Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/143/01. The contractual start date was in April 2018. The draft report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in September 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Knight et al. This work was produced by Knight et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Knight et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The World Health Organisation recommends exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months because of its many health benefits. Breastmilk-fed infants are less likely to have a range of childhood infections, and protection from infection is greater with longer duration of breastfeeding. 1 Increasing breastfeeding rates is likely to have significant economic benefits based on protection from these infections alone. 2 Similarly, breastfeeding is associated with lower rates of childhood overweight and obesity, and hence a lower likelihood of diabetes as an adult. 3 Breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration is associated with better educational attainment. 4 Mothers who have breastfed have lower rates of both breast and ovarian cancer. 3 Significant sociodemographic inequalities in breastfeeding rates persist,5 and the latest figures suggest that only around half of babies are still receiving breastmilk at 6 months of age. 6 Interventions to support breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration are therefore important. Breastfeeding support interventions have been shown to be associated with continuation of breastfeeding beyond 10 days. 7

Breastfeeding difficulties have been associated with many factors, from a societal to an individual level. 8 Tongue-tie can be diagnosed in 3–11% of babies,9 with the variation in reported prevalence thought to relate to the use of different diagnostic or severity criteria. 10 Up to half of babies with tongue-tie are reported to have breastfeeding difficulties, but the reported proportion is highly variable. Some studies report almost universal difficulties, and others report very few feeding difficulties that relate to the tongue-tie itself, instead noting that incorrect positioning and attachment are the primary reasons behind the observed breastfeeding difficulties and not the tongue-tie itself. 9 In a UK survey,10 it was noted that management of tongue-tie in infants with breastfeeding difficulties was therefore highly variable across the country. This is coupled with highly variable provision of breastfeeding support,11 which can range from minimal to expert and intensive, and using a variety of different models including peer supporter, midwife and health visitor.

A Cochrane review12 identified five prior randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of frenotomy including a total of only 302 infants. The trials are small and underpowered and/or include only very short-term or subjective outcomes, suggesting further robust evidence is needed. Hence there is considerable controversy regarding, not only the diagnosis and clinical significance, but also the management of tongue-tie. Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance13 allows for the procedure, based on lack of safety concerns, but notes very limited evidence of efficacy. In preparation for this study, we searched the literature to identify previous economic evaluations assessing the cost-effectiveness of frenotomy in a UK setting but no relevant studies were identified. There is therefore a clear need for an assessment of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of frenotomy for babies diagnosed with tongue-tie in the form of an adequately powered, pragmatic RCT, taking into account the diagnostic controversy and variation in practice.

Objective

The objective of this research was to investigate whether frenotomy is clinically and cost-effective to promote continuation of breastfeeding at 3 months in infants with breastfeeding difficulties diagnosed with tongue-tie.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The FROSTTIE trial was a multicentre, randomised, controlled parallel group trial conducted in England.

The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (ISRCTN 10268851).

Patient and public involvement

The research question was initially prioritised by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme, including patient and public involvement (PPI). In order to obtain the perspective of a wide group of women with recent breastfeeding experience and/or experience of tongue-tie, we included a PPI co-applicant from the Breastfeeding Network, who consulted with other Network members, and also established a Public Advisory Group. These two groups helped design the study processes and materials, and advised throughout the trial.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Any infant aged <10 weeks referred (by parent or other breastfeeding support service) to an infant feeding service with breastfeeding difficulties and judged to have tongue-tie, whose parent had given informed consent for participation.

Exclusion criteria

Infants were not eligible to enter the study if ANY of the following applied:

-

Infant was older than 10 weeks.

-

Infant had breastfeeding difficulties but was not judged to have tongue-tie.

-

Infant was born at <34 weeks’ gestation.

-

Infant had a congenital anomaly known to interfere with breastfeeding, for example cleft palate, Down syndrome.

-

Infant had a known bleeding diathesis.

-

Infant had a frenotomy prior to recruitment.

Setting

The trial was conducted in 12 infant feeding services in England (see Appendix 1).

Informed consent and recruitment

Information about the trial was made widely available throughout the infant feeding units in the form of posters and leaflets (with QR codes to the trial website). Written information about the trial was available to all women at participating centres when they attended for breastfeeding support. In some sites, materials were also available on the postnatal ward.

Potential participants were identified by the infant feeding service staff from the population of infants with breastfeeding difficulties referred to NHS infant feeding services through volunteer breastfeeding supporters, other breastfeeding counsellors, midwives or through self-referral by parents.

As standard, following referral to the infant feeding service, infant feeding was observed (either in person or via video conferencing) and tongue assessment conducted, and mothers received advice on positioning and attachment. Initial discussions may have taken place in person or virtually via telephone or video conferencing if this was what was being offered as part of routine care. The tongue-tie diagnosis was made according to usual hospital practice, which may have included using any suitable tool. However, all babies whose parents consented for their participation in the trial had an assessment of their tongue-tie made using the Bristol Tongue Assessment Tool (BTAT). 14

Following diagnosis of a tongue-tie associated with breastfeeding difficulties, a verbal explanation and written information (the Parent Information Leaflet) was provided to the parent(s) either as a hardcopy in person or via post, electronically via email or by being directed to the study website. The parent(s) were allowed as much time as they needed to consider the information, and the opportunity to question staff before deciding whether they consented for their baby to participate in the study. Written or remote verbal informed consent was obtained.

Written or verbal informed consent also included optional consent for linkage of their baby’s data to routine data sources to allow the potential for further follow-up beyond the funded trial.

Intervention

Infants were randomised via a web randomisation portal to either:

-

frenotomy with standard breastfeeding support (intervention arm), or

-

no frenotomy with standard breastfeeding support (comparator arm).

Breastfeeding support included as a minimum: an initial assessment of breastfeeding, for example using the LATCH (Latch, Audible swallowing, Type of nipple, Comfort, Hold) tool15 or Baby Friendly Initiative assessment tool, and advice on positioning and attachment and at least one follow-up visit, together with drop-in clinic advice as required, but available on more than 1 day a week. Assessments and breastfeeding support were provided face-to-face in person or virtually using video conferencing or telephone dependent on what was being offered as part of routine care.

Intervention arm: infants who were randomised to frenotomy with breastfeeding support underwent frenotomy according to usual hospital practice. Frenotomy was carried out by the usual trained practitioner for participating hospitals using their normal technique. The babies had an immediate postfrenotomy observed feed. Parents received further advice on positioning and attachment together with standard postfrenotomy advice concerning bleeding and other postfrenotomy adverse events. Parents were provided with details about how to access rapid breastfeeding support in the event of ongoing feeding difficulties and an appointment for at least one follow-up visit.

Comparator arm: infants randomised to breastfeeding support only did not undergo frenotomy, but received further advice on positioning and attachment. Parents were provided with details about how to access rapid breastfeeding support in the event of ongoing feeding difficulties and an appointment for at least one follow-up visit.

Randomisation and blinding

The infants entered into the trial were randomised 1 : 1 to either intervention or comparator arm. Multiples (twins or higher-order multiples) were randomised to the same arm. Stratified block randomisation (using variable block sizes) was performed via a secure 24-hour web-based randomisation system [hosted by the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), University of Oxford] stratified by infant’s age (<2 and ≥2 weeks) at randomisation and mother’s parity (primiparous or multiparous) within the centre. A telephone back-up system was available 24 hours a day (365 days per year).

A statistician independent of the trial generated the stratified block randomisation (using variable block sizes) schedule and the Senior Trials Programmer wrote the web-based randomisation program; both were independently validated. The implementation of the randomisation procedure was monitored by the Senior Trials Programmer and independent statistician throughout the trial and reports provided to the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC).

Parents were blinded to the allocation for the first 20 participants, following which the trial was conducted unblinded. Blinding consisted of parents being asked not to directly observe the procedure (tongue-tie examination with or without frenotomy) immediately before a postprocedure breastfeed. The request for a change to an unblinded design was made by the funder as it was felt to be a barrier to recruitment.

Internal pilot

We conducted an internal pilot during the first 6 months of the trial, when 266 recruits were predicted, to test recruitment and retention assumptions. The pre-defined stop–go criteria were as follows:

-

recruitment 75% or more (N ≥ 199) – continue directly with the main trial

-

recruitment 50–75% (133 ≤ N < 199) – recruit more centres and review in 6 months

-

recruitment < 50% (N < 133) – undertake an urgent detailed review of options with Trial Steering Committee (TSC) to subsequently recommend to the funder.

The pilot was restarted in September 2019, following removal of blinding, but was never completed due to a pause in recruitment between March and May 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and subsequent closure of the trial by the funder.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Any breastmilk feeding in the 24 hours prior to the infant reaching 3 months of age. 16,17 A positive response was considered indicative of continuation of breastfeeding.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were assessed at 3 months of age and some additionally at first follow-up visit (indicated by *).

