Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/72/02. The contractual start date was in November 2018. The draft report began editorial review in May 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Coates et al. This work was produced by Coates et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Coates et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Ulcerative colitis

Epidemiology

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a long-term condition of the colon with unknown cause. The incidence of UC varies, with the highest varying between 8 and 14 per 100,000 per year, and prevalence is 120–200 per 100,000 in North America, northern Europe and the UK. 1 The incidence is also increasing in areas where it has previously been low, including Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. 1 UC can occur at any age, with a peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades, from 30 to 40 years. 1 At diagnosis, an estimated 15% of people are aged > 60 years. 2 A possible peak later than 60 years may occur, although this is reported in fewer studies. 3 There may be a slight predominance of UC in male patients. 1

Aetiology

The aetiology of UC is unknown and has remained elusive for decades, despite intensive investigation. A prominent mucosal immune reaction is evident, but a trigger for this has not been identified. A genetic predisposition is also clear, but this accounts for only a small proportion of the heritability risk. 4 Therefore, it has been suggested that an abnormal immune response to some components of the host intestinal microbiota occurs in genetically predisposed individuals in association with changes in epithelial integrity with stimulation of gut immune responses. 5

Genome-wide association studies have identified at least 260 genetic susceptibility loci across inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mostly shared between UC and Crohn’s disease. 5 Specific associations with UC are mostly within the human leucocyte antigen region on chromosome 6. 6 Outside the human leucocyte antigen region, there is a strong association between UC and a missense variant in the adenylate cyclase 7 gene (ADCY7), with a twofold increase in the risk of UC. 7 Other UC-specific genes relate to epithelial integrity,8–10 and epigenetic factors may also play a role. 11,12

Pathology

Ulcerative colitis is characterised by inflammation of the colon, typically affecting the rectum, and to a variable proximal extent. The inflammation is continuously distributed. In about 50% of patients, the distal colon (i.e. rectum and sigmoid) is most commonly affected, and in the remaining patients the colonic involvement is greater, extending to the splenic flexure (i.e. left-sided colitis), to the hepatic flexure (i.e. subtotal colitis) or to the caecum (i.e. total or pancolitis).

On microscopy, overlap can be seen with other colitides, including those caused by infection, drugs and Crohn’s disease. UC is associated with acute and chronic inflammatory changes in the colonic mucosa and architectural changes including diffuse crypt abnormalities, cryptitis, crypt atrophy and abnormal crypt architecture. 13

Prognosis

Ulcerative colitis typically runs a relapsing and remitting course, and four main patterns of clinical course and disease evolution are described. 14 In approximately 90% of patients, UC has a typical relapsing and remitting course. Some patients experience just one attack followed by long-term remission (18% at 5 years and 10% at 25 years). Approximately 10% of patients have a severe presentation necessitating admission and emergency surgery within a year of diagnosis. A small percentage of patients (approximately 1% at 5 years and 0.1% at 25 years) have unremitting, continuous illness. Approximately 50% of patients have a relapse in any year, with an important minority experiencing more frequent rapidly relapsing or continuous disease. Thirty-five per cent of patients with pancolitis will undergo surgery. 14,15

The long-term survival of those with UC is not different from that of the general population, although the mortality rate from colorectal cancer and hepatobiliary complications is higher. 16

Economic burden

An estimated 620,000 patients in the UK have UC. 3 A UK national audit suggested that the costs of treating IBD (i.e. UC and Crohn’s disease) were more than £1B, with an average cost of £3000 per person per year. 17 A cost-of-care model for the UK has been reported, with estimated annual treatment costs per patient with UC of £3084. 18 Among patients in remission, patients in relapse with mild to moderately severe disease and patients with severe UC, the annual cost per patient is estimated to be £1693, £2903 and £10,760, respectively. 18

Humanistic burden

There may be societal costs to the economy, to individuals and to families and carers that are not captured in health economic analyses. These include costs of absence from work, caring responsibilities and psychological morbidity, which is widely recognised in the literature but may be under-recognised or assessed in clinical practice. These societal costs may occur as a result of the condition and also from the side effects of drugs, including steroid-related adverse effects. 19,20

Rationale

Ulcerative colitis runs a relapsing and remitting course, resulting in debilitating symptoms, impaired quality of life and severe attacks necessitating hospitalisation. For moderately active UC not requiring hospitalisation, oral corticosteroids may induce remission in those refractory to aminosalicylate therapy. 21 Corticosteroids are recommended as first-line therapy for a severe relapse of UC. 22 This programme of work applies to patients with moderately severe UC treated as outpatients.

Approximately 50% of patients with moderately severe flares do not respond fully to corticosteroids. 23,24 There are several subsequent treatment options in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) treatment pathway,21 and these have been the subject of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing individual agents with placebo or steroid comparators. To the best of our knowledge, direct ‘head-to-head’ comparisons are not available, except in the VARSITY trial, which compares adalimumab and vedolizumab. 25 NICE has recommended that the risks and benefits of methotrexate, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, adalimumab and infliximab be assessed for the induction of remission in steroid-refractory UC. 21 Subsequently, vedolizumab and tofacitinib have demonstrated efficacy in RCTs and have been recommended for use in this population. 26,27 Ustekinumab has also been shown to be effective and has been recommended for use in UC, but the guidance on this was issued after the current study was under way. 28 Other options, including surgery and the use of intravenous (i.v. ) steroids, have not been the subject of RCTs. These options vary in cost, availability, mode of administration, patient acceptability and utilisation of health-care facilities, as well as clinician experience in their use, especially for newer agents. There is insufficient information to inform patients with steroid-resistant UC about the optimum choice of agent, concomitant immunosuppression and the timing of surgery.

There is no universally adopted definition of steroid-resistant UC. Current definitions might include clinical, endoscopic and quality-of-life dimensions. There is also an overlap between patients with ongoing symptoms or endoscopic inflammation despite corticosteroids (i.e. ‘steroid resistant’) and patients who initially respond and then relapse on reducing the steroid dose (i.e. ‘steroid dependent’). Both groups of patients have been included in clinical trials of agents used for steroid-resistant disease. Pivotal trials, particularly of biologic agents, have included patients in both groups, and the results of treatment in each group have been reported together. Both situations can lead to the prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids and the attendant consequences. The prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids is considered a disutility of care. 29 In addition, these patients may be taking concomitant immunomodulator drugs.

Therefore, although national and international guidance21,26,30 reflects this range of options, there remains a lack of clarity about:

-

the definition of steroid resistance

-

the specific applicability of current evidence to a population of patients with UC resistant to corticosteroids

-

the optimum choice of treatment for this group and the importance of factors such as patient and clinician preferences, concomitant immunosuppression and prior biological therapy.

Review of existing evidence

Ulcerative colitis is associated with disability, psychological morbidity and distress. 31–33 UC also has a significant socioeconomic impact arising from disrupted education and employment,31 with 20 days of household and recreational activities per year typically lost to illness. 34 In 2000, before the widespread use of biological agents, the costs of treating UC were estimated at £3021 per patient-year in the UK35 and at €1524 per patient-year in an European Collaborative inception cohort. 36 Substantial costs relate to hospitalisation and surgery, both of which are more common in those aged < 40 years, and to drug-refractory patients. 37,38 Costs may be reduced by more effective treatment, but it is unclear whether or not newer agents are cost-effective in this population. 37

Oral corticosteroids are associated with significant side effects, which preclude long-term treatment. Therefore, it is important to escalate treatment in patients who do not respond adequately to systemic steroids. A number of treatments are available for patients thought to be resistant to systemic steroids. The anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab target the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha. Infliximab is a human–murine chimeric monoclonal antibody and adalimumab and golimumab are humanised antibodies. Infliximab is most frequently administered intravenously, but a preparation for subcutaneous administration became available in 2021. Adalimumab and golimumab are administered by subcutaneous injection. Vedolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets α4β7 integrin, an adhesion molecule on the surface of T lymphocytes, preventing it from binding to endothelial MAdCAM-1 (mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1) and preventing these lymphocytes from migrating into gut mucosa. 39 Therefore, it is suggested that this activity is gut specific. Vedolizumab is most often administered by i.v. infusion, but a preparation for subcutaneous injection became available in 2021. Tofacitinib is a ‘small-molecule’ agent that inhibits janus kinase (JAK1 and JAK3)-mediated transcription pathways, preventing inflammatory cytokine production. 40 Tofacitinib is administered orally.

Data about these agents are available from trials and also from meta-analyses. Clinical trials in patients who have not responded or responded inadequately to systemic corticosteroids show benefit of anti-TNF agents (e.g. infliximab,41 adalimumab42,43 and golimumab44,45), vedolizumab,46 tacrolimus, tofacitinib47 and ustekinumab. 48 Clinical benefit is seen in terms of inducing remission, inducing response (i.e. improvement), maintaining remission and healing the inflamed intestinal lining (i.e. mucosal healing).

In clinical practice, supported by guidance from NICE, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) (London, UK) and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) (Vienna, Austria), additional approaches are available, including inpatient i.v. steroids and surgery. 21,26,30,49,50 However, the preferred treatment or approach is not clear.

Guidance from NICE recommends the anti-TNF agents infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab as options for adults whose disease has responded inadequately to conventional therapy, including corticosteroids and mercaptopurine or azathioprine, because they either cannot tolerate them or have contraindications to them. Vedolizumab is also recommended for treating moderately to severely active UC. Tofacitinib is recommended when conventional therapy or a biological agent cannot be tolerated or when the disease has responded inadequately or lost response to treatment.

Definitions of steroid resistance also differ in the literature. Widely used guidelines define steroid resistance as a failure to aachieve symptomatic remission following treatment with systemic steroids (prednisolone at 0.75 mg or 1 mg/kg per day for 4 weeks). 26,51 Creed and Probert52 regard steroid-resistant UC as failure to respond to treatment with high-dose oral steroids within 30 days. However, consideration of escalation to additional treatment after 2 weeks is also discussed. 51 UK guidelines describe steroid dependence as the inability to wean systemic steroids below a prednisolone dose of 10 mg per day within 3 months without the development of active disease, or symptomatic relapse within 3 months of stopping steroids.

Prior steroid response or exposure is not uniform in pivotal trials. Not all patients included in these RCTs are steroid resistant, and results may not be reported separately for patents with steroid-resistant disease and those with steroid-dependent disease. For example, a minority of patients included in pivotal trials of infliximab in active UC were taking ≥ 20 mg of prednisolone per day at trial entry. 41 In addition, in trials of adalimumab and vedolizumab, remission rates were not significantly different from placebo in patients on corticosteroids42 or failing corticosteroids alone. 42,46

Side effects are also important when considering the use of drugs. The adverse effects of systemic steroids are well established, and additional treatments also have important side effects. The risk of infection, serious infection and cancer (including lymphoma) is related to the immunosuppressive properties of drugs. These risks may be low, and randomised trials involving small samples are often unable to detect risks of this size, resulting in the need for evidence from larger, longer-term studies. Therefore, clinicians and patients have to use the evidence in the forms available.

Although qualitative research highlights the diverse perspectives of medical and nursing staff,53 there are limited published patient perspectives, which are needed to inform the design of future clinical trials as well as clinical practice. Survey data suggest that patients’ ideal therapy would be an effective oral formulation that requires them to take few tablets infrequently, with minimal side effects. 54

The role of surgery also needs to be evaluated, as there is limited evidence to determine its ideal position in the treatment pathway. Emergency surgery is positioned in NICE guidance for acute severe colitis,55 but a position is not specifically defined for elective surgery for chronic relapsing disease. The NICE guidance indicates that surgery can be effective to remove symptoms of UC that recur rapidly, but does not describe its optimum timing. 55 The NICE guidance also does not take into account the differing impact of relapses of varying frequency and severity on an individual, nor the impact of drug administration regimes or side effects. Guidelines developed by the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (London, UK) advocate surgery for relapsing and remitting disease but do not say where in the pathway this should go. 56 Optimum timing of surgery is, therefore, likely to be influenced by a number of disease factors, personal patient preferences and clinician perspectives and, therefore, will differ between patients. We have previously demonstrated that patients wish to undergo surgery when faced with severe restrictions on quality of life. 57 Clinician and patient preferences are, therefore, of central importance in understanding the position of surgery in the treatment pathway.

