Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/153/14. The contractual start date was in May 2018. The draft report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Dedication

This report is dedicated to Deano, one of the SHARPS participants, who sadly died on 10 November 2020. Deano will be remembered for his humour, his strength and his love for his dog, Bailey. He will be missed by many.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Parkes et al. This work was produced by Parkes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Parkes et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Parts of this report are reproduced or adapted from Parkes et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this report are reproduced or adapted from Parkes et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter introduces the background and rationale for the research, as well as the research questions as aims.

Response to commissioned call

This report presents the findings from a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded study that was conducted between May 2018 and May 2020. The study was developed in response to a Health Technology Assessment programme call in April 2017. The study explored the feasibility and acceptability of developing and implementing a peer-delivered, relational intervention to individuals experiencing homelessness and problem substance use. The team was commissioned to develop an ‘intervention’. The team considers the Peer Navigator (PN) intervention to be a ‘complex intervention’, using the Medical Research Council’s terminology,3 as the intervention comprised several interacting components. When the term ‘intervention’ is used in this report, it is intended to have this meaning.

Homelessness and substance use in context

Homelessness is a complex issue that often involves deep social exclusion. It is a term that includes the intersections of experiences of homelessness, substance use, institutional care and ‘street culture’ activities, such as begging and street drinking, along with other challenges. 4 ‘Homelessness’ encompasses a broad range of insecure living circumstances. 5 The European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion (ETHOS) classifies the living situations that constitute homelessness or housing exclusion as rooflessness, houselessness, insecure housing and inadequate housing. 6 Indicative estimates suggest that 307,000 people in the UK,7 550,000 in the USA8 and 235,000 in Canada9 experience homelessness at any one point. Although estimates are captured differently, rates of homelessness in these countries have been increasing, and may represent a global trend.

Homelessness can be viewed as being caused by ‘individualistic’ or ‘structural’ conditions, with different explanations favoured by different countries, and also by different stakeholders in countries. 10,11 Poverty and socioeconomic disadvantage; traumatic childhood, adolescent and adulthood experiences; interactions with the criminal justice system including imprisonment; and experience of institutional care are central to the causes of homelessness. 10,12,13 Homelessness may be understood as being both created and exacerbated by systemic changes in housing and social systems, combined with situational factors that make those with the least power and resources more vulnerable to becoming homeless. 12

People experiencing homelessness are vulnerable to ‘tri-morbidity’: the experience of poor mental health, poor physical health and problem substance use. 14 People who are homeless often report significantly worse physical and mental health than the general population;5,15–17 they are also four times more likely to die prematurely and seven times more likely to die as a result of drug use than the general population. 18 The use of alcohol and drugs is often a factor contributing to someone becoming homeless, and substance use can increase as a way of coping with homelessness. 19 There are also subpopulations of individuals experiencing homelessness who experience distinct and compounding health challenges. These groups include (but are not limited to) women;20 people who are engaged in sex work;21,22 young people;23 older people;24,25 individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or + (which includes any individual who feels that they do not fit into these categories, including intersex and asexual individuals) (LGBTQ+);26 individuals with experience of the criminal justice system;27 individuals who are veterans;27 and individuals who are refugees or asylum seekers, or have no recourse to public funds. 28

Despite many people who are homeless in the UK being registered with a general practitioner (GP), a significant number report that they are not receiving help with health problems. 28 Typically, they do not access health-care services until a crisis emerges, using accident and emergency (A&E) services rather than primary care. 14,29–31 Inpatients who are homeless also have high rates of emergency re-admission and A&E visits after discharge. 32 These trends can be costly to health-care funders. 14,33 Furthermore, when people who are homeless do access mainstream health care or substance use services, their needs are generally not well met. They often experience stigma and negative attitudes from staff, and service inflexiblity. 29,30,34–36 Such negative experiences can perpetuate through a person’s life,37 thereby shaping long-term attitudes towards mainstream health care, even as an individual’s life stabilises. 38 Collaborative working between health care and housing services is therefore essential;39 correspondingly, interventions to improve the health of people who are homeless have received increased attention over the previous decade. 4 Several systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of interventions to improve health and substance use outcomes for those who are homeless, with findings indicating that having primary care services tailored to those experiencing homelessness,40,41 case management16,42,43 and provision of housing42 can be effective in improving mental and physical health and assisting with addressing problem substance use.

In terms of problem substance use, treatment approaches have traditionally been divided into those aimed at helping people to stop using alcohol and drugs, with abstinence being the goal, and those taking a harm reduction approach first and foremost, whereby the goal is to minimise harms associated with consumption. 44 More recently, there has been a move away from dichotomising these approaches. Despite recognition of commonalities between approaches, questions have been raised regarding whether or not abstinence-focused interventions are appropriate for people with very complex health and substance use needs,40 such as people who are homeless. Although abstinence-based interventions can be effective for some, they rely on people who are homeless having consistent access to services and resources, which cannot be guaranteed. Unstable living conditions can mean that treatment appointments are missed and that plans and regimes are challenging to maintain. 29 For most people experiencing homelessness who use alcohol and drugs, abstinence is unlikely to be achieved in the short term, so approaches that reduce harms associated with use are required. 44–46 It has therefore been recommended that harm reduction approaches be specifically employed to prevent harms related to substance use, with abstinence-based treatment available as an option. 25,45,47

Although there is no universal definition of harm reduction, harm reduction aims to support people ‘where they are at’, whereby substance use is met with a non-judgemental response. 48 Intervention is therefore concerned with preventing substance-related harms, rather than seeking particular goals. 49 This can facilitate greater autonomy because importance is placed on people exercising choice to set their own goals, rather than being forced to reduce use/become abstinent. 49–51 Harm reduction services can also, importantly, act as a ‘gateway’ to other services, including health and housing services, and specialised substance use treatment. 51,52 For those who are homeless, there is a need for a wide range of approaches and services to reduce risks associated with substance use, including the provision of the following: alcohol through managed alcohol programmes; overdose awareness training and naloxone; safer supplies; heroin-assisted treatment; drug consumption rooms; assertive outreach services; and non-abstinence-based housing. 48,53

In harm reduction services, the building of trusting relationships with staff is key, as is the importance of service user-directed goals, and being accepted as a person. 47,50 The participation of people who use drugs and/or alcohol (peers) in service delivery is an essential element of harm reduction services and one of its key principles. 48,54,55 Services that are accessible, with staff who are good listeners and have caring, non-judgemental attitudes, can facilitate engagement with a range of population groups that can be reluctant to engage with mainstream services. 56,57 What is essential is that people should be treated as human beings of worth,47,49 which is not necessarily what people experience when they access services. 58,59 Specifically, regarding those experiencing homelessness, the development of trusting, consistent and reliable relationships is also essential to facilitate access to services. 47,51,60–63 Although the experience of homelessness and problem substance use can be highly stigmatising, these experiences do not necessarily dominate individuals’ sense of self, as they attempt to hold on to their dignity and self-worth, and succeed in doing so. 64

Neale and Stevenson65 interviewed people who were homeless with problem substance use living in hostels in England to examine the nature and extent of their social and recovery capital. Participants viewed supportive relationships with professionals as critical to their well-being and future outcomes. Hostel staff were noted as being caring and responsive to needs, and protecting people. 65 Developing good relationships between health-care professionals and those who are homeless has also been found to be especially important for engagement with services, particularly when supporting individuals with substance use/other health problems. 40,66 Mills et al. 34 interviewed staff working in homelessness primary care services in the UK and found that development of trusting relationships and listening well to people were crucial to engagement. Importantly, when people who were homeless developed good relationships with health-care professionals, they would bring friends with them, thus extending reach. 34 Pauly67 has also highlighted the importance of trusting relationships as essential to access primary care in Canada. This literature shares commonalities with research on effective approaches for those experiencing homelessness and mental health problems, highlighting the importance of flexible services, good relationships with professionals, care based on mutual communication and advocacy, practical support, and having workers with lived experience. 68 Services viewed as unhelpful included those where staff were viewed as judgemental, lacking compassion and ‘clinically detached’, and used medical models of care. Refusing to give support because of continued substance use also featured. 41,68

Homelessness settings in the UK are increasingly employing an approach called psychologically informed environments (PIEs) to develop services for people with complex histories to enable such services to help individuals move on from homelessness and achieve a better quality of life. 69 The explicitly relational focus, working actively with a person’s experiences of trauma and ensuing emotional impact, lies at the core of PIEs. 69,70 The coping strategies that people develop to survive, including use of substances, are understood in this context. PIEs aim to help people make changes to behaviours on their own terms using supportive relationships. 70 PIEs as a concept is continually developing, but the most recent version (2.0) identifies five key areas: (1) developing greater psychological awareness of the needs of service users; (2) valuing training and support for all staff, volunteers and service users; (3) fostering a culture of learning and enquiry, which considers evaluation and improvement; (4) enabling ‘spaces of opportunity’ that seek to view the environment from service users’ perspectives; and (5) fine-tuning the rules, roles and responsiveness of the service, which focuses on managing and improving relationships. 71 Services implementing a PIE approach may, for example, change their reception areas to make them feel safer/more inviting, provide staff with opportunities for reflective practice, and review evictions protocols to allow for greater flexibility when there is an issue of compliance. PIEs aim to give benefit to service users and service staff/organisations. For example, reflective practice offers service staff dedicated time and space to process the emotions stemming from their work and, in turn, to reduce burnout and increase compassion. 72 Despite increasing implementation in practice,73,74 there is limited research exploring the effects and experiences of PIEs from a range of perspectives. 70

