Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in June 2019. This article began editorial review in September 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health Technology Assessment editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Cottrell et al. This work was produced by Cottrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Cottrell et al.

Background

Self-harm is common in adolescents and a major public health concern in the UK and globally. 1 A meta-analysis of 172 datasets from community-based studies of adolescents from 1990 to 2015 reported a lifetime prevalence of 16.9%, with rates increasing to 2015. 2 Self-harm in adolescents has serious consequences, with risk of suicide increasing more than 30 times, compared with expected rates in the general population, in the 12 months after presentation to hospital following self-harm. 3 Suicide is the second commonest cause of death in 10–24 year old,4 with rates of death from any cause showing a fourfold, and suicide, a 10-fold excess. 5 Non-fatal repetition of self-harm in adolescents is common with 1-year rates of hospital re-attendance at 18%. 6

Any intervention that reduces self-harm in adolescents, as well as saving lives, would result in significant reductions in family and peer distress. Effective interventions would also significantly reduce the cost to the health service in providing support for repeated self-harm. However, a single effective intervention to prevent repeat self-harm has not yet been identified despite several published studies, and systematic reviews as well as meta-analyses of those studies. 7–9 There are suggestions that dialectical behavioural therapies are associated with reductions in self-harm at the end of therapy7 and mentalisation-based therapies (MBT) at the end of follow-up,10 but methodological weaknesses prevent firm conclusions from being drawn. Those who self-harm are likely to do so for a variety of different reasons. It is therefore possible that there are subgroups of adolescents for whom certain treatments may be effective, or that treatment, or trial-level factors influence outcome.

An individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis (MA) would provide more reliable estimates of the effects of therapeutic interventions for self-harm than conventional meta-analyses that rely on aggregated information and reported analyses,11 The power to detect interaction between treatment and clinical and socio-demographic characteristics is greater. It also allows subsets of participants from trials with broad age ranges to be included.

A systematic search was therefore conducted to identify randomised controlled trials (RCTs) eligible for such an IPD MA and for a combined IPD and aggregated meta-analysis (where IPD was not available). In this paper, the methods employed for searches, study screening and selection, and risk of bias (ROB) assessment are described, with an overview of the outputs of the searching, selection, and quality assessment processes. The methods are reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-IPD guidelines. 12 The statistical methods and the results of the IPD and aggregated meta-analyses will be reported in separate peer-reviewed publications.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a systematic review and IPD-MA of RCTs of therapeutic interventions to reduce repeat self-harm in adolescents with a history of self-harm who had consequently presented to clinical services. We registered the systematic review and IPD-MA protocol in PROSPERO (registration number CRD42019152119)13 and a published protocol provides an overview of our planned methods. 14

Inclusion criteria

Participants

All adolescents of any gender or ethnicity:

-

Aged 11–18, where 18 is defined as up to the 19th birthday at the point of randomisation.

-

Who have self-harmed at least once at any time prior to randomisation?

-

Presented to clinical services for self-harm, where self-harm includes suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury, and excludes suicidal ideation without explicit self-harm.

No restrictions were placed on whether participants in the studies we included had comorbid mental or physical health conditions or intellectual disability. However, nearly all the studies we included in our analysis excluded young people with concurrent psychotic disorder or moderate to severe learning difficulties.

Self-harm is defined as any form of non-fatal self-poisoning or self-injury (including cutting, taking excess medication, attempted hanging, self-strangulation, jumping from height, running into traffic), regardless of suicidal intent. 15 This includes definitions of non-suicidal self-injury, commonly used by US researchers, and suicidal behaviour where lack of intent is assumed by reference to the method of self-harm. Self-harm can be self-reported.

Interventions

Any intervention, delivered by care provider(s), with an aim to reduce subsequent self-harm. This included psychological or pharmacological interventions, with/without individual, group or family involvement; delivery of social/service support; and interventions of any intensity (e.g. number of sessions) including self-help. Prevention-based interventions, not targeted specifically at adolescents who have presented to clinical services with self-harm and intensive inpatient-based interventions, were excluded.

Therapeutic interventions were grouped by consensus of RISA-IPD clinical co-applicants (DC, DO, PF), according to the study intervention’s published descriptions, theoretical underpinnings, available in Report Supplementary Material 1, and manuals. Intervention categories were:

-

cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT)

-

dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT)

-

family therapy

-

group therapy

-

mentalisation-based, psychodynamic, cognitive analytic therapy (CAT)

-

multisystemic therapy (MST)

-

problem-solving, psychoeducation, support

-

postcards, tokens, documents

-

single-session, brief interventions.

Controls

Any inactive (e.g. placebo or attention control) or any active [e.g. treatment as usual (TAU), management as usual] control.

Outcomes: primary

Repetition of self-harm: defined as a cumulative binary outcome from randomisation to last available follow-up period within 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation.

Primary-time period is at 12 months post randomisation. For the primary outcome, this included studies where the follow-up assessment of self-harm took place between > 6 and ≤ 12 months post-randomisation, with self-harm measured from randomisation.

Outcomes: secondary

-

Time to repetition of self-harm.

-

Pattern of self-harm repetition over time.

-

General psychopathology: score on a self-report measure of emotional and behavioural problems.

-

Depression: score on a self-report measure of depression.

-

Suicidal ideation: score on a self-report measure of suicidal ideation.

-

Quality of life: score on a self-report Quality of Life Scale.

-

Death of adolescent.

Follow-up assessments were grouped in the short term (up to 3 months post randomisation), and at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months post randomisation. Where studies included assessments beyond 24 months, data were included where feasible and grouped as ≥ 24 months post randomisation.

Setting/context

All countries of origin, any method of referral but ongoing intervention delivered in outpatient or community (school and voluntary sector) settings. We excluded intensive inpatient-based interventions as these are unlikely to be applicable to UK settings.

Studies

All RCTs, from the first available study, with any randomised design, length of follow-up and quality, in which data relating to self-harm or suicide attempts have been collected.

We included studies in which only a subset of participants met our eligibility criteria where we were able to obtain IPD for eligible participants: studies with only a subset aged 11–18, or not all having self-harmed at least once prior to randomisation. Studies with ˂ 20 eligible participants were excluded to ensure the logistical effort in obtaining, cleaning and organising the data was commensurate with the contribution of the dataset to the analysis.

Identifying studies

Prior to this project we undertook a scoping exercise in 2018 to determine the potential for eligible RCTs to be identified by harvesting studies that were included in published systematic reviews. When planning this project, we ran test searches for relevant RCTs and systematic reviews in MEDLINE. We estimated a search for relevant RCTs was likely to find 3800–6800 records, based on the test search identifying 1259 records and using the ‘rule of thumb’ that a systematic review search of several databases is approximately 3 to 5 times the size of the MEDLINE search. 16 The systematic reviews search identified five reviews that included 22 RCTs that met the RISA-IPD inclusion criteria. 17–21 We assessed the search strategies and inclusion criteria of these systematic reviews to determine whether they could be used as a more efficient way to find RCTs rather than a literature search finding potentially 6800 records to screen.

However, assessment of the search strategies and inclusion criteria of these systematic reviews indicated eligible studies may have been missed in these five systematic reviews if they were unpublished, recently published or contained < 85% adolescents as participants.

To ensure greater coverage of eligible RCTs, while minimising the number of records needing to be screened, we used a two-step approach, first identifying systematic reviews of self-harm in adolescents to harvest potentially eligible cited RCTs, and second to undertake literature searches for eligible RCTs likely to be missed in the systematic reviews we included in step one. This second step was important to find RCTs published, since the date of searches in our included systematic reviews, or to compensate for insufficient search methods for example where ongoing trial registries had not been searched. The search methods of the included systematic reviews were scrutinised to determine what supplementary searches were necessary to ensure our attempts to find all eligible RCTs were comprehensive, up-to-date, and mitigated publication bias.

Search 1: systematic reviews of eligible RCTs

In June 2019 we searched information resources for systematic reviews of interventions for self–harm in adolescents (see Table 1). Searches were developed for the concepts: self-harm, adolescents and systematic reviews. Subject headings and free text words were identified for use in the search concepts by the Information Specialist and project team members. Further terms were identified and tested from known relevant papers, and the strategy was not limited by publication date or language. The search was peer-reviewed by an Information Specialist using the PRESS checklist. 22 See Appendix 1 for complete details of search strategies. The results of the database searches were stored and deduplicated in EndNote X9.

| Search | Academic databases | Websites and other grey literature sources |

|---|---|---|

| Search 1 Systematic reviews of interventions for self-harm in adolescents | Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Wiley) Issue 6 of 12, June 2019 EMBASE Classic + EMBASE (Ovid) 1947 to 2019 June 20 Epistemonikos www.epistemonikos.org/ Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to June 20, 2019 PsycInfo (Ovid) 1806 to June Week 2 2019 |

PROSPERO www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ |

| Search 2 Additional RCTs of interventions for self-harm in adolescents |

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley) Issue 8 of 12, August 2019 EMBASE Classic + EMBASE (Ovid) 1947 to 2019 August 19 Epistemonikos www.epistemonikos.org/ Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to August 19, 2019 PsycInfo (Ovid) 1806 to August Week 1 2019 |

ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Web of Science) 1990+ Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (Web of Science) 1990+ Dissertations & Theses A&I (ProQuest) Europe PMC Grantfinder https://europepmc.org/grantfinder International Clinical Trials Registry Platform https://apps.who.int/trialsearch/ Headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation https://headspace.org.au/ National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) www.nhmrc.gov.au/ |

| Update of Search 2 on 11 February 2021 and again on 21 January 2022 |

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley) Issue 1 of 12, January 2022 EMBASE Classic + EMBASE (Ovid) 1947 to 2022 January 20 Epistemonikos www.epistemonikos.org/ Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to January 20, 2022 APA PsycInfo (Ovid) 1806 to January Week 3 2022 |

Headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation https://headspace.org.au/ National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) www.nhmrc.gov.au/ |

Eligible systematic reviews were selected (see Selection methods) and potentially eligible RCTs were harvested from the references linked to their included studies. Where it was unclear which references had been included in a review, we obtained reference records for the entire bibliography. All references harvested from systematic reviews were deduplicated and stored in an EndNote library, before combining with references found in Search 2 for RCTs.

