Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1153. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Richard McManus reports grants from the Department of Health, National Institute for Health Research, Career Development Fellowship and Professorship during the conduct of the study; blood pressure machines from OMRON and Lloyds Pharmacy were received for research outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Fletcher et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

SYNOPSIS

Background

Stroke accounts for about 10% of deaths internationally, and for over 4% of direct health-care costs in developed countries. 1 If other costs, such as lost productivity, benefits payments and informal care costs, are taken into account, the total costs double; for example, in the UK annual care costs are around £4.4B per annum, but total costs are £9B per annum. 2 Over 20% of strokes are recurrent events,3 and if one also takes into account prior history of transient ischaemic attack (TIA), this figure rises to about 30%. 1

The majority of patients survive a first stroke, often with significant disability. Impact of stroke is likely to increase because the prevalence of stroke in the population is likely to rise as a consequence of the ageing of the population and improvements in stroke survival. 4 The National Audit Office estimates that preventing just 2% of strokes in England would save care costs of over £37M in 1 year. 5

Blood pressure (BP), smoking status and serum cholesterol concentration are the most important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and more deaths are attributable to these than any other major disease risk factors. 6 BP and cholesterol lowering both offer enormous potential for stroke risk reduction. Each reduction of 5 mmHg in diastolic BP is associated with a 38% reduction in stroke risk7 and a 1-mmol/l reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is associated with a 20% reduction in risk. 8 The efficacy of cholesterol and BP lowering in both primary and secondary prevention9–11 has been demonstrated. Both national and international guidelines promote CVD prevention through pharmacological control of BP and lipid levels, plus encouragement of behavioural change and lifestyle modification. 12–18

Despite guidelines, previous studies across Europe19–23 and North America24 have repeatedly identified undertreatment of patients for CVD prevention in specific at-risk groups. This may be because of concerns about the applicability of the evidence base for primary care, a particular issue with regard to BP lowering following stroke,25 or it may be because better implementation strategies are needed. Implementation research suggests that improving professional education, feedback via audit and patient-level prompts and greater involvement of patients including education can all lead to greater adherence to guidelines. The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), a system for incentivising practices to achieve specific targets, has had some impact, but QOF targets for managing BP and cholesterol in people at high risk of CVD or after stroke are less intensive than guideline recommendations. Most effective guideline implementation programmes utilise multiple strategies. 26 A third barrier to optimal stroke prevention is that the existing evidence base raises further questions. What is the optimal target for BP following stroke? Is it better to focus on a population strategy (i.e. make sure that all people are treated with something)27 or to focus on achieving the intensive targets that have been set in current guidelines for BP and cholesterol?28,29

The research programme

The aim of this programme is to provide an evidence base to inform optimal stroke prevention in primary care with regard to both BP and cholesterol lowering, and to develop tools to support implementation by both users and health-care professionals. Within the general theme of generating an evidence base in the setting in which the evidence will actually be used,30 this programme focused on three areas: the potential for a polypill, the potential for self-management, and BP lowering following stroke/TIA in primary care.

A series of studies involving different approaches (surveys of practice information systems; screening of patients; interviews with patients and doctors and nurses; economic modelling; and clinical trials) were carried out to answer the following research questions:

-

Is it more cost-effective to titrate treatments to target levels of cholesterol and BP, or to use fixed doses of statins and BP-lowering agents (polypill strategy)?

-

Will telemonitoring and self-management improve BP control in people on treatment for hypertension, and in people with a history of stroke/TIA in primary care?

-

In people with a history of stroke/TIA, can intensive BP-lowering targets be achieved in a primary care setting, and what impact will this have on health outcomes?

In addition, a number of service developments were developed:

-

tools to support optimal implementation of guidelines for primary and secondary prevention of stroke in primary care, including training programmes

-

methods to optimally involve patients in self-management of their stroke risk.

The research was carried out between April 2008 and March 2014.

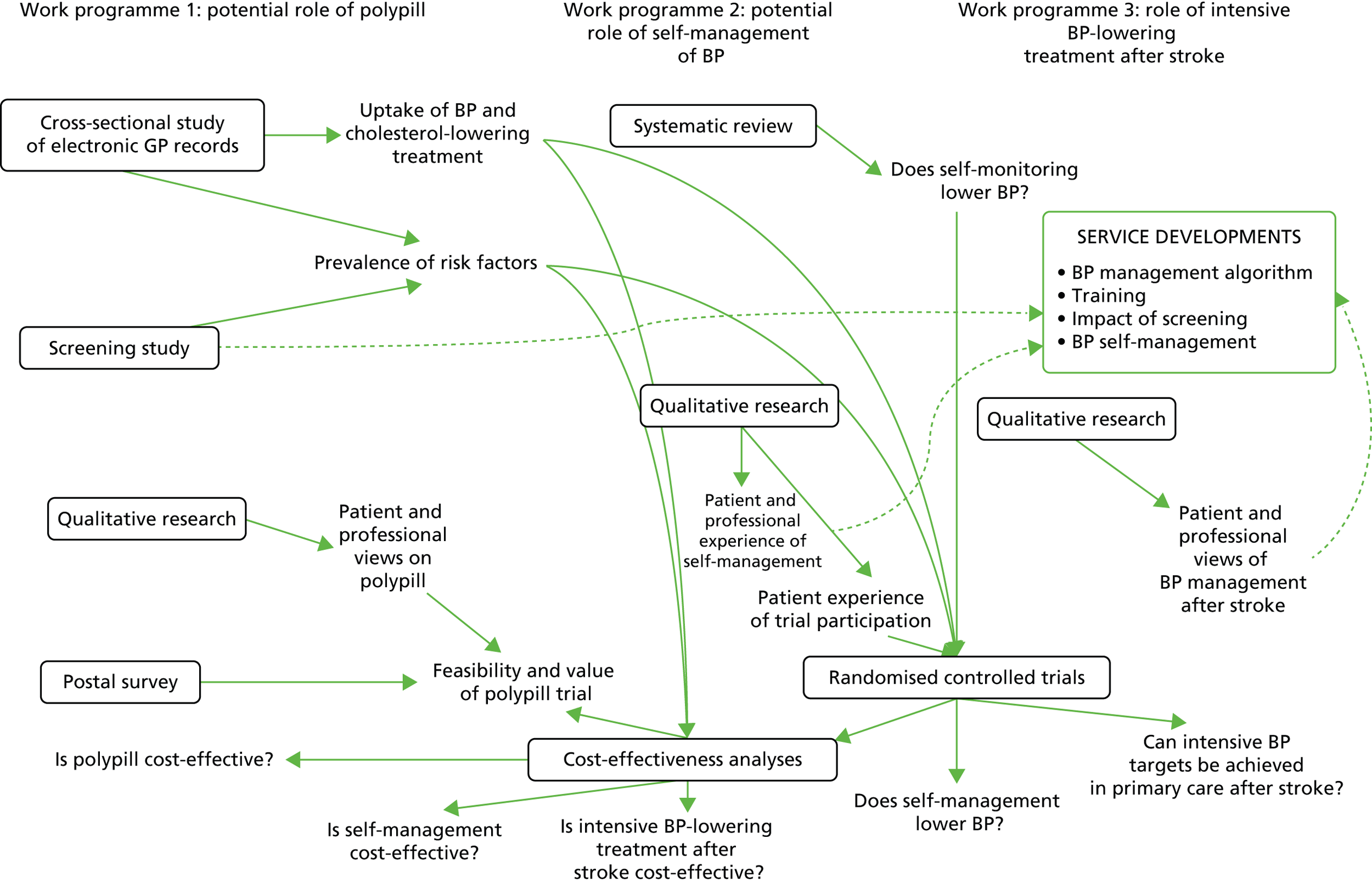

The inter-relationships between the three work programmes are summarised in Figure 1. The epidemiological data collected in work programme 1 contributed to the cost-effectiveness analyses in all three work programmes, and to aspects of trial design in work programmes 2 and 3. There was shared methodology in the health economics across the three work programmes.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the programme. GP, general practitioner.

