Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/04/03. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Lim et al. This work was produced by Lim et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Lim et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout this report has been reproduced from the trial protocol. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background and rationale

Lung cancer is a leading cause of cancer death worldwide and survival in the UK remains among the lowest in Europe. 2 In early-stage lung cancer, surgery is commonly undertaken through an open thoracotomy. However, minimal-access video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) was introduced in the 1990s, and the evolution of the technique from minor procedures eventually led to its successful application in anatomic lung cancer resections, undertaken using a telescope and television screen, with small incisions in the chest. Since then, minimal access surgery has increased in popularity on the premise that smaller incisions without rib spreading may improve recovery after lung surgery. Data from the UK demonstrates exponential growth in popularity of this technique. In 2010, 14% of lobectomy procedures were performed using VATS access, and this increased to 40% in 2014. 3

To date, much of the evidence generated for VATS is based on non-randomised studies4,5 or small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that focus on in-hospital outcomes. 6 These studies are underpowered to detect clinically meaningful differences in longer-term outcomes7 or have focused solely on operative technique. 8 Currently, the largest RCT, comparing VATS with open surgery in 206 participants followed for 1 year, reported shorter hospital stay and less pain in patients randomised to VATS lobectomy. 9 In this study,9 carried out in Denmark, all patients received epidural anaesthesia and anterior thoracotomy for open surgery, which is not the current practice for most thoracic surgery centres in the UK. In contrast, a recent trial10 in 425 patients recruited in China reported a similar hospital stay and rate of morbidity and mortality at 28 days in both the VATS and axillary thoracotomy groups. 10 To the best of our knowledge, there are no high-quality comparative data on physical function (as a global measure of recovery from surgery), hospital readmissions, the uptake and timing of chemotherapy nor cancer recurrence, and few high-quality RCT data on the cost-effectiveness of VATS compared with open surgery. The Danish investigators11 have compared VATS with open surgery from an economic societal cost perspective and there is an ongoing multicentre trial in (Lungsco01) France with a target sample size of 600 participants that plans a similar comparison. 12

A well-designed and well-conducted RCT comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of VATS and open surgery is needed to inform current UK (NHS) practice, health policy and individual surgeon and patient decision-making.

Aims and objectives

The VIdeo assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy versus conventional Open LobEcTomy for lung cancer (VIOLET) study aimed to compare the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of VATS lobectomy with open surgery for treatment of lung cancer.

Specific objectives were to estimate the differences in the primary outcome (i.e. self-reported physical function at 5 weeks) and a range of secondary outcomes, including efficacy, safety, oncological outcomes and survival, between participants allocated to VATS and participants allocated to open surgery, and to compare the cost-effectiveness of the two surgical strategies.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

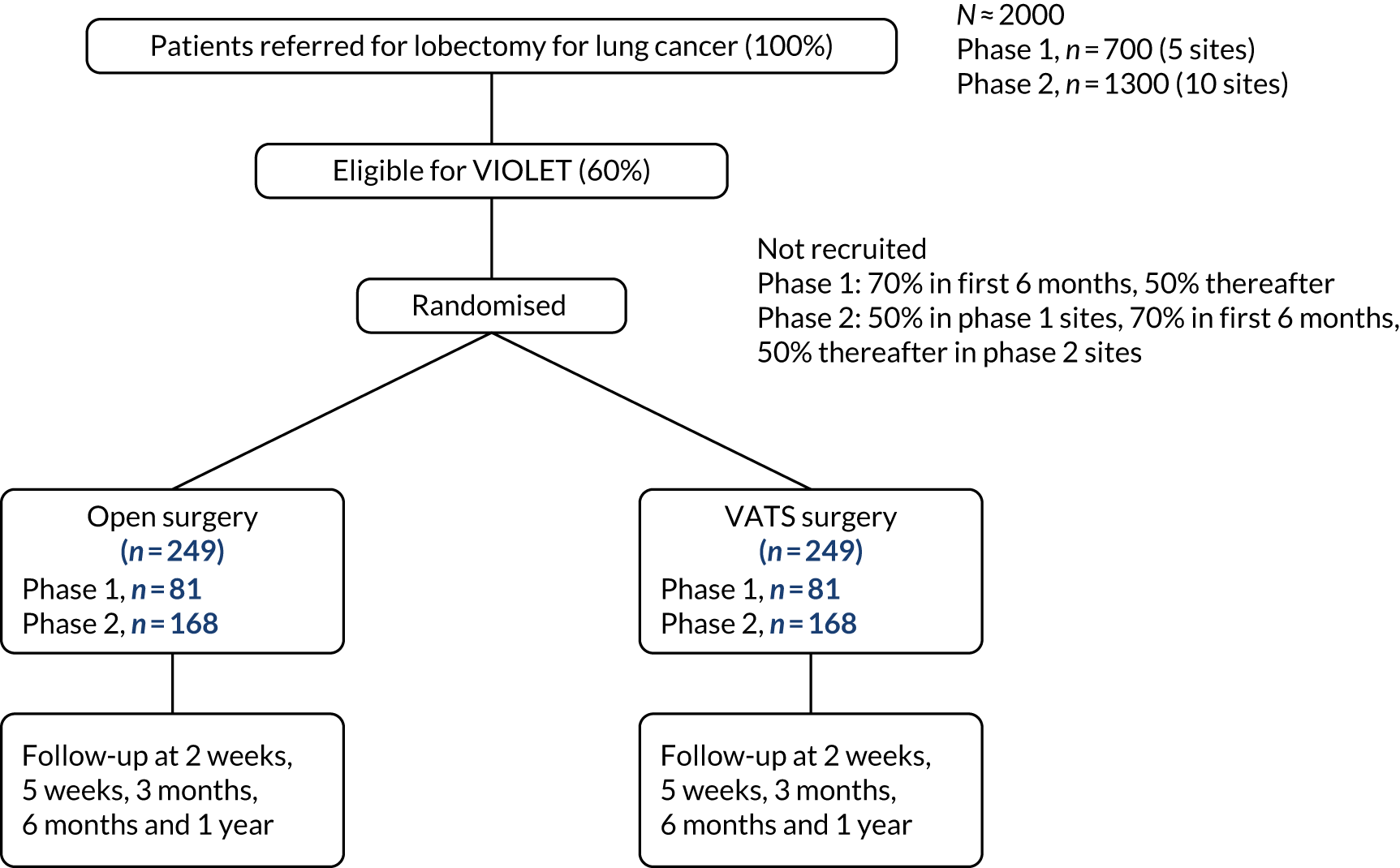

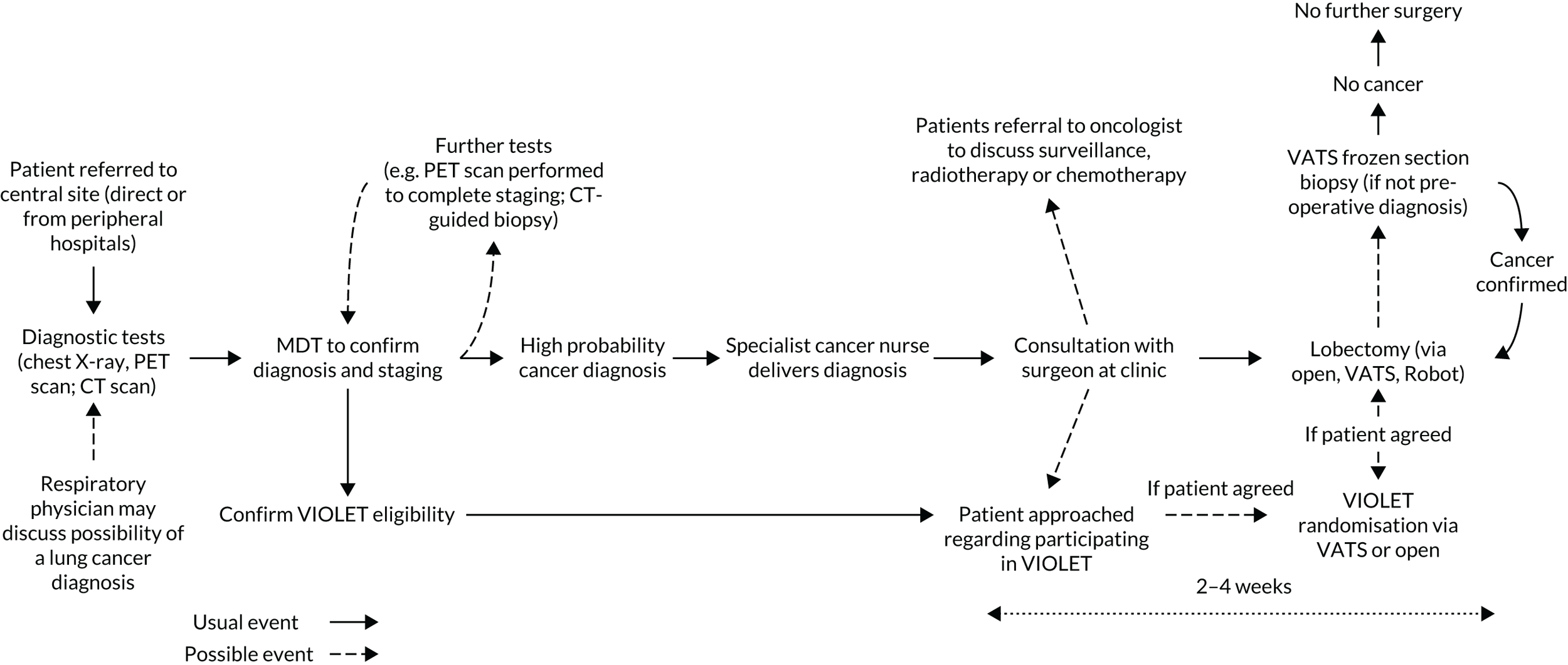

A multicentre, parallel-group, superiority RCT, with blinding of outcome assessors and participants (until hospital discharge after surgery) and active follow-up to 1 year. The trial included an internal pilot phase and a QuinteT Recruitment Intervention (QRI) to optimise recruitment (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The trial schema for the VIOLET study.

Criteria for progression from Phase I to Phase II

During the first phase, processes for trial conduct, including recruitment and consent, were established. Progression from the internal pilot (Phase I) to the full trial (Phase II) was dependent on the following criteria being met when assessed 18 months after the start of recruitment:

-

At least 60% of patients undergoing lobectomy are considered eligible for the trial (if necessary, by revising the eligibility criteria).

-

At least 50% of patients consent to randomisation after 6 months of recruitment.

-

Less than 5% of patients fail to receive their allocated treatment.

-

Less than 5% of patients are lost to follow-up (excluding deaths).

In Phase II, the number of study sites was increased and all sites used the optimum methods of recruitment established in Phase I.

Changes to trial design after commencement of the trial

There were several substantial amendments made to the study protocol throughout the course of the trial. The changes are summarised below. The protocol version in use when the trial started was version 2.0. The current full trial protocol can be found in the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Journals Library [URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/130403/#/ (accessed 27 October 2021)].

First amendment (before recruitment started)

-

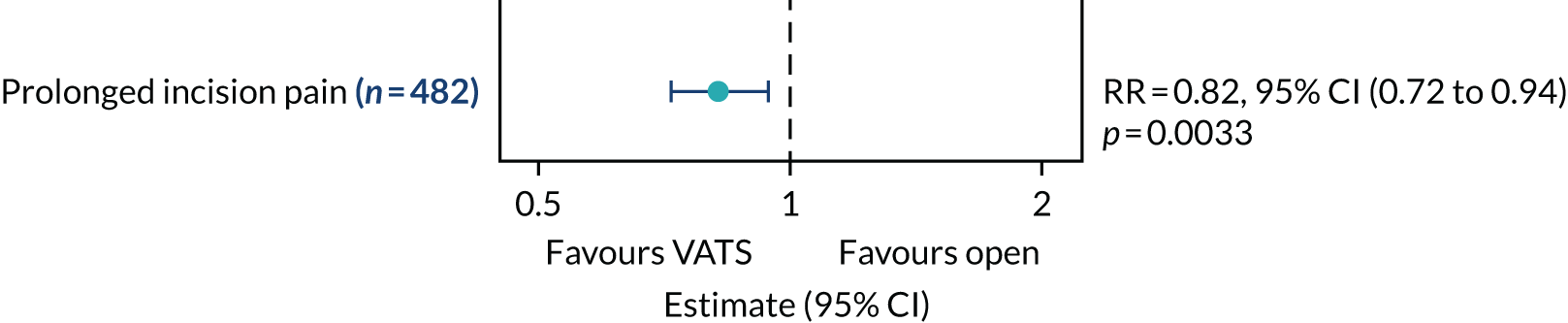

Definition of prolonged incision pain was changed from ‘need of analgesia for > 6 weeks after surgery’ to ‘need of analgesia for > 5 weeks after randomisation’.

-

Clarification that adverse health events would be collected to 1 year and graded in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) criteria, with postoperative complications classified in accordance with the Clavien–Dindo system. Surgical emphysema requiring intervention, reoperation for reasons other than recurrence or progression, and adverse events (AEs) associated with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy were added to the list of expected AEs.

-

Patient resource use questionnaires, collection of resource use at 2 weeks and computerised tomography (CT) of the pelvis were removed.

-

Clarification of measures to promote blinding of the trial participants.

Second amendment (approved 19 October 2015)

-

CT-based Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours criteria to assess recurrence/progression was replaced by specific objective criteria, as postoperative CT imaging is not routinely undertaken for patients following lobectomy. Therefore, there were no comparative images against which to reference the 12-month CT scan.

-

Addition of patient-reported pain scores at baseline and at 1 day and 2 days postoperatively.

-

Option for research team at sites to follow-up patients by telephone at 5 weeks and 1 year to facilitate data collection as some patients are referred back to tertiary or peripheral hospitals for follow-up.

-

Clarification of patient referral pathways, where potential participants may be identified and provided information, including the setup of patient identification centres.

Third amendment (approved 6 June 2017)

-

Inclusion criteria modified to include patients undergoing bi-lobectomy, and reflect the transition to TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, Eighth Edition (TNM8)13 of the TNM staging system.

-

Clarification that elective surgery, interventions and treatments during follow-up that were planned prior to recruitment to the trial will not be reported as unexpected serious adverse events (SAEs).

-

Addition of pleural effusion, venous thromboembolism and other infection to the list of expected AEs.

Fourth amendment (approved 7 June 2018)

-

Addition of molecular residual disease substudy (not reported here, funded by industry).

-

Revision to archiving plan to remove scanning of documents.

-

Clarification of form of bleeding (e.g. in or around the operation site) considered an expected AE.

-

Addition of the option for research nurses (RNs) to obtain the questionnaire data directly from participants.

Fifth amendment (approved 21 January 2019)

-

CTCAE grade scheme changed from v4.0 to v5.0.

Sixth amendment (approved 17 April 2019)

-

Addition of the secondary outcome ‘pain scores in the first 2 days post surgery’, which had previously been missed from the protocol.

-

Clarification of exploratory analysis of pain scores.

-

Clarification of molecular residual disease substudy.

Seventh amendment (approved 4 December 2019)

-

Clarification of molecular residual disease substudy.

-

Reference corrected.

Eighth amendment (approved 3 February 2021)

-

Clarification of end-of-study definition.

Participants

Patient population

Adults referred for lung resection for known or suspected lung cancer to one of the participating centres.

Patient eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible to enter the study if all the following applied:

-

Aged ≥ 16 years.

-

Undergoing lobectomy or bi-lobectomy for treatment of known or suspected primary lung cancer beyond a lobar orifice, or undergoing frozen section biopsy with the intention to proceed with lobectomy or bi-lobectomy if primary lung cancer beyond a lobar orifice is confirmed. (Note that for bi-lobectomy, the distance for the lobar orifice is in reference to the bronchus intermedius.)

-

Cancer staging using TMN8:

-

clinical tumour stage 1–3 (cT1–3) [by size criteria, equivalent to TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, Seventh Edition14 (TNM7) stage cT1a-2b] or cT3 (by virtue of two nodules in the same lobe)

-

node stage 0–1 (N0–1)

-

metastasis stage 0 (M0).

-

-

Multidisciplinary team (MDT) consider the disease is suitable for both VATS lobectomy and lobectomy via open surgery.

-

Ability to give written informed consent.

Patients were not eligible to enter the study if any of the following applied:

-

Previous malignancy that influences life expectancy.

-

Planned pneumonectomy, segmentectomy or non-anatomic resection (e.g. wedge resection).

-

Serious concomitant disorder that would compromise patient safety during surgery.

-

Planned robotic surgery.

Changes to trial eligibility criteria after commencement of the trial

In July 2015, planned segmentectomy was added as an exclusion.

In June 2017, the inclusion criteria were revised to allow for the inclusion of patients undergoing bi-lobectomy and to update the cancer staging from TNM7 to TMN8. The Trial Management Group (TMG) recommended widening the inclusion criteria to include patients scheduled for a bi-lobectomy (i.e. resection of two lobes rather than one), as this can be performed via VATS or open surgery and, therefore, the research question is equally applicable to patients having this procedure. The revisions to the TNM staging system necessitated a change to the eligibility criteria, which were widened to include patients with cT1–3 tumours (by size criteria, equivalent to TNM7 stage cT1a-2b) or cT3 by virtue of two nodules in the same lobe. The entry criteria for nodal and metastatic involvement remained unchanged at N0–1 and M0, respectively.

Settings

NHS trusts with an established and accredited lung cancer MDT, which included trusts from across the UK, were eligible to participate in the VIOLET trial if the site undertook at least 40 VATS lobectomies each year and employed at least one surgeon that had carried out ≥ 50 VATS lobectomies. Phase I was restricted to five sites and further sites were opened in Phase II.

Surgeons were eligible to participate if they had performed at least 40 VATS lobectomies. Lobectomy via open surgery is a standard procedure and, therefore, surgical ability and competence was assured by specialist General Medical Council registration.

Trial interventions

VATS lobectomy (experimental)

Surgeons were permitted to undertake the VATS lobectomy using between one and four keyhole incisions. The use of rib spreading was prohibited, as this intraoperative manoeuvre disrupts the intercostal nerves and is thought to be an important cause of pain (and is a key feature of open surgery). The procedure was to be performed with videoscopic visualisation without direct vision. The hilar structures (i.e. vein, artery and bronchus) were dissected, stapled and divided. Endoscopic ligation of pulmonary arterial branches was optional. The fissure was completed and the lobe of lung resected. The incisions were closed in layers and may have involved muscle, fat and skin layers. This definition of VATS lobectomy is a modification of CALGB 39802. 15

Open lobectomy (control)

Conventional open surgery was undertaken through a single incision. Rib spreading was mandated, but rib resection was optional. The operation was performed under direct vision, with isolation of the hilar structures (i.e. vein, artery and bronchus), which were dissected, ligated and divided in sequence, and the lobe of lung resected. Ligatures, over sewing or staplers could be used. The thoracotomy was closed in layers, starting from pericostal sutures over the ribs, muscle, fat and skin layers.

Aspects common to both groups

Participants without a confirmed tissue diagnosis at surgery

The surgeon could either take a confirmatory biopsy or proceed directly to surgery, as per MDT recommendation (see Identification of potential participants: referral and multidisciplinary team review).

Lymph node management

In both groups, lymph node management was undertaken in accordance with the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer recommendations. The Association recommends that a minimum of six nodes/stations are removed, of which three are from the mediastinum that includes the subcarinal station.

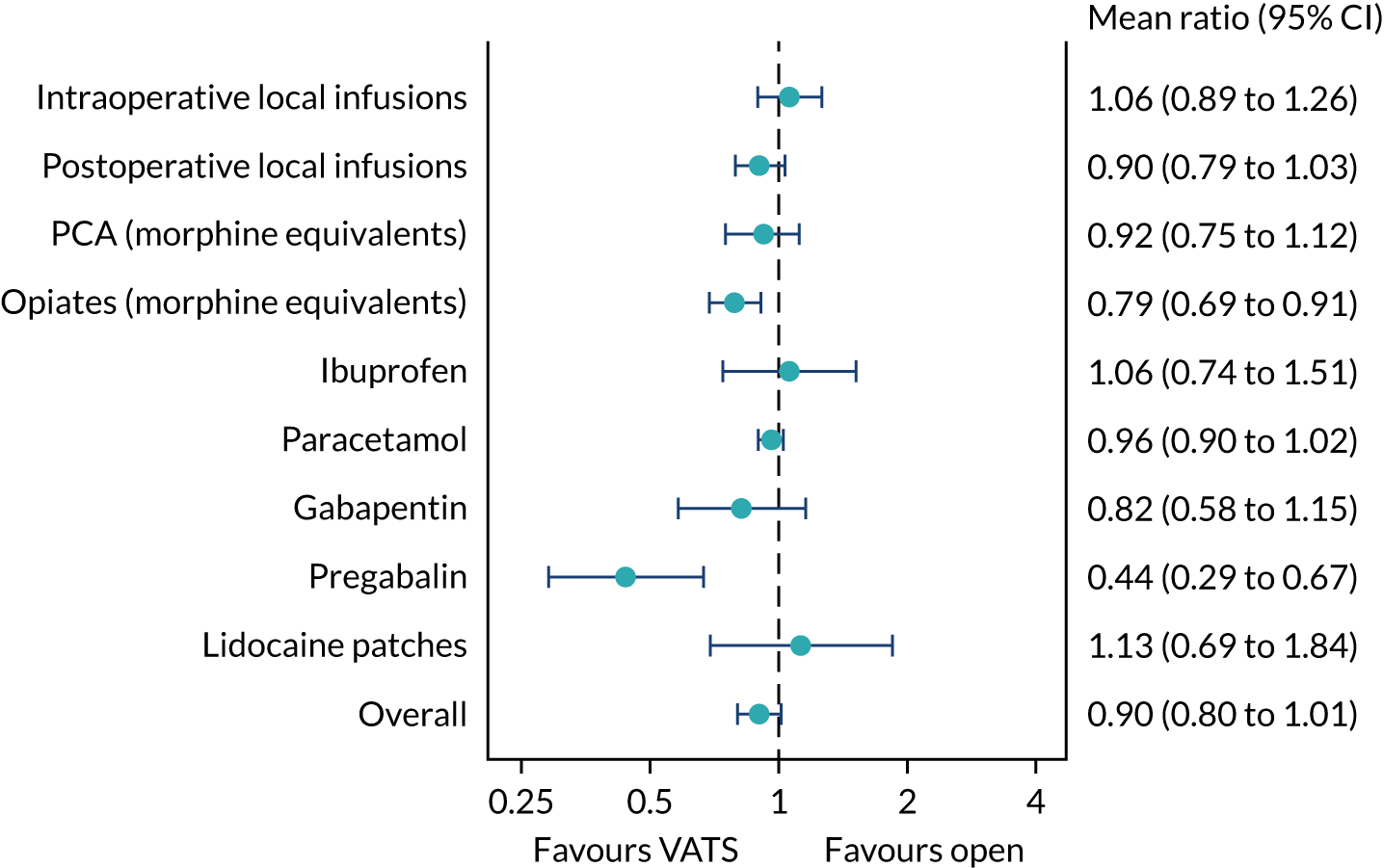

Anaesthesia and postoperative pain management

All operations were undertaken with general anaesthesia and with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. This was a pragmatic trial and so adaptations and variations of both procedures were permitted at the discretion of the surgeon (intraoperative details were captured and monitored).

Standardising the use of analgesia across all participating sites was considered impractical and, if implementable, would be unrepresentative of clinical practice in the NHS. Each participating site prescribed analgesia in accordance with their local protocols. To minimise potential bias in pain outcomes, all sites were required to administer analgesia in accordance with a standard protocol applied, regardless of treatment allocation. Local protocols for the provision of analgesia were defined by the local principal investigator (PI) prior to the start of recruitment at the site. Details of the analgesia used throughout a participant’s hospital stay were recorded and compliance with the prespecified site-specific analgesia protocol was monitored.

Other aspects of postoperative care

As this was a pragmatic study, postoperative care and the criteria for drain removal were in accordance with local practice. The decision to discharge a patient home after surgery was at the surgeon’s discretion; however, to minimise the potential for bias, the criteria by which a patient was assessed as medically fit for discharge was prespecified and adherence to these criteria was monitored.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

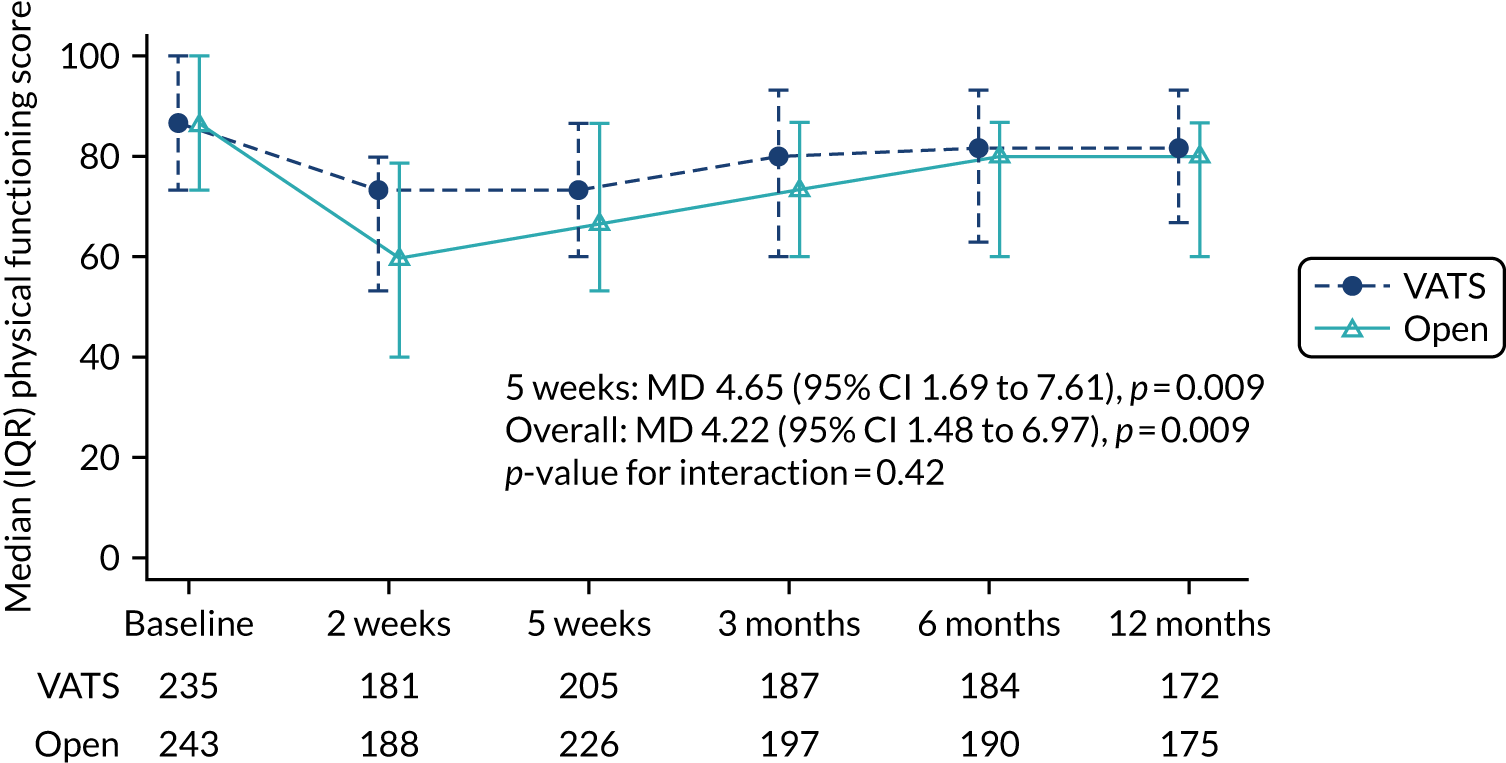

The primary end point was self-reported physical function assessed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) at 5 weeks post randomisation. Physical function was chosen because it is a patient-centred outcome that would reflect the anticipated earlier recovery with VATS. It had also been used in other minimal access surgery trials. The 5-week primary end point (approximately 1-month post surgery) was chosen to capture the early benefits of minimal access surgery on recovery.

