Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number HTA 16/31/98. The contractual start date was in March 2018. The draft report began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in November 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Blair et al. This work was produced by Blair et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Blair et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Structure of this report

In Chapter 1, the background to the research and rationale for reducing antibiotic prescriptions through use of a complex intervention is presented. Chapter 2 describes the methods employed including the details of the intervention, recruitment, outcome measures, how the data were collected, the internal pilot and the study design. Chapter 3 presents the clinical results of the study, Chapter 4 the qualitative findings and Chapter 5 the economic evaluation. Chapter 6 discusses the efficient design of the study including the facilitators and barriers to such a design. Chapter 7 presents the discussion and conclusions.

Background

Antibiotic prescribing

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) in children present a major resource implication for primary health-care services internationally for five reasons. First, they are extremely common and costly to service providers, families and employers. 1,2 Second, there is clinical uncertainty in primary care regarding the diagnosis and best management of RTIs, as reflected by the variation in the use of antibiotics in primary care for RTIs between nations,3 general practitioner (GP) practices4 and clinicians. 5 Third, antibiotic prescribing by primary care clinicians in the United Kingdom (UK) remains significantly higher than in some of our European neighbours. 6 Fourth, the overuse and misuse of existing antibiotics, combined with the slowing in the development of new antibiotics, are associated with the development and proliferation of antimicrobial resistance between7 and within8 nations as well as individuals. 6,9,10 Finally, the use of antibiotics leads to the subsequent ‘medicalisation of illness’ in which patients believe they should consult for similar symptoms in the future. 11 A number of key publications have highlighted the need for more research to define the appropriate use of antibiotics and healthcare resources for RTIs if the public health disaster of ineffective antibiotics for serious infections is to be averted. 12–14

Findings from the TARGET programme

The design of the CHIldren with Cough (CHICO) trial’s intervention was borne out of evidence from the TARGET programme’s earlier work streams. This has involved data synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence,15–19 a qualitative investigation to understand both parents’ information needs and influences on clinical decisions surrounding antibiotic prescribing, quantitative evidence in terms of a large multicentre, prospective cohort study (over 8300 children) to derive and internally validate a clinical rule to predict hospitalisation of children with RTIs,20,21 and the development of an intervention informed by a critical synthesis of all findings. 22 This culminated in a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) study to measure the acceptability of using symptoms, signs and demographic characteristics to predict hospital admittance in children presenting to primary care with RTI. 23,24 Findings across the TARGET programme were synthesised using Greene and Kreuter’s Precede-Proceed model which integrates across several behavioural theories into a unified model. 25

Qualitative work from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) TARGET programme for Applied Research in 2016 identified clinician uncertainty as a major driver of antibiotic prescribing. Primary care clinicians acknowledge that they prescribe antibiotics for a range of medical and non-medical reasons, particularly in children, who are seen as vulnerable26 and whose clinical state can change rapidly. Many clinicians report that they prescribe antibiotics just in case to mitigate perceived risk of future hospital admission and complications. 19,26 Our earlier programme work indicated that improved identification of children at very low risk of future hospitalisation could increase confidence to withhold antibiotics in low-risk groups. 15,16 Clinical prediction rules are designed to reduce clinical uncertainty in an outcome (such as a child’s risk of hospitalisation) by assessing the strength of association between the risk of it occurring and baseline characteristics (e.g. sociodemographic characteristics or symptoms and signs of illness).

Clinical prediction rule for hospitalisation

The TARGET cohort study aimed to identify symptoms, signs and demographic characteristics that may predict hospitalisation and poor prognosis of a child. In particular, such an algorithm could potentially identify a large group of children at very low risk of hospitalisation and therefore are potentially unlikely to require antibiotics.

In line with expectations, just under 1% of the children were admitted to hospital up to 30 days after their consultation with the primary care clinician. We found seven characteristics independently associated with increased risk of hospitalisation for their acute cough or RTI during the subsequent 30 days. These are described by the STARWAVe mnemonic: Short illness duration (parent reported ≤ 3 days), Temperature (parent reported severe in previous 24 hours or ≥ 37.8° on examination), Age of patient (< 2 years), Recession (intercostal or subcostal on examination), Wheeze (on listing to chest with stethoscope), Asthma (currently diagnosed) and Vomiting (parent reported moderate or severe in the 24 hours prior to consultation). The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the coefficient-based algorithm was 0.82 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77 to 0.87].

The prediction rule identifies children at very low, medium and high risk of future hospitalisation with advice given on how the clinician can use this information in conjunction with their own clinical judgement to decide the best course of action for each child. Assigning one point per predictive characteristic, a points-based algorithm was used to quantify absolute probabilities to three groups: (1) ‘very low’ (0.3%, 95% CI 0.2% to 0.4%) scoring 0 or 1 point; (2) ‘normal’ (1.5%, 1.0% to 1.9%) scoring 2 or 3 points and (3) ‘high’ (11.8%, 7.3% to 16.2%) scoring ≥ 4 points. The rule can potentially be effective in both reducing the overall prescription of antibiotics by increasing clinician confidence that they are not needed ‘just in case’ in the very low-risk group (just under 70% of children are in this group), as well as better identify those children in need of close monitoring (2% of children are in the high-risk group). Children in the medium-risk group (29%) have a similar risk of future hospitalisation as all children combined, so management should follow current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,27 which state that clinicians should decide on the use of immediate, delayed or no antibiotics based on their assessment of the child’s illness severity.

The interaction within the consultation

Our finding from our qualitative reviews was that clinicians could misinterpret parent’s communication about their concerns or ideas regarding their child’s illness as pressure for antibiotics and in some cases this led to unnecessary or unwanted antibiotics being prescribed. 26 Clinician communication was focused on differentiating minor and more serious illnesses, with the message (both implicit and explicit) that viral illnesses were minor while those that were ‘serious’ were treated with antibiotics. Clinicians and parents were often talking at cross purposes about the seriousness of the illness; parents emphasising the severity of the symptoms to demonstrate the impact on child health and to justify the consultation; clinicians seeking to justify a no-antibiotic treatment decision by minimising the problem.

The findings of our qualitative study suggested that parents want better information on the symptoms and signs of serious RTIs and when to consult,28 along with more useful advice on home management of symptoms. 29 Parents did not want to know the absolute risk of hospitalisation for their child but they did want advice and information specific to their child. 29 When parents did consult, clinician explanations of diagnosis and treatment recommendations were not well understood by parents, and they remained unclear about how to manage a RTI and when to consult. 27–29 Clinicians reported that most often they gave a simple viral diagnosis, communicating that the illness was self-limiting and did not need antibiotic treatment. 29 However, if the child’s illness appeared severe to the parent, or the parent was concerned about particular symptoms or impacts which were not addressed by the clinician, the parent reported viewing a simple viral diagnosis as inadequate. Parents’ concerns encompassed things that fell outside a simple biomedical model for RTIs, including both child health and psychosocial impacts, but reported that clinicians rarely addressed these.

The feasibility study and an ‘efficient’ design

In the feasibility trial, the intervention group antibiotic prescribing rate at consultation was 25% (compared to 37% in our earlier cohort study); however, among the control group, the overall prescribing rate was even lower at 16%. The paradoxical effects found in the feasibility study were largely explained by a post-randomisation recruitment differential, with possible Hawthorne effects. 24 In the intervention arm, there was a significantly higher recruitment rate, difference in clinician type (proportionally more practice nurses recruiting), the children were significantly younger and importantly the intervention children were more unwell at baseline (significantly higher respiratory rate, significantly higher wheeze prevalence and significantly higher parent and clinician global illness severity scores). Learning from these lessons, we proposed a more ‘efficient’ study design that would not only mitigate recruitment differential but would also be resource efficient, using an intervention designed to be replicable for the National Health Service (NHS). Rather than recruit patients and collect consent during consultation we conducted the CHICO RCT at the practice level (as a cluster RCT) using Clinical Commission Groups (CCGs) and the national NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) to recruit practices. Rather than trawl through the practice notes to collect primary outcome data we utilised routinely collected data (dispensing data collected by NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA) ePACT230 and hospitalisation rates for RTI collected by CCGs). We also took a ‘lighter touch’ to data collection using short baseline and follow-up questionnaires filled in by the practice champion (GP, nurse, practice manager or pharmacist) and embedded the intervention within the practice system rather than as a stand-alone tool. This both reduced the time it takes to open and close the tool and had the advantage of utilising data already within the system and incorporating data entered as part of the trial into the practice system, thus, not duplicating clinical work. The barriers and facilitators to this efficient design approach are reported in Chapter 6.

Rationale

Antimicrobial resistance is recognised by the UK government, governments around the world and the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the most pressing public health threats of our time. Around 80% of antibiotics prescribed for human consumption are prescribed in primary care,31 and it has been estimated that around 50% of antibiotic prescribing in this setting is unnecessary. 32 Approaches to modify antibiotic prescribing in primary care have been developed and evaluated, and prescribing rates in England have declined slightly using figures from 2014 to 2015,31 although antibiotic prescribing rates in the UK continue to be substantially higher than many other European countries. 6 The UK Five Year Anti-Microbial Resistance (AMR) Strategy 2013–2018 aims to conserve the effectiveness of existing antibiotics through effective antimicrobial stewardship, including reducing the inappropriate use of antibiotics. There is, therefore, an urgent need for an efficient intervention that can be rolled out at scale that safely addresses many of the key drivers of antibiotic prescribing in children. Recent papers suggest cluster randomised trials aimed at reducing antibiotics may be implemented efficiently in large samples from routine care settings by using primary care electronic health records in the UK. 33–35 We are aware of two ongoing studies: the first investigating the effects of an integrated package of interventions (including delayed prescribing; patient decision aids; communication training; patient information leaflets; and near-patient testing with C-reactive protein)36 and the second (an ‘efficient design’ study) investigating the effects of a multifaceted intervention consisting of practice antibiotic prescribing feedback, delivery of educational and decision support tools and a webinar to explain and promote the intervention. 37 Both studies focus on the general rather than the paediatric population and have different components compared to our complex intervention. Primary care clinicians38 and the research community39 have called for the development of a sound evidence base, currently unavailable, to help them identify children at low and high risk of complications, especially serious complications such as pneumonia, that require hospitalisation. At a minimum, it is essential to demonstrate that any change in practice does not increase the number of children with serious complications. A change in practice should improve health outcomes for children, while distinguishing children for whom antibiotics are certainly not needed and providing precise information regarding the symptoms denoting poor prognosis for which parents should be vigilant.

Aims and objectives

Aim

The aim of the CHICO RCT is to reduce antibiotic prescribing among children presenting with cough or RTI without increasing hospital admission for this condition. Objectives pertain to the practice level, as no data was collected on individual participants.

Primary objectives

To determine:

-

Whether the CHICO intervention decreases the number of paediatric formulation antibiotic suspension items dispensed for RTIs to children presenting with acute cough and RTI to primary care (superiority comparison).

-

Whether the CHICO intervention results in no change in hospital admissions for children with a hospital diagnosis of RTI (non-inferiority comparison).

Secondary objectives

To determine:

-

Whether the CHICO intervention results in no change in the accident and emergency (A&E) attendance rates of children with a hospital diagnosis of RTI (superiority comparison).

-

The costs to the NHS for using the CHICO intervention.

-

Whether any intervention effect is modified by the proportion of locums used.

-

Whether any intervention effect is modified by the practices’ prior antibiotic prescribing rate.

-

Whether any intervention effect differs between GP and nurse prescribers.

-

Whether any intervention effect differs between practices with 1 versus 2+ sites.

-

Whether any intervention effect differs within child age groups.

-

Whether any intervention effect differs between practices and over time.

-

Whether the embedded CHICO intervention is acceptable to, and used by, primary care clinicians (GPs and nurses) in consultations with carers and their children and how does this vary between practices.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The CHICO RCT is an efficient, pragmatic, open-label, parallel, two-arm (intervention vs. control) cluster randomised trial with an embedded qualitative study and health economics. The trial aimed at reducing antibiotic prescribing among children presenting with acute cough and RTI, with randomisation at the practice level, using routine antibiotic dispensing to assess effectiveness and hospitalisation data for RTI to assess non-inferiority. Randomisation of practices, to the two arms, was 1 : 1 with no involvement, or consent, from participants within them. The CHICO trial protocol has been published. 40

Ethics approval and registration

The study received North of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval on 29 October 2018 and by Health Research Authority at London-Camden and Kings Cross REC (ref: 18/LO/0345) on 14 November 2018. Trial Registration Number: ISRCTN11405239. This contains all items required to comply with the WHO Trial Registration Data Set. Any amendments to the protocol were reported accordingly to the regulatory bodies.

Practice systems

Egton Medical Information Systems (EMIS®) or EMIS® Health or EMISWeb (formerly known as Egton Medical Information Systems) supplies electronic patient record systems and software used in primary care in England. It is used in more than half the practices (56%) in England. 41 The intervention was embedded in the EMIS® system including pop-ups to identify children that may be eligible for the trial. The facilitators and barriers to this approach are reported in the results section.

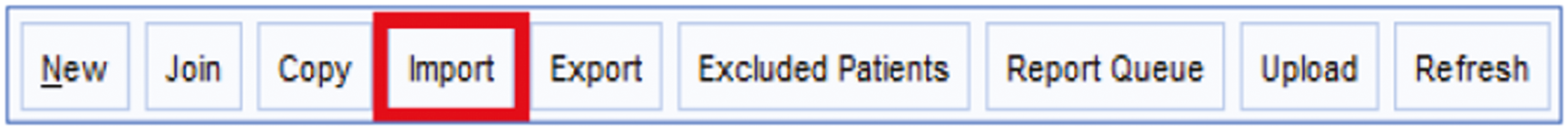

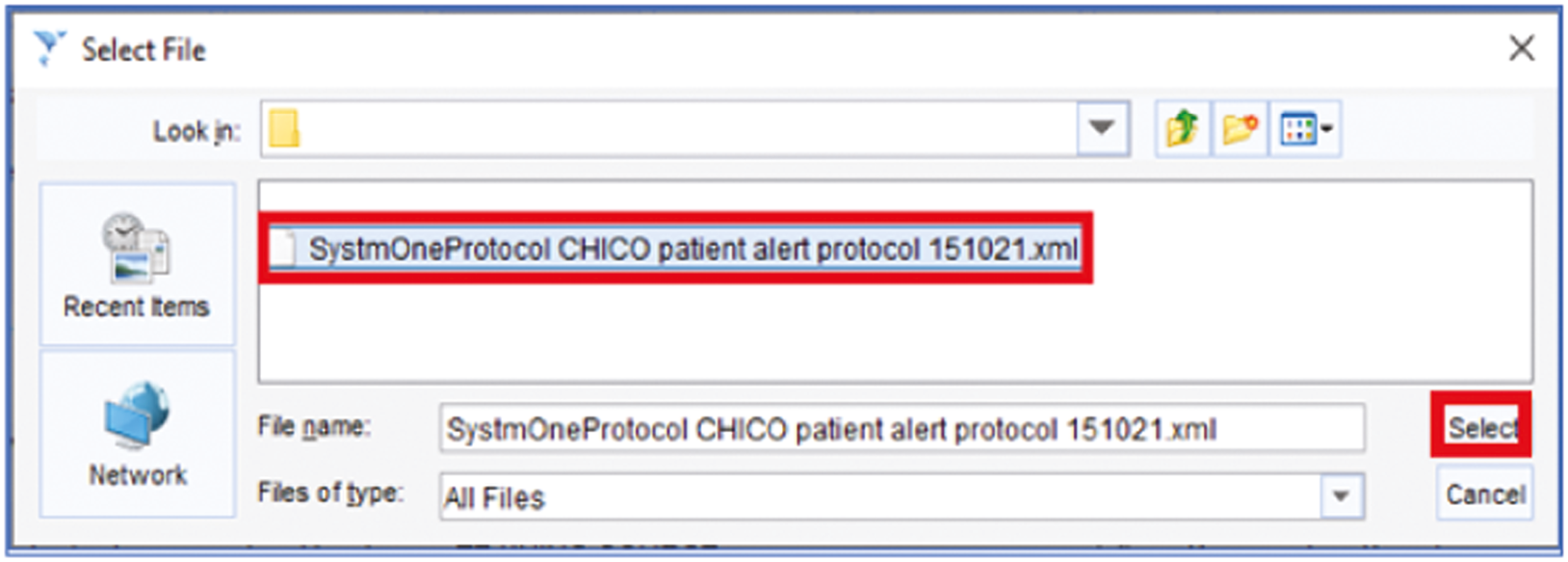

As a separate scoping exercise to inform future dissemination, we contacted users or experts in SystmOne (covers 34% of practices)41 and reported in the results section the potential of embedding the intervention in this system.

