Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/192/97. The contractual start date was in October 2016. The draft report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in August 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Bisson et al. This work was produced by Bisson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Bisson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common mental health condition that may develop following exposure to traumatic events that involve threatened or actual death, serious injury or sexual violence. The two main current classification systems differ slightly in their symptom criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD. 1,2 The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) requires the presence of symptoms in four different clusters that are associated with the traumatic event(s). At least one intrusion symptom (e.g. recurrent distressing memories and nightmares), persistent avoidance of stimuli, at least two negative alterations in cognitions and mood (e.g. exaggerated negative beliefs and feelings of detachment or estrangement from others), and at least two symptoms indicating increased arousal or reactivity (e.g. irritable behaviour and hypervigilance) are required. The eleventh edition of the International Classification of Diseases requires one intrusion symptom (flashbacks or nightmares), one avoidance symptom and one symptom indicating a current sense of threat (hypervigilance or increased startle).

According to the adult psychiatric morbidity survey, about 3% of the United Kingdom (UK) adult population have PTSD3 and average symptom duration is normally prolonged if untreated. 4 Various studies have demonstrated strong associations between PTSD and physical and mental health comorbidity. 5,6 PTSD has also been found to have a large economic burden. 7 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have repeatedly found that individual, face-to-face trauma-focused psychological treatments (TFPT), in the form of cognitive behavioural therapies with a trauma focus (CBT-TF) and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), are the best-evidenced treatments for PTSD. TFPTs are recommended as first-line treatments by guidelines across the world, including those of the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), Australia and the American Psychological Association. 8–11

There are a limited number of suitably trained therapists available to deliver TFPT in the National Health Service (NHS). Unfortunately, this often prevents timely access to treatment, with NHS waits of a year or more in some areas of the UK. TFPT is usually delivered weekly, in a face-to-face setting over several months, making it very difficult to access for some recipients (e.g. because of stigma, work commitments, travel and childcare). 12–14 Guided self-help (GSH) is an alternative approach to the delivery of treatment. GSH combines the use of self-help materials with regular guidance from a trained professional and requires less therapist time than recommended face-to-face TFPT.

GSH has been developed and evaluated for the treatment of a number of other mental disorders and there is good evidence of the efficacy of GSH for conditions such as anxiety and depression. 15,16 If effective for PTSD, GSH would offer a time-efficient and accessible treatment option (not least in the face of a pandemic), with the potential to reduce waiting times and intervention costs. These impacts, along with the ability to move more treatment delivery from high to low intensity, would herald a step change in the care pathway for people with PTSD. By treating PTSD in a timelier and more efficient manner, the burden of disease would be reduced, preventing avoidable morbidity and improving quality of life.

Development of Spring

Through careful Phase I work,17 Spring was developed systematically following Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for the development of a complex intervention. 18 The work followed an iterative process incorporating qualitative work to model the intervention, followed by two pilot studies to refine it based on quantitative and qualitative outcomes. Collaboration with a web development agency (Healthcare Learning Smile-on), as part of a Knowledge Transfer Partnership, produced an interactive web-based version of the intervention. Based on principles of CBT-TF, Spring includes eight steps designed for delivery over 8 weeks, which cover psychoeducation, grounding, relaxation, behavioural activation, real-life and imaginal exposure, cognitive therapy and relapse prevention.

Phase II19 work demonstrated Spring to be a potentially highly effective GSH intervention for PTSD. Forty-two adults with DSM-5 PTSD of mild to moderate severity were randomly allocated to receive GSH using Spring or delayed treatment. Immediately after treatment, the GSH group had significantly lower Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) scores than the delayed treatment control group (between-group effect size Cohen’s d = 2.60). The difference was maintained 14 weeks after randomisation and the difference dissipated once the delayed treatment group had received treatment. Similar patterns of difference between the two groups were found for self-reported PTSD, depression, anxiety, health-related quality of life and functional impairment.

Existing evidence

A recently published Cochrane Review20 of internet-based CBT for PTSD in adults identified 13 relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with 808 participants, 10 of which, including our Phase II RCT,19 included therapist guidance. Compared with wait-list, internet-based CBT was associated with a clinically important reduction in PTSD. There was evidence that interventions delivered with guidance were more effective at reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms than those without, in addition to evidence that trauma-focused interventions were more effective than those without a trauma focus. However, the certainty of the evidence was very low due to a small number of eligible trials. The authors concluded that further work was required to establish non-inferiority (NI) to current first-line interventions, explore cost-effectiveness, and measure adverse events.

The available research led to the inclusion of GSH as a possible treatment for people with mild to moderate PTSD in the latest NICE9 and ISTSS8 treatment guidelines. Both NICE and ISTSS recommended GSH less strongly than face-to-face TFPT due to weaker evidence; NICE stated, ‘supported computerised trauma-focused CBT should be considered as an option for adults with PTSD who prefer this to face-to-face trauma-focused CBT or EMDR’. ISTSS gave guided internet-based CBT-TF a ‘standard recommendation’, indicating that there was at least reasonable quality of evidence but with lower certainty of effect than required for a strong recommendation. The guarded recommendations of NICE and ISTSS signal the need for GSH interventions that are non-inferior to CBT-TF to provide greater choice, allow people with PTSD more control over treatment, enhance access and establish a wider range of evidence-based treatment options.

Aims and objectives

The main aim of the RAPID trial was to determine the likely clinical and cost-effectiveness of GSH using Spring, an internet-based programme based on CBT-TF for mild to moderate PTSD in the NHS in the UK. RAPID also aimed to describe the experience of receiving the GSH from the recipient’s perspective, and the delivery of GSH using Spring from the therapist’s perspective.

The objectives were to answer the following research questions:

-

For people with mild to moderate PTSD, is GSH using Spring at least equivalent in effectiveness and cost-effective relative to individual CBT-TF as judged by reduced symptoms of PTSD and improved quality of life? (main research question)

-

For people with PTSD, what is the impact of GSH using Spring on functioning, symptoms of depression, symptoms of anxiety, alcohol use and perceived social support? (secondary outcomes)

-

What factors may impact effectiveness and successful roll-out of GSH for PTSD in the NHS if the GSH programme is shown to be effective? (process evaluation)

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Trial design

This was a multicentre pragmatic randomised controlled NI trial with assessors masked to treatment allocation. Individual randomisation was used. A NI design aimed to determine if a new approach, with distinct advantages over existing strongly recommended treatments, was no worse than a current gold-standard treatment for PTSD. 22 We did not expect GSH to be more effective than face-to-face CBT-TF, and therefore, a superiority design was not appropriate. The trial followed a published protocol,21 was supported by a public advisory group and overseen by a trial steering committee and independent data monitoring committee. Nested process evaluation was included to assess fidelity, adherence and factors that influenced outcome. Quantitative and qualitative research methods were used. The trial was conducted between August 2017 and January 2021. It adhered to CONSORT guidelines23 and was granted a favourable ethical opinion by the South East Wales Research Ethics Committee.

Eligibility criteria

Wide eligibility criteria were used to ensure good external validity. Participants were aged 18 or over, had DSM-5 PTSD as their primary diagnosis, as evaluated by the CAPS-5,24 with mild to moderate symptom severity as indicated by a score of < 50 on the CAPS-5 at baseline assessment, had regular access to the internet to complete the steps and homework required by the GSH programme and were willing and able to give informed consent to take part. Exclusion criteria were inability to read and write fluently in English, previous completion of a course of TFPT for PTSD, current PTSD symptoms to more than one traumatic event, current engagement in psychological therapy, diagnosis of psychosis or substance dependence, active suicide risk and change in psychotropic medication in the past 4 weeks.

Recruitment and consent

Participants were recruited from NHS Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT) services based in primary care in England (Coventry, Warwickshire, Greater Manchester, London and Southwest Yorkshire), and NHS psychological treatment settings based in primary and secondary care in Scotland (Lothian) and South Wales (Cardiff, Gwent, Mid Glamorgan and the Vale of Glamorgan). Potential participants were identified and approached by a clinician involved in their care, screened, and then fully assessed by one of a team of researchers after providing informed consent. If individuals met the eligibility criteria, they were randomised to receive GSH for PTSD using the Spring programme, or to receive face-to-face CBT-TF.

Semistructured interviews for qualitative analysis were conducted with 19 participants and 10 therapists, to gather perspectives of receiving and delivering the interventions as part of the process evaluation. Trial participants were sampled according to intervention allocation, research site, gender, age, ethnicity, education level and nature of trauma. Therapists were sampled by gender and research site.

Randomisation

Individual randomisation was performed by Cardiff University’s Centre for Trials Research (CTR) and conducted using a pre-programmed online minimisation algorithm developed by the database designer in accordance with CTR Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). The allocation ratio was 1 : 1. This was implemented to ensure balance between trial arms on gender but retained an 80% random element. Randomisation was stratified by research centre. Randomisation was undertaken by the data manager once eligibility was confirmed. Allocations were e-mailed to the trial manager who informed the local Principal Investigators (PIs)/therapists. A randomisation protocol was written and signed off before recruitment began in line with CTR policy. Outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation as far as possible. Participants were asked not to reveal the intervention they received to assessors at follow-up interviews. Only when written informed consent was obtained from the participant, and they were randomised/enrolled into the trial, were they considered a trial participant.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind the therapists or the participants, given the complex interventions under investigation. However, the assessors were blind to treatment allocation and the therapists and participants were asked not to discuss their allocation with the assessors. Participants were reminded of the importance of this at each outcome assessment.

Interventions

Face-to-face CBT-TF

CBT-TF is one of the primary treatments for PTSD adopted by IAPT in England and psychological therapy services in Scotland and Wales. Cognitive therapy for PTSD (CT-PTSD),25 one of the CBT-TF implemented by IAPT, was adopted for RAPID. Participants received up to 12 face-to-face, individual sessions, each lasting 60–90 minutes. In-session treatment was augmented by assignments which participants were required to complete between sessions.

CT-PTSD involves identifying the relevant appraisals, memory characteristics, triggers and behavioural and cognitive strategies that maintain PTSD symptoms. These are addressed by: (1) modifying excessively negative appraisals of the trauma and/or its sequelae; (2) reducing re-experiencing by elaboration of the trauma memories through imaginal exposure or narrative-based memory updating with less threatening meanings and discrimination of triggers; (3) dropping dysfunctional behaviours and cognitive strategies, particularly those related to avoidance of triggers for intrusive symptoms; and (4) when possible, visiting the site of the trauma with the therapist to update the trauma memory.