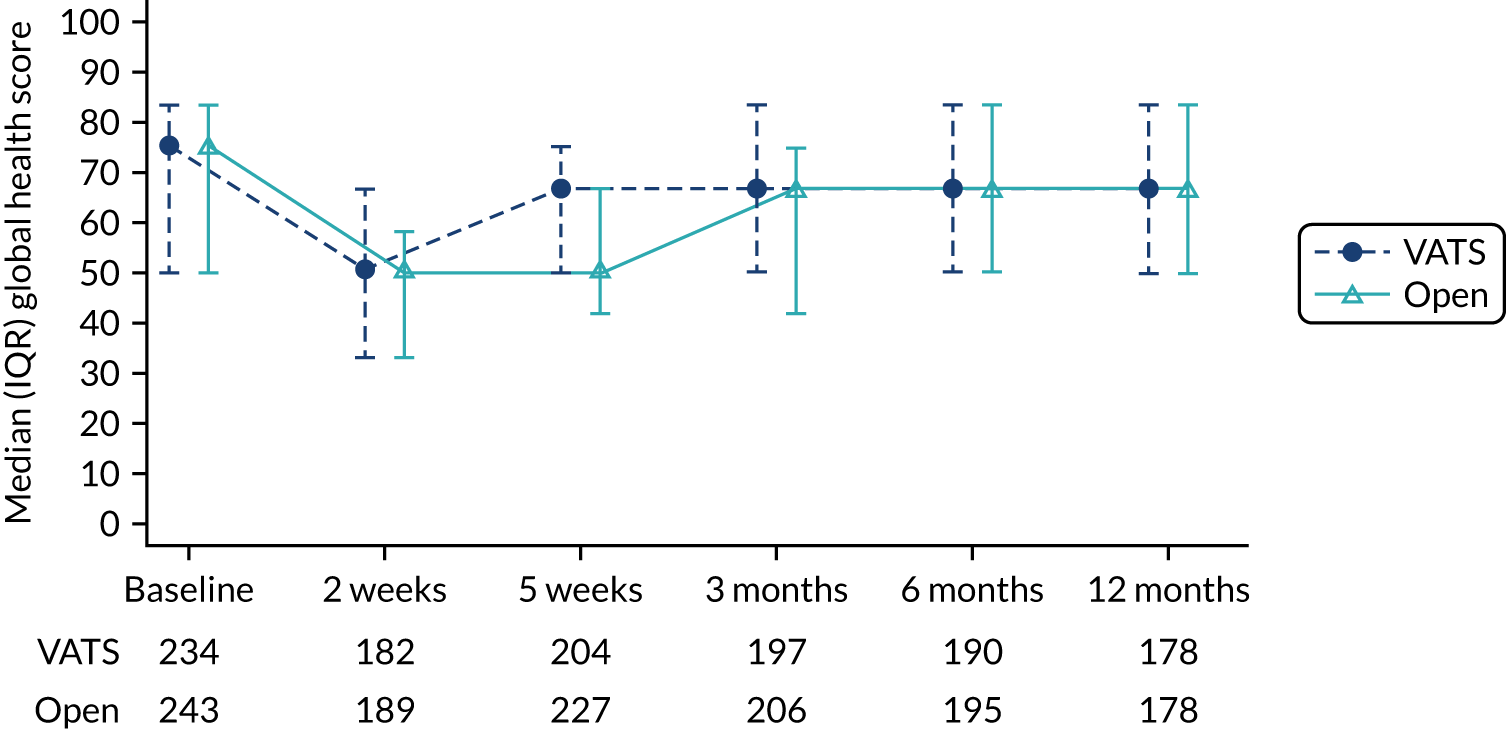

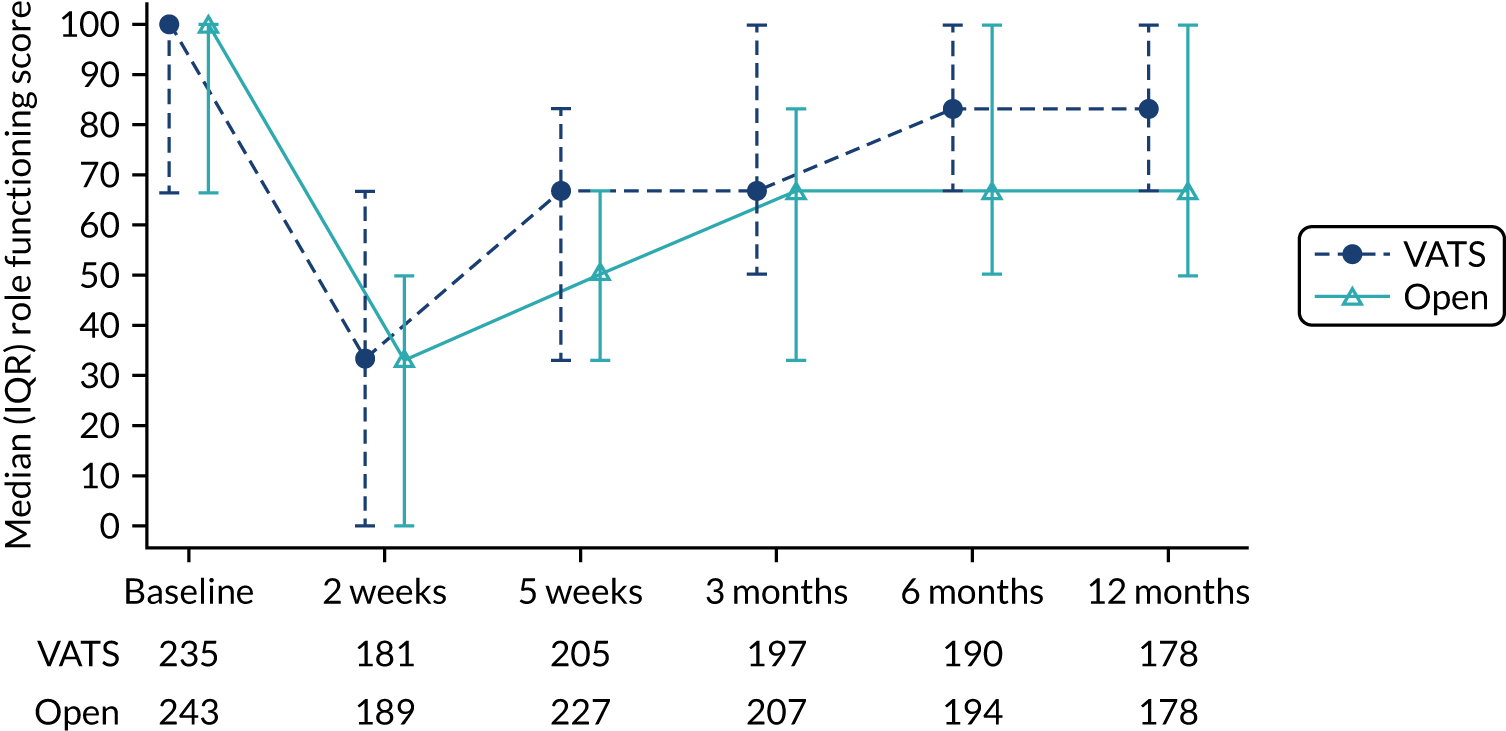

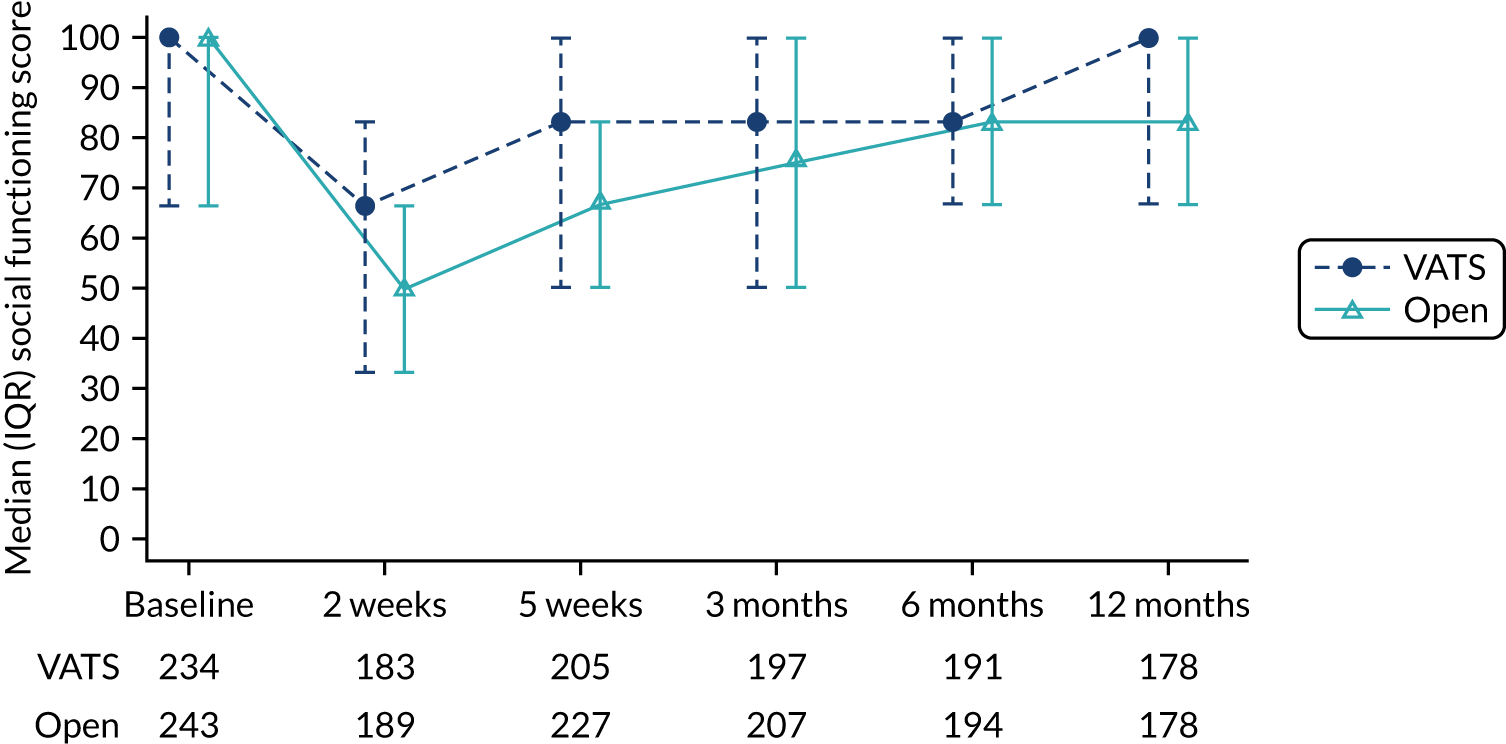

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is used to assess quality of life in cancer patients. The EORTC QLQ-C30 comprises 30 questions, which are used to derive an overall measure of global health, and a number of subscales, of which physical function is one. For all scales, higher scores indicate a higher level of functioning, symptoms or problems. The EORTC QLQ-C30 has been validated for use in European cohorts. Version 3 of the questionnaire was used.

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary outcomes were selected to assess the efficacy of the two approaches:

-

Time from surgery to hospital discharge.

-

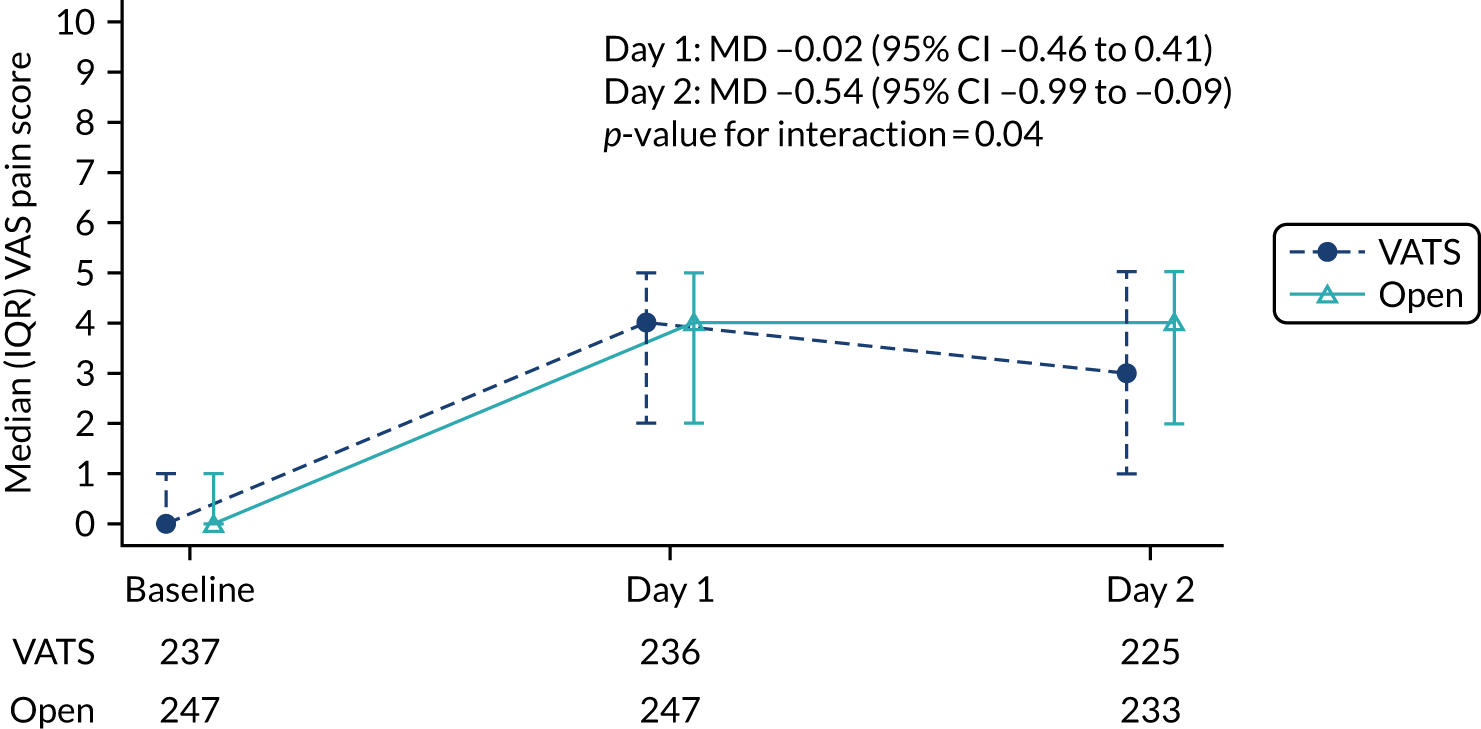

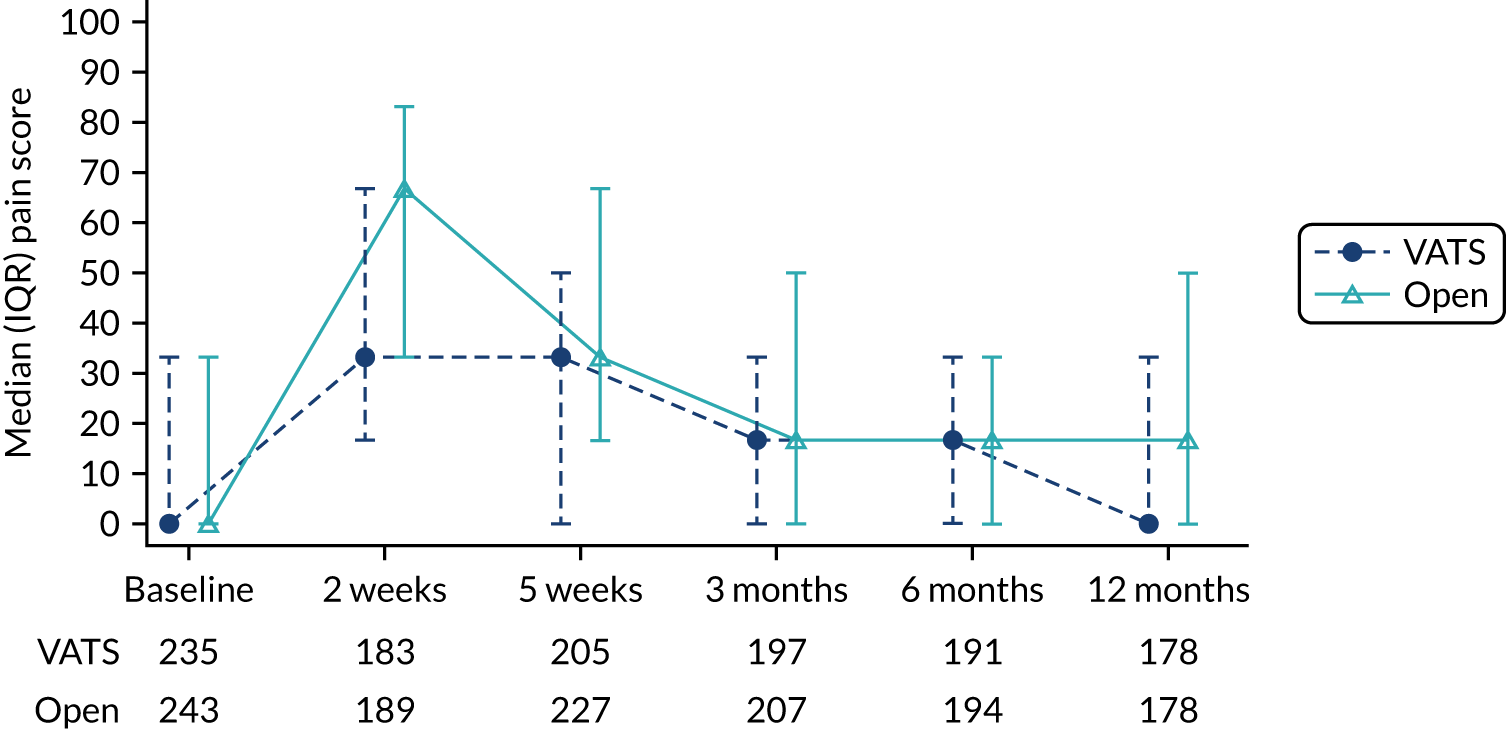

Pain scores in the first 2 days post surgery.

-

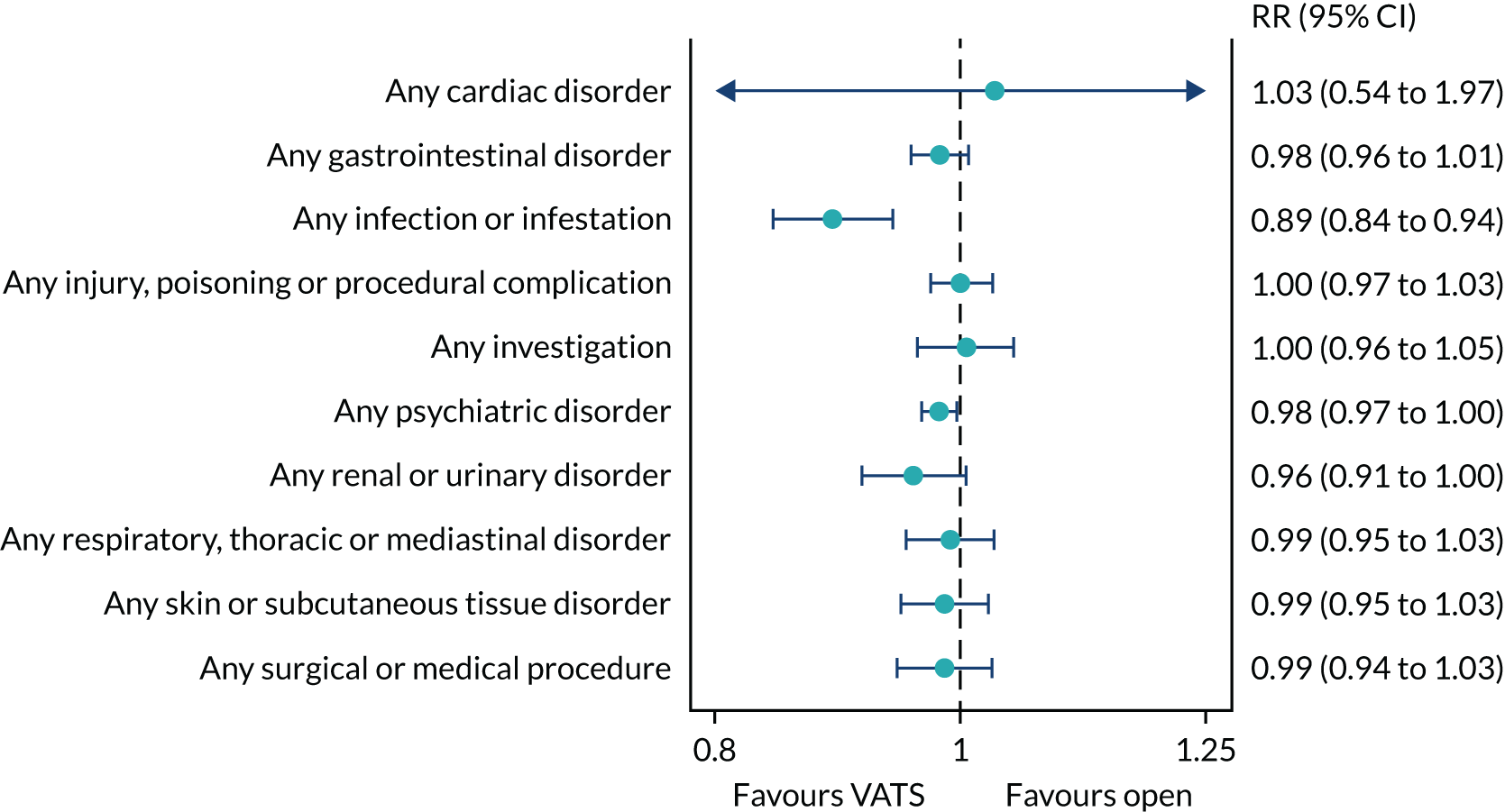

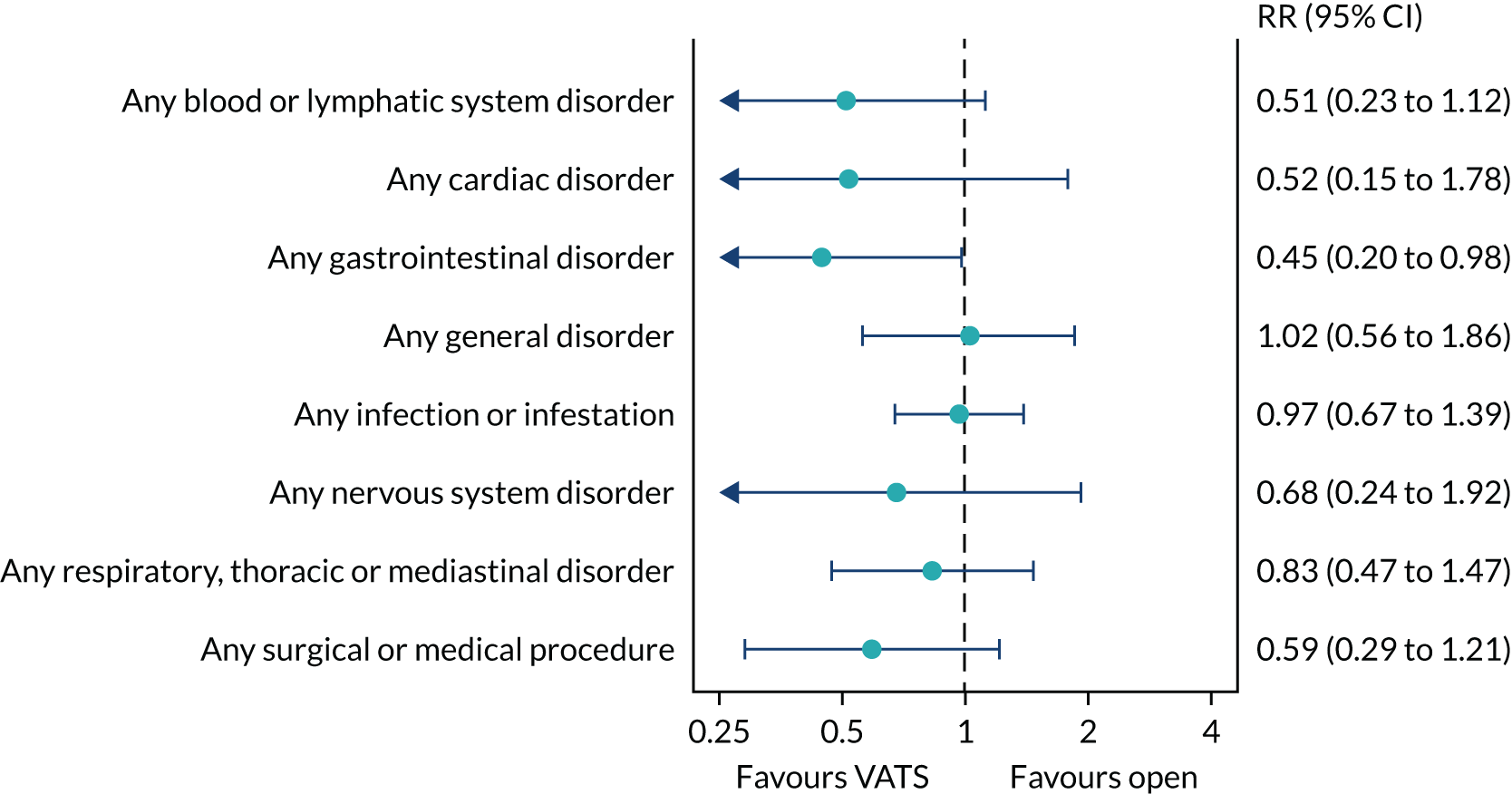

Adverse health events in the period from randomisation to 1 year.

-

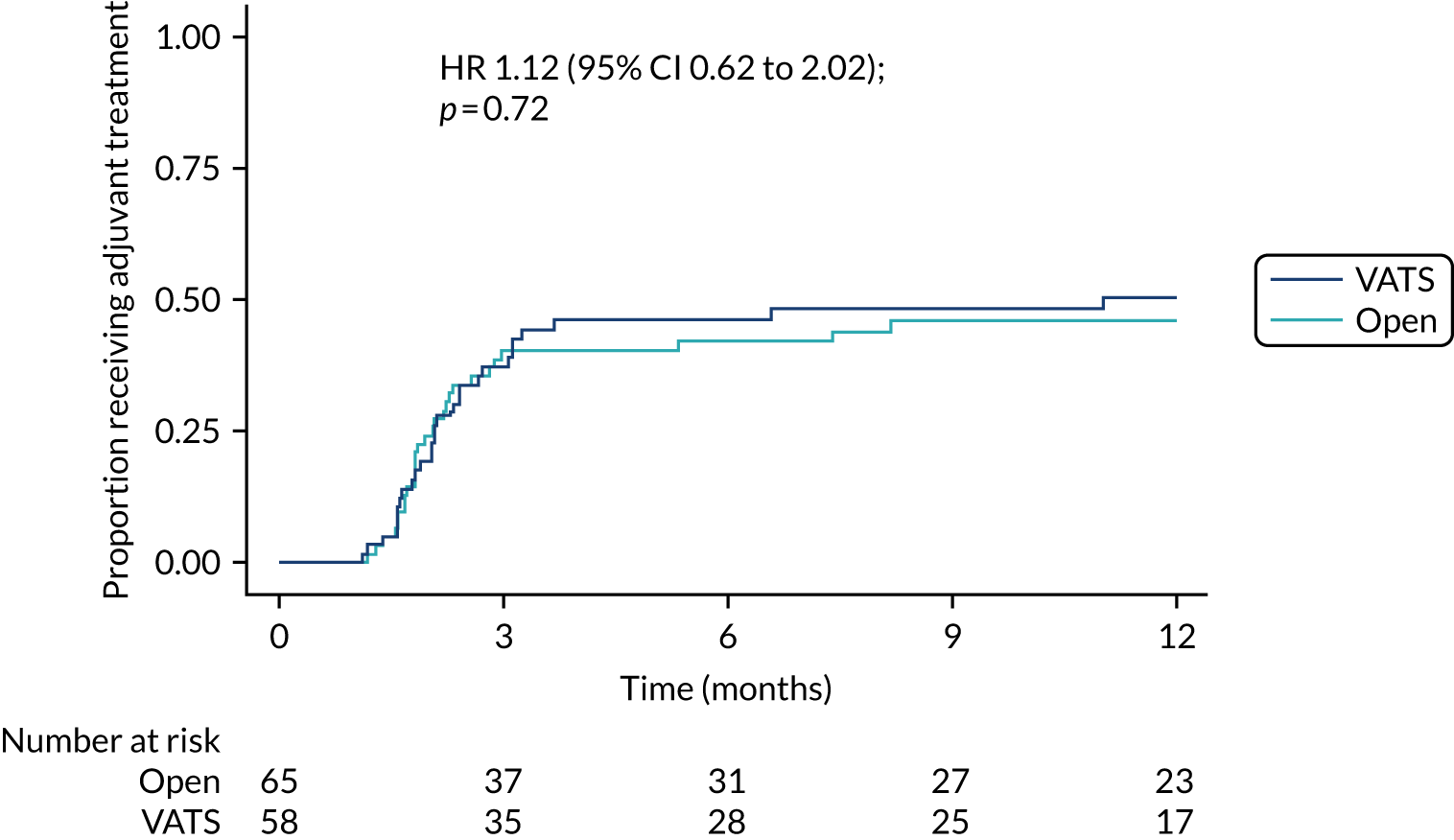

Uptake of adjuvant treatment (i.e. frequency and time from surgery).

-

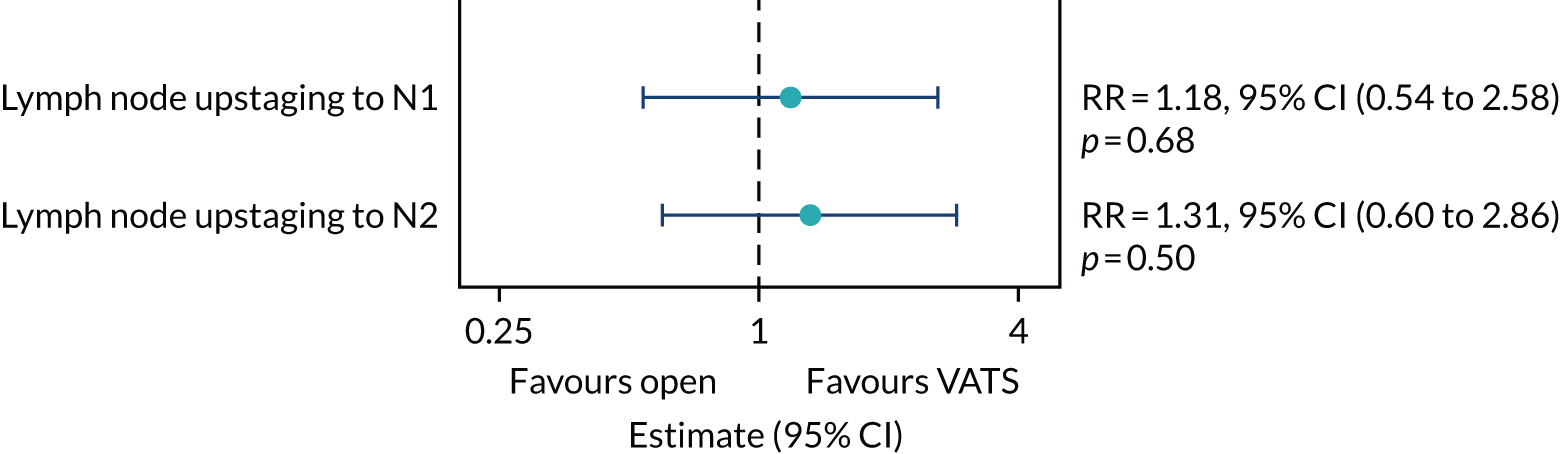

Frequency of upstaging to pathologic node stage 2 (pN2) disease after the procedure.

