Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/115/76. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The draft report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Banerjee et al. This work was produced by Banerjee et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Banerjee et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Dementia is one of the most common and serious public health issues of our time. 1 Over 46 million people have dementia worldwide, a figure set to double in the next 20 years. 2 The commonest cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which causes irreversible and progressive decline in memory, reasoning, communication skills and the ability to carry out daily activities. Alongside this cognitive and functional decline, individuals may develop neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) such as agitation, sleep disturbance, depression and psychosis. 3 These are common, occurring in up to 90% of people with dementia, with agitation as one of the most persistent symptoms. 4 Agitation is defined as inappropriate verbal, vocal or motor activity that is not thought to be caused by unmet need; it encompasses physical and verbal aggression and is particularly problematic. 5 It affects nearly half of people with AD over a month6 and 80% of those with clinically significant symptoms will have them 6 months later. 7 Agitation is associated with deteriorating relationships with family and professional carers, care home admission, increased costs of care, carer burden and burnout and decreased quality of life. 5,7,8

Agitation in dementia has substantial economic consequences, accounting for between 12% and 44% of dementia care costs annually9,10 and imposing significant costs on unpaid carers. 11 Costs rise as the severity of agitation increases. 10,12 The annual excess health and social care cost of agitation in AD in the UK has been estimated at £2B. 9

Agitation in dementia is therefore a legitimate target for therapeutic intervention, but it is a symptom with a number of possible causes, including pain, physical or psychological distress, misperception of threat (e.g. when receiving personal care), and response to hallucinations or delusions. Using non-pharmacological interventions that investigate aetiology and provide a tailored response as a first-line treatment for agitation in dementia, such as the DICE approach (Describe the problem, Investigate the cause, Create a plan, Evaluate its effectiveness), is recommended as best practice. 1,13 However, given the clinical significance of agitation, there is a need for second-line treatments when no underlying causes are found or when correction of these has not resulted in improvement. The mainstay of drug treatment is the use of antipsychotic medication. These drugs, however, have low efficacy, with the American Psychiatric Association guideline group reporting that they ‘demonstrate minimal or no efficacy with strong placebo effects’14 and have been shown to cause particular harms in those with dementia, including excess dementia-specific mortality. In 2009, around 180,000 people with dementia were prescribed antipsychotic medication across the UK per year and this equated to an additional 1800 deaths and an additional 1620 cerebrovascular adverse events (AEs) attributable to the use of antipsychotics in dementia. 15 While their rate of prescription to people with dementia has decreased,16 they are still commonly used and such treatment is largely unlicensed. In most countries, few or no treatments have been given regulatory approval for such use. In the UK, the only drugs with a relevant license are risperidone and haloperidol and these are highly restrictive. Risperidone is indicated for the ‘short-term treatment (up to 6 weeks) of persistent aggression in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s dementia unresponsive to non-pharmacological approaches and when there is a risk of harm to self or others’ and haloperidol for ‘persistent aggression and psychotic symptoms in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s dementia and vascular dementia [when non-pharmacological treatment is ineffective and there is a risk of harm to self or others]’.

Other drug treatments have been suggested for agitation in dementia but trials of antidementia medication, the acetylcholinesterase donepezil17 and the N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) inhibitor memantine,18 have been tested in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and not demonstrated efficacy. In a large multicentre trial, the anticonvulsant sodium valproate did not delay or prevent NPS in dementia. 19 Benzodiazepines are used short-term clinically but there are no trials and adverse effects such as falls are common and of concern. 20 Antidepressants have also been investigated as an alternative to antipsychotics. The CitAD trial of citalopram for agitated behaviours provided evidence that a target dose of citalopram 30 mg per day had a small positive effect on agitation in dementia21 in those who were less agitated and less cognitively impaired. 22 Adverse cardiac and cognitive effects identified in the trial limit its use in clinical practice. 21 Antidepressants are not mentioned as a potential treatment for agitation in the English National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on dementia assessment and management23 but they are increasingly used as a treatment of agitation in dementia. This substitution strategy to seek to avoid the prescription of antipsychotics has been reported in a large study of US nursing homes where the prescription rates of mood stabilisers such as sodium valproate, carbamazepine and particularly gabapentin increased as those for antipsychotics decreased. 24,25 Such prescribing of antidepressants is part of the common polypharmacy seen among people with dementia in the community. 26

Mirtazapine for agitated behaviours in dementia

Mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NASSA), is widely used in older people; from 2009 to 2014, in a study of 4.8 million antidepressant initiations in Europe, it was the antidepressant that was most commonly prescribed for older people and also to those with dementia. 27 A centrally active presynaptic α2-antagonist, it stimulates both noradrenergic and serotonergic systems mediated via 5-HT1 receptors, with 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors blocked by mirtazapine. Histamine H1-antagonistic activity is thought to cause its sedative properties. It has little anticholinergic activity, unlike citalopram, and, at therapeutic doses, has few cardiovascular effects. Mirtazapine is a relatively potent antagonist/inverse agonist at key receptors likely to be pivotal in target symptoms including antagonism of α2-adrenergic, 5-HT1A and histamine H1 receptors. The overall effects are to increase noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission which may explain its use in depression while the H1 antagonism is associated with useful acute sedative benefits. The pharmacological profile of mirtazapine is such that at higher dosages, the sedative effect decreases due to noradrenaline stimulation. It is a well-established treatment for depression and is well tolerated by older people and so a popular choice by psychiatrists which will encourage recruitment. It is available generically at low cost in the NHS. Cost implications, were it found to be effective, would be therefore minimal.

In pre-specified secondary analyses of the HTA-SADD data set, reported in the HTA-SADD final report,28 we have found a positive effect of mirtazapine on decreasing Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia (BPSD) [as measured by Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) score] at 13 weeks. Taking the top 50% of raw NPI scores (i.e. those with appreciable BPSD), there was a 7.1-point difference in NPI score [95% confidence interval (CI) −0.50 to 14.68; p = 0.067] between mirtazapine and placebo and a 13.2-point difference between mirtazapine and sertraline (95% CI 4.47 to 21.95; p = 0.003). An additional surprising but encouraging positive finding was from the cost-effectiveness analyses. Over the course of the trial, the time spent by unpaid carers caring for participants in the mirtazapine group was almost half that for patients in the placebo group (6.74 vs. 12.27 hours per week) and sertraline group (6.74 vs. 12.32 hours per week). Informal care costs were £1510 (95% CI −3088 to −136) and £1522 (95% CI −3398 to −72) less for the mirtazapine-treated group when compared with placebo and sertraline respectively. In the secondary outcome evaluation, looking at quality-of-life gains and costs, treatment with mirtazapine had a high likelihood of cost-effectiveness compared to placebo or sertraline. 28,29 The improvements in quality of life for mirtazapine relative to the other treatments contributed to the cost-effectiveness result, and there is a plausibility that comes from the putative ability of mirtazapine to ameliorate sleep disturbances and anxiety. 30,31 Improvements in sleep could potentially improve life quality and therefore patient-reported EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) scores; they could also release carer time directly and also ameliorate an important source of carer distress. 32 In this way, mirtazapine might have a general effect, beneficial for both the patient and the carer, even without exerting an antidepressant effect. Two small-scale open-label pilot studies give supportive evidence for the potential of a trial in this area [Cakir and Kulaksizoglu33 (those on mirtazapine did better); Reichman et al. 34 (NPI decreased by 5.8 points)]. This would be the first placebo-controlled RCT of mirtazapine for agitation in dementia. Given the paucity of alternatives and the priority of finding safe and effective treatments for BPSD, these data suggest that a placebo-controlled trial of mirtazapine would be of value.

Carbamazepine for agitated behaviours in dementia

Carbamazepine stabilises the inactivated state of voltage-gated sodium channels and potentiates GABA receptors. It is recommended in the BNF for epilepsy, prophylaxis of bipolar disorder and trigeminal neuralgia. It is generally safe within the proposed dose ranges; there are few data on people with AD, but it seems that there is no increase in mortality as in antipsychotics for AD. 35 Carbamazepine has been widely used in psychiatric disorders and AD, off licence, to treat symptoms including agitation, aggression, irritability and impulsivity. Open-label studies and case reports have indicated promise in agitation in AD. 36 Two small 6-week parallel-group RCTs of carbamazepine for BPSD have been published. 37,38 The first in 55 patients (modal dose 300 mg) showed significant symptom decrease. It was well tolerated with no decrease in cognition, function or increased side effects relative to placebo. The second (400 mg in 21 patients not responding to antipsychotics) showed a trend but not a significant advantage over placebo. Meta-analysis indicated significant benefit compared with placebo treatment on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (mean difference −5.5 points, 95% CI −8.5 to −2.5 points) and on the Clinical Global Impression Scale [odds ratio (OR) 10.2, 95% CI 3.1 to 33.1]. 39 A third small trial of the similar compound oxcarbazepine (n = 103) indicated a trend towards benefit (p = 0.07) with active drug performing better than placebo in all analyses. 40

Why is the study needed?

Agitated behaviours drive poor quality of life in dementia and poor outcomes including hospitalisation and care home placement and high cost. They have profound negative effects on people with dementia themselves, their family carers, services and society. They are a major issue in care homes, in general hospitals and in people’s own homes. The non-drug treatments we have are not always successful and the antipsychotic drugs that we use are associated with unacceptable increases in mortality and morbidity and low clinical effectiveness. There is a pressing need nationally and internationally for safe alternative pharmacological treatments. Research into better treatments for agitated behaviours in dementia was identified as a top 10 research priority by the Alzheimer’s Society and the James Lind Alliance. 41 This involved extensive engagement with people with dementia, carers, health and social care practitioners and organisations that represent these groups. Over 4000 questions on prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care of dementia were considered and the top 10 identified, including: ‘What non-pharmacological and/or pharmacological (drug) interventions are most effective for managing challenging behaviour in people with dementia?’ The need for better research into pharmacological treatments for agitation and aggression is also articulated in the National Dementia Strategy,42 the outputs of the 2010 Ministerial Dementia Research Summit and 2011 NIHR Dementia Research Workshop summarised in the Ministerial Advisory Group for Dementia Research (MAGDR) final report ‘Priority Topics in Dementia Research’ published by the MRC in February 2011. 43 MAGDR concluded ‘further research into behavioural and psychological symptoms in order to provide more effective management of challenging behaviour and improved quality of life’ was one of the top six headline priorities for research.

