Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1302. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none.

Disclaimer

this report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Marshall et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Cognitive remediation workstream: IMproving PArticipation in Cognitive Therapy (IMPACT) – a randomised controlled trial

This chapter has been published in a shorter format as Drake R, Day J, Picucci R, Warburton J, Larkin W, Husain N, et al. A naturalistic, randomized, controlled trial of cognitive remediation combined with cognitive–behavioural therapy after first-episode non-affective psychosis. Psychol Med 2014;44:1889–99. Available on CJO2013. doi:10.1017/S0033291713002559.

Background: Schizophrenia can be an intractable illness and so it is important to understand how far combining therapies creates synergy. Cognitive remediation (CR), which improves neuropsychological deficits, might combine well with cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), which improves symptoms.

Hypothesis: Following a first episode of non-affective psychosis, CR will enhance the efficacy and efficiency of subsequent CBT.

Methods: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) non-affective psychosis patients aged 18–35 years who were on waiting lists for routine CBT from NHS early-intervention services were randomised to receive either computerised CR over 12 weeks supported by a trained support worker or time-matched social contact (SC). All then received 6–30 weeks of CBT. The primary outcome was the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales, blind-rated at baseline, after remediation (12 weeks) and after CBT (42 and 54 weeks). Secondary outcomes included duration of CBT, cognition, insight, other symptoms, relapse and self-esteem.

Results: There was no significant difference in psychotic symptoms between the remediation group and the comparison group [coefficient 0.3, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.4 to 1.1; p = 0.39]. However, duration of CBT was shorter after remediation [median seven sessions, interquartile range (IQR) 2–12 sessions] than after SC (median 13 sessions, IQR 4–18 sessions; p = 0.011) and linked to better insight (p = 0.02). Global cognition did not improve significantly more after remediation (p = 0.20) but executive function did (Wisconsin Card Sort Task; p = 0.012). No other outcomes differed significantly.

Discussion: The duration of CBT after CR was substantially shorter than after an active control, perhaps mediated by improved neuropsychological function. Remediation was delivered by staff with minimal training and thus CR might considerably reduce the costs of CBT.

Introduction

Combination therapy has proven fruitful in many difficult-to-treat conditions. It has been widely touted as a means of targeting otherwise intractable symptomatic, social and cognitive outcomes of schizophrenia. 1–3 However, studies of combination therapy (especially of non-pharmacological interventions) are complex, expensive and difficult to organise. Typically, such trials have studied multiple interventions embedded within new service designs4–7 or complex programmes of care. 6–8 Although these studies have shown promising findings, the therapeutic offering is often so complex that it is difficult to extract precise information about the synergistic benefits, or otherwise, of combining specific interventions. 2 Studies of specific combinations of interventions are often open trials4–7,9–16 or have incompletely matched control conditions. 9–16 Hence there is a pressing need for further work in this area.

Cognitive remediation (CR) and cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) are good candidates for combination therapy in early schizophrenia for four reasons. First, both interventions have efficacy,1,16–18 even in the early stages of schizophrenia. 11,19 Systematic reviews show that CR improves cognitive measures across a range of domains,16 with effect sizes ranging from 0.15 to 0.65, whereas CBTp improves overall symptoms, with an effect size of 0.40 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.55). 17 Second, each intervention targets different but complementary aspects of the condition. Third, combining CR and CBTp makes sense in terms of service delivery, as the time spent waiting for CBTp from a specialist is a window of opportunity for computer-aided CR delivered by generic staff. Fourth, cognitive impairment is an obstacle to participation in CBTp, for example deficits in verbal memory (logical memory test) predict reduced CBTp efficacy. 20 It seems logical to offer CR to people with early psychosis before they have CBTp, as improved cognitive and social functioning arising from CR should lead to improved engagement with CBTp and ultimately to better outcomes.

In the NHS, early-intervention services look after all young adults with a first episode of psychosis and we therefore had a unique opportunity to examine the impact of CR combined with CBT in those who had suffered a recent first episode. This group is relatively unselected, as even those who will have a relatively good illness course are represented. It is also less socially and cognitively impaired and, being young and early in the illness career, perhaps neurophysiologically more plastic. Early-intervention services are expected to offer CBTp as part of their programme of care. 1,21 We planned a naturalistic trial, randomising service users to 12 weeks of CR or to a parallel time-matched SC control group, with both groups going on to receive CBTp from early-intervention services as part of usual care. CBTp offered in this way would usually last from 6 to 30 weeks, as determined by therapeutic need.

Our primary hypothesis was that CR would enhance the efficacy of CBTp, with symptoms reducing faster and further during CBTp preceded by CR. A secondary hypothesis was that CR would enhance the efficiency of CBTp, facilitating shorter courses or greater progress.

Methods

Participants

We identified potential participants among outpatients on waiting lists for CBTp from Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust’s and Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust’s early-intervention services. Inclusion criteria were age 18–35 years and first episode of DSM-IV22 schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorder, confirmed by semistructured interview. 23 Exclusion criteria were International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)24 organic brain disease; DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence; primary diagnosis of DSM-IV substance-induced psychosis; and insufficient fluency in English to participate in neuropsychological assessment. All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Bolton NHS Local Research Ethics Committee (reference 08/H1009/76) and was consistent with the UK Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. 25

Outcome assessments

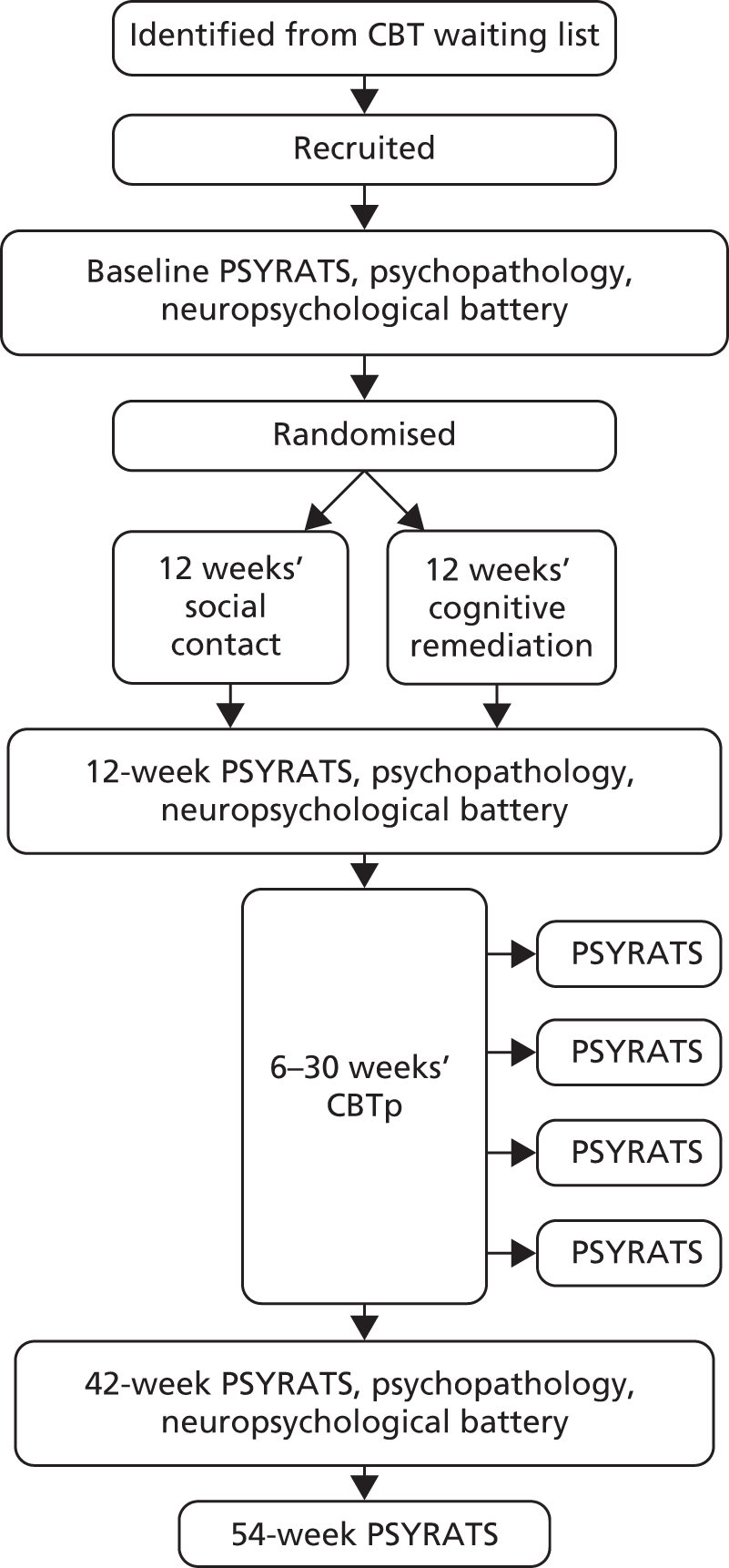

At baseline, demographic details (including self-ascribed ethnicity as a potential moderator of CR and CBTp outcome) and medication were recorded. The PSYRATS (Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales26) were the primary outcome measure, completed with other measures at baseline and after 12 and 42 weeks’ follow-up (Figure 1). The PSYRATS validly and reliably assess the severity of delusions and hallucinations in first-episode schizophrenia. 27 Intraclass correlation coefficients between assessors were > 0.99 for subtotals and the total score.

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

Assessments at baseline and 12 and 42 weeks included secondary measures of symptoms and function: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS28), the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS29), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale30 and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS31). A seven-item version of the Insight Scale (IS32), with the hospitalisation item dropped for this community sample, was scored from 0 to 14.

The PSYRATS were also rated at 6-week intervals during the CBTp envelope, at 12–42 weeks. Participants completed these interviews in person, or by telephone if they preferred. As CBTp was sometimes delayed or prolonged, and therefore incomplete by 42 weeks, the PSYRATS were also completed by telephone or in person at 54 weeks.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis typically aims to progress from engagement, through examination of the nature of individual problems, to integration of problems into a formulation describing origins, schemata and maintaining mechanisms. At the end of CBTp, therapists assessed this progression using a five-point score. 33

An assessor blind to allocation extracted the number of sessions of CBTp from case records and identified readmission and relapse (defined, as elsewhere,34 as an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms lasting at least 2 weeks, leading to a change in management).