-

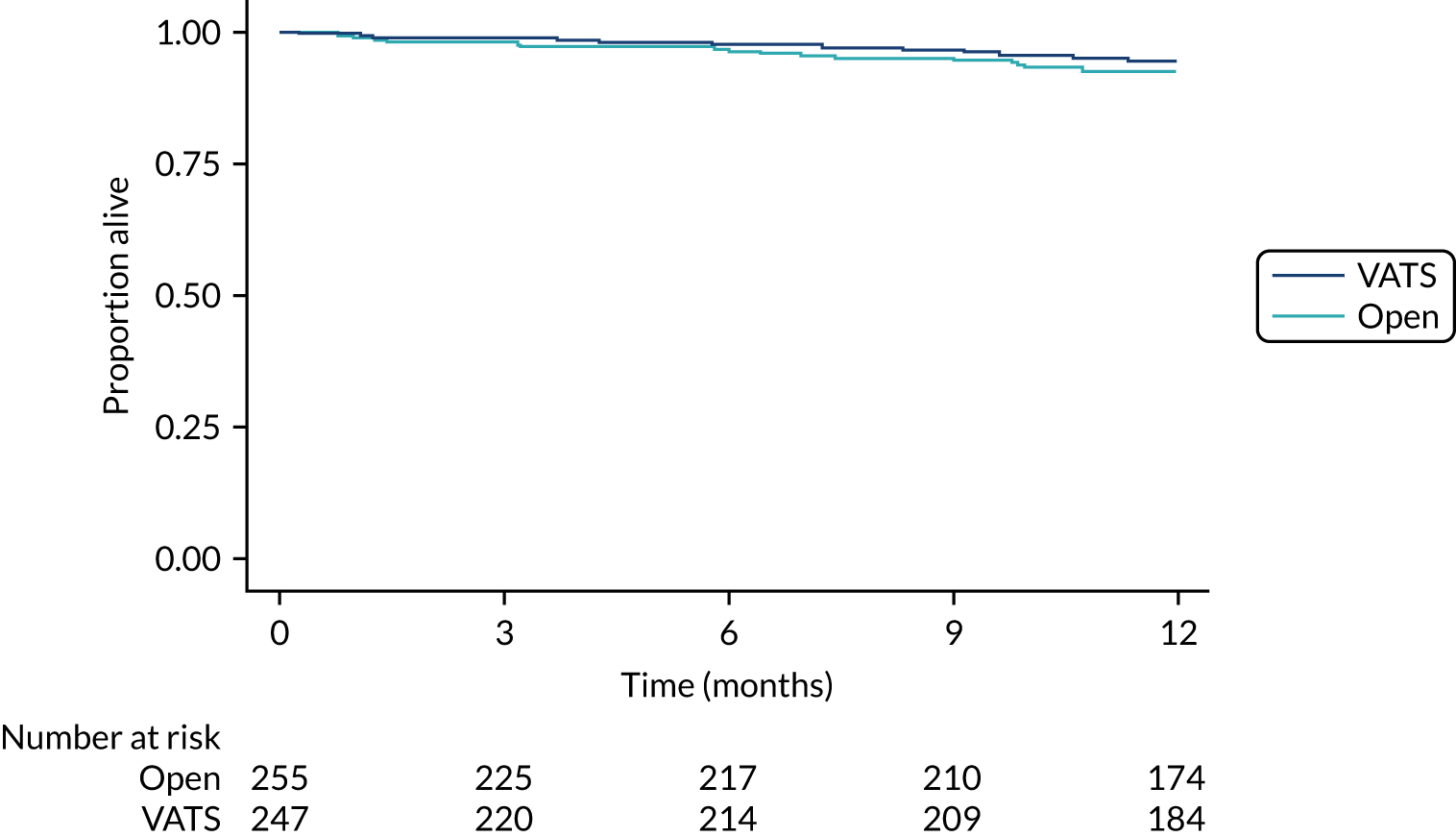

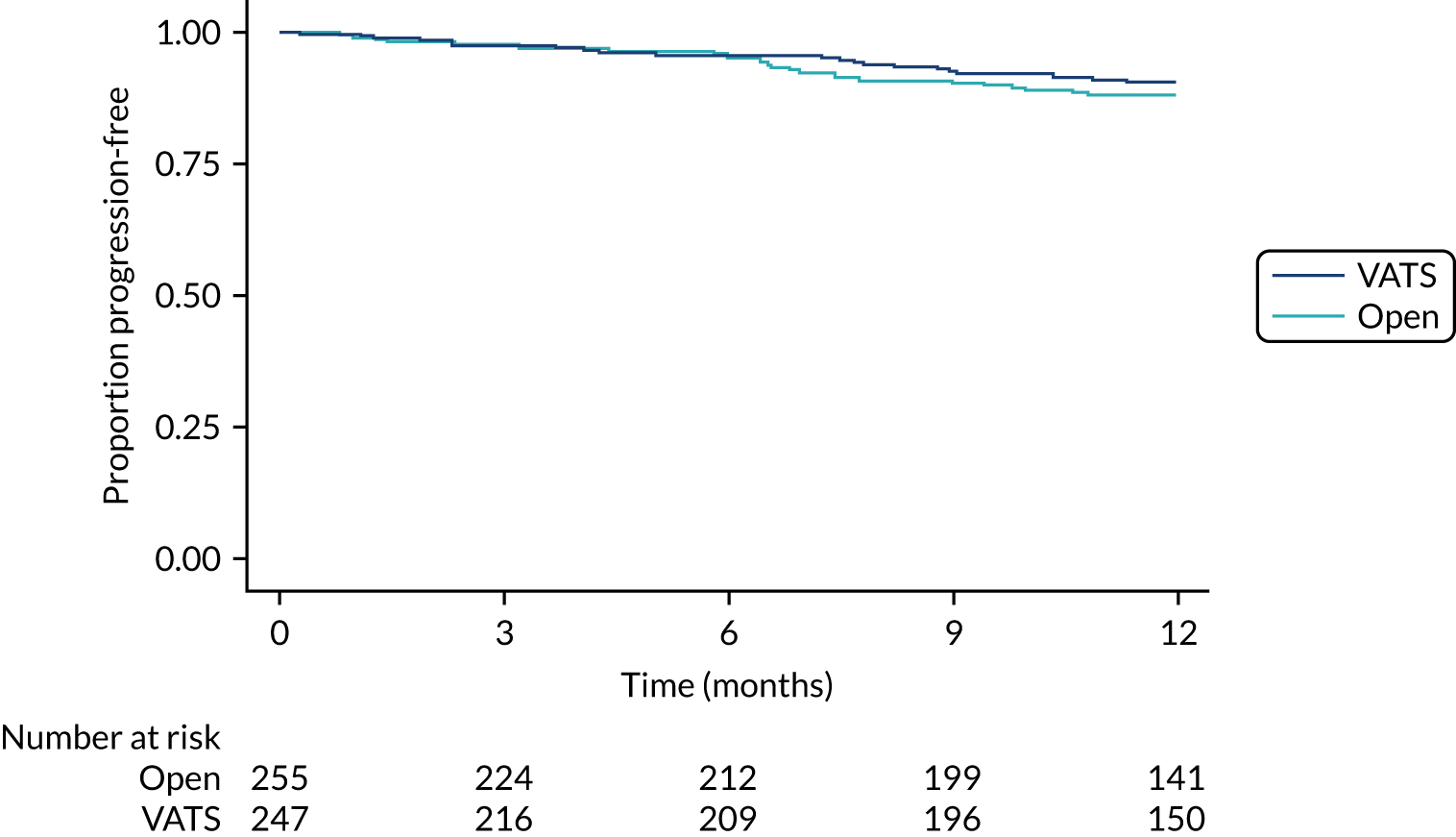

Overall and disease-free survival to 1 year.

-

Frequency of complete resection during the procedure.

-

Frequency of prolonged incision pain (defined as the need of analgesia for > 5 weeks post randomisation).

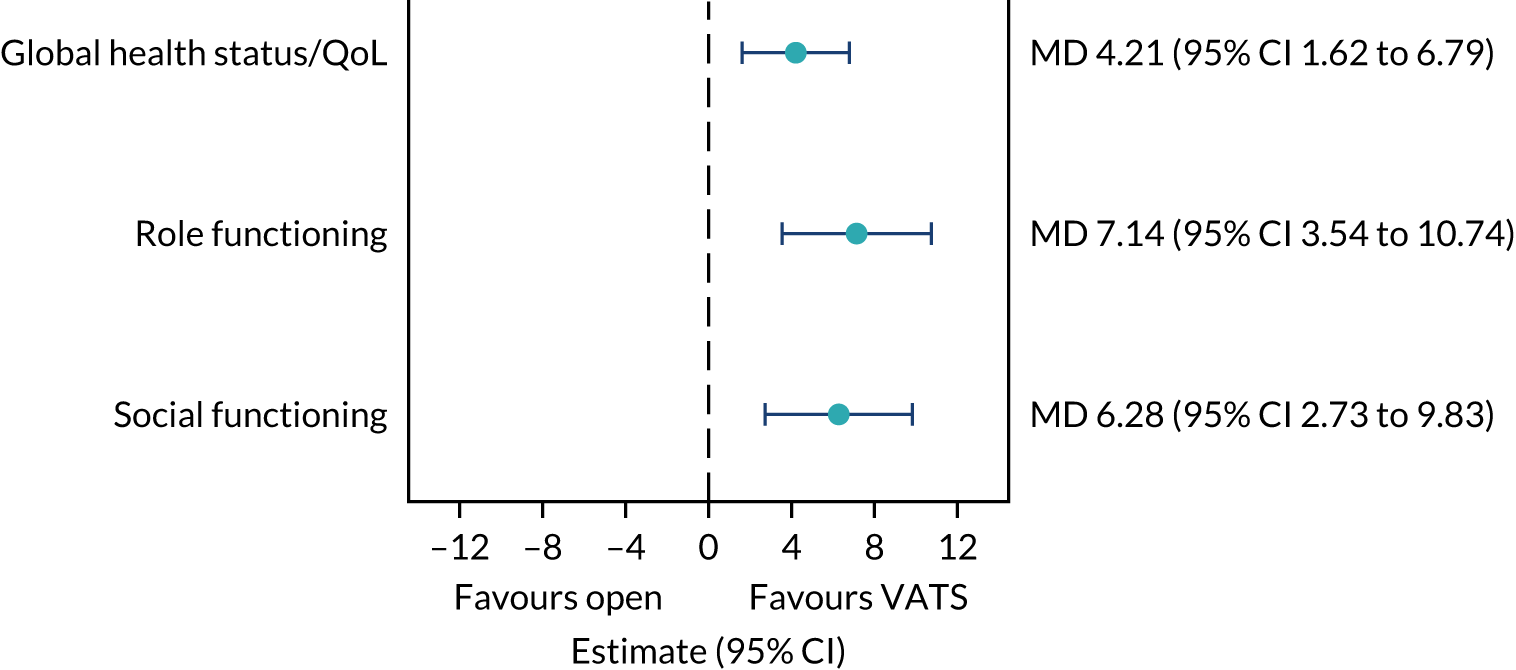

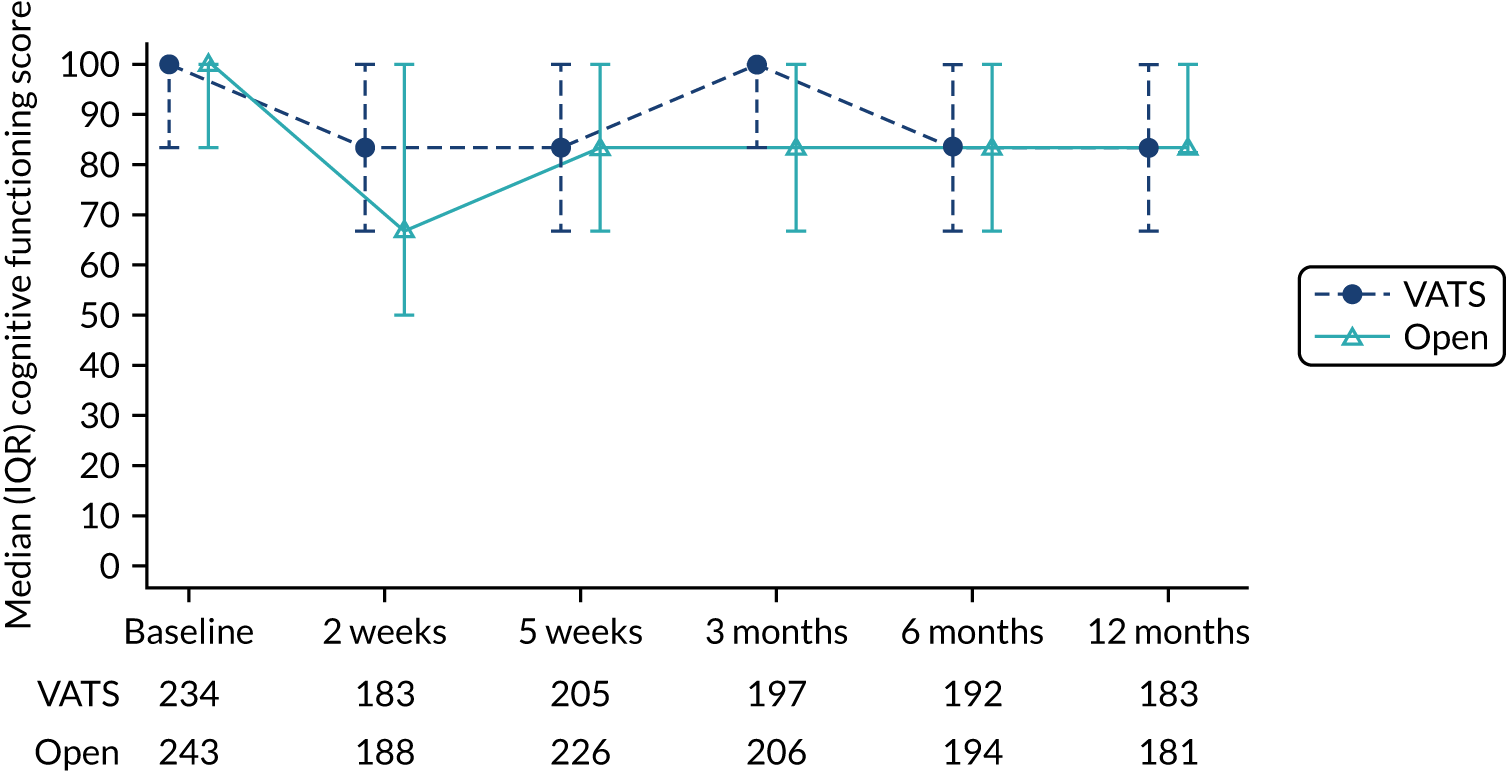

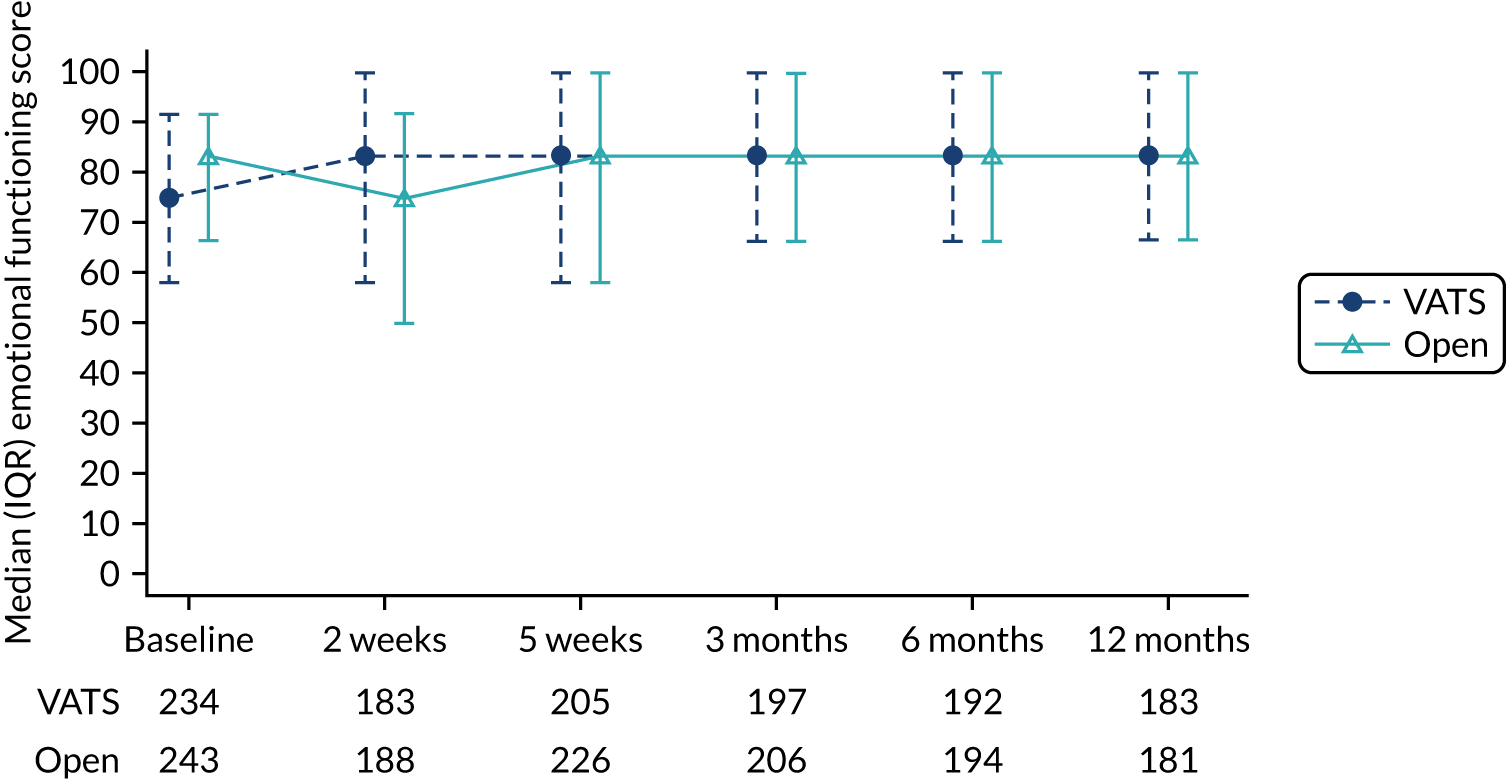

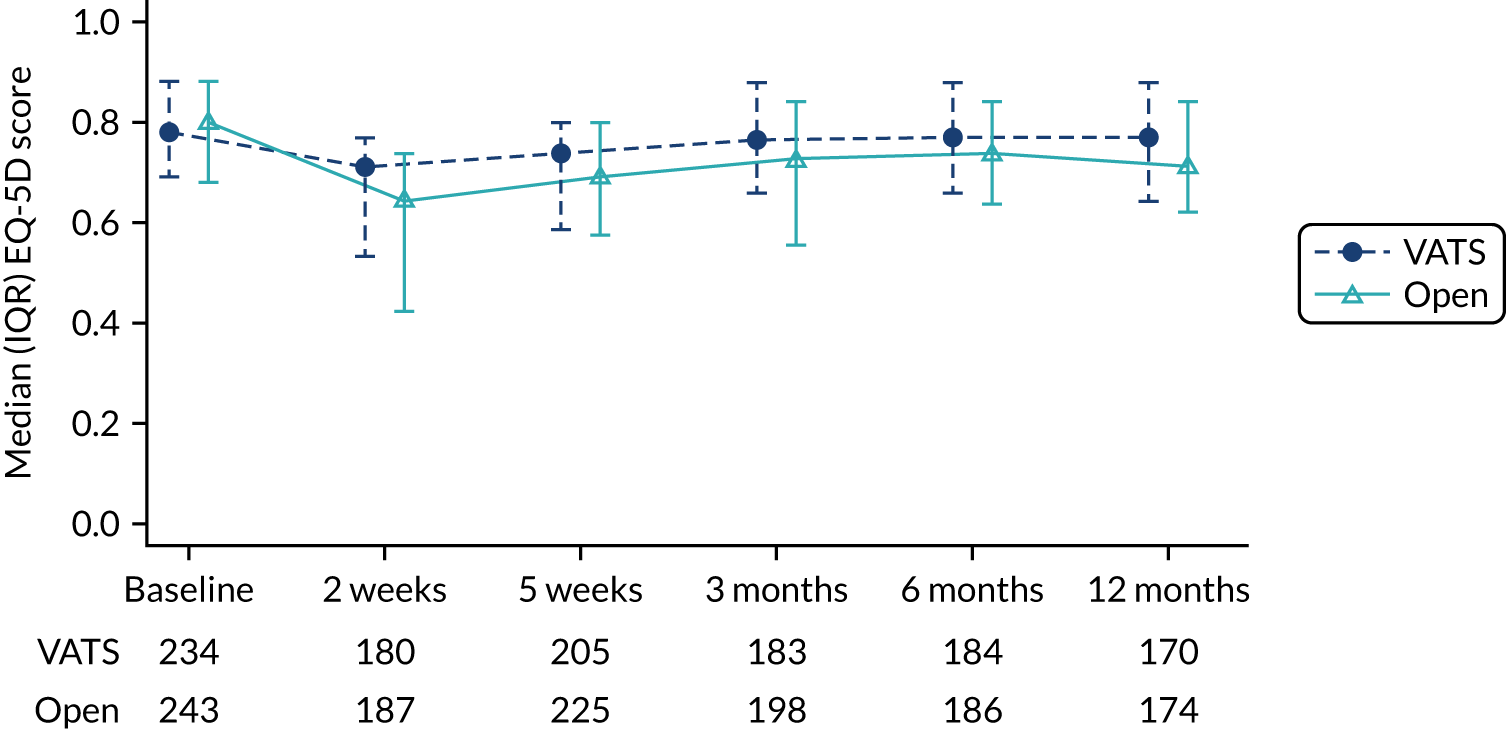

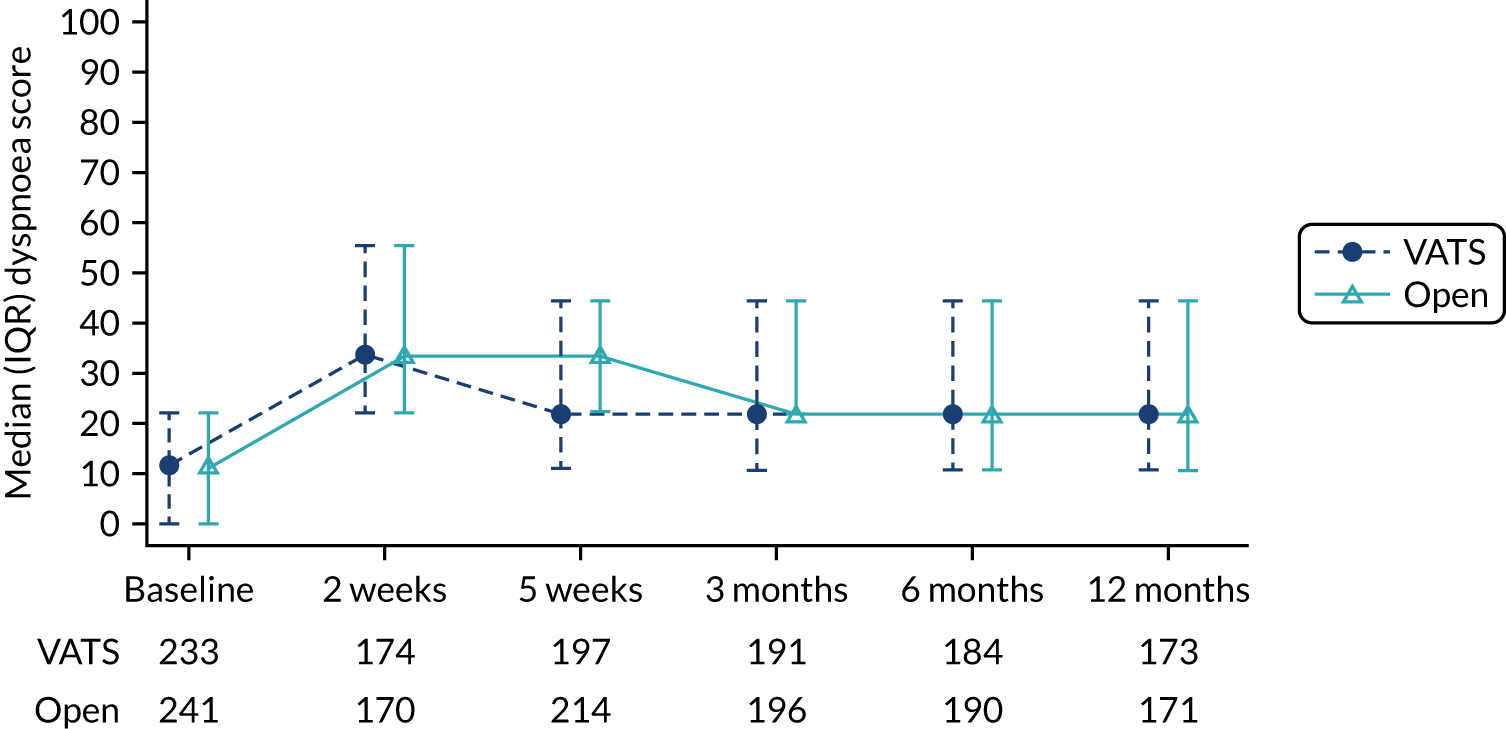

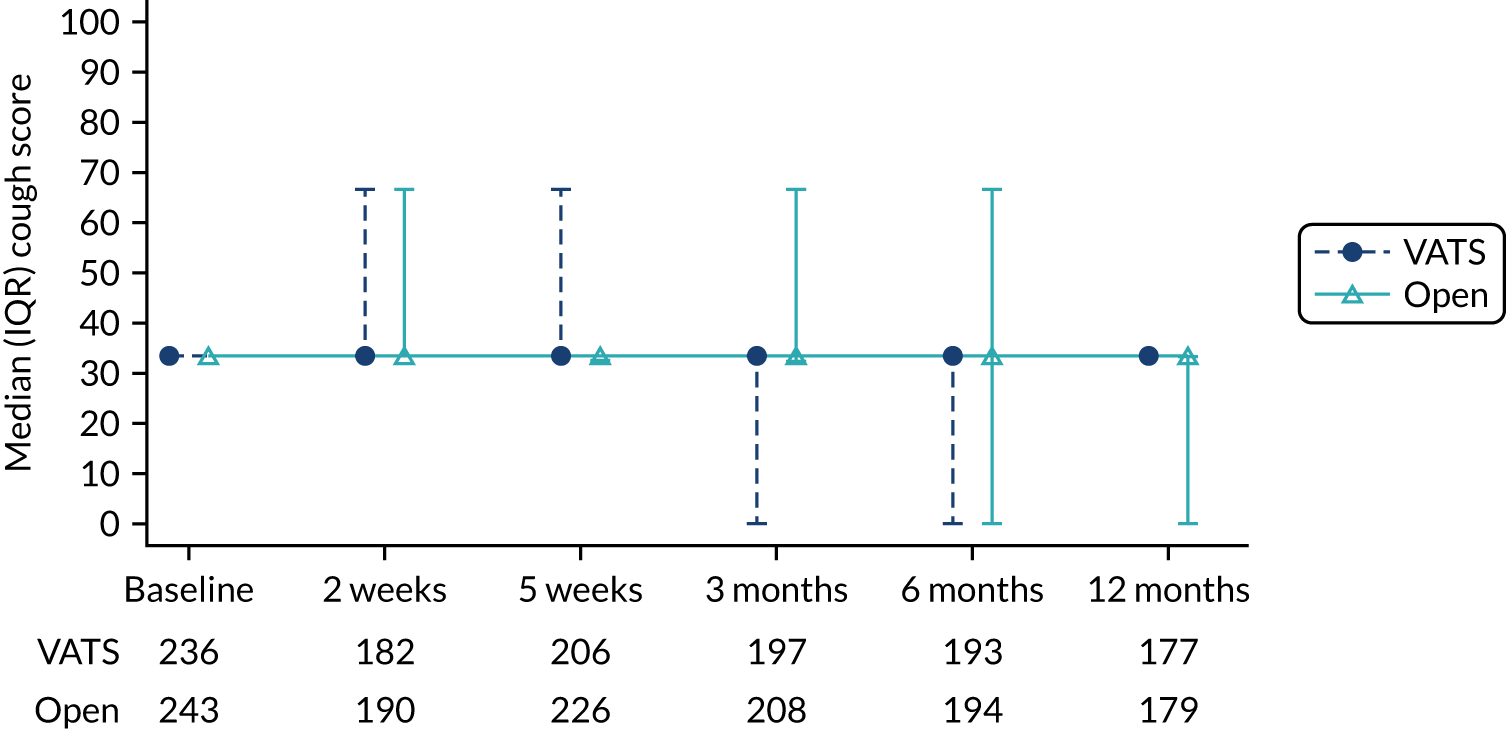

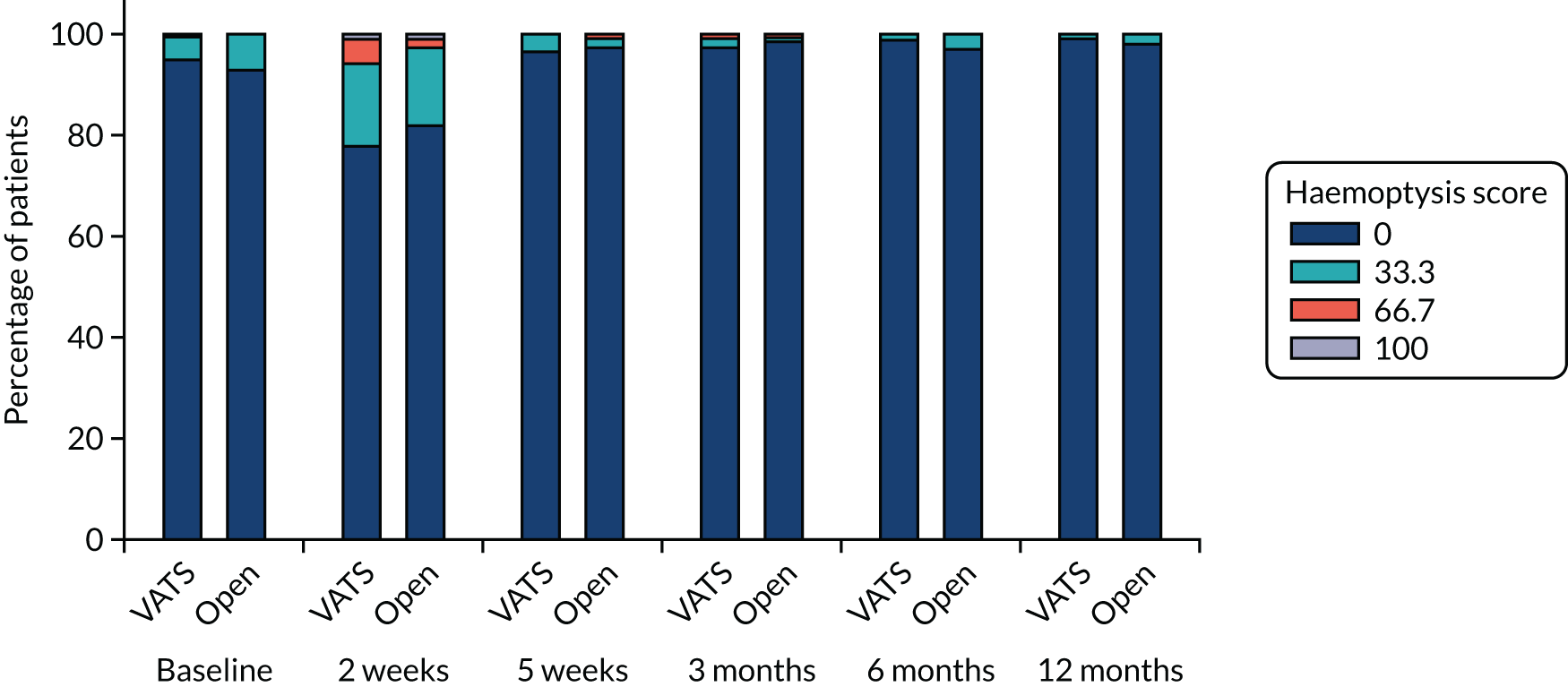

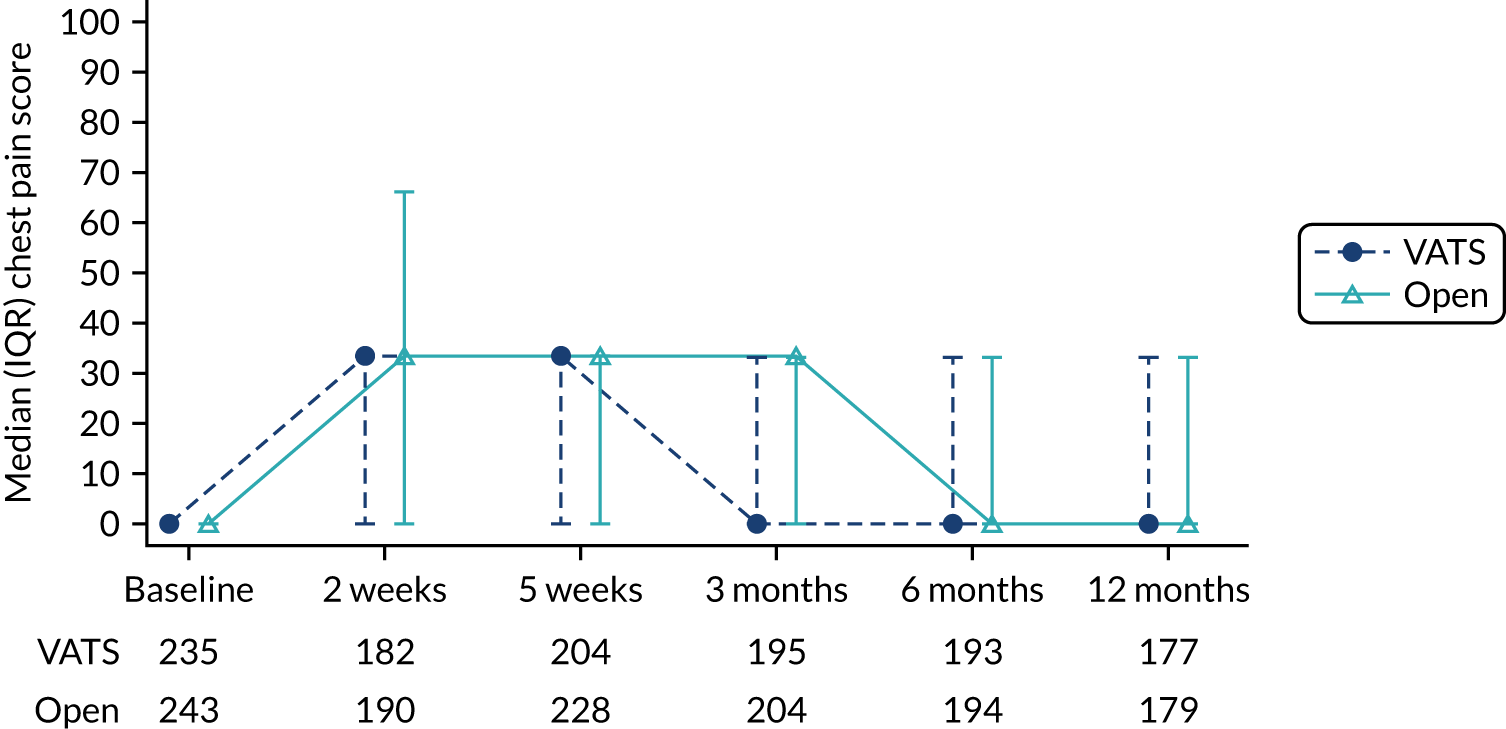

-

Generic and disease-specific patient-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measured using the EORTC QLQ-C30, Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer 13 (QLQ-LC13) and EQ-5D-5L questionnaires completed at 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 1-year post randomisation.