In a health economic assessment from our group58 (multitechnology appraisal TA329 of anti-TNF agents49) for patients in whom surgery is an option, colectomy was expected to dominate all medical treatment options. For patients in whom colectomy is not an option, infliximab and golimumab were ruled out because of dominance, with the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for adalimumab compared with conventional treatment expected to be approximately £50,278 per quality-adjusted life-year gained. However, there remains debate with regard to whether surgery should be considered a comparator or an end point and as to when surgery would not be an option. Indeed, in NICE technology appraisal guidance TA342,27 neither surgery nor tacrolimus was thought to be a suitable comparator for vedolizumab.

These issues illustrate the pressing need for a trial with a clearly defined population of steroid-resistant patients to evaluate clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. To develop such a trial, a detailed understanding of how best to describe steroid resistance, and of patients’ and clinicians’ views of treatment options and objectives, is required. This will allow appropriate identification of equipoise and acceptable invention and comparator arms in a trial.

Statement of the problem

In commissioning brief 17/72, the Health Technology Assessment programme indicated its interest in improving the understanding of how adults with steroids-resistant UC are managed, with a view to informing future commissioning briefs addressing which treatments require further evaluation in steroid-resistant UC.

Aims and objectives

The overarching research question for this study was ‘How are adults with steroid-resistant UC being managed in secondary care, and how does current practice compare with patient and clinician preferences?’.

To answer the research question, this mixed-methods study had five objectives:

-

to describe current practice in the management of adults with steroid-resistant UC and to describe how medical resistance to steroids is defined

-

to understand how treatment pathways and definitions of steroid resistance are operationalised in practice

-

to understand patient experiences of different treatment options and approaches to decision-making

-

to estimate the relative utility of different treatment options and to elicit patient and clinician preferences for these and their willingness to trade between them

-

to make recommendations about future research and treatment options.

The five objectives aligned with five corresponding work packages (WPs) delivered as part of this mixed-methods study. To understand the management and treatment preferences of patients, a survey of clinical practice (WP1) and qualitative interviews with adults with steroid-resistant UC (WP3) were carried out. A survey and qualitative interviews with a purposive sample of health-care professionals were designed to explore how health-care professionals define and treat steroid-resistant UC (WP2). A discrete choice experiment (DCE) with patients and health-care professionals was designed to quantify their preferences for, and estimate the relative utility of and willingness to trade between, different treatment options (WP4). Finally, the aim of a multidisciplinary workshop with patients and health-care professionals (WP5) was to present and discuss the study findings to generate recommendations about optimum treatment and future research.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview of methodological approach

The PoPSTER (Patient preferences and current Practice in STERoid resistant ulcerative colitis) study was a mixed-methods study and was composed of five WPs, using a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods to help achieve each of the five corresponding objectives. This included a cross-sectional survey of health-care professionals (objective 1, WP1), qualitative interviews with health-care professionals (objective 2, WP2), qualitative interviews with people with UC (objective 3, WP3), DCEs with health-care professionals and patients (objective 4, WP4) and a multistakeholder workshop (objective 5, WP5). The details of the study design, setting, eligibility criteria, sampling, recruitment, data collection and analysis for each of the WPs are described in this chapter in Health-care professional survey, Qualitative interviews, Discrete choice experiments and Multistakeholder workshop. This chapter also includes details of patient and public involvement (PPI) (see Patient and public involvement), ethics approval (see Ethics approval) and protocol management (see Protocol management and version history).

Health-care professional survey

Study design

This WP involved a cross-sectional survey of IBD health-care professionals in the UK. The aim of the WP was to describe the current management of patients with steroid-resistant UC. The survey looked at how health-care professionals define steroid resistance, health-care professionals’ preferences for different treatments and the factors that influence treatment offers.

Setting

Secondary care IBD services in the UK.

Eligibility criteria

Health-care professionals were eligible to participate in the survey if they were medical or nursing staff in an NHS trust in the UK and had specialist interest or expertise in working with patients with IBD, particularly UC. Membership of the IBD section of the BSG and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) IBD Nurses Network was taken as an indication of interest in this clinical area.

Sampling

The survey was sent to approximately 1180 health-care professionals (IBD section of the BSG, n = 950; RCN IBD Nurses Network n = 230) and was conducted online using the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA). We aimed for a 60% response rate, based on previous surveys of IBD health-care professionals,59–61 which represented an expected sample size of 700 participants.

Recruitment

Different routes were used to approach health-care professionals to participate in the survey during the 4-month recruitment period (20 March to 15 July 2019).

E-mail invitation

E-mail invitations from the chief investigator (AL) were sent to members of the IBD section of the BSG and the RCN IBD Nurses Network. The e-mail provided a detailed explanation of the study purpose, the participant information sheet and a direct link to the online questionnaire. Reminder e-mails were sent approximately every 4 weeks.

Advertising on social media and relevant websites

The survey was advertised on the dedicated Twitter page for the study (@PoPSTER_Study, URL: https://twitter.com/popster_study?lang=en-GB; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), the Facebook (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) page for the RCN IBD Nurses Network (URL: www.facebook.com/groups/RCNIBDNetwork) and the BSG website (URL: www.bsg.org.uk). Regular update tweets on survey recruitment were sent out to raise awareness of the survey and to encourage participation. All tweets contained a short summary about the survey’s purpose and a link to the online questionnaire.

Promotion at relevant national and regional meetings of inflammatory bowel disease health-care professionals

The survey was promoted at a BSG conference in June 2019. The research team had a poster presentation space. A member of the team (AB) was at the conference to raise awareness and distribute paper copies of the questionnaire to interested health-care professionals. In addition to this, the survey was presented by professional contacts of the study team at other relevant national and regional meetings of IBD health-care professionals to help boost recruitment to the survey.

Distribution via professional contacts of the study team

Finally, the survey was distributed to professional contacts of the study team via e-mail and, as a result, was distributed via other IBD professional networks, including Clinical Research Network leads for IBD and regional IBD nursing leads, as well as individual professional contacts. The approach here was to facilitate a ‘snowball sampling’ approach. As with the other recruitment methods, potential participants were provided with study information and a link to the online questionnaire.

Data collection

The survey was hosted online using the Qualtrics platform. The participant information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 1) and consent form were also hosted online, and informed consent was sought from all participants prior to commencing the survey.

To understand current practice in the management of steroid-resistant UC, the questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 2) was divided into the following six sections:

-

demographic information (e.g. clinical role, year of appointment and personal experience of IBD)

-

centre and caseload information [e.g. hospital type, region, presence of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) and composition, proportion of time spent working on IBD and use of clinical guidelines/standards in practice]

-

definitions of steroid resistance (e.g. time frame over which incomplete response represents resistance to or dependence on steroids in UC)

-

treatment pathways (e.g. preferences for different treatments in four patient scenarios, i.e. whether resistant to or dependent on steroids and whether exposed or naive to thiopurines, factors influencing treatment choices, timing of survey referral and local treatment availability)

-

case scenarios (e.g. preferences for different treatments in six patient scenarios, i.e. resistant to or dependent on steroids, relapse at 5 mg or 25 mg, whether exposed or naive to thiopurines)

-

use of endoscopy (e.g. requirements for steroid-resistant and steroid-dependent patients).

A mix of question types was used in the questionnaire, including those that required binary response (i.e. yes or no), those that required a frequency response (i.e. always, sometimes or never), those in which responses were selected from a list and those to which open-ended responses could be given, as appropriate. The content of the questionnaire was developed by the study team, piloted with 13 local clinicians from collaborating centres and refined prior to distribution. 62 All data were collected between 20 March and 15 July 2019.

Data analysis

Quantitative data from the survey were mostly analysed using descriptive statistics and exploratory testing. Continuous outcomes are presented as means and standard deviations (SDs) or as medians and interquartile ranges, as appropriate. Categorical data are presented using frequencies and percentages per categories. Chi-squared tests between demographic groups (hospital type, job role, etc.) were conducted on outcomes of interest, and McNemar’s test was used to compare binary responses of participants between different scenarios. A statistical analysis plan was defined before all data had been collected to identify important outcomes to be analysed, and subsequent analyses were included after sight of the initial results that were deemed to be of interest. Correction for multiple testing was not included in the results, testing of hypotheses was restricted to those prespecified to be interest and limited post hoc testing was completed, depending on interesting and unexpected outcomes in the data. All testing was exploratory, and the results will be used to inform future work. All results were produced using R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Qualitative interviews

Health-care professionals

Study design

This WP involved qualitative interviews with a sample of health-care professionals with expertise in IBD. The aim of the WP was to understand in more depth how patients with steroid resistance are managed and how health-care professionals define steroid resistance in practice. This work is reported in accordance with the COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) guidelines for qualitative research. 63

Setting

The WP was set in secondary care IBD services in the UK.

Eligibility criteria

A health-care professional was eligible to participate in the qualitative interviews if they were a member of medical or nursing staff with a specialist interest or expertise in working with patients with IBD, particularly UC.

Sampling

Health-care professionals were sampled purposively based on job role (i.e. medical or nursing), years of clinical experience, hospital status (i.e. secondary or tertiary referral centre) and location, and they were recruited from across the UK. In line with grounded theory, we used ‘theoretical sampling’ to allow us the flexibility to recruit health-care professionals with particular characteristics in line with emerging themes.

Recruitment

Health-care professionals were identified via the following four sources by the research team:

-

drawn from the subsample of participants in the WP1 survey who consented to being approached about a qualitative interview

-

IBD health-care professionals who opted in to the study through advertising via social media

-

IBD health-care professionals who opted in to the study through advertising via professional networks (e.g. the IBD section of the BSG e-mail)

-

IBD health-care professionals who opted in to the study following correspondence as professional contacts of the clinical members of the research team.

The initial contact e-mail invited all potential participants to take part in a telephone interview and gave a summary (reminder) of the study, and a copy of the participant information sheet was attached (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Potential participants who indicated their interest in the study were asked to provide further information on year of appointment and hospital type, to facilitate the purposive sampling strategy (note that location and gender were evident from information indicated by e-mail response). Availability for a telephone interview was also requested to help with scheduling.

Where appropriate, a member of the research team determined a mutually convenient time at which to carry out the interview. The interview date and time were then confirmed in an e-mail, and another copy of the participant information sheet and consent form, as well as the hypothetical patient case scenario, was attached. All participants were assigned a unique, anonymous study identifier at this point. Reasons for non-participation were recorded, where relevant.

Data collection

Verbal consent to participate in the interview and to this being audio-recorded was taken from all participants before data collection commenced, and participants were asked to refer to the copy of the consent form while the statements were read aloud by the researcher. Separate anonymous recordings of participants providing consent were stored securely for auditing purposes. The individual semistructured interviews were conducted over the telephone by Elizabeth Coates, Amy Barr and Nyantara Wickramasekera (all of whom are female non-clinical researchers educated to postgraduate level and have various levels of experience in qualitative research and seniority). For the duration of the interview, participants were asked to ensure that they were in a quiet and private location, in their workplace or home.

A semistructured interview schedule was used to guide the discussions (see Report Supplementary Material 2). This included questions on how health-care professionals operationalise definitions of steroid resistance, their current practice and their preferences for treatment options for patients with steroid-resistant UC. The interviews also included questions on the types of information that health-care professionals need to make decisions about the treatments that they offer. In addition, the interviews involved a case vignette of a hypothetical patient with steroid-resistant UC, which was developed by the clinical members of the research team and used to facilitate critical distance for the interviewee and as a mechanism to encourage the participant to think about different strategies for treating this patient group (i.e. to help participants explain their clinical practice). In addition to this, the qualitative interviews were used to inform the design (i.e. to identify attributes) of the DCE with health-care professionals.

All data were collected between 28 June and 24 October 2019. Data collection ceased at the point of data saturation. All interviews were recorded using a digitally encrypted device and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Data analysis

Key themes arising from the data were summarised based on thematic analysis of transcriptions. 64 A thematic analysis was completed by Elizabeth Coates and Amy Barr in accordance with six recommended stages. First, familiarisation with the data, that is, the accuracy of all transcripts, was reviewed by the researchers and notes were generated to enable the second stage, generation of initial codes. A coding framework was developed and applied to the whole data set by Elizabeth Coates and Amy Barr, and NVivo software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to help structure the coding and analysis process. This led to a further four stages: searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and, finally, writing the report.

