Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/106/04. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The draft report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Randell et al. This work was produced by Randell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Randell et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Prevalence and impact of autism

The prevalence of autism in UK primary school-aged children is approximately 1–2%1 and the effects of autism are well documented, including increased incidence of mental health disorders, most commonly anxiety. Approximately 40–90% of children with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) also meet the criteria for at least one anxiety disorder. 2,3 The impacts on family life are significant. Parents report higher levels of stress4 and loss of earnings,5 and the lifetime cost to the UK economy of supporting an autistic individual is estimated at £0.92–1.5M. 5 Relationship difficulties, particularly at school, are also commonly reported. Children with autism are significantly more likely than neurotypical peers to experience bullying6 and tend to have fewer friendships. 7

Prevalence and impact of sensory processing difficulties in autism

Difficulty in processing sensory information and, in particular, extreme sensitivity or insensitivity to sensory input from the environment is common in autism,8 with prevalence estimates of 90–95%. 9–11 Such difficulties may exacerbate social communication deficits and increase the frequency of restrictive and repetitive behaviour, and may occur because of impaired regulation of central nervous system arousal. 12 Hyper-reactivity, reflecting the autonomic nervous system ‘fight or flight’ response, may result in behaviours such as aggression, hypervigilance or withdrawal (owing to poor tolerance of noise, touch, smell or movement), or additional ‘safe space’ needs. Hyporeactivity, in contrast, is characterised by reduced awareness of sensory stimuli within the environment. 13 Impaired sensory processing may also result in poor motor control, affecting participation in daily life.

Sensory modulation difficulties (i.e. difficulty recognising and/or integrating sensory information) in children with autism probably pose substantial burden to children and families, limiting participation in leisure activities,14,15 and are linked to problems with activities of daily living, such as eating, sleeping, dressing, toileting and personal hygiene. 16 Such difficulties represent a long-term challenge for health services in terms of treating potential consequences, such as behaviours that challenge and mental health disorders. Awareness and management of sensory difficulties in mainstream educational settings is also likely to affect peer relationships and educational outcomes. The potential pathway of effect is unconfirmed [i.e. the mechanism(s) by which sensory difficulties affect key outcomes], but it is plausible that reducing sensory processing difficulties (SPDs) could lead to improvements across behavioural, social and educational domains.

Therapeutic approaches to treating sensory difficulties

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on the management and support of children and young people with autism17 highlight parental perceptions of unmet need for occupational therapy (OT) input to address sensory and functional difficulties as part of the wider supportive network spanning education, health and social care. However, despite this clear unmet need, there is insufficient evidence to recommend any single therapeutic approach for SPDs. The NICE Guideline Development Group recommended further research to establish whether or not sensory integration therapy (SIT) improves SPDs in children and young people with autism across a range of contexts.

The primary goal of OT intervention is to enable participation in activities of everyday life18 by supporting people to engage in the occupations they need, want or are expected to do,19 considering their engagement and performance within relevant environments. 20 OT intervention for children with autism and SPDs is set within this context. There is a range of approaches used to achieve occupational goals, some of which focus on addressing underlying impairment (i.e. a ‘bottom-up’ approach21) and others on adapting the activity or environment for the individual to achieve these goals (i.e. a ‘top-down’ approach22). Both approaches aim to improve occupational engagement, participation and performance, with the distinction that ‘bottom-up’ approaches address underlying SPDs to improve activities of daily living, whereas ‘top-down’ approaches focus on environmental support to accommodate sensory difficulties. These ‘top-down’ approaches include the use of sensory strategies that are not intended to address underlying neurological factors but focus, instead, on adapting the task or environment to accommodate the individual’s sensory needs, or on more targeted support (e.g. helping the child to use self-regulation to manage their sensory needs). ‘Bottom-up’ treatment approaches include Ayres Sensory Integration® (ASI) therapy, which is a play-based intervention providing sensory–motor engagement in meaningful activities while adhering to fidelity principles,23 and sensory-based interventions, which are adult-directed application of sensory input to effect change in behaviour linked to sensory modulation difficulties. These interventions are intended to influence how the child integrates sensory information to facilitate the development of adaptive responses in everyday life.

Sensory-based interventions are usually adult-directed sensory stimulation strategies applied to the child (i.e. without their active engagement) or made available to the child for regulation of their reactivity within the home or school environment. Sensory-based interventions typically focus on a single or narrow range of sensory modalities or techniques (e.g. use of weighted blankets, pressure vests, brushing and sitting on a ball). Adaptations to family routines and the environment may be suggested. Although some studies report positive effects of this approach, for example by coaching children and families to adapt routines and activities,24 effectiveness evidence for functional performance is limited, particularly if strategies are not individualised to the child. 13 However, sensory-based interventions, as well as sensory strategies and environmental adaptations, are currently reported by many professionals and carers as the most common form of ‘usual care’ in a UK setting. Treatment that meets the fidelity requirements for SIT (in terms of content and dose) is not often reported within the UK context, although evidence suggests that parents’/carers’ preference is for this more intensive type of intervention (see Chapter 2).

Sensory-based interventions

Case-Smith et al. 13 systematically reviewed evidence (from 2000 to 2012) of sensory-based interventions and SIT for children with autism and SPDs. Nineteen studies were included in the review, including 14 studies of sensory-based interventions. Sensory-based interventions were defined as those that were based on individual assessment of the child’s sensory needs and functional performance, included explicit self-regulation goals and associated behavioural outcomes, and required the child to actively participate. Few positive effects were reported for studies evaluating sensory-based interventions. 13 Thirteen of 14 studies eligible for review were multiple baseline single-case evaluations of weighted vests, therapy balls and different types of vestibular stimulation (e.g. swinging and bouncing). One study25 found a positive effect for weighted vests on attention. There was limited evidence to support the use of therapy balls to increase sitting behaviours. 26,27 A further study28 demonstrated a positive effect of a sensory diet (e.g. brushing, swinging and jumping) on self-regulation behaviours. Only one study29 was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) (n = 30) of a ‘sensory diet’ protocol (i.e. exposure to a variety of different sensory experiences and practice of specific activities), which found positive effects in terms of a reduction in sensory difficulties overall, but did not assess fidelity or blind outcome assessors. The intervention also included several behavioural techniques (e.g. modelling, prompting and cueing) and, therefore, it is not possible to isolate the effects of sensory-based approaches. 13 In summary, evidence to support the use of sensory-based interventions is limited in scope, methodology and generalisability.

Sensory integration therapy

Sensory integration therapy is a clinic-based approach that focuses on the therapist–child relationship and uses play-based sensory motor activities to address sensory–motor factors specific to the child to improve their ability to process and integrate sensation. 30 To distinguish SIT from other sensory-based interventions, a set of fidelity principles to guide delivery was developed and registered as ASI. 31,32 A fidelity measure has also been developed for use in research. 23 These principles ensure that underlying sensory–motor difficulties affecting activities of daily living are addressed through presenting a range of sensory opportunities and active engagement of the child in sensory–motor play at the ‘just-right’ level of challenge, within the context of a collaborative therapist–child relationship. Studies meeting ASI fidelity principles have been shown to lead to improvement in client-oriented goals,33,34 but research is limited and, in some cases, interventions are poorly defined. 13 Case-Smith et al. 13 identified five studies specifically examining SIT, of which only two33,34 were RCTs. SIT was described in these studies as ‘ . . . clinic-based interventions that use sensory-rich, child-directed activities to improve a child’s adaptive responses to sensory experiences’. 13

Both RCTs33,34 included in the review13 demonstrated positive effects of SIT on the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS). There were, however, methodological issues with both trials, including small sample sizes [i.e. no formal sample size calculation and use of convenience samples (n = 3733 and n = 3234)], lack of long-term follow-up33,34 and limited description of usual care. 34 There are also well-documented methodological problems (with validity and reliability) related to the use of GAS as an outcome measure in clinical trials,35,36 particularly in paediatric contexts. 37 However, more recent research indicates that GAS may be a promising approach to measuring effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in autism and some recommendations for optimising reliability, including the use of a standardised approach to writing GAS goals, have been made. 38 Nonetheless, uncertainty remains about the use of GAS as an objective outcome measure in the context of a clinical trial, despite the appeal of an individualised approach to measurement of what could be considered an individualised form of therapy.

The three remaining studies assessing the efficacy of SIT reported positive effects on behavioural outcomes linked to sensory difficulties, although it is difficult to draw meaningful conclusions given the use of non-randomised designs, very small sample sizes and insufficient descriptions of outcome measures. 13 More recent systematic reviews39,40 did not identify any additional RCTs, but reported positive effects on several functional, developmental40,41 and play outcomes39,42 in two small non-randomised pilot studies (n = 842 and n = 2041) in which SIT was delivered with adequate fidelity.

Current evidence gaps and research priorities

The current evidence base to support use of SIT for children with autism is of low quality and insufficient to recommend treatment. 17 Significant methodological issues are evident from studies conducted to date, including poorly described interventions that are unlikely to meet fidelity standards. Even in randomised studies with good fidelity of intervention delivery, of which several systematic reviews13,39,40 have identified only two (i.e. Pfeiffer et al. 33 and Schaaf et al. 34), intervention protocols were variable in terms of dose and delivery period (e.g. 18 45-minute sessions delivered over 6 weeks in the Pfeiffer et al. 33 RCT and 30 sessions delivered three times per week for 10 weeks in the Schaaf et al. 34 RCT). Conclusions from all studies to date are limited by small convenience samples, poorly described comparators or definitions of what constitutes ‘usual care’ and a lack of long-term follow-up. The latter may be particularly important, given the focus of SIT on attention and learning rather than repetition of specific behaviours. Post-intervention treatment effects may be less specific, and we do not yet know whether or not SIT demonstrates sustained effects. 13

There is also uncertainty around appropriate intervention targets and associated outcome measurement, given the focus of previous trials on goal attainment as the primary outcome of interest and associated psychometric challenges. Furthermore, aside from considerable variation in the intervention protocols, SIT is resource intensive and would require significant investment to be rolled out as a potential treatment option within the NHS. It is critical, therefore, to evaluate both the clinical effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness of SIT for children with autism and SPDs across a range of key outcomes, and to determine whether or not any effects are sustained in the longer term.

The SenITA trial

The main aims of the SenITA (SENsory Integration Therapy for sensory processing difficulties in children with Autism spectrum disorder) trial (see Chapter 3 for methods) were to (1) describe usual care in trial regions and clearly differentiate this from the proposed intervention (see Chapter 2); and (2) evaluate the clinical effectiveness of manualised ASI therapy (see Chapter 5) in a two-arm RCT for SPDs in young children with autism. The intervention was evaluated in terms of the impact on behavioural problems and adaptive skills, socialisation, carer stress and quality of life (see Chapter 6), and in terms of cost-effectiveness (see Chapter 7).

Participants with a range of autism and sensory symptom severity, as well as functional and cognitive ability, were recruited from NHS, educational and third-sector settings. The primary outcome time point was 6 months post randomisation, and was reassessed at 12 months to determine whether or not any observed effects were maintained in the longer term. An internal pilot (see Chapter 4) examined whether or not the intervention differed significantly in content or intensity from usual care and assessed recruitment and retention. Contamination, adherence and fidelity of intervention delivery were measured as part of the process evaluation (see Chapter 8). Experiences of the intervention and usual care were also explored via semistructured interviews with carers and therapists (see Chapter 9).

Chapter 2 Usual care for children with autism and sensory processing difficulties

Aim

Prior to delivering SIT to trial participants, it was important to describe the scope of usual care for children with autism and SPDs (as per the commissioning brief). This would ensure that the therapy offered to the intervention group was clearly different from any treatment offered to the usual-care group. We aimed to explore the role of OT in the management and support of primary school-aged children (i.e. children aged 4–11 years) with autism and associated SPDs living in the UK. We wanted to know how carers and children with autism and SPDs accessed OT services, the nature of any assessments and whether or not specific interventions and/or support were received along the clinical pathway. In addition, we wanted to establish the most common behaviour or occupational performance issues and the profile of associated interventions used for children with autism and SPDs.

Methods

Recruitment and sampling

We were interested in the views of carers and the approaches used by occupational therapists. We chose a mixed-methods approach. Both carers and occupational therapists completed online questionnaires and, to build a more detailed picture of OT support provided, we also carried out qualitative focus groups and subsequent telephone interviews with occupational therapists.

Carer participants

An online questionnaire was distributed to carers of children with autism and SPDs aged 4–11 years and in mainstream education. The questionnaire was made available via the National Autistic Society (NAS) website, local NAS groups, social media [Facebook (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com)], flyers at public events and through the Royal College of Occupational Therapists specialist section on children, young people and their families.

Occupational therapist participants

Online questionnaires

An online questionnaire was distributed to occupational therapists working with, or who had previously worked with, children with autism and SPDs aged 4–11 years and in mainstream education. The questionnaire was first distributed via the Welsh children’s OT network, the occupational advisory forum in Wales and the head of the children’s OT service in Cornwall. Occupational therapists from only the original trial recruitment areas (i.e. Wales and Cornwall) were asked to complete the questionnaire in this first phase and information was also collected on willingness to participate in focus groups/interviews. The questionnaire was then more widely distributed across the UK through the Royal College of Occupational Therapists.

Qualitative data collection

Occupational therapists were sampled from those who had participated in the first phase of the online survey from South Wales and Cornwall, working in the NHS and local authorities. Two focus groups and six telephone interviews were conducted with occupational therapists currently working, or having previously worked, with children with autism and SPDs aged 4–11 years and in mainstream education. Focus groups were conducted in Wales (group 1 had two participants and group 2 had three participants). Six occupational therapists in Wales and Cornwall were unable to take part in the focus groups and, therefore, were interviewed via telephone. Recruitment took place in February 2017, with the aim of carrying out focus groups before trial recruitment began.

Data collection

Online questionnaire to carers and occupational therapists

Online questionnaire data were collected using the Bristol Online Survey. Participants were presented with the purpose of the questionnaire and a data protection statement. Participants who agreed with the statements continued with the remainder of the questionnaire and participants who did not consent were automatically routed to a thank you screen. Both questionnaires consisted of a mixture of multiple choice and free-text questions. It was optional for participants to provide personal information to enable the research team to contact them directly. Respondents were asked about the nature and severity of common difficulties for children with autism. The carer questionnaire was separated into six different sections of (1) location (i.e. where the carer lived and where their child receive care), (2) child behaviours (carers were asked about 12 aspects of their child’s behaviour and how problematic each of these was for their child), (3) therapy (carers were asked whether or not their child had received therapy in the last 6 months that addressed any behaviours listed in the previous questions), (4) information received (carers were asked whether or not any teams/organisations identified in the previous section provided advice or materials), (5) intervention received (carers were asked whether their child had ever received or was currently receiving support from an occupational therapist and the extent of this) and (6) further information (carers were asked whether or not they would be interested in being contacted to take part in an interview or a focus group).

Data were merged following completion of all questionnaire phases. Questions to occupational therapists were split into two broad sections: (1) their role in the work setting and (2) their specific experience with this population. Occupational therapists were asked about their qualifications and years of experience; how many children with autism they saw; the type of assessments they completed and the type and extent of therapy delivered, including theoretical underpinnings for therapy to address SPDs; the type of occupational performance issues they associated with SPDs; the type of support and advice they offered children with autism and their families; and whether or not they would be interested in being contacted to take part in an interview or a focus group.

Focus groups, interview procedure and topic guide

Focus groups and interviews were carried out in English and audio-recorded. Verbal informed consent was obtained. Interviews were semistructured and consisted of five broad topic sections, beginning with an ‘ice breaker’ that allowed participants to introduce themselves, describe where they worked and describe the type of service provided. This ‘ice breaker’ was then followed by questions on usual practice regarding assessment of SPDs in a child with autism; advice and support given to children and carers of children with autism; background training in SPDs; and opinion of SIT. The interview topic guide was initially based on the questionnaire topics, but with further prompts and allowing for flexibility guided by participant responses. The guide was further adapted after the first focus group to shape ongoing data collection. The same topic guide was adapted for telephone interviews. Focus groups were conducted face to face, facilitated by an independent qualitative researcher with an additional note-taker/co-facilitator present. All telephone interviews were carried out following the focus groups by a second qualitative researcher, after having listened to audio-recordings of focus groups for familiarisation of the topic. All focus groups and interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis and anonymised.

Ethics approval and data management

All activities adhered to the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. Ethics approval was granted by a Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committee. All respondents consented to participate in questionnaires, interviews or focus groups.

Analyses

Online questionnaires

Descriptive analyses were used in the form of frequency tables for the quantitative data, and included summaries of the geographical area of respondents, nature of reported difficulties and contact with services, and information on OT assessment and treatment received. Free-text comments within questionnaires provided context and additional explanation for some responses. Examples have been included to give meaning and carers’ lived experience of services received. Free-text comments within questionnaires completed by occupational therapists were incorporated into the thematic analysis of focus group and interview data.

Focus groups and interviews

Transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis. This involved data familiarisation, generating initial themes, and searching, reviewing and defining themes. 43 The first two steps were carried out as a team by two experienced qualitative researchers and two members of the research team who were experienced occupational therapists. The final analyses were undertaken by the lead qualitative researcher.

