Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 12/186/01. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in June 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Wittmann et al. This work was produced by Wittmann et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Wittmann et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction/background

Hand eczema (HE) is one of the most common skin disorders and an important cause for morbidity and occupational disability. Estimated prevalence values summarised in a meta-analysis reported by Quaade et al. are 14.5% for the lifetime prevalence, 9.1% for the 1-year prevalence and 4% for the point prevalence in the general population. 1 Women are more frequently affected than men (1.5–2 times more often). This meta-analysis also showed that around one-third of patients had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD). The proportion of patients who develop severe chronic hand eczema (CHE) is estimated to be 5–7% of all patients with HE. 2,3 HE has a strong tendency to become a chronic condition, and epidemiology data have clearly shown that the longer it exists, the more difficult it becomes to treat. 4 Of note, a delay in medical attention to HE has been highlighted. 5

The impact on daily life of sufferers is considerable. 6–8 Due to the hands being constantly in use and being so important for our functioning in daily life, impairment of their use due to pain, losing of grip, loss of tactile properties or avoidance of showing the hands due to embarrassing symptoms has a significant impact – much more so than eczema symptoms on other parts of the body. The psychosocial burden of HE has been highlighted recently, whereby patients with HE have a greater level of anxiety and depression compared with a control group of hospital employees. 9 Ninety-six per cent of people with HE reported impairment of their social life due to HE. 10 Moreover, patients present with intensely itchy lesions on their hands, which can be red, scaly or vesicular, swollen, and often show cracks and splits, which are painful. 2,11 Around 27% of HE patients also experience symptoms on the feet, which can make walking painful. 12

The disease burden for the patient can be considerable, impairing functioning in daily life and at work. As a consequence the economic burden has been estimated to include the following for CHE (thus also including less severe forms) across several countries: on average, total annual costs of illness ranged from EUR 1311 to EUR 9792, and more severe HE and occupational HE resulted in higher costs. 13,14 Moreover, 57% of patients take sick leave and up to 25% reported job loss/job change due to CHE. 15

Hand eczema is a heterogeneous disease that presents with various subtypes. 14,16,17 A variety of underlying genetic and lifestyle-related causes can contribute to this complex disease. 16,18 The multiple underlying trigger factors (mechanical, psychological stress, hormonal influences, irritant exposure, etc.), different morphological presentations and co-morbidities cause difficulties in classifying disease subentities. As a consequence, there is no generally accepted disease classification. Clinical experts distinguish between different causes of HE, including atopic diathesis, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (contact allergy) and irritant dermatitis. With regard to morphology, HE is referred to as dyshidrotic, pompholyx, hyperkeratotic, rhagadiform, pulpitis sicca/fingertip dermatitis, tylotic, psoriasiform or combinations of these morphologies. However, morphology alone has not proven sufficient to choose the best-suited therapeutic approach. 19 Of note, while nail involvement has been extensively described, classified and assessed in psoriasis,20 a clear and comprehensive assessment tool for the extent and morphology of eczema-associated nail changes is lacking. There is also a shortcoming in the recognition and description of eczema lesions in skin of colour. It has become apparent that due to difficulties in assessing erythema in darker skin types, eczema severity may be under-recognised in this patient group. In line with this, potential different therapeutic responses across different ethnicities have not been investigated. As a range of assessment tools for HE severity and photographs have been performed for participants with skin of colour, the ALPHA trial provides an opportunity to further explore HE assessment challenges in this subgroup of patients.

Risk and trigger factors

A number of factors have been described that influence the onset or flare-up of HE. As mentioned, HE in the general population affects women about twice as often as men. 21–23 AD and/or childhood eczema, which is almost always associated with dry skin and skin barrier impairment, seems to be one of the most important risk factors. 24,25 Exposure to wet work, frequent hand washing and irritants are recognised relevant trigger factors. A high HE incidence rate is thus associated with contact allergy, AD, wet work and also female sex. 23

Important genetic factors are those linked to AD, and the most recognised ones are loss of function (LOF) mutations in the filaggrin gene. Filaggrin is an important constituent of the skin barrier. 26 Filaggrin significantly contributes to water retention in the skin, while LOF mutations result in increased transepidermal water loss. There are four common filaggrin mutations prevalent among Europeans and more frequently found in patients with AD. 27–29 Deletions in the late cornified envelope (LCE) genes LCE3B and LCE3C have been described to be associated with CHE with allergic contact dermatitis. 30 The LCE complex is also a key component of the skin barrier.

To date, it is not fully elucidated whether the association of HE with AD is primarily due to filaggrin and skin barrier changes or due to atopy resulting in a type 2 shift in the immune response. The ALPHA trial collected information on LOF filaggrin mutation, LCE variants and atopy status.

Lifestyle factors discussed to a great extent include tobacco smoking. However, despite a wealth of available observational, retrospective studies, the data are still not clear, and overall the association seems weak; it may be stronger for foot eczema. 31–37 No study has found an association between alcohol consumption and HE. 35 Predictive factors for HE persistence include (1) age of onset before 20 years, (2) positive history of childhood eczema (3) and moderate to severe extension of HE – thus, HE severity. 23

As there is no clear subclassification of HE, there is also a lack of clear treatment guidelines. 38 Mostly, CHE therapy is delivered in escalating steps. When patient education, allergen/irritant avoidance and topical treatment are not sufficient to control the disease, ultraviolet (UV) therapy or systemic immune-modifying drugs are used. 17,39 Alitretinoin (AL) is licensed for severe CHE unresponsive to treatment with potent topical corticosteroids. However, currently available clinical evidence for the treatment of CHE is not compelling enough to guide clinical practice. 39,40 The lack of clear evidence-based data has been outlined by different national and international expert groups as well as by a recent Cochrane review. 38,41 Given the high socioeconomic impact of the disease, there is a pressing need for comparative studies on available first-line treatments and on the long-term outcome of currently used therapies. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) has recognised this need and launched a commissioned call aiming to compare AL with other treatment options. Our choice of comparator for AL was based on published clinical trials and on feedback from UK dermatologists and the United Kingdom Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (UKDCTN). 41 As research and audit data on treatment choices for CHE were unavailable, we performed a survey among 194 UK dermatologists; the most frequent first-choice approaches for CHE were 8-methoxypsoralen combined with ultraviolet A (PUVA), oral steroids and AL. 42 When asked which strategy was thought to be most efficient for long-term outcome, 43% of clinicians reported AL, 30% PUVA and a further 20% of clinicians indicated that they did not know.

The following immunosuppressive treatments have been described as being used for the treatment of CHE: azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, ciclosporin A and systemic corticosteroids. Recently described drugs include the interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13R blocker dupilumab and Jak inhibitors including baricitinib and upadicitinib, all of which are licensed for the treatment of AD. 43,44 Clinical trials of topical Jak inhibitors are being conducted, and phase IIb results for delgocitinib have recently been reported. 45

The current literature suggests that dyshidrotic/vesicular subtypes with atopic diathesis respond preferentially to immunosuppressants and dupilumab, whereas hyperkeratotic rhagadiform subtypes may show a better response pattern to AL. However, there is insufficient clarity on which subtypes respond to which therapy approaches.

A generally unfavourable therapeutic response is believed to be linked to smoking, long disease duration and barrier defects such as LOF mutations affecting filaggrin. 5,11,39 There are two important shortcomings affecting clinical trials in CHE. Firstly, there is no consensus regarding the best outcome measures of extent and severity of the disease, disease impact on quality of life (QoL), or assessment of comorbidities, and there is a lack of measures to highlight impairment in functional use of the hands. Numerous disease severity assessments have been proposed, including photoguide, Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA), Hand Eczema Severity Index (HECSI), Hand Eczema Extent Score (HEES) and modified Total Lesion Symptom Score (mTLSS). 46,47 Although none has been fully recognised as ‘gold standard’ yet, the HECSI is predominantly used in clinical studies and has advantages regarding accurate assessment of morphology features and extent. 48,49 ALPHA has used the HECSI as the primary outcome but included other outcome measures frequently used in previous trials. The second shortcoming relates to the short duration of clinical trials, most of which have been limited to 12 weeks. This indeed seems inadequate for a disease characterised by its tendency for chronicity and which often has a long disease duration.

Summary

There is a lack of controlled clinical trials that directly compare treatments or demonstrate effectiveness under daily practice conditions. Moreover, the lack of clear evidence-based data has been outlined by a number of national and international expert groups. 38,41 Given the high socioeconomic impact of the disease, there was a pressing need for comparative studies on available first-line treatments and on long-term outcomes of currently used therapies. Therefore, we conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing AL with Immersion PUVA for patients with severe CHE, who were followed up for a maximum period of 52 weeks to understand the longer-term impact of these treatments as first-line therapies.

Chapter 2 Methods

Aims and objectives

The primary aim was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of AL compared with 8-methoxypsoralen combined with UV-A (Immersion PUVA) in conjunction with concomitant topical corticosteroids, emollients and patient education as the first-line treatment in patients with severe CHE.

Primary trial objective

The primary objective is to compare AL and Immersion PUVA in conjunction with concomitant topical corticosteroids, emollients and patient education as first-line therapy in terms of disease activity at 12 weeks post planned start of treatment.

Secondary objectives

-

To compare AL and Immersion PUVA in terms of disease activity over time with a focus on disease activity at 24 and 52 weeks post planned start of treatment.

-

To compare AL and Immersion PUVA in terms of time to relapse.

-

To compare AL and Immersion PUVA in terms of QoL and patient benefit over the 52 weeks’ duration post planned start of treatment.

-

To determine the cost-effectiveness of AL compared with Immersion PUVA at week 12, 52 (short term) and over 10 years (long term).

-

To determine the educational need for individual patients.

-

To compare AL and Immersion PUVA in terms of safety.

Exploratory objectives

-

To compare scoring systems HECSI, mTLSS, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and PGA used to monitor response to treatment in patients with severe CHE.

-

To evaluate whether response to first-line treatment is affected by the following parameters:

-

duration of disease

-

clinical phenotype

-

disease severity

-

presence of atopy

-

filaggrin LOF mutation and other potential emerging mutations affecting skin barrier or response to Immersion PUVA/AL

-

smoking history

-

body mass index (BMI)

-

foot involvement.

-

-

To collect pilot data on clinical effectiveness of second-line therapies, using HECSI and PGA.

-

To explore treatment responses in HE subgroups defined by molecular inflammatory mediators determined in tape strips or washing solution.

-

To compare AL and Immersion PUVA in terms of time in remission using different definitions of end of remission, including varying the extent of corticosteroid use.

-

To compare AL and Immersion PUVA in terms of assessment of the nails.

-

To explore the use of the photography guide for patients of non-Caucasian ethnicity.

Note that objectives 6 and 7 were added after the trial was funded and are not reported within this monograph, but will be reported in separate publications.

Overview of methods

This chapter outlines the main methods for the trial, including all data collection for the trial and substudy work and the analysis methods for the primary and secondary clinical results, which are detailed in Chapter 3. Analysis methods and results for the main trial health economics are detailed in Chapter 4. The discussion chapter draws the work together in Chapter 5.

Trial design

The trial was a multicentre, Phase III, open, prospective, adaptive, two-arm parallel group RCT, with one planned interim analysis.

Participants were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis to receive either AL at a dose of 30 mg/day (with the option to reduce to 10 mg if participants suffered with headaches and restored to 30 mg dose once headaches ceased) or Immersion PUVA (3 mg/l Meladinine® with UV A, twice weekly) for a 12-week interventional phase. Randomised treatment was given in conjunction with concomitant topical corticosteroids, emollients and patient education. Partial responders in both arms continued their randomised treatment for up to a further 12 weeks. Treatment could be discontinued between 12 and 24 weeks if participants achieved a clear/almost clear assessment (responder) or had a severe assessment (non-responder). All participants stopped treatment by 24 weeks. Participants who relapsed and non-responders continued with ‘standard clinical practice’, as determined by the attending clinical team.

The study protocol for this trial has already been published. 50 Summary details of the methods are given below.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was given by Leeds West Research Ethics Committee [REC reference: 14/YH/1259, Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project ID: 163195]. All trial activity took place according to the ethically approved protocol, principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and Declaration of Helsinki 1996.

Eligibility and informed consent

Patients were screened in secondary care dermatology outpatient, community hospital and General Practice settings. Formal eligibility assessment and recruitment was undertaken in secondary care dermatology outpatient clinics. Patients were eligible if they fulfilled the following criteria:

-

suffering from uncontrolled, severe CHE, defined as the presence of both of the following criteria:

-

PGA score of severe

-

resistance to treatment with potent topical corticosteroids for ≥ 4 weeks prior to the point of eligibility screening

-

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

able to provide written informed consent

-

expected to comply with treatment and protocol schedule.

Patients were excluded if they fulfilled any of the following criteria:

Skin-related:50

-

had a clinically suspected infection (fungal, bacterial or viral) as cause for dermatitis of the hands

-

known clinically relevant allergic contact dermatitis of the hands, unless they had made a reasonable effort to avoid the contact allergen

-

atopic eczema covering more than 10% of body surface (excluding hands)

-

had skin conditions worsened by the sun, that is, do not tolerate UV-light (for example lupus erythematosus, porphyria).

Treatment-related:

-

received systemic vitamin A derivatives or systemic immunosuppressants, for example, methotrexate or biologics treatment for HE, or received phototherapy/photochemotherapy, in the 3 months prior to randomisation

-

received ciclosporin A or systemic glucocorticoid steroid treatment for HE or topical calcineurin antagonist treatment within 1 week prior to randomisation

-

receiving concomitant treatment with tetracyclines, medication with potential for drug–drug interaction with AL (e.g. CYP3A4 inhibitor ketoconazole), or concomitant treatment with relevant photosensitisers, that cannot be suspended or switched to an acceptable alternative

-

history of melanoma skin cancer, or patients with a history of non-melanoma skin cancer depending on history, location and ‘severity’ of the non-melanoma skin cancer based on experience from routine practice

-

received prior treatment with arsenic agents or ionising radiation in the treatment area (e.g. hands).

