Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/129/261. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The draft report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Christian et al. This work was produced by Christian et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Christian et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout the report has been adapted from the trial protocol by Webb et al. 1 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Trial rationale/introduction

Minimal change nephrotic syndrome is the most common glomerular disease of childhood. 2 The presenting episode is treated with high-dose oral prednisolone and it is expected that > 90% of children will have a complete response, with responders receiving the diagnostic label of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome (SSNS). 2 The optimum duration of prednisone/prednisolone therapy at presentation was recommended by the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children as 60 mg/m2 daily for 4 weeks, followed by 40 mg/m2 on alternate days for 4 weeks. 3 Subsequent trials showed benefits with longer durations of corticosteroid;4 however, in the last decade, four well-designed randomised controlled trials have demonstrated no clinical benefit to an extended course of prednisolone beyond the accepted 8- to 12-week course. 5–8 The most recent of these was the PREDNOS (PREDnisolone in NephrOtic Syndrome) trial, which was undertaken by this trial group. Although the PREDNOS trial demonstrated no clinical benefit to an extended corticosteroid course, it did show evidence of cost-effectiveness. 9

Following successful initial treatment, at least 80% of children develop disease relapses necessitating further courses of high-dose prednisolone. The PREDNOS trial found that 80% of children relapse within 12 months of initial presentation8 and around 50% develop frequently relapsing disease. 10 Long-term low-dose maintenance prednisolone therapy is the most commonly prescribed therapy to reduce relapse frequency, although a number of children will require additional immunosuppressive agents, including levamisole, cyclophosphamide, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and rituximab.

Nephrotic syndrome relapses are associated with a risk of significant complications, including sepsis, thrombosis, dyslipidaemia and malnutrition. 11 The treatment of relapses with high-dose prednisolone is associated with major short-12 and long-term13 adverse effects, including hip avascular necrosis, hypertension, diabetes and behavioural problems. This places financial pressure on the health-care system and leads to reduced quality of life. Furthermore, children are kept off school during relapses, resulting in impaired education performance and parental absence from work.

It is well recognised that the majority of relapses are precipitated by viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). Alwadhi et al. 14 followed 68 Indian children with 76 initial presentations or relapses of nephrotic syndrome over 12 months. Of 68 episodes of nephrosis that occurred while not taking corticosteroid, there was an infectious trigger in 57 (84%). The range of infections included URTI (28%), lower respiratory tract infection (a further 19%) and other causes, including urinary tract infection (23%), peritonitis (16%) and diarrhoeal illness (11%). Arun et al. 15 carried out a study designed to evaluate the effectiveness of supplemental zinc in reducing relapse rate in Indian children with nephrotic syndrome. They reported subgroup data for children with frequently relapsing disease. Within that subgroup, 52 out of 86 relapses (60%) were preceded by infections. MacDonald et al. 16 followed 32 Canadian children with nephrotic syndrome over two successive winters. There were 61 URTIs over that period and 41 exacerbations (29 full relapses) of nephrotic syndrome. Seventy-one per cent of exacerbations (69% of full relapses) were associated with URTIs within the prior 10 days.

Furthermore, in children with frequently relapsing steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome (FRSSNS), the development of an URTI frequently precipitates a relapse. Moorani et al. 17 documented infections in 62 Pakistani children with nephrotic syndrome over 12 months. A total of 74 infections were observed. Acute respiratory infections were the most common infection (29%). Nephrotic syndrome relapse or initial presentation occurred with 78% of infections or with 80% of acute respiratory infections. In their Canadian cohort, MacDonald et al. 16 demonstrated 47.5% of URTIs associated with disease exacerbation or 32.8% associated with overt relapse.

Given these strong links between viral URTI and relapse, and the morbidity and cost associated with relapse and its treatment, it is logical that attempts are made to ameliorate the URTI-driven disease modification.

Summary of previous studies investigating the use of daily prednisolone therapy at the time of upper respiratory tract infection

Current practice in the majority of UK centres has been for no change to be made to immunosuppressive therapy at the time of development of an URTI. Between 2000 and 2011, three studies18–20 assessed whether or not the use of daily prednisolone at the time of URTI reduced the subsequent risk of relapse of nephrotic syndrome.

Mattoo and Mahmoud18 published the first of these trials in 2000. Mattoo and Mahmoud18 studied 36 Saudi children with relapsing SSNS who were receiving a long-term maintenance dose of alternate-day prednisone of approximately 0.5 mg/kg per day. Starting on the day of onset of URTI (defined by onset of cough and/or cold with or without fever), children were alternately assigned in an unblinded manner to receive either 5 days of daily prednisone at the same dose or to remain on alternate-day prednisone. Patients who did not relapse and patients who did not achieve remission with cyclophosphamide were excluded. The number of disease relapses [defined as Albustix (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Ltd, Frimley, UK) 3+ positivity on morning urinalysis for 3 days] was documented in each group. Patients were followed for 2 years and the main reported outcome was the mean number of relapses per patient over that period for each arm.

The arms were well matched for age, sex, use of prior cyclophosphamide and histology (where performed). In the 18 children assigned to daily prednisone at the time of URTI, the rate of relapse was lower than in the 18 children who continued on alternate-day prednisone [mean ± standard deviation (SD) relapse rate 2.2 ± 0.87 vs. 5.5 ± 1.33; p = 0.04]. No data on the individual risk of relapse following URTI were reported. The intervention arm received a median of seven courses of daily prednisone over the 2-year follow-up period. No difference was noted in the frequency of hospitalisations or the length of treatment for relapses between the two treatment arms.

Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter19 recruited 48 Sri Lankan children to a randomised double-blind crossover study. All were receiving long-term low-dose alternate-day prednisolone (mean 0.36 mg/kg, range 0.1–0.6 mg/kg). Children were studied over two consecutive URTIs (defined as cough, runny nose, sore throat, lethargy, body aches and fever). Throat swabs were taken and children with bacterial infection were excluded. Children were randomised, using sealed envelopes, either to receive prednisolone at their usual maintenance dose for 7 days given daily instead of on alternate days or to continue on alternate-day prednisolone. This was achieved by dispensing investigational medicinal product (IMP) in one of two containers, one of which contained prednisolone and the other placebo. Parents were asked to administer the study drug on the child’s usual non-treatment day and to continue so that a total of 7 days of daily treatment were given. In this way, children received three or four doses of study drug.

In the crossover design, those who received daily prednisolone for the first URTI received alternate-day prednisolone plus placebo for the second URTI, and vice versa. Recruitment continued until 40 children had experienced two URTIs. Children were reviewed on days 3 and 7 to assess for evidence of disease relapse (defined as Albustix 3+ proteinuria for 3 consecutive days). Those who developed prednisolone-related adverse events (AEs), those who required steroid-sparing therapy for frequent relapses, those in whom prednisolone was discontinued because of sustained remission and those who did not have two viral infections were all excluded from the study (8/48 of the recruited number). The main reported outcome was the difference in infection-associated relapse (IAR).

Overall, there were seven (18%) IARs following 40 URTIs treated with daily prednisolone and 19 (48%) IARs following 40 URTIs where alternate-day prednisolone and placebo were administered (p = 0.014; two-sided Fisher’s exact test). Response to the initial URTI was a relapse in 4 of 18 (22%) children in the intervention arm and 10 of 22 (45%) children in the placebo arm (no significance reported). No significant adverse effects were encountered.

The third and largest of these three initial studies was performed in 100 Indian children recently diagnosed with FRSSNS who were on long-term alternate-day prednisolone with or without levamisole. 20 Children were recruited in stable remission, having received alternate-day 1.5 mg/kg of prednisolone for 4 weeks and then tapered by 0.25 mg/kg every 2 weeks until a dose of 0.5–0.75 mg/kg on alternate days was reached. If a dose of prednisolone > 1 mg/kg on alternate days was required, then levamisole was added. Children were randomised, stratified according to whether they received levamisole (n = 32) or not (n = 68), to either receive daily prednisolone for 7 days or remain on alternate-day prednisolone. Prednisolone was given at the same dose for non-treatment-days in an unblinded manner at the time of development of intercurrent infection [defined as fever (i.e. axillary-measured temperature of > 38 °C on two occasions and more than 1 hour apart), rhinorrhoea or cough for more than 1 day or diarrhoea (i.e. three or more semiformed stools per day for more than 2 days)]. Children were reviewed every 2 months for a total of 12 months.

The primary end point was the incidence of IAR, with secondary end points of overall relapse rate, infection frequency and type and cumulative dose of prednisolone. Patients exited the study if there were two or more relapses in any 6-month period. Daily prednisolone therapy at the time of an URTI resulted in a reduction in the incidence of IAR [0.7 ± 0.3 vs. 1.4 ± 0.5; rate difference 0.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.3 to 1.1; p < 0.01] and the overall relapse rate (0.9 ± 0.4 vs. 1.8 ± 0.5; rate difference 0.9, 95% CI 0.4 to 1.4; p < 0.0001). Although not powered to do so, a subanalysis showed that this difference was lost in those receiving levamisole. Nineteen children in the daily prednisolone group, compared with seven in the alternate-day group, remained relapse free over the entire 12-month study period (p = 0.03). There was no difference in cumulative prednisolone dose between the two treatment arms. More infections occurred in the daily prednisolone group (226 vs. 161; p = 0.04), although no difference was detected in height SD score, cushingoid features, cataract or serious infection. Six children (two in the daily steroid group) exited the study because of treatment failure, necessitating treatment with cyclophosphamide or calcineurin inhibitors.

