Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1170. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rosalind L Smyth has been a member of the Commission on Human Medicines and Chairperson of the Paediatric Medicines Advisory Group of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) until December 2013. Munir Pirmohamed is currently Chairperson of the Pharmacovigilance Expert Advisory Group for the MHRA and is a Commissioner on Human Medicines. Anthony J Nunn is a member of MHRA Paediatric Medicines Expert Advisory Group, a member of the European Medicines Agency Paediatric Committee (PDCO) and a temporary advisor to the World Health Organization.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Smyth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Drug safety is an important issue in all disciplines. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) stated definition of an adverse drug reaction (ADR) is ‘A response to a drug which is noxious, and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological function’. 1

The problem of drug safety in paediatrics is compounded by the fact that medicines are often not tested in children, and therefore at the time of licensing there is no indication for use in children. For example, in 2006 around 75% of all 317 centrally licensed medicines were relevant for children but only half (34%) had a paediatric indication. 2 This leads to off-label and/or unlicensed (OLUL) prescribing: this has been estimated to occur in 25%3 of paediatric inpatient prescriptions and 65% of neonatal prescriptions. 4 It is clear that extrapolation of efficacy, dosing regimens and ADRs from adult data are inappropriate owing to developmental changes in physiology and drug handling. 5 Taken together with the fact that the pattern of diseases in children is different from that in adults, this puts them at high risk of serious and unpredictable ADRs from the use of medicines. As with any population, distinguishing between an ADR and non-drug-induced pathology is difficult but is further compounded in this age group. Important examples of ADRs in children include deaths associated with propofol used for paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) sedation,6 acute adrenal crisis associated with inhaled corticosteroids,7 grey baby syndrome in neonates associated with chloramphenicol,8 the threefold increase in Stevens–Johnson syndrome with lamotrigine9 and colonic strictures in cystic fibrosis owing to high-strength pancreatic enzymes. 10 The last of these examples was first reported at Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust (Alder Hey) in Liverpool; the primary author led the study confirming the association with pancreatic enzyme therapy and because of this, and subsequent regulatory measures, this problem is no longer reported in the UK. A trend towards more ADRs when OLUL medicines are prescribed in children and young people was first reported from this research group. 11 However, the recognition of serious new ADRs generally depends on a cluster of individuals presenting with a similar pattern of unexplained clinical features and there is no systematic, pre-emptive approach to this problem in children, largely because of the dearth of good-quality scientific evidence on this topic. The burden of ADRs in children has not been systematically assessed and the knowledge base of the impact of ADRs in children on morbidity, overall health economy and societal consequences is poorly understood. In addition, methods to detect and assess causality and avoidability of suspected ADRs have not been validated in children. Evidence suggests that patients are generally poorly informed about medicines and the systems to ensure drug safety. 12 There is a need to consider communication about ADRs as an integral component of medicine adherence as well as an important transaction in its own right. Particular concerns surround children’s medicines; although health-care professionals have access to mechanisms to report and manage suspected ADRs, little is known about the understanding and experiences of families who experience a suspected ADR. Given the lack of robust evidence in the broad spectrum of ADR burden and characterisation in the population of children and young people, and the lack of knowledge and understanding of the interactions between health-care professionals and families whose child experiences a suspected ADR, Adverse Drug Reactions In Children (ADRIC) was designed to address this knowledge gap.

The regulatory and policy perspective of pharmacovigilance in children and young people

The Department of Health recognised the importance of the development of medicines and drug safety science in children by establishing the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN) in 2006. Assessment of the harms of medicines is as important as assessment of their benefits and is integral to the proposals within the European regulation on medicines for children13 and the guidance on pharmacovigilance in children. In July 2012, new pharmacovigilance legislation came into effect across the European Union (EU),14 including centralised reporting by industry of ADRs to the EudraVigilance database at the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the inclusion of reports from patients as valid, reportable ADRs. The Children and Young People’s Outcomes Strategy (commissioned by the Secretary of State for Health) identified the need to optimise the safe use of medicines. 15 In 2008, there were 33,000 safety incidents in children reported to the National Reporting and Learning System by health-care professionals, and of these 19% were for a medication problem. This led to a recommendation report that ‘the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), with immediate effect, prioritises pharmacovigilance of children’s medicines, including medication errors and off-label use, in line with the new EU legislation effective in July 2012’. 16

The MHRA is responsible for monitoring the safety of medicines in the UK. 17 The collection and analysis of reports of ADRs is critical to the MHRA’s responsibility to monitor the safety of medicines in practice: this is achieved through the submission of spontaneous reports of suspected ADRs by health-care professionals and the public through the Yellow Card Scheme. 18 The Yellow Card Scheme is designed to detect signals that may indicate a potential hazard with a medicine, leading to further investigations that may result in withdrawal of the medicine or changes in prescribing recommendations and restrictions in its use. Signal detection from spontaneous reports of ADRs and subsequent guidance in risk–benefit decisions is highly dependent on the availability of reliable instruments to assess ADR causality, which presents difficulties in paediatric pharmacovigilance. There is considerable variation in reporting of ADRs by practitioners and the potential for under-reporting and, partly in response to these concerns, the Yellow Card Scheme was extended to patients and families in 2005. The detail of individual ADR reports from patients is generally superior to those of health-care professionals, contributing to the EU pharmacovigilance legislation. 16 There is a clear statement through legislation, regulation and policy recommendations that the framework for pharmacovigilance in children is suboptimal and that a broader understanding of the assessment and improvement in the systems and quality of reporting of ADRs in this age group is urgently needed.

Burden of adverse drug reactions in children and young people

Given the stated importance of medicines for children by the Department of Health and the EMA, as well as other international authorities, it is important that we perform robust studies to fill knowledge gaps in the burden of ADRs in children and young people. Drugs are the mainstay of treatment in paediatric practice, yet a high proportion of drugs have not been tested in children. This leads to OLUL prescribing, the use of inappropriate doses, the use of age-inappropriate formulations, which may result in underdosing or overdosing, and drug development without due regard for the processes that are vital for normal development of a child into an adult. There are data showing that the current practice of drug development and drug use in paediatrics leads to avoidable adverse effects, which lead to morbidity and mortality. There is a need to identify the burden of ADRs in children; this has been emphasised by recent documents from the EMA and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and is one of the important aims of the MCRN.