General:50

-

if female:

-

lactating

-

of child bearing potential [Woman of Child Bearing Potential (WCBP)] and:

-

- with positive pregnancy test (absence of pregnancy confirmed with a negative pregnancy test before randomisation)

-

- unwilling to follow pregnancy prevention programme measures (rigorous contraception for women of childbearing potential, unless exempt according to standard of care practice, was required 1 month before treatment, during the treatment period and 1 month after cessation of treatment as per usual standard practice) while receiving treatment and after the last dose of protocol treatment as indicated in the relevant summary of product characteristics (SmPC)

-

-

-

hepatic insufficiency (alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase > 2.5 times the upper limit of normal), known severe renal insufficiency, uncontrolled hyperlipidaemia [for all of the following: triglycerides, cholesterol and/or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol] or uncontrolled hypothyroidism in the 12-week period prior to randomisation

-

known hypersensitivity to peanut, soya or vitamin A derivatives or with rare hereditary fructose intolerance as determined by patient history

-

suffering from hypervitaminosis A as directed by clinical symptoms or patient history

-

previous participation in the ALPHA trial.

Blood samples were required to confirm eligibility and atopy status prior to randomisation. Research sites could choose to use either a one-stage process to obtain full informed consent or a two-stage consent process involving obtaining consent for blood sampling to confirm eligibility and atopy status, and then full informed consent for trial participation. If a period of > 12 weeks elapsed prior to the baseline visit, the eligibility blood test was redone.

If available and within the 12 weeks prior to baseline visit, existing blood results (taken for other reasons) in participants’ medical notes could have been used to confirm eligibility. Similarly, if existing atopy results {bon presence/absence of specific immune globulin E [IgE] to inhalant or other relevant allergens as appropriate [e.g. via prick test, Radioallergosorbent Test (RAST) blood test]}, were available in participants’ hospital notes, a blood sample to confirm atopy status was not required.

A log was completed of all patients screened but not recruited, either because they were ineligible or because they were eligible but declined participation. The following anonymised information was included:

-

age

-

gender

-

ethnicity

-

date screened

-

how the patient first heard about the trial

-

the reason why they were not eligible for study participation, OR

-

the reason for declining participation.

Interventions

Participants were randomised to either AL or Immersion PUVA for a minimum of 12 weeks and a maximum of 24 weeks. In both arms of the study, it was expected that patients would follow good self-care practices in the use of emollients, irritant avoidance and – if applicable – diligent continuation of contact allergen avoidance. Education on HE in using emollients, avoiding irritants and relevant contact allergens was delivered face to face in a standardised way based on study-specific educational information by the research nurse involved in the trial. The same education material was handed to participants. The information material for participants was based on sources used in clinical practice [British Association of Dermatology (BAD), National Eczema Society, Eczema Society patient information leaflets].

According to standard clinical practice and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, AL was administered at a starting dose of 30 mg, to be taken once daily with the main meal. Participants self-administered the treatment at home. Dose adjustment of AL down to 10 mg or temporary cessation (i.e. dose interruption) was permitted according to standard practice in participants who suffered from AL-related headaches.

For participants allocated to Immersion PUVA, hands were immersed for 15 minutes in a Meladinine® 0.75% solution diluted to 3 mg/l for 15 minutes followed by up to a 30-minute delay before exposure to UV-A radiation according to standard practice at the participating site; all sites operated based on ‘British Photodermatology Group’ guidelines. The exact dose of UV-A radiation that participants received was individually tailored to the participant depending on phenotype (as per BAD guidelines) and the erythematous response of the skin following treatment.

The treatment was performed in outpatient phototherapy departments within secondary care units and was administered and supervised by the specialised nurses/dermatologists. Treatments were carried out twice weekly.

As directed by NICE guidelines for AL, the PGA score directed treatment pathway decisions as determined by the treating clinician.

Criteria of response

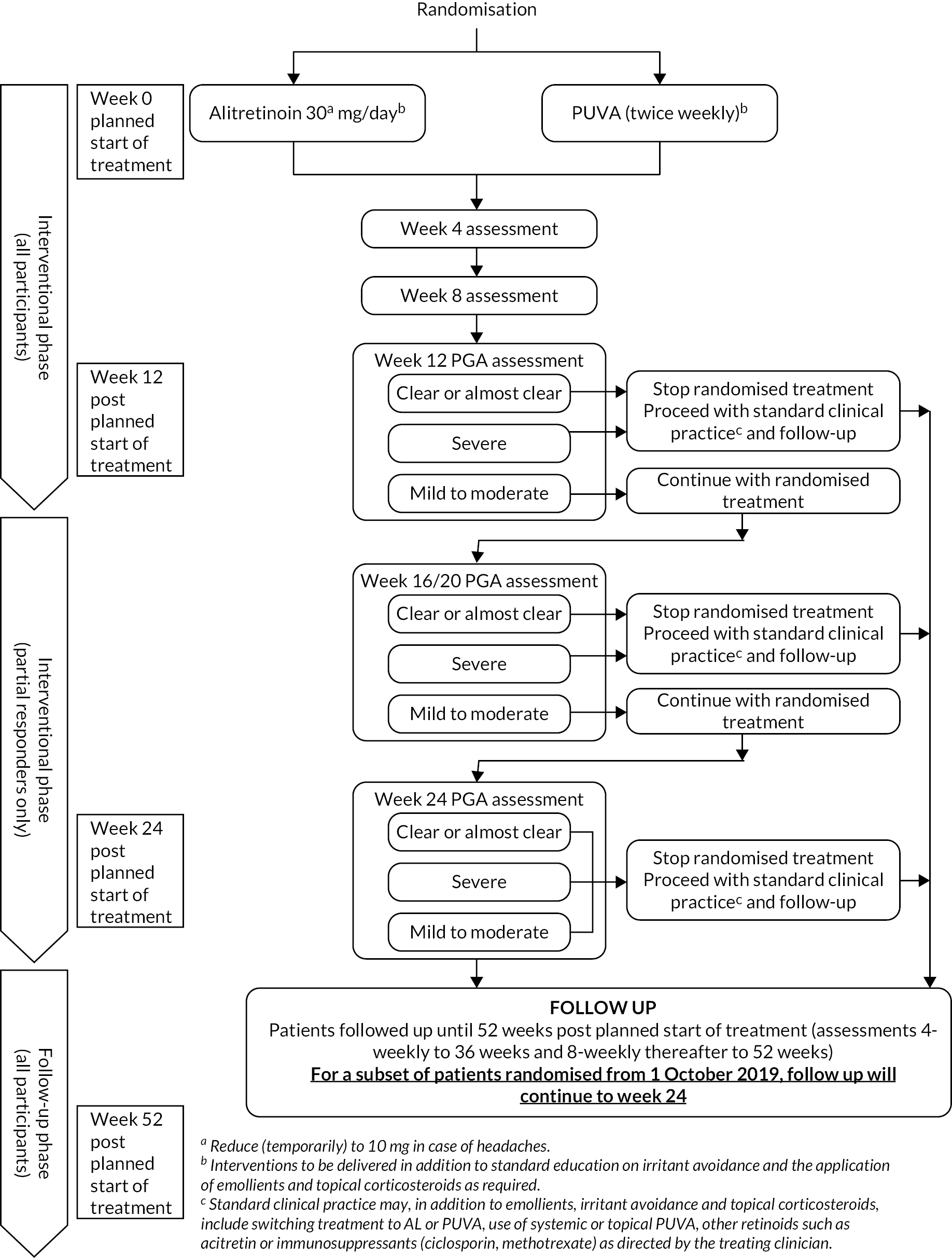

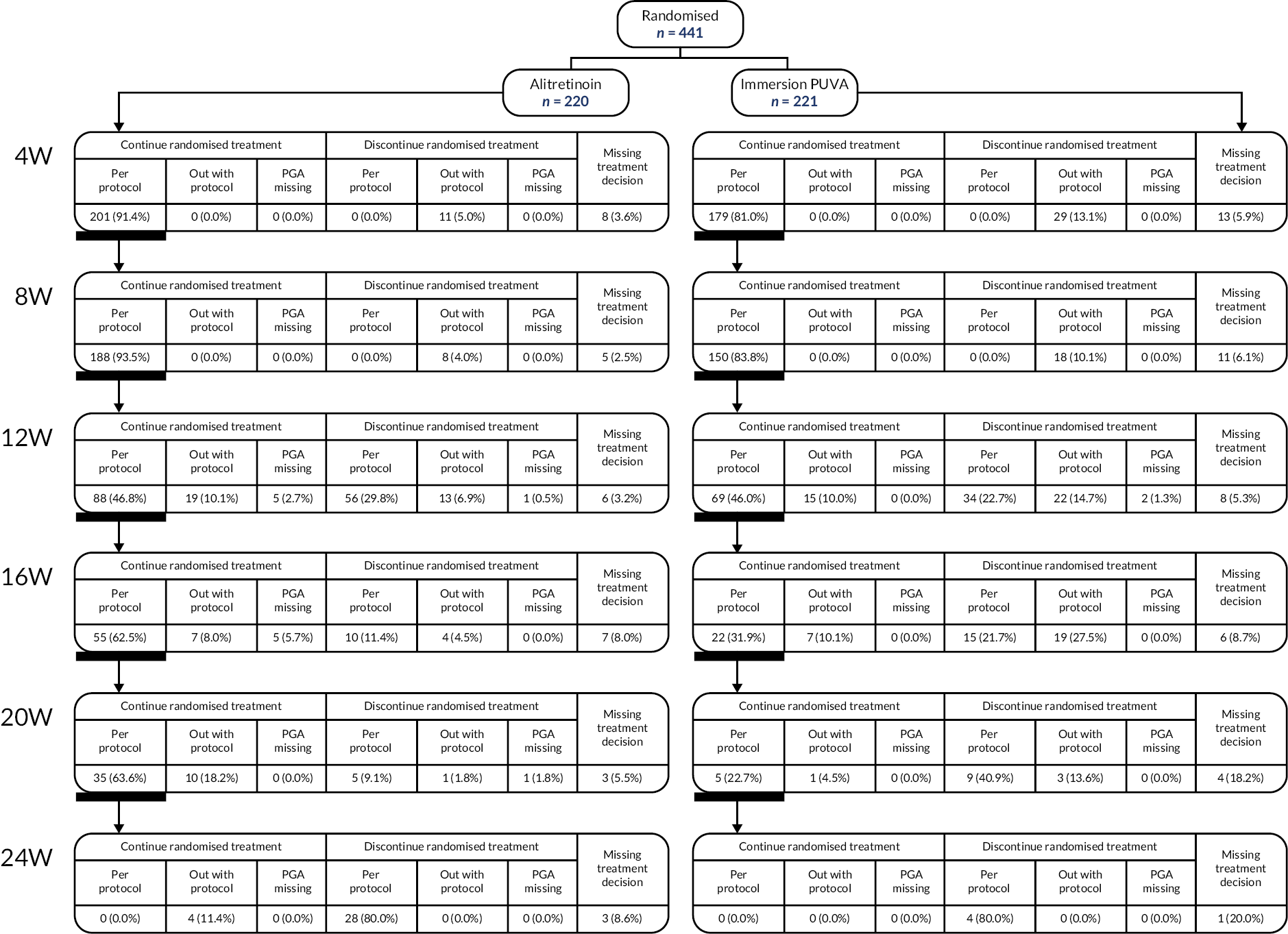

Criteria are shown in the protocol schedule (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Protocol schedule.

Responders: defined as a PGA score of clear/almost clear at 12 weeks post planned start of treatment, discontinued randomised treatment and continued to receive ‘standard clinical practice’ and follow-up monitoring.

Partial responders: defined as a PGA score of mild/moderate, continued with randomised treatment for up to 24 weeks post planned start of treatment. During this 12- to 24-week treatment period, the patients were monitored at 4-weekly intervals; randomised treatment could be stopped at any time if the patient responded (PGA score of clear/almost clear) or if the symptoms worsened (PGA score of severe) and in the opinion of the attending clinical team there was no clinical benefit to continuation. All randomised treatment was discontinued at the maximum 24 weeks’ treatment period, and patients continued to receive ‘standard clinical practice’ and follow-up monitoring.

Non-responders: defined as a PGA score of severe at 12 weeks post planned start of treatment, discontinued randomised treatment and continued to receive ‘standard clinical practice’ and follow-up monitoring.

At the end of trial treatment and during follow up, treatment was at the discretion of the attending clinical team as per ‘standard clinical practice’. Follow-up monitoring continued until 52 weeks post planned start of treatment, with the exception of participants randomised from 1 October 2019, who completed follow-up assessments for 24 weeks post planned start of treatment.

Randomisation

Recruitment of participants to the ALPHA trial required a blood sample taken within 12 weeks of the baseline visit to confirm eligibility and atopy status, and at least 1 month’s duration of the contraception prevention programme prior to randomisation (if applicable) to confirm eligibility. Patients were registered by an authorised member of the attending clinical or research team and were issued a unique trial number. Registration was performed using either the 24-hour automated registration telephone system or via a web address based at the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU).

Participants were randomised once eligibility was confirmed and the baseline assessments and questionnaires were completed. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 allocation ratio to receive either AL or Immersion PUVA in conjunction with concomitant topical corticosteroids, emollients and patient education. A computer-generated minimisation programme that incorporated a random element equal to 0.8 was used to ensure intervention groups were well balanced for the following factors:

-

randomising site

-

disease duration (< 6 months/6–24 months/> 24 months)

-

clinical phenotype (predominantly hyperkeratotic/predominantly vesicular/fingertip dermatitis)

-

atopy status as determined by presence of specific IgE to inhalant allergens (prick test or RAST blood test to detect specific IgE to inhalant or other suspected allergens as appropriate)

-

DLQI (< 15, ≥ 15)

-

skin type (white/fair/dark).

A total of 100 participants who consented to take part in a tape stripping (non-invasive epidermal sampling) substudy were selected at their baseline visit. A quota sampling approach was taken so that the first 25 participants allocated to Immersion PUVA with predominantly hyperkeratotic CHE, the first 25 participants allocated to Immersion PUVA with predominantly vesicular CHE, the first 25 participants allocated to AL with predominantly hyperkeratotic CHE, and the first 25 participants allocated to AL with predominantly vesicular CHE were selected. Participants presenting exclusively with fingertip dermatitis were excluded from this substudy. Epidermal samples in the form of tape strip samples for randomised participants were obtained from both lesional skin and non-lesional, healthy-looking skin of the forearm. Full details of the sample technique are provided in Appendix 1.

Blinding

The trial was openlabel, as participants and investigators could not be blinded to treatment allocation due to the nature of the Immersion PUVA intervention. However, the assessment of the HE severity scores (HECSI, mTLSS and PGA) was undertaken by an assessor who was blinded to the randomised treatment. Participants were reminded not to reveal which treatment they had received to the blinded assessors in order to preserve blinding.

