Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1151. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in May 2012 and was accepted for publication in May 2013. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

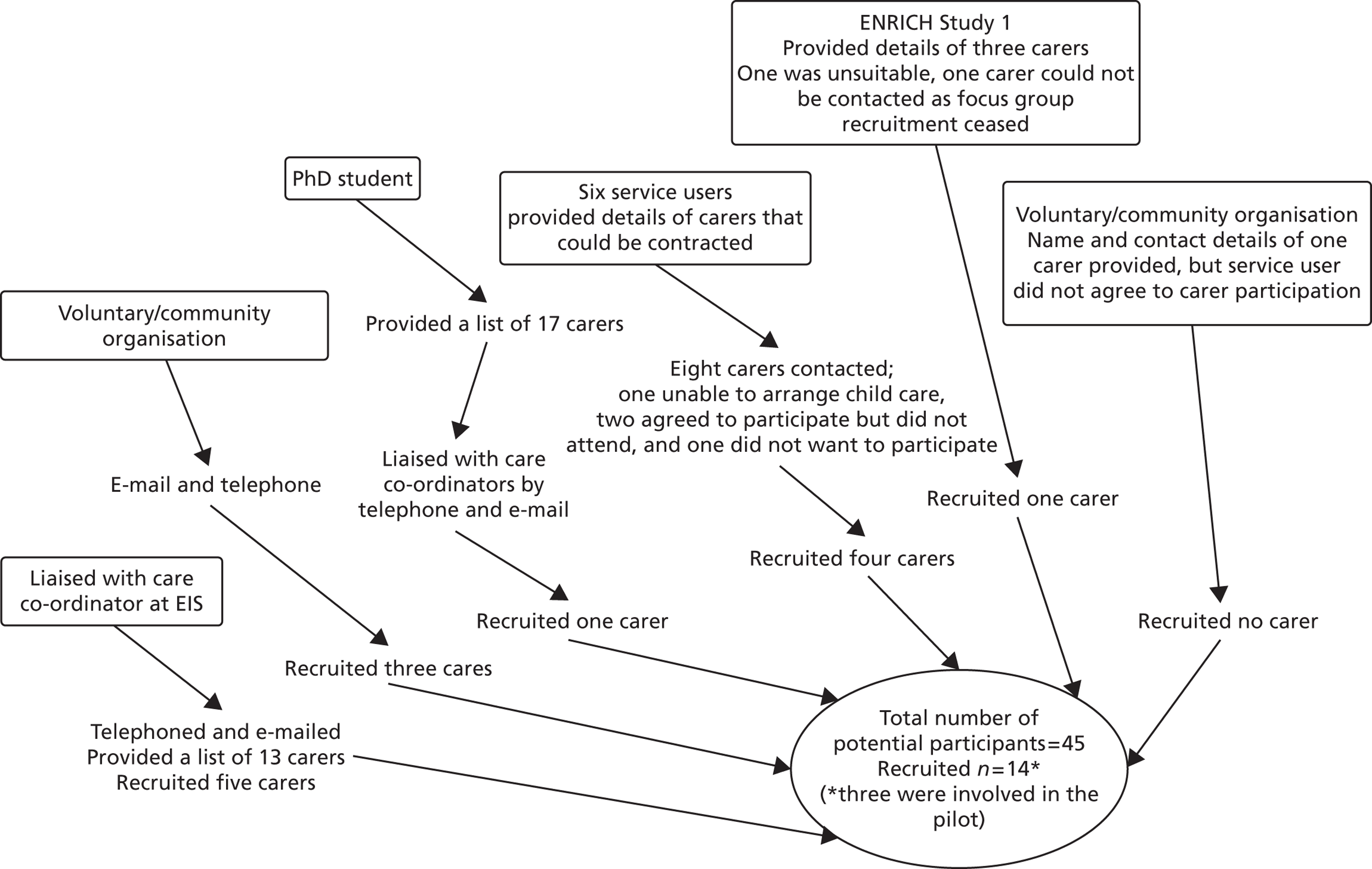

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Singh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

It occurred to me that there was no difference between men, in intelligence or race, so profound as the difference between the sick and the well.

F Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (p. 98)1

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Compared with the white population, black and minority ethnic (BME) groups in the UK, especially young African Caribbean men, have higher rates of psychosis, experience more adverse pathways into care, are at greater risk of detention under the Mental Health Act (MHA)2 and are more likely to disengage with services over time, be less satisfied with their care and have poorer outcomes, with greater social exclusion. The conventional explanation for this is based on the notion of institutional racism within psychiatry. 3 However, this view has been challenged as providing simplistic explanations for complex underlying processes. 4

Ethnic differences in rates of psychosis and pathways to care are evident even in BME patients presenting with a first episode of psychosis (FEP);5,6 therefore, contributory factors must be operating before presentation to psychiatric services. These therefore need to be understood in a wider societal context. We have argued that ‘any potential solutions (to reduce such differences) must go beyond the health sector and involve statutory as well as voluntary and community agencies. The problem does not reside exclusively in psychiatry and hence the solutions cannot emerge from psychiatric services alone’ (p. 650, italics in original). 7

Early intervention services focus specifically on reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), enhancing therapeutic engagement and reducing social exclusion by providing care in community-based, low-stigma settings. 8 The UK has been at the forefront of developing early intervention services. There is also good evidence that specialist early intervention services demonstrate both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in improving the short- to medium-term outcomes of FEP. It is reasonable to assume that the assertive, community-based, non-coercive early intervention approach may specifically benefit BME patients. The Lambeth Early Onset trial9 found that BME patients were more likely to stay engaged with early intervention services than with generic community mental health teams (CMHTs). However, it is unclear whether generic early intervention services, as currently organised, meet the specific demands and challenges of providing care for BME patients.

The need for the ENRICH programme grew out of three strands of clinical need, policy imperatives and research evidence:

-

Adverse pathways to care in BME groups during FEP. Pathways to care are adverse in BME groups even in first presentation of a psychotic illness. 5,10 The three-centre Aetiology and Ethnicity in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses study of FEP found that black patients were less likely to come to services through their general practitioner (GP) and more likely to come through criminal justice agencies and compulsory detention. In addition, family members were more likely to seek police help than medical help. 10,11 Hence, the determinants of these pathways need to be explored within the familial and wider societal context of BME patients. 12,13

-

Ethnic differences in compulsory detention rates. Detention rates for BME patients are high even for the FEP and they increase in later episodes. 6 This deteriorating relationship trajectory between BME patients and mental health services, with decreasing engagement and increasing detention rates over time, has been consistently demonstrated. 6,13–16 It is not clear, however, whether service-level intervention can reduce this detention rate and improve the engagement of BME patients.

-

Ethnic differences in outcomes and service satisfaction. BME patients, especially young black men, report less satisfaction with mental health services, with an increased number of previous admissions predicting greater dissatisfaction. 14 In the UK, the unemployment rate for patients suffering from psychosis has risen over the last 50 years and was 70–80% during the 1990s. 17 Service users and carer advocacy groups consider a return to work and occupation as one of the highest priorities for patients suffering from psychosis, which enhances their functional status and improves their quality of life. 18,19 BME patients may be doubly disadvantaged because of the combined effect of racism in the labour market and the stigma of mental illness.

The ENRICH programme aimed to develop the knowledge base essential for reducing, and if possible eliminating, ethnic differences in pathways to care in FEP. We proposed three studies conducted over 42 months of all service users referred to early intervention services in Birmingham. We wished to explore the cultural and family-related factors that facilitated or impeded access to health care. We planned to evaluate all MHA assessments to determine whether some BME patients had fewer community alternatives for care than other ethnic groups, thus leading to greater risk of detention. We wanted to seek the opinions of service users, carers, clinicians and other stakeholders on how early intervention services could become more appropriate for, and acceptable to, BME communities.

Chapter 2 Objectives and ethical considerations

The specific objectives of the programme, conducted as three distinct studies, were as follows:

-

Study 1: to understand ethnic differences in pathways to care in FEP by exploring cultural determinants of illness recognition, attribution and help-seeking among different ethnic groups.

-

Study 2: to evaluate the process of detention under the MHA and assess ethnic differences in the availability of alternative provision that could reduce the need for detention.

-

Study 3: to determine the appropriateness, accessibility and acceptability of generic early intervention services for different ethnic groups and establish the care needs and preferences of service users and other stakeholders.

In the original proposal we had also sought funding for two further studies:

-

Study 4: to understand pathways and predictors of social exclusion, especially vocational outcomes in FEP, and evaluate the effectiveness of early intervention services in enhancing social inclusion.

-

Study 5: to evaluate the longitudinal impact of early intervention services on engagement, satisfaction and coercion in FEP patients.

Funding for these studies was not approved.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval

The Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee (WREC) gave ethical approval on 10 December 2008 subject to minor amendments. Amended documents were submitted and finally approved in February 2009. The study was approved by the Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust’s (BSMHFT) Research and Development Department on the 11 March 2009.

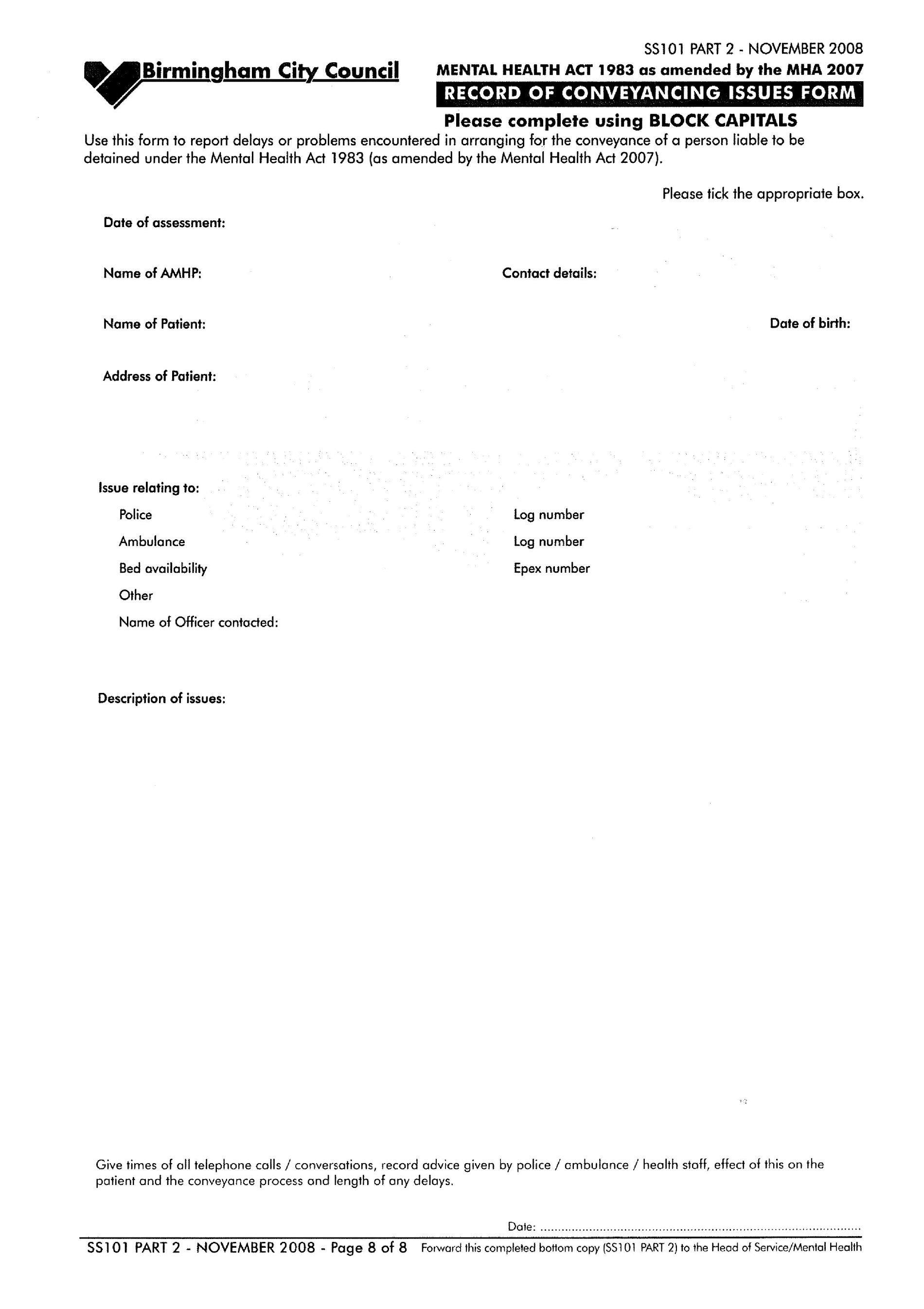

Birmingham City Council ethics

Originally we had planned to recruit patients into study 2 using data from social services, supplemented by data from home treatment teams. Although we had received ethical approval for this method from the WREC we were asked to seek separate ethical approval from an ethics committee run by Birmingham City Council (BCC). This committee did not accept WREC approval and did not agree to let us access their data set. After prolonged negotiations we received BCC approval on the 6 April 2009. We were given access to anonymised data; however, we had to pay a BCC staff member from our research funds to anonymise the data set for us. In addition, we had to seek separate BCC approval for the study 2 qualitative study; this was received on the 22 June 2010. Preparing the relevant documents and waiting for BCC approval led to a 9-month delay in data collection.

Chapter 3 Literature review

Social anthropological perspectives of health and illness suggest that a decision to seek care is, in part, mediated by beliefs about illness causality as well as the wider social and cultural networks. 16,20,21 There is evidence that some BME communities, especially those from African Caribbean and Asian backgrounds, attach greater stigma to mental illness, may attribute unusual behaviour to the individual rather than to an illness and seek police rather than medical help when dealing with an ill relative. 10 It is as yet unclear how such factors influence the observed ethnic differences in care pathways during FEP.

We reviewed the literature on ethnic and cultural determinants of help-seeking in serious mental disorders including the role of competing and contrasting explanatory models of mental illness held by BME service users and the role of stigma and shame in hindering access to care. We wished to determine whether mental health services consider the cultural, religious or spiritual needs of service users and their carers. We also conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to explore correlates and predictors of ethnic differences in pathways to care in FEP.

Ethnic and cultural determinants of help-seeking

Culture and beliefs

Culture provides a framework for making sense of experience. 22 In the health-care context this is important because the ‘cultural interpretations of mental illness held by members of a society or social group (including mental health professionals) strongly influence their response to persons who are ill and both directly and indirectly influence the course of the illness’ (p. 233). 23 Explanatory models represent the concepts and frameworks utilised by people to describe the causes and course of their mental illness. 24 Littlewood25 makes a distinction between ‘etic’ models of medical perspectives, which are clinical/scientific explanations, and ‘emic’ models, which focus on patients’ perspectives based on the cultural understanding of subjective experience. Such explanatory models influence the perceived causation, recognition and treatment preferences that determine help-seeking attitudes and behaviours for mental illness20,21 and could therefore be implicated in delays in help-seeking.

