Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/188/106. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The draft report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in April 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Roehr et al. This work was produced by Roehr et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Roehr et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background neonatal lumbar punctures

In the UK, between 15,000 and 30,000 newborns undergo a lumbar puncture (LP) each year to rule out meningitis. 1 Neonatal meningitis is associated with high mortality and morbidity. 1 Symptoms and signs are subtle, and the diagnosis can be confirmed only by analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), obtained by performing a LP. Thus, LPs are an essential part of the diagnostic work-up for meningitis. 1,2 LP techniques vary in current neonatal practice, with no level 1 evidence to determine the best approach. Owing to the technical challenges of neonatal LP, thousands of infants each year undergo unsuccessful LPs, resulting in repeat procedures, causing distress to infants and parents and often necessitating prolonged courses of antibiotics and hospitalisation for the infant, and, oftentimes, rooming-in for the accompanying mother (Box 1).

The LP procedure aims to obtain CSF from the lower spine for laboratory analysis to confirm the presence/absence of meningitis and to identify the causative organism. Infants with meningitis typically require 14–21 days of inpatient intravenous antibiotics, incurring significant financial costs, and often receive hospital follow-up because of the risk of long-term neurological sequelae. 3 Prolonged antibiotic use is associated with significant complications, such as necrotising enterocolitis,4 and a potential for the development of antibiotic resistance. 5 If meningitis can be excluded, then antibiotics are usually stopped after 5 days, allowing discharge with no further follow-up.

The definition of successful LP varies, but usually encompasses the acquisition of ‘clear’ CSF (colloquial medical term: a ‘champagne clear tap’). However, in neonates, CSF samples are often pink/red due to red blood cells (RBCs) sampled unintentionally from nearby blood vessels. Significant numbers of RBCs hinder CSF interpretation, and the presence/absence of meningitis cannot be confirmed. Therefore, LP often needs to be repeated, and many infants are treated with extended courses of antibiotics because meningitis cannot be excluded. Repeated procedures and concern about meningitis understandably lead to heightened parental anxiety. 6

The success rates of LP are much lower in neonates (50–60%)7,8 than in older children (78–87%). 9,10 Modifications to ‘traditional’ LP technique have been studied, but most data thus far are observational and have a high risk of bias,11 and so no improvements have been incorporated into widespread routine practice.

In 2017, it was believed that a trial aiming at establishing the most successful LP technique would be particularly timely. The, then recent, 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance,12 although aiming to avoid delays in diagnosing meningitis, had resulted in many more neonatal LPs being performed,12 and this led to an increase in antibiotic use, which came at a time of growing concerns about antimicrobial resistance caused by unnecessary use of antibiotics.

-

Fewer uninterpretable CSF samples.

-

Fewer repeated LP procedures.

-

Reduced distress and anxiety for infants and their families.

-

Decreased antibiotic use and risk of antibiotic resistance.

-

Reduced NHS costs due to fewer procedures, reduced length of stay, shorter antibiotic courses and minimised antibiotic-associated complications.

It was thought that a large-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) of LP technique would serve the neonatal knowledge base in several ways. First, optimising LP technique will mitigate the impact of the above-mentioned change in practice on NHS resources. Second, as the dangers of antibiotic resistance become ever more pressing, technologies that have the capacity to reduce hospital antibiotic use are invaluable in preventing antibiotic-resistance problems in the future. Third, it addresses the need, identified in a recent systematic review,11 for an investigation into alternative LP techniques.

Outcomes affected by lumbar puncture technique

If a large-scale RCT could demonstrate an improved LP technique, then its incorporation into clinical practice across the UK should follow, hopefully improving neonatal LP success over the current expected event rate of 59%, which is based on local cohort data. 13 During trial planning, a 10% improvement in LP success was deemed clinically significant. Such an increase in LP success rate can be expected to translate, each year, into 1600 fewer infants having repeat procedures, 14,400 fewer doses of intravenous antibiotics (with fewer complications) and 2680 fewer bed-days for mothers and infants. Parental anxiety would be reduced, as would healthcare costs through reduced hospitalisation and reduced antibiotic use (limiting the ongoing rise of antibiotic-resistant pathogens13), and efficiency of neonatal services would be improved.

Existing evidence

Summary of literature review at trial inception

After performing a structured systematic review of the literature, we found no formal systematic reviews or meta-analyses on LP technique in children or neonates. A limited structured review by Hart et al.,11 published in August 2016, investigated various positions of LP. This review, published in the Archimedes section (i.e. a summary of brief structured reviews that is led by a clinical question) of Archives of Disease in Childhood, examined the sitting position in both children and neonates and concluded that current evidence suggests that ‘Positions other than the lateral decubitus may be equal or superior in terms of lumbar puncture success’ and ‘Positions other than the lateral decubitus appear as safe’. 11 Hart et al. 11 further concluded that ‘A large-scale prospective clinical trial directly addressing LP success and safety in different positions would clarify the need to change current practice’. 11

Following the 2016 update of the NICE guidance, an increase in the frequency of neonatal LP was reported nationally. 2 The imperative to optimise this technique was, therefore, stronger than ever. To expand on the question raised by Hart et al.,11 we conducted our own systematic review in neonates and children (summarised below), investigating any method for improving LP success rate.

Methods

The following electronic databases were searched on 1 February 2016 via Ovid® (Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands): MEDLINE (1946–present), EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) (1974–present) and Global Health (1973–present). The search strategy included the keywords {[neonat* OR newborn OR pediatri* OR paediatr* OR infan*] AND ‘lumbar puncture’}. The search generated 56 records. Abstracts were screened for any studies comparing factors relating to LP technique, and four studies of relevance were found. Outcomes included success rates or those predicting success, for example number of attempts, anatomical benefits and safety outcomes. Searching the bibliographies of the studies identified by the electronic search strategy identified 21 further studies.

Results

We found eight studies that were RCTs and 17 that were observational studies. Interventions/factors with no consistent evidence of significant benefit were training in LP,14,15 seniority of practitioner,9,10,16–19 sedation,18,20 use of local anaesthetic,9,10,15,18,21,22 formulae for needle insertion depth (except certain subgroup analyses)23 and ultrasound assistance. 24–26 Trials investigating different body position during neonatal LP found that sitting was as safe as lying,27–29 with increased space for LP needles27,29,30 and equally effective in obtaining CSF availability. 14 In one study,31 sitting was associated with a 25% higher chance of a successful first LP attempt in infants aged < 90 days (p = 0.03). The hollow LP needle shaft contains a ‘stylet’. Most practitioners aim to insert the needle into the CSF space and then remove the stylet [i.e. late stylet removal (LSR)]. If the needle has advanced too far, then unintentional blood vessel puncture can cause RBC contamination. With early stylet removal (ESR), the stylet is removed after passing through the subcutaneous tissues, and the needle slowly advanced until CSF flows. Two studies9,10 found that ESR was associated with increased LP success compared with LSR {odds ratio 2.4 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1 to 5.2] and odds ratio 1.3 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.7), respectively}.

Updated literature search

Updated search

The above search was repeated most recently on 7 May 2017. One RCT32 was found, comparing the sitting and lying LP position in a paediatric accident and emergency setting. The trial, reporting only 167 infants, detected no statistically significant difference between groups. The authors concluded that ‘further studies are needed to establish stronger statistical power’. 32 Our trial met that recommendation, being appropriately powered, and complements this study32 by investigating a similar population (i.e. neonates) in whom the need for high-quality evidence is greater because of lower baseline success rates. 7–10 Three studies33–35 with small sample sizes and/or wide CIs found that ultrasound assistance was associated with increased LP success.

Other trials

The International Clinical Trials Registry Platform was searched (last updated on 25 July 2017) with the key words ‘lumbar puncture’, and screened as above. The trials listed in Box 2 have investigated local anaesthetic (n = 7), ultrasound assistance (n = 5), pressure transduction (n = 2), restraint (n = 1) and sedation (n = 1). None overlap with our proposal (see Box 2).

Brief summary of the evidence review at trial inception

No LP technique was backed by high-quality evidence from studies conducted in the neonatal period. LP techniques warranting further investigation, which can be studied most efficiently and reliably with a RCT, were (1) sitting position and (2) ESR. Both techniques are free ‘existing technologies’ that are already used by some practitioners. Observational evidence for these techniques has not led to a change of routine clinical practice. Randomised evidence was felt to be important and highly necessary to provide robust and convincing data. If either technique was shown to be beneficial, it would be free and easy to introduce nationwide.

Objective

We aimed to determine the optimal technique for LP in newborn infants by evaluating the success rate and short-term clinical, resource and safety outcomes of two modifications to traditional LP technique: a change of infant position (i.e. from lying to sitting) and a change in the timing of stylet removal (i.e. from LSR to ESR). This would be, to the best of our knowledge, the first appropriately powered RCT investigating different neonatal LP techniques, one with the potential to make a significant contribution to current knowledge and even change practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The trial rationale and design were closely discussed with, and received input from, parent representatives from the Oxford-based charity Support for the Sick Newborn And their Parents (SSNAP) [Oxford, UK; URL: www.ssnap.org.uk (accessed 14 June 2022)]. The final trial design and its protocol are published elsewhere. 37 Briefly, the Neonatal Champagne Lumbar punctures Every time – An RCT (NeoCLEAR) trial was planned as a pragmatic non-blinded multicentre 2 × 2 factorial RCT to compare the proportion of infants in whom CSF with a RBC count < 10,000/mm3 was successfully obtained on the first LP procedure. Investigated techniques included a combination of (1) the infant’s position (i.e. sitting vs. lying) and (2) the timing of stylet removal (ESR vs. LSR) [URL: www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/neoclear (accessed 14 June 2022)]. Following written parental consent, infants requiring LP [with a working weight of > 1000 g and corrected gestational age (CGA) of between 27+0 and 44+0 weeks] were randomised by web-based allocation to LP (1) in the sitting or lying position and (2) with ESR or LSR. The trial was powered to detect a 10% absolute risk difference in the primary outcome of an interpretable CSF sample, defined as containing a RBC count < 10,000/mm3. Clinicians undertaking LPs received practical training in the different trialled techniques. The application of topical anaesthetic cream prior to LP was encouraged. A minimum set of vital signs were monitored throughout the procedure [i.e. oxygen saturation (SpO2) and heart rate (HR)] by pulse oximetry. In addition, the duration of the procedure was timed and the clinical monitoring data were documented for the purpose of the trial. All other technical and, especially, patient management decisions were in accordance with local protocols.

