Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1335. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in April 2015 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Perez et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

SYNOPSIS

Setting the scene

Psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia and related conditions are a major concern for individuals, for society and for the NHS; they cause enormous disability and are expensive to treat. Developments in interventions have been slow. We have a clearer picture of the role of psychological therapies but the relative benefits of newer, expensive antipsychotic drugs remain uncertain. 1 However, services to deliver these interventions have changed over the last decade. For example, seminal work from around the world has led to the widespread adoption in the UK of crisis resolution and home treatment services for people with enduring mental illness such as schizophrenia, as set out in the NHS Plan. 2 In addition, a simple but radical idea concerning early-intervention services (EISs) and the evolution of psychosis through at-risk mental states has shaped service developments. Work by our research team and others has shown early developmental antecedents to psychosis. 3 As the illness becomes manifest, non-specific signs such as anxiety and depression develop and short-lived individual psychotic features form a prodrome to the full psychotic syndrome that may endure for months or even years before people seek help or receive treatment. This duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is inversely related to outcome. Treatment in the prodrome (shortening DUP) may prevent the development of severe illness, improve outcome and lead to recovery in many cases. 4

In addition to our disease focus on psychosis, this programme aimed to address a strategic issue for applied research and development (R&D) in the NHS. Although considerable amounts of clinical and social information data are processed daily within NHS and social care services, this information is disconnected from research so that it cannot be used to answer strategic questions. Many R&D developments are making important progress, but we wanted this programme to advance knowledge and understanding further by providing tools and a blueprint for connecting information, clinicians and patients in the search for the best services and interventions.

The problem we decided to tackle is cultural as well as structural.

Importance and relevance of the programme

Evidence for early intervention

At the time that our programme application was submitted the evidence base for EISs was emerging but was far from conclusive and, as ever, models successful in one area may not be suitable for another. Nevertheless, a clear blueprint was contained in the NHS Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide5 and recent years have seen the rapid development of EISs across England for young adults aged 14–35 years; hence, individual-level randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the effectiveness of early intervention are unlikely to be possible in England.

Epidemiology of high risk for psychosis

However, it was still not clear how early we should intervene as the natural history or epidemiology of individuals at high risk (HR) for psychosis was unspecified. As we began to appreciate the huge variability in the incidence of psychotic illness across different areas and communities in the UK,6 it became clear that EIS planning was significantly hindered, with the likelihood of serious mistakes from over- and underprovision because the demand was not clear. EISs in some cities are overwhelmed whereas those in affluent suburban areas have capacity to spare.

The evidence–policy–practice gap

Identification of HR individuals was difficult and unfamiliar for staff in health and social care settings, let alone in education and other arenas where more applied research was required. We knew little about the causes of psychosis in individuals and could not fully explain the major variations in risk between regions. We aimed to close these gaps with this programme of applied epidemiological and observational research and a simple application of the cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) design (see Work package 3).

In addition to having been involved in independently funded trials of psychosocial interventions aimed at earlier intervention,7 we had shown in our service that many people at an early stage of their psychotic illness have major cognitive problems that may underpin disability and be a realistic target for new interventions. 3 They also contribute to problems in functional outcome that are regarded by service users as more important than the symptoms and phenomena that professionals focus on. This functional recovery is what is important to people with psychosis, and we aimed to develop simple, patient-focused measures that could be used in everyday practice.

Unmet needs

There were gaps between the policy blueprint for EISs and existing evidence bases in epidemiology and prognosis. Furthermore, we highlighted the overarching gap between clinical practice and routine applied research.

We intended to exploit both the natural variance in our trust catchment area (Cambridgeshire and Peterborough), which covers an enormous range of demographic, social and environmental characteristics, and the planned and unplanned variation in service developments over time. With the help of recently developed statistical models for observational data we planned to build causal inferences from our observations.

We have an EIS called CAMEO [see www.cameo.nhs.uk (accessed 18 January 2016)] that includes two sister teams serving Cambridge and South Cambridgeshire, the deprived rural Fenland areas, prosperous market towns and the deprived inner-city areas of Peterborough. Our social and service variations give us sufficient capacity traction to ask, and answer, relevant questions.

By developing work from previous epidemiological and health services research studies, current descriptive research and work in our flagship EIS, CAMEO, we aimed to develop a programme of rolling observational studies and comparisons that could indicate what works and what does not work, and where a more formal RCT is needed (see Work package 3 and Work package 5). We were fully aware of the strengths and weaknesses of observational designs and considered them as complementary methods to randomised designs to address relevant questions, funded through appropriate schemes. However, we included one cluster randomised element in this programme to tell us more about HR individuals and how to detect them (see Work package 4).

Innovation

One problem with HR mental states, despite their topicality, is that we knew little (nothing) about their epidemiology. Therefore, planning services was difficult. Population-based studies suggest that individual psychotic symptoms are common in young adults. 8 However, few people appear particularly disabled by a single symptom and, although they are linked with later development of psychotic illness, the vast majority of sufferers do not seek help; we do not know how these responses are related to illness. We needed to establish the epidemiology of early psychosis through case definitions such as, but not restricted to, HR, to foster appropriate help seeking and referrals.

Later in the illness it is clear that the incidence of diagnosable psychotic disorders varies hugely in terms of age, sex, ethnic mix and social geography of local communities. We had already shown marked heterogeneity in incidence according to age, sex, ethnicity and place in the three-centre Aetiology and Ethnicity in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses (ÆSOP) study. 6 This has huge implications for EIS planners, for resource allocation decisions and for understanding where, when and why people become unwell. However, these findings are yet to be applied in a way that makes them immediately relevant to other places in the UK. Therefore, we investigated this in our diverse population and produced a service planning tool for the NHS to use nationwide (see Work package 3).

Original aims, objectives and outputs and eventual achievements

Our primary aim was to improve the identification, diagnosis and outcome of emerging and incident psychotic illness through a programme of research applied to service developments in our mental health trust. A secondary aim was to establish a system for applied R&D embedded in NHS services.

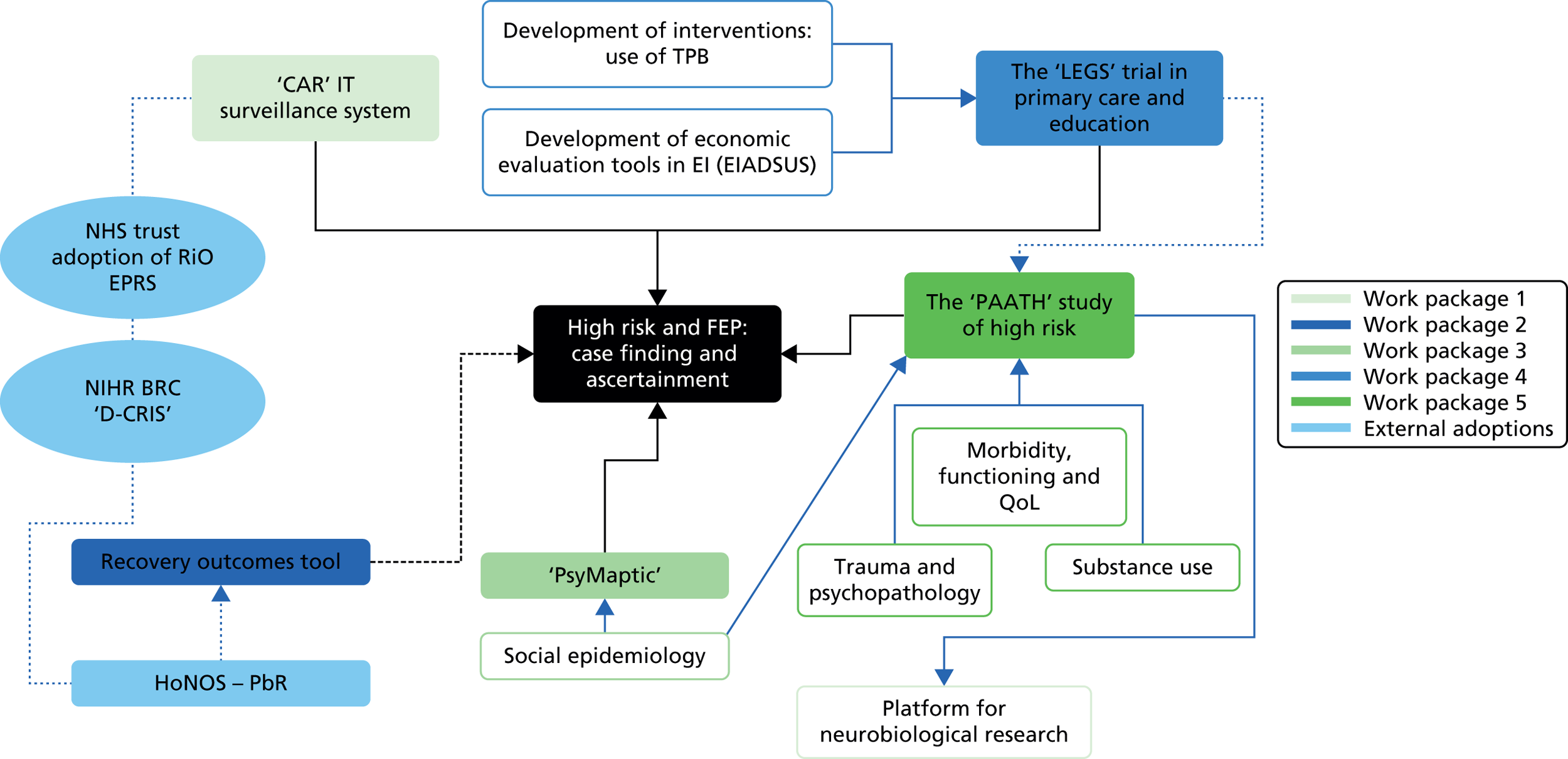

We consider that we achieved both of these aims in broad terms through a series of inter-related work packages (Figure 1), including the results of our cRCT on the identification and diagnosis of psychosis in primary care already informing NHS England commissioning guidance (see Work package 4); clinical studies on people with clinical HR mental states, function and quality of life (see Work package 5); a tool to predict the incidence of psychosis in geographical areas also informing front-line commissioning (see Work package 3); and evidence of successful embedding of researchers in clinical teams.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram depicting the whole programme and its inter-relationships. BRC, Biomedical Research Centre; CAR, Client Assessment Register; CRIS, Clinical Record Interactive Search; D-CRIS, Clinical Record Interactive Search (Collaboration Programme); EI, early intervention; EIADSUS, Early Intervention Adult Services Use Schedule; FEP, first-episode psychosis; HoNOS-PbR, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales – payment by results; IT, information technology; LEGS, Liaison with Education and General practiceS; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; PAATH, Prospective Analysis of At-risk mental states and Transitions into psycHosis; QoL, quality of life; RiO EPRS, RiO electronic patient record system; TPB, theory of planned behaviour. The neurobiological research associated with this programme was funded by the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.

These successes are evidenced by our outputs for the objectives we set ourselves to achieve our aims. These are outlined below in advance of our fuller description of each work package, but here we also note where the objectives of our original programme were unsuccessful:

-

To define the incidence and social epidemiology of psychotic disorders and those at HR for psychosis in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough and establish cohorts for research that will allow us to understand causes and target services.

Overall, this objective was achieved successfully in work package 3 (see Work package 3), with impact beyond Cambridgeshire and Peterborough to the national level. Research into the social and macrolevel environmental risk factors for first-episode psychosis (FEP) (see Appendices 1 and 2) led to the development of the PsyMaptic prediction tool [see www.psymaptic.org/ (accessed 18 January 2016) and Appendix 3], already in use by commissioners and incorporated into the NHS England commissioning guidance for EISs published in 2015. 9 In terms of causes of psychosis at this level, the work has defined and used the differences in incidence of psychosis in different localities such as population density and proportion of people in a community from black and minority ethnic groups, as well as other factors. Thus, the programme has informed national efforts to target EISs at a local level. This spatial epidemiology was extended to HR for the first time (see Appendix 4).

The case ascertainment and assessment processes that we embedded within the NHS EIS, CAMEO, to underpin this epidemiological programme (see objective 2) also supported the Liaison with Education and General practiceS (LEGS) cRCT. The cohorts of patients with HR states have been used to support mechanistic and causal research projects funded through alternative sources, complementing our applied research; these are described in Work package 5.

-

To design reliable (efficient), brief and valid assessment procedures for case mix, service use and outcome for longitudinal studies of these clinical populations and to make these data available for prognostic research to study service variations.

This objective was underpinned by work packages 1 and 2 (see Work package 1 and Work package 2), in which there was mixed success. Some aspects did not go ahead whereas others developed in unforeseen but important ways.

We describe in work package 1 the development of the Client Assessment Register (CAR), a user-friendly, computerised system that was used by clinicians and researchers within the team using local information technology (IT) systems and support. Our original ambition was to move this to a trust-wide mental health information system, not funded through the programme, to support routine clinical measurement at baseline and outcome, supporting the kind of observational studies in routine care that we had outlined in the application. In common with virtually all mental health trusts and most NHS trusts of any type, the implementation of a new IT system capable of supporting clinical work, management and research was problematic and protracted; it became clear early on that our plan would not be possible as our host trust decided to invest in the RiO electronic patient record system (EPRS) to meet its clinical and business needs.

However, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funding in the mental health Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at the South London and Maudsley (SLAM) NHS trust led to a prototypic system, the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) system, developed to provide researchers with regulated access to anonymised information extracted from electronic clinical records systems [see www.slam.nhs.uk/about/core-facilities/cris (accessed 19 January 2016)]. Originally designed for the SLAM electronic system, CRIS has now been extended as Clinical Record Interactive Search (Collaboration Programme) (D-CRIS) to five mental health trusts including the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust (CPFT), our host, and is running on our RiO electronic record system in shadow form. Thus, we were not able to implement this element of the programme, which itself was a major piece of IT development. However, this has been achieved at greater scale through larger investments in the SLAM NIHR BRC, and is being implemented in our trust at the time of writing.

As we describe in work package 2, our original intention was to use the information to develop an outcome assessment measure with considerable input from patients. Soon after we began the programme all NHS mental health trusts began to be encouraged to adopt the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS),10 later further developed for use as the ‘case mix’ adjustment for payment by results (PbR) funding of mental health services (HoNOS-PbR) (treating people with more severe disorders and greater needs attracting greater funding from commissioners and vice versa). Understandably, our host NHS trust was keen to move wholesale to this measure, something that we supported even though it made some of our programme redundant. Payment by results is not yet fully implemented as such.

-

To investigate the factors associated with transition from at-risk mental states to psychosis syndromes (true positives) and to characterise false-positive referrals.

-

To investigate the barriers to, and promoters of, functional recovery in at-risk mental states and early psychosis, in particular with relation to substance misuse.

Work packages 4 and 5 underpinned the achievement of these two objectives, with the LEGS cRCT generating referrals of FEP or HR participants (true positives) or those with a range of other disorders (false positives). Standardised assessments and instruments such as the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS)11 interview and the Mini-Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)12 were used to classify individuals’ mental health problems into psychiatric diagnoses.

The finding of the LEGS cRCT (see Work package 4) that a high-intensity liaison approach between primary and secondary care doubled, as we hypothesised, referrals of FEP and HR mental states combined, of FEP alone and of HR individuals alone (the last of these not reaching statistical significance) is important; moreover, it saved money. Our combination of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness methodology used in the trial was praised in a commentary that accompanied the publication of the LEGS trial13 and the results were incorporated in the new NHS England commissioning guidance for early intervention in psychosis. 9

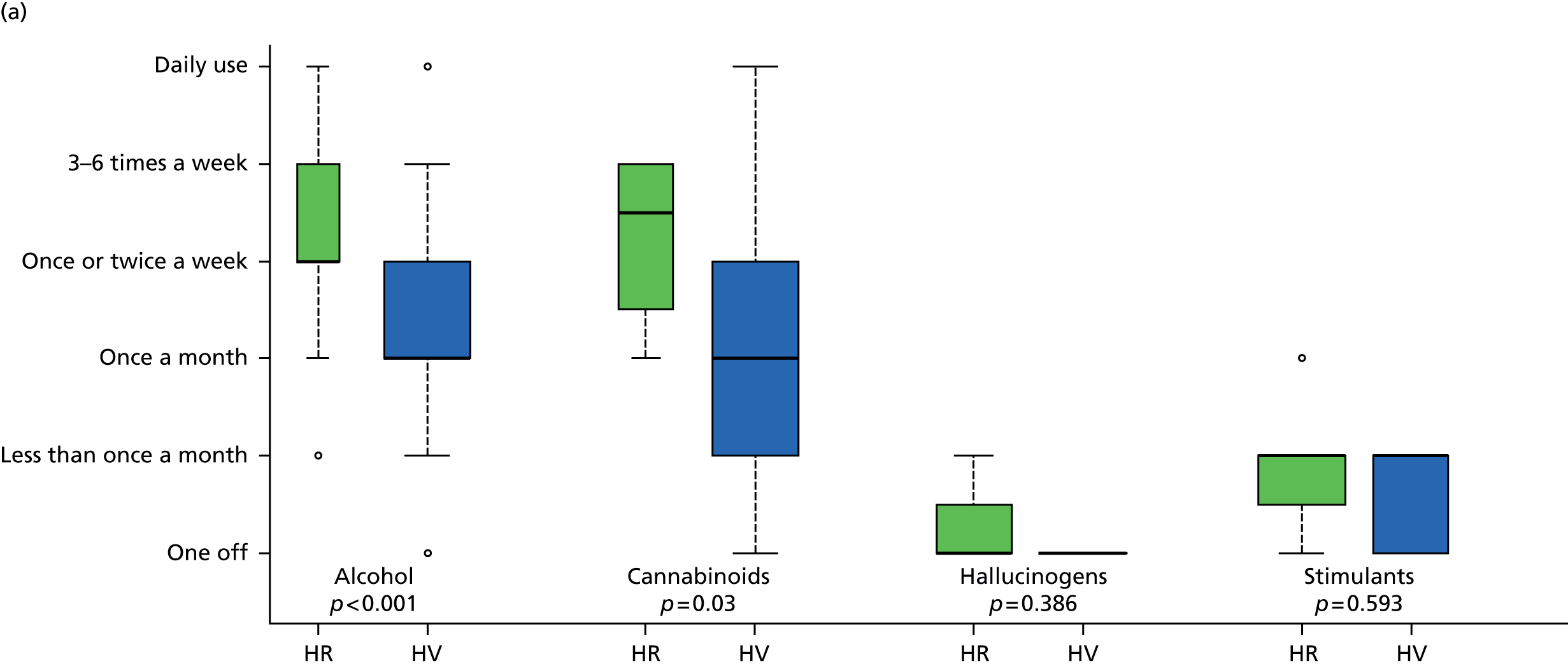

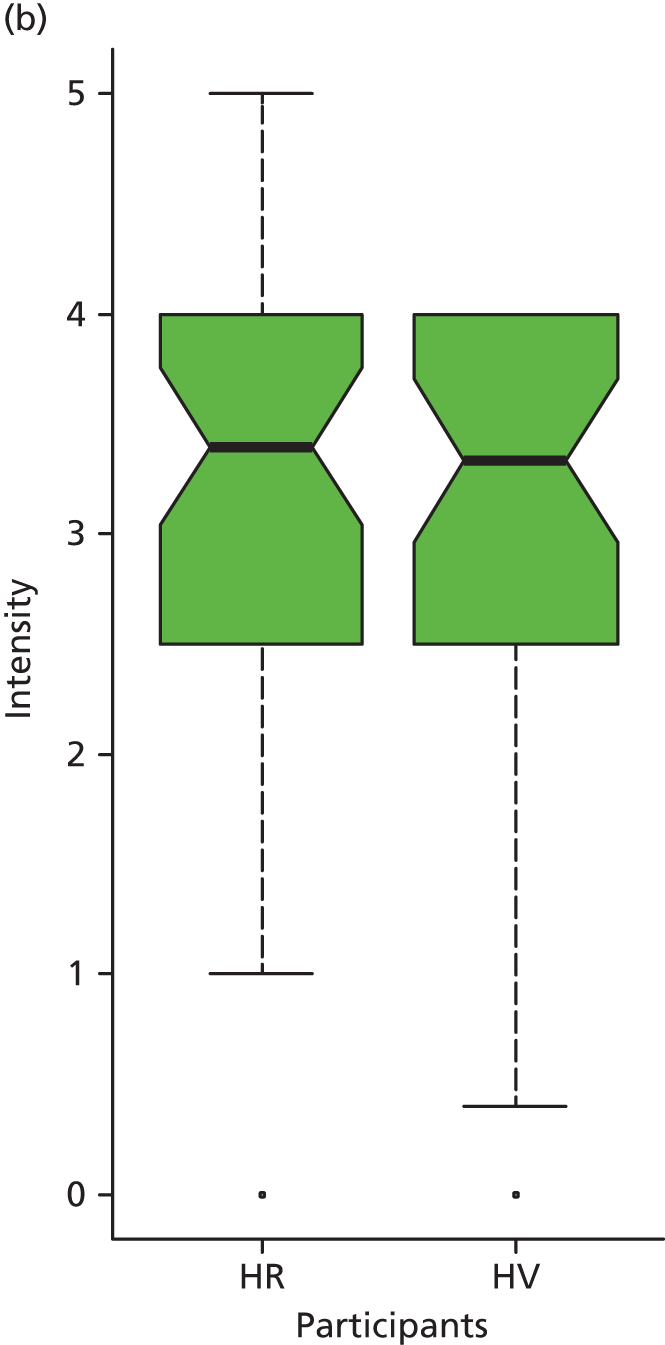

The cross-sectional follow-up of the cohort of people with HR mental states assembled through the true-positive referrals from the LEGS trial, collectively known as the Prospective Analysis of At-risk mental states and Transitions into psycHosis (PAATH) study (see Work package 5) was a success. The finding that people with mental states thought to put them at HR of psychosis almost invariably had one and often two non-psychotic diagnoses changes the way that we think about these presentations in that we should treat the disorders that they have (largely depression and anxiety), not the disorder that we think they may get (psychosis). Risk factors such as childhood maltreatment/trauma were investigated as was drug use.

-

To evaluate a range of effective interventions and service configurations that vary across our large mental health trust aimed at improving early identification outcome and promoting recovery.

This objective was achieved in a narrow sense through the LEGS cRCT (see Work package 4), which compared two specific approaches to liaison between primary and secondary care in the identification and referral of new-onset psychosis and HR states and set these in the context of practice as usual (PAU). Our broader aim to have routine measures of baseline state and outcomes embedded in practice throughout our trust and supported by an effective IT system was not achieved, largely for the reasons outlined in our comment on objective 2. No mental health trust has this yet in routine practice although it, and the aspiration for ongoing, real-time observational assessment of alternative interventions delivered through different service configurations, remains on the horizon in mental health, particularly through developments such as CRIS, as it does in other areas of health care. Randomised designs on such a platform, most likely with adaptive methods to maximise both short-term patient benefit and long-term improvements in care, remain over the horizon but are being discussed at a conceptual level. 14

The research elements that we employed to achieve our objectives are described in the work packages of this report. The publication outputs are mostly included as appendices (Table 1).

| Programme objectives | Synopsis: research development | Description of programme outputs |

|---|---|---|

| To define the incidence and social epidemiology of psychosis | Work package 3: incidence and social epidemiology of psychosis (see Work package 3) | Appendices 1 – 4 |

| To design reliable, brief and valid assessment procedures | Work package 1: IT systems (see Work package 1) | CAR IT surveillance system and CRIS (external adoption) |

| Work package 2: development of a tool to measure recovery (see Work package 2) | HoNOS-PbR (external adoption) | |

| To investigate the factors associated with transition from HR | Work package 5: follow-up of referrals of individuals identified as being at HR for psychosis (see Work package 5) | Appendices 9 – 12 |

| To investigate the barriers to, and promoters of, functional recovery in HR | Work package 5: follow-up of referrals of individuals identified as being at HR for psychosis (see Work package 5) | Appendices 9 – 12 |

| To evaluate a range of effective interventions and service configurations | Work package 4: detecting and refining referrals of individuals at HR for psychosis (see Work package 4) | Appendices 5 – 8 |

Patient and public involvement throughout the programme

As outlined in our programme grant application, we have a strong commitment to public involvement in research in the context of a mental health partnership trust and therefore patient and public involvement (PPI) has been paramount.

Involvement has been prominent in all phases. It forms a blueprint for our service development within CAMEO. We stress our commitment to research as a means of improving practice in the initial information materials that service users and their carers receive. All are invited to take part in research with the emphasis on this being entirely their own decision. We have a high (> 50%) prevalence of people becoming involved so we can tailor our research to answer questions that are relevant to them. We run dissemination ‘research groups’ for our service users and carers, keeping them informed and promoting discussion of new ideas, methods and projects. We always have a carer (family) and/or a user on interview panels for research staff when there is patient contact.

In the current programme a service user’s mother sparked the idea of working with general practitioners (GPs) and schools to try to improve detection and referral. PPI was vital for the development of the information sheets and assessment tools that we designed; if the tools were not useful to patients, they were not useful at all.

The pilot study that informed our LEGS trial (see Work package 4) interventions included 84 GPs and a similar number of teachers outside the trial area. Their contributions and comments were a significant asset in the development of interventions based on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB)15 and within the Medical Research Council framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions. 16

As part of the high-intensity intervention for general practices and colleges, educational digital versatile discs (DVDs) were produced (see Work package 4). They required input and advice from service users and college students. Two GPs, two teachers, two service users, two college students and one professor of psychiatry participated in developing the content of the scripts and production. These DVDs have been highly regarded by GPs and teaching staff participating in the LEGS trial.