Individuals with lived experience make hugely important contributions to interventions in the housing/homelessness and health-care fields. Peer support refers to a process whereby individuals with lived experience of a particular phenomenon provide support to others by explicitly viewing situations through the lens of personal experience and actively drawing from that personal experience and experiential knowledge. 75–77 Peer support can be both informal, via friends and acquaintances, and formal, whereby support is provided in a structured way. 78 Peer Support Workers have been most commonly employed in mental health settings, where peer support was first formalised. 75 Peers can improve outcomes for those using services, particularly in terms of giving hope and facilitating empowerment and self-esteem. 79,80

In terms of substance use, peers are involved in harm reduction and recovery services in a range of ways, including provision of advice on safer injecting;5,81 management of safe injecting sites; needle and syringe exchange and outreach programmes;82–86 provision of information about drug quality;87 provision of take-home naloxone;5,88 facilitation of managed alcohol programmes;89 and advocacy across a range of political and public arenas. 90–92 In their systematic review, Marshall et al. 93 identified 36 different roles of peers in harm reduction initiatives, highlighting the diversity of involvement. The involvement of peers in these services is considered to be highly beneficial in terms of facilitating engagement with services;92,94 increasing access to, and engagement with, health/social care services and specialist substance use treatment;83,95 supporting adherence to antiretroviral therapy;83 and reducing drug-related deaths5 through the development of trusting relationships. 24,94,96–98 Peer-delivered interventions have also been found to be effective, compared with traditional outreach interventions, in reducing the risks associated with injecting drugs. 95,99 Those who use drugs/alcohol are willing and able to access peer-delivered services,100 and the peers offering services themselves report a range of benefits. 93

Peer support roles have also been developed and supported in homelessness settings in the UK (e.g. Groundswell) and, although rigorous or full evaluation is sparse, it is increasing. 101 O’Campo et al. 66 examined the literature on community-based services for people who were homeless and experiencing mental health and substance use problems and found that, in one programme, peer support staff were particularly effective in developing good relationships with service users. Research indicates that peer workers can benefit from their role in terms of increased confidence and self-esteem, and as a way of reintegrating into the community,96,102 and that such work can help peers maintain their own recovery. 103 More broadly, challenges associated with implementation of peer support include lack of boundaries, power imbalances, stress, unclear/poorly defined roles, tensions over professionalism, and responding to challenging behaviours,79,96,101,104–108 as well as the unique challenge of continually navigating the dual identities of ‘peer’ and ‘professional’. 109 Effective training, supportive and reflective supervision and management, clear role descriptions and acceptable pay are all important in proactively addressing such challenges. 79,94,96,110–112

Peers have also been involved in research in the fields of substance use and homelessness at different stages of the research process, including design, data collection and analysis,93 and literature is increasing as practice evolves and expands. 113 Peer research has been argued to be ethically imperative, particularly in areas of social exclusion and potential objectification. 114 Terry and Cardwell115 describe how peer research is based on an assumption that shared experiences generate understanding and empathy. This is believed to enhance the quality of the research overall. Accessible role models can help to challenge stigmatising views of people who use substances and are homeless. 101 Common features of positive and meaningful peer involvement in research include comprehensive and ongoing training, compensation for time, and continuing support and mentorship. 116

These challenges in both service/practice and research have been highlighted in a recent ‘state of the art’ systematic review75 conducted by some members of the team that reviewed literature on peer support at the intersection of homelessness and problem substance use. Taken together, these studies highlight the importance of particular components of harm reduction that can contribute to engaging positively with people who are marginalised in mainstream health, social and housing services. The critical component to both good engagement and subsequent progress on self-identified life goals seems to be facilitation of trusting, supportive relationships in which practical elements of support are also provided, such as access to primary health care and housing options. Non-judgemental attitudes are noted to be vital in engaging people with complex needs in health care, including those with problem alcohol and drug use who are experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness. The Supporting Harm Reduction through Peer Support (SHARPS) study aimed to add to this body of knowledge by combining some of the most effective components of harm reduction, PIEs and peer delivery.

Overview of study

The SHARPS study was a feasibility and acceptability study of a relational, peer-delivered intervention to support people who are homeless and experiencing problem substance use to address a range of health and social issues on their own terms. The study aimed to examine whether or not it is feasible and acceptable to deliver a peer-to-peer intervention (by PNs), based on PIEs, that provides practical and emotional support for people experiencing homelessness and problem substance use in non-NHS third-sector housing settings.

Informed by the evidence outlined previously, the research questions were as follows:

-

Is a peer-delivered, relational harm reduction approach accessible and acceptable to, and feasible for, people who are homeless with problem substance use in non-NHS settings?

-

If so, what adaptations, if any, would be required to facilitate adoption in wider NHS and social care statutory services?

-

What outcome measures are most relevant and suitable to assess the effect of this intervention in a full randomised controlled trial (RCT)?

-

Are participants and staff/service settings involved in the intervention willing to be randomised?

-

On the basis of study findings, is a full RCT merited to test the effectiveness of the intervention?

Objectives

This study aimed to:

-

develop and implement a non-randomised, peer-delivered, relational intervention, drawing on principles of PIEs, that aims to reduce harms and improve health/well-being, quality of life and social functioning for people who are homeless with problem substance use

-

conduct a concurrent process evaluation, in preparation for a potential RCT, to assess all procedures for their acceptability, and analyse important intervention requirements such as fidelity, rate of recruitment and retention of participants, appropriate sample size and potential follow-up rates, the ‘fit’ with chosen settings and target population, availability and quality of data, and suitability of outcome measures.

Study structure

Phase 1 (months 1–3) addressed objectives 1 and 2:

-

develop an intervention using co-production methods for use in community outreach/hostel settings

-

create a manual to guide the intervention and an associated staff training manual.

Phase 2 (months 4–21) involved a study that delivered the co-produced intervention in six third-sector intervention sites and addressed the following objectives:

-

test the feasibility of recruiting to the intervention and measure the rate of recruitment/attrition to determine appropriate sample size and follow-up rates for a full RCT

-

deliver a non-randomised, peer-delivered, relational intervention based on principles of PIEs, with integral holistic health checks (conducted by researchers) based on already identified outcome measures

-

assess the acceptability and feasibility of all procedures in the intervention using normalisation process theory (NPT), including staff and participant perceptions of its value, strengths and challenges

-

assess the acceptability of the holistic health checks/outcome measures, to determine the best way to measure outcomes for this particular intervention and population in a future RCT

-

assess fidelity, adherence to the manual, ‘fit’ to context, data availability and quality, and potential for wider adoption to NHS/statutory health and social care services.

Phase 3 (months 18–24) involved the analysis and write-up of all study findings to address our research objectives, focusing on evaluating the factors needed to deliver the intervention at scale.

Intervention: key components

-

A relational intervention, drawing on the principles of PIEs, that aims to reduce harms and improve health/well-being, quality of life and social functioning for people who are homeless with problem substance use.

-

Delivered by four PNs with lived experience of homelessness and/or problem substance use.

-

Delivered in three outreach services in Scotland and three residential services in England.

-

Maximum 12 months in duration (shorter in one setting).

Chapter 2 Intervention

This chapter sets out the key partnerships involved in the SHARPS study and its governance, and provides an overview of the intervention, including its development, the process evaluation and its underpinning framework.

Study team and governance

The team was led by Professor Tessa Parkes and comprised academics from the University of Stirling (CM, HC, MF, IA; and RF), the University of Aberdeen (GM) and the University of Victoria in Canada (BP). The team also comprised non-academic partners from NHS Lothian (JB and AB) and the Scottish Drugs Forum (SDF) (DL and JW). Tessa Parkes, Catriona Matheson, Hannah Carver, Maria Fotopoulou and Rebecca Foster are based in, or affiliated with, the Salvation Army Centre for Addiction Services and Research (SACASR) at the University of Stirling, which receives external funding from The Salvation Army (TSA). Rebecca Foster was the recruited study research fellow. SACASR academics have full academic freedom, but TSA partnership enables collaborative working; the SHARPS study fitted neatly with the ethos and work of TSA in homelessness and problem substance use, and aligned with the research experience and expertise of SACASR academics. TSA was the study’s key third-sector partner, alongside Streetwork (part of Simon Community Scotland) and the Cyrenians (latterly, Change Grow Live).

The study was independently overseen by a Study Steering Group (SSG). A patient and public involvement (PPI) group was also established, comprising individuals with lived experience of homelessness and/or problem substance use, to act as a quality assurance group for the study. Both of these were convened specifically for the SHARPS study for its duration. The PPI group preferred to be named the ‘Experts by Experience’ (EbyE) group; a detailed discussion of PPI is provided in Chapter 7.

The study was managed day to day by a project management team comprising Tessa Parkes, Catriona Matheson, Hannah Carver and Rebecca Foster.

Theoretical/conceptual framework

Normalisation process theory provided a framework for the intervention and process evaluation, being well-placed to support both. 117 NPT is particularly suited to evaluating complex health interventions, and is increasingly used in this sphere,118 by providing a means of understanding and improving the way in which interventions are implemented. 119 There are four components to NPT: coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring. 120 Coherence refers to the process of understanding that individuals/organisations go through to either endorse or prevent an intervention from being embedded into practice; cognitive participation involves enrolling and engaging individuals in the new practice; collective action is the work that individuals/organisations do to embed the new intervention into practice; and reflexive monitoring refers to formal and informal appraisal of the new practice. 119,120 As Murray et al. 117 outline, NPT recognises that health care is collective and requires a range of interactions from different actors, and it provides a framework to help understand how these interactions shape each other and also how they can be optimised. NPT fitted neatly with the complex nature of the SHARPS study and guided the development and implementation of the intervention, as well as the process evaluation.