-

Mother’s breastfeeding self-efficacy*: measured using the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale – Short Form

-

Mother’s pain while feeding during the previous 24 hours: measured using visual analogue scale of the Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), modified into a Likert-type scale

-

Amount of breastfeeding support used: measured by total number of contacts (whether face-to-face or virtual) with any breastfeeding supporter since the FROSTTIE procedure

-

Infant weight gain: measured as difference in weight for age z-scores between birth and 3 months of age

-

Infant postrandomisation weight gain: measured as difference in weight for age z-scores between baseline and 3 months of age

-

Exclusive breastmilk feeding*: exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours

-

Exclusive direct breastfeeding*: exclusive breastfeeding directly from the breast with no bottle feeds of expressed milk in the previous 24 hours

-

Age of child when s/he last received breastmilk: age when child last received breastmilk, to determine when and whether switch to exclusive formula feeding has occurred

-

Time spent breastfeeding in previous 24 hours: time in minutes/hours spent breastfeeding in previous 24 hours

-

Frenotomy in comparator group*/repeat frenotomy*/bleeding following frenotomy or frenulum tear*/post-procedure adverse events (tongue cut*, salivary duct damage*)/maternal and infant NHS health-care resource use): measured by specific questions

-

Maternal anxiety and depression: dimension of EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version*

-

Maternal health-related quality of life: as elicited by the EQ-5D-5L*

-

Any breastmilk feeding at 6 months: according to maternal self-report: defined as any breastmilk feeding in the 24 hours prior to the infant reaching 6 months of age.

Process outcomes

The process outcomes for all infants included BTAT score by adherence status, reasons for non-adherence, type of breastfeeding support. For infants who had undergone frenotomy additional process outcomes were assessed – role of person performing the procedure, whether anaesthetic was used, whether frenotomy was performed using bipolar diathermy, scissors, or other, frenotomy technique, and whether the infant was able to breastfeed after the procedure.

Sample size

It was assumed that a 10% absolute increase in the rate of breastfeeding represented the minimal clinically important difference that should be detectable by the trial; and breastfeeding rates will remain high in this motivated population. Thus, assuming a breastfeeding rate of 70% in the control group and 80% in the intervention group, at 90% power with a 5% level of significance, and allowing for 5% loss to follow-up, with a further 5% increase to account for between-group contamination required a sample size of 870. Given the final sample size achieved with complete primary outcome data (n = 163), the study had 31% power to detect this difference, assuming the same control group rate.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out according to a pre-specified Statistical Analysis Plan finalised prior to unblinding. For the primary analysis for all primary and secondary outcomes infants, we compared the outcomes of all infants allocated to frenotomy with breastfeeding support with all those allocated to breastfeeding support, regardless of deviation from the protocol or treatment received (referred to as the ITT population). Demographic and clinical data were summarised with counts and percentages for categorical variables, means [standard deviations (SDs)] and medians [with interquartile range (IQR) or simple range] for continuous variables. For binary outcomes, risk ratios (RRs) and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using log binomial regression or Poisson regression with a robust variance estimator. Continuous outcomes were analysed using linear or median (quantile) regression for normally distributed and skewed variables, respectively. Analyses were adjusted for stratification factors at randomisation where possible (centre, infant’s age at randomisation and mother’s parity). 18 Both unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) are presented, with the primary inference based on the adjusted estimates. Two-sided statistical testing was performed throughout. A 5% level of statistical significance was used, and 95% CIs are presented.

Secondary analyses

Four planned secondary analyses were carried out:

-

A comparison of the characteristics and primary outcome by adherence status in the breastfeeding support arm.

-

An assessment of the impact of non-adherence to the randomised allocation using complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis. The CACE analysis assumes that the proportion of would-be non-compliers in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm (i.e. women in this group who would not have complied had they been randomised to breastfeeding support alone) is the same as the proportion of non-compliers in the breastfeeding support arm. It also assumes that the event rate among the non-compliers in the breastfeeding support arm is the same as the event rate among the would-be non-compliers in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm. Applying these two assumptions, the event rate for the primary outcome was calculated for the would-be compliers and would-be non-compliers in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm. The unadjusted CACE RR and 95% CI for the primary outcome was calculated using the event rates for compliant groups only (i.e. the observed compliers in the breastfeeding support arm and the would-be compliers in the frenotomy arm). The CI for the CACE estimated RR was estimated using the bootstrapping method.

-

Exploratory analysis: a restricted per protocol analysis, excluding participants in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm who had no frenotomy performed and participants in the breastfeeding support group who had a frenotomy performed.

-

Exploratory analysis: an as-treated analysis, grouping participants according to the allocation they received (participants in the breastfeeding only group who had a frenotomy performed and received breastfeeding support included in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm and participants in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm who had no frenotomy performed but received breastfeeding support included in the breastfeeding support group).

Pre-specified subgroup analyses

Four planned subgroup analyses were carried out, examining the primary outcome in the following groups:

-

infants aged <2 weeks versus ≥2 weeks at randomisation

-

infants with BTAT score 4 or less versus 5–6 versus 7 or more at randomisation

-

prior belief concerning frenotomy: likely to be beneficial versus uncertain versus unlikely

-

recruited pre- or posttrial pause during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The primary outcome is presented within these subgroups using descriptive statistics only due to the small achieved sample size.

Data collection

Baseline information was collected on sociodemographic and other characteristics at trial entry, including the following:

-

infant birthweight

-

infant current weight

-

estimated date of delivery

-

current feeding practices (e.g. expressed breastfeeding, use of infant formula)

-

assessment of the degree of tongue-tie using the BTAT

-

mother’s prior beliefs about frenotomy: using a 3-point Likert scale, the opinions of mothers of infants recruited to the trial were measured at the time of recruitment on their prior belief of the potential benefit of frenotomy

-

EQ-5D-5L

-

mother’s pain while feeding during the previous 24 hours: measured using visual analogue scale of the SF-MPQ, modified into a Likert-type scale (scores ranging from 0 to 10)16

-

exclusive breastmilk feeding: exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours

-

exclusive direct breastfeeding: exclusive breastfeeding directly from the breast with no bottle feeds of expressed milk in the previous 24 hours

-

pre-trial entry breastfeeding support received.

The following data were collected from the clinician performing the frenotomy on the day of the procedure:

-

in-person BTAT assessment if the baseline assessment was done virtually that is not face-to-face

-

intervention undertaken according to randomisation schedule and technique used

-

bleeding following frenotomy or frenulum tear

-

postprocedure adverse events (tongue cut, salivary duct damage).

The following data were collected from the mother at the routine follow-up visit (approximately 1 to 2 weeks posttrial entry):

-

mother’s pain while feeding during the previous 24 hours: measured using visual analogue scale of the SF-MPQ, modified into a Likert-type scale (scores ranging from 0 to 10)16

-

exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours

-

exclusive breastfeeding directly from the breast with no bottle feeds of expressed milk in the previous 24 hours

-

type of breastfeeding support received (in person or virtual)

-

frenotomy/repeat frenotomy (defined as any further procedure on tongue-tie)

-

bleeding following frenotomy or frenulum tear

-

postprocedure adverse events (tongue cut, salivary duct damage): measured by specific questions

-

maternal anxiety or depression as indicated by the anxiety and depression dimension of EQ-5D-5L

-

maternal health-related quality of life (HRQoL): as elicited by the EQ-5D-5L.

Data on the primary outcome (any breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours at age 3 months) were collected from mothers by automated text message. The following data were collected using maternal self-report via a follow-up link (by smart phone, tablet, computer, postal questionnaire or telephone) when the infant was 3 months of age:

-

mother’s breastfeeding self-efficacy: measured using the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale – Short Form19

-

mother’s pain while feeding during the previous 24 hours: measured using visual analogue scale of the SF-MPQ, modified into a Likert-type scale (scores ranging from 0 to 10)16

-

total number of contacts with any breastfeeding supporter since first referral and specific means of support used (in person or virtual)

-

infant weight

-

exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours

-

exclusive breastfeeding directly from the breast with no bottle feeds of expressed milk in the previous 24 hours

-

age when child last received breastmilk, to determine when and whether switch to exclusive formula feeding had occurred20

-

time spent breastfeeding in previous 24 hours: time in minutes/hours

-

frenotomy/repeat frenotomy

-

bleeding following frenotomy or frenulum tear

-

postprocedure adverse events (tongue cut, salivary duct damage): measured by specific questions

-

mother or infant previously diagnosed with COVID-19

-

maternal anxiety or depression as indicated by the anxiety and depression dimension of EQ-5D-5L

-

maternal HRQoL: as elicited by the EQ-5D-5L

-

maternal and infant NHS health-care resource use: collected on general practice visits and hospital admissions.

Data on any breastmilk feeding at 6 months were collected from mothers by automated text message.

Adverse event reporting

Non-serious adverse events were not routinely recorded as the procedure is part of standard clinical practice. However adverse events that were part of the study outcomes [bleeding following frenotomy (unless excessive) or frenulum tear and postprocedure adverse events (tongue cut, salivary duct damage)] were collected as part of standard follow-up.

All serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported immediately, at least within 24 hours; except the following SAEs, which were foreseeable SAEs and were subject to SAE reporting procedures:

-

admission or extension of hospital stay due to the following:

-

breastfeeding difficulties

-

poor milk supply in the mother

-

weight loss or poor weight gain in the baby

-

jaundice.

-

Economic evaluation

A within-trial cost-consequences analysis (CCA) with a time horizon of a 3-month follow-up was conducted from a NHS perspective as the primary analysis for the economic evaluation. In this case, results were presented as benefits and health-care costs in disaggregated format for both mothers and their infants in each treatment arm. 21 Costs included frenotomy and breastfeeding support-related costs, primary care, community care, secondary care and non-NHS related costs. The benefits considered in the CCA were the primary outcome of any breastmilk feeding at 3 months according to maternal self-report, maternal anxiety and depression measured using the relevant EQ-5D-5L domain22 and HRQoL measured using the EQ-5D-5L at different time points.

