Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/01/47. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The draft report began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Brunt et al. This work was produced by Brunt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Brunt et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report are reproduced or adapted with permission from Brunt et al. 2020,1 Brunt et al. 20212 and Brunt et al. 2016. 3 Sections of this report have also been reproduced from the FAST-Forward study protocol document, available from the NIHR Funding and Awards website. 4 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Breast cancer and the multidisciplinary team

Breast cancer is globally the most commonly occurring cancer in women with over 2 million new cases in 2018, including 58,000 in the UK. It is rare in men, with around 300–400 cases per year in the UK. Since the early 1990s, breast cancer incidence rates in females have increased by around a quarter (24%). 5 Despite increased incidence, UK mortality rates from breast cancer have fallen, due to advances in all aspects of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, including radiotherapy (RT).

Breast cancer usually presents as symptoms such as a lump, nipple changes or a finding of an abnormal mammogram. Patients are generally assessed in a specific Breast clinic where they have a triple assessment involving clinical assessment, imaging (mammography/ultrasound) and a biopsy. A plan for treatment is then made in a multidisciplinary meeting which nearly always involves surgery to resect the cancer. In the modern era this is a wide local excision (breast-conserving therapy), or a mastectomy, along with nodal surgery. The resected tissue is examined by a pathologist to determine the size, grade, type, receptor profile and resection margins of the cancer along with other features. The lymph nodes may be selectively sampled (sentinel node biopsy) or all removed if involved (axillary clearance).

In larger, or more biologically aggressive cancers [triple negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) positive] chemotherapy is now often given prior to surgery to downstage the cancer in the breast and the axilla, and to assess response to therapy, which may well alter subsequent treatment, including surgery, post-operative drug therapy and RT. Similarly in larger hormone receptor-positive HER-2 negative cancers, upfront antihormonal therapy may be given with similar intent. However, surgery is still used after the neoadjuvant therapy to remove any remaining cancer and to assess residual cancer burden.

Benefits and adverse effects of radiotherapy for patients with breast cancer

Radiotherapy uses high-energy X-rays to destroy cancer cells remaining in the breast after the main lump has been removed. Many studies have shown that this treatment substantially reduces the risk of cancer recurring in the breast and or lymph glands and improves overall survival. A meta-analysis from the Early Breast Cancer Trials Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) showed that after breast-conserving surgery, RT reduces relapse and breast cancer death. 6 Increased risk of local relapse is associated with age under 50 years and grade 3 cancers. Other risk factors include cancer size, cancer biology, negative hormonal receptor status, HER-2 positive status, the presence of lymphovascular invasion and axillary node involvement. The absolute benefits of RT are greatest in those with the highest risk factors. The EBCTCG meta-analysis included individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials of RT versus no RT after breast-conserving surgery, 8337 of whom had pathologically confirmed node-negative (pN0) or node-positive (pN+) disease. Overall, RT reduced the 10-year risk of any (i.e. locoregional or distant) first relapse from 35.0% to 19.3% [absolute reduction 15.7%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 13.7 to 17.7; 2p < 0.00001] and reduced the 15-year risk of breast cancer death from 25.2% to 21.4% (absolute reduction 3.8%, 1.6–6.0; 2p = 0.00005). In women with pN0 disease (n = 7287), RT reduced the first relapse risk from 31.0% to 15.6% (absolute relapse reduction 15.4%, 13.2 to 17.6; 2p < 0.00001) and risk of breast cancer death from 20.5% to 17.2% (absolute mortality reduction 3.3%, 0.8 to 5.8; 2p = 0.005), respectively. In these women with pN0 disease, the absolute relapse reduction varied according to age, grade, oestrogen-receptor (ER) status, tamoxifen use and the extent of surgery. These characteristics were used to predict large (≥ 20%), intermediate (10–19%), or lower (< 10%) absolute reductions in the 10-year relapse risk. The absolute reductions in 15-year risk of breast cancer death in these three prediction categories were 7.8% (95% CI 3.1 to 12.5), 1.1% (–2.0 to 4.2) and 0.1% (–7.5 to 7.7), respectively (trend in absolute mortality reduction 2p = 0.03). In the smaller number of women with pN+ disease (n = 1050), RT reduced the 10-year relapse risk from 63.7% to 42.5% (absolute reduction 21.2%, 95% CI 14.5 to 27.9; 2p < 0.00001) and the 15-year risk of breast cancer death from 51.3% to 42.8% (absolute reduction 8.5%, 1.8–15.2; 2p = 0.01). Overall, about one breast cancer death was avoided by year 15 for every four relapses avoided by year 10. The mortality reduction did not differ significantly from this overall relationship in any of the three prediction categories for pN0 disease or for pN+ disease.

Stepwise improvements in many aspects of patient management have led to a steady reduction in the absolute risk of relapse and death for patients over the decades. This reduction is due to many factors such as improved screening, better surgery with closer adherence to guidelines on achieving negative margins and advances in systemic therapy and RT techniques. A local relapse risk of around 2% at 5 years is a reasonable target to aim for in the current era, although the absolute risk will be higher in younger patients with grade 3 tumours and may be lower in elderly patients with grade 1 tumours. Currently patients at extremely low risk of relapse following surgery are commonly recommended no adjuvant RT based on studies such as PRIME. 7

The absolute benefit of RT for each patient is considered by the multidisciplinary team based on the biological and pathological staging of the tumour, type of surgery and patient factors, including age and comorbidities. The main short-term side effects of RT are tiredness, skin colour changes, discomfort and swelling (oedema). Long-term side effects may develop over many years following RT and these are thought to be due to damage to the small blood vessels supplying tissue that has been irradiated. Long-term side effects include the following: (1) skin changes, where the treatment area appears permanently tanned after treatment has finished, although this is not harmful. Later, the skin might appear to have very tiny broken veins in the skin called telangiectasia. (2) Breast shrinkage or distortion; RT can make the breast tissue contract so that the breast gradually gets smaller. This can happen to natural breast tissue or a reconstructed breast. An implant in a reconstructed breast can become hard (capsular contracture) and may need replacing. (3) Breast induration, where the breast feels hard and less stretchy; this is due to a side effect called radiation fibrosis. (4) Cough and breathlessness may occur in some patients who have RT to the chest area although this is not common. The problems are due to changes in the lung tissue called chronic radiation pneumonitis. They might start many months or a few years after treatment. The chances of this happening increase if the volume of lung irradiated increases, or if the patient has pre-existing lung conditions. (5) Irradiation of the ribs or clavicle may lead to radiation osteitis or rarely to osteoradionecrosis which may cause non-healing fractures. (6) Radiotherapy may cause nerve damage in the arm on the treated side, which can develop many years after treatment. Symptoms include tingling, numbness, pain, and weakness, and in some people it may cause some loss of movement in the arm and shoulder. This is extremely rare with modern RT. (7) Radiotherapy treatment may cause another type of cancer in many years’ time. These include lung cancers, especially in smokers, and the rare angiosarcoma.

Partial breast radiotherapy in low relapse risk patient subgroups

Instead of irradiating the whole breast, partial-breast RT restricted to the region of the original tumour in low relapse risk patients reduces the morbidity of RT without compromising its ability to cure the cancer. This technique is based on international reports of reductions in local relapse incidence, and the recognition that the majority of ipsilateral local relapses occur close to the region of the index tumour (the so-called tumour bed). Several studies have assessed partial-breast RT compared with whole breast RT. 8–12 Most of them show comparable rates of local control in patients receiving partial-breast RT compared with whole breast RT. However, most of the studies not only compared partial versus whole breast RT, but also used differing RT techniques and doses in the treatment groups, making toxicity comparisons difficult.

IMPORT LOW was a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial comparing the safety and efficacy of standard whole breast RT (control, whole breast group) with experimental schedules of RT to the whole breast and partial breast (reduced-dose group), and to the partial breast only (partial-breast group). 12 Patients assigned to whole breast RT (control) received 40 Gy in 15 fractions (daily doses) to the whole breast. Those assigned to the reduced-dose group received 36 Gy in 15 fractions to the whole breast and 40 Gy in 15 fractions to the partial breast containing the tumour bed, and those assigned to the partial-breast group received 40 Gy in 15 fractions to the partial breast only. Women who were aged 50 years or older who had breast-conserving surgery for unifocal invasive ductal adenocarcinoma (excluding invasive carcinoma of classical lobular type) of any grade (1–3) were recruited. Other inclusion criteria were pathological tumour size of 3 cm or less (pT1–2), axillary lymph-node negative or one to three positive lymph nodes (pN0–1), and a minimum microscopic margins of non-cancerous tissue of 2 mm or more. A total of 2018 patients were randomly assigned to the three groups, with around 670 patients per group. Patients were clinically assessed yearly for local relapse and toxicity, and around half completed questionnaires included self-assessments of side effects and health-related quality of life. After a median follow-up of 72.2 months, local relapse had been reported for 18 patients, nine (1%) of whom were in the whole breast group, three (< 1%) in the reduced-dose group, and six (1%) in the partial-breast group. The 5-year estimated cumulative incidence of local relapse was 1.1% (95% CI 0.5 to 2.3) in the whole breast group, 0.2% (95% CI 0.02 to 1.2) in the reduced-dose group, and 0.5% (95% CI 0.2 to 1.4) in the partial-breast group. At 5 years patients reported fewer moderate or marked normal tissue effects (NTE) in terms of skin change, change in overall breast appearance, breast being smaller, and breast being harder or firmer to touch in the partial-breast group than in the whole breast group although this reduction was statistically significant for change in breast appearance only (p < 0.0001). At 5 years, change in breast appearance had the highest cumulative incidence of items reported as moderate or marked by patients in all groups. Reports of breast becoming harder or firmer were significantly reduced in both the reduced-dose group (p = 0.002) and partial-breast group (p < 0.0001) compared with the whole breast group. The conclusions from IMPORT LOW were that for patients over 50, with smaller, generally lymph node-negative breast cancer, partial-breast RT was non-inferior to whole breast RT with regards local control and had less toxicity. Reduced-volume breast cancer treatment will also reduce lung and cardiac doses. Follow-up to 10 years is ongoing in the IMPORT LOW trial to collect data on longer-term efficacy and toxicity outcomes.

The control arm in IMPORT LOW was 40 Gy in 15 fractions to whole breast, which has been adopted as the standard of care for partial-breast RT. The control arm for the FAST-Forward Trial was the same. Therefore, if the 40 Gy/15 fractions schedule was found to be isoeffective for either of the test arms, then it was deemed that this would also be the same for partial-breast RT. It would make no biological sense to have different fractionation schedules with reduced-field RT (partial-breast). For FAST-Forward whole breast RT was still the standard-of-care when the study was conceived and recruiting.

Simplifying radiotherapy dose schedules for patients with breast cancer

For many years, and still in some countries, the international standard regimen for whole breast RT delivers a total dose of 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks following surgical resection of primary tumour in women with early breast cancer. Attempts to reduce the number of fractions in the 1970s made inadequate downward adjustments to total dose, resulting in unacceptable rates of late complications. 13 These miscalculations inhibited further research in breast RT fractionation for decades, but interest in fewer larger fractions delivered over a shorter overall treatment time has been rekindled by randomised clinical trials based on a better understanding of normal tissue and tumour responses (radiobiology). Fractionation sensitivity describes responses of normal and malignant tissues to RT fraction size and is quantified in terms of the α/β ratio, expressed in Gy. The lower the α/β ratio, the greater the effect on normal and malignant tissues of changes in fraction size.

Four randomised trials involving a total of > 8000 women have compared a lower total dose in fewer larger fractions against 50 Gy in 25 fractions, and all have reported favourable results in terms of local tumour control and late adverse effects (AE). 14–18 The Royal Marsden Hospital/Gloucestershire Oncology Centre (now sometimes referred to as START-P) and Ontario Clinical Oncology Group (OCOG) trials totalling 2644 women with mainly axillary lymph node-negative tumours < 5 cm diameter were the subject of a 2008 Cochrane review of altered RT fractionation in early breast cancer. 19 Radiotherapy fractions larger than 2.0 Gy did not appear to affect: (1) local relapse-free survival (absolute difference 0.4%, 95% CI −1.5% to 2.4%), (2) breast appearance [risk ratio (RR) 1.01, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.17; p = 0.86], (3) survival at 5 years (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.19; p = 0.75), (4) late skin toxicity at 5 years (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.22; p = 0.98 or (5) late radiation toxicity in subcutaneous tissue (RR 1.0, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.28; p = 0.99). The review concluded that the use of unconventional fractionation regimens did not affect breast appearance or toxicity, nor appear to affect local cancer relapse. The results of the UK START trials (N = 4451) were published too late to be included in the overview but were consistent with the findings. The START Trials tested the effects of RT schedules using fraction sizes larger than 2.0 Gy. The START-A Trial tested two dose levels of a 13-fraction regimen delivered over 5 weeks in order to measure the sensitivity of normal and malignant tissues to fraction size. Patients in START-A were randomly assigned to either 50 Gy in 25 fractions (control group) or 41.6 Gy in 13 fractions or 39 Gy in 13 fractions over 5 weeks. Patients in the START-B trial were randomly assigned to either 50 Gy in 25 fractions (control group) over 5 weeks or 40 Gy in 15 fractions over 3 weeks. The START-A trial (N = 2236) showed that the estimated absolute differences in 5-year local-regional relapse rates compared with the control schedule of 50 Gy in 2.0 Gy fractions were 0.2% (95% CI −1.3% to 2.6%) after 41.6 Gy and 0.9% (95% CI −0.8% to 3.7%) after 39 Gy. In START A, photographic and patient self-assessments suggested lower rates of late AE after 39 Gy than with 50 Gy, with a hazard ratio (HR) for late change in photographic breast appearance of 0.69 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.91; p = 0.01). In the START-B trial (N = 2215) the estimated absolute difference in 5-year local-regional relapse rates for 40.05 Gy compared with 50 Gy was −0.7% (95% CI −1.7% to 0.9%), and the HR for late change in photographic breast appearance was 0.83 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.04). Therefore, the START trials reported similar local tumour control with some evidence of lower rates of late AE after schedules with fraction sizes larger than 2.0 Gy compared with the international standard 25-fraction regimen. 18

A 15-fraction schedule has been the UK standard-of-care recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) since 2009, but it was thought to be unlikely to represent the useful limits of hypofractionation for whole breast RT. There is a history of prescribing once-weekly fractions of whole breast RT for women too frail or otherwise unable to attend for conventional schedules. In a French series of 115 patients undergoing primary RT without surgery for non-metastatic breast cancer from 1987 to 1999, the whole breast was treated with two tangential fields and received five once-weekly fractions of 6.5 Gy. 20 One hundred and one were given additional tumour bed boost doses, 7 with 1 fraction, 69 with 2 fractions and 25 with 3 once-weekly fractions of 6.5 Gy using electrons. Kaplan–Meier estimates of late effects in the breast were 24% grade 1, 21% grade 2 and 6% grade 3 at 48 months. The 5-year local progression-free rate was 78% (95% CI 66.6 to 88.4). In a separate French series, five once-weekly fractions of 6.5 Gy to the whole breast with no boost were given to 50 women after local tumour excision. 21 Grade 1 or 2 induration was reported in 33% of the patients at a median follow-up of 93 months (range 9–140). The 7-year local relapse-free survival was 91%.

The UK FAST trial (N = 915) tested two dose levels of a 5-fraction regimen delivering one fraction per week against a control schedule of 50 Gy in 25 fractions, defining RT AE as the primary endpoint. 22 The two test dose levels delivered 5 fractions of 5.7 Gy or 6.0 Gy (total dose 28.5 Gy or 30 Gy), estimated to be isoeffective with the control regimen assuming α/β values of 3.0 Gy or 4.0 Gy, respectively. Nine hundred and fifteen patients were recruited from October 2004 to March 2007. The mean age of participants was 62.7 years. Only 17 patients (5.2%) developed moist desquamation (12 after 50 Gy, 3 after 30 Gy, 2 after 28.5 Gy) out of 327 with Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) skin toxicity data available. At a median follow-up of 28.3 months [interquartile range (IQR) 24.1–33.6], 729 patients had 2-year photographic assessments available, with mild and marked change in breast appearance in 19.3% and 1.7% after 50 Gy, 26.2% and 9.3% after 30 Gy, and 20.3% and 3.7% after 28.5 Gy. RRs for mild and marked change for 30 Gy versus 50 Gy were 1.48 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.05) and 6.06 (2.14 to 17.20); p < 0.001 for trend, favouring 50 Gy; and for 28.5 Gy versus 50 Gy were 1.07 (0.75 to 1.54) and 2.25 (0.70 to 7.18); p = 0.26 for trend, favouring 50 Gy. Any clinically assessed moderate or marked AE in the breast were increased for 30 Gy compared with 50 Gy (HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.46 to 3.29; p < 0.001), but similar for 28.5 Gy (HR 1.33, 95% CI 0.86 to 2.08; p = 0.19). At a median follow-up of 37.3 months two local tumour relapses had been recorded.

The 10-year results from the FAST trial were subsequently published in 2020,23 confirming that as far as late toxicity is concerned, the 28.5 Gy schedule was isoeffective to the 50 Gy schedule. The 30 Gy schedule had an increased rate of late toxicity compared with 50 Gy. Any moderate or marked physician-assessed NTE in the breast (shrinkage, induration, telangiectasia, oedema) was reported for 92/774 (11.9%) at 5 years and 55/392 (14.0%) at 10 years. The most prevalent individual effect was breast shrinkage. Five-year prevalence of any moderate or marked breast NTE was estimated to be 10% higher (95% CI 5% to 16%) for 30 Gy versus 50 Gy (p < 0.001), with no statistically significant difference between 28.5 Gy and 50 Gy (2%, 95% CI −2% to +7%; p = 0.349). At 5 years, RRs for moderate or marked breast shrinkage versus 50 Gy were 2.03 (95% CI 1.15 to 3.58; p = 0.017) for 30 Gy and 1.20 (95% CI 0.63 to 2.27; p = 0.604) for 28.5 Gy. There were no statistically significant differences between schedules in 5-year prevalence of moderate or marked breast induration, telangiectasia and breast oedema, nor in 10-year prevalence of any moderate/marked effects, with few marked events. At 10 years, the estimated absolute differences in prevalence of any moderate or marked breast NTE compared with 50 Gy were 9% (95% CI 1% to 18%; p = 0.032) for 30 Gy and 5% (95% CI −2% to +13%; p = 0.184) for 28.5 Gy.

Five- and 10-year cumulative incidence rates of moderate or marked NTE in the breast were higher for 30 Gy compared with 50 Gy, with statistically significant differences for any NTE in the breast, breast shrinkage, breast induration, and breast oedema. Cumulative incidence rates of any moderate or marked NTE in the breast and breast induration were significantly higher for 28.5 Gy versus 50 Gy. Modeling all annual physician assessments over follow-up, rates of moderate or marked effects were statistically significantly higher for 30 Gy compared with 50 Gy [odds ratio (OR) for any breast NTE 2.12, 95% CI 1.55 to 2.89; p < 0.001], but with no significant difference between 28.5 Gy and 50 Gy (OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.72; p = 0.248; Statistically significant differences between the test schedules were found for breast shrinkage, telangiectasia, and breast oedema, with higher rates for 30 Gy compared with 28.5 Gy. The prevalence of breast shrinkage and telangiectasia increased over time, with a decline in breast oedema.

By the time of the 10-year analysis of the FAST trial only 11 local relapses had been reported (50 Gy: 3, 30 Gy: 4, 28.5 Gy: 4), hence analysis of tumour control outcomes would be underpowered.

A gain in local tumour control due to shortening treatment time to 1 week from longer 3- to 5-week schedules is theoretically possible. Evidence based on retrospective studies for an influence of treatment time on local tumour control is conflicting with recent systematic reviews drawing different conclusions. 24,25 Even without a gain in tumour control, accelerated RT is likely to be more convenient for patients, and may ease scheduling with other treatment modalities. A pilot study (N = 30) tested 30 Gy in 5 fractions of 6.0 Gy in 15 days to the whole breast in terms of acute AE and late effects at 2 years. 26 In this series, 23/30 (77%) patients scored no change in post-operative photographic breast appearance at 2 years, 7/30 (23%) scored mild change and none scored marked change. The acute skin reactions were mild, with no reaction more severe than grade 2 erythema, scored in 9/30 (27%) patients. In conclusion, it is fair to say that after decades of resistance to evaluating larger RT fraction sizes in breast cancer, expert opinion is responding to an accumulating body of evidence supporting the safety and effectiveness of this approach.

Against this background, the FAST-Forward phase III randomised trial was designed, with the primary aim of testing local tumour control in women with early breast cancer following a 5-fraction schedule of adjuvant RT delivered in 1 week.

