Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1212-20019. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Gillard et al. This work was produced by Gillard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Gillard et al.

Synopsis

Note: some text in the synopsis below has been reproduced from the published study protocol [Gillard S, Bremner S, Foster R, Gibson SL, Goldsmith L, Healey A, et al. Peer support for discharge from inpatient to community mental health services: study protocol clinical trial (SPIRIT Compliant). Medicine 2020;99(10):e19192]. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Discharge from psychiatric inpatient care

People recently discharged from psychiatric hospital often fail to continue with treatment,1 relapse and are readmitted. 2 For example, in the UK it has been reported that 36% of inpatients with psychotic disorders are readmitted within 1 year of discharge,3 while in New Zealand the readmission rate of all psychiatric inpatients has been reported at 41%. 4 A high proportion of people are readmitted shortly after discharge, with an Australian study of over 35,000 people admitted to psychiatric hospital finding that nearly a fifth of all psychiatric inpatients (half of all people readmitted) were readmitted in the first month post discharge,5 and a UK study of nearly 8000 people observing 15% readmissions within 3 months of discharge. 6 People recently discharged are also at risk of suicide and self-harm with, globally, suicide rates in the first 3 months after psychiatric discharge 100 times the suicide rate in the general population, and suicidal thoughts and behaviours 200 times the level in the general population. 7 In the UK, post-discharge suicides are most frequent in the first week after discharge, with 15% of all suicides nationally among people within 3 months of a psychiatric discharge. 8 Evidence suggests that lack of follow-up care post discharge9 and lack of continuity of care from hospital to community are predictors of early readmissions,10 with, conversely, higher levels of follow-up from community mental health services post discharge predicting lower readmission rates. 11 Systematic review evidence suggests that interventions supporting transition from inpatient to community mental health care are feasible and likely to be cost-effective. 9 Two of the studies reviewed evaluated multidisciplinary transitional discharge interventions that included peer support components. 12,13

Peer support in mental health services

Origins of peer support in mental health services are twofold. First, there is a decades-old tradition of self-help in Europe and North America, underpinned by a ‘helper therapy principle’14 that is perhaps best exemplified by the 12-step programmes of Alcoholics Anonymous and related programmes, having more recently proliferated into mental health care with the emergence of organisations such as Depression Alliance and the Hearing Voices Network. Second, peer support work in mental health grew out of reactions to negative and coercive mental health treatment15 with, by the 1970s, people building programmes focused on self-advocacy and campaigning where people focused on helping each other, acknowledging that their experiences and life stories could be a source of important knowledge. Since then peer support has gradually moved into the mainstream of mental health service provision, with state-funded and approved mental health service providers increasingly employing and training peer support workers – people with their own experiences of mental distress and of using mental health services – to role-model living well with mental illness and embody hope in the future, and to improve the ‘recovery focus’ of mental health services. 16 Peer workers (PWs) have been employed in a variety of roles in the NHS in the UK, most typically as peer healthcare assistants in inpatient settings or as peer community support workers in Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs), with a focus on telling their ‘recovery story’ alongside enacting a more conventional support worker role. 17

Peer support for discharge

An observational pilot of a transitional discharge intervention delivered wholly by PWs has shown promise,18 while comparison group studies of community-based peer support programmes have also reported reductions in readmissions19 and longer community tenure20 compared to traditional services alone. A pilot trial of a community-based peer mentoring intervention for people with a history of recurrent psychiatric hospitalisation reported fewer readmissions for people receiving peer mentoring over a 9-month period, compared to community treatment as usual. 20 In another trial, among participants who engaged with treatment, fewer people receiving assertive community treatment (ACT) from a consumer-staffed ACT team reported being hospitalised than those receiving care from a non-consumer ACT team, although length of follow-up varied between participants and was not reported. 21

The evidence base for peer support in mental health services

While this evidence suggests that interventions employing PWs might offer a strategy for improving the outcomes of discharge, meta-analyses of trials of a range of peer support interventions have indicated little difference in outcomes for people receiving peer support, either in comparison to treatment as usual or to similar support provided by other mental health workers, once data from across trials are pooled. 22,23 Those systematic reviews have also pointed to the heterogeneity of the peer support evaluated, issues with the quality of trials, an absence of formal studies of cost-effectiveness, and a lack of reporting of how peer support is designed to bring about change in comparison to other forms of mental health support. In particular, inadequate randomisation and sequence generation processes,22 lack of blinding of assessors, risk of bias resulting from missing data, and selective or incomplete reporting of outcomes measured were identified as trial quality issues that need to be addressed. 23

Processes and principles of peer support

A wider literature, including qualitative and observational research, has indicated that organisational factors supporting the implementation of peer support into practice in mental health services might impact on its effectiveness. Issues such as clarity of job description,24,25 access to appropriate training and support,26 shared expectations of the PW role25,27 and preparation and training for the team that will be working alongside PWs28 have all been identified as important facilitators of the introduction of the PW role. It has been noted how the distinctiveness of peer support, in comparison to other forms of mental health care, can be lost in a formal environment of statutory mental health services if those organisational conditions are not met. 27,29,30

The distinctiveness of peer support has been attributed to the particular qualities of peer-to-peer relationships in contrast to the conventional clinician-patient relationships: peer-to-peer relationships are underpinned by a sense of connection between peers based on a recognition of shared experiences;31 reciprocity in the relationship whereby both parties learn from each other;32 and the validation and exchange of experiential, rather than professionally-acquired, knowledge. 33 In previous research by the team we developed a general change model for peer support in mental health services31 that underpins, theoretically, the development and implementation of both our peer support for discharge intervention and our evaluation. Elsewhere, a more recent review of peer support in mental health services concluded that a lack of attention to fidelity to the core principles underpinning peer support limits the usefulness of current peer support research to policy makers and practitioners. 34

Impact of peer support on peer workers

A parallel body of research has identified potential benefits and challenges for people working in a PW capacity. It has been suggested that peer support might enhance personal recovery for PWs, but can also be a source of stress, with mental health professionals voicing concern that the PWs they work alongside might relapse and be hospitalised because of the stresses of the role. 16 A review of qualitative research about PWs’ experiences of peer support indicated improvements in confidence, self-esteem and social contacts for PWs. 35 However, more recently, a survey of 84 PWs working in a range of mental health services in one state in the United States (US) USA found that PWs experienced difficulties including poor financial compensation, limited employment opportunities, work stress, the emotional stress of helping others and in maintaining personal wellness, with 44% of the sample reporting having experienced a relapse in their mental health while working as a PW. 36 It is important to understand and evaluate the impact of working in a peer support capacity in order to ensure that implementation of peer support into mental health services is both safe and rewarding for PWs.

Rationale

Mental health policy and workforce initiatives in higher income countries are driving the introduction of PWs into statutory mental health services despite these uncertainties in the evidence base. 22,23 As such, there is a need for high-quality trials of peer support that specify, model and evaluate the distinctive processes whereby peer support brings about change in specific contexts and settings, as well as for good health economic evaluation. This study aims to address those limitations in the current evidence base while providing clear evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a PW intervention to enhance discharge from inpatient to community mental health care.

The research programme

Aims

The overarching aim of this programme of applied research was to enhance the experience of discharge from psychiatric inpatient care for mental health service users, preventing unnecessary readmission and reducing costs. The specific aim of the programme was to manualise, pilot and trial a peer support intervention to enhance discharge from inpatient to community mental health care, significantly reducing readmissions and the associated cost of care. The detailed research objectives of the programme were:

-

to refine an empirically and theoretically grounded model that explains how peer support interventions impact on outcomes for service users post-discharge

-

to develop and manualise a peer support intervention to enhance discharge

-

to develop an index to assess the fidelity of peer support interventions

-

to conduct a high-quality randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the intervention

-

to establish the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a peer support intervention to enhance discharge

-

to explore the impact on PWs of providing peer support for discharge.

This programme also aimed to deliver applied outputs that will enable mental health service providers in the NHS to effectively and cost-effectively integrate peer support into the mental health discharge pathway, including: the ENRICH training programme and intervention handbook, providing implementation guidance for managers and commissioners in the NHS, and our principles-based peer support fidelity index.

Work packages

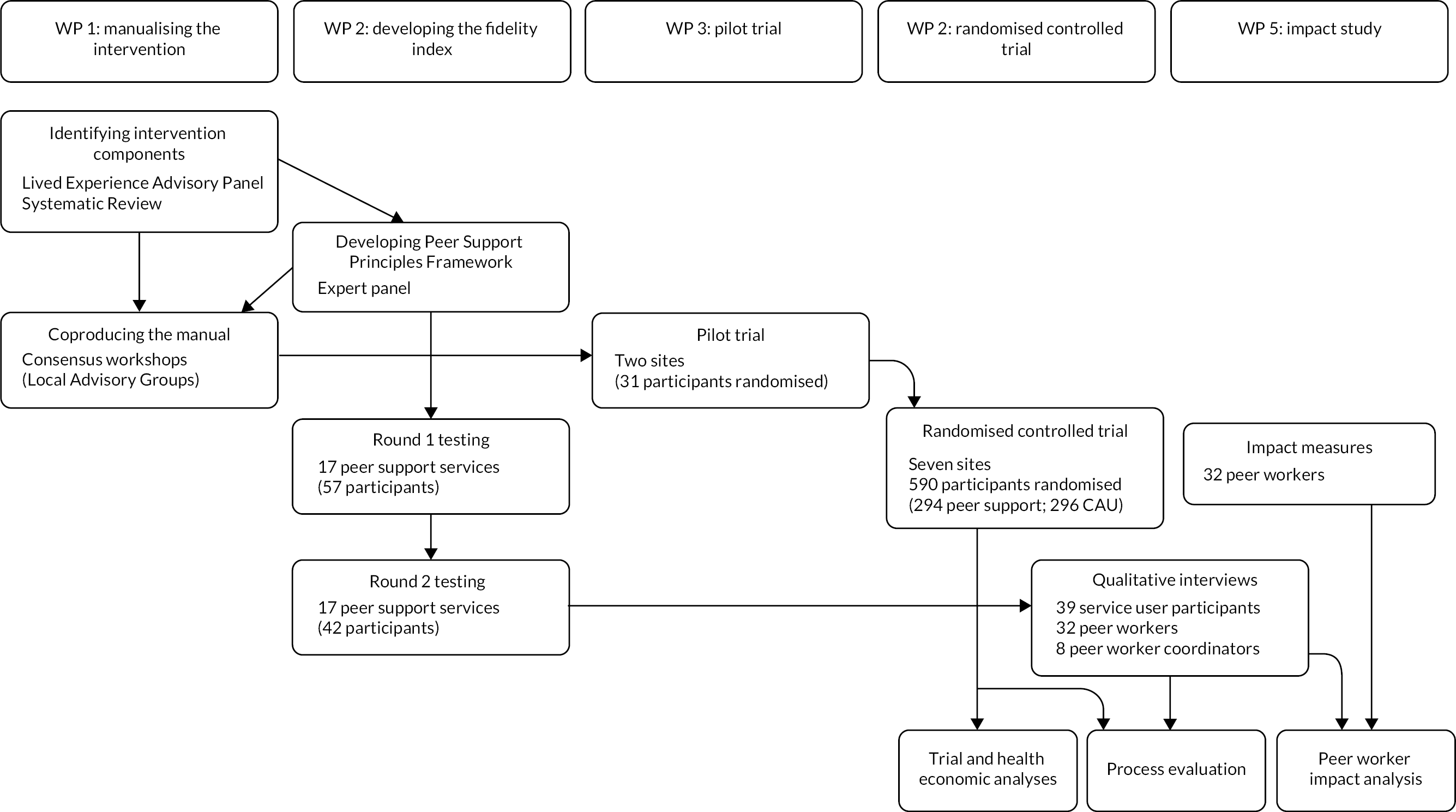

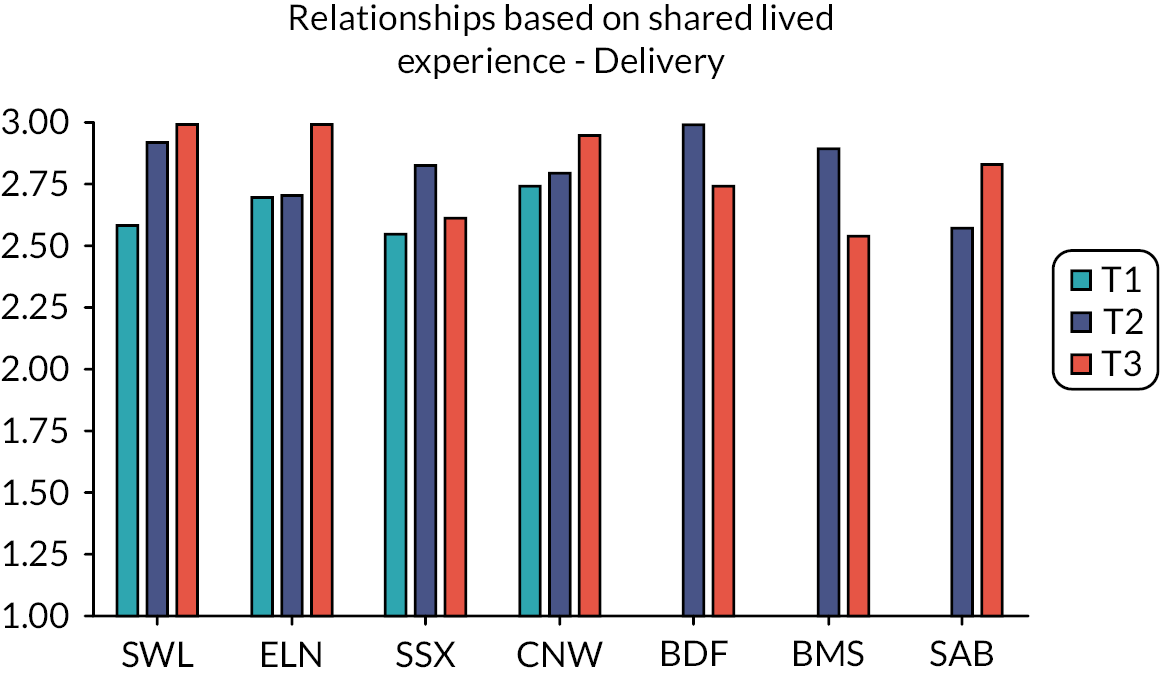

The ENRICH programme comprised five interlinked work packages (WP) that addressed the aims listed above (see Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of the programme.

WP1. Manualising the ENRICH intervention

WP1 comprised two main pieces of work. First, a systematic review of the evidence for one-to-one peer support in mental health services was undertaken to refine the model underpinning the intervention, identify intervention components and establish the effectiveness of one-to-one peer support intervention. Second, we worked with expert panels, at study site and national levels, to identity and prioritise intervention components, and to develop and refine the ENRICH training programme and peer support handbook for the trial in WP4.

WP2. Developing the peer support fidelity index

A fidelity index was developed, and its psychometric properties and acceptability tested, and used in the WP4 trial to assess the extent to which the peer support intervention was implemented to principles underpinning peer support.