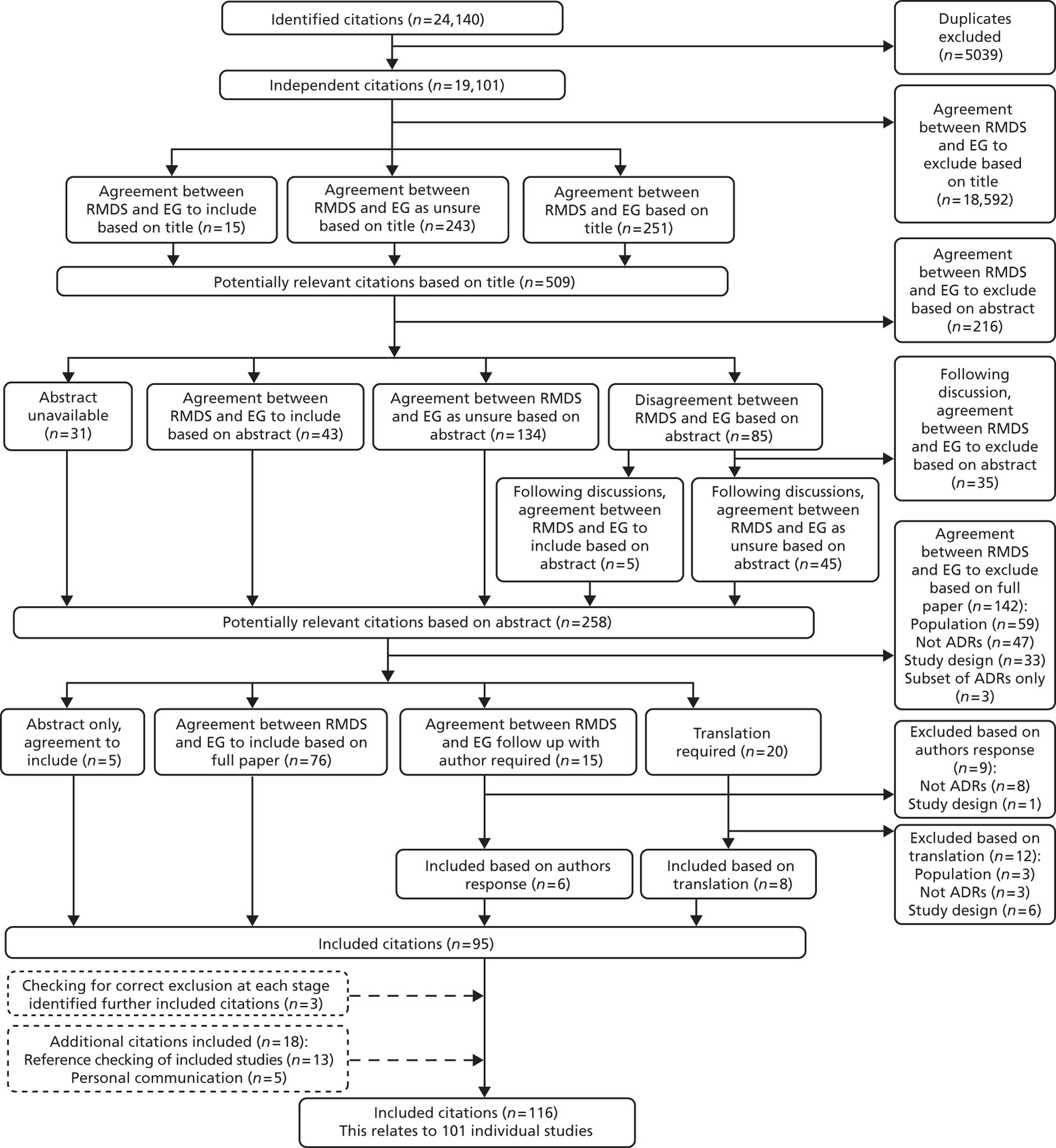

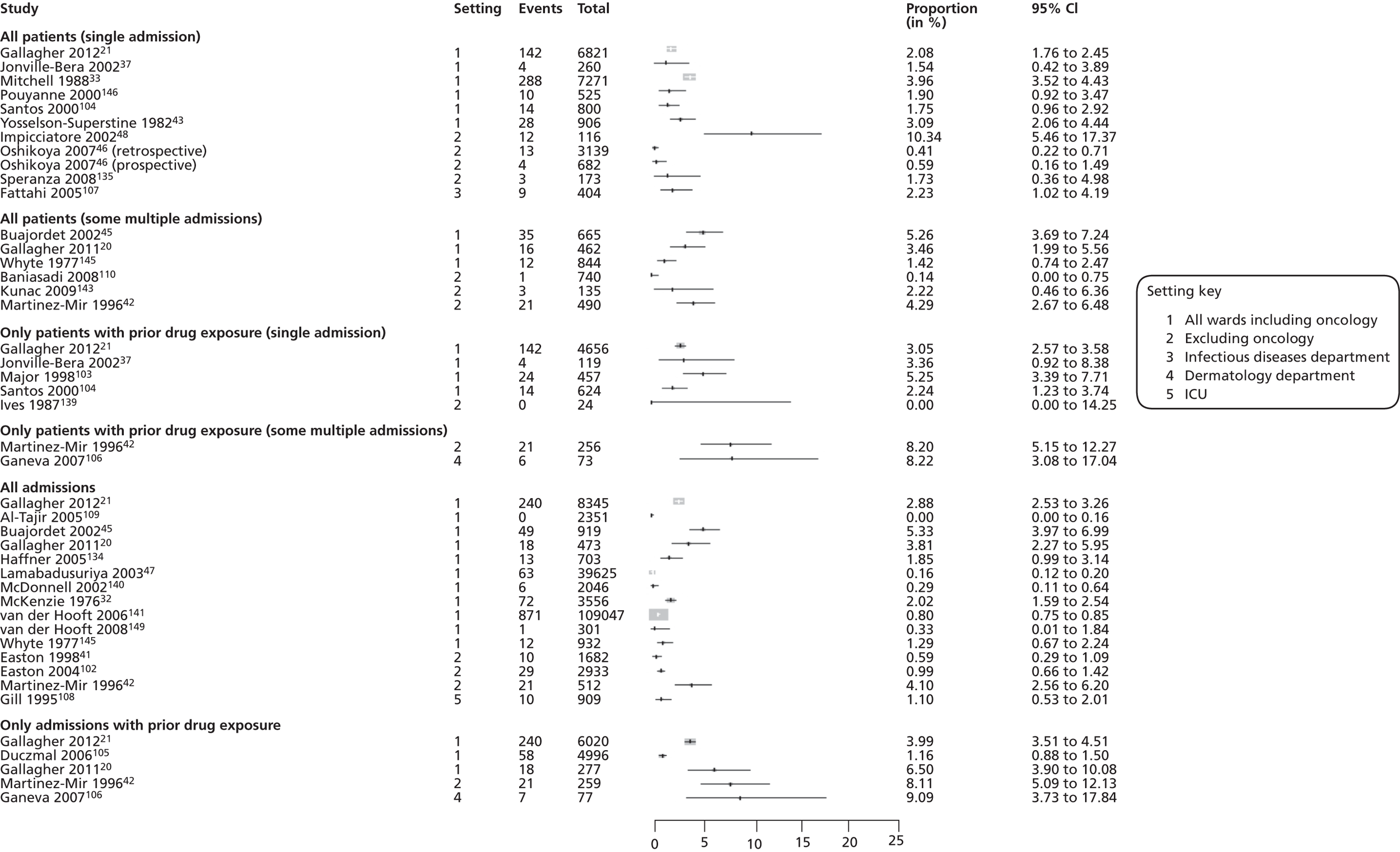

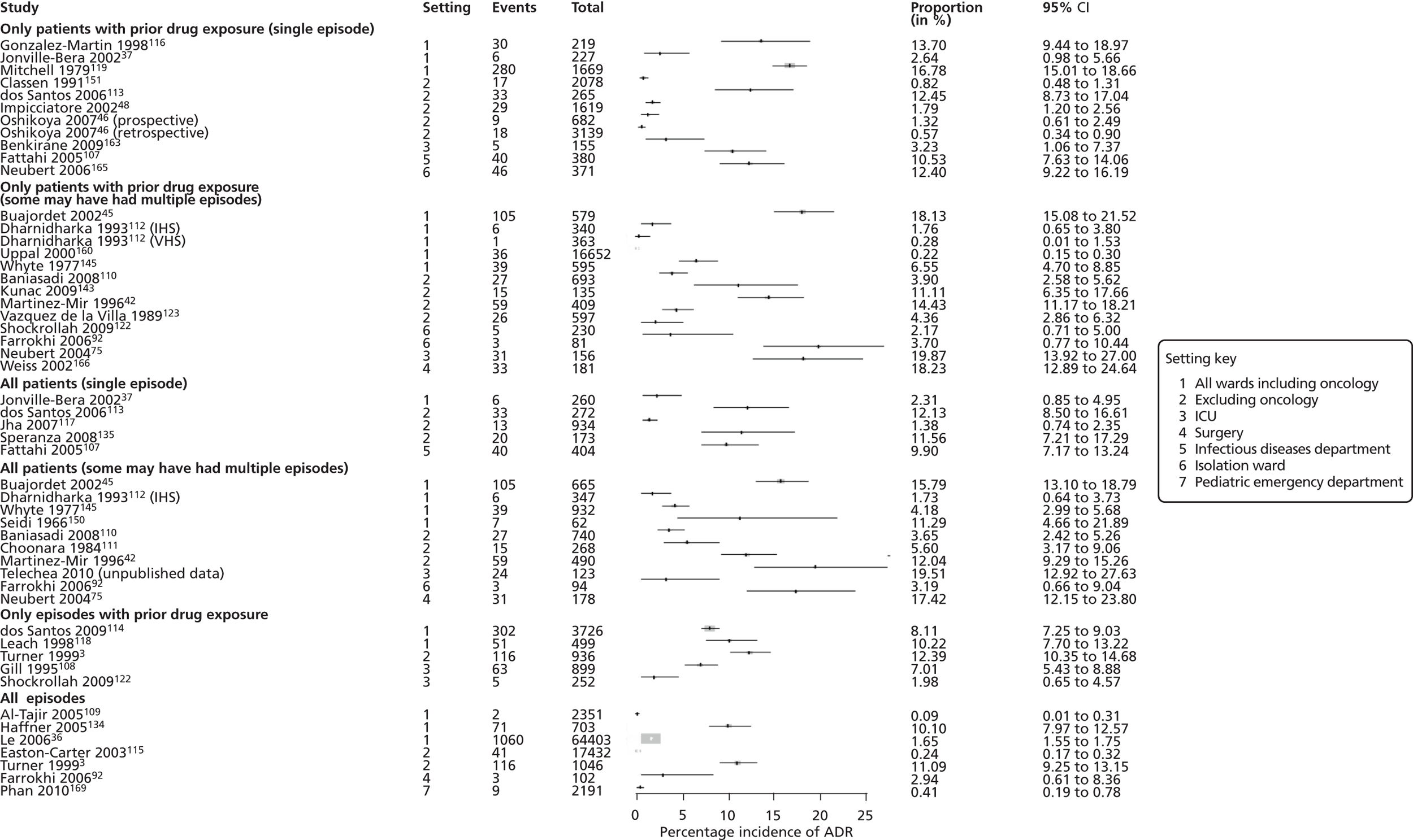

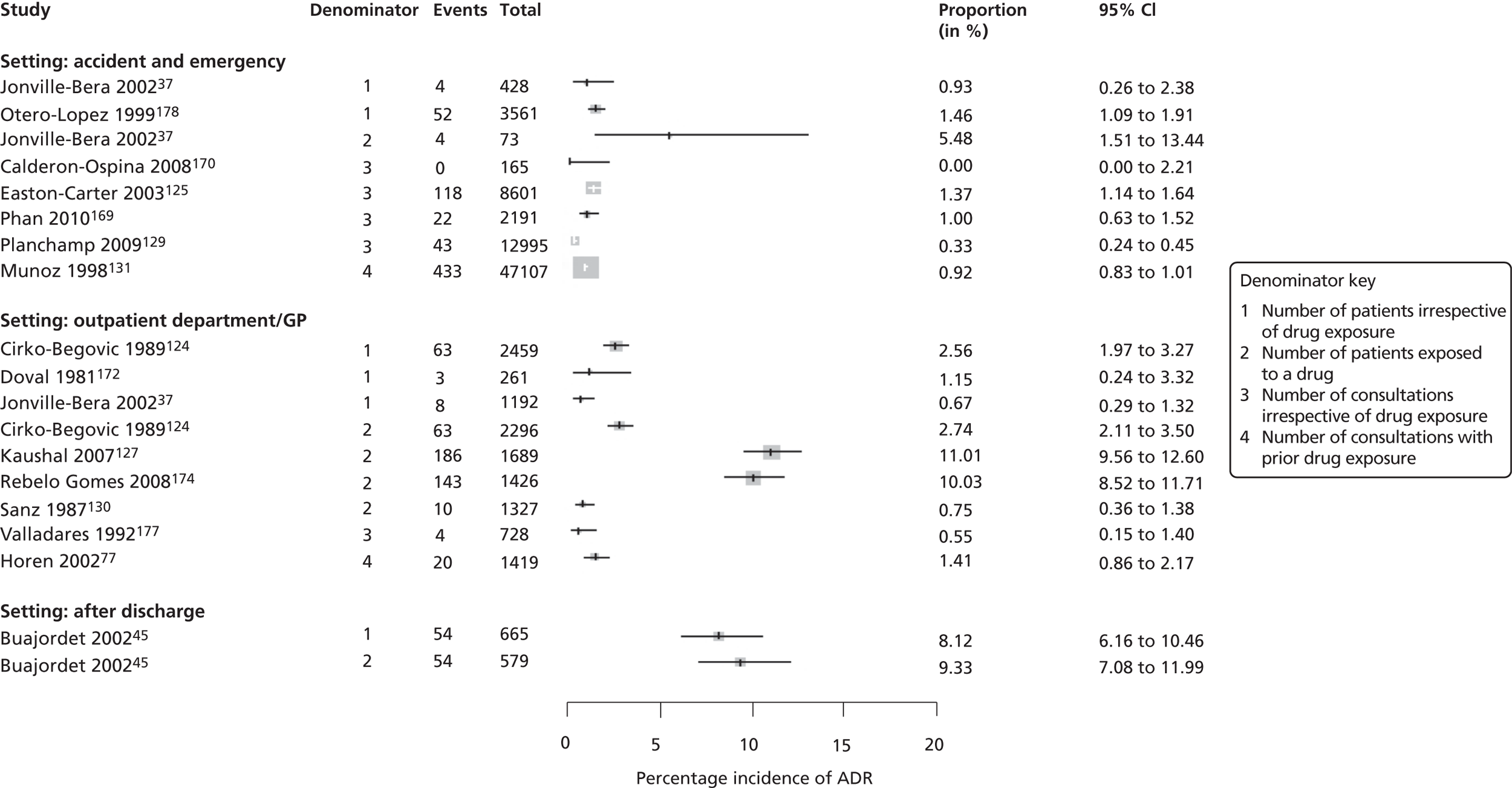

A number of studies have been performed in children to determine the incidence of ADRs; however, there are deficiencies in the evidence available at present. There is a lack of reliable and contemporary data estimating how frequently ADRs are causing admissions, how frequently they occur in general paediatric wards, how frequently they are life-threatening or cause death, and how often they could have been avoidable by better prescribing, better information in summary of product characteristics (SmPC) or better monitoring. Additionally, we do not have the tools to prevent these reactions. A number of studies have attempted to estimate the incidence of ADRs in children and have reported data on ADR rates causing admission to hospital, within inpatients and in the outpatient setting. The summary data confirmed that ADRs in children are a considerable burden. However, studies to date have varied considerably in their methodological rigour,19 including the definition of an ADR used, the age range of the study population and the clinical settings for data collection. Similarly, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies of ADRs in children also demonstrate methodological limitations, including the source bibliographical databases, definitions of ADRs to include adverse events (AEs) and exclusion of paediatric data from studies that included both adults and children. For example, a previous systematic review pointed out that there was substantial heterogeneity in the incidence estimates in the different studies reflecting differing, and often inadequate, methodologies that were used. Often the severity of the ADR was not reported, and patient age, diagnosis and drug prescription patterns were often not reported, and thus could not be considered in determining factors associated with ADRs in children. The need to conduct rigorous, prospective studies of ADRs in children, both which cause hospital admission20,21 and within the inpatient setting,22 was clearly needed. In addition, a methodologically rigorous systematic review incorporating the findings of these novel prospective studies was required. 19

Assessment of causality and avoidability of adverse drug reactions in children and young people

In addition to the overall burden of ADRs, the characterisation of individual ADRs provides essential information in the context of drug safety science: two important factors are assessment of causality and avoidability. Causality assessment estimates the strength of the relationship between drug exposure and the occurrence of an ADR. Assessment of ADR avoidability, or preventability, does not have a universally accepted definition, but there are two conventionally recognised principles: whether in the absence of error an event is preventable, and, if so, whether the event can be prevented. The concepts of causality and avoidability are relevant to health-care professionals, regulators, the pharmaceutical sector and the academic community, although the context may vary among these constituencies. Regardless of the reason or motivation to undertake causality or avoidability assessments, the availability of reliable and valid instruments to generate meaningful data is essential. Given the difficulties in distinguishing between ADRs and non-drug-induced pathology in children, these aspects are of particular importance in this population.

The Naranjo ADR probability scale23 is most widely used and reported causality assessment tool (CAT). This instrument contains 10 weighted items that generate a construct to produce a total score resulting in categorisation of the event as either unlikely, possible, probable or definite. Each item is based on concepts including temporal relationships, biological plausibility and rechallenge/previous exposure. The instrument was developed by adult physicians and psychiatrists using published case reports to validate instrument reliability. The validity and reliability of the Naranjo tool has been subject to challenge and, in addition, the use of the instrument to assess causality of ADRs in children is questionable given that individual items were developed and validated using adult case reports. 24

There is currently no standardised method for determining ADR avoidability and many of the established tools are not suitable for use in paediatric practice. A number of instruments have been developed for assessment of ADR avoidability and a systematic review found that several definitions exist for the preventability of drug-related harm as a consequence of the variability in methodological approaches to assessment of avoidability, and none fits all circumstances. 25 The authors of the systematic review proposed an approach to preventability, based on analysis of the mechanisms of ADRs and their clinical manifestations. Some authors have proposed a methodological framework for future studies of ADR avoidability and the development of valid instruments. 26 This includes reliability and validity testing, standardisation of the measurement processes, description of assessor training and experience in assessing preventability, details of independent or consensus assessments and rationalisation of assessor disagreement. These authors recommend that there is a need to modify existing instruments or develop novel instruments for use in different settings and populations.

