Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number PTC-RP-PG-0213-20002. The contractual start date was in April 2015. The final report began editorial review in April 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Williamson et al. This work was produced by Williamson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Williamson et al.

Synopsis

Research summary

Low back pain (BP) is the most common cause of disability in the world. 1 The prevalence of severe BP increases with age,2 and it is associated with immobility, disability, frailty and falls. 3–7 In the UK, estimates suggest that one in four older adults suffer from BP. 2,8 However, many older people either do not consult, or health professionals do not prioritise BP treatment, presuming nothing can be done. 2,9,10 Many clinical trials exclude older people. 11 Little attention has been paid to understanding the presentation of BP in older people and developing effective treatments.

Older adults may also experience leg pain referred from the lumbar spine. A common clinical presentation of spinal-related leg pain in older adults is neurogenic claudication (NC). 12 It presents as an easily recognised clinical pattern of symptoms radiating from the spine into the buttocks and legs which are provoked by walking or standing and relieved by sitting or lumbar flexion. 12 BP is often present, but not always. NC is particularly problematic for older people, as not only can it cause severe pain and discomfort but it substantially reduces an individual’s confidence and ability to walk and their quality of life. 13 It is estimated that 11% of community-dwelling older adults report symptoms of NC, although there were no estimates from community-dwelling UK populations. 14 Symptoms of NC are thought to arise from pressure on nerves and blood vessels in the spinal canal caused by degenerative changes narrowing the volume of the spinal canal (referred to as spinal stenosis). NC is the most common reason that older adults undergo spinal surgery,15 and physiotherapy is recommended prior to surgical intervention. However, there was a lack of high-quality evidence to guide conservative care of people with NC, including primary care management or physiotherapy. 16,17 We identified a need to better understand the presentation of BP in older people and to improve the care they receive for their BP, including conditions like NC.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the Better Outcomes for Older people with Spinal Trouble (BOOST) programme was to conduct a series of linked studies to understand and reduce the burden of BP on older people by increasing knowledge and developing evidence-based treatment strategies.

We set out the following objectives:

-

to describe the presentation and impact of BP in community-dwelling older adults (work packages 2 and 3)

-

to refine a physiotherapy intervention for older people with NC to be tested in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) (work package 1)

-

to undertake a definitive RCT evaluating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for NC (work packages 2, 4 and 5)

-

to undertake a longitudinal qualitative study embedded within the BOOST RCT to understand the participants’ experiences of taking part in the trial, including acceptability and impact of the interventions, and issues related to implementation (work package 4)

-

to develop a prognostic tool using the Oxford Pain Activity and Lifestyle (OPAL) cohort study data to predict when older people are at risk of mobility decline and to understand the role of BP (work packages 2 and 3)

-

to integrate the findings into an implementation package (work package 6).

Work packages

We have undertaken:

-

a large population-based cohort study of community-dwelling older people recruited from primary care practices (the OPAL cohort study)

-

An RCT of physiotherapy interventions for NC, including an economic evaluation (the BOOST RCT) and prespecified subgroup analyses

-

a longitudinal qualitative study embedded within the BOOST RCT.

This research was planned in six work packages. There was considerable overlap between work packages, and they were not undertaken chronologically. The original work packages as described in the funding application are described below. Overall, this proceeded as planned, with some changes to work package 3 which we describe.

Work package 1: Refinement of a physiotherapy intervention for neurogenic claudication

We planned to integrate knowledge of exercise, behavioural and pain management strategies, alongside practical issues to develop a physiotherapy-delivered group physical and psychological intervention for older people with NC.

Work package 2: Feasibility

There was a feasibility phase for the two main studies (OPAL cohort study and BOOST RCT) to establish feasibility related to site set-up, recruitment, intervention delivery and data completion.

Work package 3: Develop a prognostic tool

We planned to collect a range of factors related to participants’ BP, general health and mobility that would be used to develop a prognostic tool to identify the BP presentation likely to result in a poor outcome. We set a target of 1000 people retained in the OPAL cohort study with complete data at 2 years’ follow-up.

Work package 4: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of physiotherapy for neurogenic claudication and nested longitudinal qualitative study

We aimed to recruit a minimum of 402 patients with NC from primary care and musculoskeletal hubs to test the physiotherapy intervention developed in work package 1 with a longitudinal qualitative study, process and economic evaluation running alongside.

Work package 5: Predictors of the participants’ response to treatment – enhancing stratified approaches

We planned to investigate the role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters and a small selection of other subgrouping variables to determine who will respond best to physiotherapy.

Work package 6: Project integration and preparation for implementation

We proposed to gain the perspectives of health professionals to help inform the final integration of the project outputs and, if appropriate, ongoing implementation studies and dissemination.

Changes to the programme

During the first year of this programme of research, we made refinements to the OPAL cohort study.

We originally planned to enrol 1000 older adults with BP in the cohort study. To identify the 1000 older adults with BP, we needed to screen a minimum of 4000 older adults who responded to the invitation to participate in the cohort study. This was based on the most recent estimates of disabling BP in the population aged 70–90 years, with a prevalence of 25–30% for these age groups, respectively. 8

We decided to enrol all invitation respondents in the cohort regardless of their BP status. In addition to the original research objective (to recognise when and what types of BP presentation were important treatment targets for older people), we would be better able to evaluate the contribution of BP to mobility decline within a broader context. This change to the original proposal was reflected in the study protocol approved by the London–Brent Research Ethics Committee (16/LO/0348) on 10 March 2016. Changes were supported by the Programme Steering Committee and reviewed and accepted by the Programme Grants Manager on 30 March 2016.

Work package 6 could not be delivered as planned due to the challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. We had initially planned to run focus groups with clinicians to discuss the study results and implications. However, delays to results meant this was not completed. The OPAL cohort study was nearing completion of the 2-year follow-up mail-outs when the COVID-19 lockdown started in March 2020. Although the team managed to send out all year 2 questionnaires just prior to the lockdown, this had a major impact on the study team’s ability to process the large volume of data collected from home, which was very time-consuming using remote access. Data were available 6 months late, delaying the analysis needed to develop the OPAL prognostic tool. The BOOST trial health economic analysis was delayed by 6 months as our health economist was working at home with young children throughout lockdown. This work was essential to interpretation of the trial findings and significantly delayed our plans to publish the results. Despite these challenges, we had strong engagement with clinical collaborators throughout this research and we worked as best we could to engage with clinical staff to form our dissemination plan.

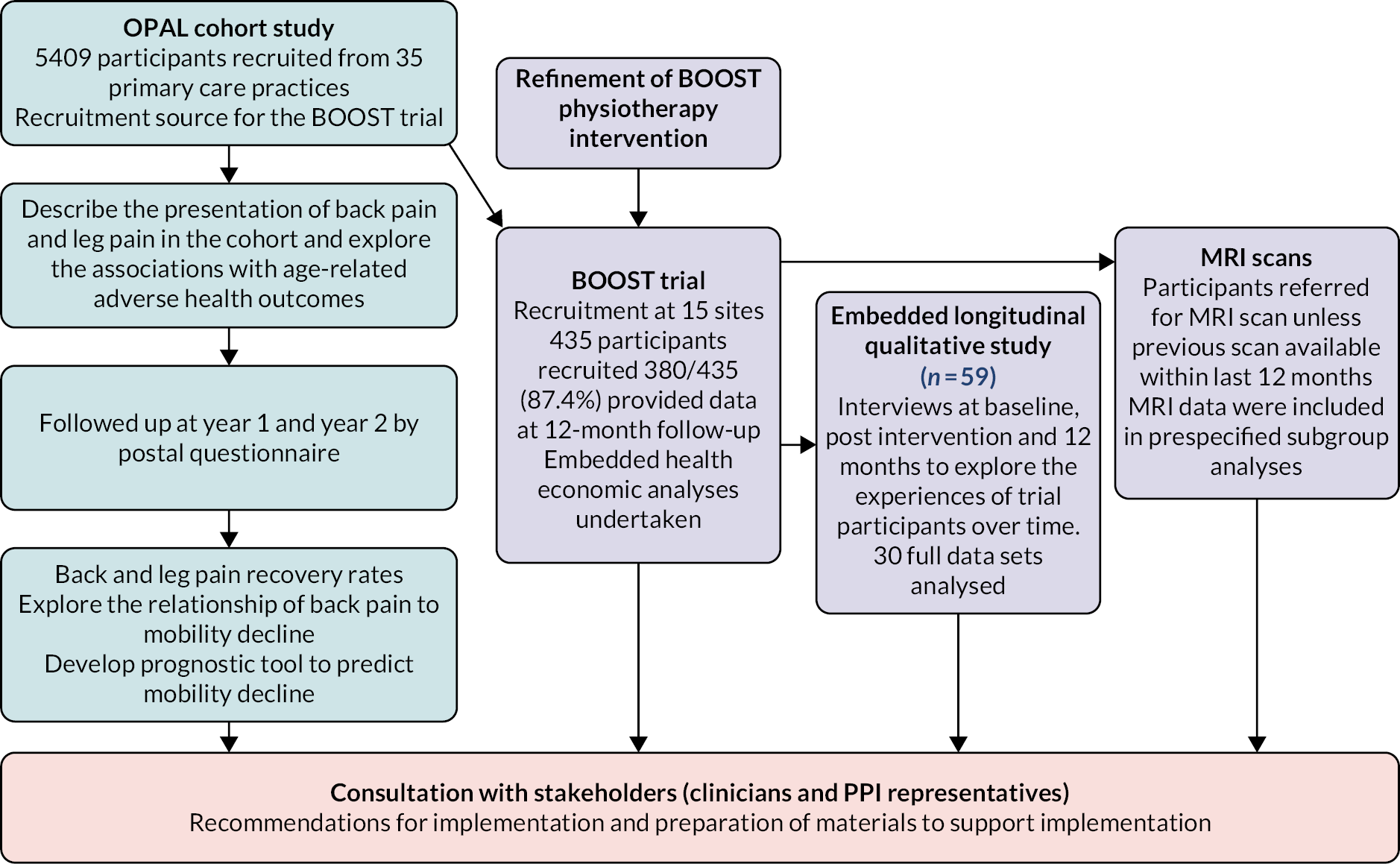

Research pathway diagram

Objective 1: To describe the presentation and impact of back pain in community-dwelling older adults

Background

We lacked a good understanding of the prevalence and impact of back and leg pain within the community-dwelling population in the UK. There were estimates for the prevalence of BP in the UK2,8 but not for back-related leg pain. A single UK-based study (n = 30) estimated the prevalence of NC among patients (50 years and over) presenting with back and leg pain to primary care to be 87%, suggesting it was the predominant cause of spinal-related leg pain when patients sought care. 18 However, we wanted to understand the extent of the problem among community-dwelling older adults and not just those seeking care.

In addition to understanding the presentation of back and leg pain, we wanted to understand the broader impact of having back and leg pain in later life. We were interested in understanding the relationship between different presentations of back and leg pain with quality of life and age-related adverse health states including frailty, mobility decline, falls, poor sleep quality and incontinence. These health states are common in later life and associated with substantial morbidity and poor outcomes. 19 Little was known about the relationship between BP and different patterns of leg pain and these age-related adverse health states. 5–7,20,21 Back and leg pain had been associated with falls and functional difficulties, but studies were limited. 22 Different patterns of back and leg pain had not been taken into consideration, and it was unknown whether certain presentations were more strongly associated with adverse health states.

There was also little information about the natural history of symptoms among community-dwelling older adults reporting back and leg pain within the UK. Cohorts of older people with BP have reported that around 50–60% of participants will continue to experience pain and disability at 12 months’ follow-up. 23,24 There were some data on the natural history of symptoms due to spinal stenosis, with the majority of people (around 55%) reporting no change in pain over a 3-year period while around one-third improved and 10–13% reported a worsening of symptoms. 25 It was unclear how recovery may differ among those with different back and leg pain presentations.

In this section, we will examine:

-

the presentation of back and leg pain symptoms among OPAL cohort participants at baseline and the association with adverse health outcomes

-

for those with back and leg pain at baseline, the persistence of symptoms at 2 years’ follow-up.

Methods

The OPAL protocol and a description of the participants at baseline26 can be accessed here: http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037516

A more detailed description of the baseline cross-sectional analyses can be accessed here: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:911cf725-135f-4951-a1b2-28eb2032d9ab

Briefly, there are 5409 community-dwelling older adults enrolled in the OPAL cohort study. Participants are over 65 years of age, registered with one of 35 participating primary care practices, and were recruited using electronic record searches. Older adults living in residential care or nursing homes were ineligible. Potential participants received an information leaflet, consent form and baseline questionnaire. Those who returned a completed consent form and questionnaire to the study office were enrolled in the study. Of the individuals invited, 42% (5409/12,839) were enrolled in the study. Follow-up was by yearly postal questionnaire. A summary of the data collected is available in Appendix 1, Table 5. Participants were included in these analyses if they completed the questions about back and leg pain.

