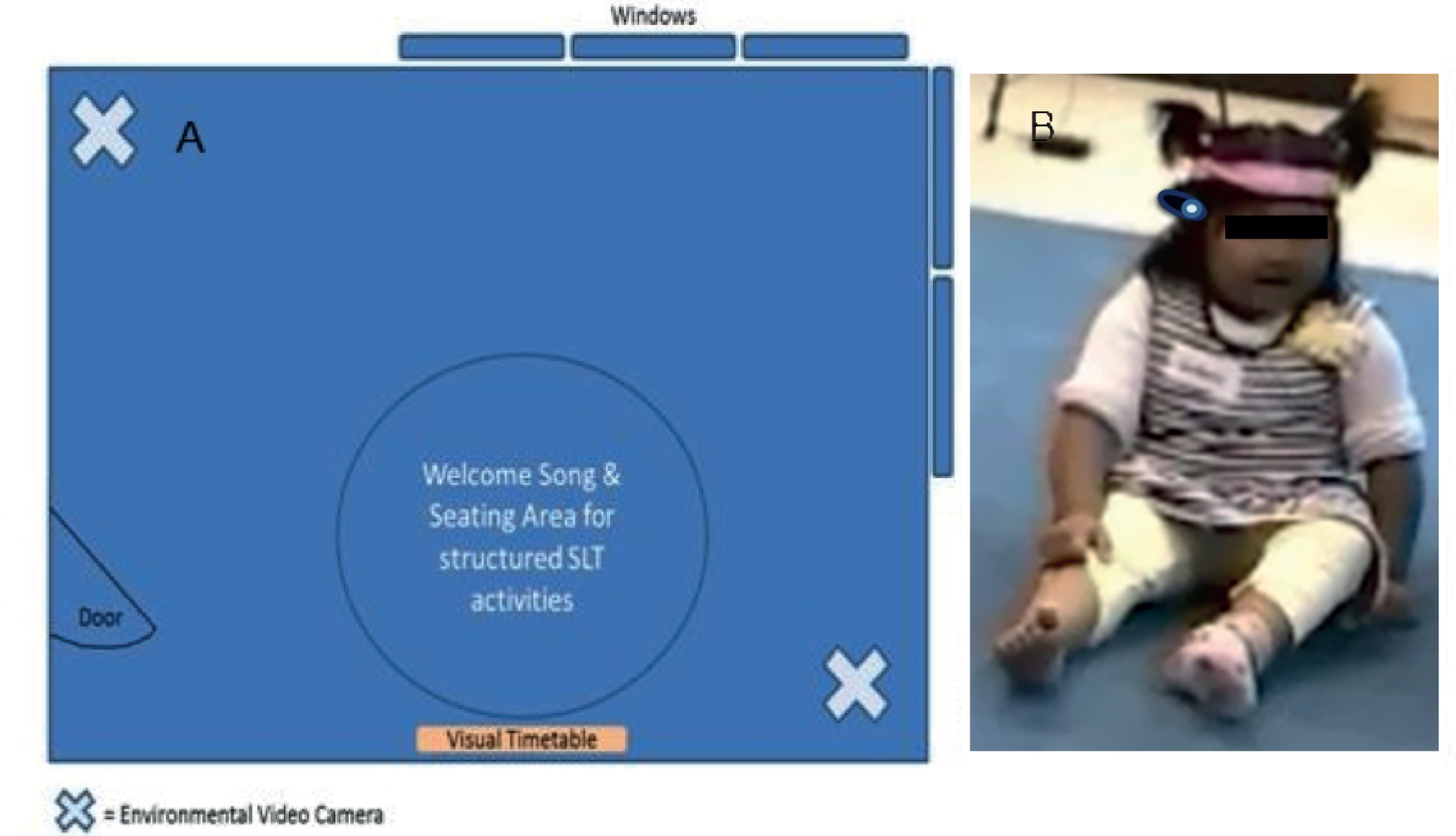

Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0109-10073. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Yvonne Wren is the director of an independent speech and language therapy provider called ChildSpeech.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Roulstone, et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and programme overview

Introduction

The focus of this research programme, known as Child Talk, is on speech and language therapist (SLT)-led interventions for preschool children with primary speech and language impairment (PSLI).

Primary speech and language impairment

Primary speech and language impairment is a relatively stable, high-prevalence condition that can persist into adolescence and adulthood and which is associated with a range of negative sequelae. Children with PSLI present with delayed speech and language, which is not associated with any other overt congenital, developmental, neurological or sensory disorders. However, the way that the impairment manifests in any individual varies considerably. Over the years, various terms have been used to refer to this impairment, the most common being specific language impairment. Currently, the Raise Awareness of Language Learning Impairments (RALLI) campaign is promoting awareness of specific language impairment and generating a discussion about agreeing consistency of terminology to avoid confusion. 1 The impairment can be particularly difficult to diagnose during the preschool years because of the wide range of what is considered to be ‘typical development’ in both language and cognition and the absence of conclusive research on the predictors of resolution. Nonetheless, delays that involve only expressive language, the so-called ‘late talkers’, are more likely to resolve before children reach school than difficulties in both receptive and expressive language skills. 2–5

Adult concern begins to consolidate at around the age of 2 years when around 50% of children will be joining words into short phrases and sentences. 6,7 Those considered to be ‘late talkers’ at this age will typically have a vocabulary of < 50 words and will not be joining words. 8 Some children may also find it hard to learn new word meanings, have difficulties understanding what is said to them or show other cognitive difficulties such as problems with attention, symbolic development and memory, despite other aspects of their development proceeding normally. Children who have difficulty with understanding language are thought to have difficulties that are less likely to resolve. 9

The majority of those children whose language is delayed at 2 years will go on to develop functional speech and language, for example they will be able to communicate their needs in everyday situations and be intelligible to strangers. However, they are more likely to have life-long difficulties with language and language-related activities, such as understanding more abstract and inferential language, literacy, social interactions and friendships. 10–16 Prevalence estimates vary, but an accepted rate of PSLI at 6 years is around 7.4%. 17,18 This is higher than for autism, for which a prevalence of 1% is commonly accepted,19,20 and for cleft palate, for which 1 in 700 births is a typically quoted figure. 21,22

Speech and language therapy

Speech and language therapy is the lead profession responsible for diagnosing and managing interventions for these children. This process typically takes place in collaboration with parents, early years practitioners (EYPs), psychologists, paediatricians and health visitors. For this preschool population, speech and language therapy services are primarily funded through the NHS, although there are increasing numbers of SLTs being funded into public health roles by the early years department of local authorities and, for older children, by individual schools.

Preschool children considered at risk for PSLI are typically, and most commonly, identified by EYPs, health visitors and parents themselves and are then referred to speech and language therapy services. Services may be delivered in a range of settings: community clinics, children’s centres, nursery classes and schools and children’s own homes. At this time, 14,016 SLTs are registered with the Health and Care Professions Council23 and it is estimated that approximately 70% of these work with children. 24 There are, however, no national data on the number who work specifically with preschool children or indeed on the spread of pay grades and expertise or the numbers who work with children with different speech and language conditions. A survey by the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) is currently under way to help gather some of this information. 25

The process of supporting children with PSLI has changed over the years. Several decades ago the approach was primarily focused on the child. Children were typically brought to a clinic by their parents and, following assessment and identification of the possibility of language impairment, the SLT would carry out interventions directly with the child. Sometimes the parent would observe the SLT working with the child, with the idea of practising the activities at home, but the focus was very much on the child and his or her performance. In recognition that speech and language skills develop in a social context through dialogue between the child and surrounding adults, the emphasis and approach has shifted over the years to focus on the adults’ interactions with the child and on the environment, opportunities and resources available to the child. 26 In most cases, these adults are the child’s parents but it may also be staff who spend time with the child in childcare and nursery settings. The assumption behind this approach is that the child has failed to acquire speech and language in the standard/typical environment and thus needs an environment that is highly adapted and more finely tuned to his or her learning needs. Despite this, the approach, which focuses on the adults’ interactions with the child, does sometimes leave parents with the impression that their interactions with their child are faulty. This increases the adults’ feelings of guilt about the origins of their child’s speech and language impairments. 27 This paradigm shift from the focus on the child to a focus on the environment is widespread throughout services; however, there is still wide variation in how services are delivered and in how interventions are described and configured. 28

What do we know about these interventions/services?

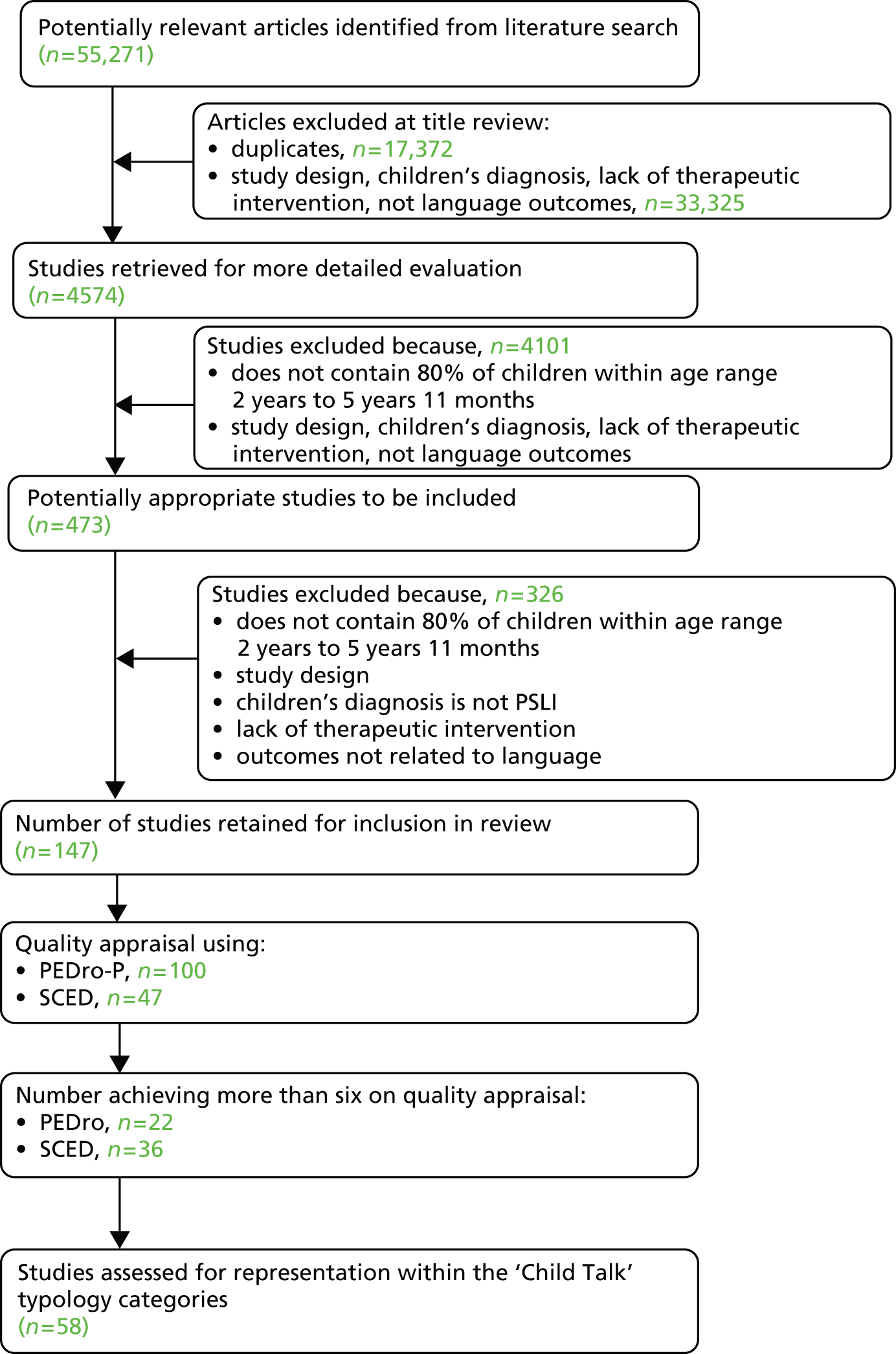

Although speech and language therapy has been found to be effective for some children, a number of systematic and service reviews have identified some limitations of SLT-led interventions for children with PSLI. For example, Law et al. 29 reviewed interventions for children of all ages with PSLI and concluded that the research to date provided evidence of the effectiveness of interventions that target expressive phonology and expressive vocabulary; interventions that target expressive sentence structure may also be effective as long as there is no accompanying receptive language impairment. The evidence to support interventions targeting receptive language impairment was limited both in terms of the volume of research and the synthesised effect sizes for the existing studies. In terms of how interventions could be delivered, no differences were found between interventions delivered in a group and those delivered in one-to-one contexts or between those delivered by therapists and those delivered by parents who had been trained to deliver an intervention. Evidence regarding the ideal frequency and amount of intervention (or ‘dosage’) has also been inconclusive so far. 30 The systematic reviews have identified evidence for the effectiveness of interventions in the short term, that is, for the period of intervention specified in the studies. Although evidence supports early intervention for children who are growing up in socially deprived conditions,31–34 the evidence does not yet extend to long-term follow-up of preschool children with PSLI; thus, the power of interventions to prevent negative sequelae of a speech and language impairment is not known.

A common finding of those attempting to review and synthesise evidence about the effectiveness of any interventions in speech and language therapy services is that the interventions themselves are poorly described. For example, Zeng et al. 30 found that ‘teaching sessions’ that were part of an intervention were rarely described and characteristics of the dosage were not always transparent. Pickstone et al. 35 commented on the variety of terminology and the lack of descriptive detail used to describe interventions. Furthermore, Pickstone et al. 35 concluded that interventions can have differential effects on subgroups of children and/or families and also that the effects of any particular component of an intervention are rarely tested and the effects of individual components are difficult to extract from research using complex interventions. The study by Landry et al. 36 was a noted exception to this. They found a differential effect of mothers’ responsiveness: mothers’ responsive affective behaviours were associated with changes in the children’s behaviour, whereas their responsive language behaviours were associated with changes in the child’s language. This suggests that a targeted responsiveness rather than merely seeking to increase a mother’s general responsiveness to her child might be needed for particular changes to occur in a child’s language.

In 2008 an independent review of services for children and young people with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) was commissioned by the UK government. 28 The review found that speech and language therapy services in particular were characterised by their variation and were described frequently by families as a ‘postcode lottery’. 28 The Bercow report recommended a programme of research to enhance the evidence base to underpin the design of services. 28 The ensuing research programme, known as the Better Communication Research Programme (BCRP), surveyed practitioners to identify the interventions in common use by SLTs working with children of all ages and with all types of SLCN. It then reviewed the evidence underpinning these interventions and found that, of the 57 interventions that were either in current use or published in the literature, 3% had strong evidence, 56% had moderate evidence and 39% had only indicative evidence. Interestingly, the intervention most commonly cited by practitioners had only indicative evidence, that is, good face validity, and lacked any independent external research evidence. 37

Relationship between the Better Communication Research Programme and Child Talk

The research of the current programme builds, in a number of ways, on the research carried out by the BCRP team described in the previous section. The principal investigator (PI) for this programme was a member of the core team of researchers for the BCRP. The BCRP was a wide-ranging programme covering all ages of children and young people and the full range of SLCN. The current research programme examines a more focused profile of interventions with a particular age group (preschool) and a particular diagnostic category (PSLI). This enables a closer and more detailed examination of both the interventions appropriate to the group and the evidence. The focus on preschool children was important for two main reasons: the difficulties of providing effective and targeted support (as set out earlier) and the policy imperative, which is driving early identification and intervention for children with PSLI.

