Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/106/01. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The draft report began editorial review in November 2020 and was accepted for publication in September 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Constable et al. This work was produced by Constable et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Constable et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Constable et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Male synthetic sling versus Artificial urinary Sphincter Trial: Evaluation by Randomised controlled trial

In 2013, the UK Government’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Health Technology Assessment programme funded MASTER (the Male synthetic sling versus Artificial urinary Sphincter Trial: Evaluation by Randomised controlled trial); this report describes the research.

MASTER was a multicentre, non-inferiority randomised controlled trial (RCT), with a non-randomised cohort (NRC) that investigated the clinical effectiveness (including safety) and cost-effectiveness of male synthetic sling surgery compared with that of the established artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) surgery in men with urodynamic stress incontinence (USI) after prostate surgery (for cancer or benign disease). MASTER also included an embedded qualitative component to explore the participant-perceived importance of outcomes, as well as exploration of participant and surgeon perspectives.

Background

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is common in men after prostate surgery [radical prostatectomy for cancer or transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) for benign disease] and can be difficult to improve. Urinary incontinence (UI) has a major impact on quality of life resulting from a profound loss of self-esteem and restrictions on work, social interaction and personal relationships, including sex life.

In two parallel RCTs,2,3 75% of men who were incontinent 6 weeks after prostate surgery still had some leakage 12 months after surgery, despite receiving physiotherapy. Pelvic floor muscle treatment and drug treatments can be suboptimal, with some men continuing to cope only with the aid of containment products. Other treatments, such as injectables and inflatable balloons, have been reviewed, but there is insufficient evidence to support their use. 1,4

For some men, surgery for persistent bothersome SUI remains the only option for active management. AUS is the recommended surgical procedure for men still affected by troublesome SUI > 12 months after prostate surgery. 5,6 Despite this, a large proportion of men (around 8% after radical prostatectomy and 2% after TURP) continue to have severe disabling incontinence following AUS implantation, which greatly impacts their quality of life, and many of these men (27% and 6%, respectively) remain reliant on containment measures, such as pads [unpublished data from 4–6-years’ follow-up of Men After Prostate Surgery (MAPS) trial responders (Charis Glazener, University of Aberdeen, 2019, personal communication)].

More recently, the male synthetic sling (male sling), which treats SUI by elevating the urethra, has been developed. In the last decade, a variety of slings have been offered to a minority of men seeking surgical treatment for post prostatectomy incontinence (PPI) from the NHS, dependent on surgeon enthusiasm and local arrangements. Male slings, of many varieties, have been reported in case series over the last 10 years and have been increasingly used for the treatment of PPI; however, thorough evaluation and high-quality RCT evidence are lacking. 5–7 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance5 also states that the male sling should be used only as part of a well-developed RCT.

Additional background information is given in the previously published protocol. 1

Scale of the problem

The number of men undergoing radical prostatectomy for localised prostate cancer is increasing [it increased from 5600 in 2011 (when MASTER was being developed), to 7704 in 2017 and 9413 in 2018]. 8,9 This trend is likely to continue as the population ages and as localised prostate cancer case finding using prostate-specific antigen testing increases, potentially leading to more men subsequently requiring surgery for prostate cancer treatment-related UI. As an indication, if 50 more people required an AUS each year, this would cost the NHS an additional £450,000 per annum.

Benign enlarged prostate occurs in around 30% (1.8 million) of men in the UK aged > 60 years and is a major cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs), with around 25,000 TURP procedures carried out annually in England alone. 4,10

The prevalence of SUI in men after radical prostatectomy is unclear, but is estimated to be between 5% and 57%, depending on definition, timing of assessment after surgery and population characteristics. The prevalence of SUI in men after TURP is clearer, and ranges from 0% to 8%. 6

The rate of recovery of continence plateaus at around 12 months after surgery. The MAPS trial found that 40% of men with incontinence 6 weeks after radical prostatectomy continued to have persistent incontinence at 12 months, and this incontinence was severe in 20% of men (requiring the use of pads or other containment measure). Levels of continence did not improve in the next 12 months, up to 24 months after surgery. 2,3

Rationale for MASTER

An AUS is invasive, and voiding involves manual manipulation of a pump located in the scrotum, which requires a sufficient degree of manual dexterity. In addition, the device is relatively expensive, its implantation requires specialist surgical skill and, in time, revision surgery may be necessary. For all these reasons, other surgical methods have been tested, but a Cochrane review in 20144 found no adequately powered RCTs to guide practice, and there have been no new RCTs since. 5,11

Although treatment with the male sling is thought to be less invasive, is more acceptable to some men and appears to be less expensive, harms, further treatment, revision surgery and longer-term effects need to be considered to determine full comparative effectiveness.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published high-quality RCTs comparing the male sling with the AUS. A Cochrane systematic review4 concluded that there was not enough evidence to guide practice for men or surgeons considering surgery for USI after prostate surgery. The authors of the review found only one small, poor-quality RCT that compared implantation of an AUS and treatment with injectable bulking agent. 11 In this RCT, the men treated with AUS were more likely to be cured (18/20, 82%) than those who had the injectable treatment (11/23, 46%) [odds ratio (OR) 5.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.28 to 25.10]. The review highlighted the need for adequately powered comparative RCTs to guide practice. 4

Current NICE guidance (CG97), last updated in 2015 (accessed August 2019), remains unchanged, recommending AUS for persistent SUI with further guidance and evaluation needed on male slings. 5 Current NHS guidance also states that the male synthetic sling should be used only in RCTs against the AUS. AUS continues to be the preferred intervention, but there is increasing opinion that the male sling is an acceptable alternative for men with mild to moderate PPI. 6,7

Both clinicians and patients lack the evidence required to make an informed choice between the AUS and the male sling, and NHS policy-makers lack information on cost-effectiveness to plan service provision. Owing to these uncertainties, MASTER was developed to compare the male sling with the AUS in men who have SUI after prostate surgery (for cancer or benign disease).

MASTER will provide the required robust evidence to allow informed treatment and health-care provision decisions for patients, clinicians and health-care policy-makers, in terms of the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and adverse events associated with the male sling and AUS.

Surgical procedures

When MASTER was designed, and to date, the design and function of the AUS appeared suitable, and, despite attempts to improve on the existing device, there are still no signs of significant innovations that would have needed to be considered prior to or during this trial. However, sling technology was, and is, less mature; we anticipated that during the trial recruitment period there would be a greater choice of implants from different manufacturers. For that reason, we did not specify which brand of male sling should be used. However, at the time of trial design, almost all slings being implanted were passive, that is non-adjustable, in type. Although there seem to have been no significant developments in the passive slings used in MASTER, there are developments in adjustable slings, although the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines 202063 reiterate that there are no data to suggest an advantage of the adjustable over the simpler passive slings. There was some information on adjustable slings, but there was inadequate evidence of efficacy and some evidence that the adjustable slings required more frequent additional surgery and were associated with more complications than passive slings. Hence, we stipulated that the male slings should be of the non-adjustable, suburethral, transobturator type only.

Male sling

The male sling (i.e. the non-absorbable polypropylene mesh implant) is placed under the urethra to elevate it and is held in place by passing it through the obturator foramen of the pelvis bilaterally. It has a passive mode of action. The aim of the sling is to stop the loss of urine on exertion and the operation is effective immediately.

Artificial urinary sphincter

The AUS consists of an inflatable cuff that is placed around the urethra, a pressure-regulating balloon that keeps the cuff inflated and a pump that is placed in the scrotum, which the man squeezes to enable voiding. The aim is to close the urethra so that the patient is dry, except when he wants to void. Once implanted, the device is deactivated in the open position for 4–6 weeks to allow postoperative swelling to subside. The device is then activated in clinic to ensure that the man can use the device correctly.

Questions addressed by MASTER

The aim of this study was to determine whether or not the male sling is non-inferior to implantation of the AUS for men with SUI after prostate surgery (for cancer or benign disease), judged primarily on clinical effectiveness, but also considering the relative harms and cost-effectiveness. To determine whether the male sling or AUS is cost-effective for the NHS in the UK, the interventions were compared in terms of continence in men after prostate surgery; the relative harms of the interventions; the costs to the patients and to the NHS, including the need for repeat surgery in both groups; and overall patient satisfaction.

Principal objectives

The primary objective was to compare (1) participant-reported continence 12 months after randomisation [a composite outcome derived from responses indicating any loss of urine to either of the two questions ‘How often do you leak urine?’ and ‘How much urine do you leak?’ from the validated International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF)] and (2) the corresponding cost-effectiveness of a policy of primary implantation of the male sling compared with AUS, measured as the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), 24 months after randomisation.

Secondary objectives

Secondary objectives compared (1) adverse events (AEs); (2) the costs of the benefits and harms; (3) the need for further treatments; (4) the differential effects on other outcomes, such as quality of life and general health; and (5) participant satisfaction with the male sling and the AUS surgeries up to 24 months after randomisation.

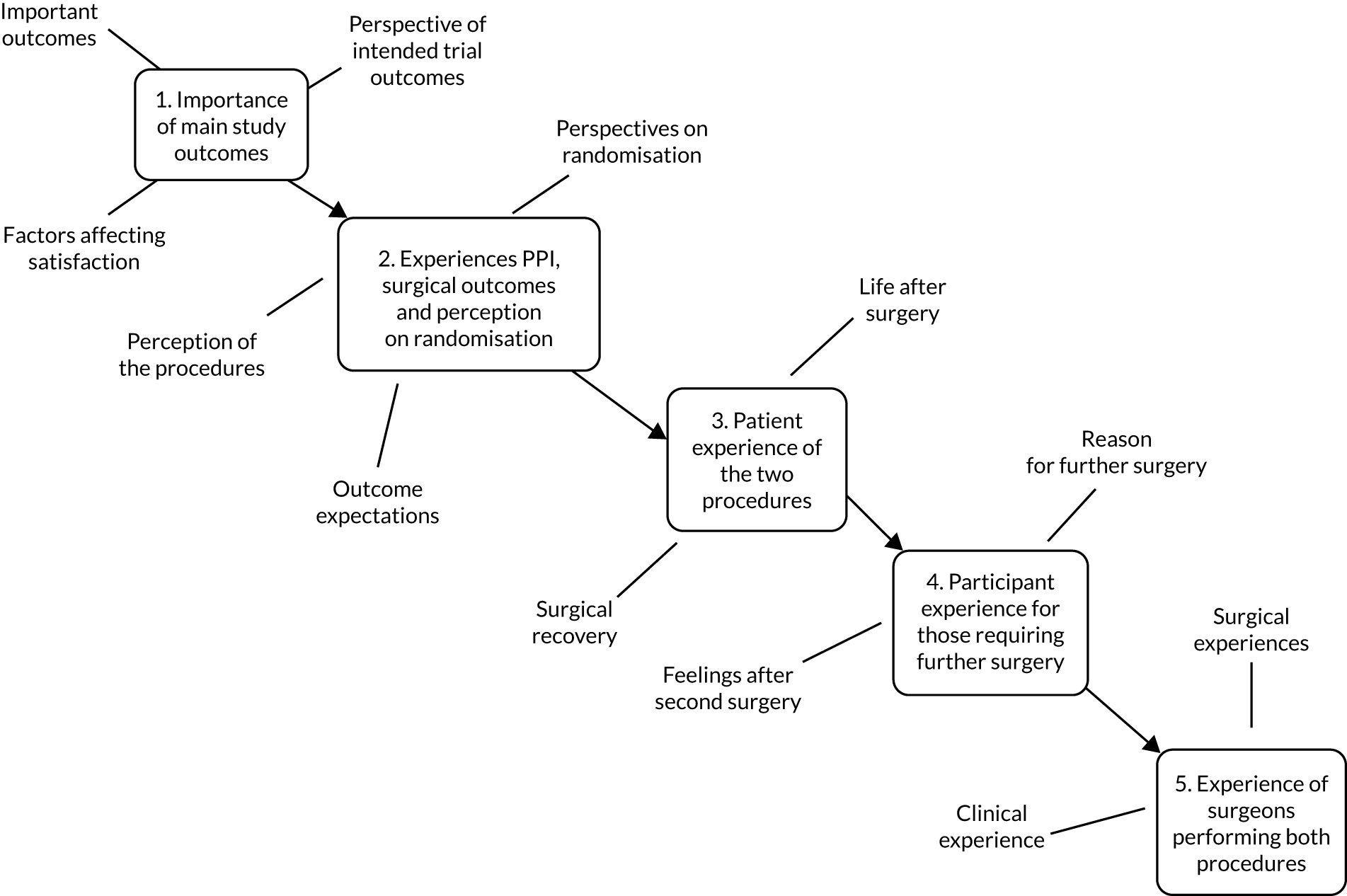

Qualitative component

MASTER included a comprehensive embedded qualitative component to establish the patient-perceived importance of outcomes and to explore participant and surgeon experiences of surgery and acceptable inferiority margins, and to determine reasons for failure that resulted in crossover to alternative surgery.

Chapter 2 Methods and practical arrangements

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Constable et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

MASTER was a multicentre, non-inferiority RCT that included a NRC and compared the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of male synthetic sling and AUS surgeries in men with PPI.

Participating centres were asked to consent and randomise (RCT) -or to consent (NRC) participants as close to surgery as was practical to minimise participant drop-out. This resulted in some delays from the date of consent to the date of randomisation/date of surgery. A significant health economic component was also included as part of MASTER to establish costs, cost-effectiveness and long-term modelling. The economic methods and evaluation are described in full in Chapter 5.

An embedded qualitative component was also included as part of MASTER to establish the importance of the main outcomes to patients, explore patient and surgeons’ experiences, and explore reasons for reoperation. The qualitative component methods and findings are discussed in full in Chapter 6.

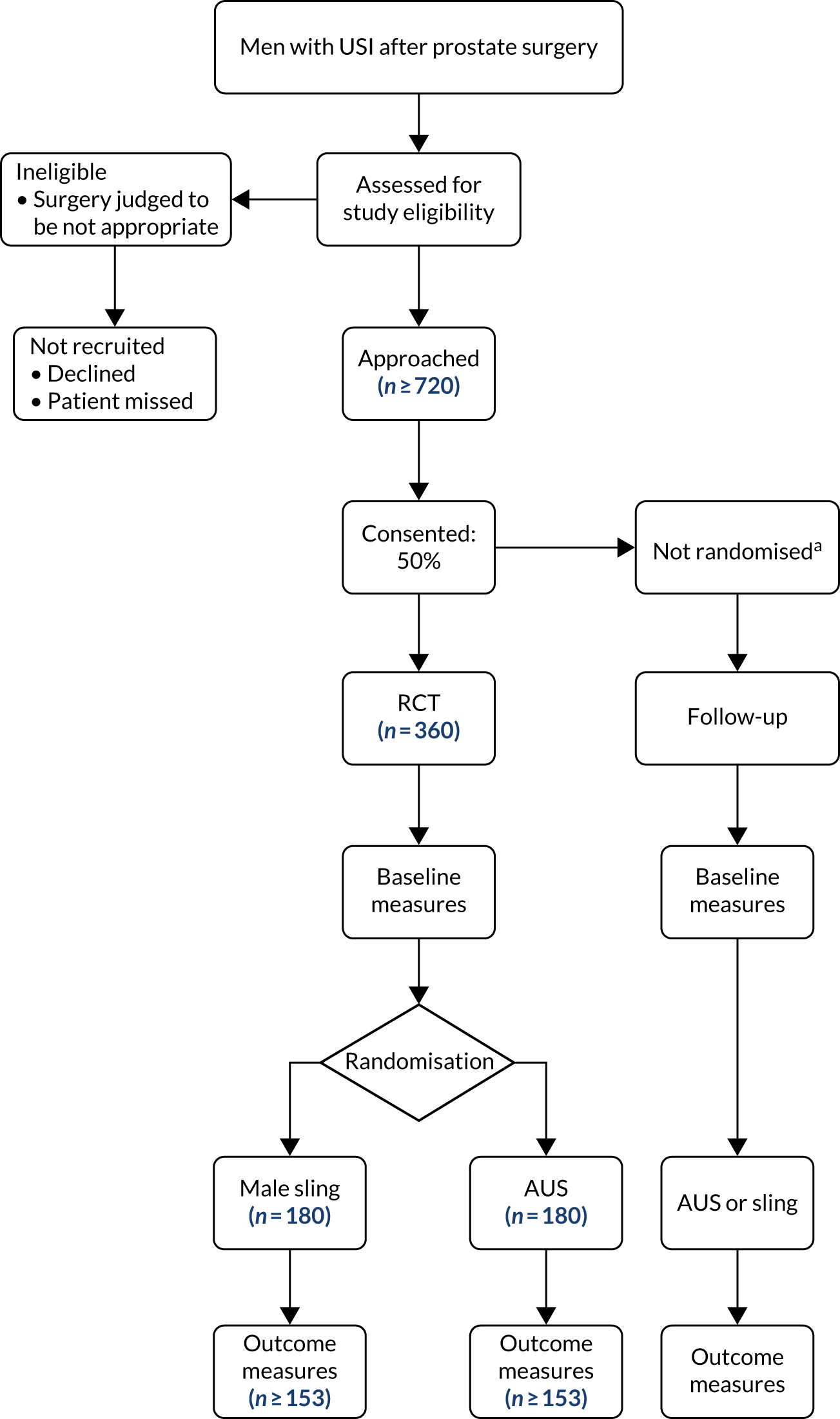

Further details of the study design, methodology and management [eligibility, consent, treatment allocation, sample size calculation and serious adverse event (SAE) reporting] described herein are also in the published protocol1 and are represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

MASTER flow diagram. a, Men in the NRC are followed up by questionnaire and electronic follow-up but not clinical review at 1 year. This figure is reproduced from Constable et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided appropriate credit is given to the original authors(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies, unless otherwise stated. The figure contains minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Study population

Men with USI after prostate surgery (radical prostatectomy or TURP) whose incontinence was considered to require surgery were eligible for MASTER.

Men were excluded if they had previously undergone sling or AUS surgery, had unresolved bladder neck contracture or urethral stricture after their prostate surgery, had insufficient manual dexterity to operate the AUS, or were unable to give informed consent or complete trial documentation. In addition, after the closure of the NRC, men who did not want to be randomised were excluded.

Treatment allocation

Eligible men consenting to the RCT were randomised to receive either male sling or AUS surgery in a 1 : 1 allocation ratio, using the randomisation application at the trial office at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT). The randomisation application was available as both an interactive voice-response telephone system and an internet-based application, using a minimisation algorithm based on type of previous prostate surgery (radical prostatectomy or TURP) and radiotherapy or not, in addition to the patients’ prostate surgery and centre.

Men eligible and consenting to the NRC chose, in discussion with their surgeon, to receive either male sling or AUS surgery.

Data collection during follow-up

Participant-reported outcomes were assessed using self-completed questionnaires at baseline (before surgery), 6 months after surgery, and 12 and 24 months after randomisation. This meant that no 6-month questionnaires were issued if a participant did not have surgery, but the 12- and 24-month questionnaires were issued to all. A self-completed 3-day bladder diary was also collected at these time points. Up to two reminders were sent to participants by post or telephone.

Men in the RCT were also reviewed in clinic 12 months after surgery, which included a 24-hour pad leakage test.

Study outcome measures

The clinical primary outcome of MASTER was participant self-report of continence following implantation of the male sling compared with AUS 12 months after randomisation.

The economic primary outcome was the cost-effectiveness of the male sling compared with that of AUS measured as the incremental cost per QALY 24 months after randomisation (methods described in Chapter 5).

The primary outcome measure was the man’s report of continence 12 months after randomisation, derived from the responses to questions 3 and 4 in the ICIQ-UI SF questionnaire. 12 The ICIQ-UI SF has been used in research and clinical practice across the world. It is a short and simple questionnaire that gives a comprehensive summary of the symptoms of incontinence and has been used to facilitate patient–clinician discussions.

Question 3 asked about the frequency of urinary leakage and question 4 asked about the volume of urinary leakage. Question 3 is scored from 0 to 5 (0 = never, 5 = all the time) and question 4 is scored 0, 2, 4 or 6 (0 = none, 6 = a large amount). To be classed as continent, men had to answer ‘never’ to question 3 and ‘none’ to question 4. A response to only one of the questions of either ‘never’ or ‘none’ was also taken to indicate continence. Men who provided any other pair of responses were classed as incontinent. The Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) recommended (on 17 October 2017) that we also report a less strict definition of absolute continence to include ‘once a week or less often’ and ‘a small amount’ as being compatible with being ‘adequately dry’ owing to a lower than anticipated success rate of both interventions.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were used to further assess continence and its impact on men’s quality of life. These were included as part of the postal participant questionnaires issued at baseline, 6 months after surgery, and 12 and 24 months after randomisation. The secondary outcomes were:

-

ICIQ-UI SF score. The ICIQ-UI SF score comprises the two questions from which the primary outcome was derived and a question on the overall impact of UI on everyday life. This question is scored from 0 to 10 (0 = not at all, 10 = a great deal) and the other two questions are scored from 0 to 5 and 0 to 6. The score was obtained by summing these three questions to give a score out of 21, where a higher score indicates more severe incontinence.

-

International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence – Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-UI MLUTS) voiding and incontinence scores. 13 The ICIQ-MLUTS module has 11 questions that are used to produce the scores, all of which are answered on a scale of 0 to 4 (0 = never, 4 = all of the time). The scores were obtained by summing the relevant questions. The voiding score is based on the answers to five questions and ranges from 0 to 20. The incontinence score is based on the answers to six questions and ranges from 0 to 24. In both cases, a higher score indicates a poorer outcome. The ICIQ-MLUTS has a comprehensive approach to assessing all LUTS. It was developed by patients for patients. It has been tested and proven reliable in numerous research and clinical settings, and is easy to understand and complete.

-

International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Male Sexual Matters Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-MLUTSsex) module. 14 The ICIQ-MLUTSsex uses four questions to evaluate male sexual matters associated with LUTS. All four questions are scored from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating no problem and 3 indicating the highest level of problem. The ICIQ-MLUTSsex is obtained by summing the responses to the four questions. It provides a robust measure of the impact of sexual matters.

-

Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12), version 2. 15 The SF-12 version 2 is a multipurpose short-form generic measure of health status. It measures eight health domains and provides physical component and mental component scores. The survey has 12 questions, with one or two questions for each health domain. The questions have between three and five possible responses. The total score for each component is obtained by summing the questions that relate to the component. Higher scores indicate better outcomes and, to achieve this, reverse scoring of questions 1, 8, 9 and 10 was implemented. The SF-12 version 2 is practical, reliable and valid and has been widely used in monitoring population health, comparing and analysing condition burden and predicting medical expenses.