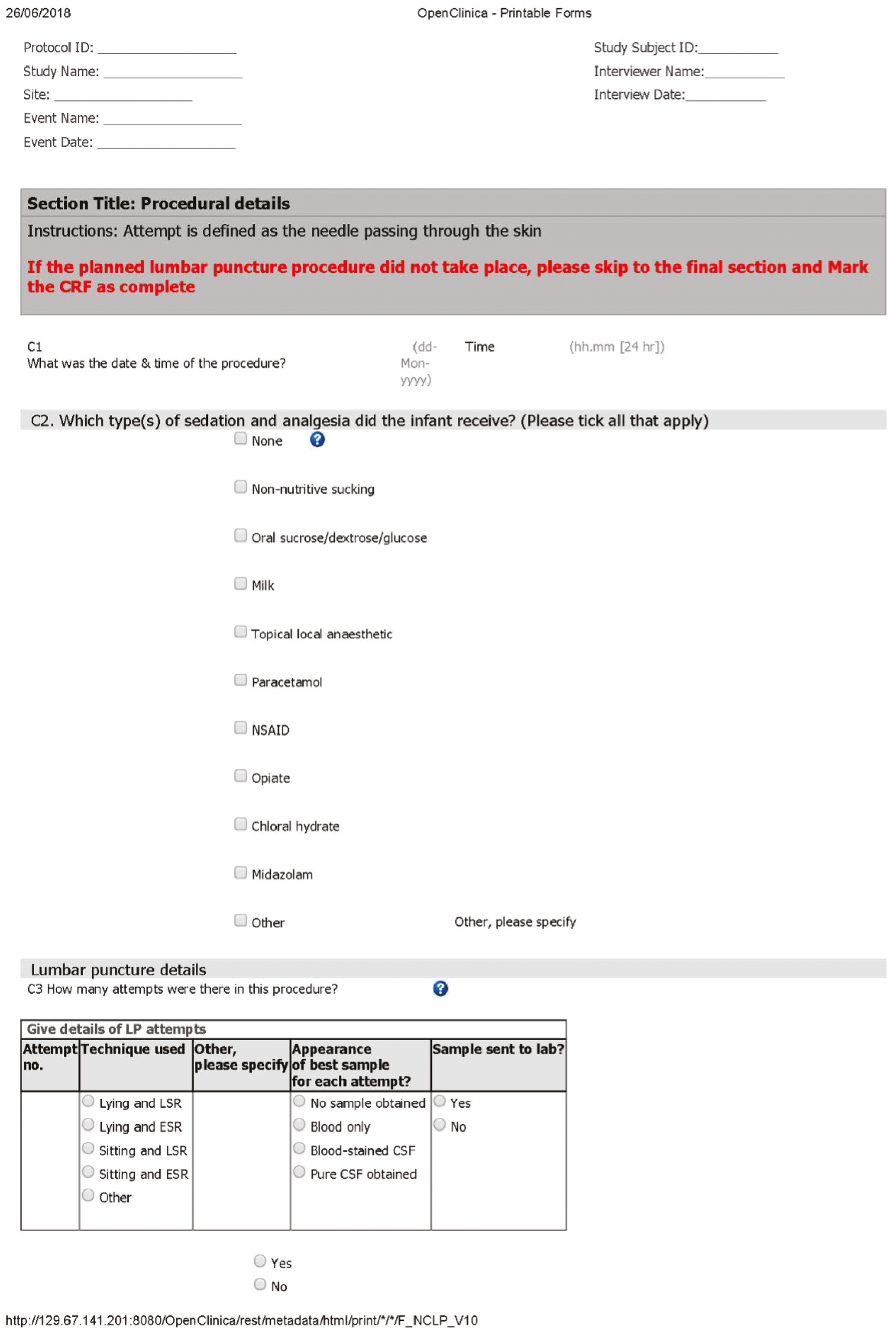

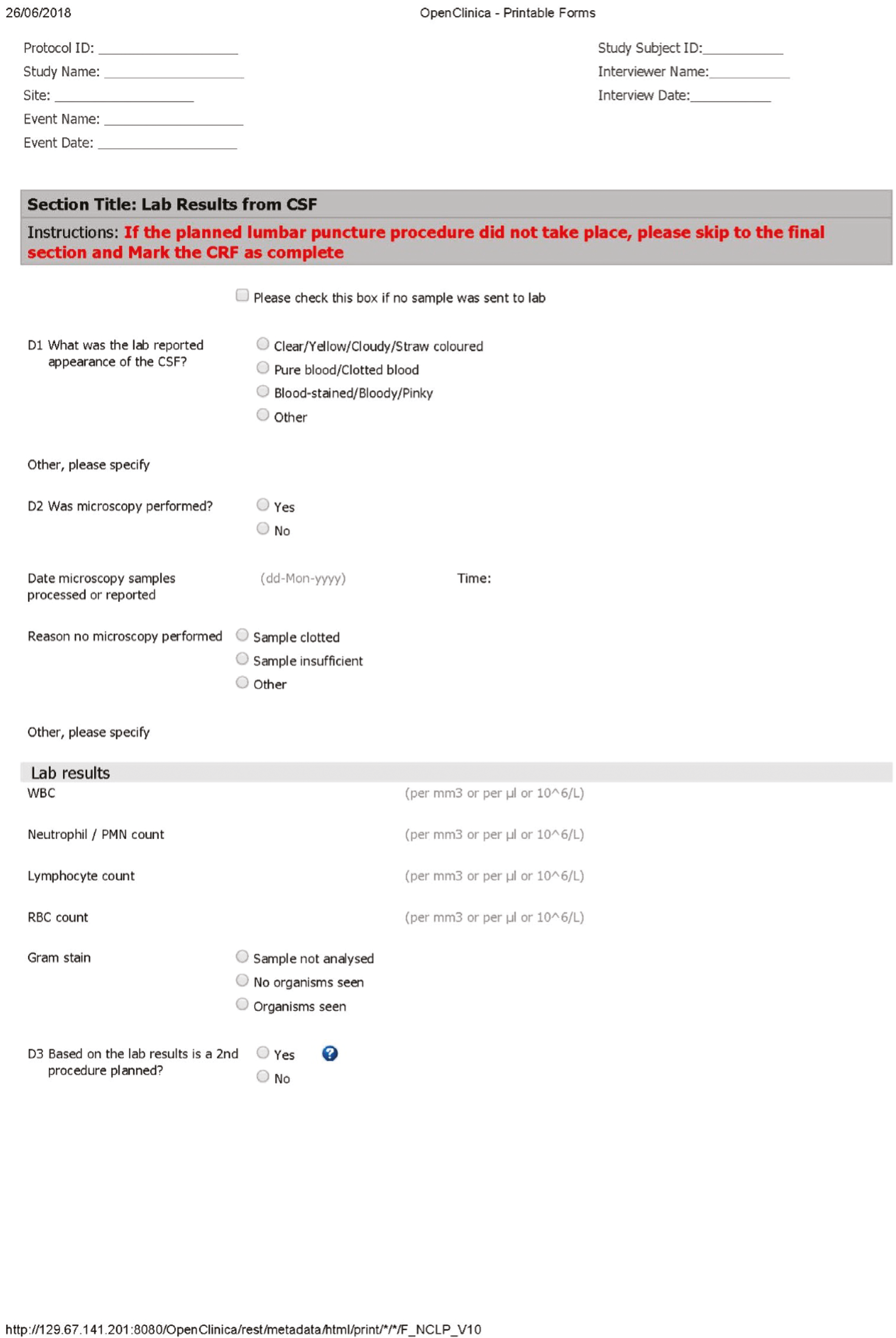

In practice, parents were approached for written consent when an eligible infant needed to undergo LP. Once consent was given, computerised randomisation proceeded. Staff were advised to make one or two attempts, defined as the needle passing through the skin once, per ‘procedure’. The randomised technique was to be used for up to two procedures. The requirement for and timing of a second procedure or any further procedures were determined by the clinical team. Patient characteristics and demographic data, as well as trial-relevant clinical data, were sourced by the local study teams from hospital records and recorded on trial-specific electronic case report forms (eCRFs). All CSF samples were sent to the local laboratories, as per recruiting site procedures, and only data from laboratory reports that were immediately relevant to the trial were entered into eCRFs.

To optimise study processes around recruitment, intervention delivery, training and outcome assessments, the trial included an internal pilot, which was carried out over 8 months at centres recruiting the first 250 randomised infants. The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) reviewed the pilot data, made recommendations and approved continuation. Details of TSC members are provided in Appendix 1.

Ethics approval and research governance

The NeoCLEAR RCT received approval from the NHS Health Research Authority, South Central Hampshire B Research Ethics Committee on 12 June 2018 (reference 18/SC/0222, nrescommittee.southcentral-hampshireb@nhs.net).

Trust confirmation of capacity and capability was obtained at each site. The chief investigator or delegate submitted an annual progress report, an end of study notification and the final report to the Research Ethics Committee, Health Research Authority, host organisation and sponsor, as required by the respective organisations.

The study was sponsored by the University of Oxford (Oxford, UK). The trial was run by a designated Project Management Group (PMG) at the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford. The core PMG met once a month, either remotely or face to face. An extended PMG (i.e. the Co-Investigator Group) met every 3 months initially and then every 4 months subsequently to troubleshoot, review progress and forward plan. The PMG reported to the TSC. Meetings were held either remotely or face to face, as permitted by COVID-19 restrictions.

The trial was overseen by the TSC, which had the ultimate responsibility for considering and, as appropriate, acting on the recommendations of the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). The TSC included an independent chairperson, at least one clinician, statistician and patient and public involvement (PPI) representative, the chief investigator and the senior co-investigator. The TSC met annually and reviewed the progress of the trial. Contributions on documentation were also received from the baby charity Bliss (London, UK).

A DMC reviewed the study data and outcomes. The DMC ensured the safety and well-being of the trial participants and, if appropriate, made recommendations regarding continuance of the study or modification of the protocol. The DMC was, therefore, also responsible for reviewing the safety reports of serious adverse events (SAEs), but, ultimately, the TSC would have the responsibility for stopping the trial on safety grounds. Lists of the members of the DMC and the TSC are in Appendices 1 and 2, respectively.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was integral in the trial design, with feedback and input coming from several channels, including (1) early involvement of a PPI representative and co-applicant, (2) advice from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) PPI division and information/details for a focus group sent to the NIHR PPI online mailing list, (3) feedback from a PPI representative for the NIHR Neonatal Clinical Study Group, (4) information/details for a focus group via SSNAP and (5) parental written feedback from a survey of parents of babies who previously received care on a neonatal unit.

As a direct result, we (1) confirmed the importance of this trial in improving the clinical care provided to newborns and their families, (2) prioritised our clinical outcomes relating to LP success, number of procedures and length of stay (as those were reported to be the most important outcomes for parents), (3) developed a procedural pain relief protocol aiming to provide better analgesia than current standard practice, (4) had assurance that the timing of our consenting process and randomisation was appropriate and acceptable to parents surveyed and (5) enhanced our plans for the LP training provided to each unit.

Participants

Participants of the trial were infants who were having a LP in UK neonatal units and their associated maternity wards.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Box 3.

-

Parent(s) willing and able to give informed consent.

-

Infants of CGA from 27+0 weeks to 44+0 weeks and with a working weight of ≥ 1000 g.

-

First LP for current indication.

-

Unable to be held in sitting position (including infants intubated and mechanically ventilated) or other clinical conditions that are likely, in the opinion of the treating clinician, to make sitting difficult or that are likely to be compromised by sitting (open gastroschisis, etc.).

-

Previously randomised to the trial schedule of study procedures.

Setting

The NeoCLEAR trial was set in UK neonatal units and their associated maternity wards. The following centres were included:

-

recruiting sites, where parental consent was obtained, infants were enrolled by randomisation and participation in the trial was commenced (n = 21) (see Appendix 3)

-

‘continuing care sites’, that is other units to which babies were discharged from the recruiting unit and where data collection continued until discharge (see Appendix 4).

Infants were eligible to participate in other clinical trials at the same time as taking part in the NeoCLEAR trial, depending on the nature of the interventions in the other trial. Other trials running concurrently were discussed by the chief investigators or their delegated representative, who then agreed if joint recruitment was appropriate.

Screening and eligibility assessment

Infants whom the clinical teams deemed necessary to undergo LP were screened for eligibility. Anonymised screening data were recorded via the randomisation website for the co-ordinating centre to review rates of ineligibility and participant uptake rates.

Informed consent and recruitment

The clinical teams provided the parents of eligible infants with both verbal information and written information, in the form of a parent information leaflet. The teams approached parents with legal parental responsibility to discuss the trial, to answer any questions the parents may have and to request consent. Parents had as much time as they needed to consider the information provided, to discuss it with the research team or other independent parties, and to decide whether or not to participate in the NeoCLEAR trial. Written informed consent for the study was then obtained by a suitably qualified member of the study team. During the study pilot parents were given a copy of a parent anxiety score [using the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory Subscale (STAI-S)] (see Parent questionnaire). 38 Parents completing the STAI-S were also asked to provide written consent for their participation (use of the STAI-S was stopped following the review of the internal pilot because completion rates were low). Consent was given with enough time to allow randomisation and to enable the clinical team to prepare for the procedure. Where this was not possible, the LP was not delayed if the infant’s clinician deemed any delay to be clinically unsound, and, in such cases, the infant was not recruited to the NeoCLEAR trial.