GSH using Spring

Spring is an eight-step online GSH programme based on CBT-TF (see Table 1 for description of steps); it uses the same principles as CBT-TF but aims to reduce contact time with the therapist by providing some of the therapy content and activities in an online format. The therapist initially meets with the participant for an hour to develop a rapport, learn about the participant’s trauma, provide log-in details and describe and demonstrate the programme, which the participant then completes online in their own time. There are four subsequent fortnightly meetings of 30 minutes, normally undertaken face-to-face, but also deliverable via the internet or telephone, according to participant preference. The participant also receives four brief telephone calls or e-mail contacts between sessions to discuss progress, identify any problems that have arisen and agree new goals. The programme was designed to be accessible through a variety of devices including PC, laptop, tablet and smartphone (via a Spring App).

| Step 1: Learning About My PTSD | Psychoeducation about PTSD illustrated by four actors describing their experience of PTSD to different types of traumatic events. |

| Step 2: Grounding Myself | Explanation of grounding and its uses along with descriptions and demonstrations of grounding exercises. |

| Step 3: Managing My Anxiety | Education about relaxation techniques with learning through videos of a controlled breathing technique, applied muscular relaxation and relaxation through imagery. |

| Step 4: Reclaiming My Life | Behavioural reactivation to help individuals return to previously undertaken/new activities. |

| Step 5: Coming to Terms with My Trauma | Provides rationale for imaginal exposure, narratives of the four video characters. The therapist helps the participant to begin writing a narrative, which they complete remotely and read every day. |

| Step 6: Changing My Thoughts | Cognitive techniques to address PTSD symptoms. |

| Step 7: Overcoming My Avoidance | Graded real-life exposure work. |

| Step 8: Keeping Myself Well | This session reinforces what has been learnt during the programme, provides relapse prevention measures and guidance on what to do if symptoms return. |

The eight Spring steps are accompanied by between-session work. At each session, the therapist reviews progress by logging into a clinician dashboard and guides the participant through the programme. The aim of the guidance is to offer continued support, monitoring, motivation and problem-solving. The eight online steps are usually completed in turn with some later steps relying on mastery of techniques taught in earlier steps. Each step provides psychoeducation and the rationale for specific components of treatment, and they also activate a tool that becomes live in the Toolkit area of the website and aims to reduce traumatic stress symptoms. Specific activities become visible (with the participant’s knowledge) to the therapist via the dashboard to facilitate discussions during guidance. The programme can be accessed online via a web browser or through an app.

Therapists

Both trial interventions were delivered by the same, experienced psychological therapists working in high-intensity IAPT services or psychological services at the trial sites. All therapists had previous experience of delivering CBT-TF for PTSD. Study therapists received one and a half days additional training in CT-PTSD, and a half day training in GSH using Spring. Training was delivered by clinicians involved in the development of CT-PTSD and Spring. Trial therapists completed at least one training case using each intervention and were assessed as being competent by a trial clinical supervisor if they were considered to have delivered the interventions appropriately. Therapists followed treatment manuals for both interventions and received trial-specific group clinical supervision once per month throughout the trial via video or telephone conference call by NK or NR. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in some of the last participants receiving their final therapy sessions via video conferencing, as opposed to in person.

Fidelity

To ensure the interventions were delivered as intended and according to the manuals, each therapist aimed to audio record at least one session with every participant, using a digital voice recorder. The audio recordings were rated using a general and an intervention-specific fidelity checklist by one of two independent, experienced clinicians.

Adherence

The trial focused on the ‘implementation’ of attending therapy sessions as the adherence element of interest. Implementation was defined as the extent to which the participant attended therapy session as intended. Given that the two arms are different in their therapy session structures, this was expressed as a binary (adhered or not adhered) based on the number of sessions attended:

-

in the GSH arm, attending ≥ 3 sessions defined adhered

-

in the CBT-TF arm, attending ≥ 8 defined adhered.

In both arms, if the therapist determined that the participant had attended a sufficient number of sessions such that that number was less than the number stated above, this also defined adhered. In all other cases, the participant was considered to have not adhered.

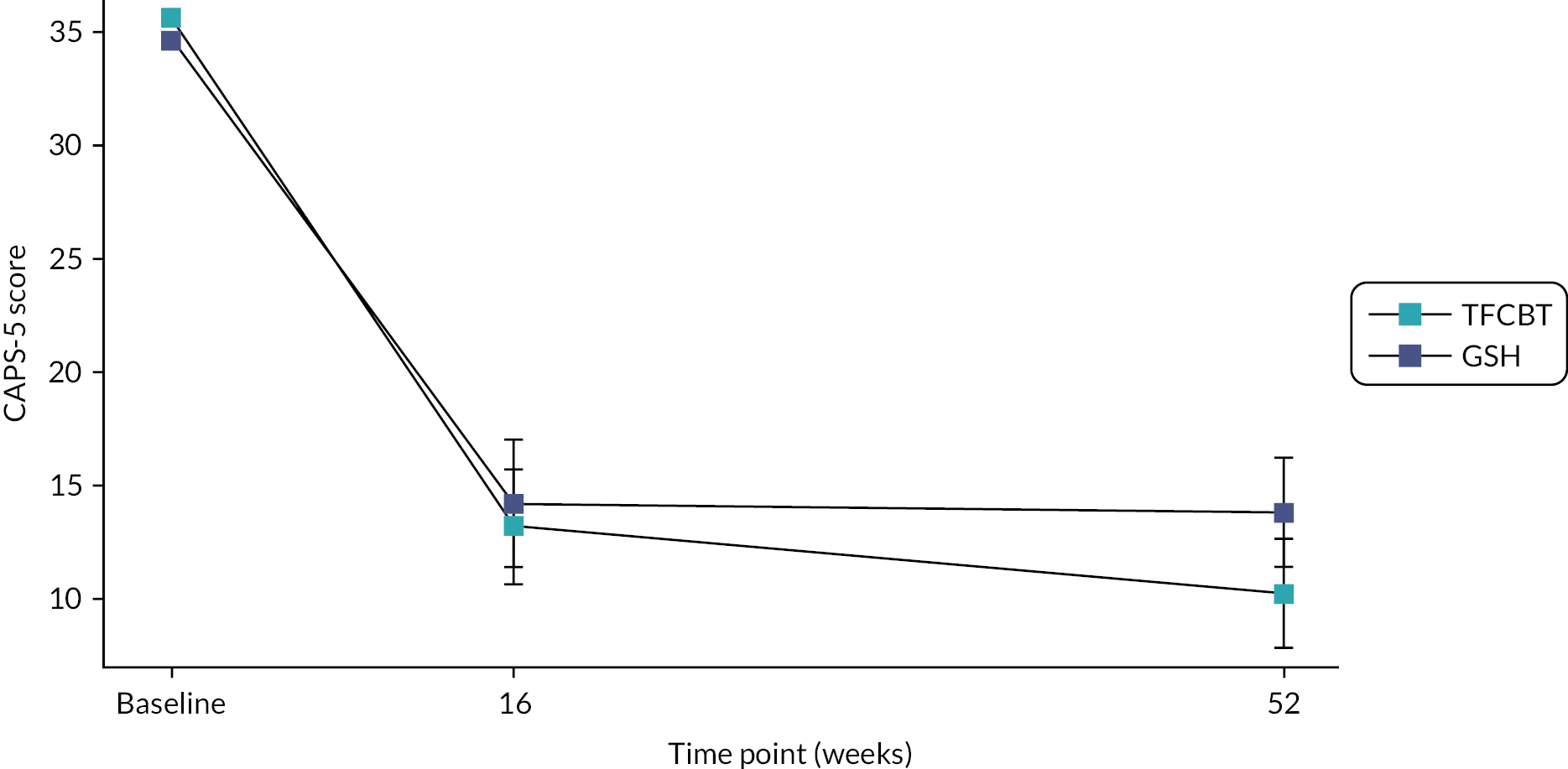

Outcomes

All outcome measures were completed at baseline, 16 and 52 weeks after randomisation. The primary outcome was the severity of symptoms of PTSD over the previous week as measured by the CAPS-525 at 16 weeks post-randomisation. Sixteen weeks was chosen as a post-intervention measurement. Severity of PTSD symptoms at 52 weeks post-randomisation, measured using the CAPS-5, was a secondary outcome along with self-reported secondary outcomes, measured using validated measures, at both 16 weeks (to determine the effect of the interventions) and 52 weeks post-randomisation (to determine sustained effects). The Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) was also collected at each therapy contact to provide clinical feedback and to facilitate imputation for missing data, if required. Information on possible adverse events was also collected.

Primary outcome

CAPS-5 (PTSD symptoms): The CAPS-525 is a 29-item structured interview for assessing PTSD diagnostic status and symptom severity. The CAPS-5 is the gold standard in PTSD assessment and can be used to make a current (past month) or lifetime diagnosis of PTSD or to assess symptoms over the past week. Items correspond to the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. The CAPS-5 has excellent reliability and convergent and discriminant validity, diagnostic utility and sensitivity to clinical change. 25 Twenty of the twenty-nine items are used to create the score.

Secondary outcomes

IES-R (PTSD symptoms): The IES-R26 is a brief PTSD self-report measure and has been used in many international studies. The IES-R is the outcome measure of choice for evaluating improvement in PTSD symptoms in IAPT services in England.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) (quality of life): The EQ-5D-5L27 is a widely used instrument in health economic (HE) analysis and recognised by NICE as an appropriate measure for health-related quality of life. The questionnaire provides a simple descriptive profile, which translates to a single utility score for health status. The first part of the instrument identifies the extent of perceived problems – across five levels – in each of five life dimensions: mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain and discomfort; and anxiety and depression. The responses to each of the five questions are used to generate a value set score for self-rated health status between −0.594 and 1, where −0.594 represents the worst possible health state and 1 the best possible health state. Given the NICE Position Statement,28 this value set is a crosswalk of EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L. 29 The second part is a visual analogue scale, which allows the responder to indicate their current health status on a 0–100 scale.

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (functional impairment): The WSAS30 is a self-report measure, which assesses the impact of a person’s mental health difficulties on their ability to function in terms of work, home management, social leisure, private leisure and personal or family relationships. The WSAS is the outcome measure of choice for evaluating improvement in functioning in IAPT services. The WSAS has been demonstrated to show good reliability and validity and is sensitive to change.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (depression symptoms): The PHQ-931 is a widely used reliable and well-validated brief self-report measure of depression. It is the outcome measure of choice for evaluating improvement in depressive symptoms in IAPT services.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) (anxiety symptoms): The GAD-732 is a widely used reliable and well-validated brief self-report measure of anxiety. It is the outcome measure of choice for evaluating improvement in anxiety symptoms in IAPT services.

Alcohol Use Disorders Test (AUDIT-O) (alcohol symptoms): The AUDIT-O33 contains 10 multiple-choice questions on quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, drinking behaviour and alcohol-related problems or reactions over the preceding 3 months.

Multidimensional Scale for Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (social support): The MSPSS34 is a widely used 12-item Likert scale measuring the subjective assessment of adequacy of social support from family, friends and partners. 35 The reliability, validity and factor structure of the MSPSS have been demonstrated with a number of populations. 34–37

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (insomnia): The ISI38 is a widely used seven-item self-report questionnaire assessing the nature, severity and impact of insomnia. It has been shown to be reliable and valid in terms of detecting insomnia and in measuring treatment response in clinical patients.

Post-Traumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI) (post-traumatic cognitions): The PTCI39 was developed as a 33-item scale, which is rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree); a shortened, 22-item form has also been developed. Scale scores are formed for three subscales: negative cognitions about self, negative cognitions about the world and self-blame. The PTCI shows good internal consistency, high test-retest reliability and good convergent validity with other measures of trauma-related cognitions. The PTCI also shows promise in being able to differentiate individuals with and without PTSD.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) (self-efficacy): The GSES is a ten-item, 4-point Likert scale that is used to measure self-efficacy. It has been used in more than 1000 studies and is reliable and well-validated. 40,41

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8) (treatment satisfaction): The CSQ-842 is a widely used eight-item, Likert Scale which was developed through literature review and expert ranking, pretested on 248 mental health clients in five settings. It is a self-report statement of satisfaction with a high degree of internal consistency, good concurrent validity and reliability and is brief and easy to complete. 43

Agnew Relationship Measure-5 (ARM-5) (therapeutic alliance): The ARM-544 is a validated short 5-item version of the 28-item ARM-5, comprising client and therapist versions containing parallel items. There are versions for both the participant (shown first) and the therapist (shown second).

