Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/84/01. The contractual start date was in October 2017. The draft manuscript began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Kyle et al. This work was produced by Kyle et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Kyle et al.

Chapter 1 Background to the research

This chapter uses material from an Open Access article previously published by the research team (see Kyle et al. 20201). This article is published under licence to BMJ. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Insomnia disorder is characterised by persistent problems with sleep initiation and/or maintenance, which leads to impairment in daytime functioning and quality of life. 2–4 Insomnia affects approximately 10% of the adult population4 and is a risk factor for several mental and physical health problems, particularly depression and cardiometabolic disease. 5,6 Insomnia is also an expensive condition, associated with substantial direct and indirect costs, chiefly reflecting increased healthcare utilisation, work-related absenteeism, reduced work productivity and elevated accident risk. 7–9

Insomnia is treatable. Clinical guidelines10–13 recommend multicomponent cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) as the first-line treatment, but access remains extremely limited, particularly in primary care where insomnia is principally managed. Studies in multiple countries show that general practitioners (GPs) almost never offer CBT as a treatment for insomnia, either directly or via referral. 14,15 For example, in a study of primary care patients in Switzerland, just 1% of patients diagnosed with insomnia disorder received CBT. 16 Instead, patients are typically prescribed hypnotics (which are indicated for short-term use, and only if CBT is not available or ineffective), off-label sedative antidepressant medication, or self-help sleep hygiene (SH) advice. None of these treatment approaches are recommended or evidence-based for the treatment of chronic insomnia. GPs are frustrated by this situation. Barriers to wide-scale adoption of CBT in routine health care relate to limited training, expertise and funding. A major development in the insomnia field, therefore, has been the dismantling of multicomponent, multisession CBT into brief and focused treatment packages17 and the training of non-specialists to deliver such therapies. 18–22

Sleep restriction therapy (SRT) has emerged as one of the primary active components within multicomponent CBT. The therapy involves restricting and standardising a patient’s time in bed with the aim of increasing homeostatic sleep pressure, over-riding cognitive and physiological arousal and strengthening circadian regulation of sleep. 23–26 Tailored prescription of bed and rise times over several weeks leads to improved sleep consolidation and reduction in insomnia severity. We recently performed a meta-analysis of randomised trials (8 studies; 533 participants) comparing SRT to control and found medium-to-large effects on sleep continuity measures and large effects for reduction in insomnia severity (Hedges’ g = -0.93) at post treatment. 27

Trials were predominantly performed within specialist research settings, recruiting small samples from the community who were typically free from comorbidity and did not use hypnotic medication. One trial was performed in primary care and tested GP delivery of brief SRT relative to a SH control, and showed encouraging results on the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) at 6 months follow-up. 28 Our view was that a pragmatic trial in primary care testing a scalable model of treatment delivery was required.

We developed a brief SRT protocol based on (1) our extensive research using multicomponent CBT18–20 and (2) systematic examination of the patient experience of SRT. 29 We aimed to test whether brief SRT (alongside SH advice) was both clinically and cost-effective, relative to SH advice on its own. We chose practice nurses (PNs) as sleep therapists because nurses are increasingly involved in supporting lifestyle change and self-management of chronic conditions in primary care, and with scalability and cost-effectiveness in mind. 30 While previous studies in UK primary care showed multicomponent CBT to be effective when delivered by nurses,18,19 counsellors31 or through self-help CBT booklets,32 there had been no large-scale evaluation of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a brief and scalable behavioural intervention. 33

Objectives

The primary objective of the Health-professional Administered Brief Insomnia Therapy (HABIT) trial was to establish whether nurse-delivered SRT for insomnia disorder in primary care improves insomnia more than SH. We hypothesised that participants allocated to SRT would demonstrate lower insomnia severity at 6 months post randomisation compared with those allocated to SH.

Our secondary hypotheses were as follows:

-

Compared with SH, participants allocated to SRT would report improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), sleep-related quality of life, depressive symptoms, work productivity, pre-sleep arousal and sleep effort (at 3, 6, and 12 months).

-

Compared with SH, participants allocated to SRT would demonstrate improvements in sleep parameters (diary and actigraphy-recorded) and report a reduction in use of sleep-promoting medication (6 and 12 months).

-

The effect of SRT on insomnia severity would be mediated via reduction in sleep effort and pre-sleep arousal.

Other objectives:

-

To establish whether nurse-delivered SRT for insomnia disorder in primary care is cost-effective compared with SH, from a NHS Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective, and from a societal perspective.

-

To undertake a process evaluation to understand intervention delivery, fidelity and acceptability.

-

To test whether insomnia phenotype moderates clinical benefit obtained from SRT. One prominent model posits that participants with objective short sleep duration are less likely to experience improvement in insomnia relative to those with normal sleep duration. 5 We will examine whether actigraphy-defined sleep duration (< 6 vs. ≥ 6 hours) at baseline moderates the effect of SRT on clinical outcomes (at 6 months).

-

To test whether SRT adherence is associated with degree of clinical change (ISI) from baseline to 3 months, and from baseline to 6 months.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter uses material from an Open Access article previously published by the research team (see Kyle et al. 2020, BMJ Open1). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Study design

The HABIT trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, individually randomised, parallel-group, superiority trial. Participants were recruited from general practices across three regions in the UK (Thames Valley, Greater Manchester and Lincolnshire). Assessments took place at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The trial was prospectively registered with the ISRCTN (ISRCTN42499563).

Practice and participant recruitment

We identified interested practices in three regions of England (Thames Valley, Greater Manchester and Lincolnshire) through local clinical research networks (LCRNs). In collaboration with the lead CRN, we devised search criteria to identify potentially eligible individuals from practice records. Since insomnia is not commonly coded within practices, records were initially searched for broad sleep-related terms (e.g. cannot sleep, insomnia, non-organic sleep disorders), sleep-related medications (e.g. hypnotics, sedative antidepressants), and key conditions characterised by insomnia (e.g. depressive disorder, fatigue), while applying exclusion criteria (e.g. pregnancy, age, dementia). While this meant that we identified and invited a large number of participants per practice (see Appendix 1), it did increase the possibility of reaching a varied group of people with insomnia. Searches were performed by practice managers, and GPs were given the opportunity to review the list prior to study invitation. Practice managers mailed invitations to identified individuals using Docmail. We also identified potential participants through (1) direct face-to-face GP referral (participants were provided with an information sheet and contact details for the research team), (2) placing posters in practices (containing study contact details) and (3) posting study adverts on practice websites.

Alongside the study invitation letter and participant information sheet, participants were provided with three potential methods to engage with the eligibility process, depending on preference: (1) web-link to complete an online eligibility questionnaire, (2) a brief paper questionnaire with return reply slip (following which the research team contacted participants by phone to complete the remainder of the screening process) and (3) contact details for the research team to arrange completion of the eligibility questionnaire over the phone. Regardless of methods, all interested participants underwent the same eligibility screening questionnaire.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participant is willing and able to give informed consent for participation, (2) screens positive for insomnia symptoms on the Sleep Condition Indicator34 and meets Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition35 (DSM-V) criteria for insomnia disorder, (3) self-reported sleep efficiency (SE) < 85% over the past month,36 (4) age ≥ 18 years and (5) able to attend appointments during baseline and 4-week intervention (both face-to-face at the practice and over the phone) and adhere to study procedures.

Exclusions were limited to conditions which may be contraindicated for SRT, or render SRT inappropriate or ineffective: (1) pregnant/pregnancy planning in the next 6 months; (2) additional sleep disorder diagnosis (e.g. restless legs syndrome, obstructive sleep apnoea, narcolepsy) or ‘positive’ screen on screening questionnaire;37 (3) dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI); (4) diagnosis of epilepsy, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; (5) current suicidal ideation with intent or attempted suicide within past 2 months; (6) currently receiving cancer treatment or planned major surgery during treatment phase; (7) night, evening, early morning or rotating shift-work; (8) currently receiving psychological treatment for insomnia from a health professional or taking part in an online treatment programme for insomnia; (9) life expectancy of < 2 years; and (10) another person in the household already participates in this trial.

On completion of screening, eligible participants were invited to a baseline appointment with a member of the research team where they provided written informed consent, completed baseline questionnaires, and were provided with a sleep diary and actigraph watch for the following week. Participants subsequently returned the completed diary and actigraph watch to the research team via postal mail, and were then randomised.

Interventions

Sleep hygiene

While CBT is the guideline treatment, in practice treatment as usual comprises hypnotic or sedative medication, and SH guidance. 14 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends12 that patients should be provided with SH advice as part of the management pathway, although there is no evidence that SH is effective as a monotherapy. 11,38 GPs commonly provide advice on SH but there is little standardisation of such information, in terms of either delivery format or content. Assuming that some participants would have been exposed to such information in the past, and to avoid potential bias, participants in both trial arms were provided with the same SH information. We provided a booklet comprising standard behavioural guidance in relation to lifestyle and environmental factors associated with sleep and sleeplessness. 39 Participants randomised to the SH arm were sent their booklet via e-mail or post.

Consistent with the requirements of a pragmatic trial, there were no restrictions on usual care for both groups. In this way, the trial represents a comparison of SRT + SH plus treatment as usual versus SH plus treatment as usual, permitting clear judgement to be made regarding the relative clinical utility of SRT in routine clinical practice.

Sleep restriction therapy

Participants in the intervention arm were offered nurse-delivered insomnia therapy in the form of SRT, a manualised behavioural intervention (see Table 1 for a detailed description). SRT is hypothesised to treat insomnia symptoms by reducing and standardising a patient’s time in bed with the aim of increasing homeostatic sleep pressure, over-riding cognitive and physiological arousal, and strengthening circadian regulation of sleep. 23–25 It involves implementation of a prescribed and restricted sleep schedule, which is reviewed and adjusted each week by a therapist in order to optimise SE (the proportion of time spent in bed asleep). Time in bed is initially restricted to match reported total sleep time (TST) (with 5 hours set as the minimum sleep opportunity). PNs and research nurses from CRN were trained to deliver SRT. Nurses received a 4-hour training session on sleep, insomnia and the delivery of SRT as well as access to supporting resources (e.g. recorded video clips and a list of frequently asked questions and answers in relation to treatment delivery). Trained nurses delivered manualised SRT over four brief, weekly sessions (total contact time = approximately 1 hour 5 minutes). In session 1 the nurse introduced the rationale for SRT alongside a review of sleep diaries, selection of bed and rise times, management of daytime sleepiness (including implications for driving) and discussion of barriers/facilitators to implementation. Participants were provided with a booklet to read in their own time, which included information on theory underlying SRT and a list of SH guidelines (identical to those provided to the control arm). Participants were provided with diaries and SE calculation grids to support implementation of SRT instructions and permit weekly review of progress. Sessions 2, 3 and 4 consisted of brief sessions (10–15 minutes) to review progress, troubleshoot any difficulties and advise on adaptation of the sleep schedule. Sessions 1 and 3 took place in person at the practice while sessions 2 and 4 were conducted over the phone. Therapy materials were reviewed by our patient and public involvement (PPI) advisory group, which included people with lived experience of insomnia and SRT.