All primary care practitioners and teachers involved in the LEGS trial have had the opportunity to contribute with comments and impressions through a biannual newsletter. These comments were taken into account to facilitate the practical implementation of the trial, except when they could potentially affect aspects related to methodological aspects of the study protocol.

With regard to the follow-up of HR referrals (the PAATH study; see Work package 5), we developed a comprehensive database to collect relevant epidemiological, clinical, functional and quality of life information. One of the peer support workers working in the CAMEO clinical team, where this research is embedded, participated in the design of the database and has facilitated its use enormously. His clinical knowledge and experience as a service user contributed to making it meaningful and easy to analyse. He has closely worked with our IT project manager and psychometrician.

Our research team, particularly JP, has built up innovative partnerships with mental health charities such as Squeaky Gate, an extraordinary and creative charity that empowers people with mental health problems through music and the arts [see www.squeakygate.org.uk (accessed 19 January 2016)], especially during the so-called Squeaky Gate Galas featuring ‘Inside an Unquiet Mind’ that usually take place in Cambridge during the annual Science Festival. This has been an excellent collaboration to publicise research such as the LEGS cRCT (see Work package 4) and the PAATH study (see Work package 5). These performances are open to the general public. For example, last year more than 500 people watched these plays. They were very well received by the public and also had a significant repercussion in the scientific literature. Indeed, the EMBO Journal, from Nature publishing group, invited us to write an article on this new venture. 17

The significant evolution of PPI in research during the last few years has been challeging at times as we had to adjust our initial objectives and plans to new and more desirable requirements. However, we feel that this progression has eventually become seamless. Now, we would naturally have included a service user or carer with research experience as a co-applicant, but at the time that the application for this programme was submitted current guidance did not recommend this; things have moved on. However, we included GPs and sought teachers’ advice in our steering groups and, as set out above, have included PPI: a patient and carer have helped with the construction of this report, including having some detailed input to the Abstract, Plain English summary and Scientific Summary.

We are committed to disseminating our results using all possible channels to reach patients and the public. We have excellent links with charities (see above) and third-sector organisations such as Rethink [see www.rethink.org/ (accessed 20 January 2016)]. We also have excellent relationships with commissioners who will advise about the best way to communicate findings that emerged from this programme. We will also provide information about the results to participants with their approval and will organise meetings to feed back our findings. We have a programme arranged to execute our strategy to further disseminate results to the public.

The following statement is not strictly related to PPI but is a fair reflection of what the research team, along with PPI, accomplished in making materials successful and worthwhile in the LEGS cRCT. This feedback was sent to us by a nurse working in a large college of further education:

Cambridge Regional College (CRC) has a population of approximately 5000 full-time students. About 1/10 students are referred to/seek help at Student Services for emotional and mental health issues. The majority of our students are aged 16-25, and a large quantity come from challenging backgrounds (e.g. abuse, domestic violence, homelessness, and substance abuse etc). Consequently, there are high risks for students developing poor emotional health and (sometimes chronic) mental health issues. Early identification and referral is critical to the students’ well-being and ability to achieve their college goals. Participating in the LEGS trial has provided staff at CRC an opportunity to increase their knowledge and understanding of psychosis (clarification of the condition, and how and when it can present). Staff were extremely positive about the CAMEO training on September 8th 2011 (to which about 50 people attended); staff stated that it increased their confidence in detecting early symptoms (indicative of psychosis), and making referrals to appropriate professionals. The laminated posters/flyers (which were displayed in staff rooms and offices), are reported to be useful resources in reminding staff what to look out for. Prior to the LEGS trial, many tutors, teachers and staff found the term ‘psychosis’ intimidating, and were not confident in dealing with the issue. Since the LEGS trial this year, many staff have stated their overall response to psychosis has improved. As the mental health practitioner at the college, I have noticed an increase in the number of students being referred to Student Services with symptoms possibly pertaining to psychosis (e.g. delusions and hallucinations) this academic year. Staff have also been quicker to identify students with unusual presentation (e.g. uncharacteristic affect/behaviour, lack of concentration/attendance) and refer them to review and identify any core underlying issues. Over the last year, there has been a significant shift and improvement in attitudes and approaches to mental health at CRC, and the LEGS trial has played a part in this. As a result of this shift, more students have been able to have their needs assessed and (if necessary) receive the appropriate support and treatment. With the right interventions, more students have been able to complete their academic courses/qualifications this year. As a professional, it is my priority to support the early identification of mental health issues, so students have the best possible treatment and prognosis. I have made several referrals to CAMEO this year, and have been extremely pleased with the quick response and quality of CAMEO’s assessment and advice. The feedback from students referred to CAMEO has generally been very positive too. Students have expressed they feel ‘comfortable’ talking to the CAMEO team, and have appreciated having their issues ‘taken seriously’ and advised accordingly. For many students being referred to a specialist mental health agency is a scary experience (for many reasons e.g. ‘I must be crazy now’, and ‘doctors and diagnoses’ are often involved). However, CAMEO’s approach has reassured students, and many have been onto the CAMEO website for further information. Overall, Cambridge Regional College has benefited from participating in the LEGS trial, and looks forward to further information and involvement with CAMEO.

Work package 1: information technology systems

Development and implementation of the Client Assessment Register

In support of various data collection requirements for service outcomes, evaluation and research trials, we have developed and implemented a clinical surveillance system to identify and electronically record all cases of clinically relevant psychotic states. This information has been gathered through predetermined sets of assessment batteries that can be modified according to clinical or research requirements. The system integrates with the central care records system of the trust to avoid data redundancy. This process synchronises with the centralised system’s basic sociodemographic data on a daily basis. The data are only editable in the central system and several data validity checks are built into the system to ensure improved data quality.

The CAR system consists of a front-end application interface designed according to industry-acceptable development standards. The front end was developed in a Visual Basic Integrated Development Environment and works on a client–server topology (Figure 2). The database side of the system was developed in Microsoft Transact Structured Query Language (Transact-SQL) database format (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and uses an Open Database Connectivity (ODBC) client to connect and transmit data.

FIGURE 2.

Screenshot of the CAR constructed for the programme and available from the authors.

As a reporting function the CAR system also allows for data to be exported from the database into external data sources such as Microsoft Excel, for analysis and manipulation for statistical analysis.

To ensure that the system stays in line with future technological development we also created a mobile module for remote capturing and reporting of the CAR data. The enhancement allows service users and staff to remotely capture a specific battery of assessments on an iPad or any tablet device that can connect to the internet and have browsing capabilities. This is achieved through a web-based application that is enhanced using the Visual Basic.NET framework. The system also allows service users to enter data. Through the scoring system, staff can immediately access the outcome of particular self-assessments, which may have clinical implications. They can then act accordingly by putting the necessary procedures in place.

During the LEGS cRCT the system was supported and maintained by an appointed IT development and project manager. This staff member was also responsible for training members of staff and service users to ensure the best quality of data capture.

The team also had access to a trust-wide data library that stores the clinical documents of trust service users. The Clinical Documents Library is a bespoke web-based solution that provides a user-friendly, secure single point of access for all authorised users throughout the trust. The library stores clinical letters, reports and assessments against service user records.

An initial requirements report recognised that existing ways of sharing clinical documents at various locations presented inefficiencies and the recommended approach is consistent with the trust’s strategic vision and principles within the Way Ahead Programme [see www.wayaheadcare.co.uk/quality-assurance.php (accessed 20 January 2016)]. The following details some of the features of the new system:

-

enables service user records to be held at a central location

-

enables a single standardised way of storing and sharing clinical documents

-

provides a secure library of clinical documentation

-

is available to all authorised clinicians throughout the trust

-

reduces time spent by staff looking for documents

-

reduces data redundancy

-

provide electronic versions of clinical information.

As stated earlier, our final goal was to implement our CAR information system at a trust-wide level, not funded through the programme, to support routine clinical measurement at baseline and outcome. In common with virtually all mental health trusts and most NHS trusts of any type, the implementation of a new IT system capable of supporting clinical work, management and research was problematic and protracted; it became clear early on that our plan would not be possible as our host trust decided to invest in the RiO EPRS to meet its clinical and business needs.

However, the NIHR BRC for mental health at the SLAM NHS Foundation Trust developed a prototypic system, the CRIS system, to provide regulated access to anonymised data from electronic patient records systems (see www.slam.nhs.uk/about/core-facilities/cris). Although the CRIS system was initially designed for SLAM NHS Foundation Trust systems, it has now been implemented as D-CRIS in several mental health trusts, including CPFT, our host, where it is running on and shadowing the RiO EPRS. Thus, we were not able to extrapolate this element of our programme, which itself was a significant IT development that was already completed and significantly contributed to the success of this programme, especially the LEGS cRCT and the PAATH study. Nevertheless, this ambitious objective has been achieved through larger investments in CRIS/D-CRIS by the NIHR BRC for mental health.

Work package 2: development of a tool to measure recovery

With regard to work package 2, we proposed to develop psychometrically and practically acceptable instruments and test them in practice to understand predictors of and barriers to recovery. Through measurement innovation we intended to create tools and the culture that could sustain (indeed welcome) constant evaluation of service structure and interventions. We considered this fundamental to guide service planning. However, this was partly resolved with the gradual adoption during the programme of the HoNOS10 by our NHS trust. As stated in our application, this simple tool was already employed in Scandinavia and Australia, but not in the UK. Its eventual adoption by the NHS significantly reduced the importance and viability of this element in our research plan. Furthermore, HoNOS seem to possess satisfactory sensitivity and validity to be used in routine assessment within early-intervention programmes. 10 The HoNOS have become the basis of PbR for mental health (as HoNOS-PBR) nationally, and our trust was in line with others by adopting them. We were disappointed not to be able to produce a psychometrically sophisticated tool for use in clincal practice but delighted that the services are using a recognised tool.

Work package 3: incidence and social epidemiology of psychosis

In this work package we describe the administrative incidence (these are data not primarily collected for research purposes) and social epidemiology of psychotic disorders and HR for psychosis in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. This was mainly intended to help understand the complex person–place interactions in the genesis of schizophrenia and other psychoses as a useful, less immediately applied but ultimately essential goal in terms of the future prevention of disability from such disorders.

To continue with our endeavour of understanding who we treat, where they come from, what is wrong, what we do for them and what happens to them, we built on our clinical and research experience in the local Cambridge EIS (CAMEO) as it expanded in stages to cover all of Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, a socially and ethnically diverse area of 800,000 people. By our alignment with other regional research projects, such as the Social Epidemiology of Psychosis in East Anglia study [SEPEA; see www.sepea.org (accessed 19 January 2016)], we also evaluated comparative epidemiological data for the whole of East Anglia.

These findings were compared with wider data that we have collected with other academic partners, such as the ÆSOP6 and East London First-Episode Psychosis (ELFEP)18 studies, to devise realistically complex statistical models of psychosis incidence.

As a result of this, we developed a web-deployed clinical epidemiology tool that will predict the numbers of people who will develop new psychotic illnesses by social geography, demographics and area, to facilitate future NHS planning. Any health economy will be able accurately to predict morbidity in its area, taking into account detailed characteristics of its population (available from census data). This will promote the right services in the right places.

In this context we also developed and implemented clinical surveillance and IT systems to identify and electronically record all cases of clinically relevant psychotic syndromes in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, linking with routine data capture for the Mental Health Minimum Data Set (MHMDS) requirements. 19 This represented a culture change within a predominantly clinical service that we implemented successfully.

Incidence of psychosis in socially and ethnically diverse settings

See Appendix 1 for the published report of this work. 20

Research aims

The aim of this study was to compare the observed with the expected incidence of psychosis and delineate the clinical epidemiology of FEP using epidemiologically complete data from the CAMEO EIS over a 6-year period in Cambridgeshire for a mixed rural urban population.

Methods for data collection

Data came from a population-based study of FEP [International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), F10–3921] in people aged 17–35 years referred between 2002 and 2007; the denominator was estimated from mid-year census statistics. Sociodemographic variation was explored by Poisson regression. Crude and directly standardised rates (for age, sex and ethnicity) were compared with pre-EIS rates from two major epidemiological FEP studies conducted in urban English settings. 6,18

Analysis

Incidence per 100,000 person-years was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated (with 95% CIs) using Poisson regression to control for possible confounding. We conducted a sensitivity analysis on subjects with missing ethnicity data by repeating the Poisson regression four times, assuming that all such subjects belonged to the white British, non-British white, black and other ethnic groups in turn. The likelihood ratio test was applied to assess statistical interactions and model fit.

