Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1048. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Tylee et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Overview of the programme

We have previously published the rationale and protocol for the UPBEAT-UK programme,1 how we subsequently developed the intervention for the pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) from the findings of the earlier work packages2 and the final protocol for the pilot RCT. 3 This chapter opens with a statement on patient and public involvement (see Patient and public involvement). We have then summarised the introductory sections of the published introductory papers1–3 (see Background), which has been updated with references to more recent literature. In Aims and objectives of the programme, the key objectives of the four work packages are outlined. Finally, all currently published papers from the UPBEAT-UK study are listed in Acknowledgments.

Patient and public involvement

We were able to recruit patient and public involvement representatives from mental health organisations (Service User Research Enterprise and Charlie Waller Memorial Trust), but we were unfortunately unable to recruit any patient representatives with coronary heart disease (CHD) to our programme over its duration, despite frequent attempts at contacting relevant organisations, such as the British Heart Foundation, through our research team members, including our cardiologist member. However, it would have been quite a commitment for a patient representative to give up 5–7 years and this may have been the limiting factor. This has been a disappointment, particularly as there could be an increasing role for providing such support from relevant third-sector organisations. The patient and public involvement initiative was in its infancy when these studies were set up; 10 years on we may have had a more positive response from patient-based voluntary organisations that would have become more familiar with the required task.

Background

Coronary heart disease and depressive disorders are two of the leading causes of burden of disease and disability, as measured by disability-adjusted life-years. It has been estimated, using data from the World Health Organization, that by 2030, unipolar depressive disorders and CHD will be the second and third leading cause of burden of disease, respectively, trailing only human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. 4 Surprisingly, however, while there are several guidelines worldwide for the management of both conditions separately, there are no clear guidelines on how best to manage patients who have both comorbid conditions. A key recommendation of a specially convened US Preventive Task Force on the management of depression and CHD was to conduct RCTs of stepped care to generate much-needed evidence. 5 So far, RCTs have shown that treating depression in CHD slightly improves depressive symptoms and quality of life, but has no effect on mortality. 6 Furthermore, cardiac rehabilitation (CR) together with mental health treatments may reduce depression, CHD events and mortality risk. 7 Despite this, limitations in the current literature show that further research is needed to improve psychological and cardiac outcomes in these patients.

Coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease, especially when chest pain is present, often causes functional limitation, distressing symptoms, is often life-threatening and requires long-term management, mostly in primary care. Many patients with CHD have a documented history of myocardial infarction (MI) or coronary artery disease shown at angiography. CHD also causes 70% of heart failure with fatigue and shortness of breath. CHD mainly comprises three groups of patients with: chronic stable angina (with exertional chest pain), post MI, and heart failure with a hierarchy of physical and emotional effects. The researchers at Imperial College London, on behalf of the Public Health Observatories of England, have developed a prevalence model. 8 They estimate the prevalence of CHD in primary care trusts and at local authority level to be 5.80%, although this number rises to 16.08% in people aged 65–74 years, and 21.91% in those ≥ 75 years. In the south London primary care trusts of Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham, the prevalence is 3.30%, 3.50%, and 3.85%, respectively (≥ 15% in those aged 65–74 years and ≥ 22% in those ≥ 75 years). 8

Depression

Depression is a major public health problem responsible for around 100 million lost working days in England and Wales each year and costing £9B per annum. 9 In the UK, depression is a common reason for consulting a general practitioner (GP). Up to one-third of people who visit the GP have mental health problems, and 90% of those are treated only in primary care. 10

Depression incurs a 50% increase in the cost of long-term medical care after controlling for the severity of the physical illness,11 and this may relate to the link between depression and adverse health risk behaviours such as smoking, diet, lack of exercise and poor self-care. Depression may exacerbate the perceived severity of symptoms and this, in turn, can bring about an increase in health service utilisation. Treating depression and improving outcomes for depression has been shown to reduce health costs in people with physical illness. 11 Furthermore, collaborative care and individualised management of patients with depression and chronic conditions, such as diabetes and CHD, has shown to improve both medical outcomes and depression. 12

Depression and coronary heart disease comorbidity

Depression occurs in up to 20% of patients with CHD and depression increases the incidence and recurrence of CHD, acute coronary syndromes and mortality. 5 A systematic review by Nicholson et al. 13 places the pooled relative risk (RR) of future CHD associated with depression at 1.81; however, the authors stop short of calling depression an independent risk factor for developing CHD, owing to the heterogeneity of studies.

The clear association that exists between these two conditions has led to a long discussion about the precise nature of the relationship. Ageing (which increases the odds of both conditions), lifestyle factors, inflammation pathways, heart rate variability, impaired arterial repair and several genes, are just some of the mechanisms that could play a role. 14 Nevertheless, the link is well established. A review by the American Heart Association15 recently recommended that depression be considered an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome, given the strength of the evidence in the current literature.

The presence of concurrent physical illness, such as CHD, is known to reduce the likelihood of major depression being recognised by GPs. 16 Diagnosing depression in elderly primary care patients is hampered by conditions such as heart disease and the drugs to treat these conditions, which can have mood-destabilising effects. 17 The natural history, morbidity and mortality of depression in primary care CHD populations are unknown.

As GP practices keep separate registers for their patients with heart failure, this programme of research is solely concerned with CHD and patients on CHD registers rather than patients on heart failure registers. This also means that the focus of research in terms of physical symptoms is purely on chest pain rather than on fatigue and dyspnoea.

Managing depression and coronary heart disease

Although there are several treatment options for managing depression in primary care that are endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)18 [e.g. antidepressant medication, supervised exercise, guided self-help, problem-solving, computerised cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), group or individual CBT or interpersonal therapy], the treatment preferences of CHD patients are unknown, as are primary care professional treatment preferences. A recent US working party on the management of depression in CHD concluded that RCTs comparing stepped depression care with treatment as usual (TAU) for patients with CHD and depression are needed. 5

It remains unclear how GPs and practice nurses (PNs) should best manage patients with depression and CHD. Previous research, which has been largely from the USA, has focused on treating depression with antidepressant medication, psychological treatment, case management and collaborative care. Because of the absence of available evidence in this area, we decided to conduct a systematic review and metasynthesis of available evidence in work package 1.

Medication and psychological treatment

Two large US-based trials19,20 have also provided an indication in post-hoc subgroup analyses that there may have been cardiovascular benefit from the management of the depression using antidepressant medication and it has been suggested that this may be owing to an effect on platelet activation. 21,22 Mortality seems to have been reduced in those whose depression improved or in those who took sertraline (Zoloft®, Pfizer) in one study. 23,24 This evidence was influential in the introduction of financial incentive payments to English GPs for screening consecutive CHD patients for comorbid depressive disorder under the General Medical Services Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), although this was abandoned in 2013.