In a secondary analysis, a within-trial cost-utility analysis (CUA) from the mother’s perspective with a time horizon up to 3 months was also conducted. Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), were used to measure benefits in the CUA with mean difference in costs and QALYs were synthesised using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) expressed as incremental costs per QALYs gained over the trial period. 23 The ICER was compared to the standard cost-effectiveness threshold as recommended by NICE to determine value for money. 24

NHS health-care resource use

Detailed information on health-care resource use was collected for women and their infants and included data on resource utilisation up to 3 months after birth. Frenotomy-related resource use was collected directly from the health-care professional undertaking the procedure. Infant and maternal health-care resource use was collected using questionnaires at the routine follow-up visit (approximately 1 to 2 weeks posttrial entry) and when the infant was three months of age. The latter one could be completed by smart phone, tablet, computer, postal questionnaire or telephone.

Health-care utilisation related to frenotomy intervention

Frenotomy-related resource use data were collected from the health-care professional performing the procedure on the day of the operation and included who performed the procedure and whether any complications occurred. The setting where the frenotomy was conducted (NHS setting or private provided) was facilitated by mothers at her routine follow-up visit or using the 3-month follow-up questionnaire.

Health-care utilisation related to breastfeeding support

Resource use data on breastfeeding support were collected using the maternal questionnaire when the infant was 3 months of age. Resource use data in this category included type of breastfeeding support service, whether it was delivered face-to-face or remotely and how many times the service was used. We also collected information on any out of pocket expenses incurred due to visits to any breastfeeding support service consultations.

Primary, community and secondary health-care utilisation

Primary and community health-care utilisation for both mothers and their infants were collected using the maternal questionnaire when the infant was 3 months of age. Primary care visits included general practitioner and practice nurse visits, medication prescribed to treat anxiety or depression, and antibiotic use (reason and number of courses received). Community care contacts included visits to community nurse or midwife contacts, infant health visitor contacts and community paediatrician visits. Secondary (hospital-based) care contacts included accident and emergency department visits, hospital outpatient clinic appointments and hospital overnight admissions. We also collected any other NHS contact to a health-care professional not captured by the previous categories and visits to non-NHS health-care professionals up to 3 months follow-up. The different items of resource use collected for each category are presented in Appendix 2, Table 22.

Unit cost data collection

Sources and associated estimates of unit costs for the different resource use categories are presented in Appendix 2, Table 22. Unit costs were extracted from national sources, including NHS Reference Costs 2019/2020 Version 2,25 Unit costs of Health and Social Care 202026 and the Electronic Drug Tariff March 2020. 27 Given the reason for the antibiotics prescribed, the generic name of the antibiotic for the medicine costs analysis was assumed based on the national guidelines. 28,29 Prescription cost analysis 2020/21 data were then used to determine the antibiotic’s most prescribed form and dosage. 30 Hospital admissions were costed using the weighted average of a non-elective short stay across relevant Health-care Resource Group codes for the reason for admission from the NHS Reference Costs. We assumed that breastfeeding services received outside a NHS setting did not incur any costs unless reported specifically by the mother as out of pocket expenses. The only other non-NHS health-care professional visits reported was a contact with an osteopath, which was costed individually from the best source available to the research team. 31 All costs were expressed in 2019/20 pounds sterling.

Health outcome measures

In the CCA, health outcome measures included the primary clinical effectiveness of any breastmilk feeding at 3 months according to maternal self-report as described above, maternal anxiety and depression as measured by the relevant EQ-5D-5L dimension, and HRQoL at different follow-up periods as measured by EQ-5D-5L index values.

The EQ-5D-5L is a multiattribute generic instrument for measuring HRQoL. EQ-5D-5L consists of a descriptive system to describe health state and a visual analogue scale to evaluate overall level of health. 22 In this study, only results from the descriptive system are reported. The instrument covers five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression, and each dimension has associated five-levels ranging from no problems to unable/extreme problems. The EQ-5D-5L describes 3125 health state profiles that need to be converted into a single preference-based score (HRQoL) using a value set obtained from a representative sample of the general population to be used in economic evaluations. 22

At the time of conducting this economic evaluation, the recommended approach to estimate EQ-5D-5L preference-based scores (HRQoL) was to convert EQ-5D-5L responses onto EQ-5D-3L preference-based scores using a mapping algorithm. 32 This mapping was based on the recent exercise conducted by Hernández-Alava and colleagues to derive EQ-5D-3L utility values from the existing EQ-5D-5L data. 33 The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire was completed by mother at the trial entry, at the routine follow-up visit (approximately 1 to 2 weeks posttrial entry) and when the infant was 3 months of age.

In the CUA, the main measure of benefits was maternal QALYs [also expressed as quality-adjusted life-days (QALDs) to facilitate interpretation given short time horizon]. Maternal QALDs and QALYs were derived as the area under the curve for the health profile created connecting EQ-5D-5L values at trial entry, at the routine follow-up visit, and 3 months after birth. A straight line relationship was assumed between the maternal utility values at the different time points.

Statistical analysis

We summarised the information about frenotomy procedures in each group using frequencies and associated proportions. Mean and SD were used to present the different categories of NHS health-care resource use and costs in each trial arm. Resource use is presented across all participants in the study and only for those who consumed a particular health-care resource use category. A mean difference between trial arms adjusted for the centre, infant’s age at randomisation and parity with associated 95% CI was computed using a generalised linear model. We present resource use and costs separately for mothers and their infants, but main categories of costs [primary care, medicines, community care, secondary (hospital-based) care, other NHS health-care professionals’ contacts, other non-NHS health care] were also presented as a single value combining information from both. Mean (SD) for each group with associated adjusted mean difference using the same approach as for costs was calculated to present EQ-5D-5L scores at baseline (trial entry), routine follow-up (approximately 1 to 2 weeks posttrial entry), 3 months after birth and overall QALYs or QALDs. The distribution of responses across the EQ-5D-5L dimensions was presented as frequencies and proportions at baseline (trial entry), routine follow-up (approximately 1 to 2 weeks posttrial entry) and 3 months after birth. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to examine differences in the distribution of EQ-5D-5L responses between the two groups.