Key findings

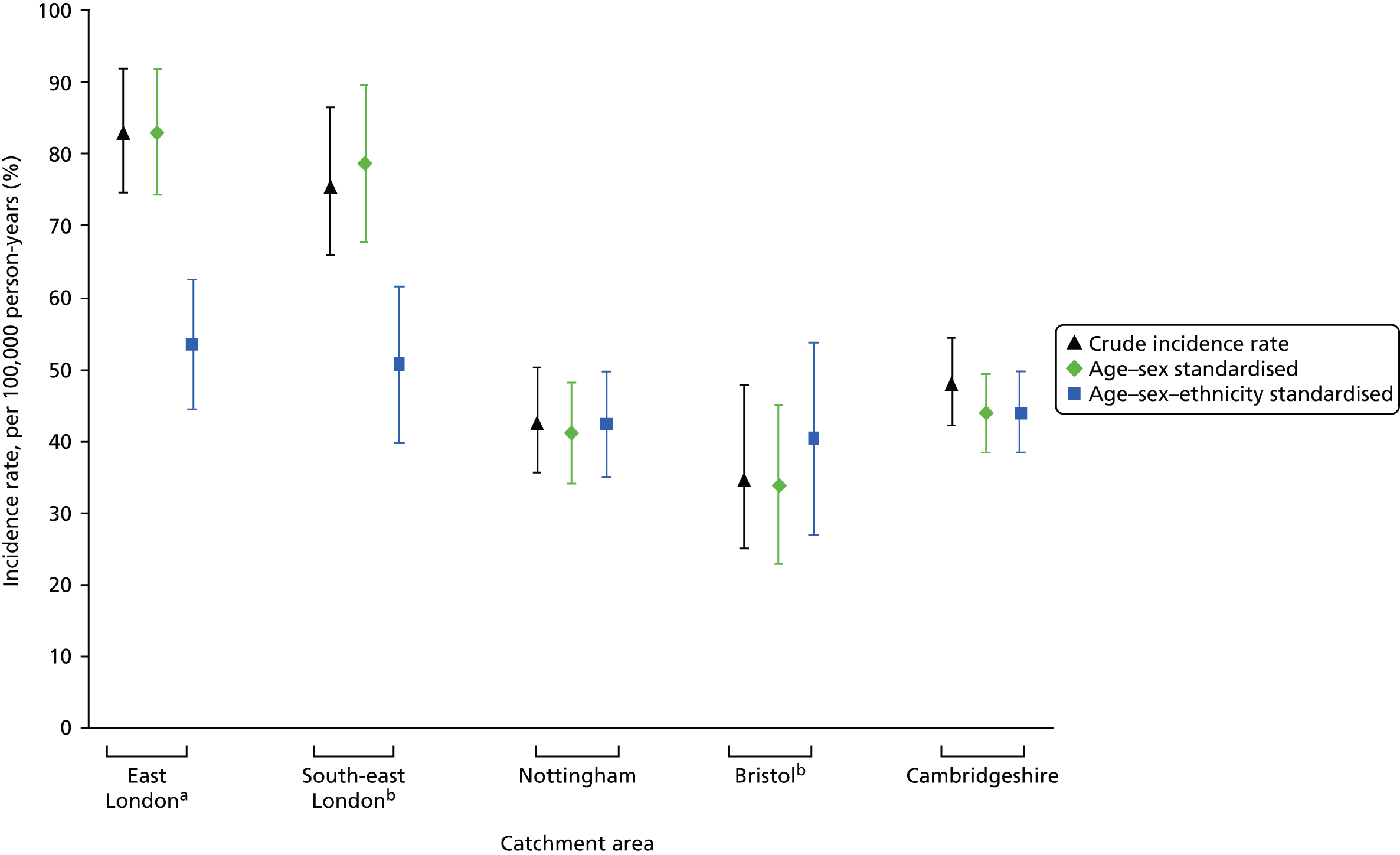

There were 285 cases over 569,921 person-years (aged 16–35 years), yielding a crude incidence of 50.0 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 44.5 to 56.2 per 100,000 person-years), higher than anticipated and comparable with estimates from more urban UK settings. These comparisons were with rates on which EISs were predicated and also with incidence rates from the two recent observational studies of FEP covering four urban catchment areas of the UK: east London and south-east London, Nottingham and Bristol. 6,18 These comparisons are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of crude and directly standardised incidence rates in Cambridgeshire and the four catchment areas of the ÆSOP6 and ELFEP18 studies. Directly standardised to the population of England aged 18–34 years estimated in the 2001 census. a, Data made available from the authors;18 b, data made available from the authors. 6

Rates in men were double those in women and declined with age for both sexes. After adjustment for age and sex, rates were elevated for people from black ethnic groups (IRR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.8). The increased risk of psychosis among people of black ethnicities demonstrated in this study was smaller than that seen in other studies.

The administrative incidence of psychosis calculated from within an EIS in a mixed urban–rural setting was similar to estimates from city-based studies and higher than originally predicted when EISs were designed in the UK. The sociodemographic characteristics of incidence rates were also similar to those of more urban studies, including higher rates in black and ethnic minority groups, indicating that psychosocial and other phenomena contributing to this variation are not confined to urban populations. Adjustment of city rates for ethnic structure of the population reduced high city rates markedly, indicating the importance of this factor to the high burden of FEP in cities. This has implications not only for our understanding of the determinants of psychosis but also for service planning.

The crude incidence rates presented from the CAMEO EIS were more than three times higher than anticipated by the original service planning estimates from the Department of Health in 2001. Possible explanations for this are:

-

There has been little evidence on incidence in rural settings compared with urban areas, such that the assumptions about overall rates in the general population have simply been wrong.

-

EISs are particularly effective in eliciting referrals of true positives and engaging them long enough for assessments to be made. That said, the fact that we did not have a formal leakage study, as was undertaken in our comparison samples, suggests to us that those studies and general mental health services did not massively underestimate morbidity.

-

More rural areas may look like cities because of the uniformly high prevalence of cannabis use by young people in the UK.

-

The most obvious reason for the discrepancy between our data and the figure for EIS planning used in England (around 15 per 100,000 person-years) is that the latter is predicated largely on the incidence of schizophrenia whereas we know that only around one-third of FEP is classified as such at first presentation.

-

The incidence of psychosis is higher in young adults aged 14–35 years than in the population as a whole, and EISs are targeted at the former group.

Limitations

Because of the lack of routine incidence data at the time of the study, we were unable to compare incidence rates presented here with those in our study population prior to the start of the CAMEO service. This is necessary to determine precisely whether or not EISs do identify excess morbidity.

Incidence of psychosis across Eastern England

See Appendix 2 for the published report of this work. 22

Research aims

The aim of this research was to present the initial 18-month findings from the SEPEA study, a large, 3-year population-based FEP study of incepted incidence observed through five EISs.

Methods for data collection

We established a surveillance system to record sociodemographic and clinical data on all people aged 16–35 years resident within East Anglia who were referred to and accepted by our EIS with FEP over the 3 years from 1 August 2009. ICD-1021 clinical and research (OPCRIT23) diagnoses for psychotic disorder (F10–39) are established at 6 months and 3 years after referral.

Analysis

Poisson regression explored covariate effects. The full method is given in the online supplement [see http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/suppl/2011/12/19/bjp.bp.111.094896.DC1.html (accessed 21 September 2014)].

Key findings

We identified 357 eligible subjects (incidence 45.1 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI 40.8 to 49.9 per 100,000 person-years). Rates varied across the EISs but were two to three times higher than those on which services were commissioned.

Risk decreased with age, was nearly doubled among men and differed by ethnic group: it was doubled in people of mixed ethnicity but was lower for those of Asian origin than for the white British population (Table 2).

| Variable | Participants, n (%) | Denominator, n (%)a | Adjustedb relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 357 (100) | 838,574 (100) | – |

| EIS (n = 357) | |||

| Cambridgeshire, Peterborough and Royston | 122 (34.2) | 306,283 (36.5) | – |

| West Norfolk | 17 (4.8) | 41,765 (5.0) | – |

| Central Norfolk | 91 (25.5) | 219,860 (26.2) | – |

| Great Yarmouth and Waveney | 38 (10.6) | 69,218 (8.3) | – |

| Suffolk | 89 (24.9) | 201,448 (24.0) | – |

| Sex (n = 330) | |||

| Women | 115 (34.8) | 405,221 (48.3) | 1 |

| Men | 215 (65.2) | 433,353 (51.7) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.2) |

| Age group (years) (n = 330) | |||

| 16–17 | 52 (15.8) | 71,929 (8.6) | 1 |

| 18–19 | 53 (16.1) | 88,976 (10.6) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| 20–24 | 118 (35.8) | 219,157 (26.1) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) |

| 25–29 | 73 (22.1) | 213,385 (25.4) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) |

| 30–35 | 34 (10.3) | 245,127 (29.2) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) |

| Ethnicity (n = 330) | |||

| White British | 261 (79.1) | 671,588 (80.1) | 1 |

| White non-British | 21 (6.4) | 50,882 (6.1) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) |

| Mixed ethnicity | 15 (4.5) | 17,364 (2.1) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.6) |

| Black | 12 (3.6) | 18,471 (2.2) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.3) |

| Asian | 12 (3.6) | 69,014 (8.2) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) |

| Other ethnicities | 9 (2.7) | 11,255 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.2 to 4.5) |

Psychosis risk among ethnic minorities was lower than reported in urban settings, which has potential implications for aetiology if whatever factors increase risk in people from black and minority ethnic groups in cities are less potent, rare or absent in rural areas. Overall, our data suggest considerable psychosis morbidity in diverse, rural communities.

Development of a population-level prediction tool for the incidence of first-episode psychosis (PsyMaptic)

See Appendix 3 for the published report of this work. 24

Research aims

Although the true incidence of FEP varies enormously according to sociodemographic factors, a single estimate of population need was used universally for developing EISs in the UK. Therefore, we sought to develop a realistically complex, population-based prediction tool for FEP, based on precise estimates of epidemiological risk.

Methods for data collection

Data from 1037 participants in two cross-sectional population-based FEP studies6,18 were fitted to several negative binomial regression models to estimate risk coefficients across combinations of different sociodemographic and socioenvironmental factors. We applied these coefficients to the population at risk of a third, socioeconomically different region to predict the expected caseload over 2.5 years, where the observed rates of ICD-10 F10–39 FEP had been concurrently ascertained through EISs.

Analysis

The main outcome measure was observed counts compared with predicted counts [with 95% prediction intervals (PIs)] at EIS and local authority district (LAD) levels in East Anglia to establish the predictive validity of each model. For the full analysis see Appendix 3.

Key findings

The use of modelling with epidemiological data from two large studies of FEP in England6,18 produced accurate FEP forecasts.

Negative binomial regression models with age, sex, ethnicity and population density performed most strongly, predicting 508 FEP participants in EISs in East Anglia (95% PI 459 to 559 FEP participants) compared with 522 observed participants. This model predicted correctly in five out of six EISs and 19 out of 21 LADs.

Our data suggested that the original figure used to commission EISs probably overestimated the true incidence of FEP in rural areas and underestimated rates in urban settings.

The initial assessment of some people who do not require subsequent EIS care means that additional service resources will be required.