In addition, photographs were taken, for 20% randomly identified, consenting participants of white ethnicity and all consenting participants from minority ethnic groups from each centre, at baseline and 12 weeks post planned start of treatment. A blinded central review of the photographs was conducted to assess intercentre differences in severity scoring.

Outcome measures

Clinical symptoms

The HECSI is a validated scoring system that resembles the clinically well-established Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) score and takes into account disease extent, which is an important prognostic factor for HE. 19,51 The hands are divided into five areas [fingertips, fingers (excluding tips), palm of hands, back of hands, wrists], and each of these five areas is given a score from 0 to 3 for the intensity of pre-specified clinical symptoms (erythema, infiltration/papulation, vesicles, fissures, scaling, oedema) and a score of 0 to 4 for the extent of disease on each area. For each area, the extent of the disease is multiplied (to obtain the product) by the sum of the intensity scores assigned to each clinical symptom. All these products are then added together to give an overall HECSI score, which ranges from 0 to 360, with a higher score indicating greater severity. The PGA is a five-level score (clear, almost clear, mild, moderate, severe) and was used in line with NICE guidelines to determine the HE severity and eligibility of patients for the study. 52 The PGA has been used in all HE studies involving AL. For the treating clinician, this was assessed as a global score for the participant, but for the blinded assessor, the PGA was recorded for each side of each hand, and the most severe score was taken as the overall PGA.

The mTLSS has been used widely in the past. 52 Similarly to the HECSI, the mTLSS considers seven eczema-related symptoms, erythema, scaling, lichenification/hyperkeratosis, vesiculation, oedema, fissures and pruritus/pain, but it does not take extent of HE into account. In line with the PGA assessment, the mTLSS was recorded for each side of each hand. Each symptom was given a score between 0 and 3, such that a score of 1 corresponded to mild, 2 corresponded to moderate and 3 corresponded to severe. The total mTLSS score, on a patient basis, was derived by adding up the scores for each side of each hand (as assessed by the blinded assessor), and the overall mTLSS was the maximum score, so that it corresponded to the most affected side of the most affected hand. The total score ranges from 0 to 21, where a higher score indicates greater severity.

The Person-Centred Dermatology Self-Care Index (PeDeSI) is a validated 10-item questionnaire that measures the education and support needs of people with long-term skin conditions. 53 It is completed in collaboration between patient and practitioner/unblinded nurse and is quick and simple to use in practice. Each item has a score range of 0–3, and total scores indicate as follows: 0–10, needs intensive education and support to develop knowledge, ability and confidence; 11–20, needs some education and support to develop knowledge, ability and confidence; 21–29, needs limited education and support to develop knowledge, ability and confidence; 30, has sufficient knowledge, ability and confidence to manage on their own.

Participant-completed questionnaires

The DLQI is a validated patient-reported outcome measure of the effect of skin disease on a patient’s daily activities and is widely used. 54,55 The DLQI has a simple method of score interpretation: no impact (0–1), small impact (2–5), moderate impact (6–10), very severe impact (11–20) and extremely severe impact (21–30). 56 The DLQI has been used in most large HE studies and is used in the definition of severe CHE in the NICE guidelines (NICE TA177).

The Patient Benefit Index for chronic hand eczema (PBI-HE) is a disease-specific patient-reported tool for HE and is an extension of the PBI, which was developed based on the finding that the physician’s perspective only partly corresponds with the patient’s perspective when it comes to benefit measurements. 57–59 The score is calculated from the importance of needs before therapy and the achievement of these needs. The PBI ranges from 0 (no benefit) to 4 (maximal benefit).

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), questionnaire consists of five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, each having three levels of response. 60 The EQ-5D is a generic instrument (www.euroqol.org) and forms part of the NICE reference case for cost per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) analysis.

The Health Resource Utilisation and Private Costs questionnaire was used to measure participant-reported healthcare use, days off work and private costs due to CHE using a bespoke short self-reported form developed at the University of Leeds. Healthcare use included the number of contacts with clinical staff (occupational health, primary care staff, dermatologists, etc.) and medications because of CHE.

Safety monitoring

This was a RCT using established medicinal products with well-known safety profiles. In recognition of this, events fulfilling the definition of an adverse event (AE) or serious adverse event (SAE) were not reported unless they were: (1) expected and related to trial treatment, (2) related to HE and classified as a- SAE or (3) related to trial treatment and classified as a serious adverse reaction (SAR) or suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR). The following expected AEs/reactions were known to be related to the trial treatments and were not reported unless assessed as serious: headaches and dry skin on regions of the body other than the hands for participants allocated to AL, and erythema (mild to moderate) or itching of skin in Immersion PUVA-treated skin locations for participants allocated to Immersion PUVA. Safety monitoring was conducted throughout each participant’s follow-up period: that is, 52 weeks post planned start of treatment for participants randomised before 1 October 2019 and 24 weeks post planned start of treatment for participants randomised from 1 October 2019.

Data collection schedule

Clinical data and patient-reported data were collected at baseline, every 4 weeks to week 36 and 8-weekly thereafter to week 52. For participants randomised after 1 October 2019, data collection was stopped at week 24. Trial activity was paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 in all centres. Some centres restarted research activity from July 2020. When trial activity restarted, visits were permitted to be conducted in person or virtually (telephone or video call), and QoL questionnaires were posted to participants where possible. The primary end point was only permitted in person, with visits at 12 weeks and 24 weeks prioritised.

Baseline

The baseline visit was booked within 7 days of the first Immersion PUVA appointment, within 12 weeks of the eligibility blood sample and after at least 1 month’s duration of the pregnancy prevention programme (if applicable).

Data collected included: full written informed consent for the study and substudies (if appropriate), treating clinician, mobile phone number for participants consenting to weekly text reminder service, relevant medical history (including date of HE diagnosis, patient and family history of relevant diseases, other eczema locations, previous treatments for HE and exposure to irritants), urine pregnancy test (for all WCBP), smoking history, height and weight, dominant hand, hand that interferes with their daily life the most, IgE results, visual assessment of HE clinical phenotype of the hands and assessment of potential foot involvement, PGA by treating clinician, PeDeSI by treating clinician/unblinded nurse, gene variant analysis blood sample. Also PGA, HECSI and mTLSS assessments by blinded assessor, nail involvement assessment by a blinded assessor (at participating centres) and patient-completed questionnaires (DLQI, PBI-HE and EQ-5D-3L).

After randomisation, the following data were collected: photographs of each side of each hand and substudy sample acquisition (tape stripping) for randomly identified participants.

Interventional phase and follow-up phase

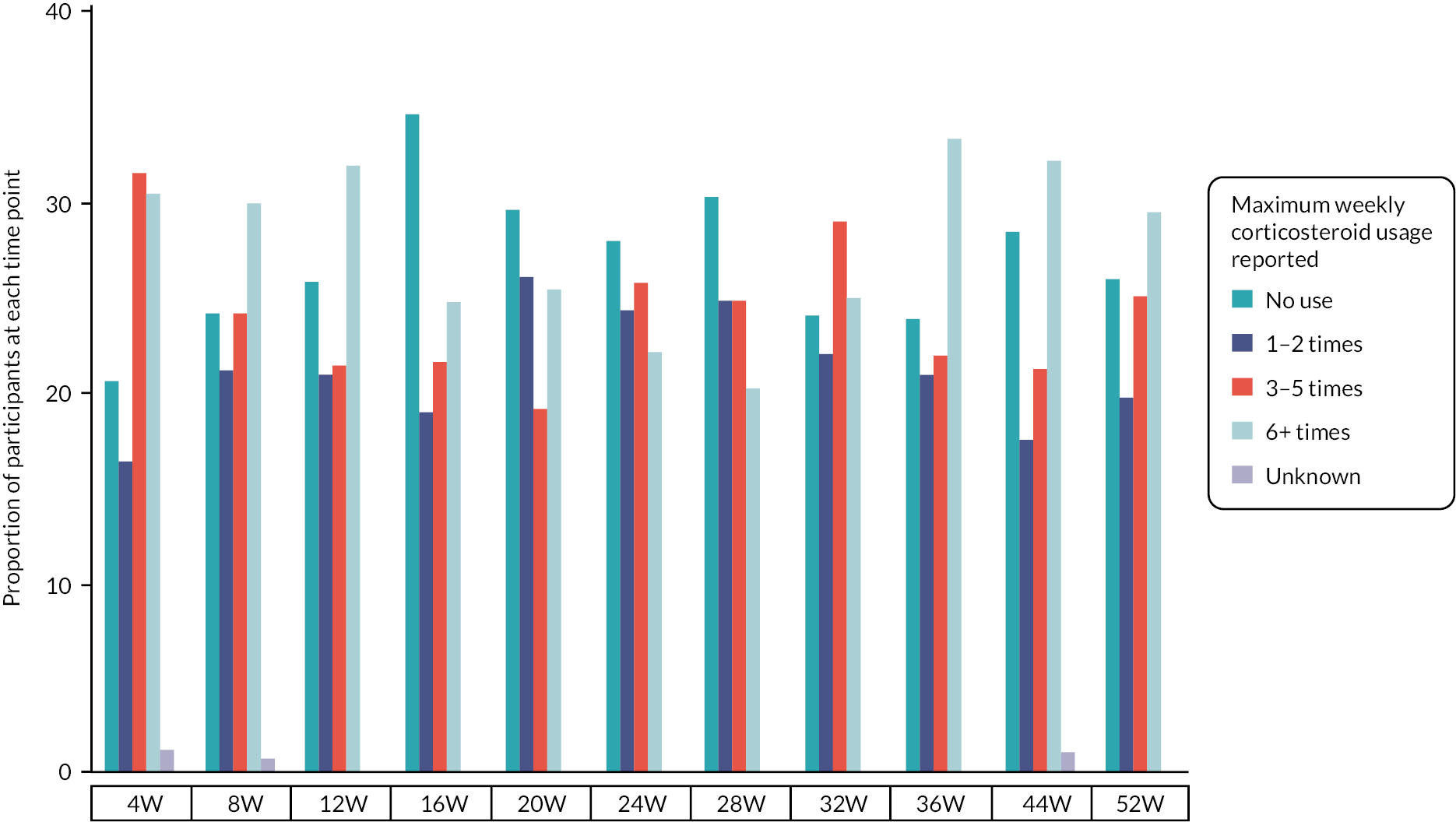

Data collected at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 44, 52 weeks included: HE topical corticosteroid usage (obtained from a review of participant medication diaries in conjunction with clinical records), reportable adverse reactions, PGA by treating clinician; PGA and HECSI by blinded assessor, nail assessment by blinded assessor (at participating centres); and patient-completed questionnaires (DLQI).

Data collected at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 weeks included: randomised treatment compliance (obtained from a review of participant medication diaries in conjunction with clinical records). Note that treatment compliance data were only collected at 16, 20, 24 weeks if the participant continued on treatment; otherwise, they moved into the follow-up phase.

Data collected at 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 44, 52 weeks included: treatment received under ‘standard clinical practice’. Note that these data were only collected at 16, 20, 24 weeks if the participant had discontinued their randomised treatment phase.

Data collected at 12, 24, 36, 52 weeks included: mTLSS by blinded assessor; patient-completed questionnaires (PBI-HE, EQ-5D and Health Resource Utilisation).

Data collected at week 12 only: photographs of each side of each hand for randomly identified participants.

Data collected at 12 and 52 weeks included: PeDeSI by treating clinician/unblinded nurse. Note that for participants randomised after 1 October 2019, the PeDeSI was collected at week 24 instead of week 52.

End points

Primary end point

The primary end point was defined as the natural logarithm of the HECSI at 12 weeks post planned start of treatment. In the event of HECSI scores of zero, a pre-planned adjustment to take the natural logarithm of the HECSI + 1 was included in the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP).

Secondary end points

-

The HECSI, mTLSS and PGA over 52 weeks post planned start of treatment.

-

Time to relapse, defined as the time between achieving clear/almost clear overall on the blinded assessor PGA and scoring 75% of their baseline HECSI, with the sensitivity of this definition assessed by redefining relapse as achieving 50% of their baseline HECSI.

-

The DLQI and PBI-HE over 52 weeks post planned start of treatment.

-

The PeDeSi at 12 and 52 (or 24) weeks post planned start of treatment.

-

Reported AEs and SAEs over 52 weeks post planned start of treatment.

-

Cost-effectiveness of AL compared with Immersion PUVA at week 12, 52 (short term) and over 10 years (long term).

Exploratory end points

-

Time to the end of remission defined as time from entering clear/almost clear according to the blinded assessor during the randomised treatment phase, to no longer being clear/almost clear.

Trial organisational structure

The Trial Sponsor was the University of Leeds; responsibilities were delegated to the (CTRU) as detailed in the trial contract.

Trial oversight and management were conducted by the Trial Management Group (TMG), the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). All groups met regularly throughout the trial.

Data quality and monitoring were performed by the CTRU.

Statistical methods50

Sample size

Due to the positively skewed nature of the data, the trial was designed to detect a relative difference in treatment effects. A minimum of 500 and maximum of 780 participants were required to detect a relative difference, or fold change, of 1.3 (clinical opinion) in HECSI score between treatment arms at 12 weeks post planned start of treatment (80% power; two-sided 5% significance level) assuming a coefficient of variation (CV) between 1.175 and 1.7 and allowing for 20% attrition. A sample size review was planned after 364 participants (precision of −0.132 and + 0.168 assuming CV = 1.2) had reached 12 weeks post planned start of treatment, to revise the CV and the final sample size.

Planned recruitment rate

At the start of the trial, we estimated that we would need to screen 3200 patients, of whom 50% were expected to be eligible and 50% of those eligible would consent. It was estimated that each centre would recruit 1–2 patients per month so that the maximum target of 780 participants could be attained within the 24 months’ planned recruitment period.

An internal pilot study was planned in order to assess the feasibility of recruitment. The internal pilot targets were set to recruit 63 participants across 12 centres over the first 6 months of the recruitment period. This target represented 8% of participants recruited across 30% of centres after 25% of the recruitment period had been completed and was based on a recruitment rate of 1–2 participants per month per centre taking into account a staggered opening of centres. The decision to continue the trial remained with the funder in the event that the target was not met.

