Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/91/04. The contractual start date was in March 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Snooks et al. This work was produced by Snooks et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Snooks et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Jones et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

In England, over half of drug deaths involve opioids, and death by drug overdose has increased since 2012. 2 In the UK, accidental overdose related to the misuse of opioid drugs (such as heroin, methadone, fentanyl and morphine) is an increasingly prevalent public health problem. 3–5 The number of deaths involving heroin and/or morphine doubled between 2012 and 2015 to the highest on record. 6 The rise in heroin-related deaths has not only caught the attention of the research community but has also received coverage from the popular press – in the UK7,8 and abroad. 9

People who misuse either illicit or prescription opioids are at an increased risk of non-fatal overdose, subsequent hospital or emergency service (ES) utilisation, and death. 10–12 Non-fatal opioid overdose is associated with long-term morbidity and increased demand on health services. 13–15 ES contact for drug-related morbidity has been found to be a predictor of future episodes of poisoning or overdose. 16,17

Naloxone is an effective fast-acting opioid antagonist used to treat opioid overdose. 18 Naloxone blocks opioid receptors to counteract the effects of opioid drugs. It reverses the life-threatening effects of an overdose such as depressed breathing, and has no psychoactive properties or intoxicating effects. 19

Naloxone can be supplied to people at risk of opioid overdose by paramedics or by laypeople in the form of take-home naloxone (THN). 20 However, the safety of naloxone in community settings is unclear. Typically, a THN kit comprises one or more doses of naloxone, an intramuscular (IM) needle and syringe for injecting the dose, and written or pictorial instructions to explain how to prepare and administer the dose and perform basic life support, and the importance of calling the ES. These materials may also describe the duration of effect, and hence why it is important that paramedics attend the patient as soon as possible; the safety of naloxone in terms of adverse events and overdose; and the legality of bystander administration of naloxone.

Non-experimental studies suggest that THN programmes which involve the training of laypersons to administer a naloxone dose in cases of overdose emergency are safe and effective. 21–23 THN kits can be used by people without formal medical training in the event of an opioid overdose. Increased access to THN kits via specialist drug services in the UK and internationally has been motivated by recommendations from influential bodies, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the British Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD). 24,25

Numerous THN distribution programmes aiming to reduce death from opioid overdose have been implemented by drug service providers in the UK and internationally since the 1990s. 26,27 However, a significant proportion of people at risk of opioid overdose do not engage with these services. 28 Additionally, high-quality empirical evidence to demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of THN is sparse. Observational data suggest that non-serious adverse reactions to naloxone administration are common while serious adverse reactions are rare. 29,30 However, the risks of inadequate response or return to a state of overdose following the administration of naloxone by laypeople remain poorly quantified. 31,32 Moreover, the uptake of THN kits in at-risk populations remains low33,34 and appropriate THN intervention by peers and witnesses may not be optimal. 35

Members of the research team (CM, HS) have previously conducted a randomised feasibility study of THN distributed through the emergency ambulance service (AS) in a single urban geographic area. 36 Their experiences, consistent with those of other researchers,37,38 have demonstrated that using traditional methods (e.g. telephone or postal methods) for capturing follow-up outcomes of participants in receipt of a THN kit (and of those not in receipt of a THN kit despite eligibility) is not feasible.

Rationale

The theory underpinning THN provision as an intervention is that by distributing a readily administrable dose of naloxone to people likely to witness opioid overdose, naloxone would be administered to victims of overdose earlier post onset of symptoms than standard care (administration of naloxone by health professional on ambulance or in ED), thus improving survival. Currently, THN provision initiatives, primarily aimed at reducing incidence of fatal heroin overdose, usually take place in non-clinical environments such as third-sector drug services or prison, rather than in emergency care settings. This means that a proportion of those at risk of opioid overdose who do not attend drug services or who are not completing a sentence of imprisonment have limited access to THN kits. Based on figures from England, Wales and Scotland, it appears that this is a sizeable population. In 2017, it was estimated that there were 340,000 high-risk opioid users in England and Wales, and 149,420 people receiving opioid substitution treatment. 39 Between 2017 and 2018 in Wales, 25,190 individuals accessed a needle exchange service, of which opioids was the primary use for 48%. 40 In comparison, only 2896 THN kits were supplied for the same year, of which 1372 were supplied to individuals for the first time and 533 were reportedly used. 41

In Scotland in 2017–8, a total of 6924 THN kits were issued in the community, of which 2458 were thought to have been issued to individuals for the first time. 42 To put this into context, figures for 2015–6 in Scotland show an estimated 55,800 to 58,900 users of opioids and/or benzodiazepines. 43 These data tell us that saturation of THN kits among opioid users in the general population remains low. However, the distribution and receipt of THN kits in communities around the country is increasing – for example, in 2019–20, Scotland had a 44.3% increase, England’s THN distribution increased by 13.8% whereas Wales’s distribution stayed the same at an average of 389 kits a month. 44 This increase in uptake underlines the urgency of establishing the safety and effectiveness of THN provision. Despite the growth in THN provision initiatives and implementation programs, questions have been raised regarding potential harms associated with the administration of naloxone to lay people in non-clinical settings. Concerns include adverse events such as acute opioid withdrawal,31,32 and an increase in high-risk drug-taking behaviour (due to the availability of an apparent ‘safety net’) or other unforeseen methods of indirectly abusing naloxone. 45 Furthermore, there is a possibility of naloxone dose being insufficient, or wearing off too quickly, resulting in patients requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or further treatment and not receiving this. 31,46 Tse et al. ’s47 systematic review of 7 studies with 2578 participants found no evidence that THN provision increased opioid use. Of the included studies which reported overdose frequency, three of the studies saw no change in overdose rate and one found a decrease. Nonetheless, a previous study found no difference in the number of ambulance call outs before or after THN implementation, suggesting that community-based THN programmes do not result in a reduction in ambulance calls for overdose, that overdose rates do not increase, and that users do not become less likely to call 999. 48 However, as the study used anonymised linked ambulance dispatch data, it was not possible to assess whether an increased number of overdoses took place where no 999 call was made.

There is currently limited published evidence regarding THN provision in emergency settings and, with little evidence from RCTs, the safety, wider effects on drug-taking behaviour, and cost-effectiveness of THN provision initiatives in the community are unknown. However, evidence suggests that THN provision programs in emergency settings are acceptable to our target population, and we can therefore expect favourable recruitment among paramedics. 38 Members of our study team completed the recruitment phase of a feasibility study of THN provision to patients following attendance and resuscitation by emergency ambulance paramedics for opioid overdose. 36 We used a cluster stepped wedge design and randomly selected paramedics in one urban centre in south Wales. We randomised paramedics to the week in which they would receive training and THN kits over the first 4 months of the 12-month recruitment period, so that all paramedics had the opportunity to deliver the intervention during the study. Eligible patients attended by participating paramedics during the period before they were trained and allocated THN kits were allocated to the control group, while eligible patients attended by paramedics who had received training and THN kits were allocated to the intervention group. We published preliminary results related to recruitment, follow-up and outcomes. 49 Eighty-five of 102 eligible paramedics took part. The number of opioid-related emergency ambulance contacts (215) exceeded those predicted (100–120) in 12 months. Of 182 cases attended by study paramedics, 148 were attended by paramedics who had been trained and issued with THN kits (intervention group). Thirty-five of 55 patients eligible for the intervention (sufficiently recovered and able to consent) were offered it. Twenty-five accepted, received training from the paramedic, and were given a THN kit; a 71% acceptance rate. Follow-up of participants for self-reported outcomes proved challenging. Of the 215 events for which we have data, 58 were repeat episodes involving 25 individual users. The number of repeat encounters experienced by these individuals ranged from two to five. Six deaths were recorded during the study period.

In addition to this work, Kestler et al. 50 carried out an anonymous survey study in the ED in which patients completed a questionnaire regarding opioid use and were offered THN kit plus training after completion. Two-thirds accepted THN, a similar proportion to that seen in our team members’ feasibility study, and multivariate analysis identified injecting drug use as a factor associated with acceptance of THN. In comparison, researchers at Boston University in the USA carried out a feasibility study of the distribution of intranasal (IN) THN via a drug outreach service based in an ED. 37 They did not use linked data but took contact details for 415 participants seen by the service. Of these 415, 12.3% (n = 51) completed follow-up by telephone and 9% (n = 37) accepted the THN kit, using IM naloxone – a much lower acceptance rate than previously reported. Of those who had received a THN kit and completed follow-up, six reported administering the naloxone.