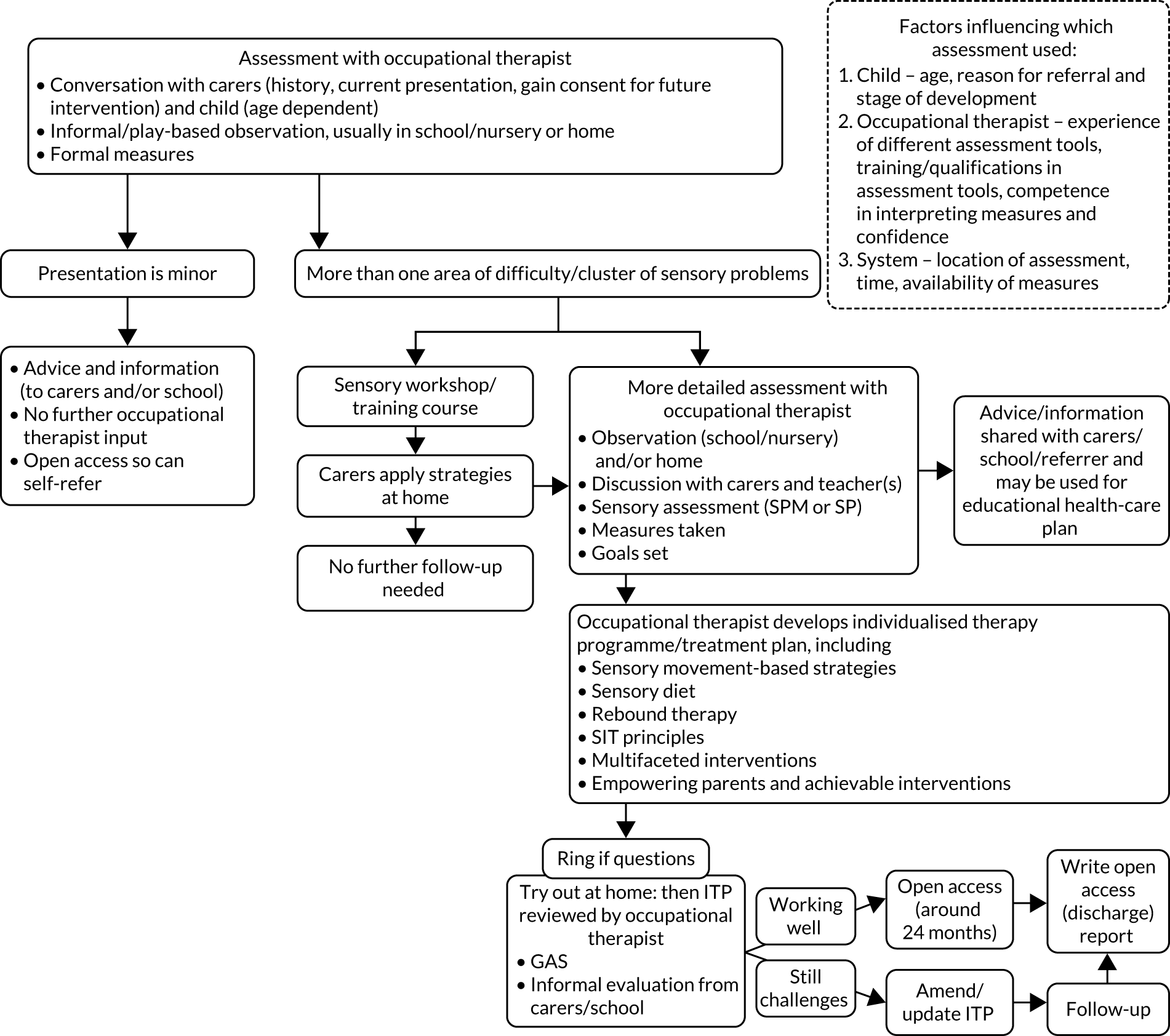

We carried out a thematic analysis using deductive methods to identify themes reflecting reality as reported across the whole data set. We initially coded data within six overarching themes (i.e. referral, initial assessment, initial management, further assessment, treatment plan/intervention, feedback and future plans) relating to the different phases of OT support for children with autism and SPDs. In addition, we used an inductive thematic approach to identify occupational therapists’ views, experiences and challenges relating to these processes, moving towards a more contextualist approach and ensuring that subthemes, which had not been pre-empted and initiated from occupational therapists themselves, were identified. These subthemes were factors influencing decisions around which assessment occupational therapists used (at child, OT and system level), factors influencing the location of assessment, the multifaceted nature of interventions, empowering others, and making interventions achievable for parents and schools. This analysis was then integrated with the results of the questionnaires. While interpreting the qualitative data we produced a visual map of the different phases of management of children with autism and SPDs (Figure 1). We developed this map this in a phased way, starting with one account in an interview and building on this with each new transcript, revising and incorporating as we progressed. In this way, data were constantly compared and contrasted. Developments in the analytic process were recorded through researcher memos and version control of the visual maps. The first transcript was discussed in detail and themes developed by a group of qualitative researchers and occupational therapists. Themes were then applied to the next transcript and discussed again. The research team were encouraged to reflect on their own professional role in asking and interpreting interview questions.

FIGURE 1.

Routes of support described by occupational therapists. ITP, individualised therapy programme/treatment plan; SP, sensory processing; SPM, Sensory Processing Measure.

Results

Carers’ views of usual occupational therapy for children with autism and sensory processing difficulties

A total of 159 carers responded to the questionnaire. Most (n = 149, 93.7%) carers were mothers. We received six (3.8%) responses from fathers, two from grandmothers (1.3%), one from a kinship carer (0.6%) and one from an educational visitor (0.6%). The spread of respondents across geographical regions is shown in Table 1. Thirty-two (20.1%) respondents were from Wales, 115 (72.3%) were from England, 11 (6.9%) were from Scotland and one (0.6%) was listed as ‘other’ (location not specified).

| Geographic area by country | n (%) | University health board/region | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wales | 32 (20.1) | Aneurin Bevan University Health Board | 7 (4.4) |

| Cardiff and Vale University Health Board | 15 (9.4) | ||

| Cwm Taf University Health Board | 4 (2.5) | ||

| Hywel Dda | 4 (2.5) | ||

| Swansea Bay University Health Board | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Wales other | 1 (0.6) | ||

| England | 115 (72.3) | Buckinghamshire | 1 (0.6) |

| Cornwall | 11 (26.4) | ||

| Dorset | 2 (1.3) | ||

| England other | 101 (63.5) | ||

| Scotland | 11 (6.9) | Scotland | 11 (6.9) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | Other | 1 (0.6) |

Nature of reported difficulties

The most frequently reported difficulties were difficulties with relationships and communication (84.3%) and difficulty making friends/joining in/playing with others (83.6%), followed by refusal to carry out daily activities (73.6%) and outbursts without any obvious reason (73.6%). A total of 77.3% carers reported at least moderate difficulty with sensory hyper-reactivity and 49.6% of participants reported at least moderate hyporeactivity. Being overactive and having repetitive behaviour that interrupts activity were reported by 64.8% of carers. Other difficulties encountered included sleeping difficulties (59%), poor co-ordination (56%), poor performance in school (54.1%) and feeding difficulties (39.6%). Less common difficulties included anxiety (n = 8, 5%), hyperacusis (n = 2, 1%), hypermobility (n = 2, 1%), poor concentration (n = 2, 1) and violent behaviour (n = 2, 1%).

Carers’ views on contact with services

A total of 119 (74.8%) carers reported some contact with services [e.g. children’s centres (health service) and local authorities (social care services)] in relation to difficulties in the last 6 months. Professionals seen within these organisations included occupational therapists (NHS and private), speech and language therapists, paediatricians, psychologists (clinical and educational), dieticians and specialist teachers. However, 40 (25.2%) carers reported that they had received no therapy/support in relation to their child’s difficulties in the same period. Further detail regarding contact with services is given in Table 2.

| Service | Contact, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Children’s centre (health service provision) |

|

| Special school |

|

| Local authority (social care provision) |

|

| CAMHS |

|

| Specialist autism team |

|

Ninety (56.5%) carers received information and advice on how to manage their child’s difficulties, such as anxiety, behavioural and sensory difficulties. Although 68 (42.8%) carers received specific advice on sensory information from services, a further 46 (28.9%) carers would have liked more information on these aspects of their child’s difficulties. Where advice and information on sensory issues had been given, this was most commonly by OT services. However, sometimes other NHS and third-sector organisations provided similar information. Information was typically in leaflet form and included information on sensory processing, exercises/programmes to do at home, social stories and contact information/websites for parent courses.

Carers’ views on occupational therapy assessments and treatment

Seventy (44.0%) carers had not received any input from OT services. Those who had received input (n = 89, 56.0%) generally received input in the form of assessment and observation plus advice. Assessment was most frequently through a carer questionnaire and observation of play. A few carers reported more formal testing of co-ordination skills. If direct intervention was offered, then this was typically for a limited block of therapy (e.g. four to eight sessions). Of the carers (89/159) who had received input from OT services, 64 (40.3%) were not currently in contact with an occupational therapist. Of the 44 carers who had seen an occupational therapist in the last 6 months, 10 had received more than five sessions in that period. In terms of length of overall contact with OT services, the majority of carers were discharged within a 6-month period (n = 76, 85%).

Of those carers who had ever received OT input, 15 (16.8%) reported that they had received weekly input and most visits were clinic based (n = 57, 35.8%), with intervention varying from sensory based (not SIT), parent-directed programmes, functional skills training, sensory diets and behavioural programmes. Most carers (n = 58, 36.5%) stated that the intervention that they received focused on sensory modulation. Fewer carers (n = 22, 13.8%) received intervention for both sensory modulation and dyspraxia, and an even smaller number of carers (n = 9, 5.7%) received intervention for dyspraxia alone. Forty-three (27.0%) carers reported that the intervention focused on other aspects, such as anger management, behavioural difficulties, speech and sleep. Carers were asked further details about specific interventions that their child received in terms of whether or not they felt that the therapy helped their child, how satisfied they were with the intervention received and whether or not they would recommend any changes to intervention delivery.

Sensory integration therapy

Five (3.1%) carers had accessed OT privately and had received, or were in receipt of, SIT at least once per week. All five carers felt that SIT had helped their child and reported high satisfaction with the intervention. However, all five carers also felt that longer-term therapy (i.e. more than six sessions) would be beneficial and/or that it should be available on the NHS.

Other interventions received

The intervention most often received by carers was adaptation to the home or school environment (n = 115, 72.3%), and 88 (76.5%) carers thought that adaptations helped their child and 83 (77%) carers were satisfied with the adaptations. Other interventions included sensory diets (n = 54, 34%), behavioural interventions (n = 42, 26.4%), parent-directed programmes (n = 45, 28.3%), functional skills training (n = 25, 15.7%) and sensory-based interventions (n = 24, 15.1%). Fewer carers (n = 16, 10.1%) received advice on desensitisation strategies. Generally, more respondents were satisfied with sensory diets (n = 40, 77%), desensitisation strategies (n = 12, 75%) and parent-directed programmes (n = 28, 65%) than behavioural interventions (n = 19, 51%). When asked whether or not interventions helped their child, carers felt that desensitisation strategies (n = 12, 75%), sensory-based intervention (n = 16, 66.7%) and functional skills training (n = 16, 64%) definitely helped their child. Carers were less certain about sensory diets (n = 28, 51.9%), parent-directed programmes (n = 20, 44.4%) and behavioural intervention (n = 15, 35.7%). When asked whether or not there was any aspect of the interventions/advice received that they would wish to change, carers commonly said that they would have liked additional input and direct support for their child, rather than just advice. Some carers noted that they would have liked more access to OT and speech and language therapy (SLT) support through the NHS. Several carers specifically requested training and support into schools to manage sensory difficulties (n = 11), as they felt that the school was not able to carry out the sensory support required. Some carers would have liked more specific advice for their child, including follow-up and monitoring visits, rather than generic information that was not personalised:

I would love for this intervention to be available as more than a one-off appointment with me as a parent. I would love to be able to access sensory support/therapy for my children on a regular basis.

Carer 66

Specific advice from a qualified OT [occupational therapist] specialising in sensory difficulties not just a parent googling what to try – trial and error as totally without support from NHS.

Carer 9

Make it available to everyone via the NHS. NHS input was limited and generalised, we had excellent input from a private OT [occupational therapist].

Carer 155

NAS website and research online; family and friends particularly those with children who have autism; colleagues at work.

Carer 145

Detailed responses of the interventions received by families are provided in Table 3.

| Strategy/intervention | Intervention received, n (%) |

|---|---|

| SIT at least once per week |

|

| Sensory-based interventions |

|

| Desensitisation strategies |

|

| Parent-directed programmes |

|

| Sensory diets |

|

| Behavioural intervention |

|

| Environmental adaptation |

|

| Functional skills training |

|

Finally, when asked what types of intervention would be the most useful, the most common carer responses were additional support for social communication (n = 16), desensitisation and other sensory issues (n = 15), support for managing behaviour, including aggression, anger and anxiety (n = 14), and specific SIT (n = 12). A significant number of carers reported having to source support via independently accessed behaviour training (n = 81, 50.9%) and regular contact with support groups (n = 87, 54.7%), and 81 respondents (50.9%) received informal support from family and friends:

Sensory integration therapy for social and behaviour skills.

Carer 5

More help with socialising with his peers so that he does not become socially isolated.

Carer 25

Help with controlling/managing violent outbursts.

Carer 47

Intervention specifically aimed at sensory issues in school.

Carer 68

Someone to work with my child teaching them about their sensory differences and how to manage them whilst exploring what works/doesn’t and teaching them coping techniques at their own pace.

Carer 77

Occupational therapist views of usual care

Questionnaire responses by occupational therapists

The questionnaire was completed by 79 occupational therapists. In phase 1, 38 questionnaires were completed by occupational therapists working in trial recruitment areas (i.e. Wales and Cornwall). In phase 2, 41 questionnaires were completed, including by occupational therapists in England and Scotland. Occupational therapists were generally very experienced: 53 (67.1%) occupational therapists reported having at least 10 years’ post-qualification experience and only 10 (12.7%) reported having < 5 years’ post-qualification experience. Eighteen (22.8%) occupational therapists reported postgraduate qualifications, with 11 (13.9%) specifically in sensory integration. Almost all (n = 77, 97.5%) occupational therapists reported seeing one or more children with autism and SPDs in the last 6 months, with 15 occupational therapists (15.2%) seeing more than 10 children each. However, only 11 (13.9%) occupational therapists were based within a specialist autism service. The settings in which children were seen included children’s centres, special and mainstream schools, local authority settings, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and the child’s home. Most occupational therapists saw children referred for one to five contacts/sessions (n = 39, 49.4%), with only three (3.8%) occupational therapists seeing children for between 10 and 20 contacts/sessions. The frequency of contact was very varied, with the most common frequencies being weekly (27.8%), monthly (19%) or twice per month (17.7%). Most occupational therapists maintained contact with families for 3 months (n = 26, 32.9%) or 6 months (n = 20, 25.3%) prior to discharge.

Focus groups and interviews with occupational therapists

Two focus groups and six semistructured telephone interviews were conducted following the online survey, representing the views of 11 occupational therapists working in South Wales, Mid-Wales and Cornwall. Respondents described themselves as occupational therapists, paediatric occupational therapists and occupational therapist senior practitioners, and had experience of working in autism assessment units, core services, in the community, within the NHS, in social services and in the local authority. This section integrates occupational therapists’ views on usual care gathered from questionnaires, focus groups and interviews. Illustrative quotes are provided.

Nature of reported difficulties and referral

Survey responses indicated that the most common problems seen by occupational therapists included poor performance in school (n = 61, 77.2%), poor co-ordination and motor planning (n = 57, 72.2%), and refusal to carry out typical daily activities, sleep and outbursts without understandable reason (n = 56, 70.9%). Sixty-seven (84.8%) respondents felt that sensory hyper-reactivity hindered children’s engagement in activities, with 50 (63.3%) respondents reporting that hyporeactivity could be a factor hindering engagement. In focus groups/interviews, occupational therapists reported that referral may be via health professionals [e.g. general practitioners (GPs), paediatricians and professionals in SLT and mental health services], other services (e.g. integrated services for children with additional needs, education services and social services) or via carer self-referral. Referral criteria varied slightly, but required a child to demonstrate functional difficulties and SPDs, rather than behavioural and emotional problems alone, and did not necessarily require a diagnosis. One occupational therapist stated that they did not have clear written criteria setting out what they would and would not accept. Occupational therapists described that a triage meeting would take place at which occupational therapists and colleagues determined the appropriateness of a referral. Occupational therapists describe using clinical reasoning and professional experience to consider the information:

So it’s difficult to say whether people meet criteria because our criteria is still, it’s not always clear; it’s a little bit woolly but I think that’s quite historically common for OT that the criteria for a service for OT is generally quite woolly because we do cover such a wide remit.

Interviewee 4

Yes, there are a few of us here that are trained in using SIPT [Sensory Integration and Praxis Test], so sometimes we will do that for the children that are more highly functioning ASD, and that’s quite good because it gives us a really good profile on what their skills are, and their things to work on.

Interviewee 5

Theoretical framework underpinning decision-making

Most OT survey respondents reported that clinical reasoning within the referral, assessment and intervention process involved using OT theory as a guide (n = 76, 96.2%), with 55 (69.6%) respondents supporting this with sensory integration theory (27 respondents specifically referred to ASI). Other approaches included neurodevelopmental (n = 47, 59.5%), applied behavioural analysis (n = 29, 36.7%) and social approach (n = 8, 10.1%).

Assessment process

Most OT survey respondents reported using informal or structured clinical observations within the home, school or clinic setting (n = 68, 86%). In the focus groups/interviews, occupational therapists also talked about the value of observing informal activity. One occupational therapist compared informal and formal clinical observations and the different ways of thinking required for occupational therapists to process information. Occupational therapists also talked about sensory play as a way to practically demonstrate the challenges that the child and carer(s) face.

Occupational therapists reported that this observation was carried out alongside interviews/questionnaires and a developmental history with carers (n = 45, 57%), teachers (n = 22, 27.9%) and the child (n = 12, 15.1%). In addition, 33 (41%) survey respondents reported using a specific OT assessment of functional daily life skills. Forty-five (57%) respondents reported using a specific measure to assess SPDs [e.g. Sensory Profile 224 and the Sensory Processing Measure™ (SPM)44]. Fewer (n = 15, 19%) survey respondents reported using measures to assess motor difficulties (e.g. Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2 and Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency-245).