Neuropsychological assessments

Intelligence quotient (IQ) was assessed at baseline with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) block design subtest and the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). 35 Secondary neuropsychological assessments of attention, executive function and memory were completed at baseline and at 12 and 42 weeks using the Wisconsin Card Sort Task (WCST),36 trail making,37 the 0-back version of the n-back task,38 paragraph recall39,40 and the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test41 (Table 1 contains details and rationales).

| Task | Neuropsychological rationale | Significance in previous CR trials |

|---|---|---|

| Computerised, meta-cognitive version of the Wisconsin Card Sort Task (MC-WCST) | Categories complete measures schema formation42 | Predicted a range of psychosocial outcomes43–45 |

| Free choice improvement measures meta-cognitive skill36 | ||

| Trail making A | Vigilance and motor speed | Predicted psychosocial outcome43,44 |

| Trail making B | Set alternation and working memory | Predicted psychosocial outcome43,44 |

| 0-back version of the n-back task | Basic CPT46 | CPT predicted psychosocial outcomes43,44,47 |

| Immediate and 30-minute paragraph recall | Memory skills related to structured narrative,48–51 expected to be important in CBTp | Predicted social skills improvement; predicted social function outcomes of linked rehabilitation programmes43,48,49,52 |

| Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test | Accuracy of copying: visual–spatial function | Comparison with structured verbal immediate and delayed recall |

| 30-minute recall: visual memory |

Allocation

Within 3 days of initial assessment assessors faxed details of participants to identified administrators who were independent of the trial team and unaware of the hypothesis. They used randomly permuted variable blocks53 to allocate participants to the experimental group or the comparison group, masked from assessors, and then communicated allocation by telephone to the researchers providing the study interventions, before faxing them participants’ details.

Interventions

Cognitive remediation was provided in patients’ homes or service bases using the CIRCUITS software, (Reeder and Wykes, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, UK)54 run from a secure website via the internet or on a DVD. Based on a CR programme validated in schizophrenia patients,42,55 it used a colourful, engaging, virtual town as an environment, guiding participants through a sequence of tasks. This provided a social context for tasks, each requiring a specific mixture of skills (e.g. sustained attention, working memory, registration and recall, planning) and with specific criteria for progression. Early tasks prepared for later ones of increasing difficulty and complexity. Trainers supported participants and could enter their virtual environment with privileges that allowed them to modify the sequence.

Trainers were psychology graduates who had undergone 1 week of specific training (a regular open course provided by Clare Reeder and Til Wykes) to deliver CIRCUITS. CIRCUITS is based on well-established CR principles (Table 2).

| Principle | Procedure | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Development of meta-cognitive (i.e. ‘thinking about thinking’) regulation and knowledge | Therapists’ and CIRCUITS prompts encourage participants to reflect on, learn about and develop strategies to systematically regulate their thinking and behaviour | Facilitates the transfer of new cognitive skills to a wide variety of situations within everyday life |

| Focus on transfer | Participants encouraged to define and work towards recovery-related goals and to consider how within-therapy cognitive skills can help improve everyday living skills | Aims to promote motivation and improved social functioning |

| Errorless learning | Therapists modulated difficulty to prevent repeated errors and participants progressed to harder tasks only once they were responding correctly | Prevents repeated errors that impair learning |

| Scaffolding | Trainers and the CIRCUITS tasks themselves initially provided strategies to support participants, but as difficulty increased this support was reduced | Forces participants to develop their capacity to strategise |

| Massed practice (frequent rehearsal) | Participants allowed to complete tasks between their sessions with trainers, with assignments reviewed at the start of sessions | Aiming for three to five 1-hour sessions per week and 40 hours’ intervention in 12 weeks |

The comparison condition was SC with support workers, with the duration of exposure matching that of exposure to the CR trainers. Both conditions provided interpersonal contact, warmth and unconditional positive regard within a professional relationship. Social activity (conversation, neurocognitively undemanding recreations) was the basis of sessions, although when necessary workers supported participants sufficiently to maintain their motivation to attend (i.e. non-directive listening concerning problems and symptoms).

Cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis was provided separately by therapists employed specifically for that purpose by the two NHS services who worked in seven different community clinics. All had specific CBTp training and were supervised by experienced senior CBTp therapists according to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) standards. 1 CBTp quality was assessed using the Cognitive Therapy Scale for Psychosis (CTSpsy57), independently rated from randomly selected audio-taped sessions, provided that therapists thought it clinically appropriate and patients provided separate written consent. The mean CTSpsy score for seven CBTp interviews was 75.2% [standard deviation (SD) 14.5%].

Analysis

The effect of group on PSYRATS score was estimated using a mixed-effects model estimated using full information maximum likelihood with Stata version 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Allocation group and a group × time interaction term modelled the intervention’s effect. Time was entered as the square root of weeks from baseline; as PSYRATS scores tended to level off during follow-up this improved the model fit. 58 Demographic and other baseline potential confounders (lack of antipsychotic prescription, previous illicit substance use, diagnosis of schizophrenia) were removed by backward elimination, the criterion for retention being p < 0.20. PANSS, SOFAS and depression and self-esteem scales were analysed in the same way. Insight, in its mixed-effects model, was transformed towards normality by squaring the Insight Scale (IS) score. Insight changed relatively linearly over time and so weeks from baseline was entered as the time variable. A logistic regression against dropout with baseline variables as predictors assessed the pattern of missing data in relation to these variables.

As a categorical outcome, remission was defined as a PSYRATS score of zero. The relative risk of remission after CR was calculated and used to derive the number needed to treat/harm.

For neuropsychological measures, a global score was calculated. Individual baseline scores were transformed to normal distributions with a mean of 100 and SD of 15, with higher scores indicating better performance, before deriving a global score with the same characteristics. The same transformations were applied to 12- and 42-week follow-up scores, giving distributions with various means and SDs. The global score was then entered into a mixed-effects model.

In this relatively able population, WCST categories complete and complex figure copying (rather than recall; see Table 1) scores were too skewed by ceiling effects for this process. Categories complete and copying were modelled by ordinal logistic regression against follow-up scores, adjusting for baseline scores and potential confounders after backward elimination, clustering by clinic. To examine the sensitivity of ordinal logistic and linear regressions to the effect of dropout, all were repeated with cases probability weighted by a function of the risk of attrition, derived from the logistic regression against dropout. That is, the number of each case (n = 1) was multiplied by the reciprocal of the risk of completion of that type of case (calculated from a logistic regression using baseline characteristics to predict which cases would finish the study), so that cases of a type who more often dropped out appeared to be more frequent (e.g. apparent or weighted n = 1.43 if the probability of completion for a case with those demographic and clinical baseline characteristics was 0.7) to make up for the cases who did, in fact, drop out.

Time to relapse and readmission for allocation groups were compared by log-rank tests. Cox regressions adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for potential demographic and clinical confounders, stratified by clinic.

Sample size

Assuming (after the trial by Eack and colleagues11) a PSYRATS effect size of 0.5, recruiting 64 participants provides > 80% power with a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, correlation of 0.5 between seven successive assessments and 25% dropout.