| Item | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Name of intervention | SRT for insomnia disorder | |

| Why | Insomnia is assumed to be maintained, in part, by excessive amounts of TIB and irregular sleep–wake schedules, which serve to fragment sleep. TIB awake further contributes to insomnia because the bed/bedroom environment may become associated with wakefulness over time, subsequently acting as a trigger for arousal and sleep fragmentation. SRT aims to (1) restrict TIB (to enhance SE), (2) regularise the timing of the sleep–wake cycle and (3) recondition the bed–sleep association. | |

| What: materials | Materials for patients: patients were provided with a folder at the beginning of the intervention. This folder contained a copy of the slides used during session 1, worksheets to complete during sessions 1–4, sleep diaries and SE grids to enable recording/calculation of SE each day during the 4-week intervention period and a booklet which contained enhanced information on the background and implementation of SRT, including quotes from patients who had previously undergone SRT, as well as guidance on SH. This guidance briefly covered lifestyle behaviours (e.g. caffeine, alcohol use, exercise), environmental factors (e.g. light, temperature) and the sleep routine (e.g. napping, regular bed and rise times). Materials for nurses: nurses were provided with a training folder (as part of a 4-hour training session) which contained background information on sleep, insomnia (including its development and maintenance) and SRT. The folder also contained a list of frequently asked questions in relation to trouble-shooting and specific patient scenarios that may arise, with standardised guidance on how to navigate. Nurses were provided with access to two recorded videos that gave an overview of insomnia and SRT implementation. Nurses were provided with a PowerPoint slide set to work through with each patient during session 1. They also worked through a structured checklist (completed online) for each session to guide content and structure, and enable recording of session attendance and duration. |

|

| What: procedures | In session 1 the nurse worked through PowerPoint slides with the participant to introduce the rationale for SRT alongside a review of (baseline) sleep diaries, selection of bed and rise times (for the following seven nights), management of daytime sleepiness (including implications for driving) and discussion of barriers/facilitators to implementation. Participants were provided with diaries and SE calculation grids to support implementation of SRT instructions and permit weekly review of progress. Sessions 2, 3 and 4 were brief sessions to review progress, trouble-shoot any difficulties and advise upon titration of the sleep schedule. | |

| Who provided | Registered PNs in primary care and research nurses from local CRNs were trained to deliver SRT. | |

| How provided | Intervention was delivered one-to-one, involving both face-to-face (sessions 1 and 3) and over-the-phone contacts (sessions 2 and 4). | |

| Where | The face-to-face sessions took place in a consultation room within general practice. | |

| When and how much | Intervention was delivered over four sessions. Duration and format of sessions were as follows:

|

|

| Tailoring | The treatment was tailored to each individual’s sleep pattern but followed standardised instructions for setting and titrating TIB. | |

| Criterion | SRT | |

| Calculation of prescribed TIB | Based on average TST from baseline 7-day sleep diary. Minimum TIB = 5 hours | |

| Rise-time selection | Time that aligns with working schedule and can be adhered to 7 days a week | |

| Bedtime selection | Typically delayed in order to equal the prescribed TIB | |

| Weekly adjustments to TIB based on average SE for 7 days (SE) (sessions 2–4) |

Adjustments (advancing or delaying) are typically made to the prescribed bedtime |

|

| Napping | Recommendation to eliminate all napping | |

| Nurses were encouraged to adapt the TIB prescription in the following circumstances: patient is struggling to adhere, or cannot tolerate the restriction; patient is excessively sleepy; or change in health precludes full implementation. In these circumstances nurses were encouraged to agree a revised TIB (increasing in 15-minute blocks) until the patient is content. | ||

| On completion of nurse sessions participants were encouraged to continue self-implementing SRT on their own according to the standardised rules. Participants were provided with sleep diaries and grids to enable self-implementation at home. Once daytime functioning had improved, and SE remained high – and no further sleep was obtained with additional TIB – the participant had reached their optimal sleep schedule. | ||

| How well | Face-to-face sessions were audio-recorded (if consent was provided) and a sample was independently appraised for fidelity by a clinical psychologist experienced in CBT for insomnia. Nurses followed and ‘signed-off’ a checklist at the end of each session to capture duration of session and adherence to treatment instructions. | |

Outcomes

A list of outcomes and time points and corresponding objectives can be found in Table 2.

| Objectives | Outcome measures | Time point(s) of evaluation of this outcome measure |

|---|---|---|

| Primary objective: To compare the effect of SRT vs. SH on insomnia severity |

Self-rated insomnia severity using the ISI questionnaire | Baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Primary outcome is at 6 months |

| Secondary objectives: To compare the effect of SRT vs. SH on HRQoL |

Self-rated HRQoL using the SF-36 questionnaire (total score, MCS, PCS) | Baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation |

| To compare the effect of SRT vs. SH on subjective sleep | Subjective sleep recorded over 7 nights using the CSD (SOL; WASO; SE; TST; SQ) | Baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisation |

| To compare the effect of SRT vs. SH on objective estimates of sleep | Actigraphy-defined sleep over 7 nights (SOL; WASO; SE; TST) | Baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisation |

| To compare the effect of SRT vs. SH on (1) patient-generated quality of life; (2) depressive symptoms; (3) work productivity; (4) hypnotic medication use; (5) use of other prescribed sleep-promoting medications and (6) pre-sleep arousal and sleep effort |

|

Baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Medication use will be quantified from diaries at baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisation |

| To compare the incremental cost-effectiveness of SRT over SH, from both NHS and societal perspectives | Trial records (time and number of nurse-led appointments), practice records* (medications), CSRI, ISI, WPAI, EQ-5D-3L | Baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months postrandomisation. *Baseline and 12 months only |

| To undertake a process evaluation to explain trial results and understand intervention delivery, fidelity and acceptability | Semistructured interviews with (1) trial participants, (2) nurses, (3) GPs or practice managers | Throughout the trial |

| Moderator analysis: Test whether objective short sleep duration at baseline (< 6 vs. ≥ 6 hours) moderates the effect of SRT on clinical outcomes (at 6 months) |

Actigraphy, ISI, GSII, SF-36 | Baseline and 6 months |

| Mediator analysis: Test whether group difference on the ISI (6 months) is mediated by change in PSAS and sleep effort (GSES) assessed at month 3 Test whether SRT adherence mediates degree of clinical change on the ISI |

ISI, PSAS, GSES Sleep diary during intervention phase, ISI |

Baseline and 3 and 6 months |

| To compare the number of specified AEs between the groups | Questionnaire | Baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months |

Measures

Insomnia severity. Insomnia severity was measured with the ISI,40 a validated self-report questionnaire, at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The ISI is a seven-item self-report measure assessing both night-time and day-time symptoms of insomnia. The possible range on the scale is from 0 to 28, with higher scores indexing more severe insomnia symptoms. The internal consistency of the measure is high (α > 0.90) in both clinical and community samples. 41 An ISI score of ≥ 11 is sensitive for insomnia disorder while a ≥ 8-point reduction is associated with moderate improvement in insomnia as assessed by an independent rater. 41

Health-related quality of life. HRQoL was assessed with the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)42 [mental component summary (MCS) score and physical component summary (PCS) score] at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

Sleep-related quality of life. Sleep-related quality of life was measured with the Glasgow Sleep Impact Index3 (GSII, ranks 1–3) at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. At baseline, the GSII asks participants to generate, in their own words, three areas of sleep-related impairment. These areas are ranked in order of concern (1–3) and then rated on a visual analogue scale with respect to the previous 2 weeks (0–100, with lower scores indicating greater level of impairment). At follow-up, participants are asked to rate the same areas of impairment, enabling group-level analyses on the three patient-generated ranks.

Depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-943 (PHQ-9) at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

Work productivity. Work productivity was assessed with the self-rated productivity and activity impairment questionnaire44 (WPAI) at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The WPAI yields three outcomes for those engaged in employment: absenteeism (% work time missed due to insomnia), presenteeism (% impairment while working due to insomnia) and work productivity loss (overall work impairment/absenteeism plus presenteeism due to insomnia). The final outcome relates to non-work activity impairment and can be completed by all participants.

Pre-sleep arousal. Pre-sleep arousal was measured with the pre-sleep arousal scale45 (PSAS) at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

Sleep effort. Sleep effort was assessed with the Glasgow Sleep Effort Scale46 (GSES) at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

Sleep parameters. Self-reported sleep parameters were derived from sleep diaries. Participants completed the consensus sleep diary47 for 7 days at baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Objective sleep-parameters were obtained from actigraphy. Participants wore an actigraph watch (MotionWatch 8, CamNtech Ltd., Cambridge, UK) for 7 days at baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisationand were instructed to press a marker button on the watch when attempting sleep. These event markers were used to define sleep periods by an experienced scorer blinded to treatment allocation. In the absence of event markers, a decision was made based on bed and rise times from the sleep diary following a decision flow-chart developed at the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute, University of Oxford. Sleep variables of interest were calculated by the validated in-built algorithm of the MotionWare software 1.2.47. The following sleep parameters were derived from sleep diaries and actigraphy recordings: sleep onset latency (SOL), wake-time after sleep onset (WASO), SE, sleep quality (SQ, diary only) and TST.

Sleep-promoting medication. Medication use was quantified from sleep diaries at baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisation. Use of prescribed hypnotics and other sleep-promoting medications (e.g. sedative antidepressants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, melatonin) was extracted in order to capture (1) proportion of nights of use per participant and (2) proportion of participants in each group at each time point who used sleep promoting medication at least once during the 7-day recording period.

Cost-effectiveness. Intervention records captured the number and duration of nurse-led sessions to quantify cost of delivery per trial participant. The Client Service Receipt Inventory48 (CSRI) captured self-reported service use, the WPAI was used to index productivity losses and utilities were measured with the EuroQol Questionnaire49 [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)] to enable calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). In addition to the EQ-5D-3L, participants completed two additional utility measures, the Short-Form-6 Dimensions (SF-6D)50 (derived from the SF-36) and the EQ-5D-3L + Sleep,51 at 3, 6 and 12 months. EQ-5D-3L + Sleep contains the same five dimensions as the original EQ-5D-3L questionnaire plus an extra dimension on sleep. A value set has been developed for EQ-5D-3L + Sleep enabling utility values to be obtained. 51 Utility values derived from the SF-6D and EQ-5D-3L + Sleep were used to estimate QALYs over the 12-month trial period so that we could assess, in pre-defined exploratory analyses, whether sensitivity to SRT could be improved with these measures (relative to the standard EQ-5D-3L).

Process evaluation. Semistructured interviews were conducted with trial participants, nurses, GPs or practice managers across the three study sites and throughout the trial. Number of appointments attended/received by participants, fidelity appraisal of recorded consultations, and adherence to the prescribed sleep window were also considered. Fidelity of sessions was assessed by a clinical psychologist for a subsample of recordings using a bespoke rating scale (range 0–26 for treatment session 1 and 0–16 for session 3) and converted to % score. Adherence to the prescribed sleep window (intervention group only) was quantified as the number of nights per week that the participant adhered (within 15 minutes) to the nurse-prescribed bed and rise times. Bed and rise times were derived from sleep diaries completed during the 4-week intervention phase and converted to a % score. Adherence was computed for participants with a minimum of 14 out of 28 diary days. Control group contamination (i.e. the possibility that participants in the SH arm access SRT via the trained PN) was assessed using an item from the CSRI and positive responses were followed up via phone interview to collect further information.

Serious adverse events (SAEs). We defined SAEs as any untoward medical occurrence that (1) results in death, (2) is life-threatening, (3) requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, (4) results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or (5) consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect. Nurse therapists and participants were prompted to self-report SAEs. Along with self-reporting of SAEs, we also used responses on the CSRI which includes questions on hospitalisations, to follow up participants who reported being hospitalised. We recorded planned hospital admissions at baseline and, when they occurred, these were not counted as SAEs. SAEs were assessed for severity, seriousness and relatedness to study procedures by a medically qualified member of the team. SAEs are reported after date of randomisation until either the date of trial withdrawal or 6-month follow-up completion, whichever was earlier.