Recruitment sites and site training

Given we needed access to CCGs to obtain primary outcome data, we endeavoured to recruit CCGs to the study first and then the practices within these CCGs. In 2018, there were over 200 CCGs in England and between 10 and 80 practices per CCG. For recruitment of CCGs, we focused on those having 15 or more EMIS® practices. One of our co-investigators (EB) is a national project lead for healthcare-acquired infections and antimicrobial resistance at NHS England and co-ordinated expressions of interest from CCGs prior to the start of the trial.

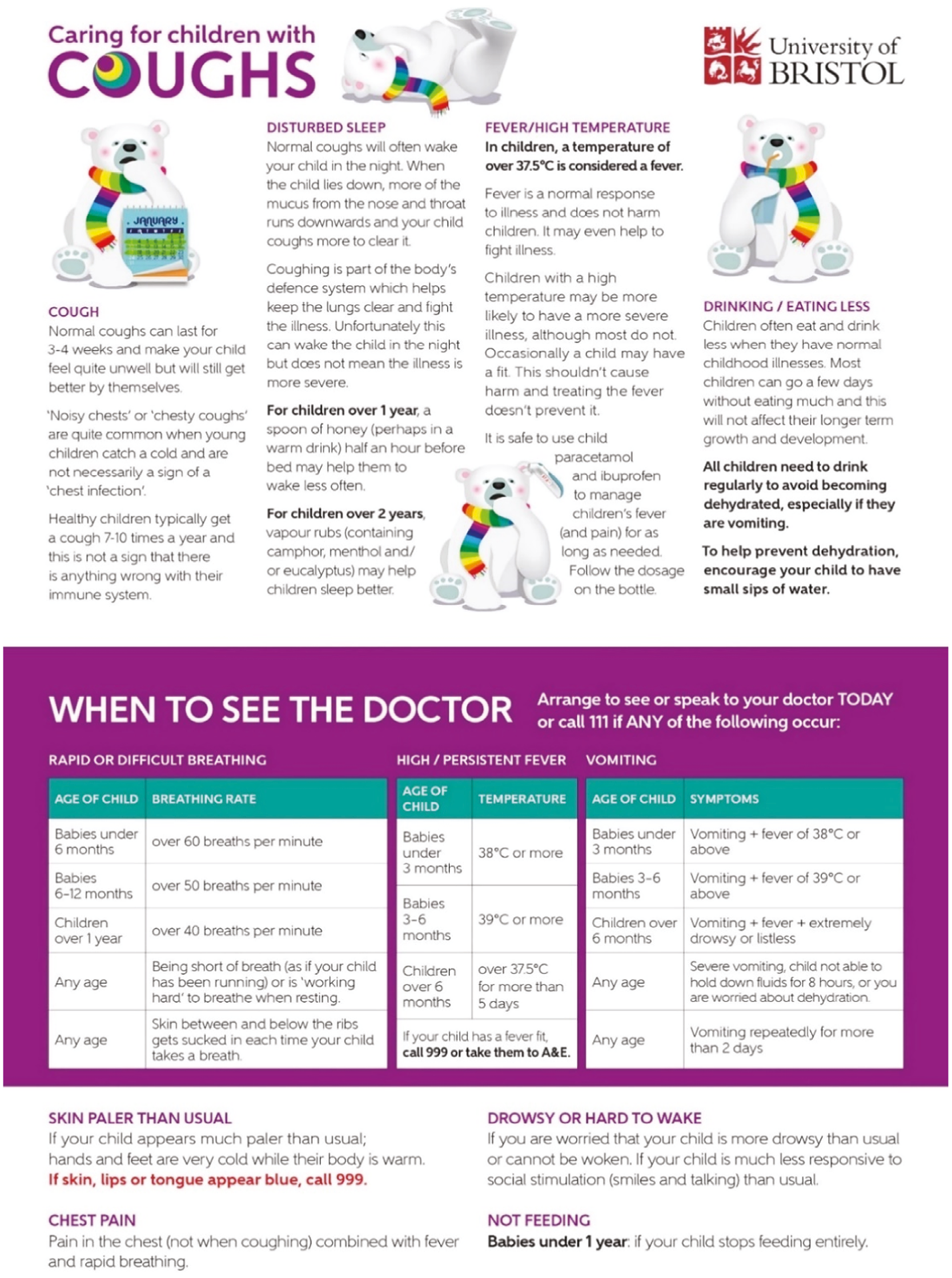

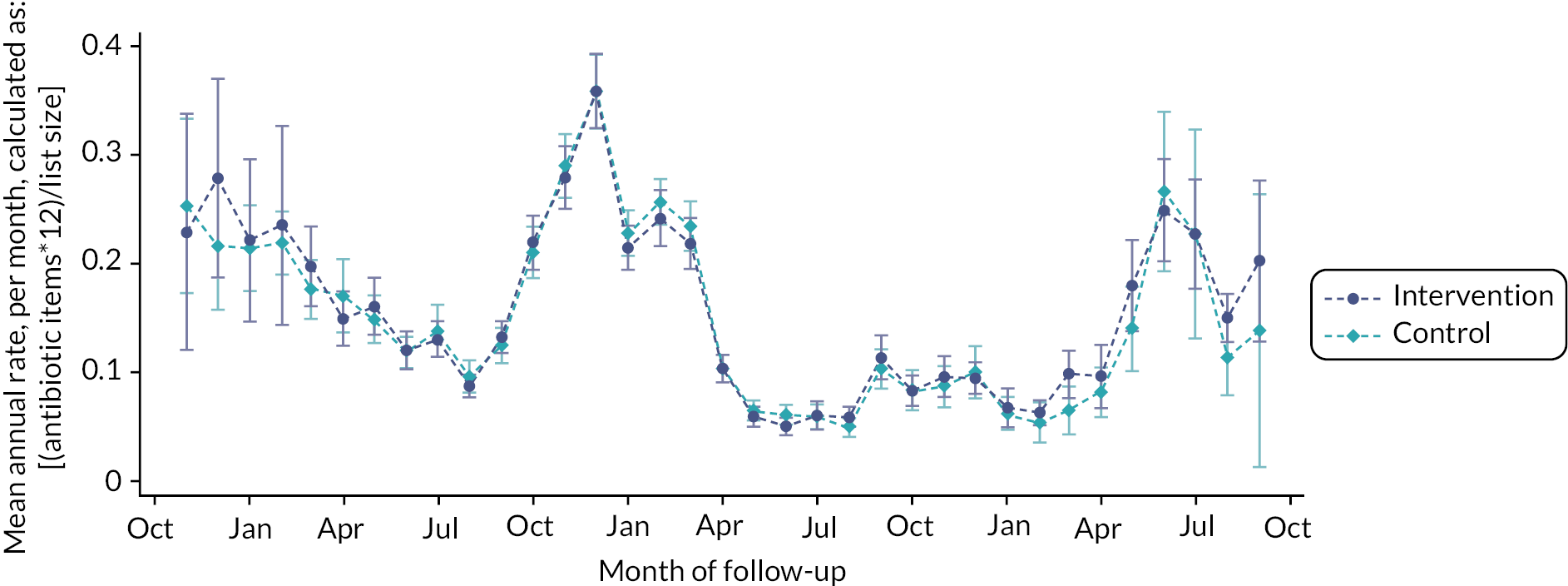

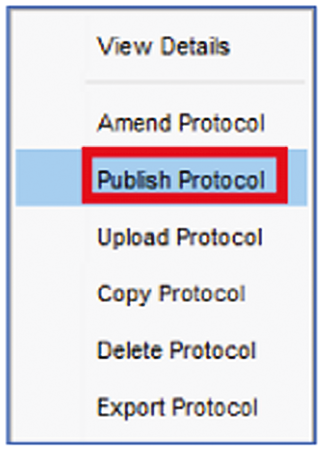

The intervention clinicians were provided with print and online evidence-based information to describe how the intervention works. This included an overview of the intervention (see Figure 1), a flowchart of how the intervention works in EMIS®, a description of how the algorithm is scored and how to use the parent leaflet (see Appendix 1).

FIGURE 1.

Children with cough clinician guide (overview of the intervention).

A practice champion was appointed at each practice to distribute training materials within the practice, co-ordinate training of practice prescribing staff, encourage all clinicians to use the intervention appropriately and report from the EMIS® system how many times the intervention was used. In the training package for clinicians, it was emphasised that the primary purpose of the intervention was to support the care of the larger proportion of children (69%) who have a very low risk of hospitalisation and this intervention was but one tool in their armoury for clinical decision making. The clinicians in practices randomised to the comparator arm were asked to treat children presenting with acute cough and RTI as they would normally.

Participants and recruitment

Recruitment of practices was via CCGs and the 15 CRNs across England using established channels of communication. NIHR CRNs support health and care organisations to be research active42 and can help recruit practices at a national level, including those serving diverse socioeconomic populations, improving the generalisability of findings. 43 CCGs are generally less involved in research but as they communicate regularly with practices can be used to help with recruitment.

A roll-out to three CCGs was performed initially to address any teething issues with the intervention, the internal pilot phase lasted 3 months and included a further four CCGs to help establish best practice for recruiting and communicating with practices before widening to the remaining CCGs.

After the pilot phase, CCGs in other regions of England were approached prioritising those with > 15 EMIS® practices which could potentially be recruited to the study.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria

General practitioner practices in England using the EMIS® electronic patient record system to house the intervention, where the local CCG has agreed to provide primary outcome data and the practice consented to take part. Children aged 0–9 years presenting with a cough or RTI to the participating practice were flagged for eligibility in CHICO via a pop-up on the EMIS® consultation screen (for practices in the intervention arm of the study). No identifiable information was collected at participant level for the study. The number of times the intervention was used at practice level, over a 12-month period, was collected via an EMIS® search.

Exclusion criteria

Practices were excluded if they were participating in any antimicrobial stewardship activities during the study period involving concurrent intervention studies, where there was a potential to confound or modify the effects of our intervention. Practices involved in the CHICO feasibility study or were merging or planning to merge with another practice were also excluded.

Children aged 10–14 were considered for inclusion but at this age an increasing number are given antibiotics in tablet form and given the much lower consultation rate in older children the research team decided to exclude this group from the study population.

Study population

The study population was children aged 0–9 years presenting with acute cough and RTI. The primary outcomes were antibiotic dispensing rates (amoxicillin and macrolide items) and hospitalisation rates for RTI over a 12-month period at each practice divided by the number of 0–9-year-olds registered at that practice.

Intervention

Overview

The intervention consists of (1) eliciting explicit carer concerns during consultation, (2) a clinician-focused algorithm to predict risk of hospitalisation for children with acute cough and RTI in the following 30 days and (3) a carer-focused personalised printout recording decisions made at the consultation and safety-netting information. 22 The algorithm was to be used as one tool among many the clinicians already have, to decide whether the child needs antibiotics. In the training package for clinicians it was emphasised that the primary purpose of the algorithm was not so much to identify the small proportion of children (2%) at higher risk of hospitalisation but rather the much larger proportion of children (69%), who have a very low risk of hospitalisation.