In this study, we therefore aimed to establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness and safety profile of carbamazepine (discontinued when 40 people had been randomised into this arm due to slower than projected recruitment) or mirtazapine in reducing agitation in AD relative to placebo.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

This is a pragmatic, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled superiority RCT of safety, clinical and cost-effectiveness of mirtazapine (with usual care) at 6 and 12 weeks on agitated behaviours in dementia. We included a long-term follow-up period to allow limited assessment of longer-term outcomes at 26 and 52 weeks. An internal pilot phase assessed trial recruitment, with progression to a full trial dependent on the number of patients recruited within the pilot recruitment period.

Important changes to methods

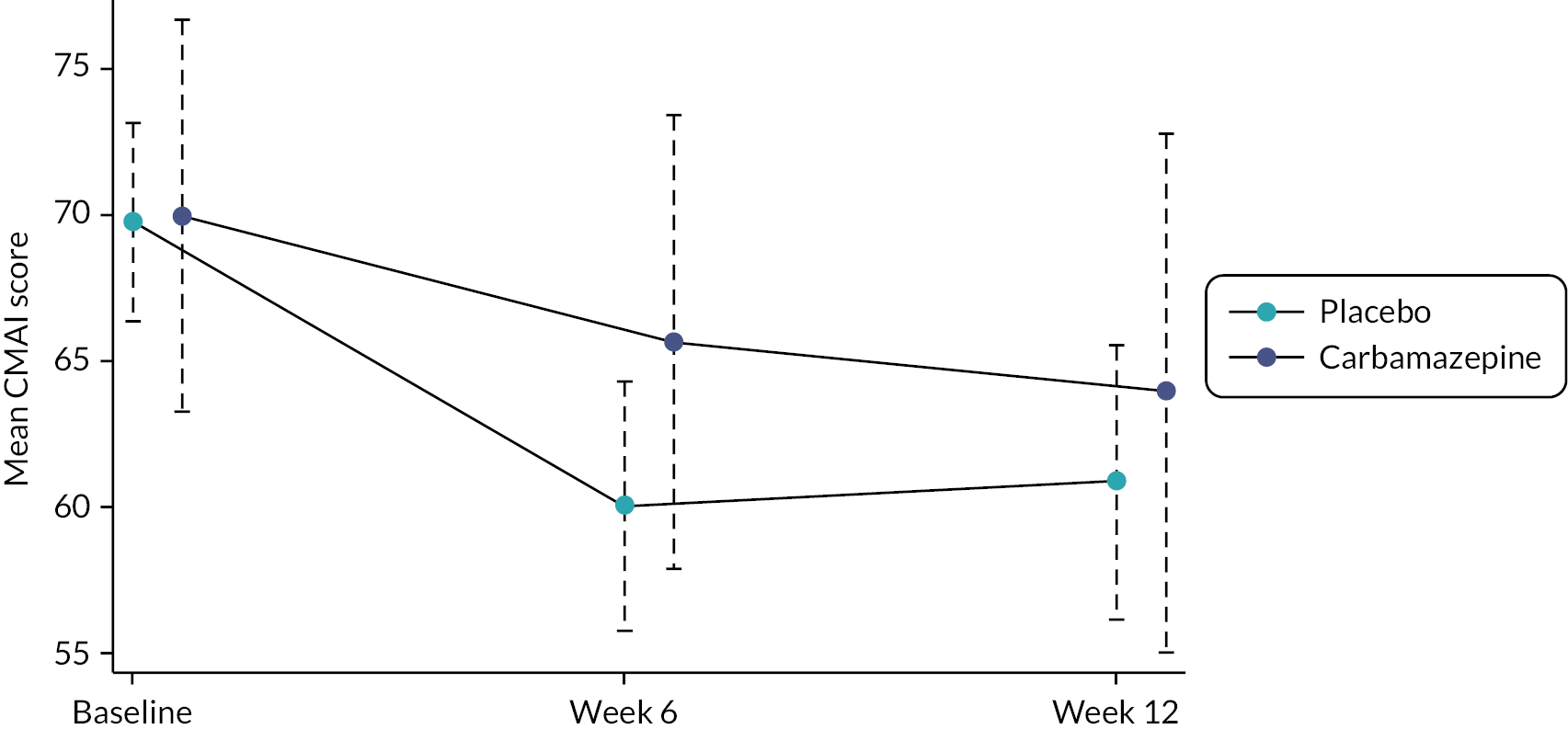

SYMBAD was initially designed as a three-arm trial, comparing both carbamazepine and placebo and mirtazapine and placebo for a difference in change in Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) score at 12 weeks as the primary objective. Challenges in recruitment in this population resulted in the funder requesting that the available data be reviewed to July 2018, with the aim of dropping one arm of the trial.

The SYMBAD independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) reviewed available data comparing the two active arms with placebo. They were asked to consider efficacy data (the primary end point, CMAI at 12 weeks), safety data [frequency of AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) on an individual basis] and compliance with treatment (dropouts and adherence with the prescribed amount of treatment medication). This was done subgroup blind: the DMC knew which was the placebo group but not the identity of the two active groups. Based on each set of data, the DMC were asked which arm they would recommend stopping or if they felt unable to make a recommendation. Taking all three sets together, the DMC were again asked whether they would recommend stopping one arm or were unable to make a recommendation.

The DMC could provide no recommendation on the basis of treatment compliance but recommended on the basis of efficacy and safety data the discontinuation of the carbamazepine arm. This recommendation did not provide, in any way, any indication that sufficient evidence had accrued to deem either drug to be effective or non-effective.

In August 2018, the protocol was submitted for a substantial amendment to change to a two-arm trial design, comparing mirtazapine with placebo as the primary objective. Protocol version 2.0 shows the new trial design. Up to the date of approval of this substantial amendment, 40 patients had been randomised to receive carbamazepine. These data have been analysed in the same way as the mirtazapine data. Chapters 2–4 reflect the amended protocol and refer only to the mirtazapine/placebo comparisons.

See Appendix 1 for summary of protocol changes.

Aim

The overall trial aim was to assess the safety, clinical and cost-effectiveness of mirtazapine in the treatment of agitation in dementia.

The null hypothesis is that there is no difference in CMAI scores between patients treated with placebo and mirtazapine at 12 weeks.

The primary objective is to determine if mirtazapine is more clinically effective in reducing agitated behaviours in dementia than placebo, measured by CMAI score 12 weeks post randomisation.

The secondary objectives are:

-

to determine if mirtazapine is more cost-effective than placebo at 12 weeks post randomisation

-

to determine if mirtazapine is more clinically and cost-effective than placebo in reducing CMAI score at 6 weeks post randomisation

-

to determine differences in effectiveness between mirtazapine and placebo on carers

-

to determine whether there are differences between the groups in AEs and adherence

-

to determine long-term differences between those randomised to placebo and mirtazapine in a head-to-head comparison of agitation (measured by CMAI score), institutionalisation, death and clinical management at 26 and 52 weeks post randomisation.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of probable or possible AD using National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria. 44

-

A diagnosis of co-existing agitated behaviours.

-

Evidence that the agitated behaviours have not responded to management according to the AS/DH algorithm. 45

-

An assessment of CMAI (Long Form46) score of 45 or greater.

-

Written informed consent to enter and be randomised into the trial.

-

Availability of a suitable informant (consenting identifiable family carer or paid carer) to provide information on carer-completed outcome measures and who consents to take part in the trial.

Exclusion criteria

-

Current treatment with antidepressants (including MAOIs) or antipsychotics. Normal clinical practice should be followed, with an appropriate wash-out period before trial drug administration. For MAOIs, this should be at least 2 weeks.

-

Contraindications to the administration of mirtazapine or carbamazepine as per the current Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC).

-

Patients with second-degree atrioventricular block [patients with third-degree heart block, with a pacemaker fitted, may be included at principal investigator (PI) discretion].

-

Cases too critical for randomisation (i.e. where there is a suicide risk or where the patient presents a risk of harm to others).

-

Female subjects under the age of 55 years of childbearing potential, defined as follows: postmenopausal females who have not had at least 12 months of spontaneous amenorrhea or 6 months of spontaneous amenorrhoea with serum FSH > 40 mIU/ml or females who have not had a hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy at least 6 weeks prior to enrolment.

Setting

Participants were drawn from existing patients and new patient referrals to old age psychiatric services, memory clinics, specific Participant Identification Centres (PICs), primary care centres and those in care homes in 26 UK sites.

Interventions

Initially there were three groups: (1) mirtazapine, (2) carbamazepine and (3) placebo. As noted above, the carbamazepine arm was dropped during the course of the study in August 2018. The target dose was 45 mg of mirtazapine or 300 mg of carbamazepine per day. Drugs and their placebos were identically presented with participants aiming to take three capsules orally once a day.

Randomisation

Once a patient’s screening CMAI score has been assessed as being ≥ 45, the research worker discussed the case with the site PI who was permitted to prescribe Investigational Medicinal Product (IMP). The PI confirmed or not the patient’s eligibility to join the study, and on confirmation, the research worker used an online randomisation system to randomise the patient for the trial. This system required confirmation of eligibility criteria. Details of the randomisation were confirmed by e-mail to the research worker, site PI, Chief investigator and co-ordinating team at Norwich Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU). A semi-blinded randomisation e-mail detailing IMP allocation was sent to site pharmacy contact/s only. The PI provided a signed prescription for the patient’s trial medication. The research worker then collected this prescription from the central pharmacy and delivered it to the patient at a scheduled ‘Week 0’ IMP delivery visit. Local policies for treating patients outside of their registered NHS Trust were followed as appropriate. Random allocation was block stratified by centre and type of residence (care home vs. own household) with random block lengths of three or six before the discontinuation of the carbamazepine arm and thereafter of two or four. The trial was double-blind, with drug and placebo identically encapsulated. Referring clinicians, participants, the trial management team and the research workers who did baseline and follow-up assessments were masked to group allocation.

Primary outcome

Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory score (Long Form) at 12 weeks.