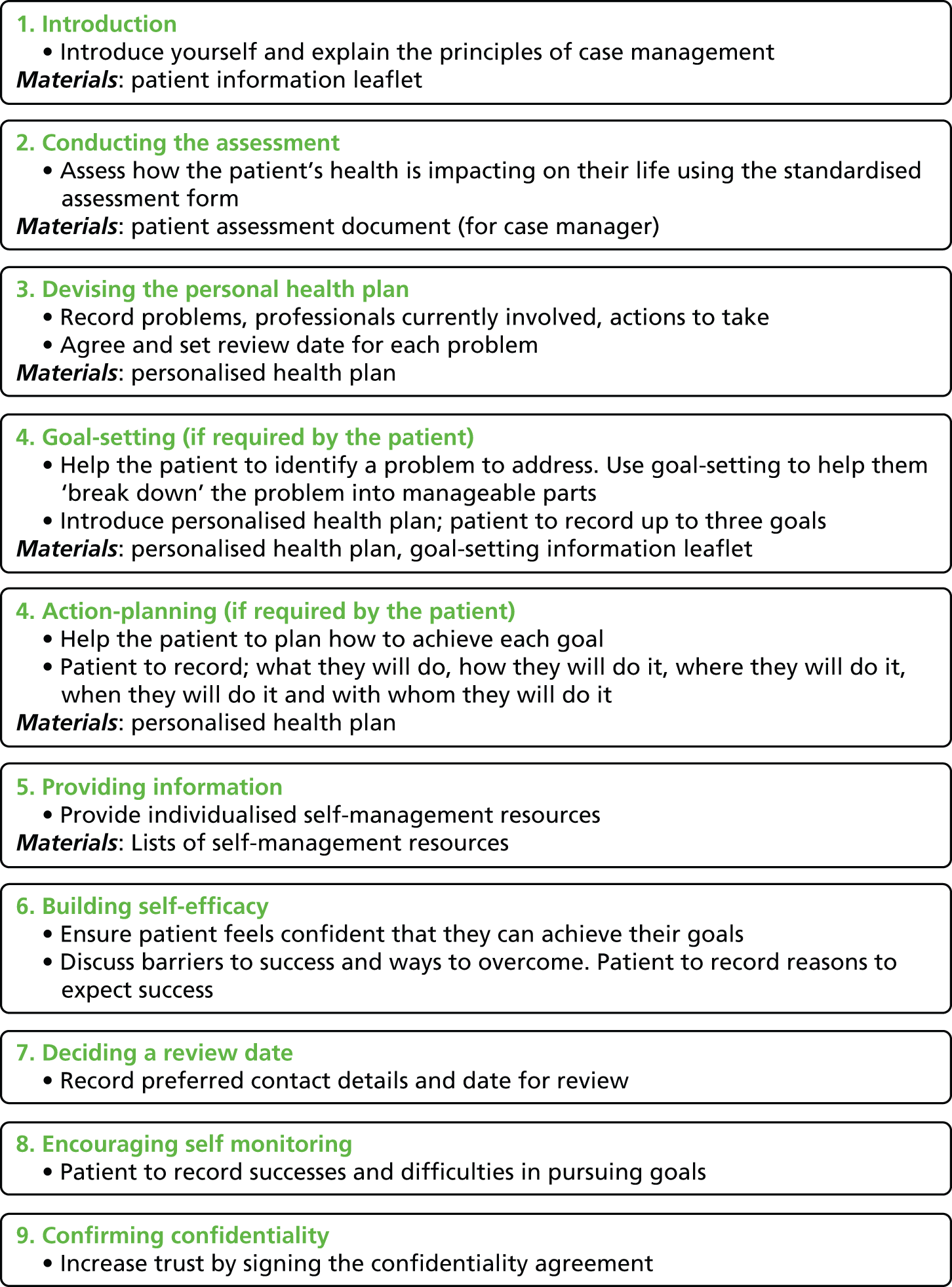

Case management

Case management has been shown to improve outcomes for depression in primary health-care settings,25 but there has been no research to determine the cost-effectiveness in patients with CHD. Case management is ‘taking responsibility for following-up patients; determining whether patients were continuing the prescribed treatment as intended; assessing whether depressive symptoms were improving; taking action when patients were not adhering to guideline-based treatment or were not showing expected improvement’. 26 It consists of five essential components:25

-

identification of patients in need of services

-

assessing individual patient’s needs

-

developing personalised treatment plans

-

co-ordination of care

-

monitoring outcomes and altering care when favourable outcomes are not achieved.

Collaborative care

An early, large US-based multicentre study of stepped collaborative depression care showed positive results regarding depression in older people as did another US trial of collaborative depression care in diabetics in motivated patients. 27,28 However, the latter trial did not improve diabetic outcome. 28 Subsequently, during the life of the UPBEAT-UK programme, Katon et al. ,12 using collaborative care, were able to demonstrate in a groundbreaking study the improvement of depression, systolic hypertension, glycosylated haemoglobin and blood lipids. As they applied rigorous nurse care to the depression, hypertension, diabetes and lipid abnormalities, it is not clear to what extent the management of depression contributed to the improvement of the physical outcome measures. Since then, and again in the lifetime of the UPBEAT-UK programme, it has been demonstrated that collaborative care as a model works in an English setting for depressive disorder, albeit with a modest effect size. 29 Collaborative care usually requires the collaboration of psychiatrists or other mental health professionals working together with their primary care colleagues to supervise case management by dedicated case workers. These care workers are usually mental health professionals brought in for the purpose of overseeing the case management and liaising with the patient’s primary and secondary care workers.

The overall design of the UPBEAT-UK programme led to a pilot RCT in order to inform a future definitive RCT of the cost-effectiveness of PN-led personalised case management in primary care for patients with CHD and depression. A pilot RCT was necessary to determine whether or not case management by PNs for this population would be a feasible and acceptable intervention compared with TAU in terms of both depression and cardiac outcomes.