The available instruments for assessment of causality and avoidability of ADRs vary in reliability and validity. 19 In particular, the assessment of avoidability is compromised by a lack of consensus on the definition of avoidability and associated heterogeneity in underpinning methodology for instrument development. No instruments are available specifically for characterisation of ADRs in children and young people, and there is a requirement to develop such instruments.

Communication about drug safety in children and young people

Previous literature on communication concerning medicines highlights the benefits of open discussion between health-care professionals and patients, at the time of prescribing, on their potential risks and the importance of supplementary written information in conveying key messages about drug safety. 12,27 Despite the movement towards patient reporting of ADRs and changes in EU legislation on pharmacovigilance in children,16 patients and their families are generally poorly informed about ADRs and pharmacovigilance systems to optimise safety of medicines. Other than in the context of understanding parental beliefs and attitudes to childhood vaccination, very little is known about the experiences of parents whose child has experienced a suspected ADR. 28 As a consequence, health-care professionals have no approriate evidence base from which to inform either generic or individualised communication strategies with the family when a child experiences a suspected ADR. In addition, there is little knowledge and documentary evidence of the experience of health-care professionals in the same circumstances. The perspectives of health-care professionals regarding what information parents require during episodes of suspected ADRs, have not been described and the mechanisms for decision analysis and motivations which underpin the timing, content and narrative of communication by clinicians has not been explored. In addition, there has been no attempt to identify if there are barriers to effective communication with families from the perspective of clinicians following a suspected ADR. More fundamentally, we did not know if the nature of the communication by health-care professionals about ADRs meets the needs and expectations of parents. Despite the beneficial impact of written supplementary information on the understanding of drug safety at the point of prescribing, this paradigm has not extended into circumstances when there is a suspected ADR in children. There are no customised written materials, generated with the involvement of relevant stakeholders, which provide a framework within which communication between health-care professionals and parents can be guided, and, in particular, documentation intended for parents, which allows enquiry and dialogue to be initiated and led from their perspective. Beyond this, it is important that further materials to guide communication pay adequate attention to key principles of transaction and process, including what and when to communicate to families, as opposed to developing and modifying the communication skills of clinicians. 29

The Adverse Drug Reactions In Children programme

Most studies of pharmacovigilance in children and young people to date have focused on individual aspects of ADRs, for example ADRs causing hospital admission and ADRs occurring within small specialised units. However, no programme of work has investigated a broad spectrum incorporating when and where ADRs occur, characterising the nature of ADRs in this age group, developing instruments customised for assessment of casuality and avoidability of ADRs in paediatric practice, and understanding the narratives and communications between families and health-care professionals during episodes of suspected ADRs. ADRIC was designed to undertake a comprehensive and coherent suite of studies aiming to add significantly to the existing evidence base and to generate outputs that can be adopted into both clinical practice and further research to improve methodologies for our understanding and management of pharmacovigilance in this vulnerable age group.

The ADRIC research strategy comprised the following component parts, which logically follow on from each other:

-

Quantification To estimate the incidence of ADRs in children, causing admission to hospital, and to estimate the burden to the health-care economy; to estimate the incidence of ADRs in hospitalised children.

-

Evaluation To identify risk factors for ADRs in causing admission to hospital and for causing ADRs in hospitalised children, and to characterise these ADRs in terms of type, drug aetiology, causality, avoidability and severity. To identify the unmet communication needs of parents whose child has experienced a suspected ADR.

-

Instrument development To develop and validate instruments to improve the assessment of causality and avoidability of ADRs in children.

-

Intervention To develop written materials that will guide the communication between parents and health-care professionals following an episode of a suspected ADR(s).

The methodologies used to undertake the above aims included two large and comprehensive single-centre prospective observational studies; a systematic review; reliability and validity testing of novel ADR assessment instruments; qualitative enquiry; structured interviews and evaluation of intervention implementation.

The ADRIC team was assembled with the necessary expertise to achieve the aims set out above. The Senior Investigator Team comprised paediatricians and neonatologists, a clinical pharmacologist with extensive experience in leadership and design of studies of assessment of ADRs in the adult population, experienced secondary researchers, a senior paediatric pharmacist, a senior academic psychologist with experience in qualitative methodologies for understanding the experience of children and families, and a NIHR Paediatric Clinical Research Network Director. Members of the team also hold executive positions within the NIHR MCRN and membership of expert committees, including the EMA and the UK Commission on Human Medicines.

The ADRIC study was supported by a steering group to provide an independent strategic overview of the programme. The steering group was overseen by an independent chairperson (Professor Sir Alisdair Breckenridge, Chairman, MHRA) and included senior representation from the MHRA (Director of Vigilance and Risk Management), US FDA, international academic paediatric pharmacovigilance expertise, and the chairperson of the NIHR Research Methods programme. A management group, comprising ADRIC senior investigators and members of the research team, was responsible for the design, implementation, analysis and reporting of each study within the overall of the programme.

A multidisciplinary research team comprised paediatric research nurses, research pharmacists, paediatric medical research fellows and research associates in qualitative methodologies. The setting for the ADRIC study was Alder Hey, widely recognised as the largest specialist children’s health-care provider in Western Europe, serving a population of children and young people in excess of two million and acting as a tertiary referral centre for much of the north-west of England and north Wales. Alder Hey provides general and all specialist paediatric services at local, regional and national levels. Community child health services are provided alongside Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) over a large geographical footprint. The full range of paediatric services is provided at a single site with 325 beds and typically there are annually 120,000 outpatient episodes, 26,000 inpatient admissions including day case episodes, 70,000 accident and emergency (A&E) attendances, 1000 critical care admissions and 13,000 CAMHS episodes at Alder Hey (with 14,400 CAMHS outpatient episodes in community teams). ADRIC was conducted over a 5-year period, between May 2008 and April 2013.

Chapter 2 Adverse drug reactions causing admission to a paediatric hospital

This chapter contains information reproduced from Gallagher RM, Mason JR, Bird KA, Kirkham JJ, Peak M, Williamson PR, et al. Adverse drug reactions causing admission to a paediatric hospital. PLOS ONE 2012;7:e50127,21 © 2012 Gallagher et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are credited; and information reproduced with permission from Bellis JR, Kirkham JJ, Nunn AJ, Pirmohamed M. Adverse drug reactions and off-label and unlicensed medicines in children: a prospective cohort study of unplanned admissions to a paediatric hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;77:545–53,30 with permission from the British Pharmacological Society and Blackwell Publishing; and information reproduced with permission from Bellis JR. Adverse Drug Reactions in Children – The Contribution of Off-label and Unlicenced Prescribing. PhD thesis. Liverpool: University of Liverpool, 2013. 31

Abstract

Objective(s)

To determine the incidence of ADRs, which were associated with admission to hospital in children, describe their causality, severity, avoidability and nature, and identify which children were particularly at risk of this complication. To identify potential areas where intervention may reduce the burden of ill health.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

A large children’s hospital providing general and specialty care in the UK.

Participants

All acute paediatric admissions over a 1-year period.

Main exposure

Any medication taken in the 2 weeks prior to admission.

Outcome measures

Occurrence of ADR.

Results

In total, 240 out of 8345 admissions in 178 out of 6821 patients who were admitted acutely to a paediatric hospital were thought to be related to an ADR, giving an estimated incidence of 2.9% [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.5% to 3.3%], with the reaction directly causing, or contributing to the cause of, admission in 97.1% of cases. No deaths were attributable to an ADR. Overall, 22.1% (95% CI 17% to 28%) of the reactions were either definitely or possibly avoidable. Prescriptions originating in the community accounted for 44 out of 249 (17.7%) of ADRs, the remainder originating from hospital. Of 16,551 prescription medicine courses, 11,511 (69.5%) were authorised, 4080 (24.7%) were off-label and 960 (5.8%) were unlicensed. A total of 120 out of 249 (48.2%) reactions resulted from treatment for malignancies. The drugs most commonly implicated in causing admissions were cytotoxic agents, corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), vaccines and immunosuppressants. OLUL medicines were more likely to be implicated in an ADR than an authorised medicines [relative risk (RR) 1.67, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.02; p < 0.001]. When medicines used for the treatment of malignancies were excluded, OLUL medicines were not more likely to be implicated in an ADR than authorised medicines (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.48; p = 0.830). The most common reactions were neutropenia, immunosuppression and thrombocytopenia.

Conclusions

Adverse drug reactions in children are an important public health problem. Most of those serious enough to require hospital admission are due to hospital-based prescribing, of which just over one-fifth may be avoidable. Strategies are needed to reduce the burden of ill health from ADRs causing admission.

Introduction

Children are vulnerable to ADRs. 32–37 A recent retrospective study by Hawcutt et al. 38 identified 31,726 of 222,755 (14.2%) ADR reports received by the UK MHRA through the Yellow Card Scheme, from 2000 to 2009, concerned children of < 17 years of age. 38 However, it is well recognised that spontaneous reporting systems, such as the Yellow Card Scheme in the UK,39 are subject to under-reporting of ADRs, even those that are severe. 40 Thus, it is likely that the number of paediatric ADR reports received each year by the MHRA is a considerable underestimate of the magnitude of the problem in the UK.

Hospital-based ADRs can be identified by retrospective studies using case note review; such studies, however, are likely to be less reliable than prospective studies in estimating the frequency with which ADRs occur owing to the inadequacy of recorded information. To obtain reliable information about the incidence of ADRs, prospective studies are needed.

A systematic review of observational studies of ADRs causing paediatric hospital admissions, between 1976 and 1996, estimated the overall rate of paediatric hospital admissions due to ADRs in children to be 2.1% (95% CI 1.0% to 3.8%). 34 This review included five prospective observational studies investigating ADRs causing admission in children. 32,33,41–43 Three of the studies were large, including > 1000 admissions each. 32,33,41 Three of the studies used published measures to assess causality of ADRs,41–43 whereas the two largest studies in the review used self-derived definitions for assessing causality. 32,33 Only one of the studies,41 with a low comparative reported ADR incidence of 10 out of 1682 admissions (0.6%), reported on avoidability of the cases using an adapted version of a published method44 but did not detail which ADRs were deemed avoidable or the reasons for assessing ADRs as being avoidable. The other studies did not report avoidability of the admissions associated with ADRs.

A further systematic review of prospective studies published between 2001 and 2007 included four studies37,45–47 but did not identify any large significant studies detailing the incidence and nature of ADRs causing admission of children to hospital. 35 Three studies37,45,46 included < 1000 admissions and the remaining study47 included a study population of 39,625 admissions but resulted in an ADR admission rate of only 0.16%. All four studies37,45–47 assessed causality using a published algorithm. However, only one study reported the avoidability of the ADR cases. 46 This study46 did not give detail of the method used for assessing avoidability, nor did the investigators detail the reasons for assigning cases as avoidable.

There have been no large paediatric studies that have looked at ADRs leading to hospital admission and then gone on to consider the influence of OLUL medicine use. There is one small pilot study48 that included ADRs to medicines administered before admission and recorded whether or not the medicines implicated were off-label. Of the 41 ADRs detected in 41 out of 1619 patients, 12 were attributed to medicines administered before admission and 29 were attributed to medicines administered in the hospital. In 16 out of the 41 patients experiencing an ADR, an off-label medicine was implicated; five of these were patients who experienced an ADR due to medicines administered before admission.

The aim of this study was to prospectively identify ADRs in children causing admission to hospital during a 1-year period in order to quantify and characterise the burden of ADRs. One important aspect of the study was to determine the avoidability of the ADRs identified and detail the reasons for categorising the reactions as ‘possibly’ or ‘definitely’ avoidable. In addition, the impact of OLUL medicine use on ADR risk in this context was examined.