-

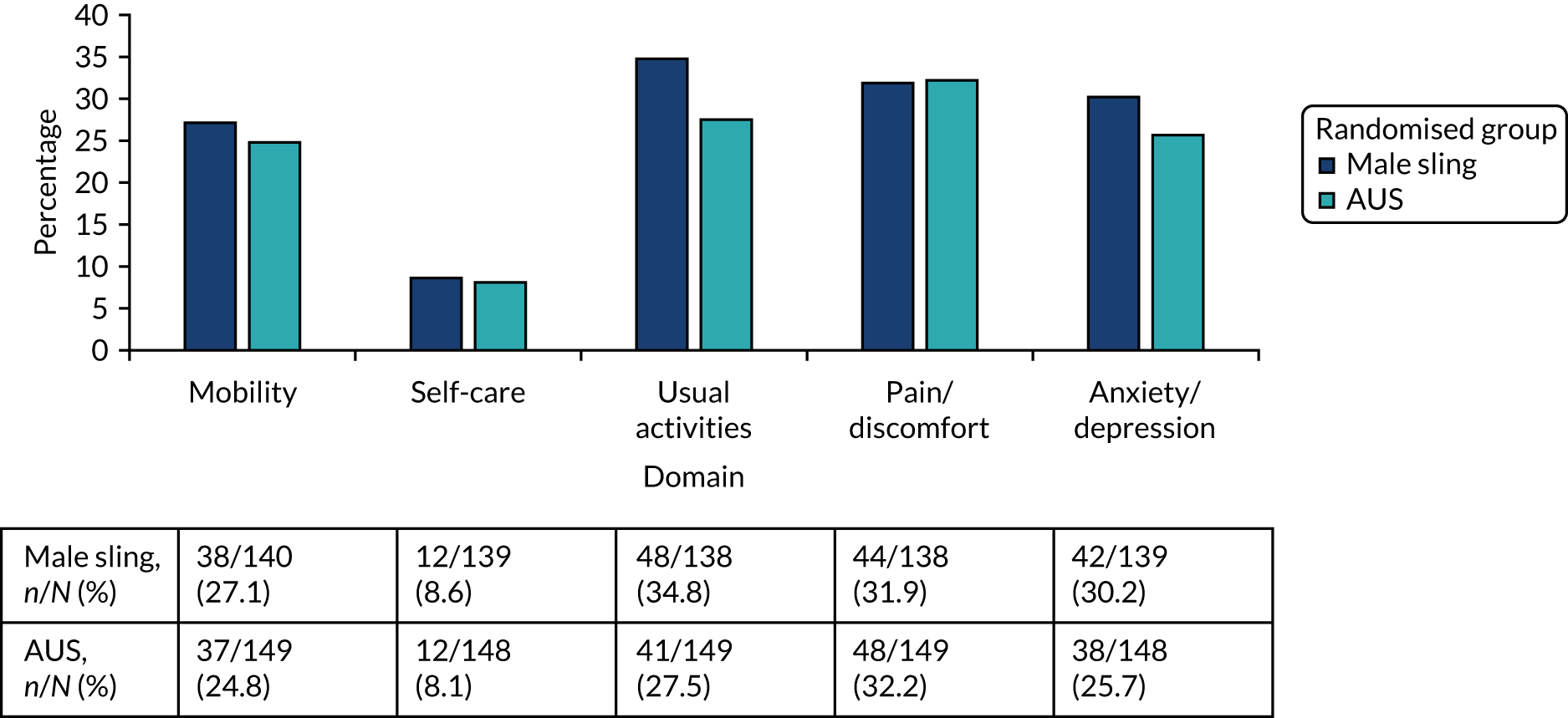

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L). 16 The EQ-5D-3L is a standardised generic instrument for use as a self-completed measurement of health. It provides a simple descriptive profile and a single value that can be used in the clinical and economic evaluation of health care, and population health surveys. It has five items on mobility, self-care, pain, usual activities and psychological status, with three possible answers for each item (1 = no problem, 2 = moderate problem and 3 = severe problem). The responses for each item/domain are converted to quality-of-life estimates using an algorithm to produce EQ-5D-3L index scores for each participant. The five scores are summed to produce a variable on the scale –0.594 to 1, where negative scores represent health states worse than death, 0 represents the state of worst health and 1 represents full health.

-

Continence at 6 and 24 months. This variable was formed in the same way as the primary outcome but uses the data at 6 and 24 months, respectively.

-

Pad weight at 12 months. Participants were asked to wear a pad for 24 hours, which was then weighed to determine the urine leakage (weight of urine leaked was determined by subtracting the weight of the dry pad from the pad weight after 24 hours). Where the participant told us that they were dry and did not need to wear pads, this was accepted and they were not required to do the pad test at 12 months.

-

Urine leakage at 12 months after randomisation compared with that before surgery. Participants were asked how their urine leakage compared with that before their MASTER surgery. Participants answered on the seven-point Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) scale: very much better, much better, a little better, no change, a little worse, much worse or very much worse.

-

Satisfaction with surgery results at 12 months. Participants were given five possible responses to choose from: completely satisfied, fairly satisfied, fairly dissatisfied, very dissatisfied or not sure.

-

Whether or not the participant would recommend the surgery at 12 months. Participants answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question of whether or not they would recommend their surgery to a friend.

-

Time until participant was able to return to work, assessed at 12 months. Participants were asked how many months it took until they were able to return to their normal daily activities.

-

Other secondary outcomes included surgical complications and AEs, operating time, length of hospital stay, number of re-admissions to hospital and time to receiving further surgery.

Choice of validated outcome measures

Outcome measures were chosen to reflect current international standards of reporting to ensure that findings would be relevant to patients, clinicians and policy-makers. Outcomes were measured at baseline to provide values for later statistical adjustments. The primary measure of continence was the man’s subjective report derived from two questions on the ICIQ-UI SF questionnaire, developed and validated in a variety of populations for both research and clinical practice.

Blinding

Baseline data were reported by men before randomisation using self-completed questionnaires. Blinding in theatre was not possible, and participants could not be blinded to surgery received owing to the nature of the devices. Outcome assessment was largely by participant-completed questionnaires. Outcome assessors for the 12-month clinic appointment were blinded to randomisation where possible and were asked to record if they knew which operation was received prior to undertaking the outcome assessment.

Important changes to the methods after trial commencement

Closure of the non-randomised cohort

Recruitment to the NRC closed in October 2015, after 100 participants had consented, because it was adversely affecting recruitment to the RCT. 1 Those men already consented to the NRC remained in the study and were followed up as per protocol.

Extension to recruitment

Slower than anticipated recruitment meant that a 9-month recruitment extension was required to achieve the full sample size.

Safety reporting

Adverse events were either notified to the study office by the local research team or reported by the men in their follow-up questionnaires. If a SAE was suspected, it was verified by the local research team, where possible. Unrelated AEs were not recorded. The published protocol1 provides more details on relatedness, potentially expected AEs and reporting.

Sample size

Evidence suggested that 20% of men would still be incontinent 12 months after receiving an AUS, whereas 35% of men would still be incontinent after receiving a male sling. 1 The sample size calculation was undertaken by simulation. Assuming that there was no difference between the arms of the trial, 310 participants would give 90% power to show that male slings were non-inferior to AUS by a margin of ≤ 15%. To allow for 15% loss to follow-up, the sample size was increased to 360.

Statistical analysis of outcomes

Predefined statistical analyses were included in the published protocol. 1 Statistical analyses were based on all randomised men, regardless of whether or not they complied with their randomised surgery. The comparisons were between those who were randomised to receive a male sling and those who were randomised to receive an AUS.

The primary outcome was analysed using a generalised linear model, clustering by centre and with adjustment for previous radiotherapy and the 24-hour pad test weight at baseline as fixed effects. Statistical significance was at 5%, with a corresponding CI, equivalent to a one-sided test for non-inferiority at 2.5%. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed with all of the participants remaining in their randomised group. ORs are presented for the primary outcome and the less strict definition to aid interpretation.

A subgroup analysis of the primary outcome on baseline urine leakage (≤ 250 g vs. > 250 g) was also performed. It was also planned to perform a subgroup analysis on previous prostate surgery (radical prostatectomy vs. TURP); however, given that 93% of randomised participants underwent radical prostatectomy, the groups were too unevenly balanced to make this worthwhile. It is also for this reason that the analysis does not adjust for type of prostate surgery. The subgroup analysis was at the stricter, two-sided, 1% level.

Secondary outcomes with multiple categories (e.g. satisfaction categories) were analysed using ordered logistic regression clustered by centre and with adjustment for previous radiotherapy and baseline pad weight. Secondary outcomes that are continuous outcomes and measured repeatedly (e.g. EQ-5D-3L, ICIQ-UI SF, ICIQ-MLUTS incontinence and voiding scores) were analysed using a mixed-effects repeated-measures model, with random effects for centre and participant and fixed effects for treatment, time point and the respective outcome at baseline, as well as for the baseline pad test weight and previous radiotherapy.

The primary outcome was tested in a non-inferiority framework with a non-inferiority margin of 15%, thought to be an acceptable lower effectiveness, in return for reduced AEs and easier operation of the sling. The null hypothesis was that the male sling was inferior to the AUS by at least 15% and a p-value of < 0.025 would indicate that the null hypothesis could be rejected, suggesting the male sling was non-inferior to the sphincter.

Secondary outcomes that measure quality of life, such as EQ-5D-3L and SF-12 version 2, were tested under a superiority framework. Continence-specific secondary outcomes, such as ICIQ-UI SF and ICIQ-MLUTS incontinence, voiding and sexual functioning scores, were also tested under a superiority framework.

Non-responder analysis

Descriptive data comparing the baseline characteristics of participants who did and did not respond at 12 months are displayed and the t-test (continuous outcomes) and chi-squared test (categorical outcomes) were used to estimate the statistical significance of the differences between responders and non-responders.

Missing data

Where an outcome was to be analysed using a model that adjusted for the baseline outcome, any individuals for whom this was missing at baseline had their outcome imputed by the centre mean or, in the case of the baseline 24-hour pad test, the overall mean.

Missing outcome data were imputed using a multiple imputation model (using chained equations) with randomised intervention, number of times leaked, quantity leaked, previous radiotherapy, previous prostate surgery and age used as covariates. Pattern-mixture models made the following assumptions: all missing data being continent; all missing being incontinent; all missing slings were continent and all missing AUSs were incontinent; and, finally, all missing slings were incontinent and all missing AUSs were continent.

Patient and public involvement

Pre-funding application and design of the research

Prior to the initial funding application, we had the benefit of a patient advisor and an expert panel of service users who were extensively involved in all stages of the initial application, including the outline stage, to ensure that the trial addressed matters of most concern to men with incontinence. Members of this panel were interviewed on their leakage problems, expectations from surgical treatment and willingness to participate in the planned research. We also benefited from their review and approval of the proposed trial documentation [including the draft application, proposed questionnaires and instructions for the 24-hour urine leakage (pad) test]. Feedback from the expert panel helped to refine the study to understand what outcomes were important.

We also had a patient advisor grant holder who advised throughout. His thoughts were:

It is helpful to the trial for the consumer rep[resentative] to have some experience of the problems being investigated. Thank you for asking me to join the PMG [Project Management Group]. As someone with the problem of leakage and an AUS fitted for many years, I was able to help with the wording and arrangements of the questionnaires given to potential participants. Being a member of the PMG I was able from time to time to ask for clarification of the wording of some of the professional statements. Receiving the paperwork and documents of the TSC [Trial Steering Committee] is very important to know how the trial is proceeding and the problems occurring. It is important to know that the trial progress and problems are circulated to other parties to gain information or avoid duplication. It has been nice to observe and know that all professionals involved in this trial have ‘gone about’ the investigations in a keen and interested manner. From my eyes the trial has been worthwhile and has found other unknown problems.

Embedded qualitative component

MASTER incorporated a significant qualitative component, which was embedded at each stage of the study, to include patient and public involvement in the following:

-

establishment of patient-perceived importance of different outcomes

-

exploration of patients’ perspectives on acceptable inferiority margins

-

patients’ experiences of procedures

-

reasons for failure resulting in crossover to alternative surgery

-

surgeons’ experiences of procedures.

The full methods, findings and evaluation of the qualitative component are reported in Chapter 6.

Oversight of the study

One of the independent members of the TSC was a patient representative. The TSC met throughout the study and reviewed all study documentation, including participant-facing documents and questionnaires that were sent to participants.

Report writing, academic paper preparation and dissemination

The patient and public involvement partner on the TSC has been actively involved in discussions of the trial results with the TSC and has been supportive of the study in report preparation.

Chapter 3 Description of the study population, baseline characteristics and treatment received

This chapter describes the baseline characteristics of and treatment received by the MASTER study population.

Throughout this chapter, the RCT data are separated from those of the NRC. Data tables for the RCT are presented in this chapter and Appendix 1, and the NRC data are presented in Appendix 2.

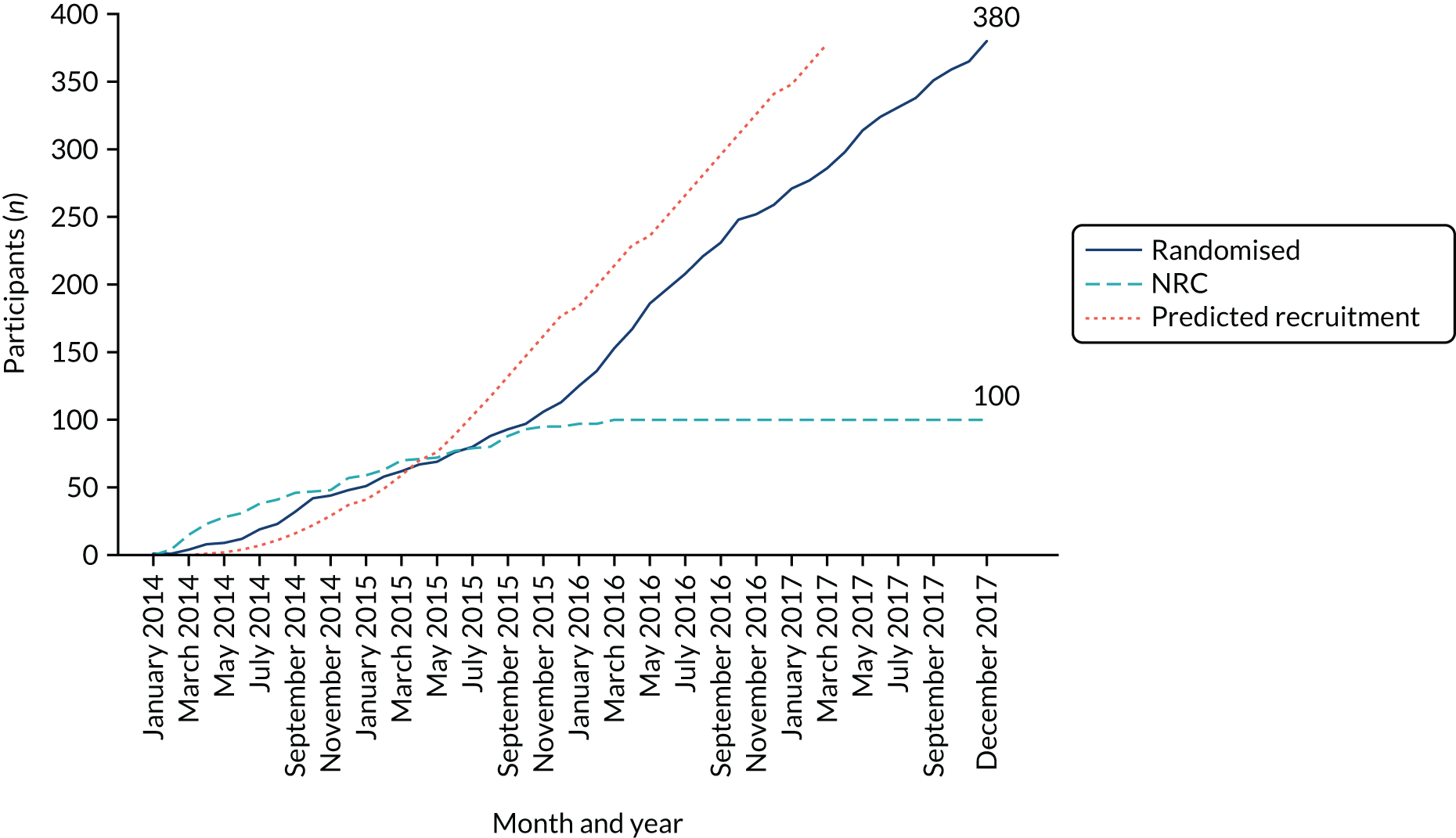

Recruitment to the study

Participants were recruited from 28 centres in the UK (Table 1). A total of 27 centres were recruited to the RCT, whereas one centre was recruited to the NRC only. Thirteen centres were recruited to both the RCT and the NRC. In total, 480 participants were recruited to MASTER: 190 consented and were randomised to receive a male sling, 190 consented and were randomised to receive an AUS, and 100 consented to the NRC. Participants were recruited to MASTER from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2017 (Figure 2).

| Centre | Number (%) of participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | NRC | Total | ||

| Male sling group | AUS group | |||

| Southmead Hospital, Bristol | 24 (12.6) | 25 (13.2) | 11 (11.0) | 60 (12.5) |

| University College London Hospital, London | 18 (9.5) | 19 (10.0) | 15 (15.0) | 52 (10.8) |

| James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough | 12 (6.3) | 14 (7.4) | 11 (11.0) | 37 (7.7) |

| Freeman Hospital, Newcastle | 17 (8.9) | 16 (8.4) | 0 | 33 (6.9) |

| Guy’s Hospital, London | 11 (5.8) | 12 (6.3) | 8 (8.0) | 31 (6.5) |

| St Richard’s Hospital, Chichester | 6 (3.2) | 6 (3.2) | 15 (15.0) | 27 (5.6) |

| Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge | 6 (3.2) | 6 (3.2) | 13 (13.0) | 25 (5.2) |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham | 6 (3.2) | 6 (3.2) | 13 (13.0) | 25 (5.2) |

| Western General Hospital, Edinburgh | 12 (6.3) | 12 (6.3) | 0 | 24 (5.0) |

| Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield | 9 (4.7) | 10 (5.3) | 2 (2.0) | 21 (4.4) |

| Stepping Hill Hospital, Stockport | 9 (4.7) | 10 (5.3) | 1 (1.0) | 20 (4.2) |

| St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust, London | 9 (4.7) | 9 (4.7) | 0 | 18 (3.8) |

| East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, Eastbourne | 8 (4.2) | 7 (3.7) | 0 | 15 (3.1) |

| University Hospital, Southampton | 6 (3.2) | 6 (3.2) | 1 (1.0) | 13 (2.7) |

| St James’s University Hospital, Leeds | 5 (2.6) | 4 (2.1) | 3 (3.0) | 12 (2.5) |

| Imperial College Hospital, London | 5 (2.6) | 5 (2.6) | 0 | 10 (2.1) |

| Royal Salford, Salford | 5 (2.6) | 5 (2.6) | 0 | 10 (2.1) |

| Pinderfields General Hospital, Wakefield | 5 (2.6) | 4 (2.1) | 0 | 9 (1.9) |

| Leicester General Hospital, Leicester | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (1.5) |

| Wrexham Maelor Hospital, Wrexham | 3 (1.6) | 3 (1.6) | 0 | 6 (1.3) |

| Lister Hospital, Stevenage | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.6) | 0 | 5 (1.0) |

| Southern General Hospital, Glasgow | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (0.8) |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 4 (0.8) |

| Aintree University Hospital, Liverpool | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 4 (0.8) |

| Royal Gwent Hospital, Newport | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 3 (0.6) |

| City Hospital, Nottingham | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust, Salisbury | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| Bedford Hospital, Bedford | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Total | 190 | 190 | 100 | 480 |

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment graph.

The centres were set up in a phased approach and did not all recruit for the full duration of the trial; therefore, the number of recruiting months (i.e. the time between the first and the last participant recruited in a centre) ranged from 1 to 47 months. Participants were recruited into the NRC until 27 October 2015, after which recruitment was stopped to the NRC because it was adversely affecting recruitment to the RCT. The database was closed to follow-up on 9 March 2020.

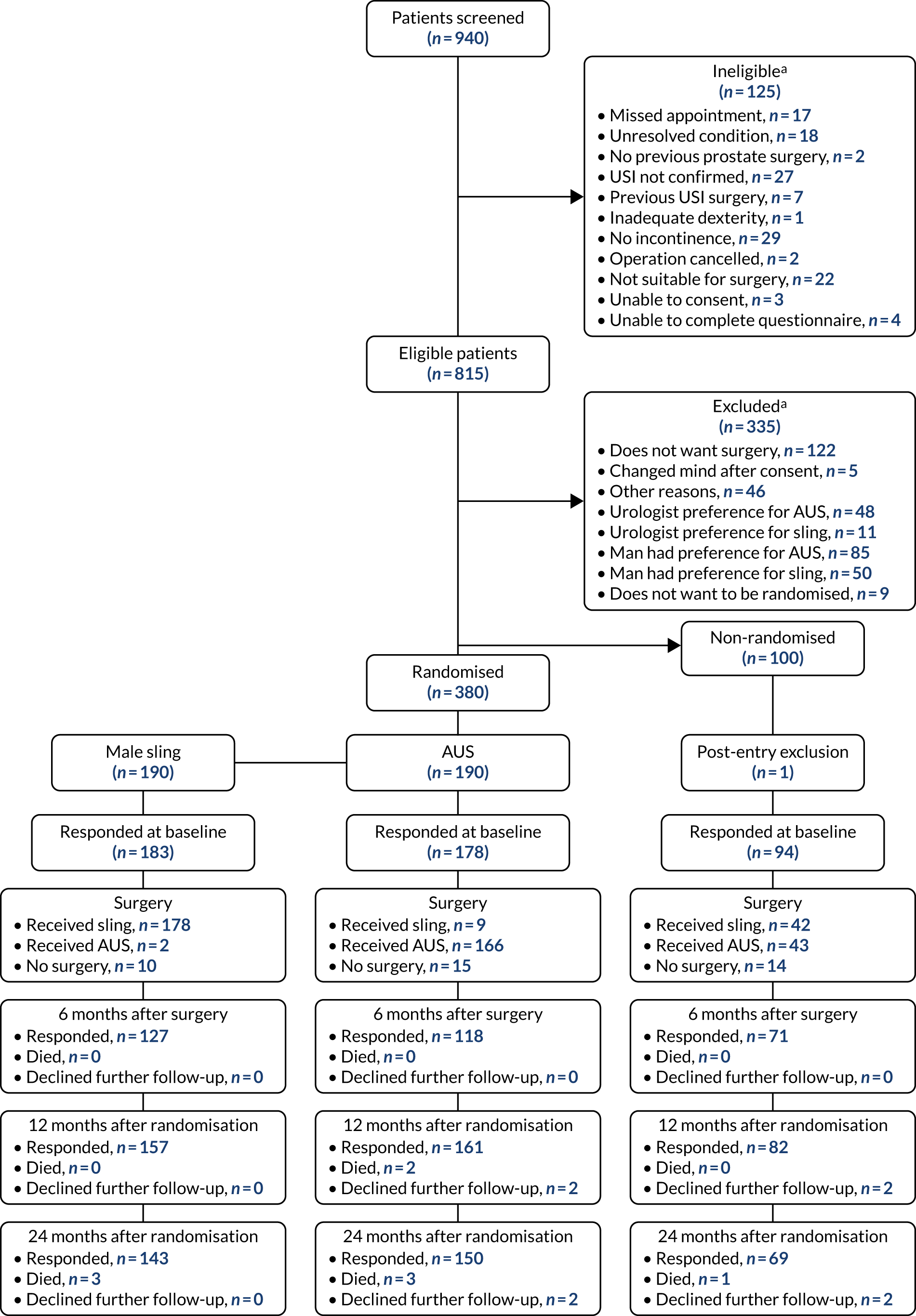

Study conduct

The progress of participants through the stages of the trial to follow-up is shown on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 3). In total, 940 potential participants were considered for entry to MASTER. Of these, 125 (13.3%) individuals failed to meet one of the eligibility criteria. Of the 815 individuals who were eligible, 335 (41.1%) were excluded; the majority of individuals were excluded because the patient did not want surgery, or the patient or the urologist preferred the sling or the AUS. One participant was excluded from the NRC after entering the trial because they were not found to have any incontinence. The time from randomisation to the intervention and the time from randomisation to each of the follow-up points was similar between the two randomised groups (Table 2) and the NRC (see Appendix 2, Table 32).