Adverse events (AEs). We recorded incidences of falls, accidents (including road-traffic accidents and work-related injuries), near-miss driving incidents, and falling asleep while driving alongside outcomes at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

Sample size

It was estimated that 235 participants would be required in each group to detect a group difference of 1.35 points [standard deviation (SD) = 4.5] on the ISI with a power of 90% at 5% level of significance (two-sided). This equates to a standardised effect size of 0.3. The SD was chosen based on the results from the primary care evaluation of SRT. 28 Accounting for 20% attrition we aimed to recruit 588 participants (294 per group). During the trial, overall attrition initially appeared higher than expected, and therefore we made a protocol amendment to increase the sample size depending upon attrition. Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval for the change was obtained in February 2020. We sought a sample size of 628 participants if attrition was 25% or less, and 672 participants if it was between 25% and 30%. Attrition was estimated to be around 25% and therefore our revised target sample size was 628.

For the process evaluation interviews, we aimed to recruit up to 15 participants from each of the 3 stakeholder groups (trial participants, nurses, GPs or practice managers), consistent with our previous experience of framework analysis52 and ensuring a sufficient number of interviews to achieve theoretical data saturation. 53

Randomisation

Participants who completed baseline assessments (including having completed at least 4 days of sleep diary) were eligible for randomisation. Participants were randomised (1 : 1) to SRT or SH using a validated web-based randomisation programme (Sortition), with a non-deterministic minimisation algorithm to ensure site, use of prescribed sleep-promoting medication (yes/no), age (18–65 vs. > 65 years), sex, baseline insomnia severity (ISI score < 22 vs. 22–28) and depression symptom severity (PHQ-9 score < 10 vs. 10–27) were balanced across the two groups. Appropriate study members at each site had access to the web-based randomisation software to complete randomisation and subsequently informed participants of their allocation.

Blinding

This was an open-label study and therefore both participants and nurses were aware of allocation. The participant information sheet informed participants that the study compared two different sleep intervention programmes but did not reveal the study hypothesis. Treatment providers (nurses) were not involved in the collection of trial outcomes. Outcomes (questionnaires, diaries and actigraphy) were self-completed, remotely, by participants. Due to impracticalities associated with blinding of the research team, combined with minimal risk of bias due to use of self-report outcome measures, researchers at each site were aware of treatment allocation. Communication from the research team to participants, post randomisation, was limited to collection of outcome assessments and not therapeutic procedures. The statisticians remained blind to allocation. A full detailed statistical analysis plan (SAP) was prepared and finalised before data collection was complete.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics of recruitment, dropout and completeness of interventions were calculated. Baseline variables are presented by randomised group using frequencies (with percentages) for binary and categorical variables, and means (and SDs) or medians (with lower and upper quartiles) for continuous variables. There were no tests of statistical significance nor confidence intervals for differences between groups on any baseline variables. There was no planned interim analysis for efficacy or futility.

The primary analysis population included all eligible randomised participants who had at least one outcome measurement. Participants who withdrew from the trial were included in the analysis until the point at which they withdrew. Participants were analysed according to their allocated treatment group irrespective of what treatment they actually received. Every effort was made to follow up all participants.

Primary outcome. A three-level linear mixed-effect model was fitted to the ISI score assessed at 3, 6 and 12 months following randomisation. Practice and participant were included as random effects. The model specified an unstructured variance–covariance structure for the random effects. Fixed effects included randomised group, minimisation factors [baseline ISI score (continuous), site, age (continuous), use of prescribed sleep promoting medication (yes/no), sex and baseline PHQ-9 score (continuous)], time, and a time by randomised group interaction term to allow estimation of treatment effect at each time point. The estimated difference between arms at 6 months was extracted from the model by means of a linear contrast statement.

Secondary outcomes. Continuous secondary outcomes were analysed using the same method. Secondary outcomes that were binary were analysed using generalised linear mixed-effect models with appropriate link function. For continuous outcomes standardised effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated as the adjusted treatment effect divided by the pooled SD at baseline.

The Mann–Whitney test was used for three of the secondary outcomes (WPAI absenteeism, proportion of days usage of prescribed hypnotic medication, and proportion of days usage of prescribed other medication) due to violation of model assumptions. The p-value for a difference is reported at each time point, and no treatment effect has been reported.

The two count outcomes of interest were the number of times falling asleep while driving and the number of falls. The SAP stated that these outcomes would be analysed using a Poisson model and if there were excess zeros and/or over-dispersion in the data, a zero-inflated Poisson model and/or a negative binomial model would be considered instead. Both outcomes had excess zeros; < 10% of participants had one or more times falling asleep while driving or number of falls. Due to the event rates being low, a simpler analysis was undertaken instead. These outcomes were defined as a binary outcome [no (0 events)/yes (1 + events)], and a logistic mixed-effect model was used.

Serious adverse events were analysed based on the number of participants who actually received the intervention and Fisher’s exact test was used to compare SRT and SH.

Missing data and sensitivity analyses. The following sensitivity analyses were pre-specified in the SAP to examine the robustness of the primary outcome results to different assumptions regarding missing data:

-

analysis adjusted for baseline covariates found to be predictive of missingness

-

exclusion of any self-rated insomnia severity scores from the analysis which were deemed to be outliers (none were observed)

-

analysis using pattern mixture model to examine the robustness of the missing at random assumption

-

analysis for missing data on the primary outcome at 6 months assuming plausible arm-specific differences between responders and non-responders.

Full details of the sensitivity analyses were specified in the SAP. Multiple imputation of the primary outcome analysis was also conducted as a post hoc sensitivity analysis.

Moderation analyses. We conducted pre-specified subgroup analysis of the primary outcome by baseline actigraphy-defined sleep duration (< 6 vs. ≥ 6 hours), sleep medication use, depression severity (PHQ-9), age, level of deprivation, and chronotype [assessed with the morningness–eveningness questionnaire, reduced version (MEQr)]. 54 The subgroup analyses were conducted using the same method above but adding a three-way interaction term between randomised group, assessment time point, and a subgroup indicator variable to allow the treatment effect to be estimated at each time point and in each level of the subgroups.

Mediation analyses. We proposed in the statistical analysis plan to use structural equation modelling for the mediation analyses; however, due to convergence problems, the analysis strategy was revised and conducted using the Baron and Kenny55 approach but adapted to make use of linear mixed-effect models (similar to Freeman et al. 56). A mixed effects model was fitted to estimate the mediator-outcome effect and another mixed effects model to estimate the treatment-mediator effect. The indirect effect was then calculated as the product of the effect of the mediator at 3 months on outcome at 6 months and the effect of treatment on mediator at 3 months. Confidence intervals and p-values were calculated using Sobel’s test. This allowed us to determine the extent to which the 3-month arousal and sleep effort outcomes (PSAS, GSES) mediated the 6-month ISI outcome. All models included baseline assessments of the mediator and ISI as covariates.

Compliance and adherence. A complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis of the primary outcome was carried out to determine the impact of compliance with the allocated intervention on the treatment effect. Compliance was defined as attending at least one treatment session. CACE models were estimated using an instrumental variable approach where the outcome is total ISI score at 6 months adjusted for baseline ISI. Additionally, models were fitted adjusting for baseline characteristics that appeared to be associated with compliance. Sensitivity analyses were carried out which adjusted the definition of compliance to attending at least two, three or four sessions, and multiple imputation was carried out on the primary CACE analysis as a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of missing data.

We also explored the effect of level of adherence to prescribed bed and rise times (captured by sleep diaries) on the primary outcome in those who received SRT. Percentage treatment adherence was categorised (≥ 0 to ≤ 40/> 40 to ≤ 60/> 60 to ≤ 80/> 80 to ≤ 100) and descriptive estimates for the ISI at 6 months (primary end point), change from baseline to 3 months, and change from baseline to 6 months are presented for each category. Treatment effects on the change scores for different levels of adherence were estimated by fitting a group by categorised adherence interaction in the model, with the reference category being the control group. The models are adjusted for baseline ISI score and a random effect is fitted for practice. Therefore, these estimated treatment effects reflect difference in the change in ISI from baseline for each adherence category as compared to control.

All analyses were conducted using Stata (version 16.1).