Search 2: additional RCTs

We assessed the search methods, used in the existing systematic reviews selected in Search 1, to see if they could have missed RCTs with data for adolescents and self-harm or suicide attempt.

We checked the comprehensiveness of the search terms, databases/sources used and publication date coverage. The most recent review23 used a search strategy that included most of the databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo, CENTRAL) and all the search terms required for our systematic review. However, the search was conducted in 2015 and did not include a search for unpublished trials. We noted that other reviews, with searches conducted since 2015, were not suitable to use because they either did not report a reproducible search strategy, did not include a sufficient set of synonyms and subject headings for ‘self-harm’, ‘suicide behaviour’ and ‘suicide attempts’, or did not search unpublished (grey) literature sources. In August 2019 we searched databases, websites and other grey literature sources for RCTs of interventions for self-harm in adolescents (see Table 1).

We designed search strategies for the search concepts ‘adolescents’, ‘self-harm or suicide’ and ‘RCTs’, by incorporating search terms used in published reviews, identifying terms from known relevant studies, checking subject heading lists and from our project expert’s suggestions. The Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity- and precision-maximising version (2008 revision)24 was used for the Ovid MEDLINE search. The PsycInfo and Cochrane CENTRAL searches were limited to studies published from 2015 as it is most likely that studies pre-2015 would have been identified and harvested from the Witt et al. review23 and our other harvested reviews. The MEDLINE and EMBASE searches were limited to studies published in the last 12 months (2018–9). They covered the time-lag when RCTs are available in MEDLINE or EMBASE but have not yet been included in the Cochrane CENTRAL. The searches of all other databases and websites were not limited by date and no searches were limited by publication language. Searches were peer reviewed by another Information Specialist using the PRESS checklist. 22 See Appendix 2 for full search strategies.

Searches for RCTs to provide data for the IPD meta-analysis

The August 2019 search results were combined and deduplicated with the RCTs harvested from the systematic reviews in EndNote. Reference lists of included studies and reviews were scrutinised for further relevant studies. The resultant set of records was imported into Covidence (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) to screen for eligible RCTs and their study contact from whom we could request IPD.

Updated searches for recent RCTs to include in the aggregate meta-analysis

On 11 February 2021 and 21 January 2022, we ran further searches to identify relevant RCTs that had been published since our 2019 searches. New studies would be incorporated in the aggregated meta-analysis and not used to seek IPD as we recognised there would not be time to request, access and include their IPD. For this reason, the update searches were only conducted in databases that contained published studies (see Table 1).

Updated searches had minor changes compared to the 2019 search due to new indexing terms used by databases, and discovery of further relevant index terms. The MEDLINE and Cochrane CENTRAL updated searches included a new MeSH ‘Suicide, Completed/’. The EMBASE search included a new EMTREE term ‘*Opiate Overdose/’ and previously missed term ‘High School Student/’. Conference abstracts were excluded from the 2022 EMBASE search (but not 2019 or 2021) as the team were close to completing the review and would not have time to follow up trials mentioned at conferences. The PsycInfo search included previously missed headings ‘head banging/, self-inflicted wounds/, self-poisoning/’. Headspace had an updated search strategy to search its research database rather than its webpage; however, the MHMRC search remained the same. The updated search strategies are listed in Appendices 1 and 2.

Reference lists of included studies and reviews were scrutinised for further relevant studies.

The results of the update searches were stored in EndNote, duplicate records were removed and only previously unseen records were included in the Covidence review for screening.

Selection methods

All titles and abstracts were initially reviewed independently by two reviewers (DC and AWH) within Covidence. The full text of any potentially eligible record was then examined independently by the same reviewers. Disagreements in screening decisions were discussed by reviewers and if agreement could not be reached, adjudicated by a further reviewer (RW).

We initially included protocols in the title/abstract screening and any other papers that were related to the main study paper to ensure a complete set of data as possible and to assist in finding study contact persons.

Where records were identified in any of the searches, but it was unclear from the study publication if they met our eligibility criteria, a clarification process was followed. Initially, additional study publications, published study protocols and/or trial registrations were sought. If this did not enable an eligibility decision to be made, direct contact was made with the study authors to seek further information. Strenuous efforts were made to establish contact, starting with e-mails to lead and corresponding authors. If this was not successful, we sent systematic e-mails to all other authors, conducted internet searches for authors who might have moved location, contacted heads of departments and used informal networks. Despite this it was not always possible to achieve successful contact and clarification.

Data collection process

Once contact details for study authors were established, a short letter of invitation accompanied by a summary of the project was sent, asking for agreement in principle to share data and inviting them to join our Study Collaborative Group (see Report Supplementary Material 1). This often led to lengthy discussion about the ethics and practicalities of data-sharing. Study authors were informed that if they had specific concerns about sharing some data items it would be possible to share a reduced dataset otherwise it would preclude involvement in the project.

In line with best practice, a formal data-sharing agreement (DSA) was drawn up for the study by the Legal Team at the Research and Innovation Service, University of Leeds (see Report Supplementary Material 1). This included a detailed list of the data we were requesting. Once study authors had agreed in principle to data-sharing, a formal request to share IPD and the DSA itself were sent to each study lead.

Once signed DSAs had been obtained, study authors were sent details of how to transfer IPD securely via the Secure File Transfer service to the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) at the University of Leeds.

Participating study authors were asked to provide pseudonymised (without identifying data) datasets in whatever format was convenient to them, along with data dictionaries, original statistical analysis plans and relevant statistical programming code, where possible. Data collection was prioritised for the primary outcome repetition of self-harm.

A copy of the raw data obtained from each study was saved in a restricted folder on receipt, prior to any modification of the data. Data were read into SAS and translated into English where required (Kaess 2019, Morthorst 2012).

Where IPD were not available, aggregated data (number of participants/events, mean, standard deviation) were extracted from study reports and publications by AWH and verified by DS. We contacted authors of studies where the full sample were eligible for further information where outcomes were collected but suitable aggregated data were not reported.

All information collected during the study was kept strictly confidential. The CTRU complies with all aspects of the 2018 Data Protection Act, which incorporates the European Union General Data Protection Regulation. At the end of the study, original datasets provided by collaborating trialists will be destroyed and the study dataset securely archived at the CTRU for a minimum of 5 years.

All principal study authors were asked to join a study collaborative group as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. 25 The group met virtually on two occasions. Early in the study to discuss a presentation of analysis plans, and later to discuss findings and their interpretation.

Data items

We sought the IPD, including baseline participant demographic and clinical data, details of therapeutic intervention, and outcomes as outlined in our protocol14 and in detail in the Report Supplementary Material 1. Individual study datasets were reformatted, and common variables derived to obtain a harmonised IPD dataset. Further detail relating to the methods and results of standardising and translating variables within the IPD datasets to ensure common scales and measurements across studies, and IPD integrity are described elsewhere.

Risk of bias in individual studies

We used version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials (RoB2) to assess ROB of all eligible studies. 26 Each study was rated by two assessors independently (DC and either FM, AT or ED). Assessors reviewed the primary trial publication and relevant trial registrations and associated protocol and methods papers. If disagreements could not be resolved a third assessor adjudicated (AWH). A key element of RoB2 relates to missing outcome data. In 10 of our eligible studies, outcome data had been collected in meaningfully different ways. For example, in the SHIFT Study,27 the primary outcome was obtained from routinely collected hospital data, whereas secondary outcomes were obtained from researcher interviews with participants. The primary outcome was available for almost all (96%) of the large (832) sample, but secondary outcomes were only available for 40–60% of the sample. We therefore completed up to two RoB2 assessments for each study, one for each method of data collection, for example where the primary self-harm outcome had been collected via hospital or medical records and secondary outcomes (depression, suicidal ideation, etc.) had been collected via self-report.

In line with PRISMA IPD guidance, following receipt of IPD, further adjustments were made to ROB ratings where information became available that was not in the published trial manuscripts. 12

Further methods

An overview of methods relating to the specification of outcomes and effect measures, synthesis, exploration of variation in effects, ROB across studies, and additional analyses are provided in our protocol paper and will be reported in more detail elsewhere in a statistical analysis plan publication.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

Prior to application we conducted discussions with service users and set up a formal Service User Advisory Group (SUAG) comprising four young people (service users with a personal experience of self-harm, aged 14–16). Input from this group led to changes in our Plain language summary and dissemination plans. Importantly the SUAG, while acknowledging that the data might not always be available, recommended that we look at the impact of LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender) status, ethnicity, autistic spectrum disorder status and learning difficulty status in relation to response to psychological treatments for self-harm. This was then included in our design.