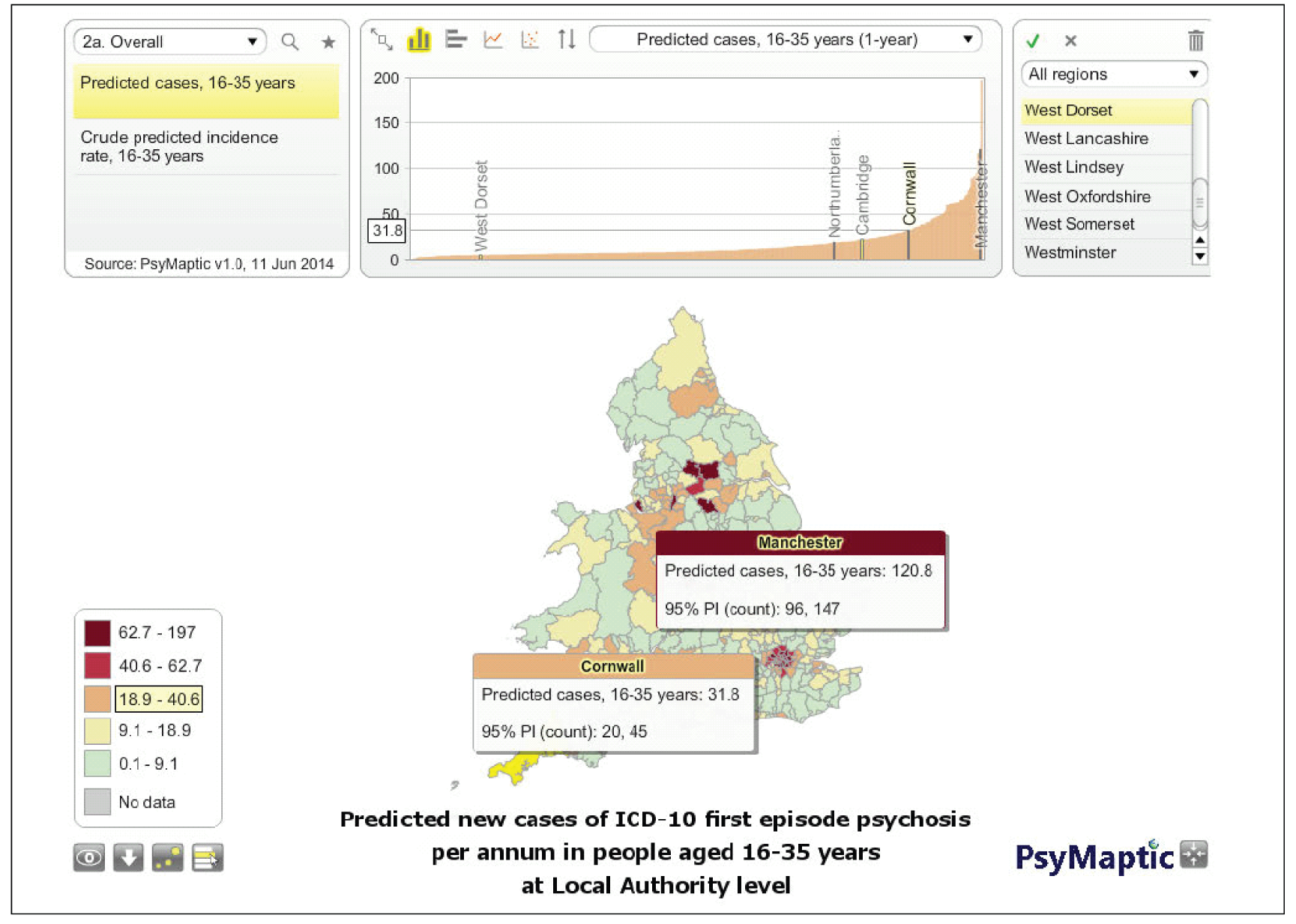

Successes

All models performed better than the current gold standard for EIS commissioning in England (716 cases, 95% PI 664 to 769 cases). We have developed a prediction tool for the incidence of psychotic disorders in England and Wales, made freely available online (see www.psymaptic.org/), to provide health-care commissioners with accurate forecasts of FEP based on robust epidemiology and anticipated local population need (Figure 4). This has already been used for service planning in London and, at the time of writing, is being used by NHS England to support the national early intervention waiting time standard and target. The work also appeared in the Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2013 [see www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/413196/CMO_web_doc.pdf (accessed 19 January 2016)].

Limitations

Although our models provide estimates of the expected clinical burden of FEP in the community, services may see a broader range of psychopathology, consuming resources, or incepted rates may be influenced by supply-side organisational factors.

It was not possible to validate our prediction tool in settings outside of England and Wales or for specific psychotic disorders. As data become available we will assess the use of our prediction tool in other settings and for disorders.

Social and spatial heterogeneity in psychosis proneness

See Appendix 4 for the published report of this work. 25

Research aims

To test whether spatial and social neighbourhood patterning of people at HR of psychosis differs from that of FEP participants or control subjects (healthy volunteers; HVs) and to determine whether or not exposure to different social environments is evident before disorder onset.

Methods for data collection

First-episode psychosis participants were identified through the SEPEA study. HR participants were identified as part of the PAATH study, which ran in parallel to the SEPEA study in CAMEO. Control participants were identified from an embedded project within the SEPEA study, the European Union Gene–Environment Interaction (EU-GEI) study [see www.eu-gei.eu/ (accessed 19 January 2016)], an international, multicentre case–sibling–control study of gene–environment interactions in schizophrenia and other psychoses in people aged 18–64 years. Using a NIHR Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) initiative designed to assist with recruitment of participants from primary care for research, HVs who met the inclusion criteria (aged 18–64 years; no previous history of psychosis) were randomly selected from 10 GP practice patient lists within the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough catchment area.

Analysis

We tested differences in the spatial distributions of representative samples of individuals with FEP, HR participants and HVs and fitted two-level multinomial logistic regression models, adjusted for individual-level covariates, to examine group differences in neighbourhood-level characteristics. For full techniques see Appendix 4.

Key findings

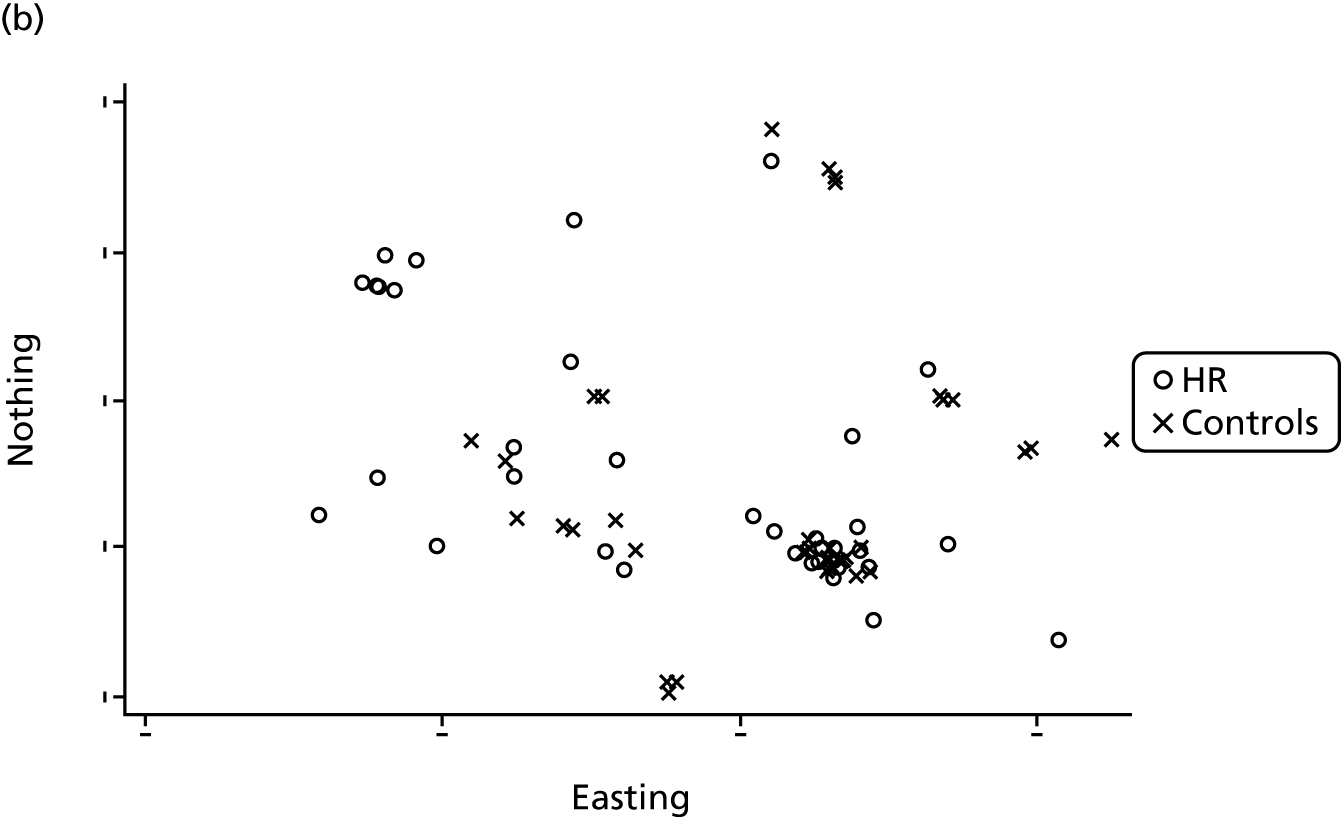

The spatial distribution of HVs (n = 41) differed from that of HR participants (n = 48; p = 0.04) and FEP participants (n = 159; p = 0.01), whose distribution was similar (p = 0.17). Risk in FEP and HR groups was associated with the same neighbourhood-level exposures: proportion of single-parent households [FEP adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.56, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.45; HR aOR 1.59, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.57), ethnic diversity (FEP aOR 1.27, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.58; HR aOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.63) and multiple deprivation (FEP aOR 0.88, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.00; HR aOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.99).