Critique of previous studies investigating the use of daily prednisolone therapy at the time of upper respiratory tract infection and summary of findings

Methodological aspects

Sample size

All of the studies that predate PREDnisolone in NephrOtic Syndrome 2 (PREDNOS2) were small (involving 36–100 children). 18–20 Mattoo and Mahmoud18 did not include a formal sample size calculation. Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter’s19 sample size was based on an observation that nearly 50% of URTIs are followed by a relapse and an assumption that the increase in the maintenance dose of prednisolone would reduce the relapse rate by 50%; however, no details of the power calculation were reported. Only Gulati et al.,20 the largest study, included details of their power calculation, which was based on a relapse rate of 4.6 ± 1.4 relapses per year in patients with frequent relapses (a figure that had been reported in a similar population). 15 Gulati et al. 20 assumed that 70% of relapses follow infections and calculated their sample size on a 50% reduction in frequency of IARs at a power of 80%, an alpha error of 5% and a dropout rate of 10%.

Target population

All three studies18–20 included children with relapsing SSNS receiving long-term alternate-day maintenance corticosteroid treatment. In addition, in Gulati et al. ’s20 study, some children were on alternate-day maintenance treatment with both prednisolone and levamisole. Mattoo and Mahmoud’s18 population was a heterogeneous group that included those with relapsing disease (not formally defined as FRSSNS) or those who had previously received cyclophosphamide for steroid-resistant or frequently relapsing disease and who then, according to local protocol, continued maintenance alternate-day corticosteroid for 2 years. Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter’s19 population had steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome, implicitly defined because all were taking maintenance corticosteroid. Gulati et al. ’s20 subjects had carefully defined FRSSNS (i.e. more than two relapses in the previous 6 months or more than three relapses in the previous 12 months).

Some studies excluded patients prior to randomisation, which limits the generalisability of results. In Gulati et al. ’s20 population, children with evidence of corticosteroid toxicity, use of non-steroid immunosuppression in the 6 months prior to recruitment and children requiring maintenance prednisolone of > 1 mg/kg on alternate days were excluded.

Study design

In all three studies,18–20 patients were asked to modify maintenance treatment at the time of an infection or URTI for a period of 5–7 days. In the blinded study of Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter,19 this was to commence the trial drug on non-corticosteroid days. In the unblinded studies,18,20 this was to take their maintenance corticosteroid every day instead of every other day.

The definitions of infection/URTI used for the three studies are shown in Table 1.

| Symptom | Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mattoo and Mahmoud18 | Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter19 | Gulati et al.20 | |

| Duration | Not defined | Not defined | For at least 24 hours |

| Definition | Any one of: | Any three of: | Any one of: |

| Cough | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cold, rhinorrhoea, runny nose | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fever | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sore throat or food refusal in younger child | ✓ | ||

| Body aches | ✓ | ||

| Diarrhoea | ✓ | ||

| Other | Bacterial infection excluded | ||

In Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter’s19 study only was there any blinding of patients or researchers. In their crossover design, the recruited patients’ families were provided with two pots of tablets. Pot A contained prednisolone tablets and pot B contained a placebo. Patients were randomised at the start of their first URTI, using sealed envelopes, to use tablets from either pot A or pot B on non-prednisolone days for 7 days. The families were asked to use tablets from the other pot for the second URTI. Although technically double blinded, it is highly possible that researchers could find out which tablet pot was being used. The other two studies were not blinded and patients in the intervention arms took their same maintenance prednisolone dose every day for 5 days (in Mattoo and Mahmoud18) or 7 days (in Gulati et al. 20). There was no placebo controlling for the non-intervention arm for these two studies.

Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter’s19 use of a crossover design, although attempting to use each patient as their own control, may have resulted in the first treatment course influencing the second. Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter19 also required each patient to have two URTIs (which was not the case for three patients).

Randomisation and allocation

Mattoo and Mahmoud18 allocated treatment groups on an alternate basis, which could have introduced selection bias due to the lack of allocation concealment. In Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter’s19 study, patients were randomised at the start of their first URTI using sealed envelopes. Gulati et al. ’s20 patients were randomised by stratified randomisation (with or without levamisole) using opaque sealed envelopes.

Post-randomisation exclusions

Potential bias was introduced by the post-randomisation exclusion of patients from the analysis populations. Eight (16.7%) of Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter’s19 initial patients were excluded from the final analysis. Reasons cited included a need for treatment escalation (n = 4), disease stability leading to discontinuation of maintenance prednisolone (n = 1) and no second URTI (n = 3). Mattoo and Mahmoud18 also excluded children who did not relapse over the 2-year study period, implying a post-randomisation exclusion. Gulati et al. 20 considered those patients who relapsed twice or more in a 6-month period and required escalation of background treatment as treatment failures, but these patients were included in the analysis.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes were not uniform among the three studies. Mattoo and Mahmoud18 studied the rate of relapses between the two arms. Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter19 assessed IAR following a first infection; however, patients were studied over the course of only two relapses that received different treatments because of the crossover design. In addition, there were no longer-term outcomes. Gulati et al. 20 assessed IAR expressed as episodes per patient per year.

Adverse events

No AE data were formally reported in the studies by Mattoo and Mahmoud18 and Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter. 19 However, in the latter, evidence of corticosteroid toxicity was a reason for maintenance treatment escalation and withdrawal from the study. The presence of cushingoid features, cataracts and the requirement for hospital admission were reported for each arm in Gulati et al. ’s20 study. Despite the high level of importance ascribed to the behavioural effects of corticosteroid,12,21 no study assessed this.

Generalisability of results

The three studies18–20 published prior to PREDNOS2 that reported a possible benefit of increasing prednisolone dose and reducing the risk of relapse were in children taking long-term alternate-day prednisolone. Therefore, there was no evidence to support a role for a short course of daily low-dose prednisolone at the time of an URTI for children not on long-term alternate-day prednisolone or, indeed, for children taking non-steroid second-line agents.

All three studies took place in specific georacial population groups and their definitions of URTI varied. Moreover, for one study,20 this was more broadly defined as ‘infection’ and included children with diarrhoeal illness. It is not appropriate to assume that the pattern of intercurrent illness in these populations can be compared with those in more temperate locations and that each type of infection carries the same risk of precipitating a relapse of nephrotic syndrome.

There was also no systemic evaluation of AEs for each arm to assess the risk/benefit of the intervention, nor was there any evaluation undertaken of cost-effectiveness.

Subsequent research

Since commencement of the PREDNOS2 trial, a second trial from Abeyagunawardena et al. 22 has been published. In contrast to the group’s previous study19 and the other two studies18,20 prior to PREDNOS2, the investigators studied children with SSNS on no maintenance therapy. In a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study, 48 children were randomised to receive 5 days of daily prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg) or placebo at the start of an URTI. Children on second-line treatments were excluded and children also had to have discontinued corticosteroid treatment at least 3 months prior to recruitment. A sealed envelope method was used to randomise patients in the same way as the group’s previous study. 19 Both investigators and patients/parents were blinded to the contents of the pot until the end of the study. Viral infections were defined more loosely than for the previous study, with the presence of two or more of the following criteria: fever > 38 °C; runny nose; cough; body aches, lethargy or loss of appetite; or sore throat. Study treatment was not given or was subsequently stopped if microbiological evidence of a bacterial infection was found. Patients were followed for 12 months, with any subsequent URTIs treated with the same study drug. Thereafter, a crossover took place, with group 1 taking placebo and group 2 taking prednisolone at the time of an URTI for the next 12 months.

A sample size matching their previous study appears to have been chosen, but no power calculation was provided. Investigators recruited 27 children who were randomised to group 1 and 21 children randomised to group 2. Of the 48 children recruited, only 33 (69%) completed the study (19 children in group 1 and 14 children in group 2). Of those exclusions, 12 children were because of non-compliance and three children needed treatment escalation in the form of maintenance immunosuppressive therapy.

There were 11 relapses following 115 episodes of URTI (9.5%) in the treatment group and 25 relapses following 101 episodes of URTI (24.8%) in the control group. Despite no significant differences in the numbers of URTIs between groups, children in the treatment group had significantly fewer relapses than children in the control group (p = 0.014). Within the treatment group, 22 of 33 children did not relapse compared with 14 of 33 children within the placebo group (p = 0.049).

The IAR in this study, at 25%, was half of that reported in earlier studies. 19,20 The authors explain that this is likely because the study was conducted in children with more stable disease, who do not require long-term prophylactic treatments. Interestingly, the only relapses reported within the study period were those following URTIs.

In common with their previous study,19 the sample size is small and the study was vulnerable to inadvertent unblinding. The high dropout rate weakens the findings and the decision to exclude children who commenced maintenance treatment introduces a potential bias. In addition, along with the studies prior to PREDNOS2, generalisability of the findings to a different georacial group is problematic.

Summary

In the 2015 update of the Cochrane review of corticosteroid treatment for nephrotic syndrome in children,4 the authors noted that the combined weight of the three studies described above18–20 increased the power of the analysis so that low-dose daily prednisolone may be considered at the time of viral infections in children on maintenance alternate-day prednisolone. Abeyagunawardena et al. ’s22 subsequent study, which was available in abstract form only at the time of the Cochrane review, has shown that the same strategy may benefit children on no maintenance treatment. In the 2020 Cochrane update,4 the authors concluded that the limited data provided by a single study of 48 children meant that it remains unclear whether or not children not already on alternate day corticosteroid should restart daily corticosteroid for around a week at the onset of viral infections.