Site and staff training

Before undertaking procedures as part of the trial, all ‘operators’ (i.e. practitioners inserting the needle for the LP) received face-to-face training in trial background and overview and how to perform all four LP techniques to be investigated in the trial. Training included safety monitoring and recommendations for analgesia. Training included demonstration and practice on a neonatal LP manikin (LumbarPunctureBaby, EMD Services, Uttoxeter, UK). Operators were asked to sign a training log to confirm that they were confident in performing any of the four trial techniques on completion of training. Only after this were operators entered onto the delegation log. Assistants (i.e. practitioners holding the baby for LP and/or collecting CSF) were offered the same training or a shortened positioning-focused training session. Uptake of training was variable between sites. Narrated videos of each trial technique were available on the trial website throughout the recruitment period and were signposted during all training sessions. The regular trainee rotation across sites made regular training sessions necessary, and this was facilitated by the clinical research fellow (CRF) and local principal investigators (PIs).

Training the trainers

Owing to junior doctor rotation, the number of participating centres and the resulting distances between the primary study sites, the number of training sessions required to ensure ongoing recruitment became large. Additional manikins were purchased and a ‘train the trainer’ competency document was constructed to allow PIs and sub-PIs to become trainers. Sign-off of this competency document was carried out by the CRF and local PI. LP manikins were couriered to the sites participating in ‘train the trainer’ to ensure that all operators had experience in practising on the manikins. Uptake of ‘train the trainer’ made restarting recruitment after the COVID-19 hiatus possible when face-to-face site visits were not permitted. Mechanical upkeep of the training manikin was ensured by the CRF together with the manufacturer.

Interventions

Infants requiring LP were randomly allocated to one of four combinations of interventions: (1) LP in the lying (lateral decubitus) position and LSR, (2) LP in the lying position and ESR, (3) LP in the sitting position and LSR or (4) LP in the sitting position and ESR. The trial protocol suggested that term-born infants were treated with local anaesthetic cream prior to LP. Infants were clinically monitored throughout the procedures through detailed clinical observation, aided by pulse oximetry (i.e. continuous measurement of peripheral SpO2 and HR). The duration of procedures was timed and recorded as part of the trial documentation.

Randomisation and blinding

The NeoCLEAR trial used 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 randomisation to one of the four arms [i.e. (1) lying (lateral decubitus) position and LSR, (2) lying position and ESR, (3) sitting position and LSR or (4) sitting position and ESR] using a 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, secure web-based randomisation facility, which ensured balance between the groups. A telephone back-up system was available 24 hours a day.

Stratified block randomisation was used to ensure balance between the groups with respect to the collaborating hospital and CGA at trial entry (four groups: 27+0 to 31+6 weeks, 32+0 to 36+6 weeks, 37+0 to 40+6 weeks and ≥ 41 weeks). If repeat LPs were warranted for the same infant for the same indication after an initial unsuccessful attempt or procedure, then the infant received the same allocated technique. Infants who had more than one indication for LP during the trial recruitment period were not re-randomised. Multiple births were randomised separately, with their study identification numbers linked on the database prior to analysis.

A statistician who was independent of the trial generated the randomisation schedule, and the senior trials programmer wrote the web-based randomisation program; both were independently validated. The implementation of the randomisation procedure was monitored by the senior trials programmer throughout the trial, and reports were provided to the DMC.

The NeoCLEAR trial was an open-label trial, as blinding of the practitioner and nursing staff to the allocated technique was not possible. The assessment of the primary outcome and major secondary outcomes was based on laboratory tests (effectively blinded). Parents were not usually told which technique their infant had been allocated to and were not routinely present for the procedure; however, if they requested this information, it was shared with them, and they were able to observe the LP, at the discretion of the practitioner.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was proportion of infants in whom the first LP procedure was successful (i.e. a RBC count in CSF of < 10,000/mm3). We chose the cut-off point as 10,000 RBC count in accordance with previous studies7,19,23 investigating LP success, as identified in our literature research (Boxes 4 and 5).

-

CSF obtained and RBC count < 10,000/mm3.

-

A CSF WBC count not requiring a correction (regardless of the RBC count).

-

If the RBC count is ≥ 500, then the WBC count would be reduced by 1 for every 500 RBCs to give a ‘corrected’ WBC count.

WBC, white blood cell.

-

A CSF WBC count of ≥ 20.

-

True-positive bacterial CSF culture.

-

Positive PCR.

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WBC, white blood cell.

Secondary outcomes

The following short-term clinical, resource and safety outcomes were defined.

-

The proportion of infants with:

-

no CSF obtained, or pure-blood/clotted blood, blood-stained or clear CSF

-

CSF obtained and a RBC count of < 500/mm3, < 5000/mm3, < 10,000/mm3 or < 25,000/mm3, or any RBC count

-

a CSF white blood cell (WBC) count not requiring a correction (regardless of the RBC count).

-

-

The total number of procedures and attempts performed per infant.

-

The proportion of infants diagnosed (by WBC count criteria, culture, Gram stain and/or clinically) via CSF with the following:

-

Meningitis, with a WBC count of ≥ 20 in CSF or a true-positive culture/polymerase chain reaction (PCR). If the RBC count is ≥ 500, then the WBC count will be reduced by 1 for every 500 RBCs to give a ‘corrected’ WBC count.

-

Equivocal, with a WBC count (or corrected WBC) of < 20 and negative (or contaminated/ incidental) culture and PCR with either:

-

polymorphonuclear leucocytes (PMNs) > 2 (and a RBC count < 500), or

-

organism found on Gram stain.

-

-

Negative, with a WBC (or corrected WBC) count of < 20, PMN ≤ 2 (if the RBC count is < 500) and negative (or contaminated/incidental) cultures, PCR and Gram stain.

-

Uninterpretable, with no CSF obtained, CSF too bloody, blood clotted, or CSF insufficient to perform a cell count.

-

-

CSF WBC, RBC, corrected WBC counts, PMNs and lymphocytes from the clearest sample.

-

Time taken on first procedure from start of cleaning skin to removing needle at end of all attempts.

-

Infant movement on first procedure using a basic 4-point scale.

-

Outcomes relating to cost, resource consumption and safety:

-

In all infants, according to CSF-defined and clinically defined diagnostic criteria:

-

duration of the antibiotic course

-

length of stay in surviving infants.

-

-

Immediate complications related to LP:

-

cardiovascular instability, including SpO2 and HR

-

respiratory deterioration (escalating respiratory support) post LP.

-

-

-

For the pilot phase, parental anxiety (assessed using the STAI-S).

The decision on treatment for any study participant was in accordance with the individual centre’s guidance. Choice of antibiotic, route of administration and length of treatment were as per the local protocols, many of which were based on those issued by NICE12 (Box 6).

1.14.1 If a baby is in a neonatal unit and meningitis is suspected but the causative pathogen is unknown (e.g. because the CSF Gram stain is uninformative), treat with intravenous amoxicillin and cefotaxime. [2012, amended 2021.]

1.14.2 If a baby is in a neonatal unit and meningitis is shown (by either CSF Gram stain or culture) to be caused by Gram-negative infection, stop amoxicillin and treat with cefotaxime alone. [2012, amended 2021.]

1.14.3 If a baby is in a neonatal unit and meningitis is shown (by CSF Gram stain) to be caused by a Gram-positive bacterium then continue treatment with intravenous amoxicillin and cefotaxime while waiting for the CSF culture result and seek expert microbiological advice. [2012, amended 2021.]

1.14.4 If the CSF culture is positive for group B streptococcus, then consider changing the antibiotic treatment to benzylpenicillin 50 mg/kg every 12 hours, normally for at least 14 days and gentamicin, with:

-

a starting dosage of 5 mg/kg every 36 hours

-

subsequent doses and intervals adjusted, if necessary, based on clinical judgement and blood gentamicin concentrations

-

treatment lasting for 5 days.

© NICE 2012 Neonatal infection (early onset): antibiotics for prevention and treatment. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg149. All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

Parent questionnaire

During the pilot phase (i.e. after consent but before the first LP), parents were asked ‘How have you felt physically during the last couple of days?’. Parents used a five-point Likert scale to answer the question. In addition, parents were asked to complete the STAI-S questionnaire. 38,39 The STAI-S is a well-validated measure that consists of 20 questions that identify how stressed/anxious someone is feeling at the time of assessment. All items on the STAI-S are rated on a four-point scale, and the mean score can be used in analyses. Discontinuation of the STAI-S was recommended by the TSC based on a review of the pilot.

Sample size

The NeoCLEAR trial was designed with 90% power to detect a 10% absolute difference in the primary outcome (with an estimated comparator group event rate of 59%), with a 5% two-sided significance level. A total of 483 infants were required for each arm of each comparison (i.e. sitting position vs. lying position and ESR vs. LSR). Allowing for 5% attrition, the recruitment target was 1020 infants. Initial recruitment was planned at 10 hospitals and this was later extended to 21 centres across England (see Appendix 3).

Statistical analyses

A statistical analysis plan was agreed prior to data lock. The analysis and presentation of results followed recommendations of the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) group.

Descriptive analysis

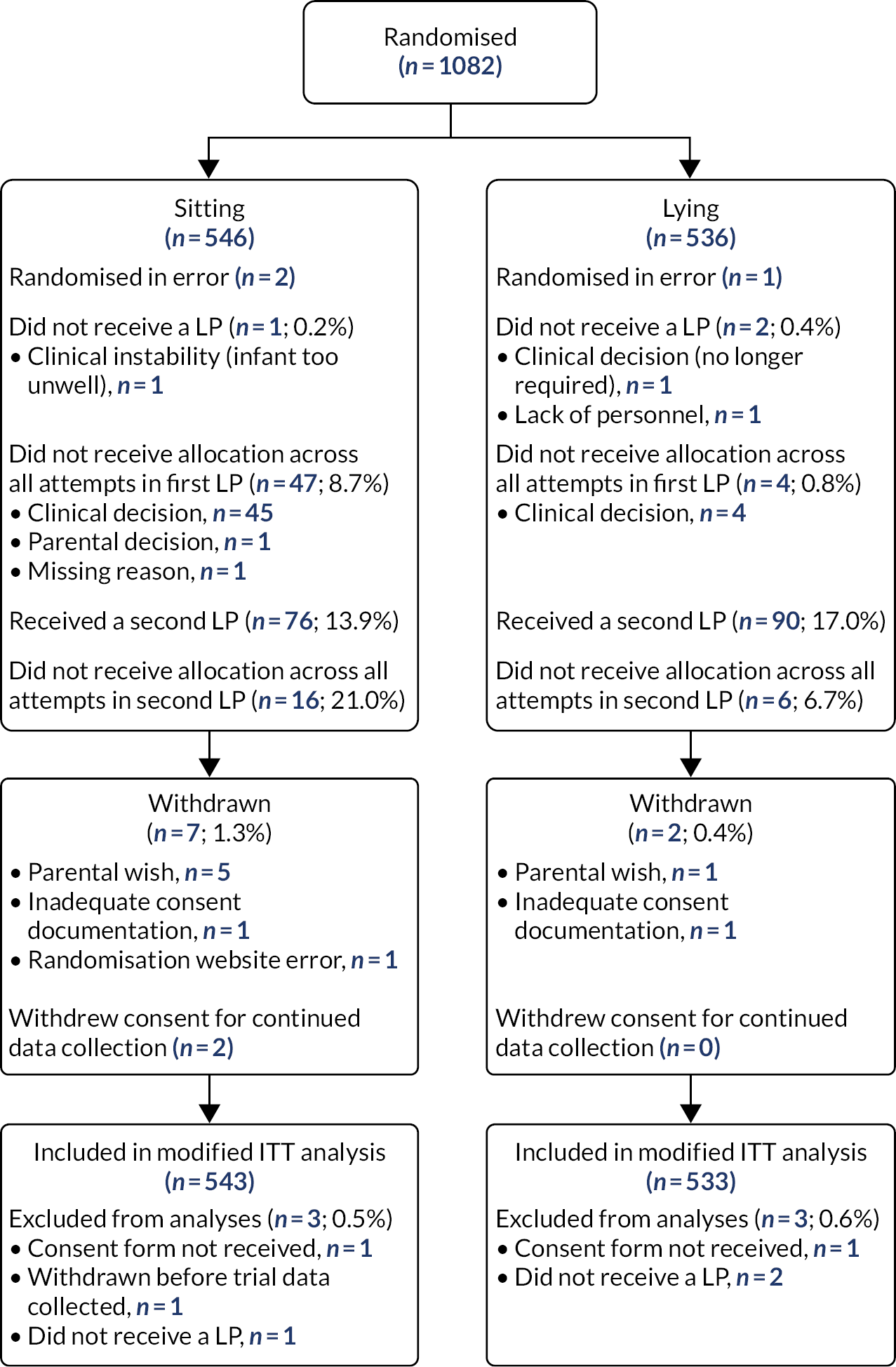

The flow of participants through each stage of the trial is summarised by principal comparison and by randomised group using a CONSORT diagram (see Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics of the infants at trial entry and characteristics of the infants at first LP are summarised by principal comparison group. Counts and percentages are presented for binary and categorical variables. The mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) are presented for continuous variables, as well as range, if appropriate. There were no tests of statistical significance of differences between groups on any baseline variable.

