Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10044. The contractual start date was in July 2008. The final report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Pinki Sahota reports a Learning Curve Grant 2011 from Danone Baby Nutrition for infant dietary analysis. Helen Ball reports consultancy work to develop and test a safe infant sleep tool for NHS Lancashire and Blackpool, consultancy work to advise on bedside sleeping promotional materials for Kindred Agency (for NCT Bednest) and a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) for the Infant Sleep Information Source website.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Description of ethnic classification

Born in Bradford is a multiethnic cohort consisting of families from around the world. However, the main ethnic groups are of South Asian origin (Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indian) and white British origin. The large majority of the South Asian-origin families are of Pakistani origin. Much research into South Asian health and well-being combines what are often very heterogeneous ethnic groups. A strength of Born in Bradford is the homogeneity of the largest ethnic group of Pakistani origin. Methodologically and statistically, the focus of much of the work in the programme has been on Pakistani and white British comparisons. For completeness some of the analyses include a third category of ‘other’ ethnicities, which includes non-Pakistani and non-white British children. When we refer to the terms ‘South Asian’ and ‘Pakistani’ we are referring to families of South Asian or Pakistani origin who have been born either in the UK or in South Asia or Pakistan.

SYNOPSIS

Childhood obesity is a major global public health threat. 1,2 Although overweight and obesity prevalence in some groups of children may be flattening or decreasing,3–5 overall prevalence remains high, particularly in children from minority ethnic groups. 6,7 Evidence from the UK and the USA shows that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in preschool children is > 33%. 8–10 Obesity acquired in childhood has been shown to persist into adulthood with over half of obese children growing up to be obese adults. 11 It is estimated that the direct cost of obesity to the NHS will be £2B by 2030 if the current trends continue. 12 The 2007 Foresight report13 estimated that the direct and indirect costs of child and adult obesity would rise to £27B by 2015.

Childhood obesity has a major impact on health and well-being in childhood and through to adult life. 14–17 Obese children experience poor health-related quality of life and low self-esteem18 and, although the contribution of obesity towards the risk of negative health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes is complex, evidence suggests a consistent positive association. 19,20

Children of South Asian origin are at particular risk of overweight and obesity, demonstrating greater central adiposity and insulin resistance than their European-origin counterparts for a given body mass index (BMI). 21–24 Evidence suggests that this fat–thin insulin-resistant phenotype is present at birth and that pregnancy is an important window of opportunity for obesity prevention. 25,26 The adoption of Western urban lifestyles that result from migration to the UK has the potential to increase the risk of rapid postnatal growth and obesity contributing to the higher risks of diabetes and CVD.

There is emerging evidence that early life environments are important in the aetiology of obesity. 27 Maternal gestational weight gain and gestational glucose metabolism, together with greater birthweight and rapid postnatal growth, are all associated with later obesity, although it is unclear if this is driven by causal mechanisms. 28–32 Infant weight gain is consistently associated with subsequent risk of childhood and adult obesity and this risk is particularly high for infants with very rapid weight gain [> 1.33 standard deviation score (SDS) or two centile band crossings]. 33 However, it is the social, behavioural and environmental influences on childhood obesity that offer most potential for modification of factors influencing obesity. 34–38 A recent review of systematic reviews of early determinants of obesity identified the following factors associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity: maternal smoking, short sleep duration, < 30 minutes of daily physical activity, consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks, screen viewing and parental feeding practices. 39 Importantly, however, the evidence of causality is not clear. 40 Thus, although reinforcement of positive health interventions such as breastfeeding should be encouraged, there is still much to learn regarding the impact it has on childhood obesity.

Interventions to prevent obesity

Despite the public health threat of obesity there is a notable gap in the research evidence on effective interventions to prevent and treat obesity, particularly in early childhood and in South Asian populations. 41

Systematic review evidence42–49 has found that efforts to prevent obesity have shown disappointing results, which may be for the following reasons:

-

intervention schemes not guided by a robust evidence-based development process and not rooted in behaviour change theory

-

intervention strategies not tailored to the most important and modifiable behaviours

-

inadequate strategies to change family, environmental and extrinsic factors in combination with health education strategies aimed at personal behaviours

-

lack of careful pre-testing and formative evaluation procedures before larger-scale implementation

-

lack of involvement of stakeholders in intervention development, resulting in reduced engagement.

One explanation for the disappointing results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in terms of reducing obesity in schoolchildren is that they begin too late. Body composition and feeding patterns may become established in infancy, providing a potentially critical period for intervention. 50 Systematic reviews of obesity prevention in early childhood provide support for targeting interventions in early childhood but highlight the limited quantity and quality of the mostly US research. 45,46 Specific gaps in the evidence include the lack of family studies and studies that attempt to improve professional–family interaction, the dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions in ethnic groups and the absence of economic evaluations.

There is a good theoretical51 and empirical33,36,52–56 basis for developing obesity prevention interventions in early childhood as unfavourable health behaviours are established in early childhood and are good predictors of subsequent behaviours. It is likely, therefore, that early childhood provides a unique and circumscribed opportunity to promote health and prevent obesity. However, there is a paucity of evidence about safe and effective interventions in preschool children. 57 A systematic review of studies to prevent obesity in children aged 0–5 years found that interventions varied widely although most were multifaceted in their approach. 58 These interventions have been found to be feasible and acceptable and there was evidence to suggest that behaviours that contribute to obesity can be positively impacted in this age group, particularly with the involvement of parents and the targeting of skills and competencies rather than just knowledge. A systematic review of qualitative studies on behaviours related to childhood obesity found that many parents felt that strategies to promote healthy weight should start in early life and also identified the importance of targeting the wider family rather than the parents alone. 59 Studies have also suggested that an intervention delivered within a parenting programme that focuses on parenting skills and style will have an enduring impact on the development of children’s healthy eating and activity patterns. 60,61

Born in Bradford

This programme harnessed the research potential of the new Born in Bradford (BiB) study, a longitudinal multiethnic birth cohort study aiming to examine the impact of environmental, psychological and genetic factors on maternal and child health and well-being. 62 Bradford is a city in the north of England with high levels of socioeconomic deprivation and ethnic diversity. Approximately half of the births in the city are to mothers of South Asian origin. Women were recruited to the BiB study while waiting for their glucose tolerance test, a routine procedure offered to all pregnant women registered at the Bradford Royal Infirmary at 26–28 weeks’ gestation. For those consenting, a baseline questionnaire was completed during an interview with a study administrator.

The baseline questionnaire for the mothers was transliterated into Urdu and Mirpuri using a standardised process so that words and phrases corresponded to the original English version. As Mirpuri does not have a written form, trained bilingual interviewers administered the transliterated questionnaires to Mirpuri speakers.

The full BiB study recruited 12,453 women during 13,776 pregnancies between 2007 and 2010 and the cohort is broadly characteristic of the city’s maternal population. Ethical approval for the BiB1000 data collection was granted by the Bradford Research Ethics Committee (reference number 07/H1302/112).