Patients

Study design

This WP involved qualitative interviews with a sample of people living with UC. The aim of this WP was to explore people’s experiences of and decision-making about different treatments, as well as their treatment preferences. This work is reported in accordance with the COREQ guidelines for qualitative research. 63

Setting

The WP was set in three IBD services in secondary care in the north of England.

Eligibility criteria

Adults aged ≥ 18 years with UC extending beyond the rectum and who had active disease at the time of participation, or who had previously had active disease successfully treated with steroids, were eligible to participate. In addition, people with UC who may have been considered to have steroid-resistant disease and had already made the decision to have surgery were eligible on the grounds that they were able to reflect on decision-making processes for each treatment stage, albeit retrospectively.

Sampling

Patients with UC were sampled purposively based on age, gender, ethnicity, duration of disease and previous treatment, and they were recruited from three NHS IBD services in the north of England. In line with grounded theory, we used ‘theoretical sampling’ to allow us the flexibility to recruit patients with specific characteristics in line with emerging themes.

Recruitment

Staff from the participating IBD services identified and recruited patients on current caseloads and approached them during clinical appointments or by telephone. The study was also advertised in local gastroenterology departments using posters and leaflets. In two of the participating centres, potential participants were given verbal explanations of the study and, if interested, were provided with a copy of the participant information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Those patients who were interested in taking part then gave verbal consent for the clinical team to pass on their contact details to the research team. To inform the purposive sampling strategy, the research team collated summary clinical and demographic information about each patient during the initial telephone call. This call was also an opportunity for patients to ask questions about the research before they agreed to take part.

If a patient was eligible, and interested, a mutually convenient time for the telephone interview was agreed. In the third centre, written informed consent was taken from participants by the IBD research nurse, who then passed on the participant’s details to the research team. To facilitate the purposive sampling strategy, the research team regularly informed the clinical team of preferred patient characteristics. A lay version of the interview questions and a list of drugs for UC were sent to all participants along with confirmation of the interview date and time. Copies of the participant information sheet and consent form were also sent to all participants from centres 1 and 2 to inform them about verbal consent procedure undertaken prior to interview. All participants were assigned a unique, anonymous study identification at this point. Reasons for non-participation were recorded, where relevant.

Data collection

Verbal consent to participate in the interview and for the interview to be audio-recorded was taken from all participants from centres 1 and 2 before data collection commenced. Participants were asked to refer to the copy of the consent form while the statements were read aloud by the researcher. Separate anonymous recordings of participants providing consent was stored securely for audit purposes. As above, written informed consent was taken locally from participants from the third centre, but verbal consent to participate was confirmed before the interview commenced.

The individual semistructured interviews were conducted over the telephone by Elizabeth Coates, Amy Barr and Nyantara Wickramasekera. All participants were made aware prior to commencing data collection that the interviewers were non-clinical researchers and were advised to contact their IBD team if they had any clinical questions arising from the discussions. Participants were asked to ensure that they were in a quiet and private location for the duration of their interview and were in their homes or work offices during data collection.

A semistructured interview schedule was used to guide the data collection (see Report Supplementary Material 2). This was used to explore patients’ lived experience of UC and approaches to treatment decision-making, and so it was structured around the Coping in Deliberation (CODE) framework. 65 The CODE framework is a multilevel, theoretically informed framework that promotes an understanding of the complexity of decision-making in preference-sensitive health-care settings. 65 In the CODE framework, deliberation is classed as a six-stage process: (1) presentation of health threat, (2) choice, (3) options, (4) preference construction, (5) the decision itself and (6) consolidation. Coping, on the other hand, is presented in three stages: (1) threat, (2) primary and secondary appraisal, leading to (3) a coping effort. Therefore, the interview schedule was split into four sections to address (1) experiences of their UC, (2) treatment options considered at each stage/change of treatment and preference construction, (3) how treatment choices were made and (4) consolidation (i.e. how they currently feel about the treatment choices they made). The interviews were tailored to the patients’ treatment choices and experiences.

All data were collected between 4 June and 29 October 2019. Data collection stopped when data saturation was reached. All interviews were recorded using a digitally encrypted device and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Data analysis

Key themes arising from the data were summarised based on a thematic analysis of transcriptions. 64 As with the health-care professional interviews, a thematic analysis was completed by Elizabeth Coates and Amy Barr in accordance with the six recommended stages (see Data analysis, above).

Discrete choice experiments

Health-care professionals

Study design

This WP involved an online DCE with health-care professionals in the UK with expertise in IBD. The DCE involves a series of tasks in which respondents select a preferred treatment option when presented with two alternative treatment profiles. These treatment profiles are constructed using a set number of attributes and levels that differ across the alternatives. An attribute is a treatment characteristic that is important to the treatment decision, and a level is a clinically plausible range for each attribute. 66

Identification of treatment characteristics

All relevant attributes and levels were identified using three approaches: (1) reviewing the literature, (2) conducting qualitative interviews and (3) consulting clinicians to select the most important attributes and levels for the DCE. As reported in WP2, qualitative interviews (n = 20) were conducted with health-care professionals with expertise in IBD to understand how patients with steroid-resistant UC are treated in the UK. From these interview transcripts, we identified 16 key themes that health-care professionals considered important when making treatment choices. To convert these themes to possible attributes and levels, we convened a panel of four IBD specialist clinicians (AL, ML, CP and SS). Using iterative rounds of discussion, the panel helped to consolidate and select the most important attributes and also refined the phrasing of attributes.

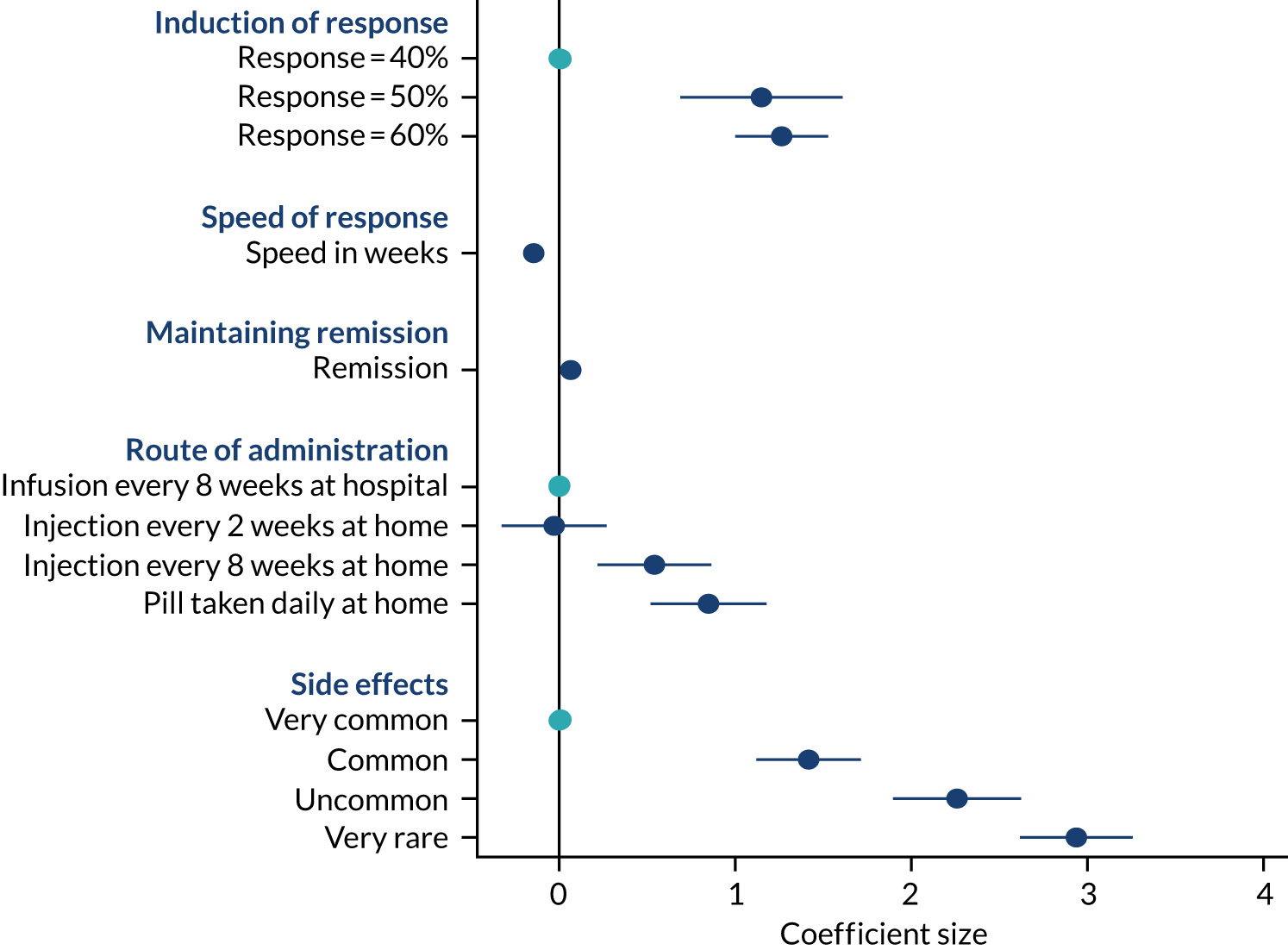

This process of selecting the key attributes is important for the structural reliability of a DCE, as evidence suggests that the DCE tasks can become cognitively challenging if attribute and level selection is not optimised. 67 When deciding the appropriate levels for each attribute, we carefully selected clinically meaningful values from the clinical trials literature that are sufficiently wide that respondents will be encouraged to trade treatment profiles. The final five attributes (each with three levels) focused on treatment efficacy and safety (Table 1).

| Attribute | Level |

|---|---|

| The likelihood of induction therapy successfully leading to a clinical response (i.e. significant improvement in clinical symptoms) |

|

| The likelihood of a treatment achieving mucosal healing (i.e. a Mayo endoscopic subscore of ≤ 1) |

|

| Remission: efficacy as a maintenance treatment – likelihood of achieving clinical response at 12 months |

|

| Risk of lymphoma |

|

| Risk of serious infection (the baseline risk in patients unexposed to immunosuppressive medication is approximately 1–2 per 100 patient-years) |