Since 1994, the UK Department of Health has conducted national surveys that show fluctuations in the general population’s attitude to mental health. The most recent survey26 suggests a slight increase in positive attitudes towards those with mental illness compared with 2008,27 but current attitudes are not as positive as those in 2009. 28 It is difficult to pinpoint the cause in these fluctuations. Even though ethnicity status was collected, the reports do not highlight any differences in attitudes within ethnic groups. Hence, the survey does not explore the consequences of negative attitudes, such as the shame and stigma that exist within communities, or how religious beliefs may play a role in the attitudes and behaviour of a community. 29

Multiple explanatory models or multiple exploratory maps

Williams and Healy’s30 study of first-time presenters to mental health services showed that individuals move between varied and complex sets of beliefs and a variety of explanations are either held simultaneously or taken up and dismissed rapidly. Some people can move from one strongly held view to another relatively quickly and unproblematically, forming an exploratory map rather than an explanatory model. The authors state that ‘such beliefs should not be regarded as taking the form of a coherent explanatory model but rather as a map of possibilities, which provides a framework for the ongoing process of making sense and seeking meaning’ (p. 473). 30 Clearly, people’s cultural perspectives and interpretations of situations change too. Hence, explanatory models remain in use as long as they fit shared experiences,31 and experiences in turn shape cultural models over time.

Explanatory models in different ethnocultural groups

In studies examining the appropriateness of mental health services for Asian populations in the UK, the most frequently mentioned causes of mental health illness were social stress, family problems and the ‘will of God’. 32 Other attributions include ‘bad thoughts’, ‘lack of will power’ and ‘weakness in personality’. 33,34

McCabe and Priebe’s35 study exploring explanatory models in schizophrenia in the UK found that white patients cited biological causes of illness more often than African Caribbean, West African and Bangladeshi patients, and both Bangladeshi and West-African patients cited supernatural causes more frequently than white patients. Small qualitative studies have suggested that such supernatural explanatory models lead to help-seeking from traditional healers rather than mental health services. 36–38 However, there are few studies in the literature that have systematically explored cultural attribution in emerging psychosis and its relationship to help-seeking.

Lack of education and information are considered to be important factors related to supernatural explanations for mental illness, both amongst BME groups in the UK39 and in the developing world. Srinivasan and Thara40 found that, in urban India, families living with someone suffering from chronic schizophrenia subscribed to a supernatural causation of the illness, which the authors suggest occurs because of lack of information. However, other research shows that supernatural causes of schizophrenia are strongly held despite a medical knowledge of mental illness. 37,41 For instance, Das et al. 41 attempted to explore the effects of a structured educational programme on explanatory models of illness among relatives of people with schizophrenia in India. They found that many of the indigenous explanatory models persisted, especially those related to treatment (i.e. visiting traditional healers), despite the educational intervention. Dein and Sembhi39 found that age (as opposed to education) of subjects was the key variable, with younger patients more likely to consult traditional healers.

Spiritual and religious beliefs

Spirituality and religion are elusive concepts that are hard to define. 42 The Royal College of Psychiatrists43 defines spirituality as:

A distinctive, potentially creative and universal dimension of human experience arising both within the inner subjective awareness of individuals and within communities, social groups and traditions. It may be experienced as relationship with that which is intimately ‘inner’, immanent and personal, within the self and others, and/or as a relationship with that which is wholly ‘other’, transcendent and beyond the self. It is experienced as being of fundamental or ultimate importance and is thus concerned with matters of meaning and purpose in life, truth and values.

p. 24

Religion is an organised and communal activity, which encompasses most if not all aspects in definitions of spirituality, particularly in the context of belief in some sort of supernatural power, or God(s). Spirituality is more personal and individual in nature. 44,45 However, it is generally accepted that they overlap46 and that spirituality concerns anything that inspires a person, whether or not this is a formal religion.

In the UK’s changing and diverse society, people move across cultural boundaries and between faiths, or from belief to unbelief and then back to belief when a crisis occurs. 47 Research demonstrates that members of BME communities explicitly express their religious needs more than members of white communities. 48 Illness attributions, however, may not be bound to one particular religion. For instance, belief in demon possession as an explanation for mental illness has been noted in many Christian, Muslim and other communities in the UK. 49

In the study by Leavey et al. 50 on clergy contact with people with mental illness, both imams and Pentecostal pastors stated that they were often contacted by individuals or families who feared that ill health or misfortune had been provoked by a curse or witchcraft, or was the result of spirit possession. In such cases, prayer and religious rituals such as deliverance (exorcism) were considered to be the appropriate response. 50 Rabiee and Smith4 also highlighted similar findings amongst Somalian carers and users of mental health services in Birmingham.

In the UK, > 50% of service users say that spirituality helps them to cope with ill health and should be nurtured. 51 In light of the focus on spirituality in mental health care, the Royal College of Psychiatrists has set up a Special Interest Group in Spirituality (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/college/specialinterestgroups/spirituality.aspx; accessed July 2013). This group produces guidance on the relationship between spirituality and psychiatry, and the practicalities of addressing spirituality in psychiatric care. The Department of Health also produced a report highlighting the value of religion and belief in health, and the duty of professionals to respect and value belief systems in care planning and delivery. 52

Stigma and shame

‘Stigma’ is a mark or discredit that sets a person aside from others. 53 Human beings have a basic need to obtain or maintain a positive self-concept (ego-defence). 54 Research has demonstrated that stigmatising attitudes towards mental illness are particularly pervasive and harmful to those experiencing mental health problems, devaluing and discrediting self-identity. 55 Stigma and shame have been heavily implicated in poor help-seeking behaviour. 56 The fear of being labelled ‘mad’ or being perceived as mentally ill can lead to sufferers distancing themselves from others in their social roles and interactions. 56 Social distance is a measurement of an individual’s readiness to inter-relate with a target person in a variety of relationships. 57 Studies have shown that those with previous extensive communications with individuals experiencing mental health problems feel the need for less social distance than those with limited or no experience of such difficulties. 57

Evidence also suggests that urbanicity and cultural beliefs have an effect on levels of social distance. High levels of urbanicity and cultural beliefs in supernatural reasons for mental illness have been related to increased levels of social distance. 58 The fear of mental illness and people with mental health problems acts as a barrier in engaging with services, which can bring about stigmatised attitudes towards mental health and cause delays in help-seeking. 59 As the clergy in the Leavey et al. 50 study acknowledge, profoundly stigmatising community attitudes towards mental illness can result in religious rather than psychiatric help-seeking for such cases.

Systematic review of ethnic differences in pathways to care in first-episode psychosis

The primary aim of this systematic review was to explore ethnic differences in pathways to care exclusively during FEP and to explore factors that influence these differences. This review is split into two parts: the first will descriptively review the literature, exploring ethnic variation in pathways to care and associated factors; the second will report the meta-analysis, exploring ethnic variation in compulsory hospitalisation and criminal justice agency and GP involvement.

Search strategy and methodological appraisal

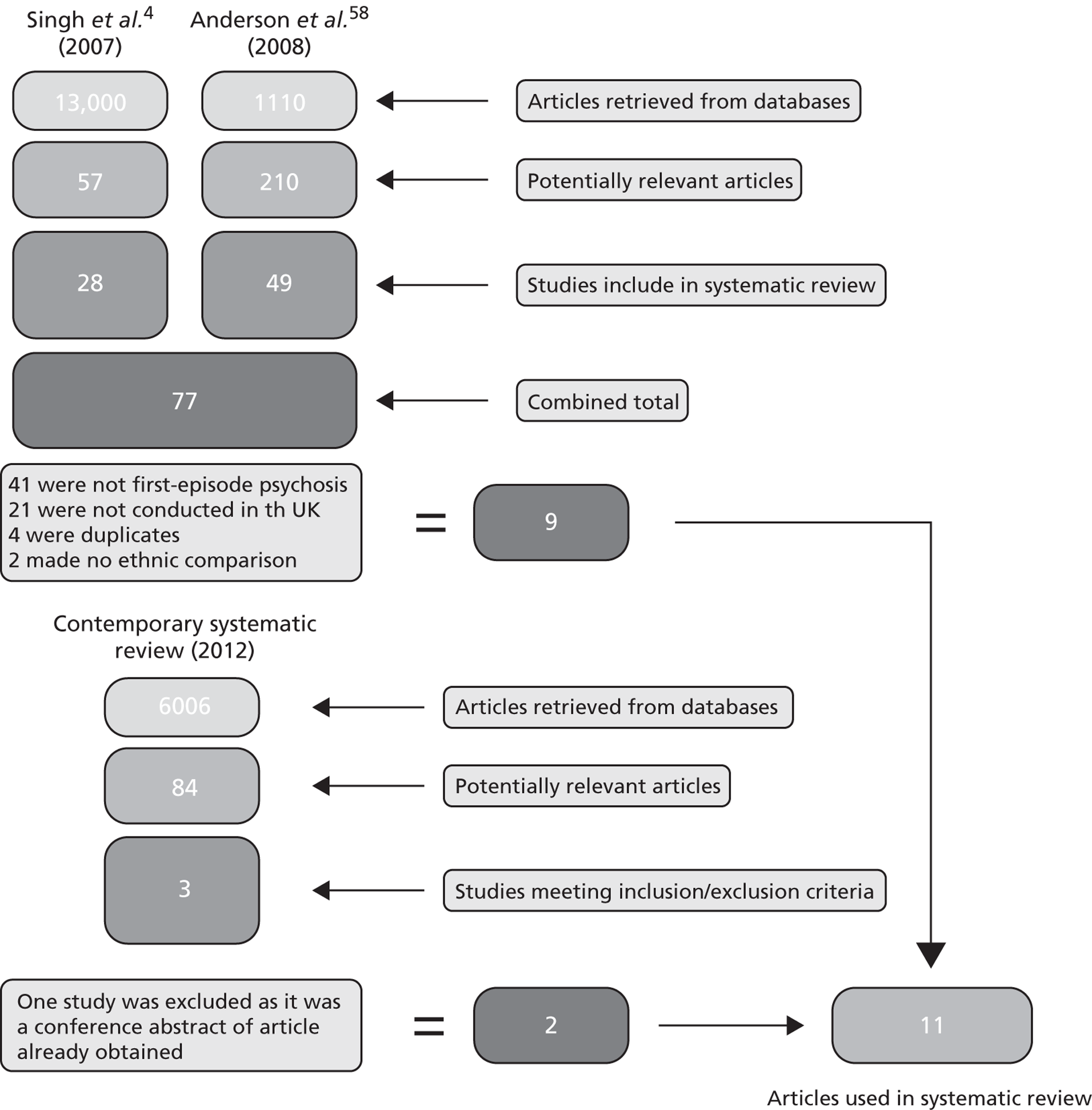

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify all studies in the UK that had explored ethnic variation in pathways to care during FEP (see Appendix 2). Singh et al. 6 had previously conducted a systematic review exploring ethnic differences under the MHA 1983, and Anderson et al. 60 conducted a systematic review exploring pathways to care during FEP. As these overlapped for the purpose of this review, relevant articles from these two reviews were carried forward (Figure 1). An additional literature review was conducted, extending the time period of these previous reviews. Bibliographic databases [MEDLINE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS) – British Library and The Cochrane Library] were searched from May 2005 to December 2011.

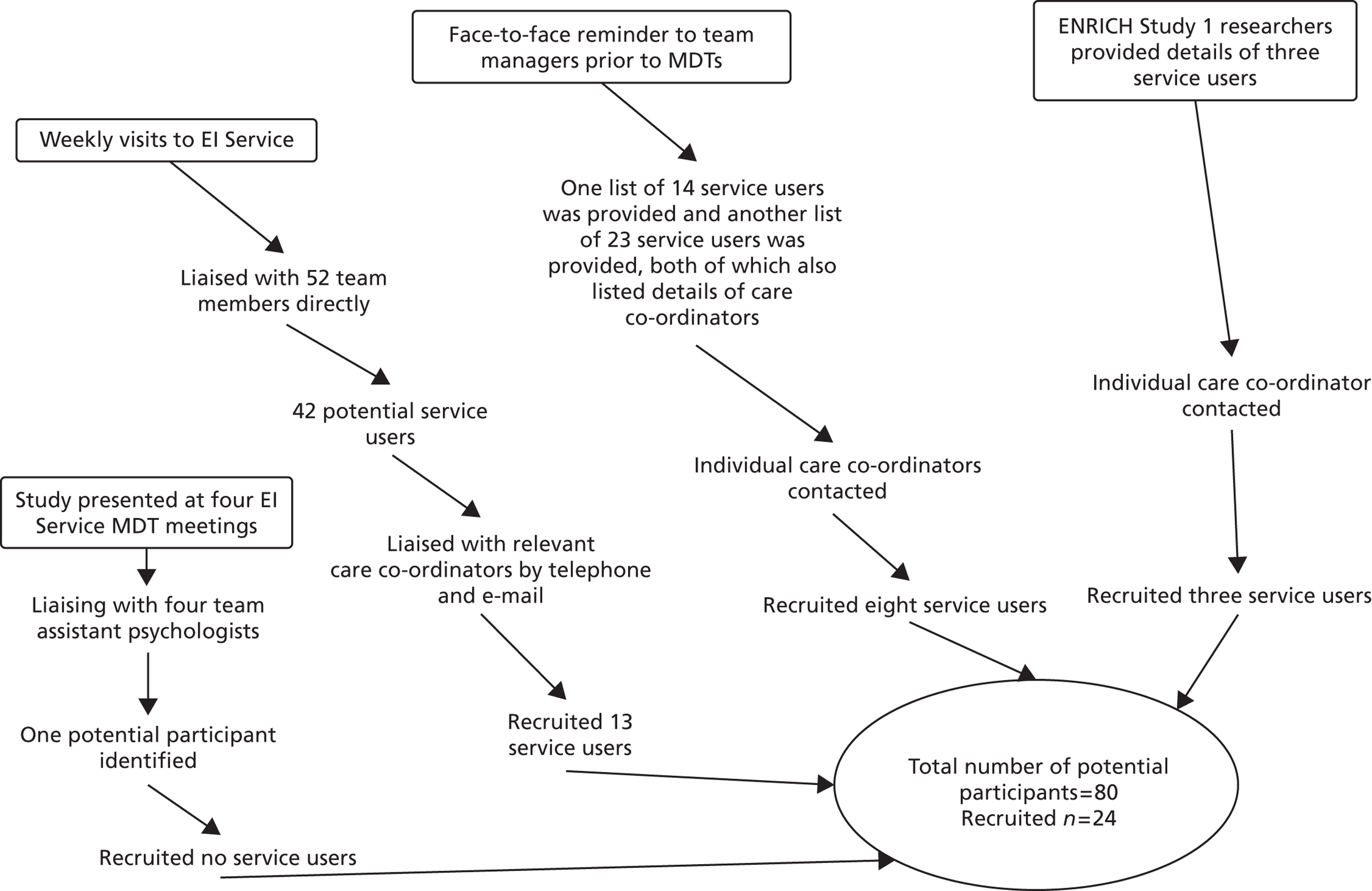

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the amalgamation of the current search with the previous systematic reviews exploring ethnic variation in pathways to care during FEP.