Occupational therapists also mentioned other measures [e.g. the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales,46 clinical observations assessment,47 the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure48 (COPM), Movement Assessment Battery for Children,49 The Roll Evaluation of Activities of Life Occupational Therapy assessment,50 Beery Visual Motor Integration51 and Kate Malcomess’ Care Aims Framework52]. Occupational therapists in the diagnostic assessment team and one other core service reported that they might use the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)53 or specific SLT assessments. Some occupational therapists used the Sensory Integration and Praxis Test54 (SIPT) in case studies if they had undertaken training in sensory integration (but did not then use this therapy in usual care), whereas others said that they did not have access to SIPT equipment. Only one occupational therapist said that they used the SIPT routinely.

In focus groups/interviews, occupational therapists reported that they talk with carers and schools/nurseries to set goals. Older children will discuss goals too. Occupational therapists described instruments used to support goal-setting [e.g. the Perceived Efficacy in Goal Setting Approach,55,56 Child Occupation Self-Assessment,57 SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time bound) goals58 and Kate Malcomess’ Care Aims Framework52]. However, one occupational therapist explained that they do not always have to use formal assessment/goals if sufficient information is gained through observation or is offered by the carer or child.

In focus groups/interviews, occupational therapists talked of assessment as an ongoing process. In deciding which assessment to use, occupational therapists considered different factors relating to three areas, that is, the (1) child, (2) occupational therapist and (3) wider system. At the level of the child, assessment choice depended on their age, stage of development, concentration level and reason for referral. At the occupational therapist level, assessment depended on their experience, training/qualifications in different tools, competence in interpreting measures, and personal confidence and preference. Finally, at the system level, assessment depended on location, time available, waiting list pressures, availability of measures and the focus for that service. The location of assessment also depended on several factors. Occupational therapists reported that location of observation was selected to limit distress to the child while determining the problem with greatest impact. The age of the child may also influence the setting for observation.

Again, reason for referral was also considered. Some occupational therapists said that they would see the child in their usual environment where difficulties presented and/or in another environment with carers (e.g. school/nursery). One occupational therapist also explained that the child would usually come to the children’s centre, as there was equipment there that could be tried out. If the child was to receive the intervention, then they would often be seen on several occasions in different locations. The location of assessment was also influenced by the ability of the carer to visit the clinic owing to, for example, socioeconomic status or learning difficulties:

Well I think in the battery of assessments that you have, and the observations that you can do it very much depends on the child because a lot of the children with autism they would get freaked out with maybe doing standardised assessments and you can’t, you have to do it by observation and play then. You’re very much guided when you meet the child on the day really . . .

Participant 1, focus group 1

. . . so we use a sensory profile, but it’s again down to the individual therapist, it’s not something that we necessarily do for everyone every time. We use just clinical observations and observing them in their home environment and their school environment, so that’s our main, I would say that’s our main first contact is just clinical obs [observations] and chatting to the parents and seeing how they are and then we may decide to use a sensory profile if we need to get a clearer picture.

Interviewee 4

If the child is going to be put in distress through coming to a new environment and a strange environment, and would be distressed in that setting, then you’re not going to get the best thing from that child, so that would influence my clinical decision of where I carried that out.

Interviewee 3

Advice and interventions

Frequency strategies described by OT survey respondents are detailed in Tables 4 and 5.

| Therapist advice to carers | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Information on the senses | 66 (83.5) |

| Introducing new/adapted sensations | 32 (40.5) |

| Sensory diet | 48 (60.8) |

| Advice to improve response | 41 (51.9) |

| Physical environment | 69 (87.3) |

| Social environment | 51 (64.6) |

| Other | 16 (20.3) |

| Intervention for children/families | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sensory based | 42 (53.2) |

| Desensitisation | 32 (40.5) |

| Parent directed | 38 (48.1) |

| Education | 56 (70.9) |

| Sensory diets | 58 (73.4) |

| Behavioural | 29 (36.7) |

| Adaptations (physical and social) | 62 (78.5) |

| SIT | 5 (6.3) |

We then used interview and focus group data to understand the different phases of OT support and interventions for children (see Figure 1).

Presentation assessed as minor after initial assessment with occupational therapist

In focus groups/interviews, occupational therapists reported that if presentation was ‘minor’ then the carer/child would receive advice and information, but no further input. The carer/child may be provided with website addresses, handouts and signposting to other services. In addition, the carer/child would usually have the option to self-refer later if needed.

Sensory carer groups

Occupational therapists reported (in focus groups/interviews) that for more than one area of difficulty and/or a cluster of sensory problems, carers may be invited to attend a parent group (e.g. a one-off workshop or course of around three sessions). These sessions often consisted of an interactive element involving peer support (e.g. where carers shared difficulties and solutions) and professional support (e.g. providing theory and professional advice). A group with multiple sessions allows carers time to identify triggers/concerns, discuss and try out strategies, and then return to evaluate effectiveness of these strategies. Occupational therapists suggested that these groups give carers a foundation knowledge about sensory processing and help them to understand their child’s individual needs.

Sensory movement-based strategies, sensory diet and rebound therapy

Survey respondents reported that the most common intervention offered was advice on adaptation to the environment to accommodate sensory needs (n = 62, 78.5%) and activities for a sensory diet (n = 58, 73.4%).

Occupational therapists reported (in focus groups/interviews) that, based on observation, assessment and goal-setting, they would develop an individualised therapy programme/treatment plan with carers and the school/nursery. This would often involve multiple sessions (around four to six). A wide range of strategies might be drawn on and a plan provided for an individual child to try at home or at school/nursery. These strategies might include sensory movement-based strategies (e.g. vestibular and proprioceptive activities, such as heavy muscle work, yoga-type movement, peanut roll, scooter board, lycra blanket, soft play and sensory-weighted equipment) and may also include deep touch pressure, massage and brushing for alerting and desensitising, calming strategies and mindfulness, and swimming. Some equipment might be used for assessment/observations and treatment, for example therapy rooms with a smartboard, Wii Fit (Nintendo Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan), weighted blankets, supportive chairs or trampolines (interview 1). Another occupational therapist (interviewee 3) mentioned that they had a loan system for sensory items (e.g. weighted products, dance mats, vibrating items, seating and lap pad). Carers might have delivered strategies themselves or a technician/occupational therapist would offer a demonstration. One occupational therapist reported that they also offered groups that families can link into, such as bike skills groups, gymnastics and social skills groups.

Occupational therapists might also advise group interventions (e.g. The Alert Programme and Sequential Oral Sensory approach) or multidisciplinary team working/referral to other services [e.g. a portage worker, a specialist health visitor, a neurodevelopmental team, NAS, Barnardos (London, UK), primary mental health, a specialist autism service in the school, Autism Puzzles (Cardiff, UK) and a disability sports officer]. Occupational therapists also spoke of linking and contributing to transdisciplinary groups, including Next Steps, Early Bird, Early Bird Plus and Cygnets.

Sensory integration therapy

Five (6.3%) survey respondents reported delivering SIT. However, most (n = 55, 69.6%) respondents reported using sensory integration theory to inform practice and 19 (24.1%) respondents had undertaken postgraduate sensory integration training equivalent to ≥ 50 hours (i.e. the minimum requirement for trial therapists). Most interventions used were targeted at sensory modulation and/or dyspraxia (n = 44, 55.7%). Similarly, most occupational therapists reported that they either were not able to use ASI therapy in its pure form because of time or space, or did not use it at all. Occupational therapists who had received training in SIT said that they try to consider its principles, but expressed frustration that they could not carry it out. Only one occupational therapist reported using SIT ‘as much as possible’ for specific children, including using swings and climbing frames, wobble cushions, scooter boards and scooter board ramps, weighted balls and a range of wet and dry tactile exploration items (e.g. texture mats, textured balls, textured quoits, vibration balls, vibrating snakes and cushions), as well as trampettes that could be used at home:

We have a very positive response to it. And the number of parents that say oh if only we had known this. So yeah, it’s a very positive way of meeting a lot of people’s needs. And it also saves the therapist’s time, because otherwise what we feel is that those parents that then seek further intervention, they have a baseline of knowledge. And we all know what that level of knowledge is, so that we can start working at that higher level rather than having to cover the same groundwork individually with each child.

Interviewee 2

We don’t provide it, we don’t have any funding to provide that type of sensory equipment, but we do have access to them to be able to trial them for a 2-week period. After the trial we then make a decision whether we suggest that for the parents or the schools, or nursery or wherever that child is, to purchase that piece of equipment. But we don’t have funding to provide that.

Interviewee 3

In the house, and in the centre, we use a lot of suspended type equipment, so we’ve got things like T-bars, we have platform swings, and we have bolster swings. We have climbing frames, tyre swings, all that type of stuff.

Interviewee 5

Multifaceted interventions

Occupational therapists tended to describe the interventions that they offered as varied and multifaceted. Some occupational therapists highlighted the non-standardised nature of developing and delivering interventions. However, occupational therapists described using an evidence base, their clinical experience and the needs of the individual child to guide intervention/strategies.

Empowering parents and achievable interventions

Many occupational therapists (in focus groups/interviews) felt that an important part of intervention delivery was the carer’s motivation to engage with the intervention, as well as their ability and confidence to deliver the intervention. An important part of the occupational therapist’s role was empowering carers to continue the intervention. Occupational therapists reported that barriers to carers implementing strategies included the carer’s understanding of their child, other family commitments and child engagement. Occupational therapists reported that the effectiveness of interventions was also dependent on teachers’ ability to deliver the intervention. Therefore, occupational therapists stressed the need to make the intervention achievable and manageable at home and/or school:

In isolation it means nothing. You can carry out 30-odd sessions, but once that intervention finished it’s finished, unless the parent and the child . . . For me, the powerful bit is carrying that over into the child’s everyday life so it continues.

Participant 2, focus group 2

So I think for me it feels like it’s empowering others to do this work and then to understand what it is to provide it every day for the child feels more normal than going to a clinic setting all the time. Less medical. Nobody wants to be going somewhere . . . Children have got lives to live themselves and fun to have.

Participant 2, focus group 2

Evaluating the intervention plan, reports and open access

Occupational therapists (in focus groups/interviews) reported that after strategies had been tried at home and/or at school/nursery for several weeks the plan was reviewed, often using the GAS,35 an evaluation questionnaire and/or informal evaluation from carers or the school.

Discussion

Representativeness of views

The views reflected within our data were collated from survey responses from occupational therapists and carers in Wales, England and Scotland, and from interviews/focus groups conducted with occupational therapists in South Wales and Cornwall. The purpose was to determine how carers and children with autism and SPDs access OT services, the assessment process and what interventions and/or support are commonly provided. Determining the nature of usual care within trial areas and the wider UK context would ensure that our comparator was sufficiently different from SIT delivered in the intervention arm of the trial.

Theoretical approaches to intervention

Survey responses indicated that occupational therapists utilised OT theory to guide assessment and intervention. This core philosophy values human participation in meaningful occupations59 and this is reflected in the criteria that occupational therapists use to choose whether or not to accept a referral for assessment. Within the broader scope of theoretical approaches, sensory integration theory was reported as the most common approach to help to understand and manage SPDs. This is consistent with findings from Kadar et al. ,60 who found that 72.7% of occupational therapists used a sensory integration frame of reference. Likewise, Brown et al. 61 reported that sensory integration and client-centred practice models were most commonly used in a survey of Canadian paediatric occupational therapists.

Accessing services and the referral process

Although services differ, there appeared to be a common trend across the regions surveyed. From both quantitative and qualitative data, it was clear that most children were seen for initial assessment only if they met specific referral criteria, particularly with regard to SPDs affecting daily functional activities. Many services would not accept a referral unless there were clear occupational performance difficulties in self-care, play or school-related activities. It is likely that this more focused approach has been driven by increasing waiting lists for access to OT,62 ensuring that only the most appropriate children received therapy. There have also been government drivers to ensure that children are seen within 14 weeks of referral (e.g. the NHS Wales Delivery Framework and Reporting Guidance 2019–202063). From the carers’ perspective, understanding of what OT services could offer their child was less clear cut. Carers wanted support for their child’s social interaction, help with dealing with aggressive outbursts/frustration, help with understanding autism and help with siblings. Fewer carers listed functional skills, such as toileting, feeding, dressing and sleeping, as behavioural issues seemed to have a greater impact on quality of life. Respondents were, therefore, frustrated because they felt that they could not always access the service that they perceived would help them and their child, and expressed disappointment that services were not always offered by the NHS.

Assessment process

Both occupational therapists and carers reported that initial assessment included observations, interviewing the caregiver, questionnaires and, sometimes, more formal assessments. Observations of the child’s behaviour and performance were typically within the clinic setting and, to a lesser extent, within the school or home environment. Standardised assessments were not used routinely. Although most therapists reported using a sensory integrative approach, only very few reported using the SIPT to formally identify the nature of the sensory integration difficulty.

Some settings used structured goal-setting with carers to establish the child’s needs. There has been a consistent drive in recent years to develop family-centred practice, with services working in partnership to address concerns and goals. 64 From this survey, it appears that some carer concerns were addressed and that most were satisfied with the advice given, but many would have liked more input. After initial assessment, most services generated a report with advice on strategies for managing SPDs in everyday life. For some parents, contact with services ended at this point or they were referred to a workshop/training group. For others, additional OT support was received with further discussion and advice, the offer of loan of suitable equipment to support their child’s needs or some sessions of one-to-one intervention.

Intervention

Therapists appeared to have a two-pronged approach: (1) giving strategies and advice to support carers to manage their child’s SPDs to improve self-regulation, and (2) attempting to address SPDs directly with the aim of remediation of the dysfunction and underlying nervous system. 65

Strategies and advice to manage sensory processing difficulties

Both occupational therapists and carers concurred that strategies and advice were most commonly provided. Occupational therapists used a range of strategies, from advice including environmental adaptations, sensory diets and desensitisation strategies, which may take the form of generic advice, to more personalised advice following individual sessions. According to carers, the sensory-based interventions, sensory diets and parent-directed programmes helped in over 65% of the children receiving them. However, carers still felt that this was not enough and wanted ongoing support. Carers also wanted better transfer of advice and strategies into the school setting, more personalised intervention and further follow-up as the child developed. In terms of transfer of knowledge and to run an efficient service, several therapy services offered parent/carer groups with general information about sensory processing. Although carers found this useful, they also wanted more specific application to their own child’s difficulties.

Direct intervention

Carers and some occupational therapists expressed frustration that direct hands-on therapy was not always possible because of resource constraints. Carers particularly felt that they were missing out on intervention and that they had to seek support privately. Respondents whose children had received SIT were extremely satisfied and all felt that it had helped their child. Very few therapists in the NHS reported using SIT meeting fidelity criteria,23 but some were using sensory-based interventions, applying theory and principles of sensory integration and delivered less intensively for shorter periods. These interventions included activities applied to the child to improve behaviour associated with modulation disorders,13 such as massage, brushing, wearing a weighted vest or sitting on a gym ball.

Summary

Sensory-based difficulties are commonly reported in this population, and there is a clearly expressed demand from carers for additional contact and support from OT services. Current provision of usual care and most services offered focus on delivering sensory strategies and advice. This may be in the form of generic written information that is web based or a bespoke leaflet, or through parent groups or one-to-one consultation with carers. Some direct therapy may be offered using a sensory integration approach, but this usually comprised fewer than 10 sessions. Intensive treatment offered by a therapist with SIT training is available within the private sector and so is inaccessible for many carers.