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow diagram of men recruited to MASTER. a, Patients can be ineligible and excluded for more than one reason.

| Time to events | Randomised group | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | |

| Days from randomisation to 6-month follow-up | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 308 (126); 125 | 318 (150); 116 |

| Median (IQR) | 275 (237–323) | 269 (224–365) |

| Minimum, maximum | 189, 1184 | 183, 1236 |

| Days from randomisation to 12-month follow-upa | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 370 (38); 152 | 362 (45); 146 |

| Median (IQR) | 360 (345–379) | 351 (342–364) |

| Minimum, maximum | 332, 552 | 323, 757 |

| Days from randomisation to 24-month follow-upb | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 760 (43); 132 | 748 (23); 138 |

| Median (IQR) | 747 (737–762) | 742 (735–755) |

| Minimum, maximum | 703, 1053 | 700, 853 |

| Days from surgery to 6-month follow-up | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 211 (31); 125 | 204 (32); 116 |

| Median (IQR) | 202 (189–218) | 195 (189–210) |

| Minimum, maximum | 177, 348 | 46, 355 |

| Days from surgery to 12-month follow-up | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 266 (123); 150 | 248 (121); 142 |

| Median (IQR) | 291 (210–338) | 267 (197–331) |

| Minimum, maximum | –630, 530 | –549, 573 |

| Days from surgery to 24-month follow-up | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 653 (125); 130 | 623 (130); 136 |

| Median (IQR) | 671 (611–718) | 652 (579–712) |

| Minimum, maximum | –257, 914 | –122, 774b |

| Days from randomisation to surgery | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 102 (110); 180 | 122 (129); 175 |

| Median (IQR) | 77 (36–133) | 92 (32–166) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 996 | 0, 939 |

The follow-up rates at 12 and 24 months for each randomised group were > 75% for the participants in the RCT. Although the follow-up rate is slightly higher for the AUS group, there was no substantive difference between the two randomised groups. Seven participants are known to have died up to the 2-year follow-up. These deaths were not related to participation in the trial.

Participant and sociodemographic factors

There was no difference in the age of the participants between the two randomised groups or the NRC (Table 3) (see Appendix 2, Table 33, for the NRC). The average age of the participants was between 67 and 68 years. All men had received a previous prostate operation and > 90% were not leaking urine prior to their prostate operation. Of those men in the RCT, 94% had their original prostate surgery for prostate cancer. Nearly all men received a radical prostatectomy and a smaller number of men underwent other procedures, such as channel TURP for obstructing prostate cancer, transurethral prostatectomy for benign prostatic obstruction or retropubic prostatectomy for benign prostatic obstruction. Approximately 50% of men had received physiotherapy for SUI and around 20% of men had received radiotherapy for prostatic disease. At least 90% of men had used pads or protection since their prostatic surgery because of leaking urine.

| Participant and sociodemographics | Randomised group | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 67 (6) | 68 (6) |

| Previous prostate surgery, n (%) | ||

| Surgery for prostate cancer | 178 (93.7) | 180 (94.7) |

| Surgery for benign prostate obstruction | 8 (4.2) | 9 (4.7) |

| Surgery for both | 4 (2.1) | 1 (0.5) |

| Type of previous surgery, n (%) | ||

| Radical prostatectomy | 183 (96.3) | 182 (95.8) |

| Channel TURP for obstructing prostate cancer | 2 (1.1) | 4 (2.1) |

| Transurethral prostatectomy for benign prostatic obstruction | 13 (6.8) | 7 (3.7) |

| Retropubic prostatectomy for benign prostatic obstruction | 1 (0.5) | 00 |

| Received radiotherapy for prostatic disease, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 38 (20.0) | 39 (20.5) |

| No | 152 (80.0) | 151 (79.5) |

| Leaking urine before first prostate operation, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 6 (3.2) | 10 (5.3) |

| No | 177 (93.2) | 174 (91.6) |

| Missing | 7 (3.7) | 6 (3.2) |

| Previous treatment for urinary/bladder problems, n (%) | ||

| Injectable treatment for SUI | 9 (4.7) | 8 (4.2) |

| Physiotherapy for SUI | 95 (50.0) | 83 (43.7) |

| Drug treatment with duloxetine for SUI | 23 (12.1) | 21 (11.1) |

| Drug treatment for other urinary/bladder problem | 40 (21.1) | 35 (18.4) |

| Any neurological disease | 2 (1.1) | 7 (3.7) |

| Do you wear pads or protection because of leaking urine?, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 175 (92.1) | 171 (90.0) |

| No | 5 (2.6) | 4 (2.1) |

| Missing | 10 (5.3) | 15 (7.9) |

| 24-hour pad test result (g) | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 384 (414); 159 | 433 (518); 159 |

| Median (IQR) | 256 (89–545) | 267 (130–554) |

| Pads used on an average day, mean (SD); n | 3.4 (1.8); 180 | 3.7 (2.2); 173 |

Clinical assessment at baseline

Prior to their MASTER surgery, men completed a 24-hour pad test and the pad weight increase caused by urinary leakage was recorded (see Table 3; see Appendix 2, Table 33, for the NRC). There were some extreme values in each group, leading to means being much higher than the medians. The mean number of pads used was similar in the two RCT groups and was slightly larger in the NRC (see Table 3; see Appendix 2, Table 33, for the NRC). In the NRC, the time to surgery was reported from the consent date rather than the randomisation date; therefore, in the two randomised groups, the median times from randomisation to surgery were 77 days (sling group) and 92 days (AUS group), whereas, in the NRC, the median time from consent to surgery was 95 days.

The responses to the two questions making up the primary outcome on the ICIQ-UI SF and the individual ICIQ-MLUTS questions for the RCT are shown in Table 4 (see Appendix 2, Table 34, for the responses for the NRC). The summary scores were similar across the RCT and the NRC. The questions that form the primary outcome show that > 90% of men leaked at least once per day when they consented to MASTER and more than one-third classed their leakage as ‘a large amount’. The ICIQ-UI SF score was similar in the RCT and the NRC. Incontinence and voiding scores were also similar in the RCT and NRC, with the low voiding scores indicating that incontinence problems were more severe than voiding problems. The sexual functioning score was high in the RCT and the NRC, which indicates that incontinence had a considerable effect on sexual functioning.

| Health status | Randomised group | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | |

| How often do you leak urine? n (%) | ||

| Once per week or less | 0 | 0 |

| Two or three times per week | 3 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) |

| About once per day | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Several times per day | 115 (60.5) | 104 (54.7) |

| All of the time | 54 (28.4) | 59 (31.1) |

| Question missing | 8 (4.2) | 12 (6.3) |

| Missing | 7 (3.7) | 12 (6.3) |

| How much urine do you usually leak? n (%) | ||

| A small amount | 38 (20.0) | 29 (15.3) |

| A moderate amount | 76 (40.0) | 84 (44.2) |

| A large amount | 68 (35.8) | 61 (32.1) |

| Question missing | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.1) |

| Missing | 7 (3.7) | 12 (6.3) |

| Score for effect on everyday life, mean (SD); n | 7.5 (2.3); 178 | 7.8 (2.1); 176 |

| Number of times pass urine during the daytime, mean (SD); n | 7.4 (3.8); 172 | 8.4 (8.6); 155 |

| Number of times get up at night to pass urine, mean (SD); n | 1.8 (1.4); 179 | 1.8 (1.5); 175 |

| ICIQ-UI SF score, mean (SD); n | 16.1 (3.4); 172 | 16.4 (3.2); 166 |

| ICIQ-MLUTS incontinence score, mean (SD); n | 12.2 (3.9); 176 | 12.1 (4.2); 168 |

| ICIQ-MLUTS voiding score, mean (SD); n | 3.9 (3.5); 178 | 3.6 (3.4); 171 |

| ICIQ-MLUTSsex, mean (SD); n | 8.1 (1.3); 137 | 8.0 (1.5); 131 |

| SF-12 mental score, mean (SD); n | 47.5 (10.7); 169 | 49.7 (11.3); 168 |

| SF-12 physical score, mean (SD); n | 48.3 (9.2); 169 | 47.5 (9.7); 168 |

| EQ-5D-3L, mean (SD); n | 0.823 (0.221); 177 | 0.814 (0.241); 172 |

The urinary symptoms for men in the RCT, taken as responses from the ICIQ-UI SF, are shown in Appendix 1, Table 30 (see Appendix 2, Table 35, for responses for the NRC). These are similar between the randomised groups.

The SF-12 mental and physical scores were also similar. In all three groups, the mean for both scores was slightly less than 50, which is the median of the scale, suggesting that participants rated their mental and physical health slightly below the average for the general population when they entered the trial.

In the RCT, 180 of the 190 men randomised to the male sling group and 175 of the 190 randomised to the AUS group received surgery (Table 5). This means that 93.4% of the RCT population underwent surgery, with 178 and 166 men, respectively, receiving their allocated intervention (90.5% of the RCT men). Of the 25 men in the RCT who did not receive surgery, reasons were recorded for 22 (male sling group, n = 8; AUS group, n = 14): two died before receiving surgery (both AUS); 11 no longer wanted surgery (male sling group, n = 3; AUS group, n = 8); six had a change in their medical condition and either no longer required surgery or surgery was no longer appropriate (male sling group, n = 3; AUS group, n = 3); one man in the sling group did not want to self-catheterise; and two men (male sling group, n = 1; AUS group, n = 1) had current care responsibilities that made surgery impracticable.

| Surgery details | Randomised group | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | |

| Received surgery, n/N (%) | 180/190 (94.7) | 175/190 (92.1) |

| Received sling, n/N (%) | 178/180 (98.9) | 9/175 (5.1) |

| Received sphincter, n/N (%) | 2/180 (1.1) | 166/175 (94.9) |

| Device replacement/removal (within 24 months), n/N (%) | 20/180 (11.1) | 4/175 (2.3) |

| Sling replaced by sphincter (n) | 18 | 00 |

| Sling replaced with a new sling (n) | 2 | 00 |

| Sphincter replaced with a new sphincter (n) | 0 | 3 |

| Time from randomisation to surgery (days) | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 102 (110); 180 | 122 (129); 175 |

| Median (IQR) | 77 (36–133) | 92 (32–166) |

| Length of surgery (minutes) | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 101 (34); 175 | 128 (37); 168 |

| Median (IQR) | 98 (75–121) | 120 (102–150) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 2 (2); 180 | 2 (2); 175 |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) |

| Time to re-admission (days) | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 331 (155); 20 | 429 (332); 4 |

| Median (IQR) | 331 (203–392) | 376 (161–698) |

Two (1.1%) men were randomised to receive a male sling but received an AUS, one at his own choice and the other because his surgery was delayed and at a subsequent review it was decided that an AUS was more appropriate. Nine men randomised to receive an AUS received a male sling: seven because of participant preference and the other two because of clinician preference.

In the NRC, 85 men (male sling, n = 42/46, 91.3%; AUS, n = 43/46, 93.5%) received surgery (see Appendix 2, Table 36).

The length of hospital stay was similar in both of the randomised groups and in the NRC. As expected, surgery for men receiving an AUS took approximately 20 minutes longer than the surgery for men receiving a male sling.

The proportion of men who were re-admitted for further surgery was larger in the male sling group than in the AUS group (see Table 5). In the majority of cases, revision surgery in the male sling group was required because incontinence had not improved. Twenty men (11%) in this group were re-admitted to have their sling removed; 18 had their sling replaced with an AUS and two had a new sling inserted. Four men (2%) randomised to receive an AUS were re-admitted for further surgery. Three received a replacement AUS and one had his AUS removed but not replaced. In the NRC, there were eight re-admissions: six men had their male sling replaced by an AUS and two men had their AUS replaced with another AUS (see Appendix 2, Table 36). A small number of device failures occurred in both randomised groups and in the NRC. The length of time to re-admission was right skewed, but the median time in both randomised groups and the NRC was between 10 and 13 months.

Adverse events and deaths

Data on the AEs that occurred during the surgical procedures were also collected (Table 6) (see Appendix 2, Table 37, for the NRC). The majority of these were events that required additional oral pain relief (pain relief is standard therapy after these procedures). More men in the male sling group than in the AUS group required postoperative catheterisation and catheterisation for > 24 hours. Otherwise, the rates of AEs were low and similar between the groups.

| Adverse event | Randomised group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 180) | AUS (N = 175) | |

| Total number of SAEs | 8 | 15 |

| Total number of AEs | 226 | 192 |

| Participants with any AEs | 152 (84.4) | 149 (85.1) |

| Number of AEs per participant | ||

| 0 | 28 (15.6) | 26 (14.9) |

| 1 | 101 (56.1) | 12 (68.6) |

| 2 | 35 (19.4) | 19 (10.9) |

| 3 | 11 (6.1) | 6 (3.4) |

| ≥ 4 | 5 (2.8) | 4 (2.3) |

| Postoperative catheter required | 28 (15.6) | 8 (4.6) |

| Catheter required for > 24 hours | 20 (11.1) | 6 (3.4) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 2 (1.1) |

| Pyrexia | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) |

| Wound infection | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) |

| Sepsis, septicaemia or abscess | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Retention requiring surgery | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Bowel obstruction | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Constipation | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) |

| New urinary tract symptoms | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| Tape or sling complications | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Device exposure/extrusion requiring no treatment | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Acute or chronic pain | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Oral pain relief given | 140 (77.8) | 139 (79.4) |

| Parenteral pain relief given | 13 (7.2) | 13 (7.4) |

| Antibiotic treatment for postoperative infection | 6 (3.3) | 10 (5.7) |

| Other AEs | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) |

There were a small number of SAEs (see Table 6; see Appendix 2, Table 37, for the NRC), experienced by eight men in the male sling group (recatheterisation requiring or prolonging hospital stay, n = 3; mesh erosion n = 3; infection urosepsis, n = 1; developed coffee ground vomit, n = 1) and 13 men in the AUS group (recatheterisation requiring or prolonging hospital stay, n = 3; infection, n = 3; erosion of device, n = 2; haematoma, n = 1; bruising and inflammation, n = 1; urinary retention/voiding difficulties, n = 1; pain, n = 1; transient hypotension, n = 1; thrombosis, n = 1; exacerbation of asthma; n = 1; one man had three SAEs). Six men in the NRC had a SAE: five in the male sling group (anaphylaxis, n = 1; haematuria, n = 1; recatheterisation requiring or prolonging hospital stay, n = 2; and wound infection, n = 1) and one in the AUS group (dysuria, n = 1).

There were six deaths in the RCT (three in each of the randomised groups) and one death in the NRC, none of which was related to their MASTER surgery. Six of the deaths were a result of cancer and one was due to pneumonia.

Chapter 4 Clinical results

This chapter describes the comparison of the male synthetic sling with the AUS at 6 months after surgery, and at 12 and 24 months after randomisation.

Analysis populations

Throughout this chapter, the 380 participants in the RCT (randomised to receive either a male sling or an AUS) are separated from the 99 participants in the NRC, whose surgery was decided by a combination of surgeon and participant preference. All of the statistical analysis is a comparison between the two groups in the RCT only. No statistical analysis was performed on those in the NRC, but summary statistics for the NRC are presented in Appendix 2.

Operative details

The surgical details for the RCT are described in Chapter 3 and, for the NRC, in Appendix 2. In the RCT, 355 (male sling, n = 180; AUS, n = 175) of the 380 randomised men received surgery and 85 (male sling, n = 42; AUS, n = 43) of the 99 non-randomised men received surgery. Adherence to the randomised intervention was high, with nearly 97% of the men who received surgery receiving their randomised procedure. The surgery time in minutes for the men randomised to the sling group was statistically significantly shorter than that for men randomised to the AUS group (–24.67 minutes, 95% CI –33.62 to–15.72 minutes; p < 0.001) (see Table 5).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the proportion of men continent at 12 months post randomisation (male sling, n = 20, 13%; AUS, n = 25, 15.8%), with continence defined as a combined response of ‘never’ and ‘none’ to the questions ‘how often do you leak urine?’ and ‘how much urine do you leak?’ in the ICIQ-UI SF participant-reported questionnaire. On the advice of the DMC, a less strict version of this was included as a secondary outcome, for which ‘less than once a week’ and ‘a small amount’ were added to the definitions of success and are, therefore, included in the continence proportion. Using the less strict definition, 52 (33.8%) men in the male sling group and 55 (34.8%) men in the AUS group were continent 12 months after randomisation (Table 7 for the RCT; see Appendix 2, Table 38, for the NRC). Table 7 also includes the data for both the 6-month and the 24-month time points.

| Analysis of continence | Randomised group, n/N (%) | Difference (male sling – AUS)a (95% CI); p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sling | AUS | |||

| ITT | ||||

| Sample size | 190 | 190 | ||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Continent (12 months) | 20/154 (13.0) | 25/158 (15.8) | –3.4 (–11.7 to 4.8); 0.003 | 0.75 (0.36 to 1.54) |

| Continent: less strict definition (12 months) | 52/154 (33.8) | 55/158 (34.8) | –1.9 (–10.4 to 6.6); 0.001 | 0.92 (0.62 to 1.35) |

| Other time points | ||||

| Continent (6 months) | 19/121 (15.7) | 24/117 (20.5) | –5.9 (–13.8 to 2.1); 0.012 | 0.67 (0.38 to 1.16) |

| Continent: less strict definition (6 months) | 45/121 (37.2) | 48/117 (41.0) | –5.1 (–14.9 to 4.7); 0.024 | 0.80 (0.53 to 1.23) |

| Continent (24 months) | 21/140 (15.0) | 22/148 (14.9) | –0.6 (–9.2 to 8.0); 0.001 | 0.95 (0.48 to 1.90) |

| Continent: less strict definition (24 months) | 44/140 (31.4) | 51/148 (34.5) | –4.0 (–16.7 to 8.8); 0.045 | 0.83 (0.46 to 1.51) |

| Per protocol | ||||

| Sample size | 178 | 166 | ||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Continent (12 months) | 20/151 (13.2) | 22/146 (15.1) | –0.025 (–0.107 to 0.056); 0.001 | 0.81 (0.40 to 1.64) |

| Continent: less strict definition (12 months) | 52/151 (34.4) | 50/146 (34.2) | –0.010 (–0.094 to 0.075); 0.001 | 0.96 (0.65 to 1.40) |

| Other time points | ||||

| Continent (6 months) | 19/119 (16.0) | 20/112 (17.9) | –0.029 (–0.119 to 0.060); 0.004 | 0.81 (0.43 to 1.54) |

| Continent: less strict definition (6 months) | 44/119 (37.0) | 44/112 (39.3) | –0.037 (–0.133 to 0.059); 0.010 | 0.85 (0.56 to 1.29) |

| Continent (24 months) | 21/136 (15.4) | 19/139 (13.7) | 0.011 (–0.072 to 0.094); < 0.001 | 1.09 (0.56 to 2.14) |

| Continent: less strict definition (24 months) | 44/136 (32.4) | 47/139 (33.8) | –0.024 (–0.159 to 0.110); 0.033 | 0.89 (0.48 to 1.66) |

Under both definitions, most men reported that they were not continent at all three time points. The ITT-estimated absolute risk difference was –0.034 (95% CI –0.117 to 0.048; non-inferiority p = 0.003), indicating a lower success rate in those randomised to receive a male sling, but with a CI that excludes the predefined non-inferiority margin of –15%. This shows that the sling was non-inferior to the AUS.

At 6 months, there was a larger difference between the male sling and the AUS, but, at 24 months, there was almost no difference when the original definition of continence was used (see Table 7). The less strict definition showed a smaller difference at 6 and 12 months than for the original definition, but a larger difference was seen at 24 months when this alternative definition was used (see Table 7).

The per-protocol estimates at 6, 12 and 24 months were similar to those of the ITT analysis (see Table 7).

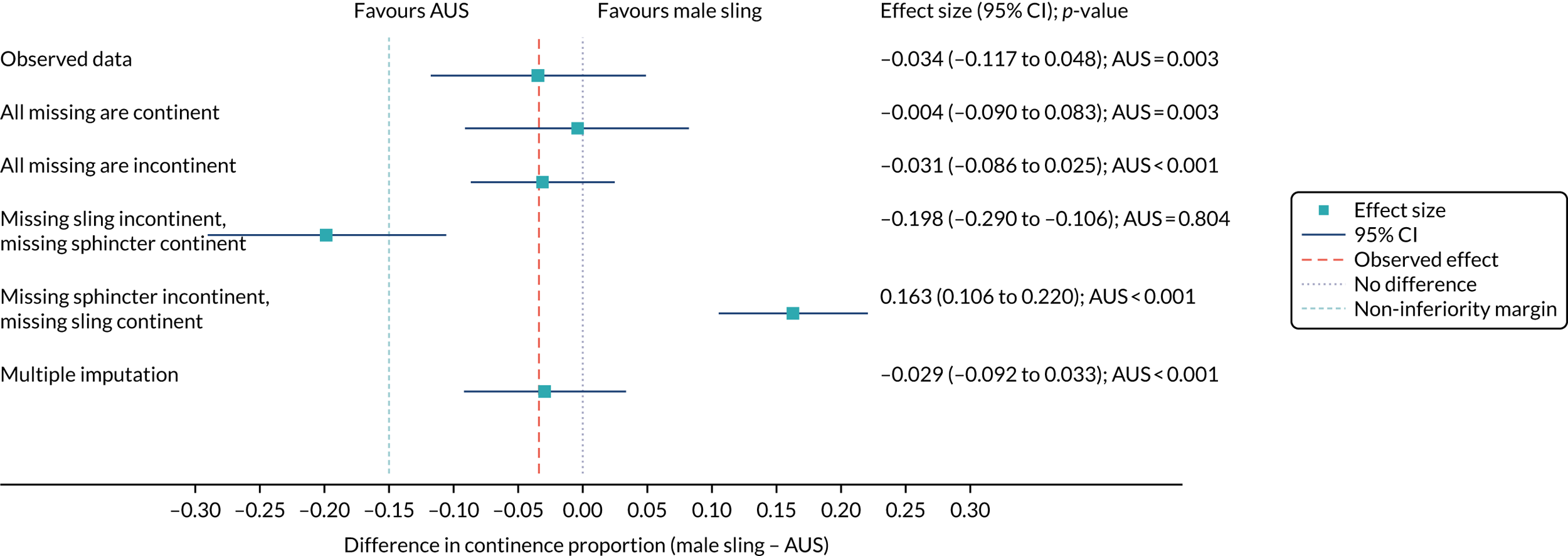

Sensitivity analysis

Figure 4 shows the sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome. Multiple imputation and pattern-mixture modelling were used. Estimates were consistent in all but the most extreme circumstances, which are unlikely to reflect the missing data.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot showing the sensitivity analysis of the primary outcomes on missing data.