Inclusion criteria included:

-

studies including FEP-only cohorts

-

studies conducted in England and Wales

-

studies conducting an ethnic comparison between two or more groups

-

studies conducting a comparison of at least one pathway to care outcome (e.g. compulsory hospital admission, GP involvement, criminal justice agency involvement).

Exclusion criteria included:

-

data used in previous articles

-

data from first-contact studies, with no specification of episode

-

qualitative papers

-

studies not in English.

Of the roughly 6000 journal articles retrieved, three61–63 met the overall inclusion criteria of our review. These were added to the 9 articles10,11,15,64–70 identified through the two previous reviews, giving a total of 12 studies. However, further examination revealed that one of these61 was a conference abstract of a paper that had already been retrieved and it was therefore excluded. Our review therefore consisted of 11 studies10,11,15,62–70 that had explored ethnic variation in pathways to care in FEP patients. These studies are listed in Table 1.

| Study | Sample size for each ethnic group (n) | Total sample size (n) | City | Adjustment for confounders | Recording of ethnicity | Quality score (max. 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harrison et al. 198964 | African Caribbean 42; non-African Caribbean 89 | 131 | Nottingham | Diagnosis, gender, age | Third-party reports | 5 |

| Chen et al. 199165 | African Caribbean 40; non-African Caribbean 40 | 80 | Nottingham | Diagnosis | Medical records, source not specified | 4 |

| Birchwood et al. 199266 | White British 74; Asian British 30; African Caribbean British 50 | 154 | Birmingham | Diagnosis | Census rated | 6 |

| King et al. 199467 | White 39; Asian 11; black 38; ‘other’ 5 | 93 | London | Diagnosis | Self-reported/census categorisation | 4 |

| Cole et al. 199568 | White 39; black 38; ‘other’ 16 | 93 | London | Diagnosis, absence of a help-seeker, lack of GP involvement | Census rated | 8 |

| Burnett et al. 199970 | White 38; African Caribbean 38; Asian 24 | 100 | London | Diagnosis | Self-reported/census categorisation | 7 |

| Goater et al. 199915 | White 39; black 38; ‘other’ 16 | 93 | London | Age, gender, unemployment, risk to others, diagnosis, criminal justice referrals, self-initiated help-seeking | Self-reported/census categorisation | 6 |

| Harrison et al. 199969 | African Caribbean 33; ‘other’ 133 | 166 | Nottingham | Diagnosis | Third-party reports | 2 |

| Brunet 200362 | White 16; black 37; Asian 30; ‘other’ 8 | 91 | Birmingham | Diagnosis | Not reported | 5 |

| Morgan et al. 200510,11 | White British 237; African Caribbean 128; black African 64; white ‘other’ 33 | 462 | London and Nottingham | Age, gender, unemployment, risk to others, criminal justice referrals, self-initiated help-seeking, diagnosis | Self-reported/census categorisation | 10 |

| Chaudhry et al. 200863 | White British 24; South Asian 24 | 48 | Lancashire | Diagnosis | Not reported | 4 |

Quality rating

The 11 studies were evaluated for methodological quality using a review tool described by Bhui et al. 13 Essentially, the tool is a scoring system, appraising each study on four domains: sample size, adjustment for confounders, measurement of ethnicity and choice in ethnic comparison (see Appendix 3). Studies are scored on each domain, with the individual scores summed (maximum 11). Higher scores reflect better methodological quality.

From each study, two types of information were extracted: (1) ethnic variation in pathways to care (ethnic differences in compulsory hospital admission, criminal justice agency involvement and GP involvement) and (2) empirically supported explanations offered for these differences.

Ethnic differences in pathways to care during first-episode psychosis

Several studies included in the review confirmed that BME patients had higher rates of MHA detention, more contact with criminal justice agencies and less involvement of GPs in the care pathway. We also identified other ethnicity-related differences that have received less attention in research. Burnett et al. 70 reported that Asian patients had a higher level of domiciliary visits than white and African Caribbean patients. Morgan et al. 10 reported significantly higher levels of domiciliary visits for African Caribbean patients than for white patients. In 35% of these visits the police were involved, suggesting that these were usually crisis referrals. In Manchester, Chaudhry et al. 63 reported that South Asian patients were more likely to have community mental health services as their first contact to seek help whereas white patients had more inpatient admissions as entry into care. Cole et al. 68 reported that white patients were more likely than black and Asian patients to make first contact with a duty psychiatrist.

Four areas that may influence ethnic variation in pathways to care were also identified in the literature. These are differences in clinical presentation, delays in help-seeking, the role of social networks and cultural attribution of emerging illness:

-

Clinical factors. Harrison et al. 64 reported ethnic differences in both clinical presentation and manifest behaviour during FEP. Informants (family, friends and clinicians) reported that African Caribbean patients were more likely to show neglect in social functioning, personal appearance and hygiene, suggesting greater impairment. African Caribbean patients were also more likely to be perceived as being a danger to themselves and more likely to commit violent attacks than patients from other groups. Chen et al. 65 reported that African Caribbean patients presented more frequently to services with behavioural disturbances and agitation (collectively defined as violence, extreme bizarre behaviour, threatening behaviour and absconding) than non-African Caribbean patients. There was also a trend towards more affective psychosis and fewer substance-related psychoses amongst the African Caribbean sample than amongst the white patients. Morgan et al. 11 reported that African Caribbean patients were significantly more likely than patients from other ethnic groups to be involved in a violent incident and/or to be perceived as threatening by others leading to inpatient admission. There were no differences in DUP between African Caribbean and other ethnic groups.

-

Delays in help-seeking. Harrison et al. 64 reported that 40% of African Caribbean patients made contact with services < 1 week before psychiatric contact, compared with 1% of the non-African Caribbean sample (p < 0.001). There was no difference in symptom duration between the two groups but, once African Caribbean patients had made contact with services, psychiatric intervention occurred much sooner than amongst the non-African Caribbean sample, suggestive of crisis referral.

-

Social networks. Surprisingly little attention has been paid to the role of social and family networks in influencing pathways to care. Harrison et al. 64 reported lower levels of past relative contact amongst African Caribbean patients than amongst those from non-African Caribbean groups [χ2 = 5.22, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, p < 0.05].

-

Illness recognition and cultural attribution. This important variable has also received minimal attention in studies of pathways into care for FEP. Harrison et al. 64 asked informants (carers) to explain the cause of their patient’s current problems. Carers of African Caribbean patients were significantly more likely to attribute cause to ‘faulty biology’ or ‘substance misuse’ than carers of non-African Caribbean patients (χ2 = 4.7, df = 1, p < 0.03). About one-third (35%) of the African Caribbean carers viewed the illness as the result of personal character/lifestyle choices, compared with 50% of non-African Caribbean carers. However, this difference was not statistically significant. Only one African Caribbean carer mentioned a supernatural cause, compared with three non-African Caribbean patients. When carers were asked what they thought the nature of the problem was, both groups frequently cited mental illness.

Meta-analyses

Compulsory hospital admission

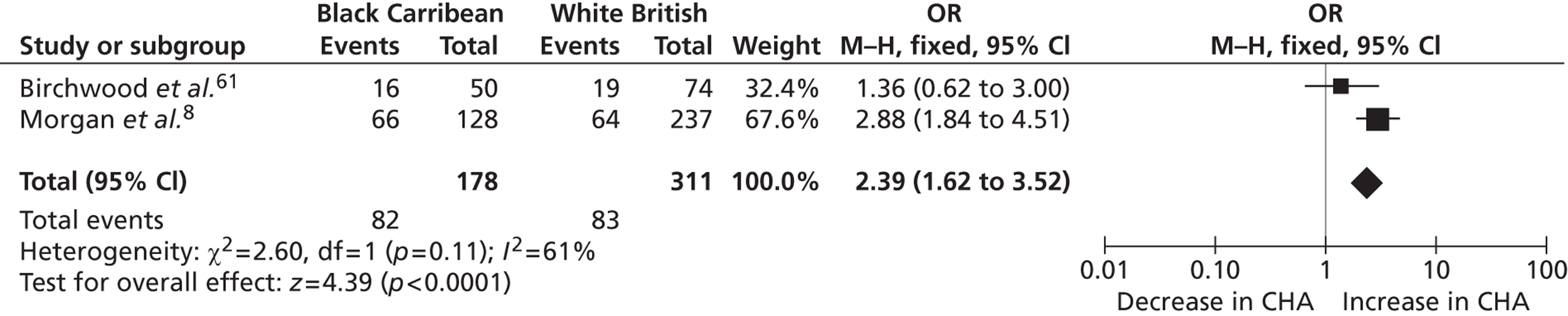

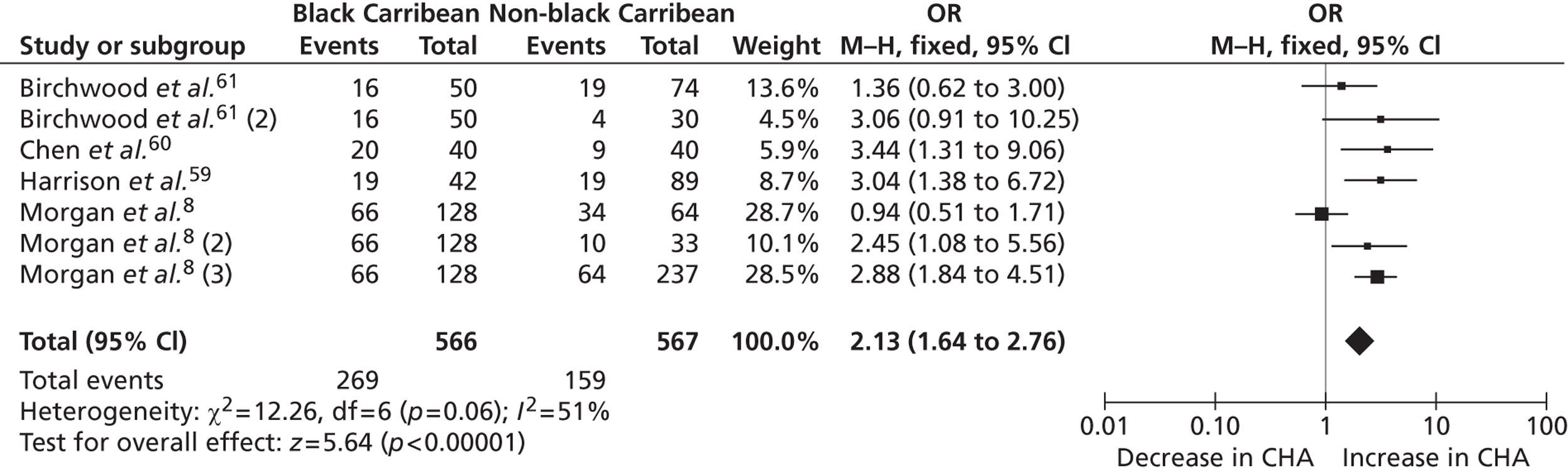

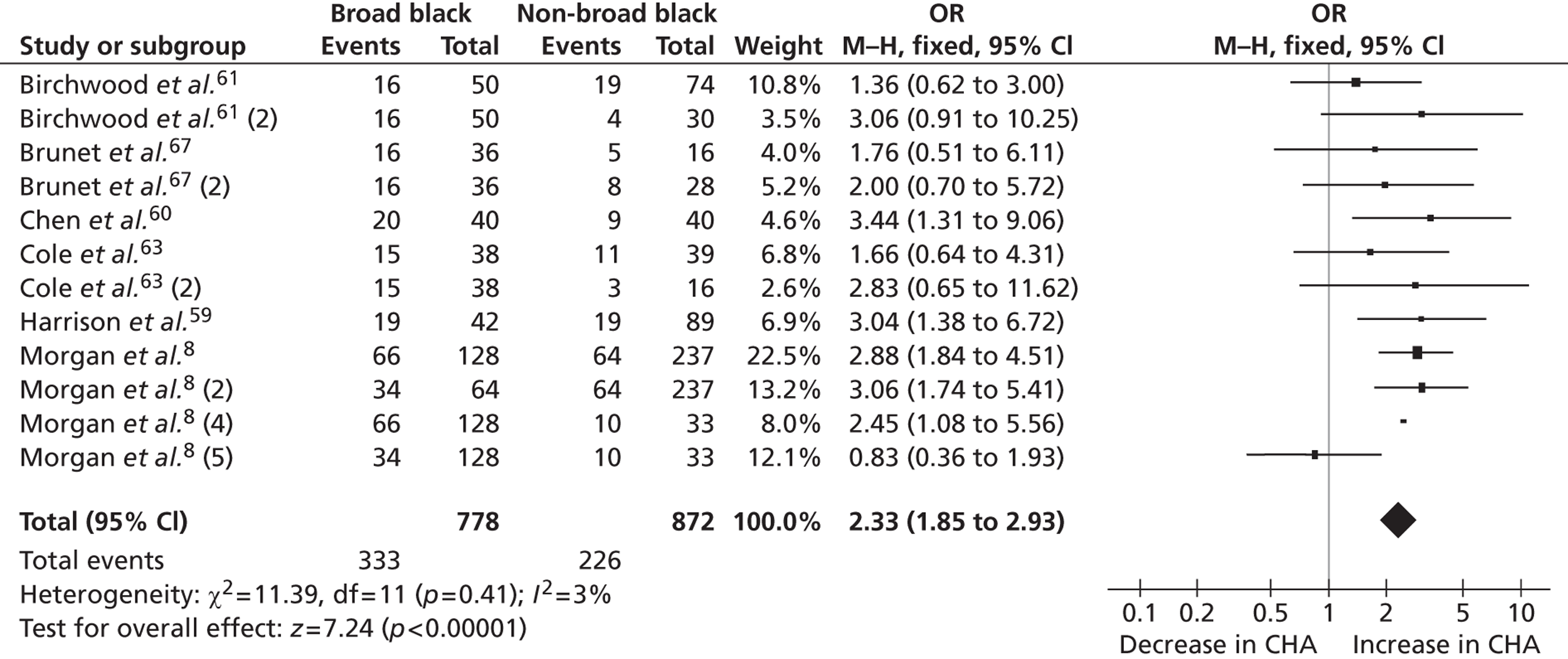

Each of the 12 studies made ethnic comparisons of the rates of compulsory hospital admission during FEP. Two studies10,11 used the same data set in this comparison and so only one of these studies was included. Meta-analyses were conducted by pooling the odds ratios (ORs) across seven studies. 10,62,64–66,68,70 The remaining studies were excluded as they either descriptively reported ethnic differences or did not include raw data. Given the variation in how BME groups were categorised in individual studies, we decided to conduct multiple comparisons to ensure meaningful ethnic comparisons. Four separate meta-analyses were conducted: (1) black Caribbean compared with white British patients, (2) black Caribbean compared with non-black Caribbean patients, (3) black (i.e. black African, black Caribbean, black ‘other’) compared with non-black patients and (4) Asian compared with non-Asian patients. Studies were included more than once in each analysis when multiple ethnic comparisons were made.