The numbers of losses to follow-up are reported for each group, with reasons, and deaths are reported separately. Missing data are described by presenting the number of individuals with missing data for each outcome.

Primary analysis

Outcomes are analysed by modified intention to treat (i.e. excluding participants who were withdrawn before collection of trial data or did not undergo LP). For infant positioning, we compared the lying/ LSR group (i.e. group 1) plus the lying/ESR group (i.e. group 2) with the sitting/LSR group (i.e. group 3) plus the sitting/ESR group (i.e. group 4). To assess the timing of stylet removal, we compared groups 1 and 3 with groups 2 and 4. Lying position and LSR were considered the reference groups.

We estimated risk ratios (RRs) for the primary outcome and all other dichotomous outcomes, the mean difference (MD) for normally distributed continuous outcomes and the median difference (Med D) for skewed continuous variables. The absolute risk difference was calculated for tested dichotomous clinical outcomes. Groups were compared using regression analysis, adjusting for the stratification variables used at randomisation (i.e. centre and CGA), with CGA as a fixed effect and centre as a random effect, where possible. Comparative analyses were also adjusted for the allocation to the other intervention (i.e. the sitting and lying comparison was adjusted for allocation to ESR/LSR, and vice versa). This adjustment was advised because of potential correlation between comparison arms after the final statistical analysis plan was signed off, and is a noted deviation. Adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) were estimated using log-binomial regression or using a Poisson regression model with a robust variance estimator in the event of non-convergence. Linear regression was used for normally distributed outcomes, and quantile regression was used for skewed continuous outcomes. Both crude and adjusted estimates are presented, with the primary inference based on the adjusted estimate. Ninety-five per cent CIs were calculated for all effect estimates, and two-sided p-values of 0.05 or less were considered to indicate statistical significance.

To mitigate multiple testing, inference was restricted to prespecified tested outcomes.

Secondary clinical outcomes tested

-

The proportion of infants with:

-

no CSF obtained, or pure-blood/clotted, blood-stained or clear CSF from clearest sample of the first procedure (any attempt)

-

CSF obtained with any RBC count on first procedure (any attempt)

-

CSF obtained with a WBC count not requiring correction on first procedure, that is, a WBC count < 20 regardless of the RBC count, or a RBC count < 500 (any attempt).

-

-

The proportion of infants diagnosed by the clinical team at discharge – in relation to their LP(s) – with:

-

definite/probable meningitis

-

possible meningitis or equivocal CSF result

-

negative CSF result

-

uninterpretable CSF result (e.g. very high RBC or clotted CSF)

-

no CSF obtained.

-

-

WBC count, RBC count, corrected WBC count, PMN and lymphocytes from clearest CSF sample.

-

Total number of procedures performed per infant.

-

Total number of attempts performed per infant.

-

Time taken to complete the first procedure, from start of cleaning skin to removing needle at end of all attempts.

-

Level of infant struggling movement on first attempt of first procedure.

Secondary clinical outcomes not tested

-

For the first attempt of the first procedure, for any attempt of first procedure if not in Secondary clinical outcomes tested and for any attempt of second procedure:

-

CSF appearance (clear CSF/blood-stained CSF/pure-blood or clotted CSF/no CSF sample obtained)

-

CSF obtained and any RBC count

-

CSF obtained and RBC count < 500/mm3

-

CSF obtained and RBC count < 5000/mm3

-

CSF obtained and RBC count < 10,000/mm3

-

CSF obtained and RBC count < 25,000/mm3

-

CSF obtained with WBC count not requiring correction (i.e. a WBC count < 20 regardless of the RBC count, or a RBC count < 500).

-

-

Number of attempts for first and second procedure per infant.

-

From first two procedures, the proportion of infants diagnosed by CSF with following:

-

Meningitis, with a WBC count of ≥ 20 in CSF or a true-positive culture/PCR. If the RBC count is ≥ 500, then the WBC count will be reduced by 1 for every 500 RBCs, to give a ‘corrected’ WBC count.

-

Equivocal, with a WBC count (or corrected WBC) of < 20 and negative (or contaminated/ incidental) culture and PCR with either:

-

PMNs > 2 (and a RBC count < 500), or

-

organism found on Gram stain.

-

-

Negative, with a WBC (or corrected WBC) count of < 20, PMN ≤ 2 (if the RBC count is < 500) and negative (or contaminated/incidental) cultures, PCR and Gram stain.

-

-

Uninterpretable, with no CSF obtained, clotted CSF or CSF too bloody or insufficient to enable a cell count.

Cost/resource consumption tested

-

Duration of the antibiotic course from trial entry to discharge home.

-

Length of stay in hospital in surviving infants from trial entry until discharge home.

Safety outcomes tested

-

Immediate complications related to first procedure:

-

procedure abandoned because of cardiovascular deterioration

-

infant’s lowest SpO2 (%)

-

infant’s lowest HR [beats per minute (b.p.m.)]

-

infant’s highest HR (b.p.m.)

-

respiratory deterioration post LP (a requirement for escalating respiratory support within 1 hour of the LP).

-

Safety outcomes not tested

-

Immediate complications related to second procedure:

-

procedure abandoned because of cardiovascular deterioration

-

respiratory deterioration post LP (a requirement for escalating respiratory support within 1 hour of the LP).

-

Secondary analysis

A descriptive multiarm analysis was performed for the primary outcome, other tested outcomes and baseline characteristics (i.e. for each of the four randomised groups). Effect modification between positions (i.e. sitting/lying) and the timing of stylet removal (i.e. ESR/LSR) was investigated for the primary outcome using the statistical test for interaction.

Subgroup analysis

Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted on the primary outcome for working weight at trial entry (i.e. < 2500 g, 2500–3500 g and > 3500 g), day of life (i.e. < 3 days and ≥ 3 days) and CGA at trial entry (27+0 to 36+6 weeks, 37+0 to 40+6 weeks and ≥ 41 weeks). It was planned to use four subgroups of CGA, but 27+0 to 31+6 weeks and 32+0 to 36+6 weeks were collapsed into a single group because of low numbers in each, which was a deviation from the statistical analysis plan. RRs and 95% CIs are presented for each subgroup, along with the interaction p-value.

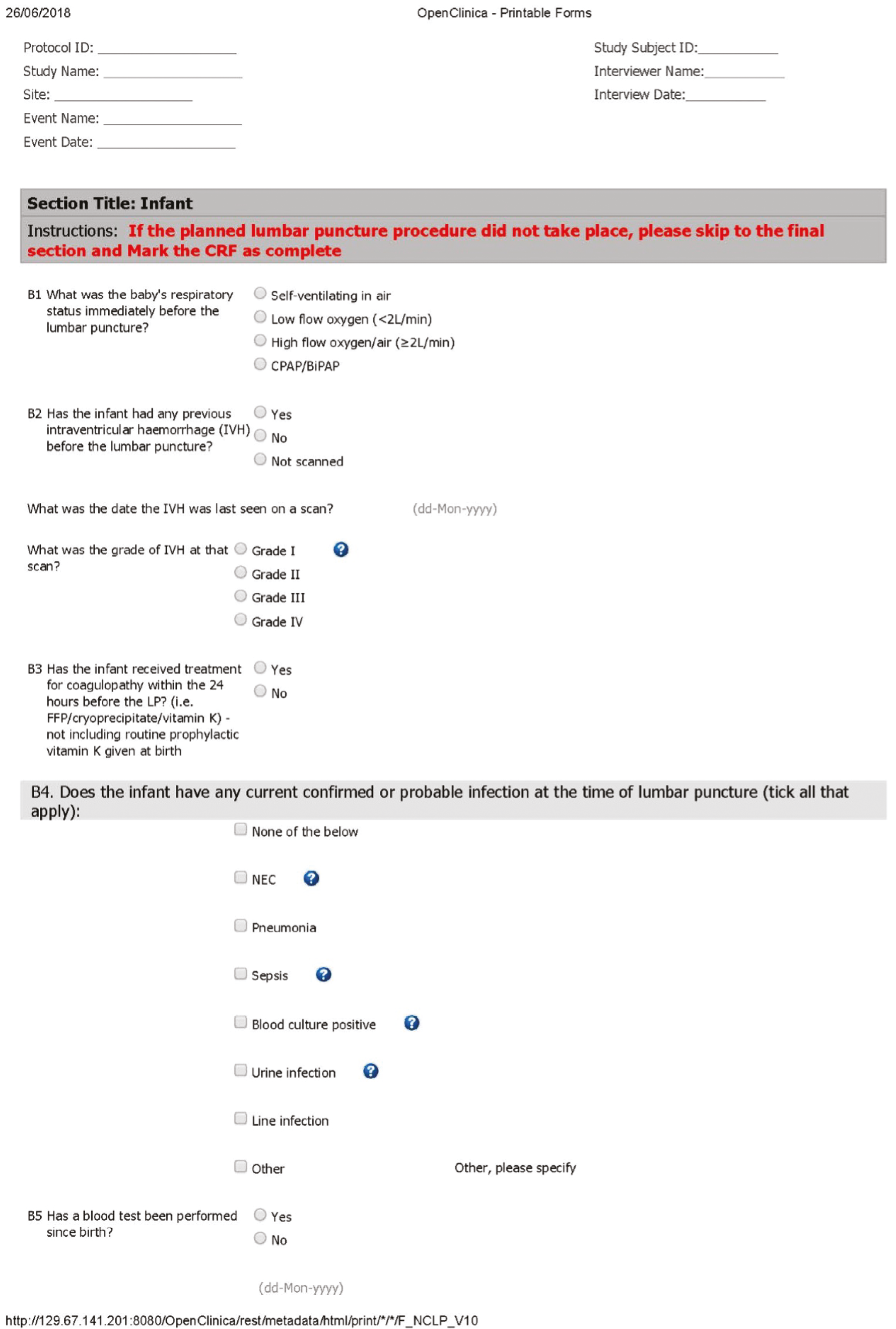

Data collection

All trial data were collected from hospital records and recorded on trial-specific eCRFs (see Appendix 6). Trial entry data included details to confirm eligibility and confirmation of parental written consent. The completion of data entry was monitored through the CTU. Most outcome data consisted of routinely recorded clinical items obtained from the clinical notes. Non-routinely collected data included procedural details, such as time taken for LP, infant movement, SpO2 and HR. No additional blood or tissue samples were required. Outcome data were collected until discharge home. Parents completing the STAI-S were asked to complete a second questionnaire within 48 hours of the first LP (pilot phase only).

Adverse event reporting

Box 7 lists known, but rare, complications of LP. Any occurrence of a complication following the LP was reported as a SAE.

-

latrogenic meningitis.

-

latrogenic haemorrhage: spinal haematoma (symptomatic), intraventricular, intracerebral and subarachnoid haemorrhage.

-

Cerebral herniation.

The full protocol and guidance sheets provided to sites also prespecified expected SAEs that were foreseeable and should not have been reported unless thought to be causally related to trial procedures. All unforeseeable SAEs occurring after consent until discharge home had to be reported.

Parents had the right to withdraw consent for any aspect of the study, including their infant’s future procedures and data collection, as well as their own questionnaire completion. The treating clinician was permitted to discontinue a participant if they considered it to be in the best interests of the infant’s health and well-being.