WP3. Pilot trial

An internal pilot trial of the intervention was conducted in two sites using the protocol for the full RCT to test procedures for recruitment, randomisation, allocation to and delivery of intervention, and collection of data. A clear set of stop-go rules was used to determine whether the programme proceeded to full trial, and if any procedures needed to be refined.

WP4. Randomised controlled trial

A fully powered superiority trial, comparing peer support for discharge plus care as usual (CAU), with CAU only at discharge from inpatient psychiatric care, was conducted to establish the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the ENRICH peer support intervention. This WP also comprised a substantial mixed methods process evaluation that used measures of process as well as in-depth qualitative interviews with trial participants, PWs and their supervisors [peer worker co-ordinators (PWCs)] to explore, quantitatively and qualitatively, the processes of peer support.

WP5. Impact study

A mixed method, longitudinal cohort study using standardised measures and in-depth interviews with PWs delivering the peer support intervention explored the impact of the role on well-being and employment outcomes for PWs.

Setting

The programme took place in adult acute psychiatric inpatient and community mental health service settings in mental health NHS trusts in England. Two trusts [South West London (SWL) & St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust and East London (ELN) NHS Foundation Trust] took part in the pilot study, with five additional trusts joining for the full trial and subsequent WPs (Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust; Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust; Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust; Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust; Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust). Two other trusts – Dorset HealthCare University NHS Foundation Trust and South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust – were involved in WP1 of the programme but were unable to remain involved for the full trial.

Population

The primary population of the research was adult inpatients of psychiatric hospital wards (acute admission wards and their equivalents) who had had at least one previous admission in the preceding 2 years. Secondary populations included the PWs employed to implement the intervention and their supervisors (PWC).

Ethical approval

A single application for NHS research ethics approval was made for all WPs. The programme was approved by the UK National Research Ethics Service, Research Ethics Committee London – London Bridge on 10 May 2016, reference number 16/LO/0470.

Governance

The Chief Investigator, Programme Manager and trial statistician reported regularly to an independent Programme Steering Committee (PSC) and an independent Data Management and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Oversight from a patient and public perspective was provided by a Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) as well as service user representation on the PSC and DMEC.

Changes to the funded programme

Changes to the funded programme were minimal. In WP1 we split the systematic review into two outputs. We initially prioritised data extraction of components of peer support to inform development of the intervention. We returned to the review and updated searches once the WP4 trial had completed recruitment (and more researcher resource was available). This was to our advantage as a sufficient number of new trials of peer support had been published in the interim to enable us to undertake a meta-analysis.

There were no major changes to the WP4 trial that required ethical approval. Minor changes to recruitment procedures were made following the pilot trial that did require amendment to ethical approval.

As noted in Process evaluation – predictors of engagement with peer support below, because we did not observe a positive effect on primary outcome, we were not able to undertake the structured equation modelling we had intended, to explore pre-specified change mechanisms. Given that our complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis had indicated a relationship between engagement with intervention and outcome, we instead undertook an analysis of pre- and post-randomisation predictors of engagement. Similarly, in Process evaluation – peer support and change in mental health services – the qualitative component of the process evaluation – instead of exploring our pre-specified mechanisms we used our qualitative dataset to refine the change model for peer support in mental health services that underpinned the intervention (thus remaining consistent with our original objectives).

Work package 1 Manualising the ENRICH peer support intervention

In this work package we aimed to address objectives 1 and 2 of the programme:

-

to refine an empirically and theoretically grounded change model that explains how peer support interventions impact on outcomes for service users post discharge

-

to develop and manualise a peer support intervention to enhance discharge.

We sought to build on what is already known about peer support interventions in order to refine our trial protocol and develop an intervention that would improve on the existing evidence base for peer support in mental health services. In previous research undertaken by the team we had developed a general change model for peer support in mental health services31 and had identified some of the key components that might comprise a PW intervention supporting discharge. 25,27 We undertook two main strands of work to fulfil these objectives:

-

a systematic review of research evaluating one-to-one peer support in mental health services

-

co-design and consensus work with advisory groups comprising people involved in delivering, developing, leading and working alongside peer support services in NHS mental health services.

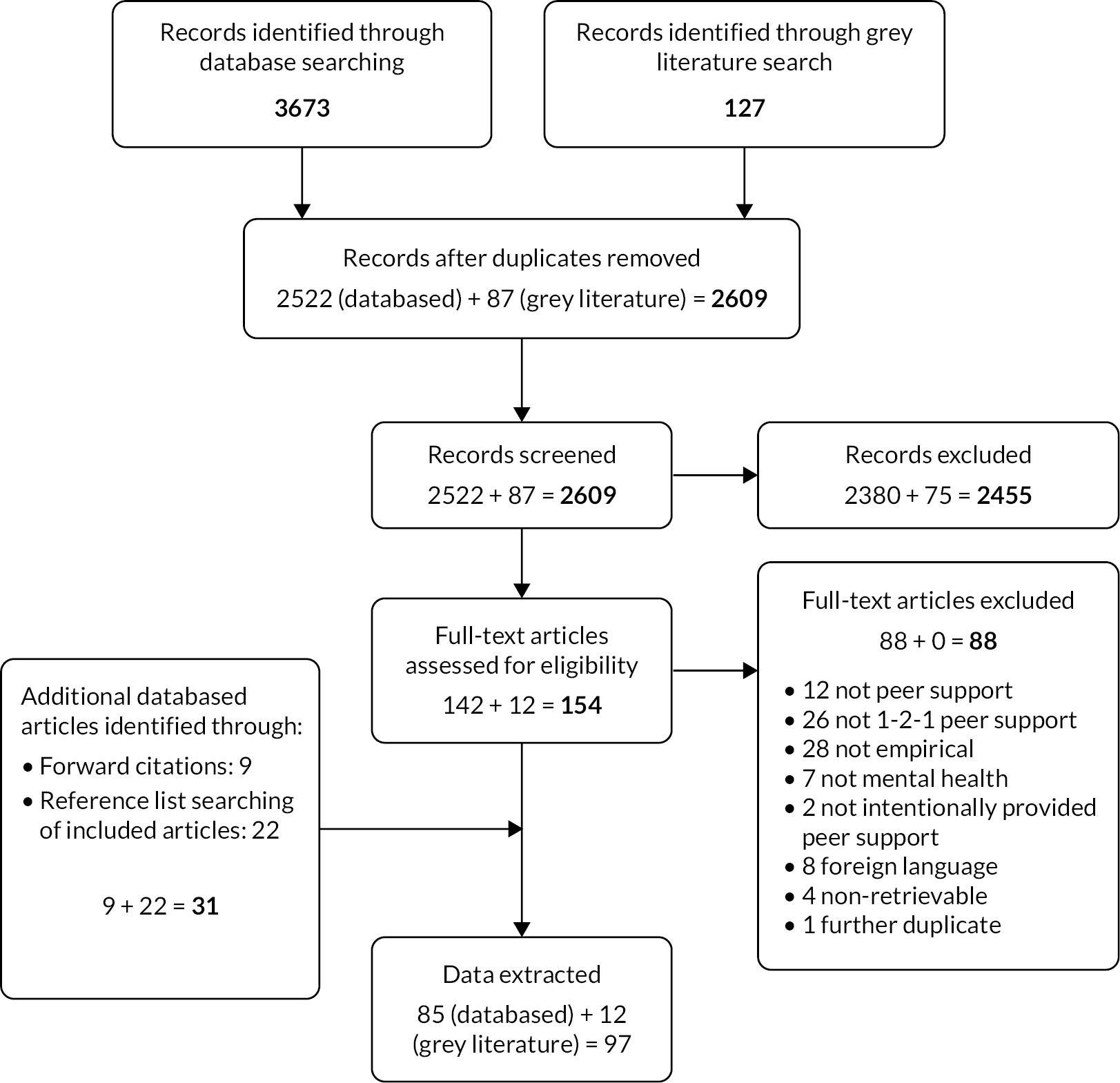

Systematic review of one-to-one peer support in mental health services

Existing systematic reviews of peer support in mental health services were not indicative of clear effects on outcome based on the evidence available at the time reviews were conducted, pointing to a high degree of heterogeneity of peer support interventions (reviews included one-to-one and group peer support, and peer-led services that comprised multiple elements) and to the generally low quality of trials undertaken to date. 22,23 We undertook a systematic review focusing on one-to-one peer support in mental health services. The review asked the following questions:

-

What are the components of one-to-one peer support interventions?

-

What are the outcomes of one-to-one peer support interventions?

-

How are the processes of peer support associated with change?

The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, identifier: CRD42015025621. 37 We undertook searches and reported the review in two stages, the first stage of which is summarised in Co-design and consensus work to develop the peer support intervention below.

White et al.38

We produced a second review, addressing questions 2 and 3 above (outcomes and process of peer support). Work on this second review was delayed while we undertook the main trial, with searches subsequently undertaken up to 13 June 2019. The full method for the search is described in the paper. 38 The search identified 23 papers reporting 19 RCTs comparing a range of one-to-one peer support interventions with either CAU or an active control arm. Fourteen trials provided data for meta-analysis of nine different outcomes. We found that one-to-one peer support in mental health services has a small but statistically significant benefit for individual recovery [standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.01 to 0.42; p = 0.042] and empowerment (SMD 0.23, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.42; p = 0.020). There was no effect on clinical outcomes such as symptoms or hospitalisation; the risk of being hospitalised was reduced by 14% for those receiving peer support but was non-significant [risk ratio (RR) 0.86, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.13].

In subgroup analyses we explored the extent to which processes of peer support impact change in outcome; we compared the effect on outcome of peer support provided in addition to CAU with peer support where PWs acted as ‘substitutes’ for other workers providing similar support, and compared the effect of peer support interventions where there were high levels of support for PWs with interventions where support for PWs was low. This indicated that peer support had a significantly greater effect on social network support (Qint = 4.27, p = 0.039) where peer support was delivered in addition to CAU (SMD = 0.23) compared to when it was provided as a substitute intervention (SMD = −0.30). We note in the review the continued heterogeneity in peer support interventions and in outcomes assessed in trials, and the importance of ensuring that the constructs that are assessed relate to the mechanisms and processes of the peer support that is being evaluated. 38