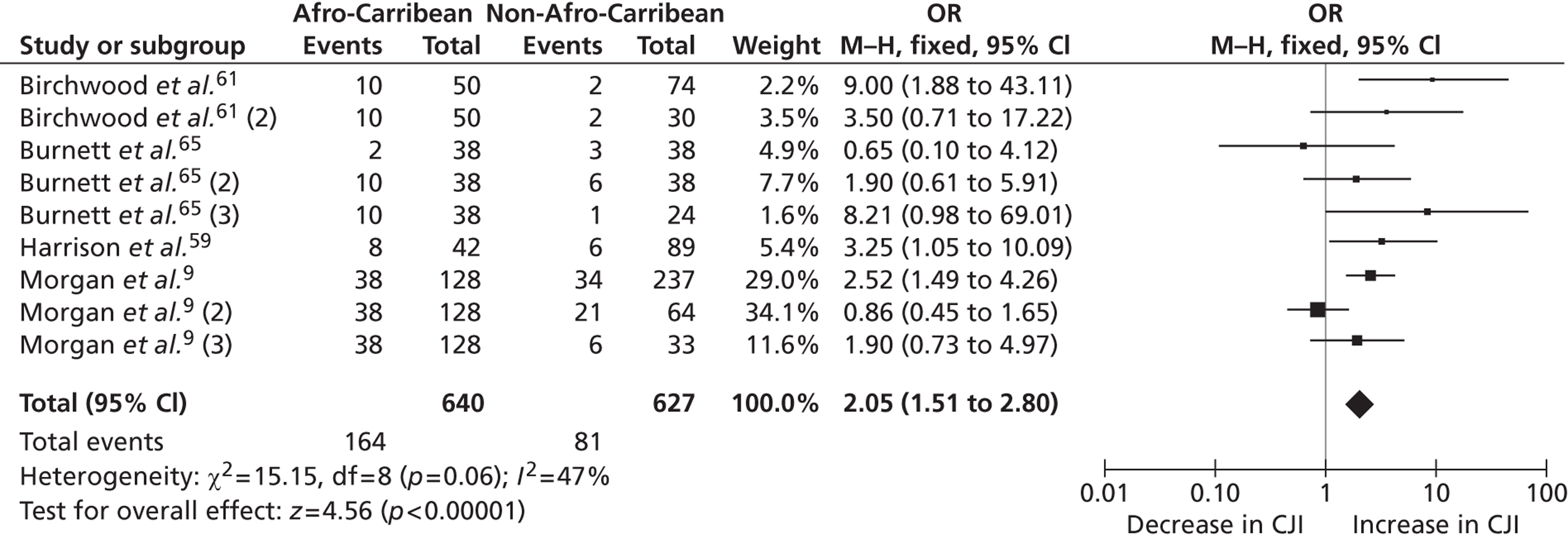

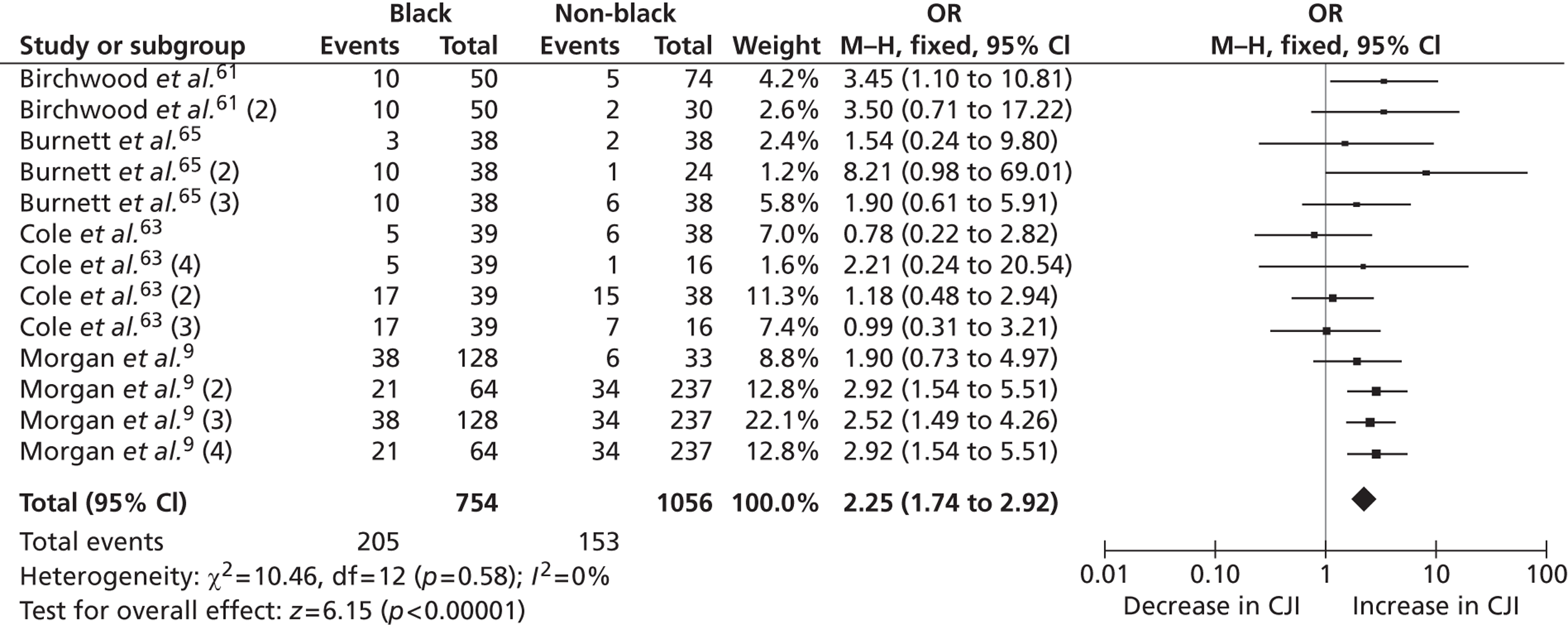

Criminal justice agency involvement

The review also investigated ethnic differences in criminal justice agency involvement. We defined this as any contact with either judicial agencies or law enforcement agencies. Of the 12 studies, five11,64,66,68,70 had explored ethnic differences in relation to criminal justice agency involvement. Of these, four64,66,68,70 were of ‘moderate’ methodological quality and one was rated ‘high’. 11 Two separate sources of data were extracted from the articles by Cole et al. 68 and Burnett et al. 70 as they used two independent measures of criminal justice agency involvement. In total, two separate meta-analyses were conducted to explore ethnic variations in criminal justice agency involvement: (1) black Caribbean compared with non-black Caribbean patients and (2) black (i.e. black African, black Caribbean, black ‘other’) compared with non-black patients. All articles except that by Harrison et al. 64 were included multiple times as the authors made comparisons between multiple ethnic groups.

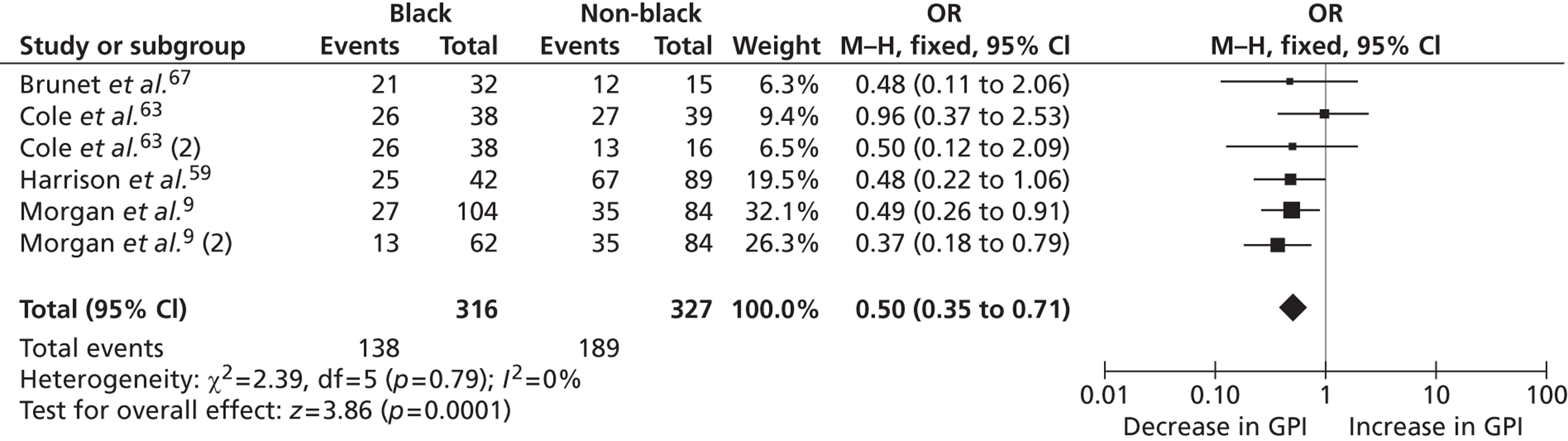

General practitioner involvement

Four studies11,64,68,70 explored ethnic differences in use of GP referral in pathways to care. Of these, one11 was rated high on methodological quality and the others were rated moderate. The study by Burnett et al. 70 used two measurements of GP referral, one by family members and the other by the patients themselves. Because of the lack of clarity surrounding how GP referral was determined in this study, we excluded it from the analyses.

Results of the systematic review

Compulsory hospital admission

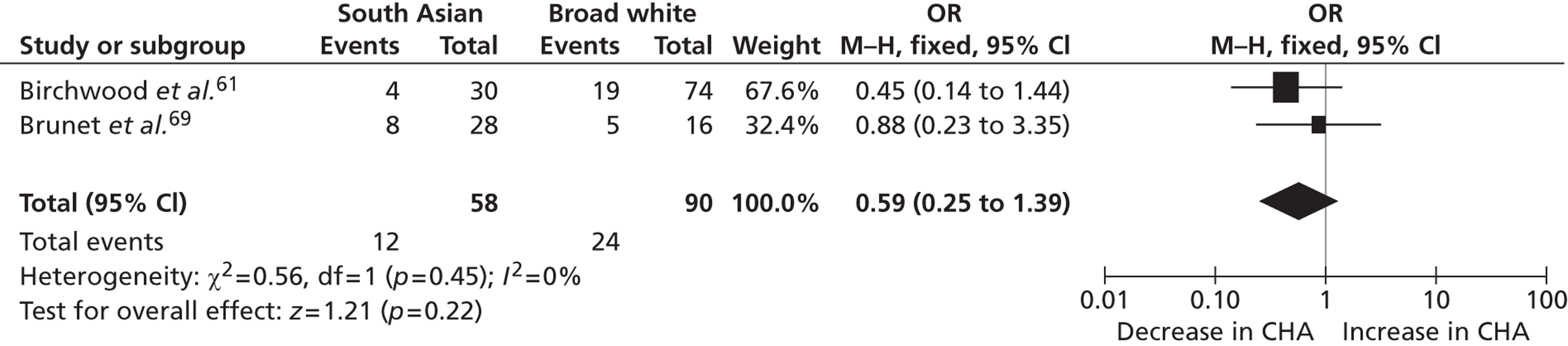

The results of the meta-analysis showed that black Caribbean patients were significantly more likely to be compulsorily detained during FEP. Specifically, black Caribbean patients were 2.39 times more likely to be detained than white British patients [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.62 to 3.52, p = 0.0001, Figure 2] and 2.13 times more likely to be detained than non-black Caribbean patients (95% CI 1.64 to 2.76, p = 0.00001, Figure 3). This finding was also true for broadly defined black patients (black Caribbean, black African and black ‘other’ patients) compared with non-black patients (2.33, 95% CI 1.85 to 2.93, p = 0.00001, Figure 4) but not for Asian patients compared with white patients (0.59, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.39, p = 0.22, Figure 5).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot for studies included in the comparison of black Caribbean patients and white British patients for compulsory hospital admission.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot for studies included in the comparison of black Caribbean patients and non-black Caribbean patients for compulsory hospital admission.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot for studies included in the comparison of broadly defined black patients and non-broadly defined black patients for compulsory hospital admission.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot for studies included in the comparison of Asian patients and white patients for compulsory hospital admission.

The following explanations were offered for ethnic variation in compulsory hospital admission.

Harrison et al. 64 found that compulsory hospital admission was significantly higher amongst black Caribbean women than amongst other British women. However, no differences were found for men across different ethnic groups. In addition, when ethnic comparisons were made for those aged < 30 years only, the increased rate of admission amongst black Caribbean patients was reduced. The authors suggested that gender and age may account for the increased detention levels amongst some BME groups.

The findings of the study by Morgan et al. 10 were in direct contrast to those of the study by Harrison et al. 64 In this study, African Caribbean men were 4.75 times more likely to experience compulsory hospital admission then white British patients (95% CI 2.41 to 9.38, p < 0.0001). Such a difference was not found for either African Caribbean women or the entire black African group. In relation to age, the authors found a higher level of compulsory hospital admissions amongst younger African Caribbean patients.

Morgan et al. 10 attempted to control for confounders using two logistic regression models. In addition to ethnicity, the first model included employment status, criminal justice agency referral, perceived risk to others, self-initiated help-seeking and diagnosis with detention as the outcome variable. In the second model, an additional interaction effect term ‘African Caribbean ethnicity against gender’ was included. The results of the first analysis demonstrated that, in addition to African Caribbean and black African ethnicity, unemployment, manic psychosis, perceived risk to others, criminal justice agency referral and self-initiated help-seeking all predicted compulsory hospital admission. In the second analysis, with the interaction effect term included, African Caribbean men were 3.52 times more likely to be detained, a rate that was higher than the unadjusted rate. Being unemployed, perceived as being a risk to others, affective psychosis and self-initiated help-seeking also remained significant in the model. It seems, therefore, that, amongst men, being African Caribbean significantly increases the risk of being detained.

Criminal justice agency involvement

The results of the meta-analyses showed that black Caribbean patients were roughly twice as likely as non-African Caribbean patients to experience criminal justice agency involvement in their pathways to care during FEP [odds ratio (OR) 2.05, 95% CI 1.51 to 2.80, p < 0.00001, Figure 6]; similarly, black patients (broadly defined) were roughly twice as likely as non-black patients to experience criminal justice agency involvement in their pathways to care during FEP (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.74 to 2.92, p < 0.00001, Figure 7).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot for studies included in the African Caribbean vs. non-African Caribbean comparison of criminal justice agency involvement.