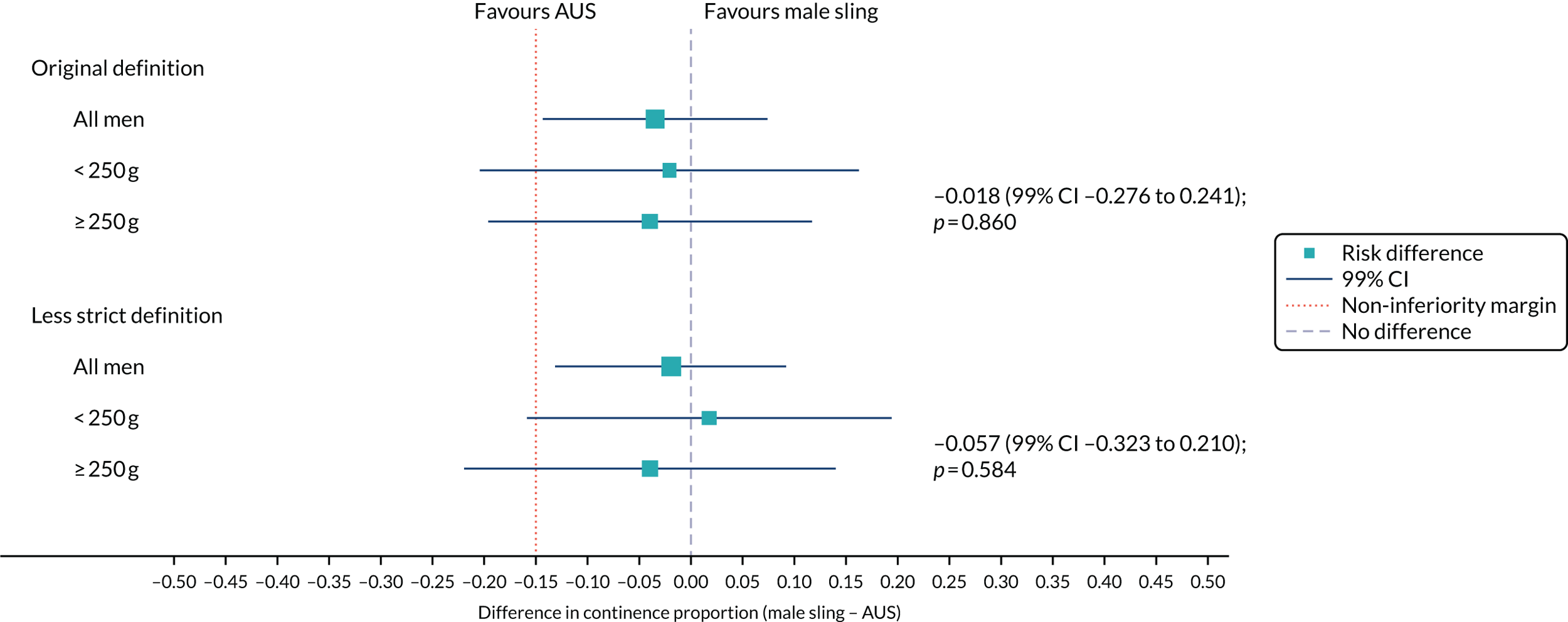

Subgroup analysis by baseline pad weight

The men’s report of continence at 12 months was available for 312 men in the RCT: 134 men with a pad weight at baseline of ≤ 250 g and 178 men with a pad weight at baseline of > 250 g.

When the original continence definition was used, in both subgroups, the proportion of men incontinent was larger for those who received the male sling than for those who received the AUS (Table 8). When the less strict definition was used, the proportion of men incontinent in the > 250 g subgroup was larger for those who received the male sling than for those who received the AUS. In the subgroup for which the baseline pad weight was ≤ 250 g, the AUS group had a larger proportion of men who were incontinent than the male sling group.

| Definition | Randomised group, n/N (%) | Effect size (male sling – AUS)a (99% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | ||

| Original definition | |||

| All men | 20/154 (13.0) | 25/158 (15.8) | –0.034 (–0.143 to 0.074); 0.003 |

| ≤ 250 g pad weight | 10/68 (14.7) | 11/66 (16.7) | –0.021 (–0.203 to 0.162); 0.034 |

| > 250 g pad weight | 10/86 (11.6) | 14/92 (15.2) | –0.040 (–0.196 to 0.117); 0.034 |

| Less strict definition | |||

| All men | 52/154 (33.8) | 55/158 (34.8) | –0.019 (–0.131 to 0.092); 0.001 |

| ≤ 250 g pad weight | 26/68 (38.2) | 24/66 (36.4) | 0.018 (–0.159 to 0.194); 0.007 |

| > 250 g pad weight | 26/86 (30.2) | 31/92 (33.7) | –0.039 (–0.219 to 0.140); 0.056 |

The forest plot (Figure 5) displays this subgroup information visually and the size of the interaction effect. There is no evidence that baseline pad weight moderates the overall treatment effect.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot showing the continence rate using the original and the less strict definitions based on baseline pad weight.

Questionnaire response over time

The 6-month questionnaire was sent post surgery and the 12- and 24-month questionnaires were sent post randomisation. Where there was a delay in surgery and the 6-month and 12-month questionnaires were due at the same time, the 12-month questionnaire was prioritised. This explains the slightly lower response rates at 6 months (which were shown in Chapter 3) (Table 9).

| Follow-up time point | Randomised group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | |

| 6 months | 127 (66.8) | 118 (62.1) |

| 12 months | 157 (82.6) | 161 (84.7) |

| 24 months | 143 (75.3) | 150 (78.9) |

Secondary outcomes

Pad use reduced from baseline, but there was no difference between the two randomised groups in the proportion of men still using pads, and there was no indication of pad use reducing during follow-up. Daily pad use was consistently slightly higher in the male sling group than in the AUS group at all three time points (Table 10) (see Appendix 2, Table 39, for the NRC).

| Follow-up time point | Randomised group | Effect size (male sling – AUS)a (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | ||

| Wears pads or other protection,b n/N (%) | |||

| Baseline | 175/190 (92.1) | 171/190 (90.0) | |

| 6 months | 79/120 (65.8) | 68/112 (60.7) | 7.6 (–4.4 to 19.6); 0.212 |

| 12 months | 102/148 (68.9) | 102/150 (68.0) | 2.1 (–1.1 to 15.2); 0.750 |

| 24 months | 83/130 (63.8) | 96/142 (67.6) | –2.2 (–16.5 to 12.2); 0.768 |

| Pads used in an average day,c mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 3.4 (1.8); 180 | 3.7 (2.2); 173 | |

| 6 months | 1.6 (2.0); 119 | 1.1 (1.5); 112 | 1.62 (1.16 to 2.25); 0.004 |

| 12 months | 1.6 (2.1); 146 | 1.3 (1.7); 150 | 1.25 (0.99 to 1.58); 0.062 |

| 24 months | 1.5 (1.8); 127 | 1.2 (1.2); 142 | 1.30 (0.92 to 1.85); 0.137 |

| Score for effect on everyday life, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 7.5 (2.3); 178 | 7.8 (2.1); 176 | |

| 6 months | 3.3 (3.4); 123 | 2.0 (2.4); 116 | 1.38 (0.68 to 2.09); < 0.001 |

| 12 months | 3.5 (3.4); 155 | 2.7 (2.9); 157 | 0.82 (0.16 to 1.47); 0.014 |

| 24 months | 3.2 (3.1); 141 | 2.6 (2.9); 147 | 0.76 (0.09 to 1.43); 0.026 |

| ICIQ-UI SF score, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 16.1 (3.4); 172 | 16.4 (3.2); 166 | |

| 6 months | 8.1 (6.0); 116 | 6.1 (4.4); 113 | 2.04 (0.75 to 3.33); 0.002 |

| 12 months | 8.7 (6.1); 151 | 7.5 (5.3); 153 | 1.30 (0.11 to 2.49); 0.032 |

| 24 months | 7.9 (5.5); 131 | 7.1 (5.0); 139 | 1.42 (0.18 to 2.65); 0.024 |

| ICIQ-MLUTS: incontinence, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 12.2 (3.9); 176 | 12.1 (4.2); 168 | |

| 6 months | 6.7 (5.0); 114 | 5.2 (3.9); 111 | 1.50 (0.47 to 2.53); 0.004 |

| 12 months | 7.3 (4.8); 146 | 5.7 (4.4); 146 | 1.66 (0.71 to 2.61); 0.001 |

| 24 months | 6.5 (4.2); 128 | 5.6 (3.9); 141 | 1.05 (0.08 to 2.03); 0.034 |

| ICIQ-MLUTS: voiding, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 3.9 (3.5); 178 | 3.6 (3.4); 171 | |

| 6 months | 4.6 (3.9); 115 | 3.0 (3.1); 108 | 1.25 (0.52 to 1.97); 0.001 |

| 12 months | 4.4 (4.0); 144 | 2.9 (2.9); 146 | 1.33 (0.66 to 2.00); < 0.001 |

| 24 months | 4.3 (3.7); 130 | 3.3 (3.3); 139 | 0.69 (0.00 to 1.37); 0.049 |

| ICIQ-MLUTSsex, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 8.1 (1.3); 137 | 8.0 (1.5); 131 | |

| 6 months | 7.6 (1.6); 82 | 7.6 (2.0); 77 | 0.22 (–0.20 to 0.64); 0.308 |

| 12 months | 7.6 (1.6); 104 | 7.6 (1.8); 117 | 0.08 (–0.30 to 0.46); 0.676 |

| 24 months | 7.7 (1.7); 89 | 7.5 (1.7); 97 | 0.19 (–0.21 to 0.59); 0.352 |

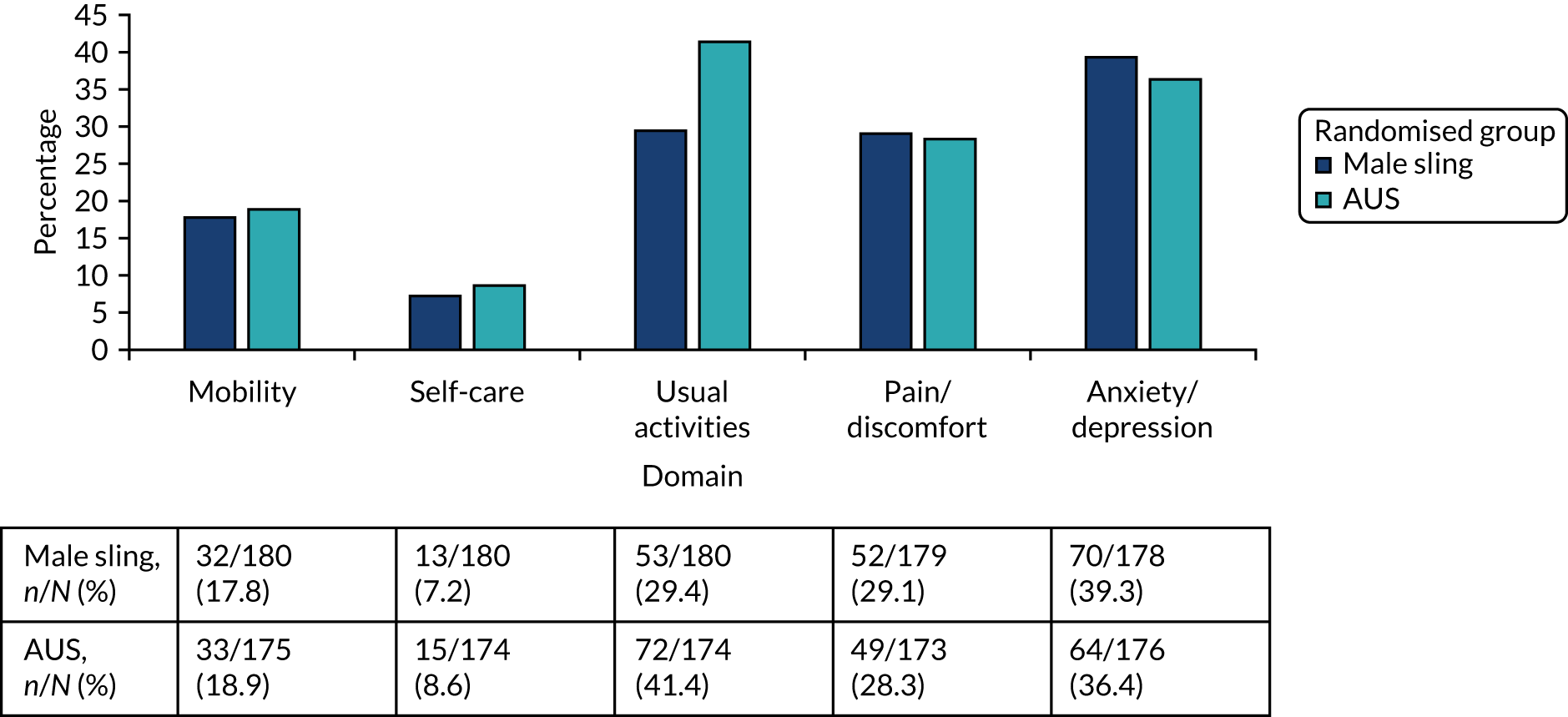

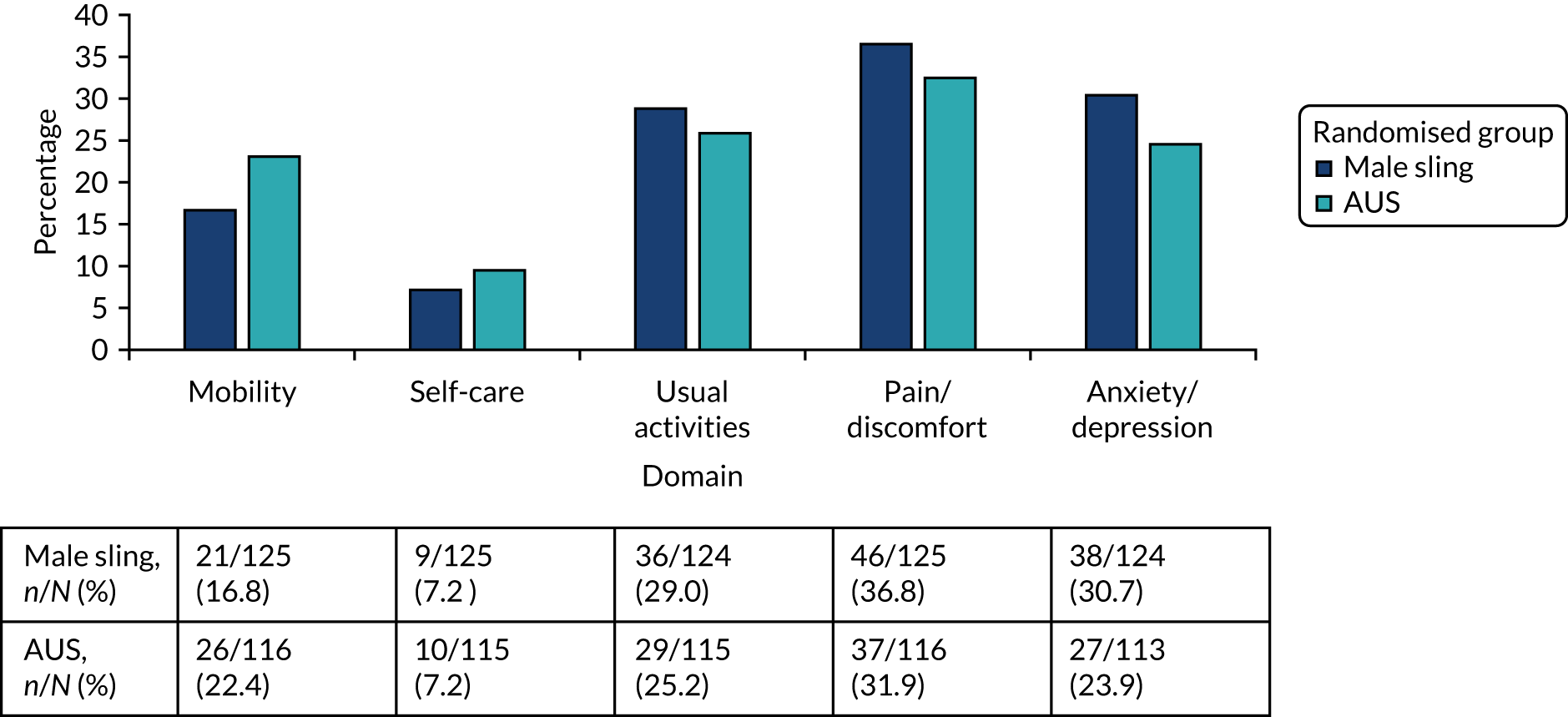

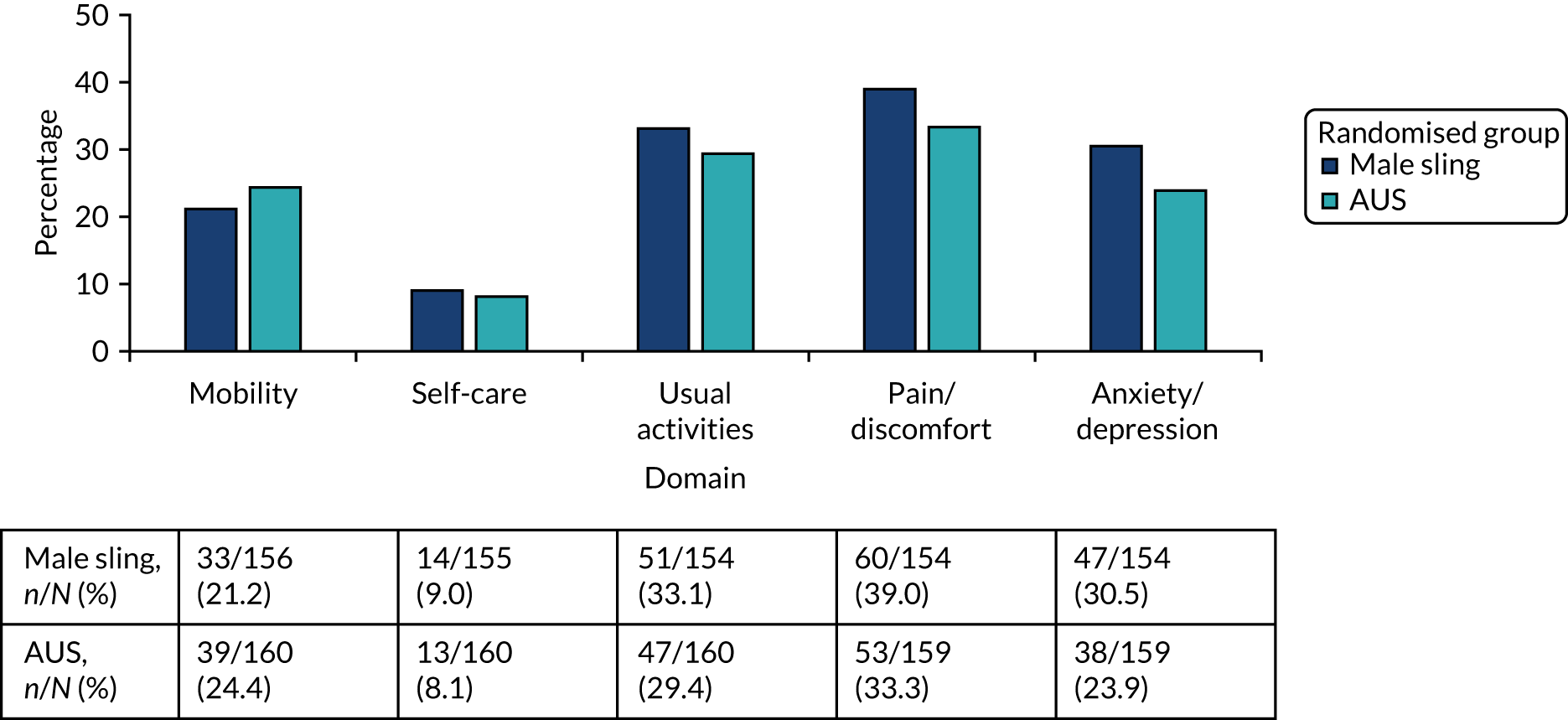

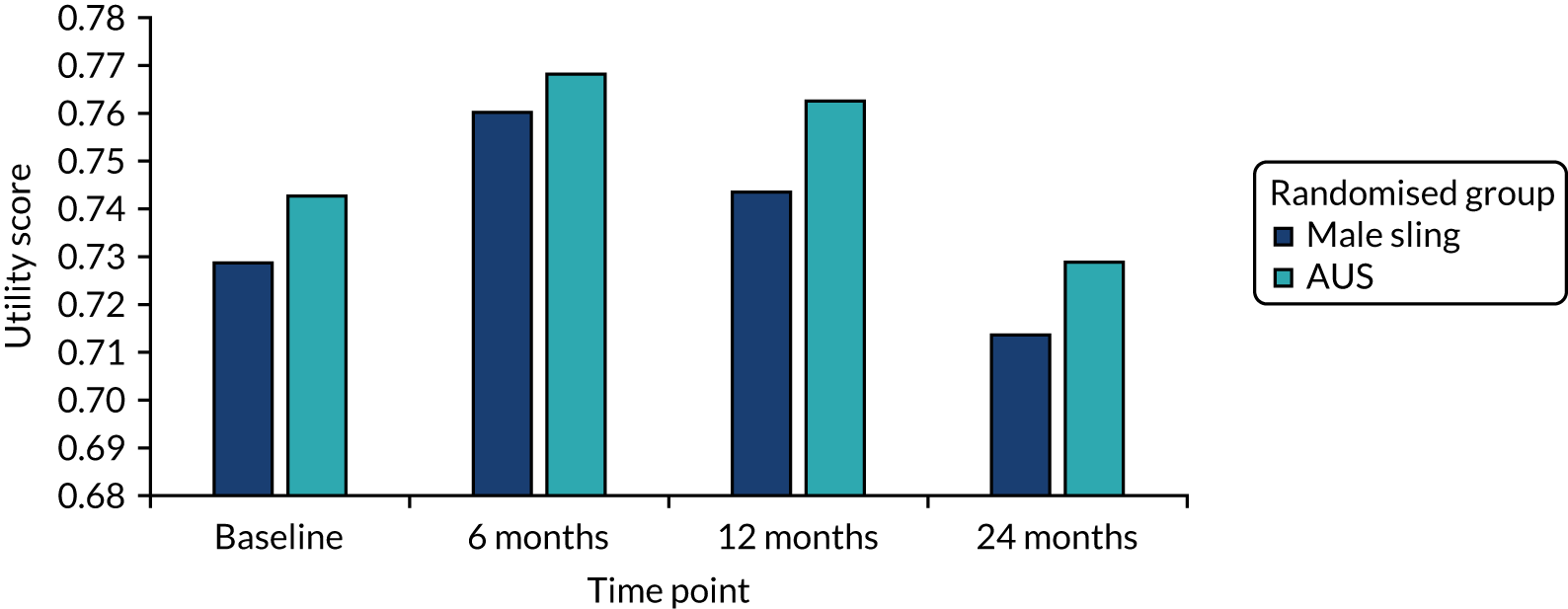

| EQ-5D-3L, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 0.823 (0.221); 177 | 0.814 (0.241); 172 | |

| 6 months | 0.822 (0.240); 125 | 0.827 (0.266); 112 | –0.023 (–0.070 to 0.025); 0.348 |

| 12 months | 0.809 (0.260); 151 | 0.813 (0.274); 158 | –0.019 (–0.062 to 0.025); 0.396 |

| 24 months | 0.820 (0.239); 136 | 0.828 (0.260); 147 | –0.014 (–0.059 to 0.030); 0.534 |

| SF-12: physical score, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 48.3 (9.2); 169 | 47.5 (9.7); 168 | |

| 6 months | 48.4 (10.0); 116 | 49.0 (10.4); 102 | –1.57 (–3.53 to 0.39); 0.116 |

| 12 months | 48.3 (10.3); 142 | 48.7 (10.3); 146 | –0.83 (–2.61 to 0.96); 0.364 |

| 24 months | 48.0 (10.1); 126 | 48.7 (10.8); 139 | –1.18 (–3.02 to 0.65); 0.207 |

| SF-12: mental score, mean (SD); n | |||

| Baseline | 47.5 (10.7); 169 | 49.7 (11.3); 168 | |

| 6 months | 49.8 (10.8); 116 | 49.8 (10.9); 102 | 0.19 (–1.90 to 2.28); 0.857 |

| 12 months | 48.8 (10.9); 142 | 51.3 (10.5); 146 | –1.09 (–2.98 to 0.81); 0.262 |

| 24 months | 49.4 (11.2); 126 | 51.2 (10.4); 139 | 0.04 (–1.91 to 1.99); 0.968 |

The effect of incontinence on everyday life was worse in men randomised to receive the male sling, and this difference is significant at all three time points (see Table 10). The ICIQ-UI SF score, which combines frequency, volume and effect of incontinence into a single outcome, is at the highest (and, therefore, worst) at 12 months. The difference between the two randomised groups was significant at all three time points, with a poorer outcome seen in the male sling group.

