Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 13/140/05. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The draft report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Coyle et al. This work was produced by Coyle et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Coyle et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter contains some text reproduced from the study protocol ‘Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotic therapy in patients with cancer who have low risk neutropenic sepsis (the EASI-SWITCH trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial’ published in Trials (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04241-1. 1

Neutropenic sepsis

Neutropenic sepsis (NS) is a long-recognised and common complication of systemic anticancer treatment (SACT). 2 The term broadly refers to a significant inflammatory response to a presumed bacterial infection, in a person with or without fever and a low blood neutrophil count. 3 A low neutrophil count occurs commonly following SACT with a trajectory that varies depending on type and timing of SACT, typically reaching a nadir around 7 days post SACT then recovering over 2–3 weeks. 4 There is significant variation in the definition of neutropenia and sepsis, with a lack of comparative data to guide threshold-setting for neutrophil count or fever in patients with potential NS. 3,5–15 Based on the available data, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline Development Group (GDG) concluded using a threshold of 0.5 × 109/l for neutrophil count and ≥ 38°C for temperature for diagnosis of NS reflected an acceptable trade-off between over- and under-treatment of what could be a potentially fatal infection. 3 However, in the NHS, NS care pathways commonly use a temperature threshold of ≥ 38°C and an absolute neutrophil count threshold of either ≤ 0.5 × 109/l or < 1.0 × 109/l and falling/expected to fall.

Robust predictors of NS risk are lacking in patients with cancer receiving SACT. It seems that NS is more common soon after treatment is initiated (within the first two cycles)16 and following administration of anthracycline or taxane-containing regimens in treatment of early-stage breast cancer. Other factors associated with risk of developing NS include age, performance status and a diagnosis of blood cancer rather than solid tumour. 17,18

Despite widespread adoption of prophylactic colony-stimulating factors (CSF) and fluoroquinolone antibiotics for patients at high risk of septic complications, NS remains potentially life-threatening, with an in-hospital mortality rate of approximately 9.5%19 and, in the setting of severe sepsis or septic shock, as high as 50%. 20 NS deaths recorded by the Office of National Statistics more than doubled in England and Wales between 2001 and 2010 to approximately two deaths per day (716 deaths in 2010),3 with significant increases in chemotherapy use likely contributing. 21

Significant patient morbidity can also occur through hospitalisation, with a strong desire not to be hospitalised during treatment cited as a common barrier to patients promptly seeking help for symptoms. 22 An episode of NS can also result in dose delays and reductions to patients’ planned SACT, potentially compromising treatment efficacy in certain tumour types and settings. 3,23–25 There are associated financial implications on healthcare systems managing NS episodes, with hospital, antibiotic, diagnostic and additional therapeutic costs involved resulting in an estimated average cost per inpatient admission in the NHS ranging from approximately £257226 to £3163. 27

Empirical management of NS

Neutropenic sepsis continues to be viewed as a time-critical medical emergency with widespread agreement that early recognition and prompt administration of broad-spectrum empirical antibiotics are essential to successful treatment. 3,21,28,29 However, there is much less consensus on optimal patient management thereafter, including when to switch from intravenous (i.v.) to oral antibiotics, and duration of antibiotic treatment and hospital admission. Widely variable practice has been noted among cancer centres in the UK. 30 A review of 51 English and Welsh centres, prior to the introduction of a national UK NS clinical guideline, highlighted the heterogeneity that existed in almost all aspects of NS management, commenting that there was ‘surprisingly little agreement’ and ‘dramatic variations’ in clinical practice. These findings were consistent with previously published audits of both adult and paediatric haemato-oncology practice. 6,31,32

The NICE GDG recommended use of empirical beta-lactam monotherapy (piperacillin/tazobactam) as immediate treatment in patients with suspected NS in the absence of local microbiological indications to use an alternative agent or combination therapy (such as addition of an aminoglycoside) based on local resistance patterns. 3 Evidence supporting a specific duration of treatment was found to be lacking by the Group but the principle of switch to oral antibiotics following risk assessment after 48 hours of i.v. antibiotic therapy could be considered. While current European guidelines suggest that following initial assessment, including prompt institution of empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics, patients identified as low risk may be suitable for inpatient oral antibiotic treatment, the authors noted clinician preference was often to continue i.v. treatment for at least 48 hours and then consider a change to oral antibiotics if fever resolves. 28

Risk stratification

A spectrum of NS severity exists, encompassing a heterogeneous group of patients with variable risk of septic complications such as organ failure, need for critical care support and death. 33

At the low-risk end of the spectrum, there are patients who do not demonstrate clear clinical or microbiological evidence of proven infection, have uncomplicated hospital admissions and are at low risk of developing septic complications. These patients potentially receive overtreatment, with the associated distress of hospitalisation and additional burden to the healthcare system. 34

Risk stratification tools have therefore been developed in an attempt to identify patients predicted to be at low risk of an adverse outcome. The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) score (Table 1) is the most widely validated risk score for SACT-induced NS. 3,28,29,33

| Characteristic | Weight |

|---|---|

| Burden of febrile neutropenia: no or mild symptomsa | 5 |

| Burden of febrile neutropenia: moderate symptomsa | 3 |

| No hypotension (systolic BP > 90 mmHg) | 5 |

| No chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 |

| Solid tumour or no previous fungal infection | 4 |

| No dehydration requiring parenteral fluids | 3 |

| Outpatient status | 3 |

| Age < 60 years | 2 |

In the original validation set, a risk index score of 21 or greater out of 26 identified low-risk patients with a positive predictive value of 91%, a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 68%. A low rate of adverse outcomes (6% serious medical complication, 1% mortality) was observed in patients with a risk index score ≥ 21 compared with 49% in those with a risk score of < 21. 35

Oral antibiotic therapy as treatment

A UK single-centre prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigated the effectiveness of oral antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and co-amoxiclav) with early hospital discharge for patients with low-risk NS in comparison to standard i.v. antibiotics (tazobacam-piperacillin and gentamicin) with hospital admission. One hundred and twenty-six NS episodes from 102 patients were evaluated for the ‘success and safety’ primary end point, which comprised: lysis of fever, resolution of symptoms and signs, absence of modification of antibiotic regimen, absence of recurrence within 7 days and occurrence of serious complications or deaths. Treatment success was 90% in the i.v. arm and 84.8% in the oral arm. Re-admission was required in five episodes (7.6%) and deemed unrelated to the episode of NS in one. It was recognised that these results were obtained within a single specialist centre but that the findings supported undertaking a multicentre RCT evaluating oral antibiotics and early discharge. 36

A Cochrane review37 of oral versus i.v. antibiotics for NS, evaluating 22 trials comprising 3142 neutropenic episodes in 2372 patients, concluded that it is not likely that significant differences exist in treatment failure or mortality rates between oral antibiotic and i.v. antibiotic strategies. There was a trend towards more adverse events (AEs) in patients receiving oral antibiotics, typically gastrointestinal events, which did not necessitate treatment discontinuation. The majority of studies did not utilise any formal risk stratification tools but excluded high-risk patients with acute leukaemia, haemodynamic instability, evidence of organ failure or localising signs of infection.

The Cochrane review therefore broadly supported the early use of oral antibiotics in low-risk NS, but it was noted most trials were small in sample size, often single-centre and with methodological concerns and so a robust recommendation for upfront or early oral antibiotic therapy could not be made. It was suggested that ‘the combination of a quinolone and a second drug active against Gram-positive bacteria (for example ampicillin-clavulanate) seems prudent’. 37 This group also recommended that this therapeutic approach should be formally evaluated in patients with low-risk NS. The NICE GDG also considered oral antibiotic therapies but were unable to make a specific recommendation given variation in local microbiological resistance patterns and variation in use of prophylactic antibiotics. 3

Outpatient management of low-risk NS

The NICE GDG reviewed the evidence for inpatient versus outpatient management of NS and concluded outpatient management can be considered for selected low-risk patients, taking into account their individual clinical and social circumstances. 3 Although the metaregression undertaken by the GDG suggested early discharge (before 24 hours) may be associated with increased likelihood of re-admission or therapy change, the quality of evidence supporting outpatient management was low to moderate. The available data were limited by a lack of reporting of key outcomes such as critical care admission or clinically documented infection and a very low event rate for adverse outcomes including death. 3 Similarly, there is negligible literature relating to impact on quality of life for different models of care, including immediate use of oral antibiotics and non-admission to hospital, with a single study suggesting role function improved more for inpatients than home care patients but that emotional function declined with hospital admission. 38 It was therefore proposed that if a short period of hospital admission was found to be safe and effective for selected patients with NS, it could provide considerable improvements in quality of life and health resource usage.

Rationale for the trial

NICE therefore recommended that a randomised trial should be undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of switching from i.v. to oral antibiotics within the first 24 hours of treatment in patients receiving i.v. antibiotics for NS. The early switch to oral antibiotic therapy in patients with low-risk NS (EASI-SWITCH) trial was developed in response to this recommendation and a commissioned call from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to address this evidence gap. It aimed to establish the clinical and cost effectiveness of an early switch to oral antibiotics 12–24 hours after i.v. antibiotic treatment commences in low-risk cancer patients with NS.