Economic evaluation

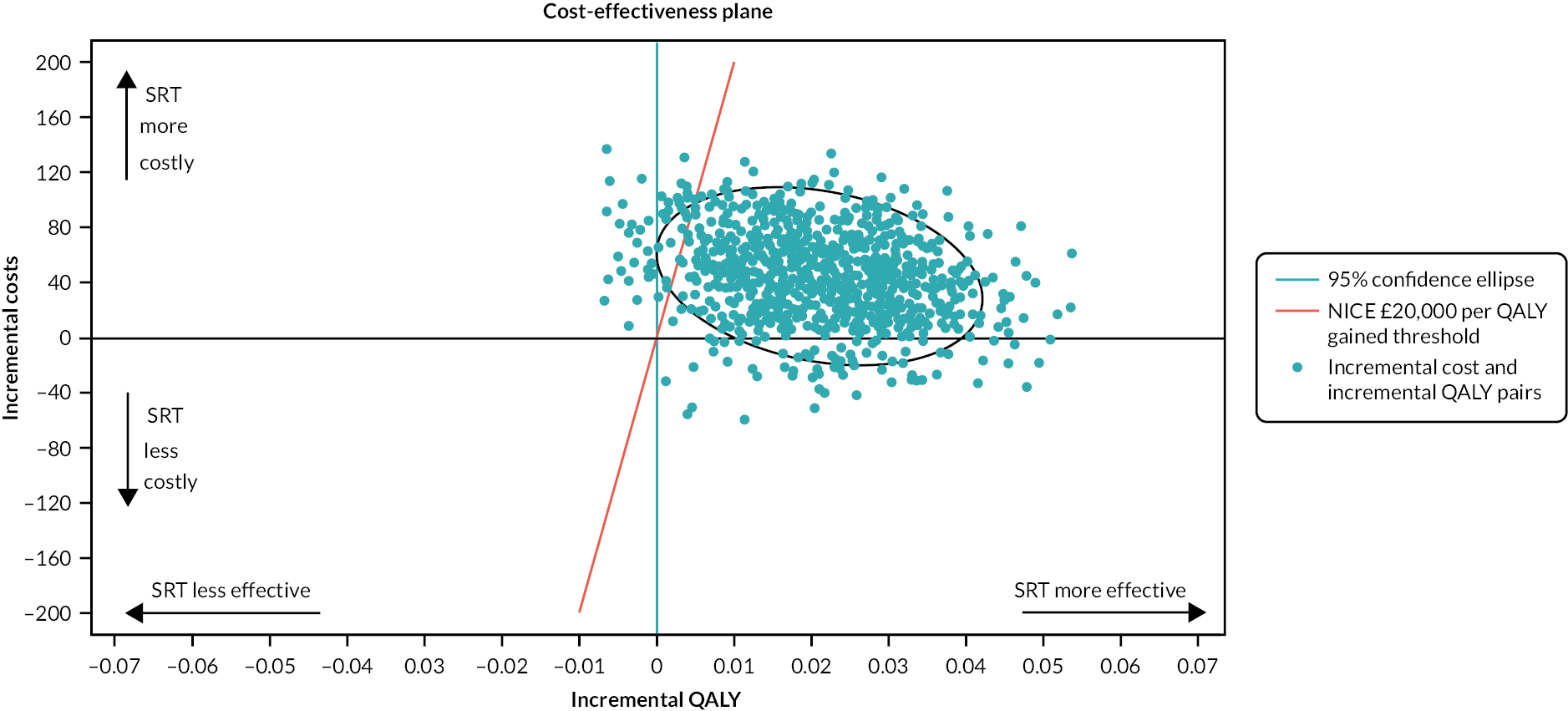

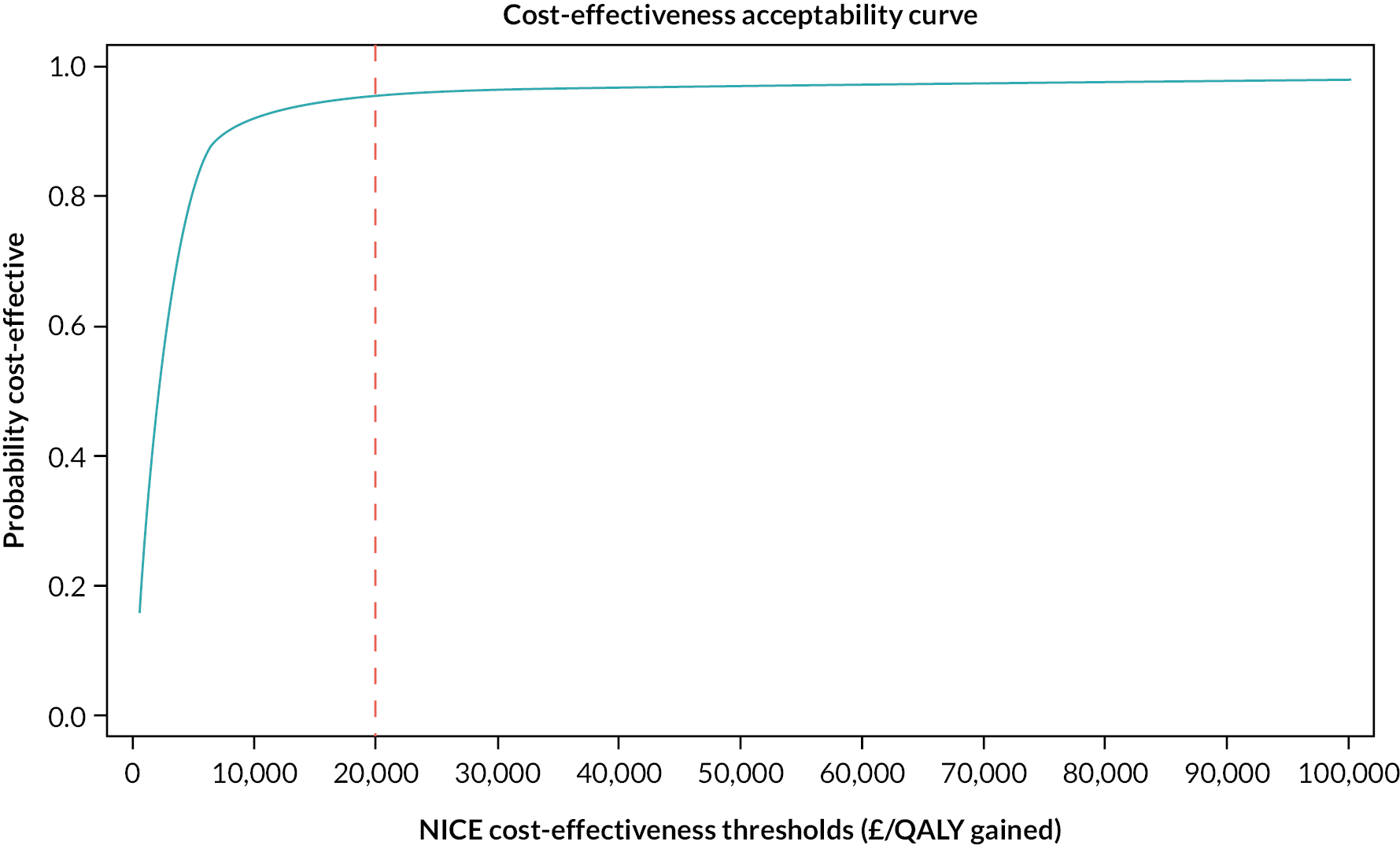

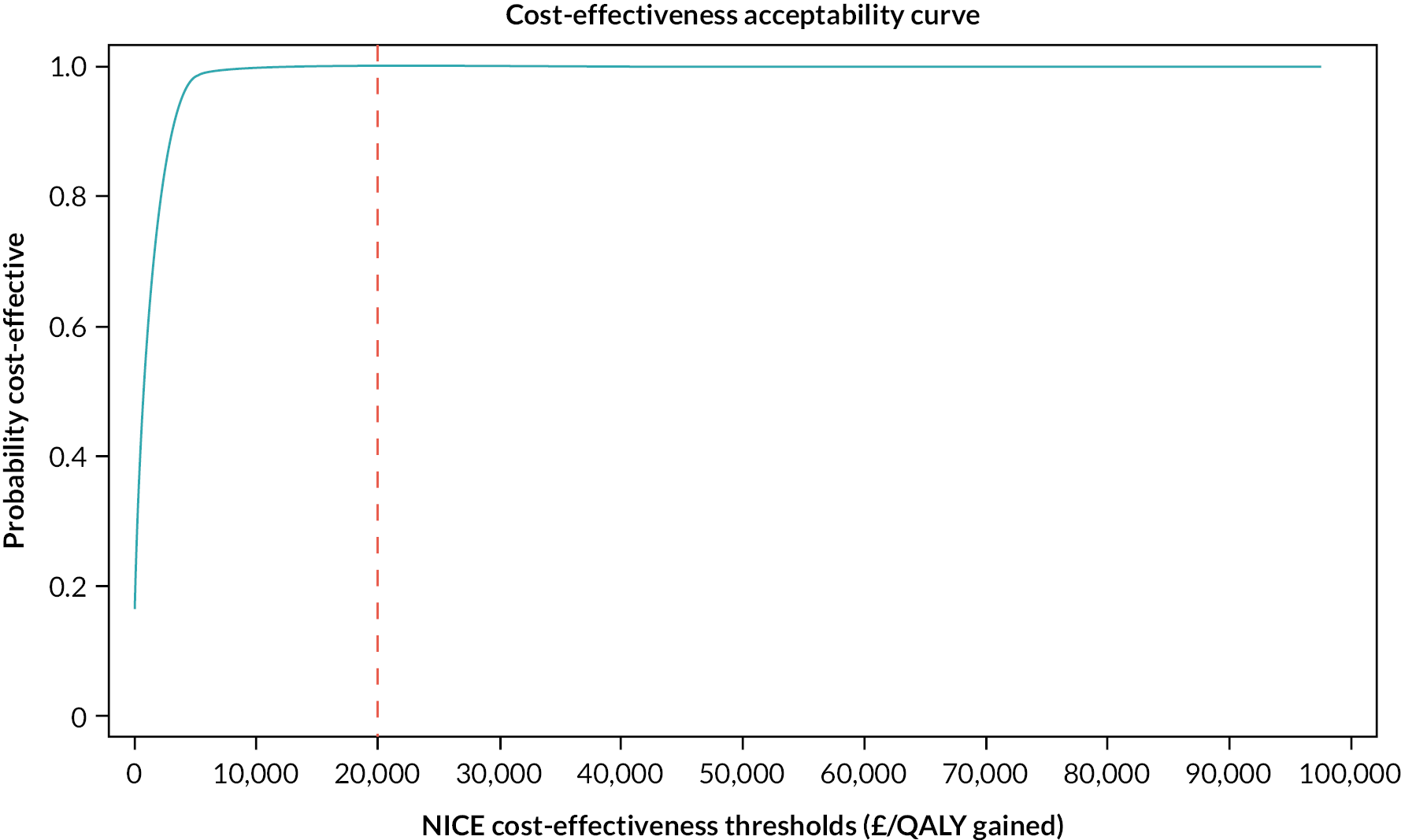

A within-trial economic evaluation was performed to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of SRT over SH. Full details are described in Chapter 4 and a brief summary is presented here for continuity.

The cost–utility analysis was conducted from the recommended NHS and PSS perspective. Individual patient data on the use of health services were collected at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation as part of the follow-up data-collection process. We calculated the cost of delivering the SRT intervention, including preparation and training of nurses, and the cost of sending SH information to the control group. HRQoL was captured through the EQ-5D-3L at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation, and was used to calculate QALYs. Cost and QALYs were combined to calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and net monetary benefit (NMB) statistics.

Process evaluation

We used a Framework approach to data analysis supported by QSR NVivo (version 10), with the framework based on the main areas of implementation, mechanisms of impact, and contextual factors together with the more detailed issues that arise from these. 57 Full details of the methodology and analysis are provided in Chapter 5. Analysis began as soon as the initial interviews were transcribed, and interview schedules were applied flexibly so that qualitative data were collected iteratively, allowing themes that were identified in earlier interviews to be explored in later ones. We analysed qualitative process data prior to knowing trial outcomes to avoid biased interpretation. Analysis of quantitative data allowed us to ascertain the extent to which we sampled participants with differences in insomnia severity at baseline, and the integration of qualitative and quantitative data enabled us to link improvements in sleep (efficiency) to interview findings from patients and staff.

Patient and public involvement

Four people from the Healthier Ageing Public and Patient Involvement group, University of Lincoln, read and provided detailed comments on the original grant proposal, helping to shape key methodological choices. For example, the group recommended adding a patient-centred measure of quality of life and assessing long-term follow-up of sleep and daytime functioning outcomes. Two individuals, one with experience of insomnia and SRT, contributed during the conduct of the trial by reviewing the participant information sheet, consent form, therapy workbooks and questionnaire measures. They recommended amendments to improve the readability and accessibility of all participant-facing documents. They also advised on recruitment procedures and methods to engage prospective participants and retain enrolled participants, and were members of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) who met every 6 months during the trial. They supported interpretation of findings and will advise on dissemination of findings once published.

Ethical approval

The trial received both Health Research Authority approval (IRAS: 238138) and ethical approval (Yorkshire and the Humber – Bradford Leeds REC, reference: 18/YH/0153).

