Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10029. The contractual start date was in July 2008. The final report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Neil Marlow reports personal fees from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), Shire plc (Dublin, Ireland) and GlaxoSmithKline plc (Middlesex, UK), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Field et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Choice of topic

At the time that this programme grant was conceived, in 2007, the intention was to improve understanding of some of the key contributors to the high rates of early childhood morbidity and mortality in the UK. This broad aim remains relevant as, although progress has been made in the intervening years, these same themes appeared in the 2012 Chief Medical Officer’s (CMO’s) report published in October 2013. 1

When planning the research it was clear that it would not be possible to target all of the factors that contribute to early childhood mortality and morbidity, but our intention, and the linking theme of the work, was to focus on important areas of practice and/or policy in which knowledge and understanding were lacking. Therefore, the original application was focused on three topic areas.

Perinatal and early childhood mortality rates

Although UK stillbirth, neonatal and infant mortality rates had generally reduced over previous decades, it was clear that there were wide health inequalities in these rates across the country2 and overall stillbirth rates had demonstrated much more limited change. 3 Furthermore, it was recognised that UK rates for each of these measures were high compared with those in similar developed countries. 4

Premature birth was known to be the major component of both neonatal and infant mortality, accounting for approximately 50% of neonatal deaths,2 with very preterm birth (< 33 completed weeks’ gestation) account for most of the deaths. Previous data from our group demonstrated that rates of delivery of < 33 weeks were particularly high in the UK, and we also found that rates of very premature birth doubled when the least deprived areas of the country were compared with the most deprived. 5 However, at the start of this programme there was little information about the extent to which variation around the country was explained by differences in other causes of early death such as congenital anomaly or, indeed, other aspects of how and where premature infants were managed.

Late and moderately preterm birth

Late and moderately preterm (LMPT) birth is defined as birth between 32 and 36 completed weeks’ gestation. At the time of our application this area was largely unstudied in the UK and yet, numerically, LMPT babies remain the largest group of preterm babies. 6,7 In particular, we did not know whether or not deprivation had the same influence on these babies or if most of them were born because it was considered safer to end a pregnancy in which some complication had arisen. Perhaps more importantly, we knew little about the degree to which these babies contributed to early childhood mortality and morbidity. Better understanding of the risks attached to delivery at this gestation was seen as important in helping families and clinicians in the management of high-risk pregnancies in which delivery between 32 and 36 weeks’ gestation was seen as an option.

Our third stream of work was intended to explore the use of biochemical markers to identify women early in pregnancy who were at high risk of preterm delivery. This stream was considered unlikely to deliver benefit to the NHS within 3–5 years [a prerequisite for National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme grants] and hence this stream was not funded.

Therefore, the report of the programme that follows describes the outputs from two streams of work.

Stream 1

This stream was designed to focus on an analysis of stillbirth and early childhood mortality rates, with the aim of improving understanding of the different influences on these rates in the UK. The work relied heavily on both routine data and more specialist data collected for other purposes.

Stream 2

This stream focused on the contribution of the group of babies born at 32–36 weeks’ gestation to both early mortality and morbidity. This work was based on a cohort of babies born LMPT and a random set of term-born control infants.

Developments during the course of the programme grant

In terms of the work focused on early childhood mortality, developments/new information during the course of the programme reinforced the need for more detailed studies to take place. In particular, in the years leading up to 2010 the NHS had a key target of reducing the health inequalities in infant mortality by 10%. 8 Despite this, health inequalities were widening at the time this programme commenced. A lack of understanding of the major influences on both neonatal and infant mortality was identified at a Department of Health workshop as one of the major difficulties in achieving the target. Therefore, even if one sets aside the huge importance to individuals and communities in reducing neonatal and infant mortality, there remains a need to understand the public health and societal influences that lead to both the UK’s relatively high rates of death in early life and the associated health inequalities. In particular:

-

the scale of the impact of deprivation on the published rates

-

the effect of cultural and religious differences between communities which, for example, could influence the management of antenatally identified severe congenital anomalies

-

the extent to which public health interventions could influence particular causes of death (such as sudden infant death syndrome).

Without such an understanding it was simply not possible to develop a rational approach to reducing perinatal and early childhood mortality rates.

During the period of the programme grant, a range of studies focusing on LMPT babies were published from around the world, but particularly in the USA, where such babies were growing in number. However, most of these studies were small and retrospective and without the opportunity to combine data about antenatal events, neonatal course and subsequent development. Certainly no such studies have emerged from the UK.

New questions did arise, in particular regarding the extent to which LMPT births contribute to the overall burden of morbidity resulting from prematurity. Routine data from Scotland9 demonstrated a link to an increased incidence of special educational need in babies born LMPT, but it remained unclear whether this was a generic risk attached to all babies born at these gestations or whether the affected babies represented a specific subset that could be identified (and potentially targeted for intervention) in the antenatal or neonatal period.

Therefore, the aims and objectives of the programme, which are set out at the start of the report from each stream, remained both topical and relevant.

Chapter 2 Understanding inequalities in cause-specific infant mortality (stream 1)

Aim

The aim of stream 1 was to understand the recent widening inequalities in infant mortality rates (death in the first year of life) by exploring cause-specific mortality, gestation and deprivation.

Objectives

Original objectives

-

To investigate if excess infant deaths related to prematurity have increased in more deprived areas.

-

To investigate how inequalities in cause-specific infant, neonatal and perinatal mortality have changed over time.

-

To explore health inequalities in neonatal and perinatal mortality among very preterm infants and to identify whether or not service use varies with deprivation.

-

To explore risk factors for mortality in the neonatal and perinatal period.

-

To develop newly defined cause-specific mortality targets for primary care trusts (PCTs) accounting for variations in case mix.

Deviations from the original planned research

The original research plan focused on one of the key determinants of inequality in neonatal mortality: deaths related to immaturity, including detailed analyses of these deaths to improve understanding of the reason(s) for these inequalities using detailed regional data. Results from early analyses indicated that another key element of the socioeconomic inequalities associated with infant mortality is congenital anomalies. Deaths as a result of a congenital anomaly accounted for the largest proportion of the deprivation gap in neonatal mortality attributable to a single cause, and also represented a significant proportion of the deprivation gap in stillbirths. It seemed clear that understanding how these inequalities related to congenital anomalies arose was key to implementing effective public health interventions to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in infant and neonatal mortality. The objectives of the study were, therefore, modified in order to allow a detailed exploration of the underlying reasons behind these issues, looking particularly at the impact of variations in patterns of termination of pregnancy for congenital anomaly on rates of stillbirth, live birth and neonatal mortality. It was felt that this should take higher priority, as little research has been undertaken in this area. The presence of the East Midlands and South Yorkshire Congenital Anomalies Register (EMSYCAR) within the same research team facilitated this analysis.

