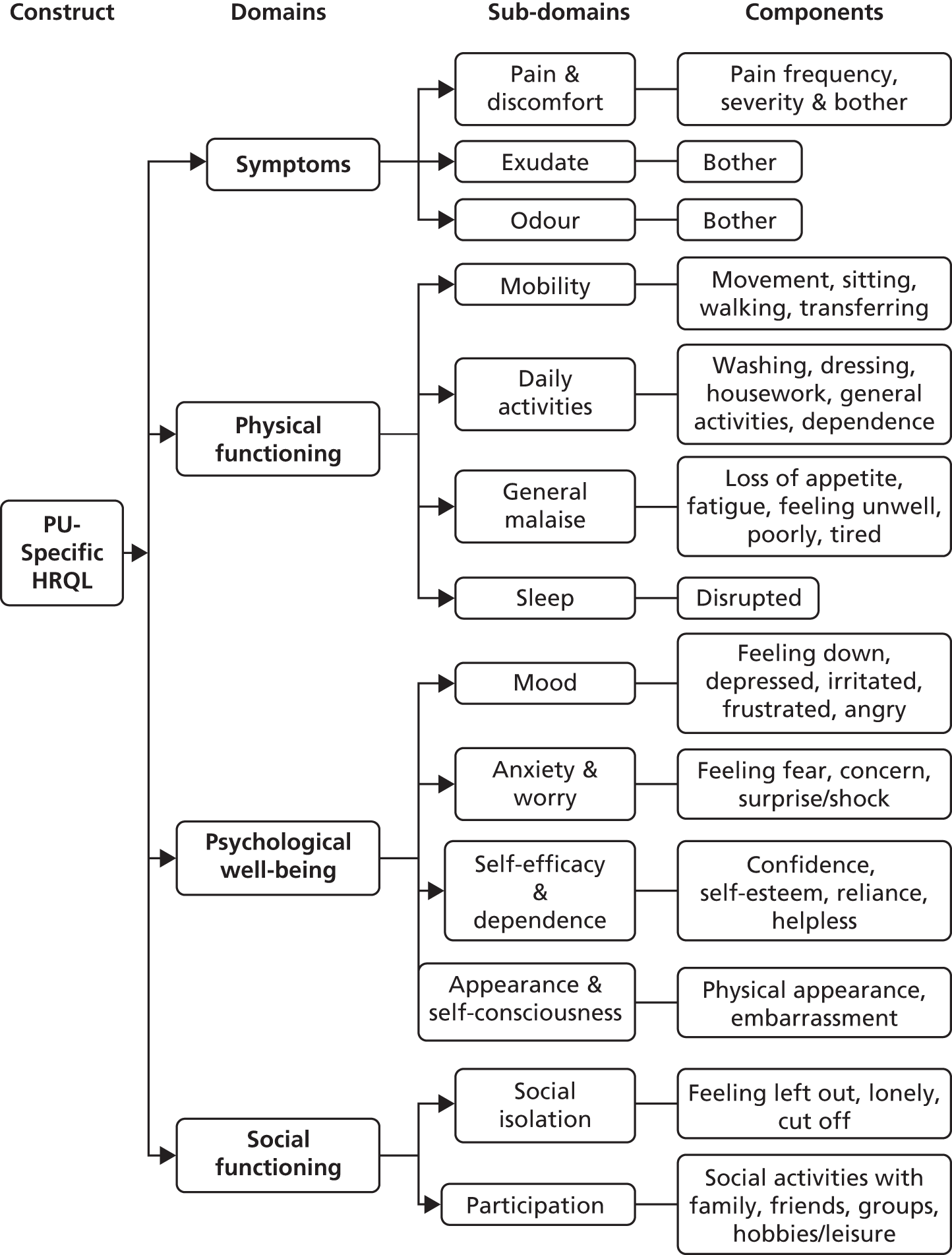

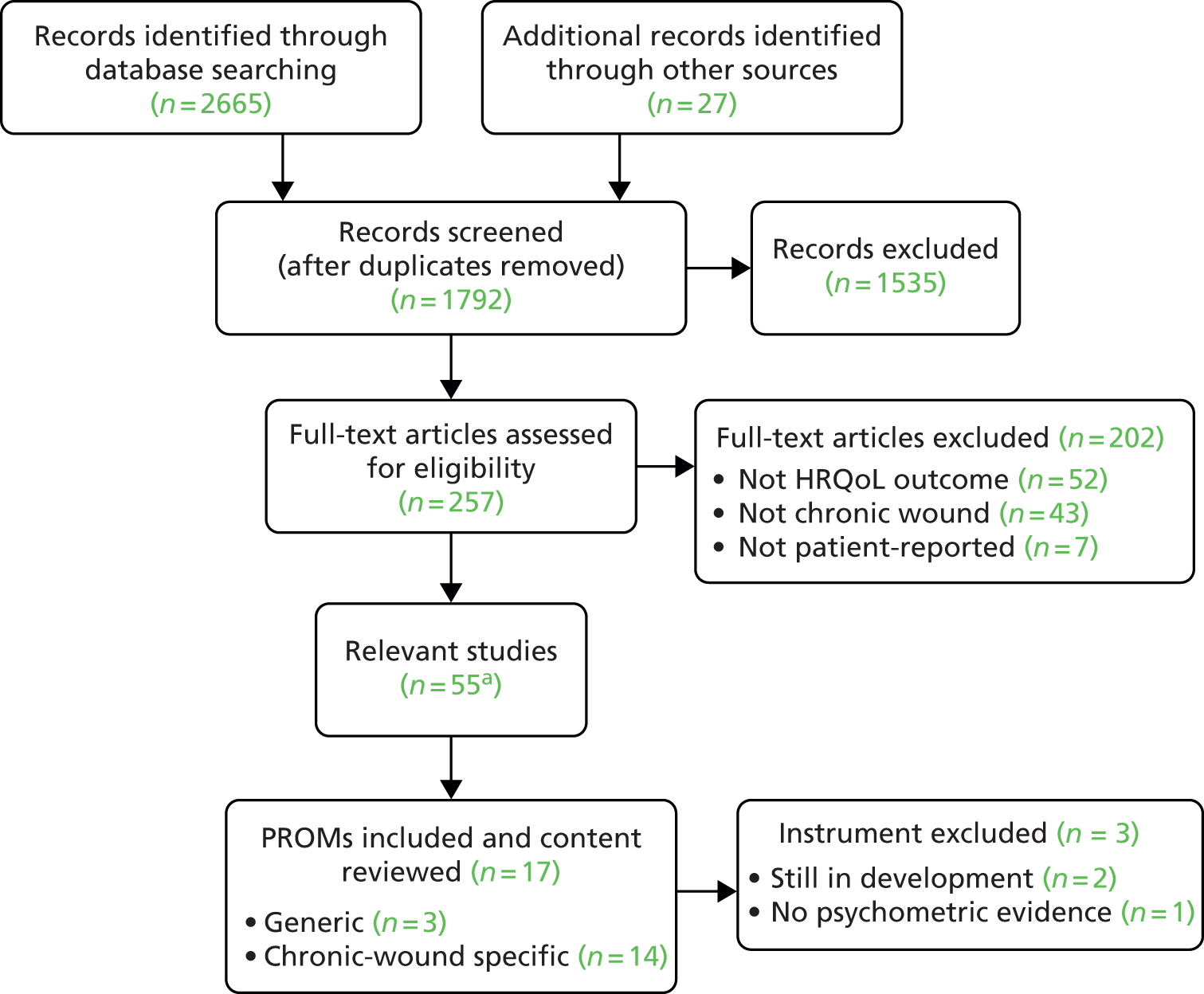

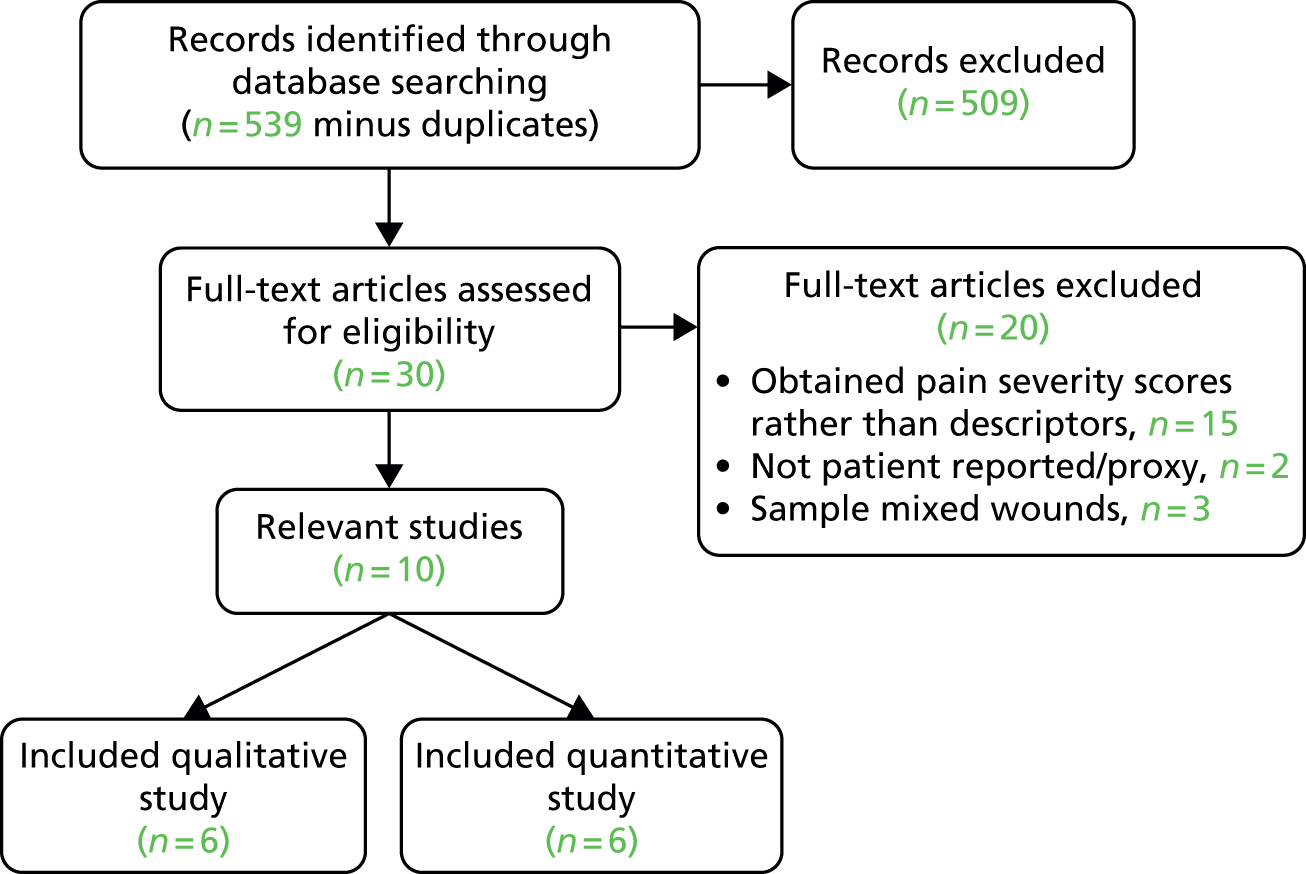

Notes

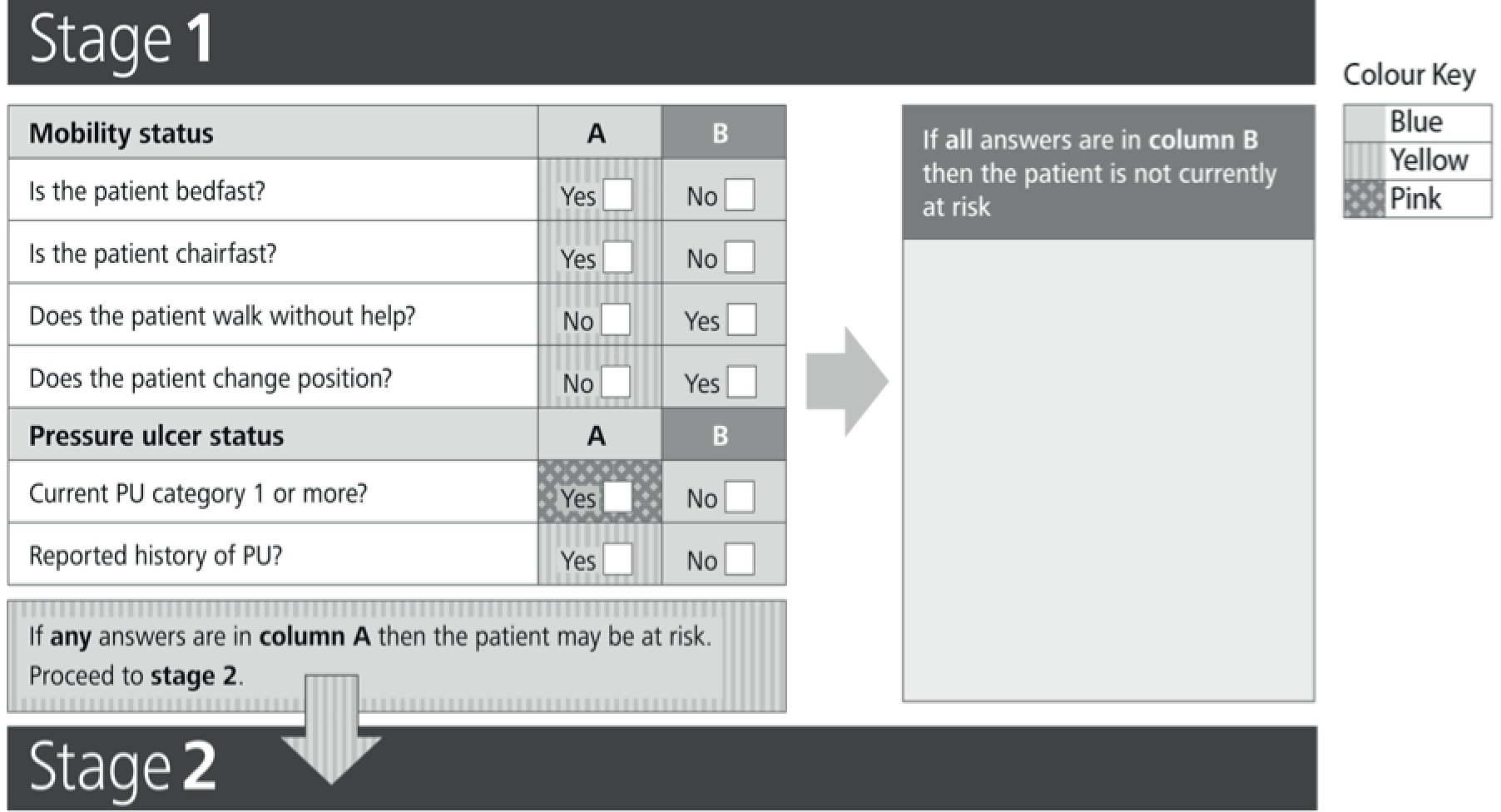

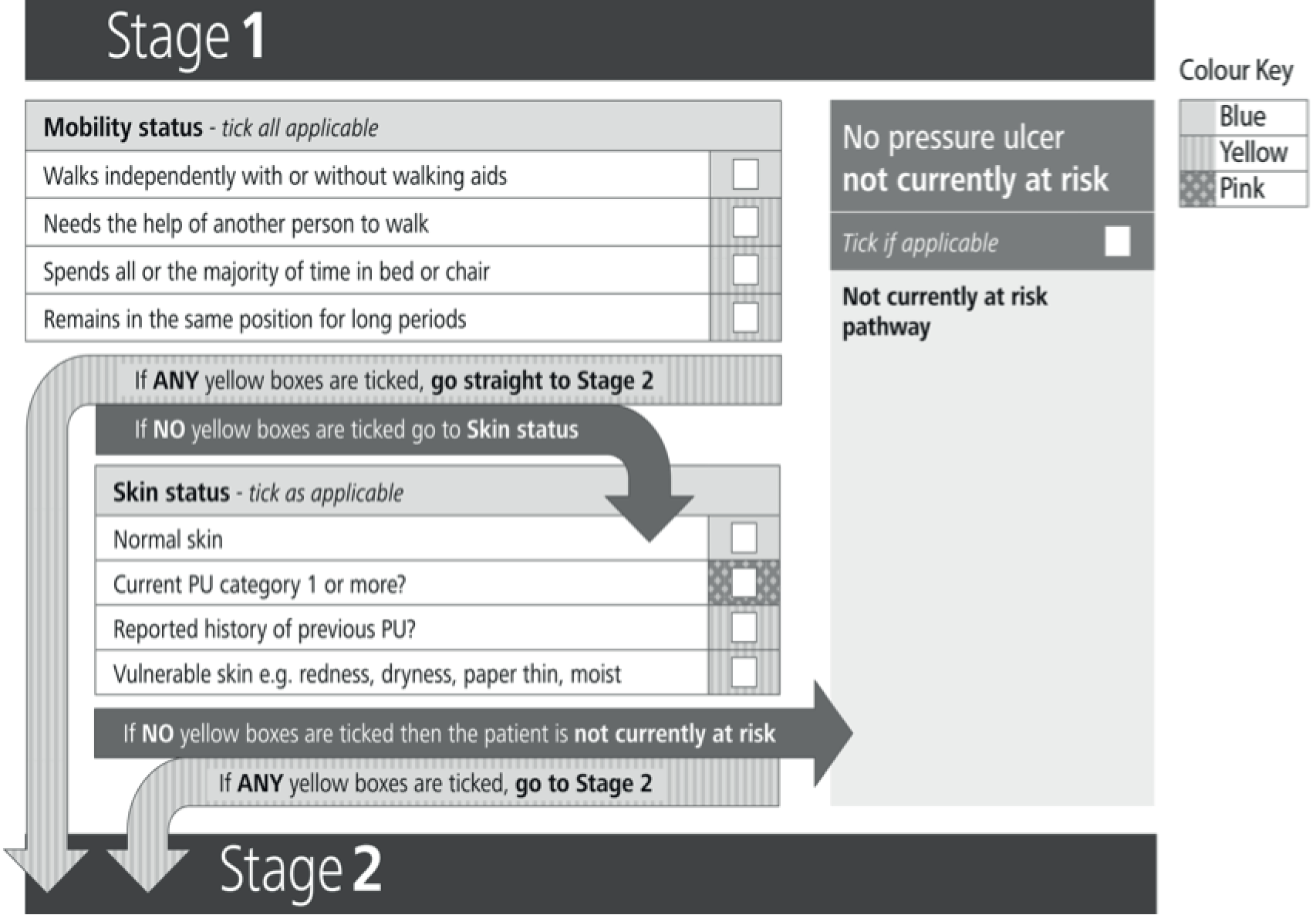

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10056. The contractual start date was in September 2008. The final report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jane Nixon has received post-doctoral fellowship grant funding from the Smith & Nephew Foundation; Jane Nixon, E Andrea Nelson, Claudia Rutherford, Susanne Coleman and Julia Brown have received grant funding from the Worldwide Universities Network Leeds Fund for International Research Collaborations; Delia Muir has received consultancy funding from Smith & Nephew PLC on behalf of the Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network for the UK (PURSUN UK) for patient and public involvement input into educational materials; and Jane Nixon, Claudia Rutherford and Carol Dealey have received grant funding from Mölnlycke Health Care. Carol Dealey is a member of an expert advisory board which advises Mölnlycke on the use of dressings for pressure ulcer prevention. We confirm that the report content is acceptable to the other funding bodies (Smith & Nephew Foundation and the Worldwide Universities Network Leeds Fund for International Research Collaborations) and that there are no competing proprietorial interests in respect of the tools and methods set out in the monograph.

Dedication to Professor Donna Lamping

It was with great sadness that the team learned of Donna's illness in 2010 and her passing in 2011 at age 58. Donna was an international expert in the field of health psychology, health status and quality of life assessment. Educated and trained in centres of excellence in Canada and the USA, she moved to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in 1992 where she established her position as an international leader in the field. Donna was an inspiration to the team, making a major contribution to the conception, design and gold standard evaluation of the Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life (PU-QOL) studies in her role as a grant co-applicant and through PhD supervision of Claudia Rutherford (née Gorecki). We feel privileged to have worked with her and dedicate this monograph to her memory.