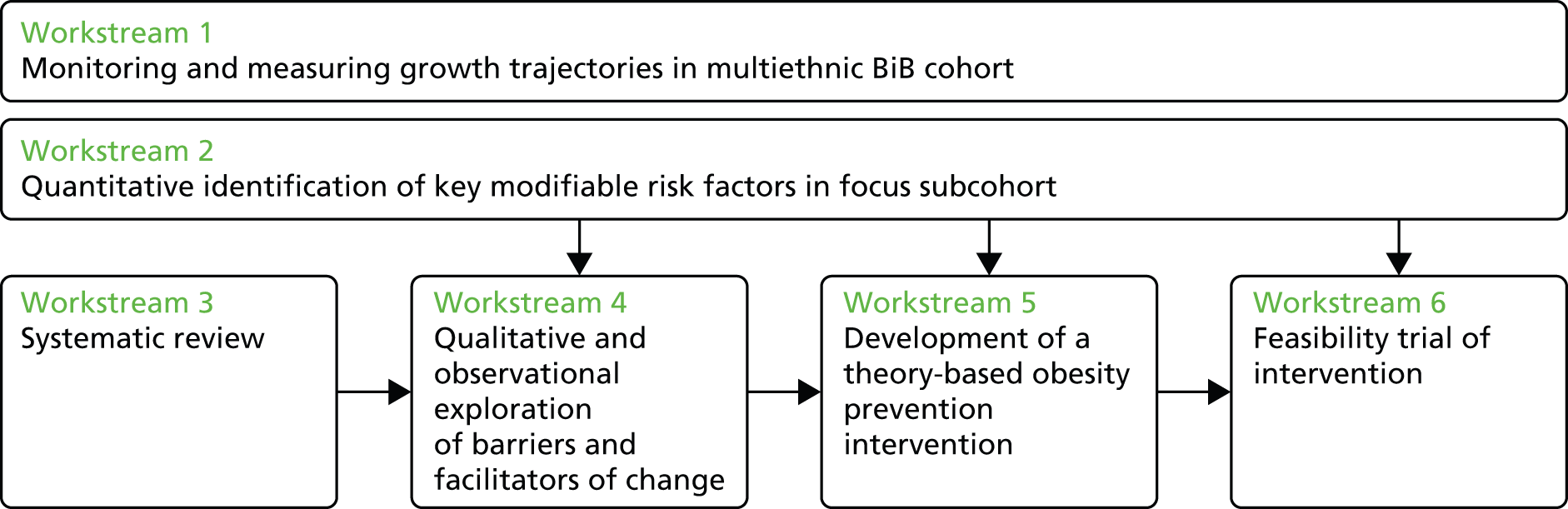

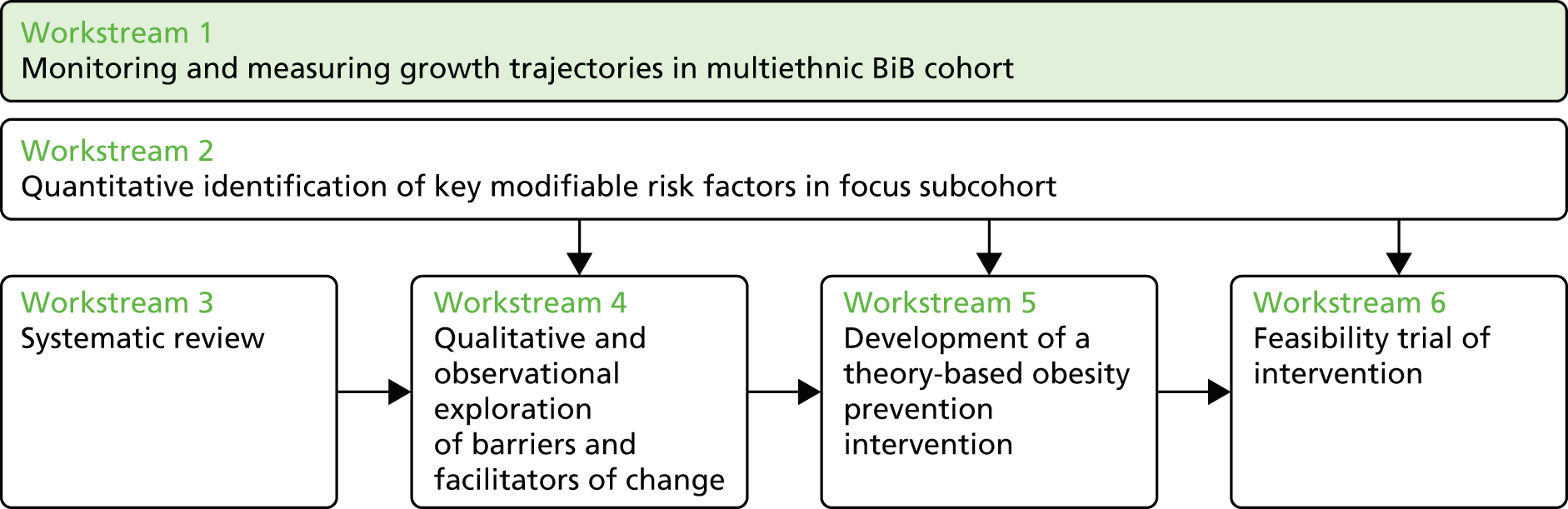

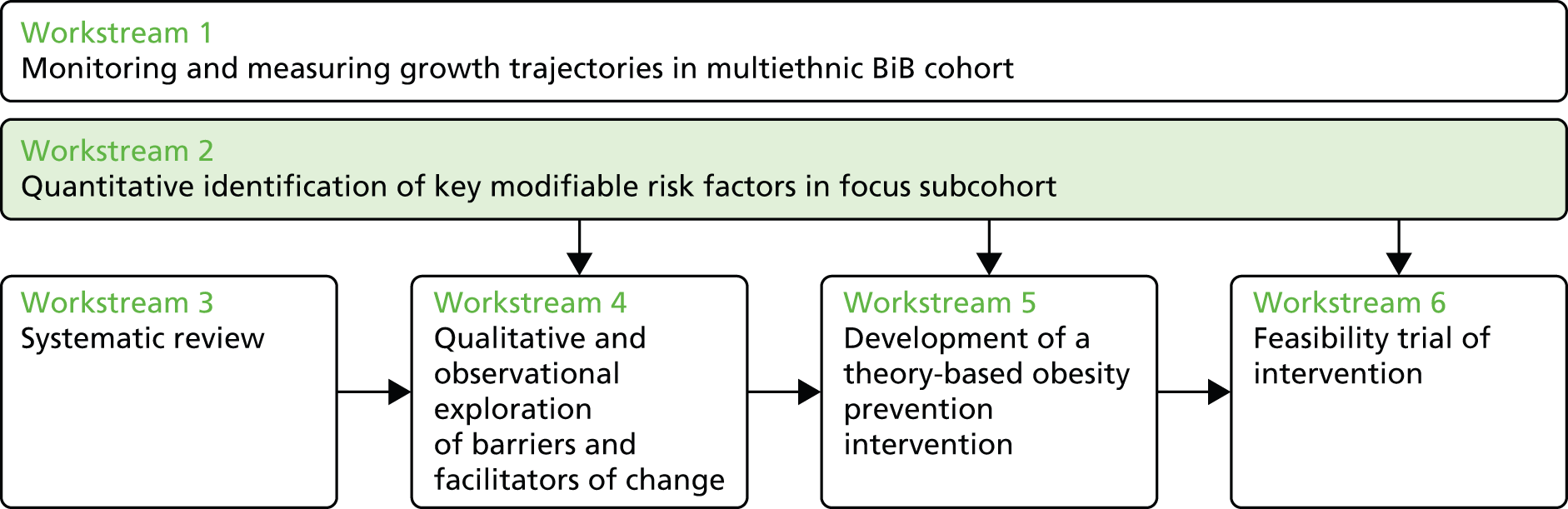

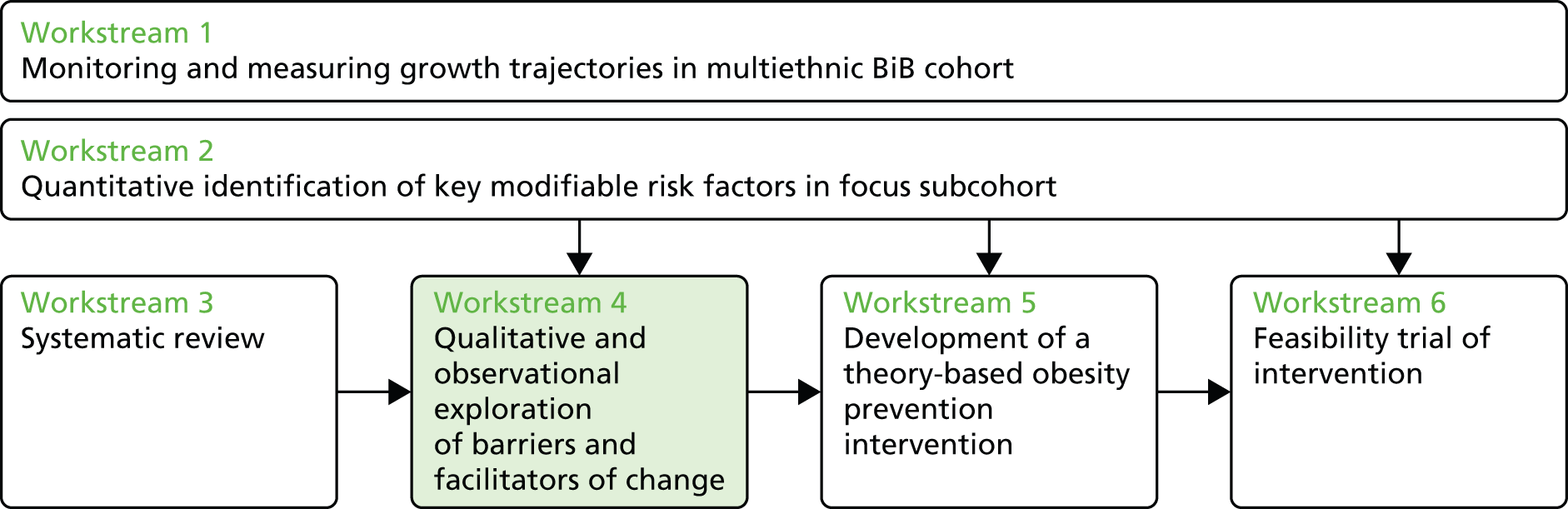

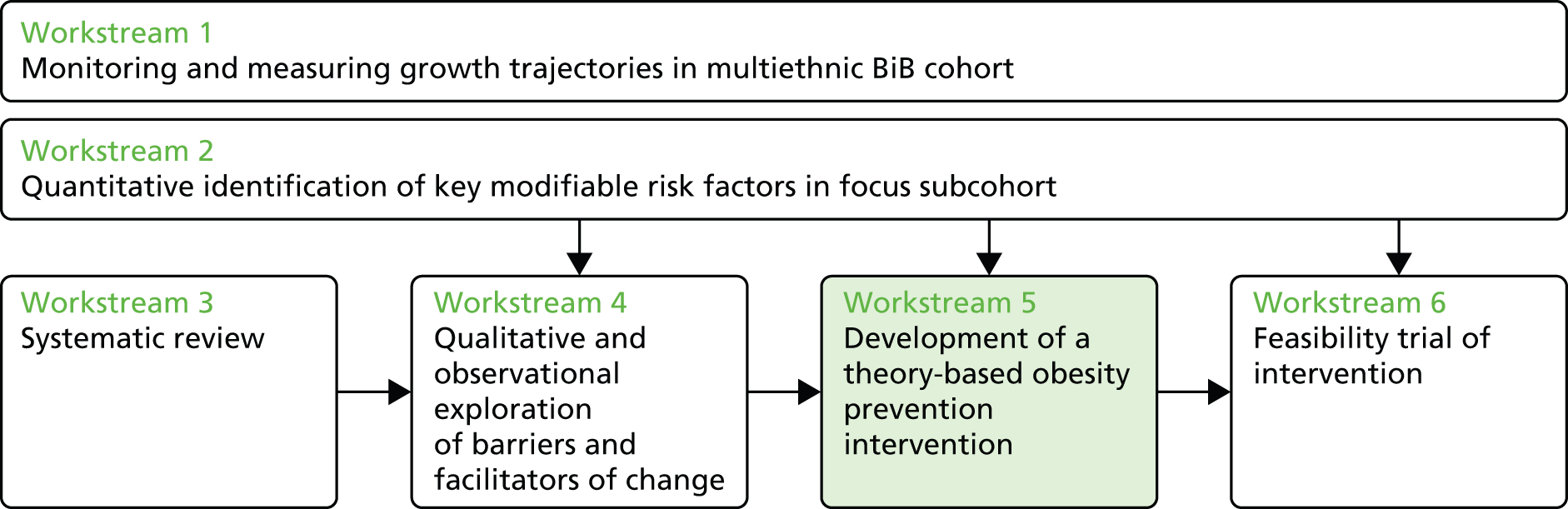

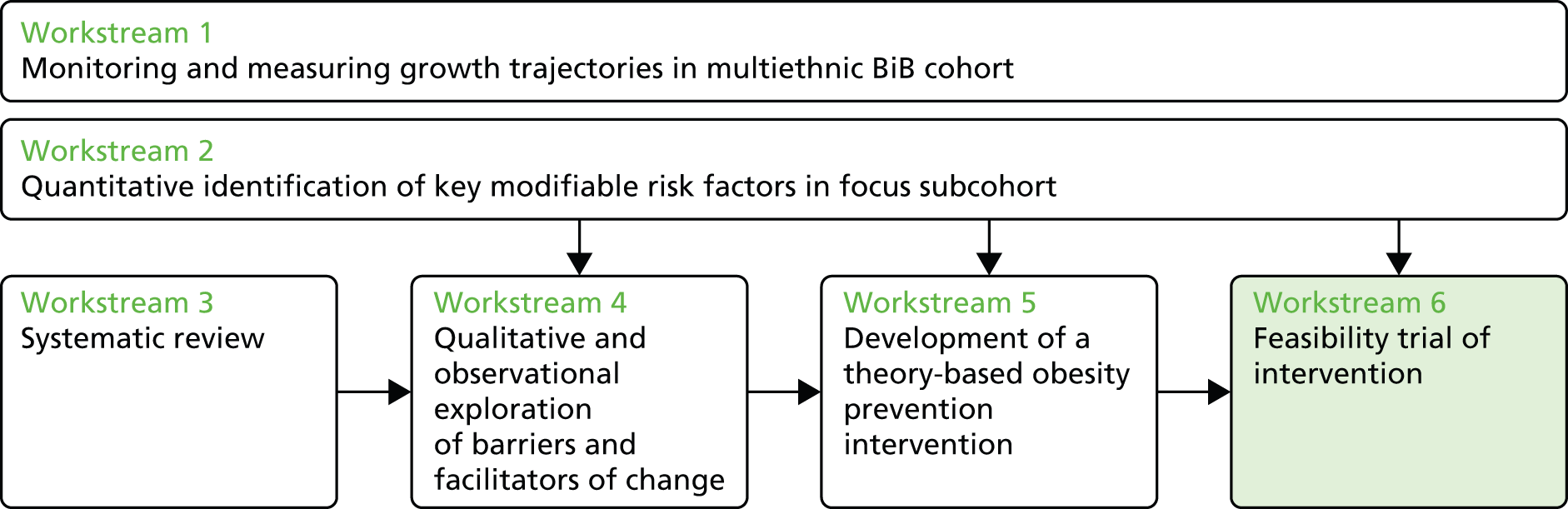

An applied research programme on childhood obesity

The aim of this National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme was to study the patterns and aetiology of childhood obesity in a multiethnic population and use this evidence to develop a tailored obesity prevention intervention.

The design and development of effective interventions requires a robust empirical evidence base to identify the right targets (modifiable behaviours) for preventing obesity and the right timing (in growth trajectory) for implementing the intervention. We set out to measure and analyse data on growth trajectories in a multiethnic population alongside assessment of hypothesised modifiable environmental and behavioural risk factors for obesity. Our intention was to determine whether or not the relative impact of any modifiable risk factor differs between South Asian and European-origin populations and to assess whether or not mechanisms for change differ between communities.

This monograph describes the results of our findings linked to the original programme objectives (a full list of publications arising from our programme of work can be found in Acknowledgements, Publications).

Recruitment of the BiB1000 cohort to investigate childhood obesity

-

Objective 1a: a 10% subsample of the BiB cohort was recruited for intensive follow-up to collect data on modifiable risk factors and growth. Data were collected from the 10% subsample through home visits by bilingual researchers, who administered survey instruments for behavioural measures and undertook anthropometry assessments.

Modelling growth trajectories and obesity risk

-

Objective 1b: the programme established research-calibre routine data collection on growth monitoring in a deprived, biethnic population through strengthening routine surveillance and monitoring growth trajectories.

Ethnic differences in obesity risk factors

-

Objective 2a: the focus for this objective was to describe ethnic differences in obesity risk factors to inform a culturally sensitive intervention.

Early risk factors for childhood obesity

-

Objective 2b: the focus for this objective was to identify modifiable behaviours and environmental risk factors that could be targeted in future interventions.

Systematic review of diet and physical activity interventions to prevent or treat obesity in South Asian children and adults

-

Objective 3: the focus for this objective was to conduct a systematic review of diet and physical activity interventions to prevent or treat obesity in South Asian children and adults.

Investigation of social and environmental determinants of childhood obesity

-

Objective 4: the focus for this objective was to determine appropriate intervention targets. Qualitative interviews, observational methods, geospatial mapping and nutritional audits were undertaken to explore determinants of feeding practices; cultural and social differences in feeding practices; the influence of key stakeholders; beliefs, attitudes and practices in relation to obesity, diet and exercise; perceptions in the South Asian community about childhood obesity; access to fast-food retailing; and eating patterns.