Chapter 3 Methods

Design

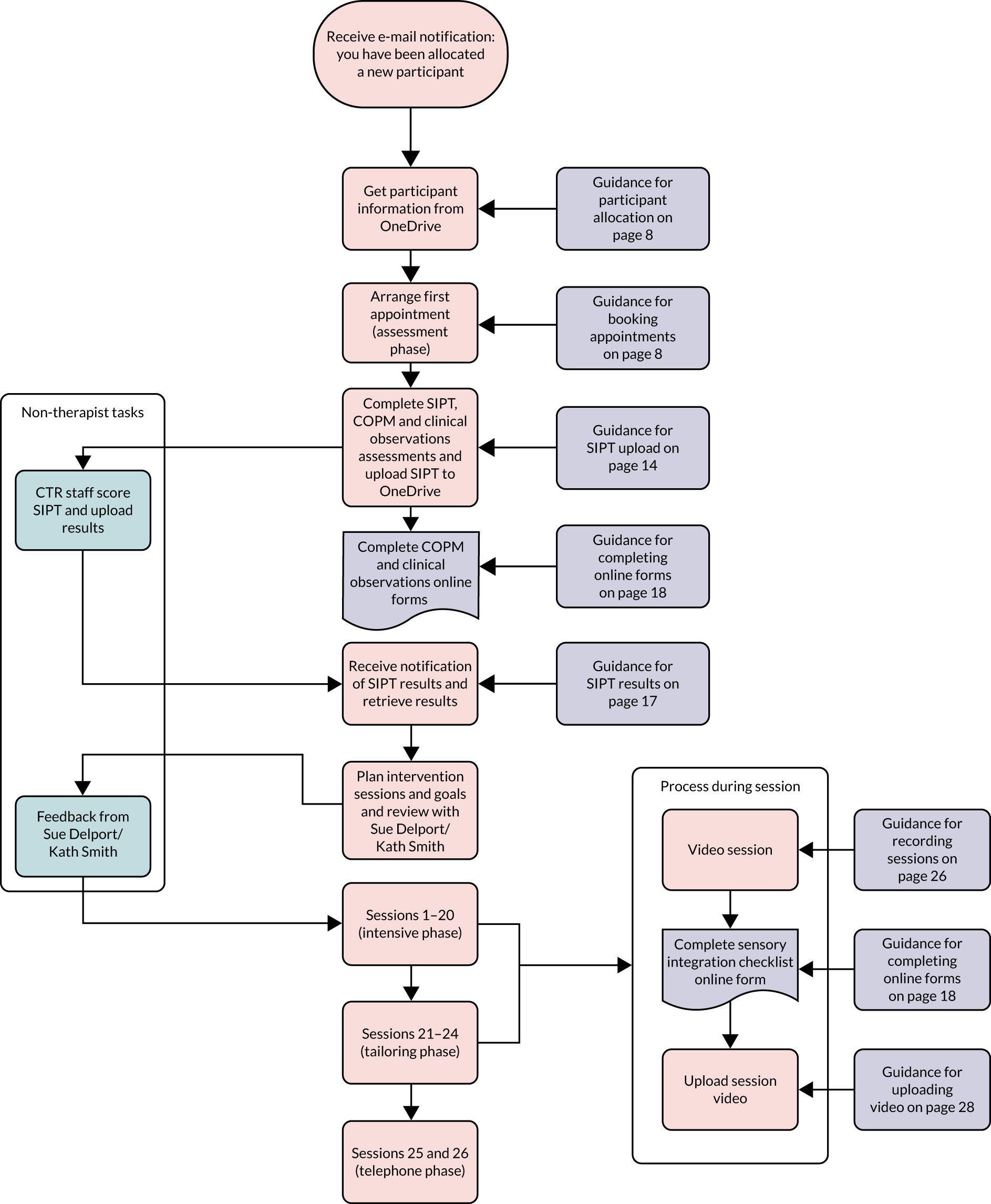

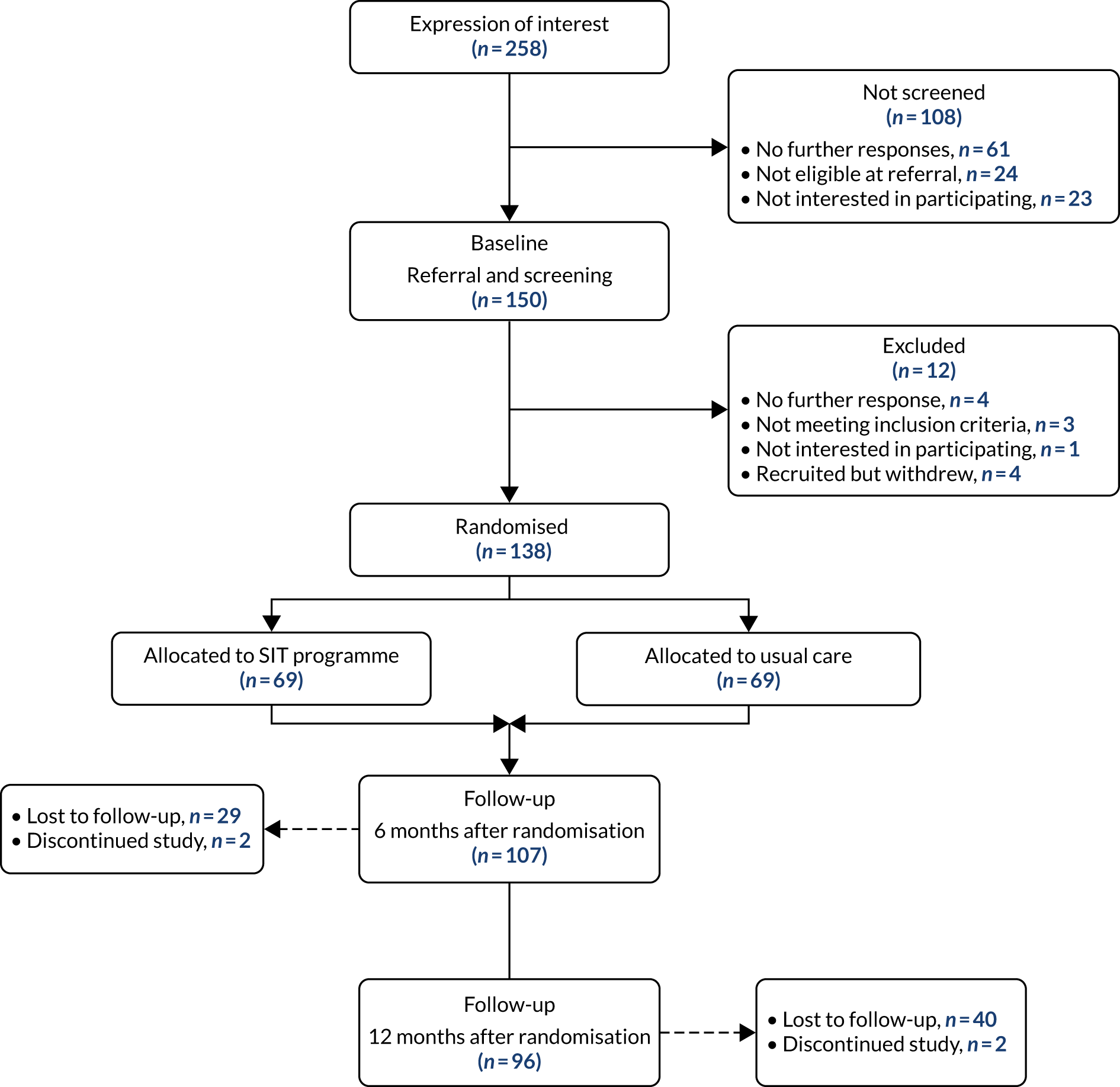

The SenITA trial was an individually randomised two-arm effectiveness trial that compared manualised SIT with usual care for children of primary school age with autism and SPDs. Randomisation was in a 1 : 1 ratio and was minimised by site, severity of SPDs (i.e. probable/definite) and sex of the child (i.e. male/female). The target was to recruit 138 children aged between 4 and 11 years in primary education. Children were recruited from a variety of sources, including CAMHS, OT services, paediatric clinics, support and/or social services and primary schools, and via self-referral. The intervention was delivered in OT clinics that were rated to ensure that they met full structural fidelity criteria for manualised SIT.

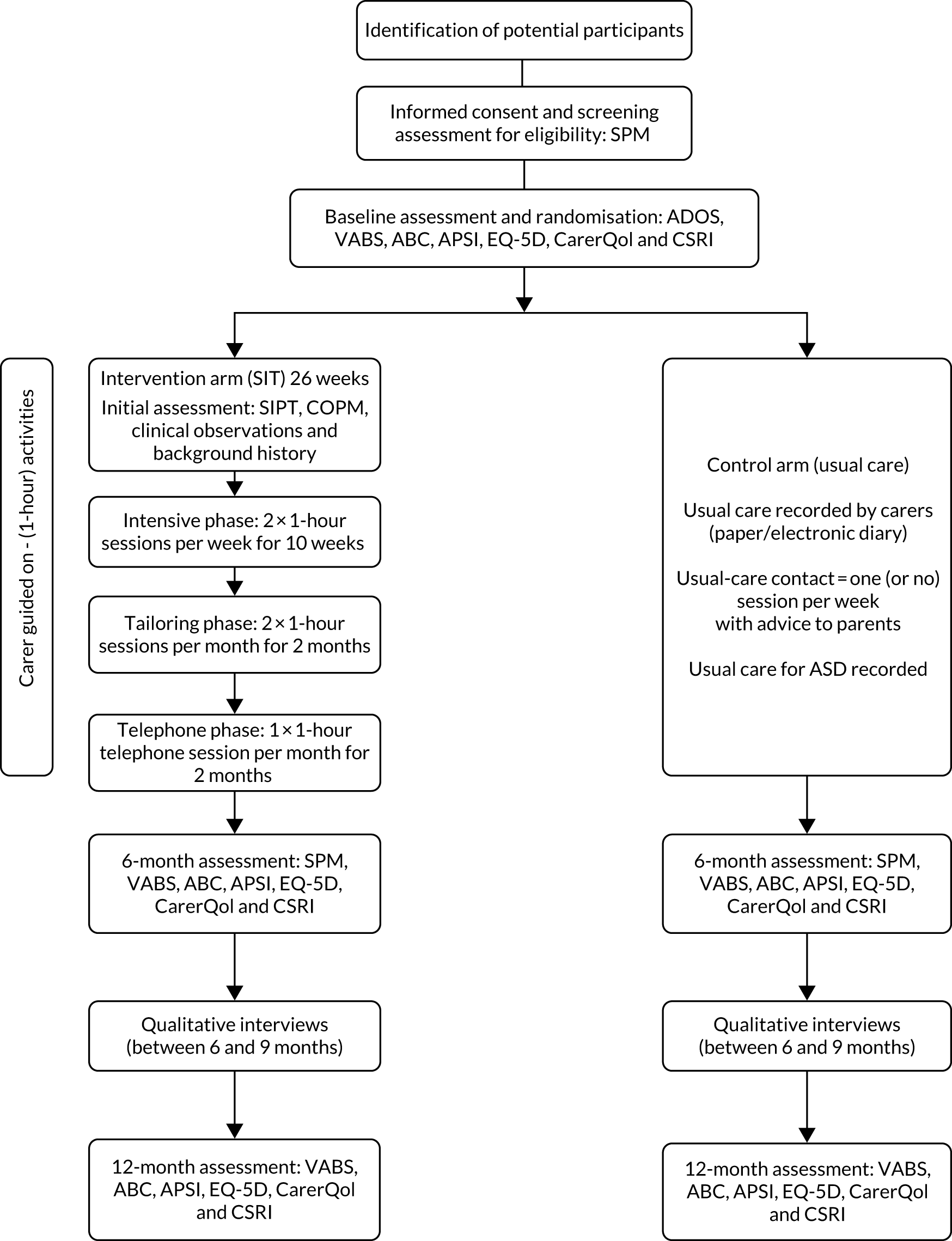

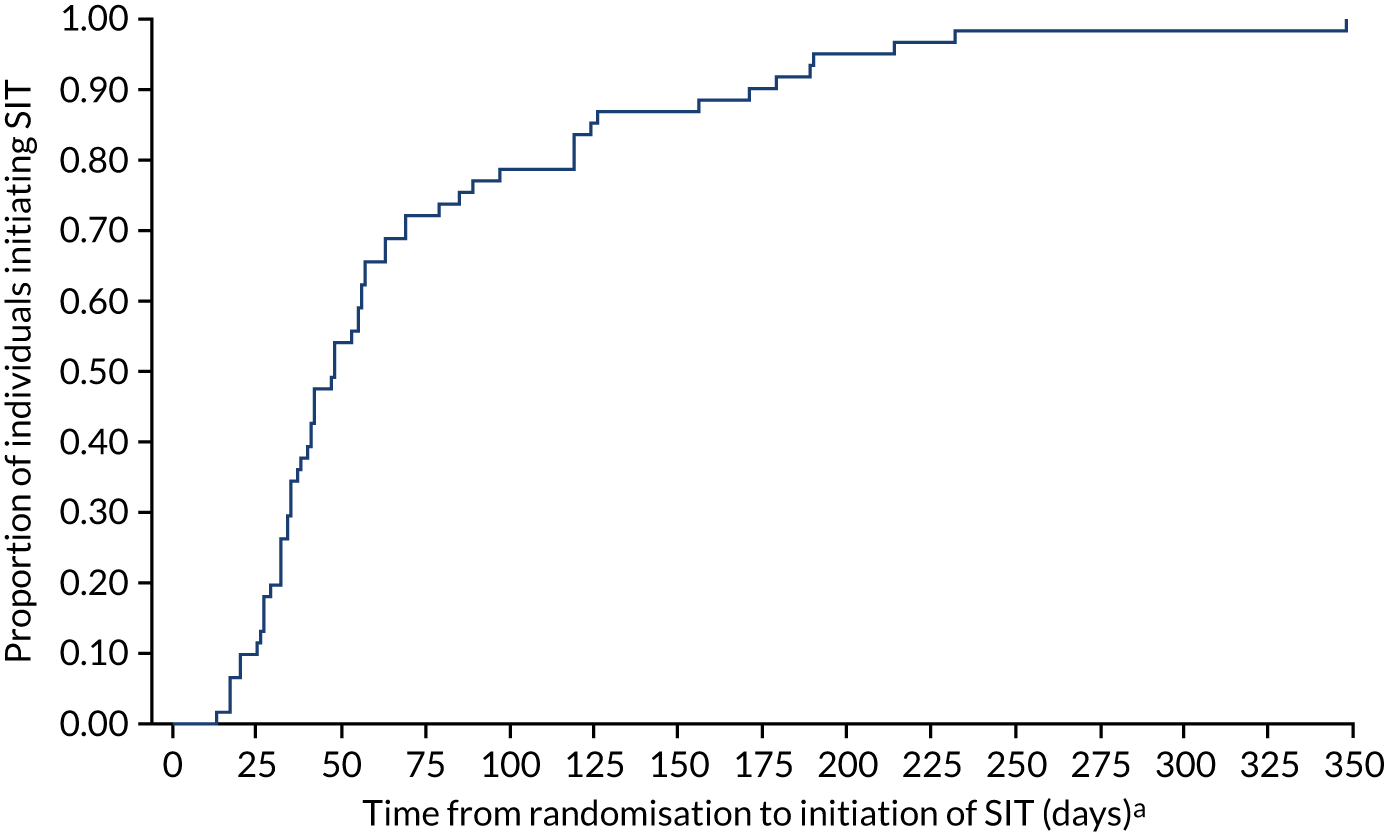

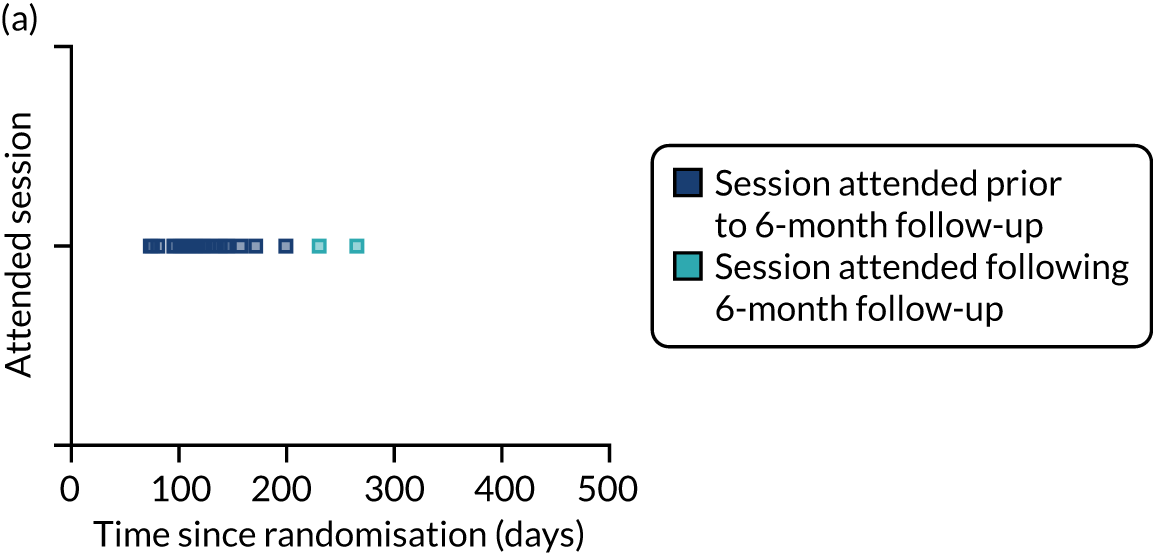

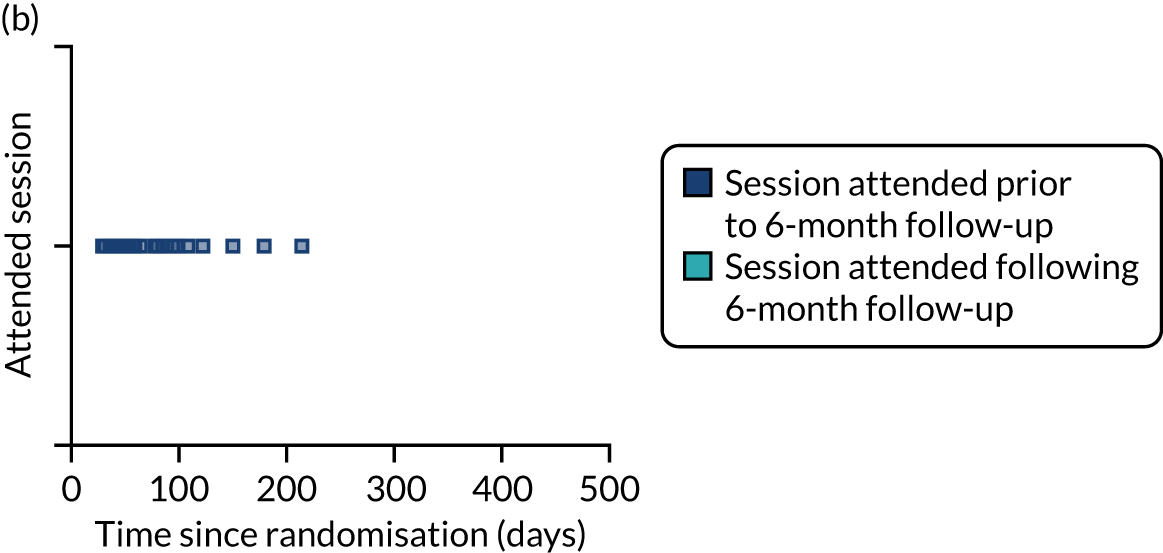

Children allocated to receive the intervention were provided with SIT in 26 1-hour sessions (Figure 2), that is face-to-face sessions twice per week for 10 weeks, tapering to twice per month for 2 months, and a telephone call once per month for 2 months. Where consent was provided, sessions were video-recorded, with a sample of recordings assessed for fidelity of delivery. 23 The comparator was usual care, which was defined as awaiting services or sensory-based intervention not meeting fidelity criteria for SIT (e.g. at least one face-to-face session per week).

FIGURE 2.

The SenITA trial participant flow diagram. APSI, Autism Parenting Stress Index; CarerQol, Carer Quality of Life; CSRI, Client Service Receipt Inventory; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimensions.

The trial also included an internal pilot (see Chapter 4) with progression criteria to assess recruitment and retention rates and whether or not usual care differed from expected provision.

Qualitative work included therapist and carer interviews to explore (1) the support experienced by families (outside the trial, i.e. usual care) and (2) the perceived impact and effectiveness of SIT for children with autism and SPDs. Interview and focus group data were double coded and analysed using a framework approach. 66 Ethics approval was granted by Wales Research Ethics Committee 3.

