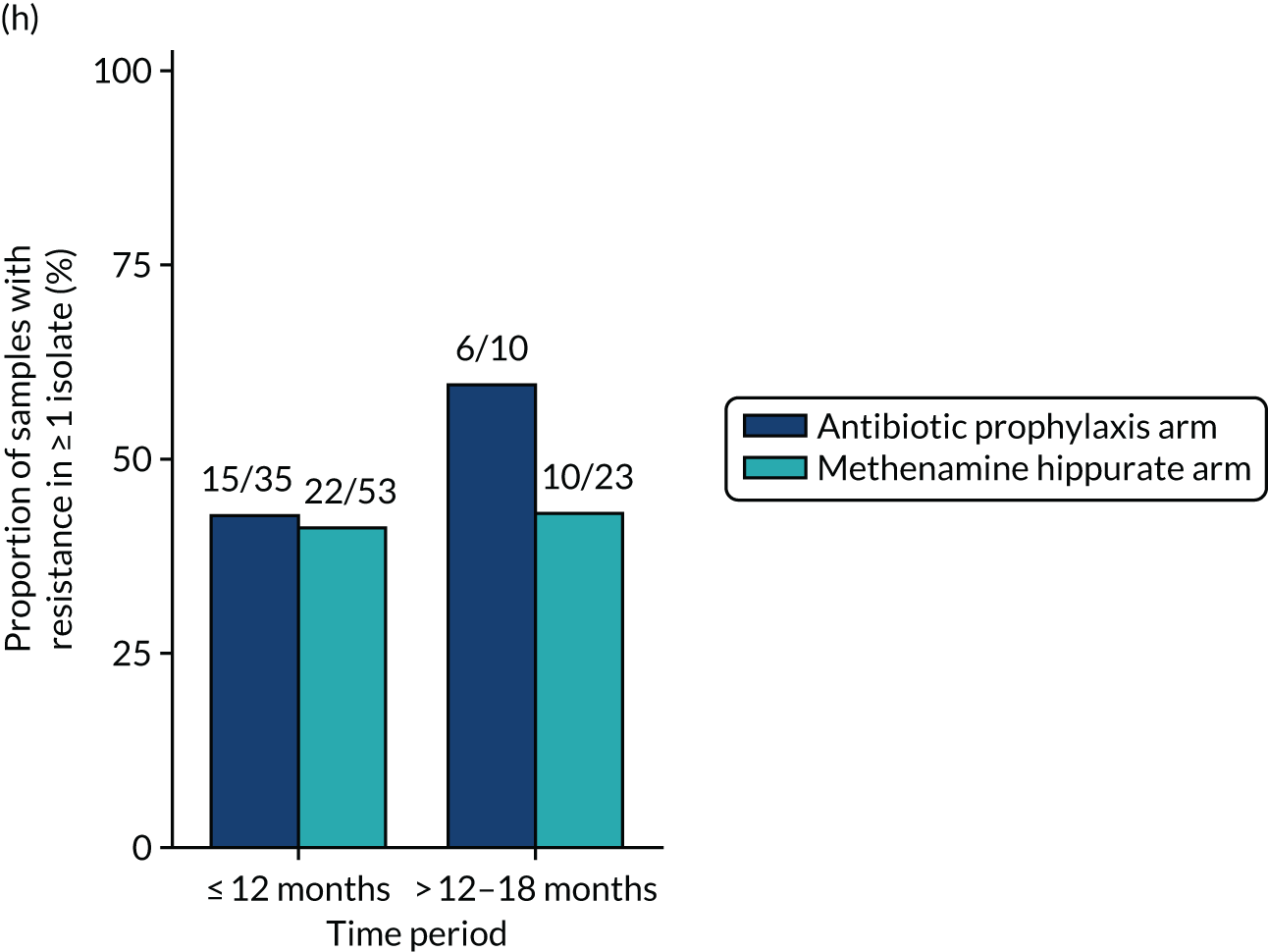

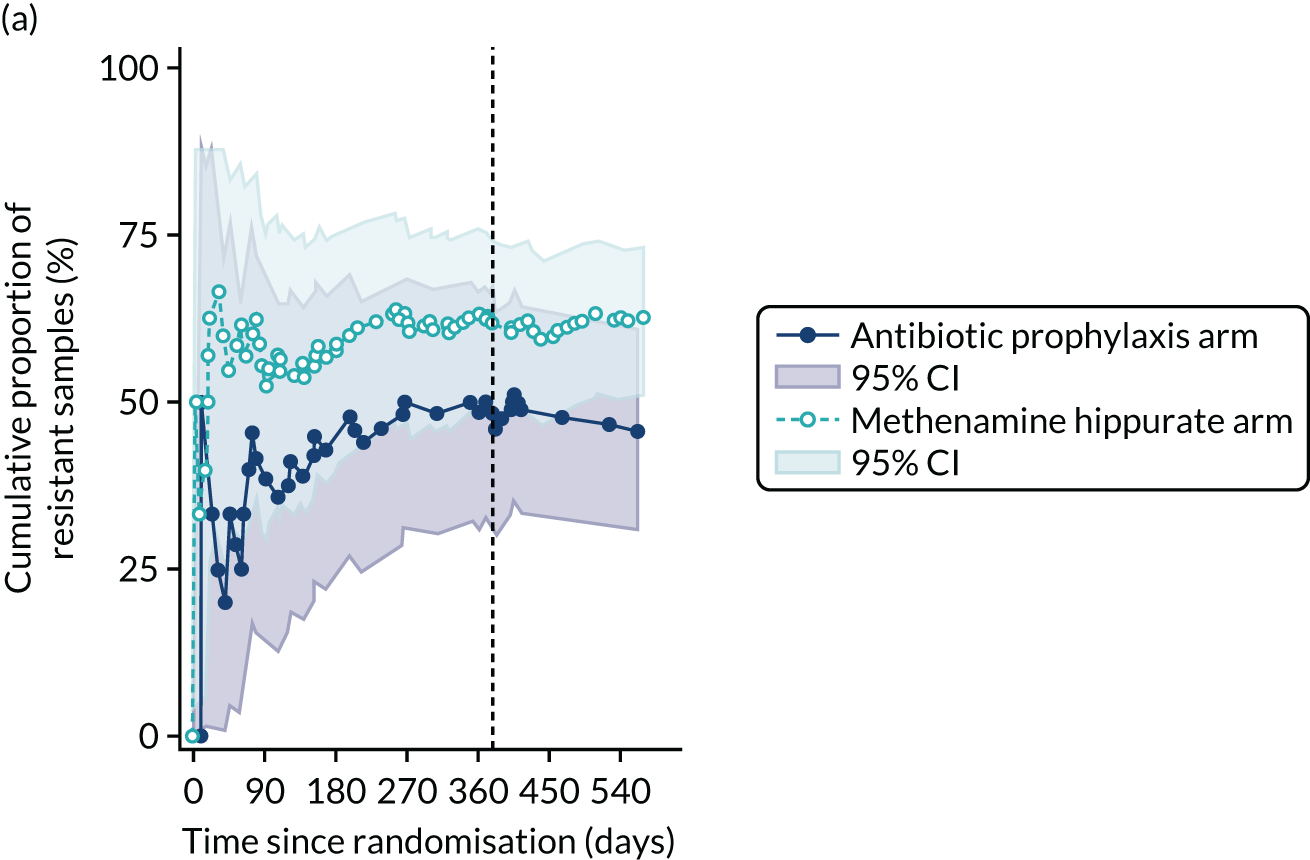

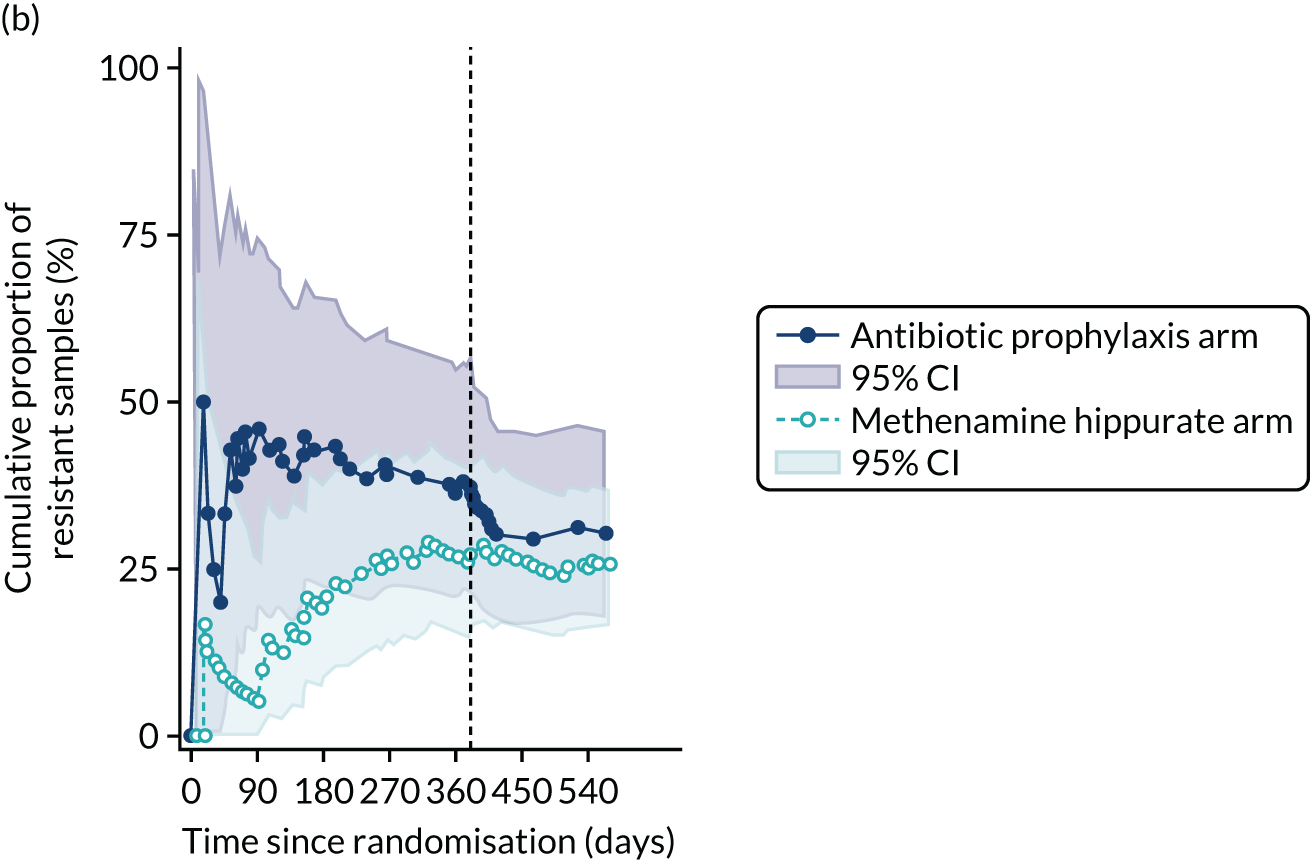

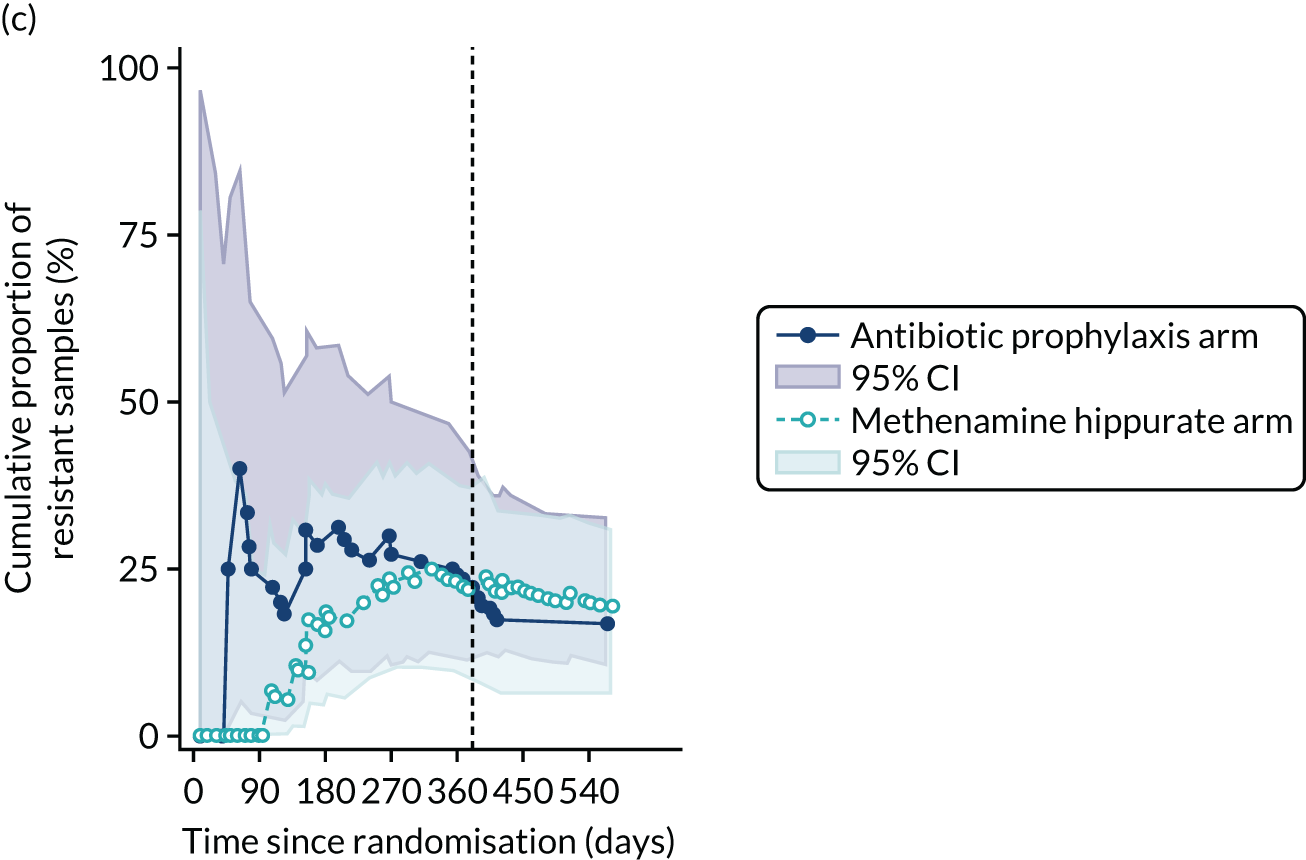

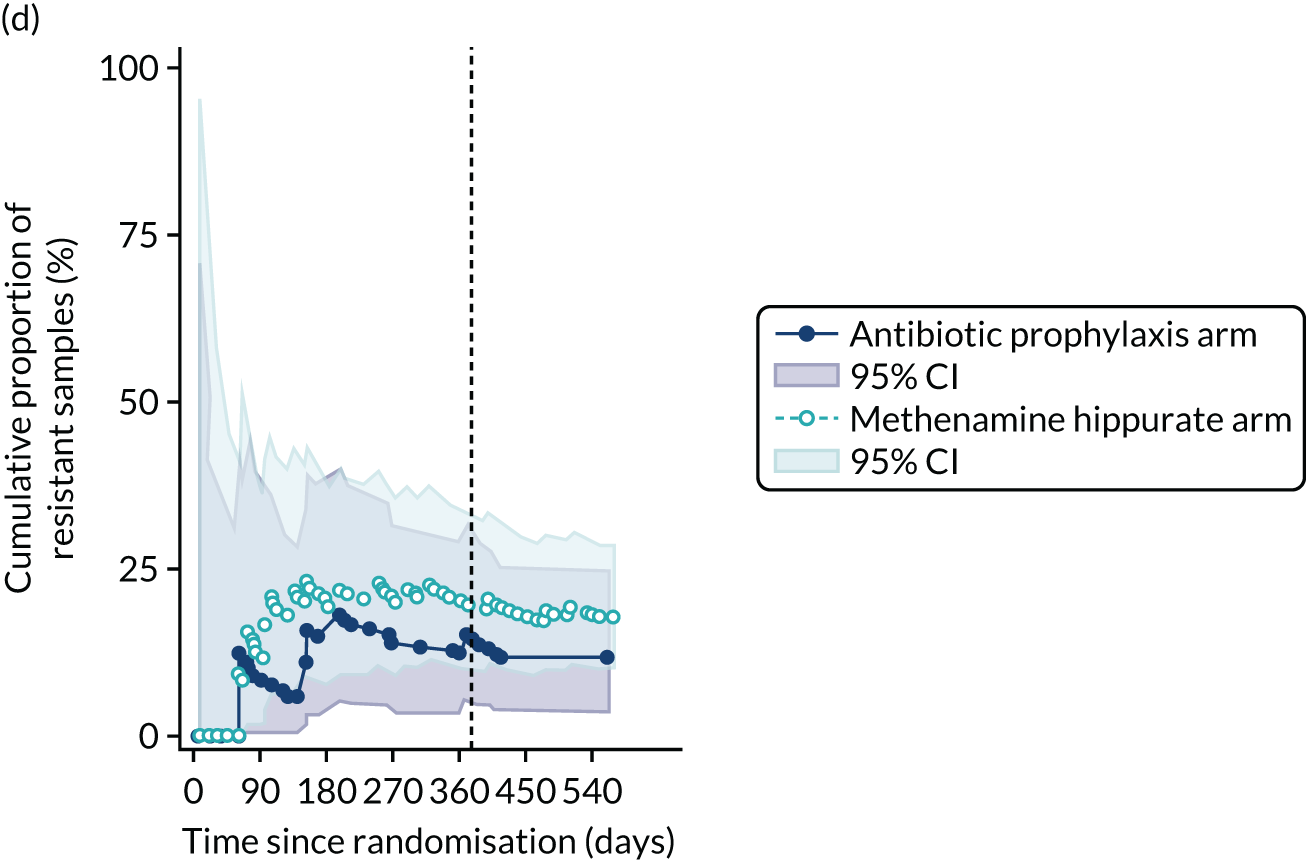

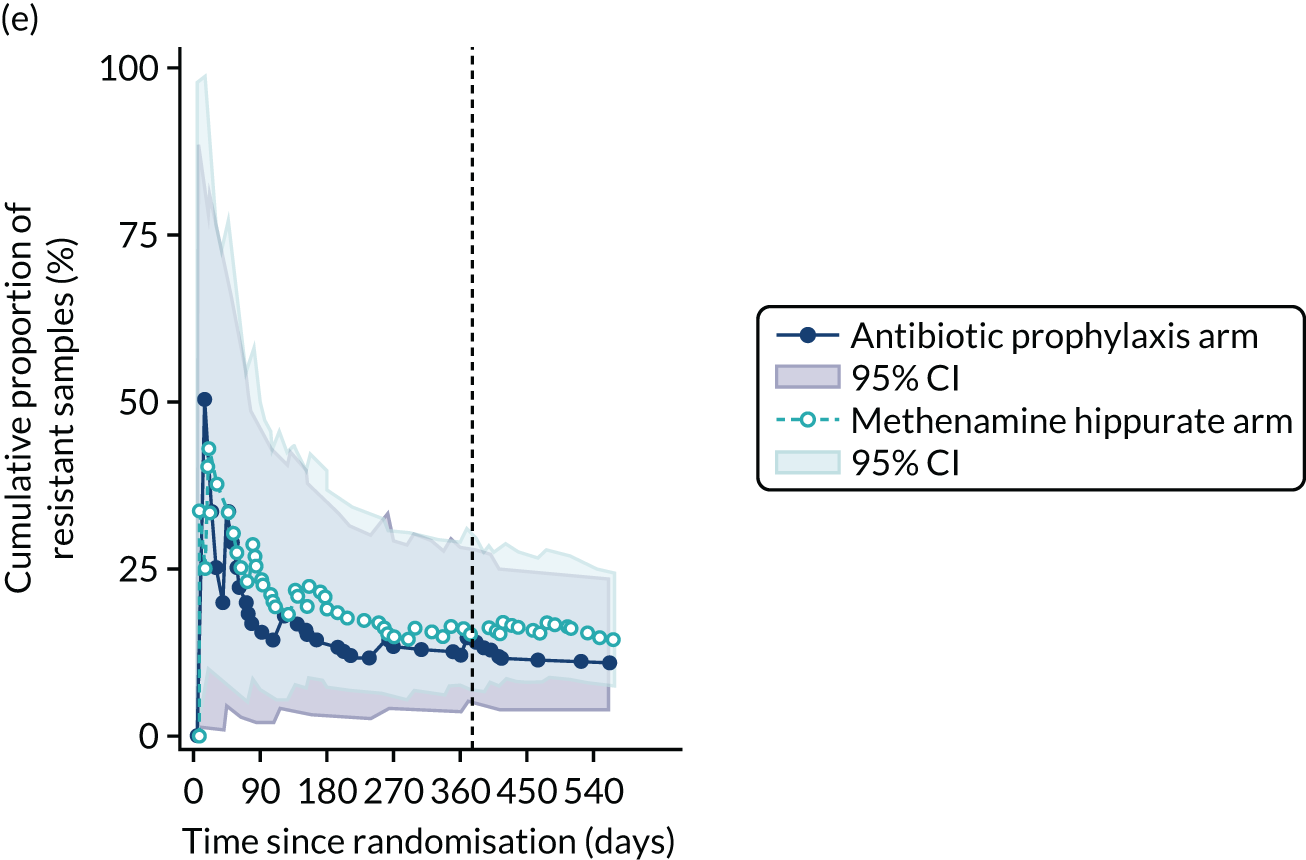

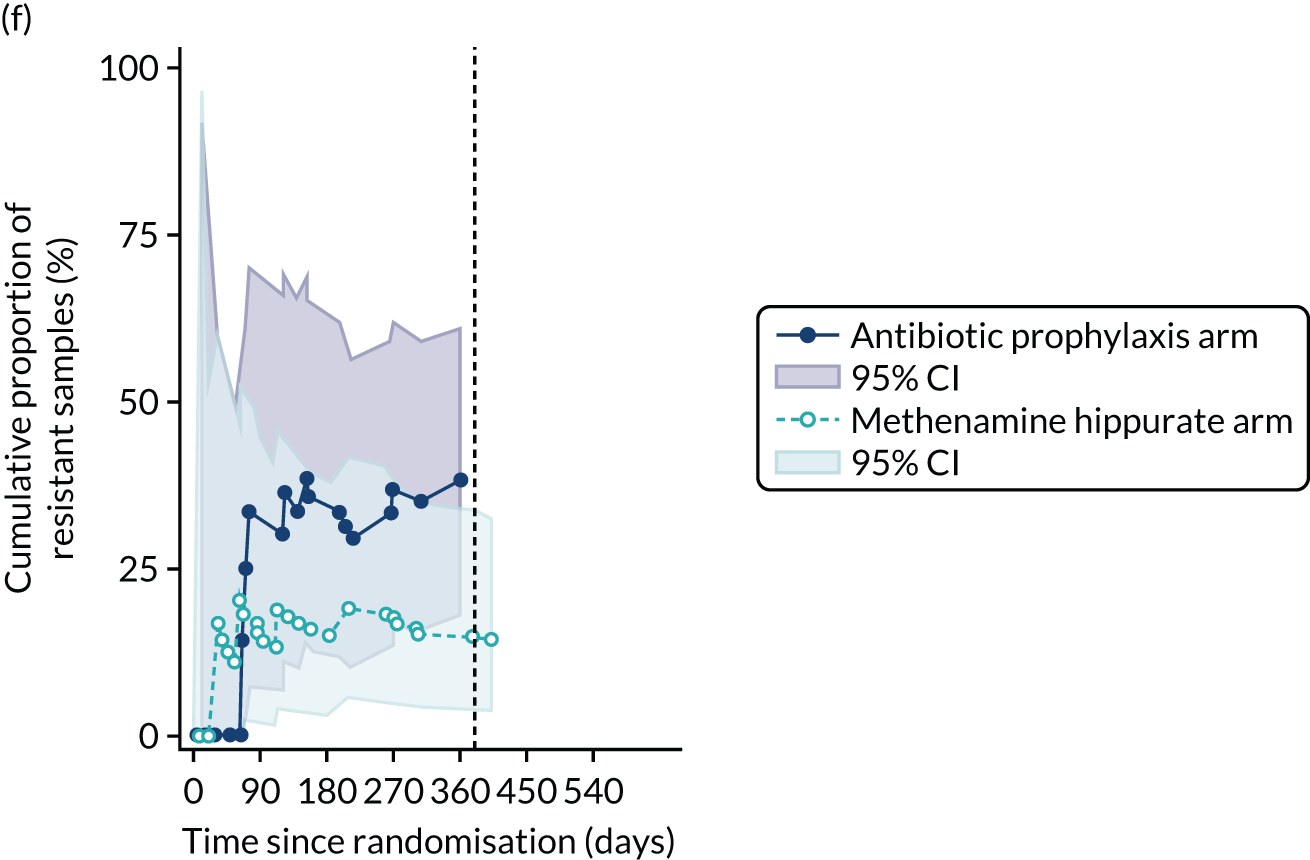

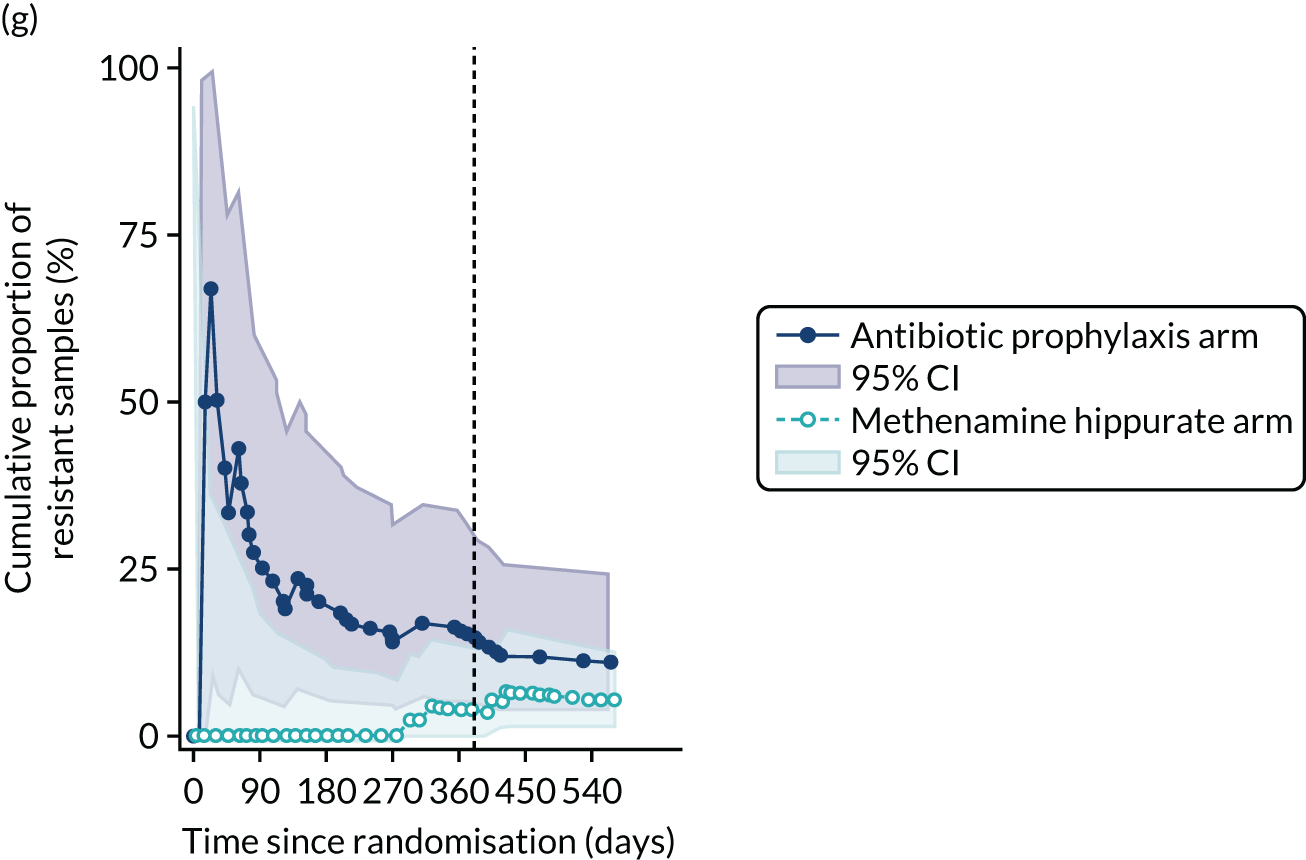

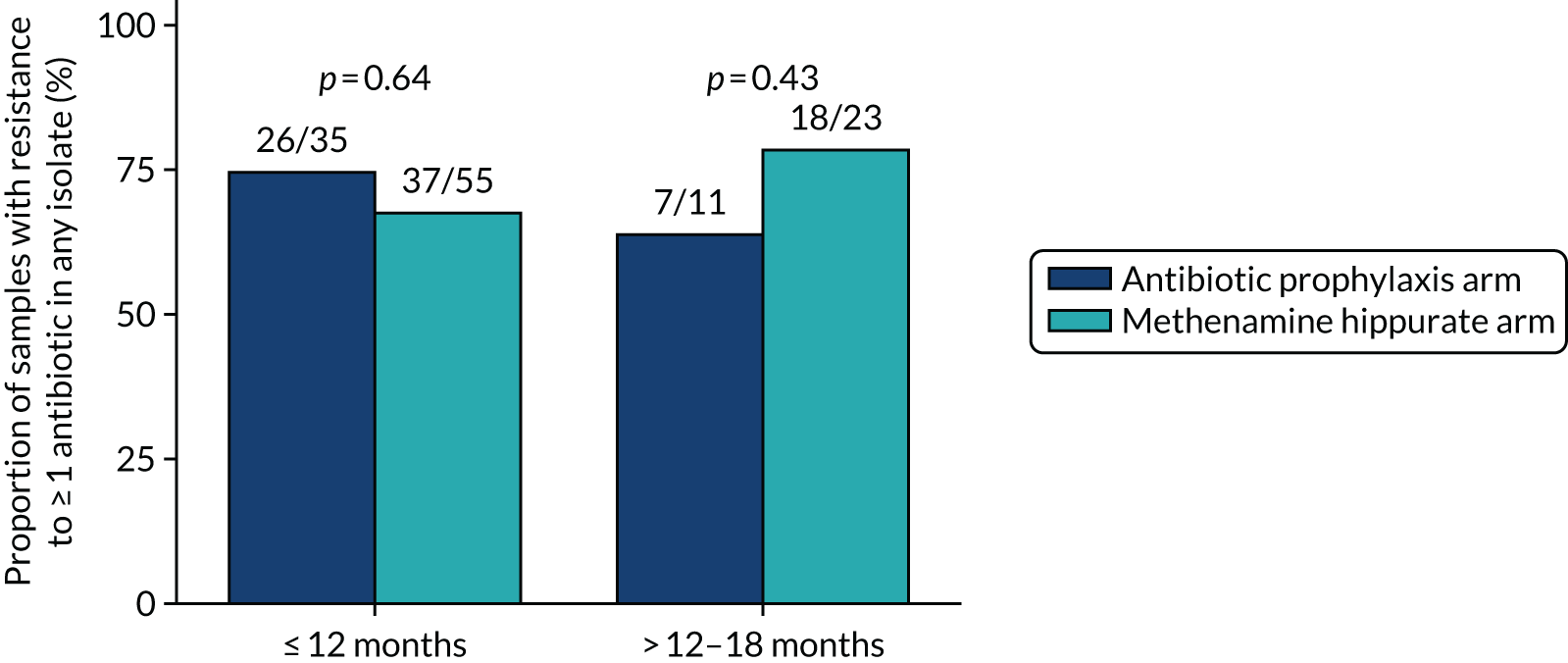