Development of an obesity prevention intervention

-

Objective 5: evidence from current and previous interventions was supplemented by a survey of nationally relevant work. Intervention mapping was used to select an appropriate theoretical foundation, identify change objectives and design the intervention and implementation. Field testing of candidate components for an intervention strategy was undertaken to test their feasibility and acceptability.

Exploratory trial of the obesity prevention intervention

-

Objective 6: the ultimate aim of the programme was to design an innovative community/family-based intervention to improve modifiable behaviours in both parent and child. The aim of the exploratory trial was to inform a definitive (Phase III) randomised trial that could be implemented within the NHS. The exploratory trial assessed the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention; eligibility, consent and recruitment rates; the acceptability of the randomisation process; and follow up rates. Outcomes were collected to inform the components and delivery of the intervention, estimate the effect size and test and validate outcome measures.

Programme management

A quarterly steering group of all 12 co-applicants and additional expert advisors was established to oversee the implementation of the research programme. An independent trials management group consisting of Julie Walker (clinical manager), Kim Cocks (statistician and triallist) and Tracy Wood (local authority parenting expert) was established in 2012 to provide monitoring and scrutiny of the feasibility trial.

Helen Ball and her team from Durham University joined the programme to support the study of sleep in early life. Aziz Sheikh and his team at Edinburgh University joined the programme to support the development of a culturally adapted intervention. Kate Tilling and Laura Howe from Bristol University joined the programme to provide expertise in the use of multilevel linear spline and latent class modelling of early life trajectories. Darren Greenwood from Leeds University joined the team to provide support for the dietary analysis. Kath Kiernan from York University provided expert support for the exploration of the association of parenting practices with obesity. Sally Barber from the Bradford Institute for Health Research joined the team to provide expertise on physical activity.

Clinical engagement

The programme was set up to promote strong clinical engagement in the research. Such engagement was fundamental to the success of the programme. Support from health visitors from Bradford District Care Trust was required to ensure high-quality additional routine postnatal measurements. Support from the midwives at Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was required for the successful recruitment of pregnant women to the pilot trial. Close involvement of local dieticians and public health consultants was required for the development of the intervention. Finally, close partnership with Barnado’s and Family Links was essential for the delivery of the intervention.