Results

Experimental and comparison group characteristics

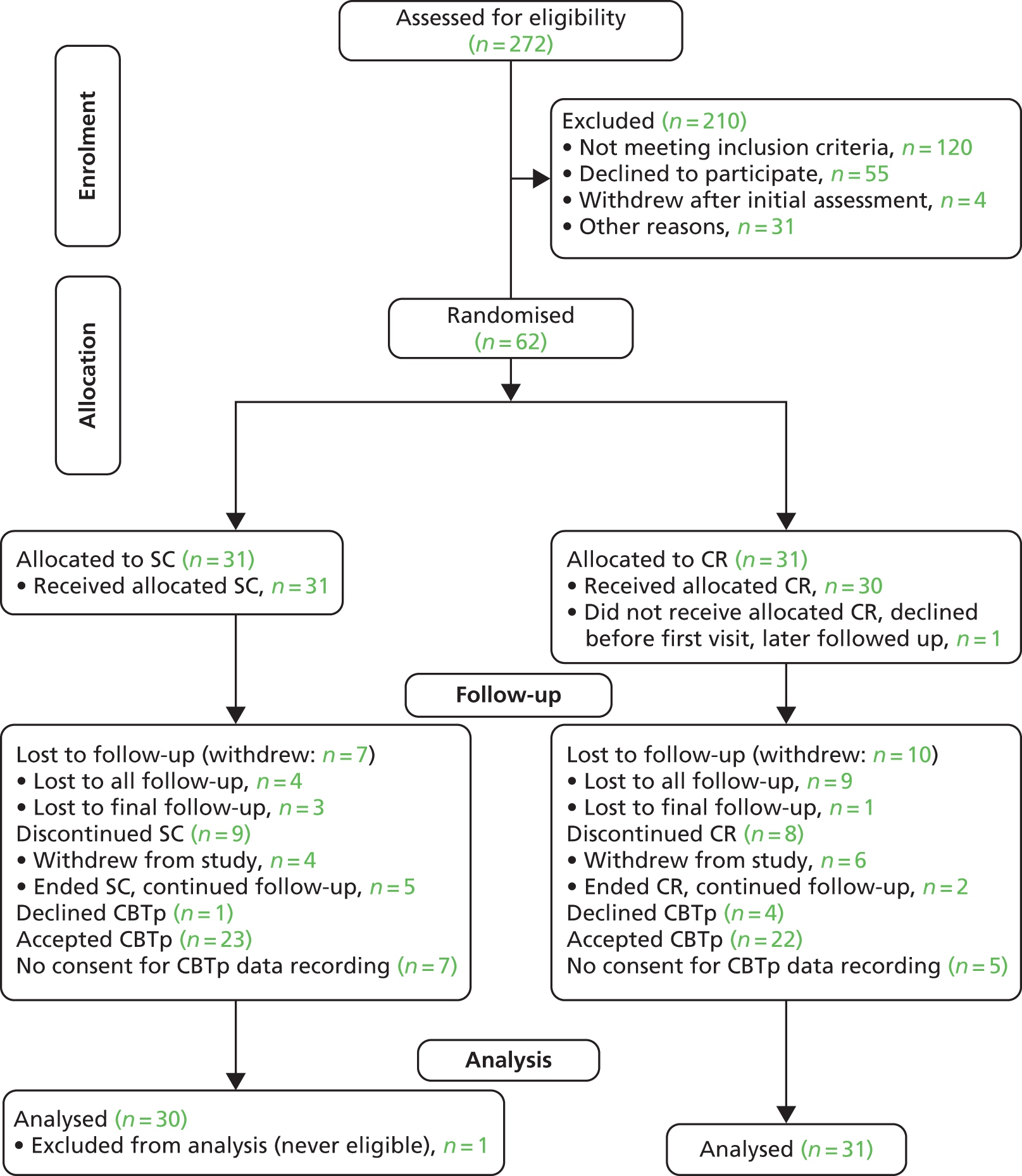

In total, 272 CBTp waiting list patients were screened for eligibility (Figure 2). Of these, 66 consented to participate, of whom four withdrew, leaving 62 to be randomised. One was subsequently excluded as a concealed history of previous psychosis rendered him ineligible and so 61 entered a modified intention-to-treat analysis (Table 3). Seven in the CR group and four in the SC group did not take maintenance antipsychotics (p = 0.51, Fisher’s exact test). No anticholinergics were prescribed and only one in each group took medication with high muscarinic receptor affinity (clozapine). Assessors accidentally discovered two participants’ allocation group during the trial, one from each group. CBTp therapists discovered eight participants’ allocation group (five CR group and three SC group) but their guesses at the allocation of the other participants were no better than chance (p = 0.43, Fisher’s exact test). Logistic regression against completion found no significant predictors of dropout.

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram showing participant flow through the trial.

| Variable | CR | SC |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 21 (68) | 16 (53) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 23 (74) | 25 (83) |

| African and African Caribbean | 1 (3) | 2 (7) |

| South Asian | 5 (16) | 3 (10) |

| East Asian | 2 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Schizophrenia | 26 (84) | 26 (87) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 5 (16) | 4 (13) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 24.7 (5.2) | 23.4 (4.4) |

| Full-time education (years), median (IQR) | 13 (11–14) | 13 (11–14) |

| PSYRATS, median (IQR) | 13 (8–22) | 16.5 (11–35) |

| PANSS, mean (SD) | 71.3 (13.9) | 69.5 (11.7) |

| IQ, mean (SD) | 105.4 (8.0) | 103.4 (10.0) |

| Global cognition, mean (SD) | 99.5 (13.7) | 100.5 (16.4) |

| WCST categories complete, median (IQR) | 5 (4–5) | 5 (4–5) |

| Complex figure copying, median (IQR) | 34 (32–36) | 34 (31–35) |

| Defined daily dose, median (IQR) | 0.75 (0–1.06) | 0.72 (0.31–1.00) |

There was no significant difference in exposure to CR trainers/exposure to support workers between the two groups (SC: median 390 minutes, IQR 145–610 minutes, CR: median 375 minutes, IQR 125–600 minutes, Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.84; SC: median 8.5 sessions, IQR 3–10 sessions, CR: median 9 sessions, IQR 4–13 sessions, Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.20).

Did cognitive remediation improve cognition?

Cognitive remediation did not predict differences in global cognition scores [intercept (baseline) –1.7, 95% CI –7.7 to 4.4, p = 0.59; gradient (group × time) –0.73, 95% CI –1.84 to 0.38, p = 0.20)]. However, after the intervention the CR group completed significantly more WCST categories: after CR, 74% completed five categories (range 4–5 categories); after SC, 63% completed five categories (range 2–5 categories) [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 2.9, 95% CI 1.3 to 6.9; p = 0.012]. By final follow-up these gains were lost (adjusted OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.2 to 2.5; p = 0.61). The median score for complex figure copying was 35 (IQR 33–36) after CR and 33 (IQR 29–35) after SC (p = 0.11, Mann–Whitney U-test). After removing an outlier with persistent, specific, severe visuospatial impairment (baseline copying score 12; range of other participants’ scores 24–36, mean 32.89, SD 3.89; Dixon’s Q59 0.50, p < 0.01), CR had a trend towards better scores at 12 weeks (adjusted OR 3.83, 95% CI 0.99 to 14.77; p = 0.052) but not at the final assessment (adjusted OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.3 to 7.7; p = 0.56).

Did cognitive remediation improve the efficacy of cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis?

Symptoms

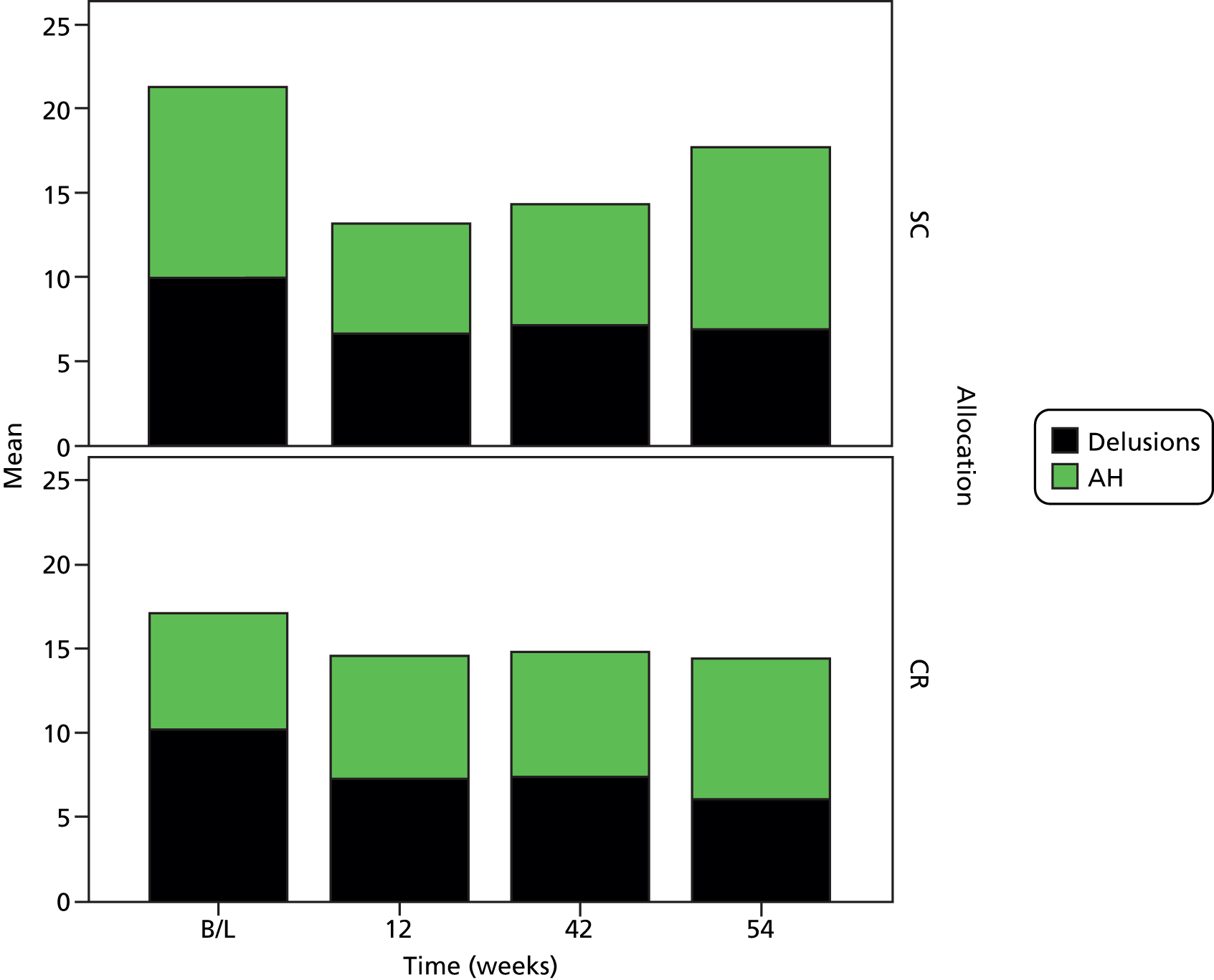

Cognitive remediation was not associated with significantly lower PSYRATS scores over the period of study (Figure 3) (intercept –2.8, 95% CI –10.7 to 5.2, p = 0.50; gradient 0.3, 95% CI –0.4 to 1.1, p = 0.39). The effect of CR on the PANSS score was non-significant (intercept 3.8, 95% CI –2.7 to 10.3, p = 0.25; gradient –0.4, 95% CI –1.5 to 0.6, p = 0.44). Eight participants in each allocation group had full remission of symptoms on the PSYRATS (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.51; p = 1.00, Fisher’s exact test), giving a number needed to harm with CR of 116 (95% CI ranging from a number needed to treat of 3 to a number needed to harm of 12).

FIGURE 3.

Mean AH and delusions subscale scores by visit for each allocation group. AH, Auditory Hallucinations; B/L, baseline.

However, insight changed significantly more positively after CR than after SC (intercept –1.9, 95% CI –27.7 to 23.8, p = 0.88; gradient 0.55, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.01, p = 0.02). At 42 weeks the median insight score was 12 after both CR and SC, but the IQRs after CBTp (CR 9.5–13; SC 6–13) showed that fewer participants in the CR group had substantially impaired insight. There was no significant effect of CR on SOFAS score, depression or self-esteem.

Repeating multiple regressions for clinical and neuropsychological variables, weighting cases according to the probability of dropout, did not alter the significance of the results.