In summary, though the efficacy of naloxone in reversing opioid overdose is established, the effectiveness of THN provision as an intervention – in either community or ES settings – is unknown. This state of equipoise warrants investigation using experimental methods. We tested the feasibility of carrying out a definitive randomised trial to evaluate safety, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of THN provision to opioid users at risk of overdose in emergency settings. In this feasibility trial, at randomly selected sites, THN was distributed to patients identified by emergency ambulance paramedics or ED clinical staff as actively taking opioids. Using this approach, we aimed to reach the very highest-risk group, who may not be registered with drug services or general practitioners (GPs). Of drug users in the UK, opioid users have the lowest rates of GP referral to drug services and have been found to be most likely to report insecure housing arrangements,51 representing a barrier to GP access. 52 The ES may be the only healthcare system that this vulnerable and underserved patient group ever access. Testing whether THN can be distributed through such settings to help minimise the risk of preventable death is an important step in establishing an evidence base for distribution of THN for peer administration of naloxone to people in an overdose.

Research aims and objectives

Feasibility study aim

To determine the feasibility of carrying out a fully powered RCT of THN in emergency settings using anonymised linked data to capture outcomes.

Feasibility study objectives

To establish:

-

the best form of THN kit, training and delivery, based on previous experience, evidence, specialist (addiction, emergency care) and service user advice

-

using agreed progression criteria, whether a trial clustered by ED catchment area and associated AS is deliverable.

In order to satisfy our study objectives, we answered the following questions:

-

Can we recruit paramedics and ED staff to trial participation?

-

Is the THN intervention acceptable to service users and practitioners?

-

Can we identify and retrieve (linked routine data) outcomes for two population groups:

-

those eligible for THN kit provision by paramedics or ED staff?

-

a further group who may receive (peer-administered) THN following an overdose?

-

-

What outcomes should we include in a full trial; how should its primary outcome be defined and in what form should it be presented for analysis?

-

What difference in primary outcome would be clinically important and justify the costs and burden on emergency care staff needed to facilitate widespread implementation of THN kit provision?

-

What sample size (and number of clusters) would we need to achieve in a full trial to be confident of detecting a specified THN intervention effect – should it exist – in this primary outcome?

-

Are there any important safety effects of distributing THN kits that we should consider (e.g. increase in risk-taking behaviour or non-fatal overdoses), and can we retrieve data on these?

-

What are the barriers and facilitators to implementation of this THN intervention in emergency settings?

-

What are the patient and peer experiences at intervention sites?

Progression criteria

We assessed whether or not to proceed to a fully powered RCT using the following progression criteria, informed by the previous Cardiff-based feasibility study (CM, HS),35,48 and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). We used a ‘traffic-light’ system to judge progress against each criteria.

Green: indicates that we have either met a criterion (in which case no modifications to the relevant aspect of the study protocol may be needed), or we are within 10% of our stated progression targets (in which case we reviewed the reasons for this and considered appropriate modifications to study methods).

Amber: indicates that we are within 20% of our stated progression target, in which case we critically reviewed reasons for this and assess whether major changes to study methods are likely to realise significant improvements.

Red: indicates that we are more than 20% from our target, in which case we would not, in the absence of clear extenuating circumstances, consider progression to a full trial.

All percentage changes were measured as relative to target.

Intervention feasibility criteria

-

Sign-up of four sites, including ≥ 50% of eligible staff to complete training in delivering the intervention at each intervention site.

-

Identification of ≥ 75% of people who have presented to ED or associated AS with opioid overdose or an opioid use-related problem over a 12-month period.

-

THN kits issued to ≥ 50% of eligible patients over a 12-month period at intervention sites.

-

Serious adverse event rate [to be defined in agreement with the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC)] of no more than 10% difference in intervention sites to control sites at the conclusion of recruitment.

Trial methods feasibility criteria

-

Identification and inclusion for follow-up of ≥ 75% of people who died of opioid poisoning in the following year in the study areas according to ONS mortality data (previous ONS data suggest between 140 and 180 such deaths across the 4 participating sites during the study period).

-

Matching and data linkage in ≥ 90% of cases not dissented at the conclusion of quantitative data collection.

-

Retrieval of primary and secondary outcomes from NHS Digital and Digital Health and Care Wales (DHCW) within 6 months of projected timeline.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Jones et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Study design

We carried out a randomised feasibility trial in the emergency care environment, involving study sites defined geographically as an ED and its catchment area within the local emergency AS.

We were unlikely to know if the naloxone dose included in any individual THN kit was administered to a peer of the recipient of the kit or to the recipient him/herself. Effects of the THN intervention could extend beyond recipients seen in the ED or by ambulance crews. In order to measure treatment effect in those likely to benefit from THN, we needed to define a wider population – those at high risk of death from opioid overdose in the general population at intervention and control study sites. We undertook work, therefore, to develop a discriminant function to identify cohorts to include in outcome comparisons.

Alongside this work, we carried out a RCT clustered by study site. We also collected qualitative data to gain an understanding of the processes of implementation of the intervention and experiences of service users and providers and assessed the feasibility of costing the intervention and its effects.

Study setting

We conducted the feasibility study in the emergency departments (EDs) and their catchment areas within the local emergency AS. The following sites were randomly allocated to intervention or control in ‘pairs’: Bristol Royal Infirmary and South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust; Hull Royal Infirmary and Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust; Northern General Hospital Sheffield and Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust; Wrexham Maelor Hospital and Welsh Ambulance Service NHS Trust.

Development of the discriminant function

We intended to identify for inclusion in outcome follow-up people at high risk of fatal opioid overdose who may benefit from naloxone from a THN kit. We attempted to define a discriminant function, similar to a risk index, incorporating known and routinely recorded predictors of opioid-related deaths. We used existing linked data about opioid deaths in Wales, including ED and inpatient data, to select predictors closely associated with those who died from opioid poisoning. We then intended to use these predictors in our discriminant function to identify participants in the study site areas to be included in the ‘high-risk population’ for outcome analyses. We previously carried out scoping of NHS Wales ED and hospital routine datasets and linked ONS mortality records with these datasets. We found that we were able to describe circumstances of death for opioid overdose decedents who had visited EDs prior to their death, as well as describe service usage over a prolonged observation period. Mortality data were of high quality, as were data items on times and dates of attendances, outcomes of attendances and demographic characteristics of attendees. Diagnostic and treatment data were of lower quality.

Scope of routine data

This retrospective study was conducted using anonymised routine data for the period from 1 January 2015 until 30 November 2021, including both dates. De-identified individual-level data were provisioned from the secure anonymised information linkage (SAIL) Databank, and made available for analysis within the SAIL Gateway, a Trusted Research Environment. 53

Data sources

The starting point was the Welsh Demographic Service Dataset (WDSD), a centralised database which comprises records for all GP registrations in Wales. WDSD is used to define the study population.

The annual district death extract (ADDE) dataset, based on UK Office of National Statistics (ONS) mortality data, is a register of all deaths relating to Welsh residents, including those that die outside Wales. The ADDE dataset includes details on the cause of death using WHO International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10) codes; these codes are used to categorise deaths as related to an opioid overdose or not.

The Emergency Department Data Set (EDDS) captures attendances at accident and emergency departments and minor injury units (MIUs) in Welsh hospitals. Attendances by Welsh residents at EDs in other UK nations are not included.

The Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW) records all episodes of inpatient and day case activity in NHS Wales hospitals, includes planned and emergency admissions, minor and major operations, and hospital stays for giving birth. Hospital activity for Welsh residents treated in other UK nations (primarily England) was also included. PEDW includes clinical information [diagnoses, Operative Procedures ICD-10 and Office of Population Censuses and Surveys 4 (OPCS-4)], hospital admissions, spell and episode level data for all in-patients and day cases undertaken by NHS Wales. 54

The Critical Care Data Set (CCDS) captures all intensive and high-dependency care activity regardless of the patient’s area of residence.