-

Resource use during the hospital stay and post discharge to 1 year after randomisation.

Changes to trial outcomes after commencement of the trial

In 2015, minor amendments were made to clarify some secondary outcomes prior to the study opening to recruitment (see Changes to trial design after commencement of the trial for details). In a further amendment in the same year, the collection of patient-reported pain scores at baseline and at 1 day and 2 days postoperatively was added to the table of assessments, but the list of secondary outcomes was inadvertently not updated in line with this addition. This error was corrected in 2019 when pain scores were added to the list of secondary outcomes in the protocol. Pain scores were added to allow further comparison between the two surgical techniques during the early postoperative period. Pain assessments are routinely undertaken by the clinical team to determine whether or not the analgesia provision is sufficient and so a patient verbal assessment of pain represented minimal additional burden to the patient.

Sample size

We hypothesised that self-reported physical function 5 weeks after randomisation for participants undergoing a VATS lobectomy would be superior to the physical function for participants having an open lobectomy, as derived from responses to the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Data from the literature on minimal clinically important differences in HRQoL scores from the EORTC QLQ-C30 were used to inform the target effect size. 16

Although the primary end point was at 5 weeks, the questionnaire was also completed at other time points, namely at baseline, 2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 1 year. In estimating the sample size, the following assumptions were made:

-

One pre-surgery measure and five post-surgery measures.

-

A correlation between pre- and post-surgery measures of 0.3.

-

A correlation between repeated post-surgery measures of 0.6.

-

An effect size of 0.25 standard deviations (SDs) would be considered clinically important.

Under these assumptions, and allowing for up to 20% loss to follow-up at 1 year, the sample size was set at 498 patients (i.e. 249 patients per group), which provided 90% power to test the superiority hypothesis at the 5% significance level.

Interim analyses

There were no interim analyses planned nor undertaken for the VIOLET trial.

Randomisation

Participants were randomly allocated to either VATS lobectomy or open lobectomy in a 1 : 1 ratio. Randomisation took place through a secure internet-based randomisation system (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK) approximately 1 week before the planned surgery, after eligibility had been confirmed and written informed consent given. This time frame was chosen to allow sufficient time for operating schedules to be arranged.

The randomisation was stratified by centre, and cohort minimisation (with a random element incorporated) was used to ensure balance across groups with respect to surgeon. Allocations were concealed until information to uniquely identify the participant and confirm eligibility was entered into the randomisation system, after which the randomised allocation was revealed. If there was a change in surgeon after randomisation, the analysis accounted for the surgeon responsible for the performing the operation and not the surgeon originally assigned to the patient.

Blinding

Research team

The surgical team, anaesthetist and other staff caring for the participant during the operation were not blinded to the patients’ treatment allocation. However, to minimise the risk of bias in the assessment of outcomes, the randomisation was performed by a member of the research team who was not responsible for the collection of outcome data.

Wound dressings

Efforts were made to minimise the risk of inadvertently unblinding the RN responsible for data collection during the patient’s postoperative stay by applying large adhesive dressings to the thorax of participants. These adhesive dressings were positioned similarly for all patients, regardless of their surgical allocation, to cover both real and potential incision/port locations. The initial adhesive dressings were applied in the operating room by the operating team. The dressings remained in place for 3 days unless the patient was discharged before day 3, when they were removed, or if the patient required replacing early because of soiling. After 3 days, dressings were changed by a nurse not involved in conducting follow-up assessments or data collection for the trial. Wound cleaning was performed on both actual and potential wounds to promote masking.

Fitness for discharge after surgery

To minimise bias in the decision-making around when a participant was discharged home, the following discharge suitability criteria were developed. Participants were evaluated against the following criteria to ensure that they are medically fit for discharge:

-

Patient has achieved satisfactory mobility with:

-

pain under control with analgesia

-

satisfactory serum haemoglobin and electrolytes (i.e. does not require intervention)

-

satisfactory chest-X-ray (which will be performed as part of routine clinical care)

-

no complications that require further/additional treatment.

-

Patients who were considered medically fit for discharge were not necessarily discharged immediately. In some instances, social and other factors may have necessitated extended hospitalisation. The time at which patients are considered medically fit for discharge and when they are physically discharged from hospital were both captured in the trial. For the two groups, the data were monitored for evidence of both early discharge before all the discharge criteria were met and delayed discharge.

Participants

To ensure that study participants remained blinded during the postoperative period to discharge home, participants were asked to turn their head away from the wound site(s) while wounds were being cleaned and dressed. Participants were advised of how best to care for their wounds when they were considered ‘fit for discharge’. Those participants who asked to know which treatment they had received were informed at this point.

Assessment of blinding

The success of blinding was assessed using Bang et al. ’s Blinding Index. 17 Participants were asked to complete the assessment 2 days postoperatively and at discharge, but before the treatment allocation was revealed. The RNs responsible for data collection and follow-up of participants completed the Blinding Index when the patient was ready for discharge, and after the 5-week and 1-year follow-up appointments.

Data collection

Overview

Data collection for the trial participants included the following elements:

-

A log of patients screened by the MDT for suitability for the trial and the date when patients were given or sent the patient information leaflet (PIL).

-

A log of patients assessed against the eligibility criteria and reason(s) if ineligible.

-

Audio-recording and transcription of consultations between surgeons and potential participants (see QuinteT Recruitment Intervention for further details).

-

Semistructured interviews with a sample of eligible patients, including patients who accept or decline to join the trial.

-

Approach and consent details, including reason(s) for non-approach or decline.

-

Baseline data, including the participant’s medical history, disease status and HRQoL prior to randomisation.

-

Operative details.

-

Histopathology of any samples (e.g. biopsies) taken intraoperatively.

-

Postoperative care, including analgesia and pain scores.

-

AEs and resource use in the period from randomisation to 1 year.

-

HRQoL during follow-up.

-

Results of scans taken to assess disease status.

An overview of the schedule of data collection is given in Table 1.

| Item | Study period | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment | Allocation | Post allocationa | Close-out | ||||||||

| –t1 | 0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t5 | t6 | t7 | t8 | t9 | |

| Enrolment | |||||||||||

| Eligibility | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Allocation | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Assessment | |||||||||||

| Imaging review (CT or PET-CT) | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Participant characteristics | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Audio-recorded consultation | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Lobectomy via VATS or open surgery | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Intraoperative details | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Histopathology staging | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Tumour sample for research | ✓ | ||||||||||

| QLQ-C30 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| QLQ-LC13 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Bang et al.’s Blinding Index17 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pain score | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| AEs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Resource use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| CT of chest and abdomen | ✓ | ||||||||||

Collection of health-related quality-of-life data

Health-related quality-of-life data were collected on paper or online, according to participant preference. If data were not returned, the participant may have been telephoned by the local RN and the data collected over the telephone.

Collection of adverse event data

Serious adverse events and other AEs were recorded and reported in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Data were collected from the time of consent until 1-year post randomisation. Events were graded in severity using the CTCAE, which is a standardised classification system used in cancer studies.

As lung resection surgery is a major surgical intervention, events related to the surgery were considered ‘expected’. Many participants would go on to receive adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy after their lung resection surgery. Such treatments have a range of common serious side effects and toxicities, which were also considered ‘expected’ for participants undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. These expected events were listed in the study protocol. Events that occurred that were not listed in the protocol were considered unexpected.

Safety data were reviewed regularly by the study team and at least annually by the Data Monitoring and Safety Committee (DMSC). Reporting to the sponsor was required only if an AE was considered serious (i.e. resulted in a hospital admission, prolonged a hospital admission, was life-threatening, resulted in significant disability or death) and unexpected or expected and fatal. Reporting to the Research Ethics Committee and DMSC was required if an unexpected SAE was found to be causally related to the intervention.

Identification of potential participants: referral and multidisciplinary team review

Potential participants were identified from MDT meetings at each study site, where patient referrals from local and satellite lung cancer MDTs or from peripheral hospitals are considered. Several peripheral referring hospitals were set up as patient identification centres to allow potential participants to receive study information in a timely way and to allow participants time to consider the trial and discuss it with friends and family before their clinical appointment with a study surgeon.

Patients had undergone CT/CT plus positron emission tomography (PET) to assess the extent of their disease, but it is common for lung lesions to be of uncertain pathology before surgery: up to 25% of patients are listed without a preoperative tissue diagnosis. 18 Both patients with proven cancer and those without preoperative tissue diagnosis were eligible to participate in the VIOLET trial. Patients without a preoperative tissue diagnosis were considered eligible if the MDT either recommended lobectomy surgery or a biopsy with the option to proceed to lobectomy if cancer is confirmed, or if there was sufficient clinical certainty for direct lobectomy without biopsy. It was estimated that 75% of patients referred had a confirmed diagnosis. Of the remaining 25% of patients, the recommendation was a biopsy with the option to proceed in 20% of cases, and in 5% of patients the MDT recommended lobectomy without biopsy confirmation. This strategy could lead to a small proportion of participants (estimated 4% in total) finally being confirmed to have benign disease. These patients are included in the primary analyses. If the (real-time) results of the frozen section biopsy diagnosed primary lung cancer, surgery proceeded as allocated. Participants with a non-cancerous diagnosis received no further surgery.

QuinteT Recruitment Intervention

Overview and aims

A QRI19,20 was integrated throughout the recruitment period of the VIOLET trial because of anticipated recruitment challenges1 arising from the nature of the trial interventions [i.e. different approaches to undertaking lung resection (lobectomy) via VATS or open surgery]. The QRI methods, first developed in the ProtecT (Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment) study,21,22 have been refined and applied in nearly 70 RCTs, including other surgical RCTs. 23–25

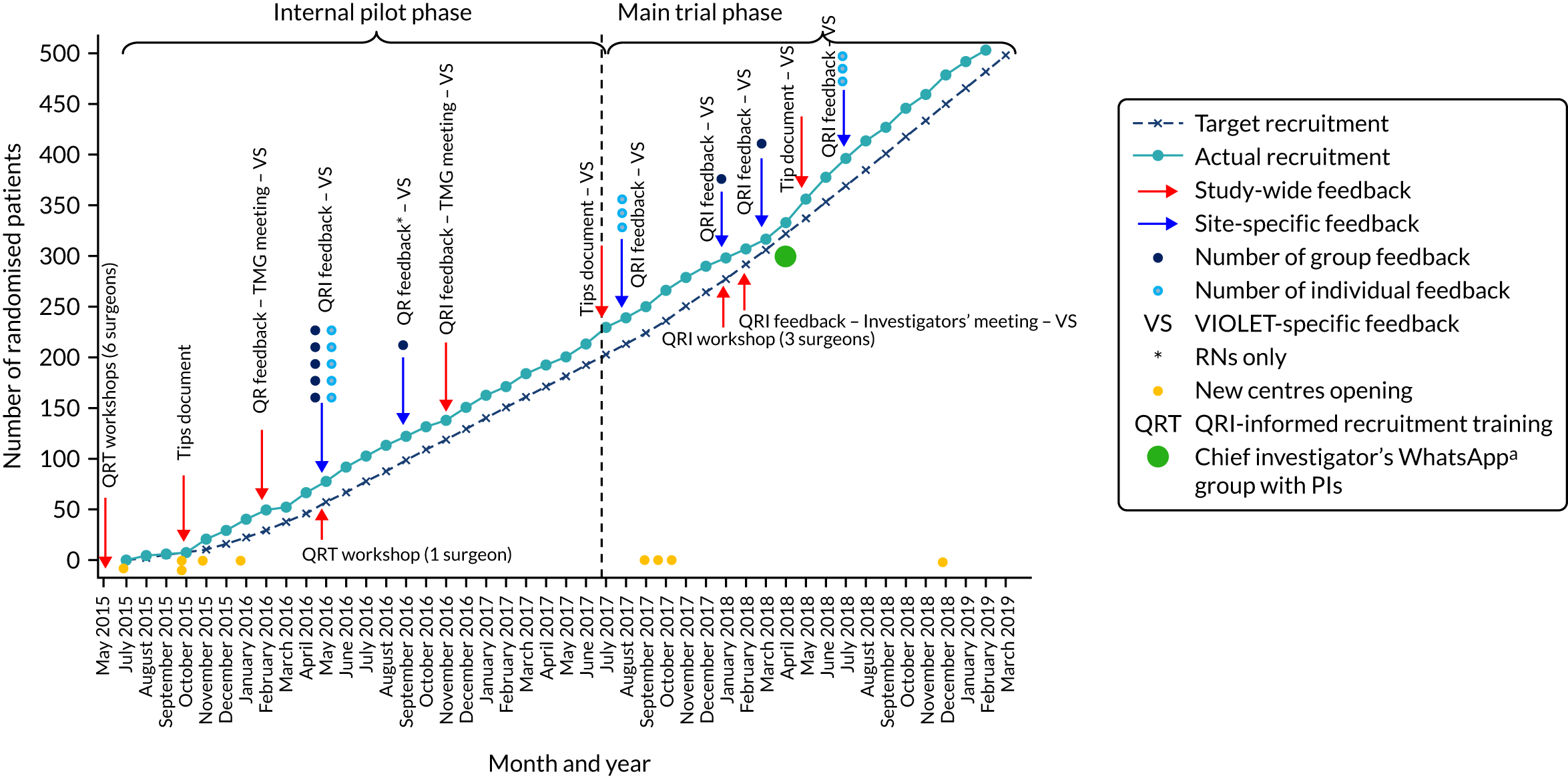

The aim of the QRI in the VIOLET trial was to optimise and sustain recruitment and informed consent by preventing recruitment difficulties from arising, identifying new challenges as they arose and addressing those that did arise rapidly. The VIOLET trial QRI began with QRI-informed recruitment training workshops aimed at helping recruiters prepare for impending recruitment activities and preventing the development of recruitment barriers. Next, when recruitment commenced, we employed established QRI methods, which comprised two iterative components19,20 aimed at (1) understanding the recruitment issues in real time and identifying the clear obstacles and hidden challenges to recruitment,26,27 and (2) developing and implementing a plan of action comprising strategies28–31 to overcome the challenges, in collaboration with the chief investigator, TMG, Bristol Trials Centre and the recruiting sites. Evaluation of the QRI was carried out throughout the recruitment period by regularly monitoring recruitment figures [using the screened, eligible, approached, randomised (SEAR) framework]32 and recruitment practice. Each of these methods is described in detail below (for further context regarding the evolution of the QRI, see Appendix 1).

Preventing recruitment difficulties: training and guidance prior to recruitment

We aimed to prevent recruitment difficulties in the VIOLET trial by disseminating strategies to optimise recruitment and informed consent to recruiting surgeons, drawing from the QRI evidence base and using multiple avenues. These activities occurred prior to recruitment and involved study-wide, as well as site-specific, activities.

At the trial set-up phase, PIs and other recruiting surgeons from the five sites in the internal pilot phase were invited to attend a 1-day QRI-informed recruitment training workshop. 29 Surgeons from the new centres were invited to subsequent workshops. The evidence-based training was aimed at raising awareness of, and providing practical tips to manage, the clear obstacles27 (e.g. logistical issues) and hidden challenges to recruitment (e.g. conveying equipoise, addressing patient preferences). 26–28,30,33 The evidence that informed the above workshops was also presented to each site during site initiation visits (SIVs), summarised in a brief tips document circulated to all internal pilot sites and used to identify aspects of patient- and recruiter-facing study documentation (e.g. information leaflets, consent forms and trial protocol) that were potentially unclear, imbalanced or open to misinterpretation.

Understanding recruitment issues

We employed a range of methods, primarily qualitative, but also drawing on descriptive quantitative data obtained from the SEAR logs, to understand the recruitment processes in the VIOLET trial and to identify the challenges to optimal recruitment.

Sampling and recruitment

Our sampling frame consisted of the VIOLET trial sites (i.e. five sites in the internal pilot Phase I and four sites added in Phase II), all staff involved in recruitment at these sites and TMG members.

Sites

All sites in the VIOLET trial were approached for participation in the integrated QRI at the time of the SIV or subsequently. QRI researchers liaised with the PIs or RNs at the sites to explain the QRI purpose and methods.

In-depth interviews

We employed a combination of sampling strategies to ensure that a wide range of views were gathered. We purposefully selected and approached staff members who were involved in trial oversight, including TMG members, as well as clinical/research staff in different roles (e.g. surgeons, RNs) who were involved with recruitment, to ensure maximum variation in the views captured. We also selected participants who were likely to provide insights into recruitment challenges identified in previous interviewees or other sources of data (e.g. theoretical sampling). Participants were initially contacted via e-mail, with a follow-up reminder when necessary.

Audio-recordings of recruitment discussions

All sites were requested to routinely audio-record the discussions that recruitment staff had with patients regarding treatment options and the trial until a decision was made regarding trial participation. The sites were provided with digital audio-recording equipment and ‘recruiter packs’, which outlined the process of obtaining consent for the QRI and provided instructions on how to operate the audio-recorders and to name and upload the audio files in a safe and confidential manner. Prior to each feedback session, audio-recordings were sampled using strategies similar to those employed to select interviewees described above (i.e. purposive, maximum variation and theoretical sampling). We purposively selected recordings of randomised and declined patients, ensuring that they featured different recruiters and spanned across centres, with further selections being made based on the themes identified in previous feedback sessions.

Data collection

In-depth interviews

Staff members who agreed to participate were sent information sheets and their written consent was obtained prior to the interview. In-depth semistructured interviews were conducted at a mutually convenient time and place (face to face or via telephone) and were digitally audio-recorded. Topic guides drew from those used in previous QRIs and helped ensure consistency across interviews, but these were used flexibly to allow the exploration of issues of importance to participants. Topics covered in interviews included the development, purpose and design of the trial; potential participants’ pathway through eligibility and recruitment; views on equipoise in relation to the VIOLET trial; and how the trial and the interventions would be discussed with patients.

Audio-recordings of recruitment discussions

Staff and patient consent were obtained prior to audio-recording of recruitment discussions. Staff members were provided with an information sheet and one-off written consent was obtained (usually by RNs), which allowed the audio-recording of their subsequent VIOLET trial recruitment discussions. The PIL for the QRI was posted to patients before their first clinical consultation with the surgeons to ensure that they had sufficient time to consider QRI participation. When patients arrived for the consultation, research teams confirmed that the patients had read and understood the information and then obtained written consent if the patient was willing to participate in the QRI. Recruitment discussions of these patients were then audio-recorded.

Patient pathway through eligibility and recruitment

All study sites were asked to maintain detailed screening logs, capturing SEAR32 information (see section Overview). Sites entered screening and recruitment data to a study database designed by the trials centre. Information on the recruitment pathways (i.e. the pathway for patients from the time they were referred for treatment to the point at which a decision was made regarding trial participation) was gathered through the in-depth interviews described above.

Observations of study meetings

QuinteT Recruitment Intervention researchers also attended regular study meetings to gain an overview of trial conduct and overarching challenges. Meetings attended included TMG meetings that took place every few months (consisting of the chief investigator and all VIOLET trial co-applicants), investigators’ meetings (similar to TMG meetings, but also attended by the key recruiting teams from participating sites) and monthly study update meetings (for key members of the TMG and research team). These meetings provided insights into the recruitment concerns of key stakeholders that warranted further exploration.

Data analysis

In-depth interviews

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed in full and verbatim. Transcripts were imported into NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and analysed using techniques of constant comparison, drawing from grounded theory. 34 This involved repeatedly moving within and across transcripts in the light of newly identified themes. We sought to develop a holistic understanding of recruitment challenges, as well as elements of good practice, and were attentive to shared, as well as disparate, views among staff members. Data collection and analysis were iterative and continued until we achieved data saturation (i.e. when we were no longer able to identify new themes).

Audio-recordings of recruitment discussions

Audio-recordings of recruitment discussions were transcribed verbatim and in a targeted manner, focusing on discussions of the trial and the operations. We employed similar methods of constant comparison as described for the interviews above. In addition, we used targeted conversation analytical techniques35 to delineate elements of good practice among recruiters for wider dissemination, as well as aspects of the discussion that could have contributed to misunderstandings among patients, precipitated patient preferences or adversely affected recruitment in other ways.

Patient pathways through eligibility and recruitment

Drawing from the interview data, we compiled recruitment pathways for each clinical centre. This comprised noting points at which patients received study information, underwent tests, had their eligibility determined and met clinical staff in different professional roles, and the timelines across these key points in the pathway. Recruitment pathways were compared across centres to identify good practice and bottlenecks that hindered recruitment.

Screened, eligible, approached, randomised data were collated and descriptively analysed by the trial statistician, with monthly summaries provided to the QRI team for each site (to aid group feedback) and individual surgeon (to inform individual feedback). QRI researchers carried out further analysis by designing a colour-coded spreadsheet for each recruiting site to facilitate easy identification of inconsistencies or missing data, as well as site-specific patterns in recruitment flow. These inconsistencies and patterns were discussed with the chief investigator/TMG during study update meetings. Data queries were often resolved by contacting site research teams or by alerting the trial manager. Patterns, such as lack of screening activity, patients not being approached or large numbers of patients declining to take part in the RCT, usually triggered further data collection and agreement on a plan of action to help sites address unhelpful patterns of recruitment.

The findings from the above data sets were brought together and detailed in a descriptive account that drew from all data sources to identify key challenges to recruitment, with brief update reports written throughout the recruitment period of the trial.

Plan of action: strategies to optimise recruitment and informed consent

Initial anonymised QRI findings that identified factors appearing to hinder recruitment were presented to the chief investigator/TMG (in February 2016, 8 months after recruitment to the VIOLET trial had commenced) so that they could agree on a plan of action to address factors impeding recruitment. This plan was implemented through the first set of group and individual feedback sessions covering all the internal pilot phase sites (May–June 2016), with the aim of optimising recruitment and informed consent. As recruitment progressed and the trial moved into the main phase, there was further QRI data collection, analysis and presentation of findings at TMG and investigator meetings and at VIOLET trial sites, which aimed to sustain the recruitment momentum gained early in the trial. The key findings were also summarised in succinct ‘tips’ documents circulated to all centres, especially during periods of low recruitment activity. Towards the end of the recruitment period, the QRI team, in collaboration with the chief investigator/TMG, developed a rapid communication strategy, which aimed to reiterate the most important QRI findings and strategies and disseminate them through monthly newsletters developed by the trials centre and e-mail communications with infographics on recruitment figures.

Evaluating the impact of the QRI

We evaluated the impact of the QRI in two ways through (1) monthly monitoring of recruitment figures (i.e. SEAR data) and (2) recruitment practice. First, SEAR data were monitored from the onset of recruitment until the achievement of the final recruitment target to check if recruitment commenced well following the training/guidance provided prior to recruitment, if any recruitment momentum gained was sustained thereafter and if there were periods of low recruitment activity that improved after rapid intervention. Second, we monitored recruitment practice by listening to the audio-recordings (and interviews where relevant) to document changes in practice following the provision of trial- and site-specific feedback and instances where recruitment challenges appeared to have been averted following the training/guidance prior to recruitment. A conventional pre- and post-intervention evaluation was not feasible in the VIOLET trial QRI, as it did not have a precise pre-QRI period of recruitment because of the preventative activities undertaken in advance of recruitment.