Acute oncology service development

While prospective RCTs evaluating upfront or early oral antibiotics remain lacking from publication of the NICE guidance, there have been significant service developments in response to acute care pressures and increasing demands due to increases in cancer incidence and available treatments with the aim of developing novel models of care for meeting cancer patients’ complex needs. 39 Ambulatory care has been introduced in acute medical and elderly care NHS settings with growing interest in developing care pathways in cancer services in recent years. This has included management of low-risk NS although it has only been implemented by a limited number of UK cancer centres. 40,41 Some have reported results from longitudinal patient series. Marshall et al. 42 reported a series of 100 patients from a large UK tertiary cancer centre over a 2-year period with NS who were assessed and given a first dose of i.v. antibiotics then managed on an ambulatory low-risk NS pathway. Patients were stratified using MASCC score and National Early Warning Score (NEWS) score and following observation for at least 4 hours were discharged for outpatient follow-up (repeat clinical assessment and routine bloods) within 48 hours. 42 Six of the 100 patients (8.8%) required re-admission within 7 days, typically with positive blood cultures, but none required critical care support. Brunner et al. 43 reported a low-risk NS ambulatory care pathway case series from another UK centre. One hundred and twenty-three patients presented with NS over a 2-year period, 41% of whom were deemed low risk based on MASCC score. Of these, 24 were managed on the ambulatory care pathway with a first dose of i.v. antibiotic and discharge with oral antibiotics and proactive telephone follow-up. A further 24 patients were admitted but had early discharge. Again, no serious complications occurred and the re-admission rate was 10%. However, despite the investment in establishing the ambulatory care pathway, approximately 80% of patients with NS were still admitted. Similarly, other international centres have reported real-world data where only a minority of patients are managed on ambulatory pathways or considered for same-day discharge. 44 For example, in a large US emergency department (ED) only 5% of NS patients were discharged home, with most low-risk patients admitted for inpatient antibiotics. 45 A subsequent large-scale review of approximately 350,000 US ED visits with NS confirmed this finding, with 94% of visits resulting in hospitalisation. 46 Cost analysis data from real-world data sets are also lacking.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter contains some text reproduced from the study protocol ‘Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotic therapy in patients with cancer who have low risk neutropenic sepsis (the EASI-SWITCH trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial’ published in Trials (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04241-1. 1

Trial design

EASI-SWITCH was a UK prospective Phase 3, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial to evaluate whether early switch to oral antibiotics is non-inferior to standard care in adult patients with cancer with NS at low risk of complications.

The main aim was to determine the clinical effectiveness of early switch to oral antibiotics 12 to 24 hours after commencement of empirical i.v. antibiotics compared to standard care, which comprises continuation of i.v. treatment for at least 48 hours, based on treatment failure rate. Treatment failure was defined by a composite measure incorporating a number of important clinical outcomes assessed at day 14 of follow-up.

The trial included an embedded pilot study across four UK sites in order to test the recruitment and adherence assumptions which had informed the trial design.

Trial objectives

Primary objective

To determine whether early switch to oral antibiotic therapy is non-inferior to standard care therapy in terms of treatment failure measured at day 14.

Treatment failure was defined as a composite measure incorporating the following important treatment outcomes:

-

persistence, recurrence or new onset of fever (temperature ≥ 38°C) after 72 hours of starting i.v. antibiotic treatment

-

physician-directed escalation from protocol antibiotic treatment

-

re-admission to hospital (related to infection or antibiotic treatment)

-

critical care admission

-

death.

Secondary objectives

To assess the effect of early switch to oral antibiotics on:

-

short-term change in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), using EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) as the measurement tool, at baseline and 14 days

-

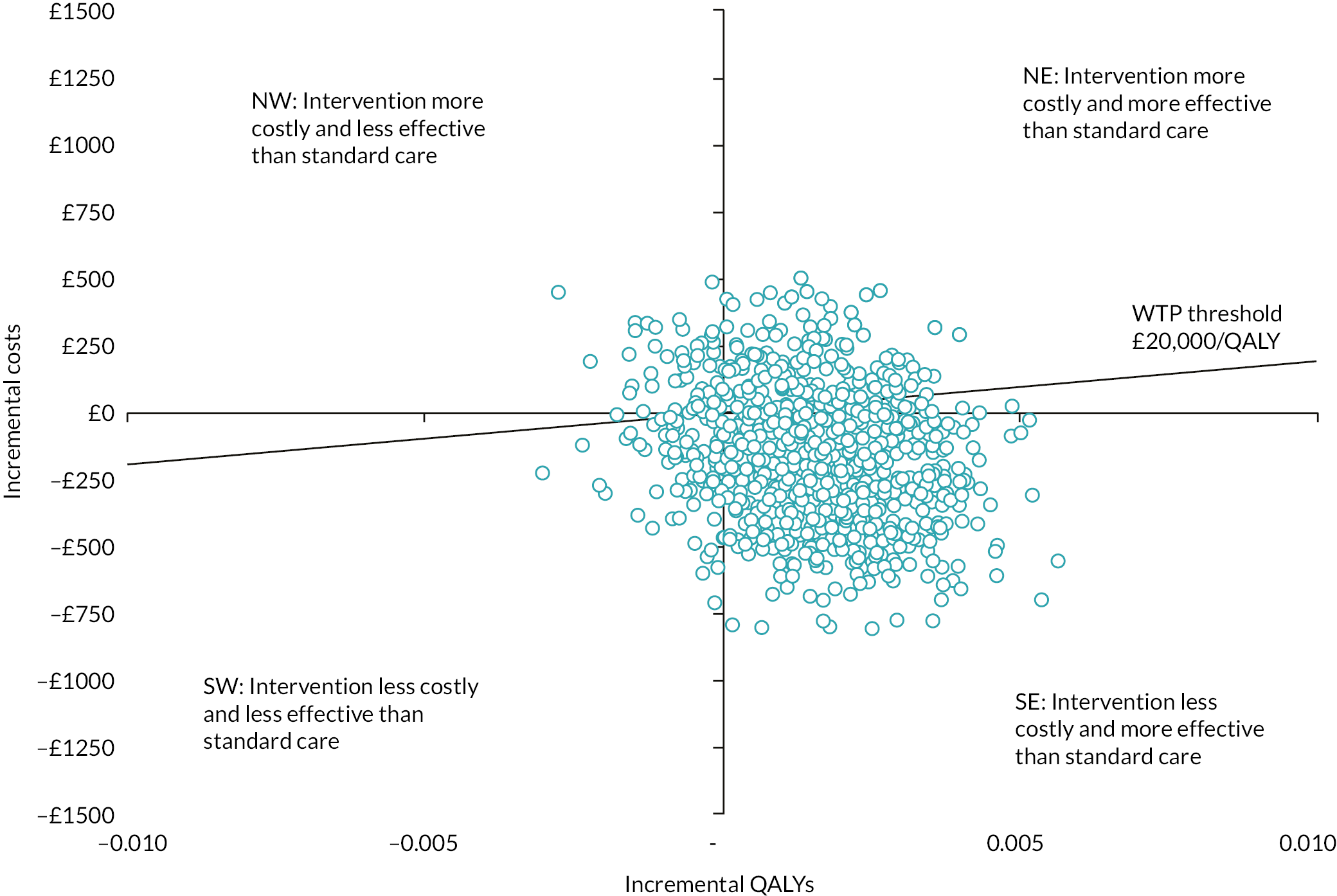

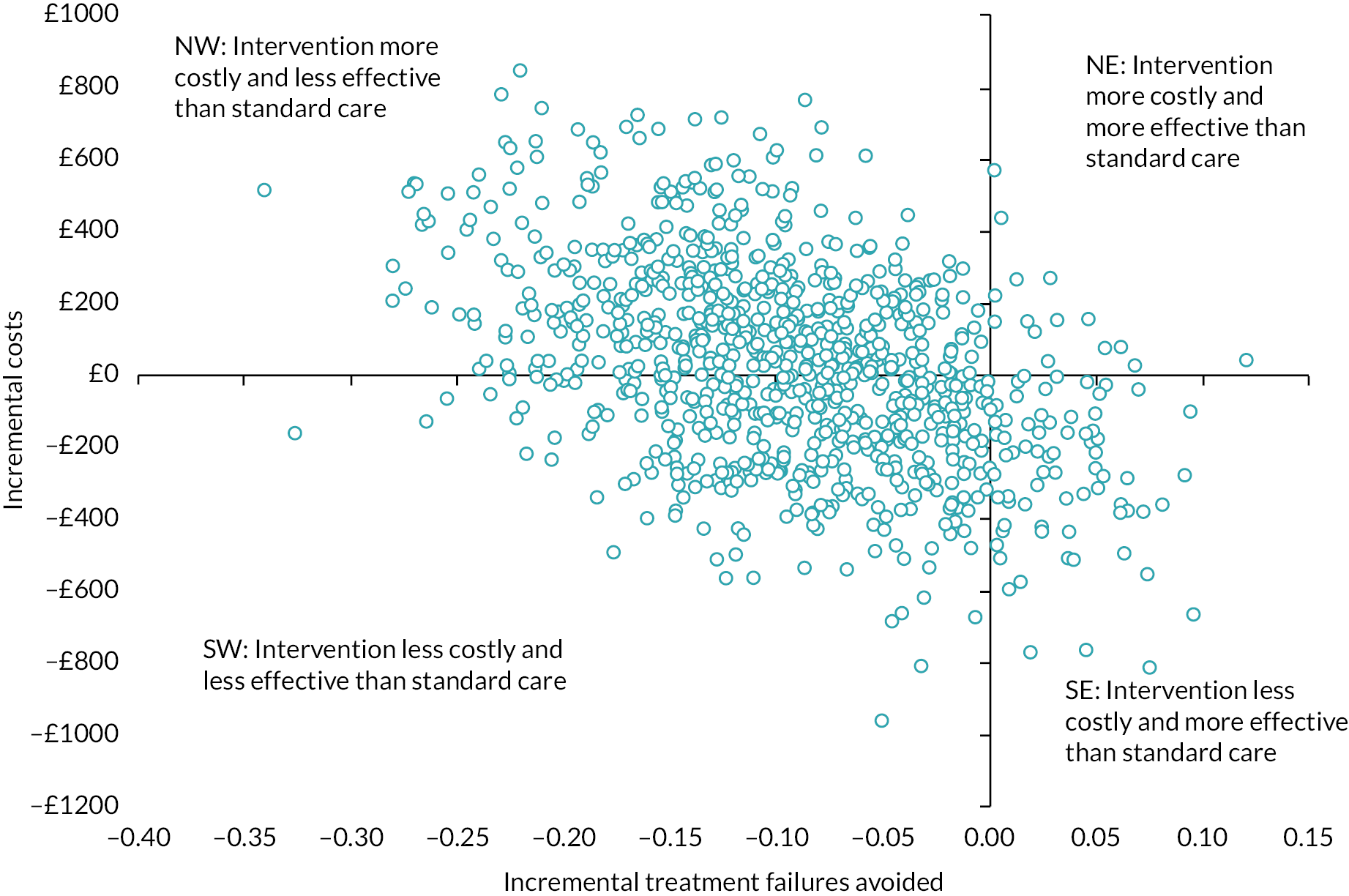

cost-effectiveness, based on the cost per treatment failure avoided at 14 days and a cost–utility analysis (CUA) estimating the cost per QALY at 14 days

-

time to resolution of fever from initial i.v. antibiotic administration

-

AEs related to antibiotics

-

hospital discharge and total length of hospital stay

-

re-admission to hospital within 28 days

-

death within 28 days

-

adjustment to the subsequent scheduled cycle of chemotherapy within 28 days

-

patient preferences for antibiotic treatment assessed at day 14.