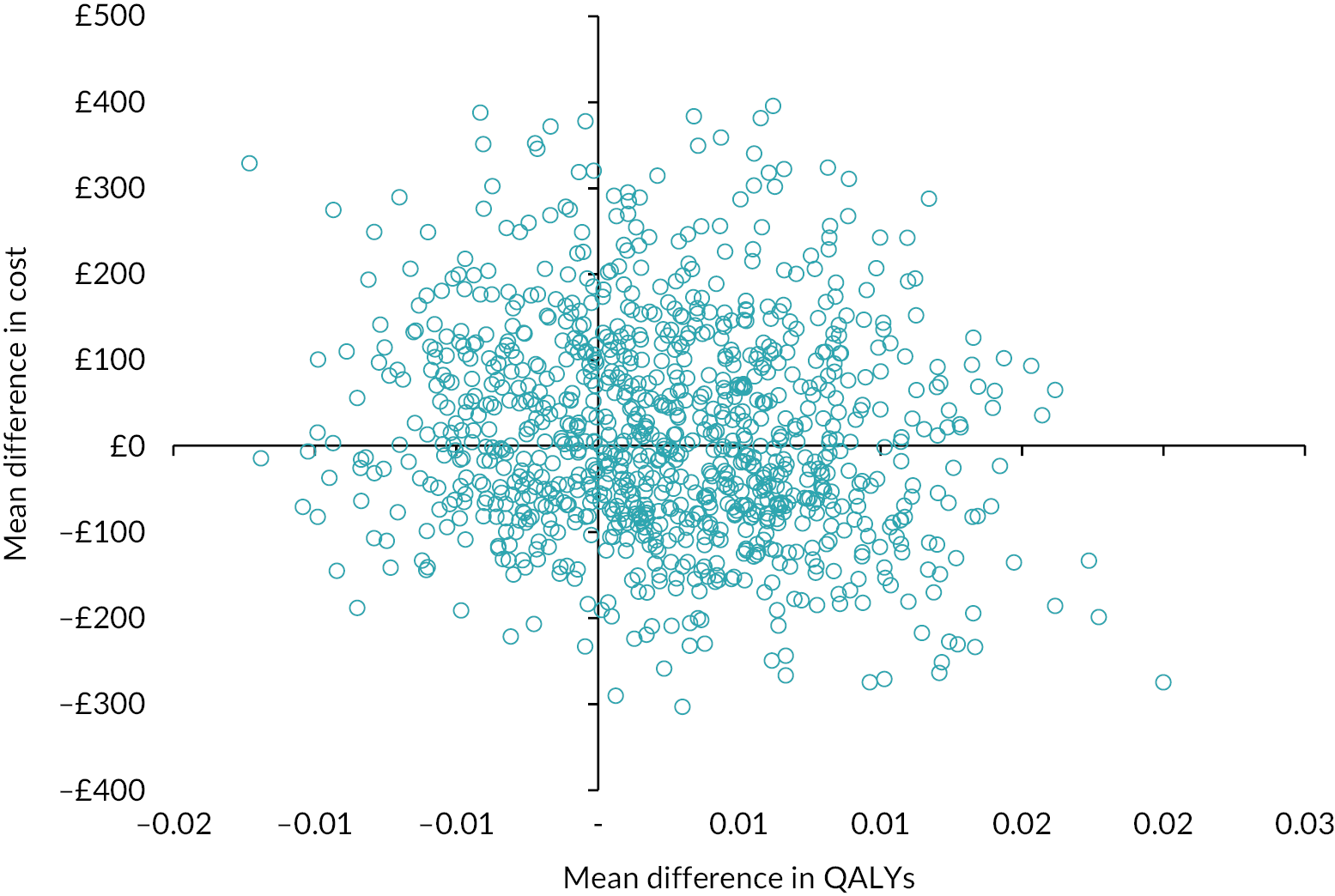

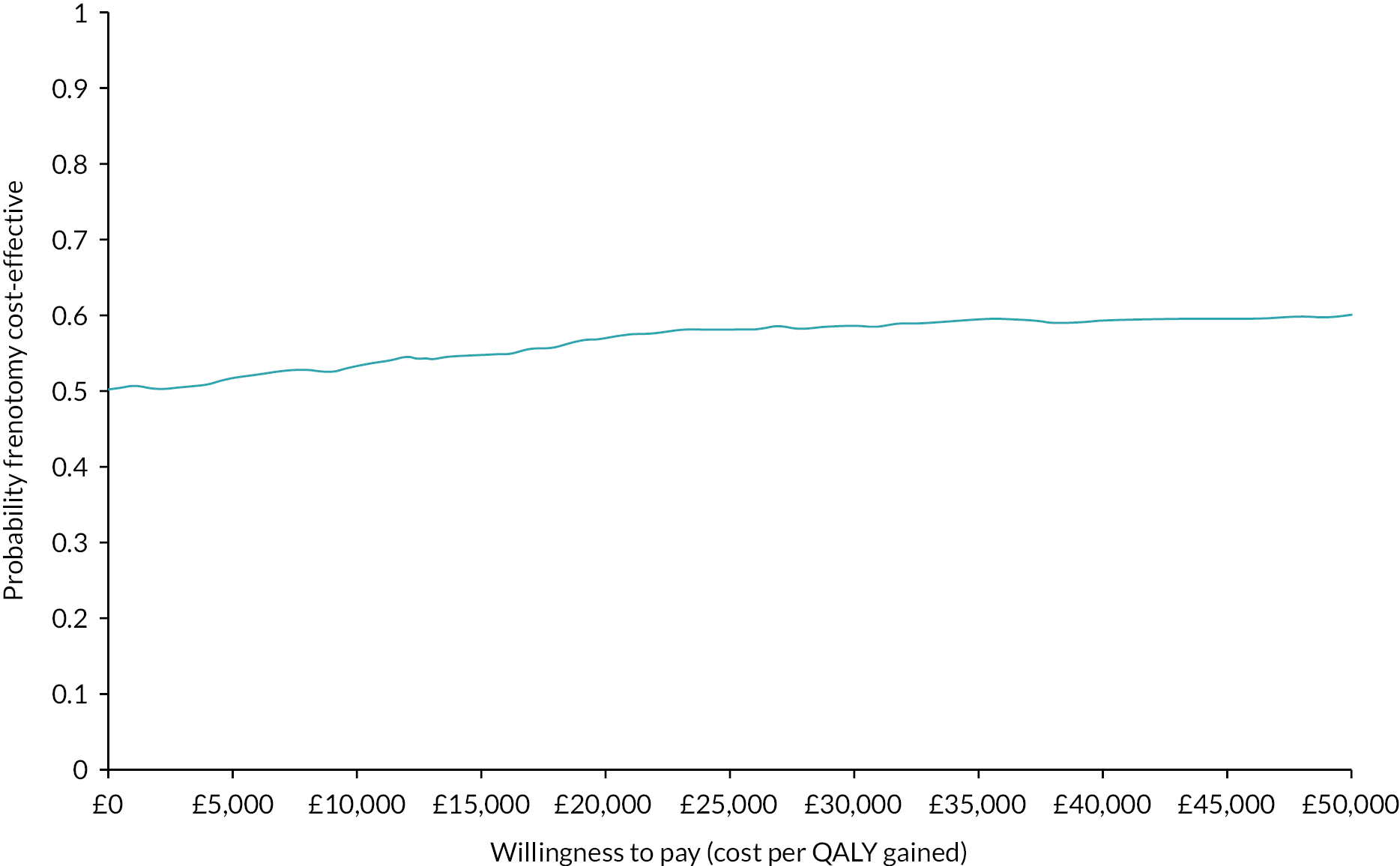

For all categories of NHS resource use, costs, HRQoL and QALYs we report the number of participants with missing data. The summary of the cost-consequence analysis therefore used different sample sizes for each of the components presented. However, the within-trial CUA was presented using a complete case analysis where mothers have complete information on total costs and QALYs over the trial period. The ICER was expressed as the ratio of the mean difference in costs divided by the mean difference in QALYs between the two groups. The breastfeeding support only arm was used as the comparator in the ICER calculation. Uncertainty around the ICER was evaluated using 95% CIs from a non-parametric bootstrap approach using 1000 replicates. Bootstrap replicates of mean difference in costs and effects were presented in the cost-effectiveness plane (CEP). Current thresholds of willingness to pay for QALY gained of £20,000 was used to determine value for money. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were derived to evaluate whether frenotomy when compared with breastfeeding support was cost-effective at different thresholds of willingness to pay.

The statistical analysis was conducted in Stata/MP version 17.0 and Microsoft Excel.

Governance and monitoring

A monitoring plan for the trial, including responsibilities, was developed prior to the start of recruitment. In person monitoring of all sites was carried out to identify barriers and facilitators to recruitment and the findings of the visits summarised to guide ongoing actions to enhance recruitment.

The trial was supervised on a day to day basis by a Project Management Group. A TSC was convened including an independent chair, four other independent members, a PPI representative(s), the NPEU CTU Director and the Chief Investigator. A DMC independent of the applicants and of the TSC reviewed the progress of the trial annually and provided advice on the conduct of the trial to the TSC.

Summary of changes to the study protocol

Masking of parents was removed from the trial at the funder request after a short pilot period as it was felt to be a barrier to recruitment. Following the restart after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, changes were made to allow virtual assessments and breastfeeding support, and virtual BTAT assessment. Verbal consent was permitted if written consent was not possible. The COVID-19 status of mother and baby was added to the data collection.

A summary of the other changes made to the original protocol is presented in Appendix 3.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and retention

Between March 2019 and November 2020, 169 infants were randomised; 80 to the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm and 89 to the breastfeeding support arm. There were no substantial differences in the response rates between the intervention arms during the follow-up period (see Figure 1). The trial was stopped in November 2020 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic due to withdrawal of breastfeeding support services, slow recruitment and crossover between arms. In the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm 74/80 infants (93%) received their allocated intervention, compared to 23/89 (26%) in the breastfeeding support arm.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants.

The number of participants recruited at each site varied from 1 to 85 (see Table 1).

| Total (n = 169) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support (n = 89) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at birth | |||

| 34+0 to 35+6 weeks, n (%) | 7 (4.1) | 3 (3.8) | 4 (4.5) |

| 36+0 to 37+6 weeks, n (%) | 15 (8.9) | 6 (7.5) | 9 (10.1) |

| 38+0 to 39+6 weeks, n (%) | 71 (42.0) | 35 (43.8) | 36 (40.5) |

| 40+0 to 42+6 weeks, n (%) | 76 (45.0) | 36 (45.0) | 40 (44.9) |

| Age at randomisation a | |||

| <2 weeks, n (%) | 64 (37.9) | 30 (37.5) | 34 (38.2) |

| ≥2 and <4 weeks, n (%) | 48 (28.4) | 24 (30.0) | 24 (27.0) |

| ≥4 and <10 weeks, n (%) | 57 (33.7) | 26 (32.5) | 31 (34.8) |

| ≥10 weeks, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3439.3 (561.3) | 3409.0 (563.6) | 3466.5 (561.1) |

| Birthweight z-score (adjusted for gestational age and sex at birth),b median (IQR) | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.2) | −0.5 (−1.2 to 0.3) | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.2) |

| Current weight (g, within last 7 days), mean (SD) | 3832.2 (857.7) | 3767.8 (841.0) | 3890.7 (873.4) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Mode of birth | |||

| Unassisted vaginal, n (%) | 87 (51.5) | 42 (52.5) | 45 (50.6) |

| Assisted vaginal, n (%) | 26 (15.4) | 14 (17.5) | 12 (13.5) |

| Vaginal breech, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| C-section before labour onset, n (%) | 22 (13.0) | 7 (8.8) | 15 (16.9) |

| C-section after labour onset, n (%) | 33 (19.5) | 16 (20.0) | 17 (19.1) |

| Sex | |||

| Male, n (%) | 100 (59.2) | 51 (63.8) | 49 (55.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 69 (40.8) | 29 (36.2) | 40 (44.9) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Degree of tongue-tie (BTAT) | |||

| 0–4, n (%) | 55 (32.7) | 29 (36.3) | 26 (29.6) |

| 5–6, n (%) | 53 (31.6) | 21 (26.3) | 32 (36.4) |

| 7–8, n (%) | 60 (35.7) | 30 (37.5) | 30 (34.1) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours c | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 111 (65.7) | 51 (63.8) | 60 (67.4) |

| No, n (%) | 58 (34.3) | 29 (36.2) | 29 (32.6) |

| Exclusive direct breastfeeding in the past 24 hours d | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 67 (39.6) | 30 (37.5) | 37 (41.6) |

| No, n (%) | 102 (60.4) | 50 (62.5) | 52 (58.4) |

| Use of infant formula | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 57 (33.7) | 28 (35.0) | 29 (32.6) |

| No, n (%) | 112 (66.3) | 52 (65.0) | 60 (67.4) |

| Phototherapy for jaundice | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 23 (13.6) | 10 (12.5) | 13 (14.6) |

| No, n (%) | 146 (86.4) | 70 (87.5) | 76 (85.4) |

| NICU admission | 19 (11.2) | 9 (11.3) | 10 (11.2) |

| 1–2 nights, n (%) | 8 (44.4) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) |

| 3–4 nights, n (%) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| >4 nights, n (%) | 7 (38.9) | 2 (25.0) | 5 (50.0) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Baby is one of a multiple pregnancy | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| No, n (%) | 168 (99.4) | 79 (98.8) | 89 (100.0) |

| Sibling enrolled in the study (in multiple pregnancies) | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | Not applicable |

| No, n (%) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Recruiting centre a | |||

| Cumberland Infirmary, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| George Eliot Hospital, n (%) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, n (%) | 85 (50.3) | 39 (48.8) | 46 (51.7) |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Royal Albert Edward Infirmary, n (%) | 5 (3.0) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.4) |

| Royal Berkshire Hospital, n (%) | 24 (14.2) | 12 (15.0) | 12 (13.5) |

| Royal Blackburn Hospital, n (%) | 13 (7.7) | 7 (8.8) | 6 (6.7) |

| Royal Cornwall Hospital, n (%) | 5 (3.0) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.4) |

| Royal United Hospital, Bath, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Royal Victoria Infirmary, n (%) | 26 (15.4) | 12 (15.0) | 14 (15.7) |

| Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital, n (%) | 5 (3.0) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.4) |