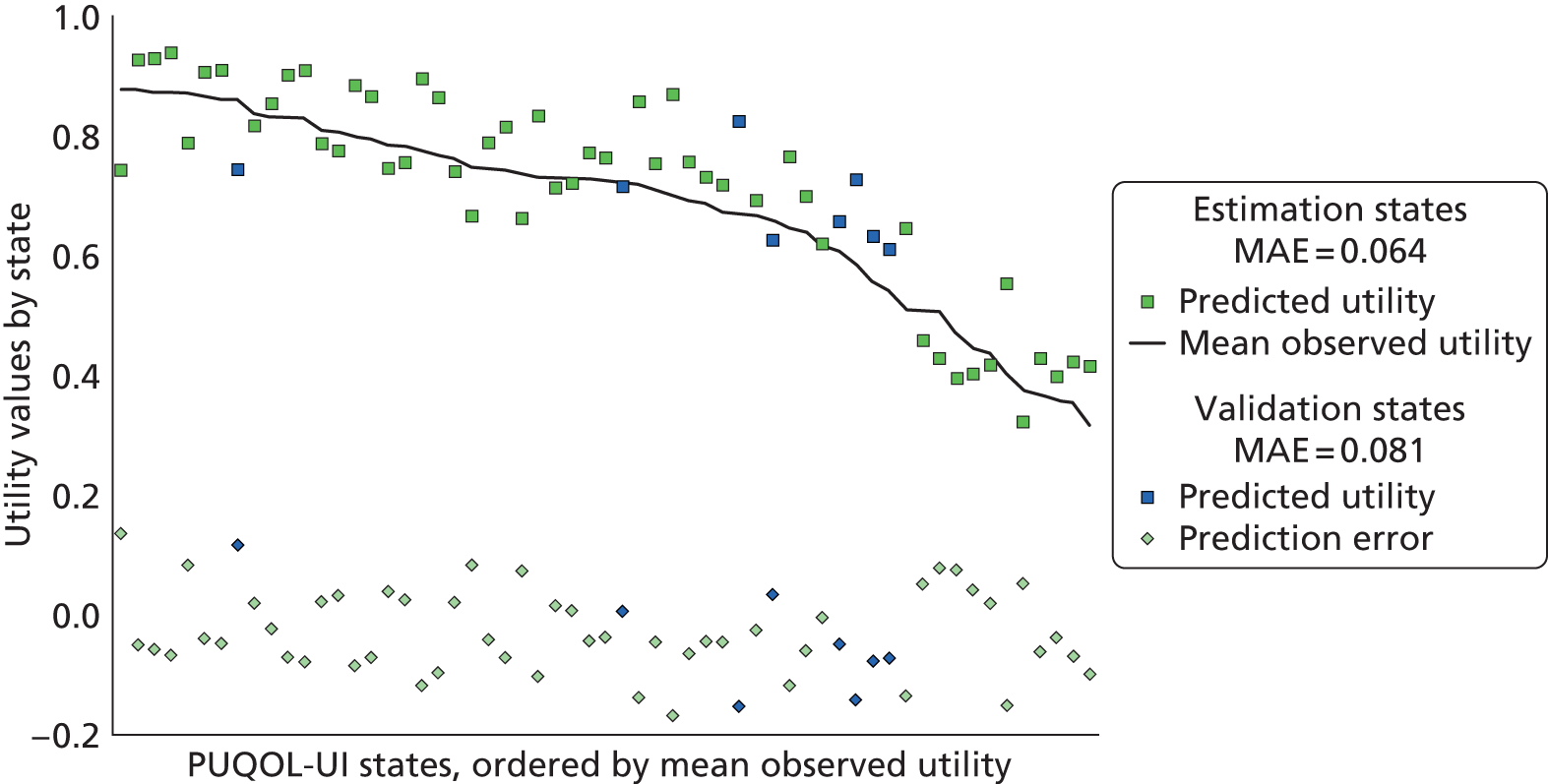

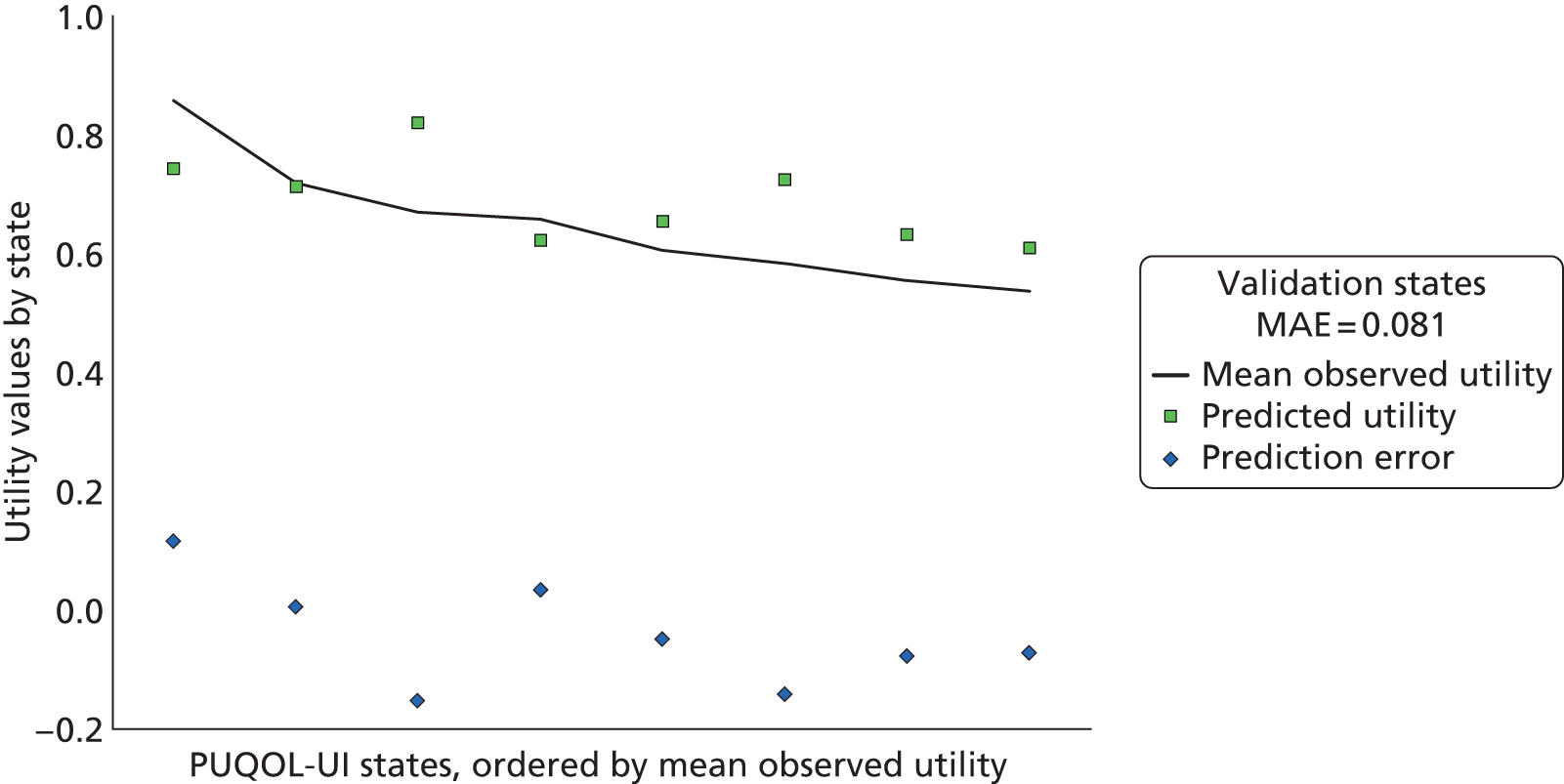

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Nixon et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Pressure ulcers are defined as ‘localised injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear’ (p.16). 1 They are a widespread2–4 and costly health-care issue. 5–8 Pressure ulcers represent a major burden to patients and carers and have a detrimental effect on patients’ quality of life. 9,10

For the past two decades pressure ulcers have been identified in successive Department of Health policies as a key quality indicator,11,12 with associated guidelines for prevention13,14 and treatment. 15 There have been widespread changes in clinical practice during this period including the introduction of systematic risk assessment processes, investment in pressure-relieving mattresses, and quality improvement initiatives. However, reflecting the belief that the development of pressure ulcers remains an indicator of service quality that impacts on patients and health-care costs, more recently the Department of Health have set out the ambitious aim of eliminating all avoidable pressure ulcers in NHS-provided care,16 developed a Commissioning for Quality and Innovation Payment Framework to facilitate this,17 identified pressure ulcers as a high-impact action for nursing and midwifery18 and incorporated them into the national Operating Framework. 19 Despite the prominence and profile afforded the problem, the research basis to inform practice in this area is limited, partly because we do not understand the clinical and organisational risks sufficiently well and partly because of the dearth of high-quality randomised controlled trials of preventative and treatment interventions. 14,15,20 Our programme of work was established to provide the foundation for the development of an evidence base for practice through improved identification of patients at risk of pressure ulcer development and improved methods of evaluating outcomes that are important to patients.

In 2004, UK costs associated with pressure ulcer prevention and treatment were estimated to be £1.4–2.1B annually, equivalent to 4% of total NHS expenditure,5 because of increased length of hospital stay, hospital admission, community nursing, treatments (reconstruction surgery/mattresses/dressings/technical therapies) and complications (serious infection). Litigation is also a burden on NHS resources and is predicted to increase because of both general societal trends and changes in the law, which has led to investigation of severe pressure ulcers by government agencies to detect institutional and professional neglect of vulnerable adults. 21,22 The NHS focus on pressure ulcer prevention is mirrored elsewhere. In the USA, for example, health insurance companies have incentivised prevention through widespread changes to reimbursement policies. Hence, health-care providers are liable for the treatment costs arising from pressure ulcers that develop during care (organisation-acquired avoidable pressure ulcers). 17

Pressure ulcer classification

Numerous classification systems have been developed to categorise the severity of pressure ulcers. Before the start of the programme grant (in 2008) the two most commonly used systems classified pressure ulcers through four levels (1–4) of ‘stage’ or ‘grade’. 15–17 The descriptors ranged from non-blanching erythema of intact skin at level 1 (stage 1/grade 1) to full-thickness tissue loss at the most severe level (stage 4/grade 4). 23–25 In 2009 the American National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) developed joint guidelines and a revised classification system. 1 The two main differences were the use of the term ‘category’ (to distance the description from the ordinal properties assumed by the use of stage and grade) and the inclusion of two new descriptors: ‘unstageable’ and ‘deep tissue injury’. In the following chapters we have adopted the use of the NPUAP/EPUAP (2009) classification and use the term ‘category’ (with Arabic numerals rather than roman for ease of reading) to classify pressure ulcers in general reference to the literature and the terms ‘stage’ or ‘grade’ when reporting directly from individual studies, to accurately report the classification system used by the authors. In addition, the terms ‘superficial’ and ‘severe’ pressure ulcers are used to summarise pressure ulcer severity. A superficial ulcer is a category 2 ulcer and the term ‘severe’ is used to describe category 3, category 4 and unstageable pressure ulcers.

For clarification, the programme excluded consideration of ulcers caused by medical devices (e.g. nasogastric tubes, surgical drains, oxygen masks, urinary catheters, cannulas and prosthetic limbs).

Summary of the programme of research

The Pressure UlceR Programme Of reSEarch (PURPOSE) was developed by a clinical/academic research collaborative to address a number of research questions. The areas of work were organised into two themes with the following aims:

-

theme 1 – to reduce the impact of pressure ulcers on patients through:

-

early identification of patients at risk of developing pressure ulceration and

-

improved identification and investigation of patients at risk of progression to severe pressure ulceration

-

-

theme 2 – to reduce the impact of pressure ulcers on patients through the development of methods to capture patient-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and health utilities for routine clinical use and in clinical trials.

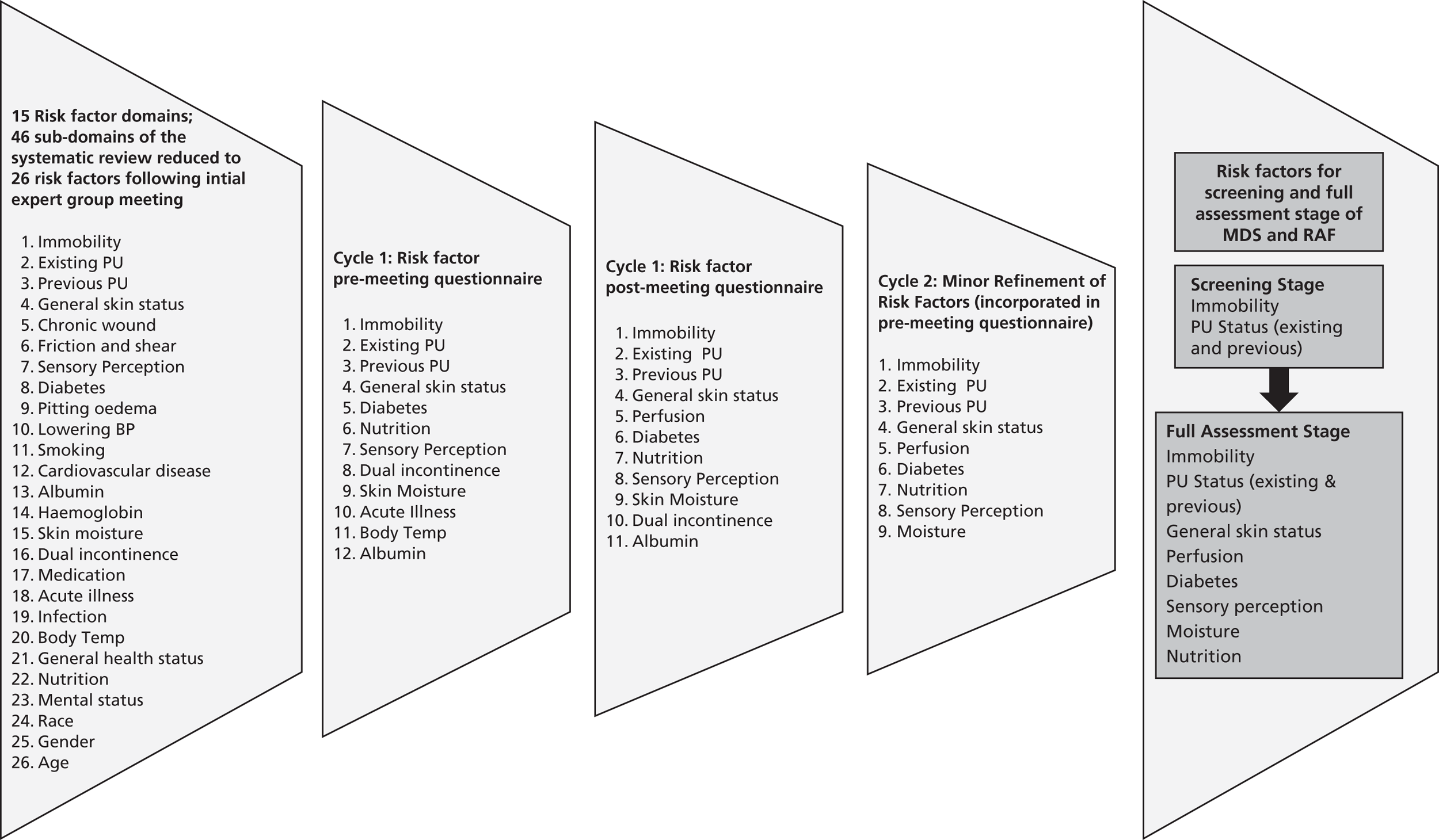

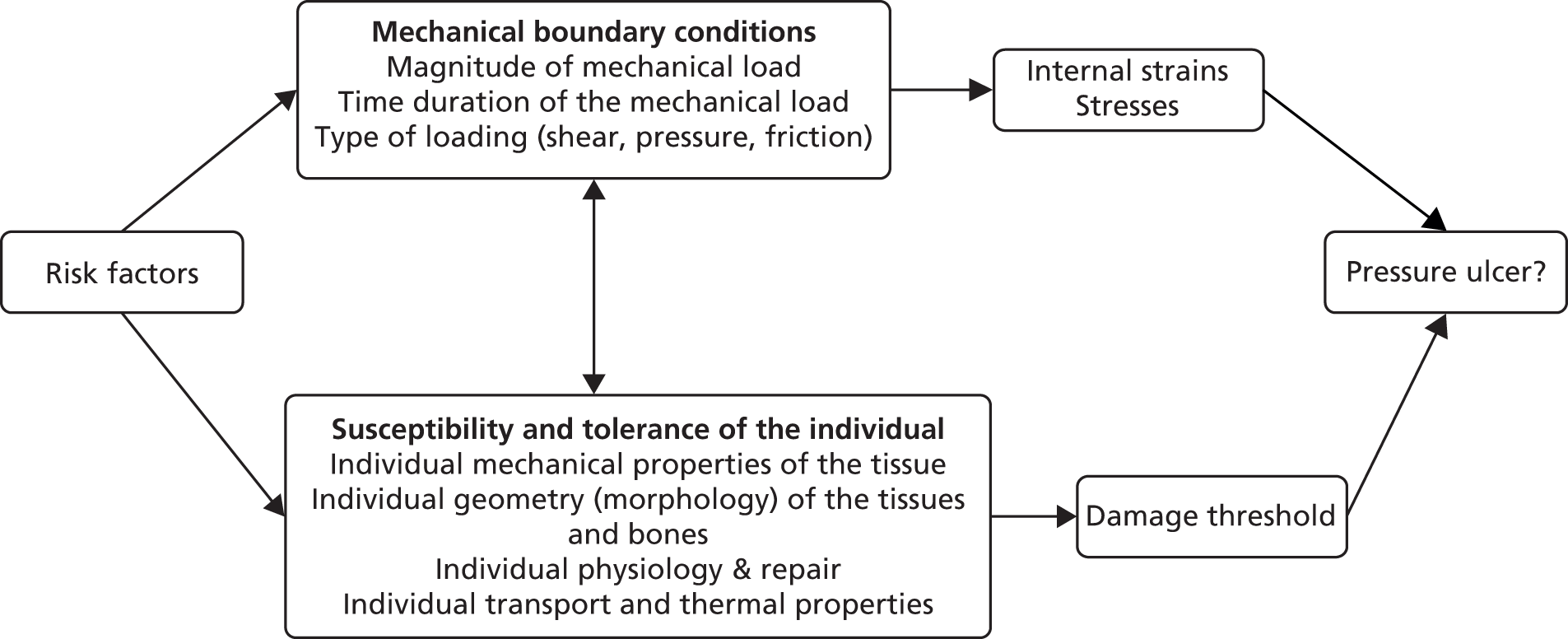

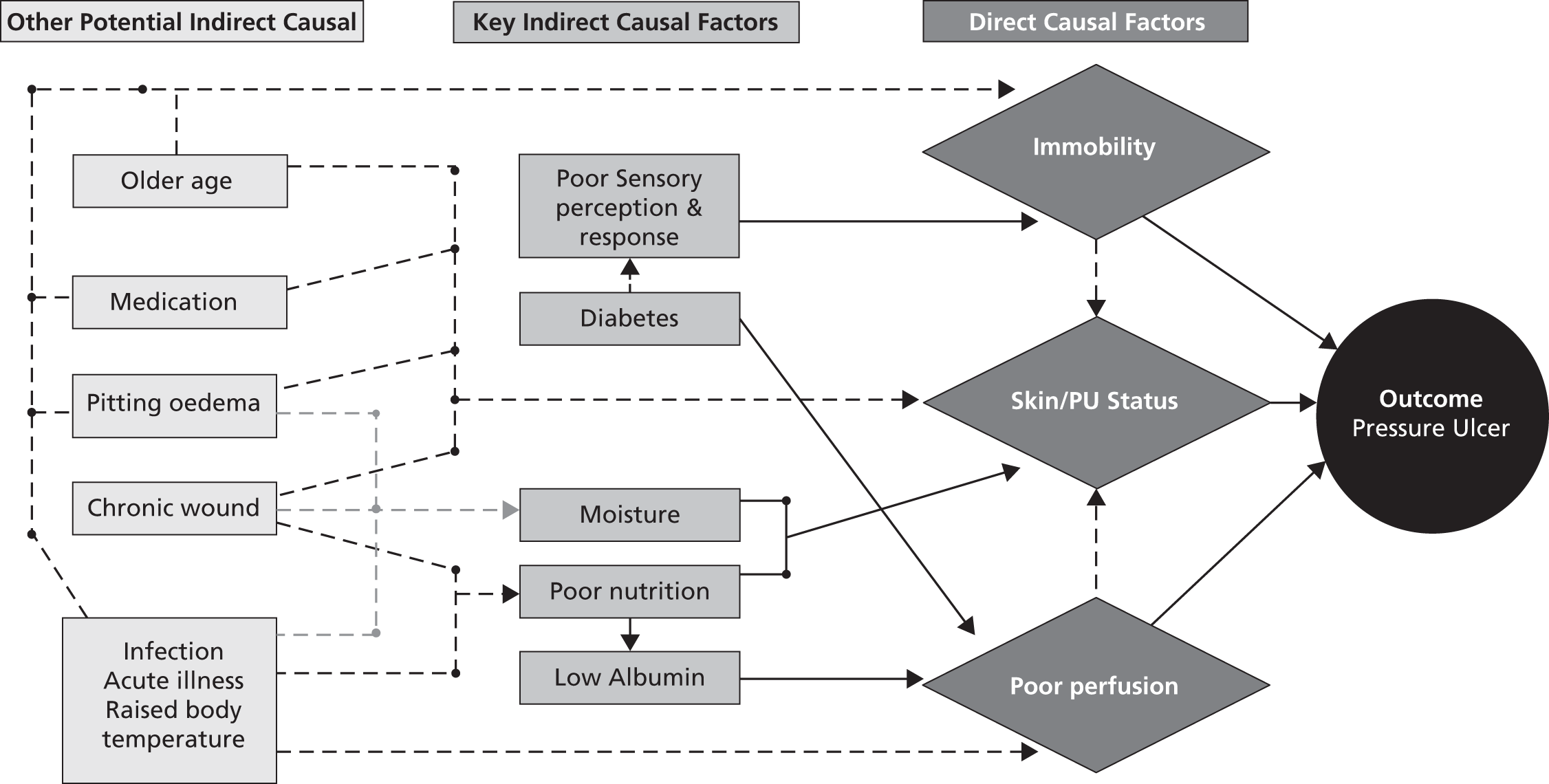

Theme 1 focused on improving our understanding of risk factors and risk assessment and consisted of three work packages with the following objectives:

-

work package 1 – pain: to determine the extent of pressure area and pressure ulcer pain and explore the role of pain as a predictor of category 2 and above pressure ulcers in acute hospital and community populations

-

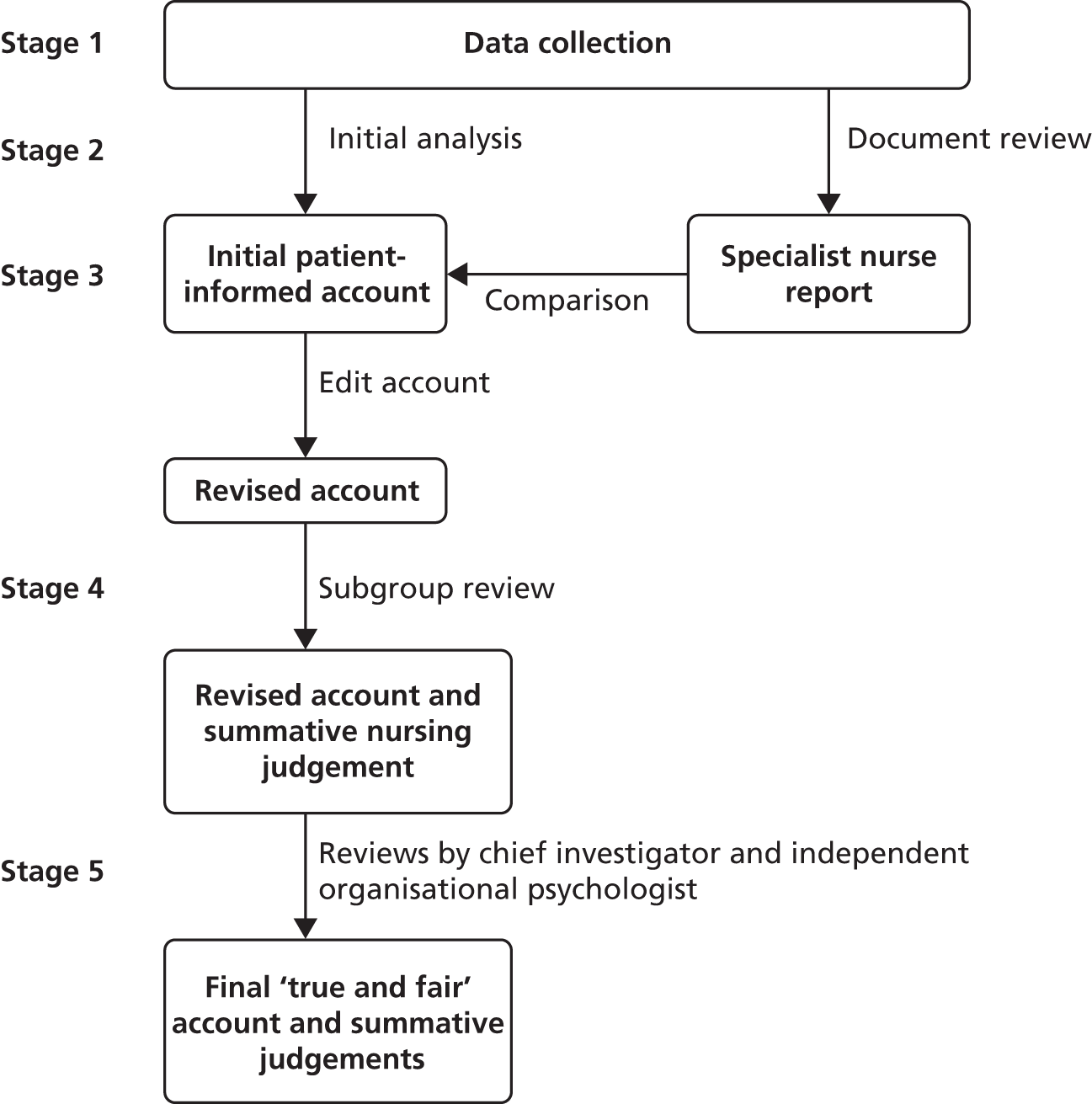

work package 2 – severe pressure ulcers: to identify individual and organisational factors that contribute to the development of severe pressure ulcers and develop a critical incident/adult neglect investigation methodology for their review

-

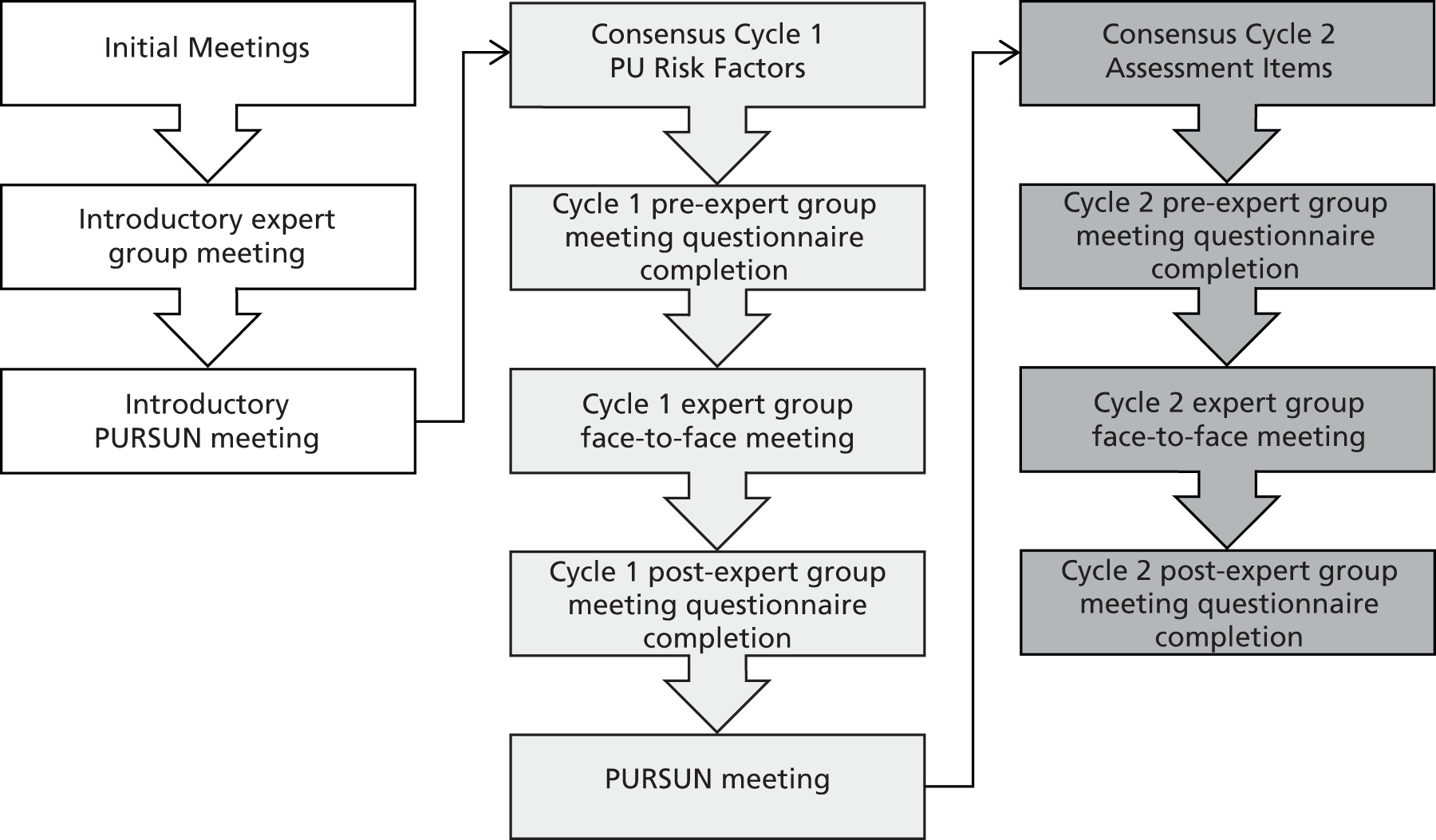

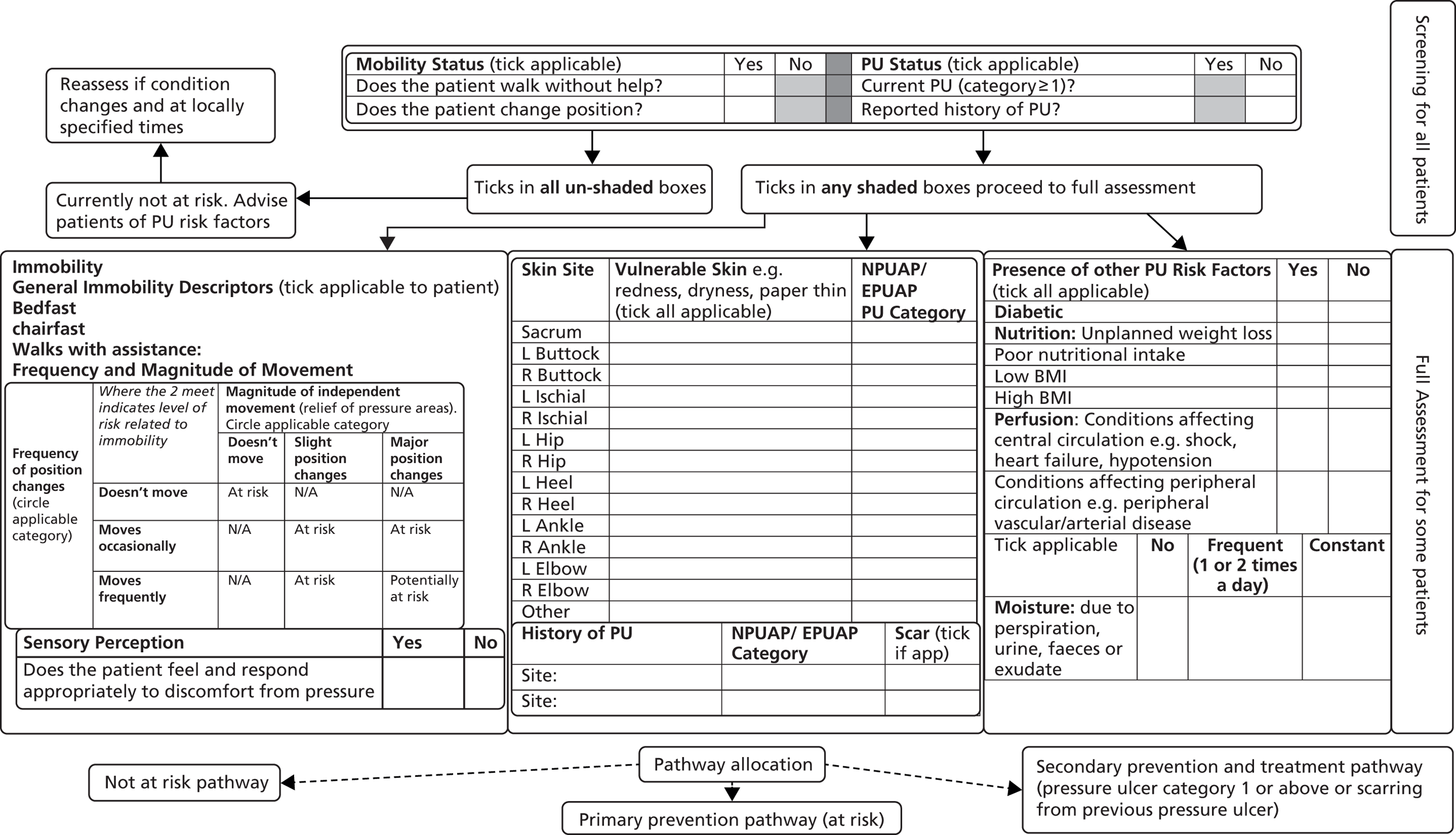

work package 3 – pressure ulcer risk assessment: to agree a pressure ulcer risk factor Minimum Data Set to underpin the development and validation of an evidence-based Risk Assessment Framework to guide decision-making about the risk of developing pressure ulceration and the risk of progression to more severe ulceration.

Theme 2 had a focus on the development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures and consisted of two work packages with the following objectives:

-

work package 4 – pressure ulcer quality of life: to determine outcomes important to patients who develop pressure ulcers and develop a psychometrically rigorous PRO measure that is reliable and valid and suitable for use in the NHS.

-

work package 5 – pressure ulcer quality of life utility instrument: to create a preference-based index that could be used to generate utility values suitable for use in cost–utility-based economic evaluations of pressure ulcer prevention and treatment interventions.