Statistical methods

All analyses were directed by a prespecified statistical analysis plan (SAP), which was finalised before the database was locked for analysis. The data are reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines. 36

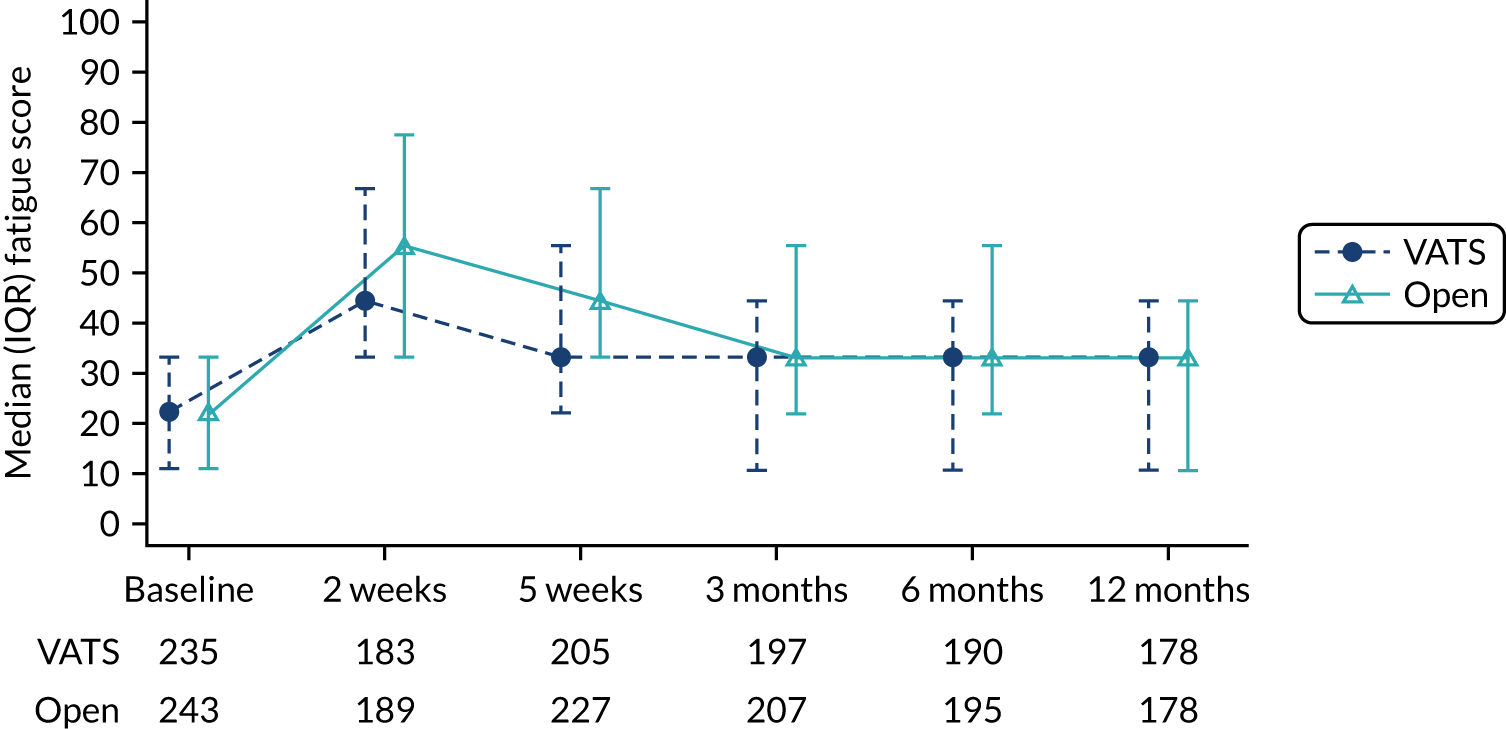

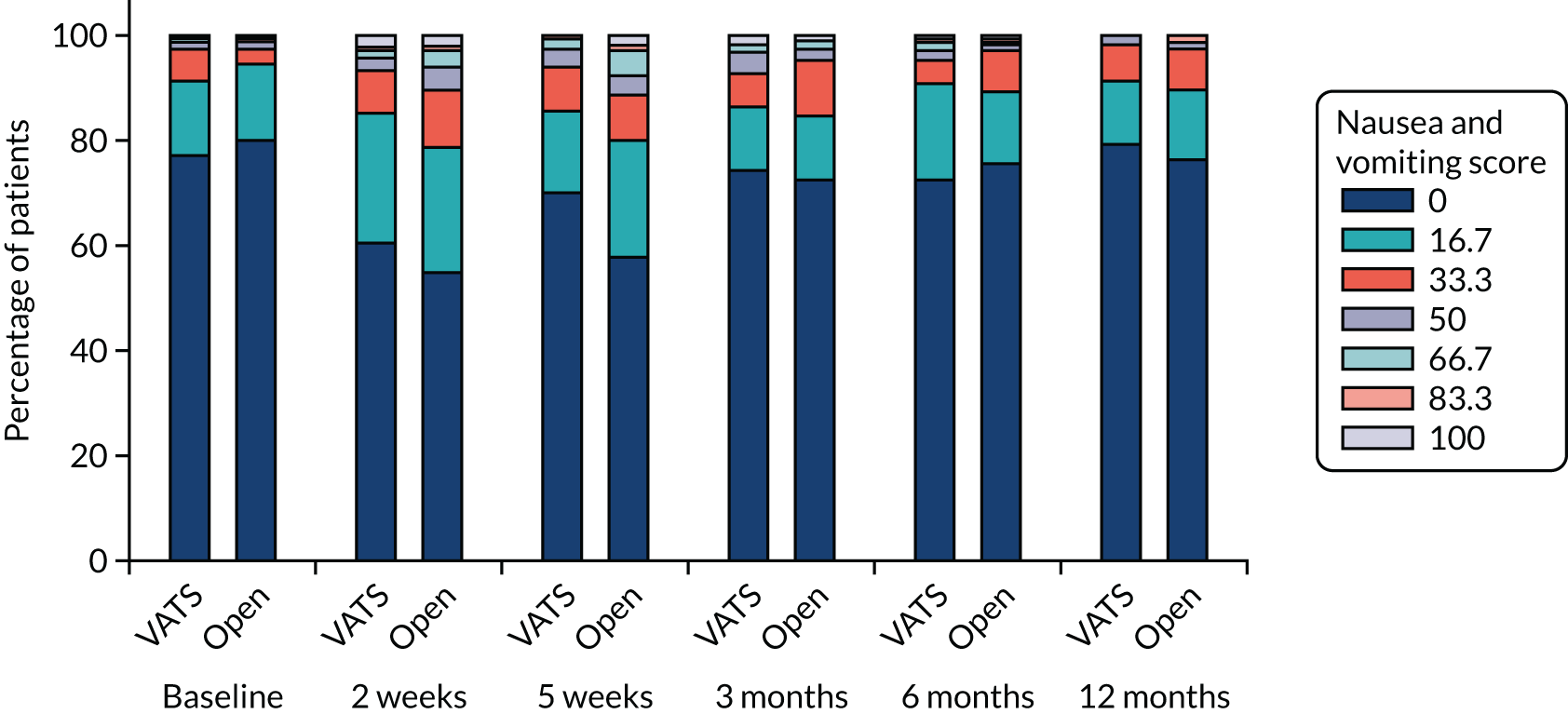

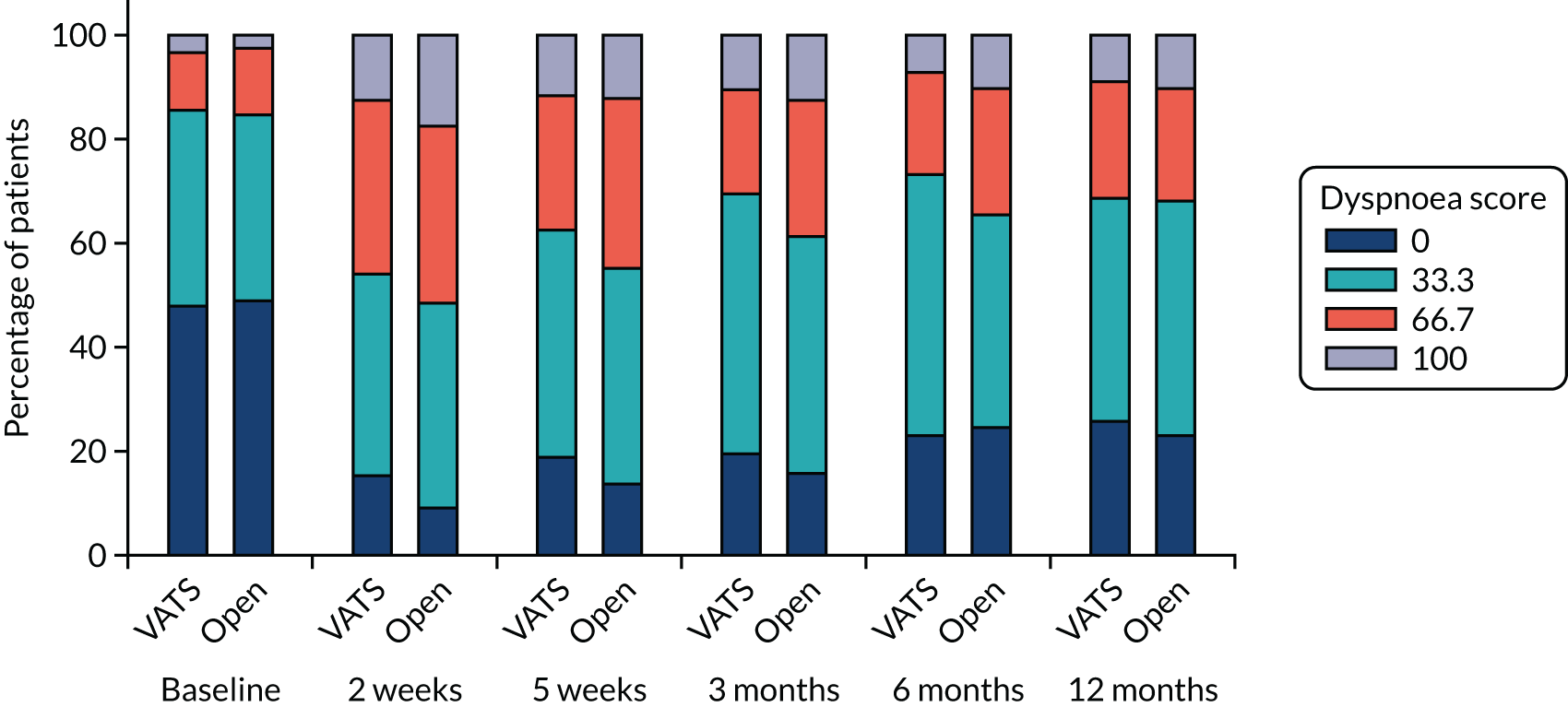

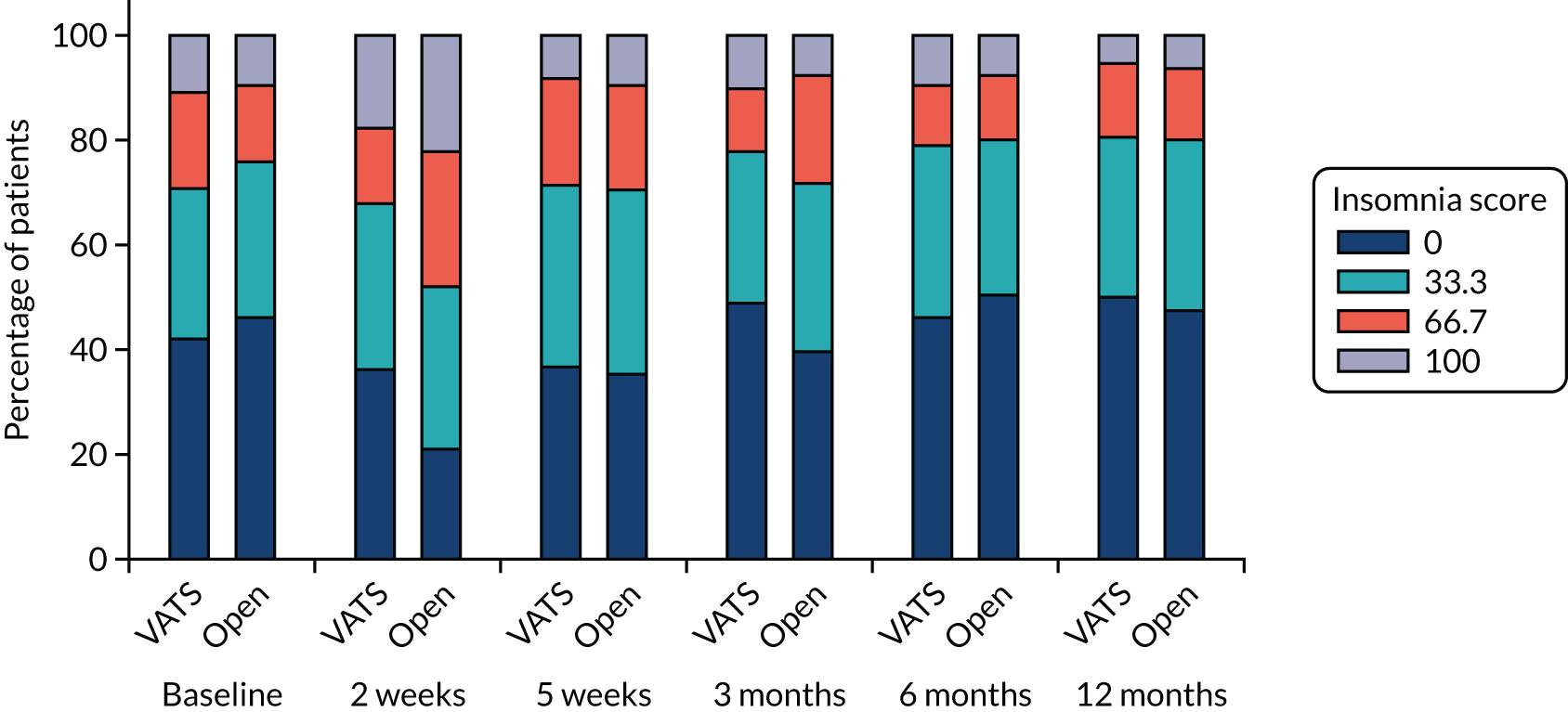

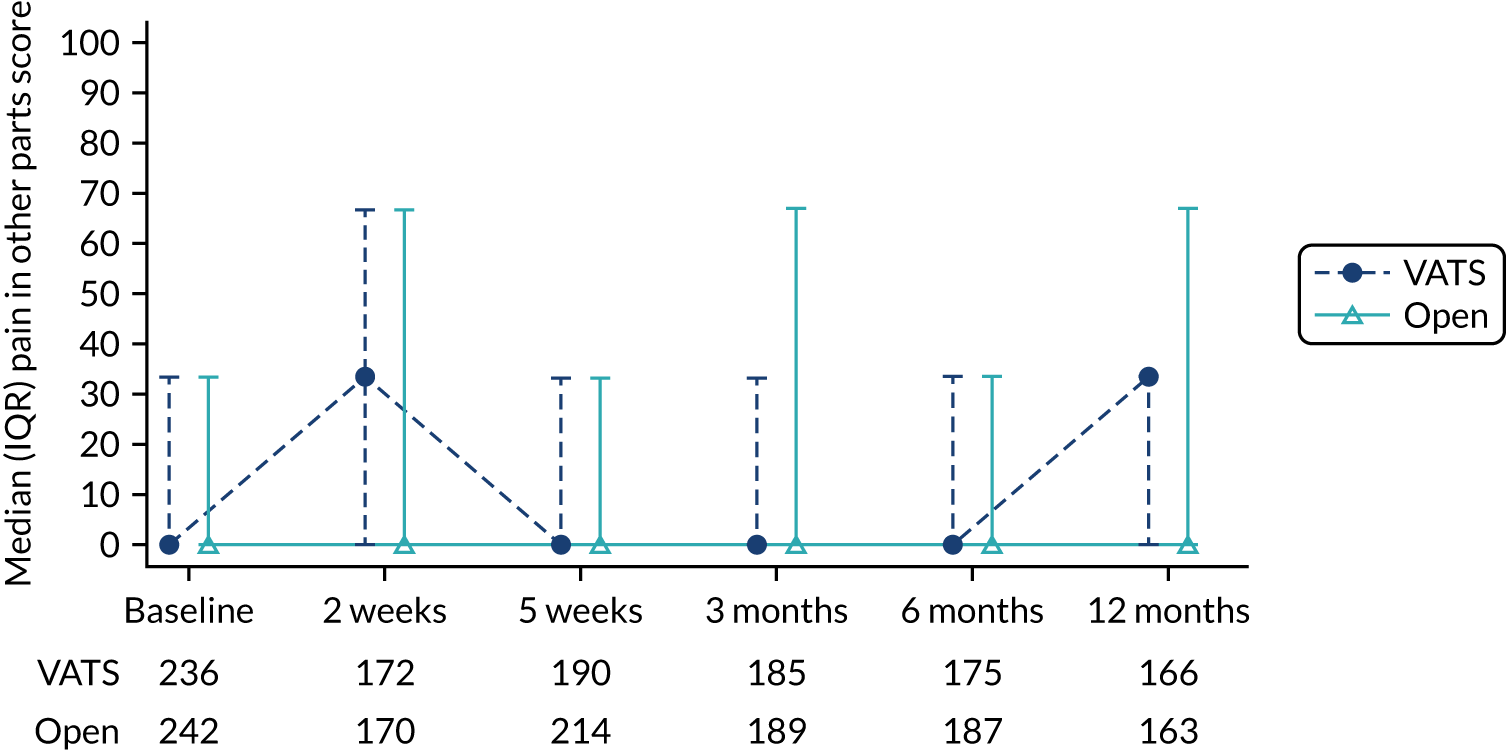

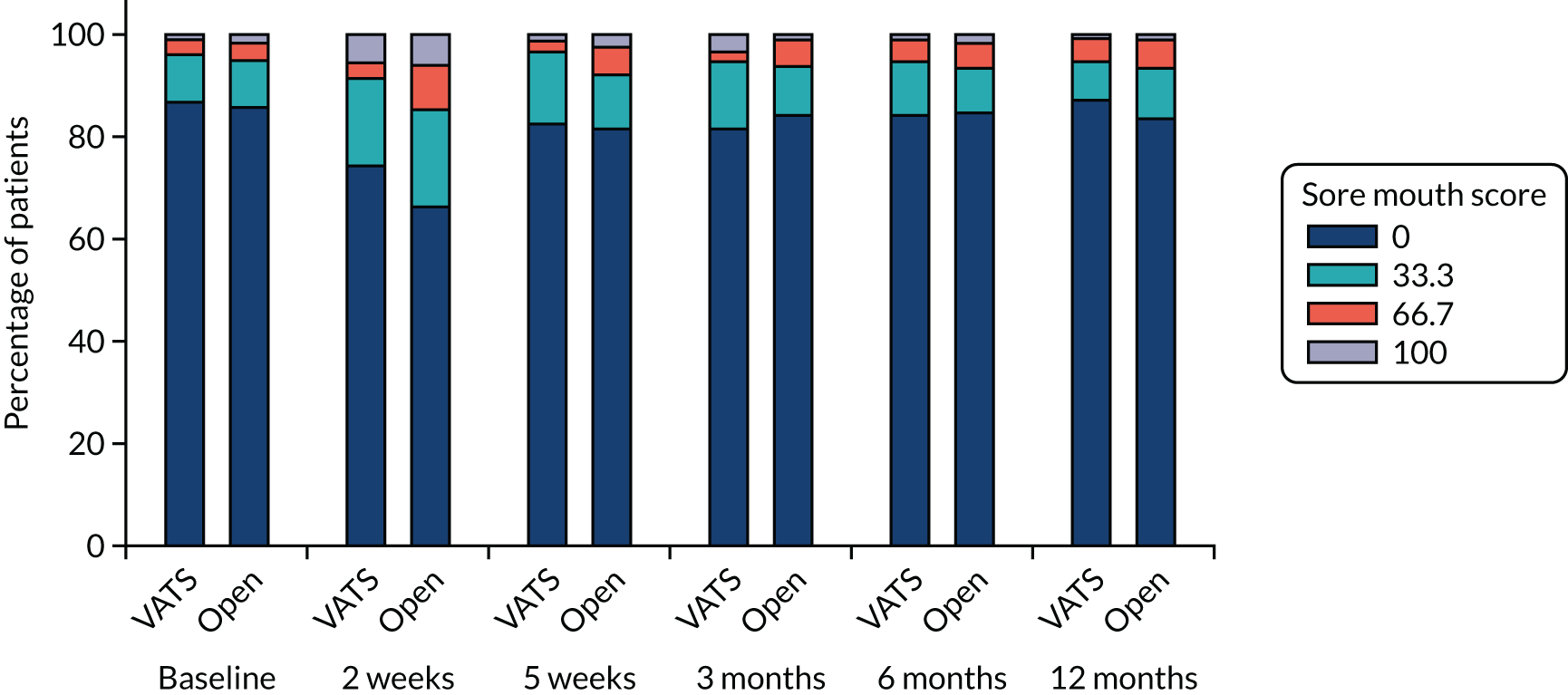

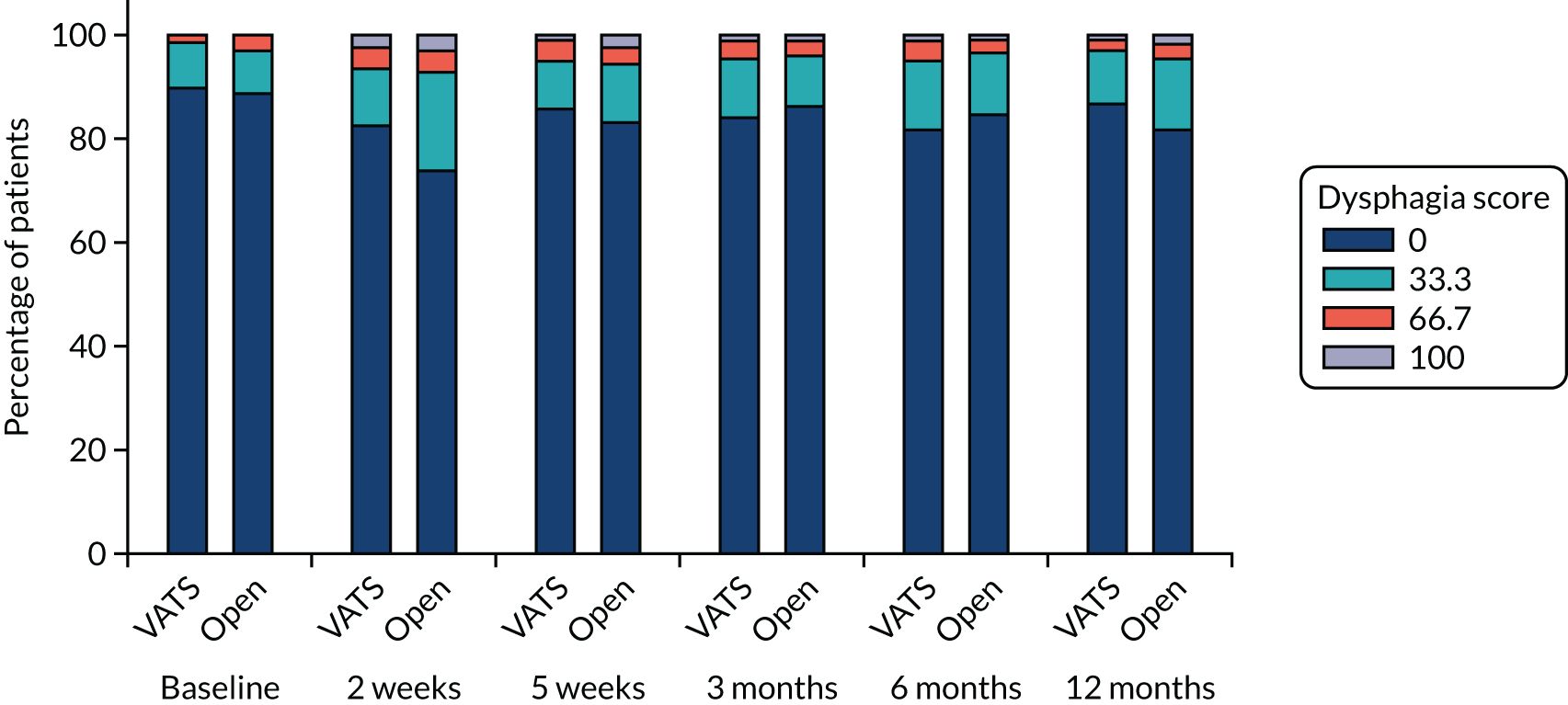

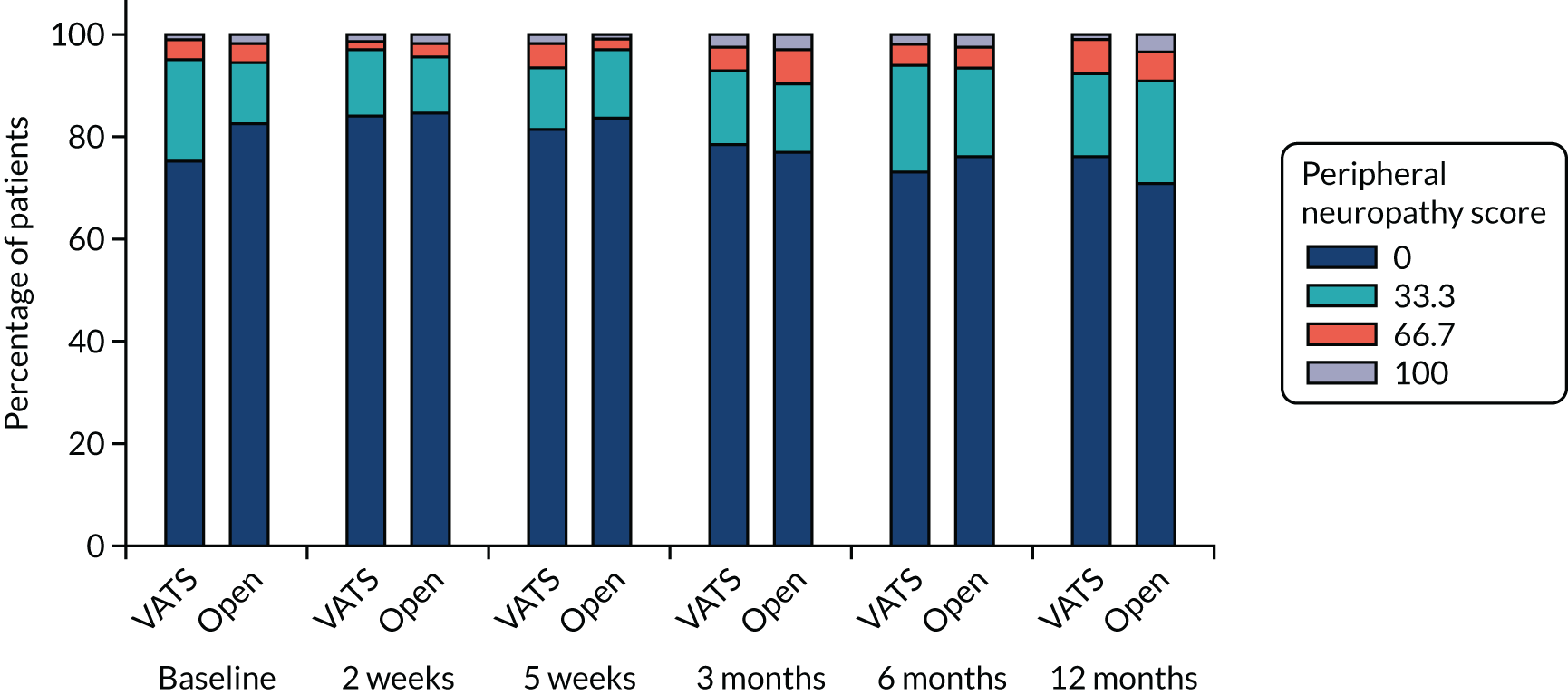

Summary statistics and analysis population

Data were described using summary statistics, using mean and SD for continuous variables [or median and interquartile range (IQR) if distributions were skewed] and number and percentage for categorical variables. HRQoL questionnaires were scored in accordance with the developer’s scoring instructions and summary scales derived from the questionnaires are reported in summary tables.

Participants were grouped according to the randomised allocation (intention to treat). The analysis population consisted of all randomised participants, excluding those who withdrew and were unwilling for data already collected to be used. Data from any participant who withdrew and was unwilling for their data to be used were included in the study flow chart, but not in any subsequent data tables or figures.

Models used to compare primary and secondary outcomes

The models used to compare longitudinal HRQoL outcomes, including the primary outcome, are presented in Table 2. The adequacy of a model fit was assessed graphically.

| Outcome | Model | Time adjustment | Survival adjustment | Effect(s) reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

QLQ-C30: physical functioning, global health status/quality of life, role functioning, social functioning and dyspnoea scores QLQ-LC13: dyspnoea, cough, pain in chest and pain in other parts scores |

Joint longitudinal survival model | Fixed or random, depending on model fit assessed using likelihood ratio tests | Survival time modelled jointly with HRQoL score | MD |

| QLQ-C30: fatigue, pain and insomnia scores | Linear mixed-effects model | Fixed: different variance/covariance structures assessed using likelihood ratio tests | None | MD |

|

QLQ-C30: emotional functioning and cognitive functioning scores EQ-5D-5L |

Two-part model, with logit first part and log-linear second part | Fixed |

No adjustment in emotional functioning model EQ-5D-5L score of 0 imputed after death |