Relapse and readmission

Cognitive remediation had no significant effect on time to relapse (adjusted HR 1.4, 95% CI 0.5 to 3.5; p = 0.50) or readmission (adjusted HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.2 to 5.5; p = 0.84).

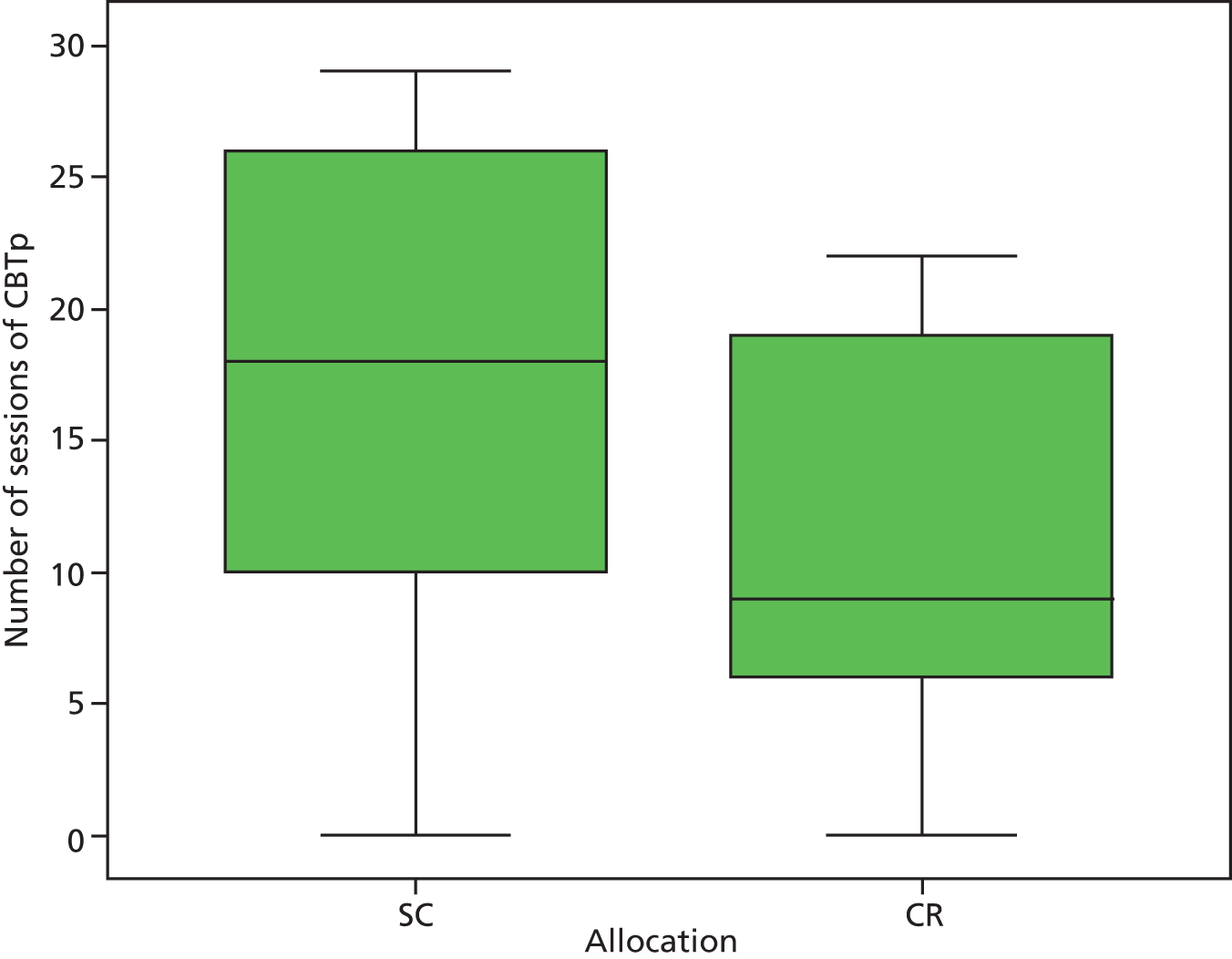

Did cognitive remediation improve the efficiency of cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis?

After CR, far fewer sessions of CBTp were required (Figure 4): a median of seven (IQR 2–12) sessions compared with a median of 13 (IQR 6–18) sessions for the SC group (p = 0.039, Mann–Whitney U-test). CR still predicted fewer sessions of CBTp after adjustment for potential confounders (coefficient –1.0, 95% CI –0.3 to –1.7; p = 0.011). Unmasking was not responsible: their allocation of 53 participants remained masked from therapists and the median number of sessions was six (IQR 1–12) after CR and 15 (IQR 7–19) after SC (p = 0.012, Mann–Whitney U-test). Allocation was unmasked for eight participants, for whom the median number of sessions was 14 (IQR 10–18.5) after CR and nine (IQR 3–18) after SC (p = 0.37, Mann–Whitney U-test).

FIGURE 4.

Number of sessions of CBTp by allocation group.

There was no evidence that level of formulation differed between the CR group and the SC group across all participants (adjusted OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.2 to 6.1; p = 0.88) or in masked patients alone (adjusted OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.2 to 2.3; p = 0.50).

Discussion

Although the hypothesis that CR would enhance the effect of CBTp on symptoms was rejected, the hypothesis that it would improve the efficiency of CBTp was supported. After CR, participants made the same amount of progress in half the number of CBTp sessions. If CBTp ended when a therapist judged that the client had progressed cognitively as far as possible, then better engagement because of improved insight and cognition after CR might have helped client and therapist reach this point more quickly. If symptom reduction determined when therapists ended CBTp, less efficient CBTp after SC could have led therapists to lengthen the duration of CBTp to compensate. Either would explain why efficiency rather than efficacy improved.

The CR group had fewer low scores on the IS at 42 weeks. The difference from the SC group became substantially greater after CBTp than before and so it appears most likely that CR enhanced CBTp and this led to relatively better insight. CR improved WCST performance, although this was not sustained. The WCST is one of the most common, robust and sensitive measures of CR outcome16 and frequently predicts progress in social skills and CR interventions,43 particularly categories complete (schema generation). 54 Silverstein and colleagues15 previously proposed that transient cognitive benefits could promote sustained changes in behaviour and performance during succeeding interventions, consistent with transient neuropsychological gains facilitating CBTp.

Global cognition did not improve but other neuropsychological measures might have been less accurate than the WCST. Short, less-demanding cognitive tasks were chosen for these process measures, mindful of the risk of alienating potential and actual participants and rendering the sample unrepresentative. Although these tasks had demonstrated validity in other trials (see Table 1), they lacked the rigor of lengthier cognitive batteries [e.g. the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB)],60 making them vulnerable to practice effects that could have concealed the benefits of CR. Nevertheless, other CR trials with more extensive batteries found that executive function effect sizes exceeded other types of cognition,55,61 suggesting that the difference was real.

One limitation of our study was that inexperienced therapists delivered CR. In addition, CBTp was delivered by NHS clinicians who, although qualified and supervised, were not research trained and supervised (although CBTp quality scores were reasonably good). Even so, we felt it important to accept these limitations to simulate routine clinical practice and make generalisation credible. One consequence of our naturalistic design was that the median number of CBT sessions was lower than that recommended by NICE guidelines;1 however, they still appeared sufficient to have an effect. A strength of the naturalistic trial design was that NHS early-intervention services take nearly all incident cases of schizophrenia in their catchment areas and so attendees at these services are reasonably representative of all those who might benefit from CBTp.

Another strength of our trial was that contact time was well matched between the CR group and the SC group, ensuring plausible matching of non-specific benefits of remediation. Even the most carefully designed randomised trials of combination therapy, for instance CR with social skills training9,14,15 or with vocational interventions,10,12,13 struggled to match exposure to the intervention and comparison conditions. 12 However, SC offered more opportunity for non-directive listening than task-oriented CR. This compensatory therapeutic effect could have led us to underestimate the specific benefits of CR.

Allocation was almost completely masked from assessors, whereas previous trials combining psychosocial interventions have often been open. 4–7,9–16 Although it is unclear how far measurement of neuropsychological performance or employment rates is affected by the open rating, previous meta-analysis of CBTp suggests that symptoms are sensitive, as limiting inclusion to studies with masking and other rigorous design features diminished the effect size of CBTp from 0.40 to 0.22. 17 Although it was difficult to mask allocation from CBTp therapists, they identified allocation in only 13% of participants. In fact, unmasking only attenuated the difference in CBTp length between the CR group and the SC group: the reduction in CBTp length after CR was greater in those participants with allocation still masked.

Overall, our findings suggest that CR delivered by relatively unskilled workers improved the efficiency of subsequent CBTp, enabling participants and therapists to achieve the same amount of progress in therapy in approximately half the number of sessions. The computer-aided CR approach that we selected was delivered by relatively inexpensive support workers within a typical clinical service. Labour costs for a course of CR were only £85. A substantial increase in the efficiency of CBTp implies that the same number of CBTp therapists could treat many more patients, whereas estimates from previous studies62,63 imply that the shortened duration of CBTp was equivalent to a saving of £335 per patient.

Key findings

-

Cognitive remediation after first episodes of non-affective psychosis improved executive function but no other neuropsychological test scores.

-

After CR, the duration of CBT was much shorter but there was no difference in efficacy.

-

At the end of CBT, those who had received CR had significantly better insight.

Chapter 2 Healthy living workstream: development of an intervention to encourage activity, improve diet and control weight gain (InterACT) and a randomised controlled trial

Reprinted from the International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49, Bradshaw T, Wearden A, Marshall M, Warburton J, Husain N, Pedley R, Escott D, Swarbrick C, Lovell K, Developing a healthy-living intervention for people with early psychosis using the Medical Research Council’s guidelines on complex interventions: Phase 1 of the HELPER – InterACT programme, 398–406. Copyright (2012), with permission from Elsevier.

Background: People with psychosis are at an increased risk of weight gain, contributing to poor physical health and early death.

Objectives: (1) Develop an effective and acceptable healthy-living intervention to prevent weight gain for people with psychosis, (2) evaluate the clinical effectiveness of the intervention and (3) evaluate the acceptability of the intervention.