Lymph node radiotherapy for breast cancer

This sub-study to the Main Trial tested the safety of 5-fraction regimens in the context of lymphatic RT. The model of breast cancer spread that was dominant in earlier decades envisaged a limited role for regional therapy beyond protection of quality of life, typically secured by surgery. Systematic overviews of RT effects by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists Collaborative Group (EBCTG) provide level 1A evidence that prevention of local-regional relapse has a major impact on breast cancer mortality. 6,27 An important conclusion to be drawn is that even heavily axillary lymph node-positive axillary patients can be cured by effective local-regional treatment, whether this is achieved by surgery, RT or systemic therapy. 27 The traditional model of breast cancer spread still has some adherents. The Z11 trial randomised 891 out of a planned 1900 patients with clinically lymph node-negative, sentinel lymph node-positive disease to axillary clearance versus no further axillary treatment. 28 Twenty-seven per cent allocated axillary clearance had additional positive lymph nodes. The axillary relapse rate at 5 years was 0.5% after axillary clearance and 0.9% after no axillary clearance, and there was no difference in breast cancer mortality. For some, this result reinforces the traditional model of breast cancer spread that discounts a role of nodal metastases in determining cancer spread. This interpretation fails to take account that standard post-operative tangential beam RT includes at least lower axillary lymph nodes and may be needed to eradicate residual disease. The same issue has been raised in discussion of the IBCSG 23-01 trial that compared axillary dissection versus no further axillary surgery in 929 sentinel lymph node-positive patients, 91% of whom were treated by breast conservation followed by whole breast RT. 29 The disease-free survival events, including axillary relapses, were non-inferior in the group spared axillary dissection, where standard whole breast RT will have included at least level I axillary lymph nodes. Although this remains a contested area, there is a wide consensus that control of axillary disease, whether by surgery, systemic therapy or RT, is an important component of curative therapy.

The AMAROS trial is informative in determining the role of surgery or RT for axillary management. 30 The study randomised 1425 patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes to either axillary lymph node dissection in 744 patients or axillary RT including photon beams to axillary apex and medial supraclavicular fossa (SCF) in 681 patients. The axillary relapse rates were low in both groups; 1.19% after RT and 0.43% after surgery, too low to assess non-inferiority. The main difference is that clinically reported arm swelling was less of a problem after RT than after surgery; 13.6% versus 28.0%, respectively, at 5 years; p < 0.0001. The implication is that lymphatic RT may increasingly be used as an alternative to surgery in this context.

Very little internal mammary chain (IMC) RT has been given in the UK in recent decades, but a modest reduction in breast cancer mortality is suggested by the NCIC MA20 trial and confirmed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 229922 trial. 6,31 Both tested IMC and SCF RT, so it is possible that therapeutic effects are attributable solely to the SCF component. This does not seem likely since, if SCF RT is needed in order to enhance cure of patients with positive IMC nodes, it is reasonable to assume that the latter require managing too. The same argument might apply to the infraclavicular (ICF) lymph nodes (level III axilla), which are usually included in unshielded (rectangular) fields to the SCF. In the EORTC trial, 4004 patients with axillary lymph node-positive disease or had cancers that were centrally or medially situated but axillary lymph node-negative were randomised to receive IMC/medial SCF RT or not. At a median of 10.9 years of follow-up, the primary endpoint of overall survival improved from 80.75% to 82.3% with the addition of IMC/SCF RT (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.00; p = 0.0556; p = 0.0496 after adjustment). It is not currently clear how these results will impact on practice. In conclusion, there was a need to test the safety of a 5-fraction schedule of lymphatic RT if the FAST-Forward Trial is to remain relevant to the 25% of patients referred for treatment with lymph node-positive disease. Whereas most are currently referred following axillary dissection, international and UK practices are changing, and more patients are likely to be referred in future for RT to axillary, SCF/ICF and perhaps IMC lymph node groups. When hypofractionation for breast cancer was first introduced in the 1960s, inappropriate dose regimens and uncertain dosimetry combined to cause unacceptably high rates of brachial plexopathy in patients with early breast cancer. 32–44 Even with hindsight, it is difficult to be sure how much of the morbidity was related to technical factors, especially beam overlap, and how much to dose-time factors. The only series describing brachial plexopathy after total dose ≤ 50 Gy delivered in 1.8–2.0 Gy fractions to breast and axilla/SCF reported 3/724 (0.6%) affected patients treated between 1968 and 1985, of whom two resolved and one progressed at 6.5 years median follow-up. 44 All patients were treated at the Joint Center, Boston, in a supine treatment position using a three-field technique with hanging block. A review of all published evidence available in 2005, suggested that brachial plexopathy after local-regional RT for early breast cancer is uncommon (< 1%) at doses < 55 Gy in 2.0 Gy equivalents. 45 Dose regimens were normalised using a linear quadratic model, assuming α/β value of 2.0 Gy.

The dose–response relationships are not difficult to reconcile with current practices in head and neck cancer, where total doses of 60 Gy in 30 fractions are standard. One recent example modelled the relationship between total dose in 2.0 Gy fractions and probability of brachial plexopathy in 330 patients systematically screened for evidence of sensorimotor symptoms a median of 56 months (range 6–135) after radical RT for head and neck cancer. Patients treated with definitive RT received a median dose of 70 Gy, and for those treated post-operatively the median dose was 60 Gy. Intensity-modulated RT was used on 62% cases, and 40% had concurrent chemotherapy, usually cisplatin. The brachial plexus was outlined using RTOG criteria on X-ray computerised tomography (CT) scans. 46

Against this background, the FAST-Forward Trial was extended beyond its original target accrual in order to test the safety of hypofractionated lymphatic RT. It is realistic to test only the common dose-limiting AE, including arm swelling and overall arm function. Very uncommon AE, including brachial plexopathy, cannot be formally tested in such a protocol, since a non-inferiority trial wishing to exclude an excess 1% risk with standard statistical power would require tens of thousands of patients.

Aims and objectives

Main Trial: to identify a 5-fraction schedule of curative RT delivered in once-daily fractions, that is at least as effective and safe as the current UK standard 15-fraction regimen after primary surgery for early breast cancer, in terms of local tumour control, AE, patient-reported outcomes (PRO) and health economic (HE) consequences.

Nodal Sub-Study (from Protocol v3.0, 8 July 2015): to show that a 5-fraction (1 week) schedule of adjuvant RT to level I–III axilla and/or level IV axilla (SCF) is non-inferior to a 15-fraction (3 weeks) standard in terms of patient-reported arm swelling and function, and to contribute additional information to the endpoints of the Main Trial.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

FAST-Forward was a multicentre, three-group, non-blind, phase III randomised controlled non-inferiority clinical trial addressing the hypothesis that a 1-week course of curative whole breast RT would be at least as effective and safe as the UK standard 3-week regimen after primary surgery for early breast cancer. Patients were allocated in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to either 40.05 Gy in 15 fractions of 2.67 Gy over 3 weeks (Control group; labelled 40 Gy throughout the reminder of this report); 27.0 Gy in 5 fractions of 5.4 Gy over 1 week (Test Group 1) or 26.0 Gy in 5 fractions of 5.2 Gy over 1 week (Test Group 2). Dose prescriptions are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 33.

A sequential tumour bed RT boost following breast conservation surgery (BCS) was allowed, with centres required to state boost intention and dose (10 Gy or 16 Gy in 2.0 Gy fractions, or radiobiological equivalent from Protocol v4.0) prior to randomisation.

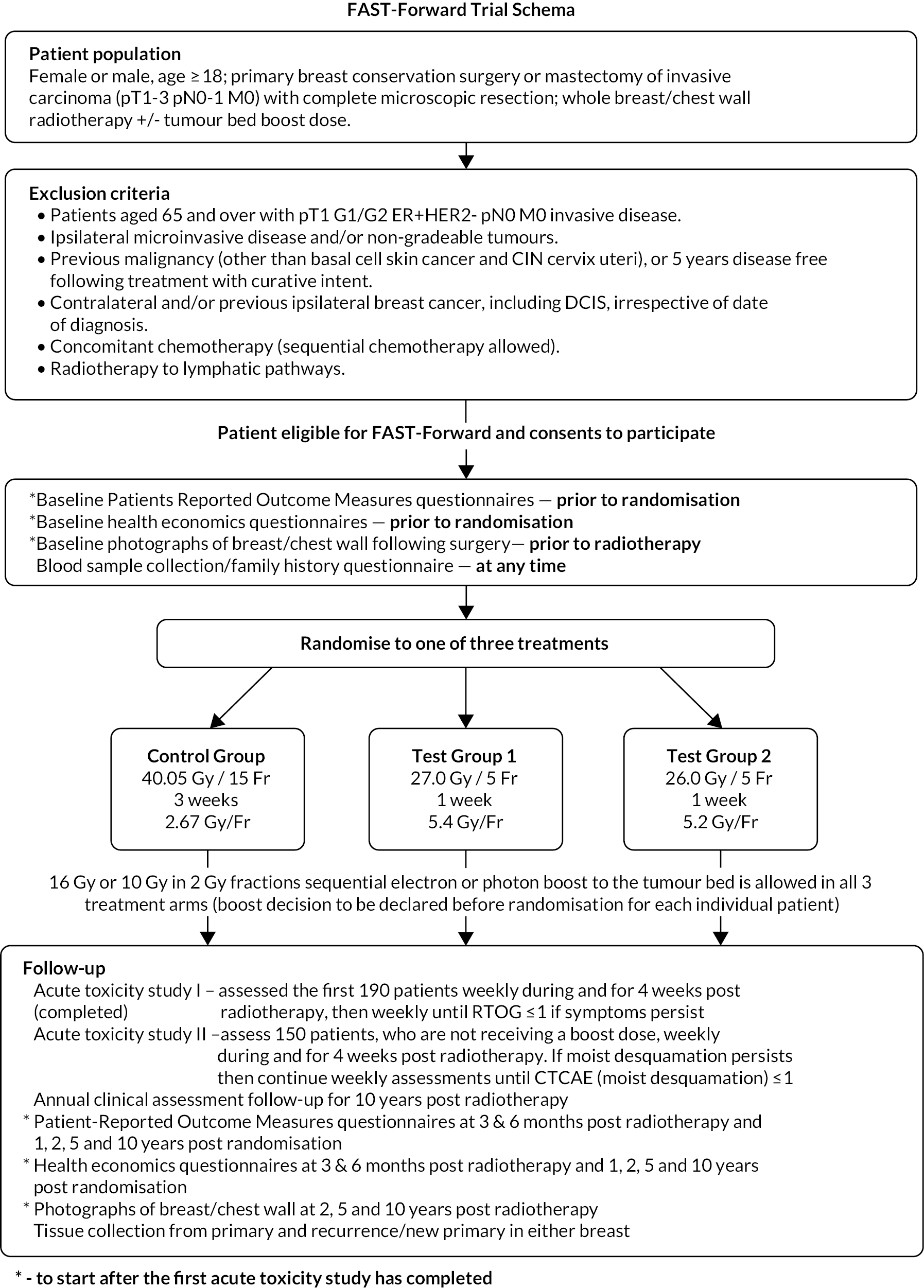

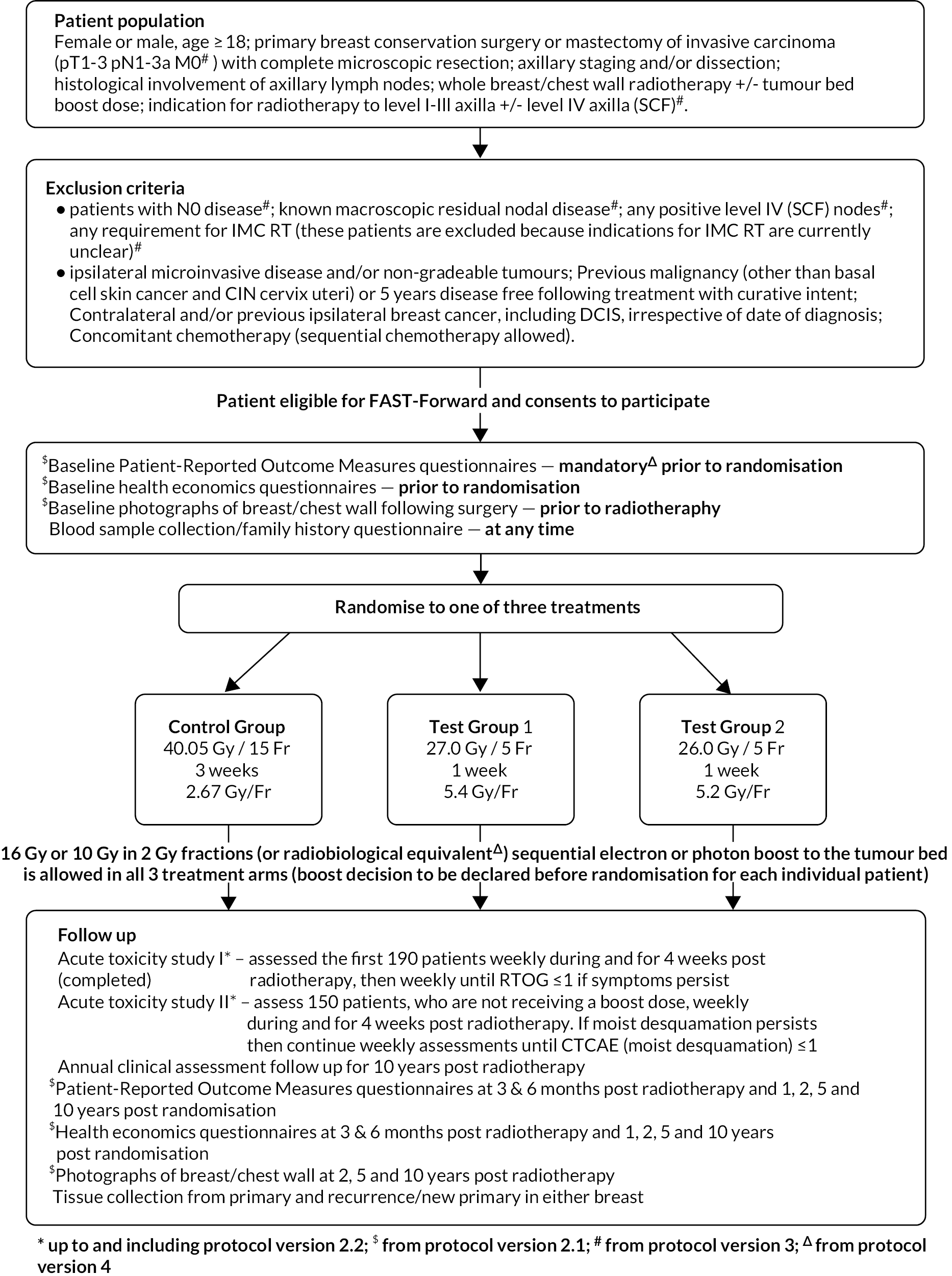

The Nodal Sub-Study (from Protocol v3.0, 8 July 2015) was an extension to the FAST-Forward Main Trial, maintaining the original design as a phase III randomised clinical trial but restricted to patients prescribed RT to level I-III axilla and/or level IV axilla (SCF) in addition to the breast/chest wall area. Trial schemas for the Main Trial and the Nodal Sub-Study are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

FAST-Forward schema: Main Trial.

FIGURE 2.

FAST-Forward schema: Nodal Sub-Study.

Test dose levels were informed by α/β estimates describing the fractionation sensitivity of late normal tissues obtained from the START and FAST trials. 17,47 Assuming α/β = 3 Gy and no effect of overall time on outcomes, 27 Gy/5 fractions of 5.4 Gy was predicted to match late NTE of 40 Gy/15 fractions of 2.7 Gy or 46 Gy/23 fractions of 2 Gy. Allowance for a possible effect of treatment time informed the choice of the slightly lower 26 Gy dose level. A 3-group design was used for the trial to allow interpolation between the two test doses in order to estimate the 5-fraction dose equivalent to 40 Gy in 15 fractions in terms of local tumour control, and late NTE.

From Protocol v5.0 (14 December 2017) onwards the trial design of the Nodal Sub-Study was amended to a 2-group trial, with no further randomisation to Test Group 1 (27 Gy in 5 fractions of 5.4 Gy). This amendment was on the advice of the Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Further details are presented in the Study Conduct section (see Chapter 2).

Embedded sub-studies

Acute toxicity

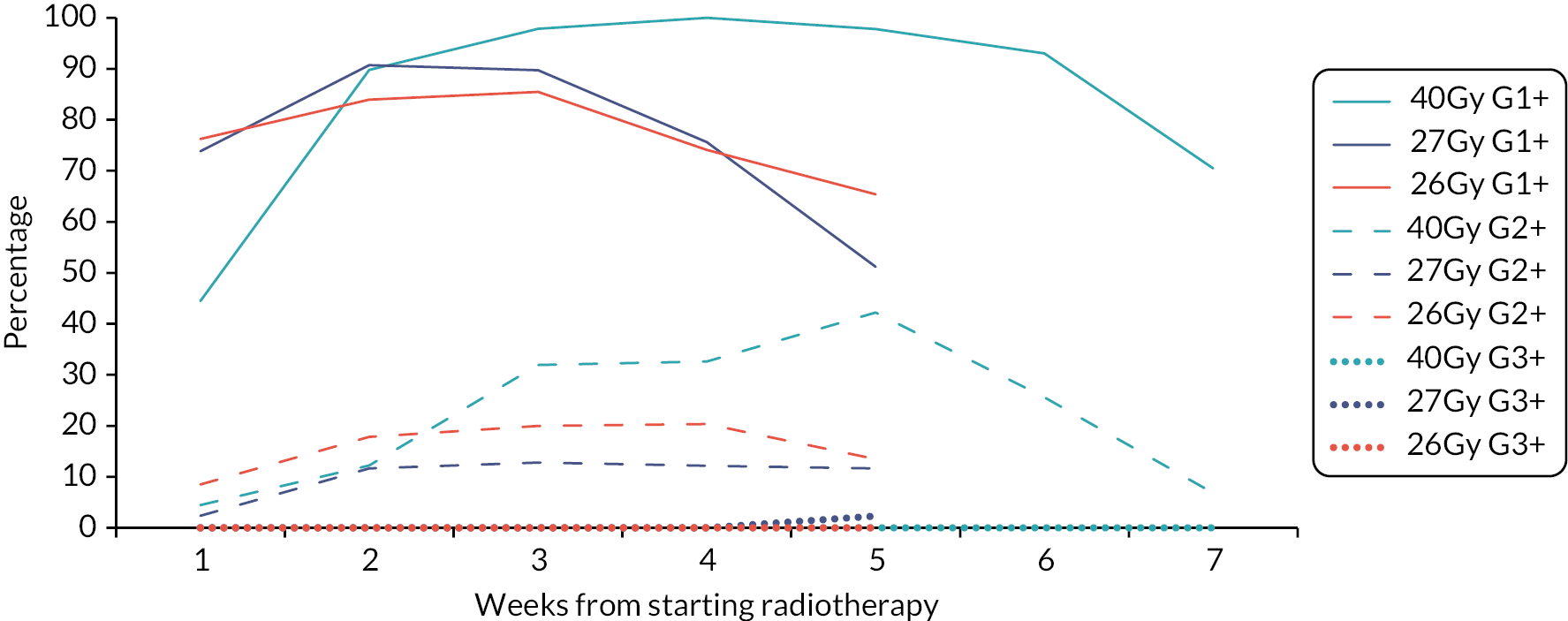

Acute skin reactions are more related to the total dose and less sensitive to fraction size than late-reacting normal tissues. Therefore the lower total doses under test in the trial are expected to reduce their severity and duration, despite the shorter overall treatment time. In order to confirm these relationships two acute toxicity sub-studies were undertaken during 2011 and 2013 in patients entered into the Main Trial from a subset of centres. Details of the acute toxicity sub-studies are presented in Chapter 4.

Patient-reported outcomes

There is evidence that RT causes long-term effects on quality of life in terms of altered breast appearance, breast, arm and shoulder symptoms, as well as a possible impact on some general aspects such as fatigue. Results from the START trial highlighted the value of patients’ self-reported post-RT symptoms in discriminating between RT regimens in favour of hypofractionation. 48 The PRO sub-study within FAST-Forward aimed to provide subjective views of key breast symptoms and body image following treatment, to add supportive data in the comparison of a trade-off between local tumour control and AE of treatment. A subset of Main Trial centres participated in the PRO sub-study. For the Nodal Sub-Study PROs were mandatory since the primary outcome was patient-assessed. Details of the PRO methods are included later on in this chapter.