Work programme 1: is it more cost-effective to titrate treatments to target levels of cholesterol and blood pressure, or to use fixed doses of statins and blood pressure-lowering agents (polypill strategy)?

There is strong evidence that antihypertensive drugs and statins are highly effective at reducing risk of vascular events in people with risk factors for CVD. 8,31 This evidence has been incorporated into international guidelines for over a decade. 14,32 Notwithstanding this general professional acceptance of the benefits of these drugs, uptake remains poor. 33 Furthermore, lack of adherence in people who are prescribed these drugs is common, and is associated with substantial morbidity. 34,35 This has generated interest in the potential for fixed-dose polypills to improve both uptake of and adherence to cardiovascular (CV) preventative drugs. There is evidence that polypills can bring about important reductions in BP and LDL cholesterol,36 and that fixed-dose combinations are associated with improved adherence to therapy. 37 While the first tranche of polypill trials were placebo controlled, a trial of the use of a polypill in comparison with usual care has recently been published. 38 The UMPIRE (Use of a Multidrug Pill in Reducing Cardiovascular Events) trial found that the use of a fixed-dose combination was associated with better adherence and lower BP and LDL cholesterol than usual care in participants with established CVD or at risk of CVD.

Evidence suggests that a polypill could lead to an 80% reduction in CVD. 39 While conceived as an approach for prevention at a population level, the polypill strategy also has potential for treatment of people with identified risk factors for CVD. It may be more efficient than treating to target as a result of reduced monitoring costs and improved effectiveness due to better adherence40 and fewer side effects. 41 Guidelines have interpreted the evidence on BP and cholesterol lowering in terms of achieving specific treatment targets. 28,29 This is based not on direct trial evidence, but from extrapolating from the results of observational studies that correlate risk to risk factor level and from non-randomised analyses of trials such as HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment). 42 Therefore, there is a case for comparing treatment to target regimens against treatment with a fixed-dose combination (polypill).

The original estimates of the likely impact of a polypill were based on giving the pill to a whole population over a given age. 39 This is difficult to apply in first-world settings, as many people are already on some of the components of the polypill, whether for BP lowering or for cholesterol lowering, or for both. In this setting there are essentially three potential populations that need to be considered: people with existing CVD, people at known high risk of CVD and people with unknown risk of CVD. The polypill has potential applications in all three groups.

This work programme planned to address the following questions:

-

What is the prevalence of ‘high CV risk’ and use of CV-risk-lowering treatments in people aged ≥ 50 years in primary care (using evidence from practice information systems)?

-

What is the prevalence of ‘high CV risk’ in people aged ≥ 50 years in primary care (using evidence from a screening study)?

-

What are patients’ and practitioners’ views of using a polypill to manage their CV risk as opposed to treatment by monitoring targets (using qualitative studies)?

-

What is the likely impact of introducing a polypill strategy for lowering CV risk (using a modelling study)?

-

What is the likely impact of a QOF indicator for assessment of CV risk (from the modelling study)?

-

How feasible is it to perform a randomised controlled trial (RCT) testing the cost-effectiveness of titrating treatment to target levels of cholesterol and BP, compared with using fixed doses of statins and BP-lowering agents (using polypill strategy)?

Evidence from practice information systems

The aim of our data analysis of practice information systems was to provide data of relevance to any future polypill trial in terms of numbers of potential participants, and data to go into our modelling studies of the potential role of a polypill in different populations. Our analyses were packaged into three separate publications. 33,43,44

The design for all three of these analyses was a cross-sectional retrospective study of electronic health records from all patients aged ≥ 40 years registered with 19 general practices in the West Midlands. 43

Sheppard et al.43

Our first analysis focused on the impact of age and sex on primary preventative treatment (namely BP- and cholesterol-lowering drugs) for CVD. In contrast with previous research on secondary prevention, we did not find important differences in the use of preventative treatments between men and women. With regard to age, we found that the proportion of people prescribed statins rose up to the age of 75 years (29% in the 70–74 years age group were on statins) and then fell, and that the proportion of people prescribed BP-lowering agents rose up to the age of 85 years (57% of people aged 80–84 years were on medication) and then fell. The low use of statins in elderly populations is likely to reflect two factors. First, there was ambiguity in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines that were in force at the time,25 which focused on people up to the age of 74 years, but this was corrected in the new 2014 NICE lipid guidelines, which extend recommendations on use of statins up to the age of 84 years. 45 Second, there is an absence of direct evidence from RCTs on the effect of statins in people aged over the age of 80 years.

This analysis raised several questions for research and clinical practice. Currently, there is not a strong evidence base for use of statins in people over the age of 80 years. With the demographic changes in developed countries with increased life expectancy and growing proportions of people in the over 80 years age group, it is important to know whether or not such drugs are effective in this age group. It is also important to better understand why CV prevention drugs are not used more in older people. Non-use may reflect appropriate prescribing, taking into account patient wishes, quality of life and comorbidity. Qualitative research is needed to better understand the reasons for low uptake from both professional and patient perspectives. The disparity between statins uptake and antihypertensive uptake in this population is of particular interest; it is not clear whether or not this reflects the stronger evidence base for antihypertensives or adverse perceptions of the side effects of statins. The analysis also provides some circumstantial support for the use of a polypill, in that this might be a strategy to increase uptake of these drugs in elderly people.

Sheppard et al.33

Our first analysis looked at the extent to which age and sex predicted use of preventative treatments in primary care. It did not specifically look at whether or not people were receiving these treatments according to current guidelines. We explored this in a second analysis of our 19 practice data sets, examining the extent to which guidelines for primary and secondary prevention were being followed for people aged 40–74 years. We found that, overall, although 64% of people eligible for primary prevention therapy were being treated according to guidelines, only about half of people with existing CVD were. There are a number of possible reasons for this poor adherence to guidelines, including concern about accuracy of risk calculators, or polypharmacy, misunderstanding (by both patients and health-care professionals) of risk information, or genuine patient preference. 46–49 This low uptake has implications for clinical practice, in that the NHS Health Check programme was predicated on a higher uptake of therapy in people identified to be at high risk of CVD. It also has implications for a polypill, in that a polypill might be an effective strategy to achieve guideline adherence based on trials of the use of a polypill that have demonstrated improved adherence to guidelines. 38,50

Sheppard et al.44

This third analysis examined the prevalence of uncomplicated stage 1 hypertension in primary care: that is, people with a BP between 140/90 and 159/99 mmHg who had no history of CVD, whose 10-year CV risk was calculated to be < 20%, and who were not on antihypertensive therapy. We found that 1 in 12 patients aged 40–74 years had uncomplicated stage 1 hypertension; this equates to approximately 1.9 million people in England and Wales. The annual cost of treating such people would be between £106M and £229M, with an estimated benefit of one CV event averted for every 128 people treated for 5 years. 51 There is variation in international guidelines as to whether or not uncomplicated stage 1 hypertension warrants medical therapy. UK guidelines do not recommend therapy, but this is out of step with European and US guidelines. The results of this analysis suggest that widening the treatment of hypertension to include uncomplicated stage 1 hypertension in England and Wales would result in the labelling of many more people as suffering from ‘hypertension’ with significant increased cost, and uncertain benefit. 51 This is a potential downside of any screening programme, such as a NHS Health Check, in that it might result in the treatment of people with stage 1 hypertension, where there remains uncertainty as to the value of treatment (a generally accepted pre-condition of screening programmes being that there is agreement on how to treat people identified as ‘positive’).

