Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/146/06. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The draft report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in November 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Wilson et al. This work was produced by Wilson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Wilson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Around 12% of the population of Great Britain experience recurrent tonsillitis, with significant associated morbidity and impacts on work, education, family and social life. 1–3 For those patients experiencing frequent, disabling tonsillitis over time, tonsillectomy (surgical removal of the tonsils) is a treatment option. Although most of those undergoing tonsillectomy report benefit, it has been unclear to what extent some of the improvements seen following tonsillectomy would have occurred without surgical intervention. This uncertainty, together with the cost and morbidity associated with surgery, has led some to question whether or not tonsillectomy should be considered a ‘low-value surgical procedure’. 4 However, in recent years, emergency hospital admissions for adults with pharyngotonsillitis have risen to 30,000 per year in England: twice as many as adults who undergo tonsillectomy. With this context, the NAtional Trial of Tonsillectomy IN Adults (NATTINA) set out to provide much-needed evidence regarding the place of tonsillectomy in the treatment of adults with tonsillitis.

Economic burden of adult sore throat disease

There have been several attempts to quantify the economic impacts of sore throat. One recent study initially estimated the annual cost of consultations and lost productivity to be £40M, but concluded that the actual all-encompassing bill might be as high as £2.35B. 5 A more current estimate of primary care costs can be drawn from the pilot data of an NHS study: Sore Throat Test and Treat. 6 Extrapolation of the Sore Throat Test and Treat pilot figures to the estimated 42,000 full-time equivalent general practitioners (GPs) in England and Scotland would translate to 5.9 million consultations per annum. Taking the cost of a GP appointment from the unit costs of health and social care produced by the Personal Social Services Research Unit7 to be £34, these consultations equate to a nationwide bill of over £201M per annum. In addition, if there are antibiotics prescribed in approximately three-fifths of those attending primary care with sore throats, the total cost even of simple penicillin V at £1.25 for 28 500-mg tablets four times per day for 1 week is £19.2M. 6 The cumulative total of consultations and antibiotic prescriptions is, therefore, in the order of £219M per annum in England and Scotland. The latest available NHS Healthcare Resource Group data give an expenditure of over £70M for tonsil surgery per year in England, in all ages. Between 2013 and 2017, there were 4600 tonsillectomies per year on average, in Scotland,8 costing an additional £7.5M, although the emergence of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidance has been reported to have impacted differently in England and Wales than in Scotland. 9

Numerous additional interventions take place in the independent sector that are not recorded in NHS digital data. The cost of pharyngeal inflammation emergency admissions, as outlined below, exceeds £20M. Adding these secondary care episodes to those in the community gives an overall, all-age cost of £309M.

Estimated cost of adult pharyngotonsillitis in secondary care

Around 60% of tonsil disease occurs in childhood; the present trial concerns optimum treatment strategies for tonsil infections in adults aged ≥16 years. In adults, the total cost of tonsil surgery in 2018–19 in England was over £29.4M. 10 At a conservative estimate, over 30,000 adults are admitted with pharyngitis and tonsillitis diagnoses as emergencies in England per annum, as outlined in the following section. 11 The cost of the associated bed occupancy alone exceeds £10M,10 a total secondary care expenditure around £40M.

Association over time between the rate of surgical tonsil intervention and admission to hospital with pharyngotonsillar inflammation

Several reports12 indicate that as the UK rate of tonsillectomy has fallen, the number of acute admissions has risen, although no causality has been proven in this association. For example, looking at English Hospital Episode Statistics data,13 in 2009–10 there were 21,540 tonsillectomy operations in adults aged ≥15 years, and around 15,000 emergency adult pharyngotonsillitis admissions. In 2019–20, there were only 16,000 adult tonsillectomy operations, whereas emergency adult admissions in England with a main diagnosis of pharyngitis and tonsillitis had risen to over 30,000. 11 A similar reduction in surgical intervention was seen in recent years in Germany, where the tonsillectomy rate fell by 46% in males and 40% in females from 2005 to 2017. 14

Sore throats and recurrent tonsillitis

‘Sore throat’ refers to pain in the pharyngotonsillar area and can be caused by viral or bacterial infection, or by non-infective irritants, such as smoke and hay fever. ‘Tonsillitis’ is a subset of sore throats in which there is inflammation of the tonsils, and this can range from relatively mild symptoms associated with viral infections to bacterial tonsillitis and quinsy (peritonsillar abscess). The pathway through which patients are offered tonsillectomy is inevitably predicated on patient complaints, not only sore throat but also, as our own NATTINA patient and public involvement (PPI) group advised, the concomitant experience of general illness and malaise. It is the systemic nature of the illness and the impact on the patients’ quality of life (QoL) that leads patients to seek treatment15 and, eventually, to be referred to secondary care. Our PPI group reported varied access to antibiotic therapy for tonsillitis in primary care.

In the USA, the term ‘strep throat’ is widely used to distinguish between bacterial tonsillitis caused by group A Streptococcus and viral (usually milder) tonsillitis, but this distinction is less commonly made in the UK, particularly in primary care. Although anyone (with tonsils) can experience tonsillitis, a subset of people experience multiple episodes of acute tonsillitis over an extended period of time: recurrent tonsillitis. Recurrent tonsillitis is more common in females, and studies in twins demonstrate a strong hereditary element. 16 A failure to differentiate between different forms of sore throat may have contributed to an inadequate understanding of the features and impacts of recurrent tonsillitis and limited the development of effective alternatives to antibiotics and tonsillectomy, in spite of the high prevalence and morbidity associated with recurrent tonsillitis. Recent work has identified specific genetic variations in the immune system that are associated with a risk of recurrent tonsillitis, suggesting potential future treatment targets. 17 In NATTINA, consistent with SIGN18 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance,19 we refer throughout to ‘recurrent sore throats’.

Role of tonsillectomy in the management of recurrent sore throats

The optimum role of tonsillectomy in the management of adults with recurrent sore throat remains uncertain. Audits consistently report over 95% of patients gaining symptom relief from surgery,20,21 but a lack of level I evidence22,23 contributes to ongoing UK regional variation in tonsillectomy rates,24 even where compliance to SIGN guidance18 approaches 90%. 25 The 2014 Cochrane review22 identified only one evaluable, small, adult trial comprising 70 participants26 with only 90 days’ follow-up. It concluded that reasonable levels of evidence were available for tonsillectomy in children only. Since then, there has been a further small (≈ 40 per arm) Finnish tonsillectomy trial,27 which demonstrated no impact on the primary outcome, that is the proportion of patients with severe inflammation of the pharynx within 5 months. However, there were 10 times as many consultations for pharyngitis in the conservative management arm.

Except in rare situations (when tonsillar material remains or regrows), tonsillectomy should remove the possibility of tonsillitis, but its impact on non-tonsillitis sore throats, if any, is unknown. The questions that patients, doctors and healthcare providers wish to answer relate to the relative costs, risks and benefits of tonsillectomy, which must be weighed against those of conservative alternative treatments for recurrent sore throat. Research may also usefully establish whether or not more refined surgical indications could maximise the benefit–risk ratio.

The risks of tonsillectomy

The most common complications of tonsillectomy are pain and bleeding. From 1995 to 2010, there were 40 claims of clinical negligence related to NHS tonsillectomy, most commonly bleeding related and followed by nasopharyngeal regurgitation. 28 Less common but intrusive complications include changes in taste29 or tongue sensation. 30 In the Swedish 2012 audit,21 almost 14% of patients had an unplanned postoperative clinic visit. A Danish study of 614 outpatient tonsillectomy patients of all age groups identified unscheduled postoperative contacts in 23% of patients, about half because of pain. Contacts were more frequent when discharge occurred in under 4 hours. 31 Comprehensive ascertainment of complications may be difficult precisely because patients are discharged promptly, increasingly on the day of operation; thus, not every complication will involve a hospital contact. Supplementing postal surveys by telephone calls can increase response rates on postoperative events following tonsillectomy by about 50%. 32

Pain

Tonsillectomy, the removal of the palatine tonsil tissue within the oropharynx, is a painful procedure33 that requires an average of 14 days sick leave. 34,35 The dissection of the tonsil can be carried out with ‘cold steel’ or using electrical (diathermy) or radiofrequency (coblation) energy. 36 In one small study,37 the level of pain correlated to the amount of bipolar diathermy used in the procedure. 37 Many trials have addressed the optimum pain relief post tonsillectomy, with the recent emphasis on any potential benefit from the addition of dexamethasone, which may reduce pain, post-operative nausea and vomiting, and overall complications. 38 Steroids do not appear to reduce pain beyond the first post-operative day nor have any impact on post-operative bleeding. 39 A recent review40 also emphasised the importance of the use of multiple painkillers on the day of surgery to maximise analgesic effect.

Bleeding

Primary post-operative haemorrhage occurs close to the time of the surgery. Its incidence was 1.3% in a Swedish audit of 54,696 tonsillectomies between 1997 and 2008. 41 Predictors of bleeding rates included older age, male sex and inpatient as opposed to day case surgery. 41 Post-tonsillectomy, delayed, secondary haemorrhage is generally much more common. Evans et al. 42 attempted to identify overlooked instances of UK post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage by a telephone survey. Of 60 patients, 40% had experienced oral blood flow for more than 1 minute. Only 8% required re-admission and 3% required a return to theatre. The authors suggested that return to theatre rates were a more valuable metric than generic reporting of any post-operative haemorrhage. A recent Scottish review8 compared 27,819 patients undergoing tonsillectomy from 1998 to 2002 with 23,184 undergoing tonsillectomy from 2013 to 2017. There was a notable increase in the adult 30-day re-admission rate from 9.8% to 19.9% between the two time periods, and also a small increase in adults returning to theatre for arrest of haemorrhage from 3.6% to 4.9%. The change was possibly thought to be the result of an underestimation of previous rates and an alteration in patient demographics. 8 Temporal changes in complication rates were also studied in a much larger German all-age series (n = 1,452,637) from 2005 to 2017. 14 As in the Swedish study of primary haemorrhage,41 male sex and increasing age were significant risk factors for haemorrhage. The sex difference was the largest in 20- to 25-year-olds, in whom males had a 12% haemorrhage rate, twice that of females, but the overall risk of bleeding was stable throughout the time period. 14 The Danish series from 2003 to 2005 showed that 4% of 614 patients of all ages were hospitalised because of bleeding, with 2% of adults returning to the theatre. 31

Dysgeusia

Taste and throat sensation changes were assessed in >180 patients 2 weeks and 6 months after tonsillectomy. At 2 weeks, 32% of patients had taste disturbance, with 8% having persisting disturbance at 6 months, which was most often a metallic taste, while 20% of patients had a foreign body sensation. 43 Late persistence (up to 3 years) was observed in about 1% of patients. 29

Conservative therapy for recurrent sore throats

Antibiotics

When considering the use of antibiotics for recurrent sore throats, sore throats caused by viral inflammation will not respond to antibiotics. In practice, the distinction between tonsillitis and other forms of sore throat can be problematic. In primary care, inappropriate antibiotic prescribing remains common. 44 Patients who have three out of four of the Centor Clinical Prediction Rule criteria45 (i.e. fever, tonsillar exudate, absence of cough and tender neck lymph glands) are more likely to have bacterial tonsillitis. 46 These criteria are widely advocated but lack specificity. 47 Nonetheless, the Centor criteria remain a key part of the current NICE decision-making guide for the use of antibiotics in treating sore throat19 because there is no good guidance on point-of-care detection of the typical bacterium, group A Streptococcus. 48 Antibiotic overuse in unselected community populations with viral/non-bacterial pharyngitis is costly for healthcare providers,49 risks selection of resistant ‘superbugs’ and provides a rationale for the continual efforts to try to curtail antibiotic prescription in general practice. 50 A comparison of immediate, no and delayed antibiotic prescribing found that the main effect of antibiotic use was the promotion of medical consultation for sore throat. 51 Patient-focused interventions, such as delayed prescription or information resources, did appear in a systematic review to affect antibiotic usage. 52 However, those with more frequent and incapacitating episodes of sore throat require special consideration. 18 It must be said, however, that the whole area is beset by different interpretations by patients, clinicians and researchers of the boundary between sore throat/non-specific pharyngitis and tonsillitis. Strictly speaking, of course, any pharyngitis is likely to involve some degree of inflammation of the tonsils.

A Dutch trial53 of the efficacy of 7 days of penicillin compared with (1) 3 days of penicillin and (2) placebo recruited 561 patients. The 7-day course of penicillin shortened the duration of illness by 1.7–1.9 days (2.5 days in those with group A streptococcal infection). 53 These results were, however, in contrast to a larger earlier UK randomised controlled trial (RCT),54 which found that antibiotics yielded only 1 fewer day of fever and a non-significant reduction in days of sore throat. Any such benefit of antibiotic treatment must, moreover, be balanced with the costs, side effects, risk of emergent antibacterial resistance and medicalisation of responses to less severe sore throats. 47,51 Penicillin V remains the antibiotic of choice for streptococcal pharyngitis,55,56 but up to 25% of patients57 fail to complete the recommended course of treatment. 57,58 Traditionally, patients with streptococcal carriage have been given a larger number of antibiotic prescriptions than non-carriers,59 and modern algorithms remain heavily predicated on protection from streptococcal infection,60 where a delayed rather than an immediate prescription appears. 61

Steroids have been considered as an alternative treatment for sore throat, but the UK Treatment Options without Antibiotics for Sore Throat (TOAST) study found insufficient evidence to support a single dose of dexamethasone. 5,62 A recent update of a systematic review of the role of corticosteroids in sore throat comprised 1319 participants, including 950 adults. 63 Corticosteroids increased the likelihood of complete resolution of pain at 24 hours by 2.40 times. No differences were found in recurrence or in days lost from normal activities63 and, in view of the potential adverse effects, the authors concluded that further research is required.

Assessment of baseline sore throat severity

Our previous North of England and Scotland Study of Tonsillectomy and Adenotonsillectomy in Children (NESSTAC)3,64 showed that the procedure reduced the prevalence of sore throats during the 24 months following tonsillectomy, but did not allow accurate mapping of outcomes to baseline severity. Baseline severity in tonsillitis, as in many other conditions, is an important predictor of outcome and may be the main determinant of patient satisfaction with tonsillectomy. 65 NESSTAC’s inability to stratify outcomes according to disease severity or QoL impact significantly curtailed the trial’s impact on clinical decision-making.

The assessment of baseline severity in tonsil disease has been simplified by the advent of the Tonsillectomy Outcome Inventory-14 (TOI-14) patient-reported outcome (PRO). The TOI-14 depicts the health-related QoL of patients with chronic tonsillitis and is validated for the German population. 66 The English TOI-14 paediatric version has also been shown to have good psychometric characteristics. 67 The TOI-14 adult version invites patients to reflect on the prior 6 months when responding. It is a straightforward PRO with appropriate face validity. We have shown the TOI-14 to have discriminant validity in a comparison of recurrent tonsillitis patients with healthy volunteers68 and in peritonsillar abscess. 69,70 Importantly, tonsillitis is a disease primarily of younger adults, usually with education or workplace activity profiles. Small descriptive series report substantial benefits in reduction in days lost from work or education following tonsillectomy. 71

The NATTINA RCT was a mixed-methods study, incorporating a feasibility study, an internal pilot and a Phase III multicentre trial, randomising patients to immediate tonsillectomy or conservative management. Access to tonsillectomy in the UK is currently governed by application of SIGN/NICE guidance. This mandates that qualifying sore throats are well documented, clinically significant and adequately treated. The ‘required’ number of episodes for consideration of NHS tonsillectomy is seven in the previous year, five in each of the two consecutive previous years, or three in each of the three preceding years. 18 Our PPI NATTINA preparatory work reported varied access to antibiotic therapy for tonsillitis in primary care, possibly as some clinicians’ therapeutic research goal has been ‘sore throat days saved’. In contrast to professionals, patients reported that they are often looking to minimise days of feeling ill rather than days of sore throat. Thus, any tonsillitis/pharyngitis treatment trial needs to reflect a wider range of outcomes than a simple count of sore throat days. 54

Research is required in the form of a modelling approach to identify what optimal treatment strategies might be and to inform future research. Patients in NATTINA were asked to identify at the time of a reported sore throat episode whether they regarded it as being (1) mild, (2) moderate or (3) severe. This distinction was supported by work in primary care showing that patients’ own perception of sore throat severity was the single best predictor of streptococcal tonsillitis. 72

Rationale

Context

UK hospital admissions related to pharyngeal inflammation

The context of NATTINA was one of increasing admissions to hospital with acute tonsillitis and complications of tonsillitis,73,74 including sepsis,75 and twice as many annual hospital admissions in England for throat infections as for tonsillectomy. The systemic features of tonsillitis in adults together with economic drivers may mean that early intervention is superior to delayed therapy.