Methods: The intervention was developed by synthesising the results of a number of inter-related studies including (1) a review of healthy-living intervention studies, (2) qualitative interviews with service users and health professionals, (3) identification of a theoretical model and (4) cultural adaptation of the intervention. It was tested with service users of two early-intervention services with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2, who were randomly allocated to the intervention group or usual care. The primary outcome was change in BMI from baseline to 12 months’ follow-up. Qualitative interviews were conducted with participants about their experience of the intervention.

Results: The intervention consisted of eight individual sessions with a trained support, time and recovery (STR) worker, supplemented by optional group activities. In total, 105 participants were recruited (54 intervention group, 51 usual-care group), with 89% retention at 12 months. There was a small but non-significant decrease in mean BMI at 12 months in the intervention group compared with no change in the usual-care group. The intervention was highly acceptable to participants.

Conclusion: The healthy-living intervention was associated with a small but non-significant reduction in BMI in the intervention group but not in the usual-care group.

Introduction

Individuals with psychosis have poorer physical health and die younger than other members of the general population. 64 Recent government policy has set targets for service providers to reduce this inequality. 65 One major contributory factor of poor physical health may be the rapid weight gain associated with the prescription of second-generation antipsychotic drugs. 66 A review by Foley and Morley67 showed average weight gain to be 5–6 kg after only 6–8 weeks of treatment with antipsychotic drugs, with unhealthy cardiometabolic changes already beginning to emerge. Commenting on the review, an editorial in the Lancet stated that in any other scenario the responsible physician would seek an alternative treatment. 68 However, for mental health professionals and their patients there are no realistic alternatives currently available. If, as the editor suggests, patients must continue to take antipsychotic medication, then there is an urgent need to develop interventions to help patients control their weight gain and protect themselves against the cardiometabolic effects and complications associated with weight gain.

Although conclusions from a Cochrane review showed that there is insufficient evidence to support the general use of pharmacological interventions for weight management in people with schizophrenia,69 there is sufficient evidence in support of non-pharmacological interventions. A meta-analysis of non-pharmacological weight management studies in people with psychosis70 showed that CBT and nutritional counselling were effective at reducing or slowing antipsychotic medication-induced weight gain. However, benefits rapidly attenuated once the intervention was discontinued. 71 An explanation for these modest effects and poor durability may lie in the development of the interventions. For the most part the interventions in the review were not obviously underpinned by theoretical models of behaviour change. For example, there was limited reporting of service users’ motivations for weight control, their beliefs about their ability to control their weight or the strategies that they would use to regulate their behaviour. Furthermore, it was not clear which (if any) of these factors were addressed in the interventions (and how). Additionally, the acceptability of interventions to service users and those delivering them was not assessed. Finally, only one study in the review had recruited patients in the early stages of treatment for psychosis.

In the last decade there has been growing interest in the development and evaluation of interventions, largely driven by the influential UK Medical Research Council (MRC) framework. 72 The MRC defines a ‘complex intervention’ as one in which there is ambiguity over the ‘active ingredients’ of the intervention and their optimal mix, and the phased development of such interventions has been advocated. 72 This involves the use of theoretical and empirical work to identify the active ingredients of the intervention (modelling), followed by an exploratory randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test the intervention, examine its delivery in routine settings and provide estimates of key trial parameters such as recruitment rates and effectiveness. In this chapter we will describe how, guided by the MRC framework,72 we have developed and tested the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a novel lifestyle intervention that aims to help people with first-episode psychosis control their weight.

The overall aim of the workstream was to develop an evidence-based, acceptable, feasible and effective intervention to encourage activity, improve diet and control weight gain in people recovering from a first episode of psychosis and to evaluate its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in an exploratory randomised controlled study. We conducted two key phases.

Phase 1: development

Phase 1 had two key aims:

-

to identify the active ingredients of a healthy-living intervention to control weight in people after a first episode of psychosis

-

to develop an evidence-based, acceptable and feasible protocol and training programme for the delivery of a healthy-living intervention.

To develop the intervention we conducted a series of separate but inter-related studies, the findings of which were synthesised to produce a prototype healthy-living intervention (Figure 5). We (1) identified the evidence base by updating a systematic review, (2) identified the most appropriate theoretical model to underpin the intervention, (3) conducted qualitative interviews with service users to examine their beliefs about weight gain in psychosis, (4) conducted both focus groups and individual interviews with mental health professionals to examine their perspectives and (5) culturally adapted our intervention to be appropriate to the needs of the ethnically diverse population that we were working with. These data were synthesised by the trial team and the draft prototype healthy-living intervention was then subject to (6) a stakeholder consensus group to finalise the intervention.

FIGURE 5.

Development of the intervention. SRM, self-regulation model.

Systematic review

Aim

The study aimed to update a systematic review of the RCT literature and then conduct a meta-regression to identify:

-

the types and relationships between components of non-pharmacological interventions used to improve healthy-lifestyle behaviours (all interventions used to improve healthy-lifestyle behaviours including exercise, diet and weight maintenance) in people with psychosis

-

the overall clinical effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for people with psychosis

-

the factors associated with effective interventions such as setting (inpatient/community), delivery mode (group/individual) and personnel delivering the interventions.

Methods

We drew on a recently published high-quality systematic review of non-pharmacological management studies of antipsychotic medication-related weight gain. 70 We supplemented this by searching for any additional RCTs using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The search of CENTRAL was then amplified by searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, the Health Technology Assessment database, the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, the National Research Register and the System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe. The reference lists of all identified studies and review papers were searched for other relevant publications up to 2007 to identify recent additional literature. Searches (available from the authors) utilised a mixture of subject headings and free-text terms.

Inclusion criteria

-

Study design. RCTs in which the majority (> 50%) of the participants were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder.

-

Study context and population. Populations eligible for inclusion included any adult group with a psychotic mental health problem using any criteria (e.g. ICD-10 criteria,24 DSM-IV criteria22 or case note diagnosis) seeking treatment with a non-pharmacological intervention to improve healthy living or prevent weight gain. All settings including community, primary care, specialist outpatient and inpatient and non-clinical settings were eligible.

-

Interventions. Lifestyle/healthy-living/health-education interventions focusing on healthy eating and/or physical activity or a combination of both delivered on either a group or an individual basis.

-

Outcomes. Primary outcome measures included self-reported and externally assessed aerobic fitness, blood pressure, weight, BMI, flouval antioxidants, abdominal girth measurement, waist-to-hip ratio and/or other outcomes of measured compliance with recognised healthy-living guidelines. Secondary outcomes included psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, self-esteem, self-efficacy, medication compliance, medication dosage, attitude or belief change, numbers lost to follow-up and number of participants approached who declined to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that focused exclusively on smoking cessation or reducing the use of illicit substances, non-randomised studies and those not written in the English language were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Eligibility judgements and data extraction were carried out independently by two reviewers. No formal measure of the reliability of data extraction was calculated but disagreements were resolved by discussion with members of the trial team.

Analysis

We completed a meta-analysis of these studies using random-effects modelling to provide an overall pooled measure of effect on BMI rather than weight as in the review by Álvarez-Jiménez and colleagues. 70 In addition, we conducted a meta-regression on intervention moderators to examine the relationship between components of the intervention and outcomes, to determine potentially critical ingredients.