Peer Navigators

Recruitment

Four part-time (30 hours per week for 18 months) posts were advertised by the lead partner agency, TSA, which employed the PNs. Posts were advertised on TSA’s vacancies web page and the SDF mailing list. As an essential criterion for the role, the PNs were required to have lived experience of homelessness and/or problem substance use. Other requirements included knowledge of the issues commonly faced by those experiencing homelessness and/or problem substance use, experience of working with individuals in these circumstances, genuine compassion for working with those in need, and excellent relational and interpersonal skills.

The PNs were recruited by the Chief Investigator (TP), Jason Wallace and a TSA service manager from each intervention setting, via an application form and interview. Four PNs were successfully recruited. Two PNs were recruited for the Edinburgh and West Lothian settings (see Settings: intervention and standard care), and one was recruited for the Bradford setting. No PNs were recruited from the local Liverpool area, as none of the shortlisted candidates attended the interview. One of the shortlisted candidates for the Bradford setting was offered the role for the Liverpool setting and accepted, with an agreement to be based in Liverpool for part of the working week, with travel and accommodation arranged and paid for by the study.

All appointed PNs underwent a Disclosure and Barring Service/Protecting Vulnerable Groups (PVG) check. The PNs were paid at TSA’s Specialist Support Worker salary scale and afforded the same terms and conditions as other staff in the organisation, including the right to continuing professional development. In its homelessness services, TSA employs a range of staff, including Assistant Support Workers, Support Workers and Specialist Support Workers. Specialist Support Workers carry additional responsibility and have enhanced knowledge/expertise in their area of specialism, for example problem substance use. The PNs started in June 2018; one PN left the role early in January 2019 and three PNs finished in December 2019. All secured further employment before finishing post.

Onboarding, training and support

The PNs received a comprehensive induction and advanced ‘front-loaded’ training in the first 4 months of their posts (June–October 2018). They also received training updates throughout the study, identifying training opportunities of particular interest/use, for example advanced motivational interviewing. ‘Core’ training encompassed areas related to the intervention, the relevance of trauma to substance use behaviour, professional boundaries, naloxone ‘train the trainer’, and therapeutic relationships and PIEs. The PNs also received training and induction to the study, including on recruitment and relevant ethics issues, such as assessing eligibility and obtaining informed consent. A training manual was produced and subsequently refined. Fidelity and adherence to the intervention manual and core components of the intervention were assessed in the interviews with PNs and are discussed in Chapter 6. Fidelity concerns the degree to which an intervention is delivered as it is intended. Adherence is defined in this study as the extent to which the PNs followed the intervention guide. These are related concepts. Although the intervention was ‘manualised’, the study team envisaged and understood that each PN would bring their own experiences and individuality to the intervention, and to their relationships with participants. The feasibility design allowed a diversity of approach to be well explored and reflected on, which is described in Chapters 4–6.

The PNs received regular one-to-one (face-to-face/telephone) clinical supervision with a consultant clinical psychologist with expertise in working with the participant group and supporting staff (AB). A WhatsApp (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) group was created for the PNs; Jason Wallace was also in this group to offer support/advice when required. The PNs were supported on a day-to-day basis by their service managers, Tessa Parkes and the project management team. They were provided with work mobile phones and Chromebook personal computers (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA).

Intervention development

Phase 1 involved development of the bespoke intervention, with associated manual and staff training guidance. The intended purpose of the manual was to provide the PNs with necessary information to carry out their roles, with detailed information about particular concepts/approaches, health and social issues affecting participants, study information, the intervention itself, and key contacts and local information.

An ‘intervention development day’ was held in month 2 (June 2018) to discuss the key components of the intervention and how these would be implemented. At this meeting, there was consensus that the manual should be referred to as a ‘guide’. Following this full-day meeting, the project management team developed draft versions of the intervention and training guidance for circulation to all parties.

The intervention and intervention guide were co-produced by experts in homelessness, inclusion, health, and PIEs and relational interventions; representatives from homelessness and third-sector organisations; people who have experienced homelessness and/or problem substance use; and relevant health/medical professionals, following INVOLVE guidance. 121 The project management team led the writing of the guide and sought and received reviews from the following key individuals/groups: the wider co-investigator team; the SSG; the EbyE group; study PNs; TSA service and regional managers; service and regional managers from partner organisations (Streetwork and the Cyrenians); and other practitioners with relevant expertise, for example in the implementation of PIEs in practice.

Feedback was provided at face-to-face meetings and via e-mail. Some reviews were light touch or focused on specific sections, whereas others were more in-depth or cross-cutting. The guide was finalised in September 2018 and entitled ‘Peer Navigators – Navigating People towards Health’. Hard copies were given to the PNs and service managers, the chairperson of the SSG and TSA leaders.

As part of their induction and training, the PNs were also asked to develop their own ‘local directories’, which were inserted into their guide. The exercise of compiling the directories helped familiarise the PNs to the areas in which they were working, which were generally fairly new or unknown. The PNs were supported in the development of these directories by the project management team.

After the guide was finalised, and shortly before they began to recruit their participants, the PNs were asked to read the full guide and Tessa Parkes had an individual follow-up telephone call to ensure that they were familiar with the guide’s content, to help ensure fidelity and adherence. The project management team developed a ‘guide insert’ for the substantial change to the quantitative data collection (see Chapter 3, Alterations to quantitative data collection). The intervention organically evolved; some changes and adaptations occurred, but none was major and no additional guide inserts were developed.

Overview of intervention

The key feature of the intervention was the relationship between the PN and their participants, with the aim of developing relationships that were positive, trusting and non-judgemental. Trust is a broad term and concept. As informed by the literature described in Chapter 1, as well as the literature on therapeutic relationships,122 we defined a ‘trusting relationship’ as a relationship in which the participants had a belief that their PN was working in their best interests, felt that they could rely on their PN, and felt able to make disclosures to their PN and generally felt safe with them.

When participants were recruited to the intervention, the PNs worked with each individual to identify unique support needs. This enabled the PN to, for example, make referrals, support participants to attend appointments (e.g. GP, dentist), and support participants to build relationships with new services including drug/alcohol services. The PNs provided emotional support to participants in a range of ways, including spending time with them and listening to their stories and the challenges they were experiencing. Two PNs also facilitated weekly biopsychosocial groups in a service, which were available to all service users and staff, and often included some of their participants.

As part of the proposal development work, EbyE advisers were consulted by Jason Wallace; the importance of practical financial support to attend appointments was highlighted. To provide participants with such support, the PNs had access to a fund in their services. Up to £10,000 was available and was split equally among the services, which translated as £2500 per PN. This was primarily used to pay for travel and food/hot drinks, but the PNs were also able to draw from this to buy or pay for useful ‘extras’, including clothes, stamps, essential telephone calls, essentials while participants were in prison, emergency electricity and gas power, and household appliances to help maintain new tenancies. A guidance document was shared to advise the PNs and service staff on spend [see the guidance document on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1615314/#/documentation (accessed 2 December 2020)].

Participants received the intervention for up to 12 months (2–12 months, depending on the setting). They were not withdrawn by PNs or the study team on the basis of either continued problem substance use or abstinence. Towards the end of the intervention, the PNs had conversations with participants to identify a ‘winding-down’ strategy that would ensure that their support needs were met in the run up to the end of the intervention, as well as afterwards when they were no longer working with their PN.

The experiences of the intervention from all perspectives (participants, PNs and staff in services) are described in detail in Chapter 5. The case studies prepared by the PNs and the project management team also offer insights into the nature and breadth of support the PNs provided (see Appendix 2).

Settings: intervention and standard care

Three homeless outreach services in Lothian, Scotland, and three Lifehouses (TSA hostels) in Liverpool and Bradford, England, were chosen for the implementation of this intervention. The team developed this partnership with TSA (as introduced in Study team and governance) and developed new partnerships with other leading third-sector organisations.

All hosting services were non-profit, third-sector housing organisations. Three homeless outreach services in Lothian, Scotland, and three TSA hostels in England were selected as intervention settings. Two PNs were based in settings in Scotland, and two PNs were based in settings in England. In the Scottish settings, the two PNs had a base in a TSA setting (Niddry Street), but each also worked in another setting managed by different third-sector providers: Streetwork (Edinburgh) and Cyrenians (West Lothian). The decision to include both outreach and residential services enabled exploration of different models of working and consideration of potential fit. One PN was based in Liverpool and worked across two TSA Lifehouses. Another PN was based in a Lifehouse in Bradford (see Intervention settings).

To enable the study to assess differences between intervention and non-intervention care pathways, we identified two standard care settings (an outreach service in Scotland and a Lifehouse in England) that were similar to the intervention sites (e.g. third sector/type of funding/types of staff roles, numbers in place/aims of service). Whether or not the settings were completely comparable was explored in the process evaluation. As non-statutory, third-sector services developed to meet the needs of specific populations, it is highly unlikely that any two services are completely comparable, which applies to all settings.

In the two standard care sites, the same health check measures were conducted with a sample of residents/service users to assess any particular population differences and the feasibility and acceptability of use of these measures among these participants, which were conducted with a researcher, without a PN present to offer any support if needed. We also undertook non-participant observation in both intervention and standard care sites to document similarities and differences. Interrogating the role of context was key to our understanding of how the intervention works, most specifically in terms of the role of each of the services in hosting the PNs and the study, and particular facilitators of and barriers to the intervention.

All chosen settings catered for individuals who are vulnerable and disadvantaged, with a particular focus on those experiencing homelessness and problem substance use. All offered a range of support based on their areas of expertise, and the needs of their service users/residents; this responsive support means that the level/nature of support offered by each setting continually evolved.