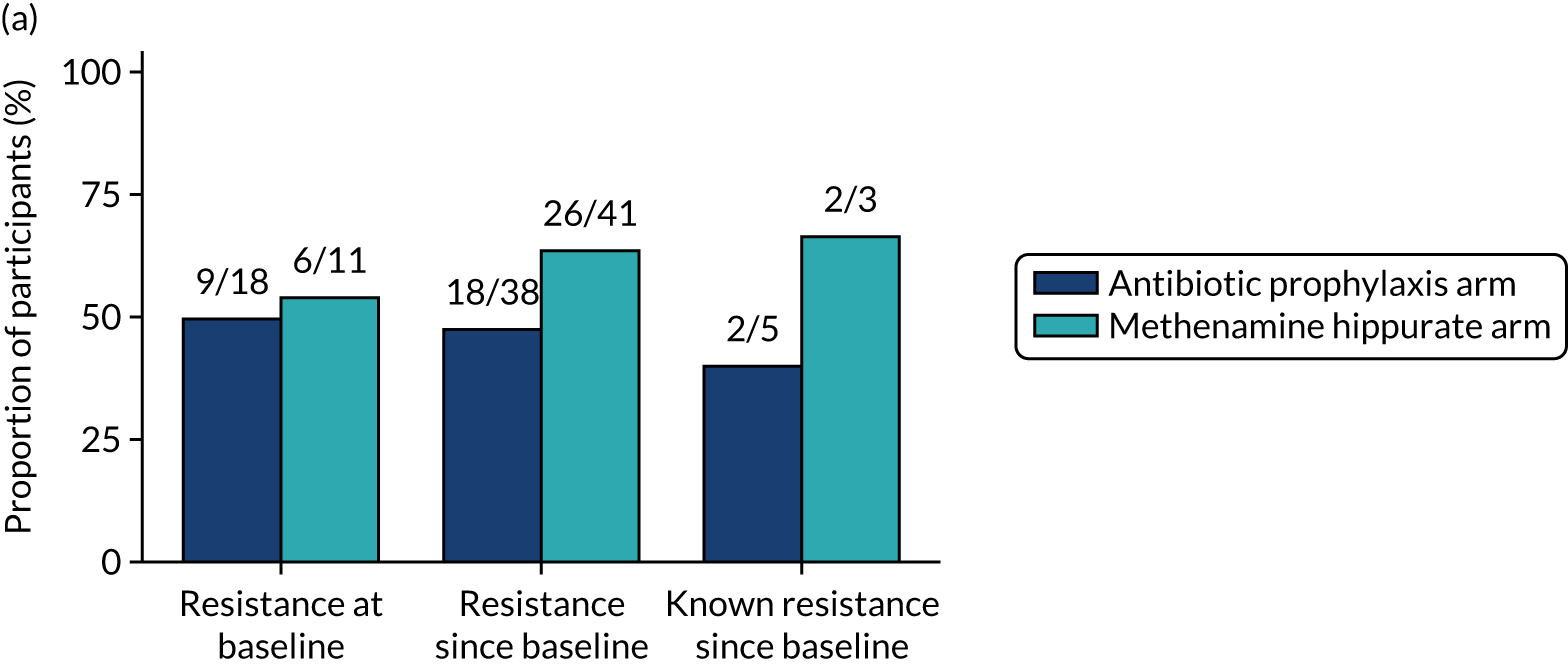

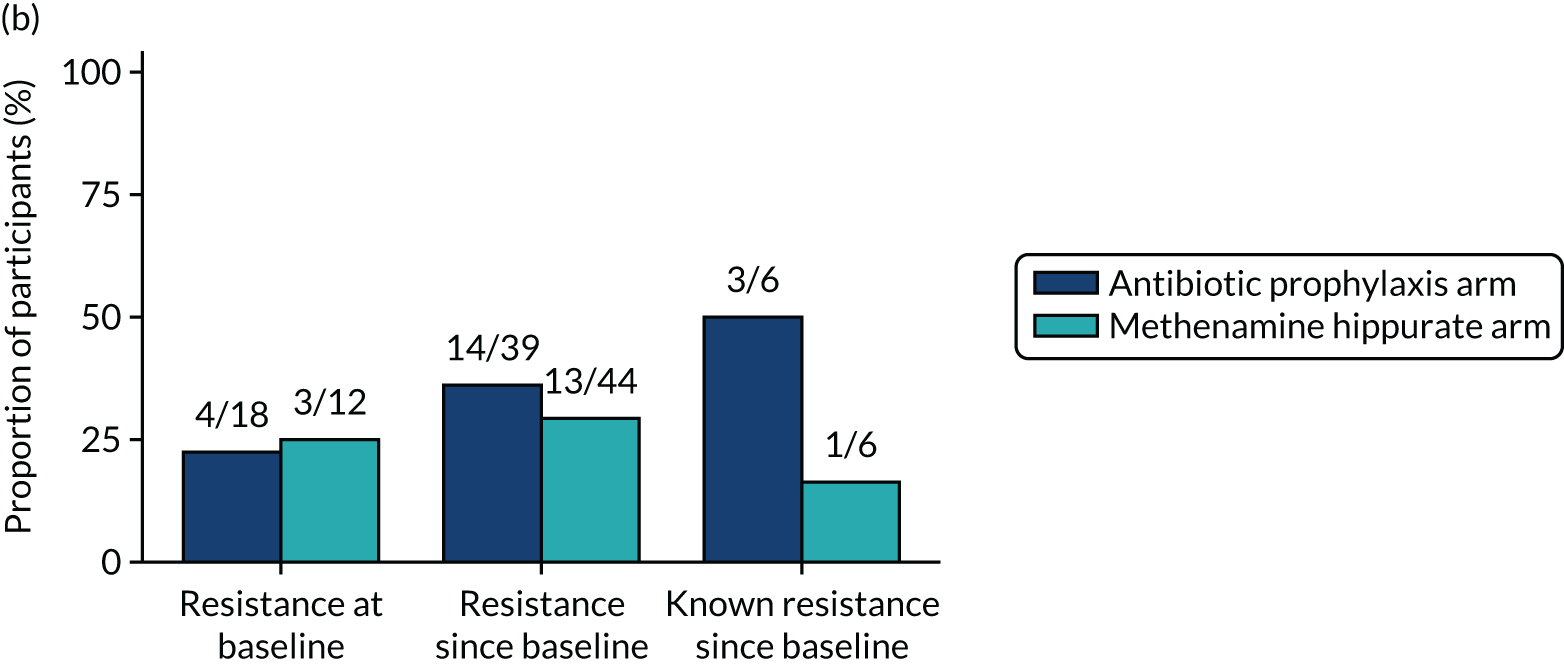

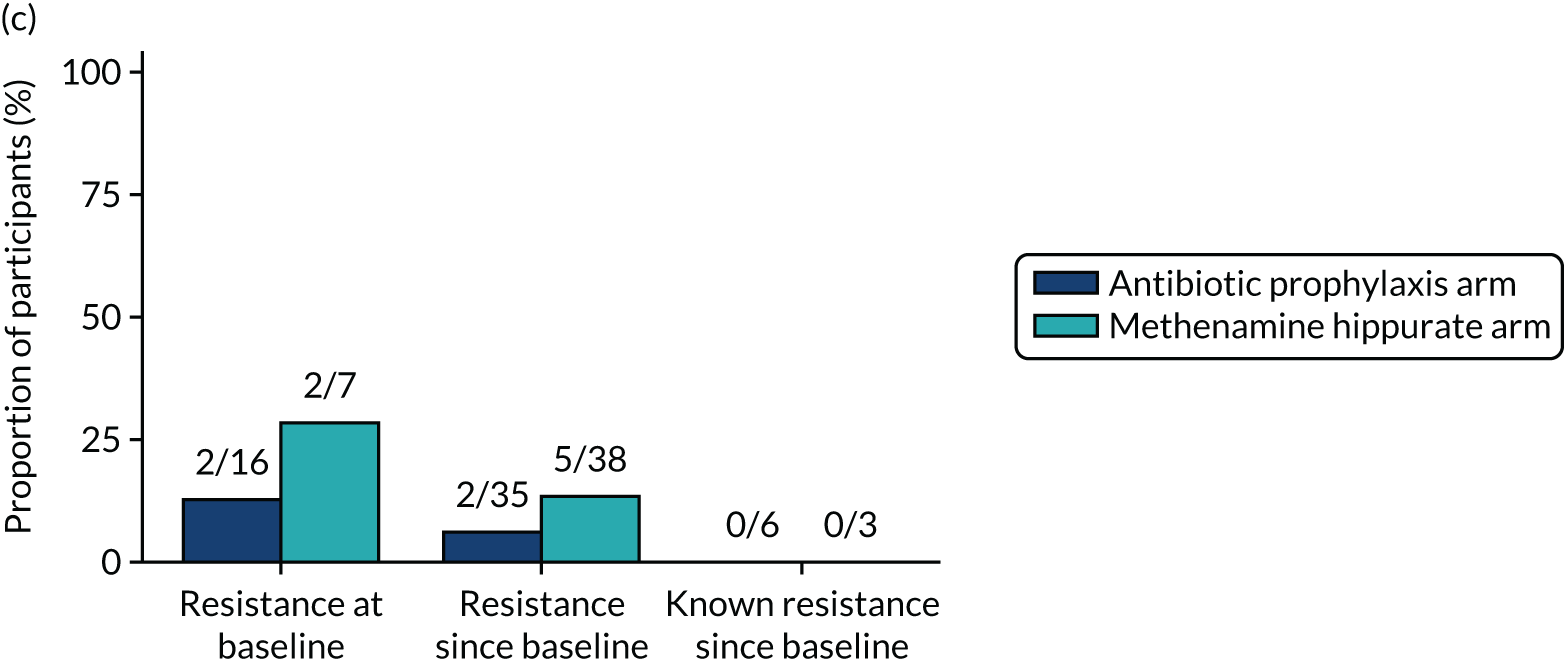

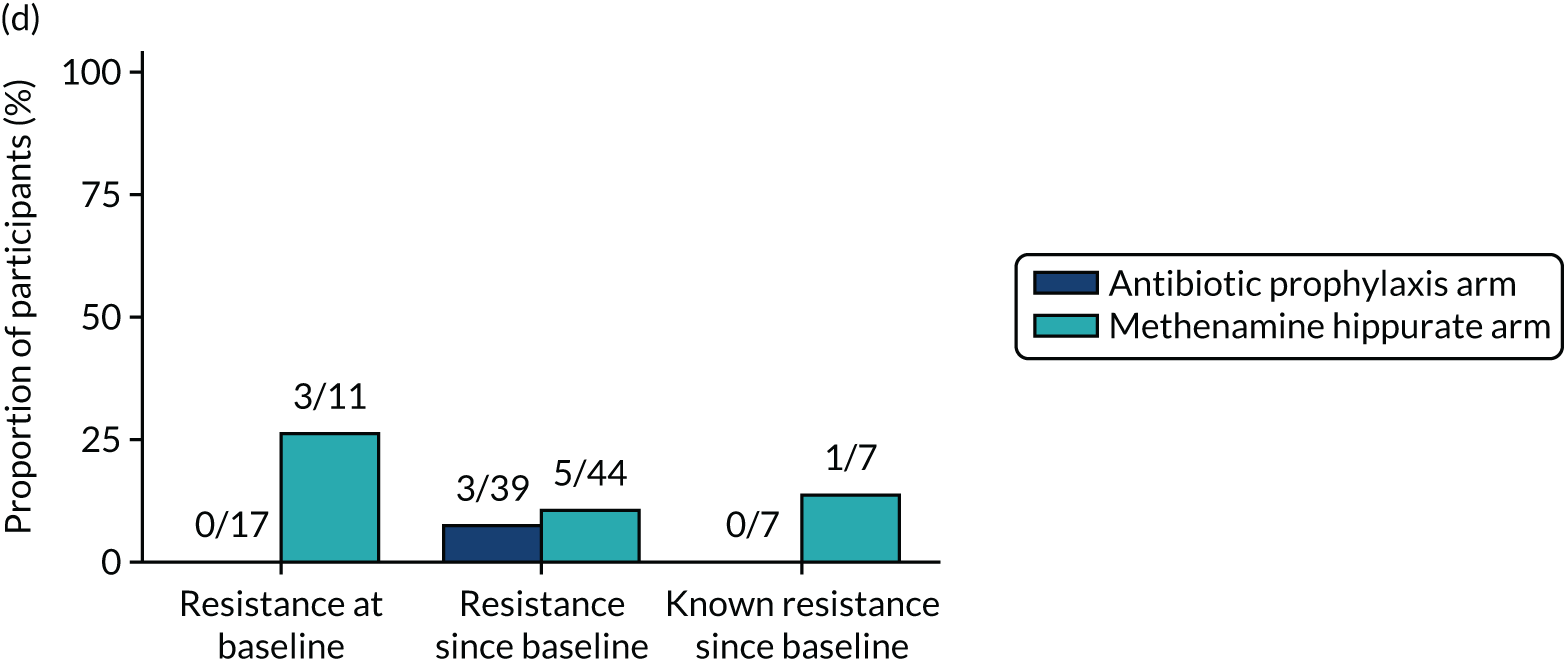

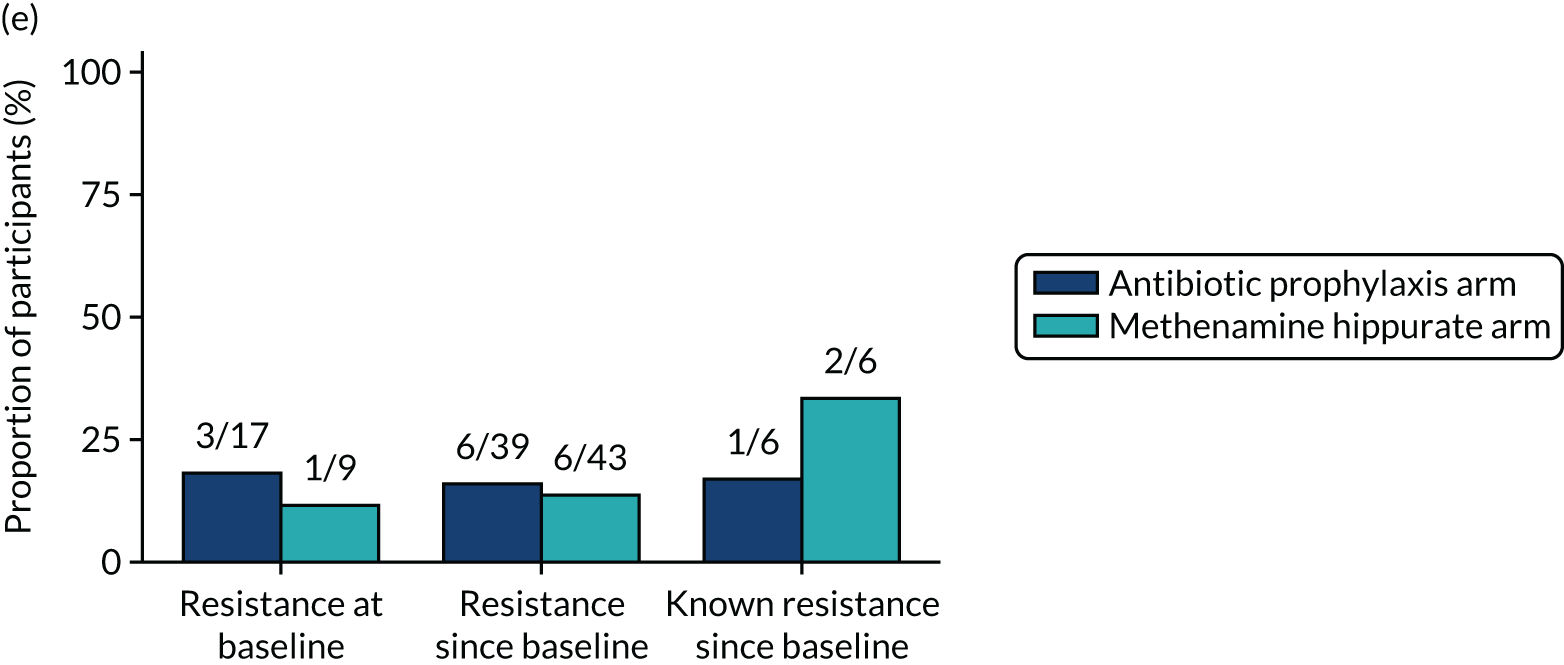

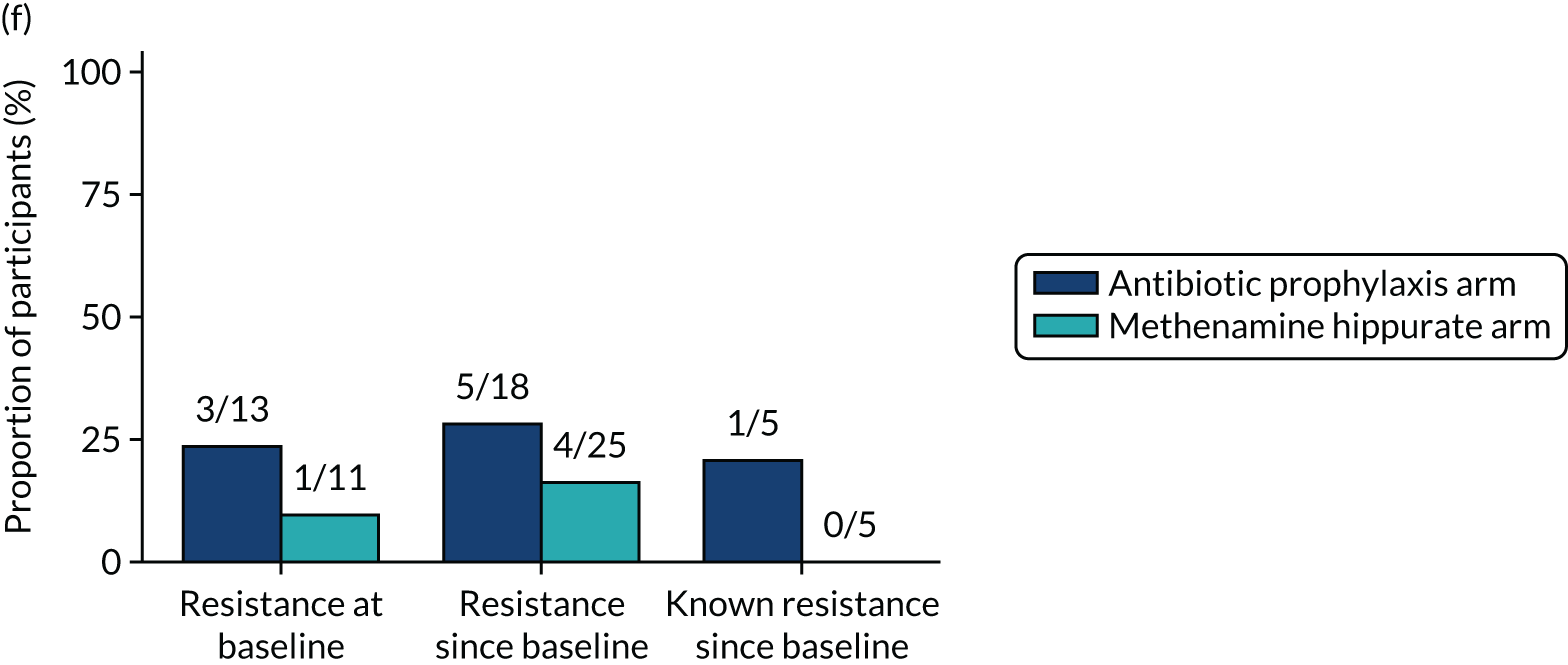

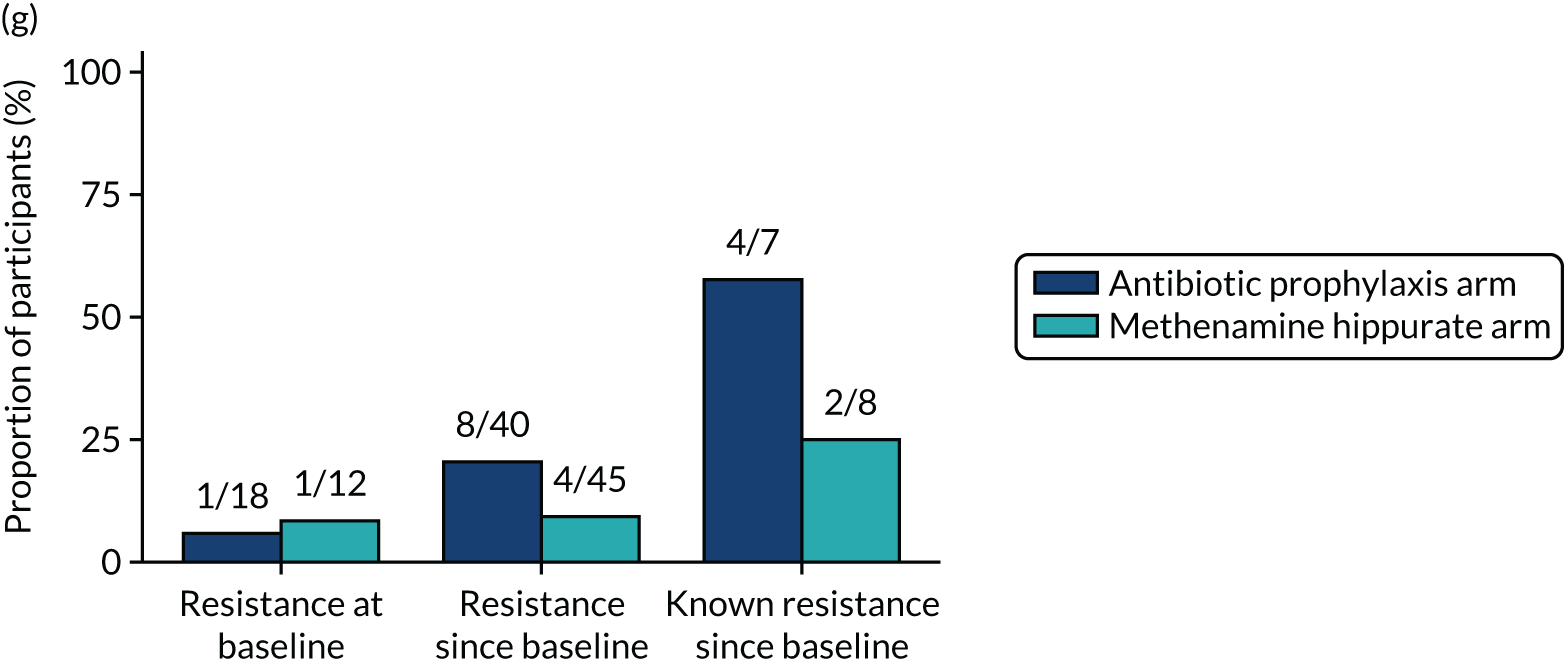

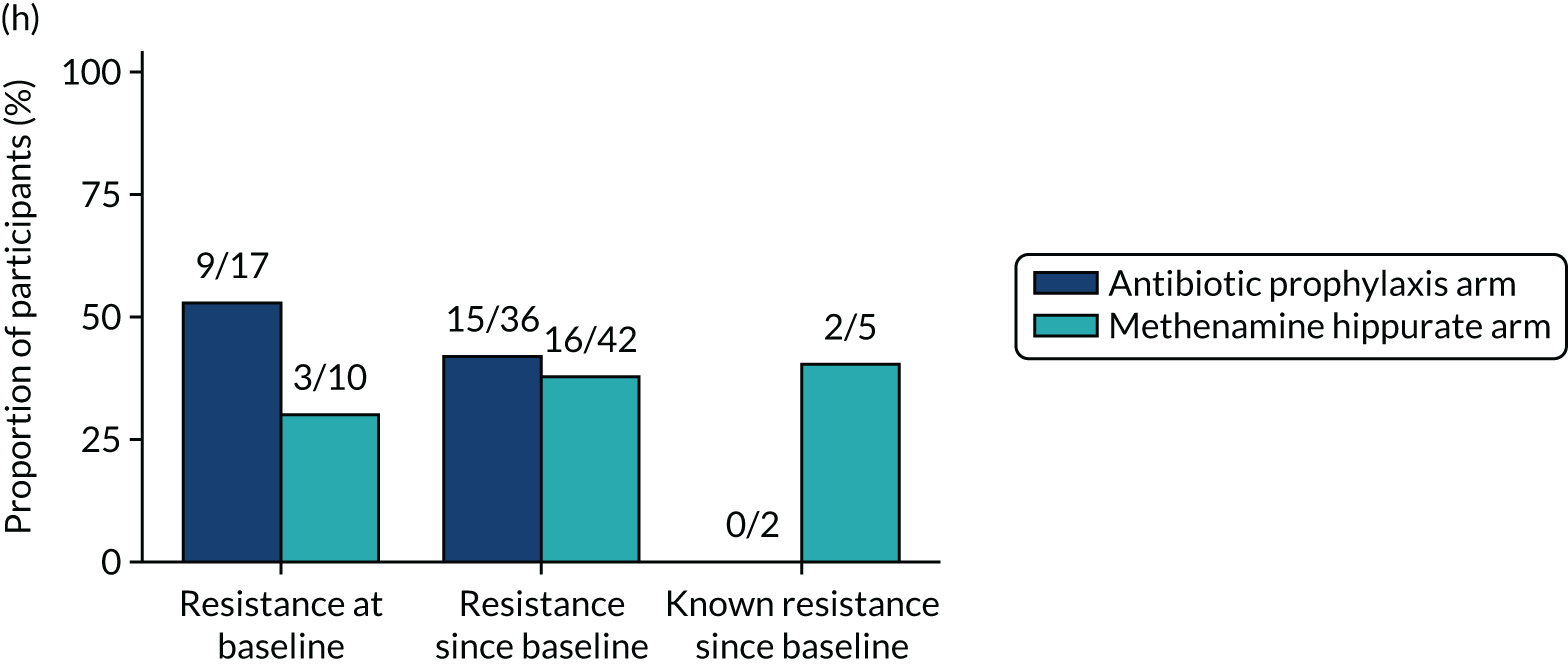

Antimicrobial resistance

The number of perineal swabs available at each time point was reported, along with the number of samples with E. coli isolated. Of the samples with E. coli isolated, the numbers of resistant antibiotic agents and antimicrobial categories (as per the MDR definition) were summarised descriptively. The number and proportion of participants demonstrating any antibiotic resistance in E. coli at baseline, 6 or 12 months and 18 months were tabulated with comparisons made between groups using a chi-squared test. The number and proportion of participants demonstrating MDR were presented similarly but with comparisons between groups made using a Fisher’s exact test. The proportion of participants demonstrating antibiotic resistance in E. coli to eight antibiotics used against UTIs (i.e. amoxicillin, cefalexin, cefuroxime, ciprofloxacin, co-amoxiclav, co-trimoxazole, nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim) was graphically summarised over time along with 95% CIs. For each antibiotic, the number and proportion of participants with E. coli isolates demonstrating antibiotic resistance since baseline (of those known to be sensitive at baseline or with no E. coli isolated at baseline) and known antibiotic resistance since baseline (of those known to be sensitive at baseline) were presented. Similarly, development of MDR since baseline and development of known MDR since baseline were also reported.