Policy imperative promoting early identification

The need for early identification and intervention for children with PSLI continues to be a policy priority because of the link between children’s early speech and language skills, their broader well-being and outcomes in later life. 10–13,15,16,38–40 It is argued that poor communication skills in children are a risk factor for their maltreatment and, later, involvement in the criminal justice system. 41,42 To date, there is no proven causative association between PSLI in preschool children and either of these outcomes in childhood and later years, or indeed an indication that SLT-led interventions in early childhood would prevent such outcomes. Nonetheless, UK government policy and initiatives have continued to stress the critical role that speech, language and communication play in a child’s life, health and well-being and to recommend early identification and intervention. 43–45 Before the commencement of the Child Talk research programme, the Better Communication Action Plan46 and Healthy Lives Brighter Futures47 talked about the government’s commitment to a range of improvements. These included early identification and intervention; better information for parents; a reduction in the variability and inequality of services; and increased individualisation of services for children with disabilities, particularly those with SLCN. Over the last 3 years of this research there has been an ongoing emphasis within government and other reports stressing the importance of the link between children’s language and their life chances, alongside a focus on children’s language in relation to the education curricula and training of the workforce. 44,48,49

In summary, PSLI is a high-prevalence condition with the potential to have a negative impact, which has resulted in calls for and expectations of early identification and intervention so that children can benefit from social and educational experiences and to mitigate negative sequelae. The evidence base for early intervention is growing but is underdeveloped, particularly in terms of informing the individualisation of interventions for what is a heterogeneous condition. The social context in which language is acquired adds to the heterogeneity. It is vital to understand how best to shape interventions to best suit the particular needs of each child and his or her family.

Assumptions underpinning an evidence-based framework

The purpose of this research was to investigate whether or not it is possible to develop an evidence-based framework that can support the decision-making of SLTs as they attempt to design and plan interventions that are appropriate to the needs of individual children and their families. Most people are now familiar with the notion of evidence-based practice (EBP) and the seminal definition of Sackett et al. ,50 which suggests that EBP occurs when external research evidence is applied with expertise and in the light of patient preferences; others have also emphasised the role of context in framing EBP. 51 Various barriers to the implementation of EBP have been identified including the time needed to search out research and, in particular, research that is relevant and appropriate to the particular context of an individual patient. 52 There is also a lack of research that attempts to advance our understanding of the process of integration of the three elements.

The emphasis to date, from both research and practice, has been on the systematic research element of EBP rather than on clinical expertise or patient preferences. For example, practitioners are taught how to search out and appraise research and are given advice on how to address the barriers to EBP that have been identified. 53 Despite this emphasis, there has been a number of discussions that have challenged the use of ‘evidence’ to mean only research evidence,54 arguing, for example, that many different kinds of ‘evidence’ are used in clinical decision-making. However, this confuses the idea of systematic research evidence and knowledge. Practitioners draw on various types of knowledge to make their clinical decisions. 55 However, it is suggested that these other types of knowledge are more usefully considered as part of clinical expertise. 56 In this research programme the ‘evidence’ component of EBP is taken to refer only to evidence gained from external, published, systematic research.

Research regarding the nature of clinical expertise and the process of clinical decision-making has rarely been the focus of research or discussion within speech and language therapy. Roulstone56 describes clinical expertise as ‘the skilful and appropriate application of knowledge to the practice situation’ (p. 45). Given the heterogeneous PSLI population, the current dearth of systematic research evidence regarding the individualisation of interventions and the lack of prominence of any particular approach to intervention, the expert practitioner applies and adapts knowledge from a variety of sources (including whatever there is from systematic research). Experts organise their knowledge to be optimally useful to the clinical context in order to retrieve it efficiently when needed. 57 Experts develop ‘theories of practice’ that guide their everyday decisions. 58 Therefore, in developing an evidence-based framework, it is necessary to investigate and understand how everyday practice is framed by practitioners and how the research evidence relates to that practice.

In 1991, The Patient’s Charter stated that patients have the right to a clear explanation about proposed treatments. 59 In the context of EBP, therefore, there is a need to provide patients with information about the evidence so that their choices and preferences can take account of the evidence base. Patients’ preferences exert an important influence on the success of interventions. 56 At the extreme, if patients do not believe in, or understand, an intervention they may not attend appointments or follow through on interventions. Therefore, to develop an evidence-based framework, some conceptualisation is needed of patient views both of the nature of a disorder and of the possible interventions.

In conclusion, an evidence-based framework of speech and language therapy for children with PSLI will take account of clinical expertise and the perspectives of service users so that these can be integrated with evidence from external research.

Aims and objectives

The overarching aim of this research programme was to improve speech and language therapy services for preschool children with PSLI through the development of an evidence-based framework that could inform SLTs’ decision-making and increase the relevance and effectiveness of interventions for individual children and their families.

Definitions of EBP emphasise the relationship between systematic research evidence, clinical expertise and user perspectives (in the case of this research, children and their families). Therefore, to develop an evidence-based framework we proposed to investigate and integrate all three elements. The Child Talk research programme was broadly divided into two phases; the specific aims and objectives for each phase are described in the following sections.

Child Talk phase 1

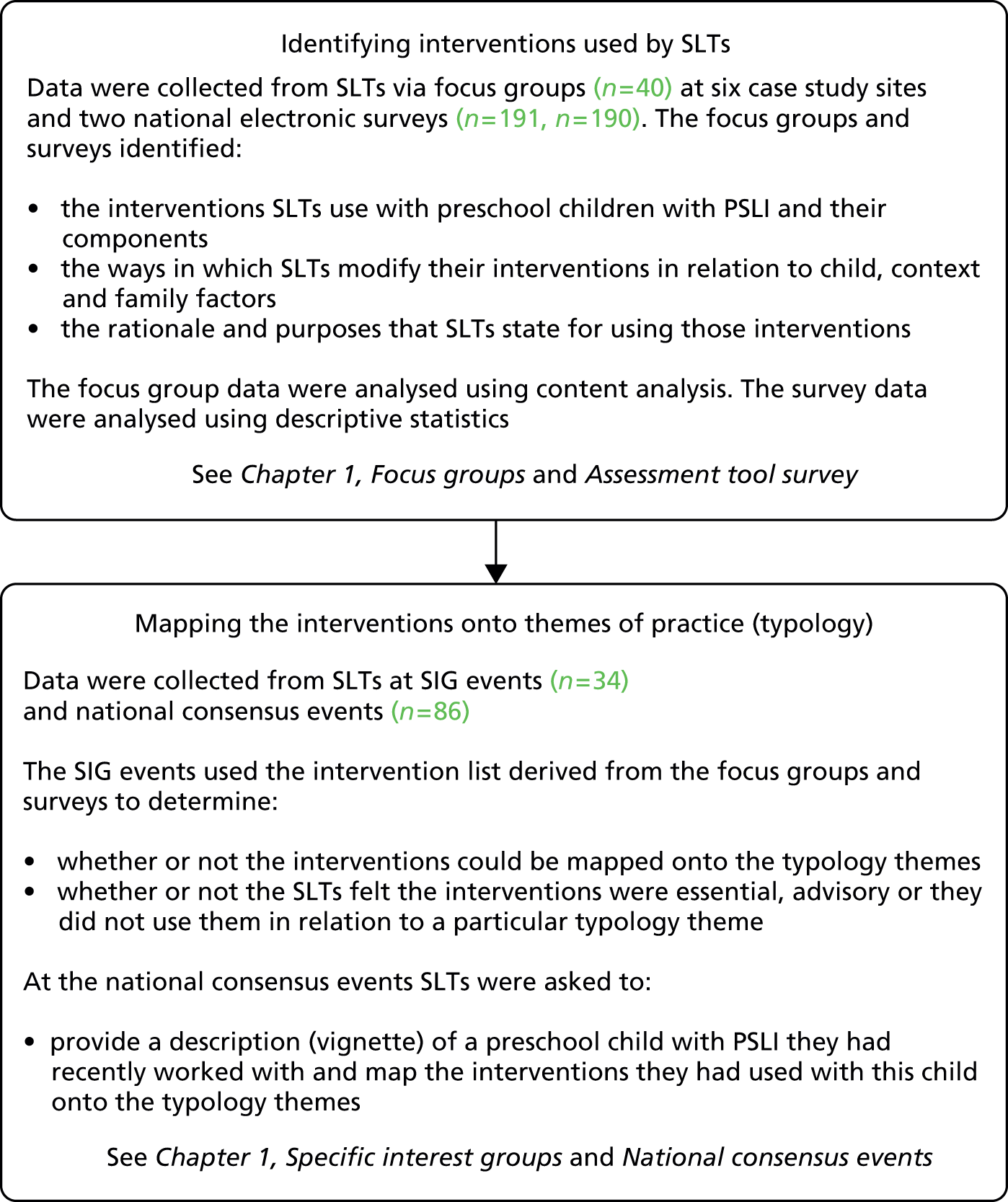

The first aim of Child Talk was to develop an evidence-based typology of SLT-led interventions for preschool children with PSLI that also incorporated the experiences of families. This typology was developed through several interacting components: a series of surveys of SLT practitioners, parent surveys, case studies, consensus exercises and systematic literature reviews.

Objectives

-

To determine current evidence, practice and user perspectives regarding SLT-led interventions for preschool children with PSLI.

-

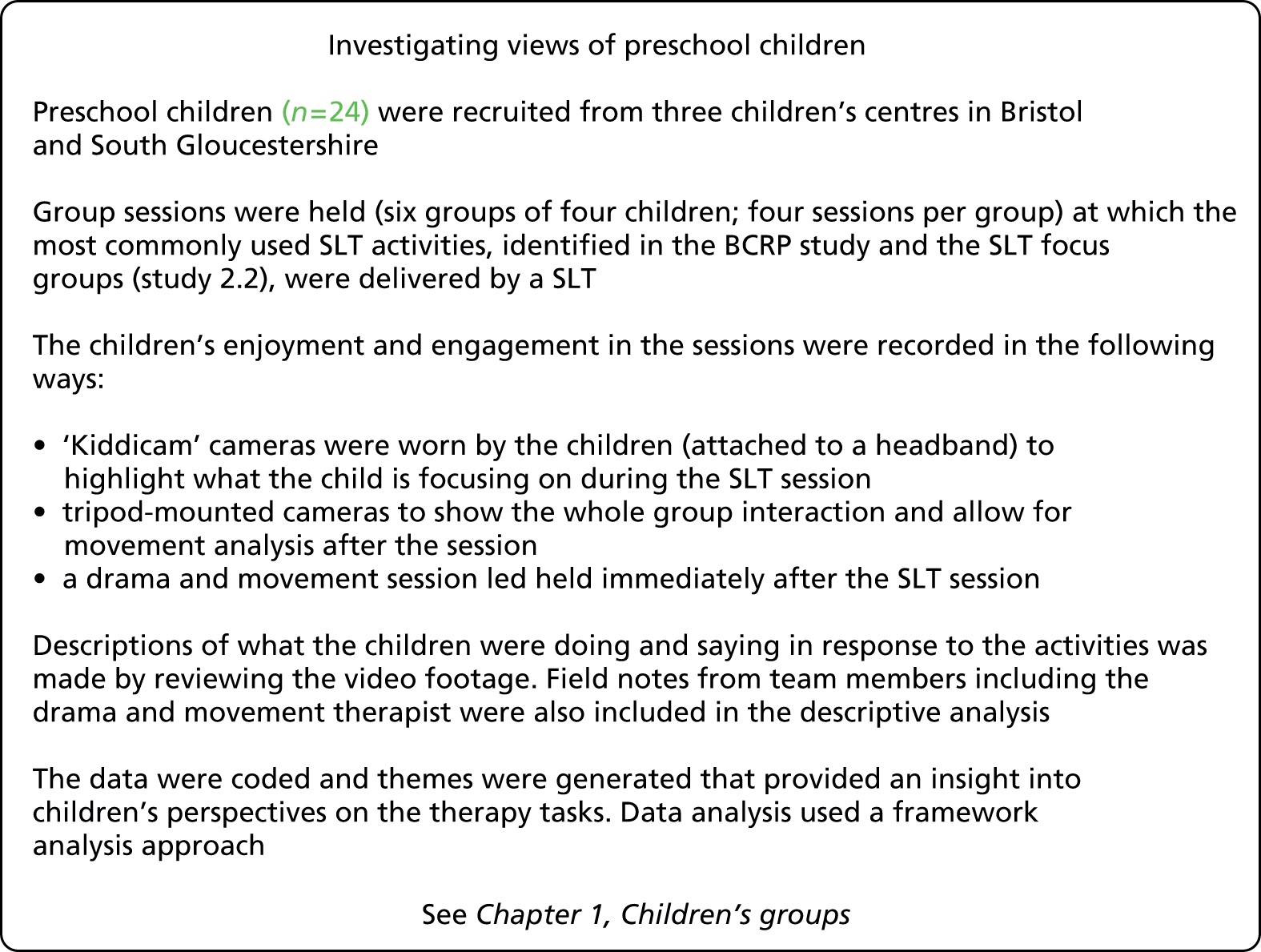

To identify how best to engage preschool children in the process of developing appropriate interventions.

-

To develop a model(s) of intervention that can integrate current evidence, professional expertise and family perspectives in ways that allow the intervention to be individualised to children’s and families’ communicative, physical, social and cultural contexts.

Child Talk phase 2

The second aim of Child Talk was to develop a framework and toolkit that could be used to establish effectiveness and cost-effectiveness and which could be used by services nationally to plan services and future evaluations.

Objectives

-

To identify tools that can be developed to ensure the appropriate stratification of interventions and the measurement of outcome.

-

To identify the measures required to develop formal economic assessments of SLT-led interventions and care pathways within speech and language therapy services.

-

To work with the RCSLT to facilitate the national take-up and ownership of the framework.

Research and development and ethics approvals

Research and development (R&D) and ethics approval were obtained in two separate applications (phase 1 and phase 2) before undertaking the research. Ethics approval to undertake phase 1 was given by the National Research Ethics Service Committee – Southmead (reference number 11/SW/0228) and approval for phase 2 was given by the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – Brent (reference number 13/LO/0240) via proportionate review. In addition, both phases underwent ethics review by the University of the West of England and Manchester Metropolitan University. Approval was also given by Barnardo’s Research Ethics Committee, with whom we collaborated to recruit participants into phase 1 of the programme (specifically underserved communities).