Revised sample size and expected accrual

The trial recruited participants at a much slower rate than originally anticipated, and the sample size re-estimation was requested by the funder and conducted in August 2017 after 126 participants had an available 12 weeks’ HECSI assessment. The re-estimation was reviewed by the DMEC, who recommended a revised sample size of 514 participants based on an updated CV of 1.2, informed by the interim analysis.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A SAP was approved prior to the relevant analysis being conducted.

Patient populations

All participants recruited into the trial were included in the analysis using ‘Intention-To-Treat’ (ITT) and analysed according to the randomised allocation and true values of minimisation factors.

A per-protocol (PP) population was defined such that it would exclude all major protocol violators and participants who did not receive at least 80% of their trial treatment or had a treatment break of more than 1 week.

The safety population was defined as all patients who were registered into the trial and was used to summarise patient disposition during the trial. This population was used to summarise any AEs, SAEs and SUSARs that occurred during the trial period.

The biomarker subgroup population consisted of all consenting participants who were selected for the biomarker substudy. The analysis population for the biomarker substudy included those for whom the relevant sample was received. This population was analysed and summarised according to the treatment they were randomised to receive.

The photography subgroup population consisted of all consenting participants who were selected for photography at randomisation.

The population to be used for the assessment of time in remission and time to relapse consisted of all participants who achieved clear/almost clear on the PGA according to the blinded assessor by the end of their randomised treatment phase. This population was analysed and summarised according to the treatment they were randomised to receive.

Participants were excluded from available case analyses if they had no available outcome data or at least one missing covariate for the relevant analysis.

Missing data

Descriptive summaries were used to compare participants with complete data to those with missing data for various variables including baseline characteristics and randomised treatment group. Under the missing at random (MAR) assumption, data were imputed using a multiple imputation technique in order to comply with the ITT analysis principle, stratified by treatment allocation and using ongoing treatment received as an auxiliary variable. 61–65 Missing data were imputed in ascending order of missingness.

Where more than 5% of data were missing for the HECSI, mTLSS, PGA and DLQI secondary end points multiple imputation in line with the method described above was employed to account for these missing data.

Where multiple imputation was used, sensitivity analyses using the available case population for the relevant end point were conducted to assess the sensitivity of the results to the multiple imputation method.

Primary end-point analysis

A multivariable multilevel repeated measures linear regression model was fitted to the loge(HECSI + 1) at 4, 8 and 12 weeks, adjusting for minimisation factors: duration of disease, clinical phenotype, DLQI, atopy status and ethnicity and the covariates: smoking history, BMI, foot involvement, baseline loge(HECSI), time since planned start of treatment and treatment group. Participant and participant–time interaction were fitted as random effects. Filaggrin LOF mutation was originally planned as a fixed effect, but due to high levels of missing data (27.6%), it was not considered appropriate. Centre was originally planned as a random effect; however, this led to challenges with multiple imputation due to the three-level structure of the data, and therefore, it was excluded from the analysis. However, a sensitivity analysis comparing the primary analysis on the available case population was conducted with and without centre as a random effect to ensure that centre was not influential in the analysis results. The relative difference in the HECSI score (+1) at 12 weeks post planned start of treatment, corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values were reported.

Secondary end-point analyses

Multivariable multilevel repeated measures linear regression models of loge(HECSI score + 1), mTLSS and DLQI, and a multilevel repeated measures ordinal logistic regression model of the PGA over 52 weeks post planned start of treatment, were fitted, adjusting for the minimisation factors, covariates as for the primary end point analysis, corresponding baseline measurement and treatment group, as fixed effects. Participant and participant–time interaction were fitted as random effects. A multivariable ordinal logistic regression model of the PeDeSI was fitted adjusting for the minimisation factors, covariates as for the primary end point analysis, corresponding baseline measurement and treatment group, as fixed effects. The parameter estimates for each of these analyses, corresponding 95% CIs and p-values were reported; treatment effect estimates at 24 and 52 weeks post planned start of treatment were also reported. The PBI-HE was reported using summary statistics.

The method of Kaplan and Meier was used to report time to relapse.

Adverse events and SAEs classified as related to treatment or HE or resulting from administration of any research procedures were reported descriptively.

Exploratory end points

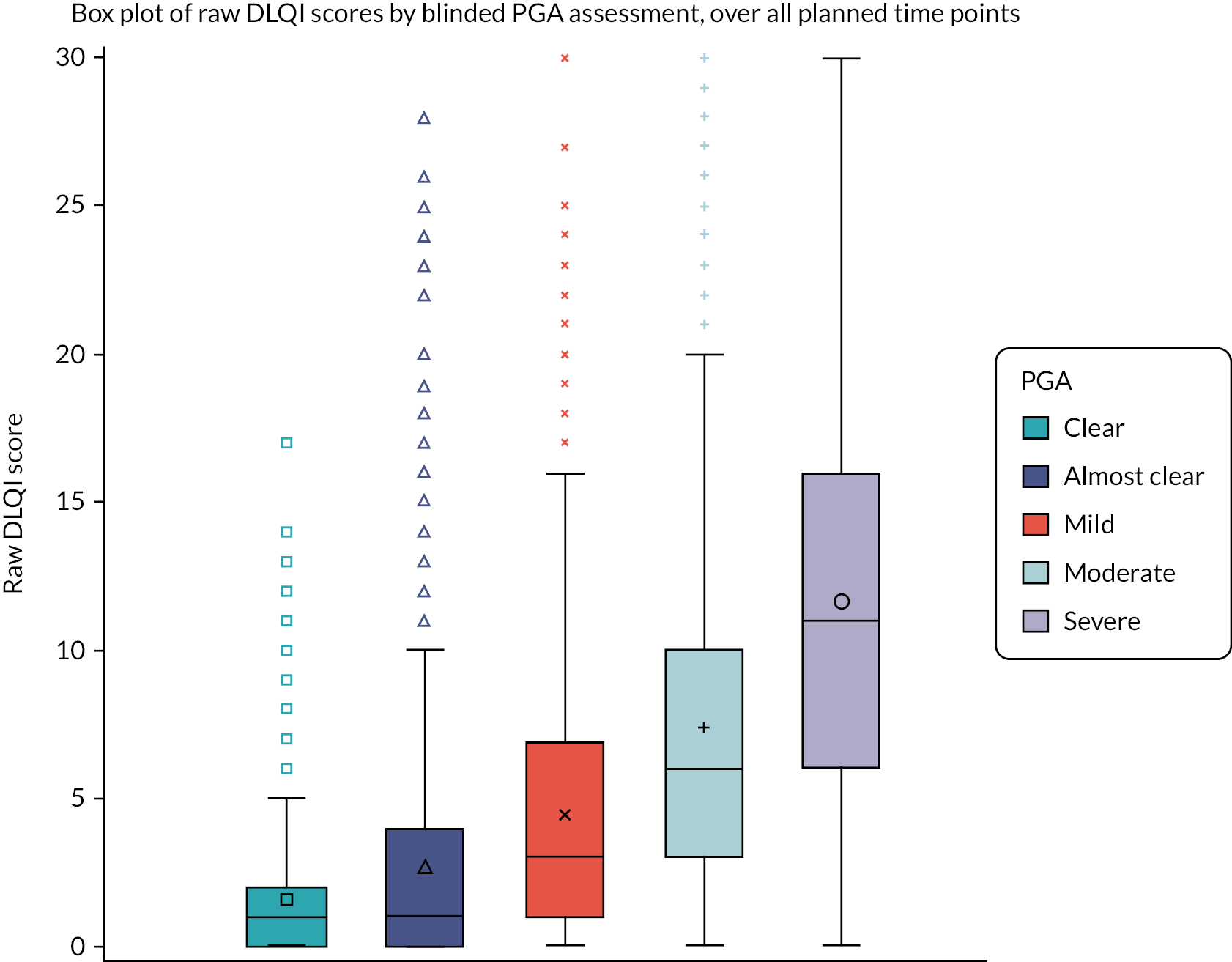

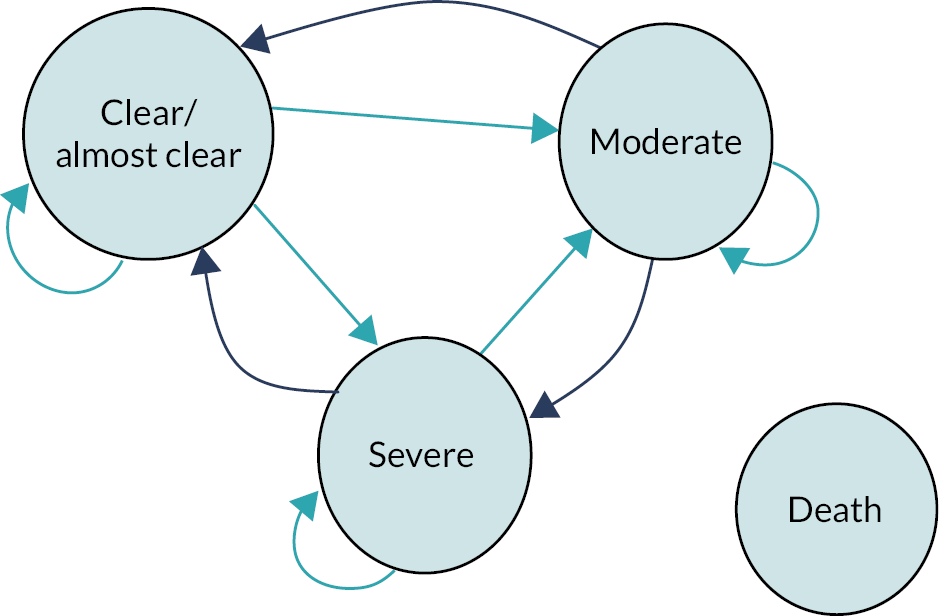

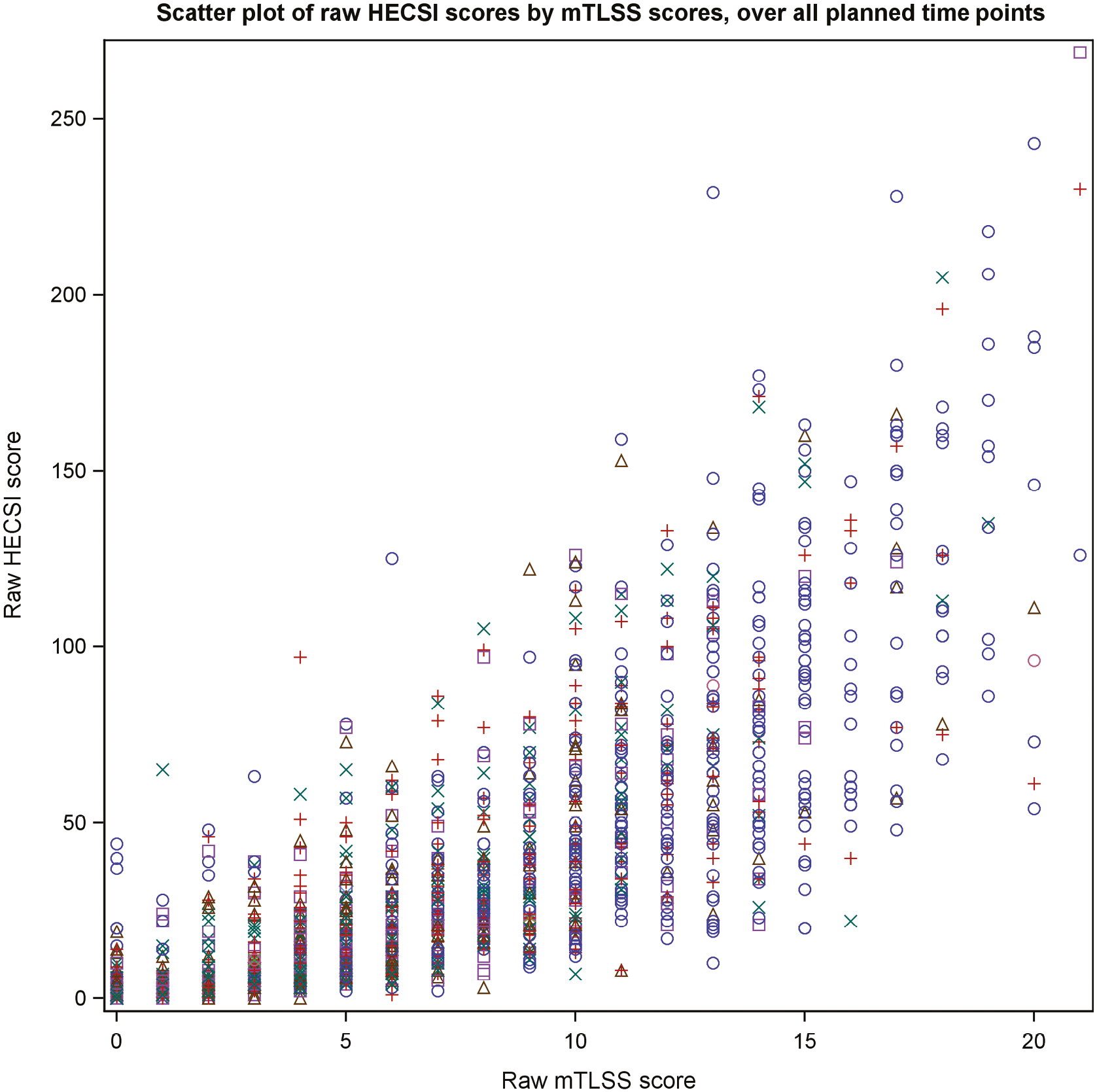

The correlation between HECSI, mTLSS and DLQI was calculated to assess convergent validity of scoring systems used to monitor response to treatment. Box plots and summary statistics of HECSI, mTLSS and DLQI within each level of the overall blinded PGA were produced.