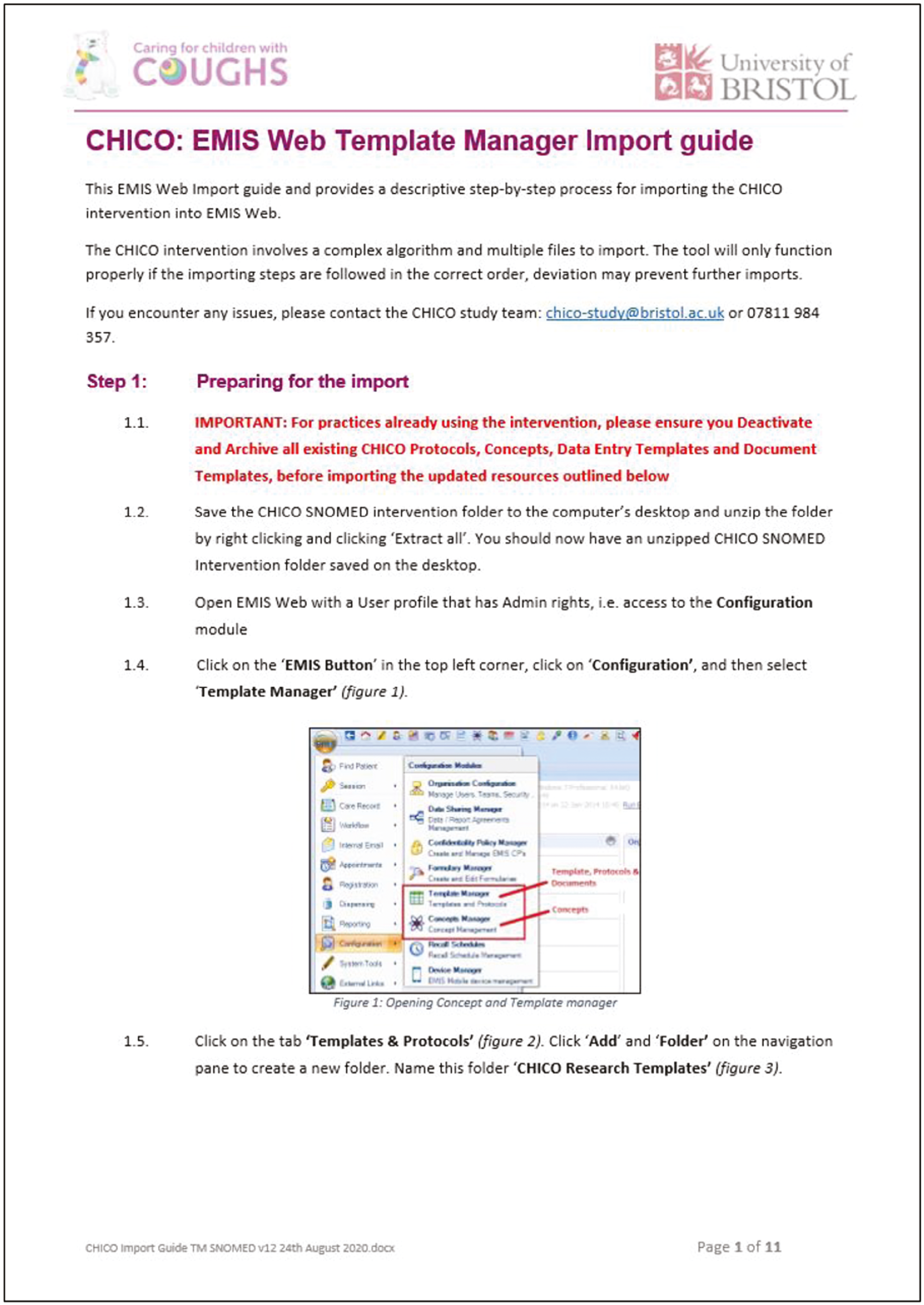

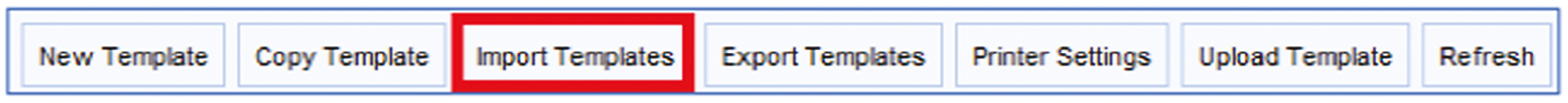

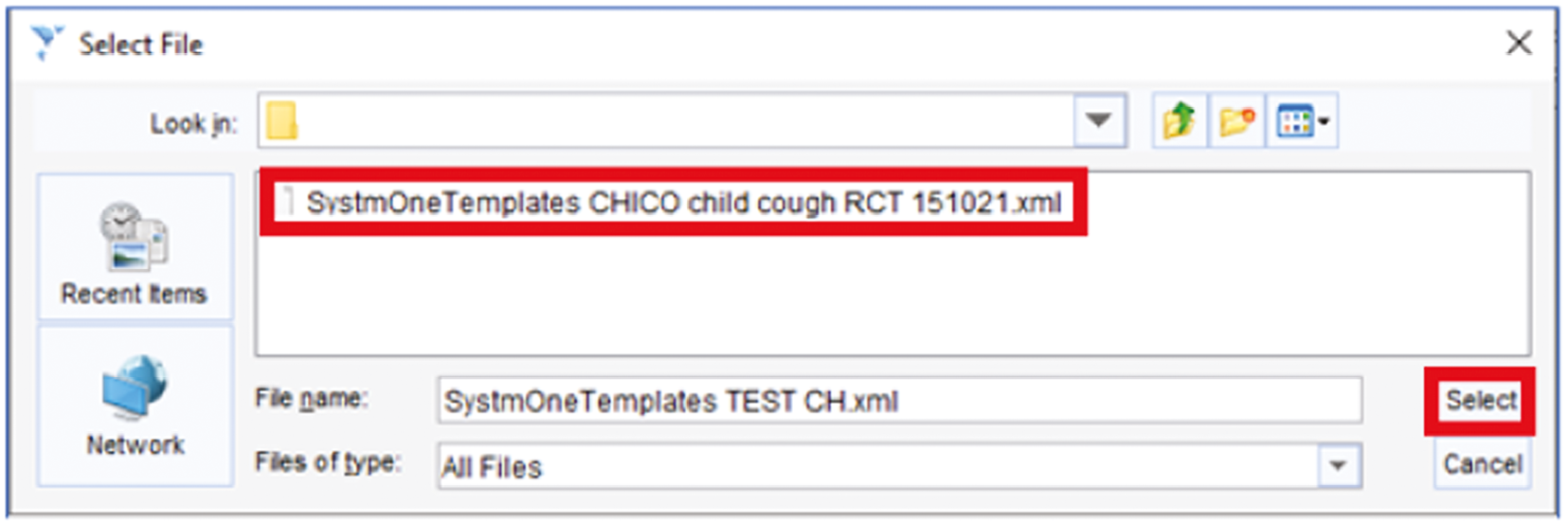

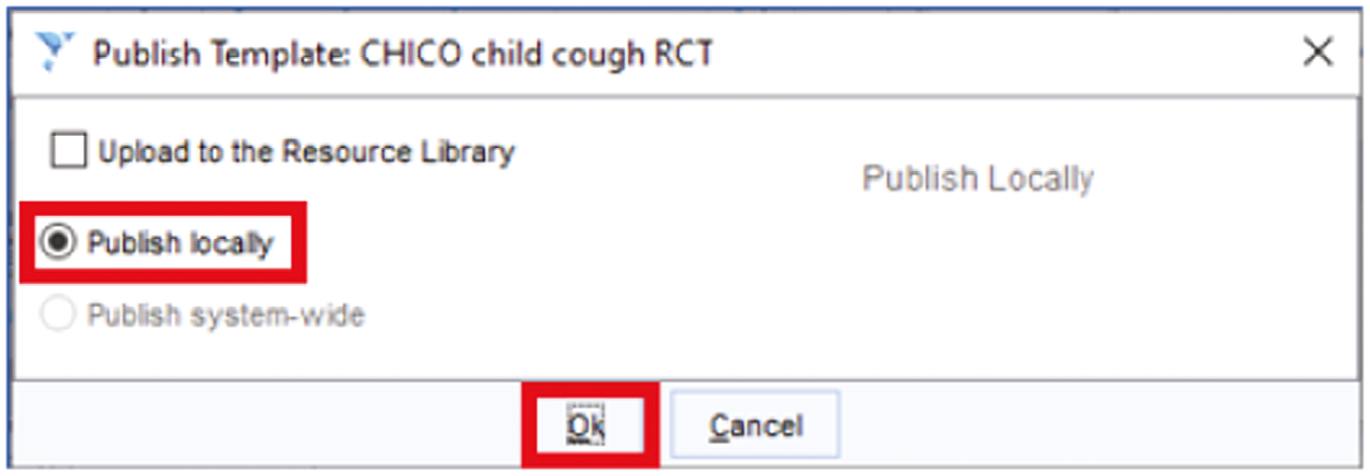

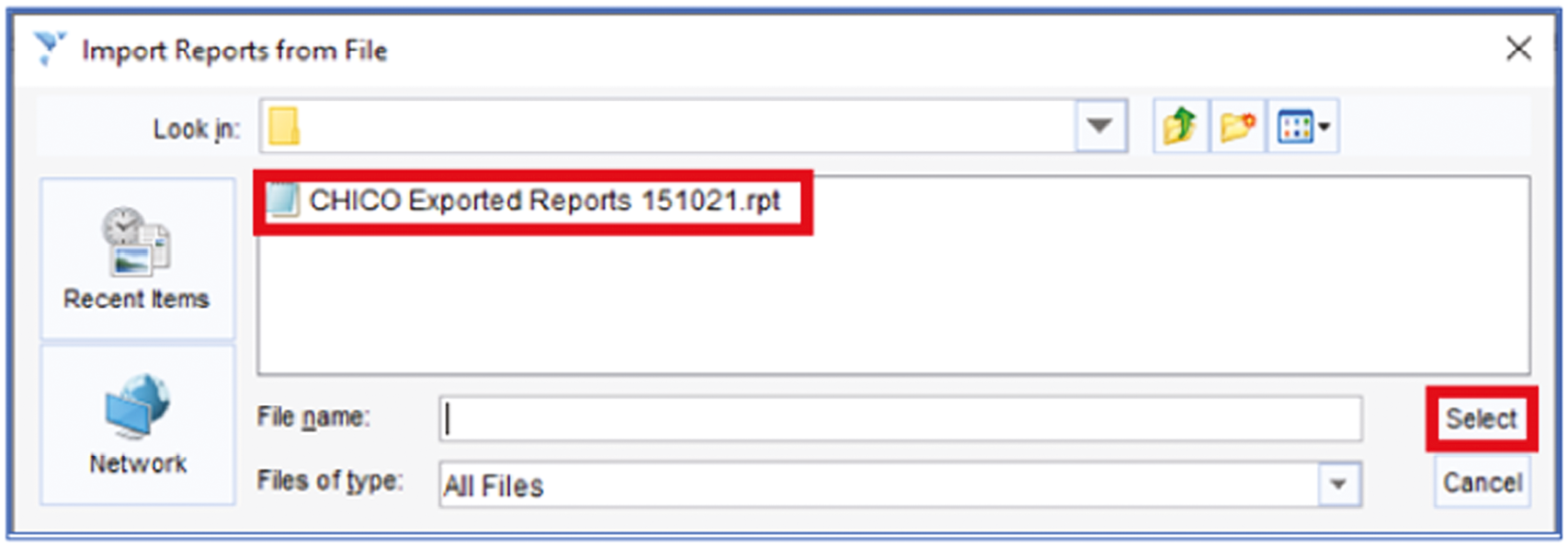

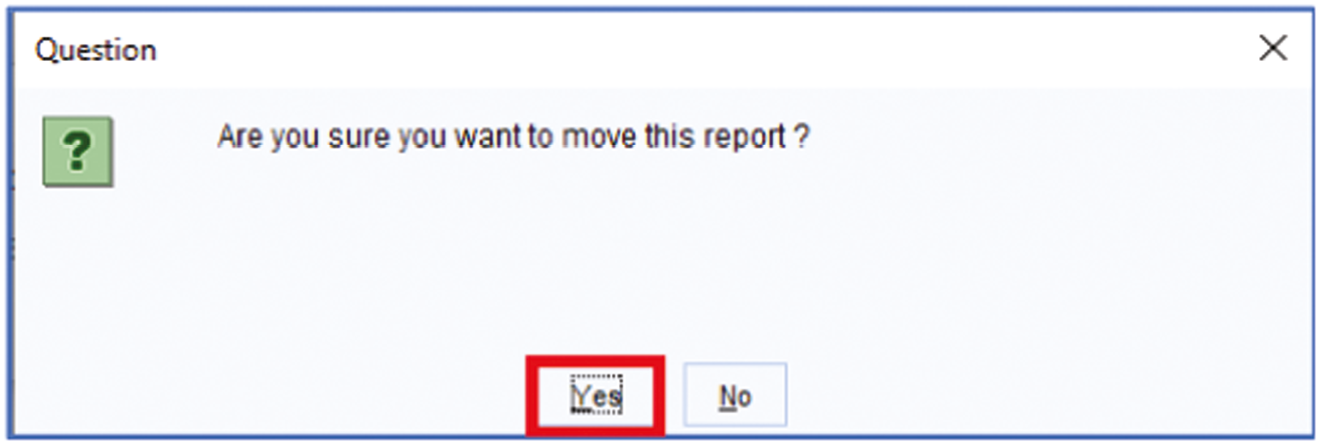

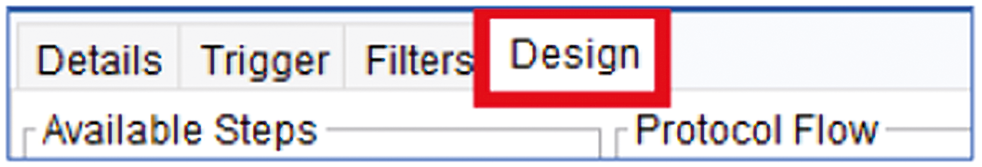

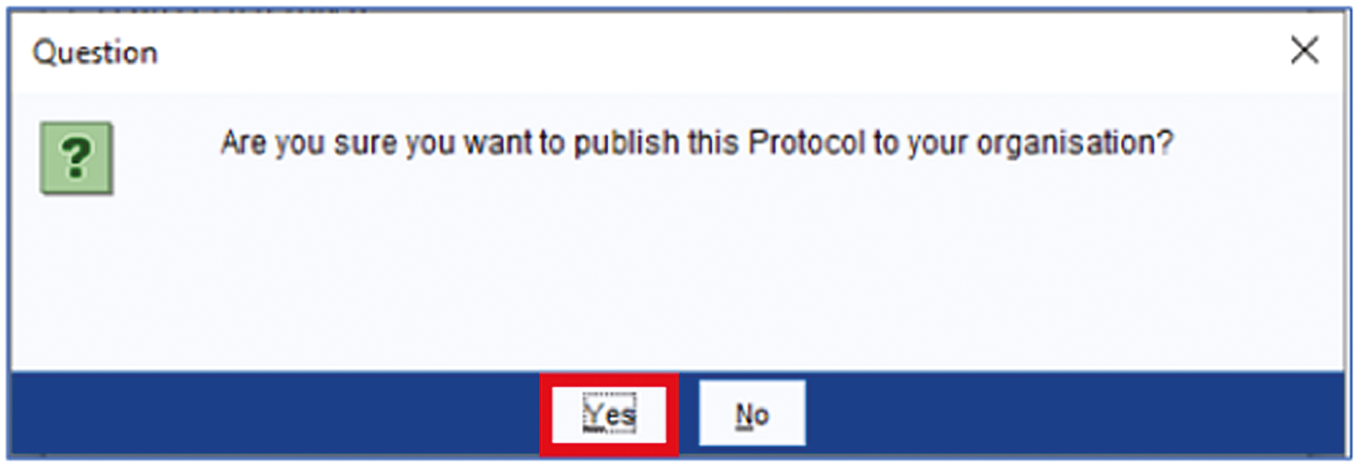

Installation

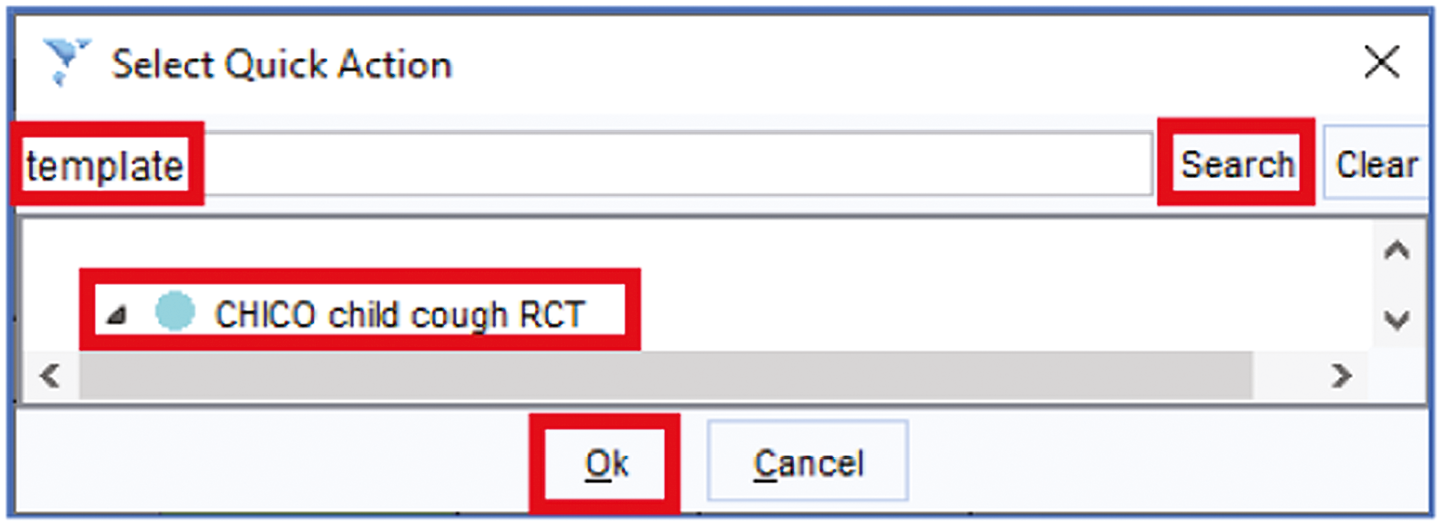

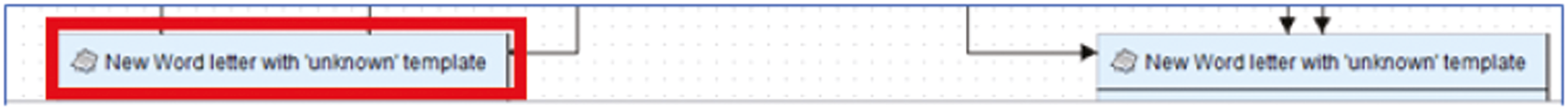

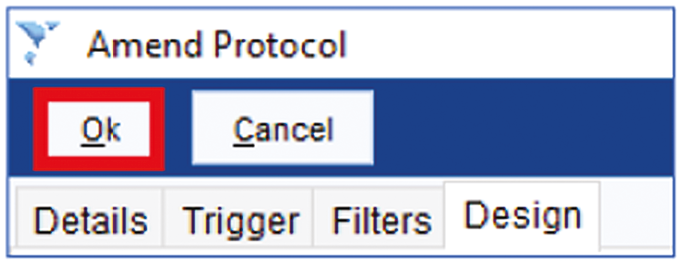

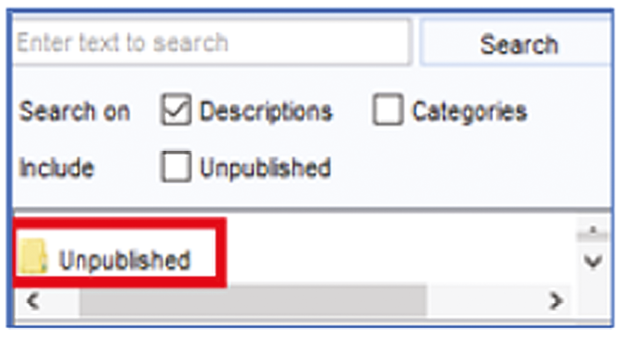

Practices randomised to the intervention were sent instructions including screenshots on how to install the intervention application on the EMIS® system. E-mail support was offered to the practice champion to help implement this and encourage appropriate use of the tool. Requests to access a practice EMIS® system remotely to assist installation, subject to appropriate data security clearance, were also used if the installation ran into any problems.

Detail of intervention workflow during a consultation

-

Step 1: Soft Pop-up. Small CHICO pops up when child aged 0–9 years presents; clinician may click to open CHICO input screen.

-

Step 2: CHICO Trigger. Specific EMIS® codes automatically trigger CHICO input screen.

-

Step 3: CHICO Input screen: closed questions (clinical prediction rule) and elicitation of parent concerns.

-

Step 4: CHICO Output. Step 4a – Additional hover text.

-

Step 5: CHICO Letter + printout. Populate EMIS® record, generate Microsoft Word document (via mail merge) for printing.

Once imported, the intervention was embedded within the primary care information system. The steps above outline how the intervention worked in practice. When a child was in the age range of 0–9 years, the healthcare professional received a soft pop-up on their screen asking if the child was presenting with RTI. The pop-up gave the option of opening the CHICO Intervention (see Appendix 2, Figures 23 and 24). The Intervention screen would also open if the healthcare professional input a RTI-specific EMIS® code during the consultation. An embedded form was presented to record the presence or absence of particular symptoms and signs. Two of the seven predictors (age of patient and history of asthma) were already available for automatic entry. The other five predictors (short illness duration, temperature, intercostal or subcostal recession on examination, wheeze and any vomiting) were recorded during the consultation. Clinical details that are required to complete the STARWAVe algorithm were documented in a standardised EMIS® proforma and the electronic medical record, then identified whether the consulting patient was at elevated, average or very low risk of hospitalisation using a 7-point scoring system. The health professional was also prompted to elicit explicit concerns of the carer. The output page appeared as a small pop-up on the screen (see Table 1), requiring no action from the healthcare professional but informed them of the child’s risk of hospitalisation.

| CHICO result | Pop-up text |

|---|---|

| Low-risk group | Very reassuring CHICO score: 0 or 1 CHICO predictors: > 99.6% of children will recover from this illness with home care. Consider a no- or delayed-antibiotic prescribing strategy. CHICO leaflet and letter covers common concerns and safety netting advice. |

| Average-risk group | Reassuring CHICO score: 2 or 3 CHICO predictors: > 98% of children will recover from this illness with home care. Consider no- or delayed-antibiotic prescribing strategy. CHICO leaflet and letter covers common concerns and safety-netting advice. |

| Elevated-risk group | Safety-netting needed: 4+ CHICO predictors: This is more than average, but > 87% of children will still recover from this illness with home care. Highlight SAFETY NETTING advice in CHICO leaflet. |

When the Intervention input page had been saved the health professional had the option to print a short, personalised letter for the carer. This letter captured the following information:

-

patient’s name and age;

-

pre-specified brief description of the function of the consultation;

-

parent/carer’s concerns; manually typed in by the healthcare professional;

-

healthcare professional’s advice regarding raised parent’s concerns;

-

name of healthcare professional.

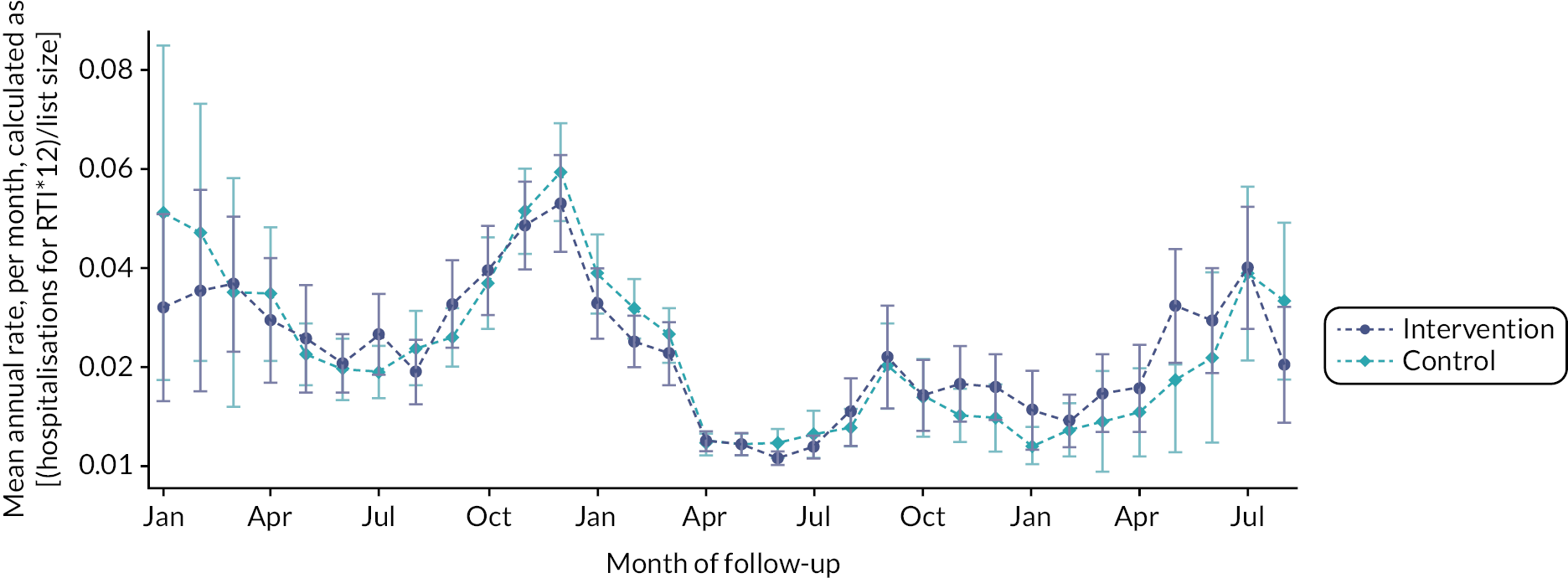

This personalised letter (project website upload) was provided to the carer alongside the ‘Caring for CHICO’ safety-netting leaflet (see Figure 2) providing further information regarding common carer concerns. The leaflet was based on one which was co-designed with parents and drew on our earlier work on the natural course of a typical RTI illness, typical duration of cough, caring for a child with a cough and safety-netting advice about when to re-consult. A slightly amended version was used in this intervention and made available in print or electronic format. 44

FIGURE 2.

Children with cough safety-netting leaflet.

Monitoring intervention use

An internal dashboard system was used for reporting frequency of use of the intervention by clinicians to practices during the 12-month participation period; where a ‘use’ of the intervention was defined as entering five or more symptom codes into the template as part of the consultation. Practices were provided with searches (EMIS® queries) which practice champions were requested to run monthly and feed back to the study team.

Encouraging intervention use

To accomplish this, the monthly searches returned by the practice champions were checked by the study team and relayed back to the practice if the intervention had not been used. In addition, practice champions were to review the search results and remind clinicians to use the intervention. CCGs were asked to support the study at both CCG levels and to endorse the use of the intervention within practices using local engagement processes and Anti-Microbial Stewardship (AMS) activities. Working with the AMS teams already established among practices and CCG pharmacists we selected CCG AMS leads to promote the use of the intervention at practice level.

Fidelity of the intervention

The consistency and reliability (fidelity) measures focused on intervention exposure and the quality of the intervention delivered (using the process interviews as part of the qualitative investigation). Using our light-touch approach to data collection meant it was challenging to measure fidelity.

Capturing intervention usage

Monthly searches collected data on intervention usage, defined as 5+ symptom codes being entered into the CHICO template (see Appendix 2). There may have been consultations that were missed (false negatives) and some that were included with fewer than five symptoms (false positives) but these were difficult to quantify. In addition, in the follow-up questionnaire sent after 12 months participation in CHICO, there were questions about the use of the intervention for practices in the intervention arm of the study. Additional questions were added, concerning change in use during the pandemic, from April 2020 (project web upload).

Usual care (control practices)