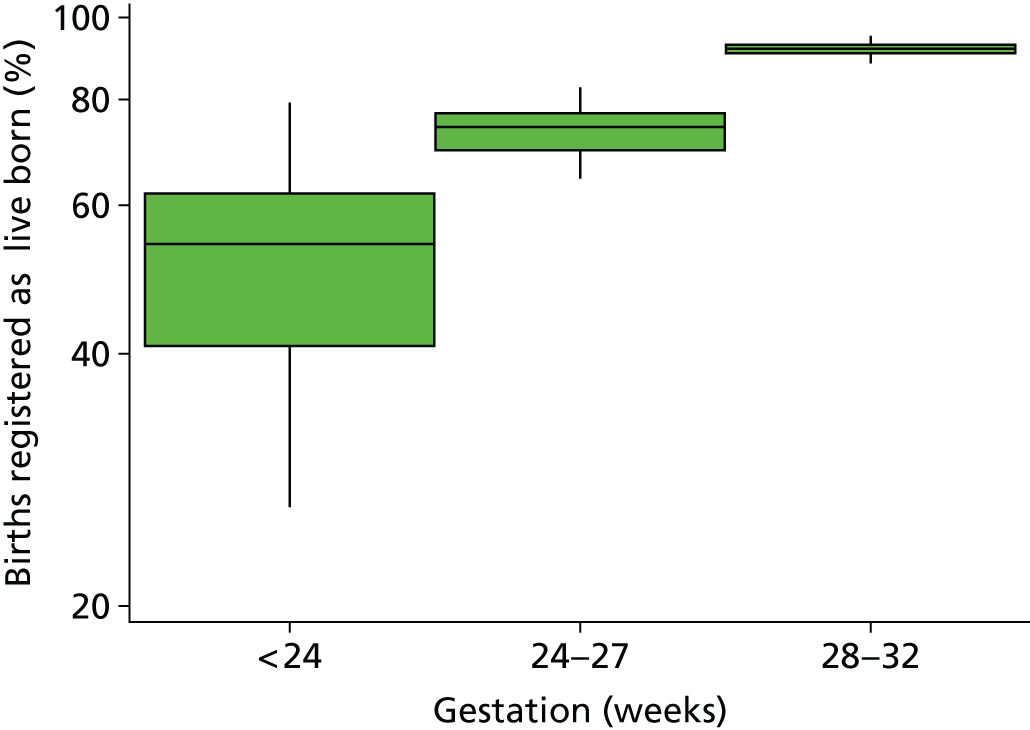

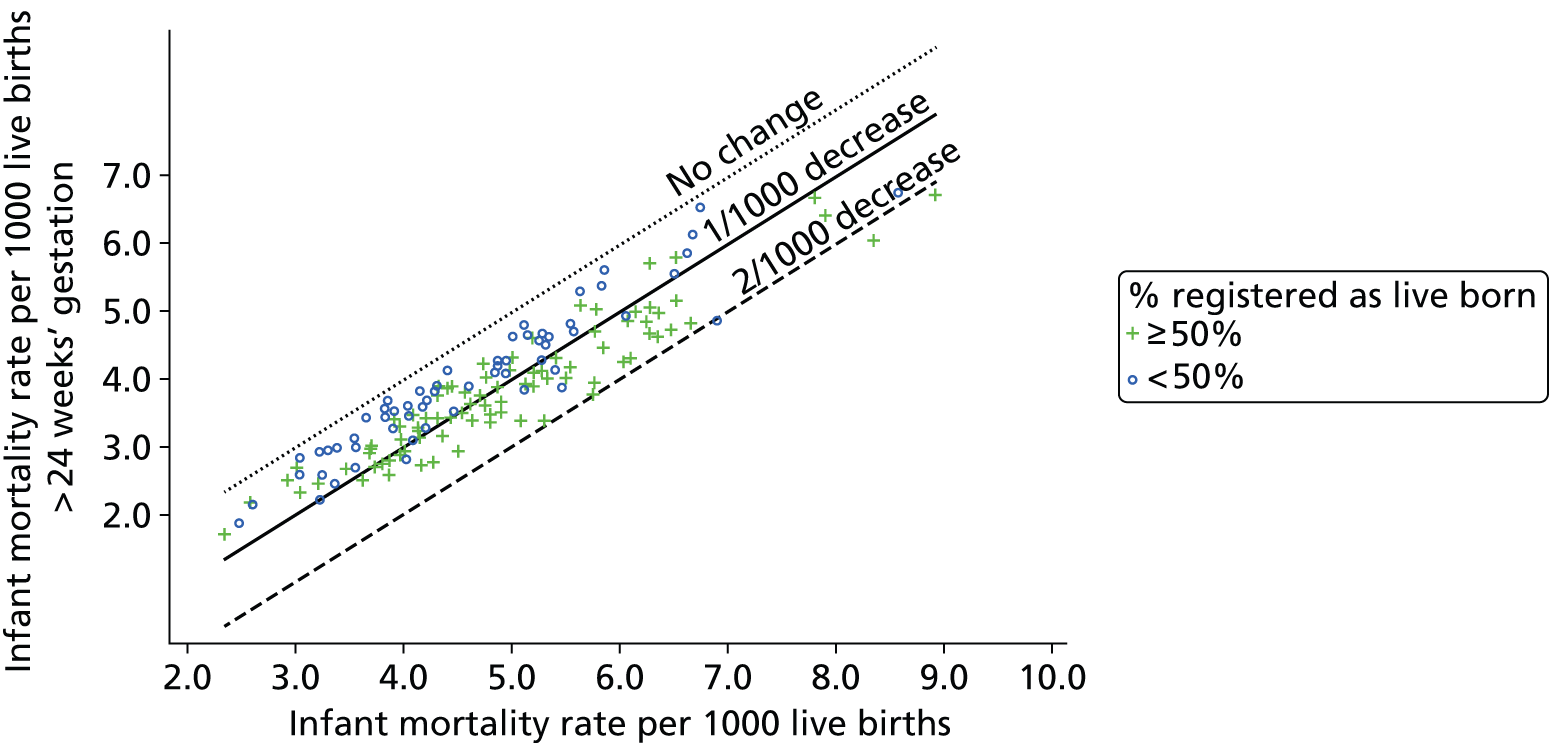

As a priority, our research planned to look at adjusting infant mortality rates at a local level for differences in case mix, particularly socioeconomic deprivation. This was intended to aid policy-makers and commissioners working in PCTs to reliably assess how they compared with other regions with broadly similar population case mix and hence assess whether or not appropriate packages of care could be implemented in their region to improve outcomes. However, it was apparent on close inspection of the data when embarking on this work that there were major differences in the reporting of live births of infants aged 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation. Based on international research, variations in birth registration practices have been shown to have a major influence on infant mortality rankings and there was clearly a need to assess the scale of this issue in the UK in order that ‘real’ variations in performance could be separated from those arising as a result of artefactual/administrative differences. Therefore, it seemed essential to explore the available data for the UK on the variation in the registration of births of infants at 22 and 23 weeks of gestation and the impact of this variation on infant mortality.

Amended objectives

-

To investigate socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific neonatal mortality rates in England (study 1).

-

To investigate socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific stillbirth rates in England (study 2).

-

To explore the reasons underlying cause-specific inequalities in mortality (study 3).

-

To improve comparisons of mortality between health regions accounting for variations in case mix (study 4).

Study 1: investigating socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific neonatal mortality in England

Background

Despite overall improvements in mortality and neonatal care, in the UK 17 babies die just before, during or just after birth every day, with around 6500 deaths per year. 10 Wide socioeconomic inequalities exist in stillbirth and neonatal mortality, with significantly higher rates in the most deprived areas of England. 11 The UK government made major attempts to tackle socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality by setting a public service agreement target in 2003 to reduce the relative deprivation gap in England and Wales by 10% by 2010. 8 However, the deprivation gap in all-cause mortality, rather than narrowing, showed evidence of widening. 12 The limitations of all-cause mortality analyses meant that it was not clear how this widening gap was influenced by changes in the underlying trends in specific causes of death.

Preterm birth is the main cause of neonatal and infant mortality, accounting for two-thirds of neonatal deaths in England. 2 Rates of very preterm birth have increased over time in the UK and internationally5,13 and, as these rates are generally higher in more deprived areas of the UK,5 it is likely that this is associated with an increase in the absolute numbers of excess deaths relating to deprivation. Such an effect clearly has the potential to result in a widening of the health inequalities in infant mortality. Therefore, this research was designed to unpick the socioeconomic inequalities in all-cause mortality, by exploring cause-specific trends over time, and identify major potentially modifiable risk factors for mortality.

This study provided a detailed exploration of socioeconomic inequalities in infant and neonatal mortality in England using routinely available data sets.

Objective

To investigate socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific neonatal and infant mortality in England.

Methods

Description of data sets utilised

In order to achieve this objective, analyses utilised data at a national level to explore health inequalities in cause-specific infant, neonatal and perinatal mortality. As this study was based on routinely collected data that were anonymised, there was no requirement for ethics approval. The study focused on the 12-year period of 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2008 and utilised several national data sets.

National (England) data: mortality

Individual-level data on all neonatal deaths (death before 28 days of life) of singleton infants born to mothers resident in England between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2008 came from the Centre for Maternal Child Enquiries (CMACE; www.cmace.org.uk), which until 2011 collected neonatal mortality data as part of its national perinatal mortality surveillance work, funded by the National Patient Safety Agency. Originally, CMACE and its predecessor organisation collected data for all stillbirths and infant deaths; however, from 1 January 2004, CMACE data collection was limited to stillbirths and neonatal mortality, although data for late fetal losses at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation were collected until 3 December 2006. The cessation of collection of postneonatal mortality data prevented analyses of infant mortality for the whole 12-year period. However, sensitivity analyses were undertaken using information on infant mortality in 1997–2003 to assess the differences in patterns between neonatal and infant mortality. Data included cause of death, type of death (i.e. stillbirth, late fetal loss, neonatal death or postneonatal death), gestation, date of birth, mother’s age, sex of the infant, birthweight, ethnic group, multiplicity and the mother’s lower super output area (LSOA) of residence an area used in the 2001 and 2011 UK censuses,14 covering around 1500 households. Only neonatal and postneonatal deaths with a valid LSOA were included; otherwise, no deprivation score could be assigned, but this excluded only 1% of deaths.

Classification of causes of deaths

For the national data on mortality, a local CMACE co-ordinator initially classified deaths using the extended Wigglesworth hierarchical classification system. 15 A CMACE regional manager then checked them with reference to post-mortem and coroner’s reports, when available. Finally, CMACE carried out central cross-validation checks to ensure consistency.

In this report, for neonatal deaths (i.e. live births ending in a death before 28 days of life) and postneonatal deaths (deaths up until 1 year of life) the Wigglesworth classification has been used but has been expanded for deaths caused by immaturity, on the basis of gestational age at birth (< 24 weeks, 24–27 weeks and 28–36 weeks). Accidental deaths were grouped with ‘other specific conditions.’ Unfortunately, because of the changes in the classification systems used by CMACE over the time period, 1997–2008, neonatal death data classified by Wigglesworth cause of death (Box 1) were available only from 1997 to 2007, as in 2008 CMACE implemented a new cause of death classification that was not comparable with previous years of data. Therefore, for analyses involving cause of death, 11 years of data were available (1997–2007) but, for analyses of overall mortality, 12 years of data were available.

Congenital anomaly.

Intrapartum event.

Immaturity (< 24 weeks).

Immaturity (24–27 weeks).

Immaturity (28–36 weeks).

Infection.

Accidents and other specific causes.

Sudden infant death.

Denominator data: live births

Ideally, individual-level birth denominator data were required from the NHS Numbers For Babies (NN4B) project. This data set was established in 2005 and part of the financial rationale for its implementation was to provide denominator live-birth data, including gestational age (not previously available in England) for easy access by researchers. However, this aim had not been achieved and the data set was not routinely available in a timely manner. Additionally, because of confidentiality issues, data for analysis were not available at the individual level and linkage and so, unfortunately, were not usable for these analyses. After a lengthy period of unproductive negotiation, a decision was made to resort to using Office for National Statistics (ONS) birth registrations for calculating mortality rates. As no gestational age information is included in these data, this limited the detailed analyses of issues relating to prematurity. Furthermore, as a result of regulatory stipulations associated with access to ONS data, it was not possible to obtain individual-level data on live births. Birth data were, therefore, obtained in two separate ways in order to facilitate the different analyses to be undertaken. First, the number of live births by year of birth and LSOA of residence were obtained to enable the calculation of mortality rates by LSOA. These data allowed exploration of trends over time. A second data set, used primarily for study 3, was obtained from the ONS on live births with additional information on birthweight, mother’s age, sex and multiplicity of birth. These data were available only in an aggregated form providing data for deprivation deciles of LSOAs across England.

Measurement of socioeconomic deprivation

Previous government targets in England and Wales measured the relative deprivation gap by using a classification of socioeconomic group based on the father’s occupation. 12 This excluded both infants whose parents had never worked and those who were solely registered by the mother. This led to the exclusion of a significantly at-risk group. Consequently, this method of measurement of socioeconomic group is inadequate. Ideally, individual measures of socioeconomic deprivation would have been used. However, as the overall aim of this programme was to utilise routine data to assess and monitor socioeconomic inequalities, an area-level measure of deprivation was chosen to fulfil this role. Therefore, socioeconomic inequalities were measured by using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) for 200416 at the LSOA level.

This measure of multiple deprivation is made up of seven domain indices at the LSOA level, which relate to (1) income deprivation; (2) employment deprivation; (3) health deprivation and disability; (4) education; (5) skills and training deprivation; (6) barriers to housing and services; and (7) living environment deprivation and crime. LSOAs are the smallest areas for which these deprivation data are available; although some degree of heterogeneity exists within them, the small size of the areas (only 1500 residents) limits this.

All LSOAs in England were ranked by deprivation score. They were then weighted by its population of births (using the live-birth denominator data) and divided into 10 groups with approximately equal populations of births in each from 1 (least deprived) to 10 (most deprived). Thus, when calculating mortality rates, if stillbirth or neonatal mortality was the same for all deprivation groups, a similar number of neonatal deaths would be expected in each of the 10 groups. This approach offered the potential not only to monitor mortality but also to allow targeted interventions at an area level in the future.

Data linkage

The national infant mortality and stillbirth data were provided with LSOA codes. The IMD 200416 was then linked to the mortality data matching on LSOA code, facilitating the linkage to the LSOA-level ONS birth denominator data set by LSOA-level code. The second, more detailed ONS births data set was linked using deprivation decile, multiplicity of birth, mother’s age, sex of the baby and the PCT of residence at birth.

Statistical analyses

The aim of these analyses was to explore the deprivation gap in neonatal and infant mortality over time, first at an all-cause level and then by specific cause to unpick the key causes of death that related to socioeconomic inequalities in mortality. In order to explore trends by socioeconomic deprivation neonatal mortality rates for each cause of death by deprivation decile and time period were calculated. Analyses were undertaken solely for singleton births in this study because, in relation to multiple births, a variety of factors (such as differential access to fertility treatment) affects the rate at which multiple births occur and, in addition, multiple births are associated with both a higher mortality rate and additional specific causes of death.