Summary of changes to the project protocol

Table 3 summarises the key changes made to the protocol during the trial.

| Change | Justification |

|---|---|

| Sample size increased from 588 up to 672 based on attrition level. | To allow for higher than expected attrition. |

| Added 1 person per household as exclusion criterion. | To minimise risk of contamination between trials arms. |

| Removed SF-36 total score as an outcome during the trial (and therefore prior to data lock). | This was initially recorded in error. A total score cannot be generated from the questionnaire. |

| Treatment sessions to be completed via web-conferencing. | To adapt nurse treatment so it could be delivered during COVID-19. |

Chapter 3 Results: clinical effectiveness

Recruitment

This chapter uses material from an Open Access article previously published by the research team [see Kyle SD, Siriwardena AN, Espie CA, Yang Y, Petrou S, Ogburn E, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of nurse-delivered sleep restriction therapy for insomnia in primary care (HABIT): a pragmatic, superiority, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2023;402(10406):975–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00683-9. Epub

10 Aug 2023. PMID: 37573859]. This article is published under licence to The Lancet. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

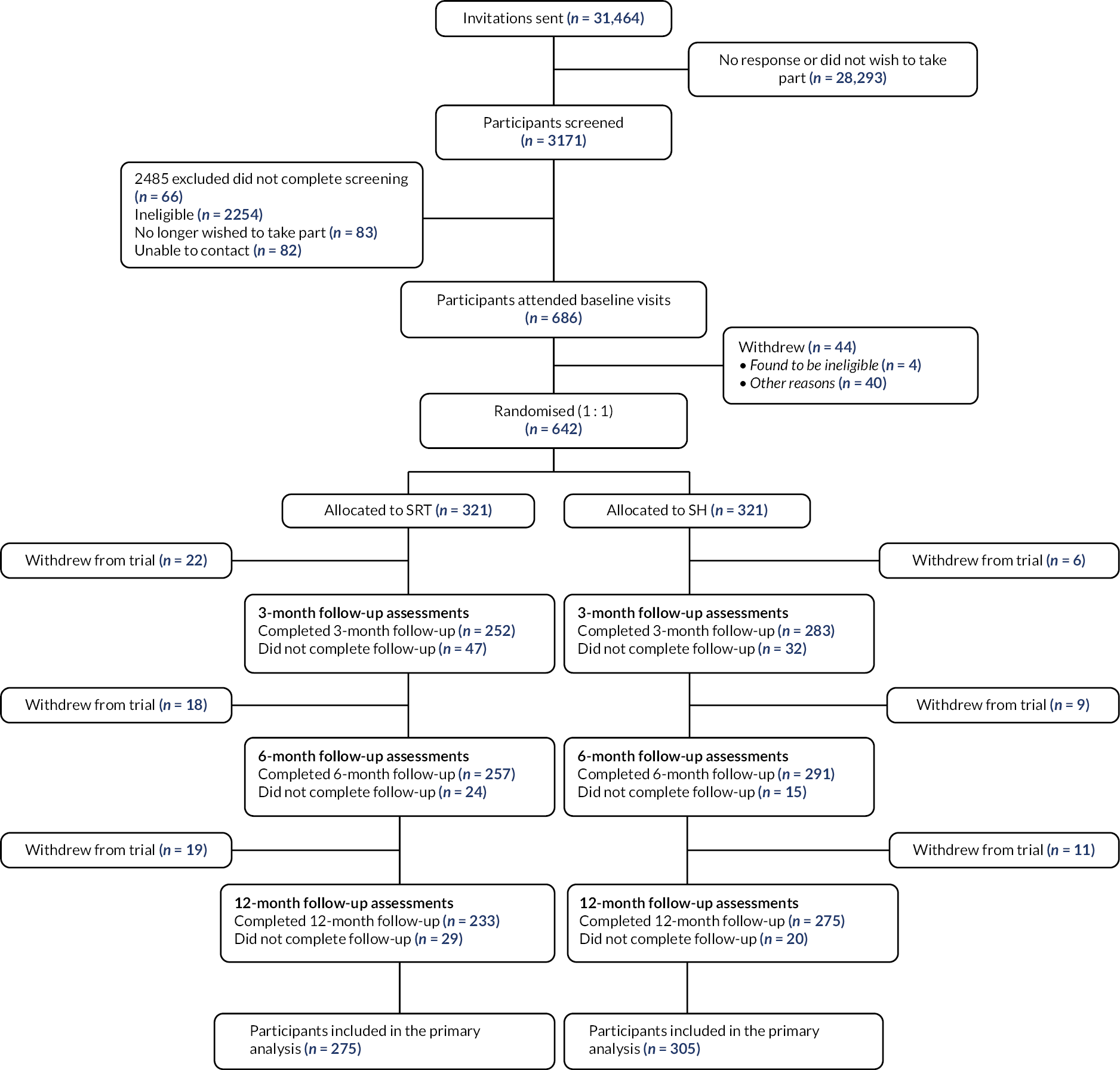

We recruited participants from 35 practices (average patient list size = 11,802) across three sites (Thames Valley, Greater Manchester, Lincolnshire) between 29 August 2018 and 23 March 2020. A total of 31,464 invitation letters were sent out from practices; 3171 people entered the screening phase and 642 participants were randomised (321 to intervention and 321 to control; Figure 1). Main reasons for exclusion following eligibility assessment were not meeting insomnia criteria, shift work and suspected sleep disorder other than insomnia (see Appendix 1, Table 33).

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow chart.

Baseline data

Baseline characteristics by randomised group are presented in Tables 4–6. Mean age (range) was approximately 55 (19–88) years old, 76% were female, 97% were from a white ethnic background, and nearly 50% had a university degree. Mean (SD) ISI scores were in the clinical range (17.5–4.1), median duration of insomnia was 10 years, 76% had previously consulted their doctor for insomnia, and 25% reported current use of prescribed sleep medication. The sample had a range of comorbid conditions. For example, 41% had a mental health problem, 30% had a musculoskeletal disorder and 20% had a respiratory illness. Seventy-one per cent had two or more medical conditions. Consistent with these data, mean SF-36 scores for mental health and physical health were lower than normative values58 and 49% met ‘caseness’ for depression on the PHQ-9 (score ≥ 10). Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups, with a slightly higher percentage of participants in the SRT group having consulted for insomnia (78% vs. 74% for SH).

| SRT (N = 321) | SH (N = 321) | Overall (N = 642) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region, n (%) | |||

| Thames Valley | 156 (48.6) | 156 (48.6) | 312 (48.6) |

| Greater Manchester | 109 (34.0) | 111 (34.6) | 220 (34.3) |

| Lincolnshire | 56 (17.4) | 54 (16.8) | 110 (17.1) |

| Age, mean (SD) (min, max) | 55.7 (15.3) (19.0 to 88.0) |

55.2 (16.5) (19.0 to 87.0) |

55.4 (15.9) (19.0 to 88.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 245 (76.3) | 244 (76.0) | 489 (76.2) |

| Male | 76 (23.7) | 77 (24.0) | 153 (23.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 312 (97.2) | 312 (97.2) | 624 (97.2) |

| Asian/Asian British | 3 (0.9) | 6 (1.9) | 9 (1.4) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) |

| Other ethnic group | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| None | 16 (5.0) | 22 (6.9) | 38 (5.9) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 82 (25.5) | 70 (21.8) | 152 (23.7) |

| A-levels or equivalent | 50 (15.6) | 76 (23.7) | 126 (19.6) |

| University undergraduate | 80 (24.9) | 65 (20.2) | 145 (22.6) |

| University postgraduate | 90 (28.0) | 85 (26.5) | 175 (27.3) |

| Choose not to say | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 6 (0.9) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 48 (15.0) | 54 (16.8) | 102 (15.9) |

| Married, or in a domestic partnership | 220 (68.5) | 195 (60.7) | 415 (64.6) |

| Divorced | 21 (6.5) | 37 (11.5) | 58 (9.0) |

| Widowed | 24 (7.5) | 22 (6.9) | 46 (7.2) |

| Separated | 7 (2.2) | 10 (3.1) | 17 (2.6) |

| Choose not to say | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (0.6) |

| Index of multiple deprivation score (quintiles), n (%) | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 10 (3.1) | 8 (2.5) | 18 (2.8) |

| 2 | 30 (9.3) | 36 (11.2) | 66 (10.3) |

| 3 | 52 (16.2) | 35 (10.9) | 87 (13.6) |

| 4 | 82 (25.5) | 93 (29.0) | 175 (27.3) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 144 (44.9) | 146 (45.5) | 290 (45.2) |

| Missing, n (%) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 6 (0.9) |

| BMI, mean (SD) (min, max) | 26.7 (5.5) (17.1 to 64.8) |

26.3 (5.3) (15.9 to 54.1) |

26.5 (5.4) (15.9 to 64.8) |

| Missing, n (%) | 18 (5.6) | 35 (10.9) | 53 (8.3) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Non-smoker | 214 (66.7) | 202 (62.9) | 416 (64.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 84 (26.2) | 94 (29.3) | 178 (27.7) |

| Smoker | 23 (7.2) | 25 (7.8) | 48 (7.5) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | |||

| Never | 62 (19.3) | 55 (17.1) | 117 (18.2) |

| Sometimes | 133 (41.4) | 151 (47.0) | 284 (44.2) |

| Every week | 126 (39.3) | 115 (35.8) | 241 (37.5) |

| Duration of insomnia (years), median (IQR) (min, max) | 10.0 (4.8–20.0) (0.4 to 66.0) |

10.0 (4.2–20.0) (0.3 to 80.0) |

10.0 (4.5–20.0) (0.3 to 80.0) |

| Consulted for insomnia, n (%) | 249 (77.6) | 237 (73.8) | 486 (75.7) |

| Work-related accident in last 3 months, n (%) | 4 (1.2) | 5 (1.6) | 9 (1.4) |

| Motor-vehicle accident in last 3 months, n (%) | 5 (1.6) | 3 (0.9) | 8 (1.2) |

| Near-miss driving incident in last 3 months, n (%) | 25 (7.8) | 24 (7.5) | 49 (7.6) |

| Times fallen asleep while driving in last 3 months, n (%) | |||

| None | 318 (99.1) | 313 (97.5) | 631 (98.3) |

| Once | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.9) | 6 (0.9) |

| More than once | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.8) |

| Times had a fall in last 3 months, n (%) | |||

| None | 265 (82.6) | 263 (81.9) | 528 (82.2) |

| Once | 30 (9.3) | 30 (9.3) | 60 (9.3) |

| More than once | 26 (8.1) | 28 (8.7) | 54 (8.4) |

| Patient currently taking prescribed sleep medication, n (%) | 83 (25.9) | 80 (24.9) | 163 (25.4) |

| Number of medical conditions, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 38 (11.8) | 34 (10.6) | 72 (11.2) |

| 1 | 60 (18.7) | 52 (16.2) | 112 (17.4) |

| 2 | 73 (22.7) | 60 (18.7) | 133 (20.7) |

| 3 or more | 150 (46.7) | 175 (54.5) | 325 (50.6) |

| Category of medical condition, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 63 (19.6) | 67 (20.9) | 130 (20.2) |

| Neurological problems, n (%) | 29 (9.0) | 49 (15.3) | 78 (12.1) |

| Respiratory conditions, n (%) | 61 (19.0) | 66 (20.6) | 127 (19.8) |

| High cholesterol or taking cholesterol-lowering medication, n (%) | 51 (15.9) | 53 (16.5) | 104 (16.2) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 22 (6.9) | 14 (4.4) | 36 (5.6) |

| Previous diagnosis of cancer, n (%) | 27 (8.4) | 23 (7.2) | 50 (7.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation or other heart rhythm problems, n (%) | 13 (4.0) | 27 (8.4) | 40 (6.2) |

| Musculoskeletal problems, n (%) | 94 (29.3) | 99 (30.8) | 193 (30.1) |

| Autoimmune diseases, n (%) | 16 (5.0) | 17 (5.3) | 33 (5.1) |

| Digestive disorders, n (%) | 72 (22.4) | 78 (24.3) | 150 (23.4) |

| Mental health problems, n (%) | 139 (43.3) | 126 (39.3) | 265 (41.3) |

| Neurodevelopment disorders, n (%) | 3 (0.9) | 5 (1.6) | 8 (1.2) |

| Pain conditions, n (%) | 86 (26.8) | 77 (24.0) | 163 (25.4) |

| Endocrine disorders, n (%) | 35 (10.9) | 31 (9.7) | 66 (10.3) |

| Other condition, n (%) | 89 (27.7) | 82 (25.5) | 171 (26.6) |

| Outcome | SRT (N = 321) | SH (N = 321) | Overall (N = 642) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISI score, mean (SD) | 17.7 (4.0) | 17.4 (4.2) | 17.5 (4.1) |

| PHQ-9 score, mean (SD) | 10.4 (5.3) | 10.1 (5.3) | 10.2 (5.3) |

| SF-36 PCS, mean (SD) | 46.9 (10.9) | 47.3 (10.2) | 47.1 (10.5) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| SF-36 MCS, mean (SD) | 39.8 (12.0) | 39.3 (11.9) | 39.6 (11.9) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| GSII rank 1, mean (SD) | 17.9 (17.4) | 20.7 (18.1) | 19.3 (17.8) |