The review authors also stated that there were some concerns about the possibility of bias4 (Table 2). Mattoo and Mahmoud’s study18 was rated as having a high risk of selection bias through inadequate random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Only the two studies by Abeyagunawardena et al. 19,22 were blinded studies. The study by Mattoo and Mahmoud18 reported that fewer than 10% of participants were lost to follow-up or excluded from the analysis. Three of the studies18,19,22 were rated as having a high risk of reporting bias due to a combination of outcome data not including one or more outcomes of FRSSNS, relapse rate and AEs, providing data in a format that could not be entered into the meta-analyses or from inability to separate first and second parts in crossover studies.

| Study | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mattoo and Mahmoud18 | – | – | – | – | + | – | ? |

| Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter19 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| Gulati et al.20 | + | + | – | – | – | + | + |

| Abeyagunawardena et al.22 | + | + | + | + | – | – | ? |

Therefore, although providing proof of concept that increased corticosteroid dosing may reduce the risk of relapses in children with SSNS, the methodological issues and other limitations of all these studies have not been able to address the following questions:

-

Do children from developed temperate countries where the pattern of childhood URTI is significantly different benefit from the same intervention?

-

Does this effect occur in children receiving long-term maintenance therapy with other immunosuppressive therapies (e.g. levamisole, ciclosporin, tacrolimus and MMF) in conjunction with prednisolone or without prednisolone or, indeed, does this effect occur in children on no long-term immunosuppressive therapy?

-

Is there an effect on the cumulative dose of prednisolone or in the incidence of corticosteroid-related adverse effects, including behavioural issues associated with the use of this intervention?

-

What are the quality-of-life implications of this strategy?

-

What would be the cost-effectiveness of such an approach?

Research question

A meeting was convened in January 2012 to discuss this trial proposal, to which the members of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Medicines for Children Research Network Nephrology Clinical Studies Group, which represents each of the 13 tertiary paediatric nephrology centres in the UK, were invited to attend. A number of consumer representatives, including the chairperson of the UK Nephrotic Syndrome Trust (NeST) (Somerset, UK), and other parents of children with nephrotic syndrome also attended.

It was clear from this meeting that interest lay not only in further generalisability of the use of daily low-dose prednisolone at the time of an URTI in children on alternate-day prednisolone and children on no maintenance treatment, but also in those receiving other immunosuppressant therapies (with or without prednisolone) for their nephrotic syndrome. Therefore, a single pragmatic trial was proposed, which would include all patients with relapsing SSNS, regardless of background therapy, to answer the overarching question of whether or not treatment with a short course of daily prednisolone at the time of URTI in children with relapsing SSNS reduced the subsequent development of nephrotic syndrome relapse.

A reduction in the nephrotic syndrome relapse rate would reduce relapse and treatment-associated morbidity, hospitalisation rates and parental time absent from work.

The research question agreed was ‘Does a 6-day course of daily prednisolone given early in the course of URTI in children with relapsing SSNS effectively and safely reduce the incidence of subsequent URTI-related relapse?’.

A 6-day course was chosen as an even number of days of administration of trial drug would be required to avoid the bias from children already taking alternate-day prednisolone who might receive different dosing of trial drug depending on whether or not it was commenced on a day on which they usually took prednisolone.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial-related information, including the protocol, trial information sheets, consent and assent forms and the case report forms, are available at the PREDNOS2 website [URL: www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/bctu/trials/renal/prednos2/index.aspx (accessed 17 December 2020)].

Aim

The aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of a 6-day course of daily prednisolone therapy at the time of URTI in reducing the development of subsequent nephrotic syndrome relapse in children with relapsing SSNS.

Objectives

The specific trial objectives were to determine whether or not a 6-day course of oral prednisolone given at the time of an URTI:

-

reduces the incidence of first upper respiratory tract infection-related relapse (URR) in children with relapsing SSNS

-

reduces the overall rate of URR in children with relapsing SSNS

-

reduces the overall rate of relapse in children with relapsing SSNS

-

reduces the cumulative dose of prednisolone over the 12-month study period

-

reduces the incidence and prevalence of adverse effects of prednisolone, including behavioural abnormalities

-

reduces the number of children undergoing escalation of background immunosuppressive therapy

-

increases the number of children undergoing reduction of background immunosuppressive therapy

-

is more cost-effective than standard therapy

-

improves quality of life as measured using the Child Health Utility 9D (CHU-9D), EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL).

Trial design

The PREDNOS2 trial was a Phase III randomised parallel-arm placebo-controlled double-blind trial that compared a 6-day course of daily prednisolone with no change in therapy using a matching placebo. Children with relapsing nephrotic syndrome who met eligibility criteria were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio (with minimisation according to background treatment for nephrotic syndrome) to receive either 6 days of prednisolone or 6 days of placebo at the time of an URTI. The participant, clinician and trial teams were masked to treatment allocation.