Back and leg pain presentation at baseline

Firstly, participants reported whether they had been troubled by BP and related symptoms in the last 6 weeks and, if so, supplied further information about frequency (every day, most days, some days, few days, rarely), troublesomeness (intensity) (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, not at all)27 and spread into the legs over the last 6 weeks. They were asked about the age when they were first troubled by BP (onset) and its pattern since onset (getting better, getting worse, fairly constant, comes and goes over time).

We categorised participants into four mutually exclusive back and leg pain presentations.

-

no BP (reference category)

-

BP only

-

BP and NC

-

BP and leg pain that is not NC (non-NC).

We used questions commonly used in clinical practice with high sensitivity and specificity when identifying people with symptomatic spinal stenosis. 28 NC was defined as the presence of BP or other symptoms that travel from the back into the buttocks or legs and are worse when standing and/or walking and better when sitting and/or bending. 28

Baseline adverse health states

We collected the following:

-

mobility decline over the last year

-

confidence to walk half a mile using a question from the Modified Gait Self-efficacy Scale31

-

falls in the last year32

-

incontinence, reported using the urinary incontinence item from the Barthel Index33,34

-

sleep quality during the past month, using the sleep quality overall rating from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. 35

We also measured health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measured by the EQ-5D-5L36 and the clock drawing test to screen for cognitive impairment. 37

Back pain and leg pain at 2 years’ follow-up

To examine recovery rates among participants who reported BP and related symptoms at baseline, we used data from the year 2 questionnaire to see how many had been troubled by BP and related symptoms in the last 6 weeks; those who had were asked about frequency and troublesomeness.

Participants rated how much their BP interfered with their daily activities (0 = no interference, 10 = unable to carry out the activities). This question was based on the Von Korff Pain Scale. 38 Severely interfering BP was defined as a report of ≥ 7/10 based on the cut point used in previous cohorts. 39,40 If a participant was no longer reporting BP at 2 years, then they were allocated a score of 0/10.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the characteristics of participants at baseline. Modified Poisson and ordered logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between BP groups (independent variable) and adverse health states (dependent variables) at baseline. Models were adjusted for age, sex, education, body mass index (BMI), socioeconomic status [Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)],41 smoking, physical demands of their main occupation, comorbidities and presence of multisite pain based on the Nordic Pain Questionnaire. 42,43 We used multiple imputation by chained equations to handle missing data. 44,45

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the BP outcomes at 2 years’ follow-up, and we stratified by baseline BP presentation.

Results

Baseline presentation

The mean age of participants included in these analyses was 75 ± 6.8 years. Over half of the participants reported BP, with 33.7% (1786/5304) reporting BP only, 11.2% (594/5304) reporting BP and NC, and 8.3% (441/5304) reporting BP and non-NC leg pain. Only the prevalence of BP and NC increased with age. BP was more common in females and those reporting more comorbidities. Those with leg pain reported poorer health behaviours (smoked more, higher BMI), lived in more deprived areas and reported lower education levels. Participants with BP had lower quality of life compared to participants without BP. Quality of life was poorest in those with NC. The age of onset was similar across BP groups. Around 30% of participants reported that their BP started 25 years ago or more. Those with leg pain reported more frequent BP. A report of pain on most days/every day was most common among those with NC. Participants with NC reported the highest ratings of pain troublesomeness. Very few reported improving symptoms since onset (3.7%) and, most commonly, symptoms fluctuated over time (75%). The proportion of participants reporting persistent pain or pain getting worse since onset was highest in those with NC (75%). See Appendix 1, Table 6 for a full description.

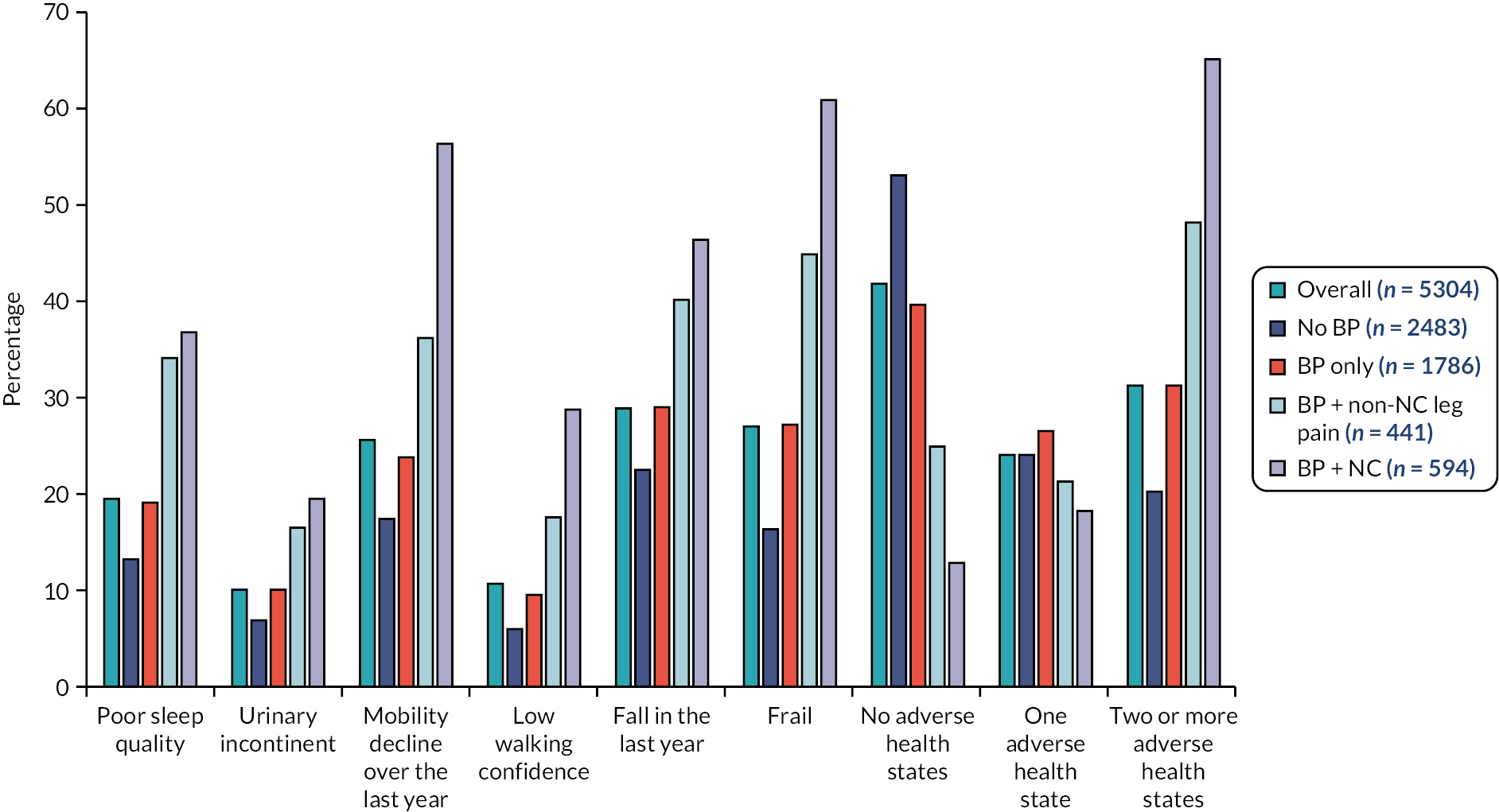

Just over half of the participants (55%; 2937/5304) reported at least one adverse health state. The most common adverse health states reported were a fall in the last year (29%; 1534/5304) and being frail (27%; 433/5304) (Figure 1). Confidence to walk half a mile was generally high among the cohort except for those reporting NC (see Appendix 1, Table 6). Across the three BP groups, there was a greater prevalence of all adverse health states compared to those with no BP; this increased further among those who reported leg pain, and it was highest among those with NC.

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of adverse health outcomes by BP groups. Notes: Poor sleep quality = fairly bad or very bad sleep quality on Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Urinary incontinence = never or less than once per week was considered continent and the remaining responses were considered incontinent. Mobility decline: ‘Compared to one year ago, how would you rate your walking in general?’ scored on a five-point scale constructed for the study. Participants reporting worsening of walking were classified as having mobility decline. Participants who rated their confidence to walk at 9–10/10 were categorised as having low walking confidence (reverse scored). Frail = ≥ 5 on Tilburg Frailty Index.

After adjusting for demographics, lifestyle factors, comorbidities and multisite pain, all BP groups were associated with the adverse health states studied (Table 1). For all the adverse health states, there was an increase in the strength of association with the addition of leg pain. This was particularly noticeable in participants with NC, where we observed the strongest associations with frailty, mobility decline, low walking confidence and falls compared to no BP.

| Age-related adverse health outcomes | BP only | BP + non-NC leg pain | BP + NC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence to walka | 1.23 (1.06 to 1.43) | 1.89 (1.52 to 2.36) | 3.11 (2.56 to 3.78) |

| Mobility decline | 1.13 (1.00 to 1.26) | 1.42 (1.22 to 1.64) | 1.74 (1.54 to 1.97) |

| Falls in previous year | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.26) | 1.40 (1.22 to 1.61) | 1.42 (1.25 to 1.61) |

| Frail | 1.38 (1.24 to 1.54) | 1.77 (1.55 to 2.02) | 1.88 (1.67 to 2.11) |

| Poor sleep quality | 1.17 (1.02 to 1.35) | 1.68 (1.41 to 1.99) | 1.67 (1.42 to 1.97) |

| Urinary incontinence | 1.17 (0.95 to 1.43) | 1.59 (1.22 to 2.07) | 1.43 (1.12 to 1.83) |

Back pain presentation at 2 years’ follow-up

Of the participants reporting BP and related symptoms at baseline, 2139/2859 (74.8%) returned the 2-year follow-up questionnaire and completed at least some of the BP variables.

Overall, 23% of respondents (489/2100) no longer reported back or leg pain symptoms (see Appendix 1, Table 7). Recovery was highest among those that reported only BP at baseline (27.4%) and lowest among those with back and NC leg pain at baseline (10.9%). Participants reporting BP only at baseline were least affected at follow-up, and participants reporting NC leg pain at baseline were the most affected. Those with NC leg pain at baseline reported BP more frequently, and this group had the highest proportion reporting very or extremely troublesome BP. Very few participants from all groups reported that their BP was improving (3%), and those with back and NC leg pain at baseline had the highest proportion reporting that it was getting worse (13.2%). Those with BP only at baseline reported the lowest amount of pain interference with daily activities (6.4%). Those with NC leg pain reported the highest pain interference ratings at follow-up and had the greatest proportion reporting severe interference with activity (26%).

Limitations

Data were collected using postal questions, so we were reliant on self-reporting of symptoms. Some participants may have been misclassified or symptoms misdiagnosed as spinal-related leg pain (e.g. vascular claudication can have similar symptoms).

Discussion

Back and leg pain is a common problem for community-dwelling older adults, and for many it is a long-standing problem, with few reporting an improving clinical picture. At 2 years’ follow-up, only 23% of participants no longer reported symptoms. Symptom persistence was highest among those with NC at baseline, with 90% still reporting symptoms.

At baseline, older adults with back and leg pain reported lower HRQoL, with those with NC most affected. The report of back and leg pain was associated with adverse health states, including frailty, falls and mobility decline, compared to no report of BP. Participants reporting symptoms of NC were most affected and the strongest associations were with mobility-related adverse outcomes. At follow-up, those with NC at baseline remained the most severely affected, with a quarter of this group reporting severe activity limitations due to their symptoms. These findings confirmed our hypothesis that NC is particularly problematic for older people and highlighted the need to develop effective interventions to reduce the burden of this condition. However, BP alone is also a widespread persistent problem associated with age-related adverse health states, so ways to reduce the burden of BP are needed.

Objective 2: To refine a physiotherapy intervention for older people with neurogenic claudication to be tested in a randomised controlled trial

Starting point

As we have described, NC is a common, debilitating spinal condition affecting older people. 28 At the start of this programme of work, we had identified a strong theoretic underpinning and limited evidence from clinical practice, cohort studies and small RCTs for a physiotherapy intervention for NC, providing us with a firm starting point to refine and test an intervention. Experts hypothesised that stretching and mobilising the spine relieved pressure on spinal nerves and blood vessels and that aerobic exercises improve circulation, alleviating ischaemic changes. 46

However, recommendations were not substantiated by high-quality evidence46 despite being used commonly in clinical practice. 47,48 Systematic literature reviews reported that the current evidence from non-operative care was of very low to low quality, thus prohibiting recommendations to guide clinical practice. 16,17,49–51 Trials to date were of small sample sizes and often included only short-term follow-up. Interventions focused on the mechanics of spinal stenosis with little regard to the psychological impact of pain or ageing. Notably, interventions did not include strengthening exercises to counter the loss of muscle mass associated with ageing that contributes to loss of mobility in older people;52 nor had the authors considered addressing negative beliefs about pain or ageing that were potential barriers to engaging with and adhering to rehabilitation. 53,54

We explored the rehabilitation needs of older people with NC during a preparatory qualitative study. 55 Participants sought rehabilitation in the hope of re-engaging with meaningful activities and reducing pain. A combination of one-to-one and group sessions was preferred to deliver rehabilitation. One-to-one time with a physiotherapist was considered an important prerequisite for treatment to allow the therapist to understand the participant’s condition and circumstances. Participants endorsed exercising in a group for peer-to-peer support and socialising. Discourses around ageing influenced their experiences – especially regarding the use of walking aids, which they considered stigmatising. These views and preferences informed the refinement of the proposed intervention to ensure it would meet the needs of people with NC.