Patient and public involvement

The BiB1000 study has benefited from extensive experience of patient and public involvement within the Bradford Institute for Health Research. This has included the use of a panel of 10 people representing the local patient community who meet regularly (3-monthly) to participate in all stages of the research process, including identifying priorities, helping to write lay summaries, reviewing methodology and supporting translational work. Panel members work in pairs to provide peer support but also meet collectively to discuss general and specific issues. The BiB study has a strong focus on wider community engagement, with regular newsletters, birthday cards, picnics and art exhibitions. One of the great strengths of the study is the close involvement of the photographer Ian Beesley and the poet Ian McMillan, whose work is featured here and in the appendices of this report.

@BiBresearch (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA)

Born in Bradford (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) (www.facebook.com/BornInBradford/)

Recruitment and data collection for the BiB1000 cohort to investigate childhood obesity

The BiB1000 study was established to help enable a deep and extensive understanding of the predictors of and influences on health-related behaviours and to develop a culturally specific obesity prevention intervention. Here we describe the methodology and characteristics of the study participants; this work has been published as a separate paper. 63

All mothers recruited to the full BiB study between August 2008 and March 2009 who had completed the baseline questionnaire were approached to take part in the BiB1000 study during their routine 26- to 28-week glucose tolerance test. Those not attending this appointment were approached elsewhere during routine hospital attendances. A sample size of 1080 was calculated based on the ability to detect a clinically significant difference in infant growth of 0.67 SDS (one centile band) in weight at age > 1 year. Based on data from the Cole UK charts,64 we needed a minimum sample of 36 participants in any analysis group for length and a minimum of 67 participants for weight (β = 0.80; α = 0.05). Stratification by gender and ethnicity meant that we required a minimal sample of 280 at the completion of the preschool study. Allowing for a 5% annual attrition rate, we therefore required a total sample of 1080 births. However, to account for the higher anticipated attrition rate in a deprived multiethnic population, the plan was to oversample the population by up to 60%. Ethical approval was obtained from the Bradford Research Ethics Committee (reference number 07/H1302/112) and all participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the research.

Bilingual study administrators who were trained in anthropometry collected baseline information from mothers using a structured questionnaire in the home, at hospital-based clinics and at local children’s centres. Participants were followed up at 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months.

The questionnaire measures included were selected based on hypothesised correlations with exposures and childhood obesity. As this was an exploratory study in a largely untested population, many of these hypotheses were driven by a combination of evidence from ‘similar’ populations in the literature and agreement by the scientific and clinical teams. Baseline data collection for the BiB study was pilot tested with a group of expectant mothers in the Bradford Royal Infirmary Maternity Unit for clarity, duration and acceptability. Except for assessment of dietary intake in infants, additional follow-up measures were not piloted in advance of data collection. However, their acceptability was determined within the BiB1000 cohort and amended as appropriate. The intended food frequency questionnaire for infants was pilot tested in children’s centres and this led to slight modifications to the clarification of items to ensure that foods were culturally representative (e.g. chapattis included within bread products).

Infant weight was measured at birth by midwives and infant head circumference, mid-upper arm circumference, abdominal circumference, subscapular skin fold and triceps skin fold were measured within the first 24 hours following delivery by paediatricians and midwives who were trained in measurement techniques according to written guidelines.

Postnatal measures of infant weight, length, head circumference and abdominal circumference were collected as part of routine practice by health visiting teams. Additional measures of weight, length, head circumference, abdominal circumference and skinfolds were taken by specially trained BiB1000 study health workers at follow-up visits.

Maternal weight was measured at all assessments, maternal height was measured at baseline and BMI was derived from the antenatal booking weight (at ≈12 weeks of pregnancy) and baseline height.

The majority of the demographic data were obtained using structured questionnaires. Items were generated and modified from the Millennium cohort study,65 Growing up in Australia,66 the 2001 census67 and the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)68 questionnaires.

Behavioural measures were collected as part of the structured administered follow-up questionnaires, including feeding style and practices, parental and infant diet, mental health, parental and infant activity, sleep patterns, home food availability, parenting practices and other health behaviours (e.g. smoking, alcohol consumption). Validated questionnaires were used when available, although appropriate ethnic modifications were made and tested using expertise within Bradford (e.g. diet questionnaires were modified based on 24-hour recall data collected from parents in Bradford alongside input from Bradford dieticians).

A full set of questionnaires used for all follow-up assessments can be found on our website [see www.borninbradford.nhs.uk/research-scientific/general-study-documentation-and-questionnaires-2/ (accessed 4 February 2016)].

Qualitative and objective methodologies were employed in subsamples to explore the lifestyles, behaviours and environments in this multiethnic population, including (1) food outlet mapping, (2) home food availability inventories, (3) a mealtime observation study of maternal feeding styles and (4) interviews with families. Further details of the methods and findings for each of these are provided in Investigation of social and environmental determinants of childhood obesity.

Out of 1916 eligible women, 1735 (91%) agreed to take part in the study. Of these, 28 mothers gave birth to twins. Descriptive statistics are provided here for singleton births only (n = 1707). In total, 77%, 75%, 74%, 70% and 70% of participants were followed up at 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months respectively; 47% of participants completed all of the assessments to date, with 17% (n = 294) formally withdrawing from the research. Participants who could not be contacted (or when the visit could not be scheduled) were not considered to be lost to follow-up unless a withdrawal form had been completed (i.e. withdrawal of consent, death or change of residence outside the area). Thus, in some instances, data are missing at one time point but are available at subsequent visits. The greatest factor that impacted on attrition rates was the inability to make contact with participants to book appointments.

The characteristics of the BIB1000 cohort were similar to those of the full BIB cohort,62 with a similar distribution of age, marital status and parity. Overall, 38% of women were of white British origin and 47% were of Pakistani origin; 41% of Pakistani women were born in the UK and, of the remainder who were born elsewhere, 24% moved to the UK before the age of 18 years. Around 20% of the sample questionnaires were administered in languages other than English, reflecting this migration pattern. Demographic differences by ethnicity within the BiB1000 cohort were also observed, with white British mothers tending to be younger, educated to a lower level and less likely to be married or cohabiting and having fewer children than mothers from other ethnic groups. More than 20% of Pakistani women had more than three children prior to the birth of the study infant. Correspondingly, household size for South Asian women, especially Pakistani women, was greater than that for other ethnicities. Infant gender, gestational age and proportion of preterm infants were similar between ethnic groups. Similarities were also observed for the mode of delivery and the proportion of stillbirths. Over 35% of white British women reported smoking during pregnancy compared with 4% and 3% of women of Pakistani and ‘other’ South Asian origins respectively. The proportion of women with gestational diabetes was greatest in the South Asian ethnic group, with a 10.5% prevalence in Pakistani women compared with a 5.5% prevalence in white British women.

Longitudinal data collection from the BiB1000 birth cohort has provided a sample for the NIHR programme to develop a deep and extensive understanding of the predictors and influences of health-related behaviours to help develop feasible and appropriate culturally specific intervention(s) for the prevention of childhood obesity. This was facilitated by experienced, enthusiastic, multilingual data collection staff. A unique quality of this cohort is its ethnic composition, with successful recruitment of approximately 50% of women from South Asian origin and a representative sample of women from across the socioeconomic groups within Bradford.

Modelling growth trajectories and obesity risk

Growth during infancy is an important indicator of health and well-being. 69 Evidence suggests that the obesity epidemic begins in early childhood and that the risk of obesity is greater in children who put on more weight in early life. Growth data for the BiB1000 cohort are available from two sources; the BiB1000 visits and the routine measurements recorded in health visitor records (Personal Child Health Record or ‘red book’). We assessed how reliable the data collected by health visitors in Bradford are by using a test–retest reliability study and investigated the agreement between data collected in the BiB1000 clinics and the routine data collected by health visitors. This work has been published in two separate papers. 70,71

We found that, in Bradford, following training, health workers can in general reliably measure child growth. The technical errors of measurements obtained in our study were comparable to those from other research studies and all coefficients of reliability were indicative of good quality control. We also found that there was good agreement between BiB1000 measurements and routine measurements, although wide limits of agreement between data sources may be observed.

The growth data collected as part of the BiB1000 study supplemented with routine measurements collected by health workers in the community have provided a comprehensive reliable data set to investigate growth in infancy. We have focused on investigating ethnic differences in growth trajectories and on the development of obesity risk in childhood. We used multilevel linear spline models with repeat measures of weight and length to describe growth trajectories for white British and Pakistani infants from birth to 2 years of age and to assess whether or not there are ethnic differences in these growth trajectories. Finally, we described the development of prediction equations to identify children at risk of obesity and integrate the equations into a novel user-friendly mobile phone application. This work has been published in two separate papers. 72,73

Modelling growth trajectories72

For the first time in the UK we estimated weight and length growth trajectories between birth and 2 years for Pakistani boys and girls and found that Pakistani boys and girls were lighter and had a shorter predicted mean length at birth than their white British counterparts but gained weight and length quicker in infancy. By age 2 years both ethnic groups had a similar weight, but Pakistani boys and girls were taller on average than white British boys and girls. Differences in maternal height explained some of the differences in weight and length at birth; however, adjustment for maternal height, smoking during pregnancy and gestational age did not explain the differences in postnatal growth rates.