The control arm for CHICO trial was usual care for this condition. The clinicians from practices randomised to the control arm were just asked to treat children presenting with cough or RTI as they normally would. Baseline and follow-up questionnaire data on control practices were collected but no data directly from the clinicians aside from routinely requesting information on serious adverse events (SAEs).

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

There were two primary outcomes:

-

The rate of amoxicillin and macrolide items dispensed, calculated using the number of items dispensed to 0–9-year-olds and the number of children aged 0–9 registered at each practice over a 12-month period (testing for superiority). The number of items dispensed, for all indications, was used as a proxy measure due to the limitations of routine data.

-

The rate of hospitalisations for RTI, calculated using the number of hospitalisations for RTI among children aged 0–9 years and the number of children aged 0–9 registered at each practice over a 12-month period (testing for non-inferiority).

Secondary outcome measures

-

A&E attendance rates for RTI, calculated using the number of A&E attendances for RTI among children aged 0–9 years and the number of children aged 0–9 registered at each practice over a 12-month period.

-

An exploration into the usage of the intervention, in terms of both usage over a 12-month period and seasonality, and the effects it has on primary outcome P1.

-

A between-arm comparison of mean NHS costs in a cost-consequence analysis (health economics).

-

Acceptability of the intervention and variation in use determined by qualitative interviews with the clinicians.

Subgroup analyses (potential effect modifiers for P1)

-

Comparison of primary outcome P1 stratified by categorisation of proportion of locums (median) used over the 12 months the practice is in the study.

-

Comparison of primary outcome P1 stratified by categorisation of proportion of nurses (median) used over the 12 months the practice is in the study. This was originally planned as a dichotomisation of practices into those with GP prescribers only and those with nurse or other prescribers as well. However, given that the majority of practices had nurse prescribers, it seemed sensible to look at nurses as a proportion of staff.

-

Comparison of primary outcome P1 stratified by categorisation of practice dispensing rates taken from the 12 months prior to the data collection from each practice.

-

Comparison of primary outcome P1 dichotomised by those practices with one site only and those with multiple sites.

-

Comparison of primary outcome P1 dichotomised by those practices with follow-up periods before the COVID-19 pandemic and those with follow-up months on or after March 2020.

-

Comparison of primary outcome P1 dichotomised by those practices with a high level of deprivation versus those with a low level of deprivation.

Data collection

In this efficient design the data were mainly being collected from the practices and CCGs rather than patients and clinicians.

Expression of interest

As part of the recruitment of CCGs to the study, a form was completed by interested CCGs denoting their willingness to participate. One of our co-investigators (EB) is a national project lead for healthcare-acquired infections and antimicrobial resistance at NHS England and co-ordinated expressions of interest from CCGs prior to the start of the trial. Eligible practices were contacted via the CCGs and CRNs to take part in the trial. When GP practices were invited to participate, they were advised on the general principles of the trial, namely that the research will investigate methods to optimise the management of childhood RTI as well to agree to provide a practice champion as our primary contact and willingness of a member of staff to take part in qualitative interviews. If they were randomised to the intervention arm, the practices would need to agree to install the CHICO intervention on EMIS® and for the practice champion to monitor its use and send monthly updates. If practices wished to take part in the study, they completed an expression of interest form confirming agreement.

Randomisation data

When CCGs agreed to take part in the CHICO trial, the latest 12 months of data available, for amoxicillin and macrolide prescribing, was collected for all practices in their area. The latest month of list size data was used as the denominator to calculate the rate of dispensing over the 12-month period. This was then used to divide the data into those with a HIGH or LOW dispensing rate for stratification purposes in the randomisation process. In a similar way, practices within the CCG were split into those with a HIGH or LOW list size, relative to other practices within their CCG. These HIGH/LOW categorisations were not shared with the trial team until a practice agreed to take part and were ready to be randomised.

Baseline questionnaire

A brief questionnaire was sent to each practice to collect data on the characteristics of all practices prior to randomisation. Data were collected on the numbers of staff at the practice (by job type), questions regarding triaging of RTI conditions and postcode (for calculating the Index of Multiple Deprivation).

Routine data

For each practice, baseline data and follow-up data after 12 months were collected along with data for the two primary outcomes (dispensing and hospitalisations) and the secondary outcome (A&E attendances). The items of amoxicillin and macrolides dispensed, each month, were collected for the 12 months prior to randomisation and the 12 months after the implementation period. A short ‘implementation period’ (usually around 1 month) was allowed prior to the 12-month data collection period, giving time for the practices to install the intervention and encourage staff to use it. Any data collected during this period were not used in the analysis. For example, if a practice was randomised on the 10th of January their typical month 1 of follow-up would be February, as routine data were available for each calendar month. The data were obtained from NHSBSA ePACT2 system. 30

For the same 24-month period, data were collected on hospitalisations and A&E attendances, via a secure NHS e-mail inbox. These data were collected directly from each CCG. Data analysts from each CCG were asked to provide the number of hospitalisations for RTI, the number of hospitalisations with a ‘missing’ diagnosis and the total number of hospitalisations. Similar data were collected on A&E attendances. List size data, per month and 5-year epoch, were obtained from the NHS digital website. 45

Intervention usage

Practices were provided with an EMIS® search, which looked at the number of times the intervention template was opened. This was collected for each of the 12 months the intervention practices were in the study. Qualitative interviews with clinicians (GPs and practice nurses) and other practice staff (managers, pharmacists) and CCG staff (medicines managers) explored the use of the intervention, how it was embedded into practice and whether it was used appropriately.