Photographic assessments

Photographic assessments of change in breast appearance following RT as used in other trials including START, IMPORT LOW and HIGH, and FAST, provide an objective assessment of late AE, since they are scored by independent observers blinded to treatment allocation and patient identity. The same centres involved in the PRO sub-study also participated in the photographic assessments. Details of the photographic assessment methods are included later on in this chapter.

Health economics

The HE evaluation aimed to establish the cost-effectiveness of a 5-fraction schedule of curative RT compared with current UK practice using quality of life and health resource data, and health states including cancer relapse. Quality of life and health resource use data were collected on the PRO questionnaires for those patients participating in the PRO sub-study. Details of the HEs evaluation are presented in Chapter 6.

Blood and tissue collection

All patients were asked to consent to donate a single blood sample and complete a family history questionnaire; these were collected at any point during the trial. All patients were also asked to consent to the donation of a tissue sample from their original tumour and to the donation of a tissue sample should a relapse occur. The consent ensured that the samples remain a resource for future use, pending separate funding for translational research.

Participants

Patient selection

Women and men with complete microscopic resection of early invasive breast cancer following BCS or mastectomy prescribed local RT.

Eligibility for Main Trial

Eligibility criteria for the Main Trial from protocol version 2.3 (11 November 2013; last version of Main Trial protocol before addition of Nodal Sub-Study) are as follows:

Main Trial inclusion criteria1

-

Age ≥ 18 years.

-

Female or male.

-

Primary invasive carcinoma of the breast.

-

Breast conservation surgery or mastectomy (reconstruction allowed, providing port of a tissue expander positioned outside the breast).

-

Complete microscopic excision of primary tumour.

-

Axillary staging and/or dissection.

-

pT1-3 pN0-1 M0 disease.

-

Written informed consent.

-

Able to comply with follow-up.

Main Trial exclusion criteria

-

Age ≥ 65 years with pT1 G1/2 ER+ve/HER-2−ve pN0 M0 invasive disease (from protocol v2.0).

-

Ipsilateral microinvasive disease and/or non-gradeable tumours.

-

Past history of malignancy except (1) basal cell skin cancer, (2) cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) cervix uteri or (3) non-breast malignancy allowed if treated with curative intent and > 5 years disease-free.

-

Contralateral and/or previous ipsilateral breast cancer, including ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), irrespective of date of diagnosis.

-

Concurrent cytotoxic chemotherapy (sequential neoadjuvant or adjuvant cytotoxic therapy allowed with ≥ 2 weeks between therapy and RT).

-

Radiotherapy to any regional lymph node area (excepting lower axilla included in standard tangential fields to breast/chest wall).

Eligibility for Nodal Sub-Study

Protocol Version 3.0 onwards included additional requirement for lymphatic RT. Typical examples of indications for lymphatic RT include (1) Patients with positive lymph nodes removed by axillary clearance who require RT to level I–III axilla and/or level IV axilla (SCF). (2) Patients with sentinel node-positive axillary disease not proceeding to axillary dissection and who require RT to level I–III axilla and/or level IV axilla (SCF). (3) Patients treated by pre-operative systemic therapy who are recommended post-operative RT to level I–III axilla and/or level IV axilla (SCF).

Eligibility criteria for the Nodal Sub-Study from protocol version 4.0 (24 February 2017) onwards are as follows:

Nodal Sub-Study inclusion criteria2

-

Age ≥ 18 years.

-

Female or male.

-

Primary invasive carcinoma of the breast.

-

Breast conservation surgery or mastectomy (reconstruction allowed, providing port of a tissue expander positioned outside the breast).

-

Complete microscopic excision of primary tumour.

-

Axillary staging and/or dissection.

-

pT1-3 pN1-3a M0 disease.

-

Histological involvement of axillary lymph nodes.

-

Indication for RT to level I-III axilla and/or level IV axilla (SCF).

-

Written informed consent.

-

Able to comply with follow-up.

Nodal Sub-Study exclusion criteria

-

Ipsilateral microinvasive disease and/or non-gradeable tumours.

-

Past history of malignancy except (1) basal cell skin cancer, (2) CIN cervix uteri or (3) non-breast malignancy allowed if treated with curative intent and >5 years disease-free.

-

Contralateral and/or previous ipsilateral breast cancer, including DCIS, irrespective of date of diagnosis.

-

Concurrent cytotoxic chemotherapy (sequential neoadjuvant or adjuvant cytotoxic therapy allowed with ≥ 2 weeks between therapy and RT).

-

Patients with N0 disease.

-

Known residual macroscopic nodal disease.

-

Any positive level IV (SCF) nodes.

-

Requirement for IMC RT3.

The eligibility criteria of Fast-Forward Main Trial were amended in versions 2.0 (13 February 2013), 2.2 (2 May 2013) and for the Nodal Sub-Study in versions 3.0 (8 July 2015) and 4.0 (24 February 2017) of the study protocol, as shown in Appendix 2, Table 34.

Eligibility for PRO and photographic assessment sub-studies

For the PRO sub-study all the patients at those centres participating were eligible (and all patients in the Nodal Sub-Study). All patients who had BCS were eligible for the photographic sub-study at participating centres, with the intention that the same group of patients were included in the PRO and photographic studies.

Protocol amendments

Protocol amendments for the FAST-Forward are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 35. The current approved version of the protocol is v5.1 (5 February 2018).

Trial procedures

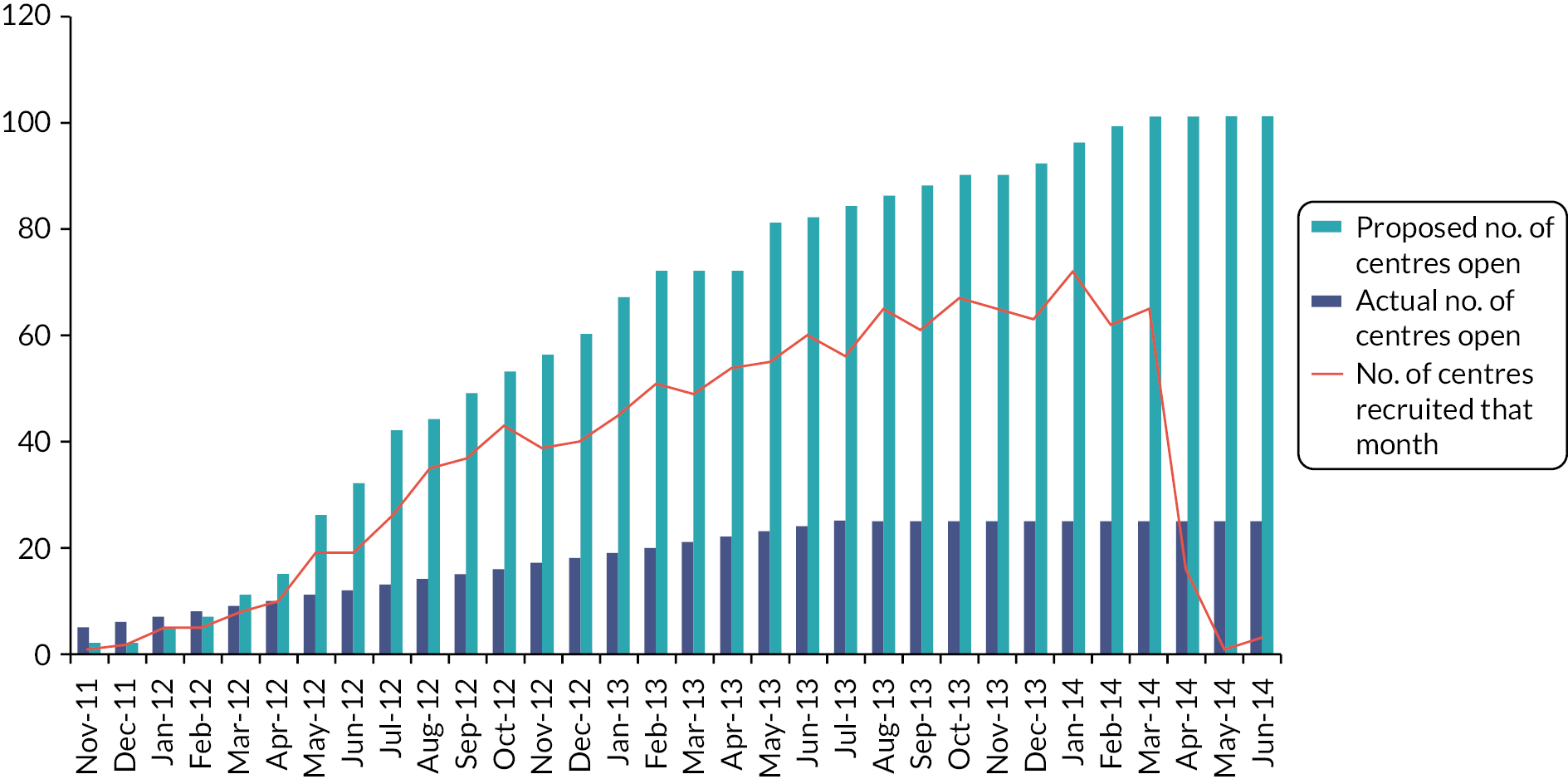

Participating centres

All hospitals in the UK were invited to participate in the trial and were designated as treating (RT) and referring (non-radiotherapy) centres. All centres had to obtain the necessary regulatory approvals and RT centres completed a rigorous radiotherapy quality assurance (RT QA) approval process (see Chapter 3 for details of RT QA programme). A site initiation visit was performed either in person or by telephone prior to opening to recruitment. Radiotherapy centres identified eligible patients, obtained informed consent, treated patients and performed assessments according to the schedule. Non-radiotherapy hospitals performed the same activities except for the RT and acute toxicity assessments. Centre staff are listed in Table 30.

Patient information and informed consent

Eligible patients (see eligibility criteria) were identified during breast cancer multidisciplinary meetings or from clinic lists at participating sites. Patients were invited to participate in the FAST-Forward Trial during consultations in oncology clinics, where treatment options were discussed. Here the local principal investigator, coinvestigator or other trained healthcare professionals, discussed the trial with the patient and provided them with a copy of the patient information sheet. Patients were given at least 24 hours to consider participation in the trial, to discuss this with their family and friends and to ask questions of the clinical team. Patients who were willing to participate were asked to provide written informed consent to the principal investigator, co-investigator or other trained individual. All patients from the start of the trial were asked to provide consent for the tissue and blood sub-studies. Other optional sub-studies were included in subsequent versions of the consent form.

There were two consent forms available at the start of the trial:

-

For centres participating in the acute toxicity sub-studies (seven centres).

-

For centres participating in the PROMS and photographic sub-studies.

There were two consent forms available from Protocol v2.1:

-

For centres opting to participate in the PRO and photographic assessment sub-studies.

-

For all other centres.

There was only one consent form from Protocol v3.0 (inclusion of Nodal Sub-Study) as the PRO assessments were mandatory, since the primary endpoint of this sub-study was patient-assessed arm/hand swelling.

Randomisation

Patients in the Main Trial and Nodal Sub-Study were allocated to 40.05 Gy in 15 fractions, 27.0 Gy in 5 fractions or 26.0 Gy in 5 fractions in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio. The 27.0 Gy group in the Nodal Sub-Study was closed to recruitment from Protocol v5.0 (14 December 2017) onwards (as described in Protocol amendments and Study Conduct sections). Treatment allocation was not blinded to patients or clinicians. Randomisation was performed by recruiting centres contacting The Institute of Cancer Research-Clinical Trials and Statistics Unit (ICR-CTSU) by telephone or fax. The randomisation allocation method was computer-generated random permuted blocks [mixed block sizes 6 and 9 (changed to 4 and 6 following the amendment of Nodal Sub-Study to 2-group design) to avoid predictability]. Patients in the Main Trial were stratified according to RT centre and risk group (high: < 50 years or grade 3 vs. low: ≥ 50 years and grade 1 or 2). Patients in the Nodal Sub-Study were stratified according to RT centre and whether or not the patient had a level II/III axillary clearance. A unique trial identifier was assigned to each patient comprising components for centre number, patient number and designated stratification.

Radiotherapy procedures

The whole breast clinical target volume (CTV) including the soft tissues from 5 mm below the skin surface to the deep fascia was either determined retrospectively from field-based tangential fields or volumed prospectively. Post-mastectomy chest wall CTV encompassed post-surgical skin flaps and underlying soft tissues to the deep fascia; both excluded underlying muscle and rib cage. Surgeons were strongly encouraged to mark the tumour cavity walls with titanium clips or gold seeds at the time of BCS in order to aid placement of tangential fields and delineation of tumour bed. A typical margin of 10 mm was added around the breast/chest wall CTV accounting for set-up error, breast swelling and breathing to create a planning target volume (PTV). A full 3D CT set of outlines covering the whole breast and organs at risk was collected with a slice separation up to 5 mm and organs at risk were outlined. A tangential opposing pair beam arrangement encompassed the whole breast/chest wall PTV, minimising the ipsilateral lung and heart exposure.

The lymph node CTV included the axillary chain and/or the supraclavicular nodes (level IV axilla). The axilla could be treated in its entirety, that is levels I–IV, or only the levels specified by the clinician. For the level IV axilla (SCF) PTV a maximum of 5 mm margin was applied medially in order to limit the dose to midline structures.

The treatment plan was optimised with 3D dose compensation to achieve the following PTV dose distribution: > 95% received 95% of prescribed dose, < 5% received ≥ 105%, < 2% received ≥ 107% and global maximum < 110%. Dose constraints for the control group were: volume of ipsilateral lung receiving 12 Gy < 15%, and volume of heart receiving 2 Gy and 10 Gy < 30% and < 5%, respectively. Dose constraints for the 5-fraction schedules were: volume of ipsilateral lung receiving 8 Gy < 15%, and volume of heart receiving 1.5 Gy and 7 Gy < 30% and < 5%, respectively.

X-ray beam energies for treatment were 6 megavoltage (MV) or 10 MV, but a mixture of energies, for example 6 MV and 10–15 MV was allowed for larger patients. Tumour bed boost was delivered via electrons or photons. Verification was carried out using electronic portal imaging using MV or kV X-rays. Control group treatment verification was required for at least three fractions in the first week with correction for any systematic error and then once weekly with a tolerance of 5 mm. The 5-fraction schedules required verification imaging for each fraction with recommendations to correct all measured displacements. A comprehensive quality assurance programme involved every RT centre before trial activation and continued throughout trial accrual (see RT QA Chapter 3).

The RT planning packs for the Main Trial and Nodal Sub-Study are available on the ICR-CTSU FAST-Forward Trial webpage at www.icr.ac.uk/fastforward.

Trial assessments

Table 1 shows the schedule of assessments for all patients participating in the trial.

| Treatment | Follow-up (all taken from date of randomisation except where shown) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Prior to randomisation | Post-randomisation | wk 1 | wk 2 | wk 3 | Weekly for 4 weeks post-RT | mth 3 | mth 6 | yr 1 | yr 2 | yr 3 | yr 4 | yr 5 | yr 6 | yr 7 | yr 8 | yr 9 | yr 10 | |

| Pre-RT | Post-RT | ||||||||||||||||||

| Eligibility checklist | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Informed consent | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Randomisation checklist | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| RT QA | Prior to centre initiation and throughout the trial recruitment period | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3D RT planning | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| RT treatment | x | x a | x a | ||||||||||||||||

| RT verification | Up to daily during treatment | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serious adverse event (if applicable) | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Acute toxicity assessmentsb | Study I (first 190 patients) | x | x | x a | x a | x | |||||||||||||

| Study II (150 patients, no boost) | x | x | x a | x a | x | ||||||||||||||

| Follow-up – annual clinical assessment (all patients) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Sub-studies | |||||||||||||||||||

| PROMSc | x (baseline d ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Photographic assessmentc | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| HEs – annual assessment | x (baseline d ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Lymphatic RT including PROMSe | x (baseline d ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Blood sample collection and family history questionnaire | At any time during the trial, ideally by the end of RT | ||||||||||||||||||

| CT scan if recurrence | At the time of recurrence | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tissue collection 1 tumour recurrence/new 1 tumour |