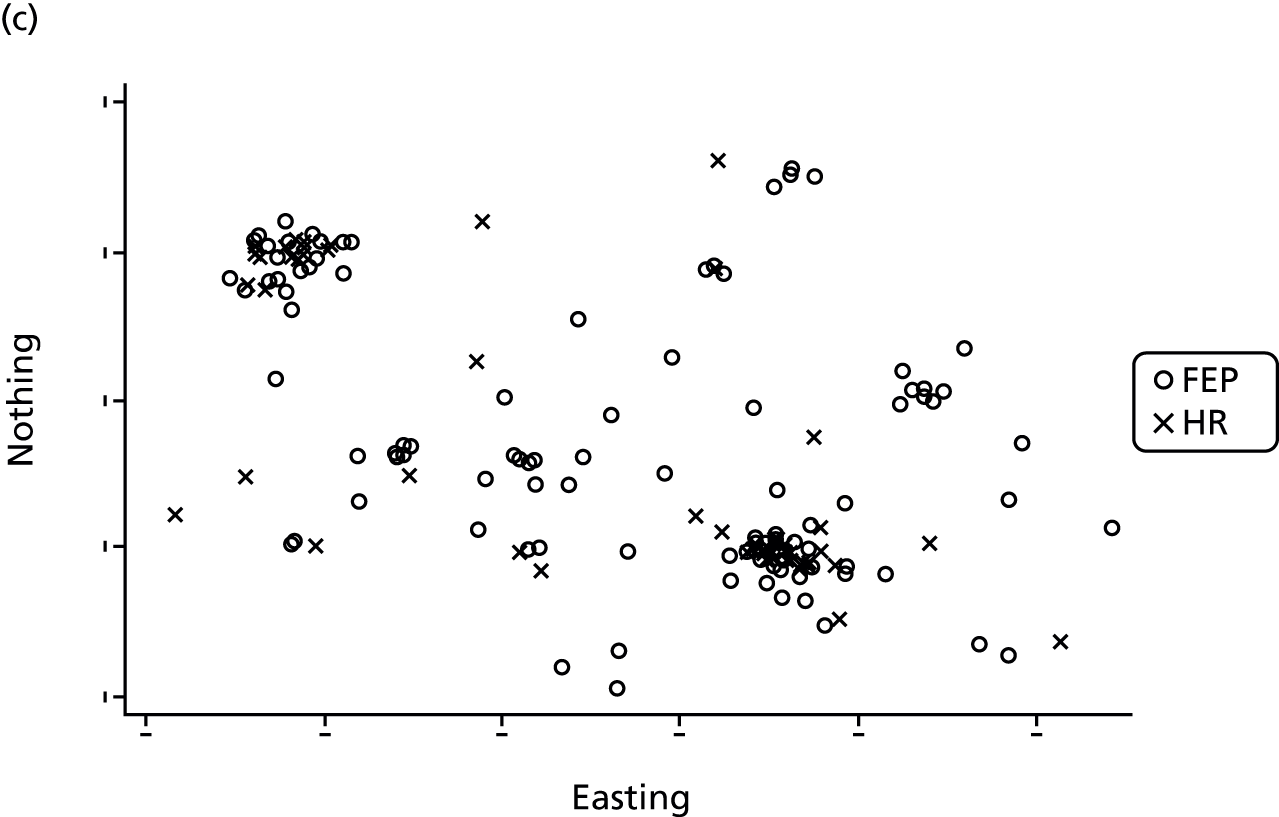

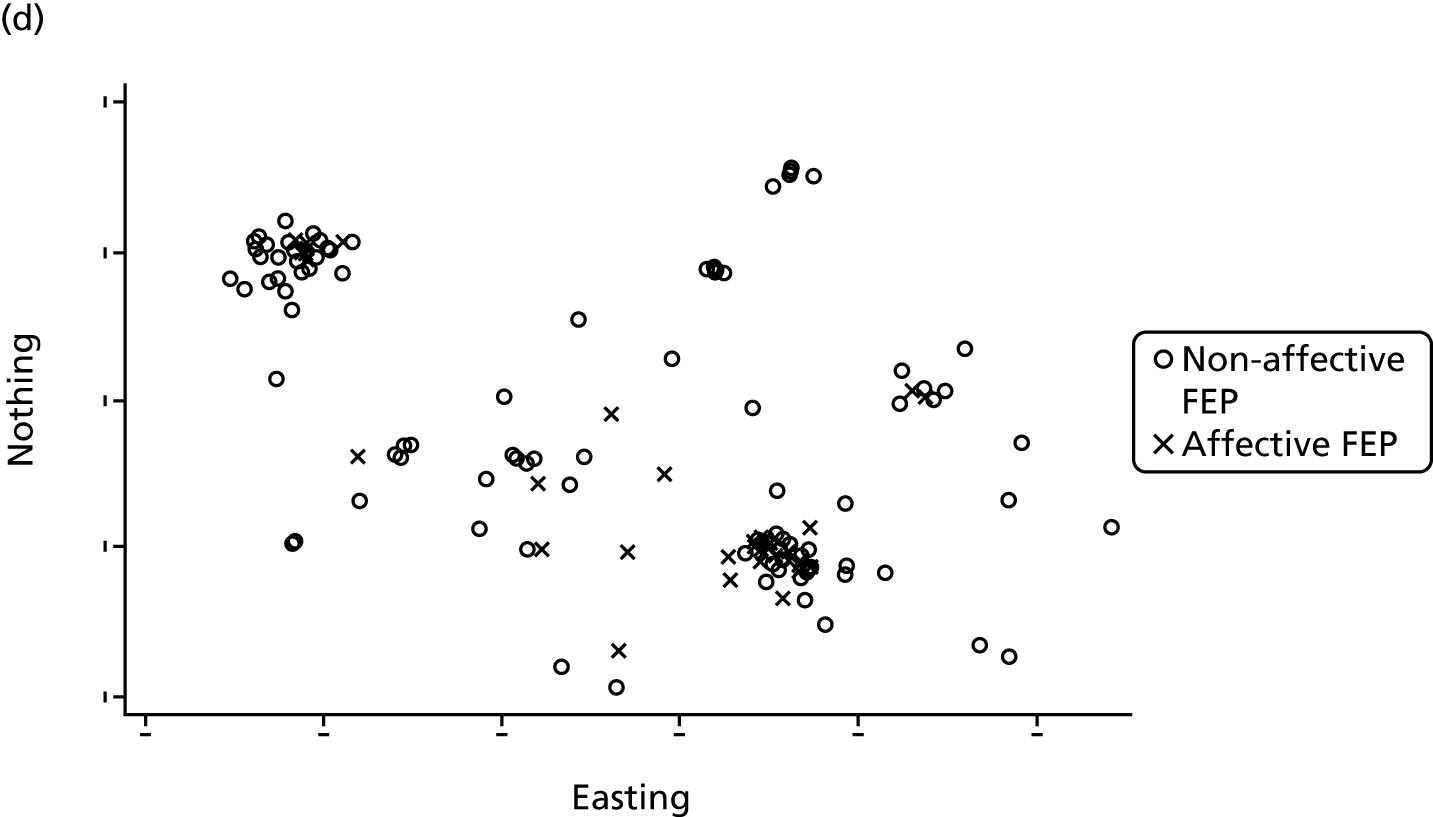

The pattern of elevated risk at the neighbourhood level was similar for both HR and FEP participants relative to HVs (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Spatial locations of participants by status. The spatial distribution of control subjects (HVs) was significantly different from that of both (a) people with FEP (p = 0.01) and (b) the HR group (p = 0.04) under a two-dimensional M-test. There was no statistically significant difference in the spatial distribution of (c) FEP and HR participants (p = 0.17). The spatial distribution of (d) people with non-affective FEP and people with affective FEP was also significantly different from each other (p = 0.01). Locations are based on postcode centroid at first contact. Axis scales are plotted according to British National Grid co-ordinates of residential postcode at first contact, but the co-ordinates and scale have been removed to preserve sample anonymity.

Social drift may begin earlier in the prodromal phase or expose people to greater socioenvironmental adversities, which increase psychosis proneness.

Limitations

This multilevel study used cross-sectional data to compare social and spatial differences in the three groups in a defined catchment area; we did not have longitudinal data on transition to psychosis in HR participants.

The odds ratios were conservative because, although the control subjects and the population at risk were similar in sociodemographic terms, they came from more densely populated neighbourhoods. The sample of HVs and HR participants was relatively small in this study.

Work package 4: detecting and refining referrals of individuals at high risk for psychosis

Liaison with Education and General practiceS to detect and refine referrals of people with at-risk mental states for psychosis

International efforts to decrease the stigma of psychosis and solicit self- and other referrals have exploited print and television media for public information campaigns, as well as educating members of relevant occupational groups. In this context we compared techniques to identify this important population, ensuring a representative sample of HR individuals for our research and finding a cost-effective way to ascertain this group for EISs to work with subsequently.

We called this initiative LEGS. We employed a cluster randomised approach to finding out which, if any, of two methods of finding HR individuals works best. We targeted those aged 16–35 years registered in and attending primary care (although the intervention will affect a broader age range) and those aged 16+ years in further education in our county. The units randomised (primary care practices and age 16+ educational institutions) in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough were balanced for social deprivation before randomisation using Index of Deprivation scores. 26 We tested whether or not a simple ‘postal’ campaign, co-ordinated from an office, was more clinically effective and cost-effective than a more elaborate and expensive system of personal liaison by health professionals with the primary care practices and the 16+ educational institutions.

The aim of both interventions was to sensitise staff working in primary care practices and 16+ educational institutions to the nature and likely manifestation(s) of common psychotic symptoms or mental states that put individuals at risk, as defined by existing definitions and established general population screening tools applied in current government epidemiological surveys. Those identified can be referred to their local EIS.

Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of tailored intensive liaison between primary and secondary care to identify individuals at risk of a first psychotic illness: a cluster randomised controlled trial

The complex educational intervention used in this trial required a number of developmental stages before implementation and evaluation. Here we outline key findings, successes, challenges, limitations and recommendations for future research for each of the stages.

Development of the educational intervention to improve detection of high-risk mental states and first-episode psychosis

A detailed description of this developmental stage has been published (see Appendix 5). 27

First, we investigated what education was required and on what to base our low-intensity intervention (a leaflet sent by post) and the high-intensity, fact-to-face and video package supported by a member of staff. The TPB15 was selected to guide the design of the educational intervention. Use of the TPB requires the development of a questionnaire to identify and measure specific beliefs associated with each of the theory’s constructs: intention, attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control (PBC). The beliefs are then targeted with strategies designed to influence behaviour. Strengthening GPs’ intentions to identify individuals at HR was predicted to increase the likelihood that they would identify and refer those at risk.

Research aims

The aim of this stage was to describe the development and psychometric evaluation of a questionnaire designed to identify and measure factors that influence the identification of individuals at HR for psychosis in primary care. This informed the design of the LEGS educational intervention to help GPs and primary care physicians detect these individuals.

Methods for data collection

Following standard TPB guidelines28 a 106-item preliminary questionnaire was constructed using a semistructured discussion group with eight GPs to elicit commonly held beliefs about identifying HR individuals. The questionnaire was distributed to 400 GPs in 38 practices across 12 counties in England, not including Cambridgeshire and Peterborough where we intended to run the trial.

Analysis

A polytomous graded response model29 was used to identify redundant items and assess the validity of the questionnaire. Factor analysis was used to assess the structural conformity of the final questionnaire with the TPB. Cronbach’s alphas were calculated to determine the reliability of the final questionnaire. Path analysis was conducted to assess the ability of the TPB’s constructs to predict intention and reveal the percentage of variance explained by intention.

Key findings

Indirect measures were well constructed and adequately covered the breadth of the measured construct. Items within all direct measures measured the corresponding construct satisfactorily. The alpha values confirmed improvement for each of the constructs in the reduced version of the questionnaire with the exception of intention, which remained the same. The final instrument consisted of 73 items and showed acceptable reliability (α = 0.77–0.87) for all direct measures. All of the direct measures of the TPB significantly predicted intention, accounting for 35% of the variance. Subjective norm (perceived professional influences) was the strongest predictor of intention. GPs had positive intentions and attitudes towards identifying individuals at HR for psychosis. The foremost motivational factors for GPs were their perceptions of whether or not other GPs identify HR individuals and whether significant others (e.g. patients, colleagues, health-care system) approved or disapproved of identification.

Successes

Theory underpinned the design of all components of the educational intervention: the understanding of the GPs’ behaviour, the development of the measures and the attempt to change behaviour. We confirmed the feasibility, reliability and acceptability of a TPB-based questionnaire to identify GPs’ beliefs and intentions concerning the identification of individuals at HR for psychosis.

Theory-based interventions provide an understanding of what works and thus are a basis for developing better theory across different contexts, populations and behaviours. They could, and should, be used more in the NHS where innovation often requires education and behaviour change by staff.

Challenges

The average time taken to complete the questionnaire was 16 minutes. Most of the declining GPs and some of the participating GPs mentioned that the length of the questionnaire was off-putting.

Limitations

The response to the pilot was very low: only 82 (20.5%) GPs returned questionnaires. The cost and time investments were high for such a low return.

Recommendations for future research

The recommendation that an original TPB questionnaire is developed every time a new behaviour is studied,28 or the same behaviour is studied in a new population, suggests that similar methodology can be used to help GPs in the identification of other pathologies and in a variety of mental health settings. Further application of the TPB in the NHS has already been mentioned.

Design of the educational intervention

Methods for data collection

The information collated from the pilot questionnaire identified specific barriers that we targeted with strategies designed to change clinical practice with respect to identifying HR individuals in primary care.

Key findings

This theory-based information could be important for improving the efficiency of referral pathways and contributing to a reduction in the DUP. We had a clear structure on which to base our low-intensity leaflet intervention and our high-intensity face-to-face and video approaches.

Successes

Mapping theoretical constructs to behaviour change techniques provided a clear framework for process analysis and increased the ability of the intervention to accomplish the desired outcome of motivating GPs to identify individuals at HR.

It was invaluable to have a guide to the different behaviour change techniques, with definitions that addressed different behavioural determinants linked to theoretical constructs. This allowed us to select the most appropriate intervention strategies for GPs.

Challenges

The mapping of theoretical constructs to behaviour change techniques was complex and time-consuming. However, this systematic approach ensured that the behaviour change techniques and delivery methods targeted the theoretical determinants of GPs’ behaviour directly.

We learnt from the pilot that individual clinicians have very different levels of knowledge about psychosis and mental health in general. Therefore, it was important to ‘pitch’ the presentation at the right level so as not to be condescending but at the same time ensure a basic level of understanding. Achieving this balance proved extremely difficult, especially given the time restraints of the 60-minute sessions. Trying to explain the complexities of the at-risk concept in a concise way but also making it educationally appropriate for both GPs and practice nurses took many drafts. Again, it was helpful to have comments from GP colleagues regarding the presentation to guide us before we approved the final version.

Limitations

Ensuring that the leaflet was specific enough to capture all possible at-risk symptoms [attenuated symptoms, family vulnerability and BLIPS (Brief Limited Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms)] without being too sensitive and producing numerous ‘false-positive’ referrals was a dilemma. Despite utilising many sources of information, including GPs practising outside the trial area, the resulting leaflet proved a little too sensitive.

Recommendations for future research

Few studies have used the TPB to predict intention to take part in an intervention. Such an application could provide valuable information about how best to recruit GPs into future studies.

Implementation of the high-intensity intervention

Successes

The PCRN was useful in terms of accessing surgeries for participation history and informing them about the study. It provided us with the Research Information Sheet for Practices (RISP). The focus of this was provision of information about the practical implications of the research for the participating GPs (What, Where, How often, etc.). This proved more useful than the trial information sheet, which, although detailed and well structured, did not cover enough of the practical details that were required to help practices reach a decision about whether or not to participate.

Having an out-of-area GP review and critique the educational materials proved invaluable for establishing the appropriate pitch and tone and reviewing the content of the intervention.

Three dedicated research and liaison practitioners (RLPs) were specifically recruited for the trial [one man, two women; mean age 45.5 years, standard deviation (SD) 4.7 years]. All were experienced mental health professionals (one psychologist, one nurse, one social worker). They acted as facilitators between secondary and primary mental health services as it is proposed that this is a fundamental role in helping individuals and teams to understand what they need to change and how they need to change it, to translate evidence into practice. Each RLP was responsible for delivering the high-intensity intervention to the surgeries within one of the three geographical areas in Cambridgeshire covered by the trial. The RLPs found that showing empathy (understanding the nature of school/practice life) was central in building a relationship with the teachers/GPs. Face-to-face meetings at the point of consent facilitated this.

A beneficial approach was conveying the research as an important medium through which problems that were relevant for a GP’s daily practice could be understood and solutions to the problems could be generated. Flexibility when arranging presentations (i.e. offering more than one session to accommodate all staff) was important for optimising participation.

Convincing the practice leads that participation in the trial would benefit individual GPs, the practice as a whole and most importantly the patients was a key factor in gaining consent to participate in the research. Another successful strategy included emphasising that, by taking part in the trial, GPs could potentially be saving themselves and the practice time because the intervention would allow them to quickly and accurately judge whether or not a young person required a specialist assessment of symptoms. The GPs could see how this would benefit everyone involved.

The GPs were also concerned about what would happen to the individuals who they referred to CAMEO. Assurance that all those identified as being at risk would be invited into the PAATH study for 2 years of mental state monitoring and easy access to a CAMEO psychiatrist if there was any concern about symptoms deteriorating also helped them see the benefits of participating in the trial. We were also able to emphasise that patients without a diagnosis of HR would have a thorough mental health assessment and would then receive appropriate referral on to other services.

Challenges

The trial did not directly involve patients; therefore, it was assumed that only the agreement of practices in the high-intensity arm would be needed for the distribution of leaflets and for their participation in the educational sessions. However, despite discussions with previous members of the Cambridgeshire 1 Research Ethics Committee (REC) about this matter, the committee stipulated that formal consent was required from all invited surgeries, regardless of which arm of the trial they were assigned to. This led to an unexpected long delay in the roll-out of the trial, with contacts, sometimes visits, needing to be arranged with > 100 practices, ultimately resulting in our being granted an 18-month no-cost extension to our programme by the NIHR. The upside was more time to develop the theory-based interventions prior to the trial beginning.