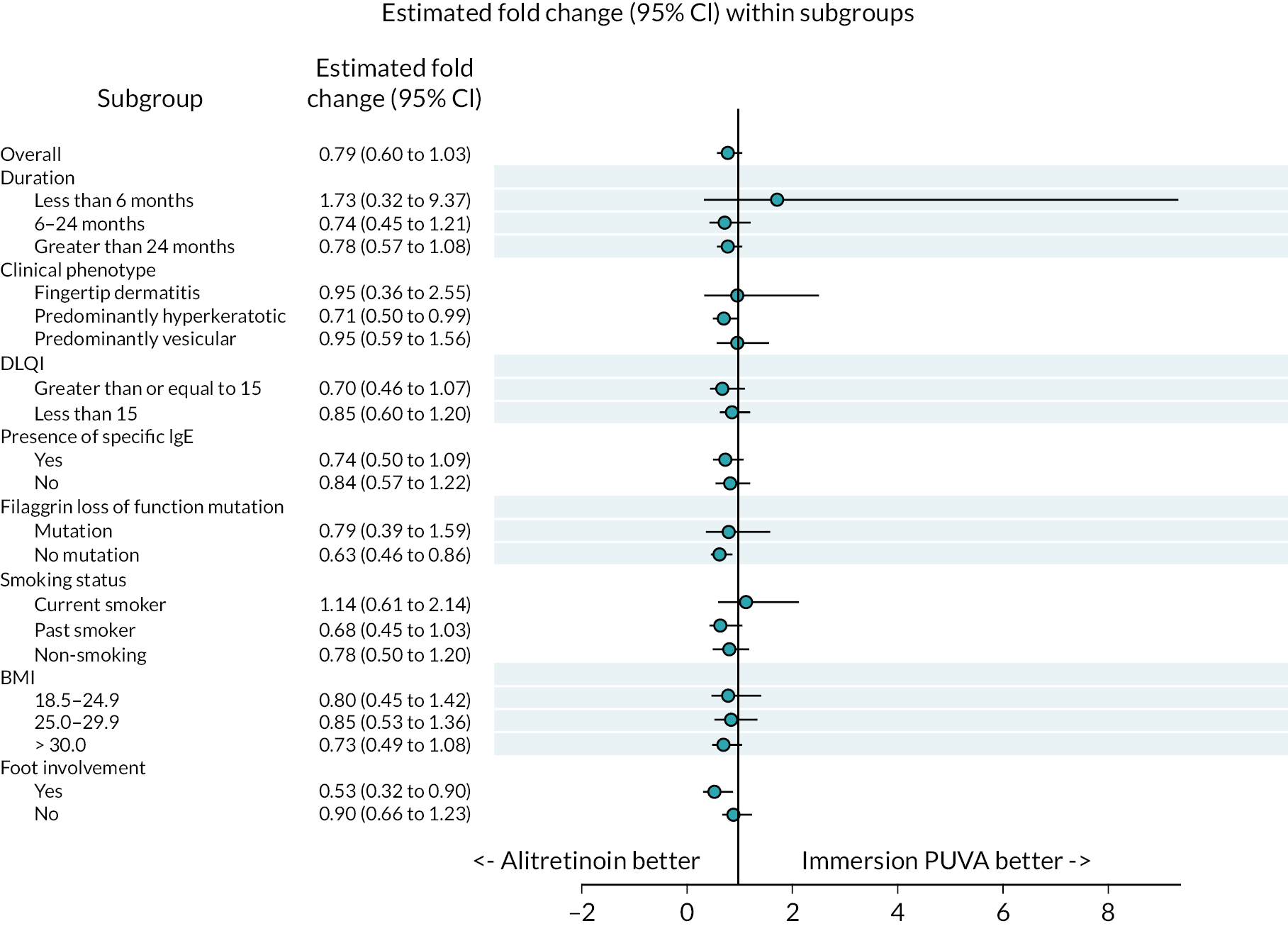

Subgroup analyses were conducted to compare treatment effects within pre-defined subgroups (duration of disease, clinical phenotype, disease severity, presence of atopy, filaggrin LOF mutation, smoking history, BMI and foot involvement). Multivariable linear regression models were fitted to the response, loge(HECSI + 1) and treatment group, and an interaction term between treatment group and the subgroup/biomarker was included in the models to explore if there were potential differential treatment effects at 12 weeks.

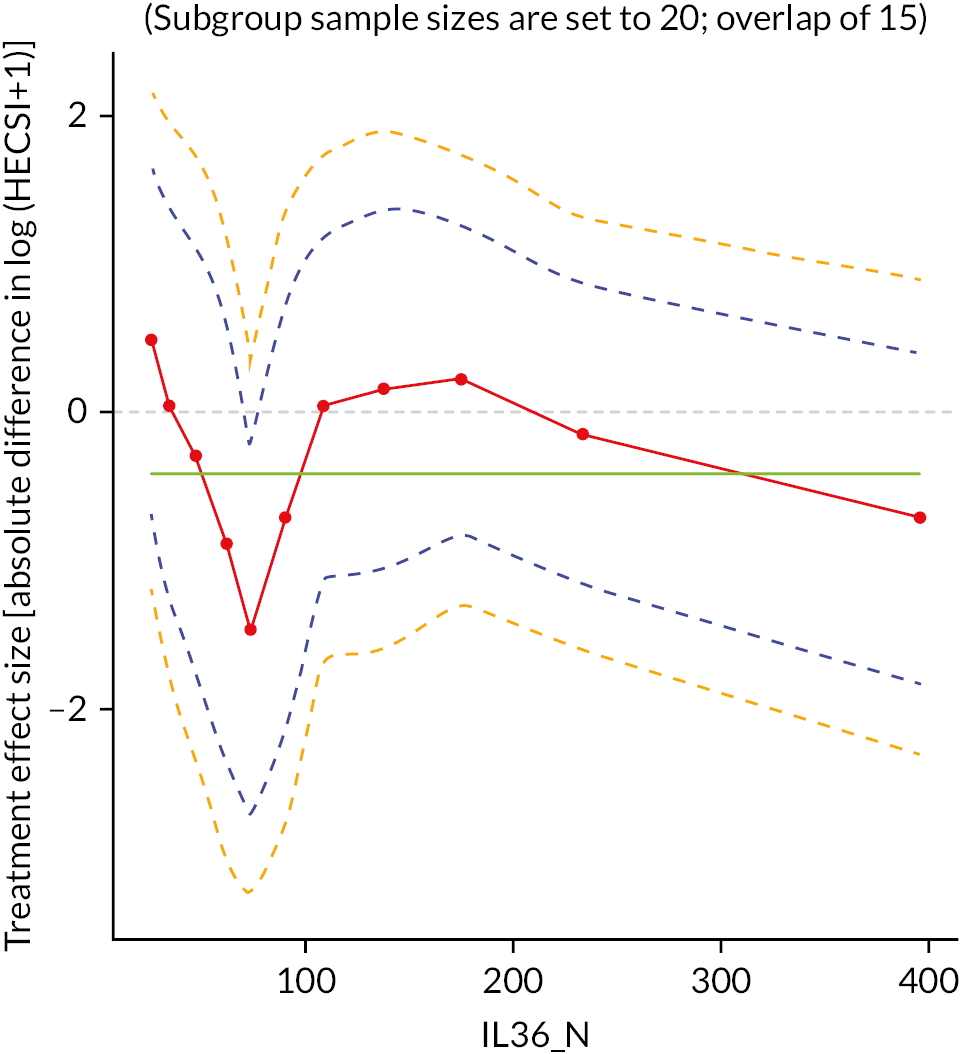

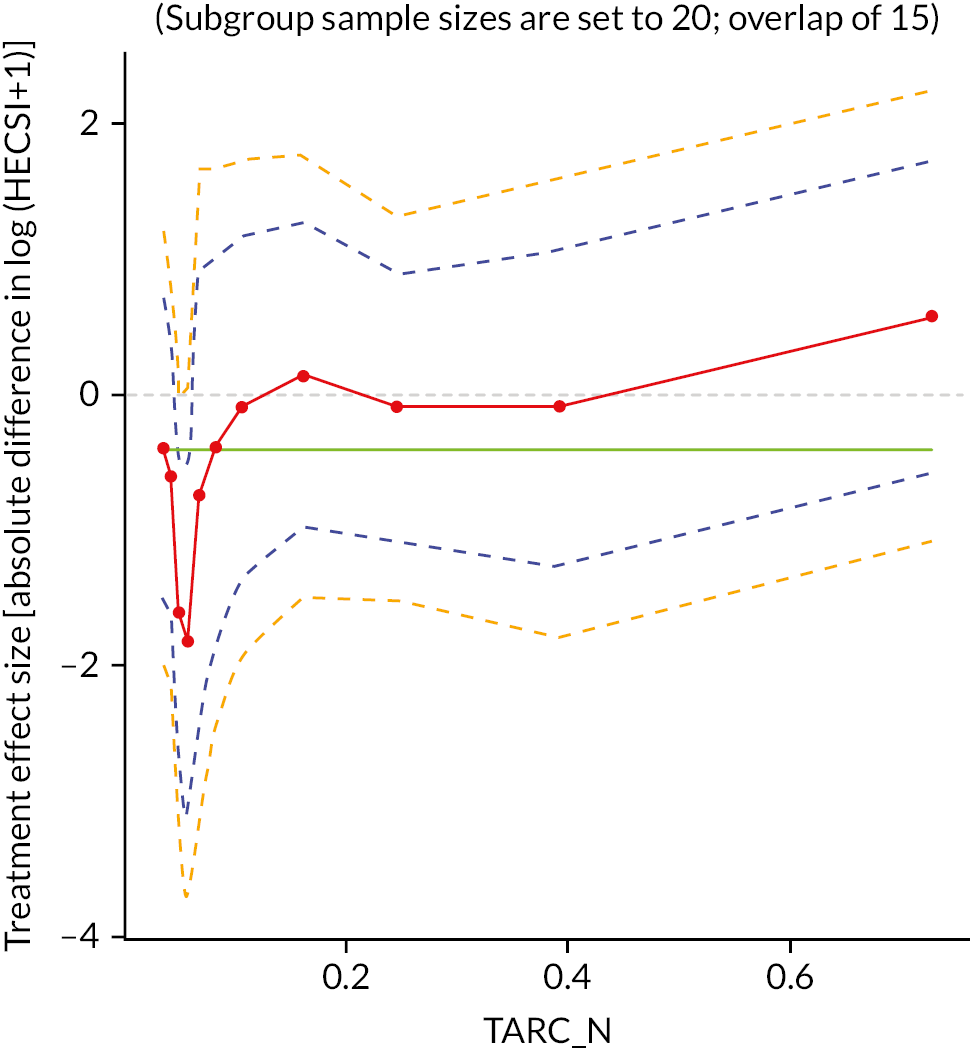

Potential biomarker subgroups were explored through the tape stripping substudy. Subpopulation treatment effect pattern plots (STEPP) were produced and examined for four biomarkers [IL-36, Thymus and Activation-Regulated Chemokine (TARC), CCL20 and IL-18] to identify whether there were any potential differential treatment effects for different levels of each biomarker. 66

Receipt of and types of second-line therapies were reported descriptively.

The end of remission, defined as the time point at which participants were no longer clear/almost clear, was reported and analysed using the method of Kaplan and Meier. Frequency of corticosteroid use was reported descriptively.

Agreement between the blinded assessor and the central review of photographs was assessed using cross-tabulations.

Treatment compliance

Descriptive statistics on the time to receiving allocated treatment, compliance with treatment pathway decisions and reasons for treatment discontinuation, proportion of treatment received during the first 12 weeks compared with expected treatment, and length of treatment breaks were reported.

Summary of main changes to the protocol

Centres opened to protocol v3.0 and patient information sheet and consent form v3.0 on 5 November 2015. The following substantial changes were made during the lifetime of the trial:

-

Addition of a nail assessment substudy at the Chief Investigator’s centre, as there are currently no validated tools available for nail assessment in eczema. Note that the results of this are not included in this report because it was outwith the grant application.

-

Following TSC and DMEC feedback, addition of a new stratification factor informed by the Fitzpatrick score for skin colour because erythema may be underestimated in darker skin.

-

As part of the original Health Technology Assessment (HTA) funding envelope, a recruitment time extension was requested and approved, with a reduction in follow up to 6 months for all patients recruited from October 2019 to maximise accruals within the trial extension period. The trial stopped recruitment in accordance with the timelines agreed with the funder.

Chapter 3 Clinical results

This chapter presents the findings of the analysis for the clinical outcomes.