We have also arranged with the Young Person’s Mental Health Advisory Group (YPMHAG) to hold discussions with a specific focus on interpretation and dissemination of findings to young people and their families. The YPMHAG (a group of 16–25 year with lived experience of using mental health services) are hosted and funded by the Service User Research Enterprise (SURE) and the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. Given the complex nature of an IPD MA, involvement of a group like this, who have considerable experience of research, will add value to our PPIE work.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

The University of Leeds is fully committed to equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI). As a secondary data study, this review did not include any research participants. We were fully inclusive in all the studies we reviewed and reported on and with our search strategy tried to ensure that key studies were not missed. We tried to ensure our PPIE group members were as inclusive of disadvantaged groups as possible.

Our PPIE group were instrumental in ensuring that in our review we looked specifically for the possibility that being a part of a disadvantaged or underserved group might increase the risk of a poor outcome.

Results

Results of searches

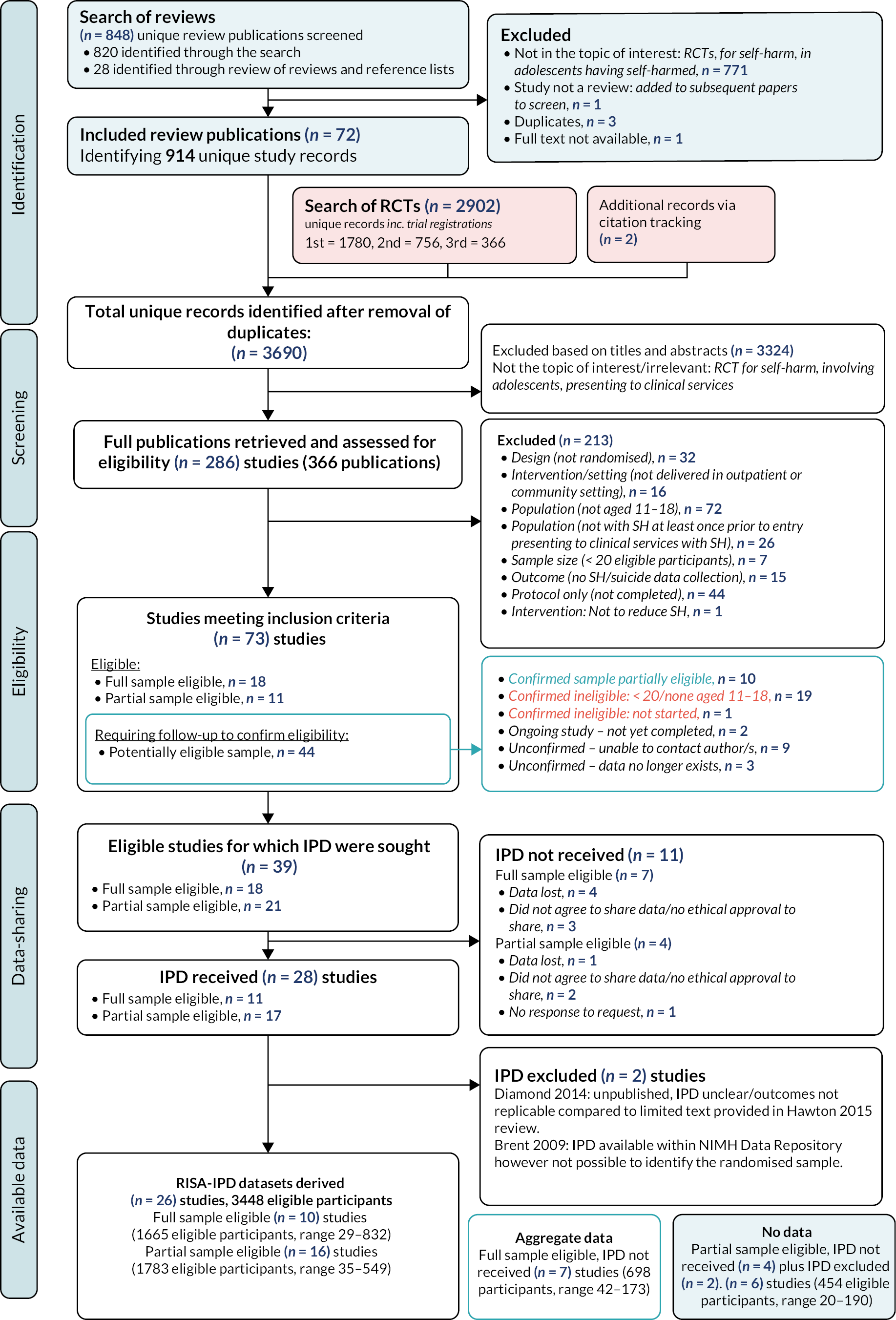

The PRISMA diagram (see Figure 1) illustrates the number of records identified during the different searches and the number of records and studies excluded during the screening processes. A total of 3690 unique records related to 3610 studies, were identified through searching sources directly for RCTs, harvesting RCT references from systematic reviews and checking the reference lists of included studies. Following title and abstract screening 366 records related to 286 studies were eligible for full-text screening.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Following full-text review, we identified 73 studies that met our inclusion criteria, including 18 studies where the full sample was eligible, 11 studies where a part of the sample was eligible (due to participants age or prior self-harm status) and 44 studies where further enquiries were necessary to establish eligibility. Of these, 10 studies were confirmed as eligible where a part of the sample was eligible, 20 were confirmed as ineligible, 2 were ongoing studies, and in 12 cases it was not possible to confirm eligibility (we were unable to trace authors in nine cases and in three the data were no longer available to establish eligibility). The 2 ongoing and 12 unconfirmed studies excluded at this stage are summarised in Appendix 3.