Urinary symptoms derived from the individual responses to the ICIQ-UI SF questionnaire are shown in Appendix 1, Table 31, for the RCT and Appendix 2, Table 41, for the NRC. There was a consistent pattern of men who received the male sling having worse outcomes on these questions than those who received the AUS.

Voiding scores and incontinence scores were worse in the male sling group than in the AUS group (see Table 10) and, although there was improvement from baseline for the incontinence score, the voiding score did not change over time. There was no difference between the groups in the sexual functioning score and there is only a small improvement from baseline across the groups.

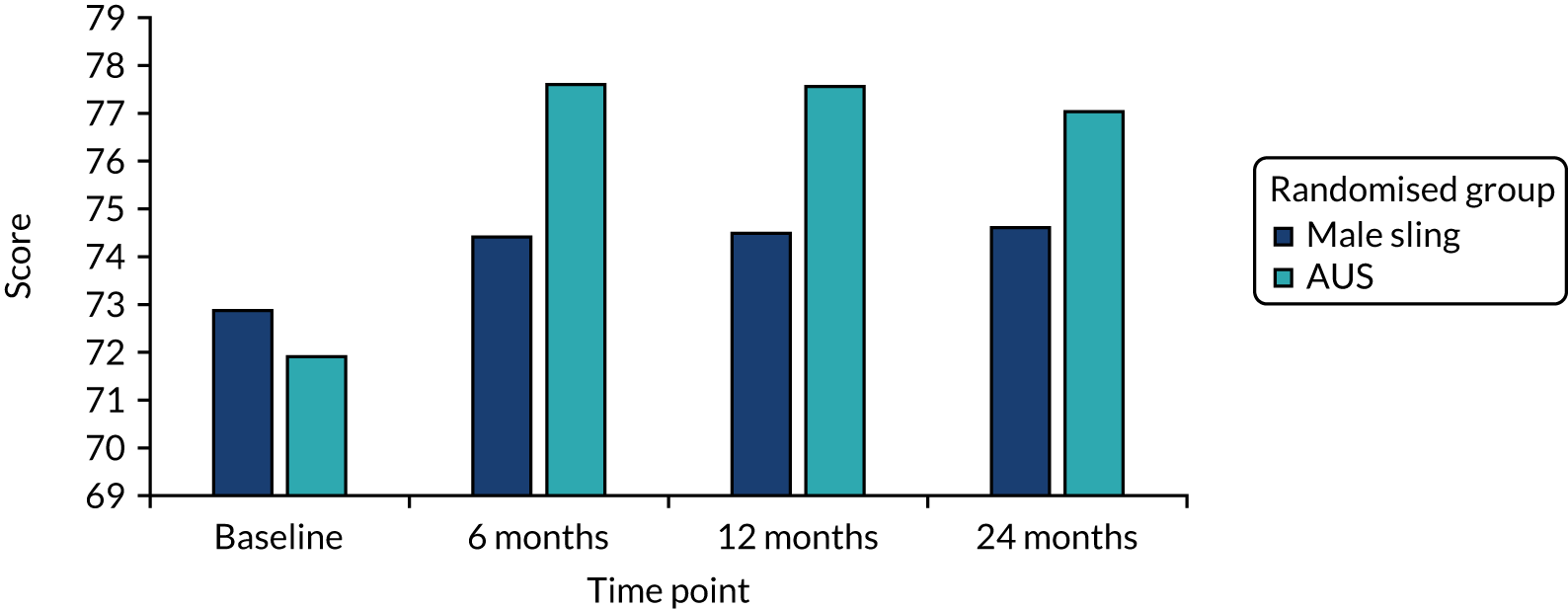

The EQ-5D-3L score at baseline showed that men rated their quality of life as good and, although this dropped slightly at 12 months, it increased again at 24 months (see Table 10). The SF-12 physical and mental scores remain very similar to the baseline values at all three follow-up points. There were no statistically significant differences in the generic quality-of-life outcomes between the two randomised groups.

Some additional outcomes were collected at 12 months only (Table 11; see Appendix 2, Table 40, for the NRC). Men were asked to compare their urinary leakage with that before their surgery using the seven-point PGI-I scale. Of the men randomised to receive the male sling, 75 (40%) reported that they were very much better compared with 99 (52%) men in the AUS group. The volume of urinary leakage at 12 months was reported to be worse than baseline by 12 men in the male sling group and five men in the AUS group. The OR showed a difference between the groups, with the men in the sling group worse off than those in the AUS group (0.39, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.62; p < 0.001).

| Outcome | Randomised group | OR (95% CI); p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | ||

| Urine leakage compared with that before surgery, n (%) | |||

| Very much better | 75 (39.5) | 99 (52.1) | 0.39 (0.24 to 0.62); < 0.001 |

| Much better | 25 (13.2) | 21 (11.1) | |

| A little better | 19 (10.0) | 9 (4.7) | |

| No change | 11 (5.8) | 5 (2.6) | |

| A little worse | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Much worse | 5 (2.6) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Very much worse | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Missing | 48 (25.3) | 51 (26.8) | |

| Satisfaction with surgery results, n (%) | |||

| Completely satisfied | 58 (30.5) | 79 (41.6) | 0.44 (0.28 to 0.69); < 0.001 |

| Fairly satisfied | 46 (24.2) | 46 (24.2) | |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 17 (8.9) | 8 (4.2) | |

| Very dissatisfied | 19 (10.0) | 3 (1.6) | |

| Not sure | 4 (2.1) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Missing | 46 (24.2) | 52 (27.4) | |

| Recommend surgery to a friend, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 108 (78.8) | 123 (95.3) | 0.18 (0.07 to 0.48); 0.001 |

| No | 29 (21.2) | 6 (4.7) | |

| Missing | 53 (27.9) | 61 (32.1) | |

| 24-hour pad weight at 12 months (g) | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI); p-value | ||

| Mean (SD); n | 30 (85); 50 | 74 (452); 44 | –50 (–228 to 128); 0.561 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.1 (0.0–7.4) | 0.1 (0.0–6.2) | |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 403 | 0, 3000 | |

| Time until return to normal activities (months) | |||

| Mean (SD); n | 2.6 (1.9); 131 | 2.2 (1.7); 124 | 0.39 (–0.09 to 0.88); 0.105 |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | |

Men randomised to receive a male sling were less likely than those in the AUS group to be satisfied with the results of their surgery (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.69; p < 0.001; see Table 11) and were also less likely to recommend their surgery to a friend (n = 108, 79%, in male sling group vs. n = 123, 95%, in AUS group; OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.48; p = 0.001).

Complications reported over the 24-month follow-up period

Complications reported by the men within their follow-up questionnaires are shown in Table 12. The higher frequency of catheter problems in the male sling group than the AUS group is also captured here. Device problems, which we described and explained more fully in Chapter 3 (device replacement/removal), are also shown here. For the other complications that are reported here, the rates are similar between the groups. Care needs to be taken when interpreting these because a device problem can be ‘need to pump several times’ or ‘small leakage’, whereas pain can be ‘soreness’ or an indication of pain that has now subsided.

| Complication | Randomised group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sling (N = 190) | AUS (N = 190) | |

| Participants with complications | 110 (57.9) | 95(50.0) |

| Number of complications per participant | ||

| 1 | 53 (27.9) | 48 (25.3) |

| 2 | 29 (15.3) | 24 (12.6) |

| 3 | 17 (8.9) | 10 (5.3) |

| 4 | 7 (3.7) | 8 (4.2) |

| ≥ 5 | 4 (2.1) | 5 (2.6) |

| Bowel obstruction | 3 (1.6) | 4 (2.1) |

| Constipation | 34 (17.9) | 27 (14.2) |

| New bladder or urinary symptoms | 25 (13.2) | 6 (3.2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 23 (12.1) | 20 (10.5) |