Sample size

As the study aimed to demonstrate NI of GSH using Spring for PTSD compared to face-to-face CBT-TF, the power calculation considered the NI margin as opposed to the effect size. The NI margin (determined a priori by clinical consensus of clinicians involved in the trial design and the research management group) was 5 points on the 80-point CAPS-5 scale. A meta-analysis45 indicated that the standardised mean difference between CBT-TF and wait-list/usual care for the treatment of PTSD is −1.62. This corresponds to 16.6 points on the CAPS-5 with a common standard deviation (SD) of 10.3. This means that if NI was demonstrated to within 5 points of the gold standard, this would also demonstrate superiority over wait-list/usual care in line with International Conference on Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guideline (Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials) E9 (ICH E9) guidance for NI studies. 46,47

Pilot work indicated an intraclass correlation coefficient of 5.6% at the therapist level at 10 weeks. At 22 weeks, however, there was no observable clustering of CAPS-5 scores among therapists. Given our primary outcome (CAPS-5) was measured at 16 weeks, we allowed for 1% clustering and recalculated the sample size. We allowed for 20% attrition. With the anticipated average therapist cluster size anticipated as four, the design effect was 1.03, requiring a 3% inflation of the sample size. This resulted in a final target sample size of 192 (inflated from 186), which provided 90% power [nQuery v7.0 (Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA, USA)48].

For the qualitative elements of the study, the sample size was guided by preliminary analysis and constant comparison (with themes from other interviews), during each data collection phase, until the research team was satisfied that there was data saturation and no new themes which were important to the research.

Statistical analysis methods

All statistical analyses were described in a statistical analysis plan (SAP) prior to data analysis being performed.

Analysis of the primary outcome

The primary analysis was performed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), modelling 16-week follow-up CAPS-5 score, controlling for baseline CAPS-5 score, research centre and the following patient characteristics: gender, comorbid depression (baseline PHQ-9) and time since trauma. Reflecting the sample size calculation, analyses were undertaken with two-level hierarchical models with patients clustered within therapists.

The primary analysis utilised multiple imputation with interim collected IES-R scores as auxiliary variables to the imputation. The number of imputations datasets created from which the analysis was averaged over was 50, which was greater than the percentage of incomplete cases (defined as a case missing the primary outcome) out of all those randomised. Given that IES-R was collected four to five times for GSH arm patients and eight to twelve times for CBT-TF arm patients, there was potential bias created by undertaking any multiple imputation model. For this analysis, we then applied a different imputation model to each arm: both containing the relevant number of auxiliary variables [along with baseline CAPS-5 score, research centre, gender, comorbid depression (baseline PHQ-9) and time since trauma]. Imputed datasets were then combined for the final analyses. Full details of the imputation procedure are given below. 49

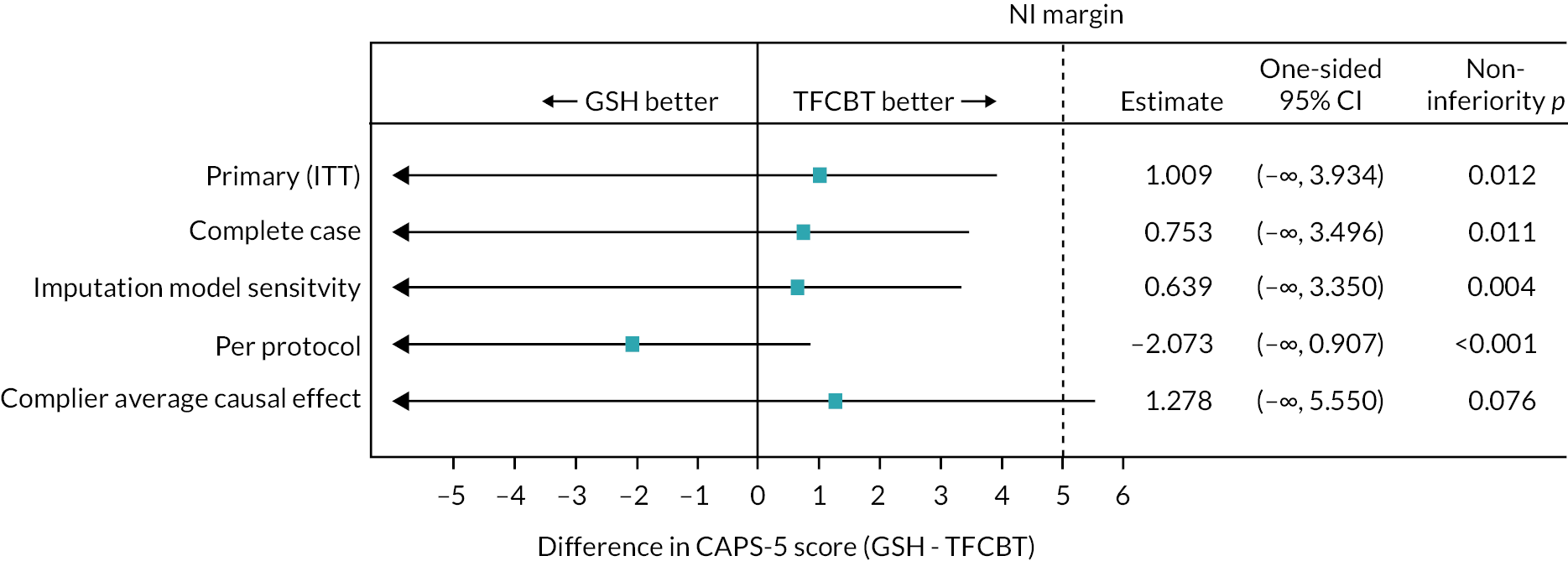

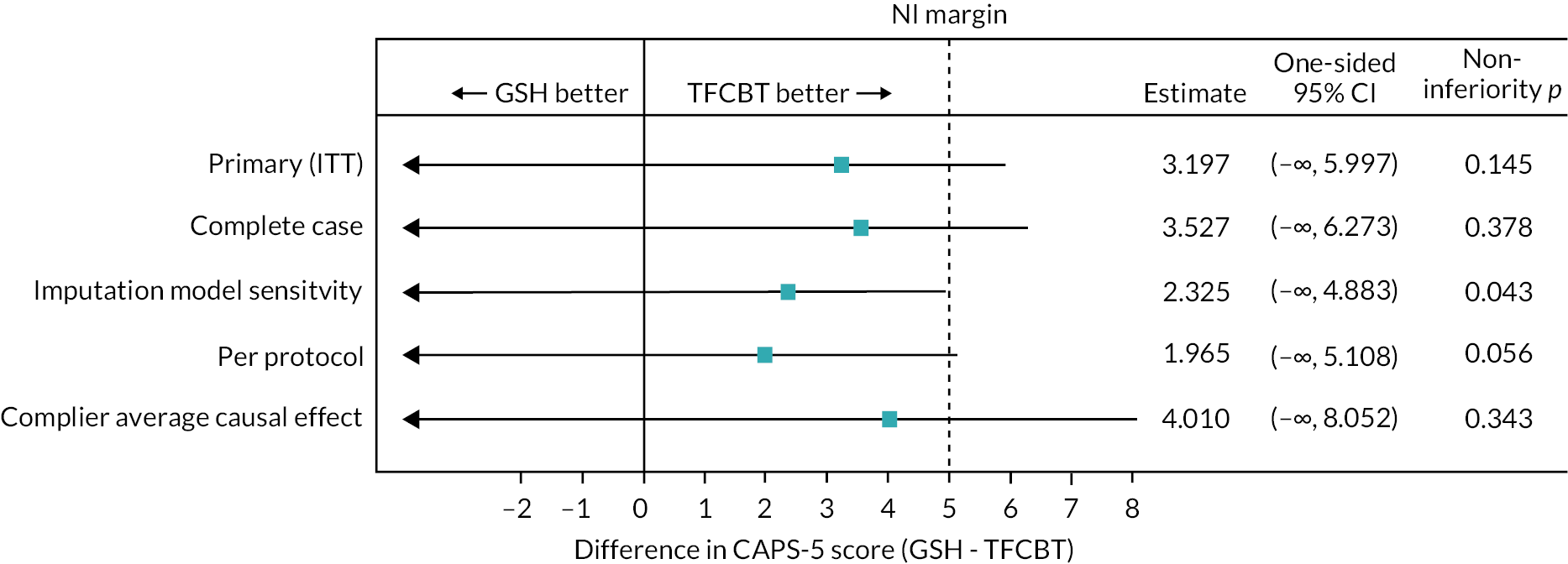

The results were summarised using point estimates, and one-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and NI p-values (in line with the sample size calculation). Since this is a NI design, we checked whether the CI for the difference between arms lay entirely within the 5-point NI margin for the primary outcome. Where the treatment effect and one-sided 95% CI were entirely > 0, then superiority was assessed with a two-sided 90% CI and relevant p-value.

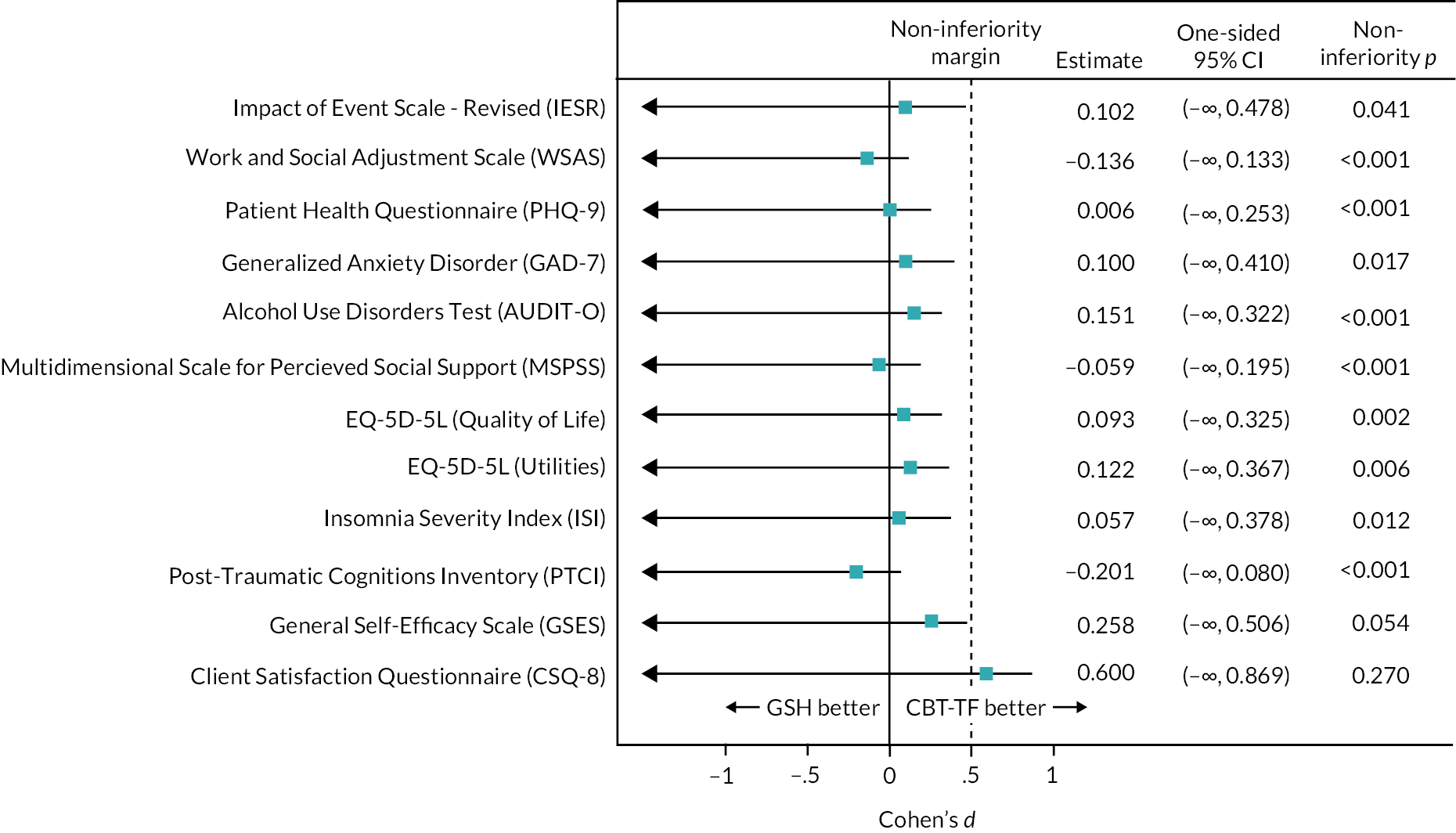

The secondary outcome CAPS-5 at 52-week follow-up was analysed in the same manner as the primary analysis. For the other secondary outcomes the notional NI margin was set as 0.5 times the pooled SD of the baseline values in each of the CBT-TF and GSH groups of the outcome.