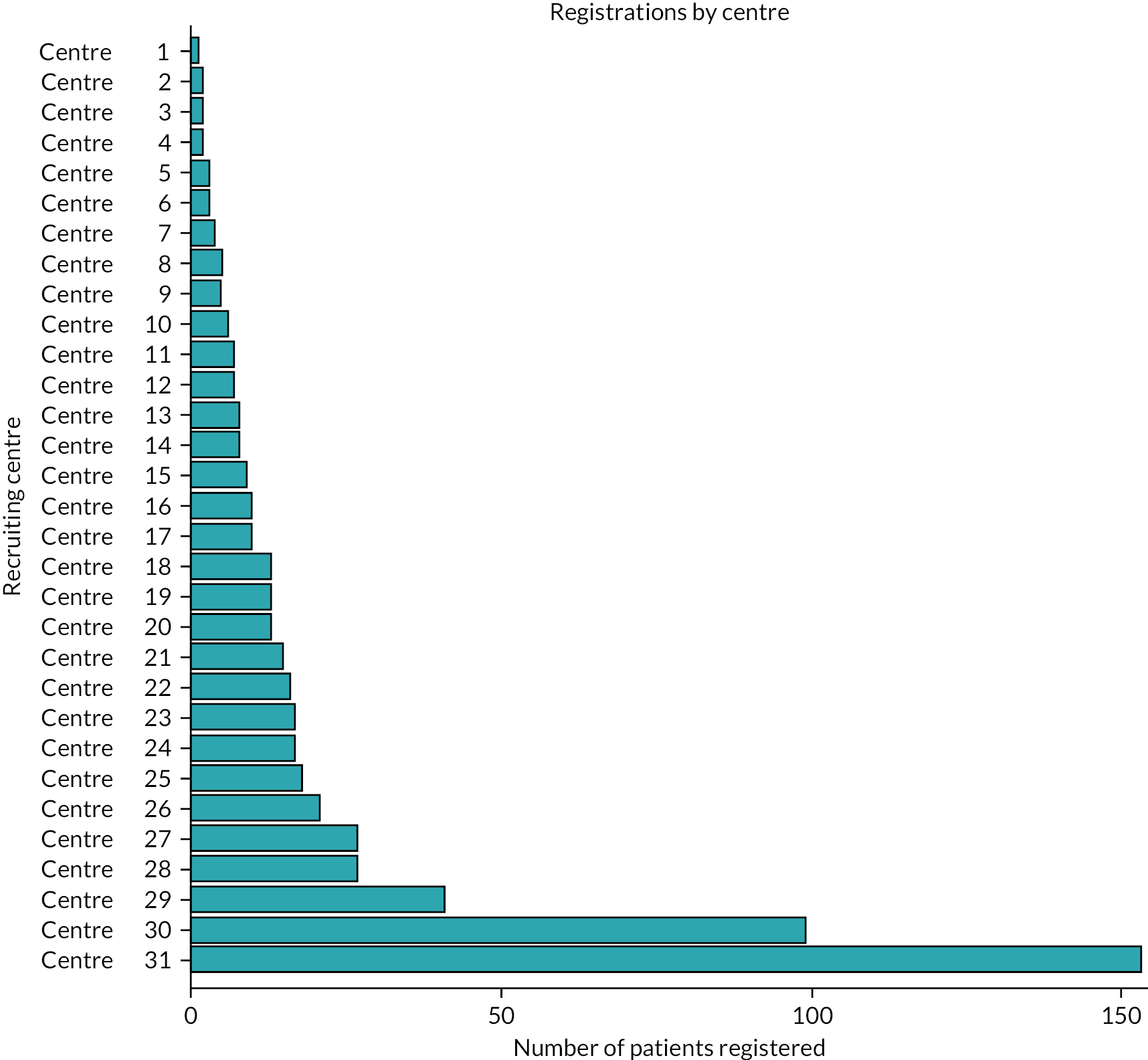

Participant flow

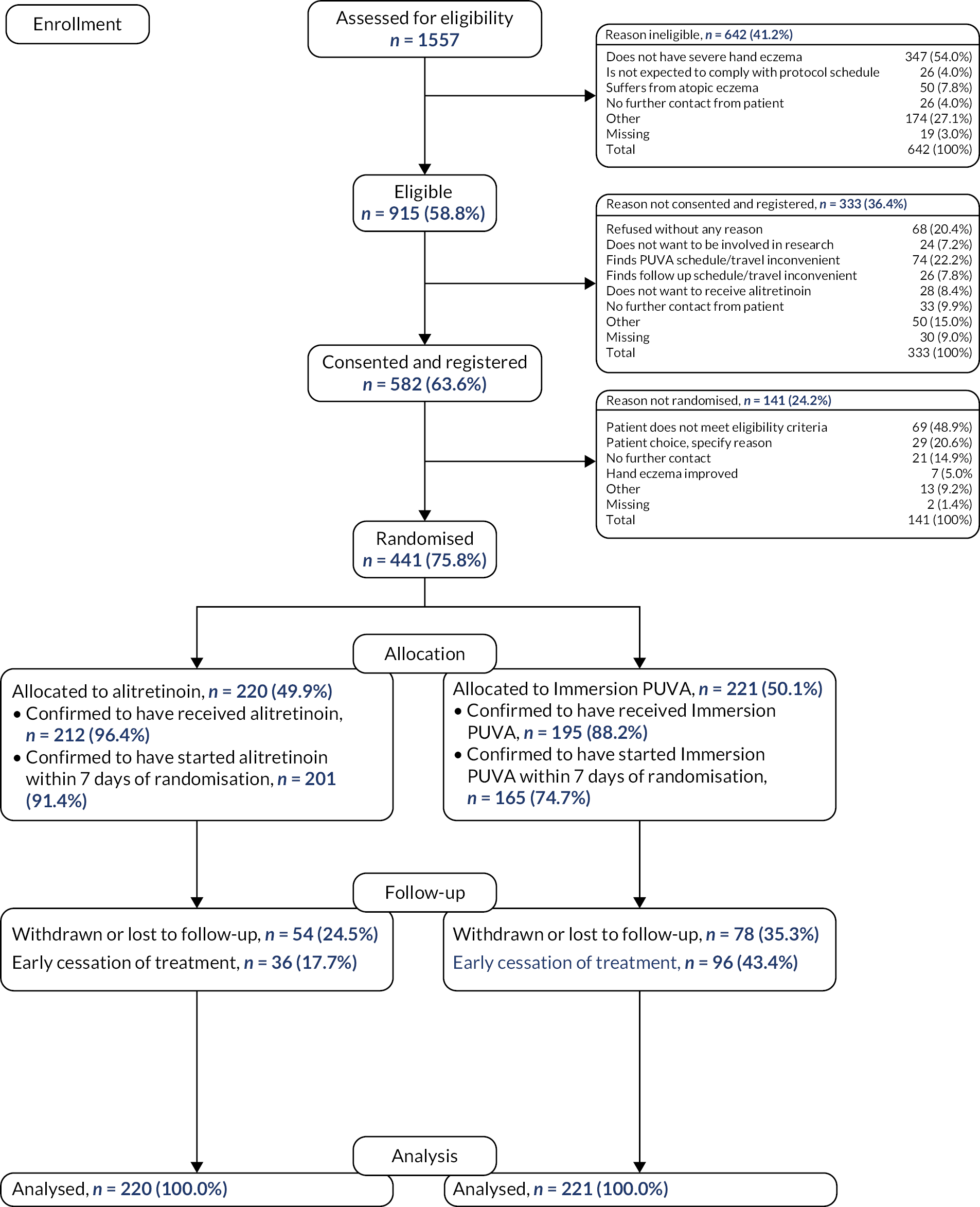

In total, 1557 participants were assessed for trial eligibility, 582 (37.4%) registrations took place to enable trial-specific tests and pregnancy prevention programmes to be implemented as required, and 441 (75.8% of those registered) randomisations took place between October 2015 and June 2021. Of those randomised, 59 (13.4%) were recruited after 1 October 2019 with a follow-up period of 6 months. Thirty-five NHS Secondary Care hospitals opened, of which 31 registered and randomised participants. The recruiting hospitals were located in England in the Yorkshire and Humber, North West, West Midlands, East Midlands, Eastern, London and South West regions, and in Scotland and Wales. The number of participants registered by each recruiting hospital ranged from 1 to 153 with a median of 10 (see Appendix 2 – Clinical results supplementary tables and figures, Figure 13). The mean number of registrations per centre was 0.30 participants per month. The number of participants randomised by each hospital ranged from 1 to 51, with a median of 4 (Figure 2). The mean number of participants randomised per centre was 0.23 per month. Follow-up was completed by 31 December 2021, after the last participant reached 24 weeks post planned start of treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Randomisations by anonymised centres.

A consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of trial progress is presented in Figure 3. Of the 1557 patients who were screened, 642 (41.2%) were ineligible, with over half of the patients not having a diagnosis of severe CHE [N = 347 (54.0%)]. Of the 915 eligible patients, 582 (63.6%) were consented and registered. Regarding the reasons for not consenting to the trial, 74 (22.2%) patients thought the Immersion PUVA schedule or travel was inconvenient and 28 (8.4%) did not want to receive AL. A total of 141 (24.2%) of those registered did not progress to randomisation; the main reasons were because they did not meet the eligibility criteria [N = 69 (48.9%)] or due to patient choice [N = 29 (20.6%)]. A total of 441 participants were randomised.

FIGURE 3.

Consolidated standards of reporting trials flow diagram.

The screened population and randomised populations were similar in respect of age, gender and ethnicity (Table 1).

| Screened | Registered | Randomised | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 44.2 (15.8) | 44.7 (15.3) | 45.7 (15.1) |

| Median (range) | 43.8 (10–87) | 43.8 (18–81) | 45.9 (18–81) |

| IQR | 30.1–56.2 | 31.5–57.1 | 32.8–57.9 |

| Missing | 83 | 0 | 0 |

| N | 1474 | 582 | 441 |

| Gender | |||

| Male (%) | 574 (36.9) | 206 (35.4) | 162 (36.7) |

| Female (%) | 968 (62.2) | 365 (62.7) | 273 (61.9) |

| Missing (%) | 15 (1.0) | 11 (1.9) | 6 (1.4) |

| Total (%) | 1557 (100) | 582 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White (%) | 1211 (77.8) | 511 (87.8) | 390 (88.4) |

| Mixed – white and Black Caribbean (%) | 12 (0.8) | 5 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) |

| Mixed – white and Black African (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mixed – white and Asian (%) | 18 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other mixed background (%) | 6 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Asian – Indian (%) | 33 (2.1) | 11 (1.9) | 7 (1.6) |

| Asian – Pakistani (%) | 45 (2.9) | 26 (4.5) | 23 (5.2) |

| Asian – Bangladeshi (%) | 6 (0.4) | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) |

| Other Asian background (%) | 19 (1.2) | 5 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) |

| Black – Caribbean (%) | 5 (0.3) | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) |

| Black – African (%) | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| Other black background (%) | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Chinese (%) | 6 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Other ethnic group (%) | 11 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Not stated (%) | 87 (5.6) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing (%) | 90 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total (%) | 1,557 (100) | 582 (100) | 441 (100) |

Of those patients randomised, 220 (49.9%) were allocated to receive AL and 221 (50.1%) to receive Immersion PUVA. Of those allocated to AL, 201 (91.4%) were confirmed to have started treatment within 7 days post randomisation compared with 165 (74.7%) of those allocated to Immersion PUVA. A total of 132 (29.9%) participants were withdrawn or withdrew from the follow-up schedule or were reported as lost to follow-up, with 54 (24.5%) in the AL group and 78 (35.3%) in the Immersion PUVA group. A total of 441 (100.0%) participants were included in the ITT population.

Baseline characteristics

Patient characteristics were balanced across randomised treatment groups and are detailed in Tables 2 and 3. In summary, the study population had a median age of 46 years (range 18–81); 61.9% (n = 273) were female and 88.9% (n = 392) were of white ethnicity. The majority of participants had been suffering with CHE for more than 2 years [n = 311 (70.5%)], and 64.9% (n = 286) participants had predominantly hyperkeratotic CHE. Just over half of the patients were atopic, as verified by the presence of allergen-specific IgE [n = 227 (51.5%)]. The baseline DLQI score was dichotomised based on the NICE TA177 threshold for prescribing AL (≥ 15), and our results showed that the majority of participants recruited with severe CHE actually had a DLQI < 15 (n = 250, 56.7%), with a median [interquartile range (IQR)] of 13 (9–18).

| AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.5 (14.9) | 45.1 (15.2) | 45.8 (15.1) |

| Median (range) | 47.7 (20–81) | 44.6 (18–79) | 46.0 (18–81) |

| IQR | 33.5–58.7 | 31.9–56.8 | 32.9–58.0 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| N | 220 | 221 | 441 |

| Gender | |||

| Male (%) | 85 (38.6) | 77 (34.8) | 162 (36.7) |

| Female (%) | 132 (60.0) | 141 (63.8) | 273 (61.9) |

| Missing (%) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 6 (1.4) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| BMI (kg/m) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 30.1 (6.6) | 28.9 (5.8) | 29.5 (6.2) |

| Median (range) | 29.3 (18–69) | 28.5 (17–50) | 28.7 (17–69) |

| IQR | 25.5–34.0 | 24.9–32.3 | 25.2–33.2 |

| Missing | 9 | 8 | 17 |

| N | 211 | 213 | 424 |

| Participant’s smoking status | |||

| Non-smoker (%) | 89 (40.5) | 85 (38.5) | 174 (39.5) |

| Past smoker (%) | 79 (35.9) | 93 (42.1) | 172 (39.0) |

| Current smoker (%) | 52 (23.6) | 42 (19.0) | 94 (21.3) |

| Missing (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Are the feet involved as well? | |||

| Yes (%) | 57 (25.9) | 60 (27.1) | 117 (26.5) |

| No (%) | 163 (74.1) | 160 (72.4) | 323 (73.2) |

| Missing (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Filaggrin LOF mutation | |||

| No mutation (%) | 141 (64.1) | 126 (57.0) | 267 (60.5) |

| Mutation (%) | 27 (12.3) | 24 (10.9) | 51 (11.6) |

| Samples taken but mutation status could not be determined (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.5) |

| No sample available for analysis (%) | 52 (23.6) | 69 (31.2) | 121 (27.4) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| AL | Immersion PUVA (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin type | |||

| White (%) | 193 (87.7) | 199 (90.0) | 392 (88.9) |

| Fair (%) | 5 (2.3) | 2 (0.9) | 7 (1.6) |

| Dark (%) | 22 (10.0) | 20 (9.0) | 42 (9.5) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Duration of disease | |||

| < 6 months (%) | 6 (2.7) | 4 (1.8) | 10 (2.3) |

| 6–24 months (%) | 57 (25.9) | 63 (28.5) | 120 (27.2) |

| > 24 months (%) | 157 (71.4) | 154 (69.7) | 311 (70.5) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Clinical phenotype | |||

| Predominantly hyperkeratotic (%) | 143 (65.0) | 143 (64.7) | 286 (64.9) |

| Predominantly vesicular (%) | 62 (28.2) | 62 (28.1) | 124 (28.1) |

| Fingertip dermatitis (%) | 15 (6.8) | 16 (7.2) | 31 (7.0) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Presence of specific IgE | |||

| Yes (%) | 114 (51.8) | 113 (51.1) | 227 (51.5) |

| No (%) | 106 (48.2) | 107 (48.4) | 213 (48.3) |

| Missing (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Baseline DLQI (categorised)a | |||

| < 15 (%) | 121 (55.0) | 129 (58.4) | 250 (56.7) |

| ≥ 15 (%) | 99 (45.0) | 92 (41.6) | 191 (43.3) |

| Total (%) | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| Baseline DLQI (continuous) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.9 (6.8) | 13.6 (6.0) | 13.8 (6.4) |

| Median (range) | 13.0 (2–30) | 13.0 (2–30) | 13.0 (2–30) |

| IQR | 8.0–20.0 | 9.0–17.0 | 9.0–18.0 |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| N | 219 | 219 | 438 |

Outcomes

Primary end point – HECSI

At baseline, the median (IQR) HECSI was 55 (31.5–91.0). There was a slight imbalance, with the Immersion PUVA group having a lower median and IQR than the AL group (Table 4); however, the baseline score was included as a covariate in the analysis to account for any imbalance. At 12 weeks, both groups had a lower median HECSI score, with an overall median (IQR) of 20 (7.0–44.0). The median (IQR) HECSI score at 12 weeks was equal to 19 (6.0–44.0) in the AL group compared with 25 (8.0–53.0) in the Immersion PUVA group; however, it should be noted that there was a larger proportion of missing data in the Immersion PUVA group, with 33.5% (n = 74) missing compared with 23.2% (n = 51) in the AL group (see Table 4).

| AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Mean (SD) | 68.2 (47.5) | 62.2 (42.0) | 65.2 (44.9) |

| CV | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Median (range) | 57.0 (2–243) | 52.5 (2–206) | 55.0 (2–243) |

| IQR | 34.0–97.0 | 30.0–86.0 | 31.5–91.0 |

| Missing | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| N | 214 | 214 | 428 |

| 12 weeks | |||

| Mean (SD) | 30.4 (33.5) | 35.8 (38.4) | 32.9 (35.9) |

| CV | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Median (range) | 19.0 (0–196) | 25.0 (0–230) | 20.0 (0–230) |

| IQR | 6.0–44.0 | 8.0–53.0 | 7.0–44.0 |

| Missing | 51 | 74 | 125 |

| N | 169 | 147 | 316 |

| 24 weeks | |||

| Mean (SD) | 29.4 (34.3) | 23.3 (31.3) | 26.6 (33.0) |

| CV | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Median (range) | 17.5 (0–205) | 9.0 (0–168) | 13.0 (0–205) |

| IQR | 6.0–40.0 | 4.0–30.0 | 5.0–35.0 |

| Missing | 84 | 106 | 190 |

| N | 136 | 115 | 251 |

| 52 weeks | |||

| Mean (SD) | 23.8 (35.9) | 20.1 (26.6) | 22.1 (32.0) |

| CV | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Median (range) | 12.0 (0–269) | 8.5 (0–120) | 10.0 (0–269) |

| IQR | 4.0–25.0 | 4.0–24.0 | 4.0–25.0 |

| Missing | 111 | 131 | 242 |

| N | 109 | 90 | 199 |

Table 4 demonstrates that the CV for the HECSI score during follow-up ranged from 1.1 to 1.4, which is broadly in line with the original sample size calculation assumption of 1.2.