Research and development approval for both phase 1 (reference number 2860) and phase 2 (reference number 3048) was given by North Bristol NHS Trust, the lead site and sponsor. The other five case study sites were set up as participant identification centres (PICs); therefore, full R&D approval was not required from these sites. It was decided that these sites should be PICs rather than research sites not only as this was the most appropriate classification for their role on the programme but also to minimise the amount of time that it would take to set up the research programme. It was our experience, however, that there is great variation in the way that R&D offices deal with setting up as a PIC site, with marked differences in their assessment of the risks involved, possibly illustrating differences in their level of experience of operating as PIC sites. In our experience, therefore, it did not expedite the set-up processes.

Both phase 1 (reference number 11461) and phase 2 (reference number 14283) were adopted onto the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network portfolio and by the Medicines for Children Research Network, Paediatrics (Non-Medicines) Specialty Group.

Management and governance arrangements

Steering group

A steering group met every 3 months throughout the programme and was the decision-making group with overall governance of Child Talk. The steering group consisted of a chair, a co-applicant who was not involved in the day-to-day activities of Child Talk, the PI, work package leads and senior members of the research team who submitted progress reports against agreed milestones. In addition the minutes of advisory group meetings were considered and actions discussed.

Advisory group

The advisory group met every 3 months throughout the programme to offer advice and guidance with regard to the development of optimal strategies for the achievement of the programme aims. Membership of the advisory group consisted of:

-

Mary Gale, Speech and Language Therapist Team Leader, North Bristol NHS Trust

-

Davina Evans, Parent Partnership Service, Supportive Parents

-

Beverley Pearce and Duncan Stanaway, Barnardo’s

-

Sally Jaeckle, Service Manager Early Years Services, Bristol City Council

-

Nicola Theobald, Early Years Improvement Officer, Bristol City Council

-

Helen Moylett, Early Years Consultant (formerly the Senior Director, Early Years at National Strategies)

-

Christine Screech, Education Faculty, University of the West of England

-

Karen Evans, Deputy Head of Nursing – Child Health, North Bristol NHS Trust

-

two members of the Child Talk parent panel (rotating membership).

The advisory group was chaired by the PI as agreed by the members of the group. The advisory group kept the research team informed of any external agendas – new policies, programmes or initiatives that might support or have an impact on the relevance of the research programme – and provided support with recruitment strategies and dissemination. The Chair of Council for the RCSLT, Hazel Roddam, contributed to early advisory group discussions on the set up of the research programme. In addition, the principal investigator maintained regular contact with the Chief Executive Officer of the RCSLT, Kamini Gadhok, to discuss study delivery and matters arising from the advisory group.

Expert reference advisors

The PI met individually with expert reference advisors – academic researchers and senior clinicians working in the field of preschool PSLI – who advised on the development of the typology:

-

Dr Catherine Adams, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Speech and Language Therapy, University of Manchester

-

Dr Caroline Bowen, Honorary Associate in Linguistics at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, and Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Health Sciences (Speech–Language Pathology) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

-

Professor James Law, Professor of Speech and Language Sciences, Newcastle University

-

Dr Caroline Pickstone, Honorary Research Associate and Senior Manager, South Yorkshire Comprehensive Local Research Network, Sheffield

-

Professor Sharynne McLeod, Professor of Speech and Language Acquisition, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, New South Wales, Australia

-

Associate Professor Jane McCormack, Discipline Leader and Lecturer – Speech Pathology, Charles Sturt University, Albany, New South Wales, Australia

-

Dr Kate Crowe, SLT with specific interest in multilingual children with hearing loss, Charles Sturt University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

-

Ms Sarah Masso, SLT with specific interests in speech sounds, phonological processing and pre-literacy, Charles Sturt University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Parent panel

A parent panel was formed to collaborate with the research team on all aspects of the research relating to parents or the public. The parent panel met every 2 months throughout the data collection period (last 2 years) of the research programme.

During the development of the research programme and the set-up phase, third-sector parties Afasic, Supportive Parents and Barnardo’s had been the parent/public representatives and their roles continued throughout the programme as co-applicant (Chief Executive Officer of Afasic) and advisory group members (Barnardo’s and Supportive Parents). During the first year of the programme, and with direction from Afasic, a parent panel was established by advertising in the community for parents of preschool children with PSLI currently accessing speech and language therapy services. It became apparent that we would need to widen the net after receiving little interest from parents. This is possibly because we were looking to engage parents who do not see their child as having an impairment but rather as just being slow to talk and who may not have felt that they had anything useful to offer the team in the long term. Subsequently, the research team advertised for parents of preschool children who may or may not have a communication difficulty. This decision was made because it is the perspective of being a busy parent of a preschool child/children, rather than experience of speech and language therapy services, that is most useful when designing recruitment strategies and materials that are engaging and accessible. From this, we established a panel of 10 parents of whom a core group of four remained until the end of the programme.

At meetings the panel was updated on progress with the research, devised recruitment strategies and developed public-facing materials, such as a recruitment video, advertising, participant information sheets and consent forms. The parent panel also took a lead on running a community-based consultation to determine the key messages for parents arising from Child Talk. Descriptions of the ways in which the panel influenced the delivery of Child Talk are embedded within the chapters of this report. In addition, a description of the impact of involvement on the parents themselves, captured using an arts method, is described in Appendix 7.

Operational project groups

Project groups were formed on an ad hoc basis with members of the research team and relevant co-applicants to plan individual studies and discuss progress. In addition, the co-applicants met annually to discuss progress against programme aims and to consider the data collected as a whole. The role of each co-applicant in the Child Talk programme is described at the end of this report (see Acknowledgements).

Website and logo

The activities of the Child Talk programme were managed through the Bristol Speech and Language Therapy Research Unit website [www.speech-therapy.org.uk (accessed 13 December 2014)], which was used to publicise the research programme and research events, register expressions of interest from potential participants, host electronic surveys and provide a secure area for the parent panel to work on documents and share ideas outside of panel meetings. A Child Talk logo was commissioned from Abigail Beverley, who grew up with a speech and language disorder and is a volunteer with the Afasic Youth Project, specialising in art workshops. The logo provided a clear identity to all of the activities and materials arising from the programme (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Child Talk logo. Reproduced with permission © North Bristol NHS Trust.

Methodology

Methodology overview

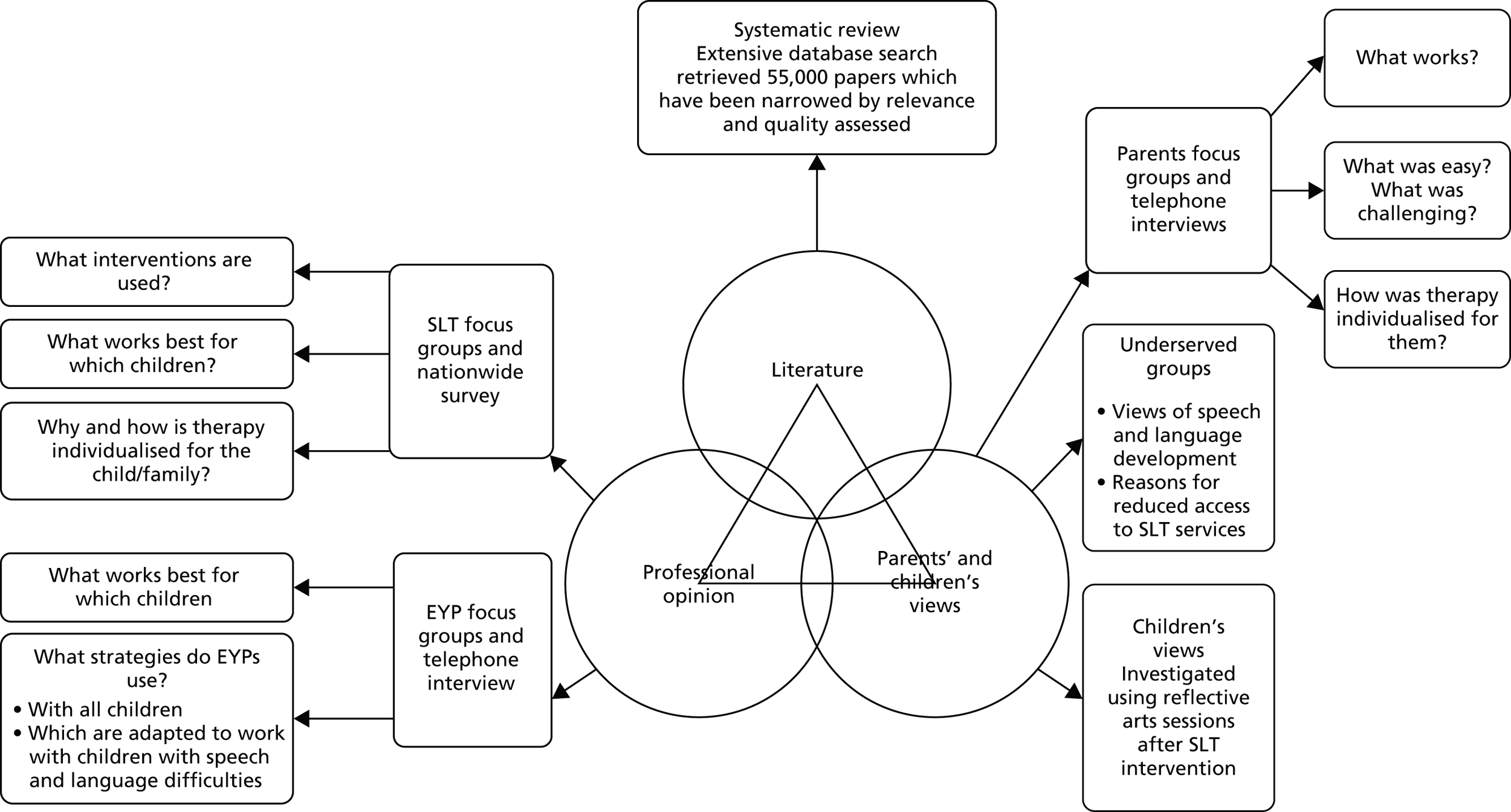

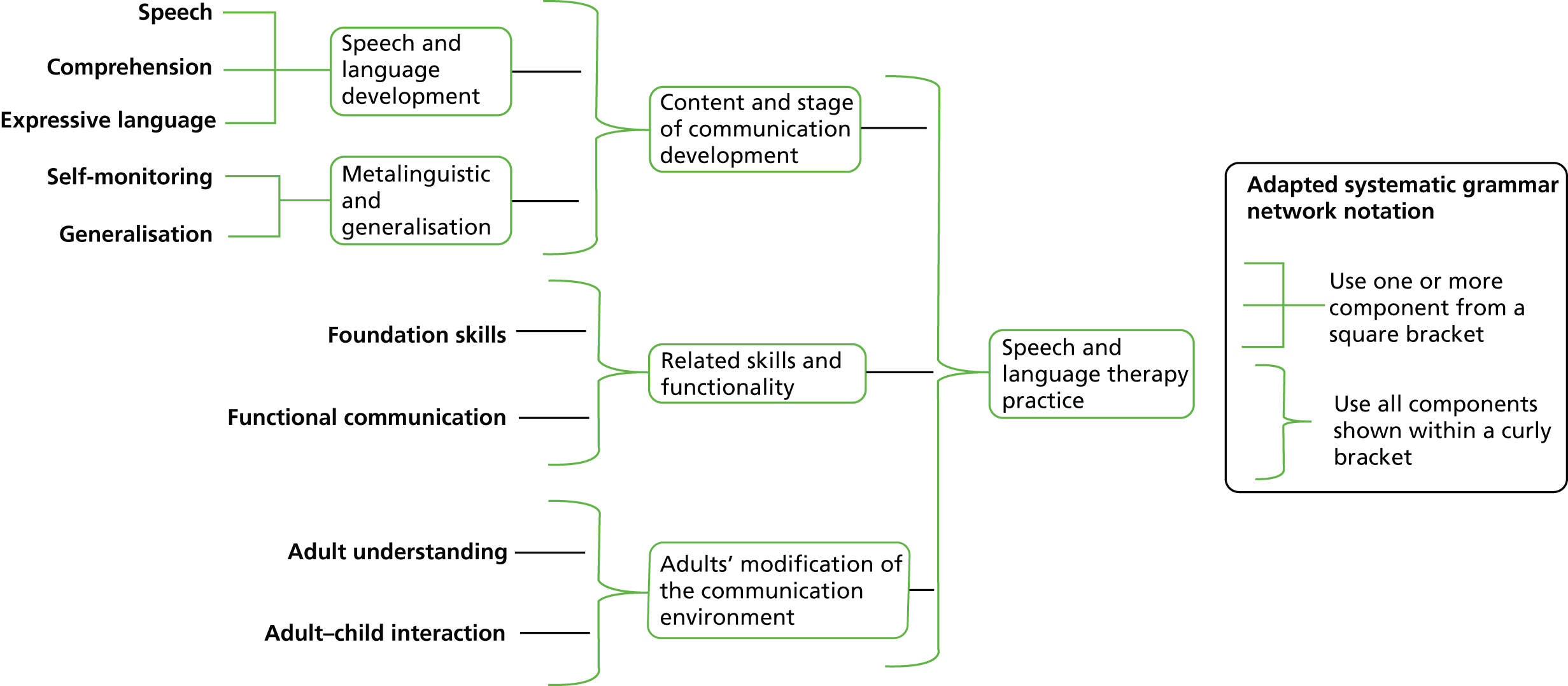

The nature of the research programme was exploratory in that it mapped and described current practice and developed a conceptual framework regarding interventions for preschool children with PSLI. The notion of EBP was used to inform the research questions and to shape the study design and the eventual framework. Sackett et al. ,50 some of the original proponents of EBP, suggested that EBP occurs when evidence from external research is applied explicitly, judiciously and conscientiously and in the light of patient preferences. Our research questions covered these three elements of EBP: systematic reviews of the research evidence, investigations of SLTs’ knowledge about the interventions and how they are used with preschool children with PSLI, and investigations of the perspectives of service users or patients, in this case parents and children with or at risk of PSLI, and EYPs. Figure 2 illustrates how the research questions map onto the three elements of the EBP model.

FIGURE 2.

Research questions mapped onto the three elements of the EBP model.

The resulting research programme adopted a multidimensional approach to evidence gathering and synthesis. It encompassed a series of projects that bring together data representing the three key elements of EBP in the development of an evidence-based framework. Our research approach was essentially pragmatic, resulting in a mixed-methods, ‘multiphase’ design60 combining both quantitative and qualitative elements iteratively to enhance our understanding of a complex problem. Within the overall multiphase design, certain elements followed an exploratory sequential process, starting with a qualitative investigation that was built on using quantitative methods. For example, findings from SLT focus groups were further explored and verified using mini-surveys to validate analyses; these were then built on using a national survey. Thus, quantitative methods included surveys and investigated aspects such as the prevalence and patterns of intervention usage, and qualitative data collection methods included focus groups, interviews and reflection to investigate participants’ perspectives and understandings of interventions. Data from quantitative and qualitative studies were analysed separately using analytical approaches of relevance to the nature of the data; therefore, for quantitative data, analysis methods included descriptive and inferential statistics and, for qualitative data, methods included thematic and content analysis and also framework analysis. Interpretation and discussion took place at the end of each element of the research, across phases of the research and, then, in a concluding section at the end of the programme. For example, the findings are reported separately for the thematic analysis of each of the user groups and for the observational study of children’s perspectives; these are then drawn together in a discussion that also relates back to the investigation of the therapists’ perspectives.

