Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1086. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Morrison et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Mental disorder and mental illness are two of the most significant burdens on society in terms of personal distress, disability and economic cost. There are currently more people on incapacity benefit than there are unemployed, with 40% having incapacity due to a primary mental health problem and a further 10% having a secondary mental health problem. 1 Our focus on mental health, and specifically psychosis, is clearly consistent with priorities and needs, as psychosis is associated with significant personal, social and economic costs, and psychosis accounts for a large proportion of the national health and social care budget. 2 Suicide risk and behaviour in patients with psychosis is a significant and serious clinical and social problem. Approximately 4–10% of patients suffering from schizophrenia will eventually kill themselves. 3 Suicide ideation and attempts are common, with over half of all patients having a history of attempted suicide or having significant suicidal ideation at any one time. 4,5 Suicidal ideation and planning are important steps that lead to an attempt of self-harm that may lead to death with previous unsuccessful suicide attempts increasing risk for later successful suicide. 3,6 Similarly, bipolar disorder (BD) affects over 1 million people in England alone and has a prevalence rate of around 2%. 7,8 In addition to repeated periods of mania and depression, most individuals with BD experience extended periods of distressing subsyndromal mood symptoms between episodes. 9–11 Consequently, BD has significant impact emotionally and functionally12 and is a substantial financial burden to society with a recent estimated cost to the English economy at £5.2B per annum. 8

Access to psychological treatments is a government priority; recently Lord Layard highlighted the challenge presented by mental health and recommended the provision of psychological treatments. 13 Although psychological intervention approaches for psychosis such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) have been demonstrated to be effective and recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for schizophrenia and BD have recommended that people be offered CBT,14,15 there are a number of limitations to the delivery of CBT in routine services. 16 Such limitations are the widespread lack of trained therapists means that provision of this type of intervention is limited; the refusal rate for participating in trials of cognitive–behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTP) is relatively high, suggesting that not all service users wish to engage in current modes of delivery of this therapy; there is some concern that the focus of CBT interventions for psychosis have been overly restrictive; and that such CBT does not necessarily target the priorities identified by service users.

Recovery-orientated services are recommended across treatment settings in adult mental health and specifically in the implementation guidance for specialist and community teams, but with little evidence base to support this. Recovery from psychosis is a relatively new concept given that psychotic disorders have historically been thought of as a severe and enduring mental illness. 17 However, research over the last two decades has begun to challenge these assumptions and it is becoming more accepted that people can, and do, recover from psychosis. 18 Clinical recovery relates to the absence of symptoms whereas the meaning of recovery to service users is much broader and recovery is seen as a process,19 having many aspects such as empowerment and quality of life. 20–22 It is also evident that there is not always a relationship between symptoms and recovery. 19 The dominant approach to identifying psychological mechanisms involved in recovery from psychosis has focused on cognitive deficits (deficiencies in intellectual functioning and basic information processes such as attention and memory). 23 Most investigations have considered attentional problems to be central to schizophrenia and BD but, despite consistent findings of poor performance in patients,24 the precise role of deficits in psychosis remains unclear. Deficits are apparent on all tasks24,25 and performance is similar in patients meeting criteria for BD and schizophrenia. 26,27 Furthermore, the severity of cognitive deficits does not predict positive symptoms,25 although they do predict social functioning. 28 Recent studies have shown that the relationship between gross cognitive functioning and social functioning is mediated by social–cognitive skills (the ability to understand social situations and respond appropriately),29 but the implications of this research for the process of recovery have hardly been studied.

Although there is an increasing recovery literature for individuals with experience of psychosis, there has been little or no research of this type specifically targeted at individuals with a diagnosis of BD. As with psychosis in general, most individuals with a bipolar diagnosis will continue to experience psychiatric symptoms despite psychiatric treatment. 11 However, as the recovery literature increasingly shows, individual definitions of recovery are diverse and rarely focus on eradication of symptoms.

Some authors have suggested that there is a lack of ‘empirical’ literature on recovery and that ‘no empirical conceptualisations of recovery have been published’. 30 Although recovery is being studied with increasing frequency, a recent literature search revealed that there are few instruments that measure recovery from the service users’ perspective in comparison to those that measure symptoms and measurement of symptoms has not benefited from user involvement. 31,32

With respect to psychological predictors of recovery, cognitive deficits might be expected to impact on the recovery domain of rebuilding life (involving re-establishing positive relationships and meaningful daily activities), whereas cognitive biases are more likely to be implicated in rebuilding the self and hope for the future. Consistent with this, research has found that service users who experience paranoia shift their beliefs about the extent to which they deserve persecution unpredictably over time and that these changes are associated with changes in self-esteem and attributional processes. 33 In the case of bipolar patients, research suggests that coping strategies, which seem to affect the stability of self-esteem, differ between different phases of the disorder. 34 Dynamical models have the potential to explain why systems of interacting cognitive processes sometimes settle in stable states that are resistant to perturbation (which might be taken as an indicator of recovery).

Recovery from psychosis clearly involves the planning for the future and ensuring future well-being. Feelings of loss and lowered expectations for future achievements can lead to depression and feelings of hopelessness. 35 Thus, part of the recovery process involves the challenges of remaining optimistic and fulfilling full potential and well-being. While there is clearly a strong evidence base for CBTP, including much of our own work,36–41 research indicates that CBTP does not significantly reduce suicide behaviour;42 thus, the development of CBT for suicide prevention is a priority. There are also other limitations with respect to the delivery of CBTP mentioned above, so alternative modes of delivery need to be explored. The most recent study of CBT for relapse prevention in BD found that there was a significant interaction between the number of episodes and the outcome, with only those with fewer episodes benefiting significantly. 43 To date, no CBT interventions have been specifically designed for delivery to individuals early in their illness course.

It is clear that mental health problems, including psychosis, suicide and BD, are a significant burden for society. National guidelines recommended a recovery-orientated approach with psychological interventions, such as CBT, be offered as part of routine practice. However, further research to investigate the psychological mechanisms of recovery in psychosis, suicide and BD would be beneficial to inform the development of evidence-based recovery-focused psychological interventions. Consideration of effective modes of delivery for psychological interventions as well as service user choice and preference are essential.

Aims

To complete a series of linked projects with the aim of understanding and promoting recovery from psychosis and BD, in a manner that is acceptable to and empowering of service users.

Objectives and research questions

Our research programme consisted of six linked project themes, each of which were designed to further our understanding of recovery. Objectives for each theme were:

-

to develop a valid and acceptable service user designed tool to assess the severity of multiple dimensions of experiences of psychosis

-

to determine levels of consensus around the service user-defined recovery concept

-

to confirm the psychological factors that are associated with recovery from psychosis and examine the longitudinal course of such factors

-

to develop and evaluate cognitive–behavioural approaches to guided self-help and group therapy for recovery, taking patient preferences into account

-

to develop and evaluate a cognitive–behavioural approach to understanding and preventing suicide in people with psychosis

-

to understand the process of recovery from BD and to develop and evaluate a cognitive–behavioural approach to recovery from a first episode of BD.

An additional aim of the programme as a whole was the development, within the lifetime of the programme, of key deliverables that will be important to the NHS, namely user-defined measures of recovery and symptoms, manuals for telephone-assisted CBT, recovery groups, CBT for suicide prevention, CBT for early BD and assessment of barriers to recovery. It can be noted that the original title of the research application was psychological approaches to understanding and promoting recovery from psychosis; the title of this report changed to incorporate the emphasis on BD as well as psychotic disorders as this is a more accurate reflection of the aims and programme content.

Service user involvement in research

Involving service users in research has been advocated for many years and has been implemented to some degree in many areas. Increasing such involvement and inclusion is important for a number of reasons.

First, professional researchers may not always effectively address the personal priorities or preferences of research participants and so collaborative consultation with service users can be helpful in focusing and shaping research to be more clinically meaningful and ethically sound. Second, service users often report that they would value the opportunity to meet and speak with others who have similar experiences and so including user researchers within research teams can help to increase such opportunities for research participants and may improve participants’ personal engagement. Third, recognising the inherent value of personal insight that service users can bring to research can help to improve service users’ own self-worth, individually and collectively. This may be an especially important aim as people who experience psychosis commonly report reduced self-esteem and disempowerment as a result of their experiences, or their treatment.

The Recovery Research Programme has fully integrated service user involvement from the outset by including two service users as grant holders, employing two part-time service user researchers throughout the programme, including 10 service users as consultants and setting up a bimonthly service user reference group [service user reference group (SURG)]. The service user researchers conducted all of the individual qualitative interviews and led the analyses of these data. They also delivered elements of peer support within the patient preference trial (PPT). The role of the service user consultants and service user reference group was to act in a consultative and advisory capacity, making recommendations on a variety of elements including the content and conduct of studies. The service user reference group was co-ordinated by a service user researcher with support from the research programme manager and administrator. Service users were paid for their time and travel expenses both for attending the meeting and preparation/reading time. The group met at a regular time and day on a bimonthly basis (every other month) throughout the programme. All SURG meetings were minuted and items for action or suggestions for amendments to studies were taken to individual project teams. Any amendments made were documented and fed back to the SURG. If suggestions made by SURG were not able to be accommodated, reasons for this decision were still fed back to the group and discussed.

The SURG agreed that they would be involved with:

-

reporting on progress of service user involvement in individual research projects (each person involved represents one project)

-

supporting and representing other service users involved in individual projects in any issues that arise from their involvement

-

responding to any requests for input from individual academics/recovery programme meetings

-

being consulted about any ‘add on’ projects to the recovery programme

-

being involved in the recruitment of staff.

Some key contributions of the SURG to individual studies included reviewing all of the topic guides for the qualitative interview studies, advocating strongly for a preference trial design in the PPT, providing input to the development of the self-help recovery guide in the PPT and developed the distress management protocol for the programme. A review of the service user involvement in the Recovery Research Programme was conducted by a service user researcher (and co-ordinator of SURG). The review highlighted that SURG has functioned well as a group and that their involvement had benefited the research and the individuals involved. It was felt that opinions of service users were taken seriously and had a wider impact including being nationally recognised as an example of good practice for service user involvement. It was noted that future service user involvement should continue to improve communications between all members of the research team (including service users) as well as involving service users from the outset in planning and standardising service user involvement for each study.

Conduct of the research programme

It was important that the research programme was conducted in a cohesive way that allowed consistency across the studies in terms of staff training and supervision, cross-programme meetings, standard operating procedures (SOPs), provision of trial management to the bipolar and suicide prevention trials and a cross-programme Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). This enabled the programme to be conducted in an efficient and effective way. The chief investigator (APM), programme co-ordinator (HL) and programme manager (MW) contributed to the provision of these cross-programme aspects. Individual project leads (GH, RPB, CB, NT and SHJ) were responsible for the conduct of the studies within their themes, as well as decisions regarding data analysis (in conjunction with the programme statisticians: GD and NS) and decisions regarding dissemination and publication of findings within their themes.

Enabling cross-learning: staff training, supervision and cross-programme meetings

To enable cross-learning and consistency across the research programme, staff were trained and supervised centrally. Weekly group supervision meetings were held with the researchers to monitor adherence to the study protocol and SOPs, as well as monthly meetings to ensure consistent scoring and inter-rater reliability for the assessment measures used across the programme. In addition, project leads met regularly to discuss progress on the individual studies in order for shared learning to take place across the studies.