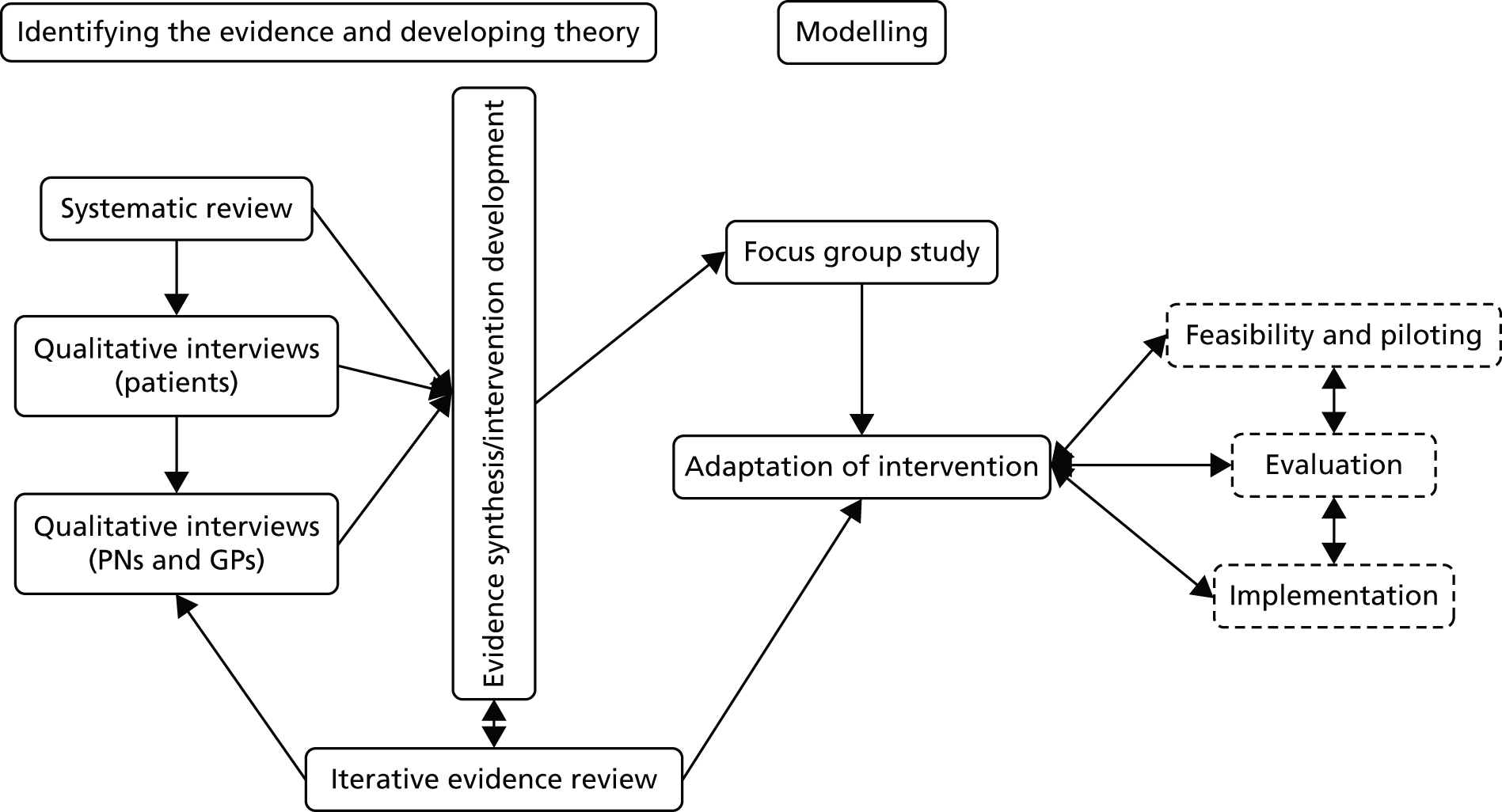

The first step was to judge the acceptability, feasibility and likely effect of case management to inform whether or not to conduct a future definitive RCT. As any future potential definitive RCT would be a complex intervention, it was necessary to follow Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines30 for the development of a complex intervention using a programme of related work packages to develop and test a new nurse-led personalised case management practice for depression and CHD in primary care. The overall scientific framework for the UPBEAT-UK programme was the MRC framework for the development and testing of complex interventions. 30 This framework has four stages:

Stage 1: development concerns the identification of existing evidence in order to develop the intervention to a point where it can be expected to have a beneficial effect. Conducting a systematic literature review or metasynthesis is recommended if such a review does not already exist. This is followed by the identification and development of theory with a rationale for the proposed intervention and likely change process. The development of theory may build on existing evidence and be supplemented with new (often qualitative) research. This should then lead to a testable model with a specific intervention, process and likely outcomes.

Stage 2: feasibility and piloting involves assessing the feasibility and acceptability of the new complex intervention and of the evaluation methods, including acceptability, compliance, delivery, randomisation, recruitment, retention, and observed variability around changes in the primary outcome to inform the power calculation for a subsequent definitive RCT. The pilot RCT examines key criteria for a definitive RCT.

Stage 3: evaluation involves the evaluation of the intervention using appropriate design usually by a definitive RCT.

Stage 4: implementation involves the routine implementation of the new intervention, surveillance, monitoring and long-term follow-up.

Stages 1–4 should be seen as cyclical rather than linear, with results from any stage informing not just subsequent stages but previous stages in continuous improvement and increasingly higher-level evaluation. 30 The UPBEAT-UK programme mainly involves stages 1 and 2 outlined above.

The four inter-related UPBEAT-UK work packages are:

-

a review of previous work in the area and qualitative study of GP and PN treatment preferences for this patient group

-

a qualitative study of patients with CHD and comorbid depression treatment preferences

-

a pilot RCT of nurse-led case management for depressed primary care patients with CHD

-

a 4-year cohort study of patients with CHD.

In this introductory chapter, the detailed methods will be described in each work package chapter.

Aims and objectives of the programme

Work package 1

A review and metasynthesis of the existing literature and a qualitative study of health professionals’ perceptions of distress and depression in patients with CHD.

Objectives

-

To review and conduct a synthesis of existing literature on primary care management of CHD and depression.

-

To explore primary care professionals’ views on distress and depression in patients with CHD.

-

To explore their current management strategies and attitudes to a range of treatments in relation to this patient group.

-

To provide guidance on the design and implementation of a PN-led case management depression intervention.

Work package 2

Study of patients’ perceptions of distress and depression in patients with CHD.

Aims

The aim was to elicit patients’ perceptions of their psychological state as linked to their CHD and explore their views on appropriate treatments for distress or depression in the context of their CHD.

Sample

Up to 50 people were to be purposively sampled from the cohort study based on age, sex, practice, CHD status, and depression severity.

Work package 3

Pilot RCT of primary care case management for depressed patients with symptomatic CHD (sCHD).

Objectives

The objectives of this pilot were:

-

Clinical efficacy of case management.

To explore whether or not case management for primary care patients with sCHD and depression, when delivered by nursing professionals, may be more effective than TAU.

-

Sample size calculation.

To calculate estimates of the location of the mean and variability around the mean [standard deviation (SD)] for the primary outcome measure (depression).

-

To enable selection of the most appropriate primary and secondary outcome measures.

-

Integrity of the study protocol.

To test all procedures for a definitive effectiveness RCT, for example:

-

inclusion/exclusion criteria

-

training of staff in the administration and assessment of the intervention

-

to test data collection forms and questionnaires

-

to ensure the acceptability of the questionnaires to participants, along with comprehensibility, appropriateness, clarity and consistency

-

patient information documents and consent forms were also tested, as was inter-rater reliability between researchers.

-

-

Randomisation procedure.

To test the randomisation process and acceptability of randomisation to primary care professionals and participants.

-

Recruitment and consent.

To test the recruitment method and the consent rate for participants, and explore barriers to recruitment of both practices and participants.

-

To determine the acceptability of the intervention and the trial to practices and participants.

To determine the possible sources of contamination, and to develop a standardised manual for case management for use in the definitive RCT. To make an informal assessment of the degree to which the intervention can be standardised and whether or not therapist effects are likely to be a major factor.

Work package 4

Cohort study

Objectives

The objectives were:

-

to determine prevalence, incidence rate and risk factors of depression in primary care patients with CHD

-

to explore and describe the course, relationship, prognosis and current management of physical and depressive symptoms in primary care patients with CHD and comorbid depression over a 3- to 4-year period

-

to determine the effect of comorbid depression on mortality, symptom severity, quality of life, disability, pain, service use (at all levels) and service costs, and lost employment costs in primary care patients with CHD.

Chapter 2 General practitioners’ and practice nurses’ perceptions of distress and depression in patients with and without symptomatic coronary heart disease: literature review and qualitative interview study (work package 1)

Plan

In the previous, introductory, chapter, we described the existing evidence demonstrating putative mechanisms linking CHD and depression. We have described how depression has previously been associated with worse cardiac prognosis and an increased cardiac mortality. We described a need to better understand the relationship between the two disorders and a pressing global public health need to improve integrated primary care for people with both disorders.

In this chapter we describe how we gathered evidence from primary care professionals – GPs and PNs – concerning their current practice, views and experience of managing depression in people with CHD, which would chiefly be people who were included on their general practice-based QOF CHD registers. We also asked a sample of south London GPs and PNs how they currently managed such patients and if there was a need for an enhanced, probably PN-led, intervention in their own general practice for their registered CHD patients complaining of chest pain and depression and if so, what they would want from such a new stepped care intervention.

Prior to commencing this qualitative study, we searched for and synthesised existing qualitative and quantitative research in general practice on the management of people with depression and CHD and used this to inform the design of our own qualitative study, especially the topics for discussion. The evidence we gathered from the metasynthesis and both qualitative studies with professionals and patients would subsequently be used to inform the development of our UPBEAT-UK pilot/feasibility intervention according to MRC guidelines30 for the development of complex interventions. How the findings from these earlier studies informed the development of our feasibility/pilot study is described in Chapter 4.