The Substance Misuse Data Set (SMDS) captures data relating to individuals (both young persons and adults), presenting for substance misuse treatment in Wales. A summary of data sources and data sets used is available in Table 1.

| Source | Data items | Coding framework |

|---|---|---|

| WDSD | Age Gender Periods of residence in Wales WIMD Date of death (secondary) |

None |

| ADDE | Date of death (primary) Cause/s of death |

ICD-10 |

| EDDS | Dates of EDDS attendances Reason/s for attendance |

NHS Wales Data Dictionary |

| PEDW | Dates related to hospital admissions Reason/s for admission |

ICD-10 |

| CCDS | Dates related to critical care admissions Reason/s for admission |

NHS Wales Data Dictionary |

| SMDS | Dates related to presentations for substance misuse treatment Reason/s for presentation |

NHS Wales Data Dictionary |

Defining the discriminant function

We used WDSD files to define the study cohort. The WDSD comprises information on periods of residency in Wales, anonymised information on period and place of residency, its lower super output area (LSOA) and characteristics of that LSOA [including its Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) quintile], and GP registrations. WDSD files also include a date of death, and anonymised linkage fields.

We then checked and reconciled WDSD and ADDE dates of death within the study window, taking ADDE data as primary. Deaths were then classified as related to opioid overdose (or not) using the coding framework outlined in Fuller et al. 55 We calculated an individual-level study end date, based on residency and mortality data and the study window end, forming demographic profiles using this study end date.

We next considered EDDS, PEDW, CCDS and SMDS attendances for the 36 months up to study end dates, also recording whether or not that attendance related to opioid overdose, based on an appropriate coding framework (where available; ICD-10 or NHS Wales Data Dictionary; see Table 2), and further recording whether or not the attendance occurred within 1 month or within 12 months of the study end date.

| ADDE status | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead | Alive | |||

| WDSD status | Dead | 233,495 | 9997 | 243,492 |

| Alive | 101 | 2,983,803 | 2,983,904 | |

| Total | 233,596 | 2,993,800 | 3,227,396 | |

We also derived a composite measure of health resource use, primarily to ascertain proportions of cohorts with no healthcare utilisation recorded in routine data within 1 month, 12 months and 36 months of their study end date.

We then used logistic regression to model the relation between the primary binary outcome (death from opioid overdose or not) and potential risk factors and covariates available from routine data sources, specifically age, gender, WIMD quintile and attendances (all, and opioid overdose-related) as recorded in and derived from EDDS, PEDW, CCDS and SMDS. Our primary analysis included data on all variables, based on attendances within 12 months of the study end date.

We undertook further analyses to assess the sensitivity of fitted models with respect to (1) the inclusion or otherwise of factors with high numbers of missing values, and (2) different versions of some explanatory variables. We finally assessed the feasibility of using fitted logistic regression models in identifying a high-risk population to include in outcome comparisons.

Testing the discriminant function

Due to delays with NHS Digital and low THN kit administration we did not apply the discriminant function, as we had intended, in a second data set from study sites in England.

Trial participants

Randomisation

We approached all UK ASs and received five positive responses from potential sites with matched EDs, who were able to demonstrate the capacity and resources to participate. Of these potential sites, four demonstrated sufficient geographic separation from other study sites to mitigate potential cross-contamination of study populations. From these four sites, we randomly selected two to be intervention sites and two to be control sites. A member of the research team (MJ) picked one set of study site allocations at random from the set of all possible allocations, each contained within separate sealed opaque envelopes.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, the study did not include blinding of participants or intervention providers.

Randomised controlled trial patient recruitment

Inclusion criteria

We included adult patients (18 +) who were attended by participating (trained) ambulance paramedics following a 999 call or ED clinicians for a problem related to opioid misuse (e.g. opioid overdose or injuries due to opioid use), who were assessed as having the capacity to consent to receipt of the kit and related training.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they:

-

were under 18 years of age

-

were known to have previously suffered an adverse reaction to naloxone

-

lacked capacity

-

were aggressive or exhibited other challenging behaviours

-

were seen by untrained staff

-

had already been recruited

-

were in police custody at the time of presentation.

Interventions

Usual care

Treatment as usual (TAU) for suspected opioid overdose involves a clinical assessment during which the healthcare staff who first come into contact with the patient seek to confirm the substance or substances which led to the overdose. Opioid overdose is assumed if the substance which led to overdose is not known and the patient presents with an altered mental state, such as reduced consciousness, bradypnoea and miosis. Treatment includes prolonged and gradual administration of naloxone followed by a period of observation. Ideally, for patients attended by ASs, the treatment begins at the scene of the overdose and then continues at the ED following conveyance. However, patients may refuse to be conveyed should they respond to the naloxone at the scene.

There was no change in usual practice at the two control sites. Patients were not supplied Prenoxad by the ED or AS, although this may have been available from drug support services in the study site areas.

Intervention (experimental) arm: clinical staff training

Paramedics, nurses and doctors at intervention site EDs and ASs, registered with their respective professional bodies, were invited to participate in the study. Volunteer eligible staff members were trained in delivering the intervention in accordance with the study protocol. Patient group directions (PGDs) were established at participating services within intervention sites to allow non-prescribing paramedics and nurses to distribute THN kits. Training, provided in a flexible manner to suit the working practices of individual departments and services, involved face-to-face group-based training, complemented by a ‘cascade’ approach whereby research support paramedics and nurses continue to train their peers on an ad hoc basis. Online resources produced by Martindale Pharma were available as refresher content for staff (www.prenoxadinjection.com). Training per person was estimated to take up to 15 minutes. Staff completed and signed a ‘Record of Completion of Training’ form once they were deemed competent by their trainer.

Intervention arm: administration of THN kits and training

The Take-home naloxone Intervention Multicentre Emergency setting (TIME) intervention is described here according to the guidance for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist. 56 Prenoxad is a multi dose THN kit containing 2 mg naloxone hydrochloride in 1 mg/1 ml solution for IM injection. This kit contains simple textual and pictorial instructions which reiterated the face-to-face training each participant receives as part of the intervention. Participants were not able to receive part of the intervention only — for example the kit but not the training — and therefore needed to consent to the whole intervention or decline the whole intervention.

The kit is manufactured by Martindale Pharma (Woodburn Green, UK) and supported by ‘train-the-trainer’ materials for participating paramedics and ED staff developed by Stephen Malloy, an independent consultant. Each Prenoxad kit retails at £21.00 before value-added tax (VAT). The decision to use the Prenoxad kit, as opposed to an IN alternative, is supported by evidence regarding the bioavailability of naloxone following IM versus IN administration,57,58 and the time taken for improvement in respiratory rate to be observable. 59 We also based our decision on feedback from drug service workers who were approached in the initial setting up of the study.

At intervention sites, participating healthcare professionals based in the specific ED or AS region and caring for patients eligible to receive the intervention offered these patients the THN kit, with an explanation of its purpose. Patients received TAU and then offered the intervention.

In the intervention arm, if the patient consented to receiving the kit, the healthcare professional provided training regarding the preparation and administration of the naloxone dose using the kit materials. The healthcare professional and the patient then completed a training checklist document which was stored as evidence that training was provided as part of the intervention.

Sample size

We expected to identify 200 records for individuals at high risk of overdose and thus eligible for the intervention (THN) in each of the four sites (n = 100 via ED; n = 100 via the corresponding AS n = 800 in total). Allowing for a dissent rate of 5%, we expected to identify prospectively for follow-up n = 760 people. We intended to use routine-linked data to identify a wider population via a discriminative function, which would be fully specified within our study. These individuals, regarded as at high risk of fatal overdose, would represent the peers of those attending during the recruitment phase. We expected the combined follow-up population to provide at least 1520 analysable outcomes. We did not carry out a power calculation for this feasibility study, which was not an attempt to assess the treatment effect, but our ability to do this in a full trial.

Participant consent

We did not attempt to gain consent to participate in the trial prospectively, at the time of attendance for opioid-related emergency, because that setting contradicts the requirements of informed consent. 60 We did not gather consent retrospectively, as the population is likely to be very difficult to reach and low contact rates could invalidate research findings. We did, however, consent patients to receive the intervention. Patients did this by signing a training sheet, giving their name and date of birth as part of this process.