Secondary outcomes

-

Costs derived from Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI), and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) from cost data alongside supplemented information from Dementia-Specific Quality of Life (DEMQOL) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) interviews 12 weeks post randomisation.

-

CMAI score and cost at 6 weeks post randomisation.

-

Patient and carer quality of life, and carer outcomes at 6 and 12 weeks post randomisation.

-

AEs from week 0 to week 16 and adherence at 6 and 12 weeks post randomisation.

-

CMAI score, AEs and adherence at 6 and 12 weeks, conditional on evidence of effectiveness of IMP over placebo.

-

Longer-term follow-up: CMAI score, institutionalisation, death and clinical management at 26 and 52 weeks post randomisation.

Instruments used in the study – range and scoring

-

CMAI (agitation): score ranges from 29 (no agitated behaviour) to 203 (very agitated behaviour).

-

Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (cognition): score ranges from 0 (severe impairment) to 30 (normal).

-

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) (mental health): score ranges from 0 (least severe problems, good) to 36 (most severe).

-

Zarit Carer Burden: range from 0 (no burden) to 88 (most severe).

-

DEMQOL (quality of life): DEMQOL range from 28 (poor) to 112 (good); DEMQOL-Proxy: range from 31 (poor) to 124 (good).

-

NPI (neuropsychiatric symptoms) total: total score range from 0 (none) to 144 (severe); NPI agitation/aggression: range from 0 (none) to 12 (severe); NPI depression/anxiety/irritation: range from 0 (none) to 36 (severe); and NPI carer distress: range 0 (none) to 60 (severe).

Change in outcomes over the time of the trial

There were no changes to the primary outcomes of the trial following the registration of the trial.

Sample size

An initial calculated sample size of 400 (randomised 1 : 1 : 1) provided 90% power using two-sided 5% significance tests to detect a drug versus placebo mean difference in CMAI score at 12 weeks of 6 points. This equated to an effect size of d = 0.4 [assuming a common standard deviation (SD) of 15] or a clinically significant 30% decrease in CMAI from placebo to active drug. With a realistic 15% attrition, a sample of 471 (157 per arm) was aimed for. Due to slower than projected recruitment, an arm of the study (carbamazepine) was dropped and sample size was amended in consultation with the funder, DMC and TMC (see Important changes to methods). Based on the same parameters, an amended sample size target of 222 was calculated (randomised 1 : 1) allowing for a 10% attrition (111 per arm).

The primary outcome measure in this trial was the CMAI. Active drug treatment, compared with placebo, may be associated with changes in the CMAI that are much > 6 points, but SYMBAD was powered to detect the smallest difference in the CMAI that could be considered clinically meaningful. This estimation was based on the changes and SD of change score seen in the CALM trial which included a similar patient population treated with donepezil where 6 CMAI points was 35% of the SD.

Blinding and unblinding

Blinding

All non-statistical members of the trial team, their clinicians, participants and their carers were blinded to trial arm allocation. To maintain the blind, active medication and the placebo were identically encapsulated.

Unblinding

Final unblinding of all trial participants occurred following the creation of a locked analysis data set. The decision to unblind a single case was made when knowledge of an individual’s allocated treatment was required:

-

to enable treatment of severe AE/s, or

-

in the event of an overdose.

Where possible, requests for emergency or unplanned unblinding of individuals were made via the trial manager, and in agreement of the Chief Investigator. However, in circumstances where there is insufficient time to make this request or for agreement to be sought, the treating clinician was able to make the decision to unblind immediately. This was done via the study database (local PIs and the CI have special logins which allowed for unblinding and was closely audited within the database management system) or by contacting the CI who authorised unblinding by the Data Management Team. All instances of unblinding were recorded and reported to NCTU by the local PI, including the identity of all recipients of the unblinding information.

Data management

Confidentiality

Any paper copies of personal trial data were kept at the participating site in a secure location with restricted access. Only non-identifiable data were kept at the NCTU office with authorised NCTU staff members having access. Only staff working on the trial had password access to this information.

Confidentiality of patient’s personal data was ensured by not collecting patient names on Case Report Forms (CRFs) that were be sent to NCTU and storing the data in a pseudo-anonymised fashion at NCTU. At trial enrolment, the patient was issued a Participant Identification Number (PIN) and this acted as the primary identifier for the patient, with secondary identifiers of initials (and date of birth as required).

The patient and carer’s consent forms carried their name and signature. These were kept at the trial site, and a copy was sent to NCTU for monitoring purposes. Consent forms were kept separate from patient data.

Data collection tools and source document identification

Research workers completed paper CRFs during their visits to participants and their carers. They entered data onto a central database via an online system once they had internet access. Research workers received training on data collection and use of the online system. Identification logs, screening logs and enrolment logs were kept locally, either in paper or electronic form.

Source data worksheets were drafted by the trial manager with the CI, trial statistician, data management team and PIs. The database specification was prepared by the NCTU data manager and approved by the CI and trial statistician prior to the database being built. The database was prepared by the CTU data programmer and tested by the trial statistician, trial manager and study site staff for user acceptability prior to the final system being launched.

Data collection, data entry and queries raised by members of the HTA-SYMBAD trial team were conducted in line with NCTU and trial-specific Data Management Standard Operating Procedures.

Clinical trial team members received trial protocol training. All data was handled in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998 and as updated in the 2018 Act, and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [European Union (EU)] 2016/679.

Data handling

Within each trial site, patients were allocated a unique trial PIN. Data were entered under this PIN onto the central database stored on the servers based at University of East Anglia (UEA). The database was password protected and only accessible to members of the SYMBAD trial team at NCTU, the participating sites and external regulators (upon request). The server is in a secure room, which is protected by CCTV, where access is restricted to members of the UEA Information Systems team by security door access. The study database was built using Microsoft SQL Server tools and direct access was restricted to NCTU data management staff. Data entry was via web pages created using Microsoft.NET technology. All internet traffic was encrypted using the standard SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) methodology. The data entry system validated data on entry to ensure they were of the expected type (e.g. integers, dates, etc.) and range of values. Periodically and at database lock the data were further validated for errors and inconsistencies. The database was linked to an audit tool where all data additions, modifications and deletions are recorded with date/time and the user ID of the person making the change. The database was designed to comply with the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), within the Standard Operating Procedures for Data Management in NCTU and also where appropriate with UEA Information Technology (IT) procedures.

The database and coding values were developed by the NCTU data manager in conjunction with the Chief Investigator, study statistician and other NCTU members and the trial team. The database software provides a number of features to help maintain data quality, including maintaining an audit trail, allowing custom validations on all data, allowing users to raise data query requests and search facilities to identify validation failure/missing data. Further details can be found in the SYMBAD Trial Data Management Plan. The database will be retained on the servers of UEA for 10 years following the end of the trial.

The identification, screening and enrolment logs, linking participant identifiable data to the PIN, were held locally by the research sites and at NCTU. This was either in written form in a locked filing cabinet or electronically in password-protected form on hospital computers. After completion of the trial, the identification, screening and enrolment logs will be stored securely by the sites for a minimum of 10 years.

Monitoring and site visits

For each site, a site initiation visit (SIV) was arranged by the trial manager with the core study team. A remote visit (teleconference or video conference call) was considered if they met predefined criteria of experience.

The minimum attendance for the SIV (in person or remotely) was the PI, lead research nurse, lead data manager (if applicable), pharmacy lead and research worker, any sub-Investigators were also encouraged to attend. All sites received a standardised copy of site initiation slides to aid the training of new staff working on the trial.

Each site was provided with a paper site file containing all the documents required to be held at site, generated at NCTU to comply with ICH GCP guidelines. A confirmation receipt was sent with the file for completion at site to confirm all documents had been received. Prior to a site being activated, the receipt was required to be received and returned to the TM or delegate at NCTU.

Before COVID-19, all sites recruiting at least five participants received one routine monitoring visit during the course of the trial. After lockdown, three sites (South West London, Central and North West London and Sheffield) that recruited more than five and were not visited, checks for these were made online. Site monitoring included the following checks:

-

ensuing that key eligibility variables match source data

-

blood test results and electrocardiogram (ECG) printouts

-

SAE [and serious adverse reaction (SAR)/suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR) where applicable] reports were verified against clinical notes where possible

-

clinic notes checked for unreported notable or serious events, where possible

-

data from participants experiencing study drug discontinuations/dose lowering

-

50% Source Data Verification from patient packs transcribed to Electronic Case Report Forms (eCRFs) will be checked for at least 20% of patients recruited at the site at the time of the visit; if time allows, more patient packs will be checked. The CMAI questionnaire/score will always be checked for the randomly selected 20% of patients; a selection of the other questionnaires up to a minimum of 50% of the data will be checked

-

sites will not be warned in advance which patient packs will be checked; the monitor will take a list with them and select the listed patient numbers from all of the available packs

-

any major or critical findings should prompt the monitoring team to increase the level of monitoring to cover as many participant files as time allows

-

completeness of trial drug dispensing, accountability and drug supply inventories

-

documentation and procedures will be checked for protocol deviations and serious breaches

-

consent forms

-

delegation logs

-

confirmation that safety checks had been completed and reviewed by the PI prior to randomisation

-

accuracy of site file (and pharmacy file checks where relevant).

After the visit, the PI and site team were provided with a report summarising the documents that had been reviewed and the corrective actions that were required by the site team. A response was required to be provided to the TT. The Trial Manager reviewed responses and compiled them alongside the on-site monitoring findings. The final report was signed off by the TT member performing the visit and the CI (reviewer). Additional monitoring visits were conducted on a ‘for cause’ approach. Monitoring of data quality, recruitment rates, pharmacy, Investigator Site File documents, consent and safety also occurred centrally.