| Other infection | 10 (5.3) | 2 (1.1) |

| Device problems | 23 (12.1) | 37 (19.5) |

| Sexual problems | 34 (17.9) | 37 (19.5) |

| Wound breakdown | 3 (1.6) | 7 (3.7) |

| Pain at site of surgery | 56 (29.5) | 44 (23.2) |

Chapter 5 Economic analysis

Methods

Summary

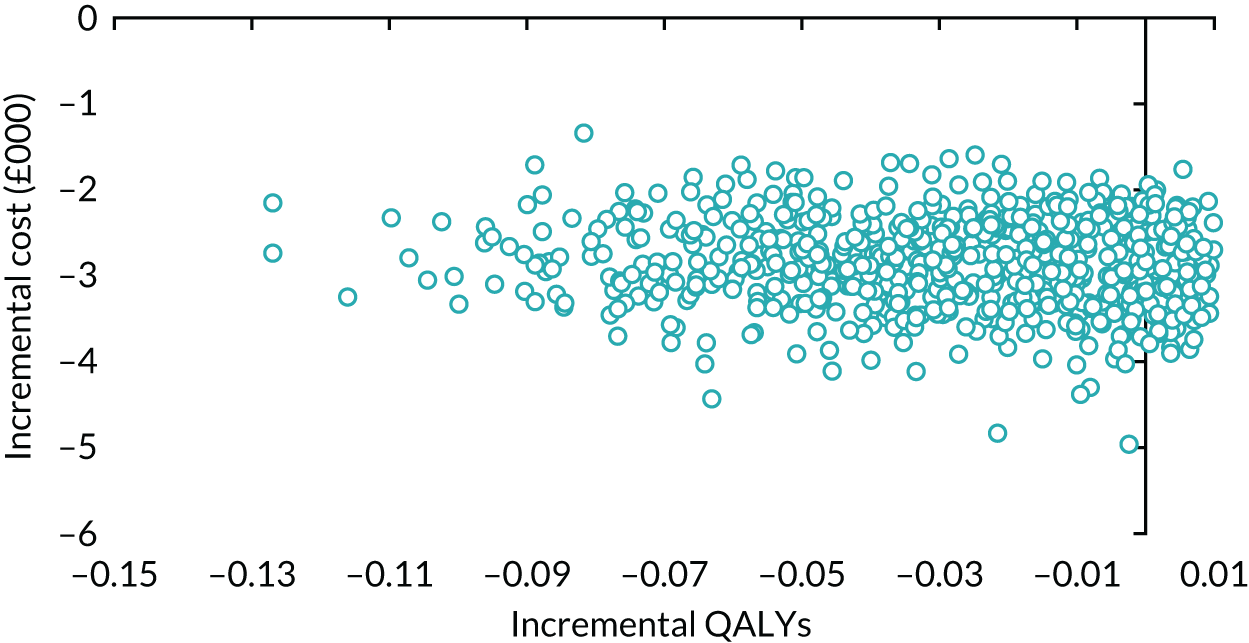

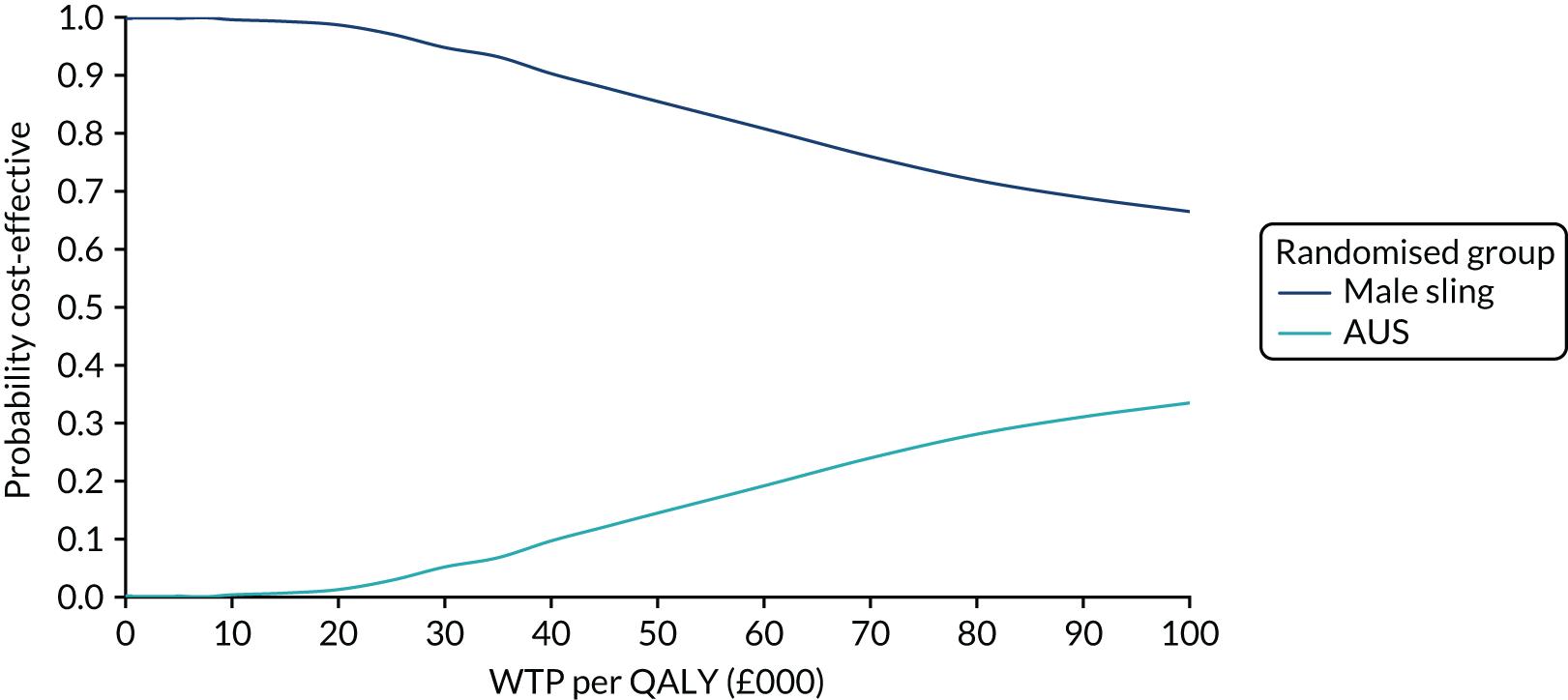

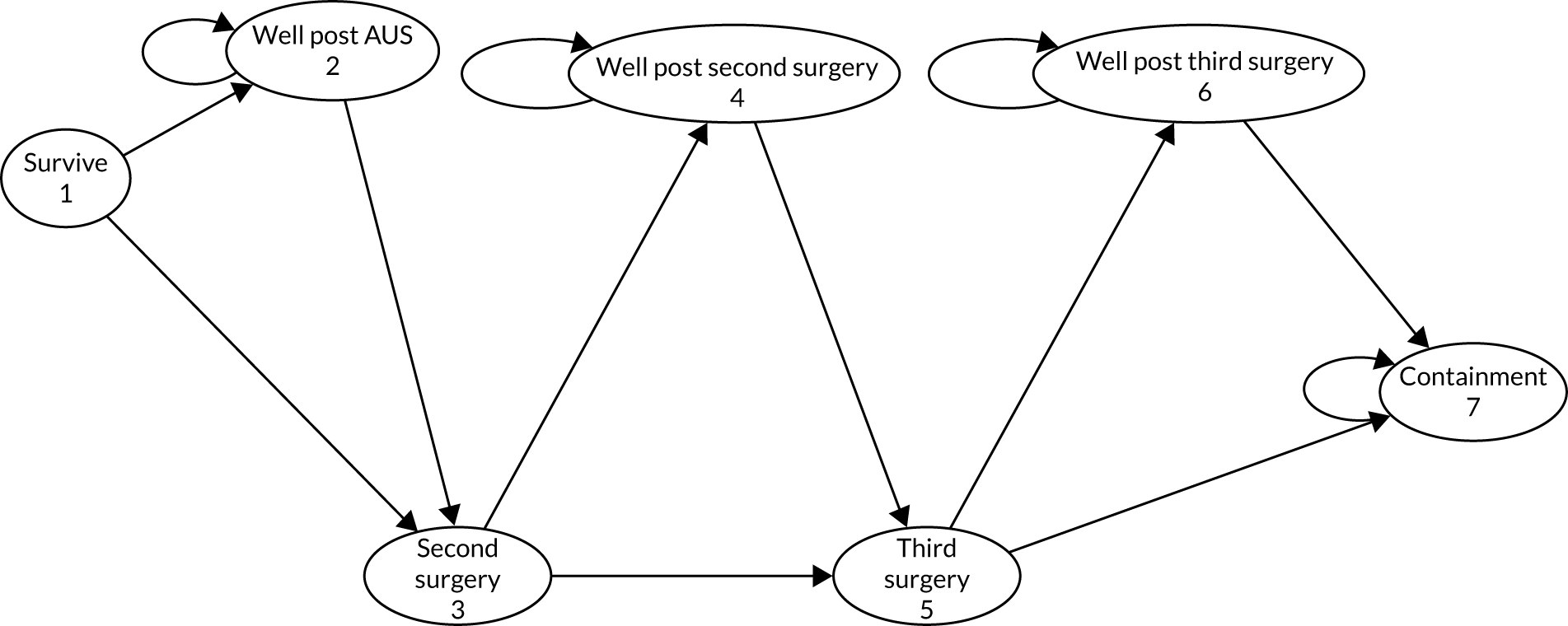

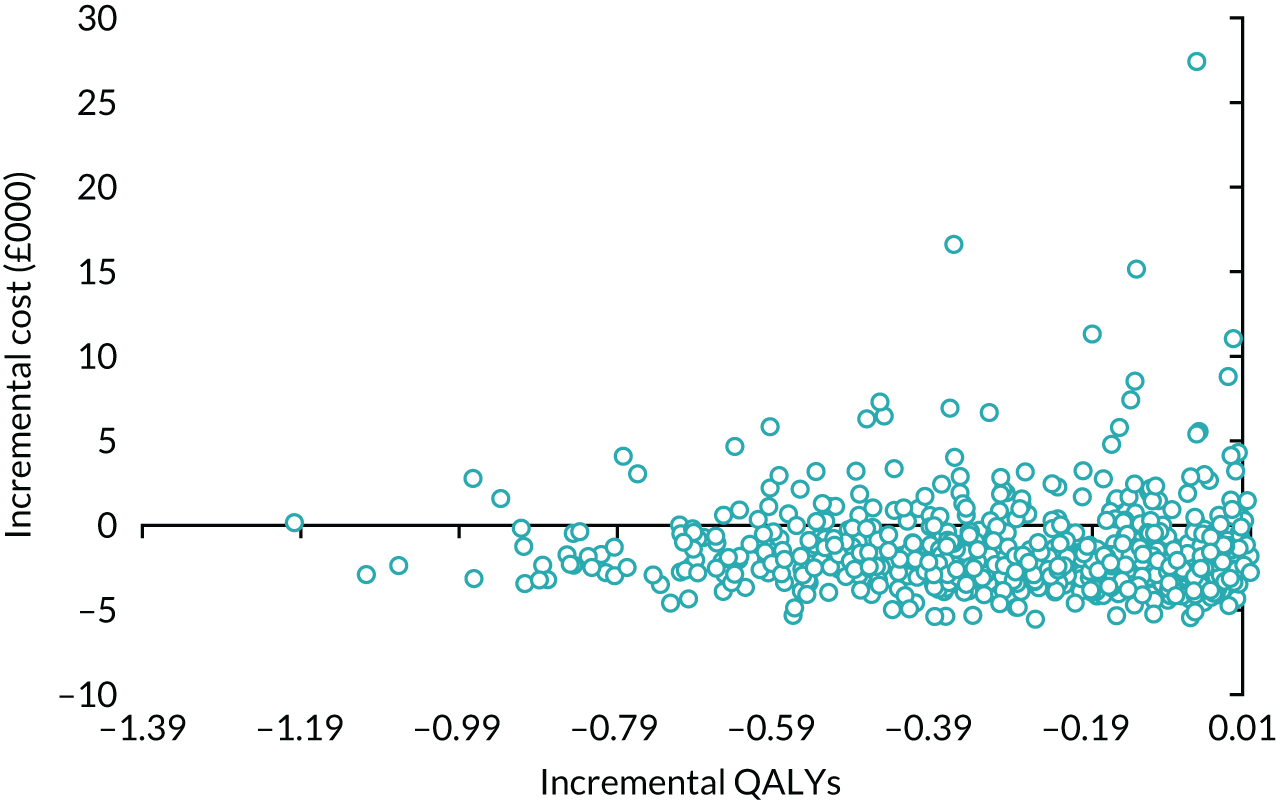

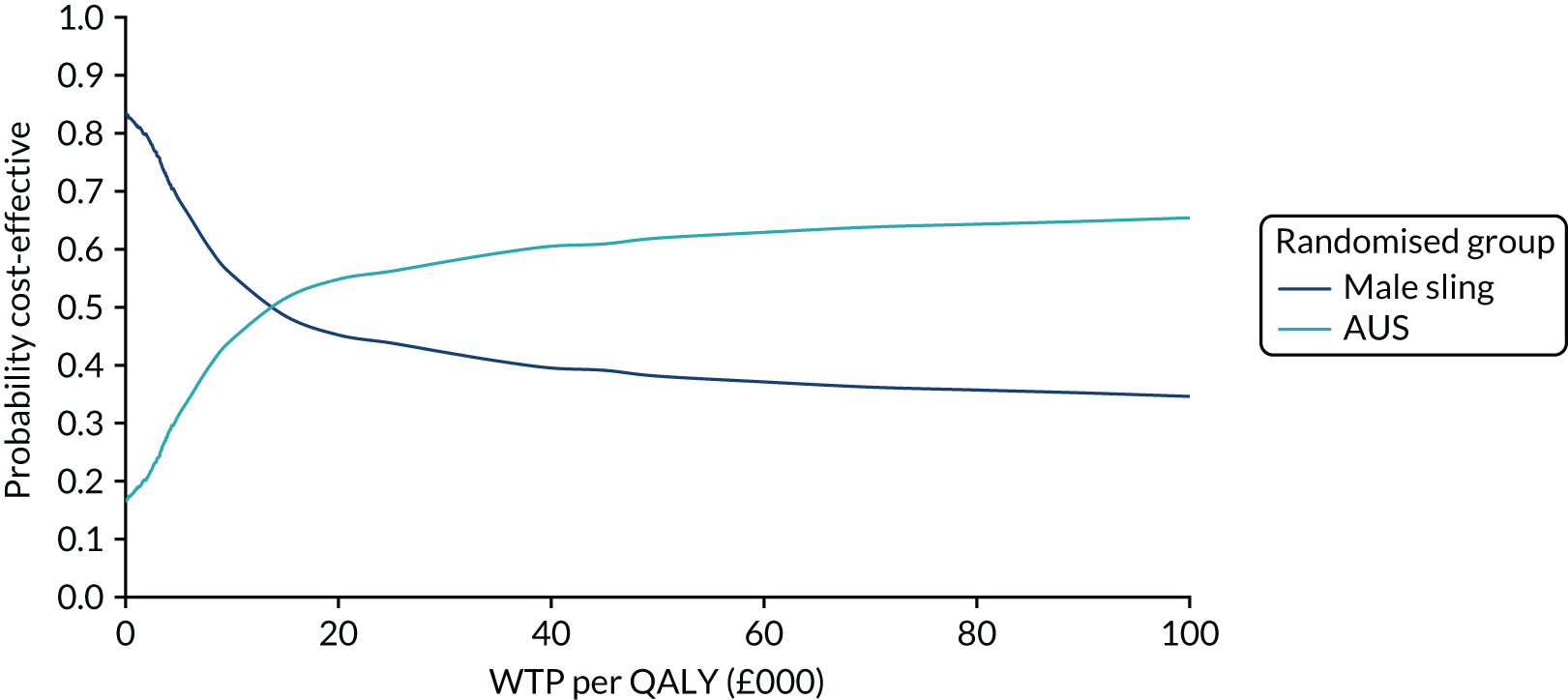

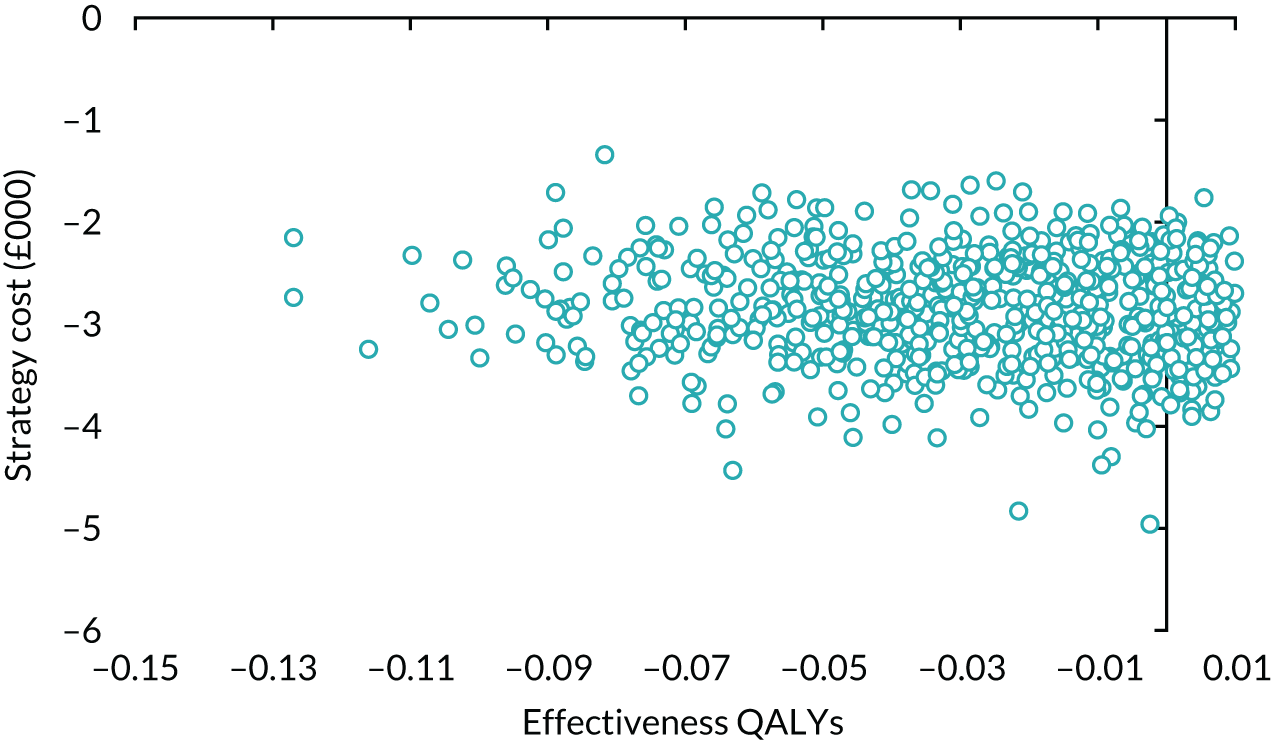

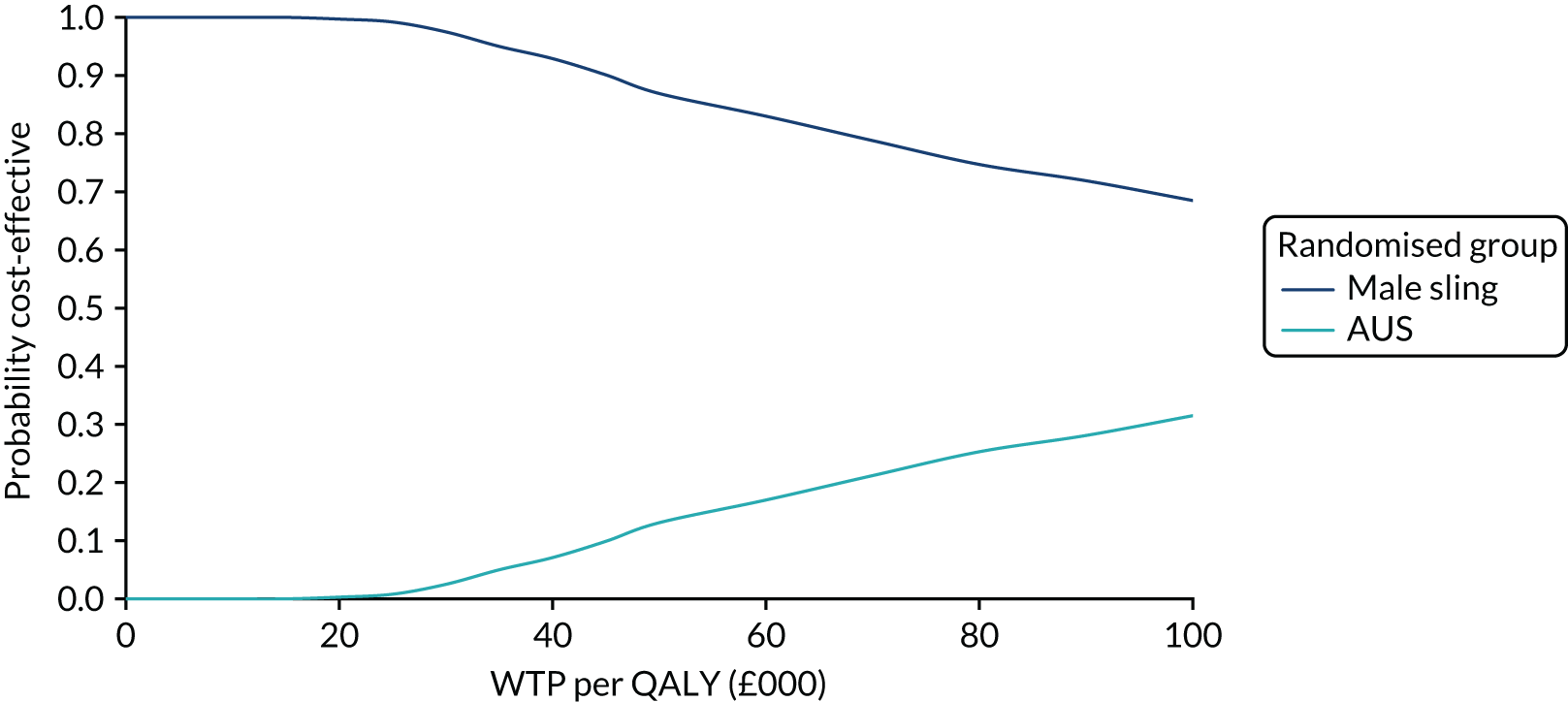

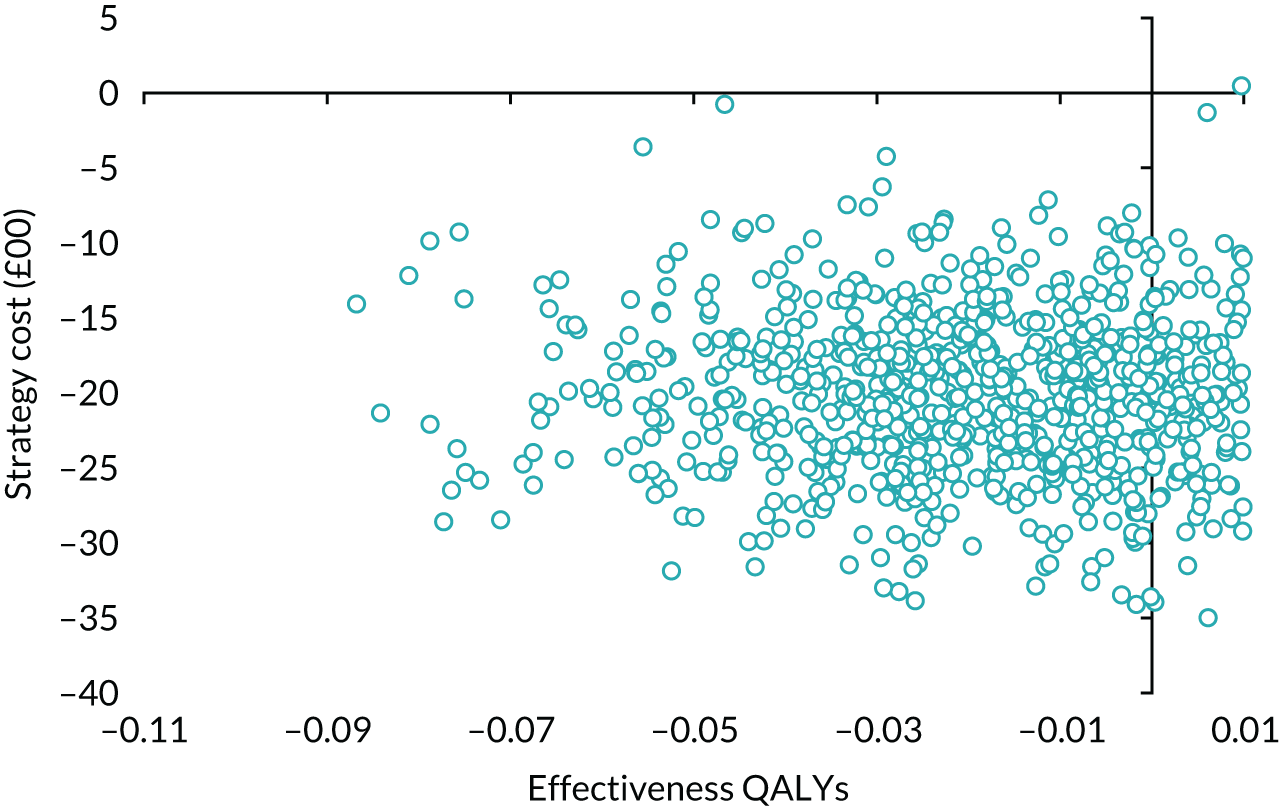

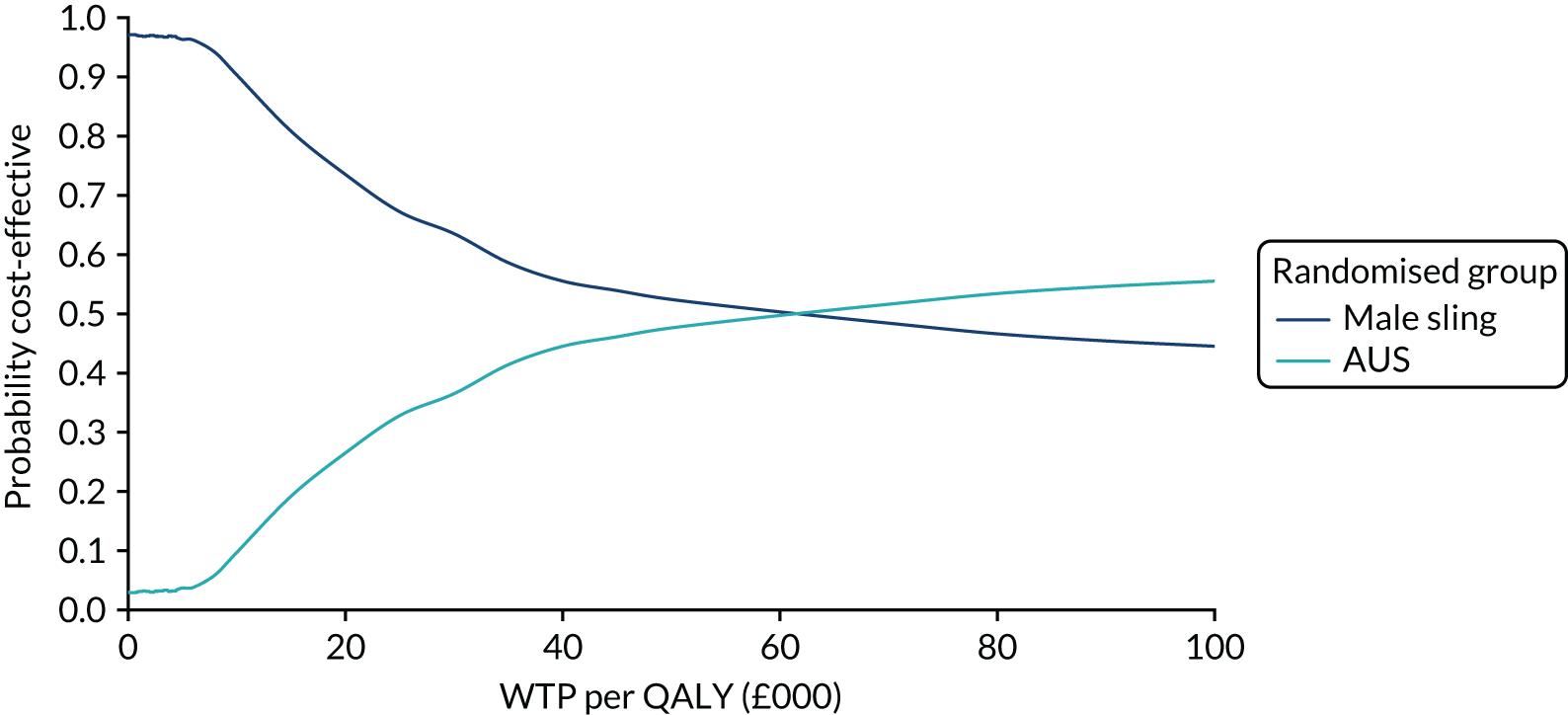

The principal research question being addressed in the economic analysis was the cost-effectiveness of a policy of primary implantation of the male synthetic sling compared with AUS, measured by incremental cost per QALY at 24 months post randomisation. The within-trial economic evaluation analysis follows the ITT principle and is based on data collected alongside the RCT and the health economics plan. A Markov cohort decision analysis model was developed to consider a longer time horizon to provide additional information for policy-makers. The base-case analysis assessed the costs and cost-effectiveness of the interventions compared with the perspective of the NHS in accordance with the NICE recommendations. 17 Sensitivity analyses exploring a broader perspective of cost were also conducted. Data were collected on resource use for the delivery of the intervention; primary and secondary NHS resource use over 24 months’ follow-up, including referral for additional specialist management; and broader societal resource use, which included personal costs to the participants for containment products, private medical costs and lost productivity costs, mainly lost income, over the 24 months. All costs were expressed in Great British pounds and were valued in 2017–18 prices. Costs and benefits experienced after the first year were discounted at the recommended 3.5% per annum. 17 The sensitivity analysis explored the impact of varying key assumptions on the base-case estimates of cost-effectiveness in accordance with NICE recommendations. The methods for within-trial and modelling analyses are described here.

Within-trial economic evaluation

Measuring resource use

Intervention resource use was recorded prospectively for every participant in the study (Table 13). Intervention resource was collected using an intraoperative (theatre) case report form (CRF). This included the grade and type of staff who administered the intervention, the operating urologist (and whether or not they were supervised), the anaesthetist and nurses. The operation time was calculated from the time of entry into the anaesthetic room to the time of leaving the theatre. The type of anaesthesia administered was identified as general, spinal or local. Information that was collected included the device that participants received, either AUS or sling; the use of prophylactic antibiotic; pre-treatment and post-treatment catheterisation; the use of either oral or parenteral pain relief; the use of postoperative antibiotic treatment; and the length of stay.

| Resource | Unit cost (£) | Notes and source of information |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention device | ||

| Slings | 2281 | Average price paid for device over the study period (personal communication with three sitesa) |

| AUS | 4519 | Average price paid for device over the study period (personal communication with three sitesa) |

| Consultant surgeon | 109 | Cost per hour (PSSRU)18 |

| Specialty registrar | 47 | Cost per hour (PSSRU)18 |

| Consultant anaesthetist | 109 | Cost per hour (PSSRU)18 |

| Theatre nurse band 6 | 45 | Average cost per hour (PSSRU)18 |

| Theatre nurse band 5 | 34 | Average cost per hour (PSSRU)18 |

| Theatre nurse band 4 | 9 | Average cost per hour (PSSRU)18 |

| General anaesthesia | 22 | Anaesthesia consumables cost per average case (BNF);19 details in Appendix 3, Table 42 |

| Spinal anaesthesia | 2 | Anaesthesia consumables cost per average case (BNF);19 details in Appendix 3, Table 42 |

| Local anaesthesia | 2 | Anaesthesia consumables cost per average case (BNF);19 details in Appendix 3, Table 42 |

| Antibiotics | 1 | Prophylactic antibiotic Gentamicin (BNF)19 |

| Catheter | 2 | Foley (male) short/medium term (single use) |

| Inpatient stay | 413 | Weighted average of LB50 and LB21: excess elective inpatient stay (cost per day) (NHS Reference Costs)20 |

| Theatre services | 740 | ISD National Statistics Theatre costs per hour excluding staff and drugs (ISD)21 |

| Secondary care costs | ||

| Sling surgery | 4374 | Based on average cost of slings in the study |

| 5529 | Used for the sensitivity analysis. Weighted average of LB21 (with CC score of 0–1 and 2 +). Elective inpatient: major open, prostate or bladder neck procedures (male) (NHS Reference Costs)20 | |

| AUS surgery | 6612 | Based on average cost of AUS in the study |

| 8465 | LB50Z Elective inpatient implantation of artificial urinary sphincter (male and female) (NHS Reference Costs)20 | |

| Antibiotics | 2 | Weekly average cost of several antibiotics to treat wound infection details in appendix (BNF)19 |

| Incontinence tablets | 4 | Weekly average cost of several incontinence medications details in appendix (BNF)19 |

| Outpatient visit | 110 | Service code 101 total outpatient attendance: average of urology department outpatient appointment (NHS Reference Costs)20 |

| Sheath | 43 | Calculated average cost per week (NHS Electronic Drug Tariff 201922) (see Appendix 3, Table 44) |

| Permanent catheter | 5 | Calculated average cost per week (NHS Electronic Drug Tariff 201922) (see Appendix 3, Table 43) |

