Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0613-20007. The contractual start date was in May 2015. The final report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Wright et al. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Wright et al.

SYNOPSIS

Summary of programme alterations

There were no substantive changes to the original study aims and objectives or changes to the investigators or grant holders.

Programme delivery

There have been a few changes in the programme to improve procedures or optimise effectiveness.

Qualitative evaluation

A focus group and an online survey were planned to capture the PIP’s experience at the end of the feasibility study; this was changed to a face-to-face workshop to facilitate a fuller understanding of the intervention delivery and research procedures.

Recruitment of triads

The unit of recruitment was refined to triads consisting of a PIP/general practitioner (GP)/care home(s). To manage workload, triad recruitment was divided into three time phases to ensure that peak activity points did not overlap.

Recruitment of resident participants

The target of residents recruited in each triad was changed from ‘20’ to a ‘mean of 20’.

Health economic model beyond trial

This was not undertaken because the intervention was estimated to increase costs and reduce quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), such that the extrapolation would not change the outcome.

Validation of methods for capturing quality of life

This was not undertaken as EuroQol Five Dimensions (EQ-5D) was the only utility measure used in the final trial. Previously, a validation work for use in care homes (by proxy) has already been undertaken.

Coronavirus

The trial was delayed in Scotland for the triads recruited at the end of Phase III. Final data collection was undertaken remotely immediately after the first lockdown was eased and with appropriate approval. The dissemination events were conducted on Zoom.

Background

The idea for Care Home Independent Pharmacist Prescriber Study (CHIPPS) resulted from three publications originating from the core research team. The 2009 Care Homes' Use of Medicines Study (Alldred) reported that prescribing, monitoring and administration of medicines could be significantly improved1 and resulted in a Department of Health alert requiring significant overhaul in the ways in which medication was managed within this environment. 2 A Cochrane review (Hughes, updated in 2018) suggested no improvement in clinical outcomes from interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy in care homes. 3 An exploratory trial (Bond, Holland, Wright) to determine the potential effectiveness of PIPs providing care for individuals with chronic pain demonstrated significant improvements in clinical outcomes. 4

The hypothesis proposed in 2012 was that improvements in clinical outcomes could be realised by allowing PIPs to assume responsibility for pharmaceutical care provision for residents within care homes. Furthermore, PIPs would be able to support all medication-related activities, thereby reducing medication errors resulting from prescription, ordering, storage, administering and recording.

The team deliberately chose not to use ‘errors’ as an outcome measure within an open-label trial owing to previous experience of a significant control arm reactivity bias in response to being planned to be observed for medication errors. 5

Whilst we were confident that with the ability to support and monitor all medication-related practices in the care home, a PIP would be able to demonstrate a positive clinical effect; we were unsure as to which clinical outcome measure would be most appropriate and created WP2 to explore this.

Recognising that the use of PIPs in care homes was a step change from current models of care within this environment, we planned to listen to all stakeholders to understand what would be appropriate to be included in such an intervention and how it should be best implemented (WP1). WP3 resulted from the need for cost-effectiveness to be captured.

With a desire to enhance intervention fidelity and recognition that pharmacist prescribers are required to be competent within their defined area of practice, we developed a training package (WP4).

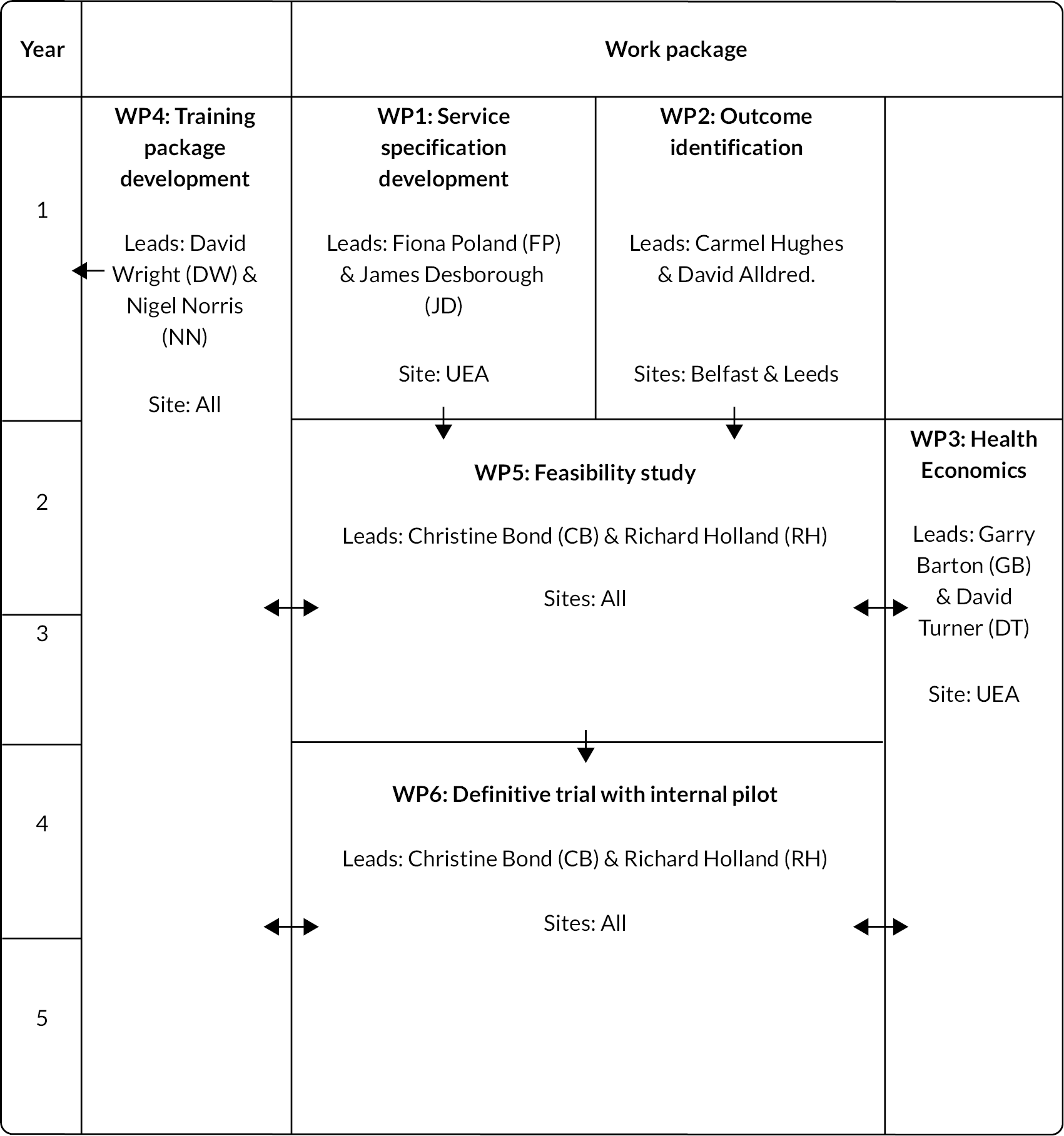

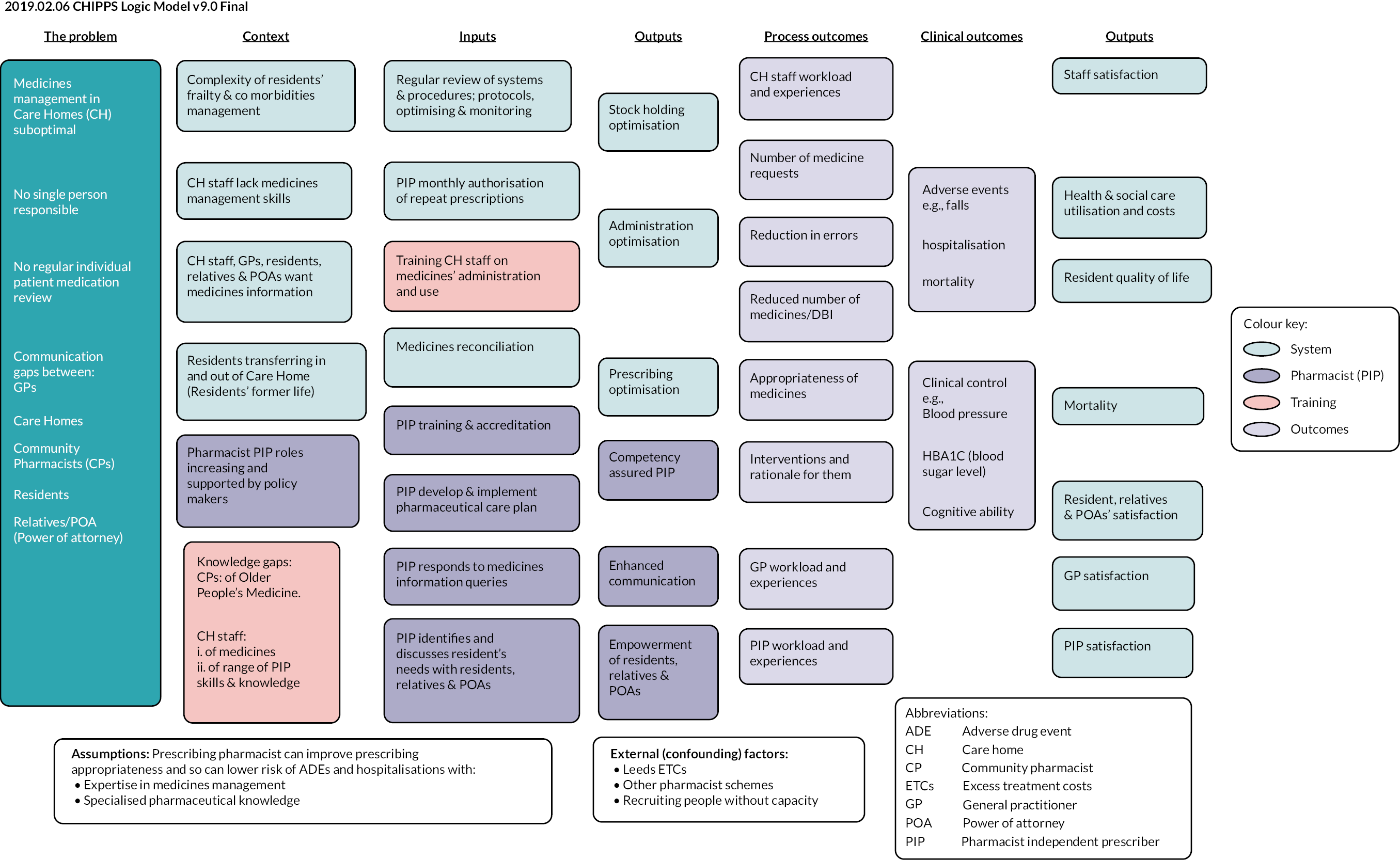

Following Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance regarding the development and evaluation of complex interventions,6 we included feasibility (WP5), pilot and definitive trial stages (WP6) (see Figure 1). Latterly, we used the MRC guidance for process evaluation7 informed by the logic model, which was refined as the project progressed.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram.

The programme of work was carried out in four locations: Norfolk (England), Yorkshire (England), Grampian (Scotland) and Belfast (Northern Ireland).

Work package 1: development of service specification

Approvals

Research ethics approved by the NRES Committee Yorkshire and the Humber Sheffield REC Ref.: 15/YH/0172.

NHS Research and Development approved by NHS Grampian R&D Ref.: IRAS: 173232.

Aim

To qualitatively explore stakeholders’ expectations and understanding of introducing a new service to inform ways to introduce an acceptable service, anticipating and mitigating potential barriers.

Research question

What components stakeholders would specify in a feasible and acceptable PIP service and what did they consider were barriers and enablers to implementing it?

Objectives

To access stakeholders in four demographically and culturally diverse study sites [England (two), Scotland and Northern Ireland (one in each)] to collect their views through focus group discussions and interviews and validate analytic themes through consensus discussions.

Method

A purposive sampling approach gained stakeholders’ views with experience of living or working in, or with, care homes, to maximise the range of data relevant to the research goals. 8 Stakeholders were GPs, pharmacists (Ps), care home managers (CHMs), care home staff (CHS), care home residents and residents’ relatives.

Our semi-structured topic guide was informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) for behaviour change9 to identify expected characteristics, barriers for and benefits of the proposed PIP role (see Appendix 1, Table 1).

We drew on the interdisciplinary research team’s broad experience to identify theory- and practice-related data collection topics relevant to

-

working in current medication management

-

stakeholders’ knowledge of scientific, procedural or environmental factors shaping care home practices

-

how a PIP service and GP-PIP partnership might work

-

potential benefits and risks

-

social and professional roles and identity

-

topics for PIP training (reported in WP4).

We contacted GPs, pharmacists and care homes – through our own and local professional networks. Additional care homes were recruited through national and site-specific regulatory bodies, local primary care and care home networks. Our maximum variation sample targeted: differently managed care homes, varying resident needs, nursing and care residents and diverse funding arrangements.

Transcripts were iteratively analysed using the TDF to identify key components, initial codes and themes for our study design.