OR and GMR |

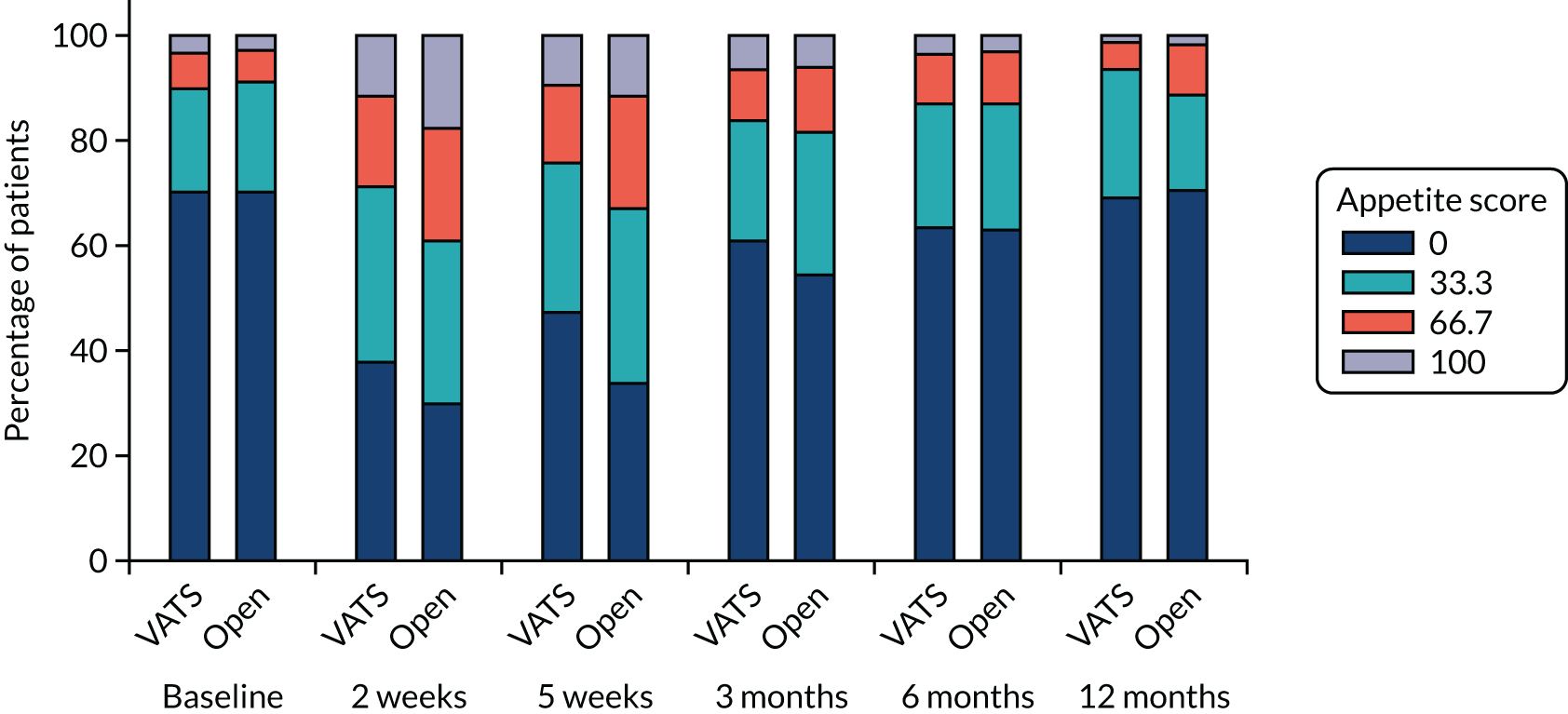

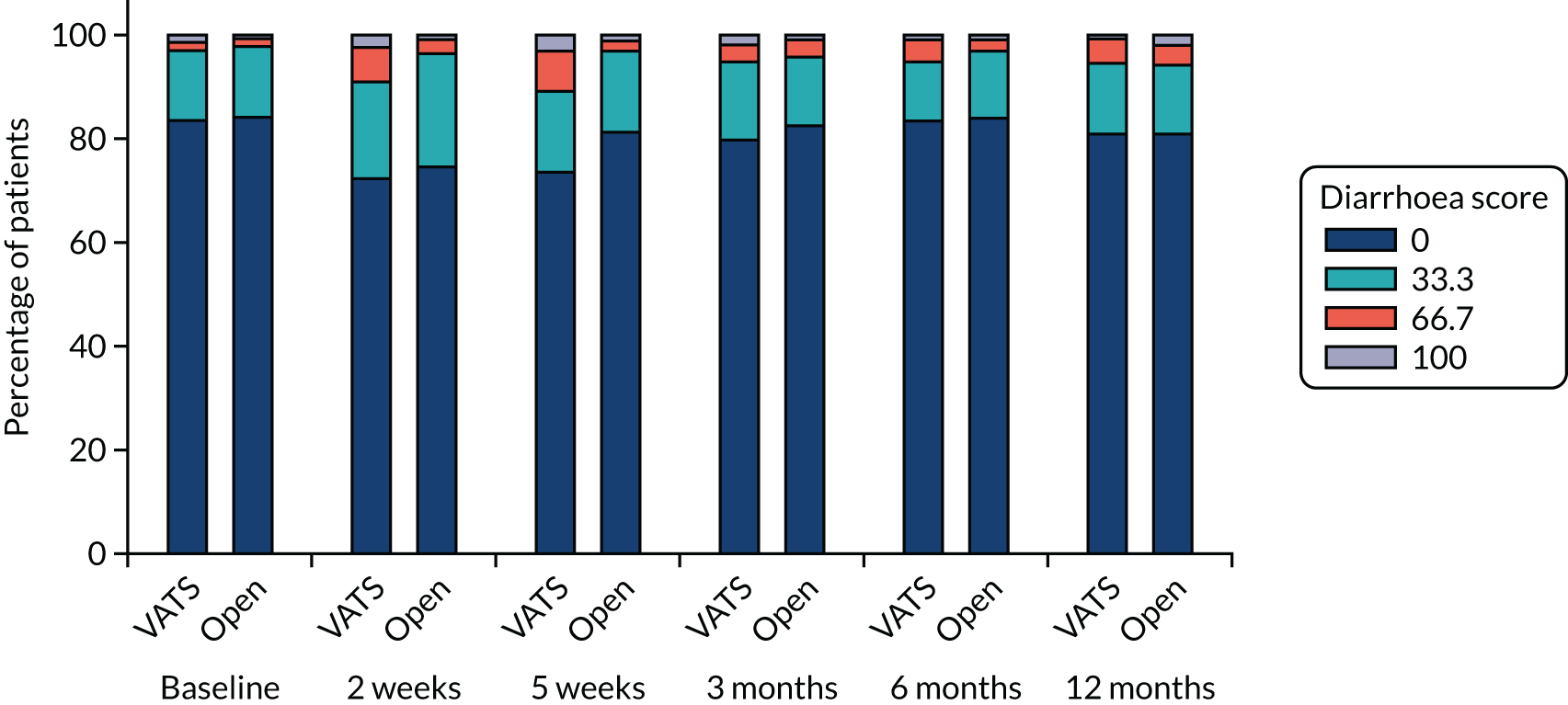

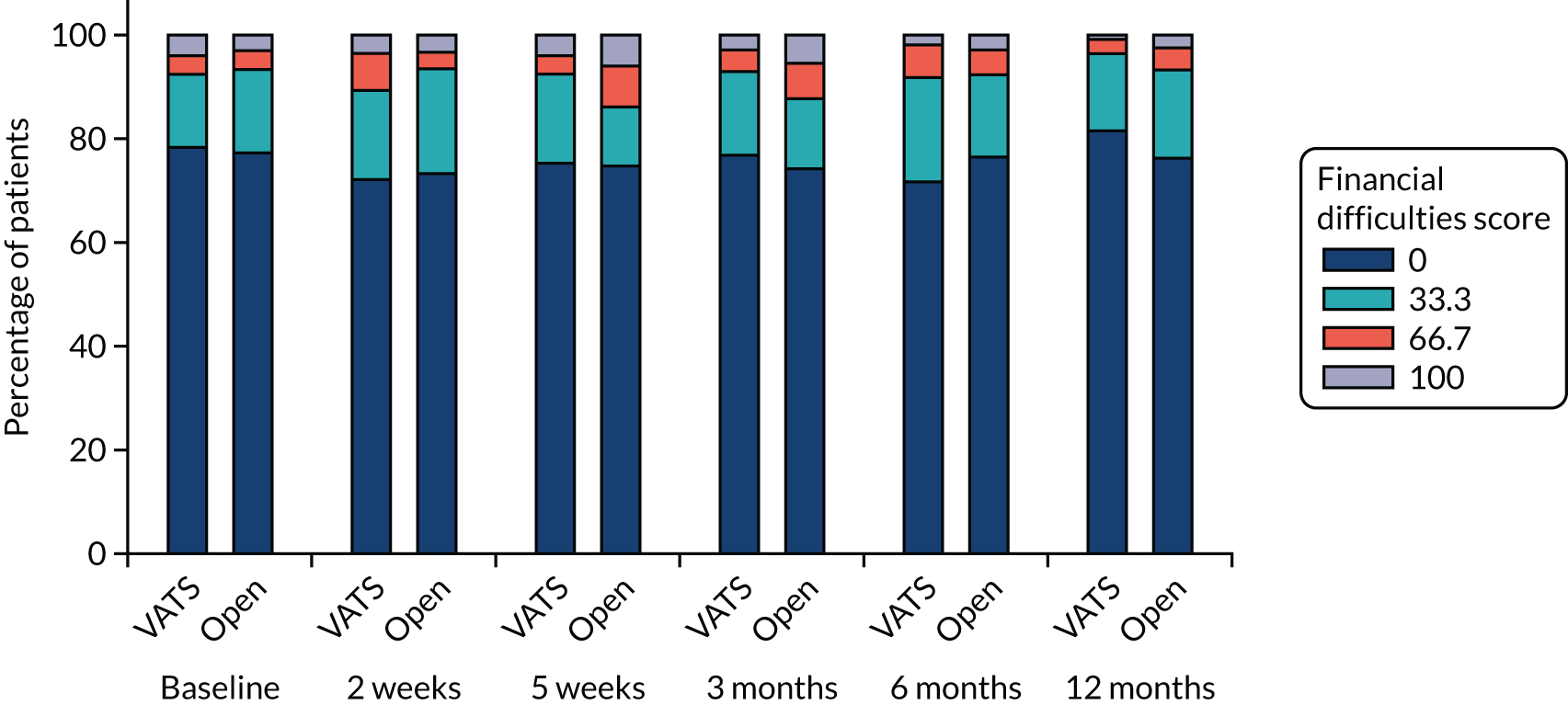

|

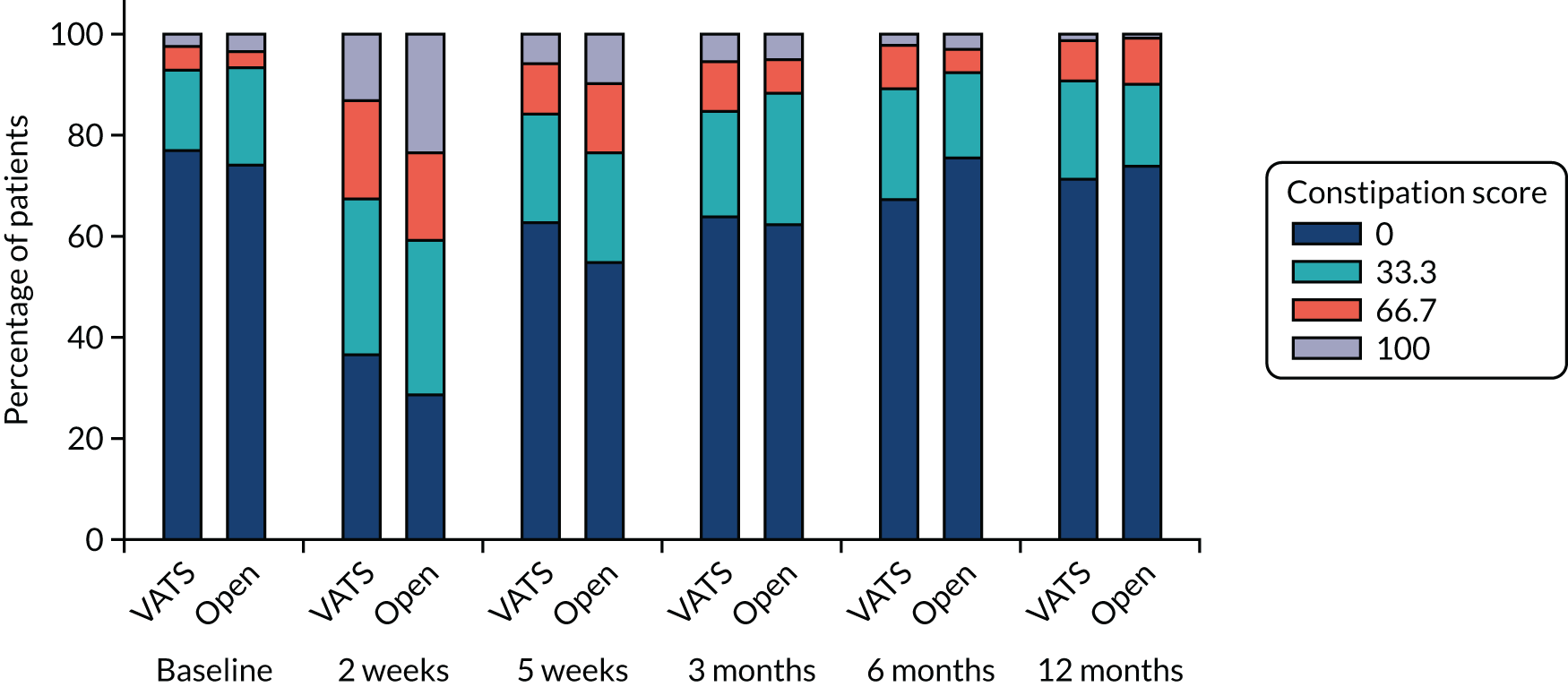

QLQ-C30: appetite loss, diarrhoea and financial difficulties scores QLQ-LC13: sore mouth, dysphagia, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia and pain in shoulder or arm scores |

Ordinal logistic regression | Fixed | None | OR |

|

QLQ-C30: nausea and vomiting, and constipation scores QLQ-LC13: haemoptysis score |

Logistic regression | Fixed | None | OR |

The strategy for modelling longitudinal HRQoL outcomes, listed in order of preference, is as follows:

-

Joint longitudinal survival model.

-

Linear mixed-effects model (chosen if the joint longitudinal survival model did not provide an adequate fit to the data).

-

Mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression (chosen if the HRQoL score could take only four possible values, the proportional odds assumptions held and the previous models were not appropriate) or partial proportional odds model (chosen if proportional odds assumption did not hold for all variables to be included in the model).

-

Mixed-effects logistic regression (chosen if the ordinal logistic regression model did not converge or the proportional odds assumption did not hold for time or treatment variables).

If the distribution of the HRQoL score was non-monotonic, with a high proportion of participants scoring perfect functioning/health, a two-part model was used. Scores were dichotomised into perfect functioning/health (i.e. a QLQ-C30 score of 100 and an EQ-5D-5L utility score of 1) and less than perfect functioning/health. The first part of the model was an occurrence model, that is a mixed-effects logistic regression model comparing perfect functioning/health with less than perfect functioning/health. The second part was an intensity model, that is a log-linear mixed-effects model for the score, conditional on a less than perfect functioning/health score.

Time-by-treatment interactions were added to all longitudinal models. Overall treatment effects are presented unless the interaction reached 10% statistical significance, in which case treatment effects for each time point are reported. For the primary outcome, the treatment effect at 5 weeks is reported, estimated from the longitudinal model with a time-by-treatment interaction included.

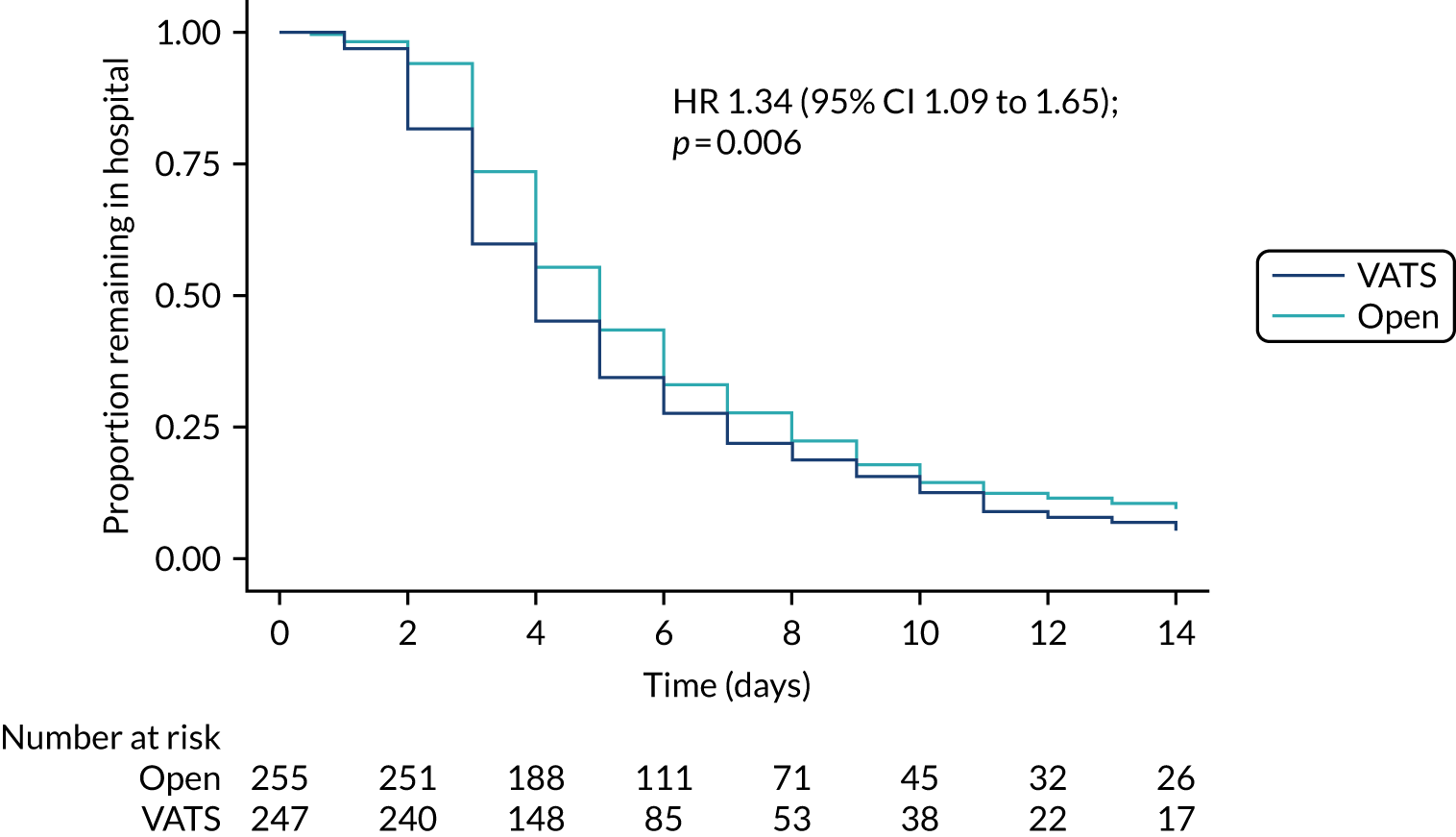

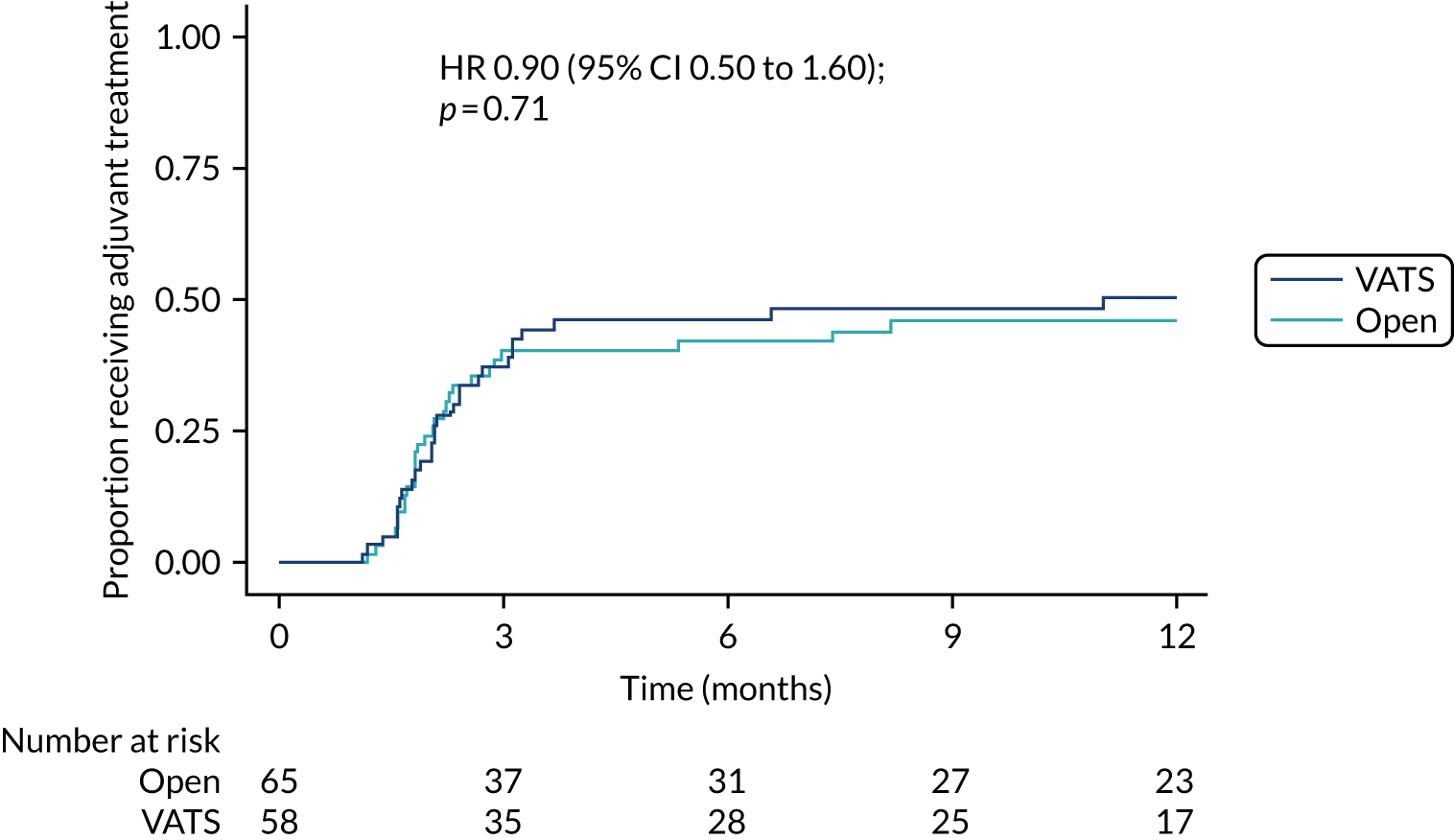

Time-to-event outcomes were compared using Cox proportional hazards models and treatment estimates are presented as hazard ratios (HRs). Time to uptake of adjuvant treatment was analysed using competing-risks regression, with death modelled as a competing risk. Overall survival, progression-free survival (with progression defined as progression of lung cancer or new primary lung cancer or death from any cause, whichever occurred first) and uptake of adjuvant treatment were censored at last follow-up for those who had not experienced the event (or competing risk). For duration of hospital stay, in-hospital deaths were censored at the maximum observed time to discharge for survivors. The exact partial-likelihood method was used to account for tied times. Model assumptions were assessed graphically.

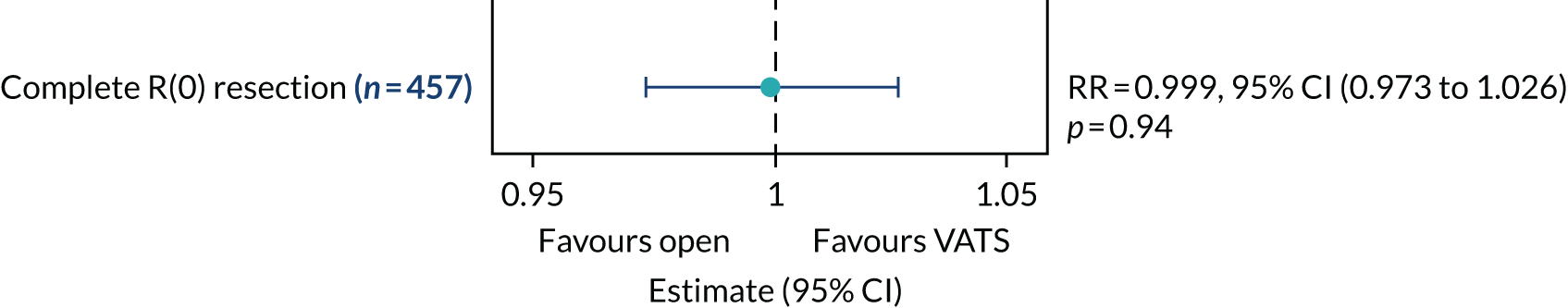

In-hospital pain scores were analysed using a linear mixed-effects model. Binary outcomes [i.e. complete R(0) resection and prolonged incision pain] were analysed using generalised linear models and multinomial outcomes (i.e. upstaging to pathologic node stage 1 (pN1) disease and upstaging to pN2 disease) using generalised structural equation models. Effect estimates are presented as relative risk (RR).

The mean daily dose of each analgesic, averaged over the hospital stay, was derived for each participant. Analgesic agents were combined into groups, where appropriate. The mean ratios were derived for each analgesic group and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using bootstrapping.

Open surgery was the reference group in all analyses. Treatment estimates are reported with 95% CIs.

Adjustment in models

The plan was to adjust all models for centre and operating surgeon fitted as random effects (or as stratification variables in time-to-event outcomes). For binary outcomes, a clustered sandwich estimator was used to account for the clustering within surgeon, as random effects were not estimable. All longitudinal analyses were adjusted for baseline preoperative score as a fixed effect.

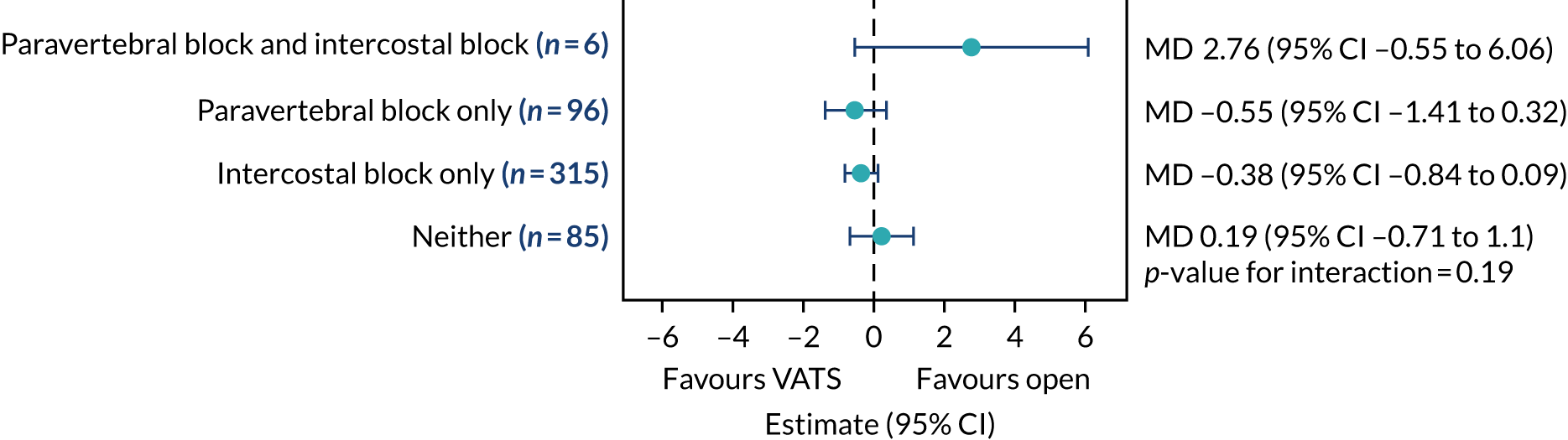

Subgroup analysis

A prespecified subgroup analysis, comparing in-hospital pain scores by type of analgesia (e.g. paravertebral block, intercostal block, both, neither) was performed. This was implemented by adding a treatment-by-analgesia interaction term into the model, comparing pain scores between groups.

Sensitivity analyses

A sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome, excluding participants with benign disease, was prespecified in the protocol. Sensitivity analyses of overall survival and progression-free survival were also performed, adjusting the model for participant’s disease stage based on pathological findings. These analyses were not in the protocol, but were added to the SAP on recommendation from the DMSC.

Exploratory analyses

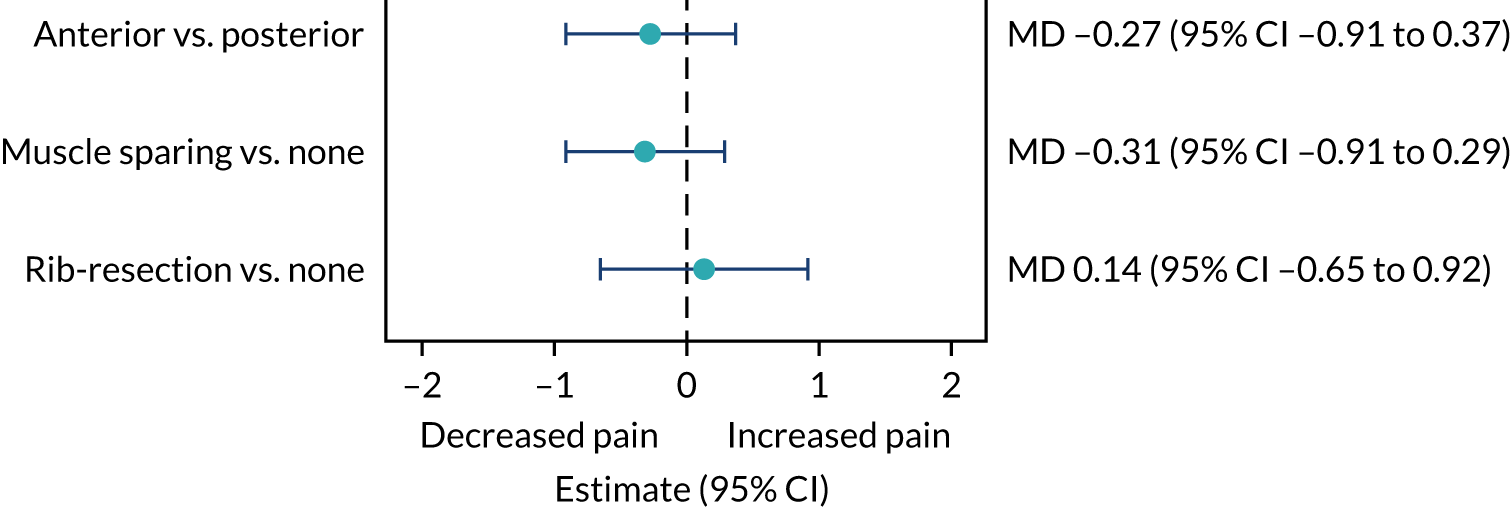

Two exploratory analyses of pain scores were undertaken. The first was stated in the protocol and the second was requested by the DMSC:

-

An exploratory analysis comparing in-hospital pain scores by number of incisions (i.e. VATS with a single port site, VATS with multiple port sites and open surgery).