A full description of the BOOST intervention56 can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2019.01.019

The preparatory qualitative study55 can be accessed here: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:92c9ee3e-30eb-4fc0-95fd-08db3bc4707b

Methods

We followed Medical Research Council guidance on developing a complex intervention. 57

Step 1: identify existing evidence

We consulted recent systematic literature reviews and interrogated the individual studies for intervention components that warranted consideration16,17,49–51 as well as National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. 58 In parallel, we considered the literature related to pain, frailty, falls and disability in older adults,3,5–7,20,21,59–63 clinical guidelines for exercise in older adults,64,65 behaviour change interventions66 and psychological models of pain and disability. 67,68 We drew on the findings from the preparatory interview study. 55

Step 2: identify and develop theory

From existing evidence, we identified treatment targets and matched possible intervention elements to them to discuss with stakeholders. Twelve clinicians, two patient representatives and nine researchers attended an intervention refinement day. The aim of this day was to gain consensus about the key elements of an intervention that would be acceptable to users and deliverable within the NHS.

Discussions firstly centred on the overall approach to take, including mode of delivery (individual vs. group), then we focused on the individual components. A physiotherapy-delivered group physical and psychological intervention was agreed utilising two parallel and synergistic approaches: (1) exercises targeting strength, balance, flexibility and endurance, and (2) education and peer support to counter negative beliefs about pain or ageing that may impede exercise engagement and adherence, underpinned by behaviour change techniques and pain management principles.

Step 3: modelling processes and outcomes

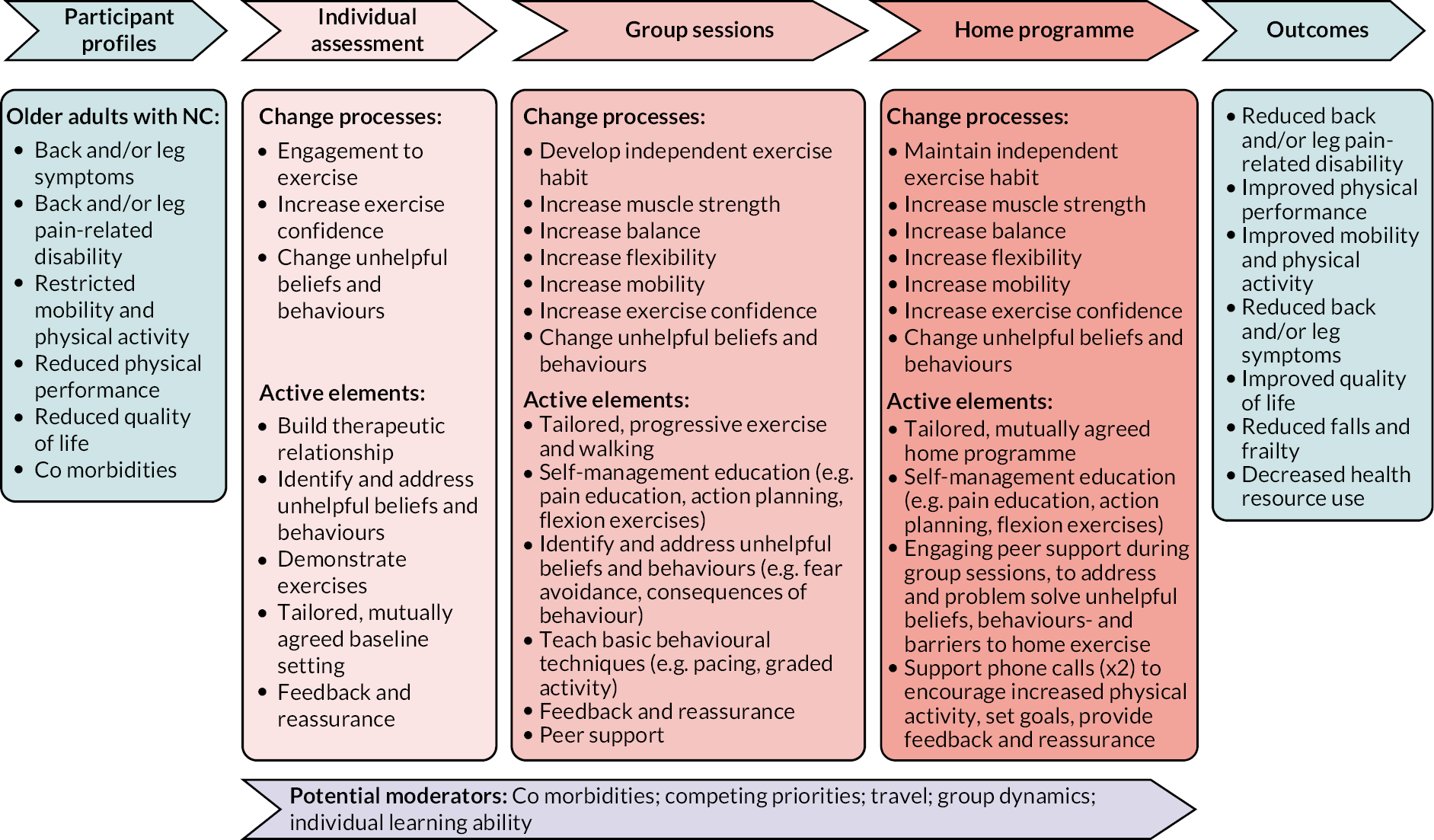

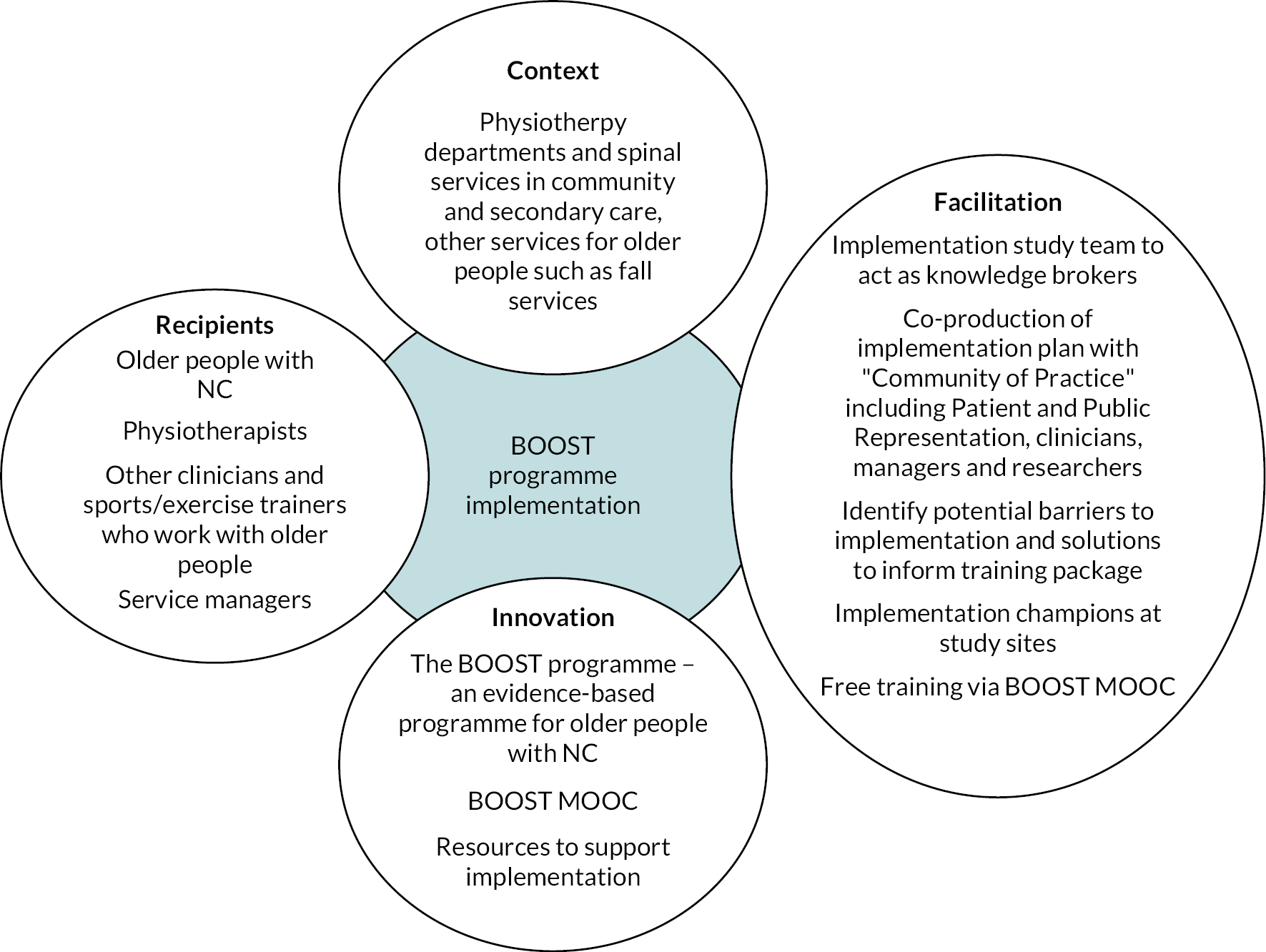

A conceptual model of the change processes, active intervention elements and potential moderators of the BOOST intervention was produced (Figure 2).

The BOOST programme

The programme consisted of an individual assessment, 12 group sessions and two support telephone calls.

Prior to attending the group programme, each participant attended an individual appointment (1 hour) for an assessment and to set their individualised exercise and walking circuit targets for the group sessions.

Participants attended twelve 90-minute group sessions over a 12-week period. Each session followed the same format. Participants took part in an education and discussion session (30 minutes) which incorporated behavioural change strategies to encourage adherence with home exercises. The topics of discussion are included in Appendix 3, Table 14. This was followed by the exercise programme, lasting approximately 1 hour.

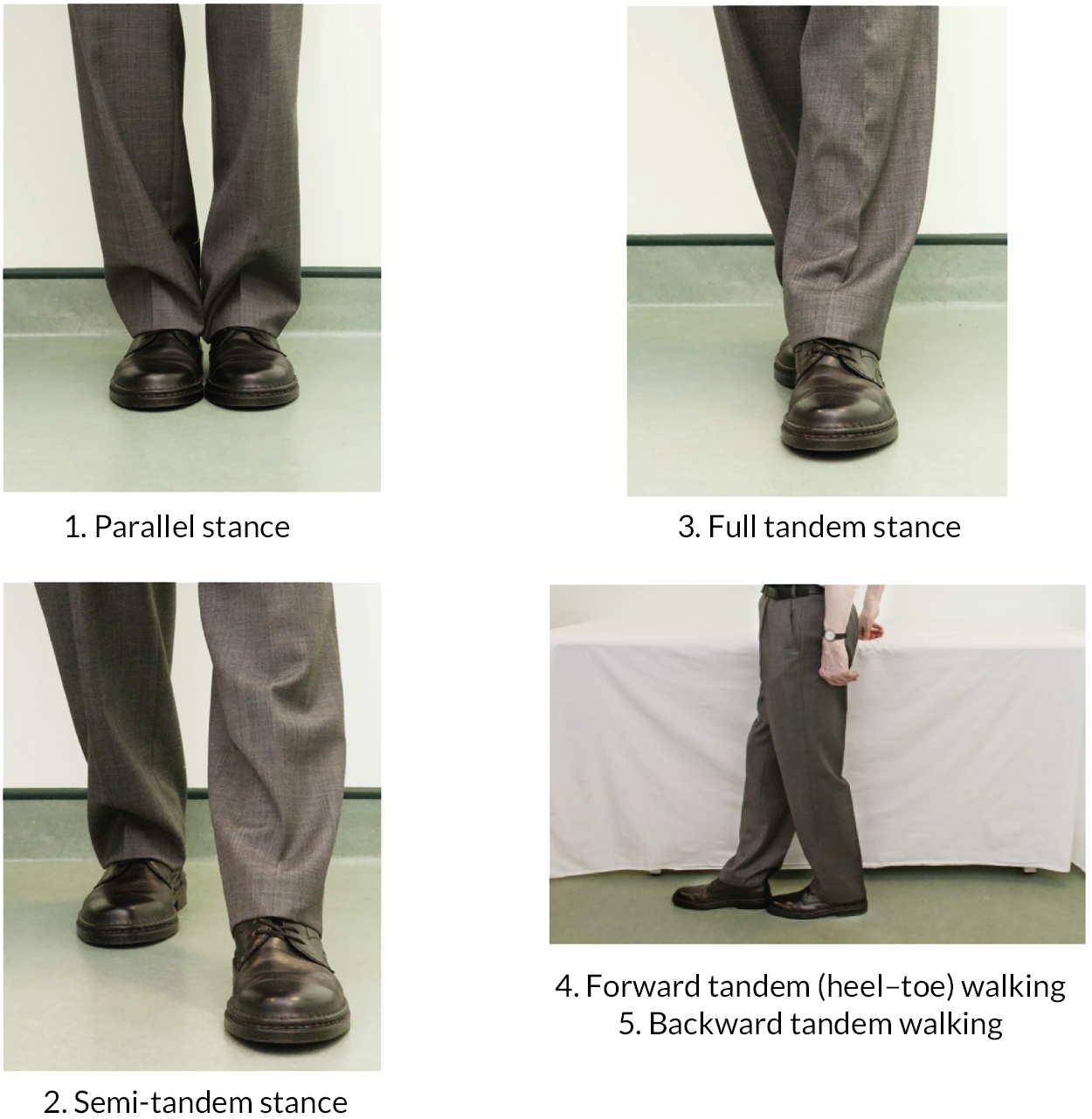

There was a short warm-up of seated exercises, which included arm raises, trunk rotation, pelvic tilting and knee lifts. Then participants undertook a circuit of strengthening which included the following exercises:

-

sitting knee extension

-

sit to stand

-

standing hip abduction

-

standing hip extension

-

a combined hip flexor and calf stretch

-

a progressive balance sequence (feet together static balance, semi-tandem stance static balance, full tandem stance static balance, forward tandem heel-to-toe walking, backward tandem heel-to-toe walking).