The aim of developing a conceptual model or framework has led to an iterative data collection and analytical process in which we have employed processes typically seen in qualitative theory-building methodologies such as grounded theory. 61 These have included theoretical sampling, deviant case analysis and constant comparative analysis. 62

Theoretical sampling is the process of sampling participants, incidents or events on the basis of their relevance to the evolving concepts and/or theory. 61 It was used in two ways in this study: first, in terms of the deliberate sampling of ever-wider and broader groups of participants; second, in terms of developing more detailed and specific research questions and data collection activities. The purpose of theoretical sampling in this study was to better understand the themes and concepts that were identified from each preceding stage of the study; sampling was thus in some part iterative with the analysis (Box 1 provides an example).

The analysis of data from the focus groups with SLTs generated 10 themes that we hypothesised capture the purpose of their interventions. Our analysis provided descriptions of the characteristics of each theme. To develop those themes we needed examples of therapists talking about their interventions in different ways. We therefore asked therapists to provide explanations of each aspect of their work under the headings of the 10 identified themes, as if they were speaking to parents.

In the process of developing the detail of the framework and in establishing the confirmability of findings, we have systematically examined the data for negative instances of the themes (deviant case analysis). Within the iterative process we used negative instances to generate new ‘hypotheses,’ which were then put back to the participants in a new round of questioning (Box 2 provides an example).

The 10 themes were presented to groups of SLTs who were asked to vote on whether or not each theme was essential to their work with preschool children with PSLI. Disagreement was used to stimulate further discussion of the nature of the interventions to generate further understanding of the themes. Additionally, the typology was presented to a small number of academic experts who have developed their own therapy models. As these experts were likely to have a strong pre-existing theory, their perspectives and data provided a strong test of the validity of the themes identified by this research.

Constant comparative analysis was used at each stage of data analysis: themes, categories or groupings that were established at one stage were examined in the light of new data to establish the characteristics and boundaries of themes and categories. This analytical process works iteratively with the theoretical sampling, by which decisions are made about which data should be collected to test and challenge developing themes (Box 3 provides an example).

SLTs’ descriptions of each theme for parents were compared with each other and with the descriptions generated from the focus groups to examine the detailed characteristics of each theme. Descriptions for one theme were also compared with those for similar themes to identify potential overlapping characteristics. To develop those themes we needed examples of therapists talking about their interventions in different ways. We therefore asked therapists to provide explanations of each aspect of their work under the headings of the 10 identified themes, as if they were speaking to parents.

Exploring consensus on the framework

One aspect of EBP is clinical expertise, the expertise of the SLTs in the case of this research programme. Expertise is commonly associated with years of experience. We are also intuitively aware that experience alone is insufficient to guarantee expertise. The research, therefore, needed a way to validate the opinions of SLTs as stemming from a body of knowledge rather than arising from individually held beliefs. 63 Examining levels of consensus about actions to be taken can give an indication of shared knowledge between participants and was thus used as an indicator of a body of expertise. Some cautionary notes are advisable here. First, just because a group of professionals agree about a course of action does not necessarily mean that this is a foolproof approach to take. The history of medicine is riddled with examples in which a consensus approach is later shown to be detrimental to health. On the other hand, lack of consensus does not necessarily indicate inexpert practice; it may be an indicator of a novel response or of a response to a novel case. The aim of this approach was therefore to make the levels of consensus explicit rather than attempting to reach consensus about a particular approach. We also expected the process of investigating consensus to enable us to more thoroughly explore diverse views. A number of ways of defining consensus were used during the course of the study. For example, the qualitative analytical approaches of deviant case analysis and constant comparative analysis by definition focus on instances of disagreement. Various definitions have been used to identify consensus. 63 In this research we have identified 60% agreement as a marker of consensus.

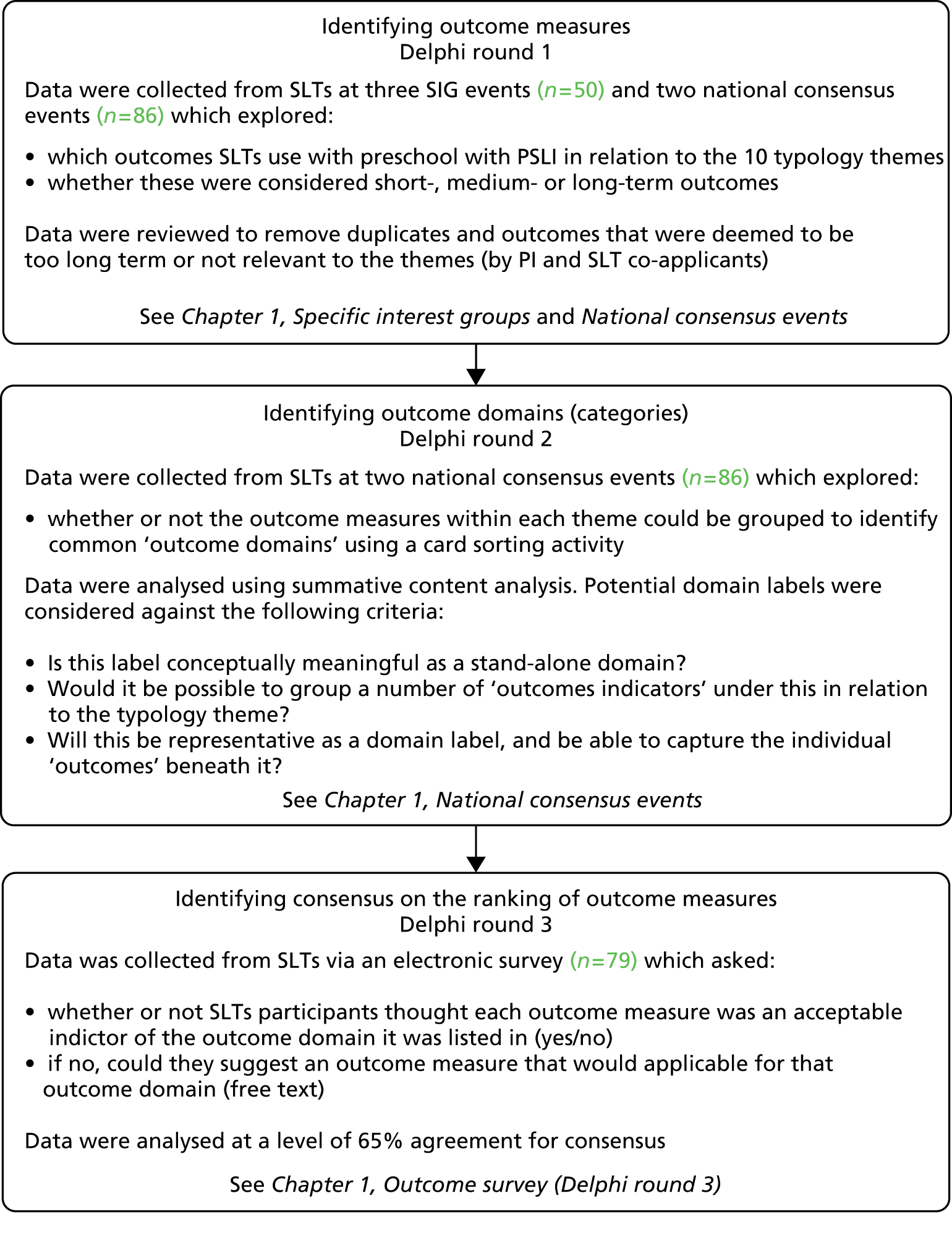

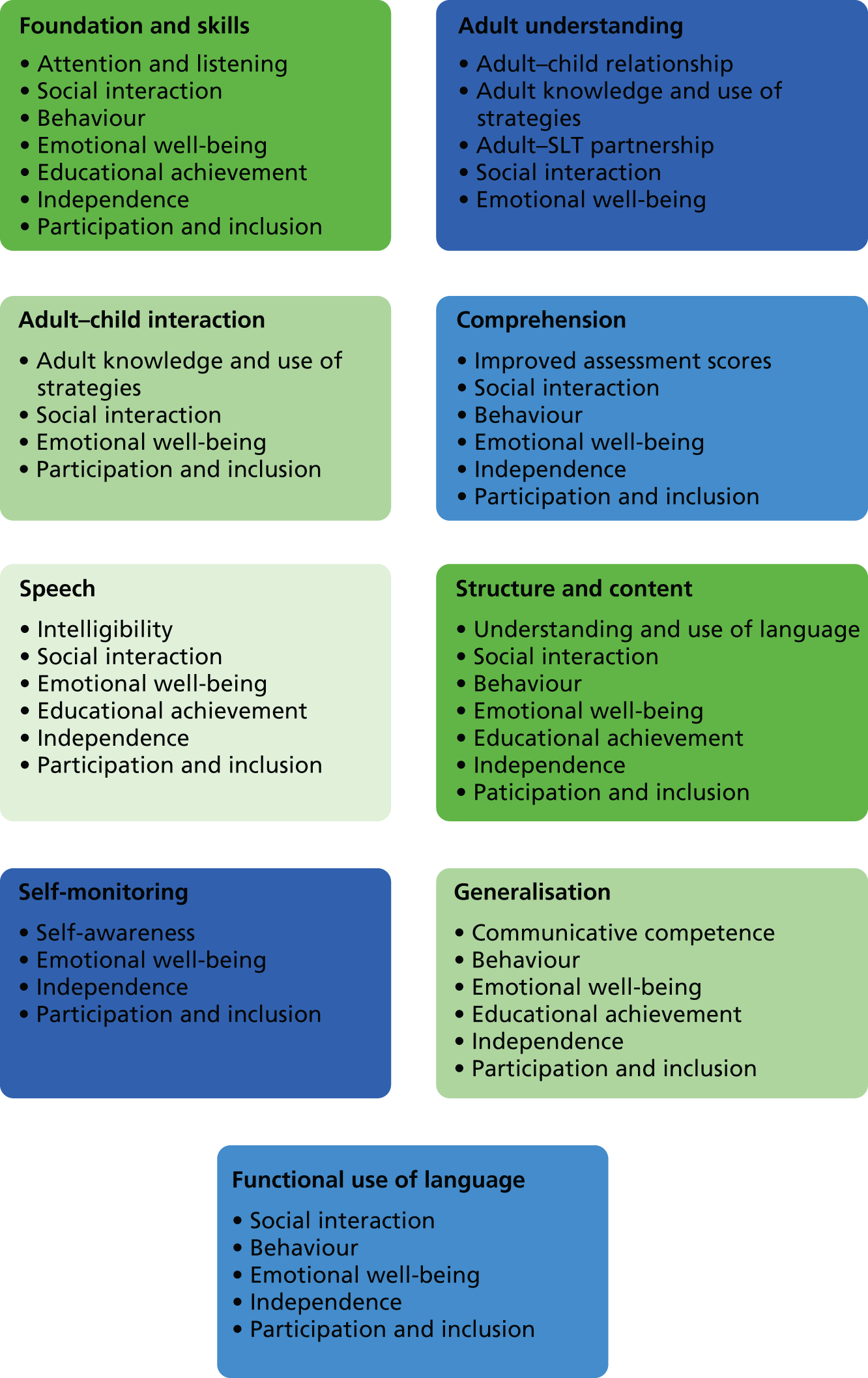

The approach used to investigate consensus on outcome measures used by SLTs (see Chapter 5, Study 5.2: identification of outcome measures for speech and language therapists) followed an iterative process similar to the Delphi process. 64–67 In the Delphi process a series of opinions or views or propositions are generated by a group of experts. These are then subjected to a series of questionnaire rounds whereby participants are asked to rank the statements. The outcomes of those rankings are then analysed and the process iterates to establish a more finely tuned set of statements. In the case of this research, the aim was not necessarily to rule out propositions (such as descriptions of outcomes) but rather to investigate levels of consensus. The process followed was iterative and gave participants information from preceding rounds. Typically, Delphi establishes consensus and priorities with a set group of participants, whereas our participants group was gradually widened to become progressively more inclusive of the profession. Thus, the same participants were not necessarily involved in the successive rounds of data processing. However, they were all SLTs and were considered to be experts in PSLI who had knowledge of the purpose, content and recent findings of the research programme on which their responses were to be based.

The mixed-methods approach pervades the entire programme; thus, each study in this report frequently includes both quantitative and qualitative elements. Furthermore, our data collection events frequently targeted more than one aspect of the framework. For example, data on the identification of outcomes, on the development of the typology and on the exploration of the use of interventions were collected at the same events but are reported in separate sections of this report. Therefore, to avoid repetition, the process of recruitment, data collection and analysis is described in detail in the rest of this chapter and should be used as a reference. The order and context in which these activities were undertaken is described in the study chapters (see Chapters 2–6).

Selection of case study sites

To support the collection of data throughout the research programme and particularly in the first phase, six speech and language therapy services in England were recruited to become case study sites. The process of identifying these sites, to reflect the variety in the current system of service provision, is described in this section.