The trial protocol for PREDNOS2 was published in open access format in 2014. 1

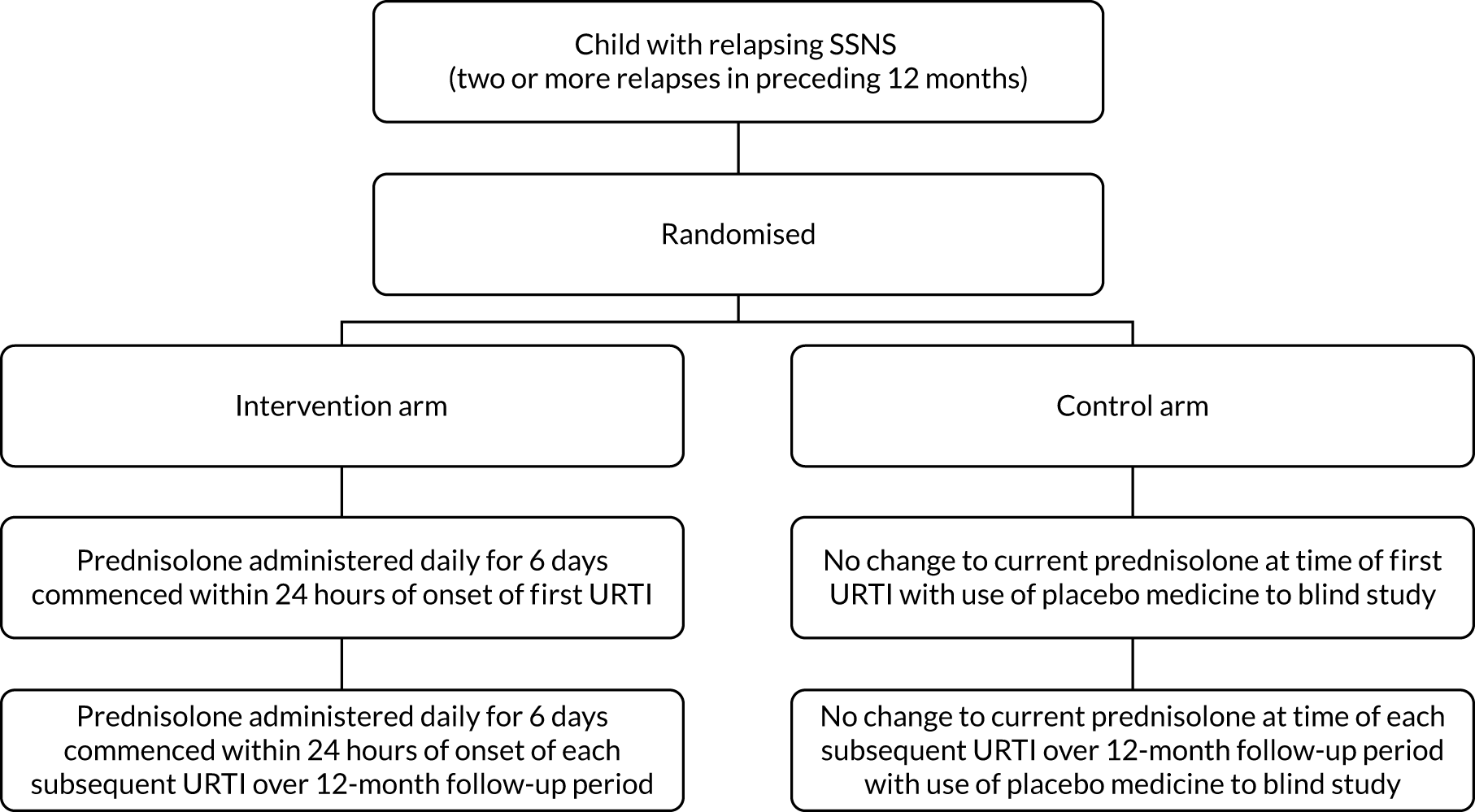

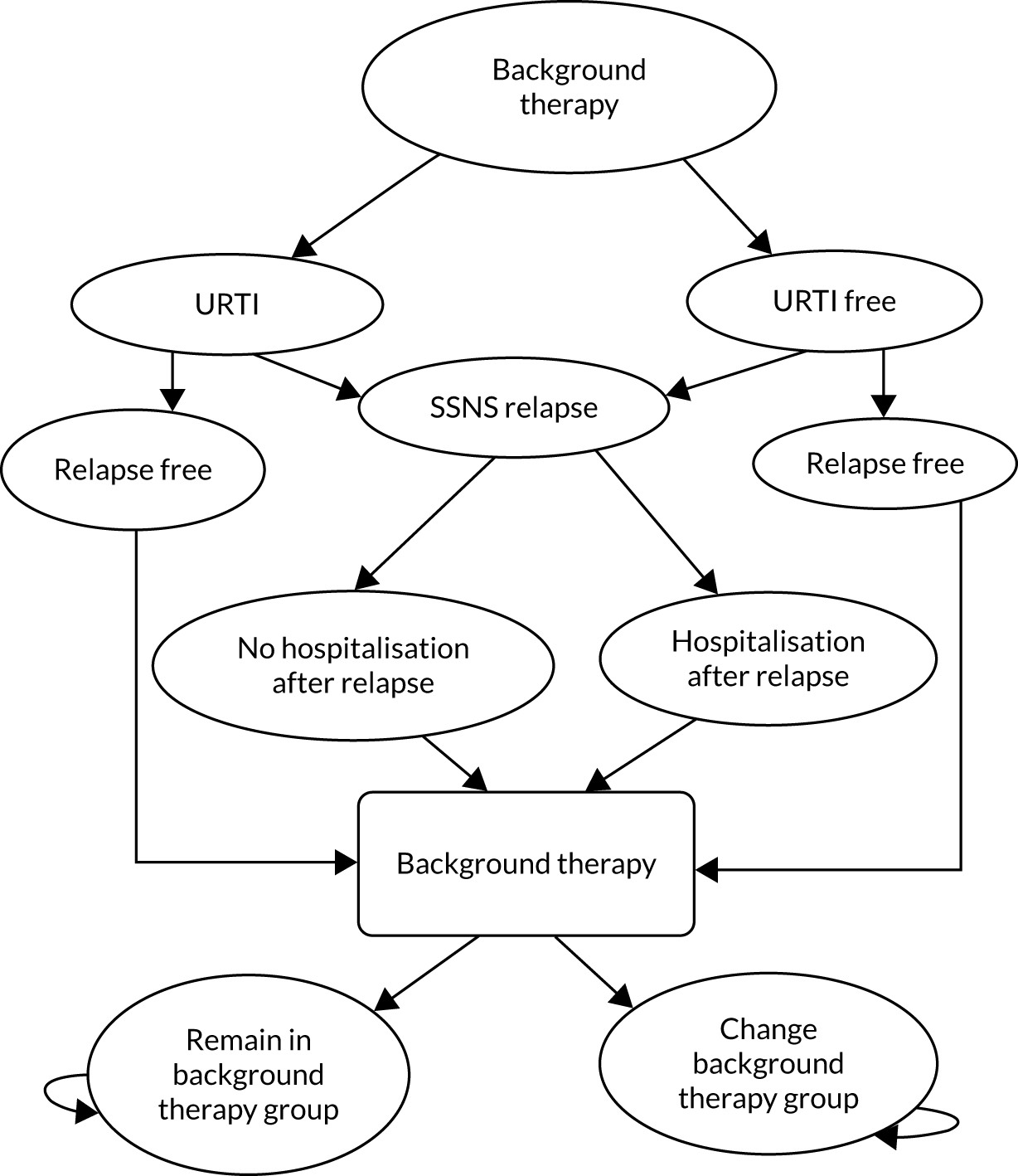

The trial schema is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial schema.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Children aged > 1 year and < 19 years were eligible for inclusion if they had relapsing SSNS, defined as having experienced two or more relapses in the preceding 12 months. This included the following groups:

-

Children on no long-term immunosuppressive therapy.

-

Children receiving long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy at a dose of up to and including 15 mg/m2 on alternate days. Note that this was the maximum dose at the time of recruitment. If children subsequently received a higher dose, for example after relapse, then they could remain in the trial.

-

Children receiving long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy at a dose of up to and including 15 mg/m2 on alternate days in conjunction with other immunosuppressive therapies, including levamisole, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, MMF, mycophenolate sodium and azathioprine.

-

Children receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapies, including levamisole, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, MMF, mycophenolate sodium and azathioprine, without long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy.

-

Children who had previously received a course of oral or intravenous cyclophosphamide –

-

Children must have experienced two relapses in the 12 months prior to randomisation (in keeping with all other children).

-

Children must have experienced at least one of these relapses following completion of cyclophosphamide therapy.

-

Children must have been at least 3 months post completion of oral or intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy.

-

-

Children who had previously received a single dose or course of intravenous rituximab –

-

Children must have experienced two relapses in the 12 months prior to randomisation (in keeping with all other children).

-

Children must have experienced at least one of these relapses following completion of rituximab therapy.

-

Children must have been at least 3 months post completion of intravenous rituximab therapy.

-

-

Parents and (where age appropriate) child understood the definition of URTI and the need to commence trial drug once this definition was met.

-

Written informed consent obtained from the child’s parents/guardians and written assent obtained from the child (where age appropriate). Young people aged ≥ 16 years provided their own written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome.

-

Children receiving or within 3 months of having completed a course of oral or intravenous cyclophosphamide.

-

Children receiving or within 3 months of having received a course of rituximab.

-

Children on daily prednisolone therapy at time of recruitment.

-

Children on a prednisolone dose of > 15 mg/m2 on alternate days at time of recruitment.

-

Children with a documented history of significant non-adherence to medical therapy.

-

Young people who would be transferred from paediatric to adult services during the 12-month trial period.

-

Children unable to take prednisolone tablets, even in crushed form.

-

Known allergy to prednisolone.

Rationale for choice of inclusion and exclusion criteria

Children with relapsing nephrotic syndrome experience relapses whether they are on maintenance immunosuppression with steroids, with other agents, with both or if they are taking no maintenance immunosuppression. In this trial, we aimed to reflect that pragmatism with a broad eligibility criterion of all children with frequently relapsing disease. At the outset of the trial, a precise definition of frequently relapsing disease (i.e. two or more relapses in the 6 months prior to recruitment) was used, but this was later relaxed to more than two relapses within the previous 12 months to optimise recruitment.

The reason for the 3-month window following treatment with cyclophosphamide or rituximab is that patients who respond to this agent (approximately 50–60%) are likely to see a significant reduction in the frequency of disease relapse, particularly when receiving and shortly after completing this therapy. The inclusion of at least one relapse following cyclophosphamide or rituximab treatment confirms the persistence of relapsing disease.

Children became eligible for recruitment if a second relapse occurred within 12 months of a previous one. Once they enter remission, normal practice is to continue prednisolone at a dose of 40 mg/m2 on alternate days for 4 weeks, sometimes followed by a slow weaning process. The cumulative dose of prednisolone required to treat children for 6 days if they developed URTI symptoms while weaning prednisolone following a relapse and taking a dose of > 15 mg/m2 on alternate days was considered unacceptably high. The families of these children were informed about the trial, but recruitment did not take place until the child’s prednisolone dose had been reduced.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the incidence of first URR of nephrotic syndrome following any URTI during the 12-month follow-up period.

Relapse was defined as Albustix-positive proteinuria (i.e. +++ or greater) for 3 consecutive days or the presence of generalised oedema plus 3+ proteinuria. URR was defined as a relapse occurring within 14 days of the development of an URTI. See below for more details.

This was chosen as the primary outcome as it was hypothesised that giving daily prednisolone at the time of URTI would reduce the subsequent development of disease relapse. If this hypothesis was correct, then those children randomised to placebo would experience more URRs than those children randomised to the active drug.

Secondary outcomes

-

Rate of URR of nephrotic syndrome (relapses per year).

-

Rate of relapse (i.e. URTI related and non-URTI related) of nephrotic syndrome (relapses per year).

-

Cumulative dose of prednisolone (mg/kg and mg/m2) received over the 12-month trial period.

-

Incidence of serious adverse events (SAEs).

-

Incidence of adverse effects of prednisolone, including assessment of behaviour using the Achenbach Child Behaviour Checklist (ACBC).

-

Incidence of escalation of background immunosuppressive therapy (e.g. addition of ciclosporin, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide).

-

Incidence of reduction of background immunosuppressive therapy (i.e. cessation of long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy).

-

Quality of life using the PedsQL, CHU-9D and EQ-5D (the latter two were used for the economic analysis).

-

Cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained.