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot for studies included in the broad black vs. non-black comparison of criminal justice agency involvement.

Of the five studies, only Morgan et al. 11 explored the determinants of these differences. First, the authors calculated the unadjusted ORs for all variables that predicted criminal justice agency involvement in addition to ethnicity. The results showed that unemployment, living status, diagnosis and family involvement were all associated with criminal justice agency involvement. In a multiple regression model, black African ethnicity no longer remained significant, suggesting that these variables accounted for the increased criminal justice agency involvement amongst this group.

General practitioner referral

The results of the meta-analyses suggested that black patients were significantly less likely than non-black patients to have GP involvement in their pathway to care during FEP (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.72, p = 0.0001, Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Forest plot for studies included in the comparison of broadly defined black patients and non-broadly defined black patients for GP involvement.

Morgan et al. 10 demonstrated that, when confounders such as living circumstances, gender, help-seeking patterns and family involvement were controlled for, the odds of excess detention in black patients were significantly reduced.

Findings from the systematic review

Overall, our review provides strong evidence for ethnic differences in pathways to care during FEP. In particular, black and African Caribbean patients are significantly more likely to experience adverse pathways to care during first presentation. There is no clear pattern in the predictors of such ethnic differences, although younger age, male gender, low level of social support and clinical differences in level of risk account for some of the observed ethnic differences in compulsory detention and criminal justice agency involvement.

There is some evidence, mainly from small qualitative studies, that mental health help-seeking amongst BME groups is strongly influenced by culturally mediated attributions of mental disorders, in particular religious and spiritual attributions, and by stigma and shame within BME communities.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has attempted to explore attributions and help-seeking behaviour in emerging psychosis to determine whether or not these might explain some of the ethnic differences in pathways to care. In particular, inter- and intra-ethnic differences have not been explored; instead, BME groups have been compared as homogeneous entities with a homogeneous and contrasting white population. These lacunae in our knowledge were the drivers for evidence gathering that is the ENRICH programme.

Chapter 4 Study 1: determinants of ethnic variation in pathways to care during first-episode psychosis

Abstract

Introduction: Black and minority ethnic patients in the UK are known to experience adverse pathways into care for FEP. Several explanations have been offered for these differences, ranging from institutional racism in psychiatry to differences in clinical presentation. However, the role of culturally mediated attributions of emerging symptoms in psychosis and how these influence help-seeking has not been explored in a systematic manner.

Methods: A prospective cohort of all consenting, newly accepted first-episode of psychosis patients was approached to take part in an in-depth semistructured interview using the Nottingham Onset Schedule (NOS), the Emerging Psychosis Attribution Schedule (EPAS) and the Amended Encounter Form. Qualitative analyses were conducted on a subsample of NOS interviews, stratified by ethnicity.

Results: A total of 132 patients were recruited (45 white, 35 black, 43 Asian and nine ‘other’ patients). There were no ethnic differences in duration of untreated psychosis and duration of untreated illness. Duration of untreated psychosis was not related to illness attribution; long duration of untreated psychosis was associated with patients being young (< 18 years) and living alone. During the prodromal phase of the illness, ‘social world’ attributions were most common and patients sought help from health agencies. With the emergence of psychotic symptoms, BME patients and carers, in particular British Asians, were significantly more likely to have ‘supernatural’ attributions and seek faith-based help.

Conclusions: Culturally mediated attributions of emerging symptoms of psychosis are an important and hitherto unexplored variable that may explain ethnic differences in pathways to care.

Aims and objectives

This mixed-methods study used both quantitative and qualitative approaches to assess ethnic variation in the process of help-seeking during FEP. The overall aim of the study was to understand ethnic variation in pathways to care in FEP by exploring sociocultural determinants of illness recognition, attribution and help-seeking among different ethnic groups. The specific research questions were as follows:

-

Are there ethnic differences in how patients and their carers recognise and understand early signs of psychosis?

-

Are such differences a function of cultural factors such as explanatory models of illness or are these related to socioeconomic status, deprivation and isolation?

-

Do biological as opposed to psychological or social explanatory models of illness predict early medical help-seeking and shorter DUP?

Quantitative study 1

Methodology

Patients were recruited from the early intervention services of the BSMHFT. The trust provides psychiatric care for the geographical area of Birmingham and the neighbouring borough of Solihull. All participants in this study were recruited from the early intervention service in Birmingham as the Solihull early intervention service was not yet established at the time of study commencement.

Birmingham city has a population of 1,073,045 (BCC, census and population data 2012) from diverse socioeconomic, ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The 2011 ethnic breakdown of the city population was estimated as 53.1% white, 4.4% Caribbean, 2.8% African and 22.5% South Asian; the remainder were from ‘other’ ethnic groups (see Appendix 4). 71 The Birmingham early intervention service provides comprehensive community-based care for all people aged between 16 and 35 years experiencing a FEP. Specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) nurses also work in this service in collaboration with local CAMHS services for patients aged < 16 years.

Sample

All patients attending the Birmingham early intervention service (within the BSMHFT) who were able to give informed consent were invited to participate in the study. Researchers regularly screened all new referral lists for potential participants. Each eligible participant’s community psychiatric nurse (CPN) was approached to determine whether the patient was well enough to take part in terms of symptoms, general well-being and recovery. If the CPN felt that the patient was suitable, the information sheet and consent form were given to the CPN to give to the patient. If the patient agreed to meet the research team, a researcher contacted the patient to explain the study and answer any questions. The initial contact with the research team took place at a venue suitable for the patient, including in the patient’s home if requested. During the consenting process, participants were also asked if the research team could invite a carer to participate in the study. The definition of a carer for the purpose of this study was someone who had played an important role in the major decisions related to the service user’s journey to care and was identified thus by the patient. Separate informed consents were obtained from patients and their carers.

Recruitment of cases

The early intervention service in Birmingham is a highly research-active service. During the 2-year period of data collection, various other research projects were being conducted, including studies carried out by medical, clinical psychology and PhD students. It is likely that this affected patient recruitment, as care co-ordinators often reported that their patients were unwilling to engage with further lengthy assessments, or were too busy with other commitments to engage with another study. Although we approached all consecutive cases over this time, we did not recruit all eligible cases as participation was voluntary. Patients who refused initially were approached once more for participation. After the second refusal they were not approached again. We made comprehensive notes detailing reasons for non-participation. For illustrative purposes, we describe here the reasons for non-participation from one early intervention services team: 34.4% were recruited, 19.4% declined as they were not interested in research, 17.9% were unsuitable to give informed consent, 7.5% were not recruited because they were not engaging clinically with services, 6% refused without specifying a reason and the remainder refused for other reasons.

Over the 2-year study period, 499 patients were accepted into early intervention services. Of these, 31.5% were white, 20.9% were black, 36.1% were Asian and 11.4% were from other ethnic groups. In total, 66.3% of the participants were male and the average age of the sample was 22.59 years.

To ensure that our sample was representative, comparisons were made between participants recruited into the ENRICH study and the 2-year total early intervention service (EIS) intake (Table 2).

| Ethnic group | Proportion of ethnic group in cohort (%) | Mean age of ethnic group (years) | Male (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-year EIS intake | ENRICH sample | 2-year EIS intake | ENRICH sample | 2-year EIS intake | ENRICH sample | |

| White | 31.5 | 34.1 | 21.97 | 23.13 | 64.30 | 80.00 |

| Black | 20.9 | 26.5 | 22.92 | 22.17 | 67.30 | 68.60 |

| Asian | 36.1 | 32.6 | 21.82 | 23.72 | 69.40 | 72.10 |

| Other | 11.4 | 6.5 | 24.91 | 21.00 | 59.60 | 66.70 |

Measures

Data were collected using the following measures.

Sociodemographics

Data were recorded on age, gender, ethnicity, religious affiliation, living and employment status, postcode and occupation. The service user general information sheet is provided in Appendix 5. Ethnicity was recorded in two ways. First, participants were asked to describe their ethnicity in their own words. This was recorded verbatim. Second, a list of census categories was presented to participants and they were asked to select the category that best represented their ethnic group. As there was consistency across the sample between these two methods, the standardised census categorisation method was used in the analysis. From this, the following four groups were created for analyses:

-

white (white British, white Irish, white ‘other’)

-

black (black/black British Caribbean, black/black British African)

-

Asian (Asian/Asian British Pakistani, Asian/Asian British Indian, Asian/Asian British Bangladeshi)

-

‘other’ (mixed white/black Caribbean, mixed ‘other’).

Nottingham Onset Schedule

The NOS72 is a short guided interview and rating schedule for establishing the chronology and components of symptom development in a FEP. The patient’s history is collected before the interview from medical notes and clinical correspondence to develop a preliminary timeline. This timeline is then used with the patient (and the carer if available) to guide the NOS interview. Once all available information is collected, a final timeline and the following four time points are derived (see Appendix 6):

-

Prodrome. The onset of prodrome is defined as the phase of illness from the emergence of prodromal symptoms to the development of psychotic disorder. Prodromal symptoms usually include non-specific disturbance of mood, thinking, behaviour, perception and functioning. For such symptoms to be considered as part of the psychotic illness there should be no return to premorbid functioning following onset of these symptoms.

-

First psychotic symptom. Unequivocal presence of one or more positive psychotic symptoms, rating 2 (minimal) or 3 (mild) on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), characterised by the definite presence of the symptom, which, though clearly evident, occurs only occasionally or intrudes on daily life mildly. In some cases this phase of illness may not be easily separated from the preceding phase.

-

Definite diagnosis. A rating of ≥ 4 on any one of the positive symptoms from the PANSS or a group of positive symptoms on the PANSS with a collective rating of ≥ 7, not including those scored as 1 (absent). Symptoms should have occurred for at least 1 week (transition into psychosis).

-

Date of start of antipsychotics at adequate dosage. Adequate dosage is defined as evidence that medication is being taken at ≥ 75% of the prescribed dosage and for ≥ 75% of the prescribed time. Compliance may be assumed when a patient is on home treatment or is hospitalised and there is no record of non-compliance. When a patient has initially been non-compliant, the start date of treatment recommencement and compliance is used.

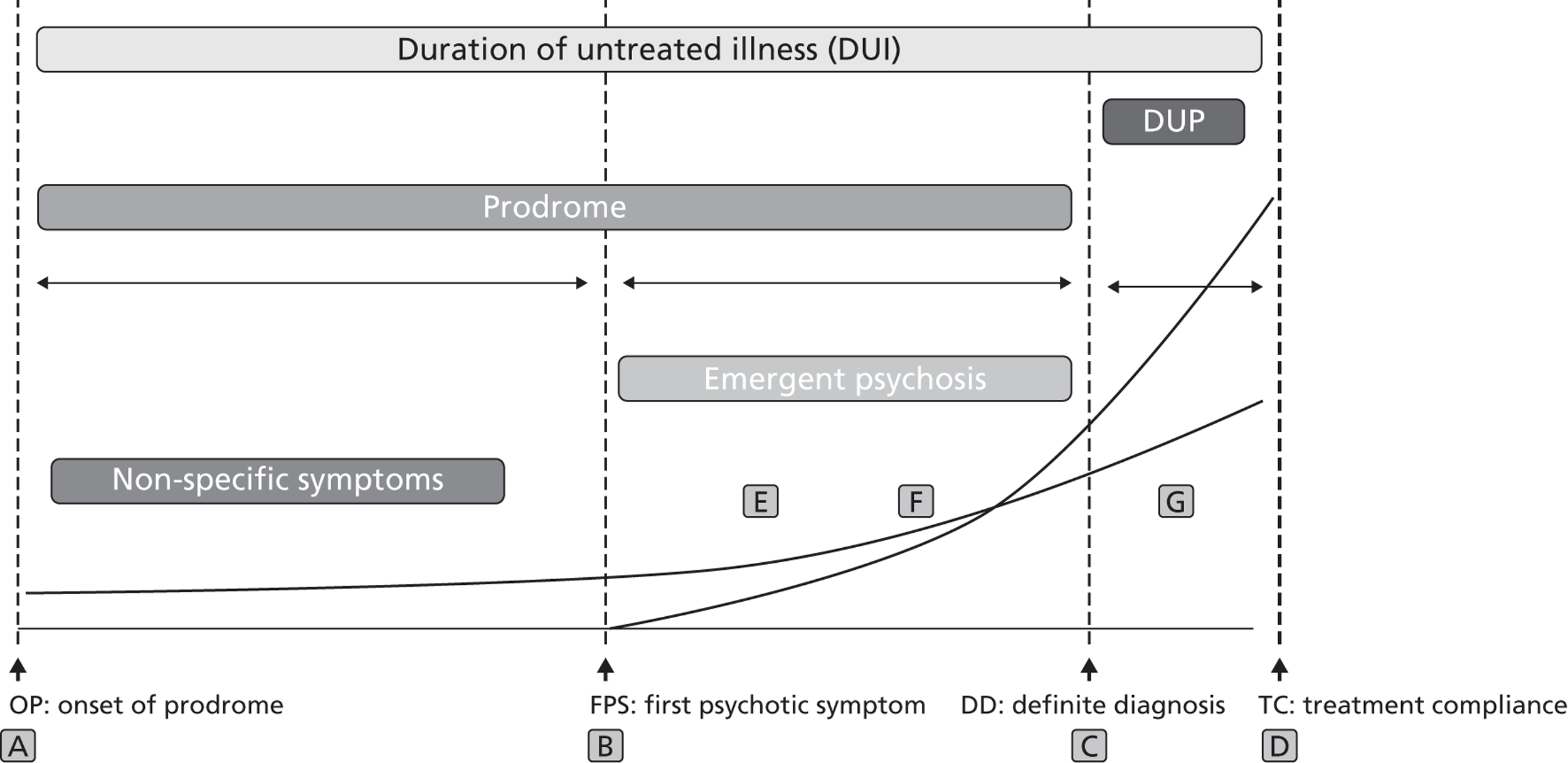

Once these time points had been established, three illness phases were created, as illustrated in Figure 9:

-

prodrome (early phase of illness between points A and C)

-

DUP (period of FEP, between points C and D)

-

duration of untreated illness (DUI) (between points A and D).

FIGURE 9.

Components in the development of FEP, as established by the NOS. Note: the thin black lines running horizontally represent the unfolding of symptoms through the various stages.

The NOS has high test–retest and inter-rater reliability72 and is a standard measure for DUP in several early intervention services. 73

Emerging Psychosis Attribution Schedule

In the original ENRICH programme proposal, we intended to use the Short Explanatory Model Interview (SEMI)74 to capture how participants attributed the causes of their symptoms. After further consideration we realised that the tool had two limitations. The first was that its terminology was overtly medical, which the research team felt might bias the responses of participants with non-medical explanations and attributions. Second, the SEMI is a cross-sectional method and does not distinguish symptom attribution during early and later stages of the disorder.