Adverse events were recorded locally and in the eCRF, and were followed up by the trials team. The DMC reviewed the study data and outcomes, including safety reports of SAEs. SAEs were collected until the infant was discharged home, as SAEs occurring after this time point were unlikely to be related to the trial intervention. As parental participation was limited to the STAI-S questionnaire, no SAE recording was conducted for this group. For the duration of the trial, the DMC ensured the safety and well-being of the trial participants and would have made recommendations to the TSC regarding discontinuance of the study or modification of the protocol, if required; however, this was not necessary throughout the NeoCLEAR trial.

Reporting procedures

All expected SAEs (see Box 7) were recorded on the eCRF and reviewed by the DMC at regular intervals throughout the trial. Any unexpected SAEs were reported by trial sites to the NeoCLEAR Coordinating Centre as soon as possible after the event had been recognised as a SAE that was not included in the list of expected SAEs. Information on each SAE was recorded on a SAE reporting form, which was electronically transferred to the NeoCLEAR Coordinating Centre. A standard operating procedure (SOP) outlining the reporting procedure for clinicians was provided with the SAE form and in the trial handbook. The NeoCLEAR Coordinating Centre processed and reported the events as specified in the CTU’s SOPs. The chief investigator informed all investigators concerned of relevant information about unexpected SAEs that could adversely affect the safety of participants. Once a year, during the recruiting period of the trial, a safety report was submitted to the sponsor and Research Ethics Committee.

Governance and monitoring

The NPEU CTU operates on a stringent set of accredited SOPs. Within this framework, the CTU oversaw the trial governance and conduct, as well as the monitoring of the trial centres. The CTU guidance comprised structured face-to-face induction visits with trial-specific training for investigators, their support team and research staff at site initiation. Written trial-specific materials were shared in printed and electronic forms. Local study centre staff were given access to multiple online training resources, which were also made available to staff at continuing care sites, together with other supporting material [URL: www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/neoclear (accessed 14 June 2022)]. A 24-hour telephone line was available to help with randomisation issues, including the option of telephone randomisation in the case of unresolvable information technology issues at the recruiting site.

Trial monitoring continued throughout the recruitment phase with review of investigator site files, the delegation logs, certificates of good clinical practice and the research curricula vitae of the local site staff. Trial data management was performed to the standards of the NPEU CTU’s SOPs, following prespecified schedules. Data from the recruiting centres were closely monitored for quality assurance. The monitoring included regular review of consent forms and reassurance of correctly assessed participant eligibility. Additional validation checks of data were carried out in intervals. Whenever needed, queries were issued to study centres for resolution. In accordance with best data management practice, final data validation checks were carried out before the database lock. Open questions were sought to be resolved through discussion with the site PI and their local teams.

The independent DMC was continuously informed of study progress in the form of written reports and at regularly scheduled physical DMC meetings. Incidents where the study statistician might raise concerns regarding the data quality were reported to the study data management staff, who would query these incidents if deemed appropriate, or followed up by further routine data validation checks, or both. DMC meetings were also used to provide external independent review of summary data, where necessary.

Summary of changes to the study protocol

A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is presented in Appendix 7.

Chapter 3 Results

The NeoCLEAR trial investigators sought to optimise LP technique in newborns by evaluating three modifications to traditional LP technique in an adequately powered randomised controlled clinical trial. An overview of the trial is given in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study participant flow diagram.

Results are presented in three parts (i.e. parts A–C). In part A, we compare the impact of infant position on LP success. In part B, we report on the LP outcomes, focusing on differences between ESR and LSR. In part C, we report on the multiarm analysis. The study flow of participants per principal comparison is outlined in Figures 2–5. Post hoc exploratory analyses are reported in Appendix 9. Further information on data collection forms (Table 29), details of changes to the study protocol (Table 30), group allocation per recruiting site (Table 31), baseline characteristics by non-adherence to position allocation (any attempt in first LP) (Table 32), baseline characteristics by non-adherence to Stylet Removal allocation (any attempt in first LP) (Table 33), characteristics at baseline/ first LP by age at randomisation (Table 34), and infant’s lowest oxygen saturation <80% at first LP by position allocation (Table 35), will also be found in the appendix.

Recruitment and retention

The NeoCLEAR trial recruited infants from August 2018 to August 2020. COVID-19 regulations forced a pause of recruitment between March and July 2020. Trial activity restarted without difficulty thereafter until completion. The trial recruited in 21 hospitals. Infant and parent characteristics at trial entry and at first LP are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. See Table 27 for the list of participating centres.

| Characteristic | Position | |

|---|---|---|

| Sitting (N = 543) | Lying (N = 533) | |

| CGA at trial entry (weeks+days), n (%) | ||

| 27+0 to 31+6 | 11 (2.0) | 11 (2.1) |

| 32+0 to 36+6 | 46 (8.5) | 47 (8.8) |

| 37+0 to 40+6 | 299 (55.1) | 295 (55.3) |

| ≥ 41+0 | 187 (34.4) | 180 (33.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (39–41) | 40 (39–41) |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks+days), n (%) | ||

| < 27+0 | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.1) |

| 27+0 to 31+6 | 12 (2.2) | 20 (3.8) |

| 32+0 to 36+6 | 48 (8.8) | 39 (7.3) |

| 37+0 to 40+6 | 329 (60.6) | 322 (60.4) |

| ≥ 41+0 | 153 (28.2) | 146 (27.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (39–41) | 40 (39–41) |

| Age (days) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| Range (minimum–maximum) | 0–76 | 0–91 |

| ≥ 3 days, n (%) | 70 (12.9) | 70 (13.1) |

| Birthweight (g), median (IQR) | 3500 (3110–3910) | 3529 (3150–3895) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 |

| Working weight (g) at trial entry | ||

| Median (IQR) | 3500 (3110–3910) | 3530 (3155–3890) |

| 1000–2499, n (%) | 55 (10.1) | 50 (9.4) |

| 2500–3500, n (%) | 217 (40.0) | 207 (38.8) |

| ≥ 3501, n (%) | 271 (49.9) | 276 (51.8) |

| Infant sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 325 (59.9) | 336 (63.0) |

| Female | 218 (40.1) | 197 (37.0) |

| One of a multiple pregnancy, n (%) | 5 (0.9) | 13 (2.4) |

| Receiving antibiotics, n (%) | 505 (93.0) | 489 (91.7) |

| Any previous LPs, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) |

| Days since last LP, median (IQR) | 22 (15–29) | 22 (19–23) |

| CSF from last LP sent to laboratory, n (%) | 2 (100) | 3 (100) |

| RBC from last LP (×106/l), median (IQR) | 230 (0–460) | 435 (0–870) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| WBC from last LP (×106/l), median (IQR) | 3 (0–5) | 1 (0–2) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Primary indication for current LP (not mutually exclusive), n (%) | ||

| Risk factor for sepsis | 201 (37.0) | 203 (38.2) |

| Clinical signs of sepsis | 137 (25.2) | 145 (27.3) |

| Abnormal WBC count/morphology | 8 (1.5) | 8 (1.5) |

| Raised CRP | 466 (85.8) | 444 (83.5) |

| Specific signs of meningitis/encephalitis | 12 (2.2) | 8 (1.5) |

| Neurometabolic investigation | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.6) |

| Therapeutic (raised intracranial pressure) | 0 | 0 |

| Recent failed LP | 0 | 0 |

| Positive blood culture | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) |

| Other | 4 (0.7) | 6 (1.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Parental anxiety score (STAI-S) | ||

| n | 95 | 102 |

| Mean (SD) | 50.2 (13.0) | 48.0 (14.4) |

| Recruiting centre, n (%) | ||

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, UK | 16 (2.9) | 14 (2.6) |

| Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, UK | 12 (2.2) | 12 (2.3) |

| John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK | 81 (14.9) | 82 (15.4) |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford, UK | 21 (3.9) | 17 (3.2) |

| Colchester General Hospital, Colchester, UK | 11 (2.0) | 14 (2.6) |

| Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK | 15 (2.8) | 13 (2.4) |

| Gloucestershire Royal Hospital, Gloucester, UK | 13 (2.4) | 12 (2.3) |

| Great Western Hospital, Swindon, UK | 8 (1.5) | 12 (2.3) |

| Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester, UK | 59 (10.9) | 58 (10.9) |

| Medway Maritime Hospital, Kent, UK | 63 (11.6) | 63 (11.8) |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, Norfolk, UK | 49 (9.0) | 48 (9.0) |

| Northampton General Hospital, Northampton, UK | 36 (6.6) | 38 (7.1) |

| Princess Anne Hospital, Southampton, UK | 20 (3.7) | 16 (3.0) |

| Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter, UK | 13 (2.4) | 14 (2.6) |

| Royal Hampshire County Hospital, Winchester, UK | 6 (1.1) | 5 (0.9) |

| Royal Oldham Hospital, Oldham, UK | 24 (4.4) | 22 (4.1) |

| Southmead Hospital, Bristol, UK | 53 (9.8) | 55 (10.3) |

| St Michael’s Hospital, Bristol, UK | 21 (3.9) | 22 (4.1) |

| St Peter’s Hospital, Chertsey, UK | 7 (1.3) | 7 (1.3) |

| Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury, UK | 12 (2.2) | 8 (1.5) |

| Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital, Basingstoke, UK | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) |

| Characteristic | Position | |

|---|---|---|

| Sitting (N = 543) | Lying (N = 533) | |

| Type of sedation and analgesia received (not mutually exclusive), n (%) | ||

| None | 24 (4.4) | 19 (3.6) |

| Non-nutritive sucking | 231 (42.7) | 199 (37.3) |

| Oral sucrose/dextrose/glucose | 443 (81.9) | 458 (85.9) |

| Milk | 13 (2.4) | 9 (1.7) |

| Topical local anaesthetic | 269 (49.7) | 261 (49.0) |

| Paracetamol | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| NSAID | 0 | 0 |

| Opiate | 3 (0.6) | 7 (1.3) |

| Chloral hydrate | 2 (0.4) | 0 |

| Midazolam | 0 | 0 |

| Phenobarbitone/phenytoin | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 |

| Respiratory status immediately before LP, n (%) | ||

| Self-ventilating in air | 466 (85.8) | 448 (84.1) |

| Low-flow oxygen (< 2 l/minute) | 13 (2.4) | 16 (3.0) |

| High-flow oxygen (≥ 2 l/minute) | 57 (10.5) | 59 (11.1) |

| CPAP/BiPAP | 7 (1.3) | 10 (1.9) |

| Previous diagnosis of intraventricular haemorrhage, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (2.5) |

| Not scanned | 334 | 336 |

| Grade of intraventricular haemorrhage at latest scan, n (%) | ||

| I | 2 (100.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| II | 0 | 2 (40.0) |

| III | 0 | 1 (20.0) |

| IV | 0 | 0 |

| Coagulopathy treatment within last 24 hours, n (%) | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) |

| Confirmed or probable infection (not mutually exclusive), n (%) | ||

| Necrotising enterocolitis | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 28 (5.2) | 35 (6.6) |

| Sepsis | 301 (55.4) | 301 (56.5) |

| Blood culture positive | 20 (3.7) | 19 (3.6) |

| Urine infection | 0 | 0 |

| Line infection | 0 | 0 |

| Other localised infection | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.6) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Results of latest blood test | ||

| Platelets (× 109/l), mean (SD) | 249.8 (70.5) | 249.6 (72.6) |

| Missing, n | 28 | 21 |

| WBC count (× 109/l), median (IQR) | 15 (11–20) | 15 (11–20) |

| Missing, n | 25 | 21 |

| Neutrophils (× 109/l), mean (SD) | 10.7 (5.7) | 10.1 (5.5) |

| Missing, n | 34 | 34 |

| RBC count (× 1012/l), median (IQR) | 5 (5–6) | 5 (5–6) |

| Missing, n | 29 | 25 |

| CRP (mg/l), median (IQR) | 39 (25–59) | 40 (24–60) |

| Missing, n | 4 | 3 |

Participants

From August 2018 to August 2020, 1082 participants from 21 centres were randomised to the principal comparisons: (1) sitting position (n = 546) compared with lying position (n = 536) and (2) ESR (n = 549) compared with LSR (n = 533).