Methods

The study hospital had an induction programme that was delivered to new members of staff to educate them about the hospital and some aspects of specific practice within the setting. This provided training to clinicians regarding medication prescribing and drug safety for children but did not specifically address ADRs, their diagnosis or how to report them. Therefore, before the start of this observational study, a comprehensive educational programme was undertaken within the hospital among clinicians of all grades. The study team attended hospital induction for new clinicians (and continued to do so through the entirety of the study period) to give formal presentations about the study and ADRs in children. The study team gave a formal presentation to an audience at the main weekly educational hospital meeting (for clinicians and staff from all specialties), as well as presenting at individual specialty team meetings occurring within the hospital.

The goal of this educational programme was to raise awareness about the aims of the study and to increase clinicians’ understanding of their role in information recording. First, clinicians were made aware of the primary aim of the study, which was to identify prospectively ADRs causing admission to the hospital. Clinicians were reminded of the importance of good record-keeping with regard to descriptions of symptoms and signs to allow for more accurate assessment of causality by the study team. Second, the study team aimed to raise awareness of taking detailed medication histories in relation to identifying ADRs accurately and assigning causality. A structured medication history was added to acute general paediatric medical admission documentation with the aim of ensuring all families were asked for details about medication taken in the preceding 2 weeks. A 2-week medication history was chosen as the time when reactions causing admission were most likely to have occurred following exposure to a drug. A 2-week pilot study to develop and refine the methodology for this larger study was conducted prior to the commencement of this study. 20

The study team prospectively screened all unplanned admissions to a large paediatric centre (which provides local and specialist regional and national services) for ADRs over a 1-year period, including weekends and public holidays, from 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2009. Weekends were included in routine daily data collection to eliminate any bias that may occur in trends of possible ADR admissions. Admissions were excluded if they were planned or occurred as a result of accidental or intentional overdose. The definition of ADR used was that of Edwards and Aronson,49 which is ‘an appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction, resulting from an intervention related to the use of a medicinal product, which predicts hazard from future administration and warrants prevention or specific treatment, or alteration of the dosage regimen, or withdrawal of the product’.

Hospital information systems at the study hospital routinely recorded demographic data about admitted patients. These data, with assistance from the hospital information technology department, were automatically downloaded each morning at 06.00, for the patients coded as having an emergency admission, from the hospital computer system to a password-protected Microsoft Access 2007 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) stored on a secure hospital hard drive. Only the study team had access to the database and the patient information recorded within.

Members of the study team, consisting of a paediatric registrar (RMG), a research pharmacist (JRB) and a research nurse (KAB) collected the following information from the case notes of each patient: presenting complaint, summary of clinical history and diagnosis (if available at the time of admission). The details of any medication taken at any time during the 2 weeks before admission were recorded, specifically drug name, route, dose, frequency, duration, indication (if this required clarification) and whether it was a prescription or non-prescription medicine. The data on prescription medicine use were scrutinised in order to define each medicine course as either authorised, off-label, unlicensed or unknown. Authorised use was defined as the use of a medicine with a UK marketing authorisation (MA), within the terms of that MA. The terms of the MA were found in the SmPC available online from the Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC). 50 If no SmPC was available, the British National Formulary for Children (BNF-C)51 was consulted for details of the product MA. If neither reference source provided adequate clarity of information, the manufacturer of the medicine was contacted. Off-label use was defined as the use of a medicine with a UK MA, outside the terms of that MA. According to the definitions described by Turner et al. ,52 unlicensed medicines were defined as those without a UK MA, and an ‘unknown’ category was reserved for medicine courses for which inadequate detail was available to decide whether use was authorised or OLUL. If any information was unclear, study team members interviewed the family, patient or carers as appropriate to clarify the history (i.e. medication history), symptoms and timing of events.

The study team cross-referenced the presenting symptoms/signs against medication history for each patient using the ADR profile for relevant drugs from the SmPC50 in the EMC or, if not available, the BNF-C. 51 Possible ADRs were identified using this information combined with the clinical history and temporal relationships of the medication(s) taken. All possible ADRs were reported by the study team to the responsible clinicians during the study. All possible ADRs were reported to the MHRA using the electronic Yellow Card Scheme at the end of the study period. Reporting to the MHRA occurred after internal causality assessment of the possible ADR cases. The origin of prescription, for drugs thought to be associated with ADRs, was classified using the following criteria:

-

Community Drugs where prescriptions originated in community settings, for example general practice, or where administration took place prior to hospital admission (e.g. paramedic administered).

-

Hospital Drugs where the prescription originated, or administration took place, in hospital and then may or may not have been continued, for example by repeat prescription, in community or outpatient settings.

-

Oncology All drugs administered, or prescribed, from the oncology ward. These drugs may or may not be cytotoxic in nature.

We performed assessment of causality for all cases using the Liverpool Causality Assessment Tool (LCAT). 53 Three investigators (RMG, JRB, KAB) independently assessed causality for all possible ADR cases. Agreement on causality category between all three investigators was taken as accepted consensus. In cases when the three investigators did not achieve consensus, a fourth investigator assessed cases to decide on causality (MPir).

Avoidability of the ADR cases was assessed by consensus meeting between the investigators, using the definitions developed by Hallas et al. 54 Cases were assessed as definitely avoidable, possibly avoidable or unavoidable. In addition, the type of ADR for each case identified was determined according to the classification of Rawlins and Thompson55 as either Type A (predictable from the known pharmacology) or Type B (not predictable). Severity was determined using an adapted Hartwig scale. 56 This adapted scale is shown in Table 1 . Grades 3 and 4 are adapted from the original schema, as not all ADR admissions necessitate cessation of the causative drug(s).

| Severity score | Description |

|---|---|

| 6 | Directly or indirectly resulted in patient death |

| 5 | Caused permanent harm or significant haemodynamic instability |

| 4 | Resulted in patient transfer to higher level of care |

| 3 | Required treatment (admission) or drug discontinued |

| 2 | Drug dosing or frequency changed, without treatment |

| 1 | No change in treatment with suspected drug |

We chose these assessment tools to describe the nature of the ADRs in our study as they have been used previously in ADR studies by other investigators and can be completed quickly. Three investigators independently assessed 217 out of 4514 (4.8%) reports of admissions exposed to medication, but deemed not to have had an ADR, to assess for occurrence of possible ADR cases wrongly classified by the study team (AJN, MPir, MAT).

Statistical analysis

Analyses of the rates of ADRs were based on the number of admissions with the rate expressed as ADR per 100 admissions, together with 95% CIs. Other results are presented either as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or percentage frequencies and 95% CI, as appropriate. The formal statistical analysis was based on the data obtained at the first admission for patients exposed to a medication. Univariate statistical analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test except for frequency data, which were analysed using a chi-squared test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was undertaken to calculate odds ratios (ORs) for possible risk factors for ADR. The RR (with 95% CI) for OLUL medicines being implicated in an ADR was calculated for prescription medicines. A p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as being significant.

Ethics

This study used routinely collected clinical data in an anonymised format. The chairperson of Liverpool Paediatric Local Research Ethics Committee informed us that this study did not require individual patient consent or review by an ethics committee.

Results

Over the study period, there were 6821 patients admitted acutely to the study hospital, accounting for 8345 unplanned admissions. Boys accounted for 3961 out of 6821 (58.1%) patients and 4793 out of 8345 (57.4%) admissions. The median number of admissions per patient was one, with 932 patients having more than one acute admission, up to a maximum of 15. A total of 178 patients experienced 240 admissions with an ADR. This gives an incidence of 2.9 ADRs per 100 admissions (95% CI 2.5 to 3.3); 233 of the 240 (97.1%) admissions were deemed to have been directly caused, or contributed to, by at least one ADR. There were 249 ADRs in 240 admissions, with nine admissions having two separate ADRs; 35 out of 178 (19.7%) patients had more than one admission with an ADR, up to a maximum of seven.

There were 4656 patients exposed to a medication in the 2 weeks prior to acute admission to the hospital. Of these patients, 142 (3%) had a suspected ADR on their first hospital admission within the study period. There was no significant difference between the proportion of boys (76/2677, 2.8%) and girls (66/1979, 3.3%) experiencing an ADR on their first admission, for the group as a whole or oncology patients studied separately ( Table 2 ). For non-oncology patients, there was a slightly higher proportion of girls admitted with an ADR [boys 48/2627 (1.8%), girls 53/1955 (2.7%); p = 0.044], although overall more boys than girls were admitted to the hospital.

| Gender | All | No ADR | ADR | Chi-squared test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All boys | 2677 | 2601 (97.2%) | 76 (2.8%) | 0.947 | 0.331 | |

| All girls | 1979 | 1913 (96.7%) | 66 (3.3%) | |||

| Oncology | Boys | 50 | 22 (44.0%) | 28 (56.0%) | 0.022 | 0.882 |

| Girls | 24 | 11 (45.8%) | 13 (54.2%) | |||

| Non-oncology | Boys | 2627 | 2579 (98.2%) | 48 (1.8%) | 4.062 | 0.044 |

| Girls | 1955 | 1902 (97.3%) | 53 (2.7%) | |||

The median age of the 4656 patients who had been exposed to a drug on their first admission was 3 years 1 month (IQR 9 months to 9 years). Patients with an ADR (6 years, IQR 2 years 4 months to 11 years) were significantly older (p < 0.001) than those without (3 years, IQR 9 months to 9 years) ( Table 3 ). There was no age difference between the 41 oncology patients admitted with an ADR (6 years, IQR 3–10 years) and the 33 oncology patients admitted without an ADR (6 years, IQR 3 years 6 months to 13 years). There was a significant age difference (p < 0.001) between 101 non-oncology patients admitted with ADR (6 years, IQR 1 year 7 months to 11 years) and 4481 admitted without ADR (2 years 11 months, IQR 9 months to 9 years).

| Age (years, months); median: quartile 1, quartile 3 | All | No ADR | ADR | Mann–Whitney U-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 3 years 1 month; 9 months, 9 years (n = 4656) | 3 years 0 months; 9 months, 9 years (n = 4514) | 6 years 0 months; 2 years 4 months, 11 years (n = 142) | 244,161 | < 0.001 |

| Oncology | 6 years; 3 years 6 months, 12 years (n = 74) | 6 years; 3 years 6 months, 13 years (n = 33) | 6 years; 3 years 0 months, 10 years (n = 41) | 580.5 | 0.296 |

| Non-oncology | 3 years; 9 months, 9 years (n = 4582) | 2 years 11 months; 9 months, 9 years (n = 4481) | 6 years; 1 year 7 months, 11 years (n = 101) | 178,319.5 | < 0.001 |

Patients admitted with an ADR had taken a greater number of drugs than those admitted for other reasons ( Table 4 ). For patients admitted with an ADR (n = 142), the number of medicines taken was higher (6, IQR 3–9; p < 0.001) than those for other reasons (n = 4514) (2, IQR 1–3). The number of medicines taken by oncology patients admitted with an ADR (8, IQR 5–10) was higher than those admitted without an ADR (4, IQR 3–7) and this difference was also found for non-oncology patients (with ADR 5, IQR 3–9; without ADR 2, IQR 1–3).

| Drug count | All (median; IQR) | No ADR | ADR | Mann–Whitney U-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 2 (1–3) (n = 4656) | 2 (1–3) (n = 4514) | 6 (3–9) (n = 142) | 115,391.5 | < 0.001 |

| Oncology | 6 (4–9) (n = 74) | 4 (3–7) (n = 33) | 8 (5–10) (n = 41) | 380.5 | 0.001 |

| Non-oncology | 2 (1–3) (n = 4582) | 2 (1–3) (n = 4481) | 5 (3–9) (n = 101) | 100,371.5 | < 0.001 |

Logistic regression analysis showed a trend towards boys being less likely to experience an ADR than girls, with an OR of 0.77 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.12; p = 0.17) ( Table 5 ). There was an increased likelihood of ADRs with increasing age (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.003 to 1.08; p = 0.03). No children were admitted with an ADR in the first month of life. Oncology patients were much more likely to have an ADR causing admission (OR 29.71, 95% CI 17.35 to 50.88; p < 0.001). The likelihood of a child being admitted with an ADR increased with the number of medicines taken (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.29; p < 0.001). Therefore, for each additional medicine taken by a patient the risk of an ADR occurring increases by almost 25%.