A literature search was conducted in July 2011 in NHS Evidence to identify factors that are reported to impact on speech and language therapy service provision. No date boundaries were used and the search used key terms suggested by the subject matter expertise of the research team (Box 4).

speech therap* department differences, variety NHS

metropolitan speech therap*

nomics speech therap*

socio-economic speech

bilingual* speech therap*

ethnic* speech therap*

parent identify speech ethnic*

speech demograph*

transient population speech therap*

education* speech therap*

The quality of retrieved papers was assessed using criteria taken from Pennington et al. 68 and the American Speech Hearing Association;69 factors identified as leading to variations between services were divided into seven categories (Table 1). Of these categories, six were mapped onto geographical areas in England to identify speech and language therapy services. From this mapping exercise, six case study sites were chosen, which provided a spread, across the categories; these six sites were invited to become case study sites. It was not possible to use the category ‘service management variation’ in this exercise but this was explored at each of the selected case study sites as part of the economic modelling (see Chapter 6). Three geographical boundaries were used – postcodes, unitary authorities and strategic health authorities – and three main data sources – the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the Department for Education and the early years census (Table 2).

| Categories | Evidence from the literature search |

|---|---|

| Urban, suburban, rural | Urban areas are more likely to have higher ethnic minority populations70–72 |

| Rural areas are more likely to have reduced availability, frequency and choice of services; SLTs in rural areas are more likely to have a consultative role73 | |

| In rural areas SLTs are more likely to have diverse roles; there are fewer specialist therapists74 | |

| In rural areas there is a greater distance between the homes of clients and services; lower availability of public transport has been found to result in lower levels of access73 | |

| Socioeconomic status | Lower SES is associated with a greater need for SLT input, a greater likelihood of speech and language delays75,76 and poor scores on SLT assessments |

| Lower SES households have been found to have different learning environments, with a lower quantity and quality of maternal speech77 | |

| Lower SES individuals are less likely to access SLT services78 | |

| Ethnic minority populations | Ethnic minority populations are associated with not accessing services. Barriers include parental communication, travel and cost, particularly for groups who are new to an area79 |

| Services for ethnic minorities might require more adaptations including providing therapy in more locations to improve access and more time spent working collaboratively with teachers70,71 | |

| Bilingual populations | Speech and language therapy services in areas with high levels of bilingual learners are likely to be required to provide additional training for their SLTs or to have a member of the team who specialises in bilingualism71,80 |

| Additional administration costs and resources may also be needed to meet additional RCSLT guidelines80 | |

| Transience of populations | Transient populations have been shown to have poorer health and are less likely to access health and education services81 |

| This reduced contact with health and education services leads to a reduced likelihood of referral to speech and language therapy services82 | |

| Early years foundation stage | Non-attendance or low attendance at preschool education provision results in lower referral rates to speech and language therapy services82 |

| Poor early years provision may lead to little/no exposure to English before entering preschool education and/or a poor home communication environment may result in language delay83 | |

| Not achieving the early learning goals can impact on later speech and literacy skills84 | |

| Service management variations | Different models of service delivery may be adopted such as consultancy/indirect therapy vs. direct therapy,85 school vs. clinic based86 |

| Services may or may not provide input to secondary school age children87 and vary in their involvement in multidisciplinary team working88 | |

| Formalised protocols vary between services: the time between initial assessment and referral,78 the severity cut-off point,87 prioritisation and discharge criteria and use of special education;85 the composition of staff varies between departments in relation to the number of full-time equivalent staff to meet case load needs and the levels of experience of staff |

| Categories | Data source |

|---|---|

| Ethnic minority populations | ONS-requested data CD – EE1: estimated resident population by ethnic group and sex, mid-2009 (experimental statistics) – ethnic table 2009a |

| Socioeconomic status | ONS-requested data CD – Economic Deprivation Index 2008b |

| Urban, suburban, rural | ONS-requested data CD – 2001 density (number of people per hectare)c |

| Transience of population | Table produced by the Migration Statistics Unit (migstatsunit@ons.gsi.gov.uk) – 1999 numbers to and from each local authority in England and Walesd |

| Bilingual populations | www.education.gov.uk/Sfr09–2010pla (accessed 14 November 2011) |

| Early years foundation stage | www.education.gov.uk/rsgateway/DB/SFR/s000961/sfr28–2010la.xls (accessed 14 November 2011) |

This sampling process aimed to ensure that a range of service types was investigated rather than a representative sample. Therefore, each of the categories was independently ‘sorted’ in Microsoft Excel (2007; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and split into groups of equal size. The individual sites within each of these groups were assigned an ordinal ‘group number’ from one to six, with ‘one’ representing ‘low’, for example a low level of ethnic diversity, a low level of socioeconomic deprivation (high income), low level of urban areas (rural), and ‘six’ representing ‘high’, for example a high percentage of pupils scoring well on the early years foundation stage (EYFS), a high percentage of children with English as a second language, a larger percentage of people moving between local authorities. The data were then scrutinised and sites were identified that provided a range of scores on each variable.

Potential sites were approached by the research team through discussions with the speech and language therapy service lead. If a service was not in a position to become a site, the data were re-examined to find a new site with a similar spread of scores. It took three iterations to recruit six sites. Table 3 shows the spread of values for the six sites.

| Case study site | Ethnicity | SES | Urban/rural | EYFS | E2L | Transience | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 31 |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 14 |

| 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 20 |

| 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 18 |

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 28 |

The six speech and language therapy services recruited as case study sites were used to identify participants for focus groups (SLTs, parents, EYPs), advertise national SLT surveys (alongside other advertising routes) and identify underserved groups and local children’s centres. In addition, information to support the economic modelling of resource use (see Chapter 6) was collected at each site in collaboration with the speech and language therapy service manager.

Focus groups

This section describes the process of recruitment to the SLT, parent and EYP focus groups at each of the case study sites and the methods for data collection and analysis.

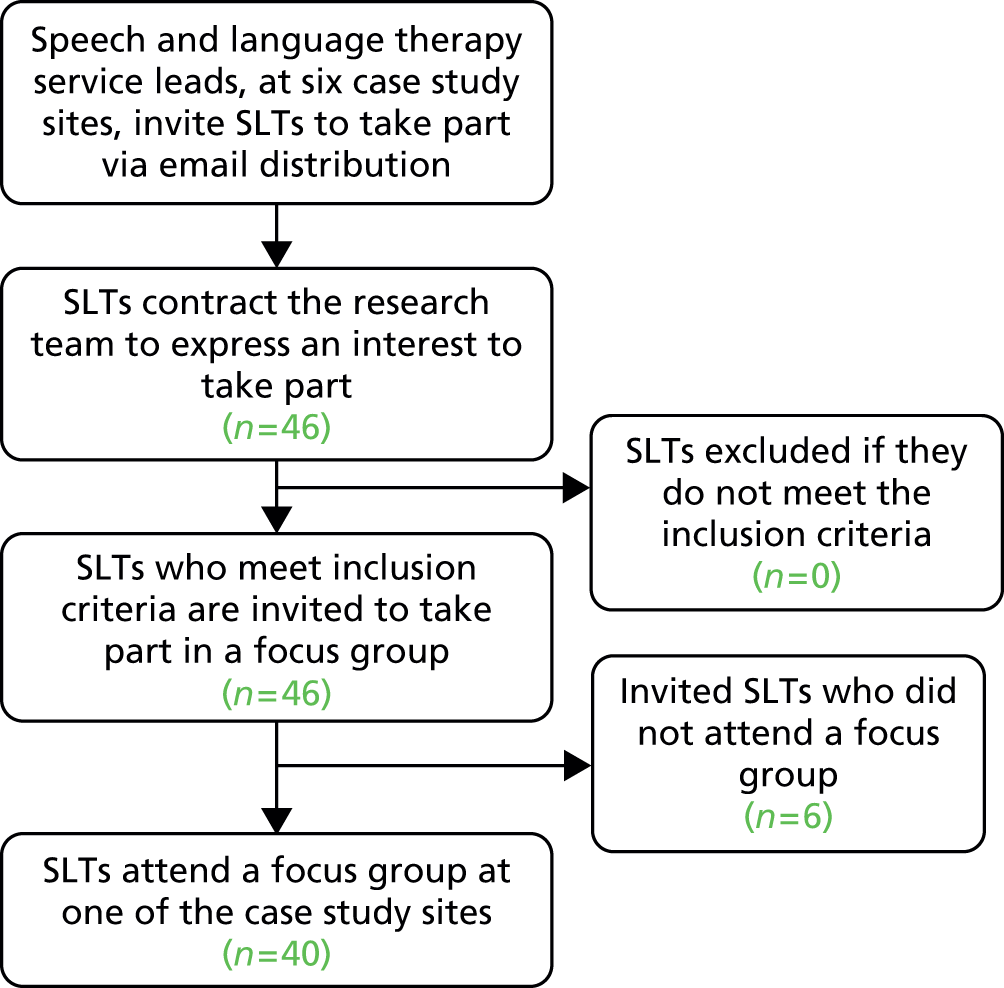

Speech and language therapists

At each of the six case study sites, invitations to participate in focus groups were e-mailed to SLTs through the speech and language therapy service leads (Figure 3). Those SLTs who were interested in participating in the study were asked to contact the research team at North Bristol NHS Trust by e-mail. On receipt of expressions of interest, a member of the research team contacted each individual to gain information about his or her case load and experience to determine eligibility: the inclusion criteria were currently practising NHS SLTs with at least 2 years’ experience of working with preschool children with PSLI.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of the recruitment process for SLT focus groups.

Those who met the inclusion criteria were e-mailed a participant information sheet (which were held in the participants’ local area) and were given the opportunity to ask questions by telephone or e-mail before attending. Nine focus groups were held across the six sites with a total of 40 SLTs. The SLTs who attended had been qualified as an SLT for an average of 14 years (range 2–43 years). They also emanated from a range of different university training courses (Table 4).

| Case study site | Number of focus groups | Number of participants | Average (range) years since qualifying |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 (2–11) |

| 2 | 2 | 8 | 15 (3–31) |

| 3 | 1 | 8 | 17 (1–32) |

| 4 | 2 | 7 | 12 (3–23) |

| 5 | 1 | 4 | 20 (3–37) |

| 6 | 1 | 5 | 17 (2–43) |

| Total | 9 | 40 | 14 (2–43) |

The nine focus groups, conducted locally on non-NHS sites, lasted between 1 and 1.5 hours. At the start of the focus groups participants were reminded that their contributions were voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw at any time. Consent forms were signed at this point.

The focus group discussions were semistructured, with a topic guide that the moderator followed. An example topic guide is provided in Appendix 8. At the beginning of the focus groups, ground rules for discussion were covered, which included covering the confidential nature of the groups. SLTs were then asked questions about:

-

the interventions that they use with preschool children with PSLI and their components

-

the ways in which they modify their interventions in relation to child, context and family factors

-

the rationales for and purposes of the interventions, including descriptions of how the interventions were thought to cause change.

During the focus groups participants were encouraged to be explicit about their interventions and give detail rather than merely the names of programmes or listing resources. When participants used these, they were encouraged to expand and provide more detail.

At the first focus group fictional vignettes were used; the types of cases that were discussed included the following groups:

-

a child aged between 3 and 4 years with speech impairment/disorder

-

a child aged between 2 and 3 years with receptive and expressive language delay

-

a child aged between 4 and 5 years with social communication problems.

Subsequent to each focus group, audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team. The data were anonymised and participants were given pseudonyms when requested. Thematic and content analysis was conducted using NVivo 9 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Issues raised in the earlier groups informed subsequent groups in terms of the questions asked.

Parents

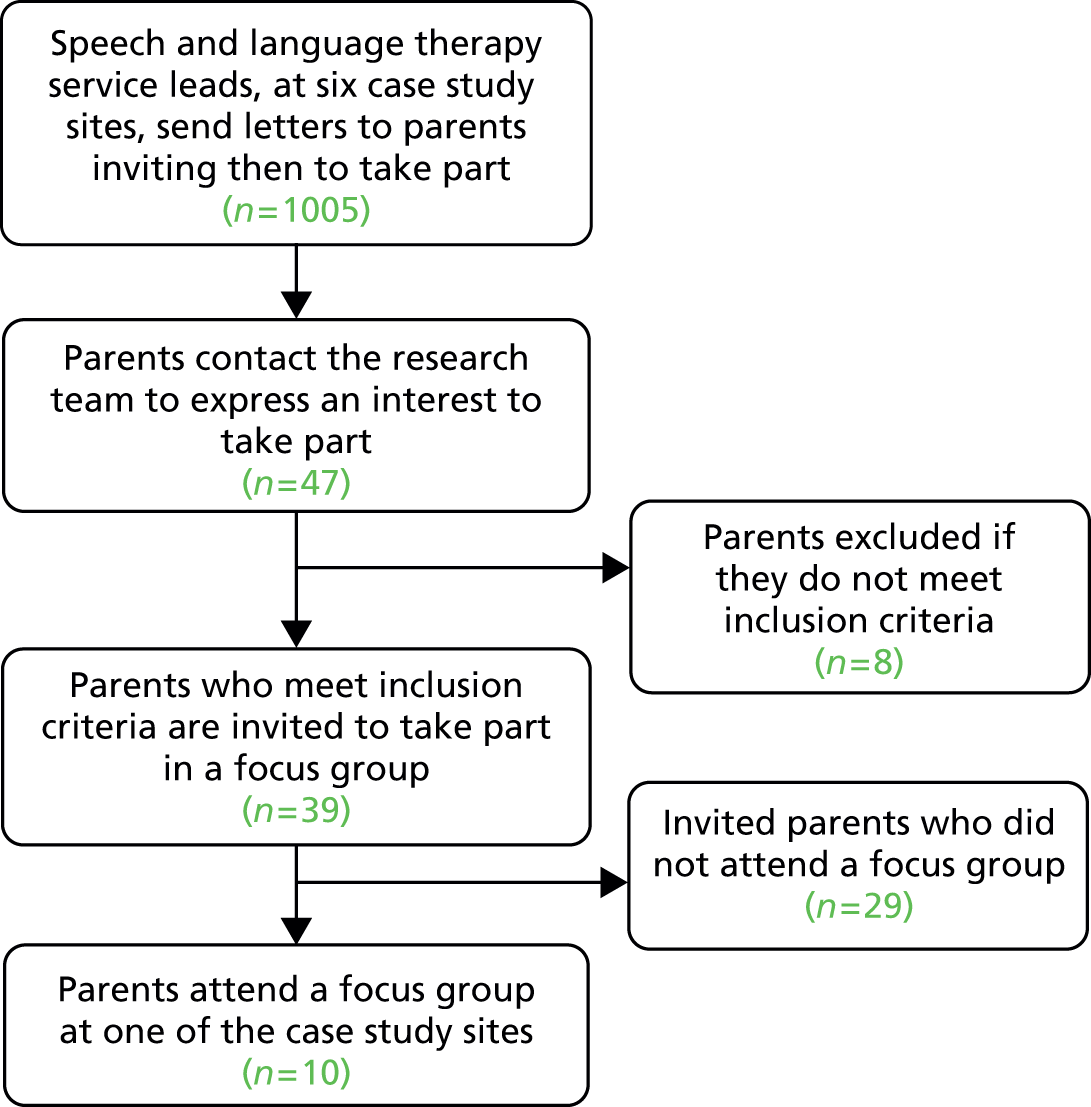

Clinical leads at each case study site were asked to identify children within their service who had received input from the speech and language therapy service, who met the criteria for PSLI and who were aged between 2 years and 5 years 11 months. Invitation letters were sent to the parents of these children by the SLT service on behalf of the research team accompanied by a participant information sheet and an expression of interest slip to be returned in a prepaid addressed envelope to the research team. The invitation letter and participant information sheet were designed in collaboration with the Child Talk parent panel.