Intervention settings

-

Streetwork, Edinburgh, Scotland (Simon Community Scotland): outreach service.

-

Niddry Street Wellbeing Centre, Edinburgh, Scotland (TSA): outreach service.

-

Pre-Sync 27 Recovery Hub, Bathgate, West Lothian (Cyrenians); managed by Change Grow Live from April 2019: outreach service.

-

The Orchard Day Shelter and Lifehouse, Bradford, England (TSA): residential service.

-

Darbyshire House/Ann Fowler House, Liverpool, England (TSA): residential services.

Standard care settings

-

Greenock Floating Support Service, Greenock, Scotland (TSA): outreach service.

-

Charter Row Lifehouse, Sheffield, England (TSA): residential service.

Process evaluation data collection

The process evaluation was informed by NPT119 and involved mixed-methods data collection. Academic researchers (RF and HC) collected all qualitative and quantitative data, except for interviews with intervention participants, which were conducted by SDF peer researchers (see Chapter 3).

Qualitative data collection involved the following:

-

intervention participants who undertook interviews in wave 1 of peer research interviews (n = 24)

-

intervention participants who undertook interviews in wave 2 of peer research interviews (n = 10)

-

participants who withdrew from the study and completed a short ‘exit’ questionnaire (n = 1)

-

PNs (n = 4), at three or four time points (15 interviews in total)

-

service staff in the intervention settings (n = 12)

-

service staff in the standard care settings (n = 4)

-

intervention participant case studies (n = 6)

-

observations in intervention settings (n = 6)

-

observations in standard care settings (n = 2).

Quantitative data collection consisted of:

-

intervention participants who completed wave 1 of the health check (n = 45)

-

intervention participants who completed wave 2 of the health check (n = 30)

-

standard care participants who completed the health check (n = 6).

Reflexive monitoring: process evaluation

The PNs were invited to complete reflective diaries to capture their personal reflections on the role and challenges experienced (see Chapter 3). Following NPT, and, specifically, the reflexive monitoring component in NPT, the project management team took detailed reflective notes for the full study duration encompassing personal views, experiences and feelings, alongside notes from conversations, meetings and interactions. These insights, alongside the formal data collection, are collectively drawn from in Chapter 6.

Outcome measures: health check

The questionnaires were chosen by the project management team, in consultation with TSA researchers and Atlas (Atlas, Cambridge, UK) developers. Atlas is TSA’s client management system. Questionnaire 1 was developed by the team, and was intended to capture key demographic information about the participants; the team was informed by discussions with the SSG chairperson on multimorbidity,123 as well as previous work by Catriona Matheson on older drug users24 and by Bernie Pauly on managed alcohol programmes. 47 Questionnaires 2–6 are validated questionnaires. The project management team made minor amendments to questionnaire 3 [the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP)] to make it more suitable for the study population, including adding a question on overdose and asking about use of other drugs not included [e.g. novel psychoactive substances (NPSs), such as synthetic cannabinoids (‘spice’)] in section A. There was also the addition of a follow-up question on residence, which asked specifically for how many days participants had lived at their current residence (section D). These adjustments mean that data from the study version of the MAP could not be fully compared with MAP data from similar populations. However, the decision was made to maximise the usefulness of this particular questionnaire for this group.

Questionnaires 2–6 are publicly available. The Substance Use Recovery Evaluator (SURE)124 and the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure125 require approval for use from the owners, which was obtained for both. The SURE and the CARE Measure are designed as self-completion questionnaires. The other measures can be completed by an individual or by a researcher on their behalf. The questionnaires were administered with participants as two ‘holistic’ or ‘whole-person’ health checks, one in the earlier stage of the intervention (November 2018–May 2019) and one at a later stage of the intervention (August–November 2019). Therefore, these questionnaires had a dual purpose of providing the study’s quantitative data and providing the PNs with information about participant health/circumstances:

-

Measure 1 – this questionnaire encompassed questions on sociodemographic characteristics, housing status/quality, general health status, education, medication use and future service use.

-

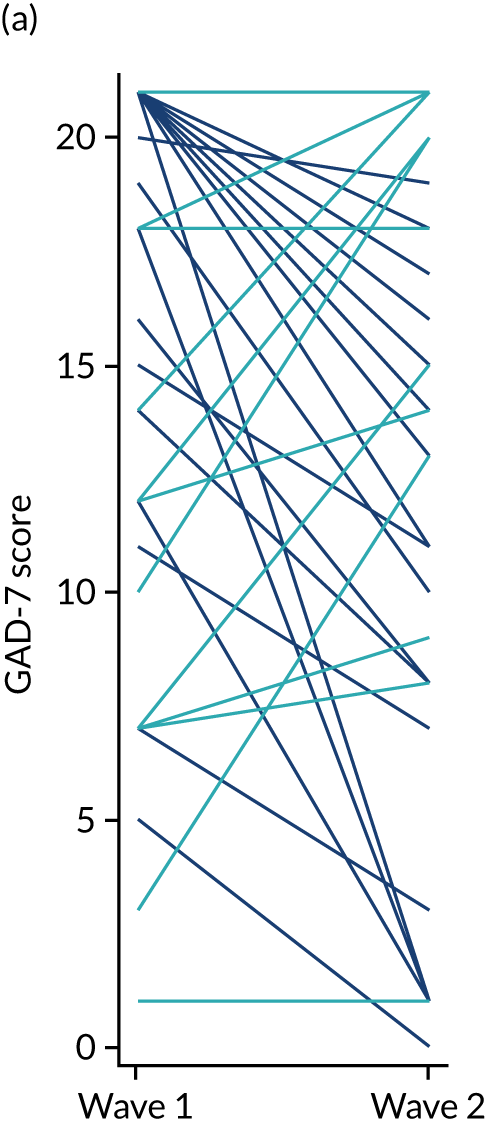

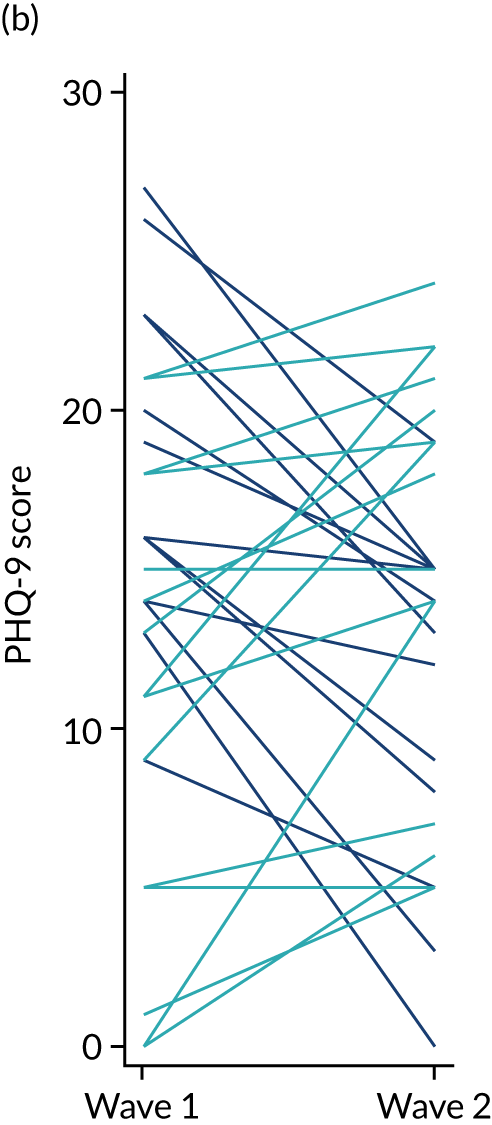

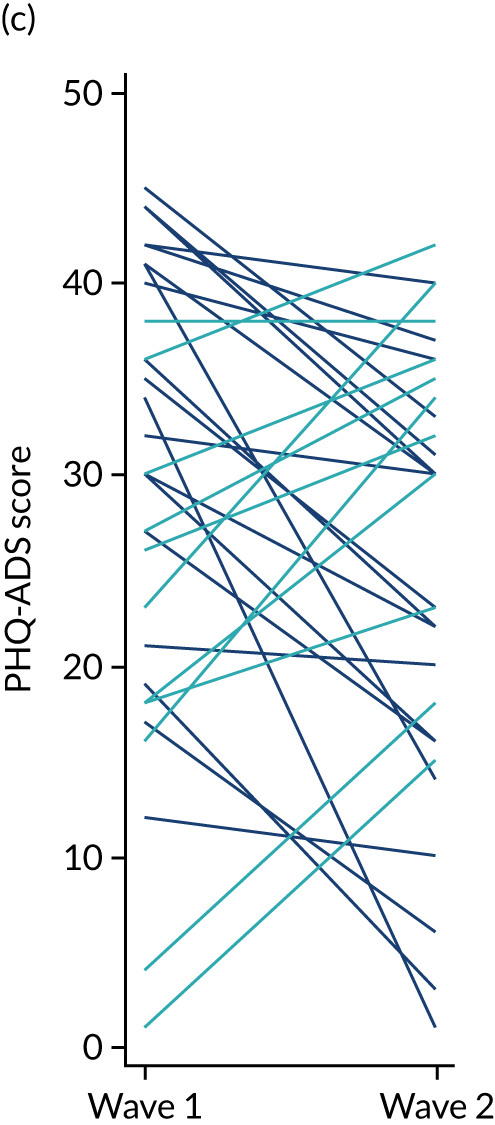

Measure 2 – the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9), a 9-item tool covering symptoms of depression, and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) anxiety and depression scale, a 7-item tool covering symptoms of anxiety. 126,127

-

Measure 3 – the MAP, measuring substance use. 128 The MAP is a 36-item tool covering substance use (type/frequency/method), overdose, treatment, injecting and sexual behaviour, physical and psychological health, social functioning, relationships and illegal activities.