|

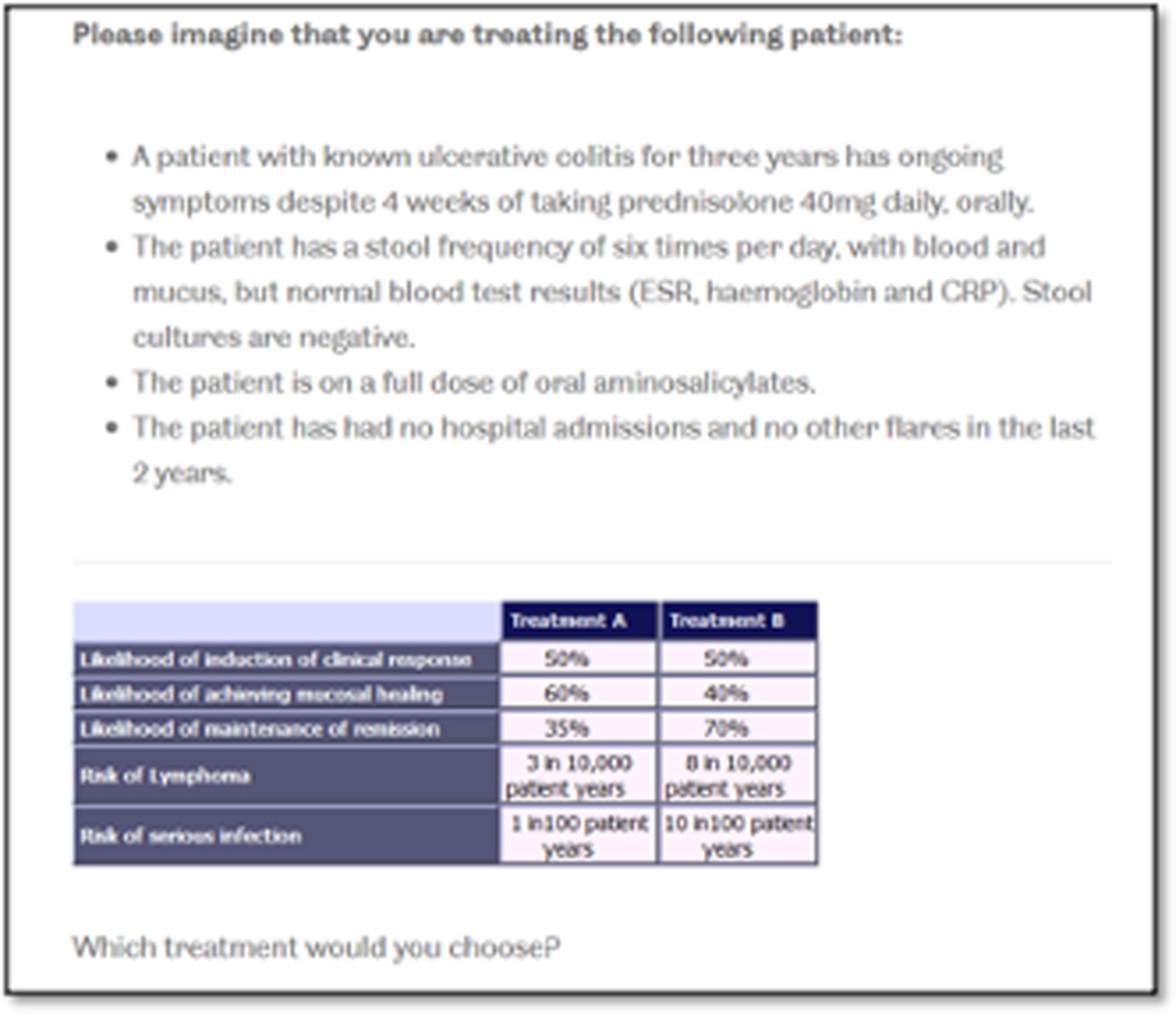

Questionnaire design

An online survey was developed that contained DCE questions, questions about respondent demographics and feedback questions about the survey. The DCE questions were generated using Ngene software (ChoiceMetrics, Sydney, NSW, Australia). Five attributes with three levels each produced 243 possible treatment profiles and, therefore, to create a manageable DCE task a fractional factorial design was used. The D-optimal design generated 12 choice questions, which followed the principles of orthogonality, minimum overlap and level balance. 68 Each DCE question contained two unlabelled treatment profiles (Figure 1). Opting out of treatment choices was not given as a response option because patients with steroid-resistant UC need treatment and doing nothing can be detrimental to their quality and length of life.

FIGURE 1.

Example of a DCE choice question from the health-care professional DCE.

At the start of the survey, a series of screens displayed instructions, including detailed descriptions of the attributes, the levels and the choice context in which the respondents should address the DCE tasks. For each question, the respondents were asked to select the treatment they would choose to offer a patient with steroid-resistant UC (see Figure 1). In addition to the 12 choice questions, a dominant choice question, where one treatment was logically better, was included in the DCE section to test the internal validity of the survey. The final version of the survey contained 13 choice questions that were displayed in a random order to the respondents. A soft launch of the survey was undertaken (n = 50) to assess any problems, including comprehension and dropouts.

Sampling and recruitment

Clinicians and specialist nurses with experience of treating patients with UC in NHS trusts were invited to take part in the online survey through the Qualtrics platform. A link to the survey was sent to health-care professionals in an e-mail (from the IBD section of the BSG and the RCN IBD Nurses Network), via social media and in newsletters during the data collection period between June and August 2020. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study and were not given any financial incentives to complete the survey. The target sample size was 100 survey respondents, which was based on the minimum sample size required (n ≥ 62.5) to estimate a model using the rule-of-thumb approach and also on the literature that reports the average sample of a DCE ranging between 100 and 300 participants. 69,70

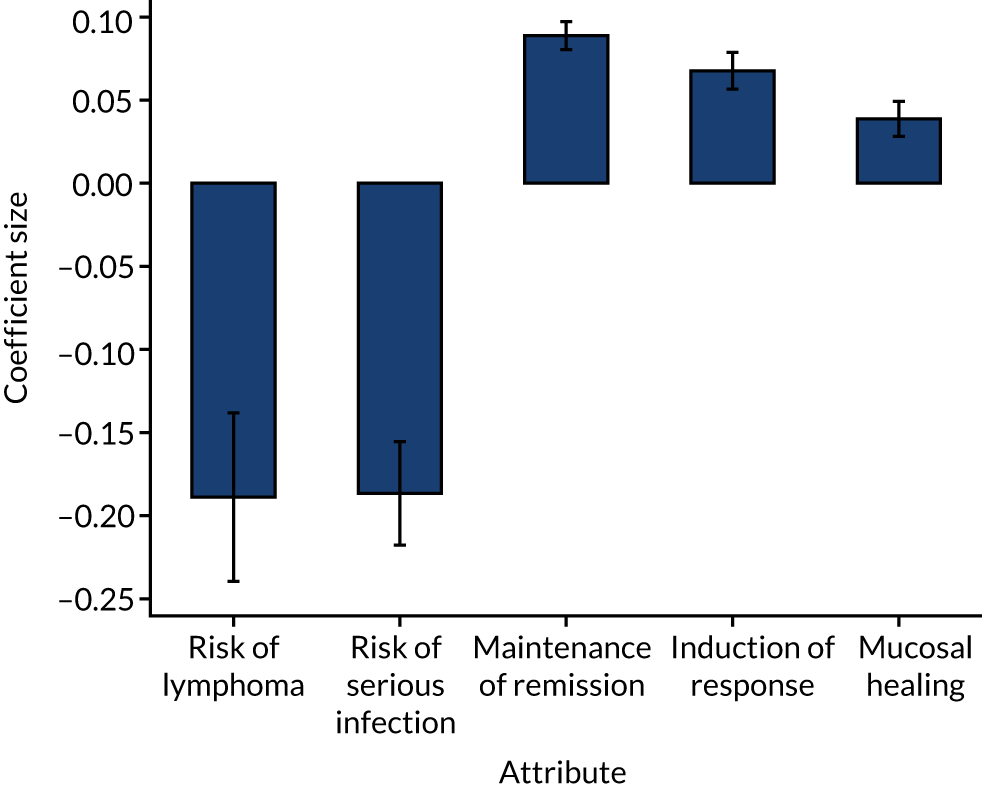

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise respondents’ characteristics and survey feedback questions. Responses to the DCE questions were analysed using a conditional logit model. Attributes were first included as categorical variables using dummy coding; however, after the linear relationship was confirmed through visual inspection and model fit, all attributes were included as continuous variables in the models. 71 The models with the full sample report only main effects, and no interaction terms were included. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata® v16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The utility function for estimating the probability of choosing the preferred treatment profile takes the following form:

where V is a binary variable (1 = the preferred treatment profile is chosen, 0 = the treatment profile is not chosen), β is the estimated coefficient for each of the treatment attributes and ε is the unobserved error term.

Exploratory analyses were also conducted to evaluate preferences across subgroups according to hospital type. This was achieved by estimating a model with interactions for all main effect variables for health-care professionals working at secondary or tertiary hospitals to identify any significant differences in their preferences.

Using the results of the conditional logit model, marginal willingness to trade benefit and risk was calculated to find the rate at which health-care professionals are willing to trade levels of one attribute for the preferred levels of another attribute. Benefit–risk trade-offs were calculated by dividing the estimated parameter coefficient for benefit attributes (i.e. induction of response, mucosal healing or maintenance of remission) by the estimated parameter coefficient for the risk attributes (i.e. risk of lymphoma or serious infection).

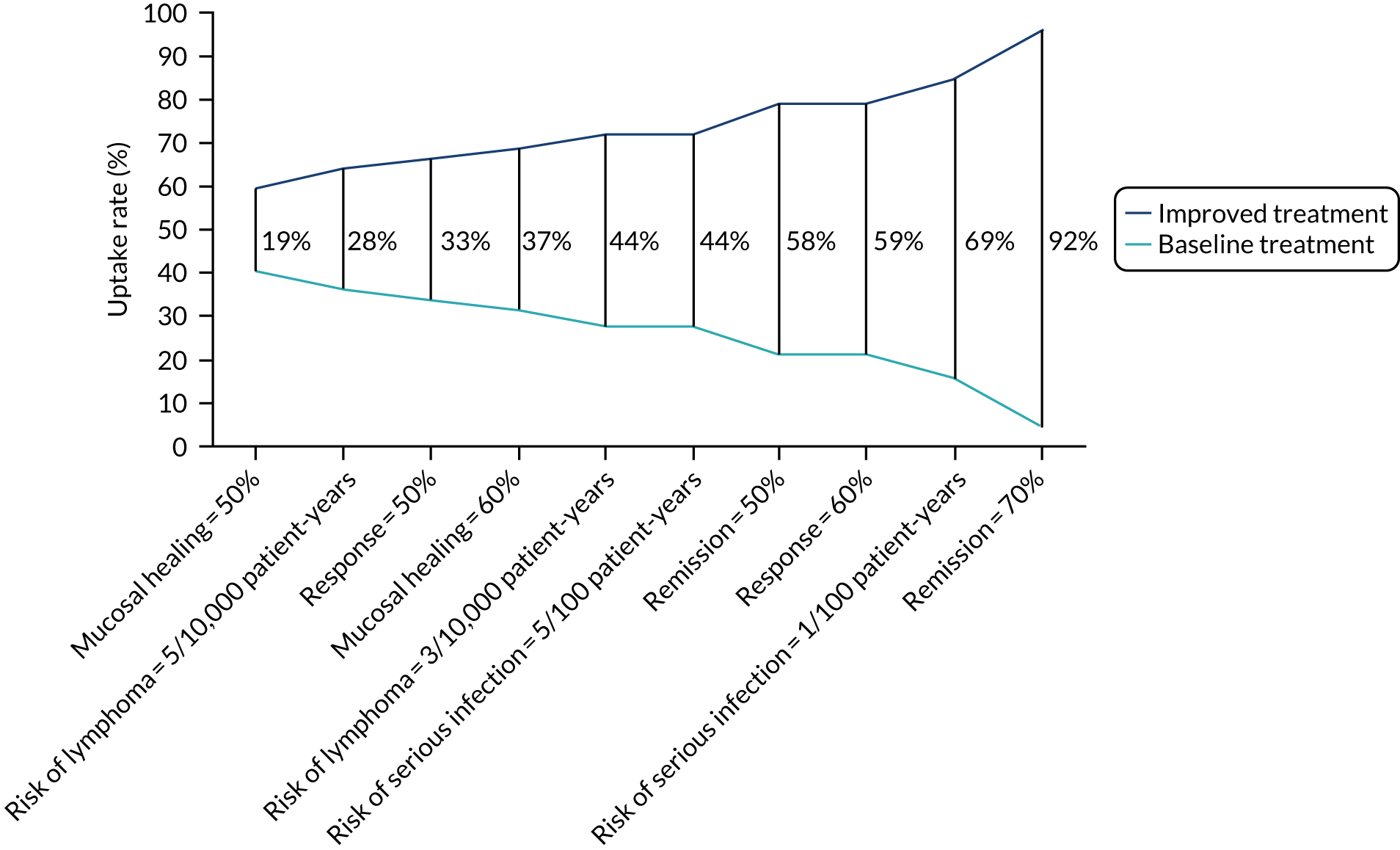

Parameter estimates from the conditional model were also used to predict uptake rates of a selected number of drugs currently commonly prescribed to patients with steroid-resistant UC. 72 The probability of choosing alternative i is:

where Vi is the estimated utility associated with alternative i and Vj is the sum of utility of j alternatives (see example calculations in Appendix 5).

Moreover, parameter estimates from the conditional model were also used to calculate the change in probability of uptake from a baseline scenario where all attributes are set to their worst level and then improving each attribute one at a time (see example calculations in Appendix 5).