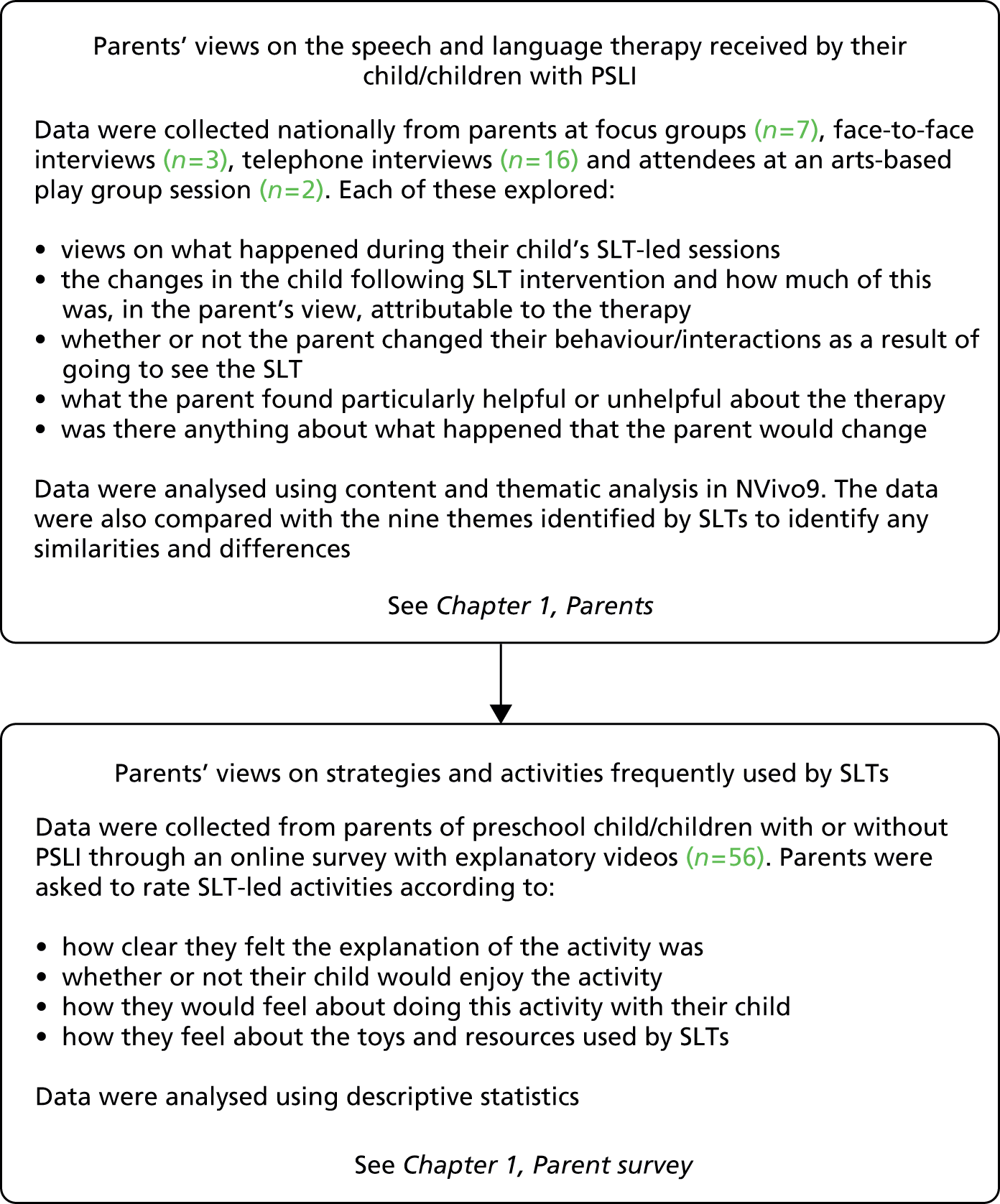

Forty-seven parents expressed an interest in taking part (Figure 4). They were contacted by telephone by a member of the research team and asked a number of screening questions to establish eligibility according to PSLI and age. Parents whose level of spoken English would significantly limit participation in an interview or focus group were excluded. After this process, 39 parents were invited to take part, of whom 10 attended a focus group or an individual face-to-face interview (when only one participant was available to attend). Focus groups did not occur in all case study sites because of the poor take-up of invitations. To boost recruitment rates, possible alternative methods of data collection were discussed with the Child Talk parent panel. Following these discussions, an amendment was submitted to the ethics committee to seek approval to contact the parents who expressed an interest and had been unable to attend the focus groups to ask if they would take part in an audio-recorded telephone interview. As a result, an additional 16 parents were interviewed by telephone by a member of the research team (a qualified SLT).

FIGURE 4.

Flow diagram of the recruitment process for parent focus groups.

The Child Talk parent panel identified lack of childcare as a barrier to participation and suggested that parents might be more likely to attend if offered something additional. In response to this, free play-based arts therapy sessions were set up by the research team and advertised locally for children to attend while parents attended a focus group. In total, 1500 flyers were distributed to advertise these sessions across the locality, and parents who had expressed an interest in taking part in a local focus group but who had been unable to attend were also made aware of the events. Two parents attended these sessions.

Following the various methodologies described above, a total of 28 parents took part in this study across England (10 focus groups, 16 telephone interviews and two play-based sessions). This number was lower than we would have anticipated but it has given an insight into the difficulties of engaging with this population and the lessons that should be learned for future studies (see Chapter 4, Discussion). A summary of the numbers of parents participating in focus groups and interviews is provided in Table 5.

| Case study site | Number of focus group/interview participants | Number of telephone interviewees | Number of arts-based play group participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 6 | 2 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 3 | 2 | 6 | NA |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 5 | 0 | 4 | NA |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Total | 10 | 16 | 2 |

Informed consent was taken by a member of the research team at the start of the group or interview. The wording of the consent form and participant information sheet was reviewed by the parent panel. Focus groups lasted on average 1 hour 40 minutes whereas individual interviews were typically shorter, lasting between 25 and 50 minutes. Telephone interviews were recorded using an audio-recorder telephone device.

The discussions were semistructured, with a topic guide that the moderator followed (see Appendix 9). At the beginning of the focus groups ground rules for discussion were covered, which included covering the confidential nature of everything that was raised in the groups. Participants in the face-to-face interviews also had the confidentiality process explained to them. Parents were asked questions about:

-

what happened during speech and language therapy sessions, including:

-

activities

-

materials used

-

length of sessions

-

how regularly they were seen

-

advice given

-

targets set

-

-

their understanding of the aim of the activities

-

whether or not any change was seen in their child following SLT intervention and their view on how much of this change was attributable to speech and language therapy

-

whether or not they modified their behaviour/interactions as a result of going to see the SLT

-

if anything was particularly helpful or unhelpful

-

if there was anything about what happened that they would change.

An iterative approach was taken to the focus groups whereby issues raised were followed up in subsequent groups and interviews. Telephone interviews used a semistructured format and followed the topic guide used for the focus groups.

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team. All data were anonymised and participants were given pseudonyms when requested.

Early years practitioners

Service managers at each of the six case study sites were asked to identify EYPs who met the inclusion criterion of working directly with preschool children with PSLI. Participants were approached and invited to participate through managers of nurseries and children’s centres in the local area, who distributed the invitation to relevant staff members. In addition, local nurseries and children’s centres were identified through the use of a search engine and government websites.

Early years practitioners who expressed an interest in participating were contacted by a member of the research team. There was no specific inclusion criteria other than that EYPs worked directly with children in an early years venue. Participants were e-mailed an information sheet before attending a focus group and were given the opportunity to ask questions by telephone or e-mail before attending. Twenty-three EYPs expressed an interest in participating in the focus groups (Figure 5), of whom 18 attended from five of the six case study sites (there were difficulties with recruiting within case study site 4). The number of EYPs who attended the focus groups varied between groups (mean 4, range 2–5).

FIGURE 5.

Flow diagram of the recruitment process for EYP focus groups.

Because of the low recruitment levels, ethical approval was sought to invite EYPs who had expressed an interest but who were unable to attend a focus group to take part in an audio-recorded telephone interview. Six EYPs were interviewed by telephone (Table 6).

| Case study site | Number of focus group participants | Number of telephone interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 |

| 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 18 | 6 |

Focus groups took place at non-NHS sites in each of the selected research sites and typically lasted between 1 and 1.5 hours. At the start of the focus groups, written informed consent was taken by a member of the research team. Telephone interviews were conducted at a time convenient to the participants and typically lasted around 25–35 minutes. Consent was taken verbally by reading each statement and the participant answering ‘yes’ or ‘no’. All participants were offered a copy of their consent form, either by e-mail or by post.

The focus group discussions were semistructured, with a topic guide that the moderator followed (see Appendix 10). At the beginning of the focus groups, ground rules for discussion were covered, which included covering the confidential nature of everything that was raised in the groups. Telephone interviews followed the topic guide used for the focus groups. EYPs were asked questions about:

-

the interventions that they use with preschool children with PSLI and their components

-

the ways in which they modify their interventions in relation to child, context and family factors

-

the rationales for and purposes of the interventions, including descriptions of how the interventions were thought to cause change.

Subsequent to each focus group and telephone interview, audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team. All data were anonymised and participants were given pseudonyms when requested.

Content analysis of data from speech and language therapist, early years practitioner and parent focus groups

After familiarisation with the transcripts, one of the co-applicants who was involved in the focus groups developed a coding framework in NVivo 9. The focus of the content analysis was on description and classification of the interventions. Interventions were classified following the definitions used in Roulstone et al. 89 as follows:

-

activities – specific tasks that are usually targeting impairment

-

strategies – principles, techniques, actions or styles

-

materials or resources – items or published materials used in the delivery of an intervention

-

programmes – published interventions that encompass specific procedures with detailed plans for how to deliver them.

Within these areas, interventions were further classified according to whether their focus was on speech, language or communication. Sections of text (which could be single words, phrases or sentences) were coded by the researchers using the relevant codes. Two members of the research team, who were both SLTs, coded the data. These researchers examined each other’s coding in a validation exercise, in which 20% of the transcript was checked for consistency of the coding technique. Any discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached.

For the SLT focus groups, data from the content analysis were used as the basis for the description of current SLT practice (see Chapter 2, Study 2.2: identifying the interventions used by speech and language therapists).

Thematic analysis of data from speech and language therapist, early years practitioner and parent focus groups

Thematic analysis followed the stages set out by Braun and Clarke. 90 The PI and one researcher read and reread the transcripts to familiarise themselves with how therapists talked about their interventions. Both researchers had also been involved with the data collection. The content analysis also supported familiarisation with the data and led to a focusing of the analytical question for the thematic analysis. The transcripts were initially read and coded on paper and then, as codes emerged, a framework was designed in NVivo 9. Additional rounds of coding were carried out directly onto the NVivo 9 framework and codes were adjusted and merged as stronger themes emerged.

For the SLT focus groups the thematic analysis focused on exploring the purposes of SLTs’ work. The thematic analysis, therefore, progressed in terms of analysing and reporting patterns (themes) in relation to the following question, ‘What are the purposes of therapy?’ The themes generated were used as the basis for constructing a typology of SLT-led practice (see Chapter 2, Study 2.1: identifying the themes of speech and language therapy practice).

The focus of the thematic analysis for the EYP focus groups was similar – to explore the purpose and aims of their activities and strategies. For the parent groups the data were analysed slightly differently, with the data being explored in terms of parents’ experiences of therapy.

Each data set was treated as separate initially and coded independently. Finally, however, data from parents and EYPs were examined in the light of the themes emerging from the SLT focus groups to identify synergies and discrepancies.

Cross-tabulation of interventions and themes from the speech and language therapist groups

NVivo 9 has a cross-tabulation function that allows the cross-tabulation of codes. For the SLT groups, each typology theme was cross-tabulated with all 12 intervention codes that were utilised in the NVivo 9 coding (activities, strategies, resources, programmes). This cross-tabulation was designed to help understand which intervention activities and strategies related to the different themes of the typology.

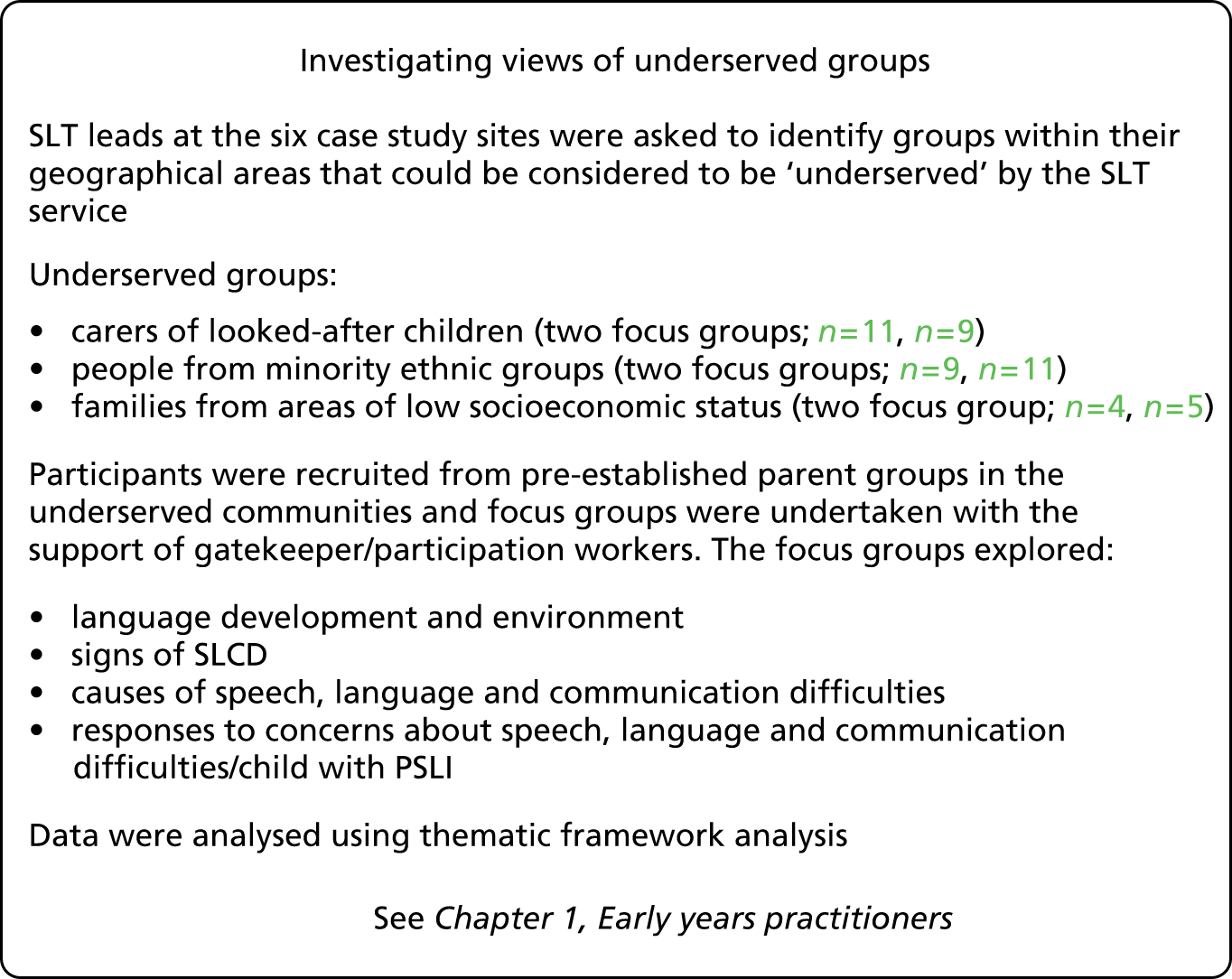

Underserved groups

To identify groups perceived to be underserved, SLT service managers from the six case study sites were asked to identify groups within their geographical areas that they considered fit into one or more of the following categories:

-

groups with poorer attendance rates than other groups in the catchment area

-

groups who were, for other reasons, under-represented on the speech and language therapy services’ PSLI caseloads compared with their representation in the general local population

-

parents/children to whom managers considered that they do not provide appropriate services.