Results

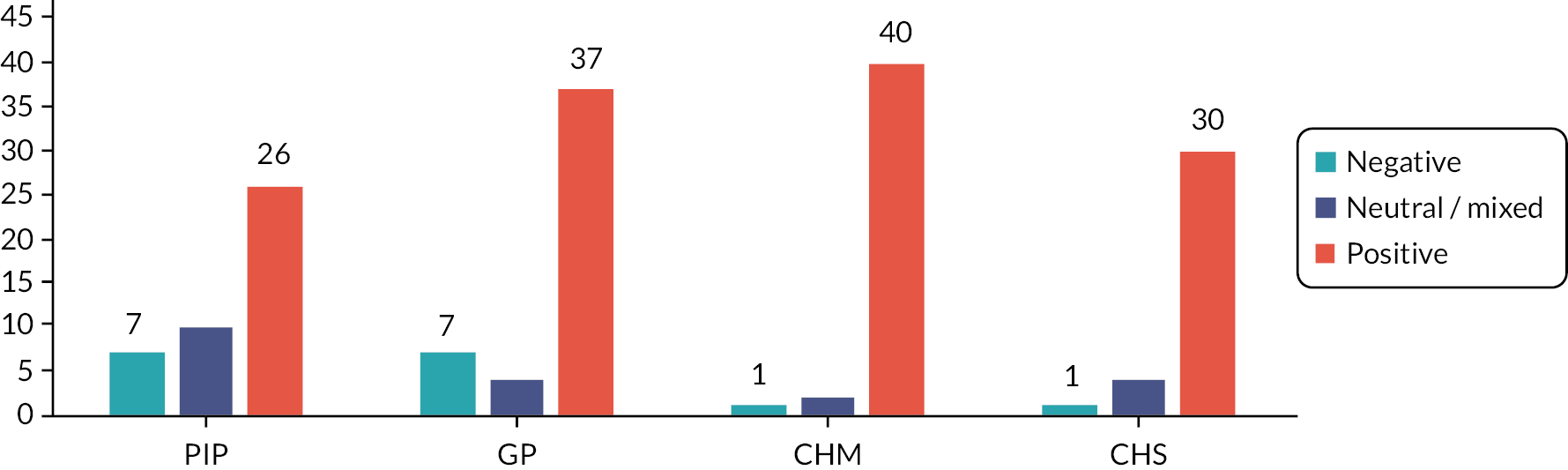

Thirteen stakeholder group-specific focus groups (n = 72 participants) and interviews (n = 13 participants) were held with GPs, pharmacists (P), one pharmacy technician, care home managers, care home staff, residents and residents’ relatives in four study sites (see Appendix 1, Table 2). Fifteen pharmacists described themselves as being employed in primary care, 11 within community pharmacy and one as split across the two (see Appendix 1, Table 3).

All focus group, interview and workshop stakeholders largely welcomed introducing the PIP service as offering benefits for residents, care homes and doctors. Reasons included viewing this new role as relevant for improving medication management, benefiting residents, overcoming communication lapses between care home, GP practice and pharmacy, residents and their relatives. Nonetheless, stakeholders identified specific potential contextual and implementation barriers and facilitators specifically in relation to

-

chronic disease management (contextual)

-

knowledge of older people’s medication and care homes (contextual)

-

clarity of PIPs’ role and responsibilities (implementation)

-

integrated social and professional team-working (implementation).

GPs’ working patterns, together with multiple care home staff involved in medication, were seen to constrain effective chronic disease management and effective communication around residents’ medication needs.

All stakeholders prioritised regular, responsive medication reviews by PIPs to address gaps in managing chronic disease and enhance the safety of residents living with comorbidities.

GPs’ onerous workload limited their capacity for ‘time-consuming’ procedures and ‘complexities’ in reviewing and managing medication (GP8-FG), and pharmacists argued that PIPs could do ‘more proactive work’ (P10-FG).

Contextual barriers and facilitators

Knowledge of older people’s medication, chronic disease management and care homes was seen as underpinning an effective PIP service.

Chronic disease management

All stakeholders emphatically identified chronic disease management as core in managing medication in care homes. Any viable PIP service must successfully address ‘many points in the circuit of prescribing where it can go wrong’ (GP15-FG), including working patterns that disrupted continuity of residents’ care, infrequent medication reviews and communication shortcomings in ordering and overseeing medications. GPs admitted that they found it ‘difficult managing all the complexity and the comorbidity’ (GP6-FG). If a PIP oversaw and bridged gaps in these processes, much communication ‘mayhem’ between care homes, pharmacies and GP practices could be eliminated (GP7-FG).

Knowledge of older people’s medication and care homes

Knowledge of older people’s conditions and their life in a care home was considered essential for the PIP, taking into account the whole person, how care homes operate and care homes’ practices and cultures. Stakeholders prioritised well-developed communication skills to interact and share knowledge with residents, ‘particularly [those] with cognitive impairment’ (P1-FG).

Implementation barriers and facilitators

Stakeholders questioned how PIPs’ specific responsibilities and roles should be understood and incorporated into care home environments. They highlighted two implementation issues: (1) clarity of a PIP’s roles and responsibilities, and (2) integrated team-working with the PIP.

-

clarity of a PIP’s roles and responsibilities

Stakeholders advocated clarity about the PIP’s role. GPs, who hold ultimate responsibility for patients’ healthcare, argued for monitoring information with the PIP, based on effective, regular mutual communication, eliminating duplicate orders and preventing omissions of medication responsibilities. For care home staff, residents and relatives, shared understanding of the PIP’s role would help improve communication in medication management.

-

integrated social and professional team working

Stakeholders believed that to embed the new service, PIPs must take time to establish communicative relationships with GP practices and care homes, to promote shared understanding of roles, working co-operatively, developing trust, providing service continuity and gaining contextual knowledge of older residents’ health.

Many participants reflected on their previous positive experiences of multi-professional working for integrating PIPs into teams, including ‘effective working relationships’ between GPs and pharmacists (GP6-FG) (P5-FG). Some GPs and care home managers envisaged PIPs educating care home staff to raise their medications’ awareness, which resonated with residents’ wishes to know about their medications as: … nobody [is there] to ask things about your medication, (RR4-FG) with staff and residents able to see PIPs as part of a resident’s ‘care package’ team, rather than ‘checking up on [staff]’ (P6-FG).

Stakeholders emphasised clarity in team-working to integrate PIPs to strengthen, not complicate, their working collaborations in care homes. Welcoming a PIP was therefore conditional on a clearly defined PIP role communicated to stakeholders; collaborating across doctors, PIPs and care home staff; dialogue with residents and relatives on developing the service and trustful and effective communication.

Discussion

Work package 1 explored stakeholders’ expectations of the components and context for a feasible PIP service, with a TDF-informed approach identifying components, stakeholders and contextual practices as relevant to mitigate implementation barriers. This identified care home environments as complex, with diverse participants, organisational processes, systems and resources providing care to frail older people, posing chronic disease management and review challenges.

A PIP model was envisaged to offer means to address this, but only if well informed about older people’s medication and care homes. Stakeholders believed that an acceptable service required the PIP to offer means to strengthen mechanisms to ensure efficient, effective ‘whole team’ approach to prescribing in care homes. 1 All stakeholders gave priority to a PIP conducting medication reviews to save GPs’ time/work. They welcomed PIP-related relationships as enhancing trustful communication around medication issues, mutually recognising remits and competencies.

We gained comprehensive understanding from stakeholders about processes to maximise chances of the impact of the PIP intervention on practice. 10 Central here was for everyone involved to ‘understand each other’s systems’ by recognising established organisational and cultural practices in care homes and primary care during implementation and improving communication around related changes. Care home managers, residents and relatives saw PIPs spending time with residents to explain and reassure around medication, to be more fully partners in their own care. 11

Integrated team-working was another key component: stakeholders were more likely to consider the PIP’s role as acceptable and viable if effective team-working were embedded in implementing such healthcare change. 12 GPs and pharmacists strongly preferred PIPs to be integrated into their practice teams.

Clearly defined PIP roles were considered crucial at micro-level experiences of individual actions and at macro-level experiences in care home and GP practice organisation. Residents and relatives were more likely to accept the new service if its purpose was carefully explained to them. GPs and pharmacists required explicit agreement on areas for PIP prescribing.

Contextual factors framed how stakeholders envisaged implementation issues. For example, effective team-working with the PIP, in GP practices and care homes (an implementation concern), depended upon the PIP acquiring appropriate knowledge of older people’s medication and frailties (a contextual issue). Guidelines and existing research underscore that specifically addressing both context and implementation barriers can better guarantee improved outcomes for older people in residential settings. 13 Multiple stakeholders shared the belief that for any proposed PIP innovation to be acceptable and viable, it would be dependent on all stakeholders understanding each other’s systems. 14

Work package 2: outcomes identification

Aim

This WP aimed to identify the most appropriate outcomes to measure the impact of the CHIPPS intervention through the development of a core outcome set (COS).

Objectives

The purpose of determining the effectiveness of the CHIPPS service was to

-

identify potentially appropriate outcome measures

-

rate and select outcome measures based on validity, reliability, utility and proximity to the intervention.

Method

In WP2, we followed methodology for the development of a COS (standardised set of outcomes that should be measured and reported at minimum in all clinical trials)15 for CHIPPS. The full study has been published. 16

The methodology used was informed by published guidance17 and conducted in two phases. Phase I encompassed the first three steps recommended by Williamson et al. : (1) to explicitly describe the scope of the COS, (2) to identify existing outcomes, and (3) to identify outcomes that are important to key stakeholders. This resulted in a long list of outcomes that fed into Phase II, corresponding to step (4) of the aforementioned guidance – prioritising the most important outcomes using a consensus method.

Phase I: Generating and refining a long list of outcomes

Step 1: Scope of COS

-

Health condition and population: older adults with any type/number of health conditions.

-

Intervention: those aiming to optimise prescribing.

-

Setting: care homes, defined as nursing and/or residential homes, skilled nursing, assisted living and aged-care facilities.

Step 2: Literature review

A relevant Cochrane review, assessing interventions to optimise prescribing in care homes, was used, as it reported outcomes pertinent to COS development. 18 Briefly, 12 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving over 10,000 older adults residing in 355 care homes were included.

Step 3: Stakeholder involvement

Focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted with GPs, pharmacists, care home managers/staff and care home residents/relatives from the four CHIPPS study sites to determine outcomes for inclusion. These stakeholder consultations were conducted primarily for the development of the CHIPPS intervention and are described elsewhere in this report (WP1: Service Specification Development). 14 Transcripts of the focus groups and interviews were independently analysed by two researchers who recorded verbatim all outcomes proposed by stakeholders. The stakeholder study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee Yorkshire and the Humber, Sheffield; reference: 15/YH/0172.

The resulting long list of outcomes was reviewed, with removal of duplicate items and process measures. Four members of the CHIPPS WP2 team then independently assessed the remaining outcomes and voted anonymously to determine whether each outcome should progress to Stage 2. All four team members involved in this process had either practised clinically or undertaken clinical trials in care homes previously.

Phase II: Delphi consensus exercise

We used the Delphi technique to achieve consensus on a final COS.

The Delphi Panel

The Delphi panel comprised the 19 members of the wider CHIPPS management team (excluding the four aforementioned team members). The group included academic pharmacists (n = 3), geriatricians (n = 2), patient-public involvement (PPI) representatives (n = 2), health economists (n = 2), senior CHIPPS research fellows (n = 2), a prescribing advisor pharmacist (n = 1), an academic sociologist (n = 1), a research governance manager (n = 1), a care home quality director (n = 1), an educationalist (n = 1), an academic doctor (n = 1), a GP (n = 1) and an academic nurse (n = 1).

The questionnaires

The first questionnaire was structured around the Phase I long list of outcomes. Each outcome formed a single questionnaire item, accompanied by a brief explanation, to prevent misinterpretation. For example, ‘Duplicate drugs’ was described as a situation where two medicines of the same pharmacological class were prescribed, such as the prescribing of two concurrent opiates. 19

Questionnaires were distributed using a web-based survey tool (Survey Gizmo®; Alchemer, Louisville, CO, USA). Panellists were emailed a link to each questionnaire and asked to complete within 4 weeks. Reminder emails were sent as needed. Panellists responding to the first questionnaire were invited to participate in the second round.

Panellists rated the importance of including each outcome in the COS, using a scoring system derived from the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group. 20 Scoring was based on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 9. Scores of 1–3 indicated an outcome of ‘limited importance’, 4–6 indicated ‘important but not critical’ and 7–9 indicated ‘critical’. Panellists were also given the option to select ‘unable to score’. During the first round, panellists were invited to suggest additional outcomes for inclusion, which were reviewed and discussed by the WP2 study team.

The second questionnaire (with the same rating method) included a revised list of outcomes, inclusive of ‘non-consensus’ outcomes (see below for a definition of consensus) and any new outcomes generated from the first round. A summary of first-round scores for each outcome (including individual score, group mean score and group median score) accompanied the link to the second questionnaire. Panellists were encouraged to consider this information whilst re-scoring outcomes.

Definition of consensus

Consensus for inclusion of an outcome in the COS (consensus ‘in’) was defined as ≥70% of respondents rating an outcome 7–9, that is, ‘critical’ and fewer than 15% of respondents rating it 1–3, that is, ‘of limited importance’. Similar thresholds have been previously reported. 21,22 Consensus for exclusion (consensus ‘out’) from the COS was defined as fewer than 15% of respondents rating an outcome 7–9, that is, ‘critical’ and ≥70% of respondents rating it 1–3, that is, ‘of limited importance’. All other score distributions were categorised as ‘no’ consensus.