Exploring the deprivation gap

Poisson regression models17 were used to assess trends in mortality by deprivation decile over time, fitting separate models for all-cause mortality and each specific cause of neonatal mortality. Previous UK targets for reducing socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality8 have been based on the relative deprivation gap identified in 2003. In the work carried out within this programme, in order to co-ordinate with the national targets, the relative deprivation gap was measured by fitting a linear trend between deprivation decile and mortality, and calculating the mortality rate ratio between the most deprived and least deprived deciles which is similar in approach to the relative index of inequality. 18 Significant change in the relative deprivation gap over time was assessed by fitting a separate deprivation effect for each time period. Reductions in neonatal mortality over time were explored by relative change (percentage reduction in mortality rate by deprivation decile).

Investigating both the relative and absolute deprivation gap can provide a better understanding of time trends in socioeconomic inequalities. For example, if a condition is relatively common, a small relative gap may be associated with a large absolute difference in rates. Adjusting for the underlying prevalence can ignore important changes in the absolute deprivation gap. Therefore, absolute changes in stillbirth and neonatal mortality over time by deprivation decile (difference in neonatal mortality per 10,000 births by deprivation decile) were calculated to assess improvements in mortality. The delta method was used to calculate confidence limits. 19 Excess mortality associated with deprivation was estimated as a percentage by separately applying the stillbirth rate and neonatal mortality rate in the least deprived decile to the total population divided by the total number of deaths observed. The proportion of the deprivation gap for both all-cause stillbirth and all-cause neonatal mortality explained by each cause for each time period was calculated. For each specific cause, the neonatal mortality rates in the least deprived decile and the most deprived decile for each time period were calculated using the Poisson regression models. The absolute difference between these two rates was calculated and expressed as a proportion of the absolute difference in rates for all causes combined.

Results

Deprivation gap in all-cause neonatal mortality over time

Between 1997 and 2007, a total of 18,524 neonatal deaths of singleton infants were notified to CMACE All-cause neonatal mortality decreased over time from 31.4 per 10,000 live births (1997–9) to 25.1 per 10,000 live births (2006–7), but this differed by deprivation group. In absolute terms, rates were significantly higher in the most deprived areas (Table 1). Between 1997–9 and 2006–7 rates decreased more in the least deprived decile than in the most deprived decile (most deprived decile, 7.4 fewer deaths per 100,00 births; least deprived decile, 5.6 fewer deaths per 10,000 births). However, the relative reduction in mortality over time was smaller in the most deprived decile (17%) than in the least deprived decile (26%), leading to a widening of the deprivation gap. Table 2 details the regression equation for all-cause mortality. In 1997–9 infants risk of neonatal death in the most deprived decile was twice that in the least deprived [mortality rate ratio 2.08, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.92 to 2.27], and this gap widened significantly over time, reaching a peak of 2.68 in 2003–5 before slightly narrowing to 2.35 in 2006–7. Consequently, the percentage of excess deaths associated with deprivation increased over the time period from 32.3% (1997–9) to 51.0% (2003–5) and then decreased to 37.5% (2006–7). Consequently, there was no evidence of an overall reduction over the time period to achieve the relevant NHS targets.

| Cause of death | Deprivation decile | Mortality per 10,000 live births | Reduction in mortality from 1997–9 to 2006–7 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997–9 | 2000–2 | 2003–5 | 2006–7 | Relative change, % (95% CI) | Absolute change per 10,000 births (95% CI) | ||

| All causes | Least deprived | 20.8 | 18.3 | 16.9 | 14.9 | 26.1 (18.9 to 32.7) | 5.55 (3.89 to 7.21) |

| Most deprived | 46.4 | 46.6 | 43.5 | 35.9 | 16.7 (10.4 to 22.6) | 7.41 (4.49 to 10.32) | |

| Cause-specific deaths | |||||||

| Congenital anomaly | Least deprived | 5.7 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 31.3 (16.9 to 43.3) | 1.60 (0.81 to 2.39) |

| Most deprived | 12.4 | 12.4 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 9.5 (–4.6 to 21.7) | 1.05 (–0.45 to 2.56) | |

| Intrapartum events | Least deprived | 2.4 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 15.6 (–9.4 to 34.9) | 0.45 (–0.23 to 1.13) |

| Most deprived | 3.6 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 29.4 (9.9 to 44.6) | 1.17 (0.37 to 1.96) | |

| Immaturity < 24 weeks’ gestation | Least deprived | 2.6 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 1.9 (–22.4 to 21.4) | 0.06 (–0.58 to 0.69) |

| Most deprived | 8.6 | 10.7 | 11.2 | 9.3 | –4.0 (–22.0 to 11.3) | –0.35 (–1.76 to 1.07) | |

| Immaturity 24–27 weeks’ gestation | Least deprived | 4.9 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 44.7 (31.4 to 55.4) | 2.19 (1.44 to 2.94) |

| Most deprived | 9.9 | 8.0 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 35.1 (22.9 to 45.4) | 3.24 (2.00 to 4.48) | |

| Immaturity 28–36 weeks’ gestation | Least deprived | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 56.8 (32.3 to 72.4) | 0.81 (0.42 to 1.21) |

| Most deprived | 3.0 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 60.4 (42.3 to 72.8) | 1.63 (1.03 to 2.23) | |

| Infection | Least deprived | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 24.6 (–1.9 to 44.3) | 0.49 (–0.02 to 0.99) |

| Most deprived | 3.7 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.1 | –5.2 (–33.0 to 16.8) | –0.20 (–1.11 to 0.72) | |

| Accidents and other specific causes | Least deprived | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 10.7 (–24.5 to 35.9) | 0.17 (–0.32 to 0.66) |

| Most deprived | 2.8 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 7.2 (–23.0 to 29.9) | 0.19 (–0.53 to 0.91) | |

| Sudden infant death | Least deprived | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 6.8 (–69.0 to 48.6) | 0.03 (–0.21 to 0.27) |

| Most deprived | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 40.3 (6.9 to 61.7) | 0.62 (0.11 to 1.14) | |

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.002 | < 0.001 | |

| Year (2000–2) | 0.85 | 0.035 | 0.78 to 0.92 |

| Year (2003–5) | 0.77 | 0.032 | 0.71 to 0.84 |

| Year (2006–7) | 0.74 | 0.035 | 0.67 to 0.84 |

| Deprivation decile | 2.08 | 0.089 | 1.92 to 2.27 |

| Deprivation decile year (2000–2) | 1.22 | 0.076 | 1.08 to 1.37 |

| Deprivation decile year (2003–5) | 1.29 | 0.081 | 1.14 to 1.46 |

| Deprivation decile year (2006–7) | 1.13 | 0.081 | 0.98 to 1.30 |

Deprivation gap in specific-cause neonatal mortality over time

The next step was to explore these deaths in more detail by investigating the cause-specific mortality. Immaturity was the most common cause (45.4%), followed by congenital anomalies (24.5%), intrapartum events (10.8%), infection (9.8%), accidents and other specific causes (7.1%), and sudden infant deaths (3.0%). The number of deaths increased with increasing deprivation for each cause, although the magnitude of this increase varied by cause. With the exception of deaths due to immaturity of < 24 weeks’ gestation, neonatal mortality fell over time for all causes, with the greatest falls seen for immaturity of 24–27 and 28–36 weeks’ gestation.

For five of the eight causes of death [congenital anomalies, immaturity (< 24 weeks and 24–27 weeks), infection and accidents and other specific causes], there was a larger relative fall in mortality over time in the least deprived decile than in the most deprived decile, although this was only statistically significant for congenital anomalies (Table 3). For these causes and immaturity (28–36 weeks) the trend in the deprivation gap over time was similar to all-cause neonatal mortality, with an initial two- to threefold ratio deprivation gap in 1997–9 (neonatal mortality rate ratio range 1.70–2.98) which increased up to 2003–5 (range 2.17–4.14) followed by a slight narrowing in 2006–7 (range 1.72–3.16) (see Table 3). The widest deprivation gap was seen for death due immaturity of < 24 weeks’ gestation, with the risk of death in the most deprived decile in 1997–9 being threefold that in the least deprived decile; the increased risk of death rose to over fourfold in 2003–5 and fell again slightly to threefold in 2006–7. As the absolute mortality did not fall over this time period, this widening of the deprivation gap led to the deaths due to immaturity of < 24 weeks’ gestation representing a larger proportion of all deaths in 2006–7 (21.7%) than in 1997–9 (16.9%).

| Cause of death | 1997–9, mortality rate ratio (95% CI) | 2000–2, mortality rate ratio (95% CI) | 2003–5, mortality rate ratio (95% CI) | 2006–7, mortality rate ratio (95% CI) | Test for interaction between deprivation and year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All causes | 2.08 (1.92 to 2.27) | 2.53 (2.32 to 2.77) | 2.68 (2.45 to 2.93) | 2.35 (2.10 to 2.63) | p = 0.0004 |

| Cause-specific deaths | |||||

| Congenital anomaly | 2.16 (1.82 to 2.56) | 2.92 (2.43 to 3.51) | 3.06 (2.54 to 3.70) | 2.85 (2.27 to 3.58) | p = 0.0264 |

| Intrapartum events | 1.37 (1.07 to 1.76) | 1.15 (0.87 to 1.53) | 1.21 (0.94 to 1.56) | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.61) | p = 0.7817 |

| Immaturity < 24 weeks’ gestation | 2.98 (2.42 to 3.67) | 3.28 (2.66 to 4.05) | 4.14 (3.40 to 5.06) | 3.16 (2.47 to 4.04) | p = 0.1217 |

| Immaturity 24–27 weeks’ gestation | 1.88 (1.57 to 2.25) | 2.49 (2.03 to 3.06) | 2.38 (1.94 to 2.92) | 2.21 (1.68 to 2.91) | p = 0.1779 |

| Immaturity 28–36 weeks’ gestation | 1.88 (1.35 to 2.62) | 1.74 (1.16 to 2.59) | 3.22 (2.10 to 4.95) | 1.72 (0.93 to 3.18) | p = 0.1393 |

| Infection | 1.92 (1.45 to 2.54) | 2.66 (2.00 to 3.53) | 2.17 (1.57 to 3.00) | 2.68 (1.88 to 3.83) | p = 0.3333 |

| Accidents and other specific causes | 1.70 (1.23 to 2.35) | 2.29 (1.65 to 3.18) | 2.71 (1.92 to 3.83) | 1.77 (1.18 to 2.65) | p = 0.1987 |

| Sudden infant death | 3.62 (2.15 to 6.07) | 2.47 (1.49 to 4.07) | 2.08 (1.26 to 3.43) | 2.32 (1.14 to 4.73) | p = 0.4806 |

Rates of intrapartum death and sudden infant death showed fell more among the most deprived decile than in the least deprived, leading to a non-significant narrowing of the deprivation gap in mortality of these causes. However, these deaths constituted only 13.5% of deaths, and their impact on all-cause mortality was small. Deaths due to intrapartum events showed the narrowest deprivation gap (ranging from 1.15 to 1.37 across the time period). Consequently, the reduction in deaths if the rates seen in the least deprived decile were applied across all deciles was small, ranging from 6.8% to 14.8%. In contrast, the deprivation gap for sudden infant deaths was the widest seen for any specific cause in 1997–9 (mortality rate ratio 3.62). This showed a non-significant decrease over time to 2.32 in 2006–7. Sudden infant deaths would have been reduced by over half in 1997–9 if mortality rates for the least deprived decile were applied to the whole population, compared with a reduction of just over one-third in 2006–7.