Methods

Metasynthesis of published qualitative and quantitative research

Review aim

We considered that issues important to the effective primary care-based management of depression in general are likely be important when managing depression in people who also have CHD, but that there may also be additional factors to consider when both conditions are comorbid in an individual. By systematically investigating similarities and differences in previous findings across published studies of primary care professionals’ experience of managing depression, our metasynthesis could provide high-quality evidence to inform our proposed qualitative study focused on primary care professionals’ depression management for people with CHD. This review, therefore, aimed to identify barriers to and facilitators of the effective management of depression in people with or without comorbid physical health problems in primary care settings.

Review methods

Terms relating to depression, primary care and primary care professionals’ attitudes to depression were combined to form a search strategy (see Appendix 1), which was adapted for four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and British Nursing Index and Archives). We also searched the reference lists of identified papers. This review was conducted early in the programme (search date 30 June 2008). We planned to use the findings to inform the GP and PN interviews reported in Qualitative interview study of general practitioners’ and practice nurses’ views and experience of managing depression in coronary heart disease. Hence we have not updated this review, but note that the paper in which the results were published31 has been highly cited. To obtain the most relevant and up-to-date evidence, we included only publications concerning studies that had been conducted in the UK and published after 2000. This was a pragmatic method of including a manageable number of studies and ensured we obtained data on current and relevant attitudes (2000 is after the publication of the National Service Framework for Mental Health32). We only included studies set in the UK as we felt that these would be most likely to inform an intervention that could be implemented in UK primary care; that is, studies conducted in other settings were excluded as we felt it would be difficult to understand the impact of different health-care delivery systems on their findings, which would impair their translation to UK primary care. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included. We assessed the identified abstracts for relevance and then we quality rated them according to standard recognised criteria. 33,34 We did not use quality judgements to exclude papers but tested the strength of findings by examining whether or not they were supported by studies in the upper tertile of scores. 35 We extracted key themes and synthesised them using principles drawn from meta-ethnography24 and guidelines for producing narrative syntheses. 36

Review results

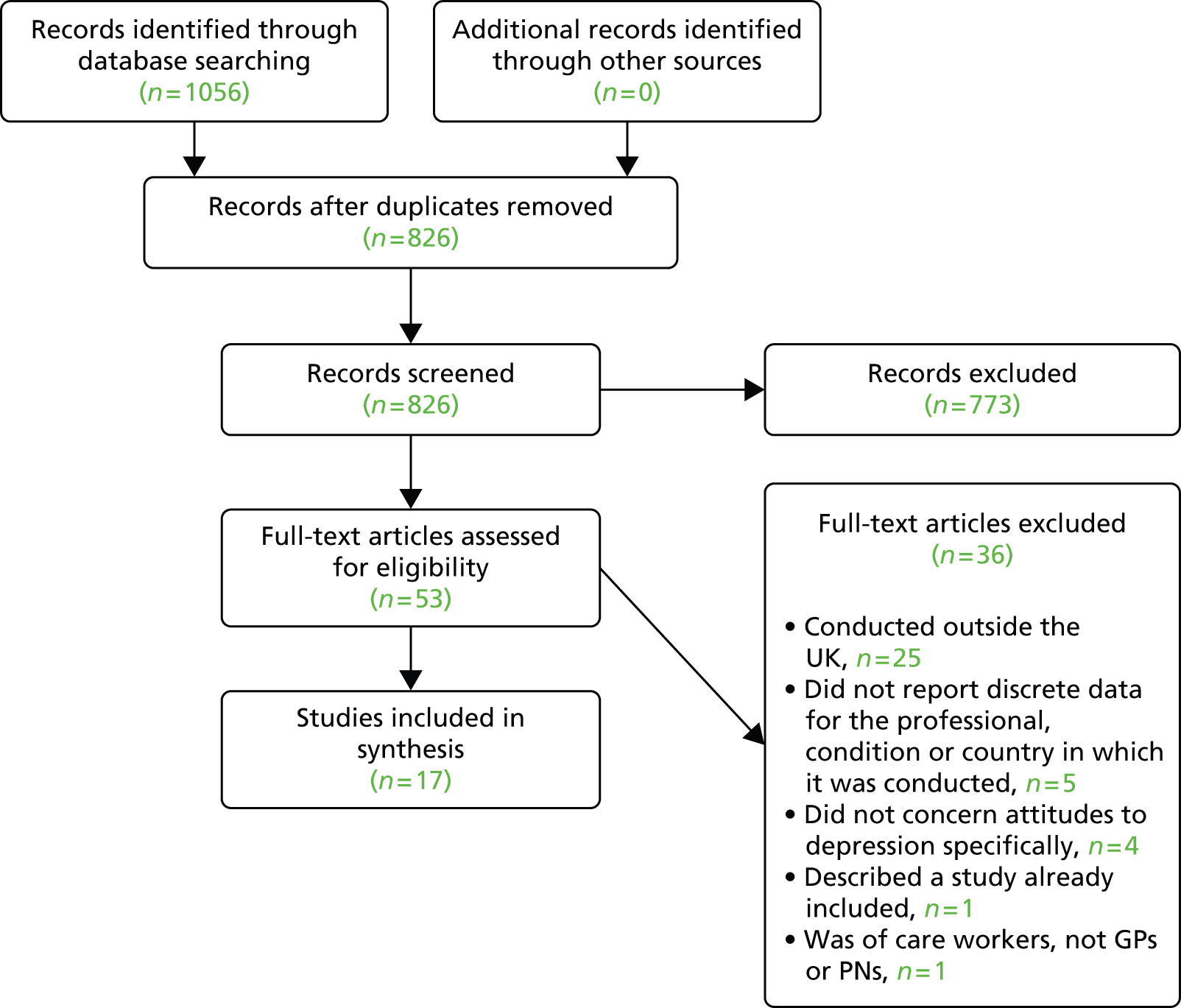

Our first finding was that no relevant paper concerning GP or PN views about depression and comorbid physical illness of any kind was identified, despite our use of a comprehensive search strategy. Seven qualitative37–43 and 10 quantitative studies of the management of primary depression were included. 44–53 Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review process.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of studies through review process. Reproduced from Barley et al. 31 © 2011 Barley et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Summary of review findings

Details of our metasynthesis findings have been published in an open access journal by Barley et al. 31 in 2011. Table 1 shows the included studies. The key themes and how they translate across the included studies are detailed in Table 2. Both tables were also published Barley et al. 2 In summary, we identified seven key themes, which were all supported by at least one good-quality study and by both qualitative and quantitative data. The first theme concerned professionals’ understanding of depression; depression was either seen as a normal response to life events, or biomedical explanations were given. The second theme concerned how clinicians recognise depression and highlighted how they struggle to distinguish between ‘normal’ distress and depression requiring treatment. Management options for depression made up the third theme, with clinicians expressing a preference for talking therapy over antidepressants, but also for being able to take a personalised approach. Shame and stigma around depression arose as a fourth theme; it was felt that this prevented some patients seeking help, but the authors of one study considered that this may be constructed to hide a reluctance to explore depression, with patients arising from a desire to avoid feelings of powerlessness when management options seem limited. A lack of interprofessional working within primary care was the main finding within our fifth theme. Our sixth theme showed that clinicians may have ambivalent attitudes to managing depression; this was reflected in our final theme which showed that although primary care clinicians felt that they needed more training in mental health, when this was offered, they did not take it up. Key findings in relation to these themes were that GPs and PNs consider depression and its diagnosis to be complex. There was ambivalence about the use of case finding tools in primary care settings, such as those that were recommended at the time for use in people with CHD and diabetes in the QOF. 56 However, most studies identified in our search did not discuss these as they had been conducted and published prior to the introduction of financial incentives under the QOF of the UK GP contract56 in 2006 when their use became routine.