Demographic and other baseline characteristics

The baseline patient characteristics at trial entry are presented in Table 1, and patient characteristics at first LP are presented in Table 2. Characteristics were well balanced throughout the four groups. Most patients were term-born infants and most had a working weight of ≥ 2500 g. We saw a slight male predominance, which was consistent between groups. The indications for LP were as per modified NICE guidance, i.e. predominantly exclusion of meningitis, suspected either because of patient and maternal history, or laboratory parameters [i.e. raised C-reactive protein (CRP)]. 12

Outcomes

A total of 1079 participants had a first LP, of whom 166 (15.4%) had a second (each of these LP ‘procedures’ involved one or more ‘attempts’) (Figure 2). Nine participants were withdrawn during the trial, but in only one case was consent withdrawn before data collection for the primary outcome. Three infants did not undergo LP, and for two infants the consent form was missing. Overall, six infants were excluded post randomisation, leaving 1076 infants for the final (modified intention-to-treat) analysis. All infants were followed up until discharge.

FIGURE 2.

Flow of participants by principal comparison: sitting position vs. lying position. ITT, intention to treat.

Part A: principal comparison – sitting position compared with lying position

Primary outcome: sitting position compared with lying position

The primary outcome – a successful first LP – was achieved in 346 of 543 (63.7%) infants in the sitting arm and 307 of 533 (57.6%) infants in the lying arm [aRR 1.10 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.21); p = 0.029; adjusted absolute risk difference 6.1% (95% CI 0.7% to 11.4%); adjusted number needed to treat (NNT) 16 (95% CI 9 to 134)] (Table 3).

| Outcome | Position | Relative risk | Absolute risk difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting (N = 543), n (%) | Lying (N = 533), n (%) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | aRRa (95% CI) | Adjusted p-value | Unadjusted risk difference (%) (95% CI) | Adjusteda risk difference (%) (95% CI) | |

| CSF obtained and RBC count < 10,000/mm3 on first LP procedure (any attempt) | 346 (63.7) | 307 (57.6) | 1.11 (1.00 to 1.22) | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.21) | 0.029 | 6.12 (0.29 to 11.95) | 6.08 (0.74 to 11.41) |

Secondary clinical outcomes: sitting position compared with lying position

Infants allocated to sitting position were less likely than infants allocated to lying position to show moderate or severe struggling at the time of needle insertion [169/541 (31.2%) vs. 202/527 (38.4%), aRR 0.82 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.94)]. Other secondary outcome data did not reach statistical significance, but predominantly favoured the sitting position (Table 4). Further untested secondary outcome data, including CSF appearance and number of procedures performed, are detailed in Table 5.

| Outcome | Position | Unadjusted effect estimate (95% CI) | Adjusteda effect estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted p-value | Unadjusted risk difference (%) (95% CI) | Adjusteda risk difference (%) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting (N = 543) | Lying (N = 533) | ||||||

| Appearance of clearest sample on first procedure (any attempt),b n (%) | RR 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12) | RR 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 0.125 | 3.57 (−1.38 to 8.52) | 3.61 (−1.03 to 8.26) | ||

| Clear CSF | 270 (49.7) | 233 (43.7) | |||||

| Blood-stained CSF | 163 (30.0) | 173 (32.5) | |||||

| Pure-blood/clotted CSF | 85 (15.7) | 100 (18.8) | |||||

| No CSF sample obtained | 25 (4.6) | 27 (5.1) | |||||

| CSF obtained with any RBC on first procedure (any attempt), n (%) | 390 (71.8) | 357 (67.0) | RR 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16) | RR 1.07 (0.98 to 1.17) | 0.136 | 4.84 (–0.66 to 10.34) | 4.82 (−1.53 to 11.17) |

| CSF obtained with WBC count not requiring correctionc on first procedure (any attempt), n (%) | 356 (65.7) | 322 (60.4) | RR 1.09 (0.99 to 1.19) | RR 1.09 (0.99 to 1.19) | 0.066 | 5.27 (−0.49 to 11.03) | 5.25 (−0.41 to 10.92) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Final clinical diagnosis at discharge [from LP(s)],d n (%) | RR 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) | RR 1.02 (0.94 to 1.11) | 0.612 | 1.68 (−3.28 to 6.65) | 1.72 (−4.95 to 8.39) | ||

| Definite/probable meningitis | 7 (1.3) | 9 (1.7) | |||||

| Possible meningitis or equivocal CSF result | 12 (2.2) | 11 (2.1) | |||||

| Negative CSF result | 424 (79.0) | 408 (77.3) | |||||

| Uninterpretable CSF result (e.g. very high RBC or clotted CSF) | 31 (5.8) | 36 (6.8) | |||||

| No CSF obtained | 63 (11.7) | 64 (12.1) | |||||

| Other clinical reason for LP, n | 6 | 5 | |||||

| From clearest CSF sample | |||||||

| WBC count (× 106/l), n | 429 | 389 | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1−6) | 2 (0−6) | Med D 1.0 (0.3 to 1.7) | Med D 0.1 (−0.7 to 0.9) | 0.786 | ||

| RBC count (× 106/l), n | 428 | 392 | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 380 (26−2370) | 240 (12−2680) | Med D 142.0 (−74.1 to 358.1) | Med D 145.9 (−124.3 to 416.1) | 0.289 | ||

| Correctede WBC count (× 106/l), n | 429 | 389 | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (0−4) | 1 (0−4) | Med D 0.0 (−0.7 to 0.7) | Med D 0.0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | 1.000 | ||

| PMN (× 106/l), n | 256 | 221 | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0−1) | 0 (0−1) | Med D 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | Med D 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 1.000 | ||

| Lymphocytes (× 106/l), n | 259 | 228 | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | Med D 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.4) | 1.000 | |||

| Total number of procedures performed,f n (%) | RR 0.86 (0.68 to 1.11) | RR 0.86 (0.68 to 1.09) | 0.215 | −2.77 (−7.46 to 1.92) | −2.68 (−6.99 to 1.62) | ||

| One | 447 (82.3) | 424 (79.5) | |||||

| Two | 83 (15.3) | 82 (15.4) | |||||

| Three or more | 13 (2.4) | 27 (5.1) | |||||

| Total number of attempts performed,f n (%) | RR 0.99 (0.88 to 1.13) | RR 1.00 (0.87 to 1.16) | 0.995 | −0.24 (−6.22 to 5.73) | −0.39 (−7.56 to 6.77) | ||

| One | 282 (51.9) | 275 (51.7) | |||||

| Two | 131 (24.1) | 111 (20.9) | |||||

| Three or more | 130 (23.9) | 146 (27.4) | |||||

| Missing | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Time (minutes) taken to complete first procedure, from start of cleaning skin to removing needle at end of all attempts, median (IQR) | 8(5−12) | 8 (5−13) | Med D 0.0 (−1.0 to 1.0) | Med D 0.0 (−0.8 to 0.9) | 0.935 | ||

| Range (minimum to maximum) | 0−55 | 0−37 | |||||

| Missing | 8 | 12 | |||||

| Level of infant struggling movement on first attempt of first procedure,g n (%) | RR 0.81 (0.69 to 0.96) | RR 0.82 (0.71 to 0.94) | 0.006 | −7.09 (−12.79 to −1.39) | |||

| None | 125 (23.1) | 85 (16.1) | |||||

| Mild | 247 (45.7) | 240 (45.5) | |||||

| Moderate | 129 (23.8) | 159 (30.2) | |||||

| Severe | 40 (7.4) | 43 (8.2) | |||||

| Missing | 2 | 6 | |||||

| Outcome | Position | |

|---|---|---|

| Sitting (N = 543), n (%) | Lying (N = 533), n (%) | |

| Appearance | ||

| Appearance of CSF on first attempt of first procedure | ||

| Clear CSF | 205 (37.8) | 186 (35.0) |

| Blood-stained CSF | 95 (17.5) | 102 (19.2) |

| Pure-blood CSF or clotted CSF | 140 (25.8) | 147 (27.6) |

| No CSF sample obtained | 102 (18.8) | 97 (18.2) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| Appearance of clearest sample from first or second procedure | ||

| Clear CSF | 289 (53.2) | 246 (46.2) |

| Blood-stained CSF | 188 (34.6) | 203 (38.1) |

| Pure-blood CSF or clotted CSF | 58 (10.7) | 68 (12.8) |

| No sample obtained | 8 (1.5) | 16 (3.0) |

| Procedures | ||

| Number of attempts in first procedure | ||

| One | 295 (54.3) | 287 (53.9) |

| Two | 191 (35.2) | 183 (34.4) |

| Three or more | 57 (10.5) | 62 (11.7) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Had second procedure | 75 | 89 |

| Number of attempts in second procedure | ||

| One | 39 (52.0) | 45 (50.6) |

| Two | 33 (44.0) | 32 (36.0) |

| Three or more | 3 (4.0) | 12 (13.5) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| Success | ||

| CSF obtained and any RBC count | ||

| First attempt of first procedure | 277 (51.0) | 258 (48.4) |

| Any attempt of first procedure | 390 (71.8) | 357 (67.0) |

| First or second procedure | 429 (79.0) | 395 (74.1) |

| CSF obtained and RBC count of < 500/mm3 | ||

| First attempt of first procedure | 163 (30.0) | 168 (31.5) |

| Any attempt of first procedure | 214 (39.4) | 216 (40.5) |

| First or second procedure | 227 (41.8) | 229 (43.0) |

| CSF obtained and RBC count < 5000/mm3 | ||

| First attempt of first procedure | 240 (44.2) | 222 (41.7) |

| Any attempt of first procedure | 328 (60.4) | 289 (54.2) |

| First or second procedure | 353 (65.0) | 312 (58.5) |

| CSF obtained and RBC count < 10,000/mm3 | ||

| First attempt of first procedure | 250 (46.0) | 235 (44.1) |

| Any attempt of first procedure | 346 (63.7) | 307 (57.6) |

| First or second procedure | 374 (68.9) | 335 (62.9) |

| CSF obtained and RBC count < 25,000/mm3 | ||

| First attempt of first procedure | 265 (48.8) | 247 (46.3) |

| Any attempt of first procedure | 369 (68.0) | 337 (63.2) |

| First or second procedure | 401 (73.8) | 368 (69.0) |

| CSF obtained with WBC count not requiring correction | ||

| First attempt of first procedure | 257 (47.3) | 239 (44.8) |

| Any attempt of first procedure | 356 (65.6) | 322 (60.4) |

| First or second procedure | 388 (71.5) | 356 (66.8) |

| Diagnoses of meningitis via CSF from first or second procedure | ||

| Positive: either diagnosed by WBC criteria (A) or by culture/PCR (B) | 22 (4.1) | 21 (4.0) |

| (A) WBC count (or corrected WBC) of ≥ 20 from clearest CSF | 21 (3.9) | 21 (4.0) |

| (B) Any true-positive culture or PCR from first or second LP | 2 (0.4) | 0 |

| Equivocal: does not have a positive diagnosis and either has isolated raised PMNs (C) or isolated organisms on Gram stain (D) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) |

| (C) In clearest CSF a RBC count of < 500, a WBC count of < 20 and PMN > 2 | 3 (0.6) | 0 |

| (D) Organism found on any Gram stain (first or second LP) and clearest CSF has a WBC count (or corrected WBC) of < 20 or no RBC count was possible | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Negative: does not have positive or equivocal diagnosis and has negative microscopy (E) or is missing PMN but would otherwise be equivocal (F) | 396 (73.7) | 359 (68.9) |

| (E) In clearest CSF a WBC count (or corrected WBC) of < 20 | 321 (59.8) | 274 (52.6) |

| (F) Equivocal diagnosis except for missing PMN | 80 (14.9) | 88 (16.9) |

| Uninterpretable: either no sample obtained (G) or no cell count possible (H) | 114 (21.2) | 139 (26.7) |

| (G) No sample obtained on any attempt in first or second LP | 8 (1.5) | 15 (2.9) |

| (H) CSF obtained but clotted/insufficient and so either not sent to laboratory or not analysed, or no RBC count possible from clearest CSF | 106 (19.7) | 124 (23.8) |

| Other clinical reason for LP | 6 | 5 |

| Unknown | 0 | 7 |

Looking at diagnoses based on CSF results from the first and second LPs (and any culture/PCR results), infants who were sitting were more likely than infants who were lying to be diagnosed as ‘negative’ for meningitis [396/537 (73.7%) vs. 359/521 (68.9%)]. Infants who were lying were more likely than infants who were sitting to be diagnosed with ‘uninterpretable CSF’, no sample obtained or CSF not possible to analyse, usually due to a blood-contaminated or clotted sample [139/521 (26.7%) vs. 114/537 (21.2%)].