Co-design and consensus work to develop the peer support intervention

Marks et al.39

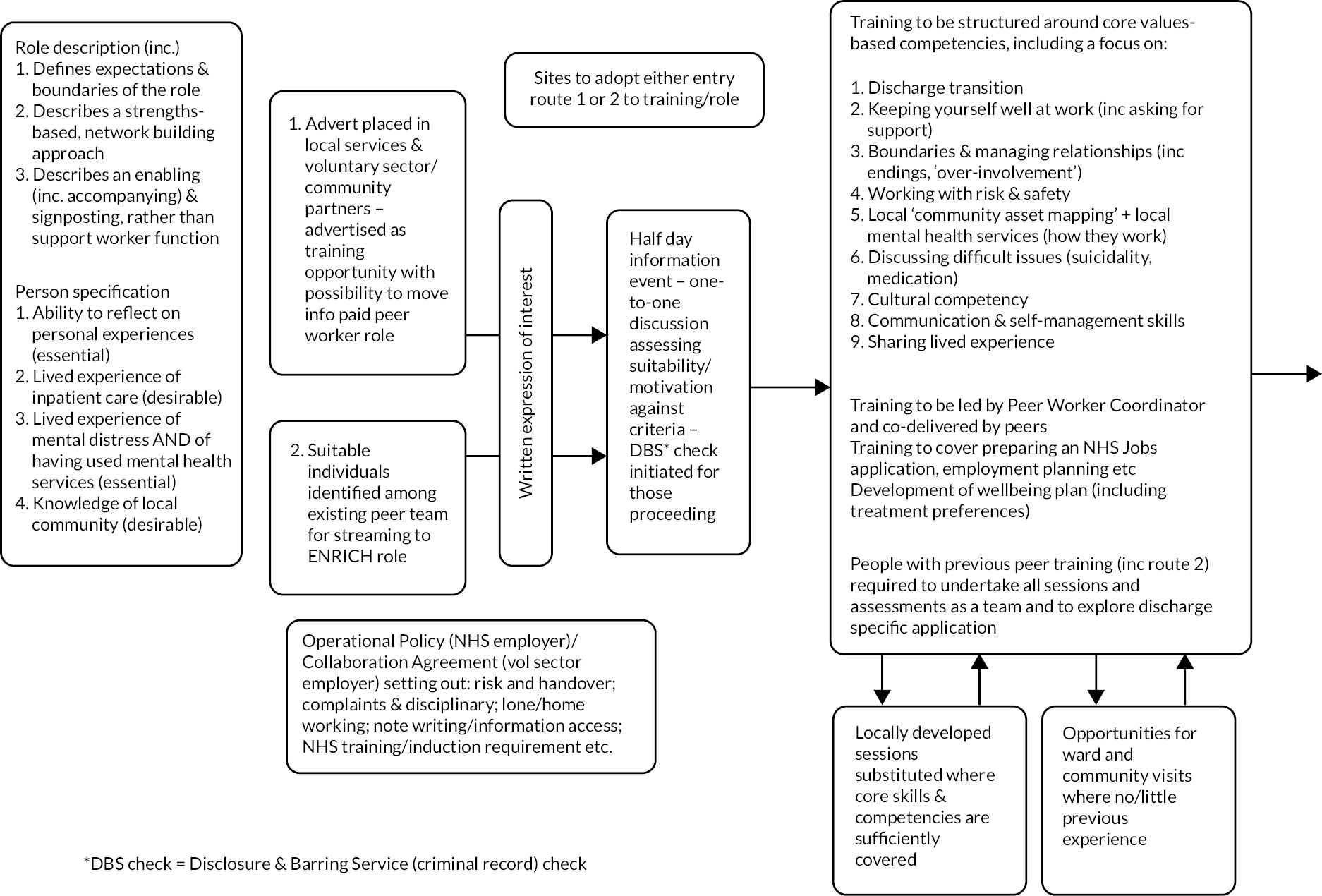

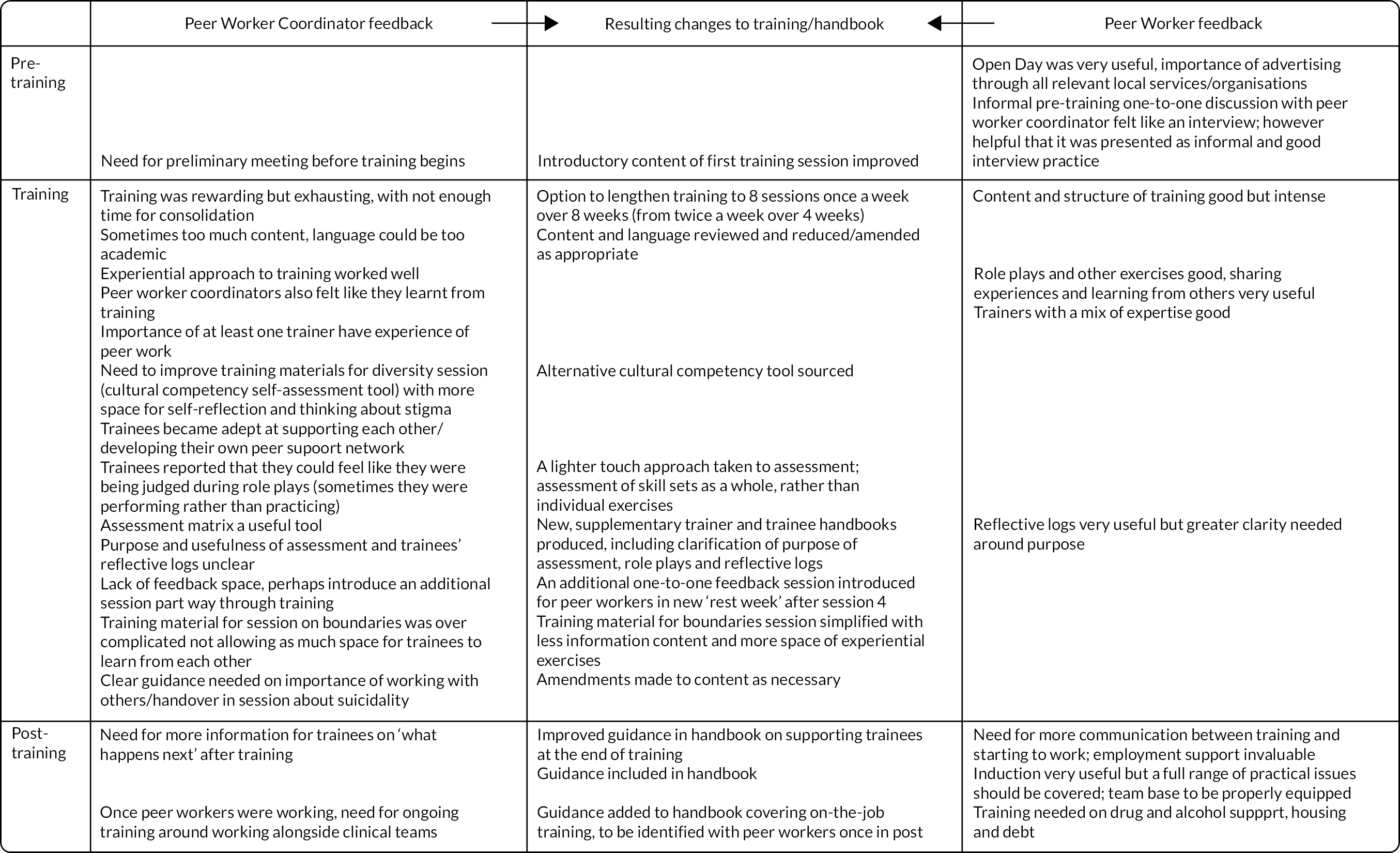

The intervention was developed in three sequential stages – (1) generating intervention components; (2) producing the intervention handbook; (3) piloting the intervention. Experiential knowledge was integrated through the development process, with several members of the research team identifying as service user or survivor researchers, or working as PWs. Our LEAP and a Local Advisory Group (LAG) at each study site also included people with experiences of using mental health services and peer support (see Table 3). Development closely followed the Medical Research Council complex interventions guidance. 40 The methods and results are summarised in Appendix 1, including the first stage of the systematic review identifying components of peer support interventions.

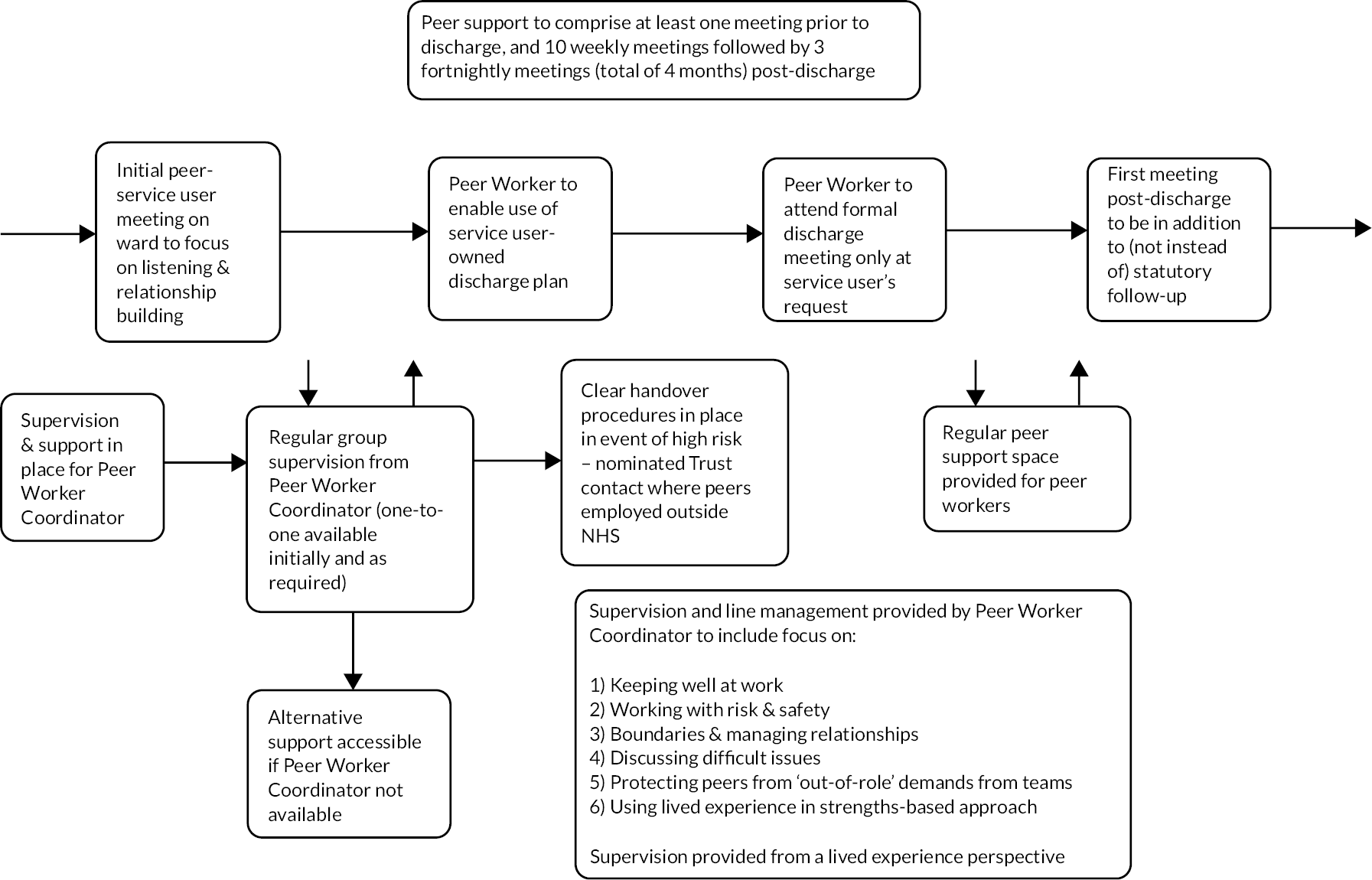

The ENRICH peer support for discharge intervention

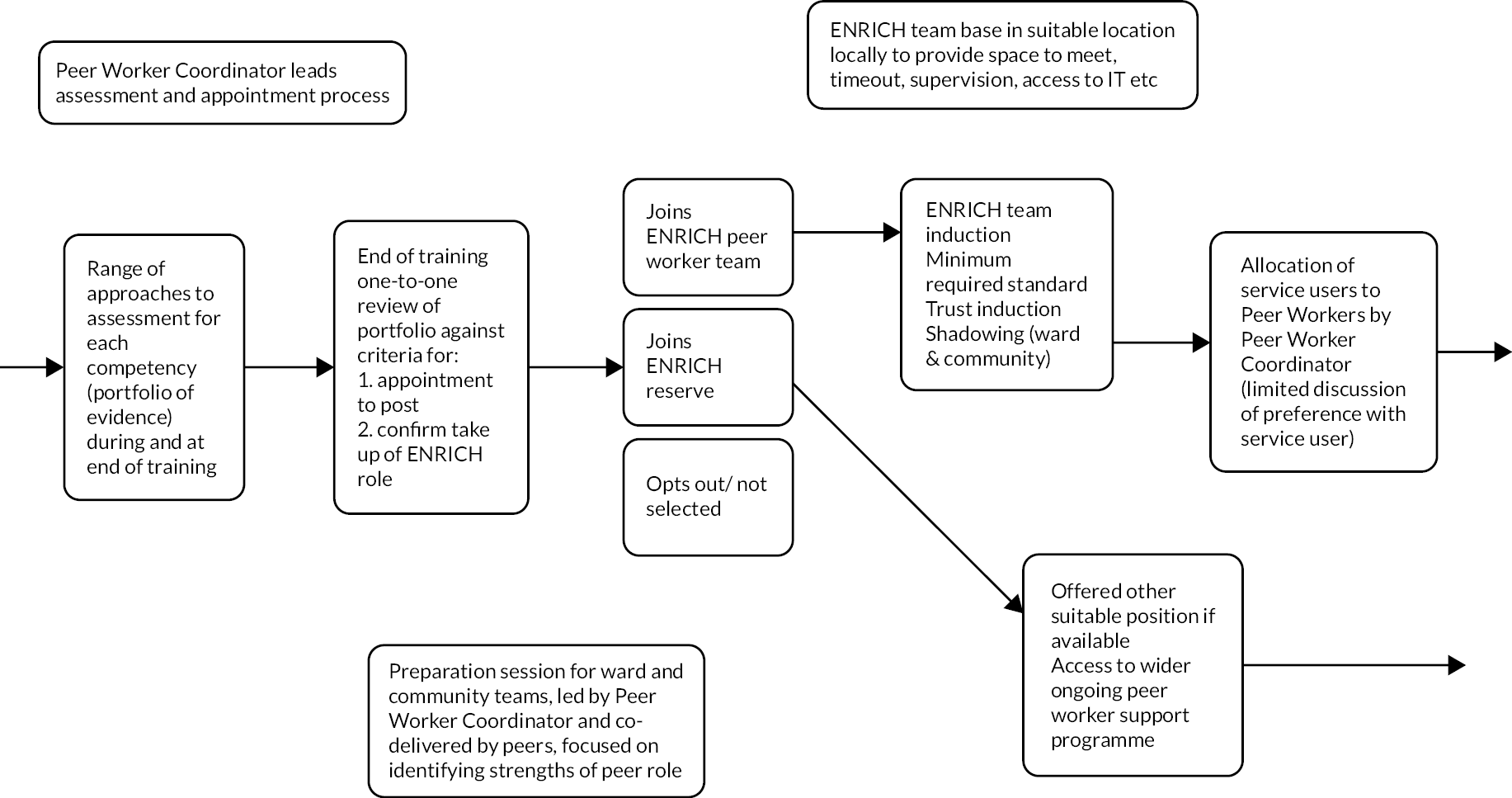

The intervention development process resulted in the production of a detailed handbook and manualised training programme for peer support for discharge from inpatient mental health care, described in detail in our trial protocol paper. 41 People receiving the intervention are offered at least one face-to-face contact with a PW in hospital prior to discharge and, once discharged, a weekly meeting with the PW for 10 weeks, stepping down to three subsequent fortnightly meetings. Meetings are flexible in length, typically ranging from 60 to 90 minutes, supplemented by phone calls and text messages. Initial meetings focus on building a relationship, with subsequent meetings making flexible use of the skills and tools covered in the training (see below). There is emphasis on enabling the supported peer (SP) to access available social support, rather than the PW directly providing support. PWs could attend discharge and care planning meetings and appointments with care professionals at the SP’s request.

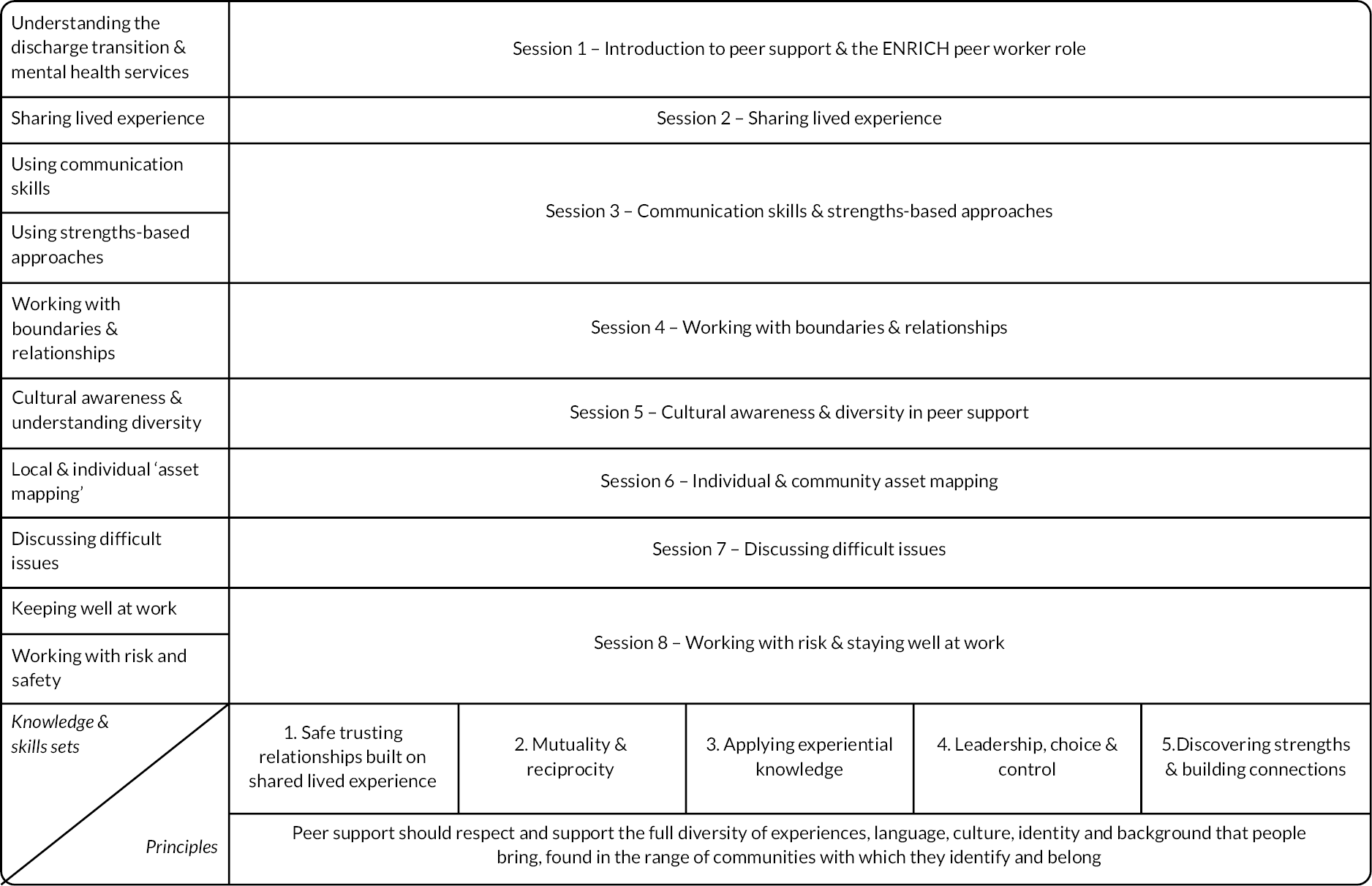

The handbook provides PW and PWC role descriptions, specifies the support and supervision PWs receive, and details preparation sessions for clinical teams where the peer support takes place. The training programme comprises 8 weekly 6-hour training sessions, plus employment support, hospital visits and structured feedback. Training covers guidance and practice for PWs in using their own experience-based knowledge, and use of a range of structured tools and exercises focused on building individual strengths and engaging with activities in the community (e.g. personal asset mapping, goal setting, and discharge, recovery and crisis planning).