Standard operating procedures

Standard operating procedures were created across the programme as a whole to facilitate consistency, quality and integrity of routine activities within the research studies. This included producing procedures for recruitment, randomisation, safe working, management of distress and risk, data quality and safety reporting. SOPs were generally prepared by the trial manager and approved by the project leads before being shared with programme staff via a secure web-based portal hosted by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). This ensured the SOPs were current, version controlled and accessible from any location. SOPs minimised variation across the studies and promoted quality through consistent implementation even if personnel changes occurred during the lifespan of the study. Compliance with SOPs was monitored directly by supervisors and line managers.

In addition to the SOPs for each study and across the programme as a whole, the service user reference group suggested the addition of a distress management protocol which included offering a follow-up telephone call to all participants to ensure that they had not experienced any distress following the research assessment. If any distress was reported the researcher would check immediate safety and well-being, followed by signposting to the appropriate clinical care team or seeking consent to share this with the participant’s clinical care team. Additionally, the distress protocol recommended that assessments were not conducted on a Friday afternoon owing to the possibility of the participant feeling distressed over the weekend and unable to easily contact their clinical care team.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was set up to review the safety and efficacy of the research studies, with a particular focus on the clinical trials of therapeutic interventions. The DMC consisted of an independent clinician and statistician, and was attended by the programme co-ordinator/trial manager to provide updates and the programme statistician to consult on the statistical aspects of the studies. Meetings were held twice a year with additional ad-hoc meetings or teleconferences when necessary to review adverse events. It was agreed that the DMC would review recruitment and retention and monitor safety and adverse events.

Cross-programme recruitment

There was a procedure for the facilitation of cross-recruitment between several of the individual studies to ensure that participants who were keen to take part in more research were offered the opportunity to do so. While many participants took part in more than one study, their data from previous studies were not generally utilised (i.e. each study was independent and built on the findings of previous phases). When possible in the time frames required for valid assessments, data could be reutilised to minimise participant burden. However, in practice this was not possible for most participants owing to the short validity periods of standardised clinical assessments. The only exception to this was the study examining longitudinal predictors of recovery in psychosis, which utilised data from the clinical trials to examine change over time.

Cross-programme measures

There was an attempt to utilise similar measures across studies in order to allow comparisons to be made and to maximise the possibility of combining samples when appropriate (e.g. in the study examining longitudinal predictors of recovery in psychosis, which utilised data from the clinical trials to examine change over time). The Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) was used throughout the programme, often as the primary outcome in a clinical trial, or as the dependent variable when examining predictors of recovery. Initial studies used the original 22-item version as this was what was available. It became apparent that the psychometric properties were not ideal for measuring recovery as a unitary and independent construct. In the first study for which this was required, which examined psychosocial and neuropsychiatric predictors of recovery, an individualised statistical analysis was conducted that resulted in a combined measure that utilised the visual analogue scale ratings in combination with five QPR items. Subsequent studies used a 15-item version of the QPR, which was one-dimensional and had improved psychometric properties [but this had not been available to the earlier studies (those before 2013)].

Structure of this report

Chapters 2–7 of this report presents findings from each of the six linked themes. Each chapter includes a brief background to the theme followed by subsections representing each phase of the project. Subsections for each phase consist of a brief overview of the objectives, methodology, results and discussion. The final chapter brings together all of the findings from the six themes, includes an overview of the development of key deliverables that will be important to the NHS and discusses implications for future research and clinical practice.

Changes to protocol or original proposal

The original plan of research was titled ‘Psychological approaches to understanding and promoting recovery from psychosis’. The original proposal outlined six key objectives and the methods used to achieve these objectives as follows:

-

Development of a valid and acceptable tool to assess the severity of multiple dimensions of psychotic experiences that can be reliably used by service users and further validation of a user-led measure of recovery. To achieve this objective the original proposal contained three phases to this research:

-

Qualitative interviews conducted by, and with, services users to generate items relating to the experience of psychotic symptoms.

-

Q-sort methodology to generate potential themes and items for the new measure.

-

Investigation of the psychometric properties of the new scale (including test–retest reliability and concurrent and predictive validity).

-

-

Confirmation of psychological factors that are associated with recovery from psychosis and examination of the longitudinal course of such factors.

-

A cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between cognitive functioning and social functioning, and assessment of the extent to which cognitive functioning and cognitive biases are associated with subjective domains of recovery of importance to patients.

-

A longitudinal assessment of cognitive processes in recovered and non-recovered schizophrenia spectrum patients including an experience sampling method (ESM) study of stability in these processes.

-

Examination of predictors of recovery. Based on the results from phases 1 and 2, production of a final battery of variables most closely linked to the process of recovery, and testing of their ability to predict specific domains in the patients participating in two of the trials. In each trial, the assessment battery was administered at inception and at 6-month follow-up. This is to enable the prospective assessment of predictors of recovery.

-

Production of a manual for the recovery prediction battery. Based on the results from phases 1–3, the optimum combination of measures were chosen to include in a brief, transdiagnostically valid battery designed to assess intrapsychic impediments to recovery. A manual describing the final battery and summarising our findings would be made available to clinicians and researchers elsewhere.

-

-

Development and evaluation of cognitive–behavioural approaches to guided self-help and group therapy for recovery, taking patient preferences into account.

-

Development of the self-help manual. The recovery manual was developed in a manual format by a multidisciplinary group of mental health professionals and users informed from both the recovery literature and cognitive–behaviourally oriented treatments for people with psychosis.

-

Piloting the manual, estimating effect size and study of patient preferences. Participants were randomly allocated to the manual plus telephone condition or treatment as usual (TAU). Baseline and post-treatment assessments were completed in the same manner as in the proposed PPT. Detailed feedback about the manual and telephone support was requested from participants.

-

An additional sample of service users meeting the inclusion criteria above were interviewed as to their hypothetical preferences in terms of treatment condition.

-

The PPT. The three conditions to be evaluated in the PPT were TAU, manual plus low support (telephone support), manual plus high support (telephone and group).

-

-

Development and evaluation of a cognitive–behavioural approach to understanding and preventing suicide in people with psychosis.

-

To investigate the psychological architecture that drives suicide behaviour, including information processing biases, suicide schema and appraisal systems using information processing tasks such as autobiographical memory tasks to investigate bias, standardised assessment to investigate appraisal and schema.

-

To derive a method of assessing this architecture through semistructured interviews that will have clinical utility.

-

To formulate and develop a manualised cognitive–behavioural treatment programme for suicide prevention in psychosis and to test the clinical acceptance and feasibility of this intervention. It was hypothesised that the treatment would be acceptable, feasible and reduce suicide behaviour.

-

At the end of the programme, to be in position to design a clinical trial to test the efficacy of the intervention.

-

-

Understanding the process of recovery from BD and the development and evaluation of a cognitive–behavioural approach to recovery from a first episode of BD.

-

A qualitative study to identify the key themes associated with recovery in individuals who have a diagnosis of BD.

-

On the basis of the information collected in phase 1, a questionnaire was constructed to conduct a quantitative study of recovery from BD. This study evaluated the reliability and validity of the measure.

-

To evaluate a CBT-based recovery intervention for individuals with a first diagnosis of BD.

-

-

The development, within the lifetime of the programme, of key deliverables which will be important to the NHS, namely user-defined measures of recovery and symptoms, manuals for telephone-assisted CBT, recovery groups, CBT for suicide prevention, CBT for first episode BD and assessment of barriers to recovery.

First, it can be noted that the original title of the research application was ‘Psychological approaches to understanding and promoting recovery from psychosis’; the title of this report changed to incorporate the emphasis on BD as well as psychotic disorders as this is a more accurate reflection of the aims and programme content.

An additional objective was added to this list during the course of the research programme (see Chapter 3) to examine consensus around conceptualisations of recovery. It was felt that this was a valuable addition to underpin the studies in this research programme and provide further clarity on the concept of recovery.

It should also be noted that the original plans for the Chapter 6 studies on recovery and suicide did not include the qualitative study (phase 1) to examine the subjective experience of participating in this type of research. However, based on service user feedback and suggestions from the SURG, the team decided to add this phase to explore service user perceptions and inform the conduct of the future studies.

Finally, the original proposal stated that the outcome of the Chapter 4 studies on understanding psychological and social predictors of recovery would be an assessment battery and manual for assessment and prediction of recovery. However, this aim proved to be unrealistic given the idiosyncratic nature of recovery, the differences between clinical populations and the diversity of approaches used to capture information about recovery. However, we have included a section at the end of the conclusion of Chapter 4 that addresses recommendations for the measurement of recovery.

Chapter 2 User-defined conceptualisation and measurement of recovery in psychosis

Background

Recovery has become an increasingly popular and important concept for mental health service providers and policy-makers following guidance in a number of government policies and the national service framework. 44 Despite this, a working definition of the concept of recovery has never been formalised.

Consequently, current approaches to defining and measuring recovery in mental health utilise a variety of approaches. For example, traditional models tend to focus on symptoms while other models are concerned with a sense of well-being regardless of symptoms. Davidson et al. 45 outlines this as two superseding models. Similarly, although measurement of recovery is sometimes concerned with only a single factor approach, such as assessment of symptoms, relapse rates or functioning,46,47 others consider recovery to be a multifactorial long-term process incorporating hope for the future rebuilding self and rebuilding life. 19 Alternative approaches have assessed recovery as a set of internal and external conditions. 48 Despite the diverse nature of understandings of the concept itself, the term recovery has become widely used and recognised by professionals and service users alike. This highlights the importance of aiming for a shared understanding of recovery to prevent misapplication and miscommunication.

Recovery from psychosis has traditional been viewed as achieving symptom alleviation. 49 The gold standard in research investigating therapies, treatments and medications would be large clinical studies such as randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which aim to reduce frequency of symptoms. The primary outcome measure in RCTs investigating CBT50–52 and medication53,54 has been symptom change scores using standardised psychiatric interviews. Similarly, mental health services often use the criteria of symptom alleviation as a benchmark for demonstrating effective practice, adopting the benchmark from RCTs.

As a result of this focus on symptom change, a number of measures of symptomatic recovery have been developed including the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS55) and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. 56 Symptoms have been shown to cause reduction in social and daily functioning as well as leading to distress,47,57 demonstrating the need to consider symptoms of psychosis when examining recovery. Although these measures have been shown to be reliable and useful in assessments of outcome in psychosis, they may not be considered by service users to reflect the multifactorial nature of recovery from psychosis. Other unidimensional approaches to measuring recovery from psychosis have included relapse reduction,58 for which rehospitalisation, remission and reoccurrence of symptoms are taken into account. 59 Periods without hospitalisation and remission of symptoms are used as indicators of periods in recovery. 59

Alternatively, services have increasingly turned to assessment of quality of life as a measurement of recovery in psychosis. 60 This approach integrates more of the elements of service user-defined recovery such as a range of life domains and individual values. 61 Measures such as the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF62) scale and the Quality of Life Scale63 are commonly used. Research studies often use these measures alongside the more traditional symptom and relapse measures. 64

Although there has been a wealth of research developing these measures and utilising them in RCTs and other studies, few have examined whether or not these outcomes are relevant and meaningful to service users and their definitions of recovery. A recent review of measures of recovery31 included examination of acceptability to service users and found that only one measure had been developed in collaboration with service users to specifically to measure recovery from psychosis: the QPR. 32 Further psychometric testing of the QPR was recommended. This measure was utilised throughout the Recovery Research Programme allowing future examination of psychometric properties and utility as well as further exploration of whether or not it covers key recovery themes as defined by service users.