A number of groups were identified by speech and language therapy service managers:

-

carers of looked-after children (children in public care, who are placed with foster carers, in residential homes or with parents or other relatives)

-

people from minority ethnic groups [including specifically the Somali community and refugees and asylum seekers (RAS)]

-

families from areas of low socioeconomic status (SES)

-

travellers or gypsies, defined as those with a cultural tradition of nomadism or living in a caravan, and all other people with a nomadic habit of life, whatever their race or origin. 91

The first three of these groups were selected for inclusion into this study for reasons related to the feasibility of completing data collection within the time frame of this programme. As these were groups perceived to be less likely to be receiving services, recruitment directly through speech and language therapy services or of those currently receiving intervention was unlikely to be successful. It was therefore decided to identify members of the groups selected who were already attending other groups in their local area as a positive strategy for recruitment. Recruitment was therefore targeted to specific groups, as discussed in the following sections.

Carers of looked-after children

Two groups were recruited. Local authority foster care co-ordinators were approached at case study site 1 to identify a group of foster carers who might be interested in taking part. The organiser of one group expressed an interest and approached the carers within the group with the study information sheet to obtain their agreement for the research team to attend their next meeting. Consent was taken by a member of the research team before data collection.

The second group was recruited through a search to identify private foster care agencies. The identified agencies were e-mailed information about the study and one agency, from case study site 3, expressed an interest in participating and facilitated the setting up of a group meeting for the programme. The agency circulated the participant information sheet to attendees before the meeting. Informed consent was obtained by a member of the research before data collection.

Parents from minority ethnic groups

Two groups of parents from minority ethnic groups were accessed, both being recruited from pre-existing parent groups. The group from case study site 1 was a support group for members of a specific ethnic minority group, the Somali community. This group was identified by members of the research team. A researcher attended meetings for a few weeks prior to data collection to establish a relationship with the members. The second group (case study site 2) was accessed through Barnardo’s, who facilitate a group for RAS.

Parents from socioeconomically deprived communities

Two young parent groups were accessed in an area of low SES through case study site 2, with the aid of Barnardo’s who facilitate both groups.

All participants either were requested to have a sufficient grasp of spoken and written English to allow them to understand the participant information sheet and consent form or were provided with translated versions of these documents to allow them to understand them (with some support, if necessary, from facilitators identified by Barnardo’s who were previously known to the participants). For all groups apart from the foster carers, a member of the research team attended one or more meetings of the group, described the study and offered opportunities for questions to be asked about participation in the study. Table 7 provides a summary of the numbers who attended the groups at each case study site.

| Case study site | Looked-after children | Minority ethnic group | Low SES |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | One focus group (n = 11) | One focus group (n = 9) | – |

| 2 | – | One focus group (n = 11) | Two focus groups (n = 4 and n = 5) |

| 3 | One focus group (n = 12) | – | – |

| 4 | – | – | – |

| 5 | – | – | – |

| 6 | – | – | – |

| Total | n = 23 | n = 20 | n = 9 |

The focus groups were scheduled to take place during preorganised meeting times and were either to cover the whole session or a designated slot within a longer meeting. All focus groups took place in the groups’ usual meeting places, which were all non-NHS settings. Participants in each group were known to each other. A topic guide was developed (see Appendix 11) covering the participants’ ideas about how children acquire language, signs and causes of language delay and responses to language delay.

Each focus group was facilitated by one of two senior researchers on the team (both SLTs) plus two other researchers from the team and, for two groups, an additional facilitator who was a psychologist specialising in work with black and minority ethnic communities. One of the senior researchers had significant practice and research experience in sub-Saharan Africa.

At the start of each session the researchers were introduced and the purpose of the session was explained. Time was spent describing the study verbally in English, allowing translation to be provided when needed, and assistance in completing the consent forms was given.

The main method of eliciting data was discussion. For one of the minority ethnic groups a fictitious case study was used to stimulate the discussion. The case study (which was aimed at being as culturally inclusive as possible) was read out and then participants split into two groups to discuss it, followed by a whole group discussion. For one of the low SES groups of young parents, role play was used to provoke thoughts about the way that they talk to children; photographs of children in various situations were also shown and participants were encouraged to describe what if any messages the photographs gave about communicating with children, including what about the images was positive and/or negative for speech and language development.

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team and all data were anonymised. As English was not the first language of a number of participants, field notes were also kept in case audio recordings were poor. Data analysis was undertaken using an adapted framework analysis92 (Box 5). The data collected from each group of participants were analysed separately. The data analysis software programme NVivo (versions 8–10) was used to support stages 1–4 outlined in Box 5.

The stages in the framework analysis were as follow:

-

Familiarisation. Immersion in the raw data; listing key ideas and recurrent themes.

-

Identifying a thematic framework. This used mainly the a priori issues from the research question and the themes identified in the familiarisation phase. An index was created by creating nodes and subnodes using NVivo 9. As NVivo 9 was used, codes and subcodes with names were used rather than a numbered system. Although the looked-after group was analysed separately, the same initial framework was used.

-

Indexing. In this stage the researcher applies the framework to the data systematically. In this project, however, new themes were added if identified and unlike the original framework the themes were not given numerical codes.

-

Charting. Once all of the data are coded the use of NVivo 9 makes it simpler to carry out the charting phase, that is, to look at the material that has been coded under one code and to consider the whole data set or individual focus groups separately. The material is then summarised and distilled.

-

Mapping and interpretation. At this stage:

-

define concepts, for example the environment

-

map the range and nature of the phenomena – map polarities

-

create typologies

-

fnd associations; provide explanations

-

develop strategies because this is for policy research.

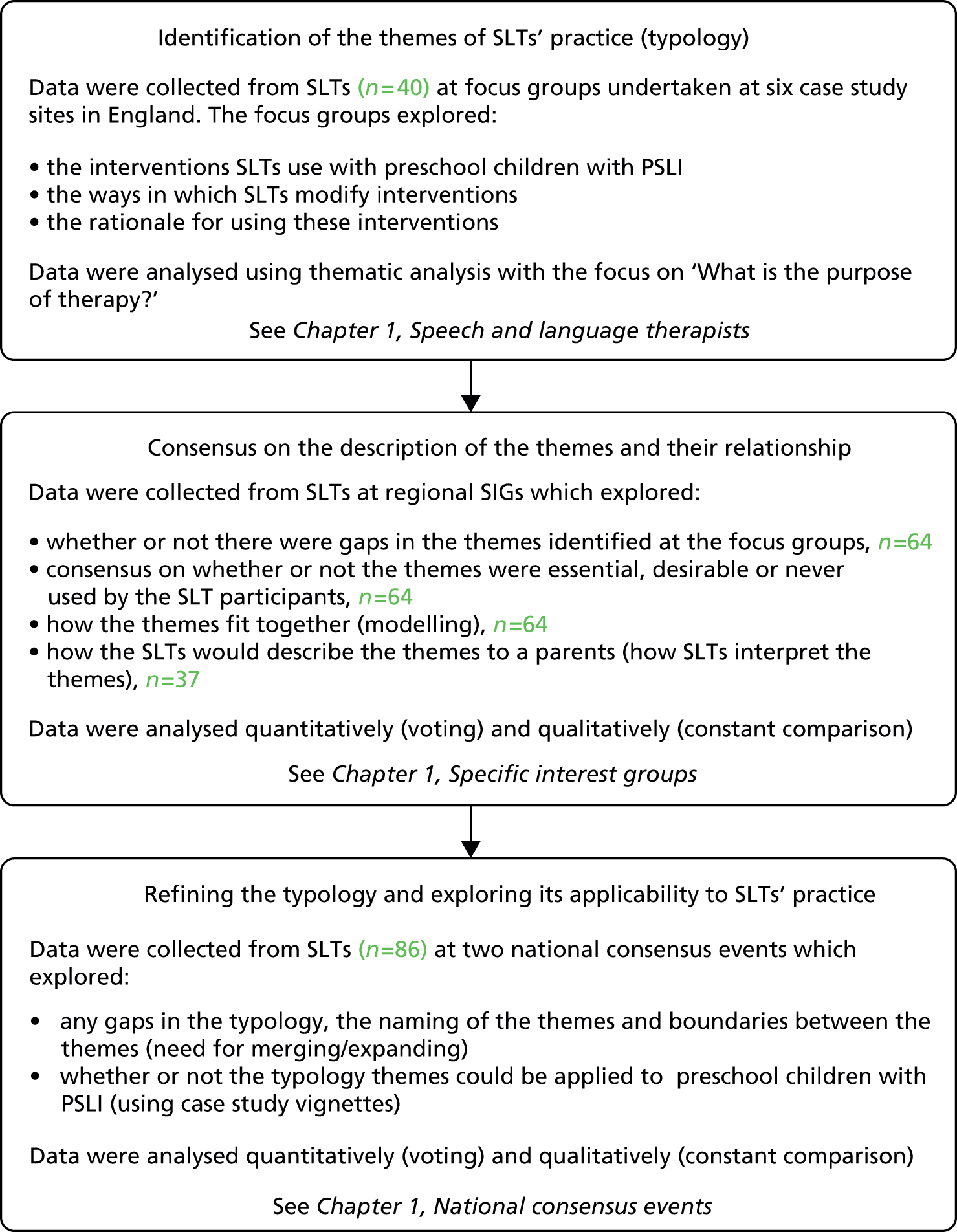

Consensus events

Consensus events were undertaken with SLTs after the focus groups to:

-

determine the level of agreement on the themes of SLT practice (see Chapter 2, Study 2.1: identifying the themes of speech and language therapy practice)

-

determine the level of agreement on how the interventions map onto the themes (see Chapter 2, Study 2.2: identifying interventions used by speech and language therapists)

-

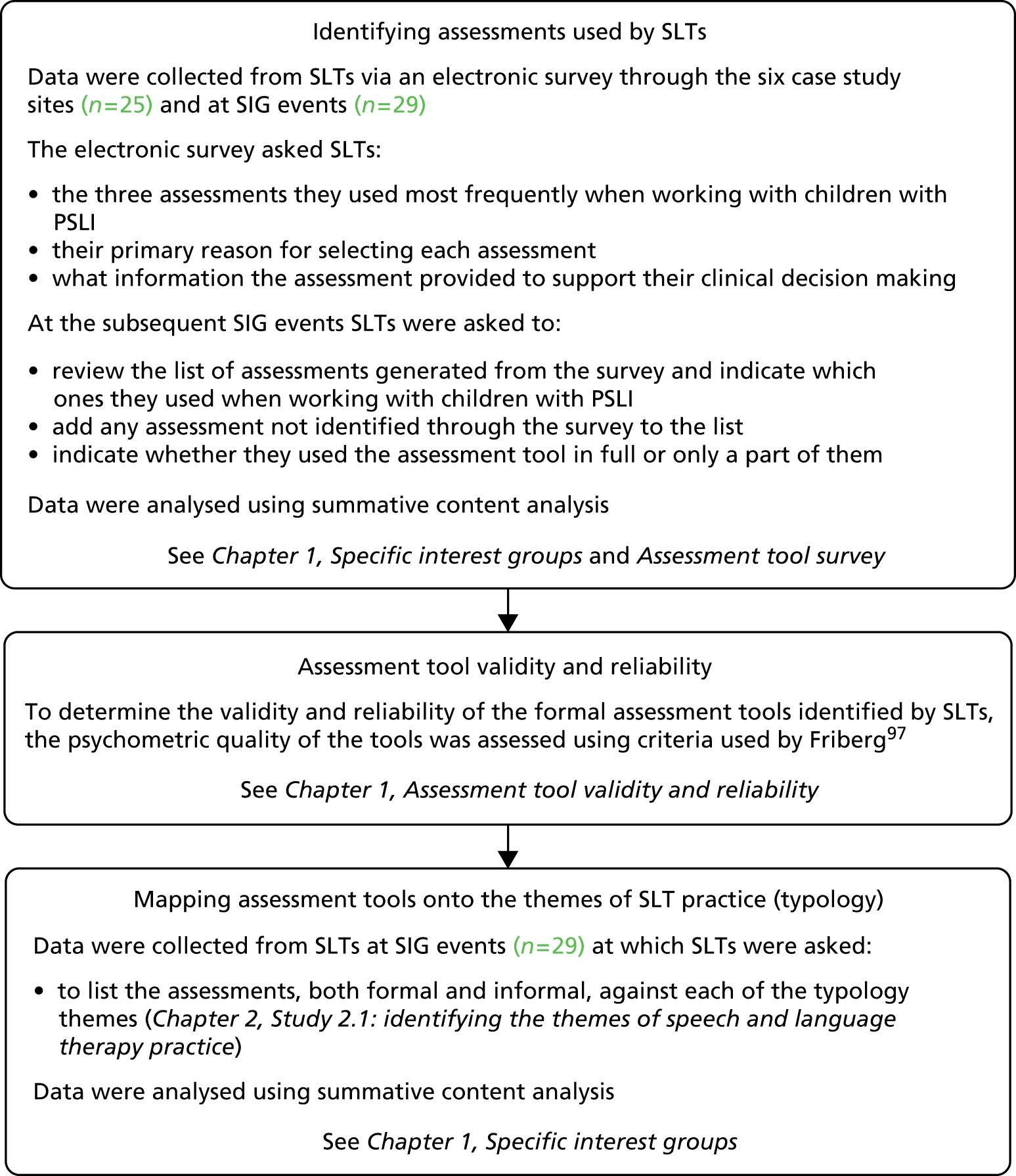

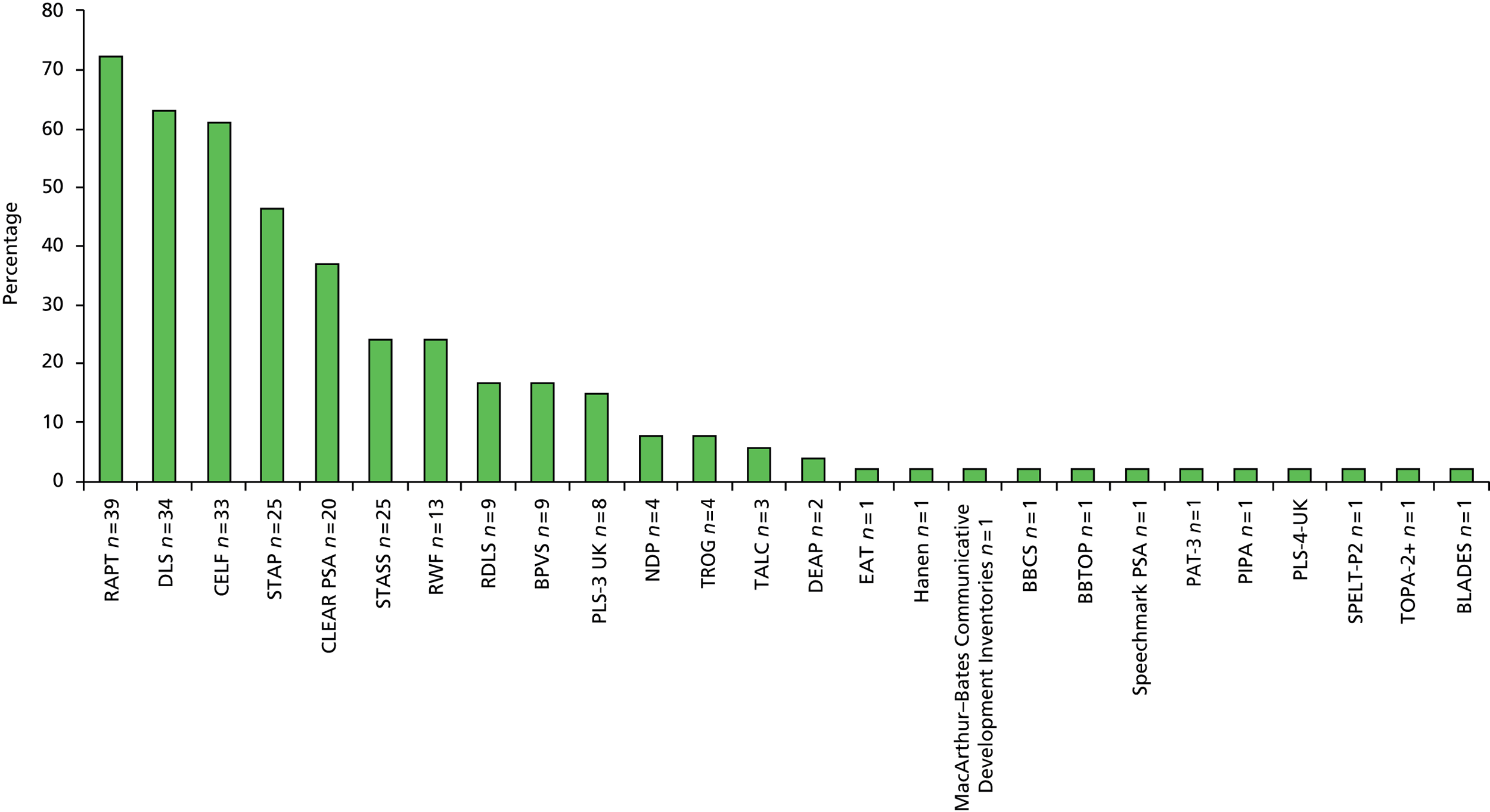

identify the assessment tools most commonly used by SLTs (see Chapter 5, Study 5.1: identification of assessment tools used by speech and language therapists)

-

identify the level of consensus on outcome measures using a modified Delphi process (see Chapter 5, Study 5.2: identification of outcome measures for speech and language therapy).