| Reference | Participants (response rate) | Aim | Setting and sample selection | Methods of collecting clinician data and research perspective (quality assessment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative studies | ||||

| Johnston et al., 200737 | 32 GPs (24%) | Identify issues of importance to GPs in depression management | 28 GP practices in and around Southampton (plus two GPs in Leicester) | Semistructured interviews; grounded theory (10/10) |

| Murray et al., 200638 | 18 GPs, 7 PNs | Identify perceptions of depression older people | 18 south London primary care teams in five Boroughs, purposive sampling based on setting (socioeconomic/ethnic groups served) and practice type | In-depth, semistructured interviews; grounded theory (9/10) |

| Burroughs et al., 200639 | 9 GPs, 3 PNs | Explore how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression | One PCT in NW England, purposive sampling but criteria not stated | Semistructured interviews; constant comparison (7/10) |

| Maxwell et al., 200540 | 20 GPs | Explore GPs’ experience of recognising and managing depression | 11 practices from a ‘random’ sample of 55 in Scotland – four NHS board areas | Semistructured interviews; critical realist perspective (5/10) |

| Pollock and Grime, 200341 | 19 GPs | Investigate GPs’ views on consultation time and depression management | Eight West Midland practices – purposeful selection based on socioeconomic/geographical setting and patient list size | Semistructured interviews (8/10) |

| Chew-Graham et al., 200242 | 35 GPs in teaching practices (66%) | Explore GPs’ attitudes to the management of depression in deprived vs. affluent populations | 22 inner city GPs vs. 13 suburban and semirural GPs in NW England, purposive sampling based on practice size | Semistructured interviews; constant comparative qualitative analysis (9/10) |

| Rogers et al., 200143 | 10 GPs | Explore GPs’ views on depression management | Eight practices in Greater Manchester (inner city/suburban) | In-depth, semistructured interviews (5/10) |

| Quantitative studies | ||||

| Kendrick et al., 200544 | 17 GPs | Explore associations between GP treatment, depression severity and patient characteristics | Six GP practices in Southampton (nine practices approached) | Questionnaire (devised for this study) ratings of patient characteristics and GP treatment decisions completed following consultation (3/7) |

| Shiels et al., 200445 | Four GPs – three principals, one assistant | Compare GPs’ and male patients’ assessments of depression | One practice in a prosperous rural area of Cheshire | Questionnaire (devised for this study) completed following consultation (3/7) |

| Naji et al., 200446 | 442 PNs (56.2%) | Assess PNs’ knowledge, attitudes, training and management of depressed patients | One in two sample of Scottish general practices (428 practices) | Questionnaire – DAQ54 plus some questions developed for this study, postal survey (5/7) |

| Manning and Marr, 200347 | 202 GPs (50%) | Compare expectations of GPs and patients in the management of relapse of depression | GP practices ‘across the UK’ | Questionnaire – devised for this study by a market research company, postal request sent with link to online questionnaire (2/7) |

| Byng et al., 200348 | 274 GPs | Describe GPs’ beliefs about their management of depression | All GPs in Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham Health Authority (inner city) | Likert scale questionnaire – (devised for this study, but piloted on 15 GPs) (4/7) |

| Oladinni, 200249 | 61 GPs (60%) | Assess the attitudes of GPs towards depression | Inner city GP surgeries in Lambeth (group and single handed), ‘randomly’ selected | Questionnaire (DAQ) – postal survey (2/7) |

| Telford et al., 200250 | 1703 GPs (48%) | Survey GPs’ perception of the availability/quality of primary care and community-based services for depressed people. Identify barriers to provision of services | 11 health authorities – one from each English region and one each from Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland. Urban, rural, deprived and privileged | Questionnaire – devised for study, piloted on 131 GPs; postal survey (4/7) |

| Rothera et al., 200251 | 263 GPs (72%) | Examine the attitudes and practice of GPs in managing late-life depression | All 116 practices in Nottingham Health Authority | Postal survey (adapted for study from previous research) – responses to attitude statements and clinical vignettes (4/7) |

| Dowrick et al., 200052 | 40 GPs | Test hypotheses that measures of GPs’ confidence in identifying depression predict ability to identify depression and that GPs who prefer antidepressants prescribe more than those who prefer psychotherapy | Practices in Liverpool and Manchester | Questionnaire (DAQ), prescribing information, Likert scale depression ratings (3/7) |

| Livingston et al., 200053 | 31 GPs, 24 PNs (12% of practices approached) | Assess acceptability and feasibility of an educational package concerning management of depression in old age | 14 practices in West Essex, East Hertfordshire, Redbridge | Vignettes and questionnaire (adapted DAQ for older people) (baseline data only used in synthesis) (4/7) |

| Summary second order constructs | Extracted key themes (authors’ ‘own words’ or paraphrase)55 | Summary translation across studies |

|---|---|---|

| Professionals’ understanding of depression | Constructing and resisting boundaries between depression, the self and ‘normal’ sadness37Depression as a normal response to life events42Inconsistency between beliefs and practice43Concerns surrounding the medicalisation of social problems40Depression as ‘understandable reaction to distressing circumstances’38Aetiology of depression49Nature of depression49,52,53 | Depression may be seen as a normal reaction to distressing events or as pathology. Understandings of depression may conflict with management strategies |

| Recognising depression | Potential for secondary gain42GPs’ accounts of diagnosing and caring for patients with depression40GPs’ experiences of the diagnosis and management of depression43consultation length/time and disclosure41Presenting complaints38Distinguishing between depression and physical illness42Avoidance of psychosocial problems38Making the diagnosis39Accuracy of diagnosis44–46,52 | Recognising depression is a complex process involving non-explicit subjective processes. Some see patients as reluctant to talk about their mood. Somatisation is common. Somatisation and/or comorbidity may complicate diagnosis. Receiving or giving a diagnosis of depression may benefit patients and GPs |

| Management strategies and tools | GP goals and management approach37GPs’ accounts of diagnosing and caring for patients with depression40GPs experience of the diagnosis and management of depression43Importance of listening37Time as a barrier to listening42 Time and consultation length, disclosure, antidepressants, time management41Management of late-life depression in primary care39Antidepressant use44,47–49,52 Role of specialist services50 Managing depression46 |

Clinicians used antidepressants, talking therapies, listening and specialist services. Listening to depressed patients takes time; this may be a barrier to effective treatment, but one in-depth study contested this |

| Stigma and shame | Stigma and shame38depression still carries a stigma in this age group39 | Depression is perceived as stigmatising for some elderly people, especially those from ethnic minority groups |

| Relationships between professionals | Primary care relationships39PNs’ position in the practice38 Confusion over the role of and lack of access to specialist services43,46,50scarcity of counselling resources41 |

There is confusion between primary care staff concerning their roles and responsibilities in the diagnosis and management of depression, and about the role of specialist services, which seems focused around lack of access |

| Attitudes to managing depression | GP responses to chronic depression37Interactional difficulties with depressed people42Pessimistic about outcome43 Positive about outcome40,41 Lack of confidence in managing depression39,46,48,53 Ambivalence49,51 |

GPs and PNs experience frustration in managing depression. Some are confident about outcomes, but commonly there is ambivalence |

| Training needs | without understanding the framework which underpins GPs views on ‘depression’ . . . educational interventions directed at GPs will not improve patient outcome42Lack of training and knowledge39,46,50,51,53education efforts should focus on increasing GPs’ sense of therapeutic optimism and providing them with sufficient skill in and knowledge of a range of psychological procedures52GPs would benefit from educational programmes that promote awareness of current treatment guidelines47 | Many PNs and some GPs say they need more training in managing depression, but this is not a priority for them. Training should be grounded in professionals’ understandings of depression and should seek to improve attitudes to working with depressed people |

Not all information was available for each study. Quality assessment score: higher score represents higher quality, qualitative studies scores out of 10 on critical appraisal skills programme checklist;33 quantitative observational studies scores out of seven on a scale devised for this study (see Appendix 2; also published in our metasynthesis paper31).