Patients

Study design

This WP involved an online DCE with adults living with UC in the UK.

Identification of treatment characteristics

The development of attributes and levels was informed by a combination of reviewing the literature, conducting qualitative interviews with patients and consulting Patient Advisory Group (PAG) members to find out what they considered the most important attributes. As reported in WP3, we conducted 33 interviews with patients to identify key characteristics that patients consider important when selecting a treatment. Thematic analysis of the qualitative interviews generated eight themes, which were ranked by the four PAG members using a dot-voting technique. 73 The patients were given 16 dots to distribute across the eight themes, with themes with the most dots indicating the most desirable treatment characteristics. Through this process the eight themes were converted and reduced to attributes. After discussions with the PAG members, one theme around the need for regular monitoring was dropped, as this was deemed the least important of the eight. Similar themes were merged; for example, route and frequency of administration were merged to create one single attribute, and quality of life and inducing a treatment response were merged to create another single attribute. The final five attributes focused on effectiveness, remission, speed of response, treatment administration and safety of treatment (Table 2).

| Attribute | Level |

|---|---|

| How effective the drug is at treating your symptoms: the drugs may improve or settle your symptoms (e.g. in reducing stool frequency and bleeding, or returning these to normal), improve your quality of life and make you feel better |

|

| Speed of response to treatment: some drugs take longer than others to take effect |

|

| Chance of your symptoms remaining improved after 12 months: after your initial symptoms improve, the drugs can help to control your symptoms over time; however, there is also a possibility that you may lose the improvement and develop a flare of your symptoms |

|

| Route and frequency of administration: how and where the medication would be taken is different according to which drug you take |

|

| Chance of experiencing side effects: drugs can cause unwanted side effects. Common side effects include nausea, headache, skin rashes and mild infections. These side effects often settle without treatment, can be easily treated or are reversed if the drug is stopped. In rare cases, the drugs may cause severe side effects over a longer period of time. These severe side effects include more severe infections (e.g. tuberculosis and viral infections, including the shingles virus), some cancers, including lymphoma (i.e. lymph gland cancer), blood clots in the leg (i.e. deep-vein thrombosis) or lung (pulmonary embolism) and nervous system problems. The chance of experiencing severe side effects is very low for all treatments |

|

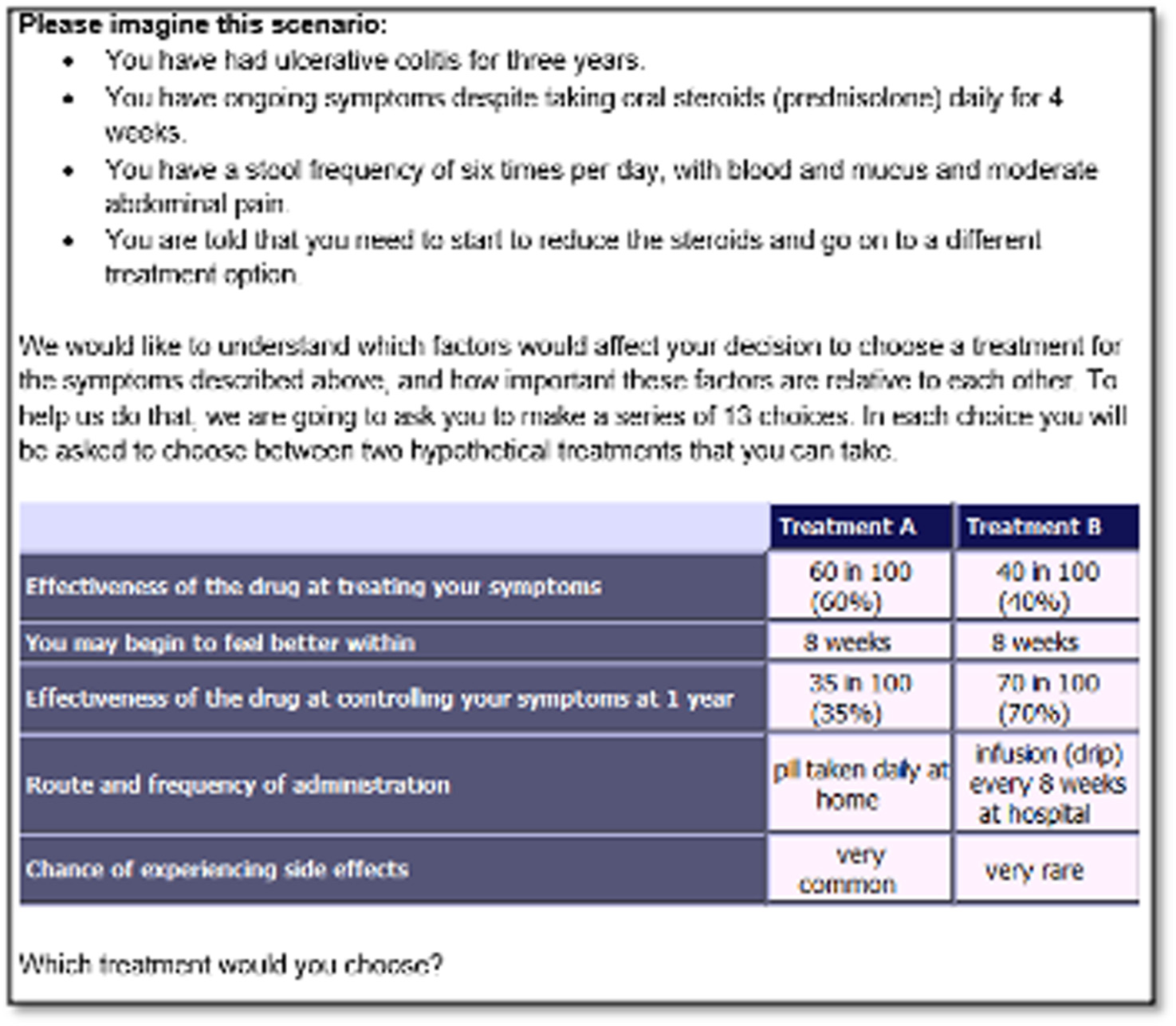

The PAG and PPI co-applicants also helped to refine the language explaining the DCE task to respondents by piloting the draft questionnaire. For example, to aid understanding, we framed the risk attribute quantitatively in the DCE task (i.e. 60/100, 60%); however, in the introduction to the DCE, risks were framed qualitatively (i.e. ‘a drug that is 60% effective means that, if 100 people had the same drug for UC, for 60 people the treatment would be effective but for 40 people treatment would not be effective’). 71 The levels for the attributes were selected to reflect plausible values from the published clinical trials literature. For the side effects attribute, we expressed the levels modelled in accordance with the categories described in printed information leaflets included with drugs that patients read and are familiar with.

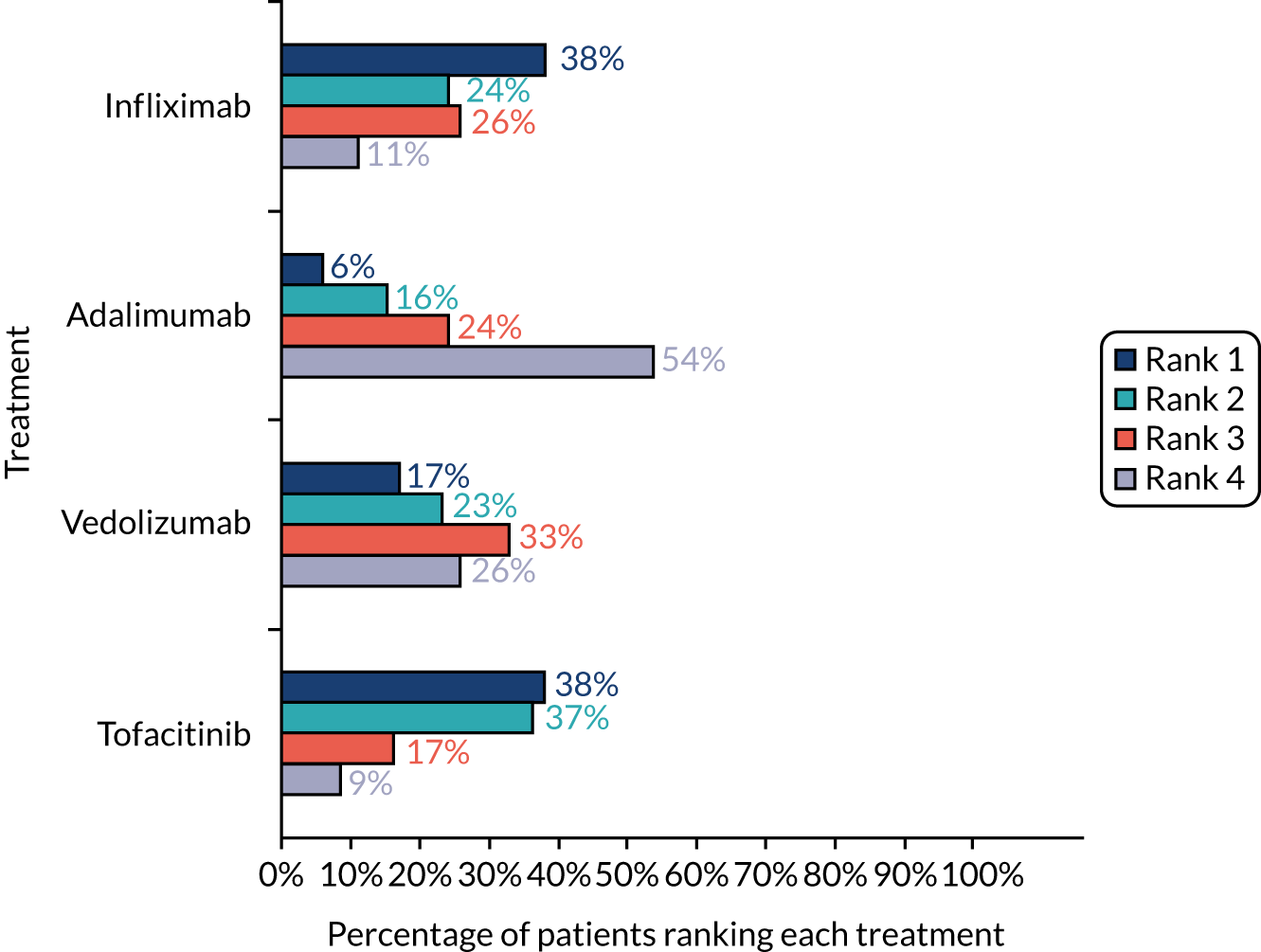

Questionnaire design

The first section of the survey contained the DCE tasks, where participants were shown a series of side-by-side comparisons of competing treatment profiles and were asked to select the preferred treatment profile (Figure 2). We used Ngene software to create 12 DCE tasks using the D-optimal method to maximise statistical efficiency, and followed the principles of orthogonality, minimum overlap and level balance. One additional dominant question that was logically better was also included to test whether or not participants understood the DCE task. 66 To make the choice realistic, participants were not given an opt-out option because treatment is necessary to improve their length and quality of life.

FIGURE 2.

Example of a DCE choice question from the patient DCE.

The second section of the survey involved a ranking exercise in which patients were asked to rank four commonly used treatments (i.e. adalimumab, infliximab, tofacitinib and vedolizumab) in order of preference from 1 to 4 (1 = best preferred treatment and 4 = least preferred treatment). To aid this task, we provided comprehensive details of the treatments, which included the effectiveness of the drug, speed of response to treatment, route of administration, side effects and whether or not concomitant medication is needed (see Report Supplementary Material 3). These treatment descriptions were developed using published literature, with clinical input from the study team, and were presented to participants in a randomised order to reduce question order bias.

In the third section of the survey, we gathered sociodemographic details and information on the respondents’ personal history and severity of UC. The survey included two validated instruments, the IBD Control-8 questionnaire and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). The IBD Control-8 questionnaire captures disease control and impact from the respondents’ perspective and generates a summary score, ranging from 0 (representing worst control of disease) to 16 (representing best control of disease). 75 The EQ-5D-5L instrument captures respondents’ overall quality of life, generating a summary score of between –0.59 and 1, where higher scores represent better quality of life (and 1 represents perfect health). 76 The four survey sections contained feedback questions about the survey. A soft launch of the survey was undertaken (n = 50) to assess any problems, including comprehension and dropouts.