Research hypotheses

-

Early oral switch (within 12–24 hours after commencing i.v. antibiotic therapy) in cancer patients with low-risk NS is non-inferior to standard care (continuation of i.v. antibiotic therapy for at least 48 hours).

-

The incremental cost effectiveness of early oral switch is significant compared to standard care.

-

AEs are comparable between the two study arms.

-

Patients’ preference will be for early oral switch.

Study conduct

Ethics, regulatory and research and development approvals

The trial was approved by the Medicines Healthcare and Regulatory Agency (MHRA) on 31 July 2015. It was approved by the Northern Island (NI) Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 6 October 2015. At each participating site, local research and development (R&D) approval was obtained prior to patient enrolment to the trial. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice (GCP), the requirements and standards set out by the WU Directive 2001/20/EC and the applicable regulatory requirements in the UK, the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2001 and subsequent amendments and the Research Governance Framework.

Sponsorship

EASI-SWITCH was sponsored by the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust (BHSCT).

Trial management

Clinical trial management was undertaken by the Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit (NICTU). Additional trial oversight committees were convened by the trial including a Trial Management Group (TMG), Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

The TMG comprised the co-chief investigators, other clinical investigators, the trial manager/co-ordinator, the trial statistician, the trial health economist, the sponsor pharmacovigilance representative and the patient and public representative. The TMG met monthly to review site set-up, screening and recruitment, trial conduct, AEs and any other issues relating to trial conduct. A TMG charter detailed the terms of reference of the TMG including roles/responsibilities.

The TSC provided oversight for the progress of the trial on behalf of the sponsor and funder. The TSC was appointed by the NIHR and comprised an independent chair (a microbiologist), an independent oncologist, an independent statistician, at least one patient/public representative and TMG members. The remit of the TSC was progression of the trial including recruitment and adherence, the well-being, safety and rights of trial participants and ensuring trial conduct was appropriate. A TSC charter described the terms of reference of the TSC including membership and roles/responsibilities.

The DMEC provided independent review of the trial. Its role was to safeguard the rights and safety of participants, to review trial data related to recruitment, protocol compliance, safety and efficacy and to recommend to the TSC whether the trial should continue or not based on ethical or safety reasons. DMEC appointments were approved by NIHR and included an independent chair (an oncologist), an independent clinician, an independent statistician and a patient/public representative. DMEC reports were provided by the trial statistician to include recruitment, AE and outcome data along with any other information requested by the Committee. These reports were confidential and not shared with the trial investigators. A DMEC charter described the terms of reference of the DMEC including memberships and roles/responsibilities.

Trial set-up

In total 19 sites in hospitals and cancer centres across the four UK nations were opened to patient recruitment. A list of these sites can be found in the Acknowledgements. Potential sites were asked to complete an eligibility questionnaire that assessed clinical trial experience and local capability and capacity for the study. Local antimicrobial guidelines and treatment care pathways for NS were also requested from sites at this stage to identify and address any potential issues with protocol compliance. Prior to sites opening to recruitment a face-to-face site initiation visit was undertaken by trial team members to provide training on trial procedures to local research team members. Additional training, where needed, was provided by teleconference. The trial team maintained regular communication with sites by e-mail and teleconferencing to provide any ongoing training needed, answer any queries arising at site and support sites in identifying and resolving barriers to recruitment.

Patient information and consent

Potentially eligible patients were those who had commenced treatment with i.v. antibiotics for NS. Patients were identified at each study site daily through local acute admission/handover processes dependent on the unscheduled care admission pathways at site. Patients meeting these criteria were discussed with their treating physician on that day prior to enrolment to confirm their agreement to patient participation. This also provided an opportunity to confirm that their treating physician would be willing to follow the treatment strategy outlined in either arm of the trial. Patients were approached by a member of the research team and a patient information sheet was provided. Patients were given time to review the patient information sheet although this time period was < 24 hours given the acute care setting and timing of the intervention.

As enrolment was occurring at ward level and patients had already been initiated on treatment, patients being approached were clinically stable and viewed as competent to give informed consent in this setting. Patients who were unable to give informed consent, for any reason, were not recruited. Patients who indicated they were unwilling or unable to make a decision within the 24-hour time period were not recruited. Regulatory approvals were obtained for patient-facing materials additional to the patient information sheet to be used at site to make patients aware of the trial. These included a summary information sheet about the trial that could be included in the standard SACT patient education materials about NS and a poster to be displayed in SACT clinics and treatment units. All of these materials were prepared in collaboration with the trial patient representatives.

Informed consent for participation was sought from patients by appropriately trained research nurses (RNs) and medically trained investigators at site supported by the site principal investigator (PI) and local infrastructure. If patients required any further clarification about the risks and benefits of participation, this was provided by other research team members or an independent senior physician (one nominated in advance at each trial site). The PI (or designee) taking informed consent was required to have completed GCP training, be suitably qualified and experienced and be delegated this duty by the PI on the delegation log.

Screening and randomisation procedures

Electronic trial screening and recruitment logs, submitted by sites to the clinical trial unit (CTU) on a monthly basis, aimed to capture all patients who received a patient information sheet and whether they proceeded to consent and randomisation. Research teams were asked to provide a reason for non-participation if patients were not recruited.

After informed consent was obtained and eligibility was confirmed, participants were allocated to intervention or standard care groups using an automated randomisation system (sealed envelopes). Blocked randomisation with randomly permuted block sizes was used and a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. There were no factors for stratification. Access to the randomisation sequence was restricted and not accessible to site staff who enrolled patients or assigned interventions. Only the allocation of the intervention was blinded. As this was a pragmatic trial, it was felt that blinding clinical teams, researchers and trial participants to the intervention would limit the ability of the trial to measure the impact of the intervention on routine care pathways. Additional support from this approach came from our patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives, who viewed that participants would be highly likely to reveal their treatment allocation during discussion with healthcare providers and outcome assessors, making it unlikely these groups could remain blinded.

Trial treatment

Patients eligible to participate were aged over 16 years, receiving SACT for a cancer diagnosis and were receiving standard-dose i.v. piperacillin/tazobactam or meropenem as initial antibiotic treatment for suspected NS for < 24 hours. Patients were only permitted to be enrolled in the trial on one occasion in line with consensus guidelines. 47 All protocolised antibiotics were considered to be investigational medicinal products (IMPs) for the purpose of the trial: co-amoxiclav 500 mg/125 mg film coated tablets; ciprofloxacin 250 mg, 500 mg, 750 mg film coated tablets; meropenem 1 g powder for solution for injection or infusion and tazocin 4 g/0.5 g powder for solution for infusion.

Standard care arm

Participants in the standard care group were allocated to continue current treatment with i.v. antibiotics for a minimum of 48 hours. This was selected based on the NICE guidance recommendations. 3 Subsequent antibiotic management was at the discretion of the treating physician, who could switch to oral antibiotics or stop antibiotics at any point thereafter, reflecting the variation encountered in routine clinical practice. 30

Intervention arm

Participants randomised to the intervention group switched from i.v. antibiotic treatment within 12–24 hours after starting treatment, to co-amoxiclav 625 mg three times daily and ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily, to complete at least 5 days antibiotic treatment in total. The combination of a quinolone and a second drug active against Gram-positive bacteria (e.g. co-amoxiclav) was based on the conclusions of the Cochrane review. 37

Other treatments

Any other treatments or investigations that patients required were carried out in accordance with standard care. It was recognised that escalation from protocol-specified antibiotic treatment might be required in the event of clinical deterioration, progression of the presumed infection, a microbiological indication based on microbiological culture results or an adverse reaction (AR) to the prescribed antibiotics. A change from protocol-specified antibiotics, including additional antibiotic treatment other than the study drugs, or persistent/recurrent fever (> 38°C) after 72 hours was within the definition of treatment failure, with such participants reaching the trial’s primary end point.

Patients were discharged home from hospital once their treating physician was content to do so, with a patient diary to record any further temperatures and oral antibiotic compliance. Due to the pragmatic nature of the trial, specific discharge criteria were not protocolised, but it was assumed the patient’s overall clinical condition and psychosocial circumstances would be considered by the treating clinician in line with their normal clinical practice.

Patient population

Patients commenced on i.v. antibiotics within 24 hours after starting treatment for low-risk NS were recruited from sites across England, Scotland, Wales and NI, comprising both large cancer centres and cancer units, to ensure that the sample is broadly representative of patients developing NS in the UK.

Inclusion criteria

-

Age over 16 years.

-

Receiving SACT for a diagnosis of cancer.

-

Started on empirical i.v. piperacillin/tazobactam or meropenem, for suspected NS, for < 24 hours.

-

Absolute neutrophil count ≤ 1.0 × 109/l with either a temperature of at least 38°C or other signs or symptoms consistent with clinically significant sepsis, for example hypothermia. Self-measurement at home or earlier hospital assessment of temperature is acceptable provided this is documented in medical notes and is within 24 hours prior to i.v. antibiotic administration.

-

Expected duration of neutropenia < 7 days.

-

Low risk of complications using a validated risk score (MASCC score ≥ 21).

-

Able to maintain adequate oral intake and take oral medication.

-

Adequate hepatic [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) < 5 × upper limit of normal (ULN)] and renal function (serum creatinine < 3 × ULN) within the 24 hours prior to randomisation.