Follow-up questionnaire

Like the baseline questionnaire, practices were asked to complete a follow-up questionnaire 12 months later. This included additional data on items such as the number of locums used during the 12 months of follow-up as well as questions around COVID-19 and how it had affected their triaging. Intervention practices were also asked what they thought of the intervention and if they would want to use it again.

Safety data (serious adverse events)

Intervention and control practices were asked to report SAEs immediately on the practice becoming aware of the event. The CHICO team sent a reminder e-mail, quarterly during follow-up, to remind practices to report SAEs. An additional reminder was sent 3 months after the practice had completed their time in the study. As the trial was collecting data on A&E attendances and hospitalisations routinely, only the following events required reporting.

Intervention and control practices

Fatal SAEs: During the trial the practice should report any deaths that are related to a RTI or its complications that occur in patients under 10 years of age to the CHICO research team. This is only applicable to patients who had attended a consultation at the practice in the 90 days prior to the date of death for a RTI-related medical complaint.

Intervention practices only

Related SAEs: During the trial any medical event that meets the standard definition of an SAE (e.g. is life-threatening), and the attending clinician at the practice suspects may be related to the use of the CHICO intervention should be reported to the CHICO research team. An event may be related if it is possibly, probably or definitely due to an adverse impact on the care of the child following using the information provided in the CHICO intervention.

Fidelity data

The fidelity measures focused on intervention exposure and the quality of the intervention delivered (using the process interviews as part of the qualitative investigation).

Sample size

Both sample size calculations assumed 90% power and a conservative two-sided alpha of 0.025 to take account of the two co-primary outcomes. Both sample sizes also assumed an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.03 (as suggested in discussion with Professor Sandra Eldridge, an expert in cluster randomised trials and complex designs), an estimated coefficient of variation of 0.65 (to take account of differences in cluster size) and an assumption of 750 children aged 0–9 years registered per practice (based on Bristol and Bath CCG data from 2016). Expected differences assumed: (1) a reduction in dispensing rate from 33 prescriptions per 100 registered children aged 0–9 years to 29 (or fewer) prescriptions (i.e. ≥ 10% overall reduction); and (2) a hospitalisation rate that was no more than 2% in the intervention arm, compared with the control arm which is estimated to be 1%. This was based on a non-inferiority margin of 1%; however, the investigators wanted to err on the side of caution and used a two-sided alpha for the sample size calculation. This gave an overall sample size requirement of 310 practices; 155 intervention and 155 control practices. Although not pre-specified, estimates of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were carried out for the primary outcomes. Mixed-effects linear regression models were used, instead of Poisson models, to allow for the calculation of an ICC using the ‘estat icc’ command in Stata. Only control practices were used to estimate the ICC and CCGs with less than five practices were not included in the calculation as these were unlikely to provide a true estimate of within-cluster variability.

Random allocation

General practitioner practices were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis by the independent Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC) unit using a web-based system, to ensure allocation concealment. All children registered at a GP practice randomised to the intervention arm followed current standard management along with the additional intervention tool. All children registered at a GP practice randomised to the control arm received current standard management. Randomisation was at the practice level. It was stratified by CCG and then further minimised for by practice list size of children (HIGH/LOW) and the baseline dispensing rates of amoxicillin and macrolides antibiotics given to 0–9-year-olds over the previous 12 months (HIGH/LOW), relative to other practices within the CCG. The trial manager was responsible for inputting these variables into the randomisation system.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention delivery, it was not possible to blind the practices to their allocation of either control or intervention group. Administrative staff had access to individual data items, for entry into the database. The trial statistician and trial manager had access to data, by arm, to be able to monitor hospitalisations and report to the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). No other member of the research team had access to these data until the findings were revealed.

Statistical methods

A full CHICO statistical analysis plan was developed and agreed by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and DMC. 46 All primary and secondary analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. A full CHICO statistical analysis plan was developed and agreed by the TSC and DMC chairs 4 months prior to the end of follow-up and 7 months prior to the final analysis commencement. The analysis plan also included details on the proposed health economic and qualitative outcomes.

Summary of baseline data and flow of participants

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram was used to present the reasons why CCGs and practices were not recruited (due to ineligibility or declining). It was also used to present the number of withdrawals and the number used in the analysis, by arm.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise characteristics of practices and compare them between groups in a baseline table. Categorical variables were summarised using frequencies and proportions while continuous variables were summarised using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs; given their skewed nature). Had any differences, between the groups, been in excess of 0.5 standard deviations (SDs)/IQRs or 10% or more they would have been controlled for in sensitivity analyses. However, this was not the case.

Primary outcome analysis

The co-primary outcomes were the rate of amoxicillin and macrolide items (antibiotics) dispensed, for all indications, and the rate of hospitalisations for RTI. The denominator for each of these outcomes was the mean number of children aged 0–9 years registered at the practice over the 12-month follow-up period. In the analysis plan, the team pre-specified that the median list size would be used; however, given the number of practices that merged it seemed more accurate to calculate the mean. All analyses were carried out in Stata 17.0 and the results were described in terms of ‘strength of evidence’ rather than significance. No formal methods of imputation were carried out as the primary outcome was obtainable for over 99% of practices.

Mixed models were used to account for the within and between CCG level variation, incorporating the latter as a random effect. A random-effects Poisson regression model was used to analyse both of these co-primary outcomes. This has the advantage of incorporating person/years follow-up (number of children at a practice) and examining clustering by practice. The dispensing record of the practices in the 12 months prior to randomisation was used as a minimisation variable and thus balance the dispensing records at baseline. This was adjusted for, in the primary analysis of dispensing rates, to resolve any residual difference. While the dispensing outcome will be testing for superiority, the hospitalisation outcome will be testing for non-inferiority where a difference of no more than 1% higher in the intervention arm is reasonable to suggest non-inferiority. Therefore, emphasis was placed on the CI when assessing this outcome.

Secondary outcome analysis

The rate of A&E attendances for RTI was calculated in the same way as the rate of hospitalisations, although it was a test for superiority rather than non-inferiority.

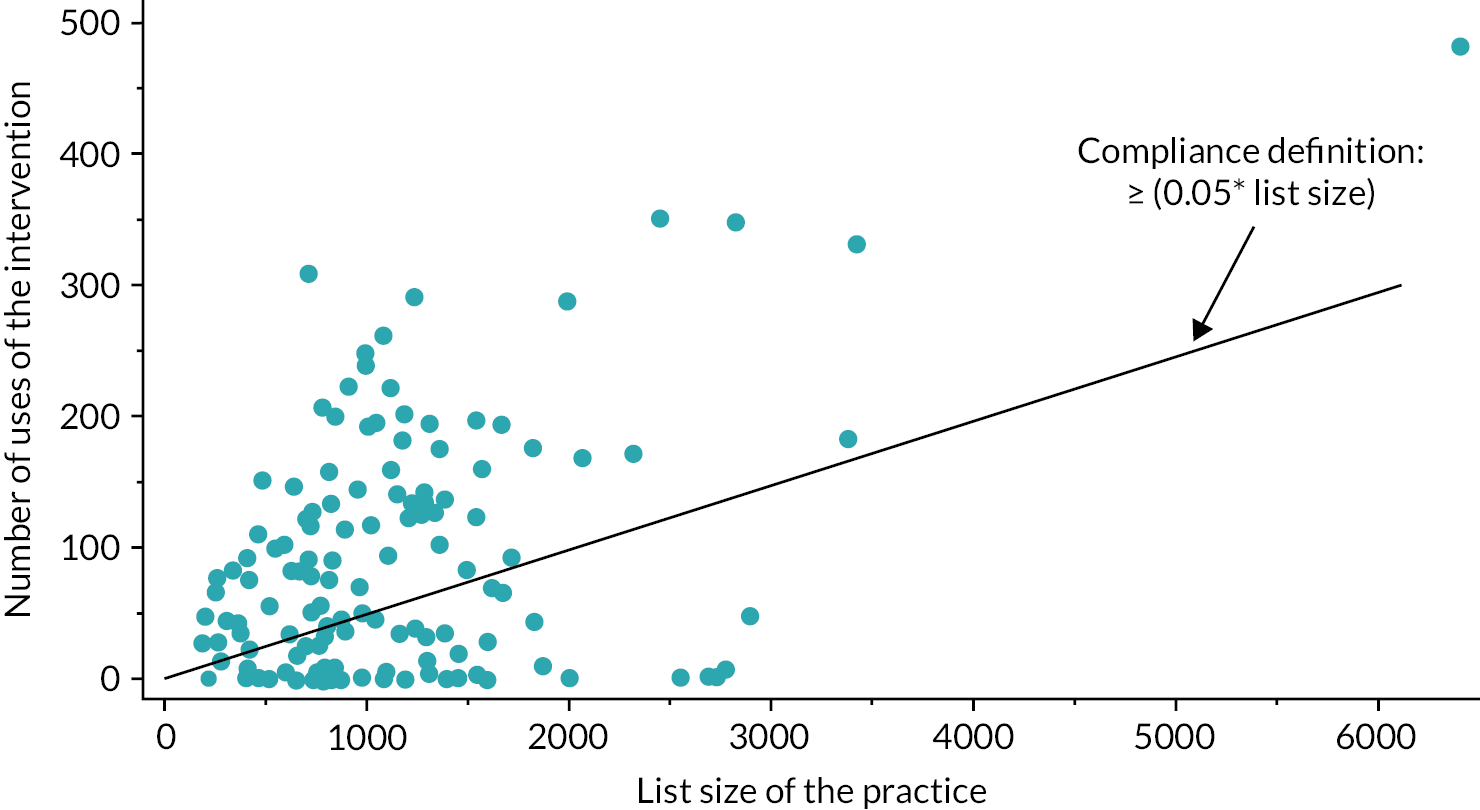

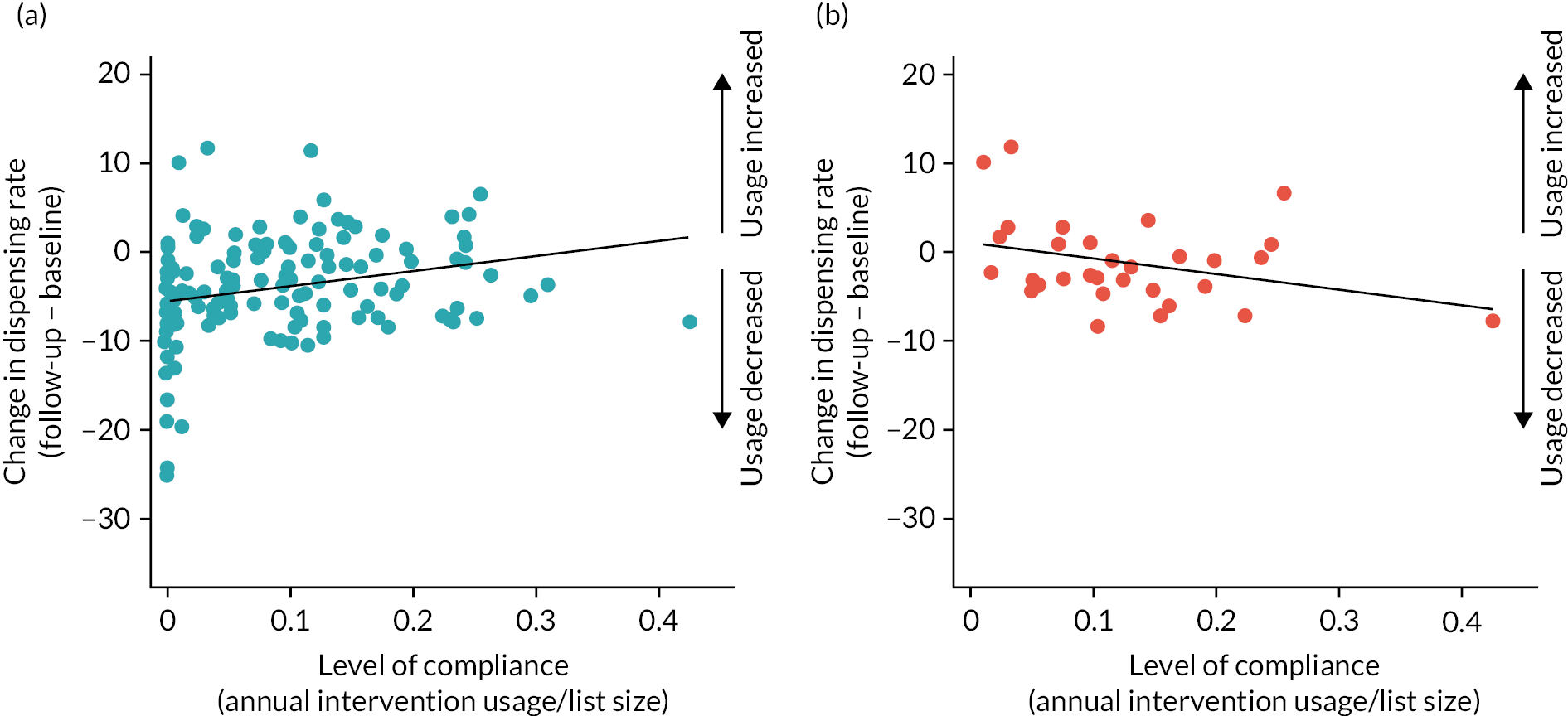

Intervention usage was explored across the seasons and across the 12 months of follow-up. Its impact on dispensing was explored and the correlation was presented using scatter plots and Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Sensitivity analyses

Dispensing outcome

-

A per-protocol analysis was utilised to exclude non-compliers in the intervention arm. The level of compliance was calculated as the number of times the intervention was used over a 12-month period divided by the list size of 0–9-year-olds at the practice. Practices were considered compliers if this figure was greater than or equal to 0.05. Practices who did not provide intervention usage data were also excluded from this analysis along with any practices that had merged with another CHICO practice during the follow-up period of the trial.

-

When calculating the level of compliance, it became clear that COVID-19 had been the cause of the majority of ‘non-compliers’. Therefore, a post hoc sensitivity analysis was included that looked at the complier average causal effect (CACE). This analysis utilised data from those who did not comply with the intervention and attempted to find a comparable group in the control arm. This was carried out using the instrumental variable analysis approach, using the ‘ivpoisson gmm’ command in Stata.

-

When the influences of COVID-19 were known, after analysis, a post hoc analysis was included to account for COVID-19. In this analysis, follow-up months prior to March 2020 were included and follow-up months on, or after, March 2020 were excluded. The exposure time variable (list size) was scaled up/down to account for the number of months included; for example, for a practice that began follow-up in January 2020 and completed it in December 2020, the first 2 months of data were utilised as: the number of items dispensed during January and February, across the exposure: list size*(2/12).

-

Small elements to the CHICO intervention were adapted during the pilot phase of the study, such as the generation of a frequently asked questions (FAQ) document; therefore, the dispensing primary outcome was repeated, without the pilot data.

-

At the time of writing the analysis plan, the COVID-19 pandemic had been present in the UK for over a year. The team added a sensitivity analysis that would add a COVID-19 time variable, ranging from 1 to 12, to account for the months of follow-up affected by COVID-19 (on or after March 2020); for example, for practices commencing follow-up between January 2020 and December 2020 the COVID-19 variable would be 10. This variable was added as a covariate in a sensitivity analysis.

-

The amoxicillin and macrolide item data are separated by 5-year epochs and the CHICO trial was primarily interested in the 0–4 and 5–9 year age groups. However, the team also collected data on dispensed items with a ‘missing’ age group. Therefore, in a sensitivity analysis, these additional items were included in the 0–9 age group.

-

A post hoc analysis was included to look at amoxicillin prescribing rates only (excluding macrolides).

-

The primary analysis was repeated for 0–4-year-olds only, utilising the 0–4 age epoch data on dispensing and the list size of 0–4-year-olds at the practice.

-

The primary analysis was repeated for 5–9-year-olds only, utilising the 5–9 age epoch data on dispensing and the list size of 5–9-year-olds at the practice.

-

After follow-up had ended, but before final analysis commenced, a post hoc analysis was added to replace the random effects for CCG with a random effect for Primary Care Network (PCN). PCNs are groups of practices working together to focus on local patient care so, in a similar way to a CCG, this sensitivity analysis accounted for the within and between variation across PCNs. PCNs are often made up of practices across different CCGs and do not lie within CCGs; therefore, the analysis was unable to account for both at the same time.

-

During analysis, an additional post hoc sensitivity analysis was included to adjust for the potential confounding effects of a delay between the baseline 12-month collection period and the 12-month follow-up period.

Hospitalisation/accident and emergency outcome

-

For hospitalisation and A&E data, diagnosis codes are sometimes missing. Therefore, data were collected on the number of ‘diagnosis missing’ hospital/A&Es as well as the total number of hospital/A&Es. Using the proportion of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) attendances out of those with a diagnosis we could then deduce the proportion of ‘diagnosis missing’ attendances that were likely to be attributable to RTI and include these in a sensitivity analysis.

-

The previous sensitivity analysis was repeated and included all ‘diagnosis missing’ attendances, rather than just a proportion.

-

As with the dispensing outcome, the team added a sensitivity analysis that would add a COVID-19 time variable, ranging from 1 to 12, to account for the months of follow-up affected by COVID-19 (on or after March 2020); for example, for practices commencing follow up between January 2020 and December 2020 the COVID-19 variable would be 10. This variable was added as a covariate in a sensitivity analysis.

-

Complete data were provided for 46 out of 47 CCGs who provided practices for the study. As monthly data were suppressed to avoid identification of patients (where n < 5), CCGs were asked to also provide annual data to avoid inaccurate summations of n < 5. Unfortunately, West Hampshire CCG did not provide these data. Therefore, their annual data may be a misrepresentation of the true figure and their data were removed in a sensitivity analysis.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were carried out for dispensing rates (P1). Formal tests of interaction between the potential effect modifiers and treatment pathway were carried out to test whether the treatment effect differed between the different subgroups. These effect modifiers are listed in Subgroup analyses (potential effect modifiers for P1). These variables were dichotomised to aid presentation and interpretation, taking the median value where the variable was continuous. Models with and without an interaction term were compared using a likelihood ratio test and this p-value was presented.

Internal pilot study

An internal pilot phase lasting 3 months and using 4 CCGs to recruit 60 practices was planned and conducted to help establish the best methods for recruiting and communicating with practices before widening to the remaining CCGs.

Stop/go assessment

There were four stop/go criteria (see Table 2).

| Criteria (all must be met, failure of one or more triggers action) | Proposed action |

|---|---|

| ≥ 80% or 48+ practices recruited | Continue as planned |

| ≥ 80% or 48+ practices naming a champion | |

| ≥ 80% of GPs/nurses using the intervention | |

| ≥ 90% or 54+ practices we can obtain antibiotic dispensing data | |

| 70–79% or 42–47 practices recruited | TSC and HTA discuss problems with the TMG and implement remedies |

| 70–79% or 42–47 practices naming a champion | |

| 70–79% of GPs/nurses using the intervention | |

| 80–89% or 48–53 practices we can obtain antibiotic dispensing data | |

| < 70% or < 42 practices recruiting | Discuss plans with TSC and NIHR HTA. Consider further pilot or stopping trial |

| < 70% or < 42 practices naming a champion | |

| < 70% of GPs/nurses using the intervention | |

| < 80% or < 48 practices we can obtain antibiotic dispensing data |

Our progression criteria at the pilot stage were based on:

-

the percentage of practices recruited against the initial practice target of 60;

-

the percentage of GP practices with a named practice champion;

-

the percentage of intervention GPs/nurses using the intervention at least once;

-

the percentage of antibiotic dispensing data we can obtain for each practice.

Internal pilot areas of assessment

In addition to stop/go criteria, the internal pilot was used to assess areas where we could improve recruitment, communication with practice champions and use of the intervention. This included:

-

the number of eligible practices within the 20 CCGs already approached and whether at this stage we needed to approach further CCGs to increase the number of practices in the study;

-

the recruitment rate of eligible practices within the four CCGs in the pilot phase, again as an indicator of whether we need to approach further CCGs;

-

the recruitment of practice champions, a focus on their role and how we maximise strategies to encourage use of the intervention;

-

the efficiency of embedding the intervention in practice systems and resolution of any barriers or delays;

-

the number of times the intervention is used between practices and over time;

-

the timeliness of the primary outcome data and consistency of format between CCGs;

-

the timeliness of the secondary outcome data and consistency of format between CCGs.

Trial oversight

The University of Bristol was the sponsor for this trial and was responsible for overall oversight of the trial. The TSC provided independent supervision of the trial and monitored trial progress. The TSC had an independent Chair, GP and clinical academic Hazel Everitt (Associate Professor at the University of Southampton) and four other independent members. These are an independent statistician (Dr Beth Stuart from the University of Southampton), a second clinician (Professor Gail Hayward from the University of Oxford) and two patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives. Meetings were held at least annually. The DMC monitored patient safety and trial data efficacy and consisted of an independent chair (Jill Mollison from the University of Oxford), two other independent members (Oliver van Hecke and Sena Jawad) and the trial statistician. The three independent members were nominated in 2018 prior to any data collection activity according to NIHR research governance guidance. The DMC received and reviewed reports on the data accruing to this trial and made recommendations on the conduct of the trial to the TSC. In the final months of follow-up, the chair stepped down from their position and another independent member (Oliver van Hecke) took up the position. Given that the CHICO trial was nearing completion, a new independent member was not sought, this approach was agreed by the funder.

All SAEs were recorded and notified as appropriate to the relevant authorities.

Safety

The trial is a low-risk study (risks to participants are no higher than that of standard medical care); thus, SAEs were only reported if fatal or serious AND potentially related to trial participation.

As one of the outcomes for the trial is hospitalisation, it was expected some participants would be admitted to hospital (e.g. due to a deterioration of their underlying illness). Hospitalisation due to RTI is an expected SAE and would not be subject to expedited reporting.

For SAE reporting, safety forms were completed for each event by the practice healthcare practitioner and subsequently reviewed by the study clinicians. All SAEs were reported by arm to the DMC prior to scheduled meetings. If there were any safety concerns, the DMC would report to the study Chief Investigator and TSC for further action.

Monitoring for SAEs took place for the duration of the 12-month data collection phase and a further 90 days after this period to allow for the collection of information about any fatalities up to 90 days after consultation.

All practices were regularly prompted by the CHICO study team during their participation in the trial to remind them to report any SAEs and to confirm if zero SAEs arose during the reporting period.

Hospitalisation and A&E attendance data were reported each month for participating practices by their local CCG organisation.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was represented by a Parent Advisory Group (PAG). The CHICO intervention was developed in collaboration with the PAG during the final year of the CHICO feasibility trial (Workstream 4 of the Applied Health TARGET programme).

We met with the parent group several times during the development of the intervention and design of the study. They felt that it was important to conduct a national study and to use a whole practice intervention. They also thought it would be acceptable to conduct the future study without consenting individual patients, as this took time within GP consultations, and that using a prediction tool on the computer during consultation would be fine and would provide reassurance. They strongly endorsed and encouraged us to use the well-designed parent leaflet as it provided very useful information.

Patient and public involvement was maintained throughout the trial through a group of three parents, two of whom (in rotation) attended and contributed to all the TSC meetings including the final results reveal meeting.

Clinical and Practitioner Advisory Group

As the intervention focus was on GP practices and not on recruiting individual patients, we made extensive contact with the Clinical and Practitioner Advisory Group (CPAG) during the trial period, which was important for the study. The CPAG was made up of clinical staff from seven Bristol practices, including GPs, nurse practitioners with paediatric expertise, practice pharmacists and a practice paramedic. We held several meetings with the group in May 2018 and subsequently communicated by e-mail. Advice was sought on the use of hard or soft pop-ups and trigger codes in a consultation, format of the template and the personalised letter. We discussed potential barriers and how to overcome them and any staff training needs to use CHICO. We also ran some ‘think aloud’ sessions with several GPs to see the intervention in action in EMIS® and gather their thoughts about any problems or changes needed. Input on the draft design of follow-up questionnaires was also requested from the CPAG, including how easy it would be for practices to answer the questions.

Chapter 3 Clinical results

Internal pilot review

A TSC took place on 25 February 2019 to assess the stop/go criteria for the RCT pilot, based on the practices recruited between October and December 2018 (see Table 3).

| Criteria (all must be met, failure of one or more triggers action) | Met | Detail |

|---|---|---|

| 1. ≥ 80% or 48+ practices recruited from 7 CCGs | ☑ | By 31 December, 48 practices had been randomised. |

| 2. ≥ 80% or 48+ practices naming a champion | ☑ | All 48 practices recruited had a named champion. |

| 3. ≥ 80% of GPs/nurses using the interventiona | ☑ | The team received responses from 18/23 intervention practices. Of these, 16 met the criteria. |

| 4. ≥ 90% or 54+ practices we can obtain antibiotic dispensing data | ☑ | 100% of baseline dispensing data were available when the criteria were assessed. |

In addition to the stop/go criteria above, other assessment areas listed in Internal Pilot areas of assessment were used to improve recruitment and resolve any barriers implementing the intervention. Criteria (1) suggested more than 4 CCGs would be required to recruit at least 48 practices; thus, a further 3 CCGs were recruited to the pilot.

The TSC was supportive of the progress that had been made at that time and the achievement of the stop/go criteria. The CHICO trial continued to recruit practices from the pilot CCGs and went on to recruit additional CCGs and practices after the pilot ended.

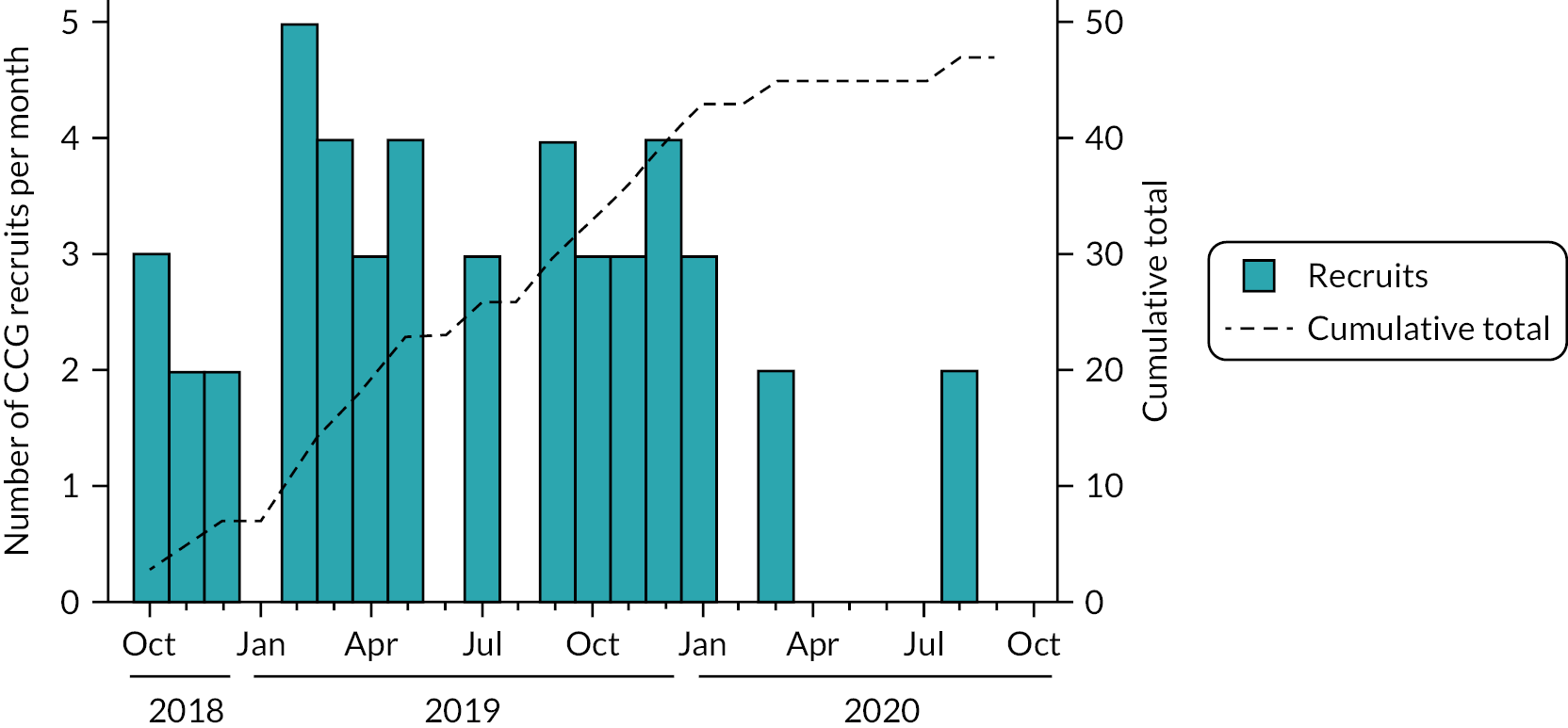

Recruitment

The CHICO trial recruited CCGs, and randomised practices within them, between October 2018 and October 2020. There was a 3-month pause in recruitment between March 2020 and June 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the study team, TSC and funders re-assessed the feasibility and safety of the intervention during the pandemic. By mid-June 2020, there seemed to be an appetite for restarting recruitment again with perceived capacity in practices and new expressions of interest from some regions such as the South-West. A budgeting exercise suggested an un-costed 4-month extension could support the study to reach the target recruitment figure by the end of September 2020. Recruitment restarted again on 16th June, following a non-substantial amendment (following the COVID-related halt) being approved by the sponsor. In total, 52 CCGs agreed to take part in the study but only 47 of the CCGs (see Figure 3) provided the 294 practices (see Figure 4). Practices were randomised between October 2018 and October 2020, with the 12-month follow-up period continuing until September 2021.

FIGURE 3.

Children with cough recruitment of CCGs.