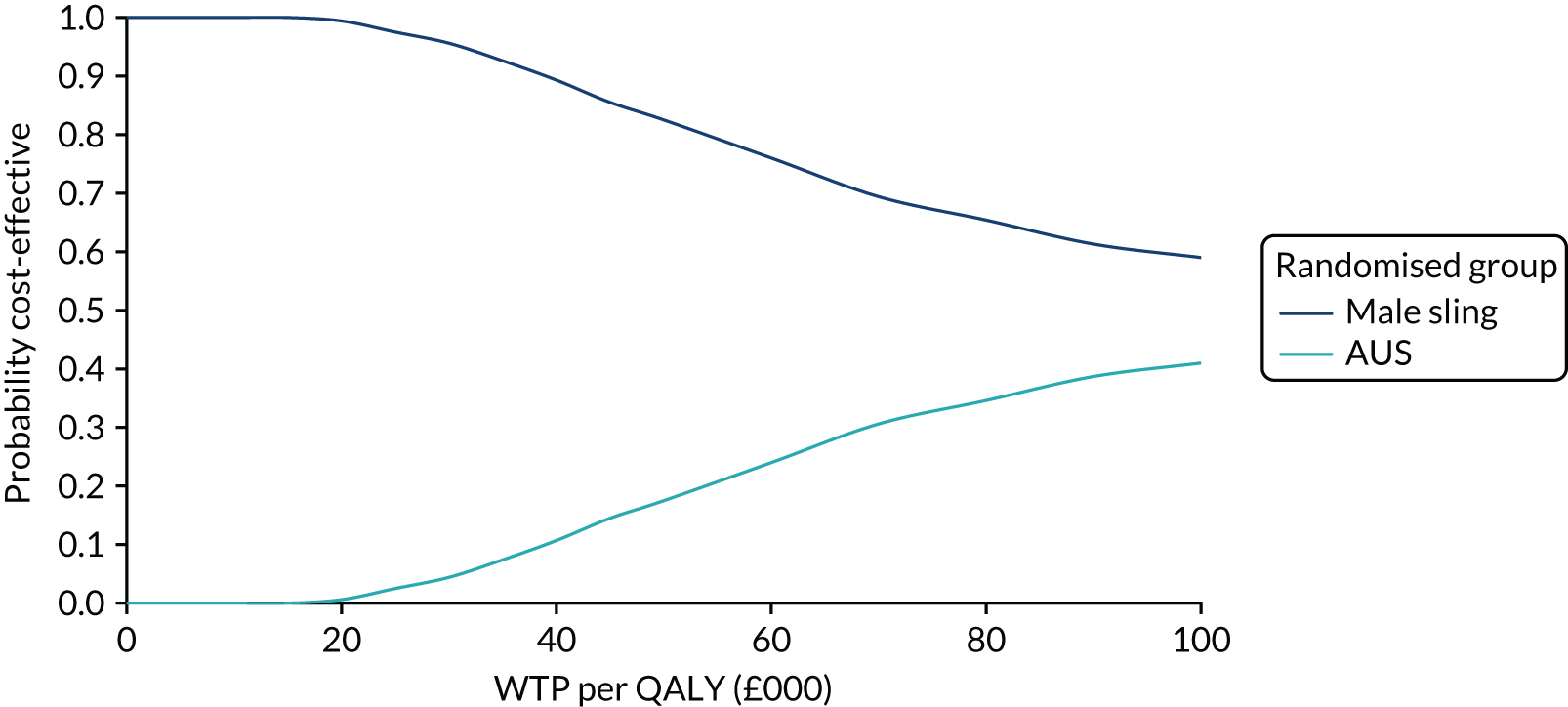

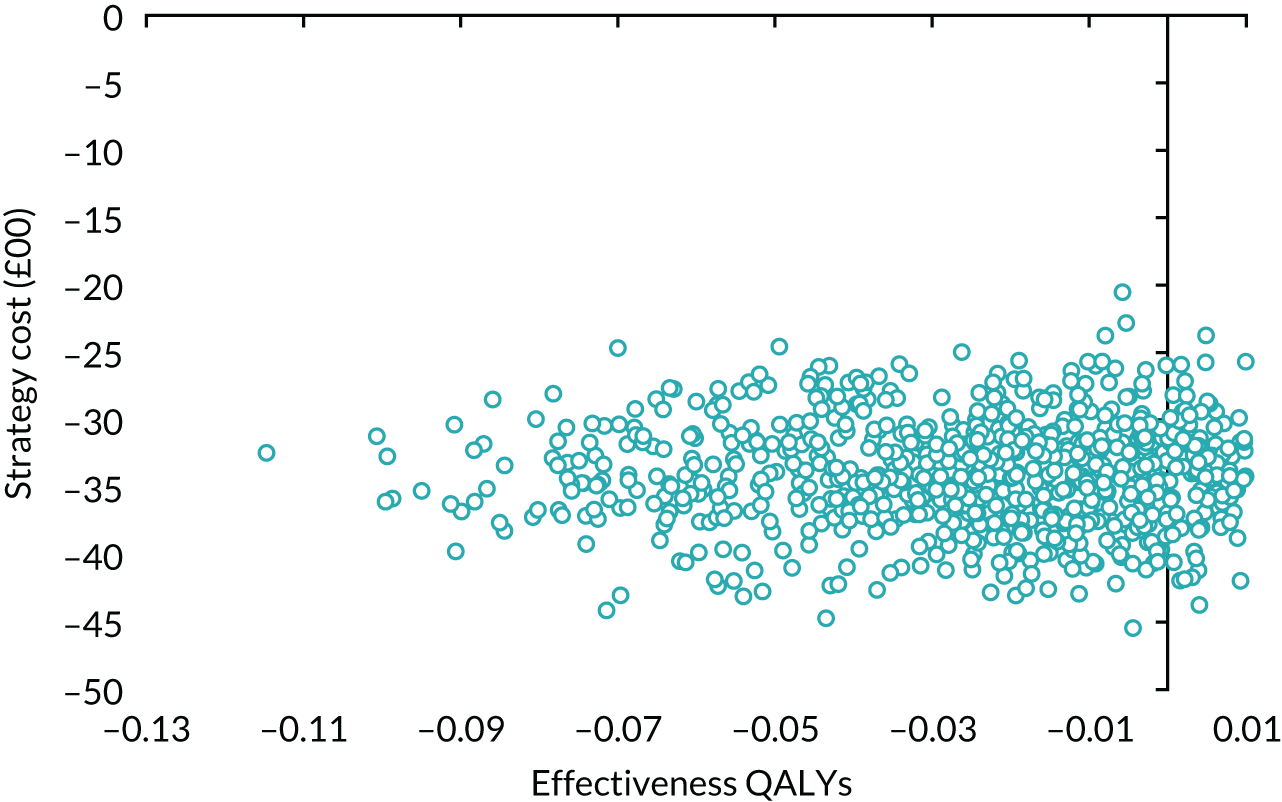

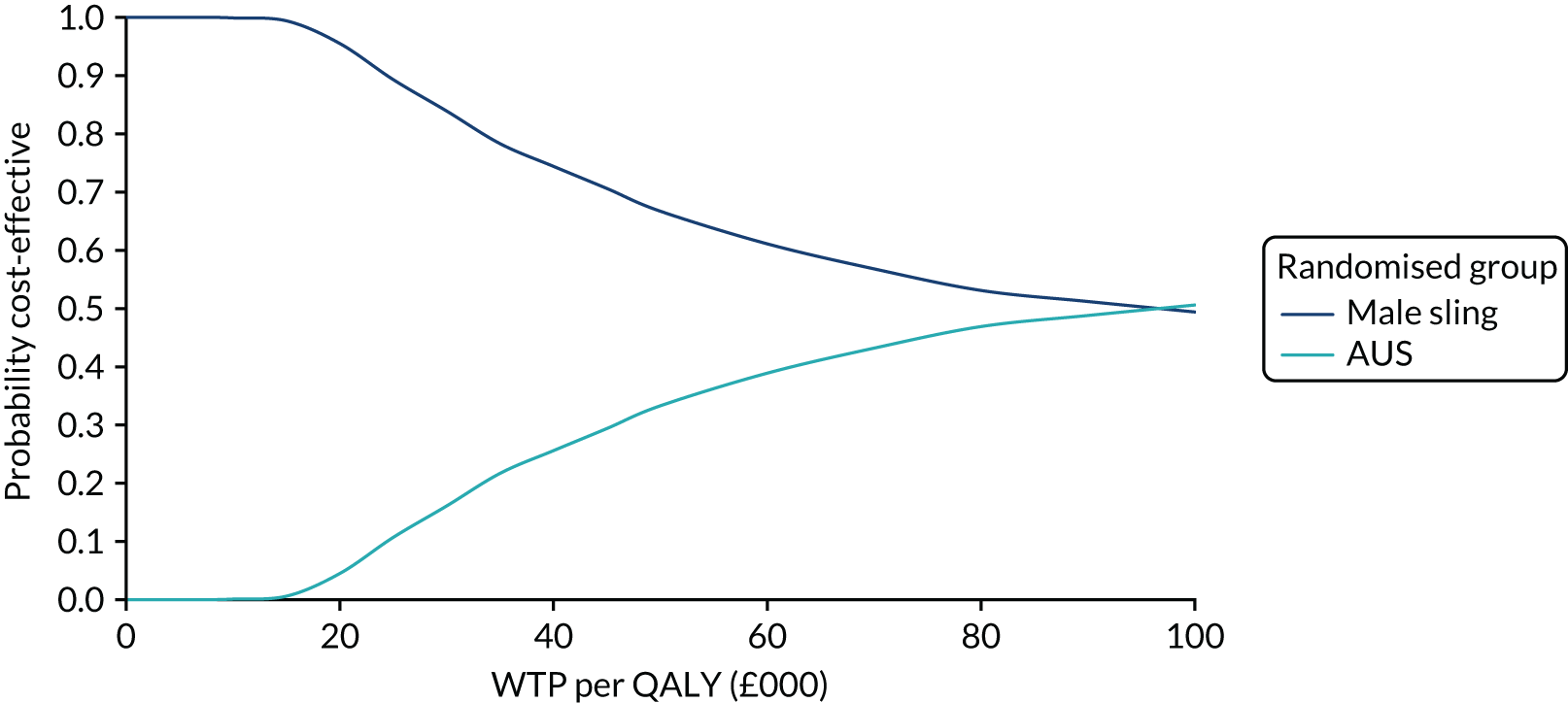

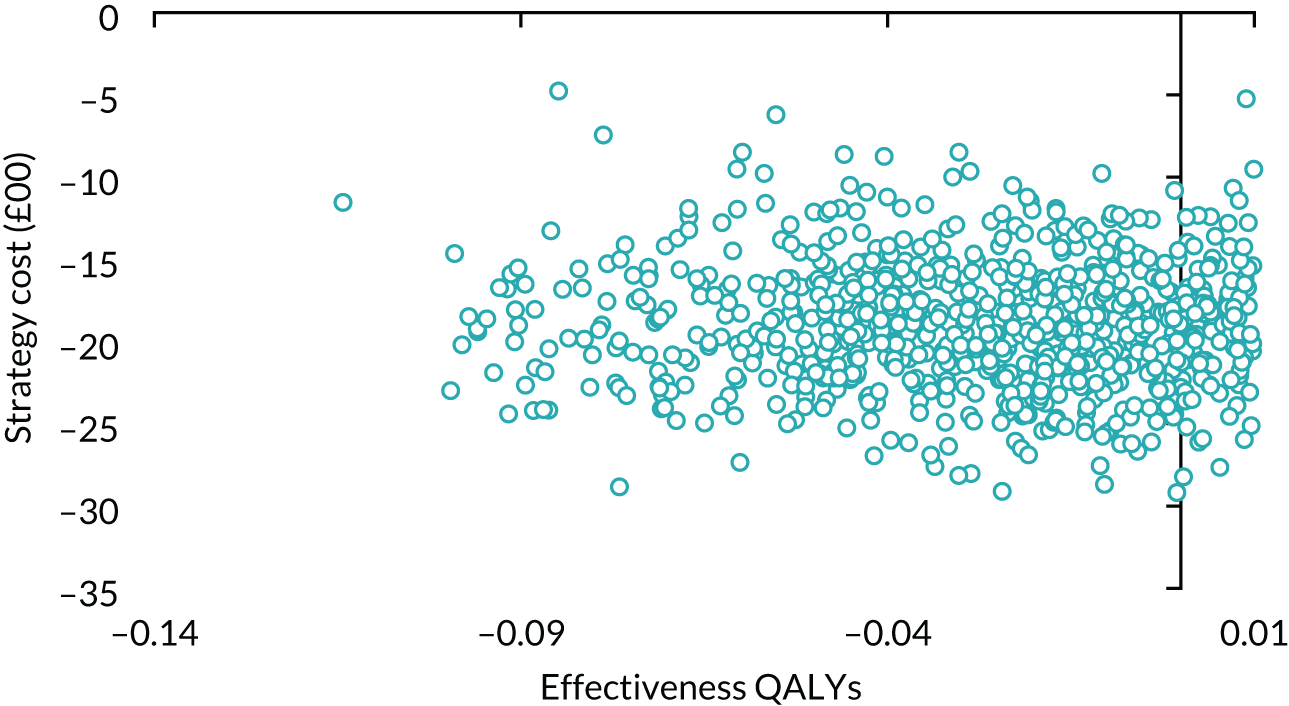

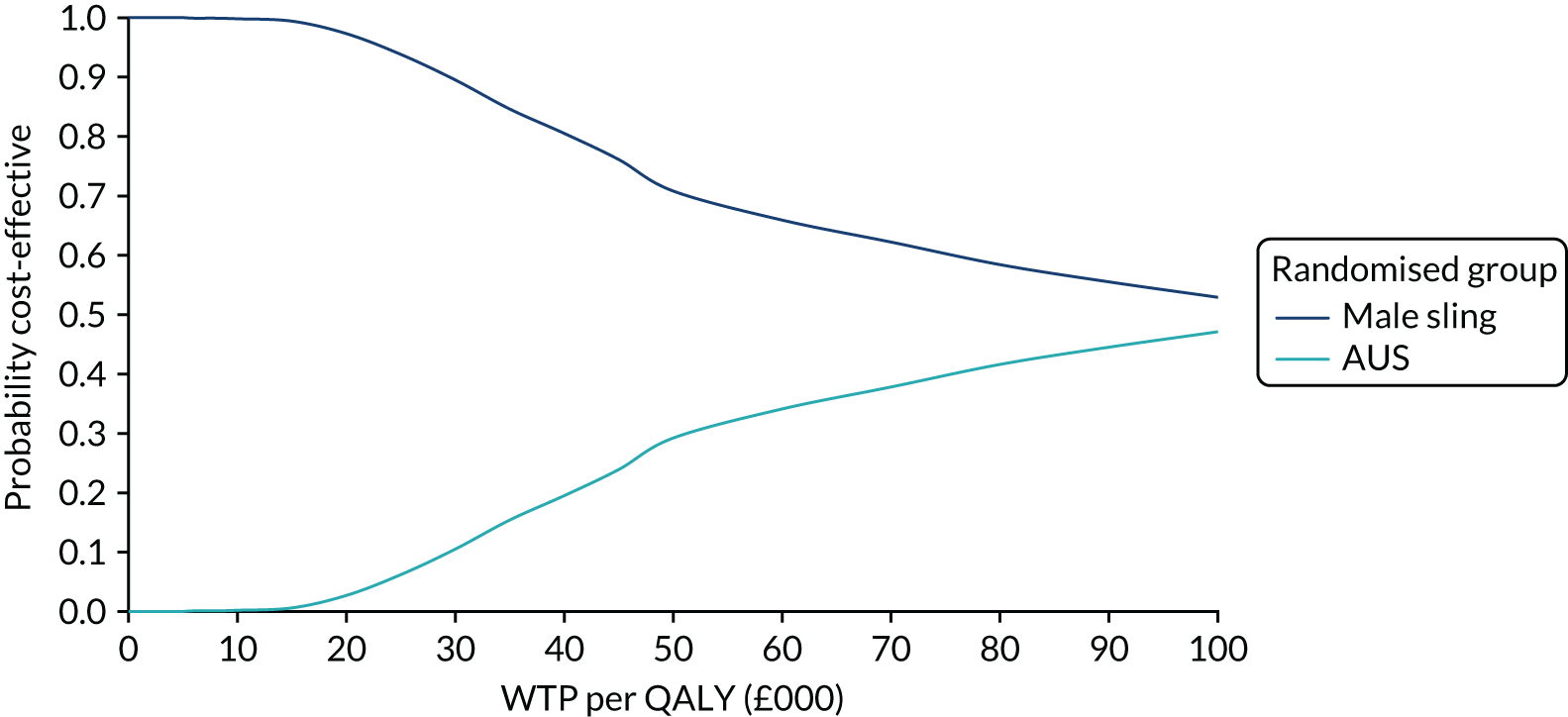

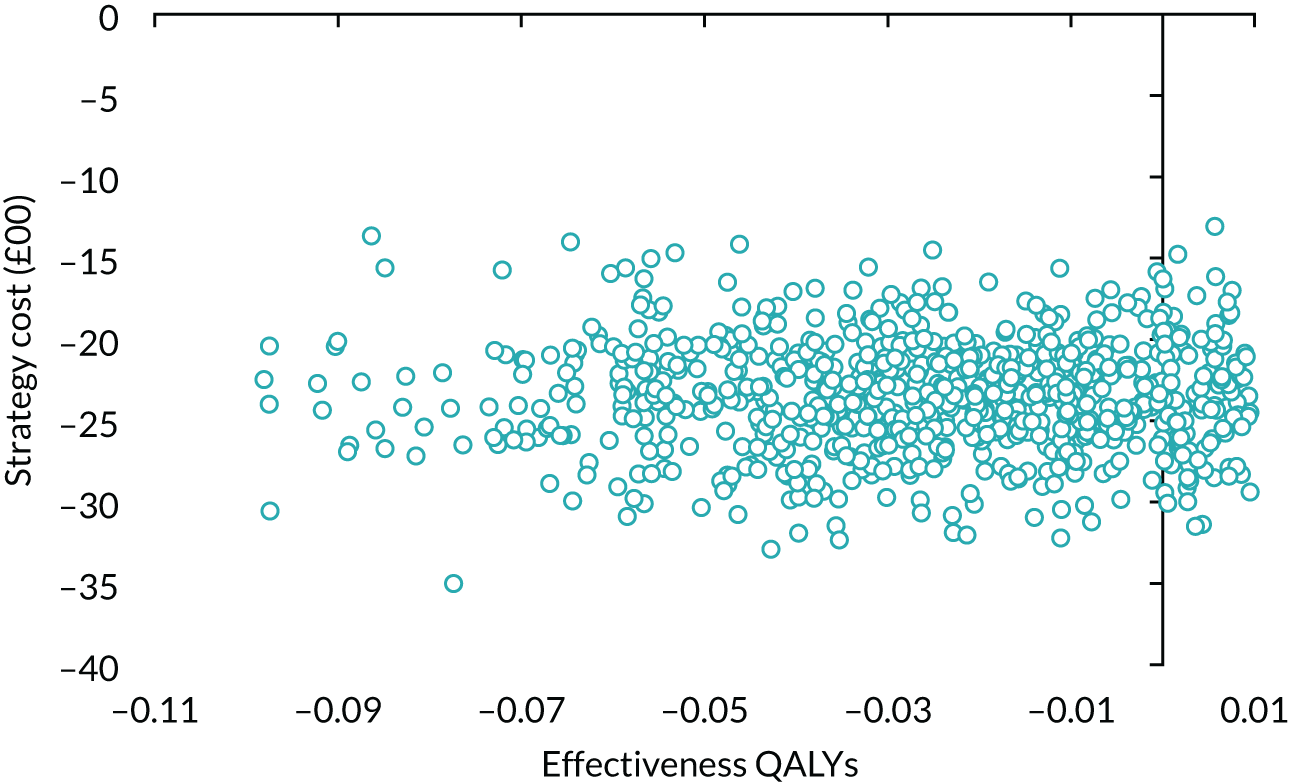

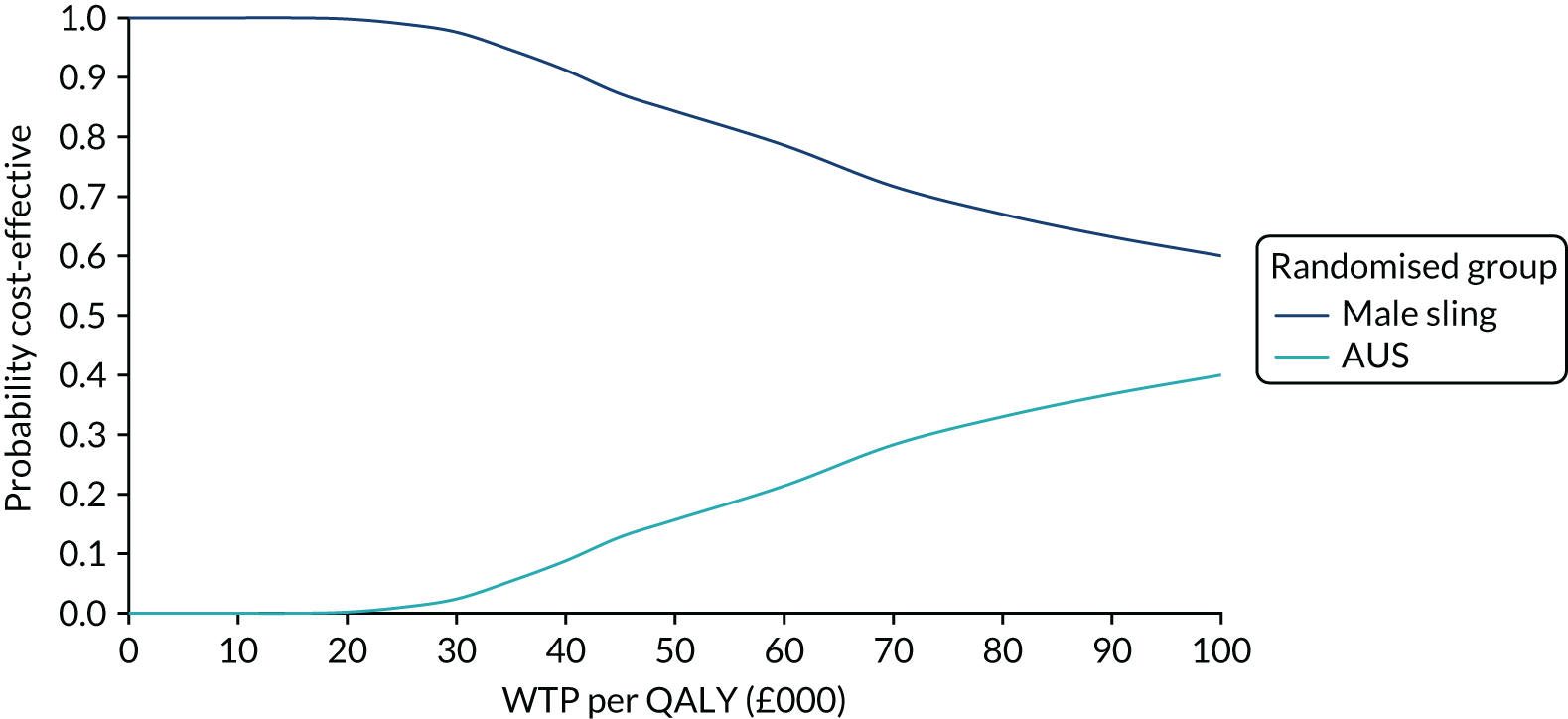

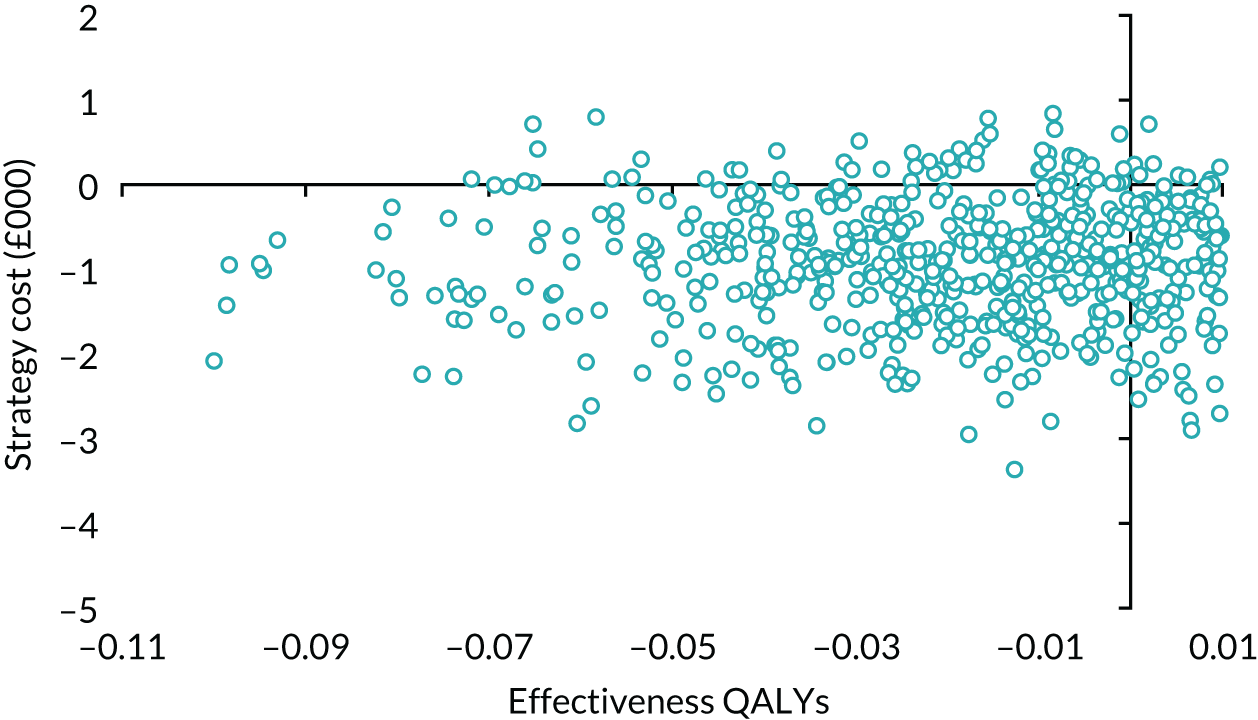

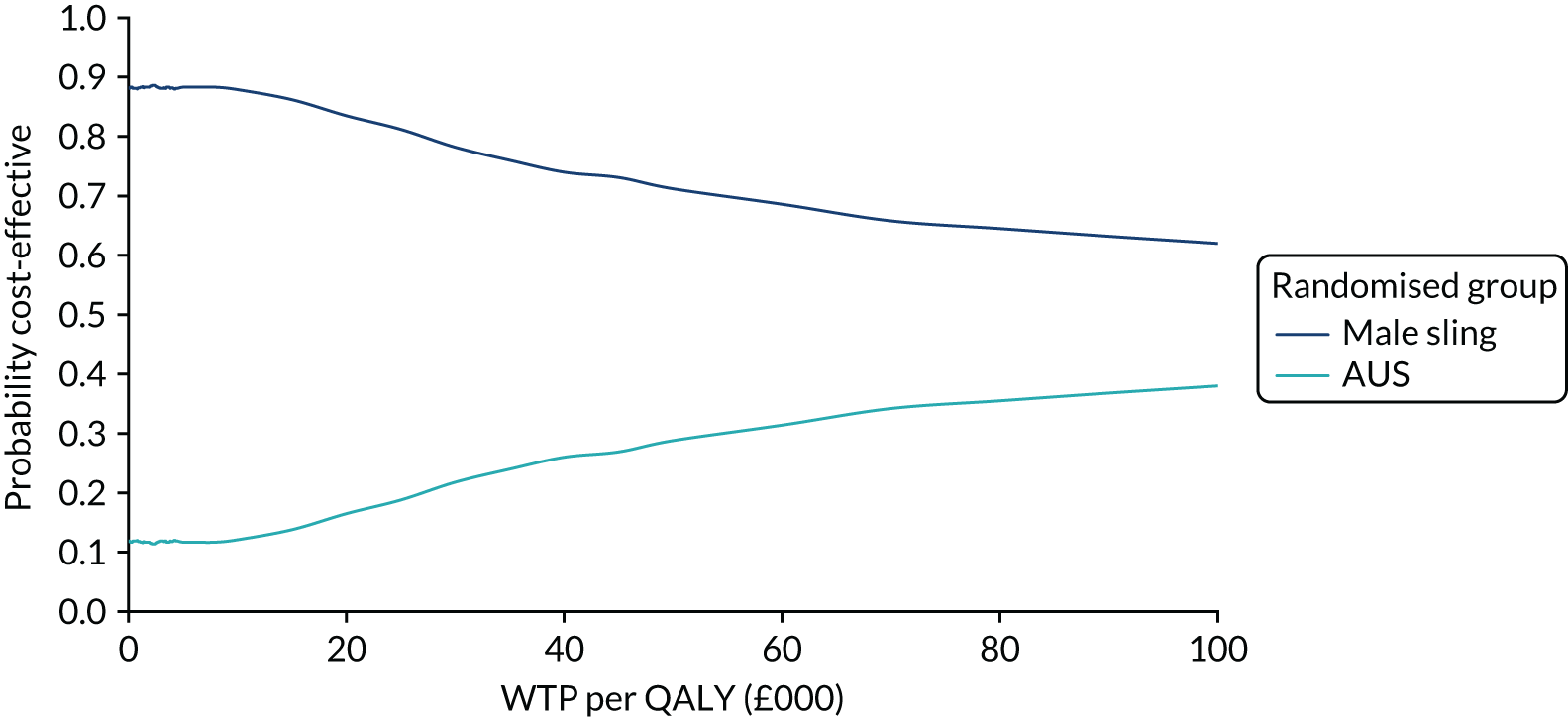

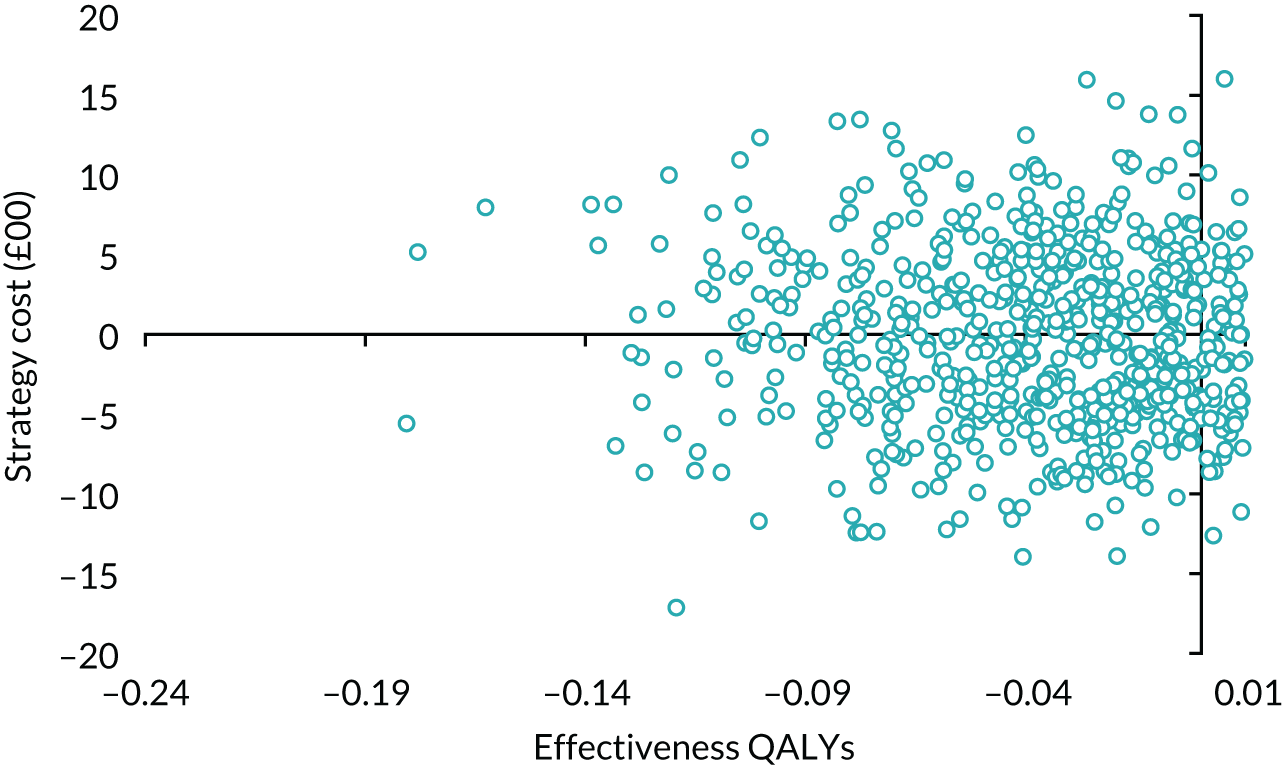