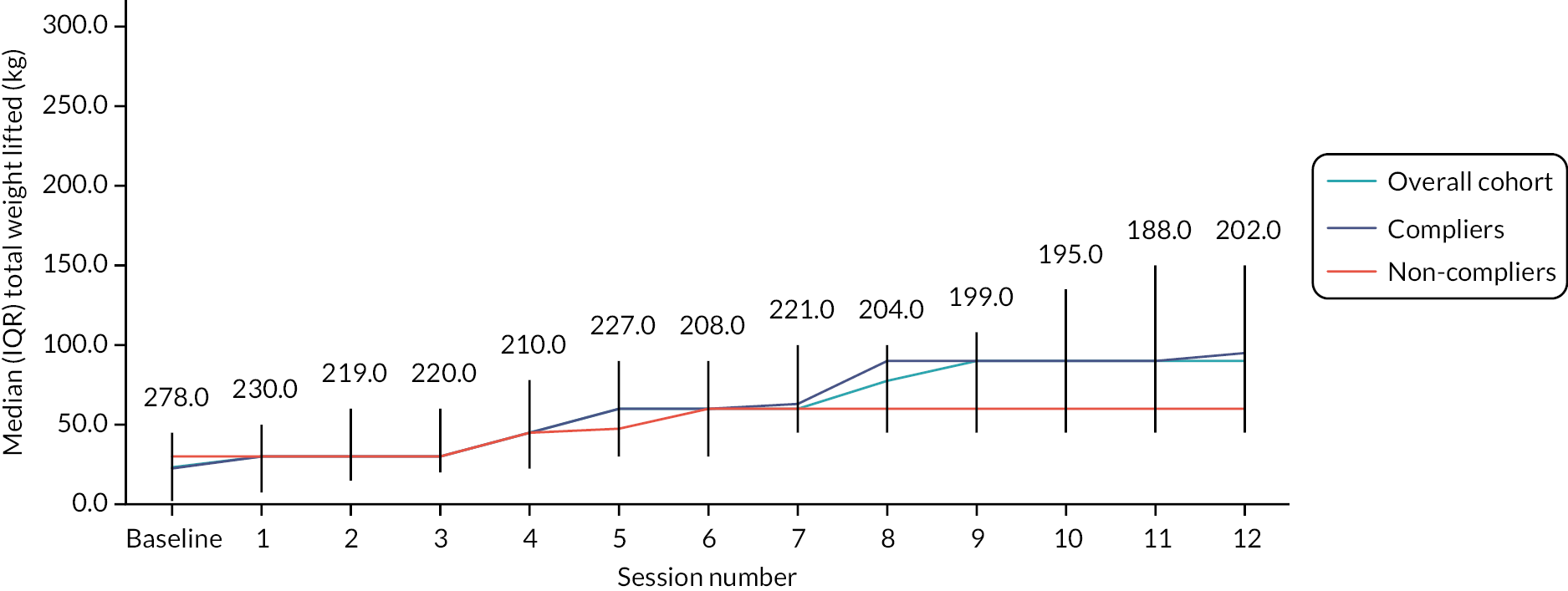

Each participant completed their individually tailored programme. Exercises were progressed over the 12 weeks. We used the Borg Rating Scale of Perceived Exertion to ensure participants achieved an adequate stimulus to promote strength gains and encouraged them to work at level 5–6 on this scale (the exercise feels hard) during the strengthening exercises (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Borg scale.

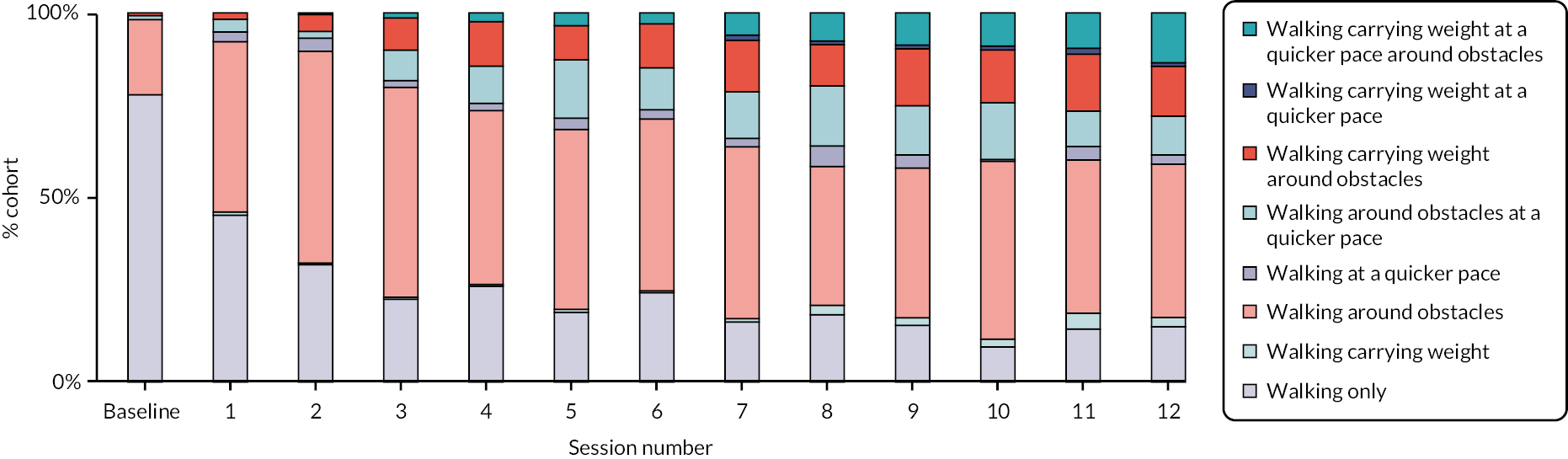

Participants then undertook a supervised walking circuit, designed to improve walking ability and fitness, which also progressed over the 12 weeks by increasing the distance walked, increasing walking speed, adding balance challenges such as stairs or obstacles, or adding weights. The exercises carried out during the supervised sessions made up the home exercise programme (warm-up, exercise circuit and walking).

On completion of the 12 group sessions, participants were asked to carry out their home exercise programme at least twice per week. The physiotherapist reviewed each participant by telephone 1 and 2 months after they completed the supervised sessions, to promote long-term adherence with home exercises.

Control intervention

The control intervention was best practice advice (BPA) delivered in individual physiotherapy appointments, which reflected what we considered a ‘good’ standard of usual care physiotherapy. This intervention was informed by a survey of current physiotherapy practice47 and a recent trial,56 and through consultation with clinicians and patient representatives. We recommended that participants receive one session of advice and education. However, the clinicians highlighted situations where a review would be necessary (e.g. to review walking aids) so this was permissible.

Participants attended a 1-hour appointment consisting of an assessment followed by the provision of tailored advice and education and written information. Participants were prescribed up to four home exercises. Flexion and trunk stabilisation were recommended. The physiotherapist could prescribe a walking aid if indicated. A maximum of two half-hour review appointments were permitted. During review sessions, physiotherapists reinforced the verbal advice given, and reviewed walking aids or exercises.

Intervention delivery training

We developed a clinician manual and training programme. Physiotherapists delivering the BOOST programme attended a full day of training with the research team. They were also asked to complete some online training prior to attending. Those delivering the control intervention attended a separate half-day of training.

Pilot work

We piloted the training, which was refined following feedback. We conducted the first BOOST programme with two participants, and feedback indicated satisfaction with the programme content, duration and timing of sessions. Minor modifications were made. A researcher observed the control interventions, which were delivered as intended.

Summary of work undertaken

We focused on refining a complex intervention that was underpinned by existing knowledge, would meet the needs of older people with NC, and would be acceptable to clinicians and deliverable in the NHS. By combining group delivery with an individual assessment and follow-up calls, we ensured each participant underwent a thorough assessment so they were confident in the programme but could benefit from peer-to-peer support and socialising. This was also a way to deliver a longer-duration intervention for participants, which would increase the likelihood of achieving meaningful gains in muscle strength and mobility without placing excessive burden on physiotherapy departments.

Objective 3: To undertake a randomised controlled trial evaluating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for neurogenic claudication

Methods

The full protocol69 is available here: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037121

The statistical analysis plan70 is available here: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04590-x

The paper reporting clinical effectiveness71 is available here: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glac063

The paper reporting the cost-effectiveness72 is available here: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-022-00410-y

Design

This study was a pragmatic, multicentre, superiority RCT.

Participants

Community-dwelling adults, aged 65 years and over, who reported symptoms consistent with NC, were eligible. Exclusion criteria included nursing home residents, inability to walk 3 metres independently, awaiting surgery, cauda equina syndrome or signs of serious pathology, cognitive impairment, registered blind, or unable to follow instructions in a group setting. Potential participants were identified through community-based physiotherapy clinics and secondary care spinal clinics in 15 NHS Trusts in England.

Participants were also identified through the OPAL cohort study. 26 Potential participants were identified from questions asking about symptoms suggestive of NC in their most recent questionnaire and invited for eligibility screening.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised to the BOOST programme or BPA in a 2 : 1 ratio (intervention : control) to ensure that we could fill BOOST groups without participants experiencing long waiting times.

Intervention fidelity

The research team monitored intervention fidelity by observing treatment sessions (see Appendix 3 and Report Supplementary Material 1) and checking physiotherapy treatment logs.

Data collection

Participants completed a questionnaire, and the blinded researcher conducted physical testing at baseline and 6 and 12 months after randomisation. If participants did not attend the follow-up appointment, then the physical tests were not completed, and participants were sent a postal questionnaire.

The variables collected at outcomes are presented in Table 2. The primary outcome was the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI v2.1a)73 at 12 months after randomisation. This participant-reported measure of pain-related disability is scored 0–100, with a higher score indicating greater disability. We collected adverse events. At baseline, we also collected demographic information and factors related to health and mobility, which are listed in Appendix 2, Table 10.

We used data from lumbar spine MRI scans. Pre-existing scans, taken in the 12 months preceding randomisation, were used if available to reduce the need for scanning. Otherwise, participants were referred for a scan. Information about the assessment of the MRI scans is available in the trial protocol69 and in the thesis by Gagen (http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/161673). 84

| Outcomes (0, 6 and 12 months unless indicated) |

BP and leg symptoms | ODI Troublesomeness of back and leg problems27 Swiss Spinal Stenosis Scale (symptom subscale)75 Ability to manage back and leg pain (0–10: 0 = not managing at all; 10 = extremely well) |

| Mobility | Walking item from the ODI 6MWT76,a |

|

| Physical performance | SPPB77,a | |

| Balance and falls | Self-reported falls and fall-related injuries32 | |

| Physical activity | Two items from Rapid Assessment Disuse Index78 [(1) time moving; (2) time sitting] | |

| Frailty | Tilburg Frailty Index29 hand grip strength79,a |

|

| Global rating of change | Change in back and leg problems80,b | |

| Satisfaction | Changes in back and leg problem; treatment (0–4; 0 = very dissatisfied; 4 = very satisfied)b | |

| Exercise adherence | Self-reported adherence to home exercisesb | |

| Quality of life | EQ-5D-5L81,82 | |

| Health resource use | Client Service Receipt Inventory83,b |

Sample size

At 80% power and 5% two-sided significance levels, a sample size of 321 participants (214 in the intervention group and 107 in the BPA group) was required. With an inflation for potential loss to follow-up (20%), this led to an overall target of 402 (268 intervention, 134 control). The sample size assumed a between-group difference of five points in the ODI to be clinically significant, with a baseline standard deviation (SD) of 15. 74

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of ODI at 12 months’ follow-up was analysed in an intention-to-treat (ITT) population and effect estimates with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported at a 0.05 significance level. The ODI difference between the two treatment groups was estimated using a repeated measures linear mixed-effects regression multilevel model with fixed effects for participant age, gender and baseline ODI, and random effects for recruiting centre and observations within participant (6 and 12 months). A model additionally accounting for potential heterogeneity due to the treating physiotherapist was assessed in a sensitivity analysis. Similarly, we assessed whether there was a group effect. We assessed the impact of intervention compliance using a complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis. 85 Compliance with the BOOST programme was defined as attending at least 9 out of the 12 sessions (75%).