As the wider population for inclusion in follow-up was to be identified through anonymised routine data sources, we would not have identifiable data with which to contact people for consent purposes. We offered the option to dissent from the research at all sites via patient information leaflets supplied with THN kits and made available at ED waiting areas. We also included this information on the Wales Centre for Primary and Emergency (including unscheduled) Care Research (PRIME) website www.primecentre.wales. We gained ethical, research and information governance permissions to allow this study to follow this approach, in which all information about processes and outcomes of care were anonymised to the research team except for clinical members at each site. The clinical researchers then split the identifiable data from clinical and operational study data before sending files separately to NHS Digital in England and DCHW in Wales for linkage to routinely held outcomes in ED, inpatient and mortality datasets held centrally. This split-file approach, in which identifiable and clinical data are separated, preserves patient anonymity. 53

For the qualitative component, we obtained written informed consent from all service users and healthcare professionals who participated in interviews and focus groups. Service user participants were identified by members of the NHS care team and third-sector drug treatment services. Participants were eligible to receive a thank-you gift card voucher with a monetary value of £10 for their time.

Outcomes

We measured outcomes related to the feasibility of the study in terms of the intervention and methodology, as reflected in the progression criteria.

The proposed primary outcome for a future trial was mortality (all deaths and those known to be opioid-related). Secondary outcomes included intensive treatment unit (ITU) admissions, ED-visits, and inpatient admissions (all visits/attendances as well as those known to be opioid-related), further 999 calls as well as THN kits issued and costs. Our feasibility study was not adequately powered to detect statistically significant differences in these proposed outcomes between intervention and control arms.

Qualitative study methods

We used qualitative data to explore the feasibility and acceptability of THN from the perspective of service users, based upon their previous knowledge and experience of overdose. We also explored the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention from the provider perspective by undertaking interviews and focus groups with paramedics, clinical ED-staff, and health service managers at participating sites regarding THN in emergency settings. We explored awareness and experiences of naloxone, perceived benefits and challenges of THN, and views on the feasibility and acceptability of distributing THN via ambulance paramedics and hospital EDs. Interviews were recorded, with participants’ consent, and professionally transcribed prior to analysis. We used normalisation process theory (NPT) to guide analysis of the provider data and to help understand how the intervention can be optimised within the ED and prehospital settings, and to explore whether difficulties in implementation were due to the intervention itself or other factors. 61

Service users

The perspectives of people with lived experiences of opioid use, accessing treatment centres or attending third-sector group counselling sessions were examined qualitatively in order to understand peoples’ knowledge and experience of naloxone, THN and overdoses. A semistructured topic guide was developed to explore issues identified within the literature around experiences of opioid overdose and emergency administration of naloxone by clinical staff and others, as well as experience of, and attitudes to, THN kits for use in overdose situations by peer opioid users or family and friends. Within this context, the study aimed to explore how experiences of opioid use and overdose experiences interact with knowledge, understanding, behaviour and attitudes around access to, and use of, THN kits to reduce risk of death. As well as aiming to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the facilitators and barriers to use of THN kits from an opioid user perspective, we examined specifically how participants felt about receiving THN kits and accompanying training from ED and ambulance or first responder staff.

Recruitment

Interviews were carried out in two drug treatment outpatient clinics (Sheffield and Hull) and one third-sector drug organisation (Bristol) in three major cities in the UK. Participants were referred by clinical staff if they were over eighteen and were either a current or a past drug user with experience of opioid injection use. Carers or partners of opioid users could also participate. All participants were given a patient information sheet and had the opportunity to discuss the research with staff and the researcher before consent was taken. Interviews took place in a private room. Before the start of the interview, consent was confirmed and the patient was informed they could stop the interview at any time and withdraw. At the conclusion of the interview, participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and provide additional information if they wished. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to maintain data integrity and accuracy. Interviews lasted approximately 15–50 minutes. Interviews loosely followed the topic guide, which focused on the participant’s experiences with overdose, experience of THN kits and attitudes and behaviours surrounding THN kits. The interview guide identified general topic areas for discussion and contained specific prompts designed to elicit more detailed information as needed. Participants received a £10 gift token as an appreciation of their taking part in the study. In total, 28 interviews took place. One participant was a carer but also had past experience of opioid use, and 27 were either current or former opioid users.

Inclusion criteria

Drug service users either currently using opioid drugs or abstinent and in recovery, and their friends and family members (18 years of age or older) who have the ability to consent to involvement were eligible to participate in the qualitative component of TIME.

Service providers

We undertook a focus group and individual interviews with AS and ED staff (paramedics, ED clinical staff and service managers) at intervention sites – Site 1 ED, Site 1 AS, Site 2 AS – to understand barriers and facilitators to THN implementation, and to gain an insight into how the intervention may be assimilated into everyday work practices.

Recruitment

The initial recruitment plan was to conduct up to four focus groups, each involving approximately 6 staff who had recruited patients at each site, to take place during the first 2 months of the recruitment period, with further focus groups planned at 6 months after the start of the recruitment period to understand how the intervention was being delivered. Where rotas did not permit participation in planned focus groups, individual face-to-face interviews were offered as an alternative. In September 2019 we submitted an ethics amendment to HRA to allow us to undertake individual telephone interviews to accommodate shift patterns and to maximise participation among the mobile ambulance workforce. We also requested the provision of staff payments to encourage participation. After low uptake, we expanded the inclusion criteria to include employees who had signed up for the trial but had not recruited patients into the trial, to try to understand reasons for poor recruitment.

At Site 1, we undertook a baseline focus group (n = 8) and supplementary interviews with two ED staff at the 1 ED in August 2019. The planned focus group with Site 1 AS was delayed until February 2020 due to winter pressures, then cancelled due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. We were unable to recruit staff for a focus group at Site 2 AS, with only one person responding to initial invitations and recruitment to individual interviews was similarly postponed in February 2020. We recommenced recruitment for individual telephone interviews at both ambulance sites in February 2021 and recruited two further ED staff from Site 1 ED. We were unable to recruit any staff from Site 2 ED, despite several meetings and invitations.

Participant information sheets were provided and informed consent was obtained and documented prior to the interviews. Participants were given a £20 Amazon voucher as a thank-you for participating in the study. All interviews and focus groups were undertaken by either FS or JH, and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The researcher added reflexive notes immediately following the interview.

Inclusion criteria

Paramedic and ED clinical staff and managerial staff from both branches of the ES (18 years of age or older), who were fully qualified to practice in their chosen discipline, were eligible to participate in the qualitative component of TIME.

Changes to study design

Following difficulty in recruiting staff to qualitative focus groups, it was decided to offer the £20 Amazon voucher to staff as an incentive to take part. Also, due to staff rotas, it was decided to conduct interviews for individual staff rather than focus groups as originally planned.

Due to delays in permissions for routine data access, and low numbers of THN kits distributed during the trial recruitment period, a decision was taken by the Trial Management Group (TMG) to not go ahead with the planned retrieval of datasets from English sites (originally planned to be used for testing of discriminant function and comparison of outcomes between trial arms).