Graphical approach to understanding the deprivation gap

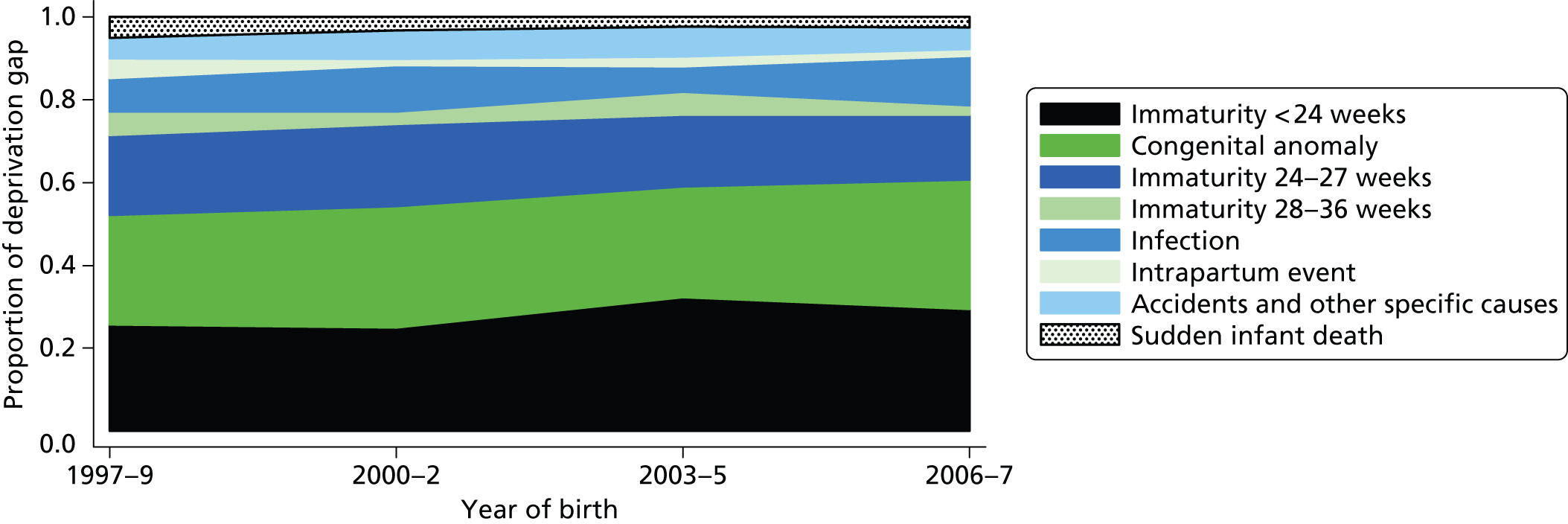

In order to best convey the cause-specific socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, a graphical approach was chosen. Figure 1 demonstrates the percentage of the deprivation gap in all-cause neonatal mortality explained by each specific cause. The width of the bands is directly related to the proportion of the deprivation gap in neonatal mortality that each cause accounts for. This graph clearly demonstrates that deaths due to immaturity (babies of < 24, 24–27 and 28–36 weeks’ gestation) and congenital anomalies explain the majority of the deprivation gap in all-cause mortality. Thus, all deaths due to immaturity and congenital anomalies combined accounted for 77% of the deprivation gap in 1997–9, rising to a peak of 81.9% in 2003–5 and then declining again to 79% in 2006–7. This increase in the proportion of the deprivation gap explained by prematurity and congenital anomalies was due to a combination of a widening deprivation gap in mortality for these causes, the high proportion of deaths due to these causes and a lack of decline in mortality due to immaturity at < 24 weeks. The remaining causes (sudden infant death, intrapartum events, infection, accidents and other causes) account for only 20% of the deprivation gap. Their reduced impact is partially related to their relatively smaller contribution to overall mortality, but also the narrow deprivation gap in mortality for intrapartum deaths. The percentage of the gap explained by sudden infant deaths fell over time from 5% (1997–9) to 2.5% (2006–7).

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of the deprivation gap in all-cause neonatal mortality rates explained by each cause of death over time. Reproduced from Smith et al.,20 © 2010, British Medical Journal Publishing Group, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Licence (CC BY-NC 2.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and is otherwise in compliance with the licence.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses of infant mortality rates (1997–2003) showed extremely similar trends in the deprivation gap over time for all-cause mortality and death from each specific cause, but deprivation gaps for individual causes of death tended to be higher than for neonatal mortality overall. In 1997–9, sudden infant deaths explained 20% of the deprivation gap in all-cause infant mortality, but this declined to 8% by 2003. In contrast, immaturity and congenital anomalies accounted for 53% of the deprivation gap in 1997–9, increasing to 73% in 2003, similar to the percentage seen in neonatal mortality. Hence, although the percentage of infant deaths due to each cause differed from neonatal deaths in 1997–9, over time the patterns became increasingly similar as immaturity and congenital anomalies played a greater role.

Conclusions

Key findings

-

As there was a decrease in neonatal mortality over the period 1997–2007, the relative deprivation gap (the ratio of mortality in the most deprived decile to that in the least deprived decile) increased, particularly for deaths related to congenital anomalies and immaturity.

-

Almost 80% of the relative deprivation gap in all-cause mortality was explained by premature birth and congenital anomalies.

Limitations and strengths

Availability of death data

This work focused on neonatal mortality, as data on gestation-specific postneonatal deaths after 2003 were not available. However, patterns in infant mortality in 1997–2003 were extremely similar to those seen for neonatal mortality, with a slightly wider deprivation gap.

Individual-level socioeconomic data

No routine data on individual risk behaviour, lifestyle, health and ethnicity were available for the mothers included in this work. Inevitably this has limited the extent of the conclusions that can be drawn and has the potential to have introduced a degree of confounding. For example, epidemiological work using individual-level data has shown wide differences in stillbirth rates associated with maternal smoking during pregnancy, hypertension and maternal obesity. Neonatal deaths are also known to be more common in sole registrations. The lack of individual-level data also meant that it was not possible to identify women who had had more than one neonatal death over the time period. However, while women who had had a neonatal death were more likely to have a recurrence, the proportion of neonatal deaths that were likely to have shown this pattern was low and, therefore, negligible in terms of our findings.

Despite these caveats, provided the results are treated with caution and trends are not extrapolated beyond the time period under study, our methods are relatively straightforward and provide a way for health service planners to monitor the latest trends in mortality.

Implications for policy and practice

Although targets were set to reduce inequalities in infant mortality by 2010 in the UK,8 the deprivation gap did not narrow. Cause-specific analyses provide more detailed information, highlighting the contribution of each causal group and the impact of interventions or changes in society over time.

In the absence of cause-specific analyses various identifiable actions were recommended in England and Wales to reduce the deprivation gap in infant mortality by the target 10% (Dr Marilena Korkodilos, Specialist Public Health Services at Public Health England, 2010, personal communication). These are, in order of magnitude of anticipated reduction:

-

increasing breastfeeding rates and reducing obesity in the routine and manual group

-

reducing rates of smoking during pregnancy

-

alleviating overcrowded housing

-

reducing teenage conceptions.

However, while these were all laudable aims, it seems clear from the work presented here that, unless interventions target specifically the risk of very premature birth and potentially lethal congenital abnormalities, the impact on the deprivation gap is likely to be minor. For example, even accounting for the higher rates of infant mortality due to sudden infant death compared with neonatal mortality, based on our findings the contribution to the total mortality gap is simply too small to have a significant impact. The situation is somewhat different for smoking, as there is evidence to suggest that smoking is an important factor in the aetiology of preterm birth and, as a consequence, infant mortality. 21 The potential impact of reducing obesity and teenage pregnancy is less clear, in terms of existing evidence. However, smoking, obesity and teenage pregnancy have all been the subject of longstanding public health campaigns of limited success and the UK suggested goals required major behavioural changes. Our lack of understanding about the everyday environmental influences on the risk of preterm birth and major congenital abnormalities appears to be a significant impediment to the development of a rational strategy for diminishing the influence of deprivation on measures of early childhood mortality. Research has previously demonstrated the importance of immaturity in the UK compared with other European countries22 and the March of Dimes has highlighted the problem in global terms. 13 Tackling the wide deprivation gap among those less born at than 24 weeks’ gestation is likely to be achievable not through further progress in neonatal care but only through prevention. The need for a greater understanding of the mechanistic link between deprivation and prematurity is a major research priority, which would then allow a focus on primary preventative strategies to reduce the rate of prematurity itself. Our lack of understanding about the influence of health inequality in relation to major congenital anomalies deserves no less attention.

These findings point to ways in which our understanding of the social influences on early childhood mortality rates in particular localities might be improved, for example:

-

The annual cause-specific mortality should be measured and overall neonatal and infant mortality rates should be reviewed. Cause-specific analyses provide much greater insight into socioeconomic inequalities in neonatal mortality on a global level, thus facilitating each country’s/area’s understanding of its early childhood mortality rates and identifying appropriate interventions for prioritisation.

-

The use of the father’s occupational class to assess socioeconomic group should be avoided, as this excludes single mothers from analyses, a significant at-risk group. Area-level deprivation measures offer an inexpensive and quick way to continue monitoring inequalities. However, the collection of, and timely access to, comprehensive individual-level information for neonatal deaths and denominator data would be a further improvement.

-

Improved data linkage between large routine data sets such as NN4B would facilitate considerable improvement in the research related to socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality.

-

Greater focus should be placed on the influence of preterm birth and congenital anomalies in neonatal mortality.

-

Strategies for reducing socioeconomic inequalities should focus on the prevention of preterm birth rather than improvements in neonatal care, particularly for babies born before 24 weeks’ gestation.

Recommendations for future research

-

There is a great need for a greater understanding of the mechanistic link between deprivation and prematurity. In order to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in neonatal mortality rates, there needs to be a shift in focus from targeting risk factors that have a minimal effect on prematurity rates to major primary prevention strategies for preterm birth.

-

The methods proposed here for monitoring inequalities in neonatal mortality provide a quick and straightforward way of monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in the future. However, the collection of, and timely access to, comprehensive individual-level information for neonatal deaths is required to confirm the findings at an individual level.