All translated second-order constructs were supported by at least one good-quality study (bold references are studies scoring in top tertile of quality scores: qualitative studies ≥ 8/10, quantitative studies ≥ 4/7) and by both qualitative and quantitative studies.

The management of depression in a general practice setting is perceived as particularly complex when patients also present with concurrent social problems. GPs and PNs are very aware of the relationship between social problems and mood, but they are unsure of its exact nature and of their role in managing it. This uncertainty may be exacerbated by a lack of attention in guidelines concerning the influence of social problems on response to treatment. 54

There are ambivalent attitudes among GPs and PNs towards working with depressed people. This was reflected in a lack of confidence among some clinicians in their ability to manage mental health problems and the use of a limited number of management options. Most of these data are from GPs, perhaps because PNs may be less likely to manage depression than GPs; however, where depression is comorbid with physical illness PNs’ views may be more important since they are taking an increasing lead in long-term condition management and particularly since practices began to be reimbursed for screening their diabetic patients and patients with CHD for depression under QOF, although this payment has since ceased.

There was also evidence that GPs avoid giving a diagnosis of depression based on a belief that some patients, especially older people and those of Caribbean or South Asian ethnicity, will feel stigmatised by it. One high-quality study39 suggested, however, that concern about stigmatisation might be constructed to hide a reluctance to explore depression in order to avoid feelings of powerlessness when management options seem limited. At the time of the review, there were no data available to determine whether or not the same issues are important when managing patients with depression and comorbid physical illness. We, therefore, used the findings of this review to inform our planned study of GPs’ and PNs’ views and experience of managing depression in CHD.

Our review had demonstrated variation both between and within studies in views expressed concerning the management of depression in general. When considering the management of depression comorbid with CHD, we therefore decided to use a semistructured interview design. This would allow us to focus the interview on the topics that we considered important for informing our future intervention, while allowing participants to highlight topics important to them. Similarly, we realised that it would be important to use an iterative process for the data collection and analysis so that new themes arising in early interviews could be tested with later participants. The review findings also informed our topic guide (see Appendix 3). With the plan to develop a new intervention in mind, we ensured that each interview would cover three broad areas: defining depression in CHD, current management of depression in CHD and future management of depression in CHD. The key findings from our review related to each broad area were then used as prompts during the interview. In this way, we were able to test whether or not the findings of our review were relevant when considering depression in people who also had comorbid CHD and which issues would need to be addressed by the future CHD-specific intervention. For instance, when asking clinicians about how they defined depression in CHD, if they did not mention social problems (which we had found in our review to be important), we planned to prompt them to consider this issue. Hence, our metasynthesis allowed us to conduct a more relevant and focused qualitative study, which is described in the following section.

Qualitative interview study of general practitioners’ and practice nurses’ views and experience of managing depression in coronary heart disease

Study aim

This qualitative interview study was designed to help understand GPs’ and PNs’ views and experience of managing depression specifically when it is comorbid with CHD and to determine their preferences for our planned UPBEAT-UK nurse-led pilot intervention for people with CHD reporting chest pain, which could be angina or non-anginal chest pain, and depression.

Study methods

The initial sampling frame was the 16 GP practices participating in our cohort study, the design of which is described in Chapter 5. In recruiting the participants from these practices, we used a purposive, maximum variation approach to recruitment based on ethnicity, age, practice setting (inner city vs. suburban) and size (single handed vs. group). After several interviews, we noticed that participants often mentioned their involvement in our cohort study and we became concerned that this was an indication of heightened awareness of depression in CHD. From then on, only those clinicians from UPBEAT-UK practices who were not personally involved in the cohort study were interviewed. We also used a snowballing technique to identify GP and PN participants independent of the UPBEAT-UK research programme, that is, practices that we had not recruited to the cohort study.

We conducted individual semistructured interviews using a topic guide (see Appendix 3) based on the findings of our metasynthesis. We revised the topic guide iteratively: for instance, early participants introduced the problems of ‘erectile dysfunction’ and ‘housebound patients’ so we explored these topics with later participants. In order to ground opinions in practice, we asked participants to recall specific patients. We audio-recorded the interviews and transcribed them verbatim following written informed consent.

We conducted the interviews and analysis concurrently, and stopped recruitment at data saturation; that is, when no new themes or information emerged. We applied a staged procedure of thematic analysis to the data57 adding rigour to the process with the techniques of constant comparison. 58 Three researchers (EB, JM and PW) independently coded the first interview and met to discuss preliminary descriptive codes. Following this, two of the researchers (EB and JM) independently applied these and, where appropriate, new codes to the following four transcripts when consistency in coding was achieved. Descriptive codes were collated into themes and a preliminary explanatory framework devised. This was then used as the basis for coding and for informing future interviews. Data for each theme were gathered and coded using computer software (NVivo version 8; QSR International, Warrington, UK). The robustness of themes was tested by examining differences and similarities between coded data.

Study results

In total, EB interviewed 10 GPs and 12 PNs. Male and female GPs were recruited but no male PNs were identified. GPs and PNs appeared to have similar views. We have published the findings of this study, including illustrative quotes and participant details, in open access journal papers by Barley et al. 2,59 in 2012. The identified themes and topics discussed are listed in Box 1 and the main findings are summarised below.

Distress vs. depression.

Distress or depression in CHD.

-

vs. ‘general depression’.

-

vs. depression in other chronic diseases.

-

CHD severity.

-

Why some CHD patients become depressed.

-

Disease impact.

-

Individual difference.

-

Social factors.

-

Illness perceptions.

Impact of understandings on decisions to treat.

Theme: recognising and screening for depressionQOF questions.

-

Benefits of QOF questions.

Reservations about QOF.

Clinical judgement.

Theme: assessing the severity of depression Theme: current management of depression in CHDManagement goals.

Current management options.

Choosing management options.

-

Antidepressants.

-

Talking therapy.

-

Informal counselling.

-

Exercise.

-

Specialist NHS and community services.

-

Other issues influencing management choices.

Erectile dysfunction.

Housebound patients.

Theme: future intervention for depression in CHDType of intervention.

Timing of intervention.

Who would deliver the intervention.

Summary of study results

Current attitudes and practices

General practitioners and PNs expressed diverse views, which indicates uncertainty about this topic. However, for most of the themes, a majority view could be identified, even if some individuals also offered alternative opinions. For instance, most of the participants appeared to consider CHD depression similar to other types of depression. Distress and depression were viewed, by most, as lying on a continuum of severity and/or chronicity. Individuals may ‘naturally’ become distressed following a diagnosis of CHD or a cardiac event, but only when the distress becomes severe and enduring is it seen as depression requiring treatment.

Most participants used the QOF questions to screen for depression, followed by a more detailed questionnaire, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) or the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); however, use of additional questionnaires was not routine, even when responses to the QOF questions were positive (indicating possible risk of depression or a need for further exploration). In several practices, PNs did not have access to the detailed questionnaires, suggesting that there may be ambivalence towards their use. That most participants stressed the importance of their clinical judgement both in assessing depression and making management decision supports this. These findings are also supported by a recent study which also showed that although GPs used the questionnaires, they preferred to rely on their ‘practical wisdom and clinical judgement’ to guide their assessments. 60

The clinicians identified a range of management options for CHD depression. Antidepressants and talking therapies were most often cited. This is not surprising since each of these treatments or a combination is known to be effective for depression in other populations. There is also some evidence that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may have a direct beneficial effect on platelets,61 although only one GP in our study, who is also an academic, mentioned this. However, in CHD depression, many considered antidepressants as a last resort. This appeared to be owing to a perceived reluctance in CHD patients to accept them, either because of fear of stigma associated with mental health problems or to a general dislike of medications, which is exacerbated when patients are already taking multiple medications for their heart condition. Data from patients are required to assess the validity of this perception.