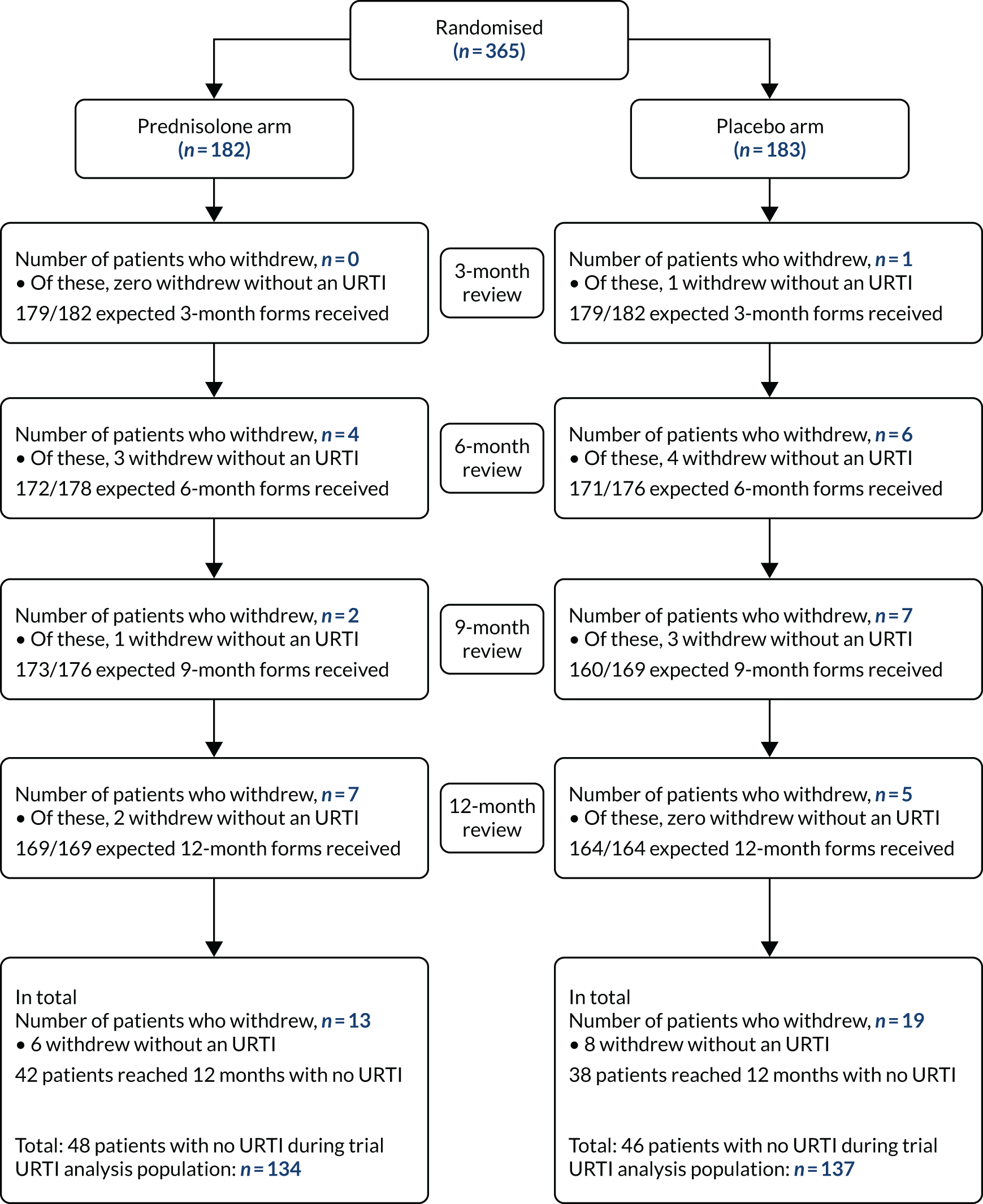

Change to the primary outcome

The original primary outcome was the incidence of URR following the first URTI.

An interim analysis for the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) in late 2015 showed that the URR rate following the first URTI was 22%. This was much lower than the 50% event rate used in the sample size calculation (see below). It was also noted that a larger number of children than expected were completing the 12-month trial period and not experiencing an URTI (see Sample size).

At the request of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme and the DMC, a futility analysis was undertaken and presented to the DMC in January 2016. Following the results of the futility analysis, the DMC advised the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) that, based on the planned sample size and current event rate, it was unlikely that the trial would show a difference in primary outcome between the two treatment arms, should there be one. They did, however, acknowledge that there were still important secondary end-point data that the trial could address.

Following this, the Trial Management Group (TMG), the TSC and the HTA programme discussed the best way to proceed. It was agreed for the primary outcome to be changed to incidence of first URR following any URTI during the 12-month follow-up period, rather than URR following the first URTI. This had the advantage of being correlated with the original primary outcome and had a (combined) event rate of 42%, which was closer to the sample size assumptions.

Sample size

In children with FRSSNS, the development of an URTI results in relapse in around 50% of instances. 19 In the Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter19 study, 40 URTIs treated with placebo were followed by 19 relapses (48%), compared with seven relapses (18%) in the prednisolone-treated group. This corresponds to an absolute difference of 30% (a 62.5% proportional reduction). In the first treatment period, there were 10 relapses (45%) in 22 placebo-treated children, compared with four relapses (22%) in 18 prednisolone-treated children (i.e. a 23% absolute difference and 51% proportional reduction). 19 This was a large treatment effect based on a small study of children on long-term maintenance alternate-day prednisolone therapy in a developing country. Therefore, to detect a more conservative difference of 17.5% (i.e. 35% proportional reduction) in URR rate (i.e. from 50% to 32.5%), with 80% power, a two-sided test and an alpha of 0.05, required 250 children in total (comparison of two proportions23). An allowance was made for between 10% and 20% dropout (e.g. subject withdrawal, lost to follow-up or subject not having an URTI during the 12-month follow-up period), which required recruitment of between 280 and 320 children. Therefore, it was proposed to recruit 300 children, 150 to each arm. However, with a treatment effect more in line with the 50% reduction observed in the first treatment period of the Abeyagunawardena and Trompeter19 study, the PREDNOS2 trial would have sufficient power (> 95%) to detect this difference [i.e. to detect a 50% proportional reduction (i.e. from 50% to 25%) with 90% power and an alpha of 0.05, required 160 children, increasing to 200 with allowance for 20% dropout].

During the trial, it became apparent that a larger number of children than expected were reaching the end of the 12-month follow-up period without experiencing an URTI and, therefore, were unable to contribute to the analysis. The original sample size was increased by between 10% and 20% to account for this, but, in late 2015, the actual number of children who had completed 12 months’ follow-up without an URTI was 28%. Therefore, the TSC recommended revising the sample size using a 30% attrition rate, which increased the sample size to 360 patients.

Recruitment

Children with relapsing SSNS under the care of a paediatric nephrologist and/or a general paediatrician were recruited from throughout the UK. Potentially eligible children were identified from clinic lists and departmental databases. Information sheets outlining the trial were mailed to the parents or guardians of potentially eligible children (and the child, where age appropriate) 1–2 weeks prior to their next clinical appointment. Following confirmation of eligibility with regard to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a further full discussion of the trial, informed consent was sought from the parents (or guardians) and children (informed consent or assent, according to age) at the time of this appointment.