| Parametera | OR | 95% CI for OR | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 0.77 | 0.52 to 1.12 | 0.17 |

| Age | 1.04 | 1 to 1.08 | 0.03 |

| Oncology | 29.71 | 17.35 to 50.88 | < 0.01 |

| No. of medicines | 1.24 | 1.19 to 1.29 | < 0.01 |

A further univariate analysis was carried out which included only patients on their first admission who had received at least one prescription medicine in the 2 weeks prior to admission (n = 3869). This analysis compared each continuous variable in the group of patients who had experienced at least one ADR with those who had not in three subpopulations: all patients, patients who had been exposed to at least one OLUL medicine and patients who had received only authorised medicines. There was no significant difference in the proportion of each gender in any of the subpopulations. The median age and median number of medicines was greater in patients who had experienced at least one ADR; however, within the population of patients exposed to authorised medicines only there was no difference. The median number of medicines was significantly greater in children who experienced an ADR for all subpopulations. Oncology patients and patients exposed to OLUL medicines were significantly more likely to experience an ADR ( Table 6 ). Multivariate analysis indicated oncology patients were more likely to have experienced an ADR: OR 25.70 (95% CI 14.56 to 45.38; p < 0.001). The number of authorised medicines courses administered in the 2 weeks before admission was a significant ADR risk factor (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.35; p < 0.001) but so was the number of OLUL medicines administered (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.36; p < 0.001). In addition, increasing age was associated with an increased risk of ADR; OR 1.04 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.08; p = 0.045). There was a trend towards females being more likely to experience an ADR: OR 0.74 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.09; p = 0.130) ( Table 7 ).

| Variable | All | No ADR | ADR | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| All boys | 2247 | 2172 (96.7%) | 75 (3.3%) | 0.271a | |

| All girls | 1622 | 1557 (96.0%) | 65 (4.0%) | ||

| OLUL exposed | Boys | 869 | 812 (93.4%) | 57 (6.6%) | 0.982a |

| Girls | 627 | 585 (93.3%) | 42 (6.7%) | ||

| Authorised only | Boys | 1321 | 1303 (98.6%) | 18 (1.4%) | 0.063a |

| Girls | 953 | 930 (97.6%) | 23 (2.4%) | ||

| Age (years, months): median; quartile 1, quartile 3 | |||||

| All | 3 years 1 month; 8 months, 9 years (n = 3869) | 3 years; 8 months, 9 years (n = 3729) | 6 years; 2 years 4 months, 11 years (n = 140) | < 0.001b | |

| OLUL exposed | 2 years 5 months; 3 months, 8 years (n = 1595) | 2 years 1 month; 3 months, 7 years (n = 1496) | 7 years; 3 years 7 months, 12 years (n = 99) | < 0.001b | |

| Authorised only exposed | 3 years 8 months; 1 year, 10 years (n = 2274) | 3 years 8 months; 1 year, 10 years (n = 2233) | 3 years 9 months; 8 months; 8 years 6 months (n = 41) | 0.968b | |

| No. of medicines: median; quartile 1, quartile 3 | |||||

| All | 2; 1, 4 (n = 3869) | 2; 1, 4 (n = 3729) | 6; 3, 9 (n = 140) | < 0.001b | |

| OLUL exposed | 3; 2, 6 (n = 1565) | 3; 2, 5 (n = 1496) | 8; 5, 10 (n = 99) | < 0.001b | |

| Authorised only exposed | 2; 1, 3 (n = 2274) | 2; 1, 3 (n = 2233) | 3; 2, 6 (n = 41) | 0.003b | |

| Specialty | |||||

| Oncology | 73 | 32 (43.8%) | 41 (56.2%) | < 0.001a | |

| Non-oncology | 3796 | 3697 (97.4%) | 99 (2.6%) | ||

| OLUL exposure | |||||

| OLUL exposed | 1595 | 1496 (93.8%) | 99 (6.2%) | < 0.001a | |

| Authorised only exposed | 2274 | 2233 (98.2%) | 41 (1.8%) | ||

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 0.74 (0.51 to 1.09) | 0.130 |

| Specialty (oncology) | 25.70 (14.56 to 45.38) | < 0.001 |

| No. of authorised medicines | 1.25 (1.16 to 1.35) | < 0.001 |

| No. of OLUL medicines | 1.23 (1.10 to 1.36) | < 0.001 |

| No. of unknown medicines | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.18) | 0.303 |

| Age in years | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) | 0.045 |

Drug classes and drugs

The main class of drugs contributing to ADR-related admissions (n = 110; 44.2%) was cytotoxic drugs ( Table 8 ). Corticosteroids (n = 102, 41%), NSAIDs (n = 31, 12.4%), vaccines (n = 22, 8.8%) and immunosuppressant drugs (n = 18, 7.2%) were the next most commonly implicated drug classes causing ADR-related hospital admissions.

| Drug class (no. of cases) | No. of drugs | Drugs | ADRs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxics (110) | 275 | Vincristine, 51; doxorubicin, 38; methotrexate, 35; etoposide, 30; mercaptopurine, 27; cytarabine, 24; ifosfamide, 18; cyclophosphamide, 15; carboplatin, 7; vinblastine, 5; peg asparaginase, 5; dactinomycin, 5; daunorubicin, 4; cisplatin, 3; irinotecan, 3; temozolomide, 2; fludarabine, 1; amsacrine, 1; imatinib, 1 | Neutropenia, 89; thrombocytopenia, 55; anaemia, 38; vomiting, 8; mucositis, 8; deranged liver function tests, 7; immunosuppression, 7; diarrhoea, 5; nausea, 4; constipation, 3; headache, 2; abdominal pain, 1; back pain, 1; haematuria, 1; leucoencephalopathy, 1; deranged renal function, 1 |

| Corticosteroids (102) | 107 | Dexamethasone, 68; prednisolone, 33; hydrocortisone, 2; betamethasone, 1; mometasone, 1; methylprednisolone, 1; fluticasone, 1 | Immunosuppression, 71; postoperative bleeding, 23; hyperglycaemia, 3; hypertension, 1; gastritis, 1; increased appetite, 1; impaired healing, 1; adrenal suppression, 1 |

| NSAIDs (31) | 43 | Ibuprofen, 28; diclofenac, 15 | Postoperative bleeding, 27; haematemesis, 2; constipation, 1; abdominal pain, 1 |

| Vaccines (22) | 37 | Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, inactivated polio Haemophilus influenzae vaccine, 11; pneumococcal conjugate, 9; meningococcal C, 8; measles; mumps and rubella (MMR), 7; Haemophilus influenzae type b, 1; influenza, 1 | Fever, 8; rash 5; irritability, 4; seizure, 4; vomiting, 3; pallor, 1; apnoea, 1; limb swelling, 1; lethargy, 1; thrombocytopenia, 1; diarrhoea, 1; abdominal pain, 1; respiratory distress, 1; Kawasaki disease, 1 |

| Drugs affecting the immune response (18) | 26 | Tacrolimus, 15; mycophenolate, 7; azathioprine, 2; methotrexate, 1; infliximab, 1 | Immunosuppression, 18 |

| Antibacterial drugs (16) | 17 | Co-amoxiclav, 4; penicillin v, 3; amoxicillin, 3; flucloxacillin, 2; cefaclor, 1; cefalexin, 1; cefotaxime, 1; teicoplanin, 1; erythromycin, 1 | Diarrhoea, 7; rash, 4; vomiting, 4; lip swelling, 1; deranged LFTs, 1; thrush, 1 |

| Drugs used in diabetes (9) | 13 | Insulin detemir, 4; insulin aspart, 3; isophane insulin, 2; biphasic isophane, 2; human insulin, 2 | Hypoglycaemia, 9 |

| Drugs used in status epilepticus (8) | 12 | Lorazepam, 5; diazepam, 5; midazolam, 2 | Respiratory depression, 8 |

| Opioid analgesia (6) | 7 | Dihydrocodeine, 3; codeine phosphate, 3; fentanyl, 1 | Constipation, 4; ileus, 1; decreased conscious level, 1 |

| Drugs used in nausea (4) | 4 | Ondansetron, 4 | Constipation, 4 |

| Antiepileptic drugs (2) | 2 | Carbamazepine, 1; nitrazepam, 1 | Constipation, 1; respiratory depression, 1 |

| Drugs that suppress rheumatic disease (2) | 2 | Methotrexate, 1; anakinra, 1 | Immunosuppression, 2 |

| Other (16) | 4 | Calcium carbonate and amlodipine, 1; oxybutynin, 1; baclofen, 1 | Constipation, 3 |

| 2 | Dimethicone, 1; carbocysteine, 1 | Rash, 2 | |

| 2 | Desmopressin acetate, 1; alimemazine, 1 | Seizure, 2 | |

| 10 | Glucose and dextrose, 1; propanolol, 1; acetazolomide, 1; spironolactone, 1; loperamide, 1; macrogols, 1; captopril, 1; alfacalcidol, 1; ethinylestradiol, 1 | Hyperglycaemia, 1; wheeze/difficulty in breathing, 1; headache, 1; hyperkalaemia, 1; intestinal obstruction, 1; diarrhoea, 1; renal dysfunction, 1; hypercalcaemia, 1; intermenstrual bleed, 1 |

A total of 551 courses of medicines contributed to the 249 ADRs causing 240 admissions. The median number of drugs causing an ADR admission was two (n = 79), with a maximum of six (three admissions). Seven admissions were caused by five drugs, 25 by four drugs and 57 by three drugs. A total of 69 admissions were caused by one drug only. None of the ADRs, caused by more than one drug, occurred as a result of a pharmacokinetic drug–drug interaction. All of the ADRs caused by more than one drug were a result of pharmacodynamic interactions.

There were 17,758 prescription medicine courses given to 3869 patients in the 2 weeks prior to admission. Of these, 1207 (6.8%) could not be categorised, 11,511 (64.8%) were authorised, 4080 (23.0%) were off-label and 960 (5.4%) were unlicensed. OLUL medicines were more likely to be implicated in an ADR than authorised medicines [RR 1.67 (95% CI 1.38 to 2.02)]. In total, 14,923 out of 16,106 medicine courses administered to non-oncology patients could be categorised. Of these, 71% were authorised, 24% off-label and 5% unlicensed and OLUL medicines were not more likely to be implicated in an ADR than authorised medicines [RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.48)]. In comparison, among the 1652 medicine courses administered to oncology patients, 1628 could be classified and 57% were approved, 34% were off-label and 9% were unlicensed, and OLUL medicines were more likely to be implicated in an ADR than authorised medicines [RR 1.39 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.71)].

Nature of the adverse drug reactions

The most common ADRs were oncology related, including neutropenia (n = 89), thrombocytopenia (n = 55) and anaemia (n = 38). The next most common ADR was immunosuppression (n = 74), occurring in both oncology and non-oncology patients. Overall, 84 cases of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anaemia and/or immunosuppression among oncology patients involved at least one OLUL medicine, and 12 cases of immunosuppression among non-oncology patients involved at least one OLUL medicine. Postoperative bleeding, linked to perioperative corticosteroid administration and/or NSAIDs, caused 28 admissions (26 post tonsillectomy), and 21 of the post-tonsillectomy bleeds were attributed to at least one OLUL medicine. Vomiting (n = 15), diarrhoea (n = 14), rash (n = 11) and constipation (n = 9) were all common ADRs causing admission. Hypoglycaemia in diabetic patients treated with regular insulin caused nine admissions and none of the insulin prescriptions were off-label. Respiratory depression following treatment for status epilepticus caused eight admissions to the hospital’s PICU: unlicensed buccal midazolam liquid was implicated in two of these.

Origin of adverse drug reaction drug prescriptions

Prescriptions originating from community settings accounted for 44 out of 249 (17.7%) of the ADRs, and 85 out of 249 (34.1%) ADRs arose from prescriptions originating in hospital for the treatment of conditions other than oncology. Prescriptions originating from oncology accounted for 120 out of 249 (48.2%) of ADRs. Of the patients with one ADR (n = 140) in the study period, 39 (27.9%) occurred with community-originated prescriptions, 71 (50.7%) with hospital-originated prescriptions and 30 (21.4%) with oncology-originated prescriptions. Of patients with two ADRs (n = 22) in the study period, two (9.1%) occurred with community prescriptions, six (27.3%) with hospital prescriptions and 14 (63.6%) with oncology prescriptions. Prescriptions originating from oncology accounted for 15 out of 16 patients with three or more ADRs. One patient, with three ADRs in the study period, had two ADRs to hospital-originated prescriptions and one ADR to a community prescription.