Talking therapies were favoured; however, only a few GPs differentiated between types of therapy. This suggests a lack of clarity about the aims and process of different therapies, which may reduce their ability to make appropriate referrals. Some patients had been observed to reject talking therapy, again out of fear of being stigmatised. However, the main barrier to the use of talking therapy was a lack of availability. This has been reported previously. 42 It appears that the government’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme has not yet reached these south London practices. 62

Access to other management options that clinicians felt would improve aspects of CHD depression, such as exercise on referral schemes, clubs to reduce loneliness and agencies to help with financial or housing problems, varied widely between the practices. Furthermore, there was variation between clinicians in their knowledge of the availability of such options. This may reflect variation in clinicians’ attitudes to managing problems that they believe are social in origin. Previous research39 has identified ‘therapeutic nihilism’ in which clinicians feel helpless in the face of the complex social problems which impact on their patients’ health. This attitude was seen in several participants in this study, although others actively sought to address social difficulties; one GP even expressed enjoyment in this aspect of her work. This latter attitude is encouraged in the government White Paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: A New Direction for Community Health Services. 63 This calls for greater integration of health and social care for patients with long-term conditions. One method may be ‘social prescribing’, which signposts patients to non-medical facilities and services available in the wider community, such as financial advice agencies and social clubs, which they can access to address the factors that influence their well-being. One practice involved in this study was providing this service, but our findings suggest that there is considerable scope to develop this for CHD depression in south London.

Informal counselling activities, such as reassurance and education, were performed by all the participants to some extent. With a few exceptions, most GPs were unwilling or unable to give much time to this. Some PNs reported that they did have the time, but even among these, there was doubt about how useful this was and many were left wondering how to progress and so would welcome guidance. Other nurses were open that they did not enjoy dealing with mental health problems or that they did not consider it to be part of their role either owing to lack of training or interest. These nurses would avoid raising the possibility of depression for fear of ‘opening a can of worms’ with which they felt unable to cope.

Future coronary heart disease depression intervention

This study has identified issues that should be addressed when designing a new CHD depression intervention. Findings from this study, along with those from previous work, may inform the type of intervention, the timing of the intervention and who should deliver the intervention.

Type of intervention

The participants were very clear that any intervention should be easily accessible. This was both in terms of being carried out locally, as they had observed a reluctance or inability in many patients to travel, and in terms of having clear and simple referral criteria so that clinicians would not be burdened by having to remember complex rules. Some participants reported difficulties remembering what treatment options and facilities were available for the multiple conditions that they managed; this could be a barrier to effective treatment.

The need for multiple treatment options was also stressed. This was so that options could be matched with the varying needs identified in individual CHD patients; because the participants recognised the importance of patient choice in improving adherence to treatment; and because clinicians value the opportunity to use their clinical judgement. Interventions that improve adherence to treatment were considered especially important as most of the clinicians considered that this was poor in CHD patients. However, although clinical judgement was valued, several nurses said they would favour the development of a protocol to guide their management decisions. This appeared to arise from their reported uncertainty as to what management options are available and appropriate for CHD depression.

Any new intervention should be evidence and theory based. Having goals and social support are known to be important to well-being. 64 Although no participant specifically mentioned goals, several noted that the causes of depression are specific to individuals and that to be effective, management plans should be patient driven. Evidence-based interventions that involve patients deciding which areas of their lives to address, such as problem-solving therapy, motivational interviewing or the technique of ‘SMART goals’, where individuals identify an area to change that is Specific, Measurable, Appropriate, Realistic and Timely, may therefore be useful in CHD depression and would most likely be accepted by GPs and PNs.

All participants mentioned the importance of social support. Some raised the role of the family in directing patients to care and helping with self-management. Most participants stressed the importance of combating isolation, which they felt is a determinant of depression in many CHD patients. This issue was considered to be especially relevant to housebound CHD patients, for whom, in many practices, no specific system of care had been devised. Identification by the patient of an individual who can support them in their self-management is a commonly used and effective strategy in several health-care interventions, for example weight loss and health training. 64 This type of intervention may be appropriate for many CHD patients and would be supported by GPs and PNs.

Cognitive habits are known to influence depression and, as such, CBT is now an established treatment for depression. 65 Similarly, in chronic disease, the ways in which individuals think about their illness and approach its management are known to influence outcome. 66,67 Given the strength of this evidence, it is surprising that cognitive factors were not discussed in detail or by all participants. It appears that some of the clinicians considered physical and mental health separately and were more focused on the former.

Some participants, however, did mention the importance of cognitions such as illness perceptions and motivation or commitment to change in improving mood or health in general. Some participants said they or a colleague within the practice had had training in brief cognitive interventions such as ‘10-minute CBT’68 or problem-solving therapy. 69 It appears that GPs and PNs vary in their understanding of and willingness to address cognitions when managing CHD depression. A new CHD depression intervention is likely to be most effective if it involves some level of cognitive change in the patient. Increasing self-efficacy, motivation, readiness and commitment to change, and changing illness perceptions have all been shown to improve outcomes in a range of chronic illness, including heart disease. 67 Some GPs and PNs may need education to accept such interventions.

Timing of the intervention

The participants were divided into whether an intervention for CHD depression would be most effective if delivered immediately following a cardiac event or several months later. The rationale for early intervention was to prevent the distress that they believed is commonly experienced following a CHD diagnosis or cardiac event from developing into a lasting depression. An early intervention should, therefore, focus on helping the patient come to terms with the feelings, observed by the clinicians, of shock and vulnerability and help them to adjust to changes in role or functioning. However, several clinicians felt that the majority of people recover without intervention. Previous research has shown that the medical condition and depression status of individuals within 6 months of MI fluctuate. 5 It has been suggested by an expert panel on depression and CHD5 that a population whose depression is likely to remit spontaneously may not be the best group in whom to test the hypothesis that reducing depression will reduce the risk of CHD-related mortality and morbidity.

However, the panel also point out that early treatment with antidepressants, as opposed to depression symptom interventions, may be appropriate, to the extent that the former may have direct cardiovascular benefit. A further argument for early intervention concerns the role of illness perceptions in disease progression, which is well documented. 67 This issue was raised by two participants who felt that patients could be disabled more by their perceptions than by their actual CHD severity. There is some trial evidence to suggest that early modification of illness perceptions may lead to improved outcomes. In a small RCT,70 inpatients who received a brief intervention designed to alter their perceptions about their MI had improved functional outcomes and reduced angina symptoms compared with controls at 3 months post discharge.

The participants’ rationale for a later intervention, that is, some months after an event or initial diagnosis, was that if spontaneous recovery had not occurred, CHD-associated distress would have become chronic and therefore could be described as depression that needed treatment. Patients had, therefore, not adapted to having CHD or to its effects. Effects, such as loss of function or role due to CHD, and symptoms, such as erectile dysfunction (which may occur any time in CHD and up to 5 years prior to diagnosis,71 were identified as particular predictors of depression. These may need to be addressed at this time. It was also suggested that after a few months, when their medical condition has stabilised, the support available to CHD patients, such as CR and outpatient appointments is reduced. This may increase patients’ risk of depression.