The availability of routine urine samples at baseline and 3-monthly follow-up visits was reported along with the number of samples with E. coli isolated. Of those samples in which E. coli was grown, the isolate’s antimicrobial resistance was summarised descriptively, noting the number of antibiotic agents and antimicrobial categories to which it was resistant (as per the MDR definition, i.e. resistance to at least one antimicrobial agent in at least three antimicrobial categories, following the principles described by Magiorakos et al. 27).

The number and proportion of participants demonstrating any antibiotic resistance in E. coli isolated from any urine sample submitted during periods of symptomatic UTI within the 12-month treatment period and 6-month follow-up period were tabulated. Comparisons between groups were performed using a Fisher’s exact test. The number and proportion of participants with E. coli isolates demonstrating MDR was presented similarly. In addition, the number and proportion of E. coli isolates (rather than participants) demonstrating any antimicrobial resistance and MDR were reported.

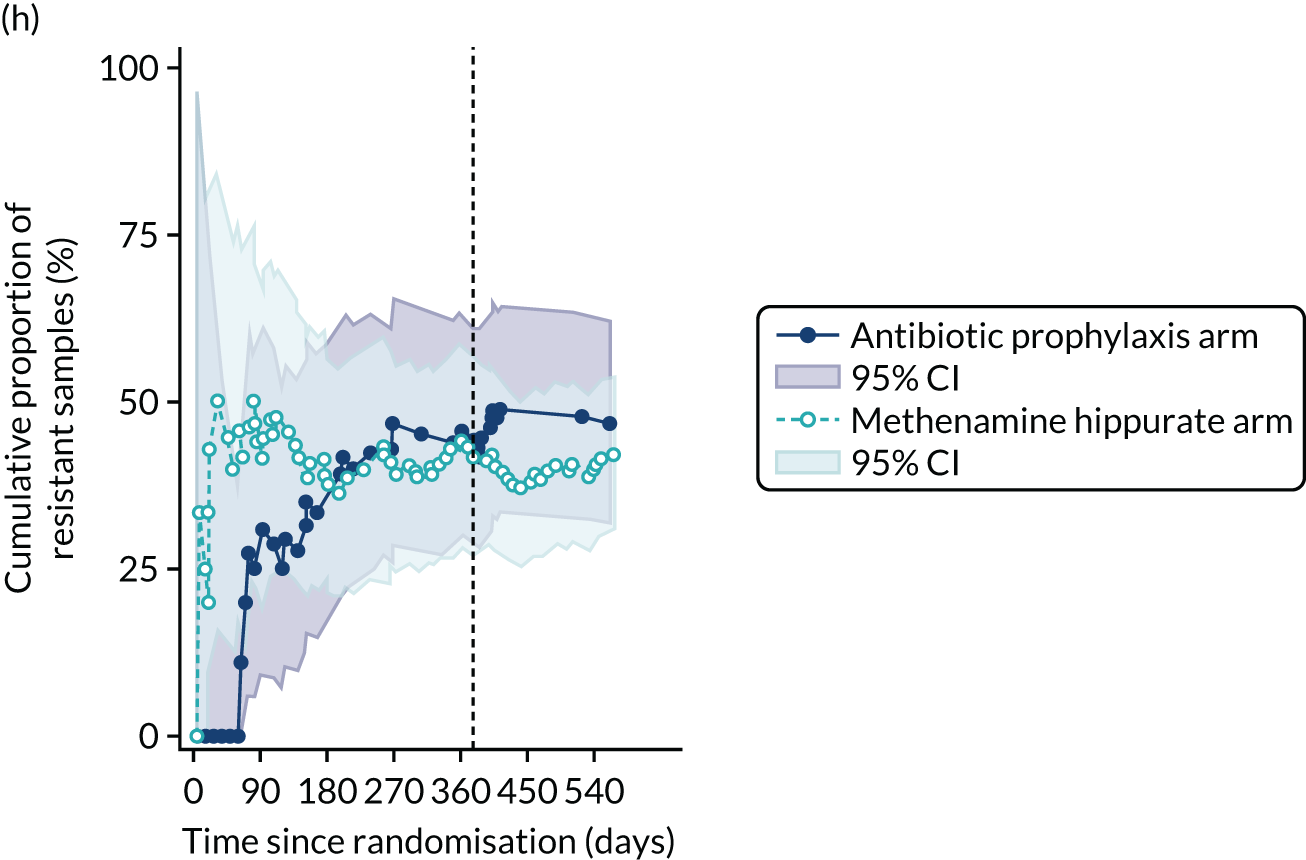

For each antibiotic, the number and proportion of participants with urinary E. coli isolates demonstrating antibiotic resistance isolated from any symptomatic urine sample during the 12-month treatment period and 6-month follow-up period were presented. Data were also presented as the number and proportion of resistant E. coli isolates (rather than participants). The cumulative proportion of resistant E. coli isolates was plotted, with 95% CIs, over the 18-month trial period for each antibiotic.

For each antibiotic, utilising all submitted urine samples, the number and proportion of participants demonstrating likely antibiotic resistance since baseline (out of those known to be sensitive at baseline or with no E. coli isolated at baseline) and known antibiotic resistance since baseline (out of those known to be sensitive at baseline) were presented. In the same way, development of MDR since baseline and development of known MDR since baseline were also reported.

All analyses of antimicrobial resistance data from urine samples (except MDR) were repeated based on any bacteria isolated, rather than only E. coli.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

The number and proportion of positive urine cultures detected from routine samples taken in the absence of symptoms was presented by treatment group. Data were summarised over the whole 18-month trial period and also grouped by time periods (baseline, 3–12 months and 15–18 months). Post hoc comparisons between randomised treatment groups were performed using chi-squared tests.

Hospitalisation due to urinary tract infection

Hospitalisation due to UTI was summarised descriptively.

Participant satisfaction with treatment

Four separate subscale scores (effectiveness, side effects, convenience and global satisfaction) from the TSQM were calculated as per the scoring algorithm at 12 and 18 months, and summarised descriptively. Comparisons between treatment groups were made using a two-sample t-test and an analysis of covariance model adjusted for baseline stratification factors: prior UTI frequency and menopausal status.

Adverse events

Adverse events were reported throughout the 18-month trial period. All events were graded as mild, moderate or severe, and relationship to trial medication was reported as unrelated, unlikely, possible, probable or definite. All events were coded systematically at the end of the trial using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 22.0.

To account for any participants who were switched to the alternative treatment group, AEs are primarily reported by treatment received (antibiotic prophylaxis or methenamine hippurate) at the time of AE onset. Data were also summarised by randomised treatment group.

The numbers of AEs and adverse reactions (ARs) (possibly, probably or definitely related to treatment) reported per participant were summarised descriptively. The worst grade of AE and AR reported per participant was also presented.

The number of participants reporting each type of AE was tabulated. Only those occurring in at least 3% of participants in either treatment group are shown, owing to a large number of different AEs being reported in a small number of participants.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) and serious ARs were listed.

Trial progress and monitoring

The monitoring of trial conduct and data collected was performed by a combination of off-site, on-site and central monitoring to ensure that the trial was conducted in accordance with the trial protocol and GCP trial monitoring. This included the review of consent procedures, source data verification, SAEs, trial conduct and essential documentation, and was undertaken by members of the Trial Management Group (TMG).

Microbiological methods

Urine samples

Participants were requested to submit MSU samples to the central laboratory when they suspected a UTI, based on symptoms, and routinely at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 months. The specimens were sent to the central reference laboratory (Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne) in a standard urine specimen container pre-loaded with boric acid at a concentration of 18 g/l (International Scientific Supplies Ltd, Bradford, UK), within secure packaging (Safebox™; Royal Mail Ltd, London, UK) and accompanied by a sample shipment checklist, completed by the participant, identifying the time point and type of sample. On arrival at the laboratory, the specimens underwent semiquantitative urine culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing was carried out in triplicate against a panel of agents on significant isolates. Isolates were deemed significant if semiquantitative bacterial culture yielded ≥ 104 CFU/ml of a single organism or ≥ 105 CFU/ml of up to two different organisms.

To measure microbiologically proven UTI and altered bacterial phenotype and genotype (secondary outcome measures), MSU specimens were collected. Participants collected their own samples, in accordance with standard instructions for MSU collection (which were included in their trial information packs) at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 months post randomisation, and during the early part of any episodes of UTI prior to antibiotic treatment. The specimens were sent to the central reference laboratory (Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) in a standard urine specimen container pre-loaded with boric acid at a concentration of 18 g/l (International Scientific Supplies Ltd), within secure packaging (Safebox) and accompanied by a sample shipment checklist, completed by the participant, identifying the time point and type of sample. On arrival at the laboratory, a semiquantitative urine culture was conducted, with samples deemed significant if they achieved specified criteria: ≥ 104 CFU/ml of a single isolate or ≥ 105 CFU/ml of up to two isolates.