Study 2: investigating socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific stillbirth in England

Background

Although there have been considerable improvements in health care in developed countries, stillbirth remains a common adverse pregnancy outcome,23 and in the UK rates have been particularly high. 24 This issue appears to be intractable and, in contrast to the improvements seen in neonatal mortality, there has been little or no reduction in rates of stillbirth over time. 3 This has led to an increase in the contribution of stillbirths to perinatal mortality. Consequently, stillbirth is a major public health burden that is frequently overlooked, since stillbirths are often excluded from international comparisons of maternal and infant health. 25,23

This burden has not affected all groups alike. Socioeconomic inequalities in stillbirth rates have been found in the UK and internationally,24,26,27 with women in deprived areas at higher risk of stillbirth. These deprivation differences persist even after adjusting for factors such as attendance at antenatal appointments or previous reproductive history. 28 Inequalities in stillbirth in England and Wales have existed for many years and research based on data from 1981–92 showed no signs of them diminishing. 29

Little is known about the differences in the deprivation gap by specific causes of stillbirth in the UK. Stillbirths are an extremely diverse group, with a variety of possible causes potentially resulting in a stillbirth. Consequently, identifying specific causes of stillbirth is extremely difficult. However, stillbirth is known to be linked to factors such as placental abruption, congenital anomalies and intrapartum events. It has been noted that the deprivation gap is different for different causes of neonatal mortality20 and it is likely that this is also true for stillbirths. Neasham et al. 30 investigated the extended perinatal mortality rate and noted that increased deprivation was associated with increased mortality as a result of non-chromosomal anomalies. Guildea et al. 27 noted a deprivation gap in unexplained antepartum stillbirths. However, these and other studies have been based on relatively small populations and addressed a limited number of causes.

In the UK, the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (SANDS) has campaigned for further research into stillbirth, and in particular the extent to which deprivation is a risk factor for stillbirth. 31 As discussed above, successive UK governments have made major attempts to tackle socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality culminating with the setting of a public service agreement target in 2003 to reduce the relative deprivation gap in England and Wales by 10% by 2010. 8 However, these targets neglected the issue of socioeconomic inequalities in stillbirth. Furthermore, the boundaries between early neonatal deaths and stillbirth are in many cases extremely blurred. There has been no recent evidence relating to the effect of deprivation on the overall stillbirth rate or indeed whether or not the deprivation gap has changed over time. An analysis of socioeconomic inequalities in stillbirth in England using routinely available data sets in conjunction with the analyses of neonatal deaths allowed a more detailed picture of socioeconomic inequalities in relation to early-life mortality.

Objective

The aim was to investigate socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific stillbirth rates in England.

Methods

Description of data sets utilised

In order to achieve these objectives, analyses utilised national-level data to explore health inequalities in cause-specific stillbirths. As this study was based on routinely collected data that were anonymised, there was no requirement for ethics approval. The study focused on the 12-year period between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2008, and utilised several national data sets.

Individual-level data on all singleton stillbirths (infants born at ≥ 24 weeks’ gestation and showing no signs of life at birth) born to mothers resident in England between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2008 were obtained from the CMACE, which had collected neonatal mortality and stillbirth data as part of its national perinatal mortality surveillance work funded by the National Patient Safety Agency until 2012. Data included cause of death, gestation, date of birth, mother’s age, sex of the infant, birthweight, ethnic group, multiplicity and mother’s place of residence (LSOA). Only stillbirths with a valid LSOA were included as, otherwise, no deprivation score could be assigned, but this excluded only 1% of deaths.

Classification of causes of deaths

For the national data on stillbirth, a local CMACE co-ordinator initially classified deaths using the obstetric (Aberdeen) classification system32 for stillbirths (Table 4). A CMACE regional manager then checked them with reference to post-mortem and coroner’s reports when available. Finally, CMACE carried out central cross-validation checks to ensure consistency.

| Category | Comprised deaths due to |

|---|---|

| Congenital anomalies | Neural tube defects |

| Other anomalies | |

| Pre-eclampsia | Pre-eclampsia without antepartum haemorrhage |

| Pre-eclampsia complicated by antepartum haemorrhage | |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | Antepartum haemorrhage with placenta praevia |

| Antepartum haemorrhage with placental abruption | |

| Antepartum haemorrhage of uncertain origin | |

| Mechanical | Cord prolapsed or compression with vertex or face presentation |

| Other vertex or face presentation | |

| Breech presentation | |

| Oblique or compound presentation, uterine rupture, etc. | |

| Maternal disorder | Maternal hypertensive disease |

| Other maternal disease | |

| Maternal infection | |

| Miscellaneous | Isoimmunisation because of rhesus or other antigens |

| Neonatal infection | |

| Other neonatal infection | |

| Specific fetal condition | |

| Unexplained antepartum (SGA) | Unexplained antepartum (birthweight ≤ 10th percentile) |

| Unexplained antepartum (not SGA) | Unexplained antepartum (birthweight > 10th percentile) |

| Unclassifiable | Unclassified |

| Missing |

Several of the rarer classification groups of the obstetric (Aberdeen) classification system were combined. As so many deaths were in the unexplained antepartum deaths category, these were then divided on the basis of birthweight (≤ 10th percentile or > 10th percentile), resulting in nine categories (see Table 4). Similar to the situation for neonatal deaths, data on stillbirths, with information on cause of death according to the Aberdeen classification, were available for only 8 years (i.e. from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2007).

Denominator data: live births

The ONS birth registrations were combined with CMACE data on stillbirths to obtain a denominator of all births, used for calculating stillbirth rates. As there is no gestational age information in these data, this limited the detailed analyses of prematurity. As discussed in the analyses of neonatal deaths, birth data were obtained on the number of live births by year of birth and LSOA of residence in order to calculate mortality rates by LSOA. This allowed exploration of trends over time.

Measurement of socioeconomic deprivation

The same methodology was used for measuring socioeconomic deprivation as in the analyses of neonatal deaths, utilising routine data to assess and monitor socioeconomic inequalities. The IMD for 200416 at the LSOA level enabled allocation of a deprivation score to all infants with a valid postcode. These data were obtained from the ONS.

As for the analyses of neonatal deaths, all LSOAs in England were ranked by deprivation score. The LSOAs were then weighted by their population of births (using all births as a denominator) and divided into 10 groups with approximately equal populations of births in each from 1 (least deprived) to 10 (most deprived). Thus, when calculating mortality rates, if stillbirth rates were the same for all deprivation groups, a similar number of stillbirths would be expected in each decile.

Data linkage

National stillbirth data were provided with LSOA codes. The IMD 200416 was then linked to the mortality data matching on LSOA code. These data were then linked to the LSOA-level ONS birth denominator data set by LSOA-level code.

Statistical analyses

First, analyses were undertaken at an all-cause level and then by specific cause to identify the key causes of death that related to socioeconomic inequalities in stillbirth. In order to explore trends by socioeconomic deprivation, stillbirth rates were calculated for each cause of death by deprivation decile and time period. Analyses were undertaken for singleton births only, as, in relation to multiple births, a variety of factors (such as differential access to fertility treatment) affect the rate at which multiple births occur and, in addition, it is known that multiple births are associated with both a higher mortality rate and additional specific causes of death.

Exploring the deprivation gap

As for the analyses of neonatal mortality, Poisson regression models were used to assess trends in mortality by deprivation decile over time,17 fitting separate models for all-cause mortality and each specific cause of death for stillbirths. As discussed, UK targets for reducing socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality8 were based on the relative deprivation gap, to avoid the influence of the underlying prevalence. The relative deprivation gap was assessed by fitting a linear trend between deprivation decile and mortality and calculating the mortality rate ratio between the most deprived and least deprived deciles, which is similar in approach to the relative index of inequality. 18 Significant change in the relative deprivation gap over time was assessed by fitting a separate deprivation effect for each time period. Reductions in stillbirth over time were assessed by calculating the relative change (percentage reduction in stillbirth rate by deprivation decile).

Once again the absolute change in the outcome (in this case stillbirth) was calculated over time by deprivation decile to assess improvements in mortality. The delta method was used to calculate confidence limits. 19 Excess mortality associated with deprivation as a percentage was estimated by separately applying the stillbirth rate in the least deprived decile to the total population and dividing that by the total number of stillbirths observed. The proportion of the deprivation gap in all-cause stillbirth rates explained by each cause was calculated for each time period. Then for each specific cause, the stillbirth rate was estimated in the least deprived decile and the most deprived decile for each time period by using the regression models. The absolute difference in these two rates was then calculated and expressed as a proportion of the absolute difference in rates for all causes combined.

Results

Deprivation gap in all-cause stillbirth rates over time

From 2000 to 2007, 21,472 singleton stillbirths were reported to CMACE; of these, LSOA was missing in 120 (0.6%) and cause of death was missing or unclassifiable in 919 (4.3%), leaving 20,433 for analyses. First, the overall rate of stillbirth over time and by deprivation was assessed (Table 5). The overall stillbirth rate was 4.4 per 1000 births and there was no evidence of a change in stillbirth rate over time (2000–3 rate, 4.4 per 1000; 2004–7, 4.4 per 1000; p = 0.80). The total number of stillbirths in each deprivation decile increased as deprivation increased, with the number in the most deprived decile approximately double that in the least deprived. Women from the most deprived decile were twice as likely to experience a stillbirth of any cause than those from the least deprived (rate ratio 2.1, 95% CI 2.0 to 2.2; p < 0.0001). There was no evidence that this changed over time.