Randomised controlled trial

Data collection

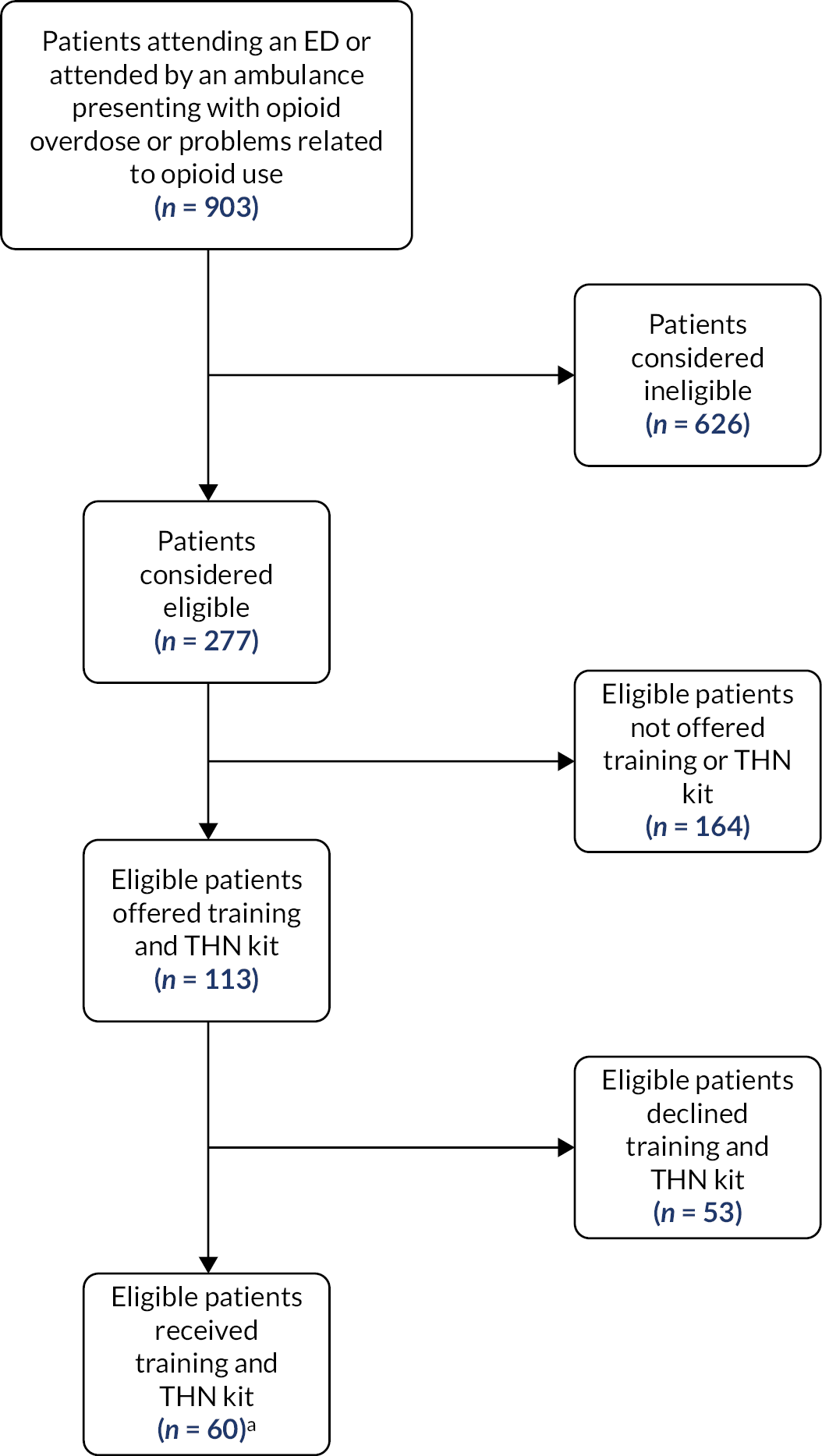

At intervention sites, participating clinical staff completed an intervention flowchart for each eligible participant and recorded if the participant received a THN kit and training, declined the training and/or kit, if the patient was eligible but not offered a kit and if not why. Reasons an individual were considered ineligible were also recorded and this included reduced capacity, in police custody or abusive to staff. We also collected data from electronic records of patients that received naloxone at both control and intervention sites. These data were then uploaded to the SAIL Databank for analysis. 53 THN kit stocks were also audited weekly to ensure all kits were accounted for.

Serious adverse events

We monitored for instances of serious adverse events, including deaths following THN use, by interrogating routine health service data and also requests for data made to services on behalf of coroners across intervention and control sites. We included control sites because we expected THN to be available from specialist drug services in control sites.

Data analysis

The main analysis addressed the progression criteria with regard to the percentage of eligible staff trained, percentage of eligible patients given a THN kit.

Interim analysis and stopping guidelines

No interim analyses were planned or performed.

Health economics

We aimed to assess the feasibility of generating costs relating to staff training, distribution of the THN kits and the use of routine data sources to estimate healthcare costs.

We aimed to calculate training costs using records of completion of training and staff recall of patient training, and then combined with NHS salary data.

Data collection

Separate methods of data collection are required for the four cost components described above and are described in turn.

Naloxone kits

The handing over of naloxone kits to patients was recorded by the Naloxone Case Report Form as described by the intervention flow chart.

Staff time to undergo training

The length of time taken for staff to complete training was measured prospectively using staff-reported estimates which were recorded on the training sign-off form (TSF). This was combined with the number of staff trained and unit costs from the most recent edition of Unit Costs of Health and Social Care,62 to produce a staff training cost for each Trust.

Translating this organisation-level cost into a per-patient cost requires a further mathematical transformation. This requires data on frequency of training within the organisation (which requires information on staff turnover and possible ‘top-up training’) and annual patient numbers. It was not thought necessary to attempt to collect these data and undertake these further calculations for the purposes of a feasibility study.

Staff time to give training to patients

Estimates of these times were to be collected retrospectively using staff recall. The focus groups were used as the vehicle for this. These data were to be combined with unit costs from Unit Costs of Health and Social Care,62 to produce a mean cost per patient.

Associated health service contacts

The assessment of these costs within the feasibility study was opportunistic. Being based on routine data, the feasibility of measuring health service contacts is beyond doubt; however, as a data request was needed for the assessment of effectiveness, it was felt that the opportunity should be taken to refine the analytical approach. In order to undertake this, additional fields relating to healthcare resource groups (HRGs) for all events were to be requested. Alternative ways of incorporating HRGs into the analysis would be tested and estimates of overall costs would be produced. The unit costs for this analysis were to be based on the most recent edition of NHS Reference Costs. 63

Data analysis

The cost data were to be summarised in terms of mean values.

Qualitative data

Data collection instruments

We used NPT64 to guide design of topic and interview guides and analysis. NPT is suitable for use in feasibility studies, can be applied flexibly and can be used to help understand what people do rather than what they say they will do. We developed the topic guides around the four NPT constructs of coherence (what the intervention involves and what its purpose is), cognitive participation (who has a role in delivering the intervention), collective action (how has the intervention been delivered and what has enabled or hindered uptake) and reflexive monitoring (how participants reflect on and appraise effectiveness). Topic guides used open-ended questions to encourage participants to offer their own perceptions and experiences of the THN training, implementation processes and uptake, as well as the potential harms and benefits of THN.

We originally planned to conduct focus groups to draw on the interaction between group members to explore both shared and divergent experiences of the phenomenon under study (in this case, the implementation of THN within the workplace). However, after the first focus group and supplementary interviews (for people who were unable to attend the focus group), we had to change the research plan and undertake individual interviews due to COVID-19 restrictions. To accommodate this change, we created an interview schedule which used the same questions as the intended 0–3-month focus group topic guide, but also incorporated the follow-up questions from the intended 6-month topic guide. This was to enable us to retrospectively examine how work practices were reported to have been adapted over time. In addition, analysis of the initial interviews and focus groups undertaken at Site 1 ED identified that staff found it difficult to respond to some of the questions, and engagement of some members of staff in the initial focus group was limited. We therefore simplified some of the questions and added additional explanatory prompts to obtain more useful data.

Service user data analysis

Data were thematically analysed using QSR International’s NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative data analysis software program. 65 Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim and then analysed by JL, JH and FS through an iterative process. 66 Major themes for the initial round of coding were identified in the interview guide as well as from interviewers’ written notes made during and immediately after the interviews. Using a hybrid approach of reading the first few transcripts combined with using codes loosely defined a priori based on the research questions, an initial coding framework was developed. 67 During coding, researchers identified additional thematic categories and subcategories emerging from the analysis. Following this, the research team collaboratively evaluated the initial coding process to assess cross-coder reliability, resolve any coding discrepancies and establish a set of coding categories for the remaining transcripts. Throughout, an iterative process of coding, cross-checking and discussions was carried out to establish consensus around the final set of themes. 66 As data saturation was not felt to be achieved by the initial set of 18 interview transcripts, a further eight interviews were conducted, and the transcripts analysed to reach data saturation. The identified themes centred on experience of overdose either personally or as a bystander, experience of emergency treatment of an overdose; positive and negative attitudes regarding naloxone and THN; experiences, beliefs and behaviours surrounding naloxone-precipitated withdrawal symptoms; and perceptions/experiences regarding risky drug use, opinions about delivery of THN and training by both ambulance staff at scene and staff within the ED.