-

Physician in charge of care willing to follow either the intervention or standard care protocol per randomisation, at enrolment, including not treating with CSF. Prophylactic CSF is not an exclusion criterion.

Exclusion criteria

-

Underlying diagnosis of acute leukaemia or haematopoietic stem cell transplant.

-

Hypotension (systolic pressure < 90 mmHg on > 1 measurement) within the 24 hours prior to randomisation.

-

Prior allergy, serious AR or contraindication to any study drug.

-

Enrolled in this trial with prior episode of NS.

-

Previously documented as being colonised with an organism resistant to a study drug regimen, for example MRSA.

-

Localising signs of severe infection (pneumonia, soft-tissue infection, central-venous access device infection, presence of purulent collection).

-

Patients unable to provide informed consent.

-

Pregnant women, women who have not yet reached the menopause (no menses for ≥ 12 months without an alternative medical cause) who test positive for pregnancy, are unwilling to take a pregnancy test prior to trial entry or are unwilling to undertake adequate precautions to prevent pregnancy for the duration of the trial.

-

Breastfeeding women.

Co-enrolment

Patients who were enrolled in other Phase I IMP studies and other antimicrobial IMP studies were excluded. Patients enrolled in other Phase II–IV IMP or observational studies were eligible for enrolment in this study at the PI’s discretion and when the burden on participants was not considered to be onerous.

Withdrawal of consent

Participants were able to withdraw consent to participate in the trial at any time. If the participant withdrew consent during protocolised treatment, no further treatment within the trial was given and the clinician responsible for their care determined the safest and most appropriate continued management plan. A withdrawal of consent form identified which parts of the trial the patient wished to withdraw from: protocol-specified antibiotic therapy; future data collection (all data collected or data collected at day 14 and/or day 28 follow-up). Participants could be withdrawn from the study at the discretion of the investigator if any safety concerns arose.

Data management

Trial database

The EASI-SWITCH trial database is an electronic clinical trial database (MACRO) held by the NICTU. Trial data were entered on to a web-based case report form (CRF) with imposed rules for data entry with valid responses and linkage of dates and trial identification numbers by trained and delegated site personnel. Data were processed in accordance with the trial Data Management Plan and CTU Standard Operating Procedures. Data queries were ‘raised’ electronically via MACRO where clarification was needed for data entries or to complete missing data and staff at site ‘responded’ electronically to queries and amended database entries where applicable. A final review for missing or inconsistent data was carried out by the trial statistician with subsequent opportunity for query resolution / data completion prior to the database lock for end of trial analyses. All essential documentation and trial records were stored securely with access restricted to authorised staff only.

Data quality

Data management within the CTU was governed by Standard Operating Procedures to ensure standardisation and compliance with International Conference of Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidance and regulatory requirements. NICTU provided site staff training in data collection and CRF completion. On-site monitoring visits during the trial checked accuracy of CRF entries against source documents in addition to protocol and trial procedure adherence. Discrepancy reports were generated after data entry to identify inconsistent or out-of-range data and protocol deviations based on data validation checks programmed into the clinical trial database.

Data collection

Data were collected by delegated research team members. Each participant was allocated a unique Participant Study Number at randomisation, alongside their initials for identification for the duration of the trial. Data were collected from the time of trial entry until day 28 (± 1 day) in accordance with the schedule of assessments shown in Table 2. Baseline data collection occurred in the hospital setting. Primary and secondary outcome data were collected via a review of patient medical notes (including laboratory results), submission of participant questionnaires, patient diary, GP records and telephone calls with patients. Participants discharged before day 14 were asked to complete a diary noting administration of oral antibiotics, any new medications and a temperature diary (if required) until day 14. Questionnaires were administered face-to-face or via telephone (if discharged or no scheduled outpatient visit) at day 14 (± 1 day).

| Time point | t-24 hours | Day 0 | Study visits and procedures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-consent (standard care) | Pre-randomisation | Randomisation | Day 1–2 | Day 3–5 | Day 6–14 | Day 28 | |

| Pre-consent eligibility screening | |||||||

| Eligibility screening as appropriate (per standard care) for example full blood count, blood culturea | ✗ | ||||||

| Informed consent | |||||||

| Informed consent obtained | ✗ | ||||||

| Pre-randomisation eligibility and assessments | |||||||

| Eligibility screening as appropriate (non-standard care) for example pregnancy test, MASCC score, max temp ≤ 24 hours prior to randomisation. | ✗ | ||||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ||||||

| Randomisation | |||||||

| Standard care antibiotic administrationb | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Intervention (early switch) antibiotic administrationb | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Send GP letter | ✗ | ||||||

| Baseline assessments to be recorded on CRF after eligibility is confirmed | |||||||

| Demographics | ✗ | ||||||

| Vital signs (HR, RR and BP) | ✗ | ||||||

| Medical historyc | ✗ | ||||||

| Symptoms indicative of mild localised infection | ✗ | ||||||

| Cancer assessmentd | ✗ | ||||||

| SACT administered prior to presentatione | ✗ | ||||||

| Relevant microbiological results | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Hospital admission details | ✗ | ||||||

| Concomitant medications | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Daily data collection | |||||||

| Antibiotic regimenf | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Highest daily temperatureg | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Protocol compliance | |||||||

| Adherence to protocol specified intervention | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Patient follow-up | |||||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ||||||

| Patient follow-up questionnaire | ✗ | ||||||

| Follow-up contact | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Survival status | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| New medications | ✗ | ||||||

| Changes to next planned SACT | ✗ | ||||||

| Hospital discharge/re-admission/critical care admission details | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Recording and reporting of AEs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

Adverse event reporting

Directly observed or patient-reported AEs that were not related to underlying medical conditions were recorded by the site PI or designee. AEs clearly related to SACT administration (such as peripheral neuropathy) were not required to be recorded; however, if an AE could be due to SACT, NS or antibiotic therapy (such as fever or gastrointestinal symptoms), then it was required to be recorded. Initially the AE reporting period for the trial was from enrolment until 28 days after randomisation. This was amended subsequently to 14 days from enrolment until 14 days after randomisation in recognition that antibiotic AEs generally occurred within this time frame and that patients were typically receiving a further course of SACT within the 14–28 day window, resulting in AEs that were more likely to be SACT-related or a new episode of NS rather than related to the episode of NS that had resulted in trial entry or antibiotic therapy.

The PI (or designee) was required to make an assessment of expectedness of any AE deemed possibly, probably or definitely related to any of the trial IMPs based on the relevant Summary of Product Characteristics (SPCs).

AEs related to IMP exposure were deemed ARs. ARs were classified as expected (consistent with IMP side effects listed in the SPC) or unexpected (not consistent with the SPC).

Serious adverse event

In the trial, a serious adverse event (SAE) was defined as any AE that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

was any other important medical event(s) that carried a real, not hypothetical, risk of one of the outcomes above.

All deaths that occurred within 28 days of randomisation were recorded and reported as a SAE regardless of the nature of the event (even if due to progressive cancer). PIs were required to report SAEs to NICTU using the trial-specific SAE form within 24 hours after becoming aware of the event.

Treatment failure due to persistence, recurrence or new occurrence of fever after 72 hours of antibiotic commencement and/or clinician-directed escalation of protocolised antibiotic therapy during the first 14 days was captured as part of the primary outcome measure. This was only reported as an AE when categorised as a SAE.

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction

Adverse reactions that were unexpected (not consistent with the relevant SPC) and met the criteria for seriousness were deemed suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) and required expedited safety reporting. NICTU reporting procedures report SUSARs to relevant competent authorities within 7–15 calendar days in accordance with UK regulations.

Serious breaches

A serious breach was defined as an occurrence which represented a deviation from the trial protocol that was likely to result in significant effect on the safety of a trial participant or the scientific value of the trial.

The PI (or designee) was responsible for direct reporting of serious breaches to the trial sponsor with onward reporting to the relevant competent authorities in accordance with UK regulations.

Protocol amendments

All amendments to the trial protocol, patient information sheet, informed consent form and other key documents were submitted to the relevant regulatory authorities for approval prior to implementation. Local research and development approval was also obtained at each site. Version 2 of the trial protocol was the protocol approved for use as trial commencement and subsequent substantial protocol amendments are summarised below.

July 2016

Version 3 of the protocol was submitted to the regulatory authorities. This incorporated changes to the eligibility criteria in order to align better with the NICE guidance and routine practice in the NHS setting. The NICE guidance stated ‘Diagnose neutropenic sepsis in patients having anticancer treatment whose neutrophil count is 0.5 × 109 per litre or lower and who have either: a temperature higher than 38°C or other signs or symptoms consistent with clinically significant sepsis’. On initial design, the trial had only incorporated the objective definitions (i.e. temperature and neutrophil count) because of possible difficulty in defining ‘signs or symptoms consistent with clinically significant sepsis’ for a trial population. This protocol amendment permitted recruitment of patients with either:

-

a neutrophil count of ≤ 0.5 × 109 per litre who have either a temperature of at least 38°C or other signs or symptoms consistent with clinically significant sepsis (to align fully with the NICE guidance); or

-

a neutrophil count of < 1.0 × 109 per litre, and falling or expected to fall, who have a temperature of at least 38°C (to reflect usual NHS practice). Given the pragmatic nature of the trial this amendment was felt to allow a more realistic evaluation of the intervention in routine care.

August 2016

Versions 4 and 5 of the protocol incorporated an extension to the pilot phase of the study including the addition of up to four new sites, the resultant change in the overall study duration and clarification of eligibility criteria and outcome measure definitions. The key change within these amendments was the extension of the embedded pilot study to 12 months to assess the impact of the change in eligibility criteria on recruitment, which had been lower than anticipated after the trial commenced.

April 2017

Protocol version 7 was submitted to the regulatory authorities (protocol version 6 was a non-substantial amendment). The purpose of this amendment was to clarify use of non-protocolised antibiotics and reporting of AEs.