Practice variation

Practice variation is a longstanding feature of tonsillectomy within and between countries. Paediatric tonsillectomy rates in England were noted some time ago to be seven times higher in some regions than in others. 24 More recently, in Scotland, considerable variation was found to persist, despite fairly consistent application of prevailing guidance across the country,25 and in Germany inter-regional variation is described in all age tonsillectomy rates. 76

Access to tonsillectomy in 21st century UK

Current UK tonsillectomy practice is governed by SIGN guidance,18 outlined above, which was, perforce, drawn up without the benefit of level I or health economic evidence. By modelling the costs and consequences and setting these against the baseline TOI-14, patients, clinicians and health service funders will be presented with a range of options as to what might be the optimum threshold for surgical intervention. Looking at the considerable excess of adult medical admissions with inflammation of tonsils over the number of adults with tonsillectomy, it may be that, for adults with recurrent tonsillitis, the present UK consensus-based surgical threshold18 has been set too high. 11

To our knowledge, there has been no previous attempt to map the current NHS referral criteria against any other metrics of severity. In other words, the characterisation of the population currently undergoing tonsillectomy is incomplete. NATTINA, which tracked the progress of over 450 adults across 27 UK centres, sought to address this. The modelling of outcomes in relation to baseline presentation generated a number of pathways for evaluation by patient, clinician and funding stakeholders. In addition, the trial design aimed to capture anonymised TOI-14 data from potentially eligible patients who declined trial recruitment, not only to check the representativeness of the trial sample but also to increase the bank of TOI-14 data captured nationally.

Aims and objectives

The overall aims of NATTINA were to:

-

determine a design that will result in a trial achieving recruitment target in a timely fashion through a preliminary feasibility and internal pilot trial rehearsal

-

establish, via the definitive, multicentre RCT, the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of tonsillectomy, compared with conservative management, for tonsillitis in adults

-

evaluate the impact of alternative sore throat patient pathways by observation and statistical modelling of outcomes

-

compare the costs and consequences (symptomatic and QoL) for patients and the NHS from each management strategy

-

inform future research.

Feasibility study aim and objectives

The aim of the feasibility study was to address the key methodological issues raised via our PPI group and clinicians.

The objectives of the feasibility study were as follows:

-

Evaluate otolaryngologists’ and recruiting specialist nurse practitioners’ willingness to randomise and randomly allocate patients to the randomised arms, and patients’ willingness to be randomised, taking account of predicted variation in severity of sore throat.

-

Identify barriers to and facilitators of, and propose strategies to address, the above items.

-

Define clear-cut eligibility criteria for a trial acceptable to all stakeholders.

-

Assess the acceptability of the usual-care randomised arm to patients whose primary care clinicians have referred them for specialist intervention. In addition, to review primary care clinicians’ willingness to refer.

-

Provide further information to maximise patients’ equipoise when they present in the tonsil study secondary care clinic, including meetings/seminars with research participants from other sites.

-

Investigate the feasibility of our proposed data collection methods and outcome measures.

-

Explore illness features of concern to our PPI group to ensure that these were captured in trial outcome measures.

-

Develop and test sore throat weekly data collection methods and storage, and Sore Throat Alert Return (STAR).

-

Explore the processes of patient identification and recruitment.

-

Develop patient recruitment materials, including the production of the standardised NATTINA randomisation online video-recording/digital versatile disc (DVD). 77

Patients who met the proposed inclusion criteria were identified and invited by study otolaryngologists to participate in the feasibility study (involving qualitative interviews, role play and cognitive interviews).

Internal pilot objectives

The NATTINA internal pilot target was 72 patients randomised in 6 months among six of our nine sites. In addition to assessing the ability to recruit, the internal pilot aimed to:

-

ascertain whether or not all of the trial processes, including patient identification, eligibility criteria, randomisation and data collection processes, work as intended and cohesively

-

gauge more precisely the number of potentially eligible patients identified in NATTINA screening clinics

-

investigate referral, recruitment and acceptability across the baseline severity spectrum

-

identify barriers to patient recruitment, suggest improvements to have an impact on recruitment rates and measure patient compliance in weekly submission of days of sore throat, plus STARs, during sore throat episodes

-

identify any major emerging systematic differences between recruited patients and patients who declined to participate

-

collate and report reasons for ineligibility/non-consent

-

quantify missing data and measure attrition in sore throat data

-

review activity against the go criterion – six screening clinics established, with target throughput of 396 eligible patients screened in 6 months and a minimum target of 72 randomised patients.

The structure of the internal pilot was, however, eventually abandoned, as described in Chapter 2, owing to unexpectedly severe barriers to recruitment, particularly in certain regions of England where Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) appeared to be following an audit commission health briefing, which labelled tonsillectomy among a number of ‘relatively ineffective procedures’. 4

Main trial objectives

Primary objective

-

To compare the clinical effectiveness (as number of sore throat days) and cost-effectiveness, over 24 months, of tonsillectomy with conservative management in adults with recurrent acute tonsillitis who have been referred to otolaryngology outpatient clinics.

Secondary objectives

Clinical effectiveness

-

To provide group and subgroup comparisons of:

-

other metrics of sore throat severity, including responses on the TOI-14 and STARs for any sore throat episodes experienced

-

QoL, as recorded by the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12), from baseline throughout the study and during any episodes of sore throat experienced.

-

-

To report the number of adverse events (AEs) and additional interventions required, supported by linkage to community prescribing data and, in Scotland, by Information Services Division linkage to SMR01 (acute hospital discharge episodes).

-

To adjust the estimate of effectiveness in the light of other baseline covariates, including severity of tonsillitis. 78

-

To evaluate the impact of alternative sore throat patient pathways by observation and statistical modelling of outcomes.

-

To assess to what extent trial participants are representative of the total population of sore throat patients referred to ear, nose and throat (ENT) clinics.

Economic evaluation

-

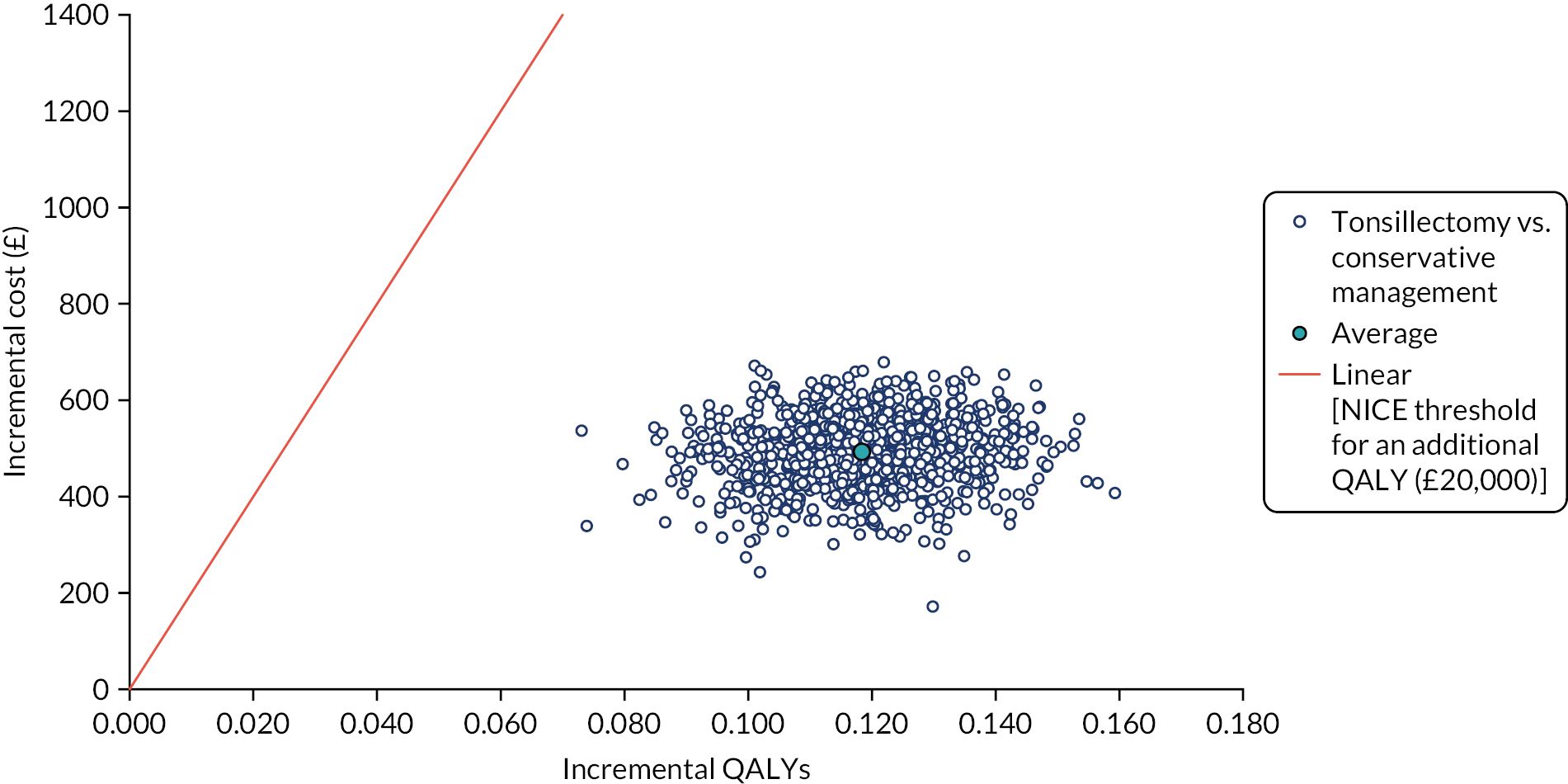

To compare cost-effectiveness measured in terms of the incremental cost per sore throat day avoided from the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) over 24 months.

-

To compare cost-effectiveness with outcomes reported as incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained from the perspective of the NHS and PSS over 24 months.

-

To compare cost-effectiveness with outcomes reported as net monetary benefits from the perspective of the NHS and PSS over 24 months.

-

To compare costs to the NHS and patients of the different randomised treatments over 24 months.

-

To compare QALYs based on SF-6D values derived from responses to the SF-12 administered at baseline and 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation and when participants’ experienced a sore throat.

-

To assess participants’ willingness to pay (WTP) to avoid a day with sore throat derived from a contingent exercise administered at baseline and to compare QoL valued in monetary terms (i.e. WTP to avoid a day with sore throat × number of days of sore throat experienced).

Qualitative process evaluation

-

To document the views and experiences of patients and clinicians regarding tonsillectomy and conservative management and how patient experience may shape any future research required.

Dissemination

-

To consider the role of the trial outputs in informing shared decision-making between adults with recurrent tonsillitis and their GPs.

-

To inform decisions by healthcare professionals in secondary care and their clinical commissioners.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter includes information about the NATTINA trial participants, interventions, objectives, outcomes, sample size, randomisation and statistical methods, and a summary of any substantial changes to the protocol during the trial.

Overview of the trial design

The NATTINA trial was a multicentre, randomised controlled, two-arm surgical trial that was set in NHS secondary care within the UK; this was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR).

Adult patients aged ≥16 years who presented with recurrent acute tonsillitis and were referred to ENT outpatient clinics were identified and recruited.

The trial aimed to establish the effectiveness and efficiency of tonsillectomy for recurrent sore throat compared with non-surgical management over a 24-month period. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive immediate tonsillectomy or conservative management with surgery deferred.

The trial included a qualitative feasibility study,1,79 a 6-month internal pilot, a qualitative process evaluation (see Chapter 5), a full statistical evaluation (see Chapter 3) and an economic evaluation (see Chapter 4).

Trial registration and protocol availability

The trial was registered in the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry on 4 August 2014: registration number ISRCTN55284102.

The latest version of the full protocol is available on the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1214606/#/; accessed 7 October 2020).

Ethics and governance

The sponsor for the trial was the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (reference 07065). Favourable ethics opinion was obtained on 10 November 2014 from the NHS Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Tyne and Wear South [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference 14/NE/1144]. Subsequent approval was gained for the 11 substantial protocol amendments (see Appendix 1, Table 28).

Setting

The trial was conducted in the following 27 NHS secondary care hospitals in England, Scotland and Wales (the date of opening is presented in brackets):

-

Aneurin Bevan University Health Board (12 July 2016)

-

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (20 July 2015)

-

City Hospital Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust (now South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust) (28 July 2015)

-

Dorset County Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (16 February 2016)

-

East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust (2 March 2017)

-

East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust (Royal Blackburn Hospital) (13 September 2016)

-

East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust (Royal Preston Hospital) (30 September 2016)

-

Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust (11 March 2016)

-

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (22 August 2014)

-

James Paget University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (5 October 2016)

-

NHS Ayrshire and Arran (2 March 2017)

-

NHS Grampian (30 April 2015)

-

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (30 April 2015)

-

NHS Tayside (9 September 2014)

-

North Cumbria University Hospitals NHS Trust – Cumberland Infirmary (now North Cumbria Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust) (15 February 2016)

-

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (18 July 2016)

-

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (7 April 2017)

-

Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust (29 September 2016)

-

Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust (18 August 2016)

-

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (24 March 2016)

-

South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (13 October 2016)

-

The Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (15 April 2015)

-

United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust (13 February 2017)

-

University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (23 October 2016)

-

West Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (26 September 2016)

-

Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust (26 August 2016)

-

Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust (8 February 2016).

Participants

A total of 455 NATTINA participants were recruited and randomised following referral by their GP to an ENT clinic at one of the participating centres. Two individuals were randomised into the study in error; no data were collected for these individuals and they were withdrawn. All remaining individuals were assessed as eligible for tonsil dissection in accordance with prevailing NHS regulations. RCT participants were recruited from 22 of the 27 open sites.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥16 years.

-

Recurrent sore throats that fulfil current SIGN guidance18 for elective tonsillectomy. This guidance stipulates that to be eligible for tonsillectomy on the NHS sore throats should be a result of acute tonsillitis and that:

-

the episodes of sore throat should be disabling and prevent normal functioning

-

the patient has experienced seven or more well-documented, clinically significant, adequately treated sore throats in the preceding year, five or more such episodes in each of the preceding 2 years, or three or more such episodes in each of the preceding 3 years.

-

-

The patient has provided written informed consent for participation in the trial prior to any trial-specific procedures.

Exclusion criteria

-

Previous tonsillectomy.

-

Listed directly (i.e. added to waiting list without prior elective ENT outpatient appointment) during emergency admission (e.g. owing to peritonsillar abscess/quinsy).

-

Primary sleep breathing disorder.

-

Suspected malignancy.

-

Tonsilloliths (as primary referral).

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding.

-

Bleeding diathesis (including haemophilia, sickle cell disease and platelet dysfunction).

-

Therapeutic anticoagulation.

-

Inability to complete self-reported questionnaires and STARs.

Intervention

Current standard care, according to NICE and SIGN,18,19 is for adult patients with a qualifying frequency of recurrent sore throat to be referred by their GP to ENT outpatient clinics to be considered for tonsillectomy. Those confirmed by a member of the specialist team as being eligible for tonsillectomy, who consent to surgery and who do not have any pressing medical exclusions are then offered elective tonsil dissection. Non-surgical candidates revert to conservative management in primary care (analgesia with or without antibiotic therapy). NATTINA aimed to be a pragmatic trial, reflecting normal NHS practice; therefore, the process of referral to an ENT clinic by GPs was not altered. Eligible consenting participants were randomly allocated to one of two arms: tonsillectomy or conservative management.

Tonsillectomy

Participants randomised to the tonsillectomy arm received elective surgery to dissect the palatine tonsils, preferably within 6 weeks and no longer than 8 weeks following randomisation. The method of the surgical procedure was at the discretion of staff at the participating sites and was identical to that in standard care. Except for randomisation allocation, participants in both arms received standard non-surgical care, as per local policies. Participants who were randomised to undergo a tonsillectomy, but whose surgery was delayed owing to severe tonsillitis or other reasons, remained in the trial and continued to follow the surgery pathway.

Conservative management

Participants randomised to the conservative management arm had the option of deferred surgery for up to 24 months in addition to standard non-surgical care. A 12-month face-to-face review allowed confirmation of willingness to remain in the conservative management arm. This pathway was informed by the NATTINA PPI group and the qualitative feasibility study for NATTINA. 80–82 A participant contemplating surgery was required to fulfil the SIGN guidance18 at the time point of review to be considered for tonsillectomy.

Participants in the conservative management arm received standard non-surgical care, which typically comprised self-administered analgesia plus or minus ad hoc primary care prescription of antibiotics, and attendance at walk-in centres or the accident and emergency (A&E) department for more severe episodes of sore throat. Participants were permitted to cross over to the tonsillectomy arm at any point in the trial on the condition that they continued to be eligible for surgery in accordance with the SIGN guidance. 18

Funding of the trial intervention

Funding for the surgery was not required, as the procedure was a part of the usual standard-care pathway for this cohort of patients.

Outcome measurement

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the number of sore throat days collected through weekly ‘returns’ from the participants over the 24-month period following randomisation. The data allowed comparison of tonsillectomy with conservative management to determine their effectiveness in treating recurrent sore throat.

Primary outcome data collection

A discrete database was designed for use in the trial to collect the number of sore throat days that participants experienced per week. The company who provided the software and who worked with the trial team to design the STAR database was Tay Dynamic, later rebranded as Inteleme (Huddersfield, UK) and then as CI Data (but referred to throughout this report as Tay Dynamic). Tay Dynamic specialised in software for direct participant communication.

The weekly number of sore throat days was collected from 1 week after randomisation, throughout the follow-up period, to the 24-month follow-up visit.

Following recruitment, the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) team liaised with sites to register the participant into the STAR system, indicating their preferred method of contact: e-mail, text message or IVR via telephone. Participants’ identifiable data were stored securely on a Newcastle University (Newcastle, UK) server, and Tay Dynamic were provided with access to e-mail addresses and telephone numbers for the purpose of sending out the alerts and STAR questionnaires.