Characteristics of participants

Characteristics of participants were similar between the two trial arms. Infants had a mean age of 3 weeks, a mean birthweight of 3439 g and 87% were born at ≥38 weeks’ gestation. Overall 33% of infants had a BTAT score of 4 or less, 66% had exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours, and 40% had exclusive direct breastmilk feeding. Thirty-four per cent of infants had also received formula milk in the previous 24 hours (see Table 1). Mothers were a mean of 32 years old, 94% were of white ethnicity and 48% had a previous live birth. Only 8% were resident in the most deprived quintile of areas. Mothers reported a mean pain score of 4 out of 10 while feeding during the previous 24 hours and 42% had some anxiety or depression. More than half of women recruited to the trial believed a frenotomy would help their baby (see Table 2). Only one infant, in the breastfeeding support group, was reported to have had COVID-19.

| Total n = 169) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support (n = 89) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age (years), mean (SD) | 32.3 (5.0) | 32.7 (4.8) | 31.9 (5.1) |

| Missing, n | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Mother’s ethnic group | |||

| White, n (%) | 156 (94.0) | 72 (92.3) | 84 (95.5) |

| Asian, n (%) | 7 (4.2) | 5 (6.4) | 2 (2.3) |

| Black, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.3) |

| Other, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Index of multiple deprivation of area of residence | |||

| 1 (most deprived), n (%) | 13 (7.7) | 3 (3.8) | 10 (11.2) |

| 2, n (%) | 40 (23.7) | 22 (27.5) | 18 (20.2) |

| 3, n (%) | 38 (22.5) | 21 (26.3) | 17 (19.1) |

| 4, n (%) | 40 (23.7) | 15 (18.8) | 25 (28.1) |

| 5 (least deprived), n (%) | 38 (22.5) | 19 (23.8) | 19 (21.4) |

| Previous live birth(s) a | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 81 (47.9) | 39 (48.7) | 42 (47.2) |

| No, n (%) | 88 (52.1) | 41 (51.3) | 47 (52.8) |

| Breastfed before | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 73 (92.4) | 33 (89.2) | 40 (95.2) |

| No, n (%) | 6 (7.6) | 4 (10.8) | 2 (4.8) |

| Not applicable – no previous live birth, n | 88 | 41 | 47 |

| Missing, n | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Pre-trial breastfeeding support received | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 140 (84.3) | 66 (84.6) | 74 (84.1) |

| No, n (%) | 26 (15.7) | 12 (15.4) | 14 (15.9) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Mother’s pain while feeding during previous 24 hours,b median (IQR) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (1–7) | 4 (2–7) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Mother’s prior beliefs about frenotomy | |||

| Think it will help my baby, n (%) | 86 (51.8) | 41 (52.6) | 45 (51.1) |

| Do not know if it will help my baby, n (%) | 79 (47.6) | 37 (47.4) | 42 (47.7) |

| Think it is unlikely to help my baby, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Maternal anxiety or depression c | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 69 (41.8) | 29 (37.2) | 40 (46.0) |

| No, n (%) | 96 (58.2) | 49 (62.8) | 47 (54.0) |

| Missing, n | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Maternal HRQoL,d mean (SD) | 0.77 (0.17) | 0.77 (0.18) | 0.77 (0.16) |

| Missing, n | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Recruited pre- or posttrial pausee during the COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| Pre-pause, n (%) | 107 (63.3) | 52 (65.0) | 55 (61.8) |

| Postpause, n (%) | 62 (36.7) | 28 (35.0) | 34 (38.2) |

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Primary outcome data were available for 163/169 infants (96%). There was no evidence of a difference between the arms in the rate of breastmilk feeding at 3 months, which was high in both groups (67/76, 88% vs. 75/87, 86%; aRR 1.02, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.16) (see Table 3).

| Total (n = 169) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding Support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support (n = 89) | Unadjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusteda risk ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any breastmilk feeding b | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 142 (87.1) | 67 (88.2) | 75 (86.2) | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.15) | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.16) | 0.73 |

| No, n (%) | 21 (12.9) | 9 (11.8) | 12 (13.8) | |||

| Missing, n | 6 | 4 | 2 | |||

Secondary outcomes

There was no evidence of differences between the intervention arms for any secondary outcomes (see Tables 4 and 5). Sixty-three infants in the breastfeeding support only arm had undergone frenotomy by their first follow-up visit. An additional two infants underwent frenotomy by the third month of follow-up. None of the infants had a repeat frenotomy. Adverse events were reported for three infants postsurgery (one infant had bleeding, one infant had salivary duct damage, and the third infant had accidental cut to the tongue and salivary duct damage) (see Tables 4–6). No other causally related SAEs were reported.

| Total (n = 169) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support (n = 89) | Unadjusted effect estimate (95% CI) | Adjusteda effect estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours b | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 117(70.9) | 51 (65.4) | 66 (75.9) | 0.86 (0.60 to 1.24) | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.24) | 0.42 |

| No, n (%) | 48 (29.1) | 27 (34.6) | 21 (24.1) | |||

| Missing, n | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Exclusive direct breastfeeding in the past 24 hours c | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 78 (47.3) | 35 (44.9) | 43 (49.4) | 0.91 (0.58 to 1.42) | 0.92 (0.59 to 1.45) | 0.73 |

| No, n (%) | 87 (52.7) | 43 (55.1) | 44 (50.6) | |||

| Missing, n | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Mother’s pain while feeding during previous 24 hours,d median (IQR) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 0.0 (−0.9 to 0.9) | 0.0 (−0.9 to 0.9) | 0.99 |

| Not currently breastfeeding, n | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Missing, n | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Maternal anxiety or depression e | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 52 (31.7) | 23 (29.9) | 29 (33.3) | 0.90 (0.52 to 1.55) | 0.92 (0.53 to 1.63) | 0.79 |

| No, n (%) | 112 (68.3) | 54 (70.1) | 58 (66.7) | |||

| Missing, n | 5 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Frenotomy performed | - | - | - | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 138 (81.7) | 75 (93.8) | 63 (70.8) | - | - | - |

| No, n (%) | 31 (18.3) | 5 (6.2) | 26 (29.2) | - | - | - |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Total (n = 169) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support (n = 89) | Unadjusted effect estimate (95% CI) | Adjusteda effect estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s breastfeeding self-efficacy,b median (IQR) | 58 (47–65) | 60 (47–65) | 56.5 (47–65) | 4 (−1.8 to 9.8) | 0.3 (−5.2 to 5.8) | 0.92 |

| (Min to max) | (14, 70) | (14, 70) | (14, 70) | |||

| Missing, n | 26 | 11 | 15 | |||

| Exclusive breastmilk feeding in the previous 24 hours c | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 95 (65.1) | 45 (63.4) | 50 (66.7) | 0.95 (0.64 to1.42) | 0.92 (0.61 to 1.39) | 0.69 |

| No, n (%) | 51 (34.9) | 26 (36.6) | 25 (33.3) | |||

| Missing, n | 23 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Exclusive direct breastfeeding in the past 24 hours d | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 77 (53.1) | 38 (53.5) | 39 (52.7) | 1.02 (0.65 to 1.59) | 1.03 (0.65 to 1.62) | 0.90 |

| No, n (%) | 68 (46.9) | 33 (46.5) | 35 (47.3) | |||

| Missing, n | 24 | 9 | 15 | |||

| Mother’s pain while feeding during previous 24 hours,e median (IQR) | 0 (0–1.5) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.3) | 0.45 |

| Missing, n | 24 | 10 | 14 | |||

| Not currently breastfeeding, n | 21 | 9 | 12 | |||

| Amount of breastfeeding support used (number of contacts),f median (IQR) | 3 (1–4) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–4) | 1 (0.1 to 1.9) | −0.3 (−1.5 to 1.0) | 0.68 |

| Missing, n | 22 | 8 | 14 | |||

| Not applicable, ng | 36 | 22 | 14 | |||

| Maternal anxiety or depression h | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 55 (37.2) | 29 (39.7) | 26 (34.7) | 1.15 (0.67 to 1.95) | 1.12 (0.65 to 1.93) | 0.69 |