Secondary outcomes were analysed in the ITT population, using similar methods and adjusting for the relevant baseline covariate where applicable. All analyses were completed using Stata® version 15.1 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

We undertook a series of prespecified subgroup analyses to see whether we could identify subgroups of participants who responded better or worse to the interventions tested (see Appendix 2, Table 8). Subgroup effects were analysed using interaction with treatment tests. 86

Economic evaluation

The economic analyses involved evaluation of economic costs, HRQoL outcomes and cost-effectiveness of the BOOST programme, where cost-effectiveness was expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. The base-case economic evaluation took the form of an ITT, imputed analysis conducted from a UK NHS and personal social services (PSS) perspective in line with the NICE reference case,87 and separately from a societal perspective. A 12-month time horizon for the economic evaluation was used, mirroring the trial follow-up period, and therefore no discounting was required.

Three broad resource use and costs categories were estimated: (1) intervention costs; (2) broader health and PSS use during the 12 months’ follow-up; and (3) broader societal resource use and costs encompassing economic values of lost productivity (e.g. income lost by participants and carers). All costs were expressed in GBP and valued in 2018–19 prices. Participants completed the Client Service Receipt Inventory83 at 6 and 12 months. HRQoL was assessed using the EQ-5D-5L instrument88 completed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

A bivariate regression of costs and QALYs, with multiple imputation of missing data, was conducted to estimate the incremental cost per QALY gained and the incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) of BOOST in comparison to BPA.

Results

Recruitment and follow-up

Recruitment was undertaken between 1 August 2016 and 29 August 2018 at 15 sites. We selected sites in different areas across England to maximise recruitment of participants from different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. A list of trial sites and description of the local population is provided in Appendix 2, Table 9.

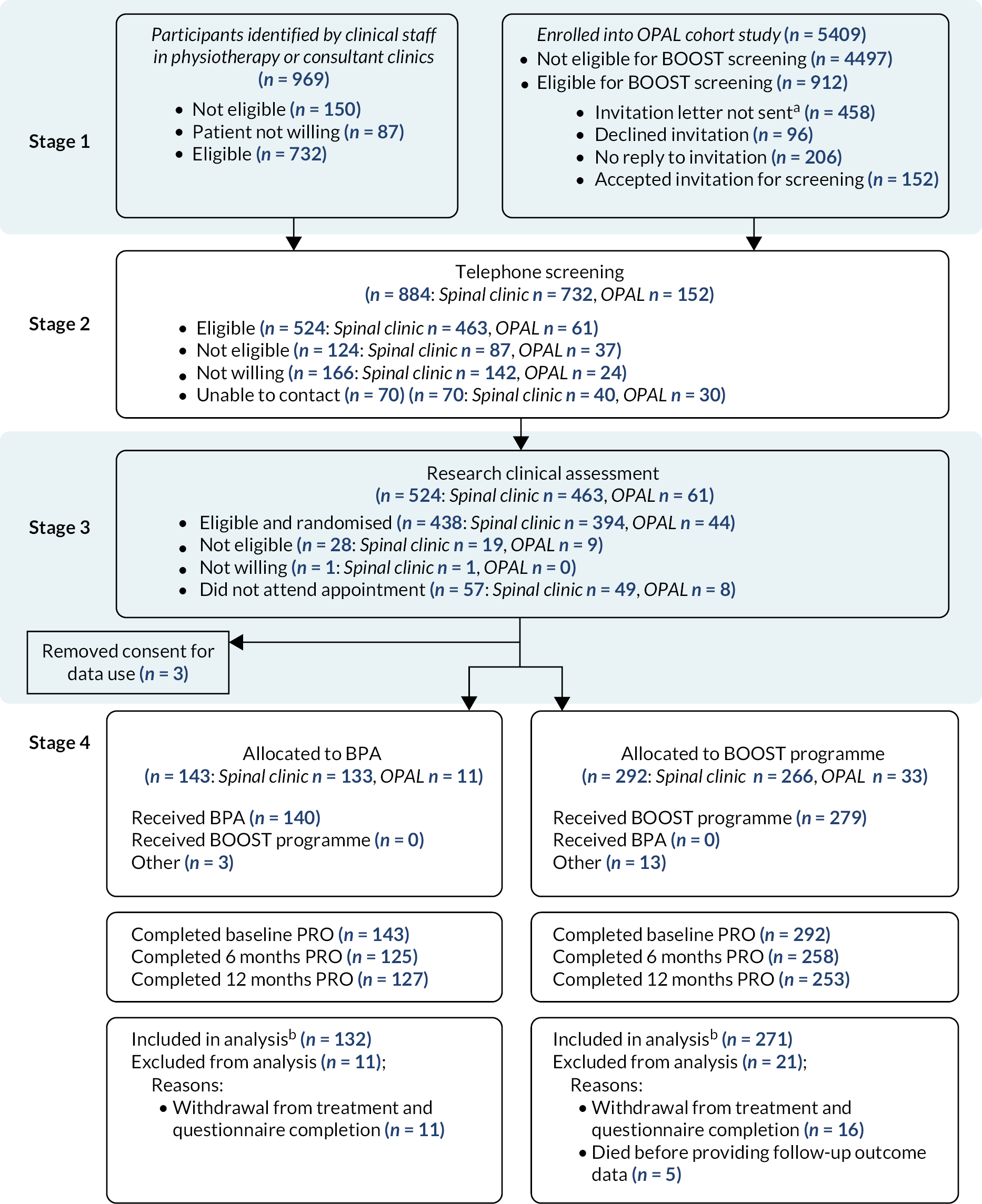

In total, 438 participants were found to be eligible, provided informed consent and were randomised (spinal clinics n = 394, OPAL n = 44). Three participants withdrew post randomisation and removed consent to use their data, so the final sample size was 435 participants (BPA n = 143, BOOST programme n = 292) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

CONSORT diagram. a Not all participants who were eligible to be screened for BOOST were invited. b Numbers included in analysis are all participants with at least one follow-up ODI outcome and the baseline variables used in the model. This was due to lack of staff capacity at sites to accept additional referrals for screening or due to lack of a referral pathways between primary care centres and study sites.

The primary outcome was obtained for 88.0% (383/435) and 87.4% (380/435) of participants at 6 months and 12 months, respectively, with 93.0% (403/435) contributing data to the primary analysis.

Baseline characteristics

Participants had a mean age of 74.9 years (SD 6.0) and were predominantly white (400/435; 91.9%). The randomised groups were well matched on baseline characteristics (see Appendix 2, Tables 10 and 12). In the BPA group, a larger proportion of participants were classified as frail (55.9% vs. 44.5%) using the Tilburg Frailty Index but other markers of frailty (6MWT, SPPB and hand grip strength) were similar. Four-fifths of participants (351/435; 81%) reported more than one health condition. The most frequently reported conditions were arthritis (272/435; 62.5%) and high blood pressure (252/435; 57.9%).

The proportion of BOOST RCT participants also taking part in OPAL was 10.1% (44/435). Twenty-five participants were identified from their baseline questionnaire and 18 from their year 1 questionnaire. We were interested in understanding how similar the OPAL–BOOST participants, who had NC confirmed by clinical assessment, were to OPAL participants categorised as having NC based on self-report. This was to help us understand the generalisability of the trial findings to the general population reporting symptoms of NC. In Appendix 2, Table 11 we present a description of participants at baseline using variables available in both data sets. At baseline, there were 594/5304 (11.2%) OPAL participants who were categorised as having symptoms of NC. 28 OPAL–BOOST participants and OPAL participants were broadly similar in age, sex, BMI, number of comorbidities, BP troublesomeness scores, multisite pain, change in walking over the last year and falls. However, compared to OPAL–BOOST participants, OPAL participants reported lower levels of education, lived in areas of higher deprivation, and reported lower quality of life and walking self-efficacy, and a greater proportion were classified as frail.

Intervention delivery

Sixty-nine physiotherapists delivered the interventions. Thirty physiotherapists delivered BPA, 34 physiotherapists delivered the BOOST programme, and five physiotherapists delivered both. In total, 24/143 (16.8%) participants allocated to BPA were treated by physiotherapists who were also trained in the BOOST intervention.