Covariate adjustment

All analyses contained the following covariates:

-

treatment arm (categorical; GSH or CBT-TF)

-

gender (categorical; male or female; minimisation variable)

-

research centre (categorical; Cardiff and South Wales, Pennine, London, NHS Lothian; Coventry, South-West Yorkshire; stratification variable)

-

comorbid depression (baseline PHQ-9)

-

time since trauma in months.

In all cases, except those of CSQ-8 and ARM-5, the covariate of the relevant baseline version of the same measure was included in the model such that an ANCOVA model was formed. For PHQ-9, this covariate was only included in the model once.

Sensitivity analyses

For the primary outcome, the complete case intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and per-protocol analysis were conducted and reported under a NI framework. Results are presented using point estimates, and one-sided 95% CIs and p-values (in line with the sample size calculation). Since this is a NI design, we checked whether the CI for the difference between arms lay entirely within the 5-point NI margin.

A further sensitivity analysis (SA) of the primary outcome under a NI framework implemented a different multiple imputation model: IES-R scores taken from five clinic visits for the CBT-TF arm participants that aligned similarly in time to those of the GSH arm participants were used as auxiliary variables in an imputation model (this one with both arms combined) along with baseline CAPS-5 score, research centre, gender, comorbid depression (baseline PHQ-9) and time since trauma. The results were summarised using point estimates, and one-sided 95% CIs and NI p-values (in line with the sample size calculation). Since this was a NI design, we checked whether the CI for the difference between arms lay entirely within the 5-point NI margin.

To explore the impact of departures from randomised treatment on our primary analysis, we estimated the complier average causal effect (CACE), with the following definition of ‘complier’ considered:

-

Participants who attend the necessary number of therapy sessions to be described as having adhered (as defined above).

In this case, ‘compliers’ form a principal stratification strategy as defined in the ICH E9 Draft Addendum. 50 That is, by defining compliers as the stratum in the trial population that do not experience the post-randomisation intercurrent event of non-compliance.

We used instrumental variable methods to conduct these analyses, using randomisation as an instrument. 51–53 The models were fit using two-stage least squares instrumental variables regression, including those covariates used in the primary analysis model. The results were summarised using point estimates, and one-sided 95% CIs and NI p-values (in line with the sample size calculation). Since this is a NI design, we checked whether the CI for the difference between arms lay entirely within the 5-point NI margin.

In addition, for the 52-week outcome measures, we explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by examining the impacts on the primary analysis by further stratifying by two time periods, namely, before the initial national lockdown date of 23 March 2020, and after that date. Since the trial was not powered to explore the interaction effect of the two time periods and the intervention, these analyses were primarily exploratory in nature. Further analyses were also performed examining the effect of changes in the mode of data collection from face-to-face to remote collection via video and telephone calls. This analysis was conducted on the primary outcome at 16 weeks as by the 52-week outcome the choice of method of data collection was confounded by the switch to telephone/video call due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes IES-R, EQ-5D-5L (Value Set and Visual Analogue Scale), WSAS, PHQ-9, GAD-7, AUDIT-O, MSPSS, ISI, PTCI, GSES, CSQ-8 and ARM-5 were also analysed using multiple imputation to account for missing data under a NI framework. The number of imputations datasets created from which the analysis was averaged over was 50, greater than the percentage of incomplete cases (defined as a case missing that secondary outcome) out of all those randomised. The imputation model used the variables defined above. The results are presented as point estimates, one-sided 95% CIs and NI p-values. To allow comparison to be made across all outcomes the results are standardised to Cohen’s d effects size and the relevant point estimates, one-sided 95% CIs and non-inferiority p-values are expressed likewise.

The Cohen’s d effect size was calculated as the estimated mean difference from the regression model divided by the pooled SD calculated by pooling the SD measured in each trial arm at baseline for the relevant secondary outcome. The NI margin for secondary outcomes was set as 0.5 times the pooled SD. The value of 0.5 was chosen as this approximates the effect size used in the sample size calculation for the primary outcome of CAPS-5, that is, a 5-point margin divided by an assumed SD of 10.3. This gives an effect size 0.48 which was rounded to 0.5.

Exploratory analyses

A pre-specified subgroup analysis considered the differences in treatment effects by gender, including an interaction term between treatment arm and gender. Estimates from the statistical models (stratum-specific mean differences) are presented alongside two-sided 95% CIs and p-values.

Missing data

Individual questionnaires were inspected for missing values. If specific items were missing, they were imputed using the guidance for that questionnaire or if that information was not available then by mean imputation. This was a minor issue as most questionnaires were complete if the participant had been assessed.

Dealing with missing data for the primary outcome is listed above. For the multilevel multiple imputation, a joint modelling approach was chosen as implemented in the JOMO R package. 54 This uses a Bayesian approach utilising Monte Carlo Markov Chain to fit a joint two-level model. For the level 1 model this was fit as a random intercept and slope mixed regression model of the IES-R total scores with time. In addition, the following covariates were added to the model: site, baseline CAPS-5 score, gender, baseline depression score (PHQ-9) and time since traumatic event. The level 2 model was the primary analysis model consisting of a regression of the 16-week CAPS-5 score on the baseline CAPS-5 score, gender, baseline depression score (PHQ-9) and time since traumatic event. As described above, for the primary analysis each treatment group was imputed separately due to the varying number of therapist contacts.

For the SA, the same imputation model framework was used except the IES-R scores and other model variables were combined into a single imputation model. For the 52-week outcomes it was not possible to also include the site variable in the imputation model for each group due to data sparseness in the smallest sites. However, when compared to the sensitivity and complete case analyses the results were consistent.

For each multiple imputation run we used a burn-in period of 10,000 iterations, 500 iterations ‘in-between’ to account for serial correlation; and for all outcome variables 50 multiply imputed datasets were generated. The robustness of the imputation models was checked using a range of diagnostic statistics and convergence plots available in the JOMO package and described there. Based on these diagnostic measures there was no evidence of any issues with the imputation framework.

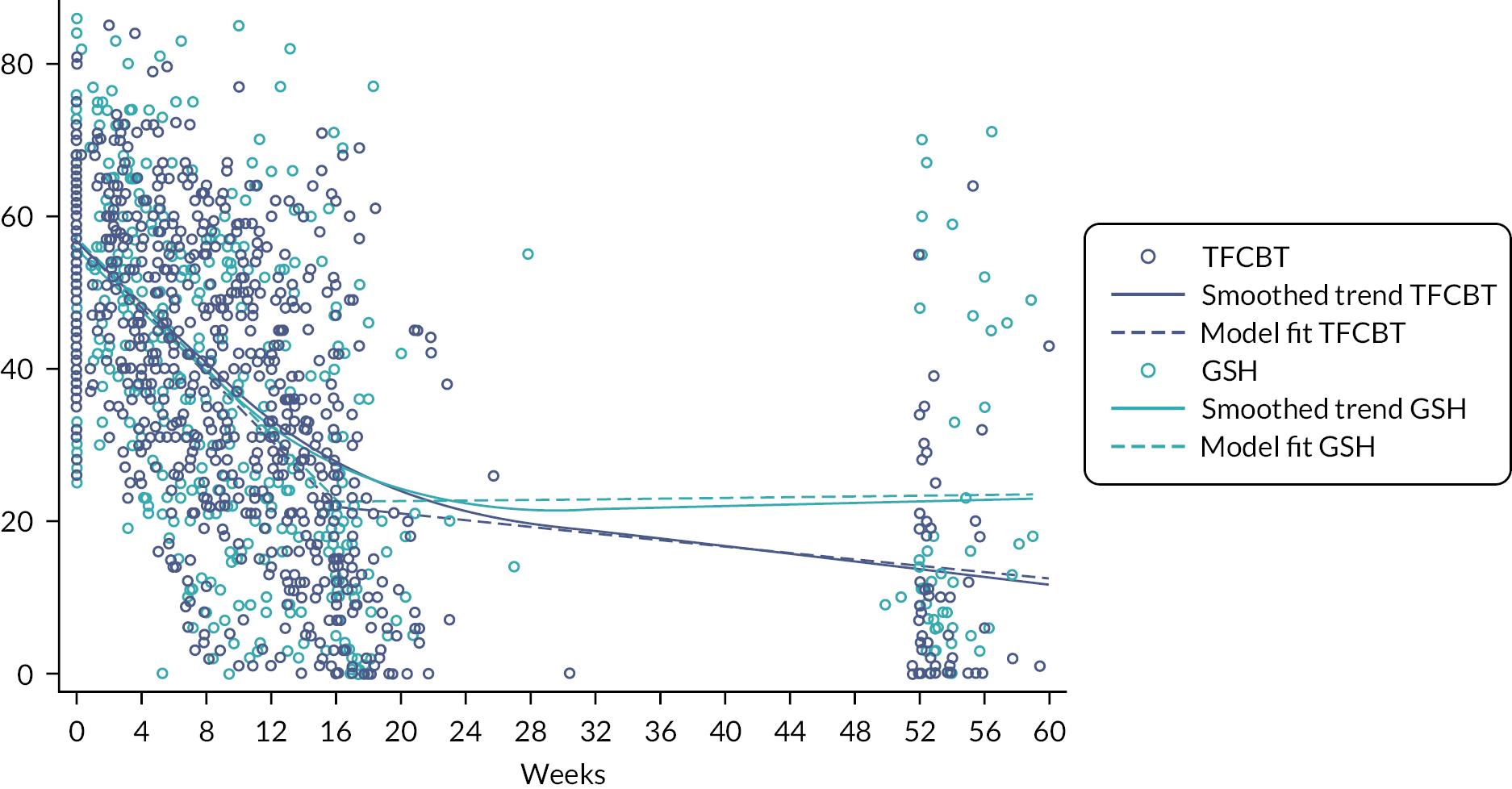

Additional analyses

IES-R scores over time were analysed using a hierarchical modelling fitting a random slope and intercept model, also allowing for clustering by therapist as in the primary analysis. We modelled the time dimension as a linear spline with a knot at 26 weeks. Both elements of the spline were included as random effects in the form of random slopes. We fitted IES-R trajectories over time (since randomisation) interacted with intervention arm, while also controlling for the same covariates as the primary analysis. Note that these were likely collected four to five times for GSH arm patients and 8 to 12 times for CBT-TF arm patients.

An analysis explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by examining the treatment effect stratified by the period before and after lockdown, defined as any contact that took place after 23 March 2020. For participants with missing outcome data, we calculated the notional 16- or 52-week date of the expected contact with their therapist. This notional date was then used to define the before or after lockdown period.