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.0004 | < 0.001 | |

| Year (2004–7) | 0.991 | 0.029 | 0.94 to 1.05 |

| Deprivation decile | 2.117 | 0.068 | 1.99 to 2.25 |

| Deprivation decile year (2004–7) | 0.999 | 0.045 | 0.91 to 1.09 |

Deprivation gap in cause-specific stillbirth rates

Looking at stillbirths by cause of death (Table 6) revealed that antepartum deaths of unknown cause accounted for the highest percentage of stillbirths [59.2%: 21.3% small for gestational age (SGA); 37.9% not SGA] followed by antepartum haemorrhage (13.0%); maternal disorders (9.1%); congenital anomalies (7.8%); pre-eclampsia (4.2%) and mechanical issues during labour (2.4%). The remaining 4.3% were due to miscellaneous or unclassified reasons and were excluded from the Poisson regression analyses.

| Cause of death | Deprivation decile (1 = least deprived, 10 = most deprived) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total | |

| Live births | 463,148 | 464,092 | 464,487 | 465,295 | 465,814 | 466,377 | 467,227 | 467,767 | 468,144 | 469,044 | 4,661,395 |

| Stillbirths | |||||||||||

| All cause | 1489 | 1526 | 1642 | 1783 | 1991 | 2099 | 2372 | 2647 | 2760 | 3043 | 21,352 |

| Cause-specific stillbirths | |||||||||||

| Congenital anomalies | 106 | 111 | 116 | 114 | 159 | 132 | 184 | 229 | 258 | 258 | 1667 (7.8) |

| Pre-eclampsia | 60 | 66 | 70 | 71 | 80 | 96 | 121 | 112 | 111 | 107 | 894 (4.2) |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | 141 | 152 | 185 | 229 | 261 | 287 | 302 | 366 | 372 | 478 | 2773 (13.0) |

| Mechanical | 52 | 40 | 46 | 46 | 51 | 67 | 52 | 55 | 47 | 56 | 512 (2.4) |

| Maternal disorder | 130 | 126 | 157 | 156 | 190 | 181 | 222 | 258 | 275 | 251 | 1946 (9.1) |

| Miscellaneous (including isoimmunisation) | 26 | 32 | 37 | 31 | 25 | 32 | 38 | 47 | 42 | 47 | 357 (1.7) |

| Unknown antepartum (SGA) | 293 | 290 | 351 | 385 | 374 | 438 | 527 | 574 | 613 | 709 | 4554 (21.3) |

| Unknown antepartum (not SGA) | 650 | 682 | 635 | 701 | 790 | 802 | 874 | 942 | 960 | 1051 | 8087 (37.9) |

| Unclassifiable | 31 | 27 | 45 | 50 | 61 | 64 | 52 | 64 | 82 | 86 | 562 (2.6) |

There was no evidence of trends of increasing or decreasing rates of stillbirth over time for any specific cause (Table 7); however, the deprivation gap varied by cause. Mechanical issues during labour was the only specific cause for which there was no evidence of a deprivation gap [relative risk (RR) 1.2, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.5]. All other causes of stillbirth showed a significant deprivation gap, varying from a 1.7- to a 3.1-fold difference. The widest deprivation gap was seen for deaths due to antepartum haemorrhage; women from the most deprived decile were 3.1 (95% CI 2.8 to 3.5) times more likely to experience stillbirth of this cause than those from the least deprived decile. Wide deprivation gaps were also seen for deaths due to congenital anomalies (rate ratio 2.8, 95% CI 2.4 to 3.3) and maternal disorders such as hypertension (RR 2.2, 95% CI 1.9 to 2.5). The deprivation gap was wider for stillbirths of infants who were SGA (RR 2.5, 95% CI 2.3 to 2.7) than for those who were not SGA (RR 1.7, 95% CI 1.5 to 1.8; p = 0.26) (see Table 4). The percentage excess deaths of all causes related to deprivation was 33%, suggesting in total one-third more stillbirths were observed than would have been expected if the stillbirth rate for all deprivation groups were the same as that for the least deprived decile.

| Cause of death | Deprived decile | Rates of stillbirth per 10,000 births (95% CI) | Change in mortality from 2000–3 to 2004–7 (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–3 | 2004–7 | Absolute change per 10,000 births | Relative change (%) | ||

| All stillbirths (N = 20,433) | Least deprived | 29.3 (28.1 to 30.5) | 29.3 (26.0 to 32.9) | –0.3 (–2.0 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) |

| Most deprived | 61.9 (59.9 to 64.0) | 61.2 (59.3 to 63.2) | –0.7 (–3.5 to 2.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0) | |

| Cause-specific stillbirths | |||||

| Congenital anomalies (n = 1667; 8.1%) | Least deprived | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.4) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.4) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

| Most deprived | 6.3 (5.6 to 7.0) | 5.2 (4.6 to 5.8) | –1.1 (–2.0 to -0.2) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | |

| Pre-eclampsia (n = 894; 4.4%) | Least deprived | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.5) | –0.2 (–0.6 to 0.2) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Most deprived | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.3) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.9) | –0.4 (–1.0 to 0.2) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | |

| Antepartum haemorrhage (n = 2773; 13.6%) | Least deprived | 3.3 (2.9 to 3.7) | 3.1 (2.2 to 4.3) | –0.2 (–0.7 to 0.3) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) |

| Most deprived | 10.5 (9.7 to 11.4) | 9.2 (8.5 to 10.1) | –1.2 (–2.4 to –0.1) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | |

| Mechanical (n = 512; 2.5%) | Least deprived | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.4) | 0.2 (–0.2 to 0.5) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.6) |

| Most deprived | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | –0.2 (–0.5 to 0.2) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | |

| Maternal disorder (n = 1946; 9.5%) | Least deprived | 2.5 (2.2 to 2.8) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.2) | 0.5 (–0.03 to 1.0) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) |

| Most deprived | 5.9 (5.3 to 6.6) | 6.1 (5.5 to 6.7) | 0.2 (–0.7 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | |

| Unknown antepartum (SGA) (n = 4554; 22.3%) | Least deprived | 6.0 (5.5 to 6.6) | 6.1 (4.7 to 7.8) | –0.2 (–0.9 to 0.6) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| Most deprived | 14.9 (13.9 to 16.0) | 14.7 (13.7 to 15.7) | –0.2 (–1.6 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | |

| Unknown antepartum (not SGA) (n = 8087; 39.6%) | Least deprived | 13.5 (12.6 to 14.3) | 15.2 (12.7 to 18.3) | –0.3 (–1.5 to 0.8) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

| Most deprived | 20.9 (19.7 to 22.1) | 23 (21.9 to 24.2) | 2.1 (0.5 to 3.8) | 1.1(1.0 to 1.2) | |

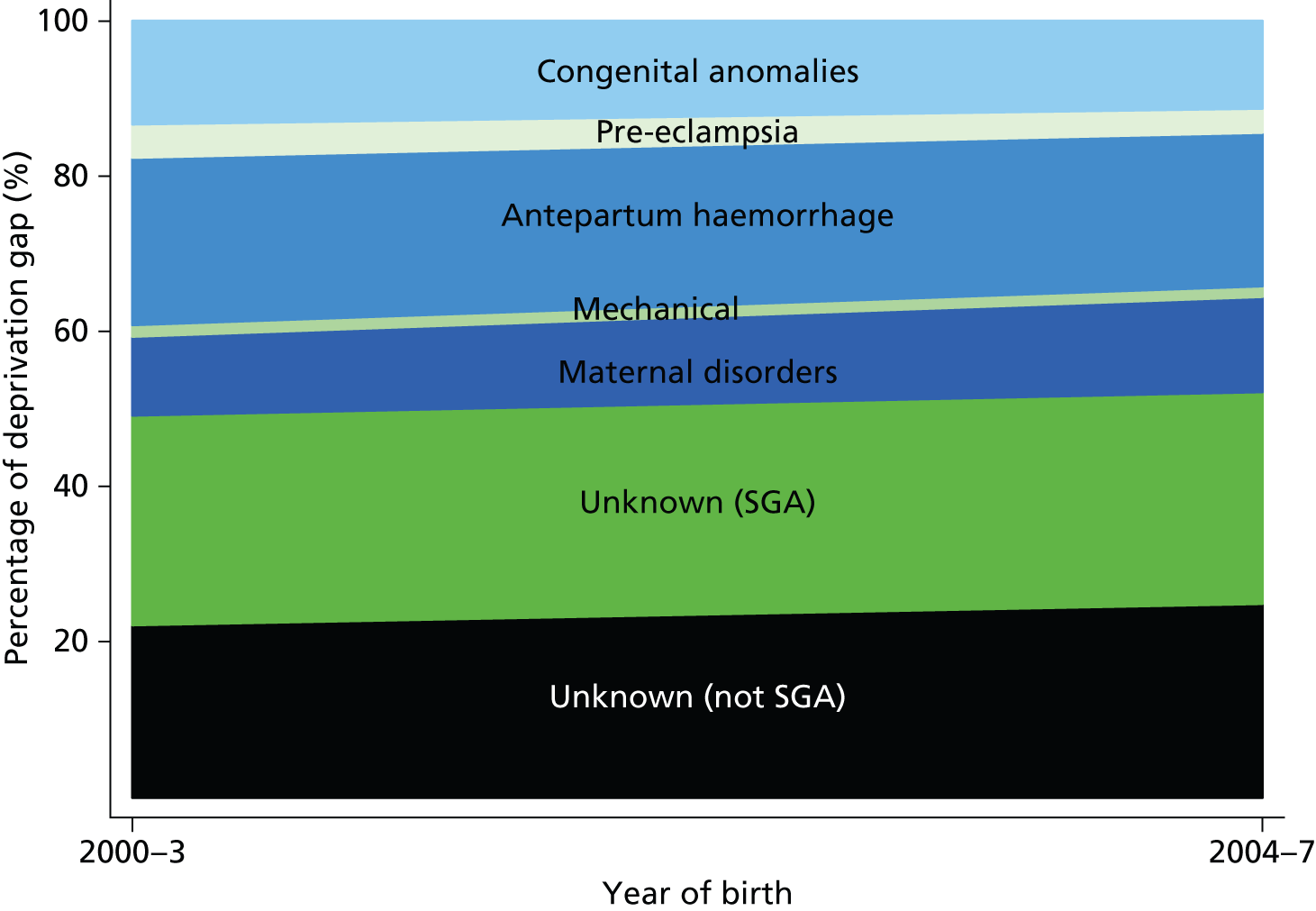

Graphical approach to understanding the deprivation gap

Again, in order to best illustrate the cause-specific socioeconomic inequalities in stillbirth, a graphical approach was chosen. Figure 2 demonstrates the percentage of the deprivation gap in all-cause stillbirth mortality explained by each specific cause estimated from the Poisson regression models. This figure highlights that those deaths due to unexplained antepartum events account for 50% of the deprivation gap. Although, overall, among unexplained antepartum deaths, the proportion of infants who were SGA were smaller than the proportion who were not (22.3% SGA and 39.6% not SGA), the SGA group explains more of the deprivation gap. This is because the deprivation gap was wider for stillbirth infants who were SGA (RR 2.5, 95% CI 2.3 to 2.7) than for those who were not SGA (RR 1.7, 95% CI 1.5 to 1.8). There was no evidence of a change in the proportion of the deprivation gap explained by any of the different causes over time, which can be seen by the lack of change in the gradient of the lines representing each specific cause. Mechanical causes are seen to constitute a very small, insignificant proportion of the deprivation gap.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of the deprivation gap in all-cause stillbirth rates explained by each cause of death over time. Reproduced from Seaton et al. 33 © 2012, British Medical Journal Publishing Group, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Licence (CC BY-NC 2.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and is otherwise in compliance with the licence.

Conclusions

Key findings

-

Rates of stillbirth were twice as high in the most deprived decile as in the least deprived.

-

This wide gap remained constant over time and was not diminishing.

-

There was a significant deprivation gap for most specific causes of stillbirth.

-

Unexplained antepartum stillbirths accounted for 50% of the deprivation gap.

Limitations and strengths

Classification of deaths

A limitation of much stillbirth research, including this work, is that many stillbirth classifications, such as the obstetric (Aberdeen) classification,32 classify the majority of stillbirths as occurring for unknown reasons and hence further analysis to improve understanding is restricted. Alternative classifications of these deaths were not available for this work as for the time period under study national routinely collected data in England used only the Aberdeen classification for stillbirth. There are currently 35 published classification systems for stillbirth,25 many relying on advanced diagnostics that are not globally available. These systems are not comparable and there has been a strong case made to have one universal system for all countries. 34 Consequently, there has been a call for a consensus on definitions and classifications in order to better understand the causes of stillbirth. 24 Alternative systems, such as the classification of stillbirth by relevant condition at death (ReCoDe)35 or the Cause of Death and Associated Conditions (CODAC)36 classification, provide a possible cause of death for approximately 85% of stillborn infants, providing greater insight to guide those developing interventions to reduce future mortality.