Results

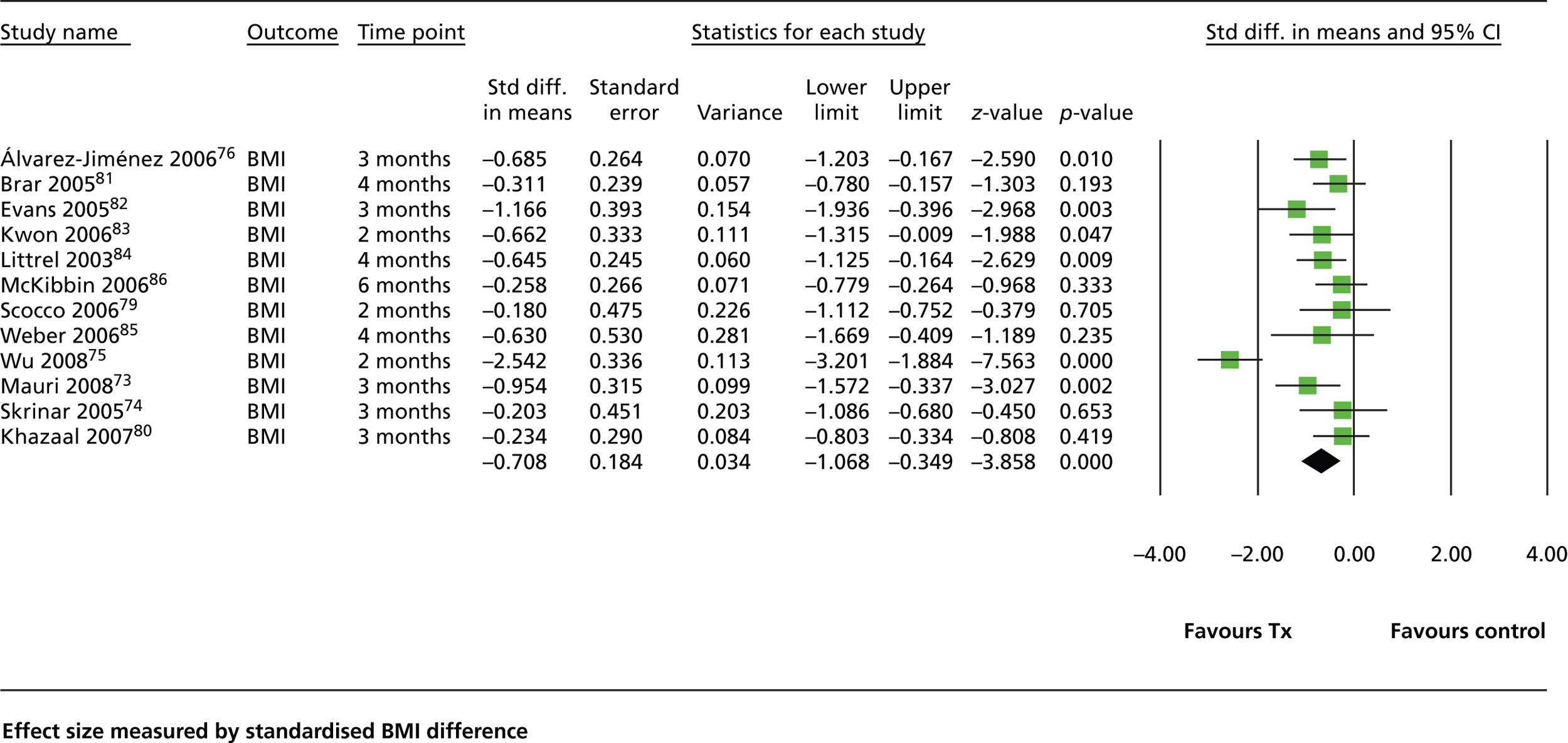

Three additional studies were identified. 73–75 We identified 12 studies in total73,75–85 Eleven compared the intervention with routine care and one80 used brief nutritional education as a control. The review by Álvarez-Jiménez and colleagues70 found that weight-management interventions resulted in a mean weight difference of 2.56 kg compared with treatment as usual (TAU). No difference in efficacy was shown between interventions delivered to groups and interventions delivered to individuals or between CBT interventions and nutritional counselling. Similar to the review of Álvarez-Jiménez and colleagues,70 our analysis showed that weight-management interventions are moderately effective, resulting in an average change in BMI of approximately 1 point (–0.708, 95% CI –1.07 to –0.349; Figure 6). We found no difference between studies that were CBT based and studies based on other therapeutic approaches. Unlike the study by Álvarez-Jiménez and colleagues,70 our analysis showed a trend towards greater effectiveness for individual interventions compared with group interventions [standardised mean difference (SMD) –1.04 (95% CI –1.68 to –0.41) vs. SMD –0.376 (95% CI –0.61 to –0.14) respectively]. We also found that studies in which supervised exercise actually formed part of the intervention showed a trend towards greater effectiveness than those that merely advised or encouraged exercise [SMD –1.153 (95% CI –2.57 to 0.27) vs. SMD –0.533 (95% CI –0.73 to –0.32) respectively]. In general, the effect of these interventions attenuated rapidly once the intervention had ceased. None of the reports indicated that the components of the intervention were underpinned by a specific psychological model of behaviour change and only one study had focused specifically on people with early psychosis. 76

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot showing the effectiveness of healthy-living interventions. Std diff., standard difference; Tx, treatment.

Key findings

-

Weight management interventions are moderately effective, with an average change in BMI of approximately 1 point or an average weight loss of 4% body weight. Effects seem to attenuate once the intervention stops, although most studies did not conduct follow-up assessments beyond 3 months.

-

Interventions that aimed to prevent weight gain were more effective than those that targeted weight loss.

-

Interventions that were delivered to individuals were more effective than those delivered solely to groups.

-

Interventions that have a supervised exercise component may be more effective than those that do not.

-

None of the interventions was underpinned by a specific psychological model of behaviour change.

Qualitative interviews with service users

Aim

To explore users’ views of illness and treatment beliefs, healthy living, preferences with regard to healthy-living interventions and barriers to and facilitators of healthy-living interventions.

Methods

All patients from an early-intervention service in the north-west of England (n = 260) were contacted to participate in interviews to ensure inclusion of a range of patient baseline characteristics (i.e. age, gender and ethnicity) to ensure a diversity of views. Semistructured interviews with consenting participants were conducted in patients’ homes by the researcher. An interview guide (see Appendix 1) was designed by the trial team to ensure exploration of key areas, including illness and treatment beliefs, beliefs about psychosis, obesity and weight control, antipsychotic medication and its side effects, current dietary, exercise and smoking habits and barriers to and facilitators of healthy-living interventions, and to establish preferences about key aspects of a potential healthy-living intervention including content, setting, format and delivery of the intervention. Interviews were digitally recorded and lasted between 30 and 45 minutes.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and data were analysed using framework analysis. 87 An initial coding framework was developed and transcripts were checked against the framework to ensure that there were no significant omissions. Codes in each interview were examined across individual transcripts as well as across the entire data set and allocated to the framework. Using the constant comparative method of analysis,88 broader categories used linked codes across interviews. Data were interpreted and analysed within the framework to distil, interpret and structure component statements about illness beliefs, healthy living and the intervention. Direct quotes are given an ID number and other characteristics have been removed to ensure anonymity.

Results

In total, 13 service users were interviewed. 10 were male and the mean age was 25.5 years (range 19–32 years). With regard to ethnicity, two were black African, eight were white British and three were South Asian. Ten participants were taking antipsychotic medication, one was taking a mood stabiliser and two were not taking any medication. Eight were unemployed, three were employed part-time, one was employed full-time and one was a student.

Three key themes in the data related to:

-

illness and treatment beliefs about weight gain and the role of medication

-

current lifestyles and perceptions of health risks

-

preferences regarding the type of healthy-living intervention.

These are briefly summarised in the following sections.

Illness and treatment beliefs

Service users’ descriptions about the onset of their psychosis and their initial reaction to symptoms reflected the individualistic and varied nature of their experiences. Two themes emerged from these explanations: (1) a response to stress resulting from life events and (2) the use of illicit substances including cannabis and ecstasy. Participants reported that lack of sleep, stress and stigma made their symptoms worse whereas a good sleep pattern and social support improved symptoms.

Participants taking antipsychotic medication expressed positive views regarding its helpfulness. The key negative views about medication were that it resulted in increased appetite, weight gain, tiredness and lethargy. All participants said that they had gained weight since starting antipsychotic treatment. The average self-reported weight gain was 10.5 kg. Participants had been given information about possible weight gain but had not understood why this was likely to happen or what they should do to prevent it.

The doctor mentioned it. He said that when you’re taking this medication you could put on a bit of weight . . . because the water content in your body increases and so when you feel hungry you sort of want to eat more, there’s an increase of water in your body and you put on weight but it’s easily counteracted if you remain fit and active and if you take regular exercise it’ll automatically go.

SU10

Some participants believed that they had not received sufficient information to manage the side effects, including increased appetite, which led to binge eating, and drowsiness, leading to reduced levels of physical activity, both of which were believed to have contributed to weight gain.

Current lifestyles and perceptions of health risks

Most participants felt that they had a fairly healthy lifestyle in relation to dietary intake and level of physical activity and thought that this was important to prevent further weight gain, although more than half smoked. Participants believed that early in their recovery from the episode of psychosis the amount of physical activity they had undertaken had reduced but that this had improved as recovery progressed. Weight gain was not seen as posing a current health risk but could in the future. Participants’ awareness of the degree and risk of weight gain was limited. Two participants viewed their weight gain as positive, as they had previously been underweight. Most were confident that they could manage weight gain through diet and exercise. Motivation to lose weight included the desire to stay fit and healthy and to regain their pre-illness body image.

I think I’m not too overweight but not where I want to be, really . . . about 12.5 stone, something like that. I’m not particularly bothered about the weight, it’s more like the beer belly kind of look, you know? I’d rather be . . . you know, I don’t want to be some big muscly . . . it’s the appearance. It’s the not the weight aspect, it’s the appearance, really.

SU7

Preferences regarding the type of healthy-living intervention

There was a mixed response to the question of whether a healthy-living intervention should be delivered on a group or an individual basis. Participants who placed greater importance on social interaction favoured a group intervention. No specific preference was expressed about who should facilitate the intervention and suggestions included a community mental health nurse, a support, time and recovery (STR) worker or an expert such as a physical fitness trainer or dietitian. Participants wanted the intervention to be cost neutral to them and, therefore, based locally. A strong preference was expressed for an intervention that could provide the opportunity to undertake physical activity, rather than being focused on education. Potential barriers to success expected by service users included financial barriers to participation, work hours, problems with memory and concentration and fluctuating motivation.

I think something cardiovascular. If people have got weight gain then the best way to maintain a healthy heart and to burn these calories off . . . because I think the medication makes people retain the weight much more worse than what they would do normally so you need to do things like running and rowing machines, things like that, access to the gym . . . Or maybe even learning how to do a few exercises at home for people who have got, I don’t know, agoraphobia and stuff like that where they’ve got a fear of going to places and meeting new people, maybe exercises at home that they can do.

SU13

Key findings

-

Most participants had gained weight and they attributed weight gain to an increased appetite and drowsiness from taking antipsychotic medication.

-

Most participants felt that managing the increase in their appetite and staying physically active to prevent further weight gain were important issues to them.

-

Participants perceived a low level of risk to their current health because of the weight that they had gained but many were sufficiently concerned about it to be taking some active steps to manage it and would be motivated to accept additional help were it to be made available.

-

Participants expressed specific preferences regarding the type of healthy-living intervention that would be acceptable, which needed to be active, promote physical activity, be geographically accessible, be cost neutral and be delivered flexibly on an individual or a group basis according to personal preference.

Qualitative interviews and focus groups with health professionals

Aim

To explore health professionals’ views of their respective roles and responsibilities in the area of physical health care and the feasibility and acceptability of a healthy-living intervention for people experiencing a first episode of psychosis.

Methods

All qualified health professionals from three early-intervention service teams in a north-west of England early-intervention service were asked to participate in the study. Consenting participants were given the option of a telephone interview or a focus group. An interview guide (see Appendix 2) was developed by the trial team to ensure exploration of key areas with regard to the healthy-living intervention, including participants’ views of their respective roles and responsibilities in the area of physical health care, the need for and capacity to deliver the suggested intervention and barriers to and facilitators of its uptake in various settings (e.g. community, secondary, primary). Interviews and focus group were digitally recorded.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. The interview data were analysed using the principles of framework analysis. 87

Results

In total, 14 health professionals consented (eight were interviewed individually and six attended a focus group). All health professionals recognised the importance of monitoring their clients’ physical health, which included their weight, and were in agreement that their clients’ lifestyle should be monitored. They felt that any healthy-living intervention should focus on food intake, exercise, alcohol use, smoking and substance misuse. Participants felt that they had received insufficient training on physical health and health promotion. The majority were aware of weight gain in service users as an important and distressing side effect.