For those with observed data at 12 weeks, the median (IQR) change in score from baseline was equal to −30 (−61 to −10) for the AL group, compared with −20 (−47 to −2) in the Immersion PUVA group (Table 5). In terms of a relative change, the median (IQR) score at 12 weeks was equal to 30% (10–70%) of that at baseline for the AL group compared with 50% (20–100%) in the Immersion PUVA group (see Table 5). At 24 and 52 weeks, the overall median (IQR) score compared with that at baseline was equal to 30% (10–60%) and 20% (10–50%), respectively (see Table 5).

| Absolute change from baseline | Relative change from baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | |

| 12 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | −37.5 (45.0) | −25.8 (46.1) | −32.0 (45.8) | 0.7 (2.4) | 0.8 (2.0) | 0.8 (2.2) |

| Median (range) | −30.0 (−222 to 99) | −20.0 (−150 to 220) | −27.0 (−222 to 220) | 0.3 (0–30) | 0.5 (0–23) | 0.4 (0–30) |

| IQR | −61.0 to −10.0 | −47.0 to −2.0 | −57.0 to −6.0 | 0.1–0.7 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.1–0.8 |

| Missing | 57 | 76 | 133 | 57 | 76 | 133 |

| N | 163 | 145 | 308 | 163 | 145 | 308 |

| 24 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | −39.3 (46.2) | −42.1 (46.8) | −40.6 (46.4) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) |

| Median (range) | −37.0 (−191 to 90) | −32.0 (−180 to 104) | −34.0 (−191 to 104) | 0.3 (0–5) | 0.2 (0–4) | 0.3 (0–5) |

| IQR | −65.0 to −12.0 | −70.0 to −13.0 | −66.0 to −12.0 | 0.1–0.6 | 0.1–0.6 | 0.1–0.6 |

| Missing | 89 | 108 | 197 | 89 | 108 | 197 |

| N | 131 | 113 | 244 | 131 | 113 | 244 |

| 52 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | −46.8 (43.5) | −39.9 (43.3) | −43.6 (43.4) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.9) |

| Median (range) | −43.0 (−152 to 112) | −35.0 (−184 to 74) | −38.0 (−184 to 112) | 0.2 (0–4) | 0.2 (0–9) | 0.2 (0–9) |

| IQR | −69.0 to −20.5 | −60.0 to −13.0 | −62.0 to −16.0 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.1–0.6 | 0.1–0.5 |

| Missing | 116 | 132 | 248 | 116 | 132 | 248 |

| N | 104 | 89 | 193 | 104 | 89 | 193 |

The results of fitting a linear mixed model to log(HECSI + 1) show that there was a statistically significant benefit of AL compared with Immersion PUVA at 12 weeks, with an estimate of the fold change of 0.66 (0.52 to 0.82), p = 0.0003 at 12 weeks (Table 6). This is equivalent to a fold change of 1.52 (1.22 to 1.92) for Immersion PUVA compared with AL at 12 weeks. This CI includes the target treatment effect of a fold change equal to 1.3. The estimated parameters of the full model are included in Appendix 2 – Clinical results supplementary tables and figures, Table 39.

| Time since planned start of treatment (weeks) | Randomisation allocation | Adjusted mean log(HECSI + 1) scores (95% CI) | Treatment comparison | Difference in adjusted mean log(HECSI + 1) scores (95% CI) | Adjusted fold change (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | AL | 3.12 (2.81 to 3.42) | Immersion PUVA | −0.29 (−0.46 to −0.11) | 0.75 (0.63 to 0.89) | . |

| 4 | Immersion PUVA | 3.40 (3.09 to 3.72) | . | . | ||

| 8 | AL | 2.83 (2.53 to 3.13) | Immersion PUVA | −0.35 (−0.52 to −0.19) | 0.70 (0.60 to 0.83) | . |

| 8 | Immersion PUVA | 3.18 (2.87 to 3.49) | . | . | ||

| 12 | AL | 2.54 (2.22 to 2.85) | Immersion PUVA | −0.42 (−0.65 to −0.19) | 0.66 (0.52 to 0.82) | 0.0003 |

| 12 | Immersion PUVA | 2.96 (2.63 to 3.29) | . | . |

Secondary objective – hand eczema severity index over 52 weeks

The results of fitting a linear mixed model to log(HECSI + 1) collected over the full 52 weeks show that there is no evidence of a difference between AL and Immersion PUVA at 24 weeks, with the estimate of the fold change (95% CI) equal to 0.92 (0.798 to 1.08) (Figure 4). At 52 weeks, there continues to be no evidence of a difference between AL and Immersion PUVA, with the estimated fold change (95% CI) equal to 1.27 (0.97 to 1.67) (see Figure 4). The estimated parameters of the full model are included in Table 40. The adjusted mean log(HECSI + 1) scores and corresponding differences by treatment arm are included in Table 41.

FIGURE 4.

Estimated fold change in HECSI + 1 scores (AL vs. Immersion PUVA), with ongoing treatment decision up to 24 weeks used as auxiliary variable.

Secondary objective – mTLSS over 52 weeks

At baseline, the median (IQR) mTLSS score was equal to 12 (9–15), and the distribution of scores between randomised treatment groups was similar. At 12 weeks, both groups had a lower median mTLSS score, with an overall median (IQR) of 6 (3–10) (Table 7). The overall median (IQR) reduction in mTLSS was equal to 5 (2–8) at 12 weeks and equal to 6 (3–10) at 52 weeks (see Table 7). The proportions of missing data at each time point were similar to that observed for the primary end point.

| Raw score | Absolute difference from baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | |

| Baseline | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 11.4 (4.3) | 11.7 (4.2) | 11.5 (4.2) | |||

| Median (range) | 12.0 (0–21) | 12.0 (0–20) | 12.0 (0–21) | |||

| IQR | 8.5–14.0 | 9.0–15.0 | 9.0–15.0 | |||

| Missing | 0 | 4 | 4 | |||

| N | 220 | 217 | 437 | |||

| 12 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (4.3) | 7.0 (4.7) | 6.5 (4.5) | −5.4 (4.9) | −4.7 (4.9) | −5.1 (4.9) |

| Median (range) | 5.0 (0–18) | 6.5 (0–21) | 6.0 (0–21) | −6.0 (−16 to 8) | −4.0 (−17 to 12) | −5.0 (−17 to 12) |

| IQR | 3.0–9.0 | 3.0–10.0 | 3.0–10.0 | −8.0 to −2.0 | −8.0 to −2.0 | −8.0 to −2.0 |

| Missing | 50 | 75 | 125 | 50 | 77 | 127 |

| N | 170 | 146 | 316 | 170 | 144 | 314 |

| 24 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (4.2) | 5.0 (3.8) | 5.6 (4.0) | −5.5 (5.2) | −7.1 (4.8) | −6.2 (5.1) |

| Median (range) | 6.0 (0–19) | 4.0 (0–14) | 5.0 (0–19) | −6.0 (−18 to 9) | −7.0 (−19 to 3) | −6.0 (−19 to 9) |

| IQR | 3.0–9.0 | 2.0–8.0 | 3.0–8.0 | −9.0 to −2.0 | −10.0 to −3.5 | −10.0 to −3.0 |

| Missing | 89 | 107 | 196 | 89 | 109 | 198 |

| N | 131 | 114 | 245 | 131 | 112 | 243 |

| 52 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.1 (4.0) | 4.9 (4.2) | 5.0 (4.1) | −6.3 (4.9) | −6.7 (4.8) | −6.5 (4.9) |

| Median (range) | 4.5 (0–21) | 4.0 (0–15) | 4.0 (0–21) | −6.0 (−17 to 6) | −7.0 (−18 to 8) | −6.0 (−18 to 8) |

| IQR | 2.0–7.0 | 2.0–8.0 | 2.0–7.0 | −10.0 to −3.0 | −10.0 to −3.0 | −10.0 to −3.0 |

| Missing | 77 | 96 | 173 | 77 | 96 | 232 |

| N | 114 | 95 | 209 | 114 | 95 | 209 |

After fitting a linear mixed model to the mTLSS scores collected over 52 weeks, the results show that there was no evidence of a difference between treatment groups over 52 weeks, with each CI for the estimated difference at each time point including 0 (no difference) (Table 8). Note that model checking gave slight concern that the residuals might deviate from the normal distribution due to a potential floor effect; however, a sensitivity analysis on transformed scores (square root) led to consistent conclusions with the untransformed data. The estimated parameters of the full model are included in Table 42.

| Time since planned start of treatment (weeks) | Randomisation allocation | Adjusted mean mTLSS scores (95% CI) | Treatment comparison | Difference in adjusted mean mTLSS scores (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | AL | 5.50 (4.24 to 6.76) | Immersion PUVA | −0.37 (−1.23 to 0.48) |

| 12 | Immersion PUVA | 5.87 (4.68 to 7.07) | . | |

| 24 | AL | 5.18 (3.98 to 6.37) | Immersion PUVA | −0.14 (−0.84 to 0.56) |

| 24 | Immersion PUVA | 5.31 (4.15 to 6.48) | . | |

| 52 | AL | 4.42 (3.16 to 5.68) | Immersion PUVA | 0.41 (−0.59 to 1.40) |

| 52 | Immersion PUVA | 4.01 (2.62 to 5.40) | . |

Secondary objective – Physician’s Global Assessment over 52 weeks

At 12 weeks, the proportion of participants with available data who had achieved clear or almost clear according to the blinded assessor was equal to 27.6% (47/170) for the AL group and 23.6% (35/148) for the Immersion PUVA group (Table 9). Over the full 52 weeks, 59.4% (123/207) of AL participants with available data achieved at least one clear/almost clear assessment compared with 61.5% (118/192) of those in the Immersion PUVA group with available data (Table 10).

| AL (%) | Immersion PUVA (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 weeks | |||

| Clear | 14 (6.4) | 10 (4.5) | 24 (5.4) |

| Almost clear | 33 (15.0) | 25 (11.3) | 58 (13.2) |

| Mild | 37 (16.8) | 29 (13.1) | 66 (15.0) |

| Moderate | 62 (28.2) | 52 (23.5) | 114 (25.9) |

| Severe | 24 (10.9) | 32 (14.5) | 56 (12.7) |

| Missing | 50 (22.7) | 73 (33.0) | 123 (27.9) |

| Total | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| 24 weeks | |||

| Clear | 9 (4.1) | 10 (4.5) | 19 (4.3) |

| Almost clear | 24 (10.9) | 39 (17.6) | 63 (14.3) |

| Mild | 37 (16.8) | 23 (10.4) | 60 (13.6) |

| Moderate | 58 (26.4) | 29 (13.1) | 87 (19.7) |

| Severe | 9 (4.1) | 15 (6.8) | 24 (5.4) |

| Missing | 83 (37.7) | 105 (47.5) | 188 (42.6) |

| Total | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| 52 weeks | |||

| Clear | 9 (4.1) | 12 (5.4) | 21 (4.8) |

| Almost clear | 33 (15.0) | 27 (12.2) | 60 (13.6) |

| Mild | 31 (14.1) | 25 (11.3) | 56 (12.7) |

| Moderate | 28 (12.7) | 21 (9.5) | 49 (11.1) |

| Severe | 6 (2.7) | 8 (3.6) | 14 (3.2) |

| Missing | 113 (51.4) | 128 (57.9) | 241 (54.6) |

| Total | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

| AL (%) | Immersion PUVA (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGA | |||

| Clear | 50 (22.7) | 49 (22.2) | 99 (22.4) |

| Almost clear | 73 (33.2) | 69 (31.2) | 142 (32.2) |

| Mild | 45 (20.5) | 37 (16.7) | 82 (18.6) |

| Moderate | 30 (13.6) | 28 (12.7) | 58 (13.2) |

| Severe | 9 (4.1) | 9 (4.1) | 18 (4.1) |

| Missing | 13 (5.9) | 29 (13.1) | 42 (9.5) |

| Total | 220 (100) | 221 (100) | 441 (100) |

After fitting an ordinal logistic mixed model, the results show that there was no evidence of a difference between treatment groups over 52 weeks, with the CI at each time point for the estimated odds ratios (AL vs. Immersion PUVA) for achieving lower PGA scores including 1 (no difference) (Table 11). The estimated parameters of the full model are included in Table 43.