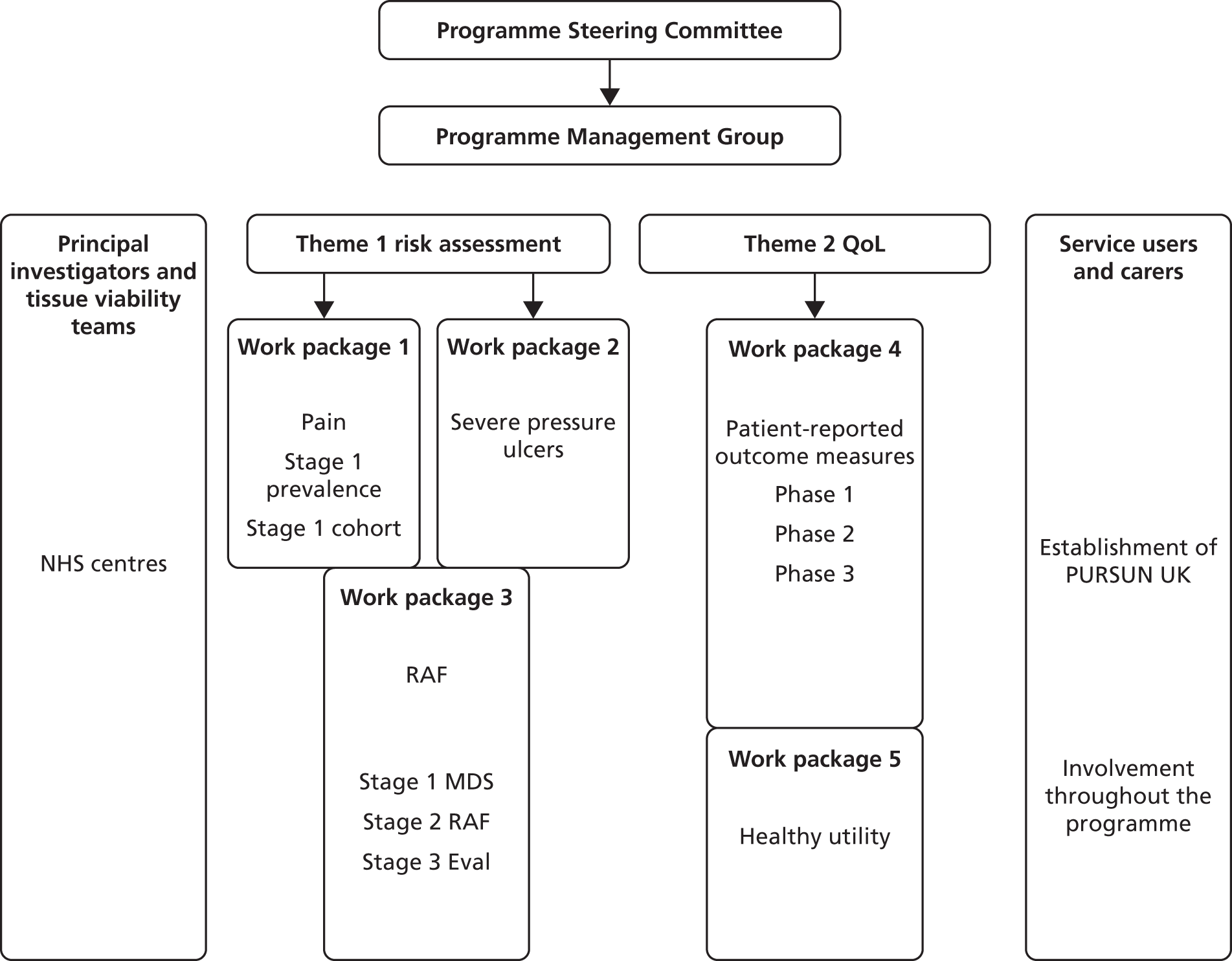

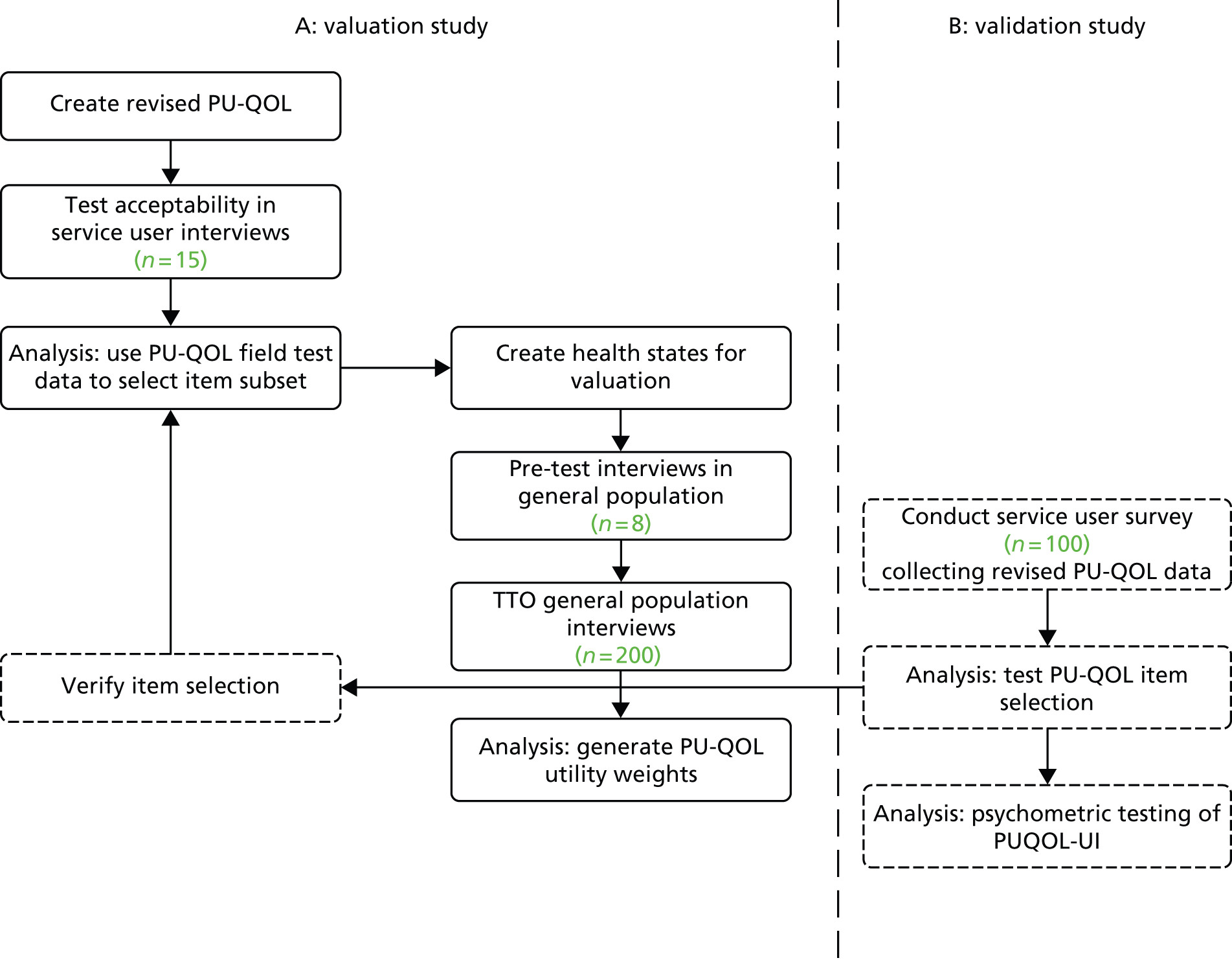

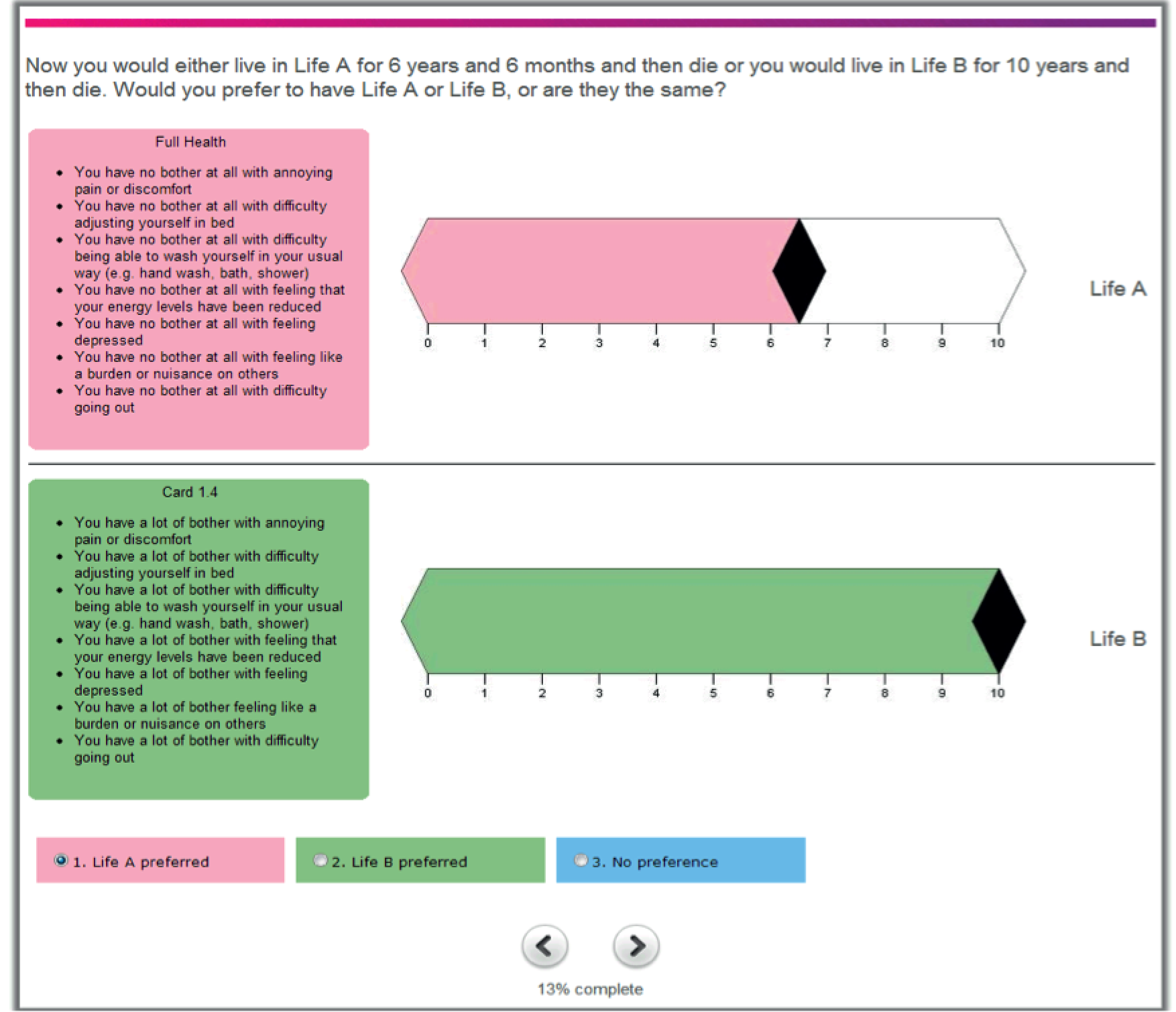

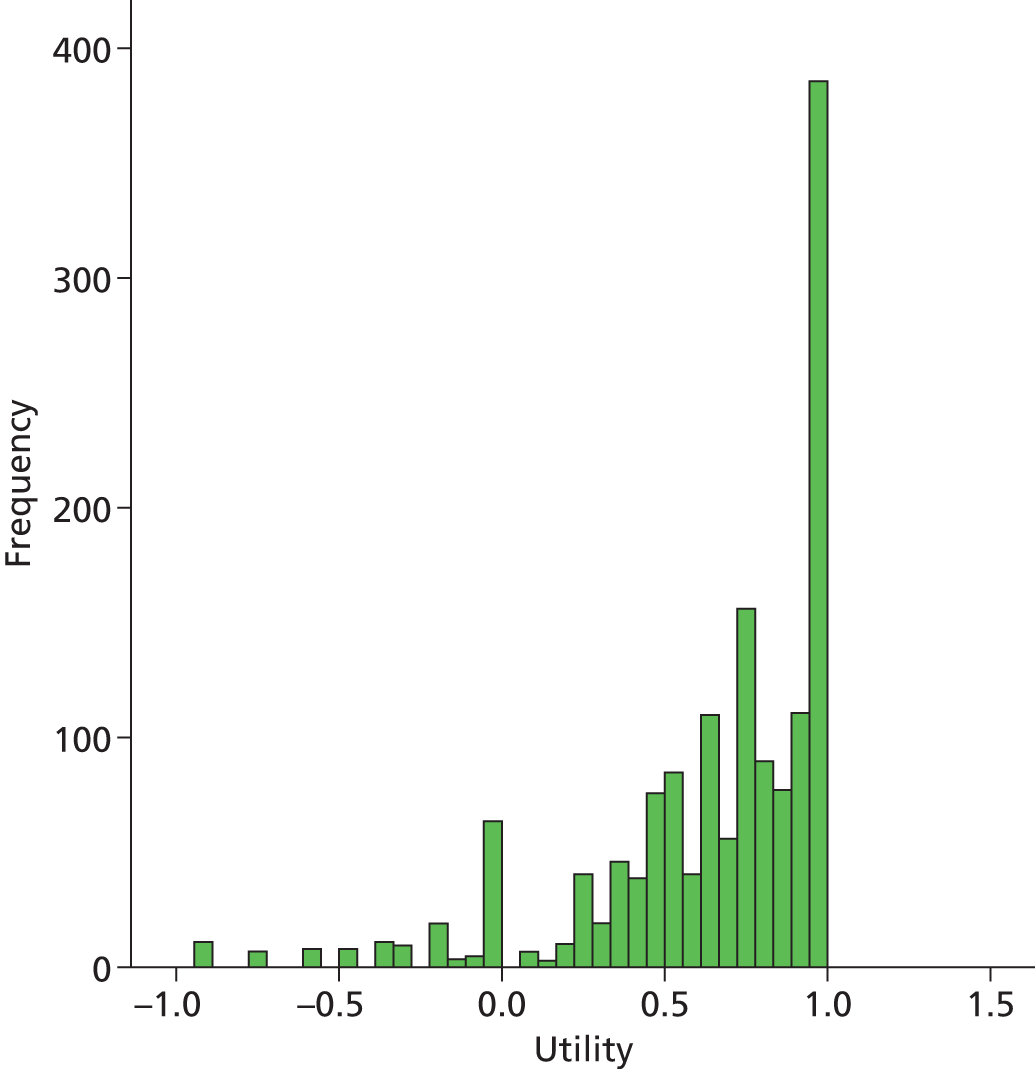

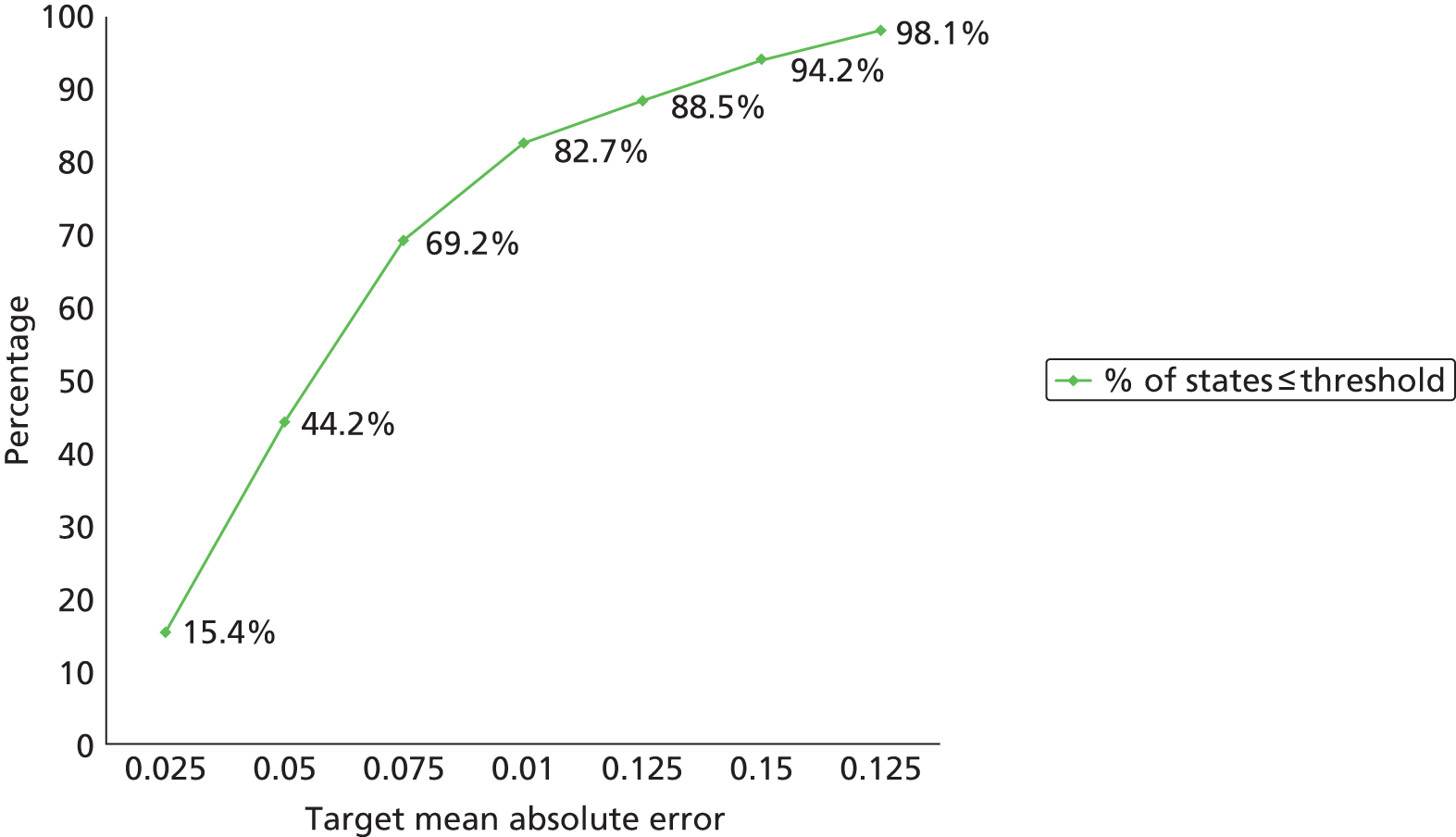

Both themes 1 and 2 were planned to progress in parallel. Within each theme, planning ensured that the early work contributed to later studies. Work packages 1 and 2 contributed to work package 3, and work package 4 contributed to work package 5 (Figure 1). In addition, within each work package we utilised a range of research methods in sequential phases including (for example) systematic reviews, prevalence studies, prospective cohort study, case study consensus methods, psychometric evaluation and time trade-off (TTO) task valuations of health states (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Outline of the programme. Eval, evaluation; MDS, minimum data set; PURSUN UK, Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network UK; QoL, quality of life; RAF, Risk Assessment Framework.

| WP1 – pain (see Chapter 3) | WP2 – severe pressure ulcers (see Chapter 4) | WP3 – risk assessment (see Chapter 5) | WP4 – pressure ulcer quality of life (see Chapter 6) | WP5 – pressure ulcer quality of life utility instrument (see Chapter 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Development of the research programme

During the course of the programme, delivery enhancements to the original proposal were made including NHS capacity development, patient and public involvement (PPI) and additional reviews and methodological research.

NHS research capacity development

Patient populations in pressure ulcer research are characterised by high levels of comorbidity, and are distributed across multiple care environments. This poses challenges in study design, recruitment and follow-up. The programme grant application was underpinned by a strong network of NHS collaborators across 13 acute and community NHS trusts (see Figure 1). During the programme of research (2008–13) this was further developed through support from the West Yorkshire Comprehensive Local Research Network, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) portfolio adoption and incorporation onto the Dermatology and Primary Care portfolios, facilitating access to service support costs through the NIHR Comprehensive Local Research Networks and the participation of 30 acute and community NHS trusts (see Appendix 1 and Acknowledgements).

Patient and public involvement in pressure ulcer research

In addition, our original PPI plan was limited and this was significantly enhanced. We established a partnership with service users through the set-up of the UK Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network (PURSUN UK) (see Figure 1 and Chapter 2). Service-user involvement underpinned our development and delivery of the programme of research as well as the dissemination and identification of ongoing research priorities. Indeed, PURSUN UK made a major contribution to the design, conduct and interpretation of the research, with the use of innovative involvement activities (see Table 1 and Chapter 2).

Additional reviews and methodological research

The original programme of work was enhanced through an additional two systematic reviews and five methodological substudies (see Table 1) addressing methodological issues with wider relevance to the applied health research field.

Structure of this report

Within each work package there are a number of components, including systematic reviews, primary research and methodological substudies. In total, 21 pieces of work have been undertaken, as illustrated in Table 1.

The monograph is structured as follows:

-

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the PPI activities, innovation and support

-

Chapters 3–7 present the rationale and research (including substudies), PPI and implementation components of each work package

-

Chapter 8 describes the wider benefits accrued through the PURPOSE programme award and 5-year investment period and summarises the key findings and their implications for practice, PPI, policy and research.

Chapter 2 Patient and public involvement

Chapter written by Delia Muir, Susanne Coleman, Lyn Wilson, Nikki Stubbs, Justin Keen, Elizabeth McGinnis and Jane Nixon.

Background

The importance of PPI within PURPOSE was recognised at the start of the programme. PPI in pressure ulcer research has not been strong to date and the project team identified an opportunity to address this through the programme. PPI can contribute at all stages of the research process, from commissioning and priority setting through to dissemination and implementation. 26–28 There is a danger, however, that PPI activities can become tokenistic, particularly when driven by ‘top-down’ policy initiatives rather than a genuine desire to learn from, and with, service users. 29

In recent years there has been a growth in PPI literature;26 however, inconsistencies in reporting and the variety of research methodologies covered by this literature make comparing studies and establishing quality challenging. 26,27 Recent reviews do highlight some general good practice principles. Shippee and colleagues30 describe four key components of involvement: (1) service user initiation (i.e. preparation, negotiating roles, establishing shared interests and goals), (2) building reciprocal relationships between service users and researchers (i.e. establish service users as valued members of the team rather than an optional addition), (3) co-learning (i.e. development of both service users and researchers) and (4) feedback (i.e. ongoing, iterative evaluation of PPI processes). This review also highlights the importance of involvement starting as early as possible in the research process. In addition, advocates of the co-production approach (used mainly in a service design and delivery context) highlight the need for peer support networks; to recognise and build on people’s strengths; and to build communities. 31

There is a paucity of literature related specifically to PPI in pressure ulcer research. The only other pressure ulcer PPI initiative that we are aware of is the James Lind Alliance Pressure Ulcer Partnership. This ran in parallel to this programme and focused on setting future research questions rather than on involvement in carrying out that research (see Supporting further research for additional information).

The PURPOSE project team set out to develop mechanisms for working in partnership with service users, to have a positive impact on the research methods and outputs for all strands of the programme. In line with the principles set out above, we also wanted to ensure that involvement would be a positive and rewarding experience for the individuals taking part.

Challenges

In the early stages of the programme PPI proved challenging. The project team tried to identify individuals with experience of pressure ulcers or people managing the risk of pressure ulceration (e.g. people with chronic conditions that limit mobility or people who have experienced periods of very acute illness). During the first year, two service users were identified (through clinical members of the project team) and agreed to be members of the PURPOSE steering committee. Finding more people proved difficult for a number of reasons. First, there was no infrastructure to support PPI in this field, unlike in some other areas that have established PPI networks that can support recruitment to research and offer guidance on working with particular populations. Some health and social care charities also support research and promote PPI activities. However, pressure ulcers are a cross-specialty problem; they are secondary to other serious illnesses/conditions and do not fit easily into existing national/charitable structures.

Despite efforts to recruit through generic PPI networks, our only success in identifying service users was through the project team’s clinical contacts. This approach raised some ethical considerations. There were concerns that service users might feel obliged to become involved to ‘repay’ good care or for fear of future care being affected. It was also felt that there needed to be a clear distinction between ‘caring for patients’ and ‘working with service users’. Clinical members of the team recruiting and supporting their own patients could potentially blur these boundaries and create unequal relationships within the team. This was a consideration when developing a PPI recruitment strategy for the programme.

Another challenge was provided by the complex health needs of many people with experience of pressure ulcers or pressure ulcer risk. As pressure ulcers affect people with serious long-term conditions or acute illness/injury, many service users with relevant experience may be unable to take part in traditional involvement activities.

To address these challenges, a PPI officer post was created. The aim of this post was to develop a pressure ulcer-focused service user network, which would both facilitate PPI throughout the programme and build PPI capacity within pressure ulcer research more generally.

The Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network UK

The Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network UK was established in 2010 and now has 18 members. The network is made up of service users and carers with personal experience of pressure ulceration and/or risk of pressure ulceration. Members have been identified through:

-

local, generic PPI groups/networks

-

snowball recruitment, whereby existing PURSUN UK members contact friends, colleagues or family members

-

advertising meetings and events in the local media and via e-mail networks

-

engaging with charities that focus on a topic related to pressure ulcer risk, such as conditions that limit mobility, for example the Multiple Sclerosis Society and Spina bifida, Hydrocephalus, Information, Networking, Equality (SHINE)

-

social media (@PURSUN_UK)

-

the distribution of PURSUN UK leaflets alongside recruitment of study participants

-

tissue viability nurse specialists.

Concerns about clinical members of the research team approaching their own patients, thereby blurring roles and boundaries, have been addressed by the introduction of the PPI officer as a neutral party. Nurses in practice hand out information about PURSUN UK and service users then have the option to contact the PPI officer for further discussions and induction to the network if desired.

The Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network UK (www.pursun.org.uk) has a minimum of two management meetings a year at which a core group of the most active members consider the direction of the network, the terms of reference, recruitment, the website and other network materials. Research involvement opportunities are sent out via the mailing list as they arise, for example invitations to help interpret data, become co-authors or input into the study methods.

All members of PURSUN UK are prepared for involvement through a minimum of one induction meeting with the PPI officer (either face-to-face or by telephone). During this meeting service users are encouraged to discuss the skills and experience that they bring to the group, as well as any support that they may need. The remit of PURSUN UK is also discussed along with practical issues such as payment of fees and expenses. Ongoing support is provided based on the individual needs of each member. Many of the core group have also been through a more in-depth process of preparation based on the Patient Learning Journey model. 32 The Patient Learning Journey model was originally developed by the Leeds Institute for Medical Education as a way of preparing service users for involvement in the education of health professionals. The model was adapted for use in a research context, keeping the original Patient Learning Journey principles of sharing stories with other service users in a safe, facilitated environment and working together to identify themes within those experiences. Participants are also encouraged to think about which aspects of their stories they feel happy sharing with professionals and how best to communicate key messages. This novel approach to research preparation aims to help service users recognise the expertise that they have developed through their personal experiences. It also helps with group forming, encouraging empathy and peer support. Further development opportunities have been sought for members where possible, such as conference attendance and local research training. Offering a range of development opportunities has been useful: some members have travelled to large, national conferences whereas others have found shorter, local events or one-to-one meetings more manageable.

Pressure UlceR Programme Of reSEarch involvement activities

Between 2008 and 2010, PPI was limited by our ability to recruit service users. Following the establishment of PURSUN UK in late 2010, involvement activities increased across the programme. Furthermore, the methodology and focus of each work package have guided the nature of involvement. An overview of PPI activities at different stages of the programme of research is given in the following sections. Involvement in individual PURPOSE studies is also discussed in subsequent chapters.

Programme management

The PURPOSE steering committee includes two service user members. This led to the identification of the need for further PPI not only in the PURPOSE programme but also in the field of pressure ulcer research more generally. This recommendation was supported by the steering committee and led to the decision to appoint a PPI officer. A service user was involved in the recruitment process for the PPI officer post, including being a member of the interview panel.

Protocol and patient information leaflet development

Members of PURSUN UK have formally reviewed all of the PURPOSE study protocols via the PURPOSE steering committee. In addition, PURSUN UK members have made more detailed contributions to the design of the risk assessment (see Chapter 5) and Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life – Utility Index (PUQOL-UI) (see Chapter 7) studies. This has been through contributing to study protocols and advising on the development of patient information leaflets.

Data interpretation

The results of the pain studies (see Chapter 3) have been presented to PURSUN UK. Members have helped to put the pain results in context from a service user perspective and consider next steps for the research. They also worked with the project team to interpret qualitative data from the severe pressure ulcer study (see Chapter 4). This was achieved through a workshop utilising video and role play to make the interpretation process engaging and accessible for service users with little or no experience of data analysis and interpretation. This workshop is described in more detail in Chapter 4 (see Patient and public involvement).