Consensus activities were undertaken with regional SLT Specific Interest Groups (SIGs) and at two national events.

Specific Interest Groups

Speech and language therapist SIGs and services focusing on preschool and early years populations were identified through a number of sources:

-

local SLTs and the research team’s knowledge of relevant SIGs

-

scanning for SIG advertisements placed in the RCSLT Bulletin magazine over the previous 12 months

-

scanning for advertisements placed by other relevant organisations or groups, for example early years forums, in the RCSLT Bulletin magazine.

Special Interest Group chairs (n = 7), service leads (n = 2) and leaders of other relevant groups and organisations (n = 1) were contacted by e-mail (taken from their adverts) with information about the project. They were invited to express an interest in hosting research events for Child Talk.

Four groups expressed an interest in hosting a research event (Table 8). The organisers of these groups used their normal advertising routes to alert their members to the events. A week before each event the potential participants were sent copies of the information sheet and consent form for information. The potential participants were invited to contact the research office by e-mail or telephone before attending the event if they had any questions regarding the research. Informed consent was taken at the start of the research event by a member of the research team. A total of 66 SLTs took part across the four groups (see Table 9). Of the activities that were undertaken at the four groups, 64 SLTs participated, with two therapists leaving one of the events before the voting activity (see Activity 1: validity of the themes from the speech and language therapists’ perspective).

| Location | Group | n |

|---|---|---|

| A | Internal early years SIG | 16 |

| B | SLTs in children’s centres | 13 |

| C | North-west community clinic SLTs | 18 |

| D | Preschool children SLT continuing professional development day | 19 |

| Total | 66 |

Since these research events took place, the RCSLT have renamed SIGs as Clinical Excellence Networks. We have retained the nomenclature of SIG as the groups were called this at the time of recruitment and data collection.

The data collection activities undertaken at these events are described in the following sections (see Activity 1 to Activity 4); as the activities undertaken varied across the events, the numbers of participants taking part in each activity vary.

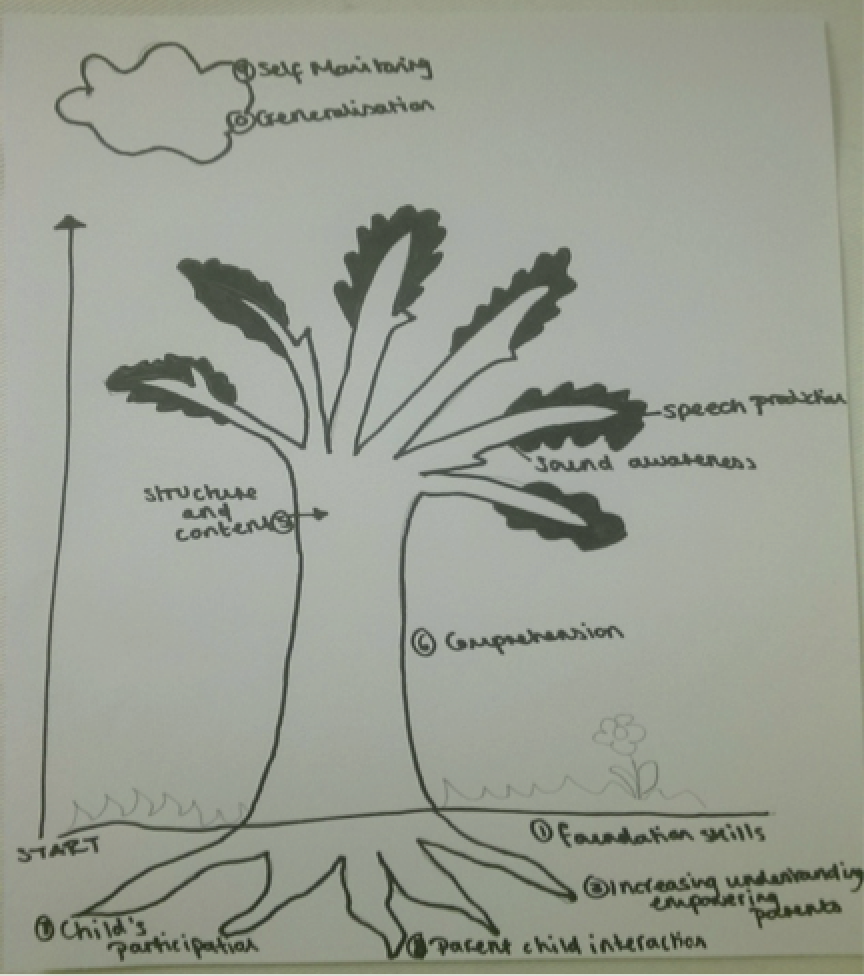

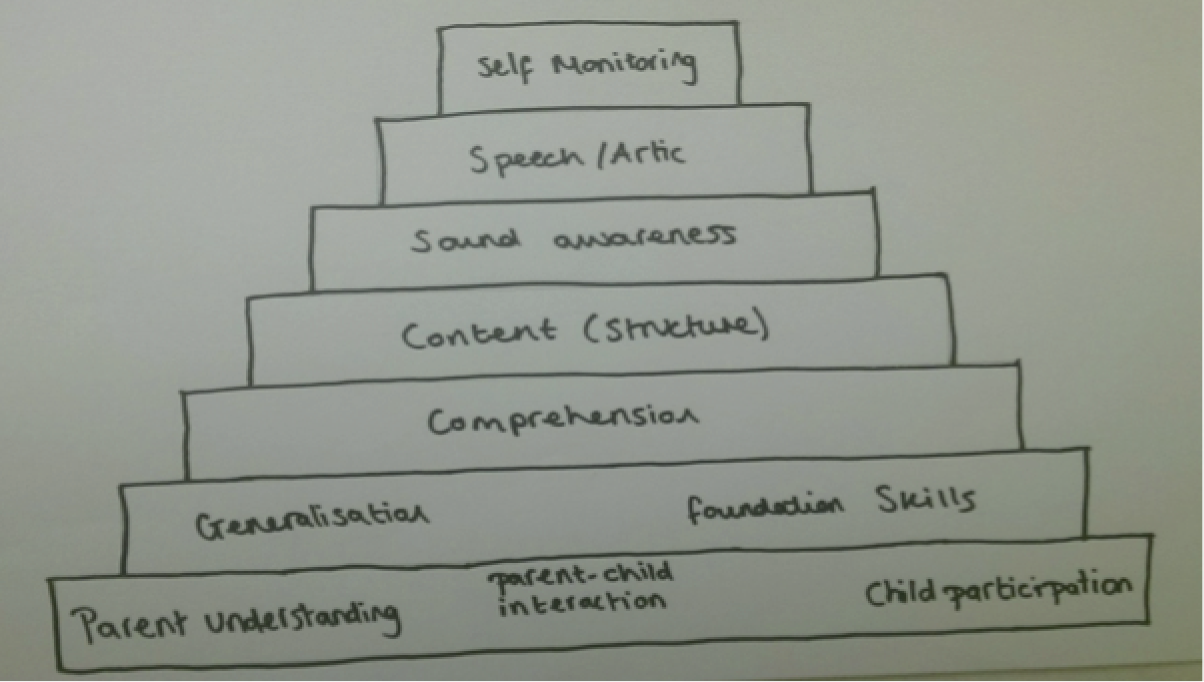

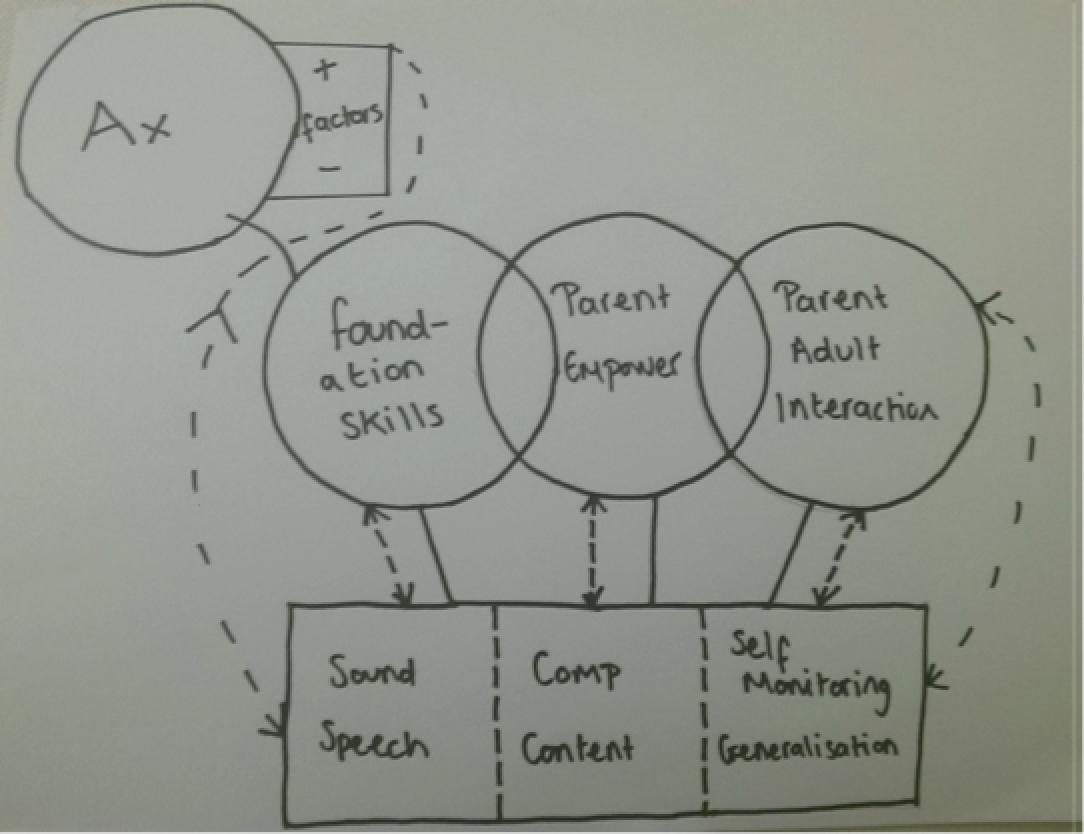

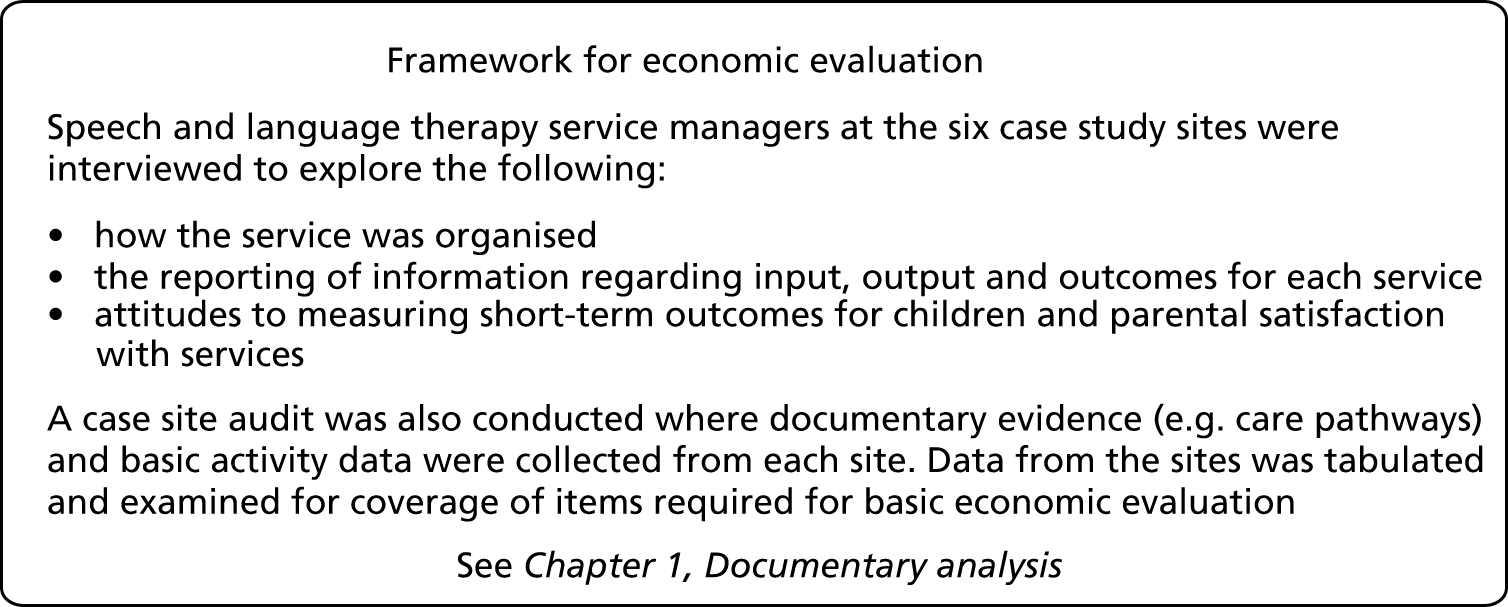

Activity 1: validity of the themes from the speech and language therapists’ perspective