Evidence from a screening study

Our analysis of general practitioner (GP) information systems identified that a substantial proportion of the population aged 40–74 years were of unknown CV risk. We therefore carried out a screening study in which we invited those individuals of unknown risk to a ‘health check’ to assess their CV risk. We restricted these invitations to people aged 50–74 years, as mean CV risk in people below this age is not high enough to warrant blanket population treatment with a polypill. This study provided key data for our modelling studies (see Modelling studies); see Appendix 1.

A total of 2642 people were screened (39% of those invited). Of these, 1.3% were found to have existing CVD that had not been apparent from the electronic searches; 28.7% were found to have a > 20% 10-year risk of CVD, and 69.2% had a < 20% 10-year risk (in 0.8%, a valid serum cholesterol was not taken, so overall risk remained uncalculated). This indicates that screening in the over 50 years age group identifies a substantial proportion (approximately 1 in 3) of people screened who would require pharmacological treatment according to current guidelines. As the age threshold is raised, so the proportion increases, again raising the possible rationale of switching to a population strategy of treating everyone over a certain age. The recent change in the NICE lipid guidelines45 that now recommend offering statins to all people with a > 10% 10-year CV risk further raises the possibility of treatment purely on the basis of age, rather than on an assessment of CV risk, as even higher proportions of people over a given age will exceed the risk threshold.

Qualitative studies

A key consideration in whether or not a polypill strategy might be useful is its acceptability to health-care professionals and to patients. This was the focus of two qualitative studies which have been published. 52,53

Virdee et al.52

We conducted semistructured interviews with 16 primary health-care professionals. We found considerable resistance to the idea of using a polypill for primary prevention for all people over a specific age, but some acceptance of a role for a polypill in secondary prevention. The paradigm shift of switching from an individual-based strategy, in which individual drugs were titrated on the basis of effect on BP and cholesterol and changed according to side effects, to a population-based strategy, in which a cocktail of drugs was given without regard to individual characteristics (apart from age), was generally regarded as unwarranted, with particular concerns expressed around medicalisation, the need for continued monitoring of risk factors, and side effects. Perhaps the strongest reservations were around reducing monitoring. This was felt to be necessary for reasons of safety and checking compliance. A couple of participants went as far as to say it would be negligent not to monitor. Monitoring for safety (e.g. renal function and electrolytes) if the polypill included an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker would be required as per existing guidelines, but, in theory, monitoring of BP and cholesterol would not be. This research suggests considerable scepticism of this concept from health-care professionals, and so, if a polypill was used, it is likely that there would not be significant savings in terms of monitoring.

Virdee et al.53

We interviewed 17 people recruited from general practices as part of the CV risk screening study (see Evidence from a screening study). The results were similar to those elicited from health-care professionals, in that patients felt that it might be useful in people who needed to take the medicines anyway (secondary prevention or people at high CV risk), but was unnecessary otherwise. Again, concerns were expressed about side effects and the inflexibility of a single pill, and that monitoring should not be reduced.

Taken together, these two studies indicate that there is a reluctance of both patients and health-care professionals to consider using polypills, particularly for primary prevention in people not known to be at high CV risk. However, for some people there was the hint that their views might change if there was robust evidence that polypills were worth taking.

Modelling studies

We identified three different scenarios in which a polypill might be used: as an alternative to ‘health checks’ (i.e. offering a polypill rather than a health check); as an alternative to ‘treat to target’ management of BP and cholesterol for people at high risk of CVD; and as an alternative to ‘treat to target’ for secondary prevention of vascular events. The third scenario was subsequently funded as a separate Stroke Association/British Heart Foundation programme grant to conduct a trial, so we focused on the first two scenarios. We had also originally intended to conduct a subanalysis of whether or not it might be cost-effective to introduce a QOF indicator for assessment of CV risk. However, the roll-out of the ‘health checks’ programme (the national introduction of this programme post-dated the application for this research programme) made this question redundant, so we did not pursue it.

Cost-effectiveness analysis of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a polypill for all versus screen and treatment as per guidelines in a population with unknown cardiovascular risk (see Appendix 1)

In this analysis we were interested in exploring the cost-effectiveness of a polypill as it was originally proposed: that is, for primary prevention in a population in whom CV risk was unknown. We felt that the comparator needed to be the offering of a ‘health check’, as this is national policy in England and Wales. Our study population was, therefore, people aged ≥ 50 years with unknown CV risk and no history of CVD who were not on statins or antihypertensive therapy. The characteristics of this population that were fed into our model were derived from our own data from our screening study. Our intervention was a polypill with 40 mg of simvastatin and three half-dose antihypertensives. We found that offering a polypill was cost-effective for both men and women and for all age groups over the age of 50 years. The polypill strategy was more expensive than screening and treating as per guidelines (we had factored in a pill cost of £1 per pill in our base case, which is substantially more than the generic costs of using these drugs). However, our results were sensitive to the assumptions that we made. In particular, if only 25% of people took up a polypill, then usual care dominated. Given the results of our qualitative findings, it cannot be assumed that take-up would be even as high as 25%. Nevertheless, as questions continue to be raised over the cost-effectiveness of health checks, this analysis suggests that use of a polypill in this context should be explored further, ideally in a trial.

Cost-effectiveness of use of a polypill versus usual care or best practice for primary prevention in high-risk patients in the West Midlands, UK (see Appendix 1)

An alternative way of using a polypill is to use it to treat people already identified as having indications for the CV-risk-lowering components of the pill. We found from our qualitative studies that such a use of a polypill is less problematic as far as health-care professionals and the public are concerned than offering it to people of unknown risk. Therefore, in this model we wanted to assess whether or not a polypill would be cost-effective compared with conventional treatment of CV risk factors in people known to have a 10-year CV risk of > 20%. We used two comparators: current practice (as identified from our analysis of GP databases described in Evidence from a screening study), and optimal practice, namely full adherence to national guidelines. Our study population was people aged ≥ 40 years without CVD who were being treated with a statin or a BP-lowering agent or both. The characteristics of this population were derived from our GP database study. We found in our base-case analysis that optimal guideline care was the most cost-effective option. Comparing use of a polypill with current practice, we found that a polypill was more effective, but the costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) were high, and it was cost-effective only using a threshold of £20,000 per QALY in men over the age of 70 years. These results were sensitive to the cost of a polypill; if the polypill was 50 pence per tablet rather than £1 per tablet (as assumed in our base case), then polypills are cost-effective compared with current practice [with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £1878 per QALY], and, indeed, cost-effective compared with optimal guideline care (with an ICER of £16,827 per QALY). Recent trials have found that polypills do improve adherence compared with standard care in this population,38,50 and this fits with our analysis. The key question, however, is whether the optimal strategy to improve primary prevention in people at high risk of CVD is to implement strategies to optimise guideline adherence or to use polypills. In our analysis, we did not define (or cost) what strategy would achieve optimal guideline adherence. Therefore, in conclusion, a polypill strategy can improve risk factor control compared with current practice, but whether or not this is a cost-effective option will depend on the cost of the pills. Optimising guideline adherence, rather than using polypills, might be the most cost-effective option but, as we did not factor in additional costs of achieving better guideline adherence, the relative cost-effectiveness of this option must remain speculative.

Patient feedback about a primary prevention polypill trial: questionnaire survey (see Appendix 1)

How feasible is it to perform a RCT testing the cost-effectiveness of titrating treatment to target levels of cholesterol and BP, compared with using fixed doses of statins and BP-lowering agents?

Our original intention was to conduct a pilot RCT. We were planning to use a pill which included 40 mg of simvastatin and amlodipine. However, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued an advisory statement against such a combination because of the potentiating effects of amlodipine on simvastatin bioavailability. 54 Therefore, it was no longer practical to use this combination and so we did not perform this trial. In agreement with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), we did perform a questionnaire survey of potential participants in a polypill trial to gauge likely participation.

We sent a hypothetical patient information sheet with a questionnaire to patients who, from a review of electronic records of one general practice in the West Midlands, would have been eligible for our planned trial (of polypill vs. ‘health check’ in people of unknown CV risk aged 50–74 years). We sent a single mail shot and had 53 responses (10% response rate). Of these, 25 (48%) indicated that they would have taken part in the trial. The most common reason that people gave for not wanting to take part in the trial was that they had concerns about taking drugs that might not be necessary (this reason was given by 12 people, i.e. 46% of those who said that they would not take part). This is consistent with the findings from our qualitative research. In conclusion, this small study suggests that people would take part in a polypill trial for primary prevention in people of unknown risk. In terms of planning a trial, approximately 5% of the potentially eligible study population might be expected to take part (assuming that recruitment to the trial would start with a mailshot to potentially eligible people registered with a practice). This equates to 25 participants in a typical practice. Although such a trial would be feasible, the low uptake might raise concerns over the generalisability of any trial findings. The importance of this would depend on how a polypill might be used in clinical practice. If it is to be used in a population that is unselected (other than by age) as an alternative to health checks and treatment on the basis of CV risk, then this low uptake suggests that the population impact of such an approach would be considerably lower than we had found from our modelling. If, on the other hand, it were offered to patients known to be at high CV risk, then a trial of this sort would provide valid information despite the low uptake, as it would only need to apply to people who would be prepared to take a polypill.

Conclusions

In this programme we have explored the potential role of a polypill for improving prevention of CVD. There are a number of concluding observations to make:

-

Our analysis of current patterns of use of pharmacological therapy for modifying CV risk in general practice shows that, for many patients, current care does not adhere to national guidelines. This raises the question of whether the way forward is to develop better mechanisms to implement the evidence base, or whether an entirely different approach should be adopted. In this section, we explored the entirely different approach, namely using a polypill. In Work programme 2: will telemonitoring and self-management improve blood pressure control in people on treatment for hypertension or with a history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack in primary care? we explore the potential for a different mechanism (using patient self-management for the control of hypertension).

-

Our second analysis found that CV risk-modifying therapy, particularly statins, was used less in older populations (over the age of 75 years for statins). Again, this raises the question of whether or not a simple strategy such as use of a polypill might lead to higher uptake of these treatments in this age group compared with conventional strategies of targeting treatment on the basis of risk.

-

Our screening study, which was primarily used to inform our cost-effectiveness analyses, found that about one-quarter of people aged ≥ 50 years who attend screening are found to have 10-year CV risk of > 20%. These are key data for informing the relative value of treating a population without screening compared with current practice of screening and treating those at high risk.

-

Our qualitative work found that health-care professionals raised concerns about using a polypill for primary prevention, although they felt that it might have a role in secondary prevention.

-

This view was echoed in our qualitative work with patients, who voiced misgivings about people taking treatments that were not ‘necessary’.

-

Our cost-effectiveness analysis suggested that using a polypill strategy was likely to be highly cost-effective when compared with the current practice of screening people and treating those found to be at high risk. However, this is in the absence of any empirical evidence that a polypill would be used by this population, and so this conclusion has to remain speculative.

-

Furthermore, our cost-effectiveness analysis of using a polypill in people known to be at high risk (the more acceptable strategy from our qualitative research) found that such a strategy was unlikely to be cost-effective against better implementation of guidelines.

-

Finally, we collected helpful pilot data on the feasibility of a trial of polypill against screening and treating. Although the response rate was low, we did have sufficient interest (about 50% of respondents) indicating that a trial of this strategy would be feasible, at least in terms of patient recruitment.

On the basis of these observations, we conclude that there is a need for further evidence through RCTs to determine what role the polypill should play in CV prevention in first world countries such as the UK. There are two types of trial that need to be performed. One type of trial is to compare a polypill with usual care in people with high CV risk or existing CVD. Such trials are now under way in several countries. Indeed, our own research group is leading a trial on use of a polypill for secondary prevention of stroke, funded by the Stroke Association. The second type of trial is to compare offering a polypill rather than a CV screen. Our outputs from this programme suggest that such a trial will be challenging, but possible, and with the potential for leading to important health gains.

Research recommendations

-

A RCT of offering a polypill against offering health checks in people aged ≥ 50 years. Our economic modelling suggests that use of a polypill for all people aged > 50 years is likely to be highly cost-effective compared with current practice (screening for CV risk and treating those at high risk). However, our qualitative work and our patient survey suggest that uptake to such a trial might be low. Therefore, preliminary feasibility and pilot work should be carried out prior to such a trial.

-

Qualitative research should be carried out to better understand the attitudes of older people (aged ≥ 80 years) to taking drugs to reduce the risk of CVD. We demonstrated that the uptake of CV risk-reducing therapy falls in people over the age of 80 years. It is not clear whether or not this is appropriate. One possible explanation is that it reflects patient choice. There is little evidence on the attitudes of this age group towards taking such drugs and, therefore, qualitative work is required to understand whether this reflects informed underuse or possible inequity in access to such treatment. This research would also be relevant to understanding issues around polypharmacy and multimorbidity in this older population. There is little research to understand how older people regard strategies such as withdrawal of antihypertensives and lipid-lowering agents in older age. Therefore, such qualitative research could inform interventions to facilitate initiation/up titration of these drugs where appropriate, and also to inform withdrawal and down titration.

-

A RCT of statin therapy for prevention of CVD in people aged ≥ 80 years. Although there is a good evidence base, thanks to the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)55 that BP lowering is effective in people aged over the age of 80 years, there is a lack of evidence with regard to lipid lowering. Therefore, we do not know whether or not the low uptake in this age group that we observed is appropriate. This is an important question to answer, as the absolute benefits of statins in the very elderly are potentially very high. The qualitative work that we propose (see above) will also give us an indication of the likely attitude of the target population to this intervention.

Reflections on work programme 1

Over the timespan of the programme, there have been parallel developments in CV prevention in primary care. The QOF has influenced practice to some extent, but the targets used in the QOF are below those recommended in guidelines. Guidelines have changed, so that in effect NICE now promotes offering statins to everyone with a 10-year CV risk of > 10%, which is similar to offering them to everyone over a certain age (given that age is the strongest determinant of CV risk). Therefore, implicitly, NICE has endorsed one aspect of the polypill concept. NICE has also supported a second component of the polypill concept: the idea of not measuring cholesterol levels in people on statins. Our research suggests that primary care does not widely accept these two ideas, as evidenced by our interviews with health-care professionals.

A polypill approach runs counter to the growing interest in personalised medicine: the idea that drug therapy can be increasingly targeted, through better assessment of the genotype and phenotype, at patients who will directly benefit from them. It may be, therefore, that the role of the polypill will be limited to developing countries who cannot afford personalised medicine. However, it remains an open question whether or not a polypill approach might nevertheless be more cost-effective, even in first-world countries.

In all three work programmes, we used cost-effectiveness analysis in which we extrapolated beyond the trial data to estimate the impact of polypill, self-management and intensive BP lowering on long-term CV risk reduction. We had to select a number of study parameters, and any of these can be criticised, though we used what we felt were the best available. For example, we used the Framingham Risk Scores, even though they are US based, rather than the UK-based QRISK2, as we recognised that the latter underestimates the true impact of cholesterol and BP as it relies on electronic general practice data (which is often missing for the former and unreliable for the latter). To explore the potential impact of the parameters that we had used, we tested the impact of plausible variations in them using sensitivity analysis. Reassuringly, these sensitivity analyses did not suggest that parameter selection was a critical issue in any of the economic analyses. For work programme 1, the economic analyses were weaker than for work programmes 2 and 3, in that they were not based on RCT data on polypill impact.

Notwithstanding this limitation, our cost-effectiveness analysis suggested that a polypill would be cost-effective, at the right price, but in the absence of direct empirical data such a conclusion needs to remain speculative. At the time of writing it has been 12 years since the polypill concept was launched, but still it has not been taken up in first-world countries. An alternative approach to the two extremes of personalised medicine and polypill pharmacy is to look at ways of better treating people with existing risk factors. This is where the second work programme, on self-management of hypertension, comes to the fore.

Work programme 2: will telemonitoring and self-management improve blood pressure control in people on treatment for hypertension or with a history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack in primary care?

Hypertension is a key risk factor for CVD, the leading cause of death worldwide. 56 Therapeutic reduction of BP leads to significant reduction in both stroke and coronary heart disease risk and is cost-effective, especially for individuals at higher risk of CV events. 57,58 However, international community-based surveys indicate that only a minority of people treated for hypertension are controlled to recommended treatment levels. 59

Self-monitoring of hypertension has been proposed as a method for reducing BP over and above standard care by increasing the involvement of individuals in their own treatment and, therefore, aiming to increase adherence, reduce clinical inertia and provide patients and professionals with common information about the efficacy of treatment. 60,61 Self-measurement is a better predictor of end organ damage than office measurement62 and is well tolerated by patients. 63,64

This work programme planned to address the following research questions:

-

Does self-monitoring reduce BP (using meta-analysis with meta-regression of RCTs)?

-

Does telemonitoring and self-management by people with poorly controlled hypertension lead to better BP control than usual care (using a RCT funded by the Department of Health)?

-

How could a trial of self-management with or without telemonitoring for secondary prevention (using two qualitative studies and an economic analysis) be designed?

-

What is the effect of self-monitoring and medication self-titration on systolic BP in hypertensive patients at high risk of CVD (using a RCT, a cost-effectiveness analysis and a qualitative study)?

Meta-analysis of trials of self-monitoring

This has been published as Bray et al. 65 For a full-text version of this paper, see Appendix 2.

Our aim in this systematic review was to determine the extent to which self-monitoring on its own led to reductions in BP, and to seek to understand through meta-regression the reasons for previously observed heterogeneity in the results of self-monitoring trials. We found that self-monitoring was associated with a 4 mmHg reduction in systolic BP. There was significant heterogeneity, but we could not explain this by any of the six factors that we explored through meta-regression (age, sex, length of follow-up, diastolic BP, adjustments made for self-monitored readings and use of additional cointerventions). However, the presence of cointerventions seemed to explain some of the heterogeneity with regard to one of our secondary outcomes, namely whether or not an office target BP was achieved. We concluded that self-monitoring does have a small but significant effect on reduction of office BP when compared with usual care.

Randomised controlled trial of Telemonitoring and Self-Management in the Control of Hypertension (TASMINH2)

Our systematic review had demonstrated that self-monitoring per se has a beneficial impact on BP. A logical component to add to self-monitoring is self-management: leaving the decision to up-titrate medication to the patient on the basis of their home BP readings. There has also been increasing interest in telemonitoring, whereby readings at home are relayed to a health-care professional. Therefore, we conducted a trial that tested an intervention based on these three components: patient self-monitoring, patient self-titration and telemonitoring.

The protocol of this trial and the principal results have been published. 66,67 The full text of the Lancet paper is given in Appendix 2.

In our trial, we randomised 527 patients, with a mean age 66 years and whose BP at baseline was > 140/90 mmHg, to self-management with telemonitoring or to usual care, and followed them up for 1 year. Our primary outcome was change in mean systolic BP, for which we obtained data for > 90% of participants. We found that in the self-management arm, mean BP reduced by 17.6 mmHg at 1 year, and in the usual care arm by 12.2 mmHg [difference between groups 5.4 mmHg, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.4 to 8.5 mmHg]. Furthermore, there were no differences in quality of life or important differences in side effects between the two groups. A major contributor to the lower BP is likely to have been the increased use of antihypertensive medications in the self-management arm. In terms of applicability, self-management is not suitable for everyone, but even if only 20% of people with hypertension engaged in self-management, this would still equate to around 2 million individuals. Therefore, we concluded that self-management represented an important new addition to the control of hypertension in primary care.

How to design a trial of self-management with or without telemonitoring for secondary prevention

Our original intention was to follow on the TASMINH2 (Telemonitoring and Self-Management in the Control of Hypertension) trial with a trial in people with a history of cerebrovascular disease. However, we noted in the subgroup analysis of the TASMINH2 trial that people with high-risk conditions (diabetes and chronic kidney disease) appeared to derive less benefit from self-management (1.3 mmHg reduction, compared with 5.8 mmHg without a condition). This difference was not significant, but, nevertheless, we thought it would be of most value to test self-management in high-risk conditions, including these conditions as well as stroke. We also noted that the telemonitoring aspect of the intervention in TASMINH2 had little impact on the management, so we decided to drop that aspect of the intervention. Therefore, we decided to plan a trial of self-management in people with a high-risk condition. To inform the design of this trial, we carried out three further studies based on the TASMINH2 population: a cost-effectiveness analysis, and qualitative studies of patients’ and health-care professionals’ experiences of patient self-management. These three studies have been published. 68–70

Kaambwa et al.68

We ran a model which extended the results of the TASMINH2 trial on from 1 year to 35 years to compare costs and outcomes of self-management with those of usual care. Self-management was found to be cost-effective, with an ICER of £1624 for men and £4923 for women. This result was robust to sensitivity analyses around the assumptions made in the model, provided that the effects of self-management lasted for at least 2 years in men and 5 years in women. We concluded that self-management with telemonitoring was not only effective, but also cost-effective.

Jones et al.69

We interviewed 23 patients (and six family members) who had participated in the self-management arm of the TASMINH2 trial. We found that patients were confident about self-monitoring, and felt that their own readings were more accurate than those taken by the GP. However, some were reluctant to initiate an increase in medication without consulting their GP, especially if their BP readings were only just above threshold.

Jones et al.70

We interviewed 13 GPs, two practice nurses and one health-care assistant in practices that took part in the TASMINH2 trial. We found that health-care professionals were supportive of patient self-monitoring, although sometimes the procedures for ensuring that patients measured their BP properly (outside the trial) were haphazard, and there was no consistency in the way in which GPs interpreted or used home readings. This study (and the preceding one) identified important training issues for both health-care professionals and patients that are relevant both to trial management and to subsequent implementation into routine practice. The two studies also have important implications for self-monitoring in its own right. Self-monitoring of BP is increasingly being used, but these qualitative findings suggest that patients may not be measuring their BP properly, and GPs are not necessarily using the results of home readings appropriately. Given the popularity of self-monitoring and its potential value, it is relevant to consider ways in which GPs can better integrate self-monitored readings into their everyday clinical practice. This is an important theme of a new programme of research funded by NIHR that is being led by Professor McManus (RP-PG-1209-10051, ‘Optimising the diagnosis and management of hypertension in primary care through self-monitoring of blood pressure’).

What is the effect of self-monitoring and medication self-titration on systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease?

The protocol for this trial and the main results have been published. 71,72

We performed a RCT to determine the effect of self-management of hypertension compared with usual care in people with CVD, diabetes or chronic kidney disease. We recruited 552 patients, who had a mean age of 69 years and whose BP at baseline was > 130/80 mmHg (i.e. above the target for BP control in national guidelines at the time the trial was performed). We followed them up for 1 year, using a primary outcome of difference in systolic BP between the intervention and the control groups. We obtained primary outcome data on 81% of participants. The mean systolic BP in the self-management arm at 1 year was 128.2 mmHg, compared with 137.8 mmHg in the usual care arm, a difference between arms of 9.2 mmHg after adjustment for baseline BP. As in TASMINH2, there were no differences in adverse events or quality of life between arms. 9.2 mmHg is an important difference in BP, equating to approximately a 30% reduction in stroke risk. Its importance is magnified in that this trial was in a high-risk group, who had more to gain in absolute terms than the typical hypertension population. We had lower follow-up for the primary outcome in this trial than in TASMINH2, reflecting the greater comorbidity in the TASMIN-SR (Targets and Self-Management in the Control of Blood Pressure in Stroke and at Risk Groups) population. Nevertheless, multiple imputation for missing values did not make any important differences to the overall results. We concluded that self-management is an important management option for the control of hypertension in people with CVD, diabetes or chronic kidney disease.

Cost-effectiveness of self-management of blood pressure in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease (see Appendix 1)

A cost-effectiveness analysis has been published. 73

We conducted a modelling study to estimate the long-term impact of self-management compared with usual care for the control of hypertension in people with CVD, diabetes or chronic kidney disease. We found that self-management was dominant, resulting in improved outcomes at lower overall cost to the health service: an average gain of 0.2 QALYs per person with mean cost savings (over the lifetime) of £830 per person. This improved cost-effectiveness compared with the TASMINH2 findings reflects the greater effect on BP, the reduced cost of the intervention (no telemonitoring) and the higher risk of CV events in the study population.

Qualitative study (see Appendix 1)

We embedded a very simple qualitative study in the TASMIN-SR trial, in which we gave participants a blank postcard at their final follow-up (at 1 year), on which we asked them to write a few sentences about their experiences of the trial. A total of 149 of 450 (33%) of people who attended the 12-month follow-up sent us a postcard. They provided us with reasons that they had taken part in the trial (the most common being altruism), positive feedback on the attitude of trial staff, insights into their perspectives on the treatment programme, feedback on the trial paperwork (repetitive and boring) and attitudes to self-monitoring and self-management. In general, these reinforced our findings from the TASMINH2 qualitative studies. In conclusion, we felt that this was a very simple adjunct to a clinical trial that enabled us to gain qualitative insights into patient perspectives on the trial at minimal research cost (the main cost being the researchers’ time to analyse the postcards).

Conclusions

The self-management work programme has presented evidence from a systematic review and two trials (TASMINH2 and TASMIN-SR) with embedded qualitative and economic studies that self-monitoring of hypertension with self-titration of antihypertensives is both effective and cost-effective using standard criteria and that, in comparison with the review, self-management appears to result in greater reductions of BP than seen in self-monitoring alone. The trial in high-risk groups (TASMIN-SR) benefited from running directly on from the trial in uncomplicated hypertension and resulted in significantly greater reductions in BP with expected linked improvement in cost-effectiveness (9.2 mmHg vs. 5.4 mmHg). TASMIN-SR was conducted in a frailer group and, subsequently, follow-up was reduced (81% vs. 91% after 1 year) but there was no evidence of increased side effects or adverse events. TASMIN-SR found the intervention effective even without the telemonitoring used in TASMINH2, but this may reflect the difficulties of integrating home monitored BP into electronic medical records. Patients in both trials were enthusiastic about the increased involvement and knowledge gained by self-management but there were understandable anxieties about actually self-titrating. Professionals were interviewed in TASMINH2 only and they were also keener on self-monitoring than self-management. The cost-effectiveness studies required a number of assumptions but both showed that, provided the interventions provided sustained benefits for at least 1 year (TASMIN-SR) or 2/5 years (men/women in TASMINH2), they are likely to be cost-effective. Overall, this body of work includes around 90% of patients in the published literature on self-monitoring and self-titration in hypertension and provides strong evidence that self-management should be offered to patients with poorly controlled hypertensions, with or without other CV comorbidities.

Research recommendations

A randomised controlled trial of management of hypertension based on self-monitored blood pressure readings

Self-management involves two components: self-monitoring, and self-titration of therapy. Self-monitoring is also widely used outside self-management, but the results of self-monitored readings are not routinely incorporated into clinical practice in a consistent way. Therefore, it is important to see if incorporating the results of self-monitoring into BP management by the GP might also be an effective approach to improving the management of hypertension. This is indeed a major theme of a NIHR-funded programme grant on self-monitoring of BP, led by Professor McManus.

A randomised controlled trial of self-management of hypertension that is sufficiently powered to detect impact on clinical end points

Although there is a strong evidence base that lowering BP lowers the risk of CV events, there is a case for conducting a trial of self-management of sufficient size to measure such an effect directly. Before such a trial was done, feasibility would need to be established, for example exploration of using routine GP databases such as Clinical Practice Research Datalink for follow-up.

Reflections on work programme 2

In contrast to the polypill, self-management as a strategy seems to be becoming widely adopted in the NHS. Although in some areas the evidence is lacking, in terms of BP control we have provided consistent evidence that it is a potentially very important approach. Why does it work? A major factor that we have demonstrated is that it increases the likelihood that up-titration will occur when BP is above target. Patients who self-managed were on more drugs than patients that did not self-manage. This suggests that health-care professionals may overestimate the risks of side effects on antihypertensive treatment; this is relevant to the third work programme of exploring the value of intensive BP lowering after stroke. It is interesting to speculate as to whether or not self-management leads to better adherence to existing therapy. Unfortunately, we did not have sufficiently robust measures of adherence in this work programme and so cannot directly comment on this. One reason we did not is that the more accurate measures of pill taking may also influence pill-taking behaviour. Therefore, had we measured adherence, we might unwittingly have reduced the potential impact of self-management.

Work programme 3: in people with a history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack, can intensive blood pressure lowering targets be achieved in a primary care setting, and what impact will this have on health outcomes?

There is good evidence that lowering BP in people who have had a stroke is effective in reducing risk of a further stroke. 10 However, there is concern over the applicability of the trial findings to primary care,25 and controversy over what should be the optimal systolic BP target. Therefore, this work programme planned to do the necessary trial platform work to determine whether or not a clinical trial of different targets for systolic BP after stroke is warranted and feasible. A key question is whether lower BP targets can be achieved, or lead to a worthwhile reduction in BP, compared with standard targets. Therefore, this work programme had the following three research aims:

-

Does setting a lower systolic BP target for people with stroke in primary care lead to a lower BP (using a RCT)?

-

What are patients’ and health-care professionals’ views on BP targets after stroke (using a qualitative study)?

-

Is a lower BP target likely to be cost-effective (using an economic modelling study)?

Does setting a lower systolic blood pressure target for people with stroke in primary care lead to a lower blood pressure?

The protocol74 and trial report75 have been published. A version of this paper (prior to responding to referee comments) is provided in Appendix 1.

In this RCT, we recruited 529 patients (mean age 72 years) with a history of stroke or TIA from 99 general practices. Patients were randomised to an intensive systolic BP target (< 130 mmHg or a 10 mmHg in BP if baseline BP was < 140 mmHg) or a standard systolic BP target (< 140 mmHg). Apart from the systolic BP target, the management of BP was the same in both groups, with the frequency of review determined by whether or not the BP was above target (therefore, there was more health-care professional contact with participants in the intensive arm). The primary outcome was systolic BP at 1 year. Systolic BP went down by 16.1 mmHg in the intensive target arm and by 12.8 mmHg in the standard target arm. After adjustment for baseline BP, a 2.9-mmHg greater reduction in BP was achieved in the intensive target arm. The most striking finding in this study was the size of the reduction in BP in both arms, which was larger than would have been expected because of regression to the mean or accommodation effects. Therefore, our overall conclusion was that although aiming for a 130 mmHg or lower target for systolic BP in people with cerebrovascular disease in primary care can lead to small additional reductions in BP, the more important lesson for primary care is that active management of BP in this population will lead to clinically relevant improvements in BP control.

What are patients’ and health-care professionals’ views on blood pressure targets after stroke?

See Appendix 1 for the full report.

In this study, we sought to understand what barriers there might be to more intensive BP lowering in people who had had a stroke. We interviewed 13 patients who had taken part in the PAST-BP (Prevention After Stroke – Blood Pressure) trial (seven in the intensive target arm and six in the standard target arm) and eight health-care professionals (five GPs and three practice nurses). Key concerns (expressed by both patients and health-care professionals) were that the medication needed to be long term and that there was a risk of side effects. Health-care professionals in particular were concerned about side effects of hypotension, and therefore questioned the value of intensive BP lowering and whether or not the extra effort was worthwhile. Our own trial suggested that these concerns were probably misplaced, but we acknowledge that this may reflect a recruitment bias in the trial. However, it is of note that in the TASMINH2 and TASMIN-SR trials of self-management (see Work programme 2: will telemonitoring and self-management improve blood pressure control in people on treatment for hypertension or with a history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack in primary care?), greater use of antihypertensive therapy was not associated with any extra side effects. Our conclusion was that if more intensive targets were to be introduced into routine practice, there would be some resistance to this from health-care professionals, which would require specific intervention (e.g. educational initiative) to overcome.

Is a lower blood pressure target likely to be cost-effective?

See Appendix 1 for the full report.

We carried out a modelling study to determine what the long-term costs and benefits of intensive BP lowering would be in people with cerebrovascular disease in primary care, compared with using a standard target using the results of the PAST-BP trial. We extrapolated from the trial results using existing evidence from the literature to estimate what impact the different achieved BP in the two arms would have on CV events. We found that intensive BP lowering was dominant: that is, it lowered cost and improved outcomes. However, this conclusion was based on the assumption that a difference in BP was maintained between the arms. We noted that the difference between arms in the trial dropped between 6 months and 1 year, and so were concerned that the effect would become attenuated over time. Therefore, we are unable to make firm conclusions about whether or not more intensive targets would be cost-effective.

Conclusions

The overall aim of this work programme was to determine whether or not a trial of intensive BP lowering in people with cerebrovascular disease in primary care was warranted and feasible. In the trial that we carried out, we found that recruitment was difficult, requiring nearly 100 practices to randomise just over 500 patients. Therefore, to scale it up to an end-point trial would need to involve 1200 practices [e.g. PROGRESS (The perindopril protection against recurrent stroke study) had over 6000 patients followed up for 4 years]. 10 This might be potentially feasible with automated collection of end-point data (e.g. using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink with Hospital Episode Statistics in practices when the data were linked), but it is likely from our qualitative research that continued input would be required to practices to maintain the intervention. Thus, we concluded that we had not demonstrated that such a trial would be feasible. Furthermore, we did not feel that a further trial was warranted, given the impressive reduction in BP achieved in the standard care arm in the PAST-BP trial. We drew the overall conclusion from this work programme that the focus should be on more active management of BP to a standard target (< 140 mmHg) rather than to an intensive target. This would result in many more strokes being prevented than would be by aiming for more ambitious targets, which our qualitative research suggests would alienate patients and health-care professionals alike.

Research recommendation

Development and evaluation of interventions to improve active management of blood pressure in people after a stroke/transient ischaemic attack to achieve a target of < 140 mmHg systolic blood pressure

It is plausible that trials of different BP targets following stroke can be conducted in secondary care settings of sufficient size to detect impact on cerebrovascular events. These might then inform what optimal targets might be (with the proviso that they might not be generalisable to primary care settings). From a primary care perspective, research should focus on how to support GPs to better achieve current systolic BP targets.

Reflections on work programme 3

This work programme perhaps encapsulates better than the other work programmes the potential conflict between primary care and secondary care. Specialists in general are keen to promote intensive BP lowering after stroke. Primary care remains sceptical. Our research suggested that it would not be worthwhile to do an end-point powered trial to determine the impact of more intensive BP lowering in primary care. This raises the interesting question as to what should be policy if a secondary care-based trial indicates that intensive BP lowering does improve outcomes.

Service developments

We developed a hypertension management algorithm to support the PAST-BP trial (see Appendix 3). This took the form of a web-based decision support tool. Screen shots to illustrate how this tool supported GPs in their decision-making over which antihypertensive to use (and at what dose) are provided in Appendix 3. The algorithm was based on the NICE and British Hypertension Society guidelines in operation at the time,18,29 and drug information was taken from the British National Formulary. 76 Informal feedback suggested that the algorithm was very positively regarded by participating GPs.

We developed a training course on the primary and secondary prevention of stroke aimed at GPs and practice nurses (see Appendix 3 for details). This was to support the management of people identified as being at high risk of CVD in work programme 1 and to underpin ‘usual’ care in the RCTs (although attendance at the course was not mandatory for participating practices). Feedback was positive.

We took the opportunity of carrying out screening for CV risk factors in work programme 1 to carry out a before-and-after study of the impact of our screening programme (which was similar in concept to the NHS Health Checks programme), by comparing the prevalence of ‘high CV risk’ and the use of CV risk-lowering treatments before and after the screening programme, and in comparison with data taken over the same time period from control practices in which screening was not carried out. The main finding was that, between 2008 and 2012, there was a significant drop in people with uncontrolled hypertension in both intervention and control practices. There was no difference in prevalence of ‘high CV risk’ or use of antihypertensives or lipid-lowering agents between screening and control practices either in 2008 or in 2012. The main weaknesses of this study (apart from its non-randomised nature) were that we had no information on patients who were no longer registered with a practice after 2008, and we could not quantify the extent to which NHS Health Checks had been introduced into control practices. Our conclusion was that it was unlikely that, against the backdrop of NHS Health Checks, practice-based screening initiatives would have a major impact on better management of CV risk.

As part of the intervention development for the TASMINH2 trial (see Work programme 2: will telemonitoring and self-management improve blood pressure control in people on treatment for hypertension or with a history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack in primary care?), we developed a training programme to ensure that patients were confident and accurate in their self-management of BP. Over 90% of participants randomised to self-management successfully completed the training package, which included an assessment of their own ability to measure their BP and understand what they should do depending on the readings obtained. After 12 months’ participation, 72% of patients randomised to self-management continued to self-monitor and self-manage, although only 55% of recommended medication changes were implemented (sufficient to lead to significant reductions in BP in the whole group compared with usual care; see Appendix 2).

Research recommendations

-

Further develop web-based hypertension management algorithms to support clinical decision-making in general practice, and evaluate in a RCT. Informal feedback in our programme suggested this approach was very popular among GPs. Implementation of evidence-based guidelines for management of hypertension remains suboptimal, so there is potential value in developing and evaluating new interventions to support implementation of guidance.

-

Further develop self-management for BP to adapt and simplify procedures with the aim of improving adherence to the self-management schedule. Self-management has been shown to be effective in both TASMINH2 (see Appendix 2) and TASMIN-SR (see Appendix 4). The service development work suggests this is despite some attrition of adherence to the self-management guidelines over time. Therefore, further simplification and adaptation is likely to be important, to both maximise effectiveness and facilitate roll-out of the intervention.

Overall conclusions

In this programme of work, we have explored different approaches to optimise stroke prevention in the community. We have examined three different broad approaches: self-management, setting intensive treatment targets and using a polypill. The evidence for self-management of BP is broadly very positive. We did not explore the relative importance of non-pharmacological interventions in this programme, such as diet and exercise and smoking cessation, so we do not draw any conclusions as to the relative importance of pharmacological versus non-pharmacological interventions. In essence, we have shown through two RCTs that self-management can lead to important reductions in BP compared with usual care, and that this applies both to people with uncontrolled hypertension and to people whose BP needs tight control because they are at high risk of vascular events. We have found that setting intensive treatment targets for BP control in people with stroke or TIA does lead to lower BPs than standard targets, but the effect size was smaller than was achieved with self-management. Likely explanations for this are that self-management avoids some of the problems of clinical inertia that were demonstrated in the PAST-BP trial and associated qualitative research, and that the standard care arm in PAST-BP did receive an active intervention to achieve the standard target. Our overall conclusion from the work on intensive targets is that primary care should focus on better achievement of less aggressive targets for BP lowering (namely use a 140 mmHg target in people who have had a stroke). A polypill approach offers an alternative solution to aiming to achieve targets for risk factors such as BP. In our analyses of the possible role of a polypill, we found that it did potentially have a role to play as a cost-effective alternative to the current paradigm of screening and treating risk factors. However, our qualitative work suggests that this approach would be of limited acceptability to health-care professionals and patients. That said, the cost-effectiveness analysis suggests that this approach is worth pursuing further. Using a polypill in people already known to be at high CV risk seemed to be more acceptable to patients and health-care professionals, although, in health economic terms, this is a less cost-effective strategy. Further empirical work in the form of RCTs is required before firm recommendations about the role of a polypill can be made.

Patient and public involvement

Patient representatives formed part of the Trial Steering Committees for each trial within the programme. These groups advised on any issues that arose while the trial was ongoing, for example issues with patient recruitment. Patient representatives on these committees were fully involved with the advice and decisions during these meetings. In addition, there was a lay representative on the Programme Steering Group who advised on the progress and direction of the overall programme rather than on its individual components. Further patient and public involvement (PPI) took place within each individual work programme.

The focus of the polypill work programme from a PPI perspective was to inform the design of a RCT which in the event was not carried out. We had qualitative studies within this work programme to understand patient and public attitudes towards a polypill and a trial testing such a drug. In hindsight, PPI in designing these studies would have enhanced them. As it was, we used findings from the qualitative research to inform the questions asked in the questionnaire study (see Work programme 1: is it more cost-effective to titrate treatments to target levels of cholesterol and blood pressure, or to use fixed doses of statins and blood pressure-lowering agents (polypill strategy)? and Patient feedback about a primary prevention polypill trial: questionnaire survey), which aimed to determine the most appropriate information to include in patient information sheets. Again, this in hindsight would have benefited from PPI input. For example, such input might have led to a higher response rate.

Patients were involved in advising on the design of information sheets and trial procedures. The protocol and information sheets for a potential polypill trial were discussed with the Much Wenlock Stroke Survivors’ Group (an informal support group for stroke survivors and carers organised by the North Midlands Stroke Research Network). This group was made up of approximately 12 stroke survivors (ranging in ages from 55 to 80 years) who had varying degrees of deficit from their stroke, from full recovery to significant disability or communication difficulties. This group discussed the polypill concept and the proposed trial design. As we found in the research itself, there was a range of views about the polypill, with some people being very keen to be involved in such a trial and others saying that they would not want to participate. They also discussed the proposed information sheet and fed back some useful comments that were incorporated into its design, for example clarity about the time commitment that would be expected of participants. This amended information sheet was then included in the questionnaire study (see Work programme 1: is it more cost-effective to titrate treatments to target levels of cholesterol and blood pressure, or to use fixed doses of statins and blood pressure-lowering agents (polypill strategy)? and Patient feedback about a primary prevention polypill trial: questionnaire survey). The trial design itself was also discussed. The participants agreed that the time commitment required by patients (a baseline consent visit and two follow-up appointments at 1 and 3 months) in the proposed trial was reasonable and would not be off-putting to most people. They did comment, however, that if the trial were to continue longer than 3 months, the design should take into account the fact that many potential participants would already have regular blood tests with their GP, and that too many extra blood tests as part of a trial may discourage many people from taking part; participants felt that consideration should be given to whether or not study blood tests could be incorporated into routine blood tests wherever possible.

This group also discussed the PAST-BP trial and gave similar feedback about the information sheets and trial design. Their comments were very similar to those given about the polypill study. The group felt that it was a useful study that answered an important question because many of them felt that their stroke had occurred as a result of their high BP, and this was an issue that continued to concern them. The time commitment required by patients for this study was higher than that for polypill (for people whose BP was above target, there were a potential 12 visits with their GP/practice nurse per year, plus two study-specific visits with a research nurse). Despite this, control of their BP was an important issue for most in the group, and as such they felt that many people would be willing to attend that number of visits. They had no other comments on the design of either of the information sheets for this trial.

For work programme 3, similar processes were followed: there was a PPI representative on all Trial Steering Committees, and information sheets and trial design were discussed with a group of patients who had taken part in previous BP trials. They too provided useful feedback about the readability and understandability of information sheets, which was then incorporated into the sheets used for the trial.

The patient groups who were involved in the design of the various trials provided some very different perspectives. The Stroke Survivors Group, for example, were very research naive, with very few having any experience of research in any capacity. The group advising on work programme 2, however, had taken part in previous research and therefore had experience of the kind of questions and considerations that people will often go through when deciding whether or not to participate in a trial. Both perspectives provided valuable information for the research team and were instrumental in improving the quality of information given to patients.

Acknowledgements

This report is based on a programme of work that included multiple contributions from several authors. These are listed in full in Appendix 5.

Contributions of authors

Kate Fletcher compiled the original full report that was submitted to NIHR.

Jonathan Mant was lead and Richard McManus and Richard Hobbs were coapplicants on the original programme grant.

Jonathan Mant wrote the first draft of this pilot report, with contributions from Richard McManus on work programme 2.

Richard McManus, Kate Fletcher and Richard Hobbs contributed to the second draft of the pilot report.

Data sharing statement

Requests for access to data should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, CCF, NETSCC, PGfAR or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the PGfAR programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Rothwell PM, Algra A, Amarenco P. Medical treatment in acute and long-term secondary prevention after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke. Lancet 2011;377:1681-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60516-3.

- Saka O, McGuire A, Wolfe C. Cost of stroke in the United Kingdom. Age Ageing 2009;38:27-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afn281.

- Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF, Howard SC, Silver LE, Bull LM, et al. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study). Lancet 2004;363:1925-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16405-2.

- Mant J, Wade DT, Winner S, Stevens A, Raftery J, Mant J, et al. Health Care Needs Assessment: The Epidemiologically Based Needs Assessment Reviews. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2004.

- Reducing Brain Damage: Faster Access to Better Stroke Care. London: National Audit Office; 2005.

- Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander HS, Murray CJ. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 2002;360:1347-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6.