Staff training

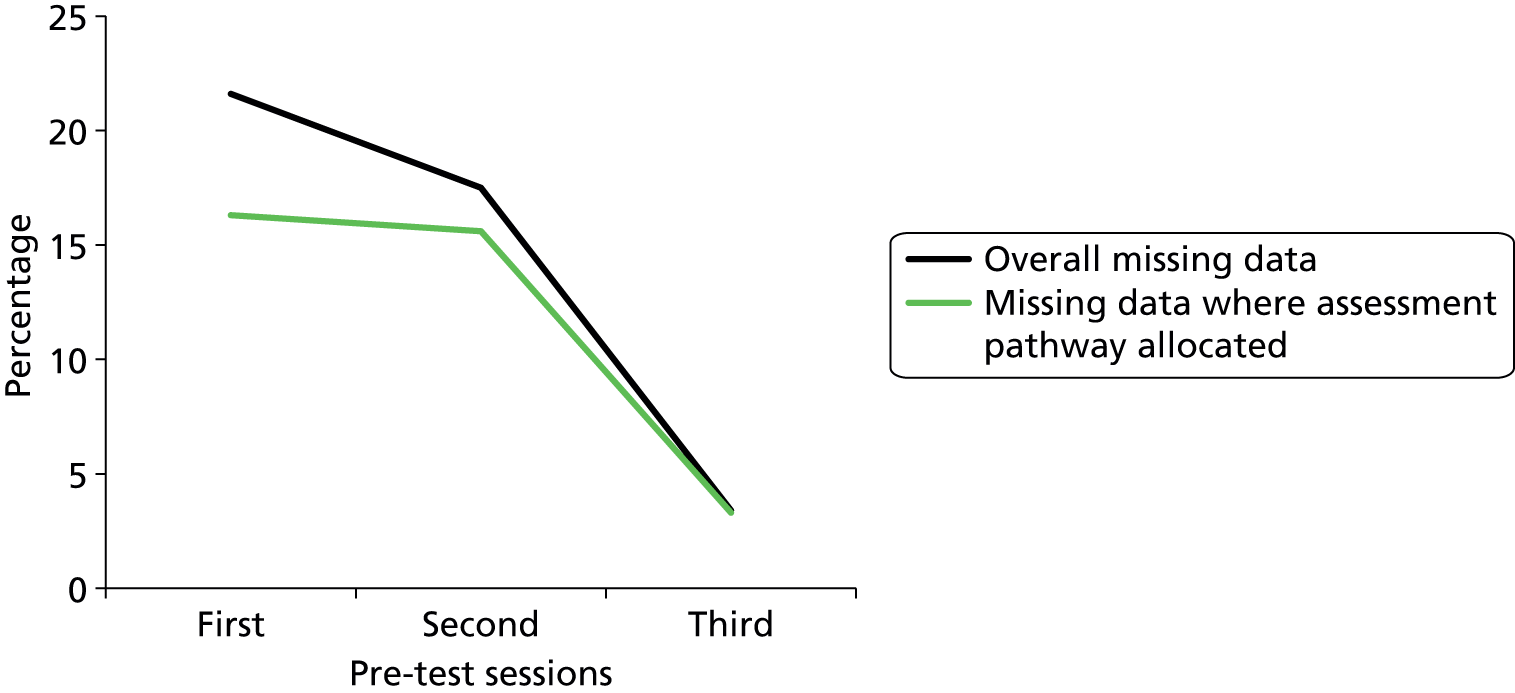

Case studies based on the real experiences of PURSUN UK members were developed. These were then used as part of the Pressure Ulcer Risk Primary or Secondary Evaluation Tool (PURPOSE-T; a pressure ulcer risk assessment tool) pretest training sessions with nurses (see Chapter 5, Phase 3: development of a new conceptual framework and theoretical causal pathway for pressure ulcer development). This allowed nurses to apply the tool to authentic case studies, in a safe learning environment.

Instrument development

Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network UK has had considerable input into developing PURPOSE-T, with particular focus on making the tool acceptable for patients in practice. Its involvement was integrated within the consensus methodology and had a direct influence on the items included in the tool. This is discussed further in Chapter 5. Members also reviewed the Pressure Ulcer Quality of Life (PU-QOL) instrument (see Chapter 6), providing feedback about clarity, comprehension, design, layout and item wording. This process led to some modifications to the PU-QOL instrument (e.g. clarification of instructions, revisions to the wording of some items). Members with experience of living with a pressure ulcer have also been involved in developing the PUQOL-UI (see Chapter 7). This involved giving feedback on the questionnaire through ‘think out loud’ interviews and document review.

Dissemination and knowledge transfer

Three members of PURSUN UK are currently contributing to a paper in which their real-life narratives are used to illustrate findings from the pain studies and emphasise the relevance to clinical practice. They will be co-authors on the paper. Video podcasts are also being developed with service users. Their stories will be combined with input from clinicians and used to highlight key messages from the programme. The videos will be available online.

Implementation

Members of PURSUN UK reviewed the user manual for the PU-QOL instrument. One member is also involved in piloting a new method for investigating the development of severe pressure ulcers in practice (following on from the work described in Chapter 4).

Wider impact of the Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network UK

In addition to PPI throughout the programme, PURSUN UK has begun to impact the wider tissue viability and PPI communities, as described in the following sections.

Professional development activities

Members of PURSUN UK have been invited to speak about their experiences at several events. Locally, this has included training for tissue viability link nurses, presenting to PURPOSE principal investigators, speaking at the launch of the NIHR Bradford Wound Prevention & Treatment Healthcare Technology Co-operative and working with medical students. Nationally, members have presented at the Tissue Viability Society conference, tissue viability education events and the INVOLVE (a national PPI advisory group) conference.

We have developed an effective model for presenting service users’ experiences in which the PPI officer interviews a member of PURSUN UK in front of a live audience. This provides an alternative to a traditional presentation for people who do not feel confident presenting personal experiences in that way. This model has received very positive feedback from both audiences and the service users involved. We have found that real-life stories are extremely powerful and can create a common focus for professionals from a variety of backgrounds.

Collaboration with industry

Medical devices play an important role in pressure ulcer prevention and treatment. With this in mind, PURSUN UK has collaborated with industry partners on projects such as education days and product development workshops. This collaboration has helped to diversify the involvement opportunities offered to PURSUN UK members and has been useful in terms of members’ personal development, as it has given people an insight into another aspect of tissue viability research. This work has also generated some funds for PURSUN UK, moving the network towards a sustainable model post PURPOSE.

Supporting further research

One member of PURSUN UK is a co-applicant on PRESSURE 2 [a NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-funded trial comparing two mattresses; http://medhealth.leeds.ac.uk/info/423/skin/1717/pressure_2 (accessed 31 August 2015)]. The wider network both helped to develop this trial and continues to be involved with it. PURSUN UK has also been a partner in the James Lind Alliance Pressure Ulcer Partnership, with members contributing to the prioritisation of pressure ulcer treatment and prevention uncertainties. These uncertainties are publicly available to inform future research [see www.jlapressureulcerpartnership.co.uk (accessed 20 February 2015)].

Developing materials

A website has been developed by PURSUN UK [see www.pursun.org.uk (accessed 20 February 2015)]. In addition, PURSUN UK has contributed to the international consensus document Optimising Wellbeing in People Living with a Wound, published by Wounds International [see www.woundsinternational.com/clinical-guidelines/international-consensus-optimising-wellbeing-in-people-living-with-a-wound (accessed 20 February 2015)].

Developing and sharing patient and public involvement methods

Developing a completely new service user network has given us the opportunity to be creative in our approach and develop innovative involvement models. These models have been shared with the UK PPI community. The PPI model used as part of the severe pressure ulcer study (see Chapter 4, Patient and public involvement) has been presented at three national conferences (INVOLVE, Involving People Wales and Tissue Viability Society) and forms part of an INVOLVE video resource on PPI in data interpretation and analysis [see www.invo.org.uk/resource-centre/conference/involve-conference-gallery/ (accessed 20 February 2015)]. A video about the Severe Pressure Ulcer PPI event was also made by PURSUN UK and has been widely disseminated online [see https://youtu.be/bgg6zkbILrg (accessed 21st July 2015)]. The novel approach of using the Patient Learning Journey as a model for service users contributing to research rather than health education has also been included as a case study in the INVOLVE training and development guidelines [see www.invo.org.uk/training-case-study-13-2/ (accessed 20 February 2015)].

Media

Working with service users has enabled us to more effectively engage with local and national media. Members of PURSUN UK have been interviewed for the Yorkshire Evening Post [see www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/at-a-glance/general-news/yorkshire-group-spearheads-bedsores-care-drive-1-3786988 (accessed 20 February 2015)] and the Daily Mail [see www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2093904/Bed-sores-How-does-local-hospital-compare.html (accessed 20 February 2015)] and we have found that journalists are more likely to run a health-related story if it has a real-life, human interest aspect to it.

Discussion

Our patient and public involvement methods

The growing role of PPI throughout the PURPOSE programme has been described. This likely reflects the situation in other research projects that need to recruit service users once the project is already under way, especially when projects span a number of years. This may be because of recruitment challenges or because it is determined that additional input from a particular group of people is needed or may be because of existing service user partners stepping down. Introducing service users to studies that are already under way can be challenging, particularly when relationships have already been formed within the project team.

Although members of PURSUN UK were not involved at the grant application stage and were therefore not part of setting the programme themes, they have found common ground with both each other and the project team. These shared goals have made collaboration possible. We recognise that early involvement is considered good practice30 and that there are areas throughout the PURPOSE programme (particularly in the early stages of programme delivery) where additional PPI might have been useful, for example involvement in the qualitative part of the PU-QOL study. However, the lack of a PPI infrastructure in the field made this difficult. The establishment of PURSUN UK and associated innovative approaches to PPI has addressed this need and is just one way in which PURPOSE intends to leave a legacy beyond the life of the programme.

Facilitating PPI effectively requires specialist skills. The creation of the PPI officer post brought specialist engagement expertise, dedicated time, innovative solutions, continuity and a single point of contact for service users. This enabled us to provide the individualised support that members of PURSUN UK require to be actively involved, for example briefing and debriefing meetings; information technology tuition and support; peer support opportunities; and practical support such as accessible venues and large-print documents.

The development of the PURSUN UK network has allowed us to move from ad hoc PPI activities at the start of the programme to a more strategic approach. Furthermore, we have found that members of PURSUN UK have helped to bridge the gap between research and practice, for example putting the PURPOSE findings in a NHS context and thinking about how findings can have the most impact. They have also highlighted continued gaps in the research and unanswered questions from the service user perspective, which will be taken forward in a future programme of work.

Our model involves a small number of service users in programme management and working with the wider network at key milestones throughout each study; this has worked well throughout the programme. We recognise that not all service users will feel comfortable in formal research environments such as the PURPOSE steering committee meetings. More informal meetings and workshops, which focus on the service user perspective, have proved invaluable. These meetings have highlighted key issues such as the importance of patient engagement in pressure ulcer prevention and treatment; the anxiety and stigma that can be felt as a result of a pressure ulcer; and the need to raise awareness of pressure ulcers with both patients and professionals.

To effectively engage with this group we have adopted a highly flexible and innovative methodology. We have used an asset-based approach. 31 This means building on the strengths of network members by adapting our research processes, rather than risk excluding people from traditional PPI activities. For example:

-

the use of role play and video to facilitate PPI in the interpretation of data from the severe pressure ulcer study (see Chapter 4, Patient and public involvement)

-

the adaptation of the Patient Learning Journey model32 for use in a research context

-

the use of a live interview model as an alternative to traditional presentations

-

the addition of a service user group to the consensus methodology used in the risk assessment study (see Chapter 5, Service user group participants)

-

individualised support for steering committee members, including one-to-one debriefs with the PPI officer

-

the integration of service user narratives into the dissemination of the quantitative pain studies.

The value of the Pressure Ulcer Research Service User Network UK to the service users involved

The reciprocal nature of engagement has been central to the success of PPI in this programme. In addition to PPI having a positive impact on research processes and outputs, service users have also reported that it has been a positive and rewarding experience for them. People have commented on increased confidence, self-worth, knowledge of research and awareness of their own health. They have valued the peer support that PURSUN UK provides and the opportunities to enter into an equal dialogue with researchers and clinicians.

I’ve loved putting my input into the work the group are doing. I had to give up everything [because of my severe pressure ulcer] and it has given me something to do. I feel like I’m back in the world again!

PURSUN UK member

PURSUN is a safe place to learn from sharing experiences with each other, and the comfort that comes from knowing that it is a safe environment cannot be underestimated. This should be acknowledged, even if it wasn’t originally on the radar of those wanting to set up a service user group

PURSUN UK member

The networks formed as part of their work with PURSUN UK have led to other opportunities for people, including paid positions. For example, people have become involved in teaching activities elsewhere in the University of Leeds and have joined research projects/service user groups in other topic areas.

Conclusion

This chapter outlines both the challenges and advantages of engaging with a previously seldom-heard group. A mixture of established good practice techniques and innovative PPI approaches has allowed us to move beyond the PPI plan outlined in our grant application and beyond what others have achieved in this field. Although we have worked exclusively within pressure ulcer research, the strategies outlined here could help service users and researchers work together in other contexts.

Chapter 3 Work package 1: pain

Chapter written by Jane Nixon, Isabelle L Smith, Michelle Collinson, Elizabeth McGinnis, Michelle Briggs, Sarah Brown, Susanne Coleman, Carol Dealey, Delia Muir, E Andrea Nelson, Rebecca Stevenson, Nikki Stubbs, Lyn Wilson and Julia M Brown.

Abstract

Introduction: Patients with pressure ulcers have reported that pain is their most distressing symptom and that pain at ‘pressure areas’ was experienced before the clinical manifestation of pressure ulcers but that the pain was ignored by nurses. The primary aim of the research was to determine the extent of pressure area and pressure ulcer pain and explore the role of pain as a predictor of category 2 and above pressure ulcers in acute hospital and community populations.

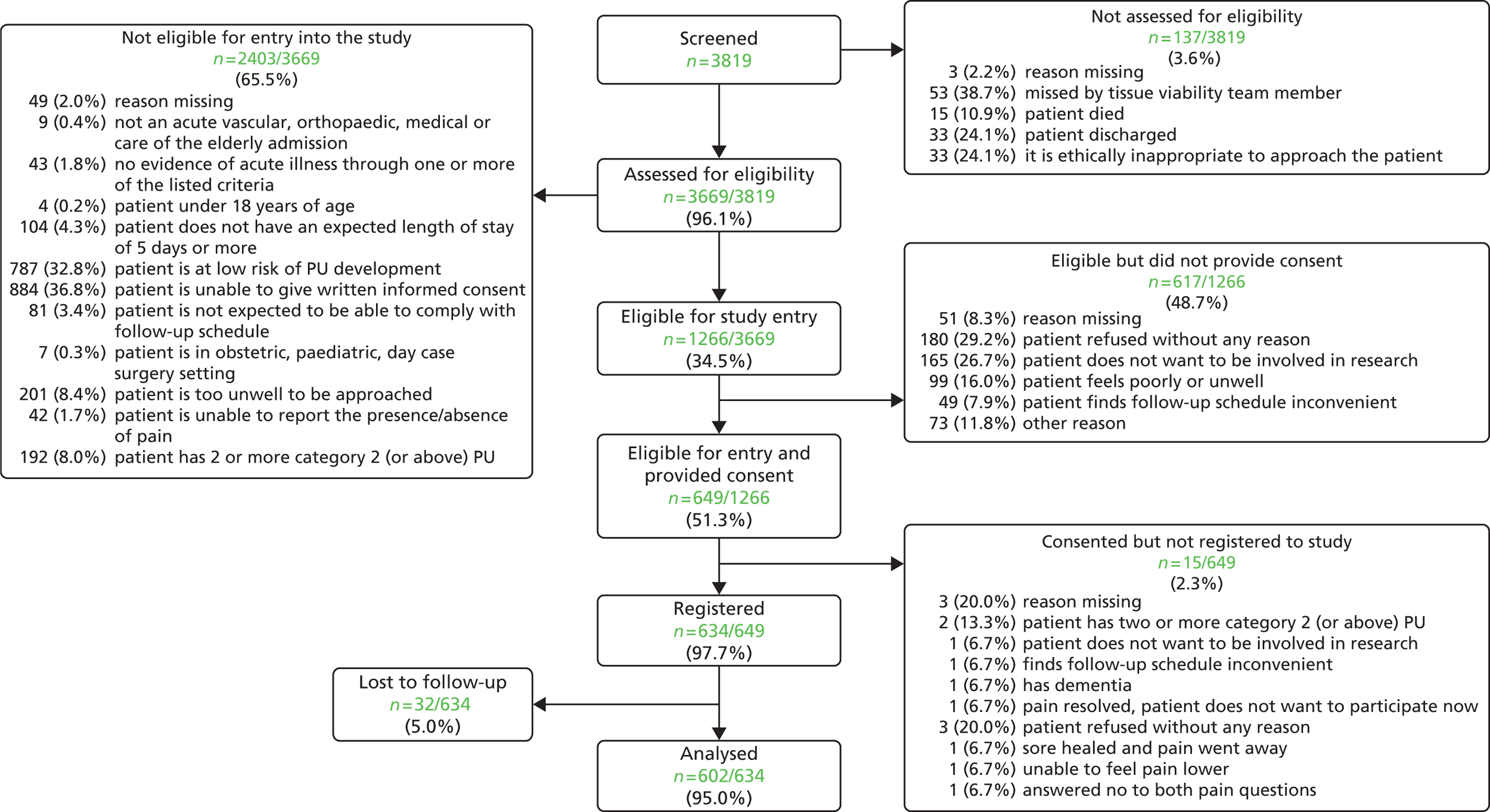

Methods: The pain work package comprised three research projects: (1) a nested multicentre pain prevalence study in three NHS acute hospital trusts, including all inpatients; (2) a nested pain prevalence survey in two community NHS trust localities incorporating a comparison of case-finding methods, including only patients with pressure ulcers; and (3) a multicentre prospective cohort study of pressure ulcer risk factors in acute hospital and community patients.