I’ve got quite a few young women who’ve been quite resistant to some medications because of the likely increase in weight and things like that.

HP4

Case managers welcomed the idea of a specific healthy-living intervention and clearly highlighted the benefits to patients. Health professionals felt that the healthy-living intervention should identify service users’ current health behaviours and provide information about improving health and assistance with behaviour change. Health professionals felt that the key components of a healthy-living intervention should address (1) healthy eating, including buying healthy foods on a budget, cooking skills and recipes, (2) the risks of weight gain and how to monitor weight, (3) exercise: what is available, physically possible, affordable and accessible, (4) dental hygiene, (5) substance misuse and (6) physical health monitoring such as blood checks.

The ideal format of an intervention was seen as a mix of group and individual sessions, which should be informal, relaxed, local and delivered within a sufficient timescale to allow for behaviour change and the maintenance of new behaviours. Although health professionals recognised the benefits of a healthy-living intervention, they felt that they did not have the necessary time or expertise to deliver the intervention and felt that STR workers were most appropriately placed to do so.

Well my own personal, if it was up to, you know like you say in my power I’d be looking at kind of it being you know like a couple of the STR workers who are particularly interested in that and leave it up to and empowering them, letting them you know have, putting out the guidelines where they want to go, because again they tend to have, you know, a better relationship.

HP1

Key findings

-

Health professionals felt that the monitoring of clients’ physical health and lifestyle was part of their day-to-day work but they were less optimistic about their own role in providing a healthy-living intervention.

-

The ideal format of an intervention was seen as a mix of group and individual sessions, which should be informal, relaxed, local and on a sufficient time scale to allow for behaviour change and the maintenance of new behaviours.

Theoretical framework

The common-sense model (CSM) of self-regulation89 was chosen as the theoretical framework for the healthy-living intervention because it provides guidance on both motivation and the implementation of behaviour change. In the context of rapid weight gain in early psychosis, the CSM would suggest that people’s motivation to lose weight, and the behaviours selected to pursue that goal, depend on their personal beliefs about, or models of, the weight gain – what is causing it, what its consequences will be and how controllable it is. These personal models are influenced by information gained from abstract (knowledge-based) and concrete (experiential) sources. Furthermore, the CSM suggests that people are more likely to change (e.g. to eat more healthily and to exercise more) if they develop belief-congruent,90 ‘if–then’ action plans that they can use to regulate their behaviour. Feedback plays an important role in the CSM, as it suggests that behavioural attempts to regulate weight gain will be appraised and will feed back into both beliefs and subsequent behaviours. Thus, the model suggests combining motivational approaches (including education to bring about belief change) with action-planning interventions and the opportunity to review the effectiveness of changed behaviour. 90 Therefore, the CSM suggested that when planning our intervention we should begin by assessing participants’ own perceptions of their health and weight gain. By doing so we could then ensure that information about healthy living that was provided would be tailored to the needs of each individual. There would also need to be monitoring of the impact of behavioural feedback (e.g. increasing activity levels) on beliefs and of belief change on behaviour. A variety of techniques to modify perceptions would be incorporated to help service users benefit from abstract (knowledge-based) information derived from their own experiences of weight gain. Action planning would be incorporated, with goals set in accordance with motivational beliefs, plans would be developed to regulate behaviour (including using helpful cues and overcoming potential barriers) and explicit monitoring of the effectiveness of behaviour would be carried out.

Cultural adaptations

The area where the study was conducted had a large South Asian population, particularly among the younger members of the community who were likely to access the early-intervention service. In recognition of the importance of culture in influencing lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise, we used the relevant literature91 and consulted with one of the authors (NH) who has expertise in developing and delivering culturally sensitive interventions. Using both sources we identified the key issues that would need to be considered when delivering the intervention to young South Asians. Cultural adaptations to the intervention included recognition of the need to address the importance of understanding the wider family’s view of health education and to involve them when developing action plans. There was a need to translate written materials related to the delivery of the intervention into the predominant language of Urdu, which was still spoken by older family members. Some of the healthy living materials that were developed needed to have culturally specific advice such as information on healthy eating in specific communities. Personnel involved in the delivery of the intervention needed to have a cultural understanding and awareness of the ethnic groups with whom they were working.

Synthesis

The research team held a 2-day workshop meeting in August 2008 to synthesise the data collected and model the draft intervention. The synthesis meeting was conducted in two stages. In the first stage members of the study team presented the findings of each of the preliminary studies, which were then summarised (Table 4). The second stage involved interactive exercises and discussions, focusing on the possible content, duration and delivery of the intervention, drawing on the evidence presented in Table 4. The aim of this stage was to determine the optimum content, delivery and duration of the intervention as well as who should deliver it, what training they would require and any additional materials that might be needed (Table 5).

| Systematic review and meta-regression | Qualitative interviews with users experiencing first-episode psychosis | Qualitative interviews with health professionals working in early-intervention services | Core dimensions of the self-regulation model | Incorporation of cultural issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| An individual intervention is likely to be more effective than a group intervention | Interventions need to be free and geographically accessible | Case managers think that they do not have the time to deliver a healthy-living intervention | Partly individualised | Need to recognise the role of families in decision-making |

| Lifestyle interventions are effective in promoting weight loss but this only borders on clinical significance and falls below this at 6 months’ follow-up | Preference for an active intervention rather than a purely educational intervention | STR workers or assistant case managers are more likely to be delivering the more time-consuming and active interventions Active interventions are important |

Needs measures of representations | Workers delivering the intervention would need some training in cultural awareness Materials need to be translated into key languages, particularly for the relatives of South Asian participants |

| Length of follow-up is insufficient to see longer-term gains and there was rapid attenuation of effects over time In terms of key components, actual exercise seems to enhance outcome The difference in effect size between preventative trials and weight loss trials is minimal |

Mixed views on group vs. individual interventions Information provided about healthy living was from variable sources and of variable content Service users perceived a low level of risk from the weight gained |

Case managers thought that promoting healthy living in service users was important Case managers had clear ideas about what the content of a healthy-living intervention should be Early intervention around healthy eating is important Cost and accessibility Healthy-living interventions can be individualised in a group setting |

Development and monitoring of action plans Variety of methods for presenting information Focus on behaviour and emotion |

Need to explore families’ as well as individuals’ explanatory models of poor health As an engagement strategy for the intervention, emphasise the cultural sensitivity of the intervention |

| Component | Systematic review | User interviews | Professionals interviews/focus groups | Self-regulation model | Cultural adaptations | Incorporated into the intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Format: Individual/group/mixed model |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Who should deliver the intervention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Setting of the intervention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Number/duration of sessions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In summary, the draft healthy-living intervention that we developed was to be delivered in eight individual sessions over a 12-month period by a STR worker specially trained for this purpose. To promote consistency we produced a manual, outlining the content and key activities to be followed in each session. In addition to individual sessions, optional active group sessions were offered to encourage people to make healthy-lifestyle changes. The intervention was culturally adapted to meet the needs of young people from the South Asian community and strategies for behaviour change are underpinned by the principles of the common sense model. 89 Information about healthy living, including a range of healthy recipes, was provided for participants in a booklet.

Stakeholder consultation

The final stage of the development work involved presenting the draft intervention to a range of stakeholders including service users (n = 3), carers (n = 2) and professionals (n = 3) to elicit their views regarding its acceptability and to gather suggestions for the group activities and the duration of the intervention. There was agreement that the intervention was both acceptable and feasible. Two key suggestions emerged: (1) to develop a website that had similar intervention to the healthy-living book and (2) that we should involve service users in the running of the groups.

Following the stakeholder consultation we started to develop materials to support the delivery of our intervention. These included a training manual for the STR workers who would deliver the intervention, a healthy-living booklet for participants in the study and a website (see www.helper-interact.co.uk/: website active at time of writing). We also recruited four service users who were interested in running groups for the study and organised a workshop to train both the STR workers to deliver the individual intervention and the service users to support the STR workers when delivering group activities.

The healthy-living intervention

The healthy-living intervention included eight individual sessions over a 12-month period with an emphasis on facilitating participatory exercise and dietary change through the development and implementation of patient-led action plans. These sessions were delivered by a STR worker trained in the delivery of the intervention. To facilitate implementation of exercise and dietary change a range of optional active group sessions was offered by the STR worker for those who prefer a group-based activity. To optimise engagement, choice and self-management, a booklet was given to all participants providing educational advice, action plans, goals, details of the group sessions, healthy-eating recipes on a budget, etc. (see Appendix 3). A strong emphasis was placed on maximising carer/family engagement.

Individual sessions

The intervention comprised eight individual sessions, five in the first 3 months followed by two in months 4–6 and a final session in months 7–12 to ensure that gains were incorporated into the individual’s lifestyle. The decision to include eight individual sessions was based on recommendations given during the synthesis day event, as there were no data to suggest an appropriate number of sessions (see Table 5). In brief, sessions one and two focused on eliciting health beliefs and developing a collaborative individualised action plan and goals for change. Such goals took account of previously and currently enjoyed activities that were exercise related. Sessions three to five focused on the implementation of the action plan (and, when agreed, the inclusion of family/carer involvement). Collaborative problem-solving identified and facilitated solutions to barriers to implementing the action plan. STR workers accompanied clients to particular activities (gym, swimming, etc.) to maximise implementation. Sessions six and seven focused on progress and monitoring of the goals and action plan and adaptions made as necessary. Session eight focused on working with the user to try to ensure that implementation is embedded within his or her everyday routine.

Group sessions

In addition to the individual sessions a range of optional group sessions, some of which were already being delivered by the early-intervention service teams (e.g. football, cycling), was delivered by STR workers, who also set up a range of group sessions including walking and cycling groups.