| No, n (%) | 93 (62.8) | 44 (60.3) | 49 (65.3) | |||

| Missing, n | 21 | 7 | 14 | |||

| Maternal HRQoL,i median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 0.94 |

| Missing, n | 23 | 8 | 15 | |||

| Infant weight gain from birth (z-score),j mean (SD) | −1.2 (1.2) | −1.1 (1.3) | −1.2 (1.1) | 0.10 (−0.62 to 0.82) | 0.17 (−0.60 to 0.95) | 0.65 |

| Infant weight gain from randomisation (z-score),j mean (SD) | −1.1 (1.4) | −1.0 (1.6) | −1.1 (1.3) | 0.04 (−0.82 to 0.90) | 0.10 (−0.83 to 1.03) | 0.83 |

| Frenotomy performed | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 140 (82.8) | 75 (93.8) | 65 (73.0) | - | - | - |

| No, n (%) | 29 (17.2) | 5 (6.2) | 24 (27.0) | |||

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Infants who continued to breastfeed | n = 142 | n = 67 | n = 75 | |||

| Time spent breastfeeding in previous 24 hours (hours), median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | 0 (−1.1 to 1.1) | 0.1 (−1.1 to 1.2) | 0.90 |

| Total (n = 140) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 75) | Breastfeeding support (n = 65) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of infant at first frenotomy (days), median (IQR) | 24 (13–38) | 23 (11–35) | 26.5 (16–42.5) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Time from randomisation to frenotomy (days) | |||

| <1 day, n (%) | 42 (30.2) | 30 (40.0) | 12 (18.8) |

| 1–2 days, n (%) | 34 (24.5) | 20 (26.7) | 14 (21.9) |

| 3–6 days, n (%) | 22 (15.8) | 12 (16.0) | 10 (15.6) |

| 7–13 days, n (%) | 26 (18.7) | 10 (13.3) | 16 (25.0) |

| 14–<28 days, n (%) | 10 (7.2) | 3 (4.0) | 7 (10.9) |

| ≥28 days, n (%) | 5 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.8) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Data on age at cessation of breastfeeding was only available for 6/21 infants, five in the breastfeeding support arm, who stopped breastfeeding at a median of 5 weeks (IQR 5–7).

Mothers had high breastfeeding self-efficacy at 3 months’ follow-up and exclusive breastfeeding rates were high during follow-up (first follow-up: 71%, third month: 65%). Compared to first follow-up, pain during breastfeeding was lower at 3 months (median score out of 10: 0 vs. 2).

Process outcomes

In the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm, 74/80 (93%) received the allocated intervention whereas in the breastfeeding support arm this was 23/89 (26%). More than four-fifths of the infants in the breastfeeding support arm who adhered to their allocation (19/23, 83%) had a BTAT score >4. Infants in the breastfeeding support arm who had a frenotomy had the operation a median of 5.5 days after randomisation (IQR 2–9 days). Frenotomies were mostly performed by midwives, the technique most commonly used was division of an anterior membrane plus posterior fleshy attachment, and 85% of infants were able to breastfeed immediately after the procedure (see Table 7).

| Total (n = 169) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support (n = 89) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allocation adhered to a | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 97 (57.4) | 74 (92.5) | 23 (25.8) |

| BTAT score 0–4 at randomisation, n (%) | 31 (32.0) | 27 (36.5) | 4 (17.4) |

| BTAT score 5–6 at randomisation, n (%) | 28 (28.9) | 20 (27.0) | 8 (34.8) |

| BTAT score 7–8 at randomisation, n (%) | 38 (39.2) | 27 (36.5) | 11 (47.8) |

| No, n (%) | 72 (42.6) | 6 (7.5) | 66 (74.2) |

| BTAT score 0–4 at randomisation, n (%) | 24 (33.8) | 2 (33.3) | 22 (33.9) |

| BTAT score 5–6 at randomisation, n (%) | 25 (35.2) | 1 (16.7) | 24 (36.9) |

| BTAT score 7–8 at randomisation, n (%) | 22 (31.0) | 3 (50.0) | 19 (29.2) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Received no intervention, n (%) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) |

| Reason for non-adherence | |||

| Parental wish, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Clinician decision, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Other,b n (%) | 14 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (87.5) |

| Missing, n | 51 | 1 | 50 |

| Type of breastfeeding support received | |||

| In person, n (%) | 29 (26.4) | 15 (30.0) | 14 (23.3) |

| Virtual, n (%) | 45 (40.9) | 18 (36.0) | 27 (45.0) |

| In person and virtual, n (%) | 36 (32.7) | 17 (34.0) | 19 (31.7) |

| Missing, n | 56 | 28 | 28 |

| Not applicable,c n | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Infants who underwent frenotomy | ( n = 140) | ( n = 75) | ( n = 65) |

| Person performing procedure | |||

| Midwife, n (%) | 117 (85.4) | 61 (81.3) | 56 (90.3) |

| Nurse, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Doctor, n (%) | 19 (13.9) | 13 (17.3) | 6 (9.7) |

| Other, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Frenotomy performed with | |||

| Bipolar diathermy, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Scissors, n (%) | 129 (100.0) | 75 (100.0) | 54 (100.0) |

| Missing, n | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Technique | |||

| Division of an anterior membrane only, n (%) | 12 (9.2) | 11 (14.7) | 1 (1.8) |

| Division of an anterior membrane plus posterior fleshy attachment, n (%) | 102 (78.5) | 54 (72.0) | 48 (87.3) |

| Division of posterior fleshy attachment only, n (%) | 14 (10.8) | 8 (10.7) | 6 (10.9) |

| Other, n (%) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing, n | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Baby able to breastfeed after procedure | |||

| Straight away, n (%) | 116 (84.7) | 65 (86.7) | 51 (82.3) |

| Within 15 minutes, n (%) | 11 (8.0) | 6 (8.0) | 5 (8.1) |

| No, n (%) | 10 (7.3) | 4 (5.3) | 6 (9.7) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Exploratory analyses

There was no significant difference (aRR 1.27, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.64) in the rate of breastmilk feeding at 3 months between the arms per protocol analysis where the 70 infants who did not receive their allocated intervention were excluded (infants in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support who had no frenotomy performed and infants in the breastfeeding only group who had a frenotomy performed) (see Table 8).

| Total (n = 99) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 75) | Breastfeeding support (n = 24) | Unadjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusteda risk ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any breastmilk feeding b | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 81 (86.2) | 65 (90.3) | 16 (72.7) | 1.24 (0.95 to 1.62) | 1.27 (0.99 to 1.64) | 0.06 |

| No, n (%) | 13 (13.8) | 7 (9.7) | 6 (27.3) | |||

| Missing, n | 5 | 3 | 2 | |||

There was a significant difference in the rate of breastmilk feeding at 3 months in the as-treated analysis where infants were analysed according to the intervention received (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.74), noting that for this analysis, the groups compared were not the groups originally randomised and hence this difference may be due to confounders not accounted for in the analysis (see Table 9).

| Total (n = 166) | Received frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 139) | Received breastfeeding support only (n = 27) | Unadjusted risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusteda risk ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any breastmilk feeding b | ||||||

| Yes, n (%) | 141 (87.0) | 123 (90.4) | 18 (69.2) | 1.31 (1.00 to 1.70) | 1.35 (1.05 to 1.74) | 0.02 |

| No, n (%) | 21 (13.0) | 13 (9.6) | 8 (30.8) | |||

| Missing, n | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

Pre-specified subgroup analyses

There were no notable differences between both the arms for any of the selected subgroups except that the rate of breastmilk feeding at 3 months appeared higher in the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm compared to the breastfeeding support arm (92% vs. 83%) before the trial paused due to the coronavirus pandemic (see Table 10). After the trial restarted, the rate was higher in the breastfeeding support arm compared to the frenotomy with breastfeeding support arm (91% vs. 81%).

| Primary outcome | Total (n = 169) | Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support (n = 89) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant’s age at randomisation | ||||

| ≥2 weeks | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 93 (92.1) | 43 (91.5) | 50 (92.6) | |

| No, n (%) | 8 (7.9) | 4 (8.5) | 4 (7.4) | |

| Missing, n | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| <2 weeks | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 49 (79.0) | 24 (82.8) | 25 (75.8) | |

| No, n (%) | 13 (21.0) | 5 (17.2) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Missing, n | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Degree of tongue-tie (BTAT score) at randomisation | ||||

| ≤4 | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 46 (83.6) | 23 (79.3) | 23 (88.5) | |

| No, n (%) | 9 (16.4) | 6 (20.7) | 3 (11.5) | |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5–8 | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 95 (88.8) | 44 (93.6) | 51 (85.0) | |

| No, n (%) | 12 (11.2) | 3 (6.4) | 9 (15.0) | |

| Missing, n | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mother’s prior beliefs about frenotomy | ||||

| Think it will help my baby | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 73 (88.0) | 34 (87.2) | 39 (88.6) | |

| No, n (%) | 10 (12.0) | 5 (12.8) | 5 (11.4) | |

| Missing, n | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Do not know if it will help my baby | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 66 (85.7) | 32 (88.9) | 34 (82.9) | |

| No, n (%) | 11 (14.3) | 4 (11.1) | 7 (17.1) | |

| Missing, n | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Think it is unlikely to help my baby | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| No, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing, n | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Recruited pre- or posttrial pause a during the COVID-19 pandemic | ||||

| Pre-pause | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 89 (87.3) | 45 (91.8) | 44 (83.0) | |

| No, n (%) | 13 (12.7) | 4 (8.2) | 9 (17.0) | |

| Missing, n | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Postpause | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 53 (86.9) | 22 (81.5) | 31 (91.2) | |

| No, n (%) | 8 (13.1) | 5 (18.5) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Secondary analyses