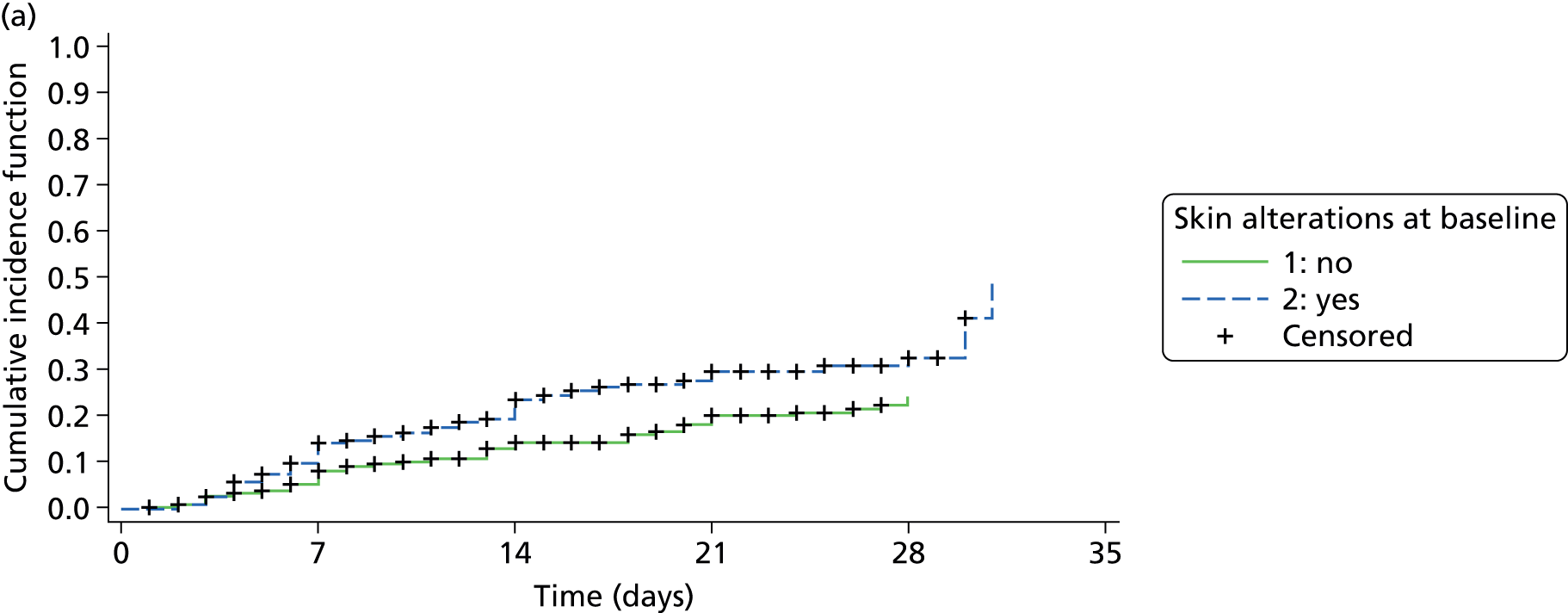

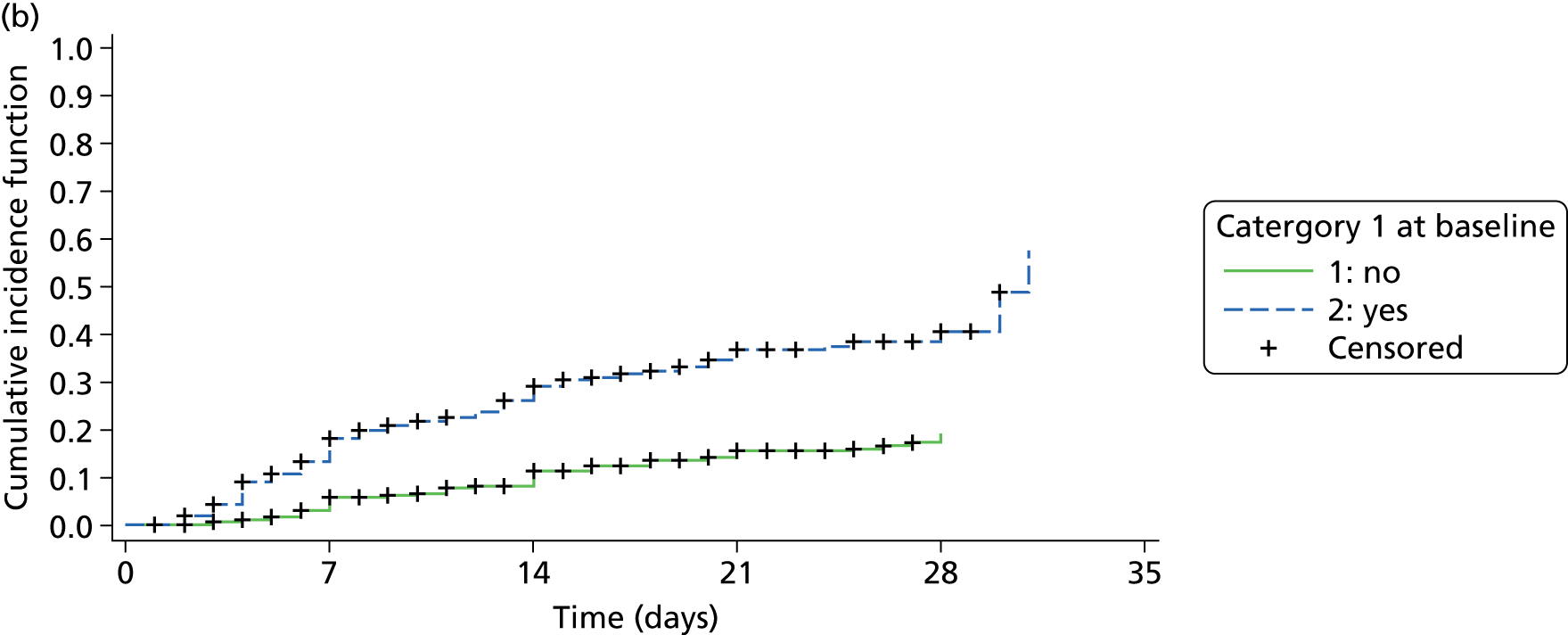

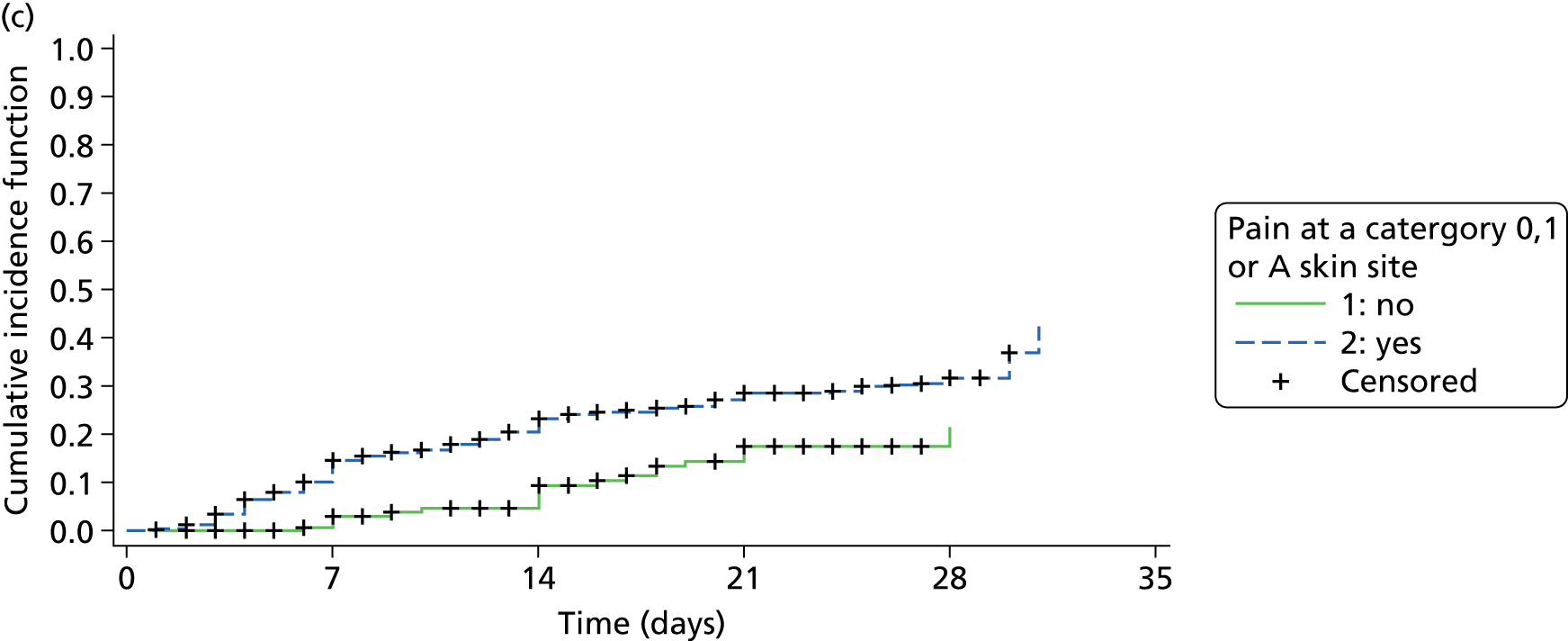

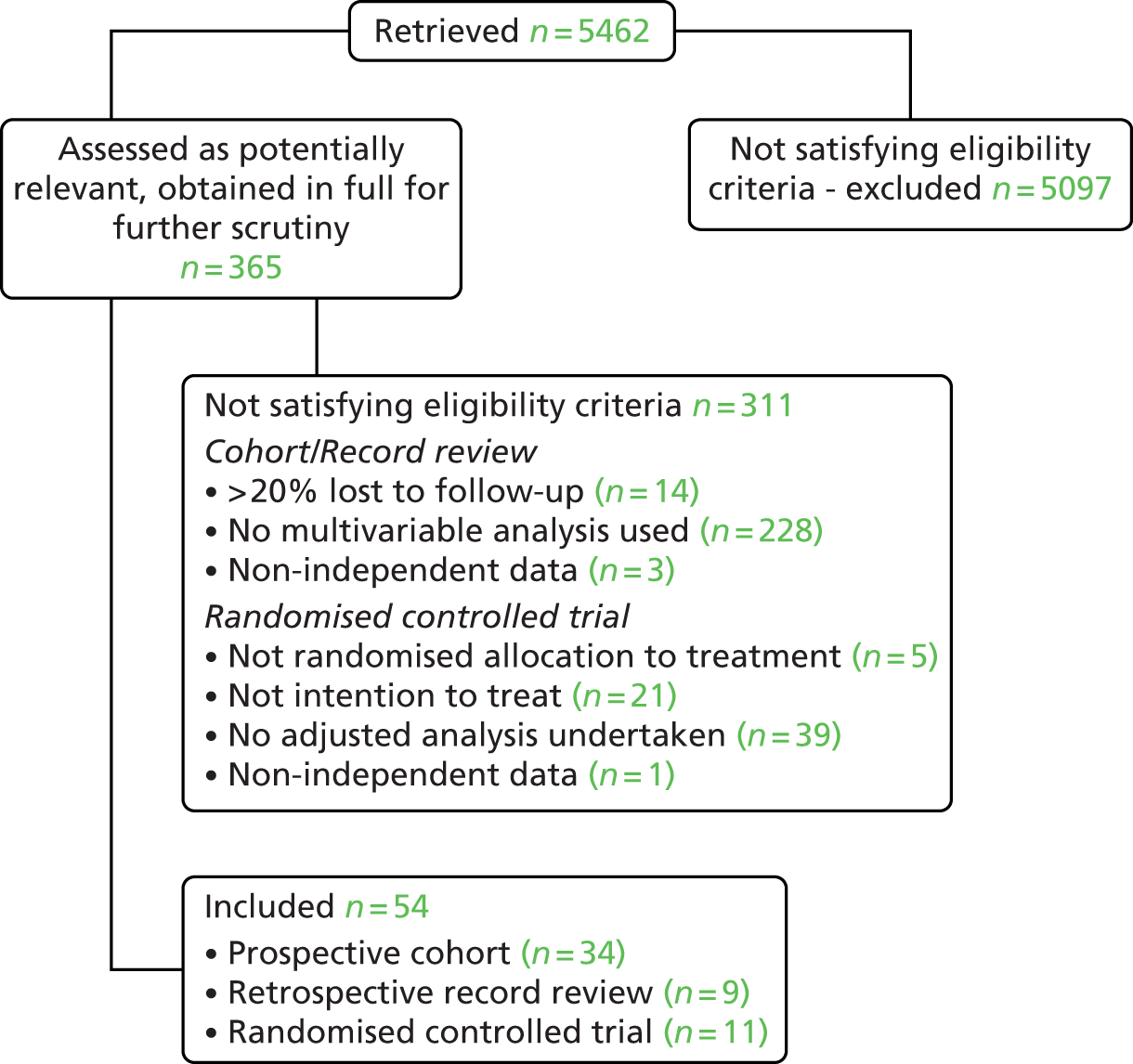

Results: In the hospital prevalence study a total of 3397 patients in nine acute hospitals were included in routine pressure ulcer prevalence audits and, of these, 2010 (59.2%) participated in the nested pain prevalence study. The community routine pressure ulcer prevalence audit identified 287 patients with pressure ulcers and, of these, 176 (61.3%) participated in the nested pain prevalence study. The overall prevalence of pressure ulcers was 0.58 per 1000 adult population, with differences observed between localities (locality 1 = 0.77 and locality 2 = 0.40). The unattributed pressure area-related pain prevalence was 16.3% (327/2010) in the hospital population, which included patients with and without pressure ulcers. In the hospital population with no observable pressure ulcers, 12.6% (223/1769) reported unattributed pressure area-related pain. The prevalence of unattributed pressure area-related pain in patients with pressure ulcers was 43.2% (104/241) in hospital patients and 75.6% (133/176) in the community patients. The detailed pain assessment of 160 hospital and 37 community patients identified pressure area-related pain on skin areas assessed as normal as well as all grades of pressure ulcer. The distribution of pain intensity measured using a 0–10 nominal rating scale was similar for all grades. The dominant type of pain in hospital patients was inflammatory pain (70.3% torso and 60.3% limb), whereas in the community patients neuropathic pain was dominant (54.5% torso and 61.1% limb). The cohort study of 632 acutely ill hospital and community patients identified significant evidence that the presence of pain at a skin site (assessed as normal, altered but intact or category 1) is an independent predictor for developing a category 2 or above pressure ulcer in four multivariable models: a priori logistic regression model, overdispersion logistic regression model and an accelerated failure time model for analyses conducted on a patient level and a multilevel logistic regression model for the analysis conducted on a skin-site level.

Conclusions: We have identified that a significant minority of hospital inpatients without pressure ulcers suffer pressure area-related pain, that approximately 40% of hospital patients and 75% of community patients with pressure ulcers report pain, that pain severity is not related to the severity of the ulcer and that both inflammatory and neuropathic pain are observed. Differences in pressure ulcer prevalence rates highlight the need for effective case ascertainment in the community setting. We have also established that the presence of pain (on skin areas assessed as normal, altered but intact or category 1 pressure ulcer) increases the risk of development of category 2 and above pressure ulcers and accelerates the time to their development. This is an area of practice that requires improved pain assessment; the incorporation of pain into risk assessment; preventative interventions in response to pain; and treatment strategies to alleviate pain.

Introduction

Our pre-programme grant qualitative work33,34 and systematic review of the pressure ulcer quality-of-life literature9 found that patients with pressure ulcers report that pain is their most distressing symptom. In addition, the work highlighted that pain at ‘pressure areas’ (see Definition of terms) was experienced by patients before the clinical manifestation of pressure ulcers but that the pain was ignored by nurses. Patients blamed nurses when a pressure ulcer developed subsequently, because of the lack of action. ‘Patients felt that they were responsible for communicating pain and that their care provider was responsible for attending to it, but patients’ views and concerns did not always prompt action and many healthcare professionals dismissed patients’ reports of pain at pressure areas’. 9,33,35

As part of the programme grant we carried out a mixed-methods systematic review, in which qualitative and quantitative studies of patients’ reports of pressure ulcer pain were identified and synthesised36 (see Chapter 6, Pressure ulcer-related pain: systematic review). Pain was reported as debilitating, reducing the individual’s ability to participate in physical and social activities, adopt comfortable positions, move, walk and undergo rehabilitation. 36 Patients with pressure ulcer pain described their experience as ‘endless pain’ characterised by a constant presence, needing to keep still and equipment and treatment pain. 9,34,37 This confirmed the importance of pain as a feature of living with a pressure ulcer.

Reviews of the epidemiological literature carried out by Girouard and colleagues38 and Pieper and colleagues39 identified eight studies reporting the prevalence of pain associated with pressure ulcers in study populations ranging from 20 to 186 participants, in diverse settings including hospitals and community and palliative care. In the four largest studies (> 100 participants), pressure ulcer pain prevalence estimates ranged from 37% to 66%. 40–43 The reviews highlight the limitations of the existing literature, including small sample sizes, the use of non-validated measures of pain, including nurse-assessed pain outcomes, and an absence of studies that report the dominant types of pain: nociceptive pain (inflammatory) and neuropathic pain (resulting from nerve damage or tissue ischaemia). 44 “Understanding the characteristics of pain is important as successful pain management depends upon using interventions that address the cause(s) of the pain. A further problem with research in the field is that pain reports are limited to Category 2 and above PUs [pressure ulcers]. 35,38,39,45 Pain associated with Category 1 PUs is not reported in most studies, nor is the presence of pain at ‘pressure areas.’” Despite patient reports that pain at ‘pressure areas’ preceded pressure ulcer development, our risk factor systematic review46 (see Chapter 5) did not identify any risk factor studies that included pain as a candidate risk factor in univariate or multivariable analysis.

‘In summary, qualitative evidence identifies pain preceding PU development and in PU management [as an important issue for patients]. Previous epidemiological research has focused on patients with existing PUs and a limitation of the literature is the lack of evidence relating to the extent of pain preceding PU development, the extent of pain associated with Category 1 PUs (the most prevalent PU Category), the type of pain (i.e. inflammatory or neuropathic)’45 and the relationship between pain at ‘pressure areas’ and subsequent category 2 pressure ulcer development. We therefore proposed to determine both the extent of the problem and explore the role of pain as a predictor of pressure ulcer development in acute hospital and community populations.

Research overview

Work package 1 comprised the following pain prevalence and cohort studies:

-

the prevalence of pressure area-related and pressure ulcer pain in hospitalised patients (see Pain prevalence in the hospital population)

-

the prevalence of pressure area-relataed and pressure ulcer pain in community patients (see Pain prevalence in the community population), including a substudy comparing community pressure ulcer case-finding methods (see see Routine pressure ulcer audit: community setting)

-

pain cohort study exploring the role of pain as a predictor of category 2 pressure ulcers in acute hospital and community populations (see Pain and pressure ulcer risk: cohort study)

Definition of terms

This is the first pain research undertaken in patient populations with and without pressure ulcers. To describe pain in the study populations, we developed and used the following four terms: (1) pressure area; (2) pressure area-related pain; (3) pressure ulcer pain and (4) unattributed pressure area-related pain as follows (see Glossary for description of terms):

-

Pressure area. A body site where pressure ulcers commonly develop; most commonly these include the sacrum, buttocks, ischial tuberosities, hips, heels, ankles and elbows.

-

Pressure area-related pain. Defined as pain, soreness or discomfort on any pressure area.

-

Pressure ulcer pain. Defined as pain, soreness or discomfort on a body site with an observable pressure ulcer of category 1 or above.

-

Unattributed pressure area-related pain. Defined as pain, soreness or discomfort reported by patients on a pressure area/pressure ulcer but in which the body site is not specified/recorded. 35

Pain prevalence in hospital and community populations

To assess the extent of pressure area-related and pressure ulcer pain we undertook two cross-sectional studies in three acute and two community NHS trusts to estimate prevalence. In the hospital setting we were able to nest the pain prevalence study into routine annual pressure ulcer audit methods and pain was assessed for all patients able to respond to pain screening questions, including those with and those without pressure ulcers. Our original plan (see the protocol in Appendix 3) assumed that community prevalence methodology was similar to long-standing and well-established acute hospital methods, with nurses undertaking a comprehensive skin assessment of each patient. 47 However, the two participating community trusts had developed different case-finding methods48 and this, together with the scale of the data collection task in the community setting, led to an adaptation of the original plan and limited the pain prevalence estimates to the patient population with pressure ulcers, which is reflected in the objectives.

Objectives

Pain prevalence in the hospital population

Objectives were to:

-

estimate the unattributed pressure area-related pain prevalence in a hospital population of patients with and without pressure ulcers

-

estimate the pressure area-related pain prevalence in patients with no observable pressure ulcers

-

estimate the pressure ulcer pain prevalence in patients with pressure ulcers

-

describe the intensity and type of pressure area-related and pressure ulcer pain in a hospital population of patients with and without pressure ulcers

-

explore the association between pain intensity, type of pain and pressure ulcer classification in a hospital population of patients with and without pressure ulcers.

Pain prevalence in the community population

Objectives were to:

-

estimate the prevalence of unattributed pressure area-related pain within a community population of patients with pressure ulcers

-

assess the intensity and type of pressure area-related and pressure ulcer pain within a community population of patients with pressure ulcers

-

describe the intensity and type of pressure area-related and pressure ulcer pain within a community population of patients with pressure ulcers

-

explore the association between pain intensity, type of pain and pressure ulcer classification within a community population of patients with pressure ulcers

-

compare and contrast community pressure ulcer prevalence case-finding methods.

Methods

Study design

We undertook nested, multicentre, cross-sectional studies in three acute hospital NHS trusts35 and two large community trusts in England45 embedding the pain prevalence study into routine pressure ulcer audits. To identify patients who had unattributed pressure area-related pain, questions about pain were added to the routine annual pressure ulcer prevalence audits undertaken in the participating NHS trusts. To estimate the prevalence of pressure area-related and pressure ulcer pain and to explore the association between pain and pressure ulcer classification, patients who reported pain were invited and consented to undergo a full pain assessment (see Appendix 5 for the consent form).

Nesting the pain prevalence study within routine pressure ulcer prevalence audits meant that we collected data for the total eligible patient population in each setting. The routine NHS audits collect unlinked anonymous data and patient consent is not required to ensure that accurate pressure ulcer prevalence data are obtained for the total eligible population. Nesting the study within routine pressure ulcer prevalence audits, however, limited the number of data items that could be collected. Furthermore, in the community the two trusts defined their denominator population differently and adopted different pressure ulcer case-finding methods. 48

Setting

Three acute NHS hospital trusts took part. One trust included three district general hospitals. The other two NHS trusts were large teaching hospitals and together included four main and two satellite hospitals. This meant that the patient population consisted of those in general secondary care and regional/supraregional specialist services from a total of nine hospitals.

The community NHS trusts consisted of locality 1, serving an urban population of 292,179, and locality 2, serving a rural population of 311,991. 49

Each NHS community trust provides general and tissue viability specialist nursing care to patients residing in their own homes and residential homes as well as community/rehabilitation/hospice inpatient facilities. In addition, each trust provides tissue viability specialist nursing care to patients residing in nursing home settings.

Routine pressure ulcer audit: hospital setting

Eligibility

The population included ‘all inpatients of 18 years of age or older who were in hospital on the date of the participating Trusts’ PU prevalence audit. Patients in paediatric, obstetric and psychiatric care settings were excluded from the study as the prevalence of PU in these settings is very low, and hence the data collection to information burden ratio is unacceptably high in these settings.’50

Patient identification method

Routine pressure ulcer prevalence audits in the participating acute trusts included training of a responsible nurse for each ward, completion of an audit form for each inpatient at 06.00 on the audit day, cross-referencing of the number of occupied beds on each ward and the number of audit forms submitted by an audit team and verification of data by an audit team comprising the tissue viability team and members of the mattress suppliers of the participating NHS trusts (as part of their mattress supply contract). The date of the prevalence audit for each hospital was determined locally.

Routine pressure ulcer audit: community setting

Eligibility

The target population was all patients aged ≥ 18 years who were identified as having a pressure ulcer. Patients in paediatric, obstetric and psychiatric community care settings were excluded.