Public participation

A public advisory group, comprising five people with lived experience of PTSD, was formed, and met every 2–3 months to inform study design, conduct, data analysis and dissemination strategy and activity. This included participation in the interpretation of findings and identifying implications. The group was chaired by coauthor SC, a co-applicant with lived experience of PTSD and a participant in a previous study of GSH using Spring. The public advisory group reviewed and approved all participant-facing material. The trial steering committee included two members of the public, who were separate from the public advisory group.

Chapter 3 Quantitative trial results

Introduction

This chapter describes the results of the quantitative analysis of the RAPID trial.

Recruitment

Screening and randomisation

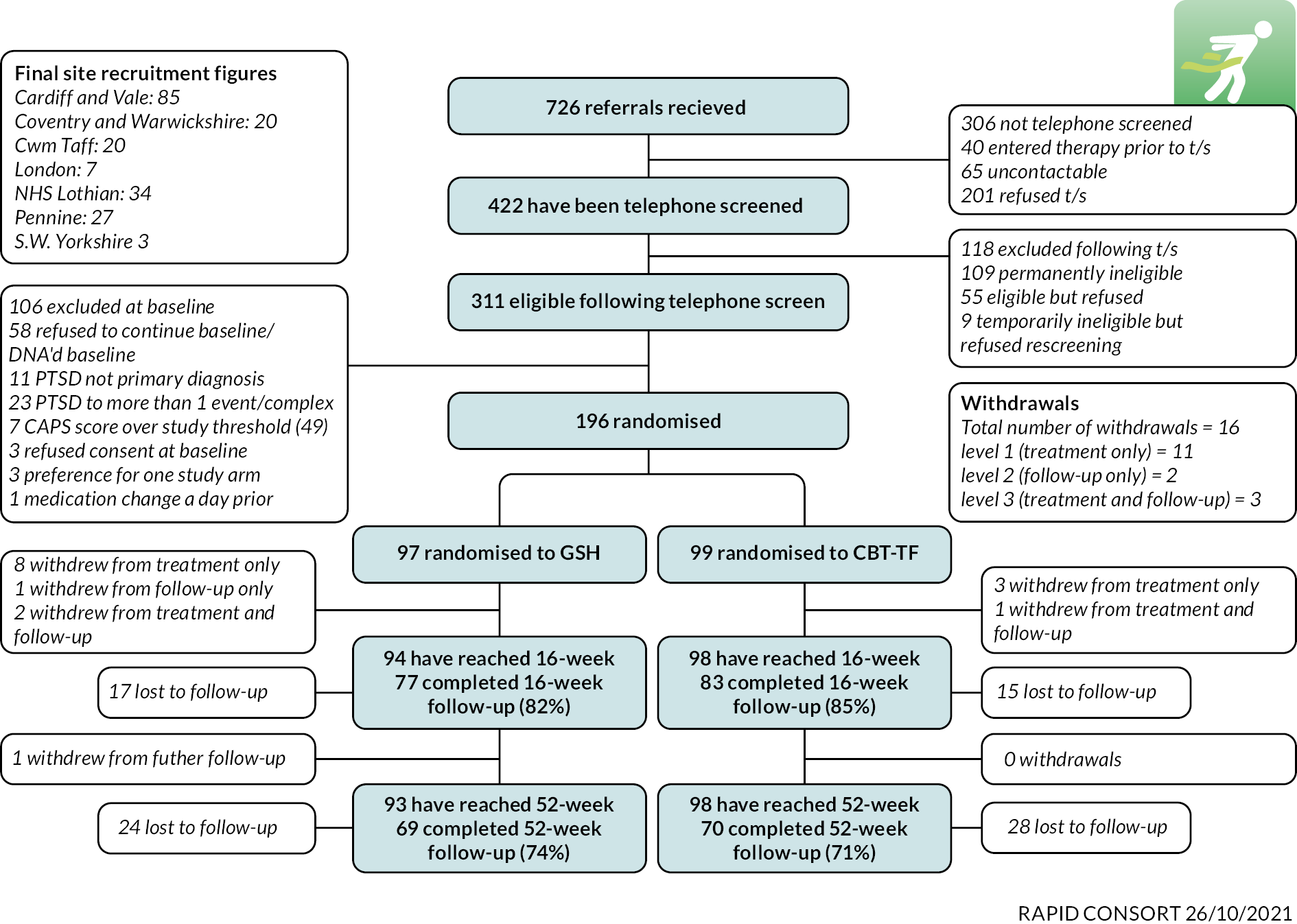

In all, 196 participants were recruited into the trial, 99 in the CBT-TF arm and 97 in the GSH arm. This exceeded the planned sample size of 192 participants. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT patient flow diagram. A more detailed breakdown of the reasons for inclusion and exclusion is shown in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow and CONSORT diagram for the RAPID trial.

| Cardiff and South Wales | Site | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coventry and Warwickshire | East London Foundation Trust | NHS Lothian | Pennine | S.W. Yorks | Total | ||

| Number screened | 250 | 38 | 13 | 73 | 44 | 4 | 422 |

| Number eligible | 178 (71.2) | 28 (73.7) | 9 (69.2) | 53 (72.6) | 39 (88.6) | 4 (100.0) | 311 (73.7) |

| Attended baseline | 178 (100.0) | 24 (85.7) | 9 (100.0) | 49 (92.5) | 39 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 303 (97.4) |

| Randomised | 105 (59.0) | 20 (83.3) | 7 (77.8) | 34 (69.4) | 27 (69.2) | 3 (75.0) | 196 (64.7) |

| Inclusion criteria | |||||||

| Are you aged 18 or over? | 250 (100.0) | 38 (100.0) | 12 (92.3) | 73 (100.0) | 43 (97.7) | 4 (100.0) | 420 (99.5) |

| Has the patient experienced a trauma that meets the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD? | 249 (99.6) | 37 (97.4) | 10 (76.9) | 73 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 417 (98.8) |

| Have any other traumatic events contributed to your symptoms? | 51 (20.4) | 13 (34.2) | 2 (15.4) | 17 (23.3) | 11 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 94 (22.3) |

| Does the patient have PTSD following a single traumatic event? | 229 (91.6) | 33 (86.8) | 10 (76.9) | 62 (84.9) | 39 (88.6) | 4 (100.0) | 377 (89.3) |

| Does the patient answer yes to six or more questions on the Traumatic Screening Questionnaire? | 204 (81.6) | 33 (86.8) | 9 (69.2) | 66 (90.4) | 42 (95.5) | 4 (100.0) | 358 (84.8) |

| Do you have regular access to the internet in order to complete the GSH? | 210 (84.0) | 36 (94.7) | 10 (76.9) | 63 (86.3) | 42 (95.5) | 4 (100.0) | 365 (86.5) |

| Exclusion criteria | |||||||

| Inability to read and write fluently in English | 7 (2.8) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (2.8) |

| Have you previously completed a course of CBT-TF for PTSD? | 3 (1.2) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (4.1) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.4) |

| Are you currently receiving any kind of psychological therapy? | 1 (0.4) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.7) |

| Are you taking any medication for a mental health condition? | 21 (8.4) | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (6.9) |

| Are you suffering from psychosis, for example, hearing voices or seeing things? | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Are you currently dependent on alcohol or drugs? | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Have you been having thoughts of ending your life? | 60 (24.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (20.5) | 7 (15.9) | 1 (25.0) | 84 (19.9) |

| Do you feel suicidal? | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.5) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.7) |

Overall, 726 referrals were made to the RAPID team and 422 were telephone screened (58.1%). Of the 422 participants telephone screened, 311/422 (73.7%) were eligible for enrolment and 303/311 (97.4%) attended a baseline assessment. Of these, 196/303 (64.7%) were randomised to the trial. Of those not randomised, 58/303 (19.1%) participants chose not to continue the baseline assessment or did not attend the assessment. A further 48/303 (15.8%) patients did not meet the eligibility criteria for entry to the trial with the reasons being PTSD was attributed to more than one event or was a complex PTSD diagnosis (23/303, 7.6%); not having PTSD as a primary diagnosis (11/303, 3.6%); and 7/303 (2.3%) having a CAPS-5 score above the eligibility threshold of 49. In addition, three patients refused consent at baseline, three participants showed a preference for one trial arm and one patient had a medication change close to the baseline assessment.

Withdrawals during the trial

During the trial, 18/196 (9.2%) participants withdrew from the trial. Of the 18 patients, 12/18 (66.7%) were in the GSH group and 6/18 (33.3%) in the CBT-TF group. 2/18 (11.1%) participants were withdrawn at the request of the therapist and 16/18 (88.9%) withdrew at the request of the participant. Of the 18 participants who withdrew, 14/18 (77.8%) withdrew from the trial intervention but allowed themselves to be followed up, 2/18 (11.1%) withdrew from further data collection and 2/18 (11.1%) withdrew from both the intervention and further data collection.

In terms of timing of withdrawals, 6/18 (33.3%) withdrew prior to randomisation, 11/18 (61.1%) withdrew after randomisation but before the 16-week assessment and only 1/18 (5.6%) withdrew between the 16-week and 52-week assessments.

There was a difference in the number of withdrawals between the CBT-TF group and GSH group. There was one participant withdrawal at the request of the therapist in each group. The participant in the CBT-TF group had an ill family member, and no reason was recorded for the GSH participant. The remaining 16 participants (11 in the GSH group and 5 in the CBT-TF group) who withdrew at their own request gave a variety of reasons for withdrawing. Examining the free text comments revealed that three participants (one in the CBT-TF group and two in the GSH group) had no reason recorded. In the four participants who gave reasons in the CBT-TF group, one patient felt the therapy was not helping and the other three participants had difficulty attending the sessions for work-related or family illness reasons. For the GSH group, where a reason was recorded, three participants indicated a desire for more intensive therapy, one participant felt the intervention was too difficult to use, one participant preferred to do individual research, one participant was taking medication to treat their PTSD symptoms, one participant did not want to revisit their PTSD event, one participant could not commit the time and finally one participant had a cancer diagnosis and did not wish to juggle two health issues. Participant withdrawal information is presented in Table 3.

| CBT-TF | GSH | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 6 | N = 12 | N = 18 | |

| Nature of withdrawal | |||

| Participant withdrew consent | 5 (83.3) | 11 (91.7) | 16 (88.9) |

| Participant withdrawn by therapist/trial team | 1 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (11.1) |

| Missing (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Withdrawal level | |||

| Withdrawal from the trial intervention | 5 (83.3) | 9 (75.0) | 14 (77.8) |

| Withdrawal from follow-up interviews/questionnaires | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (11.1) |

| Withdrawal from both the trial intervention and follow-up interviews/questionnaires | 1 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (11.1) |

| Missing (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Lost to follow-up

There were 36/196 (18.4%) patients lost to follow-up at the 16-week assessment, 20/97 (20.6%) in the GSH group and 16/99 (16.2%) in the CBT-TF group. This includes those patients who withdrew permission for future data collection, one in the CBT-TF group and three in the GSH group. As expected, loss to follow-up was higher at the 52-week assessment with 57/196 (29.0%) not reporting data collection overall with 29/99 (29.3%) in the CBT-TF group and 28/97 (28.9%) in the GSH group. There was no strong evidence of a differential loss to follow-up between the CBT-TF or GSH groups.

Description of the trial population

This section describes the trial population in terms of the data collected at the baseline assessments.

Demographics

The average age of participants was 36.5 years (SD 13.4). Female participants represented 63.8% (125/196) of the total trial population. The overwhelming self-reported ethnicity was white (all groups) which comprised 91.8% of the trial population (180/196). In terms of education and qualification, 64/196 (32.7%) participants reported having a higher education qualification and 46/196 (23.5%) reported having two or more A levels. Only 8/196 (4.1%) reported having no qualifications or education achievements.