-

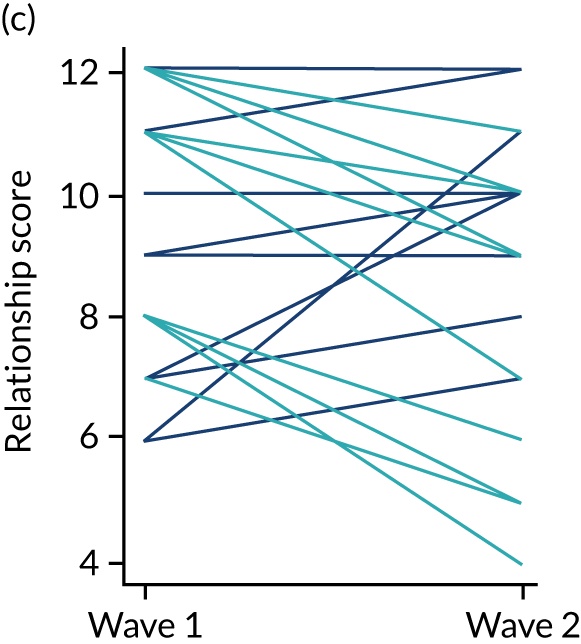

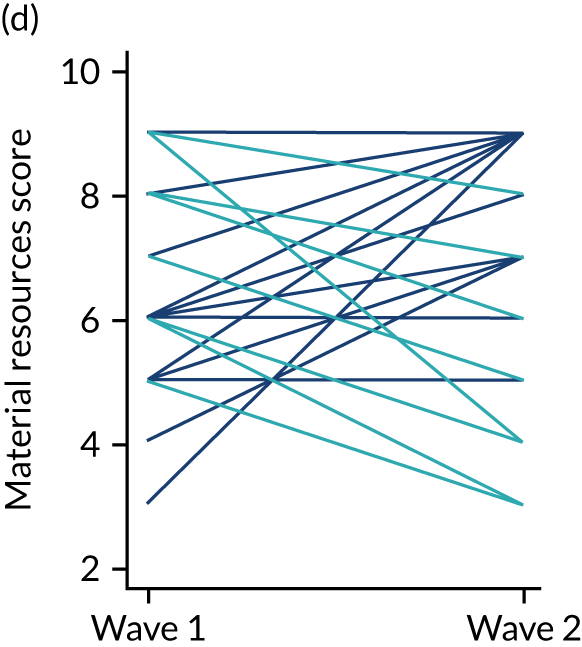

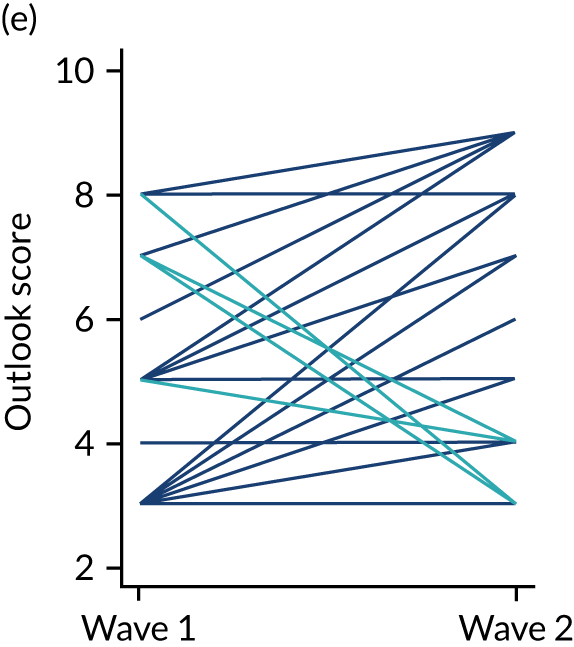

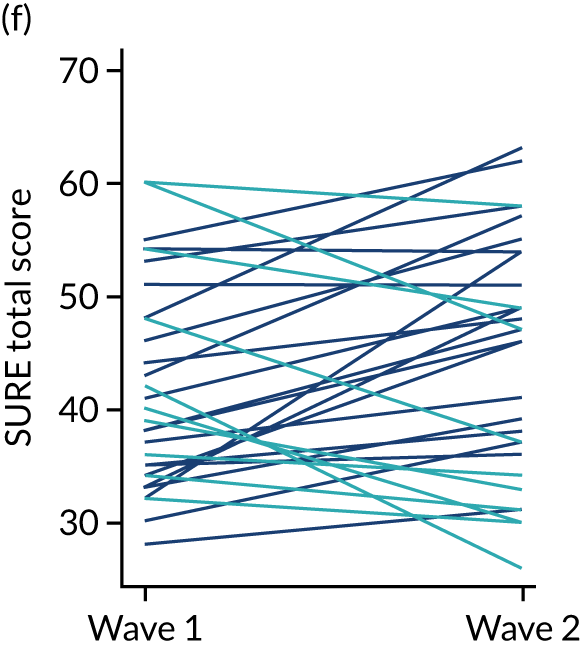

Measure 4 –the SURE,124 a 26-item tool covering drinking and drug use, self-care, relationships, material resources, outlook on life and the importance of each of these items to respondents.

-

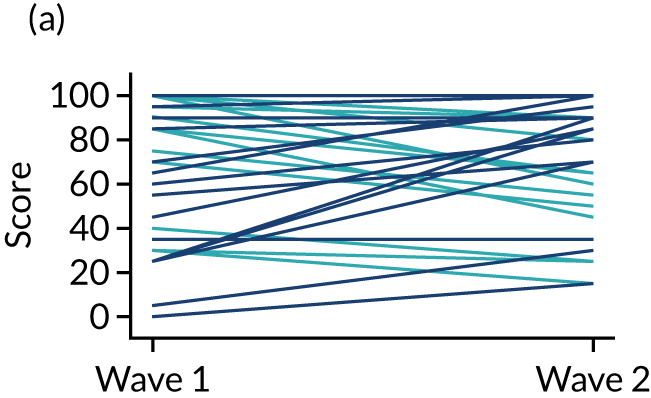

Measure 5 – RAND Corporation Short Form survey-36 items (RAND SF-36),129 a 36-item tool covering physical and emotional health status, the effect of health on daily activities and social activities, and experiences of pain.

-

Measure 6 – the CARE Measure,125 10-item tool assessing empathy in the context of a relationship, to measure the relationship between a participant and their PN.

The list of outcomes and corresponding measures can be found in Table 1.

| Characteristic/outcome | Measure |

|---|---|

| Demographics, living/housing circumstances | Measure 1 |

| Drug and alcohol use | Measure 3 (MAP) and measure 4 (SURE) |

| Mental health | Measure 1, measure 2 (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) and measure 3 (MAP) |

| Physical health | Measure 3 (MAP) and Measure 5 (RAND SF-36) |

| Perceptions/experiences of relationship with PN | Measure 6 (CARE Measure) |

Eligibility criteria for intervention participants

To take part in the intervention, participants had to be:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

homeless or at risk of becoming homeless

-

using drugs and/or alcohol in a way that has a negative impact on their lives (self-identification)

-

able to provide informed consent.

Participants were required to fulfil all inclusion criteria to take part. To capture all forms of precarious housing situations, this study adopted broad definitions of ‘homelessness’ and ‘at risk of homelessness’, as informed by the ETHOS framework. 6 ‘Problem substance use’ was defined as use of drugs and/or alcohol that has a negative impact on an individual’s life. The level and nature of this negative impact varied between individuals; the study was not prescriptive on this. Most participants were experiencing problem substance use that was severe and had a substantial impact on their daily lives. The self-assessment required individuals to recognise that their substance use was affecting their lives in a detrimental way. If an individual did not recognise this, the intervention was not offered (i.e. participant did not receive a participant information sheet), as it was not considered to be appropriate for that individual at that stage. Recruitment and retention are discussed in Chapter 4.

Approvals obtained

The University of Stirling’s NHS, Invasive or Clinical Research (NICR) ethics committee provided ethics approval in April 2018 (NICR 17/18 Paper 35). The ethics subgroup of the Research Coordinating Council of TSA provided ethics approval in June 2018. Four subsequent submissions were made and approved to both committees for approval for protocol changes; the dates are recorded in the trial registry.

Changes to protocol

The final version of the protocol is version 1.6. All changes made to the protocol are set out in Appendix 1, with the majority of changes being minor. The substantive changes involved one PN leaving post early, and a change to quantitative data collection. The latter is discussed in Chapter 3, and the PN’s resignation is discussed in the following section.

Peer Navigator resignation

The Liverpool-based PN resigned from post in November 2018 and left in January 2019, 11 months earlier than the end of their contract, for a combination of personal and professional reasons. The study team, in consultation with TSA and the SSG, did not feel that it was ethical or practical to re-recruit a PN for this vacant post for the remainder of the study period for a number of reasons. The Liverpool-based participants had consented to work with a specific PN with whom they had developed a relationship. The PNs each received a comprehensive 4-month induction: the time taken to recruit and re-offer this would not have been compatible with the tight study time scales. In addition, we had a commitment and responsibility to the other PNs and intervention participants, which meant that the study could not be paused. Taking all considerations into account, the PN offered a shortened 2- to 2.5-month intervention to their participants (n = 9) who were still involved, until mid-January 2019, when they finished in post. The decision was made to cap the case load at nine participants (rather than 15) to maximise the support available to these participants. The PN provided participants with the option to leave the intervention or stay under the shorter intervention terms; all chose the latter. At the end of the intervention, all nine participants were supported to access other support and services and also supported by staff in the Lifehouse.