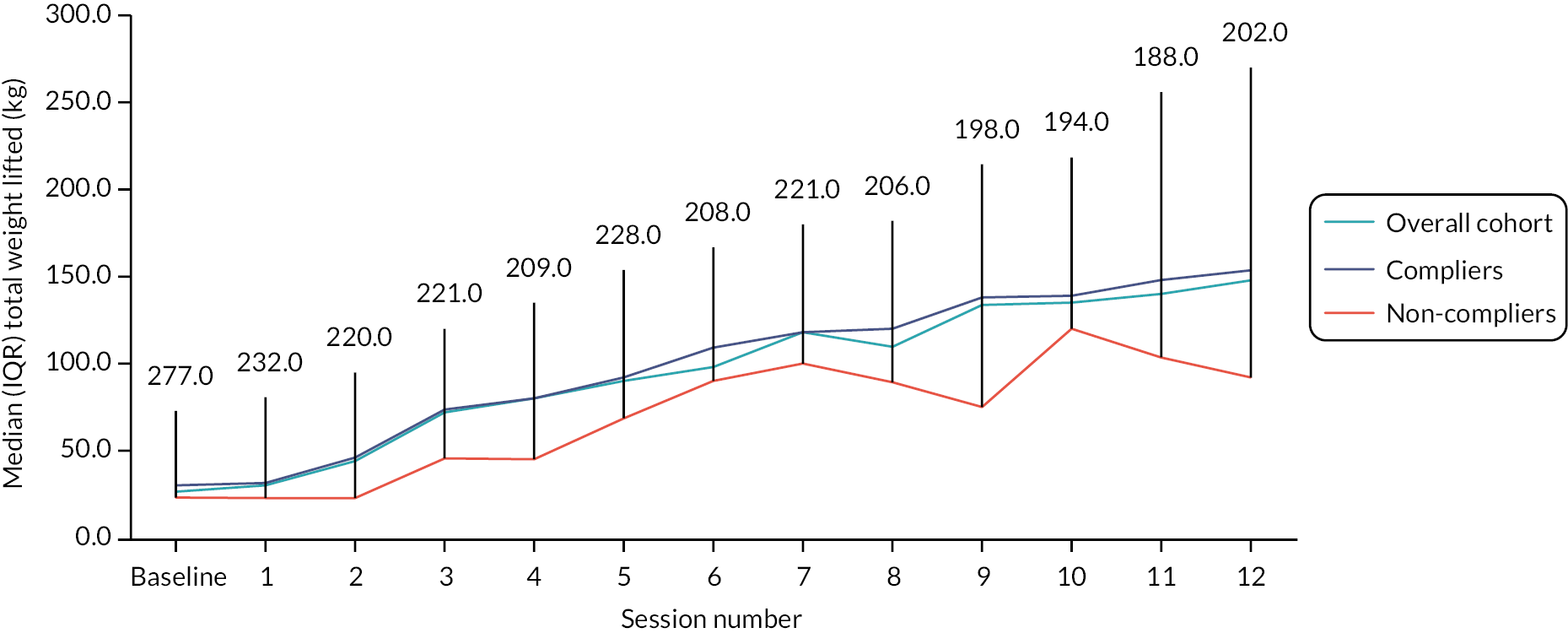

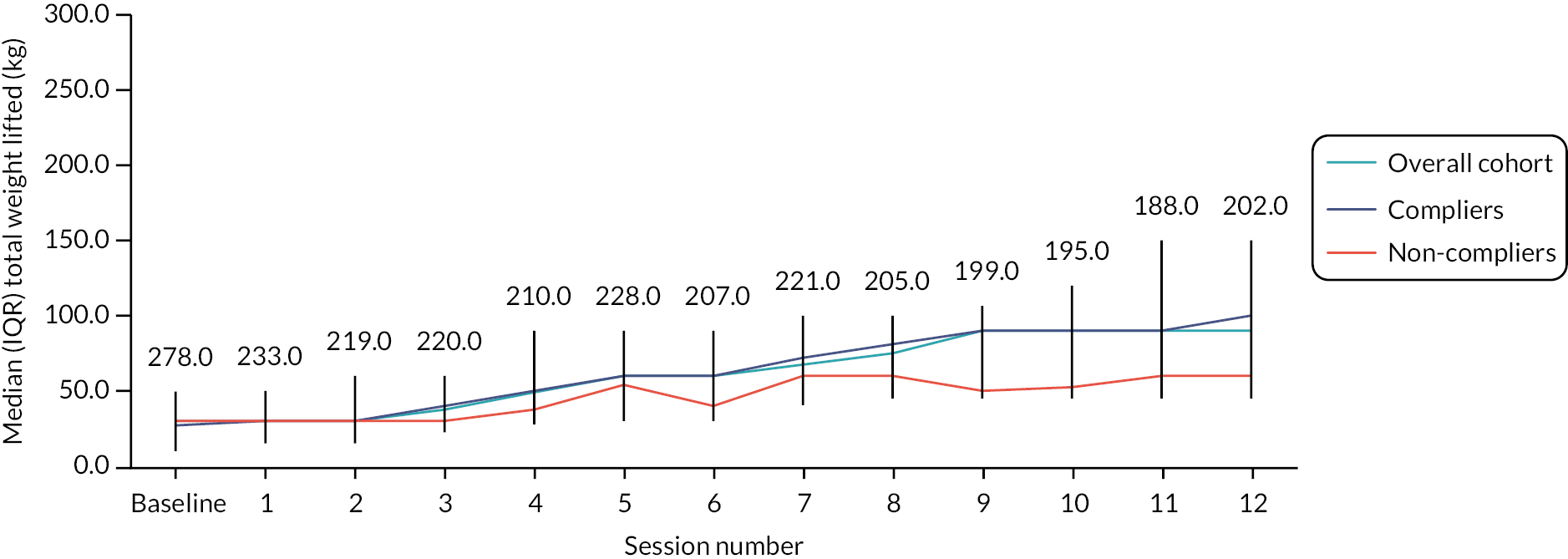

Treatment attendance was good for both interventions. Of the 143 participants allocated to BPA, 140 (98%) received the intervention. Most commonly, participants attended two BPA appointments (59/143; 41.3%). Of the 292 participants allocated to the BOOST programme, 279 (96.0%) attended the individual physiotherapy assessment. Thirteen participants (4.5%) did not attend this assessment. After the individual assessment, participants joined the next available group. In total, 203/292 (69.5%) attended at least 9 of the 12 sessions, indicating compliance. Having attended the individual assessment, 13 participants (4.5%) subsequently did not attend any group sessions.

We conducted 48 fidelity assessments. Interventions were delivered to a high standard. Eighteen fidelity assessments were undertaken of BPA sessions and 97.2% of checklist items were fully achieved. Thirty fidelity assessments of the BOOST programme group sessions were conducted, with 97.4% of checklist items fully achieved. Monitoring of treatment logs showed that exercises were progressed regularly across the key parameters, including increased repetitions and load and the addition of speed to the strengthening exercises. During the walking circuit, increasingly difficult elements were added. More information about delivery of the BOOST programme is contained in Appendix 3.

Primary outcome

Participants randomised to BPA showed a small increase in ODI scores at 6 months with very little subsequent change at 12 months. BOOST programme participants showed a reduction in ODI scores at 6 months which increased again at 12 months but remained lower than baseline scores. At the 12-month primary end point, there was no statistically significant difference in ODI scores between the two treatment groups (adjusted mean difference −1.4, 95% CI −4.03 to 1.17). There was a statistically significant difference in ODI in favour of the BOOST programme group (adjusted mean difference −3.7, 95% CI −6.27 to −1.06) at 6 months. There was no evidence of a therapist or group effect.

In the CACE analysis, the difference favouring the BOOST programme was larger, reaching the predefined clinically significant threshold (five points on the ODI) when group attendance was taken into consideration (−5.0, 95% CI −8.02 to −1.88) at 6 months. At 12 months, this difference was reduced (−2.4, 95% CI −6.02 to 1.32).

Key secondary outcomes

See Williamson et al. 71 for a full report of the secondary outcomes (see also Appendix 2, Tables 12 and 13).

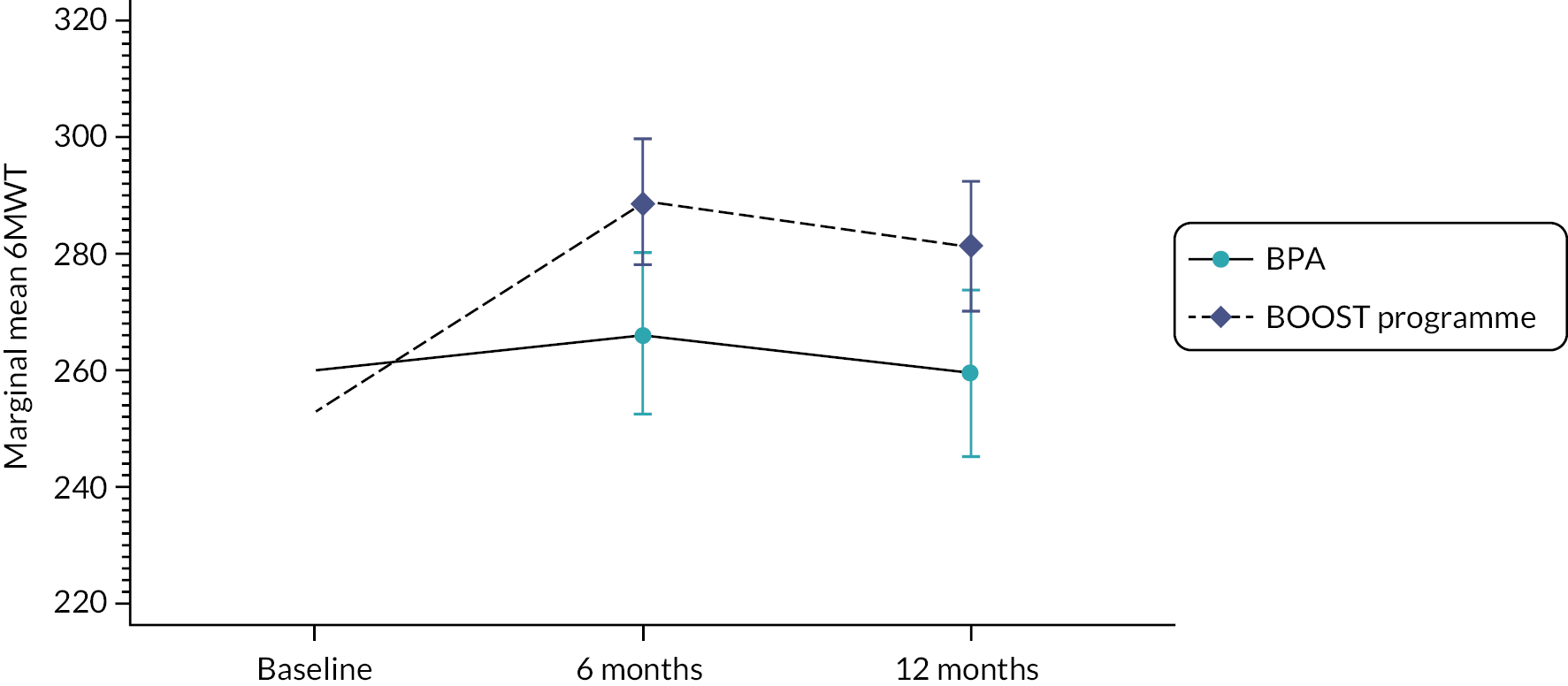

Walking and physical performance

The BOOST programme had a lasting impact on walking capacity (6MWT) (Figure 5) at 6 and 12 months’ follow-up, favouring the BOOST programme. The ODI walking item also reflected this finding. BPA participants showed very little change across the two follow-up time points. A similar response was observed for physical performance (SPPB) (see Appendix 2, Table 13).

Falls

Participants in the BOOST programme had a substantially reduced risk (by 40%) of reporting a fall over the 12-month period. The proportion of participants sustaining a fall-related fracture was very small but similar between groups.

Pain and other symptoms

Both groups reported a small reduction in Swiss Spinal Stenosis Scale (SSSS) symptoms subscale scores at 6 months, and these were larger for the BOOST programme. Small reductions were maintained at 12 months, and there was no longer a difference between the groups at 12 months. Similar findings were observed for troublesomeness, global rating of change and satisfaction with changes in back and leg problems.

Participant satisfaction

Participants in the BOOST programme were more likely to be satisfied with their treatment at 6 and 12 months compared to the control group.

Exercise adherence

Participants were asked how often they performed their home exercises. At 6 months, 190/257 (73.9%) BOOST programme participants reported performing their exercises at least twice per week, which reduced to 143/250 (57.2%) at 12 months. At 6 months, 102/125 (81.6%) BPA participants reported doing their exercises at least twice a week, which reduced to 89/125 (71.2%) at 12 months.

Adverse events

One serious adverse event (cardiac symptoms) occurred during a BOOST session which was deemed unrelated to the intervention. There were no serious adverse events reported for BPA. There were 12 adverse events reported for the BOOST programme. Four were assessed as definitely related to the programme, including aggravation of joint pains (n = 2), a fall during the walking circuit (no injuries) and skin irritation by an ankle weight. Two adverse events were reported for BPA, and neither was definitely related to the intervention.

Prespecified subgroup analyses

Overall, 354 MRI scans from 435 participants (80.8%) were available: 120 MRI scans from 143 (83.4%) BPA participants and 234 MRI scans from 292 (80.1%) BOOST programme participants. There were no statistically significant subgroup effects identified at 12 months’ follow-up.

Economic analyses

Complete QALY profiles were available for 357 (82%) participants based on the EQ-5D-5L. Completion of health resource use data for the base-case economic evaluation was similar at each time point between the BOOST and BPA groups. All data needed to calculate the cost components were available for 75–88% of health resource categories apart from hospital outpatient services, which ranged from 57% to 75%.

Intervention costs and resource utilisation

Mean total intervention costs varied between £242 and £911. The average cost per group session per participant varied from £11.80 to £67.00 depending on the number of participants per session. The mean cost per participant was generally lower across all sites if the target number of participants (n = 6) was achieved.

For health and PSS use, there were non-significant differences between the two groups in utilisation of hospital inpatient and outpatient care, community-based health care and social services, and days off work.

For the primary analysis, mean NHS and PSS costs, inclusive of intervention costs, over 12 months were £1974.06 for the BOOST programme versus £1826.64 for the BPA group. There was a non-significant cost difference in favour of the BPA group of £147.42 (95% CI £419 to £714). Mean total societal costs, inclusive of the intervention cost, were £2176.01 in the intervention group compared with £2140.54 in the BPA group. This generated a mean cost difference of £35.47 (95% CI £469.57 to £540.51) in favour of the BPA group. Societal costs (excluding NHS and PSS costs) were higher in the BPA group and primarily driven by economic valuation of time taken off work by a small number of patients and carers in the BPA group.

Health-related quality-of-life outcomes

The adjusted mean participant-reported QALY estimate for the base-case analysis over 12 months favoured the BOOST programme [0.621 (standard error 0.009) vs. 0.599 (standard error 0.006); between-group difference 0.021 (95% CI 0 to 0.044)].