Assessment by time point

For an overview of assessments over time, please see Table 1.

| Assessment | Baselinea | Rx ‘week 0’ visit (0–7 days after last baseline or randomisation visit) | Week 2 (12–16 days after week 0 visit date)b | Week 4 (21–35 days after week 0 visit)b | Week 6 (35–49 days after week 0 visit)a | Week 12 (77–91 days after week 0 visit)a | Week 16h (105–119 days after week 0 visit)b | Week 26c, (week 25–27) | Week 52c,d (week 51–53) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent | X | ||||||||

| CMAI (Long Form) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Safety bloodsd (FBC, U&Es, LFT) |

Xe | Xf | |||||||

| ECGd | Xe | Xf | |||||||

| CSRIg | X | X | X | ||||||

| Disease-specific Quality of Life DEMQOL | X | X | X | ||||||

| Carer assessed disease-specific Quality of Life DEMQOL-Proxy | X | X | X | ||||||

| Generic Quality of Life EQ-5D-5L (Proxy) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment sMMSE | X | X | X | ||||||

| BPSD | X | X | X | ||||||

| C-SSRS (Cognitively impaired version) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Randomisation | X | ||||||||

| Dispensing | X | X | |||||||

| Adherence | X | X | X | X | |||||

| AEs | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Medication assessment (for dose changes) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Use of rescue medications | X | X | |||||||

| Concomitant medications | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Withdrawal of treatment | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Carer mental health GHQ-12h | X | X | X | ||||||

| Carer quality of life EQ-5D-5Lh | X | X | X | ||||||

| Carer burden Zarit CBIh | X | X | X | ||||||

| Carer proxy report of CMAI scoreb | X | X | |||||||

| Carer proxy report of treatmentb | X | X | |||||||

| Institutionalisationb | X | X | |||||||

| Deathb | X | X |

Safety assessments

Definitions of harm of the EU Directive 2001/20/EC Article 2 based on the principles of ICH GCP applied to this trial: any unfavourable and intended sign, symptom or illness that developed or worsened during the period of the study was classified as an AE, whether or not it was considered to be related to the study treatment. AEs included unwanted side effects, sensitivity reactions, abnormal laboratory results, injury or intercurrent illnesses, and may be expected or unexpected. These were recorded on the CRF.

The period for SAE reporting was from the time of randomisation until 4 weeks post final trial medication administration. The participants were followed up by a telephone interview 4 weeks after the last dose of trial medication (the week 16 call). All events were followed until resolution, including if that meant beyond 4 weeks’ post final trial medication implementation.

Definitions

Definitions of AEs are presented in Table 2.

| Adverse event (AE) | Any untoward medical occurrence in a patient or clinical trial participant administered a medicinal product and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this product |

| Adverse reaction (AR) | Any untoward and unintended response to an IMP related to any dose administered |

| Unexpected adverse reaction | An adverse reaction, the nature or severity of which is not consistent with the applicable product information (e.g. Investigator’s Brochure for an unauthorised product or summary of product characteristics (SmPC) for an authorised product |

| Serious adverse event or serious adverse reaction | Any AE or AR that at any dose: |

Recording and reporting adverse events

NCTU were notified of all SAEs within 24 hours of the investigator becoming aware of the event. Investigators notified NCTU of any SAEs that occurred from the time of randomisation until 4 weeks after the last protocol treatment administration. SARs and SUSARs were notified to NCTU until trial closure. Any subsequent events that could be attributed to treatment were reported to the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) using the yellow card system (https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/the-yellow-card-scheme/).

The SAE form was completed by the investigator (the consultant named on the delegation of responsibilities list who is responsible for the participant’s care in the trial) with attention paid to the grading, causality and expectedness of the event. In the absence of the responsible investigator, the SAE form was completed and signed by a member of the site trial team and e-mailed as appropriate within the timeline. The responsible investigator checked the SAE form at the earliest opportunity, made any changes necessary, signed and then e-mailed it to NCTU. Detailed written reports were completed as appropriate. Systems were in place at each site to enable the investigator to check the form for clinical accuracy.

The minimum criteria required for reporting an SAE were the patient trial number and date of birth, name of reporting investigator and sufficient information on the event to confirm seriousness. Any further information regarding the event that was unavailable at the time of the first report was sent as soon as it became available. The SAE form was scanned and sent by e-mail to the trial team at NCTU.

Participants were followed up until clinical recovery was complete and laboratory results had returned to normal or baseline values, or until the event had stabilised. Follow-up visits continued after completion of protocol treatment and/or trial follow-up if necessary. Follow-up SAE forms were completed and e-mailed to NCTU as further information became available. Additional information and/or copies of test results (etc.) could be provided separately. The participant was identified by trial number, date of birth and initials only. The participant’s name was not used on any correspondence and was blacked out and replaced with trial identifiers on any test results.

Assessment of adverse events

The severity of all AEs and/or ARs (serious and non-serious) in this trial was based on the Research Worker and site PI’s clinical judgement. For general (e.g. non-haematological) AEs/ARs, they were graded using the following definitions:

-

mild: an event that is easily tolerated by the participant, causing minimal discomfort and not interfering with everyday activities

-

moderate: an event that is sufficiently discomforting to interfere with normal everyday activities

-

severe: an event that prevents normal everyday activities.

For haematological (e.g. from blood test results) AEs/ARs, they were graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.03 (CTCAE) 14 June 2010 criteria:

-

Grade 1: mild; asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated

-

Grade 2: moderate; minimal, local or non-invasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADL (preparing meals, shopping for groceries or clothes, using the telephone, managing money, etc.)

-

Grade 3: severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalisation or prolongation of hospitalisation indicated; disabling; limiting self-care ADL (bathing, dressing and undressing, feeding self, using the toilet, taking medications and not bed-ridden, etc.)

-

Grade 4: life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated

-

Grade 5: death related to AE.

In addition to severity, the investigators assessed the causality of serious events or reactions in relation to the trial therapy using the definitions in Table 3. SAEs that were considered related to the trial treatment were reviewed against the list of expected events in the approved version of the mirtazapine SmPC. Events that did not appear on the list or happened more frequently than listed were considered unexpected and reported as SUSARs.

| Relationship | Description | Event type |

|---|---|---|

| Unrelated | There is no evidence of any causal relationship | Unrelated SAE |

| Unlikely to be related | There is little evidence to suggest that there is a causal relationship (e.g. the event did not occur within a reasonable time after administration of the trial medication). There is another reasonable explanation for the event (e.g. the participant’s clinical condition or other concomitant treatment) | Unrelated SAE |

| Possibly related | There is some evidence to suggest a causal relationship (e.g. because the event occurs within a reasonable time after administration of the trial medication). However, the influence of other factors may have contributed to the event (e.g. the participant’s clinical condition or other concomitant treatment) | SAR |

| Probably related | There is evidence to suggest a causal relationship and the influence of other factors is unlikely | SAR |

| Definitely related | There is clear evidence to suggest a causal relationship and other possible contributing factors can be ruled out | SAR |

Statistical methods

Primary outcome measures

Analyses were based on intention-to-treat (all participants were analysed according to the group to which they were randomised, irrespective of the treatment or dose received). The primary outcome (CMAI at 12 weeks) was analysed using a general linear regression model including baseline CMAI score as a covariate, place of residence as a fixed effect and recruitment centre as a random effect. Treatment group was added as a fixed effect, with two levels (placebo vs. mirtazapine). Model assumptions were checked by use of diagnostic plots. The primary analysis used complete cases (excluding those with missing values). Imputation was done under the MAR assumption. A sensitivity analysis imputed missing values using multiple imputation with chained equations approach [the mi impute chained command in Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA)].

Secondary outcome measures

Analysis of secondary outcomes, including long-term outcomes at 26 and 52 weeks followed an analogous approach using general linear regression models including baseline outcome, stratification variables and treatment group. We completed a post hoc analysis comparing death rates in the groups using Fisher’s exact test.

Health economics

Economic evaluation

The primary outcome for the economic evaluation was the incremental cost per 6-point difference in CMAI score at 12 weeks, from a health and social care system perspective. A 6-point difference represents a clinically significant minimum difference, or 30% decrease on the measure from placebo to mirtazapine. In addition, we conducted a secondary cost-effectiveness analysis on this outcome measure from the societal perspective. We conducted secondary cost-utility analyses of participants’ and unpaid carers’ QALYs at 12 weeks, from both the health and social care and societal perspectives (encompassing health and social care, unpaid care and out-of-pocket costs of purchasing adaptive equipment). Three measures of health-related quality of life were used to derive participant utilities: informant-rated EQ-5D-5L,47,48 informant-rated DEMQOL-Proxy-U and participant-rated DEMQOL-U. 49,50 Unpaid carers’ utilities were derived from carer self-rated EQ-5D-5L. QALYs were calculated using the area under the curve method, assuming linear change between assessment points. 51 Six-week costs and outcome measures were reported but a full cost-effectiveness analysis of the CMAI outcome at 6 weeks was not undertaken, given the very short time horizon for observing changes in service utilisation.

In addition, a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis was planned, examining lifetime costs and QALY gain beyond the intervention period. However, on the basis of the clinical and cost-effectiveness findings, this was not progressed and no results have been reported.

Resource use

Comprehensive costs of care for participants with dementia were calculated (including the costs of formal/paid care such as that provided by health and social services and also the costs associated with unpaid care) using data gathered using the CSRI52 at baseline, 6 and 12 weeks.

Unit costs

The base year for prices was 2016–17. Unit costs were taken from nationally representative published sources. 53–55 The price of generic mirtazapine was taken from the NHS Prescription costs analysis. 53 Unpaid carer time was valued at opportunity cost in the main analyses (following the lost productivity approach described elsewhere). 56,57 The costs of unpaid care were estimated as either the cost of time spent in caring or of time taken off from work to care, whichever cost was the greater. In estimating the cost of unpaid carer time in caring, those in work were considered to have given up work time (lost production), valued at the national average wage;58 those not working were considered to have given up leisure time, valued at 35% of national average wage. The CSRI, which was used to estimate carers’ caring hours, covered time spent over the previous week in all caring tasks (including supervision and also care home visiting). Unpaid carers chose a time band for the hours of care provided per week (ranging from no hours to 100 + hours per week). A continuous variable for total hours of care was calculated by taking the mid-point of each band. The maximum of the topmost band was first adjusted to account for nightly sleep time (assumed to be 8 hours if carers reported no lost sleep in caring or the hours remaining once hours of lost sleep were deducted). All time spent in caring tasks received the same valuation (rather than attributing a lower value to supervision than hands-on care tasks).