There were minimal differences between infants of mothers who complied with the intervention compared to non-compliers in the breastfeeding support arm for most baseline characteristics (see Table 11). However, a higher proportion of mothers who did not comply believed that frenotomy was helpful for their baby compared to mothers who complied (39/65, 61% vs. 6/24, 25%). A higher proportion of infants in the complier group had a BTAT score >4 compared to non-compliers (21/24, 88% vs. 41/64, 64%). The rate of breastmilk feeding at 3 months was higher among non-compliers compared to compliers (59/65, 91% vs. 16/24, 73%) (see Table 12), but the results from the CACE analysis showed no evidence for a difference in rates of breastmilk feeding at 3 months between the arms (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.64) (see Table 13).

| Total (n = 89) | Non-complier (frenotomy performed) (n = 65) | Complier (frenotomy not performed) (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age (years), mean (SD) | 31.9 (5.1) | 32.1 (4.8) | 31.6 (5.8) |

| Missing, n | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Mother’s ethnic group | |||

| White, n (%) | 84 (95.5) | 61 (95.3) | 23 (95.8) |

| Asian, n (%) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (4.2) |

| Black, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Deprivation index | |||

| 1 (most deprived), n (%) | 10 (11.2) | 8 (12.3) | 2 (8.3) |

| 2, n (%) | 18 (20.2) | 14 (21.5) | 4 (16.7) |

| 3, n (%) | 17 (19.1) | 11 (16.9) | 6 (25.0) |

| 4, n (%) | 25 (28.1) | 17 (26.2) | 8 (33.3) |

| 5 (least deprived), n (%) | 19 (21.4) | 15 (23.1) | 4 (16.7) |

| Previous live birth(s) a | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 42 (47.2) | 32 (49.2) | 10 (41.6) |

| No, n (%) | 47 (52.8) | 33 (50.8) | 14 (58.3) |

| Breastfed before | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 40 (95.2) | 30 (93.8) | 10 (100.0) |

| No, n (%) | 2 (4.8) | 2 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not applicable – no previous live birth, n | 47 | 33 | 14 |

| Pre-trial breastfeeding support received | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 74 (84.1) | 53 (82.8) | 21 (87.5) |

| No, n (%) | 14 (15.9) | 11 (17.2) | 3 (12.5) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mother’s pain while feeding during previous 24 hours,b median (IQR) | 4 (2–7) | 5 (2–7) | 3.5 (0–6) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mother’s prior beliefs about frenotomy | |||

| Think it will help my baby, n (%) | 45 (51.1) | 39 (60.9) | 6 (25.0) |

| Do not know if it will help my baby, n (%) | 42 (47.7) | 25 (39.1) | 17 (70.8) |

| Think it is unlikely to help my baby, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.2) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Maternal anxiety or depression c | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 40 (46.0) | 30 (47.6) | 10 (41.7) |

| No, n (%) | 47 (54.0) | 33 (52.4) | 14 (58.3) |

| Missing, n | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Maternal HRQoL,d mean (SD) | 0.77 (0.16) | 0.75 (0.14) | 0.80 (0.20) |

| Missing, n | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Recruited pre- or posttrial pausee during the COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| Pre-pause, n (%) | 55 (61.8) | 35 (53.8) | 20 (83.3) |

| Postpause, n (%) | 34 (38.2) | 30 (46.2) | 4 (16.7) |

| Degree of tongue-tie (BTAT) | |||

| 0–4, n (%) | 26 (30.0) | 23 (35.9) | 3 (12.5) |

| 5–6, n (%) | 32 (36.4) | 24 (37.5) | 8 (33.3) |

| 7–8, n (%) | 30 (34.1) | 17 (26.6) | 13 (54.2) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total (n = 89) | Non-complier (frenotomy performed) (n = 65) | Complier (frenotomy not performed) (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any breastmilk feeding a | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 75 (86.2) | 59 (90.8) | 16 (72.7) |

| No, n (%) | 12 (13.8) | 6 (9.2) | 6 (27.3) |

| Missing, n | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Frenotomy w/ breastfeeding support (n = 76) | Breastfeeding support (n = 87) | CACE risk ratio (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | Event rate (%) | Compliance | Primary outcomeb | Event rate (%) | ||

| Compliers | 15/19 | 78.9 | 22 (25.3) | 16/22 | 72.7 | |

| Non-compliers | 52/57 | 91.2 | 65 (74.7) | 59/65 | 90.8 | 1.09 (0.53 to 1.64) |

| Total | 67/76 | 88.2 | 75/87 | 86.2 | ||

Economic evaluation

NHS health-care resource use

Tables 14 and 15 present health-care resource use associated with the intervention-related health-care resource use. Table 14 presents the number of frenotomies performed from trial entry up to 3 months after birth across all participants. All frenotomies were performed by NHS providers, with 61 (76.25%) and 56 (62.9%) of procedures conducted by midwives in the frenotomy and no frenotomy groups, respectively. In the frenotomy with breastfeeding support group, 75 participants (93.75%) had the procedure whereas 65 participants (73.0%) had the procedure in the breastfeeding support group. Total numbers of frenotomies conducted across all participants in the trial are presented in Appendix 2, Table 23. Table 15 reports the different types of breastfeeding support received up to 3 months of age across all participants. Different types of support services were accessed including the NHS infant feeding service and/or other breastfeeding support services. The latter included access to a breastfeeding café, the Breastfeeding Network, La Leche League, the NCT (formerly National Childbirth Trust) or contacts with any other trained breastfeeding supporter. Table 24 reports the same information as Table 15 but only for those women who received breastfeeding support. There were no statistically significant differences in the breastfeeding support received between trial arms.

| Frenotomy with breastfeeding support (n = 80), n (%) | Breastfeeding support only (n = 89), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Frenotomies performed by a private provider | 0 | 0 |

| Frenotomies performed by the NHS provider | 75 (93.75%) | 65 (73.0%) |

| Doctor | 13 (16.25%) | 6 (6.7%) |

| Midwife | 61 (76.25%) | 56 (62.9%) |

| Other | 1 (1.25%) | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 3 (3.4%) |

| Frenotomies with complications | 1 (1.25%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| Frenotomies not performed | 5 (6.25%) | 24 (27.0%) |

| Frenotomy with breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support only (n = 89) | Mean difference in number of contacts (95% CI)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | Mean number of contacts (SD) | Number of patients (%) | Mean number of contacts (SD) | ||

| Total breastfeeding support received | 50 (62.5) | 2.53 (2.87) | 60 (67.4) | 2.69 (2.65) | −0.26 (−1.12 to 0.61) |

| NHS contacts | 43 (53.75) | 1.62 (1.85) | 49 (55.0) | 2.07 (2.46) | −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.29) |

| Phone | 26 (60.5) | 0.72 (1.13) | 32 (65.3) | 0.73 (1.23) | |

| In person | 29 (67.4) | 0.9 (1.51) | 37 (75.5) | 1.33 (2.09) | |

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 14 (15.73) | --- | |

| Other contacts | 18 (22.5) | 0.9 (2.06) | 15 (16.85) | 0.59 (1.49) | 0.18 (−0.39 to 0.75) |

| Phone | 9 (50.0) | 0.39 (1.23) | 12 (75.0) | 0.38 (1.18) | |

| In person | 14 (77.8) | 0.51 (1.31) | 10 (62.5) | 0.22 (0.73) | |

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 15 (16.58) | --- | |

| Not received | 22 (27.5) | --- | 14 (15.73) | --- | |

Maternal health-care resources consumed at 3 months of age is presented in Table 16 across all participants. Similar information is presented in Table 25 but the mean number of resources consumed is calculated only for those consuming the health-care resource use category. No significant differences for any resource use categories between groups were detected in any of the resource use categories: primary care, community care, secondary care and any other health-care professionals.

| Resource use category and item | Frenotomy with breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support only (n = 89) | Mean difference in number of contacts (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants (%) | Mean number of contactsa (SD) | Number of participants (%) | Mean number of contactsa (SD) | ||

| Primary care | |||||

| General practitioner visits | 73 (91.25) | 0.92 (1.05) | 73 (82.0) | 0.64 (0.95) | 0.26 (−0.07 to 0.58) |

| Yes | 73 (91.25) | 73 (82.0) | |||

| No | 0 | 0 | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 16 (18.0) | --- | |

| Practice nurse visits | 73 (91.25) | 0.16 (0.94) | 74 (83.15) | 0.11 (0.48) | 0.07 (−0.19 to 0.33) |

| Yes | 73 (91.25) | 74 (83.15) | |||

| No | 0 | 0 | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Medicines | 73 (91.25) | 0.29 (0.72) | 74 (83.15) | 0.15 (0.51) | 0.17 (−0.03 to 0.37) |

| Yes | 14 (17.5) | 7 (7.9) | |||

| No | 59 (73.75) | 67 (75.25) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which antibiotics | 73 (91.25) | 0.25 (0.6) | 74 (83.15) | 0.12 (0.47) | |

| Yes | 13 (16.25) | 6 (6.7) | |||

| No | 60 (75.0) | 68 (76.45) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which for anxiety/depression | 73 (91.25) | 0.04 (0.26) | 74 (83.15) | 0.03 (0.16) | |

| Yes | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 71 (88.75) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Community care | |||||