Perineal swabs

To measure altered gut commensal bacterial phenotype and genotype (secondary outcome measures), optional perineal swabs were collected from participants. Perineal swabs were chosen as a surrogate for rectal swabs as they were felt to be less invasive and, therefore, potentially more acceptable to participants, while still enabling sampling of the individual’s enteric flora. Participants collected their own samples, according to standard instructions for perineal swab collection (included in their trial information packs), at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months after randomisation. Using the labels and Safeboxes provided, the samples were sent to the central reference laboratory using surface mail. On arrival at the laboratory, the samples were cultured to establish the presence of E. coli and isolates were tested for antibiotic sensitivity in triplicate.

Any isolated E. coli were temporarily stored in the laboratory for later transfer to the UTI laboratory (Cookson Building, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University). Where consent had been obtained from participants for storage and further analysis of samples, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted and stored in the laboratory for analysis of genotypes related to the UTI host response. Samples will be destroyed once the trial and necessary analyses are complete.

Definition of end of trial

The definition of the end of the trial was the last recruited participant’s last follow-up visit at 18 months post randomisation, which took place on 27 January 2020. With approval from the TSC, a 9-month extension to the trial recruitment period was granted by the trial funder in October 2017 (variation to contract, January 2018) to accommodate additional time to meet the trial recruitment target.

Compliance and withdrawal

Assessment of trial adherence

Outcome data were collected by both participant-reported completion of trial questionnaires and attendance at regular trial clinic visits. Trial clinic visits were used to ensure participant compliance with the completion of trial documentation, the provision of samples and adherence to medication allocation.

Participant attrition rates were monitored regularly throughout the trial and appropriately reported to the trial oversight committees (TSC and DMC) when required.

Some participants or their clinicians sought to change their allocated group at some point during trial participation because of either lack of efficacy or adverse effects of either treatment. The trial literature emphasised the need to adhere to the allocated strategy during the 12-month trial period, if possible, and any deviations were recorded. Multiple switching between prophylactic antibiotic agents was allowed. If participants stopped their allocated treatment within the 12-month treatment period or if they recommenced prophylaxis during the subsequent 6-month observation period, this was recorded and the participant continued on the trial unless they withdrew consent.

Data monitoring, quality control and assurance

Data Monitoring Committee

An independent DMC was established, which included two consultant urological surgeons not otherwise involved in the trial and an independent statistician. The DMC reviewed emerging efficacy and safety data by randomised treatment group. Prior to final database lock, only the trial statistician and independent DMC members (i.e. those who were not trial team members) had access to outcome data by randomised treatment group. The DMC operated in accordance with an agreed charter, based on the DAMOCLES (DAta MOnitoring Committees: Lessons, Ethics and Statistics) recommendations,32 and met six times during the trial.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was established to provide overall supervision of the trial. The TSC included an independent chairperson, two independent urological surgeons, an independent GP, two independent lay representatives and the chief investigator. Other members of the TMG attended as required. The committee met approximately every 6–12 months for the duration of the trial.

Data monitoring

Quality control was maintained by compliance with relevant standard operating procedures (sponsor and NCTU), local research policies, principles of GCP, the trial protocol, research governance and clinical trial regulations.

Monitoring of trial administration and data collection was performed using both central review and site monitoring visits conducted by the NCTU trial team. Monitoring included review of patient consent procedures, eligibility assessment, source data verification and completeness of investigator site files. Trial data were monitored centrally throughout the trial to ensure data completeness and accuracy; sites were contacted to help resolve queries when they arose.

An audit was conducted on data entered centrally by NCTU staff. As the UTI records relate directly to the primary outcome, a full audit of all such records was conducted to ensure accuracy. In addition, an audit of a random sample of 10% of the participant questionnaires and a further random sample of 10% of the uploaded laboratory sample data was conducted. These quality control checks resulted in an error rate below the threshold of 5%.

Ethics and governance

The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development Directorate sponsored the trial (reference 06867). A favourable ethics opinion for the trial was obtained on 23 December 2015 from the NHS Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Tyne and Wear South (reference 15/NE/0381). Health Research Authority approval was issued for the trial on 20 June 2016 and subsequent local research and development approvals were sought for each participating site. Approval was sought and obtained for all substantive protocol amendments.

Trial registration and protocol availability

The trial was registered as International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) 70219762 on 31 May 2016 and in the UK NIHR portfolio (reference HTA 13/88/21). The latest version (version 3.0) of the full protocol is available at the NIHR Journals Library project web page (URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/138821/#/) and a published version is also available. 1

Serious adverse event reporting

The trial protocol provided guidance on AE and SAE reporting, as well as determining the degree of relatedness and assessment of causality for SAEs that may be related to trial participation. The reference safety information for assessment of expectedness of related events was contained in the summary of product characteristics for trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, cefalexin and methenamine hippurate. SAEs excluded UTI, since this was the primary outcome collected and documented throughout the trial. All SAEs were reported for the duration of the trial and for 4 weeks after the trial intervention was stopped.

Chapter 3 Embedded qualitative study of the views of patients and recruiting staff on the ALTAR trial

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Lie et al. 33 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

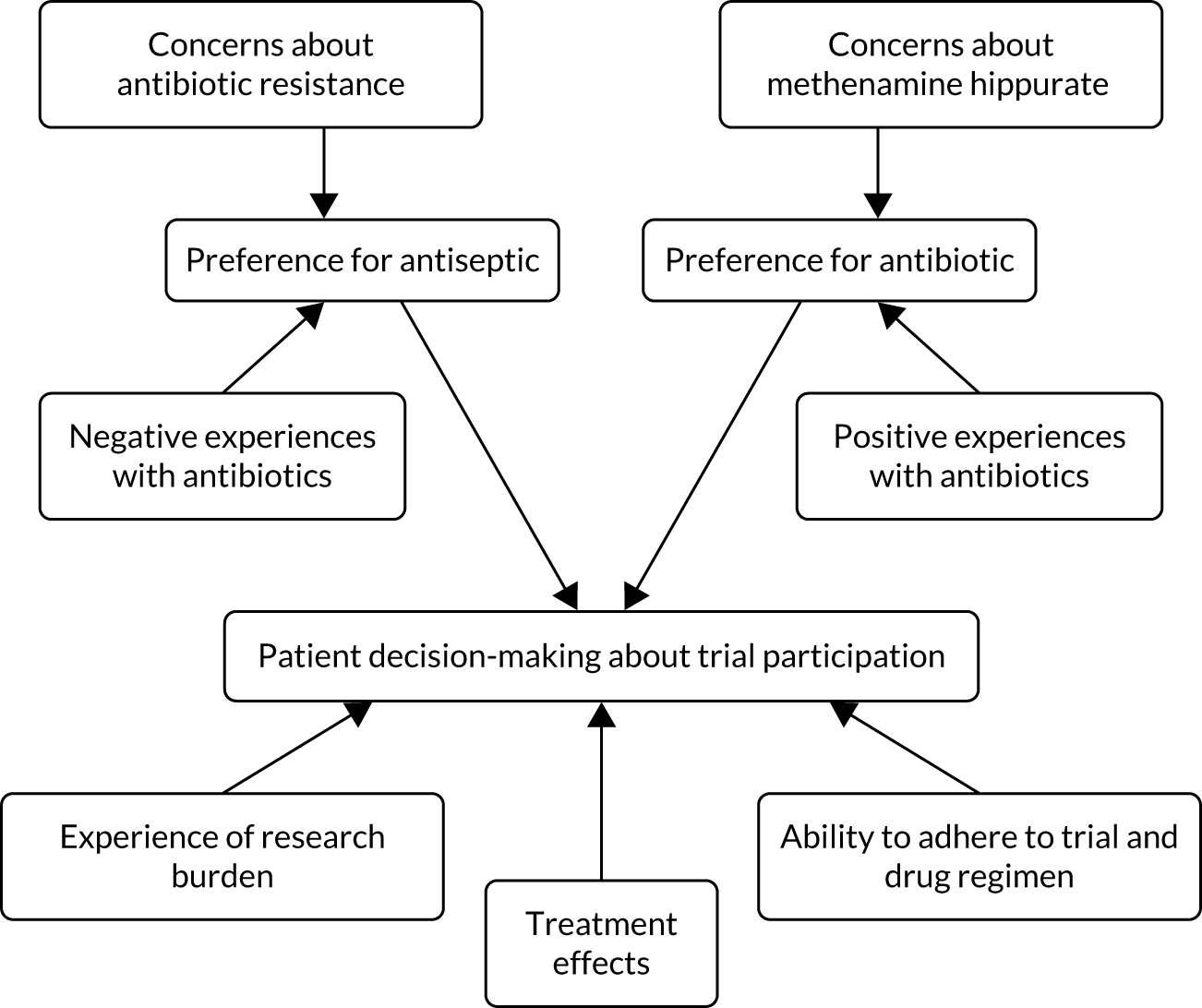

Understanding why patients agree or decline to participate in clinical trials is a crucial factor in the successful delivery of trials on time and to target. Embedded qualitative studies can provide in-depth information on the views and experiences of potential patient participants and recruiting staff that quantitative research cannot provide and highlight issues that may affect recruitment and retention. 34 To identify modifiable factors that could improve the conduct of the ALTAR trial, an embedded qualitative study was proposed. In the first 8 months that sites were open to recruitment, the plan was to conduct up to 15 in-depth interviews with patients approached about the ALTAR trial in each of three groups: (1) those who agreed to participate in the trial and continue on the trial until its end, (2) those who dropped out of the trial and (3) those who declined to participate. In addition, a focus group of eight recruiting staff participants was planned to explore views on recruiting to and delivering the trial.

Aim and objectives