| GSII rank 2, mean (SD) | 27.5 (17.7) | 31.0 (20.7) | 29.2 (19.3) |

| GSII rank 3, mean (SD) | 40.4 (22.0) | 40.4 (21.5) | 40.4 (21.7) |

| WPAI absenteeism, mean (SD)a | 5.9 (16.9) | 7.5 (21.6) | 6.6 (19.2) |

| Missing, n (%) | 157 (48.9) | 186 (57.9) | 343 (53.4) |

| WPAI presenteeism, mean (SD)a | 44.2 (22.1) | 43.3 (22.5) | 43.8 (22.2) |

| Missing, n (%) | 160 (49.8) | 192 (59.8) | 352 (54.8) |

| WPAI work productivity loss, mean (SD)a | 45.9 (22.9) | 44.8 (23.2) | 45.4 (23.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 160 (49.8) | 192 (59.8) | 352 (54.8) |

| WPAI activity impairment, mean (SD) | 53.2 (23.5) | 51.8 (23.4) | 52.5 (23.5) |

| PSAS cognitive arousal, mean (SD) | 25.4 (6.7) | 25.1 (6.5) | 25.3 (6.6) |

| PSAS somatic arousal, mean (SD) | 14.3 (6.4) | 14.4 (6.2) | 14.3 (6.3) |

| GSES, mean (SD) | 8.0 (2.9) | 7.8 (3.0) | 7.9 (2.9) |

| SRT (N = 321) | SH (N = 321) | Overall (N = 642) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep diary | |||

| SOL (minutes), mean (SD) | 45.0 (36.8) | 47.4 (39.5) | 46.2 (38.2) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (0.6) | 7 (2.2) | 9 (1.4) |

| WASO (minutes), mean (SD) | 104.1 (62.9) | 104.7 (60.6) | 104.4 (61.7) |

| Missing, n (%) | 17 (5.3) | 16 (5.0) | 33 (5.1) |

| SE (%), mean (SD) | 65.3 (13.1) | 64.5 (13.6) | 64.9 (13.4) |

| Missing, n (%) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 6 (0.9) |

| TST (minutes), mean (SD) | 351.1 (73.7) | 346.7 (75.6) | 348.9 (74.6) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| SQ, mean (SD) | 2.6 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) |

| Missing, n (%) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 6 (0.9) |

| Actigraphy | |||

| SOL (minutes), mean (SD) | 12.5 (15.0) | 12.1 (12.7) | 12.3 (13.9) |

| Missing, n (%) | 12 (3.7) | 10 (3.1) | 22 (3.4) |

| WASO (minutes), mean (SD) | 73.8 (35.1) | 72.5 (28.7) | 73.1 (32.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 12 (3.7) | 10 (3.1) | 22 (3.4) |

| SE (%), mean (SD) | 80.7 (7.3) | 80.8 (6.5) | 80.8 (6.9) |

| Missing, n (%) | 14 (4.4) | 11 (3.4) | 25 (3.9) |

| TST (minutes), mean (SD) | 436.4 (60.0) | 437.4 (52.5) | 436.9 (56.3) |

| Missing, n (%) | 12 (3.7) | 10 (3.1) | 22 (3.4) |

Treatment receipt and fidelity

Sleep hygiene

All participants in the SH group were sent their SH booklet by e-mail or postal mail. No participant in the SH group met criteria for contamination (i.e. receiving nurse-delivered SRT) at 3 months (0/265) or 6 months (0/285).

Sleep restriction therapy

Sleep restriction therapy sessions were provided by 40 nurses (31 PNs and 9 research nurses). The median number of participants treated per nurse was 10 (min = 1, max = 24). Median time between randomisation and first treatment session was 23 days (min = 2, max = 306).

Table 7 summarises the number of treatment sessions attended by participants in the SRT arm: 92% attended one or more nurse sessions, while 65% attended all four treatment sessions; 8% did not attend any SRT sessions.

| Number of sessions attended | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 25 (7.8) |

| 1 | 296 (92.2) |

| 2 | 250 (77.9) |

| 3 | 219 (68.2) |

| 4 | 207 (64.5) |

Table 8 provides a breakdown of reasons for withdrawal from SRT. The most common reasons were (1) finding implementation of SRT challenging, (2) not finding SRT useful and (3) personal circumstances.

| Randomised Withdrawal from intervention |

321 n = 62 (19.3%) (%) |

|---|---|

| Reason | |

| SRT too challenging | 19 (5.9) |

| Did not find intervention useful | 16 (5.0) |

| Personal circumstances | 13 (4.0) |

| Medical circumstances changed | 5 (1.6) |

| No reason given | 4 (1.2) |

| Sleeping better | 2 (0.6) |

| Previously tried SRT with no benefit | 1 (0.3) |

| Conflict with existing TAU | 1 (0.3) |

| Appointments not accessible | 1 (0.3) |

Fidelity of sleep restriction therapy sessions

Seventy-nine audio recordings of therapy sessions (53 session 1, 26 session 3) were sampled and reviewed by a clinical psychologist experienced in sleep medicine. Fidelity ratings were high for session 1 [median % = 100, interquartile range (IQR) 96.2–100] and session 3 (median % = 87.5, IQR 75–100).

Numbers analysed

Table 9 summarises data on completion of follow-up assessments, withdrawals (and reasons) and analysis population. Five hundred and eighty participants (90.3%) provided data at a minimum of one follow-up time point.

| SRT (%) | SH (%) | Overall (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants attended baseline visits | 686 | ||

| Withdrew between baseline and randomisation | 44 | ||

| Found to be ineligible | 4 | ||

| Assessments too demanding | 4 | ||

| Participant not contactable | 9 | ||

| Watch and/or diary not received within randomisation window | 4 | ||

| Personal reason | 13 | ||

| No reason given | 5 | ||

| Did not like wearing actiwatch | 2 | ||

| Participant no longer met eligibility criteria after rescreening | 1 | ||

| Previously taken part in CBT for insomnia and not found useful | 1 | ||

| Sleeping better | 1 | ||

| Randomised | 321 | 321 | 642 |

| Withdrew from trial between baseline and 3-month follow-up | 22 (6.9) | 6 (1.9) | 28 (4.4) |

| Moved location | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Due to being in control group/did not find SH useful | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.5) |

| Personal reasons | 9 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.4) |

| No reason given | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Did not find SRT useful or challenging to implement | 8 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.2) |

| Died | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Scheduling difficulties for SRT appointments | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Medical circumstances changed | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Sleeping better | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| 3-month follow-up | 299 | 315 | 614 |

| Completed | 253 (84.6) | 287 (91.1) | 540 (87.9) |

| Did not complete | 46 (15.4) | 28 (8.9) | 74 (12.1) |

| Withdrew from trial between 3- and 6-months follow-up | 18 (6.0) | 9 (2.9) | 27 (4.4) |

| Moved location | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Due to being in control group/did not find SH useful | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) |

| Personal reasons | 10 (3.3) | 3 (1.0) | 13 (2.1) |

| No reason given | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Did not find SRT useful or challenging to implement | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Did not like monitoring sleep | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) |

| Died | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Medical circumstances changed | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Sleeping better | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| 6-month follow-up | 281 | 306 | 587 |

| Completed | 257 (91.5) | 291 (95.1) | 548 (93.4) |

| Did not complete | 24 (8.5) | 15 (4.9) | 39 (6.6) |

| Withdrew from trial between 6- and 12-months follow-up | 19 (6.8) | 11 (3.6) | 30 (5.1) |

| Due to being in control group/did not find SH useful | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Personal reasons | 14 (5.0) | 5 (1.6) | 19 (3.2) |

| No reason given | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) |

| Did not find SRT useful or challenging to implement | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Died | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Medical circumstances changed | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) |

| Sleeping better | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| 12-month follow-up | 262 | 295 | 557 |

| Completed | 234 (89.3) | 276 (93.6) | 510 (91.6) |

| Did not complete | 28 (10.7) | 19 (6.4) | 47 (8.4) |

Table 10 summarises the availability of data for the primary and secondary outcomes at each time point by randomised group and overall. Eighty-five per cent of participants provided data on the primary outcome (ISI) at 6 months post randomisation. Of note, data completion for sleep diaries and actigraphy at 6 and 12 months was low (≤ 41%), chiefly due to the pandemic, which precluded sending out watches and diaries. Data on absenteeism, presenteeism and work productivity loss (from the WPAI) were only available for those in employment.

| SRT | SH | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 321) | (N = 321) | (N = 642) | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| Self-rated insomnia severity, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 252 (78.5) | 283 (88.2) | 535 (83.3) |

| 6 monthsa | 257 (80.1) | 291 (90.7) | 548 (85.4) |

| 12 months | 233 (72.6) | 275 (85.7) | 508 (79.1) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| SF-36 PCS, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 244 (76.0) | 285 (88.8) | 529 (82.4) |

| 6 months | 233 (72.6) | 280 (87.2) | 513 (79.9) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 265 (82.6) | 489 (76.2) |

| SF-36 MCS, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 244 (76.0) | 285 (88.8) | 529 (82.4) |

| 6 months | 233 (72.6) | 280 (87.2) | 513 (79.9) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 265 (82.6) | 489 (76.2) |

| Diary-SOL, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 111 (34.6) | 148 (46.1) | 259 (40.3) |

| 12 months | 92 (28.7) | 124 (38.6) | 216 (33.6) |

| Diary-WASO, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 107 (33.3) | 146 (45.5) | 253 (39.4) |

| 12 months | 88 (27.4) | 122 (38.0) | 210 (32.7) |

| Diary-SE, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 114 (35.5) | 150 (46.7) | 264 (41.1) |

| 12 months | 95 (29.6) | 125 (38.9) | 220 (34.3) |

| Diary-TST, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 114 (35.5) | 150 (46.7) | 264 (41.1) |

| 12 months | 95 (29.6) | 126 (39.3) | 221 (34.4) |

| Diary-SQ, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 114 (35.5) | 149 (46.4) | 263 (41.0) |

| 12 months | 95 (29.6) | 125 (38.9) | 220 (34.3) |

| Actigraphy-SOL, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 97 (30.2) | 123 (38.3) | 220 (34.3) |

| 12 months | 91 (28.3) | 117 (36.4) | 208 (32.4) |

| Actigraphy-WASO, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 97 (30.2) | 123 (38.3) | 220 (34.3) |

| 12 months | 91 (28.3) | 117 (36.4) | 208 (32.4) |

| Actigraphy-SE, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 95 (29.6) | 122 (38.0) | 217 (33.8) |

| 12 months | 91 (28.3) | 117 (36.4) | 208 (32.4) |

| Actigraphy-TST, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 97 (30.2) | 123 (38.3) | 220 (34.3) |

| 12 months | 91 (28.3) | 117 (36.4) | 208 (32.4) |

| GSII rank 1, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 246 (76.6) | 282 (87.9) | 528 (82.2) |

| 6 months | 234 (72.9) | 278 (86.6) | 512 (79.8) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 266 (82.9) | 490 (76.3) |

| GSII rank 2, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 246 (76.6) | 283 (88.2) | 529 (82.4) |

| 6 months | 234 (72.9) | 279 (86.9) | 513 (79.9) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 266 (82.9) | 490 (76.3) |

| GSII rank 3, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 246 (76.6) | 283 (88.2) | 529 (82.4) |

| 6 months | 232 (72.3) | 279 (86.9) | 511 (79.6) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 266 (82.9) | 490 (76.3) |

| PHQ-9, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 244 (76.0) | 284 (88.5) | 528 (82.2) |

| 6 months | 234 (72.9) | 278 (86.6) | 512 (79.8) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 264 (82.2) | 488 (76.0) |