Sampling and recruitment

The study population included adults aged ≥ 18 years who had a diagnosis of UC. Participants were recruited primarily through two NHS trusts where staff working in IBD services advertised the study by sending participants invitation letters. The study was also advertised on social media (via Twitter and Facebook) to recruit further participants from across the UK. If participants decided to take part, then they were able to access the online survey via the Qualtrics platform and complete the survey after providing informed consent. Respondents were not offered any financial incentives for completing the survey. We hoped to recruit up to 300 survey participants as the literature shows that DCE sample sizes can range from 100 to 300 participants. 70 However, the minimum sample size required was n ≥ 83.3 to estimate a model using the rule-of-thumb approach. 69

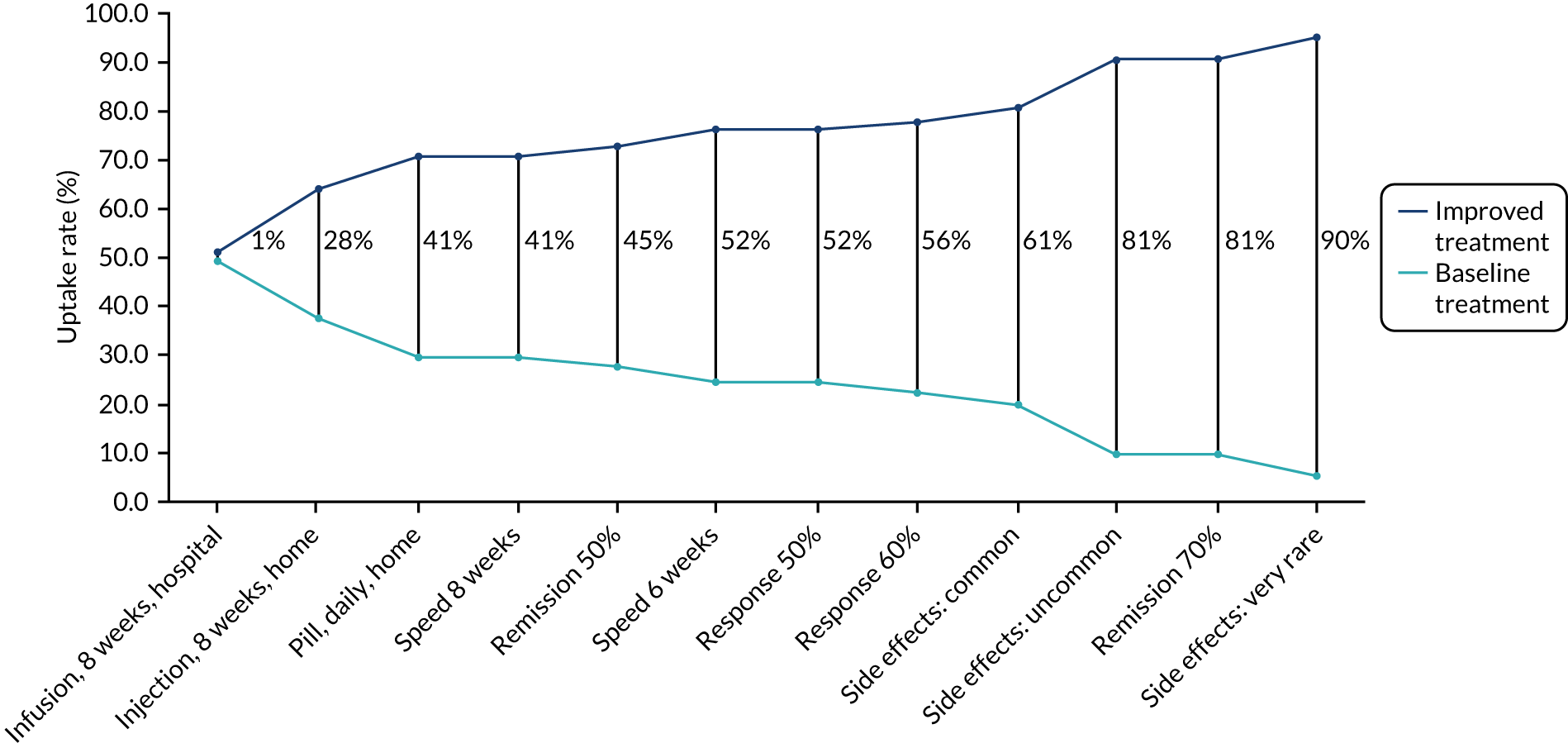

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to analyse the demographic data and IBD characteristics of the respondents and to rank medications in order of importance. We performed conditional logistic regression models to analyse the DCE task data. All of the models report main effects, and no interaction terms were included. Attributes were first included as categorical variables using dummy coding; however, after confirming the linear relationship through visual inspection and model fit, speed and remission attributes were treated as continuous variables and effectiveness, administration and side effects as categorical variables in the main model. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata.

The utility function to estimate the probability of choosing the preferred treatment profile takes the following form:

where V is a binary variable (1 = the preferred treatment profile is chosen, 0 = the treatment profile is not chosen), β is the estimated coefficient for each of the treatment attributes and ε is the unobserved error term.

Parameter estimates from the conditional model were also used to calculate the change in probability of uptake from a baseline scenario in which all attributes are set to their worst level and then one attribute is improved at a time72 (see Appendix 6).

Multistakeholder workshop

Study design

This WP involved a multistakeholder workshop with people with UC and IBD health-care professionals. The workshop was conducted remotely in line with COVID-19 restrictions on face-to-face contact. The workshop involved direct knowledge mobilisation, using the findings to help generate realistic and meaningful recommendations from the PoPSTER study in collaboration with key stakeholders.

Setting

The workshop was conducted online via the Blackboard Collaborate platform (Blackboard Inc., Washington, DC, USA).

Eligibility criteria

Adults with UC and health-care professionals who were medical or nursing staff working with patients with IBD were eligible to participate in the workshop.

Sampling

Statements were included on the consent forms for the qualitative interviews in WPs 2 and 3 to ascertain whether or not participants were interested in attending this workshop (in principle) to generate the sampling frame. In addition to this, a small number of professional contacts of the study team were invited to participate in the workshop. Both groups were sampled purposively to achieve representation of various patient and professional groupings.

Recruitment

Invitation e-mails were sent to all potential participants reminding them about the research and the purpose of the workshop and providing the date and time, and the participant information sheet was attached (see Report Supplementary Material 1). People who were interested in attending the workshop were then asked to register with the research team. More information about the workshop (i.e. log-in details and the agenda) were sent to those people who were able to attend. Informed consent to participate in the online workshop and to have their contributions video- and audio-recorded for use for research purposes was taken from participants remotely (hosted on Qualtrics) prior to the start of the workshop to facilitate smoother running from the outset.

Data collection

At the workshop, the key research findings from WPs 1–4 were presented to participants by the research team. To encourage reflection, to provide a focus for discussion and to promote clearer decision-making, the workshop was structured around Borton’s77 reflective prompt questions, that is, ‘what?’, ‘so what?’ and ‘now what?’. The motivation for this was to enable workshop attendees to consider the research findings and to generate recommendations for future research and practice for steroid-resistant UC. Therefore, the workshop was structured as follows.

What?

The research team gave a presentation of key research findings from WPs 1–4 of the PoPSTER study.

So what?

Small discussion groups considered the implications of the findings for future research and practice.

Now what?

We sought agreement from participants about what needs to happen next and key recommendations.

The small discussion groups (each including patient representatives, medics and nurses, and two members of the PoPSTER team who acted as facilitators) considered and discussed the key findings and agreed recommendations. A final plenary session was used to share recommendations from each small group.

Data analysis

A summary descriptive report of the workshop discussions and decision points was generated, using the ‘what?’, ‘so what?’ and ‘now what?’ framework (see Chapter 8).

Patient and public involvement

The PoPSTER study was developed in collaboration with people with UC. PPI activity is reported here and in Chapter 9 in accordance with the GRIPP2 (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2). 78

At the initial grant application stage, we invited Sue Blackwell to join the co-applicant team and, as part of this, she reviewed the stage 1 application (leading to changes to the design of WPs 2 and 3 and to the content of the Plain English summary). At the second stage of grant application, clarifications were made to the dissemination strategy based on Sue Blackwell’s feedback. Sue Blackwell has expertise in digital marketing, which was helpful to study promotion throughout the grant.

During the preparation of the second-stage application, a local group of patients from Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust were convened to seek wider feedback on the design and scope of the study. The group of patients varied in age (ranging from 20 to 80 years), gender and ethnicity, but they shared a positive response to the research. The group provided encouraging feedback on the study aims and methods, highlighting that these were easy to understand and appropriate to the aims of the research call. This group also made some specific recommendations for improving the study design, including making explicit the maximum interview duration for patients (i.e. 60 minutes), offering breaks to encourage and support those people experiencing a UC flare and including a measure of health-related quality of life in WP4, all of which were introduced. Through this group, Hugh Bedford was identified and was invited to join the team of co-applicants on the grant.

In addition to this, Alan Lobo and Elizabeth Coates worked closely with Sue Blackwell to organise a remote feedback session with patient representatives across the UK. Sue Blackwell distributed an appeal for patient feedback via her Facebook networks and nine people with UC shared their views on the proposed research. Again, this group welcomed the focus on research addressing treatment for steroid-resistant UC. As with the Sheffield group of patients, this group also highlighted the importance of offering breaks during interviews and providing flexible timings for the patient interviews. This group also suggested that limited patient knowledge about the treatment options could make participation in the DCE challenging (highlighting the importance of ongoing PPI input to study documentation and data collection materials). Again, all of these suggestions were incorporated into the final grant application. In addition to this, Nicola Dames was identified and was invited to join the team as a third PPI co-applicant.

During the conduct of the PoPSTER study, the three patient co-applicants (SB, HB and ND) were integral members of the Study Management Group. Therefore, the three patient co-applicants were invited to all Study Management Group meetings and asked to provide input to relevant study documentation, outputs and key issues arising during the delivery of the research, alongside the clinical and methodologist co-applicants. This ensured that the patient perspective informed the design, delivery and reporting of each stage of the studies.

In parallel with this, Nicola Dames and Sue Blackwell helped the research team to establish a separate PAG of four people living with UC (please refer to the Acknowledgements for information on the membership of this group) to get a wider perspective. This group was convened three times to coincide with key stages of the study. At the first meeting (April 2019), the members gave detailed feedback on the content of the qualitative interview schedules for patients. This feedback included comments on the importance of mental health and trauma in the lived experience of UC, comments on the influence of health-care professionals on treatment choices and the significance of that relationship to informing those decisions, a number of helpful clarifications to question wording and practical suggestions, such as sending the list of questions to patients in advance. At the second meeting (November 2019), the PAG members were presented with the headline findings from the WP2 and WP3 interviews and were asked to help with prioritising the long list of attributes for the patient DCE. Subsequent to the meeting, the PAG and the patient co-applicants piloted the DCE questionnaire and gave helpful feedback to improve content and presentation. At the final meeting (March 2021), the headline findings from the patient DCE were presented and the group gave feedback on those, as also helped to interpret the results.

Other PPI activity included promotion of patient DCE on social media by SFB to help support recruitment and ongoing support for study recruitment on Twitter by Sue Blackwell and Nicola Dames. Sue Blackwell, Hugh Bedford and Nicola Dames also gave valuable input by reviewing the Plain English summary and PPI sections of this report.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the PoPSTER study was granted by the NHS East Midlands – Derby Research Ethics Committee on 10 January 2019 (reference 19/EM/0011) and governance approval was granted by the Health Research Authority on 17 January 2019 (Integrated Research Application System reference 255616).

Protocol management and version history

See study protocol version 5.0, which is available online at URL: www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/72/02 (accessed 26 April 2022). A protocol version history is provided in Appendix 1.