Adverse drug reaction assessments (reaction type, causality, severity, avoidability)

A total of 238 out of 249 (95.6%) ADRs were classified as type A (predictable from the known pharmacology), with 11 out of 249 (4.4%) being type B (not predictable). Assessment of causality using the LCAT showed the highest proportion of cases (94/249, 37.8%) to be in the ‘definite’ category. Oncology cases accounted for 80 of these 94 definite causality cases ( Table 9 ). In total, 41 out of 55 (74.5%) of possibly or definitely avoidable cases were classified as ‘definite’ or ‘probable’, 92 out of 238 (39.1%) type A reactions were assessed to be of definite causality, and 8 out of 11 (72.7%) type B reactions were assessed to be ‘possible’. The majority (16/17, 94.1%) of the more severe reactions (adapted Hartwig severity score of grade 4 or more) were assessed to have definite or probable causality.

| Origin of prescription | Type of reaction | Severity score | Avoidability | Causality | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Unavoidable | Possibly | Definitely | Possible | Probable | Definite | |

| Oncology (120) | 119 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 111 | 2 | 2 | 112 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 31 | 80 |

| Hospital (85) | 85 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 74 | 8 | 0 | 57 | 25 | 3 | 51 | 24 | 10 |

| Community (44) | 34 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 38 | 4 | 1 | 25 | 14 | 5 | 23 | 17 | 4 |

A total of 223 out of 249 (89.6%) of the ADRs were classified as grade 3 (‘required treatment or drug administration discontinued’) according to the Hartwig severity scale, as we defined anyone requiring admission to hospital as ‘needing treatment’. Fourteen (5.6%) were classified as grade 4 (‘resulted in patient transfer to higher level of care’), including respiratory depression (n = 8), immunosuppression (n = 4), neutropenia (n = 1), fever/seizure (n = 1) and leukoencephalopathy (n = 1). Three ADRs were classified as grade 5 (‘caused permanent harm or significant haemodynamic instability’). Two of these most severe ADRs occurred in oncology patients with febrile neutropenia and septicaemia, and the remaining case was a child who required bowel resection for ileus, with impacted faecal matter, following treatment with loperamide. No ADRs contributed to death. Two ADRs were classified as grade 2 (‘drug dosing or frequency changed, without treatment’) and seven were classified as grade 1 with (‘no change in treatment with the suspected drug’).

Of the ADRs, 194 out of 249 (78%) were assessed as ‘unavoidable’, whereas 45 (18%) were classified as ‘possibly avoidable’ and 10 (4%) as ‘definitely avoidable’. Five of the cases deemed to be definitely avoidable were associated with hospital-prescribed drugs and five with community-prescribed drugs; 31 possibly avoidable cases were associated with hospital-prescribed drugs and 14 with community-prescribed drugs. A total of 114 (47.5%) of the ADR admissions occurred in oncology patients, accounting for 120 ADRs. Of the ADRs due to oncology drugs, 112 out of 120 (93.3%) were unavoidable, with a further six being possibly avoidable and two definitely avoidable. These ‘definitely avoidable’ cases were oncology patients with constipation following treatment with vincristine and ondansetron (with one also having dihydrocodeine) without laxative prophylaxis.

Of the ADR admissions not associated with oncology patients (n = 126 admissions and 129 ADRs), 82 out of 129 ADRs (63.6%) were classified as unavoidable, 39 (30.2%) as possibly avoidable and eight (7.6%) as definitely avoidable. The eight ‘definitely avoidable’ cases comprised four patients who were prescribed antibiotics, for whom the antibiotic choice or indication was deemed to be inconsistent with good practice: one patient with intestinal obstruction being treated with loperamide, who had not passed stool for 2 days prior to admission; one patient who had a seizure after alimemazine, having had two previous occurrences of seizure after the antihistamine; one patient with deranged renal function, which improved after cessation of captopril, for whom the ADR may have been avoided through improved renal function monitoring; and one patient who presented with adrenal suppression following 2 years of continuous treatment with intranasal corticosteroids. The possibly and definitely avoidable cases and the reasons for their allocation are summarised in Table 10 .

| Avoidable? | Frequency | ADR(s) | Drug classes | Reason for potential avoidability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely | 3 | Diarrhoea and/or vomiting | Antibacterial drugs | Inappropriate indication, signs/symptoms of viral illness |

| 2 | Constipation | Cytotoxic drugs, drugs used in nausea, opioid analgesia | Appropriate prophylaxis not used | |

| 1 | Lip swelling, rash | Antibacterial drugs | Same ADR previously to same medication | |

| 1 | Seizure | Antihistamine | Same ADR previously to similar medication | |

| 1 | Adrenal suppression | Corticosteroids | Avoidable with more rational prescribing (prolonged use of drugs) and improved monitoring | |

| 1 | Intestinal obstruction | Antimotility drugs | Could be prevented by improved parent/patient education | |

| 1 | Deranged renal function | Drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system | Avoidable with improved monitoring | |

| Possibly | 9 | Hypoglycaemia | Drugs used in diabetes | Avoidable with improved patient education (e.g. insulin use when unwell) and more rational prescribing |

| 8 | Respiratory depression | Drugs used in status epilepticus, hypnotic drugs | Alternative medicine available, multiple doses given; avoidable with more rational prescribing | |

| 6 | Diarrhoea/vomiting | Antibacterial | Inappropriate indication, symptoms suggested viral infection | |

| 5 | Constipation | Antiepileptic drugs, opioid analgesia, drugs used in nausea, NSAIDs, cytotoxic drugs, calcium channel blockers, calcium supplements | Prophylaxis not used | |

| 4 | Immunosuppression | Drugs affecting the immune response, corticosteroids | Possibly avoidable with improved monitoring of drug levels; avoidable with more rational prescribing | |

| 2 | Haematemesis | NSAIDs | Avoidable with improved patient education/more rational prescribing (less NSAID use) | |

| 1 | Neutropenia | Cytotoxic drugs | Same ADR previously at same dose of medication | |

| 1 | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anaemia | Cytotoxic drugs | Superficial infection after recent admission with febrile neutropenia; possibly avoidable by prolonging antibiotic use or commencing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor | |

| 1 | Hyperglycaemia | Corticosteroids | Avoidable with more rational prescribing (prolonged course steroids used) | |

| 1 | Hyperglycaemia | Parenteral preparations | Avoidable with more rational prescribing (more judicial use) or improved monitoring | |

| 1 | Seizure | Posterior pituitary hormones | Possibly inappropriate medication used for a patient with seizures | |

| 1 | Diarrhoea | Laxatives | Avoidable with improved patient education | |

| 1 | Ileus | Opioid analgesia | Avoidable with more rational prescribing (possibly use alternative analgesia) | |

| 1 | CNS depression | Opioid analgesia | Avoidable with improved patient education | |

| 1 | Vomiting | Cytotoxic drugs | Possibly avoidable with more appropriate antiemetic prophylaxis | |

| 1 | Gastritis | Corticosteroids | Previous gastritis; possibly avoidable with improved prophylaxis | |

| 1 | Hypercalcaemia | Vitamins | Avoidable with improved monitoring |

Drug exposure prior to acute admission

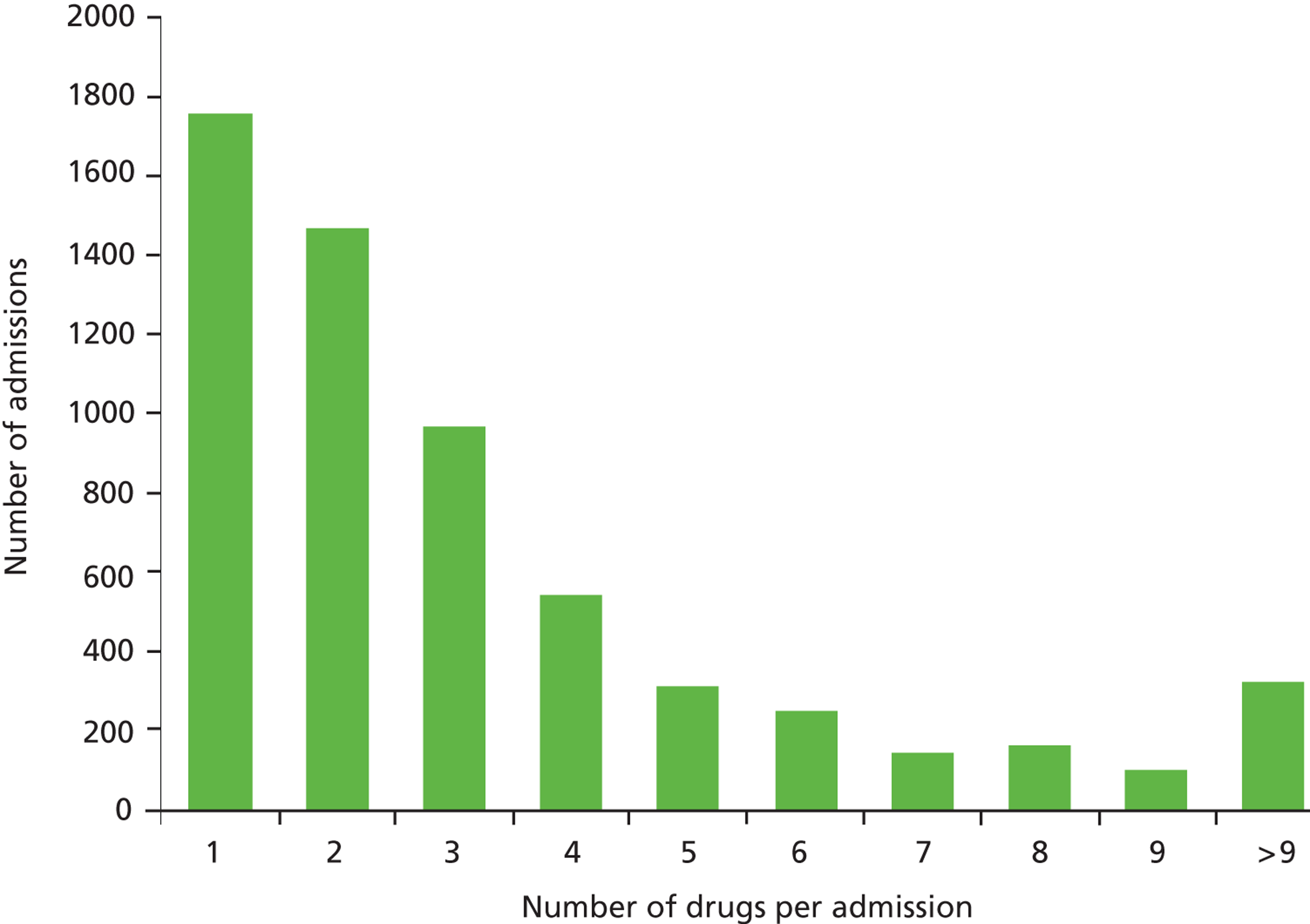

Of 8345 admissions, 6020 (72.1%) were exposed to medication in the 2 weeks prior to admission; 3417 (56.8%) of these were male and 2603 were female (43.2%). The median number of drugs taken was 2 (IQR 1–4), with one child exposed to 34 courses of medication owing to an admission for cardiothoracic surgery in the 2 weeks prior to readmission. Figure 1 shows the distribution of drugs per admission.

FIGURE 1.

Number of drugs per admission.

