Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number NIHR129713. The contractual start date was in September 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in August 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Snowsil et al. This work was produced by Snowsil et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Snowsil et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Overview

Lynch syndrome (LS), previously referred to as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is a hereditary cancer predisposition syndrome caused by pathogenic variants in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) mismatch repair (MMR) genes. Although mostly undiagnosed, around 1 in 300 people are born with variants causing LS. 1 LS confers a higher lifetime risk and earlier onset age of developing colorectal (CRC), endometrial (EC) and ovarian (OC) cancers. 2 These cancers are also associated with morbidity and mortality. 3

The risks in those with confirmed MMR pathogenic variants are managed through risk-reducing measures including surveillance, risk-reducing surgery and aspirin chemoprophylaxis. 4

Although colonoscopic surveillance is recommended to manage the risk of CRC and is generally accepted to reduce the risk of mortality from CRC,5 surveillance for gynaecological cancer is more contentious. 6 Instead, risk-reducing gynaecological surgery is recommended to virtually eliminate the risk of endometrial and OC. 7

Risk-reducing surgery can have some negative consequences. Removal of ovaries prior to the age of natural menopause leads to surgical menopause. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is generally safe and effective for women with no prior cancer. Removal of female reproductive organs also forecloses natural fertility. Therefore, many women with LS seek to delay risk-reducing surgery until they have completed their families and are closer to the age of natural menopause.

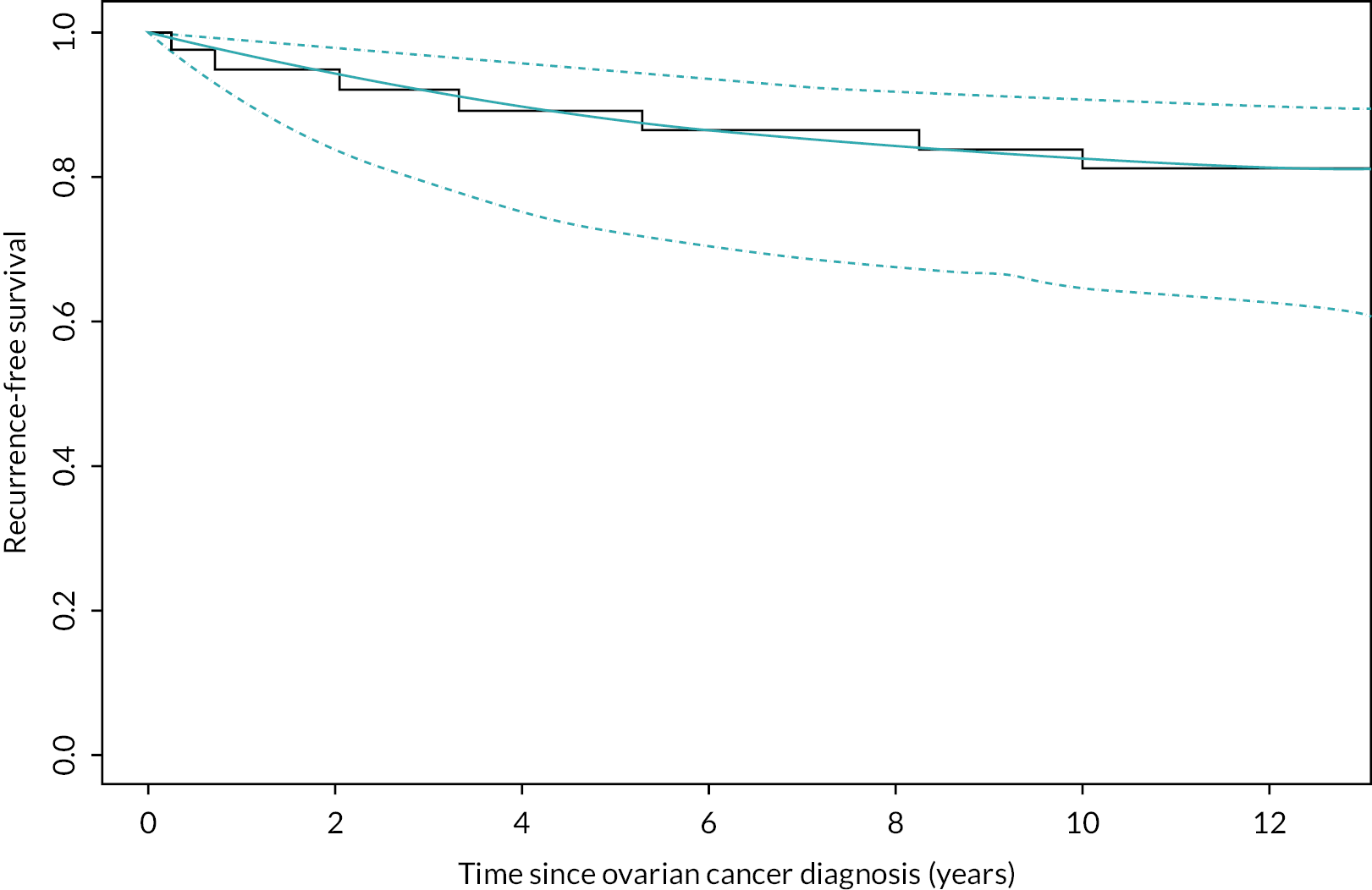

Until they undergo risk-reducing surgery, women with LS may be anxious that their risk of gynaecological cancer is unmanaged. Many will know relatives who have had gynaecological cancer and this can contribute to their anxiety.

Many women with LS are keen to undergo surveillance to manage their risk of gynaecological cancer, and some will resort to private healthcare spending if their local NHS does not offer this surveillance.

The aim of this study was to find out whether surveillance for gynaecological cancer in LS is effective and whether it would be cost-effective in the NHS.

Description of health condition

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Lynch syndrome is an inherited autosomal dominant disorder,8–10 meaning that a child with one parent with LS has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease. It is caused by pathogenic mutations in one of four DNA MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2). 11,12 MMR proteins recognise and repair errors in DNA replication. As a person with LS only inherits one functional allele, there is a high risk that MMR function is lost because of somatic mutation. Loss of DNA MMR activity in cell division induces inability to repair mutations, eventually leading to cancer. 9,10,13

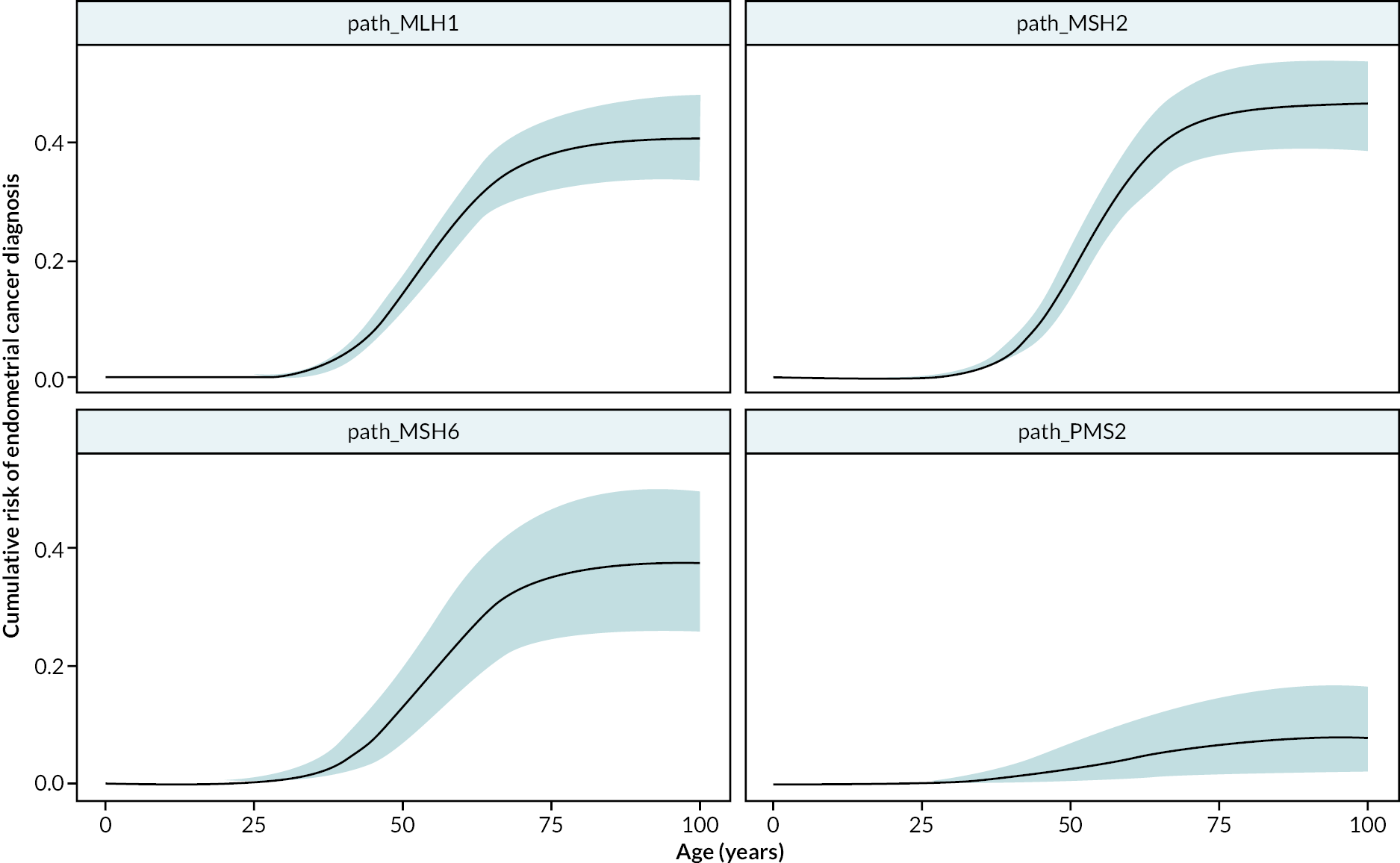

Lynch syndrome is associated with early-onset cancer as tumours develop at a young age. Depending on which MMR gene is affected, the cumulative cancer risks by 70 years can exceed 50% and 20% for EC and OC,2,8,14 compared with cumulative risks of 1.3% and 1.0% in the general population. 15

Diagnostic criteria/measurement of disease

Historically, families with LS were identified through family history criteria, such as the Amsterdam criteria, followed by MMR gene mutation testing in constitutional DNA. 16 Recently, universal testing for LS among those with new colorectal or endometrial cancer has been recommended. 17,18

Impact of the health problem

Significance for patients

An individual with LS may develop several clinical and pathological features, including cancers such as EC and OC, early onset of cancer, multiple independent cancers. 19 The value of a surveillance regimen for women at risk of EC or OC has yet to be established. 20 The Manchester International Consensus Group concluded that ‘further research is required to establish the value of gynaecological cancer surveillance in LS’. 6

The risks of endometrial and ovarian cancer affect people with female reproductive organs, and this may include transgender men as well as cisgender women. We are not aware of any research beyond isolated case reports in LS involving transgender men, and it is possible that evidence that is collected (believed to relate entirely to cisgender women) may be less reliable when applied to transgender men who have used exogenous sex hormones, GnRH analogues or anti-oestrogens. In this monograph, we may at times refer to women – in this context we mean all people with female reproductive organs, which could include transgender men. Our preference is to avoid the noun ‘females’ for people of female sex, as this term can be seen as dehumanising.

Significance for the NHS

The majority of individuals with LS caused by path_MLH1 or path_MSH2 will go on to develop at least one cancer in their lifetime, and LS accounts for around 3% of CRC and ECs. 21,22 In 2017, there were nearly 35,000 CRC diagnoses in England and over 7000 cases of EC. 23 This suggests that over 1000 cancers each year are being diagnosed in people with LS, which may be preventable through risk management strategies.

Current service provision to manage gynaecological cancer risk in Lynch syndrome

Clinical guidelines and why this research is needed now

As a result of publication of recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on identifying LS,17,18 more women will have a diagnosis of LS and need to manage their gynaecological cancer risk. Evidence is needed to determine which interventions are effective and cost-effective to reduce the morbidity and mortality from gynaecological cancer and to contribute to the NHS Long Term Plan goal of improving early diagnosis of cancer. 24 Surveillance is a preferred option for patients managing cancer risk, but good-quality estimates of its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness have not been produced.

Care pathways

Two main interventions are available to manage the gynaecological cancer risk in LS: risk-reducing surgery (removal of the uterus and ovaries) and surveillance. Some patients may have surveillance initially and then have risk-reducing surgery. In addition, chemoprevention with aspirin4 and hormone therapy25 may be considered, as well as lifestyle changes.

Gynaecological surveillance can identify precancerous lesions in the uterus, for which there are fertility-sparing treatments. Surveillance may also be able to identify OC in the early stages, where management options could maintain fertility or allow egg harvesting.

Gynaecological surveillance has previously been estimated to cost the NHS £473 per year for a woman with LS. 9 Later-stage gynaecological cancers can be costly to treat; for example, stage 3 OC costs twice as much to treat as stage 1 cancer. 26

Surgery is widely offered, since its effectiveness is well documented,7 typically at 40–45 years when most women have completed their families. 27 This prevents women from becoming pregnant and artificially brings on menopause, which can detrimentally affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and long-term health unless managed with HRT. In some cases, women do not have risk-reducing surgery because of technical difficulties due to past surgery for CRC, high anaesthetic risk due to medical comorbidities or patient preferences. 28

Some NHS providers offer surveillance for gynaecological cancer in women with LS not undergoing risk-reducing surgery; others do not because of a lack of evidence-based guidelines and resource constraints. Some women opt to pay privately for surveillance, but not all women can afford this service.

Chapter 2 Decision problem

The key research questions for this study were:

-

Is gynaecological cancer surveillance in LS clinically effective?

-

Is gynaecological cancer surveillance in LS cost-effective in the NHS?

Furthermore, we were interested to determine whether certain groups would benefit more or less from surveillance, experience more or fewer harms from surveillance or whether surveillance would be more or less cost-effective for certain groups.

To answer the first key research question, our objective was to conduct a systematic review of existing studies on the effectiveness of gynaecological cancer surveillance in LS. This systematic review is reported in Chapter 3.

To answer the second key research question, we had the following objectives:

-

To conduct a systematic review of existing studies on the cost-effectiveness of gynaecological cancer surveillance in LS (reported in Chapter 4).

-

To conduct a systematic review of health state utility values which may be relevant for the cost-effectiveness of gynaecological cancer surveillance in LS (reported in Chapter 5).