Most participants reported having salary or wages as their main source of income (123/128, 96.1%). However, just under 35% of participants declined to report their main source of income (68/196). Participants were more inclined to report their income category (only eight declined) and 110/188 (58.5%) participants reported income below £20,000 per annum. This is lower than the UK median income as reported by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for 2019 which was £29,900. Of participants’ current occupations the three most common responses were customer service occupations (24/96, 12.2%), teaching and education profession (17/196, 8.7%) and healthcare professionals (16/196, 8.2%). While customer service occupations remained the most common response in terms of lifetime vocation (62/196, 31.6%) the next two categories were sales occupations (31/196, 15.8%) and administrative roles (30/196, 15.3%). Very few participants reported managerial or scientific roles currently or over their lifetime.

There were no major imbalances reported among the two groups indicating the randomisation process had been successful. There were a few smaller imbalances noted. More CBT-TF participants reported having achieved a higher education qualification (37/99, 37.4%) than GSH participants (27/97, 27.8%). Slightly more CBT-TF participants reported being employed than the GSH group, 63/99 (63.6%) versus 56/97 (57.7%). This was reflected in the proportion of participants not receiving benefits which was 69/99 (69.7%) for the CBT-TF group and 57/97 (58.8%) for the GSH group. There were a larger number of participants not able to work in the GSH group (12/97, 12.4%) compared to the CBT-TF group (6/99, 6.1%). Full details of the demographic profile of the trial participants are shown in Table 4.

| Treatment comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-TF | GSH | Total | ||||

| N = 99 | N = 97 | N = 196 | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.6 | (13.4) | 35.4 | (13.4) | 36.5 | (13.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 37.0 | (25.7–48.3) | 31.4 | (24.7–43.8) | 32.3 | (25.2–47.1) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 23 | (23.2) | 26 | (26.8) | 49 | (25.0) |

| 25–34 | 23 | (23.2) | 33 | (34.0) | 56 | (28.6) |

| 35–44 | 20 | (20.2) | 15 | (15.5) | 35 | (17.9) |

| 45–64 | 31 | (31.3) | 20 | (20.6) | 51 | (26.0) |

| 65+ | 2 | (2.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 5 | (2.6) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 36 | (36.4) | 35 | (36.1) | 71 | (36.2) |

| Female | 63 | (63.6) | 62 | (63.9) | 125 | (63.8) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Site name | ||||||

| Cardiff and South Wales | 52 | (52.5) | 53 | (54.6) | 105 | (53.6) |

| Coventry and Warwickshire | 11 | (11.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 20 | (10.2) |

| East London Foundation Trust | 4 | (4.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| NHS Lothian | 17 | (17.2) | 17 | (17.5) | 34 | (17.3) |

| Pennine | 14 | (14.1) | 13 | (13.4) | 27 | (13.8) |

| S.W. Yorks | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White: Welsh/English/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 86 | (86.9) | 86 | (88.7) | 172 | (87.8) |

| White: Irish | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| White: Any other white background | 3 | (3.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups: White and Black Caribbean | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups: White and Black African | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups: any other mixed/multiple ethnic background | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Asian/Asian British: Indian | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Asian/Asian British: Pakistani | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Asian/Asian British: Bangladeshi | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Asian/Asian British: Chinese | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: African | 2 | (2.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: Caribbean | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: any other black/African/Caribbean background | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Any other ethnic group | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Highest level of qualification | ||||||

| None | 1 | (1.0) | 7 | (7.2) | 8 | (4.1) |

| 1–4 GCSE/O levels | 12 | (12.1) | 12 | (12.4) | 24 | (12.2) |

| 5 + GCSE/O levels | 19 | (19.2) | 17 | (17.5) | 36 | (18.4) |

| Apprenticeship | 3 | (3.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 4 | (2.0) |

| 2 + A levels | 22 | (22.2) | 24 | (24.7) | 46 | (23.5) |

| Higher education | 37 | (37.4) | 27 | (27.8) | 64 | (32.7) |

| Other | 5 | (5.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 14 | (7.1) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Main income source | ||||||

| Salary/wage | 64 | (94.1) | 59 | (98.3) | 123 | (96.1) |

| State benefits | 3 | (4.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (2.3) |

| Other | 1 | (1.5) | 1 | (1.7) | 2 | (1.6) |

| Missing (%) | 31 | (31.3) | 37 | (38.1) | 68 | (34.7) |

| Gross income (individual, without benefits) | ||||||

| Up to £10,000 | 36 | (37.1) | 36 | (39.6) | 72 | (38.3) |

| £10,000–20,000 | 19 | (19.6) | 19 | (20.9) | 38 | (20.2) |

| £20,000–30,000 | 23 | (23.7) | 16 | (17.6) | 39 | (20.7) |

| £30,000–40,000 | 14 | (14.4) | 14 | (15.4) | 28 | (14.9) |

| £40,000–50,000 | 3 | (3.1) | 3 | (3.3) | 6 | (3.2) |

| £50,000–60,000 | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.2) | 2 | (1.1) |

| £60,000 + | 2 | (2.1) | 1 | (1.1) | 3 | (1.6) |

| Missing (%) | 2 | (2.0) | 6 | (6.2) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Current employment | ||||||

| Employed (including being on temporary leave from work for any reason) | 63 | (63.6) | 56 | (57.7) | 119 | (60.7) |

| Self-employed or freelance | 5 | (5.1) | 4 | (4.1) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Homemaker | 6 | (6.1) | 3 | (3.1) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Student | 12 | (12.1) | 15 | (15.5) | 27 | (13.8) |

| Retired | 4 | (4.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Volunteering | 3 | (3.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Unable to work (including those receiving DLA) | 6 | (6.1) | 12 | (12.4) | 18 | (9.2) |

| Out of work and looking for work | 4 | (4.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Out of work but not currently looking for work | 3 | (3.0) | 6 | (6.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Current vocation | ||||||

| Corporate managers and directors | 4 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Science, research, engineering and technology professionals | 3 | (3.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Health professionals | 7 | (7.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 16 | (8.2) |

| Teaching and educational professionals | 10 | (10.1) | 7 | (7.2) | 17 | (8.7) |

| Business, media and public service professionals | 4 | (4.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 5 | (2.6) |

| Other managers and proprietors | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Science, engineering and technology associate professionals | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Health and social care associate professionals | 4 | (4.0) | 5 | (5.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Protective service occupations | 3 | (3.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Culture, media and sports occupations | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Business and public service associate professionals | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Skilled agricultural and related trades | 3 | (3.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Skilled metal, electrical and electronic trades | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Skilled construction and building trades | 4 | (4.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Textiles, printing and other skilled trades | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Administrative occupations | 8 | (8.1) | 3 | (3.1) | 11 | (5.6) |

| Secretarial and related occupations | 4 | (4.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 5 | (2.6) |

| Caring personal service occupations | 6 | (6.1) | 2 | (2.1) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Leisure, travel and related personal service occupations | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Sales occupations | 2 | (2.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Customer service occupations | 10 | (10.1) | 14 | (14.4) | 24 | (12.2) |

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 4 | (4.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Transport and mobile machine drivers and operatives | 1 | (1.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Elementary trades and related occupations | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Elementary administration and service occupations | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Lifetime vocation | ||||||

| Corporate managers and directors | 5 | (5.1) | 3 | (3.1) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Science, research, engineering and technology professionals | 4 | (4.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Health professionals | 5 | (5.1) | 12 | (12.4) | 17 | (8.7) |

| Teaching and educational professionals | 18 | (18.2) | 10 | (10.3) | 28 | (14.3) |

| Business, media and public service professionals | 5 | (5.1) | 4 | (4.1) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Other managers and proprietors | 4 | (4.0) | 7 | (7.2) | 11 | (5.6) |

| Science, engineering and technology associate professionals | 3 | (3.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Health and social care associate professionals | 11 | (11.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 20 | (10.2) |

| Protective service occupations | 3 | (3.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Culture, media and sports occupations | 5 | (5.1) | 4 | (4.1) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Business and public service associate professionals | 2 | (2.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Skilled agricultural and related trades | 3 | (3.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Skilled metal, electrical and electronic trades | 5 | (5.1) | 3 | (3.1) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Skilled construction and building trades | 10 | (10.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 19 | (9.7) |

| Textiles, printing and other skilled trades | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Administrative occupations | 18 | (18.2) | 12 | (12.4) | 30 | (15.3) |

| Secretarial and related occupations | 6 | (6.1) | 5 | (5.2) | 11 | (5.6) |

| Caring personal service occupations | 8 | (8.1) | 7 | (7.2) | 15 | (7.7) |

| Leisure, travel and related personal service occupations | 9 | (9.1) | 12 | (12.4) | 21 | (10.7) |

| Sales occupations | 14 | (14.1) | 17 | (17.5) | 31 | (15.8) |

| Customer service occupations | 30 | (30.3) | 32 | (33.0) | 62 | (31.6) |

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 5 | (5.1) | 3 | (3.1) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Transport and mobile machine drivers and operatives | 3 | (3.0) | 9 | (9.3) | 12 | (6.1) |

| Elementary trades and related occupations | 3 | (3.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Elementary administration and service occupations | 3 | (3.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Homemaker | 7 | (7.1) | 5 | (5.2) | 12 | (6.1) |

| Never worked (including those receiving DLA) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Benefits | ||||||

| No benefits received | 69 | (69.7) | 57 | (58.8) | 126 | (64.3) |

| Income support | 5 | (5.1) | 7 | (7.2) | 12 | (6.1) |

| Jobseeker’s allowance | 4 | (4.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 6 | (3.1) |

| DLA | 10 | (10.1) | 11 | (11.3) | 21 | (10.7) |

| Statutory sick pay | 4 | (4.0) | 5 | (5.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Housing benefit | 5 | (5.1) | 6 | (6.2) | 11 | (5.6) |

| State pension | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Child benefit | 12 | (12.1) | 17 | (17.5) | 29 | (14.8) |

Experience of trauma

Participants reported previous experience of trauma using the Life Events Checklist (LEC) tool. 56 Figure 2 shows the prevalence of the worst experience reported and Table 5 reports the full details of the LEC questionnaire. Participants reported on average being 32.7 (SD 13.9, range 5–69) years old at the time of their worst trauma experience and that the event had occurred a median of 16 [interquartile range (IQR) 6–32, range 2–720] months ago. Most participants responded that the event lasted a median of 1 hour (IQR 0.2–4); however, some participants reported much longer durations, range 0–720 hours.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of most traumatic event reported.