Economic analysis per intervention group: sitting position compared with lying position

Economic analysis was carried out with a focus on resource consumption, as calculated for the individual trial procedures. The median duration of antibiotics and length of stay were not significantly different when comparing sitting and lying groups [median 5 (IQR 4–6) days in each arm] (Table 6).

| Resource use | Position | Unadjusted Med D (95% CI) | Adjusteda Med D (95% CI) | Adjusted p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting (N = 543) | Lying (N = 533) | ||||

| Received antibiotics during trial, n | 530 | 521 | |||

| Duration (days) of antibiotic course from trial entry to discharge home, median (IQR) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.0 (–0.2 to 0.2) | 0.0 (–0.2 to 0.2) | 1.000 |

| Range (minimum to maximum) | 1–24 | 0–25 | |||

| Missing, n | 1 | 2 | |||

| Surviving infants, n | 541 | 533 | |||

| Length of stay (days) in hospital (in surviving infants) from trial entry until discharge home, median (IQR) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–7) | 0.0 (–0.3 to 0.3) | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.3) | 0.585 |

| Range (minimum to maximum) | 1–158 | 1–371 | |||

Safety outcomes: sitting position compared with lying position

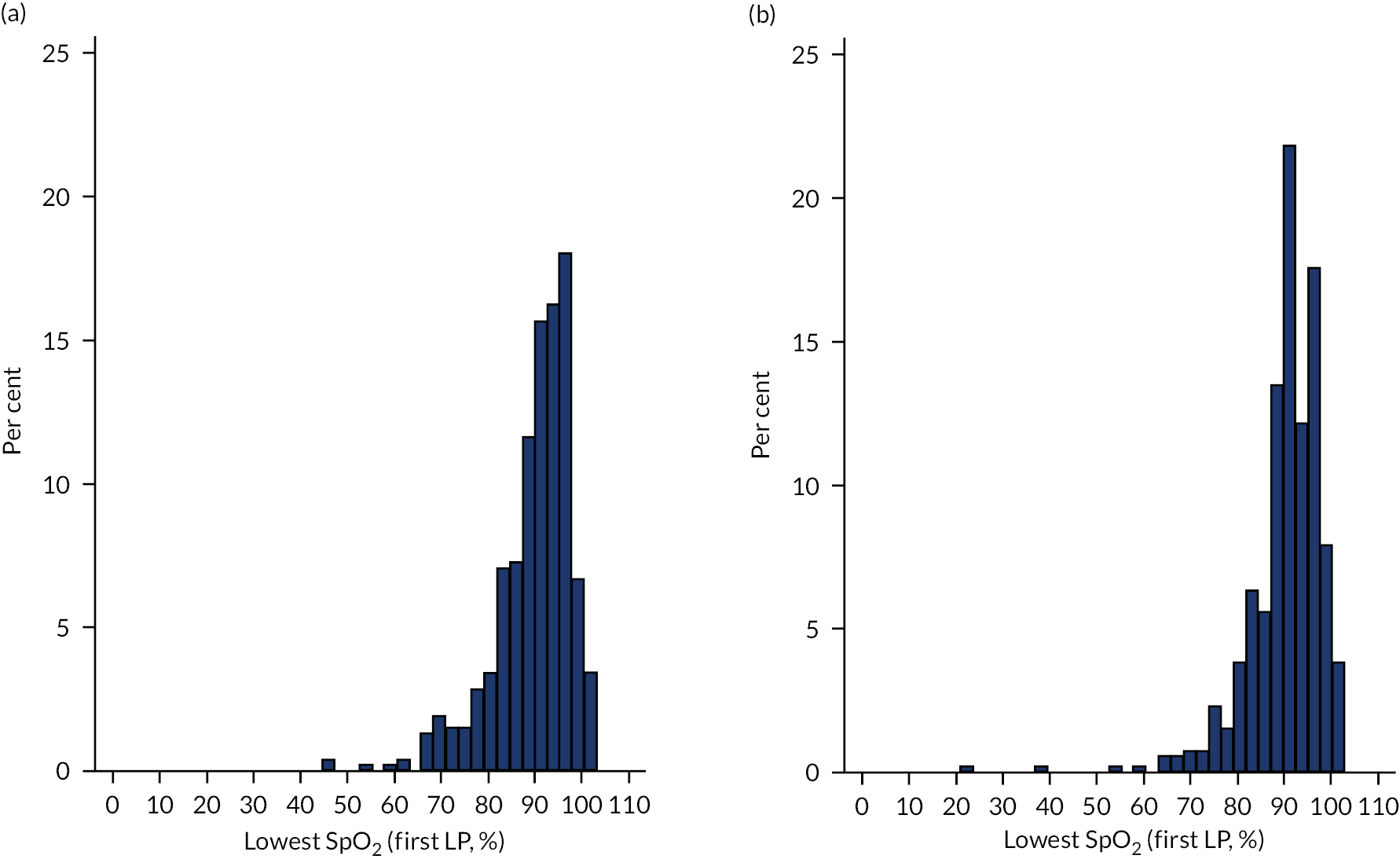

Four (0.3%) of 1241 first or second LPs, two in each arm, were abandoned because of cardiovascular deterioration. Lowest SpO2 during the first LP averaged a median of 93% (IQR 89–96%) in the sitting position and 90% (IQR 85–94%) when in the lying position (adjusted Med D 3.0, 95% CI 2.1 to 3.9; p < 0.001). Three of 1075 (0.3%) infants required increased respiratory support within 1 hour of their first LP (sitting, n = 1; lying, n = 2; not significantly different). To explore the clinical implication of this, we analysed (post hoc) the proportion of infants whose lowest SpO2 fell below 80% during the first LP, and this was 35 of 532 (6.6%) infants during sitting LPs and 72 of 508 (14.2%) infants during lying LPs (Table 7).

| Outcome | Position | Unadjusted effect measure (95% CI) | Adjusteda effect measure (95% CI) | Adjusted p-value | Unadjusted risk difference (%) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting (N = 543) | Lying (N = 533) | |||||

| Procedure abandoned because of cardiovascular deterioration (first procedure), n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | RR 1.96 (0.18 to 21.55) | RR 1.95 (0.17 to 22.08) | 0.588 | 0.18 (−0.45 to 0.81) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Procedure abandoned because of cardiovascular deterioration (second procedure), n/N (%) | 0/76 (0.0) | 1/90 (1.1) | ||||

| Infant’s lowest SpO2 (%) (first procedure), median (IQR) | 93 (89−96) | 90 (85−94) | Med D 3.0 (2.1 to 3.9) | Med D 3.0 (2.1 to 3.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Missing, n | 11 | 25 | ||||

| Infant’s lowest HR (b.p.m.) (first procedure), mean (SD) | 129.5 (19.9) | 127.0 (21.5) | MD 2.5 (−0.1 to 5.0) | MD 2.5 (0.6 to 4.4) | 0.011 | |

| Missing, n | 20 | 32 | ||||

| Infant’s highest HR (b.p.m.) (first procedure), mean (SD) | 163.7 (21.7) | 163.6 (21.9) | MD 0.1 (−2.6 to 2.8) | MD 0.1 (−2.1 to 2.4) | 0.897 | |

| Missing, n | 18 | 32 | ||||

| Respiratory deterioration post LP (requirement for escalating respiratory support within 1 hour of LP) (first procedure), n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | RR 0.49 (0.04 to 5.39) | RR 0.49 (0.04 to 5.71) | 0.567 | −0.19 (−0.82 to 0.44) |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Respiratory deterioration post LP (requirement for escalating respiratory support within 1 hour of LP) (second procedure), n/N (%) | 0/76 (0.0) | 0/90 (0.0) | ||||

A depiction of the safety data on changes in SpO2 and HR during either lying or sitting LPs can be found in the Appendix 9, Figures 7 and 8, and a depiction of the safety data on changes in SpO2 and HR during either ESR and LSR for LPs can be found in Appendix 9, Figures 9 and 10.

Compliance with allocated technique: sitting position compared with lying position

In 47 of 543 (8.7%) first LPs in infants allocated to the sitting position, at least one attempt involved switching to the lying position. [For comparison, an attempt in the sitting position was carried out in only 4/533 (0.8%) infants allocated to the lying position.] The decision to change position was usually made by a clinician (45/47 LPs), and mostly on the second (22/247) or third (24/57) attempt at LP. The sitting allocation was followed even less often in the case of the second LP: in 16 of 76 (22.5%) infants allocated to the sitting arm, at least one attempt to carry out the second LP was made in the lying position. [For comparison, an attempt in the sitting position was carried out in 6/90 (7.0%) infants allocated to the lying position.] There were no obvious differences in the characteristics at baseline of infants in whom the allocated position was adhered to and those in whom it was not (Table 8). Appendix 9 shows the baseline characteristics of infants in whom non-adherence to position allocation occurred.

| Procedure | Position | |

|---|---|---|

| Sitting | Lying | |

| First LP only | ||

| N | 543 | 533 |

| Time from randomisation to first LP (hours), median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) |

| ≥ 12 hours, n (%) | 9 (1.7) | 11 (2.1) |

| Missing, n | 13 | 12 |

| At least one attempt at LP in which the allocated technique was not adhered to, n (%) | 47 (8.7) | 4 (0.8) |

| Clinician decision | 45 (97.8) | 4 (100.0) |

| Parental decision | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unintentional use of alternative technique | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Attempt in which the allocated technique was not adhered to, n/N (%) (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| First | 7/543 (1.3) | 1/532 (0.2) |

| Second | 22/247 (8.9) | 0/245 (0.0) |

| Third | 24/57 (42.1) | 3/62 (4.8) |

| Total number of attempts, n | 848 | 844 |

| Number of attempts in which the allocated technique was not adhered to, n (%) | 53 (6.3) | 4 (0.5) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Second LP only | ||

| N | 76 | 90 |

| At least one attempt at LP in which the allocated technique was not adhered to, n (%) | 16 (22.5) | 6 (7.0) |

| Clinician decision | 14 (93.3) | 6 (100.0) |

| Parental decision | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Attempt in which the allocated technique was not adhered to, n/N (%) (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| First | 9/71 (12.7) | 2/86 (2.3) |

| Second | 10/34 (29.4) | 2/42 (4.8) |

| Third | 2/3 (66.7) | 3/11 (27.3) |

| Total number of attempts, n | 114 | 145 |

| Number of attempts in which the allocated technique was not adhered to,a n (%) | 21 (18.4) | 7 (4.8) |