Given the relationship of early postnatal growth to normal development and adult health, together with known anthropometric differences at birth in South Asian compared with white European infants, it is important to understand how size differs in this group in the postnatal period and what factors might explain these differences. The faster growth in South Asian children shown in our study could be beneficial for their early infant/childhood health as observed in low-income countries. 74 However, if the greater rate of weight gain in this population is driven by greater fat gain it may have adverse long-term consequences for cardiometabolic health75 and contribute to the increased risk of diabetes and CVD observed in South Asian adults. 76–78 South Asian children have been shown to be fatter for a given BMI than their European counterparts and markers of diabetes and CVD risk are increased in South Asian children and adolescents, suggesting that this faster early growth may indeed be contributing to adverse later cardiometabolic health. 24,79,80 We acknowledge that further replication of our findings by others and longer-term follow-up to examine associations with a range of early life and later outcomes will be required to clarify the importance of these ethnic differences in growth.

Development of a mobile phone app to predict childhood obesity73

Innovative strategies to identify infants at the greatest risk of childhood obesity are necessary for the prevention of obesity. We present the development of a practical mobile phone app (Figure 1) that can be used for a wide range of ages (4.5–13.5 months) in infancy when growth monitoring is part of routine health care. 81 The app requires information on a baby’s sex, date of birth, birthweight and current weight and users can optionally add maternal height and weight (to calculate BMI). We chose not to include ethnicity and gestational age because, although they were significant predictors, neither of these factors was significant in the internal and external validity analyses. Furthermore, ethnicity in our sample was restricted to white British and South Asian ethnicities and it was felt that this would not reflect the ethnic diversity (or lack thereof) in many areas. Maternal BMI was a significant predictor in the 6- and 9-month equations but, again, this information may not be available and so we developed two sets of prediction equations so that the app would work whether or not maternal BMI was available, with a negligible effect on the model fit.

FIGURE 1.

The Healthy Infant Weight? app.

In the future the app could be developed to incorporate any number of other functionalities, such as plotting of growth measurements on a growth chart, geospatial mapping of an infant’s obesity risk score compared with those of his or her peers and administration of an obesity prevention programme for those infants identified as being at high risk.

Ethnic differences in obesity risk factors

Epidemiological evidence has highlighted the importance of a number of exposures in pregnancy and early life that are associated with the development of obesity in childhood. In this study we investigated ethnic differences in five early-life risk factors for childhood obesity that are modifiable and can be targeted in future interventions. The risk factors considered were (1) breastfeeding, (2) infant diet, (3) infant sleep, (4) physical activity and (5) parenting style. The work on breastfeeding and parenting style has been published in two separate papers;82,83 the full reports for the other risk factors are presented in Appendix 1.

Ethnic differences in the initiation and duration of breastfeeding82

Compared with white British mothers, we found that mothers in all other ethnic groups examined were significantly more likely to initiate breastfeeding and continue any breastfeeding until their infant was 4 months of age, which is consistent with previously reported findings from the UK. 84,85 However, we found no significant differences by ethnicity after adjustment for covariates in the rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 4 months.

Ethnic differences in infant diet (see Appendix 1.1)

Analyses of dietary patterns found that, by 12 months of age, foods and drinks high in sugar and foods high in fat were consumed by infants. There was no fruit and vegetable consumption in 3% of infants; a higher intake of sweet commercial foods, fruit and high sugar drinks in Pakistani infants; and higher intakes of savoury baby foods and processed meat products in white British infants.

In comparison to intakes of key indicator food groups at 12 months, the 18-month data showed large statistically significant and nutritionally concerning increases in the consumption of unhealthier food items across the cohort. Large increases were observed in the intake of chips, processed meat products, savoury snacks and sugar-sweetened drinks. Encouragingly, the intake of fruit, vegetables and low-sugar drinks had also increased.

At 18 months Pakistani infants had a higher intake of chips, roast potatoes or potato shapes and consumed substantially less processed meat than white British infants. Pakistani children continued to drink more sugar-sweetened drinks and more pure fruit juice than their white British counterparts.

There were ethnic differences in the consumption of key nutrients and these also changed over time. These changes in diet may simply reflect different weaning strategies between the ethnic groups, with Pakistani babies breastfed for longer, reflected in lower protein and fibre intakes at 12 months, but patterns relating to the consumption of solid food becoming more established by 18 months.

This analysis contributes to the limited evidence on dietary patterns in early childhood and highlights ethnic differences in some consumption patterns. There was evidence of dietary patterns that emerged at 12 months tracking to 18 months and, once established, these may form the basis of an unhealthy diet that may become ingrained and difficult to shift. This information helps us to characterise early-life dietary patterns and will allow us to examine how early diet influences later outcomes. It can be used to inform the development of community-tailored and culturally appropriate obesity prevention interventions aimed at improving the nutritional health of infants, toddlers and children.

Infant sleep patterns (see Appendix 1.2)

We found ethnic differences in night-time sleeping patterns, with later sleep onset and wake times for Pakistani infants than for white British infants at both 18 and 36 months and with Pakistani infants experiencing a shorter maximum sleep duration. Ethnic differences in sleeping arrangements may be affecting infant sleep duration or maternal knowledge of infant sleep duration. For example, South Asian families tend to practise familial co-sleeping, with all children sharing a room with their parents for sleeping, whereas white British families practise separate sleeping arrangements, often with one child per room. Such differences may affect maternal knowledge of an infant’s sleep duration such that South Asian mothers may be more likely to be aware of night wakings. Sleep duration may also be affected if family members are more frequently disturbed by one another in the night.

Physical activity (see Appendix 1.3)

The majority of children in the BiB1000 cohort at age 2 years were meeting the Chief Medical Officer’s guideline of 180 minutes of physical activity each day. 86 There were no differences between the ethnic groups in total time spent on daily physical activity and, in addition, sedentary behaviour and television/DVD viewing were high for the whole group (on average 1.5 hours per day). There were, however, ethnic differences in the types of physical and sedentary activities that the children engaged in. White British children were reported to spend longer walking, in organised physical activity, playing outside and in proactive sedentary behaviours (e.g. being read to) than Pakistani children, who spent longer each day playing inside and in passive sedentary behaviour (watching television/DVDs). The differences in time spent in different types of activities may result in important lifestyle differences as the children grow up as observational studies have shown that time spent outdoors correlates with physical activity levels in school-aged children. 87,88 Time outdoors has also been associated with higher objectively measured physical activity levels89,90 and with a lower prevalence of overweight. 89 There were other marked differences between the ethnicities in possible determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour that may also contribute to the reported differences between ethnic groups later in childhood. 91 These included Pakistani children being less frequently restricted in their television viewing, having more barriers to physical activity and receiving less frequent support to be physically active from their parents.

Ethnic differences in parenting style83

There were no ethnic differences in parental self-efficacy and parental warmth; however, Pakistani mothers reported feeling more confident about their parenting abilities and were less likely to adopt a hostile approach to parenting. To our knowledge, no such data have been reported previously for UK-resident women and further work is needed to link these parenting styles with children’s current and future health. Women of both ethnic groups with more self-efficacious, warm and less hostile parenting styles reported significantly fewer problems with their infant’s temperament.

Understanding of these ethnic differences in modifiable risk factors has implications for the effective cultural adaptation of interventions to reduce childhood obesity.

Early risk factors for childhood obesity

In the last section we described ethnic differences in five early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Here, we investigate the association between several early-life modifiable risk factors for childhood obesity and infant BMI at 3 years of age. This work has been published as a separate paper. 92

It is important to understand whether or not modifiable characteristics are related to BMI in infancy to ensure that appropriate interventions are developed to promote maintenance of healthy BMI levels into mid-childhood, when important relationships to future coronary heart disease risk emerge. Furthermore, knowing whether or not associations differ between South Asian- and white European-origin infants is important in knowing whether or not interventions should target different risk factors in these groups to reduce the ethnic differences in risk. In this section we describe the differences in the prevalence of potentially modifiable risk factors for childhood obesity between infants of white British origin and infants of Pakistani origin and investigate the association between these risk factors and childhood BMI measured at 3 years of age. We also examine possible ethnic differences in associations between the risk factors and child BMI.

We found that the prevalence of early-life risk factors for a higher BMI differed between mothers of white British ethnicity and mothers of Pakistani ethnicity. White British mothers were more likely to smoke during pregnancy (28% vs. 4%), have a higher BMI (obese: 24% vs. 16%), breastfeed for a shorter duration (> 4 months: 20% vs. 29%) and wean earlier, whereas Pakistani mothers had a higher rate of gestational diabetes (14% vs. 7%) and were less active (sufficiently active: 26% vs. 57%). There were consistent associations between BMI z-score and maternal smoking [mean difference in BMI z-score 0.33, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.13 to 0.53], maternal obesity (0.37, 0.19 to 0.55), indulgent feeding style (0.15, −0.06 to 0.36), lower parental warmth scores (0.21, 0.05 to 0.36) and higher parental hostility scores (0.17, 0.01 to 0.33). Associations with mean BMI were the same for white British and Pakistani infants, with the exception of breastfeeding duration. Although we did not have sufficient statistical power to examine ethnic differences in the associations of risk factors with relative risks of overweight/obesity, the similarity in the associations with mean BMI between the two ethnic groups suggests that differences on a binary scale are unlikely.