The health check measures were conducted once with these participants before the PN finished (n = 5). A sample of these participants were interviewed in wave 1 of the peer research interviews (n = 3). Owing to the capped case load, we envisaged that these participants would still benefit from a shortened, but slightly more intensive, version of the intervention. The implications of this are considered in Chapter 6.

Chapter 3 Methods

As part of the feasibility study, we conducted a concurrent process evaluation employing a mixed-methods approach and informed by NPT. 119 The qualitative component involved conducting semistructured interviews with intervention participants, PNs and staff in intervention and standard care settings, alongside conducting non-participant observations in all intervention and standard care settings, collecting intervention participant case studies and reflective diaries kept by the PNs. The quantitative component involved collecting key quantitative data from participants via a range of measures at two time points. As mentioned in Chapter 2, academic researchers (RF and HC) conducted all interviews and observations, except for interviews with intervention participants, which were conducted by SDF peer researchers. Academic researchers (RF and HC) also conducted all quantitative data collection.

Part 1: qualitative data collection

Qualitative interviews with staff and Peer Navigators

The purpose of undertaking interviews with staff and PNs was to explore experiences of, and views on, the intervention from these perspectives, as well as to assess any changes in perceptions and practice over the course of the intervention. The purpose of interviewing members of staff from the standard care settings was to explore views on the potential fit of the PN intervention to these settings [see the interview topic guides on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1615314/#/documentation (accessed 2 December 2020)].

Peer Navigator interviews

When the PN role was advertised, applicants were made aware that an essential criterion for the role would be a willingness to participate in research interviews. The PNs were reminded of this when they were formally offered their positions; all appointed PNs were comfortable with this arrangement.

The intention had been to interview the PNs at three time points over the course of the intervention. Given the additional data collection of the case studies, a fourth interview was conducted with three PNs, who were consulted on this in advance of seeking ethics approval for this change. This additional interview was shorter and focused primarily on the collection of the case studies.

The first interviews took place in the induction/intervention development phase (June–July 2018). The second interviews took place in the middle of the intervention: November 2018 for the PN who left early and April 2019 for the others. The additional third interview took place in June 2019. The final interview for the PN who left early took place in January 2019, and in November 2019 for the others, nearing the end of the full intervention. In this way, the evolving experience of the intervention was captured. Two interviews took place via telephone; the rest were face to face in the intervention settings.

Staff interviews

Twelve members of staff in intervention settings and four members of staff in standard care settings were interviewed. A range of roles were represented in the interview sample, including Assistant Support Worker, Specialist Support Worker and service manager/service lead (or equivalent roles if organisations adopted different terminology). Members of staff had varied professional experience and different backgrounds, both within and beyond health and social care and housing/homelessness. Both male and female members of staff were interviewed and a broad age range was included in the sample.

The intention was to interview two members of staff across the six intervention settings to ensure, as much as possible, an equal representation of views across the intervention sites. We were unable to interview two members of staff in the Liverpool settings, as invitations to interview were not responded to; however, two out of the four originally allocated for the Liverpool settings were still conducted. The decision was made to substitute these interviews with an additional interview with a member of staff from two other intervention settings. All interviews were face to face.

Peer Navigator reflective diaries

The PNs kept reflective diaries from the start of their time in post until the end to capture their views, experiences and feelings. The decision to ask the PNs to complete diaries was in response to proposal reviewer feedback that suggested that diary-keeping could serve as a useful outlet, particularly at times of challenge. The study team shared this view, and also felt that insights shared in these diaries could constitute useful qualitative data. Although these data do not form part of our formal qualitative data collection, and are not discussed in Chapter 5, they were analysed and key themes are drawn from them in Chapter 6 to contextualise the findings.

Approach

Given the data collection and sharing dimension of the diary-keeping, a participant information sheet and consent form were created. It was emphasised to the PNs that completing these reflective diaries was a voluntary exercise. All agreed to keep diaries and to share entries with the project management team. The PNs were invited to complete entries in their preferred format and complete these as frequently as they wished: if they did complete diary entries, this took place during work time. Two PNs typed up reflections in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents, and another two audio-recorded reflections on their mobile phones, which were then transcribed. It was emphasised to the PNs that they could choose what they shared; for example, they could complete a full entry and share only an excerpt from it. The PNs shared their entries in full. A template with some suggested bullet points was created to help facilitate diary-keeping [see the template on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1615314/#/documentation (accessed 2 December 2020)].

Observations

Semistructured, non-participant observations were conducted in all sites to gain an understanding of the culture and context of the settings, staffing levels, client group, activities provided, and fit of the intervention. Observations were also conducted in the standard care settings to provide comparison data. Forty-two hours of observation time was split across all intervention and standard care settings, meaning that ≈ 5 hours of observation were conducted at each setting.

Observations were conducted between June 2018 and June 2019. The observations in the standard care settings were prioritised and took place in the summer of 2018. Observations in the intervention settings required the PNs to be fully inducted and formally working with their participants. Intervention observations took place from October 2018 (start of the intervention) to June 2019.

An observation pro forma was developed to guide these observations [see the pro forma on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1615314/#/documentation (accessed 2 December 2020)]. The key prompts were ‘environment’, ‘social interactions’ and ‘activities’, and a number of subprompts were contained within these. Researchers took posters to all settings [see the observations poster on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1615314/#/documentation (accessed 2 December 2020)] to inform staff and service users/residents about the observations when they were taking place, but they also spent time introducing themselves and the study to service users/residents and staff. Researchers observed communal areas only. Researchers recorded the observations on-site using a notepad and pen; fieldnotes were later typed up, along with any additional reflections.

Case studies

The Salvation Army regularly use case studies to demonstrate its work in clear and accessible ways, and case studies are regular features of TSA briefings, reports and business cases. The study team also felt that case studies could be effective in outlining the range and depth of practical and emotional support PNs provided to their participants, alongside other data collection. After consulting with the PNs and their service managers, the project management team made the decision to develop six case studies with the PNs and a small sample of their participants.

Approach

A researcher (RF) led the collection of these case studies. The PNs were asked to each identify two participants. The decision on which participant(s) to approach was the PNs, but each spoke with Rebecca Foster and their service manager, and the following points were considered:

-

availability of the participant

-

‘distance travelled’ from the start of the relationship to now, and how this presented an opportunity to emphasise this progress to the participant

-

relationship between the PN and the participant, including changes over time

-

type of support the PN offered.

Rebecca Foster asked the PNs to approach two participants to be involved in the case studies, but also to have two ‘in reserve’: all participants approached agreed to be involved and separately provided informed consent. A template was prepared and sent in advance for the PNs to help prepare and to ensure consistency of content. The PNs shared these stories in interviews with Rebecca Foster, which were audio-recorded and transcribed. Rebecca Foster removed/edited identifying details and edited these transcripts to one or two pages to cover the key aspects. Rebecca Foster met the PNs face to face for the PN to review their case studies; each PN made minor edits for accuracy.

Rebecca Foster then met with the pairings of participants and PNs face to face; meetings took place either in the intervention setting or in a participant’s residence, depending on where the participant felt comfortable. Rebecca Foster and the PNs strongly encouraged participants to make changes if they wished to; none did and Rebecca Foster and the PNs were satisfied that participants were content.

Participants chose their own pseudonym, which some seemed to particularly enjoy doing. Rebecca Foster made minor proofreading edits to the case studies; the case studies are presented in Appendix 2. As the case studies were collected as part of interviews with the PNs, these have been analysed alongside other sources of data; the themes arising, along with excerpts, are presented in Chapter 5, and reflected on further in Chapter 6.

Qualitative interviews with intervention participants: peer research

Background and rationale

Peer researchers with lived experience of problem substance use interviewed a sample of intervention participants at one or two time points over the course of the intervention. The aim of the interviews was to examine participant experiences of being involved, focusing on the acceptability of the intervention in their lives and to their circumstances. The purpose of the second wave of interviews was to capture any change, in both an individual’s circumstances and in their relationship with their PN.

In addition, the intention was for peer researchers to interview participants if they withdrew from the study, to understand the underlying reasons for this decision (protocol version 1.0). However, the team decided that this would not be practical, both from the perspective of arranging the data collection and from the perspective of participants who may be experiencing additional challenges, perhaps underlying the decision to withdraw. Instead, we offered participants who withdrew the opportunity to complete an ‘exit’ questionnaire [see the questionnaire on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1615314/#/documentation (accessed 2 December 2020)].

Peer researcher role

The peer researchers who participated in this study were recruited as volunteers for the peer researcher programme organised by the SDF. They received a generic SDF induction and specific training on research, including questionnaire design and interviewing techniques. Peer researchers all undergo a PVG check prior to starting to volunteer. The peer researchers volunteer on research projects in their local area for approximately 1 day per week. They are supported by the SDF’s local user involvement officer and have regular ‘meet-ups’ with other volunteers. The peer researchers can also undertake other training offered by the SDF and other development opportunities.

Peer researchers in study

Eight SDF peer researchers were recruited to the study from this wider pool of peer researchers. Although some of these peer researchers also had experienced homelessness and aspects of severe and multiple disadvantage,10 the only requirements to be a peer researcher for the SHARPS study was that they had lived experience of problem substance use and were committed to supporting the study. Each peer researcher’s experiences with substances were unique, and each was at a different stage of their journey. The peer researchers also had varied research experience. Recruitment was informal and via one of the SDF’s user involvement officers. Academic researchers did not meet the peer researchers until the training session or on the data collection days.