Objectives

The overarching objective was to answer the following research question: ‘what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SIT for children with autism?’.

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine the impact of SIT on irritability and agitation, as measured by the corresponding subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC). 67

Secondary objectives

Secondary objectives were included to examine:

-

the effectiveness of SIT for additional behavioural difficulties (e.g. hyperactivity/non-compliance, lethargy/social withdrawal, stereotypic behaviour and inappropriate speech)

-

the impact of SIT on adaptive skills, functioning and socialisation

-

sensory processing scores post intervention (i.e. at 6 months) as a potential mediator of any association observed between SIT and the primary outcome at 12 months

-

age, severity of SPDs, adaptive behaviour, socialisation and comorbid conditions as potential moderators of any association between SIT and irritability/agitation, adaptive functioning (child) and carer stress

-

the impact of the intervention on carer stress and quality of life

-

cost-effectiveness (including direct intervention costs, costs of health, social care and education services, carer expenses and lost productivity costs)

-

fidelity, recruitment, acceptability, adherence, adverse effects and contamination in a process evaluation conducted alongside the main trial.

Site selection

Secondary care NHS and private OT treatment settings (where NHS capacity was insufficient to support the trial or no appropriate NHS treatment setting was available) across South Wales and South England were included as research sites. Sites evidenced that they met structural fidelity criteria for intervention delivery.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Participants were eligible to take part if they:

-

had a diagnosis of autism (as documented on medical and/or educational records) or had probable or likely autism (defined as undergoing assessment within the local autism pathway)

-

were aged 4–11 years at the start of the trial

-

planned to remain in mainstream primary education until the primary outcome time point (i.e. 6 months post randomisation)

-

had definite or probable SPDs defined as (1) definite dysfunction on at least one sensory dimension (defined as all domains except social participation) and the total score on the SPM44 or (2) at least a probable dysfunction on two or more sensory dimensions and the total score

-

provided carer consent/child assent.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded if they were:

-

currently undergoing or had previously undergone SIT

-

currently undergoing applied behaviour analysis therapy.

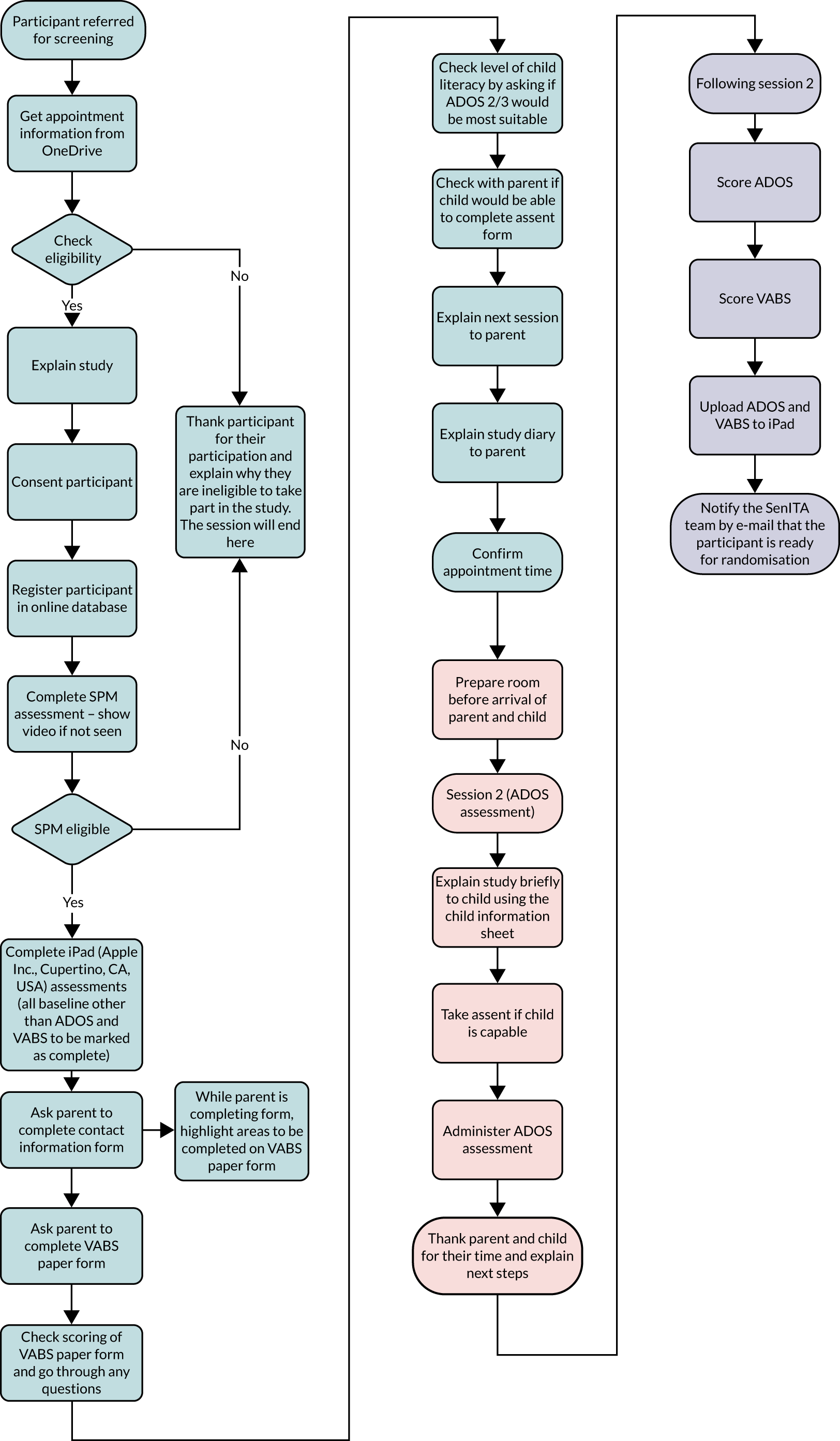

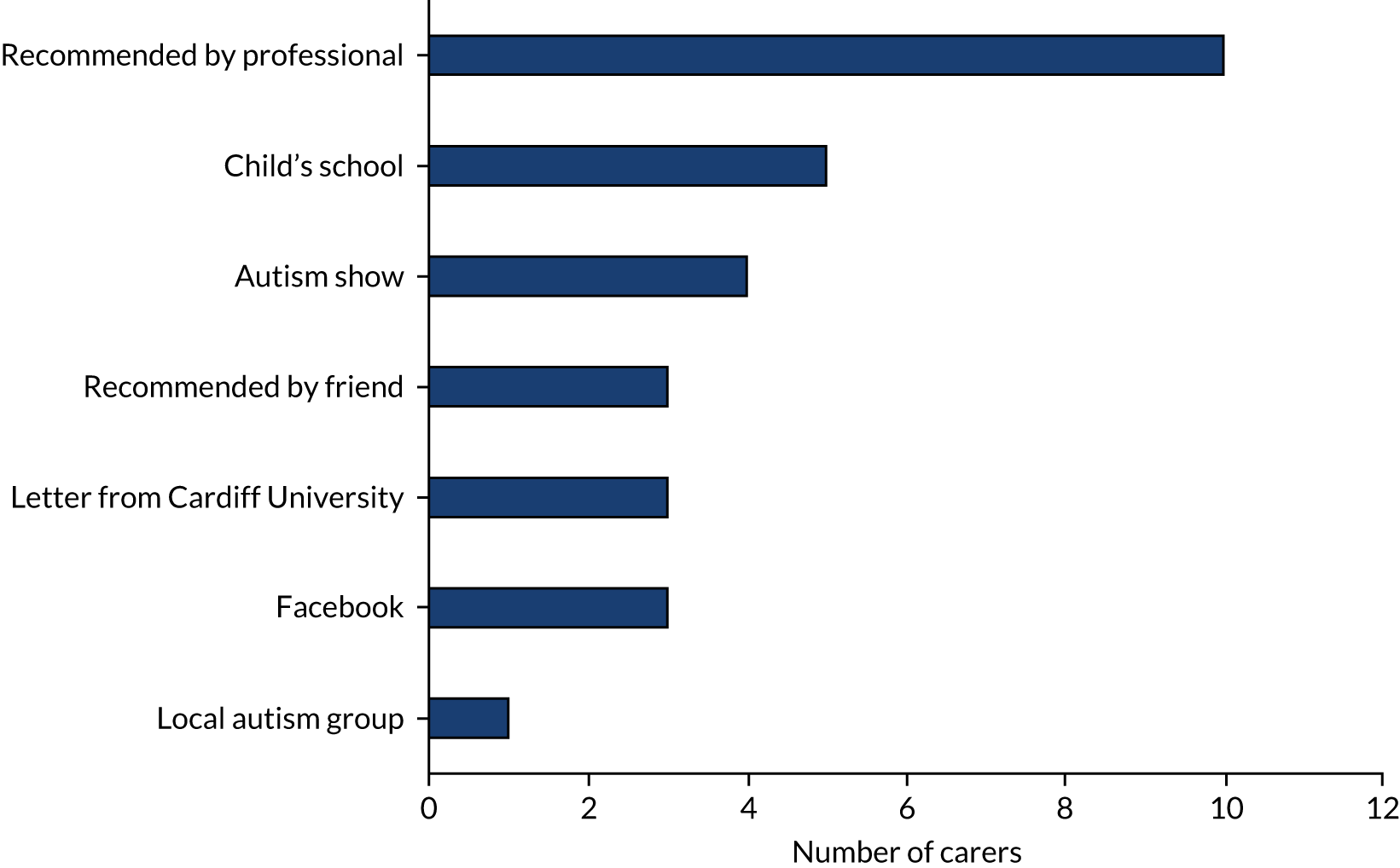

Recruitment process

Children were recruited from CAMHS, paediatrics, OT, schools and support or social services. Services sent carers of children referred into their service a letter informing them about the trial, as well as a participant information sheet (PIS) and details of how to express an interest in taking part. Details of the study were also posted on relevant websites (e.g. related charities’ websites) and via social media. A trial-specific website [URL: http://senitastudy.weebly.com (accessed 7 April 2022)] was also created as a place where individuals could get more information on the trial and could download information sheets. Carers were also able to self-refer into the study.

Informed consent

It was likely that potentially eligible children could have a range of impairments, including a degree of intellectual disability (ID). Provided that all inclusion criteria were met and exclusion criteria were not met, no child was excluded for this reason or for other comorbid conditions. In accordance with good clinical practice (GCP), written informed consent was taken from each child’s carer (i.e. their parent or legal guardian) and assent from children before any trial-related activities were undertaken. In signing the consent form, carers also consented to their participation in the trial (including completion of some outcome measures) and for the study team to contact the child’s school to ask for feedback on the child’s behaviour if necessary. Schools were also asked to complete the Aberrant Behavior Checklist – irritability (ABC-I) at the 6-month time point. Consent could be withdrawn by carers at any time. To complement the carers information sheet, age-appropriate information was presented to the child where appropriate and the views of children capable of expressing an opinion considered. Children deemed to have capacity and who were able to write were asked to sign an age-appropriate assent form.

Consent was sought from carers to video-record intervention sessions to assess fidelity of intervention delivery and for supervision feedback. Carers could also consent to video-recordings being used in future research or for training opportunities. In addition to intervention sessions, ADOS53 assessments were video-recorded to evaluate consistency among ADOS assessors. Refusal of consent to any video-recording did not affect the participants’ eligibility to otherwise take part in the trial. Carers received a copy of any consent form that they signed, with the original filed in the site file and a further copy held with participants’ clinical notes.

Once recruited to the trial, treating therapists remained free to give participants alternative treatment to that specified in the protocol if it was in the child’s best interest; however, the child would remain a participant in the trial for the purpose of follow-up and data analysis according to original treatment allocation. Further informed consent was taken from a small number of carers for participation in qualitative interviews. In compliance with Welsh-language requirements, the PIS, consent form and any other required participant documentation were available in Welsh. However, all outcome measures were available in English only, as none was validated in Welsh.

Risk assessment

A trial risk assessment was completed to assess:

-

known and potential risks and benefits to participants

-

the level of intervention risk compared with standard practice

-

how risks were to be minimised/managed.

The SenITA trial was categorised as low risk (i.e. no higher risk than standard medical care). This categorisation was used to inform the level and focus of monitoring activity undertaken during the trial.

Intervention

Sensory integration therapy

The intervention was delivered in regional clinics by OTs trained in SIT (typically NHS band 7) (see Chapter 5 for a description of the intervention). None of the therapists delivering the intervention delivered therapy to participants in the control arm. Fidelity of intervention delivery was assessed using the ASI intervention fidelity measure (see Chapter 8). 23

Comparator

To define usual care, scoping work in the form of a short survey, interviews and focus groups with therapists and carers was completed before the trial opened to recruitment (see Chapter 2). Carers also recorded usual care using a diary that was specifically designed for the trial. This could be completed either on paper or electronically. Usual care for autism was also recorded more generally, including any contact with NHS services (e.g. SLT, paediatrics and CAMHS). Therapists recorded usual care in accordance with local policy.

Outcomes

Screening and baseline measures

Screening measure

Sensory processing difficulties were assessed at screening using the SPM Home Form. 44 This version of the SPM provides eight standard scores: (1) social participation, (2) vision, (3) hearing, (4) touch, (5) body awareness (proprioception), (6) balance and motion (vestibular function), (7) planning and ideas (praxis), and (8) a total sensory symptoms score. Scores on each of these dimensions are classified as typical, some problems or definite dysfunction. To be eligible, participants’ SPD was defined as either (1) definite dysfunction on at least one sensory dimension (defined as all domains except social participation) and the total score or (2) at least probable dysfunction on two or more sensory dimensions and the total score. Participants scores on this measure were made available to treating SIT therapists to aid planning of intervention delivery.

Baseline-only measure

An ADOS assessment was completed at baseline to characterise the sample according to autism symptoms. Results of the ADOS were not shared with carers or therapists and it was not used as a diagnostic tool to determine eligibility. Members of the study team attended research reliability training for the ADOS and cascaded essential training to other members of the study team undertaking assessments. Reliability and consensus of administration and scoring was assessed as per the ADOS manual. A sample of video-recorded ADOS administrations were also used to facilitate assessment of reliability.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was irritability/agitation at 6 months post randomisation, as measured by the corresponding ABC subscale (i.e. the community version ABC-I with 15 items67,68). The ABC-I was also measured at baseline and at 12 months post randomisation. The primary outcome comparison was based on carer ratings of ABC-I. However, teacher/teaching assistant ratings of ABC-I (assessed at 6 months post randomisation only for intervention and control arms) were also explored.

Secondary outcome measures

Problem behaviours

Other problem behaviours were measured at baseline and at 6 and 12 months using the remaining four ABC subscales: (1) lethargy/social withdrawal (16 items), (2) stereotypic behaviour (seven items), (3) hyperactivity/non-compliance (16 items) and (4) inappropriate speech (four items). Although moderate correlations between subscales are generally observed, researchers are advised not to use a total score, as construct validity is poor. 69 For all ABC subscales, items were rated on four-point Likert scales, ranging from 0 (not at all a problem) to 3 (the problem is severe in degree).

Adaptive behaviours, socialisation and functional change

Adaptive behaviours, socialisation and functional change were assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months using the parent/carer rating version of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, second edition (VABS II). 70 VABS II comprises four main domains: (1) communication (i.e. receptive, expressive and written), (2) daily living skills (i.e. personal, domestic and community), (3) socialisation (i.e. interpersonal relationships, play and leisure time, and coping skills) and (4) motor skills (i.e. gross and fine motor skills). Start points of each Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) subdomain vary depending on the child’s chronological age. Gross and fine motor skills are included in the composite score for younger children only (i.e. children aged 0–6 years).