Data analysis

Responses were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The proportion of respondents rating the outcome as ‘critical’, ‘important but not critical’ or ‘not important’ was calculated for each outcome to determine whether consensus had been reached, as described above.

After the first Delphi round, outcomes that reached consensus ‘in’ were included in the COS, and outcomes that reached consensus ‘out’ were excluded. ‘No’ consensus outcomes proceeded to the second round. This approach was also used after the second round; however, ‘no’ consensus outcomes were excluded from the final COS.

Key findings

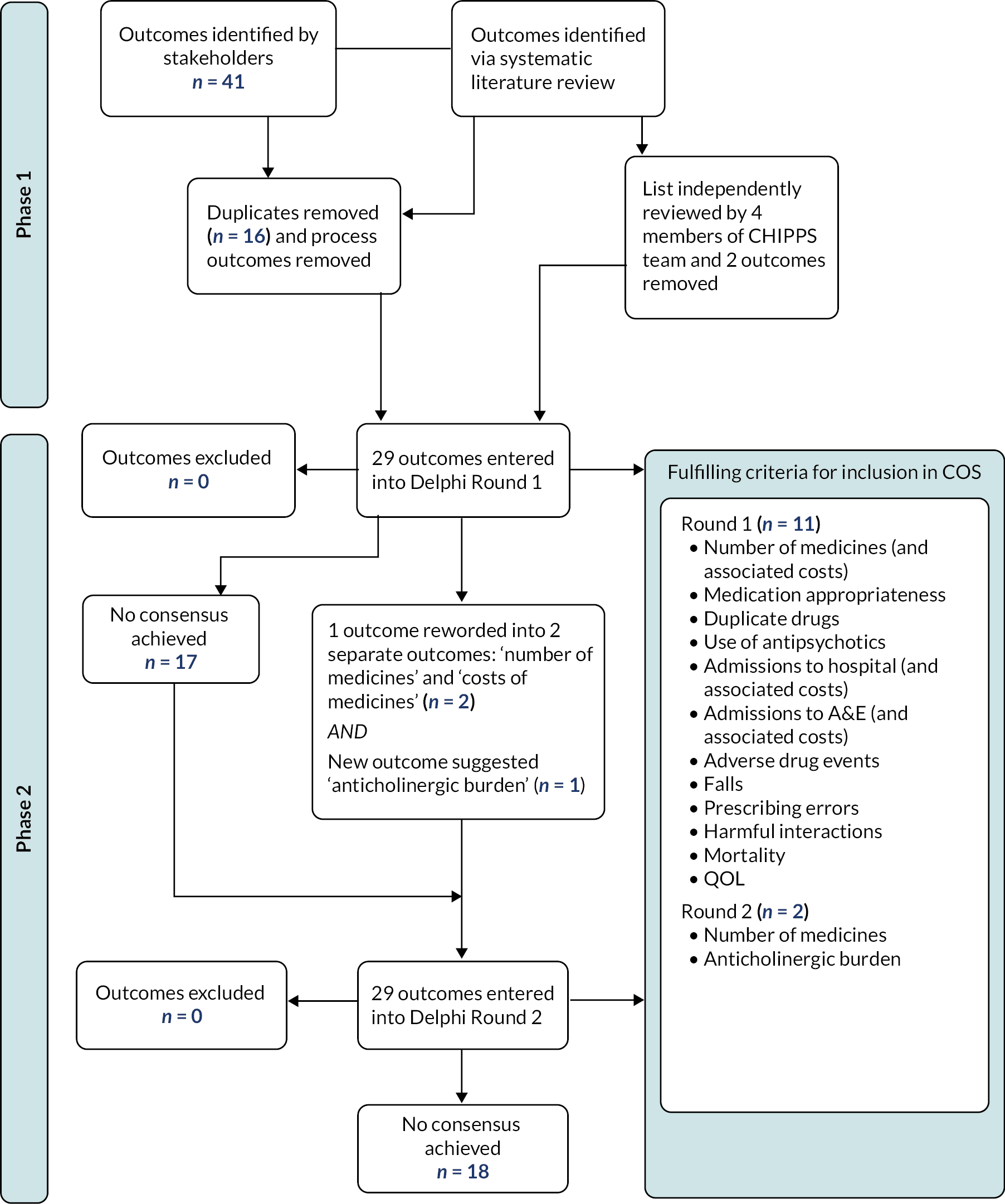

An overview of the COS development process is provided in Appendix 1, Figure 2.

Phase I

Sixty-three outcomes for potential inclusion in the COS were identified in Phase I (22 from 12 studies included in the Cochrane review and 41 from stakeholder focus groups and interviews). Sixteen duplicates were removed. Further 16 were classified as process outcomes (e.g. ‘satisfaction with PIP service’) and excluded. Two outcomes (‘pain’ and ‘accidents’) were also excluded unanimously by the CHIPPS review panel. A total of 29 outcomes (see Appendix 1, Figure 2 and Table 1) were considered by the Delphi panel in the consensus exercise.

Phase II

The first round of the Delphi consensus exercise was completed by all 19 Delphi panellists (100% response rate). Twelve outcomes met the consensus criteria for inclusion in the COS. No outcomes met the exclusion criteria, and no consensus was achieved for 17 outcomes.

Outcomes (n = 6) suggested by the panel during the first Delphi round were discussed by three members of the research team (AM, CH and DA). The outcomes were ‘patient mobility’; ‘making sure drug charts are kept up to date’; ‘anticholinergic burden’; ‘nutritional status’, for example, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool score or ‘use of nutrition supplements’; and ‘appropriate use of covert medication.’ ‘Anticholinergic burden’ was added to the second Delphi round. ‘Patient mobility’ was not added because it was considered a subset of ‘physical functioning’. The other suggestions were considered beyond the COS scope. Another outcome, ‘number of medicines (and associated costs)’, was reformulated into two separate outcomes: ‘number of medicines’ and ‘costs of medicines’.

The 17 outcomes for which consensus had not been achieved, together with the three outcomes added/reformulated based on panel feedback, resulted in a total of 20 outcomes being included in the second Delphi round (see Appendix 1, Table 4).

The second round was completed by 18 of the 19 respondents (94.7% response). Two outcomes (‘number of medicines’ and ‘anticholinergic burden’) met the criteria for inclusion in the COS, with the remainder (n = 18) being excluded (see Appendix 1, Table 5).

Therefore, a total of 13 individual outcomes met the inclusion criteria in the COS (see Appendix 1, Table 6).

Discussion

This WP was informed, in part, by the stakeholder engagement activities organised in WP1. Stakeholder engagement is a crucial part of COS development methodology to ensure that outcomes represent those that are considered of importance to service users and/or their representatives.

The final COS provided the basis for planning the next phases of the trial, notably the feasibility study (WP5), internal pilot and main trial (WP6).

Work package 3: health economics

A summary of the health economic work undertaken is given below. More details on the Methods and Results for the health economics component of the main trial/WP6 are given in the associated health economics report (see Appendix 8).

Background

Medication administration errors are common within care homes. 1 The PIP intervention therefore has the potential to improve outcomes. However, not all treatments can be provided. We therefore undertook an economic evaluation of the PIP intervention to assess whether it represented a good use of scarce resources. This was deemed feasible for the full trial (outlined in WP6) based on, amongst other things, the high response rate achieved for proxy EQ-5D scores in the feasibility study (see WP5). The methods of resource use data collection were also informed in a previous work in the care home setting. 23

Objective

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of the PIP intervention.

Methods

Study overview

The economic evaluation was conducted alongside the CHIPPS cluster randomised trial (see WP6 of this report).

Costs

The methods used to estimate costs are described in the associated health economics report (see Appendix 8). In brief, costs were estimated in Great British pounds (£) at 2017/2018 financial year levels, from the perspective of the NHS and PSS, over the 6-month trial (no discounting was undertaken).

To estimate the cost of the PIP intervention applied in WP6, each PIP was asked to complete a training log and a log of all activity associated with the intervention, including contacts with others, for example, care home residents, care home staff, GP or any other professionals (geriatricians, community pharmacists, district nurses, etc.). Subsequently, unit costs24 (see Appendix 1, Table 22) were assigned to estimated times for all PIPs and other staff time.

It was envisaged that the PIP intervention would enable GPs to spend less time undertaking prescription management for intervention arm participants. Accordingly, based on previously published work,24 the estimated GP time (cost) saving per resident was also estimated.

The total PIP intervention cost was subsequently estimated by summing the PIP training and activity costs and deducting the estimated GP time/cost saving.

Other costs

As informed in previous research,24,25 GP and practice nurse visit data were extracted from primary care records, along with medication data, outpatient attendances, inpatient stays, tests and investigations. All other health professional contacts (phone calls, visits and their location) were extracted from care home records.

Data for the previous 3 months were collected at baseline and those for the previous 6 months were collected at 6-month follow-up. Unit costs24,26 were assigned to each contact/admission in line with Underwood et al. ;27 medication costs were extracted from the prescription cost analysis (PCA). 28,29

Outcomes

Quality of life was measured using the EuroQol Five Dimensions and Five Level Rating Scale (EQ-5D-5L). 30 The EQ-5D-5L (proxy version) was chosen as it is deemed the preferred measure of utility in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) methods guide31 and in the light of work undertaken in the CHIPPS feasibility study32 (see WP5). The latter included an assessment of outcome measures used in the CHIPPS feasibility study where the EQ-5D-5L was chosen to be used in the full RCT, as it had been previously validated,33 and had a relatively good completion rate and low time taken to collect. It is recommended that QALYs are used to measure and value health effects, as QALY is a generic measure of health benefit that considers both mortality and health-related quality of life. 34

For all participants, proxy respondents were asked to report participants’ level of problems (none to extreme/unable) in five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) at baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-up. In line with the NICE position statement,33 the crosswalk mapping function was used to convert these responses into utility scores. 35 Those who were known to have died by the particular follow-up points were assigned a utility score of zero. QALY scores were subsequently estimated based on the total area under the curve method and the assumption of linear interpolation. 36

Analyses

Base-case results were based on those with complete cost data at both baseline and 6-month follow-up and those with complete EQ-5D data at baseline, 3- and 6-month follow-up. Bivariate regression37 was used to analyse the cost and QALY data, based on the intention-to-treat approach, enabling the mean incremental cost (mean difference in cost between the two arms) and the mean incremental effect (the mean difference in QALYs) to be estimated. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC)38 was also used to estimate the probability of the PIP intervention being cost-effective at the λ value of £20,000/QALY compared with standard care. In addition, three key sensitivity analyses were undertaken: using multiple imputation to account for missing values, removing training costs (as they are one-off cost) and undertaking a threshold analysis to establish at what threshold the intervention would be effective (in terms of cost or effect).

Results

PIP intervention costs

The training logs were returned by 23/25 PIPs, and the activity logs by 22/25 PIPs. Training costs were assigned to the two non-responding PIPs, but activity costs were not assigned to three non-responding PIPs, as they did not implement the PIP intervention. Overall, the mean reported activity time for each PIP was equivalent to an average of just over 3 hours per resident (see Appendix 1, Table 23). The total PIP intervention cost was subsequently estimated to be £323 per resident by summing the PIP training and activity costs and deducting the estimated GP time/cost saving.

Other costs

It is notable that the mean cost associated with the intervention was lower than that associated with overall medication costs, GP/practice nurse contacts, other professional contacts and in-patient stays. In terms of total (NHS and PSS) costs, the (unadjusted) mean difference between arms was £246. This might suggest that some of the aforementioned PIP intervention costs were partially offset, for example, by lower medication costs (see Appendix 1, Table 24).

Outcomes

EQ-5D scores are shown in Appendix 1, Table 25, where it can be seen that both arms had lower mean scores at the 3- and 6-month follow-up points. Although the mean QALY score was higher for the intervention arm, the mean baseline EQ-5D score was also higher for these participants. This means we cannot infer that the intervention was more effective based on these results and that there is a need to adjust for, amongst other things, the baseline difference in EQ-5D scores between arms.

Analyses

A total of 609 participants (70%) had complete cost and EQ-5D data. Bivariate regression estimated that the mean (95% confidence interval) incremental cost of the intervention, compared with standard care, after adjusting for baseline costs, age and gender was £279.86 (£19.39–540.33). The estimated mean incremental effect was −0.004 (−0.016 to 0.009) QALYs. The PIP intervention was therefore estimated to be dominated, as it was associated with higher costs and lower effect, and the CEAC estimated that it had a 3.8% probability of being cost-effective at the £20,000/QALY value. These results suggest that there would be no added benefit of a long run model as (given lower effect and higher cost) as the results of a long-term model would be unchanged/in line with the within trial analysis, that is, the PIP intervention would not be estimated to be cost-effective. All sensitivity analyses were not found to change conclusions from the above findings.