Cost-effectiveness results: base-case analysis

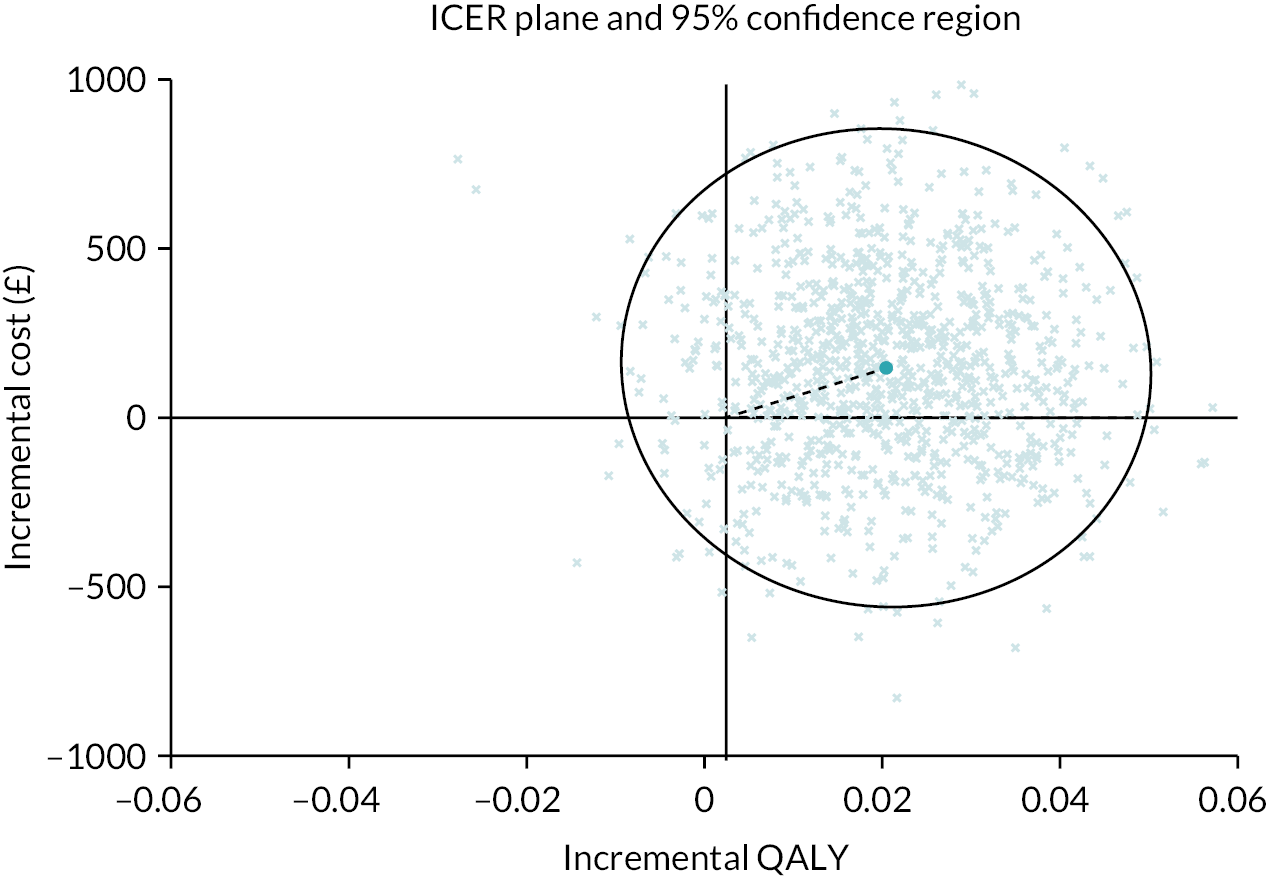

NHS and PSS perspective

The baseline economic evaluation indicated that the BOOST programme was associated with marginally higher NHS and PSS costs (£147, 95% CI −419 to 714) and an increase in QALYs (0.020, 95% CI −0.003 to 0.045). The mean incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for the BOOST programme was estimated at £7211 per QALY gained; that is, on average, the BOOST programme was associated with a higher cost and an increase in QALYs. The associated mean INMBs at cost-effectiveness thresholds of £15,000, £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY were £145, £244 and £464, respectively. The base-case mean INMB was >0, suggesting that the BOOST programme would result in an average net economic gain of approximately £244 (INMB = £244, 95% CI −£570 to £1058). The probability of cost-effectiveness for the BOOST programme was estimated as 67%, 78% and 83% at cost-effectiveness thresholds of £15,000, £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY, respectively (Figure 6). The joint distribution of costs and outcomes for the base-case analysis is presented graphically in Figure 7.

FIGURE 6.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for the base-case imputed (covariate-adjusted) analysis. (From Maredza et al. 72)

FIGURE 7.

Cost-effectiveness plane for the base-case imputed (covariate-adjusted) analysis. (From Maredza et al. 72)

Societal perspective

The probability that the BOOST programme is cost-effective was higher from a societal perspective, ranging between 79% and 89% across cost-effectiveness thresholds.

Limitations

Five physiotherapists trained in delivery of the BOOST programme also treated 24/143 participants (16.8%) allocated to BPA due to physiotherapist availability. There was a risk that these physiotherapists could integrate elements of the BOOST programme such as behaviour change principles into their treatment sessions and provide treatment beyond the BPA protocol. However, the proportion of participants exposed to potential contamination is well below the 30% threshold considered a serious threat. 89 We carefully monitored intervention delivery, including fidelity assessments, and are confident that the risk of contamination between arms was minimised.

Resource use data for the health economic analyses were retrospectively recalled by participants, which may mean they were affected by recall bias. However, we would expect any bias to be similar in each randomised group. Also, our approaches to collecting resource use data did not disentangle resource use associated with NC from use associated with broader health factors.

Discussion

The BOOST programme improved walking capacity and physical performance and reduced walking disability and falls risk compared to a control intervention of BPA for older adults with NC at 12 months’ follow-up. There were also larger short-term improvements in symptoms and pain-related disability. We plan to optimise the programme to better target pain-related disability and symptoms for longer-term impact as part of the planned implementation. Exercise adherence decreased over time, and we will also focus on improving long-term adherence during optimisation.

The economic analyses suggest that the BOOST programme is a good use of NHS resources.

There were broadly similar clinical presentations between OPAL participants with NC and BOOST–OPAL participants (BP troublesomeness, comorbidities, multisite pain, change in walking and falls), meaning that we should be able to generalise findings from the BOOST RCT to the OPAL participants reporting NC. However, there were differences in socioeconomic factors and frailty, which may have been barriers to OPAL participants seeking treatment through the trial. This has implications for our implementation strategy to ensure the programme is available to all older people with NC.

With limited treatment options available to older people with NC, based on improvement in mobility and value for money, implementation of the BOOST programme should be considered.

Objective 4: To undertake a longitudinal qualitative study embedded within the randomised controlled trial to understand the participants’ experiences of taking part in the trial

Methods

A full description of methods90 is available here: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060128

We used a longitudinal qualitative design with semistructured interviews and open-ended questions. All BOOST RCT participants were eligible to take part. Consecutive participants were invited to take part. From those who agreed, we sampled participants to ensure that a range of age, gender, ethnicity, treatment allocation and recruitment sites were represented.

We conducted face-to-face interviews at participants’ homes after randomisation (T1), and telephone interviews (or face-to-face if requested) 1 month after the interventions (T2) and 12 months post randomisation (T3). Interviews were audio-recorded.

We aimed to recruit 60 participants, as we expected 50% attrition. We planned to analyse up to 30 participants interviewed at each time point. 91 Retention was better than expected, and 49/59 (82%) participants completed all three interviews (one withdrawal).

Analysis

We sorted the T1, T2 and T3 interviews of 49 participants into five batches based on the richness of data. The narratives provided by participants varied, and some participants provided more detailed and thorough descriptions of their experiences (richer data) compared to others. As per the original plan, we analysed 30 data sets. These were the interviews with the richest data (30 participants, 90 interviews), which were split into three batches of 10. The T1, T2 and T3 interviews of the first batch and T1 interviews of the second and third batches were transcribed verbatim. For the T2 and T3 which were not transcribed verbatim, we took notes from the audio recordings. This was to limit costs related to the study, and the lead qualitative researcher was experienced in gathering data in this way.

To facilitate analyses of data in a time-efficient way, firstly, we read the transcripts of the first batch of interviews and developed data summaries called ‘pen portraits’. 92 These portraits became the source documents to develop a coding template. From the pen portraits, we wrote mini-statements to describe participants’ narratives. The mini-statements, accompanied by supporting participant quotes from T1, T2 and T3, were added to the coding template to produce individual frameworks (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for an example). For the second and third batches, the individual frameworks included mini-statements and supporting quotes at T1, but only mini-statements at T2 and T3 taken from listening to the interview recordings. Finally, we combined individual frameworks in a master Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) sheet for analysis.

We undertook an inductive thematic analysis of T1 interviews using the information in the frameworks to understand participants’ experiences of living with NC before taking part in the BOOST trial. We then comparatively analysed T1, T2 and T3 interviews to explore their experiences with the trial interventions, including the impact on their symptoms and their experiences of continuing with the home exercises independently.

Through comparative analysis, we also identified and explored participant trajectories over time for the domains of pain, mobility and activities of daily living, psychological impact, and social and recreational participation. We explored the interactions between domain trajectories to understand the pathway to improving social and recreational participation, which we considered essential to well-being in older age. This analysis is published here: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060128

Results

Interviews from 16 men and 14 women were included in this analysis; 14 participants were allocated to BPA and 16 were allocated to the BOOST programme. The demographics of interview participants are included in Appendix 4, Table 19 but they were broadly similar with regard to age and gender. We interviewed a greater proportion of non-white participants compared to white participants in the trial to ensure we heard from participants from different backgrounds.

Experience of living with neurogenic claudication

At T1, we identified four categories to describe how NC impacted on participants’ lives (see Appendix 4, Table 20).

Pain and its psychological impact

Pain was experienced by all participants. However, the onset, nature, intensity and location varied. Participants also reported a wide range of psychological responses such as depression, frustration, low mood, worry and lack of motivation in carrying out day-to-day or leisure activities.

Activity limitation

Most participants had difficulty in everyday activities due to the NC. This included self-care, walking, doing household chores, accessing public transport and using stairs.

Restricted participation

In two-thirds of the participants, pain and mobility issues negatively impacted their ability to participate in social, leisure and recreational activities like gardening, socialising in clubs and voluntary organisations, and going on holidays.

Coping strategies

Participants adopted a variety of coping strategies. Examples included sitting/resting between walks (activity pacing), limiting shopping trips or choosing online shopping (activity planning), using a stairlift (home adaptations), driving to local shops (activity modification) and using walking sticks (mobility aids).

Experiences of trial participation and Better Outcomes for Older people with Spinal Trouble interventions

Expectations and preferences

Participants participated in the trial expecting pain relief and improved walking, independence and general well-being. They also felt participation would help healthcare professionals to provide better treatments for other people with NC.

… whether through part of a study it gives a wider understanding to professionals about what they can do to help people of my age deal with the problems in a more proactive way.

08, T1

Most participants had no treatment preference on entry to the trial. Some preferred BPA due to the time commitment, while others preferred additional appointments and opportunities to interact with other people in the group sessions.

… the 12 sessions may be an embarrassment to me if I’m trying to run my business, and all the other things that are going on, and it does mean I presume an hour and a half plus, because I’ve got to get there and get back again, of my time.

37, T1

Acceptability of BOOST trial interventions

Satisfaction with BPA was mixed. Just over half the participants in the BPA arm (8/14) were satisfied with their sessions and felt the number of sessions was adequate. However, others were less satisfied (6/14) and a few mentioned that there was neither adequate feedback nor a follow-up.

But as far as going there, I only had a couple of sessions with them and that’s about it really; it wasn’t any proper sort of treatment or guidance or anything like that.

02, T2

In contrast, most participants (14/16) in the BOOST programme arm found it enjoyable and satisfactory.

I thank everybody for putting me on to the course because that’s what helped me … If they (other people) were in a similar condition, I would say, go for it!

57, T3

However, one participant was dissatisfied as he saw no clear benefit from the BOOST programme. Another participant joined the trial to get an MRI scan. This participant felt that the BOOST programme did not provide any new information and the exercises did not help.

Intervention components and perceptions about impact

Best practice advice participants were provided with an information booklet containing self-management advice and home exercises. Most BPA participants felt the booklet was useful and informative. The majority of participants (10/14) felt that the home exercises were appropriate and benefited them.

I felt it was enough information for me ... I think it is nicely produced, easy to read leaflet. Certainly in my case, going on the fear factor, it reassured right away.

15, T2

I get it [back pain] a bit first thing of a morning. But if I do the standing exercise, where you bend forward to touch your toes, that seems to put things right in a way.

31, T2

However, some participants did not perceive the exercises as helpful:

the exercises I was given, or any exercises I do, do not improve the problem.

03, T3

When assessing the overall impact of BPA on participants’ symptoms, 9/14 participants experienced some improvements in pain over the course of their involvement in the study, although the timing of this varied (five improved in a progressive manner; four reported being improved at T1 compared to entry into trial, or immediately after T2 that was maintained at T3, or only at T3). Pain did not change in four participants and worsened in one participant.

Participants in the BOOST programme liked the information folder containing session notes, photos and instructions for BOOST exercises and a home exercise planner. Participants reported benefits from the discussion and education element of the group sessions. They appreciated the peer support and interactions and the opportunity for group problem-solving. They were encouraged by their peers, enjoyed being part of the group and learnt skills to manage their condition, such as managing a flare-up or understanding the need to exercise for the long term (see Appendix 4, Table 21).

All participants except two described benefits from the exercise, which included reducing pain and improving posture, muscle strength and self-confidence.

And I think the exercises that I did has strengthened the muscles that I wanted strengthening – I think.

30, T2

One participant felt that exercise and physical activity would aggravate the condition.

Personally, I don’t think it [exercise and physical activity] would help. Full stop. I’ve had it so long now, and the wear and tear on my spine, overdoing it I think it would worsen the situation and that would be catastrophic … So the more you wear it, it’s going to get worse, in my eyes it is.

11, T2

Another participant had a mixed response to the programme, finding the BOOST walking regime and exercises with weights difficult but the hip mobility and balance exercises helpful.

In the BOOST programme arm (n = 16), we see similar variability in changes in pain. Pain improved in seven participants [four progressively improved; three improved at T1 (compared to entry into trial) or T2 that was maintained at T3, or only at T3]; one participant had initial improvements between T1 and T2 that got reversed to the baseline level of pain at T3. Pain did not change in seven participants and worsened in one participant.

Self-reported adherence to home exercises

Participants in both arms felt that the exercises prescribed by their physiotherapists could be fitted into their daily routine, but how successfully they did this varied.

At T2, most BPA participants (12/14) reported continuing exercises prescribed by their physiotherapist at least once a day. Low motivation and competing priorities such as work were reasons for stopping.