Service user-defined recovery has been examined in a recent meta-analysis26 which identified five processes that are important to recovery: (1) personal and self-empowerment; (2) motivational processes including hope; (3) developing competencies such as seeking knowledge and making sense of distress; (4) social and community participation; and (5) utilising available resources, including services and voluntary support agencies. Development of a measure that takes into account these factors and other elements which service users highlight as essential to recovery, as well as their relationship to symptoms, would further our understanding of recovery and the ability of services to effectively measure recovery-focused outcomes.

In order to develop a measure of recovery that incorporates dimensions of symptoms, but which is meaningful and relevant to service users, resolution around the meaning of recovery must first be addressed. This would then progress to developing and validating a service user generated measure, which would encompass this definition. The psychometric properties of this measure would then be established. This chapter includes three distinct phases of a study to address this deficit. This study aims to alleviate uncertainty about the concept of recovery by adopting an inclusive approach, scrutinising factors that are important to a multidimensional approach to recovery before using this information to develop a service user generated, self-report scale to assess recovery in relation to symptoms in psychosis. The three phases to this study include (1) a qualitative approach to exploring service user experiences of recovery; (2) a Q-methodology approach to further refine what factors are important to service user definitions of recovery; and (3) utilisation of information from phases 1 and 2 to develop a service user designed measure of recovery in relation to symptoms of psychosis and establish its psychometric properties.

Phase 1: conceptualisation and perceptions of recovery from psychosis – a service users perspective

This research was previously published as Wood L, Price JF, Morrison AP, Haddock G. Conceptualisation of recovery from psychosis: a service-user perspective. Psychiatrist 2010;34:65–47065 and much of this text has been reproduced with permission from the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Objectives

This study aimed to explore peoples’ subjective experiences of recovery using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to elicit data from participants.

Method

Participants

Participants were invited to take part in the study if they had experience of psychosis in the last year, were aged 16–65 years and were currently in contact with mental health services. Exclusion criteria included not being able to speak English, not able to give informed consent and having taken part in other research with the past 6 months. Participants were recruited from statutory care providers across the Greater Manchester West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust. Recruitment was conducted until the research team felt that saturation of themes was achieved.

Design

The study utilised a semistructured interview approach, with an interview schedule developed by a clinical psychologist and service user researcher (GH and MK). A service user group facilitated generation of questions surrounding personal background, experience of symptoms, recovery and impacts of symptoms. These questions were piloted with three service users and amendments were made following their feedback. The final version included the following headings: information on initial contact with mental health services, background on personal experiences, current experiences, what they felt had changed over time/recovered, how they feel they have changed (over time/recovered, ways of coping, impacts and changes to their life).

Procedure

Recruitment for the study took place in early intervention services (EISs), assertive outreach (AO) teams and community mental health teams (CMHTs). Participants were given a minimum of 24 hours to read the information sheet before being asked to sign a consent form. A service user researcher conducted the majority of the interviews (75%). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the service user researcher and research assistant in order to help familiarise themselves with the data.

Analysis

Interpretative phenomenological analysis66 is an approach to qualitative research with a focus on how an individual makes sense of an event or phenomenon. IPA involves collecting information from participants, in this case using interviews, on a given experience and how the individual has interpreted and made sense of that experience. IPA was utilised to explore the data in this study, as it is well suited to the exploration of subjective experience. 66 A core concept of IPA is that the analyst should become immersed in the data66 to enable the researcher to gain an insider perspective. This was achieved by listening to the audio-recorded interviews and reading through the final transcripts a number of times. Two researchers analysed all the interviews independently and extracted pertinent themes. The third researcher acted as a mediator if there was any disagreement.

Results

Eight people were interviewed (six males and two females) with an age range of 24–35 years. All had experiences of delusions and/or hallucinations within the last 12 months and six were recruited from EISs and two were from CMHTs.

Initially, 132 themes were generated from the interviews, which were condensed into 50 clear themes that were representative of the expansive concourse. The process of condensing these themes involved identifying overlapping and repetitive items and reaching consensus about removal of these items. These were then fine-tuned to remove themes that were felt to reflect the same concepts as others. The final 50 themes broadly covered eight areas of recovery: symptoms, emotional aspects, the self, behaviour, services and support, coping mechanisms, social functioning and occupational aspects. From these eight broad themes, a logical grouping of four superordinate themes emerged.

The four superordinate themes were described as ‘impacts on mental health’, ‘self-change and adaptation’, ‘social redefinition’ and ‘individualised coping mechanisms’. These themes were underpinned by change, highlighting that recovery is a process, not an end point. These themes each had two further subthemes that consisted of smaller themes (Box 1).

-

Preoccupation with experiences.

-

The content of experiences.

-

The frequency of experiences.

-

The duration of experiences.

-

Amount of distress.

-

Conviction.

-

Overcoming depression and low mood.

-

Feeling of happiness and enjoyment.

-

Overcoming anxiety and stress.

-

Overcoming anger and frustration.

-

Changes in the amount of emotions experienced.

-

Stable living conditions.

-

Job seeking and maintaining employment.

-

Financial stability.

-

Being less withdrawn and isolated.

-

Finding the ability to trust others.

-

Taking part in meaningful activities and hobbies.

-

Developing and depending on relationships with friends and loved ones.

-

Increasing social activity.

-

Overcoming being judged and stigmatised.

-

Positive self-beliefs.

-

Redefining who you are.

-

Feeling less vulnerable.

-

Overcoming embarrassment.

-

Regaining personal freedoms and rights.

-

Having a positive outlook for the future.

-

Improvements in sleep.

-

Energy and lethargy.

-

Motivation for change.

-

Reduction in self-harm and suicidal ideation.

-

Regaining independence.

-

Changes in drug and alcohol use.

-

Benefits of medication.

-

Benefits of therapies.

-

Peer support.

-

Support from loved ones and/or friends.

-

Receiving help from mental health services.

-

Concerns over side effects of medication.

-

Importance of spirituality/religion.

-

Help seeking with experiences.

-

Recognising the early signs of becoming unwell.

-

Being able to cope with experiences.

-

Understanding your experiences and/or diagnosis.

-

Feeling empowered over your experiences.

-

Having control over experiences.

-

Thinking clearly about experiences.

-

Having control over own thoughts.

Theme 1: impacts on mental health

All people interviewed discussed alleviation of symptoms and/or negative emotions as key to their recovery. Participants discussed specific changes in symptom characteristics as well as changes in their emotional state.

Reduction in symptoms of psychosis

All participants considered a change in symptom characteristics as important to their recovery.

. . . they’re not as aggressive as they were when the were really bad . . . they were really, really nasty and they used to really upset me but they’re not as bad anymore . . .

(Reflecting the importance of the subordinate theme of ‘the content of experiences’.)

Emotional changes

Affective and emotional changes are often associated with experiences of psychosis:

. . . it was definitely the most difficult time I’ve ever experienced, and I’ve had depression since, on and off since I was 14 maybe. But it [the depression that coincided with the psychosis] was far worst than that.

(Showing the importance of the ‘overcoming depression and low mood’.)

Theme 2: self-change and adaptation

Experience of psychosis was shown to have great impact on one’s self. The themes illustrated the importance of overcoming psychosis and being able to regain self-identity.

Personal change and belief

Interviewees described negative self-belief and negative personal change since experiencing psychosis. Their previous self wanted to be redefined in spite of current experiences:

I feel better about myself now, the voices used to make me feel like a rubbish person, they made me feel like I wasn’t worth anything, now I can control this I feel better about myself.

(The theme ‘ positive self-beliefs’ was key to personal change and belief.)

Behavioural change

The research also identified a number of behavioural changes; participants expressed the importance of motivation, independence, and changing harmful behaviours:

‘I think I’m over most of it you know, but I think there’s still little things, like a routine of looking after myself which can sometimes suffer, . . . sometimes my appearance can get quite bad’

(Illustrating the self-care is key to subordinate theme ‘regaining independence’)

Theme 3: social redefinition

Mental health problems were shown to have a direct impact on an individuals’ social role. Redefining and reconciling their social circumstances was frequently spoken about in all interviews.

Occupational change

Changes in finance, work, and living arrangements are acknowledged to be great stressors to individuals with and without mental health problems. A return to these situations was identified as a struggle but something that people do want to tackle:

Not having much luck getting a job at the moment which is quite frustrating really.

I was in lots of debt and it was stressing me out.

(Illustrating subordinate themes ‘job seeking and maintaining employment’ and ‘financial stability’ are main occupational issues.)

Relationship/social behaviour

Social isolation, the breakdown of social networks, judgement and stigmatisation is often a common with mental health experiences. It was important to interviewees to rebuild these networks and relationships to assist in recovery:

One of the main things [that made me feel better] is the support that my family gave me really, although it was strained at times, after a while, not at first but after a while they would understand what I was going through.

(All interviewee’s supported the theme ‘developing and depending on relationships with loved ones.)

Theme 4: individualised coping mechanisms

Developing an individualised coping mechanism was considered important to all people interviewed. By accessing support and treatment, people were able to assist their recovery. Furthermore, gaining insight and understanding was also shown to be important.

Support and treatment

Interviewees had diverse views about what support and treatment they found beneficial illustrating the individuality in appropriate support and treatment:

And [care co-ordinator] has been a great help, you know working through everything . . . and the team [were helpful].

(Subordinate theme ‘receiving help from the mental health services’ was important to some interviewee’s recovery.)

Understanding and control

Understanding and coping with experiences was highlighted by all interviewees as important to their recovery. However, each individual had different approaches and found a range of things helpful:

I would have to think something rational and take control of my own beliefs and it was really empowering.

(This quote reflects the need for subordinate theme ‘having control over experiences’.)

Discussion

This study found four main themes that are important to consider when conceptualising recovery: impacts on mental health, self-change and adaptation, social redefinition and adapting an individual coping style. The study also supported previous research that found recovery is felt to be a process rather than an end point and that recovery in psychosis is multidimensional.

All participants felt the four themes were important to recovery, although there was varied emphasis placed on each theme by each individual. Consistent with previous research, this highlights the complexities of conceptualising recovery and indicates that recovery is not an outcome with clear-cut differences between recovered and not recovered.

Self-change and adaptation was often felt to be central to recovery. Changes to character, personality and identity were noted by all participants and reduced motivation, energy and confidence were often reported. Previous research19 has indicated that rebuilding the self understandably plays a key part in recovery and this study emphasises the importance of consideration of this factor in therapy and research.

Participants did report that symptom alleviation had a major impact of their recovery, highlighting the importance of symptoms as an indicator of outcome. However, participants found that symptoms are important in conjunction with a range of other factors. Indeed, for some service users there may be a continued presence of symptoms but without their negative impacts.

It may be of particular interest that the emotional impacts of having psychosis were also identified. The effects on depression, anxiety, anger and frustration illustrate that emotional change is also important to consider. This could have significant implications for measurement of outcomes that do not typically take factors such as anger and frustration into account.

The social impact of psychosis was also common throughout the themes and is often noted as a key area of recovery. Financial stability, living arrangements and employment status were affected by having experienced psychosis for the majority of participants. Participants discussed a decrease in social activity, feeling alone and isolated and the huge impacts that psychosis had on relationships with loved ones. Services that aim to be recovery orientated should consider the continued need for social relationships and impacts on social behaviour.