This is a relevant point to place a general comment about our programme. We had to manage challenging situations, a protracted ethical review and subsequent adjustments to our protocol. All of these were ultimately beneficial (see in particular the PAATH study in Work package 5), other than the requirement to gain consent from practices to take part in the cRCT. That reduced our sample size but allowed a PAU comparator in those practices that did not consent, and we retained sufficient power to reject our null hypothesis and confirm the hypothesis of doubling referrals with uncanny accuracy. In retrospect, we would have benefited from a Programme Steering Group as is now required by the NIHR, but we drew on valuable advice from the Central Commissioning Facility and from the late Professor Helen Lester, who inspired some of our programme and was generous with her advice.

The recruitment process was lengthy and at times extremely frustrating. Busy GPs were difficult to contact directly but practice managers were good liaison intermediaries. However, many of the practice managers were very protective of the GPs’ time and were occasionally more negative about the likelihood of the practice participating than were the GPs when we eventually spoke to them. It took many attempts to persuade some practice managers to facilitate discussion of the research trial at team meetings, despite the fact that information had already been sent to the lead GPs within the practices.

The time commitment required to participate in the trial was a key issue for GPs. Reassurance that participation involved essentially just the 2 hours of educational sessions over the whole 2 years of the trial, for which the practice would receive income, was helpful in motivating them to participate.

Recommendations for future research

As has become evident in much health research, the process of ethical review can be protracted and frustrating for researchers. GPs’ negative attitudes, concerns and ambivalent feelings should be elicited and addressed with recruitment strategies.

We relied on the assumption that lead GPs would read the trial information sheet, discuss it with their colleagues and decide whether or not they wanted to participate. It became apparent during the trial that this was not always the case, as many GPs with other demands on their time did not know about our trial. A more advantageous approach could be to advertise the trial with individual GPs prior to gaining consent.

Implementation of the Liaison with Education and General practiceS cluster randomised controlled trial with general practices

The full protocol for this trial has been published. 30

Research aims

Our main aim was to test the null hypothesis that, in terms of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of detecting individuals at HR aged 16–35 years, a theory-based educational intervention for primary care was not different from a postal information campaign co-ordinated from an office in a secondary care-based EIS (CAMEO). The journal, Trials, where we published the protocol, insisted on this null construction, which is not easy to follow.

Formulated in a positive manner, this cRCT compared two different approaches to liaising with primary care to increase detection and early referral of people at HR to a specialist early-intervention team for young people with psychosis. We predicated the sample size and power on a doubling of HR and FEP referrals by the high-intensity intervention.

Methods for data collection

General practices were randomly allocated into two groups to establish which is the most effective and cost-effective way to identify people at HR for psychosis. One group received postal information about the local EIS, including how to identify young people who may be in the early stages of a psychotic illness. The second group received the same information plus an additional ongoing theory-based educational intervention with dedicated liaison practitioners to train clinical staff at each site.

The primary outcome was count data per practice site on the number of HR referrals to a county-wide specialist EIS (CAMEO). This was conducted over a 2-year period. All referrals during the duration of the trial were assessed clinically by the study team and stratified into those who met criteria for HR or FEP according to the CAARMS11 (true positives) and those who did not fulfil such criteria (false positives).

Analysis of the effectiveness of the intervention

Given that the main outcome (referrals per practice) was count data, the yield, our primary statistical approach was Poisson regression. Results were adjusted for surgery size and the number of GPs working in each site was considered as a covariate in the model. We also employed Pearson’s chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test to compare demographic characteristics of the general practices. All of the analyses were performed using the statistical package R (version 3.0.0; the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Analysis of the cost-effectiveness of the intervention

Decision-analytic modelling was used to investigate the cost-effectiveness of the high- and low-intensity interventions compared with PAU. A decision tree was constructed in Microsoft Excel 2013 to model the care pathways of the young people in the trial and assess the costs and effects over 2 years associated with the two active interventions and PAU. The costs of (a) the high- and low-intensity interventions, (b) diagnosing referrals who did not meet criteria for HR or FEP (false positives), (c) diagnosing and treating identified HR and FEP cases (true positives) and (d) the subsequent treatment of HR and FEP cases who were not identified (false negatives) were included.

Results of the Liaison with Education and General practiceS cluster randomised controlled trial

The results from this trial have been published online (see Appendix 7). 31

Key findings on the effectiveness of the intervention

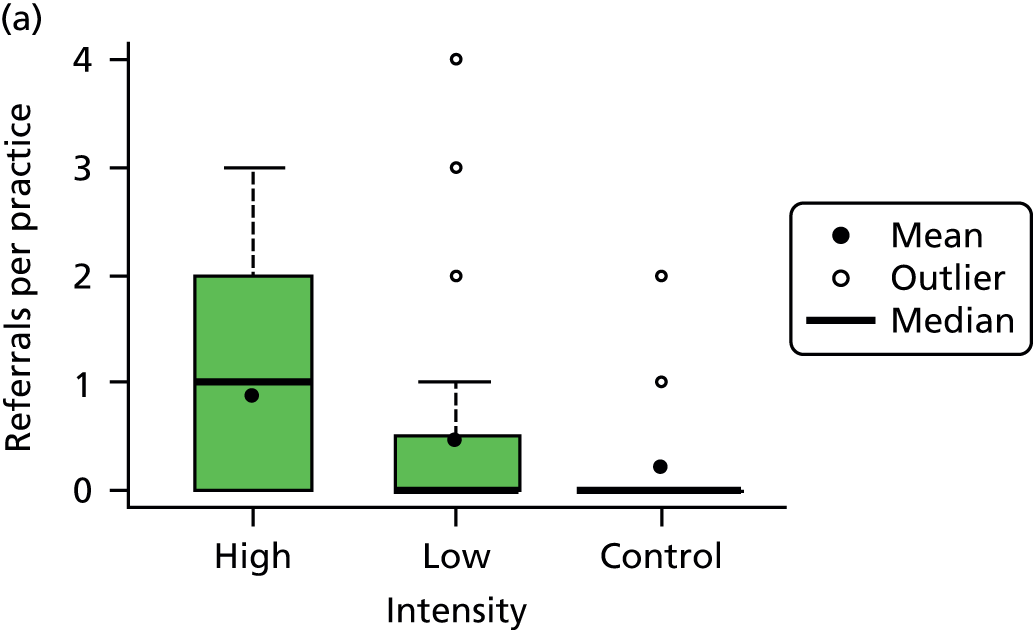

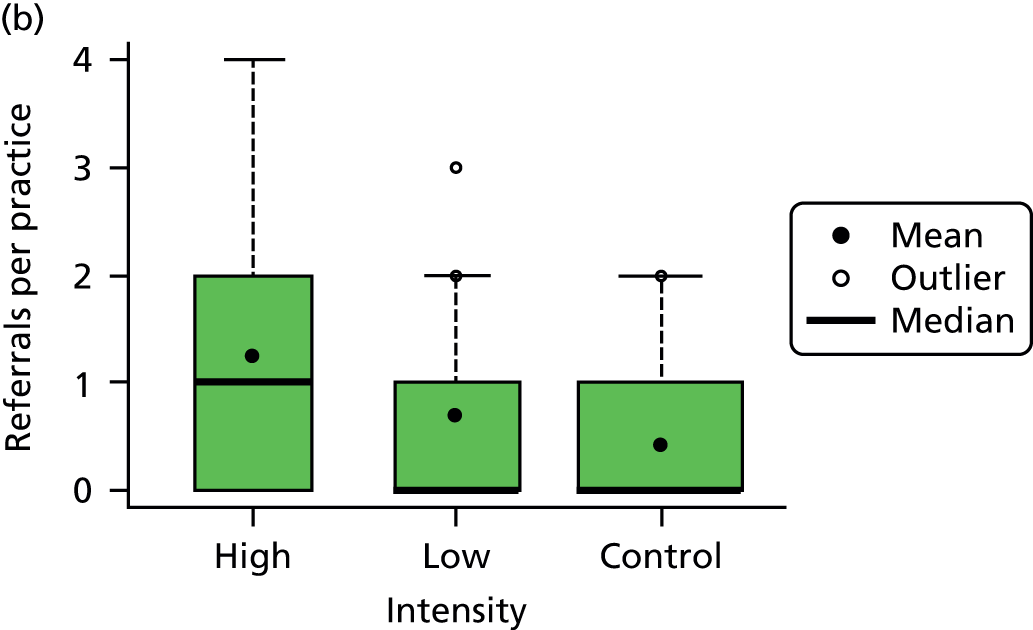

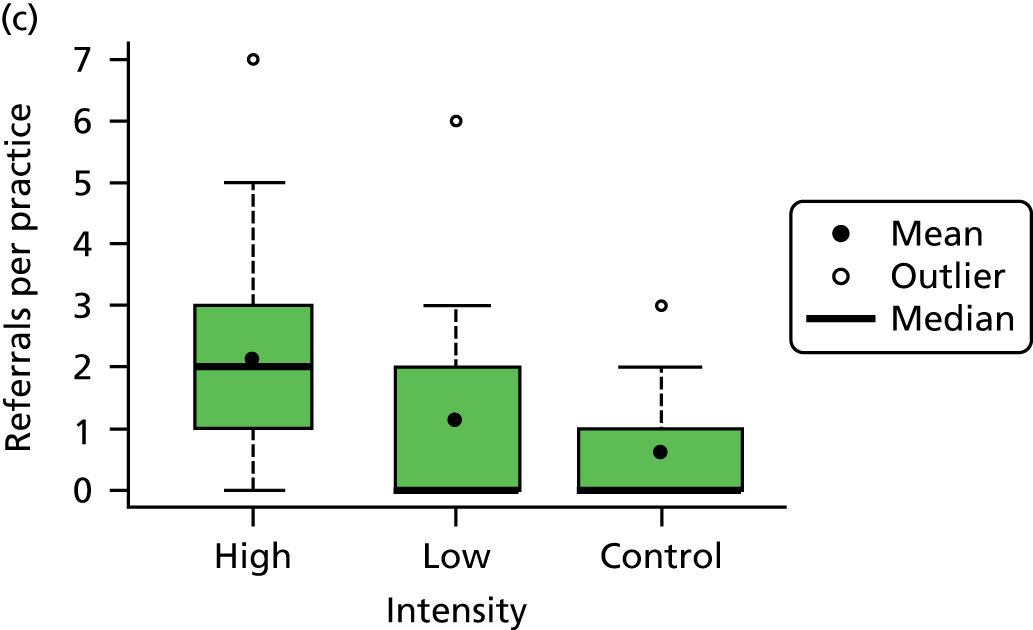

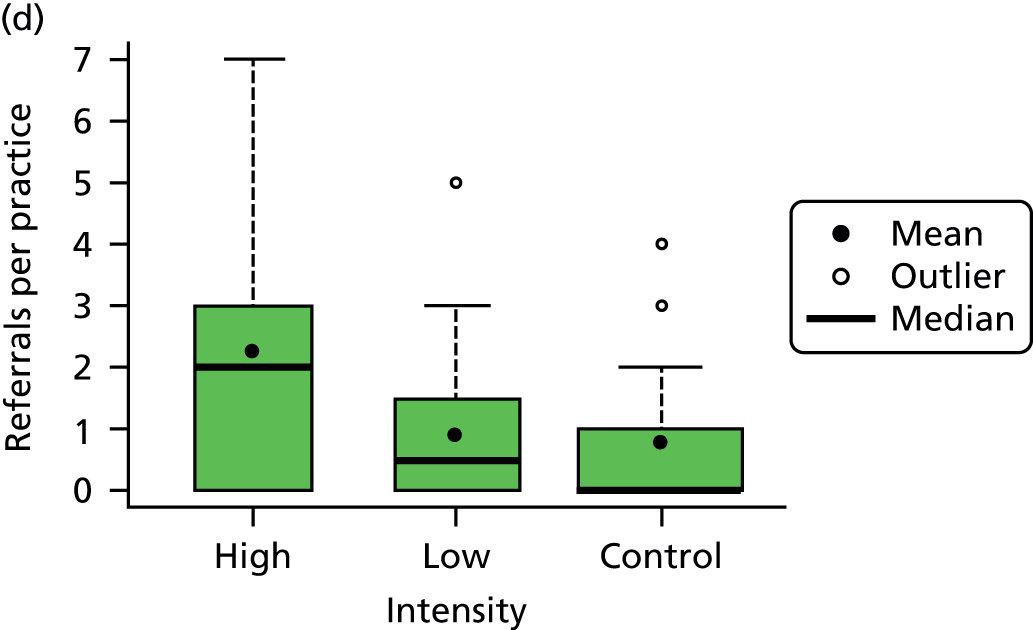

The intervention succeeded in raising awareness of potential psychotic symptoms. Between 22 December 2009 and 7 September 2010, 54 of 104 eligible practices provided consent and between 16 February 2010 and 11 February 2011 these practices were randomly allocated to the interventions (28 to the low-intensity intervention and 26 to the high-intensity intervention); the remaining 50 practices constituted the PAU group. Two high-intensity practices were excluded from the analysis. In the 2-year intervention period, high-intensity practices referred more FEP cases than low-intensity practices [mean (SD) 1.25 (1.2) for high intensity vs. 0.7 (0.9]) for low intensity; IRR 1.9, 95% CI 1.05 to 3.4; p = 0.04], although the difference was not statistically significant for individuals at HR of psychosis [mean (SD) 0.9 (1.0) for high intensity vs. 0.5 (1.0) for low intensity; IRR 2.2, 95% CI 0.9 to 5.1; p = 0.08]. For HR and FEP cases combined, high-intensity practices referred both more true-positive [mean (SD) 2.2 (1.7) for high intensity vs. 1.1 (1.7) for low intensity; IRR 2.0, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.6; p = 0.02] and more false-positive [mean (SD) 2.3 (2.4) for high intensity vs. 0.9 (1.2) for low intensity; IRR 2.6, 95% CI 1.3 to 5.0; p = 0.005] cases. Most of these (68%) were referred on to appropriate services. Referral patterns did not differ between low-intensity and PAU practices (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of the distribution of referrals by intervention group. (a) HR; (b) FEP; (c) true positives; and (d) false positives. Lower hinge = 25th centile; upper hinge = 75th centile; line = median; filled dots = means; open dots = outliers.