Cost estimation

Items of resource use were grouped into categories for the purposes of costing: hospital services, primary and community health, mental health, accommodation (domestic/communal), overnight respite care (in communal settings), community social care, day services, equipment and adaptations (including memory aids), medications and unpaid care provided to participants. Unpaid care included lost working time (work cut down/given up) and hours of help and support provided by the main carer and family/friends.

Health economic statistical analysis

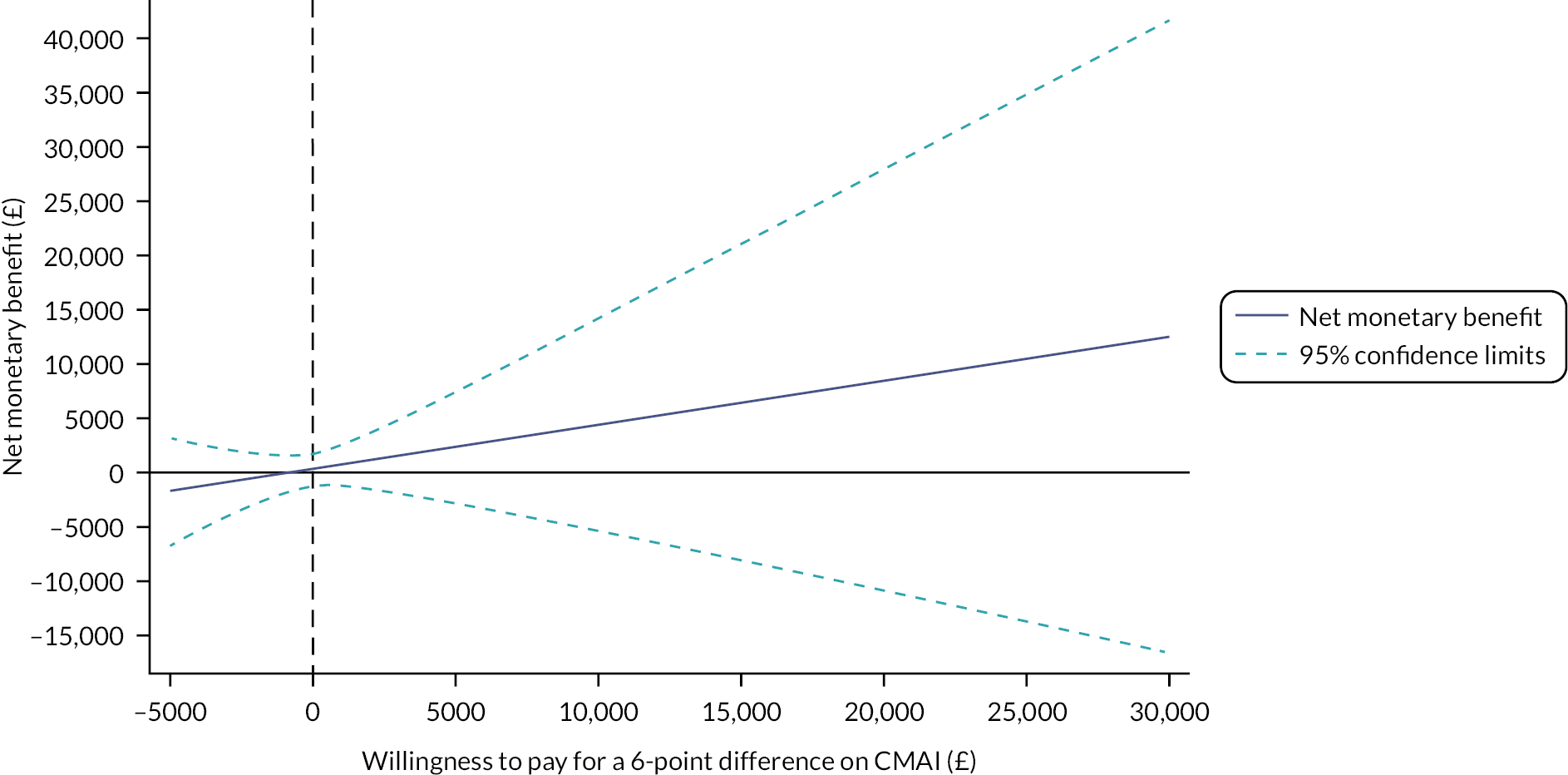

The cost per unit of effect of the intervention is known as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). It is calculated as the mean difference in costs in mirtazapine and placebo groups (ΔC) divided by the mean difference in outcome (ΔE) between groups.

Mirtazapine would be considered cost-effective if it was significantly more effective and less expensive than placebo. The treatment would also be cost-effective if it was significantly more effective and more expensive than placebo, but the decision-maker was willing to pay the additional cost (up to a threshold, λ) to achieve the additional effect; or, put another way, if the ICER was below some threshold of willingness to pay for a unit of additional effectiveness, λ. 59 The cost-effectiveness decision rule in this case can be expressed as:

Mirtazapine might also be considered cost-effective if it was significantly less effective and less expensive and the decision-maker considered the sacrifice of some effectiveness worth making to achieve the savings. Mirtazapine would be considered unambiguously to be not cost-effective if it is both significantly less effective and more expensive.

The incremental net monetary benefit (NMB)59,60 is the monetary value of gains in effects associated with the treatment at a given value of λ, once the additional cost of the treatment has been deducted. Rearranging the decision rule in (1), NMB is expressed as:

Multilevel bivariate regressions were estimated for costs and outcomes with fixed effects for baseline cost/outcome and living arrangement at randomisation (stratifying variable) and a random effect for centre. Multilevel models (MLM) were estimated by restricted maximum likelihood. Where the sample providing data consisted of 50 or fewer observations, models applied small sample inference for fixed effects and residual denominator degrees of freedom in tests of fixed effects. 61 NMB over a range of willingness-to-pay values was derived from model estimates and their 95% CIs were calculated following Fieller’s theorem. 62,63

There is no societal consensus on what should be paid for a minimum clinically significant difference in the CMAI. A NMB plot and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) were produced to show the extent to which the primary outcome could be judged cost-effective. The plot of the NMB and its confidence limits over a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds illustrates not only the size of any positive values of NMB but also whether the ICER has confidence limits. The point ICER is found where the NMB line intersects with the x-axis (the net benefit for a unit of effect is zero), that is the point where the decision-maker is prepared to pay just the cost of achieving a benefit. 59 The confidence limits of the ICER are found where the confidence limits of the NMB line intersect with the x-axis. 60 An unbounded ICER (when the NMB confidence limit lines never intersect with the x-axis) indicates that neither the intervention nor the control strategy can be considered more cost-effective. 63 The CEAC depicts the probability that the NMB at a given level of willingness to pay (λ) is > 0. 64 This approach is useful for demonstrating the level of uncertainty associated with deciding that mirtazapine is cost-effective at different levels of willingness-to-pay values.

For secondary analyses of QALY and health and social care costs outcomes, the ICER and the NMB at £20,000 (the lower limit of the NICE threshold for a QALY gain)65 were calculated and presented alongside descriptive and cost-effectiveness analysis results. Probability of cost-effectiveness over a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds was calculated for narrative commentary in the text. MLM analyses were conducted in Stata 16. 66

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses explored the impact on results of varying key assumptions made in the base case for primary and secondary analyses: including accommodation of participants in domestic as well as residential care in total health and social care costs; examining total (EQ-5D-5L) QALY and costs for the dyad (person with dementia and unpaid carer); and using an alternative valuation and definition of unpaid carer time. Accommodation costs of domestic residence were sourced from UK Household expenditure statistics (Office for National Statistics 2019) and ‘sheltered’ domestic housing. 54 Unpaid carer time was valued at replacement cost, using the hourly cost of a home care worker. This valuation was also used to calculate unpaid care time defined as the hours of the day that the person with dementia could not be left alone by the carer.

In addition, we explored the impact on results of varying the modelling approach in the primary cost-effectiveness analyses. First, we included a covariate for gender in the MLM to adjust for a baseline imbalance between groups. Second, as an alternative approach to the MLM and to address skewness typical of cost data, we applied seemingly unrelated regressions67 (where cost and outcome equations were the same as in the MLM) to 4000 replicates generated by a two-stage bootstrapping procedure suitable for clustered data. 68 This analysis was conducted in R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 69

Ethics and regulatory approvals

The study was approved by the Hampshire A South Central Research Ethics Committee (15/SC/0606), and the MHRA. It received local NHS Trust approvals and consent or assent (with legal representative consent) was obtained from all participants (see trial protocol for more details). This protocol was submitted to the UK national competent authority (MHRA).

This is a clinical trial of an IMP as defined by the EU Directive 2001/20/EC. The progress of the trial, safety issues and reports, including expedited reporting of SUSARs, was reported to the competent authority (MHRA).

Patient and public involvement

Ensuring the involvement of people living with dementia and their carers has been integral to the SYMBAD trial. This section provides further information on their important role in the trial.

Application for funding and trial design

SN is a co-applicant and has been leading on public/carer involvement in the trial throughout, from support and active involvement in the initial application of funding and trial design to the dissemination of results. Trial design also received input from a Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) group hosted by Sussex Partnership Foundation Trust (SPFT) and the Dementias and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network (DeNDRoN) group. The need for this trial received tremendous support from patients, public representatives and service users, keen to express the great need for a specific, effective and safe medicinal treatment for those with dementia and agitation. The protocol design was influenced through patient and public involvement (PPI) feedback, with increased attention to monitoring of AEs and review of participant burden, particularly with regard to data completion. It was felt that community-based data collection would be appropriate for this population and provide carers with additional support to make trial-based decisions in this vulnerable population.

Trial set up

Our PPI lead co-applicant (SN), along with SPFT LEAP co-ordinators (JF and JS), was involved in frequent communication to develop the trial documents and review the participant/carer-facing information. Among other points, this resulted in the ‘patient summary sheet’, aimed specifically at informing people living with dementia themselves about what being a participant in the trial would entail. Although the ethics committee felt this document alone was not sufficiently detailed to allow informed consent to be taken, it did mean that a concise summary could be provided to participants with dementia and enable them to be fully included in the decision-making process. PPI members also reviewed and advised on initial recruitment strategies, posters and information leaflets. SN, a former carer for her husband, is a member of the Alzheimer’s Society Research Network of volunteers working to raise awareness of the trial. The lead Trust (SPFT) was also supportive in raising awareness through the Clinical Research Network and leading on hosting the ‘Join Dementia Research’ website recruitment strategy [Join dementia research – register your interest in dementia research: Home (nihr.ac.uk)].