An important implication of the findings of this study is the need to understand recovery using a holistic approach, which incorporates personal factors as well as symptoms. Social and personal change and coping styles should be considered alongside symptom alleviation, with equal importance being given to each factor. Assessment tools that take into account the important element of symptom alleviation alongside these broader personal and social themes would be desirable with consideration of the impact that these experiences have on life.

The main strength of this research is that the majority of the interviews were carried out by a service user researcher. As the service user researcher had shared experience with the interviewee, it could be expected that richer and more detailed information may have been elicited. This has been illustrated in other service-user-led studies about recovery19 and impacts of diagnosis. 67

In contrast, one main limitation to the study was also the service user researcher conducting the majority of the interviews. The service user researcher felt that his personal experiences influenced the direction and data extracted by the interview process. The central role of the researcher in interpreting qualitative data is a core feature of IPA. The supervisory process and reflections of the service user researcher in discussion with both colleagues and members of the SURG provided a forum for the researcher to balance their own views with those of others, in relation to both the conduct of interviews and the analysis of the transcripts.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that recovery is a multifaceted process that incorporates symptoms, social factors, personal adaption and development of individualised coping mechanisms. Future research as well as development of services and therapy should consider these four factors with equal weighting of importance to create a more holistic approach to recovery.

Phase 2: exploring service users perceptions of recovery from psychosis – a Q-methodological approach

This research was previously published as, and much of this text has been reproduced with permission from, Wood L, Price JF, Morrison AP, Haddock G. Exploring service users perceptions of recovery from psychosis: a Q-methodological approach. Psychol Psychother 2013;86:245–61,68 John Wiley & Sons. © 2012 The British Psychological Society.

Objectives

This study aimed to explore, using Q-methodology, the factors important to service users in relation to recovery from psychosis.

Method

Development of the Q-sort

Q-methodology is undertaken in a number of steps. 69 First, a database of relevant codes (Q-concourse) is developed. This usually consists of a large database of diverse information from a variety of sources about the topic being examined. The Q-concourse was developed from two main sources: themes identified from the interviews conducted in phase 1 and also from existing literature. This Q-concourse codes are then grouped together to form a final set of descriptive themes. These are then translated into statements cards (this is called the Q-set). An initial set of 132 codes was condensed into 52 clear themes that were representative of the expansive concourse by a multidisciplinary team that included service users. These themes were then categorised by the research team and deemed to broadly cover eight areas of recovery: symptoms, emotional aspects, social functioning, the self, cognitions, services, coping mechanisms and occupational aspects. Participants (known as the P-set) are required to sort these statements in order of importance in relation to one another using a forced normal distribution table.

Participants

Forty participants were identified as being required to take part in the study, which was deemed to be a sufficient number for a study of this design based on previous research. 69,70 The inclusion criteria for the participants in the study were: aged between 18 and 65 years, experienced delusions and/or hallucinations for at least 1 year and in contact with a statutory mental health service in Greater Manchester in the North West of England.

Participants’ self-report demographics are outlined in Table 1. Participants’ diagnoses were self-report, with the majority (40%) reporting a diagnosis of schizophrenia, or experience of psychosis (20%).

| Total sample (N = 40) | Factor 1 (N = 8) | Factor 2 (N = 10) | Factor 3 (N = 9) | Factor 4 (N = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (SD; range) | 36.97 (12.01; 20–65) | 38.63 (13.43; 27–65) | 35.60 (10.81; 25–59) | 32.22 (11.61; 20–58) | 34.25 (14.10; 20–53) |

| Delusions, n (%) | 32 (75) | 6 (75) | 7 (70) | 8 (88.9) | 5 (100) |

| Average duration of delusion (months) (range) | (3–360) | 160 (12–120) | (3–164) | (24–360) | (12–184) |

| Hallucinations, n (%) | 27 (67.5) | 6 (75) | 6 (60) | 4 (44.5) | 5 (100) |

| Average duration of hallucination (months) (range) | (3–360) | 152 (9–120) | (3–240) | (18–360) | (12– 84) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 25 (62.5) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (70) | 8 (88.9) | 3 (60) |

| Female | 15 (37.5) | 7 (87.5) | 3 (30) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (40) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |||||

| White | 35 (87.5) | 8 (100) | 9 (90) | 9 (100) | 4 (80) |

| Black | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||||

| Unemployed | 35 (87.5) | 5 (62.5) | 9 (90) | 8 (88.9) | 5 (100) |

| Student | 2 (5) | 2 (25) | 1 (10) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) |

| Employed | 2 (5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||||

| Primary/secondary | 18 (45) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (40) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (20) |

| Further/higher | 22 (55) | 5 (62.5) | 6 (60) | 4 (44.4) | 4 (80) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||

| Single | 25 (62.5) | 4 (50) | 6 (60) | 7 (77.8) | 3 (60) |

| In a relationship | 10 (2.5) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (30) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (40) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (7.5) | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 2 (5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Procedure

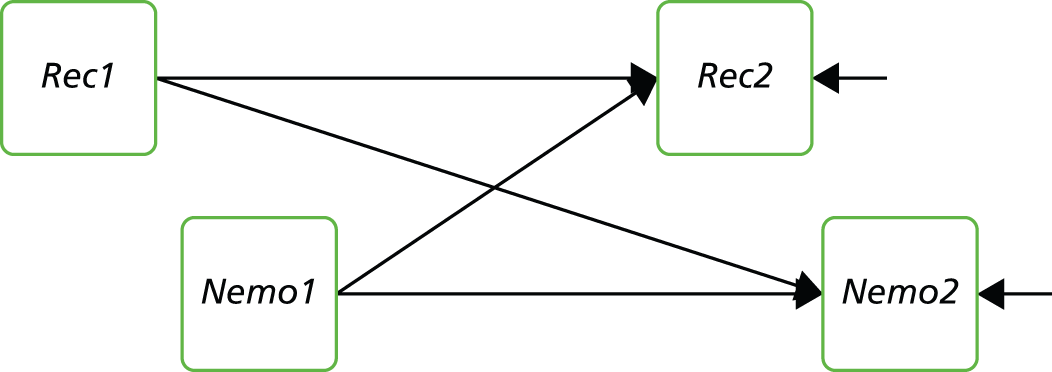

Participants were shown the Q-sort matrix (Figure 1) and given 52 shuffled statement cards (the Q-set). They were asked to read through them thoroughly to ensure they understood them before sorting the cards into three piles, one that represented things that were important to their recovery, one for things that were not important and ones that they were not sure about. They were then asked to consider the ‘most important’ pile and pick the two most important statements and place them on the far right of the grid (column 12), they were then asked to pick the three next most important and place it onto column 11, and so forth until they placed all the most important cards onto the grid. The same procedure was repeated with the least important pile and the not sure pile until the table was full. Participants were given the opportunity to move the statements around until they were happy with their final sort and were asked follow-up questions about the reasoning behind the rating of the two highest and two lowest items, if they thought any recovery items were missing, and for any further comments.

FIGURE 1.

Q-sort response matrix.

Data analysis

A Q-method software package (PQ method version 2.11; Kent State University, Kent, OH; URL: http://schmolck.userweb.mwn.de/qmethod/pqmanual.htm) was used to analyse the data. Principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was implemented to sort factors and to explain the maximum amount of variance. Q-method analysis factors groups of people together as opposed to items in traditional factor analysis.

Results

Q-method analysis resulted in a four-factor solution that 32 out of the 40 participants loaded on. These other eight participants were excluded from the factor arrays and do not contribute to the interpretations detailed below. In the Q-sort people are factor analysed instead of items. Therefore, to explain the most variance we had to lose eight participants from the factor analysis to come up with a factor solution that explained the most variance in recovery views. With this type of analysis, a loss of participant data cannot be avoided. The factor solution explained 36% of the variance and had an Eigenvalue of 2.74. Eight participants loaded onto factor 1 (accounting for 10% of the variance), 10 participants loaded onto factor 2 (10%), nine participants loaded onto factor 3 (9%) and five people loaded onto factor 4 (7%). Factors identified will be referred to as ‘viewpoints’.

Most important viewpoints of recovery

All 52 items were endorsed (placed in columns 9–12) by at least two of all 40 participants (5%). The number of endorsements and percentage of endorsements are shown in Table 2.

| Statement | Numbers endorsing each statement (9, 10, 11, 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| 35. How much support I get from loved ones in helping with my experiences | 26 | 65 |

| 45. How much I have changed as a person/personality since I have had these experiences | 21 | 52.5 |

| 33. How my experiences effect my relationships with friends and loved ones | 18 | 45 |

| 31. How my experiences effect how positive I am for the future | 17 | 42.5 |

| 1. How depressed my experiences make me feel | 16 | 40 |

| 26. How my experiences effect how happy I feel | 14 | 35 |

| 49. How concerned I am of the side effects of taking medication for my experiences | 13 | 32.5 |

| 42. How clearly I can think about my experiences | 13 | 32.5 |

| 40. How much I feel mental health services are helpful with my experiences | 13 | 32.5 |

| 34. How much I understand my experiences | 13 | 32.5 |

| 29. How trusting of others I am as a result of my experiences | 13 | 32.5 |

| 15. How helpful I feel my medication is with my experiences | 13 | 32.5 |

| 39. How bothered I am about the stigma/being judged about my experiences | 12 | 30 |

| 27. How anxious or stressed I am from my experiences | 12 | 30 |

| 25. How well I was able to recognise the early signs of becoming unwell | 12 | 30 |

| 22. How my experiences have effect my memory and concentration | 12 | 30 |

| 17. How convinced I am that my experiences are real | 12 | 30 |

| 41. How my experiences alter my ability to control my own thoughts | 11 | 27.5 |

| 30. How much I socialise as a result of my experiences | 11 | 27.5 |

| 3. How unpleasant my experiences/voices are | 11 | 27.5 |

| 28. How withdrawn I am as a result of my experiences | 11 | 27.5 |

| 2. How much I dwell on my experiences | 11 | 27.5 |

| 19. How my experiences effect the quality/and or amount of sleep I get | 11 | 27.5 |

| 47. My ability to find work as a result of my experiences | 10 | 25 |

| 11. How positive I view my experiences to be | 10 | 25 |

| 51. How motivated I feel about changing my experiences | 9 | 22.5 |

| 43. The amount to which I can cope with my experiences | 9 | 22.5 |

| 37. How ashamed and/or embarrassed I feel about my experiences | 9 | 22.5 |

| 23. How my experiences effect my ability to look after myself | 9 | 22.5 |

| 21. How my experiences effect the amount of anger and frustration I feel | 9 | 22.5 |

| 13. The amount I think about harming myself as a result of my experiences | 9 | 22.5 |

| 5. How much control I have over my experiences | 8 | 20 |

| 48. How financially stable I am as a result of my experiences | 8 | 20 |

| 18. The amount of support I get from other service users | 8 | 20 |

| 16. How helpful I feel psychological therapies are with my experiences | 8 | 20 |

| 46. My living arrangements as a result of my experiences | 7 | 17.5 |

| 20. How my experiences effect my personal freedoms and rights | 7 | 17.5 |

| 12. How much religion/spirituality was involved with my experiences | 7 | 17.5 |

| 9. How loud my voices are | 6 | 15 |

| 50. How vulnerable I feel as a result of my experiences | 6 | 15 |

| 44. In alcohol and drug use that worsens my experiences | 6 | 15 |

| 4. How pleasant my experiences/voices are | 6 | 15 |

| 10. My belief that my experiences come from my own mind | 6 | 15 |

| 7. How much time in my life they take up | 5 | 12.5 |

| 52. How concerned I am that my experiences will happen again | 5 | 12.5 |

| 38. How my experiences effect the amount of emotion I feel | 5 | 12.5 |

| 32. How enjoyable I find hobbies/activities as a result of my experiences | 5 | 12.5 |

| 8. Amount to which my voices are inside my head compared to outside my head | 4 | 10 |

| 6. How often my experiences happen | 4 | 10 |

| 14.How my experience effect how energetic I feel | 3 | 7.5 |

| 36. How empowered I feel over my experiences | 2 | 5 |

| 24. How active I was in seeking help with my experiences | 2 | 5 |

Interpretation of viewpoints

The Q-sort resulted in four viewpoints: collaborative support and understanding, emotional change though social and medical support, regaining functional and occupational goals, and self-focused recovery. The correlations between the factor scores indicated no overlap between factors.