The SDF convene two peer research groups in different areas of Scotland. The project management team did not have a preference regarding which group the peer researchers were from, as the budget was sufficient to allow for travel from either location. This flexibility made it easier for the user involvement officer to gender-balance the pairings or ‘threes’ of peer researchers who were involved in each data collection session. This was important given that the study included women participants, with gendered needs and experiences and, traditionally, with less visibility in services. 20,130 There was an attempt for the pool of researchers to be as consistent as possible, but the changing circumstances of people’s lives made this difficult. Some of the peer researchers did more than one session (some multiple sessions), but others did only one.

Onboarding and training of peer researchers

An academic researcher (HC) led a training session in January 2019 with two peer researchers who undertook the Liverpool data collection session. This involved giving a detailed introduction to the study and reviewing all participant materials, and the topic guide [see the topic guide on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1615314/#/documentation (accessed 2 December 2020)]. This also involved practising using the topic guide and the audio-recorders. Hannah Carver gave a presentation and all peer researchers were given a SHARPS study information booklet specifically designed for them, either at this training session or on site. This booklet introduced the SHARPS study and explained the important role of peer research within it. At the January training session, the peer researchers present reviewed the topic guide (which had previously been reviewed by the EbyE group and amended following the group’s feedback) and minor amendments were made. The participant topic guide was therefore strengthened from receiving two separate reviews by people with relevant lived experience.

The user involvement officer refreshed the training in advance of the sessions and academic researchers were available to provide additional information on the study and to answer any questions.

Participant recruitment

At recruitment to the intervention, participants were informed about another associated data collection element of the study prior to providing informed consent to participate: two semistructured qualitative interviews. This information was conveyed in a participant information sheet for the intervention itself (see Chapter 4 for an overview of intervention participant recruitment and the participant information sheet). The PNs reminded participants about this opportunity once the intervention was under way.

Academic researchers worked with the PNs to identify participants interested in taking part, taking account of inclusion criteria. For example, researchers asked the PNs to encourage some of their women participants to take part in these interviews, to ensure gendered experiences were captured. However, given the challenging circumstances experienced by many participants, a pragmatic approach was also adopted: the opportunity to take part in the peer research was made available to all participants so that no participant was denied this opportunity.

Participant interviews: waves 1 and 2

Wave 1 took place in the different settings between January and March 2019. Interviews were conducted with 24 intervention participants in wave 1. Wave 2 took place in the different settings between August and September 2019. The interviews were not re-attempted in the Liverpool site, given the shortened intervention there. Interviews were conducted with 10 participants in wave 2, out of a potential total of 21, taking out the participants who received the shortened intervention. The reasons for not being able to re-interview the participants were varied and included being in custody, being physically or mentally unwell, securing employment incompatible with scheduled interview times, or participants having less contact with PNs at the time of wave 2.

Data collection approach

Although the interviews were intended to be mid-length (20–40 minutes), most were shorter than this: on average, ≈15 minutes. The peer researchers were responsible for explaining the participant information sheet to participants, answering any questions prospective participants may have had, and gaining written informed consent from participants via a consent form. The PNs sometimes also reviewed the participant information sheet with participants in advance as they gave them more information about this opportunity, but this was not done on all occasions.

For all of the peer research data collection periods, the user involvement officer and an academic researcher were present, along with the PNs who supported their participants to attend. All of the services had private spaces in which to conduct the interviews, although access to these spaces was often limited, so they were pre-booked. After a peer researcher completed an interview, they handed over the consent form and audio-recording to an academic researcher, who then immediately uploaded the recording to their secure laptops and deleted the recording from the audio-recorder.

Reimbursement: peer researchers and participants

The SDF pays travel expenses for peer researcher volunteers, but does not reimburse them for their time, given that it is a voluntary role. The study budget covered travel, accommodation and subsistence expenses. The peer researchers were also given a £20 voucher per day to acknowledge their contribution to the SHARPS study, and this included their participation in meetings, interviews and in the analysis. Interview participants received a £10 voucher as a ‘thank-you’ for taking part in an interview. They received another £10 voucher if they completed a second interview.

The vouchers paid to both participants and the peer researchers were One4All® vouchers (The Gift Voucher Shop Ltd, Hemel Hempstead, UK), which can be used in store and online in a range of shops, excluding supermarkets. The monetary value was considered very carefully, as we did not wish to unduly persuade both groups to be involved in the study in these capacities, but we wanted to demonstrate that we valued individuals’ contributions. We hope that this balance was struck appropriately, but we also know that these tensions are recognised and discussions in the field are ongoing. 131

Debrief

The SDF peer researchers were sent thank-you cards after each wave of data collection. The intention was to involve the peer researchers in the analysis of a sample of the wave 1 interviews prior to wave 2 (see Appendix 1 for protocol changes). This meeting was cancelled owing to lack of peer researcher availability; instead, the EbyE group reviewed transcripts. The team still wanted to get the peer researchers’ perspectives on these interviews, so the decision was made to hold a meeting after both waves were complete, and to combine this with a general debrief/wrapping-up. A study researcher (RF) led this meeting, supported by the user involvement officer (in December 2019).

Qualitative data analysis

The framework method132 was used for the management and analysis of all qualitative data because of its ability to support the analysis of the six different settings as cases and because it allows straightforward within-case and between-case comparison. The framework method involves five stages: (1) familiarisation, whereby the transcripts are read multiple times; (2) identifying a thematic framework whereby the researchers recognise emerging themes in the data set; (3) indexing, which involves identifying data that correspond to a theme; (4) charting, in which the specific pieces of data are arranged in tables according to themes; and (5) mapping and interpretation, involving analysis of key characteristics in the tables and providing an interpretation of the data set. All stages were closely followed.

All qualitative data were analysed with the support of the computer software package NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), with some manual coding of staff interviews piloting the approach. The staff interviews from all settings were analysed together, and the views and experiences from intervention and standard care settings compared. The interviews from all PNs were analysed together. The peer researcher interviews were analysed together (waves 1 and 2 were combined). As we collected data at different time points with both PNs and participants, the data analysis sought to specifically explore whether or not, and how, perceptions of the intervention, and of its challenges and benefits, changed over time. Data analysis was iterative throughout phases 1 and 2 of the study, supported by the use of NPT119 to identify contextual influences on the implementation of the intervention across the different settings. The application of NPT to the analysis is discussed in Chapter 5.

In addition to their other roles as outlined (see Chapters 4 and 5 for detailed accounts of EbyE group role), the EbyE group and study peer researchers were invited to participate in the data analysis and interpretation, supported by the study team. This acted as a form of ‘member checking’ to enhance the validity and trustworthiness of the findings. 133 At face-to-face meetings, these individuals were provided with an anonymised selection of interview transcripts and asked to provide their interpretations of the themes arising and their significance. These were then discussed in the meeting. Although the analysis at these meetings was very light touch, the themes raised were consistent with the themes identified by the academic researchers, enabling a consensus to be built on the themes from the data from these varied perspectives. 134

Part 2: quantitative data collection – holistic/‘whole-person’ health check

Introduction

As well as the qualitative data, a key part of the process evaluation involved the collection of quantitative data from participants via six questionnaires. As noted in Chapter 2, the completion of these questionnaires had a dual purpose of providing information about the health and circumstances of participants to the PNs and providing quantitative data for the study. Participants were asked to complete these questionnaires at two time points over the course of the intervention: once towards the beginning and the second towards the end. These were the ‘outcome measures’ for the study and were colloquially referred to by the PNs and researchers as ‘doing the measures’, as reflected in some of the interviews. Participants consented to undertake these measures as part of the consent process for participating in the intervention. A sample of service users/residents in the standard care settings were also asked to complete the quantitative measures (n = 6).

As well as providing key quantitative data, the purpose of conducting these measures was to assess the acceptability and feasibility of the data collection, and the selected measures (see Chapter 6). The purpose of undertaking these questionnaires with a sample of standard care service users/residents was to assess the acceptability and feasibility of conducting these with individuals who were not working with a PN, as well as to provide an indication of the comparability of the populations. Standard care participants took part in a short follow-up feedback exercise (of 5 minutes) with the researcher to share their views on the measures and the process.

Alterations to quantitative data collection

The original proposal was for the PNs to complete the questionnaires with each of their participants. This was intended to take place over a 2-week period at the beginning of the intervention, and then repeated towards the end. The information provided from the quantitative measures had a dual purpose, given that it informed participant support plans.

The intention was that the PNs would complete questionnaires 1–5 with the participants in a relational way using TSA’s Atlas client management system on their Chromebooks. The participants would be able to see the questions and their responses on the screen. As informed by the accompanying guidance for the CARE Measure, questionnaire 6 would be completed separately and by the participants themselves, with the aim of encouraging honest feedback on their relationship with their PN.