June 2018

Protocol version 8 was submitted to the regulatory authorities. This incorporated revisions to the study design following review of the pilot study and discussions with the research team, trial sites, trial oversight committees. While the extended pilot study did meet the pre-specified recruitment target for study continuation, the trial team and oversight committees concluded that it would not be possible to recruit the originally planned sample size of 628 patients within a meaningful time frame to ensure the results remained relevant to clinical practice. Both the trial team and oversight committees continued to view the research question as important and relevant to current practice; opinion sought from the oncology clinical community and PPI representatives nationally also supported this view. The DMEC confirmed in November 2017 that there were no concerns regarding treatment adherence, separation between treatment groups or the observed treatment failure rate. Therefore, the assumptions that had underpinned the original trial design remained valid but, in retrospect, the choice of non-inferiority margin and statistical analysis may have been too stringent for a pragmatic trial where the risk of treatment failure was unlikely to result in serious risk to patients (in particular critical care admission or death). Following extensive stakeholder discussion and consideration of alternative assumptions for sample size recalculation, the sample size was recalculated using a 15% non-inferiority margin as this was felt to maintain an acceptable trade-off between the possibility and consequences of treatment failure for this low-risk patient population. This amendment included a sample size recalculation that comprised both a widening of the non inferiority margin from 10% to 15% and a change in the one-sided confidence interval (CI) from 97.5 % to 95%. This was recommended by the TSC independent statistician and following discussion with the wider TSC felt to be reasonable given the original 97.5% CI had been based on regulatory agency recommendations for licensing studies of new treatments which require a greater degree of certainty than was felt warranted for a pragmatic trial testing antibiotics already licensed or within routine clinical use for the same indication. This amendment also included an increase in the total number of study sites and an extension to the project duration.

Embedded pilot study

The trial contained an embedded pilot study involving four UK sites to test the recruitment and adherence assumptions underpinning the study design. Progression to the full study was based on the following criteria:

-

Recruitment rate:

-

progression without major modification if at least 75% of target reached

-

progression with addition of further trial sites if between 50% and 75% of target reached

-

progression unlikely if < 50% of target reached – discussion with trial oversight committees and funder required.

-

-

Adherence to protocol-specified intervention:

-

progression without major modification if at least 75% adherence in both trial arms

-

if adherence was between 50% and 75% of target, progression would be supported by a detailed analysis of the process and decision-points that led to non-adherence and a recognised strategy to address this identified

-

progression unlikely if < 50% adherence in either arm.

-

-

Separation:

-

separation in terms of the timing of antibiotic switch of at least 24 hours between the trial arms to enable progression was required.

-

The four-site pilot study was expected to run for 6 months between February and July 2016. Recruitment was < 50% target threshold for progression and the study was halted to review progress and proposals to address under-recruitment. This review identified the stringent eligibility criteria as a barrier to recruitment and not reflective of the routine management of patients with suspected NS. A protocol amendment (July 2016, described above) was submitted to address this. Recruitment was resumed with a 3-month extension to the pilot study (December 2016 to February 2017) with an improvement in recruitment rates (11 patients of an anticipated 13.5 recruited). On the recommendation of the HTA Programme Director, a larger pilot phase extension followed from April until November 2017. Progression with addition of new sites continued from this point until the end of the study.

Statistical analysis plan

Non-inferiority design and non-inferiority margin

A non-inferiority design was felt to be appropriate as it was not anticipated that early switch to oral antibiotics would offer superior treatment efficacy to standard care (i.v. antibiotics for at least 48 hours based on NICE guidance). It would also enable the evaluation of an intervention of broadly comparable efficacy to standard care based on available literature but with potential for reduced cost and improved quality of life.

It was estimated that the treatment failure rate in the control arm would be 15% based on data from three studies with patient populations most comparable to the proposed EASI-SWITCH population. Selecting the non-inferiority margin, the maximum clinically acceptable extent of non-inferiority, was challenging due to the limited evidence available to help guide this selection. A 10% non-inferiority margin was originally chosen to reflect the recommendations of a published expert consensus in NS antibiotic trials but this did not take into consideration risk stratification. 47 Input from patient representatives was also considered, but it is important to note that feedback initially came predominantly from our PPI co-applicant rather than a wider range of patient representatives, who felt if an extra 10% failed an early switch, in addition to the expected 15% treatment failures that occur with standard care, the advantage of 75% of early switch patients having successful treatment outweighed this.

Sample size

The original target sample size for the trial was 628 patients. This was based on the assumed 15% treatment failure rate in the standard care arm and a 10% non-inferiority margin, at 90% power (one-sided 97.5% CI), which would require 269 patients per arm. A dropout rate of up to 5% was also accounted for based on previously reported NS trial data and a crossover rate of up to 10% from the control to the intervention arm, giving 314 patients per arm (628 in total).

Review of study design post-pilot phase and revision of sample size

As outlined above, a protocol amendment related to review of the study design following the embedded pilot phase was submitted in June 2018. This included a review of the assumptions that had underpinned the original trial design, including the rationale for the choice of non-inferiority margin and statistical analyses. As previously described, extensive discussion took place with stakeholders including the research team, trial oversight committees, funder, sponsor and clinicians and PPI representatives nationally, in relation to the study design. The consequent revisions to the study design had implications for the sample size, which was recalculated using the same treatment failure rate in the standard care group (15%), power (90%), dropout rate (5%) and crossover rate from control to intervention (10%) while widening the non-inferiority margin from 10% to 15% and using a one-sided 95% CI. This gave a revised sample size of 230 patients.

Statistical methods

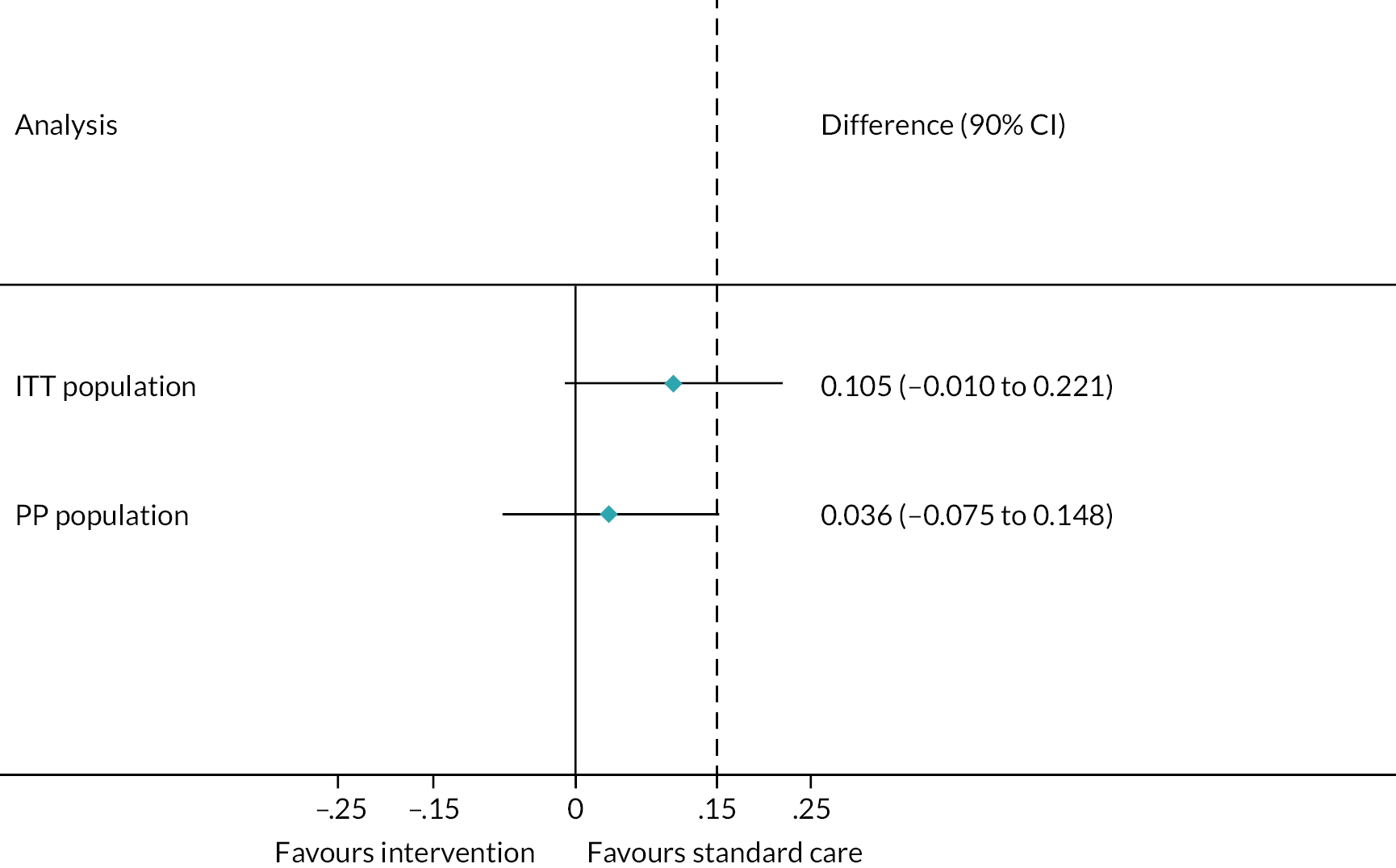

The primary analysis was conducted on both the per-protocol (PP) population and the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Given the potential risk of bias arising from either of these analyses alone within a non-inferiority trial, it was pre-specified that non-inferiority of the intervention would only be proven if demonstrated in both the PP and ITT groups.

Analyses were one-sided and at a significance level of 0.05. The difference in treatment failure rate (one-sided 95% confidence limit) was compared to the non-inferiority margin of 15%. As this was a non-inferiority trial, the null hypothesis was that the degree of inferiority of the intervention to the control was greater than the non-inferiority margin of 15%. The alternative hypothesis was therefore that the intervention was inferior to the control by less than the non-inferiority margin of 15%. Therefore, non-inferiority would be established by showing that the upper limit of a 90% CI for Intervention – Control is < 15%.

A secondary comparison of the primary and other binary outcomes between the two groups was investigated using logistic regression, adjusting for covariates (such as extent of neutropenia). Comparison of continuous outcomes between the two groups was investigated using independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney. Statistical diagnostic methods were used to check for violations of the assumptions, and transformations were performed where required.