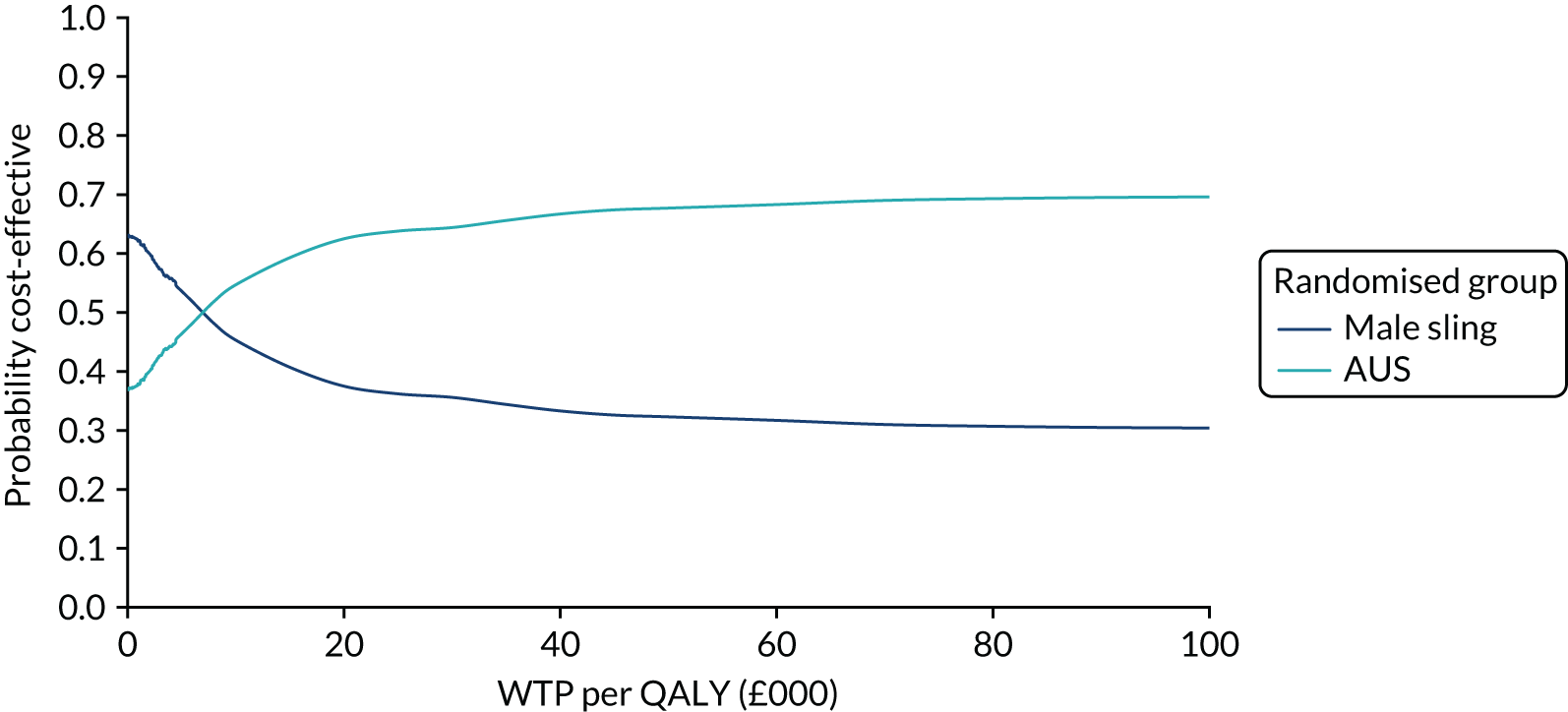

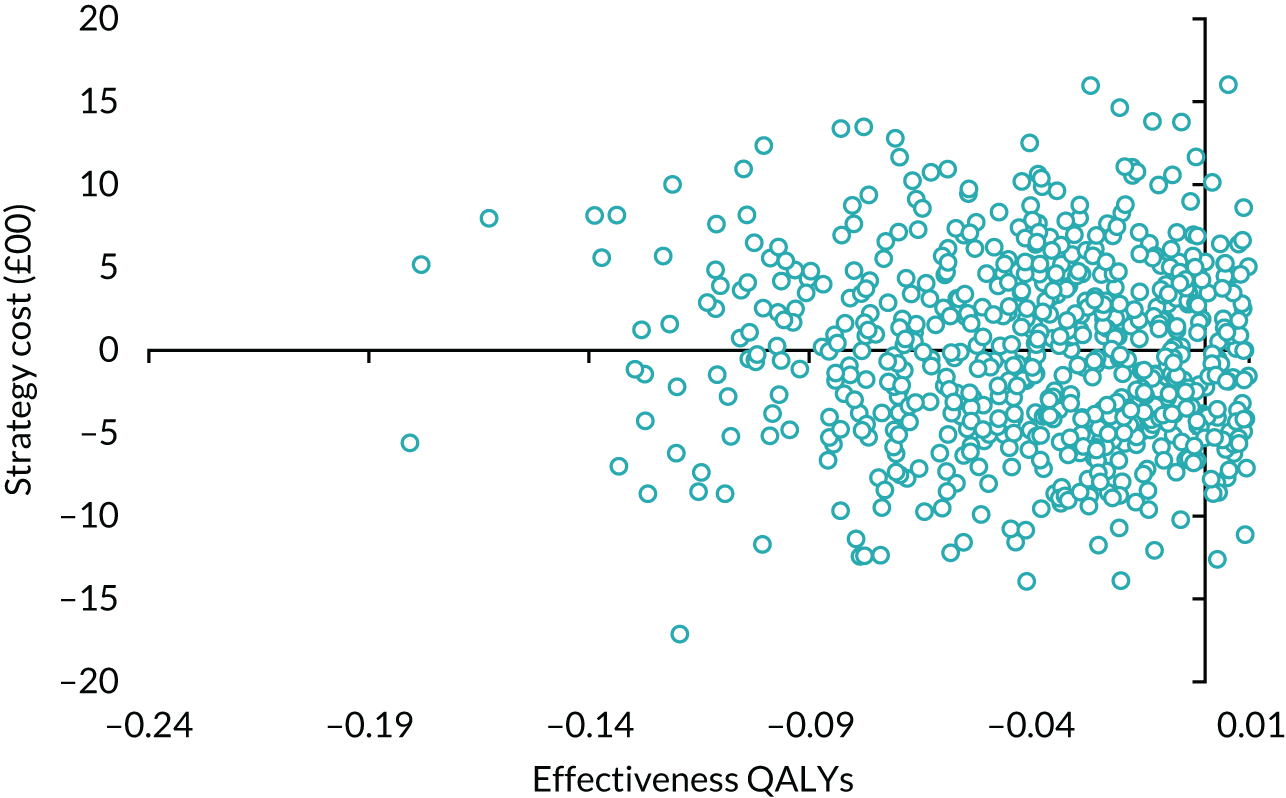

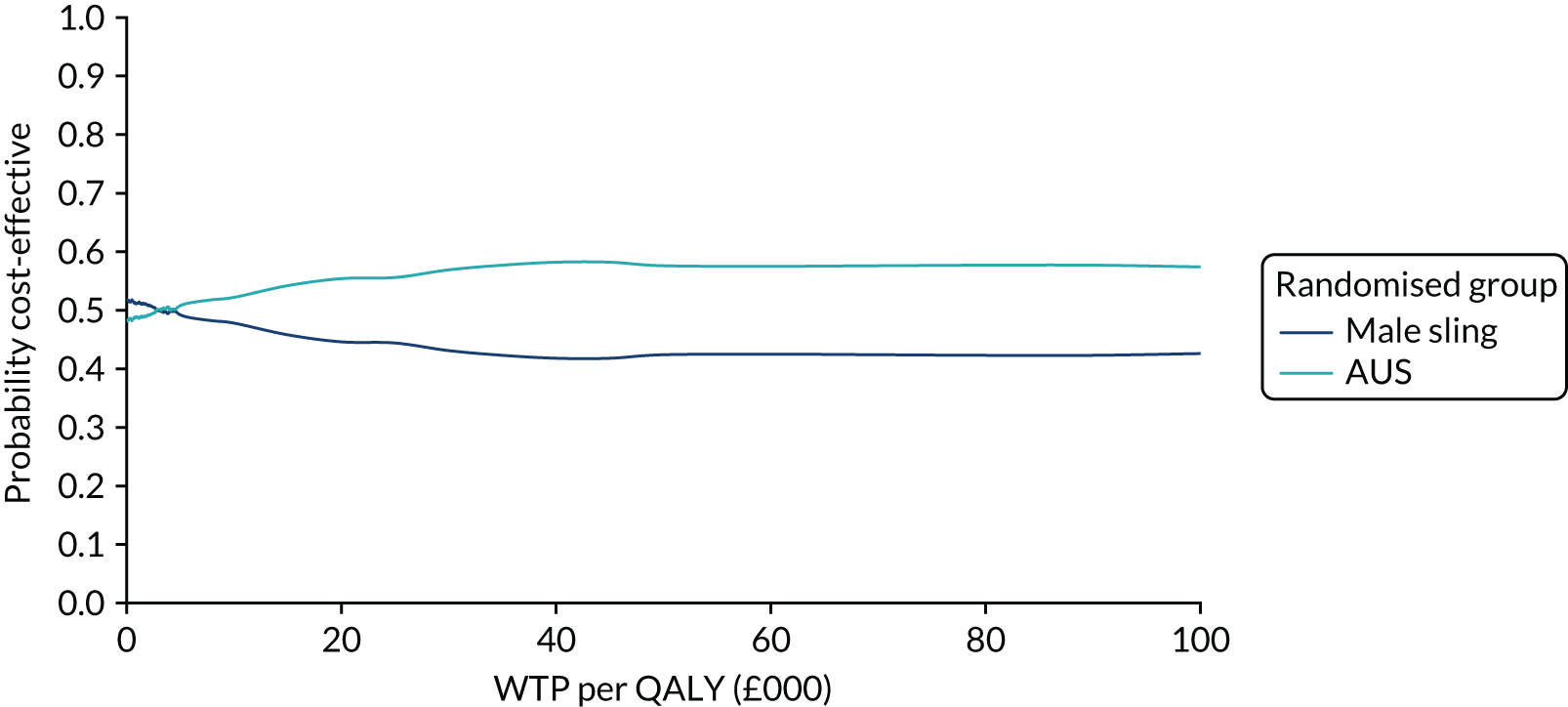

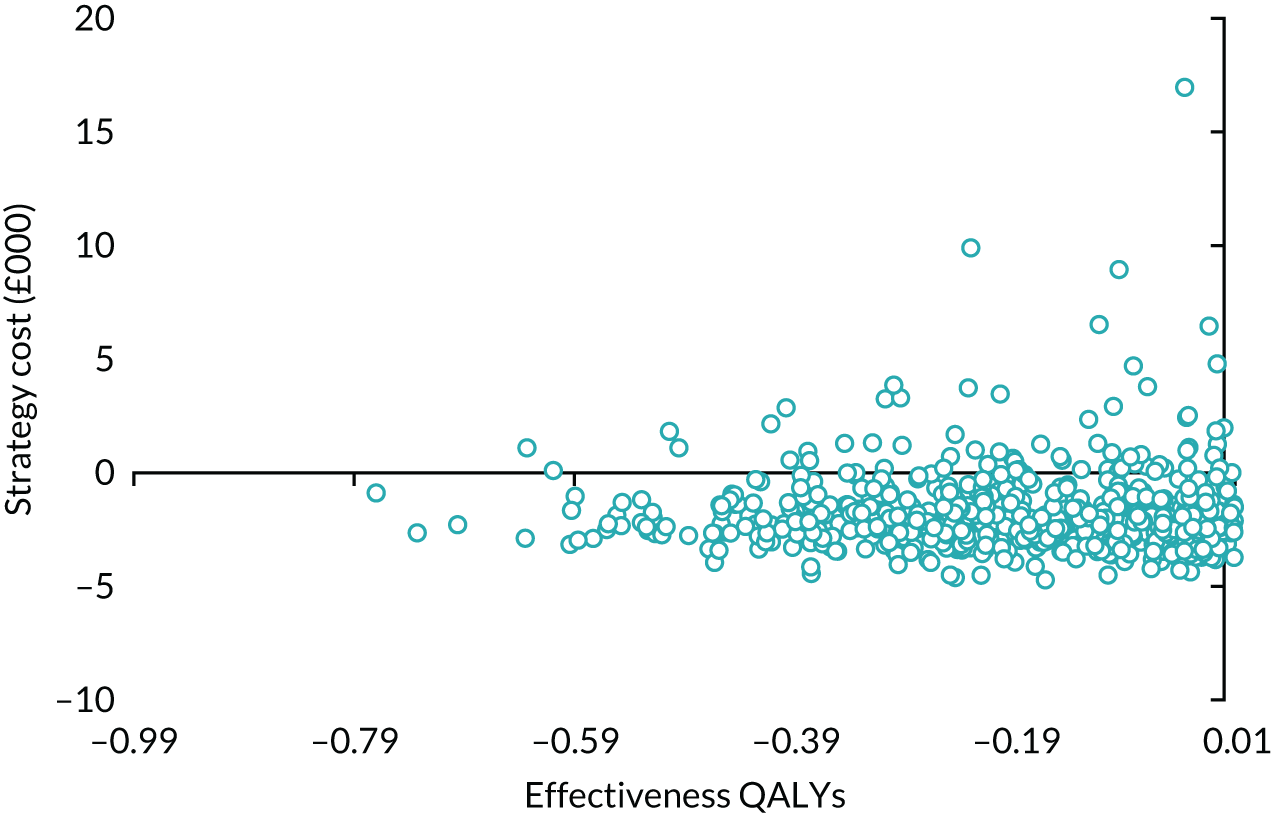

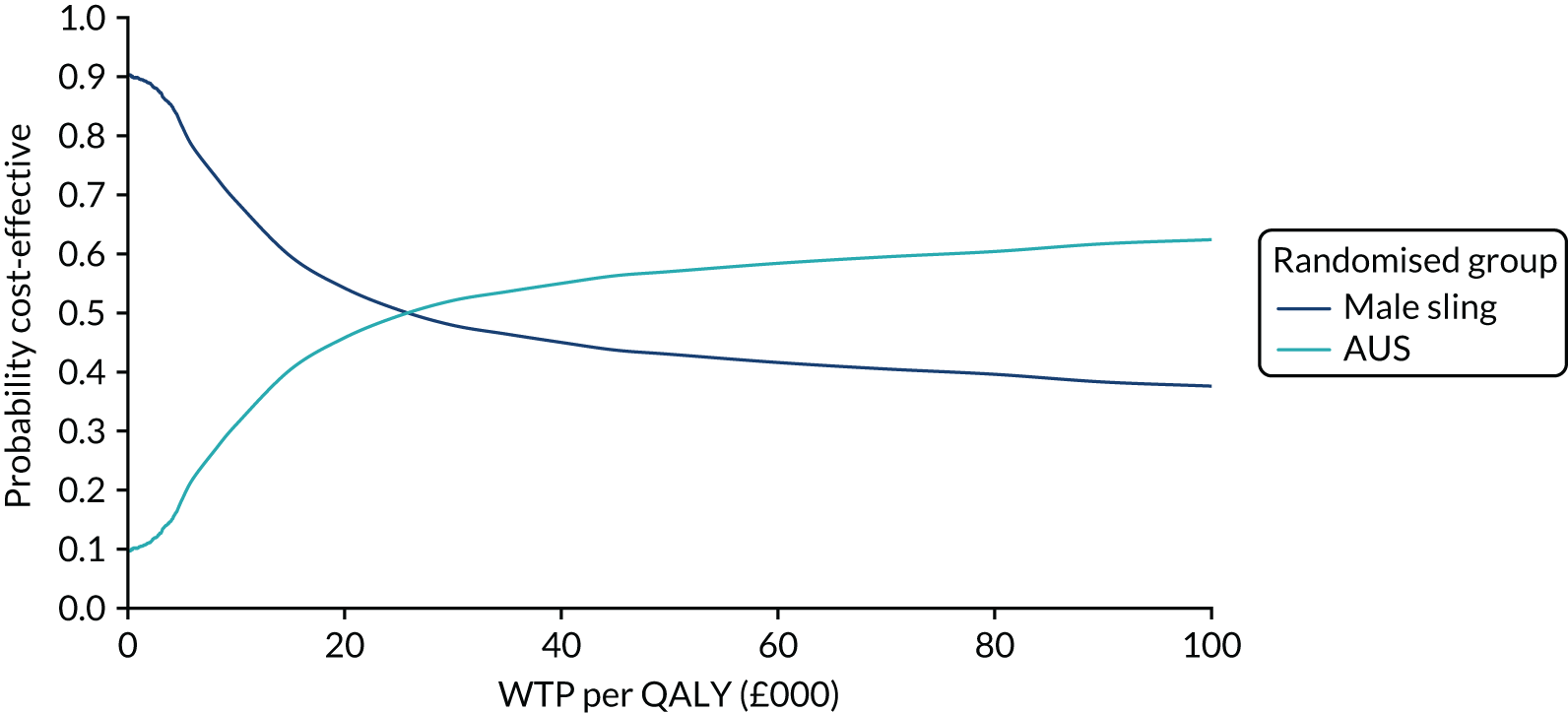

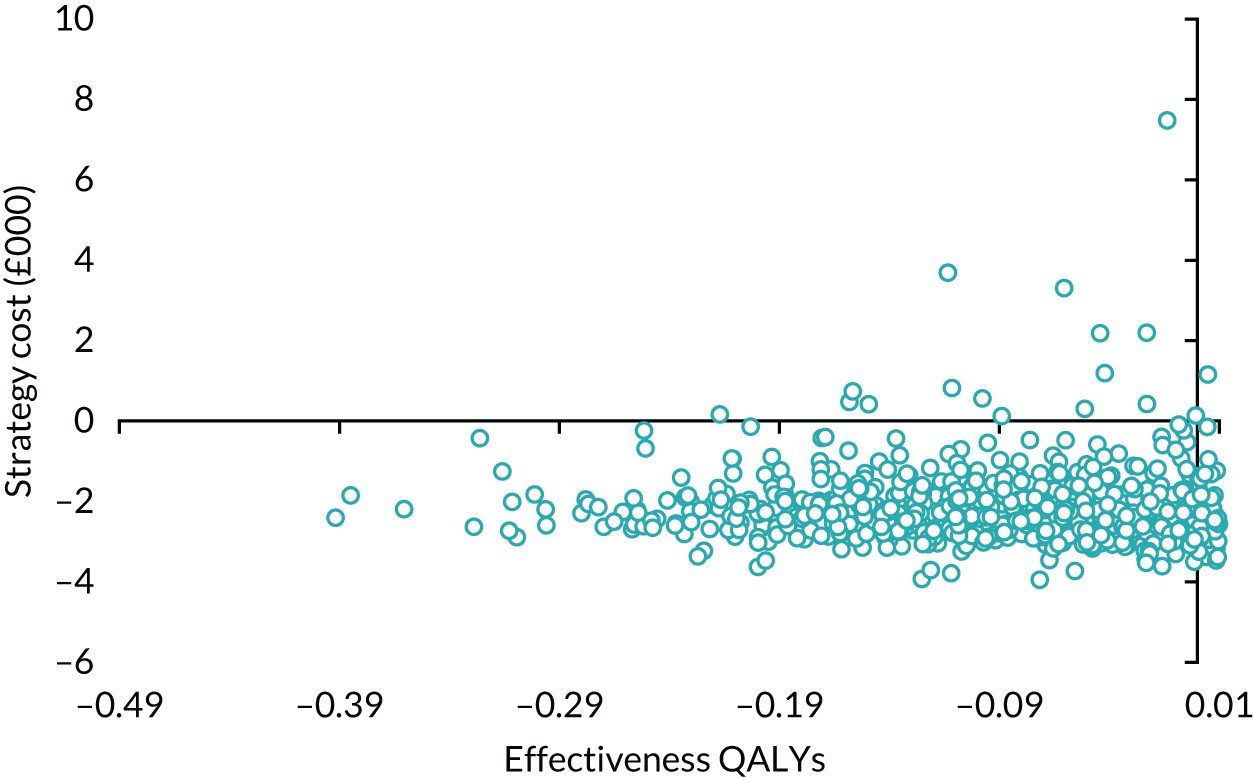

| Removal of AUS | 5529 | Weighted average of LB21 (with a CC score of 0–1 and 2 +); elective inpatient: major open, prostate or bladder neck procedures (male) (NHS Reference Costs)20 |