Work package 2 Developing a peer worker fidelity index

Developing the index

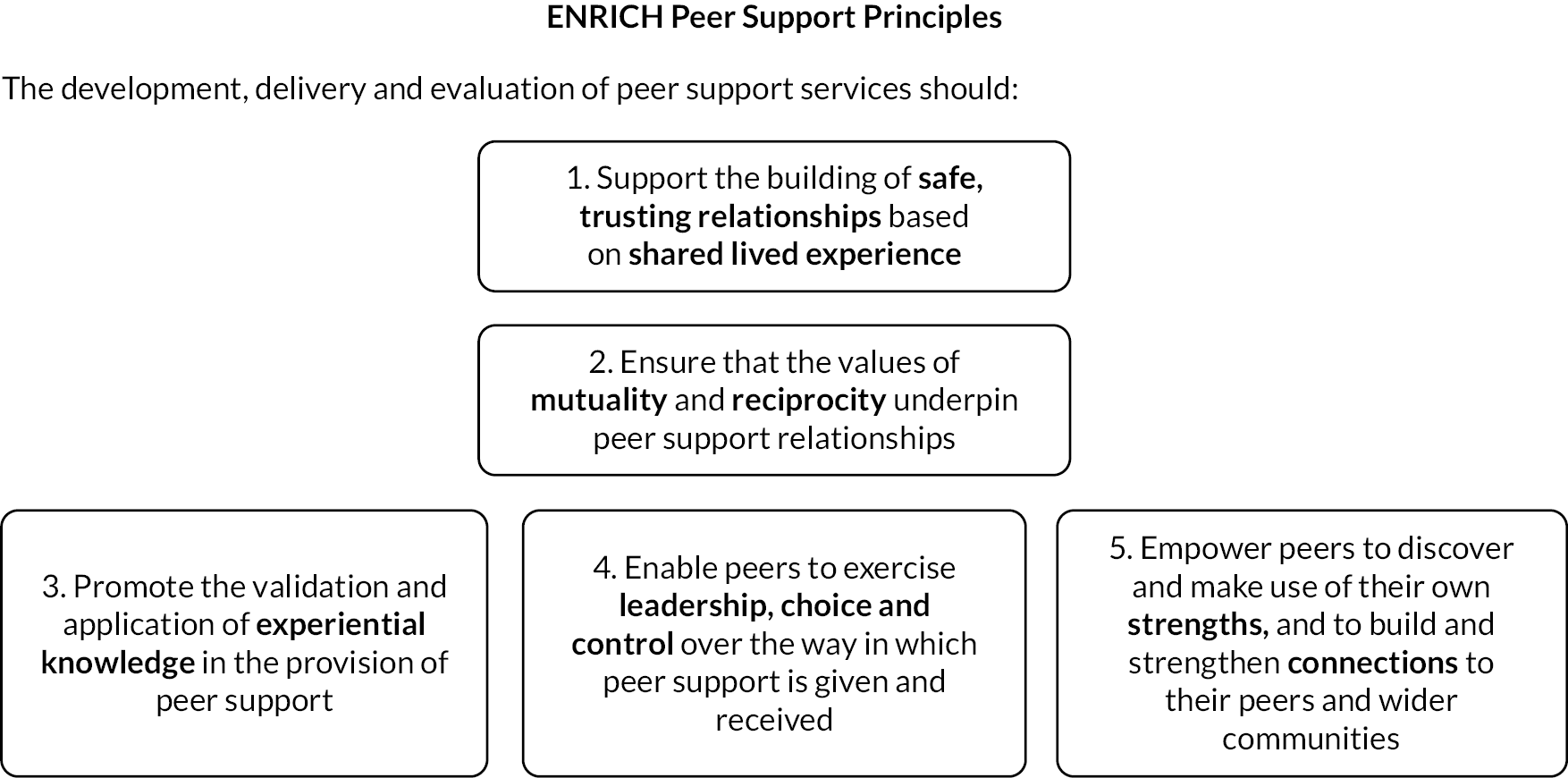

To improve the utility of the evidence base, measurement of fidelity to peer support principles in trials of peer support has been called for. 34 This WP reports the development and testing of a fidelity index for one-to-one peer support in mental health services, designed to assess fidelity to principles that characterise the distinctiveness of peer support.

Gillard et al.42

An iterative process of developing and testing the fidelity index is described in detail in this report. A draft index was developed using expert panels including service user researchers and people doing peer support, with fidelity criteria generated for each of the peer support principles identified in WP1 and index items written as a means of testing criteria. Two rounds of testing took place in 24 mental health services providing peer support in a range of settings. Fidelity was assessed through interviews with PWs, their supervisors (PWCs) and people receiving peer support. Index items were rated by members of the research team, with responses tested for spread and internal consistency, and independently double rated for inter-rater reliability. Feedback from interviewees and service user researchers was used to refine both the content of the index and the rating procedure.

A fidelity index for one-to-one peer support in mental health services was produced with good psychometric properties. Fidelity is assessed in four principles-based domains – building trusting relationships based on shared lived experience; reciprocity and mutuality; leadership, choice and control; building strengths and making connections to community – and is separately assessed for the set-up and ongoing delivery of peer support, while an overall score can also be generated.

We conclude that the index offers the potential to improve the evidence base for peer support in mental health services, enabling future trials to assess fidelity of interventions to peer support principles, and giving service providers a means of ensuring that peer support retains its distinctive qualities as it is introduced into mental health services. We suggest that further testing of the internal structure of the index is necessary to fully establish the psychometric properties of the index, for example through a confirmatory factor analysis, and testing the construct validity for the index by exploring the relationship between fidelity scores and outcomes that might be expected to be associated with fidelity.

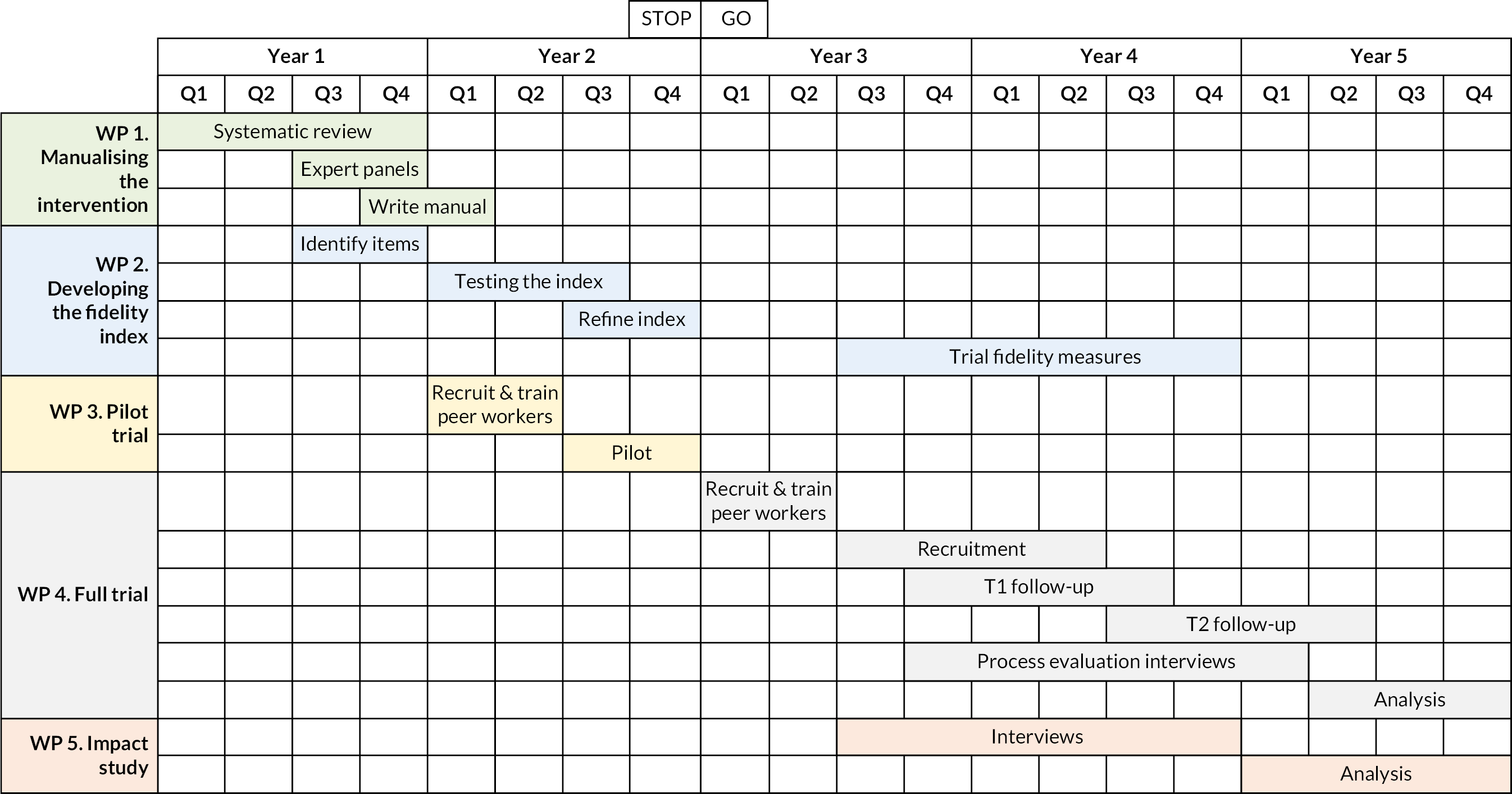

Fidelity in the ENRICH trial

We report, descriptively, fidelity at site level and over time in the WP4 ENRICH trial, and (graphically) association between measurement of fidelity and outcomes in the trial. As can be seen in Figure 3, fidelity was consistently reasonably good at set-up across sites, which might be expected as all sites were using the same handbook and training manual and had the support of the study team to do so. There were some inconsistencies in set-up scores in the SWL site, but it is noted that the PWC was absent at the site for much of the set-up period which may have been disruptive. Scores were lower in the Sussex (SSX) site where PWs were employed by a third-sector organisation that had a long tradition of peer support and so may have used a more idiosyncratic approach to supporting PWs.

FIGURE 3.

Fidelity set-up scores by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders.