Delivery and support of the trial

SN and JF have been members of the Trial Management Group (TMG) throughout. The group had a standing agenda item to discuss trial management and delivery from the patient, carer and public perspective. This included support of the trial when recruitment became challenging and looking at ways to engage further with clinicians in order to raise awareness of the trial for potential participants.

The trial team has been grateful for the input of the two PPI members on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), who have balanced their support for the trial to continue alongside closely reviewing recruitment levels and strategies, thus ensuring the trial achieved its objectives.

The trial team has also been grateful for the input from the dedicated LEAP, co-ordinated initially by JS, then by JF. Over the course of the trial, nine people were members of the LEAP. All of the members had experience of living with dementia, whether diagnosed themselves or as a family carer. They have asked challenging questions of the trial team and provided excellent and thoughtful guidance on the writing and phrasing of patient facing information, including advising on the content of a participant newsletter where and how to raise awareness of the trial and suggested ways to disseminate the findings accordingly. The LEAP members were keen to balance the need for this trial to answer the important question it posed while stressing the need to reduce participant burden as far as possible.

A video was produced with support from patients and their carers in Norfolk and Suffolk Foundation Trust and CRN Eastern Patient and Public Involvement Manager, as one of the strategies to overcome potential clinician ‘gatekeeper’ behaviours and increase recruitment. Previous participants in the trial volunteered to share their experiences and support of the trial.

Dissemination

SN, JF and our LEAP panel have been involved with the dissemination activities and helped with appropriate wording to convey the, perhaps less hopeful, findings of the trial from a patient and public perspective, while stressing the value of the trial findings. This has been invaluable, since although the results are extremely important in understanding what should (or should not) be prescribed in this population, it is not a step forward regarding finding a treatment that helps. The PPI team have helped in reading the main academic outputs, as well as the preparation of the plain language summary of this report and the end-of-study information sheet for trial participants. They will continue to be involved in the most effective ways to communicate the important outcomes of the trial through their respective networks.

Chapter 3 Mirtazapine versus placebo results

Patient flow

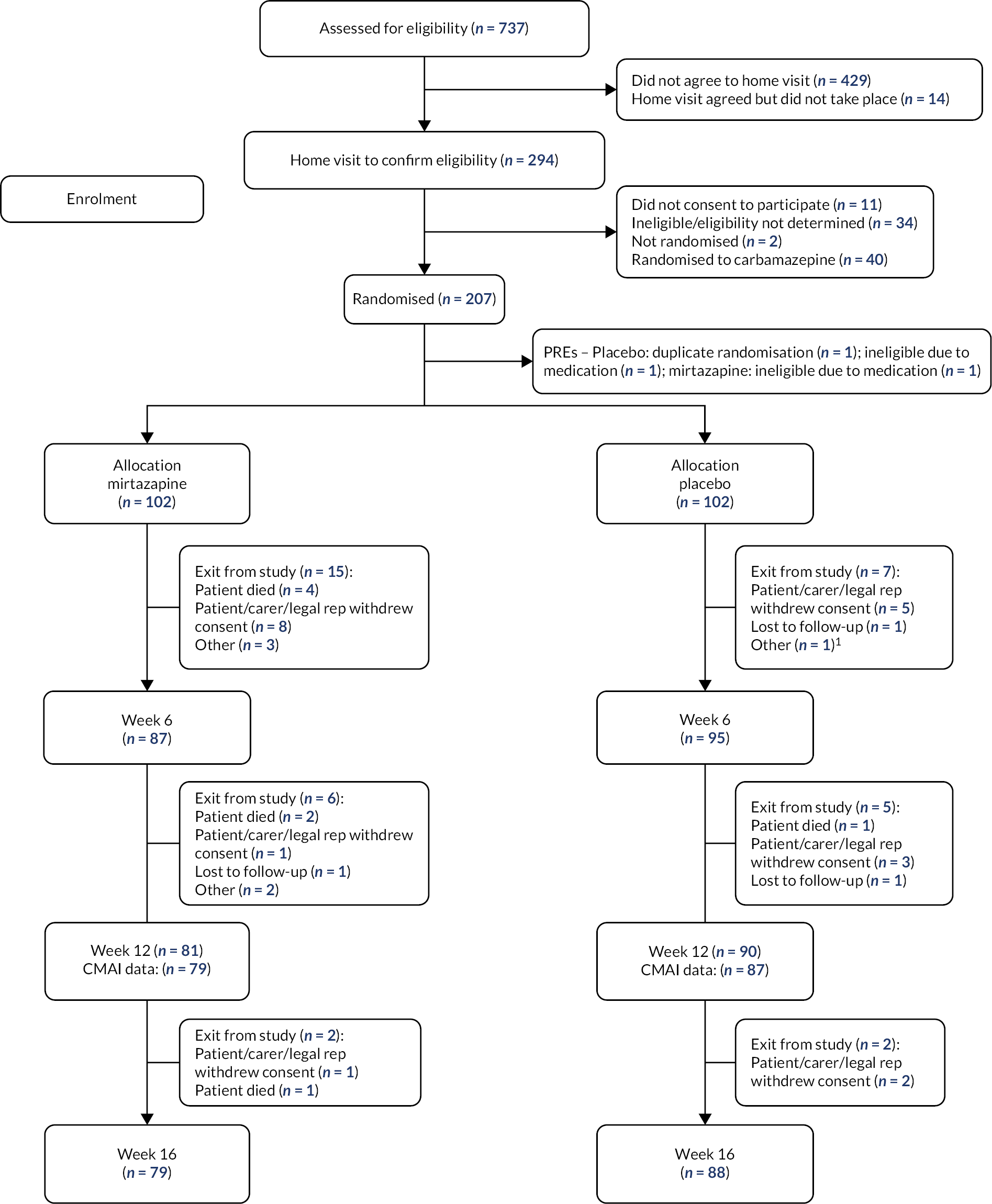

We recruited participants between January 2017 and February 2020 and completed week 12 follow-up interviews by May 2020 (See Figure 1). See Appendix 2 for recruitment by site and month.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of recruitment and testing for mirtazapine and placebo groups.

Baseline characteristics

Table 4 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants and carers. Groups were similar at baseline except for sex with more females randomised to mirtazapine (n = 77, 75%) than placebo (n = 59, 58%). In light of this difference, sex was included in an additional model as a sensitivity analysis. By week 12, similar numbers remained in the mirtazapine (80/102, 78%) and the placebo group (89/102, 87%).

| Mirtazapine (n = 102) | Placebo (n = 102) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Participants | ||

| Age (years) (SD) | 82.2 (7.8) | 82.8 (7.7) |

| Sex | n = 102 | n = 102 |

| Female | 76 (75%) | 59 (58%) |

| Residence | n = 102 | n = 102 |

| Own household | 55 (54%) | 57 (56%) |

| Care home | 47 (46%) | 45 (44%) |

| Agitation | n = 102 | n = 102 |

| CMAI (29–203) | 71.1 (16.4) | 69.8 (17.1) |

| Cognition | n = 52 | n = 50 |

| Standardised MMSE (0–30) | 13.4 (8.1) | 16.1 (6.7) |

| Condition-specific quality of life | n = 41 | n = 37 |

| DEMQOL (28–122) | 92.4 (10.8) | 95.8 (10.2) |

| DEMQOL-Proxy (31–124) | n = 100 | n = 99 |

| 92.3 (15.0) | 90.9 (14.4) | |

| Generic quality of life | n = 100 | n = 101 |

| EQ-5D (proxy report by carer) (0–1) | 0.46 (0.34) | 0.50 (0.32) |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms | n = 98 | n = 102 |

| NPI total score (0–144) | 32.7 (16.7) | 34.9 (18.2) |

| NPI agitation/aggression subscore (0–12) | n = 99 | n = 102 |

| 5.6 (3.2) | 5.6 (3.4) | |

| NPI depression/anxiety/irritability subscore (0–36) | n = 99 | n = 102 |

| 9.9 (6.2) | 10.5 (7.0) | |

| Suicidality | ||

| CSSRS | n = 102 | n = 102 |

| Suicidal ideation (lifetime) | 18 (18%) | 13 (13%) |

| Suicidal ideation (past month) | 11 (11%) | 11 (11%) |

| Suicidal behaviour (lifetime) | 4 (4%) | 0 |

| Suicidal behaviour (past 3 months) | 2 (2%) | 0 |

| Carers | ||

| Carer | ||

| Paid | 39 (38%) | 31 (30%) |

| Family | 63 (62%) | 71 (70%) |

| Family carer relationship | ||

| Partner or spouse | 34 (54%) | 35 (49%) |

| Son or daughter | 21 (33%) | 31 (44%) |

| Sibling | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Other relative | 5 (8%) | 3 (4%) |

| Friend | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) |

| Other | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Family carer occupation (pre-retirement) | ||