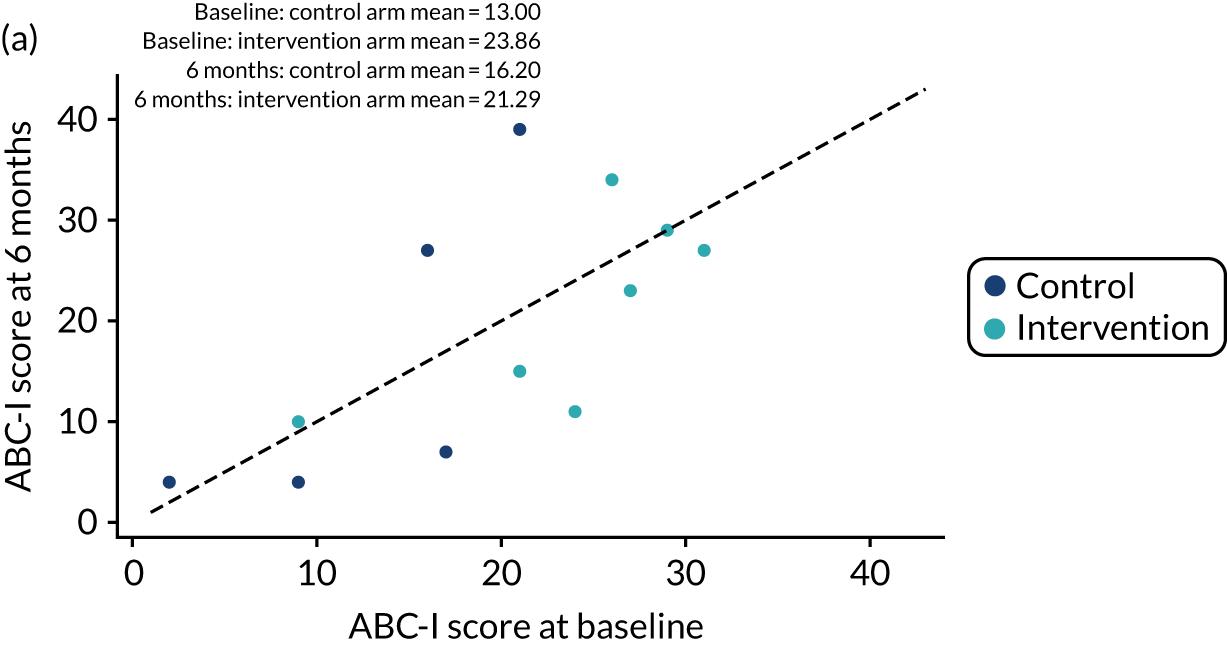

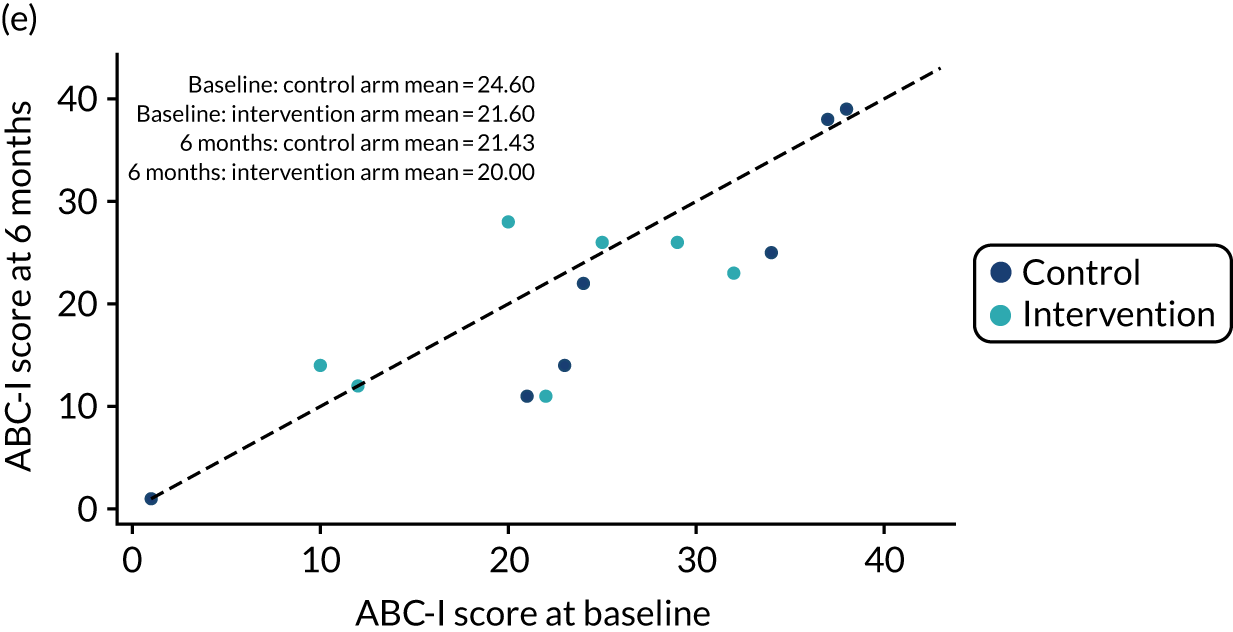

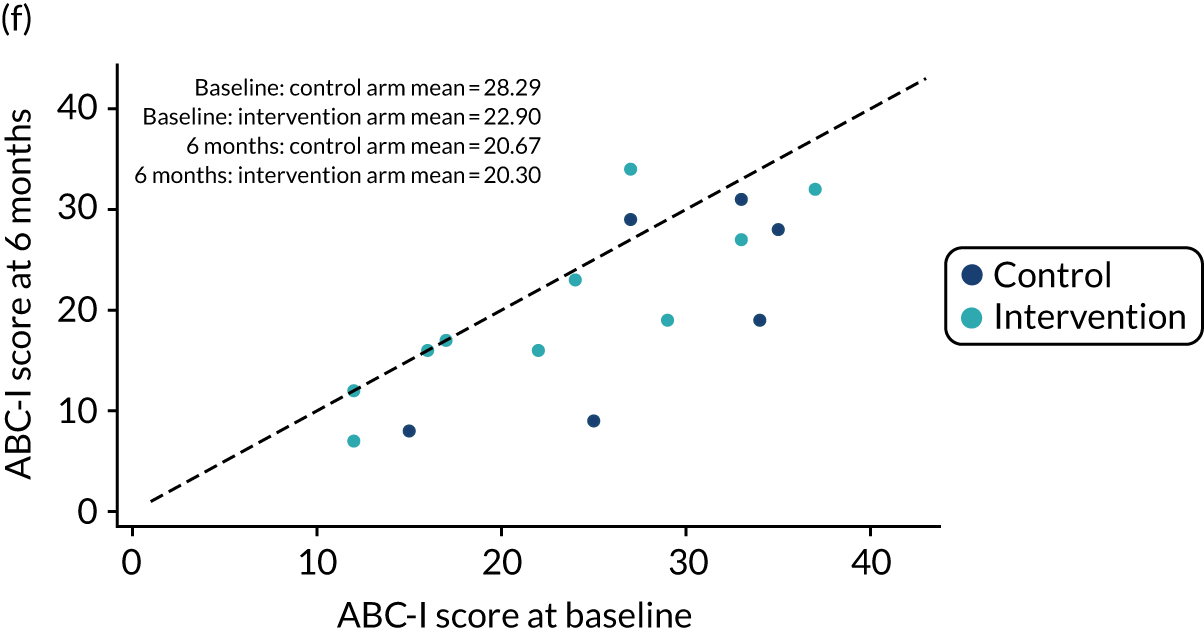

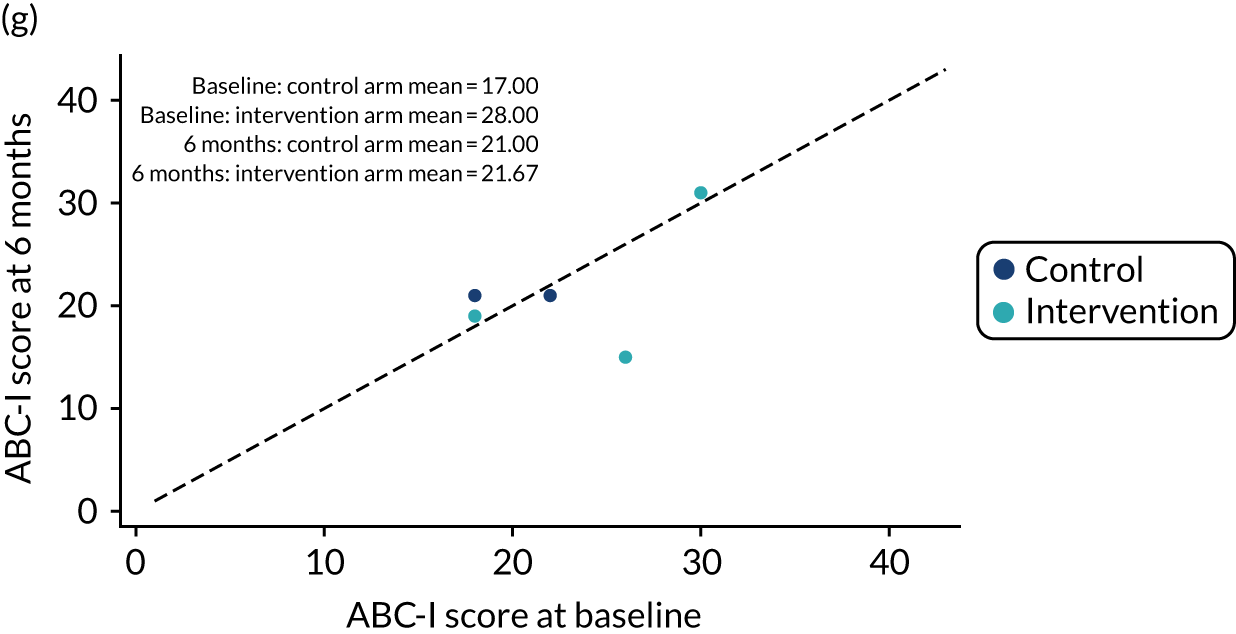

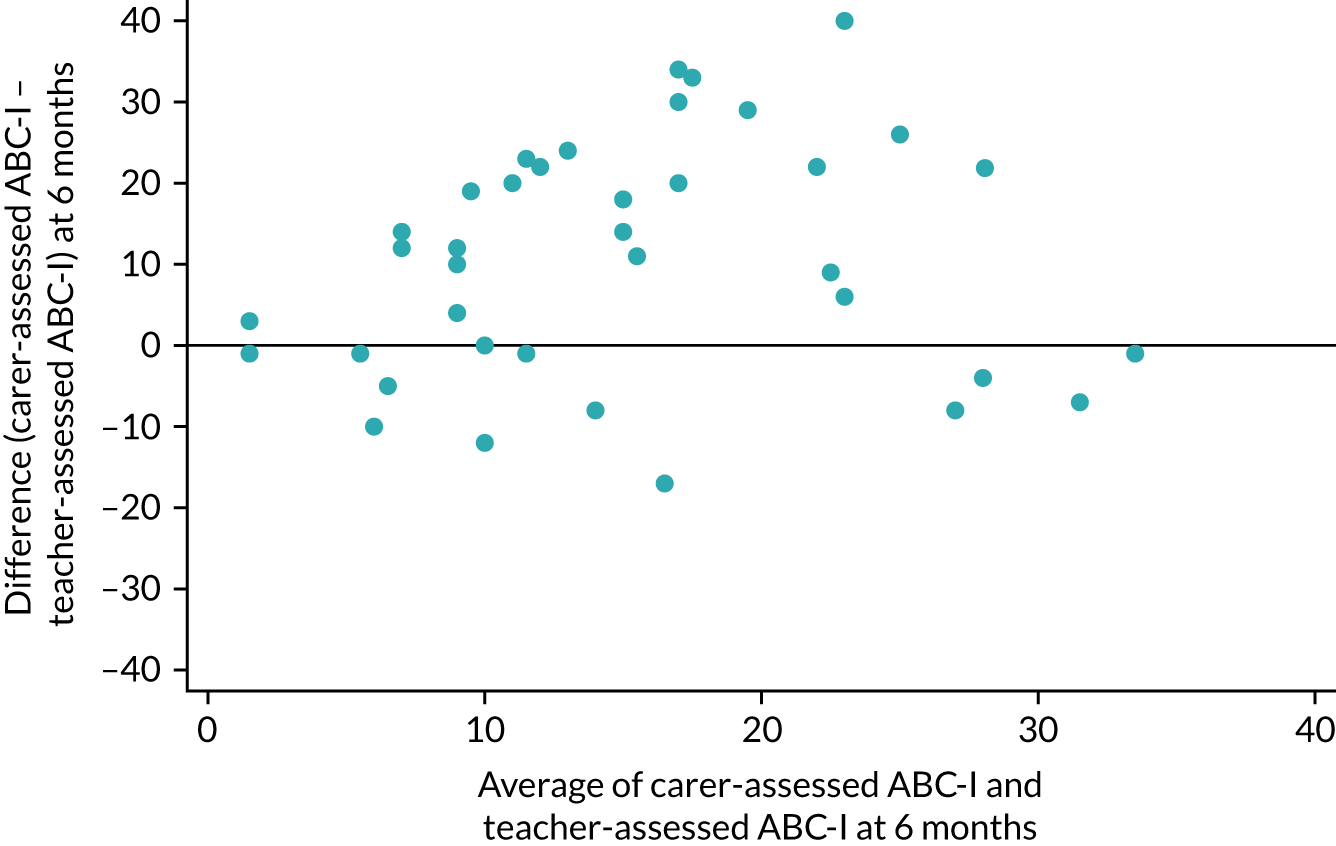

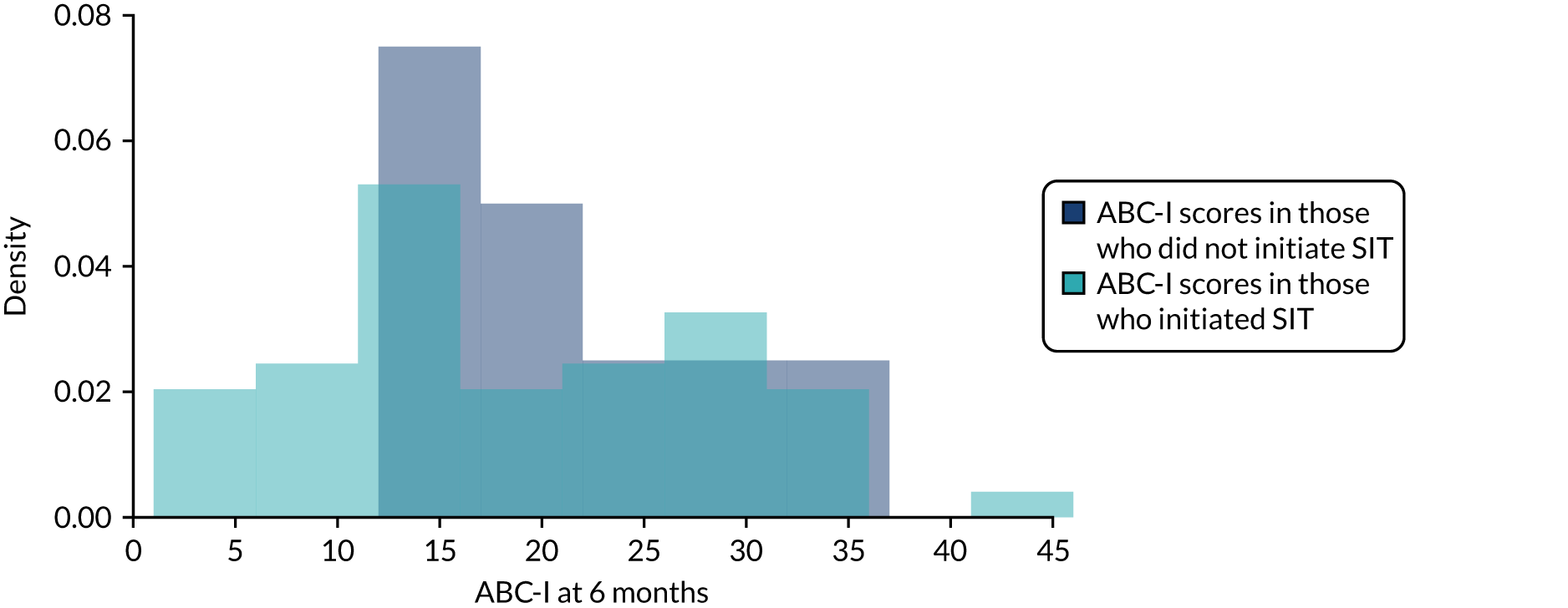