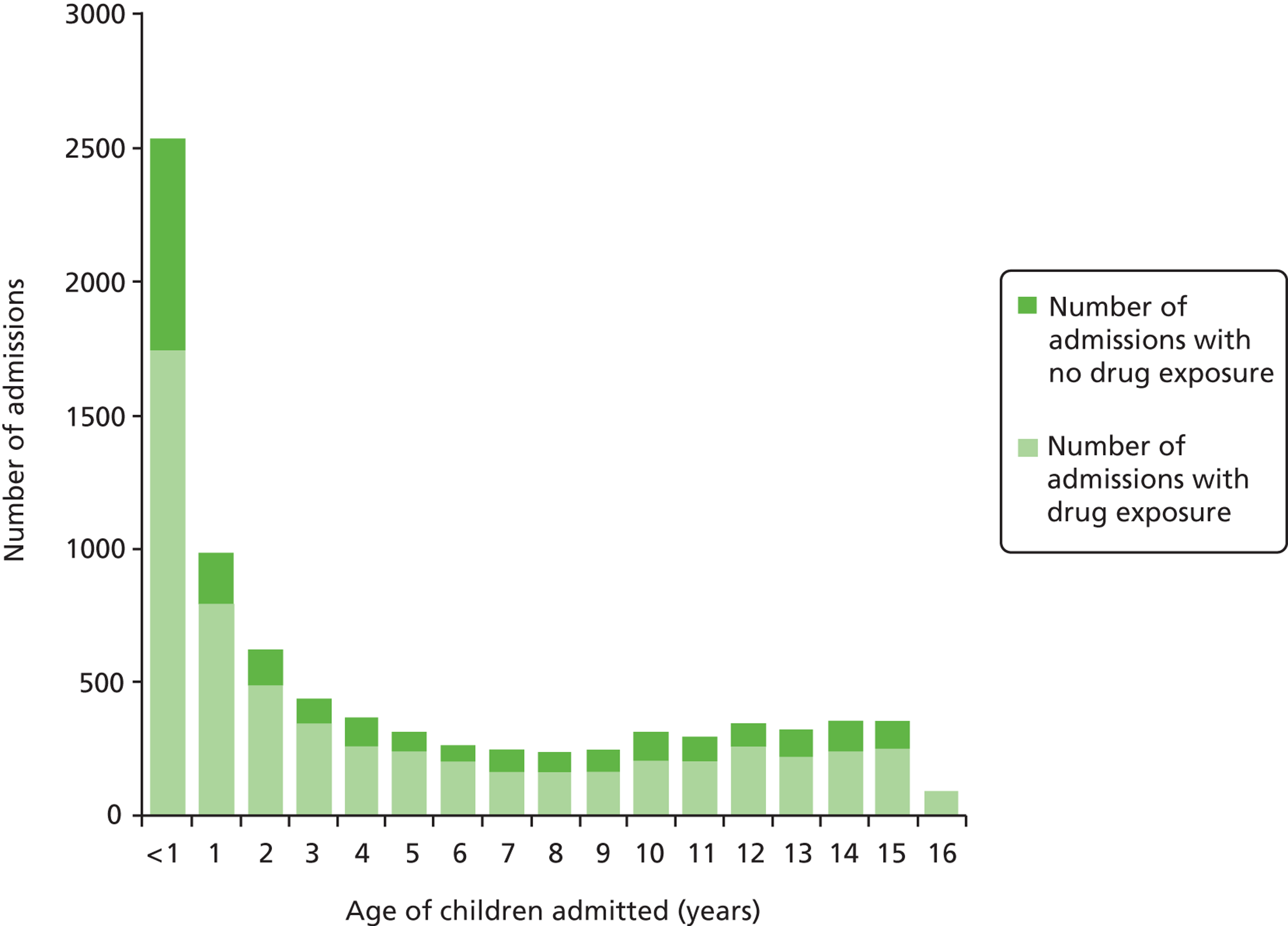

Children of < 1 year of age accounted for the most number of admissions: 1737 out of 2539 (68.4%) of < 1-year-olds had been exposed to medication prior to admission ( Figure 2 ). Of the other children admitted, the age group most frequently exposed to medication was the 16-year-old group (95/99 admissions, 96%). Children aged 7 years were the least exposed to medication (163/245, 66.5%) prior to admission.

FIGURE 2.

Age (1-year intervals) and number of children exposed to medication prior to admission.

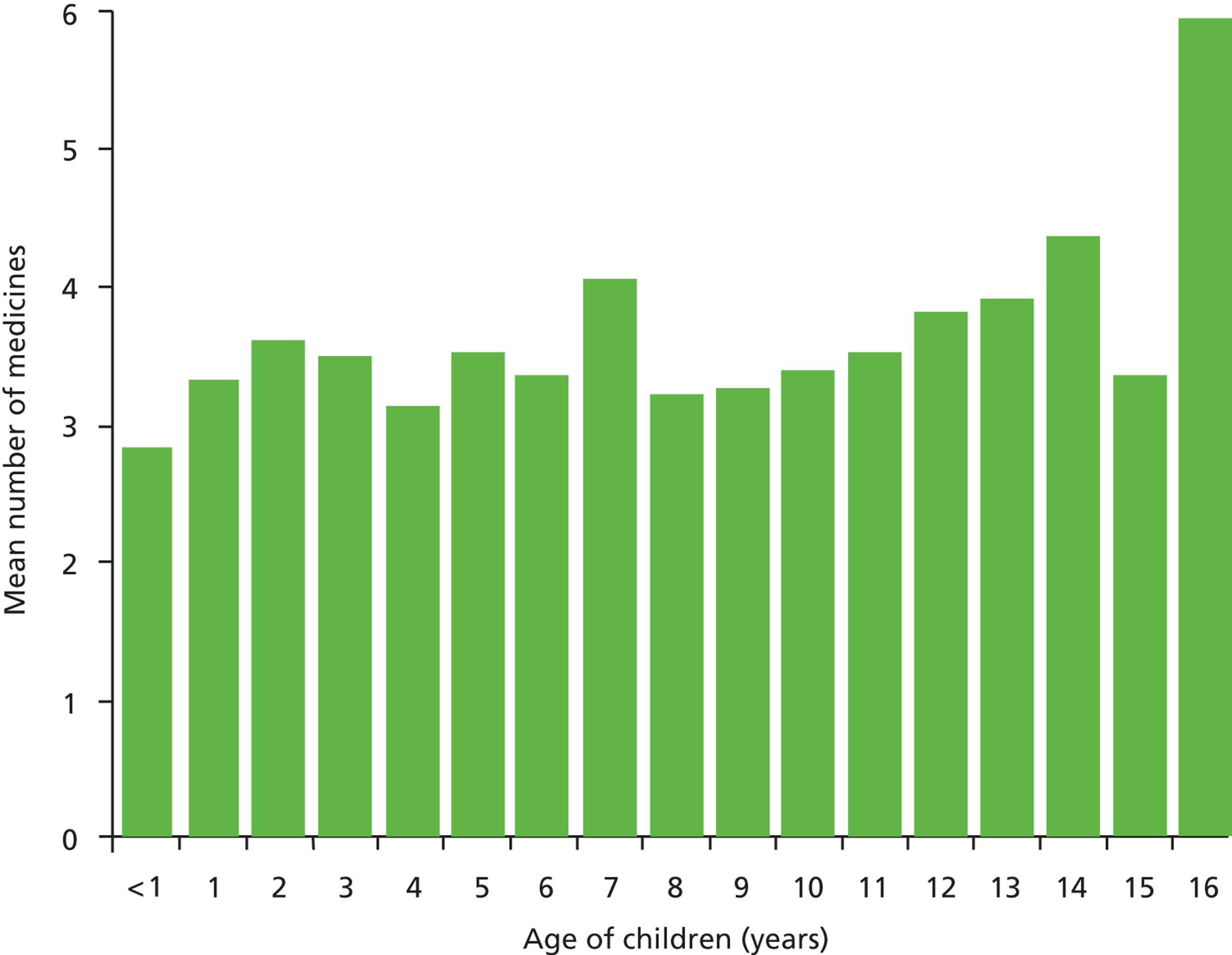

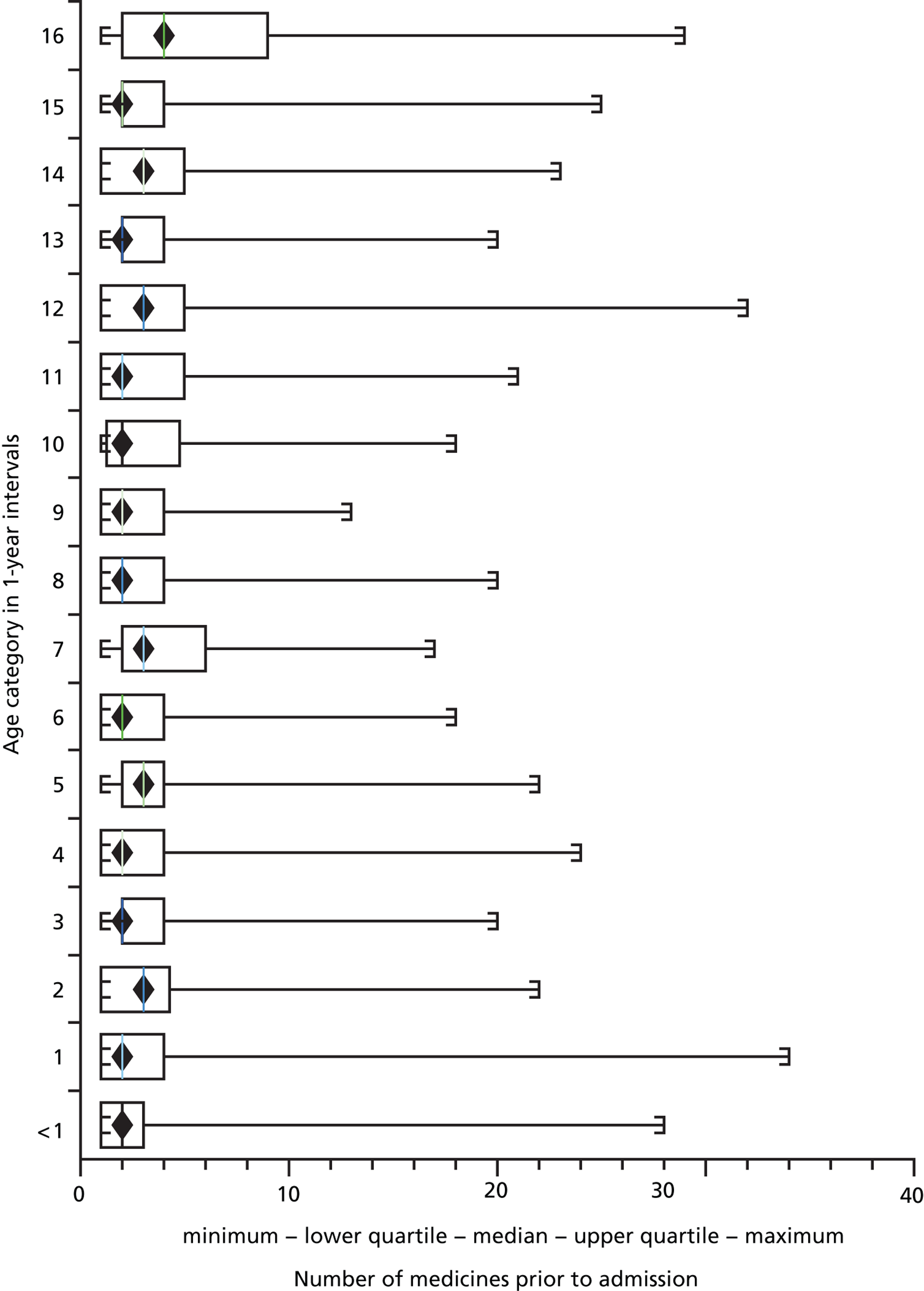

Of 6020 children exposed to at least one medicine prior to admission, those aged 16 years were exposed to the greatest number of drugs per admission, with a mean of 5.93 (95% CI 4.92 to 6.93) drugs. Children aged < 1 year were exposed to fewer medicines on average, with a mean of 2.82 (95% CI 2.71 to 2.93) drugs per admission ( Figures 3 and 4 ).

FIGURE 3.

Mean number of drugs taken by each age group (1-year intervals).

FIGURE 4.

Box and whisker plot of number of medicines taken by age group.

Cost of adverse drug reactions and length of stay

The mean cost of 238 out of 240 ADR admissions to the study hospital, using information provided by the finance department, was calculated to be £4753 per admission (95% CI £3439 to £6066). Cost data were missing for two ADR admissions: one oncology admission and one non-oncology patient admission. The mean cost of 113 oncology ADR admissions to the study hospital was £5428.91 (95% CI £4041.24 to £6816.58). The mean cost of 125 non-oncology admissions was £4141.40 (95% CI £1963.84 to £6318.95). The mean length of stay (LOS) of all 240 ADR admissions was 5.67 (95% CI 3.28 to 8.06) days. The mean LOS for the oncology admissions was 5.45 (95% CI 4.35 to 6.55) days, and 5.87 (95% CI 1.4 to 10.34) days for the non-oncology admissions.