| Randomisation allocation | Treatment comparison | Time since planned start of treatment (weeks) | Estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | Immersion PUVA | 12 weeks | 1.22 | (0.90 to 1.64) |

| AL | Immersion PUVA | 24 weeks | 1.18 | (0.89 to 1.56) |

| AL | Immersion PUVA | 52 weeks | 1.10 | (0.64 to 1.89) |

Secondary objective – DLQI over 52 weeks

At baseline, the median (IQR) DLQI score was 13 (9–18), and the distribution of scores between randomised treatment groups was similar. At 12 weeks, both groups had a lower median DLQI score, with an overall median (IQR) of 4 (1–9) (Table 12). At 12 weeks, the median (IQR) reduction was equal to 7 (3–12), and at 24 and 52 weeks, the median (IQR) reduction was equal to 9 (5–13) and 9 (6–14), respectively (see Table 12). At 12 weeks, the proportion of missing data overall was lower than the blinded assessments (primary end point), with 16.8% (37/220) in the AL group, 27.1% (60/221) in the Immersion PUVA group and 22.0% (97/441) overall (see Table 12).

| Raw score | Absolute difference from baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | |

| Baseline | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 13.9 (6.8) | 13.6 (6.0) | 13.8 (6.4) | |||

| Median (range) | 13.0 (2–30) | 13.0 (2–30) | 13.0 (2–30) | |||

| IQR | 8.0–20.0 | 9.0–17.0 | 9.0–18.0 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| N | 219 | 219 | 438 | |||

| 12 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (5.8) | 6.7 (6.2) | 5.9 (6.1) | −8.3 (7.1) | −6.7 (6.5) | −7.6 (6.9) |

| Median (range) | 3.0 (0–30) | 5.0 (0–30) | 4.0 (0–30) | −7.0 (−30 to 9) | −6.0 (−30 to 8) | −7.0 (−30 to 9) |

| IQR | 1.0–8.0 | 2.0–9.0 | 1.0–9.0 | −12.0 to −4.0 | −10.5 to −3.0 | −12.0 to −3.0 |

| Missing | 37 | 60 | 97 | 38 | 61 | 99 |

| N | 183 | 161 | 344 | 182 | 160 | 342 |

| 24 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.7 (4.8) | 4.0 (4.7) | 4.4 (4.7) | −9.0 (7.1) | −9.6 (5.9) | −9.3 (6.6) |

| Median (range) | 3.0 (0–25) | 2.0 (0–27) | 3.0 (0–27) | −8.0 (−30 to 7) | −9.0 (−30 to 3) | −9.0 (−30 to 7) |

| IQR | 1.0–7.0 | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–7.0 | −14.0 to −4.0 | −13.0 to −6.0 | −13.0 to −5.0 |

| Missing | 62 | 82 | 144 | 63 | 83 | 146 |

| N | 158 | 139 | 297 | 157 | 138 | 295 |

| 52 weeks | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.2 (4.9) | 4.3 (4.8) | 4.2 (4.9) | −9.3 (6.9) | −9.5 (5.9) | −9.4 (6.5) |

| Median (range) | 2.0 (0–24) | 3.0 (0–29) | 3.0 (0–29) | −9.0 (−29 to 13) | −9.0 (−30 to 6) | −9.0 (−30 to 13) |

| IQR | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–6.0 | −15.0 to −4.0 | −12.5 to −6.0 | −14.0 to −6.0 |

| Missing | 92 | 117 | 209 | 93 | 117 | 210 |

| N | 128 | 104 | 232 | 127 | 104 | 231 |

After fitting a linear mixed model to the DLQI scores collected over 52 weeks, the model results are broadly consistent with the analysis of the primary end point, such that there is a statistically significant benefit of AL compared with Immersion PUVA at 12 weeks, with mean scores estimated to be 0.95 (CI 0.09 to 1.82) lower (Table 13). The model suggests that there is no statistically significant treatment effect at 24 weeks [estimated difference in mean scores = −0.18 (−0.92 to 0.56)], but at 52 weeks, there is a statistically significant treatment effect, with an estimated increase in the AL group of 1.62 (0.62 to 2.62) compared with the Immersion PUVA group (see Table 13). Note that as with the analysis of the mTLSS end point, model checking gave slight concern that the residuals might deviate from the normal distribution due to a potential floor effect; however, a sensitivity analysis analysing transformed scores (log transformation) led to consistent conclusions with the untransformed data. The estimated parameters of the full model are included in Table 44.

| Time since planned start of treatment (weeks) | Randomisation allocation | Adjusted mean DLQI scores (95% CI) | Treatment comparison | Difference in adjusted mean DLQI scores (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | AL | 5.46 (4.10 to 6.81) | Immersion PUVA | −0.95 (−1.82 to −0.09) |

| 12 | Immersion PUVA | 6.41 (4.96 to 7.86) | . | |

| 24 | AL | 5.10 (3.77 to 6.43) | Immersion PUVA | −0.18 (−0.92 to 0.56) |

| 24 | Immersion PUVA | 5.28 (3.88 to 6.68) | . | |

| 52 | AL | 4.25 (2.83 to 5.67) | Immersion PUVA | 1.62 (0.62 to 2.62) |

| 52 | Immersion PUVA | 2.63 (1.17 to 4.09) | . |

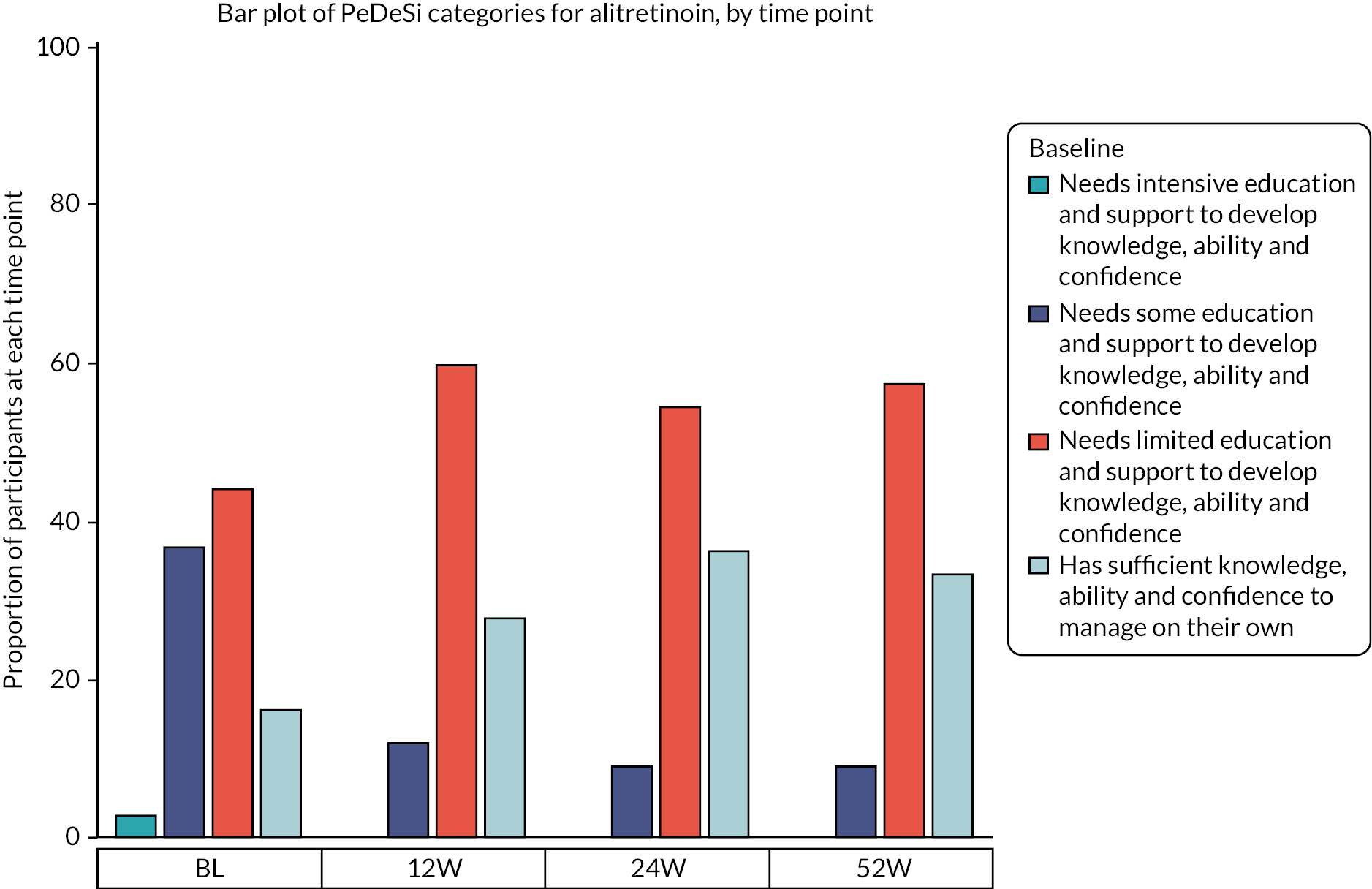

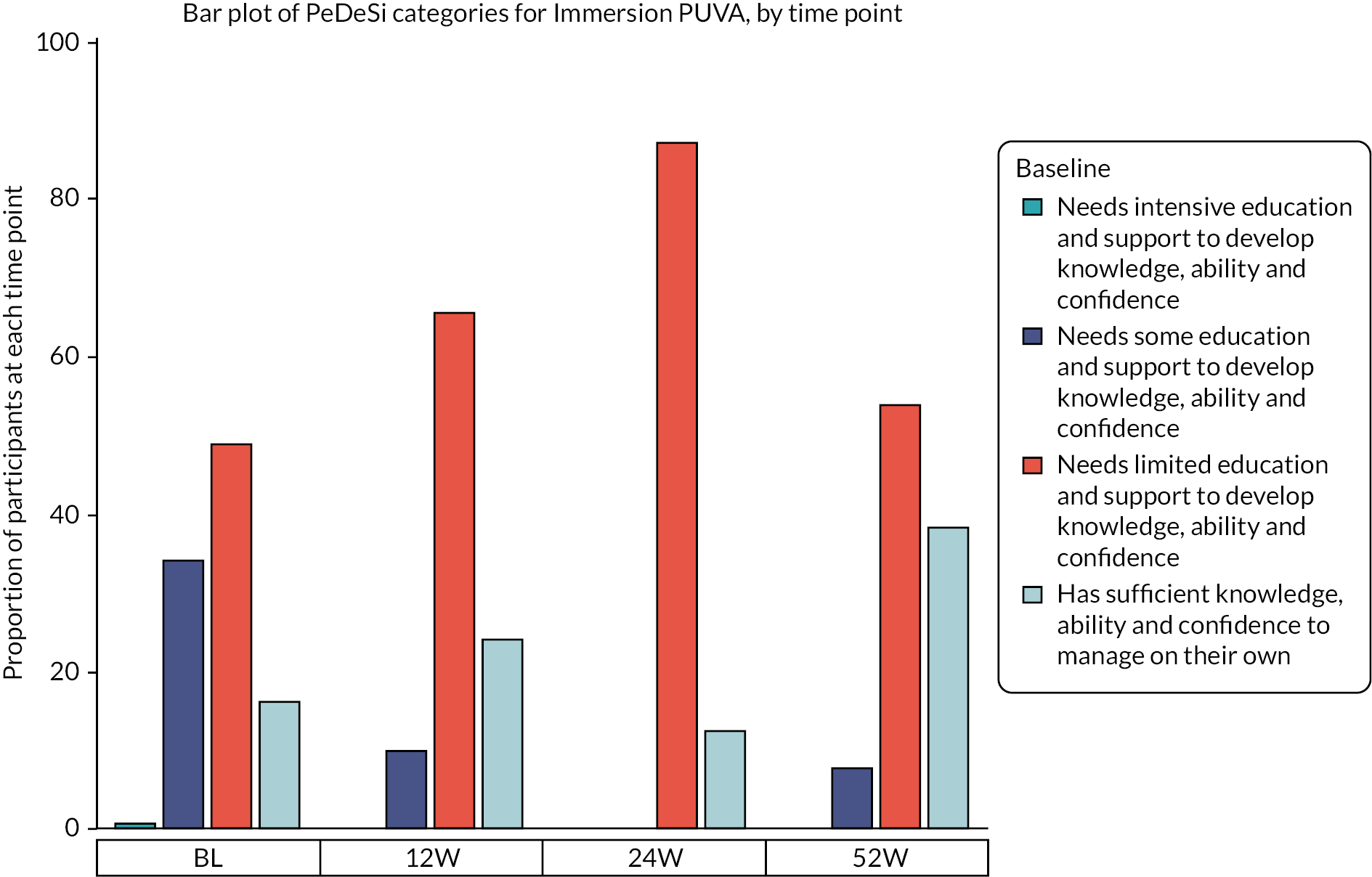

Secondary objective – PeDeSI over 52 weeks

At baseline, just 16.1% (n = 71) were assessed as having sufficient knowledge, ability and confidence to manage their condition on their own according to the PeDeSI, with a similar distribution of education needs across the treatment groups (Figures 5 and 6). At 12 weeks, the proportion of participants with available data who had sufficient knowledge and education was equal to 26.2% (117/324), with 28.0% (49/175) in the AL group and 24.2% (36/149) in the Immersion PUVA group (Appendix 2, Table 45). The results observed at 24 weeks should be treated with caution due to the smaller number of participants who provided data at 24 weeks instead of at 52 weeks due to the protocol amendment.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of PeDeSI categories over time, AL.

FIGURE 6.

Distribution of PeDeSI categories over time, Immersion PUVA.

After fitting an ordinal logistic mixed model to the PeDeSI scores at 12 weeks, the results show that there was no evidence of a difference in terms of educational need between treatment groups at 12 weeks, with an estimated odds ratio (AL vs. Immersion PUVA) for lower educational need (i.e. higher PeDeSI score) of 0.65 (CI 0.39 to 1.08) (Appendix 2 – Clinical results supplementary tables and figures, Table 46).

Secondary objective – Patient Benefit Index (hand eczema) over 52 weeks

The PBI-HE was derived in relation to identified needs at baseline. At 12 weeks, the median (IQR) score was equal to 2.3 (1.4–3.2) in the AL group and 1.9 (0.9–2.8) in the Immersion PUVA group (Table 14). A PBI score > 1 is considered to show a treatment benefit. At 24 weeks, the median (IQR) score was unchanged at 2.3 (1.2–3.5) in the AL group but had increased to 2.8 (1.4–3.5) in the Immersion PUVA group (see Table 14). At 52 weeks, the median (IQR) score was equal to 2.6 (1.6–3.3) in the AL group and 3.0 (1.7–3.6) in the Immersion PUVA group (see Table 14). These results are purely descriptive and should be treated with caution, given the high proportion of missing data at each visit.

| AL | Immersion PUVA | Total | |