We decided to develop a specific schedule to complement the NOS interview, using a similar approach as SEMI but capturing symptom attribution over time and without a medical bias. The EPAS is a semistructured interview guide, implementation protocol and coding manual used to elicit attributional responses of symptoms identified during the NOS (see Appendix 7). Both patients and carer-informants are asked to recall how they attributed a symptom at the time the symptom first appeared, as recalled during the NOS interview. Individual responses are then categorised into one of six broad groups, loosely based on the anthropological work of Cecil Helman21 on cultural beliefs of illness:

-

Within the individual. Attributions that locate the origin of ill health within, or arising from within, the individual. Here, attributions are likely to refer to psychological and/or physiological causes, genetic or hereditary factors and factors relating to the sufferer’s personality or character.

-

The natural world. Relating the cause of the illness to natural occurrences, such as germs/infections or environmental agents/toxins. In addition, attributions described as reactions to accidents, injuries or medicinal/illicit drug use are included here.

-

The social world. Related to factors in the sufferer’s social world, such as other people or social experiences and adverse events.

-

The supernatural world. Emanating from non-natural domains, such as interactions with supernatural forces, superhuman influences, spiritual possession and supernatural punishment.

-

Unawareness of symptoms. This category was specifically developed to capture responses in which no attribution of causation was reported, despite the participant being aware of symptoms.

-

Cannot code. When no attributions were made or attributions did not fit with the categories above.

All responses were then grouped and assigned to either the prodromal or the psychotic phase of illness (see above for definition).

The inter-rater reliability of the EPAS was determined. A total of 15 randomly selected transcripts of symptom attribution interviews were coded by two researchers. In all, 64 separate attribution statements were elicited across the transcripts, which both researchers independently coded into one of the six codes. Before coding, both researchers were trained in attribution coding and were familiar with the EPAS coding manual. Inter-rater agreement was good between researchers, achieving a kappa coefficient of 0.763 across all elicited attributions.

Illness encounters and pathways to care

Although several pathways to care measures are available,5 we could not identify an illness encounter tool that specifically met the needs of this study. We therefore used an amended version of the encounter form from Gater et al. 75 in which an interview and coding protocol were created to ensure consistency between researchers (see Appendix 8). As with the NOS, all medical notes and correspondence are collated into a timeline detailing the patient’s journey to psychiatric care. This is presented to the patient and carer-informant and they are asked to confirm that it is correct as well as describe any other help-seeking avenues (illness encounters) that they may have used. Participants are specifically asked to recall help-seeking during the prodromal phase of the illness, as medical records rarely capture such information. Likewise, third-sector/voluntary and faith-based illness encounters are specifically asked for. From this, three main sets of data are established:

-

Encounter type – the types of contact that each participant made on his or her pathway to psychiatric services (e.g. faith organisation, mental health services, local GP, police).

-

Help-seeking initiation – the person(s) responsible for the initiation of the encounter contact (patient own choice, joint decision with family/friends or family choice alone).

-

Help-seeking support – people who attended each encounter (patient on his or her own, with family and friends, or family/friends on their own).

All researchers were trained on this measure before study commencement.

Data collection procedure

After a patient had consented to participate in the study, a date, time and location for the interview were agreed between the patient and the researcher. Before the assessment began, patients were asked whether the interview could be digitally audio recorded. If they declined, one of the two researchers present at the interview conducted the interview to complete the schedules and the other made comprehensive notes for later scrutiny.

Before appointments, researchers screened medical records to create NOS, EPAS and Encounter timelines. During the interviews, participants were reminded about the reasons for the assessments and any queries/concerns were addressed. Once the sociodemographic data had been collected, the NOS and EPAS were administered. In addition, researchers listened carefully for instances of participants giving spontaneous attributions during the NOS phase of the interview. Finally, help-seeking attempts and pathways to care were determined using the ENRICH encounter form. The same procedure was followed in interviews with carers/informants.

Data coding and storage

After the interviews, two researchers rated the schedules to agree the final timelines, attributions and pathways to care. Causal attribution data were coded into categorical variables and clustered into developmental phases identified by the NOS (i.e. prodrome and FEP). Carer-informant and patient data remained separate through this process. After coding, all information was electronically input onto a secure clinical database (openCDMS), designed and hosted especially for the study by the Heart of England Mental Health Research Network (MHRN). The database is a secure password-protected interface that allows multiple researchers to input data simultaneously onto one database. Data were then output into SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) data files for analysis.

Data analysis

The data were analysed in an agreed sequence. We first explored ethnic variation in sociodemographic variables, clinical variables such as DUP, help-seeking and encounter variables, and symptom attributions. Descriptive statistics were used to identify trends, which were then subjected to statistical testing. Second, we identified ethnic differences in relation to pathway to care encounters using the chi-squared test. Third, we attempted to understand the determinants of these differences. Unadjusted ORs were calculated for all variables against each pathway to care encounter that was shown to have some association with ethnicity in the previous phase. Factors shown to influence these outcomes were taken forward into a logistic regression model, in addition to ethnicity, in the final and fourth stage.

Attribution analyses

It was clear, even during data collection, that participants gave multiple, sometimes conflicting, symptom attributions during both the early and the later stages of illness. We therefore devised a system to give a proportional score for each attribution type. For each illness phase (prodrome and DUP), the number of attributions given for each attribution category was divided by the overall number of attributions in that phase and then multiplied by 100. A standardised score, interpreted simply as a percentage, was therefore calculated for each of the five attribution types for each participant. When an ethnic comparison was made, the mean scores for each group were used. An example of the attribution scoring method is shown in Box 1.

Participant ENR089 gave eight attributions in total during her interview, five for prodromal symptoms and three for psychotic ones. During the prodromal phase of the illness, one was ‘within the individual’, three were in the ‘social world’ and one was in the ‘natural world’. During the psychotic phase of the illness she gave one ‘social world’, one ‘natural world’ and one ‘unaware’ attribution.

Attribution scoring matrix| Attribution category | Prodrome score | Psychosis score |

|---|---|---|

| Within the individual | 1/5 × 100 = 20 | 0/3 × 100 = 0 |

| Social world | 3/5 × 100 = 60 | 1/3 × 100 = 33.3 |

| Natural world | 1/5 × 100 = 20 | 1/3 × 100 = 33.3 |

| Supernatural world | 0/5 × 100 = 0 | 0/3 × 100 = 0 |

| Unawareness of symptoms | 0/5 × 100 = 0 | 1/3 × 100 = 33.3 |

During the prodromal phase of the illness, participant ENR89 gave predominantly ‘social world’ attributions (60%) followed by ‘within the individual’ (20%) and ‘natural world’ (20%) attributions equally. During the psychotic phase of the illness she gave ‘social world’, ‘natural world’ and ‘unaware’ attributions equally (33.3%).

Encounter analyses

The same approach was used for comparisons between each of the encounter variables. For each, we divided the number of reported categories within that variable by the overall number of help-seeking attempts. A score was then derived, which was comparable between participants and across groups when group averages were taken (e.g. participant A made 10 help-seeking attempts during the psychotic phase of her illness; three of these were with her local GP and therefore her GP help-seeking score is 30%). Further details are provided in Box 2.

Participant ENR04 made a total of 10 encounter contacts in his pathways to care. In total, he made three visits to the GP, was referred to his local CMHT, sought help from a local pastor, went to the A&E department twice, was hospitalised, was placed on home treatment and finally came into the care of early intervention services. Once coded under the ENRICH encounter coding system, patient ENR04 made five GP/A&E encounters, one faith encounter, three mental health service encounters and one early intervention encounter.

Attribution scoring matrix| Attribution category | Encounter score |

|---|---|

| Mental health service encounters | 3/10 × 100 = 30 |

| Faith encounters | 1/10 × 100 = 10 |

| GP/A&E encounters | 5/10 × 100 = 50 |

| Early intervention encounters | 1/10 × 100 = 10 |

| Voluntary and third-sector organisation encounters | 0/10 × 100 = 0 |

In this case, this patient predominantly sought help within primary care and emergency services. It is also clear that he made no contact with third-sector and voluntary organisations.

Help-seeking analyses

Finally, we attempted to explore ethnic variation in help-seeking initiation and help-seeking support. In doing so, we calculated a proportional score for ‘within each participant’ and ‘within each group’. Higher scores reflect a higher rate of occurrence than lower scores. The following scores were calculated:

-

help-seeking initiation scores:

-

patient only: the proportion of help-seeking initiated solely by the patient

-

patient and family: the proportion of help-seeking initiated jointly by patients and carers

-

family and friends only: the proportion of help-seeking initiated by family and friends only

-

encounter contact approached client: the proportion of help-seeking initiated by services (police and compulsory admission).

-

-

help-seeking social support scores:

-

patient only: the proportion of encounters attended by the patient alone

-

patient and family: the proportion of encounters attended by both patient and family members

-

family only: the proportion of encounters attended by family members only.

-

It is important to note that these scores are not percentages because they do not add up to 100, as not every participant can be categorised.

Deprivation levels

Postcodes were collected from each participant during the interviews. In cases in which participants had recently moved, the postcode of their residency during their psychotic illness was requested. The English Indices of Deprivation (IMD) 201076 is a composite measure of deprivation in England scoring geographical location (postcode proxies) based on income level, employment, health and disability, education, skills and training, barriers to housing and services, crime, and living environment. Postcode deprivation scores were categorised into decile, with the bottom decile representing the highest levels of deprivation and the top the lowest. Each participant was then assigned to one IMD decile category, which was then used to explore ethnic differences.

Results

A total of 132 participants were recruited from early intervention services in Birmingham over a 2-year period (2008–10). Of these, 45 (34.1%) were categorised as white, 35 (26.5%) as black, 43 (32.6%) as Asian and nine (6.8%) as ‘other’. Table 3 shows the sociodemographic profile of the sample. Participants predominantly were male (73.5%), were young [20.73 years, standard deviation (SD) 5.53 years], had a psychotic disorder (schizophrenia 68.9%) and were born in the UK (81.8%).

| Characteristic | White (n = 45), n (%) | Black (n = 35), n (%) | Asian (n = 43), n (%) | Other (n = 9), n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: male | 36 (80.0) | 24 (68.6) | 31 (72.1) | 6 (66.7) | 0.643 |

| Age at assessment (mean years) | 23.13 | 22.71 | 23.72 | 21 | 0.320 |

| Educational achievement | |||||

| To school level | 22 (48.9) | 20 (57.1) | 22 (51.2) | 4 (44.4) | 0.960 |

| Beyond school level | 23 (51.1) | 15 (42.9) | 21 (48.8) | 5 (55.6) | |

| Religious affiliation | |||||

| Christianity | 15 (33.3) | 29 (82.9) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (55.6) | – |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Islam | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.9) | 36 (83.7) | 1 (11.1) | |

| None | 29 (64.4) | 4 (11.4) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Not practising religion | 38 (84.4) | 16 (45.7) | 11 (25.6) | 6 (66.7) | – |

| Migrant generation | |||||

| First generation | 1 (2.2) | 13 (37.1) | 13 (30.2) | 1 (11.1) | – |

| Second generation | 0 (0.0) | 8 (22.9) | 24 (55.8) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Third generation | 1 (2.2) | 14 (40.0) | 6 (14.0) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Not applicable | 43 (95.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Country of birth | |||||

| Africa | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.160 |

| Caribbean | 0 (0.0) | 8 (22.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | |

| South Asia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (23.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| UK | 44 (97.8) | 23 (65.7) | 33 (76.7) | 8 (88.9) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 3 (6.7) | 1 (2.9) | 9 (20.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.081 |

| Single | 42 (93.3) | 34 (97.1) | 34 (79.1) | 9 (100) | |

| Living status | |||||

| Alone | 8 (17.8) | 17 (48.6) | 4 (9.3) | 5 (55.6) | – |

| With family/friends/others | 37 (82.2) | 18 (51.4) | 39 (90.7) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Age at onset (years) | |||||

| < 18 | 15 (33.3) | 12 (34.3) | 16 (37.2) | 5 (55.6) | – |

| > 18 | 30 (66.7) | 23 (65.7) | 27 (62.8) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Not in work or education at time of onset | 18 (40.0) | 14 (40.0) | 16 (37.2) | 4 (44.4) | 0.978 |

| IMD | |||||

| Bottom 10% | 16 (35.6) | 16 (50.0) | 28 (68.3) | 6 (75.0) | – |

| 10–20% | 10 (22.2) | 7 (21.9) | 6 (14.6) | 2 (25.0) | |

| 20–30% | 5 (11.1) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 40%+ | 14 (31.1) | 4 (12.5) | 5 (12.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

There were very few demographic differences between the ethnic groups; however, there was some variation in religious affiliation and practice. In total, 83.7% of the Asian sample reported having a religious affiliation to Islam and 82.9% of the black sample reported a religious affiliation to Christianity; 64.4% of the white group declared no religious affiliation at all. In relation to religious practice, 74.4% of the Asian participants, 54.3% of the black participants and 15.6% of the white participants practiced a religion. On the whole, deprivation levels in the cohort were high, with the whole sample falling into the bottom 40% of national deprivation levels. About two-thirds (68.3%) of the Asian sample were in the bottom 10% in comparison to 50.0% of the black sample and 35.6% of the white sample (see Table 3).