Data from the Health and Social Care Information Centre57 showed that in 1 year, between 2009 and 2010, the total number of paediatric emergency admissions in England was approximately 597,800 (includes paediatrics and paediatric surgery, cardiology and neurology). We estimate the annual mean cost of paediatric ADR admissions to the NHS in England to be £82.4M using the mean cost of all ADR admissions to the study hospital. Using the upper and lower CIs for both our estimate of ADR incidence and study hospital costs we estimate the cost to the NHS in England of paediatric ADR admissions to be between £51.4M and £119M.

Discussion

This prospective observational study is the largest of its kind in children and the only one to comprehensively assess causality, type of reaction (predictable or not), severity, origin of drug prescription and avoidability. This is the first large study in children to investigate risk factors for the occurrence of an ADR-related admission inclusive of the use of OLUL medicines. The majority of admissions associated with ADRs in children occurred as a result of prescriptions originating in hospital. Potential preventative strategies for ADRs causing admission in children should therefore be targeted at hospital prescribing. Analysis of the ‘definitely avoidable’ ADRs in this study suggests that more careful attention to practical aspects of care – such as improved monitoring, following prescribing guidelines, improved patient education and heightened suspicion about potential adverse reactions – could lead to a reduction in the frequency of ADRs causing admission.

The incidence of ADRs causing admission in this study (2.9%, 95% CI 2.5% to 3.3%) was similar to the incidence in two systematic reviews: 2.09% (95% CI 1.02% to 3.77%) and 1.8% (95% CI 0.4% to 3.2%) but was significantly less than that of a large US study published in 1988. 33 In that study, the top three drugs causing ADRs were phenobarbital, aspirin and phenytoin, all of which are used in children much less now than in 1988. As these medicines were hardly used in our population, it is possible that the discrepancy in incidence rates relates in part to the reduction in use of these medicines.

This prospective observational study is the first to attempt the identification of possible risk factors for ADRs causing hospital admission in children. Older children, those exposed to more medicines in the 2 weeks prior to admission and oncology patients were shown to have an increased risk of ADR in this study. Girls showed a trend towards being more likely to experience an ADR than boys but this result was not statistically significant. An increased risk of ADRs occurring in the female gender has been described in studies in adult populations. 58,59 The number of authorised medicines and the number of OLUL medicines administered in the 2 weeks before admission were both significant predictors of ADR risk in this study, which supports the finding that the administration of multiple medicines increases ADR risk.

Causality was determined, of the ADR cases, using a novel CAT, the LCAT. The largest proportion of ADR causality classifications were ‘definite’ and most of these occurred in oncology patients. In order for a case report to achieve a score of ‘definite’ it would have to include a positive rechallenge or a previous history of the ADR to the same medication, a condition which these oncology-related ADRs satisfied. Type A reactions were more likely to be assigned a definite or possible causality, and type B reactions were more likely to be deemed possible. This may be due to assessors being less confident with type B ADRs, which are unpredictable and less frequent. The more severe reactions in our study were more often assessed to have definite or probable causality. This may reflect a confidence in assessing severe ADRs, which are more likely to be described in the drug safety literature.

The majority of the ADRs seen during the study were oncology related. These were mainly children with a febrile illness who developed neutropenia 1–2 weeks after intravenous chemotherapy. Clearly, patients with malignancy are often exposed to medications that cause ADRs,60 such as neutropenia (with fever), nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, anaemia and bleeding secondary to thrombocytopenia, all of which may require hospital admission. ADRs to cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs are expected and, for the most part, may be unavoidable given the nature of the underlying illness and the treatment options currently available. Although several studies have evaluated a potential preventative strategy for neutropenia,61 no definitive evidence exists regarding the routine prophylactic use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factors to prevent ADRs due to myelosuppression. 62

Steroids, along with other immunosuppressant drugs, increase the risk of infection. 63 Immunosuppressant drugs featured frequently in our study as causative agents for ADRs. The nature of ADRs associated with immunosuppressive therapy included proven bacterial infections and viral infections (e.g. shingles). Although we recognise that infections may also occur in healthy children, the role of immunosuppressive therapy in predisposing patients to infections is well recognised. 64–66

Another frequently recorded ADR in our study was postoperative bleeding, in particular secondary haemorrhage following elective tonsillectomy. The majority (23 out of 28 admissions) of these occurred in patients exposed to intravenous dexamethasone (as prophylaxis for postoperative nausea and vomiting) and NSAIDs, with ibuprofen being used commonly in the postoperative period. A few patients received either dexamethasone or NSAIDs. Dexamethasone has been linked to post-tonsillectomy bleeding67 but its role, and the role of NSAIDs, in causing secondary haemorrhage in these children needs further study. 68,69 However, intraoperative steroid has played a major role in improving outcomes for postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in children undergoing operations68,70 and has enabled day-case surgery for many conditions, thereby reducing the LOS in hospital.

Respiratory depression following treatment of seizures with benzodiazepines – a well-recognised and potentially serious event71 – was the cause of eight admissions to PICU for ventilation until recovery. Some of these cases were transfers from other regional district general hospitals to the study hospital tertiary PICU. Some, in fact, occurred as a result of rectal diazepam being used by paramedics in out-of-hospital care of seizures. Drugs used to treat status epilepticus have been widely studied and their efficacy and adverse reactions compared. 72,73 There may be drugs, other than diazepam, which have an improved benefit–risk ratio when used to treat seizures in children. 74 Further research is therefore warranted to optimise strategies for treating seizures, for both in-hospital and out-of-hospital care.

In terms of OLUL medicine use, the results described here cannot be compared easily with those of other studies, as this is the first large admissions study of this type. Previous inpatient studies report 27–45% of prescriptions being OLUL,3,75,76 and two previous community-based studies report 7% and 43% of prescriptions being off-label;77,78 compare this to 28% of prescriptions in this study. With the exception of Neubert et al. 75 these studies all found an increased ADR risk associated with OLUL medicine use. In this study, OLUL medicines were more likely to be implicated in an ADR than medicines used within the terms of their MA; however, it is important to highlight that 87.2% of ADRs that involved at least one OLUL also involved at least one other medicine; in some cases the OLUL medicine may not have caused the ADR in the absence of an approved medicine. Previous studies have examined exposure to OLUL medicines as an explanatory variable in their multivariate analysis. 3,75,76 Unlike our analysis, this approach to analysis does not take into account the relative contribution of authorised medicines. We have been able to demonstrate that, although the number of OLUL medicines contributes to ADR risk, it does so to a similar extent as the number of authorised medicines. Different OLUL medicines have different propensities to cause ADRs, it is not appropriate to consider them to be a homogeneous group. There are various types of OLUL medicines used, some of which may carry a greater risk of being implicated in an ADR than others. A key consideration is whether these medicines would be any less likely to be implicated in an ADR if they were used within the terms of their MA or if licensed preparations were used. A more detailed examination of the characteristics of the OLUL medicines that are implicated in ADRs may improve our understanding of why these medicines increase ADR risk and inform potential interventions to reduce that risk.

The design of the cohort study had limitations. The detection of suspected ADRs by the study team relied on two things: (1) signs and symptoms associated with the ADR being recorded by the clinical team looking after the patient and (2) the study team suspecting a link between signs and symptoms recorded and the medicines administered before admission. When signs and symptoms were not recorded or the study team missed the link, the ADR will not have been highlighted or evaluated. Although this was a single-centre study, it was carried out in a large centre providing a comprehensive range of paediatric services to a diverse population. The ADRs reported in this study highlight some of the adverse consequences of drugs in children. A limitation of this study is that we have not taken into account the benefits of these medications. Furthermore, we cannot be certain of the aetiological fraction (the risk of an event occurring in the presence of a risk factor) for some of the drugs in our study (e.g. immunosuppressant drugs) in their contribution to the stated reactions. For these drugs, more research is needed to accurately assess their contribution to ADRs and the ill health of children, to allow for more detailed risk–benefit evaluation. In this study, we have not considered ADRs caused by medications during inpatient stay in hospital. This aspect of drug reactions is likely to add greatly to the burden of ill health to children, and requires investigation of paediatric inpatient ADRs using a similar prospective study design to accurately identify the epidemiology of the problem.

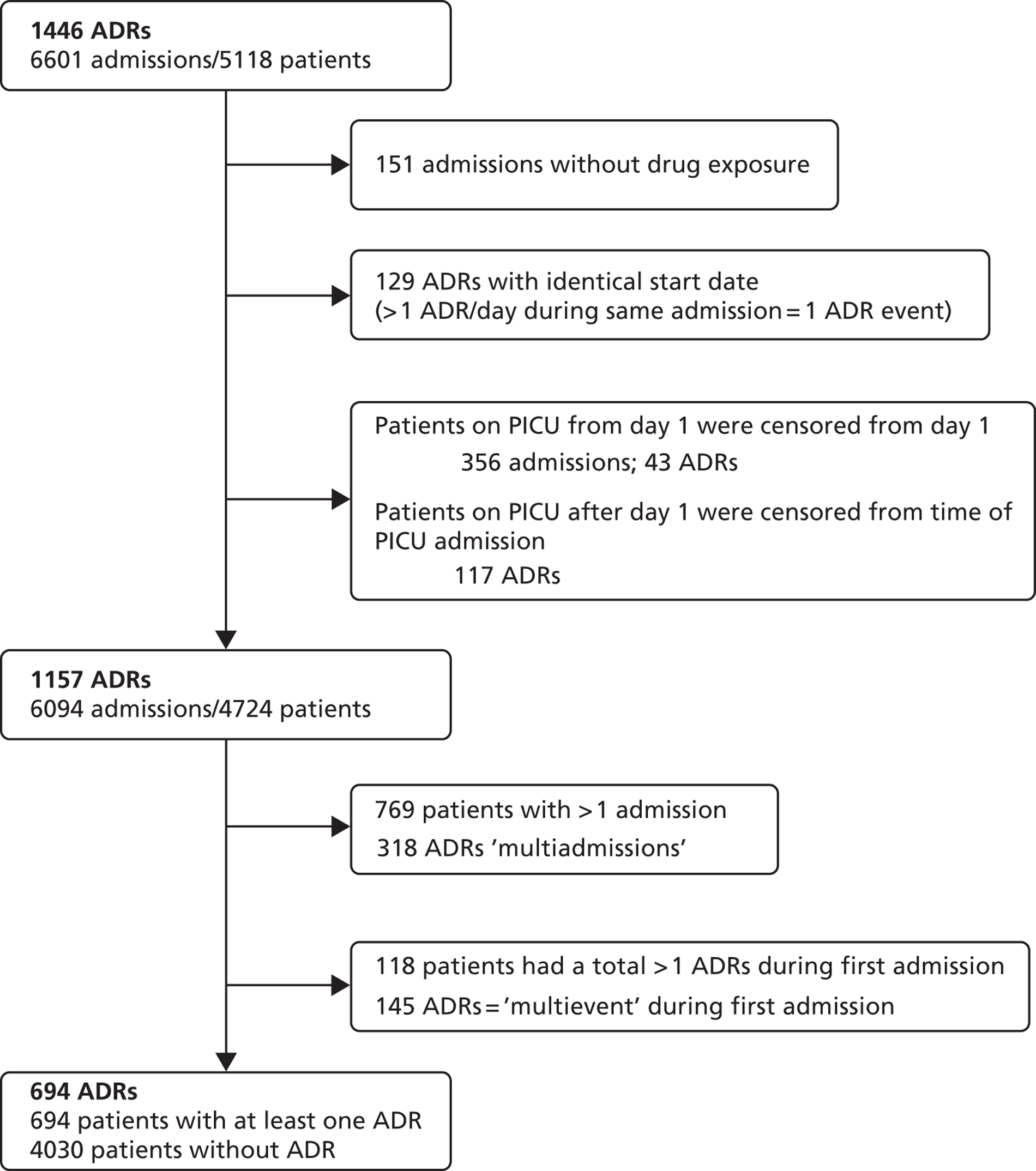

The cost of ADRs to the NHS in England was calculated using knowledge of the cost of admissions to the study hospital, our estimate of the incidence of ADRs causing admission and an estimate of total paediatric admissions annually to hospitals in England. Information regarding total annual admissions does not include emergency paediatric admissions from other specialties, thereby underestimating the total number of emergency paediatric admissions to hospitals in England. Although the ADR admission incidence from this study includes oncology cases, which is not included in the total annual admissions number used for our cost calculation, our estimate of costs of paediatric ADR admissions may be an underestimation.