Patient identification method

A number of challenges are faced when determining ‘community prevalence’: (1) defining the time period for data collection, (2) defining the term ‘community’ for case ascertainment to estimate the numerator and (3) defining the denominator population. ‘In the UK, within each locality there are six key healthcare providers in the community including community nursing services, residential homes, rehabilitation units, specialist palliative care units, nursing homes and General Practitioners. NHS community trusts provide general and specialist community nursing services to patients residing at home and also tissue viability specialist nursing to high risk patients and those with complex wounds residing in independent sector residential and nursing home facilities. Residential home facilities provide only social care and therefore a patient in this setting with a pressure ulcer would be referred to the community nursing service. Rehabilitation units, specialist palliative care units and nursing home facilities include ‘nursing care’ and only complex patients are referred to the community nursing service. General Practitioners usually refer patients with a pressure ulcer to community nursing services. To establish true community prevalence would require named patient data from each health-care provider. However, this is not achievable without considerable resource’48 and the data burden and use of named patient data in routine audits is not considered justified for the gain in precision of prevalence estimates.

Both localities completed data collection over a 6- to 8-week period. ‘The two localities applied different methods for case finding as per their local pressure ulcer audit practice.’48 Locality 1 requested that community nurses assess all of the patients on their community nursing caseload and that a nominated nurse in each residential home, specialist palliative care unit, rehabilitation unit and nursing home in the locality assess all inpatients/residents to identify patients with pressure ulcers. 47 An audit form was completed for each patient (i.e. those with and those without pressure ulcers). Locality 2 identified patients with known pressure ulcers from the community nursing caseload records and the community nurses completed an audit form only for those patients identified as having a pressure ulcer48 [note that patients treated by a general practitioner only (i.e. not also under the care of a general or specialist community nursing service) were not identified in the case-finding method by either locality 1 or locality 2]. In both trusts each patient identified through case finding as having a pressure ulcer had a tissue viability team member visit to verify the skin assessment recorded by the community nurse.

Pain prevalence eligibility criteria

Pain prevalence inclusion criteria

In addition to the standard pressure ulcer audit data, the ward/community nurses were asked to consider whether each patient was able to report the presence or absence of pain. Patients who were considered able to report pain were eligible for inclusion in the pain prevalence study and were asked two screening questions (see following section on assessments) relating to pressure area-related pain by a member of the tissue viability team.

Pain prevalence exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the pain prevalence study when it was considered ethically or clinically inappropriate by the ward nurse/clinical team, for example very sick patients or those for whom death was considered to be imminent. When patients were assessed as not able to report pain, this was recorded along with the reason for ineligibility.

Detailed pain assessment inclusion criteria and consent

Patients in the hospital and community settings who answered ‘yes’ to both pain screening questions were provided with a verbal explanation of the detailed pain assessment component of the study and a written information leaflet (see Appendix 4) by the tissue viability team member and were then invited to take part in a full pain assessment. Consenting patients underwent a detailed pain and skin assessment (see Detailed pain assessment).

Assessments

Unlinked anonymised individual patient audit data were recorded by a designated ward or community nurse trained in the use of the data collection form and skin assessment as part of the preparation for the audit. Data recorded included place of assessment (hospital/community and ward specialty, patient’s own home, nursing home, residential home, hospice, community bed), date of birth, gender, height, weight, ethnicity, mobility and risk assessment scale total score (using either the Waterlow score50 or the Braden scale51 as per local policy). Skin was assessed using the 1998 EPUAP24 classification and recorded for a minimum of 13 skin sites (sacrum, left and right buttocks, ischial tuberosities, hips, heels, elbows and ankles). The 1998 EPUAP classification (and not the revised EPUAP/NPUAP 2009 version)1 was used as this was the version in routine use at the participating centres/localities. In addition, the presence of an unstageable pressure ulcer, other type of wound or normal skin were confirmed or skin status was recorded as not applicable (e.g. amputation) or unable to assess.

When patients were assessed as not able to report pain this was recorded along with the reasons for ineligibility. When ward/community staff indicated that the patient was well and able to report pain, a member of the tissue viability team asked the patient two pain screening questions as follows:35,45

-

At any time, do you get pain, soreness or discomfort at a pressure area (prompt: back, bottom, heels, elbows or other as appropriate to the patient)? (Yes or no)

-

Do you think this is related to either your pressure ulcer OR lying in bed for a long time OR sitting for a long time? (Yes or no)

These questions were adapted from the case screening questions used in a large postal survey of pain prevalence in the UK. 35,52 Unlinked anonymous individual patient data were recorded for both questions. The site of the pain, soreness or discomfort was not recorded (i.e. the pressure area/pressure ulcer pain was unattributable to individual body sites).

Detailed pain assessment

Patients who answered ‘yes’ to both pain screening questions and who consented to further assessment underwent a detailed pain and skin assessment by a member of the tissue viability team that included pain intensity, type of pain and skin status/grade of ulcer (as above) on a minimum of 13 skin sites (as above). The patient risk profile was assessed using the Braden scale subscales to allow description of the patient population and comparison with the wider literature.

‘Pain was assessed by asking patients to report the pain intensity (for most severe pain over the past week) for all pressure area sites using a numerical rating scale of 0–10.’45,53,54 Patients were also asked to identify their ’most painful torso and limb skin sites and these were assessed using the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) Pain Scale. 55 The LANSS Scale is a clinically validated tool which allows assessment of neuropathic and inflammatory pain [and has been used in a wide variety of clinical settings55]. It consists of a brief assessment and is easy to score in the clinical setting. The questionnaire contains 5 symptom items and 2 clinical sensory testing items associated with neuropathic pain.’45 The responses to each of the seven items are scored and summed to provide a total score. If the LANSS total score is < 12, neuropathic mechanisms are unlikely and the pain is classified as inflammatory pain. If the LANSS total score is ≥ 12, neuropathic mechanisms are likely to be contributing to the pain and it is classified as neuropathic.

Staff training and preparation

Ward and community nurses were trained locally as per local trust standard pressure ulcer audit practice. Members of the tissue viability team were trained in study procedures, including pain assessment and skin assessments, by the programme manager (LW). No formal inter-rater reliability assessment was undertaken as previous research has demonstrated high agreement between specialist nurses and clinical research nurses in skin assessment and pressure ulcer classification. 56

Data processing

All data returned to the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) for data processing were anonymous. Data were entered into a bespoke MACRO (version 3; MACRO, Infermed, London, UK) database and range and consistency data checks were carried out to assess the accuracy of the data.

Sample size

For the priori sample size we planned to use a minimum of two acute NHS trusts with an estimated patient population of 2000 and two community NHS trusts with an estimated community nursing caseload of 6000 community patients; therefore, it was planned to include approximately 8000 patients in the prevalence audit.

The a priori sample size was based on the following assumptions:

-

the prevalence of pressure ulcers in hospital patients is 10% and in community patients is 5%2

-

30% of patients have pressure ulcers of grades 2–4/unstageable ulcers, of whom 25–50% would report pressure-area related pain40–43

-

70% of patients have pressure ulcers of grade 1, of whom 10–30% would report pressure area-related pain

-

90% of hospital and 95% of community patients have no pressure ulcers

-

2.5–5% of patients without pressure ulcers would report pressure area-related pain.

Based on these assumptions we estimated that between 259 and 555 patients would report pressure area-related pain (i.e. that 3–7% of patients would report pressure area-related pain; Table 2). A sample of 8000 patients would enable us to estimate a pressure area-related pain prevalence of 3% to within ±0.38% (n = 7742) and a pressure area-related pain prevalence of 7% to within ±0.56% (n = 7975).

| Setting | Pressure ulcer status | Pressure area-related pain | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | |||

| Hospital (n = 2000) | No PU (90%; n = 1800) | 45–90 | 2.5–5 | |

| PU (10%; n = 200) | Category 1 (70%; n = 140) | 14–42 | 10–30 | |

| Categories 2–4 (30%; n = 60) | 15–30 | 25–50 | ||

| Community (n = 6000) | No PU (95%; n = 5700) | 142–285 | 2.5–5 | |

| PU (5%; n = 300) | Category 1 (70%; n = 210) | 21–63 | 10–30 | |

| Categories 2–4 (30%; n = 90) | 22–45 | 25–50 | ||

Analysis

Analysis included data summaries and no inferential statistical testing was planned or undertaken. The denominator for the acute hospital pressure ulcer prevalence was the total inpatient population. The community pressure ulcer prevalence was calculated per 1000 of the estimated total population of adults aged ≥ 18 years for each site (240,038 locality 1 population aged ≥ 18 years; 251,891 locality 2 population aged ≥ 18 years). 49

‘Percentages were calculated using the total number of patients from the relevant population as the denominator (i.e. including all patients with missing data for that variable).’45 When another skin condition or chronic wound was indicated, the specific skin site was excluded from the analysis. ‘All analyses were carried out using SAS software [version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA]. All percentages were rounded to 1 decimal place. Means, medians, standard deviations [SDs] and ranges were summarised to one more decimal place than the data collected.’45

Type of pain was determined using the results of the seven-item LANSS scale,5 with the responses to each of the seven items scored and summed to provide a total score. Pain was classified as inflammatory pain when the LANSS total score was < 12 and neuropathic pain if the LANSS total score was ≥ 12.

Ethical approval

The studies were approved by the Leeds Central Research Ethics Committee prior to data collection (reference number 09/H1313/14).

Results

Pressure ulcer prevalence: hospital population

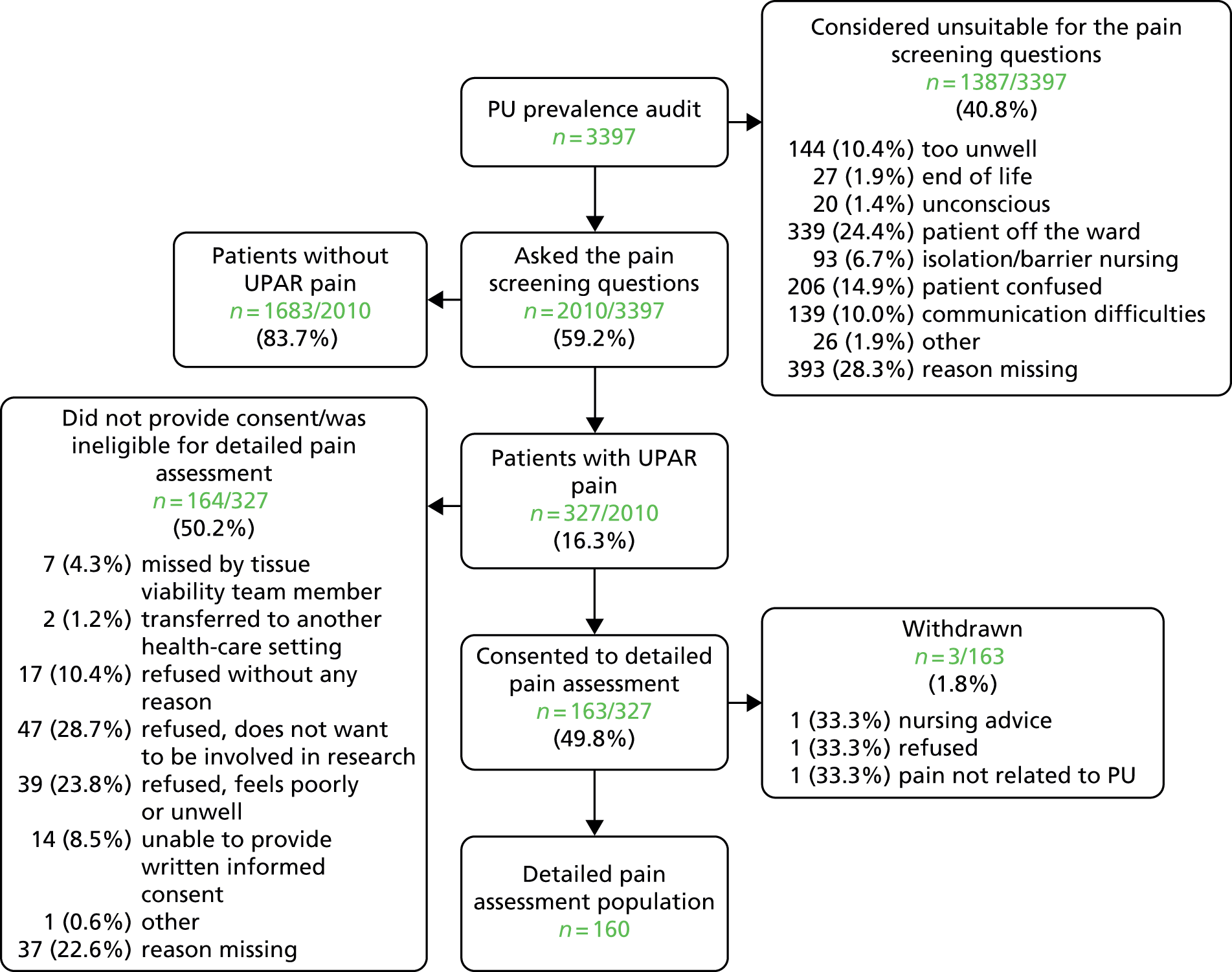

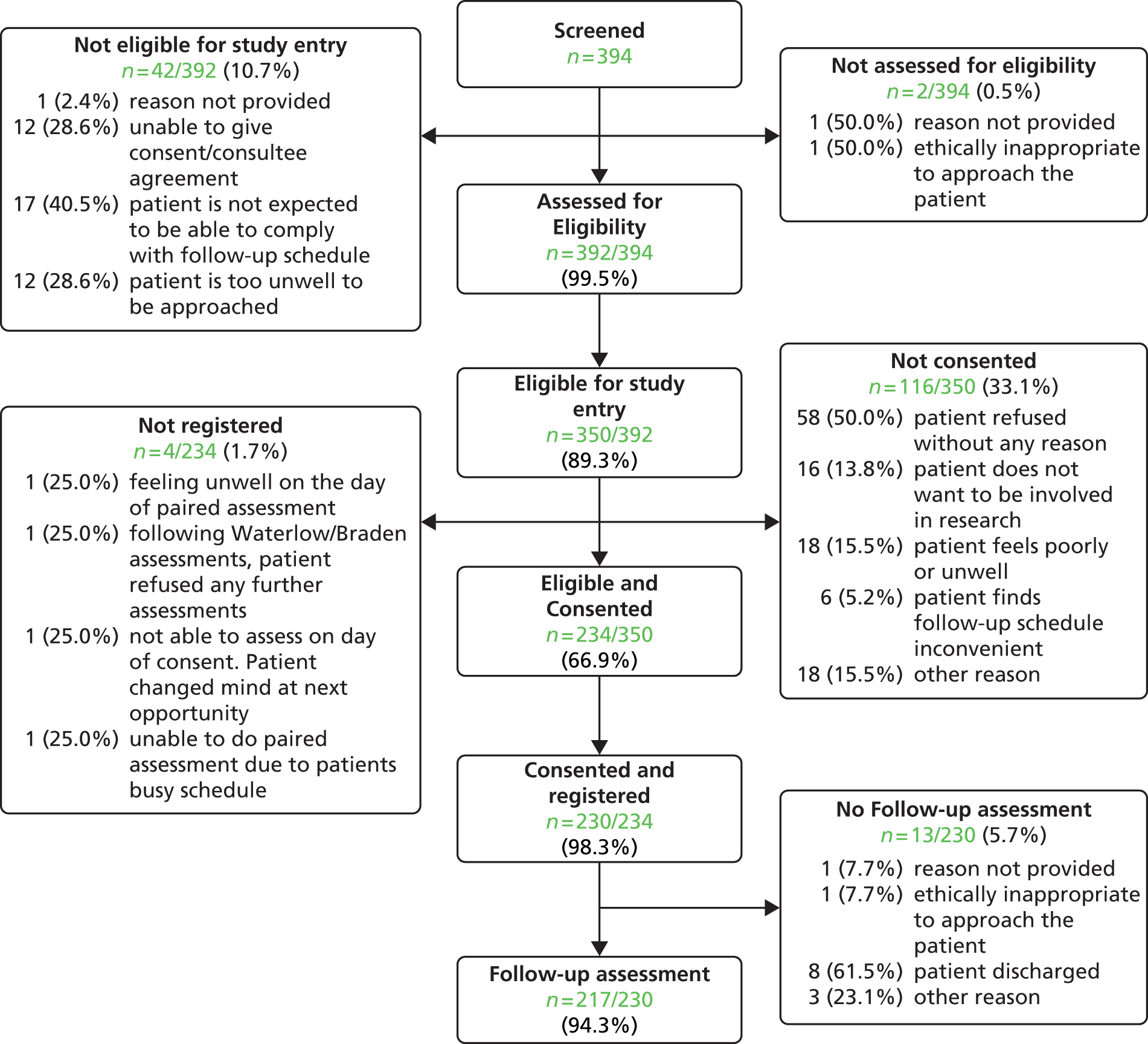

Data collection was undertaken between 15 September 2009 and 3 March 2010. From across nine acute hospitals, a total of 3397 patients (see Appendix 1) were included in the routine pressure ulcer prevalence surveys and this is our target hospital population. 50 Figure 2 details the flow of patients through each stage of the process. The number of patients audited by specialty is presented in Table 3.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow: hospital population. PU, pressure ulcer; UPAR, unattributed pressure area-related.

| Specialty | Numbers of participants | % |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine | 1348 | 39.7 |

| Surgery | 868 | 25.6 |

| Elderly medicine | 380 | 11.2 |

| Orthopaedic and trauma | 305 | 9.0 |

| Oncology | 211 | 6.2 |

| Critical care | 179 | 5.3 |

| Rehabilitation | 79 | 2.3 |

| Burns | 15 | 0.4 |

| Clinical decision units | 8 | 0.2 |

| Missing | 4 | 0.1 |

| Total | 3397 | 100 |

The median age of patients was 70 years [mean 65.8 (SD 19.23), range 18–103 years]. The numbers of men and women were similar (48.7% male; 1655/3397) and 7.2% (243/3397) were non-Caucasian. 35 In total, 53.9% of patients (1830/3397) were assessed using the Waterlow scale and of these 1062 (58.0%) were classified as ‘at risk’ (score of ≥ 10); 46.1% of patients (1567/3397) were assessed using the Braden scale and of these 532 (34.0%) were classified as ‘at risk’ (score of ≤ 18) (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Total hospital prevalence population | Pain prevalence population | Detailed pain assessment population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population, n | 3397 | 2010 | 160 |

| Age (years) | |||

| Median | 70.0 | 68.0 | 69.0 |

| Mean (SD) | 65.8 (19.23) | 64.8 (18.57) | 66.2 (18.23) |

| Range | 18.0–103.0 | 18.0–100.0 | 18.0–99.0 |

| Male, n (%) | 1655 (48.7) | 980 (48.8) | 80 (50.0) |

| ‘At risk’, n/N (%) | |||

| Waterlow | 1062/1830 (58.0) | 504/997 (50.6) | |

| Braden | 532/1567 (34.0) | 263/1013 (26.0) | 114/160 (71.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 2963 (87.2) | 1774 (88.3) | 154 (96.3) |

| Other | 243 (7.2) | 118 (5.9) | 4 (2.5) |

| Missing | 191 (5.6) | 118 (5.9) | 2 (1.3) |

| Patients with PUs, n (%) | 502 (14.8) | 241 (12.0) | 75 (46.9) |

| Total number of PUs | 1066 | 491 | 139 |

| Number of PUs per patient | |||

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.63) | 2.0 (1.44) | 1.9 (1.23) |

| Range | 1.0–13.0 | 1.0–9.0 | 1.0–5.0 |

| Grade of PUs reported, n (%) | |||

| Grade 1 | 752 (70.5) | 357 (72.7) | 97 (69.8) |

| Grade 2 | 237 (22.2) | 100 (20.4) | 32 (23.0) |

| Grade 3 | 45 (4.2) | 18 (3.7) | 4 (2.9) |

| Grade 4 | 18 (1.7) | 10 (2.0) | 3 (2.2) |

| Unstageable | 14 (1.3) | 6 (1.2) | 3 (2.2) |

Of the 3397 patients included, 502 (14.8%) were reported to have 1066 pressure ulcers [median 1.0, mean 2.1 (SD 1.63), range 1–13 per patient]. The majority (70.5%; 752/1066) of reported pressure ulcers were grade 1, approximately one-fifth were grade 2 (22.2%; 237/1066) and a small percentage (7.2%; 77/1066) were grades 3–4/unstageable. 35

Pain prevalence: hospital population

Of the 3397 hospital patients in the pressure ulcer audit sample, 2010 (59.2%) were considered well enough to respond to the pain questions and hence were eligible for the pain prevalence study (see Figure 2).

The pain prevalence population demographics were similar to those of the total hospital prevalence population (see Table 4). The median age of patients was 68 years [mean 64.8 (SD 18.57), range 18–100 years], almost half (980/2010; 48.8%) were male and 122 (6.1%) were non-Caucasian. In total, 49.6% (997/2010) were assessed using the Waterlow scale and of these 504 (50.6%) were classified as ‘at risk’ (score of ≥ 10); 50.4% (1013/2010) were assessed using the Braden scale and of these 263 (26.0%) were classified as ‘at risk’ (score of ≤ 18).

A total of 241 patients (12.0%) were reported to have 491 pressure ulcers [median 1.0, mean 2.0 (SD 1.44), range 1–9 per patient]. As shown in Table 4, there were similar grades of pressure ulcers in both the total hospital prevalence population and the pain prevalence population. The majority (357/491; 72.7%) of reported pressure ulcers in the pain prevalence population were grade 1, 20.4% (100/491) were grade 2 and 6.9% (34/491) were grades 3–4/unstageable.