In total, 71 carers were recruited of whom 28 (39.4%) were white, 16 (22.5%) were black, 23 were Asian (32.4%) and four (5.6) were in the ‘other’ group (Table 4). Like the patients, there were clear differences between religious affiliation and practice, with 20 carers (87%) from the Asian group having a religious affiliation to Islam and 15 carers (53.6%) from the white group and 14 (87.5%) carers from the black group having a religious affiliation to Christianity. The majority of the black and Asian carers but not the white carers reported that they did practice a religion (see Table 4).

| Characteristic | White (n = 28), n (%) | Black (n = 16), n (%) | Asian (n = 23), n (%) | Other (n = 4), n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: male | 4 (14.3) | 5 (31.3) | 7 (30.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.287 |

| Age at assessment (mean years) | 43.89 | 43.19 | 43.95 | 46.67 | – |

| Educational achievement | |||||

| To school level | 13 (46.4) | 7 (43.8) | 12 (52.2) | 2 (50.0) | 0.958 |

| Beyond school level | 15 (53.6) | 9 (56.3) | 11 (47.8) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Religious affiliation | |||||

| Christianity | 15 (53.6) | 14 (87.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | – |

| Other | 2 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Islam | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (87.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| None | 11 (39.3) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not practising religion | 23 (82.1) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (50.0) | – |

| Migrant generation | |||||

| First generation | 1 (3.6) | 6 (37.5) | 12 (52.2) | 1 (25.0) | – |

| Second generation | 0 (0.0) | 8 (50.0) | 10 (43.5) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Third generation | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not applicable | 27 (96.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Country of birth | |||||

| Africa | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Caribbean | 0 (0.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| South Asia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (73.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| UK | 27 (96.4) | 8 (50.0) | 6 (26.1) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 14 (50.0) | 10 (62.5) | 16 (69.6) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Single | 14 (50.0) | 6 (37.5) | 7 (30.4) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Living status | |||||

| Alone | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| With family/friends/others | 26 (92.9) | 16 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | |

Ethnic comparison of clinical variables

The descriptive statistics of the clinical factors for each ethnic group are shown in Table 5.

| White (n = 45), n (%) | Black (n = 35), n (%) | Asian (n = 43), n (%) | Other (n = 9), n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DUP (median dichotomised) | |||||

| Short | 26 (57.8) | 18 (51.4) | 18 (41.9) | 4 (44.4) | 0.500 |

| Long | 19 (42.2) | 17 (48.6) | 25 (58.1) | 5 (55.6) | |

| DUP (6-month cut-off) | |||||

| Short | 19 (42.2) | 13 (37.1) | 16 (37.2) | 1 (11.1) | – |

| Long | 26 (57.8) | 22 (62.9) | 27 (62.8) | 8 (88.9) | |

| Prodrome length | |||||

| Short | 16 (35.6) | 20 (57.1) | 26 (60.5) | 5 (55.6) | 0.920 |

| Long | 29 (64.4) | 15 (42.9) | 17 (39.5) | 4 (44.4) | |

| DUI | |||||

| Short | 18 (40.0) | 19 (54.3) | 24 (55.8) | 5 (55.6) | 0.432 |

| Long | 27 (60.0) | 16 (45.7) | 19 (44.2) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Broad schizophrenia | 27 (60.0) | 27 (77.1) | 30 (69.8) | 7 (77.8) | – |

| Depressive psychosis | 14 (31.1) | 7 (20.0) | 9 (20.9) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Manic psychosis | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (4.4) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

Duration of untreated illness

Overall, the median DUI in our sample was 1095 days (mean 1454.7 days, SD 1416 days, range 8–8093 days). We dichotomised DUI using the median into two categories: long DUI (> 1095 days) and short DUI (≤ 1095 days). In our sample, 60% of the white group had a long DUI whereas the other groups had a predominantly short DUI (see Table 5). However, across the four groups, there was no significant difference in DUI length (χ2 = 2.750, df = 3, p = 0.432).

Prodrome length

Overall, the median prodrome length was 365 days. As with the DUI data, we dichotomised prodrome length into two groups: long prodrome length (> 365 days) and short prodrome length (≤ 365 days). Two-thirds (64%) of the white sample had a long prodrome length whereas in the BME groups the prodrome length was predominantly short (see Table 5). However, again, no significant difference was observed across all ethnic groups (χ2 = 6.436, df = 3, p = 0.092). When individual BME groups were compared with the white group, a significantly shorter prodrome length was found for both the black group (B = 0.414, 95% CI 0.167 to 1.024, p = 0.05) and the Asian group (B = 0.361, 95% CI 0.152 to 0.856, p = 0.02).

Duration of untreated psychosis

Duration of untreated psychosis was analysed using two methods. The first method dichotomised DUP by the overall median. The median DUP for the overall sample was 357 days (11.9 months) and so the group was split into long DUP (> 357 days) and short DUP (≤ 357 days). Second, DUP was dichotomised using a 6-month cut-off (182.62 days). This is because of recent evidence that the critical DUP length that influences FEP outcome is 6 months; Drake et al. 77 have found poor recovery trajectories for those patients with a DUP > 6 months.

No significant ethnic differences in DUP length were observed based on median DUP dichotomy (χ2 = 2.368, df = 3, p = 0.500). Likewise, no significant differences were observed based on DUP dichotomised using a 6-month cut-off (χ2 = 3.110, df = 3, p = 0.375).

Encounter pathways

The descriptive statistics of the encounter pathways for each ethnic group are shown in Table 6. During the psychotic phase of illness there was a clear trend in the types of encounters that each group made during their pathways to care. In relation to faith encounters (spiritual and religious), 41.9% of Asian patients made contact with such services at least once, compared with 20.0% of the black group, 11.1% of the ‘other’ group and 0.0% of the white group. This difference was statistically significant (χ2 = 24.813, df = 3, p = 0.0001). Overall, black patients were 11 times more likely (B = 11.00, 95% CI 1.28 to 94.26, p = 0.029) and Asian patients were almost 32 times more likely (B = 31.680, 95% CI 3.99 to 251.72, p = 0.001) to experience faith encounters during their psychotic phase of illness than white patients.

| Encounter | White (n = 45), n (%) | Black (n = 35), n (%) | Asian (n = 43), n (%) | Other (n = 9), n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one faith encounter | 0 (0.0) | 7 (20.0) | 18 (41.9) | 1 (11.1) | 0.0001 |

| At least one criminal Justice agency encounter | 11 (24.4) | 16 (45.7) | 14 (32.6) | 4 (44.4) | 0.217 |

| At least one third-sector, education or social welfare encounter | 7 (15.6) | 9 (25.7) | 5 (11.6) | 3 (33.3) | 0.243 |

| At least one incidence of general practice involvement | 30 (66.7) | 18 (51.4) | 30 (69.8) | 7 (77.8) | 0.271 |

| At least one A&E encounter | 17 (37.8) | 17 (48.6) | 8 (18.6) | 3 (33.3) | 0.043 |

| At least one compulsory detention | 10 (22.2) | 20 (57.1) | 13 (30.2) | 3 (33.3) | 0.011 |

| Median number of encounters in prodrome | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Median number of encounters in FEP | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | – |

We also explored the interaction between ethnicity and criminal justice agency involvement and crisis (A&E) presentations. Almost half (45.7%) of the black group had at least one criminal justice agency encounter during the psychotic phase of illness compared with one-third (32.6%) of Asian patients and a quarter (24.4%) of white patients. The black group was roughly twice as likely to experience criminal justice agency involvement then the white group (B = 2.603, 95% CI 1.006 to 6.737, p = 0.049).

Black patients had the highest number of A&E encounters, with 48.6% making contact with services on one or more occasions during their psychotic episode; comparative figures for the Asian and white groups were 18.6% and 37.8% respectively (χ2 = 8.130, df = 3, p = 0.043). Asian patients were less likely to experience A&E encounters in their pathways to care (B = 0.376, 95% CI 0.142 to 0.999, p = 0.050) than white patients. No difference was found between the white and black groups (B = 1.556, 95% CI 0.635 to 3.810, p = 0.334). Black patients were less likely to make GP contact; however, no statistically significant differences were observed for GP contact between the three groups (χ2 = 3.912, df = 3, p = 0.271).

Finally, we explored ethnic variation in the use of compulsory hospital admission. Table 6 shows that 57.1% of black patients experienced compulsory hospital admission compared with 22.2% of white patients, 30.2% of Asian patients and 33.3% of ‘other’ patients. These differences were significant (χ2 = 11.235, df = 3, p = 0.011). Comparison with white patients, black patients were almost five times more likely to be compulsorily detained (B = 4.667, 95% CI 1.768 to 12.318, p = 0.002).

Rank order of help-seeking encounters

We further explored ethnic variation in the rank order of help-seeking encounters within each ethnic group. In doing so, we decided to use the encounter scoring system (see Box 2) to prevent ethnic variation in the total number of encounters score biasing our interpretation of the data. The results demonstrated that, during the prodrome phase of the illness, all three ethnic groups were most likely to seek help from NHS services (GPs and A&E departments). However, after NHS contact, black patients were more likely to seek help through community/voluntary organisations whereas white patients utilised specialised mental health services and Asian patients utilised faith organisations.

During the psychotic phase of illness there was similarity between the groups. All groups most often consulted mental health services. The second and third commonest help-seeking agencies were early intervention services and general health-care services (GPs and A&E). Criminal justice agency involvement ranked fourth for the black, white and ‘other’ ethnic groups whereas faith organisations ranked fourth for the Asian group.