The participants then received weekly alerts asking them how many sore throat days they had experienced in the previous 7 days. Their response (a number from 0 to 7) was automatically recorded and a reminder was sent to complete a STAR questionnaire if the participant had experienced any sore throat days (score of >0). The STAR questionnaire collected the following secondary outcome data:

-

the severity category of sore throat days (mild/moderate/severe)

-

the name and frequency of over-the-counter and prescription medications used

-

the nature of any professional healthcare advice sought (e.g. GP, walk-in clinic and pharmacist)

-

the number of hours unable to undertake usual activities (including time off work and studies)

In the initial trial design, the STAR questionnaire was planned to be a paper form that would be completed and (free) posted to NCTU. Substantial amendment 1 (see Appendix 1, Table 28) was implemented prior to the recruitment start date, allowing the STAR questionnaire to be completed and submitted electronically if participants had access to a mobile telephone or computer. Those without such access submitted a paper copy.

Fifteen months into recruitment, it became apparent that the rate of electronic STAR responses considerably outnumbered the rate of paper STAR questionnaire returns. The STAR system was, therefore, modified (see substantial amendment 5 in Appendix 1, Table 28). The report of a sore throat day triggered a second STAR e-mail/text/call asking for a severity grade (1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe) (i.e. corresponding to the first item on the original the STAR questionnaire) (see Chapter 4). Receipt of the severity response generated a further text/e-mail request to submit an electronic or paper STAR questionnaire (one per 7-day reporting period).

The Tay Dynamic software identified non-responders. If participants did not return STAR questionnaires after several sore throat day reports, the trial management team issued at least one reminder letter.

Approximately 24 months after the recruitment of the first participant, the items on the STAR questionnaire used to inform the economic analysis were abbreviated as the STARLET questionnaire (see substantial amendment 7 in Appendix 1, Table 28):

-

whether or not the participant had taken any over-the-counter and prescribed medications

-

number of days unable to undertake work and usual activities

-

SF-12.

The main weekly STAR text message/e-mail/IVR system continued to collect information on the number of sore throat days and the severity category of the sore throat episode. Report of at least 1 sore throat day in the previous week generated a request to complete the STARLET. Details of how the economic data from the STAR and STARLET were combined are provided in Chapter 4.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were:

-

Clinical effectiveness. Intergroup comparison over the 24-month follow-up period of:

-

STAR severity scores of any sore throats experienced.