| Missing | 5 | 4 |

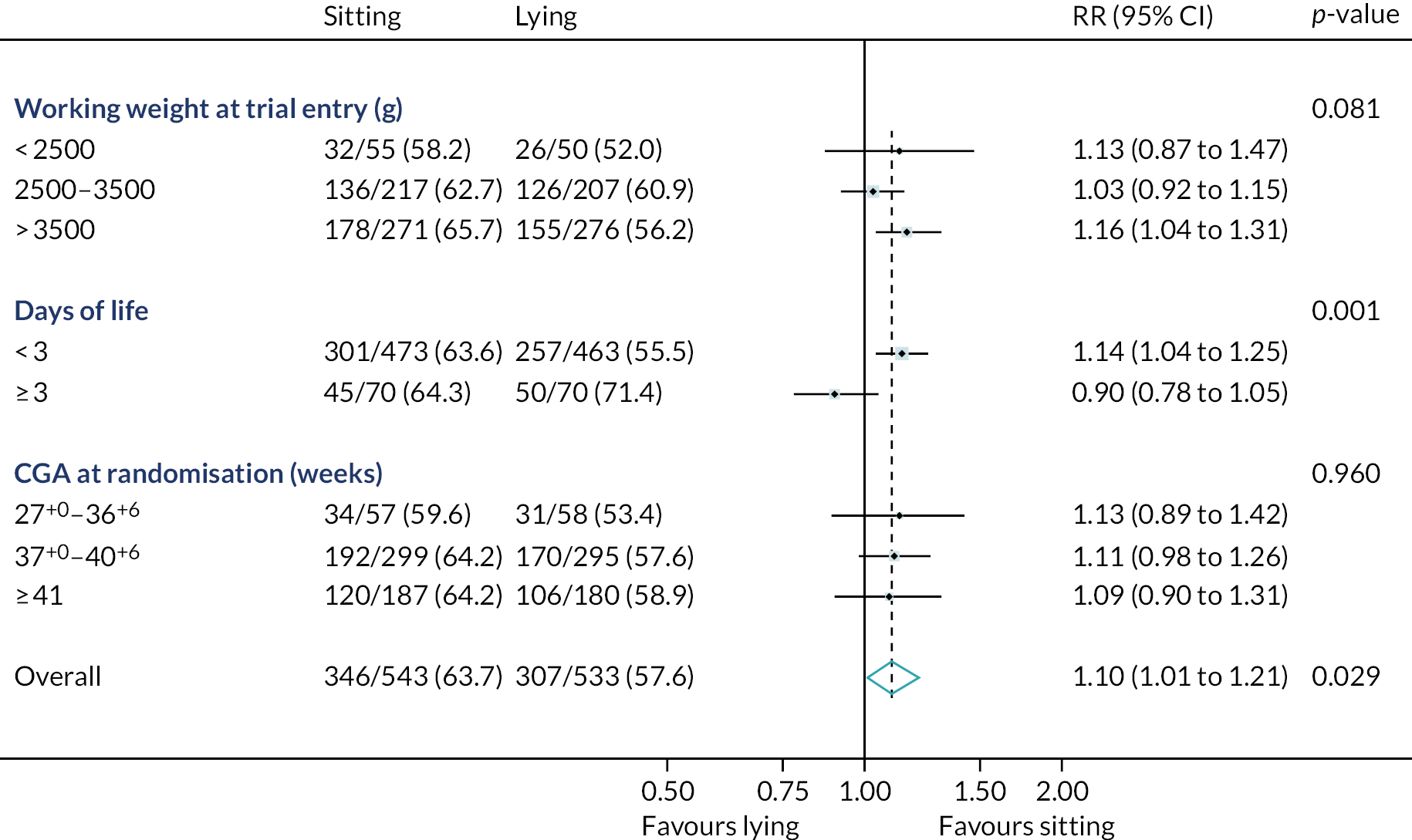

Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome: sitting position compared with lying position

The prespecified subgroup analysis of the primary outcome overall confirms the statistically and clinically significant advantages of performing neonatal LP in the sitting position (success rate 63.7%) over the lying position (success rate 57.6%).

The effect of sitting position was consistent across all subgroups of CGA and weight. The benefit of sitting was less clear in the small subgroup of infants enrolled at ≥ 3 days old. As expected, this subgroup of infants had a lower gestational age at birth and a lower birthweight and, therefore, may have been more likely to require respiratory support at the time of LP. It is also reassuring that the results for infants with a working weight of < 2500 g and a CGA of 27+0 to 36+6 weeks were consistent with the overall findings (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Subgroup analysis forest plot: principal comparison – sitting position vs. lying position. Adjusted for timing of stylet removal allocation, gestational age at randomisation and centre (as a random effect).

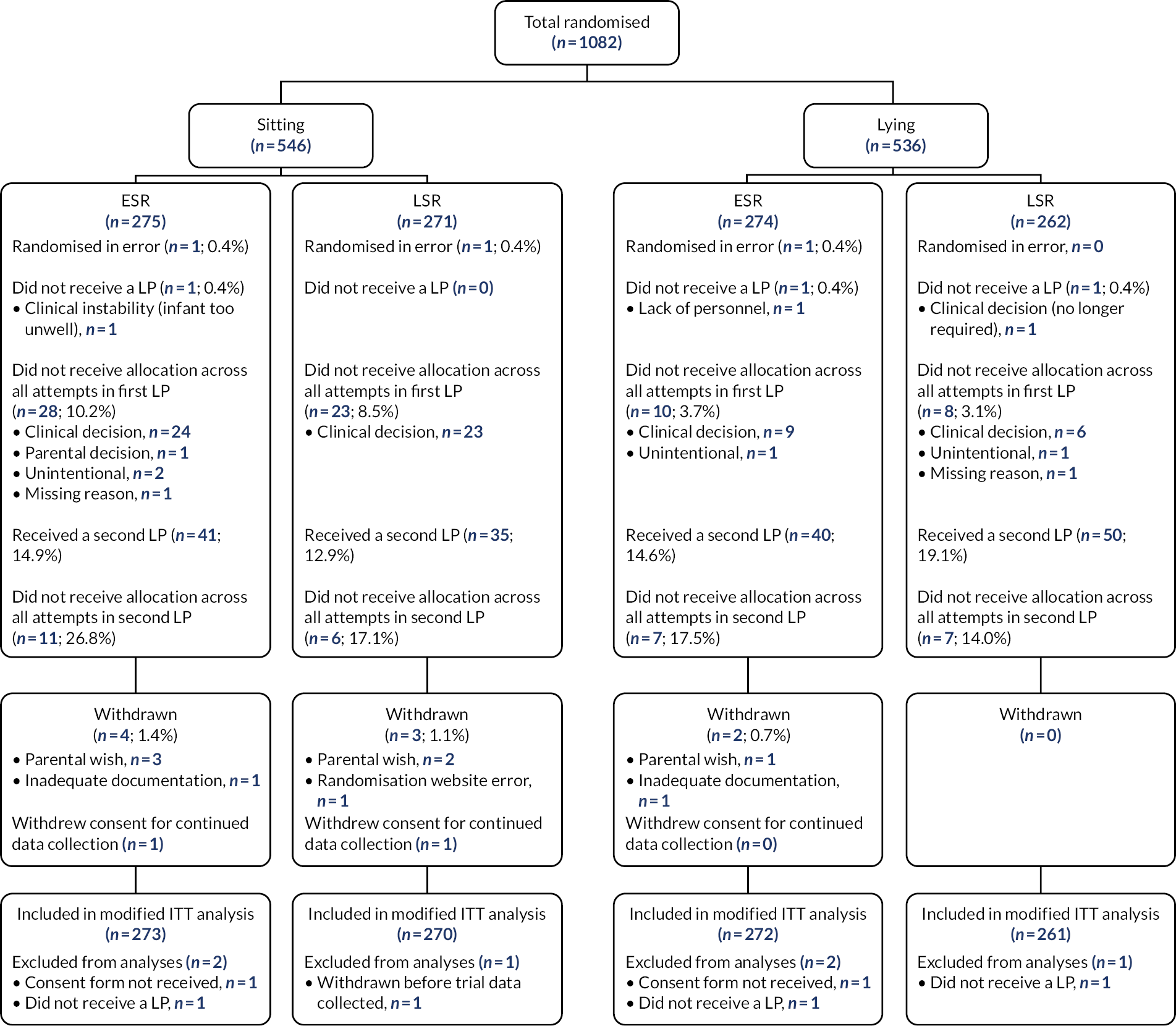

Part B: principal comparison – early stylet removal compared with late stylet removal

The flow chart of participants by principal comparison for the interventions with ESR compared with LSR is shown in Figure 4. The infants’ characteristics at trial entry (Table 9) and at first LP were comparable, with no relevant differences between the groups (Table 10).

FIGURE 4.

Flow of participants by principal comparison: ESR vs. LSR. ITT, intention to treat.

| Characteristic | Stylet removal allocation | |

|---|---|---|

| ESR (N = 545) | LSR (N = 531) | |

| CGA at trial entry (weeks+days), n (%) | ||

| 27+0 to 31+6 | 10 (1.8) | 12 (2.3) |

| 32+0 to 36+6 | 49 (9.0) | 44 (8.3) |

| 37+0 to 40+6 | 297 (54.5) | 297 (55.9) |

| ≥ 41+0 | 189 (34.7) | 178 (33.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (39–41) | 40 (39–41) |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks+days), n (%) | ||

| < 27+0 | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) |

| 27+0 to 31+6 | 16 (2.9) | 16 (3.0) |

| 32+0 to 36+6 | 45 (8.3) | 42 (7.9) |

| 37+0 to 40+6 | 327 (60.0) | 324 (61.0) |

| ≥ 41+0 | 152 (27.9) | 147 (27.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (39–41) | 40 (39–41) |

| Age (days), median (IQR) | 2 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) |

| Range (minimum to maximum) | 0–91 | 0–50 |

| ≥ 3 days, n (%) | 74 (13.6) | 66 (12.4) |

| Birthweight (g), median (IQR) | 3518 (3133–3895) | 3510 (3140–3910) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 |

| Working weight (g) at trial entry | ||

| Median (IQR) | 3520 (3130–3890) | 3510 (3155–3910) |

| 1000–2499, n (%) | 57 (10.5) | 48 (9.0) |

| 2500–3500, n (%) | 207 (38.0) | 217 (40.9) |

| ≥ 3501, n (%) | 281 (51.6) | 266 (50.1) |

| Infant sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 336 (61.7) | 325 (61.2) |

| Female | 209 (38.3) | 206 (38.8) |

| One of a multiple pregnancy, n (%) | 12 (2.2) | 6 (1.1) |

| Receiving antibiotics, n (%) | 503 (92.3) | 491 (92.5) |

| Any previous LPs, n (%) | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) |

| Days since last LP, median (IQR) | 21 (17–26) | 22 (22–22) |

| CSF from last LP sent to laboratory, n (%) | 4 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| RBC from last LP (× 106/l), median (IQR) | 230 (0–665) | |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 |

| WBC from last LP (× 106/l), median (IQR) | 1 (0–4) | |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 |

| Primary indication for current LP (not mutually exclusive), n (%) | ||

| Risk factor for sepsis | 196 (36.0) | 208 (39.2) |

| Clinical signs of sepsis | 147 (27.0) | 135 (25.5) |

| Abnormal WBC count/morphology | 9 (1.7) | 7 (1.3) |

| Raised CRP | 457 (83.9) | 453 (85.5) |

| Specific signs of meningitis/encephalitis | 11 (2.0) | 9 (1.7) |

| Neurometabolic investigation | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.6) |

| Therapeutic (raised intracranial pressure) | 0 | 0 |

| Recent failed LP | 0 | 0 |

| Positive blood culture | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.9) |

| Other | 6 (1.1) | 4 (0.8) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Parental anxiety score (STAI-S), n | ||

| n | 94 | 103 |

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (13.8) | 49.1 (13.7) |

| Recruiting centre, n (%) | ||

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital | 15 (2.8) | 15 (2.8) |

| Royal Berkshire Hospital | 11 (2.0) | 13 (2.4) |

| John Radcliffe Hospital | 83 (15.2) | 80 (15.1) |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | 19 (3.5) | 19 (3.6) |

| Colchester General Hospital | 12 (2.2) | 13 (2.4) |

| Derriford Hospital | 16 (2.9) | 12 (2.3) |

| Gloucestershire Royal Hospital | 13 (2.4) | 12 (2.3) |

| Great Western Hospital | 10 (1.8) | 10 (1.9) |

| Leicester Royal Infirmary | 60 (11.0) | 57 (10.7) |

| Medway Maritime Hospital | 63 (11.6) | 63 (11.9) |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital | 47 (8.6) | 50 (9.4) |

| Northampton General Hospital | 38 (7.0) | 36 (6.8) |