| Community nurse/midwife contacts | 73 (91.25) | 0.07 (0.35) | 74 (83.15) | 0.04 (0.26) | −0.01 (−0.1 to 0.08) |

| Yes | 3 (3.75) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 70 (87.5) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which virtual | 73 (91.25) | 0 (0) | 74 (83.15) | 0.013 (0.116) | |

| Yes | 0 | 1 (1.15) | |||

| No | 73 (91.25) | 73 (82.0) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which in person | 73 (91.25) | 0.07 (0.35) | 74 (83.15) | 0.03 (0.16) | |

| Yes | 3 (3.75) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 70 (87.5) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Secondary (hospital-based) care | |||||

| Accident & emergency department visits | 73 (91.25) | 0.027 (0.234) | 74 (83.15) | 0.013 (0.116) | 0.004 (−0.057 to 0.065) |

| Yes | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.15) | |||

| No | 72 (90.0) | 73 (82.0) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Hospital outpatient clinic appointments | 73 (91.25) | 0.14 (0.51) | 74 (83.15) | 0.05 (0.37) | 0.07 (−0.08 to 0.22) |

| Yes | 6 (7.5) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 67 (83.75) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which virtual | 73 (91.25) | 0.03 (0.23) | 74 (83.15) | 0 (0) | |

| Yes | 1 (1.25) | 0 | |||

| No | 72 (90.0) | 74 (83.15) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which in person | 73 (91.25) | 0.11 (0.39) | 74 (83.15) | 0.05 (0.37) | |

| Yes | 6 (7.5) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 67 (83.75) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Hospital admissions | 72 (90.0) | 0.014 (0.118) | 75 (84.25) | 0.013 (0.115) | 0.015 (−0.013 to 0.044) |

| Yes | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| No | 71 (88.75) | 74 (83.15) | |||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 14 (15.75) | --- | |

| Length of stay (days) | 0.014 (0.118) | 0.027 (0.231) | 0.015 (−0.013 to 0.044) | ||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 14 (15.7) | --- | |

| Any other NHS health-care professionals contacts | |||||

| Other NHS health-care professionals contacts | 73 (91.25) | 0.19 (0.64) | 74 (83.15) | 0.16 (0.66) | 0.03 (−0.19 to 0.25) |

| Yes | 7 (8.75) | 5 (5.5) | |||

| No | 66 (82.5) | 69 (77.5) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which virtual | 73 (91.25) | 0.05 (0.33) | 74 (83.15) | 0.09 (0.58) | |

| Yes | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 71 (88.75) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which in person | 73 (91.25) | 0.14 (0.45) | 74 (83.15) | 0.07 (0.34) | |

| Yes | 7 (8.75) | 3 (3.35) | |||

| No | 66 (82.5) | 71 (79.8) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Any other non-NHS health-care professionals contacts | |||||

| Osteopath visits | 73 (91.25) | 0 (0) | 74 (83.15) | 0.07 (0.42) | −0.07 (−0.17 to 0.03) |

| Yes | 0 | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 73 (91.25) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

Table 17 presents health-care resource utilization for infants from trial entry up to 3 months across all participants in the study. Table 26 presents health-care utilization but only for those infants consuming the health-care resource use category. Similar to maternal health-care utilization, we did not observe any mean differences in visits for any of the categories: primary care, community care, secondary care and any other health-care professionals.

| Resource use category and item | Frenotomy with breastfeeding support (n = 80) | Breastfeeding support only (n = 89) | Mean difference in number of contacts (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | Mean number of contactsa (SD) | Number of patients (%) | Mean number of contactsb (SD) | ||

| Primary care | |||||

| General practitioner contacts | 73 (91.25) | 0.86 (0.92) | 72 (80.9) | 0.86 (1.12) | 0.03 (−0.30 to 0.37) |

| Yes | 42 (52.5) | 37 (41.6) | |||

| No | 31 (38.75) | 35 (39.3) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 17 (19.10) | --- | |

| Of which virtual | 73 (91.25) | 0 (0) | 72 (80.9) | 0.014 (0.083) | |

| Yes | 0 | 1 (1.1) | |||

| No | 73 (91.25) | 71 (79.8) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 17 (19.10) | --- | |

| Of which in person | 73 (91.25) | 0.86 (0.92) | 72 (80.9) | 0.85 (1.1) | |

| Yes | 42 (52.5) | 37 (41.6) | |||

| No | 31 (38.75) | 35 (39.3) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 17 (19.10) | --- | |

| Practice nurse visits | 73 (91.25) | 0.12 (0.47) | 74 (83.15) | 0.13 (0.48) | −0.02 (−0.19 to 0.14) |

| Yes | 5 (6.25) | 6 (6.75) | |||

| No | 68 (85.0) | 68 (76.4) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Medicines (antibiotics) | 73 (91.25) | 0.05 (0.23) | 74 (83.15) | 0.08 (0.27) | −0.03 (−0.11 to 0.06) |

| Yes | 4 (5.0) | 6 (6.75) | |||

| No | 69 (86.25) | 68 (76.4) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Community care | |||||

| Community nurse/midwife visits | 73 (91.25) | 0.11 (0.94) | 74 (83.15) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.08 (−0.15 to 0.30) |

| Yes | 1 (1.25) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 72 (90.0) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Infant health visitor contacts | 72 (90.0) | 0.25 (1.0) | 74 (83.15) | 0.19 (0.65) | 0.07 (−0.22 to 0.36) |

| Yes | 5 (6.25) | 7 (7.9) | |||

| No | 67 (83.75) | 67 (75.25) | |||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which virtual | 72 (90.0) | 0.08 (0.71) | 74 (83.15) | 0.01 (0.12) | |

| Yes | 1 (1.25) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| No | 71 (88.75) | 73 (82.05) | |||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Of which in-person | 72 (90.0) | 0.17 (0.73) | 74 (83.15) | 0.18 (0.63) | |

| Yes | 4 (5.0) | 7 (7.9) | |||

| No | 68 (85.0) | 67 (75.25) | |||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Community paediatrician visits | 73 (91.25) | 0.01 (0.12) | 74 (83.15) | 0.03 (0.16) | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) |

| Yes | 1 (1.25) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 72 (90.0) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Secondary (hospital-based) care | |||||

| Accident & emergency department visits | 73 (91.25) | 0.07 (0.3) | 74 (83.15) | 0.04 (0.2) | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.12) |

| Yes | 4 (5.0) | 3 (3.35) | |||

| No | 69 (86.25) | 71 (79.8) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Hospital outpatient clinic appointments | 73 (91.25) | 0.16 (0.96) | 74 (83.15) | 0.04 (0.26) | 0.12 (−0.12 to 0.36) |

| Yes | 5 (6.25) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 68 (85.0) | 72 (80.95) | |||

| Missing | 7 (8.75) | --- | 15 (16.85) | --- | |

| Hospital admissions | 72 (90.0) | 0.1 (0.51) | 75 (84.25) | 0.13 (0.38) | −0.03 (−0.18 to 0.11) |

| Yes | 4 (5.0) | 9 (10.1) | |||

| No | 68 (85.0) | 66 (74.15) | |||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 14 (15.75) | --- | |

| Length of stay (days) | 0.33 (2.16) | 0.24 (0.75) | 0.14 (-0.38 to 0.67) | ||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 14 (15.75) | --- | |

| Any other NHS health-care professionals visits | |||||

| Other NHS health-care professionals visits | 72 (90.0) | 0.05 (0.37) | 72 (80.95) | 0.04 (0.26) | 0.01 (−0.09 to 0.12) |

| Yes | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.2) | |||

| No | 70 (87.5) | 70 (78.75) | |||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 17 (19.05) | --- | |

| Any other non-NHS health-care professionals visits | |||||

| Osteopath visits | 72 (90.0) | 0.04 (0.26) | 72 (80.95) | 0.11 (0.49) | −0.07 (−0.21 to 0.07) |

| Yes | 2 (2.5) | 4 (4.55) | |||

| No | 70 (87.5) | 68 (76.4) | |||

| Missing | 8 (10.0) | --- | 17 (19.05) | --- | |

NHS health-care costs

Table 18 reports the cost analysis results for mothers and their babies over the study period. A borderline statistically significant mean cost difference (95% CI) of £27 (£0.3–54) between groups favouring the frenotomy was observed in the intervention-related costs. There were no significant differences in any cost categories incurred by mothers or their babies between the frenotomy with breastfeeding support and breastfeeding support groups. The mean (SD) total cost per woman/infant pair was estimated to be £497 (£854) and £483 (£529) in the frenotomy and no frenotomy groups, respectively, and a non-significant mean cost difference (95% CI) of £21 (−£221 to £263) was detected. Maternal and infant cost analysis across all participants in the study is presented in Table 27.

| Resource use category and item | Frenotomy with breastfeeding support (n = 80), mean (SD) | Breastfeeding support only (n = 89), mean (SD) | Mean cost differencea (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | Infant | Mother | Infant | Mother | Infant | |

| Frenotomy [1] | £120 (£74) | £94 (£97) | £27 (£0.3 to £54) | |||

| Missing, n (%) | 0 | 0 | --- | |||

| Breastfeeding support | ||||||

| NHS contacts, phone | £33 (£52) | £34 (£57) | £2 (−£16 to £20) | |||

| NHS contacts, in person | £73 (£122) | £108 (£170) | −£36 (−£80 to £8) | |||

| Total NHS contacts, breastfeeding support [2] | £106 (£131) | £142 (£180) | −£34 (−£83 to £14) | |||