| CBT-TF | GSH | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 99 | N = 97 | N = 196 | ||||

| Natural disaster (e.g. flood, hurricane, tornado, earthquake) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 6 | (6.1) | 7 | (7.2) | 13 | (6.6) |

| Witnessed it | 3 | (3.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Learned about it | 9 | (9.1) | 11 | (11.3) | 20 | (10.2) |

| Part of my job | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Not sure | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 81 | (81.8) | 80 | (82.5) | 161 | (82.1) |

| Fire or explosion | ||||||

| Happened to me | 6 | (6.1) | 6 | (6.2) | 12 | (6.1) |

| Witnessed it | 7 | (7.1) | 11 | (11.3) | 18 | (9.2) |

| Learned about it | 10 | (10.1) | 7 | (7.2) | 17 | (8.7) |

| Part of my job | 6 | (6.1) | 4 | (4.1) | 10 | (5.1) |

| Not sure | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Does not apply | 75 | (75.8) | 72 | (74.2) | 147 | (75.0) |

| Transportation accident (e.g. car accident, train wreck, plane crash) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 47 | (47.5) | 46 | (47.4) | 93 | (47.4) |

| Witnessed it | 10 | (10.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 19 | (9.7) |

| Learned about it | 11 | (11.1) | 12 | (12.4) | 23 | (11.7) |

| Part of my job | 3 | (3.0) | 5 | (5.2) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 36 | (36.4) | 36 | (37.1) | 72 | (36.7) |

| Serious accident at work, home or during recreational activity | ||||||

| Happened to me | 25 | (25.3) | 27 | (27.8) | 52 | (26.5) |

| Witnessed it | 9 | (9.1) | 11 | (11.3) | 20 | (10.2) |

| Learned about it | 4 | (4.0) | 5 | (5.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Part of my job | 3 | (3.0) | 4 | (4.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Not sure | 4 | (4.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 5 | (2.6) |

| Does not apply | 63 | (63.6) | 53 | (54.6) | 116 | (59.2) |

| Exposure to toxic substance (e.g. dangerous chemicals, radiation) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 3 | (3.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Witnessed it | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Learned about it | 5 | (5.1) | 1 | (1.0) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Part of my job | 7 | (7.1) | 1 | (1.0) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 5 | (5.2) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Does not apply | 87 | (87.9) | 89 | (91.8) | 176 | (89.8) |

| Physical assault (e.g. being attacked, hit, slapped, kicked, beaten up) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 43 | (43.4) | 37 | (38.1) | 80 | (40.8) |

| Witnessed it | 7 | (7.1) | 11 | (11.3) | 18 | (9.2) |

| Learned about it | 4 | (4.0) | 12 | (12.4) | 16 | (8.2) |

| Part of my job | 3 | (3.0) | 6 | (6.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 45 | (45.5) | 43 | (44.3) | 88 | (44.9) |

| Assault with a weapon (e.g. being shot, stabbed, threatened with a knife, bomb) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 13 | (13.1) | 13 | (13.4) | 26 | (13.3) |

| Witnessed it | 4 | (4.0) | 4 | (4.1) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Learned about it | 5 | (5.1) | 8 | (8.2) | 13 | (6.6) |

| Part of my job | 2 | (2.0) | 6 | (6.2) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Does not apply | 74 | (74.7) | 67 | (69.1) | 141 | (71.9) |

| Sexual assault (rape, attempted rape, forced sexual acts) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 15 | (15.2) | 14 | (14.4) | 29 | (14.8) |

| Witnessed it | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Learned about it | 7 | (7.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 16 | (8.2) |

| Part of my job | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Does not apply | 77 | (77.8) | 73 | (75.3) | 150 | (76.5) |

| Other unwanted or uncomfortable sexual experience | ||||||

| Happened to me | 13 | (13.1) | 15 | (15.5) | 28 | (14.3) |

| Witnessed it | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Learned about it | 1 | (1.0) | 6 | (6.2) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Part of my job | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 84 | (84.8) | 76 | (78.4) | 160 | (81.6) |

| Combat or exposure to a warzone (in the military or as a civilian) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 2 | (2.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Witnessed it | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Learned about it | 7 | (7.1) | 7 | (7.2) | 14 | (7.1) |

| Part of my job | 2 | (2.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Not sure | 2 | (2.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Does not apply | 87 | (87.9) | 88 | (90.7) | 175 | (89.3) |

| Captivity (e.g. being kidnapped, abducted, held hostage, prisoner of war) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 3 | (3.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 5 | (2.6) |

| Witnessed it | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Learned about it | 2 | (2.0) | 6 | (6.2) | 8 | (4.1) |

| Part of my job | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Not sure | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Does not apply | 93 | (93.9) | 89 | (91.8) | 182 | (92.9) |

| Life-threatening illness or injury | ||||||

| Happened to me | 14 | (14.1) | 24 | (24.7) | 38 | (19.4) |

| Witnessed it | 15 | (15.2) | 20 | (20.6) | 35 | (17.9) |

| Learned about it | 7 | (7.1) | 8 | (8.2) | 15 | (7.7) |

| Part of my job | 3 | (3.0) | 4 | (4.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Not sure | 2 | (2.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Does not apply | 64 | (64.6) | 50 | (51.5) | 114 | (58.2) |

| Severe human suffering | ||||||

| Happened to me | 4 | (4.0) | 5 | (5.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Witnessed it | 6 | (6.1) | 14 | (14.4) | 20 | (10.2) |

| Learned about it | 7 | (7.1) | 4 | (4.1) | 11 | (5.6) |

| Part of my job | 2 | (2.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 83 | (83.8) | 75 | (77.3) | 158 | (80.6) |

| Sudden, violent death (e.g. homicide, suicide) | ||||||

| Happened to me | 6 | (6.1) | 5 | (5.2) | 11 | (5.6) |

| Witnessed it | 9 | (9.1) | 10 | (10.3) | 19 | (9.7) |

| Learned about it | 18 | (18.2) | 12 | (12.4) | 30 | (15.3) |

| Part of my job | 3 | (3.0) | 7 | (7.2) | 10 | (5.1) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 63 | (63.6) | 67 | (69.1) | 130 | (66.3) |

| Sudden, unexpected death of someone close to you | ||||||

| Happened to me | 37 | (37.4) | 34 | (35.1) | 71 | (36.2) |

| Witnessed it | 11 | (11.1) | 11 | (11.3) | 22 | (11.2) |

| Learned about it | 12 | (12.1) | 15 | (15.5) | 27 | (13.8) |

| Part of my job | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Not sure | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 42 | (42.4) | 41 | (42.3) | 83 | (42.3) |

| Serious injury, harm or death you caused to someone | ||||||

| Happened to me | 3 | (3.0) | 4 | (4.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Witnessed it | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Learned about it | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Part of my job | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Not sure | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Does not apply | 95 | (96.0) | 88 | (90.7) | 183 | (93.4) |

| Any other stressful event or experience | ||||||

| Happened to me | 28 | (28.3) | 31 | (32.0) | 59 | (30.1) |

| Witnessed it | 5 | (5.1) | 5 | (5.2) | 10 | (5.1) |

| Learned about it | 5 | (5.1) | 2 | (2.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Part of my job | 4 | (4.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 6 | (3.1) |

| Not sure | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| Does not apply | 60 | (60.6) | 58 | (59.8) | 118 | (60.2) |

| Childhood physical abuse | ||||||

| Happened to me | 10 | (10.1) | 8 | (8.2) | 18 | (9.2) |

| Witnessed it | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Learned about it | 3 | (3.0) | 6 | (6.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Part of my job | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Not sure | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Does not apply | 86 | (86.9) | 84 | (86.6) | 170 | (86.7) |

| Childhood sexual abuse or molestation | ||||||

| Happened to me | 5 | (5.1) | 2 | (2.1) | 7 | (3.6) |

| Witnessed it | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Learned about it | 4 | (4.0) | 5 | (5.2) | 9 | (4.6) |

| Part of my job | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Not sure | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Does not apply | 90 | (90.9) | 89 | (91.8) | 179 | (91.3) |

| Which one of these was the worst event that has happened to you? | ||||||

| Natural disaster | 1 | (1.0) | 4 | (4.1) | 5 | (2.6) |

| Fire or explosion | 2 | (2.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 4 | (2.0) |

| Transportation accident | 16 | (16.2) | 17 | (17.5) | 33 | (16.8) |

| Serious accident not transportation | 12 | (12.1) | 11 | (11.3) | 23 | (11.7) |

| Physical assault | 15 | (15.2) | 6 | (6.2) | 21 | (10.7) |

| Assault with a weapon | 8 | (8.1) | 5 | (5.2) | 13 | (6.6) |

| Sexual assault | 9 | (9.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 18 | (9.2) |

| Other unwanted sexual experience | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Captivity | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Life-threatening illness or injury | 5 | (5.1) | 12 | (12.4) | 17 | (8.7) |

| Severe human suffering | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Sudden, violent death | 9 | (9.1) | 7 | (7.2) | 16 | (8.2) |

| Sudden, unexpected death of someone close to you | 12 | (12.1) | 10 | (10.3) | 22 | (11.2) |

| Serious injury, harm or death you caused to someone | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Any other stressful event or experience | 4 | (4.0) | 10 | (10.3) | 14 | (7.1) |

| Childhood physical abuse | 2 | (2.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Childhood sexual abuse or molestation | 2 | (2.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| How old were you when the event started/happened? (age in years) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 33.5 | (14.4) | 31.8 | (13.5) | 32.7 | (13.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 33.0 | (20.0–45.0) | 27.0 | (21.0–42.0) | 30.0 | (21.0–43.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | (5.0, 69.0) | (8.0, 68.0) | (5.0, 69.0) | |||

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| How long did the event last? (time in hours) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 36.2 | (128.7) | 25.3 | (80.4) | 30.8 | (107.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.5 | (0.2–3.0) | 1.0 | (0.2–6.0) | 1.0 | (0.2–4.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | (0.0, 720.0) | (0.0, 600.0) | (0.0, 720.0) | |||

| Missing (%) | 5 | (5.1) | 6 | (6.2) | 11 | (5.6) |

| How long ago did the event end? (time in months) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.5 | (73.6) | 36.3 | (80.9) | 37.4 | (77.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 16.0 | (6.0–33.0) | 17.0 | (6.5–28.0) | 16.0 | (6.0–32.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | (2.0, 600.0) | (2.0, 720.0) | (2.0, 720.0) | |||

| Missing (%) | 2 | (2.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 3 | (1.5) |

The most prevalent event reported as the worst experience was a transportation accident (33/196, 16.8%). The next most common category was serious accident (not transportation) (23/196, 11.7%) and then the sudden, unexpected death of someone close to the participant (22/196, 11.2%).

There were some small imbalances observed, for example, physical assault where 15/99 (15.2%) reported this in the CBT-TF arm compared to 6/97 (6.2%) in the GSH arm. Similarly, in the life-threatening illness or injury category only 5/99 (5.1%) participants in the CBT-TF arm reported this as their worst event experience versus 12/97 (12.4%) in the GSH arm. These are relatively small numbers and so some imbalances are to be expected by chance alone even under perfect execution of the randomisation method. There was also a small difference in the ‘Any other stressful event or experience’ but the version of the LEC questions used did not ask the participant to specify the exact event or experience.

