Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/148/01. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The draft report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in January 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mark Gabbay reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study and membership of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Devices Topic Identification Development and Evaluation board. Rod Taylor reports membership of HTA Themed Call and HTA Efficient Study Designs Boards.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Gabbay et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2012, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme invited research teams to submit proposals to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intervention to integrate debt counselling and advice within a primary care setting (HTA commission call number 11/148). The research question set out in the commissioning brief was ‘Does the provision of debt counselling and advice in primary care improve the health and well-being of people with depression and related debt problems compared with usual GP care?’. 1

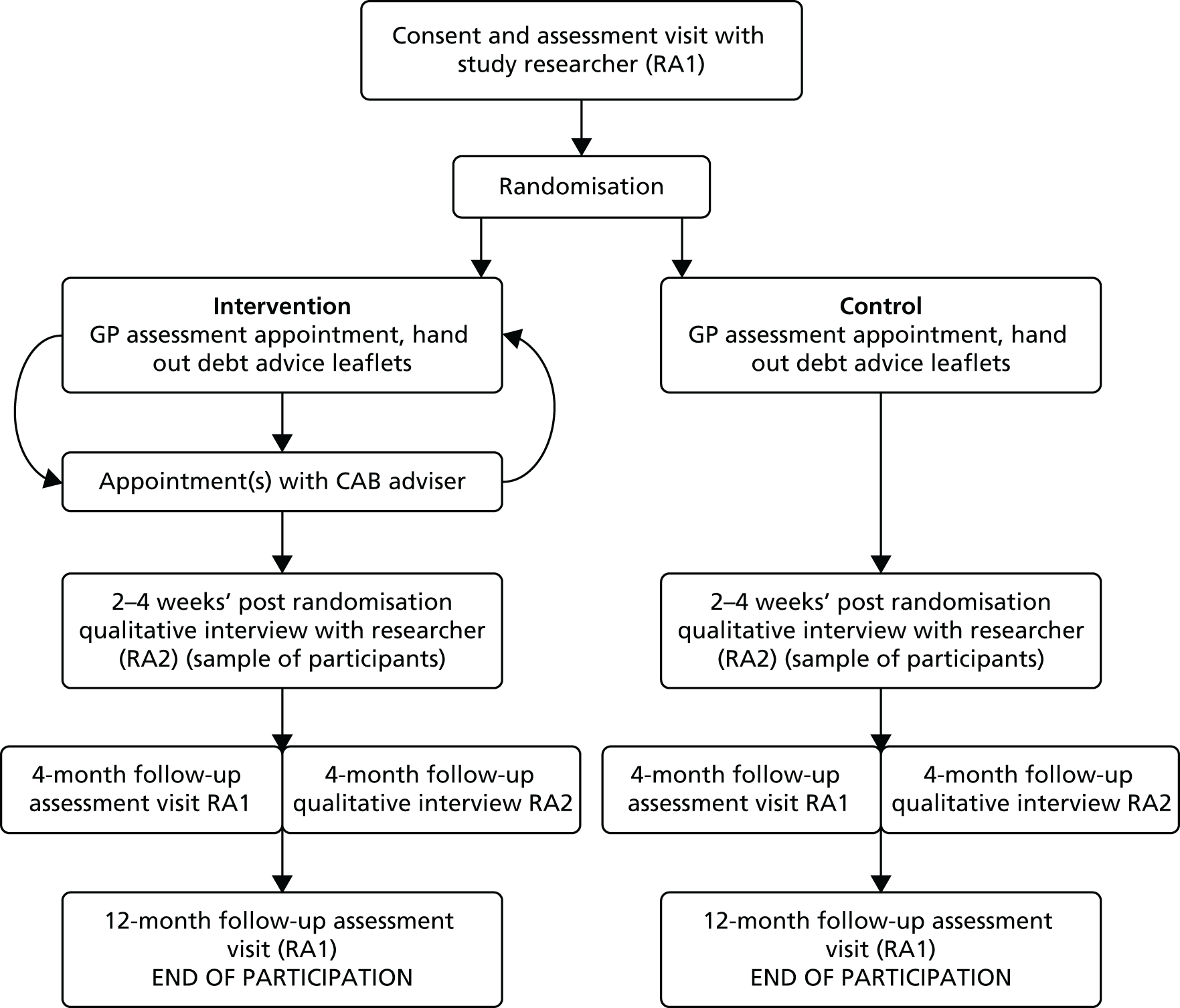

In response to this call, we designed an adaptive, parallel, two-group, multicentre randomised controlled trial [Debt Counselling for Depression in Primary Care: an adaptive randomised controlled pilot trial (DeCoDer)] with a nested mixed-methods process and economic evaluation.

The purpose of our trial was to deliver an intervention for patients with depression and worries about debt within a primary care setting. The intervention was debt advice from a Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB) advisor that incorporated a shared biopsychosocial assessment by a general practitioner (GP) and debt advisor. We planned to evaluate this intervention in terms of its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, collecting data at baseline and at 4 and 12 months, to compare mental health, well-being and cost-effectiveness outcomes. We also planned to assess the acceptability and accessibility of the intervention, and facilitators of and barriers to recovery through both quantitative and qualitative data collection. We conducted an internal pilot trial to test the procedures, recruitment processes and operational strategies planned for use in the main trial, so that we could identify and resolve any problems and thereby assess the feasibility of continuing with the main trial. As a result of issues related to practice recruitment, trial set-up and participant recruitment, the target sample size for the pilot trial was not achieved according to the pre-defined stopping rules. After consultation with the NIHR HTA, the trial was stopped and data collection was completed at 4 months for those already recruited at that stage.

Given that the study failed to reach its recruitment target and was terminated early during the internal pilot phase, and therefore did not progress to main trial, we report here the findings of the pilot trial including descriptive statistics [mean and standard deviation (SD)] for the primary, secondary and economic outcomes by group, at baseline, and at 4- and 12-month follow-up (when available). We also present the findings of our qualitative analyses concerning participants’ experiences of debt and depression, the intervention and their involvement in the trial. Using the normalisation process theory (NPT) approach,2 we report some of the potential barriers to and facilitators of implementing the intervention in practice.

We also report in detail the recruitment process and outcomes, our comparison of cluster versus individual randomisation and the various challenges we faced in trial set-up and in recruiting general practices and participants to the study. Our account provides key learning points that will be particularly beneficial to future researchers planning randomised controlled trials with hard-to-reach and vulnerable groups in primary care. This group of patients is typically those who are suffering the greatest health inequalities and it is, therefore, important for the future of research design to understand how we can access such patients and maximise data collection in these populations.

We note at this point that by the time the current study had been approved for funding and was ready to commence recruitment, an advice service provided by CAB had already been commissioned by the Clinical Commissioning Group in one of the three study sites. In April 2012, the Clinical Commissioning Group in this site agreed to pilot as part of their primary mental health care strategy, a CAB service called the ‘Advice on Prescription Programme’. The proposed model, new for primary mental health care, included a ‘practical offer’ of advice based in primary care aimed at the most vulnerable patients. This service offered quality-assured advice on benefits, debt, housing and employment support. The service was originally piloted in nine GP surgeries from April 2012 to March 2013 and then rolled out across all practices from April 2013, following independent evaluation. 3

The service continued throughout the current pilot trial period and was aimed at people who were at risk of developing mental health problems as a result of their circumstances. Although this service differed from that proposed in the pilot trial, it is evidently possible that the availability of this service within general practices might have contributed to the difficulties we encountered recruiting general practices to the study in this particular research site.

Scientific background

History of the problem

Depression is estimated to affect 5–19% of adults at any one time. 4,5 Depression is a common presentation in primary care. 6 However, research suggests that only around 2.5% of patients are formally recorded by GPs as having active depression or depressive symptoms. 7,8 Alongside anxiety and stress, depression is considered the most common cause of prolonged work absenteeism,9 as well as presenteeism (working below normal capacity when unwell). Recent work on the cause of sickness absence indicates that the proportion of absence due to mild to moderate mental health problems is increasing. 10 Mental ill health is estimated to cost the UK economy £40B per year overall. 11,12

Around 16% of the UK population is estimated to be struggling with personal debt,13 and there is increasing evidence of a link between debt and poor mental health. 14,15 In a recent study on the association between suicide and the 2008–10 economic recession in England, Barr et al. 16 identified a link between rising episodes of suicide and rising debts.

The changing composition of debt and the rise of debt problems

Indebtedness and poverty are endemic in Great Britain,17 particularly in areas of deprivation and high unemployment, and the economic downturn has only further exacerbated these problems. A report by Lucchino and Morelli18 found that the difference in consumption growth and income growth was largest among those on the lowest incomes. The authors concluded that people in the lowest income decile appeared to be reliant on credit to maintain consumption. Similarly, a UK study that analysed data from clients seen by the then Consumer Credit Counselling Service (now called StepChange) found high debt-to-income ratios in households with incomes of up to £13,500. These households held unsecured debts worth 20% more than their annual net income. 19

In a recent study examining the relationship between the increasing number of food banks across the UK and current austerity, it was found that food banks were more likely to open up in areas of higher unemployment and those most affected by welfare cuts and benefits sanctions. 20

Summary of management of depression in primary care

Most episodes of depression are managed in primary care, following the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence-recommended four-step approach. 7 This involves a range of low-intensity interventions including social prescribing to support lifestyle changes (e.g. for exercise), short-term talking therapies and antidepressants for more persistent symptoms. However, a recent HTA trial21 found a marginal benefit of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (antidepressants) for new cases of mild to moderate depression managed in primary care over treatment as usual (TAU). Consequently, many questions remain about the most cost-effective ways to manage depression. 7

Current debt advice services: issues and gaps

In 2013, the Money Advice Service reported that nearly one in five adults in the UK was affected by problem debt. 22 There has been a sharp rise in demand for debt advice. A recent survey found a 56% increase in demand for debt advice in the 3 years since 2012. 23 The last few years have seen an increase in the number of ‘priority’ debts, including housing, utilities and government debts (issues about benefits and tax credit overpayments, social fund debts, child support arrears and magistrate court fines), and a decrease in non-priority debts. 24 Between 2005–6 and 2014–15, the number of priority debts that CAB provided advice for more than doubled, whereas personal loan and credit card debt (non-priority debts) over the same period more than halved since their peak in 2008. 24

Recognising the increasing burden of indebtedness and the link between debt and mental ill health outlined in the Foresight Report,25 the UK government now provides web-based advice and guides on debt management, highlighting a range of providers. 26 Debt advice services are, therefore, now freely available from commercial, public and third-sector providers. Topping this list is CAB, a charity-based service that is widely available across the UK in > 3500 locations and provides support to > 2.5 million people per year. 27 Its principal online recommended site is provided by the government, funded by a statutory levy from the financial services industry and backed by a national advertising campaign (the Money Advice Service; www.moneyadviceservice.org.uk/). However, currently there is no robust evidence regarding the impact of these services on mental health outcomes or their cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, those with depression, especially those from socioeconomically deprived groups, may be particularly likely to find such online services insufficient or inaccessible (because of travel cost, low mood, poor information technology skills and no/low access to information technology and telephone); therefore, a locally accessible, nationally provided advice service was thought, at the time of our application submission, to be a potentially important way to provide easier access to those with the greatest need. Debt is more common among poorer populations, and is a problem in around one in four of those experiencing mental health problems. This group with mental health problems make up 50% of those with debt overall. 28,29 The strategic economic case for providing debt advice for people experiencing mental health problems has been made in recent influential reports, and the intervention we proposed in the current study fell within the suggested service provision costs and model. 30,31

Relationship between debt and depression

A clinical knowledge summary on assessing people with depression advises recording psychosocial factors ‘contributing to the development of depression’;32 at the top of the list are employment and financial worries. In discussing the relationship between debt and depression, it is important to stress that the debt relates to financial liability that is large in relation to income and is difficult or impossible to repay. 33

Social surveys have consistently found a negative correlation between unsecured personal debt and subjective measures of happiness and life satisfaction. 34,35 One debt charity found that debt affected people’s sleep and concentration at work, and put a strain on family relationships. 23 Another debt charity, Citizens Advice, released data suggesting that 60% of its clients had received a mental health diagnosis within the previous 6 months and that in 56% of cases its debt advisors felt that their clients’ mental state had a negative impact on their ability to make ‘reasonable decisions’ about credit. 36

A survey by Mind37 identified an increase in rates of debt among people with mental health problems. This report suggests that a two-way relationship can exist between debt and mental health. Of those people surveyed, nearly three-quarters thought that their mental health problems had made their debt worse. This rose to more than four-fifths among those in problem debt, which was defined as occurring ‘where an individual is two or more consecutive payments behind with a bill or repayment’ (p. 1). 37 In addition, almost 9 out of 10 of those in problem debt said that they thought that their financial difficulties had made their mental health problem(s) worse.

A recent meta-analysis on the relationship between personal unsecured debt and health38 found a significant relationship between debt and depression. The authors identified psychological elements, such as worry and stress, hopelessness, and locus of control, as potentially playing a role in mediating the relationship.

In a large household survey, Bridges and Disney39 found a strong association between depression and self-reported indebtedness and financial stress. They also found a weaker link between the onset of depression and subsequent financial difficulties. Although they found no direct association between objective measures of depression and debt, the authors did find an indirect association via subjective indicators of financial well-being.

Fitch et al. 40 conducted a systematic narrative analysis of peer-reviewed literature on the relationship between personal debt and mental health. They found that indebtedness may contribute to the development of mental health difficulties and mediate accepted relationships between those difficulties and poverty and low income.

Drawing on data from a national household survey, Gathergood41 has explored some of the causal links between problem debt and depression and has introduced the idea of social norm effects. He concluded that exogenous factors, such as the level of social stigma in relation to debt, may have both positive and negative effects on the links between debt and depression.

In conclusion, the literature suggests that social and psychological factors may mediate the relationship between debt and depression, in either direction. Longitudinal research is needed to explore aspects of the relationship between debt and depression further, such as (the direction of) causality and the specific mechanisms and mediators that are involved. This may help in developing appropriate policies and practices to help (depressed) people avoid and manage problem debt, and to prevent and treat depression in those with debt. Research would also help identify which type of intervention works best for whom.

Aims and objectives of the main trial

As reported above, the early termination of this study in the pilot phase precluded statistical evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention. However, we were able to address most of key objectives of the main trial in a modified form, as detailed below in italics.

The objectives of the main trial were:

-

to compare depression between intervention and control groups – we report descriptive statistics (mean and SD) at baseline and at 4 and 12 months, when available

-

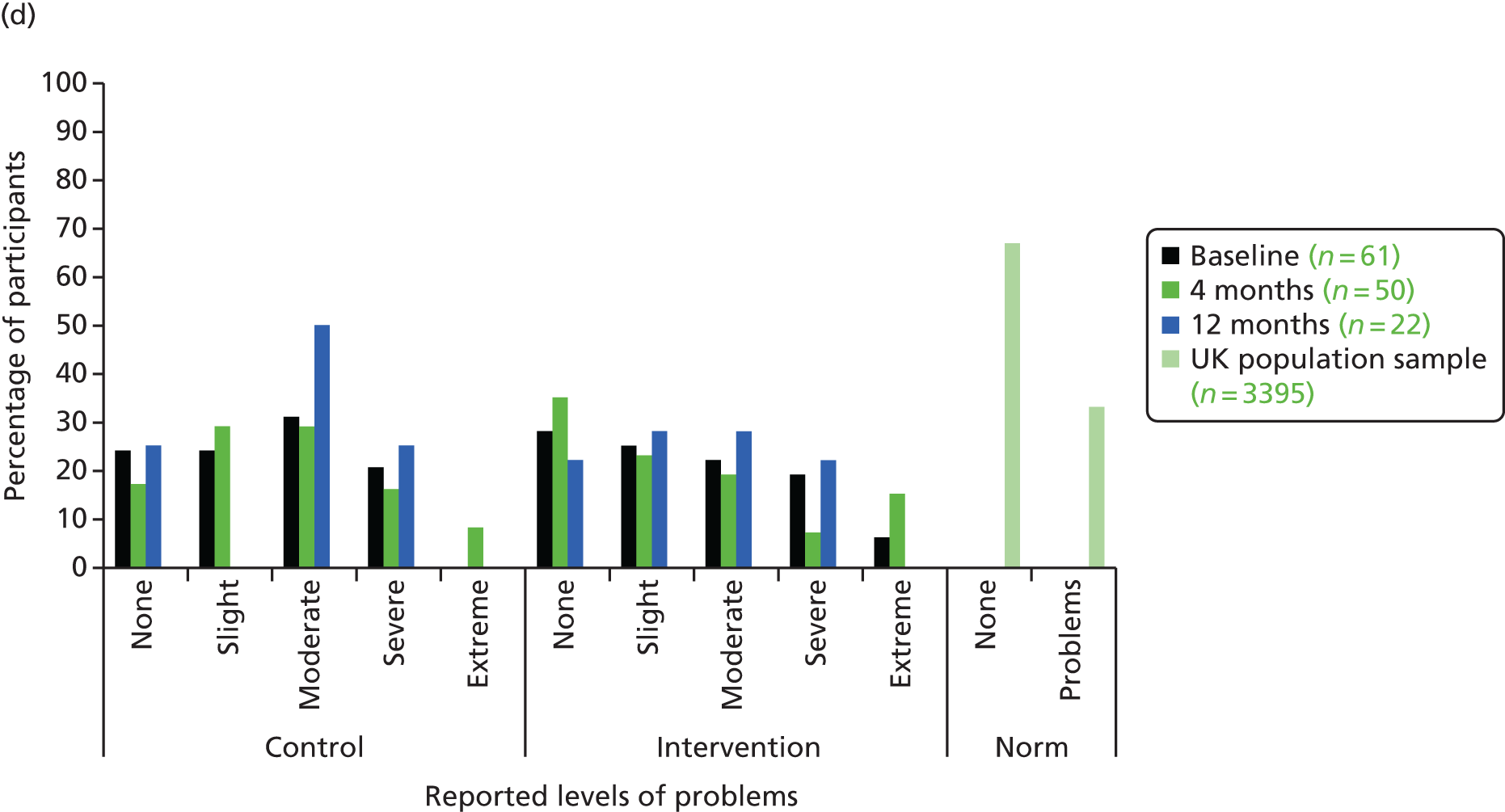

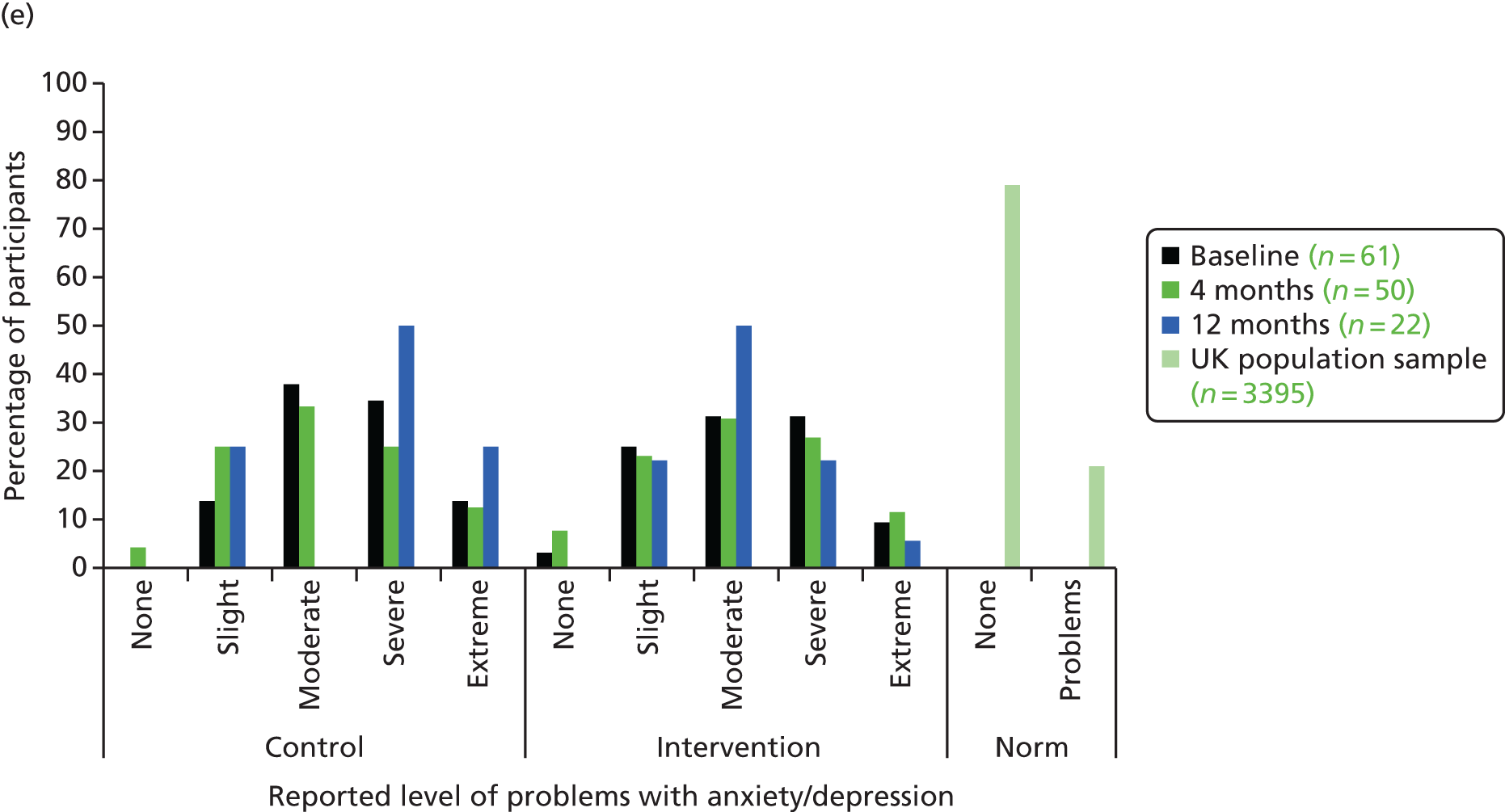

to compare anxiety, mental well-being, debt/financial status, satisfaction, health-related quality of life and societal costs between intervention and control groups – we report descriptive statistics (mean and SD) at baseline and at 4 and 12 months, when available

-

to explore outcomes referred to in (1) and (2) in terms of the following potential predictors – substance misuse problems, self-esteem, life events and difficulties, hope, optimism, resilience and attribution style – we report descriptive statistics only

-

to determine core outcome domains and measures using the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials initiative approach to define a standard outcome measure for mental health trials in deprived and hard-to-reach groups in primary care, adapted to this specific study – we make tentative recommendations only

-

to manualise debt assessment, joint comprehensive assessment (GP/patient/CAB) and counselling intervention for use within the intervention – we undertook limited testing

-

to recruit new and chronic/recurrent cases from a variety of practices and populations to enhance generalisability – we could not address

-

to undertake a mixed-methods process evaluation to assess fidelity of intervention (using NPT) and explore reasons for observed outcome differences and relationships between depression, anxiety, debt, stigma, shame and psychosocioeconomic factors; triangulating economic, psychological factors analysis and qualitative interview data – we have partially addressed

-

to undertake knowledge exchange events to inform adoption into care pathways (implementation) – we will undertake a reduced dissemination plan

-

to work closely with service users in research/patient and public involvement (PPI) groups across the study sites to inform trial methodology, intervention development, aspects of analysis and the implementation of preparatory work – we addressed in full

-

to recruit a virtual group of commissioners, providers and health and well-being board members to check willingness to commission the intervention and advise on domains and measures – we undertook a modified activity

-

to work with CAB leads, GPs and PPI advisors on developing the intervention and comprehensive assessment, qualitative topic guides and aspects of data analysis – we addressed in full.

Aims and objectives of the pilot trial

The aim of the pilot trial was to test the procedures, recruitment processes and operational strategies that were planned for use in the main trial and to identify and resolve any problems in continuing with the main trial. We addressed this aim and all of the following objectives of the pilot trial:

-

to confirm methods for recruitment of practices

-

to test the ability to recruit patients via the proposed approaches

-

to confirm the acceptability of the study interventions

-

to confirm acceptability of data collection (outcome measures)

-

to assess contamination and confirm the randomisation method for the main trial

-

to assess the level of participant attrition

-

to check the robustness of data collection systems

-

to identify and resolve potential difficulties in implementing the shared assessment

-

to assess intervention fidelity.

Intervention: theory and development

Our intervention was informed by the principles of collaborative care. 42,43 The principles of collaborative care include (1) adopting a multiprofessional approach (e.g. a GP plus at least one other professional), (2) a structured management plan, (3) scheduled patient follow-up and (4) enhanced interprofessional communication. A collaborative approach to patient care has been shown to improve quality of life, healthy behaviours, self-efficacy and other health outcomes. 44 In addition, our intervention aimed to redress inequalities and promote social inclusion of marginalised groups. 45 Our intervention was based on the assumption that social context plays an important role for mental illness onset and recovery, particularly in the case of debt and depression. 40

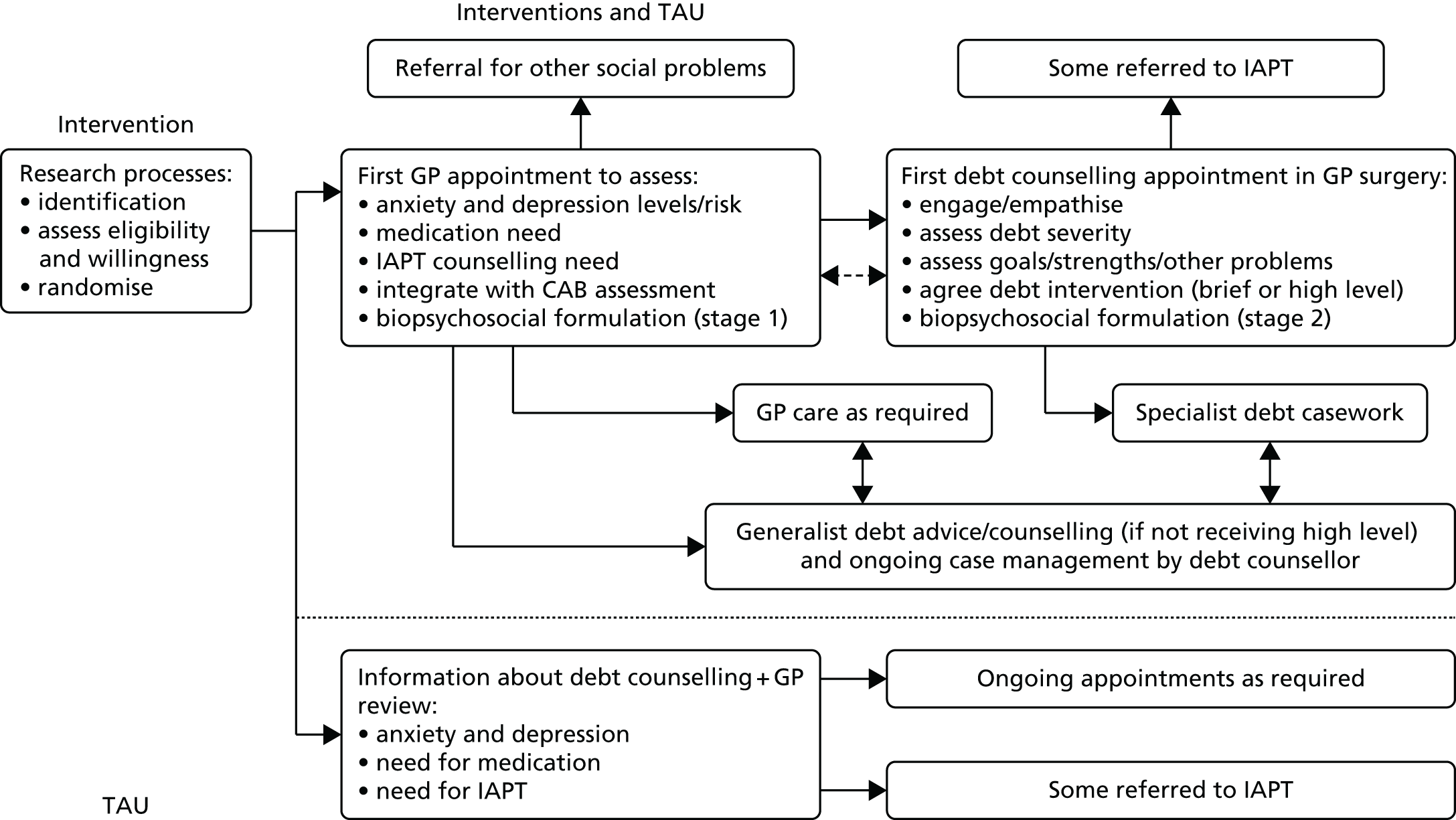

Our intervention brought together two existing services: (1) primary care mental health services provided by general practices, supplemented by Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services in England, and in Wales a variety of counselling and psychological therapies services; and (2) debt counselling provided by third-sector providers, such as CAB (see Figure 1).

Our model of debt advice – debt advice provided by CAB advisors – was distinct from many of the commercially available offers of debt consolidation as the focus of our intervention was on face-to-face debt advice, assessing the level and urgency of debts and arrears, and then triaging clients to specific detailed advice on debt or money management.

Liaison has been shown to be an important element of collaborative care and shared care more generally. 46 In developing the intervention we considered that communication would be enhanced through a comprehensive assessment that was cocreated by, and shared among, the patient, CAB advisor and GP. The purpose of the shared comprehensive assessment (SCA) was to combine social, psychological, environmental, economic and medical perspectives with personal goals, in the production of a biopsychosocial management plan. We developed a SCA form for sharing of information between GPs and CAB advisors with input from GPs, CAB advisors and managers and service users (see Appendix 1).

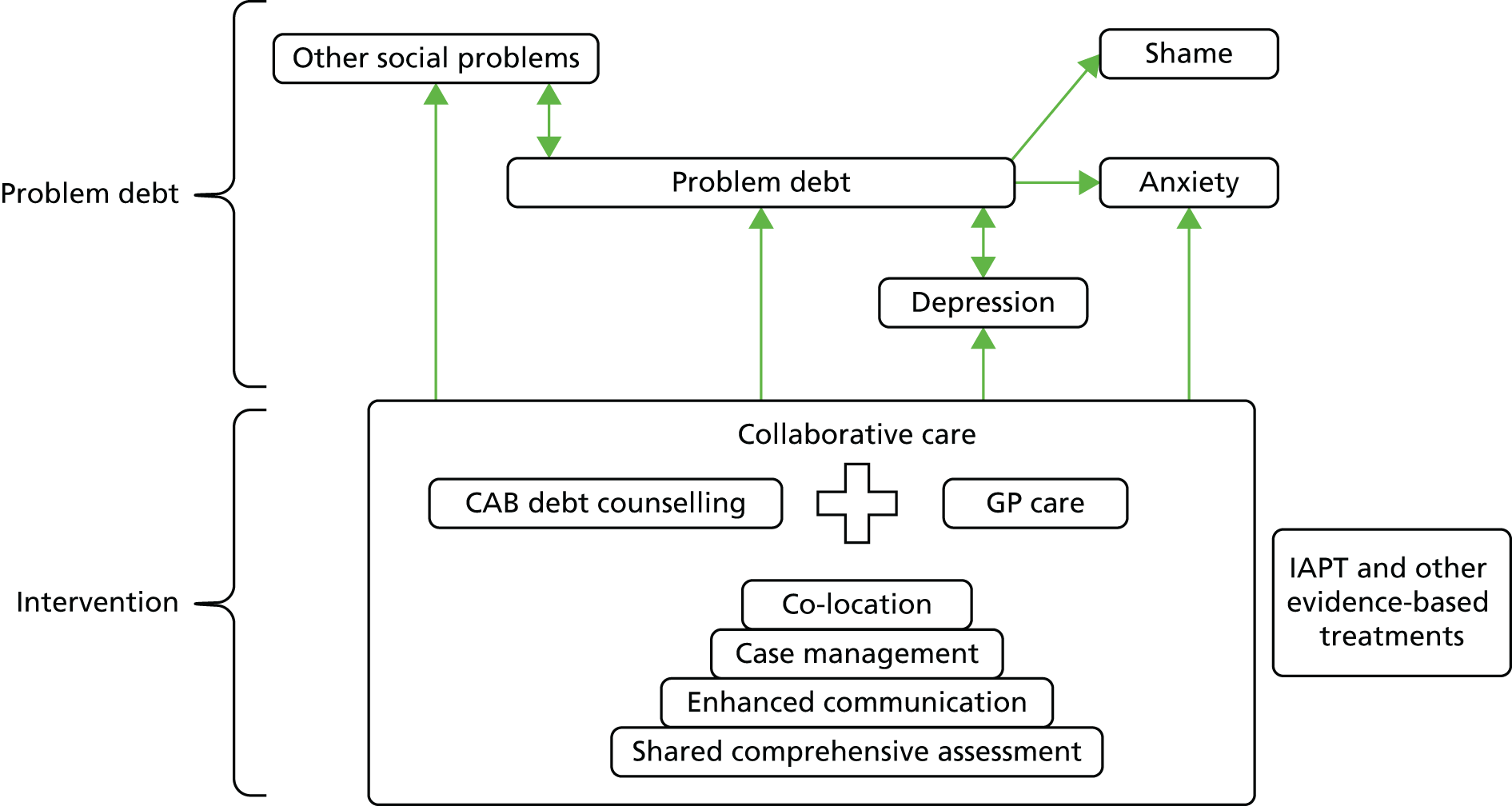

The active parts of our intervention as a whole were the combining of primary care treatment of depression with the addition of debt counselling and a comprehensive shared assessment, supported by the co-location of GP and debt advisor in primary care; the additional pathways of care; enhanced communication between the GP and debt advisor; and case management for participants (see Appendix 2). Figure 1 summarises all the aspects of the intervention and TAU options, whereas Table 1 summarises and compares the contributions of the GP and CAB advisor within the intervention. Figure 2 maps the key components of this approach: co-location, shared assessment and enhanced interdisciplinary communication.

FIGURE 1.

Intervention diagram.

| GP | CAB advisor |

|---|---|

| Undertake initial part of shared assessment and complete form (estimated to take up to 20 minutes – double appointment slot) | Undertake CAB section of shared assessment |

| Commitment to share care and decisions with the CAB advisor, with patient at the centre of care | Commitment to share care and decisions with the GP, with patient at the centre of care, sharing information with GP as part of structured agreed plan, plus informal case liaison as required |

| Share additional information with CAB advisor as appropriate (using shared comprehensive GP follow-up form) as part of structured management plan and enhanced communication between GP/CAB | Case manage patient and work with GP team to encourage engagement and retention within the planned intervention taking account of contexts of shame, stigma and chaotic life circumstances, the patient and their attendances during intervention |

| Work with patient and CAB advisor to encourage engagement and retention within plan in contexts of shame, stigma and chaotic life circumstances | Support patient to devise and deliver solutions to debt problems sensitive to mental health contexts |

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual map of the intervention and potential impact for individuals.

Process evaluation

We used semistructured interviews with participants, GPs and CAB staff to evaluate the process of integrating the intervention within primary care. We adopted a NPT approach2 to data analysis, which focuses on the various actors, objects and context of the intervention (see Chapter 2, Intervention process evaluation, Data analysis, for more detail of this approach).

Chapter 2 Methods

Pilot trial design

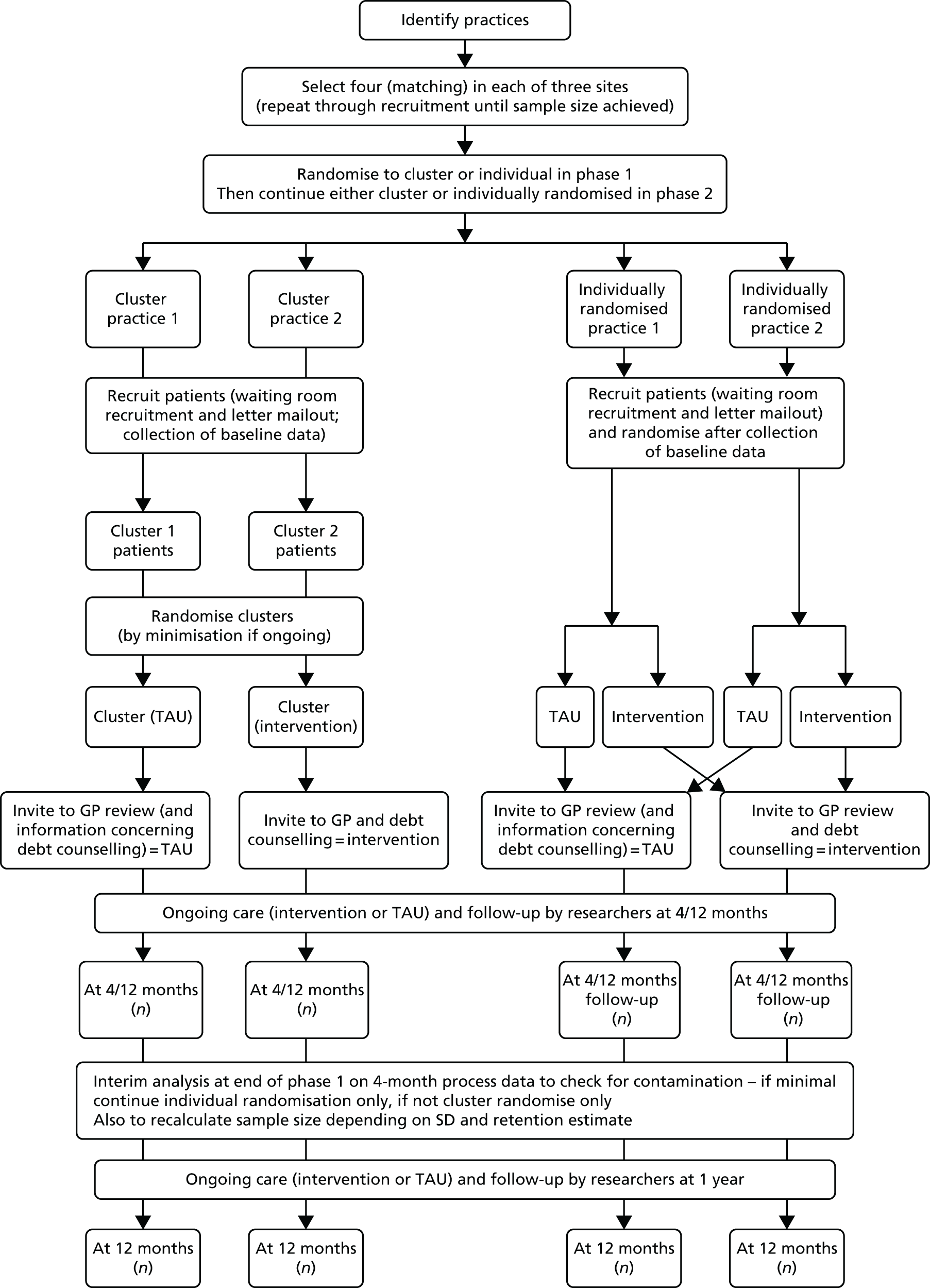

We designed an adaptive, parallel, two-group, pragmatic randomised controlled trial with 1 : 1 allocation to intervention or TAU control, with a planned mixed-methods process and economic evaluation. During the pilot trial we assessed intervention fidelity and any implementation problems, seeking to resolve any issues without change to the intervention so that data collected in the pilot trial could be used in the final analysis at the end of the full trial. We used both individual and cluster randomisation methods in the pilot trial to assign participants to the intervention or the control arm (see Table 1), with the aim of using individual-level randomisation in the main trial (should it have gone ahead) if the pilot trial showed no substantive evidence of contamination (crossover of the intervention between trial arms).

Changes to trial protocol and methods

We undertook several revisions of the protocol and study methods over the course of the pilot trial in response to the differing issues we encountered. This was within the parameters of the adaptive design within which we anticipated a degree of iterative protocol development in the internal pilot phase. The changes to the protocol and methods (listed in this section) were approved by the NIHR HTA programme, the University of Liverpool (research sponsor), Research Ethics Committee North West, in Preston, and the local research management and governance offices [Clinical Research Network (CRN), North West Coast (lead CRN), Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust and Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board].

Changes to exclusion criteria

Following confirmation from CAB that participants could be visited in their own home by CAB advisors, we removed ‘housebound’ from the exclusion criteria.

Following early contacts with interested patients, we made an addition to the study exclusion criteria to exclude patients (prior to consent) who did not wish to take up support for debt/money worries provided via the general practice. This was to ensure that potential participants were clear about what their participation might involve, and that we consented into the study only those who were interested in receiving support for their money worries through this route.

Changes to participant recruitment procedures

Our original intention was that CRN staff would support research assistants (RAs) in handing out flyers (advertising the study) and expression of interest (EOI) forms to patients in general practice waiting rooms. As a result of resource issues, CRNs were unable to support these activities, so we approached general practices to ask if their staff would be willing to hand out flyers/EOI forms; following necessary approvals, general practice staff (including reception staff) in some practices did this. The potential benefits of this change were twofold: first, if all patients were simply handed the flyer at reception, patients would not feel like they were being singled out in the waiting room; and, second, patients would still be able to receive information about the research when RAs were not in the practice, ensuring that as many patients as possible were given the opportunity to be made aware of the study and register their interest. We also made a change to the information pack sent out to patients by post, namely adding the advertisement flyer. This meant that patients could read the brief summary information in the flyer and decide whether or not they were interested in the study before they went on to read through the much more detailed participant information sheet.

Change to requirement for general practitioners to check identified patient lists

Towards the end of the pilot trial we changed the directive for GPs to check patient lists generated from practice database searches to a neutral suggestion that GPs may choose whether or not to check the patient list. The reasons for this change were twofold. First, although all GPs received similarly worded advice, our experience showed that individual GPs were checking patient lists in very different ways. Some were looking at records in great detail and excluding substantial numbers of potential participants, some of whom might have been eligible to participate and were potentially being denied the opportunity. Other GPs adopted much narrower exclusion criteria, simply confirming no errors in coding and that a patient’s participation was not impractical (e.g. because they were recently bereaved, terminally ill or sleeping rough). We considered the ethical issues regarding this change, and felt that, although the original protocol was based on the idea that GPs should exclude those patients whom they deemed unsuitable for us to approach, it was also equally valid that patients make this choice for themselves on reading the flyer and letter of invitation. Second, based on recruitment rates at that time, we needed to increase considerably the number of patients approached by letter, at least doubling the number of patients we had originally planned to approach in each practice. We were already aware that some GPs were struggling to find time to check the number of patients originally planned, resulting in delays to patient recruitment. This difficulty would have been further compounded by increasing numbers of patients for review. In the event, this change was introduced just before the trial was closed, so only one practice was recruited after the change came into effect, and it was not possible to judge the impact of this change on recruitment delays.

Change to mail-out procedure

Following a request from one practice, we introduced the option for practices to use the Docmail® v2.0 (CFH Docmail Ltd, Radstock, UK) service for sending out the information pack to patients, but this practice was the only one to adopt this method. It did not result in any important delays or additional complexities to recruitment.

Practice identification, recruitment and training

In the pilot trial, we planned to recruit 12 general practices across the three research centres (with an average of approximately 10,000 patients per practice). Two of these practices were to be those in which GP members of the research team were based. Using these two sites early in the pilot enabled the GP academics on the study team to closely monitor how the systems worked within their practices. This facilitated feedback from colleagues about problems, enablers and barriers to delivering the study, thus informing team discussions about adaptations during the pilot. The remaining practices were randomly selected (by the study statistician) from the full list of practices at each site. All practices were matched according to whether situated in high- or low-deprivation communities and practice size (large/medium/small).

Identified practices were initially approached by CRN staff (and in one centre by research staff) and sent an invitation letter with brief information about the study (see Appendix 3). We followed up this initial communication with a telephone call (from the CRN officer or a member of the research team, if appropriate) to ascertain if the practice was interested in the study. When a practice declined to participate, the study statistician identified further matched practices.

When a practice registered interest in participating in the study, we arranged a meeting between GPs/practice staff and members of the research team to discuss this. In some sites, CRN staff also attended practice meetings to discuss the support they could provide to practices.

No financial incentives were offered to practices for taking part in the study. Service support costs were reimbursed for meetings with the research team, for administrative activities carried out by practice staff (e.g. practice database searches) and for a GP’s time spent checking patient lists, and excess treatment costs were met for GPs delivering the shared assessment component of the intervention. Control GPs did not receive any payment for providing TAU and handing out the two debt advice leaflets to participants in the control arm of the trial.

Following paired practices’ agreement to take part, we informed practices of their allocation and asked them to select the GPs and staff members who would be involved in the study. Principal investigators and/or research managers arranged further meeting(s) with GPs and selected staff for the purposes of training, and CAB staff met with GPs and practice staff (when appropriate) to explain the debt advice process and what this would entail. We provided GPs with a study pack containing supporting documentation including a participant pathway flow diagram (see Appendix 4), a protocol guidance sheet (relevant to practice allocation) (see Appendices 5 and 6), a serious adverse events form (see Appendix 7), a copy of the study debt advice leaflet (see Appendix 8), a copy of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ debt advice leaflet47 and the SCA form (see Appendix 1), when appropriate. For intervention practices we also discussed the shared biopsychosocial assessment and stressed that this was an important component of the intervention, intended to support case management by the CAB advisor and facilitate the sharing of relevant key elements of the history and progress. We sent GPs and relevant practice staff a link and login to the password-protected study website, and training was provided using test data. Research managers and/or RAs provided ongoing support for GPs and practice staff via telephone calls, e-mail communications and further visits to the practice.

Trial participants: selection and recruitment

Patients with a history of depression (with or without anxiety) within the last 12 months and who also had worries about personal debt were identified through participating general practices at the study centres.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were eligible to take part if they:

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

scored ≥ 14 on the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II)

-

had worries about personal debt.

Patients were excluded from taking part if they:

-

were actively suicidal or psychotic and/or severely depressed and unresponsive to treatment

-

were experiencing severe problems with addiction to alcohol or illicit drugs

-

were unable or unwilling to give written informed consent to participate in study

-

were currently participating in another research study including follow-up data collection phase

-

had received CAB debt advice in the past 12 months

-

did not want support about debt or money worries provided through the general practice.

Participant recruitment

We recruited patients to the study via two approaches.

-

GP database searches and letter mail-out: practice database searches were conducted by CRN officers or practice staff to identify adult patients potentially with current depression or who had depression-related treatment in the last 12 months. GPs subsequently screened generated patient lists to exclude any patients they deemed inappropriate for the study (with one exception after a protocol amendment, see Change to requirement for general practitioners to check identified patient lists). Practices sent a standard introductory pack (including covering letter, advertisement flyer, participant information sheet, EOI form and freepost envelope) (see Appendices 9–12) to potentially eligible patients.

-

Waiting room recruitment: publicity posters (see Appendix 13) were displayed in the waiting rooms of participating general practices and flyers with attached EOI forms (see Appendices 10–12) were placed around the practice waiting room. Flyers/EOI forms were also handed out by study RAs in practice waiting rooms, and in some practices by practice staff. Interested patients were able to either hand the completed EOI form back to the RA or return it at a later date in the freepost envelope provided.

Participant eligibility checking and consent

On receipt of a completed EOI form, local RAs contacted the respondent by telephone to discuss the study and assess initial eligibility (i.e. that the patient had worries about debt that they were personally responsible for, was not currently taking part in any other research, had not received debt advice from the CAB in the past 12 months and was interested in receiving support for money worries provided via their general practice). If, after this, the patient was still interested in taking part in the study (and eligible at this point), the RA arranged a date and time to meet with the patient to complete the formal consent to participate process, including obtaining formal written consent (see Appendix 14), a final-stage eligibility check (completing the BDI-ll) and the collection of baseline data (Table 2). Participants scoring < 14 on the BDI-ll were advised that they were not eligible to take part in the study, thanked for their time and willingness to participate, and given the same two debt advice leaflets as those given to study participants.

| Data/measure | Baseline | 4 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic (age, sex, deprivation score, etc.) | ✓ | ||

| BDI-II | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) (adapted for trial) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 levels (EQ-5D-5L) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life questionnaire (MANSA) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Stanford Presenteeism Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CAB/Control Debt Assessment and Outcomes questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| General Satisfaction Questionnaire (GSQ) | ✓ | ||

| Hope Trait Scale | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Life Events and Difficulties Schedule-short (LED-S) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Other as Shamer scale (OAS) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Response Style Questionnaire-24 (RSQ-24) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Qualitative interviews | |||

| Participant purposive sample | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Professional (GP/CAB staff) purposive sample | Once all participant consultations complete | ||

Outcomes of pilot trial

Assessment of approach to practice recruitment

We assess our approach to practice recruitment by comparing figures for number of practices approached versus number recruited (see Table 4), and we record the reasons why practices declined to participate (see Table 5). We also evaluate our recruitment approach by recording the time (in days) from the initial contact with each practice to the practice’s recruitment (see Table 6). We also report findings from a focus group analysis on trial processes (barriers to and facilitators of recruitment of practices) and information recorded by CRN staff and study team members.

Assessment of ability to recruit patients via proposed recruitment approaches

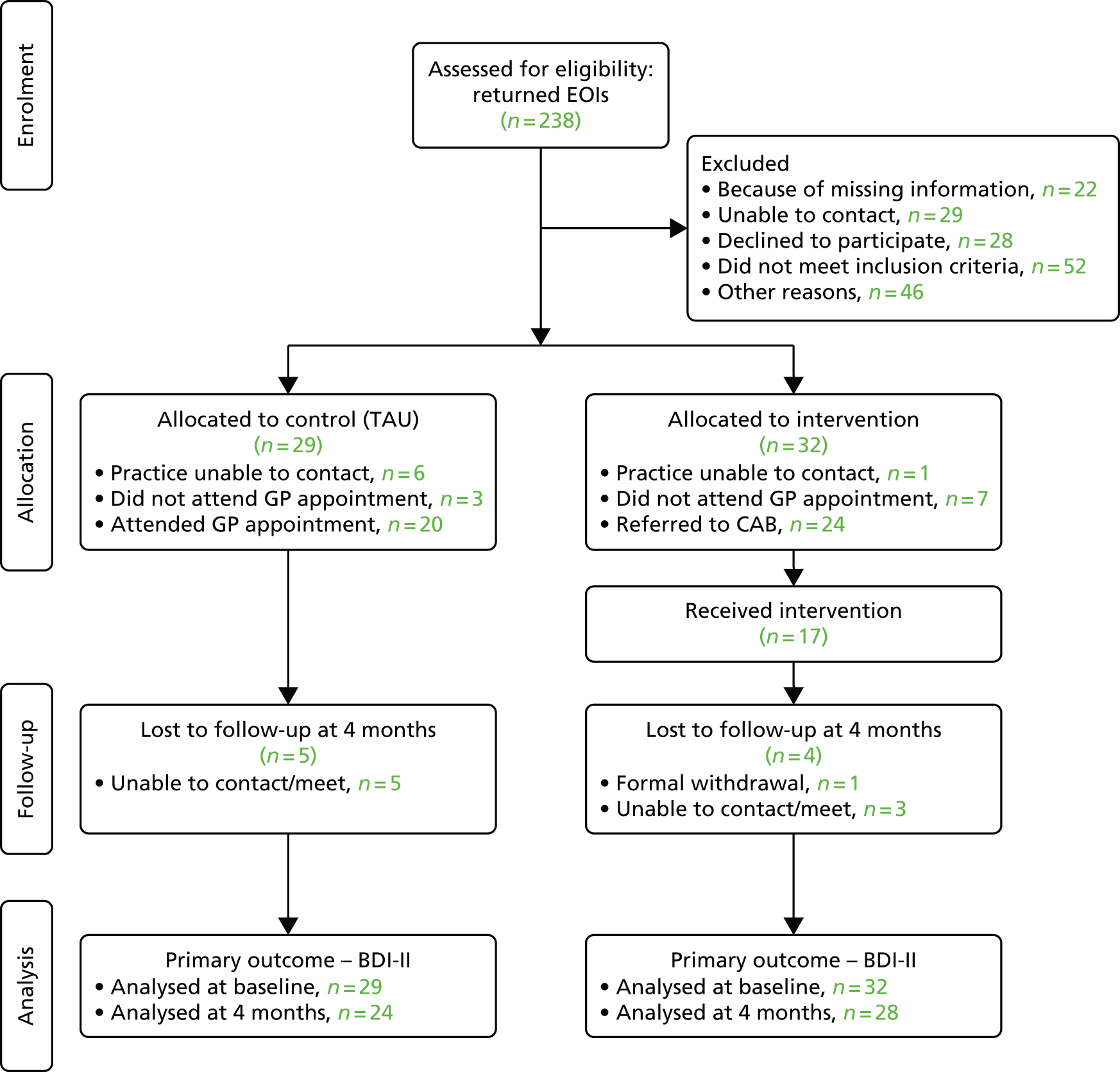

We assess the two approaches to participant recruitment (database search and letter mail-out vs. waiting room recruitment) by comparing the number of participants recruited via each approach (see Table 9). We report the number of participants recruited during the pilot stage of the trial compared with target recruitment (see Table 12) and we report the conversion rate from participants returning an eligible EOI to being randomised into the study (see Table 10). We report reasons for dropout, ineligibility and loss to follow-up rates (Figure 3) and we compare the cost per returned EOI form between the two recruitment approaches (see Table 11).

FIGURE 3.

Trial flow diagram.

Assessment of contamination

We assessed contamination based on self-reported information about receipt of CAB advice provided by participants at the 4- and 12-month follow-up visits. We report the proportion of control participants within each site with an individual allocation receiving CAB advice versus those in cluster-allocated control sites receiving CAB advice.

Assessment of patient satisfaction with intervention

We assessed participants’ satisfaction with the intervention based on data from the self-report General Satisfaction Questionnaire (GSQ) collected at 4-month follow-up and from participants’ reported experiences of the intervention during the qualitative interview.

Assessment of acceptability of data collection (outcome measures)

We assessed acceptability of data collection (outcome) measures based on participants’ reported experiences (from qualitative data) of data collection measures and from RAs’ feedback about comments of participants at the time of the assessment.

Assessment of intervention fidelity

Intervention fidelity was assessed based on information from the clinician and CAB advisor qualitative interviews.

Assessment of data collection systems and data completeness

Data collection and entry systems

Data were collected using paper-based participant booklets and researcher-completed case report forms (CRFs). Paper documents were sent to Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU) so that the data could be entered into a password-protected database. Data were double entered (by two independent staff members) and then compared by standard scripts for any errors. All errors were checked back to the original forms or queried with sites and then corrected. Data were centrally tracked using a web-based trial management system. Microsoft SQL Server 2014 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used as the database software behind the websites.

Data completeness

Data that were ‘missed’ were chased when appropriate and, if still missing, were marked as such. Pre-defined rules (as recommended in the relevant literature and supporting documentation) were employed for dealing with missing data; for example, for the main outcome (BDI-II), if the missing count of items was ≥ 10 the total score was computed.

Data exports

Various reports for study management were created in Microsoft Access® v15.0 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Microsoft Excel® v15.0 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) using tables linked directly to the website data. These links were read only. Data were extracted from the website using Microsoft Access. The data were complemented by an export dictionary, which listed all the fields and their possible values and meanings.

Participant outcomes

Primary outcome and measurement

The primary outcome was severity of depression measured using the 21-item self-report BDI-II. 48 All measures of mood are essentially self-reported; although a person’s demeanour, dress and behaviour can tell us something about their internal emotional status, their mood cannot be directly observed. It can be argued, therefore, that instruments such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, which are applied by professionals, are no more valid than those that are completed directly by patients. Furthermore, it has been shown that a professional rating of a person’s emotional state adds nothing of value over and above a self-report. 49 Thus, the BDI-II is commonly used to assess depression in primary care mental health studies.

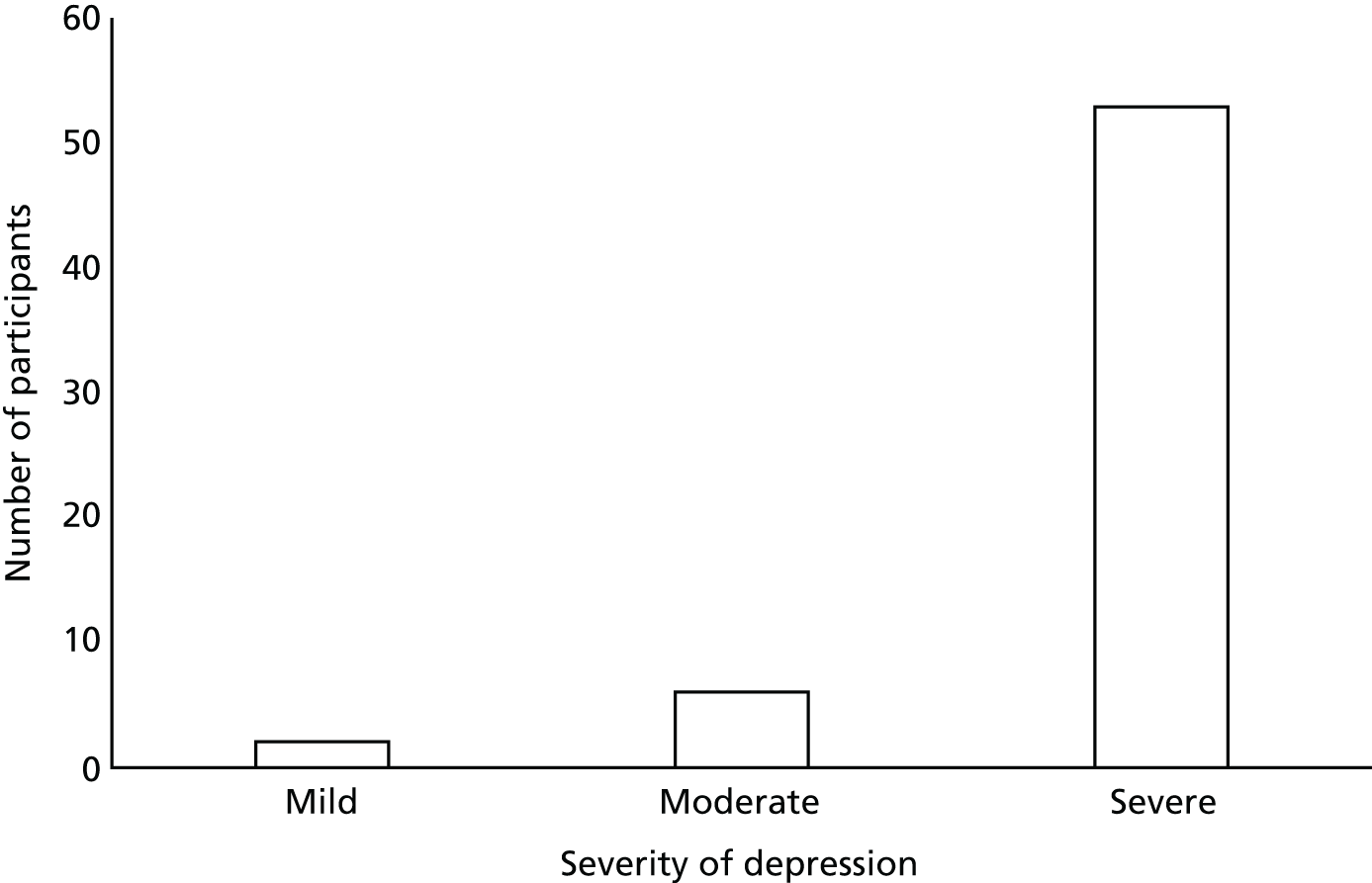

The BDI-II was completed by participants at baseline and at the 4- and 12-month (for participants completing their participation before the trial was closed down) follow-up assessments. Participants were classified according to the following categories: 14–19 points (mild depression), 20–28 points (moderate depression) and > 28 points (severe depression).

Secondary outcomes and measurement

The secondary outcomes included psychological well-being, health-related quality of life, cost-effectiveness, participant satisfaction and explanatory factors. For data collection time points for secondary outcome measures, see Table 2. We discussed the proposed data collection plan with a panel of NHS commissioners to ensure that the types of data we were planning to collect were considered relevant to influencing commissioning decisions, and to confirm that a positive trial result had the potential to positively influence service commissioning (as per the HTA brief).

Measures of psychological well-being

-

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),50 a 21-item self-report measure, was used to assess severity of anxiety. The BAI was chosen for consistency with the BDI-II.

-

The Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS)51 was used to measure aspects of positive psychological function, covering both hedonic (e.g. positive feelings and emotions) and eudaimonic (e.g. positive functioning) aspects. The SWEMWBS is a shortened version consisting of seven of the original 14 items. The SWEMWBS was chosen for inclusion in the North West Mental Wellbeing survey and identified as the psychological well-being indicator in the government’s Public Health Outcomes Framework. 52

Measures of health-related quality of life

-

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 levels (EQ-5D-5L)53 is a well-known and commonly used generic measure of health status. It is used to measure outcomes in clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and population health studies. 54 It is a patient-reported outcome measure in the Patient Reported Outcome Measures programme run by NHS England. 55 A key feature of the EQ-5D-5L is the ability to generate ‘utilities’ for health states (reflecting the preferences of the general public), which can be used to estimate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

-

The Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life questionnaire (MANSA)56 was chosen because it is preferred by service users, is more specific for mental health studies and has good reliability and validity. 56

Measures of health and social care utilisation

-

A version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory,57 together with a comprehensive ‘guide’ describing all the resource use items, was adapted for this study population and used to measure NHS and social services resource use, and also contact with criminal justice services.

Employment factors

-

Work-related issues were measured by self-report (absence and partial work). We decided against a primary care records ‘Fitnote’ search, as the Medical Certificate of Fitness for Work (MED 3s) is a recommendation not a measure of actual absence, with modified or partial work subject to employer agreement.

-

Impact of health problems on work performance was measured using the Stanford Presenteeism Scale-6 items (SPS-6). 58

Record of personal debt issues

We recorded priority and non-priority debts in participants’ CRFs at all three assessment points (baseline, 4 months and 12 months). Priority debts are those that must be dealt with first because of the sanctions available to priority creditors in the event of non-payment; such debts include mortgage or rent arrears, secured loans, council tax, gas/electricity, child support, income tax, fines, value-added tax, hire purchase and telephone arrears. Non-priority debts are those debts for which the only course of recovery action is to sue the client in the county court. They do not involve the legal sanctions that are available in response to priority debts, such as eviction or service disconnection. Generally speaking, therefore, all other types of debt are non-priority and include, but are not limted to, credit cards, personal loans, charge cards, catalogues, personal debts to family and friends, doorstep-collected loans, credit sale agreements, trading cheques and vouchers.

We chose to record priority and non-priority debts as opposed to absolute amount of debt because comparing the absolute amount of debt at baseline and outcome is less important than comparing the extent of arrears and priority debts. The risks from debt may be reduced, alongside the associated worries, without the absolute amount necessarily also reducing; it is the potentially serious consequences that often provoke distress and the resolution of these that provides relief, even though the outstanding amounts may remain. Study RAs were provided with guidance from the CAB in recording priority and non-priority debts.

Service satisfaction

Service satisfaction was measured with the GSQ. 59 The GSQ was chosen because it is a brief measure with good psychometric properties and has been used before in studies of people with mental health problems.

Measures of substance misuse

-

Alcohol use was measured with the self-report version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). 60 We chose to use the AUDIT because it is a well-recognised and widely adopted measure of alcohol consumption in primary care, and its reliability and validity have been established.

-

Illicit drug use was measured with an adapted version of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. 61 We chose this measure because it is simple and relevant, and widely used in the USA; there is no UK-specific equivalent.

Record of life events and difficulties

Life events and difficulties were assessed using the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule-short (LED-S). 62 The LED-S is a researcher-led semistructured interview schedule that has been widely used and acknowledges the difference between the respondent’s personal reported actual reaction to a stressor and the ‘contextual’ severity of that stressor, namely how severely most people in the respondent’s biographical circumstances (or ‘context’) would be expected to react to an event with those same ramifications. Raters have to undergo detailed training and lengthy manuals of examples of various types of events and ongoing difficulties to inform their ratings of the tape-recorded interviews. It pays special attention to dating of stressors in relation to symptoms, and can be used in both quantitative and qualitative research.

Life events and difficulties were assessed for the 12 months prior to baseline assessment and for the period between baseline and the 4-month follow-up assessment.

Research assistants received extensive training in LED-S from Tirril Harris, one of the authors of this monograph and co-applicant on the grant, who is an original author of the LED-S. All RAs attended an initial intensive training session with Tirril Harris and had the opportunity to undertake practise LED-S interviews with members of the public with a history of depression and debt. Tirril Harris also conducted consensus meetings with RAs throughout the data collection period to discuss and advise on coding of LED-S data. Further guidance and support was provided by Tirril Harris via telephone and e-mail to support RAs in coding of LED-S data.

Explanatory measures

Research on the relationship between debt and psychological distress consistently suggests that the relationship between distress and subjective measures of debt severity is stronger than that with objective measures. For example, Drentea and Reynolds63 analysed data from a large two-wave panel survey in the USA. Their analysis found that although debt (uniquely among the socioeconomic variables studied) was significantly related to a clinically valid measure of depression, the strength of the relationship did not vary as a function of individuals’ financial position; that is, being in debt was experienced as bad irrespective of its objective severity. In a British study, Bridges and Disney39 analysed the UK Families and Children Survey. They identified a strong positive association between subjective debt problems and self-reported mental health difficulties in the family, which persisted when objective financial circumstances were controlled for; hence, they concluded that ‘only a weak link exists between “objective” measures of the financial position of the household and psychological stress’. 39

Given these and other findings, it was felt important to include measures of psychological factors that might plausibly mediate the debt–distress relationship within the DeCoDer study, because this would offer the possibility of exploring within-group variability in outcomes. However, research evidence bearing directly on the question of which constructs might be most significant to perceptions of debt severity was limited. Hypotheses were therefore generated on the basis of psychological mechanisms known to be implicated in depression in other settings.

We had planned to assess three psychological constructs, each having been strongly associated with depression in previous work and that might reasonably be hypothesised to mediate the debt–depression relationship. As a result of the early closure of the trial and smaller than anticipated sample size, mediational analyses were not possible, but we report instead descriptive data for the following three constructs.

-

Hopelessness: the feeling of little or no hope for the future has long been associated with both depression and suicide. An analysis of the British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity in 2011 suggested that hope/hopelessness may be a strong mediating factor in the relationship between self-reported debt problems and suicidal ideation. 64 A positive association between suicidal ideation and self-reported indebtedness and a ‘strong indirect effect through hopelessness’ has been described previously. 64 There are two widely used psychometric instruments to measure hope: the Adult Hope Scale65 and the Beck Hopelessness Inventory. 66 These measures conceptualise hope in slightly different ways. The latter measures hopelessness in terms of just negative expectations about the future, whereas the former conceptualises hope in terms of a sense of agency (feeling that it is possible to effect change in one’s life) and a pathway (having the ability to find a solution to the problem). The Adult Hope Scale was, therefore, better suited to the current trial, as a central aspect of the intervention was helping people to see practical ways to better manage their finances.

-

Shame: depression has been associated with the experience of negative social comparison, such as comparing oneself unfavourably to someone else or imagining their judgement. 67 There is evidence that debt problems may cause people to judge themselves negatively compared with others. For example, Gathergood41 found that people in debt were more likely to experience mental health problems if they lived in areas where the wider prevalence of debt problems was low. We used the Other as Shamer scale (OAS)68 (a psychometric instrument developed in order to measure external shame) to assess a participant’s beliefs about how others evaluate the self. The OAS is conceptualised as a trait measure, reflecting an individual’s characteristic and global beliefs about how they are viewed. We decided to use this measure, instead of the originally proposed Attributional Style Questionnaire, because the OAS appeared to capture more accurately the experience of being judged negatively by other people – hypothesised as a mediating factor in the debt–depression relationship.

-

Rumination: rumination is defined as ‘repetitively focusing on one’s symptoms of distress and the circumstances surrounding these symptoms’. 69 Rumination is strongly associated with depression70 and impairs problem-solving ability. 71 Ruminating on debt is likely to increase negative affect and limit the extent to which individuals are able to conceive ways to improve their financial situation. We assessed rumination with the Response Style Questionnaire-24,72 the most commonly used measure of depressive rumination. 73

Sample size

For the full trial we estimated that we would require 135 patients per arm in order to have 90% power to detect a clinically meaningful difference in the primary outcome of 3.5 BDI-II units between groups at 5% two-sided alpha (based on a SD of 9). 74 To allow for a cluster (practice-level) allocation of patients, we inflated the sample size by a design effect of 1.45 (assuming an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.05 and an average cluster size of 10). 75 Based on this proposed sample size for the full trial, we proposed a sample size of 120 patients for the pilot trial, randomised to intervention and control (TAU) arms, nested by individual or cluster randomisation. Given its early termination, the study did not progress to a full trial and achieved a recruited patient sample size of 61 patients (32 in the intervention group and 29 in the TAU group) in the pilot phase.

Trial interventions

Treatment as usual plus two debt advice leaflets

Following randomisation, participants assigned to TAU were contacted by their general practice to arrange an initial consultation with the GP participating in the study. We asked practices to arrange this initial GP assessment within 1 week of the participant being randomised, whenever possible. During this initial appointment, GPs managed participants in line with their trial arm allocation, conducting an initial assessment (or review for those already in treatment) of both anxiety and depression, discussing treatment options and/or progress (medication/psychological therapy) and negotiating an ongoing management plan. We advised GPs that TAU could include a referral to the local IAPT service and might normally include up to 12 further GP contacts; they were also free to refer participants to other treatment/services as they deemed appropriate (see Appendices 5 and 6). We also asked TAU GPs to hand out the study debt advice leaflet (see Appendix 8) and the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ debt advice leaflet. 47 GPs were asked to record all non-attendances in the password-protected study website and to make reasonable attempts to recontact patients to check if they wished to rebook their appointment with the GP.

Intervention: treatment as usual plus primary care-based Citizens Advice Bureau debt advice plus two debt advice leaflets

Following randomisation, participants assigned to the intervention arm of the trial were contacted by their general practice to arrange an initial consultation with the GP participating in the study. We asked practices to arrange this initial GP assessment within 1 week of the participant being randomised whenever possible. During this initial trial appointment, GPs conducted the same patient assessment and review as for TAU participants. In addition, intervention GPs were asked to confirm the participant’s willingness to continue in the trial and obtain their written consent for completion of the SCA form (see Appendix 1), sharing of information with CAB advisor and referral for an appointment with a CAB advisor. The signed SCA form was retained by the practice and participants were offered a printed copy. As in the TAU arm, we asked intervention GPs to hand out the two debt advice leaflets to participants during the consultation (see Appendices 5 and 6 for intervention GP protocol). We asked GPs to record all non-attendances on the password-protected study website and to make reasonable attempts to recontact participants to check if they wished to rebook the GP appointment.

When participants agreed to CAB referral, CAB advisors contacted participants to arrange an initial assessment appointment. We asked CAB advisors to arrange the initial appointment within 2 weeks of receipt of the referral whenever possible. The advisors were asked to case manage the participants and send them appointment reminders as required.

The aim of the initial CAB appointment was to assess the severity of debt and other social problems, and to draw up a management plan. At the end of the assessment there was an agreement regarding whether the participant required a higher-level debt counselling intervention or the basic debt counselling provision. The CAB intervention was implemented utilising protocols (see Appendix 15 for the CAB advisor protocol), manuals, training and organisational agreements. Appointments between the CAB advisor and participant usually took place at the participant’s own general practice (to facilitate liaison between GP and CAB services), although CAB advisors visited some participants at alternative venues at the request of the participant. More detailed information about the CAB advisor and GP roles is provided in section 4.1 of the protocol (see Appendix 2).

We followed up all participants who were still willing to participate in the study but did not wish to be contacted by a CAB advisor, as planned per protocol. We asked GPs (or agreed member of practice staff) and CAB advisors to access the password-protected study website following appointments with participants to record study-specific information (e.g. dates of scheduled appointments, and if and when participants attended).

Randomisation

Demographic information (size and deprivation index score) for all general practices in the three study localities was sent to the study statistician (RST). General practices in each locality were matched on their size (‘small’, < 3500 patients; ‘medium’, 3500–8000 patients; ‘large’, > 8000 patients) and deprivation index score76 (‘not deprived’ indices of multiple deprivation score of ≤ 21.7, ‘deprived’ score of > 21.7, where 21.7 is the UK 2010 average score) before being randomised to intervention or control arms either at the cluster (practice) or individual (patient) level (see Table 1).

The randomisation sequences and matching was computer generated and undertaken by the study statistician.

In practices allocated to individual patient allocation, a member of the research team (usually the RA) gained informed consent and then accessed the password-protected randomisation website developed by PenCTU and entered participant details. Once data entry was complete, participant allocation was automatically generated by the computer but did not appear on the screen, thereby maintaining RA blinding.

When a general practice dropped out post randomisation, we replaced it with a practice of similar size and deprivation index by matching it with practices on a waiting list. Practice staff in the cluster randomisation arms were not informed about their allocation before they agreed to participate in the trial.

Individual randomisation procedure

Following the obtaining of informed consent and the completion of the baseline assessment, RAs accessed the password-protected study website (designed by PenCTU) and entered the required participant details (including general practice and participating GP’s e-mail address) in order to generate the participant’s allocation and study number. The participant’s study number was visible to the RA on the database screen but the participant’s allocation was not, thereby maintaining blinding of the RA who was conducting the participant assessments. This randomisation procedure triggered an automatic e-mail to an identified member of the practice staff, informing them of the participant’s allocation. This e-mail identified the participant by their initials and unique trial number. Based on this information, the practice staff (and study GP) were able to identify the participant when they accessed the web-based password-protected study database.

We maintained separation between GPs seeing TAU and intervention participants within individual randomisation sites in an effort to reduce the risk of contamination. A member of the practice staff forwarded the automatic e-mail to the appropriate study GP (intervention or control GP), and the participant’s personal details were retrieved from the password-protected study website so that practice staff could call the patient to arrange an appointment with that GP at the practice.

Cluster randomisation procedure

Participants recruited from cluster-randomised practices were registered into the study as soon as possible after giving their written consent and completing the baseline assessment. The RA accessed the password-protected study website and entered the required participant details (including general practice and participating GP’s e-mail address) in order to register the participant on the trial. This process triggered an automatic e-mail to the relevant member of the practice staff, confirming the participant’s consent and registration. The same administrative process was undertaken as for individual randomised patients: a member of practice staff accessed the web-based password-protected study database to retrieve the participant’s personal details so that they could call the participant to arrange an appointment with a named GP at the practice.

Blinding

In the pilot trial both researchers and participants were kept blind to practice and participant allocation.

Researcher blinding

Researchers conducting assessment interviews were not informed of participant allocation. RAs entered the same information into the study website for all participants and were unaware which participants had been individually randomised and which participants were from cluster practices. At the start of each visit, RAs explained to participants that they did not know what type of debt advice the participant had received and requested that this not be discussed during the visit to avoid RA unblinding. Instead, participants self-completed a questionnaire about the debt advice they had received (see Appendix 16), which they then placed in a sealed envelope so that the RA did not see the questionnaire. The sealed envelope was sent to PenCTU along with the participant’s other data to be entered onto the study database by PenCTU staff. If the RA was inadvertently made aware of the participant’s trial arm during the assessment visit, ‘unblinding’ was recorded on the participant’s CRF at the time of the data collection visit. Practices were advised that researchers carrying out the assessment interviews were blind to participant/practice allocations and that they should refrain from referring to participants’ allocations in discussions with RAs. Local research managers liaised with the practice on matters related to practice and participant allocation (e.g. training about the referral process and use of the study database).

Participant blinding

Participants were also blind to their allocation. The reason for not telling participants whether they were in the intervention or TAU arm of the trial was the belief that there was genuine equipoise about the benefits of the intervention versus GPs providing TAU plus signposting with advice leaflets about managing debt.

To maintain participant blinding, the participant information sheet explained that the study was evaluating different ways of providing debt advice but did not refer to ‘intervention’ and ‘control’ groups. The information sheet explained that participants would be ‘randomly allocated’ to a particular way of providing debt advice. The information sheet made it clear that one type of debt advice was referral to a CAB advisor and that this type of advice would not be available to all, but this was not identified as an ‘intervention’. GPs told patients their trial allocation during their initial consultation, explaining that they had been allocated to receive debt advice from a CAB advisor or that they were to receive two debt advice leaflets. GPs were asked not to refer to ‘intervention’ or ‘control’ arms in discussions with participants.

Data collection

Participant assessment visits were undertaken at baseline and at 4 and 12 months (for some participants who had reached this stage when the study was closed) (see Table 2). Data were collected through a combination of participant self-report and researcher-led questioning. Booklets containing self-complete measures were handed to participants at the start of each assessment visit. Researcher-administered measures were entered into study-specific CRFs by the RAs. The order of completion of the measures was predetermined, giving consideration to the sensitive nature of some questionnaires (see Appendix 17). The original CRF pages and self-complete booklets were sent to PenCTU for double-data entry onto a password-protected database. Double-entered data were compared for discrepancies using a stored procedure, and discrepant data were checked and verified with RAs who retained a photocopied version of the CRF. Participants were able to complete data measures (see Table 2) over more than one visit if they preferred to do so. However, subsequent visits were required to be completed within 1 week of the first assessment visit. Participants received a £10 voucher at the end of each assessment (baseline and 4 and 12 months) as a form of recognition of their participation in the study.

Baseline data collection

All participants (with consent) had the LED-S component of the baseline assessment visit audio-recorded. The participant’s unique trial number was included on all parts of all participant data collection booklets and CRFs.

Follow-up data collection

Further data collection visits (before the closure of data collection) were completed at 4 and 12 months after the baseline assessment visit (see Table 2). Follow-up data collection visits were completed as close as possible to the follow-up due date (generated by a computer). If participants did not want or were unable to complete follow-up visits, we asked them if they would be willing to complete the primary outcome measure (BDI-II) by telephone.

Quantitative data analysis

Statistical analysis

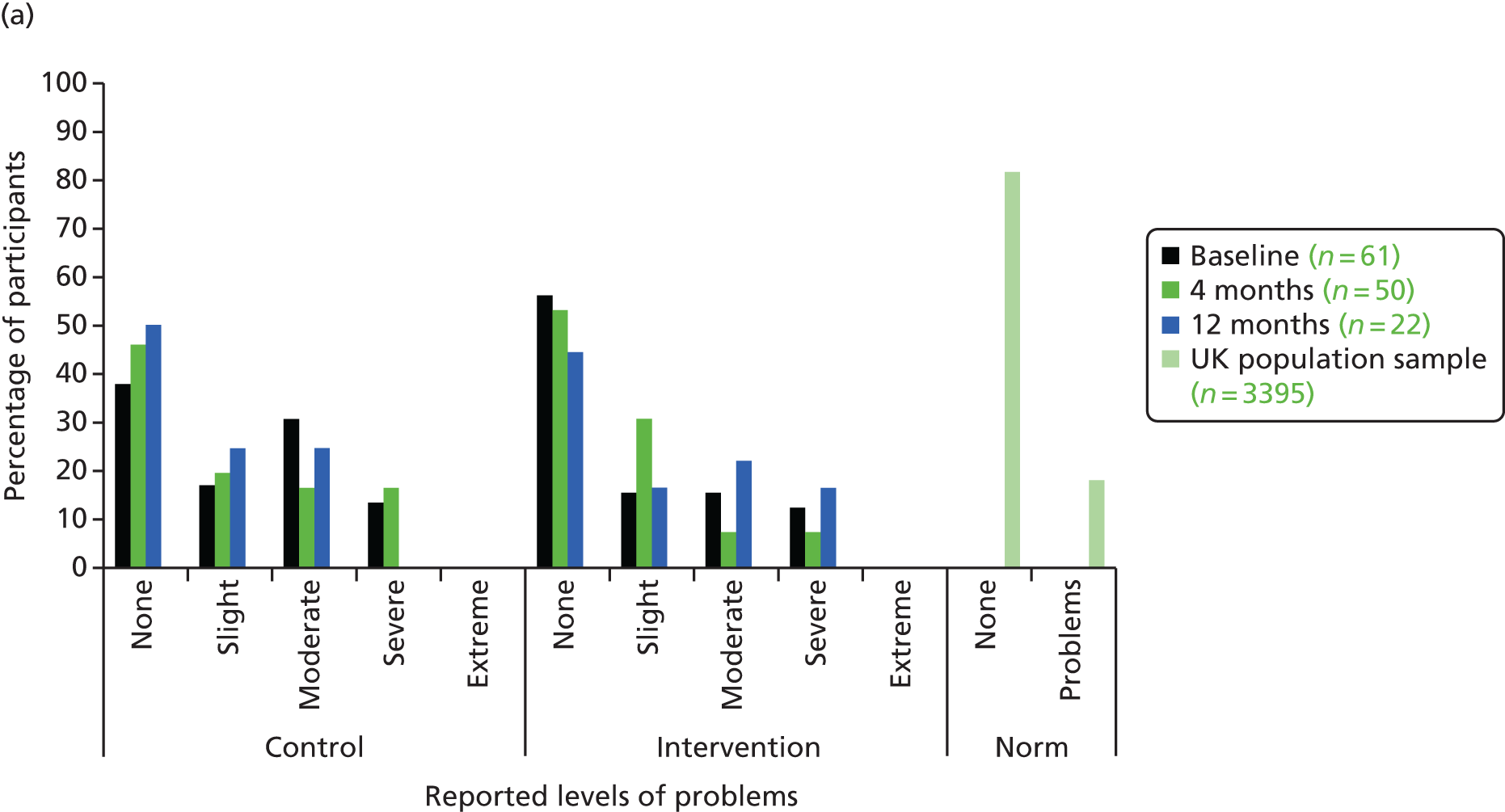

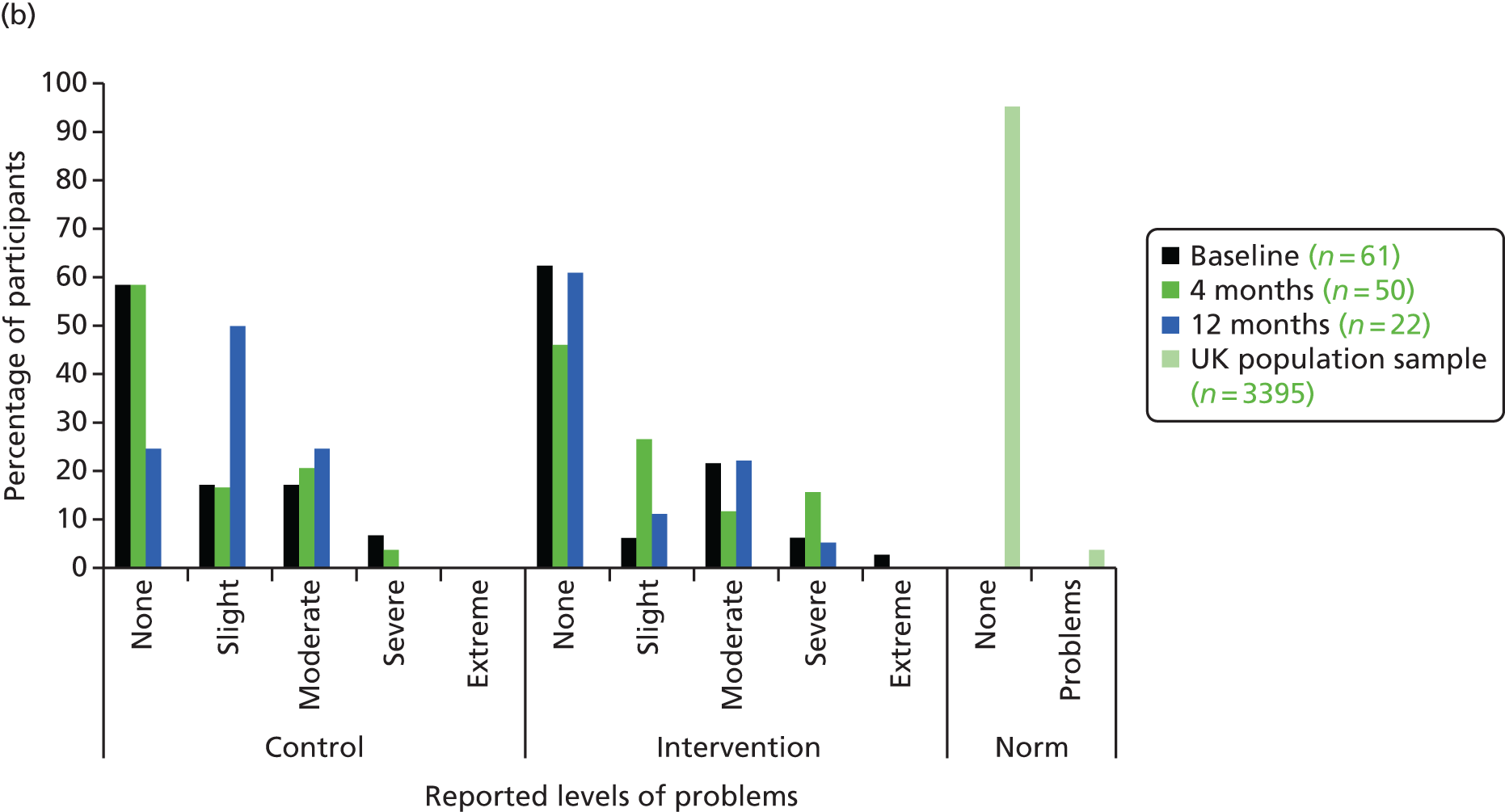

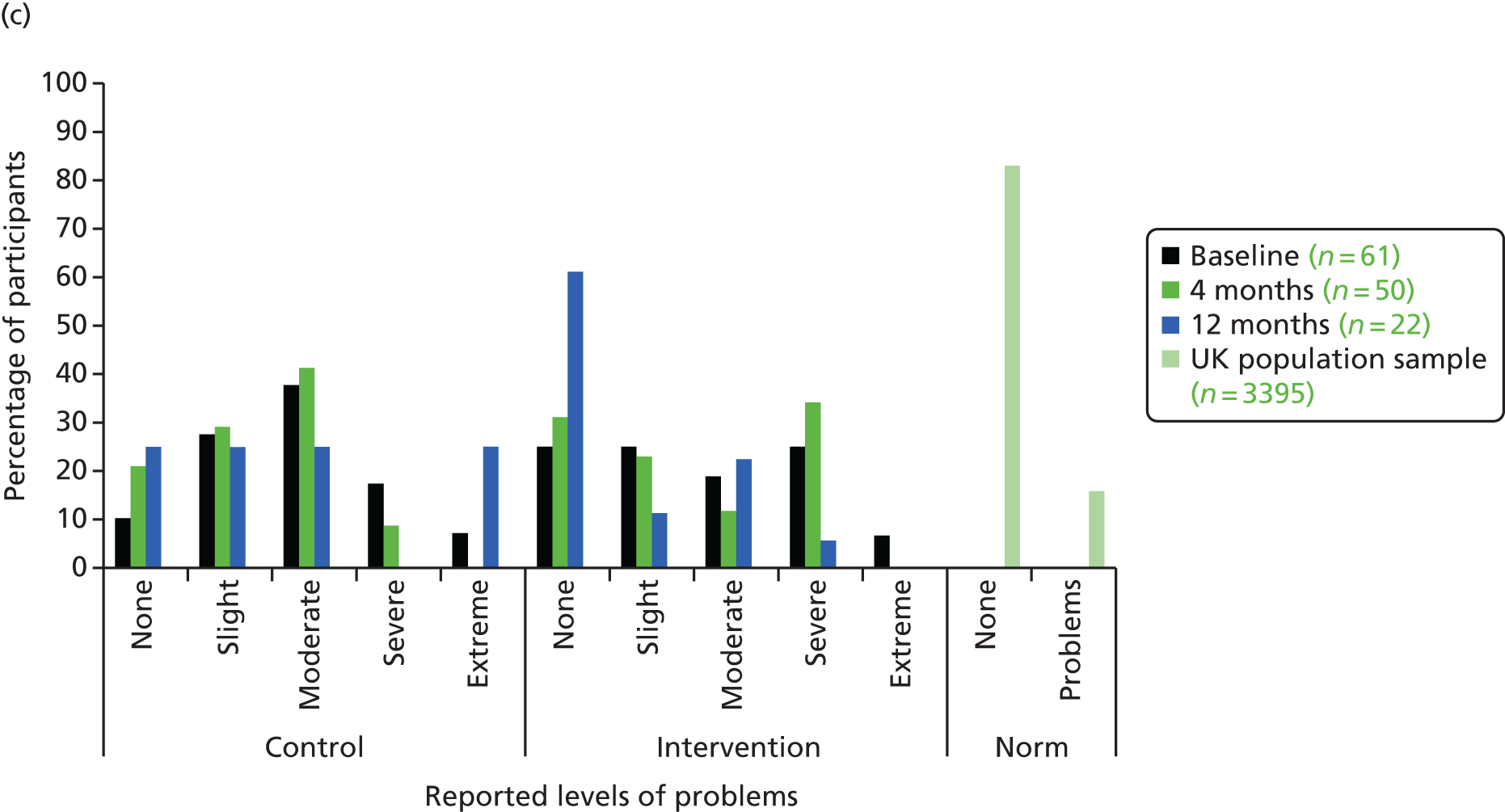

Given that the study did not progress to a full trial and achieved a reduced sample size in the pilot trial phase, we were not powered to undertake an inferential statistical comparison of outcomes between intervention and control groups. Instead, outcomes findings are reported descriptively (means and SDs, or numbers and percentages) for primary and secondary outcomes for the two groups at baseline and at 4 and 12 months post randomisation. Using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) framework, we provided a detailed summary of the flow of participants through the study from approach to participation to 4- and 12-month follow-up for those completed before close-down.

Health economics analysis

The ‘true’ cost of the intervention has been estimated using CAB standard rates for the NHS. The CAB also provided their records to confirm the time taken to complete the intervention. Given the reduced sample size in the pilot trial, the focus of the health economics analysis is descriptive: we present a summary of mean QALYs, health-care utilisation and costs by group. No incremental cost per QALY analysis was undertaken; instead, we have undertaken a disaggregated analysis of costs and consequences.

Participant qualitative data collection and analysis

Data collection

We originally planned to conduct two qualitative interviews (one at baseline and one 4 months later) with 30–45 participants (10–15 from each of the three research sites). As a result of early closure of the trial and the smaller than anticipated sample size in the pilot trial, only 23 participants had been recruited for a qualitative interview at the point of trial closure (see Table 39).

We selected participants for qualitative interview by first identifying participants who had registered their interest in taking part in qualitative interviews on the main study consent form. As participant recruitment was gradual and baseline qualitative interviews had a timeline for completion within 2–4 weeks of baseline assessment visits, it was agreed with the qualitative research team that the first six participants registering their interest in a qualitative interview would all be contacted for interview. Subsequently, participants were purposively sampled based on their age, sex, BDI-II score and allocation. We also sought to ensure that there was representation in the qualitative sample from each of the three study sites and, whenever possible, at least one participant from each general practice. One of the three research sites started participant recruitment much later than the other two sites; consequently, only five participants were recruited from this site before the trial was closed down. All five participants registered their interest in a qualitative interview and so all were approached by a study RA for interview.

Research assistants contacted participants by telephone, e-mail or letter to check if they were still interested in taking part in a qualitative interview and, if they were, to arrange a date and time for the interview. Not all participants who were contacted to participate in qualitative interviews actually completed an interview (see Chapter 6, Participants). We asked participants taking part in qualitative interviews to complete a further consent form specific to the qualitative interview that included providing consent for the use of anonymised quotations (see Appendix 18). The qualitative interviews were conducted by different study RAs from those conducting the assessment interviews to avoid unblinding. Interviews took place face to face and in a setting convenient for the participant. Interviews were audio-recorded with the participant’s consent and were anonymised during transcription. Transcripts were identified by the participant’s unique trial number and each participant was assigned a pseudonym.

Baseline qualitative interview

We conducted the baseline qualitative interview with the aid of a topic guide (see Appendix 19). This topic guide was developed by the qualitative team, including the service user lead, and refined iteratively. The baseline interview adopted a semistructured approach, commencing with a broad opening question inviting participants to tell their story about their experience of money worries. This was followed up with additional prompts (as appropriate) to explore participants’ biographies of depression, anxiety and debt, and the impact of these on their lives. The interview also explored participants’ experiences relating to the practical aspects of debt (e.g. contact with creditors).

Four-month follow-up qualitative interview

We conducted a further topic-guided (see Appendix 19) interview with participants 4 months later. The 4-month topic guide was developed using the same approach used to develop the baseline topic guide. The follow-up interview was semistructured in form and enquired about developments since the participant’s baseline interview, including any changes in debt and depression, and any possible influences on changes in mental distress. We also asked participants about their experiences of the intervention (as appropriate) and involvement in the trial. We explored in particular each participant’s acceptability of the intervention, assessment visits with the researcher and outcome measures, and views about costs in terms of time and convenience with respect to study participation.

Data transcription and management

Digital audio-recordings were transcribed by an independent professional transcriber. The recordings were transcribed verbatim, although it was agreed that brief pauses and verbal idiosyncrasies (e.g. ‘er’) would not be transcribed. The reason for any significant pause in the interview (e.g. where participant left the room for any reason or the audio-recording was paused) was recorded in brackets on the transcript. In addition to participant identification number, participants’ age, sex and a pseudonym were added during transcription. When participants referred to another individual by name, the other individual’s relationship to the participant was inserted instead for purposes of anonymity. When direct reference was made to the name of a service or place, this was replaced with a generic term such as ‘hospital’ or ‘GP’. Qualitative RAs subsequently checked the transcripts against the audio-recording for accuracy and the recordings were then deleted. For ease of management and coding, transcript data were imported into NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Data analysis

The first five transcripts were read and underwent open coding77 by members of the qualitative team, and emerging concepts were discussed. We transformed the data through an iterative process of reading and rereading transcripts, working actively with the data to develop a framework that enabled conceptual development of the data. The framework included both in vivo concepts (concepts using the participants’ own words)77 and researcher-generated concepts. Through a further process of axial coding, a sense of the relationships between concepts was developed. 77

One member of the qualitative team conducted a subsample analysis focusing specifically on the phenomenological experience of debt and the psychological mechanisms linking these to the experience of distress. 78

Intervention process evaluation

Data collection

In each of the three research centres we interviewed a number of GPs and CAB advisors about their experiences of participating in the trial. GPs and CAB advisors were provided with an information sheet (see Appendix 20) prior to the interview and completed a consent form (see Appendix 21) before the start of the interview.

The interviews with GPs and CAB advisors were topic guided (see Appendix 19) and semistructured in form. The topic guide was developed with the professional members of the team (CAB and GPs plus the qualitative team and PPI lead) and followed the NPT framework approach. We explored clinicians’ and CAB advisors’ experiences of implementing the intervention, their views about the processes involved and their thoughts about the feasibility of integrating the intervention into everyday practice, including any potential barriers to or facilitators of this.