As requested during the trial | ||||||||||||||||||

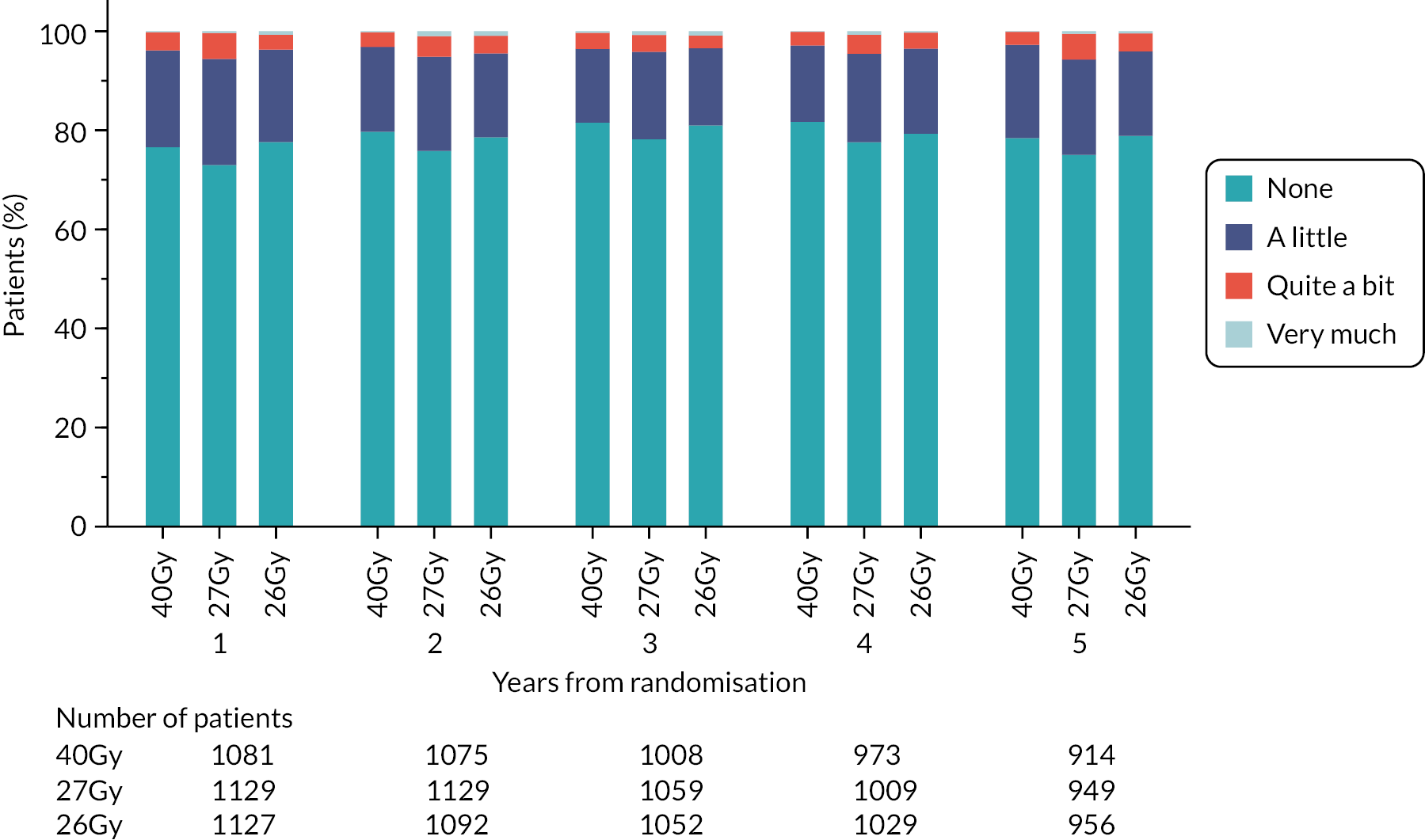

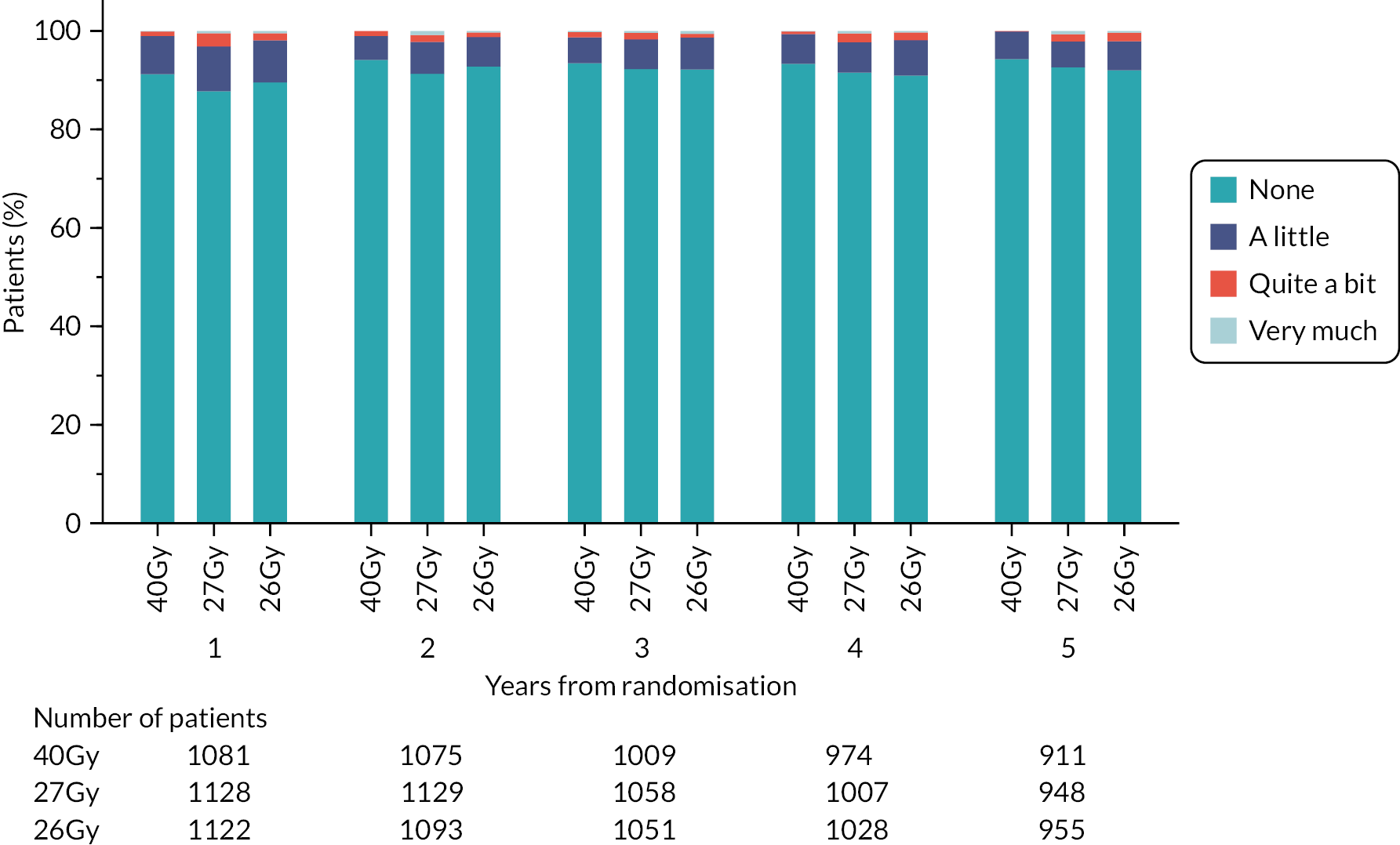

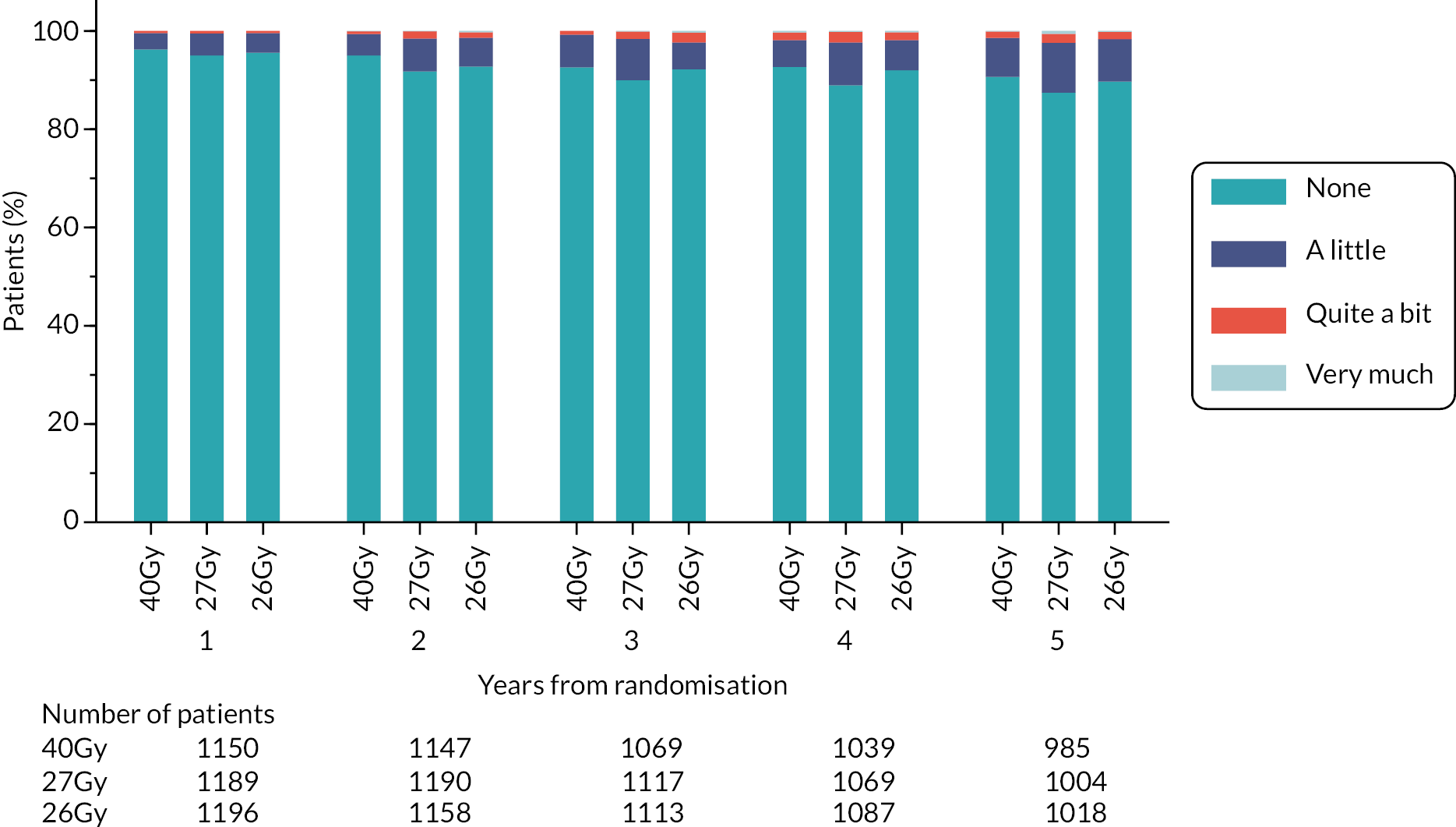

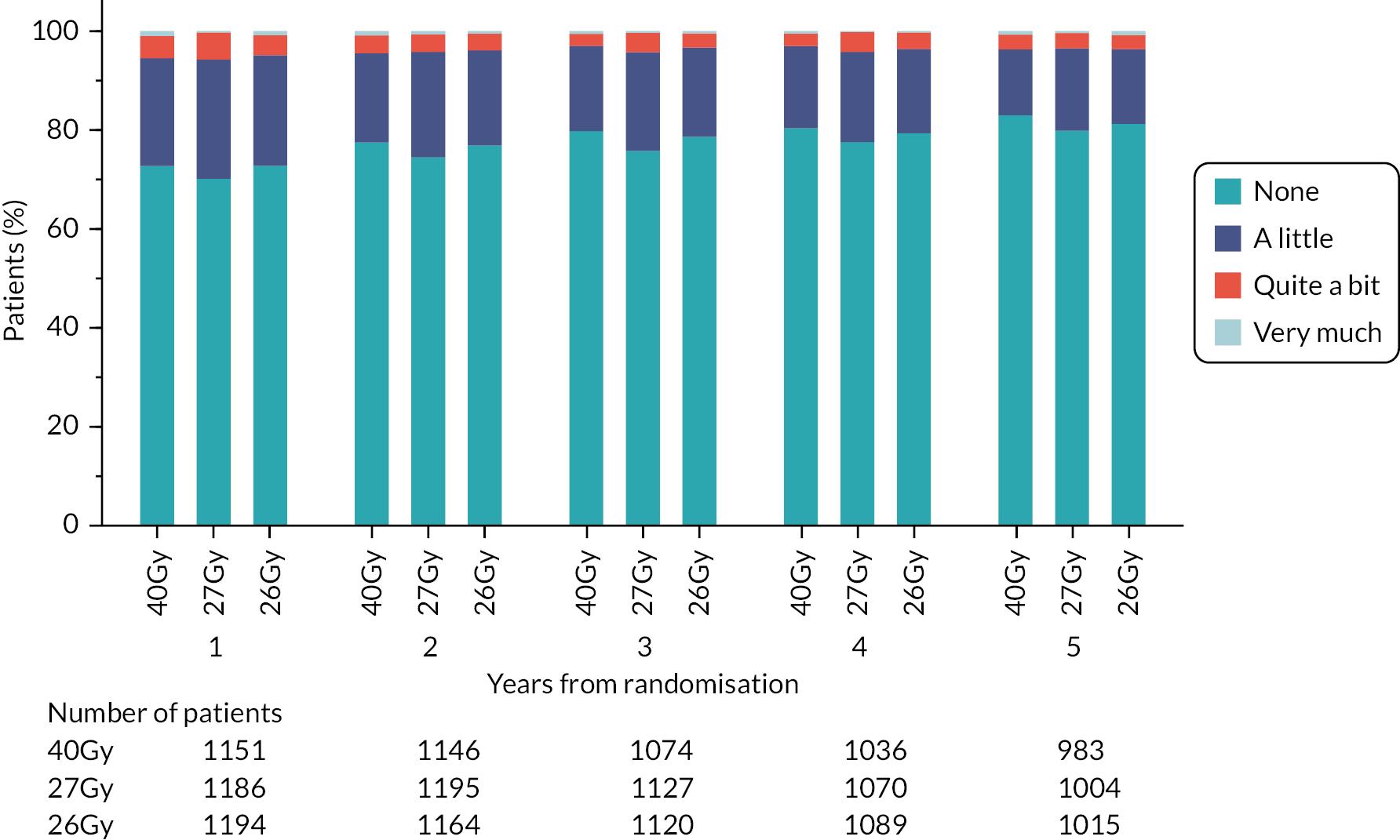

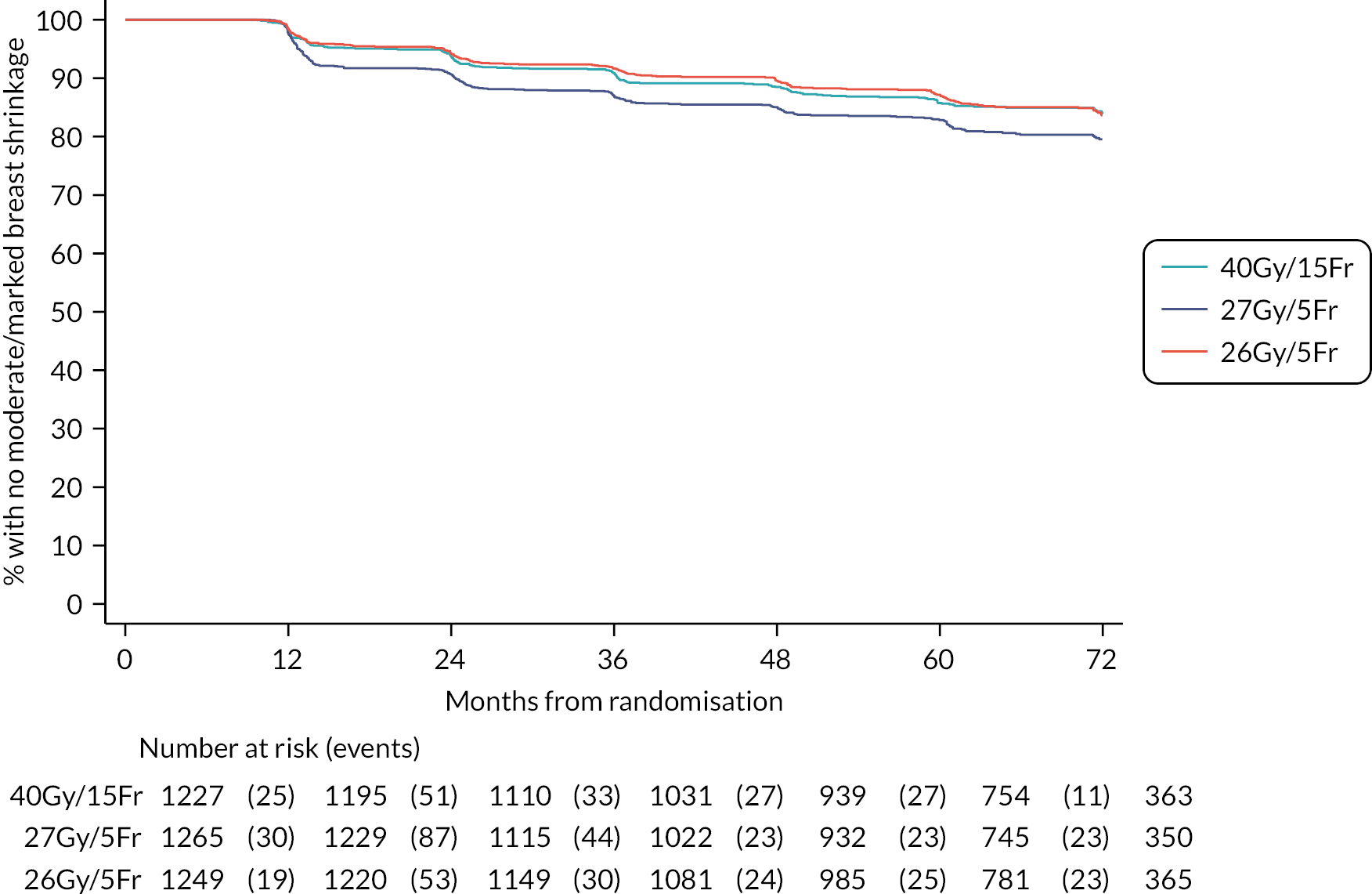

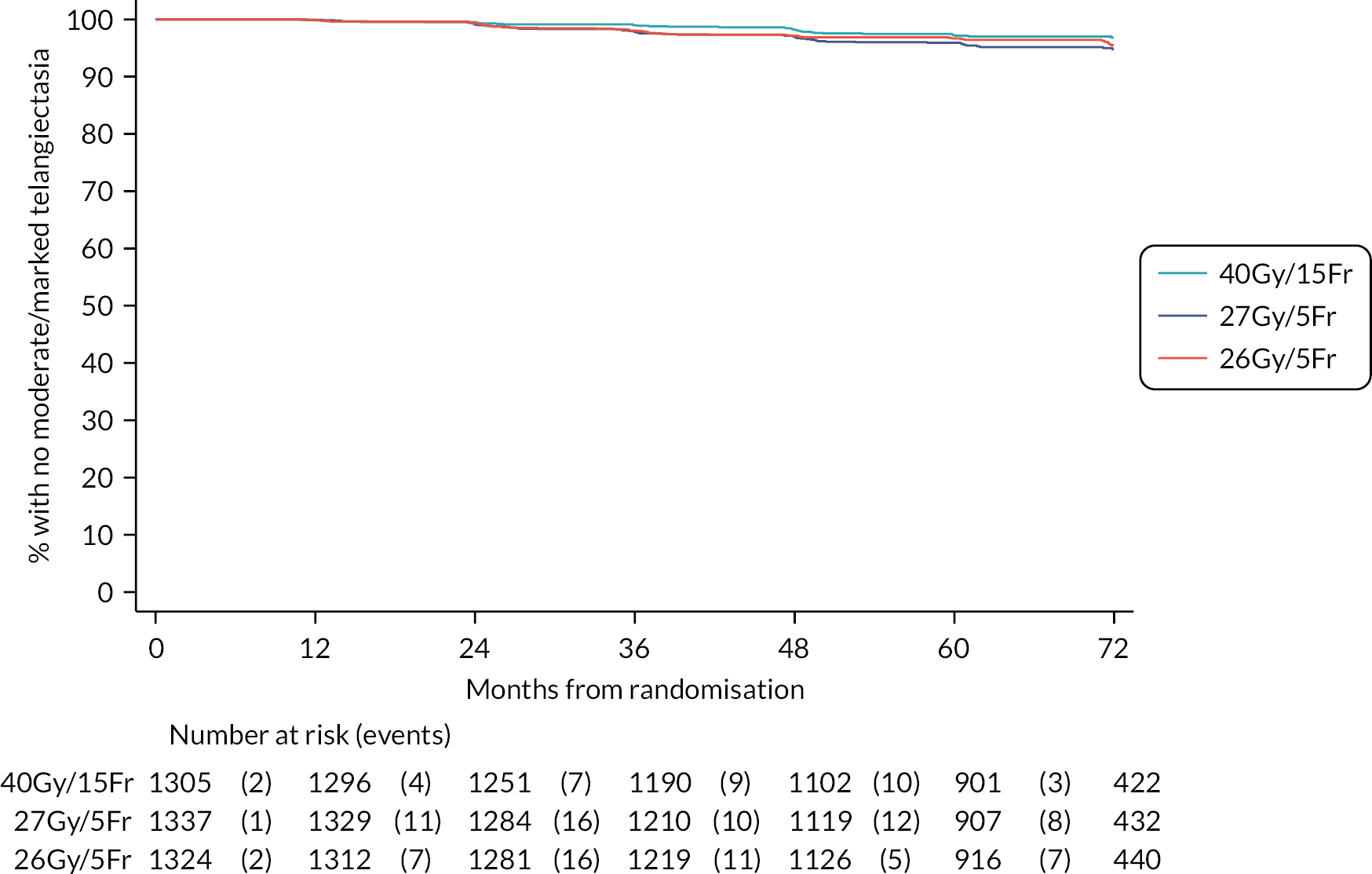

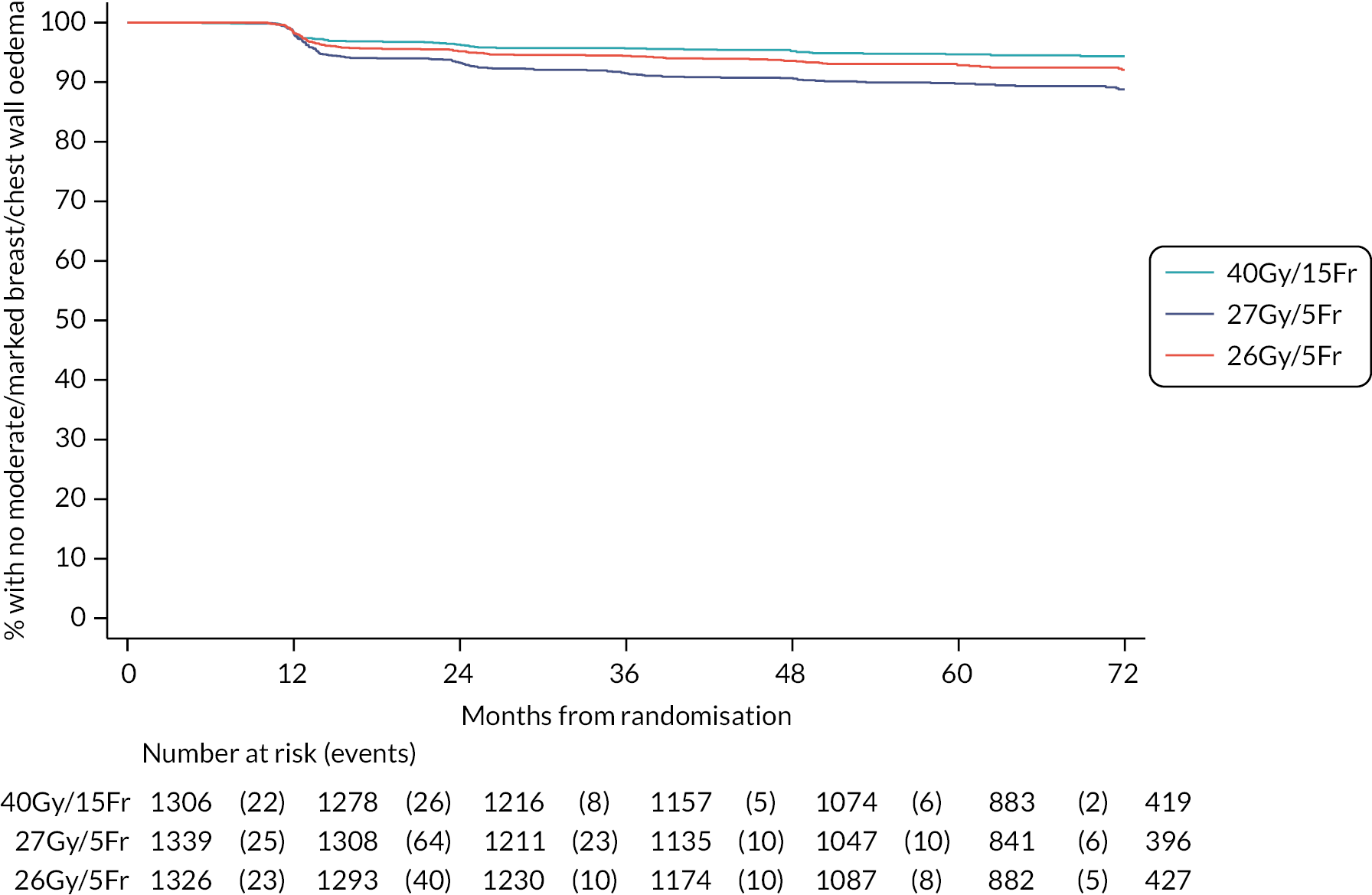

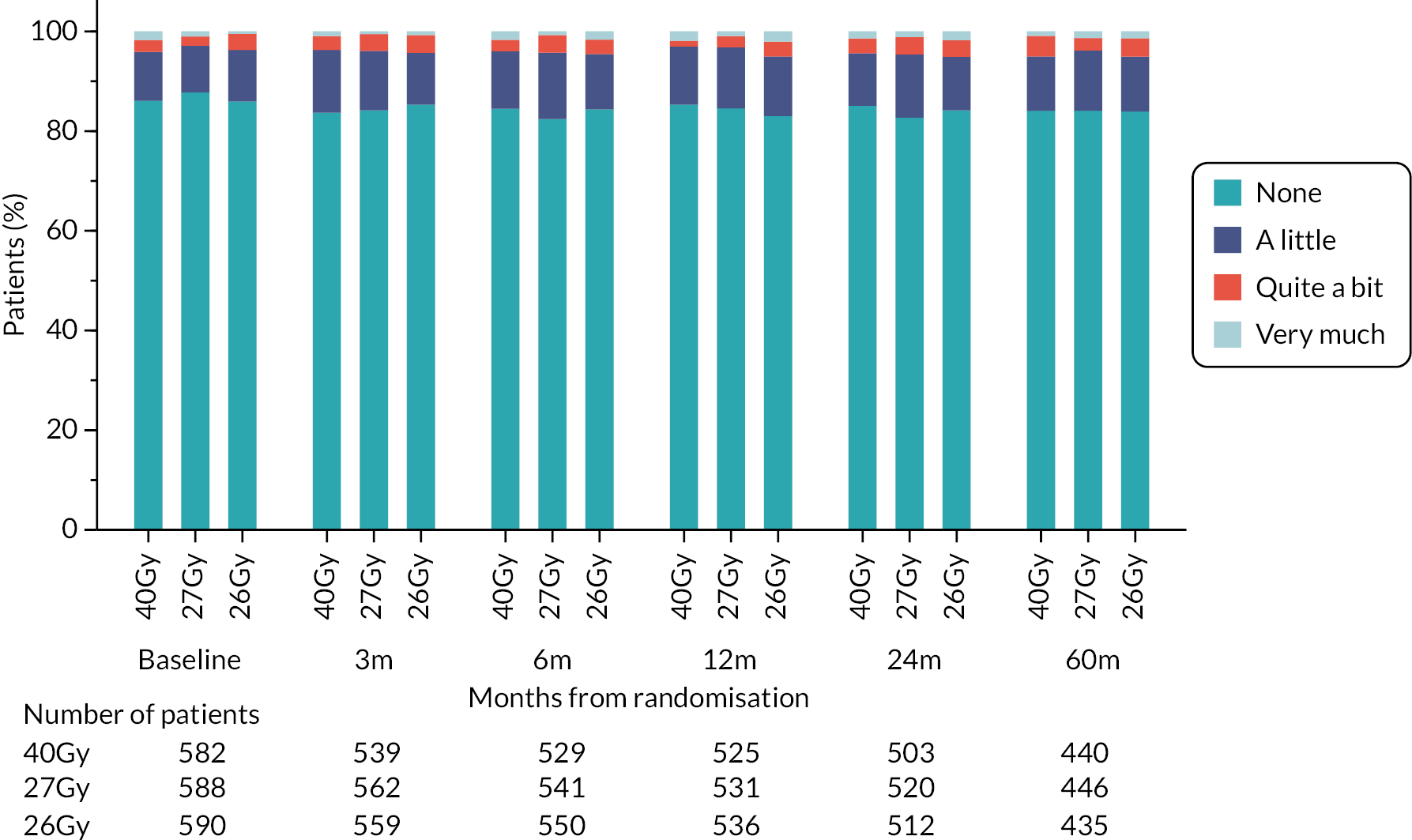

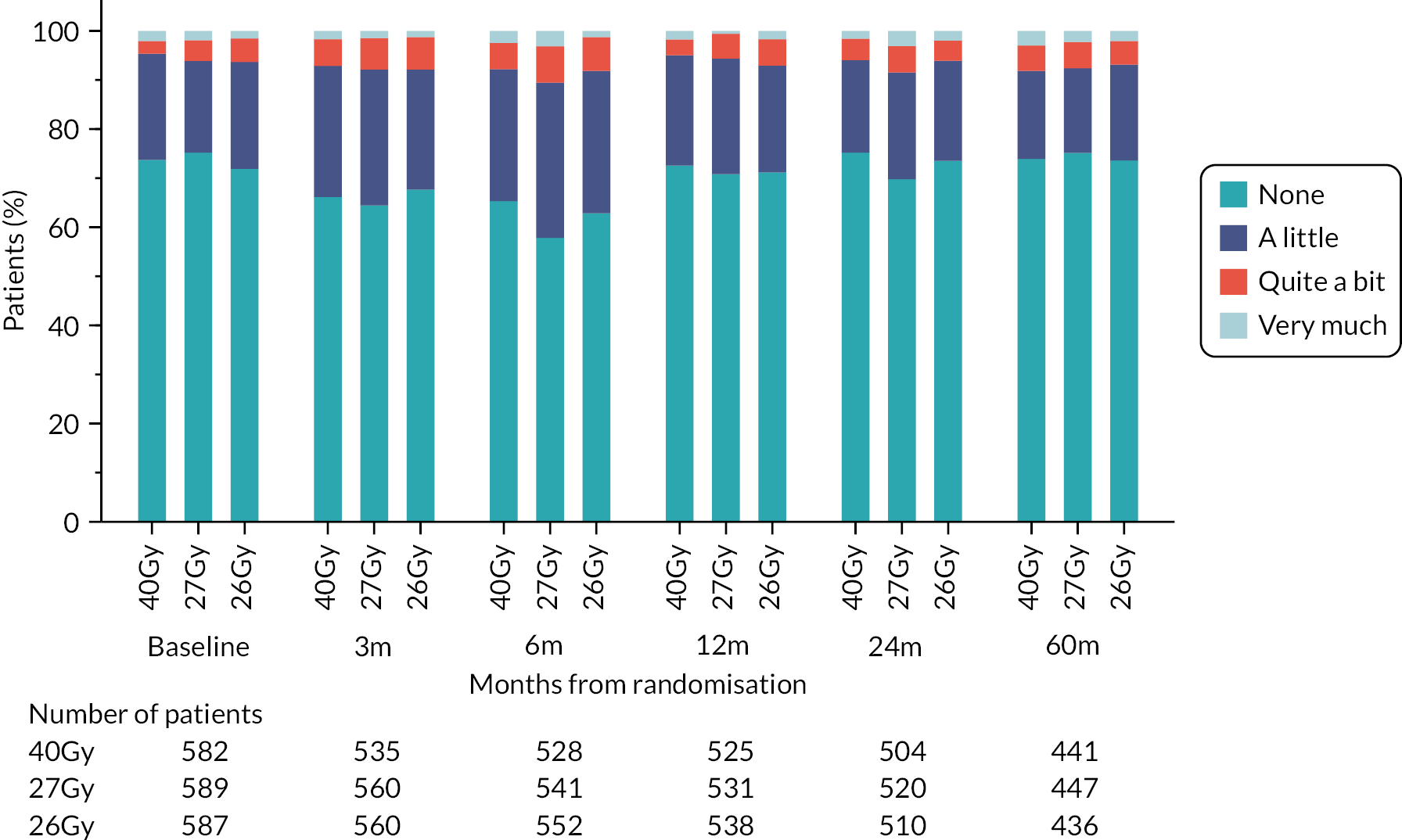

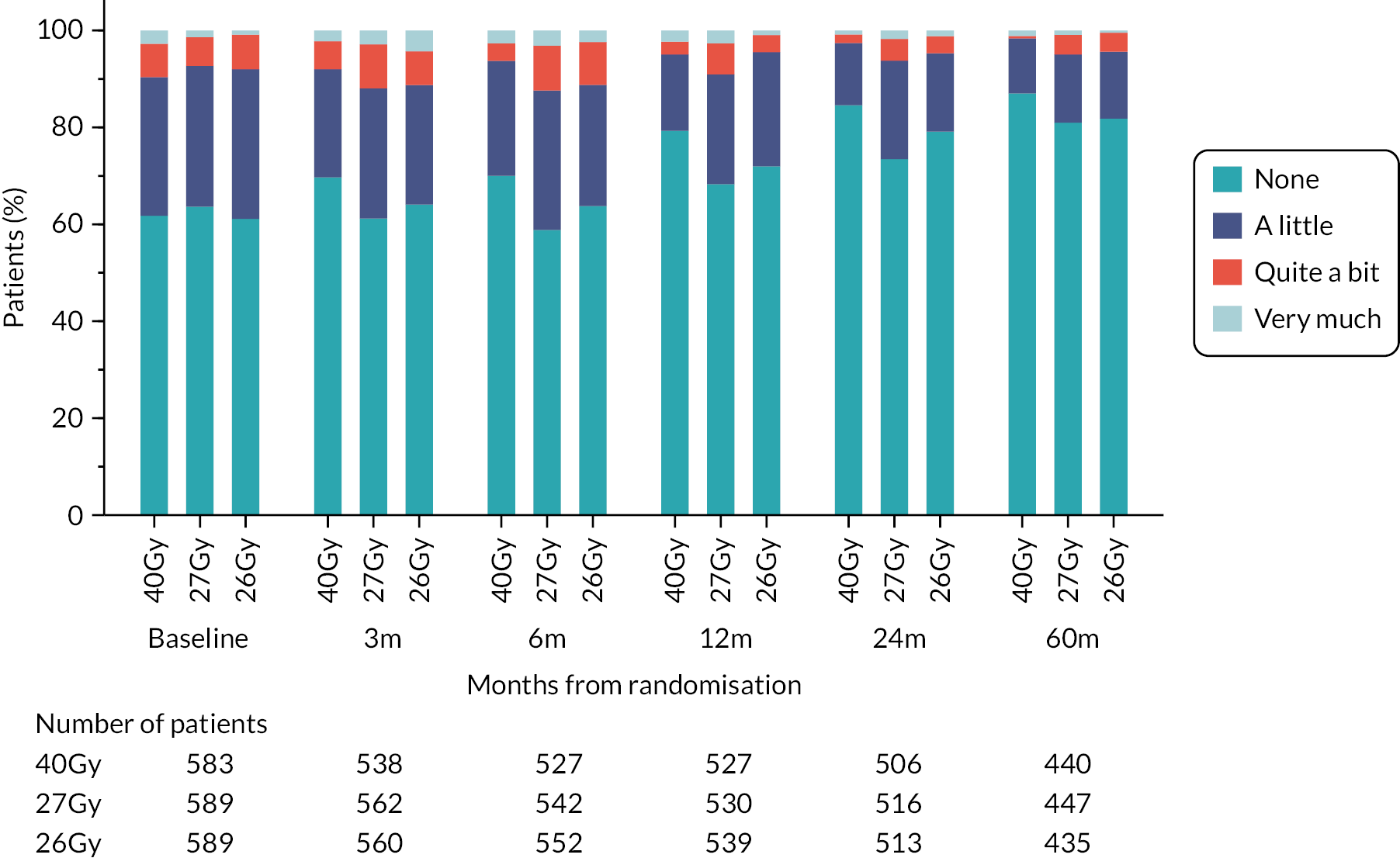

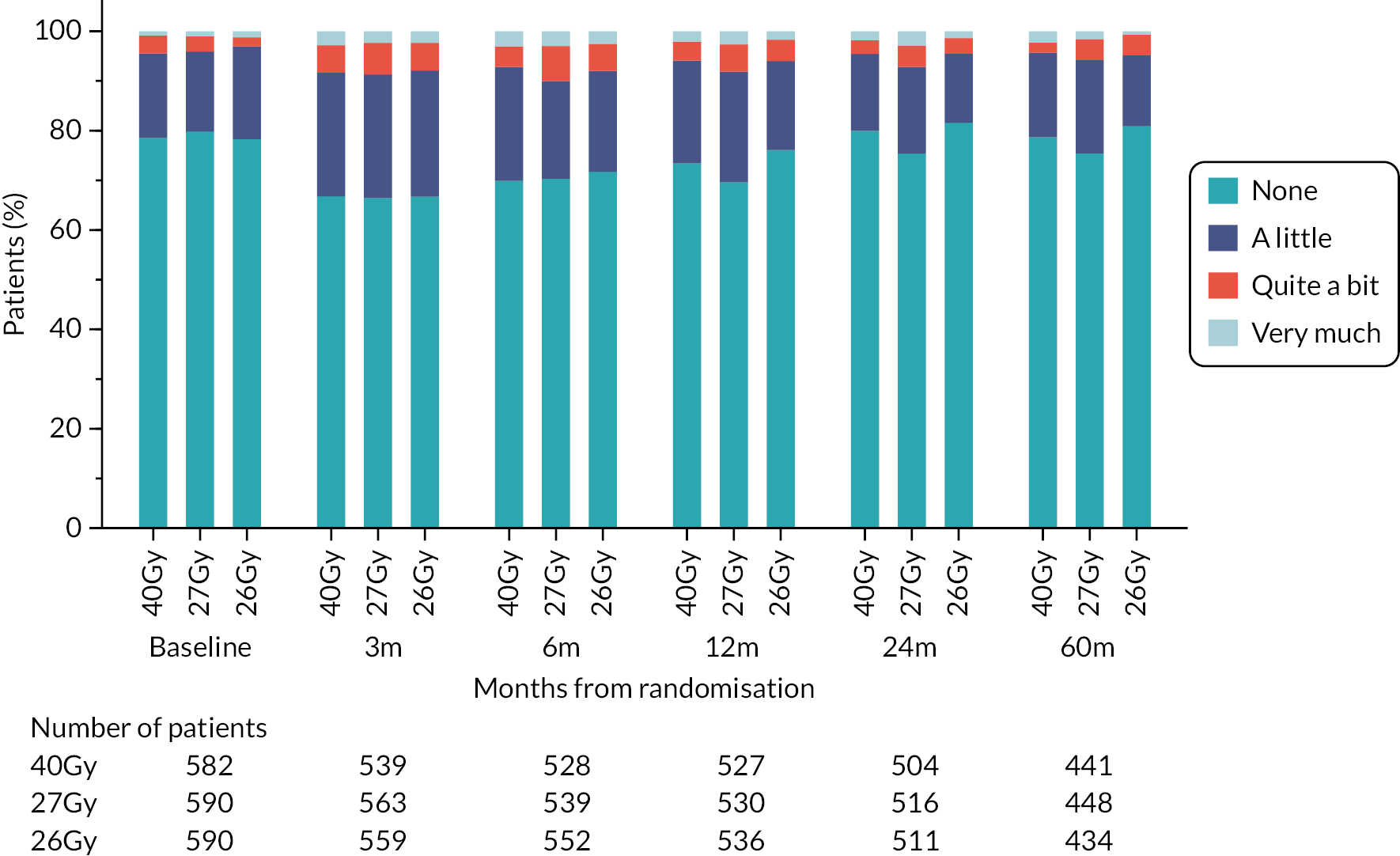

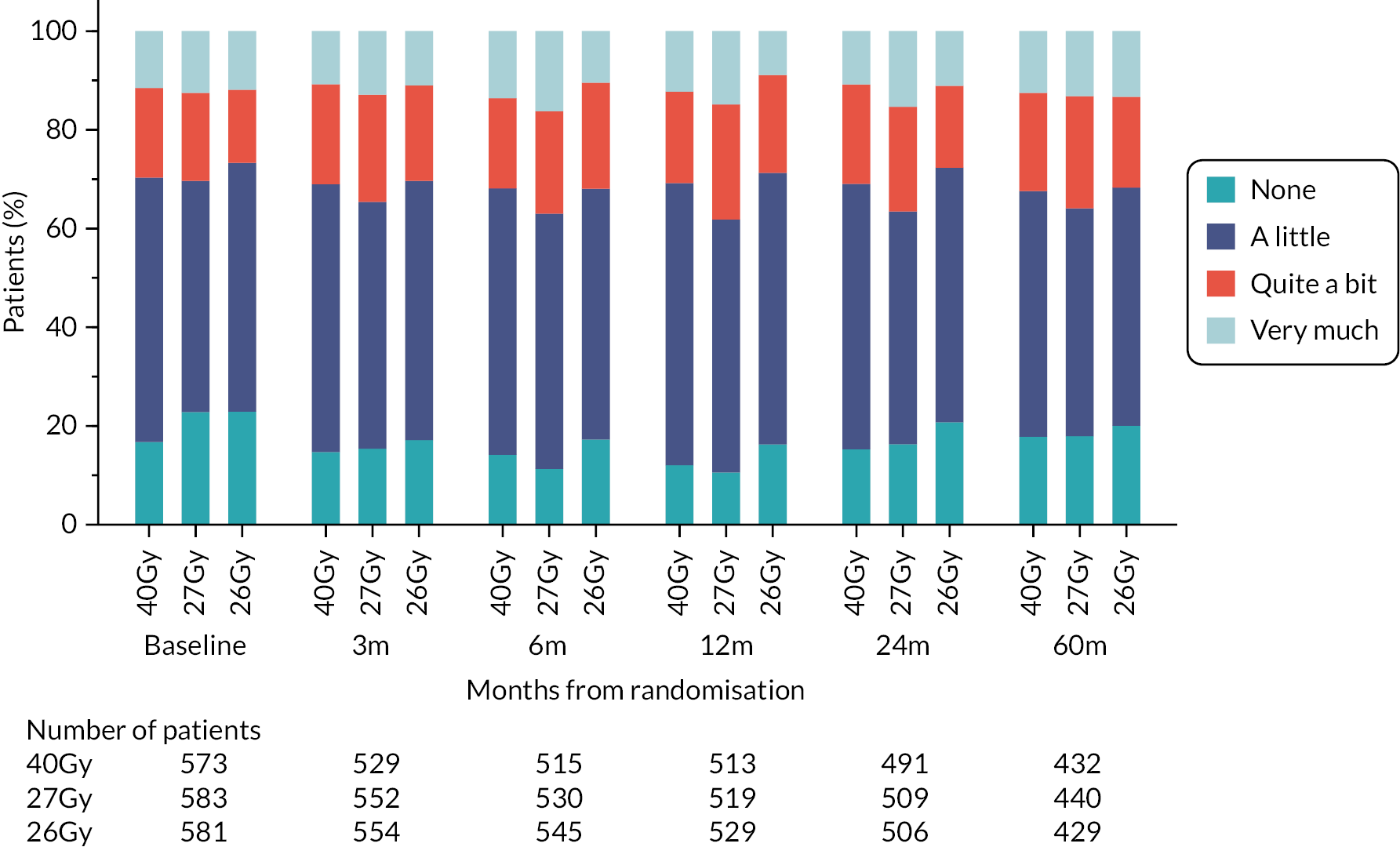

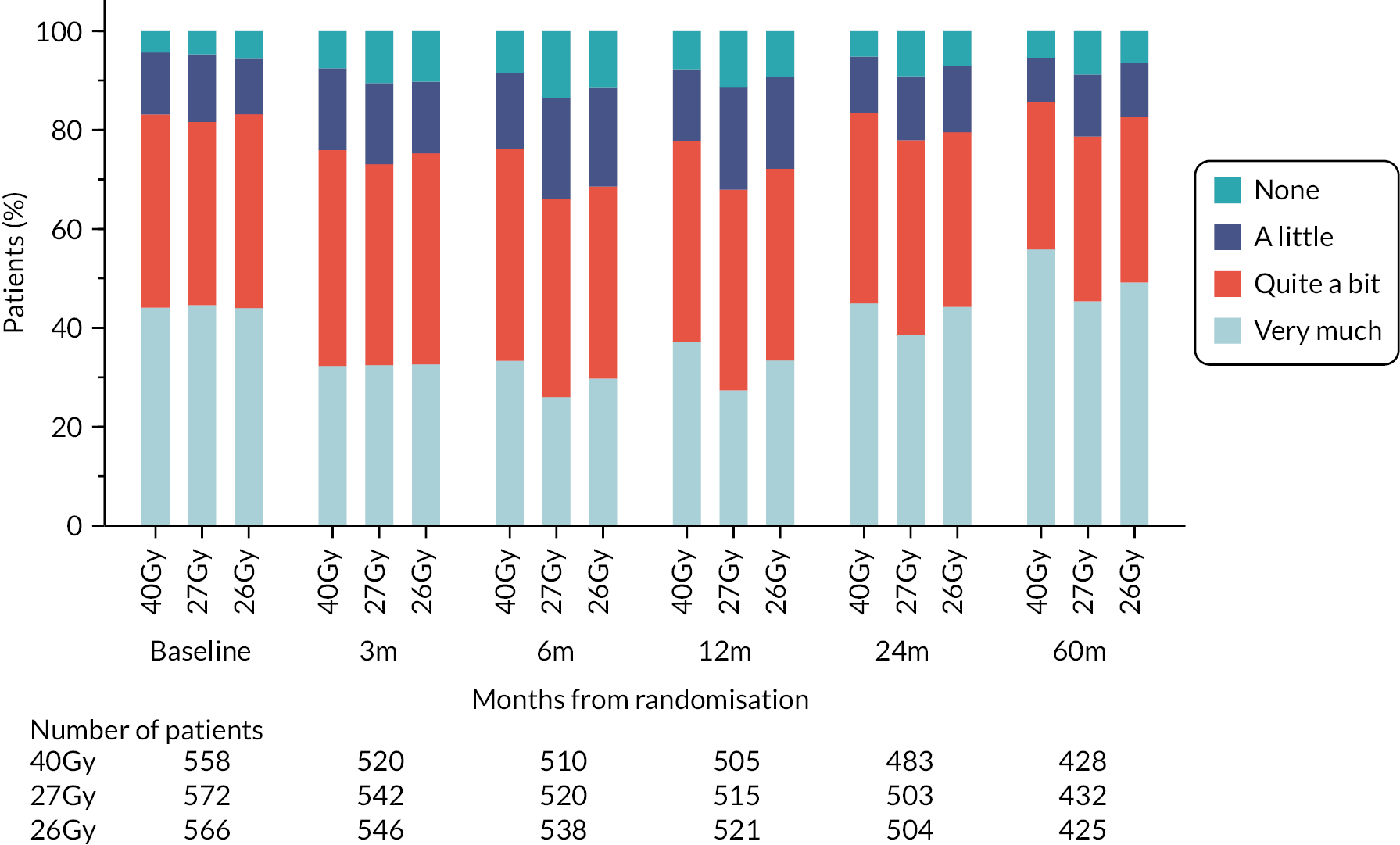

Patients were assessed by clinicians for ipsilateral breast tumour relapse (IBTR) and late NTE at annual follow-up visits. Starting 12 months after trial entry, late NTE in ipsilateral breast/chest wall (breast distortion, shrinkage, induration and telangiectasia; breast/chest wall oedema and discomfort) were graded by clinicians on a 4-point ordinal scale (none, a little, quite a bit or very much), interpreted as none, mild, moderate or marked. In addition, patients in the Nodal Sub-Study were assessed annually for the presence of breast lymphoedema, arm lymphoedema and sensorimotor symptoms. Symptomatic rib fracture, symptomatic lung fibrosis and ischaemic heart disease were recorded.

In the PRO sub-study, questionnaires were administered at baseline (pre-randomisation), 3, 6, 12, 24 and 60 months, including the EORTC QLQ-C30 core questionnaire, EORTC QLQ-BR23 breast cancer module, EORTC QLQ-FA13 fatigue module, body image scale (BIS) and protocol-specific questions relating to changes to affected breast following treatment (including breast appearance changed, smaller, harder/firmer, skin appearance changed). Patient assessments used a 4-point ordinal scale (not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much). The EuroQol 5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L) was also included in the PRO questionnaire booklets and healthcare service use questions.

All patients in the Nodal Sub-Study were asked to consent to the PRO sub-study and photographic assessments. The following PRO were included in the Nodal Sub-Study (but not the Main Trial): patient assessments of shoulder stiffness, upper limb pain, sensorimotor symptoms and arm function.

In the photographic sub-study, photographs were taken at baseline, 2 and 5 years after RT. At each visit two frontal views of the chest were taken, one with hands on the hips and the other with hands raised as far as possible above the head; photographs excluded the patient’s head. Change in photographic breast appearance and distortion compared with the post-surgical (pre-radiotherapy) baseline were scored on a 3-point ordinal scale (none, mild or marked) based on changes in breast size and shape relative to the contralateral breast. Patients were ineligible for further photographic assessments following breast reconstruction surgery and further ipsilateral disease. Digital photographs were scored by three observers blind to patient identity and treatment allocation following scoring procedures established in the START trials. 49 Breast size and surgical deficit were assessed from the baseline photographs on a 3-point scale (small, medium, large).

Data management

Data collection

All participating centres were supplied with NCR case report form (CRF) booklets and paper copies of the baseline PRO booklets. Site staff were trained in trial procedures during the site initiation visit which was performed either in person or by telephone. Data were collected according to the schedule in Table 1 and used to populate the CRFs. All CRFs and baseline PRO booklets were returned to the ICR-CTSU where they were logged into a tracking database. The clinical data were entered into a clinical database (MACRO).

Data queries

Visual checks were performed on all CRFs received at ICR-CTSU. Consistency checks of the data were written into the clinical database to identify any discrepancies in the data entered. Data queries were raised for these anomalies, discrepancies and omissions and were sent to centres on a regular basis. Queries were resolved by centres and returned to ICR-CTSU.

Central statistical data monitoring

Details of data monitoring were described in the FAST-Forward Central Statistical Data Monitoring Plan (v1.0 May 2018). Checks of the data stored on the MACRO database were performed regularly and on an ongoing basis, including prior to each analysis for an IDMC report, and queries raised with the study sites. In addition, a formal comparison between FAST-Forward CRFs received (clinical CRFs and PRO booklets) and data entered onto the MACRO database was done for 5% of Main Trial patients for all CRFs from baseline up to and including year 5 follow-up. The error rate found in this data quality control exercise was very low (0.2% of items checked).