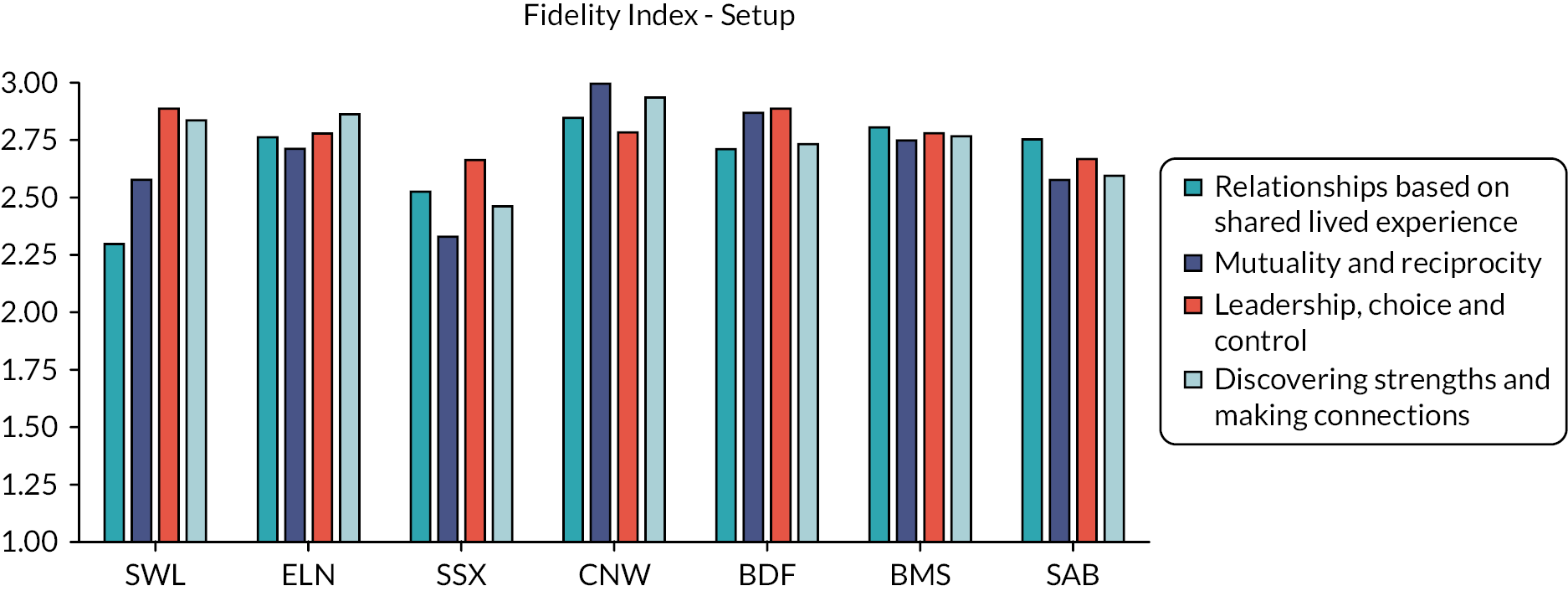

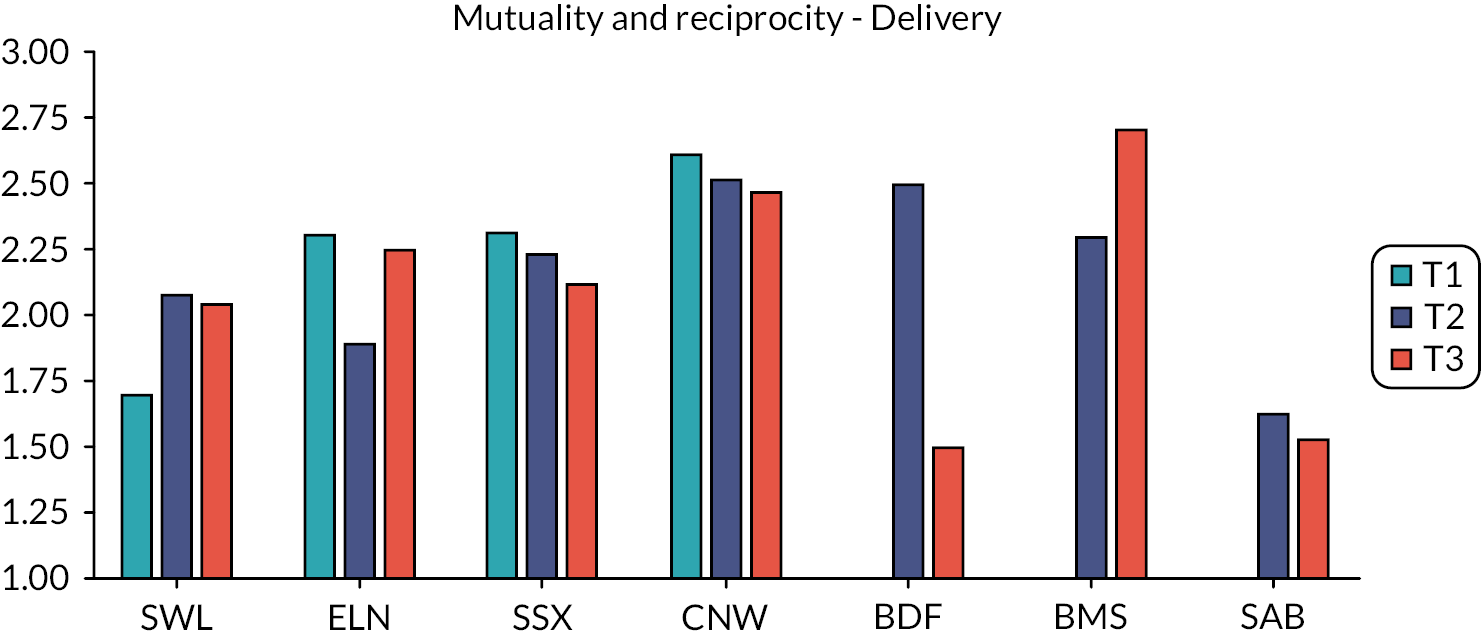

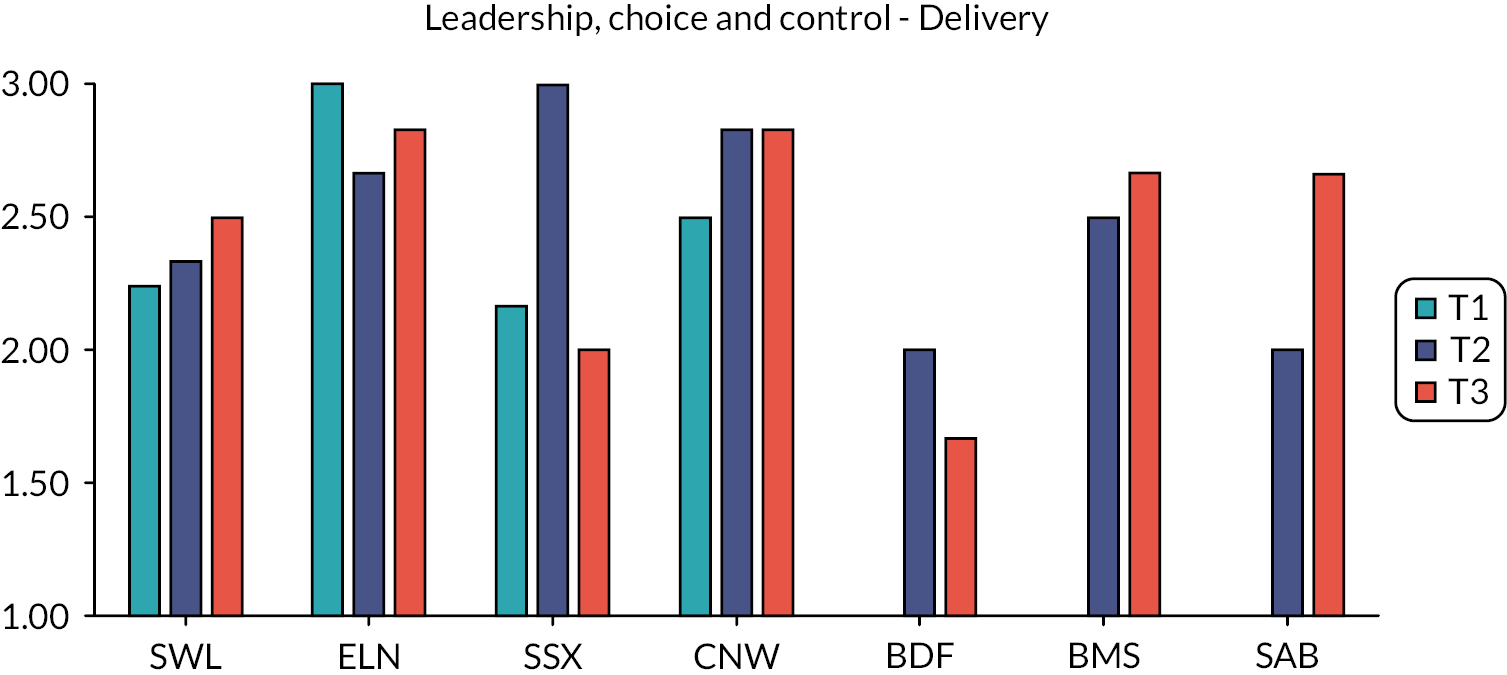

There was more variability in delivery scores, both between sites and over time (see Figures 4–7), with the exception of scores in domain 1 – relationships based on shared lived experience (see Figure 4) – which were generally high. The Central and North West London (CNW) site had consistently good scores in all delivery domains, with other sites showing more variability over time and lower scores in some domains.

FIGURE 4.

Fidelity delivery scores – relationship domain by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders; T, timepoint.

FIGURE 5.

Fidelity delivery scores – mutuality and reciprocity domain by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders; T, timepoint.

FIGURE 6.

Fidelity delivery scores – leadership, choice and control domain by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders; T, timepoint.

FIGURE 7.

Fidelity delivery scores – strengths and connections domain by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders; T, timepoint.

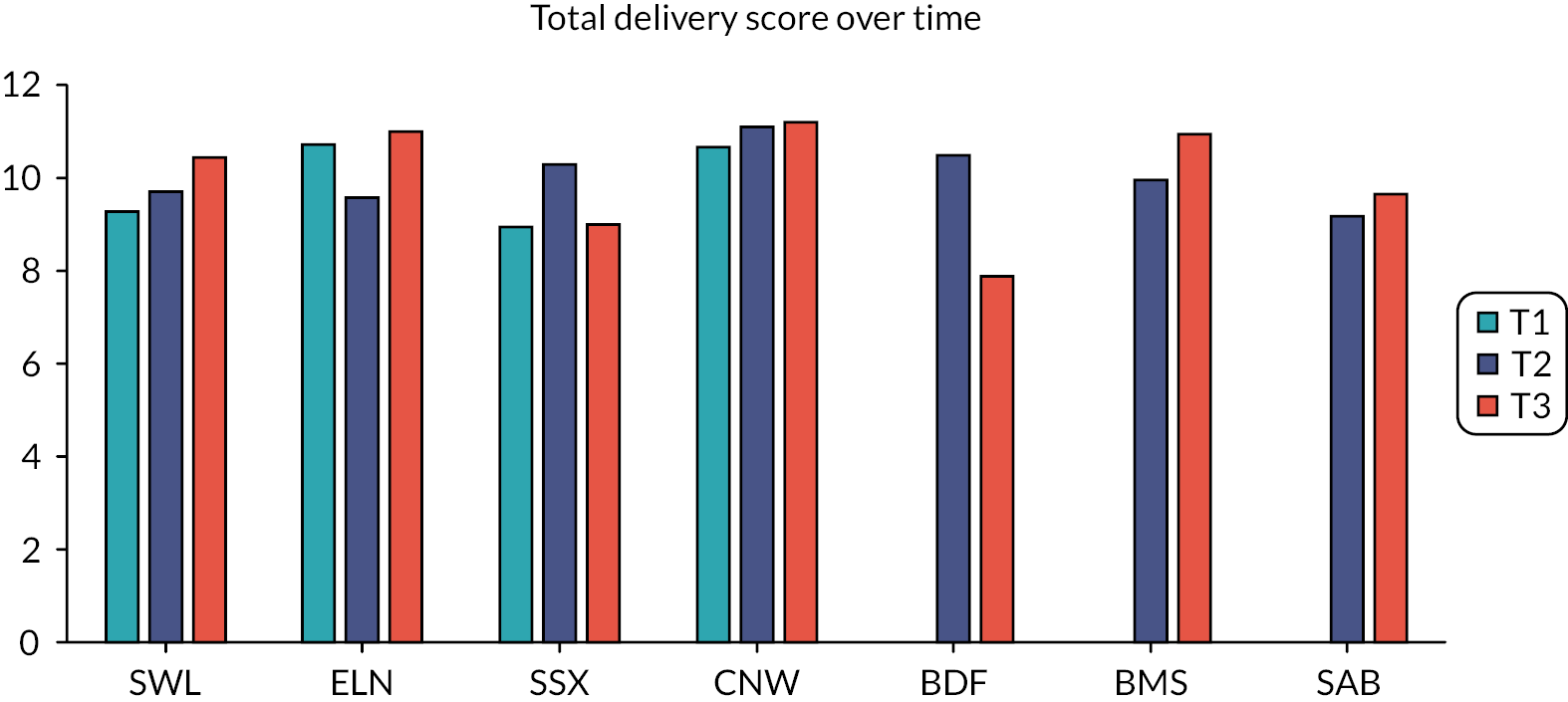

Total delivery score improved slightly at most sites over time (see Figure 8) with the exception of the SSX and Bradford (BDF) sites where total delivery score dropped from T2 to T3. SSX and BDF were the two sites where PWs were employed by a third-sector partner where, as noted above, a more independent way of working might have been in place.

FIGURE 8.

Change in total delivery score by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders; T, timepoint.