-

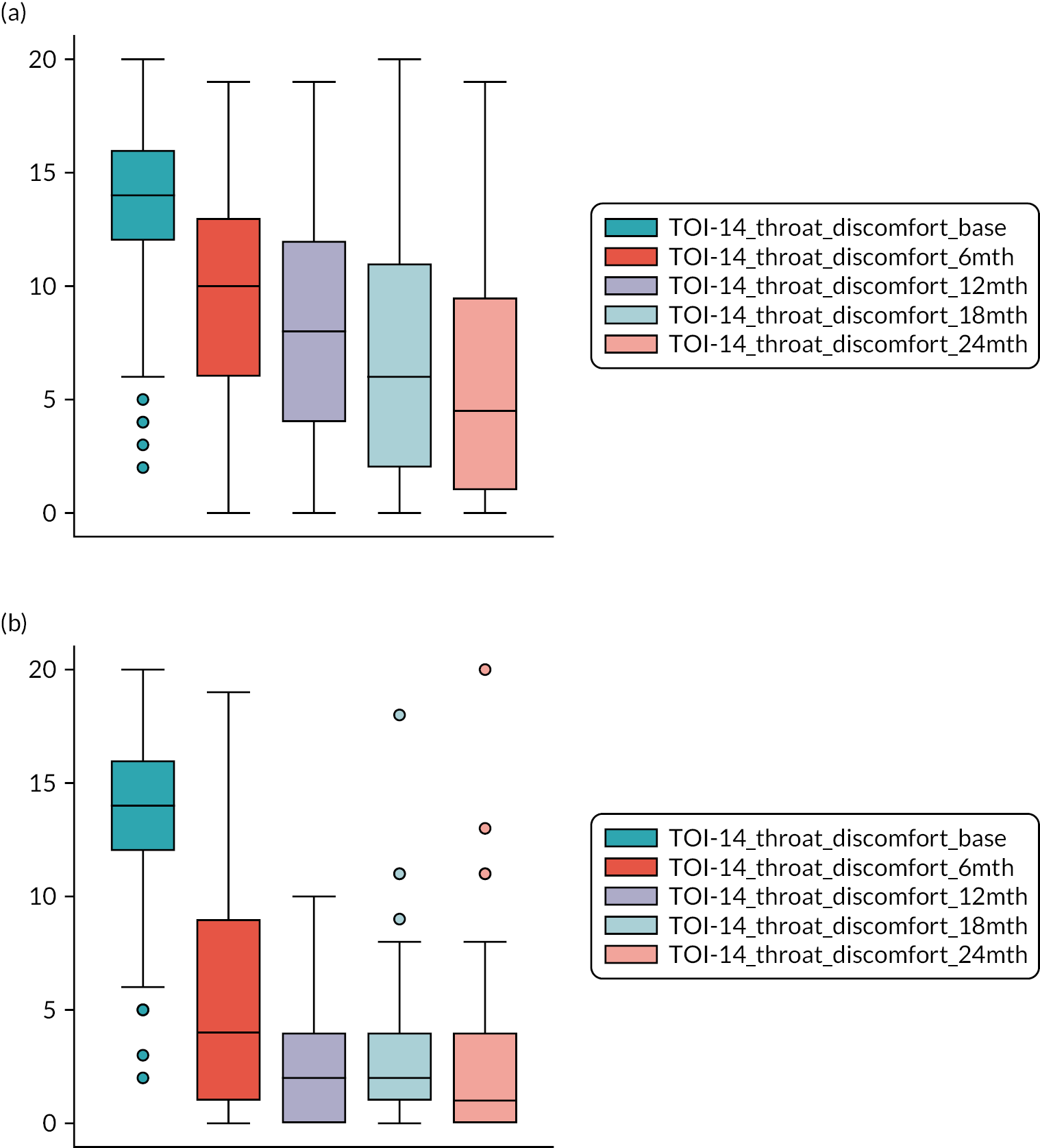

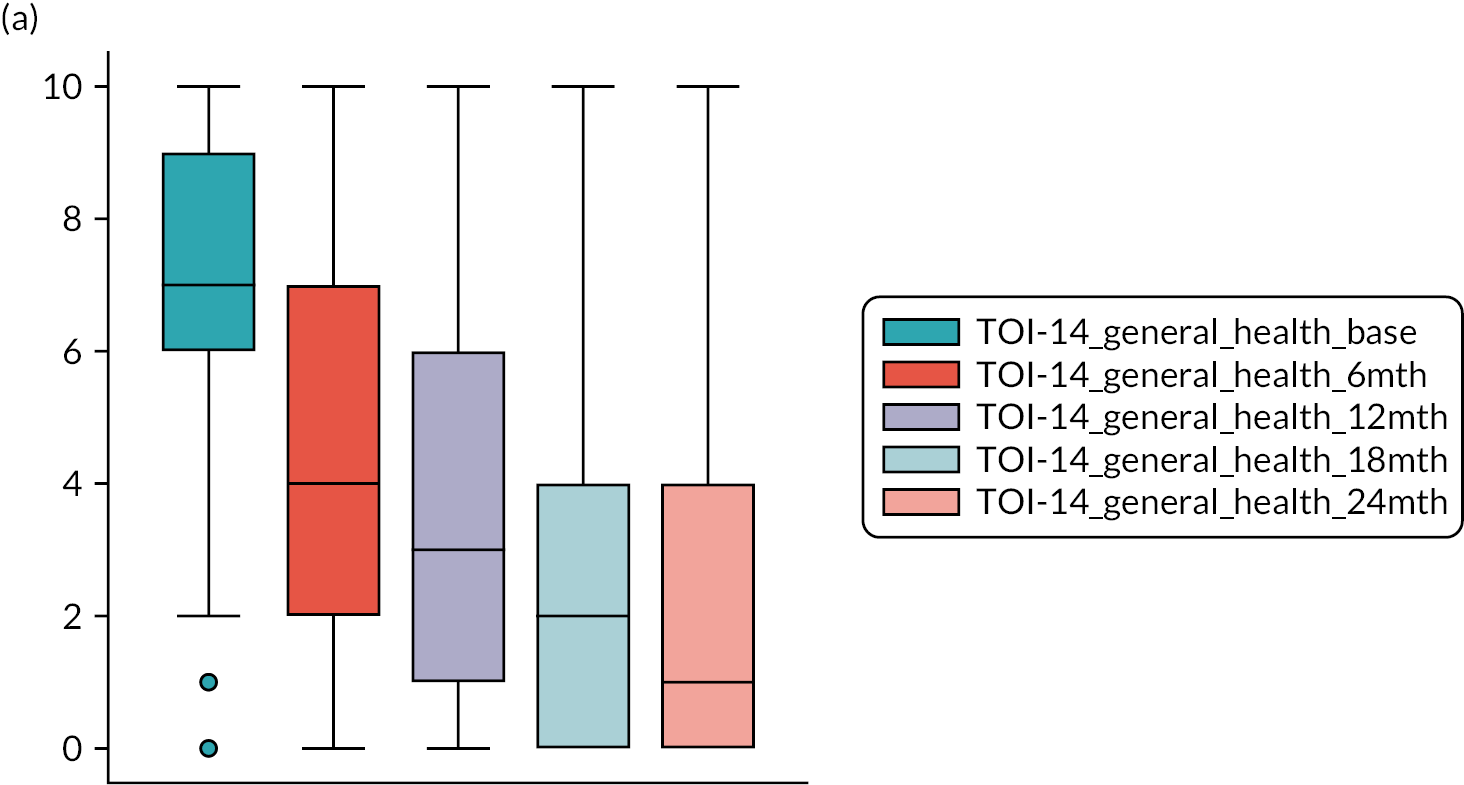

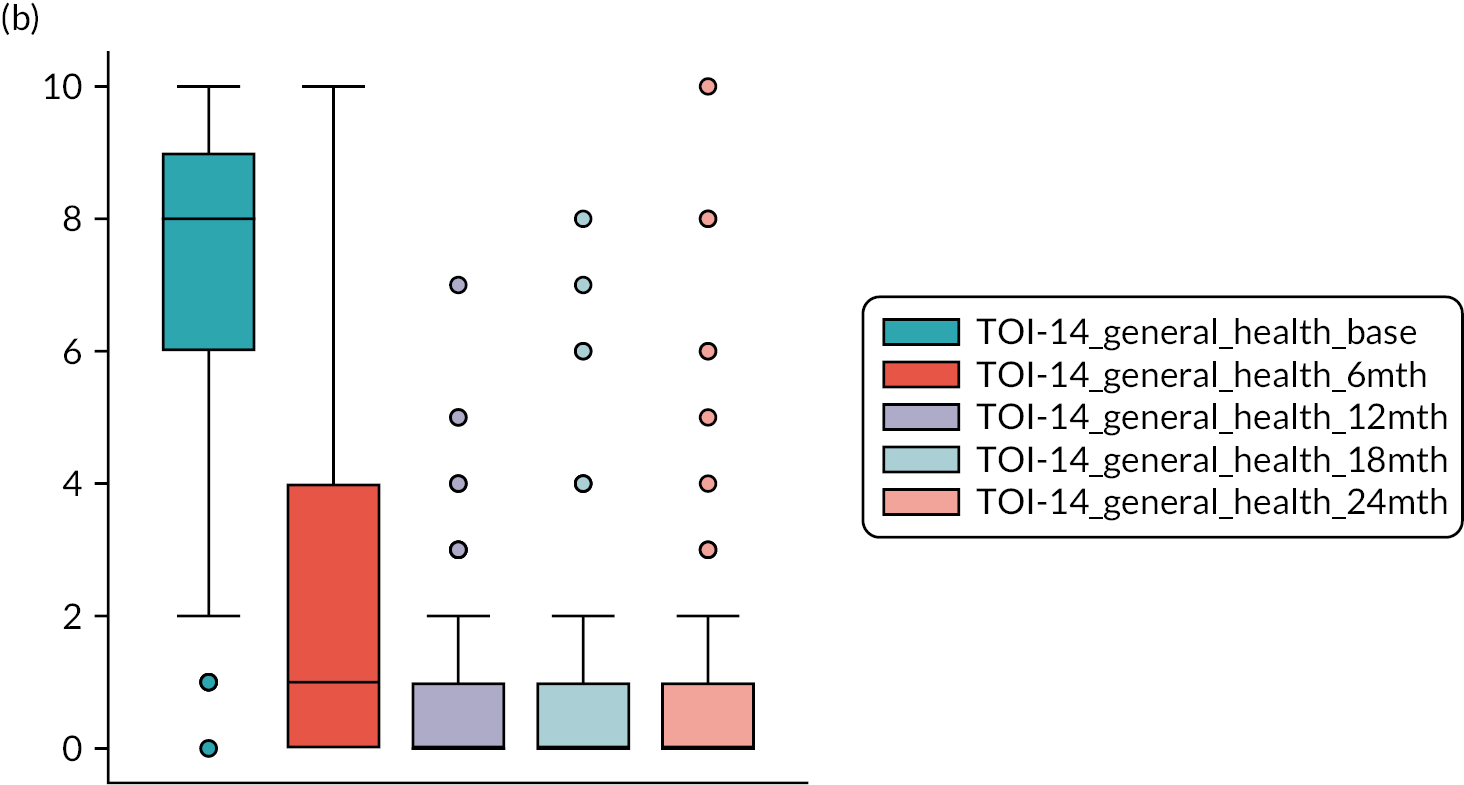

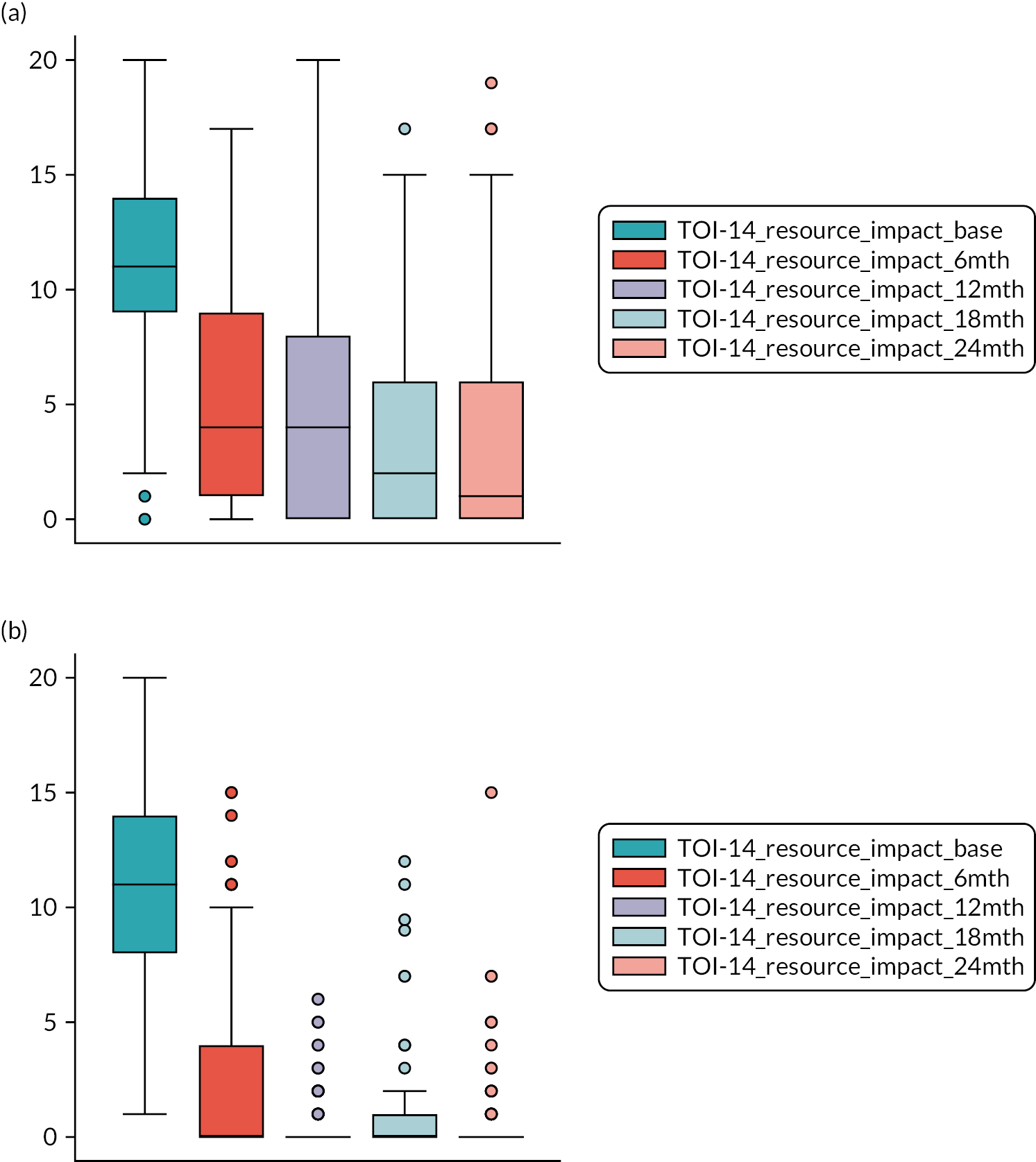

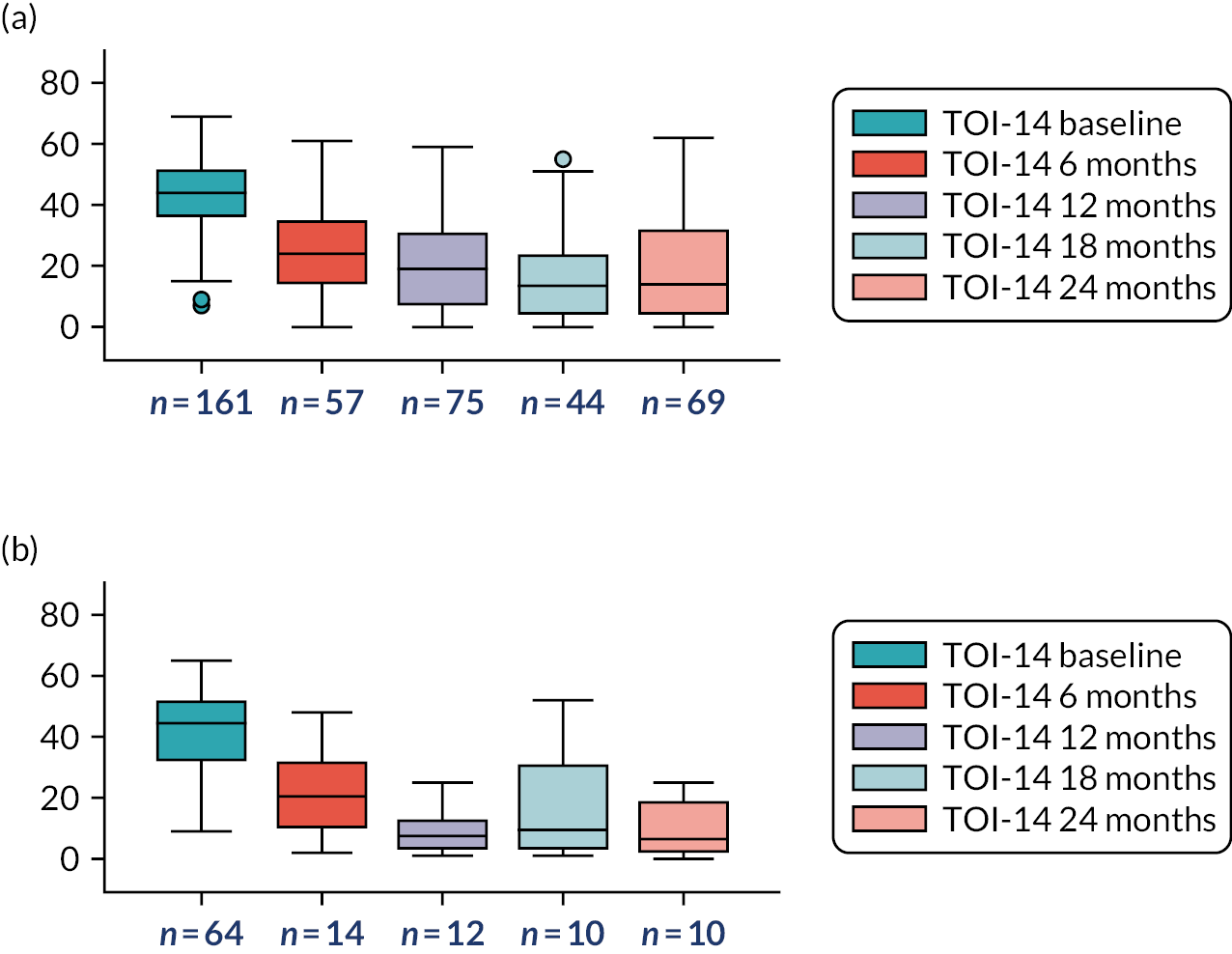

TOI-1466,68 scores collected 6-monthly. The TOI-14 is a 14-item questionnaire with a supplementary final open response item for additional symptoms that are related to tonsillitis over the preceding 6 months. 84 We have shown the TOI-14 to have discriminant validity in a comparison of recurrent tonsillitis patients with healthy volunteers85 and in peritonsillar abscess. 69,70

-

An adjusted estimate of intervention effectiveness in the light of baseline covariates, including severity of tonsillitis, estimated from TOI-14 baseline scores and categories.

-

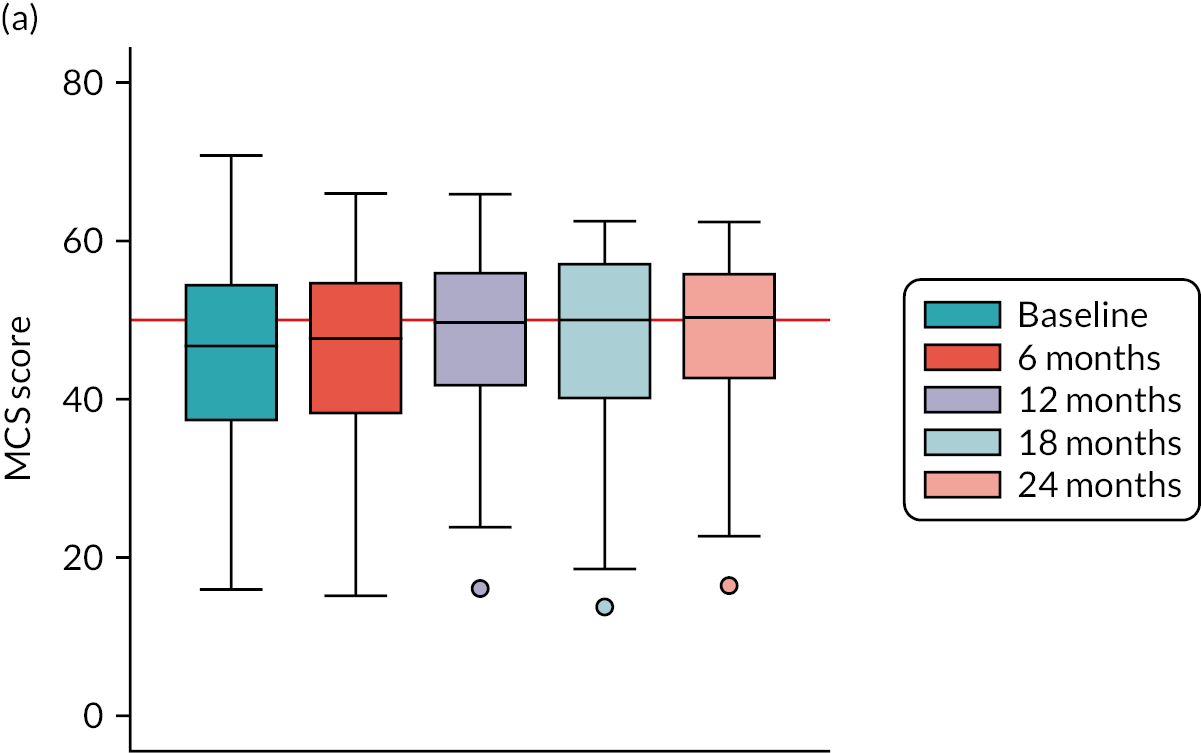

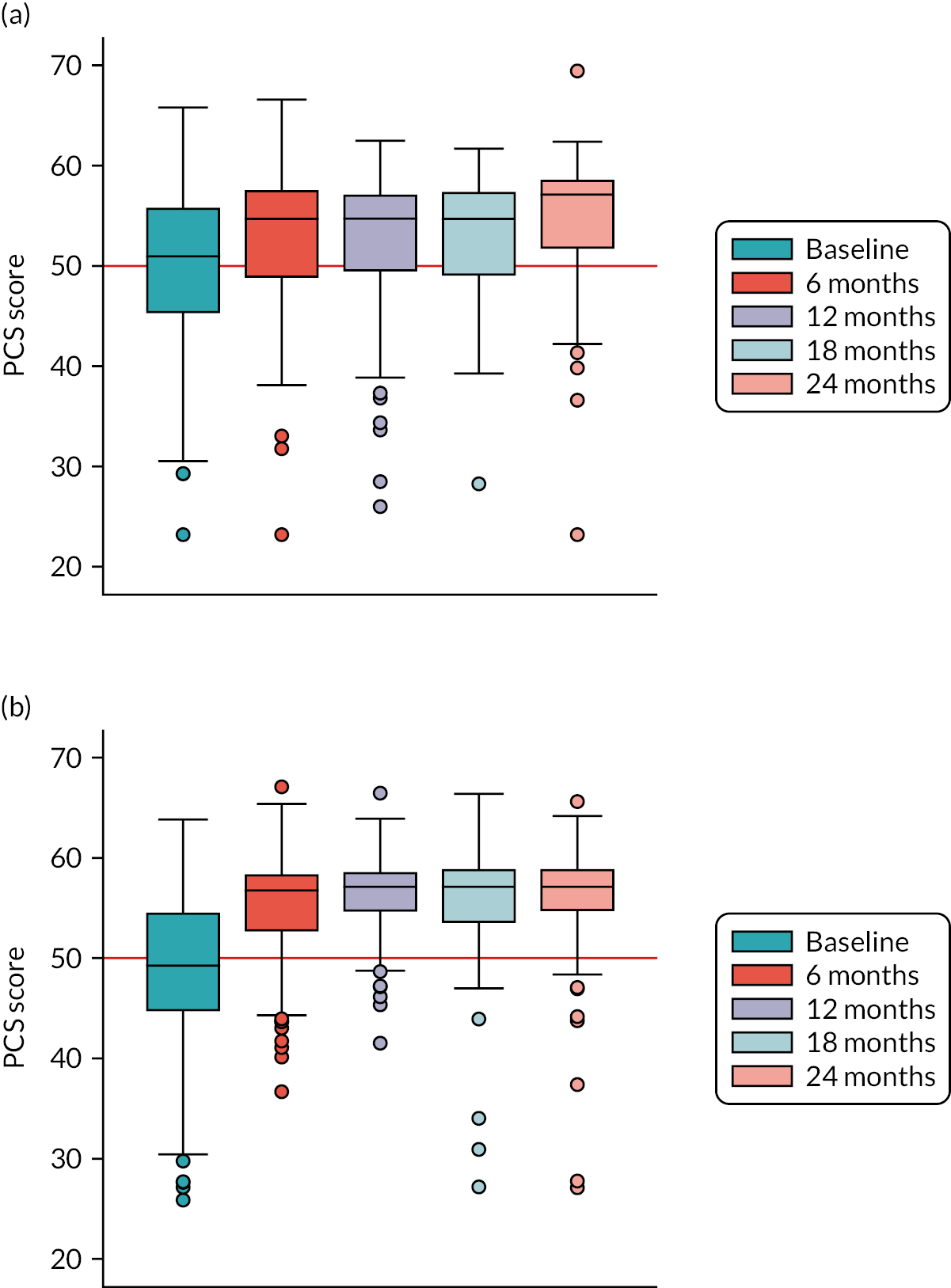

Intergroup comparison of QoL as recorded over 24 months by the SF-12. 83 This 12-item Short Form Survey is an abbreviated Short Form questionnaire-36 items generic QoL assessment tool, covering the same eight health domains of physical and mental health over the previous 4-week period.

-

The impact of alternative NHS sore throat patient pathways by observation and statistical modelling of outcomes.

-

To assess to what extent trial participants are representative of the total population of sore throat patients referred to ENT clinics through interrogation of site screening logs.

-

-

Economic evaluation. To compare the following between the two arms over 24 months:

-

Costs. The average total cost per participant to the NHS and PSS to manage recurrent sore throats. Participant costs were considered in a sensitivity analysis.

-

QALYs using the area-under-the-curve method based on SF-6D scores derived from the SF-12 responses. 86

-

Willingness to pay to avoid a sore throat day. A contingent valuation questionnaire was administered at baseline to quantify the effect that a sore throat day has on individuals’ QoL in monetary terms.

-

The number of AEs, visits to the GP/walk-in clinic/A&E, prescriptions issued and additional interventions required for sore throats and related events through STAR/STARLET data, and supported by data linkage to primary care patient records.

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) – incremental cost per sore throat day avoided.

-

Cost–utility analysis (CUA) – incremental cost per QALY gained.

-

Cost–benefit analysis (CBA) – incremental net benefit.

-

-

Qualitative process evaluation. To document the views and experiences of patients and clinicians regarding tonsillectomy and conservative management, and how patient experience may shape future research (see Chapter 5).

-

Future research. To propose further research questions using newfound cost–benefit information to develop algorithms that guide and assess management of health services.

Secondary outcome data collection

The questionnaires used for secondary outcome data collection can be found on the project webpage (https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/12/146/06; accessed 29 September 2021). Participant-reported outcomes were collated into questionnaire packages for each 6-month contact (Figure 1 and Table 1).

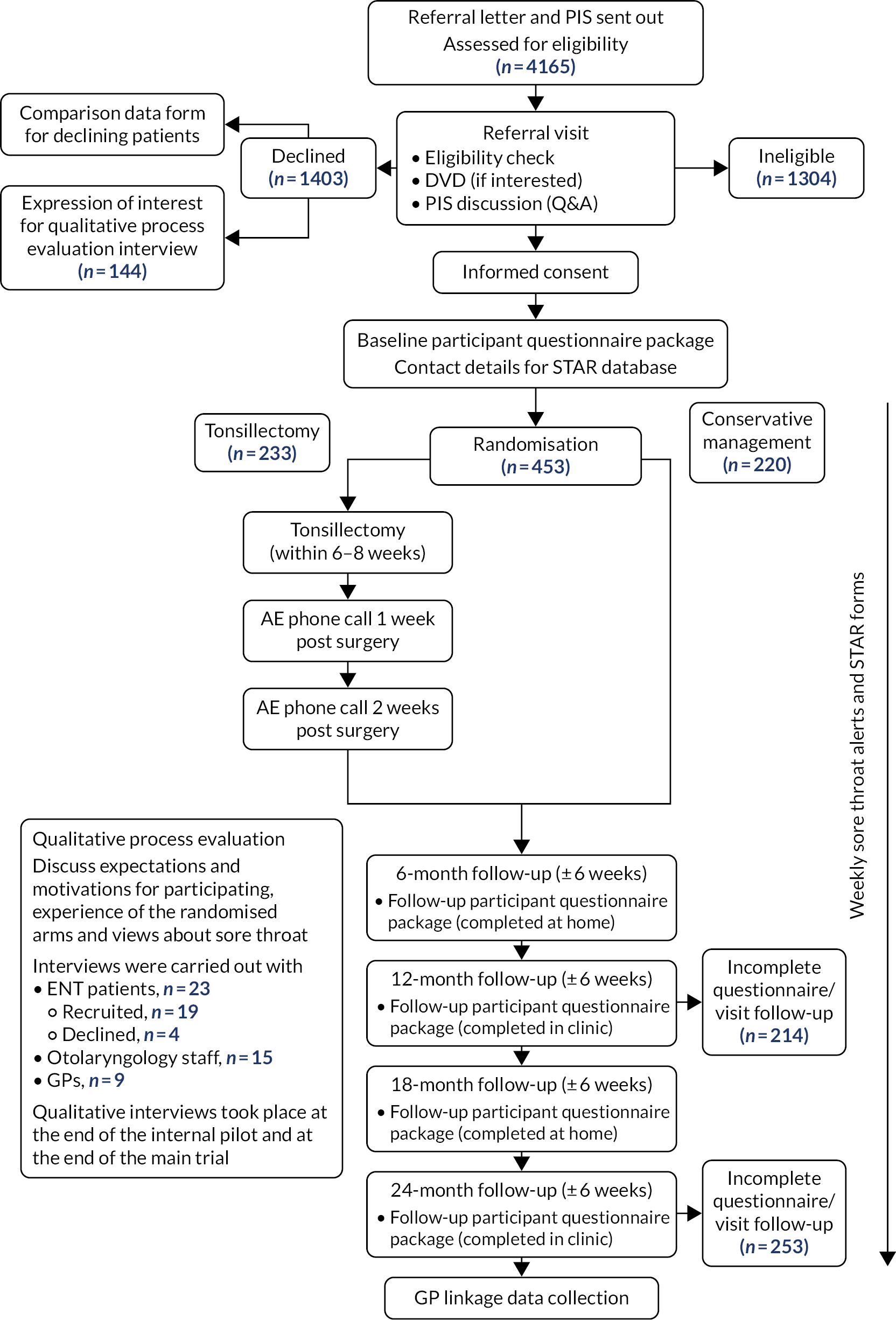

FIGURE 1.

Study pathway. PIS, participant information sheet; Q&A, question and answer.

| Visit | Questionnaires collected at each time point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOI-14 | SF-12 | Health Service Utilisation | About You | Value of Avoiding a Sore Throat Day | Participant Time and Travel | |

| Baseline | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 6 months | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| 12 months | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| 18 months | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗a | ||

| 24 months | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

The ‘About You’ set of questions collected data about participants’ ethnic origin, education and employment. Primary healthcare service data were accessed from the participants’ general practices following the completion of the 24-month follow-up visit, including the 12 months prior to randomisation. NCTU initially sent a GP linkage case report form for completion by the practice for each participant, along with a prepaid return envelope. A move to an electronic process achieved a higher response rate. The participant record report form defined the time window of enquiry – 12 months prior to 24 months post randomisation – on the following episodes for a sore throat or related event:

-

attendance at a general practice (with a GP/nurse)

-

telephone call with a GP/nurse from the practice over the telephone

-

attended a walk-in clinic

-

attended A&E

-

attended an outpatient appointment

-

admitted to hospital

-

had any other intervention or contact with a healthcare service

-

any medications prescribed.

The purpose of collecting these data was to capture participants’ consultation rates, outcomes, prescribing information and additional interventions required for sore throat or related events throughout the period stipulated above. GP practices were paid £50 for each participant return.

Economic analysis

The NATTINA economic analysis aimed to determine the relative efficiency of tonsillectomy compared with conventional management, and is detailed in Chapter 4.

Qualitative analysis

The NATTINA qualitative analysis aimed to document the views and experiences of patients and clinicians regarding tonsillectomy and conservative management, and how patient experience may shape any future research required, and is detailed in Chapter 5.

Participant timeline

Feasibility study

The aim of the feasibility study was to assess the willingness of clinicians to refer and randomly allocate patients to the study arms, patients’ willingness to be randomised and the acceptability of the deferred surgery randomised arm.

Qualitative and cognitive interviews were carried out by a researcher from Newcastle University. The study was planned to last for approximately 5 months, or until data saturation, and to take place over nine sites.

Fifteen ENT patient interviews were planned: these were with adult patients with acute tonsillitis who had been referred to ENT outpatient clinics for recurrent sore throat and who met the eligibility criteria (inclusion and exclusion criteria for the feasibility study were the same as for the main trial listed in Participants).

Twenty ENT staff interviews were planned for ENT staff members at one of the nine participating sites that were likely to be involved in the proposed NATTINA trial. Ten GP interviews were planned, with no eligibility criteria for this group of participants.

The outcome measures were:

-

Patient identification and recruitment, eligibility criteria and ENT clinic staffs’ willingness to randomise and randomly allocate patients to the randomised arms.

-

Primary care clinicians’ willingness to refer.

-

Patients’ willingness to be randomised and their acceptability of the conservative management arm for patients whose primary care clinicians have referred them for specialist intervention. Feedback on proposed data collection methods, including weekly sore throat alerts, STARs and questionnaires, was also collected.

In total, 15 ENT patients, 11 GPs and 22 ENT staff were recruited.

The success criteria for progression to the internal pilot study were met, with a plan to address potential barriers to recruitment and patient equipoise. Patient participants reported that recurrent sore throats severely affected their family, work and social life; ENT staff reported that patients faced increasing barriers to secondary care service access; and GPs were guided to reduce referrals for tonsillectomy owing to it being seen as having limited clinical value. This highlighted the need for further research regarding the effectiveness of tonsillectomy for this cohort of patients.

Internal pilot

NATTINA was originally planned to include a 6-month internal pilot with six of its nine sites that were planned to be opened to recruitment. The process was overseen by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and was reviewed by the NIHR HTA programme to decide whether or not to continue with the main trial phase.

The proposed ‘stop/go criteria’ to be achieved in the 6-month pilot79 were:

-

six sites to be opened with screening clinics established

-

396 eligible patients screened over the six sites

-

a minimum of 72 participants randomised.

Other aims were to:

-

ascertain if all trial processes, including patient identification, eligibility criteria, randomisation and data collection, worked as intended and if the eligibility criteria were cohesively operational

-

gauge more precisely the number of potentially eligible patients identified in NATTINA screening clinics

-

investigate referral, recruitment and acceptability across the baseline severity spectrum

-

develop participant recruitment materials, including the production of the standardised NATTINA randomisation online video-recording/DVD

-

identify barriers to participant recruitment and suggest improvements to have an impact on recruitment rates

-

measure participant compliance with the proposed weekly submission of number of sore throat days per week, plus STARs during sore throat episodes

-

develop and test sore throat weekly data collection methods and storage, and STARs (participant interviews, cognitive interviews) with input from Tay Dynamic software

-

explore illness features reported to us as of concern by our PPI group to ensure that they were captured in trial returns, for example chronic sore throat, night-time sore throat and disruption of ability to undertake not only usual activities but also leisure pursuits

-

identify any major emerging systematic differences between recruited participants and individuals who declined to participate

-

collate and report reasons for participation/ineligibility/decline

-

quantify missing data and measure attrition in sore throat data.

The recruitment target of 72 participants was, however, not met in the pilot timescale. The Trial Management Group (TMG) and the NIHR HTA programme monitoring team met on 10 September 2015, 4 months from the first patient’s first visit, and agreed that the proposed nine-site model would not succeed. The conversion rate from screening to recruitment had been lower than expected, and the embedded qualitative work81,82 showed that this was because patients’ willingness to participate in the trial, particularly in certain regions, was much less than that anticipated. Some patients were having to wait so long to gain a referral to ENT clinics that they were unwilling to contemplate the prospect of further delay. The NIHR HTA programme team suggested a recovery plan with an increase in the number of sites from 9 to at least 20, as rapidly as was practicable. It also came to light that a draft sample size of 600 had been carried forward into the trial, but in fact applied to an earlier design with a third arm; therefore, the total number of participants required was only 510, not 600. The recovery plan was discussed at a second meeting on 23 May 2016 and was agreed in summer 2016.

Identification, screening and recruitment of participants

The clinical team identified potential participants who had been referred by a GP to be considered for tonsillectomy. A participant information sheet (PIS) along with an invitation letter and appointment letter, if appropriate, were posted out to the patients. The NATTINA PIS outlined details of the trial and signposted potential participants to the NATTINA information DVD/online video-recording on the trial website. 77 The recruitment DVD/online video-recording was developed for the study because it was found to be useful in the NESSTAC trial. 3,64 Video information is more accessible to those who do not read extensive documents regularly and also ensured a degree of consistency of verbal information given across all of the trial sites.

As many patients as possible who were referred to ENT clinics with recurrent sore throat were screened for NATTINA eligibility. All site staff who were involved in screening and recruitment activities were fully trained on the trial protocol, had the necessary experience and qualifications to perform these tasks, and were delegated to do so on the site delegation log. Potential participants, who were previously posted a PIS, were shown the information DVD/online video-recording at their referral visit (unless already viewed online)77 and were given the opportunity to discuss the trial with the designated member of the research team. Patients interested in NATTINA participation underwent an entry eligibility criteria check. Eligible patients were invited to join the trial. Potential participants at the clinic who did not previously receive a PIS were given verbal information. Those with initial interest took away a PIS to read and consider, and if they were interested a further appointment was made for the consent visit, allowing a minimum intervening interval of 24 hours for their decision-making.

Screening and recruitment logs were completed at all sites to document all subjects who attended a referral visit, including their outcome status, reasons for ineligibility, if applicable and, where offered, reason for declining participation.

Declining patients

Patients who were eligible but decided not to take part were invited to provide anonymised baseline comparison data for the NATTINA database. These included age, sex, an estimate of number of sore throat days over the prior 6 months and the completion of a TOI-14 questionnaire. This allowed an analysis of the comparability of trial participants with the total pool of those referred at each of the sites. Patients who declined were also invited to take part in a qualitative interview with a researcher (see Chapter 5). Those who declined the trial will be the subject of a separate publication, incorporating factor analysis of the TOI-14 (in preparation). For the number of declining patients with data, see Table 5. Information on reasons for declining to be randomised and the missing TOI-14 items for these patients are presented separately in Appendix 3, Tables 31 and 32.

Consent procedure

Eligible patients wishing to take part were given the opportunity to discuss the trial and ask any questions before providing written informed consent on the informed consent form (ICF), which was witnessed, signed and dated by a member of the research team who had documented, delegated responsibility to do so. All consent forms were monitored by the NCTU for completeness and accuracy.

Randomisation

Randomisation was carried out via the NCTU secure web-based computer allocation system by delegated site research team members.

Participants were randomised to receive tonsillectomy or conservative management in a 1 : 1 ratio stratified by centre and severity using a blocked allocation (permuted random blocks of variable length) system.

The participant’s severity category was determined by the total TOI-14 score: mild = 0–35, moderate = 36–48 or severe = 49–70.

Treatment, crossover and withdrawals

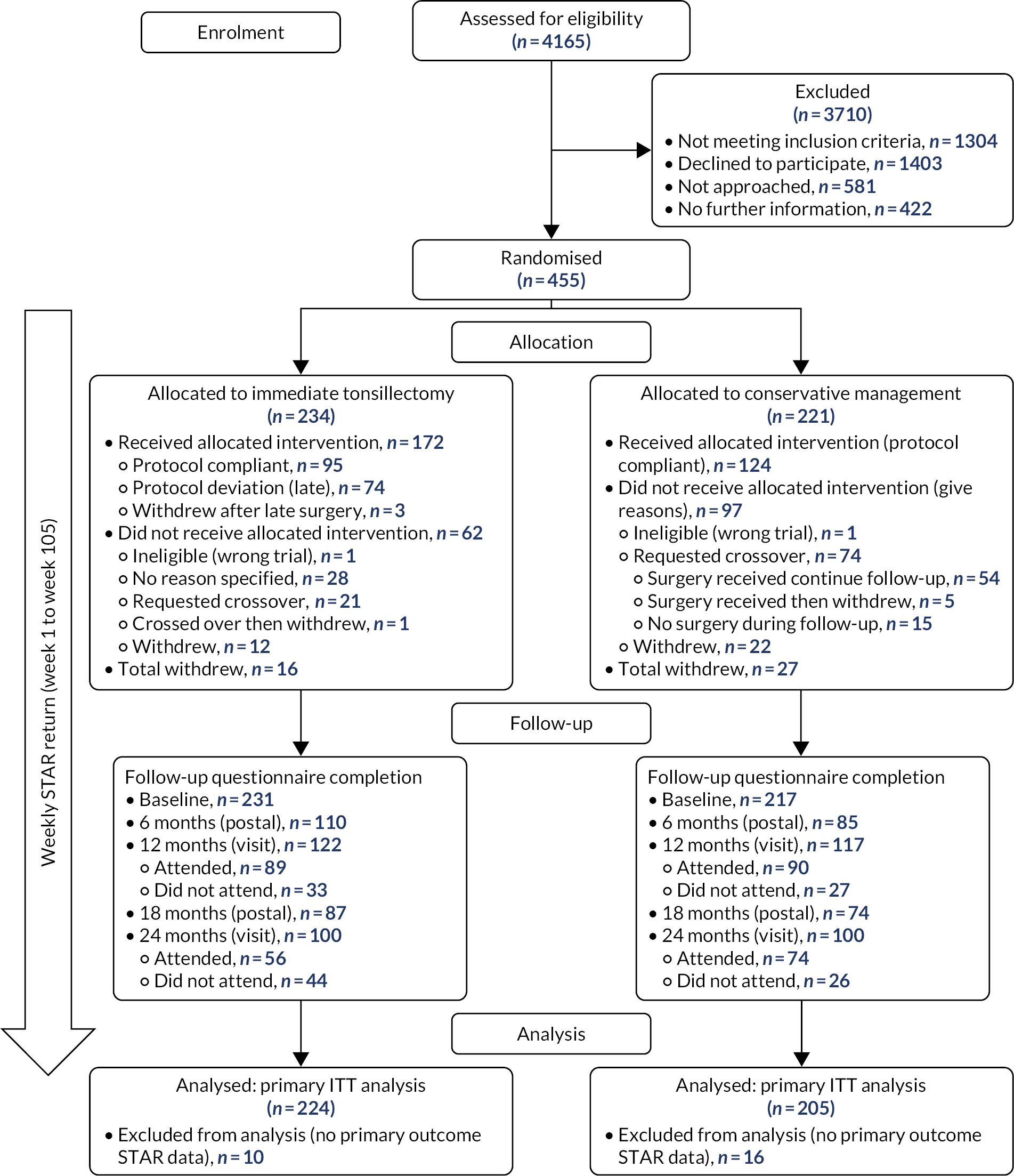

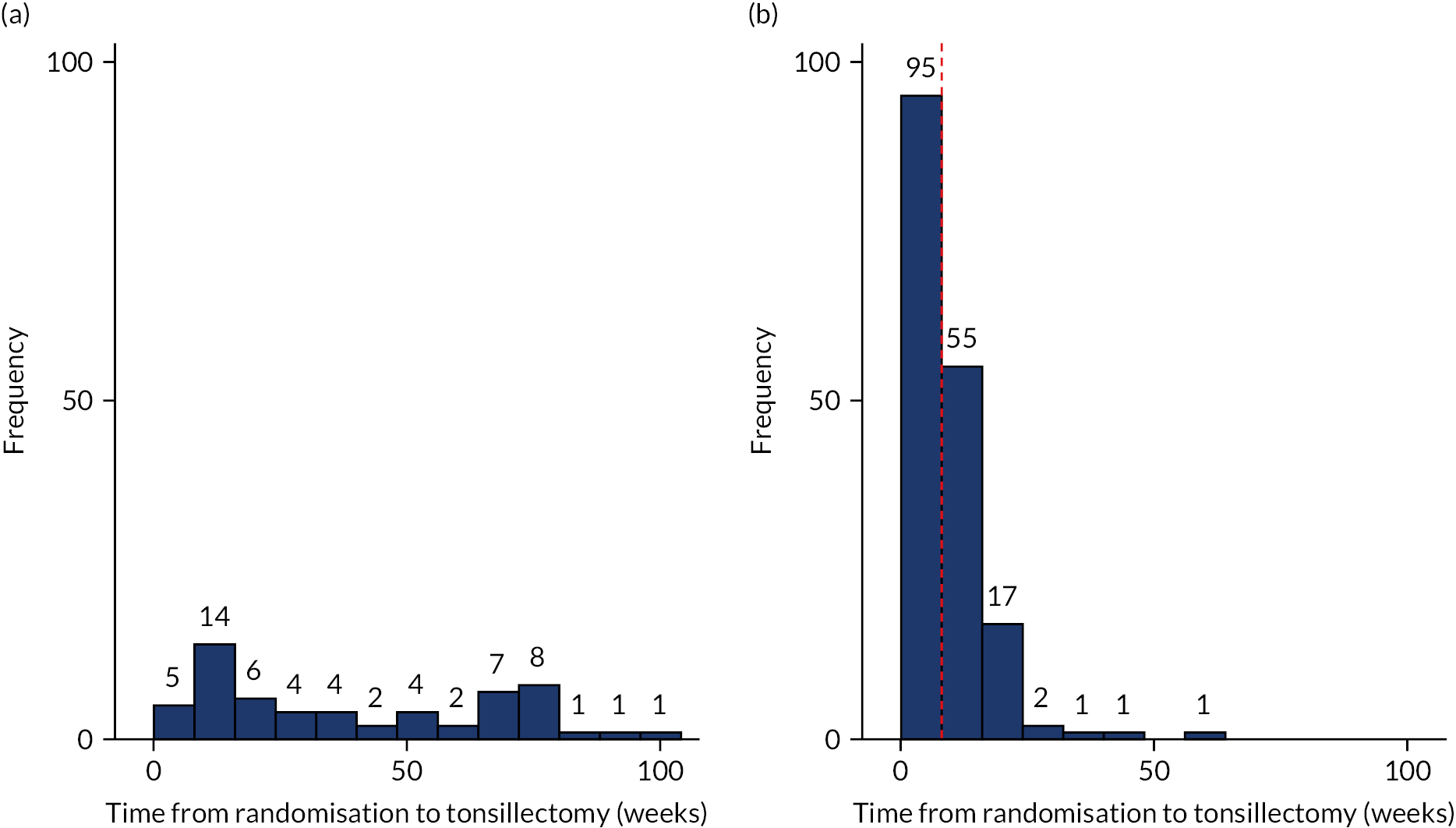

Participants randomised to receive conservative management were asked to defer surgery for up to 24 months and were informed that they would be assessed on their willingness to continue to delay surgery at the 12-month follow-up visit. However, these participants could decide to cross over to have the tonsillectomy at any point of the study, if they continued to meet the SIGN guidelines for tonsillectomy at that time point. 18 Some participants who were randomised to receive tonsillectomy (see Figure 2) changed their minds prior to receiving the surgery and crossed over to the conservative management pathway, and some crossed over otherwise, for example some failed to receive surgery owing to reasons at the site level. The investigator could also withdraw a participant from the trial intervention if this was believed to be in the participant’s best interests. Any reason for treatment withdrawal offered was recorded.

The number of withdrawals was recorded along with the time from randomisation (see Figures 2 and 3, and corresponding summary statistics can be found in Appendix 8, Table 36). The number of crossovers was also recorded (see Table 6). The number of participants crossing over and reasons for crossover were tabulated (see Appendix 2, Tables 29 and 30). Those crossing over randomised arms could either continue with follow-up visits and data collection or withdraw completely and undertake no further follow-up visits or data submission if this was their wish.

Participants had the right to withdraw from the trial at any time without giving a reason. All data collected up until the point of withdrawal were included within the analysis.

Schedule of events

Figure 1 details the participant flow through the trial, which was designed to maximise data accrual from the greatest available number of sources.