‘Of the 2010 people asked the pain questions, 327 said yes to both questions, indicating they had pain on one or more skin sites with or without a PU, providing an overall UPAR [unattributed pressure area-related] pain prevalence of 16.3%’ (see Figure 2). In total, 1769 patients did not have any pressure ulcers and 223 of these patients ‘reported pain, an UPAR pain prevalence of 12.6%. Of the 241 people with PUs, 104 patients reported pain at one or more PU site, an UPAR pain prevalence of 43.2%.’35

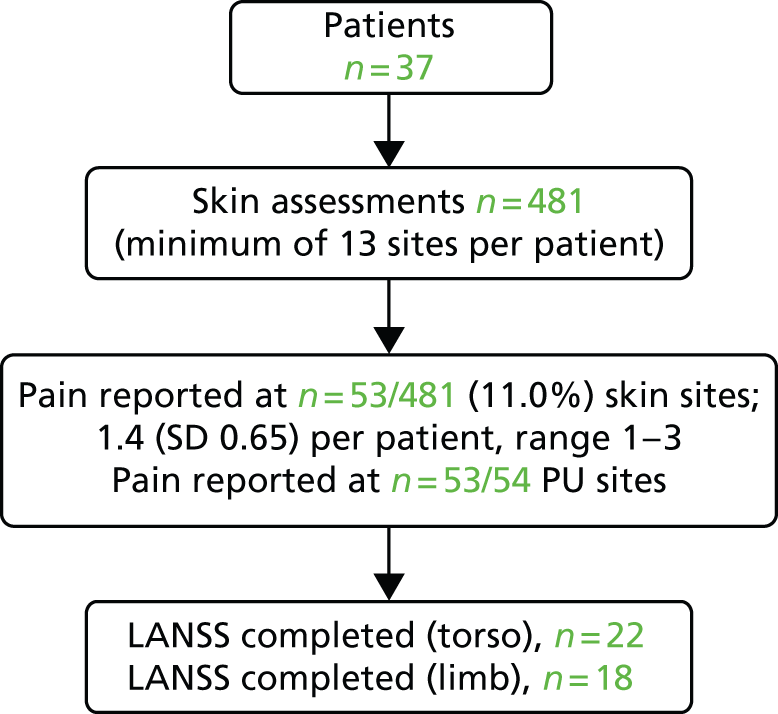

Detailed pain assessment: hospital population

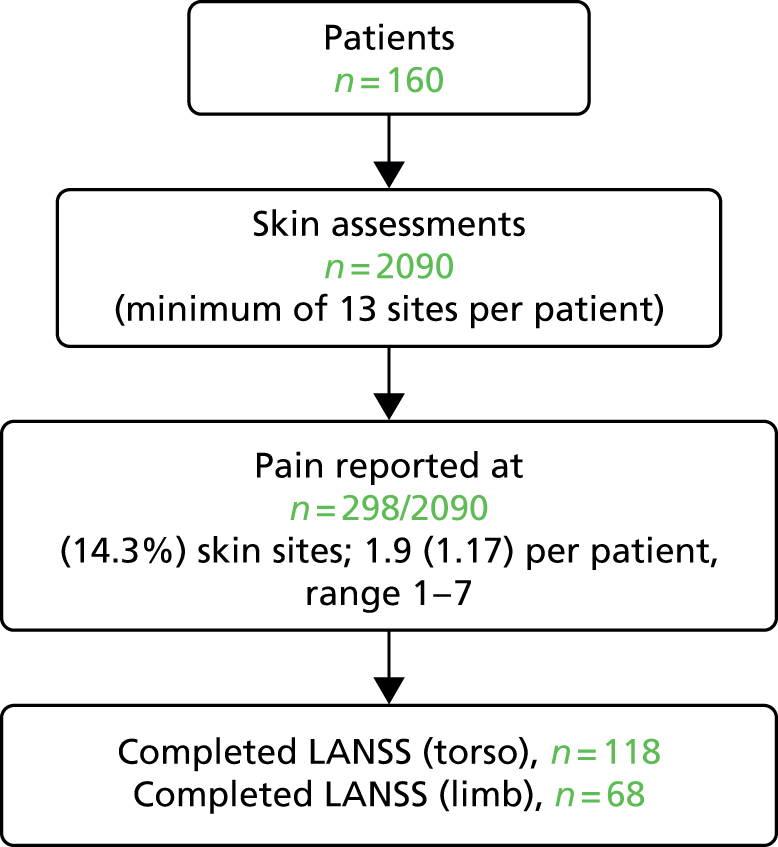

Of the 327 who answered ‘yes’ to both pain screening questions, 164 (50.2%) were not able, or declined, to participate in the full pain assessment and 163 (49.8%) consented. Three patients were subsequently withdrawn and therefore the analysis population of eligible patients with unattributed pressure area-related pain who participated in the detailed pain assessment was 160 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Participant flow: detailed pain and skin assessments: hospital population.

The median age of these 160 patients was 69.0 years [mean 66.2 (SD 18.23), range 18–99 years] and half (80/160; 50.0%) were men. Almost three-quarters (114/160; 71.3%) of patients with unattributed pressure area-related pain were assessed as ‘at risk’ on the Braden scale and four (2.5%) were non-Caucasian. A total of 75 (46.9%) patients were reported to have 139 pressure ulcers [median 1.0, mean 1.9 (SD 1.23), range 1–5 per patient] (see Table 4).

A total of 2090 skin sites were assessed (see Figure 3), with 1933 skin sites assessed as normal, 139 assessed as pressure ulcers and skin status was not able to be assessed for 18 sites. The majority (69.8%) of reported pressure ulcers were grade 1, 23.0% (32/139) were grade 2 and 7.2% (10/139) were grades 3–4/unstageable (see Table 4).

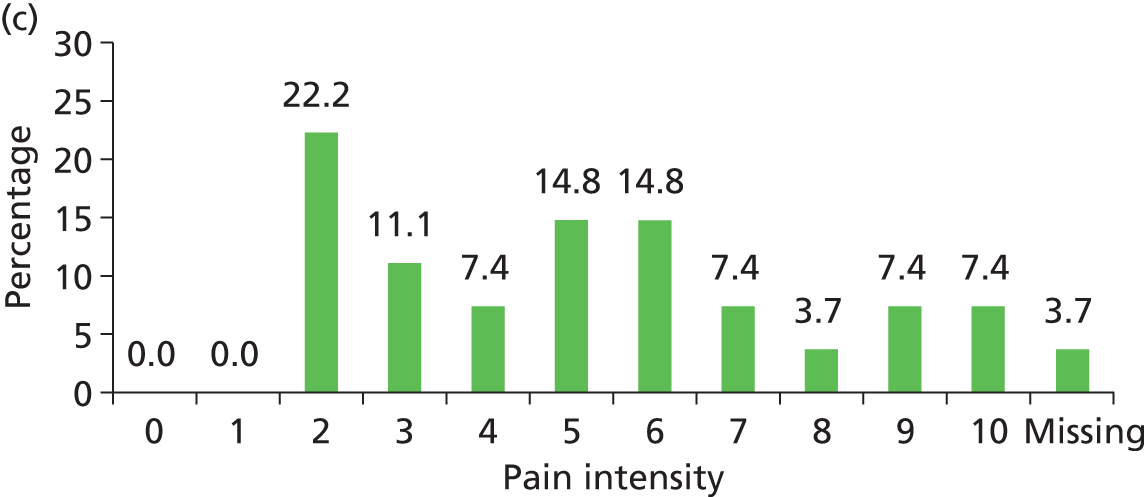

Pain was reported by 157 patients on 298 skin sites (mean 1.9, SD 1.17, range 1–7 per patient). This included pressure area-related pain reported on 9.8% (190/1933) of skin sites assessed as ‘normal’ and pressure ulcer pain for 68.0% (66/97) of grade 1 pressure ulcers, 84.4% (27/32) of grade 2 pressure ulcers and 90.0% (9/10) of grades 3–4/unstageable ulcers (Table 5). The worst pain intensity reported by each patient ranged from 1 to 10, with a mean of 5.4 (SD 2.30) and median of 5.0.

| Skin classification | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Missing, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal skin | 190 (9.8) | 1730 (89.5) | 13 (0.7) | 1933 (100.0) |

| Grade 1 | 66 (68.0) | 30 (30.9) | 1 (1.0) | 97 (100.0) |

| Grade 2 | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (100.0) |

| Grade 3 | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) |

| Grade 4 | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) |

| Unstageable | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) |

| Unable to assess | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (66.7) | 9 (100.0) |

| Classification missing | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (100.0) |

| Total | 298 (14.3) | 1772 (84.8) | 20 (1.0) | 2090 (100.0) |

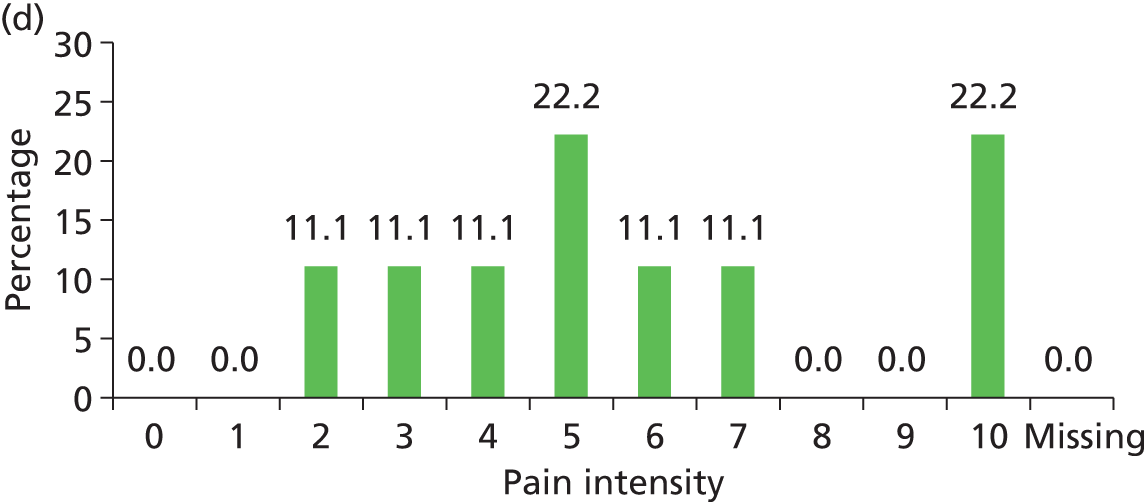

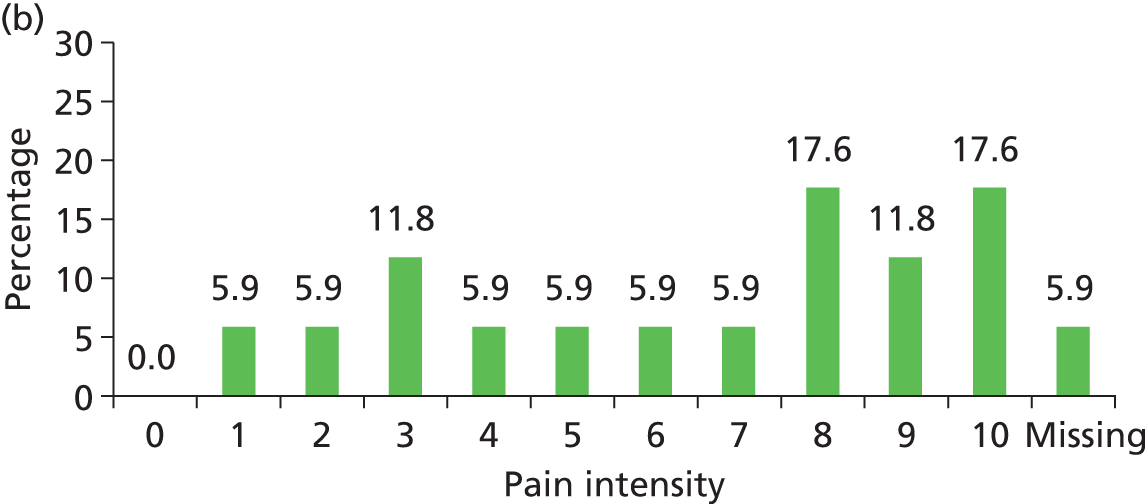

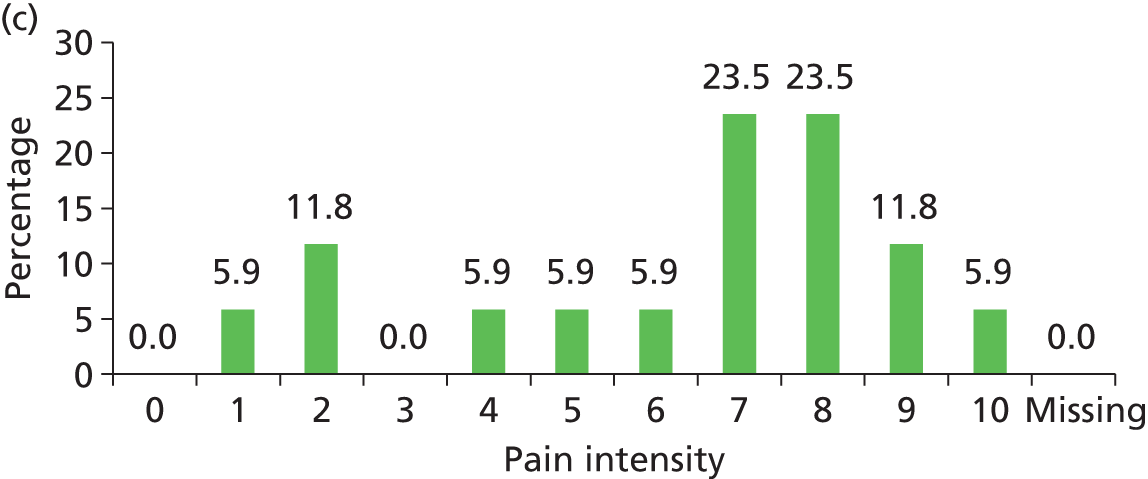

The distribution of pain intensity is similar for each grade of pressure ulcer (Figure 4). In total, 128 patients identified one skin site for LANSS assessment (89 torso and 39 limb skin sites) and 29 patients identified both a torso and a limb skin site for LANSS assessment, providing 118 torso and 68 limb LANSS assessments. Nociceptive pain was dominant in both torso and limb skin sites, with 70.3% (83/118) of painful torso skin sites and 60.3% (41/68) of painful limb skin sites scoring < 12 on the LANSS assessment (Table 6). Neuropathic pain was observed on skin assessed as normal as well as for all grades of pressure ulcer (see Table 6).

FIGURE 4.

Pain intensity by skin classification: hospital population. (a) Normal skin; (b) grade 1 pressure ulcers; (c) grade 2 pressure ulcers; and (d) grades 3–4/unstageable pressure ulcers.

| Location | Skin classification | Nociceptive, n (%) | Neuropathic, n (%) | Missing, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torso | Normal skin | 56 (76.7) | 17 (23.3) | 0 (0.0) | 73 (100.0) |

| Grade 1 | 12 (54.5) | 8 (36.4) | 2 (9.1) | 22 (100.0) | |

| Grade 2 | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Grade 3 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Grade 4 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unstageable | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) | |

| Totala | 83 (70.3) | 32 (27.1) | 3 (2.5) | 118 (100.0) | |

| Limb | Normal skin | 27 (61.4) | 16 (36.4) | 1 (2.3) | 44 (100.0) |

| Grade 1 | 11 (73.3) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) | 15 (100.0) | |

| Grade 2 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100.0) | |

| Grade 3 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Grade 4 | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Unstageable | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Totalb | 41 (60.3) | 24 (35.3) | 3 (4.4) | 68 (100.0) |

Pressure ulcer prevalence: community population

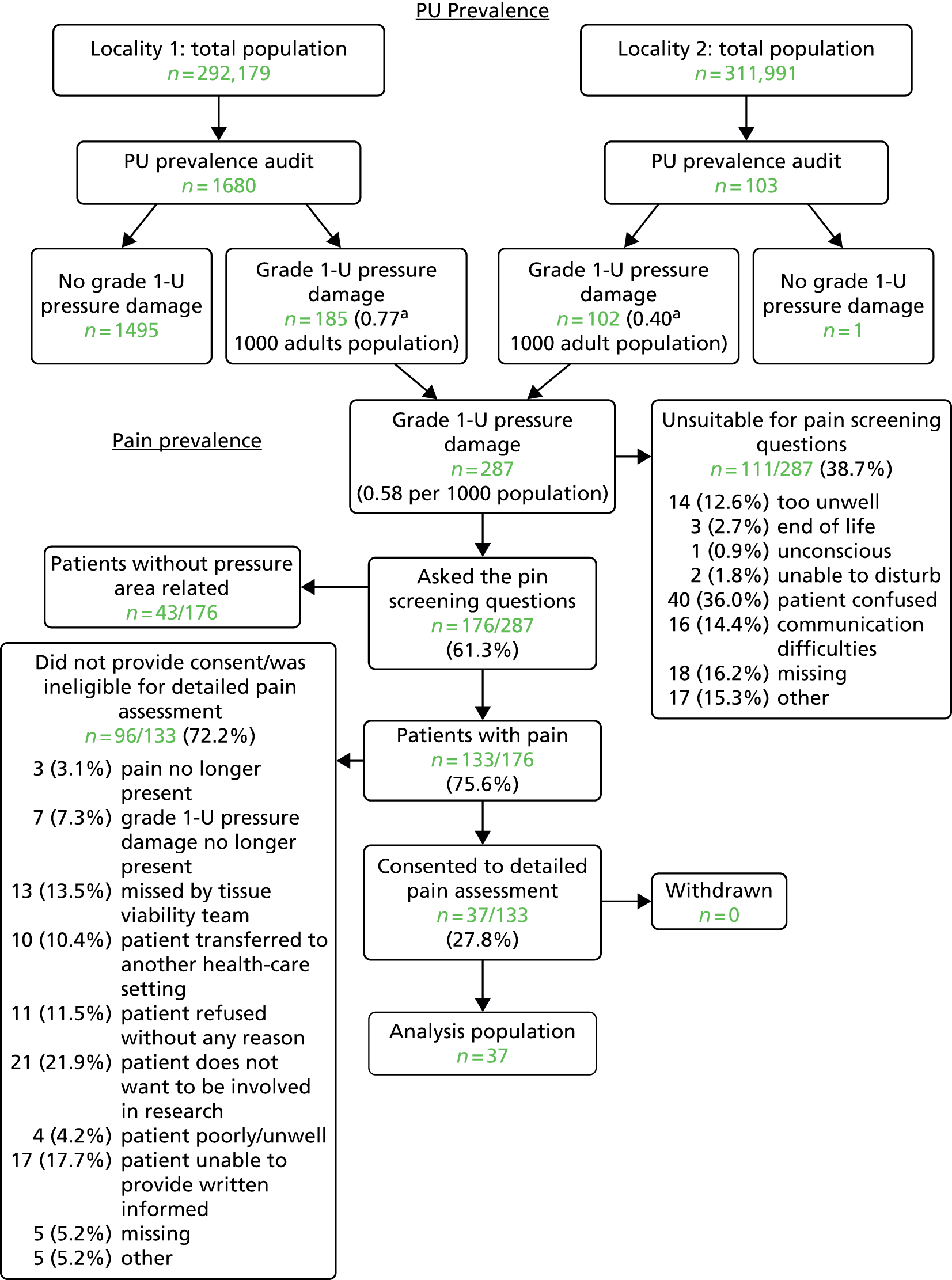

Locality 1 collected data between 8 February and 2 April 2010 and locality 2 collected data between 12 April and 7 May 2010. Figure 5 shows the patient flow through the stages of the process. 45

FIGURE 5.

Participant flow: community population. Grade 1-U, grade 1 or above. a, Locality 1 audited all patients on the caseload whereas locality 2 audited all patients with existing pressure damage. Adapted from McGinnis et al. 45 © 2014 McGinnis et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. 45

‘The two community NHS Trusts identified 287 patients with Grade 1–4/Unstageable pressure damage. The case finding methods resulted in differing prevalence rates. In locality 1, 1680 patients were assessed, and of these 185 patients were assessed as having a pressure ulcer ≥ Grade 1, a prevalence rate of 0.77 per 1000 [(185/240,038) × 1000 adults]. In locality 2, 102 patients were identified from the community nursing caseloads and assessed as having a Grade ≥ 1 pressure ulcer, a prevalence rate of 0.40 per 1000 [(102/251,891) × 1000 adults]’45. A notable difference between the two sites, and one that could also contribute to the difference in reported prevalence, was the patients’ place of residence. In locality 1, 93 out of 185 (50.3%) patients were resident in a nursing home, whereas in locality 2 only five out of 103 (4.9%) patients were resident in a nursing home.

The median age of patients with pressure ulcers was 81 years (mean 77.8, SD 13.44, range 23–106 years), just over one-third of patients were male (100/287; 34.8%),45 89.6% (251/280) were assessed as being ‘at risk’ using either the Waterlow scale or the Braden scale and only 1.4% (4/287) were non-Caucasian (Table 7).

| Characteristic | Total community prevalence population | Pain prevalence population | Detailed pain assessment population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population, n | 287 | 176 | 37 |