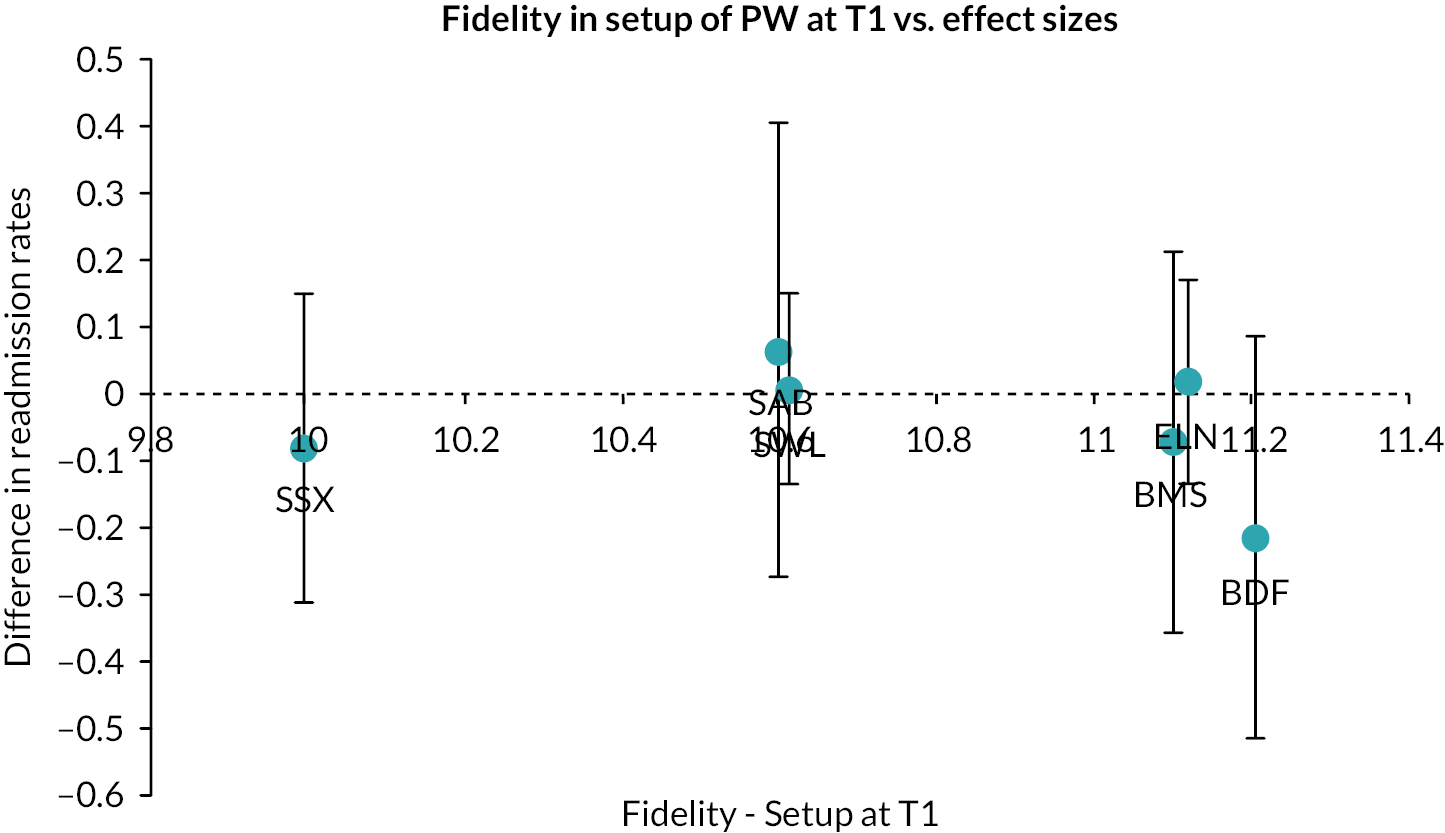

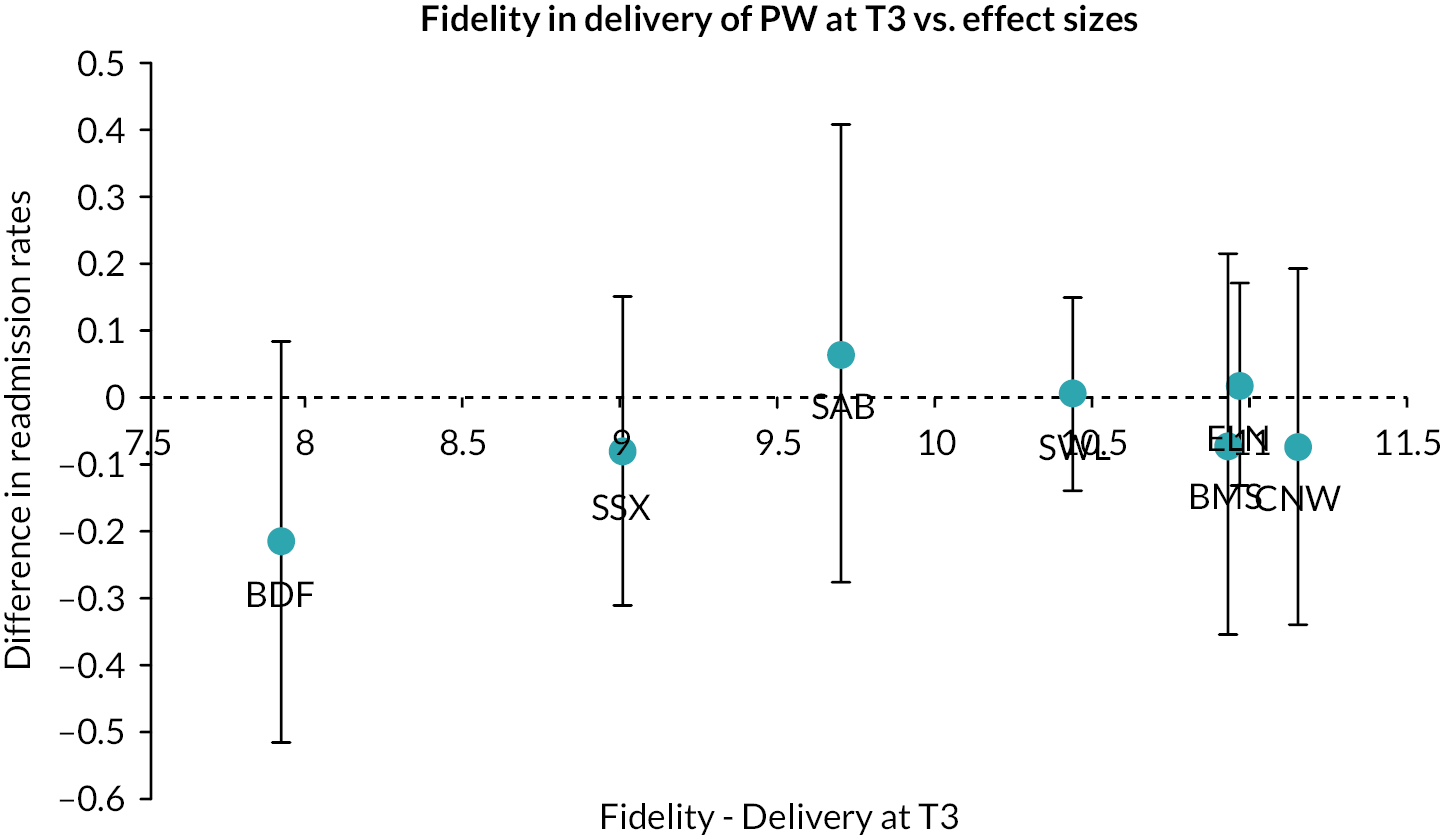

Figures 9 and 10 show no clear relationship, at site level, between effect and fidelity at set-up or T3. However, relationship between effect and total fidelity score – the most reliable score42 – is interesting. The two sites with lowest total fidelity – SSX and BDF, the two sites with third-sector providers – reported a difference in readmission rate favouring peer support. However, we note that these sites had low numbers of participants and therefore wide error bars. We observe, graphically, a trend in the relationship between fidelity and outcome (favouring peer support in sites where fidelity is higher) in the five sites where PWs were employed in the NHS. However, we note that error bars for all sites encompass no difference in outcome between peer support and control (and that the study was not powered to detect a difference at site level, our main trial reporting no site subgroup effect). While we cannot, as a result, be confident in these observations, it would be interesting to pool data from further peer support studies that made use of the fidelity index in order to further explore the relationship between fidelity and effect on outcome.

FIGURE 9.

Relationship between fidelity set-up score and primary outcome by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders; T, timepoint.

FIGURE 10.

Relationship between fidelity delivery score and primary outcome by site. BMS, Birmingham and Solihull; SAB, Surrey and Borders; T, timepoint.

Work package 3 Piloting the ENRICH peer support intervention

An internal pilot trial was conducted in two sites, SWL and ELN, following the same protocol as the full trial,41 commencing on 1 December 2016. The stop-go rules for the pilot trial were agreed by the PSC as follows:

-

to recruit a total of at least 32 participants to the pilot trial by end of February 2017 with a recruitment rate of 8 participants a month achieved in both sites for at least 2 months

-

to demonstrate 90% completeness of electronic patient record (EPR) data (including primary outcome) of all participants enrolled at end of pilot

-

to recruit, train and sustain a team of 2.0 full-time equivalent (FTE) PWs to deliver the intervention at each site.

Assessment of progression to full trial

Recruitment to the pilot trial at the two sites in the period leading up to the end of February 2017 was as follows (see Table 1):

| SWL | EL | Total for both sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised | Randomised | Randomised | ||||

| Date | Number | Total | Number | Total | Number | Total |

| 1 December 2016 to 31 December 2016 | 3 | 3 | - | - | 3 | 3 |

| 1 January 2017 to 31 January 2017 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 16 | 19 |

| 1 February 2017 to 28 February 2017 | 8 | 20 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 31 |

Completeness of outcomes data, as collected using EPRs (patient notes) at both sites, of all participants enrolled to the study as of 8 February 2017, was as follows (see Table 2):

| Missing | Non-missinga | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | |

| EPR data | 0 | (0) | 20 | (100) | 20 |

While the data collected here were baseline data, this was the same dataset that would be collected at 12 months follow-up (for the 12 months post discharge from index admission), including the primary outcome (psychiatric admission).

Both sites successfully recruited and trained a team of four PWs working to a total of 2.0 FTE per site. The ELN team comprised two PWs at 0.4 FTE each and two at 0.6 FTE each. The SWL team comprised three PWs at 0.4 FTE each and one at 0.8 FTE. The ELN team had one additional trained PW who could act as a reserve; the SWL team had two reserve PWs.

Actions to support progression

Rules two and three were met, and while rule one was met in the SWL site it was not met in the ELN site (and therefore narrowly missed overall). The PSC asked the study team to produce an analysis of barriers to recruitment and propose measures to improve recruitment. The flow of potential participants in the pilot trial at both sites is given in Figure 11 and Appendix 1, Figure 12 indicating reasons for potential participants not progressing. We spoke in depth to researchers [Research Assistants (RAs)], Clinical Studies Officers (CSOs) and clinical staff at each site to enable us to better understand these data. We proposed the following actions to improve recruitment going forward:

-

The proportion of patients eligible for the study was lower than we had anticipated. We would open the study on an additional ward at each site and take a flexible approach to the number of wards we would open at additional sites in the main trial.

-

We identified misunderstanding of eligibility criteria around potential risk to PW and likelihood of discharge in the next month. Members of the study team would make visits to participating wards as necessary to ensure that clinical staff were fully aware of eligibility criteria and recruitment processes.

-

Potential participants were lost between initial screening and confirmation of eligibility by the clinical team, or between confirmation of eligibility and first contact with a CSO, because patients could be discharged between weekly visits to the ward by CSOs. We increased the flexibility of the recruitment process so that RAs could liaise directly with the clinical team when the CSO was not present on the ward.

-

Some potential participants were declining to meet a RA after they had been first approached about involvement in the study. Members of the study team and/or PWs would attend weekly community meetings on wards to provide general information about the study.

The PSC received and reviewed our report and proposed actions, and recommended to the funder that the study progress to the main trial. We obtained NHS ethical approval for amendments to the study protocol and procedures as necessary.

Work package 4 Trialling the ENRICH peer support intervention

Randomised controlled trial

This WP aimed to establish the effectiveness of a PW intervention to reduce psychiatric readmission following discharge, as developed in WP1 above. We hypothesised that participants receiving peer support for discharge, in addition to CAU, would be significantly less likely to be readmitted in the year following discharge than participants receiving CAU only.

Gillard et al.41

The study was a parallel, two-group, individually randomised controlled superiority trial, with trial personnel (outcome assessors, data analysts) masked to allocation of participants. The study took place in the inpatient and community mental health services of seven NHS mental health trusts in England (sites). In five sites where participants were recruited from two inpatient facilities, and one site where recruitment was from three facilities, these were treated as single sites for stratification. A detailed trial protocol has been published;41 trial procedures are summarised only here.

The trial is registered with the ISRCTN clinical trial register, number ISRCTN 10043328,43 and was overseen by an independent steering committee and a data monitoring committee.

All new admissions to participating adult acute inpatient wards were screened for eligibility. Inpatients were eligible if they had at least one psychiatric admission in the preceding 2 years, were aged 18 years or older, were assessed by the ward clinical team as likely to be discharged within the next month and had capacity to give written informed consent to participate in the research. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of any organic mental disorder, had a primary diagnosis of eating disorders, learning disability or drug or alcohol dependency (as recorded in clinical notes), or were assessed by the clinical team on the ward as presenting a current, substantial risk to a PW. Following completion of baseline assessments, consenting patients were randomised to treatment groups in a 1 : 1 ratio, stratified by site and diagnostic group (psychotic disorders, personality disorders, other eligible non-psychotic disorders). Measures to ensure protection of masking of assessors are detailed in the study protocol. 41

Participants in the intervention group received the peer support intervention, delivered one-to-one by a designated PW, a Discharge Information Pack and CAU at discharge. Participants were assigned a PW after allocation and prior to discharge by the site PWC who also provided support and supervision to the PW team. The peer support intervention, including the PW training programme, is specified in a handbook and described in detail in the trial protocol41 and summarised in Co-design and consensus work to develop the peer support intervention above. The Discharge Information Pack provided information about potentially useful statutory and voluntary sector services. CAU post-discharge from inpatient psychiatric care is mandated nationally in England as follow-up by community mental health services or primary care mental health team within 7 days of discharge. Within a week of discharge, a discharge summary should be sent by the inpatient team to the patient’s GP and others involved in developing their care plan, including information about why the patient was admitted and how their condition has changed during the hospital stay. A member of the CMHT or primary care mental health team to which the patient has been discharged will typically telephone or visit the patient within 1 week of discharge to make arrangements for their ongoing care. Participants in the control group received CAU and a copy of the Discharge Information Pack to control for any effect of access to information alone on outcome. We conducted the trial in sites where there was no offer of one-to-one peer support in either inpatient or community settings. In some sites group peer support was on offer, typically as peer-facilitated support groups in inpatient settings that people could ‘drop in’ to on an ad hoc basis. It is possible that participants in either peer support or control groups accessed group peer support. Stratification of randomisation by site was used in part to address this.

Data were collected at baseline (T0), and at 4 months (T1) and 12 months (T2) post-discharge from the index admission. Mental health service use data were extracted from the site EPR at baseline and 12 months. The primary outcome for the trial was psychiatric inpatient readmission in the 12 months post-discharge, including both formal and informal admissions. Secondary outcomes were number of voluntary admissions, involuntary admissions and total number of admissions, total number of days in hospital, time to first readmission, use of accident and emergency (A&E) services for a psychiatric emergency (measured as number of episodes of liaison psychiatry contact), and number of contacts with crisis resolution and home treatment teams in the year post discharge, plus standardised measures of psychiatric symptom levels, subjective quality of life, social inclusion, hope for the future and strength of social network, measured at end of intervention (4 months post discharge). Adherence to the intervention was assessed using a structured online survey completed by PWs following each contact. Serious adverse events (SAEs), as defined in the trial protocol,41 were recorded and followed up until the end of the 12-month follow-up.

We required a sample of 530 participants, allocated on a 1 : 1 ratio, to detect a reduction of 12% in readmission (from 34% to 22%) in the intervention group compared to the CAU group, with 80% power at the 5% significance level. This calculation allowed for clustering by PW in the intervention group only,44 assuming an intracluster correlation of 0.05 with an average cluster size of 10 participants. We inflated the sample size by 10% to allow for missing primary outcome data at follow-up,45 resulting in a final sample size of 590. All analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, meaning that all randomised participants with a recorded outcome were included in the analysis and analysed according to the group to which they were randomised. We also estimated the CACE for the intervention on the primary outcome46 (where compliers were participants who had at least two PW meetings, at least one of which was in the community following discharge). The CACE was estimated with a two-stage estimation procedure. In the first stage, a logistic regression of treatment receipt regressed on randomisation was conducted. In the second stage, a Poisson regression of the outcome on treatment receipt was conducted. The analysis was adjusted for the same covariates as the ITT analysis. A bootstrap (1000 samples) was used to obtain bias corrected and accelerated CIs. Subgroup analyses for the primary outcome were pre-specified: ethnicity (any black ethnicity, all other ethnicities); primary diagnosis at index admission (psychotic disorders, personality disorders, other eligible disorders); first language (English, other). Full details of the analyses undertaken are given in the trial protocol. 41

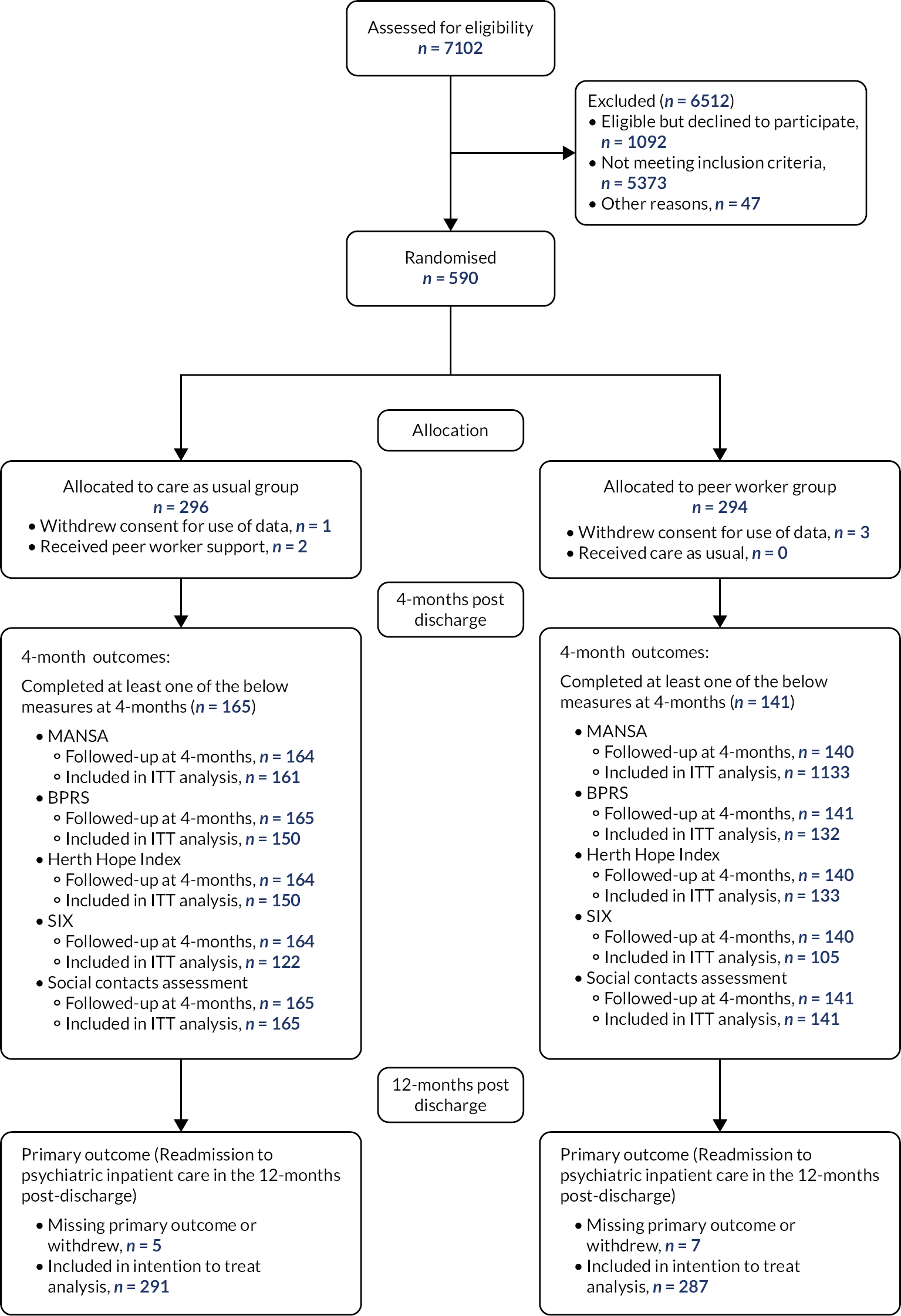

Gillard et al.47

Results for the trial are given here pending peer review and publication of the main trial paper. 47 We note that recruitment into the full trial at additional sites was delayed while we waited for approval for the checkpoint report at end of the pilot trial, and then as some sites secured approvals to employ PWs locally. A seventh site (in addition to the original six) was opened to support recruitment, with recruitment taking 6 months longer than originally planned. The target of 590 participants was successfully recruited, with flow of participants into the study given in Figure 11. Participant characteristics were well-balanced between groups (see Tables 3 and 4).