Consistent with other studies we found that children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy were more likely to have a higher BMI SDS and a greater risk of being overweight,40,93,94 as were infants of overweight and obese mothers. 28,93,95

We found that certain aspects of feeding and parenting style were associated with a child’s BMI. Caregivers with an ’indulgent’ feeding style had infants with a higher BMI SDS and who were more likely to be overweight; this is consistent with other studies. 96,97 Children of parents with less warm and more hostile parenting styles were more likely to be overweight. Different measures and constructs of parenting styles have been previously studied; however, evidence linking the specific domains analysed in the current study to childhood BMI is scarce, although some studies have looked at associations with dietary and activity behaviours. 98,99 Evidence suggests that children raised by authoritative parents had lower BMI levels than children raised with other styles. 98

In this study we did not find strong evidence of an association between gestational diabetes, age at weaning, infant energy intake, infant protein intake and infant sleep duration and infant mean BMI or risk of overweight at age 3 years, despite evidence of associations between these risk factors and BMI in other studies. 40,93,100–104 However, many of these studies were conducted in older age groups and in non-UK populations with different ethnic compositions to that of the BiB study population.

The main strength of this analysis is that we have considered several key modifiable risk factors that have been collected longitudinally during pregnancy and infancy in a multiethnic cohort. To our knowledge this is the first time that these risk factors have been studied in early infancy in infants of Pakistani origin. The limitations of the study are that it was undertaken in a single centre and so may lack generalisability. The questionnaire relied on self-report to collect information on risk factors and there may have been reporting or social desirability bias.

This work adds to the literature on the role of the early life environment and later childhood obesity and is useful in identifying suitable targets for obesity prevention interventions in infancy. It has highlighted key differences in early-life risk factors between white British and Pakistani mothers and so has highlighted the importance of cultural adaptation of interventions. It has also helped identify key modifiable risk factors to target in pregnancy and postnatally.

Systematic review of diet and physical activity interventions to prevent or treat obesity in South Asian children and adults

The previous workstreams identified the important modifiable determinants of obesity to form targets for intervention and identified key differences in the patterns of these risk factors by ethnicity and socioeconomic status. These findings highlight the need for culturally sensitive interventions to be developed.

We performed a systematic review to identify evidence that could inform the development of an obesity prevention intervention for pregnant South Asian women and their children aged < 6 years. This systematic review has been published105 and is freely available at www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/12/1/566 (accessed 1 February 2016).

The metabolic risks associated with obesity are greater for South Asian populations than for white or other ethnic groups and levels of obesity in childhood are known to track into adulthood. Tackling obesity in South Asian populations is therefore a high priority. The rationale for this systematic review was the suggestion that there may be a differential effect of diet and physical activity interventions in South Asian populations compared with populations of other ethnicities. The research territory of the present review is an emergent rather than a mature field of enquiry, but it is urgently needed. Thus, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the effectiveness of diet and physical activity interventions to prevent or treat obesity in South Asian populations living in or outside South Asia and to describe the characteristics of effective interventions.

Systematic reviews of any type of lifestyle intervention, of any length of follow-up that reported any anthropometric measure for children or adults of South Asian ethnicity were included. There was no restriction on the type of comparator and RCTs, controlled clinical trials and before-and-after studies were included. A comprehensive search strategy was implemented in five electronic databases: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CCTR), EMBASE, MEDLINE and Social Sciences Citation Index. The search was limited to English-language abstracts published between January 2006 and January 2014. References were screened and data extraction and quality assessment were carried out by two reviewers. The results were presented as a narrative synthesis and meta-analyses were carried out.

In total, 29 studies were included, seven in children, 21 in adults and one in a mixed-age population. No studies in children aged < 6 years were identified. Sixteen studies were conducted in South Asia, 10 in Europe and three in the USA. Effective or promising interventions included physical activity interventions in South Asian men in Norway and in South Asian schoolchildren in the UK. A home-based, family-orientated diet and physical activity intervention improved obesity outcomes in South Asian adults in the UK when adjusted for baseline differences. Meta-analyses of interventions in children showed no significant differences between intervention and control groups for BMI or waist circumference. Meta-analyses of adult interventions showed a significant improvement in weight in data from two trials when adjusted for baseline differences (mean difference −1.82 kg, 95% CI −2.48 to −1.16 kg) and in unadjusted data from three trials following sensitivity analysis (mean difference −1.20 kg, 95% CI −2.23 to −0.17 kg). Meta-analyses of adult interventions showed no significant differences between intervention and control groups for BMI and waist circumference. Twenty of 24 intervention groups showed improvements in adult BMI from baseline to follow-up; the average improvement in high-quality studies (n = 7) ranged from 0.31 kg/m2 to −0.8 kg/m2. There was no evidence that interventions were more or less effective according to whether or not the intervention was set in South Asia or by socioeconomic status.

Meta-analysis of a limited number of controlled trials found an unclear picture of the effects of interventions on BMI for South Asian children. Meta-analyses of a limited number of controlled trials showed significant improvements in weight for adults but no significant differences in BMI and waist circumference. One high-quality study in South Asian children found that a school-based physical activity intervention that was delivered within the normal school day and which was culturally sensitive was effective. There was also evidence of culturally appropriate approaches to, and characteristics of, effective interventions in adults that we believe could be transferred and used to develop effective interventions in children.

Investigation of social and environmental determinants of childhood obesity

To further explore the impact of social and environmental factors on health we conducted a range of further focused studies. The aim was to understand how these factors might constitute determinants of childhood obesity, how they might vary according to mothers’ ethnicity and how they might be modified, with a view to informing any subsequent intervention. Specific areas of focus were parental attitudes to eating and infant growth, interactions that accompany mealtimes and the availability of certain foods in the home and in the neighbourhood. The work on food availability in the home and in the neighbourhood has been published in two separate papers;106,107 the full reports for the other topics are presented in Appendix 1.

Investigation of social and environmental determinants of childhood obesity (see Appendix 1.4)

Fourteen mothers (n = 9 Pakistani and n = 5 white British mothers) were recruited and interviewed when their infant was aged between 3 and 5.5 months. Issues around perceptions of a ‘healthy baby’, breastfeeding and weaning and sources of support were explored. Transcripts and field notes were independently coded by two authors. Analysis sought to identify emerging themes using a thematic narrative approach;108 differences between ethnic groups were explored.

There was considerable shared ground between white and Pakistani mothers in relation to how they perceived a ‘healthy’ baby. Mothers expressed some anxiety about very underweight babies, but a concern about them being overweight was not strongly evident. For younger children who might be overweight the expectation (hope) was that ‘they will grow out of it’; for older children the problem was seen as being a cosmetic one rather than primarily a health concern.

At the time of interviewing, only three mothers were still breastfeeding. Approximately half of the remaining mothers had tried to breastfeed, averaging between 1 week and 10 days, and had then stopped. The most common reason why they had stopped was that the ‘baby was not getting enough food’. Most of the mothers interviewed were weaning already, often starting at around 4 months. Mothers were aware that there was guidance from health visitors about the correct time to wean. Some had heard advice from health visitors about baby-led weaning, but none reported trying this.

With regard to sources of advice and support there were two strong and inter-related themes: the importance of consistent advice and the many sources of advice that were available. Mothers received inconsistent advice from different professionals about breastfeeding and between professionals and family members in relation to weaning. Adding to this challenge was the wide range of sources used for advice (e.g. extended family, friends, midwives and health visitors).

In summary, the interviews provided data that were consistent with those previously reported in the literature. 59 Parental perceptions are developed through interactions with a range of sources of influence including family, friends and health professionals. The internet was of increasing prominence as a source of information. There was not a clear hierarchy of influence.

A mealtime observation study: obesity, ethnicity and observed maternal feeding styles (see Appendix 1.5)

Having identified the importance of parent and family beliefs in decisions to breastfeed and wean in early infancy, we sought to explore how feeding patterns were influenced by the shared family environment. Parents are key role models for their children, socialising children to their food choices, eating habits and feeding behaviours. Parenting styles have been shown to impact on eating behaviour and outcomes related to obesity. 98 General parenting styles have been summarised as having two dimensions: control/demandingness and warmth/responsiveness. 109,110 These independent dimensions yield four different parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive and uninvolved parenting. Research has linked authoritative feeding styles to increased consumption of fruit and vegetable products. 111 However, many authors question whether these styles are invariant across different cultural groups. 112 There is an absence of research regarding parenting styles of social Asian families, especially those living in the UK. International studies regarding ethnicity and feeding practices are similarly limited.

The current study aimed to explore the influence of maternal weight and ethnicity on observed mealtime interactions. Twenty obese mothers (10 Asian and 10 non-Asian mothers) and 18 ‘healthy weight’ mothers (8 Asian and 10 non-Asian mothers) participating in the BiB1000 study consented to take part in the study along with their children. Children were aged between 18 months and 2 years, 24 were male and 14 were female.