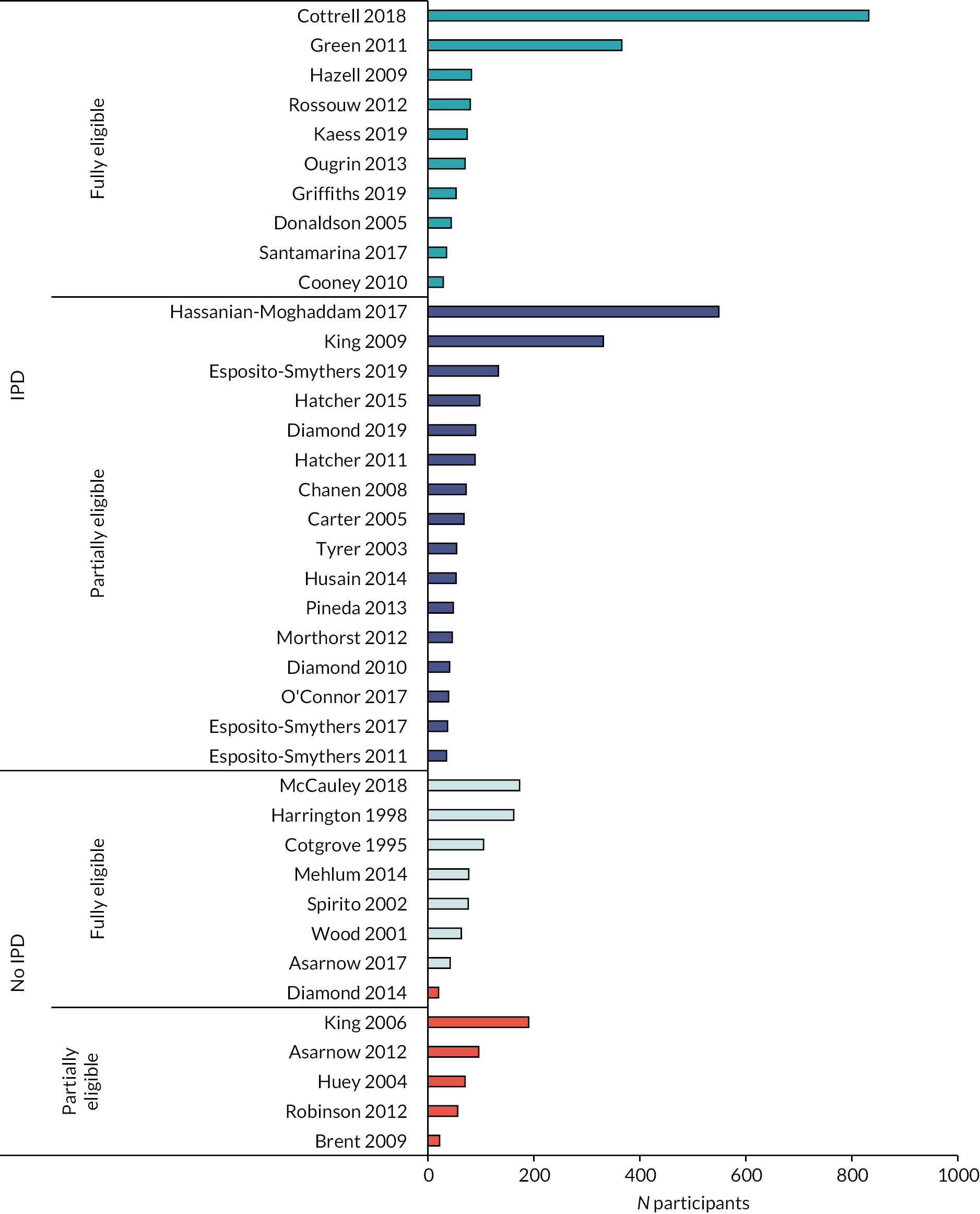

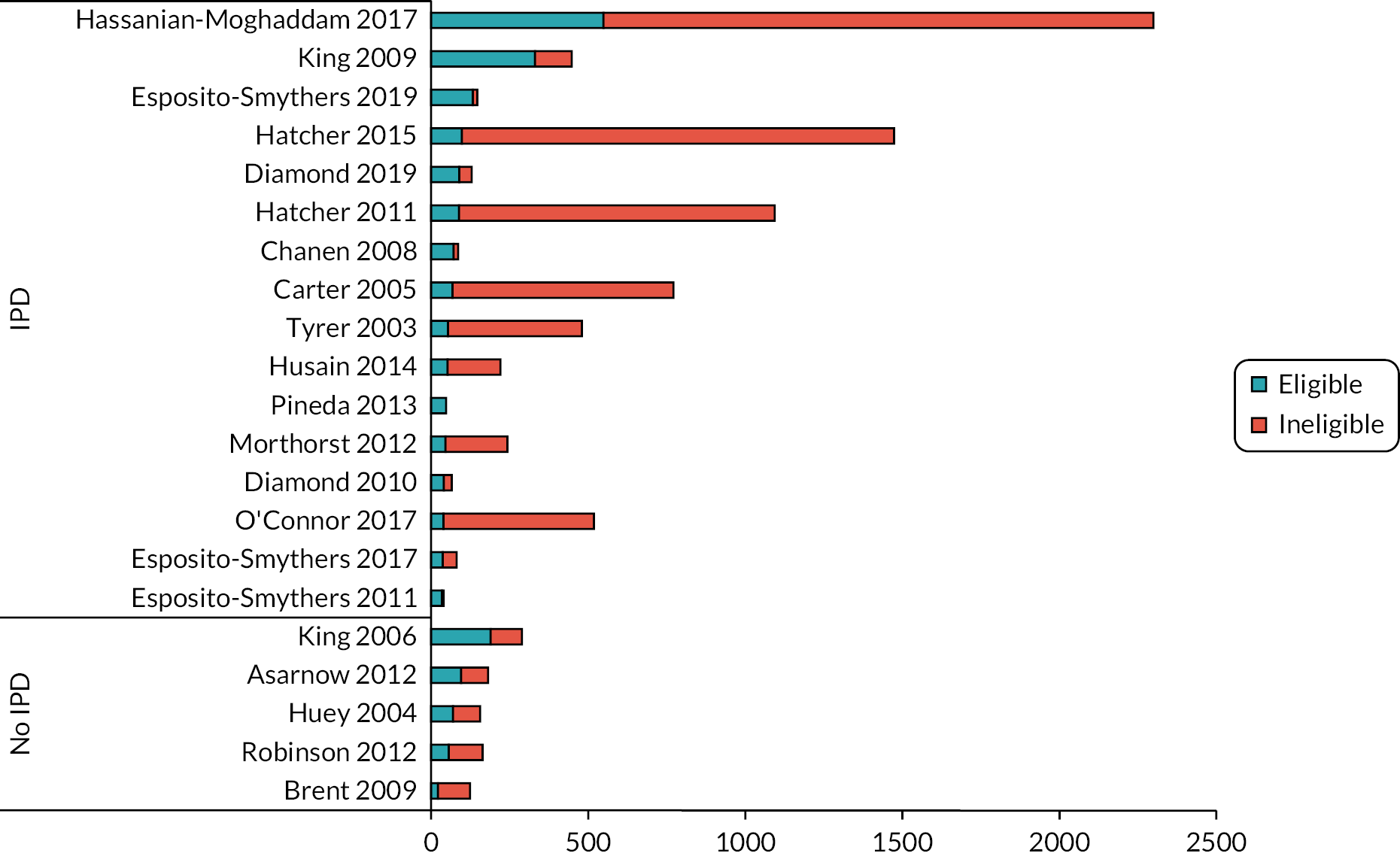

At the end of this process, we identified and thus included 39 studies, where we sought IPD, of which the full sample of participants were eligible in 18 studies and a partial sample of participants were eligible in 21 studies (see Table 2, Figures 2 and 3).

| Study | Sample size (eligible partial sample) | Designa | Country | Inclusion criteria | RISA intervention: description | Control | Follow-up period | Outcomeb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary SH | T-SH | GP | D | SI | QoL | ||||||||

| Full sample eligible, IPD included | |||||||||||||

| Cooney 2010 28 | 29 | 2-arm pilot RCT | NZ | Aged 13–19 years, suicide attempt or self-injury within the past 3 months | Dialectical behaviour therapy: Weekly individual and family group (open) sessions for 26 weeks. Telephone consultation as needed. Additional family sessions as needed. |

TAU | 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 months | Self-report/interview | |||||

| Cottrell 2018 27 | 832 | 2-arm RCT | UK | Aged 11–17 years, self-harmed at least twice and presented to services after self-harm | Family therapy: Manualised family therapy. Approximately 8 sessions over 6 months. | TAU | 12 and 18 months with long-term follow-up > 36 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Donaldson 2005 29 | 44 | 2-arm pilot RCT | USA | Aged 12–17 years, hospital presentation following suicide attempt | Problem-solving, psychoeducation, support: Skills-based treatment focused on problem-solving and affect management skills. A 3-month active phase with 6 individual and 1 family session, followed by 3 monthly sessions with optional 2 family and crisis sessions. | Active control: supportive relationship treatment | 3, 6, 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Green 2011 30 | 366 | 2-arm RCT | UK | Aged 12–16 years, 2 + episodes of SH during the previous 12 months | Group therapy: Developmental group psychotherapy, a 6 weekly session acute phase followed by a booster phase of weekly groups as long as needed (groups had rolling entry at site, mean 10 sessions in sample). | TAU: routine care | 6, 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Griffiths 2019 31 | 53 | 2-arm pilot RCT | UK | Aged 12–18 years, SH in the past 6 months, in receipt of CAMHS treatment | Mentalisation, psychodynamic, CAT: Mentalisation-based group therapy for adolescents. Weekly sessions over 12 weeks. | TAU | 12, 24 and 36 weeks | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ||||

| Hazell 2009 32 | 82 | 2-arm RCT | Australia | Aged 12–16 years, ≥ 2 episodes of self-harm in the past year, one within past 3 months | Group therapy: Developmental group therapy (informed by CBT), a 6-weekly session initial engagement phase followed by an optional long-term weekly group (likely rolling group in each site). | TAU | 2, 6, 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kaess 2019 33 | 74 | 2-arm RCT | Germany | Aged 12–17 years, engaging in repetitive NSSI (≥ 5 times within the past 6 months) | Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT): Cutting Down Programme (elements of CBT and DBT). 8–12 weekly individual sessions, over 2–4 months. | TAU | ~4, 10 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ||||

| Ougrin 2013 34 | 70 | 2-arm cluster-RCT | UK | Aged 12–18 years, SH and referred for a psychosocial assessment | Other single-session, brief intervention: Single therapeutic assessment with individual and family member where possible. | TAU: assessment as usual | 3, 24 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Rossouw 2012 35 | 80 | 2-arm RCT | UK | Aged 12–17 years, presented to community MH services/ED with SH and ≥ 1 episode of SH within the past month | Mentalisation, psychodynamic, CAT: Mentalisation-based treatment for adolescents. Weekly individual sessions and monthly family sessions over 12 months. | TAU | 3, 6, 9, 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ||||

| Santamarina 2017 36 | 35 | 2-arm RCT | Spain | Aged 12–17 years, repetitive NSSI or SA over the last 12 months and high suicide risk | Dialectical behaviour therapy: Adapted dialectical behaviour therapy for adolescents. Biweekly individual sessions, separate weekly adolescent and family group skills training sessions, and telephone consultation over 16 weeks. | Active control: weekly individual and weekly group sessions for children and parents separately | 4, 16 weeks | Combined hospital/medical records and self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Full sample eligible, IPD excluded, aggregate data not availablec | |||||||||||||

| Diamond 2014 37 | 20 | 2-arm pilot RCT | USA | Adolescents aged 12–17 years, ≥ 1 suicide attempt in the previous month | Family therapy: Attachment-based family therapy. Weekly individual, parent and family sessions over 16 weeks. | Enhanced TAU: Therapeutic Bridge Program | 16 weeks | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Full sample eligible, IPD not provided, aggregate data availablec | |||||||||||||

| Asarnow 2017 38 | 42 | 2-arm pilot RCT | USA | Suicide attempt within 3 months of study or 3 episodes of self-harm within lifetime | CBT: Cognitive-behavioural family treatment. Individual, parent and combined sessions. Mean of 10 sessions over 12 weeks. | Enhanced TAU: in-clinic parent session plus 3 or more telephone calls | 3, 6–12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Cotgrove 1995 39 | 105 | 2-arm RCT | UK | Hospital presentation following suicide attempt deliberate self-injury or self-poisoning | Postcards, tokens, documents: Token for readmission to hospital. |

TAU: standard follow-up and treatment | 12 months | Hospital/medical records | |||||

| Harrington 1998 40 | 162 | 2-arm RCT | UK | Hospital presentation following deliberate self-poisoning (ingestion of substances not for human consumption, or overdose) | Family therapy: Home-based family intervention. Short term, intensive, 5 family sessions. | TAU | 2, 6 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ||||

| McCauley 2018 41 | 173 | 2-arm RCT | USA | Suicide attempt and/or engaged in self-harm within 6 months prior to randomisation | Dialectical behaviour therapy: Dialectical behaviour therapy with weekly individual psychotherapy, multifamily group skills training, family sessions, youth and parent telephone coaching over 6 months (compliant if attend at least 24 individual sessions). | Active control: manualised intensive weekly individual and group sessions plus 7 parent sessions over 6 months | 3, 6, 9, 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Mehlum 2014 42 | 77 | 2-arm RCT | Norway | ≥ 1 episode of self-harm within 16 weeks of study/fulfilment of 2 criteria of BPD/fulfilment of 1 + 2 subthreshold criteria of BPD (intention self-inflicted injury irrespective of intent) | Dialectical behaviour therapy: Brief dialectical behaviour therapy for adolescents with weekly individual therapy and multifamily skills training. Additional family sessions and telephone coaching as needed over 19 weeks. | Enhanced TAU: TAU but with commitment to attend weekly sessions for at least 19 weeks | ~2, 4, 5, 18 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Spirito 2002 43 | 76 | 2-arm RCT | USA | Suicide attempters receiving care in ED or paediatrics ward | Other single-session, brief intervention: Single compliance enhancement intervention with problem-solving format with adolescent and parent plus 4 telephone contacts over 8 weeks. | TAU: standard disposition planning | 3 months | Self-report/interview | |||||

| Wood 2001 44 | 63 | 2-arm pilot RCT | UK | Hospital presentation following incident of self-harm (intentional self-inflicted injury irrespective of intent) | Group therapy: Developmental group psychotherapy with initial assessment, 6 acute group sessions, followed by weekly long-term group therapy over 6 months (open rolling group). | TAU: routine care | 7 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Partial sample eligible, IPD included | |||||||||||||

| Carter 2005 45 | 772 (68 aged 11–18) | 2-arm Zelen RCT | Australia | Aged 16+, with deliberate self-poisoning presenting to hospital | Postcards, tokens, documents: 8 postcards sent to individuals over 12 months. |

TAU: standard treatment | 12, 24, 60 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ||||

| Chanen 2008 46 | 86 (72 with prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | Australia | Aged 15–18 years, 2–9 DSM-IV Criteria for BPD, 1 or more: personality disorder, disruptive behaviour disorder or depressive symptom/s, low socio-economic status, history of abuse or neglect | Mentalisation, psychodynamic, CAT: CAT. Up to 24 weekly individual sessions. | Enhanced TAU: structured good clinical care, primarily problem-solving with CBT elements | 6, 12, 24 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Diamond 2010 47 | 66 (41 with prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | USA | Aged 12–17 years, clinically significant levels of suicidal ideation and depression (> 31 SIQ score, > 20 BDI-II) | Family therapy: Attachment-based family therapy. Weekly individual, parent and family sessions over 12 weeks. | Enhanced TAU: found providers, set up appointments and encouraged attendance | 6, 12, 24 weeks | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Diamond 2019 48 | 129 (90 with prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | USA | Aged 12–18 years, clinically significant levels of suicidal ideation and depression (≥ 31 SIQ score, > 20 BDI-II) | Family therapy: Attachment-based family therapy. Weekly individual, parent and family sessions over 16 weeks. | Active control: non-directive supportive therapy | 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 40, 52 weeks. | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Esposito-Smythers 2011 49 | 40 (35 with prior SH) | 2-arm pilot RCT | USA | Aged 13–17 years, suicide attempt within 3 months or SIQ ≥ 41 in the past month, had an alcohol or cannabis use disorder, recruited from a psychiatric inpatient unit | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Integrated outpatient cognitive-behavioural intervention for co-occurring alcohol/drug use disorder and suicidality over 12 months. Individual adolescent, family and parent training sessions. Acute 6-month phase with weekly adolescent and weekly/biweekly parent sessions. Continuation 3-month phase with biweekly adolescent and biweekly/monthly parent sessions. Maintenance 3-month phase with monthly adolescent and parent sessions. | Enhanced TAU: diagnostic report and medication management from study team | 3, 6, 12, 18 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Esposito-Smythers 2017 50 | 81 (37 with prior SH) | 2-arm pilot RCT | USA | Aged 13–18 years, receiving mental healthcare in the community | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Cognitive-behavioural family-based alcohol, DSH and HIV prevention program (ASH-P) delivered over 2 workshops including adolescent, parent and family groups, followed by an individual booster session. |

Enhanced TAU: Assessment plus ‘psychoeducational packet’ | 1, 6, 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ||||

| Esposito-Smythers 2019 51 | 147 (133 with prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | USA | Aged 12–18 years, hospitalised for a SA or SI with at least one co-occurring risk factors: SA prior to the index admission, NSSI or a substance use disorder | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Family-focused outpatient cognitive behavioural treatment over 12 months. Acute 6-month phase with weekly adolescent and weekly/biweekly parent sessions. Continuation 3-month phase with biweekly adolescent and biweekly/monthly parent sessions. Maintenance 3-month phase with monthly adolescent and parent sessions. |

Enhanced TAU: two study team contacts and medication management by study team | 6, 12, 18 months | Combined hospital/medical records and self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hassanian-Moghaddam 2017 52 | 2300 (549 aged 11–18) | 2-arm RCT | Iran | Aged 16 + years, hospital admission following suicide attempt | Postcards, tokens, documents: 9 postcards sent to individuals over 12 months. | TAU | 12, 24 months | Self-report/interview | |||||

| Hatcher 2011 53 | 1094 (89 aged 11–18) | 2-arm Zelen RCT | New Zealand | Aged > 16, presented to hospital with self-harm | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Problem-solving therapy/CBT. 9 individual sessions over 3 months. | TAU | 3, 12 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hatcher 2015 54 | 1474 (98 aged 11–18) | 2-arm Zelen RCT | New Zealand | Aged ≥ 17, presented to hospital with self-harm | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Package of measures: 1–2 individual support sessions within 2 weeks, 4–6 individual problem-solving therapy sessions within 4 weeks, 8 postcards over 12 months, improved access to primary care and risk management checklist. | TAU | 3, 12 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Husain 2014 55 | 221 (53 aged 11–18) | 2-arm RCT | Pakistan | Aged 16–64 years, hospital admission following self-harm | Problem-solving, psychoeducation, support: Culturally adapted manual assisted problem-solving therapy (based on principles of CBT). 6 individual sessions over 3 months. | TAU | 3, 6 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| King 2009 56 | 448 (331 prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | USA | Aged 13–17 years, Significant suicidal ideation or suicide attempt within the past 4 weeks defined by parent or adolescent report on the NIMH DISC-IV | Problem-solving, psychoeducation, support: Youth nominated Support Team II + TAU: psychoeducation session with adolescent nominated support person/s with weekly telephone contact for 3 months. Support persons encouraged to have weekly structured contact with adolescents for 3 months. Mean 3.4 nominated support persons per adolescent, often including at least one parent (28%); mean 9.5 contacts. |

TAU | 3, 6, 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Morthorst 2012 57 | 243 (46 aged 11–18) | 2-arm RCT | Denmark | Aged 12 + years, hospital admission following suicide attempt | Problem-solving, psychoeducation, support: Assertive intervention for deliberate self-harm (AID): case management with crisis intervention and flexible, problem-solving, assertive outreach through motivational support. 8–20 individual outreach consultations over 6 months. Family consultation offered. | TAU | 12 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ||||

| O’Connor 2017 58 | 518 (39 aged 11–18) | 2-arm RCT | UK | Aged 16 + years, hospital admission following suicide attempt | Postcards, tokens, documents: Volitional helpsheet (VHS) – single researcher session with individual for self-completed VHS followed by postal VHS after 2 months. | TAU | 6 months | Hospital/medical records | ✓ | ||||

| Pineda 2013 59 | 48 (48 with prior SH)d | 2-arm RCT | Australia | Aged 12–17 years, presented to hospital and ≥ 1 episode of suicidal behaviour (ideation, intent, attempt or self-injury) within the last 2 months before referral to hospital, residing with at least 1 | Problem-solving, psychoeducation, support: Resourceful Adolescent Parent Program. 4 parent psychoeducation sessions over 4–8 weeks. |

TAU: routine care | 3, 6 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ||||

| Tyrer 2003 60 | 480 (54 aged 11–18) | 2-arm RCT | UK | Aged 16–65 years, AE presentation following self-harm, at least 1 prior episode of self-harm | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Manual-assisted cognitive-behaviour therapy. Booklet plus 5 individual sessions of CBT and 2 booster sessions over 3 months. | TAU | 6, 12 months | Combined hospital/medical records and self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Partial sample eligible, IPD excluded, aggregate data not availablec | |||||||||||||

| Brent 2009 61 | 124 (22 randomised) | 3-arm pilot RCT/patient preference | USA | Suicide attempt within past 90 days and at least moderate symptoms of depression | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Cognitive-behaviour therapy, and CBT plus medication management. Up to 22 individual/parent-youth CBT sessions over 6 months. Up to 11 medication management sessions. |

Active control: medication | 6, 12, 18, 24 weeks | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Partial sample eligible, IPD not provided, aggregate data not availablec | |||||||||||||

| Asarnow 2011 62 | 181 (96 with prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | USA | Hospital presentation following suicide attempt or suicidal ideation | Cognitive-behavioural therapy: Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention – Family-based CBT with initial crisis session followed by up to 4 structured telephone contacts over 4 weeks. |

TAU: usual care enhanced by staff training | 2 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Huey 2004 63 | 156 (70 with prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | USA | Hospitalization due to suicidal ideation/planning, attempted suicide, homicidal ideation or behaviour, psychosis, or other threat of harm to self or others | Multisystemic therapy: MST – intensive (daily contact when needed) family-centred home-based intervention over 3–6 months (average 4 months). |

Active control: hospitalisation | 12 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ||||

| King 2006 64 | 289 (190 prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | USA | Significant suicidal ideation or suicide attempt with 1 month of study/score of 20 or 30 on Self-harm subscale of the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS) | Problem-solving, psychoeducation, support: Youth nominated Support Team I: psychoeducation session with adolescent nominated support person/s with regular follow-on contact. Support persons encouraged to have weekly supportive contact with adolescents for 6 months. Mean 3.2 nominated support persons per adolescent, often including at least one parent (62%); mean total 39 contacts. |

TAU | 6 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Robinson 2012 65 | 164 (~56 aged 11–18 with prior SH) | 2-arm RCT | Australia | History of suicidal threats, ideation, attempts and/or DSH | Mentalisation, psychodynamic, CAT: Mentalisation-based treatment for adolescents. Weekly individual sessions and monthly family sessions over 12 months. | TAU | 12, 18 months | Self-report/interview | ✓ | ✓ | |||

FIGURE 2.

Eligible studies, sample sizes and potential data availability.

FIGURE 3.

Eligible participants in partial sample eligible studies.

Individual patient data-sharing

Following our initial search in August 2019, the first DSA requests were sent in October 2019. The first signed DSA was received the same month while the last was not received until December 2020.

As shown in Figure 1, we were successful in obtaining DSAs and IPD in 28 (72%) of the 39 studies. Of the 18 full sample eligible studies, we obtained agreement for 11 (61%) studies, however: we were told that datasets for four studies were lost, these were all studies conducted before 2005; in one study the author was clear that their original ethical approval did not allow for data-sharing; and in two others the authors were concerned about permission to share and the possibility of participant identification. Of the 21 partial sample eligible studies, we obtained agreement for 17 (81%) studies, however, the dataset was lost for one study, in another study the author was clear that their original ethical approval did not allow for data-sharing, and in another the author was concerned about permission to share because of the possibility of participant identification. Further details, concerning reasons for not sharing data, are in the footnote to Table 2.

Having obtained signed DSAs our first request for IPD sharing went out in May 2020, the first dataset was received in June 2020 and the last in May 2021. IPD were cleaned and verified on receipt and data were harmonised between May 2020 and finished in March 2022. Further details of IPD integrity and harmonisation in practice are reported elsewhere.

In the process of cleaning and verifying the datasets, two studies were excluded from the final analysis (see PRISMA diagram, Figure 1). One study was an unpublished pilot and had insufficient data to derive the variables we needed for our study. In the second, the study had started as a RCT but difficulties in recruitment meant that randomisation was halted after 22 participants were recruited and thereafter participants could choose their intervention. Those 22 participants were eligible for our study but although the full dataset was available within the NIMH Data Repository, it proved impossible to identify the randomised subsample.

We concluded this stage of the review with IPD from 26/39 (66.7%) of eligible studies, providing data for 3448/4600 (75%) eligible participants (see Figures 2 and 3). These included: 10/18 (55.6%) studies in which the full study sample was eligible providing data for a total 1665/2383 (69.9%) eligible participants (range 29–832); and 16/21 (76.2%) studies where a partial sample of study participants was eligible, providing data for a total 1783/2217 (80.4%) additional eligible participants (range 35–549).

In addition, published aggregated data from seven of the full sample eligible studies will be included where possible in our secondary IPD plus aggregated meta-analysis (contributing an additional 698 participants, range 42–173).

In the five studies where a partial sample was eligible, but aggregated data were not available, we estimated 434 eligible, randomised, participants from the total 914 participants but without IPD it was not possible to confirm exactly how many participants would have been eligible, or include the participants in IPD or aggregate datasets.

Study characteristics

Table 2 provides an overview of study characteristics, and Table 3 provides a comparison of study characteristics for studies with and without IPD. The majority of studies evaluated effectiveness (76.9%) as opposed to pilot or feasibility (23.1%) and were 2-arm RCTs (87.2%) with three 2-arm Zelen RCTs, one 2-arm cluster RCT and one 3-arm RCT/patient preference design.

| IPD included | Total (n = 39) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 26) | No (n = 13) | ||

| N eligible participants | |||

| Mean (SD) | 132.6 (187.54) | 88.6 (55.37) | 117.9 (156.68) |

| Median (range) | 69.0 (29, 832) | 76.0 (20, 190) | 70.0 (20, 832) |

| Total | 3448 | 1152 | 4600 |

| Eligibility | |||

| Full sample eligible (%) | 10 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | 18 (46.2) |

| Partial eligible (%) | 16 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 21 (53.8) |

| Pilot/feasibility or effectiveness trial | |||

| Pilot/feasibility (%) | 5 (19.2) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (23.1) |

| Effectiveness (%) | 21 (80.8) | 9 (69.2) | 30 (76.9) |

| Design | |||

| 2-arm RCT (%) | 22 (84.6) | 12 (92.3) | 34 (87.2) |

| 2-arm Zelen RCT (%) | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.7) |

| 2-arm cluster-RCT (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| 3-arm individually randomised/patient preference (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) |

| Years since primary publication | |||

| N | 26 | 13 | 39 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.3 (4.79) | 14.1 (7.53) | 10.9 (6.18) |

| Median (range) | 10.0 (2.0, 19.0) | 13.0 (4.0, 27.0) | 11.0 (2.0, 27.0) |

| Country | |||

| Australia (%) | 4 (15.4) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (12.8) |

| Denmark (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Germany (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Iran (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| New Zealand (%) | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.7) |

| Norway (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) |

| Pakistan (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Spain (%) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| UK (%) | 7 (26.9) | 3 (23.1) | 10 (25.6) |

| USA (%) | 7 (26.9) | 8 (61.5) | 15 (38.5) |

| RISA control group | |||

| TAU/standard care/assessment (%) | 18 (69.2) | 7 (53.8) | 25 (64.1) |

| Enhanced TAU/good clinical care (%) | 5 (19.2) | 3 (23.1) | 8 (20.5) |

| Active control (%) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (15.4) |

| RISA intervention | |||

| CBT (%) | 7 (26.9) | 3 (23.1) | 10 (25.6) |

| Dialectical behaviour therapy (%) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (10.3) |

| Family therapy (%) | 3 (11.5) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (12.8) |

| Group therapy (%) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (7.7) |

| Mentalisation, psychodynamic, CAT (%) | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.7) |

| MST (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) |

| Problem-solving, psychoeducation, support (%) | 5 (19.2) | 1 (7.7) | 6 (15.4) |

| Postcards, tokens, documents (%) | 3 (11.5) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (12.8) |

| Other single session, brief intervention (%) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (5.1) |

| Risk of bias (RISA-IPD primary outcome) | |||

| D1. Randomisation process | |||

| Low (%) | 23 (88.5) | 9 (69.2) | 32 (82.1) |

| Some concerns (%) | 3 (11.5) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (10.3) |

| High (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 3 (7.7) |

| D2. Deviations from the intended interventions | |||

| Low (%) | 23 (88.5) | 10 (76.9) | 33 (84.6) |

| Some concerns (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (5.1) |

| High (%) | 3 (11.5) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (10.3) |

| D3. Missing outcome data | |||

| Low (%) | 23 (88.5) | 8 (61.5) | 31 (79.5) |

| Some concerns (%) | 2 (7.7) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (12.8) |

| High (%) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (7.7) |

| D4. Measurement of the outcome | |||

| Low (%) | 11 (42.3) | 1 (7.7) | 12 (30.8) |

| Some concerns (%) | 15 (57.7) | 12 (92.3) | 27 (69.2) |

| D5. Selection of the reported result | |||

| Low (%) | 8 (30.8) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (20.5) |

| Some concerns (%) | 18 (69.2) | 12 (92.3) | 30 (76.9) |

| High (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (2.6) |

| Overall ROB | |||

| Low (%) | 6 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.4) |

| Some concerns (%) | 17 (65.4) | 8 (61.5) | 25 (64.1) |

| High (%) | 3 (11.5) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (20.5) |

A greater proportion of studies without IPD were from the USA (61.5%) compared to studies that did provide IPD (26.9% from the USA), and studies without IPD tended to have been published earlier (median 13 vs. 10 years). IPD was obtained for all studies rated as low ROB overall, with a greater proportion of studies rated as high ROB where IPD were not obtained (38.5% vs. 11.5%).

Risk of bias within studies

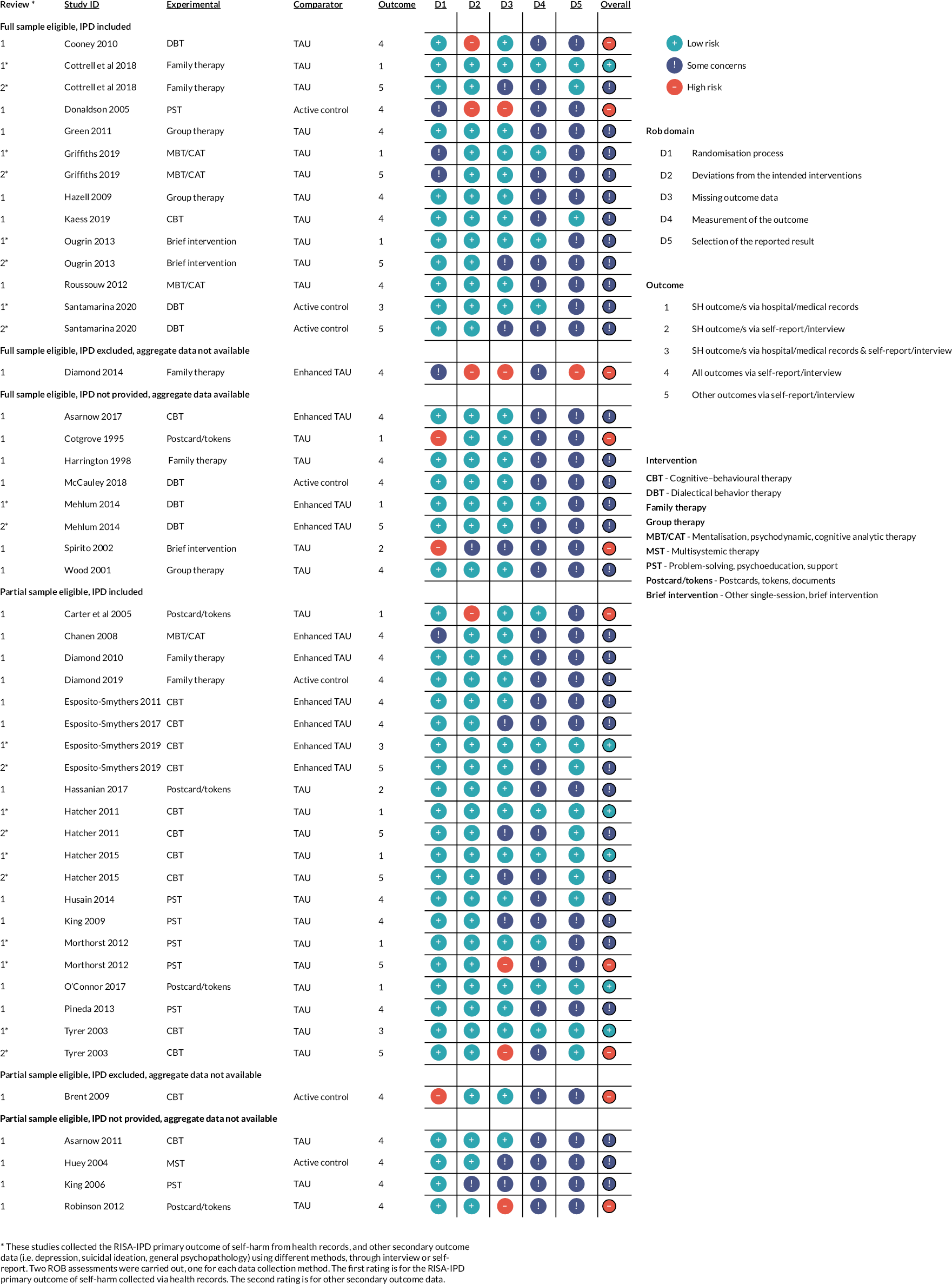

The results of the ROB assessment can be seen in Figure 4 and Table 3. For our primary outcome, repetition of self-harm, only six studies were rated as low ROB (Cottrell 2018; Esposito Smythers 2019; Hatcher 2011 and 2015; O’Connor 2017 and Tyrer 2003) with eight rated as high risk (Brent 2009, Carter 2005, Cooney 2010, Cotgrove 1995, Diamond 2014, Donaldson 2005, Robinson 2012, Spirito 2002). The small number of low-risk studies was largely because most outcomes were via self-report from non-blinded participants (Domain 4) and most trials did not have pre-specified, published, analysis plans (Domain 5).

FIGURE 4.

Summary of ROB ratings.

Studies where we did not have IPD, tended to be rated as showing more concerns (see Table 3), with the larger differences being in D4, measurement of the outcome (42% rated low risk if we had IPD; 8% rated low risk if not), D5 selection of the reported result (31% vs. 0%) and overall ROB (23% vs. 0%).

From the thirteen studies using health records for the RISA primary self-harm outcome (either alone or in combination with self-report), six studies were rated as low ROB (as reported above), five as showing some concerns, and two were rated as high ROB (Cotgrove 1995; Carter 2005). Ten of these studies also collected secondary outcomes via self-report/interview; none remained as low risk when ROB ratings were made for secondary outcomes, two studies were rated as high risk (Morthorst 2012; Tyrer 2013) and four (Cottrell 2018; Esposito 2019; Hatcher 2011; Hatcher 2015) moved from low risk to some concerns.

Domain 1: bias arising from randomisation process

Random allocation was an inclusion criterion for this study and so it is not surprising that most trials were rated as being of low risk in this domain. Three trials were rated as being of high risk. In two trials (Brent 2009; Spirito 2002) there were differences in baseline scores and insufficient information about allocation concealment. In the third (Cotgrove 1995) there was insufficient information about allocation concealment and baseline differences post randomisation.

Four trials were rated as having some concerns. One had insufficient information about allocation concealment (Donaldson 2005), two had some differences in baseline scores suggesting problems with randomisation (Chanen 2008; Griffiths 2019) and one had insufficient information about baseline differences post randomisation (Diamond 2014).

Domain 2: bias due to deviations from intended interventions

The nature of the interventions meant that participants and their caregivers were not blind to allocation. Most trials were still rated as low risk as there was little evidence of deviation from the intended assigned intervention, and intention to treat analyses were used. Four trials were rated as high ROB. Two trials reported deviations in the intended intervention (Carter 2005: 20 control participants received the intervention in error; Cooney 2010: per protocol analyses were undertaken). In one study there was insufficient information about possible deviations from the intended assigned intervention or about the intention to treat analysis plan (Diamond et al. , 2014). One study (Donaldson 2005) was originally rated as low risk in this domain but examination of the IPD supplied, showed that there were 44 participants initially randomised; not the 39 reported in the trial publication. The analysis was therefore not intention to treat, and the rating was changed to high risk.

Two trials were rated as having some concerns, in one (King 2006) there was insufficient information about possible deviations from the intended assigned intervention, and in the other (Spirito 2002) insufficient information about the intention to treat analysis plan.

Domain 3: bias due to missing outcome data

The majority of trials were rated as being of low ROB in this domain.

Three trials were rated as high risk: Diamond (2014), where there was insufficient information about availability of outcome data, and Robinson (2021) where the level of missing data was significant and rated likely to depend on the true value of the missing data.

One study (Donaldson 2005) was originally rated as low risk in this domain but examination of the IPD supplied showed that there were 44 participants initially randomised, not the 39 reported in the trial publication. Data on these participants were not available and likely to be related to outcome as they were excluded due to lack of compliance with the intended intervention. The rating was therefore changed to high risk.

Two further trials that collected RISA-IPD primary and secondary outcomes, using different methods, were rated as high risk for self-reported secondary outcomes. Morthorst (2012), where more data were missing from the control group than the intervention group, and in Tyrer (2003) data from both arms were missing; in both cases the missing data were likely to depend on the true value of that data. Both the Morthorst and Tyrer trials were rated as low risk with respect to RISA-IPD primary outcome data collected through hospital records.

Ten trials were rated as having some concerns (Cottrell 2018; Esposito-Smythers 2017; Hatcher 2011 and 2015; Huey 2004; King 2006 and 2009; Ougrin 2013; Santamarina 2020 and Spirito 2002). In each case this was because of missing outcome data but with the missing data rated as unlikely to be related to the true value of the data. The exception was Huey et al. (2004), where there was insufficient information to know if acceptable levels of outcome data had been collected.

Five trials in this group (Cottrell 2018; Hatcher 2011 and 2015; Ougrin 2013 and Santamarina 2020) were rated as some concerns for self-reported secondary outcome data only. These studies were rated as of low risk in the same domain, where primary outcome data were collected through hospital records.

Domain 4: bias in measurement of the outcome

For the RISA-IPD primary outcome, only 12 trials (Carter 2005; Cottrell 2018; Esposito Smythers 2019; Griffiths 2019; Hatcher 2011 and 2015; Mehlum 2014; Morthorst 2012; O’Connor 2017; Ougrin 2013; Santamarina 2020 and Tyrer 2003) were rated as being of low ROB where measurement of the outcome was via, or verified by, hospital or medical records. No studies were rated as being at high ROB, with the remainder typically rated as having some concerns as measurement of outcomes was by self-report alone and participants were aware of allocation status. For self-reported secondary outcomes all studies were rated as having some concerns.

Domain 5: bias in selection of the reported result

Only eight studies (Cottrell 2018; Esposito-Smythers 2019; Hatcher 2011 and 2015; Husain 2014; Kaess 2019; O’Connor 2017 and Tyrer 2003) were rated as low risk in this domain. One study (Diamond 2014) was rated as being at high ROB, with the remainder rated as having some concerns. In almost all cases, this was because of a lack of a published, detailed, pre-specified analysis plan, either in the form of a published protocol paper with analysis plan or with a detailed analysis plan in the trial registration.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This paper reports on the methods employed for searches, study screening and selection, and ROB assessment, with an overview of the outputs of the searching, selection, and quality assessment processes. We have reported in accordance with PRISMA-IPD guidelines. 12 The statistical methods and the results of the IPD and aggregate meta-analyses will be reported in separate peer-reviewed publications.

The systematic review

We identified 39 studies that met our inclusion criteria and where we sought IPD. Of these, there were 18 studies where the full sample were eligible and 21 where a part of the sample was eligible. The main reasons for partial sample eligibility were age and self-harm prior to randomisation. We were able to obtain IPD in 28 (72%) of these studies. Two studies were then excluded from the final analysis. For one unpublished pilot study there were insufficient data to derive the variables we needed for our study. In the second, the only one where data were obtained from a data depository, it proved impossible to identify the randomised subsample.

Our final IPD-analysis set included 26 studies with 3448 eligible participants: 10 studies in which the full study sample were eligible providing data for 1665 participants; and 16 studies where a partial sample were eligible, providing data for an additional 1783 participants.

We were missing IPD on approximately 1152/4600 (25%) eligible participants, including: 20 and 22 participants from the two studies in which IPD were excluded; a further 412 estimated participants from four studies in which only a partial sample were eligible; and 698 participants in seven full sample eligible studies where IPD was not provided, although data on these 698 will be included in our secondary IPD plus aggregate meta-analysis.

The risk of bias assessment

For our primary outcome, repetition of self-harm, only six studies were rated as low ROB with eight rated as high risk. The small number of low-risk studies was largely because most outcomes were via self-report from non-blinded participants (Domain 4) and most trials did not have pre-specified, published, analysis plans (Domain 5), necessitating a rating of ‘some concern’.

Potential time trends were discernible in the ROB ratings. Studies with a higher ROB in Domains 1 and 2 (randomisation processes and deviations from intended interventions) tended to be from earlier studies and/or pilot studies. Many of the trials commenced before the 2015 International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ requirement that all trials be preregistered in a publicly available clinical trials registry, and before it became common for publication of trial protocols. The resulting absence of trial registrations and published statistical analysis plans led to few ratings of low bias in Domain 5 (selection of the reported result). This may also explain our finding that studies where we could not obtain IPD had higher ratings of bias. With older studies it was more likely that data would no longer be available.

Strengths and limitations

We adopted a detailed two-step search approach that enabled a rigorous identification of RCTs. Harvesting RCTs from existing systematic reviews (search 1) and conducting supplementary literature searches for recent or unpublished RCTs (search 2) to fill gaps from search 1, limited the screening workload for reviewers. Analysis of the 39 eligible studies revealed 30 were found from harvesting RCTs from systematic review and 9 were found from the RCT update and ‘gap-filling’ searches, including one unpublished study (Diamond, 2014) discovered by following up on a trial registration record.

Our rigorous inclusion criteria and inclusion of trial registrations in the search, allowed us to minimise selection and publication bias. All records were screened independently by two authors with a third adjudicating if agreement could not be reached, enhancing the credibility and trustworthiness of findings. We were able to ensure our included studies were representative of clinical populations as a key inclusion criterion was the requirement for self-harm prior to randomisation, ensuring that studies that recruited from non-clinical samples (e.g. by screening healthy populations for suicidal ideation) were excluded.

An important strength of this study is that the IPD approach allowed us to include studies where only a part of the sample was eligible. We were able to identify 21 studies with an additional 1783 participants, more than in the studies with full sample eligibility where we had IPD. The most recent Cochrane review9 included only 17 trials with a total of 2280 participants.

We adopted a similarly rigorous approach to ROB ratings, using the well-established Cochrane tool, with each study rated independently by two authors with a third adjudicating if agreement could not be reached. Our decision to carry out two separate ratings on studies that used two different methods of data collection appears justified by our findings. Thirteen studies used health records for our primary self-harm outcome (either alone or in combination with self-report), of these six were rated as low ROB, five as showing some concerns, and two as high risk for the primary outcome. However, when ratings were made for secondary outcomes collected via self-report/interview, no studies remained as low risk, and two studies were moved to a rating of high ROB.

Working with our collaborative group of study authors added strength to the process. Authors of the studies included were able to make many helpful suggestions related to interpretation of the findings in relation to their particular study and its context.

There were, however, several limitations in this review. A main limitation was missing IPD, although for the full sample eligible studies we can at least include data in our secondary IPD plus aggregate meta-analysis. It is unfortunate that some authors felt unable to share data with us. Although we were seeking anonymised data and were willing to receive a reduced dataset, if study authors had concerns about participant identification, some authors felt the risk of sharing data and participants being identified was too high. Others informed us that they did not believe their original ethical approval would allow them to share anonymised data.

We were not able to obtain IPD for two important studies often cited in systematic reviews and meta-analyses as showing evidence for effectiveness of DBT. Neither of these was rated in our study as being of low ROB. The lack of availability of data that is being used in treatment recommendations is a potential concern.

Also of concern is the lack of replication of findings, especially so given that the one occasion when this occurred, Hazell et al. ’s32 replication of Wood et al. ,44 resulted in the earlier findings being contradicted.

For those authors who were willing to share data, obtaining agreement to share IPD and then obtaining the data and checking its integrity and alignment with already published results, was not straightforward. Clinical investigators were largely supportive of the aims of this project, but faced several challenges were faced. In most cases the DSA had to be signed by somebody authorised to make such decisions on behalf of the institution, not the study authors themselves. Identifying the appropriate person, and then persuading them to prioritise the DSA proved problematic in several cases. The DSA itself was also a reason for delay. Understandably, study authors outside the UK needed an agreement that complied with local legislation and governance standards. This necessitated rewriting the agreement, which in turn had to be reviewed and approved in its revised form by the legal team at the University of Leeds: some DSAs went through multiple iterations before agreement could be reached.

Scutt et al. 66 have written about their experience of obtaining IPD for two collaborative analyses. This study appears to have fared better in terms of percentage of datasets shared (29/39, 72% for this study; 78/391, 20% for Scutt et al.) but faced many of the same problems such as difficulty in contacting authors, concerns about the appropriateness of sharing, and long delays between initial requests for data and the actual sharing of that data.

The other potential limitations such as types of intervention and control groups, geographical distribution, sample size and data integrity will be discussed in a subsequent paper that will present the results of the IPD MA.

Conclusions and implications

An IPD MA provides more reliable estimates of the effects of therapeutic interventions for self-harm than conventional meta-analyses that rely on aggregated information and reported analyses. 11 It has greater potential power to detect interaction between treatment, clinical and socio-demographic characteristics, and it allows subsets of participants from trials with wide inclusion age ranges to be included.

Obtaining IPD for such analyses is possible but very time-consuming, despite clear guidance from funding bodies that researchers should share data appropriately. 67,68 In this study it is described how the researchers went about this and included copies of their approaches to potential collaborators and of their DSA in the hope that this will help other researchers. Timelines were set out to aid other researchers in planning similar projects. This research took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this may have added to delays but the experience of others,66 suggests that these are very time-consuming undertakings.

To facilitate future data-sharing more attention needs to be paid to seeking appropriate consent from study participants for (pseudo) anonymised data-sharing and institutions need to collaborate on template DSAs.

The relatively low number of studies rated as low ROB also suggest that researchers and funders need to consider issues of research design more carefully, although this may be improving with time.

Given the significant potential benefits of the IPD approach this study will hopefully inform future researchers in conducting similar studies.

Additional information

Contributions of authors

David Cottrell (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8674-0955) (Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol; reviewed titles, abstracts and full text where relevant, and contributed to the ROB reviews; and is the guarantor of the review.

Alex Wright-Hughes (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8839-6756) (Principal Statistician) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol and reviewed titles, abstracts and full text where relevant, and contributed to the ROB reviews.

Amanda Farrin (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2876-0584) (Professor of Clinical Trials and Evaluation of Complex Interventions) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol.

Rebecca Walwyn (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9120-1438) (Associate Professor of Clinical Trials Methodology) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol.

Faraz Mughal (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5437-5962) (General Practitioner and NIHR Doctoral Fellow) reviewed titles, abstracts and full text where relevant, and contributed to the ROB reviews.

Alex Truscott (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5952-8745) (Research and Policy Officer) reviewed titles, abstracts and full text where relevant, and contributed to the ROB reviews.

Emma Diggins (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3325-3659) (Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and NIHR Doctoral Research Fellow) reviewed titles, abstracts and full text where relevant, and contributed to the ROB reviews.

Donna Irving (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8439-6038) (Medical, Healthcare and AFBI Librarian) designed and carried out the literature searches.

Peter Fonagy (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0229-0091) (Professor of Contemporary Psychoanalysis and Developmental Science) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol.

Dennis Ougrin (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1995-5408) (Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Global Mental Health) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol.

Daniel Stahl (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7987-6619) (Reader in Biostatistics) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol.

Judy Wright (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5239-0173) (Senior Information Specialist) provided initial input for the study design, grant application and protocol; designed and carried out the literature searches.

All the authors read, had the opportunity to comment on, and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the Chief Investigators of the studies identified in the search, and their team colleagues, including organisational legal departments for their help in clarifying issues of eligibility and agreeing data-sharing agreements. They would also like to thank the members of our Independent Steering Committee and the PPI representatives who assisted us throughout. They also thank William Cragg, Regulatory and Governance Affairs Officer at the Clinical Trials Research Unit at Leeds, and Lucy Sheehan, administrative assistant to the project for their helpful contributions. Special thanks are due to Ms Karen Ogier, Contracts Manager, Research and Innovation Service Legal Team, University of Leeds. Without her help with agreeing data-sharing agreements this study would not have been possible.

Data-sharing statement

The data from the individual studies in this report were obtained under formal data-sharing agreements which do not allow further sharing of the data. Any queries should be submitted to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Formal ethical approval for the project was provided by the University of Leeds, Faculty of Medicine and Health Ethics Committee – MREC 18-098.

Information governance statement

The project was sponsored by the University of Leeds (Grant Number: RG.PSRY.116370). An independent Study Steering Group including independent clinical and statistical experts with relevant expertise and a PPI representative provided independent oversight of the project. Under the Data Protection legislation, the University of Leeds is the Data Controller, and you can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and the contact details for our Data Protection Officer here: https://dataprotection.leeds.ac.uk/.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/GTNT6331.