FIGURE 11.

Flow of participants in the ENRICH trial.

| Baseline characteristics | Number of patients with available data – n (%) | Summary measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAUa (n = 296) | PWb (n = 294) | CAU | PW | |

| Gender – n (%) | 292 (98.6) | 286 (97.3) | ||

| Female | 159 (54.5) | 147 (51.4) | ||

| Male | 130 (44.5) | 137 (47.9) | ||

| Transgender | 2 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) | ||

| Age (years) | 291 (98.3) | 280 (95.2) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 40.0 (13.1) | 39.4 (14.2) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 38 (31–50) | 38 (27–51) | ||

| Sexual orientation – n (%) | 290 (98.0) | 286 (97.3) | ||

| Bisexual | 26 (9.0) | 20 (7.0) | ||

| Gay | 6 (2.1) | 10 (3.5) | ||

| Heterosexual | 232 (80.0) | 239 (83.6) | ||

| Lesbian | 5 (1.7) | 5 (1.7) | ||

| Not completed/declined to answer | 21 (7.2) | 12 (4.2) | ||

| Diagnostic group – n (%) | 295 (99.7) | 291 (99.0) | ||

| F20–29 (schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders) | 134 (45.4) | 129 (44.3) | ||

| F60 (specific personality disorders) | 61 (20.7) | 58 (19.9) | ||

| Other eligible non-psychotic disorders | 100 (33.9) | 104 (35.7) | ||

| First language – n (%) | 288 (97.3) | 280 (95.2) | ||

| English | 243 (84.4) | 226 (80.7) | ||

| Other | 45 (15.6) | 54 (19.3) | ||

| Ethnicity – n (%) | 293 (99.0) | 283 (96.3) | ||

| Asian/Asian British | 32 (10.9) | 36 (12.7) | ||

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 48 (16.4) | 46 (16.3) | ||

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 18 (6.1) | 30 (10.6) | ||

| Other ethnic group | 5 (1.7) | 8 (2.8) | ||

| White | 190 (64.8) | 163 (57.6) | ||

| MANSAc | 292 (98.6) | 283 (96.3) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.9 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.1) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.2–4.7) | 4.2 (3.4–4.8) | ||

| Objective social outcomes index (SIX)d | 251 (84.8) | 244 (83.0) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | ||

| Herth Hope Index (HHI)e | 280 (94.6) | 275 (93.5) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 33.1 (7.9) | 33.1 (8.1) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 34 (28–39) | 34 (28–39) | ||

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)f | 268 (90.5) | 272 (92.5) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 36.6 (10.2) | 34.5 (9.9) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 36 (29–43) | 33 (27–41) | ||

| Pre-index admission characteristics (12 months prior to index admission) | Number of patients with available data – n (%) | Summary measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAU (n = 296) | PW (n = 294) | CAU | PW | |

| Number of admissions to psychiatric inpatient care – n (%) | 293 (99.0) | 291 (99.0) | ||

| 0 | 84 (28.7) | 101 (34.7) | ||

| 1 | 144 (49.1) | 130 (44.7) | ||

| 2 | 39 (13.3) | 35 (12.0) | ||

| 3 or more | 26 (8.9) | 25 (8.6) | ||

| Number of voluntary admissions – n (%) | 255 (86.1) | 258 (87.8) | ||

| 0 | 158 (62.0) | 166 (64.3) | ||

| 1 | 69 (27.1) | 56 (21.7) | ||

| 2 or more | 28 (11.0) | 36 (14.0) | ||

| Number of involuntary admissions – n (%) | 255 (86.1) | 258 (87.8) | ||

| 0 | 154 (60.4) | 161 (62.4) | ||

| 1 | 81 (31.8) | 79 (30.6) | ||

| 2 or more | 20 (7.8) | 18 (7.0) | ||

| Total length of stay over all admissions (calendar days) | 293 (99.0) | 291 (99.0) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 32.7 (48.0) | 28.9 (41.3) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 16 (0–42) | 14 (0–39) | ||

| Number of A&E attendances – n (%) | 293 (99.0) | 291 (99.0) | ||

| 0 | 123 (42.0) | 113 (38.8) | ||

| 1 | 64 (21.8) | 75 (25.8) | ||

| 2 | 37 (12.6) | 43 (14.8) | ||

| 3 or more | 69 (23.5) | 60 (20.6) | ||

| Number of crisis resolution or home treatment team contacts – n (%) | 293 (99.0) | 291 (99.0) | ||

| 0 | 72 (24.6) | 86 (29.6) | ||

| 1 | 45 (15.4) | 30 (10.3) | ||

| 2 | 15 (5.1) | 14 (4.8) | ||

| 3 or more | 161 (54.9) | 161 (55.3) | ||

In the PW group, 136 (47.4%) participants were readmitted to psychiatric inpatient care within 12 months post-index admission, and 146 (50.2%) in the CAU group (see Table 5). The unadjusted risk difference was −3% (95% CI −0.11 to 0.05; p = 0.5070) in favour of the peer support group. The adjusted relative risk of readmission in the ITT analysis was 0.97 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.14; p = 0.6777), and the adjusted odds ratio (OR) was 0.93 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.30). In the CACE analysis, the relative risk of readmission according to the natural indirect effect (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.99) was lower than from the ITT analysis and was significant. In subgroup analyses, for participants of any black ethnicity the adjusted OR of readmission was 0.40 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.94), while for any other ethnicity the OR was 1.12 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.63; interaction p = 0.0305). No other subgroup effects were found (see Table 6).

| Primary outcome | Number of patients with available data and included in analysis – n (%) | Summary measure | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAU (n = 296) | PW (n = 294) | CAU | PW | |||

| Readmission to psychiatric inpatient care in the 12 months post dischargea | 291 (98.3) | 287 (97.6) | 146 (50.2) | 136 (47.4) | 0.93 (0.66 to 1.30)b | 0.6777 |

| 0.97 (0.82 to 1.14)c | ||||||

| −0.03 (−0.11 to 0.05)d | 0.5070 | |||||

| Subgroup variable | Number of participants with available data and included in analysis – n (%) | Readmission to psychiatric inpatient care in the 12 months post discharge – n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAUa (n = 295/296) | PWb (n = 291/294) | CAU | PW | |||

| Ethnicityc,d | ||||||

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 48/48 (100.0) | 46/46 (100.0) | 28/48 (58.3) | 17/46 (37.0) | 0.40 (0.17 to 0.94) | 0.0305 |

| Any other ethnicity | 241/245 (98.4) | 233/237 (98.3) | 117/241 (48.5) | 117/233 (50.2) | 1.12 (0.77 to 1.63) | |

| Diagnostic groupd | ||||||

| F20–29 (schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders) | 132/134 (98.5) | 128/129 (99.2) | 65/132 (49.2) | 54/128 (42.2) | 0.79 (0.48 to 1.31) | 0.6704 |

| F60 (specific personality disorders) | 59/61 (96.7) | 56/58 (96.6) | 35/59 (59.3) | 32/56 (57.1) | 0.98 (0.45 to 2.11) | |

| Other eligible non-psychotic disorders | 100/100 (100.0) | 103/104 (99.0) | 46/100 (46.0) | 50/103 (48.5) | 1.11 (0.63 to 1.95) | |

| First languaged,e | ||||||

| English | 240/243 (98.8) | 222/226 (98.2) | 124/240 (51.7) | 105/222 (47.3) | 0.88 (0.60 to 1.28) | 0.3055 |

| Other | 44/45 (97.8) | 54/54 (100.0) | 19/44 (43.2) | 28/54 (51.9) | 1.42 (0.62 to 3.23) | |

Observed differences in the secondary outcomes collected at 4 months were small and none were statistically significant (see Table 7). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in any of the secondary outcomes assessed at 12 months (see Table 8). Adherence to the intervention was assessable in 268 (91.2%) participants with a mean of 1.8 [standard deviation (SD) = 2.9) face-to-face contacts with a PW in hospital, 4.4 (SD = 4.6) post discharge. Assessors were unmasked by 52/306 (17.0%) patients revealing their allocation during collection of secondary outcome data at 4 months (38 in the peer support group, 14 in the CAU group).

| Outcomes | Number of patients with available data and included in analysis – n (%) | Summary measure | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAU (n = 296) | PW (n = 294) | CAU | PW | |||

| MANSA | 161 (54.4) | 133 (45.2) | 4.1 (1.0)a | 4.4 (0.9)a | 0.17 (−0.01 to 0.36)b | 0.0713 |

| BPRS | 150 (50.7) | 132 (44.9) | 31.7 (10.7)a | 29.5 (9.6)a | −0.59 (−2.70 to 1.52)b | 0.5832 |

| HHI | 150 (50.7) | 133 (45.2) | 32.3 (7.2)a | 33.8 (7.0)a | 0.50 (−0.80 to 1.79)b | 0.4529 |

| SIX | 122 (41.2) | 105 (35.7) | 3.2 (1.0)a | 3.2 (1.0)a | 0.10 (−0.13 to 0.34)b | 0.3778 |

| Social contacts assessment | 165 (55.7) | 141 (48.0) | 3 (1–4)c | 2 (1–5)c | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.34)d | 0.5607 |

| Outcomes | Number of participants with available data and included in analysis – n (%) | Summary measure | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAU (n = 296) | PW (n = 294) | CAU | PW | |||

| Number of readmissions to psychiatric inpatient care in the 12 months post discharge | 291 (98.3) | 287 (97.6) | 1 (1–2)a | 1 (1–2)a | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.19)b | 0.6413 |

| Number of voluntary admissions to psychiatric inpatient care in the 12 months post dischargec | 253 (85.5) | 257 (87.4) | 1 (0–1)a | 1 (0–2)a | 1.07 (0.77 to 1.48)b | 0.7079 |

| Number of compulsory admissions to psychiatric inpatient care in the 12 months post dischargec | 253 (85.5) | 257 (87.4) | 1 (0–1)a | 1 (0–1)a | 0.88 (0.64 to 1.22)b | 0.4443 |

| Total length of stay over all readmissions (calendar days)c | 291 (98.3) | 287 (97.6) | 57 (27–128)a | 61 (26–99)a | 0.81 (0.51 to 1.29)b | 0.3783 |

| Number of separate episodes of liaison psychiatry contact in hospital A&Ec | 291 (98.3) | 287 (97.6) | 0 (0–1)d | 0 (0–1)d | 1.18 (0.84 to 1.66)b | 0.3351 |

| Number of crisis resolution and home treatment team contactsc | 291 (98.3) | 287 (97.6) | 3 (0–13)d | 2 (0–16)d | 0.90 (0.66 to 1.23)b | 0.5267 |

| Time to first readmission to psychiatric inpatient care (calendar days)c | 291 (98.3) | 287 (97.6) | 107 (46–180)a | 104 (36–201)a | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.20)e | 0.6563 |

There was a total of 67 SAEs reported in the trial (34 in the peer support group, 33 in the CAU group) from 51 participants (26 in the peer support group, 25 in the CAU group). One SAE in the peer support group, an incident of self-harm, was reported as related to the intervention. Number and type of SAEs included 12 deaths, none of which were reported as related to the study.

The trial indicated that one-to-one peer support for discharge from psychiatric inpatient care, offered in addition to CAU, did not have a significant effect on readmission when compared to CAU only. There were neither significant effects on any secondary service use outcomes in the year following discharge nor any reduction in symptom severity or benefit to psychosocial outcomes after 4 months. The CACE analysis indicated that a smaller proportion of participants in the peer support group who received a pre-defined minimal amount of the intervention were readmitted than participants in the control group who – according to the analysis – would also have received the minimal amount of peer support if such support had been offered to them. Additionally, compared to CAU, participants of any black ethnicity in the peer support group were significantly less likely to be readmitted than participants of any other ethnicity (see Table 6).

The study reflects findings from our systematic review of one-to-one peer support in a range of mental health service settings which suggests that, on the basis of pooled data from trials to date, peer support is unlikely to have an effect on psychiatric hospital admission, length of stay in hospital or clinical severity. 38 Engagement in the peer support intervention was low. However, the findings of the CACE analysis, suggesting that participants who engaged better may have benefited from the intervention, raised the question as to why engagement with the intervention was not more complete. We were encouraged that black participants were significantly less likely to be readmitted in the year post-discharge compared to control than those of any other ethnicity (see Table 6). While we need to better understand how and why peer support seemed to work better for this group of participants, this finding offers hope that peer support might help address persistent inequalities. 48,49

Predictors of readmission

A secondary aim of WP4 was to explore predictors of readmission across our sample. Of the 590 participants recruited to the study, EPR data, which provided all service use data, was available for 578 (98%). Of these 578 participants, 282 (49%) were readmitted within 1 year post discharge. Fifty-nine (10%) were readmitted in 30 days or less, 123 (21%) in 90 days or less.

The following variables were tested as predictors of readmission (binary outcome) and time to readmission (time to event outcome): age, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis, SIX, BPRS, Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA), number of admissions in the previous year, number of compulsory admissions in the previous year, number of A&E attendances in the previous year, compulsory or voluntary index admission, length of index admission. Univariate analysis was carried out using logistic regression to estimate the relationship between each potential predictor and the readmission outcome. Those predictors found to be statistically significant (significance level = 5%) univariately were entered into a multiple logistic regression model. This strategy was followed for the time to readmission outcome using Cox regression.

Diagnosis, BPRS, MANSA, number of admissions in the previous year and number of A&E attendances in the previous year were found to be univariately associated with both outcomes. Number of compulsory admissions in the previous year and type of index admission (compulsory or voluntary) were also significantly associated with time to readmission. However, both variables had more than 10% missing data and so were not entered into the final regression models. All univariate analyses are reported in Report Supplementary Material 2.