-

To conduct a model-based economic evaluation of gynaecological cancer surveillance in LS.

We decided that there would be value in developing a whole-disease model for LS rather than a model only capable of addressing the focused research question in this study. The development of the whole-disease model is reported in Chapter 6.

The model-based economic evaluation is reported in Chapter 7.

Population

People with LS (i.e. with confirmed pathogenic variants in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2) or suspected LS at risk of EC and/or OC.

Intervention

Gynaecological cancer surveillance

Strategies for gynaecological cancer surveillance in women with LS may include a number of different modalities. Surveillance is typically conducted at 1- or 2-year intervals and initiated between the ages of 25 and 35 years. 6,8

Hysteroscopy and directed biopsy

An endoscopic technique for inspecting the uterine cavity (in this case to identify endometrial neoplasia) by inserting a hysteroscope via the cervical os. Hysteroscopy can allow for directed biopsy (targeted extraction of tissue for pathological examination). It can often be performed in outpatient or office settings with no anaesthesia or analgesia, although in some cases local or general anaesthesia (GA) may be used.

Undirected biopsy

Techniques for sampling the endometrium without visualising the interior of the uterus. Numerous samples are taken from different parts of the endometrium. Aspirate biopsy (e.g. Pipelle) is typically conducted in an outpatient or office setting while dilatation and curettage is conducted under sedation or GA in an inpatient or daycase setting.

Transvaginal ultrasound

An ultrasound probe is inserted into the vagina to visualise organs in the pelvic cavity, which can identify signs of endometrial and ovarian malignancy (e.g. increased endometrial thickness).

Transabdominal ultrasound

An ultrasound probe is pressed against the abdomen to visualise the uterus and ovaries to identify malignancies.

Cancer antigen-125

A blood serum biomarker which is raised in around 90% of women with advanced ovarian cancer. NICE recommends that serum cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) of 35 iu/ml or greater is an indication for further investigation in women with symptoms of OC. 29

Comparators

The relevant comparators are risk-reducing surgery or no risk reduction.

Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) is commonly used in clinical practice to all but eliminate the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancers. 7 However, it is an operation under GA, which can carry surgical risk (particularly with women who have had prior surgery, e.g. for CRC) and artificially brings on menopause in premenopausal women.

There is evidence from a retrospective cohort study that prolonged use of hormonal contraceptives lowers the rate of endometrial cancer in women with LS. 25 This comparator falls outside the scope of this research, although it may be a concomitant treatment for some individuals in the included studies as a significant proportion of women engage in prolonged use of hormonal contraceptives.

Symptom awareness, with optional annual clinical review, has been recommended by a consensus group,6 together with rapid access to investigation for suspicious signs and symptoms.

Outcomes

Outcomes are specified in detail in the subsequent chapters.

Chapter 3 Systematic review of clinical effectiveness evidence

Review aims

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of different gynaecological cancer surveillance strategies in LS, the ability of those strategies to detect gynaecological cancers, and the harms associated with those strategies.

Under these three broad aims the review sought to evaluate ten specific research questions which are listed below.

Cancer detection:

-

What are the cancer detection rates/incidence rates (malignancies and premalignancies) for gynaecological surveillance strategies in people with LS?

-

What are the cancer detection rates/incidence rates for gynaecological surveillance among asymptomatic women with LS?

-

What is the incidence of interval cancers among people with LS taking part in gynaecological surveillance programmes?

-

What are the incidental detection rates of other medical findings (e.g. ovarian cysts) among people with LS undergoing gynaecological surveillance?

-

What are the diagnostic test accuracies of different gynaecological surveillance strategies for people with LS?

-

What are the test failure rates for gynaecological surveillance procedures in LS?

Clinical effectiveness:

-

Do gynaecological surveillance strategies improve mortality, survival, cancer prognosis, treatment response and fertility in people with LS?

-

Do gynaecological surveillance strategies improve early diagnosis (i.e. stage at diagnosis) in people with LS?

Harms:

-

What are the rates (and severity) of adverse events (including pain) observed in different gynaecological surveillance strategies among people with LS?

-

What risk factors impact the occurrence (and severity) of adverse events among people with LS undergoing gynaecological surveillance?

Methods

The methods of the review were conducted following a protocol, which was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020171098). Deviations from the protocol and protocol clarifications are described in the relevant sections that follow or in Protocol amendments. Changes and additions made due to patient and public involvement (PPI) activities (see Patient and public involvement) were not considered to be protocol deviations but are highlighted where applicable.

Study identification

A bibliographical database search was developed using MEDLINE by an information specialist (SB) in consultation with the review team. The search strategy combined two components: (1) search terms for LS, MMR and HNPCC (i.e. the population/problem of interest); and (2) a relevant selection of gynaecological screening methods (i.e. the interventions of interest). A combination of free-text terminology and indexing terms (e.g. MeSH) was used. No date or language limits were applied. The final search was translated for use in an appropriate selection of bibliographic databases including: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (via the Cochrane Library); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (via EBSCO); MEDLINE (via Ovid); EMBASE (via Ovid); Web of Science Science Citation Index (SCI) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI – S; via Clarivate Analytics). The search strategies are reported in full in Appendix 1.

Bibliographical database searches were carried out on 21 September 2020, with update searches carried out on 3 August 2021. The results were exported to Endnote X8 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and deduplicated using the automated deduplication feature and manual checking. The resulting library was then exported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, Australia, www.covidence.org) in preparation for the study selection process.

To identify further studies, forward and backward citation searches of all included studies were conducted using Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics). We used Google Scholar to carry out forward citation searching on included studies that were not indexed in Web of Science. Any relevant systematic reviews identified in the process of screening the results of our searches were also manually checked for relevant primary studies. The results of forward and backward citation searches were exported to Endnote X8 for deduplication and then exported to Covidence for the study selection process.

Relevant conference proceedings were scrutinised. Finally, the clinical trials registries ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched for ongoing trials on 9 August 2021. The clinical trials registry search strategies are reported in Appendix 1.

Study selection

A two-stage screening process was used to select studies: two reviewers (HC and SB) independently screened titles and abstracts against the Eligibility criteria (see below). The full texts of studies that appeared to meet the eligibility criteria were retrieved and independently screened by the same two reviewers. At both stages of screening, disagreements were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer (TS) where necessary.

Screening was carried out in Covidence for both title and abstract screening and full-text screening. This was a deviation from the protocol where the intention had been to conduct screening in EndNote. This change in software was to enable ease of remote working due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Eligibility criteria

The following prespecified eligibility criteria were used to select studies:

Population

Studies must have been based on an adult population (age ≥ 18 years) at risk of EC and/or OC (individuals born with and retaining a uterus and/or ovaries, including trans men, and intersex individuals at risk of EC and/or OC) and with confirmed or suspected LS.

Prior to screening being conducted, it was clarified that studies based on a wider population should be included if subgroup data were provided for the eligible population. In these cases, only the relevant subgroup data were included. This clarification was an omission from the published protocol.

Intervention

Studies that evaluated any gynaecological surveillance strategy either alone or in combination with a comparator were included. The target conditions of surveillance had to be EC and/or OC. Surveillance strategies included (but were not limited to): hysteroscopy and directed biopsy, undirected biopsy, ultrasound (transvaginal or transabdominal) and cancer antigen-125 testing. Studies were not excluded based on the surveillance schedule.

Comparators

For controlled study designs, eligible comparators included no surveillance, alternative surveillance programmes, surgical or hormonal prevention. In diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, any eligible surveillance test result could be used as a reference standard for another test but, primarily, cancer diagnosis using histology was the preferred reference standard.

Outcomes

To be eligible for inclusion, studies needed to evaluate at least one of the following outcomes: all-cause mortality, cancer-specific mortality, cancer survival, cancer treatment response, fertility, cancer stage, cancer detection rates (in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals), interval cancer rates, incidental medically important findings, diagnostic accuracy, test failure rates, adverse events (including pain/discomfort), risk factors impacting adverse events or HRQoL.

Study design

Eligible study designs included randomised and non-randomised controlled trials (RCTs; for all review questions), prospective and retrospective comparative and non-comparative observational designs (review questions related to cancer detection and harms), DTA studies, including any study from which 2 × 2 data could be ascertained (for the diagnostics test accuracy question only), surveys, interviews and studies with visual analogue scale (VAS) or Likert-type scales (for the questions related to harms). Case reports, opinion pieces, editorials and studies that only published in abstract form were excluded.

Few comparative studies were found to address the clinical effectiveness questions, so a protocol amendment was made to also present relevant clinical effectiveness data (mortality, survival and stage of cancers) from non-comparative cohort studies.

Data extraction

A bespoke data extraction form was used to extract publication details, study characteristics, participant characteristics, methods and results for each outcome. The form was refined in consultation with PPI representatives, to include data about HRT use (at baseline and during the study) and the need for GA during surveillance procedures. The PPI processes also clarified and expanded the data that should be extracted that are relevant to fertility (parity at baseline, pregnancies and births during the study, comparison between pre-and postmenopausal women).

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (HC or SB) and checked by a second (HC, NM or SB). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer (one of HC, SB, NM or TS) where necessary.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias (ROB) was assessed at study level using appropriate tools for the study design: the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I)30 for non-randomised comparative studies and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) cohort study checklist for non-comparative cohort studies. 31 Studies were deemed to be comparative if more than one group of participants was compared for at least one outcome and these groups were either entirely separate or overlapping (e.g. registry data from different time periods). Studies that provided separate data for different tests or procedures from the same sample were deemed to be non-comparative cohort studies. QUADAS-2 (a revised tool for quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies) was completed in addition to the ROBINS-I/CASP if DTA data were extracted. 32

Over the course of the data extraction process, and to ensure a consistent approach across studies, a decision was made to complete the CASP checklist, in addition to the ROBINS-I, for comparative studies. This additional assessment was a deviation from the review protocol and was introduced because these studies provided limited comparative data (usually on a single outcome), so the ROBINS-I judgements were not relevant for the other study outcomes where only single-arm data were provided.

Risk of bias assessments were performed by one reviewer (HC or SB) and checked by a second (HC, NM or SB). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer (one of HC, SB, NM or TS) where necessary.

Synthesis of evidence

Study methods and results were described in a narrative synthesis supported by cross-tabulation. There were insufficient numbers of clinically and methodologically homogenous studies to enable meta-analysis to be conducted for any of the review outcomes.

For test accuracy data, where full 2 × 2 data were available, STATA 17 (Stata Press, College Station, TX, USA) was used to generate sensitivity, specificity, positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV), likelihood ratios and prevalence (using the diagti command). These values were reported if they were not already provided by the study report (see Diagnostic test accuracy data).

Where possible, subgroups were considered in narrative and quantitative syntheses according to participant age (and/or pre- or postmenopause status), participant ethnicity, frequency and age of commencement of surveillance, surveillance prior to the study start, diagnostic status, MMR gene affected, previous gynaecological or colorectal surgery, women for whom risk-reducing surgery is not considered appropriate (particularly those with previous CRC), other previous cancer, family history of gynaecological cancer, parity (nulliparous or parous), method of previous deliveries (vaginal or caesarean section).

Protocol amendments

In addition to the clarifications and amendments described above, the protocol stated that quality of life (QoL) data would be extracted, and these data are treated as clinical effectiveness data. Only one study provided QoL data (see Quality of life and mental health outcomes). This study also provided data on anxiety and depression as clinical effectiveness outcomes. It was decided that, for completeness, these data would also be reported.

Results

Studies identified by the review

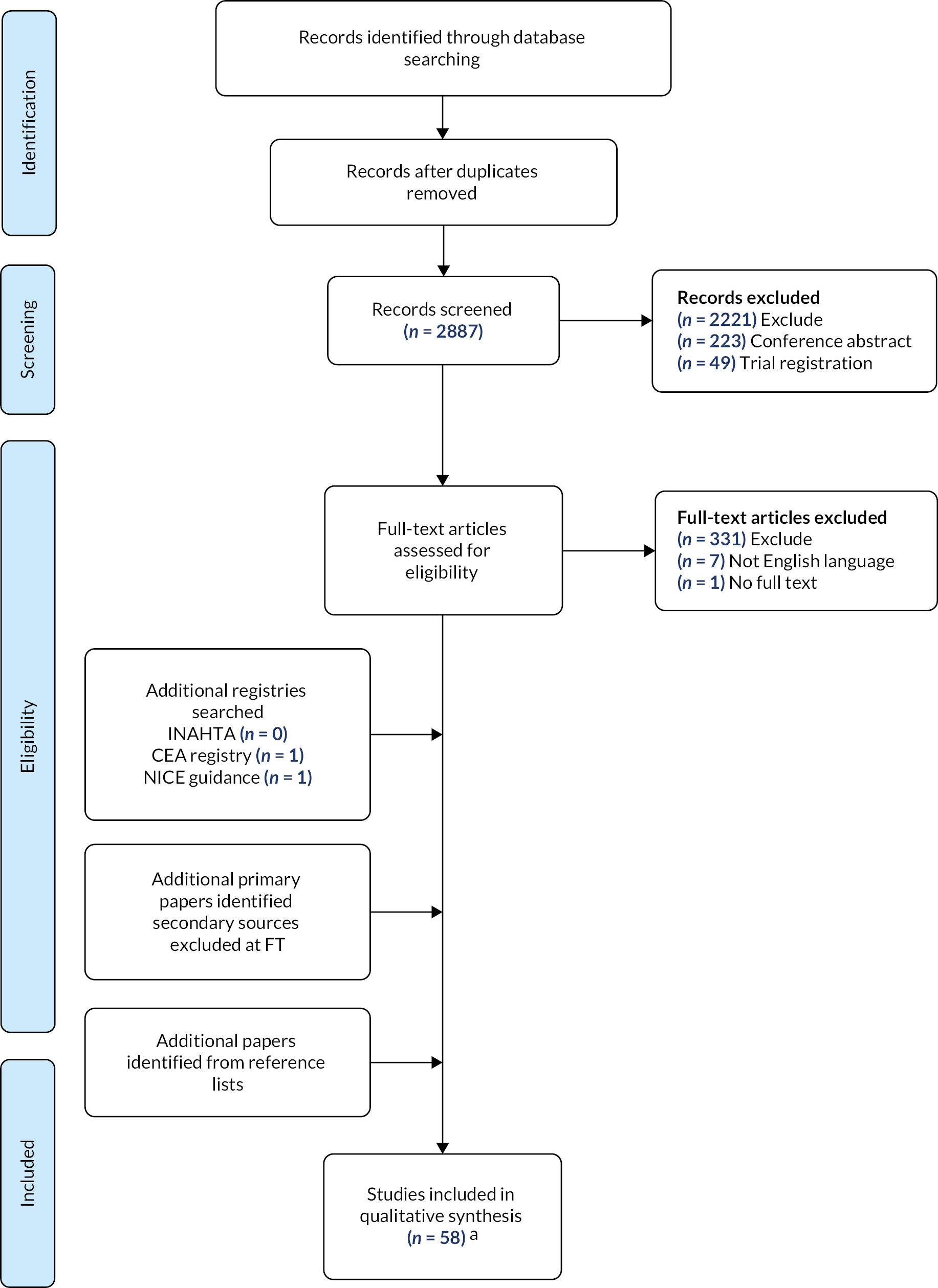

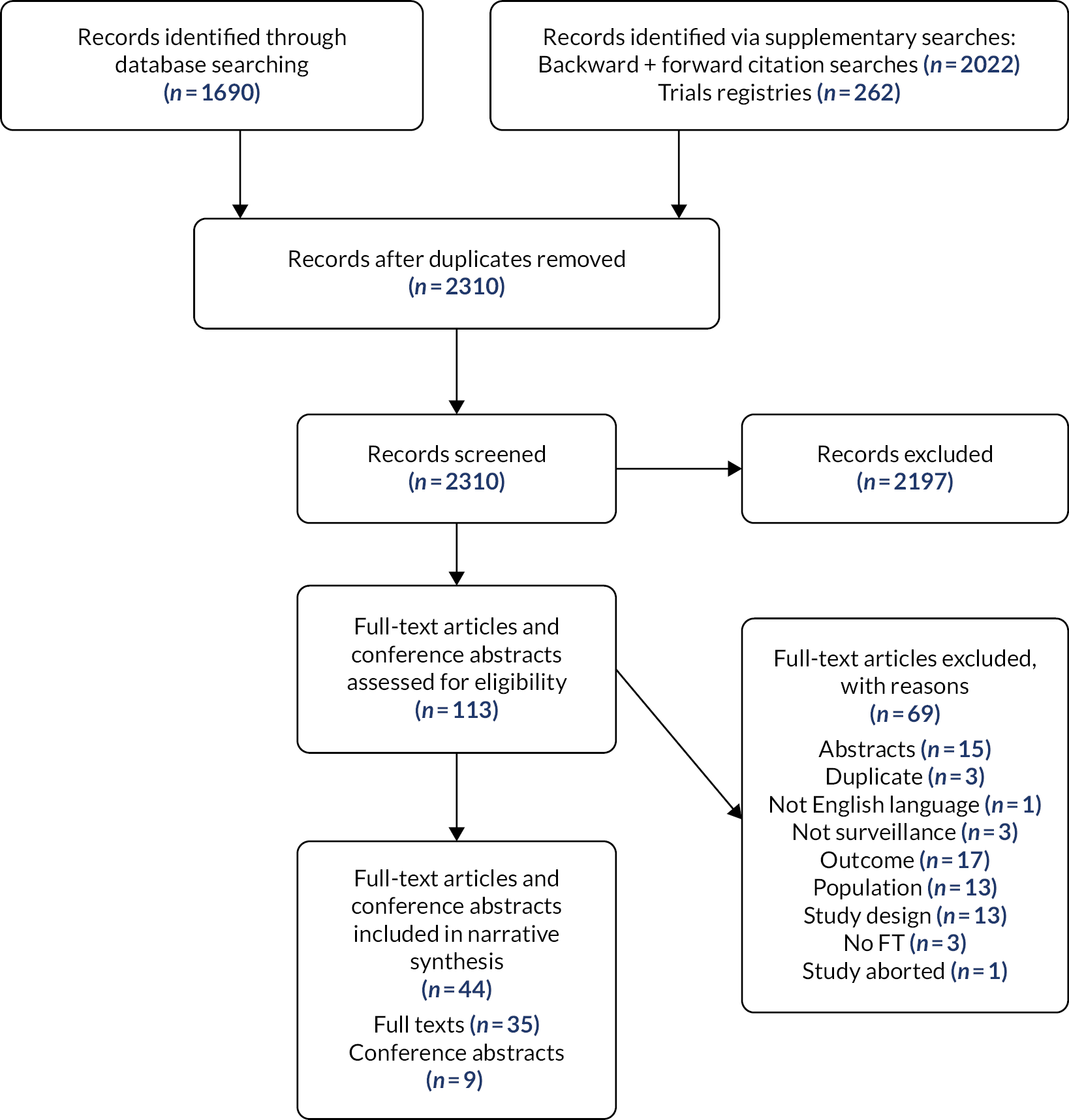

A total of 2310 titles and abstracts were screened (Figure 1). After exclusions based on title and abstract, 113 articles were sought in full, with 110 successfully obtained and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 66 were excluded (reasons for exclusion are provided in Table 25, Appendix 2). The remaining 44 articles (including 34 full-length articles, 9 conference abstracts and 1 correction) covering 30 studies were included in the review.

FIGURE 1.

Study flowchart for the systematic review of clinical effectiveness. FT, full text.

The included studies each contributed to different review questions, with some studies providing data for more than one question (Table 1). Most studies provided data concerning the detection of gynaecological cancers by surveillance, with fewer studies contributing to other review questions. A data map is provided in Table 26, Appendix 3.

| Broad aim | Specific research question | Included studies contributing data |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of gynaecological cancers by surveillance strategies in indivsiduals with LS | What are the cancer detection rates/incidence rates (malignancies and premalignancies)? | 27 studies reported across 41 publications8,33–72 |

| What are the asymptomatic cancer detection rates/incidence rates? | 10 studies reported across 16 publications34,35,40,43–50,52,67,69–71 | |

| What is the incidence of interval cancers? | 18 studies reported across 29 publications37,40,42–52,54–58,60–67,69–71 | |

| What are the incidental detection rates of other medical findings (e.g. ovarian cysts)? | 11 studies reported across 18 publications40,41,43,44,47–52,54–58,60–62 | |

| What are the diagnostic test accuracies of the surveillance strategies/tests? | 5 studies reported across 7 publications34,35,50–52,63,64 | |

| What are the test failure rates? | 5 studies reported across 6 publications34,35,41,50,62,72 | |

| Clinical effectiveness of gynaecological surveillance strategies in individuals with LS | Does surveillance improve mortality, survival, cancer prognosis, treatment response and fertility and QoL?a | Mortality or survival: 11 studies reported across 17 publications8,37–39,42–44,53,59–61,65,66,69–71,73 Cancer prognosis: none Treatment response: noneb Fertility: nonec QoL and mental health: Wood 200868 |

| Does surveillance improve early diagnosis (i.e. stage at diagnosis)? | 8 studies reported across 12 publications38–40,42,47,48,52,65,67,69–71 | |

| Harms associated with gynaecological surveillance strategies in individuals with LS | What are the rates (and severity) of adverse events (including pain)? | 7 studies reported across 13 publications41,43–46,54–58,72,74,75 |

| What risk factors impact the occurrence (and severity) of adverse events? | 4 studies reported across 9 publications41,45,46,54–58,72 |

Characteristics of included studies

Summary of included studies

Of the 30 included studies, 10 were comparative cohort studies (Table 2) and 20 were single-arm cohort studies (Table 3). The comparative studies were those that included data from more than one cohort (either completely separate or overlapping due to the use of two periods) who received different surveillance programmes, or where one group received surveillance and at least one other was an eligible comparator. Cohort studies providing some separate data for different tests within a surveillance programme, but for the same individuals, were not considered to be comparative studies. In these cases, data were extracted separately for the different tests.

| Study | Country | Study design | Centres (N) | Total (N) | Groups; interval | Patients in group (N) | Total visits; visits per person (n) | Programme duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Jong et al. 200673 | Netherlands | Registry data/prospective hospital data/period comparison | UC | 1375a | Surveillance 1990–2004: TVUS, CA-125; 1 year | NRc | NR | NR |

| 1965–75b | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| 1975–90b | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Dueñas et al. 202038,39 | Spain | Retrospective hospital data | 1 | 531 | Surveillance: clinical examinationd, TVUS; 1 year | 465 | NR | 10.4 years (median), range 0–45 years |

| Surgery (preventative); previous surveillancee | 66 | NR | 8.7 years (median), range 0–43 yearsf | |||||

| Eikenboom et al. 202140 | Netherlands | Retrospective hospital data | 1 | 164g | Surveillance: TVUS, routine biopsy, CA-125; 1–2 years | 111 | 570; 3.48 (mean)h | 5.6 years (median), IQR 3–9 yearsh |

| Surgery (preventative); previous surveillance | 53 | |||||||

| Gerritzen et al. 200942 | Netherlands | Prospective hospital data/period comparison | 1 | 100i | Surveillance post-2006: clinical examination, TVUS, routine biopsy, CA-125; 1 year | NR | 64; NR | NR |

| Surveillance pre-2006: clinical examination, TVUS, non-routine biopsy, CA-125; 1 year | NR | 221j;NR | NR | |||||

| Helder-Woolderink et al. 201343,44 | Netherlands | Retrospective hospital data/period comparison | 1 | 75k | Surveillance 2008–12: TVUS, routine biopsy, CA-125; 1 year | 63 | 149; 2 (median), range 1–3 | 28 months (median), range 2–51 months |

| Surveillance 2003–07: TVUS, non-routine biopsy, CA-125; 1 year | 44 | 117; 3 (median), range 1–6 | 36 months (median), range 1–60 months | |||||

| Kalamo et al. 202074 | Finland | Survey data | 1 | 76l | Surveillance: UCm | 24n | NR | 11 years (median), range 6–29 years |

| Surgery (preventative); some previous surveillance | 42o | n/a | n/ap | |||||

| Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. 200760,61 | Finland | Retrospective hospital data/registry data | UCq | 385r | Surveillance: varieds; 2–3 yearst | 175 | 503; 2.87 (mean) | 3.7 years (median), (range 0–13 years) |

| Surgery (preventative/treatment); not eligible for surveillance | 138 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| Stuckless et al. 201366 | Canada | Retrospective hospital data | UC | 204u | Surveillance: TVUS, endometrial biopsy, CA-125; 1–2 years | 54 | NR | 8.5 years (median) |

| No surveillancev | 120 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| Age-matched controls (no surveillance)w | 54 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| Tzortzatos et al. 201567 | Sweden | Retrospective hospital data | 5 | 86x | Surveillance: TVUS, endometrial biopsy, CA-125; 1–2 years | 45 | NR; 2.8 (mean), range 1–20h | NR |

| Surgery (preventative); previous surveillancey | 41 | NR | ||||||

| Woolderink et al. 201869–71 | Netherlands | Prospective hospital data/registry data | UC | 878 | Surveillance: TVUS, endometrial biopsy, CA-125; 1 year | NR | NR | NR |

| No surveillance | NR | NR | NR |

| Study | Country | Centres (N) | Surveillance interval and strategies | Patients in surveillance (N) | Total visits; visits per person (n) | Programme duration at data cut-off point | Person years at risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single visit, single-arm, cohort studies (based on hospital data) | |||||||

| Bats et al. 201434,35 | France | 1 | Single visit: uterine cavity washings (MSI analysis) | 9 | 9; 1 (median) | n/a – single visit | n/a |

| Elmasry et al. 200941 | UK | 1 | Single visit: TVUS, hysteroscopy (plus saline hysterosonography)a, endometrial biopsy | 25 | 25; 1 (median) | n/a – single visit | NR |

| Wood et al. 200868 | UK | 1 | Single visitb: TVUS, hysteroscopy, endometrial biopsy, CA-125 | 15 | NR | n/a – single visit | NR |

| Woolderink et al. 202072 | Netherlands | 2 | Single visit: TVUS, endometrial biopsy, endometrial sampling with tampon | 25 | 25; 1 (median) | n/a – single visit | n/a |

| Single-arm cohort studies (based on retrospective registry data) | |||||||

| Ketabi et al. 201447,48 | Denmark | UC | 2 years: varied techniques, likely based on guidelinesc | 871d | 1945; 2.2 (mean), range: 1–11 | 7.9 years (mean), range 0.1–21.7 years | NR |

| Pylvänäinen 2012 et al.59 | Finland | UC | 2 years: varied techniques, likely based on guidelines | 548e | NR | NR | NR |

| Single-arm cohort studies (prospective hospital data) | |||||||

| Bucksch et al. 202036 | Germany | 6f | 1 year: unclear, included clinical examination | 865 | NR | NRg | NR |

| Dove-Edwin 2002 et al.37 | UK, Netherlands | UC | 1–2 years: TVUS/pelvic USh | 292 | 522; 1.79 (mean) | 3.62 years (mean) | 825.7 |

| Helder-Woolderink 201745,46 | Netherlands | 2 | 1 year: TVUS, endometrial biopsy, CA-125 | 52 | 97; 1.87 (mean) | NR | NR |

| Lécuru et al. 200749 | France | 1 | 1 year: TVUS, hysteroscopy, CA-125 | 57i | 91 | NR | NR |

| Lécuru et al. 200850 | France | 1 | 1 year: clinical examination, pelvic US, hysteroscopy, endometrial biopsy, CA-125 | 62 | 125; 2.02 (mean) | NR | 125 |

| Manchanda et al. 201252 | UK | 1 | 1 year: TVUS, hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsyj | 41 | 69; 2 (median), range 1–2 | 12 months (median), range 6–23.5 months | 49.2 |

| Rosenthal et al. 201363,64 | UK | 37 | 1 year: TVUS, CA-125 | 99 | NR | NR | NR |

| Ryan et al. 201765 | UK | 1 | 1 year: TVUS, hysteroscopy, ovarian US, CA-125k | 87l | NR | 50 months (mean) | NR |

| Single-arm cohort studies (retrospective hospital data) | |||||||

| Barrow et al. 200933 | UK | 1 | Interval UC: clinical examination, TVUS, hysteroscopy, endometrial biopsy | Unclearm | NR | NR | NR |

| Lécuru et al. 201051 | France | 1 | 1 year: pelvic US, hysteroscopy, endometrial biopsy | 58 | 96; 1.66 (mean) | 51.4 months (median), range 1–106 months | 246 |

| Nebgen et al. 2014,54–58,86 | USA | 1 | 1–2 years: clinical examination, TVUS, endometrial biopsy, pap smear, CA-125 (combined with colonoscopy at some visits) | 55 | 111; 2 (median), range 1–6 | NR | NR |

| Rijcken 2003 et al.62 | Netherlands | 1 | 1 year: clinical examination, TVUS, endometrial biopsyn, CA-125 | 41 | 179; 4.37 (mean) | 5 years (median), range 5 months – 11 years | 197 years |

| Single-arm cohort study (survey data) | |||||||

| Ryan 2021 et al.75 | UK | 21 | Interval varied: Varied techniqueso | 59p | 204; 3.46 (mean) | n/a | n/a |

| Pooled data from various studies | |||||||

| Møller 2017 et al.8,53 | Multiq | UC | Interval varied; varied techniquesr | 1057s | NR | NR | 7264 |

Comparative cohort studies

The 10 comparative cohort studies varied in size, ranging from 75 participants eligible for surveillance in Helder-Woolderink et al. (2013)43,44 to 1375 participants in de Jong et al. (2006),73 although in the latter study it was unclear how many of these individuals were eligible for or received surveillance. The duration of surveillance was not reported in many of these studies. Where these data were reported, duration varied greatly, ranging from 28 months (median; range 2–51 months) for the most recent period in Helder-Woolderink et al. (2013)43,44 to 11 years (median; range 6–29 years) in the survey by Kalamo et al. (2020). 74

The studies by de Jong et al. (2006),73 Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. (2007)60,61 and Woolderink et al. (2018)69–71 were based primarily on registry data. Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. (2007)60,61 followed 313 individuals relevant to this review (175 under gynaecological surveillance and 138 in a surgery comparator group), but in both Woolderink et al. (2018)69–71 and de Jong et al. (2006)73 it was unclear how many participants were undergoing gynaecological surveillance. The other comparative studies were either based on hospital data38–40,42–44,66,67 or used survey methodology. 74

Three of the comparative studies investigated the differences between different surveillance time periods. 42–44,73 Two of these were single-centre studies with different processes for initiating endometrial biopsy in the different time periods (biopsy was only offered when clinically indicated during the earlier period but added as a routine test in the later period). 42–44 The remaining study was larger,73 and based on registry data, but it was unclear what the differences were between the time periods (although it is probable that gynaecological surveillance was only available during the latest period).

Five studies compared surveillance with surgery. 38–40,60,61,67,74 In Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. (2007),60,61 the comparator group comprised individuals who had surgery prior to the start of the surveillance programme and who were, therefore, not eligible for surveillance. In Kalamo et al. (2020),74 some of the comparator group had previously received surveillance (68/76 survey respondents across both groups), but were not undergoing surveillance at the time of the survey. In the other three surgical comparator studies, all the comparator group started on surveillance but then opted for preventative surgery. 38–40,67

The remaining two comparative studies used ‘no surveillance’ comparator groups. 66,69–71 Stuckless et al. (2013)66 included a comparator group who did not have any surveillance for a variety of reasons including ineligibility (due to gynaecological cancer, hysterectomy or age < 30 years). To mitigate survivor bias, a second comparator group was also used. This second comparator group was a subsample of the first comparator group and comprised individuals who did not receive surveillance, who were matched with the surveillance group on age and who were alive and disease-free when the matched case started surveillance. 66 The study by Woolderink et al. (2018)71 provided limited data for those who had surveillance and those who did not, but it was unclear how many individuals were under surveillance or why individuals were not under surveillance (e.g. whether preventative surgery had taken place). 69–71

Single-arm cohort studies

The 20 single-arm cohort studies included in the review are presented in Table 3. These studies comprise a range of designs, including four small studies that were limited to evaluating a single surveillance visit,34,35,41,68–71 two retrospective registry-based studies,47,48,59 four retrospective studies of hospital data,33,51,54–58,62 eight hospital-based prospective cohort studies,36,37,45,46,49,50,52,63–65 one of which comprised data entered on to a prospective registry,36 one survey75 and one study that pooled individual data from 10 countries. 8,53 Some of the data that were pooled in that study are also included in this review, but the actual samples may have differed from the samples in the individual published studies,8,53 although a high degree of overlap is likely. Further information on the potential overlap between studies is provided in the section Potential overlap between included studies.

The single-arm cohort studies were variable in size, ranging from 9 eligible participants in a pilot study by Bats et al. (2014)34,35 to 871 eligible participants in the study by Ketabi et al. (2014),47,48 not including the pooled data from Møller et al. (2017). 8,53 A wide range of surveillance strategies were used, including pilot or lesser used techniques such as endometrial sampling using tampons72 and microsatellite instability (MSI) analysis of uterine cavity washings,34,35 as well as more standard surveillance techniques such as transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), pelvic/abdominal ultrasound, hysteroscopy, endometrial biopsy and CA-125 testing. One study included surveillance visits where gynaecological surveillance was combined with colonoscopy. 54–58

Across the 20 single-arm cohort studies, the median or mean length of time that individuals were undergoing surveillance (as part of the study) was not frequently reported. When these data were reported, they also varied greatly, ranging from single visit studies34,35,41,68–71 to registry data which had a mean surveillance duration of 7.9 years (range 0.1–21.7 years). 47,48 For studies with more than one surveillance visit, the interval between visits was generally 1 or 2 years (see Table 3).

Potential overlap between included studies

Two reviewers (HC and SB) initially evaluated 59 articles and abstracts to group together those that clearly represented the same study. Conference abstracts that did not appear to report data connected to any of the included full articles were subsequently excluded (n = 15; see Figure 1 and Table 25, Appendix 2).

The design of the included studies meant that the likelihood of participant overlap between the included studies was high. Two reviewers (HC and NM) evaluated the studies for potential overlap, paying particular attention to studies conducted in the same country. This evaluation concluded that none of the 30 studies clearly overlapped sufficiently to be deemed the same study, but there were several studies based in the UK and the Netherlands, where overlap between participants was probable or possible. Furthermore, the study by Møller et al. (2017) pooled data from several countries and would, therefore, include participants from other included studies. 8,53

Meta-analyses were not conducted for this review, but potential double-counting of participants could impact upon narrative syntheses and was considered.

Overlap between studies based in the UK

Seven of the included studies were based in the UK,33,41,52,63–65,68,75 with one further study based in both the UK and the Netherlands. 37 Scrutiny of the study locations, centres, sample sizes, participant characteristics, recruitment dates and methods could not rule in or out any participant overlap. Some overlap is likely where participants were recruited from the same region, or between regional studies and UK-wide studies, but this was not clear from the study publications. For example, participant overlap is plausible between the Manchester-based samples in Barrow et al. (2009)33 and Ryan et al. (2017),65 and the Ryan et al. (2021) UK-wide survey where almost half of participants were recruited from the north-west of England. 75 Participant overlap between Rosenthal et al. (2013)63,64 and Manchanda et al. (2012)52 is also possible because both studies are associated with the UK Familial OC Screening Study (UKFOCSS). 76

Overlap between studies based in the Netherlands

Eight of the included studies were based in the Netherlands,40,42–46,62,69–73 with one study additionally based in the Netherlands as well as the UK. 37 In most cases, it was not possible to establish clear participant overlap between studies. An exception to this was Helder-Woolderink et al. (2017),45,46 which reported overlap (exact number not reported) with Helder-Woolderink et al. (2013). 43,44 Both studies were based in Groningen with a 1.5-year overlap in data collection. 43–46 Furthermore, recruitment periods for Helder-Woolderink et al. (2013)43,44 and (2017)45,46 fall within the data collection timeframe for Woolderink et al. (2018), which also recruited some participants from Groningen, so participant overlap is possible. 69–71 Two other studies recruited participants from Groningen62,73 and may partially overlap with Helder-Woolderink et al. (2013),43,44 Helder-Woolderink et al. (2017)45,46 and Woolderink et al. (2018)69–71 and also with each other. Finally, the study by Gerritzen (2009) used HNPCC registry data from across the Netherlands and, therefore, overlap with the other studies from the Netherlands is plausible. 42

Overlap between Møller et al. (2017) and other included studies

One included study8,53 pooled data across ten countries and overlaps with three of the other studies included in this review,41,47,48,60,61 although the extent of overlap is unclear; the pooled data may have been collected from different periods to the data published for each of the individual studies. However, a high degree of overlap was deemed likely.

Two of the datasets included in Møller et al. (2017; from Cardiff, UK, and from Spain) were reported to be unpublished. 8,53 It is not clear whether the data collected in Spain were related to the more recently published study by Dueñas et al. (2020). 38,39 The remaining datasets included in Møller et al. (2017) do not appear to be connected to studies already included in this review. 8,53 The references for these studies provided in Møller et al. (2017) report data for colorectal rather than gynaecological surveillance, so although it is not clearly stated, the remaining gynaecological data in Møller et al. (2017) appear to be previously unpublished. 8,53

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias assessments are provided for all studies (see Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for cohort studies) using the CASP31 checklist for cohort studies, and additionally using the ROBINS-I30 for the 10 comparative studies (see ROBINS-I). These assessments were made across all outcomes, with particular attention paid to ROB with regards to the primary outcomes in each study that were relevant to this review. The ROB assessment made for the pooled data study was based upon the information provided in the two Møller et al. (2017) publications rather than cited publications for all of the individual datasets. 8,53

For studies reporting DTA data, QUADAS-232 assessments are provided (see Risk of bias in test accuracy data).

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for cohort studies

Risk of bias ratings for all 30 included studies, according to the CASP checklist for cohort studies,31 are given in Table 4.

| Study | Section A | Section B | Section C | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear focus | Acceptable recruitment methods | Exposure accurately measured | Outcome accurately measured | Confounders identified | Confounders accounted for | Follow-up complete enough | Follow-up long enough | Bottom line results | Precision of results | Believe results | Applicable to the UK | Fit with other evidence | Implications for practice | |

| Bats et al. 201434,35 | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | CTa |

| Barrow et al. 200933 | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | Y | CT | R | R | Y | Y | CT | CTb,c |

| Bucksch et al. 20204 | Y | Y | CT | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | CTb |

| de Jong et al. 200673 | Nd | Y | CT | Y | N | N | Y | CT | R | R | Y | CT | CT | CTb,c |

| Dove-Edwin et al. 200237 | Y | CT | Y | Ye | N | N | Nf | CT | R | R | Y | CTg | CT | Y |

| Dueñas et al. 202038,39 | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | Y | CT | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Eikenboom et al. 202140 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Elmasry et al. 200941 | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Yh | Y | Y | R | R | Y | Y | CT | CTa |

| Gerritzen et al. 200942 | Yi | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | R | R | Y | CT | CT | CTc |

| Helder-Woolderink et al. 201343,44 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | CT | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Helder-Woolderink et al. 201745,46 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Yj | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Kalamo et al. 202074 | Y | CT | CT | CT | Yk | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Ketabi et al. 201447,48 | Y | Y | CT | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Lécuru et al. 200749 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Lécuru et al. 200850 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Lécuru et al. 201051 | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Manchanda et al. 201252 | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | Y | CT | Y |

| Møller et al. 20178,53 | Y | CT | CT | Y | N | N | CT | CT | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Nebgen et al. 201454–58 | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Yl | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Pylvänäinen et al. 201259 | Y | Y | CT | Y | N | N | Y | CT | R | R | Y | CT | CT | CTb |

| Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. 200760,61 | Y | Y | CT | Y | N | N | Y | N | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Rijcken et al. 200362 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Rosenthal et al. 201363,64 | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | Y | CT | CTb |

| Ryan et al. 201765 | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | R | R | Y | Y | CT | Y |

| Ryan et al. 202175 | Y | CT | CT | CT | Y | N | CTm | Y | R | R | Y | Y | CT | Y |

| Stuckless et al. 201366 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Tzortzatos et al. 201567 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | Y |

| Wood et al. 200868 | Y | CT | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | R | R | Y | Y | CT | CTa |

| Woolderink et al. 201869–71 | Nn | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | CT | R | R | Y | CT | CT | CTb,c |

| Woolderink et al. 202072 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Yo | Y | Y | R | R | Y | CT | CT | CTa |

It is important to consider whether the included studies had sufficiently long follow-up periods to assess the primary outcomes of interest. For cancer detection rates and data on adverse events, follow-up periods were likely to be sufficient. However, 12 studies reported data on mortality and/or survival (see Mortality and survival) and none of these reported a follow-up period of 10 years or more: three had a mean/median follow-up period of < 5 years,42,60,61 two had a follow-up period between 5 and 10 years,62,66 and it was also likely that the study by Møller et al. (2017) had a mean follow-up period between 5 and 10 years, but this is assumed (mean observation years were given for each mutation and ranged from 8.0 years for MLH1 to 4.3 years for PMS2). 8,53 The remaining six studies providing mortality and/or survival data did not clearly report the follow-up period. 37–39,43,44,59,69–71,73 However, with the exception of Woolderink et al. (2018),69–71 these studies provided other information indicating that follow-up was unlikely to be long enough to assess mortality/survival.

Risk Of bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions

For the 10 studies providing comparative data, additional ROB ratings using the ROBINS-I tool were made (Table 5). It is important to remember that ratings refer to the level of ROB and not the amount of bias. For each study, ROBINS-I ratings were made in consideration of all outcomes that were provided for both surveillance and an eligible comparator; where ROB differed according to outcome, this was noted and the highest ROB rating was recorded.

| Study | Cause of bias | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confounding | Selection of participants into the study | Classification of interventions | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of the reported result | Overallc | |

| de Jong 200673 | S | M | S | NI | NI | L | L | S |

| Dueñas 202038,39 | Ca | M | L | NI | NI | NI | L | C |

| Eikenboom 202140 | Ca,b | M | L | NI | L | NI | L | C |

| Gerritzen 200942 | S | M | S | NI | L | M | L | S |

| Helder-Woolderink 201343,44 | S | M | L | NI | L | M | L | S |

| Kalamo 202074 | S | M | L | NI | L | M | L | C |

| Renkonen-Sinisalo 200760,61 | Ca,b | M | L | NI | L | NI | L | C |

| Stuckless 201366 | S | M | L | NI | NI | NI | L | S |

| Tzortzatos 201567 | Ca | L | L | NI | NI | NI | L | C |

| Woolderink 201869–71 | Cd | M | S | NI | L | NI | L | C |

For all included comparative studies, selection to groups was based on participant preference (likely influenced by confounding factors) or was dictated by comparison of different periods. 42–44,73 Four of the five studies comparing surveillance with RRS were at critical ROB due to confounding, as baseline characteristics of the participants in each group were not considered or accounted for, including factors which could impact upon key outcomes (e.g. previous cancers, family history of gynaecological cancer). 38–40,60,61,67 Additionally, the meaningfulness of comparisons between surveillance and RRS is inherently limited, particularly with regard to cancer detection rates: except for cancers detected during surgery, it is expected that few post-surgical endometrial or ovarian cancers would occur (depending on the exact nature of the surgical procedure) and, conversely, a negative impact on fertility would be expected due to surgery. These critical ROB ratings were, therefore, applicable to data on detection rates (fertility data were not reported).

Participant characteristics at baseline

Baseline participant characteristics data for the 30 included studies are presented in Table 6. In general, few participant characteristics were reported, with several studies reporting very limited data. In particular, Barrow et al. 200933 and de Jong et al. 200673 provided no relevant data on participant characteristics because of a lack of disaggregated data for participants at risk of gynaecological cancer. This paucity of participant baseline characteristics data limits both the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the generalisability of the studies’ results and the assessment of ROB.

| Study | Confirmed LS, n (%) | Suspected LS, n (%) | Age (years) | Menopausal status, n (%) | LS mutations (all female participants in sample unless indicated), n/N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLH1 | MSH2 | MSH6 | PMS2 | EPCAM | |||||

| Barrow et al. 200933 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 (0.0) |

| Bats et al. 201434,35 | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | NR | NR | 3/9 (33.3)a | 2/9 (22.2)a | 3/9 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Bucksch et al. 202036 | 550 (59.5)b | 315 (34.1)b | 38.0 (median), IQR 31.0–45.0c | NR | 222/865 (25.7) | 265/865 (30.6) | 63/865 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| de Jong et al. 2006d73 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dove-Edwin et al. 200237 | NR | 269 (100.0) | Netherlands: 42.0 (median), range 23.0–68.0; UK AC-positive group: 40.0 (median), (range 24.0–64.0); UK HNPCC-like group: 45.0 (median), range 20.0–71.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Dueñas et al. 202038,39 | Surveillance: 465 (100.0) | 0 | NR | NR | Surveillance: 226/465 (48.6) | Surveillance: 127/465 (27.3) | Surveillance: 75/465 (16.1) | Surveillance: 22/465 (4.7) | Surveillance: 15/465 (3.2) |

| Surgery: 66 (100.0) |

Surgery: 33/66 (50.0) |

Surgery: 19/66 (28.8) |

Surgery: 10/66 (15.2) |

Surgery: 3/66 (4.5) |

Surgery: 1/66 (1.5) |

||||

| Eikenboom et al. 202140 | Surveillance: 111 (100) | 0 | 46.0 (median), range 21.5–75.0 | NR | Whole sample: 38/164 (23.2)e | Whole sample: 25/164 (15.2)e | Whole sample: 82/164 (50.0)e | Whole sample: 19/164 (11.6)e | Whole sample: 0 (0.0)e |

| Surgery: 53 (100) |

Surgery: 10/53 (18.9) |

Surgery: 3/53 (5.7) |

Surgery: 34/53 (64.1) |

Surgery: 6/53 (11.3) |

Surgery: 0 (0.0) |

||||

| Elmasry et al. 200941 | 1 (4.0) | 24 (96.0) | 43.6 (median), range 30.0–62.0 | Pre: 19 (76.0); post: 6 (24.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Gerritzen et al. 2009f42 | 67 (67.0)g | 16 (16.0)g | 46.0 (median), range 23.0–72.0 | Pre: 72 (72.0); post: 22 (22.0); unknown: 6 (6.0) | 22/100 (22.0) | 22/100 (22.0) | 23/100 (23.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Helder-Woolderink et al. 201343,44 | 2008–12: 42 (66.7)h |

2008–12: 21 (33.3)h |

41 (median), range 23–67 | Pre: 61 (81.0); post: 14 (19.0)i | 2008–12: 13/63 (20.6) |

2008–12: 10/63 (15.9) |

2008–12: 10/63 (15.9) |

2008–12: 6/63 (9.5) |

2008–12: 3/63 (4.8) |

| 2003–7: 25 (56.8)h |

2003–7: 19 (43.2)h |

38 (median), range 26–61 | 2003–7: 9/44 (20.5) |

2003–7: 9/44 (20.5) |

2003–7: 6/44 (13.6) |

2003–7: 1/44 (2.3) |

2003–7: 0/44 (0.0) |

||

| Helder-Woolderink et al. 201745,46 | NR | NR | 45.1 (mean), range 33.0–69.0j,k | Pre: 40 (76.9); post: 12 (23.1) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kalamo et al. 202074 | Surveillance: 24 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) | At time of survey, 48.8 (median), range 30.0–76.0; at time of LS diagnosis, 35.2 (median), range 22.0–65.0m,n | NR | 47/76 (61.8)n | 22/76 (28.9)n | 7/76 (9.2)n | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Surgery: 42 (100.0)l |

|||||||||

| Ketabi et al. 201447,48 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lécuru et al. 200749 | 11 (16.4) | 46 (68.7) | 42.0 (mean), SD 11 | NR | 2/57 (3.5) | 9/57 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lécuru et al. 200850 | 13 (21.0) | 49 (79.0) | 42.0 (mean), SD 11.3 | Pre: 47 (75.8); post 15 (24.2) | 4/62 (6.5) | 9/62 (14.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lécuru et al. 201051 | 14 (24.1) | 44 (76.0) | 42.5 (mean), SD 11.6 | NR | 4/58 (6.9) | 10/58 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Manchanda et al. 201252 | 16 (39) | 25 (60.9) | 42.9 (median), IQR 39.4–49.7 | Post: 9 (22.0) | 10/41 (24.4) | 6/41 (14.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Møller et al. 20178,53 | 1057 (100.0)o | 0 (0.0) | NRp | NR | 514/1057 (48.6)q | 325/1057 (30.8)q | 170/1057 (16.1)q | 48/1057 (4.5)q | 0 (0.0)r |

| Nebgen et al. 201454–58 | 32 (58.0)s | 23 (42.0)t | 39.5 (mean), range 25.8–73.8u | Pre: 47 (85.5); peri: 2 (3.6); post: 6 (10.9) | 8/55 (14.55)v | 17/55 (30.91)w | 4/55 (13.0)x | 3/55 (9.0)y | 0z |

| Pylvänäinen et al. 201259 | 548 (47.0) | 618 (53.0) | NR | NR | 427/1166 (36.62) | 86/1166 (7.38) | 35/1166 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. 200760,61 | Surveillance: 175 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 333/385 (86.5)bb | 32/385 (8.3)bb | 20/385 (5.2)bb | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Surgery: 138 (100.0) |

|||||||||

| Rijcken et al. 200362 | 11 (26.8) | 30 (73.2) | 37.0 (median), range 27.0–60.0 | Pre: 35 (85.4); post: 6 (14.6) | 8/41 (19.5) | 2/41 (4.9) | 1/41 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Rosenthal et al. 201363,64 | 65 (65.7) | 34 (34.3) | NRcc | NR | 28/99 (28.3) | 33/99 (33.3) | 4/99 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ryan et al. 201765 | 437 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 148/437 (33.9) | 210/437 (48.1) | 48/437 (11.0) | 22/437 (5.0) | NR |

| Ryan et al. 202175 | 298 (100.0)eeff | 0 (0.0) | 51 (mean), SD 14.1 | NR | 71/298 (23.8) | 108/298 (36.2) | 52/298 (17.4) | 19/298 (6.4) | 7/298 (2.3) |

| Stuckless et al. 201366 | Surveillance: 53 (98.1) | Surveillance: 1 (1.9)gg | NR | NR | 0 (0.0) | Surveillance: 54/54 (100.0)hh | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No surveillance: 98 (81.7) | No surveillance: 22 (18.3)gg | No surveillance: 120/120 (100.0)hh | |||||||

| Matched controls: 46 (85.2) | Matched controls: 8 (14.8)gg | Matched controls: 54/54 (100.0)hh | |||||||

| Tzortzatos et al. 201567 | Surveillance: 45 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | NR | NR | 40/86 (46.5)ii | 26/86 (30.3)ii | 17/86 (19.8)ii | 3/86 (3.5)ii | 0 (0.0) |

| Surgery: 41 (100.0) | |||||||||

| Wood et al. 200868 | NR | NR | Survey responders, 41.3 (mean), range 37.2–45.3; survey non-responders, 43.6 (mean), range 38.8–48.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Woolderink et al. 201869–71 | 871 (99.2) | 7 (0.8) | 56.6 (median), range 23–98jjkk | NR | 268/878 (30.5) | 294/878 (33.5) | 255/878 (29.0) | 54/878 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Woolderink et al. 2020nn72 | 20 (80.0) | 5 (20.0) | 47.0 (median), (range 37.0–71.0)oo | Pre: 15 (60.0); post: 10 (40.0) | 3/25 (12.0) | 5/25 (20.0) | 6/25 (24.0) | 5/25 (20.0) | NR |

Participants all had female reproductive organs and were, therefore, at risk of gynaecological cancer. None of the studies reported participants’ gender identity, so it is not known how many transgender men and people with genders other than male or female were included in the study samples.

Baseline data on ethnicity, parity, HRT use, previous CRC and previous gynaecological cancer were sparsely reported and are not provided in Table 6. Only two studies reported data on ethnicity. 54–58,75

Only five of the included studies reported baseline data on parity, despite the fact that our PPI workshop highlighted parity data as being of particular importance to patients with LS. 41,45,46,72,74,75 Kalamo et al. (2020) reported that 21 (87.5%) survey respondents who had not undergone gynaecological surgery and 37 (88.1%) of those who had undergone surgery had one or more previous delivery. 74 Similarly, Elmasry et al. (2009) reported that of the 25 women who consented to the study (and underwent a single surveillance visit), 21 (84.0%) had 1 or more previous delivery. 41 Helder-Woolderink et al. (2017) reported that 36 of 52 women (69%) had one or more previous delivery at the time of the first surveillance visit, and 5 (9.6%) had unknown parity status. 45,46 Ryan et al. (2021) reported that 261 (87.6%) of the study sample had been pregnant at least once and 173 (58.1%) had previously had at least 1 live birth. The mean number of pregnancies was 6.4 [standard deviation (SD) 7.2]; the mean number of live births was 1.57 (SD 1.2) and of the participants who had been pregnant, 18 had used assisted reproduction technology (2 as a result of complications related to LS). 75 Woolderink et al. (2020) reported that 16 of 25 (64.0%) women who underwent surveillance had 1 or more previous delivery and 5 (25.0%) had unknown parity status. 72 One study reported HRT use at baseline, reporting that 1 of 25 participants (4.0%) was undergoing treatment. 72 This study also reported that three participants (12.0%) were using oral contraceptives as hormone treatment, five participants (20.0%) were using the Mirena® (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) intrauterine system and one participant (4.0%) was using progestogen. 72

Two studies reported numbers of participants with CRC prior to commencing surveillance. 53–58 Nebgen et al. (2014) reported that 11 (20.0%) of participants had CRC at baseline. 54–58 In a subsample of participants from Møller et al. (2017),53 it was reported in a table that 530/718 participants (73.8%) had CRC prior to study inclusion (but a lower percentage, 49%, is reported in the text of the study report). However, the data reported in Møller et al. (2017)53 were specifically subsample data on subsequent cancers (i.e. all participants in the subsample would have had a previous cancer) and therefore rates of CRC would be expected to be high. Two studies reported numbers of participants with gynaecological cancers prior to commencing surveillance. 8,53,66 In the Møller et al. (2017) subsample,53 it was reported that 377 of 718 (52.51%) participants had a previous diagnosis of gynaecological cancer (including 296 ECs, 61 OCs and 20 cervical cancers). 53 Again, all participants in the subsample would have had a previous cancer, so rates of previous gynaecological cancer would be expected to be high. Stuckless et al. (2013) reported 15 of 174 (8.6%) participants had a previous gynaecological cancer, all of which were in the comparator arm (first comparator arm, the second comparator arm used age-matched participants who were alive and disease-free). 66

Detection of gynaecological cancers (and other medical findings)

Detection of malignancies and premalignancies

Data are summarised in Table 7.

| Single-arm studies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Surveillance (frequency) | Detection timea | Participants with cancer detected n/N participants (%) | FIGO stage of cancers | Symptomatic n/N when cancers detected n (%) | Participants with premalignancies n/N participants (%) | Participants with incidental findings n/N participants (%) |

| Barrow et al. 200933 | CE, TVUS, OPH, Bx (frequency UC) | Over study | EC: 86b | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| OC: 24b | |||||||

| Bats et al. 201434,35 | UCW (single visit) | At visit | EC: 2/9(22.2) | NR | 2/2 (100.0) | 2/9 (22.2) | NR |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Bucksch et al. 202036 | UCc (1 year) | Over study | EC: 28/865 (3.2) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| OC: 5/865 (0.6) | |||||||

| Dove-Edwin et al. 200237 | TVUS/PUS (1–2 years) | At visit | EC: 0/292 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NR |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 2/292 (0.7)d | EC: 2× I | 2/2 (100.0) | NR | NA | ||

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Elmasry et al. 200941 | TVUS, OPHe, Bx (single visit) | At visit | EC: 0/25(0.0) | NA | NA | CAH: 1/25 (4.0) | Polyps: 2/25 (8.0) |

| OC: 0/25 (0.0) | |||||||

| Helder-Woolderink et al. 201745,46 | TVUS, Bx, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: NR | OC: 1× IA | 0/1 (0.0) | NR | NR |

| OC: 1/52 (1.9) | |||||||

| Interval | EC: NR | NA | NA | NR | NA | ||

| OC: 0/52 (0.0) | |||||||

| Ketabi et al. 201447,48 | UCf (2 years) | At visit | EC: 7/871 (0.8) | EC: 1× NR, 1× IA, 2× IB, 2 × IC, 1× IV | 4/7 (57.1) | CAH: 2/871 (0.2) | FTC: 1/871 (0.1); MBOC: 1/871 (0.1) |

| OC: 1/871 (0.1) | OC: 1× IIB | 0/1 (0.0) | CH: 1/871 (0.1) | ||||

| Interval | EC: 6/871 (0.7) | EC: 3× IB, 1× II, 1× IIC, 1× IIIC | 6/6 (100.0) | CAH: 2/871 (0.2) | |||

| OC: 3/871 (0.3) | OC: 2× IC, 1× IIIC | 3/3 (100.0) | |||||

| Lécuru et al. 200749 | TVUS, OPH, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 2/57 (3.5) | EC: 1× IB, 1× IC | 2/2 (100) | NR | Endometrial polyps: 12g Fibroids/adenomyosis: 7g |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/57 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NA | ||

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Lécuru et al. 200850 | CE, PUS, OPH, Bx, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 3/62 (4.8) | EC: 2× IB, 1× IC | 3/3 (100.0) | CAH: 0/62 (0.0) | Atrophy: 22;h myoma/adenomyosis: 8;h endometrial polyps: 26;h simple hyperplasia: 9h |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/62 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NA | ||

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Lécuru et al. 201051 | PUS, OPH, Bx (1 year) | At visit | EC: 2/58 (3.4) | EC: NR | NR | CAH: 0/58 (0.0) | Atrophy: 21;g endometrial polyps: 7;g simple hyperplasia:2g |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/58 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NA | ||

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Manchanda et al. 201252 | TVUS, OPH, Bx (1 year) | At visit | EC: 3/41 (7.3) | EC: 3× I | 0/3 (0.0) | CAH: 1/41 (2.4) | Simple hyperplasia: 2/41 (4.9) Endometrial polyps: 6/41 (14.6); endocervical polyps: 2/41 (4.9) |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 1/41 (2.4)i | EC: 1× IA | 0/1 (0.0) | NR | NA | ||

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Møller et al. 20178,53 | Variedj | Over study | EC: 72/1057 (6.7)k | EC: NR OC: NR |

NR | NR | NR |

| OC: 19/1057 (1.8)k | |||||||

| Nebgen et al. 201454–58 | CE, TVUS, Bx, pap smear, CA-125l (1–2 years) | At visit | EC: 1/55 (1.8) | EC: 1× IA | NR | CAH: 1/55 (1.8) | Simple hyperplasia: 1/55 (1.8);m CH no atypia: 2/55 (3.6)m |

| OC: 0/55 (0.0) | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/55 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NA | ||

| OC: 0/55 (0.0) | |||||||

| Pylvänäinen et al. 201259 | Varied (2 years) | Over study | EC: 139/548 (25.4) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Rijcken et al. 200362 | CE, TVUS, Bxn, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 0/41 (0/0) | NA | NA | CAH: 3/41 (7.3) | Myoma: 1/41 (2.4); polyps: 2/41 (4.9); DPE: 2/41 (4.9) |

| OC: 0/41 (0.0) | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 1/41 (2.4) | EC: 1× IB | 1/1 (100) | NR | NA | ||

| OC: 0/41 (0.0) | |||||||

| Rosenthal et al. 201363,64 | TVUS, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 0/99 (0.0) | OC: 1× IA, 2× IC | NR | NR | NR |

| OC: 3/99 (3.0)o | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/99 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NA | ||

| OC: 0/99 (0.0) | |||||||

| Ryan et al. 201765 | TVUS, OPH, OUS, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 2/87 (2.3) | EC: 2× IA | NR | AEH: 1/87 (2.3) | NR |

| OC: 2/87 (2.3) | OC: 2× IC | ||||||

| Interval | EC: NR | OC: 1× IA, 1× IB, 1× II | NR | NR | NA | ||

| OC: 3/87p,q(3.4) | |||||||

| Ryan et al. 202175 | Variedr | Survey | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Wood et al. 200868 | TVUS, OPH, Bx, CA-125 (single visit) | At visit | EC: 0/15 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NR |

| OC: 0/15 (0.0) | |||||||

| Woolderink et al. 202072 | TVUS, Bx, ETS (single visit) | At visit | EC: 0/25 (0.0) | NA | NA | 0/25 (0.0) | NR |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Comparative studies | |||||||

| de Jong et al. 200673 | 1990–2004: TVUS, CA-125 (1 year) | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 1965–75s | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 1975–90s | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Dueñas et al. 202038,39 | CE, TVUS; 1 year | Over study | EC: 123/465 (26.5)t | EC: 57× I, 8× II, 8× III, 4× IV, 39× NK, 7× NR | NR | NR | NR |

| OC: 36/465 (7.7)t | OC: 16× I, 2× II, 7× III, 11× NK | ||||||

| RRSu | At surgery | EC: 6/66 (9.1)v | EC: 3× pTis, 1× I, 1× II, 1× III | 0/6 (0.0) | NR | NR | |

| OC: 0/66 (0.0) | |||||||

| Eikenboom et al. 202140 | TVUS, Bx, CA-125 (1–2 years) | At visit | EC: 6/111 (5.4)w | EC: 1× I, 4× IA, 1× IB | 4/6 (66.7) | NRx | EH: 8/111 (7.2)x |

| OC: 1/111 (0.9) | OC: 1× IV | 1/1 (100.0) | |||||

| Interval | EC: 0/111 (0.0) OC: 0/111 (0.0) |

NA | NA | NR | NR | ||

| RRSu | At surgery | EC: 1/53 (1.9) | EC: 1 × 1A | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/53 (0.0) | NR | |

| OC: 0/53 (0.0) | |||||||

| Gerritzen et al. 200942 | Post-2006: CE, TVUS, Bx, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 1/64 (1.6)y | EC: 1× IB | NR | CAH: 3/64 (4.7) | NCRaa |

| OC: NCRz | OC: NCRz | ||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/64 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NR | ||

| OC: 0/64 (0.0) | |||||||

| Pre-2006: CE, TVUS, non-routine Bx, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 2/221 (0.9)y OC: NCRz |

EC: 1× IC, 1× IIIC OC: NCRz |

NR | CAH: 1/221 (0.5) | NCRaa | |

| Interval | EC: 0/221 (0.0) | NA | NA | NR | NR | ||

| OC: 0/221 (0.0) | |||||||

| Helder-Woolderink et al. 201343,44 | 2008–12: TVUS, Bx, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 0/63 (0.0) | NA | NA | CAH: 1/63 (1.6) | Simple hyperplasia: 1/63 (1.6); ovarian cysts: 5/63 (7.9)bb |

| OC: 0/63 (0.0) | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/63 (0.0) | NA | NA | 0/63 (0.0) | NA | ||

| OC: 0/63 (0.0) | |||||||

| 2003–7: TVUS, non-routine Bx, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: 1/44 (2.3) | EC: 1× IB | 1/1 (100) | CAH: 1/44 (9.1) | Simple hyperplasia: 3/44 (6.8); ovarian cysts: 2/44 (4.5) | |

| OC: 0/44 (0.0) | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 0/44 (0.0) | NA | NA | 0/44 (0.0) | NA | ||

| OC: 0/44 (0.0) | |||||||

| Kalamo et al. 202074 | PUS, Bxcc | Survey | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| RRSdd | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Renkonen-Sinisalo et al. 200760,61 | Varied (2–3 years)ee | At visit | EC: 11/175 (6.3) | EC: 5× IA, 4× IB, 1× IIB, 1× IIIA | 0/11 (0.0) | CAH: 4/175 (2.3); SAH: 1/175 (0.6) | CH no atypia: 3/175 (1.7); simple hyperplasia: 1/175 (0.6) |

| OC: 0/175 (0.0) | |||||||

| Interval | EC: 3/175 (1.7) | EC: 2× IA, 2 × 1Bff | 2/3 (66.7) | ||||

| OC: 4/175 (2.3) | OC: NR | 2/4 (50.0) | |||||

| RRS/STgg | At visit | EC: 83/138 (60.1) | EC: 27× IA, 32× IB, 8 × IC, 1× IIA, 1× IIB, 4× IIIA, 7× IIIC, 2× IVB, 1× NK | NR | NR | NR | |

| OC: NR | |||||||

| Stuckless et al. 201366 | TVUS, Bx, CA-125 (1–2 years) | At visit | EC: 5/54 (9.3) | EC: 4× I, 1× III | NR | NR | NR |

| OC: 1/54 (1.9) | OC: 1× II | ||||||

| Interval | EC: 4/54 (7.4) | EC: 3× I, 1× NK | NR | NR | NR | ||

| OC: 5/54 (9.3) | OC: 1× I, 2× II, 2× NK | ||||||

| No surveillancehh | Over study | EC: 44/120 (36.7) | NCR | NR | NR | NR | |

| OC: 16/120 (13.3) | |||||||

| Age-matched no surveillanceii | Over study | EC: 20/54 (37.0) | NCR | NR | NR | NR | |

| OC: 6/54 (11.1) | |||||||

| Tzortzatos et al. 201567 | TVUS, Bx, CA-125 (1–2 years) | At visit | EC: 3/45 (6.7) | EC: 1× IA, 2× II | 0/3 (0.0) | CAH: 2/45 (4.4) | NR |

| OC: 2/45 (4.4) | OC: 2× I | 0/2 (0.0) | |||||

| Interval | EC: 4/45 (8.9) | EC: 1× IA, 2× IB, 1× II | 4/4 (100) | 0/45 (0.0) | NR | ||

| OC: 0/45 (0.0) | |||||||

| RRSu | At surgery | EC: 3/41 (7.3) | EC: 3× IA | 0/3 (0.0) | CAH: 2/41 (4.9) | NR | |

| OC: 0/41 (0.0) | |||||||

| Woolderink et al. 201869–71 | TVUS, Bx, CA-125 (1 year) | At visit | EC: NCRjj | OC: 5× IA, 1× IB, 3× IC, 1× IIA, 1× IIB | 8/11 (72.7) | NCRjj | NR |

| OC:11kk | |||||||

| Interval | EC: NCRjj | OC: 1× IA | 1/1 (100.0) | NCRjj | NR | ||

| OC: 1kk | |||||||

| No surveillance | Over study | EC: NCRjj | OC: 28× I, 6× II, 7× III | 41/41 (100.0) | NCRjj | NR | |

| OC: 41kk | |||||||

Detection during surveillance

Fifteen of the single-arm studies and seven of the comparative studies provided data on gynaecological cancers detected during surveillance visits (Table 7). These data are provided separately for EC and OC. However, one of the studies reported analyses of data for EC and OC combined, suggesting that cumulative lifetime incidence of these cancers was similar before and after surveillance being introduced [31.6%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 28.2 to 35.0] and 32.5% (95% CI 29.1 to 35.9), respectively] as were annual incidence rates (0.6 and 0.7%, respectively). 33 This study was treated as a single-arm study and not a comparative study because no data were provided for the separate periods and the study was presented as a single-arm cohort study.

Endometrial cancers detected during surveillance

Of the 15 single-arm studies that provided data on cancer detection during surveillance visits, 14 reported the proportion of participants who had an endometrial cancer detected. In 6 of these 14 studies, no ECs were detected with surveillance. 37,41,62–64,68,72 Among the remaining eight single-arm studies, the absolute numbers of ECs detected was low; in these studies, detection rates ranged from 0.8%47,48 to 22.2%,34,35 but the study by Bats et al. (2014) was unusual in that it was a pilot study where only a single visit was used, the sample was extremely small (nine participants) and thus likely to produce less accurate detection rates, and the surveillance technique used was not typical of clinical practice or similar to other studies (uterine cavity washings). 34,35 The next highest rate of EC detected during surveillance visits was 7.3%, where participants underwent surveillance with TVUS, outpatient hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy over a median of two annual surveillance visits. 52

Among the seven comparative studies that provided data on detection of gynaecological cancers during surveillance visits, six provided data on ECs (the remaining study71 only reported ECs among participants with OCs). 69–71 One of these studies found no ECs at surveillance visits where biopsies were routinely conducted, and only one at surveillance visits during the period prior to this (non-routine biopsies). 43,44 The other study providing data on the detection of ECs during surveillance at different periods found low rates during both periods (1.6% and 0.9%, respectively). 42

Stuckless et al. (2013) compared surveillance with two no-surveillance groups (those who did not receive surveillance and age-matched controls). Endometrial cancer was detected in 9.3% of participants during surveillance visits, in 36.7% across the study period in the no-surveillance group and in 37.0% across the study period in the age-matched controls who were alive and disease-free at the point at which the surveillance group participants entered surveillance. 66 Even if interval cancers were added to the surveillance group data, fewer ECs were detected among those receiving surveillance.

The remaining three comparative studies compared surveillance with surgery. 40,60,61,67 In these three studies, detection of ECs at surveillance visits was similar to that reported in the single-arm studies (5.4%, 6.7%, 6.3%, respectively). 40,60,61,67 Two of these studies provided data on ECs detected during RRS in participants who had previously received surveillance (where no cancer was found). 40,67 These could be missed/interval cancers and are discussed in that section of the report [see Interval (missed) cancers]. In the other study, the surgery group included participants undergoing surgical treatment as well as RRS – this would increase the number of cancers found and would not be a meaningful comparator group; indeed, ECs were detected in 60.1% of participants in this group. 60,61

Seven of the single-arm studies and six of the comparative studies reporting data on EC detected during surveillance visits provided some data on the stage of the cancers. There was no clear indication from these data that EC detected at surveillance was detected at an earlier stage to interval ECs or those detected during surgery. This may be, in part, because the low numbers of cancers detected do not allow for any clear patterns to be seen.

Following PPI input, it was agreed that detection rate data would be presented according to LS mutation. Fourteen studies provided some data on ECs detected according to LS mutations; these data are given in Table 8. Data were too sparse for any patterns to be ascertained, although in one study it appears that ECs were more commonly detected among participants with MSH2 and MSH6 mutations. 39

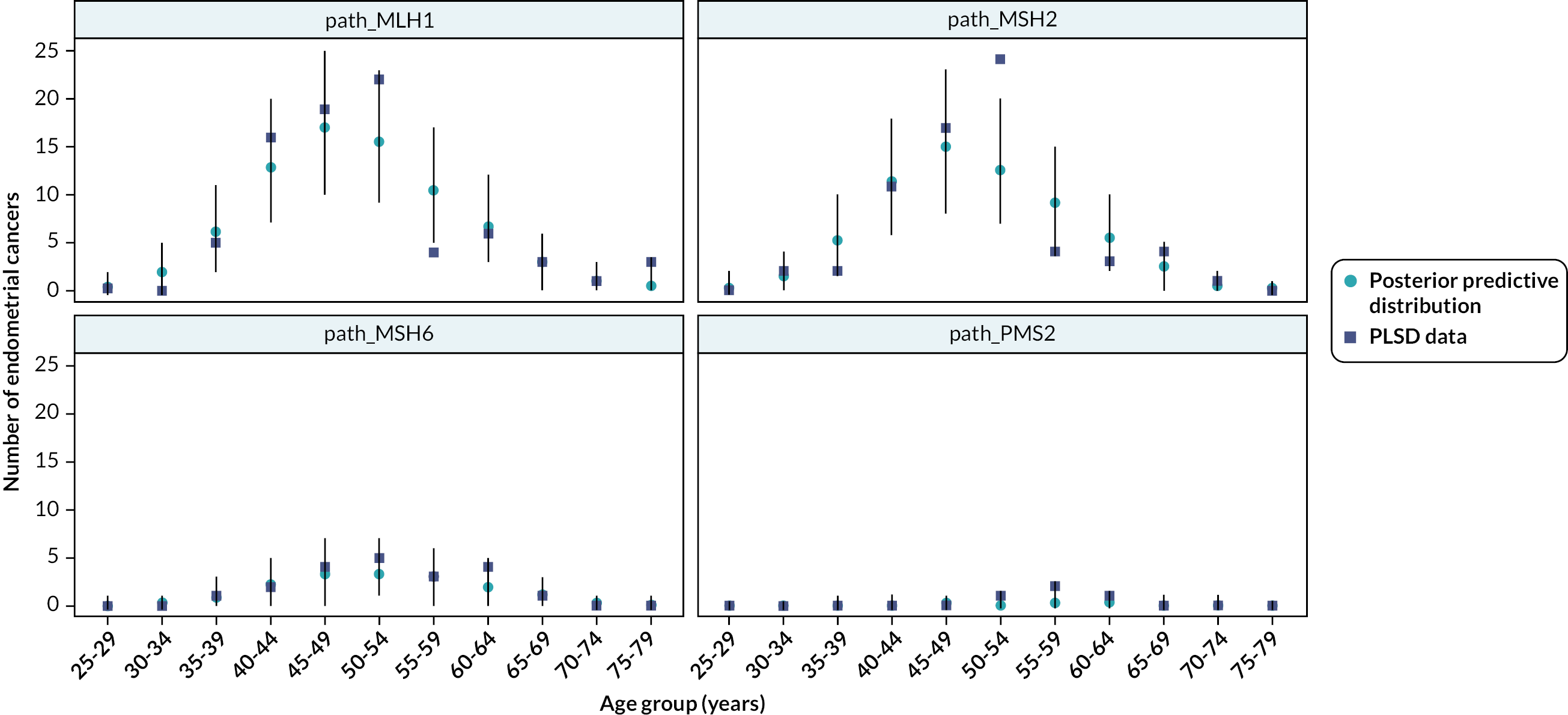

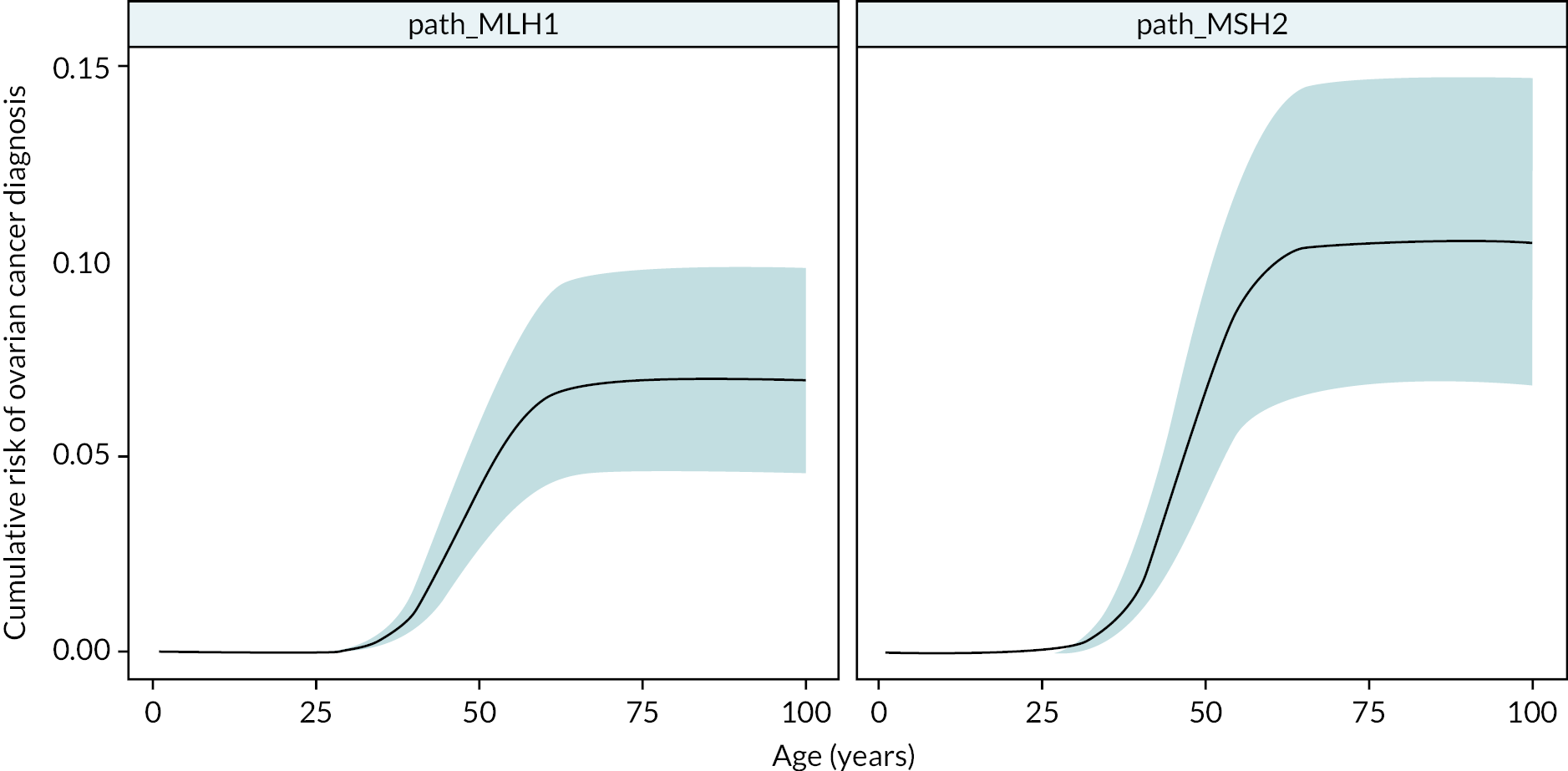

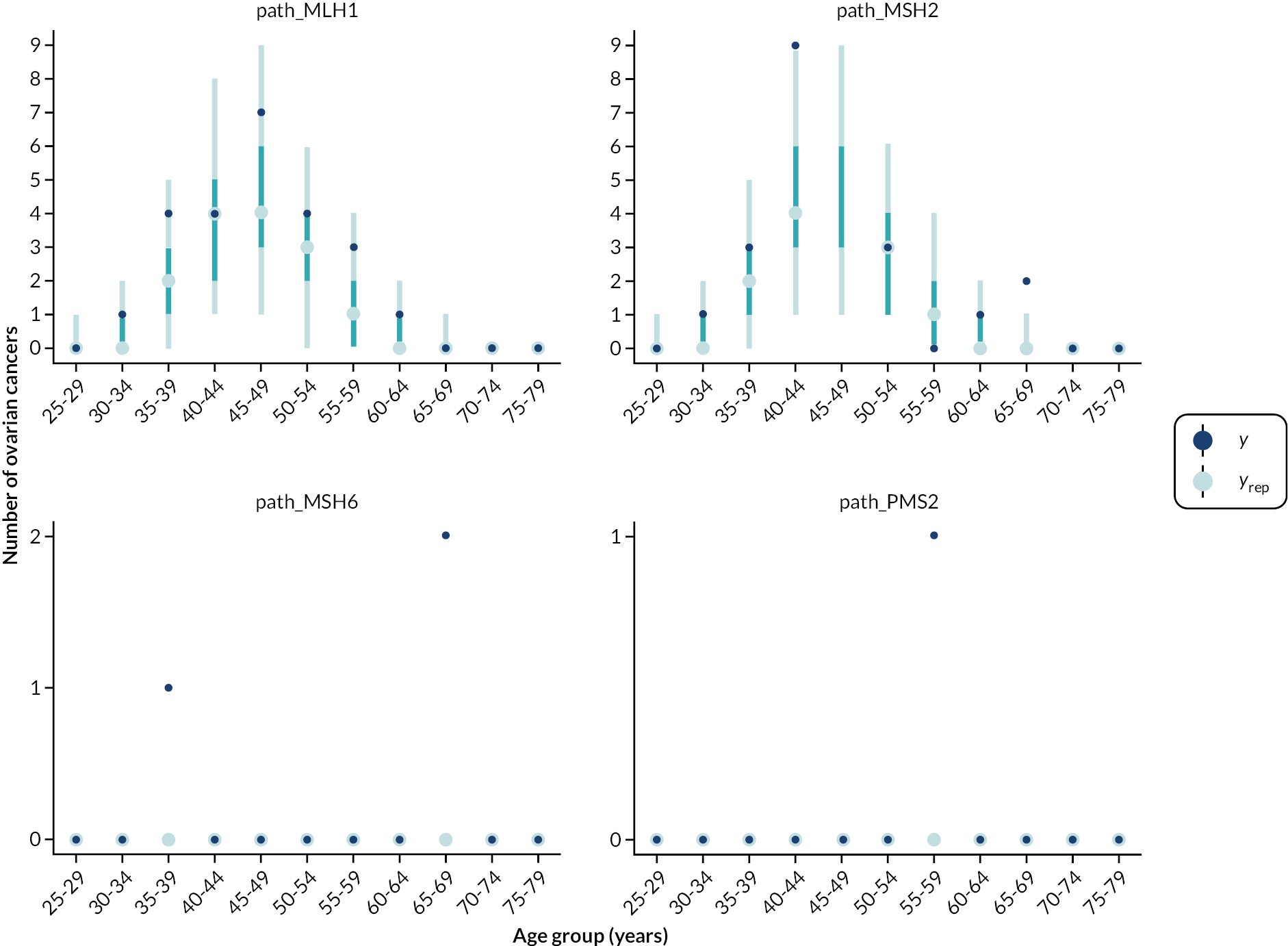

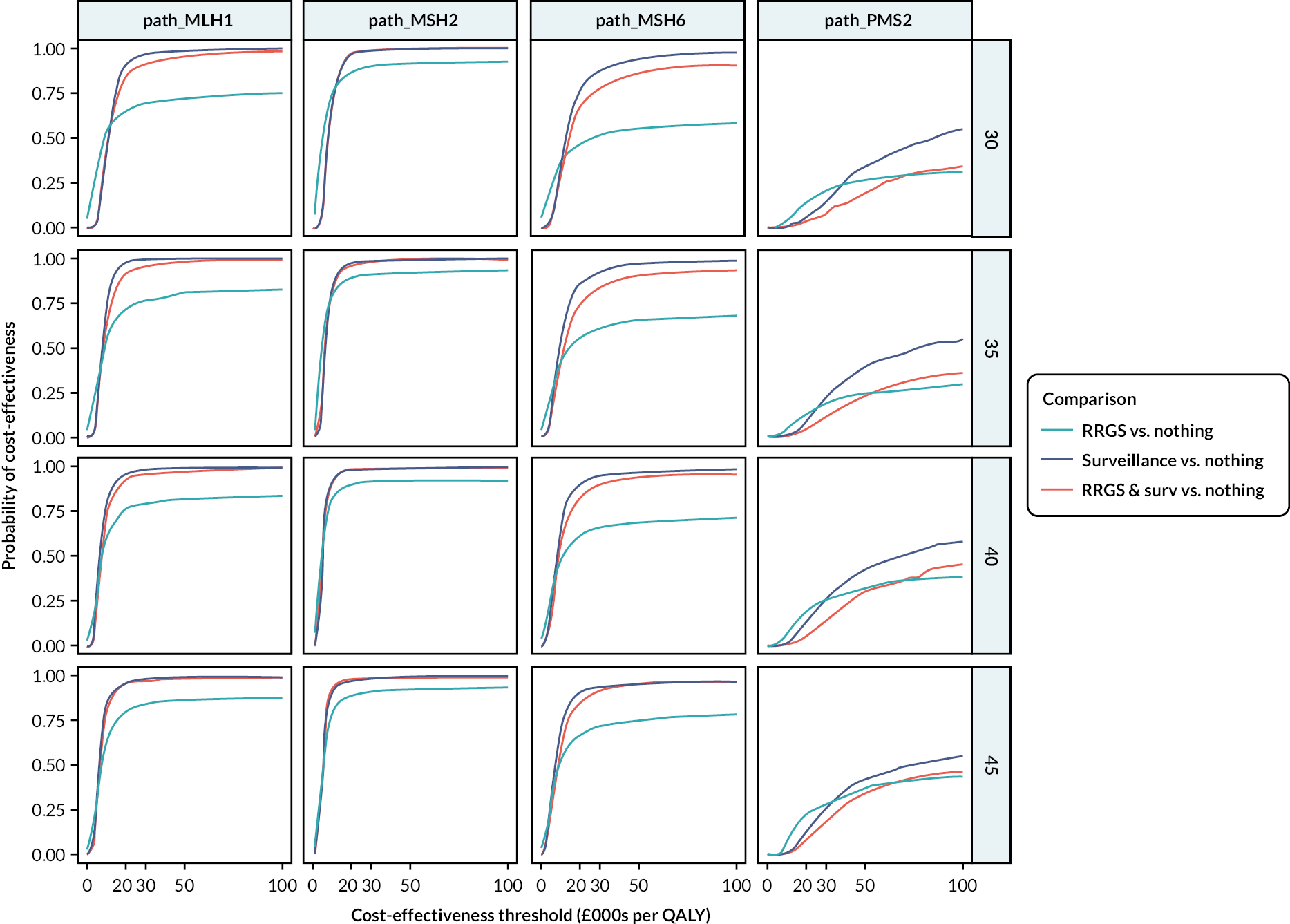

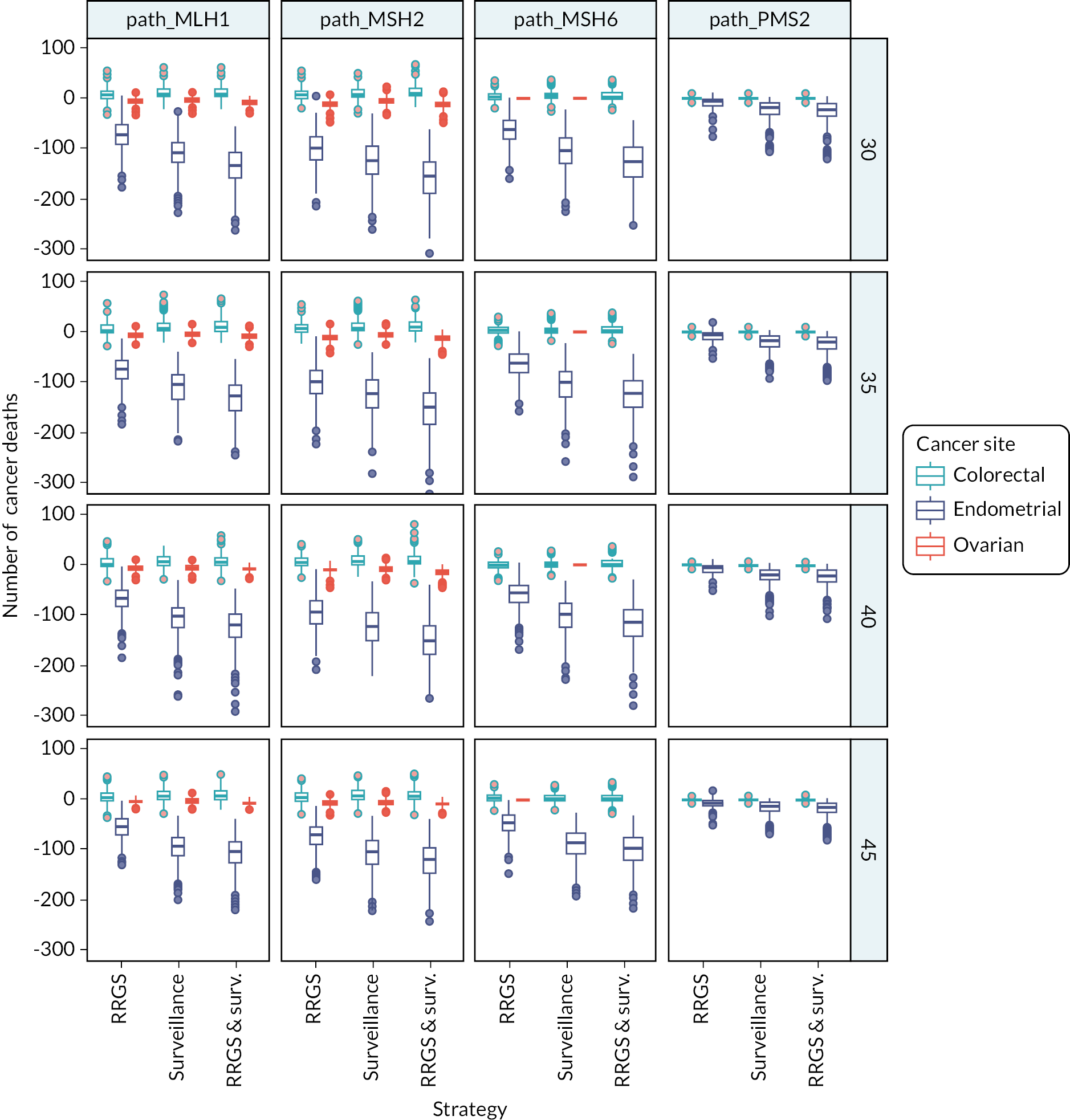

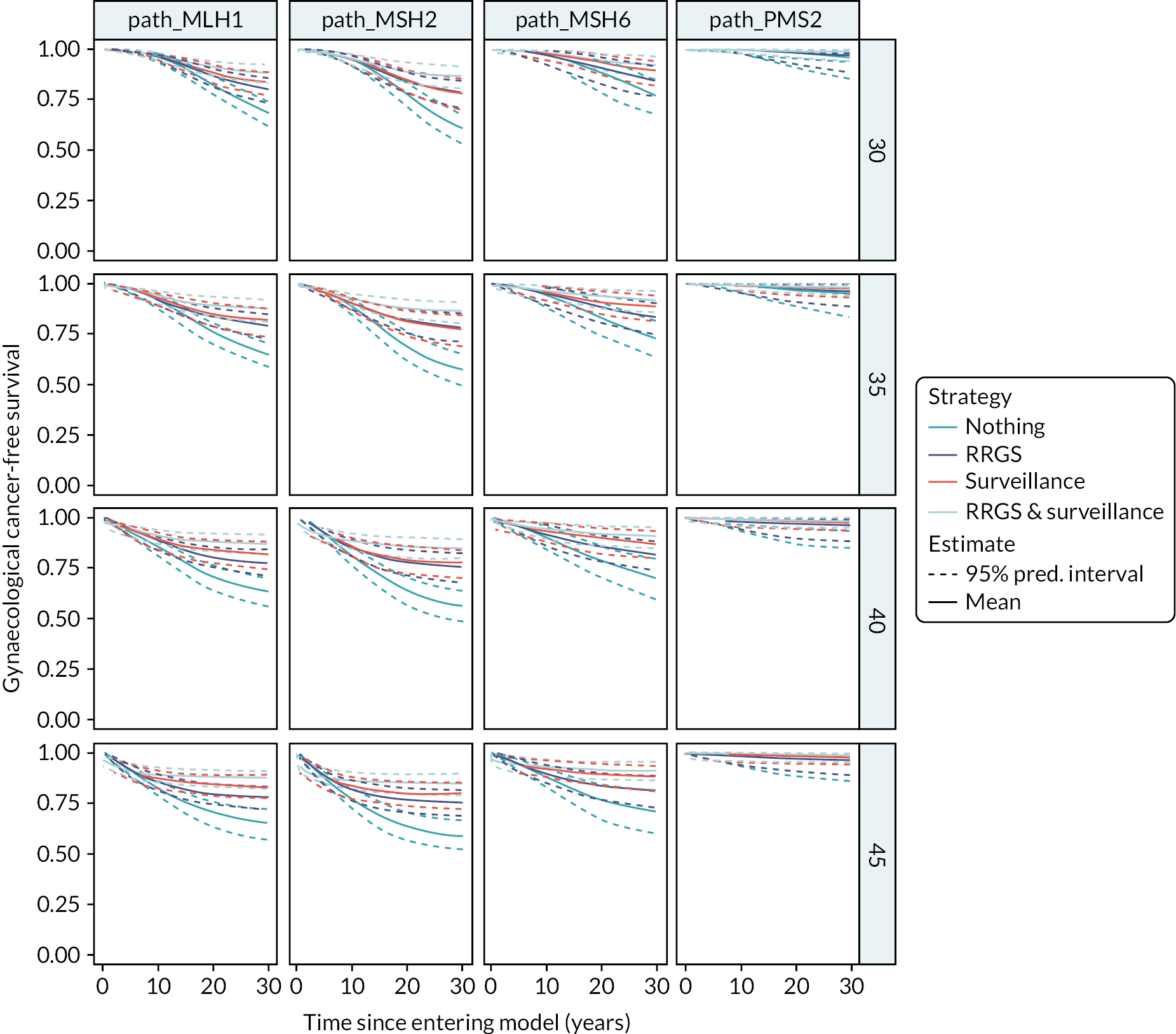

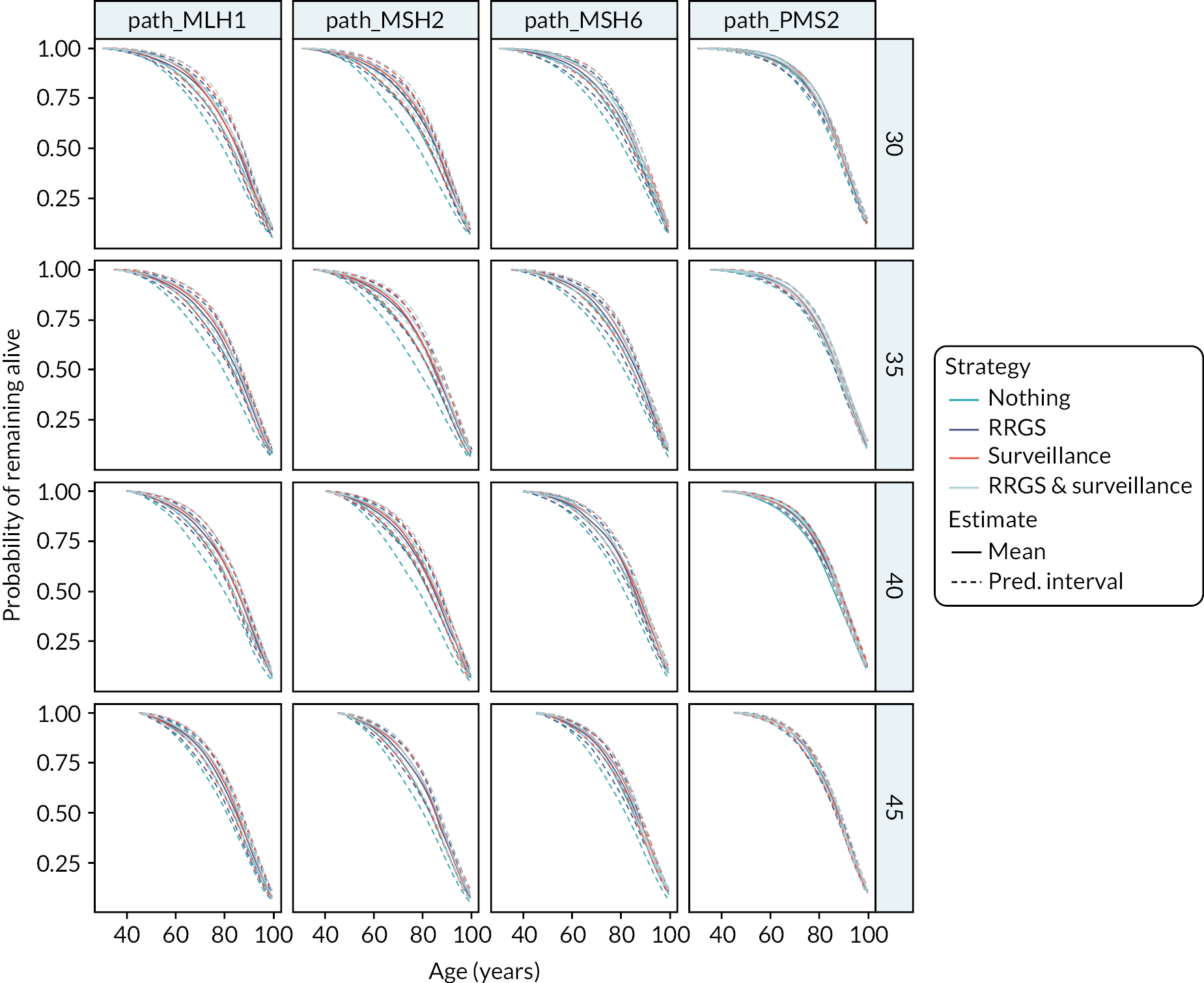

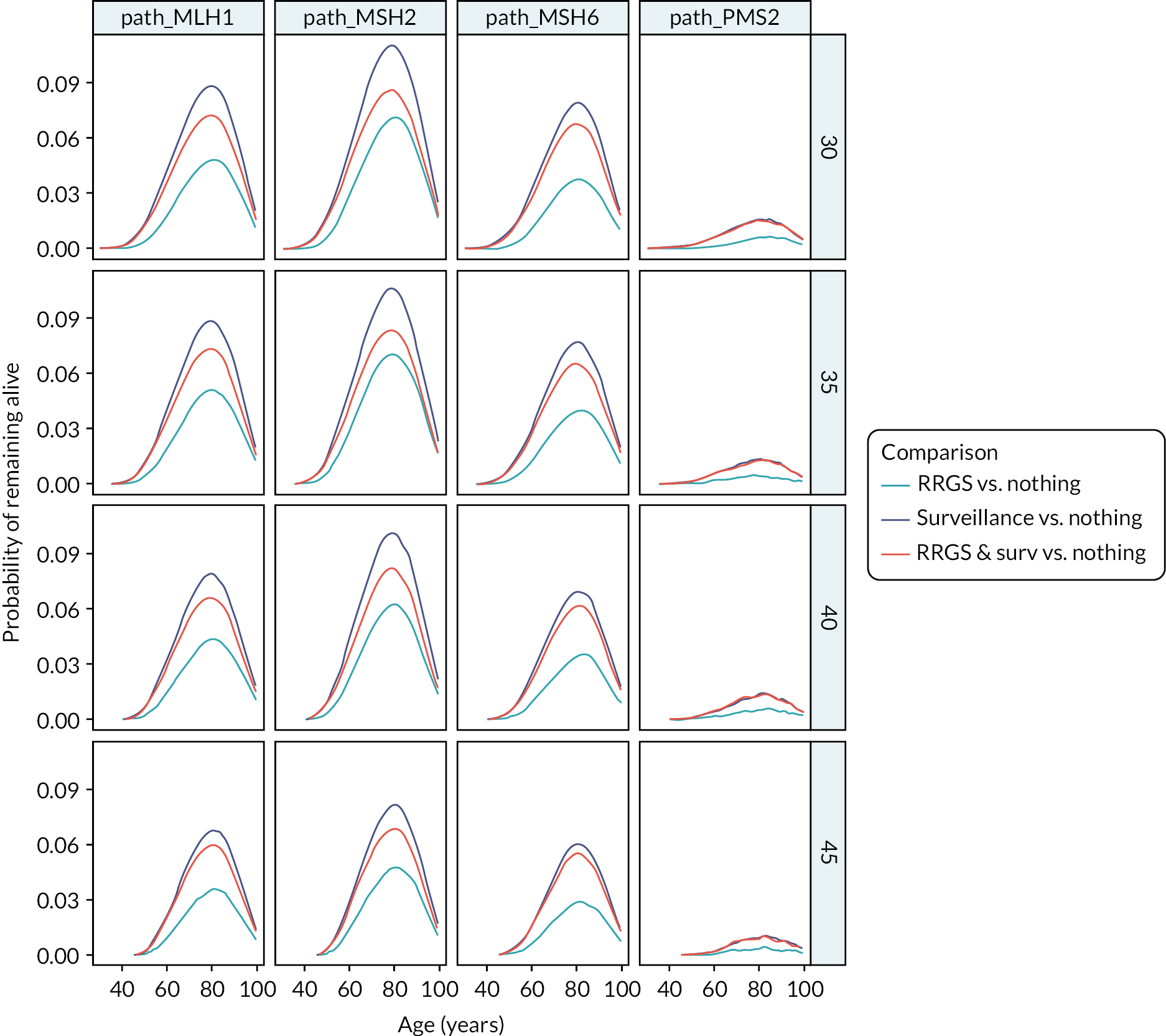

| Study | Surveillance (frequency) | Detection timea | Participants with cancers detected n/N (%) | |||||