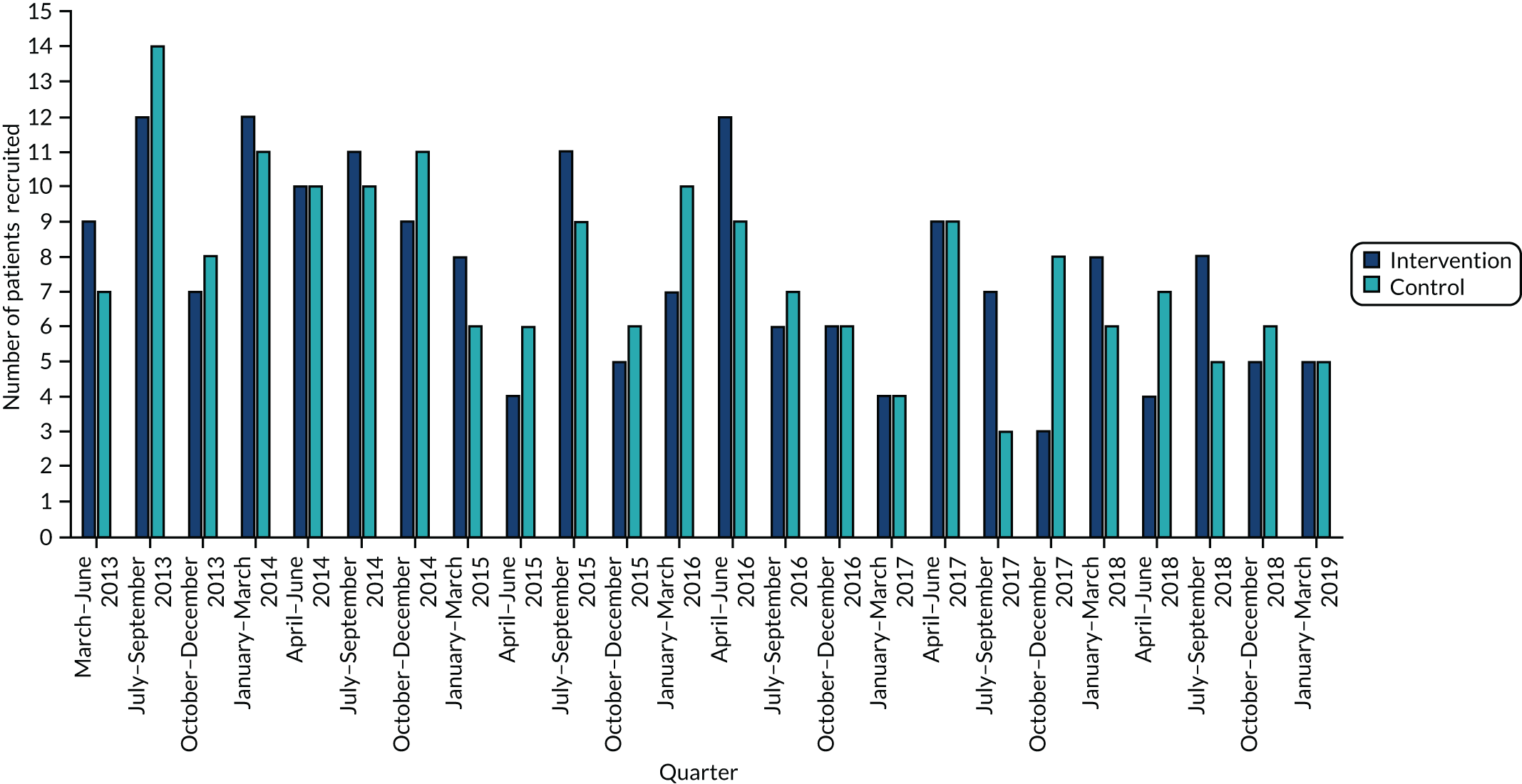

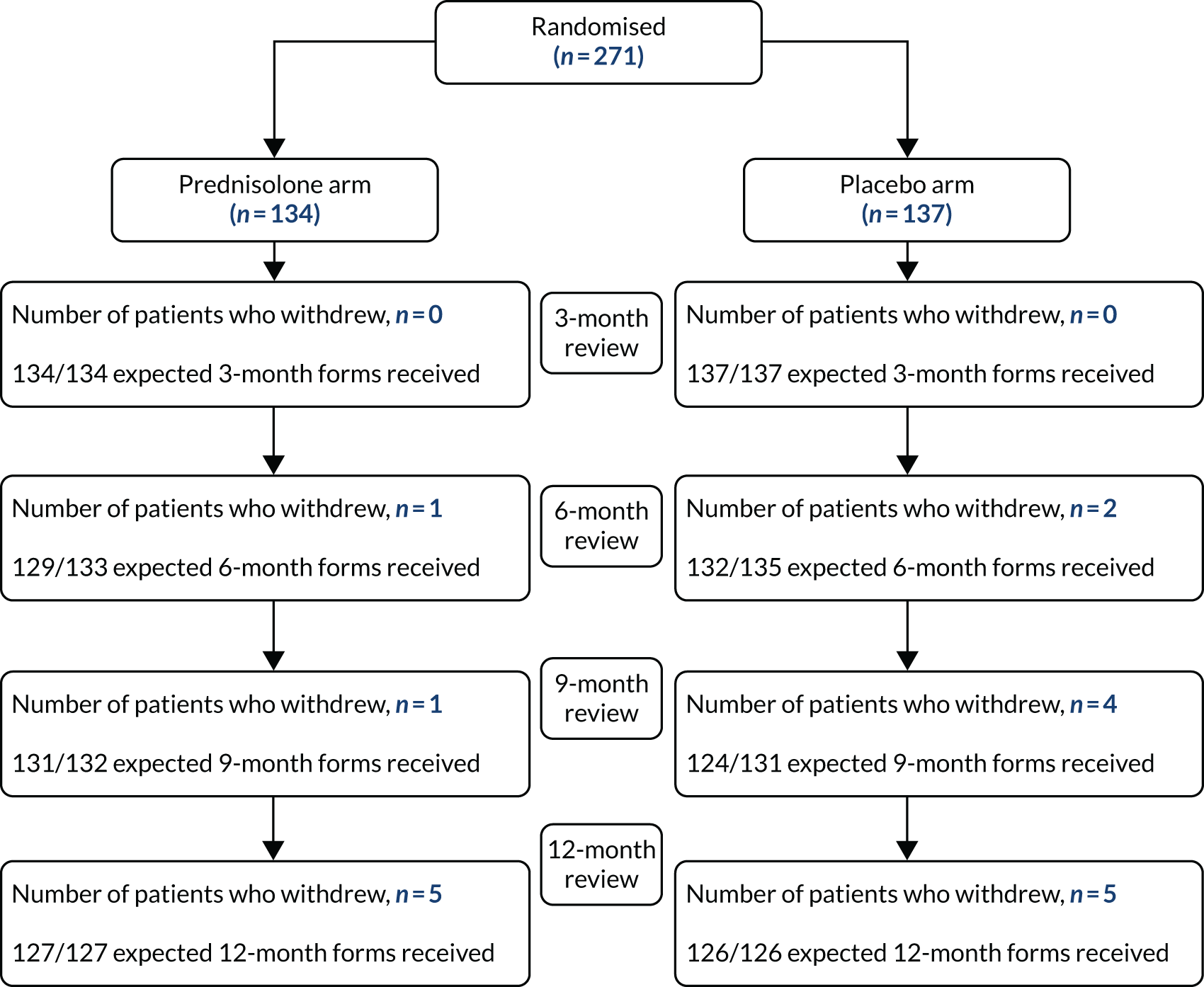

Trial sites

A total of 153 sites were set up throughout the UK and 122 of these proceeded to full approval. Figure 2 shows the location of these centres on a map. These sites included all 13 tertiary paediatric nephrology units, as well as general paediatric units within university and district general hospitals.

FIGURE 2.

Map of recruiting centres for the PREDNOS2 trial. Map data © 2021 GeoBasis-DE/BKG (© 2009) Google, Inst. Geogr. National.

Informed consent

The conduct of the trial was in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and applicable regulatory requirements.

For children aged < 16 years, the parent’s written informed consent for their child to participate in the trial and the child’s assent, as appropriate, given the child’s competence, were obtained before randomisation and after a full explanation had been given of the treatment options and the manner of treatment allocation. Young people aged 16–18 years gave their own consent to participation in the trial. Examples of patient information can be seen in the supporting documentation [see NIHR Journals Library, URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/11129261/#/documentation (accessed 21 July 2021)].

Electronic copies of the parent/patient information sheet and informed consent/assent forms were printed or photocopied onto the headed paper of the local institution.

It was the responsibility of the investigator or designate (e.g. research nurse if local practice allowed and this responsibility had been delegated by the principal investigator, as captured on the site signature and delegation log) to obtain written informed consent for each parent/child prior to performing any trial-related procedures. Investigators ensured that they had adequately explained the aim, trial treatment, anticipated benefits and potential hazards of taking part in the trial to the parent/child. The investigator also stressed that the child was completely free to refuse to take part or to withdraw from the trial at any time. The parent/child were given ample time (e.g. up to 1 week) to read the parent/patient information sheet and to discuss their participation with others outside the site research team. The parent/child was given an opportunity to ask questions to be answered to their satisfaction. The right of the parent/child to refuse to participate in the trial without giving a reason was respected.

If the parent expressed an interest in their child participating in the trial, then they were asked to sign and date the current ethics-approved version of the informed consent form. The young person signed their own consent form if aged 16–18 years (inclusive). If the young person was aged < 16 years, then they could sign an assent form, if age appropriate. The investigator or designate then signed and dated the form. A copy of the informed consent/assent form was given to the parent/child, a copy was filed in the hospital notes and the original was placed in the investigator site file (ISF).

Once the child was entered into the trial, their trial number was entered on the informed consent/assent form maintained in the ISF. In addition, a copy of the signed informed consent/assent form was sent by fax to the Birmingham Children’s Hospital Pharmacy Department (Birmingham, UK). Details of the informed consent discussions were recorded in the child’s medical notes, including the date of the initial discussion, information regarding the initial discussion and the outcome, the date consent was given, the name of the trial, the version number of the parent/patient information sheet, the version number of the informed consent form and confirmation that the person signing the consent form on behalf of the child had been determined to have the parental responsibility to do so.

Throughout the trial, the parent/child had the opportunity to ask questions about the trial and any new information that may be relevant to the child’s continued participation was shared with them in a timely manner.

Details of all children approached about the trial were recorded on the subject screening/enrolment log and, with the parent’s/child’s prior consent, their general practitioner (GP) was informed that they were taking part in the trial. A GP letter was provided electronically for this purpose.

Randomisation

Following the informed consent process and completion of the baseline assessments, eligible children were randomised at the level of the individual in a 1 : 1 ratio to either the intervention arm or the control arm. To ensure concealment of treatment allocation, randomisation was provided using a central secure 24-hour internet-based randomisation service, or by a telephone call to the University of Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU) (Birmingham, UK). The randomisation process used minimisation by the background treatment regimen that the child was receiving at randomisation (i.e. no treatment, long-term maintenance with prednisolone therapy only, long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy with other immunosuppressant therapy, and other immunosuppressant therapy only).

Randomisation took place at the time of the initial trial visit, prior to the development of the first URTI, to ensure that the trial drug reached the parents/child by the time the first URTI developed. The investigator completed the randomisation notepad to prepare for randomisation. The randomisation notepad was signed by the investigator to indicate that all of the eligibility criteria had been checked. It was also noted in the medical records that the investigator had checked all of the eligibility criteria and that the child met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. The signed randomisation notepad was kept in the ISF and a copy sent to the trials office.

After randomisation, each child was assigned a unique trial identification number to be used on all trial-related material for the child. Confirmation of the randomisation and trial identification number was forwarded to the trial manager, the local investigator and the Birmingham Children’s Hospital Pharmacy Department by e-mail immediately on randomisation. Once a PREDNOS2 trial number had been obtained, the investigator faxed or e-mailed a signed copy of the clinical trial prescription form and the consent/assent form(s) to the pharmacy at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital to order the PREDNOS2 trial drug, which was then sent directly to the parents/child (see Investigational medicinal product). Only delegated staff at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital NHS Trust Pharmacy were able to view the treatment allocation to dispatch the pots of trial drug. This was carried out using a secure login link to the randomisation program once the child had been randomised. This ensured that investigators and the trial office remained blind to the treatment allocation.

Blinding

The PREDNOS2 trial was a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The secure internet-based central randomisation service provided by BCTU ensured concealment of treatment allocation. Essential Nutrition Ltd (Brough, UK), a Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)-licensed good manufacturing practice manufacturer of solid oral dosage form products, manufactured both the active and placebo tablets for the PREDNOS2 trial. To ensure that the tablets were identical in size, shape, taste and smell, Essential Nutrition Ltd conducted batch testing throughout the trial. To maintain blinding, children randomised to the control arm received the same number of study tablets as they would have received in the intervention arm through supplemental placebo tablets. Therefore, outcome assessments by families and local investigators were carried out masked to treatment allocation. Only staff at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital Pharmacy Department were aware of the individual allocations of children. The trial statistician was unblinded to the intervention code for all of the interim analyses and presented unblinded analyses to the DMC.

Planned interventions

Current practice in the UK has been for no change to be made to immunosuppressive therapy at the time of development of an URTI. The intervention being assessed within the PREDNOS2 trial was a 6-day course of daily prednisolone therapy at the time of onset of URTI.

Those randomised to the intervention arm commenced a 6-day course of daily prednisolone each time they developed an URTI during the 12-month follow-up period (see Definition of upper respiratory tract infection for strict definition). Those randomised to the control arm received an identical number of placebo tablets, therefore allowing double blinding of the trial. If the child was receiving background long-term immunosuppressive therapy (e.g. levamisole or ciclosporin), then this continued unchanged.

Definition of upper respiratory tract infection

An URTI was defined as the presence of at least two of the following for at least 24 hours:

-

sore throat

-

ear pain/discharge

-

runny nose

-

cough (dry/barking)

-

hoarse voice

-

fever of > 37 °C (measured using tympanometric electronic thermometer).