| Absenteeism, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 111 (34.6) | 117 (36.4) | 228 (35.5) |

| 6 months | 101 (31.5) | 113 (35.2) | 214 (33.3) |

| 12 months | 100 (31.2) | 111 (34.6) | 211 (32.9) |

| Presenteeism, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 111 (34.6) | 113 (35.2) | 224 (34.9) |

| 6 months | 99 (30.8) | 111 (34.6) | 210 (32.7) |

| 12 months | 98 (30.5) | 107 (33.3) | 205 (31.9) |

| Work productivity loss, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 111 (34.6) | 113 (35.2) | 224 (34.9) |

| 6 months | 99 (30.8) | 111 (34.6) | 210 (32.7) |

| 12 months | 98 (30.5) | 107 (33.3) | 205 (31.9) |

| Activity impairment, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 247 (76.9) | 285 (88.8) | 532 (82.9) |

| 6 months | 234 (72.9) | 280 (87.2) | 514 (80.1) |

| 12 months | 222 (69.2) | 267 (83.2) | 489 (76.2) |

| Proportion of days usage of prescribed hypnotic sleep-promoting medication, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 112 (34.9) | 146 (45.5) | 258 (40.2) |

| 12 months | 93 (29.0) | 116 (36.1) | 209 (32.6) |

| Proportion of days usage of prescribed other sleep-promoting medication, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 112 (34.9) | 146 (45.5) | 258 (40.2) |

| 12 months | 93 (29.0) | 116 (36.1) | 209 (32.6) |

| Pre-sleep cognitive arousal, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 246 (76.6) | 284 (88.5) | 530 (82.6) |

| 6 months | 235 (73.2) | 279 (86.9) | 514 (80.1) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 266 (82.9) | 490 (76.3) |

| Pre-sleep somatic arousal, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 246 (76.6) | 283 (88.2) | 529 (82.4) |

| 6 months | 234 (72.9) | 280 (87.2) | 514 (80.1) |

| 12 months | 223 (69.5) | 267 (83.2) | 490 (76.3) |

| GSES, n(%) | |||

| 3 months | 246 (76.6) | 282 (87.9) | 528 (82.2) |

| 6 months | 235 (73.2) | 279 (86.9) | 514 (80.1) |

| 12 months | 223 (69.5) | 266 (82.9) | 489 (76.2) |

| Prescribed hypnotic sleep-promoting medication use over 7 days, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 112 (34.9) | 146 (45.5) | 258 (40.2) |

| 12 months | 93 (29.0) | 116 (36.1) | 209 (32.6) |

| Prescribed other sleep-promoting medication use over 7 days, n (%) | |||

| 6 months | 112 (34.9) | 146 (45.5) | 258 (40.2) |

| 12 months | 93 (29.0) | 116 (36.1) | 209 (32.6) |

| Work-related accident resulting in injury, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 245 (76.3) | 285 (88.8) | 530 (82.6) |

| 6 months | 235 (73.2) | 279 (86.9) | 514 (80.1) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 267 (83.2) | 491 (76.5) |

| Motor-vehicle accident, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 245 (76.3) | 285 (88.8) | 530 (82.6) |

| 6 months | 235 (73.2) | 280 (87.2) | 515 (80.2) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 267 (83.2) | 491 (76.5) |

| Near-miss driving incident, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 245 (76.3) | 285 (88.8) | 530 (82.6) |

| 6 months | 235 (73.2) | 280 (87.2) | 515 (80.2) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 267 (83.2) | 491 (76.5) |

| Number of times fallen asleep while driving, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 244 (76.0) | 284 (88.5) | 528 (82.2) |

| 6 months | 234 (72.9) | 280 (87.2) | 514 (80.1) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 266 (82.9) | 490 (76.3) |

| Number of falls, n (%) | |||

| 3 months | 245 (76.3) | 285 (88.8) | 530 (82.6) |

| 6 months | 235 (73.2) | 280 (87.2) | 515 (80.2) |

| 12 months | 224 (69.8) | 267 (83.2) | 491 (76.5) |

Table 11 shows that randomised group was associated with missingness of the primary outcome, with the SRT more likely to have missing data at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

| SRT | SH | Odds ratio (95% CI)a |

p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 321) | (N = 321) | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| 3-month follow-up, n (%) | 2.04 (1.33 to 3.14) | 0.001 | ||

| Available | 252 (78.5) | 283 (88.2) | ||

| Missing | 69 (21.5) | 38 (11.8) | ||

| 6-month follow-up,c n (%) | 2.42 (1.52 to 3.85) | < 0.001 | ||

| Available | 257 (80.1) | 291 (90.7) | ||

| Missing | 64 (19.9) | 30 (9.3) | ||

| 12-month follow-up, n (%) | 2.26 (1.52 to 3.36) | < 0.001 | ||

| Available | 233 (72.6) | 275 (85.7) | ||

| Missing | 88 (27.4) | 46 (14.3) | ||

Outcomes and estimation

Primary outcome

The primary objective of the HABIT trial was to compare the effect of SRT versus SH on insomnia severity (assessed by the ISI) at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. The primary end point was the 6-month time point.

Table 12 summarises the adjusted treatment effect at each time point from the linear mixed-effect model (Figure 2). At 6 months post randomisation, the estimated adjusted mean difference on the ISI was −3.05 (95% CI −3.83 to −2.28; p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.74), indicating that participants in the SRT arm reported lower insomnia severity compared to the SH group. Treatment effects were also evident at 3 and 12 months. Mean differences between arms were reflected in the number of participants showing a treatment response (ISI change score reduction ≥ 8 points) and scoring in the non-clinical range (ISI absolute score < 11). At 6 months, 42% (108/257) of the SRT group met criteria for a clinically significant treatment response, while only 17% (49/291) of the SH arm did. Fifty per cent (128/257) of the SRT arm were in the non-clinical range at 6 months compared with 28% (80/291) in the SH arm.

| SRT (N = 321) |

SH (N = 321) |

Adjusted treatment difference (95% CI)a |

p-valueb | Cohen’s dc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis | |||||

| Self-rated insomnia severity, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 10.9 (5.47) (252) | 14.8 (5.11) (283) | −3.88 (−4.66 to −3.10) | < 0.001 | −0.95 |

| 6 monthse | 10.9 (5.51) (257) | 13.9 (5.23) (291) | −3.05 (−3.83 to −2.28) | < 0.001 | −0.74 |

| 12 months | 10.4 (5.89) (233) | 13.5 (5.52) (275) | −2.96 (−3.75 to −2.16) | < 0.001 | −0.72 |

FIGURE 2.

Changes in the primary outcome, insomnia severity, across groups and time points. Raw means (±SD) are presented for both groups at each time point.

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess missingness of the primary outcome (ISI). Table 13 shows the results for the primary outcome when (1) adjusting for characteristics associated with non-completion of the ISI at 6 months and (2) performing multiple imputation. Both models yielded similar estimates as the primary analysis, demonstrating superiority of SRT over SH. A pattern mixture model was also conducted where missing ISI outcome values were imputed by up to five points either side of the observed average, both overall and in the SRT and SH arms separately. Even under these conservative assumptions the treatment effect and 95% CI would still not include 0 (see Appendix 2, Figure 21). Analyses assuming informative missingness of insomnia severity scores at 6 months [i.e. data missing not at random (MNAR)] indicated that even with asymmetrical differences between responders and non-responders conclusions are similar to the primary analysis (Appendix 2, Table 34).

| SRT | SH | Adjusted treatment difference (95% CI)a | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 321) | (N = 321) | |||

| Self-rated insomnia severity, mean (SD) (N) | ||||

| Adjusting for characteristics associated with non-completion of ISI | ||||

| 3 months | 10.9 (5.47) (252) | 14.8 (5.11) (283) | −3.64 (−4.42 to −2.85) | < 0.001 |

| 6 monthsc | 10.9 (5.51) (257) | 13.9 (5.23) (291) | −2.83 (−3.61 to −2.05) | < 0.001 |

| 12 months | 10.4 (5.89) (233) | 13.5 (5.52) (275) | −2.71 (−3.50 to −1.91) | < 0.001 |

| Multiple imputation | ||||

| 3 months | 11.4 (5.86) (321) | 15.0 (5.25) (321) | −3.86 (−4.63 to −3.08) | < 0.001 |

| 6 monthsc | 11.3 (5.88) (321) | 14.1 (5.40) (321) | −3.03 (−3.78 to −2.29) | < 0.001 |

| 12 months | 11.1 (6.86) (321) | 13.7 (5.75) (321) | −2.84 (−3.66 to −2.01) | < 0.001 |

Secondary outcomes

Adjusted treatment effects are presented for secondary outcomes in Tables 14 and 15.

| SRT (N = 321) |

SH (N = 321)) |

Adjusted treatment difference (95% CI)a | p-valueb | Cohen’s dc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| SF-36 PCS, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 48.4 (10.78) (244) | 46.1 (10.80) (285) | 1.87 (0.76 to 2.98) | 0.001 | 0.18 |

| 6 months | 48.1 (10.90) (233) | 47.2 (10.28) (280) | 0.77 (−0.35 to 1.89) | 0.179 | 0.07 |

| 12 months | 48.6 (10.26) (224) | 47.4 (10.47) (265) | 0.94 (−0.20 to 2.09) | 0.105 | 0.09 |

| SF-36 MCS, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 44.6 (11.27) (244) | 41.2 (11.79) (285) | 2.80 (1.37 to 4.23) | < 0.001 | 0.24 |

| 6 months | 44.7 (11.88) (233) | 42.2 (11.79) (280) | 1.97 (0.52 to 3.43) | 0.008 | 0.17 |

| 12 months | 44.7 (11.29) (224) | 42.3 (11.29) (265) | 2.01 (0.53 to 3.49) | 0.008 | 0.17 |

| GSII rank 1, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 48.2 (28.39) (246) | 35.4 (21.63) (282) | 12.82 (8.71 to 16.93) | < 0.001 | 0.72 |

| 6 months | 50.6 (28.00) (234) | 37.7 (23.42) (278) | 12.80 (8.63 to 16.96) | < 0.001 | 0.72 |

| 12 months | 52.1 (29.42) (224) | 40.3 (24.79) (266) | 11.77 (7.54 to 16.00) | < 0.001 | 0.66 |

| GSII rank 2, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 51.5 (26.78) (246) | 38.6 (22.23) (283) | 12.78 (8.79 to 16.77) | < 0.001 | 0.66 |

| 6 months | 53.2 (27.74) (234) | 40.7 (23.66) (279) | 12.45 (8.40 to 16.49) | < 0.001 | 0.65 |

| 12 months | 54.9 (28.63) (224) | 41.5 (24.55) (266) | 13.72 (9.60 to 17.84) | < 0.001 | 0.71 |

| GSII rank 3, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 51.6 (27.01) (246) | 41.1 (23.14) (283) | 10.06 (6.02 to 14.10) | < 0.001 | 0.46 |

| 6 months | 54.2 (27.11) (232) | 43.0 (23.90) (279) | 10.93 (6.82 to 15.03) | < 0.001 | 0.50 |

| 12 months | 57.1 (28.97) (224) | 45.1 (24.11) (266) | 11.70 (7.53 to 15.87) | < 0.001 | 0.54 |

| PHQ-9, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 7.2 (5.72) (244) | 9.1 (5.62) (284) | −1.86 (−2.56 to −1.16) | < 0.001 | −0.35 |

| 6 months | 7.2 (5.77) (234) | 8.8 (5.75) (278) | −1.60 (−2.31 to −0.90) | < 0.001 | −0.30 |