Baseline characteristics, follow-up measurements and safety data were described using appropriate descriptive summary measures depending on the scale of measurement and distribution.

Subgroup analyses

Exploratory subgroup analyses were pre-specified using 99% CI. Logistic regression was used with interaction terms (treatment group by subgroup) for the following subgroups:

-

tumour type (solid tumour vs. lymphoma)

-

neutrophil count at randomisation (≤ 0.5 × 109/l vs. > 0.5 × 109/l < 1.0 × 109/l)

-

maximum temperature on the day of presentation (< 38°C vs. ≥ 38°C).

An additional post hoc subgroup analysis was requested for those patients who had a positive blood culture versus those who did not at baseline.

Survey design and delivery

A series of surveys were undertaken to obtain stakeholder feedback on important questions relating to the trial. All electronic surveys were conducted using the SurveyMonkey tool (www.surveymonkey.co.uk). Ethical approval was not required for these projects as they sought only to define clinicians’ current standard of care and were categorised as service evaluation rather than research according to UK Health Research Authority definitions. All were designed pragmatically for data collection and to encourage responses. They were piloted informally by clinical and PPI colleagues at the lead site prior to wider dissemination to improve clarity and understanding but did not undergo formal reliability or validity testing. Participation was voluntary, with potential responders assured that no site or personal information would be publicly shared. Onward e-mail circulation to appropriate colleagues was encouraged to maximise responses, accepting this makes estimation of response rates challenging. At least one e-mail reminder was sent also to encourage responses, with all surveys open for completion for at least 8 weeks in total.

The analyses of the survey responses are presented descriptively, with percentages rounded to the nearest 1%. If the survey contained questions where respondents had the opportunity to leave comments, these are presented thematically, with representative illustrative quotes.

Site interviews

To understand factors impacting trial recruitment at sites, a series of purposeful semistructured interviews with key personnel at each site, including PIs and lead RNs, were conducted by the trial Clinical Research Fellow over a 2-month period (April to May 2018). Qualitative research has previously been demonstrated as one of the most helpful tools in identifying and overcoming barriers to recruitment. 48,49 The aim of the interviews was to explore clinician’s experience of recruiting and delivering the trial at their site and identify barriers to recruitment.

An initial e-mail invitation describing the nature and purpose of the interviews was sent to all PIs and lead RNs at all 12 open sites in March 2018. Participation was voluntary, and participants were reassured that no individual or site-specific information would be identified in summary reports. Interviews could be conducted either face to face or via telephone depending on participant preference. On receipt of a positive response, an interview was arranged and all were conducted in April and May 2018. Verbal consent was confirmed at the commencement of each interview. A short interview guide was prepared based on broad themes that had already emerged from previous discussions about the trial’s progress and difficulty recruiting. Participants were first asked in an open-ended question to simply comment on their experience recruiting to the trial and then highlight any challenges encountered. If not already discussed, they were then prompted to provide feedback on the trial’s screening and recruitment processes, including eligibility criteria. They were also prompted to comment on any issues encountered with local support for the study, research capacity, participant follow-up and data collection. Finally, interviewees were asked to highlight any strategies they felt had facilitated recruitment at their individual site. Interviews ranged from 15 to 50 minutes in length.

With the participant’s permission field notes were taken during the interview to capture key responses. A summary of the main findings was then verbally confirmed by the participant at the end of each interview to ensure content validation. Data saturation (i.e. no new information raised in later interviews) was reached during the interviews.

Thematic analysis of the qualitative data was then undertaken50 to generate a summary list of reported barriers to trial recruitment. The field notes for each interview were first scrutinised individually and organised into themes relating to barriers to recruitment. This systematic process was repeated for all interviews and then combined to produce a final group analysis summary list. Post analysis of the data, the co-chief investigators reviewed the data for completeness, reporting coherence between the data and reported themes to ensure robustness of the interpretation of the data.

Patient and public involvement

The trial has benefitted from having an experienced PPI member in the team, Mrs Margaret Grayson, from study conception to completion. The trial was developed in response to a commissioned call, meaning the main research question was pre-defined; however, input from the Northern Ireland Cancer Research Consumer Forum (NICRCF) via Mrs Grayson was that this was an important research question of value to patients where potential overtreatment and prolonged hospital admission may negatively impact upon quality of life. From this position, Mrs Grayson contributed to the trial design with particular input in the following areas: (1) helping to define the composite outcome measure and define secondary outcome measures important to patients and the health service; (2) defining the non-inferiority margin to incorporate patients’ views on acceptable trade-offs for treatment de-escalation; and (3) providing the patient viewpoint on the most appropriate method to obtain day 14 outcome data balancing the need for data quality with burden on patients. Additional support was given by the readers panel of the NICRCF at this stage through development and review of the trial protocol, the patient information sheet, the informed consent form and other patient-facing materials, for example brief summary flyers and posters for sites to use in SACT treatment units to make patients aware of the trial.

As the trial progressed, there was ongoing input from Mrs Grayson through both her membership of the TSC and participation in the TMG. Her input was critical when the overall study design was reviewed during the course of the trial, co-ordinating PPI opinion on the proposed changes and contributing to the final amended design. Through her linkages with the NICRCF and nationally (with the Independent Cancer Patient Voice group) she sought opinion on the ongoing importance of the research question and whether there was support for continuation of the trial with changes to the study design. As part of this process, she co-developed with the study team a PPI survey outlining proposed changes to the study design with particular focus on whether additional uncertainty around treatment effectiveness arising from a change in the non-inferiority margin and sample size would be acceptable to patients. She then collated responses, reporting to the study team the support of the majority of respondents and providing written and verbal communication with the funder in decision-making about these proposed changes.

The trial was also supported by additional independent PPI representation on the TSC and DMEC. Input from these representatives in review of trial data and progress was critical at decision-making points relating to trial progression and potential amendments to study procedures. Dissemination of results is an ongoing area of activity for all of the PPI team trial team members.

Chapter 3 Pilot study results and review of study design

This chapter contains some text reproduced from the study protocol ‘Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotic therapy in patients with cancer who have low risk neutropenic sepsis (the EASI-SWITCH trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial’ published in Trials (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04241-1. 1

Pilot study aim

The aim of the internal pilot study was to carefully evaluate the recruitment and adherence assumptions underpinning the main study design. The main parameters of interest were:

-

recruitment rates

-

adherence to the protocol-specified treatment

-

separation in terms of timing of the antibiotic switch between the two arms.

These criteria were set to guide trial progress and inform the procedures to be utilised in the delivery of the main trial.

Recruitment rates

A target recruitment rate of 1.7 patients per site per month was set based on historical published data30 and service evaluation data from two of the pilot sites. Progression of the trial without modification beyond the embedded pilot study was contingent upon at least 75% of this recruitment target being met. It was otherwise pre-specified that progression would continue with the addition of further trial sites if 50–75% of this target was met but that progression at a recruitment rate lower than 50% of this target rate would require review of the trial and discussion with oversight committees, funder and sponsor for trial progression. The embedded pilot study was intended to last 6 months with 4 participating sites but was extended to 17 months and 10 sites in total, as summarised in Table 3.

| Dates | Sites | Recruitment target | Expected recruitment | Actual recruitment | Cumulative trial recruitment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial pilot phase | February to July 2016 (6 months) | 4 pilot sites | 1.7 patients/month/site | 22 | 7 | 7 |

| Extended pilot phase (I) | December 2016 to February 2017 (3 months) | 4 pilot sites | 1.7 patients/month/site | 13.5 | 11 | 18 |

| Extended pilot phase (II) | April to November 2017 (8 months) | 10 4 pilot sites 6 additional sites |

1 patient/month/site | 49 | 24 | 42 |

Initial pilot phase (February to July 2016)

The internal four site pilot study was expected to run for 6 months. It commenced on the 17 February 2016, when Site 1 opened and completed on the 21 July 2016. Progress is summarised in Table 4.

| Site | Date open | Number screened | Duration of recruitment (months) | Expected recruitment | Actual recruitment | Recruitment rate (patients/site/month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 February 2016 | 32 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 14 March 2016 | 26 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 4 May 2016 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 4 | 31 March 2016 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0.75 |

| Total | 22 | 7 | ||||

Recruitment of 31 patients was originally projected if all four sites had been open to recruitment for the full 6 months. This was based on a recruitment rate of 1.7 patients per month per site, allowing for a 50% reduction in recruitment at each site during the first 3 months as sites became established. However, delays encountered at site level resulted in only one of the four sites being open for the full 6 month period. Taking this into account recruitment of 22 patients was anticipated, but only 7 were recruited. In view of this, the study was halted to enable review of screening and recruitment activity and recruitment target.

The original accrual target was based on historically published NS surveys and audit data from two sites, suggesting approximately 20 patients were admitted per month with NS in 2011 and 2013. This was consistent with the NICE guidance,3 which suggested active specialist units admitted at least 20 patients with NS per month. Allowing for exclusion of high-risk patients (approximately 30%51) and trial ineligibility it was assumed that 10 patients per month at each site would be eligible and recruitment of two of these appeared an achievable target.