Key findings on the cost-effectiveness of the intervention

Details of the quantitative economic results and how this part of the trial was conducted can be found at www.thelancet.com/cms/attachment/2035390784/2050868157/mmc1.pdf (accessed 19 January 2016).

Total cost per true-positive referral in the 2-year follow-up was £26,785 in high-intensity practices, £27,840 in low-intensity practices and £30,007 in PAU practices. The lower cost was attributable to fewer false negatives (HR and FEP cases that are not identified), which are assumed to be associated with treatment costs at a later point. The high-intensity intervention was the most cost-effective strategy.

Interpretation

This intensive intervention to improve liaison between primary and secondary care for people with early signs of psychosis was clinically effective and cost-effective. Increasing the resources aimed at managing the primary–secondary care interface provides clinical and economic value in this setting.

Successes

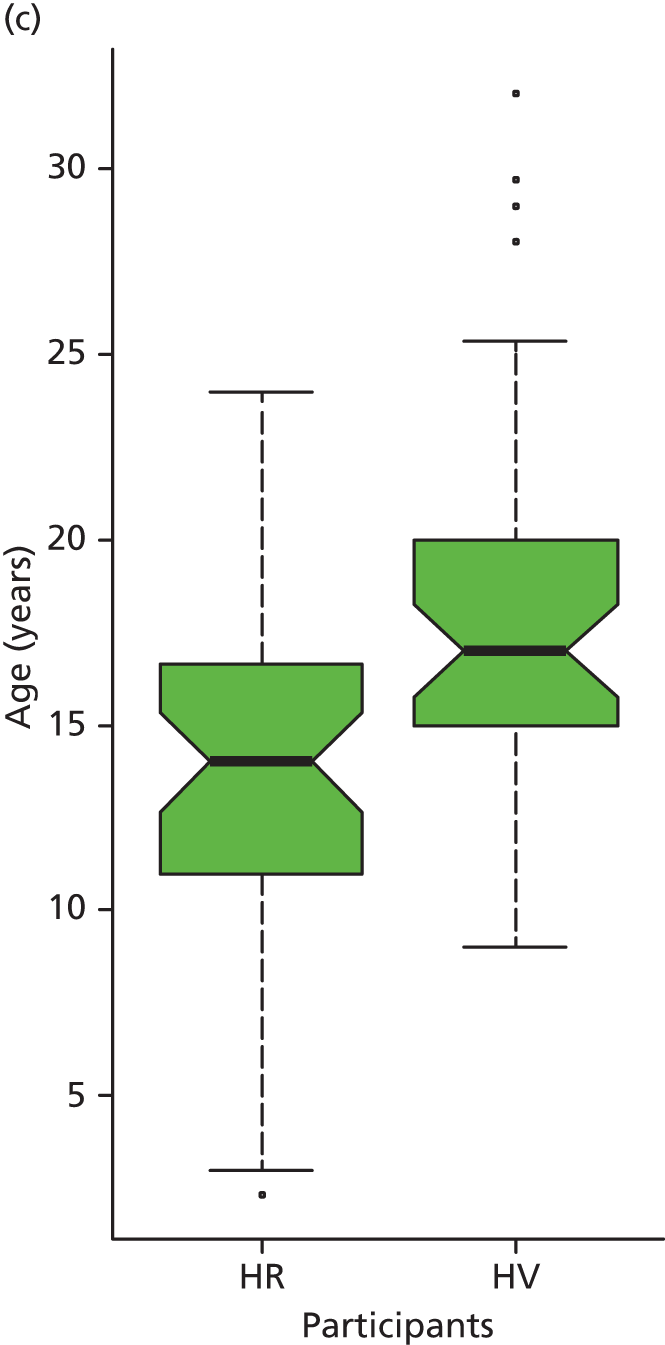

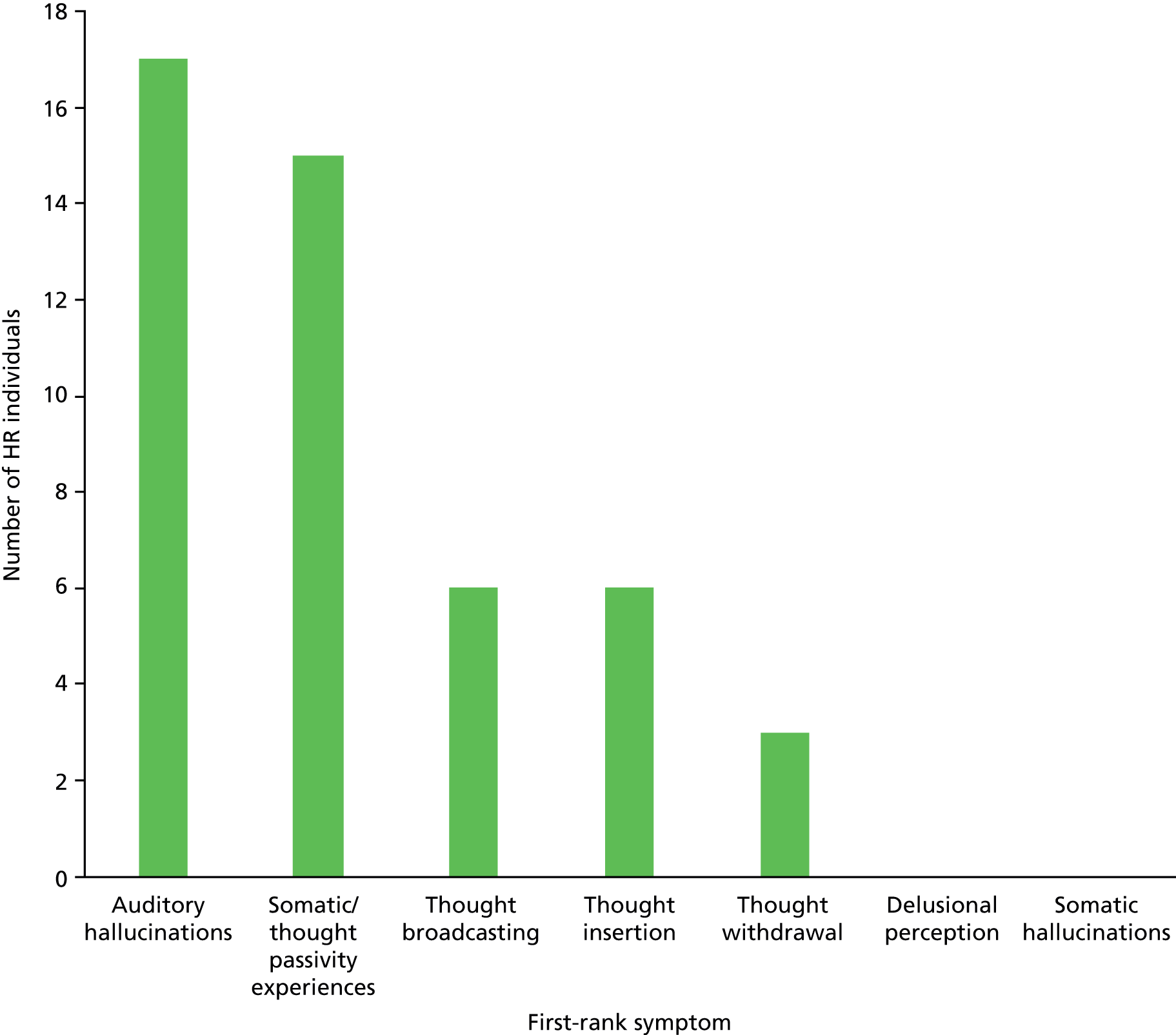

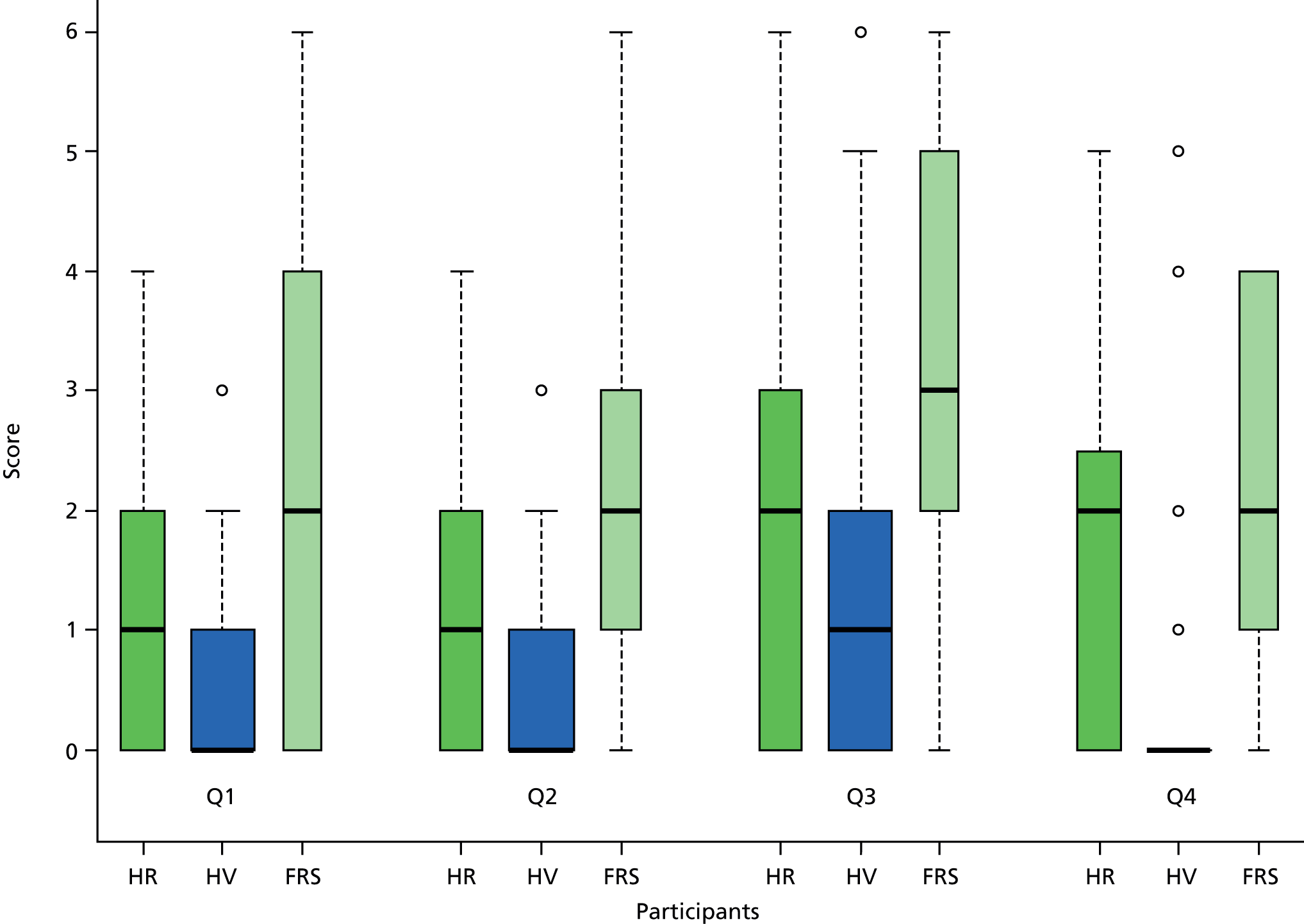

In the south of the county, mental health services were cohesive and the early-intervention team was well established. Generally speaking, the GPs in the south of the county were much better informed about the CAMEO team and what it could offer patients. As a result, they were more open to participating in research connected to psychosis.