Individual-level socioeconomic data

As discussed in the analyses of neonatal deaths, data on individual risk behaviour, lifestyle, health and ethnicity were not available for the mothers included in this work as it has been in other research. Inevitably, this has limited the extent of our conclusions and has the potential to have produced a degree of confounding. For example, epidemiological research using individual-level data has shown wide differences in stillbirth rates associated with maternal smoking during pregnancy24 and maternal obesity. 37 Stillbirths are also known to be more common in sole registrations. 38 In women from deprived areas of Scotland, maternal smoking status accounted for 38% of the inequalities seen in stillbirths. 21 The lack of individual-level data also meant that it was not possible to identify women who had more than one stillbirth over the time period. However, as women who have had a stillbirth are more likely to have a recurrence, the proportion of stillbirths that are likely to show this pattern is low and, therefore, negligible in terms of our findings.

Despite this, provided the results are treated cautiously and trends are not extrapolated beyond the time period under study, our methods are relatively straightforward and provide a way for health service planners to monitor up-to-date trends in stillbirth.

Implications for policy and practice

Cause-specific analyses provide more detailed information, highlighting the contribution of each causal group to deprivation differentials and the impact of interventions or changes in society over time.

Recent reductions in the stillbirth rate in other high-income countries24 suggest that there exist modifiable risk factors and that by the introduction of targeted interventions, an improvement in stillbirth rates could be seen, in particular the early identification of close monitoring of fetal movements. 39 Maternal smoking may be targeted successfully to impact on the rate of stillbirths, but effective tools to reduce maternal obesity and rates of teenage pregnancy are currently lacking. 40 Smoking, obesity and teenage pregnancy have all been the subject of longstanding public health campaigns of limited success and the UK suggested goals require major behavioural changes.

Some practical measures could help in improving our understanding of the role of deprivation in relation to stillbirth:

-

Cause-specific socioeconomic inequalities in stillbirth should be monitored annually.

-

Avoid the use of the father’s occupational class to assess socioeconomic group, as this excludes single mothers from analyses, a significant at-risk group. Area-level deprivation measures offer an inexpensive quick way to continue monitoring inequalities.

-

Improved data linkage between large routine data sets such as NN4B would facilitate considerable improvement in the research related to socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality.

-

The implementation of an improved, internationally adopted, classification system would enhance the ability to identify other modifiable risk factors. In addition, such a system would facilitate the implementation of appropriate targets and interventions and reduce the proportion of stillbirths assigned to unknown causes.

Recommendations for future research

-

The lack of change in stillbirth rates in the UK and the persistent wide socioeconomic inequalities highlights the need for further research to understand this intractable problem.

-

Assessment of the impact of recent professional recommendations on the classification of births after 24 weeks’ gestation known to have died earlier as ‘late fetal losses’.

Study 3: exploring the reasons underlying cause-specific inequalities in mortality – congenital anomalies

Background

Socioeconomic inequalities in deaths associated with congenital anomaly

Following the national work on understanding socioeconomic inequalities in neonatal mortality and stillbirth, it became apparent that a key area of concern was the widening gap in socioeconomic inequalities in neonatal mortality relating to congenital anomalies. Deaths as a result of a congenital anomaly accounted for the largest proportion of the deprivation gap in neonatal mortality due to a single cause, and also represented a significant proportion of the deprivation gap in stillbirths. Understanding how these inequalities relating to congenital anomalies arose seemed key to implementing effective public health interventions to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in infant and neonatal mortality.

Socioeconomic inequalities in congenital anomalies have been demonstrated in the rates of stillbirth and perinatal, neonatal and infant mortality. 20,30,41,42 Research had shown an increasing risk of non-chromosomal anomalies with increasing deprivation, in contrast to a decreasing risk of chromosomal anomalies. 43 This last finding was predominantly a result of the increased risk of chromosomal anomalies with increasing maternal age. However, the influence of socioeconomic deprivation along the pathway from antenatal detection to delivery and possible neonatal mortality was not fully understood because of the lack of clearly defined standardised data in the antenatal period. Countries that have introduced the use of prenatal diagnostic techniques and access to termination of pregnancy because of congenital anomaly have reported large reductions in neonatal mortality rates, in contrast to those countries with more restrictive policies on pregnancy termination. 44–47 Nevertheless, the impact of these secondary preventative measures might vary with socioeconomic deprivation in terms of access to, and timing of, antenatal detection services through to the provision of information, the interpretation of risk, and the consequent decision-making regarding continuation or termination of a pregnancy.

Evidence in this area is sparse. A systematic review of UK studies showed no evidence of social inequalities in the uptake of prenatal screening,48 whereas research in Northern Ireland,49 where there is no provision of termination services, showed inequalities in both the offer and the uptake of screening. Further research suggested that socioeconomic differentials in decision-making following antenatal detection are a result of maternal age differences. 50 The term ‘congenital anomaly’ covers a very wide spectrum from the relatively minor to those with an exceptionally poor prognostic outcome and it is secondary preventative measures targeted at the latter that have the potential to improve infant mortality rates.

A detailed analysis of regional data was undertaken to identify the underlying reasons behind the inequalities seen in the analyses of neonatal mortality and stillbirth. Data were used from a large population-based congenital anomaly register in England (EMSYCAR) covering about 10% of the births in England and Wales, for 1998–2007, to investigate socioeconomic inequalities in the risk of congenital anomalies with a poor prognosis from antenatal diagnosis to end of pregnancy. The impact of variations in rates of termination of pregnancy for congenital anomaly on rates of stillbirth, live birth and neonatal mortality associated with congenital anomaly were explored to aid understanding of the reasons for the widening socioeconomic inequalities in neonatal and infant mortality in England.

Objective

The objective was to explore the reasons underlying cause-specific inequalities in mortality.