On review of screening and recruitment logs the number of NS admissions was lower than expected. This was consistent with updated audit data from sites and may reflect changes in standard care relating to growing use of targeted therapies and immunotherapies in place of cytotoxic chemotherapy and continued improvements in the care of patients with suspected sepsis, including NS. However, even within this it was clear that the majority of patients screened for study entry were considered ineligible, as highlighted by activity at Sites 1 and 2 in the previous table where 1 of 32 patients and 2 of 26 patients were screened and recruited, respectively. The reasons for exclusion are summarised in Table 5; as expected around 30% of patients were high risk based on MASCC score, but for the remainder it seemed that the eligibility criteria did not reflect the patient population receiving treatment for NS in routine care pathways.

| Principal reason for exclusion | Site 1 (n) | Site 2 (n) |

|---|---|---|

| High risk (MASCC score < 21) | 9 | 7 |

| Pyrexial but absolute neutrophil count (ANC) between 0.5 and 1.0 × 109/l | 4 | 5 |

| ANC between 0.5 and 1.0 × 109/l Apyrexial but other signs and symptoms |

9 | 6 |

| Penicillin allergy | 6 | 3 |

| Recent prophylactic ciprofloxacin/other oral antibiotics | 2 | 3 |

| Total number of patients excluded | 30 | 24 |

From discussion with the clinical and research teams at study sites, specific issues with the trial eligibility criteria mainly related to the stringent requirements for fever, neutropenia, use of other antimicrobials and organ function, summarised in Table 6.

| Eligibility criteria | Impact on recruitment |

|---|---|

| 1. Neutrophil criteria |

|

| 2. Fever criteria |

|

| 3. Prophylactic antibiotics and recent antibiotic use |

|

| 4. Organ function |

|

| 5. Hypotension |

|

Review of eligibility criteria

It was therefore concerning from screening data that the trial population was not going to fully reflect the patient population being managed as low-risk NS, with a significant proportion of patients commenced on NS care pathways who did not meet the study eligibility criteria, negatively affecting recruitment. Moreover, as this was intended to be a pragmatic trial within the setting of standard care therapies (all agents used within the trial were already licensed for treatment of NS or used within routine care for this indication), it was also felt important that the trial was not restrictive around organ dysfunction beyond the parameters of standard care.

On initial trial design, the fever and neutrophil thresholds had been aligned with the objective elements of the NICE definitions of NS with the rationale that it might be difficult to define the non-objective elements of the NICE definition in which a diagnosis of NS may be appropriate in patients without documented fever but with other ‘signs or symptoms consistent with clinically significant sepsis’. It was clear this excluded a significant number of patients commencing treatment for NS.

Adjustments to the eligibility criteria were therefore proposed focused on ensuring they were less stringent and more pragmatic, as summarised in Table 7. These adjustments would widen the pool of eligible patients and ensure the trial population more accurately reflected patients being commenced on NS pathways in standard clinical practice, providing a more realistic evaluation of the intervention in routine care.

| Original eligibility criteria (Version 2.0, 30 July 2015) | Adjusted eligibility criteria (Version 3.0, 14 July 2016) |

|---|---|

| Absolute neutrophil count < 0.5 × 109/l | Absolute neutrophil count ≤ 1.0 × 109/l with either

|

| Fever > 38°C | |

| Self-measurement at home or hospital assessment acceptable provided this is documented in the medical notes and within 24 hours of i.v. antibiotic administration | |

| Received i.v. piperacillin/tazobactam or meropenem for < 24 hours | Systemic antibiotic administered prior to randomisation is not a reason for exclusion Patients who have been started on additional antimicrobial drugs (e.g. gentamicin or teicoplanin) are eligible provided the physician in charge of their care is willing to stop this additional antimicrobial at the time of enrolment |

| Adequate hepatic (AST and/or ALT < 2.5 × ULN) function within 24 hours prior to randomisation | Adequate hepatic (AST and/or ALT < 5 × ULN) function within 24 hours prior to randomisation |

| Physician in charge of care willing to follow either the intervention or standard care protocol per randomisation at enrolment, including not treating with CSF | Highlighted that prophylactic use of CSF is not an exclusion criterion |

| Hypotension (systolic pressure < 90 mmHg) within 24 hours of randomisation | Hypotension (systolic pressure < 90 mmHg on greater than one measurement) within 24 hours of randomisation |

| Treatment with fluoroquinolone or penicillin antibiotics in preceding 14 days | No longer an exclusion criterion |

With the adjusted eligibility criteria, a further 15 patients at Site 1 and 14 patients at Site 2 would have been potentially suitable during this 6 month pilot phase. It was therefore expected the revised eligibility criteria would increase the number of eligible patients to 1–2 patients per site per month. A 6-month extension to the pilot phase was proposed to assess the impact of the adjusted eligibility criteria on recruitment.

Extended pilot phase I (December 2016 to February 2017)

A 3-month, four-site extension to the pilot study was delivered from 1 December 2016 to 28 February 2017, using the adjusted eligibility criteria, summarised in Table 8.

| Site | Date open | Number screened | Duration of recruitment (months) | Target recruitment | Total recruitment | Recruitment rate (patients/site/month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 December 2016 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 3 January 2017 | 0 | 2 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 December 2016 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 1 February 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 13.5 | 11 | 0.9 | |||

The expected recruitment rate was 1.7 patients per site per month, with again a 50% reduction permitted for the first 3 months of site opening. With recruitment on hold from 21 July 2016 until 1 December 2016 there was significant loss of momentum at sites, which was difficult to recover and combined with local site capacity issues resulted in a very short window of potential recruitment at two sites. Consequently, both of these sites failed to recruit during this extension phase, despite having been active in screening and recruitment during the first phase of the pilot study. The other two sites achieved an average monthly recruitment between the two sites of 1.8 patients per month, similar to the predicted recruitment rate, with review of screening data suggesting a positive impact of the adjusted eligibility criteria on recruitment. It was, however, again noted that the number of NS admissions remained lower than historical data, with an average of six admissions per month.

Extended pilot phase II (April 2017 to November 2017)

Due to the longer than anticipated pilot phase, under-recruitment was now inevitable if the project timeline was not modified, even if the number of recruiting sites for the main trial was expanded significantly from 12 to 20. To maximise the potential for successful completion of the trial, with the research question as fully addressed as possible, the preferred option was to increase the number of recruiting sites to 20 and extend the project timeline by approximately 1 year. To mitigate risk, it was agreed first to further extend the pilot phase until November 2017, aiming to open an additional seven sites during this period. This would allow an assessment of the potential recruitment at a broader selection of sites. A revised recruitment target was set of one patient per month per site to account for the lower frequency of neutropenic admissions.

A further 8 month period of recruitment to the pilot phase of the trial occurred between April and November 2017. Six additional sites were opened during this phase and a summary of recruitment by site is shown in Table 9. Even with the revised recruitment target of one patient per site per month, only 50% of the expected recruitment was met, with 24 patients recruited compared with the predicted 49 (average monthly recruitment rate across all sites was 0.4 patients).

| Site | Start date | Target recruitment | Total recruitment | Recruitment rate (patients/site/month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 February 2016 | 8 | 11 | 1.4 |

| 2 | 14 March 2016 | 8 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 3 | 4 May 2016 | 8 | 2 | 0.3 |

| 4 | 31 March 2016 | 8 | 6 | 0.8 |

| 5 | 22 June 2017 | 4 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 6 | 17 July 2017 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 26 June 2017 | 5 | 3 | 0.4 |

| 9 | 18 September 2017 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 28 September 2017 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 13 November 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 49 | 24 | 0.4 | |

Summary of pilot phase recruitment

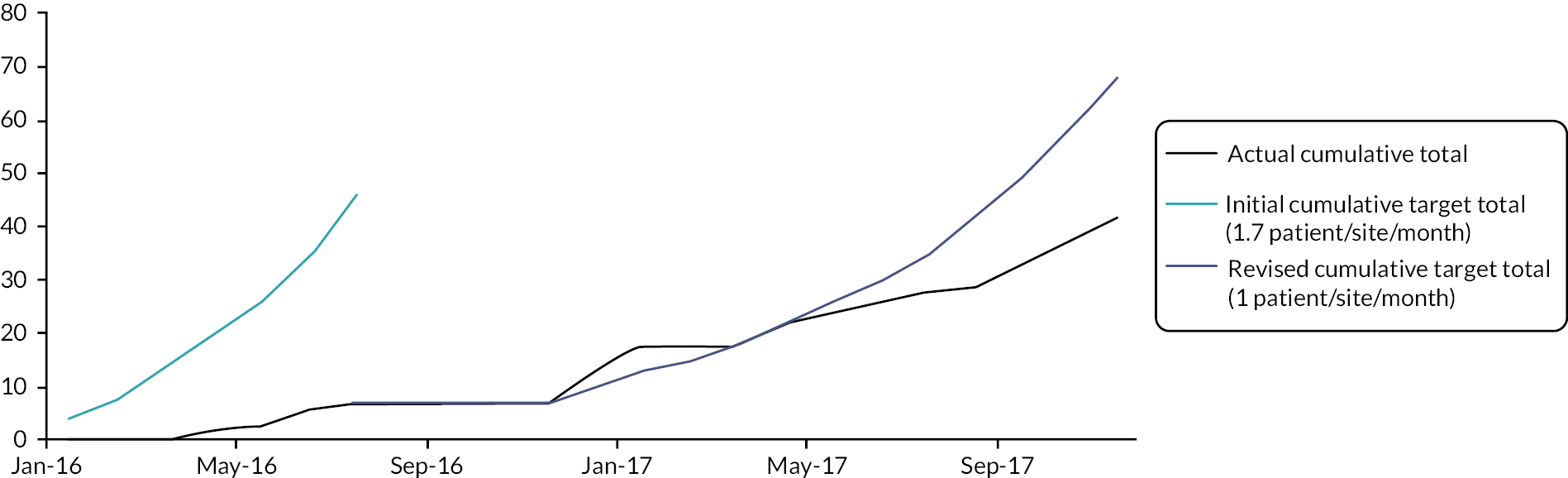

By 30 November 2017, there had been 17 months of active recruitment to the study, with as planned 10 sites open to recruitment and an eleventh due to open shortly. Forty-two patients had been recruited compared with a revised target of 68 patients as summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of recruitment activity at the end of the pilot phase (February 2016 to November 2017): total recruitment of 42 patients.

Adherence to the protocol-specified treatment

Adherence to the protocol-specified intervention was assessed by whether patients switched to co-amoxiclav and ciprofloxacin, 12–24 hours after starting i.v. meropenem or piperacillin tazobactam i.v. therapy for at least 5 days total treatment. Adherence to the standard care arm required receipt of at least 48 hours of i.v. piperacillin/tazobactam or meropenem. The pre-specified threshold for adherence of 75% in both arms was achieved with adherence 86% and 83% in the intervention and control arms, respectively.