At T3, only 50% of BPA participants reported continuing the home exercises.

I mean I don’t ever miss at home, you know, and I said to [research clinician], I’ve done my exercises every day.

31, T3

Some reported still doing them at least once a day, but others had reduced the exercise frequency or stopped doing particular exercises that caused pain. Reasons for stopping the exercises were low self-motivation, recent surgery and impact on other pain problems (e.g. irritated hip pain).

Don’t ask me about them … No … Well, last time because it was really starting to hurt me on some of the exercises … and I do have a problem with motivation about that sort of thing on my own, as you will know. If I was with a group of people doing this, it would have been a lot much better for me.

33, T3

In contrast to the main trial results, self-reported adherence to the exercises prescribed by the physiotherapist was better with the BOOST programme than with BPA. At T2, all BOOST programme participants (16/16) reported doing their home exercises between one and three times every week or daily.

At T3, all but two participants continued their home exercises. Those who exercised independently tended to perceive the exercises as beneficial. At both time points, participants who exercised regularly described how they integrated the BOOST exercises into their daily activities; for example, exercising while watching television. One participant felt they were easily transferable to the daily routine and home environment because no special equipment was needed.

Some had made adaptations to allow them to continue exercising. This included one participant avoiding the weighted exercises that caused pain, and another avoiding specific exercises which aggravated a knee problem. Another participant had stopped the walking element as she felt she got enough walking in her everyday activities.

Two participants reported ceasing the BOOST exercises completely. One found the walking element overwhelming. Another participant found his usual activities such as walking the dog, going to the gym and swimming were adequate exercise.

For more information, see Appendix 4, Table 22.

Limitations

We analysed data sets from a selected sample of 30 participants who provided a rich description of their experiences. The BOOST trial participants who did not take part in the interviews may have had different experiences from those described here. However, the strength of the study is that we used in-depth repeated interviews that focused on the participants’ current experience, so we were not reliant on their recollection of past experiences and can be confident that the data available reflected their experiences of the trial.

Discussion

Our interview findings resonate with the previous qualitative studies in NC,93,94 as pain was the main complaint impacting on their activities and leading to negative psychological responses. Expectations of trial participants were aligned well with the treatment targets of the BOOST programme. BOOST programme participants appeared more satisfied with their intervention compared to BPA. Dissatisfaction among BPA participants seemed to arise from lack of feedback and follow-up. BOOST participants benefited from peer support and discussions, which may have added to their satisfaction with the programme. Most participants felt the exercises were appropriate and helpful, although this did not necessarily translate to improvements in pain. Dissatisfaction with the BOOST programme was mostly related to lack of pain relief. Pain remained a substantial problem for some participants, and this highlights the importance of trying to better target pain. The BOOST programme participants talked about other improvements from the exercises, including improved posture, strength and confidence, highlighting the broader benefits of the BOOST programme. These types of changes were less evident in the narratives of BPA participants. BOOST participants also reported benefit from the cognitive–behavioural component of the programme, highlighting how the programme helped them to find their own solutions, manage flare-ups and understand the importance of long-term exercise.

Reasons for stopping the home exercises were similar between treatment arms. These included competing priorities, lack of motivation and aggravation of pain. Adaptations allowed some participants to continue at least some of the exercises. Some participants did not make adaptations when finding the exercises difficult or unhelpful, and stopped altogether. One participant had stopped the BOOST exercises to focus on participating in activities they enjoyed. These types of physical activity or exercise were not captured in the main trial follow-up questions, so it is not possible to know how many other participants may have gone on to other activities in lieu of the BOOST programme.

The barriers to long-term exercise identified in this study were not unique95,96 but highlight areas where we can optimise the BOOST programme. These include additional support to provide motivation for ongoing exercises, either by the physiotherapist or by linking to exercise opportunities in the community; to provide greater guidance on how to adapt exercises, rather than stopping altogether, if they are painful or if patients have a flare-up of symptoms; and to help plan integration into everyday life or transition to activities they enjoy for long-term adherence.

Objective 5: To develop a prognostic tool using the Oxford Pain Activity and Lifestyle cohort study data to predict when older people are at risk of mobility decline

Methods

The full description of this study97 is available here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.09.002

The aim was to develop a tool to identify when older people were at risk of mobility decline. In particular, we wanted to understand whether BP was important, alongside other health conditions and symptoms, physical ability, psychological factors, and lifestyle and sociodemographic factors.

Baseline candidate predictors

We completed a systematic literature review to inform the selection of baseline predictors (searches for this review were conducted on 26 June 2019, with an update run on 2 June 2020),98 held discussions with our patient and public involvement (PPI) group, and utilised the expertise within the study team (including, but not limited to, primary care, geriatrics, mobility decline, falls, pain, and prognostic tool design and statistical analysis). Thirty-one candidate variables (Table 3) were preselected from the OPAL baseline variables (see Appendix 1, Table 5).

| Domain | Variables | Domain | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | Socioeconomic | Receive enough support Yes/no |

| Sex | Yes/no | ||

| Living arrangements | Miss other people around | ||

| Education | No/sometimes/yes | ||

| Higher education | No of organisations/clubs/societies | ||

| Secondary education | Adequacy of income | ||

| None or primary | Quite comfortably off | ||

| Manage without much difficulty | |||

| Careful with money | |||

| Mobility-related factors | Mobility problems | Occupational physical demands | |

| None | Very light | ||

| Slight | Light | ||

| Moderate | Moderate | ||

| Severe | Strenuous | ||

| Unable to walk | Very strenuous | ||

| Usual walking pace | Physical activity | Hours/day moving around | |

| Fast/fairly brisk | 7 hours/day or more | ||

| Normal | 5–7 hours/day | ||

| Stroll at any easy pace | 3–5 hours/day | ||

| Very slow/unable to walk | < 3 hours/day | ||

| Difficulties maintaining balance | Falls | Falls last year | |

| Confidence to walk (0–10) | None | ||

| Use of walking aid inside | One | ||

| Use of walking aid outside | More than one | ||

| Change in walking ability compared to last year | Fractures last year | ||

| General health | BMI | ||

| Better | Number of health conditions | ||

| About the same | Physical tiredness | ||

| Worse | Yes/no | ||

| Anxiety/depression | |||

| Pain | BP and leg symptoms | No | |

| No BP | Slightly | ||

| BP only | Moderately | ||

| BP with leg symptoms | Severely/extremely | ||

| Pain distribution | Poor hearing Yes/no | ||

| No pain | Poor vision Yes/no | ||

| One site pain | Problems in daily life due to lack of hand strength Yes/no | ||

| Multisite pain | |||

| Widespread pain | Unintentional weight loss Yes/no | ||

| Lower limb pain in the last 6 weeks Yes/no |

Self-reported general health (0–100) |

||

| Current pain/discomfort severity (0–4) |

Outcomes

The outcome was mobility decline at 2 years’ follow-up, defined using the EQ-5D-5L Mobility Question (no problems with mobility, mild problems, moderate problems, severe problems, unable to walk).

Among participants who could walk at baseline, mobility decline was considered present if a participant reported a worsening change in mobility status at year 2; that is, mobility progressed from one level to another or an individual had no problems at baseline and reported any problems at follow-up.

Sample size

The prevalence of mobility decline among the OPAL cohort at 2 years was 18.6%. Based on a conservative Nagelkerke’s R2 of 0.15 and a prespecified maximum number of predictor parameters of 50, the minimum sample size required to develop the model to minimise overfitting was estimated to be 4585, with 853 events. 99

Analysis

We present the baseline factors stratified by the 2-year outcome and estimated the univariate associations between baseline variable and the outcome using logistic regression.

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was used to select potential predictors for the multivariable model to predict mobility decline. 100 Model performance was assessed by calculating the c-statistic and the Brier score. 101 Models were internally validated using bootstrapping. 102 Missing data were imputed using the ‘multiple imputation by chained equation’ technique. 103,104

As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the analyses, including participants who died during 2-year follow-up, who were added to those with mobility decline.

To facilitate application into clinical practice, we simplified the presentation of the model to a simple scoring system based on the procedures described by Sullivan et al. 105

Results

There were 5358 participants who could walk at baseline and were eligible for this analysis. However, 174 (3.2%) died before the 2-year follow-up. Therefore, 5184 participants were included in the main model. Two-year follow-up data were provided by 4115/5184 (79.4%) participants. The mean age of participants was 74.7 years (SD 6.6), and 51.8% (n = 2683/5184) were women. At baseline, the majority of participants reported no mobility problems (3146/5184; 60.7%), and 5.4% (280/5184) reported severe mobility problems.

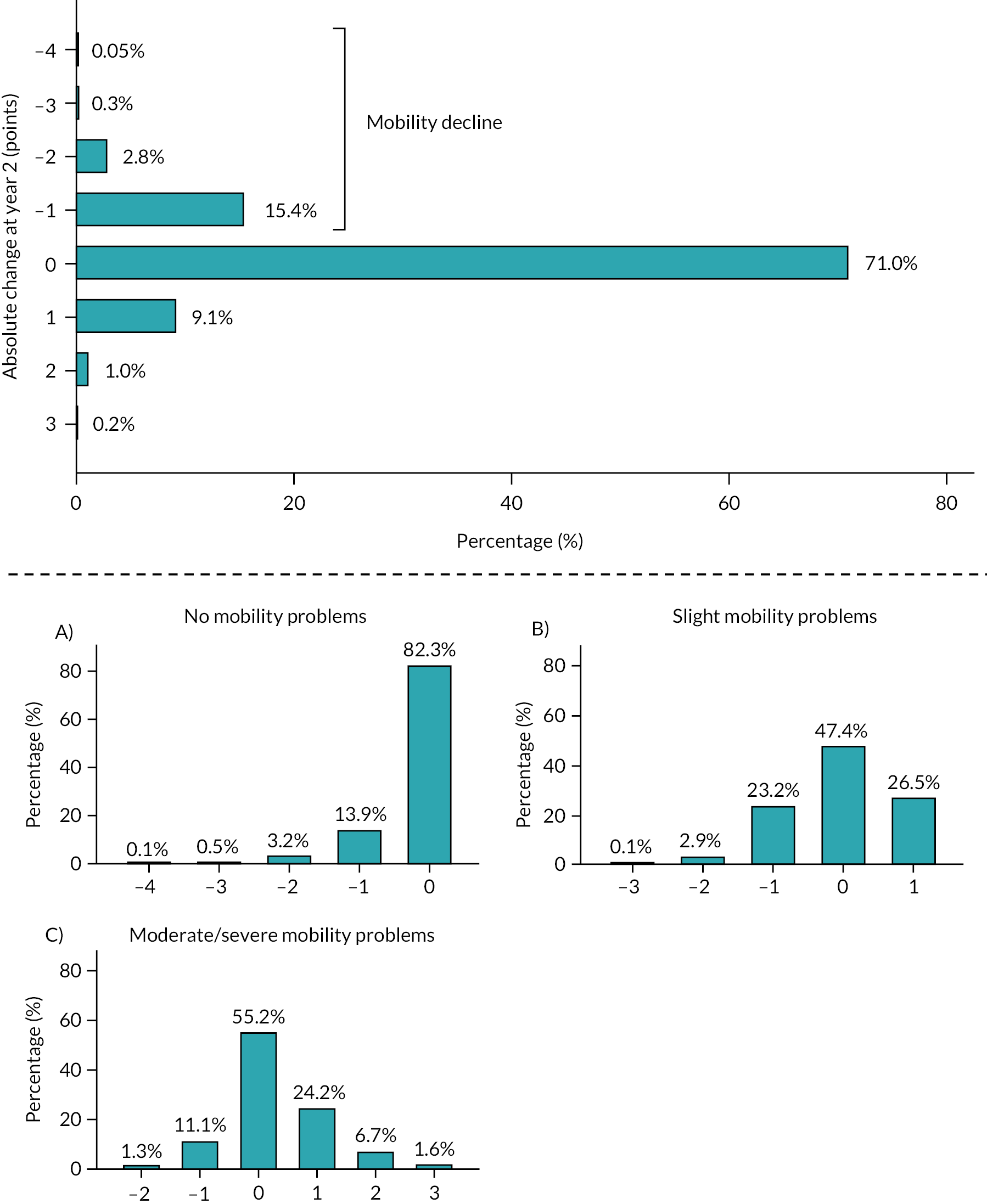

Among responders at 2 years, 18.6% (n = 765/4115) reported mobility decline (Figure 8). There were 375 (9.1%), 42 (1.0%) and 10 (0.2%) individuals who improved their mobility status by one, two and three points at 2 years, respectively. Participants who reported slight mobility problems (see lower panel, plot A) at baseline had the biggest decline over the 2 years of follow-up (35.6%).

FIGURE 8.

Absolute change in mobility status between baseline and year 2. Note: Participants who could walk at baseline (upper panel). Stratified by mobility status at baseline (lower panel): (A) no mobility problems; (B) slight mobility problems and (C) moderate or severe mobility problems. (From Sanchez et al. 97)