The baseline questionnaire package was completed by the participants at the screening/baseline visit after consent and before randomisation so that the total TOI-14 score was available to inform baseline stratification. Baseline, 12-month and 24-month contacts were in the clinic. Six-month and 18-month questionnaires were postal. Table 1 lists the questionnaires completed at each time point.

At both clinic visits, conservative management participants were asked if they preferred to undergo surgery. The operation date for those in the surgery arm was cross-checked in clinic to facilitate identification of sore throat days directly attributable to surgery in the subsequent statistical modelling. After the final visit, participants’ GPs were asked to provide information on participants’ healthcare resource use for the previous 3 years via the GP linkage case report form (see Chapter 4).

Safety

Only AEs related to the trial intervention (tonsillectomy) were reported for this trial; these were captured and documented at the 1-week and 2-week post-surgery telephone calls. Participants were asked if they had experienced any AEs immediately after, or during recovery from, the tonsillectomy. Only participants who received the surgery were contacted.

All serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded throughout the duration of the trial for all participants, regardless of whether or not participants underwent tonsillectomy; these did not include pre-planned hospitalisations, routine follow-up of the studied condition or treatment for pre-existing health conditions, not resulting in clinical deterioration. SAEs that were related to the trial intervention have been listed for the trial (see Appendix 10, Table 42).

All AEs that occurred in this trial, whether or not they were serious, were expected following the tonsillectomy procedure, with the exception of two SAEs that were related to the anaesthetic. The following AEs may be expected after receiving tonsillectomy:

-

common AEs

-

post-operative pain

-

post-operative bleeding

-

temporary changes in taste/tongue sensation

-

difficulty swallowing

-

nausea

-

vomiting

-

infection

-

-

uncommon AEs

-

long-term changes in taste/tongue sensation

-

chip/knock out of tooth

-

-

very rare AEs

-

death.

-

Frequencies were estimated from the available data. Full requirements for the reporting of AEs and SAEs were described in the protocol, including guidance for the assessment of the relatedness and causality for SAEs in relation to the intervention. 79

Definition of the end of the trial

The end of the trial was the date when the final participant’s 24-month follow-up data were obtained and when all SAEs were resolved.

Participant expenses

In recognition of the completion of the weekly returns and follow-up questionnaires, the participants received two £25 gift vouchers, one after the 12-month follow-up and the second after the date of the 24-month follow-up visit, totalling £50. Participants were reimbursed reasonable travel expenses incurred as a result of taking part in the NATTINA trial. Participants who gave a qualitative interview were given a £15 gift voucher.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was incorporated from the funding application stage throughout the trial until the very end, including anticipated input into the trial dissemination phase.

Structured interviews were performed with PPI members and were used to develop the research proposal. Following this, PPI meetings were held in England and Scotland, at which PPI representatives provided input into the recruitment strategy, including the content of the recruitment DVD/online video-recording and the adequacy and accessibility of study documents, such as the study summary sheet, PIS, ICF and STAR form. Input was also given in relation to the weekly alert system and trial advertisement. Feedback was provided on a one-to-one basis on the health economics WTP to avoid a sore throat day question in the baseline questionnaire to provide further validation for the values used. Representatives attended TSC meetings throughout the trial, and towards the end of the trial PPI representatives reviewed the WTP paper and provided input into the dissemination of the final results.

Statistical methods

Analysis followed the full statistical analysis plan (SAP) written in accordance with published guidance87 and approved by the chief investigator (CI), TMG and TSC. The fully signed-off SAP was in place prior to any comparative analysis and the final version was in place prior to the final data lock. Analysis was reported according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) recommendations88 and the data analyses were conducted in the validated statistical software package Stata® v16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Sample size calculation

The planned target recruitment number was 510 participants, which included 72 participants in the internal pilot. This allowed for a total loss to follow-up of 25% over 24 months. In total, 382 participants (two groups of 191 participants providing complete data at 24 months) gave 90% power to detect an effect size of 0.33 [corresponding mean intergroup difference of 3.6 days of sore throat, based on a pooled estimated standard deviation (SD) of 10.8 days], assuming a type 1 error rate of 5%. The choice of this effect size was based on a number of considerations, including our prior experience with the NESSTAC study. 64,89