Separation between trial arms

The final criteria for trial progression was evidence of adequate separation in terms of the timing of antibiotic switch of at least 24 hours between the trial arms. The time on i.v. antibiotics was calculated for each patient and then the mean calculated for each trial arm and the difference between the two arms assessed. The mean duration of i.v. antibiotics was 19 hours in the intervention arm and 48 hours in the control arm; hence, mean separation in terms of timing of antibiotic switch was acceptable at 29 hours.

Summary of embedded pilot study results

The internal pilot phase of the EASI-SWITCH trial demonstrated that while recruitment was challenging there were no other concerns relating to treatment failure, protocol adherence or safety concerns. Based on recruitment between April and November 2017, it was likely that on average each site would only be able to recruit one patient every 2 months. The pilot phase had demonstrated that recruitment to the original proposed sample size of 628 patients for the main trial was not going to be achievable. Recruitment had originally been scheduled to complete at the end of December 2018. With 10 sites open and recruiting on average one patient every 2 months, based on current recruitment activity total recruitment was estimated to complete at approximately 100 patients. This would result in a significantly underpowered study, with results unlikely to have any significant impact and the evidence gap for an early oral switch identified by NICE remaining unanswered. It was clear important assumptions underpinning the trial design would have to be urgently reviewed to decide about whether to progress beyond the pilot phase to main trial delivery.

Determining continued importance of the research question

In view of the recruitment difficulties and the longer than anticipated pilot phase, an updated understanding of how low-risk NS patients were currently being managed across the UK was critical to assess the continued importance of the research question and assess whether there remained equipoise between the trial arms.

Between January and June 2018, NS management policies were reviewed and a survey of practice was undertaken nationally. Local NS policies from throughout the UK were sought via an e-mail request distributed to acute oncology nurse specialists within United Kingdom Oncology Nursing Society (UKONS) and EASI-SWITCH team members. Policies were reviewed for compliance with NICE recommendations, with particular focus on those advocated as key priorities for implementation in the guideline and their approach to low-risk management.

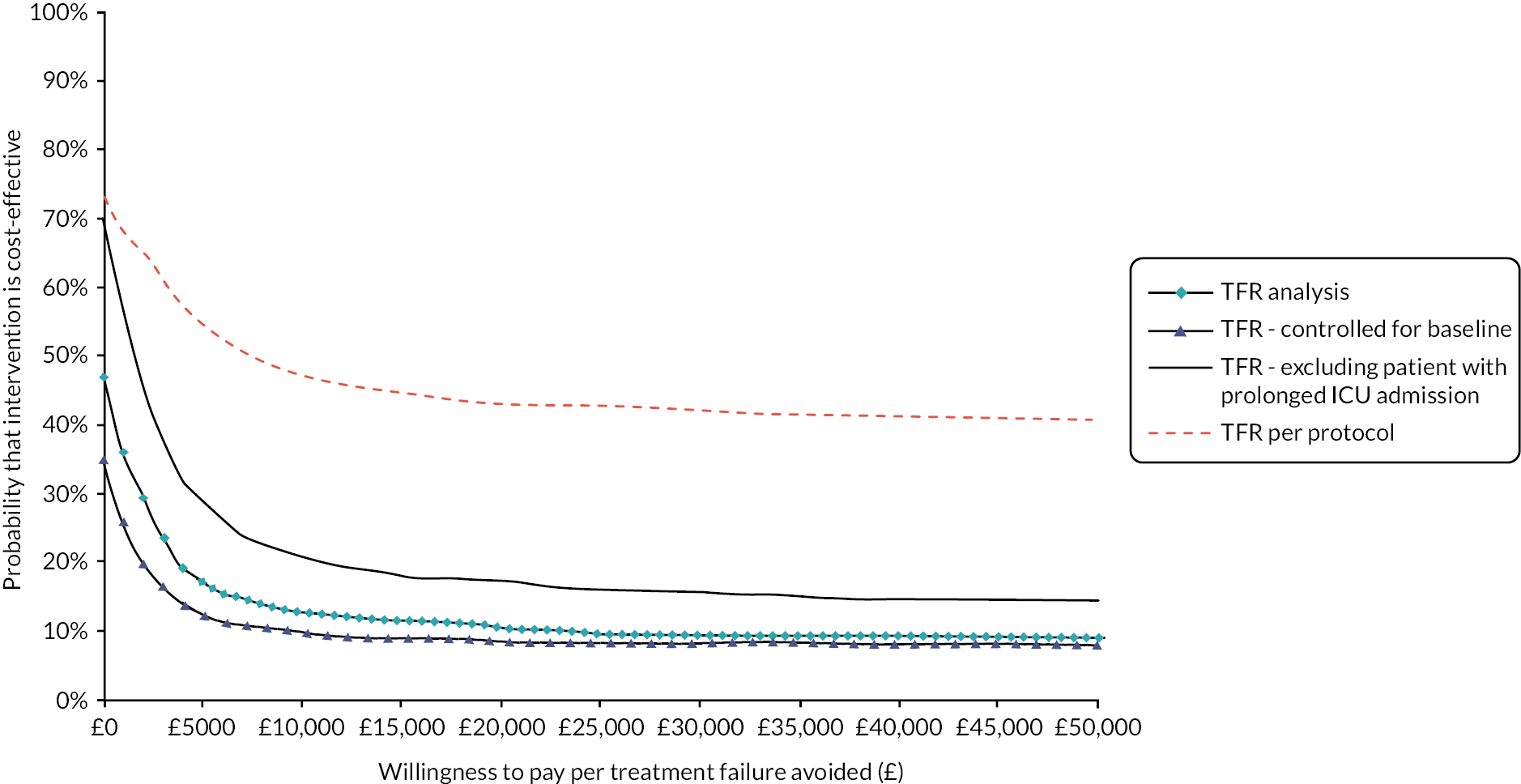

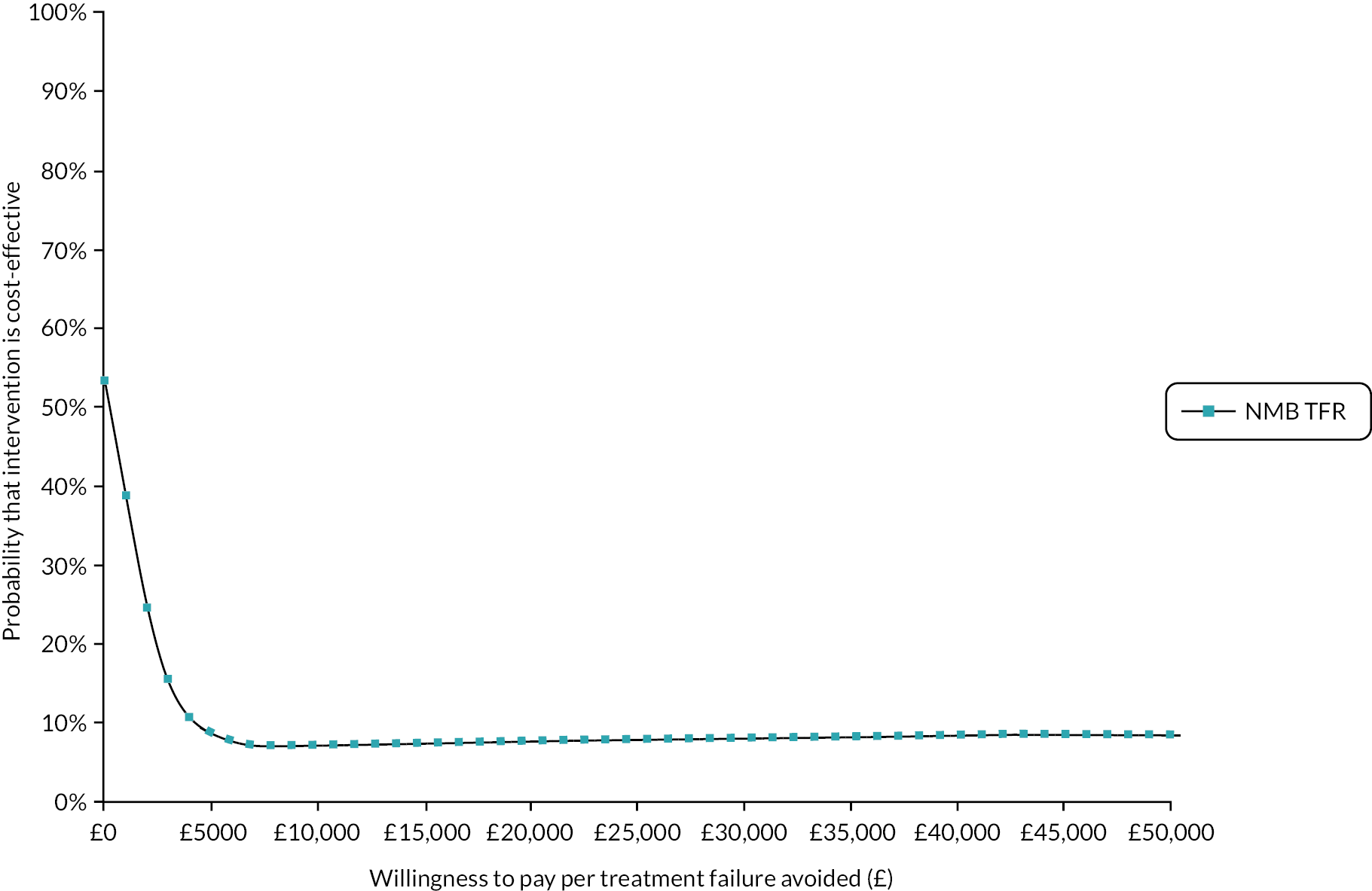

It is likely that a wide range of factors, including awareness of guidance, personal treatment preferences and clinical experience, will influence individual compliance with local policies when delivering NS care. A complementary electronic survey aimed to more fully reflect clinicians’ daily clinical practice, attitudes and preferences when managing NS. The survey link was disseminated via the UKONS, Royal College of Pathologists’ electronic newsletter and the clinicians involved in the EASI-SWITCH trial with onward dissemination to colleagues encouraged. In the survey, respondents were encouraged to reflect on their individual routine practice, rather than what their local institution’s NS policy or national guidelines might recommend.