Mothers were asked to prepare an ordinary meal for their child on the day of the observation. The mealtime was recorded and recordings were analysed using the Mealtime Observation Schedule (MOS). 113 The schedule codes parent behaviours as positive (e.g. praise, positive contact) or negative (e.g. negative eating comments) and child behaviours as positive (e.g. ‘self-bites’, appropriate verbal behaviour) or negative (e.g. refusing food, leaving the table). Validated questions assessing caregiver feeding style (authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent and uninvolved),114 parenting practices (self-efficacy, warmth and hostility66) and infant characteristics (adaptability, fussiness/difficultness, dullness and predictability)115 were administered at 6, 12 and 24 months as part of the standard schedule of measurement of the BiB1000 cohort. 63

Analyses found that South Asian mothers presented food more times to their child than non-Asian mothers. Meal duration was shortest for children whose mothers were South Asian and of healthy weight and longest for children whose mothers were non-Asian and of healthy weight.

South Asian mothers exhibited significantly less positive behaviours and significantly more negative behaviours during mealtimes than non-Asian mothers. Children with South Asian mothers demonstrated marginally greater levels of negative behaviours during mealtimes, with no difference in positive behaviours between the two ethnic groups. Children of South Asian, healthy-weight mothers spent more time ‘away from the table’ than children in the other groups. There were no effects of maternal weight on these measures.

In summary, there were no differences in parenting styles of feeding behaviours by maternal weight. Distinct ethnic differences were apparent, both in the physical organisation of mealtimes (more South Asian mothers did not sit their child in a chair or use a table for mealtimes) and in the types of interactions during mealtimes (with South Asian mothers showing slightly reduced positive behaviours and slightly increased negative behaviours). This is consistent with the observation that their children demonstrated less independent eating. Overall, the results indicate that South Asian mothers exert a different type of control during mealtimes with their children by giving a greater number of specific and clear direct instructions. This may be in response to more challenging behaviour of their children.

Researcher-conducted home food availability inventories106

For children, the home is a key environment as it serves as the primary physical and social context in which habits and norms are developed, including those specific to diet and physical activity. Home food availability/accessibility has been shown to relate to child food consumption,116–131 which is intuitive given that children’s food intake is largely dependent on what is provided to them by others. 124,127,132,133 The aim of this study, therefore, was to explore the home food availability of South Asian and white British participants in the BIB1000 study to describe what foods are available and to identify key differences by ethnicity or weight status.

Direct observations of food and drinks in the home were made for an opportunistic sample of 97 BiB1000 participants (n = 46 white British, n = 41 Pakistani, n = 10 ’other’ ethnicity) using a standardised protocol. 51 The inventory included counting portions of fruits (fresh, frozen, tinned, dried), vegetables (fresh, frozen, tinned), savoury snacks (crisps/tortillas, nuts), sweet snacks (cakes, biscuits, chocolate, sweets, ice cream) and beverages (sugar-sweetened drinks, diet drinks). See Appendix 2.3 for a copy of the home food availability inventory.

Findings from this exploratory study showed that all homes had some form of fruit and some form of vegetable available in them. Overall, the presence of foods and drinks was similar in all of the ethnic groups. More homes had fresh fruits and vegetables available than canned, frozen and dried fruits and vegetables. At least one type of snack food was also available in all of the included BiB1000 homes. Of these, crisps and biscuits were most likely to be available. Descriptive analysis compared differences by ethnicity and weight. Although no differences were found for the latter, unadjusted comparisons by ethnicity showed that homes of Pakistani mothers had approximately three times the quantity of sweetened beverages available in them. Although this finding may be dependent on confounding factors (a study within the USA found that household size, presence of the maternal grandmother and shopping habits all related to home food availability134), it does suggest that targeting these types of drinks would be useful within an intervention to prevent obesity, as these drinks offer no nutritive value.

Food outlet availability, deprivation and obesity in a multiethnic sample of pregnant women in Bradford, UK107

The final environmental factor influencing obesity addressed in the current workstream was the neighbour environment in which respondents lived. The conceptualisation of an obesogenic environment has changed the way that obesity is viewed and is key to national policy documents that address obesity. 13 The obesogenic environment operates on several levels and describes the changes in daily living, transport and access to recreational facilities, foods and food outlets that have contributed to positive energy balance and weight gain. It follows that the availability of, or people’s access to, food may be related to obesity. This could be through proximity to multiple fast-food outlets or the way that people shop at large out-of-town supermarkets and stockpile food at home. However, supportive evidence is far from compelling, even though there has been increasing attention paid to the location of food outlets, especially those selling fast foods.

There is equivocal evidence for a relationship between the location of fast-food outlets and weight status135–143 or fast-food consumption. 135,136,138,139,144 In contrast, the relationship between fast-food outlet density and deprivation is much clearer. Research from the UK, the USA and New Zealand has shown higher numbers of fast-food outlets in areas of high deprivation. 145–157 However, there has been relatively little attention paid to whether or not access to, and the consumption of, fast food are affected by ethnicity, outside the USA at least, and how this is related to obesity. 158

This study aimed to measure access to all food outlets and to investigate the relationship with body weight, obesity and deprivation in a biethnic sample of adult women using geographic information systems (GIS) methodology. It was hypothesised that food outlet availability would be related to deprivation and that availability would be greater for South Asian participants. In addition, obese women would have greater access to food outlets, especially those selling fast foods.

Our study population came from five inner wards in the Bradford Metropolitan District, chosen because they had a range of ethnic population mix (1.2–63.8% South Asian). We included data from 1198 women within the BiB1000 cohort who lived in the study area and who provided information on age, ethnicity, height, weight at booking of pregnancy and weight at 28 weeks of pregnancy.

To map food outlet availability, we increased the study area to a total of 16 wards (five wards in which participants lived and a further 11 wards immediately bounding those areas) in recognition that individuals would not necessarily stick to the ward boundaries for local shopping and eating patterns. This search area included 819 ‘output areas’ (OAs) (these are census geographical areas; an OA contains on average 125 households). Administrative information from the Bradford Metropolitan District Council (lists of food outlets held for health and hygiene purposes) and Bradford Yellow Pages (index of local businesses) was used to identify food outlets. A random selection of 90 OAs, stratified by deprivation, were visited to audit data collected from administrative sources.

A pool of 886 outlets was identified. These outlets were classified as ‘fast food’ (n = 364), other ‘eating out’ (restaurants, cafes; n = 247), supermarkets (n = 47), specialist food shops (e.g. butcher, bakery; n = 100) and smaller retail shops selling food (e.g. convenience stores; n = 128). Four measures of food access were used: the distance to the nearest food outlet (proximity) in each category for each participant, the number of outlets within each food outlet category in a 250-m, 500-m and 1000-m radius of each individual’s residential postcode, the number (density) of food outlets of each category in each super OA (containing four to six OAs) and proximity to clusters of three or more fast-food outlets. Univariable generalised estimating equation modelling, with obesity status as the outcome and maternal age, deprivation score and food access measure as the independent variables, was undertaken for both ethnic groups. The independent variables that were significant in the univariable analyses were combined in the multivariable analyses in a forced entry method. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Our results found increased food outlet availability within more deprived areas and for South Asian populations. However, the relationship between having fast-food outlet access or availability and weight status (BMI or being obese) in the South Asian group was opposite to what was hypothesised and in the non-Asian group was non-existent. This would seem to indicate that, in the current sample, increased access or availability is not related to increased consumption. Another important finding is that > 95% of participants lived within 500 m of a fast-food outlet. This degree of saturation has not been demonstrated previously but may be characteristic of UK inner cities.

This workstream aimed to explore the context and circumstances in which food choices are made. The results from these studies have the following implications for the development of a childhood obesity prevention intervention:

-

Understandings are arrived at, and choices are made, in the context of many interlinked systems of influence and these systems should be targeted in any intervention. Delivering interventions within a group setting may help to set up positive influences through peer support.

-

Intervention effectiveness will be enhanced if practitioners know which components of parenting to target within a culturally sensitive context. Parenting styles vary according to ethnicity and those practices that might constitute targets for intervention in one group would not be applicable to another, or at least would not be of equal salience.

-

Seeking to change food and drink consumption should focus on (a) promoting the availability and quantity of all types of fruits and vegetables (e.g. encouraging the purchase of tinned/frozen fruit in addition to the purchase of fresh fruit); (b) reducing the purchase of crisps and biscuits (which were both available in > 80% of homes); and (c) discouraging the purchase of sweetened beverages, especially within homes of Pakistani mothers (with 85% of these homes having at least one type of sweetened beverage available).

-

Living in close proximity to a fast-food outlet (within 500 m) was commonplace in the Bradford wards that were studied. This degree of proximity was observed in > 95% of participants. This should be considered when applications for further food outlets are made.