| Professional | 13 (21%) | 13 (18%) |

| Managerial and technical | 23 (37%) | 22 (31%) |

| Skilled non-manual | 9 (14%) | 11 (15%) |

| Skilled manual | 11 (17%) | 8 (11%) |

| Partly skilled | 2 (3%) | 8 (11%) |

| Unskilled | 3 (5%) | 0 |

| Unemployed or unwaged | 2 (3%) | 5 (7%) |

| Unanswered | 0 | 4 (6%) |

| Carer mental health (family carers only) | n = 61 | n = 66 |

| GHQ-12 | 15.0 (5.8) | 14.5 (4.9) |

| Carer burden (family carers only) | n = 58 | n = 66 |

| Zarit Carer Burden Inventory (CBI) | 33.8 (15.7) | 34.1 (13.9) |

| Carer generic quality of life (family carers only) | n = 61 | n = 66 |

| EQ-5D | 0.79 (0.21) | 0.81 (0.22) |

| NPI carer distress subscore (0–60) | n = 94 | n = 99 |

| 14.1 (8.6) | 15.5 (9.0) | |

Primary outcome measures

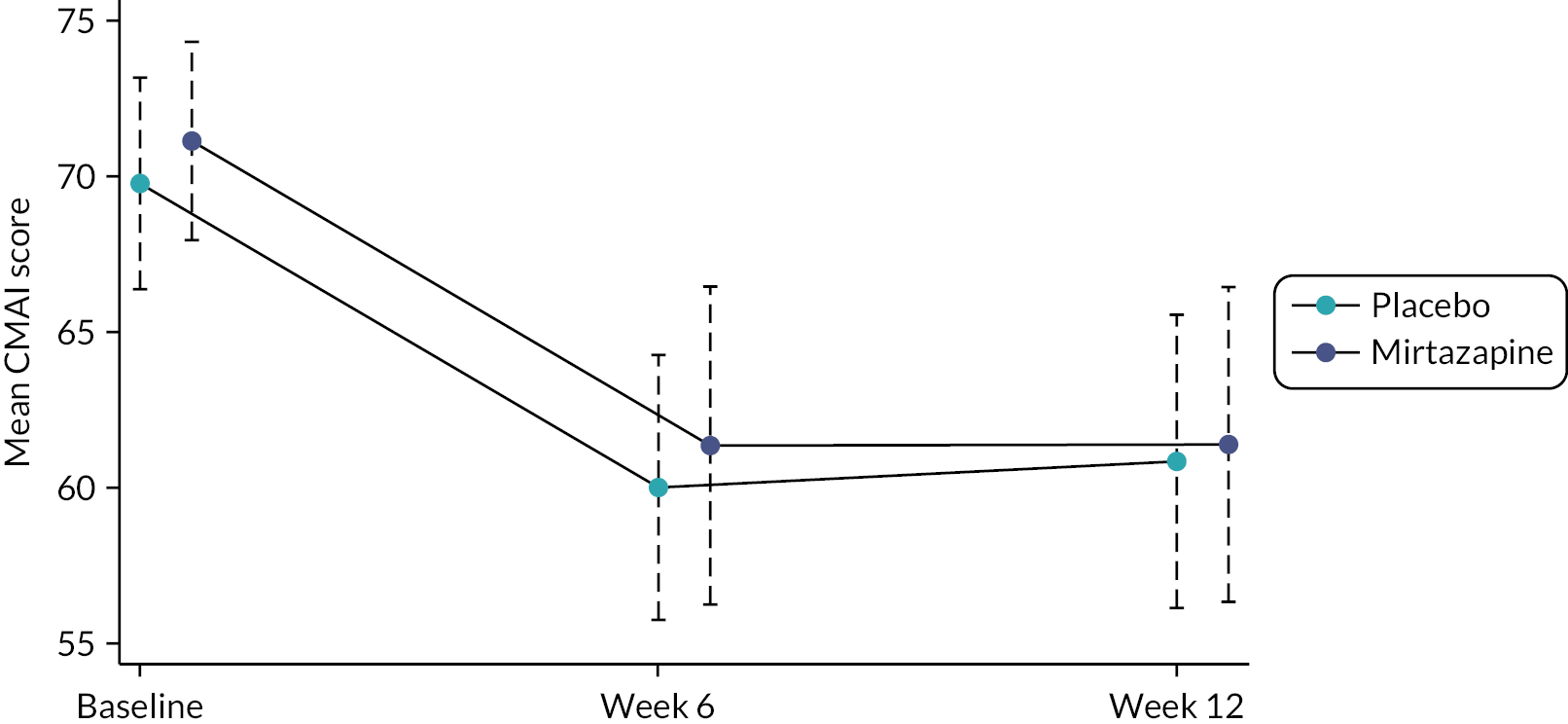

Severity of agitation decreased in both groups at 6 weeks by around 10 points and continued to be lower than baseline scores at 12 weeks (see Figure 2); this change between baseline and 6- and 12-week outcomes is illustrated by the separation in 95% confidence limits. At no point was the unadjusted or adjusted CMAI difference between the groups statistically significant (see Table 5). Table 5 presents the results from the general linear mixed modelling for the primary outcome. There was no evidence that mirtazapine improved agitation relative to placebo. The estimated adjusted effect on the CMAI was −1.74 (95% CI −7.17 to 3.69; p = 0.530). This changed little with the addition of sex into the model.

FIGURE 2.

Unadjusted mean CMAI scores (95% CI) by treatment group.

| Mirtazapine (n = 102) |

Placebo (n = 102) |

Difference | (95% CI) | Adjusted differencea | (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-week primary outcome | |||||||

| Agitation (CMAI) | n = 79 | n = 87 | |||||

| 61.4 (SD 22.6) | 60.8 (SD 21.8) | 0.59 | (−6.22 to 7.40) | −1.74 | (−7.17 to 3.69) | 0.530 | |

| −0.93b | −6.42 to 4.56 | 0.739 | |||||

| 6-week secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Agitation (CMAI) | n = 84 | n = 88 | |||||

| 61.4 (23.5) | 60.0 (19.9) | 1.39 | (−5.15 to 7.93) | −0.55 | (−6.18 to 5.08) | 0.848 | |

| Cognition (sMMSE) | n = 33 | n = 31 | |||||

| 15.5 (7.1) | 16.2 (7.2) | −0.68 | (−4.25 to 2.89) | 0.14 | (−1.17 to 1.45) | 0.836 | |

| Quality of life (DEMQOL) | n = 32 | n = 32 | |||||

| 95.1 (10.2) | 96.8 (8.4) | −1.69 | (−6.38 to 3.00) | 1.12 | (−2.74 to 4.97) | 0.570 | |

| Quality of life (DEMQOL-Proxy) | n = 79 | n = 86 | |||||

| 96.6 (14.7) | 94.6 (16.2) | 2.03 | (−2.74 to 6.79) | 0.80 | (−3.18 to 4.77) | 0.694 | |

| Quality of life EQ-5D (proxy report by carer) | n = 82 | n = 87 | |||||

| 0.48 (0.33) | 0.56 (0.30) | −0.08 | (−0.17 to 0.02) | −0.07 | (−0.13 to 0.00) | 0.061 | |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms | |||||||

| NPI total score | n = 84 | n = 88 | |||||

| 27.1 (20.0) | 24.8 (20.0) | 2.29 | (−3.73 to 8.31) | 2.03 | (−2.89 to 6.95) | 0.419 | |

| NPI agitation/aggression subscore | n = 84 | n = 88 | |||||

| 4.0 (3.6) | 4.2 (3.5) | −0.20 | (−1.28 to 0.87) | −0.34 | (−1.30 to 0.62) | 0.490 | |

| NPI depression/anxiety/irritability subscore | n = 84 | n = 88 | |||||

| 7.9 (7.7) | 7.2 (8.2) | 0.68 | (−1.72 to 3.07) | 0.70 | (−1.24 to 2.63) | 0.482 | |

| 12-week secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Cognition (sMMSE) | n = 23 | n = 27 | |||||

| 18.0 (6.0) | 15.6 (7.5) | 2.44 | (−1.48 to 6.37) | 1.45 | (−0.20 to 3.10) | 0.084 | |

| Quality of life (DEMQOL) | n = 24 | n = 24 | |||||

| 94.3 (7.1) | 97.1 (8.4) | −2.83 | (−7.35 to 1.68) | −1.36 | (−5.82 to 3.10) | 0.549 | |

| Quality of life (DEMQOL-Proxy) | n = 71 | n = 82 | |||||

| 98.4 (14.5) | 97.5 (12.4) | 0.93 | (−3.37 to 5.23) | 0.44 | (−3.09 to 3.96) | 0.809 | |

| Quality of life EQ-5D | n = 77 | n = 84 | |||||

| (proxy report by carer) | 0.46 (0.35) | 0.50 (0.33) | −0.04 | (−0.14 to 0.07) | −0.01 | (−0.08 to 0.07) | 0.822 |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms | n = 75 | n = 84 | |||||

| NPI total score | 23.9 (17.8) | 25.7 (19.6) | −1.80 | (−7.69 to 4.09) | −2.02 | (−6.67 to 2.62) | 0.393 |

| NPI agitation/aggression subscore | n = 76 | n = 84 | |||||

| 4.1 (3.4) | 4.5 (3.6) | −0.40 | (−1.49 to 0.70) | −0.52 | (−1.52 to 0.47) | 0.305 | |

| NPI depression/anxiety/irritability subscore | n = 75 | n = 84 | |||||

| 6.9 (6.7) | 7.3 (8.0) | −0.44 | (−2.77 to 1.88) | −0.58 | (−2.43 to 1.27) | 0.541 | |

Secondary outcome measures

Table 5 shows the effect of mirtazapine compared with placebo on secondary outcomes in participants and Table 6 in carers. Again, there was no evidence of difference between the groups, apart from: a single statistically significant difference in the Zarit Carer Burden Inventory at 12 weeks which indicated higher carer burden in the mirtazapine group (adjusted difference 5.01 points, 95% CI 0.80 to 9.23; p = 0.020); weaker evidence at 6 weeks (3.76, −0.03 to 7.83); p = 0.069) in the same variable; and a weak association between higher proxy-rated ED-5D quality of life in the placebo group at 6 weeks (−0.07, −0.13 to 0.00, p = 0.061) that was not maintained at 12 weeks (−0.01, −0.08 to 0.07, p = 0.822).