Parents were provided with clear written and (if requested) downloadable electronic information informing them of the trial definition of an URTI, as outlined above. They were also provided with abbreviated versions of this printed onto laminated cards, which could be kept in multiple locations within the family home, including in fridge magnet format.

An electronic tympanometric thermometer (Braun Thermoscan®; Braun, Kronberg, Germany) was provided to the parents of all children to allow them to measure their child’s temperature. A diary was also provided for parents to record the results of the daily morning urinalysis (standard care in children with relapsing SSNS), development of URTI, commencement of trial drug, other ongoing treatment, acute illnesses and other issues.

Investigational medicinal product

The trial drug (5-mg prednisolone tablets and matching placebo tablets) was manufactured, packed and labelled by Essential Nutrition Ltd. Following randomisation, children were provided with a supply of 100 tablets (two containers of 50 tablets) of the trial drug (5 mg of prednisolone) for those randomised to the intervention arm or a matching placebo for those randomised to the control arm. This was sent directly to the family home from the central pharmacy at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital by Royal Mail (London, UK)-registered post on a day convenient for the family. The trial drug containers and their contents appeared identical in every way, therefore maintaining the double blind. Trial drug labelling complied with the applicable regulatory requirements and clinical trial-specific labels were attached to all treatments. The pharmacy at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital maintained drug accountability logs for dispensed and returned trial drug doses according to its local policy. The central pharmacy at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital documented when they were contacted by the parent/patient to confirm receipt of the IMP.

For children unable to swallow the tablets whole, the prednisolone and placebo tablets could be crushed and a tablet crusher was supplied with the trial drug at the prescriber’s request.

Every child participating in the trial was issued with a standard pack containing the following:

-

A diary in which the results of the morning urinalysis, treatment administration and any consultations with health-care professionals [e.g. GP, nurse, hospital accident and emergency (A&E) department], development of URTI, commencement of trial drug and details of medicines prescribed or purchased over the counter could be recorded.

-

Instructions on contacting the central pharmacy at Birmingham Children’s Hospital on receipt of IMP at the family home. This included date of receipt and number of bottles received.

-

An electronic tympanometric thermometer to measure temperature at the time of suspected URTI.

-

Written and (if requested) electronically downloadable information regarding URTI definition.

-

Written and (if requested) electronically downloadable information regarding the dose of the trial drug to be commenced in the event of URTI developing.

-

Other ‘aides-memoires’ regarding definition of URTI, etc., displayed on fridge magnets and laminated sheets.

Compliance with trial drug was assessed at each trial visit. This was carried out by a manual pill count by an appropriate staff member at the local site, using a standard counting triangle.

Commencement of trial drug

Once the child met the definition for URTI (i.e. two or more criteria as listed above for at least 24 hours), the parents or guardians commenced the child on the trial drug (prednisolone tablets for those in the intervention arm or placebo for those in the control arm) (see Dosing of trial drug for dosing schedules). It was anticipated that parents or guardians would have no difficulties in identifying that their child had met the URTI criteria and would commence the trial drug unassisted, having been provided with comprehensive advice on this at the time of their recruitment. However, a back-up service was also provided. If they were in any doubt, parents or guardians were instructed to contact their local trial site or, if this was not possible, to call a PREDNOS2 trial telephone number, which was manned by the chief investigator or his nominated deputy during periods of annual leave. This meant that parents or guardians were able to seek advice regarding whether their child met the URTI criteria, the dose of trial drug required and any other issues or concerns they may have had relating to the trial. A log of any telephone calls was maintained and the chief investigator reported their content to the local principal investigator by e-mail. This back-up service was used on fewer than five occasions during the trial.

To ensure patient safety, the information provided to parents and guardians also contained information about the signs of a more serious infection (e.g. non-blanching rash, leg pain, cool extremities, rapid breathing, blue lips, fitting, unconsciousness, any other major concern). If any of these features were present, parents and guardians were instructed not to start the trial drug and to seek urgent medical attention for their child from their GP or local A&E department.

Parents or guardians were asked to contact their local trial site within 24 hours of commencing the trial drug to inform the principal investigator or nominated deputy and to allow them the opportunity to discuss any of their child’s symptoms that may be of concern to them.

The above intervention was repeated every time the child developed a URTI over the 12-month follow-up period. The only exception to this was if the child was receiving daily prednisolone therapy (e.g. in the early stages of treatment for a previous relapse). In these instances, the trial drug was not commenced.

Dosing of trial drug

The precise dose of the trial drug at time of the development of URTI depended on the child’s current treatment regimen, in particular whether or not they were receiving long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy and, if so, at what dose.

Children not receiving long-term maintenance prednisolone

Those randomised to the intervention arm received prednisolone (15 mg/m2) daily (maximum dose of 40 mg) for a total of 6 days. The dose was rounded up or down to the nearest 5 mg and given as a single morning dose. Children randomised to the control arm received an identical number of placebo tablets.

Children receiving a long-term maintenance prednisolone dose of ≤ 15 mg/m2 on alternate days

Those randomised to the intervention arm received prednisolone (15 mg/m2) daily (maximum dose of 40 mg) for a total of 6 days. The dose was rounded up or down to the nearest 5 mg and given as a single morning dose. Children randomised to the control arm received an identical number of placebo tablets. Children receiving long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy received a different number of tablets of the trial drug on regular treatment-days (i.e. those days when they usually take prednisolone) from non-treatment-days. For example, a child of 1.0 m2 receiving a long-term maintenance dose of 5 mg of prednisolone on alternate days took an additional two 5-mg prednisolone tablets (or matching placebo) on treatment days and three 5-mg prednisolone tablets (or matching placebo) on non-treatment days. Therefore, this particular child received either prednisolone 15 mg (15 mg/m2) daily for 6 days if in the intervention arm or continued unchanged on prednisolone 5 mg on alternate days if in the control arm.

Children receiving a prednisolone dose of > 15 mg/m2 on alternate days

A small number of children may have been receiving a prednisolone dose of > 15 mg/m2 at the time of URTI development. These were likely to be children who had already relapsed during the 12-month trial period and had their prednisolone dose increased accordingly, as the inclusion/exclusion criteria excluded those on a dose of prednisolone > 15 mg/m2 at trial entry. These children converted to the same dose on a daily basis for a total of 6 days. The dose was rounded up or down to the nearest 5 mg and given as a single morning dose (maximum dose 60 mg). Children randomised to the control arm received an identical number of placebo tablets. For example, a child of 1.0 m2 receiving a long-term maintenance dose of 20 mg of prednisolone on alternate days took their regular dose on treatment days and four 5-mg prednisolone tablets (or matching placebo) on non-treatment days. Therefore, this particular child received either 20 mg (20 mg/m2) daily for 6 days if in the intervention arm or continued unchanged on 20 mg on alternate days if in the control arm.

To allow for changes in dosing of trial drug with the child’s growth throughout the trial, the precise regimen to be administered was discussed with parents and guardians, along with a written treatment plan at the time of recruitment, and re-discussed at each trial visit. Information about the precise number of trial drug tablets to administer was provided to the family in written form, using a standard form, which was completed by the local principal investigator.

The trial drug was always given as a single dose in the morning. If the child was receiving any additional immunomodulatory therapy (e.g. ciclosporin, levamisole, etc.), then this continued unchanged throughout the 6-day course of the trial drug. Other drug treatment also continued unchanged. At the end of the 6-day course of the trial drug, the child continued on their previous dose of long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy (or no prednisolone treatment if they were not previously receiving this). If an URTI occurred when a child was receiving daily prednisolone (e.g. in the early stages of treatment for a disease relapse), then the trial drug was not commenced. These children continued to participate in the trial and the subsequent URTIs were treated with the trial drug, provided that they were receiving alternate-day prednisolone at that point.

Trial procedures

Trial visits and data collection

All children underwent a comprehensive assessment at the randomisation visit and were then followed up for 12 months from randomisation, with visits at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months for trial follow-up assessments. This follow-up schedule is entirely in keeping with the normal frequency of follow-up of this population in routine clinical practice. The information captured at the randomisation and subsequent visits are shown in Table 3.

| Information | Visit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Month | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 |

| Window | ± 2 weeks | ± 2 weeks | ± 2 weeks | ± 2 weeks | |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | ✓ | ||||

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | ||||

| Allocation of trial number | ✓ | ||||

| Documentation of URTI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Documentation of commencement of trial drug | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Documentation of recent relapse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Recent medical/drug history | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| AE documentation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Compliance check (tablet count using counting triangle)a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Physical examination | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Assessment of steroid toxicity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Height and weight | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Blood pressure | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Calculation of trial drug dose to be administered in the event of URTI and explanation/documentation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| If three or more courses of the trial drug have been administered since the previous visit, confirm parental understanding of URTI definition | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Blood sample for DNA/RNAb | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ACBC | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PedsQL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CHU-9D and EQ-5D | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Trial drug returned to Birmingham Children’s Hospital Pharmacy Department for accountability | ✓ | ||||

At each visit, there was a full clinical review of the child and a number of different questionnaires were administered. The clinical review included assessment of whether or not the child had experienced any URTI or non-URRs since the last visit and a review of the current treatment regimen.

To evaluate changes in the child’s behaviour associated with the different prednisolone regimens, the ACBC24 was completed by the parents/guardian. The ACBC is a standardised measure made up of 120 items that measure internalising behaviour problems (i.e. withdrawn, somatic complaints, anxiety/depression, thought problems) and externalising behaviour problems (i.e. social problems, attention problems, delinquent and aggressive). It was used as part of the behavioural effects of prednisolone for the PREDNOS trial that preceded this trial. 9 A total behavioural problem score is calculated from these problem scales and forms the basis of comparison with age- and sex-matched normative data.