Methods

Description of data sets

Regional data: congenital anomalies incidence and mortality

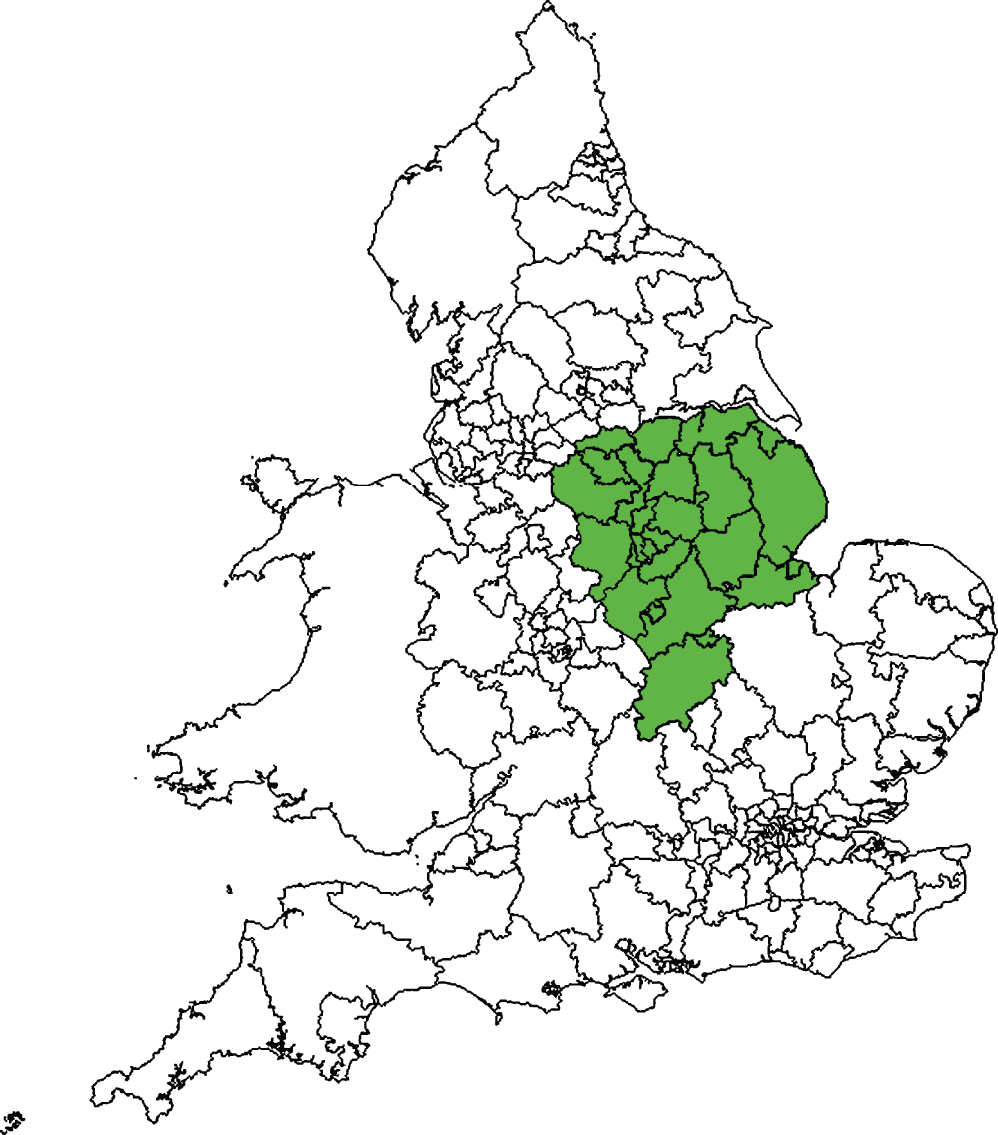

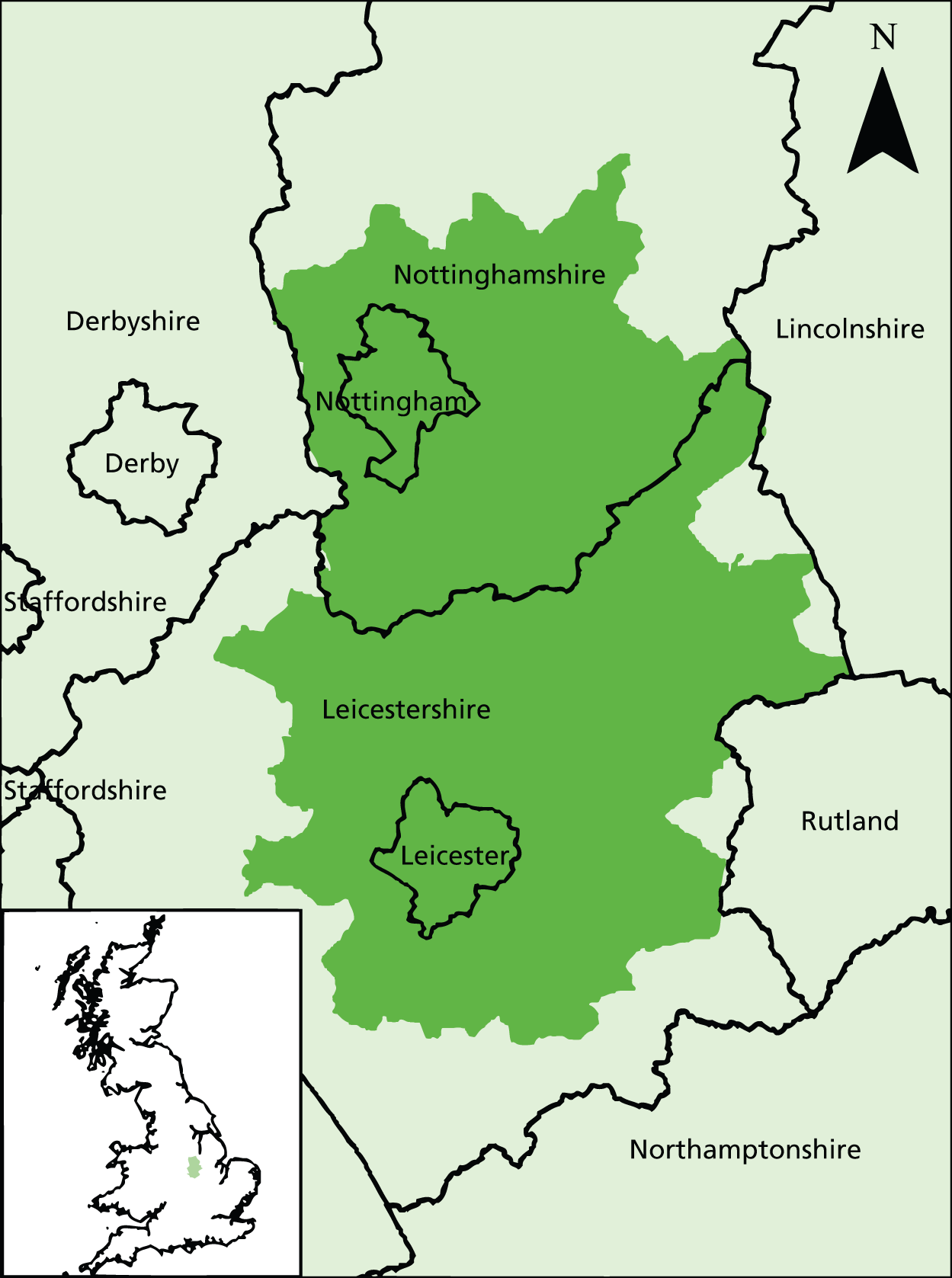

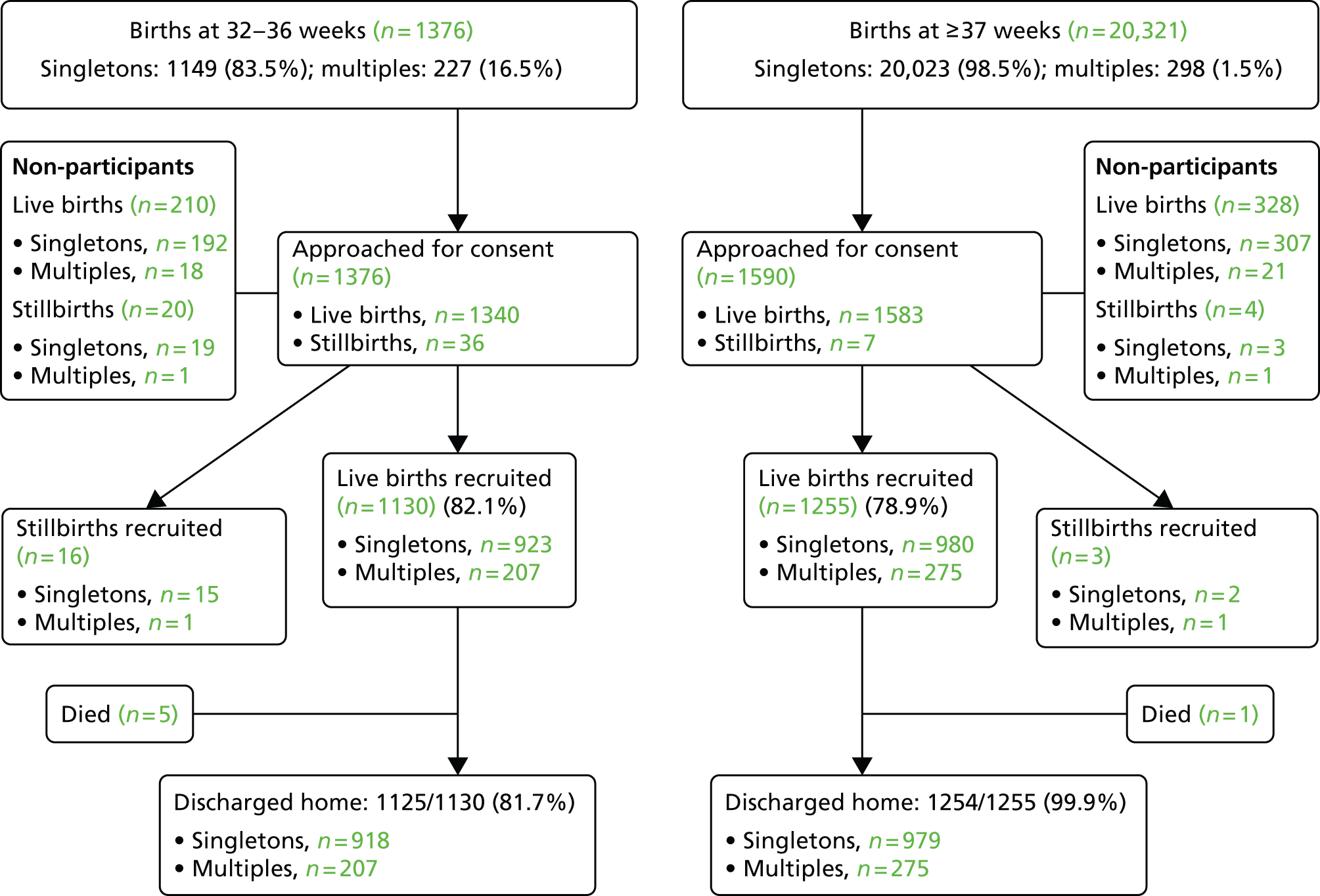

The EMSYCAR currently covers about 74,000 births annually (about one-tenth of all births in England and Wales), with around 2200 reported cases per year. The region covered by the register can be seen in Figure 3. Data for Northamptonshire, which joined the register only in 2003, were excluded, leaving a geographical area with about 60,000 births annually.

FIGURE 3.

English counties covered by the EMSYCAR.

This register is population based and includes all structural and chromosomal congenital anomalies in fetuses and infants of mothers living within the region at the time of delivery. It includes live births, stillbirths (from 24 weeks’ gestation), spontaneous fetal loss (before 24 weeks’ gestation) and termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly at any gestational age. The register uses multiple sources of case ascertainment from within the care pathway, including antenatal ultrasonography, antenatal screening, delivery reports, birth notifications, pathology, cytogenetics, clinical genetics and paediatric surgery. All reported anomalies are coded in accordance with the International Classification Of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10). Information on maternal age and ethnicity, mother’s postcode of residence at delivery, end date of pregnancy and gestation at delivery were available from data collected by the register. The study included fetuses with an anomaly with an end of pregnancy date between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2007. These data were linked to the ONS birth registrations and the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) data by LSOA to look at morbidity and mortality. Ideally, analyses would be based on the mother’s postcode at conception, but this was not available from the register. Analyses were therefore based on the mother’s postcode at delivery. To assess the potential impact of changes in the mother’s residence through the pregnancy on the observed socioeconomic inequalities, deprivation at antenatal detection and delivery was assessed separately for those fetuses for which this information was available (i.e. fetuses detected in the antenatal period when the mother opted to continue with the pregnancy).

Classification of congenital anomalies

The focus of the study was to investigate how socioeconomic inequalities arise along the care pathway from antenatal detection to delivery. Serious congenital anomalies were defined as those incompatible with life or associated with severe morbidity and for which screening systems are in place, leading to a precise antenatal diagnosis that allows parents to make an informed decision about continuation of the pregnancy. As a starting point, therefore, the 11 anomalies identified by the Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme (FASP)51 in the UK were used (Table 8). Two anomalies were excluded – cleft lip and gastroschisis – as they were much less likely to have a poor prognostic outcome. Only those anomalies associated with a unique ICD-10 code and for which there is a high level of certainty about an adverse prognosis were included. Nine anomalies met these criteria: two chromosomal anomalies (trisomy 13 and trisomy 18) and seven non-chromosomal anomalies (anencephaly, spina bifida, hypoplastic left heart, bilateral renal agenesis, lethal skeletal dysplasia, diaphragmatic hernia and exomphalos). For the majority of these, the FASP definition of the anomaly was directly related to an ICD-10 code. However, for cardiac anomalies this was much more difficult, as one ICD-10 code could relate to a less certain prognosis. Hypoplastic left heart was chosen as it is the main cardiac anomaly diagnosed antenatally for which prognosis is clear and recognised to be poor. In the case of fetuses registered with a chromosomal diagnosis, any coexisting congenital anomalies were considered as secondary to the underlying chromosomal problem, rather than separate non-chromosomal anomalies, as such associations are well established. Additional information on antenatal detection was obtained from the register on these selected anomalies, including the method and timing of diagnosis. An anomaly was deemed to be ‘antenatally detected’ if the date of detection of the exact, or a closely related, anomaly predated delivery or the date of detection of an antenatal soft marker related to the anomaly present at delivery predated the date of delivery. Ethnicity [classified into four groups: white British, Asian or Asian British (Indian), Asian or Asian British (Pakistani) and other or missing] was included in the regression models to assess whether or not the inclusion of ethnic group attenuated any observed socioeconomic inequalities in the rate of antenatal detection and termination of pregnancy.

| Anomaly | ICD-10 code | Total cases (N) | Antenatal detection, % (n) | Termination in cases detected antenatally, % (n) | Outcome of pregnancy for all cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Termination, % (n) | Fetal loss and stillbirth, % (n) | Live birth (surviving > 28 days), % (n) | Neonatal death, % (n) | |||||

| Selected anomalies | ||||||||

| Anencephaly | Q000 | 257 | 97 (249) | 88 (218) | 85 (218) | 8 (20) | 0 (1) | 7 (18) |

| Spina bifida | Q050–9 | 339 | 90 (303) | 78 (235) | 70 (235) | 6 (20) | 22 (75) | 2 (8) |

| Hypoplastic left heart | Q234 | 171 | 85 (146) | 56 (82) | 48 (82) | 8 (14) | 25 (42) | 19 (33) |