FIGURE 4.

Children with cough recruitment of practices.

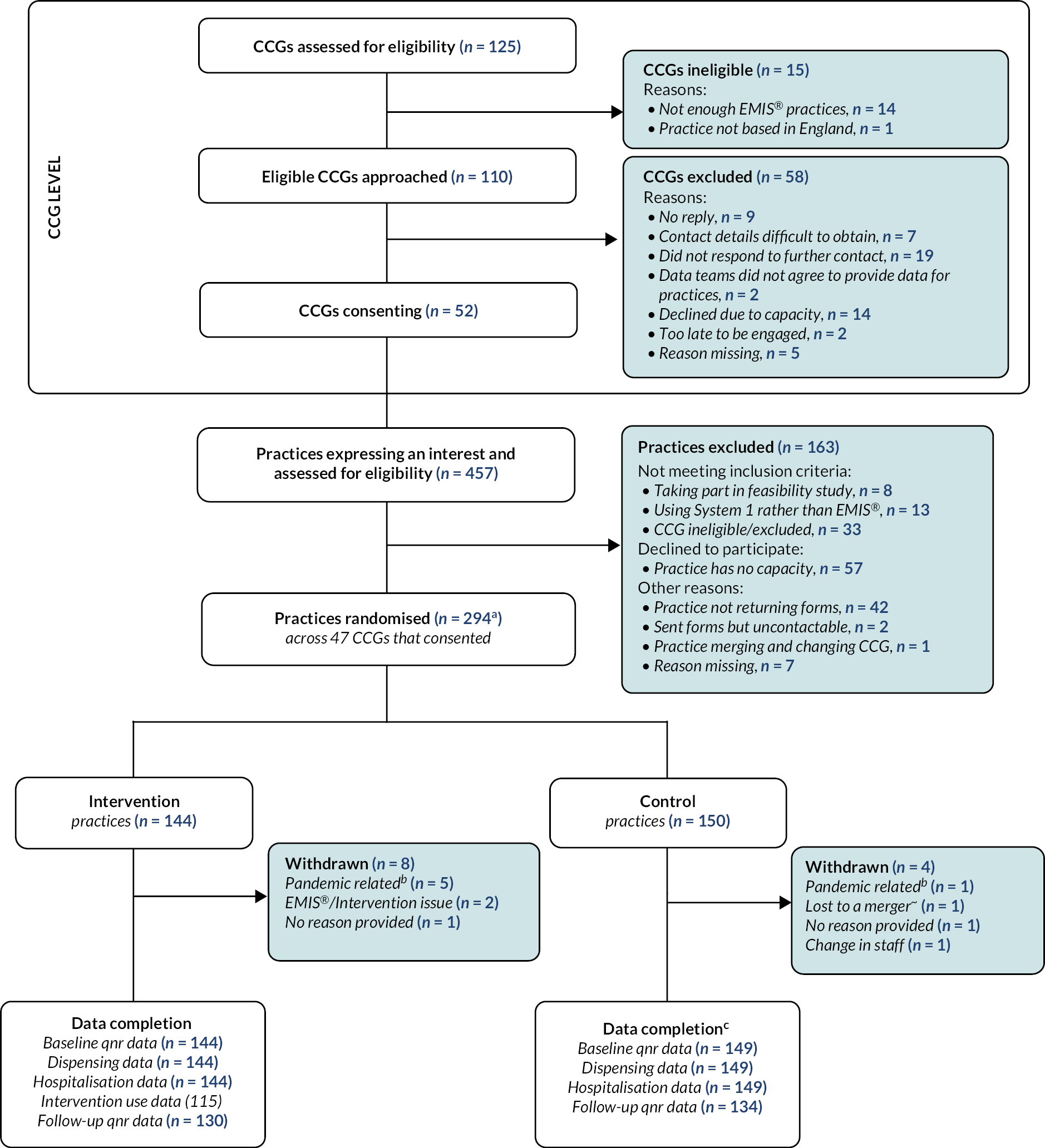

Trial flow

In total, 125 CCGs were assessed for eligibility (see Figure 5). For the CHICO intervention to work, practices had to be using EMIS®.

FIGURE 5.

The CHICO trial CONSORT flowchart. EMIS®, Egton Medical Information Systems® (electronic health records); qnr, questionnaire; a One of the practices randomised is made up of two practices who work closely and were due to merge; b Reasons include lack of staff, lack of resources or lack of consultations for CHICO; c Two practices within the control arm merged, therefore their outcome data was compiled into one practice.

The majority of CCGs found to be ineligible (n = 14) did not have enough practices using EMIS®. Of the 110 eligible CCGs that were then approached, 52 (47%) consented to take part. Practices from within those CCGs were then approached and asked for expressions of interest. An additional 33 practices expressed interest but were not recruited, as their CCG had not consented to take part. The majority of practices were excluded due to having no capacity to take part (n = 57) or because they stopped responding to communications (n = 42). By the end of recruitment, the CHICO study had randomised 294 practices, 144 to the intervention arm and 150 to the control arm.

Over the course of the trial, there were 12 practice withdrawals, 8 in the intervention arm of the trial and 4 in the control arm (see Table 4). The majority of withdrawals in the intervention arm were listed as ‘pandemic related’, which included lack of time/resources to take part in the trial but also a lack of children consulting with a cough. Other reasons include issues with installing the intervention, a complete change in staff at the practice and a merger (two practices in the control arm merged together to form one larger practice).

| Intervention, N (%) | Control, N (%) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCG withdrawals | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Practice withdrawals | 8 (6) | 4 (3) | 0.211 |

| Pandemic related | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.089 |

| Intervention/EMIS ® issues | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.148 |

| No reason provided | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.977 |

| Complete change of staff | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.326 |

| Merged with another practice | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.326 |

| Loss to follow-upb | 14 (10) | 16 (11) | 0.789 |

Of the 144 practices randomised to the intervention arm, 100% provided baseline data and routine data on dispensing rates and hospitalisations could be obtained for 100% of practices. Intervention usage data were complete (12 months of data) for 115 (80%) practices and partially complete for 16 (11%) of practices. The other 13 (9%) of practices provided no intervention usage data. The follow-up questionnaire was then completed by 130 (90%). Similar proportions of follow-up data were available for the control arm (89%), with one missing due to the Gloucestershire practice merger.

Randomisation

Randomisation of practices was stratified by CCG and minimised for list size and previous dispensing rate. Table 5 shows that the stratification across CCGs allowed for a relatively equal share of intervention and control practices across each CCG.

| Total | Intervention | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire | 39 | 20 (51) | 19 (49) |

| Birmingham and Solihull | 9 | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| Brenta | 17 | 7 (41) | 10 (59) |

| Buckinghamshire | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Cambridge and Peterborough | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| Cannock Chase | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Canterbury and Coastalb | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| Devon | 3 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) |

| Dudleyc | 13 | 5 (38) | 8 (62) |

| East Berkshired | 5 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) |

| East Lancashire | 7 | 4 (57) | 3 (43) |

| East Staffordshire | 4 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) |

| Eastbournee | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Gloucestershire | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Guildford and Waverlyf | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Hastings and Rothere | 5 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) |

| Herts Valley | 7 | 5 (71) | 2 (29) |

| Kernow | 4 | 2 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Leeds | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Liverpool | 15 | 7 (47) | 8 (53) |

| Manchester | 12 | 7 (58) | 5 (42) |

| Medwayb | 6 | 4 (67) | 2 (33) |

| Morecambe Bay | 14 | 6 (43) | 8 (57) |

| Newcastle and Gateshead | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| North East Essex | 3 | 2 (67) | 1 (33) |

| North Hampshireg | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| North Staffordshire | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| North West Surreyf | 4 | 1 (25) | 3 (75) |

| Nottinghamh | 3 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) |

| Oxfordshire | 15 | 8 (53) | 7 (47) |

| Salford | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) |

| Sandwell and West Birminghamc | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Shropshirei | 4 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) |

| Somerset | 27 | 14 (52) | 13 (48) |

| South East Hampshireg | 4 | 2 (50) | 2 (50) |

| South East Staffordshire and Seisdon | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| South Cheshirej | 3 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) |

| Southwarkk | 6 | 3 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Staffordshire and Surrounds | 3 | 2 (67) | 1 (33) |

| Stoke on Trent | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Sunderland | 8 | 4 (50) | 4 (50) |

| Thanetb | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Vale of York | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Walsallc | 9 | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| Wandsworthl | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| West Hampshireg | 9 | 5 (56) | 4 (44) |

| West Kentb | 6 | 4 (67) | 2 (33) |

However, some CCGs were only able to recruit one or two practices, which hindered this process. During the 2-year recruitment period, almost half of the CCGs underwent a merger, either with other CCGs in the study or with CCGs outside of the study. Details of these mergers can be found in the footnote of Table 5. There were five errors when randomising practices that will have affected the minimisation process, which are summarised in Table 6.

| Error | Practices affected | Potential issue |

|---|---|---|

| Randomised three times (due to false error message). | 1 | The randomisation system will have counted the same practice three times, therefore this will have affected the minimisation. |

| Typo when entering the CCG number. | 3 | The stratification/minimisation process was not successful in these practices as they were entered as a new CCG. |

| Practice entered as having a ‘High’ list size, when in fact it had a ‘Low’ list size. | 1 | This will have affected the minimisation for this CCG. |

Baseline data

Baseline comparisons for the CHICO study are given in Table 7. The team pre-specified in the analysis plan46 that any baseline characteristics that differed by more than 10% (categorical variables), half a SD or half an IQR (continuous variables) would be investigated. None of the baseline characteristics met these criteria so no investigations were carried out. The two arms were well balanced with respect to baseline characteristics, suggesting that stratification by CCG and minimisation had been successful. Of the practices randomised, 62% had a high list size relative to other practices within their CCG suggesting that smaller practices were less likely to be recruited. In a similar way, 42% of the practices randomised had a high baseline dispensing rate, relative to other practices within their CCG suggesting that high prescribers were less likely to be recruited.

The median number of GPs was 6 per arm and this was well recorded (290/294). However, there were varying completion rates for the numbers of each type of staff, at each practice, therefore these figures may not be a true representation of practice staff. The Index of Multiple Deprivation was used to assess whether the CHICO study was recruiting practices from high or low levels of deprivation is based on data available from 2019. 47 In general, there was a larger proportion of practices in quintiles 1 and 2 (higher levels of deprivation) than quintiles 4 and 5 (lower levels of deprivation) reflecting an excess of practices located in urban areas and a similar distribution to the geographical location of all GP practices in England.

The Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI)48 measures the proportion of all children aged 0–15 living in income-deprived families and this was 15% in both arms. There were 43 practices that were randomised on, or after, March 2020. The other 251 were randomised before March 2020. The proportion of RTIs consulted over the phone changed immensely; going from ~25% mostly/always consulting over the phone pre-COVID-19 to ~65% during the pandemic.

Serious adverse events

There were four events that were reported during the CHICO study (see Table 8). There was one hospitalisation in the intervention arm. There were three deaths reported, two of which were in the intervention arm; all unrelated to the intervention.

| SAE | Arm of the study | SAE description | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAE-001 | Intervention | Patient admitted to hospital for RTI | Based on information available the event was not considered related to the intervention |

| SAE-002 | Control | Fatality – no details of cause but patient history suggests unrelated to RTI | Not considered related to the intervention |

| SAE-003 | Intervention | Fatality (unrelated to RTI, intervention not used) | Not considered related to the intervention |

| SAE-004 | Intervention | Fatality (unknown whether a RTI consultation took place within 90 days of the fatality) | Not considered related to the intervention |

Intervention usage

Complete 12-month intervention usage data were available for 115/144 (80%) practices. Data from these practices allowed us to look at intervention usage over time, both in terms of calendar year (January–December) and follow-up time point (months 1–12). Twelve practices (8%) provided between 6 and 11 months of intervention usage data and four (2%) practices provided < 6 months of data. The remaining 13 (9%) intervention practices did not provide any intervention usage data. Across the 121 practices that provided at least 1 month of intervention usage data, we recorded a total of 11,944 uses of the intervention. The median usage across the practices with 12 months of data (n = 115) was 70 uses (IQR 9–142). Twenty practices (17%) recorded zero usage over the 12-month period. All of these 20 practices started follow-up after May 2019 and 13 (65%) began follow-up from March 2020.

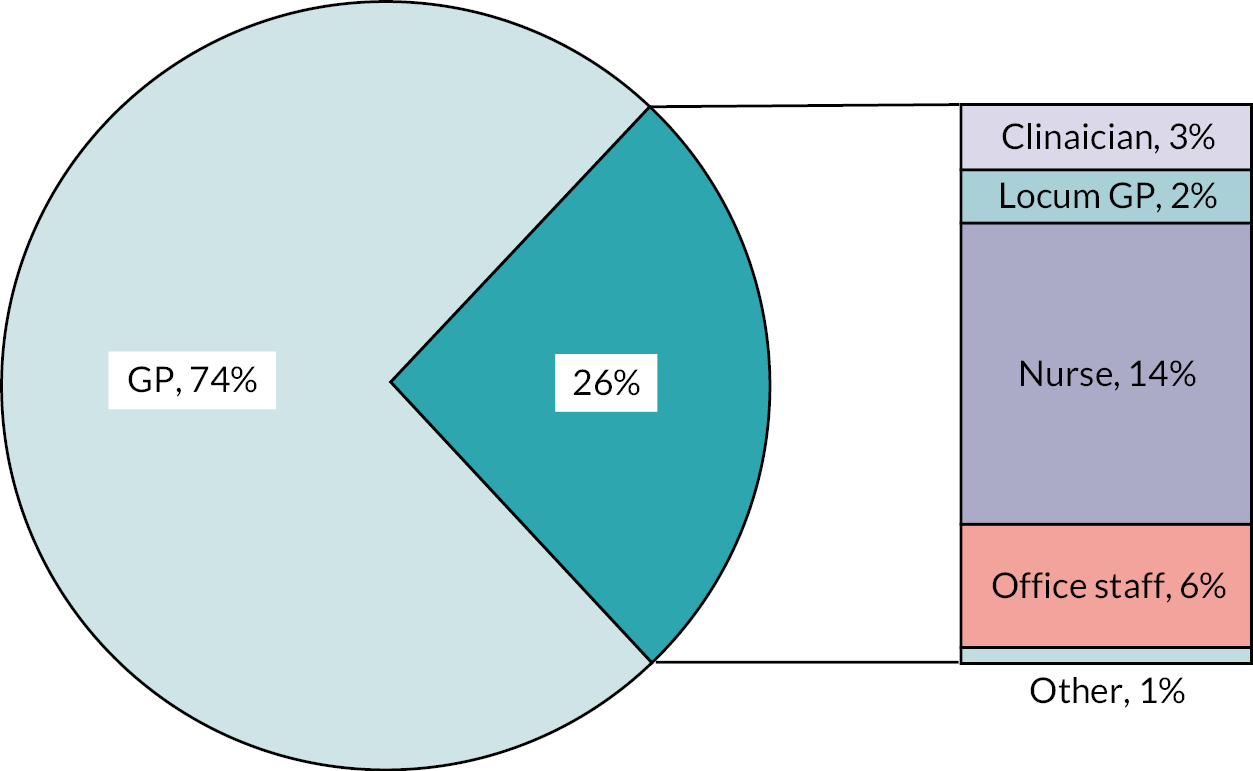

Users of the intervention

Using the EMIS® user mnemonic (a unique username for each healthcare practitioner using system), the CHICO template recorded 1399 individual users of the intervention. The median number of users per practice (n = 131) was 9 (IQR 3–16). This figure remained the same when looking at practices providing 12 months of data (n = 115); median 9 (IQR 3–17). Figure 6 shows the job roles of the intervention users. Of the 1399 users identified, the job role type was available for 1341 of them. Of these, 994 (74%) were GPs, 187 (14%) were nurses, 77 (6%) were office staff, 40 (3%) were clinicians, 34 (3%) were locum GPs and 7 (1%) were pharmacists. There was also one consultant and one phlebotomist.

FIGURE 6.

Job roles of those using the intervention.

There were four individual users who used the intervention more than 100 times; two GPs, one nurse and one clinician. Overall, the GPs and nurses used the intervention the most, with a median of five uses per GP/nurse over the 12-month period (see Figure 7). Office staff (e.g. analysts and medical secretaries) used it the least, averaging one use per member of staff.

FIGURE 7.

Uses of the intervention, per job role.

Usage of the intervention over the 12 months of participation in the study

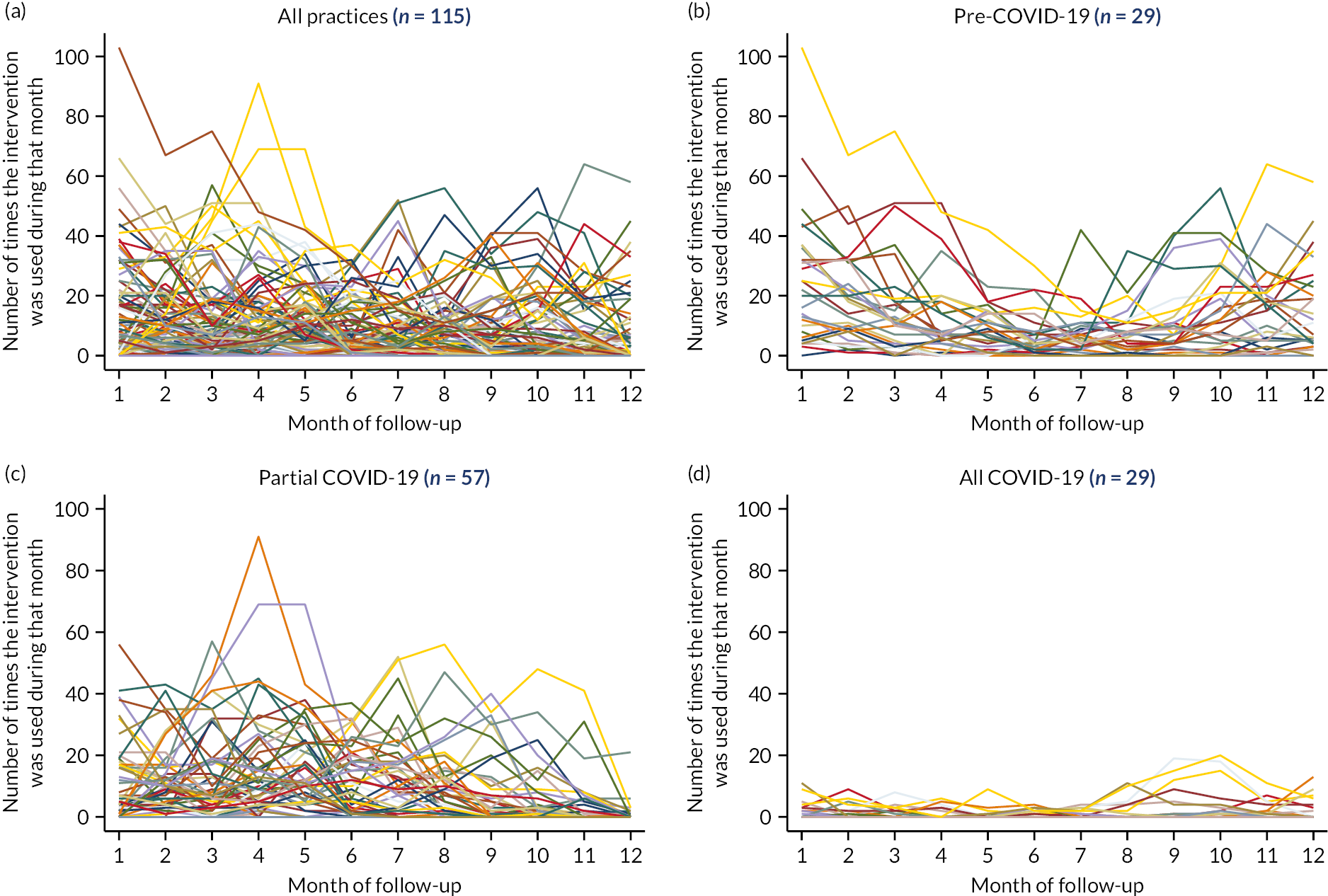

Practices with 12 months of intervention usage data available allowed for a detailed inspection of trends over months 1–12 of follow-up. Panel A of Figure 8 shows usage over the 12-month period for all 115 practices. Due to COVID-19, it is difficult to determine what a typical pattern of intervention usage may look like. Table 9 provides the median use per month based on the individual practices presented in Figure 8. Panel B of Figure 8 and row 2 of Table 9 show the data for the 29 practices that completed follow-up prior to March 2020 and were, therefore, unaffected by COVID-19 lockdowns. Generally, the majority of use was at the start of follow-up, in months 1 (median = 22) and 2 (median = 18). However, for these 29 practices who completed follow-up prior to the pandemic, month 1 had to be between November 2018 and March 2019. Therefore, the increased usage in months 1 and 2 may coincide with the seasons, rather than indicate an increased usage at the start of follow-up. Panel C shows the practices that had 1–11 months of follow-up data on, or after, March 2020 (n = 57). Given the variety of months affected by COVID-19, it is difficult to spot trends or patterns in the intervention usage data.

FIGURE 8.

Intervention usage, by follow-up month for (a) all practices, (b) pre-COVID-19 (completed before March 2020), (c) partial COVID-19 (≥ 1 month from March 2020), (d) all COVID-19 (complete follow-up from March 2020).

| Month of follow-up | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | M11 | M12 | |

| All practices (n = 115) | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pre-COVID-19a (n = 29) | 22 | 18 | 11 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 7 |

| Partial COVID-19b (n = 57) | 4 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All COVID-19c (n = 29) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

For practices with complete follow-up on or after March 2020 (n = 29), the median usage was 0 for all months and panel D of Figure 8 shows how the maximum usage recorded over that period was 20.

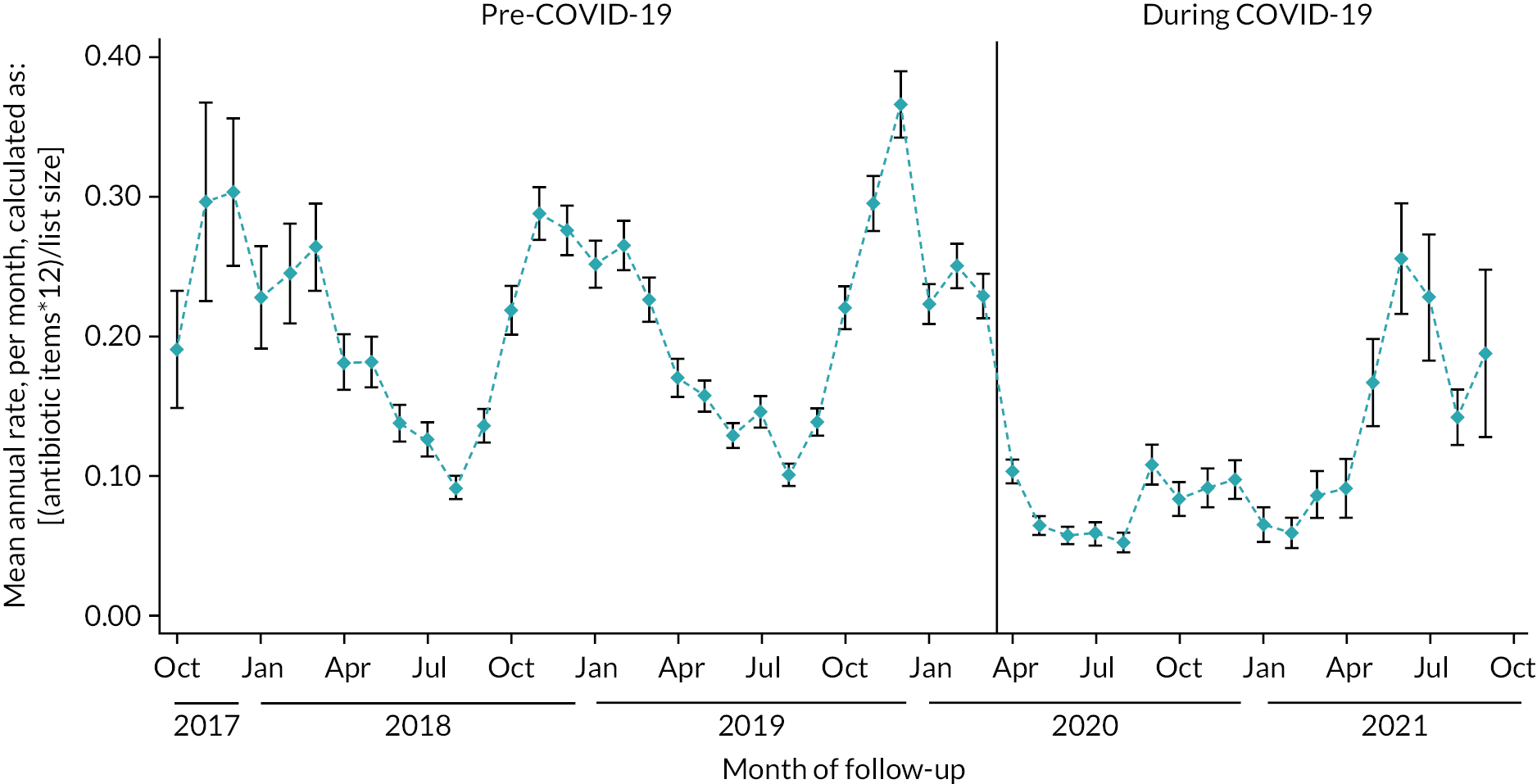

Usage of the intervention across the seasons

If we combine all practices and look at the data across calendar months, we can see the seasonal effects on intervention usage. In Figure 9, we can see the seasonal variation between October 2018 and February 2020, with increased usage during the winter months and fewer uses during the summer months. This suggests that usage did correlate with the number of children presenting with RTIs. However, from March 2020 the effects of COVID-19 lockdowns are clear, with very little usage of the intervention. There is a small increase in May, June and July 2021, when restrictions were relaxed and RTIs were more prevalent in the population.

FIGURE 9.

Intervention usage over time, with each practice (n = 115) contributing 12 months of data.

Looking at usage per calendar month, with all years combined, the seasonal variation is clear (see Figure 10 and Table 10). Looking specifically at practices that completed follow-up before COVID-19 (n = 29), median usage was highest in November (19), December (14) and January (15). This was also evident in practices with at least 1 month on, or after, March 2020 (n = 57). For practices with all 12 months of follow-up data on, or after March 2020 (n = 29), median usage bucked the usual seasonal trends, with summer months providing the highest number of uses.

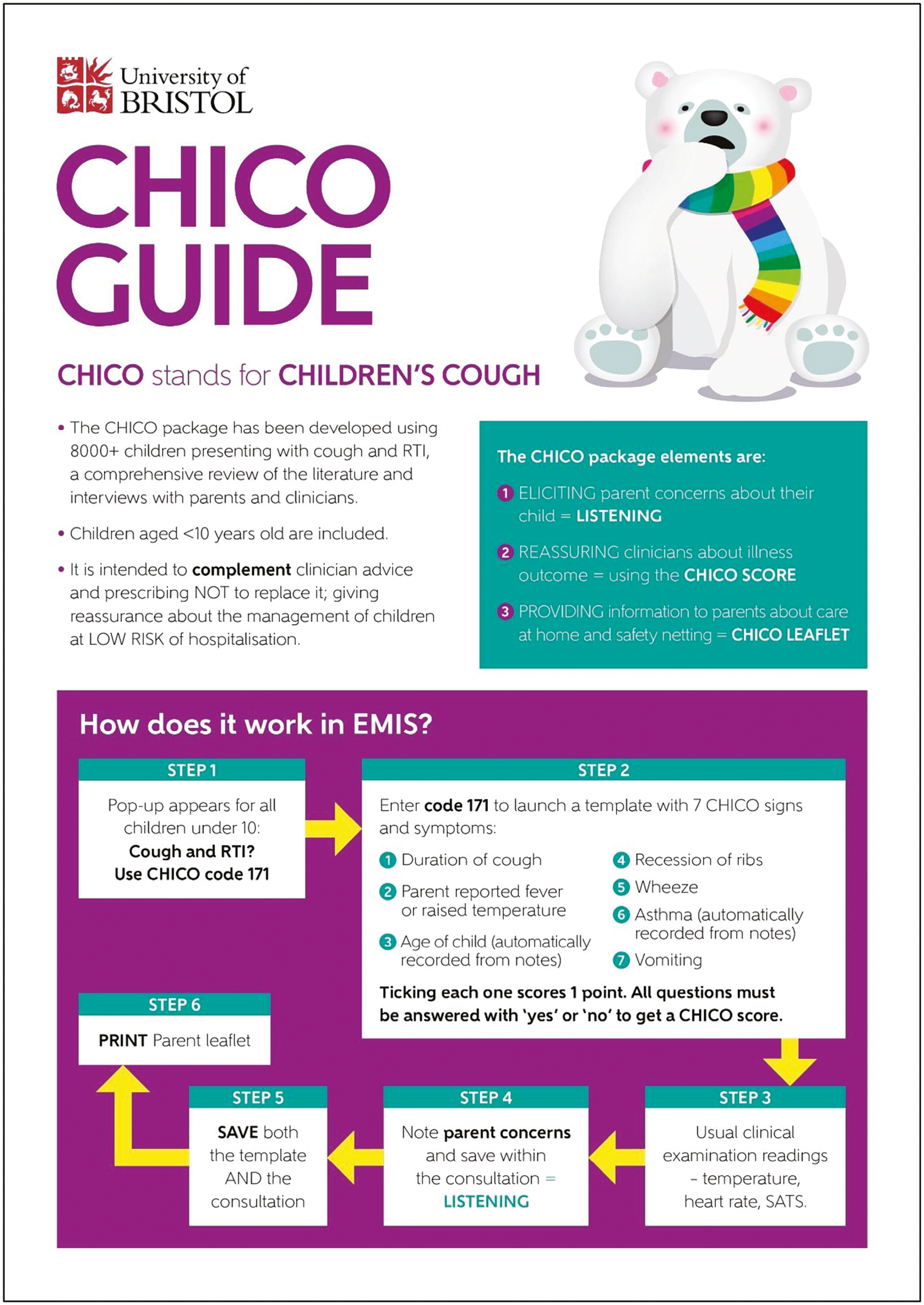

FIGURE 10.