| Mirtazapine (n = 102) |

Placebo (n = 102) |

Difference | (95% CI) | Adjusted differencea | (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-week outcomes | |||||||

| Carer GHQ-12b | n = 50 | n = 54 | |||||

| 12.8 (6.2) | 12.1 (4.9) | 0.69 | (−1.47 to 2.85) | 0.61 | (−1.21 to 2.42) | 0.512 | |

| Carer EQ-5Db | n = 50 | n = 55 | |||||

| 0.83 (0.16) | 0.83 (0.15) | 0.00 | (−0.06 to 0.06) | 0.01 | (−0.04 to 0.05) | 0.821 | |

| Zarit CBIb | n = 46 | n = 49 | |||||

| 34.7 (16.3) | 29.4 (13.9) | 5.35 | (0.82 to 11.53) | 3.76 | (−0.30 to 7.83) | 0.069 | |

| NPI carer distress subscore | n = 78 | n = 84 | |||||

| 11.5 (1.1) | 10.2 (8.8) | 1.37 | (−1.45 to 4.19) | 1.48 | (−0.78 to 3.73) | 0.199 | |

| 12-week outcomes | |||||||

| Carer GHQ-12b | n = 44 | n = 52 | |||||

| 13.1 (6.0) | 12.2 (5.4) | 0.88 | (−1.43 to 3.19) | 0.36 | (−1.58 to 2.31) | 0.714 | |

| Carer EQ-5Db | n = 46 | n = 49 | |||||

| 0.80 (0.16) | 0.82 (0.19) | −0.02 | (−0.09 to 0.06) | 0.02 | (−0.04 to 0.07) | 0.561 | |

| Zarit CBIb | n = 42 | n = 48 | |||||

| 35.5 (17.2) | 29.0 (15.8) | 6.48 | (−0.43 to 13.39) | 5.01 | (0.80 to 9.23) | 0.020 | |

| NPI carer distress subscore | n = 72 | n = 81 | |||||

| 10.0 (8.6) | 10.5 (8.3) | −0.52 | (−3.22 to 2.17) | −0.27 | (−2.34 to 1.80) | 0.798 | |

Adverse events and severe AEs were ascertained to 16 or 4 weeks after last dose of IMP; deaths were recorded up to 16 weeks after randomisation. Examining AEs by week 16, there were 192 in 102 participants in the placebo group, of whom 65 (64%) individuals had at least one AE, compared with 225 events in 102 participants in the mirtazapine group of whom 67 (66%) had at least one. There were 35 SAEs in 18 individuals in the placebo group, compared with 13 in 8 individuals in the mirtazapine group. Mortality differed between groups with a potentially higher rate in the mirtazapine group (seven deaths in the mirtazapine and one in the placebo group by 16-week safety follow-up). Post hoc statistical analysis suggested weak evidence of a mortality difference between groups (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.065). Causes of death coded with MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) terms showed no consistent pattern with the one death in the placebo group attributed to dementia, and the seven in the mirtazapine group to: (i) dementia; (ii) pneumonia, aspiration; (iii) emphysema, dementia, pneumonia, aspiration; (iv) dementia Alzheimer’s type; (v) cardiac failure; (vi) pelvic fracture, osteoporosis, vascular dementia; and (vii) chronic kidney disease, dementia, congestive cardiac failure. See Table 7. See Appendix 3 for a summary of AEs and severe AEs by randomisation group.

| Mirtazapine (n = 102) |

Placebo (n = 102) |

|

|---|---|---|

| AE | ||

| Number of events | 225 | 192 |

| Number of individuals | 67 (66%) | 65 (64%) |

| SAE | ||

| Number of events | 13 | 35 |

| Number of individuals | 8 (8%) | 18 (18%) |

| Deaths | 7 (7%) | 1 (1%) |

| MedDRA codes for deaths |

|

|

Long-term outcomes at 26 and 52 weeks

CMAI outcomes at 26 and 52 weeks

CMAI outcomes at 26 and 52 weeks are presented in Table 8. There were no statistically significant differences between mirtazapine and placebo at either time point. This applied to both the raw and adjusted differences.

| Mirtazapine (n = 102) |

Placebo (n = 102) |

Difference | (95% CI) | Adjusted differencea | (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 weeks | ||||||

| n = 67 | n = 62 | |||||

| 61.9 (SD = 21.0) |

56.8 (SD = 19.7) |

5.1 | (−2.02 to 12.20) | 1.36 | (−4.32 to 7.05) | 0.638 |

| 52 weeks | ||||||

| n = 53 | n = 56 | |||||

| 56.8 (SD = 16.2) | 58.5 (SD = 20.8) | −1.6 | (−8.76 to 5.46) | −3.26 | (−9.91 to 3.39) | 0.337 |

| Mirtazapine (n = 102) |

Placebo (n = 102) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Hospitalisations by 26 weeks | ||

| Yes | 4 (5.6%) | 10 (14.3%) |

| No | 68 (94.4%) | 60 (85.7%) |

| No information | 30 | 32 |

| Days in hospital by 26 weeks | ||

| N | 4 | 10 |

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (4.9) | 16.8 (30.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (5.5–11) | 5.5 (1–14) |

| N missing | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalisations between 26 and 52 weeks | ||

| Yes | 6 (10.2%) | 9 (15.0%) |

| No | 53 (89.8%) | 51 (85.0%) |

| No information | 43 | 42 |

| Days in hospital between 26 and 52 weeks | ||

| N | 6 | 8 |

| Mean (SD) | 16.3 (23.0) | 20.1 (30.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–44) | 9 (3–22) |

| N missing | 0 | 1 |

Hospitalisation at 26 and 52 weeks

Hospitalisation by 26 weeks and between 26 and 52 weeks are presented in Table 9. There were no statistically significant differences between mirtazapine and placebo for either time period.

Deaths at 26 and 52 weeks

The cumulative number of deaths at 26 and 52 weeks are presented in Table 10. The marginal differences observed at 12 weeks were not maintained at 26 and 52 weeks and there were no statistically significant differences between mirtazapine and placebo at either time point.

| Mirtazapine (n = 102) |

Placebo (n = 102) |

|

|---|---|---|

| By 26 weeks | ||

| Died | 7 (9.0%) | 6 (8.1%) |

| Alive | 71 (91.0%) | 68 (91.9%) |

| No information | 24 | 28 |

| By 52 weeks | ||

| Died | 15 (19.7%) | 13 (18.6%) |

| Alive | 61 (80.3%) | 57 (81.4%) |

| No information | 26 | 32 |

Economic evaluation

Data were reasonably complete for most service-use items (see Table 11) (ranging from 96% to 100% at baseline, 94% to 100% at 6 weeks, 94% to 100% at 12 weeks). Data on carers’ care time and service use were similarly complete at baseline (94–99%) but slightly less so at 6 weeks (87–90%) and 12 weeks (91–94%). A filter question in the database classified informants as paid or unpaid carers to determine which carer measures should be completed. A few cases that were reported to be family/friend carers in the demographics question were classified as paid carers on this question, resulting in the loss of unpaid carer resource-use data from placebo participants (three cases at baseline; four at 6 and 12 weeks).

| Service/item | Units | Valid N | Mirtazapine No. users (%) |

Mirtazapine Mean (SE) |

Valid N | Placebo No. users (%) |

Placebo Mean (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (prior 12 weeks) | Expected = 103 | Expected = 103 | |||||

| Community health | |||||||

| GP | Visits | 99 | 65 (66) | 1.61 (0.28) | 101 | 71 (70) | 1.84 (0.30) |

| Practice nurse | Visits | 98 | 25 (26) | 0.52 (0.20) | 101 | 19 (19) | 0.25 (0.06) |

| Community nurse | Visits | 98 | 23 (23) | 0.69 (0.20) | 101 | 19 (19) | 0.75 (0.28) |

| Physiotherapist | Visits | 98 | 6 (6) | 0.11 (0.06) | 101 | … | … |

| OT | Visits | 99 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Geriatrician | Visits | 99 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Neurologist | Visits | 99 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Specialist nurse | Visits | 98 | 8 (8) | 0.12 (0.05) | 101 | 14 (14) | 0.25 (0.09) |

| Mental health | |||||||

| Mental health nurse | Visits | 99 | 37 (37) | 0.75 (0.18) | 101 | 43 (43) | 0.74 (0.11) |

| Psychiatrist | Visits | 98 | 33 (34) | 0.39 (0.06) | 101 | 31 (31) | 0.38 (0.06) |

| Psychologist | Visits | 99 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Mental health team | Visits | 98 | 11 (11) | 0.27 (0.12) | 101 | 6 (6) | 0.15 (0.07) |

| Community care | |||||||

| Home care | Visits | 101 | 15 (15) | 9.73 (3.07) | 102 | 14 (14) | 13.28 (4.31) |

| Home care | Hours | 101 | 15 (15) | 30.54 (20.19) | 102 | 14 (14) | 46.13 (27.81) |

| Social worker | Visits | 98 | 16 (16) | 0.19 (0.05) | 101 | 17 (17) | 0.36 (0.13) |

| Cleaner | Visits | 101 | 10 (10) | 2.56 (1.68) | 102 | 8 (8) | 1.07 (0.41) |

| Meals on Wheels | Visits | 102 | … | … | 103 | … | … |

| Sitting service | Visits | 102 | … | … | 103 | … | … |

| Carer support worker | Visits | 102 | … | … | 103 | … | … |

| Day services | |||||||

| Day centre | Attendances | 99 | 15 (15) | 3.84 (1.77) | 101 | 10 (10) | 1.52 (0.56) |

| Lunch club | Attendances | 99 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Hospital care | |||||||

| ED | Attendances | 99 | 18 (18) | 0.24 (0.06) | 101 | 15 (15) | 0.20 (0.05) |

| Inpatients services | Days | 99 | 12 (12) | 1.86 (0.79) | 101 | 9 (9) | 0.95 (0.43) |

| Day hospital services | Days | 99 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Outpatients services | Visits | 99 | 21 (21) | 0.29 (0.07) | 101 | 19 (19) | 0.32 (0.09) |

| Care home resident | |||||||

| Residential home | Days | 100 | 14 (14) | 16.17 (3.30) | 102 | 12 (12) | 13.73 (3.03) |

| Nursing home | Days | 100 | 32 (32) | 30.01 (4.02) | 102 | 32 (31) | 29.17 (3.95) |

| Residential respite | |||||||

| Residential home | Days | 100 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Nursing home | Days | 100 | … | … | 102 | … | … |

| Medications | |||||||

| Number of medications | Units | 102 | 92 (90) | 5.00 (0.34) | 102 | 95 (93) | 5.25 (0.33) |

| Equip. & adaptations | |||||||

| Equip. (HSC) | Items | 102 | 11 (11) | 0.25 (0.08) | 103 | 10 (10) | 0.24 (0.08) |

| Unpaid care;a out-of-pocket | |||||||

| Equipment (private) | Items | 101 | 11 (11) | 0.15 (0.05) | 102 | … | … |

| Unpaid care – carerb | Hours | 60 | 60 (100) | 857.90 (68.60) | 67 | 67 (100) | 716.78 (66.00) |