Chapter 3 Results from the health-care professional survey

Participants

There were 387 unique visitors to the online survey, and 168 of these visitors consented to take part in the survey (i.e. a 43% participation rate). Of these 168 participants, 145 started the survey and 88 completed every survey question, giving an overall completion rate of 52%. The denominator for individual questions varied from 88 to 145, and is reported for each question to help facilitate interpretation of the results.

The characteristics of participants are summarised in Table 3 (see also Appendix 2, Table 24). The majority of survey respondents were medics (n = 99, 68%) and 44 (31%) were nurses. Fifty-five (38%) participants were working as consultant gastroenterologists with a special interest in IBD. On average, the participants were appointed 9.6 years ago. Eighty-one per cent of participants had no personal experience of IBD. Eighty-eight (62%) participants were from secondary referral centres, 48 (34%) from tertiary referral centres and five (3%) from quaternary referral centres. All UK regions were represented in the survey. Most participants stated that some (n = 59, 41%) or the majority (n = 53, 37%) of their clinical time was dedicated to working with IBD. The majority of participants were part of a MDT (n = 133, 93%) containing, on average, 14 health-care professionals. Most participants reported that they were using national and European guidelines for managing UC (77% and 87%, respectively), as well as NICE guidance for specific treatments (66–83%).

| Characteristic | Frequency (N = 145) |

|---|---|

| Profession, n (%) | |

| Doctor | 99 (68) |

| Nurse | 44 (30) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

| Current job title, n (%) | |

| Consultant IBD specialist | 19 (13) |

| Consultant gastroenterologist with special interest in IBD | 55 (38) |

| Consultant gastroenterologist with special interest that is not IBD | 24 (17) |

| IBD specialist nurse | 44 (30) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 3 (2) |

| Years since appointment | |

| Mean (SD) | 9.6 (6.9) |

| Range | 1–27 |

| Median (IQR) | 7.5 (11) |

| Personal experience of IBD, n (%) | |

| Yes, I have IBD | 6 (4) |

| Yes, one of my family or friends has IBD | 20 (14) |

| No | 117 (81) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

Definitions of steroid resistance

As shown in Table 4, definitions of steroid-resistant UC varied, with 68% (92/135) of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing that this is indicated by an incomplete response to prednisolone at 40 mg per day (or equivalent) after 2 weeks. Of the remaining participants, 58% (25/43) agreed or strongly agreed that steroid resistance was indicated by an incomplete response after 4 weeks. If participants did not agree with either of the definitions presented (n = 13), then they were given the opportunity to design their own definition of steroid-resistant UC using pre-set response categories (see Appendix 2, Box 1).

| Time frame | Level of agreement with statement: corticosteroid resistance constitutes an incomplete response to prednisolone 40 mg/day (or equivalent) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree or disagree | Agree | Strongly disagree | Missing | |

| After 2 weeks (N = 135), n (%) | 4 (3) | 18 (13) | 18 (13) | 72 (53) | 20 (15) | 3 (2) |

| After 4 weeks (N = 43), n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (12) | 8 (19) | 23 (53) | 2 (5) | 5 (12) |

Table 5 shows that 77 (57%) of participants agreed that steroid resistance did not include those patients who relapse after initial remission with corticosteroids (i.e. steroid dependent). A greater proportion of participants felt that treatments should be different for steroid-dependent and steroid-resistant disease at each time interval from 2 weeks to 3 months. Whereas, at 6 months, more participants felt that the treatment options should not differ. Only 13% of participants felt that steroid-dependent and steroid-resistant disease should be treated identically, regardless of the interval between remission and subsequent relapse.

| Definition of steroid resistance | Response (N = 135), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unsure | Missing | |

| Does corticosteroid resistance include any patients who go into clinical remission after starting prednisolone treatment, but then relapse on corticosteroid reduction? | 32 (24) | 77 (57) | 12 (9) | 14 (10) |

| If no, after what period of remission would you consider a relapse to be classed as steroid dependent or resistant and, therefore, require different options for treatment? | ||||

| 2 weeks | 45 (58) | 17 (22) | 6 (8) | 9 (12) |

| 4 weeks | 57 (74) | 5 (6) | 6 (8) | 9 (12) |

| 3 months | 40 (52) | 18 (23) | 5 (6) | 14 (18) |

| 6 months | 20 (26) | 38 (49) | 7 (9) | 12 (16) |

| The situations should be managed identically after any interval | 10 (13) | 34 (44) | 6 (8) | 27 (35) |

Treatment options for steroid-resistant and steroid-dependent clinical scenarios

Clinical scenarios

To elicit their treatment preferences for patients with moderately severe UC, both steroid-resistant and steroid-dependent participants were presented with four typical clinical scenarios (Table 6). Participants were presented with six further typical clinical scenarios to elicit their treatment preferences for steroid-dependent disease that relapses at different levels of steroid reduction (Table 7).

| Patient | Scenario |

|---|---|

| Steroid resistant: on thiopurine | In treating a patient with UC, which additional treatment(s) (assuming that all of these are available in your centre) would you offer to someone with moderately severe disease and with no, or inadequate, response to systemic outpatient corticosteroid treatment? |

| Steroid resistant: thiopurine naive | As above, but patient is naive to thiopurine treatment |

| Steroid dependent: on thiopurine | In treating a patient with UC, what treatments (assuming that all of these are available in your centre) would you offer either alone or in combination for someone with moderately severe disease, who responds to steroids, but rapidly relapses when the dose is reduced? |

| Steroid dependent: thiopurine naive | As above, but patient is naive to thiopurine treatment |

| Patient | Scenario |

|---|---|

| Steroid resistant: thiopurine naive | Steroid resistant after 4 weeks of prednisolone 40 mg/day: thiopurine naive |

| Steroid resistant: on thiopurine | Steroid resistant after 4 weeks of prednisolone 40 mg/day: on thiopurine |

| Steroid dependent with relapse at 25 mg/day: thiopurine naive | Response to prednisolone 40 mg/day followed by relapse when dose reduced to 25 mg/day: thiopurine naive |

| Steroid dependent with relapse at 25 mg/day: on thiopurine | Response to prednisolone 40 mg/day followed by relapse when dose reduced to 25 mg/day: on thiopurine |

| Steroid dependent with relapse at 5 mg/day: thiopurine naive | Response to prednisolone 40 mg/day followed by relapse when dose reduced to 25 mg/day: thiopurine naive |

| Steroid dependent with relapse at 5 mg/day: on thiopurine | Response to prednisolone 40 mg/day followed by relapse when dose reduced to 25 mg/day: on thiopurine |

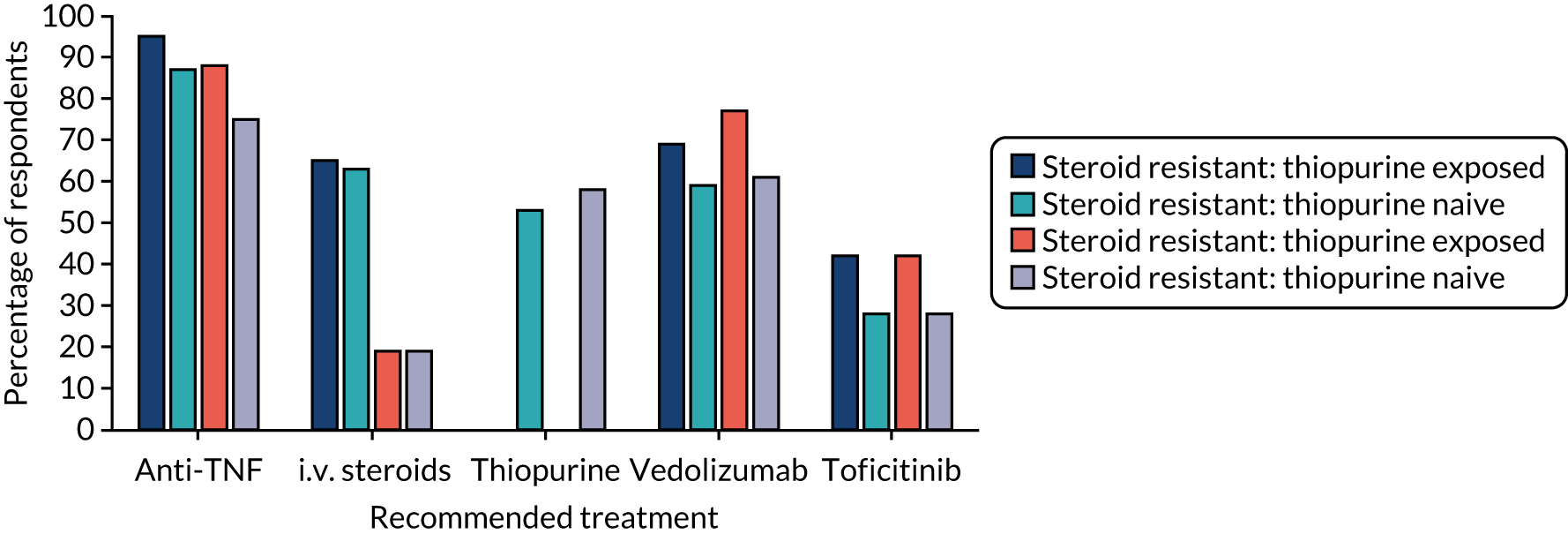

Treatment options for steroid-resistant and steroid-dependent clinical scenarios

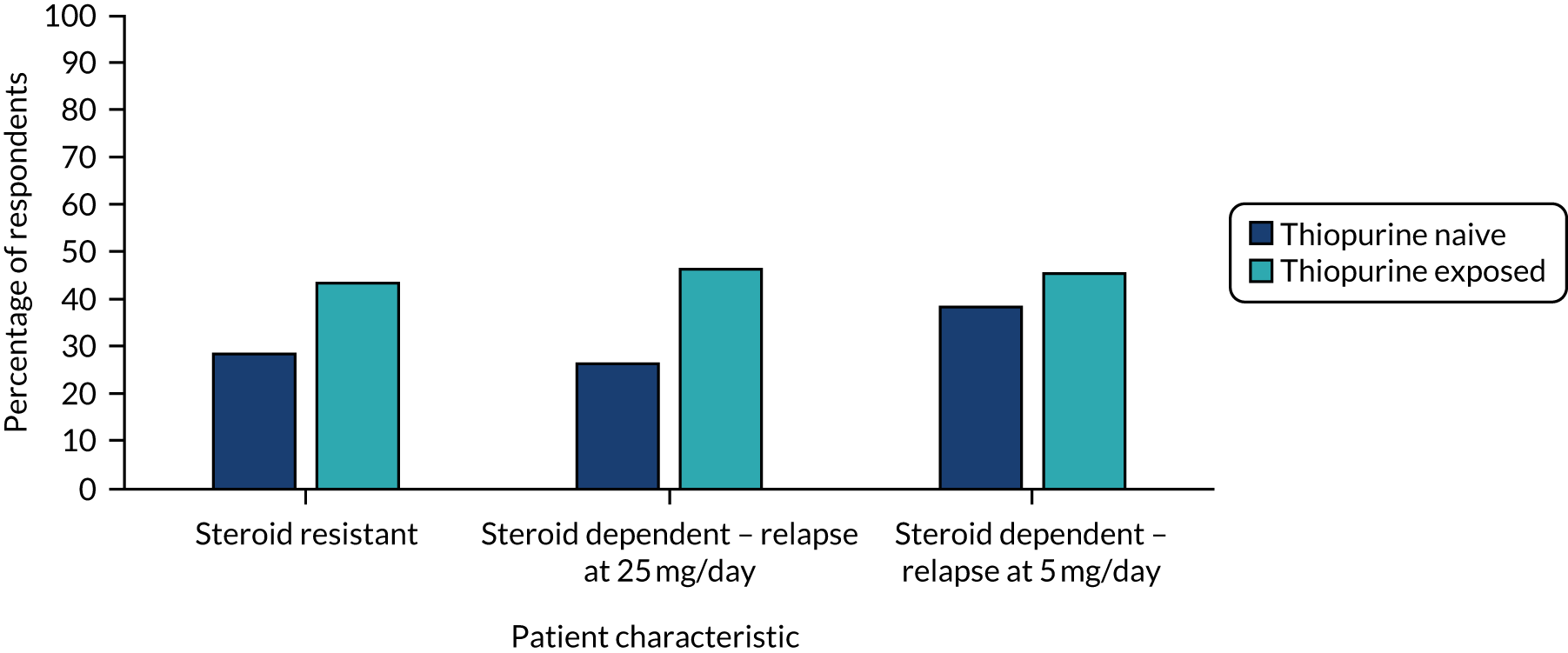

The results are shown in Table 8 and Figure 3, with additional information on treatment preferences given in Appendix 2, Tables 25–28. In steroid-resistant patients, anti-TNF agents (i.e. infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab) were the most frequently suggested treatments for both those exposed to thiopurines and those who were thiopurine naive [95% (n = 114) and 87% (n = 104), respectively]. In steroid-dependent patients, anti-TNF agents remained the most frequently offered [88% (n = 105) in thiopurine-exposed patients and 75% (n = 90) in thiopurine-naive patients]. In all scenarios, infliximab was the most frequently suggested treatment, suggested by 94% (n = 113), 73% (n = 88), 86% (n = 103) and 67% (n = 80), respectively (and albeit with thiopurine or methotrexate in the thiopurine-naive groups).