Service provider data analysis

We analysed data using Framework Analysis, based broadly on the constructs of NPT (using the framework of Huddlestone et al. , 2020)68 but also reported additional themes relating to the trial itself, rather than the intervention. Throughout, we attempted to differentiate between problems relating to the intervention and those relating to the process and conduct of the trial. Specifically, we considered how stakeholders embraced and used THN, any adaptations made to the clinical and research process, and how they reported recruiting patients to the trial itself.

We imported transcripts into NVivo, and read and re-read transcripts to ensure familiarity with the data before coding. Coding was undertaken with reference to the NPT framework while remaining ‘grounded’ in the data. Initial coding was carried out by JL and emerging concepts used to develop themes. Two other researchers (FS and JH) independently coded a subsample of transcripts for comparison and discussion. The coding structure was further refined and analysis undertaken after discussion between JH, FS, JL and PB.

Trial management

A TMG was established to manage the project and report to the independent TSC at appropriate intervals. The Chief Investigator chaired the TMG, which met quarterly. The TMG comprised of all co-applicants, named collaborators, public contributors and researchers.

The independent TSC oversaw the conduct and progress of the trial and adherence to the protocol, patient safety, and the consideration of new information of relevance to the trial. Two public contributors were members of the TSC.

A Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) monitored the study data at interim periods and made recommendations to the TSC on whether there are any ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue.

Chapter 3 Epidemiology and discriminant function results

Given difficulties in using conventional methods to follow-up recipients of THN kits and peers who may experience an opioid overdose, we used routine data to test the feasibility of identifying a high-risk cohort, postulating that outcomes associated with the intervention would be most visible within this cohort. This chapter summarises this feasibility work, which was based on routine data for the population of Wales for the period from January 2015 to November 2021. Summaries of analyses, undertaken within the SAIL Databank, are subject to the SAIL Databank’s dissemination policies.

Routine data

The combined WDSD files comprise information on n = 5,640,113 individuals. No ALF_PE (unique patient identifier in SAIL) was recorded for n = 504 cases; a further n = 1,740,317 individuals had no recorded residency in Wales during the study window; and a further n = 151 individuals had a recorded date of death indicating death before the study window – although date of death is recorded in ADDE, only ADDE data on or after the beginning of the study window were available, and so could not determine whether people were alive or not at this timepoint. Excluding these individuals leaves for further consideration n = 3,899,140 individuals deemed to be alive and resident in Wales at the start of the study window.

Of these, we then excluded another n = 664,050 individuals with week of birth recorded as on or after 1 December 2003; these individuals would be < 18 years old at the end of the study window. A further n = 7694 individuals were aged 17 or under at their final date of residency in Wales, or at their date of death. Excluding these individuals leaves n = 3,227,396 individuals in our study population.

For our derived cohort of n = 3,227,396 individuals, we extracted basic demographic data and then assessed mortality and healthcare resource utilisation, as recorded in the available routine data sources. We start with mortality, which defines both our primary outcome (death from opioid overdose) and study end dates.

Baseline characteristics

Mortality and date of death

Deaths within the study window are recorded in both WDSD and ADDE (see Table 2); we note that WDSD records only the date of death, while ADDE also records cause of death. We regard ADDE data as primary, noting generally good agreement between these datasets.

Combination A: there are n = 233,495 cases where both WDSD and ADDE record death on or before 30 November 2021, with good agreement on the date of death – exact agreement in over 99% of cases. Where there are discrepancies, we take the ADDE date as primary unless that date of death is contradicted by records of subsequent health events, defined as a recorded health event extending beyond the day after the ADDE date of death.

Combination B: there are n = 101 cases where ADDE records a date of death, but WDSD does not. We consider three possible scenarios.

-

B1: ADDE date of death is 14 days or more after the last recorded date of residency in Wales.

-

B2: ADDE date of death is within 14 days of the last recorded date of residency in Wales.

-

B3: ADDE date of death is more than 14 days before the last recorded date of residency in Wales.

For cases in B1, we censor at the last recorded date of residency in Wales; no further data processing is necessary. For cases in B2 and B3, we use the ADDE date of death to define the final date in the study for these individuals, except where that date is contradicted by records of subsequent health events.

Combination C: there are n = 9997 cases where WDSD records a date of death but ADDE does not. We consider two possible scenarios.

-

C1: WDSD date of death is 14 days or more after the last recorded date of residency in Wales.

-

C2: WDSD date of death is within 14 days of the last recorded date of residency in Wales.

For cases in C1, we censor at the last recorded date of residency in Wales; no further date processing is required. For cases in C2, we use the WDSD date of death to define the final date in the study for these individuals, except where that date is contradicted by records of subsequent health events. Cases in C2 are deaths still to be confirmed within ADDE, and we have no further information available on the cause of death – specifically, we are unable to classify death as opioid-related or otherwise. We note that including these as non-opioid deaths will dilute further the relatively small number of deaths ascribed to opioid overdose. Further dilution will occur on categorising as opioid-related any health events associated with these cases.

Combination D: there is no date of death recorded for n = 2,983,803 cases. For these individuals, we define the study end to be the earlier of the end of the study window or their final recorded date of residency in Wales.

Mortality due to opioid overdose Coding of ADDE mortality data followed the methods outlined in Fuller et al. ,55 based on the ICD-10 classification system. Specifically, we classified deaths as opioid overdose-related where codes for primary and/or secondary underlying causes of death included (see Table 3):

| Code | Cause of death description |

|---|---|

| F11–F19 | Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use |

| X40-X44 | Unintentional poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics |

| X60-X69 | Intentional self-poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics |

| X85 | Assault (homicide) by drugs, medicaments and biological substances |

| Y10-Y19 | Poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and psychodysleptics (undetermined intent) |

| T40 | Opium |

| T40.1 | Heroin |

| T40.2 | Other opioids (morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone) |

| T40.3 | Methadone |

| T40.4 | Synthetic opioids excluding methadone (fentanyl, propoxyphene, meperidine) |

After linkage with the WDSD cohort, we identified three subcohorts: these comprise n = 1105 cases with deaths related to opioid overdose; a further n = 237,212 cases with deaths from all other causes; and remaining n = 2,989,079 individuals, still alive at their study end date.

Tables 4–6 summarise demographic data for these three study subcohorts.

| Gender | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose-related (n = 1105) | ||||

| Male | 1,486,846 | 49.7% | 118,125 | 49.8% | 785 | 71.0% |

| Female | 1,502,211 | 50.3% | 119,087 | 50.2% | 320 | 29.0% |

| Missing | 22 | < 0.1% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Age band (years) | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose related (n = 1105) | ||||

| 18–25 | 445,029 | 14.9% | 868 | 0.4% | 49 | 4.4% |

| 26–30 | 260,684 | 8.7% | 766 | 0.3% | 93 | 8.4% |

| 31–35 | 251,301 | 8.4% | 1046 | 0.4% | 152 | 13.8% |

| 36–40 | 231,821 | 7.8% | 1490 | 0.6% | 198 | 17.9% |

| 41–45 | 209,045 | 7.0% | 2257 | 1.0% | 142 | 12.9% |

| 46–55 | 459,262 | 15.4% | 9914 | 4.2% | 279 | 25.2% |

| 56–65 | 459,656 | 15.4% | 21,153 | 8.9% | 114 | 10.3% |

| 66–75 | 374,612 | 12.5% | 45,551 | 19.2% | 44 | 4.0% |

| 76 + | 297,669 | 10.0% | 154,167 | 65.0% | 34 | 3.1% |

| WIMD quintile | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose-related (n = 1105) | ||||

| WIMD available | 2,863,661 | 231,794 | 1083 | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 549,492 | 19.2% | 47,231 | 20.4% | 425 | 39.2% |

| 2 | 563,071 | 19.7% | 48,666 | 21.0% | 297 | 27.4% |

| 3 | 580,844 | 20.3% | 49,131 | 21.2% | 177 | 16.3% |

| 4 | 581,988 | 20.3% | 45,999 | 19.8% | 106 | 9.8% |

| 5 (least deprived) | 588,266 | 20.5% | 40,767 | 17.6% | 78 | 7.2% |

We next categorised records in EDDS, PEDW, CCD and SMDS for the 36 months up to immediately prior to and including an individual’s study end date, censoring at the start of the study window where necessary. For each attendance, admission or presentation, we used further routine data and appropriate coding framework (ICD-10: as per Table 2; codes 10B, 10C, 10D, 10Z and 31B in the NHS Wales Data Dictionary) to determine whether that event was related to opioid overdose, and further recording whether or not the event occurred within 1 month or within 12 months of an individual’s study end date.