Information relating to quality of life was also collected using the CHU-9D, EQ-5D (dependent on child age)25 and PedsQL26,27 questionnaires. The information was collected from parents/guardians or the child/young person themselves, depending on their age. The CHU-9D is a newly developed utility measure designed for children aged 5–11 years. The EQ-5D is a validated utility measure routinely used in adult and adolescent populations. Both the CHU-9D and the EQ-5D were used to generate data for the health economic analyses. The PedsQL questionnaire is a well-validated approach to measuring health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in healthy children and adolescents and those with acute and chronic health conditions.

Adverse effects due to prednisolone were assessed by studying growth (i.e. height, weight and body mass index), cushingoid features, hypertrichosis, striae, appetite (all Likert scales), behaviour (ACBC), blood pressure and urine dipstick analysis for glycosuria. The development of significant bacterial, viral or fungal infections and the use of post-varicella exposure prophylaxis (zoster immune globulin or antiviral therapy) were also recorded. Information was also collected regarding all episodes of consultation with GPs or hospital medical teams, including data on treatments prescribed. This was incorporated into the costs measured as part of the health economic analysis (see Chapter 4).

Information recorded by parents and guardians

Parents or guardians performed dipstick testing for proteinuria (using an Albustix, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Ltd, Frimley, UK) of the child’s first morning urine on a daily basis in accordance with routine clinical care. They were provided with a record book to enter the results (to allow the early detection of nephrotic syndrome relapses) and the medication administered on a daily basis. This was maintained for the 12 months of the trial. Parents and guardians also used this diary to record any intercurrent illnesses and consultations with health-care professionals (e.g. GP, nurse, hospital A&E department), development of URTI and commencement of trial medicines, along with details of medicines prescribed or purchased over the counter.

Diagnosis and treatment of relapse

Relapse was defined as Albustix 3+ or more for 3 consecutive days or the presence of generalised oedema and Albustix 3+ on urine testing. An URR was defined as a relapse occurring within 14 days of the onset of an URTI. Where disease relapse occurred, parents or guardians contacted their trial centre in accordance with routine clinical care and treatment for disease relapse was commenced. A relapse was treated in accordance with the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children relapse regimen:28 prednisolone was commenced at a dose of 60 mg/m2 daily (maximum dose of 80 mg) until the urine tests were negative or trace for 3 consecutive days, then reduced to 40 mg/m2 (maximum dose of 60 mg) on alternate days for 4 weeks (14 doses). A subsequent tapering dose was used at the individual physician’s discretion. When relapse therapy was commenced, long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy (e.g. 10 mg on alternate days) was discontinued.

Where relapse occurred while the child was receiving the 6-day course of the trial drug, the trial drugs were discontinued and relapse treatment was initiated. Once the relapse regimen was completed, long-term maintenance prednisolone therapy could be recommenced at any dose at the principal investigator’s discretion. Background immunomodulatory therapy other than prednisolone (e.g. ciclosporin, MMF, levamisole, etc.) continued unchanged throughout the relapse treatment period.

Escalation of background immunomodulatory therapy

Children underwent intensification of background immunomodulatory therapy (i.e. the addition of, or change to, a new immunomodulatory agent, e.g. ciclosporin, MMF, levamisole, etc.) only when there were two or more relapses (URTI related or unrelated) in any 6-month period or where there were unacceptable adverse effects of prednisolone or other therapy. These children remained under follow-up, as intensification of immunomodulatory therapy was an important secondary outcome for this trial. Similarly, immunomodulatory therapy was discontinued only when the child remained relapse free for at least 6 months or there were unacceptable adverse effects of therapy.

Changes in certain types of non-corticosteroid immunosuppression were predefined as escalations, for example a move from cyclophosphamide to ciclosporin/tacrolimus, the addition of mycophenolate or the addition of rituximab. This is in line with guidelines, such as those written by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) group. 28 Any time cyclophosphamide was given, even if it was following ciclosporin/tacrolimus, it was considered to be an escalation, as the overwhelming rationale for using it would be poorly controlled nephrotic syndrome relapses. As both cyclophosphamide and rituximab are disease-modifying drugs given as short courses that are not repeated at all (usually in the case of cyclophosphamide) or for at least 6 months (in the case of rituximab), absence of either drug in a 3-month time period following one where it had been given was not considered to be a reduction in background therapy.

Safety assessment and reporting

Pharmacovigilance reporting complied with the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 200429 and the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Amended Regulations 2006. 30 Annual development safety update reports were submitted to the main Research Ethics Committee (REC) and MHRA.

The investigator assessed the seriousness and causality (relatedness) of all AEs experienced by patients (this was documented in the source data), with reference to the prednisolone tablet (Wockhardt UK Ltd) summary of product characteristics (dated 31 March 2008, section 4.8). 31 This was the reference safety information for the trial. 31

Within the PREDNOS2 trial, the steroid prednisolone and the matching placebo were both defined as IMPs.

Adverse events

An AE is any untoward medical occurrence in a patient or clinical trial subject administered a pharmaceutical product that does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment. An AE could, therefore, be any unfavourable and unintended sign (including an abnormal laboratory finding), symptom or disease temporally associated with the use of a (investigational) medicinal product, whether or not related to the medicinal product.

Expected AEs for the PREDNOS2 trial were those listed in the reference safety information for prednisolone.

The following were not considered AEs for the purposes of this trial:

-

a pre-existing condition (unless it worsened significantly during treatment)

-

diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, such as surgery (although the medical condition for which the procedure was performed was reported if new).

Only data on the AEs listed on the case report forms were routinely collected during the trial.

Serious adverse events

All AEs that met the definition of being SAEs were reported for the duration of the 12-month trial and for 3 months following completion of the trial drug.

A SAE is defined as any AE that results in death, is life-threatening, requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, results in a congenital anomaly or a birth defect or is otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Note that life-threatening in this context refers to an event in which the child was at risk of death at the time of the event. It does not refer to an event that, hypothetically, might have caused death if it were more serious. Hospitalisation was an admission that resulted in an overnight stay in hospital. Day admissions did not need to be reported as a SAE. Medical judgement was exercised in deciding whether or not an AE was serious in other situations. Important AEs that were not immediately life-threatening or did not result in death or hospitalisation, but may have jeopardised the child or may have required intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes listed in the definition above, were considered serious.

All AEs were evaluated by a doctor to determine severity and causality between the IMP and/or concomitant therapy and the AE. The causality and severity of all AEs was recorded in the medical notes. Investigators reported all AEs that met the definition of being serious immediately and within 24 hours of being made aware of the event using the trial-specific SAE form, other than the following events.

Hospitalisations for the following expected events did not require expedited reporting:

-

routine treatment or monitoring of the studied indication not associated with any deterioration in condition

-

treatment that was elective or pre-planned for a pre-existing condition that was unrelated to the indication under study, and had not worsened.

These events were reported on the trial-specific SAE form and sent to the trial office at the BCTU within 1 week of the site being made aware of the date of hospitalisation.

Vaccination

Where the child was due for routine vaccination or specialised vaccinations, there were some contraindications that needed to be taken into account, as stated in the Department of Health and Social Care’s Immunisation Against Infectious Disease, otherwise known as ‘The Green Book’. 32

Live vaccines can, in some situations, cause severe or fatal infections in immunosuppressed individuals because of extensive replication of the vaccine strain. For this reason, severely immunosuppressed individuals should not be given live vaccines and vaccination in immunosuppressed individuals should be conducted in consultation with an appropriate specialist only. Inactivated vaccines cannot replicate and so may be administered to immunosuppressed individuals, although they may elicit a lower response than in immunocompetent individuals.

Children who receive prednisolone, orally or rectally, at a daily dose (or its equivalent) of 2 mg/kg per day for at least one week or 1 mg/kg per day for 1 month are classified as a special risk group for being given live vaccines. Administration of live vaccines should be postponed for at least 3 months after immunosuppressive treatment has stopped or 3 months after levels have been reached that are not associated with immunosuppression. Routine live vaccines given in the UK include the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine and the BCG (bacillus Calmette–Guérin) vaccine for tuberculosis. For parents who may wish to travel with their children, other live vaccines include Yellow Fever and oral typhoid vaccines. Where these issues arose with a child within the trial, the advice of an immunologist was sought.

Unblinding

Should there have been any medical emergencies where it was necessary for a child’s treatment to be unblinded, a codebreak was available via Birmingham Children’s Hospital Pharmacy Department. Subject to clinical need, where possible, members of the research team were to remain blinded. No unblinding was required during the trial.

Trial withdrawals

Trial participants were followed up for the entire trial provided that consent for their ongoing participation in the trial was not withdrawn. Where consent was withdrawn, parents and children could choose any of the following:

-

The child wished to withdraw from the investigational treatment, but was willing to be followed up in accordance with the trial protocol (i.e. agreed that follow-up data could be collected and used in the final analysis).

-

The child did not want to attend trial-specific follow-up visits, but was willing to be followed up in accordance with standard practice (i.e. agreed that follow-up data could be collected at standard clinic visits and used in the trial final analysis).

-

The child was not willing to be followed up for trial purposes at any further visits (but agreed that any data collected prior to the withdrawal of consent could be used in the trial final analysis).

Blood samples

A genome-wide association study of SSNS and a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) mutation substudy are planned as part of the PREDNOS2 trial, and are funded separately. The results do not form part of this report and will be published elsewhere.

There are multiple reasons to suggest that SSNS may be a genetic disorder. As part of the PREDNOS2 trial, we obtained DNA and ribonucleic acid samples to identify changes that may be the cause of or contribute to the disease process of SSNS. The discovery of genetic changes that are unique to SSNS would increase our understanding of the disease and may lead to improved and more specific therapies becoming available.