Discussion

In terms of overall costs, the estimated mean incremental cost of £280 was lower than the estimated cost of the PIP intervention, suggesting that intervention costs were partially offset by certain lower costs, for example, medication. However, as the PIP intervention had higher mean costs and was not estimated to be associated with an improved QALY score, it is not estimated to be cost-effective. These conclusions are based on the 6-month within trial analysis for those with complete data, but the conclusions were the same when multiple imputations or other sensitivity analyses were carried out (see Appendix 1, Table 26).

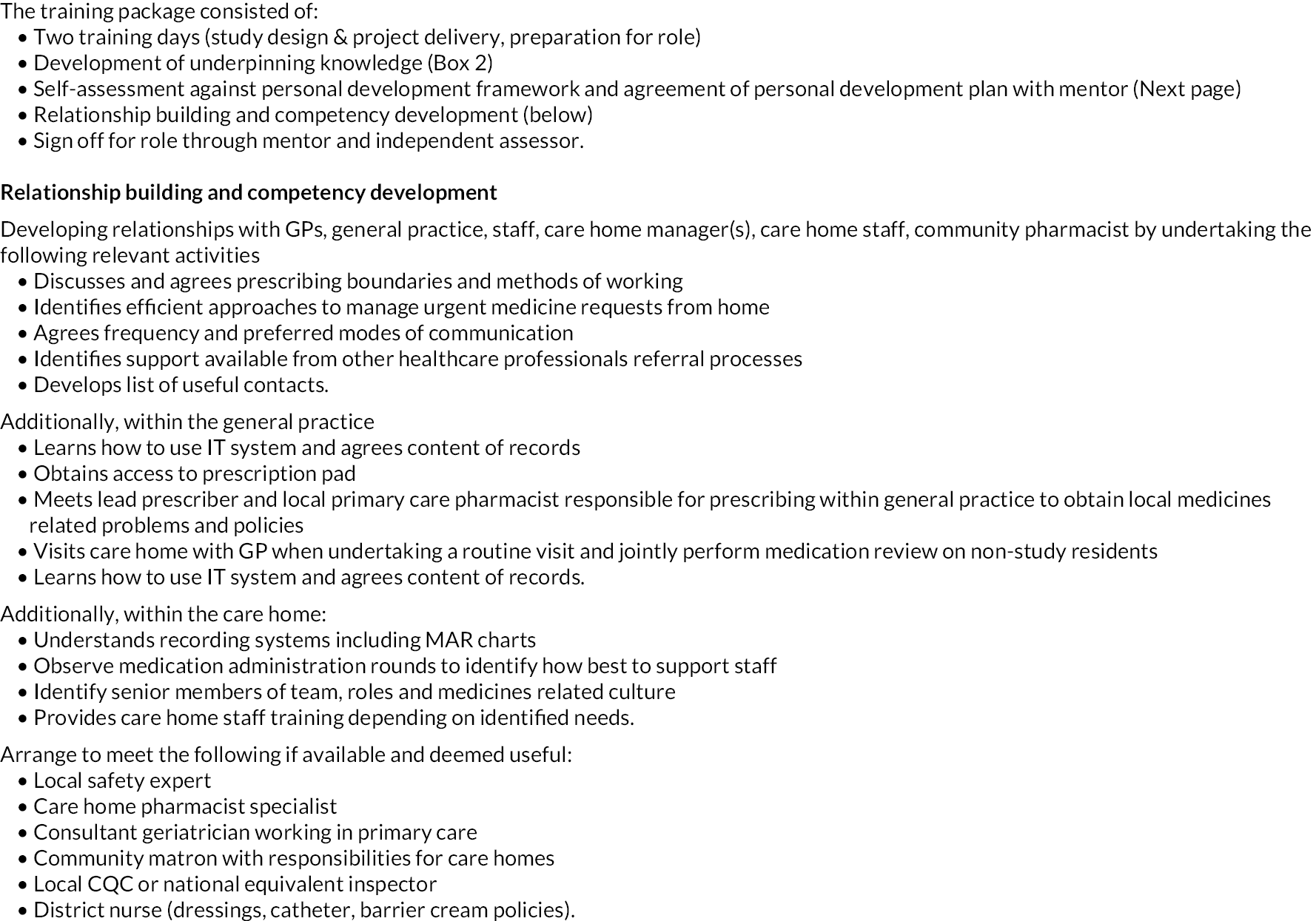

Work package 4: development of PIP training package

Approvals

Research ethics approved by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee Ref.: 20142015-77.

NHS Research and Development approved by NHS Grampian Research and Development Ref.: NRS15/PH18.

Aim

Develop a training package to ensure that pharmacist independent prescribers are appropriately prepared to deliver the service.

Method

WP4 consisted of six phases:

-

systematic review and narrative synthesis

-

initial stakeholder engagement

-

training specific interviews and focus groups

-

stakeholder engagement and consensus

-

feasibility testing

-

validation.

Systematic review

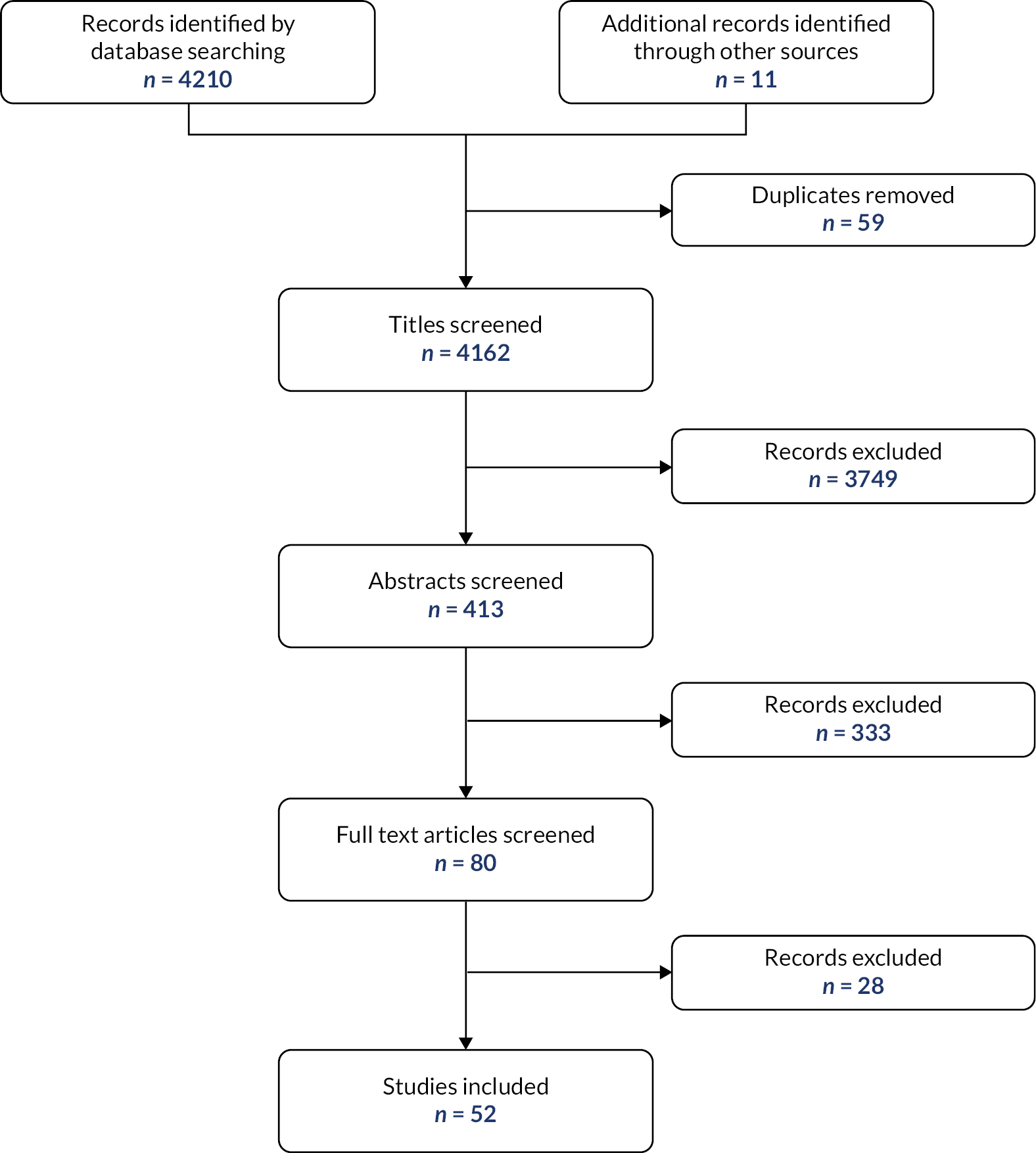

The systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42015026693) and adheres to PRISMA. 39 Papers and abstracts were selected for review to inform both content and design of any future pharmacist training package.

Synonyms for care home (population), pharmacist (intervention), education and training (outcome) and pharmaceutical care (intervention) were used. This review included articles published until 30 June 2015.

Inclusion criteria:1

-

Description of education and training of pharmacists before service/intervention delivery in a care home, OR

-

Description of expertise of the pharmacist, for example, title denoting additional expertise or training to perform role, OR

-

Training provided by pharmacists to care home staff for which they would need to have sufficient knowledge to deliver, OR

-

Materials provided to support the pharmacist in service delivery in care homes, AND

-

English language.

Exclusion criteria:2

-

Studies not primarily focused on provision of services to older people residing in care homes

-

Studies where the primary focus was to determine the effectiveness of an individual drug, OR

-

Papers without empirical data for example, editorials, opinion pieces commentaries, OR

-

Abstracts, OR systematic reviews and narrative syntheses.

Databases searched (July 2015) were Academic Search Complete, EBSCOH, Ovid MEDLINE® and EMBASE, OvidSP, ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts), CSA, ProQuest XML, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Reviews (Issue 6 of 12, June 2015), E-theses online service (EThOS), Ingenta Connect (Ingenta), Wiley Online Science, EPOC Group Specialised Register, Reference Manger, Ageline (EbscoH), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), EBSCOH, International Pharmaceutical Abstract (OvidSP) and PsycINFO (EbsoH).

Titles, abstracts and full-text papers were screened for eligibility, independently by two authors. Differences were resolved by consensus. A PRISMA diagram39 was populated, and Kappa coefficients40 calculated.

As the narrative synthesis focused on learning from the content of published care home interventions, the quality of the included papers was not appraised.

In line with Cochrane guidance, the following information was extracted from papers and abstracts by two independent researchers (DW and VM):

-

year, design, location, setting

-

main findings

-

pharmacist expertise

-

education and training provided

-

service delivery support tools provided

-

training of care staff provided by pharmacist

-

clinical and therapeutic area(s) of intervention focus (three most commonly reported)

-

intervention description.

The results were compared and again agreed by consensus by two independent reviewers.

Analytical approach

Data were themed and collated to inform the development of a care home pharmacist training package. All training methods outlined within selected papers were extracted.

Initial stakeholder engagement

As part of the main programme of CHIPPS work, focus groups and interviews were undertaken primarily to define the PIP service specification. 14 Incorporated into the topic guides was a question regarding the pharmacist-training package.

The elements from the content analysis were combined with those from the previously reported literature review41 by NN and DW to create a training package including a personal development framework (PDF) consisting of domains (i.e. our grouping name for a selection of similar competencies), competencies and behaviours. This was presented to the External Advisory Panel (EAP) to review and amend.

Training-specific focus groups and interviews

Focus groups with different healthcare professional groups were organised and located across four locations as follows:

-

primary care pharmacists (Yorkshire and Humber)

-

general practitioners (Aberdeen)

-

community pharmacists (Belfast)

-

care home staff (Norwich).

Within each location, an appropriate healthcare professional with significant local care home experience regarding medication management was interviewed to enable identification of local environmental and contextual factors.

The current draft of the training package was provided before focus groups and interviews. The topic guide consisted of the following:

-

initial views on the draft training package

-

therapeutic and clinical areas to be included

-

care home-specific processes which pharmacists would need to be aware of

-

knowledge required to be effective

-

inter-professional related knowledge required

-

advice relating to pharmacist preparation.

Where possible, consensus on how best to amend and enhance the training package and framework was identified within the focus groups. All the focus groups/interviews were recorded digitally and transcribed verbatim. Interviews and focus groups were content analysed by DW and validated by NN.

To create the next draft of the training package, where consensus was not clear, a final decision was sought from the EAP.

Expert consensus

A consensus day held at each study site (outlined in WP1), included a session to obtain feedback on the draft training package regarding:

-

training content

-

PDF

-

assessment processes

-

Points of dissonance identified within the stakeholder focus groups and interviews.

Detailed notes were taken from the consensus panels and used by NN and DW to create a final draft training package for feasibility testing.

Feasibility testing

Four PIPs and four care homes, each with 10 consented residents, were recruited and PIPs trained to deliver the intervention over 3 months. 42 At the end of the feasibility phase, a face-to-face focus group with the PIPs was convened to obtain feedback regarding

-

personal development planning and support process

-

PDF

-

assessment processes

-

impact of the training

-

elements that worked well and those that worked less well.

Focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim and content analysed to create the final draft training package for use within the main trial.