Statistical analysis

Definition of the primary outcome measure

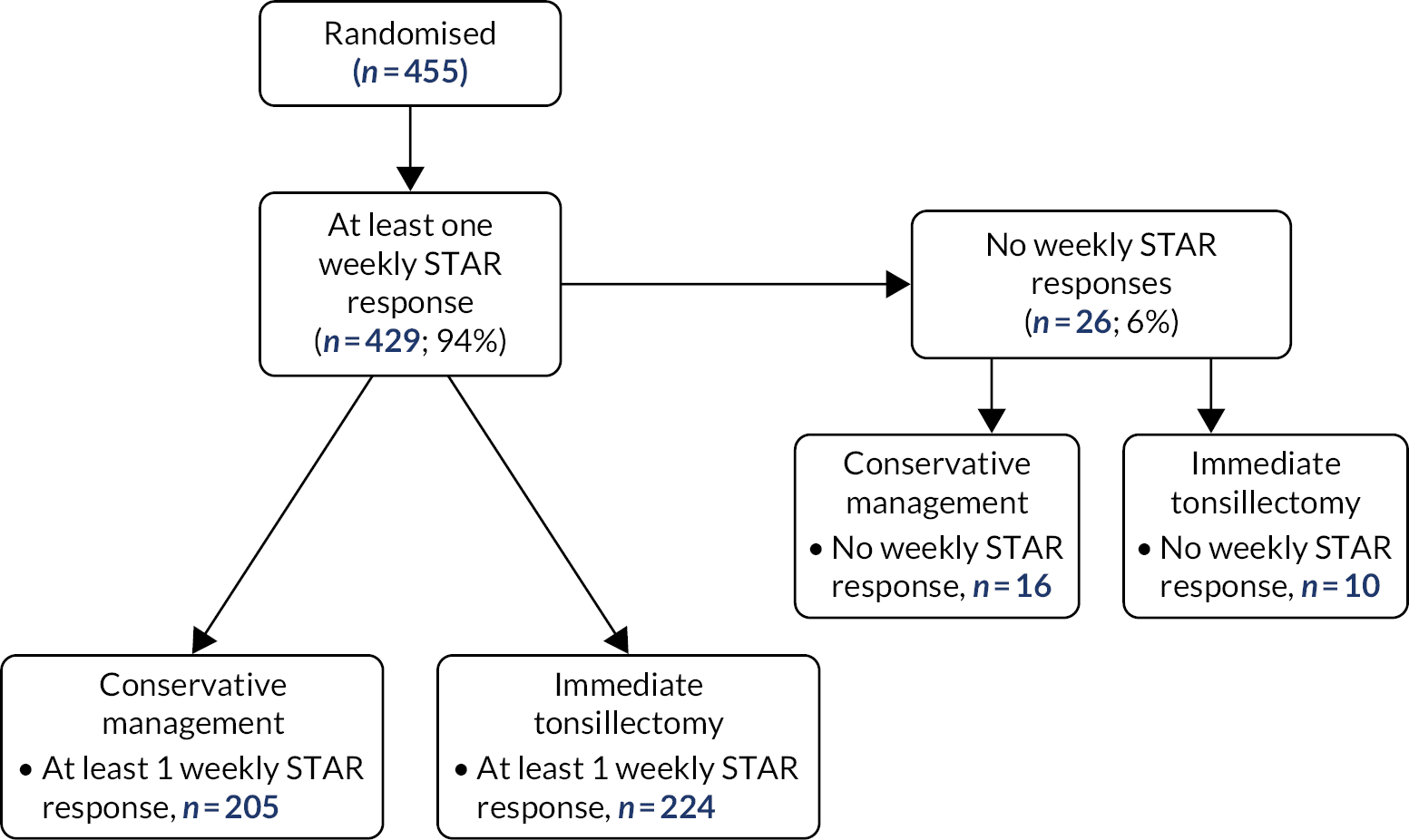

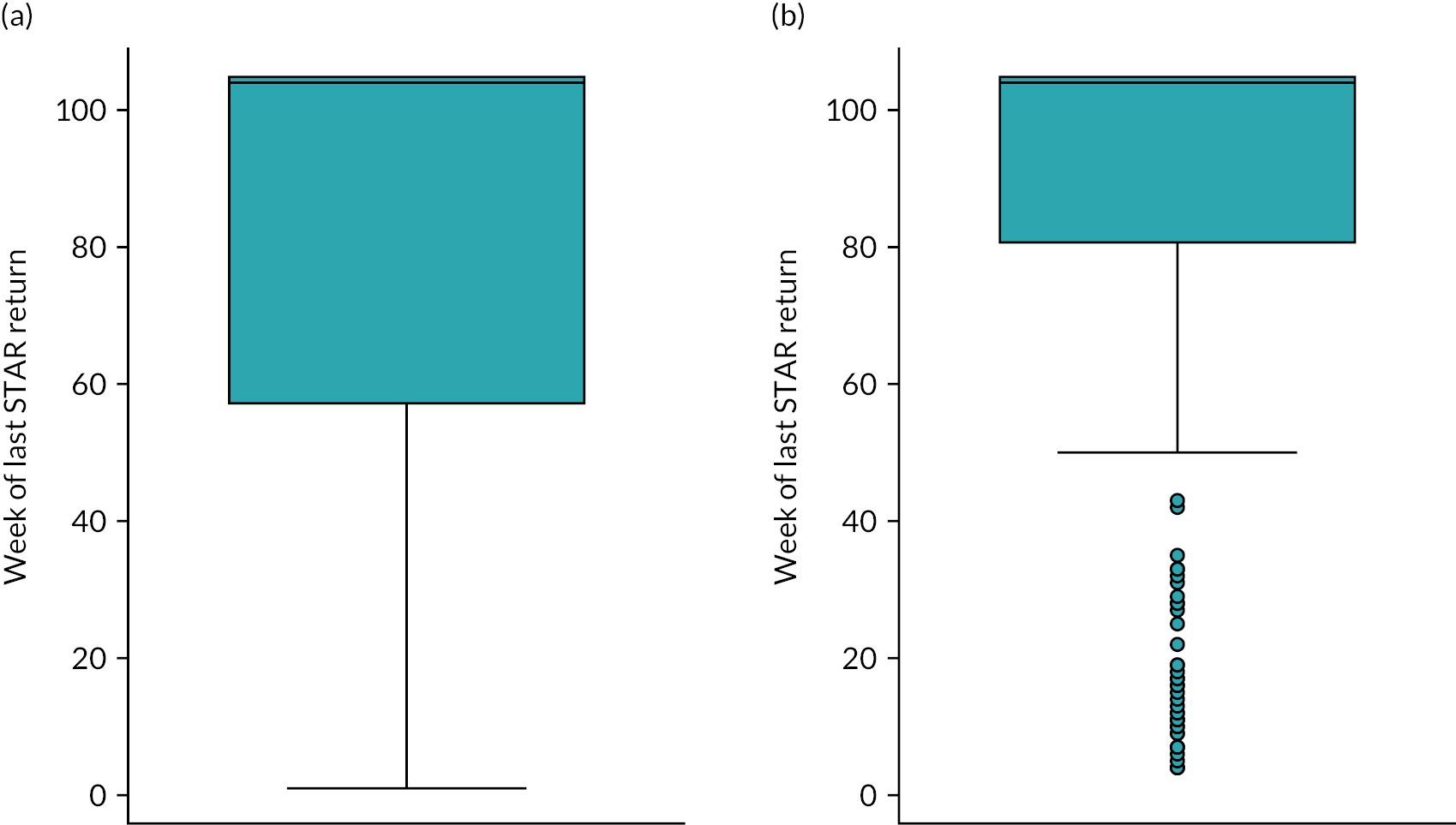

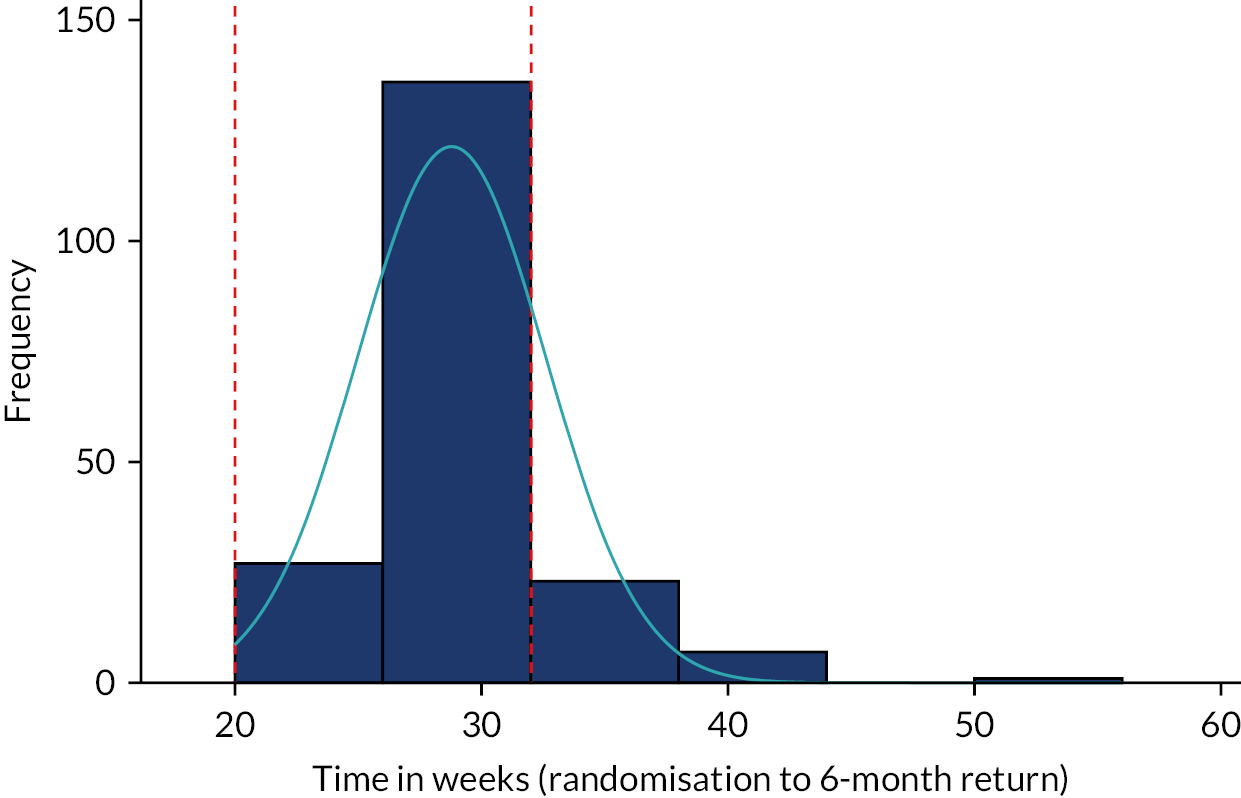

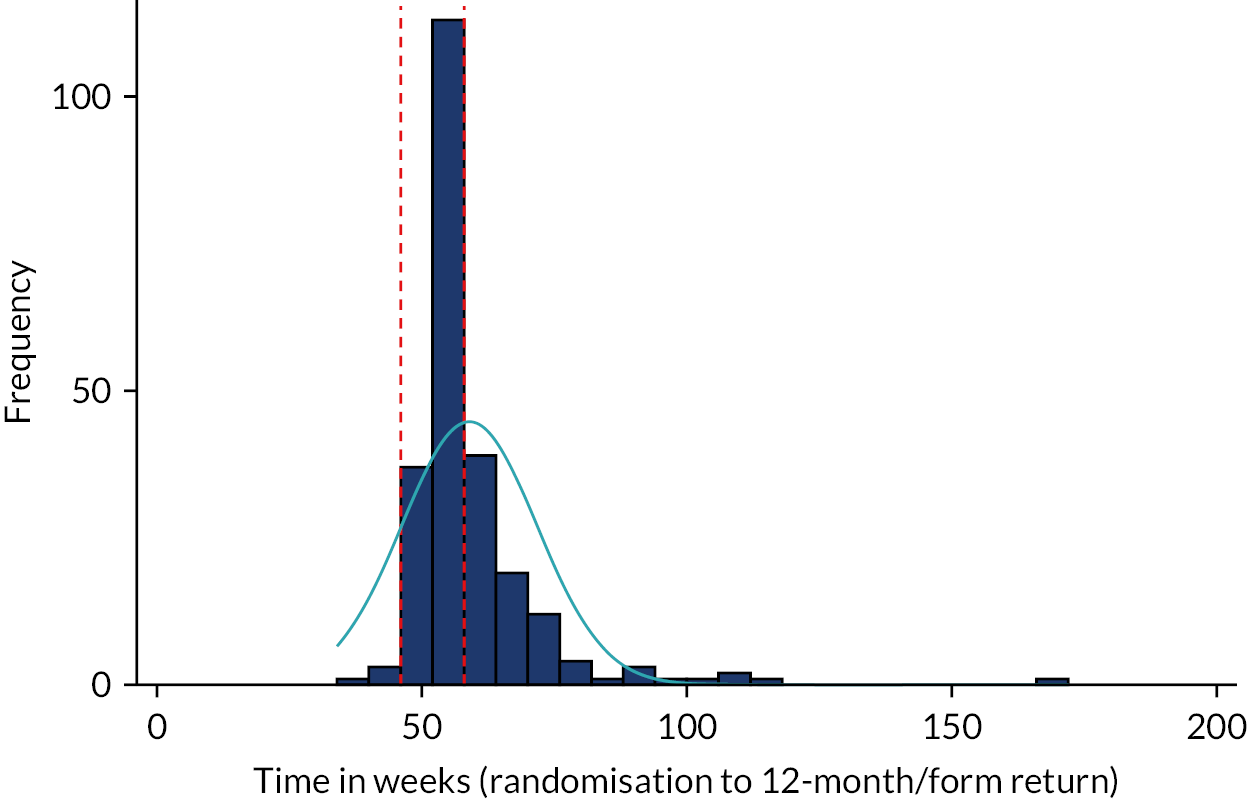

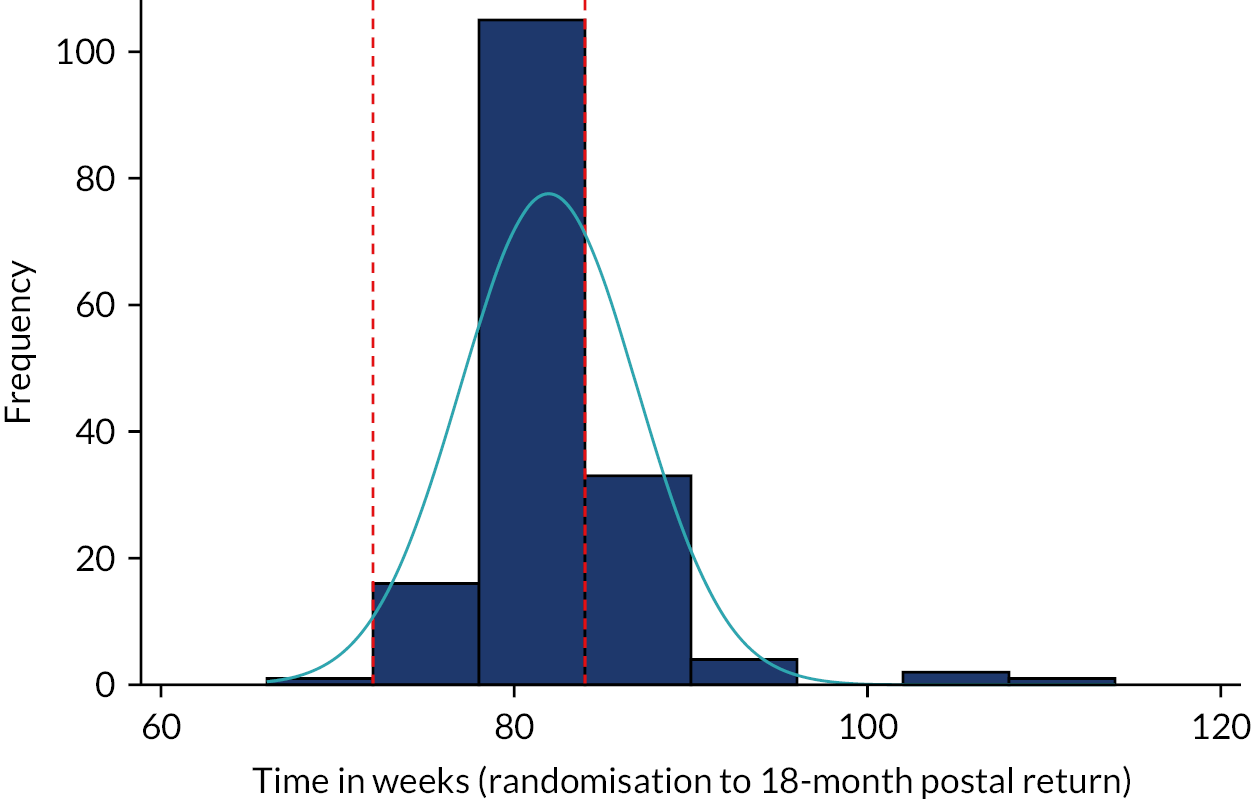

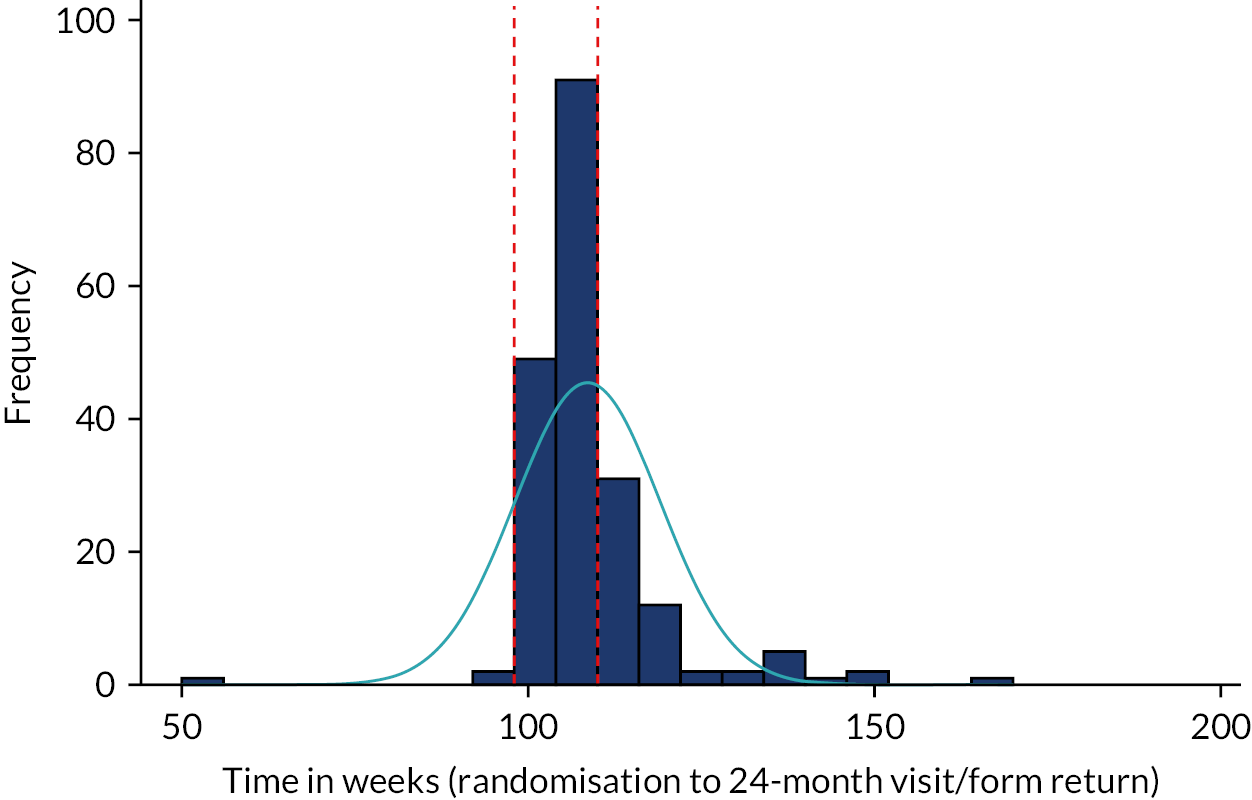

The primary outcome measure was the total number of sore throat days during the 24 months following randomisation. Retention was defined as the time on the trial, which was calculated as the time from the date of randomisation to the date of the last weekly response. The average time in the trial for the participants who sent at least one weekly STAR response was calculated and is presented in box plots (see Figure 9); this allowed us to assess if retention was balanced by randomised arms.

Please note that the primary analyses were quality checked and validated (August 2020) by a member of the Biostatistics Research Group (Newcastle University) who was not otherwise involved in the NATTINA trial. This validation was for the univariate [unadjusted negative binomial regression (NBR)] and for the multivariate (adjusted for stratification variables of site and baseline severity) analyses. The validation results confirmed the primary analysis results.

Defining populations for analysis

The primary statistical analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, retaining patients in their randomised arms. However, patients could switch over from conservative management to tonsillectomy and could also switch from tonsillectomy to conservative management and remain in the trial. In the NATTINA design in this situation, patients in the conservative management arm were asked to commit to ‘deferred surgery’. The implication of such crossover, which typifies surgical trials, is that the ITT analysis may produce a conservative estimate of the effect of tonsillectomy. We, therefore, also carried out supplementary analyses to compare outcomes allowing for treatment switches.

The three analyses by population were as follows:

-

ITT group – all eligible and ineligible participants as randomised were included in the analysis on an ITT basis, with participants kept in their randomised arm (n = 429).

-

Per-treatment group – all randomised participants who started treatment were included in the analysis according to the treatment that they received (n = 429).

-

This is in effect a per-surgery analysis.

-

A second analysis of the per-treatment group (unplanned) further split into original randomised group with surgery status (four categories).

-

-

Per-protocol as randomised – this was limited to patients who were randomised to receive surgery and received surgery within the 8-week window and those patients randomised to the conservative management arm who did not crossover and have tonsillectomy before end of follow-up (n = 224).

-

Sensitivity analysis population (unplanned), including all participants who had returned ≥80% of the expected STARs (n = 263).

-

This population was not specified in the SAP but we carried out this sensitivity analysis as part of our assessment of missing primary outcome data.

-

Weekly Sore Throat Alert Return response counts over the 24-month follow-up period

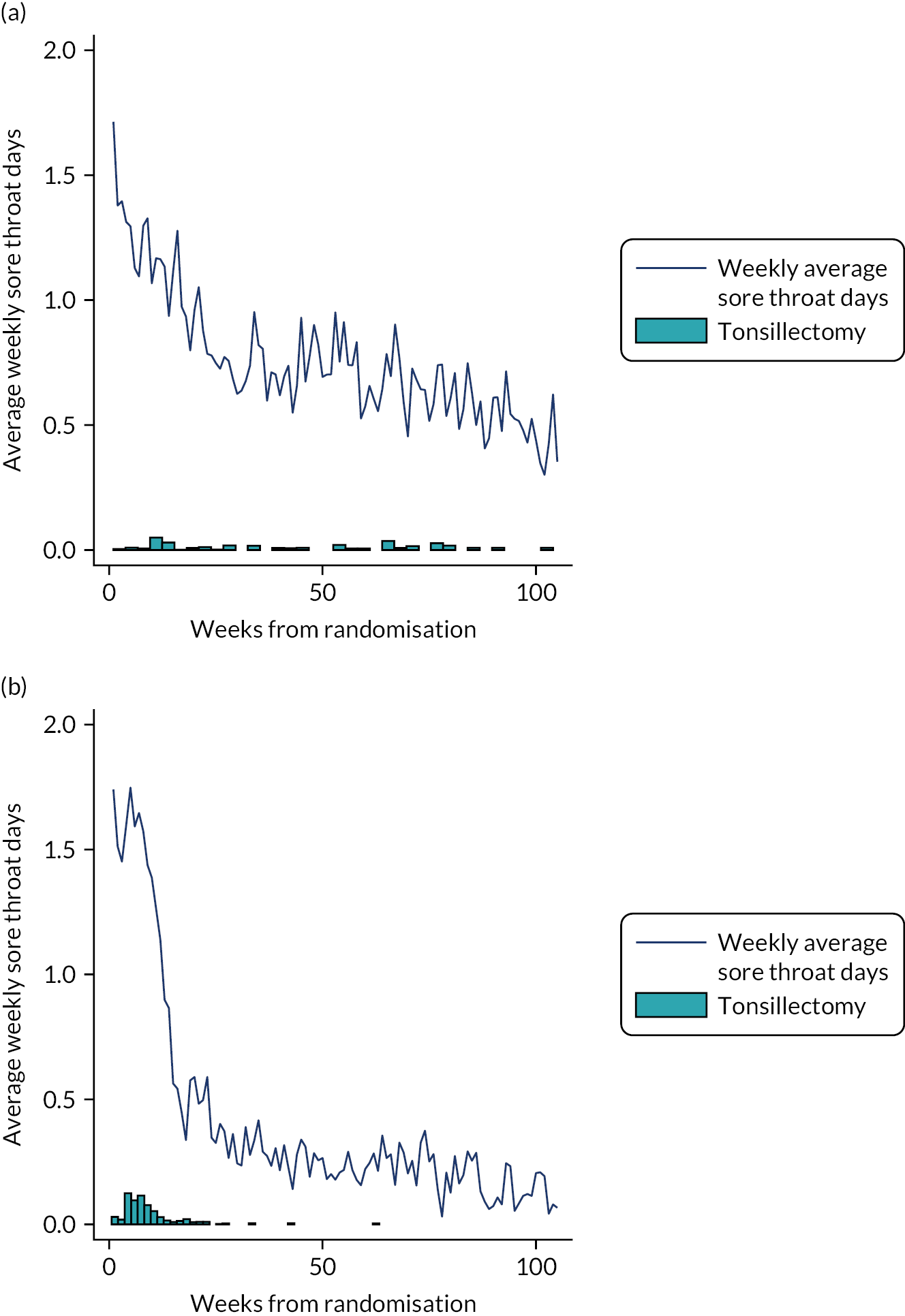

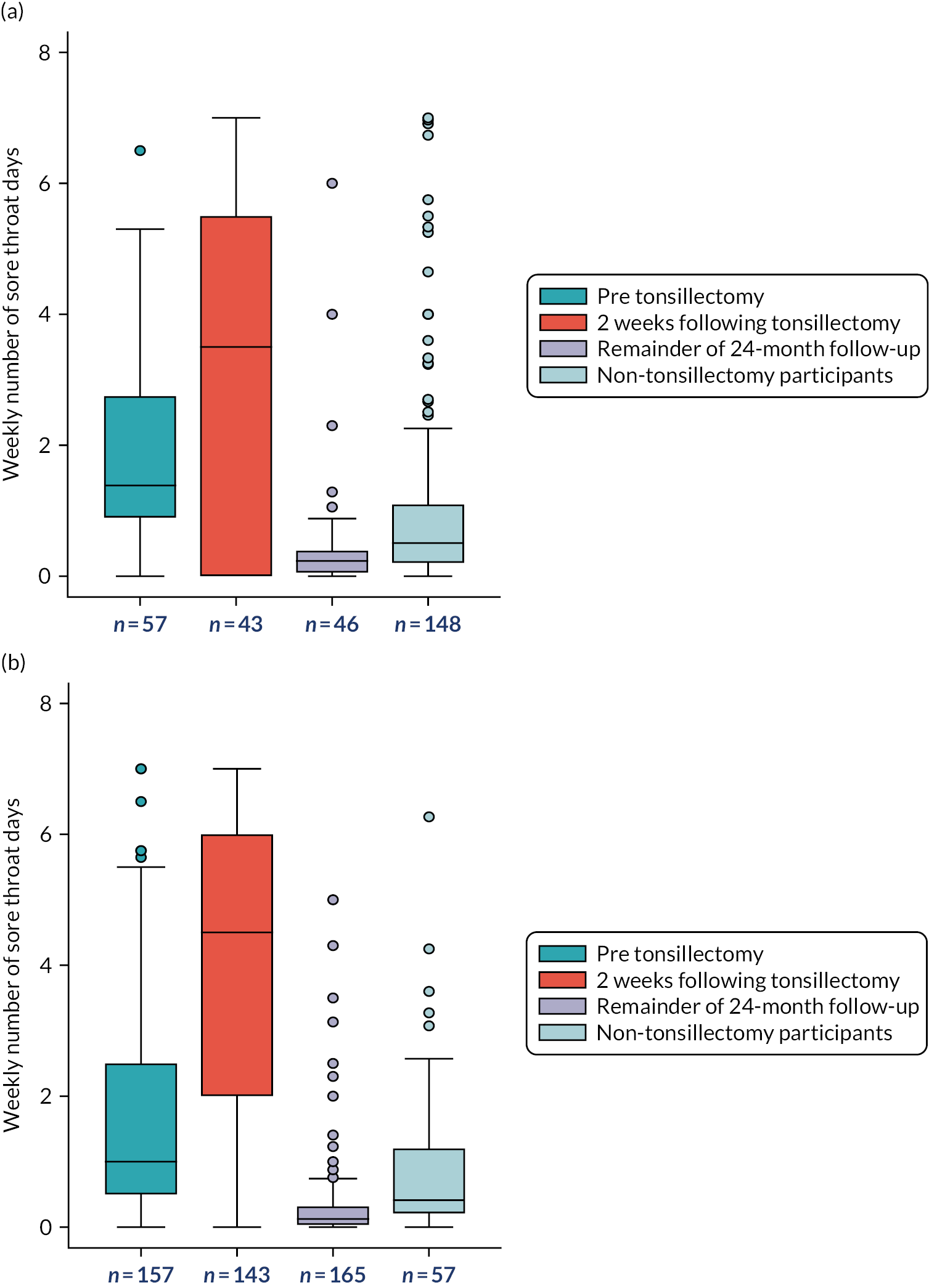

Counts of weekly STAR responses in both arms from baseline to week 105 were observed. The cumulative total number of sore throat days reported on a participant level has been provided separately for each randomised arm (for surgery split into pre surgery, surgery plus 2 weeks, and the remainder of the 24-month follow-up period) (see Figure 7 and corresponding summary statistics in Appendix 12, Table 44). The STARs have been sub grouped and summarised for the never surgery, pre-surgery, immediate 2 weeks post-surgery and remainder of the post-surgery follow-up. The day of surgery was identified and the ensuing two STARs were taken to reflect the 2-week postoperative period.