Tables for each factor array, indicating where all statements were ranked for all four viewports are provided in Table 3.

| Viewpoint 1 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –6 | –5 | –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9. How loud my voices are | 8. Amount to which my voices are inside my head compared to outside | 3. How unpleasant my experiences/voices are | 4. How pleasant my experiences/voices are | 1. How depressed my experiences make me feel | 14. How my experiences effect how energetic I feel | 12. How much religion/spirituality there was involved with my experiences | 10. My belief that my experiences come from my own mind | 30. How much I socialise as a result of my experiences | 15. How helpful I feel my medication is with my experiences | 5. How much control I have over my experiences | 16. How helpful I feel psychological therapies are with my experiences | 31. How my experiences effect how positive I am for the future |

| 44. In alcohol and drug use that worsens my experiences | 13. The amount I think about harming myself as a result of my experiences | 7. How much time in my life they take up | 37. How ashamed or embarrassed I feel about my experiences | 2. How much I dwell on my experiences | 22. How my experiences effect my memory and concentration | 33. How my experiences effect my relationships with friends/loved ones | 24. How active I was seeking help with my experiences | 19. How my experiences effect the quality/and or amount of sleep | 17. How convinced I am that my experiences are real | 11. How positive I view my experiences | 34. How much I understand my experiences | 40. How much I feel mental health services are helpful with my experiences |

| 6. How often my experiences happen | 21. How my experiences effect the amount of anger/frustration I experience | 45. How much I have changed as a person/personality since I have had my experiences | 27. How anxious or stress I am from my experiences | 28. How withdrawn I am as a result of my experiences | 38. How my experiences effect the amount of emotion I feel | 29. How trusting of others I am as a result of my experiences | 20. How my experiences effect my personal freedoms and rights | 43. The amount to which I can cope with my experiences | 18. The amount of support I get from other service users | 35. How much support I get from loved ones in helping with my experiences | ||

| 46. My living arrangements as a result of my experiences | 47. My ability to find work as a result of my experiences | 42. How clearly I can think about my experiences | 50. How vulnerable I feel as a result of my experiences | 39. How bothered I am about the stigma/being judged about my experiences | 32. How enjoyable I find hobbies/activities as a result of my experiences | 23. How my experiences effect my ability to look after myself | 51. How motivated I feel about changing my experiences | 25. How well I was able to recognise the early signs of becoming unwell | ||||

| 49. How concerned I am of that side effects of taking medication | 52. How concerned I am that my experiences will happen again | 41. How my experiences alter my ability to control my own thoughts | 36. How empowered I feel over my experiences | 26. How my experiences effect how happy I feel | ||||||||

| 48. How financially stable I am as a result of my experiences | ||||||||||||

| Viewpoint 2 | ||||||||||||

| –6 | –5 | –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 12. How much religion/spirituality there was involved with my experiences | 16. How helpful I feel psychological therapies are with my experiences | 8. Amount to which my voices are inside my head compared to outside | 4. How pleasant my experiences/voices are | 18. The amount of support I get from other service users | 5. How much control I have over my experiences | 7. How much time in my life they take up | 13. The amount I think about harming myself as a result of my experiences | 2. How much I dwell on my experiences | 3. How unpleasant my experiences/voices are | 27. How anxious or stress I am from my experiences | 1. How depressed my experiences make me feel | 26. How my experiences effect how happy I feel |

| 44. In alcohol and drug use that worsens my experiences | 24. How active I was seeking help with my experiences | 9. How loud my voices are | 34. How much I understand my experiences | 30. How much I socialise as a result of my experiences | 14. How my experiences effect how energetic I feel | 23. How my experiences effect my ability to look after myself | 21. How my experiences effect the amount of anger/frustration I experience | 6. How often my experiences happen | 33. How my experiences effect my relationships with friends/loved ones | 29. How trusting of others I am as a result of my experiences | 15. How helpful I feel my medication is with my experiences | 35. How much support I get from loved ones in helping with my experiences |

| 46. My living arrangements as a result of my experiences | 10. My belief that my experiences come from my own mind | 47. My ability to find work as a result of my experiences | 32. How enjoyable I find hobbies/activities as a result of my experiences | 17. How convinced I am that my experiences are real | 25. How well I was able to recognise the early signs of becoming unwell | 38. How my experiences effect the amount of emotion I feel | 22. How my experiences effect my memory and concentration | 41. How my experiences alter my ability to control my own thoughts | 31. How my experiences effect how positive I am for the future | 45. How much I have changed as a person/personality since I have had my experiences | ||

| 11. How positive I view my experiences | 48. How financially stable I am as a result of my experiences | 36. How empowered I feel over my experiences | 19. How my experiences effect the quality/and or amount of sleep | 37. How ashamed or embarrassed I feel about my experiences | 43. The amount to which I can cope with my experiences | 28. How withdrawn I am as a result of my experiences | 50. How vulnerable I feel as a result of my experiences | 40. How much I feel mental health services are helpful with my experiences | ||||

| 42. How clearly I can think about my experiences | 20. How my experiences effect my personal freedoms and rights | 39. How bothered I am about the stigma/being judged about my experiences | 51. How motivated I feel about changing my experiences | 49. How concerned I am of that side effects of taking medication | ||||||||

| 52. How concerned I am that my experiences will happen again | ||||||||||||

| Viewpoint 3 | ||||||||||||

| –6 | –5 | –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8. Amount to which my voices are inside my head compared to outside | 28. How withdrawn I am as a result of my experiences | 17. How convinced I am that my experiences are real | 11. How positive I view my experiences | 12. How much religion/spirituality there was involved with my experiences | 21. How my experiences effect the amount of anger/frustration I feel | 7. How much time in my life they take up | 13. The amount I think about harming myself as a result of my experiences | 22. How my experiences effect my memory and concentration | 29. How trusting of others I am as a result of my experiences | 15. How helpful I feel my medication is with my experiences | 35. How much support I get from loved ones in helping with my experiences | 19. How my experiences effect the quality/and or amount of sleep |

| 9. How loud my voices are | 3. How unpleasant my experiences/voices are | 4. How pleasant my experiences/voices are | 18. The amount of support I get from other service users | 16. How helpful I feel psychological therapies are with my experiences | 31. How my experiences effect how positive I am for the future | 9. How loud my voices are | 24. How active I was seeking help with my experiences | 27. How anxious or stress I am from my experiences | 44. In alcohol and drug use that worsens my experiences | 23. How my experiences effect my ability to look after myself | 33. How my experiences effect my relationships with friends/loved ones | 47. My ability to find work as a result of my experiences |

| 36. How empowered I feel over my experiences | 6. How often my experiences happen | 26. How my experiences effect how happy I feel | 20. How my experiences effect my personal freedoms and rights | 34. How much I understand my experiences | 14. How my experiences effect how energetic I feel | 1. How depressed my experiences make me feel | 2. How much I dwell on my experiences | 45. How much I have changed as a person/personality since I have had my experiences | 30. How much I socialise as a result of my experiences | 46. My living arrangements as a result of my experiences | ||

| 38. How my experiences effect the amount of emotion I feel | 41. How my experiences alter my ability to control my own thoughts | 25. How well I was able to recognise the early signs of becoming unwell | 42. How clearly I can think about my experiences | 32. How enjoyable I find hobbies/activities as a result of my experiences | 43. The amount to which I can cope with my experiences | 39. How bothered I am about the stigma/being judged about my experiences | 50. How vulnerable I feel as a result of my experiences | 37. How ashamed or embarrassed I feel about my experiences | ||||

| 5. How much control I have over my experiences | 52. How concerned I am that my experiences will happen again | 40. How much I feel mental health services are helpful with my experiences | 48. How financially stable I am as a result of my experiences | 49. How concerned I am of that side effects of taking medication | ||||||||

| 51. How motivated I feel about changing my experiences | ||||||||||||

| Viewpoint 4 | ||||||||||||

| –6 | –5 | –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9. How loud my voices are | 3. How unpleasant my experiences/voices are | 6. How often my experiences happen | 50. How vulnerable I feel as a result of my experiences | 51. How motivated I feel about changing my experiences | 5. How much control I have over my experiences | 49. How concerned I am of that side effects of taking medication | 45. How much I have changed as a person/personality since I have had my experiences | 52. How concerned I am that my experiences will happen again | 7. How much time in my life they take up | 46. My living arrangements as a result of my experiences | 11. How positive I view my experiences | 20. How my experiences effect my personal freedoms and rights |

| 19. How my experiences effect the quality/and or amount of sleep | 13. The amount I think about harming myself as a result of my experiences | 27. How anxious or stress I am from my experiences | 47. My ability to find work as a result of my experiences | 24. How active I was seeking help with my experiences | 15. How helpful I feel my medication is with my experiences | 17. How convinced I am that my experiences are real | 4. How pleasant my experiences/voices are | 48. How financially stable I am as a result of my experiences | 14. How my experiences effect how energetic I feel | 2. How much I dwell on my experiences | 12. How much religion/spirituality there was involved with my experiences | 28. How withdrawn I am as a result of my experiences |

| 21. How my experiences effect the amount of anger/frustration I feel | 8. Amount to which my voices are inside my head compared to outside | 16. How helpful I feel psychological therapies are with my experiences | 33. How my experiences effect my relationships with friends/loved ones | 18. The amount of support I get from other service users | 23. How my experiences effect my ability to look after myself | 30. How much I socialise as a result of my experiences | 1. How depressed my experiences make me feel | 39. How bothered I am about the stigma/being judged about my experiences | 26. How my experiences effect how happy I feel | 22. How my experiences effect my memory and concentration | ||

| 10. My belief that my experiences come from my own mind | 35. How much support I get from loved ones in helping with my experiences | 40. How much I feel mental health services are helpful with my experiences | 32. How enjoyable I find hobbies/activities as a result of my experiences | 25. How well I was able to recognise the early signs of becoming unwell | 42. How clearly I can think about my experiences | 31. How my experiences effect how positive I am for the future | 38. How my experiences effect the amount of emotion I feel | 34. How much I understand my experiences | ||||

| 43. The amount to which I can cope with my experiences | 37. How ashamed or embarrassed I feel about my experiences | 29. How trusting of others I am as a result of my experiences | 44. In alcohol and drug use that worsens my experiences | 41. How my experiences alter my ability to control my own thoughts | ||||||||

| 36. How empowered I feel over my experiences | ||||||||||||

Viewpoint 1: collaborative support and understanding

This viewpoint (n = 8) consisted of people who felt that positive and collaborative engagement with others and services was key to their recovery. This group of people was positively motivated to overcome their experiences and willingly accepted help from others to achieve this. This group did not focus on the negative aspects of having a mental health problem. Aspects such as ‘the amount of alcohol and drug use that worsens my experiences’ (−6), ‘the amount I think about harming myself as a result of my experiences’ (−5) and similar aspects were not considered important.