| Treatment option | Number (%) of responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid resistant: thiopurine exposed | Steroid resistant: thiopurine naive | Steroid dependent: thiopurine exposed | Steroid dependent: thiopurine naive | |

| Anti-TNF agent | 114 (95) | 104 (87) | 105 (88) | 90 (75) |

| Admit for i.v. steroids | 78 (65) | 76 (63) | 23 (19) | 23 (19) |

| Thiopurine | 64 (53) | 70 (58) | ||

| Vedolizumab | 83 (69) | 71 (59) | 92 (77) | 73 (61) |

| Tofacitinib | 51 (42) | 34 (28) | 50 (42) | 33 (28) |

| Other | 87 (72) | 73 (61) | 74 (62) | 82 (68) |

FIGURE 3.

Treatment options for steroid-resistant and steroid-dependent patients.

Vedolizumab was more frequently offered to steroid-dependent patients on thiopurines than to those with steroid-resistant disease on thiopurines, but this difference was not statistically significant [n = 92 (77%) vs. n = 83 (69%); p = 0.137]. As would be expected, admission for i.v. steroids was less frequently offered in steroid-dependent scenarios than in steroid-resistant scenarios [n = 23 (19%) vs. n = 76/78 (63–65%); p < 0.001]. Across all four scenarios, tofacitinib would be more likely to be offered in patients already on thiopurines than in patients naive to thiopurine [n = 101 (42%) vs. 67 (28%), χ2 = 10.586(1); p = 0.001].

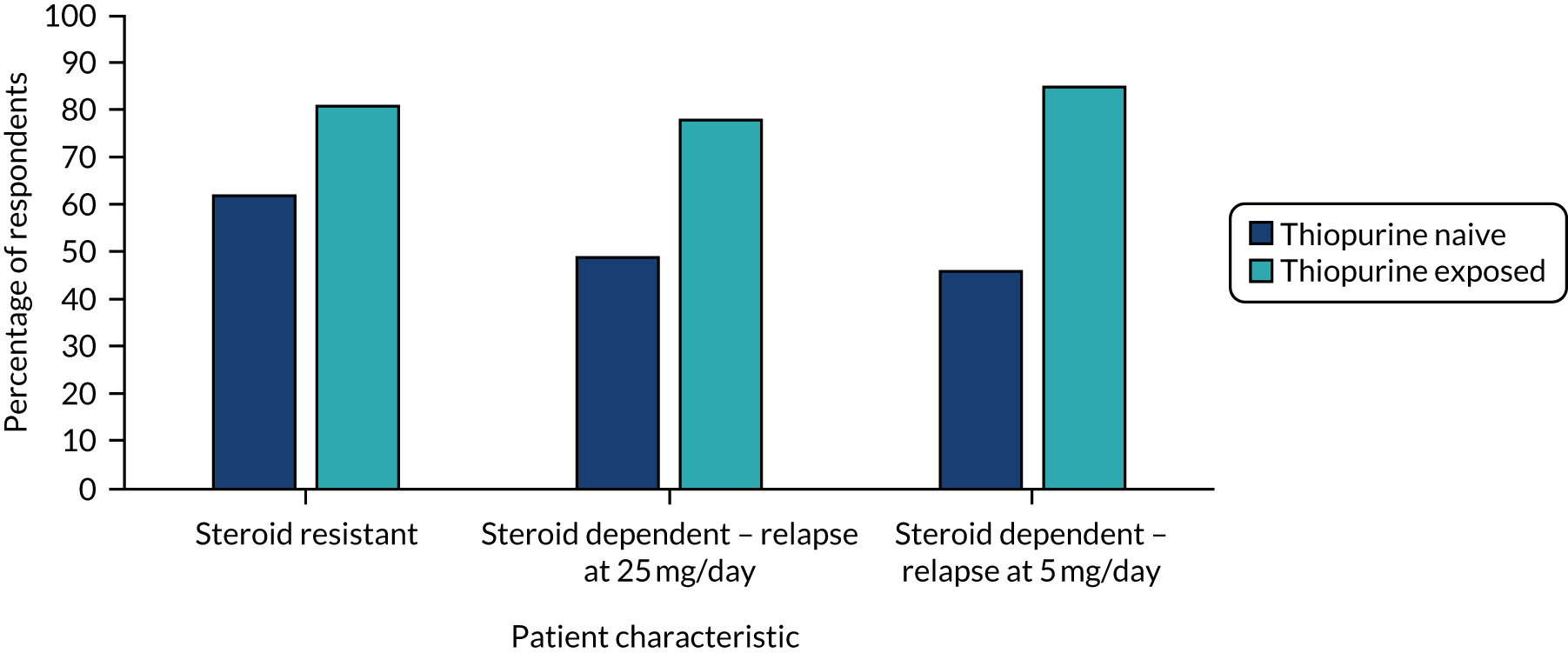

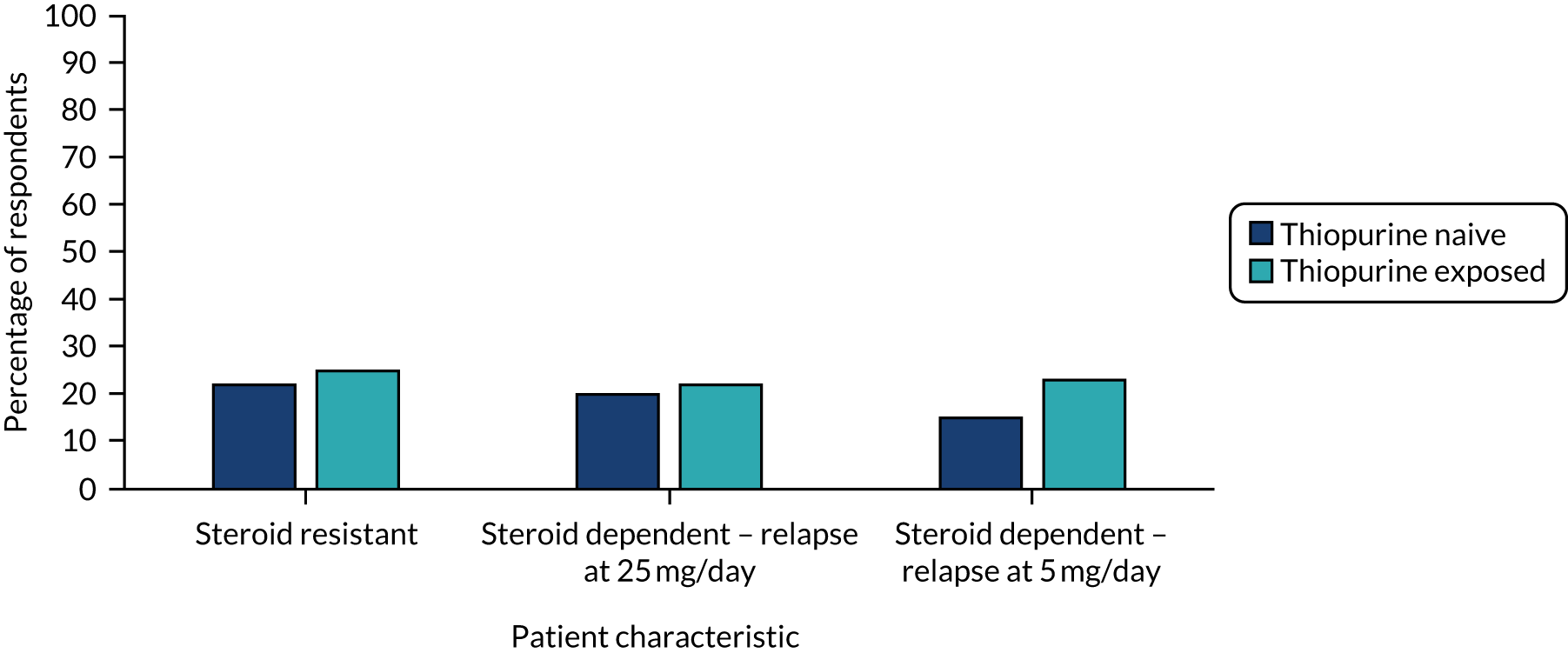

Treatment options for clinical scenarios with steroid-dependent disease and relapse at different doses

The results are shown in Table 9 and in Figures 4–6, and in full in Appendix 2, Tables 29–34. Anti-TNF drugs were, again, the most frequently suggested treatment for steroid-resistant disease, with significantly more patients on thiopurines being offered anti-TNF agents than patients who were thiopurine naive [n = 75 (81%) vs. n = 58 (62%); p < 0.001]. For patients receiving prednisolone at 25 mg per day, on relapse, 78% (n = 73) of clinicians would offer an anti-TNF agent to thiopurine-exposed patients and 49% (n = 46) of clinicians would offer an anti-TNF agent to thiopurine-naive patients (p < 0.001). Forty-four (47%) clinicians would offer thiopurine-naive patients a further increase in steroids to allow thiopurine or methotrexate introduction and 46 (49%) clinicians would introduce thiopurines alone. Sixty-seven (72%) clinicians would offer either of these options in thiopurine-naive patients. For patients receiving prednisolone at 5 mg per day, on relapse, 43 (46%) clinicians would offer anti-TNF agents for a thiopurine-naive patient and 65 (70%) clinicians would introduce a thiopurine. In an individual on thiopurine, 79 (85%) clinicians would offer an anti-TNF agent, 43 (46%) clinicians would offer vedolizumab, 23% (n = 21) clinicians would offer tofacitinib and 20 (22%) clinicians would increase the steroids alone.

| Treatment option | Number (%) of responses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid resistant | Steroid dependent with relapse at 25 mg/day | Steroid dependent with relapse at 5 mg/day | ||||

| Thiopurine naive | Thiopurine exposed | Thiopurine naive | Thiopurine exposed | Thiopurine naive | Thiopurine exposed | |

| Anti-TNF agent | 58 (62) | 75 (81)* | 46 (49) | 73 (78)** | 43 (46) | 79 (85)*** |

| Admit for i.v. steroids | 30 (32) | 36 (39) | 11 (12) | 15 (16) | 10 (11) | 7 (8) |

| Thiopurine (including increase in steroid dose and addition of thiopurine) | 39 (42) | 6 (6) | 67 (72) | 11 (12) | 65 (70) | |

| Vedolizumab | 27 (29) | 41 (44) | 25 (27) | 44 (47) | 36 (39) | 43 (46) |

| Tofacitinib | 20 (22) | 23 (25) | 19 (20) | 20 (22) | 14 (15) | 21 (23) |

| Other | 44 (47) | 50 (54) | 52 (56) | 45 (48) | 42 (45) | 49 (53) |

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of respondents who would offer an anti-TNF agent according to steroid dose at relapse (thiopurine naive and exposed).

FIGURE 5.

Percentage of respondents who would offer vedolizumab according to steroid dose at relapse (thiopurine naive and exposed).

FIGURE 6.

Percentage of respondents who would offer tofacitinib according to steroid dose at relapse (thiopurine naive and exposed).