Site monitoring

The quality of the data received from sites was assessed on a regular basis by the number of data queries generated per centre. Early intervention with the centre was initiated to discuss the queries and to avoid repeat of the errors. Central statistical monitoring of the data was also performed on a regular basis as described above. No centres were identified as needing an on-site monitoring visit.

Data assumptions/coding

Adverse effects reported under ‘other’ on the annual follow-up forms were reviewed (blind to randomised treatment schedule) by the Chief Investigator and coded according to whether they were likely to be radiotherapy-related. Prior to the Main Trial primary analysis all reported local and regional relapses were reviewed (blind to randomised treatment schedule) along with pathology reports to check coding of the relapses, including location and whether invasive or DCIS.

Endpoints

Efficacy endpoints

The protocol specified that ipsilateral tumour relapse and contralateral primary tumour must be confirmed by cytological/histological assessment. Distant relapse was to be determined by an appropriate combination of clinical, haematological, imaging and pathological assessment, recognising that pathological confirmation was not always possible. Patients remained evaluable for local relapse after distant relapse. Patients without an event were censored at the last follow-up assessment or death. Patients were to have annual clinical assessments for 10 years and annual mammograms for 5 years or until screening age if younger (as per NICE guidelines). 50

Primary endpoint (Main Trial)

-

Ipsilateral local tumour control, where an event was defined as any tumour relapse (invasive or non-invasive) or a new primary tumour in the ipsilateral breast unless confirmed by pathology to represent nodal relapse, in which case classified as regional, see below. Analyses used the date an event was confirmed.

Secondary disease-related and survival endpoints (Main Trial and Nodal Sub-Study)

-

Contralateral breast tumours (invasive and non-invasive).

-

Relapse-free survival, defined as time from randomisation until local relapse, regional relapse (axilla, SCF or other regional) or distant relapse (originating from the primary breast tumour).

-

Disease-free survival, defined as time from randomisation to first confirmed occurrence of local relapse, regional relapse, distant relapse, contralateral breast cancer or death due to breast cancer.

-

Time to distant metastases, defined as time from randomisation to the first confirmed occurrence of any distant metastases originating from the original breast cancer. For patients with second cancers reported and metastases, centres were asked to confirm that the metastases had originated from the primary breast cancer.

-

Overall survival, defined as time from randomisation to death from any cause.

-

Other second primary cancers, reported as incidence of other second primary cancers.

Endpoints of late adverse effects of radiotherapy

Patient questionnaires were to be completed at baseline, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 60 months after randomisation. Clinical assessments of radiotherapy-related late AE were carried out annually from the date of randomisation up to at least 5 years.

Primary endpoint (Nodal Sub-Study)

-

Patient-assessed arm/hand swelling from EORTC QLQ-BR23 breast cancer module (Q18: Did you have a swollen arm or hand?). Scored on a 4-point ordinal scale: ‘not at all’, ‘a little’, ‘quite a bit’, ‘very much’.

Secondary adverse effect endpoints (Main Trial and Nodal Sub-Study)

Patient and clinician assessments of late RT AE were scored on a 4-point scale: ‘not at all’ (none), ‘a little’, ‘quite a bit’, ‘very much’.

-

Patient self-assessments of late AE: These were assessed using the EORTC QLQ-BR23 breast cancer module, BIS and additional protocol-specific items relating to AE in the breast and arm/shoulder/hand. Key AE specific to the Nodal Sub-Study included shoulder stiffness, upper limb pain, sensorimotor symptoms and arm function.

-

Clinician assessments of late AE: The following late AE were assessed on a 4-point ordinal scale: breast distortion, breast shrinkage, breast induration (tumour bed), breast induration (outside tumour bed), telangiectasia, breast/chest wall oedema and breast/chest wall discomfort. A composite endpoint of any clinician-assessed late AE in the breast was defined as the worst grade reported for breast distortion, breast shrinkage, breast induration, telangiectasia and breast oedema. Breast discomfort was not included in the composite endpoint as it was not an external assessment by the clinician (scored by asking the patient), unlike the other assessments. AEs reported under ‘other’ were classified according to whether they were likely to be radiotherapy-related and analysed separately from the other clinician-assessed AE listed above (not included in the composite endpoint as some effects reported under ‘other’ on the CRF were indicated as having resolved prior to the follow-up visit and so were no longer present, unlike the other clinician-assessed effects). Clinical assessments for the Nodal Sub-Study included the following additional AE reported as present/absent (with laterality): breast lymphoedema, arm lymphoedema and sensorimotor symptoms. A separate sensorimotor symptoms CRF was completed if symptoms were noted on the follow-up form.

-

Incidence of symptomatic rib fracture, symptomatic lung fibrosis and ischaemic heart disease.

-

Specialist referral for management of radiotherapy-related AE.

Statistical considerations

Sample size

Main Trial

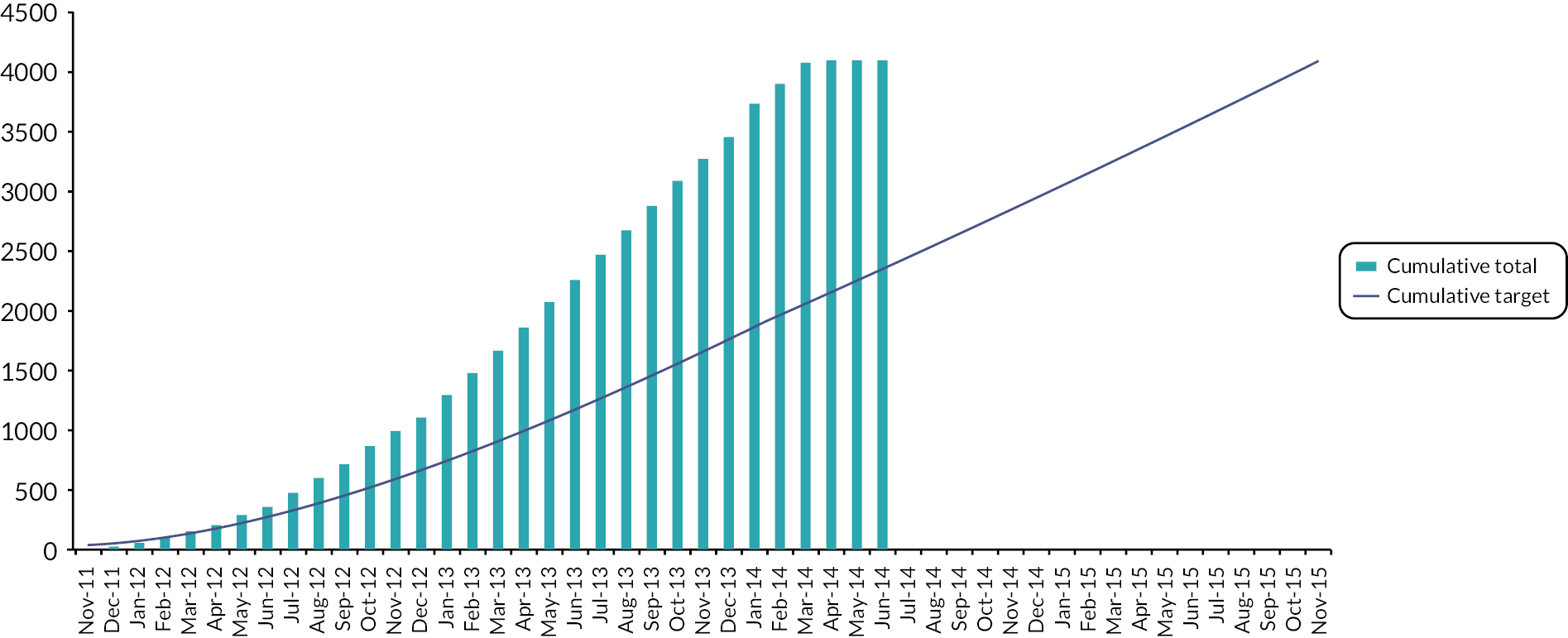

The target sample size for the Main Trial was 4000 patients, with numbers balanced between randomised groups. This provides 80% power (one-sided α = 0.025 to allow for one-sided hypothesis and a Bonferroni correction accounting for comparisons between each test group and the control group) to exclude an absolute increase of 1.6% in 5-year IBTR incidence for a 5-fraction schedule versus control. A 5-year rate of 2% in the 40 Gy schedule was assumed (using START trial data and allowing for reduction in IBTR due to evolution of systemic therapy and surgical techniques). The 1.6% absolute non-inferiority margin was defined at the trial design stage by the protocol development group including clinicians and patient advocates and was considered to be acceptable. Binary proportions were used for the sample size calculations due to the low expected event rates. Estimates allowed for 10% loss to follow-up or unevaluable (primarily due to development of metastatic disease). A total of 2196 patients (732 per group) was estimated for the photographic and PRO sub-studies to provide 80% power to detect an 8% difference in the 5-year prevalence of late NTE between the 5-fraction schedules (assuming 35% with 5-year mild/marked change in photographic breast appearance from START-B 40 Gy results), allowing for 10% loss to follow-up or unevaluable.

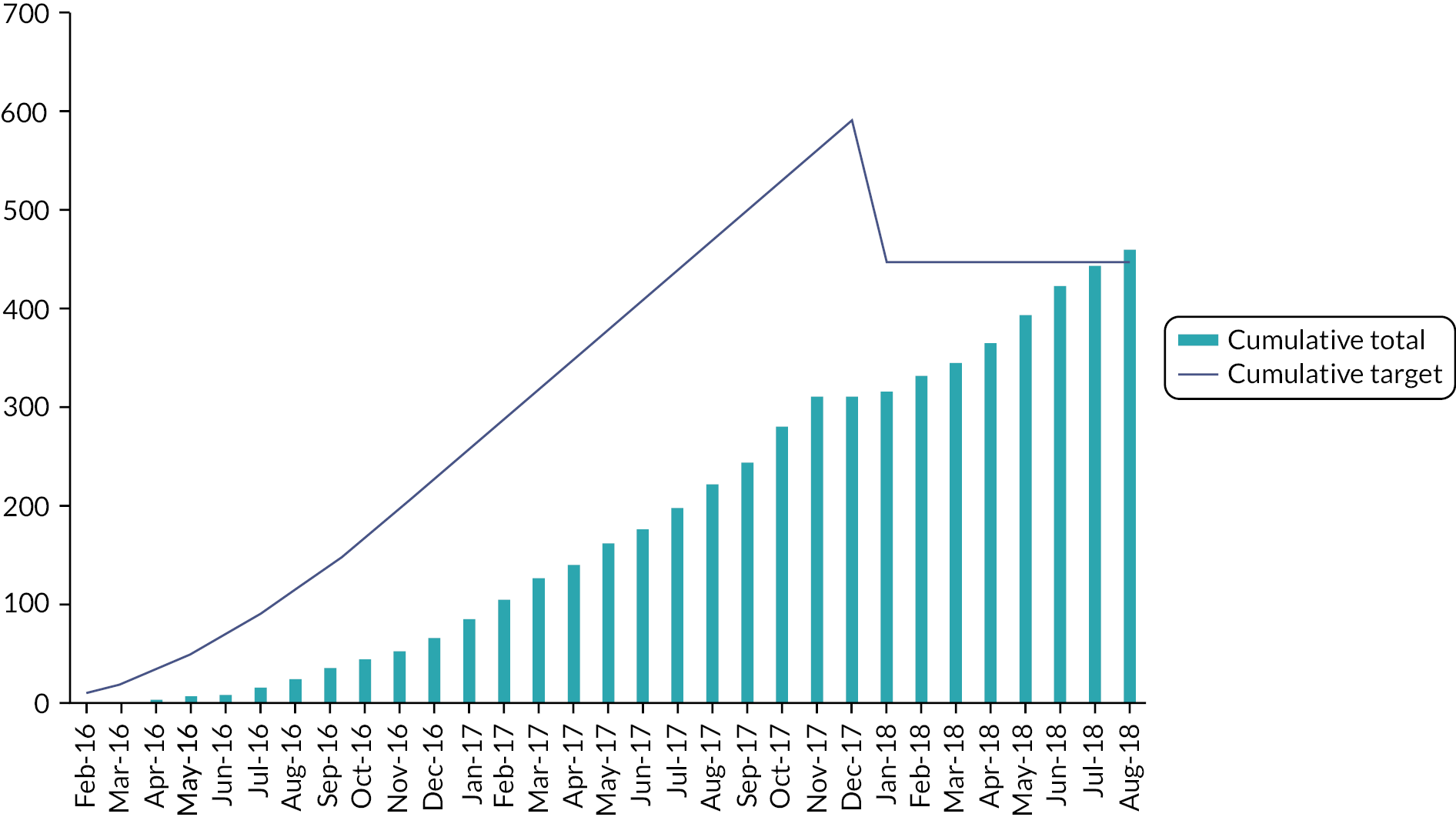

Nodal Sub-Study

The sample size for the Nodal Sub-Study was based on the primary endpoint of patient-assessed arm swelling at 5 years. The original design of the sub-study had three groups that mirrored the Main Trial design but was revised to a 2-group design in Protocol v5.0 (14 December 2017), when accrual into Test Group 1 (27 Gy) was closed. The original and revised sample size justifications for the Nodal Sub-Study are given below.

Original target sample size for Nodal Sub-Study

The target sample size was 627 patients with numbers balanced equally in each of the three randomised groups. This provided 90% power (one-sided α = 0.025 to allow for one-sided hypothesis and multiple testing) to exclude an arm swelling rate at 5 years of 20% in each of the test groups compared to an assumed rate in the control group of 10% (allowing for 10% attrition due to illness or death based on experience from the START trial).

Revised target sample size for Nodal Sub-Study

From Protocol v5.0 onwards the target sample size for the Nodal Sub-Study was reduced to 344 (172 in each of the Control group and Test Group 2). This provided 90% power (one-sided α = 0.05) to exclude an arm swelling rate of 20% in Test Group 2 compared with an assumed rate of 10% in the Control group at 5 years (allowing for 10% attrition). With the numbers recruited into Test Group 1 up until Protocol v5.0, comparison of arm swelling between Test Group 1 and the Control group would have approximately 73% power using the same assumptions as above.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics

Baseline patient, clinical and treatment characteristics were described according to randomised group using summary statistics, with no formal comparative tests as these data would be expected to be balanced between the groups due to randomisation.

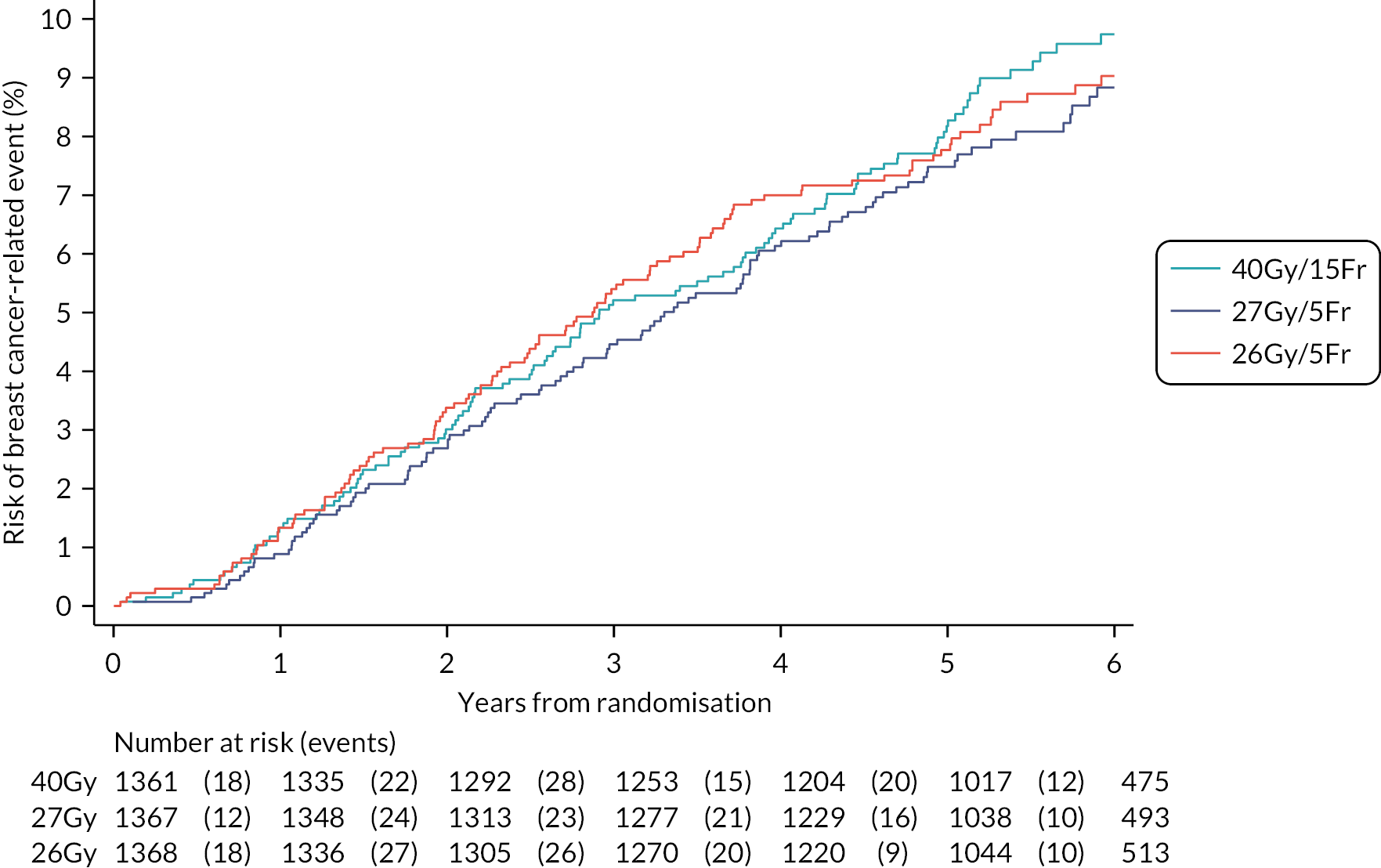

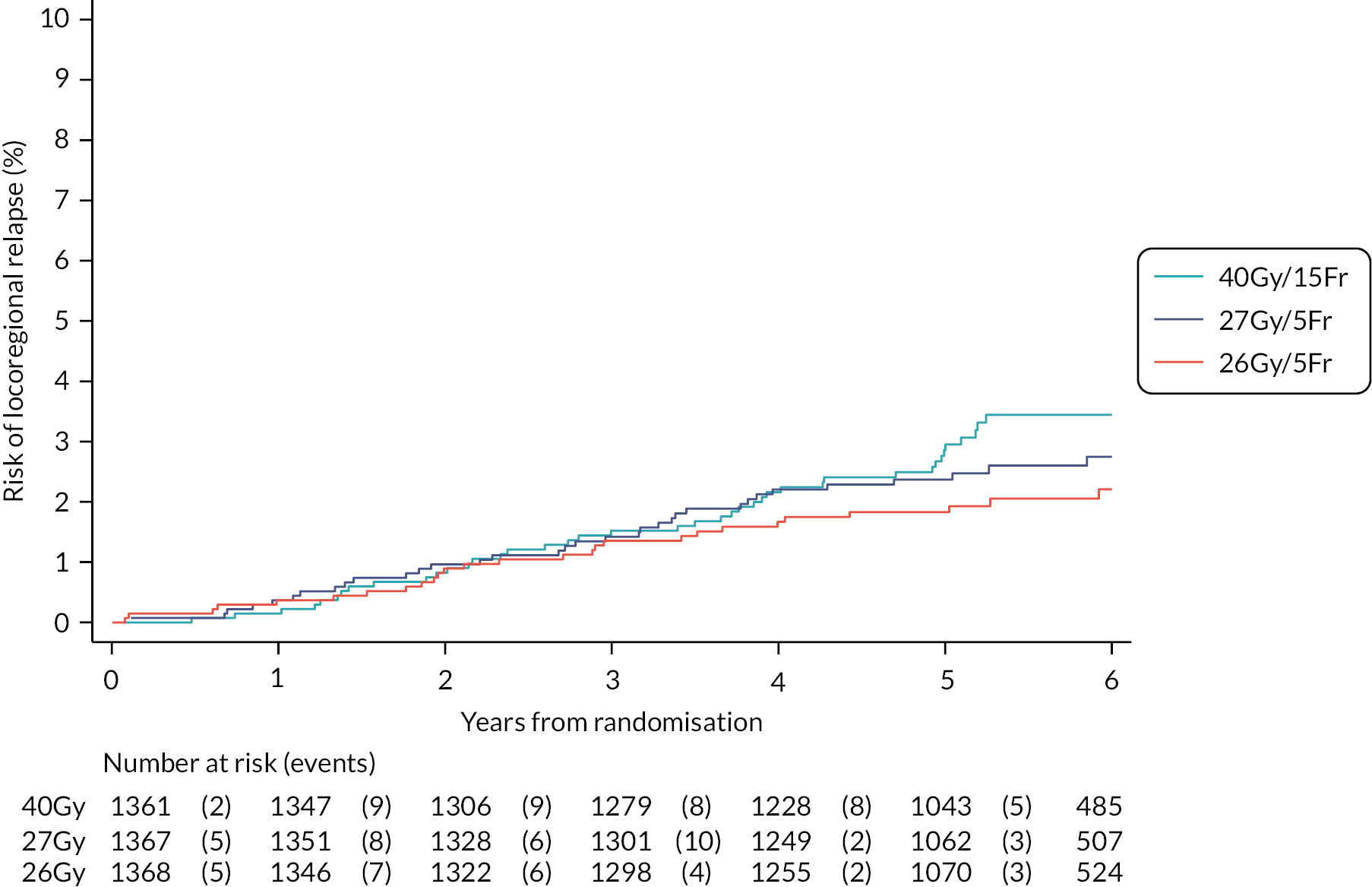

Primary endpoint (Main Trial)

The number of IBTR primary endpoint events were tabulated by treatment group. Survival analysis methods compared IBTR between treatment groups, censoring patients at date of death or last follow-up. Kaplan Meier methods were used to estimate event rates and graphically display local control rates and cumulative incidence in each treatment group. Kaplan–Meier estimates of 5-year IBTR cumulative incidence were presented along with 95% CI for each group and each Test Group was separately compared with the Control group using the log-rank test.

Crude estimates of treatment effect for each Test Group compared with the Control group were described by HRs (with 95% CI) obtained from an unadjusted Cox regression model. All comparisons were expressed relative to the Control group so that a HR less than one indicates a decreased risk of the event in the Test Group. Absolute treatment differences were calculated (by applying the HRs to the control group’s 5-year event-free estimate) along with both one- and two-sided 95% CI (calculated from the CIs for the HRs and the control group 5-year event-free estimate). As the protocol-defined non-inferiority margin is an absolute excess of 1.6%, the primary assessment of non-inferiority was whether the upper limit of the two-sided 95% CI for the absolute difference in 5-year local tumour control (calculated as above) is < 1.6%.

Additionally, non-inferiority of each Test Group versus Control was tested using the a priori critical HR of 1.8 (ln0.964/ln0.98, derived from the absolute rates specified in the protocol); a p-value of < 0.025 will be deemed statistically significant (the probability of incorrectly accepting an inferior test group treatment). Assessment of non-inferiority using the HR, a measure of relative rather than absolute treatment effect, will aid interpretation of the primary endpoint results particularly if the 5-year rate of ipsilateral disease events in the control group is < 2% assumed in the protocol, in which case relative excess may be deemed important to consider. If non-inferiority in terms of the a priori critical HR of 1.8 was not shown, a sensitivity analysis would be carried out using methods stated above to test the critical HR calculated from the observed (rather than protocol-specified) 5-year event-free rate in the control group and 1.6% absolute excess in the test groups. An exploratory competing risks analysis was done for IBTR, with death from any cause as a competing event in a Fine–Gray competing risks regression model.

Primary endpoint (Nodal Sub-Study)

The primary outcome of patient-assessed arm/hand swelling (‘Did you have a swollen arm or hand?’ Q18 from EORTC QLQ-BR23 breast cancer module) was summarised at each time point from baseline up to 2 years using frequencies and percentages of each response category (‘not at all’, ‘a little’, ‘quite a bit’, ‘very much’) according to treatment group.

Secondary endpoints

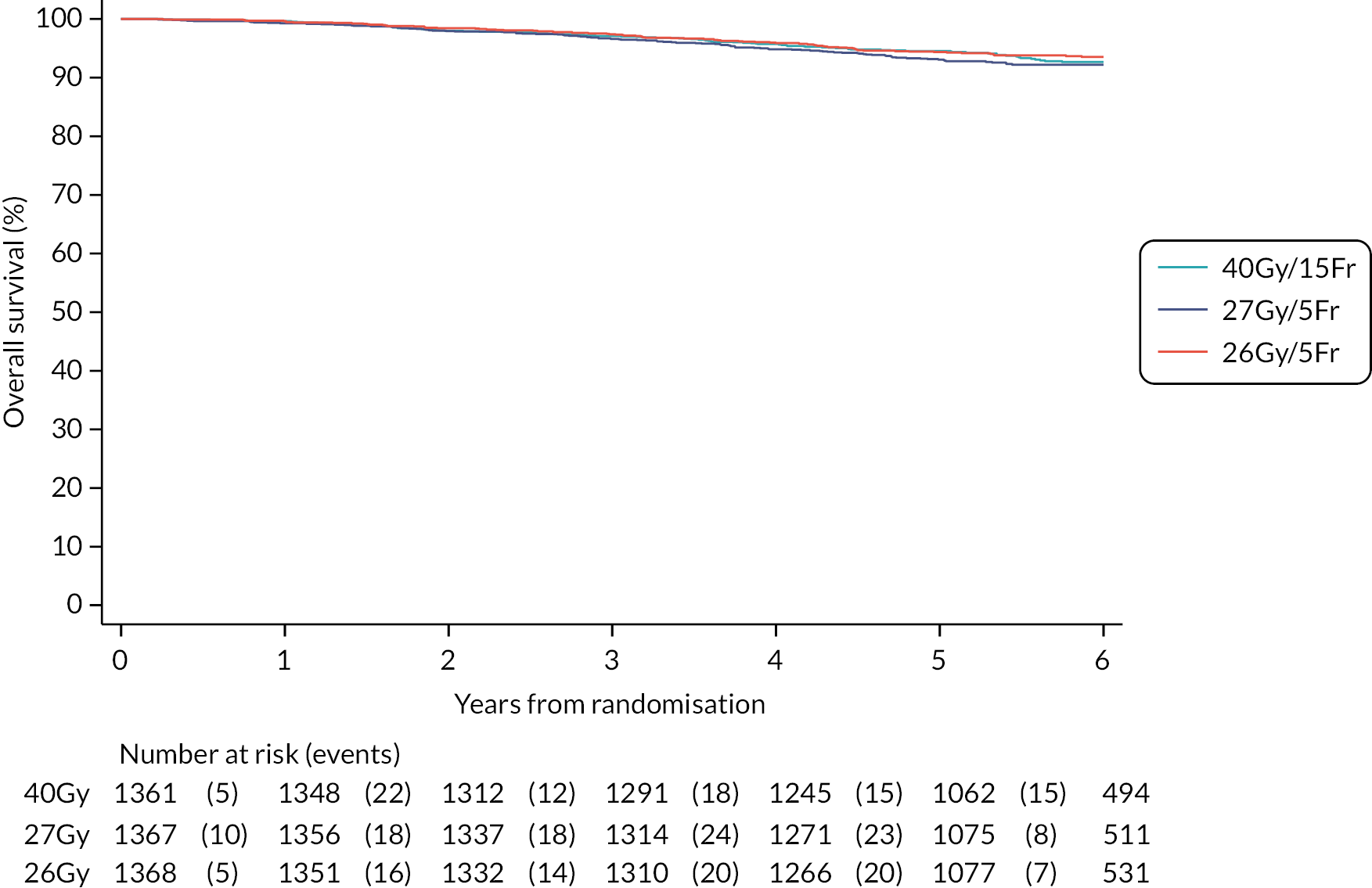

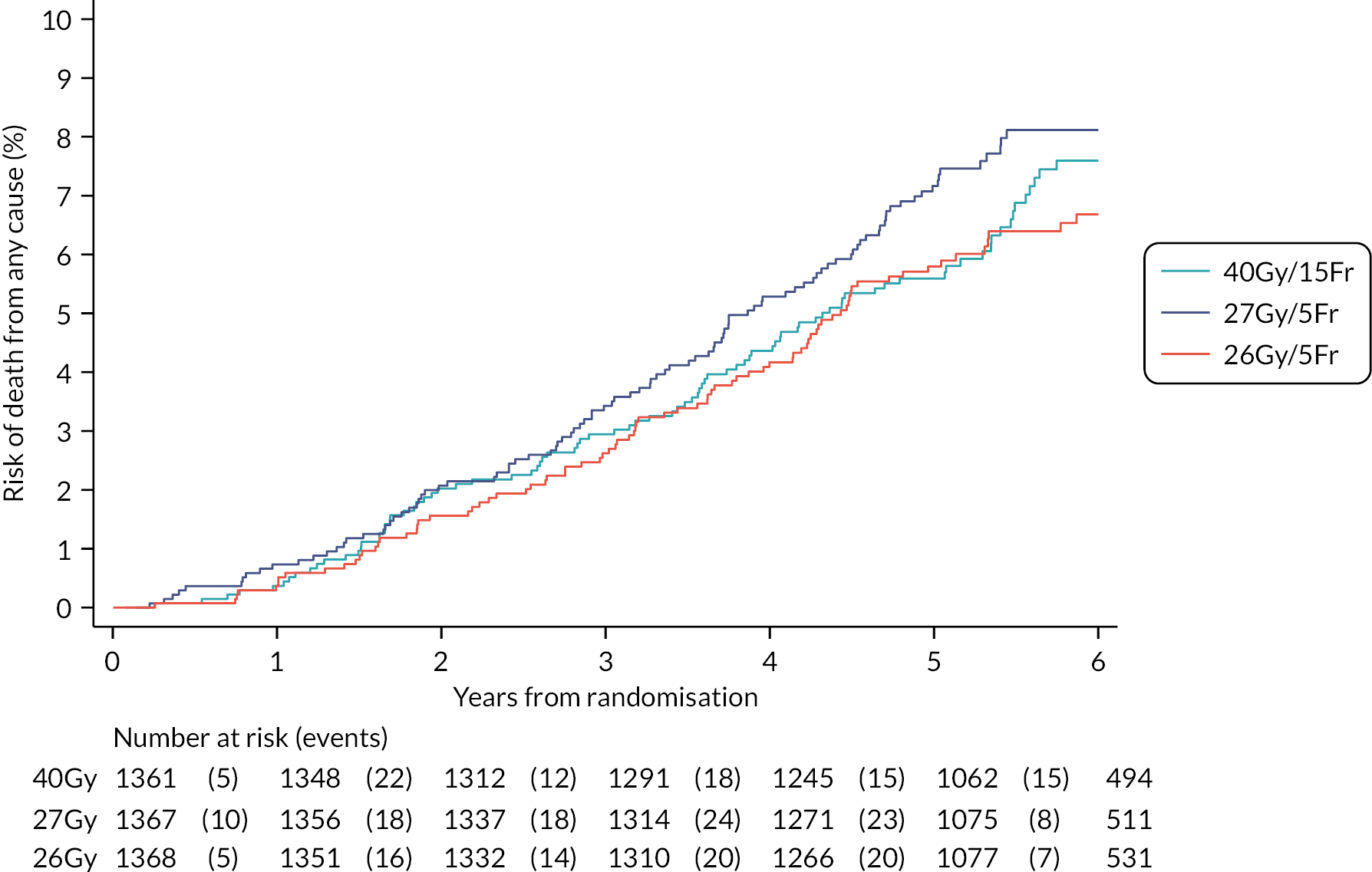

Other efficacy outcomes were tabulated in the Main Trial according to treatment group, with deaths presented according to whether or not breast cancer-related or cardiac-related. Analyses of other efficacy outcomes including regional relapse, distant metastases, disease-free survival and overall survival used survival analysis methods as described for IBTR above. Analysis of efficacy outcomes in the Nodal Sub-Study will await 5-year follow-up, when a meta-analysis is conducted with data from the Main Trial.

Clinician and patient assessments of late NTE were tabulated for each treatment group and time point separately for the Main Trial and the Nodal Sub-Study. Descriptive data are shown for the Nodal Sub-Study up to 2 years for PRO and to 3 years for clinical assessments. Formal statistical analysis of primary and secondary endpoints for the Nodal Sub-Study will await 5-year follow-up (as specified in the protocol).