Validation

All intervention PIPs undertook the final training plan. The PIPs’ experience of the training days and the aligned professional development and assessment of competence were evaluated through training day evaluation forms (PIP n = 21), online survey (PIP n = 17) and semi-structured interviews (PIP n = 14). Using a mixed-methods approach, each dataset was analysed separately and then triangulated to provide a detailed evaluation of the process. The evaluation forms and online survey were described quantitatively and tabulated. Qualitative interview data were coded by two researchers, and descriptive categories and interpretative themes identified through thematic analysis were agreed upon among the researchers.

Results

Systematic review

Paper selection and description

Fifty-two papers were selected for the review (see Appendix 1, Figure 3). Characteristics of the included papers are provided in Appendix 1, Table 7. All studies reported that their intervention was effective.

Pharmacist, education and training characteristics

Descriptions regarding qualifications and training provided before pharmacist role in care homes were generally vague. Six papers reported the pharmacists being provided with a tool to support the service.

Two papers described the pharmacists being trained in inter-professional relationship development. Ten papers described some form of training in a limited manner.

Codified and practical knowledge

A summary of the main clinical and therapeutic areas identified and the most commonly cited activities is provided in Appendix 1, Table 8.

Care home–specific cultural knowledge

Care home staff training was seen as important for developing relationships and changing care home medication-related cultures, for example, requests for medication such as antibiotics, antipsychotics, analgesia and laxatives43 and willingness to implement changes in therapy. Care home culture was cited in one paper as a reason for medication changes not being implemented. 43,3

Stakeholder engagement

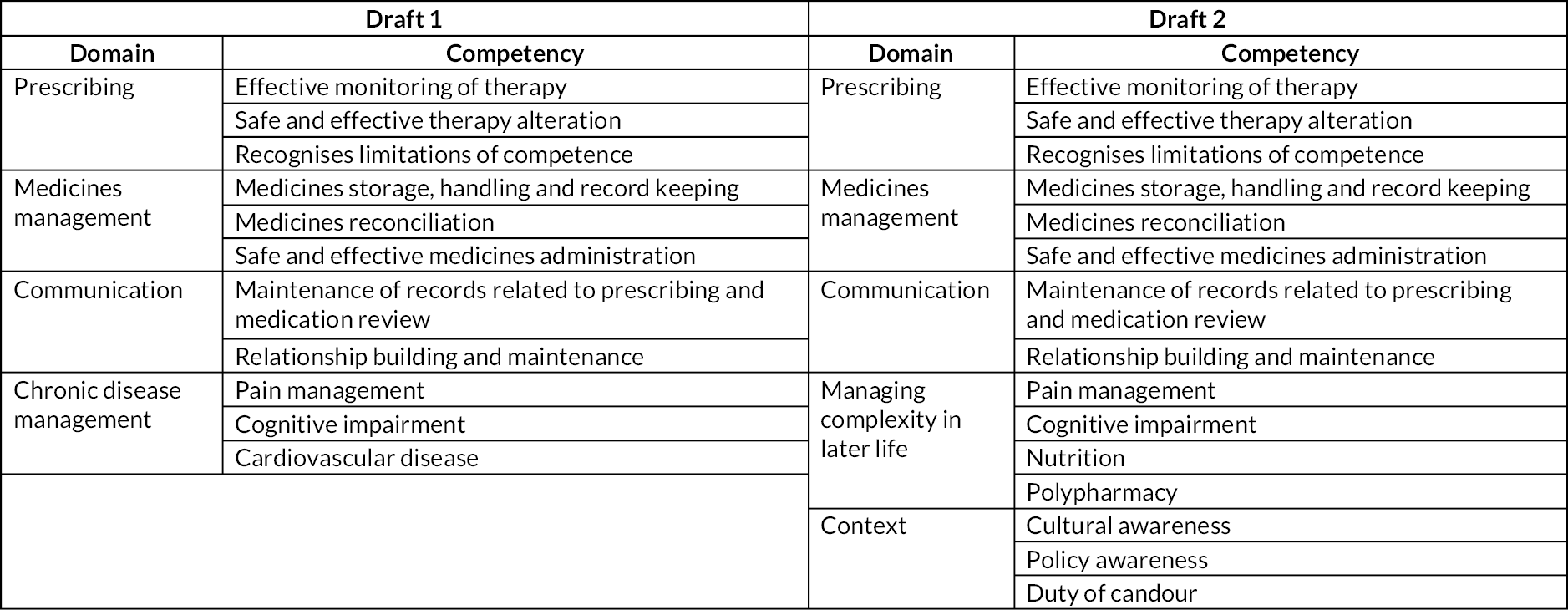

Thirteen interviews and 13 focus groups with 72 participants were undertaken. The main results have been reported elsewhere. 44 The different types of knowledge identified as important through the interviews and focus groups are summarised in Appendix 1, Box 1. Appendix 1, Figure 3: Draft 1 provides a copy of the first draft of the PDF used to underpin the training package.

A variety of activities were added to enable the development of identified cultural knowledge requirements, for example, spending time with different medical practice and care home staff to identify expectations and preferences and learning to use local systems.

The practical knowledge identified as important was how to provide pharmaceutical care for older people with frailty.

The EAP identified the need for ‘context’ to be included as a domain within the PDF and to change the ‘chronic disease management’ domain to ‘managing complexity in late life’ (see Appendix 1, Figure 4: Draft 2).

Training-specific focus groups and interviews

Six primary care pharmacists, six GPs, five community pharmacists, six care home staff and four local experts participated. Additional changes to the training package were identified as being required, including the addition of activities to enable the PIP to understand local cultures and to integrate into the teams.

Expert consensus

Four consensus panels were held (Grampian n = 12, Yorkshire and Humber n = 12, Norfolk n = 15, Belfast n = 14). The content of the face-to-face training days was agreed along with the expectation that a geriatrician should be involved in delivery.

The consensus panel emphasised the need for a significant amount of time to be allocated to the development of relationships and that training care home staff was an important element within this.

A number of further changes to competencies and behaviours were recommended.

A large number of topics about which PIPs should be knowledgeable were identified (see Appendix 1, Box 2). It was agreed to provide this information through a knowledge pack, consisting of relevant links.

It was proposed that the PIPs would use the PDF for self-assessment purposes and they should be allocated a mentor (senior care home pharmacist) to support them through the process.

Completion of these competencies would be signed off both by their mentor and by a medical practitioner with expertise in providing medical care to care home residents (independent assessor). Sign-off by both parties would provide the ‘accreditation’ for the PIPs.

A copy of the training package and PDF created following this exercise and before feasibility testing is provided in Appendix 1 and Figure 5.

Feasibility testing

The PIPs reported that the process of personal development planning, being supported by a mentor and assessed on their final competence through oral viva, was appropriate and effective. Greater guidance on evidence collection for assessment purposes was requested at the outset.

The elements of the face-to-face training that were perceived as particularly effective were the case studies surrounding the management of complexity, legal issues and covert administration and the session on the management of psychotropic medication.

The training was viewed positively and reported to be motivational, helping to enhance confidence. This resulted in no major changes to the training package.

Evaluation

All PIPs found the training useful, specifically the input from the geriatric specialists who produced case studies on medication management in older people: ‘probably about the best CPD I’ve done for a long time’. Overwhelmingly, the PIPs strongly agreed that the training content was appropriate.

-

Comprehensive training, mentorship, competency assessment and explanation of research processes amply equipped these experienced PIPs to carry out their role.

-

Input from older people psychiatric specialists and specific training on antipsychotics was reported to be of huge value to the majority of PIPs, increasing their confidence and understanding around this area of medication management.

Post-training mentorship by a qualified pharmacist with extensive care home experience was reported as being extremely helpful in guiding their CPD and in preparing a portfolio of evidence for the assessment of competence by a GP. All PIPs achieved competency at first attempt and within expected timelines. Only one PIP stated that mentorship was not very useful at this stage. The PIPs reported that they had less contact with the mentor as the intervention progressed.

The training days and mentoring appeared to increase confidence, especially in PIPs with limited experience in older people medicine. Even for those with extensive experience in older people medicine, the training provided a chance to consolidate knowledge. Alongside consolidating clinical knowledge, the PIPs needed to be able to successfully develop relationships with care home staff and primary care staff if they were joining a new practice. PIPs reported arranging peer support through the cloud-based messaging app ‘Telegram’. Mentorship and peer support was reported as useful in the early stages of the intervention but use tailed off as individuals’ confidence grew.

The need to demonstrate competency through completion of the competency framework and professional discussion with a GP was appreciated by the PIPs. Evidence from the PCP reviews suggested all were competent in the role. PIPs’ comments on their practice during the trial, evidence the increased competency and confidence they had due to the training programme:

There were a few people that we’d got off a medication, antipsychotics particularly, because that’s something I probably wouldn’t have touched, but after having the training session, and the group discussions, and more of an awareness, I felt more comfortable

Pharmacist independent prescribers suggested that individualised country-specific sessions could run in tandem during main training days without affecting the length of the training programme. An additional refresher event mid-intervention was recommended as was advice on building relationships in CHs where work cultures may be new to pharmacists.

Discussion

The results from the feasibility study suggest that the iteratively designed training package is likely to ensure that PIPs are competent to undertake their envisaged role. Evaluation within WP6 will enable the researchers to determine whether it is generalisable to a broader range of PIPs.

Work package 5: feasibility study4

Approvals

Research ethics approved by NRES East of England – Essex REC Ref: 16/EE/0284 and Scotland A REC Ref.: 16/SS/0125.

Health Research Authority approved Ref: IRAS 206970.

Aims

To test and refine the service specification and proposed study processes to inform the cRCT (WP6).

Objectives

To

-

test processes for participant identification, recruitment and consent and assess retention rates

-

determine suitability of outcome measures and data collection processes from care homes and GP practices

-

assess service and research acceptability

-

test and refine the service specification.

Method

Design

This was a single-arm, open-feasibility study conducted in care homes for older people in all four locations across the UK from August 2016 to April 2017.

The recruitment target was one eligible general practice, one PIP and up to three care homes associated with each participating practice in each location. Each GP/PIP/care home(s) triad had a target of recruiting 10 residents.

Inclusion criteria

GP practice

General practitioner practice managing sufficient care home residents to recruit a minimum of 10 residents in up to three (in case one or more care homes did not have sufficient eligible participants) care homes. An existing arrangement with a PIP was preferred, but not mandatory.

PIPs

Pharmacists registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council or Pharmaceutical Society of Northern Ireland as independent prescribers.

Care homes

Care home primarily caring for residents aged ≥65 years, registered as caring for adults aged ≥5 years.

Residents

Permanent residents under the care of the participating GP practice, prescribed at least one regular medication, aged ≥65 years; they should be able to provide informed consent/assent, or for this to be provided by a nominated representative.

Residents on an end-of-life care pathway were excluded.

Patient identification and recruitment

PIPs and GP practices

Each location used locally defined strategies and networks (see Appendix 2) to obtain expressions of interest (EOIs) from GP practices and PIPs, for either the feasibility study or the planned main RCT.

Care homes

The consenting GP practice in each study location approached up to three care homes. Care home managers expressing interest were sent a formal invitation pack by the local researchers. A second or third care home was contacted only if there were insufficient residents in one home.