-

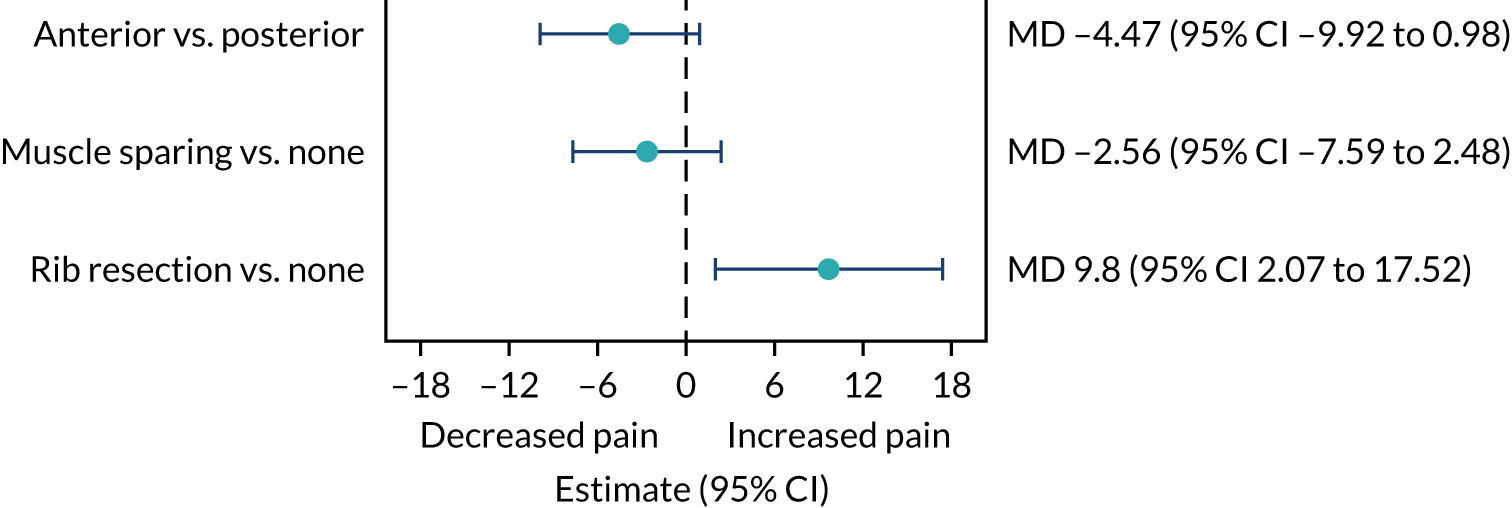

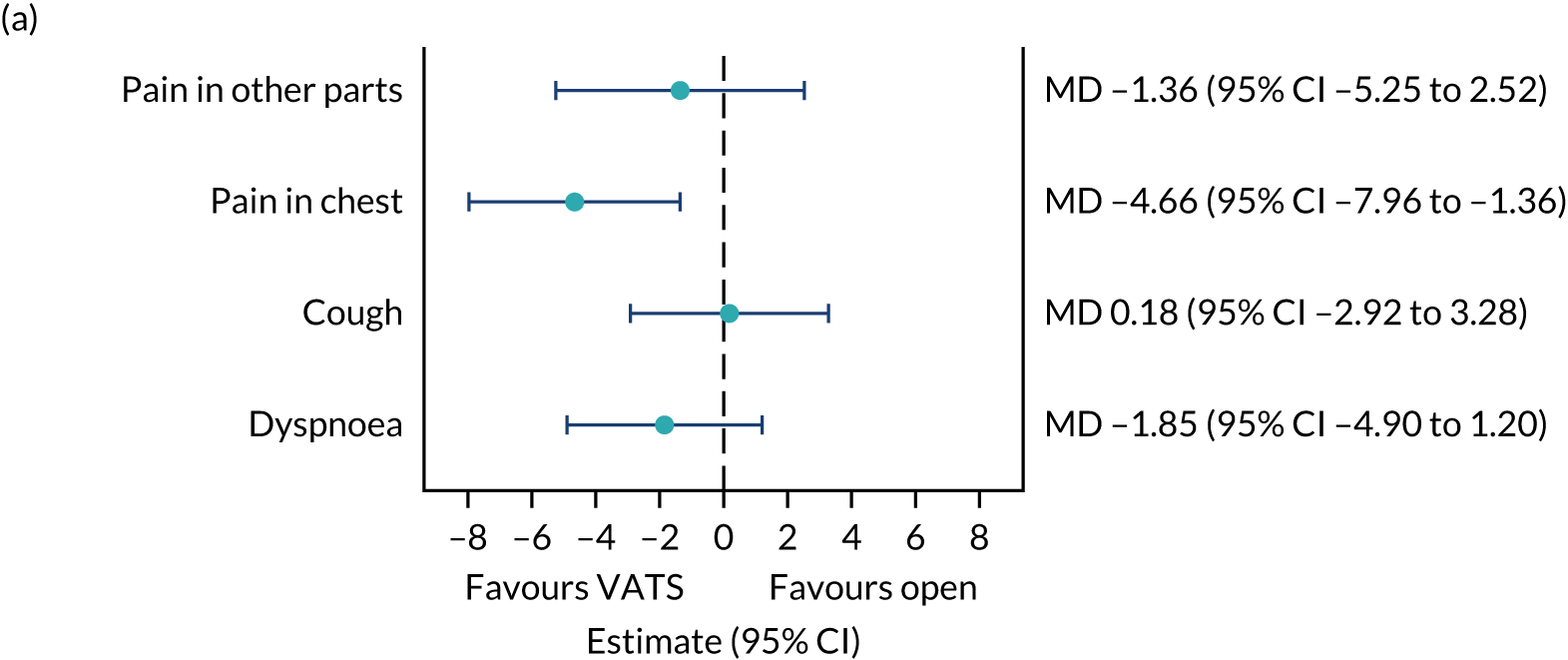

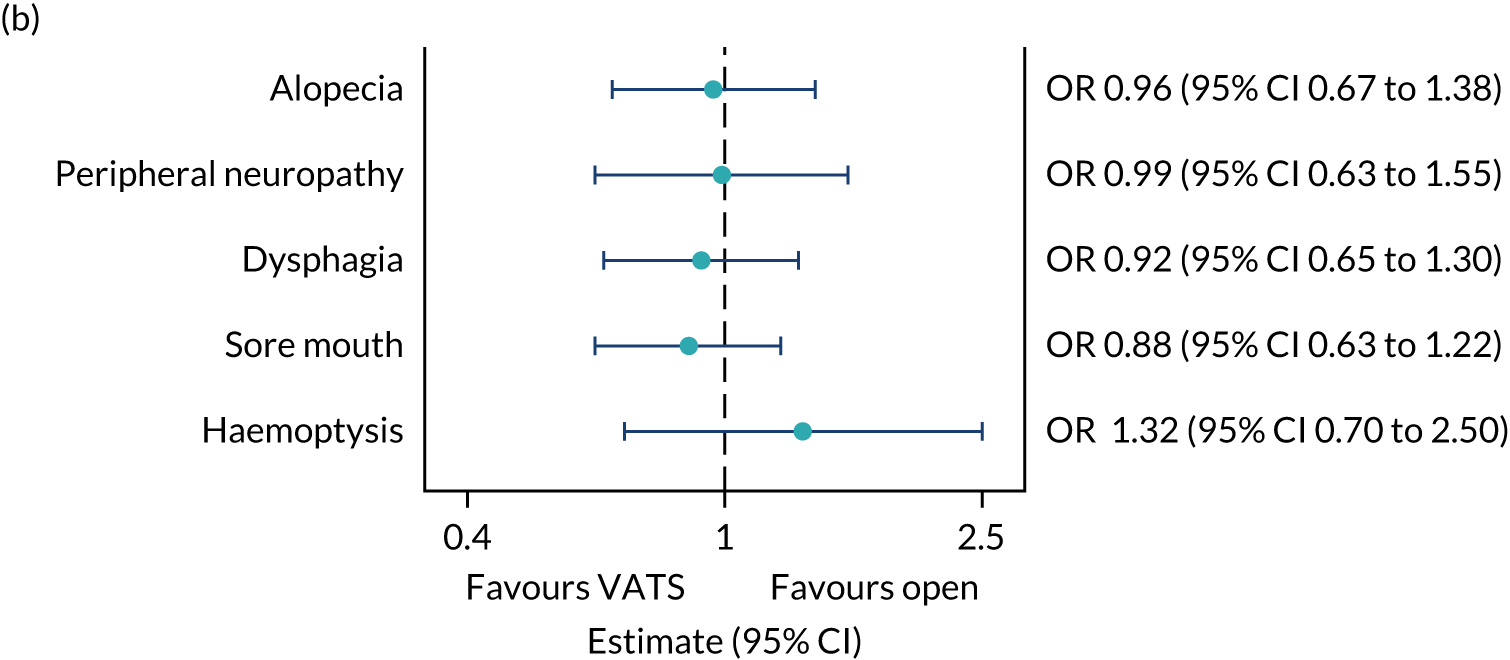

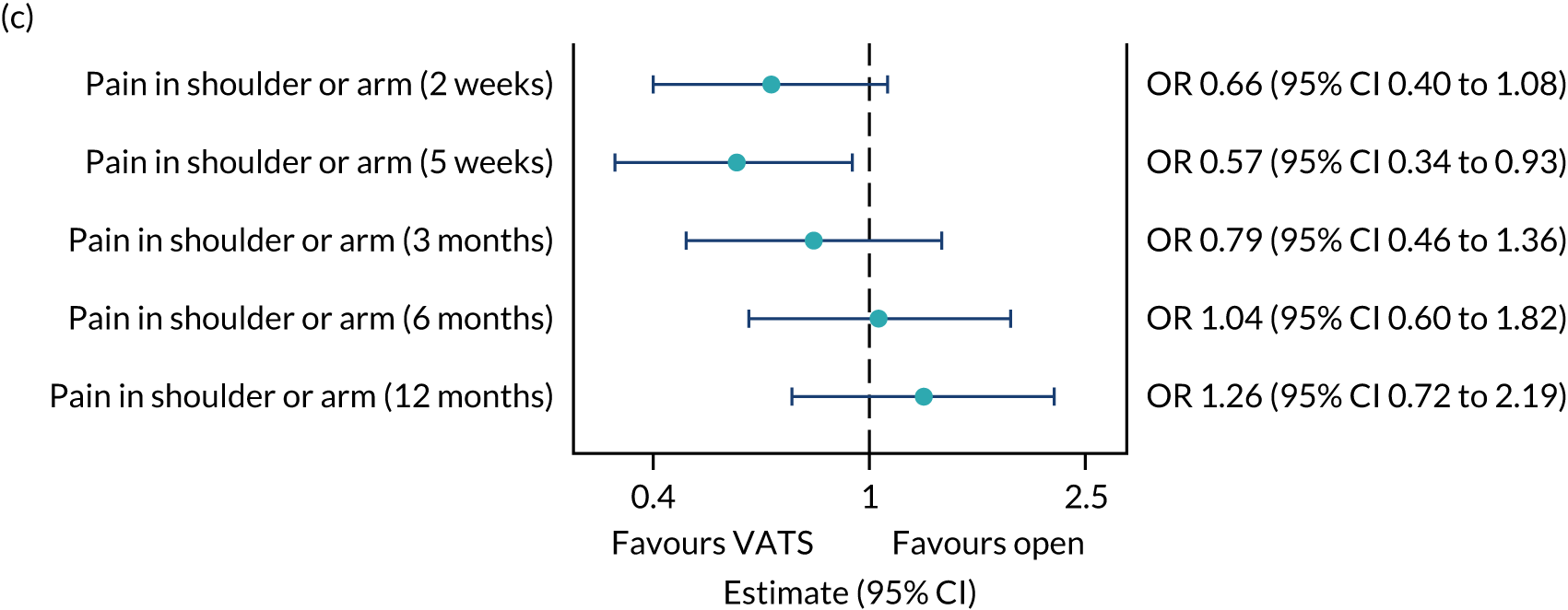

An exploratory analysis comparing in-hospital pain scores and QLQ-C30 pain scores by type of thoracotomy (i.e. anterior thoracotomy vs. posterolateral thoracotomy, muscle sparing vs. no muscle sparing, and rib resection vs. no rib resection).

An exploratory analysis comparing length of stay by incisions (i.e. single-port VATS vs. multiport VATS vs. open surgery) was not prespecified in the protocol, but was requested by the chief investigator before any comparative analyses had been undertaken.

Missing data

Missing data are described in footnotes to all tables. Rules for imputing missing data outlined in the SAP were dependent on the level of missing data. All HRQoL analyses and the in-hospital visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score analysis met the threshold for multiple imputation. For other outcomes, participants with missing data were excluded. For HRQoL analyses, each subscale was imputed separately. Imputation by chained equations was used to generate multiple complete data sets [using the Stata® version 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) -ice- command] and results were combined using Rubin’s rules. Factors included in the imputation models used were baseline HRQoL score, treatment allocation, centre and operating surgeon.

Significance levels and adjustment for multiplicity

For hypothesis tests, two-tailed p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Likelihood ratio tests were used in preference to Wald tests. For HRQoL outcomes derived from the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC13 questionnaires, significance levels were adjusted for multiplicity using the false discovery rate method proposed by Benjamini and Hochberg. 37 The adjustment was applied within each instrument (e.g. for QLQ-C30 functional scale scores, QLQ-C30 symptom scale scores and QLQ-LC13 scores). No formal adjustment for multiplicity was made for other outcomes. Formal statistical comparisons were not made for outcomes with low-event rates and only prespecified subgroup analyses were performed. The number of statistical tests performed should be considered when interpreting results.

All statistical analyses were performed with the use of Stata software.

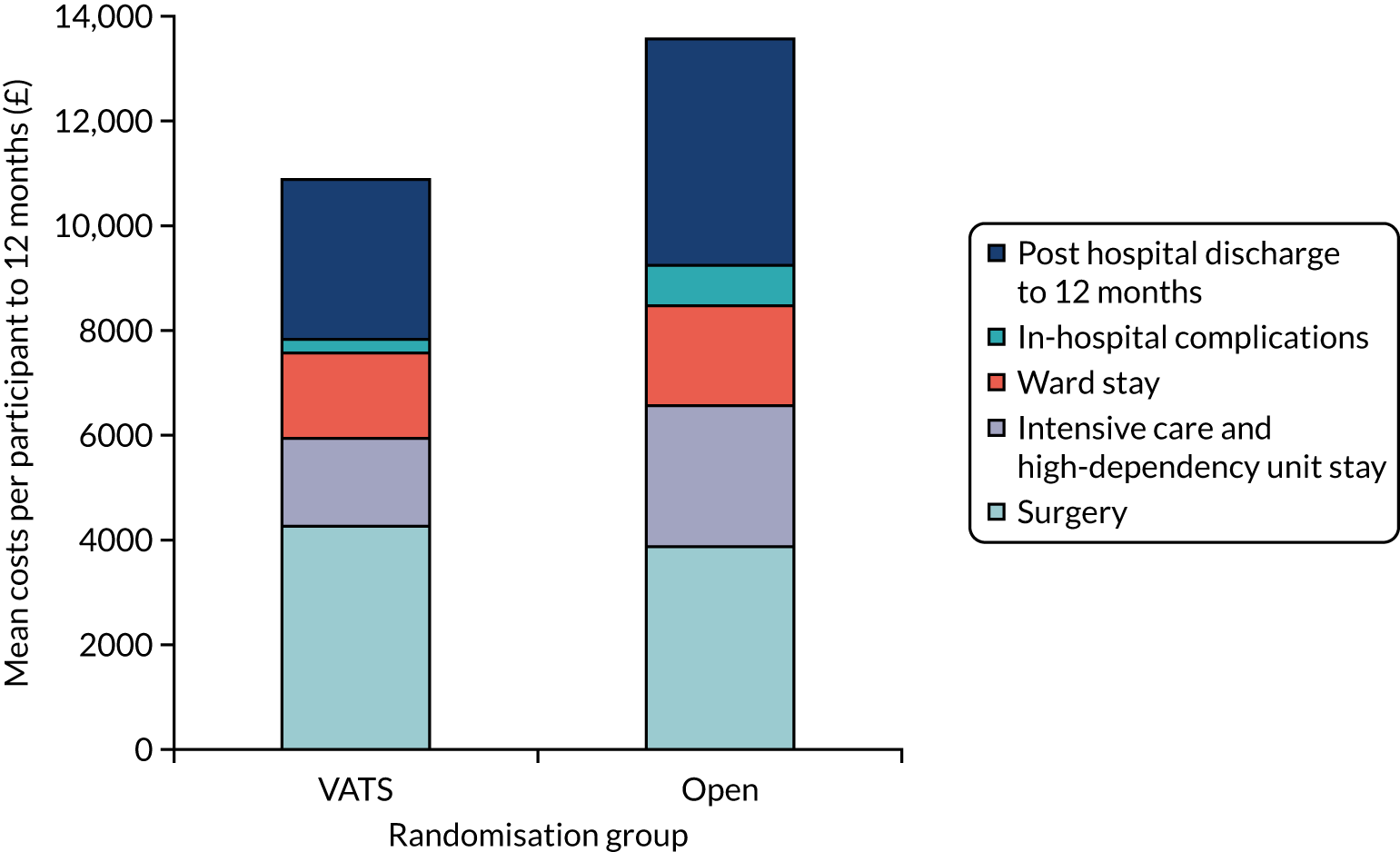

Economic evaluation

Economic evaluation aim

The economic evaluation aimed to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of VATS lobectomy compared with open lobectomy for the treatment of lung cancer, in line with the VIOLET trial.

Economic evaluation overview

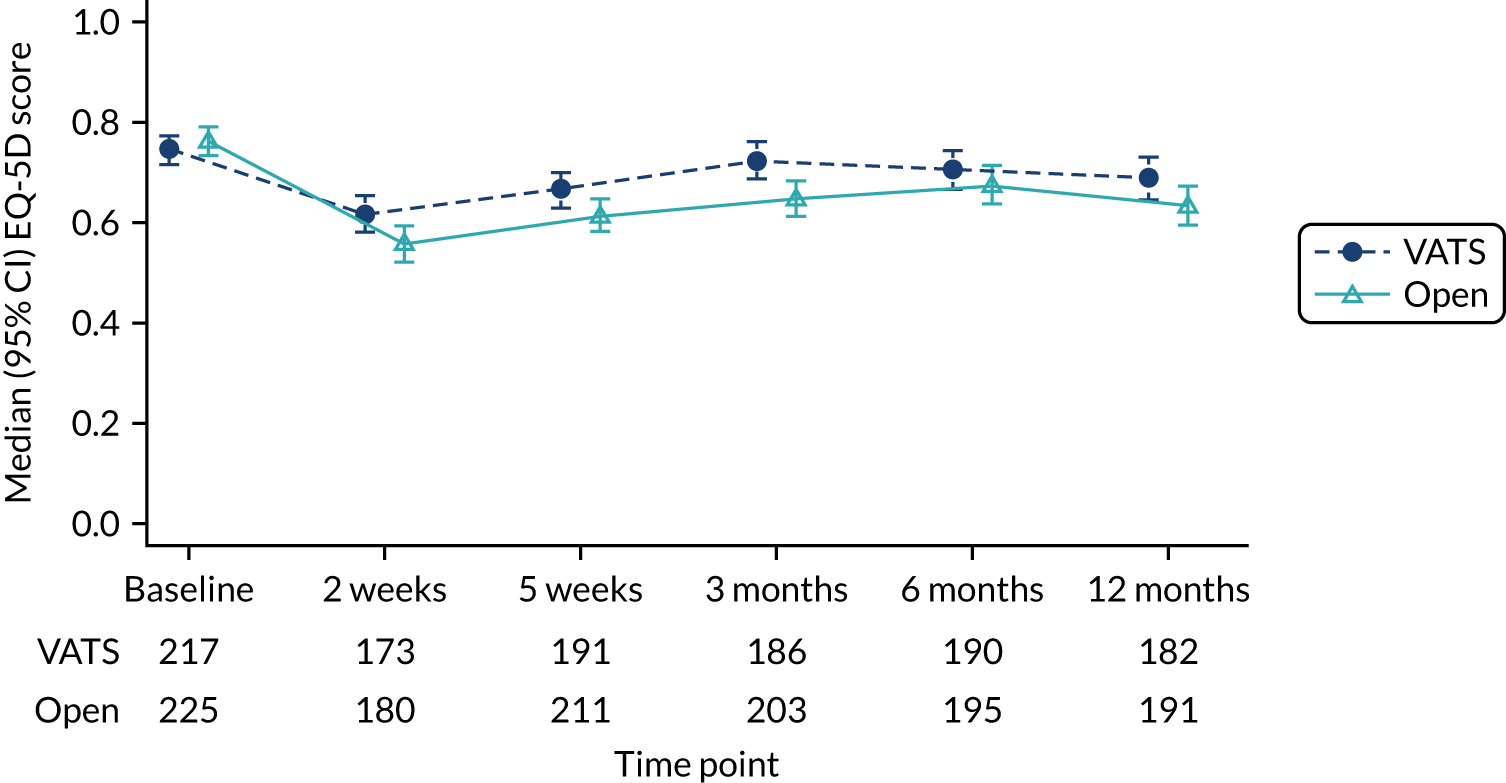

The perspective of the evaluation was that of the UK NHS and Personal Social Services, as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 38 The perspective for outcomes comprised the patients undergoing treatment. The primary outcome measure for the cost-effectiveness analysis was quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), estimated using the EQ-5D-5L. 39,40 Established guidelines on the conduct of economic evaluations set out by NICE were followed. 38 Table 3 summarises the key aspects of the economic evaluation, and further details are provided below.

| Aspect of methodology | Strategy used in base-case analysis |

|---|---|

| Form of economic evaluation | Cost-effectiveness analysis for comparison between VATS lobectomy and open surgery |

| Perspective | NHS and Personal Social Services |

| Time horizon | A within-trial analysis, taking a 1-year time horizon |

| Data set | All randomised participants were included (see Patient eligibility criteria for eligibility criteria) |

| Costs included in analysis | Index admission:

|

| Utility measurement | EQ-5D-5L administered at baseline (pre randomisation), 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 1 year post randomisation |

| QALY calculations | Assume that participants’ utility changes linearly between utility measurementsa |

| Adjustment for baseline utility | Regression used to adjust QALY calculations for differences in baseline utility |

| Missing data | Multiple imputation |

Form of analysis, primary outcome and cost-effectiveness decision rules

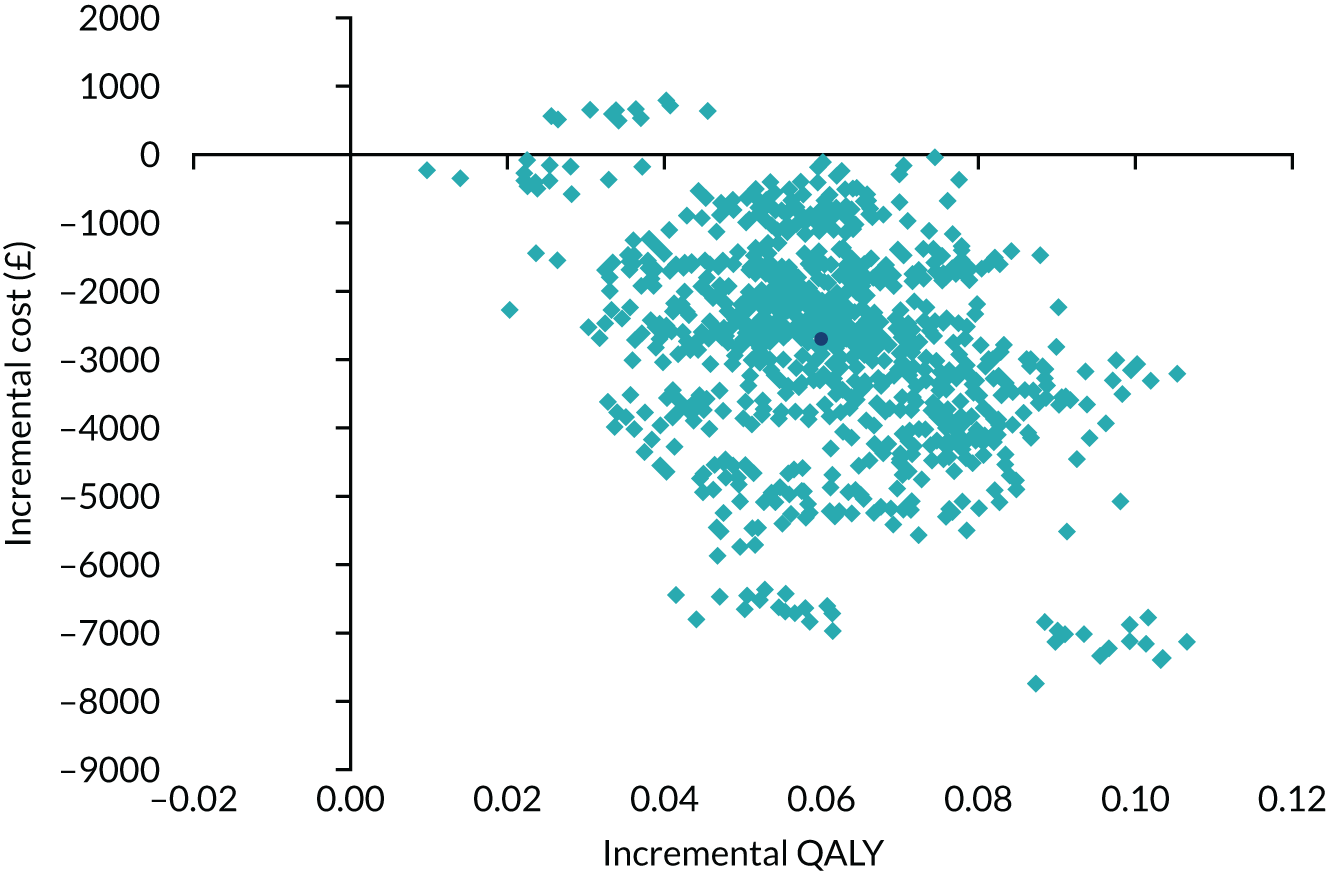

As advocated by NICE, a cost-effectiveness analysis (specifically a cost–utility analysis) was conducted, using QALYs as the primary outcome measure. 38 QALYs combine both quantity and quality of life into a single measure. Incremental costs (i.e. the difference in mean costs between the VATS and open lobectomy groups) were divided by incremental QALYs (i.e. the difference in mean QALYs between the groups) and presented as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which quantifies the incremental cost per QALY gained by switching from using open surgery to VATS lobectomy. The economic evaluation analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis.

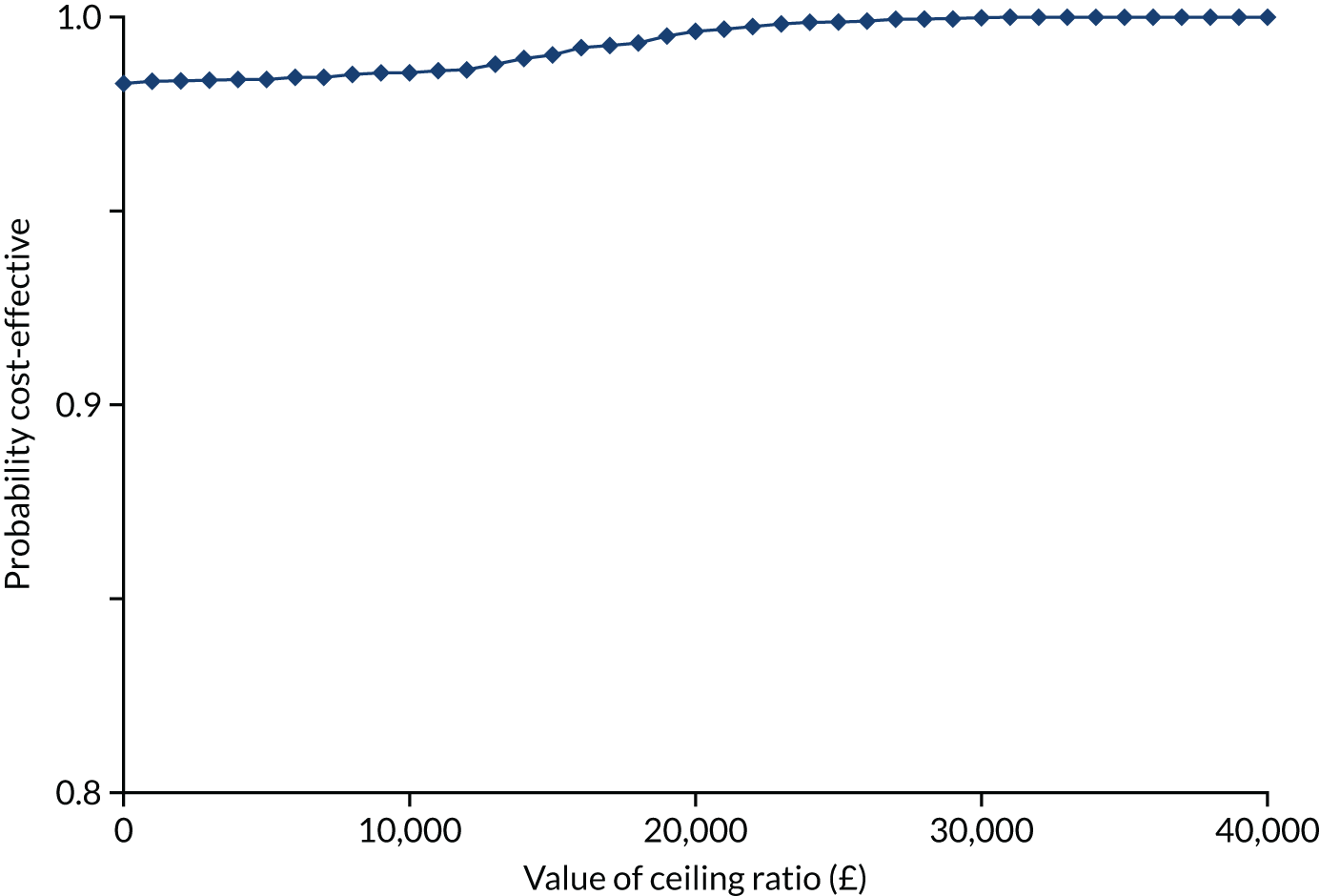

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy was considered cost-effective if the ICER fell below £20,000, which is generally considered as the threshold that NICE adopts for considering an intervention to be cost-effective. 41

Time horizon

A within-trial analysis, taking a 1-year time horizon, was conducted. It was anticipated that all major resource use (i.e. surgery, complications relating to surgery and adjuvant therapy) would occur within this time frame and would, therefore, be captured.

The starting point for our analysis was from the point of surgery, rather than the point of randomisation, as was the case with the trial effectiveness analysis. Randomisation was performed within 1 week of the planned operation date. The time point for baseline costs and outcomes was not quite the same. The EQ-5D-5L data were collected preoperatively, whereas detailed resource use data collection began on the day of surgery. However, as no difference in resource use was expected between the groups until the time of surgery, we did not anticipate this being an issue. Our time horizon continued until 1-year postoperatively.

Collection of resource use and costs

Resource use data were collected on all significant health service resource inputs for the trial participants to the end of the 1-year follow-up period. Collection of detailed resource use data was integrated into the trial case report forms (CRFs) for the index admission, and captured from telephone calls with participants at 5 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 1-year post randomisation. The main resource use categories that were captured and costed were initial thoracic surgery, hospital stay post surgery (by ward type), complications, adjuvant therapy, imaging, recurrence/progression of cancer, hospital readmissions, outpatient and emergency department (ED) attendances, and community health and social care contacts. Appendix 2, Table 25, details the sources of unit cost information for each of these categories. Costing decisions (e.g. resource use assumed for complications) were made without knowledge of the allocation of participants to trial groups.

Thoracic surgery

The key differences in resources required for VATS lobectomy and open surgery are the time in theatre and the number of staples required. These were captured on the trial CRFs and were used to cost the index surgery. Pathology costs associated with a biopsy and frozen section analysis are also included.

Treatment complications and serious adverse events

Trial CRFs captured postoperative complications that participants experienced, including pulmonary, cardiac, renal, gastrointestinal, infective and neurological complications, and the need for reoperations. We discussed with the research team the likely resource implications of complications that were not already being captured. Trial CRFs also captured resource use around SAEs. SAEs were individually reviewed and additional resources were costed, only if not already captured in complication costs to avoid double counting. Appendix 3, Tables 29–31 and 33–35, show all the complications, the corresponding diagnostic tests and treatments assumed and their unit costs.

Hospital readmissions and other post-discharge primary and secondary health and social care visits

The costs of hospital readmissions included all expected and unexpected thoracic surgery and chemotherapy/radiotherapy complications in terms of AEs and SAEs, but excluded all unexpected unrelated complications. For example, our analysis included the cost of readmissions for wound pain, but excluded the cost of readmissions for ophthalmology. Clinical opinion was sought to clarify whether unexpected complications were possibly related or were unrelated to the index surgery. Treatment relating to known pre-existing conditions (i.e. conditions known prior to randomisation) were excluded unless lung related. Similarly, resource use associated with lung cancer progression or recurrence was included, but resource use related to new non-lung cancer and totally unrelated cancer (e.g. prostate cancer) was excluded. The cost of an ED attendance was included if a participant was admitted via ED or referred by their general practitioner (GP) (and assumed to be admitted via ED).