Emergency department attendances

After linkage with the WDSD cohort, we identified EDDS records in n = 1,187,033 cases, with breakdown of the number of attendances by subcohort and period summarised in Table 7.

| Time period and attendance category | Number of attendances | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose-related (n = 1105) | |||||

| Within 36 months | |||||||

| All attendances | 0 | 1,985,462 | 66.4% | 54,633 | 23.0% | 268 | 24.3% |

| 1–3 | 876,091 | 29.3% | 128,365 | 54.1% | 462 | 41.8% | |

| 4–12 | 121,955 | 4.1% | 51,322 | 21.6% | 306 | 27.7% | |

| 13 + | 5571 | 0.2% | 2892 | 1.2% | 69 | 6.2% | |

| Opioid overdose-related attendances | 0 | 2,975,604 | 99.5% | 235,316 | 99.2% | 887 | 80.3% |

| 1–3 | 13,054 | 0.4% | 1836 | 0.8% | 206 | 18.6% | |

| 4 + | 421 | < 0.1% | 60 | < 0.1% | 12 | 1.1% | |

| Within 12 months | |||||||

| All attendances | 0 | 2,520,674 | 84.3% | 76,000 | 32.0% | 423 | 38.3% |

| 1–3 | 443,898 | 14.9% | 137,261 | 57.9% | 502 | 45.4% | |

| 4–12 | 23,772 | 0.8% | 23,541 | 9.9% | 165 | 14.9% | |

| 13 + | 735 | < 0.1% | 410 | 0.2% | 15 | 1.4% | |

| Opioid overdose-related attendances | 0 | 2,984,543 | 99.8% | 236,191 | 99.6% | 961 | 87.0% |

| 1+ | 4536 | 0.1% | 1021 | 0.4% | 144 | 13.0% | |

| Within 1 month | |||||||

| All attendances | 0 | 2,926,591 | 97.9% | 14,5622 | 61.4% | 815 | 73.8% |

| 1–3 | 61,609 | 2.1% | 91,259 | 38.5% | 279 | 25.2% | |

| 4 + | 879 | < 0.1% | 331 | < 0.1% | 11 | 1.0% | |

| Opioid overdose-related attendances | 0 | 2,988,521 | ~100.0% | 236,974 | 99.9% | 1064 | 96.3% |

| 1 + | 558 | < 0.1% | 238 | 0.1% | 41 | 3.7% | |

Hospital admissions

After linkage with the WDSD cohort, we identified PEDW records in n = 998,563 cases, with breakdown of the number of attendances by subcohort and period summarised in Table 8.

| Time period and admission category | Number of attendances | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose-related (n = 1105) | |||||

| Within 36 months | |||||||

| All admissions | 0 | 2,192,076 | 73.3% | 36,309 | 15.3% | 448 | 40.5% |

| 1–3 | 668,456 | 22.4% | 119,399 | 50.3% | 476 | 43.1% | |

| 4–12 | 110,284 | 3.7% | 64,795 | 27.3% | 158 | 14.3% | |

| 13 + | 18,263 | 0.6% | 16,709 | 7.0% | 23 | 2.1% | |

| Opioid overdose-related admissions | 0 | 2,987,393 | 99.9% | 236,842 | 99.8% | 1019 | 92.2% |

| 1–4 + | 1686 | 0.1% | 370 | 0.2% | 86 | 7.7% | |

| Within 12 months | |||||||

| All admissions | 0 | 2,616,002 | 87.5% | 52,332 | 22.1% | 622 | 56.3% |

| 1–3 | 336,773 | 11.3% | 137,906 | 58.1% | 418 | 37.8% | |

| 4 + | 36,304 | 1.2% | 46,974 | 19.8% | 65 | 5.9% | |

| Opioid overdose-related admissions | 0 | 2,988,572 | ~100.0% | 236,992 | 99.9% | 1049 | 94.9% |

| 1 + | 507 | < 0.1% | 220 | <0.1% | 56 | 5.1% | |

| Within 1 month | |||||||

| All admissions | 0 | 2,904,066 | 97.2% | 94,044 | 39.6% | 910 | 82.4% |

| 1+ | 85,013 | 2.8% | 143,168 | 60.4% | 195 | 17.6% | |

| Opioid overdose-related admissions | 0 | 2,989,013 | ~100.0% | 237,146 | ~100.0% | 1081 | 97.8% |

| 1 + | 66 | < 0.1% | 66 | < 0.1% | 24 | 2.2% | |

Critical care admissions

After linkage with the WDSD cohort, we identified CCDS records in n = 35,489 cases, with relatively few cases with multiple admissions within this number; approximately 90% had a single admission over 36 months, and only 2% had more than two such admissions in this period. The breakdown of the number of attendances by subcohort and period summarised in Table 9; no coding was available to categorise admissions as opioid overdose-related or otherwise.

| Time period | Number of attendances | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose-related (n = 1105) | |||||

| Within 36 months | |||||||

| All admissions | 0 | 2,974,728 | 99.5% | 216,220 | 91.2% | 959 | 86.8% |

| 1 + | 14,351 | 0.5% | 20,992 | 8.8% | 146 | 13.2% | |

| Within 12 months | |||||||

| All admissions | 0 | 2,984,216 | 99.8% | 219,825 | 92.7% | 987 | 89.3% |

| 1 + | 4863 | 0.2% | 17,387 | 7.3% | 118 | 10.7% | |

| Within 1 month | |||||||

| All attendances | 0 | 2,988,554 | ~100.0% | 224,073 | 94.5% | 1025 | 92.8% |

| 1 + | 525 | < 0.1% | 13,139 | 5.5% | 80 | 7.2% | |

Substance misuse treatment presentations

After linkage with the WDSD cohort, we identified SMDS records in n = 32,774 cases, with relatively few cases with multiple presentations within this number; under 10% had more than three such presentations in this period. The breakdown of the number of attendances by sub-cohort and period summarised in Table 10.

| Time period and presentation category | Number of attendances | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose-related (n = 1105) | |||||

| Within 36 months | |||||||

| All presentations | 0 | 2,959,595 | 99.0% | 234,283 | 98.8% | 744 | 67.3% |

| 1 + | 29,484 | 1.0% | 2929 | 1.2% | 361 | 32.7% | |

| Opioid overdose-related presentations | 0 | 2,974,825 | 99.5% | 236,576 | 99.7% | 851 | 77.0% |

| 1 + | 14,254 | 0.5% | 636 | 0.3% | 254 | 23.0% | |

| Within 12 months | |||||||

| All presentations | 0 | 2,976,864 | 99.6% | 235,559 | 99.3% | 862 | 78.0% |

| 1 + | 12,215 | 0.4% | 1653 | 0.7% | 243 | 22.0% | |

| Opioid overdose-related presentations | 0 | 2,983,446 | 99.8% | 236,867 | 99.9% | 940 | 85.1% |

| 1 + | 5633 | 0.2% | 345 | 0.1% | 165 | 14.9% | |

| Within 1 month | |||||||

| All presentations | 0 | 2,987,754 | ~100.0% | 236,979 | 99.9% | 1076 | 97.4% |

| 1 + | 1325 | < 0.1% | 233 | 0.1% | 29 | 2.6% | |

| Opioid overdose-related admissions | 0 | 2,988,468 | ~100.0% | 237,173 | ~100.0% | 1083 | 98.0% |

| 1 + | 611 | < 0.1% | 39 | < 0.1% | 22 | 2.0% | |

Proportions of individuals with no records in routine data in the 12 months prior to study end date

Based on linkages between the WDSD cohort and EDDS, PEDW, CCDS and SMDS records, we assessed the numbers of individuals within cohorts with no records in the 12 months prior to study end date; the breakdown of numbers and proportions by subcohort and period is summarised in Table 11.

| Time period (months prior to study end date) | Study subcohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at study end date (n = 2,989,079) | Death: all other causes (n = 237,212) | Death: opioid overdose-related (n = 1105) | ||||

| 12 months | 2,316,451 | 77.5% | 39,236 | 16.5% | 307 | 27.8% |

| 1 month | 2,857,958 | 95.6% | 81,882 | 34.3% | 755 | 68.3% |

Discriminant function data analysis

For analysis, we combined the group of those alive at their study end date with the group of deaths from all other causes and contrasted this combined group with the (much) smaller group of decedents from opioid overdose. We examined the extent to which factors and covariates (recorded in routine data) (1) are associated with death from opioid overdose; and (2) enable us to identify these decedents, or a relatively small subset of an overall population that contains most or all of them.