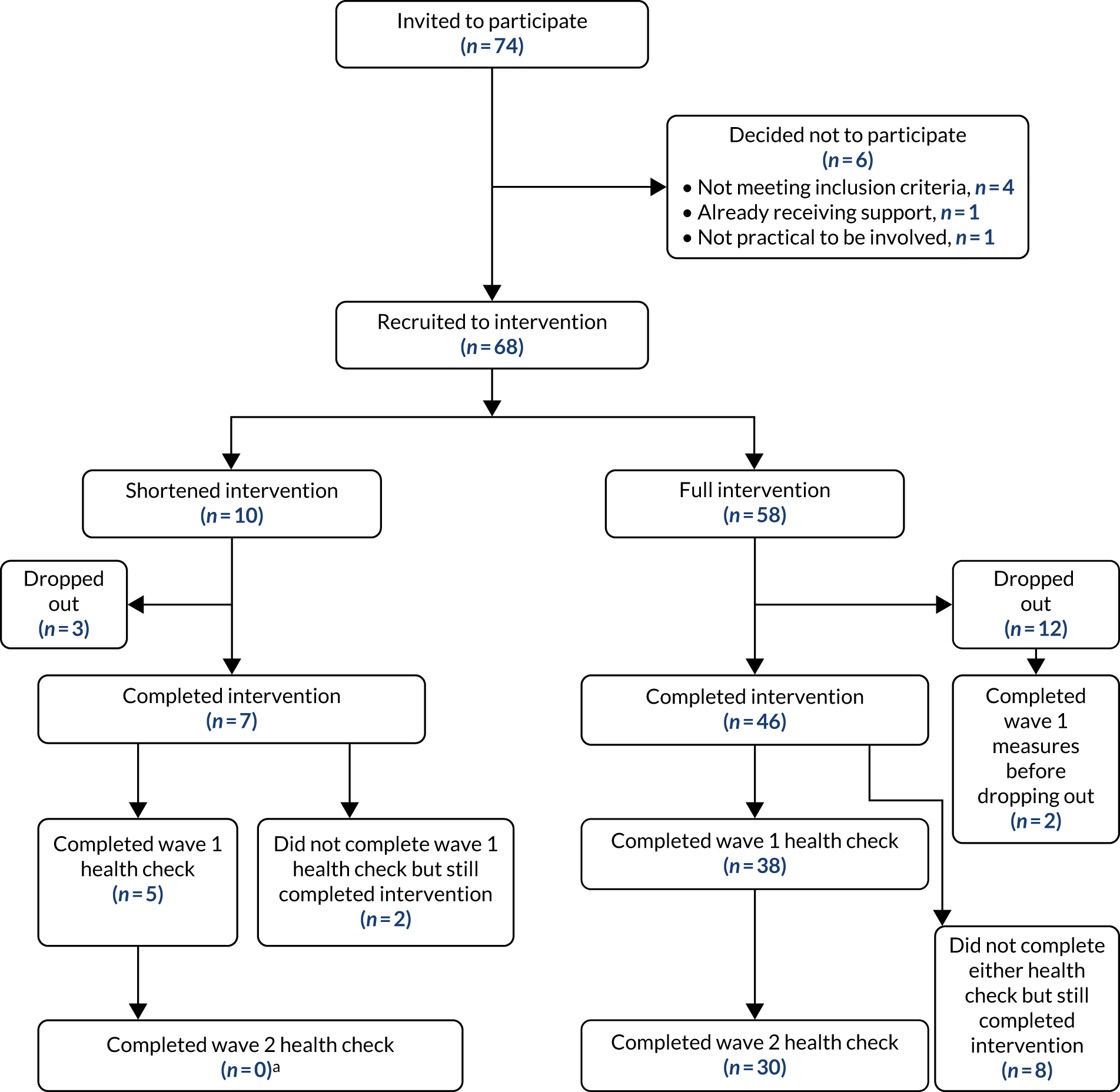

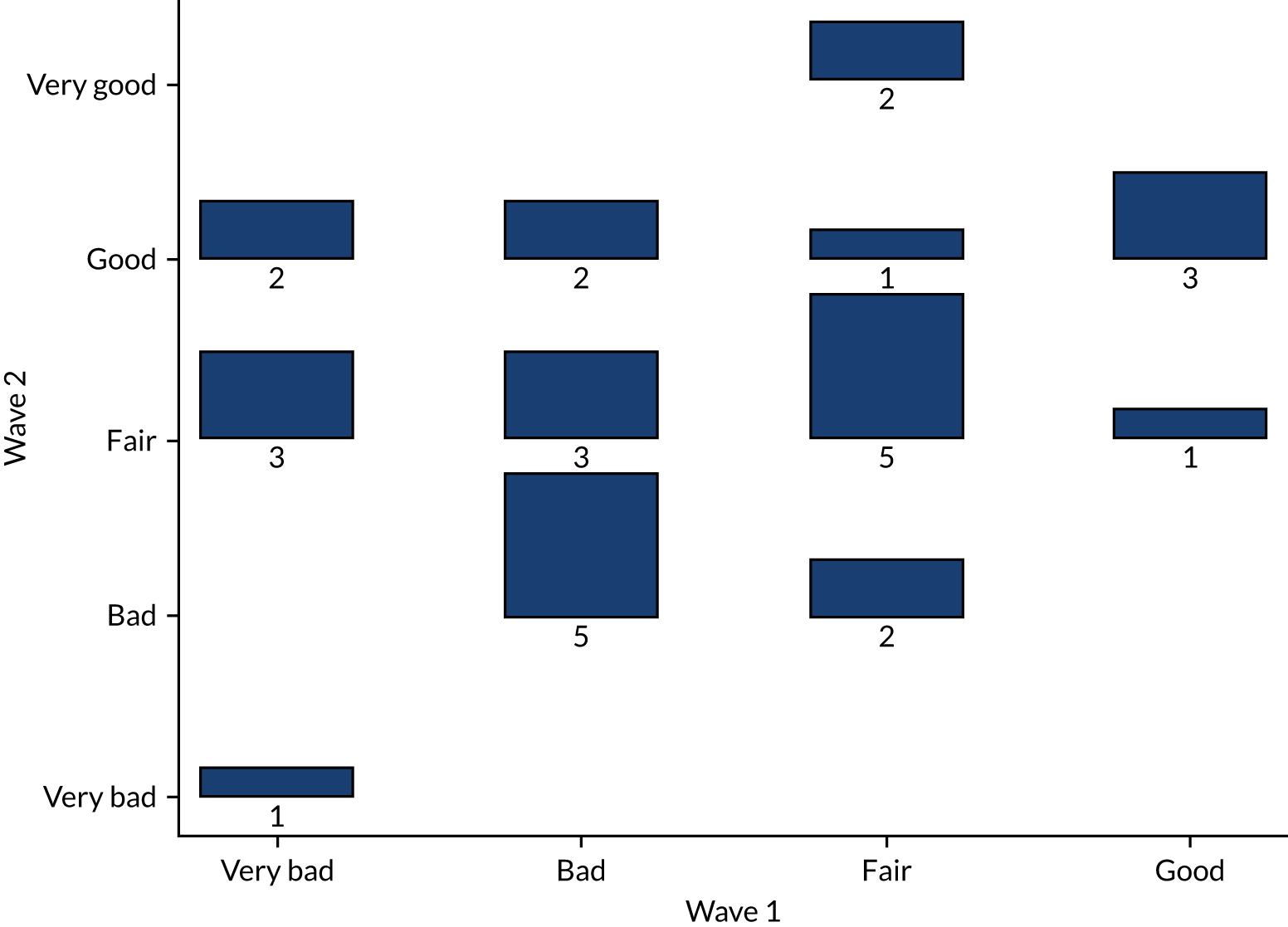

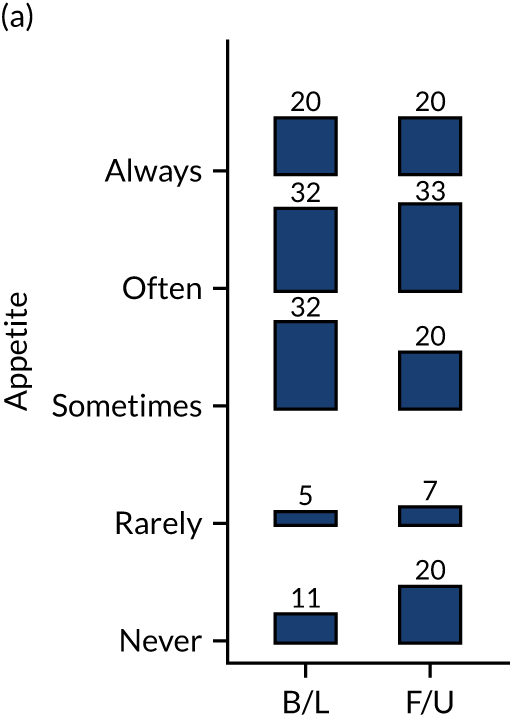

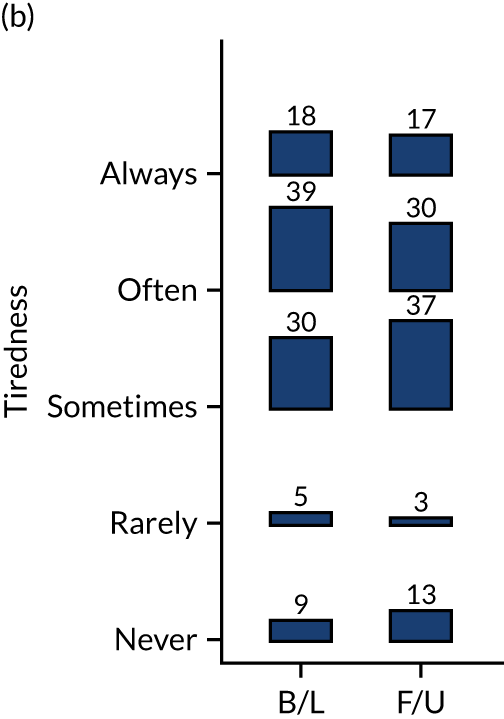

The Salvation Army Atlas developers created a bespoke version of Atlas for the SHARPS study, with measures uploaded. An Atlas expert delivered training to the PNs, the project management team and the Scottish TSA service managers. The training provided a detailed description of how to use Atlas and a half day was spent practising the questionnaires using Atlas before the PNs practised further themselves.