The healthy-living intervention booklet

A healthy-living intervention booklet was given to all participants and provided accurate information about healthy living, including government guidelines on exercise and diet; strategies for implementing such changes into usual daily routines; culturally varied recipes; barriers to and facilitators of implementing healthy living that are specific to the participants’ mental health problems, including fatigue and motivation; a section for families and carers; and information on local activities. Following the suggestion from the stakeholder group during the development work, a website was commissioned and developed by a service user (see www.helper-interact.co.uk/).

Training

Training was provided by the trial team to three STR workers and four service users and consisted of a 3-day intensive training programme. The training was accompanied by a training handbook that included detailed session-by-session outlines (see Appendix 4). The training focused on all aspects of delivering the intervention from initial assessment to elicitation of health beliefs, developing collaborative action plans and goals, engaging family/carers, monitoring and collaborative problem-solving and overcoming barriers to implementation and running groups. A significant portion of the training was spent practising the above skills using fictitious but typical cases to enhance learning and skill. Because of staff turnover the training was repeated on two occasions.

Supervision

Clinical supervision for the STR workers was provided on a 2-weekly basis by a member of the trial team.

Phase 2: evaluation of a healthy-living intervention to control weight in people taking antipsychotic medication after a first episode of psychosis

In phase 2 we aimed to determine the uptake, adherence and clinical effectiveness of a healthy living intervention designed to reduce weight gain. We conducted an exploratory RCT, comparing the intervention with treatment as usual in two early intervention services for psychosis in England. Evidence from this phase has been published elsewhere. 92

A summary of the work is described below.

Aims and objectives

Our overall aim was to determine the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of our developed health living intervention utilising an exploratory RCT.

Objectives

-

To estimate the effect size of a healthy intervention by comparing outcomes between:

-

individuals receiving the intervention with treatment as usual

-

the subgroup of the intervention arm prescribed olanzapine or clozapine at randomisation compared with the remainder of the intervention group.

-

-

To examine recruitment rates, uptake and adherence to the intervention.

-

To determine the direct costs associated with the intervention.

Methods

Design

An exploratory single blind RCT using a parallel group design to compare a healthy living intervention plus TAU with TAU only.

Participants

Current users of early intervention services in the north-west of England experiencing a first episode of psychosis in the preceding 3 years with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2, or ≥ 24 kg/m2 for individuals from the South Asian community. 92

Procedure

Case managers screened their personal caseloads to identify service users meeting study criteria. All potentially eligible individuals were provided with a study information sheet. Those service users consenting to be contacted were contacted by a researcher and offered an appointment to assess their eligibility. Randomisation of eligible individuals entering the trial was undertaken by an electronic software program (Open Source Clinical Data Management System: OpenCDMS, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, www.opencdms.org) and stratified by whether or not the individual had commenced olanzapine or clozapine medication in the preceding 6 months. Randomisation outcomes were concealed from the researchers (who remained blind when undertaking assessments) but were communicated to the trial manager, who notified the STR worker if allocated to treatment. Researchers reported unblindings if these occurred during the follow-up assessments conducted at 6 and 12 months.

Interventions

Healthy-living intervention

Full details of the development of the healthy-living intervention are reported elsewhere. 93 The format of the intervention constituted eight individual sessions with a support time recovery worker (who had undertaken a 3-day intervention training course), across a 1-year period and supported by an accompanying intervention manual/website. The content of the individual sessions involved the elicitation of existing health beliefs, psychoeducation, the development of personalised goals/action plans and an ongoing review of goal achievement progress. These sessions were supplemented by optional STR worker-supported group activities such as cycling and cooking.

Treatment as usual

Individualised case management in the early intervention service and enhanced care planning.

Measures

The primary outcome was BMI. Secondary outcomes included physical activity levels, depression, diet, quality of life, medication usage, health status and health economics. Assessments were conducted at baseline, 6-month and 12-month follow-up. (For full details, see Lovell et al. 92)

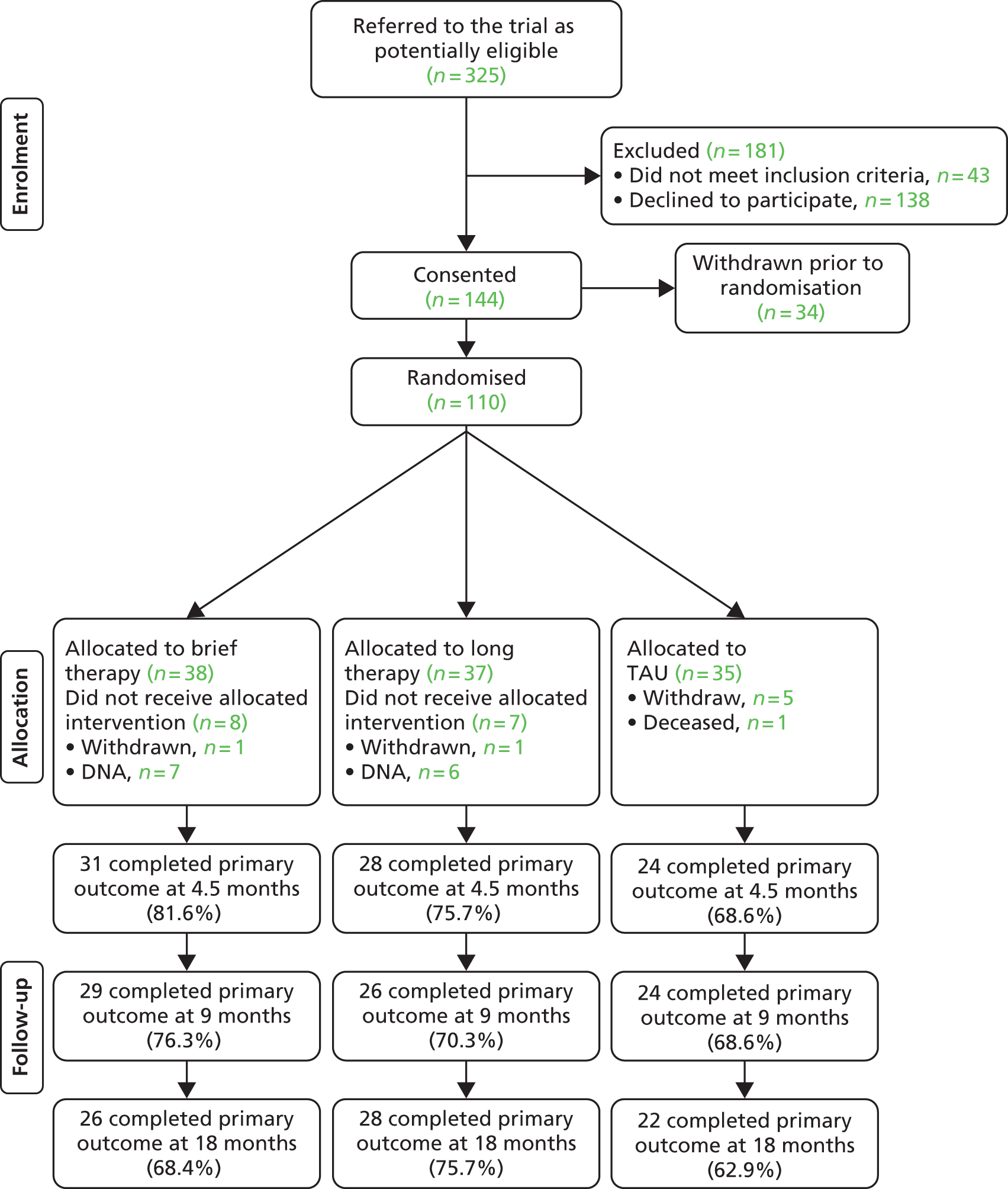

Results

A total of 971 participants were caseload screened (for flow diagram see figure 1 in Lovell et al. 92). Potentially eligible participants providing consent to be contacted were approached by the researcher (n = 148), of whom 105 individuals providing consent and meeting eligibility criteria were randomised. Of the 54 individuals randomised to the intervention (51 to TAU), five withdrew. The follow-up completion rate at 12 months was 88.6%.

Results found no significant effects between the intervention and TAU group. However, the effect of the intervention was larger (effect size 0.54, not significant) in 15 (28%) intervention and 10 (20%) TAU participants who were taking olanzapine or clozapine at randomisation.

Discussion

We found that our healthy-living intervention had a small but non-significant reduction in BMI compared with TAU. We found that in those participants who were taking olanzapine or clozapine at randomisation, there was a larger but non-significant effect. We successfully recruited to target and achieved an 89% retention rate at 12-month follow-up rate. Of the intervention participants, 78% completed 6–8 sessions. Overall costs of health and social care services used were lower but not statistically significant in the intervention group, compared with the TAU group.

Qualitative acceptability interviews

Aim

The aim of the qualitative acceptability interviews was to explore the acceptability of the healthy-living intervention from the perspective of those receiving the intervention.

Methods

To explore acceptability from the patients’ perspective, all patients randomised into the intervention arm were asked to participate in an interview to ensure inclusion of a range of patient baseline characteristics (i.e. age, gender and ethnicity to ensure a diversity of views). Semistructured interviews with consenting participants were conducted by a researcher. An interview guide (see Appendix 5) was developed by the trial team to ensure exploration of key areas including timing, content and duration of the intervention, STR workers’ qualities and barriers to and facilitators of the intervention.

Analysis

For acceptability the tapes were transcribed verbatim. Data were analysed using a framework analysis,94 as described in the section on interviews with service users/health professionals.

Results

Of the 49 participants randomised to the intervention, 25 were included in the acceptability study. The age range of participants was 17–39 years (SD 5.72 years) and 15 were male. Recorded interviews were of 24–64 minutes’ duration (mean 41.4 minutes). Participants who participated in the acceptability interview undertook a significantly greater number of intervention sessions (mean 7.3 sessions, SD 1.2 sessions) than those who did not (mean 5.8 sessions, SD 2.6 sessions). However, there was no significant difference in BMI at 12 months’ follow-up between those who did and those who did not take part in the acceptability interview.

Two main themes emerged from the analysis: (1) views on the delivery method and (2) the STR worker.

Views on the delivery method