| 12 months | 7.0 (5.82) (224) | 8.6 (5.51) (264) | −1.61 (−2.32 to −0.89) | < 0.001 | −0.30 |

| Absenteeism, median (IQR) (n)e | |||||

| 3 months | 0.0 (0.0−0.0) (111) | 0.0 (0.0−0.0) (117) | − | 0.095 | − |

| 6 months | 0.0 (0.0−0.0) (101) | 0.0 (0.0−0.0) (113) | − | 0.014 | − |

| 12 months | 0.0 (0.0−0.0) (100) | 0.0 (0.0−0.0) (111) | − | 0.005 | − |

| Proportion of participants who missed work because of insomnia (absenteeism > 0), n/N (%) | |||||

| 3 months | 14/111 (12.6) | 23/117 (19.7) | − | − | − |

| 6 months | 7/101 (6.9) | 21/113 (18.6) | − | − | − |

| 12 months | 5/100 (5.0%) | 20/111 (18.0) | − | − | − |

| Presenteeism, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 29.6 (23.66) (111) | 41.4 (21.91) (113) | −10.56 (−16.25 to −4.87) | < 0.001 | −0.48 |

| 6 months | 24.6 (22.01) (99) | 34.5 (23.38) (111) | −10.69 (−16.56 to −4.81) | < 0.001 | −0.48 |

| 12 months | 22.4 (22.62) (98) | 33.8 (24.37) (107) | −11.76 (−17.73 to −5.79) | < 0.001 | −0.53 |

| Work productivity loss, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 30.6 (24.71) (111) | 42.7 (22.93) (113) | −10.90 (−16.80 to −5.01) | < 0.001 | −0.47 |

| 6 months | 25.0 (22.39) (99) | 35.9 (24.71) (111) | −11.96 (−18.04 to −5.87) | < 0.001 | −0.52 |

| 12 months | 22.7 (22.98) (98) | 35.1 (25.34) (107) | −12.96 (−19.14 to −6.77) | < 0.001 | −0.56 |

| Activity impairment, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 33.5 (25.07) (247) | 46.7 (23.37) (285) | −13.23 (−16.79 to −9.68) | < 0.001 | −0.56 |

| 6 months | 31.0 (25.05) (234) | 42.9 (24.03) (280) | −11.99 (−15.60 to −8.38) | < 0.001 | −0.51 |

| 12 months | 31.0 (26.44) (222) | 40.1 (24.42) (267) | −9.11 (−12.80 to −5.43) | < 0.001 | −0.39 |

| Pre-sleep cognitive arousal, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 19.6 (6.88) (246) | 23.0 (6.77) (284) | −3.30 (−4.24 to −2.35) | < 0.001 | −0.50 |

| 6 months | 19.6 (7.14) (235) | 22.1 (6.91) (279) | −2.36 (−3.32 to −1.41) | < 0.001 | −0.36 |

| 12 months | 19.2 (7.04) (224) | 22.2 (6.83) (266) | −2.99 (−3.96 to −2.02) | < 0.001 | −0.45 |

| Pre-sleep somatic arousal, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 12.0 (5.41) (246) | 13.6 (5.64) (283) | −1.30 (−1.99 to −0.60) | < 0.001 | −0.21 |

| 6 months | 12.2 (5.38) (234) | 13.3 (5.39) (280) | −1.24 (−1.94 to −0.54) | 0.001 | −0.20 |

| 12 months | 12.1 (5.27) (223) | 13.4 (5.80) (267) | −1.27 (−1.99 to −0.56) | < 0.001 | −0.20 |

| GSES, mean (SD) (n)d | |||||

| 3 months | 5.6 (3.25) (246) | 7.0 (3.11) (282) | −1.49 (−1.93 to −1.05) | < 0.001 | −0.51 |

| 6 months | 5.4 (3.15) (235) | 6.7 (3.12) (279) | −1.27 (−1.71 to −0.83) | < 0.001 | −0.44 |

| 12 months | 4.9 (3.08) (223) | 6.6 (3.23) (266) | −1.64 (−2.09 to −1.20) | < 0.001 | −0.57 |

| SRT (N = 321) |

SH (N = 321) |

Adjusted treatment difference (95% CI)a | p-valueb | Cohen’s dc | |

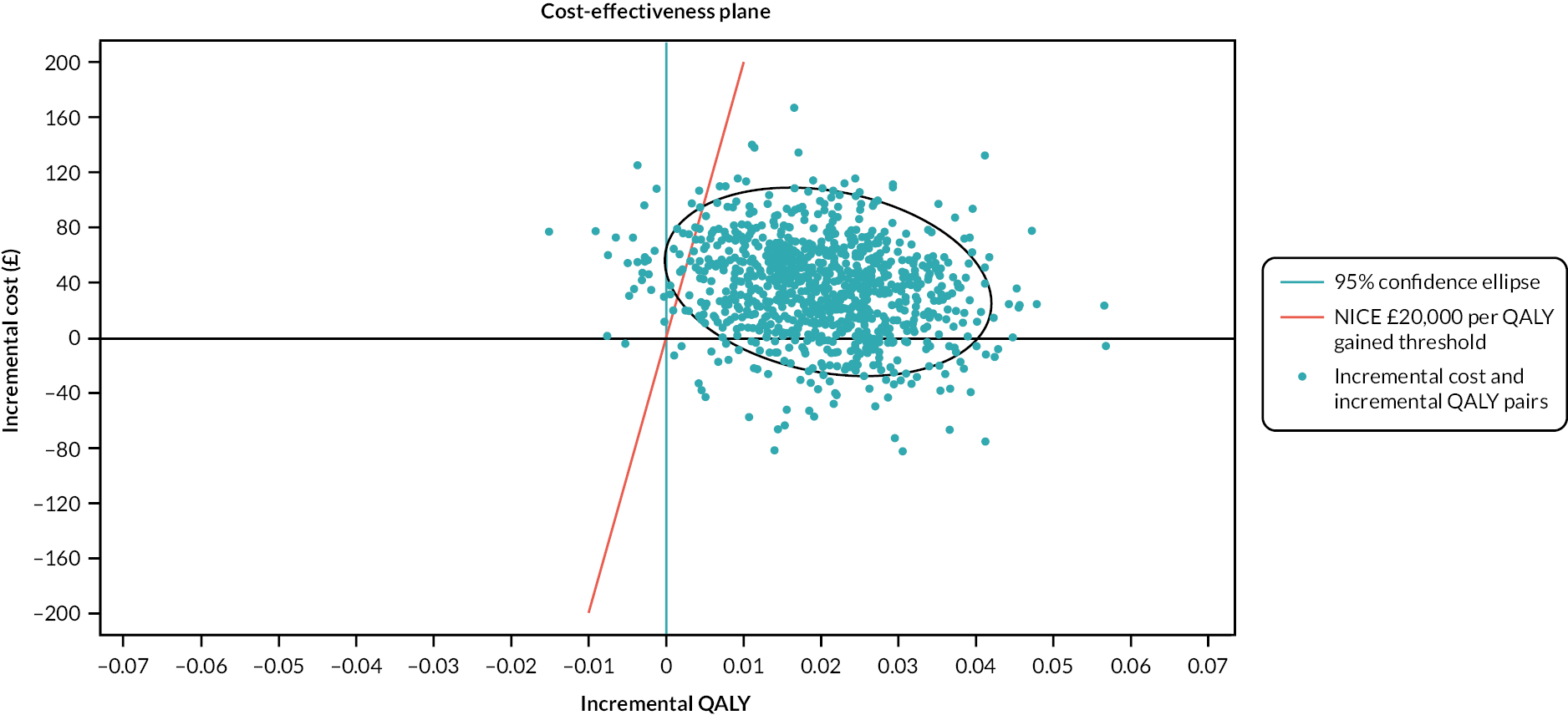

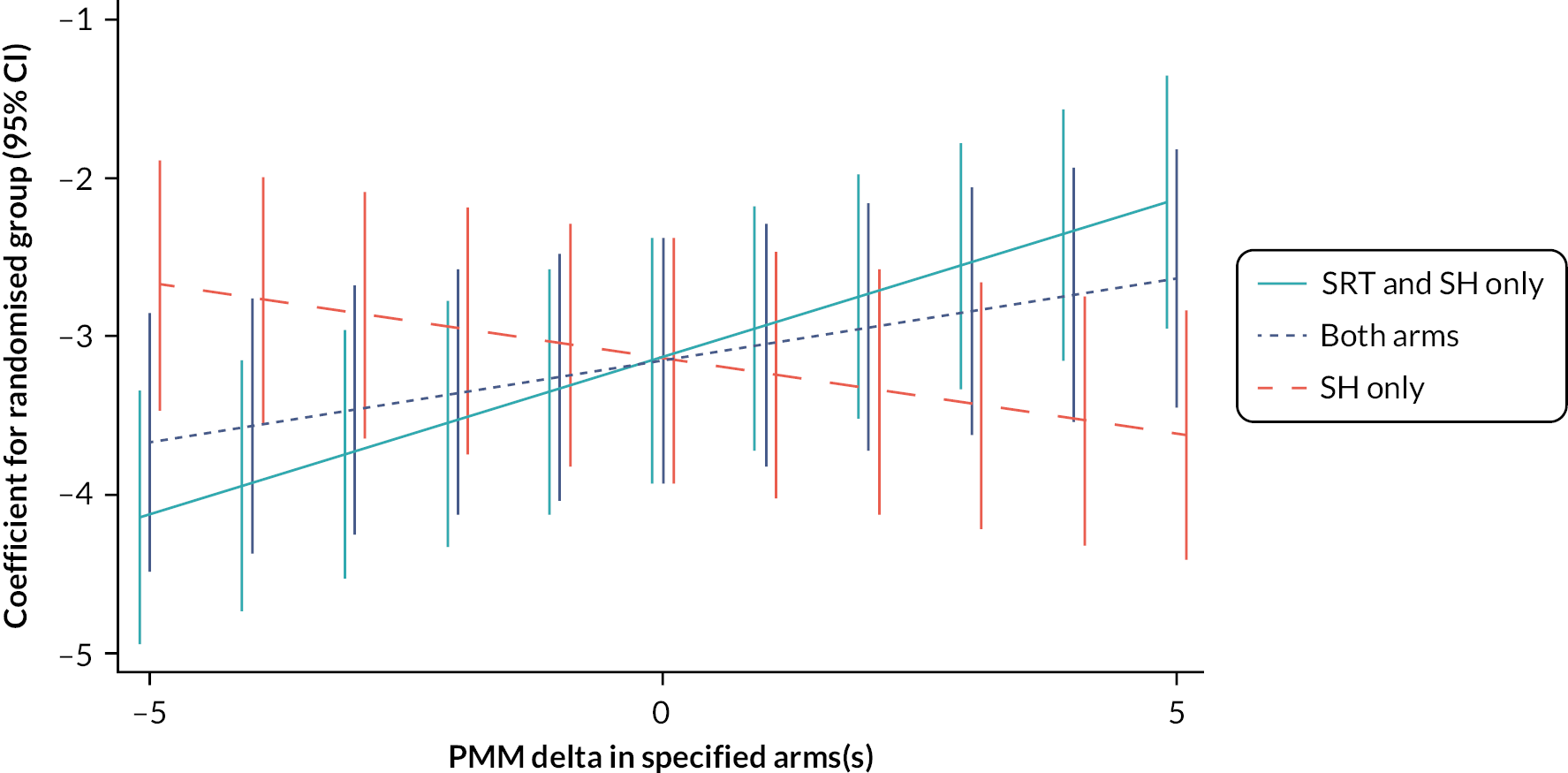

|---|---|---|---|---|---|