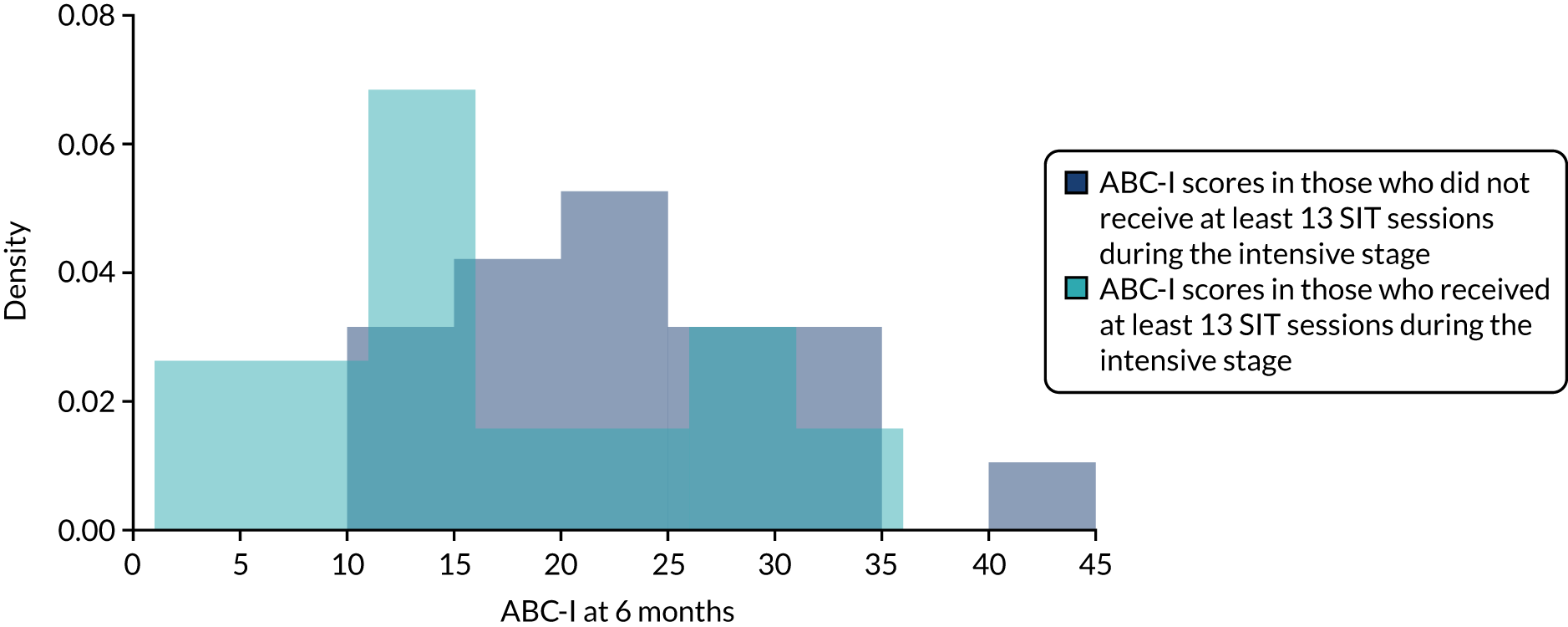

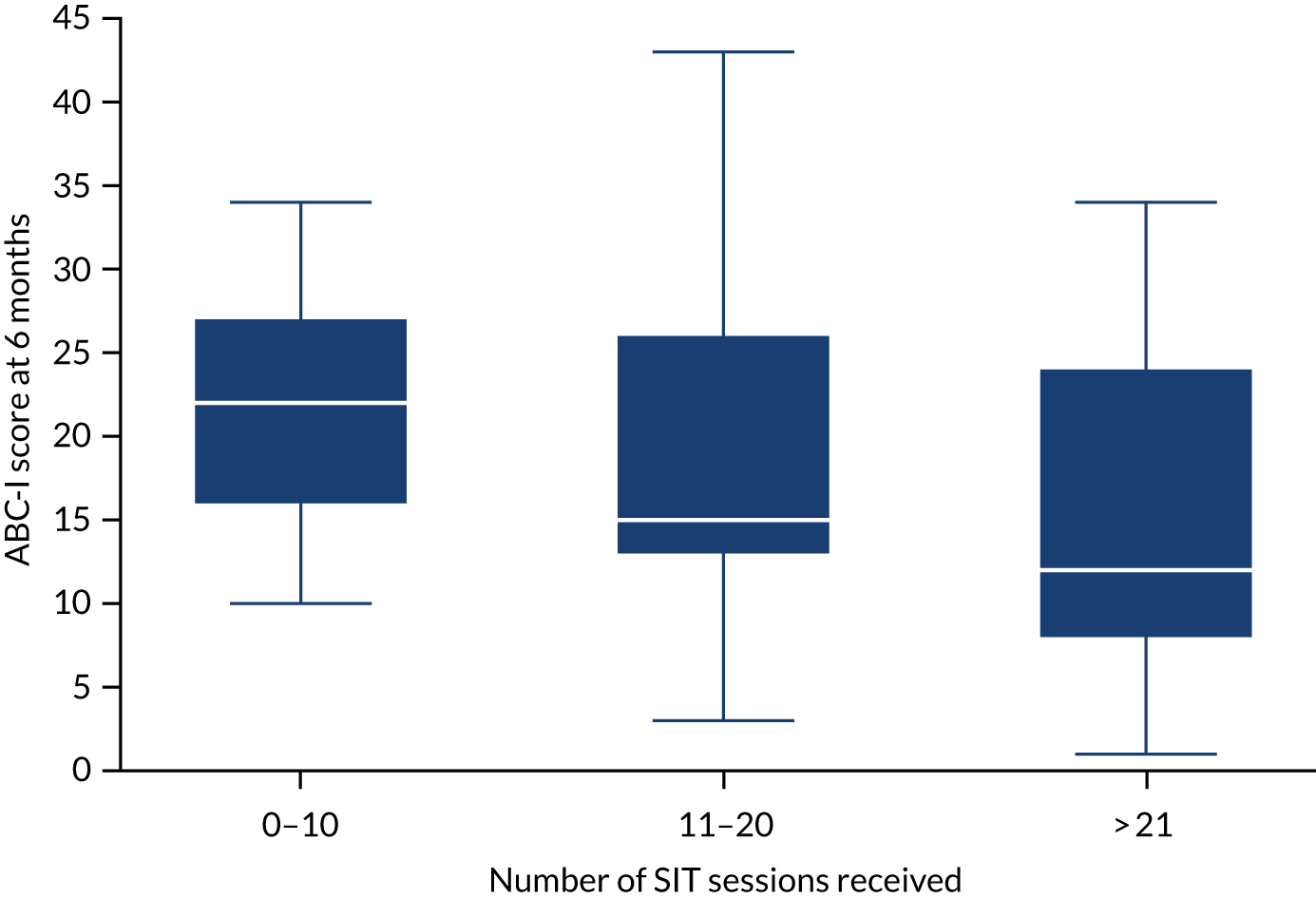

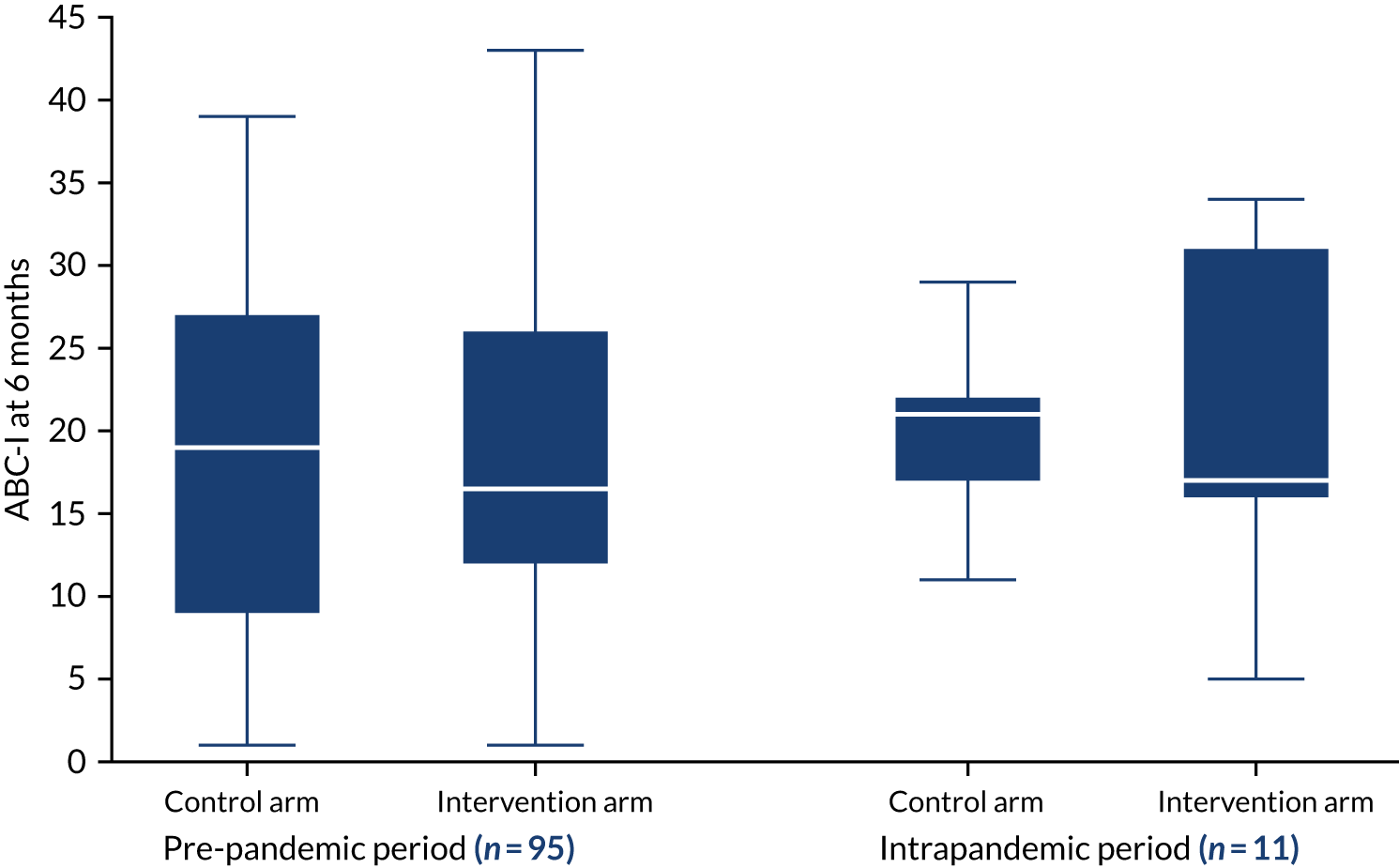

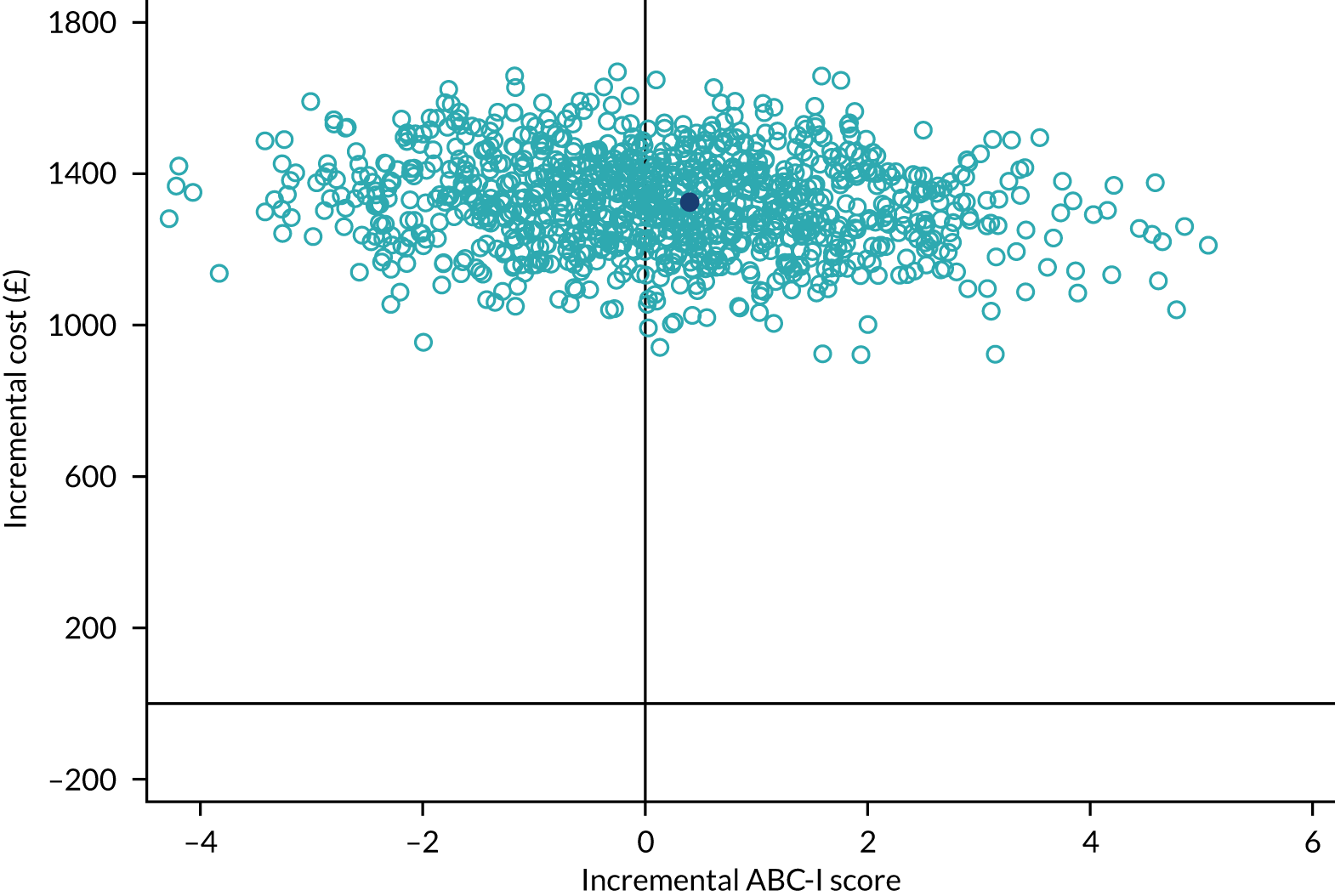

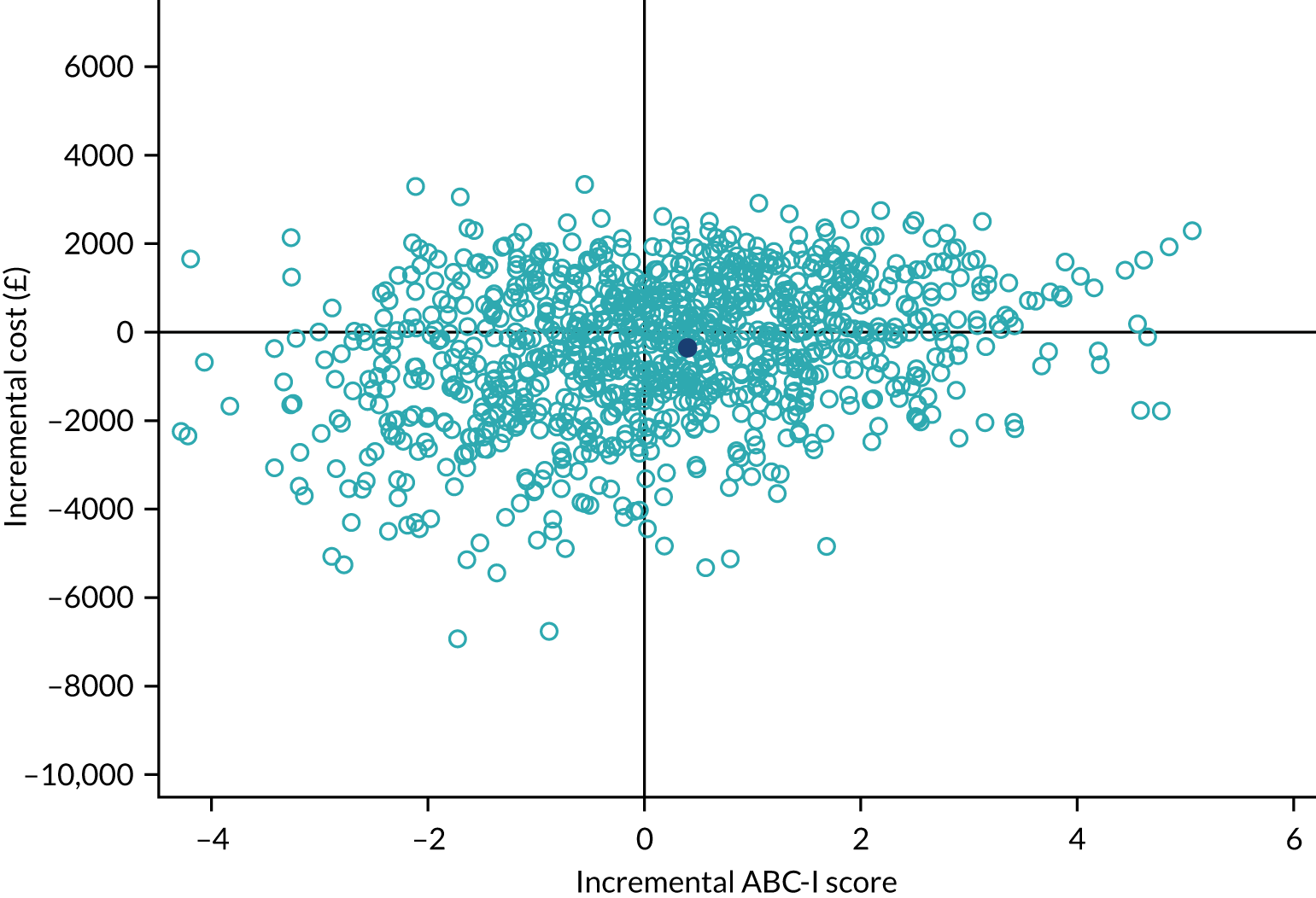

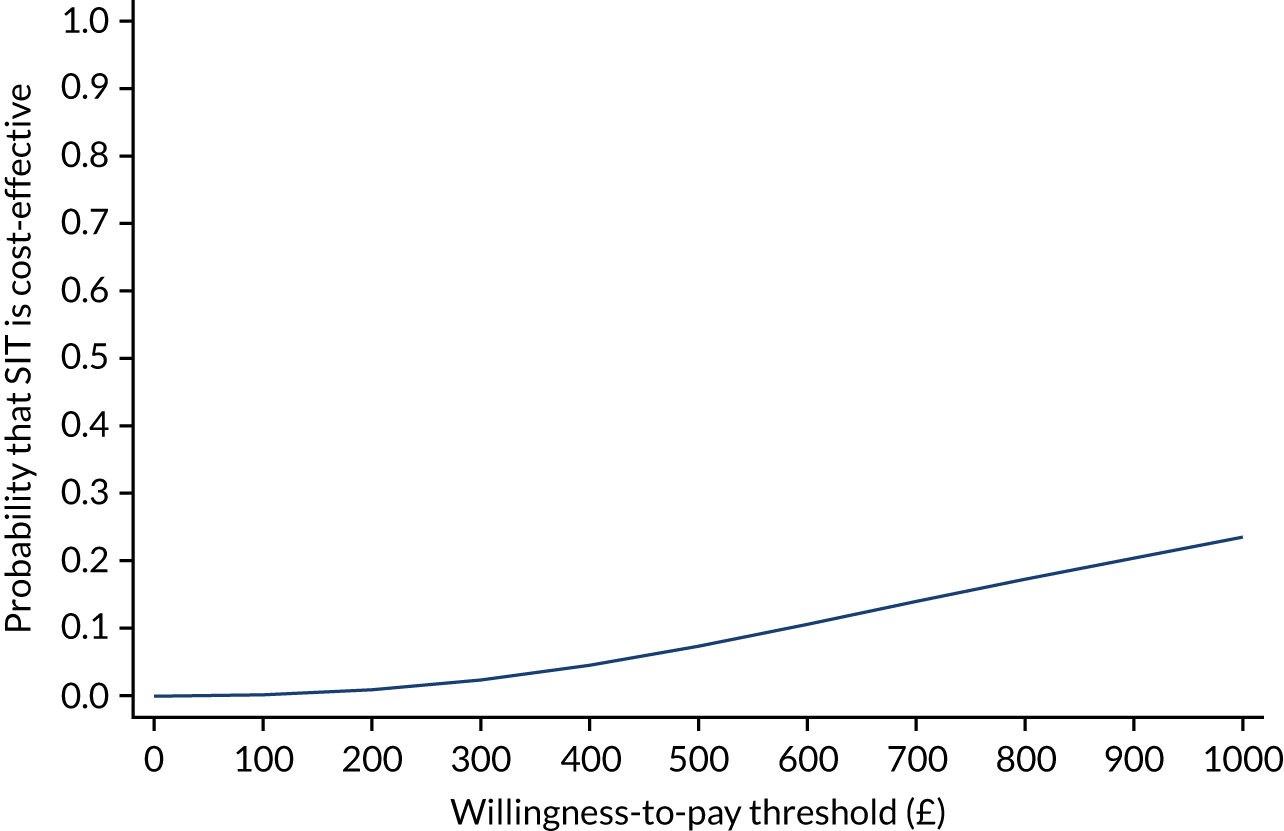