In the multiple logistic regression model (n = 529) readmission was associated with higher BPRS (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.05; p = 0.009) and number of admissions in the previous year (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.57; p = 0.002). In the multiple Cox regression model (n = 529) shorter time to readmission was associated with higher BPRS [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.01, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.03; p = 0.031] and number of admissions in the previous year (HR=1.24, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.38; p < 0.001). These findings are in line with previous similar analyses (see Table 9). 50,51

| Readmission | Time to readmission | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | OR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |||

| Socio-demographic and psychosocial variables | |||||||

| Age (years) | 563 | 1.0 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0.429 | 1.0 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.383 | ||

| Gender | Female | 301 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Male | 264 | 0.9 (0.63 to 1.21) | 0.409 | 0.9 (0.69 to 1.10) | 0.259 | ||

| Ethnicity | Asian | 68 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Black | 94 | 1.0 (0.55 to 1.92) | 0.918 | 1.0 (0.65 to 1.60) | 0.939 | ||

| Mixed | 48 | 1.0 (0.45 to 2.00) | 0.896 | 1.0 (0.55 to 1.64) | 0.863 | ||

| Other | 12 | 2.3 (0.62 to 8.18) | 0.218 | 1.6 (0.74 to 3.50) | 0.228 | ||

| White | 346 | 1.1 (0.68 to 1.87) | 0.689 | 1.1 (0.75 to 1.60) | 0.624 | ||

| Social inclusion (SIX T0) | 488 | 1.1 (0.96 to 1.26) | 0.178 | 1.1 (0.96 to 1.16) | 0.255 | ||

| Quality of life (MANSA) | 568 | 0.9 (0.73 to 0.99) | 0.037 | 0.9 (0.79 to 0.98) | 0.017 | ||

| Clinical and service use variables | |||||||

| Diagnosis | F20–F29 | 260 | 1 | 1 | |||

| F60 (Specific personality disorder) | 115 | 1.7 (1.06 to 2.58) | 0.026 | 1.5 (1.13 to 2.05) | 0.006 | ||

| Other eligible non-psychotic disorders | 203 | 1.1 (0.74 to 1.54) | 0.745 | 1.1 (0.84 to 1.43) | 0.508 | ||

| Severity of symptoms (BPRS T0) | 533 | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05) | 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | 0.001 | ||

| Index admission | Voluntary | 246 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Compulsory | 261 | 0.8 (0.54 to 1.08) | 0.126 | 0.8 (0.59 to 0.98) | 0.033 | ||

| Length of index admission (days) | 578 | 1.0 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.113 | 1.0 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.263 | ||

| Number of admissions in the year prior | 578 | 1.4 (1.20 to 1.65) | < 0.001 | 1.3 (1.21 to 1.41) | < 0.001 | ||

| Number of compulsory admissions in the year prior | 510 | 1.3 (0.99 to 1.61) | 0.058 | 1.2 (1.05 to 1.46) | 0.011 | ||

| Number of A&E attendances in the previous year | 578 | 1.1 (1.06 to 1.23) | 0.001 | 1.1 (1.04 to 1.10) | < 0.001 | ||

Health economic evaluation

Our primary economic analysis aimed to evaluate the impact of patient access to peer support for psychiatric discharge on the total cost of NHS mental health service utilisation over a 12-month period following hospital discharge, allowing for the cost of peer support itself.

Secondary economic analyses aimed:

-

to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of peer support based on cost and quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) outcomes observed for trial participants at 4 months post hospital discharge

-

to examine the association between exposure to peer support and wider service utilisation and costs over 4 months post discharge beyond costs attributable to contact with NHS mental health services.

Methods and results for this WP are summarised in Appendix 2. The primary analysis of total costs over 12 months and the secondary cost-effectiveness analysis at 4 months were carried out from an NHS mental health service perspective, though a wider ‘societal’ perspective was taken when analysing non-NHS mental healthcare costs over 4 months. Mental health service contacts for all trial participants were collected from EPRs for 12 months post discharge from the index hospital admission and over 12 months prior to the index admission. Non-NHS mental healthcare costs were collected by self-report at 4 months post discharge, as was health-related quality of life, measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version instrument. 52 Number, type and length of contacts with PWs were collected using the online contact log completed by PWs after each contact. Total costs per trial participant were calculated using appropriate unit costs (see Appendix 2). All analyses were conducted on an ITT basis using a generalised linear modelling (GLM) with a logarithmic link function. 53 A ‘net benefit’ framework was used54 to evaluate whether the peer support intervention offered a cost-effective alternative to usual care after 4 months post-discharge from the index hospital admission using an appropriate cost-effectiveness threshold. As with the main clinical analysis, missing data from EPRs on service contacts and other patient covariates was not a serious problem; we assumed that it was ignorable and likely to be missing at random. Missing data on self-reported service contacts and quality of life at 4 months were more problematic – as self-report data are likely to be not missing at random, we did not seek to impute values where data were missing.

A cost analysis of mental health service contacts over a 12-month period following discharge from acute inpatient care showed that, on average and accounting for sampling error in the trial data, the addition of peer support to a patient’s care bundle prior to leaving hospital could reduce the average cost of mental health service contacts by more than £2500 per patient. This allows for the additional cost of peer support itself – a mean cost of around £540 per participant. Most of the cost advantage over follow-up was due to reductions in the cost of bed day utilisation. There was a moderate (18%) risk that usual care would be more favourable in cost terms. Over months, and considering patient quality of life outcomes as well as cost, peer support was also found to be cost-effective from an NHS mental health service perspective. This finding is driven in large part by lower total cost of mental health service contacts for trial participants over the first 4 months after leaving hospital. The expected QALY gains associated with peer support were marginal: a 0.002 QALY improvement per participant, equivalent to less than a single day in full health. Compared to the cost of NHS mental health care contacts, there was a relatively weak association between exposure to peer support and the cost of wider community-based and police-related service contacts over 4 months after leaving hospital, with much less pronounced differences in costs between intervention and control participants.

We conclude that peer support delivered to the type of population recruited to this study could lower costs of mental health care use principally arising from bed day utilisation, though there is a moderate degree of uncertainty associated with this conclusion. Based on quality-of-life data and QALY outcomes estimated at 4 months, there is also tentative evidence that this could be achieved without necessarily being harmful to patient outcomes.

Process evaluation – predictors of engagement with peer support

We originally proposed a process evaluation to explore three distinct mechanisms of peer support in our intervention, derived from a change model developed in earlier research:31

-

Peer workers role-model recovery, increasing levels of hope and enabling participants to function well in the community and so avoid hospital admission.

-

Peer workers build strong therapeutic relationships with participants and reduce their experiences of stigma within services, improving engagement with services, increasing planned service use and decreasing emergency service use and compulsory admission.

-

Positive experiences of relationship building with PWs decreases anticipation of stigma, enabling participants to strengthen social networks, and decrease emergency service use and compulsory admission.

The quantitative process evaluation reported here differs from what was planned in the programme protocol given the non-significant findings of the primary analysis. However, as noted in Randomised controlled trial, a CACE analysis indicated that participants who met the criteria for having received a minimal amount of the peer support intervention were significantly less likely to be readmitted in the year post-discharge than a counter-factual group of similar participants who were not offered peer support. With only 62% of participants engaging with the intervention, an understanding of engagement in peer support should be considered as part of a change model for peer support in mental health services. We therefore sought to identify pre-randomisation and pre-discharge predictors of engagement with peer support in the trial.

Methods and results for this WP are summarised in Appendix 3. We included all trial participants randomised to peer support in this analysis. Pre-randomisation and pre-discharge variables were obtained from baseline interviews, EPRs and PW contact logs. Logistic regression was used to model the relationship between the two groups of predictor variables and ‘engaged with peer support’, defined as having had at least two face-to-face contacts with the PW, at least one of which was in the community post discharge.

The change model informing the trial31 indicated that ‘building a trusting relationship based on shared lived experience’ was fundamental to the process of peer support. Our analysis supports that, suggesting that the length of first contact is positively associated with engaging with peer support, and participants who went on to engage with peer support experienced more relationship-building activity in that first contact. We had hypothesised that a longer period of time between joining the study and discharge, and more contacts with the PW during that period, would also support the relationship-building process and therefore engagement. However, not only were more pre-discharge contacts with the PW not associated with engagement, but the longer period pre discharge was associated with non-engagement. It might be that extended uncertainty about discharge arrangements was disruptive of the peer support relationship although we lack data to explain this finding. However, our findings do suggest that both length and quality of the first contact with the PW are key to engagement. (We note that the amount of relationship-building activity in the first contact was significantly associated with engagement when analysed separately – those who engaged with peer support had on average one more relationship-building activity than those who did not engage with peer support; OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.76 – but was no longer significant when included in the regression model, suggesting that length of first session and amount of relationship-building activity might be correlated).

We found that participants who identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual were significantly more likely to engage with peer support than heterosexual participants. This is an important finding given that people who are gay, lesbian or bisexual are more likely to experience mental health problems than the general population. 55 However, we had relatively few participants in this group and did not collect the data needed to explore this finding further. Future research should focus on the experiences of peer support for this group of people.

Process evaluation – peer support and change in mental health services

Given the lack of an effect on our primary outcome we did not explore hypothesised mechanisms explicitly in the qualitative component of the process evaluation. One of the programme objectives was ‘to refine an empirically and theoretically grounded model that explains how peer support interventions impact on outcomes for service users post-discharge’. To do this we explored, in depth, the peer support change model informing the trial31 from the perspective of trial participants and PWs.

We conducted a qualitative interview study using a ‘co-production’ approach designed to integrate the full range of perspectives on the research team – clinical, academic and experiential – into the interpretive process (see below). 56 We held a workshop with our LEAP to refine our original change model31 (see Appendix 1, Figure 14).

Service user participants were a subsample of trial participants allocated to peer support, interviewed at end of intervention. We aimed to recruit five trial participants at each of the seven sites and used a sampling framework to guide selection (see Appendix 2, Table 14), developed with the service user researcher team. PW participants were PWs delivering peer support as part of the trial, interviewed shortly after finishing training, and at 4 and 12 months after they had been in post. Interview schedules were informed by the literature on peer support cited above, including our earlier research on the processes31 and principles of peer support,57 the output of the LEAP workshop described above (see Appendix 1, Figure 14) and the experiential knowledge of members of the service user researcher team. All interviews were conducted by service user researchers, and they were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis took a hybrid inductive/deductive approach58 in two main stages. In the first stage we took a co-produced approach as a multidisciplinary team to developing, inductively, a semantic-level59 or descriptive thematic framework. Following processes that we had developed previously,56 members of the team, including service user researchers, clinical academics and social scientists, individually undertook preliminary analyses of a selection of interview transcripts. We then presented our emerging ideas to each other, with illustrative examples of data (verbatim quotes), while, through discussion, we combined and collapsed thematic ideas into coherent categories to produce a provisional coding framework that captured the diversity as well as shared aspects of our interpretation. We repeated this process a second time working with a further set of transcripts, refining the framework. The service user researcher team then used the framework to code the full set of interview transcripts, further refining the framework where transcripts contained data that did not fit existing codes. In the second, more deductive stage of the analysis process, we took a critical interpretive approach,60 seeking to use data from our interviews to critique and refine the change model that informed the research. A service user researcher (RF), working with the lead author (SG), identified codes in the final coding framework that related to each of the components in the revised change model (see Appendix 1, Figure 15), before re-coding those data to themes that reflected, or challenged and refined the components of the original change model. We retained inductive space in this process to identify new themes, enabling us to produce a final change model for peer support for discharge from inpatient psychiatric care.

A total of 39 trial participants were interviewed, with characteristics of the sample indicated in Report Supplementary Material 3, Appendix 2, Table 14. A total of 32 PW participants were interviewed across the seven sites after training, 20 of whom were interviewed again at 4 months and 21 at 12 months (see Appendix 4, Table 25). The coding framework developed following the first, inductive stage of the analysis process is given in Report Supplementary Material 3, Appendix 2, Table 16. The final, adapted change model for peer support for psychiatric discharge is shown in Report Supplementary Material 3, Appendix 1, Figure 16. Report Supplementary Material 3 reports data that illustrate each of the themes in the final change model, summarised in brief below.

-

Building trusting therapeutic relationships

As described in our original model, building a trusting, therapeutic relationship was the essential first step for successful peer support to take place.

-

Unique role – Participants described the PW role as being more informal and relaxed in comparison to other professional roles. PWs were seen as more authentic, less judgmental and willing to explore topics that others seemed uncomfortable with (e.g. experiences of psychosis or relationship problems). Authenticity and trust were conveyed through sharing lived experience (of mental illness and personal life); support peers (SPs – the trial participants) commented that PWs persevered and never gave up on them.

-

Unique relationship – Participants described the relationship they shared as unique, equal and non-directive. Communication was open, honest and non-judgmental so that SPs felt that they could truly be themselves and were able to say whatever they needed as power in the relationship felt balanced. The relationship had boundaries that provided a safer, more neutral space than with friends or family.

-

Whole-person approach – PWs took a whole-person approach towards each SP and the activities they did together. This included getting to know the individual without a focus on mental health, and the opportunity for mutual enjoyment and to explore interests together. PWs supported people with a variety of difficulties, including relationship problems, financial concerns and healthy routines.

-

Connecting socially

Once a therapeutic relationship had been established, participants described how PWs supported them towards living and functioning well in the community.

-

Embodying recovery and hope – SPs often described PWs as embodying successful recovery and hope, by coping well with symptoms or showing resilience through leading a successful life in spite of mental health. Sometimes PWs literally embodied connecting by going with the SP the first time they tried out a new activity.

-

Connecting to people – Participants described feeling more comfortable around other people since taking part in the peer support, which motivated them to socialise more and make new friends. PWs encouraged SPs to make healthy connections, either by motivating people to make new friends, or by supporting them to identify and avoid negative relationships.

-

Adapting back to society – Peer support subtly supported the process of adapting back to everyday life, whether this meant relearning appropriate cultural/societal norms or learning helpful daily living skills. These processes occurred through a combination of active guidance, renegotiating boundaries in the relationship or breaking complex social processes down into achievable steps.

-

Changing attitudes to community resources – Participants described increased confidence and motivation to try new activities, a desire to have more structure in daily living, confidence to go out and cope independently and to explore hobbies and interests.

-

Tailored recommendations – SPs valued and trusted the personalised recommendations that their PWs made and were more likely to try suggestions from PWs even if other people had previously made the same suggestions.

-

Interacting with services

Participants described the different ways that they felt towards, and used, statutory services since taking part in peer support, including increased willingness to use statutory services.

-

Role modelling interactions with statutory staff – PWs seemed to play an important role by role modelling communication with staff. SPs described feeling more able to talk to ward and community staff since the peer support.

-

‘Bridging the gap’ – Peer support increased communication and helped to build trust between SPs and their teams. PWs were often trusted to liaise with staff from statutory services on behalf of their SPs, thereby bridging the gap in communication.

-

Intrapersonal changes to ‘navigate the system’ – Participants described feeling more knowledgeable and confident about who to contact and where to go for support since spending time with their PW, whether that was statutory or voluntary services.

-

Social functioning

-

Intrapersonal changes towards others – SPs felt trust and motivation to make and maintain new relationships; they described wanting to go out more to be around people, joining groups and enjoying shared time with people.

-