Residents

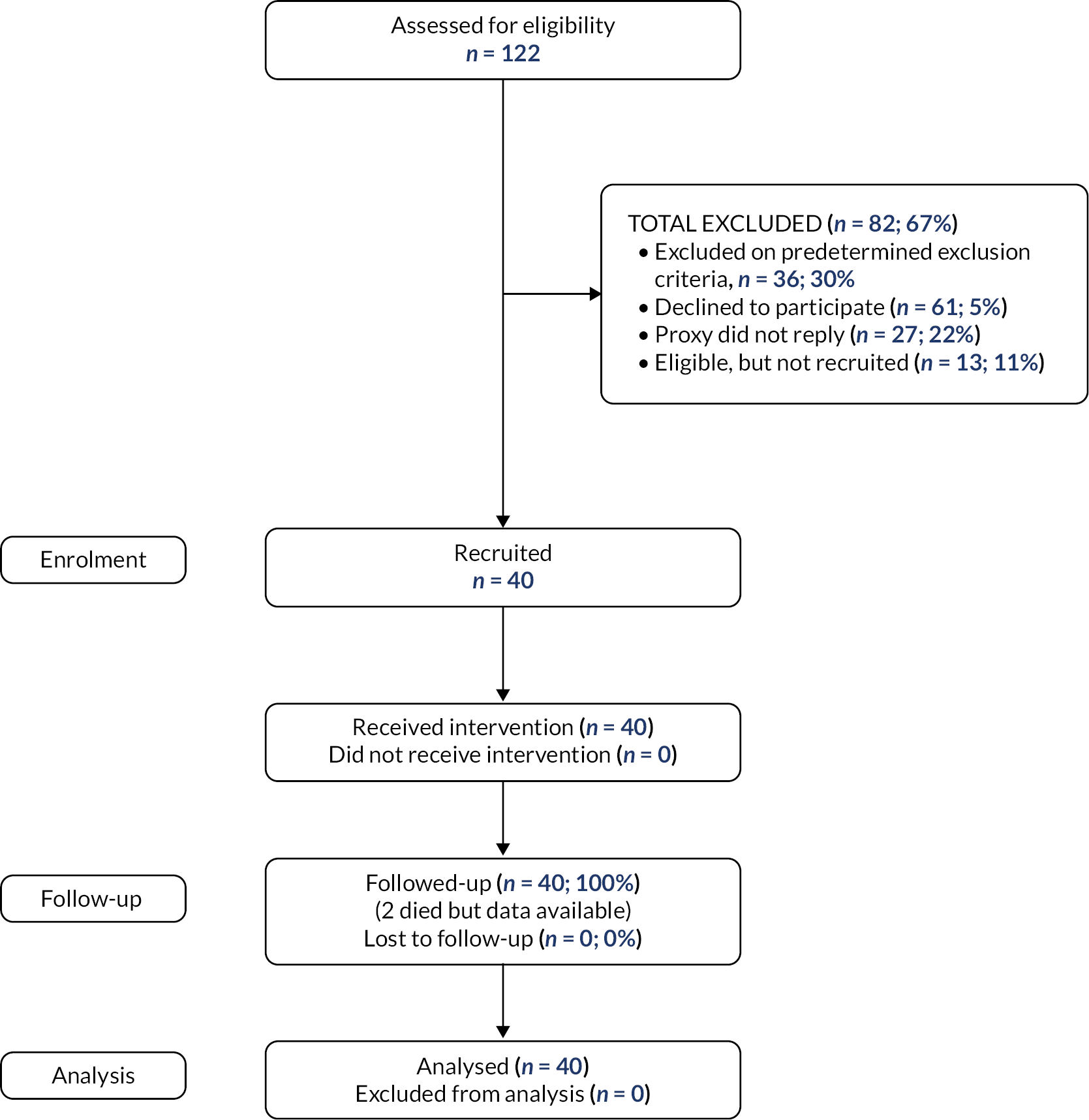

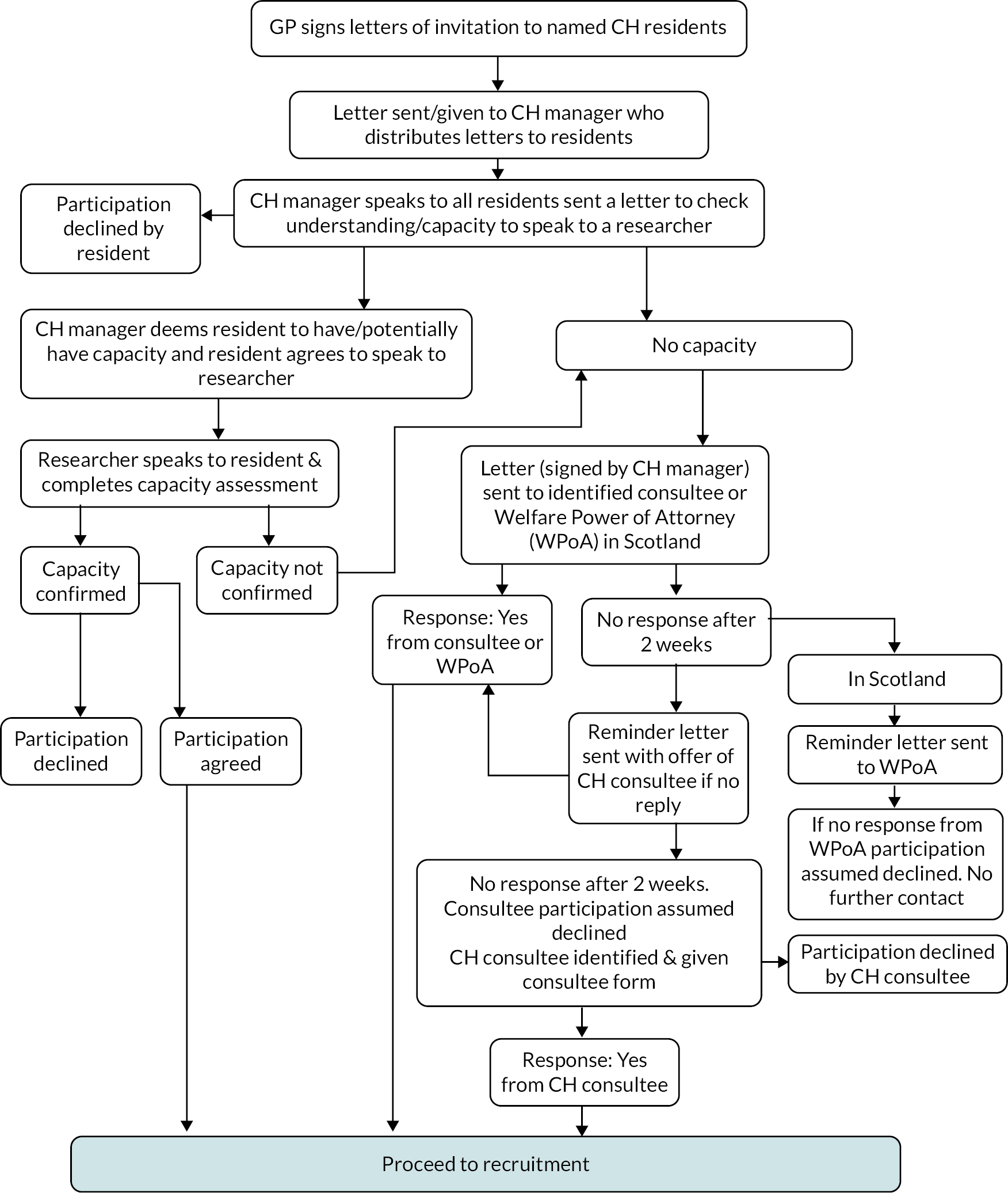

General practitioners identified eligible care home residents from their computerised records. An invitation pack [letter from the GP, participant information sheet (spoken version, if necessary) and consent form] was distributed to each resident by the care home manager. After a minimum of 24 hours, the care home manager visited each resident and obtained verbal consent from residents willing to discuss the study with the study research associate (RA) who then visited the care home, met with interested residents and assessed resident capacity to give consent. Where a resident was identified by the care home manager or RA as lacking capacity, a legally appropriate third party [e.g. relative/friend known as consultee (England and Northern Ireland)] or welfare power of attorney (WPOA; Scotland), was contacted by mailed invitation pack, through the care home. Reminder letters were issued after 2 weeks as needed. In England and Northern Ireland, a member of the care home staff could be nominated as the consultee, but in Scotland, a member of staff could not be the WPOA. The recruitment process is outlined in Appendix 1, Figure 5.

Sample size

No formal power calculation was conducted. The recruitment target was 10 participants per site (a total of 40), judged as sufficient to assess feasibility. 45

Intervention

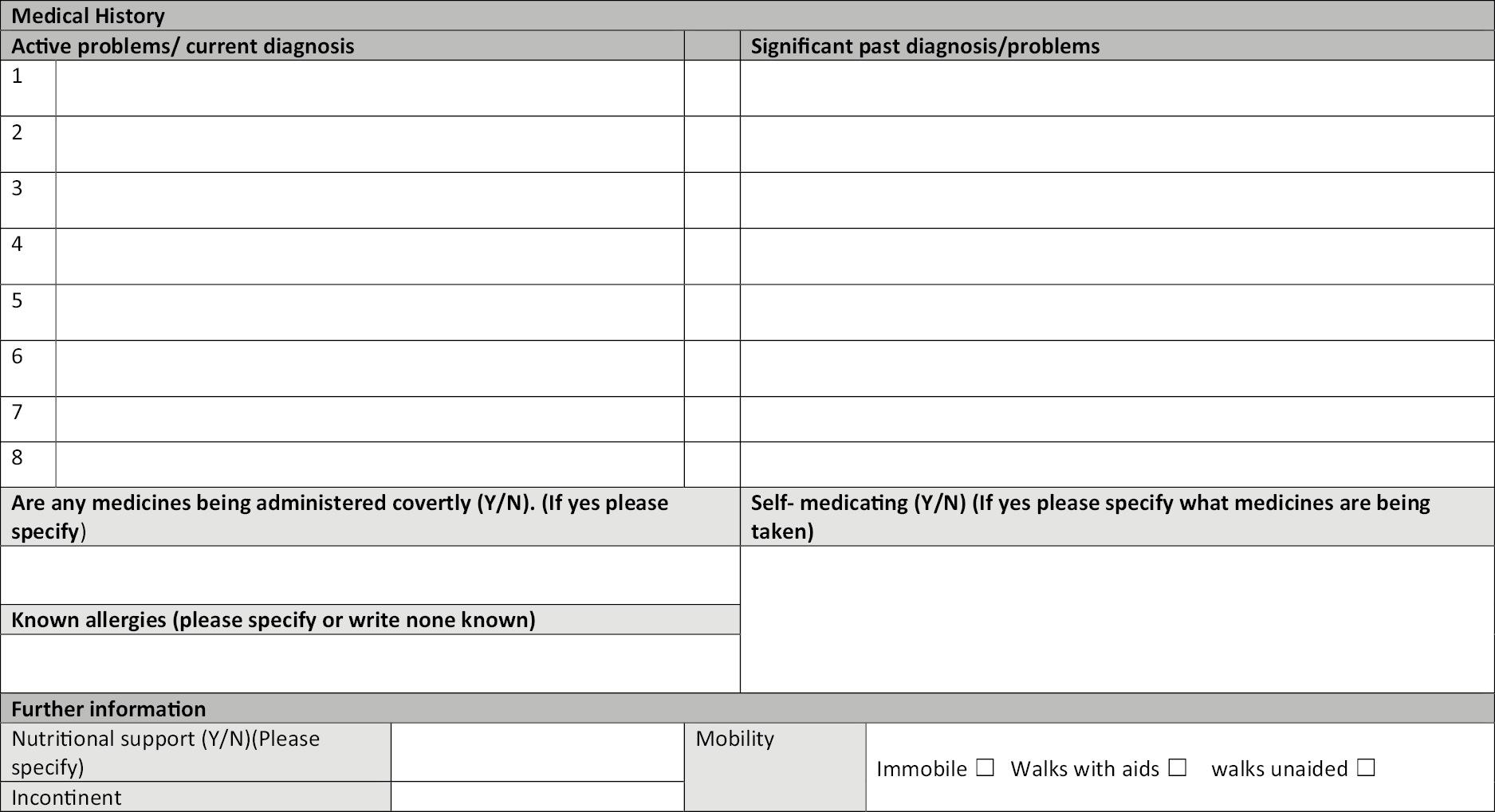

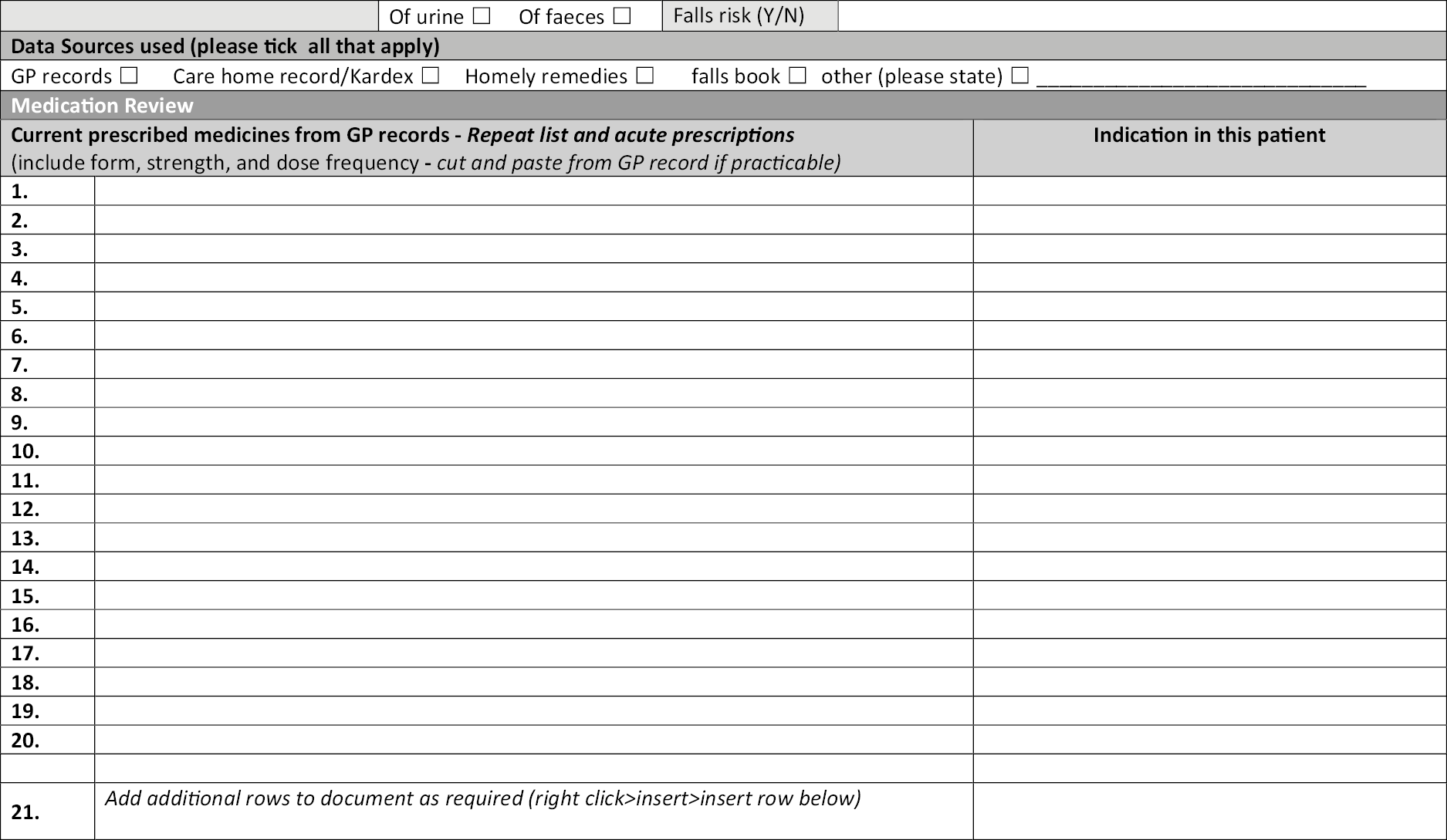

The intervention included medication review; prescribing and deprescribing; care home staff training, medication-related support and communication (see Appendix 3). It spanned for 90 days (4 hours per week per PIP per 10 patients). Before the intervention, PIPs attended training (described in WP4). Pharmaceutical care plans (see Appendix 4) were used by the PIPs to document each intervention. A random sample of eight PCPs (two per location) was selected for review of appropriateness (based on professional judgement) by one of the two specialists in ‘care-of-the-elderly’ grant holders.

Estimating the participating proportion of the eligible population

The proportion of general practices, pharmacists, care homes and residents approached and consented was recorded along with the proportion of residents followed up at 3 months to assess recruitment and retention.

Suitability of outcome measures

Potential outcome measures identified in WP2 (see Appendix 1, Box 3) were collected at baseline and 3-month follow-up for each participant. To determine their suitability for inclusion in the RCT, each outcome measure was assessed against the following criteria: availability of the data source, potential for bias, potential for missing data, resident centeredness, sensitivity to the intervention, reliability, whether validated, potential for third party completion, ability to blind and time taken to collect per patient and quantity of data. At minimum, the measure had to be judged objective, discriminating and efficient to collect.

Assessment of service acceptability and trial feasibility

Participant views

After the intervention, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were held with stakeholders at each location and a focus group held with the PIPs. Proceedings were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Serious adverse drug events

All admissions to hospital and deaths were recorded as serious adverse events (SAEs) and assessed for causality by a medical doctor in the study management team, using professional judgement.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the quantitative outcome measures at baseline and follow-up. No statistical comparisons were conducted. Interview and focus group transcripts were thematically analysed.

Approvals and registration information

A favourable ethical opinion was received from East of England – Essex Research Ethics Committee (5 September 2016: 16/EE/0284) and Scotland A Research Ethics Committee (8 September 2016:rec ref. number 206970) with subsequent approval from the Health Research Authority/NHS Research and Development.

The trial was registered on the ISRCTN registry Registration number ISRCTN10663852.

Results

Recruitment and retention

In total, 4 PIPs, 4 GPs, 6 care homes and 40 residents were recruited (see Appendix 1, Table 9 and Figure 6). The four recruited PIPs were employed directly either by the practice (1) or by the NHS (one with no existing relationship with a GP) (2) or were self-employed (1). The GP or PIP identified 122 residents from GP records and invited 86. Thirty-six (30%) residents were excluded on screening and 33 (27%) of those invited declined the invitation or did not reply. Forty were recruited and retained for 3 months.

Suitability of outcome measures

There were data for all outcome measures (see Appendix 1, Table 10) for all or most residents, other than the MMSE, which could be completed only by 40% and 35% of residents, respectively, at baseline and follow-up. The direction of change between baseline and follow-up suggested that the intervention could improve care.

Appendix 5 provides a review of the suitability of outcome measures following feasibility testing. The outcome ‘falls per patient’ met most criteria and was selected as the primary outcome measure with Drug Burden Index (DBI),46 hospitalisations, mortality, Barthel (proxy)47 and ED-5Q-5L (face-to-face and proxy). 30,33 Whilst hospitalisations and mortality were also considered as the potential clinical primary outcome, when considering the sample size necessary to detect a clinically important difference, falls was the only feasible option. STOPP/START was not used due to perceived subjectivity. 19 The QUALIDEM48 and MMSE49 were excluded as too time-consuming to complete, a better measure was available (to replace the QUALIDEM) or a high potential for bias existed and/or data were missing.

Quality of pharmaceutical care plans and adverse events

Eight pharmaceutical care plans (PCPs) were reviewed. Six PCPs were considered appropriate. Two included insufficient detail to fully judge appropriateness. Just over 10% of residents [5/40 (12.5%)] were admitted to hospital (11 hospital admissions), and two residents (5%) died. None of these events were related to the intervention.

Participants’ views of service and research acceptability

All 28 participants invited to interviews agreed (6 care home managers, 6 GPs, 12 care home staff, 12 residents, 3 relatives and 1 dietician). Lack of capacity restricted the number of residents interviewed.

Perceived benefits of the service

All participants expressed positive views about the service. The main themes are summarised below and illustrated with exemplar quotes detailed in Appendix 1, Table 11 and indicated in the text.

Improved patient care and safety

Regular medication review led to improved patient care and quality of life (quote 1). The key pharmacist skills were their knowledge, ability to prescribe, professionalism, autonomy and ability to provide training and communication (quote 2). Care home managers highlighted that medication practice had become safer (quote 3) and efficiency was increased. The PIP facilitated prompt implementation of medication changes and acute prescriptions (quote 4) and saved care home manager time (quote 5). A nurse highlighted the value of having pharmacists who could prescribe (quote 6). The PIP had time to communicate with relatives and care home staff (quote 7) and had more time than GPs to complete detailed medication reviews (quote 8).

The PIP service freed up GP time and was the most ‘efficient’ way of conducting medication reviews (quote 9), with the ability of the PIP to work autonomously being valued (quote 10). Conversely, some care home managers did not feel it freed up any time for them (quote 12), but neither did it impede care home processes (quote 11). However, it did reduce stress levels and improve communication (quote 13).

Potential disadvantages of the service

Few disadvantages were mentioned. The main one was that the PIP was not as familiar with the patients as the GP (quote 14). GPs also expressed concern that they would become less familiar with the residents and the care home staff if they were less involved (quote 15).

Refinements to service specification

Only two of four PIPs attended the focus group. Two were unwell, and views were obtained by later telephone interviews. Few changes were proposed. Delivering the service took more than the indicative 4 hours per week, not having an existing relationship with the GP was a disadvantage, and PCPs needed simplifying.

Discussion

The acceptability of the service and feasibility of proceeding to the main trial were confirmed. The processes to identify and recruit trial participants (GPs, PIPs, care homes and residents) were successful and scalable, including those for participants without capacity. Participants were retained for 3 months. The primary outcome measure for the main trial was confirmed as the fall rate per person. In contrast to other potential outcomes, a clinically important difference in falls would be detectable with acceptable power within a realistic sample size. Minor areas of refinement to the service specification and the research process were identified. For example, using the professional judgement of a study team member to assess causality between reported adverse event(s) (AEs) and the intervention was subject to bias, and an alternative approach was developed, that is, using independent GPs for WP6. Similarly, a review of the PCPs, conducted subjectively by the study team members, could have been biased, and WP6 includes details of the standardised protocol and reporting templates used in the main trial.

The participant demographics were similar to those of the UK care home population. 1 Participation rates were high, suggesting there had not been selective recruitment. The PIPs participating in this study included pharmacists employed by either primary care or the GP practice, providing evidence that this service specification is adaptable to either model; PIPs with a pre-existing relationship with the GP found it easier to arrange meetings.

The level of EOI confirmed that there would be sufficient participants for the main trial, and the consent rate of residents informed the target number of care home patients required to be registered with the participating GP.

Work package 6: definitive trial with internal pilot

Approvals

Research ethics approved by NRES East of England Central Cambridge REC Ref.: 17/EE/0360 and Scotland A REC Ref.: 17/SS/0118.

Health Research Authority approved, Ref.: IRAS 233964.

Aim

To estimate the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and safety of a PIP assuming responsibility for providing pharmaceutical care to residents in care homes.

Methods

This was a cRCT conducted in primary care involving triads of a GP practice, PIP and a sufficient number of care homes to provide 20 care home residents per triad. 50

Recruitment

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Pharmacist Independent Prescribers were excluded if they were already providing an intensive service to the care home or could have a conflict of interest by holding employment with the community pharmacy supplying the home(s).

General practitioner practices were included where they managed sufficient care home residents to support recruitment of our target of approximately 20 eligible participants.

Care homes needed to be primarily caring for adults aged ≥65 years and associated with a participating general practice. Homes were excluded if they already received a regular medication-focused review service (monthly or more) or were under formal investigation by a regulator [e.g. Care Quality Commission (CQC) for England].

Care home residents needed to be under the care of the participating GP practice if they were ≥65 years old, a permanent resident in a participating care home, prescribed one or more medications and able to provide (directly or through an appropriate representative) informed consent or advice. They were excluded if they were receiving end-of-life care or additional instructions on their residence (e.g. held securely) or were participating in another study.

Participant identification and recruitment

Pharmacist Independent Prescribers were identified using local networks and related GPs (if links already established) were recruited concurrently, followed by their relevant care home(s) who were approached by participating GPs. Where one single linked home had too few potential resident participants, up to two further homes were recruited.

Resident recruitment

General practitioners identified residents in participating care homes taking one or more medications and screened them against the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Care home managers handed out invitation packs to potential residents, re-visited each resident after at least 24 hours and obtained verbal consent for the local researcher to approach them to discuss study participation. For residents who were considered to lack capacity, packs were posted to the resident’s next of kin. The process is summarised in Figure 7.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was at triad level to minimise contamination occurring between two homes in the same practice where one received the intervention but the other did not. Residents were not individually randomised, as part of the intervention was for PIPs to help care homes improve their overall medication management processes. Randomisation was stratified by the four geographical areas, using a web-based electronic system integrated into the study database, in an allocation ratio of one intervention triad to one control triad. Because of the nature of the intervention, PIPs, care homes and GPs were not blinded to their allocation arm once the intervention began. Researchers, however, were blinded to arm allocation during the recruitment phase.

Six weeks were provided for PIP training to be undertaken and completed. Consequently, time zero for data collection purposes was standardised at 6 weeks after randomisation.

Intervention

This was delivered by trained PIPs for a period of 6 months and involved the PIP, in collaboration with the care home resident’s GP and care home staff, assuming responsibility for managing the medication of each resident, including

-

reviewing the resident’s medication and developing and implementing a PCP

-

assuming prescribing/deprescribing responsibilities

-

supporting systematic ordering, prescribing and administration processes with each care home, general practice and supplying pharmacy where needed

-

providing care home staff training

-

liaising with GP practice, care home and supplying community pharmacy.

We anticipated each PIP providing approximately 4 hours of intervention per week per 20 residents for 6 months.

Control: Triads allocated to the control arm received usual GP-led care, which could include pharmacist review/services to care homes where routinely provided, excluding those of an intensity equivalent to the study intervention.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was fall rate per person over 6 months after time zero, as documented in care home falls record for those residents recruited into the trial only.

Secondary outcomes, all at 6 months after time zero unless stated otherwise:

-

Resident (i.e. self-report) or proxy resident quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) at 3 months and 6 months: utility scale where a score of 0 indicates equivalent to death and that of 1 indicates full health. 30

-

Proxy modified physical functioning score (Barthel): a score of 0 is most dependent on 20, which indicates least dependent. 47

-

DBI: a measure of anti-cholinergic and sedative drug exposure, which was collected through GP-recorded medication data: higher scores indicate greater anticholinergic potential and increased risk of drug-related morbidity. 46

-

Health service utilisation (and associated costs); notably unplanned hospital admissions in the past 6 months, at 6-month follow-up, collected from care home and GP records (see WP3 for health economics results of WP6).

-

Mortality.

Sample size

A sample size calculation indicated that 880 participants (440 in each arm) would detect a 21% decrease in fall rate from 1.50 per resident over 6 months with 80% power, at the 5% significance level and an assumed intraclass correlation coefficient not more than 0.05. With approximately 20 patients per triad, this equated to 44 triads. The relative reduction of 21% was half of that detected within a UK-based, pharmacist-led medication review service provided to care homes. 51 Furthermore, we assumed a loss to follow-up of 20% based on mortality and loss observed in the CAREMED study. 23

Statistical methods

All analyses were by intention-to-treat, and it was anticipated that the primary outcome (‘falls per resident’) would follow a Poisson distribution; hence, the between-arm comparison of falls was to be made using a Poisson Regression model. Data subsequently demonstrated that the best fit was in fact a negative binomial model and parameters were estimated using a generalised estimating equation approach adjusted for the clustered design. The final model included baseline fall rate, prognostic variables (specifically DBI, Barthel Index and Charlson scores) and home status (nursing/residential) with arm as a fixed factor.

Safety

Processes were developed for recording sudden unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs), SAEs and AEs. SAEs were defined as inpatient hospitalisation and death requiring immediate reporting. If SAEs were believed to be related to the study intervention, then they were reported as SUSARs. We used a mixture of prospective and retrospective SUSAR notification by asking GPs to report SUSARs immediately, and retrospectively, and by our trial manager proactively contacting care homes each month to ask about SAEs. The resident’s GP was then assessed for causality of the SAE, and whether it was linked, or not, to the PIP intervention.

Concerns could also be confidentially raised by any member of care home staff using a dedicated email address.

A random (computerised number generation) 20% sample of the PCPs and associated resident documents were assessed by a study geriatrician, to ensure clinical appropriateness and safety.

Process evaluation

Complementary to the main RCT, a process evaluation was conducted,52 following MRC guidance. 7 This evaluation used a mixed methods approach to inform interpretation of trial findings and subsequent implementation, should the intervention be effective. Objectives were as follows: to provide description of the intervention in terms of quality, quantity and variability in delivery; to explore the effect of individual components on the primary outcome; to investigate the mechanisms of action; to describe views of the intervention (including training of PIPs and care home staff) from GP, care home, PIP, resident and relative perspectives; to describe the characteristics of each arm and to estimate how ‘normalised’ the intervention became.

A mix of quantitative (surveys of care home staff, GPs and PIPs, PIP activity logs, PCP review and the trial outcomes) and qualitative (interviews with care home staff, residents, GPs and PIPs) approaches were used. Data were collected relating to delivery of detailed tasks required to implement the new service, to collect data to confirm the mechanism of action as hypothesised in the logic model (see Appendix 6), to collect explanatory process data and data on contextual factors that could have facilitated/hindered effective and efficient delivery of the service. Detailed analysis of PCPs additionally involved determining which medication-related changes would be associated with the risk of falls guided by recent comprehensive systematic reviews. 53–55

All data were collected, from intervention arm participants only, after the study period for each home had finished. The tasks, aims, data and data sources are summarised in Appendix 1, Tables 18–21.

Interviews schedules were informed by normalisation process theory (NPT),56,57 and questionnaires included a set of NoMaD questions that translates NPT domains for survey use. 58 Interviews were conducted face-to-face or by telephone; all were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis of qualitative data was based on the NPT framework, but a complementary inductive approach enabled recognition of unexpected emergent themes. All data sets (qualitative and quantitative) were integrated to identify relationships, explain findings and identify optimal intervention contexts. 52 Full details are published elsewhere. 50

Ethics

Ethics approval was provided by East of England Central Cambridge Research Ethics Committee (for England and Northen Ireland) – Ref.: 17/EE/0360; and by Scotland A REC – Ref.: 17/SS/0118.

Protocol

This is published and is available at: https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-019-3827-0.

Results

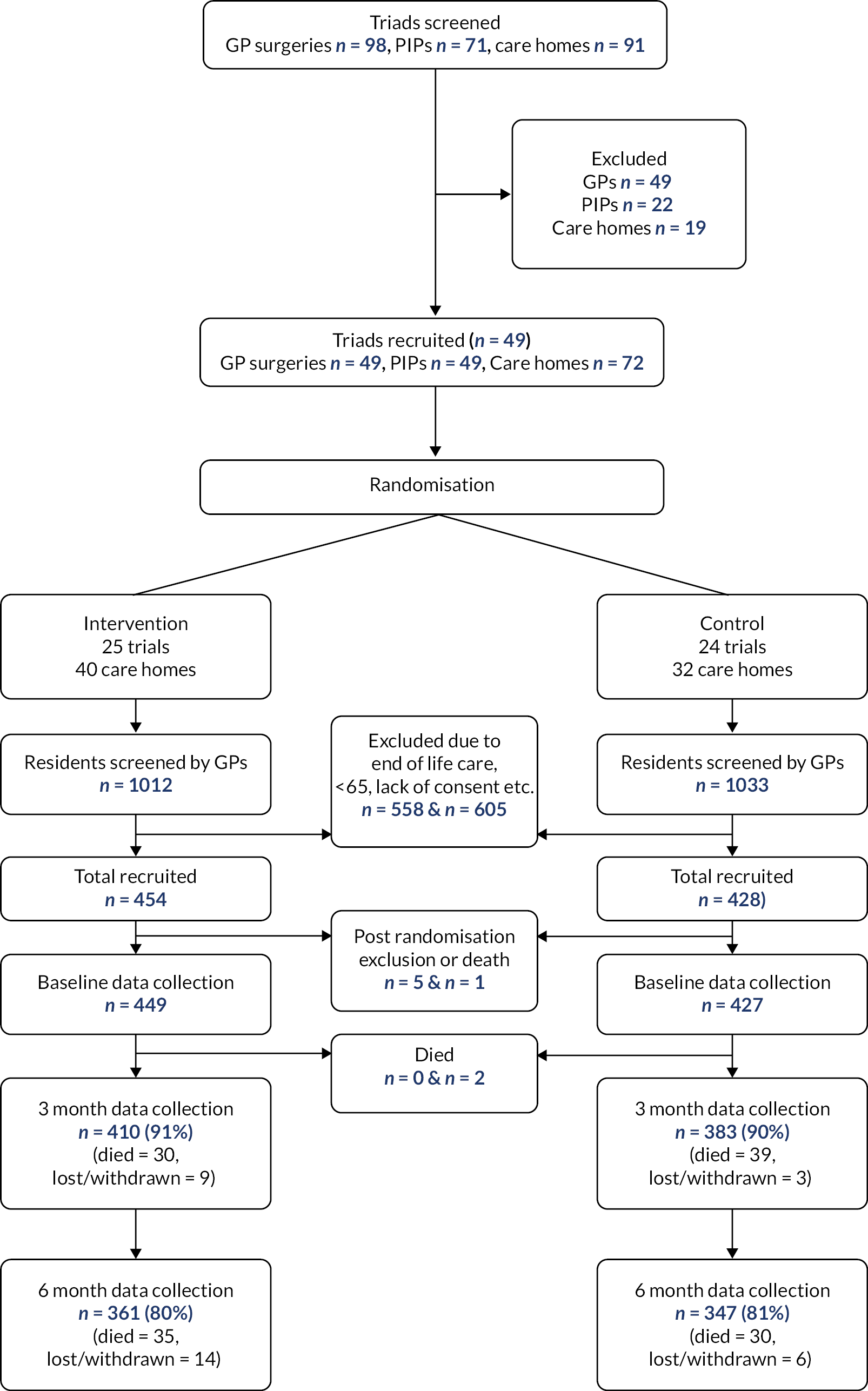

As shown in Appendix 1, Figure 8 (CONSORT diagram), we recruited 49 triads (49 general practices, 49 PIPs and 72 care homes) between December 2017 and May 2019. Of these 49 triads, 25 were randomly allocated to the intervention arm and 24 to the control arm. There were 454 residents in the intervention arm and 428 residents in the control arm. Almost all losses were due to resident deaths (134/166 losses = 81%). Three intervention PIPs (12%) failed to deliver the service due to personal reasons.

Baseline comparison between arms is provided in Appendix 1 and Table 12. Whilst most variables including age, medications, admissions, DBI, Charlson comorbidity, and EQ-5D-5L proxy scores were similar between arms, the control arm had a slightly greater proportion of male residents (33% vs. 28%), and a considerably greater proportion in nursing home care (59% vs. 42%). In line with those findings, the intervention arm had a higher Barthel score (8.34 vs. 7.07 of 20, where higher scores imply greater independence) and those self-reporting EQ-5D (11% of participants) reported better health 0.50 versus 0.35 (scale 0–1, 1 = perfect health). Residents in the intervention arm had a mean number of falls of 0.78 in the previous 90 days compared with that of 0.57 in residents of the control arm. Follow-up data collection commenced in September 2018 and concluded in July 2020 (this was delayed by 4 months for the final triads due to COVID-19).

Primary outcome analysis

Although there were a greater number of falls recorded in the intervention arm in the 6-month follow-up period (697 vs. 538) and a higher crude rate of falling, when adjusted for baseline falls, no difference was observed between arms (RR = 1.00, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.36; p = 0.99). Further adjustment for key potential confounders reduced the RR, in favour of the intervention, to 0.91, although this too was not statistically significant (95% CI 0.66 to 1.26; p = 0.58; see Appendix 1, Table 13).

Similarly, there was no evidence of an effect on fall rate at 3 months. The RR favoured the intervention arm (RR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.19; p = 0.36), but this was not statistically significant.

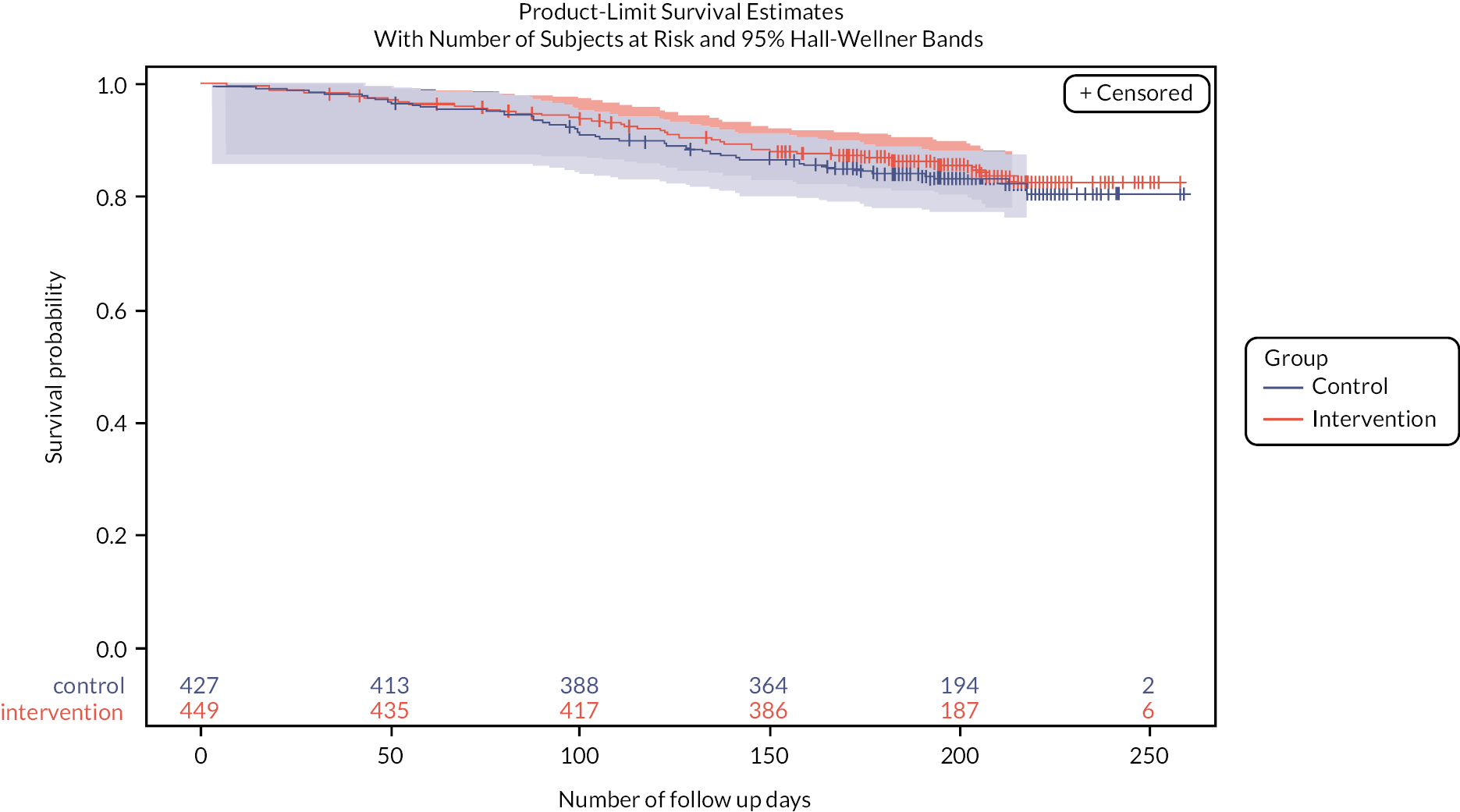

Mortality

There were 66 (14.7%) deaths in the intervention arm compared with 71 (16.6%) deaths in the control arm, with a mean time to death of 109 versus 103 days. However, a Cox’s proportional hazards model indicated no evidence of a beneficial effect on the death rate (hazard ratio = 0.93, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.35; p = 0.68). Appendix 1 and Figure 9 illustrate the Kaplan–Meier survival curves.

Other secondary outcomes

The remaining secondary outcomes included DBI, hospitalisation, Barthel score (see Appendix 1, Table 14), and quality of life as measured using the EQ-5D (see Appendix 1, Table 15). Of these outcomes, the intervention improved (decreased) residents’ DBI by 8% from 0.72 at baseline to 0.66 at 6 months. By contrast, the DBI among control arm residents increased from 0.70 to 0.73. When analysed using a natural log transform, the rate ratio of DBI scores at 6 months between the intervention and control arms was 0.83 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.92; p < 0.001), suggesting that more effective deprescribing occurred in the intervention arm. No other secondary outcome showed a statistically significant difference. No evidence of a decrease in hospital admissions between arms was found (RR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.46; p = 0.93), nor was there any evidence of any difference between arms with respect to the Barthel Index at 6 months, although scores favoured the intervention arm (ratio of means = 1.20, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.49; p = 0.11).