Only data for the 24-month follow-up after randomisation were included in the statistical analysis for all participants, despite additional STAR responses being submitted by a small number of participants post 24-month follow-up.

The total number of sore throat days was calculated by summing all of the STARs for each participant. Negative binomial regression was used to analyse the primary outcome data, which allowed for an exposure variable to be included that takes account of the number of STARs received to make up this total. However, this means that viewing the raw totals themselves for the descriptive analysis may be misleading because they do not take account of the missing returns (unless it is assumed that missing returns mean there were no sore throats to report, which is not a reasonable assumption). We therefore transformed the data so that each participant’s total sore throats was divided by the proportion of STARs returned.

Incident rate ratio

In NBR, coefficients are obtained that are interpreted as the difference between the log of expected counts, corresponding to a 1-unit change in the predictor variable. The parameter estimate can also be interpreted as the log of the ratio of expected counts, technically a rate. The response variable is the total number of sore throat days reported over follow-up, which by definition, is a rate. A rate is defined as the number of events per time, so can also interpret the regression coefficients as the log of the rate ratio.

Incident rate ratios (IRRs) are presented in Primary analyses and Sensitivity analysis. Note that the IRR is obtained by exponentiating the coefficients of the regression model.

Differential loss to follow-up

Of 455 patients randomised, 26 participants did not complete any weekly STAR responses: 10 randomised to receive tonsillectomy and 16 randomised to receive conservative management. This includes the two ineligible participants and was balanced across arms (see Figure 5). The details of compliance to follow-up in terms of visits and postal questionnaire completion was also balanced across arms (see Table 6). The relatively low levels of engagement with follow-up visits and postal questionnaire completion did not affect the primary analysis of the trial.

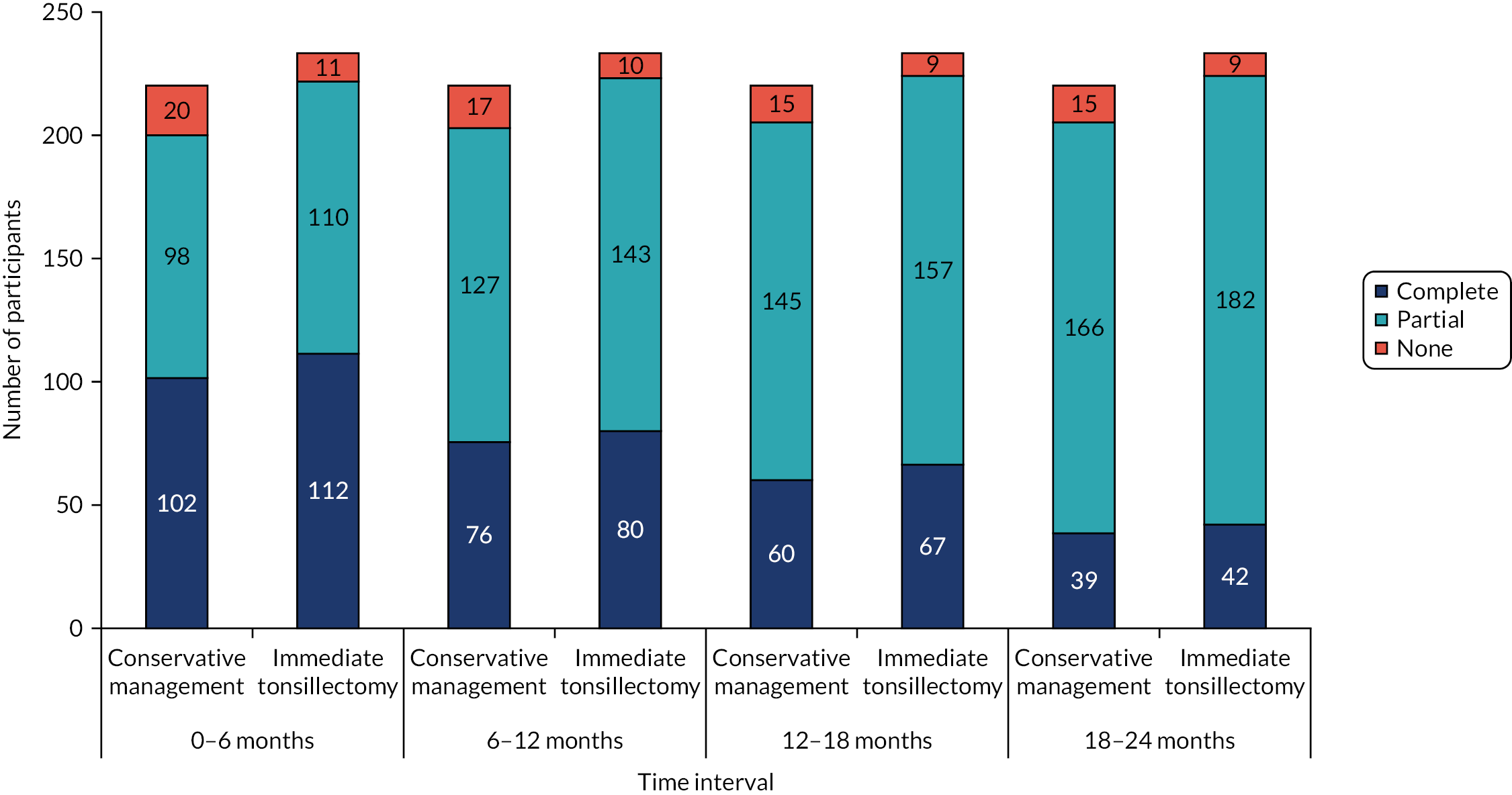

Missing primary outcome data

Weekly STAR response was categorised at each time point (6, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation), as (1) complete; (2) partial, where some but not all expected weekly STAR responses were received; and (3) no returns (see Table 15).

In addition to assessing missing primary outcome data (STAR responses), we also assessed the exposure variable (i.e. a measure of missing data) in terms of the four per-treatment categories in terms of how this relates to the baseline severity (mild, moderate and severe). We also carried out a similar check regarding the secondary outcome measure of TOI-14 scores in a similar manner. Further details can be found in Appendix 15, Tables 52 (exposure by baseline severity), 53 (summary statistics for overall return rate), 54 (crosstab showing numbers completing at least 80% STARs and 80% TOI-14 questionnaires at the follow-up time points).

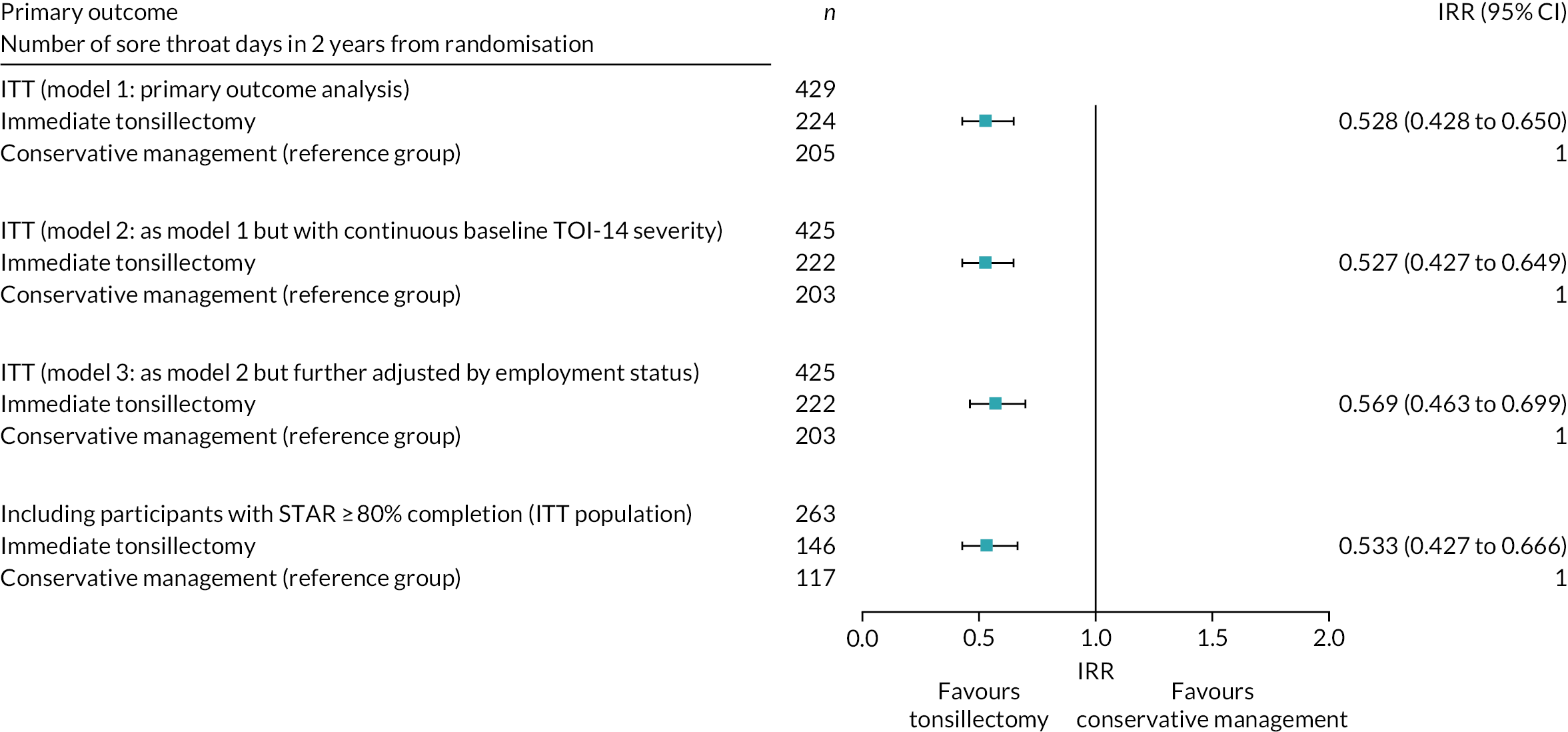

Primary analyses

The primary hypothesis to be tested was H0: the number of sore throat days in 24 months is same for both randomised arms. A two-sided significance level of p < 0.05 was used throughout.

The primary outcome measure of the total number of sore throat days experienced over the 24 months of follow-up was analysed using NBR to compare the change between the NATTINA arms while adjusting for potential confounders, including the stratification variables: recruiting centre (as a random effect) and baseline severity (as a fixed effect). This analysis was undertaken on an ITT basis; however, patients could switch over from conservative management to tonsillectomy. In the NATTINA design, patients were asked to commit to ‘deferred surgery’ (model 1).

Count data, by convention, often have an exposure variable indicating the duration of the observation period. Exposure variables for the NATTINA models were applied to the NBR model developed to account for differences in the proportion of the weekly returns completed by each participant (range from 0 to 1, with 1 representing a situation whereby all follow-up data were present).

The response variable is the total number of sore throat days over 24 months from randomisation to last follow-up. All participants were included in the analysis on an ITT basis with participants kept in their randomised arm, with the exception of the two participants randomised in error, as described in Chapter 2.

Sensitivity analysis

The true effect of tonsillectomy is likely to lie between the estimate from the ITT analysis, which is the most parsimonious account owing to anticipated crossover into surgery, and the as-treated analyses, which tend to maximise the effect size of any surgical intervention. Outcome data analysis was at the end of the study and for DMC review, and followed the full SAP developed prior to the start of the analysis. Secondary analysis included estimation of the effects of tonsillectomy adjusted for potentially important clinical and demographical variables.

Sensitivity analyses on the ITT population were carried out to examine continuous baseline severity measure TOI-14 (model 2) and any other important baseline factors found to be potentially significant (model 3).

Further multivariable analyses considered other important baseline factors in the NBR model, including sex, age, ethnicity, education level, employment status, site and baseline levels. Non-linear continuous covariates were transformed when appropriate using simple first-degree polynomial transformations.

Additional analyses of the primary outcome

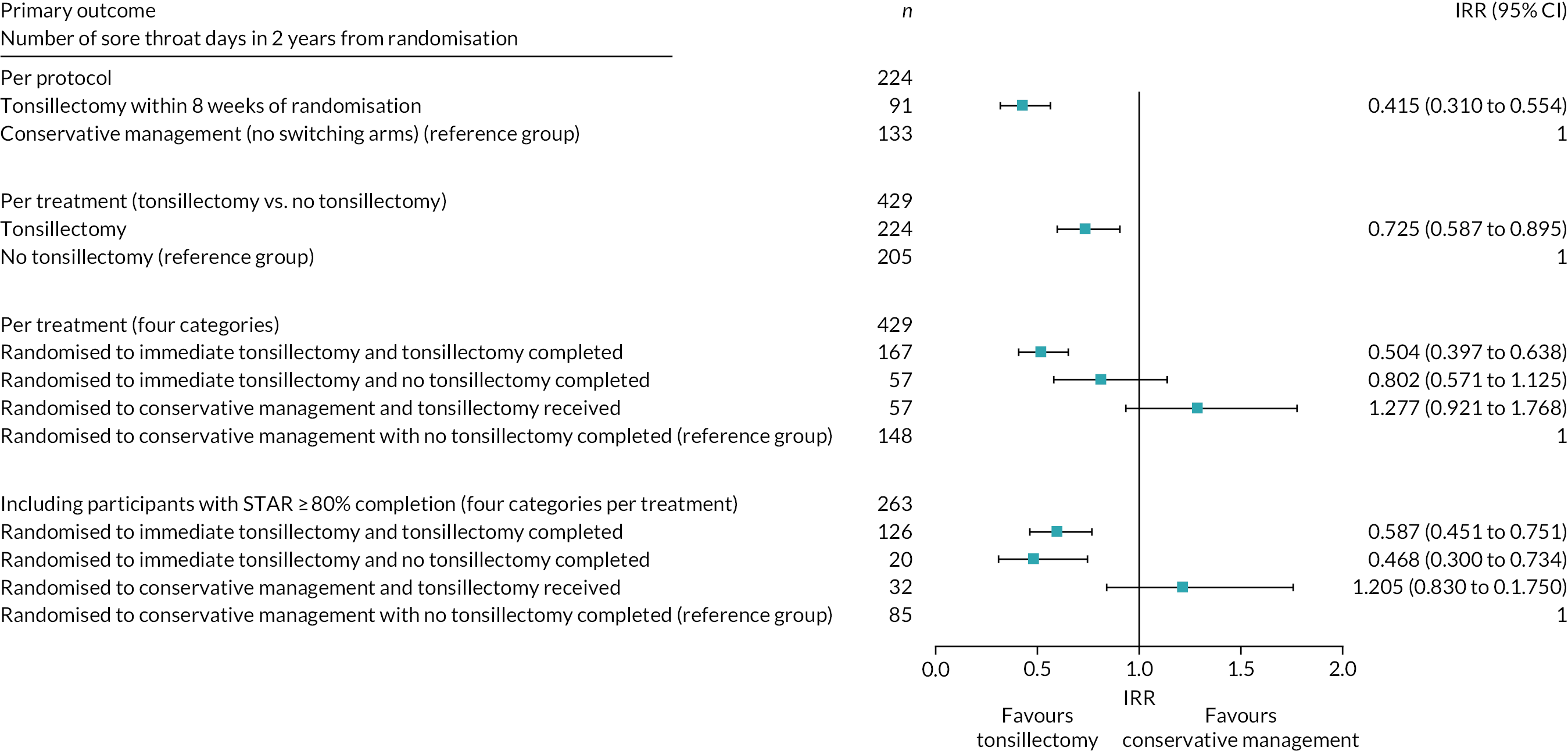

Addressing crossover (per-treatment analysis)

Participants in the conservative management arm of NATTINA were asked to commit to ‘deferred surgery’. We anticipated that a number of participants would elect to cross over to surgery (see Appendix 6). The implication of such crossover, which typifies surgical trials, is that the ITT analysis would produce a very conservative estimate of the effect of tonsillectomy. We therefore also undertook sensitivity analyses for as treated, comparing those who received tonsillectomy with those who did not, as well as another four category per-treatment analysis that still considered randomised arm, but with each arm further divided into participants who received tonsillectomies and those who did not. A further unplanned sensitivity analysis included only participants who had returned ≥80% of the STAR responses. A per-protocol sensitivity analysis was also carried out to confirm the results seen in the ITT primary analysis. This restricted the analysis to those participants who complied with the protocol and received tonsillectomy within 8 weeks after randomisation, after being initially randomised to the immediate tonsillectomy arm, compared with those randomised to the conservative management arm who did not cross over to receive a tonsillectomy. Non-compliance (including crossover) was addressed further using an ‘as-treated’ approach or complier-average causal effect (CACE) approach, given that the ITT analysis under non-compliance is biased when the intervention effect is large. 90 Alternative analysis can provide less biased estimates. 91 The CACE approach results are reported in Appendix 12 (instrumental variables).

Data with missing observations owing to loss to follow-up were examined to determine both its extent and whether it was missing at random or was informative. Owing to incomplete follow-up on the primary outcome for some patients as anticipated, an appropriate exposure variable in the NBR model addressed this.