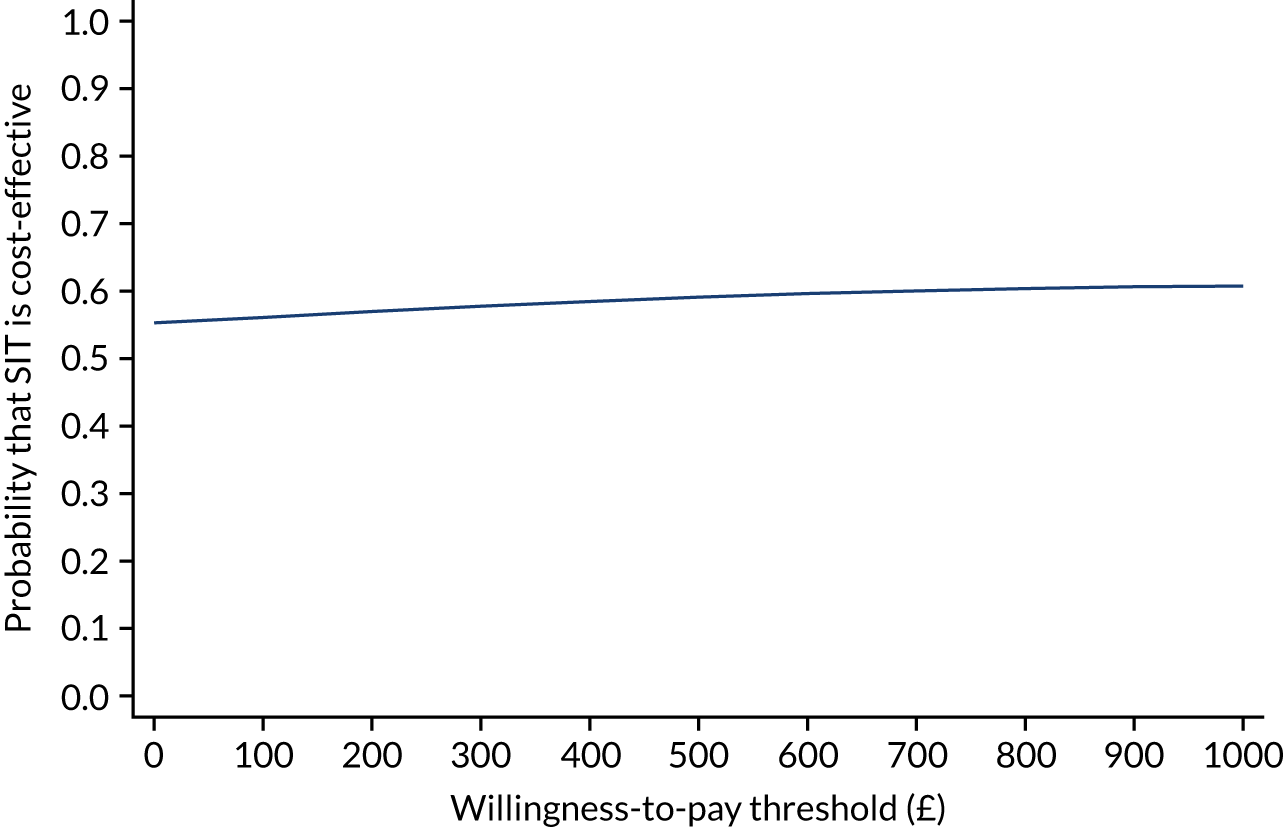

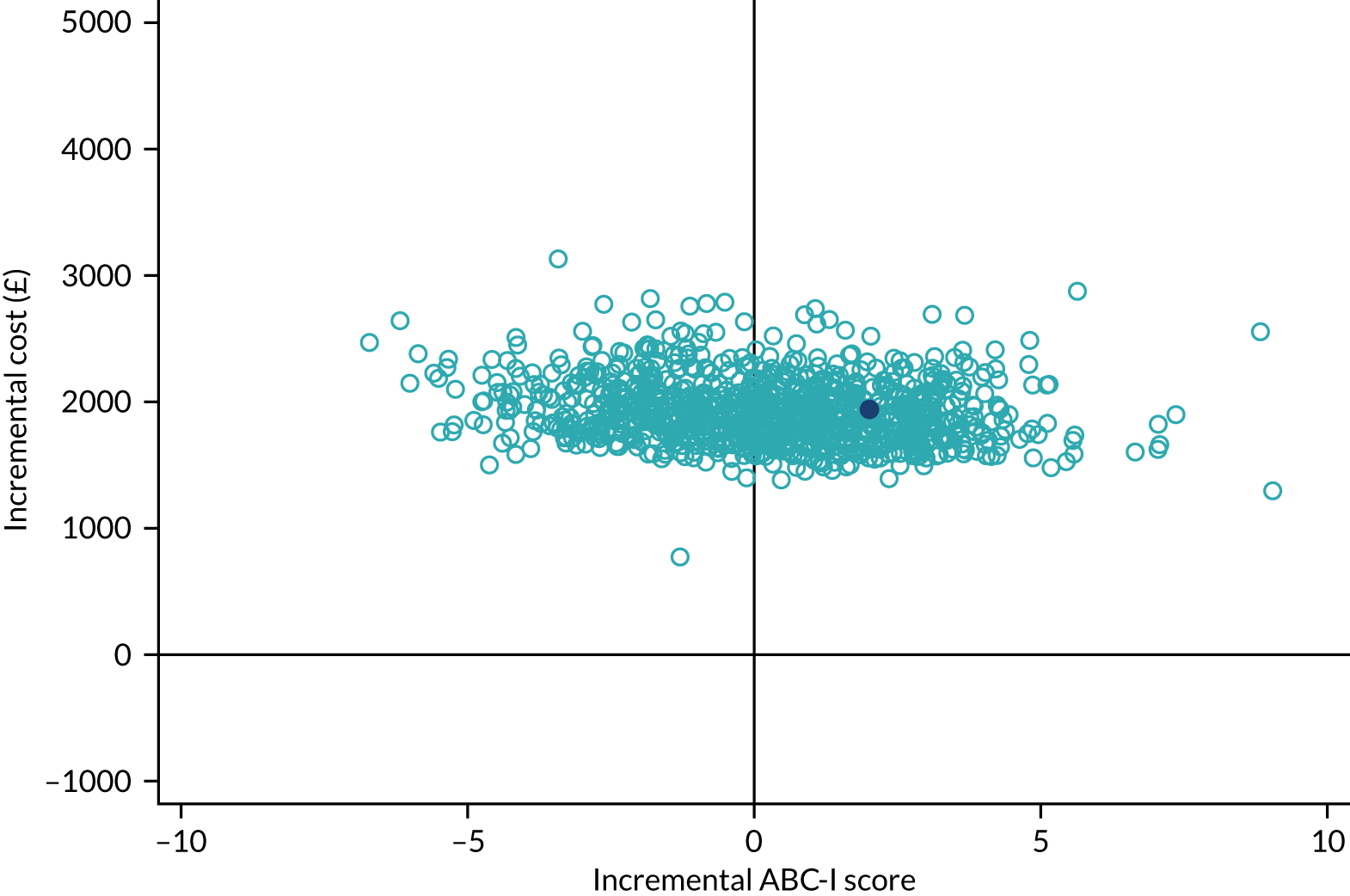

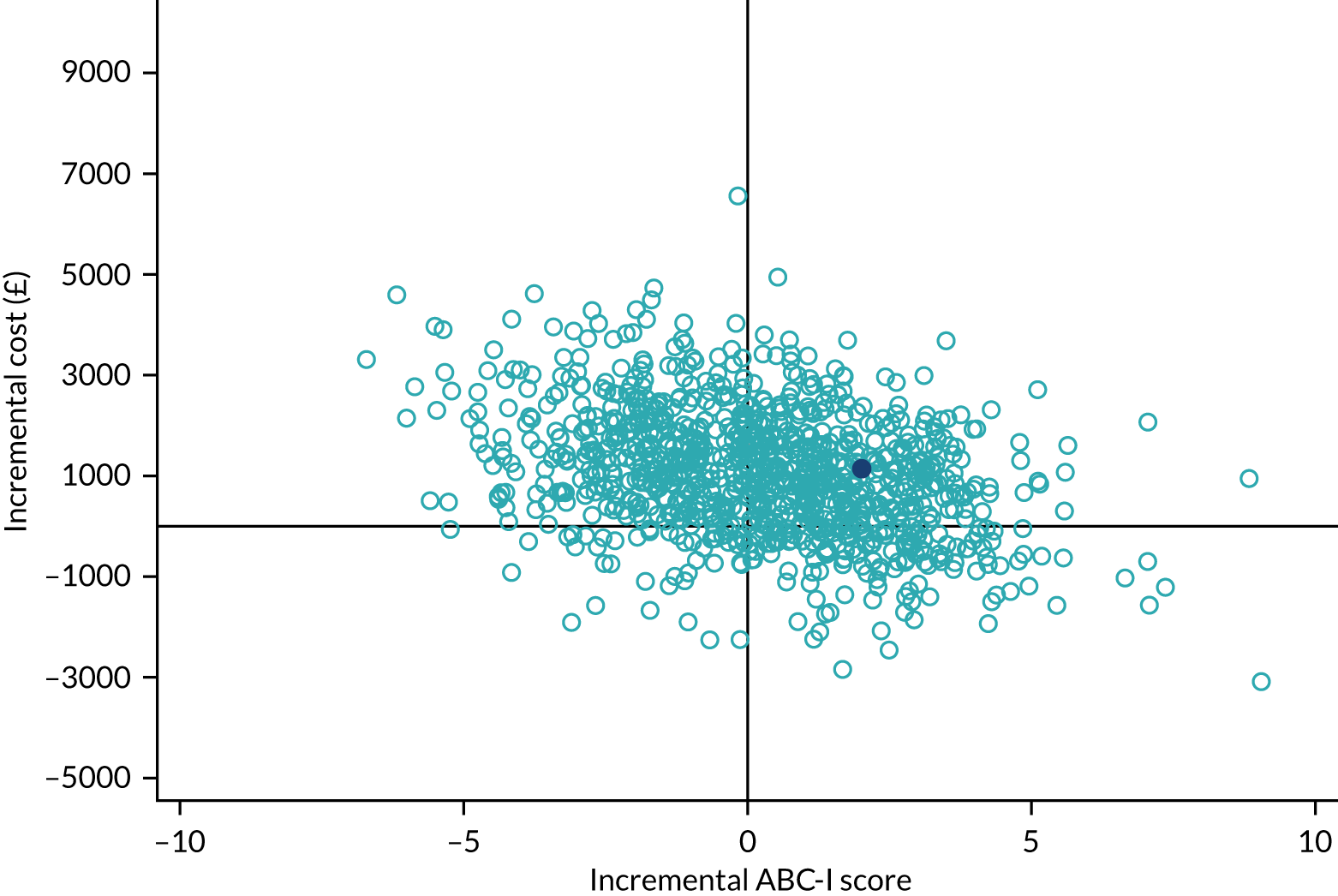

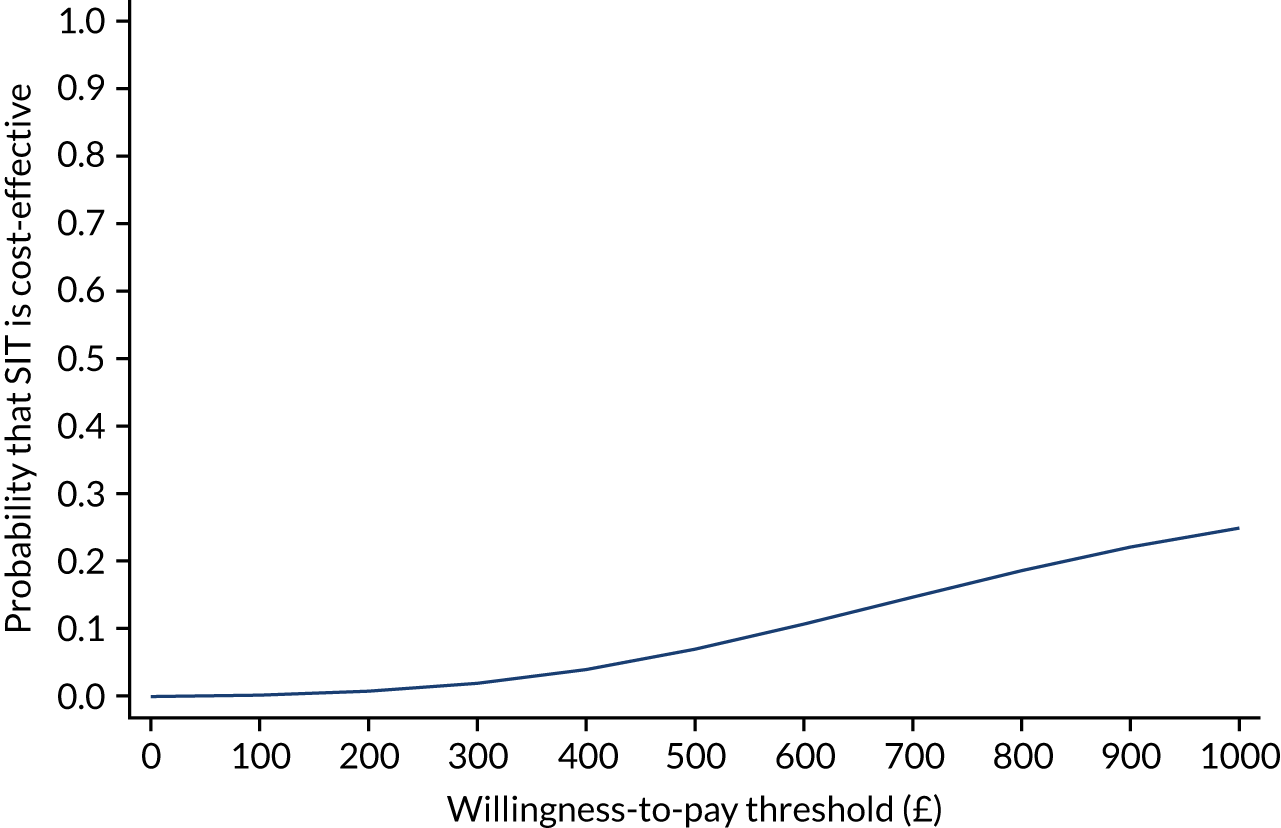

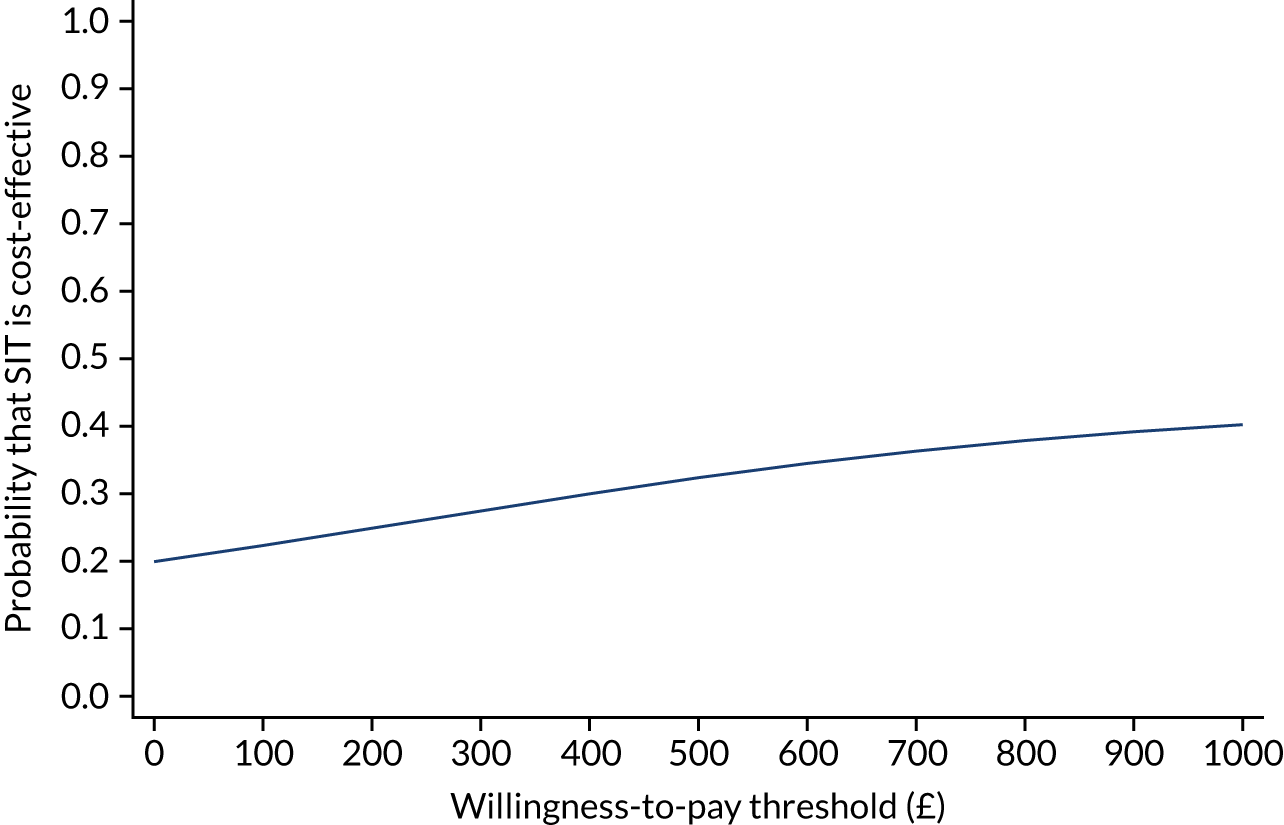

Carer stress