We reviewed the reasons for outpatient attendance and discussed with the trial research team whether or not these were likely to be linked to the surgery to avoid costing any outpatient visits that were totally unlinked to the trial. Similarly, the reasons for ED visits and community health and social care contacts were reviewed, and any unrelated activity excluded.

Attaching unit costs to resource use

Unit costs for hospital and community health-care resource use were largely obtained from national sources, for example the National Schedule of Reference Costs42,43 for ward costs, scans and many complications, and Unit Costs of Health and Social Care44 for community costs. Resources were valued in 2018/19 GBP and any unit costs not in 2018/19 prices have been adjusted to 2018/19 prices using the NHS cost inflation index. 45 Where available, costs of drugs given in hospital were taken from the electronic marketing information tool (eMIT),46 which provides the reduced prices paid for generic drugs in hospital. Otherwise, costs were obtained from the British National Formulary. 47 For a summary of the sources of unit cost information, see Appendix 2, Table 25. For further details on all unit costs and their source, see Appendix 3, Tables 28–39.

Measurement of health-related quality of life and quality-adjusted life-years

Measurement of health-related quality of life

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, advocated for use in economic evaluations by NICE,38 was used to measure HRQoL. 39,40 The EQ-5D is a generic measure of health outcome, covering five dimensions: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort and (5) anxiety/depression. The EQ-5D-5L was completed by participants at six time points: (1) baseline (pre-randomisation), (2) 2 weeks, (3) 5 weeks, (4) 3 months, (5) 6 months and (6) 1-year post randomisation. Although data were gathered using the EQ-5D-5L (the five-level version, with five possible responses for each dimension), responses recorded on the instrument were converted into a single index value using the original three-level UK valuation set. 48 Scores were then used to facilitate the calculation of QALYs. Utility values were calculated by mapping the five-level descriptive system to the three-level valuation set using the crosswalk developed by van Hout et al. 49 in accordance with NICE recommendations at the time of analysis. 49,50

Calculation of quality-adjusted life-years

The QALY profile for each participant was estimated from surgery to 1 year, and the area under the curve of utility measurements was used to calculate the number of QALYs accrued by each participant. QALYs were calculated assuming that each participant’s utility changes linearly between each of the time points [i.e. that utility changes at a constant rate (in a straight line) between measurements]. For participants who died during the trial, their utility was assumed to change linearly between the preceding time point and the time of death, and to take the value of zero from death onwards.

Missing data

We first summarised the number of missing data for resource use and outcomes (EQ-5D scores) descriptively. Exploratory analyses were conducted to explore the possible mechanisms and patterns of missing data. 51 Logistic regressions were used to explore associations between missingness and baseline variables, and missingness and previously observed outcomes. If the number of missing data was small (< 1% of cases), then unconditional or conditional mean imputation was considered to be sufficient. However, we anticipated that it would be necessary to use multiple imputation to impute missing values. Multiple imputation is a flexible approach, which is valid if data are assumed to be missing at random (i.e. the probability that data are missing does not depend on the unobserved values; it is conditional on the observed data). 51,52 This assumption was assessed.

Multiple imputation uses regression to predict m values for each missing data cell, and enables all key variables used in the economic evaluation and demographic data (i.e. both complete and incomplete) to be used to predict the values of missing data cells. In accordance with guidelines,51,53 multiple imputation using chained equations was conducted and the number of imputations set to be at least equal to the percentage of incomplete cases. 53 Multiple imputation was performed separately for each treatment group.

Multiple imputation can be conducted at an aggregated level of total costs, for example, or at a disaggregated level of individual resource use items or EQ-5D domains. Given that imputing large numbers of variables may make the model difficult to estimate, a balance between the two is likely to be required. The patterns of missing data for resource use/costs and outcomes were used to determine the approach to multiple imputation. For example, data collected on a patient follow-up questionnaire may have similar patterns of missing data, in which case the total costs for that follow-up can be imputed rather than individual resource use items. For each variable with missing data, individual regressions were specified and tailored to the type of data being predicted. Linear regression with prediction mean matching was used, as it is particularly flexible.

Once multiple imputation had been conducted, tabulations and summaries of the observed and imputed data were compared to check the validity of the imputations. Rubin’s rule was then used to summarise data across the m data sets. 54 This approach accounts for the variability both within and between imputed data sets and takes uncertainty in the estimated mean into account.

Adjustment for baseline utility

Given that baseline utility directly contributes to QALY calculations, it is important to control for any potential imbalances in baseline utility in the estimation of the mean difference (MD) in QALYs between treatment groups to avoid introducing bias. 55 Regression adjustment also allows for regression to the mean and increases precision. Therefore, if there is an imbalance at baseline, we planned to adjust QALYs for baseline EQ-5D.

Within-trial statistical analysis of cost-effectiveness results

Analyses were conducted in Stata version 15 and Microsoft Excel® 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Initially, descriptive summaries of resource use, costs and HRQoL were performed using means, SDs and standard errors around the means using the central limit theorem. Cost data are typically positively skewed; however, regardless of this, costs were summarised using the arithmetic mean, as it is this combined with the total number of patients that relates to the total budget impact of an intervention.

The ICER was derived from the average costs and QALYs gained in each trial group, producing an incremental cost per QALY gained of VATS lobectomy compared with open surgery. Non-parametric bootstrapping of costs and QALYs was used to quantify the degree of uncertainty around the ICER. Results are expressed in terms of a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC), which indicates the likelihood that VATS lobectomy is cost-effective for different levels of willingness to pay for health gain. Although VATS lobectomy is considered cost-effective if the ICER falls below £20,000, the ICERs and CEACs presented allow decision-makers to assess cost-effectiveness at a willingness-to-pay threshold of their choice.

Discounting

Costs and effects were not discounted, as our time horizon was 12 months.

Sensitivity analysis

Univariate sensitivity analyses were used to investigate the impact on costs and cost-effectiveness results of variation in key parameters and major cost drivers, and to investigate the impact of uncertainty on the cost-effectiveness results.

Factors examined in the sensitivity analyses for costing were varying the unit costs for key cost drivers, including surgery and ward stays. The impact of any high-cost participants was also investigated. For outcomes, we examined not adjusting for baseline utility and the impact of any missing survival status.

For details of all sensitivity analyses, see Appendix 4.

Subgroup analysis

No subgroup analyses were pre-planned for the cost-effectiveness analyses; comparing pain scores by type of analgesia, as per the clinical analyses, would not be meaningful here.

Chapter 3 Results: trial cohort

Study sites

Five sites took part in Phase I of the trial and a further four were opened in Phase II. Sites were well spread geographically and represented a mix of university and NHS trusts that are representative of NHS practice. The study sites and the dates they opened to recruitment are given below.

Phase I: study sites and dates opened to recruitment

-

Royal Brompton Hospital and Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust (29 July 2015).

-

Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (6 October 2015).

-

Bristol Royal Infirmary and University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust (14 October 2015).

-

The James Cook University Hospital and South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (29 October 2015).

-

Harefield Hospital and Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust (18 December 2015).

Phase II: study sites and dates opened to recruitment

-

John Radcliffe Hospital and Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (25 September 2017).

-

Castle Hill Hospital and Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (12 October 2017).

-

Birmingham Heartlands Hospital and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (28 September 2017).

-

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, NHS Lothian (20 September 2018).

Patients screened and recruited

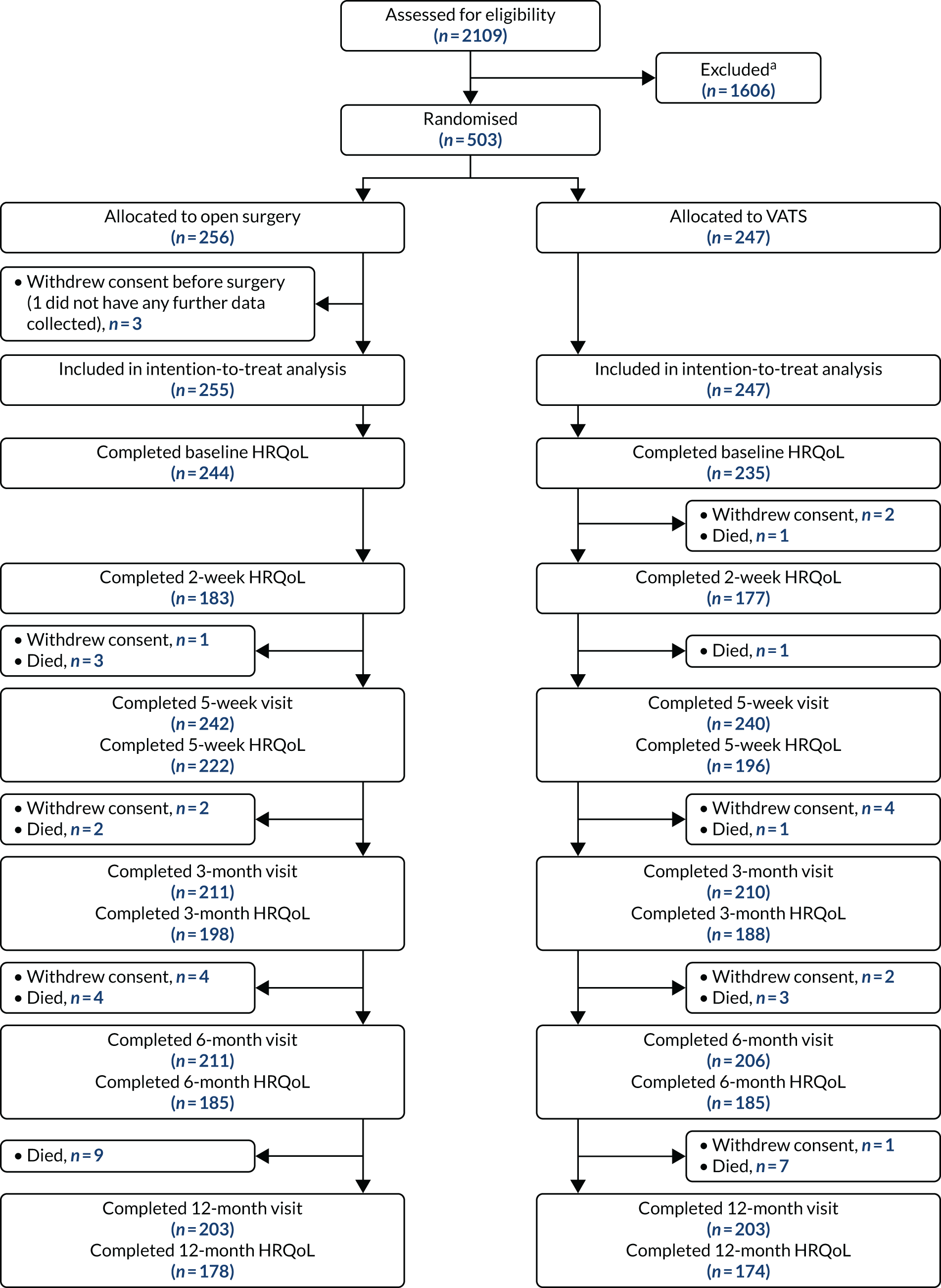

Between 23 July 2015 and 14 February 2019, a total of 2109 patients were assessed for eligibility, of whom 1606 were excluded (1110 patients were ineligible, 147 patients were not approached by the local team, 315 patients were approached but declined to take part and 34 patients agreed to take part but then withdrew their consent prior to randomisation). Therefore, 503 patients (i.e. 50% of eligible patients and 59% of patients approached) were recruited and randomised. The main reasons for screened patients not being recruited, by study site, are shown in Appendix 5, Table 44. Participant flow through the trial is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The VIOLET trial CONSORT flow diagram. a, Reasons for exclusion are provided in Appendix 5, Table 44. Adapted with permission from NEJM Evidence, Lim E, Batchelor TJP, Dunning J, Shackcloth M, Anikin V, Naidu B, et al. , Video-assisted thorascopic or open lobectomy in early-stage lung cancer, Volume 1, Copyright © 2022 Massachusetts Medical Society. 56

Recruitment

Between 30 July 2015 and 26 February 2019, 503 participants consented to take part and were randomised (VATS group, n = 247; open-surgery group, n = 256). One participant withdrew after randomisation and before surgery and no further data were collected (see Figure 2). The final follow-up for the last participant was completed on 23 March 2020.

Recruitment rate

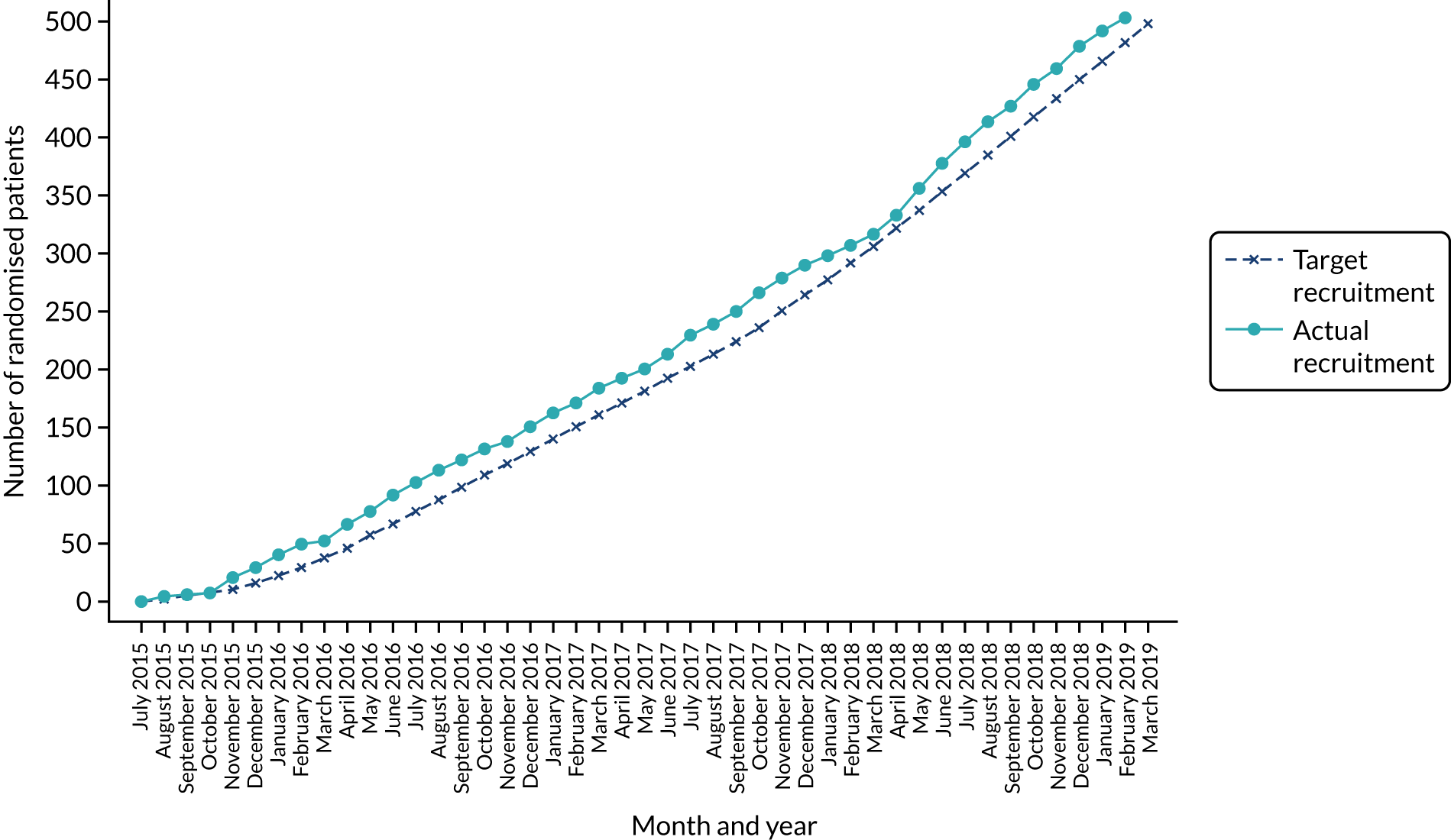

When the study was designed, the estimated recruitment rate was expressed in terms of the proportion of eligible patients recruited, rather than as a recruitment per site per month. The proposed study sites were asked to estimate the number of lobectomies performed for early-stage lung cancer each year and from this the anticipated recruitment rate was derived, allowing for a staggered opening of study sites. It was estimated that 60% of patients would be eligible for the trial and that the participating surgical teams would initially recruit 30% of eligible patients, but that with training and feedback provided by the QRI team this might increase to 50% after 6 months. The anticipated recruitment rate for each of the participating centres is documented in Appendix 5, Table 45.

The actual recruitment rate is illustrated in Figure 3. The trial was assessed for progression 18 months after the start of recruitment. Recruitment was ahead of target at that time and remained so throughout the trial, completing 2 months ahead of schedule. The trial over-recruited by five participants. The number of patients recruited by site and the rate per month at each site is given in Appendix 5, Table 46.

FIGURE 3.

Predicted and actual recruitment.

Progression from Phase I to Phase II

Progress against the predefined progression criteria was assessed in December 2016. Performance against the prespecified criteria is shown in Appendix 5, Table 47. The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) recommended progression to Phase II. Following review of the screening data and reasons for ineligibility, the eligibility criteria were widened to include bi-lobectomies to increase the generalisability of the trial results.

Comparison of recruited and non-recruited patients

The age of trial participants was similar to those patients who were screened but did not join the trial because they were ineligible, not approached or did not wish to take part (see Appendix 5, Table 48).

Patient withdrawals

In total, 34 participants withdrew consent prior to randomisation. Nineteen participants withdrew after randomisation (before surgery, n = 3; after surgery, n = 16). The reasons for post-randomisation withdrawal are detailed in Table 4. The most cited reason was that the participant ‘changed their mind’ about trial participation.

| Withdrawal detail | Participant allocation | Overall (N = 503), n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised to VATS (N = 247), n/N (%) | Randomised to open surgery (N = 256), n/N (%) | ||

| Any withdrawal | 9/247 (3.6) | 10/256 (3.9) | 19/503 (3.8) |

| Timing of withdrawal | |||

| Before surgerya | 0/9 (0.0) | 3/10 (30.0) | 3/19 (15.8) |

| After surgery | 9/9 (100.0) | 7/10 (70.0) | 16/19 (84.2) |

| Reason for withdrawal | |||

| Clinician’s advice | 1/9 (11.1) | 2/10 (20.0) | 3/19 (15.8) |

| Surgery no longer appropriate | 0/1 (0.0) | 1/2 (50.0) | 1/3 (33.3) |

| Patient no longer eligible | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/2 (50.0) | 2/3 (66.7) |

| Patient’s decision | 8/9 (88.9) | 8/10 (80.0) | 16/19 (84.2) |

| Patient changed their mind about the study | 6/8 (75.0) | 2/8 (25.0) | 8/16 (50.0) |

| Patient does not want to continue with follow-up | 2/8 (25.0) | 3/8 (37.5) | 5/16 (31.3) |

| Refused to give reason | 0/8 (0.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 1/16 (6.3) |

| Other | 0/8 (0.0) | 2/8 (25.0) | 2/16 (12.5) |

| Further details | |||

| Withdrawn from follow-up | 9/9 (100.0) | 10/10 (100.0) | 19/19 (100.0) |

Protocol deviations

Eligibility and surgery

Overall, the number of protocol deviations were low at 13% (66/502) (Table 5). Forty-nine patients did not undergo a lobectomy (31 patients were found to have benign disease on frozen section, 11 patients underwent a wedge resection, three patients underwent a segmentectomy, two patients were found to have extensive malignancy and so no resection was performed, and two patients underwent a pneumonectomy). A further 17 participants who underwent a lobectomy received the other trial intervention to that they were allocated [15 participants randomised to VATS received open surgery (one participant decided preoperatively to have open surgery and the remaining 14 participants were intraoperative conversions necessitated by the surgeon) and two participants randomised to open surgery had a VATS procedure (both participants decided preoperatively to have VATS)]. Reasons for conversions from VATS to open surgery can be found in Table 6.

| Protocol deviation | Participant allocation | Overall (N = 502), n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised to VATS (N = 247), n/N (%) | Randomised to open surgery (N = 255), n/N (%) | ||

| Protocol deviation | 41/247 (16.6) | 25/255 (9.8) | 66/502 (13.1) |

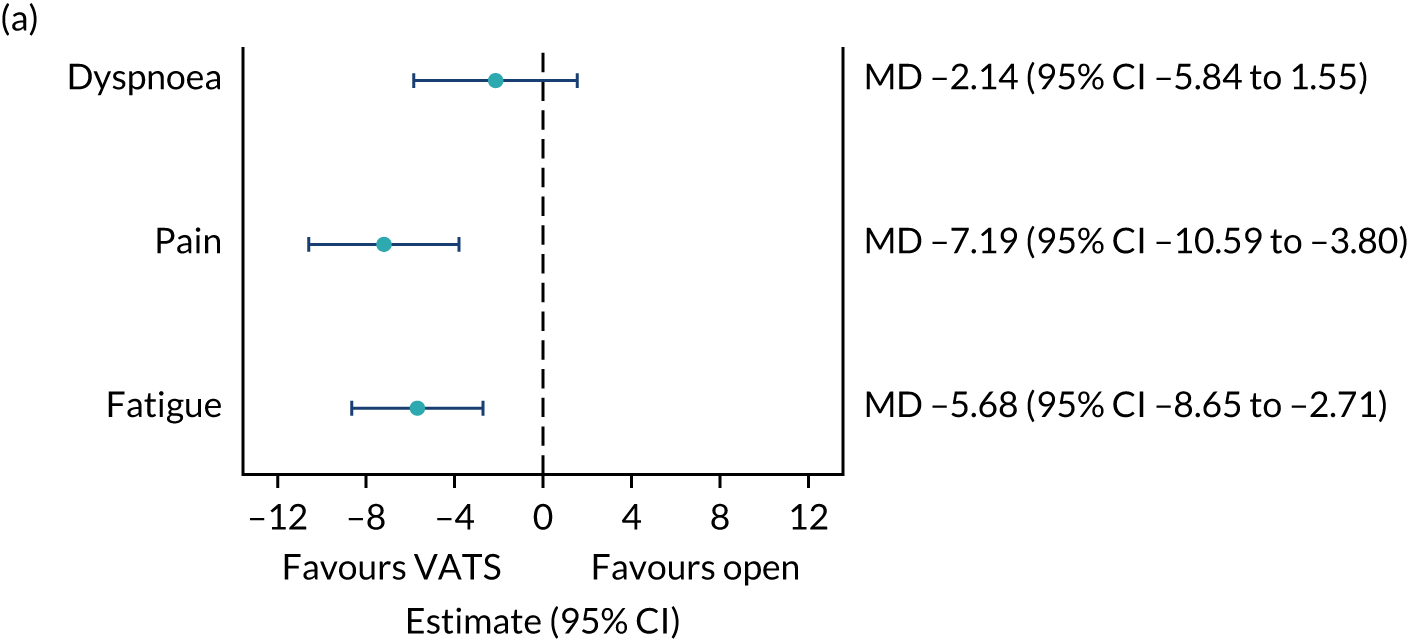

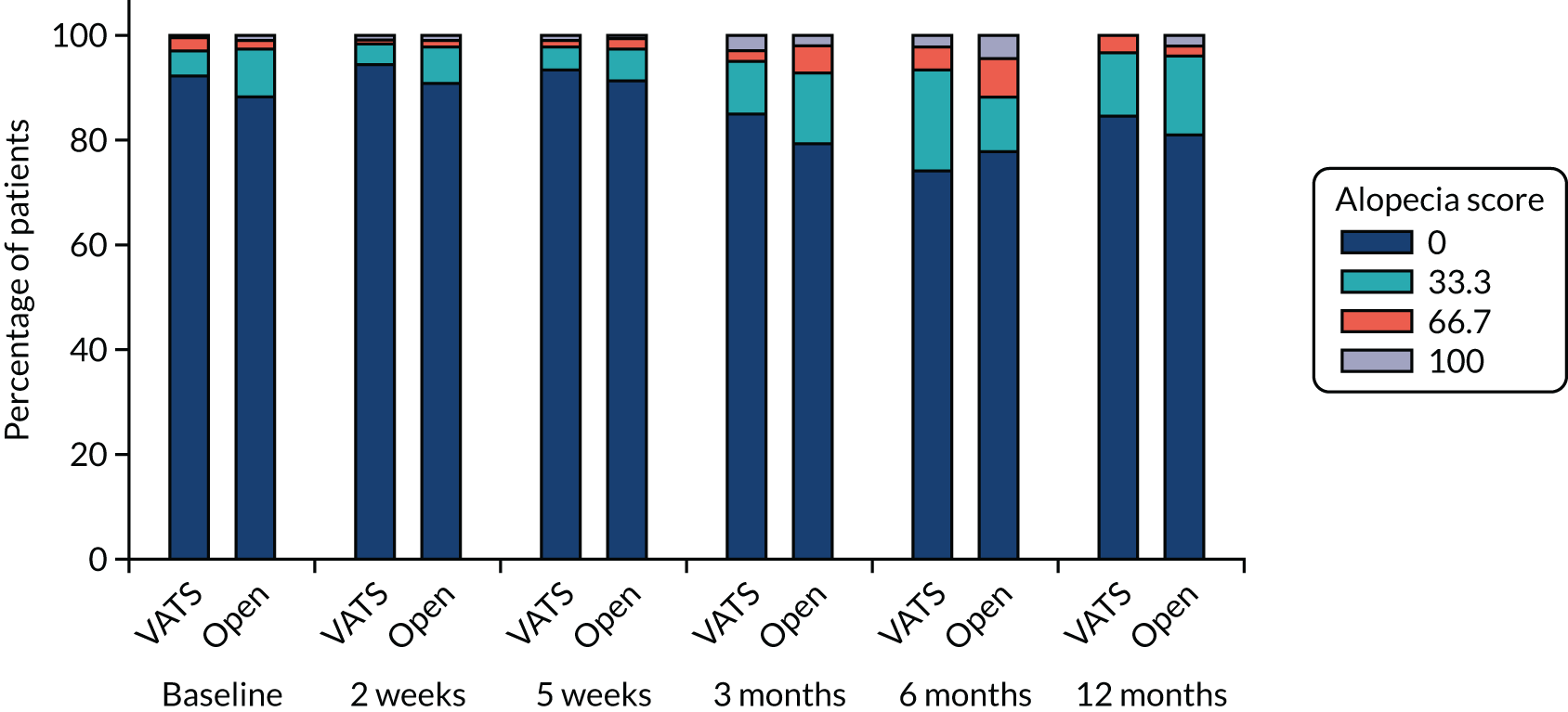

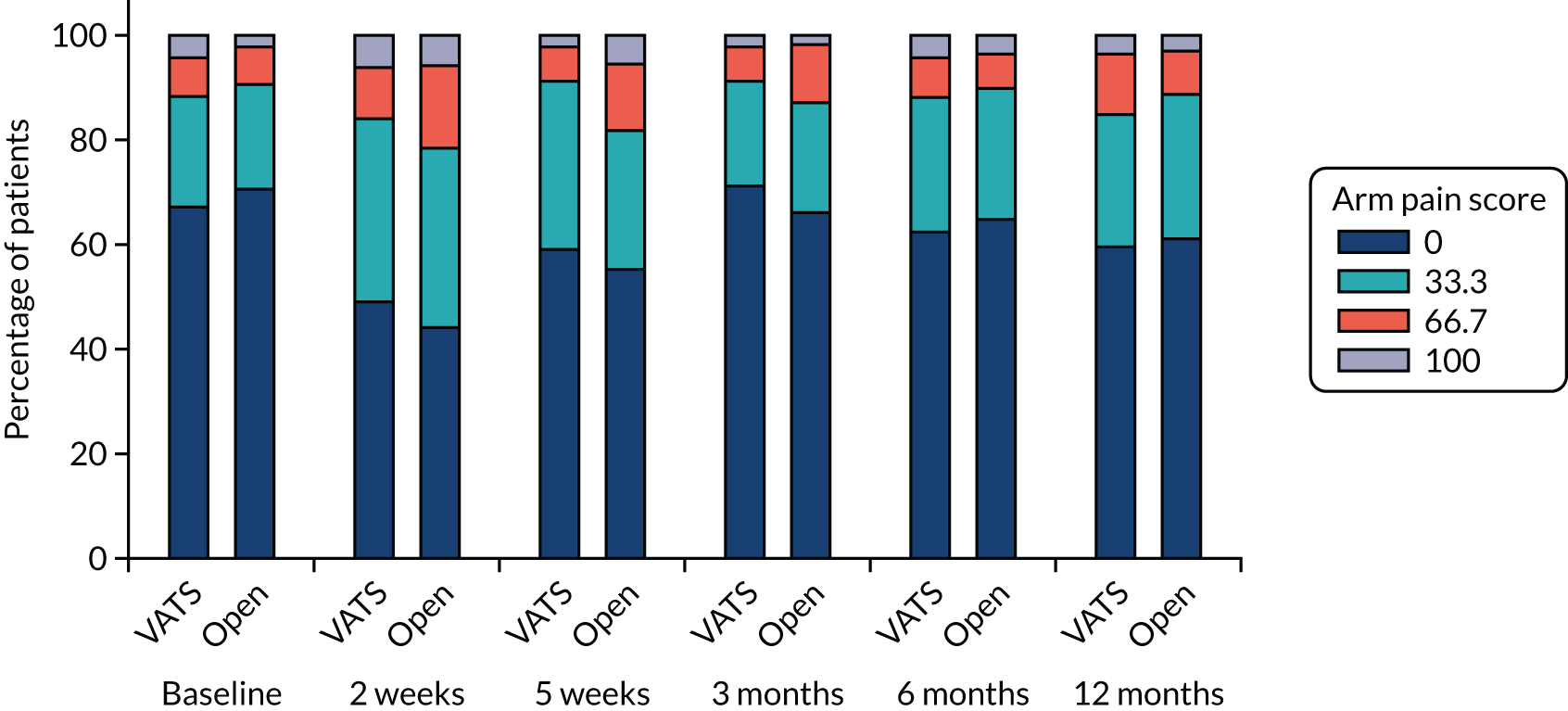

| Patient ineligible but treated in the study | 0/247 (0.0) | 0/255 (0.0) | 0/502 (0.0) |