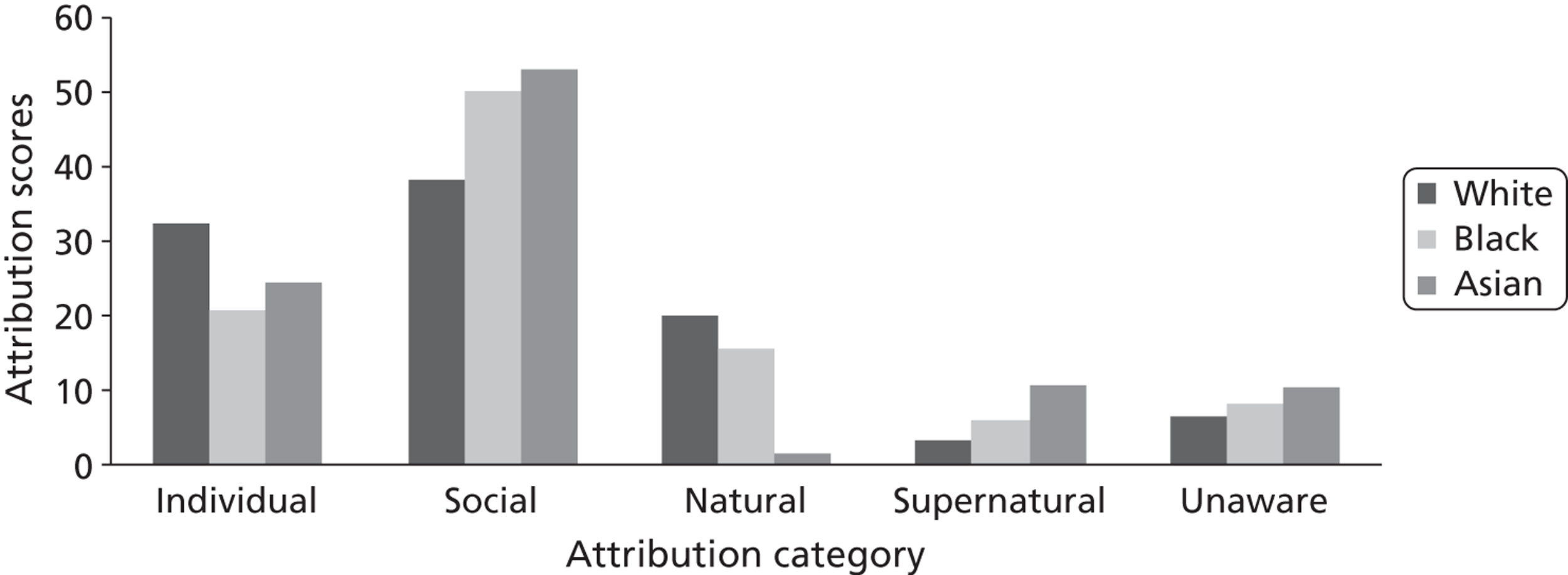

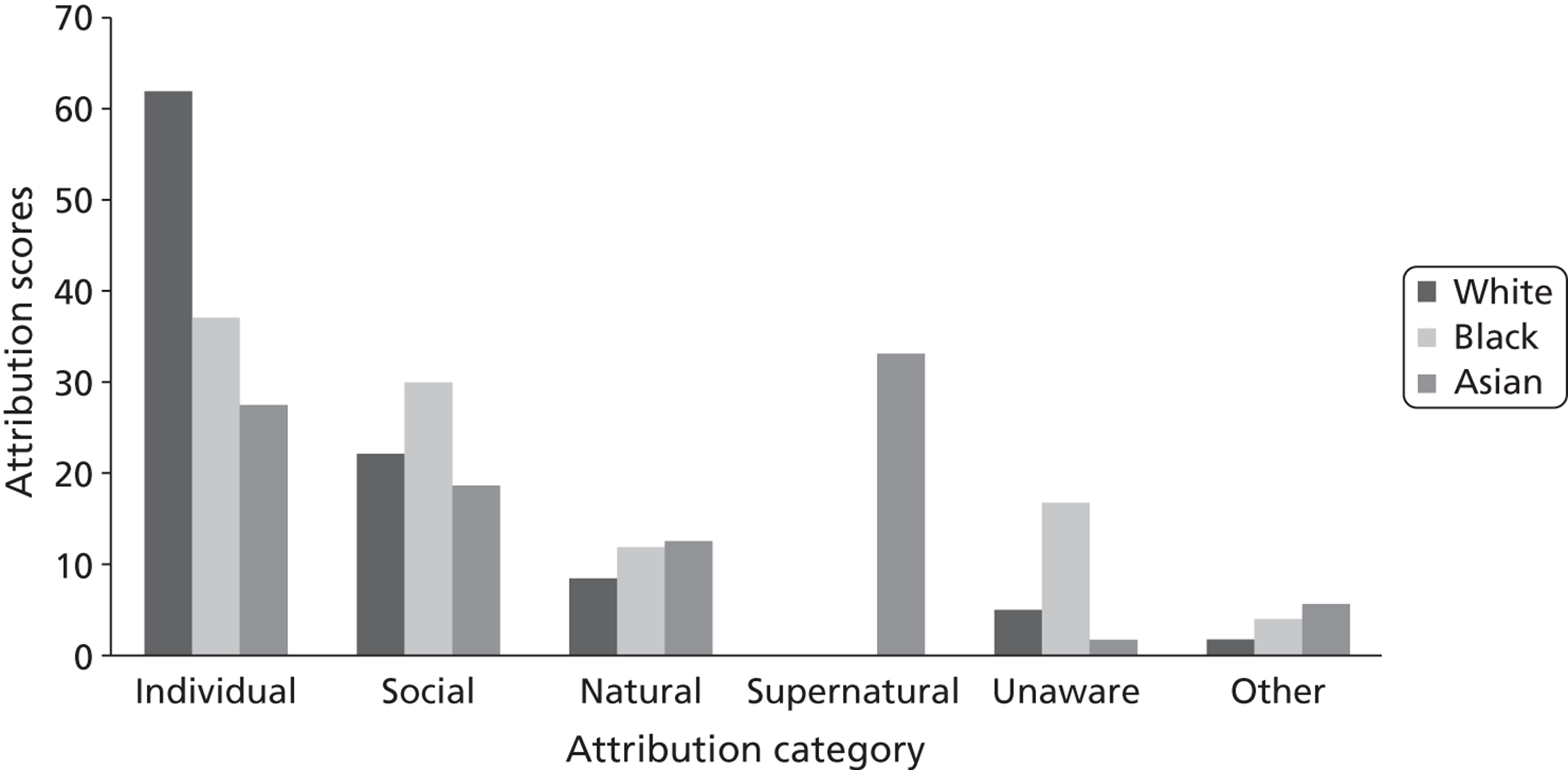

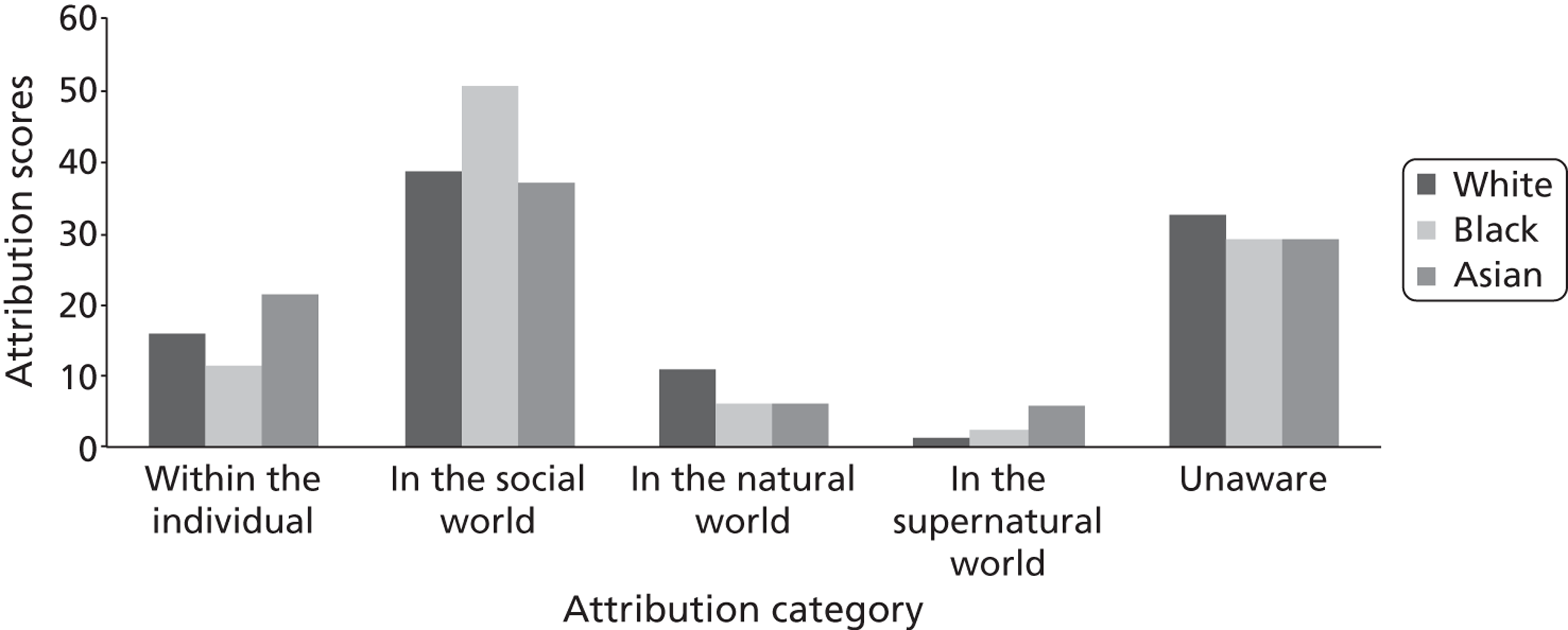

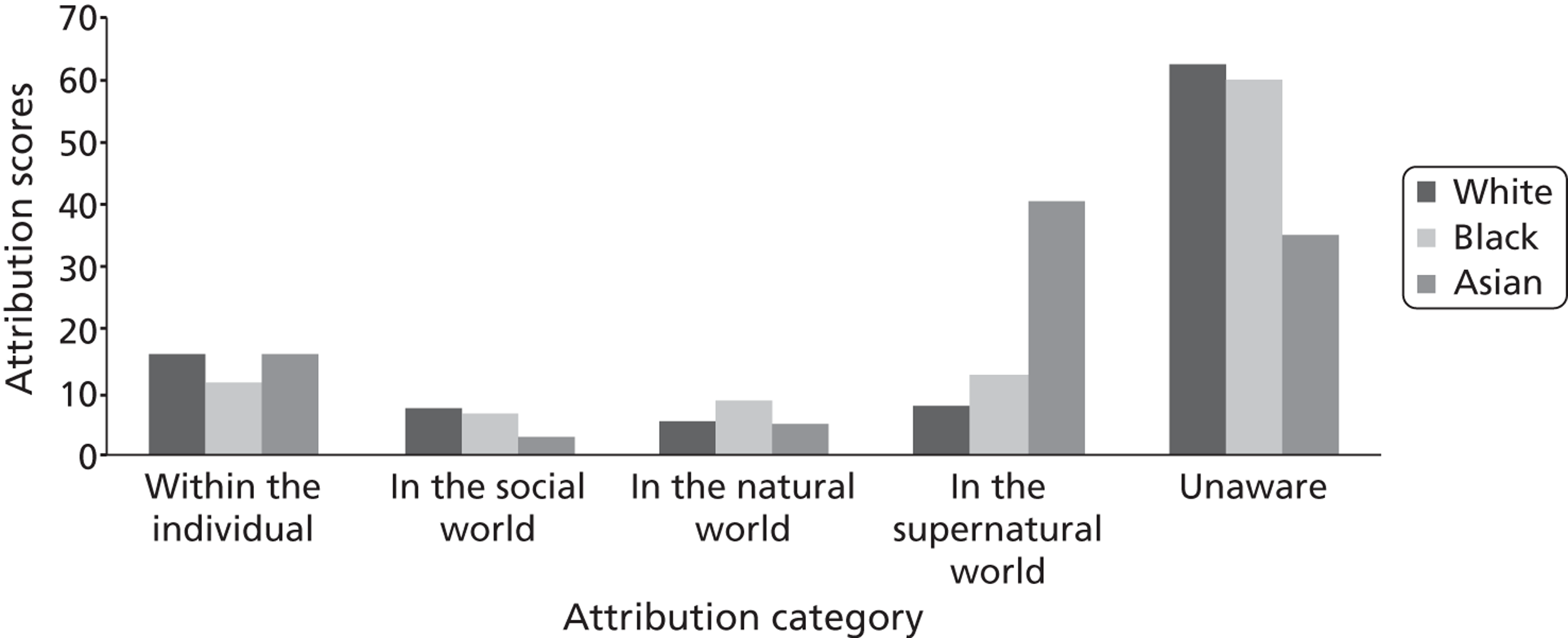

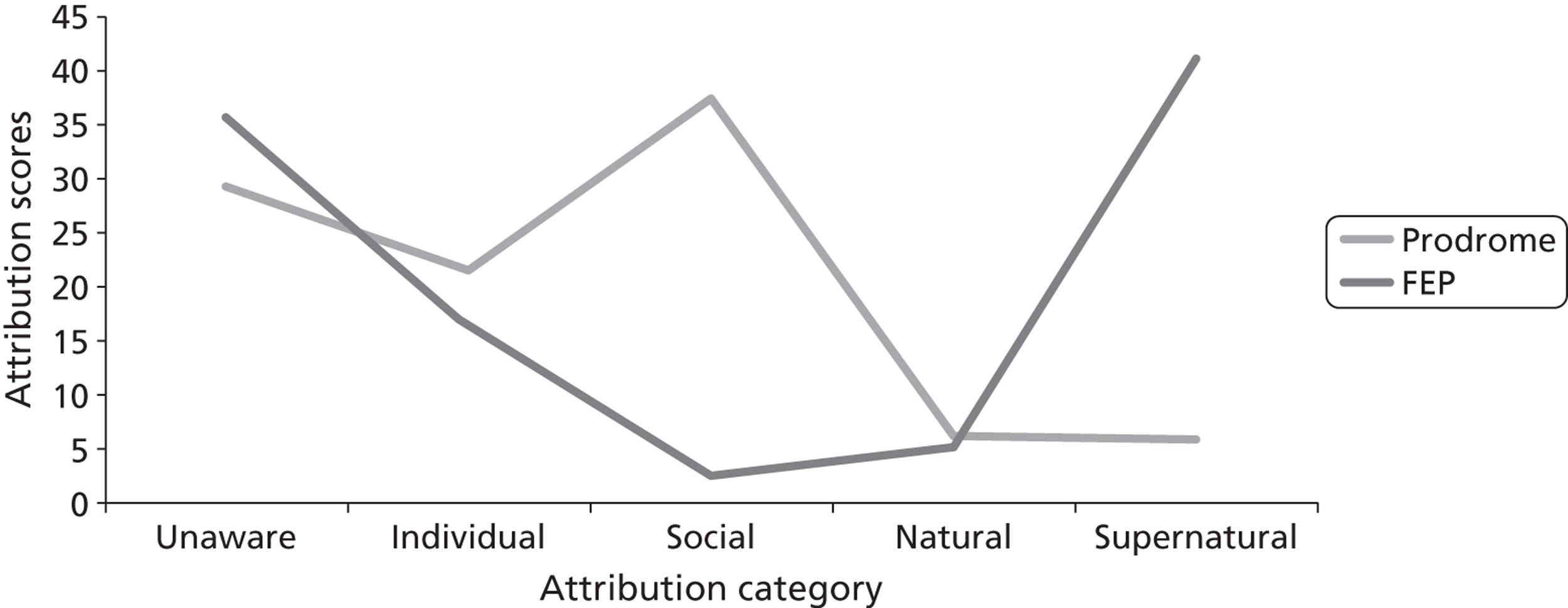

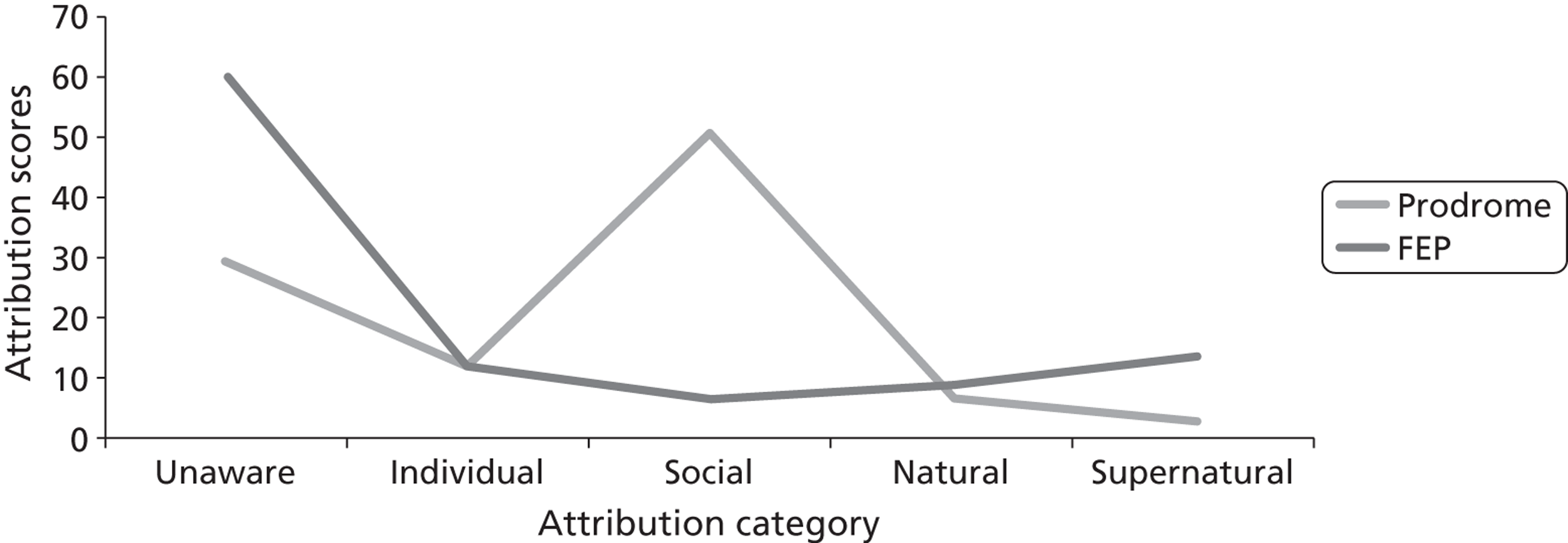

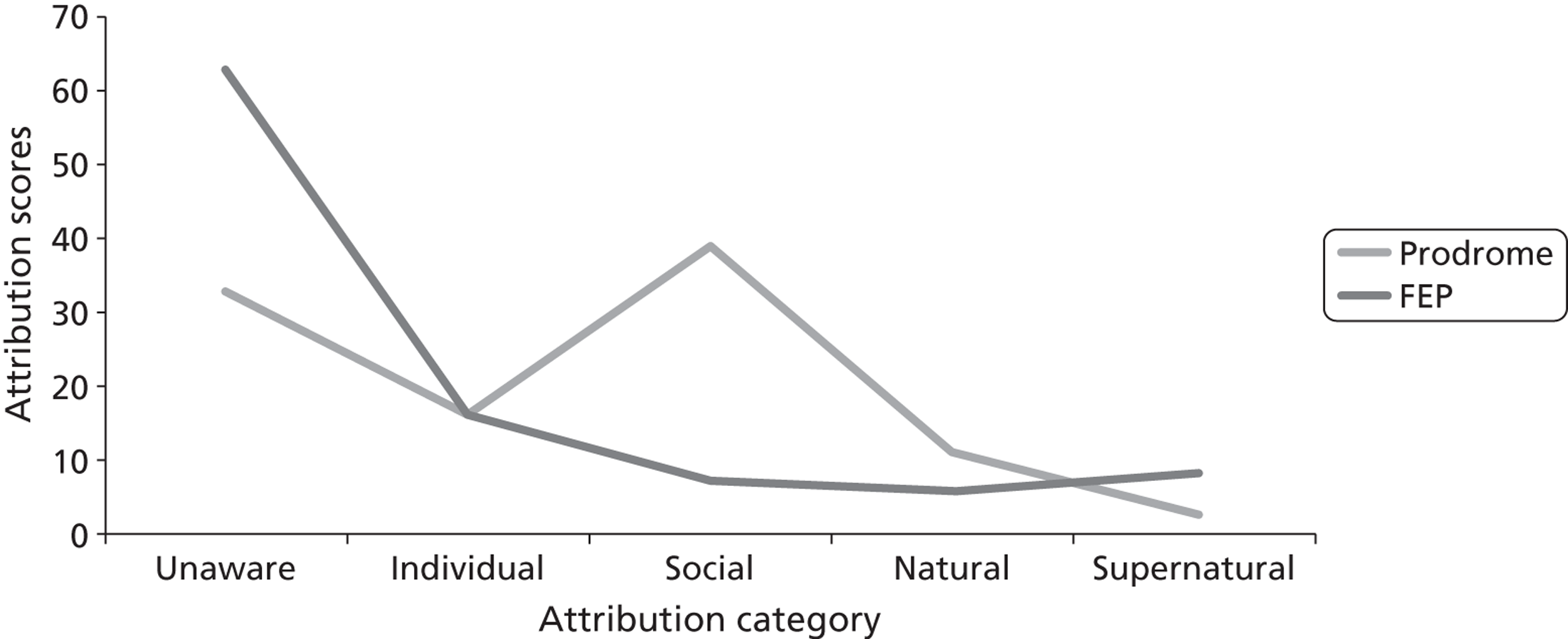

Help-seeking behaviours: help-seeking initiation and help-seeking support