Using intervention mapping to develop a culturally appropriate intervention to prevent childhood obesity: development of the Healthy and Active Parenting Programme for Early Years intervention

The previous workstreams provided a wealth of epidemiological information about the risk factors for childhood obesity and the types of interpersonal, contextual and environmental factors that can influence eating behaviours. All of these are important targets for intervention. In addition, our work, including our systematic review, highlighted the importance of considering the cultural acceptability of interventions for different ethnicities and also the acceptability of interventions for low-income groups. In the current workstream we describe the development of a culturally acceptable childhood obesity prevention programme using a technique called intervention mapping. 159 This has been published as a separate paper. 160

Intervention mapping refers to a rigorous and systematic approach to developing evidence-based interventions. We followed the six key steps as follows: (1) needs assessment of parents, the wider community and practitioners and consideration of the evidence base, policy and practice; (2) identification of outcomes and change objectives following identification of barriers to behaviour change; (3) selection of theory-based methods and practical strategies to address barriers to behaviour change; (4) design of the intervention by developing evidence-based interactive activities and resources; (5) creating an adoption and implementation plan in which parenting practitioners were trained by health-care professionals to deliver the intervention within children’s centres; and (6) creating an evaluation plan.

A multidisciplinary intervention development team was convened that included experts in the areas of parenting, nutrition, breastfeeding and physical activity as well as a group of experienced community health practitioners. The group met every 6–8 weeks over the course of a 12-month period to develop the intervention. The intervention was informed by behavioural change principles161,162 and a typology of ways of ensuring the cultural adaptation of interventions informed the development of the intervention at each stage of the process. 163

The overall desired outcome of the intervention was to prevent childhood obesity. The intervention was targeted at overweight or obese pregnant mothers. Specifically, it aimed to (1) encourage mothers to make healthy food choices antenatally and maintain a healthy diet postnatally; (2) encourage mothers to increase their level of physical activity during pregnancy and meet the recommended guidelines for physical activity (150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week164) within 12 months of giving birth; (3) encourage breastfeeding (or appropriate bottle-feeding) until at least 6 months of age; (4) encourage infants to develop healthy food preferences and a healthy dietary intake; and (5) facilitate physical activity in infants and limit sedentary time.

Given that parenting skills were highlighted as an important predictor of later obesity (see Early risk factors for childhood obesity), it was agreed that the intervention should be developed in conjunction with an established community parenting programme: the Family Links Nurturing Programme (FLNP). The FLNP is one of the preferred parenting programmes in Bradford; its aims are to develop parents’ self-esteem and self-efficacy and their understanding of their own, and their children’s, emotional and physical needs. Qualitative research has demonstrated that parents value the programme and feel that it has had a positive impact on family relationships, their children’s behaviour, relationship quality and their own mental health. 165,166 This integration with the FLNP was key to ensure the sustainability of the intervention and represented a channel to ensure delivery as part of ’usual care’ that could continue without the involvement of the research team. The parenting aspects of the intervention developed by the FLNP aimed to reduce the risk of child abuse and neglect, improve couple relationships, reduce stress and perinatal depression and increase prospective parents’ understanding of child development. In recognition of this core component of the intervention, the intervention was designed to be delivered by facilitators trained and accredited by the FLNP [see https://familylinks.org.uk/train-with-us (accessed 8 March 2016) for details of the training].

The final intervention consisted of six group antenatal sessions and six group postnatal sessions and was named HAPPY (Healthy and Active Parenting Programme for early Years). It was planned that the antenatal sessions would take place weekly, starting when the mother was at 26–28 weeks’ gestation. Each session lasted approximately 2.5 hours. The postnatal sessions started when the infant was aged 4–6 weeks and continued at key developmental milestones (9 weeks, 12 weeks, 5 months, 7 months and 9 months). A summary of the intervention content for the antenatal sessions and the postnatal sessions can be found in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. Each session was detailed in a facilitator manual with step-by-step instructions on how to deliver the intervention. A 2-day training programme was developed to supplement the existing FLNP training that practitioners had already received. This included information on the background to the intervention mapping approach taken to develop the intervention; evidence-based practical education on the key messages of the intervention (nutrition, infant feeding and physical activity); time to explore the manual and practice delivering activities; and information on the importance of intervention fidelity, including how to record deviations in delivery.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1. Brain, science and bonding | Parent diet: healthy diet in pregnancy; links between what you eat when pregnant, you and your baby; links between maternal and childhood obesity; reflection on own diet and importance of food in the family |

| Parent physical activity: how the baby is developing in the womb and how physical activity can facilitate this | |

| Breastfeeding: identifying and overcoming barriers to breastfeeding | |

| 2. A celebration of birth | Parent diet: importance of eating well for the baby; dispel myths about weight gain in pregnancy and provide up-to-date information; Smart Snacks handout; food diaries |

| Parent physical activity: being active during pregnancy; discussion regarding myths about physical activity in pregnancy | |

| 3. Personal power, self-esteem and healthy choices about food | Parent diet: address barriers to healthy eating and plan for ways to overcome them; signpost to cooking information points; healthy foods can be convenient and inexpensive; impact of mother eating unhealthy foods; plan alternative cooking methods |

| Parent physical activity: list activities that women think they could do, work through from easy to difficult; gentle strengthening and conditioning exercises: demonstration by practitioners; worries about physical activity; visualise and positive self-talk; identify when activity can be freely integrated into normal life | |

| Breastfeeding: advantages/disadvantages of breastfeeding and bottle-feeding; the more you feed, the more milk is produced; encourage the identification of an influential family member, clarify likes and dislikes, talk with family members about these issues to enlist their support; learn more about breastfeeding skills; overcome stigma about breastfeeding in public, stories from other mothers | |

| 4. Boundaries, beliefs and values | Parent diet: additional information about snacks, food treats, swaps |

| Parent physical activity: back-up plan for physical activity at different times | |

| Breastfeeding: values and beliefs about bringing up children and linking this to breastfeeding | |

| 5. Feelings and how we communicate | Parent diet: food swaps and healthy meals feedback; identify vulnerable points in time and have contingencies for when want unhealthy foods |

| Parent physical activity: partners review their progress with regard to the collaborative plans made for physical activity in session 4; discussion about feelings relating to whether or not activity plans were fulfilled | |

| 6. Beyond labour day | Parent diet: identify someone at home/friend to discuss food habits with |

| Parent physical activity: pelvic floor exercises for immediately after pregnancy if uncomplicated; what activities are OK after pregnancy | |

| Breastfeeding: how to make up bottle correctly; signpost to health professionals; environmental changes: clothes that facilitate feeding; locations nearby; family members can do other things with the baby (than formula feed), e.g. bottle-feed using expressed milk; infant diet: planning ahead |

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 7. A celebration of birth (4 weeks) | Parent diet: information about what a healthy diet should consist of; food diaries; reflect on own diet and importance of food in the family |

| Parent physical activity: what activities are OK after pregnancy; gradually introduce more strenuous activity; leaflet with activity examples; physical activity for new mums quiz sheet; practitioner dispels myths | |

| Breastfeeding: reinforce that the more you feed, the more milk is produced; identifying someone to obtain support from; responsive feeding | |

| Infant physical activity: guidelines for baby activity; myths about physical activity for babies and infants; practitioner dispels myths; weekly age-appropriate activities; encourage structured and unstructured play | |

| 8. Bringing structure to your life (2 months) | Parent diet: healthy eating for parents vs. children; reflect on own eating patterns and provide ideas; balancing diet and avoiding takeaways |

| Parent physical activity: likes/dislikes about physical activity; activities for after pregnancy; identify barriers; integrating activity into normal life; small changes to family environment; structured activities in the house; the local area; self-talk and visualisation; choose a physical activity to learn or can already do | |

| Breastfeeding: identifying barriers; concerns about feeding baby; how to deal with life while trying to feed; encourage asking for help to enable breastfeeding to continue and other things to be accomplished | |

| Infant diet: introducing solids: why and when; follow signs of readiness for weaning | |

| Infant physical activity: structured play activities in the house without expensive toys; introducing games; recognising when baby wants to play; being flexible with playtime; making baby-active time a priority | |

| 9. Feeding and feelings (3 months) | Parent physical activity: identifying and addressing barriers; coping planning; the ’Pram Pedometer Challenge’ |

| Infant diet: what food and drinks to give; weaning: how to do it – texture and variety, developmental stages, equipment; repeated exposure and coping with food refusal; consequences of an unhealthy diet; facial expressions and tongue thrusting | |

| Infant physical activity: importance of other family members engaging the baby in activity; weekly age-appropriate activities for baby and mum; making home modifications to improve child physical activity and/or eating | |

| 10. Families and food (5 months) | Parent diet: feeding a family – what does it take; meal planning; shopping lists; healthy foods can be convenient and inexpensive; reading food labels; impact of mother eating unhealthy foods |

| Parent physical activity: review of group progress and setting goals for forthcoming weeks | |

| Infant diet: eating together; modelling behaviour and feeding role of family and parents; time issues with food planning and preparation | |

| Infant physical activity: discussion of television watching; entertaining baby/keeping baby safe when doing chores; doing activity as a family; weekly age-appropriate activities for baby and mum are demonstrated and practised; how to baby proof your house for safe physical activity | |

| 11. Making the most of your day (7 months) | Parent physical activity: review of group progress and setting goals for forthcoming weeks |

| Infant diet: weaning: how it’s going, introducing lumps | |

| Infant physical activity: visualisation and self-talk to build confidence; discussion of barriers and how to overcome them; planning for meal preparation, infant napping and active play; when can activity be integrated into normal life; environmental changes; weekly age-appropriate activities for baby and mum are demonstrated and practised; revisit discussion of sedentary behaviour and use of television | |