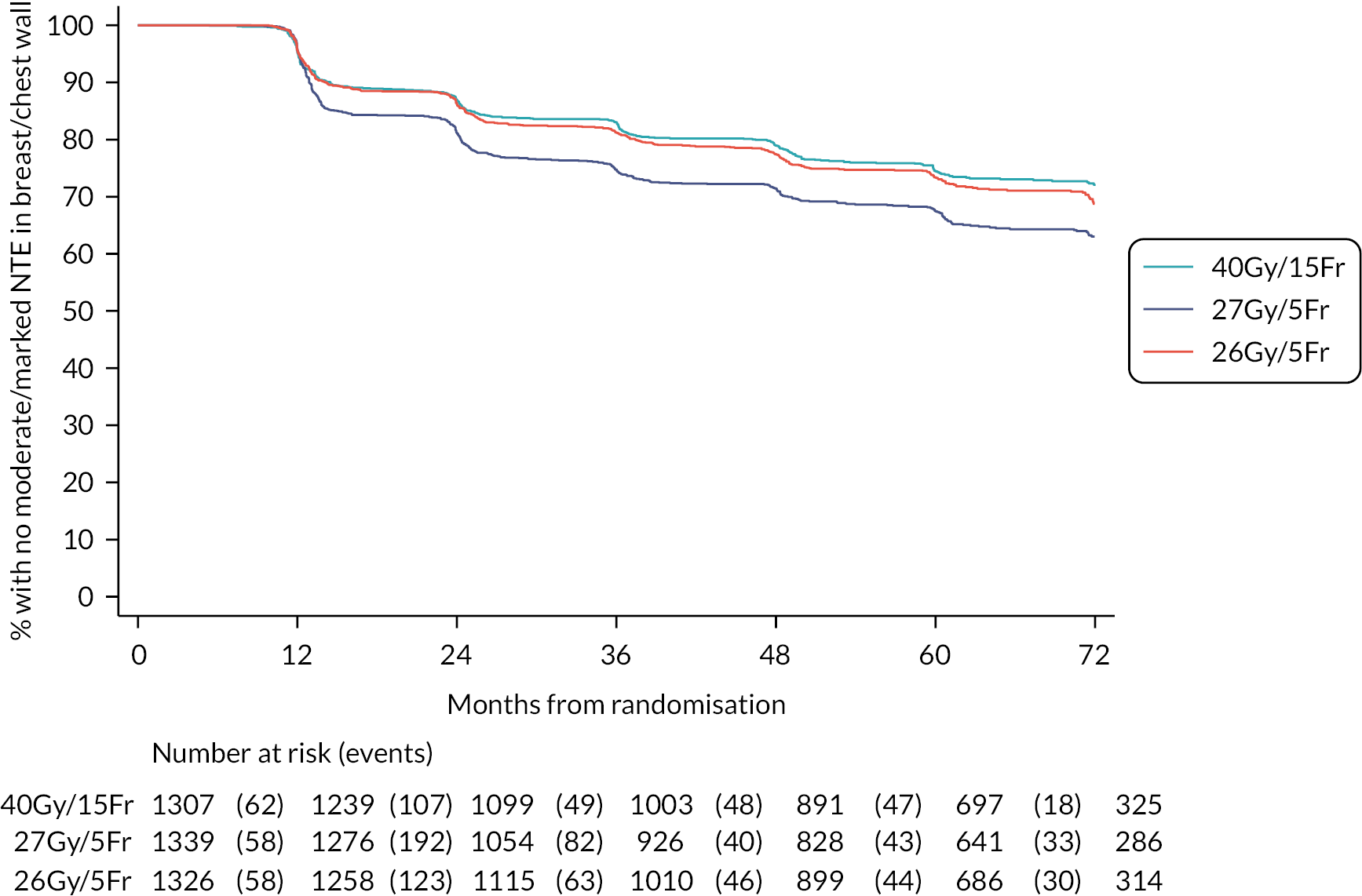

NTE endpoints in the Main Trial were dichotomised as ‘not at all’/’a little’ (none/mild) versus ‘quite a bit’/’very much’ (moderate/marked) and analysed as follows: (1) cross-sectional analyses at key time points compared prevalence of moderate/marked effects versus none/mild between groups using risk differences (95% CI), and Fisher’s exact test; (2) longitudinal regression analyses of moderate/marked effects (vs. none/mild) using generalised estimating equations (GEE), comparing groups across the whole follow-up period including assessments from all timepoints using (ORs, 95% CI) and the Wald test; GEE models included a term representing years of follow-up to assess time trends. RRs are not presented in this report for the 5-year cross-sectional analyses of clinician and patient-assessed NTE since they may be open to over-interpretation given the low absolute event rates for many of the endpoints, as reflected by the wide CIs. Survival analysis methods analysed time to first moderate/marked clinician-assessed NTE; Kaplan–Meier estimates of cumulative incidence were obtained and groups compared using HR (95% CI) from Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression and the pairwise log-rank test. The PH assumption was not met for patient-assessed NTE endpoints, and so time-to-event analyses were not performed.

For the Main Trial photographic assessment scores for change in photographic breast appearance at 2 and 5 years were modelled using GEE. Categories of mild and marked change in photographic breast appearance were combined for analysis as there were very few with marked change. Pairwise comparisons of mild/marked change at 2 and/or 5 years between groups were described by OR (95% CI) obtained from the GEE models and the Wald test.

For the Nodal Sub-Study comparisons between the Control group and Test Group 1 only included Control group patients randomised concurrently (i.e. up to end of 2017 prior to protocol amendment dropping Test Group 1).

For all patient and clinician-assessed NTE endpoints a significance level of 0.005 was used for Main Trial analyses, to allow for multiple testing. No formal testing is done for the Nodal Sub-Study at this stage of follow-up.

Estimates of fractionation sensitivity (α/β values, 95% CI) were obtained for the Main Trial primary endpoint of IBTR and late NTE using methodology from the START and FAST trials. 17,47 The α/β estimate for breast cancer was obtained from a Cox PH regression model of time to first IBTR, and for late NTE from GEE models including all follow-up assessments (separate models for clinician and photographic assessments). Terms for total dose (D) and total dose multiplied by fraction size (Dxd) were included in each model; the α/β ratio was calculated by dividing the two-parameter estimates (D/Dxd), with an estimated 95% CI derived using the covariance of the two estimates (lower confidence limits truncated at zero). Isoeffect equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) were calculated for both 5-fraction schedules, together with an estimate of the 5-fraction schedule isoeffective in terms of local control and late NTE with 40 Gy in 15 fractions.

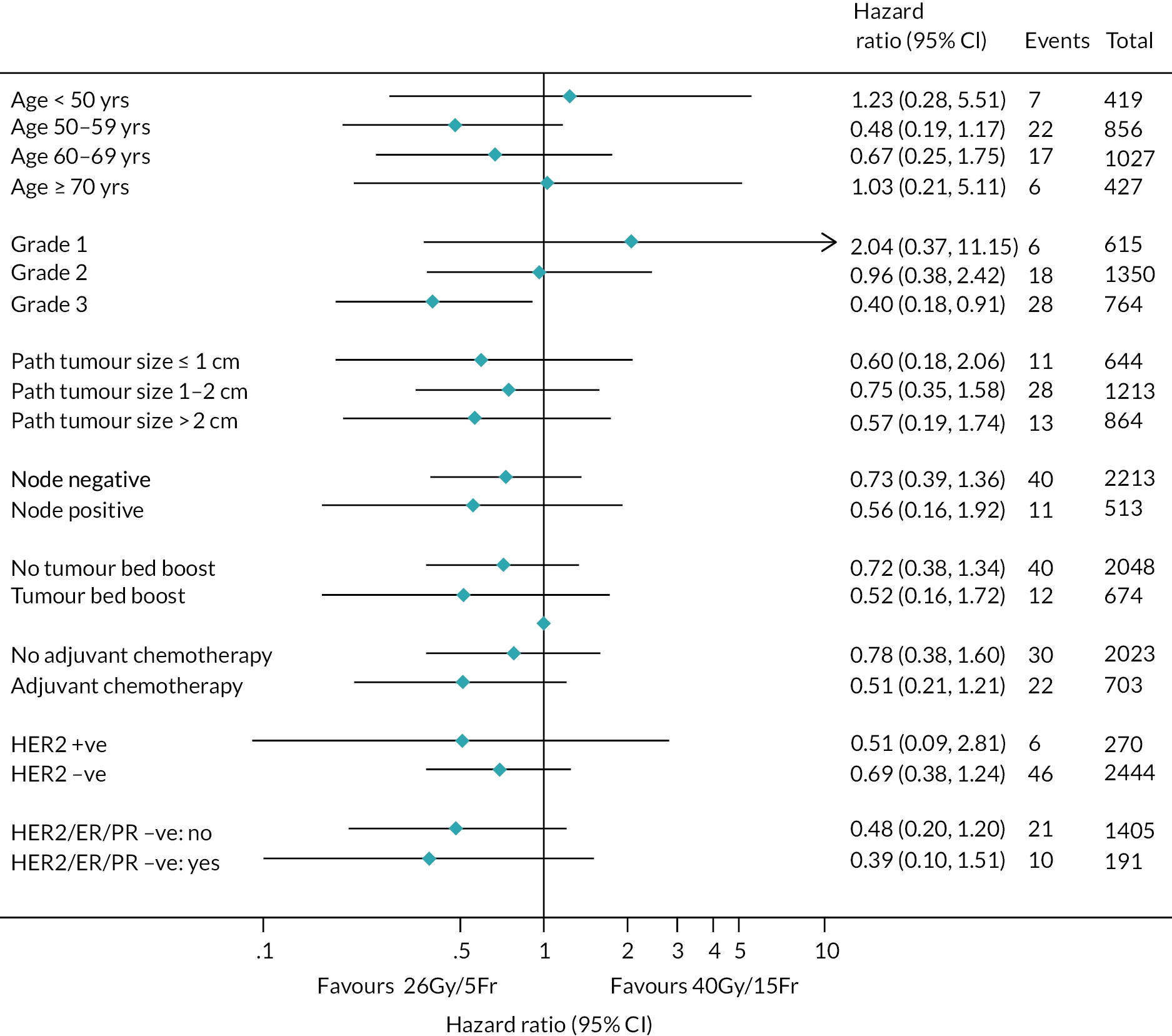

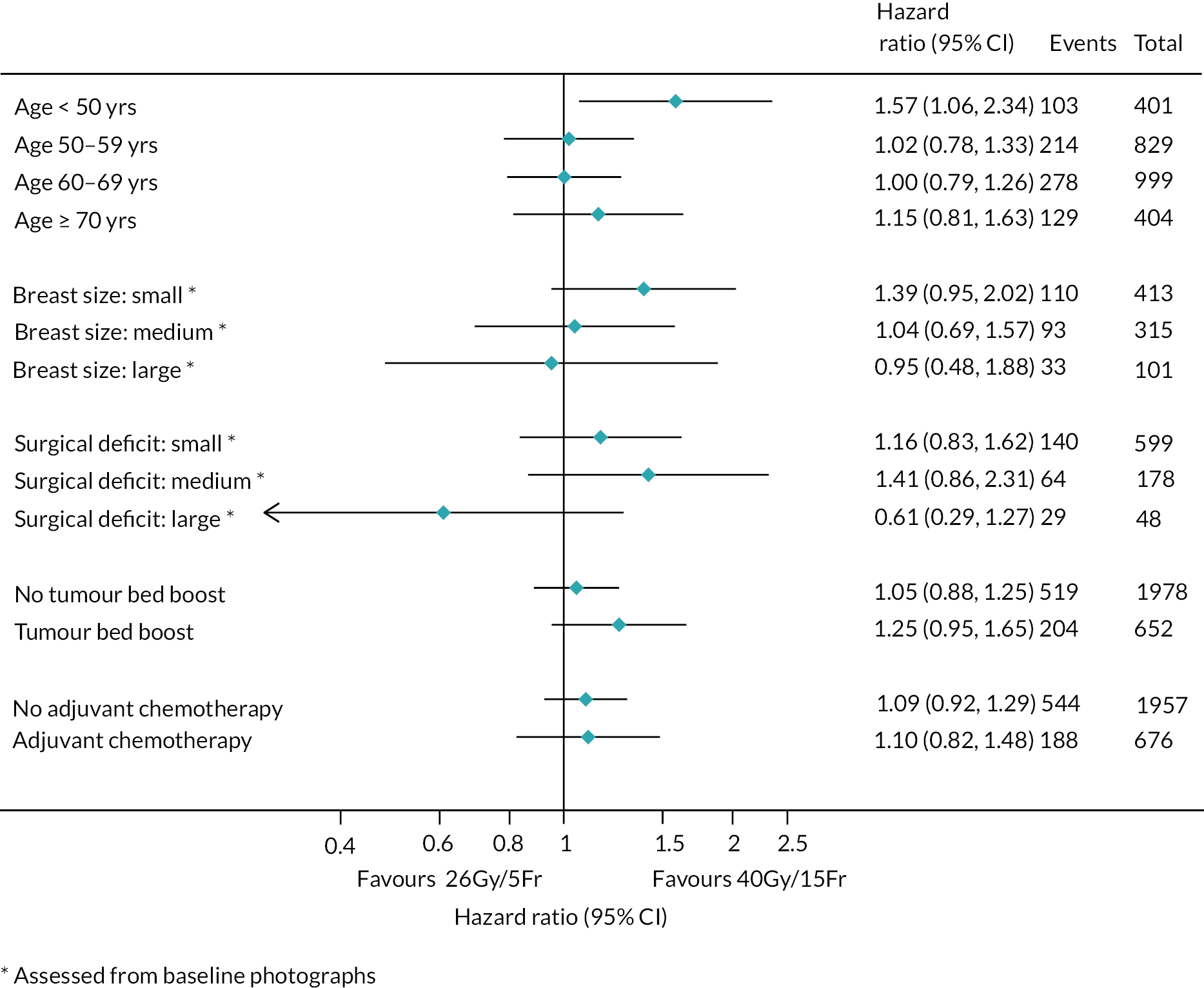

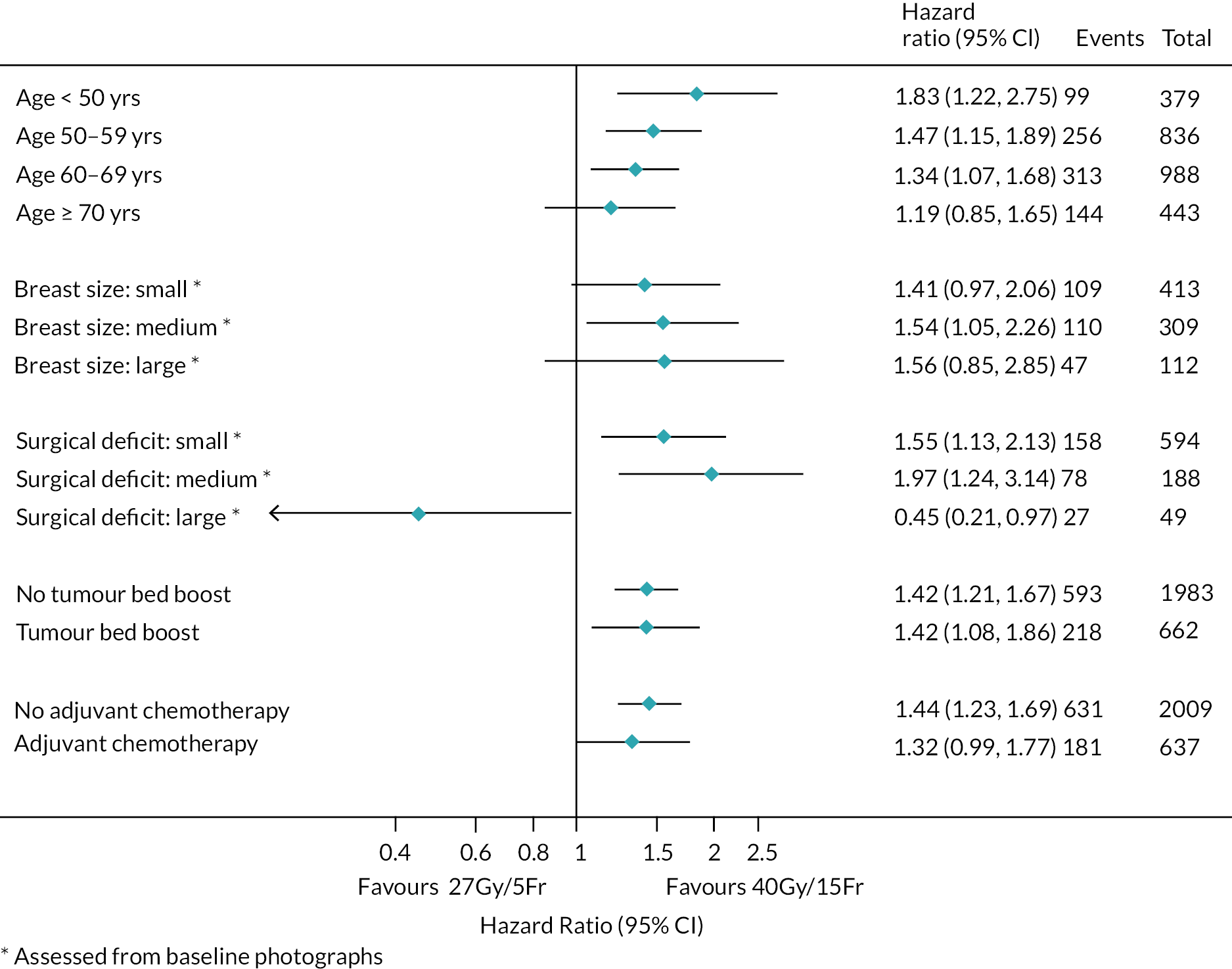

There were no pre-planned subgroup analyses for the Main Trial specified in the protocol. Exploratory post hoc subgroup analyses were conducted in the Main Trial for the primary endpoint according to risk factors including age, grade, pathological tumour size, pathological node status, ER/progesterone receptor (PR)/HER-2 status, tumour bed boost and adjuvant chemotherapy. Additionally, exploratory post hoc analyses of NTE in the Main Trial were done according to age, breast size, surgical deficit, tumour bed boost and adjuvant chemotherapy.

There were no formal interim analyses other than for the acute toxicity studies; accumulating data were monitored annually by the IDMC. All analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis that included all patients according to their allocated treatment regardless of what was actually received. As the main hypothesis for the Main Trial was non-inferiority the primary endpoint was also tested in the per-protocol population excluding patients for whom a major treatment deviation was reported.

The database snapshot for the Main Trial was taken on 22 November 2019 and Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) used for analyses. For the 3-year descriptive analysis of the Nodal Sub-Study the database snapshot was taken on 1 December 2021; Stata version 17 (StataCorp) was used for the Nodal Sub-Study analyses.

Study conduct

Patient and public involvement

FAST-Forward was part of a broader portfolio of patient-centred ICR-CTSU and National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Breast Group trials where patient representatives with lived experience of breast cancer have been partners from concept, formalising their role as members of the protocol working group and Trial Management Group (TMG). In FAST-Forward patient representatives helped shape the trial with active involvement from trial concept, through recruitment, reviewing trial documents, discussing trial results prior to publication and helping to write lay summaries of the results for trial participants. A link to the lay summary of the Main Trial results that was distributed to trial participants following publication of the primary analysis in 2020 can be found on the ICR-CTSU FAST-Forward webpage (www.icr.ac.uk/fastforward). Our patient and public involvement (PPI) partnerships enabled design of an efficient and cost-effective follow-up schedule that truly reflects the patient experience with minimal burden and is patient-centred.

In addition, ongoing links have been forged with local (Royal Marsden) and national (Independent Cancer Patients’ Voice, UK Breast Intergroup, NCRI) patient advocate groups, embedding patient representation in the whole clinical trial lifecycle. PPI work in breast RT trials co-ordinated by ICR-CTSU has included development of alternative patient information formats, focus groups where patients emphasised the need for information on risks/benefits of RT at all stages of treatment and recovery, and future plans to collaborate within a PhD project optimising data capture of AE from trial participants.

The TMG had preferentially at least two patient representatives which enabled mutual support and empowerment. All TMG members were included in any email discussions, encouraging PPI input at all times. A mentoring programme for new TMG members was also initiated which included conversations with the Chief Investigator and PPI lead at ICR-CTSU.

Trial oversight committees

The TMG, TSC and IDMC each worked to a charter issued by ICR-CTSU and met annually until the time of Main Trial publication, with the TMG and TSC continuing to meet thereafter.

Trial Management Group

The FAST-Forward Trial Management Group was responsible for day-to-day trial conduct. Membership included the Chief Investigator, additional Principal Investigators from recruiting sites across the UK, physics and radiographer staff from recruiting sites, members of the NCRI radiotherapy trials quality assurance (RTTQA) group, key ICR-CTSU staff and patient representatives. Members are listed in the Acknowledgements section.

Trial Steering Committee

The ICR-CTSU Breast RT Trials Steering Committee (Chair Professor Malcolm Mason) provided strategic oversight of the study on behalf of the Funder and Sponsor and met annually from the start of the trial. The independent membership comprised four members (listed in Acknowledgements).

Independent Data Monitoring Committee

The IDMC (Chair Professor Matthew Sydes) reviewed emerging trial data on an annual basis. Following each meeting, the IDMC reported their recommendations to the TSC. There were no stopping rules for the Main Trial (only the acute toxicity sub-studies), and no formal interim analyses were done. Following review of the report prepared for the IDMC meeting in October 2016 the IDMC recommended to the TSC that the 27 Gy/5 fractions group be dropped from the Nodal Sub-Study, which was recruiting at the time. The IDMC reviewed emerging results of the Main Trial at a median follow-up of 3 years and recommended presentation or publication of the 3-year NTE data to inform the worldwide evidence base. 51 The IDMC noted that previous breast RT trials (START, FAST and IMPORT LOW) confirmed that normal tissue effect rates at 3 years had been shown to predict 5- and 10-year comparisons. Absolute rates of moderate/marked NTE in the Main Trial were reassuringly low at 3 years, but there was evidence of increased late toxicity for Test Group 1 compared with the control schedule, which although statistically significant was not felt by the TSC and TMG to be clinically significant, as the rate of NTE was comparable to that after 50–52 Gy in 2.0 Gy fractions. Data were shared confidentially with the TSC following further discussions with the IDMC in 2016/2017, and the TMG produced a guidance document for the IDMC to aid interpretation of differences in late NTE between the schedules. It was concluded that Test Group 1 was no longer needed in the Nodal Sub-Study, given that the optimal 5-day schedule was highly unlikely to involve fraction sizes > 5.2 Gy. This allowed simplification of the trial design for the Nodal Sub-Study, allowing a 2-group design to test the safety of 26 Gy in 5 fractions against the Control schedule of 40 Gy in 15 fractions. The design of the Nodal Sub-Study was revised to a 2-group trial in December 2017. IDMC members are listed in the Acknowledgements section.

Approvals, reporting and compliance

FAST-Forward was sponsored by The Institute of Cancer Research and was registered as ISRCTN19906132.