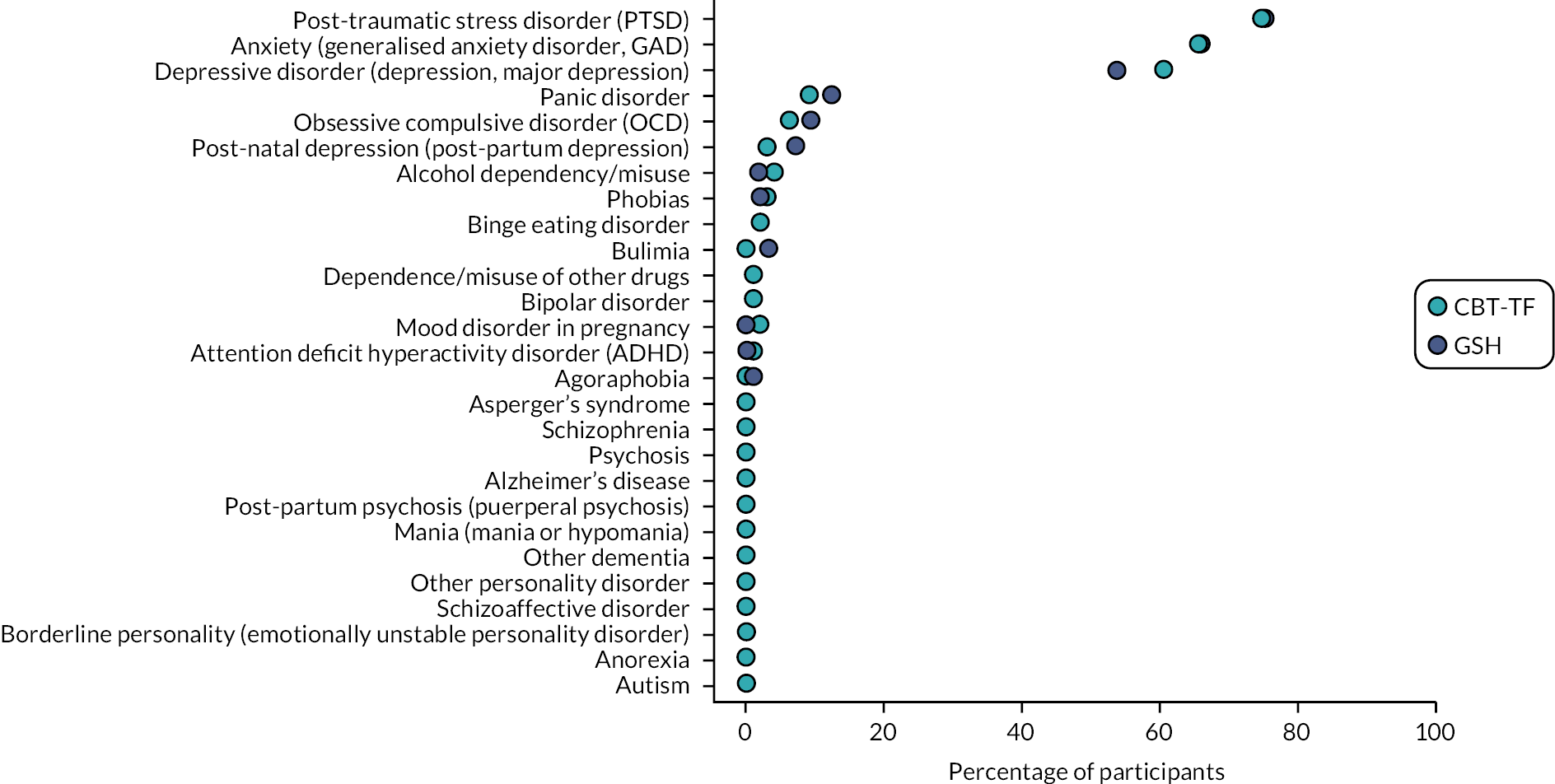

Mental health

During the baseline assessment, participants were asked to report if they had ever been told by a health professional that they had a particular mental health diagnosis. Figure 3 shows the prevalence of the reported mental health conditions. The most prevalent condition was PTSD reported by 147/195 (75.4%) participants. Generalised anxiety was the next most prevalent, reported by 129/196 (65.8%) participants, and depressive disorder the third most prevalent with 112/196 (57.1%) reporting having been told they had this condition. These three conditions were the most prevalent by a long margin. The next most prevalent condition was panic disorder which was reported by 21/196 (10.7%) participants with the remaining conditions reported by 0.0–7.7% of participants. Many conditions which were asked about had no participants reporting as being diagnosed.

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of mental health diagnoses reported at baseline assessment.

There were no serious imbalances observed between the two intervention arms although a small imbalance was observed in participants reporting depressive disorder with 60/99 (60.6%) in the CBT-TF group compared to 52/97 (53.6%) in the GSH arm. Table 6 shows the complete details of the participant responses.

| CBT-TF | GSH | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 99 | N = 97 | N = 196 | ||||

| Have you ever been told by a health professional that you have? | ||||||

| PTSD | ||||||

| Yes | 74 | (75.5) | 73 | (75.3) | 147 | (75.4) |

| No | 24 | (24.5) | 24 | (24.7) | 48 | (24.6) |

| Missing (%) | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| Anxiety (GAD) | ||||||

| Yes | 65 | (65.7) | 64 | (66.0) | 129 | (65.8) |

| No | 34 | (34.3) | 33 | (34.0) | 67 | (34.2) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Agoraphobia | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 96 | (99.0) | 195 | (99.5) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Panic disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | (9.1) | 12 | (12.4) | 21 | (10.7) |

| No | 90 | (90.9) | 85 | (87.6) | 175 | (89.3) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Phobias | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | (3.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 5 | (2.6) |

| No | 96 | (97.0) | 95 | (97.9) | 191 | (97.4) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| OCD | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | (6.1) | 9 | (9.3) | 15 | (7.7) |

| No | 93 | (93.9) | 88 | (90.7) | 181 | (92.3) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Depressive disorder (depression, major depression) | ||||||

| Yes | 60 | (60.6) | 52 | (53.6) | 112 | (57.1) |

| No | 39 | (39.4) | 45 | (46.4) | 84 | (42.9) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | (1.0) | 1 | (1.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| No | 98 | (99.0) | 96 | (99.0) | 194 | (99.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Mania (mania or hypomania) | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Borderline personality (emotionally unstable personality disorder) | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Other personality disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Schizophrenia | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Psychosis | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Autism | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Asperger’s syndrome | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | (1.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) |

| No | 98 | (99.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 195 | (99.5) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Anorexia | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Bulimia | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (3.1) | 3 | (1.5) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 94 | (96.9) | 193 | (98.5) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Binge eating disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | (2.0) | 2 | (2.1) | 4 | (2.0) |

| No | 97 | (98.0) | 95 | (97.9) | 192 | (98.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Mood disorder in pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | (2.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (1.0) |

| No | 97 | (98.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 194 | (99.0) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Post-natal depression (post-partum depression) | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | (3.0) | 7 | (7.2) | 10 | (5.1) |

| No | 96 | (97.0) | 90 | (92.8) | 186 | (94.9) |

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Post-partum psychosis (puerperal psychosis) | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| No | 99 | (100.0) | 97 | (100.0) | 196 | (100.0) |

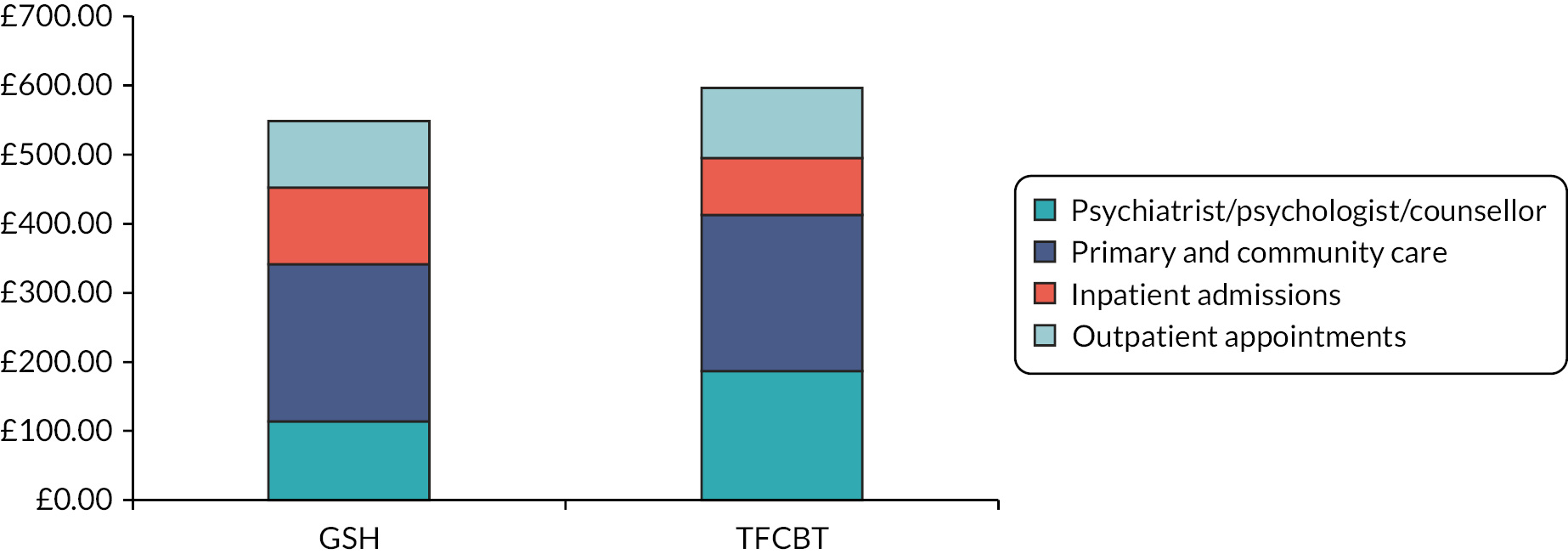

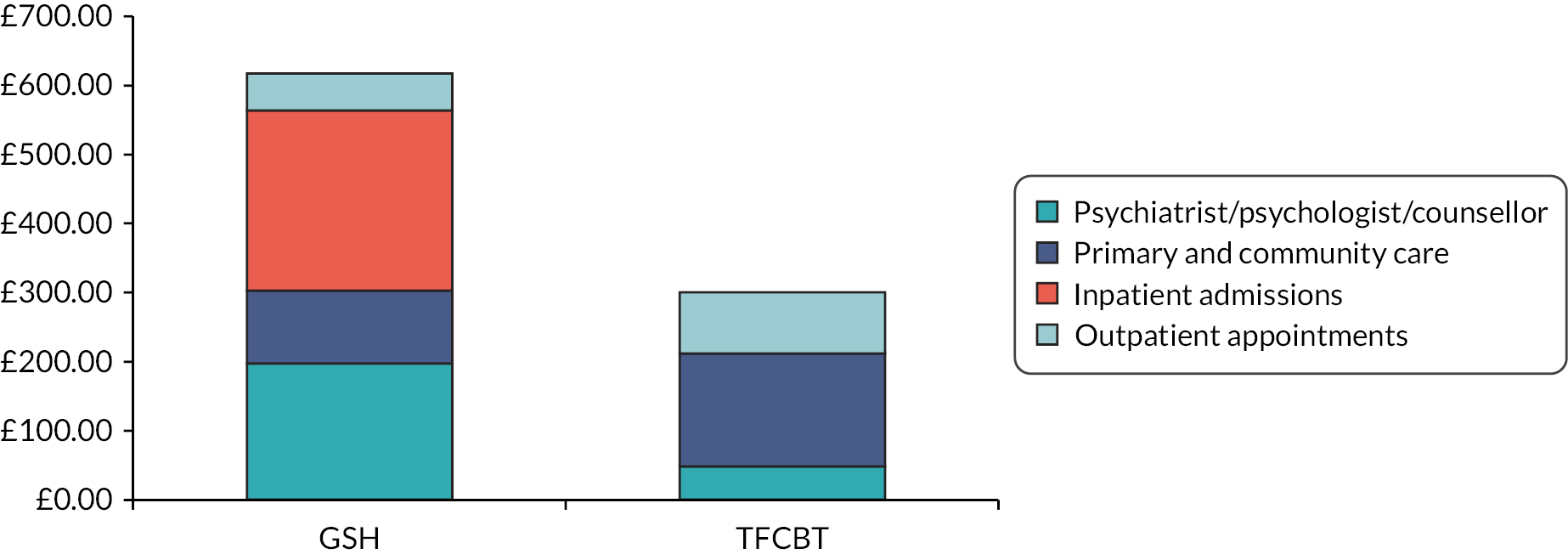

| Missing (%) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |