Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0707-10123. The contractual start date was in April 2009. The final report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Membership of the following committees was declared: Professor M Morgan: National Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Transplant Alliance; Professor B Farsides: UK Donation Ethics Committee; Professor Gurch Randhawa: UK Donation Ethics Committee; Human Tissue Authority; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Evidence Update Group (Organ Donation Guidelines); National Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Transplant Alliance; Transplant 2020 Stakeholder Group (chairperson).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Morgan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Developments in transplantation

Solid organ transplantation is described as one of the most remarkable therapeutic advances in medicine during the past 60 years, with significant benefits for patient survival and quality of life. 1 In 1954, the first successful kidney transplantation was undertaken between identical twins, and between 1962 and 1967 the first successful transplants of the kidney, heart, lung, pancreas and liver from the organs of deceased donors were performed. However, the discovery of ciclosporine (Neoral®, Novartis) (the first targeted immunosuppressive drug), and its commercial availability from 1982, is regarded as marking the beginning of the modern era of transplantation with its substantial benefits for graft survival. 2 Currently, over 93% of kidneys from deceased donors and 83% of heart transplants are functioning well after 1 year and many continue to function for at least 10 years. 3

The population’s need for transplantation has steadily increased, with an estimated increase of 8% per year in the numbers of people requiring a transplant in the UK. 4 This increasing need reflects both the ageing population and the increasing scope and success of transplant surgery, which itself increases clinical need. Thus, although 4212 solid organ transplants were performed in the UK in 2012/13, as of 31 March 2013 there were 7332 patients on the active transplantation list. 3 In addition, a total of 466 patients died during 2012/13 while on an active waiting list and a further 766 were removed from the list as a result of deteriorating health and ineligibility for transplant. 3 Altogether, 82% of patients were waiting for a kidney transplant, with 62% of kidney transplants currently involving a kidney from a deceased donor.

Long waiting times for transplantation are associated with reduced quality of life and increased mortality risks. Moreover, transplantation not only has substantial benefits for patients and families but also is generally cost-effective for the NHS, particularly for the large numbers of people with end-stage renal failure (ESRF). On 1 April 2009, there were 6920 patients with ESRF waiting for a transplant, with the majority on dialysis, at an estimated total cost of around £193M per year. If all of these patients received a transplant, the approximate cost is estimated at £41M per year, representing a saving to the NHS of £152M per year. 5

Donation and transplantation among minority ethnic groups

The problem of long waiting times is of particular significance for the Asian population (mainly people of Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage) and the black population (mainly people of Caribbean and African origin). These ethnic groups make up around 10.6% of the UK population but accounted for 27% of patients waiting for a kidney transplant and had a median waiting time for a kidney-only transplant in 2013 of over 1400 days, representing nearly 1 year longer than for the general adult population. 3

One major factor explaining the over-representation of ethnic minorities on kidney transplant waiting lists is their relatively high level of need, reflecting a high incidence of chronic kidney disease and ESRF, with risk of ESRF for the black and South Asian populations three to four times that of the general population. 6 The other main determinant of the waiting list and long waiting times for transplantation relates to the supply side in terms of the availability of organs for transplantation. Although the rate of living donation among minority ethnic groups is comparable to that of the general population, the rate of deceased donation is much lower, with just 4% of all deceased donors being of black or South Asian ethnicity. 3

This low rate of deceased donation is of particular significance for minority ethnic groups given requirements for matching human leucocyte antigen (HLA) tissue type and blood group. Matching these aims to reduce risks of graft rejection and the amount of immunosuppressive drugs required with their associated risks of severe side effects. However, for members of ethnic minorities with a HLA tissue type and blood group that is less common in the general population, the effect is to restrict the potential donor pool and thus increase waiting times for transplantation. This situation identifies the importance of increasing organ donation among minority ethnic groups. It has also led to questioning of the merits of further relaxing the criteria for matching employed by the NHS given the advances in immunosuppression, although recognising that immunosuppressive drugs carry risks of cancers, cardiovascular disease and other severe side effects. 7,8

Reducing the gap between need and supply

One approach to bringing demand for transplantation and availability into equilibrium among minority ethnic groups is through more effective detection and management of diabetes, hypertension and renal disease, thus preventing the onset of chronic kidney disease, which is associated with high rates of type 2 diabetes, obesity and hypertension. 9,10 There is also some evidence of a lower quality of diabetes and renal care, and of patient compliance, among South Asian and African/Caribbean populations, thus increasing risks of renal failure. Reducing demand for transplantation through improving both primary and secondary prevention is therefore an important strategy in improving individuals’ quality of life and reducing risks of ESRF and the need for kidney transplantation. Clinical guidelines and incentive-based care schemes in the UK therefore now focus on tackling cardiovascular risk and renal disease progression in all patients with chronic kidney disease. 11–13

The other main approach to bringing demand and availability into equilibrium is to increase supply through increasing both rates of registration on the Organ Donor Register (ODR) and family consent to donation. It is estimated that 3.5% of the black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) population are on the ODR, compared with one-third of the white population. 3 The main source of registration is through checking the appropriate box on applications for a driving licence (58% registrations by March 2013), followed by applications to register with a general practice (21% registrations), with other sources including online registration or applying for a passport or a Boots Advantage Card. 14 However, ethnicity is recorded for only 18% of registrations, mainly because of some sources for sign-up not recording ethnicity, with estimates of the ethnic composition of the ODR therefore derived from limited data. 14

For people who die in an intensive care unit (ICU) or emergency department and are identified as potential donors, family consent is required for donation to proceed. In the UK, in 2012/13, only 33% of bereaved ethnic minority families consented to donation (56 donors), compared with 61% of eligible white donor families (1155 donors). 15 Family consent rates are significantly higher when their deceased relative is on the ODR (or if their deceased relative’s wishes are otherwise known), although currently 10% of families override the wishes of a relative who has joined the ODR. 15

The low rate of deceased organ donation among minority ethnic groups in the UK has parallels with the situation in other countries, including the USA and Canada (see Chapters 2 and 3). There are also similarities with the less studied topic of blood donation, with 5% of the eligible UK population donating blood, of whom just 3% are from the Asian, African and Caribbean communities. 16 This again raises issues of matching, as blood group B is more prevalent among Asian and black communities, whereas blood group U negative is almost entirely found among African and Caribbean populations.

In summary, BAME groups in the UK have a relatively high need for transplantation mainly because of a high rate of ESRF. These groups also experience long waiting times for kidney transplantation associated with a low donation rate and thus a shortage of well-matched organs with implications for quality of life and survival. One approach to address this and thus reduce inequalities in transplantation is through the improvement of primary and secondary prevention to reduce rates of ESRF. The other approach is to increase donation rates among minority ethnic communities.

Donation policies

The situation of high levels of unmet need and long waiting times for transplantation among minority ethnic groups occurs within a system in which the need for transplantation continues to increase and far outstrips availability. For example, in 2006 the UK ranked 14th out of 18 countries with a donation rate per million population (pmp) of 12.9, compared with 35.5 pmp in Spain. 4 Since 2006, the position in the UK has improved, with a donation rate of 19.1 pmp by 2013, although this is still lower than in many other European countries. 15 This national situation thus forms the broader context within which the particular needs of minority ethnic groups require to be addressed.

The Organ Donation Taskforce (ODT) was set up in 2006 to provide advice on how best to address the relatively low transplantation and donation rate in the UK. The taskforce initially considered the requirements and likely impact of redesigning services while retaining the current model of informed consent (opt-in system). The opt-in system enshrines individual autonomy and choice, with individuals able to indicate their willingness to donate their organs should the situation arise by joining the ODR. For those who are identified as a potential donor, their relatives are asked for their consent to donation.

The ODT report Organs for Transplant4 was published in January 2008 and set out 14 recommendations for redesigning the organ donation services while retaining an opt-in system. In addition, the ODT set up an independent Working Group to examine the likely impact of moving to a system of presumed consent (opt out) that involves an assumption of donation unless individuals opt out. The range of evidence assembled by the Working Group to consider the merits of a change to a presumed consent system identified a complex situation, particularly with ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ versions of both informed and presumed consent that vary in their provision for relatives to influence the donation decision (Box 1). 17

‘Soft’ version: it is normal practice to let relatives know if a person has registered on the ODR and doctors can decide not to proceed if there is opposition from relatives (e.g. current UK).

‘Hard’ version: individuals can decide if they wish to opt in and relatives are not able to oppose a deceased person’s wishes.

Presumed consent model‘Hard’ version: doctors can remove organs from every adult who dies unless a person has registered to opt out (e.g. Austria) OR the person belongs to a group that is defined by law as being against an opt-out system (e.g. Singapore, where Muslims chose to opt out as a group).

‘Soft’ version: in some countries relatives are allowed to tell doctors not to take organs, but it is up to the relatives to tell doctors because the doctors may not ask them (e.g. Belgium). In other countries it is good practice for doctors to ask relatives for their agreement at the time of death (e.g. Spain).

Evidence that is often cited to support a shift to presumed consent is the increased rates of deceased donation following implementation of a presumed consent model. However, Rithalia et al. 18 concluded, based on a detailed review of the evidence, that changes in the system of donation have often been accompanied by educational campaigns and improvements in infrastructure and that these changes may have formed the major catalyst leading to increased donation rates. 18 This view is supported by Dr Rafael Matesanz, President of the Spanish National Transplant Organisation,19 who cast doubt on the impact of presumed consent in achieving the high donation rates in Spain, noting that whereas informed consent was introduced in 1979 in Spain, donation rates only significantly increased from 1989 following the major redesign of donation services.

Further difficulties in the interpretation of between-country variations area arise from the wide range of other factors that influence rates of donation, including the level of mortality rates from road traffic accidents, overall health expenditure, religion, education and transplant infrastructure. Important exceptions to the generally positive association between presumed consent and donation rates have also been noted, including the situation in Sweden where presumed consent was introduced in 1996 but the country continued to have one of the lowest donation rates in Europe.

The Working Group reported in September 200817 and concluded that evidence for a change to presumed consent was not sufficiently robust to support this shift, although acknowledging, ‘The question of whether or not changing to an opt-out system for organ donation is right for the UK is a finely balanced one . . .’17 (p. 4). The potential downsides of such a move were identified as including the potential negative impacts on the relationship of trust between clinicians and their patients and families, the importance for both recipient and donor families that organs are freely given as a ‘gift’ and the possibility that some groups may opt out (or may need provision not to be included), together with practical, cost and security issues of setting up and running a system of presumed consent. 17 Thus, on balance, it was concluded that, ‘moving to an opt-out system at this time may deliver real benefits but carries a significant risk of making the current situation worse’ (p. 5).

The UK has, therefore, retained a system of informed consent and during 2008–13 implemented the ODT’s 14 recommendations. 4 These recommendations were influenced by both the successful ‘Spanish model’19 and service redesign in the USA. 20 They aimed to increase donation and hence transplantation rates through both public campaigns and the redesign of hospital donation services. The latter aimed to achieve better identification of potential donors, increased family consent rates, more effective organ retrieval, and more efficient allocation and use of donated organs.

These wider national issues provide a context for a focus on the particular issues for minority ethnic groups who received specific consideration in relation to increasing organ donation and transplantation rates with the ODT’s recommendation 13 stating:

There is an urgent requirement to identify and implement the most effective methods through which organ donation and the ‘gift of life’ can be promoted to the general public and to the BME [black and minority ethnic] population

Paragraph 1.474

This sentiment was subsequently echoed by the Nuffield Bioethics Council report ‘Human bodies: donation for medicine and research’,21 which acknowledged that ‘BME [black and minority ethnic] populations are significantly less likely to become donors (across a range of different forms of bodily material)’ and argued that ‘a stewardship state has a direct responsibility to explore the reasons why some populations are hesitant to donate, and if appropriate to take action to promote donation’ (p. 16). 21 A co-ordinating voice is now also provided by the recently formed National Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority Transplant Alliance (www.nbta-uk.org.uk/) that brings together the NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) and a number of charities, with the aim of increasing donor numbers and attitudes to donation and transplantation within the BAME population.

Whereas the policy in England, Northern Ireland and Scotland continues to be one of increasing donation on a voluntary basis, Wales is introducing a system of presumed consent in 2015, albeit a ‘soft’ version. 22 Wales will, therefore, provide a pilot test case of this model, including issues of the responses of ethnic and faith groups.

Another approach to increasing donation rates is the Israeli system of giving priority for transplantation surgery to those previously registered as a donor for 3 years. 23 It is argued that this could serve as an impetus for ethnic minorities who would have an even longer wait under a prioritisation system if they do not commit. 24 However, such a prioritisation system raises ethical issues of coercion, constraints or strategic behaviour. 25,26 It also requires ample public awareness of embedding incentives in a new allocation system plus assuring that registration details are up to date. Translating such a policy into practice in the UK is, therefore, acknowledged to raise both ethical and administrative difficulties.

England, Northern Ireland and Scotland have continued to support an opt-in system of donation and aim to achieve increased donation rates within this voluntary system. The present programme aimed to contribute to this objective by providing guidance to increase the acceptability and effectiveness of both national campaigns to increase registration and family consent with particular reference to minority ethnic groups.

Chapter 2 Overview of the research

The research programme referred to as Donation, Transplantation and Ethnicity (DonaTE) took up the challenge relating to ethnic minorities identified by recommendation 13 of the ODT report. 4 The main objectives of the programme were therefore to:

-

identify barriers to registration as an organ donor and family consent to deceased donation among minority ethnic groups of African/Caribbean and Asian descent

-

develop and pilot a hospital-based intervention to enhance quality of care and consent rates.

Our research examined issues of both registration and family consent to donation. Family consent is the key determinant of deceased donation in an opt-in system but whether or not the patient has expressed their wishes and is registered on the ODR has an important influence on family decision-making. For example, in the UK in 2012/13, 90% of all families whose relative was registered on the ODR consented to donation, but 60% of families where the deceased was not on the ODR. 15 This has led to a move towards reducing the rights of families to reject donation where their relative has expressed their wishes by joining the ODR, thus increasing the importance of registration. 15

Components of the research programme

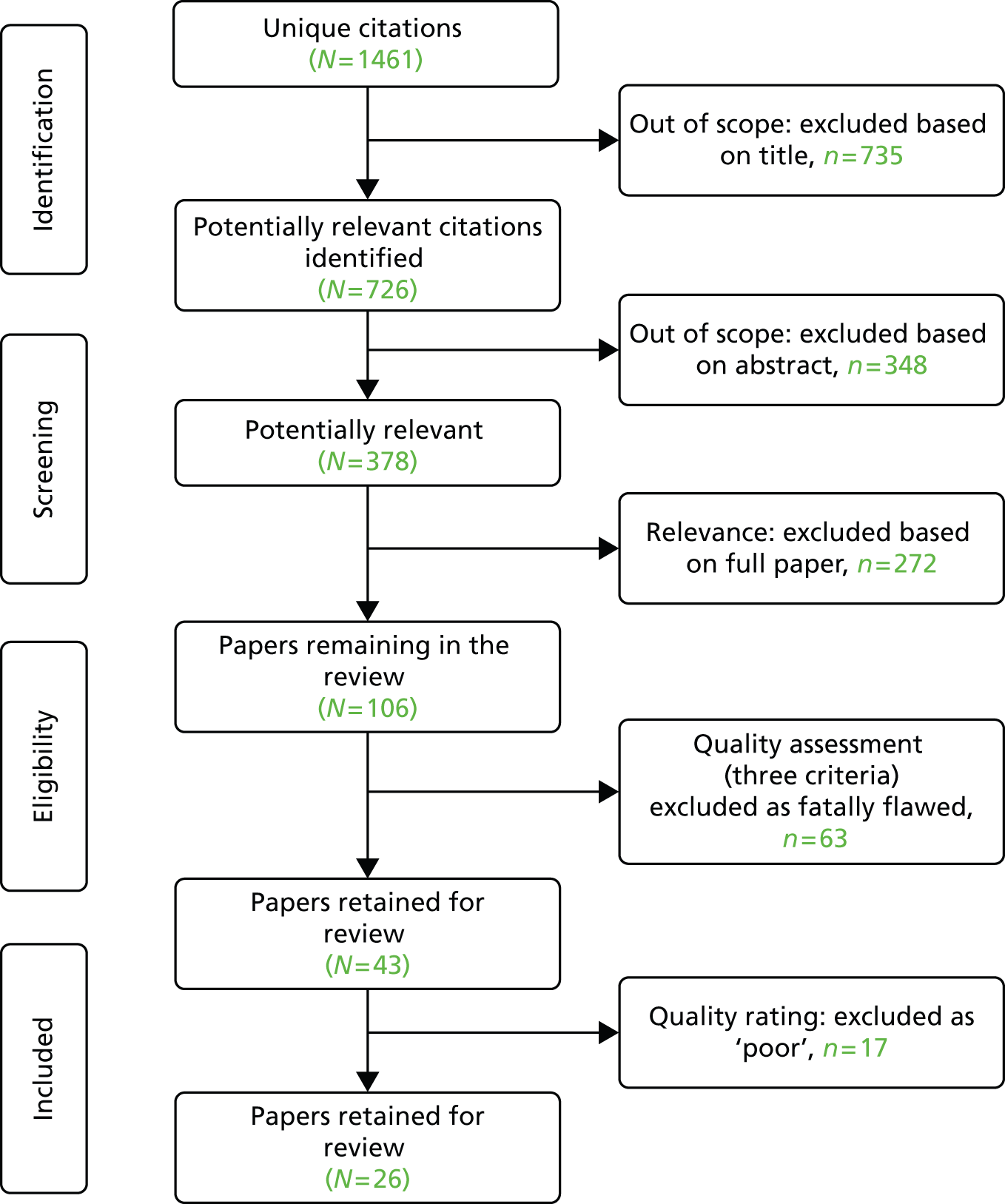

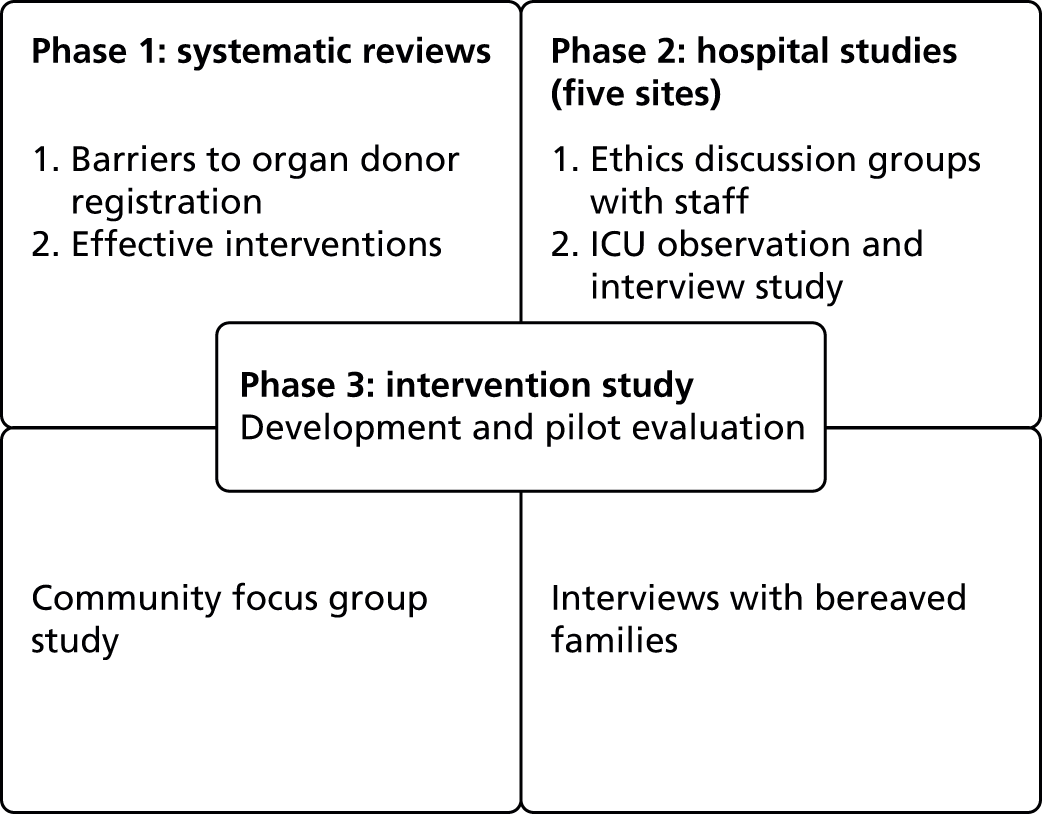

The research involved three phases comprising seven linked studies as indicated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the DonaTE programme of research.

The first community-level phase involved a systematic review to examine the current knowledge regarding attitudes and practices to ODR among minority ethnic groups based on studies undertaken in both the UK and North America. This was followed by a study based on 22 focus groups, which aimed to respond to gaps in knowledge identified by the systematic review. The final phase of the community-based research comprised a second systematic review to identify the characteristics of those interventions demonstrated to be effective in achieving increased knowledge and/or registration as an organ donor among minority ethnic groups.

The second hospital-level phase examined issues of consent to donation by families from minority ethnic groups. This focused on the structures and practices that may influence family decision-making and examined the perspectives and practices of different groups of professionals involved in caring for families, namely clinicians, specialist nurses for organ donation (SNODs), bedside nurses and hospital chaplains, and also elicited the experiences of bereaved families themselves. This phase involved several forms of data collection: interviews with ICU staff; observation of the work of SNODS, ethics discussion groups (EDGs) with a range of staff, and interviews with bereaved families at least 3 months post bereavement.

The third phase of developing and piloting a professional development package drew on data collected in earlier phases of the research, particularly the hospital-based studies, to develop a professional development package. This package is designed to influence the attitudes, motivation and skills in cross-cultural communication of junior ICU staff, so as to enhance staff confidence and the quality of support provided to minority ethnic families.

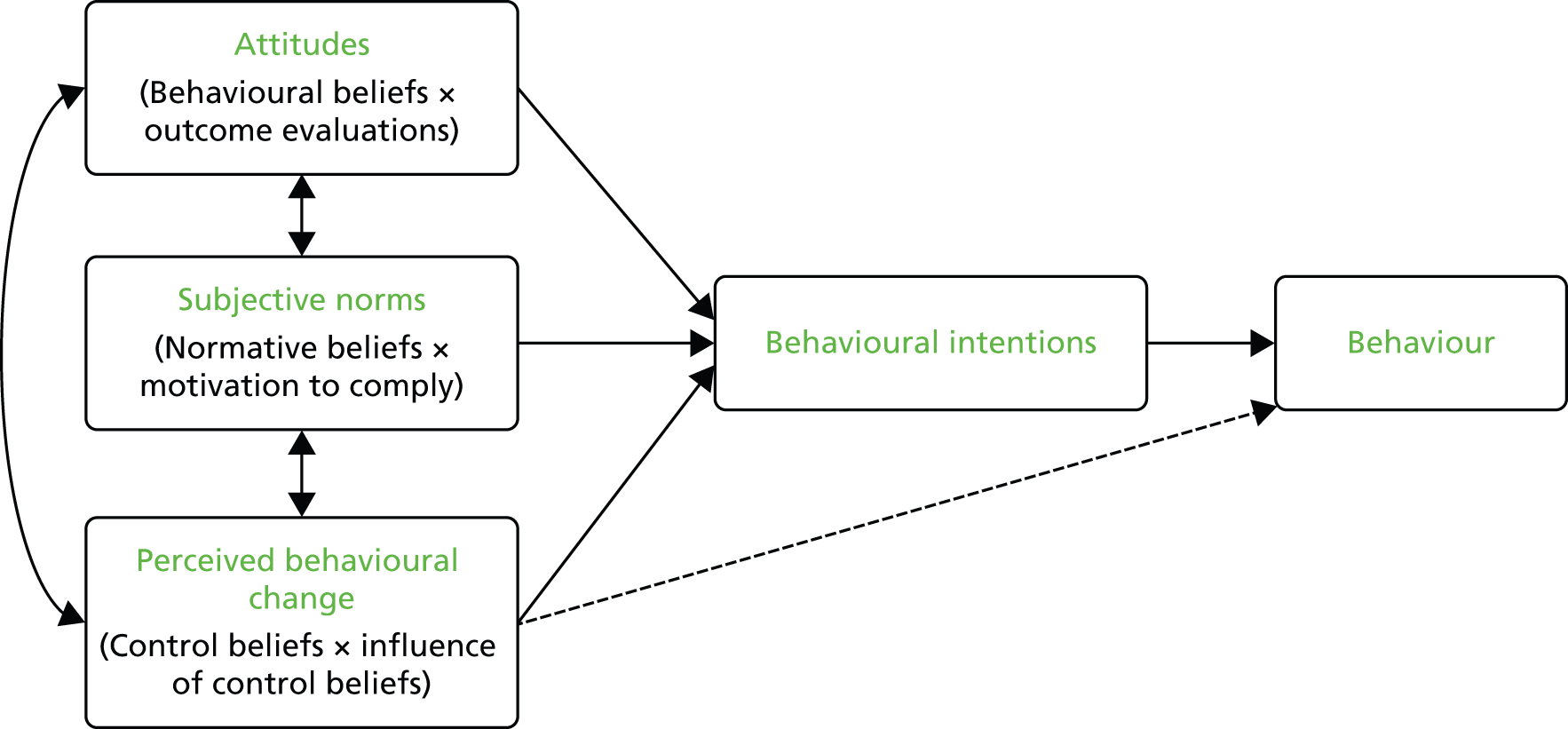

The package comprises a main video, short family drama and a workbook based on principles of behavioural change integral to Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour (TPB). 27 Evaluation involved piloting the package with groups of ICU staff with before-and-after studies to examine outcomes in terms of rates of family consent and changes in staff attitudes factors and skills.

Data analysis

Both the focus groups and hospital studies involved qualitative methods. The discussions and interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed. Formal analysis involved, first, entering data into NVivo9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and reading and re-reading transcripts to identify major issues for analysis. Data relating to these key issues were initially coded line by line followed by grouping into categories. For the hospital interview and observational study, this coding and analysis was undertaken separately in relation to three areas of enquiry that were managed and written up as separate themes. These were hospital staff’s beliefs and practices in relation to supporting patients from minority ethnic groups, factors limiting the SNODs’ participation in collaborative donation discussions with families and hospital chaplains’ perception of their role in end-of-life care.

Analysis involved comparisons both between and within ethnic groups in the focus groups, and between study sites and staff groups for the hospital data, with the aim of identifying similarities and explain differences in practices at both community and hospital levels. Emerging explanations and interpretations were checked with subsequent data and, when necessary, by re-reading the original transcripts. Interpretations were also checked through informal discussions with ICU staff and the lay advisory group.

Evaluation of the intervention involved quantitative data analysis. Details of the before-and-after design and analysis of the TPB questionnaire and family consent rates are given in Chapter 5.

Approach to ‘ethnicity’

This research responds to a policy aim of increasing rates of deceased donation among minority ethnic groups, which, in turn, has benefits of reducing waiting times for transplantation for minority ethnic groups and thus improving quality of life and survival. However, this approach with its emphasis on changing the practices of ethnic minorities as fundamental to achieving a positive gain runs the risk of problematising ethnic groups and what Ahmed and Bradby28 refer to ‘cultural racism’. In contrast, we sought to achieve a more contextualised approach based on the following aims and assumptions:

-

We attempted to reflect the range of influences that potentially shape ethnic patterning by studying not only an individual’s knowledge and beliefs but also encompassing wider conditions and practices that may facilitate or form barriers to deceased donation. Thus, whereas the initial community-based research mainly focused on an individual’s awareness and beliefs regarding organ donation (informed by the synthesis of existing studies), we also examined issues relating to effective interventions and the provision of services. In particular, the hospital-based research shifts the focus from the beliefs and practices of minority ethnic groups to the perceptions and practices of different groups of staff that may impact on the quality and acceptability of end-of-life care and thus have implications for families’ consent to donation.

-

We also aimed to move beyond the notion of static and homogeneous ethnic groups associated with broad census classifications and instead sought to take account of the contingent and changing nature of ethnicity, acknowledging how this varies in relation to particular sets of social circumstances and responses of the wider society that often leads, over time, to changes in both individual and collective ethnic identities. For example, the focus group study aimed to examine beliefs and practices associated with country of origin, faith, length of residence in the UK, age and gender, etc. This study also allowed for linguistic diversity with discussions with older South Asian groups being conducted by bilingual researchers familiar with the community languages and cultural practices.

The wider UK policy context

The DonaTE research was undertaken over the period September 2009–January 2014 (initial 48-month period extended by 4 months because one researcher was on maternity leave for 1 year). The research, therefore, took place in an evolving policy context that involved gradual implementation across the country of the Taskforce’s 14 recommendations4 under the direction of a Taskforce Implementation group and in conjunction with NHSBT as the new national organ donation organisation. The research therefore aimed to provide information to inform strategies to address the needs of minority ethnic groups. This included identifying barriers to full implementation of the SNODs’ role in engaging in early contact with families and their participation in the donation discussion and exploring issues with doctors, nurses, hospital chaplains and the hospital Organ Donation Committee (ODC).

The various changes introduced over the period 2008–2013 were successful in achieving the government’s target of increasing donation by 50%. However, this target was largely reached through a greater number of approaches made to potential donors after circulatory (or cardiac) death (DCD), with the UK now having one of the highest rates of DCDs, accounting for 42% of all donation, with donation after brain stem death (DBD) accounting for 57% of donations. In contrast, there was little change in consent rates, with the overall family consent rate remaining fairly stable at 57%. 15 Increasing the family consent rate, including among minority ethnic groups, therefore, remains a key policy objective. This is reflected in NHSBT’s new policy document, Taking Organ Transplantation to 2020, which identifies increasing family consent as the ‘single most important strategy’ (p. 15). 15

The DonaTE programme, therefore, links with the continuing policy priority in England, Northern Ireland and Scotland of increasing donation rates within an informed consent model through further community campaigns and changes in donation services. The current goals, as set out in Taking Organ Donation to 2020, are to increase the authorisation/consent rate to > 80% by 2020 and achieve a deceased donor transplant rate of 74 pmp (increasing from 49 pmp). 15

Structure of the report

The research studies are presented in the next three chapters. Chapter 3 describes three community-based studies that focus on registration as an organ donor and Chapter 4 describes three studies examining issues relating to family consent to donation. Chapter 5 then describes the development of the professional development package that draws on these earlier studies and outlines its piloting and evaluation with groups of ICU staff.

Chapter 6 brings together the different elements to provide an overview of the programme and considers the implications of the findings for practice and for further research. It also includes a discussion and assessment of some of the particular challenges of undertaking research in this area to assist future studies.

Each phase of the research benefited from input by DonaTE’s lay advisory group, whose recruitment and activities are described in Chapter 6, Public engagement and dissemination. Academic dissemination to date through publications and conference presentations is also listed in Chapter 6.

Ethics approval

The National Ethics Service Hampstead granted approval for the programme of research (REC 09/H0720/134). Following initial approval amendments were submitted as the research progressed. Research and development (R&D) approval was granted by all NHS trusts involved in the research. The hospital-based fieldwork initially involved five trusts (increased from four trusts in original application) with a sixth added to complete the EDGs. The bereaved family study then expanded beyond the six study sites, given difficulties of recruiting ethnic minorities who had been approached about donation to include 40 trusts identified by NHSBT as having one or more families from mixed or minority ethnic groups consenting to donation in 2011/12.

Chapter 3 Community studies: registration as an organ donor

Introduction

This chapter describes three community-based studies that examined issues relating to the particularly low rates of registration as a donor among minority ethnic groups. These were:

-

a systematic review to identify current knowledge and gaps in knowledge of the barriers to organ donor registration among minority ethnic groups

-

a focus group study to examine the knowledge and attitudes of members of five ethnic minorities, namely people of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Nigerian and Caribbean descent, and identify variations within these groups by age, generation and gender

-

a systematic review to identify the characteristics of effective community-based interventions to increase registration as a donor among minority ethnic groups based on UK and North American literature.

Study 1: systematic review of barriers to organ donor registration among minority ethnic groups

Abstract

This systematic review aimed to identify current research knowledge relating to community attitudes and barriers to organ donor registration among minority ethnic groups in the UK and North America. A systematic search of databases, websites and hand searching was conducted, followed by assessment of relevance and quality. Altogether, 26 papers29–53 (14 quantitative, 12 qualitative) were retained. Note that one of the retained papers is unpublished (Poonia J. South Asian and Black Organ Donation Research Project: Key Findings. Prepared for Central Office of Information on behalf of UK Transplant London NHSBT; 2006).

The synthesis followed the methods of narrative synthesis and it initially involved separate syntheses of the quantitative and qualitative studies, followed by their integration. This focused on five key barriers to registering as a donor: (1) knowledge of organ donation and registration; (2) talking with family about donation; (3) faith and cultural beliefs; (4) bodily concerns; and (5) issues of trust.

Lack of knowledge about the need for deceased donation and transplantation among ethnic minority groups, and how to register as a donor was identified as a key barrier that continues to be highly prevalent. Faith barriers mainly related to uncertainty about their faith’s position and the need for guidance rather than the belief that donation was prohibited. Religious uncertainty was particularly common among people of Islamic faith, whereas issues of trust in allocation procedures and in doctors were most common among the black populations. Specific gaps identified included a lack of explanation of the continuing low knowledge despite campaigns focusing on ethnic minorities; the very limited investigation of how beliefs and practices may vary with age; place of birth or socioeconomic status; and lack of attention to possible structural barriers, including perceptions of the accessibility of registration and needs for discussion regarding registration as an organ donor to supplement media campaigns.

Rationale and review question

Community-based studies in the UK and North America examining barriers to registering as an organ donor among ethnic minorities have been published in a range of clinical, health service and social science journals, with little attempt to integrate this literature. A key initial objective was, therefore, to undertake a systematic review of community-based research to identify current knowledge and existing gaps.

The specific review question was, ‘What are the barriers to organ donor registration and willingness to become a donor among minority ethnic groups?’

In this context, the term ‘barrier’ refers to a range of individual- and service-level factors that inhibit registration and willingness to become an organ donor. Individual-level barriers potentially include religious beliefs, cultural expectations and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender or social position). Service-level barriers relate to aspects of the infrastructure and pertain to awareness, acceptability and accessibility of the processes of registration. The participants were regarded as belonging to visible minority ethnic groups in the countries where the studies were undertaken.

Review methods

Design of review: a systematic search was undertaken, followed by the procedures of narrative synthesis described by Popay et al. 54 This adopts an interpretive approach to synthesis while retaining the rigour of traditional systematic reviews and provides a range of tools through which quantitative and qualitative studies can be descriptively explored and synthesised.

Narrative synthesis involves four broad phases:

-

Phase 1: systematic search and quality appraisal.

-

Phase 2: preliminary synthesis – initial description of the results of the included studies and identification of factors that have influenced the results reported.

-

Phase 3: exploring relationships and main synthesis – this goes beyond simple description and focuses on exploring relationships in greater detail. Methods depend on the nature of the data and questions to be addressed.

-

Phase 4: assessing the robustness of the synthesis – this relates to assessment of both methodological and theoretical quality.

Phase 1: systematic search and quality appraisal

Specific inclusion criteria for the review are shown in Box 2.

Country: UK and North America – a systematic review of modifiable risk factors for organ donation identified most current research on the topic as conducted in these countries. 23

Type of donation: deceased organ donation.

Ethnicity: focus on a visible (non-white) ethnic minority or analysis of one or more minority ethnic groups.

Date: studies published between January 1980 and 2010. A preliminary Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.co.uk) of relevant research indicated that most studies were undertaken from the 1990s, given the increased development of transplantation services over the past 20 years. An ethnic question was also first asked in the 1991 UK census. 55

Language: relevant papers in all languages were to be included. However, the systematic review of modifiable risk factors by Simpkin et al. 56 indicated that nearly all papers would be in the English language.

Research design: both quantitative and qualitative studies were included to encompass the cross-disciplinary and methodologically pluralistic nature of research on the topic.

Age: ≥ 18 years. The focus is exclusively on adults given that people aged < 18 years require parental agreement for donation.

Setting: non-hospital.

Barriers: include attitudes, knowledge, beliefs, faith, trust, motivation, access, worry, understanding and fear.

Source: reproduced with permission from Morgan M, Kenten C, Deedat S. Attitudes to deceased organ donation and registration as a donor among minority ethnic groups in North America and the U.K.: a synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research. Ethn Health 2013;18:367–90. 57

Systematic search: databases were searched during November and December 2010 (Box 3, name of host databases in bold). Relevant websites were also searched [i.e. Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), Department of Health website] and key journals searched by hand. Experts in the field were contacted regarding recently published or ongoing projects and grey literature.

Ovid: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Transplant Library Database, Social Policy & Practice.

Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science (CPCI-S), Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH).

Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSA) Illumina: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Sociological Abstracts, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC).

EBSCOhost: International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

Scopus.

WebsitesGoogle, Department of Health website.

Other searchesKey journals, grey literature, contact made with experts in the field.

Source: reproduced with permission from Morgan M, Kenten C, Deedat S. Attitudes to deceased organ donation and registration as a donor among ethnic groups in North America and the U.K.: a synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research. Ethn Health 2013;18:367–90. 57

It was not possible to obtain all relevant grey literature commissioned by NHSBT and undertaken by a range of private research companies. Although we attempted to get access to full reports of these reviews via senior staff at NHSBT, via the market research companies commissioned by NHSBT to conduct research and from the Central Office of Information, none of these organisations was prepared to share this information.

The search strategy was written in conjunction with an information specialist. Terms employed reflected previous and current phrasing associated with deceased donation (e.g. cadaveric and deceased donation included), and included a range of terms to identify the correct populations across the UK, USA and Canada. Specific ethnic categories were those attributed in the papers reviewed. Following the initial MEDLINE search, this was slightly modified to be applicable to other databases (see the medical subject heading search terms in Appendix 1).

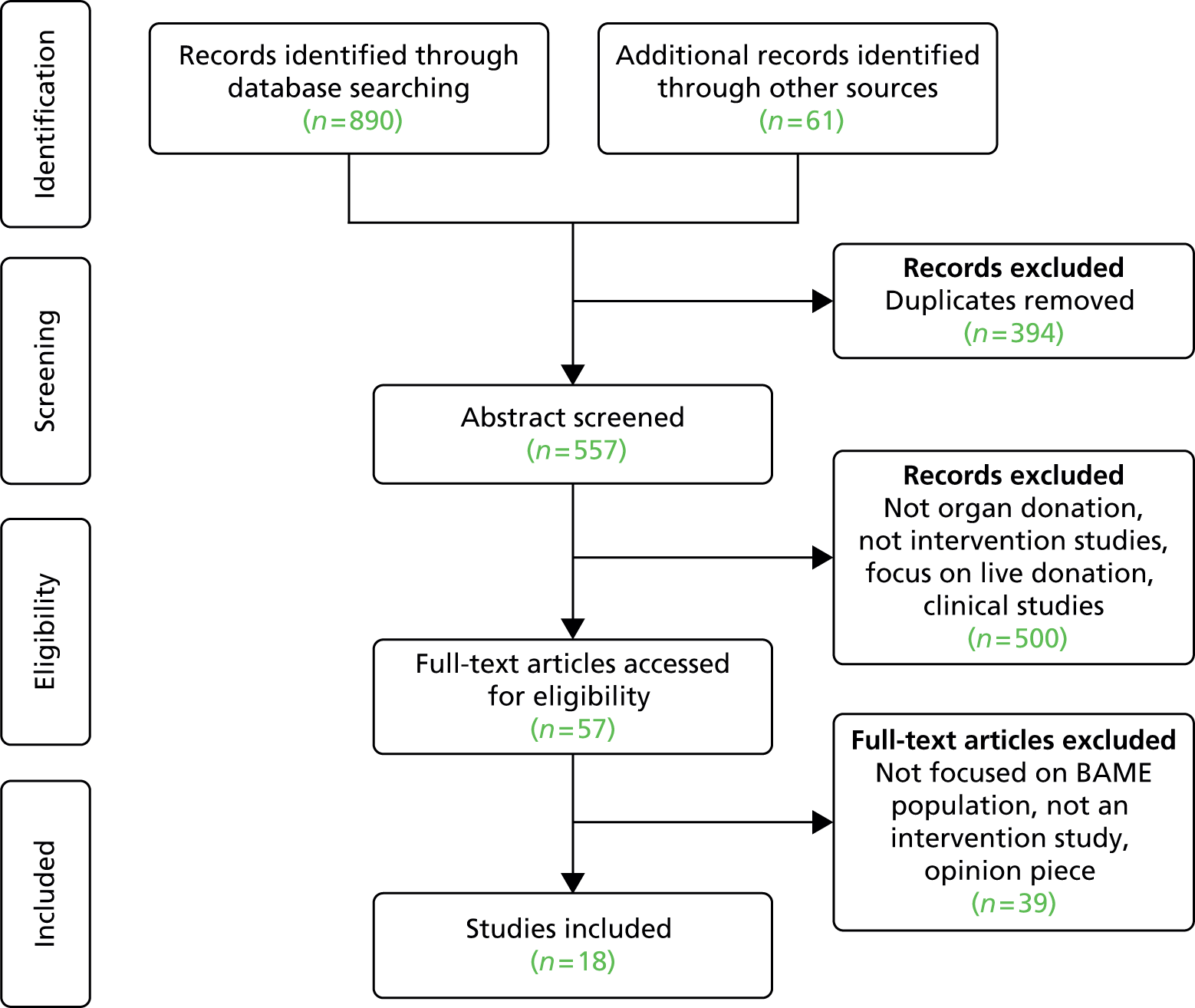

The initial database and grey literature searches yielded a total of 2185 returns, reducing to 1461 following deduplication. These papers were initially screened for relevance based on the title and abstract, and those failing to meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. When it was not possible to determine relevance from the title or abstract, the full-text papers were retrieved and assessed. The main reasons for exclusion were that studies related only to children (students were included), were conducted in a country other than the UK, USA or Canada, focused on living donation/donors or on transplantation or treatment/follow-up rather than donor issues. Following relevance assessment 106 papers were retained (Figure 2).

Quality assessment

This was undertaken by two authors, with any differences discussed and a consensus reached. Papers were initially assessed using three of five criteria proposed to identify ‘fatally flawed papers’ that are applicable to both qualitative and quantitative research. 58 These were (1) are the aims and objectives of the research clearly stated?; (2) is the research design clearly specified and appropriate for the aims and objectives of the research?; and (3) is there a clear account of the process by which their findings were produced?

Following this initial assessment, 43 papers (17 qualitative and 26 quantitative) were retained. The 17 qualitative papers were further were assessed using two criteria that focus on the quality of analysis and interpretation identified by Dixon-Woods et al. 58 These criteria were (1) are enough data displayed to support the interpretations and conclusions? and (2) is the method of analysis appropriate and adequately explicated? This assessment resulted in three qualitative papers rated as ‘sound’ (sufficient in-depth data and interpretation), eight papers as ‘adequate’ and six papers rated as ‘poor’ on at least one criterion.

The 26 quantitative papers retained were reviewed at this stage using questions specifically designed to assess survey research:59 (1) Is the response rate adequate to ensure response bias is not a problem? (2) Are sample size or power calculations reported? (3) Is the survey method likely to introduce significant bias? (4) Are reporting of the results of analyses adequate? and (5) Is the statistical analysis appropriate?59 Altogether, 11 quantitative papers were rated as ‘adequate’, three papers were rated as ‘sound’ and 12 papers were rated as ‘poor’ on two or more criteria.

The 12 quantitative and six qualitative papers rated as ‘poor’ were further assessed as ‘thick’ or ‘thin’, based on their descriptive and interpretive content. 60 This resulted in the retention of one qualitative paper otherwise rated as ‘poor’ because limited methodological detail was available. A total of 14 quantitative and 12 qualitative papers were therefore retained for the synthesis (see Figure 2 and Appendix 2). 29–53 See also summary of included studies in Appendix 2, Table 16.

Approach to synthesis

The preliminary synthesis initially involved making descriptive summaries of the characteristics and methods of each paper. Grouping and clustering was then undertaken to describe the set of retained papers.

Parallel syntheses of the 14 quantitative and 12 qualitative papers were undertaken and the two syntheses were then juxtaposed to develop an integrated synthesis. The key barriers identified from the quantitative data provided the initial framework for this synthesis, with the findings then elaborated with the qualitative data and explanations developed.

Results

A detailed synthesis is published in Morgan et al. 57 The characteristics of included studies are shown in Appendix 2 and the main findings are briefly summarised below.

Phase 2: preliminary synthesis (grouping and clustering of studies)

Only five retained studies were published prior to 2000,33,34,38,41,53 reflecting the fairly recent growth in transplantation and deceased organ donation. Altogether, 15 studies were conducted in the USA,29–34,37,39,41,47–50,52,53 and these were primarily quantitative surveys to identify self-reported donation attitudes and behaviour among African Americans. The three Canadian studies were all qualitative and examined barriers relating to native, Chinese and Indo Canadians. 42–44 Seven of the eight UK studies were also qualitative (focus groups or semistructured interviews)35,36,38,40,46,51 and studied black African, black Caribbean and South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi) ethnic groups, with just one quantitative survey in south London. 45

The papers focused on knowledge and attitudes, with a lack of attention to the effects of access to information or sources of registration, although such barriers have been identified as common in disadvantaged communities in the USA. 61

Phase 3: main synthesis and relationships

Knowledge

The most commonly studied barrier in quantitative studies was respondents’ knowledge about the need for organ donation or the process of registration. Knowledge was generally identified as lower among ethnic minorities than in the white population. Some studies showed that this held after adjusting for age and education,45 although adjustment for education or other socioeconomic variables was rare. However, two US studies37,41 that employed composite knowledge scores reported no significant difference in scores between black, white or Asian medical students,37 or between African American and Hispanic participants. 41 These differing findings may reflect the nature of study samples, with ethnicity often interacting with social disadvantage to contribute to relatively low knowledge.

Talking with family

Families’ awareness of the deceased’s wishes regarding donation is of considerable importance in an opt-in system, in which donation requires the consent of next of kin. However, two quantitative37,47 studies in the USA identified ethnic minorities as significantly less willing than the general population to talk with their family about organ donation. In the UK, similar differences in willingness to talk with family were reported, with black African, African Caribbean and South Asian minority groups being significantly less likely than the general white population to have discussed the topic of organ donation with friends or family, following adjustment for age, gender and number of years in education. 45

Qualitative studies identified several reasons for a lack of willingness to talk with family about organ donation, including superstitions around talking about death, parents not wanting to think about their children dying and concerns about offending elders. 40 The older generation were also less likely to support organ donation as it was generally not part of their traditions and their views could have a dominant influence. For example, black Africans in the UK described a fear of family rejection if they went against their views on this issue,36 and a study of Indian Sikhs indicated that the younger generation felt a duty to respect the wishes of their elders, particularly during bereavements. 38

Faith and cultural beliefs

Two quantitative studies41,47 identified African Americans and Hispanics as significantly more likely than white Americans to regard organ donation as contrary to their religious beliefs, as did a study comparing UK minority groups (black Caribbean, black African and South Asian) with the white population. 45 In contrast, a study of medical students did not identify the statement ‘donation is against religious viewpoints’ as a significant predictor of willingness to donate among African American and Asian American medical students compared with white medical students. 37 Similarly, religious objections were not identified as a significant predictor of willingness to donate among black and white Seventh-day Adventist students in the USA after adjusting for race, gender, age and a range of attitudinal barriers to donation. 32 Evidence of the influence of religion on willingness to donate was therefore mixed, possibly reflecting both differences between faith groups and the varying significance of faith for different age and socioeconomic groups.

Although people of Islamic faith are generally regarded as less likely to view deceased donation as acceptable, one study (Poonia et al. , unpublished) identified differences in knowledge and views between Muslims in the south and those in the north of England. Those in the north were less likely to consider organ donation and were described as a group for whom ‘religion defines who they are, colours all aspects of their daily life’, and were thus characterised by a strong ethnic/faith identity. 40 However, another key characteristic of respondents’ accounts was their uncertainty as to whether or not their faith permitted organ donation or has a single standpoint on the issue. 38,40

Bodily concerns

Concerns about the body took various forms that, in part, linked with faith and cultural beliefs, particularly a belief in the need for an intact body for the afterlife but also reflected general fears and feelings of disgust and concerns about bodily disfigurement that were particularly prevalent among ethnic minorities. 29,32,37,41,45

Uncertainty about their faith’s stance to the body remaining intact following death formed a particular concern for those of Islamic faith40 (Poonia et al. , unpublished), but was also raised by other ethnic and faith groups. 39,43,44,53 Other concerns related to donation interfering with traditional death rituals and practices involving appropriate care of the body after death42 or delaying burial and the body being ‘put to rest’. 39 In addition, a qualitative study in the UK identified respondents of second and third generation Caribbean origin as having an idealised desire that their body should return intact to their ‘home’ country for burial, which reflected the importance for them of reconciling a divided identity at death by returning home with their body intact. 46

Issues of trust

Trust involved various aspects. One key concern was trust in the fairness of the organ allocation system, with African Americans being less likely than white respondents to regard organs as allocated fairly and more likely to be allocated to the ‘rich and famous’. 37,47,50

Studies in the USA37,50 and a survey in the UK45 also indicated that black Caribbean and black African respondents in the UK and African Americans were significantly less likely than white correspondents to ‘feel confident that medical teams would try as hard to save the life of a person who had agreed to donate their organs’ (adjusting for age, gender and education), and were significantly more likely to worry that donated organs may be used ‘without consent for other purposes like medical research’. 45

Qualitative studies also provided further evidence of fairly widespread concerns among all ethnic groups that less would be done to save their life if they were known to be an organ donor. 35,38,46,53

Phase 4: robustness of the synthesis

This synthesis is one of a small number of reviews that have integrated quantitative and qualitative research and thus bring together studies that differ in their design, measures and study populations. These differences limited precise comparisons, although the inclusion of both types of data enabled a more detailed understanding of beliefs and practices.

Retained studies were, however, mainly ‘thin’ in interpretive content, thus restricting the possibility of more complete explanatory models. This may partly reflect the particular challenges of research in this area, including the cultural taboos and fears surrounding death and notions of organ donation, as well as people not having previously engaged in discussion of this topic.

Despite acknowledged limitations of the research, there was evidence of commonalities in attitudes and beliefs across race/ethnic groups, particularly the similarities between African Americans beliefs and those of the black population in the UK, as well as evidence of some variations between ethnic groups.

Conclusions

The review identified a number of consistent themes regarding barriers to donation.

-

Knowledge of deceased donation: this was fairly limited among all sections of the population, although minority ethnic groups in both the UK and North America demonstrated relatively low awareness and knowledge about needs for donation and how to register. Low knowledge was associated with less willingness both to register as a donor and to talk with their family about donation.

The relatively low knowledge among minority ethnic groups has persisted despite campaigns in the UK since 1999 that have specifically focused on increasing knowledge and encouraging registration as an organ donor among minority ethnic groups (see Table 2). This raises questions of the reasons for lack of awareness and how campaigns could be more effective.

-

Attitudinal and cultural barriers: a common barrier for many African Americans and for the black UK populations was a pervasive lack of trust in the health-care system, which was reflected in concerns regarding inappropriate withdrawal of treatment and perceived inequities in the allocation of organs. This perception may be shaped by their shared histories and feelings of marginalisation, together with the significant inequalities in access to health-care resources in the USA.

For many people of Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnicity, their faith beliefs formed the most significant barrier. However, rather than regarding Islam as prohibiting organ donation, respondents often felt uncertain and expressed the need for guidance from faith leaders. This situation exists despite jurisdiction rulings stating that Islam permits organ donation. 62 Lack of awareness of such formal authority has also been shown to extend to individual faith leaders, who differ in their interpretations and views on this topic. 63

The review also identified important gaps in knowledge. First, ethnic groups were mainly treated as discrete and largely homogeneous groups whose attitudes and beliefs are at variance with a socially desired practice, with little attention given to either variations within ethnic groups by age/generation or education/socioeconomic status, or to the ways in which age and social disadvantage may interact with ethnicity to influence knowledge and beliefs about organ donation. Second, there was little attempt to explain the lack of knowledge about organ donation among ethnic minorities or to consider possible structural barriers to practices, including access to information and sources of registration, although these have been identified as contributing to spatial variations in overall donation rates in the USA. 61

Study 2: focus group study – beliefs and attitudes to registration

Abstract

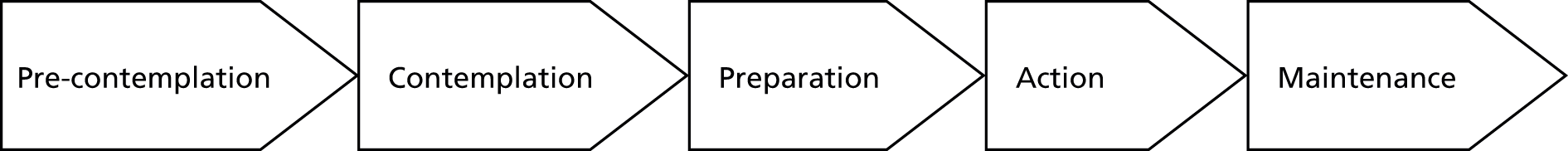

This study had two main aims: (1) to explain the continuing low knowledge regarding organ donation and registration as a donor among minority ethnic groups and (2) to identify similarities and variations in beliefs and practices between and within ethnic groups. Data collection involved a brief questionnaire and 22 focus groups comprising six ethnic/faith groups (who identified as Nigerian Christian, Caribbean Christian, Indian Sikh, Indian Hindu, Pakistani Islamic and Bangladeshi Islamic). Separate groups were held for older and younger members of each ethnic group, and for men and women among older South Asian groups. Discussion was facilitated by the use of vignettes. Sessions were recorded and transcript data analysed qualitatively. The discussions indicated that participants varied in their position on the ‘pathway’ towards registration as a donor; however, the majority were at a ‘pre-contemplation’ stage, despite ongoing campaigns to promote organ donor registration. We explain this by drawing on Schutz’s theory of relevance. 64 This describes a filtering process in which information that lacks perceived relevance to participants’ lives and which does not relate to their ‘stock of knowledge’ often ‘passes by unnoticed’. Second, we examined perceived barriers to deceased donation and the ways in which these were influenced by ethnic background, age, length of time in the UK and other life circumstances, thus leading to considerable heterogeneity within ethnic groups. The implications of these findings are considered for approaches to increasing knowledge and changing attitudes to deceased donation.

Background

A series of national campaigns have focused specifically on raising awareness of the need for organ donors among minority ethnic groups. These began in 1999 with a campaign focusing on the South Asian community, followed by three further national campaigns (Table 1). The campaigns differed in their specific theme/strapline, but all aimed to increase knowledge and change attitudes, and thus influence practices among minority ethnic groups. The campaigns generally involved national adverts, local radio shows and leaflets distributed to health centres, community centres, social centres, places of worship, etc. In 2010, they also included street plays in areas with relatively high BAME populations.

| Years | Organisation | Title | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2001 | Department of Health | South Asian community organ donation campaign | South Asians |

| 2002–5 | UK Transplant | Be part of the solution | Black population |

| 2006–7 | NHSBT | Can we count on you? | Black and South Asian |

| 2009–10 | NHSBT (Prove It campaign) | If you believe in organ donation, prove it | General population (2009), BAME groups (2010) |

| 2011–12 | NHSBT | Real people, real lives, real action | General population and BAME groups |

National campaigns have been supported by considerable local activity that is often targeted on specific ethnic and faith groups. The extent of this activity has not been documented, but it appears to have increased significantly since 2009, particularly through the activities of ODCs associated with NHS trusts.

Aims

This study aimed to address two key issues raised by the prior systematic review of the literature:

-

Why is there a continuing low level of knowledge about deceased donation and registration as a donor despite public campaigns focusing on minority ethnic groups?

-

How do beliefs and attitudes to organ donation and registration vary between and within different ethnic groups with a particular focus on African (Nigerian), Caribbean and South Asian (Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi) populations, particularly in terms of the influence of cultural and religious barriers?

We also initially aimed to elicit views regarding the possible introduction of a system of presumed consent in the UK; however, neither the participants’ level of knowledge nor the time available for focus groups enabled us to do this.

Design and method

Focus groups were selected as the method of data collection, as they have the advantage of encouraging debate about a topic that is not normally discussed and for which people may have limited knowledge. Addressing this topic as a group may also be more comfortable compared with the one-to-one situation of a personal interview.

Participant recruitment

Our research protocol identified the need to employ a recruitment company with experience of engaging people from minority ethnic groups in academic research, given the demands of recruitment and a limited timescale. We identified a company that had a network of local fieldworkers and was willing to undertake only the recruitment stage, with our team then conducting the groups and undertaking the analysis.

The recruitment strategy (Table 2) aimed to allow beliefs and attitudes to be examined both between and within ethnic groups. Separate focus groups were, therefore, conducted with people of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Caribbean and Nigerian ethnic origin (the Nigerian and Nigerian British population was selected representing the largest proportion of the black African population in the UK). 65 These ethnic groups were also divided into younger (18–40 years) and older age groups (≥ 41 years). For the South Asian groups, separate groups were held for men and women to reflect cultural traditions and promote discussion among participants.

| Age | 18–40 years and ≥ 41 years |

| Gender | Male and female |

| Ethnicity | Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Afro-Caribbean and West African |

| Religion | Islam, Hindu, Christianity and Sikh |

| South Asian recruitment boroughs | Brent, Tower Hamlets, Harrow, Newham |

| Caribbean and Nigerian recruitment boroughs | Croydon, Southwark, Lambeth, Lewisham |

The recruitment company was tasked with recruiting participants in line with our stratified sampling and to organise suitable locations for holding the discussions. Initially we hoped to recruit some groups outside the London area; however, the logistics of recruitment resulted in our recruiting groups from the eight London boroughs with the greatest ethnic minority populations. With the exception of the African and Caribbean groups, recruitment of a particular minority group took place in single boroughs, where a significant proportion of the population was made up of the ethnic minority groups under study as identified by Ethnic Group Projections for 2010. 65 Table 2 shows which boroughs each ethnic group were recruited from.

Agency fieldworkers were of the same ethnicity, faith and gender as the population to be recruited, and often resided within in the recruitment borough, thus benefiting from local knowledge, recruited the participants. Recruitment occurred on a door-to-door basis, in the street, at places of worship and community organisation, and through snowballing.

The recruitment company was supplied with a brief information sheet for potential respondents, which outlined the purpose of the research, what to expect if participating, assurances of confidentiality and the promise of expenses (£25). Potential participants were invited to contact the researcher if they wished to discuss any aspect of the research before making up their mind to join the study.

The aim was to recruit 10 participants for each focus group to ensure that approximately eight participants attended. Altogether, just over two-thirds of those recruited attended the focus groups, with attrition between recruitment and attending the event being greater among Caribbean and Nigerian populations (Table 3).

| Ethnicity | Recruited | Attended | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | Percentage of recruited | |

| Bengali | 49 | 45 | 92 |

| Caribbean | 41 | 19 | 46 |

| Indian Gujarati | 44 | 37 | 84 |

| Indian Punjabi | 45 | 40 | 89 |

| Nigerian | 70 | 31 | 44 |

| Pakistani | 62 | 36 | 58 |

| Total | 311 | 208a | 67 |

Throughout the recruitment process the research team was in close contact with the company to provide feedback and to ensure that the high level of attendance was achieved, with participants drawn from our designated minority ethnic groups and age groups. The split between employing a specialist company for recruitment and facilitating the focus groups ourselves seemed to work well.

Non-English-language groups

Recognising that English was likely to be a second or third language for some members of the older generation, we employed bilingual fieldworkers with experience of conducting qualitative research to facilitate the discussion with older Pakistani groups in Urdu, older Bangladeshi groups in Sylheti, older Indian Hindu groups in Gujarati and Indian Sikh groups in Punjabi.

A training session was held to brief the fieldworkers and familiarise them with the topic guide. The DonaTE team also developed an annotated version of the focus group topic guide that explained the rationale for the questions being asked in each section and gave an indicative list of potential topics to probe further (see Appendix 4). The day also included training on the conduct and facilitation of focus groups. These sessions provided ‘top tips’ for effective facilitation and covered issues such as how to break the ice, managing dominant participants and dealing with the ‘group expert’. This phase of training also involved discussion of what areas to prompt and probe and how to do this effectively. The training day also allowed an opportunity to consider issues in translating the topic across languages when direct translations of words associated with organ donation are not available or the concepts around donation are unfamiliar. As the final stage of training, the fieldworkers were observed in facilitating practice focus groups involving other members of the group.

Topic guide and vignettes

The topic guide covered individual knowledge and attitude towards organ donation, wider social benefits, and religious and moral issues regarding donation (see Appendix 4).

Piloting the topic guide confirmed that participants knew little about deceased donation and had little direct experience of the situations in which organs are requested to be donated or required for transplantation. When initially asked about organ donation, they therefore mainly talked positively about the benefits of transplantation and any conversation about donation was mainly situated within narratives of doing a good deed and saving the life of another, reflecting prevailing narratives of organ donation/transplantation in the media.

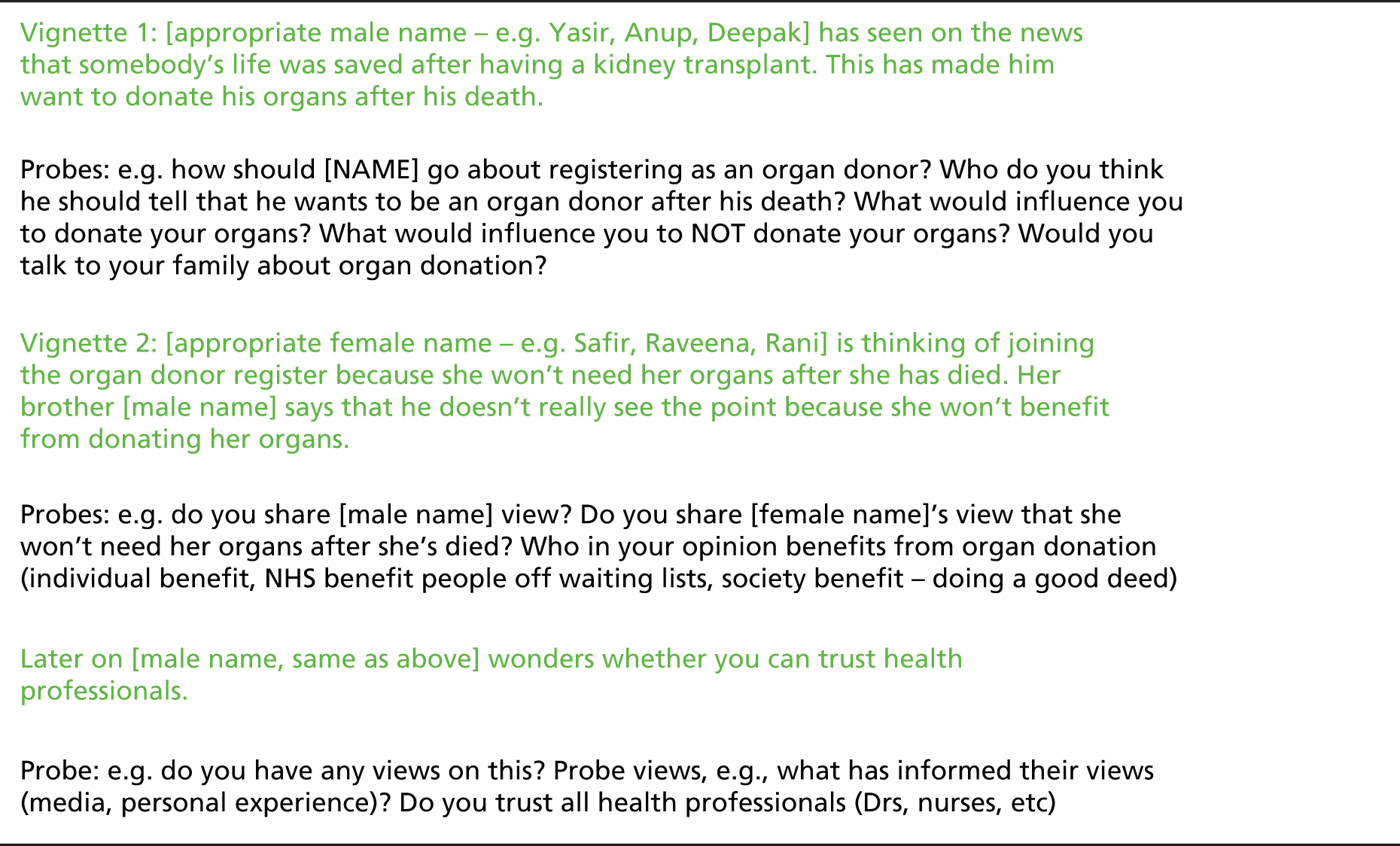

In an attempt to prompt more detailed discussion, we revised the topic guide and included factual information about donation to introduce each section, including information on the disparities in donation and consent between the general population and minority groups (see Appendix 4). We also developed vignettes that required participants to consider how they might behave in a particular donation situation and how they would advise a friend faced with a similar situation (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Vignette scenarios relating to registering as a donor. Reproduced with permission from Morgan M, Deedat S, Kenten C. ‘Nudging’ registration as an organ donor: Implications of changes in choice contexts for socio-cultural groups. Curr Sociol 2015:63:714–28. 66

The vignettes were informed by the literature and campaigns to promote organ donation. We also sought feedback from our lay advisory group to ensure that the situations depicted seemed plausible and comprehensible. Those attending the meeting felt that the topic guide and vignettes were appropriate and a few minor comments were incorporated. The decision to stratify by gender for the younger Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups was not regarded as necessary but at that stage it was too late to alter the recruitment strategy to reflect this sentiment.

Two vignettes are considered in this chapter and relate directly to registering as an organ donor. A third vignette focused on issues of family consent to donation. This was less successful in promoting discussion as participants were becoming tired and lacked understanding of the donation process within ICUs that required a new set of information. Moreover, their over-riding concern and almost sole focus of discussion was about whether or not you know if someone is really dead or may come back to life.

Conducting the focus groups

A total of 22 focus groups were held over 3 months (March–May 2010). Two researchers (CK and SD) facilitated 14 groups. The other eight community language groups were facilitated by bilingual fieldworkers, with a researcher also present to ensure that the groups ran smoothly and clarify any questions that the group might have about organ donation.

The focus groups were conducted in community spaces that were local to and often known by the participants and were also close to public transport. The groups were mainly held in the late afternoon/evenings or weekends, as this was the most convenient times for the participants. Each lasted 60–90 minutes. Participants received £25 in cash to cover expenses that they incurred attending the group. It was clear that, for some, this payment was an incentive to participation.

At the start of the group, the researcher provided an overview of the study and explained how the focus group would proceed. Written consent was obtained and a short questionnaire completed to provide summary sociodemographic information (see Appendix 5).

Data analysis

The bilingual fieldworkers interpreted and transcribed their focus group discussions into English. Other audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber and checked for precision by CK and SD. Listening to the transcripts and reading them for accuracy of transcription aided the identification of potentially relevant analytical concepts and patterns of response across groups.

To assist the analytical process, each transcript was imported into the qualitative software package NVivo (version 9). Analysis and interpretation occurred concurrently with data collection. Initial line by line coding was undertaken, with the responses grouped into categories that related to the five themes identified in the systematic review of barriers to donation. However, the analysis was not intended to be limited to these themes, with emphasis also given to the variations within and between groups, as well as to emerging thematic categories and interpretations.

Findings

Characteristics of participants

Table 4 summarises the characteristics of participants (see Appendix 6). Of the participants, students, retirees and those caring for family accounted for 29%. In general, the sample was biased towards the lower occupational and socioeconomic groups, with those employed (44%) mainly being in low-skilled or semi-skilled occupations, such as taxi drivers, security guards, and teaching and kitchen assistants. An exception was the group of younger Indian Hindu women, several of whom were in professional occupations, including an engineer and a general practitioner (GP).

| Focus group numbers | Ethnic group and age (years) | Number of participants | Place of birth | Work | Know person waiting for or had transplant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Caribbean (Christian), 18–40 | 8 | UK, n = 7 Jamaica, n = 1 |

Employed, n = 5 Care for family, n = 1 Student, n = 2 |

2/8 |

| 2 and 20 | Caribbean (Christian), > 40 | 19 | UK, n = 3 Jamaica, n = 6 Barbados, n = 2 St Kitts, n = 1 Guyana, n = 1 Sierra Leone, n = 1 Not stated, n = 5 |

Employed, n = 6 Care for family, n = 3 Unemployed, n = 6 Retired, n = 4 |

6/19 |

| 13 and 22 | African (Nigerian Christian), 18–40 | 21 | UK, n = 5 Nigeria, n = 16 |

Employed, n = 13 Care for family, n = 1 Student, n = 7 |

2/21 |

| 21 | African (Nigerian Christian), > 40 | 11 | UK, n = 1 Nigeria, n = 8 Not stated, n = 2 |

Employed, n = 6 Unemployed, n = 4 Not stated, n = 1 |

1/11 |

| 7 and 8 | Pakistani, 18–40 | 27 | UK, n = 6 Pakistan, n = 16 India, n = 1 Bangladesh, n = 1 Kenya, n = 2 Russia, n = 1 |

Employed, n = 9 Care for family, n = 8 Student, n = 5 Unemployed, n = 5 |

4/27 |

| 15 and 16 | Pakistani, > 40 | 16 | UK, n = 1 Pakistan, n = 11 Not stated, n = 4 |

Employed, n = 2 Care for family, n = 6 Unemployed, n = 1 Retired, n = 2 Not stated, n = 5 |

0/16 |

| 3 and 4 | Bangladeshi, 18–40 | 26 | UK, n = 7 Bangladesh, n = 15 Not stated, n = 4 |

Employed, n = 9 Student, n = 8 Unemployed, n = 9 |

2/26 |

| 17 and 18 | Bangladeshi, > 40 | 21 | Bangladesh, n = 15 Not stated, n = 6 |

Employed, n = 8 Care for family, n = 3 Unemployed, n = 5 Retired, n = 5 |

1/21 |

| 5 and 6 | Indian Hindu, 18–40 | 20 | UK, n = 1 India, n = 18 Zambia, n = 1 |

Employed, n = 13 Care for family, n = 1 Student, n = 6 |

5/20 |

| 12 and 14 | Indian Hindu, > 40 | 19 | India, n = 14 Yemen, n = 3 Kenya, n = 1 Not stated, n = 1 |

Employed, n = 3 Care for family, n = 3 Student, n = 1 Unemployed, n = 9 Retired, n = 2 Not stated, n = 1 |

0/19 |

| 9 and 10 | Indian Sikh, 18–40 | 22 | UK, n = 11 India, n = 8 Tanzania, n = 1 Not stated, n = 2 |

Employed, n = 18 Care for family, n = 1 Student, n = 2 Unemployed, n = 1 |

4/22 |

| 19 and 23 | Indian Sikh, > 40 | 18 | India, n = 16 Not stated, n = 2 |

Employed, n = 8 Care for family, n = 7 Unemployed, n = 2 Retired, n = 1 |

1/18 |

The participants included a high proportion of recent migrants; of the 202 who stated their place of birth, 79% were born outside the UK. These characteristics of relatively low socioeconomic status and a high proportion of overseas born people are fairly typical of areas with a high multiethnic population.

Knowledge about organ donation

A small number of people attending each focus group knew someone who was waiting for a transplant or who had received a transplant; however, few people were sure they had definitely joined the ODR. An exception was four highly educated Hindu women who had signed up to the ODR following participation in a cord blood donation project at a London hospital that led to their knowledge and interest in donation. Another rather larger group were unsure if they had checked the relevant box agreeing to be registered as an organ donor when renewing their passport, applying for a driving licence or applying for a Boots Advantage Card.

With few exceptions, individuals tended to reflect positively and with some enthusiasm about the abstract notions of donation and transplantation, with responses frequently situated within narratives of doing a good deed and saving the life of another. However, when asked to discuss the first vignette and to share their opinions or what they knew about organ donation, their responses were limited:

I don’t have knowledge on it to be honest. I’ve never looked it up to be honest, nothing really – I don’t know anything about it, all I know is that they take things out of your body.

Bengali Muslim woman, 18–40 years

When asked about how they would go about registering on the ODR, most participants’ responses drew on what Schutz64 terms ‘cook book knowledge’. This refers to ‘recipes’ for dealing with routine matters encountered in daily life that can be drawn on by individuals when faced with new or unfamiliar situations. For example, given their lack of awareness and knowledge of how and where to register as a potential organ donor, participants suggested logical places where it would be assumed individuals should or could possibly register. These tended to be local hospitals or GP surgeries. As registration was perceived to be a medical matter and an important decision, registering in a ‘health space’ was regarded as appropriate and to have the advantage of the opportunity to ask questions about an unfamiliar topic:

And I think, you know, with the GP you’ve been, hopefully, with that GP for a long time, they know all your history . . . trust is built over time, you know, it’s, you go with all your personal issues, and so yes the trust is definitely there.’

Indian Sikh woman, 18–40 years

Awareness of the shortage of organs was also limited. Across the groups, a number of participants (both older and younger) were of the opinion that the NHS holds a store of organs within hospitals that would be available for transplant when required. Within this context there was little imperative to register as an organ donor as they perceived there to be abundant stores of organs available.

Oh, sorry, I don’t know much about it, but do they freeze these until someone needs them?

Nigerian Christian woman, 18–40 years

. . . my organs may be removed after my death and put in a freezer box for a while. Doctors may use these organs from the freezer box later . . .

Bengali Muslim man, ≥ 41 years

If they don’t find a person [suitable recipient], they will put it [donated organ], keep it in a freezer for a long time.

Bengali Muslim man, 18–40 years

Explaining low knowledge

The national ‘Prove it’ campaign focused on minority ethnic groups in 2010 and coincided with the focus group study (see Table 1). However, few respondents were aware of this or of any other campaign. We believe this lack of awareness is because organ donation has limited ‘topical relevance’ for the majority of participants. Schutz64 described the notion of ‘topical relevance’ as something that is imbued with meaning for an individual because it stands out for them (p. 125). Schutz described individuals as structuring their knowledge into zones of relevance, which decrease in degrees of clarity and precision as they move outwards from areas of personal concern. Within this context, the potential exists for information that is not perceived by an individual as ‘topically relevant’, in terms of being of close personal concern and relating to their existing ‘stock of knowledge’, to ‘pass by unnoticed’ rather than being actively rejected. This lack of personal relevance was often reflected in participants’ accounts:

. . . you see leaflets and cards in everywhere like surgeries, and you don’t really give it that much importance . . .

Bengali Muslim woman, 18–40 years

Yes exactly the thought [of registering as a donor] has been there when you’ve read a poster or something but as soon as you walk away from that poster . . . as soon it comes in it goes out . . .

Indian Sikh man, 18–40 years

Analysis of participants’ accounts identified several reasons why organ donation campaigns lacked topical relevance for them.

Lack of direct personal experiences

Participants often cited an absence of any direct personal experiences of donation or transplantation, with the topic seeming remote for them:

I’ve seen lots of adverts, seen loads of donor cards and even been given them but not done anything . . . well . . . I think if it was somebody close who I loved or really felt for that would influence me a lot more than maybe the advertising.

Pakistani Muslim man, ≥ 41 years