Viewpoint 2: emotional change through social and medical support

This viewpoint (n = 10) consisted of people who considered emotional stability through support and treatment as a key factor to the recovery process. The affective impacts of having psychosis were prioritised whereas the symptoms of psychosis were not considered as important. This group do not find the psychiatric characteristics of symptoms or occupational aspects of any importance.

Viewpoint 3: regaining functional and occupational goals

This viewpoint (n = 9) consisted of people who considered functional and occupational goals as key to their recovery. It was important to this group of people to regain life functioning and aspects that hindered this process were considered important to change in their recovery. This group did not find the internal cognitive aspects important.

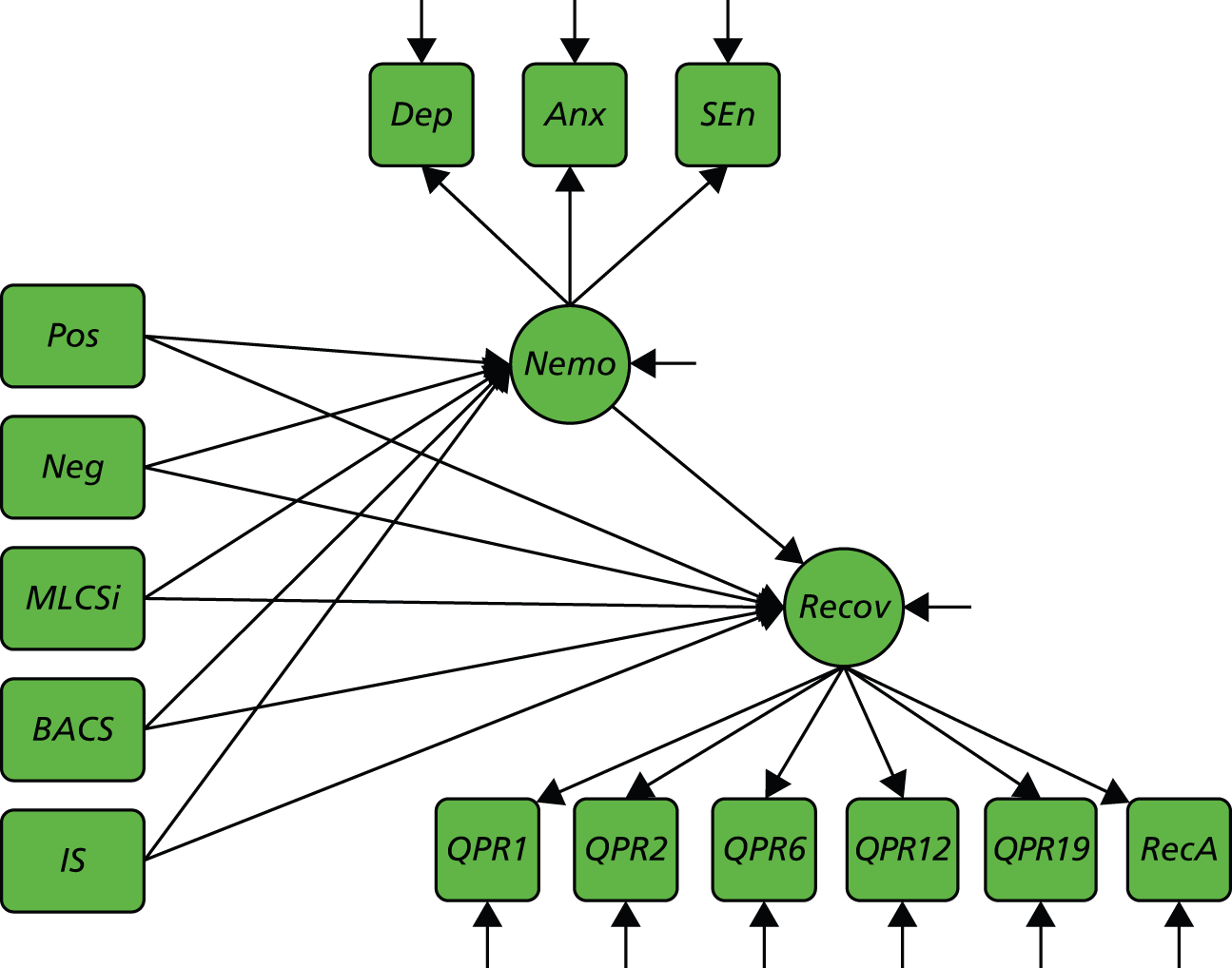

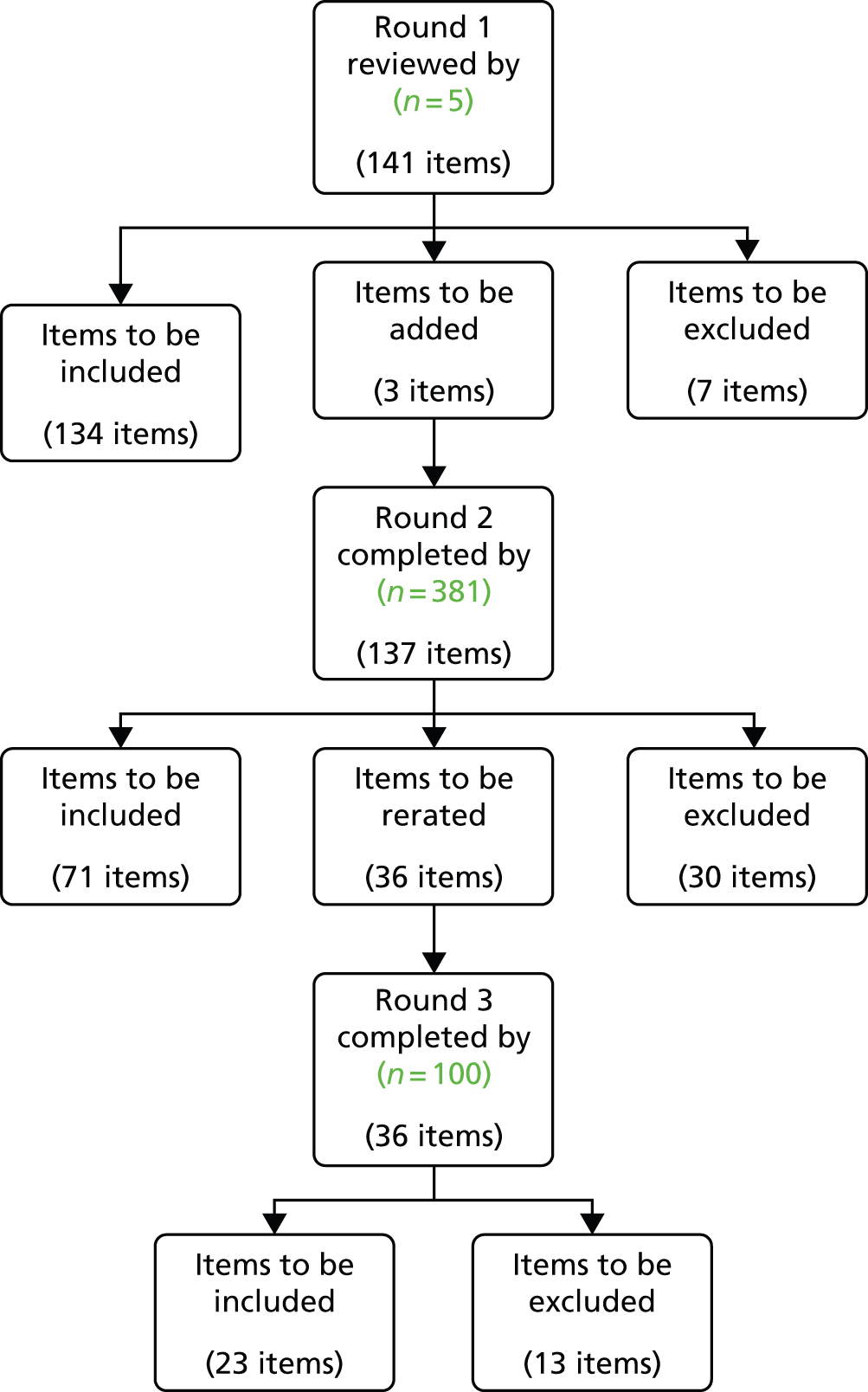

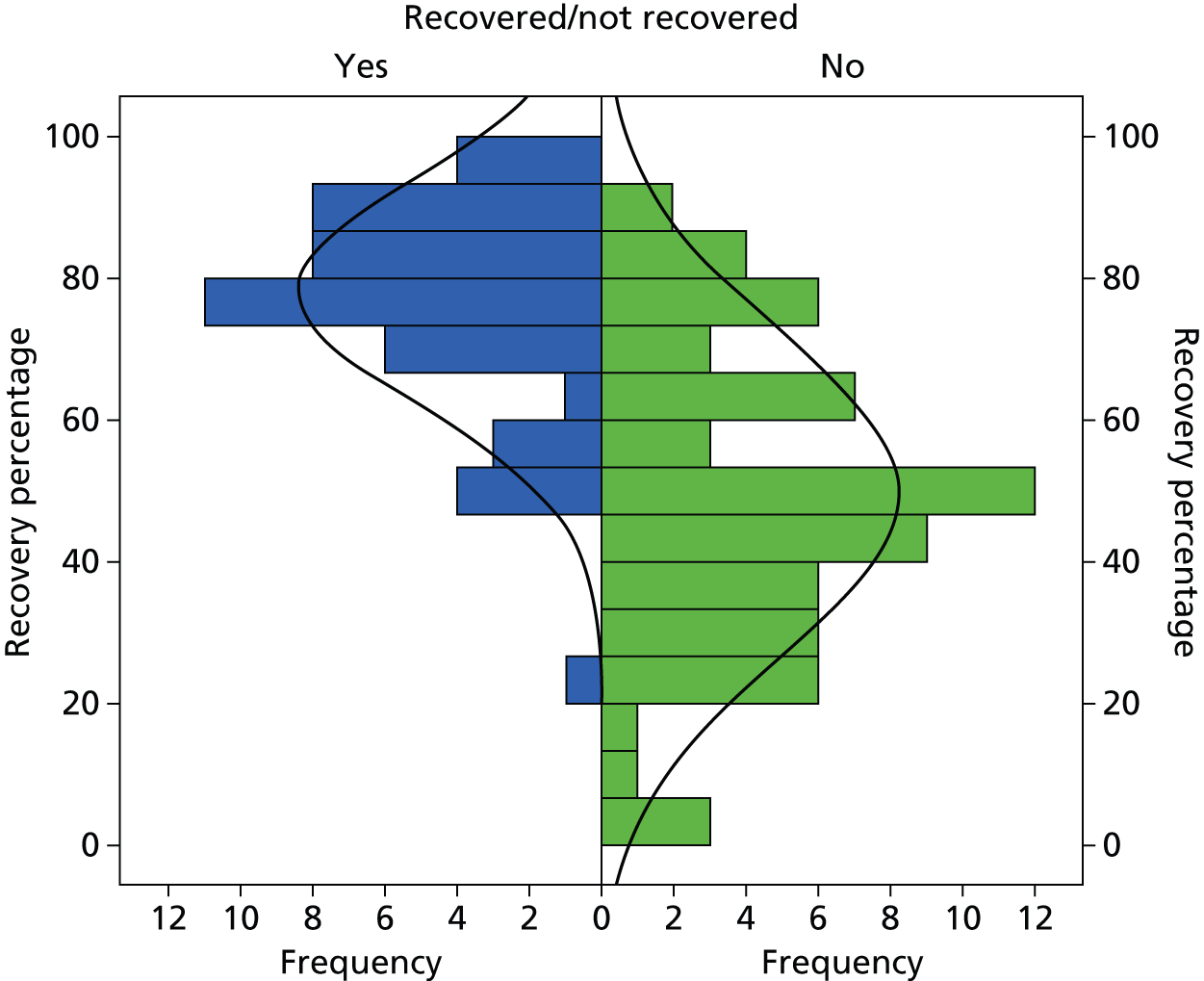

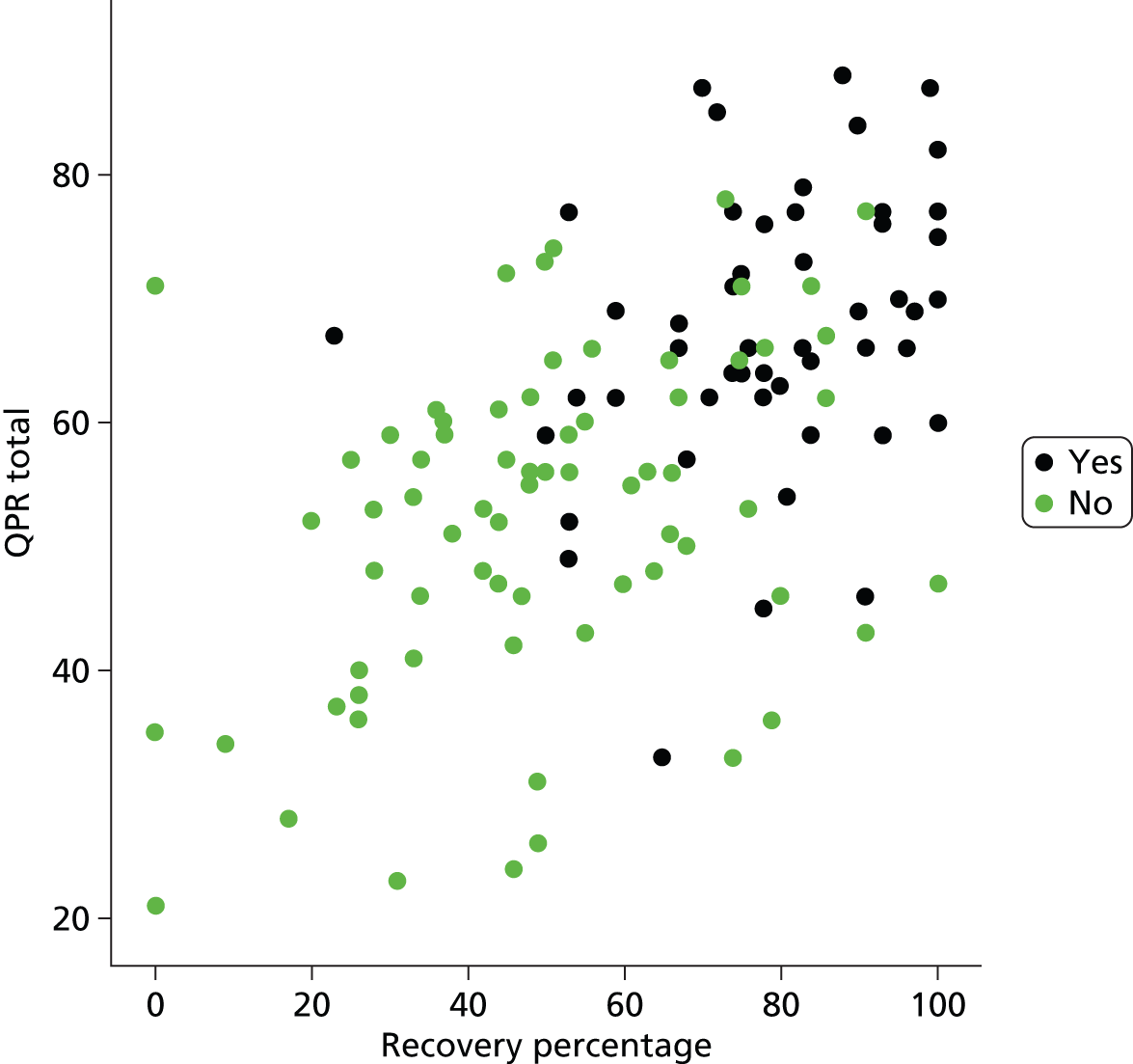

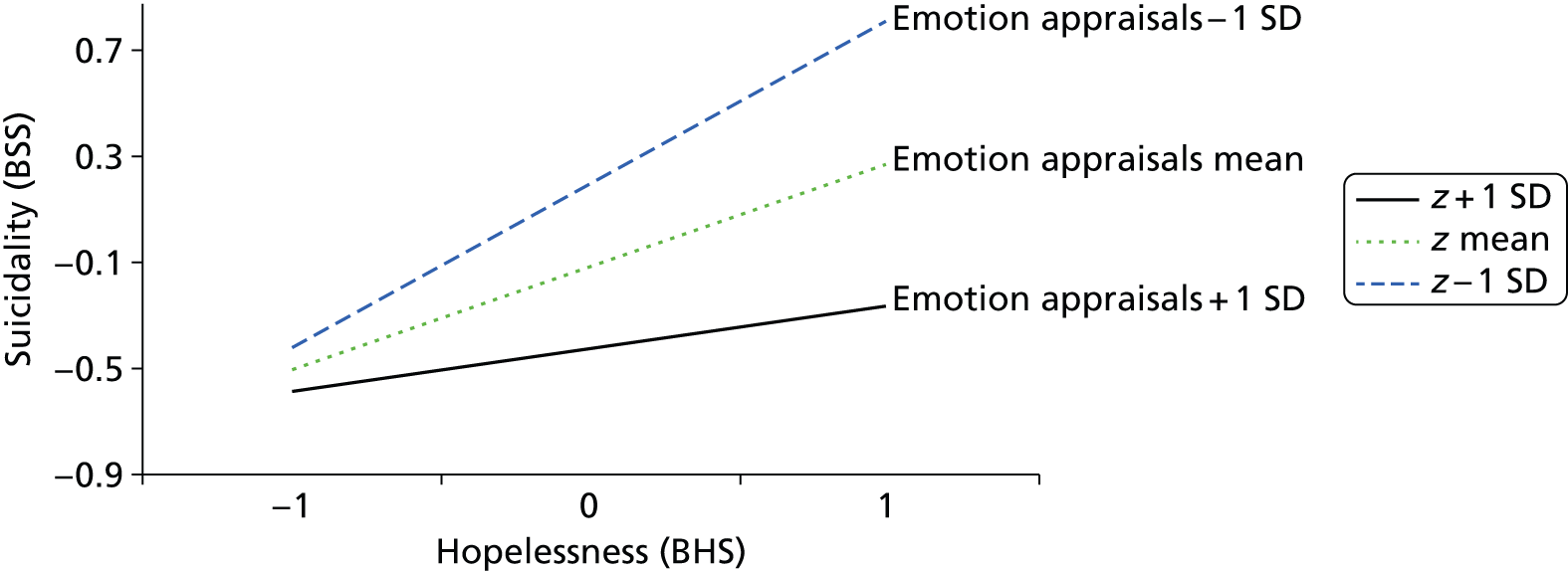

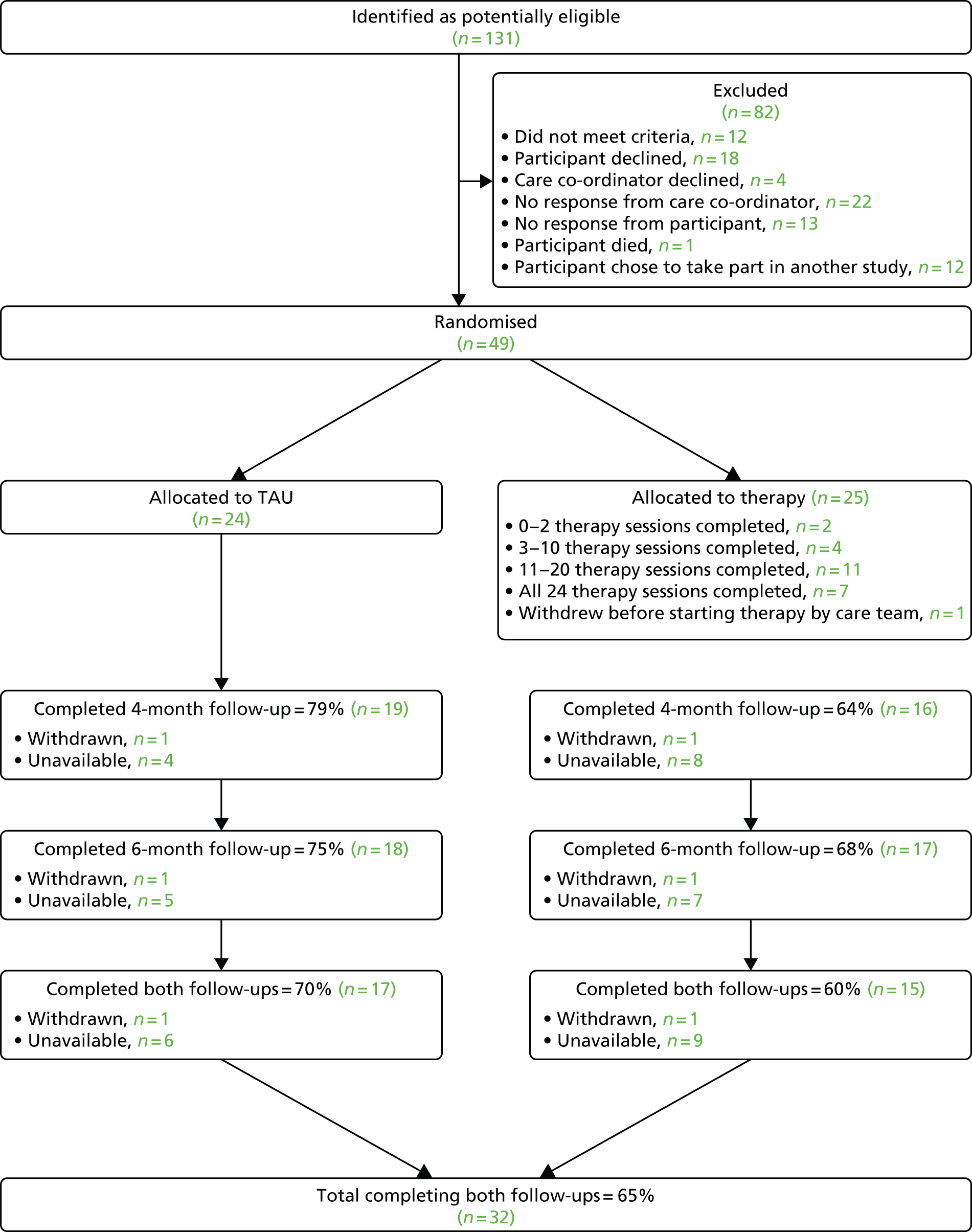

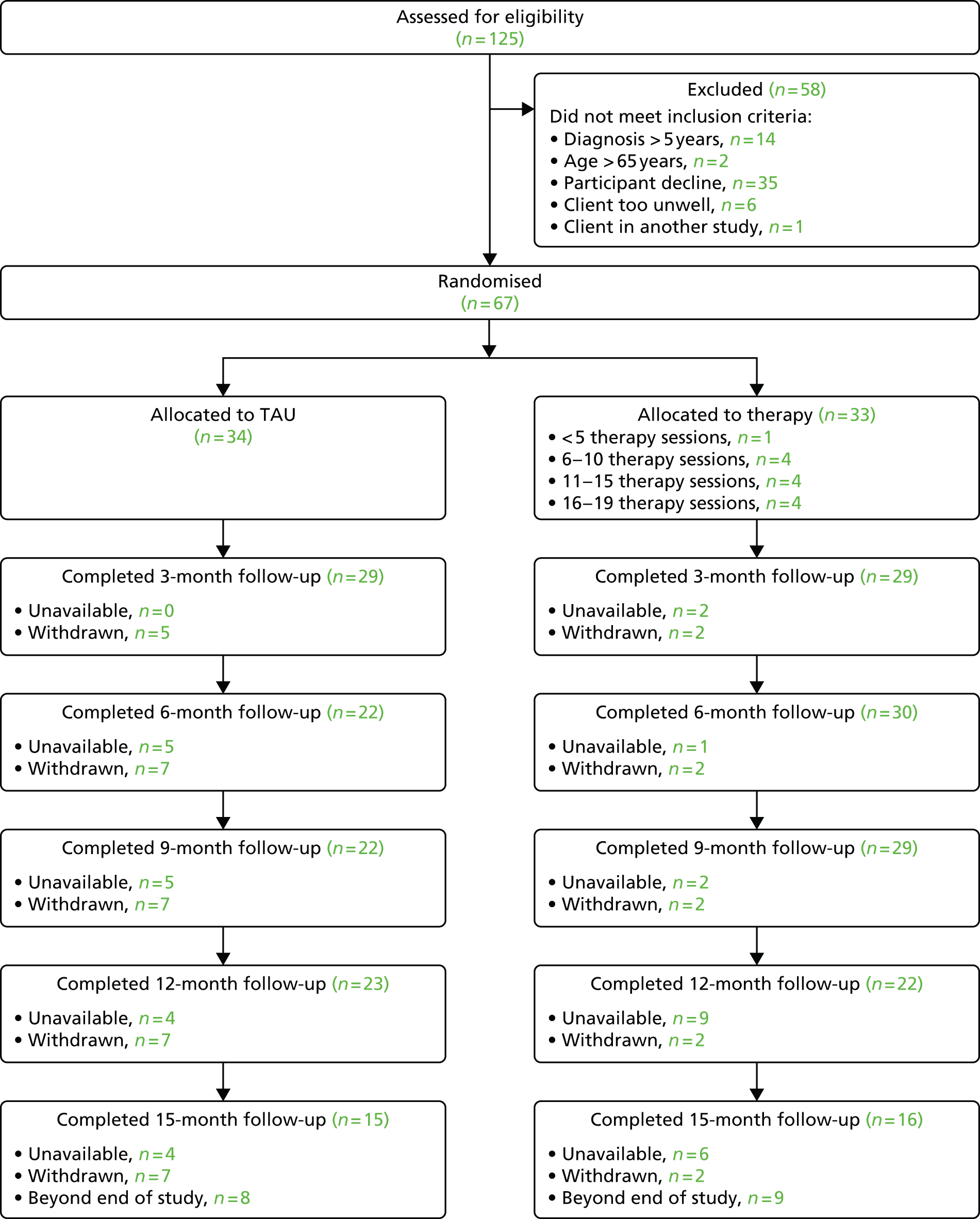

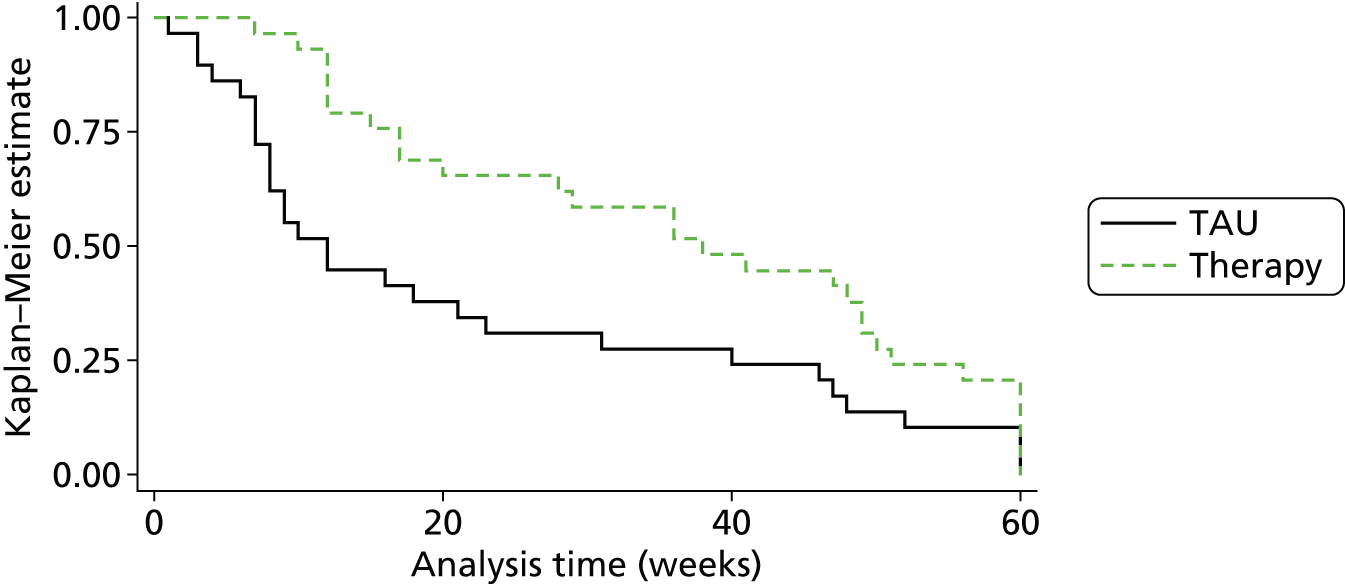

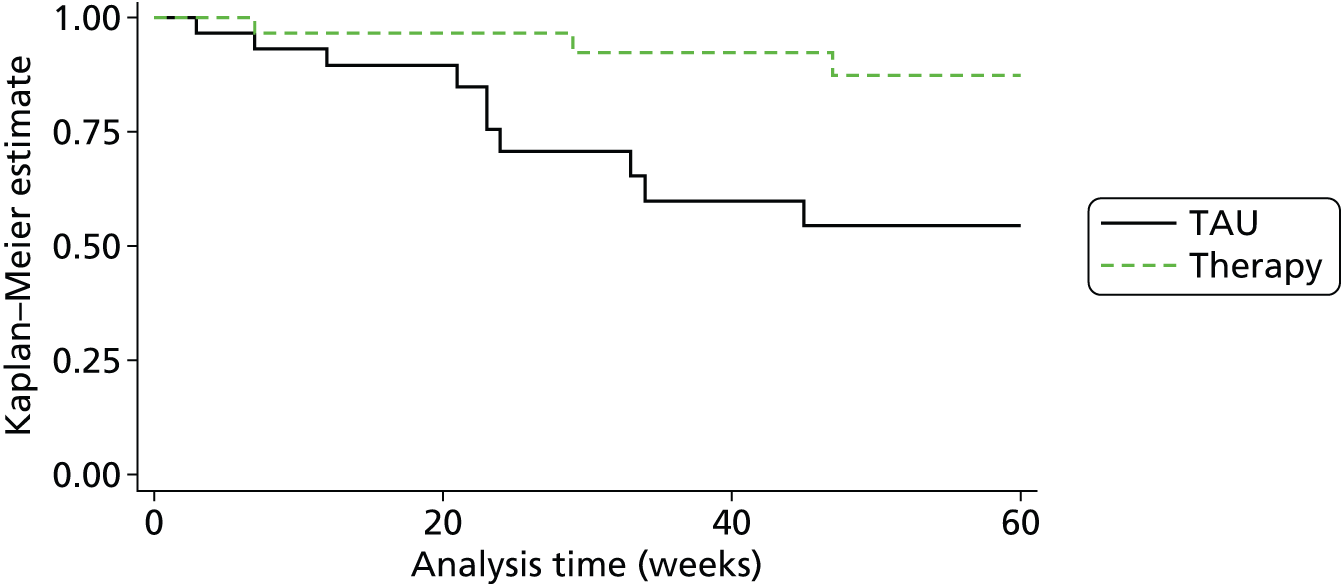

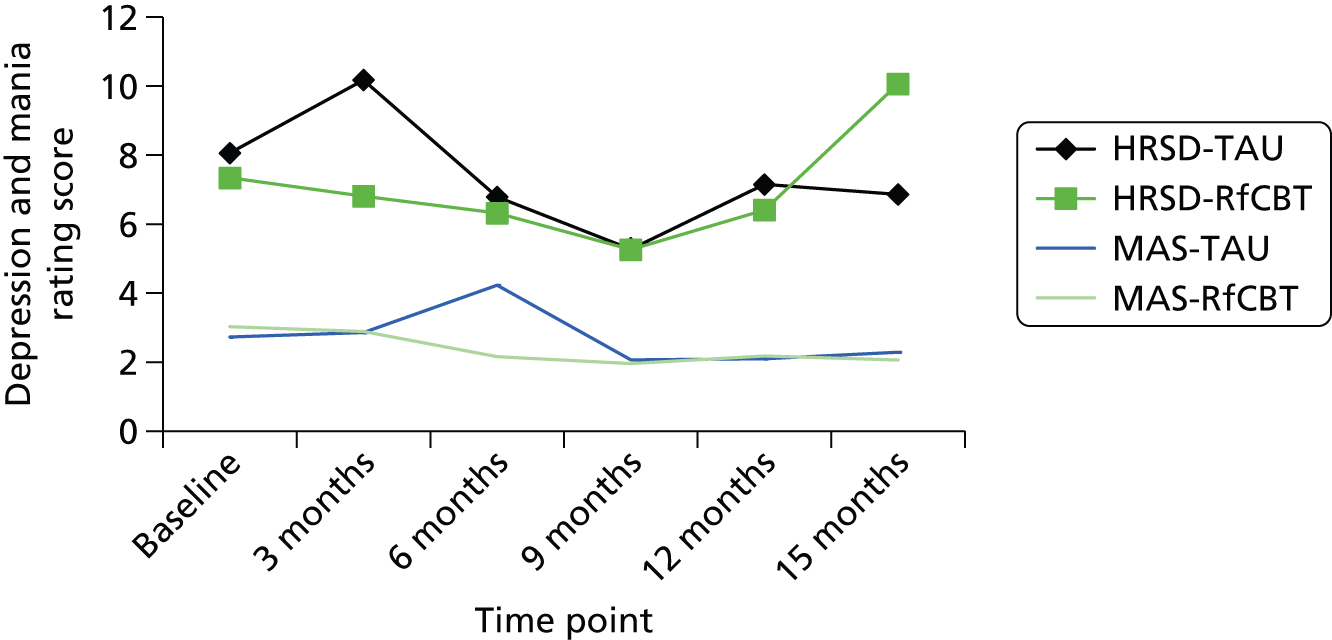

Viewpoint 4: self-focused recovery