Prediction via logistic regression

We fitted alternative versions of the logistic regression model, using (1) raw rather than banded counts of EDDS attendances and PEDW admissions, (2) all admissions and attendances rather than just those coded as opioid-related and (3) omitting WIMD quintile as a factor, thereby including data on all but 22 individuals in fitting the model.

Sensitivity and specificity

We obtain predicted probabilities by a logistic transformation of the linear predictor, including the constant term.

Logistic regression analysis

The appropriate methodology here is logistic regression; we illustrate its potential effectiveness using age and gender. Table 4 above shows that the decedents from opioid overdose are disproportionately male – 785 males and 320 females; compared with a near-equal split in both other groups in Table 4, and hence in the combined group. This observed difference in proportions is highly statistically significant.

Table 5 shows differences in the age profiles across the three original groups; for the combined group, as described above, the mean (standard deviation) age (in years) is 50.7 (20.6), while the corresponding value for the 1105 deaths from opioid overdose is 44.3 (13.3). Again, this observed difference is highly statistically significant.

For (1), therefore, the raw data indicate that both variables – separately and jointly – appear as statistically significant explanatory variables in logistic regression models for the binary outcome of death from opioid overdose (or not). Table 12 gives details on the fitted model, including age, gender, WIMD quintile; and the number of EDDS, PEDW, CCDS and SMDS attendances within 12 months of study end date.

| Variable | Coefficienta,b | OR | 95% CI | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | –8.145 | |||

| Femalec | –0.774 | 0.461 | (0.403 to 0.527) | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | –0.013 | 0.987 | (0.984 to 0.990) | < 0.001 |

| WIMDd | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 1.439 | 4.218 | (3.302 to 5.388) | < 0.001 |

| Quintile 2 | 1.188 | 3.280 | (2.551 to 4.217) | < 0.001 |

| Quintile 3 | 0.696 | 2.006 | (1.533 to 2.623) | < 0.001 |

| Quintile 4 | 0.244 | 1.276 | (0.951 to 1.712) | 0.104 |

| EDDSe (opioid-related attendances) | 2.726 | 15.273 | (12.024 to 19.401) | < 0.001 |

| PEDWc (opioid-related admissions) | 2.309 | 10.064 | (6.793 to 14.908) | < 0.001 |

| CCDSe (all admissions) | 2.235 | 9.343 | (7.429 to 11.751) | < 0.001 |

| SMDSe (drug-related attendances) | 3.094 | 22.071 | (17.872 to 27.256) | < 0.001 |

We fitted alternative versions of this model, using (1) raw rather than banded counts of EDDS attendances and PEDW admissions, (2) all admissions and attendances rather than just those coded as opioid-related, and (3) omitting WIMD quintile as a factor, thereby including data on all but 22 individuals in fitting the model.

All fitted models had broadly similar characteristics to those summarised in Table 12; factors and covariates were (generally) highly statistically significant, and the predicted probabilities of death from opioid overdose are lower for females, reduce with age, and increase with WIMD quintile, and opioid-related attendances and admissions in EDDS, PEDW, CCDS and SMDS.

For (2), we consider the predictive ability of fitted logistic regression models: we obtain predicted probabilities by a logistic transformation of the linear predictor, including the constant term. For illustration, based on the fitted model above, a female aged 23, living within a LSOA categorised as the most deprived (WIMD Quintile 1), and with an opioid-related attendance at a substance misuse centre but no opioid-related ED attendances or hospital or critical care admissions, would have a predicted probability of 0.00916 of death from opioid overdose.

For the current routine data cohort, these predicted probabilities (of death from opioid overdose) range from –0.00003 to –0.96150, distributed with considerable skewness – 99% of individuals have a predicted probability < 0.001; 99.5% of individuals have a predicted probability < 0.0035.

We can now, in any cohort with the requisite individual-level data, take the high-risk population to include the set of individuals each with a predicted probability greater than some (arbitrary) threshold value. For instance, with a threshold value of 0.0004, applying this model across the entire cohort identifies 708 of the 1083 decedents – a true positive rate (sensitivity) of 65.4%; however, it also identifies 646,750 individuals with no death from an opioid overdose. This gives a total of 647,458 individuals to include in the high-risk population. Table 13 gives the full 2 × 2 classification for this threshold value and shows a true negative rate (specificity) of 2448685/3226269 or 79.1%.

| Predicted status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid overdose death | Alive or non-opioid death | ||

| Recorded status | Opioid overdose death | 708 | 375 |

| Alive or non-opioid death | 646,750 | 2,448,685 | |

The sensitivity, specificity and potential contributions to the high-risk population for a range of threshold values are shown in Table 14, along with a summary of known outcomes.

| Threshold value | Opioid overdose decedents identified (sensitivity, %) | Identified for high-risk population | Total deaths in high-risk population | Excluded from high-risk population and without opioid overdose-related mortality (specificity, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0002 | 933 (86.1) | 1,597,342 | 87,797 | 1,499,026 (48.4) |

| 0.0003 | 809 (74.7) | 989,151 | 60,980 | 2,107,093 (68.1) |

| 0.0004 | 708 (65.4) | 647,458 | 40,751 | 2,448,685 (79.1) |

| 0.0005 | 662 (61.1) | 432,962 | 25,943 | 2,663,135 (86.0) |

| 0.0006 | 566 (52.3) | 312,131 | 20,006 | 2,783,870 (89.9) |

| 0.0007 | 473 (43.7) | 193,751 | 17,597 | 2,902,157 (93.8) |

| 0.0008 | 381 (35.2) | 108,487 | 16,677 | 2,987,329 (96.5) |

| 0.0009 | 350 (32.3) | 57,022 | 15,839 | 3,038,763 (98.2) |

| 0.0010 | 346 (31.9) | 28,345 | 14,827 | 3,067,436 (99.1) |

Table 14, in conjunction with Tables 7 – 13, illustrates the extent of the ability of predictive methods using this set of routine outcomes; the majority of decedents from opioid overdose are essentially indistinguishable both from other decedents and those still alive at their study end date. As the latter two groups are considerably more numerous than the cohort of decedents from opioid overdose, it follows that one must either include in the high-risk population a substantial minority (or even a majority) of the overall population, or restrict the high-risk population to a relatively small proportion of the overall population, with a lower proportion of decedents from opioid overdose.

Accuracy of discriminant function

From the data we had available, we were not able to distinguish between decedents from opioid overdose and other decedents and those still alive using the discriminant function, partly due to the number of decedents from opioid overdose cohort being considerably smaller.

Based on logistic regression models we would need to monitor approximately one-third of the population to capture 75% of the decedents from opioid overdose in 1-year follow-up. Furthermore, as mortality in the 1-year period is estimated to be 6% of the third of the population, it is estimated that only 1–2% of these deaths would be categorised as a result of opioid overdose. As a high proportion of this population have no records of a healthcare event in the 12 months prior to death, it is generally the case that usage by decedents is matched or surpassed by individuals in other cohorts, therefore making the predictive link between death and healthcare events associated with opioid overdose weak.

Summary