A complicating factor when deciding on the timing of a new intervention is that many participants were aware that their CHD patients were depressed prior to their diagnosis or cardiac event. This was explained in terms of the difficult social lives that many patients in south London lead; CHD was just another problem that added to their depression. An intervention that addressed multiple problems would therefore be necessary for such patients. This could be delivered at any time following diagnosis.

Findings from this study and from previous research therefore indicate that it is likely that different types of intervention may be more or less effective at different times following diagnosis or a cardiac event.

Who should deliver the intervention?

The participants of this study varied in their opinions as to who should deliver or manage a new CHD depression intervention, although no one suggested that a GP should lead. There was a majority opinion, however, that there is currently no suitable person within primary care, at least, not without training. It was felt important that the person delivering the intervention should be knowledgeable about and have experience of managing both CHD and depression.

The PNs were all experienced in managing the physical aspects of CHD, but their confidence and interest in dealing with psychological problems varied widely. This could be addressed through training. Nurse-led psychosocial interventions have been shown to be effective, including in heart disease. 72,73 However, many nurses complained of a lack of time. A previous study41 has shown that it is possible to have a flexible attitude to time management in primary care in order to manage depression effectively. This was supported by data from GPs and a PN in one practice where the policy was to be flexible with time in order to address their patients’ psychosocial needs. The observation from this study that PNs with 30-minute, as opposed to the more usual 15-minute, appointments often tended to be more willing to provide informal counselling to depressed CHD patients also supports this. If the new CHD depression intervention is to be delivered by PNs, it could be made attractive to them if it could be shown that it would save them time. This may be achieved by pointing out reports by PNs, gathered during this study, that they currently spend a lot of time delivering informal counselling despite being unsure that it is effective.

Finally, this study has identified that some primary care clinicians may be reluctant to raise the subject of depression with their CHD patients. In addition, several of the clinicians perceived that their patients were also unwilling to do this or to accept treatment. This may explain findings that depressed patients with comorbidity, including CHD, were less likely to be treated for depression. 74 In this study, one reason cited for this reluctance to discuss mood was fear of stigma, both in patients, who did not want to be stigmatised, and doctors, who did not want to create stigma. Stigma around mental health is well documented. 75 Some participants suggested that the use of screening questionnaires helped them to raise mental health issues in a non-threatening manner. This is supported by recent findings that patients liked their GPs using questionnaires as they saw them as an efficient and structured supplement to medical judgement and as evidence that the doctor was taking their problem seriously. 60

Other reasons for not addressing mood were lack of confidence or interest in treating mental health problems, prioritisation of physical health problems and a belief that ‘nothing could be done’ about the depression, which occurred mainly when depression was perceived to stem from social difficulties. These views suggest that, although they are very aware of the social difficulties experienced by their patients, some clinicians are still working with a biomedical model of health, where mental health and physical health problems are viewed as separate entities. This is despite the widespread acceptance of the biopsychosocial model76 as a more useful explanatory model of health. 77

Adoption of the biopsychosocial model may empower clinicians to manage mental health problems that they see as social in origin. Care systems built around an understanding that physical and mental health are interlinked and occur in a social context may lead clinicians to explore management options other than those that are traditional within primary care, for instance local clubs to combat isolation and advice agencies. Some of our participants were aware that such facilities may be useful, but there did not appear to be any system for identifying local facilities or for matching them to their patients’ needs. For this to work, such facilities must be available and accessible. This study shows that provision does vary within the limited geographical area of south London, but also that many clinicians are not fully aware of all the local facilities that are available to them. Any new intervention should aim to optimise use of existing facilities.

Therefore, as well as aiming to improve patient health, any new intervention for CHD depression should aim to increase clinicians’ awareness of the inter-relationship between physical and psychological health, and the social context in which it occurs. It should also be aimed at increasing primary care clinicians’ feelings of self-efficacy in managing complex psychological needs that may appear to be social in original.

Conclusions

The study suggests that for many GPs and PNs, only depression that is severe and chronic is considered to need treatment in CHD. QOF screening questions are valued in detecting depression, but use of these is not routinely followed up with a more detailed questionnaire, such as the PHQ-9, which may be more accurate. Routine use of more detailed questionnaires, especially by PNs, many of who currently do not have access to these, may increase identification of CHD depression.

The GPs and PNs in this study felt that managing depression in CHD was worthwhile. To be accepted by clinicians and patients, a new intervention should have clear referral criteria and be local to the practice. The participants valued their clinical judgement and recognised the importance of patient choice in successful management; a new intervention should offer a range of treatment options that clinicians and patients can select together. These should include options for problems identified as exacerbating or causing depression in CHD, such as erectile dysfunction and being housebound. This study suggests that housebound patients currently may not receive adequate psychological care. Many clinicians felt that exercise is useful in managing CHD depression; there may be potential to develop this as a management option.

Depression in CHD may be exacerbated by, or may exacerbate, distress or depression associated with social problems. Potential exists, in CHD depression management, for greater use of existing local resources to combat problems common in CHD, such as social clubs for loneliness or agencies for financial or housing advice. However, clinicians vary in their perceived responsibility and ability to manage such problems. Some may need to be supported and empowered to manage problems that they consider social in origin.

Similarly, despite good evidence that cognitions are important predictors of response to chronic disease and that changing cognitions may improve health outcomes, GPs and PNs appear to vary in their understanding of this. A new CHD depression intervention should include education for clinicians concerning the role of cognitions such as illness perceptions, self-efficacy and motivation in chronic disease management.

Factors associated with depression in CHD may vary according to the time elapsed following receipt of a diagnosis or a cardiac event. Distress or depression immediately following diagnosis or an event may resolve spontaneously in many patients. An early intervention to manage unhelpful illness perceptions may reduce the number of patients whose distress or depression does not resolve. In patients whose depression is persistent, a more complex intervention may be needed to address adjustment problems or social issues which are exacerbating the mood problems.

Finally, this study suggests that there is currently no suitable professional within primary care to deliver a CHD depression intervention, at least not without training. Some nurses say that they would be willing to be trained to do this, but others would need persuasion owing to a lack of interest in or perceived responsibility to manage mental health problems. Given their current heavy workload, all PNs would need to be convinced that any new CHD depression intervention was effective and would have timesaving benefits. Time may be saved by reducing the time spent in informal counselling, which the PNs report to be time-consuming and of uncertain benefit.

Summary: what we learned from reviewing existing literature and conducting our own qualitative study

The findings of our metasynthesis of studies of primary care management of depression in general and our qualitative study of primary care management of depression comorbid with CHD were complementary. On balance, GPs and PNs expressed uncertainty in the management of depression, citing lack of time, training and available management options that are acceptable to patients. That these findings were similar for our metasynthesis and this qualitative study indicates that GPs and PNs have similar struggles when managing depression whether or not it is comorbid with CHD. Social problems, in both studies, were seen as important contributing factors, which should be addressed; our qualitative study indicated that these might be especially important in CHD patients who often come from low socioeconomic groups. However, GPs and PNs are uncertain in their role in and responsibility for addressing social problems and existing resources are underused; a finding from both our review and this qualitative study which highlights the need for a new intervention to help address this. Nurses’ attitudes towards and confidence in managing depression varied enormously. This was a finding of both our review and qualitative study, and, as primary care patients with CHD commonly receive most of their care through nurse-led clinics, suggests that the development of interventions for depression in these patients should include sensitive consideration of nurses’ views.

By asking clinicians, in our qualitative study, to consider depression comorbid with CHD, we not only confirmed that the findings of our review were relevant when managing people with CHD, but also identified issues that may be particularly important to people living with CHD. For instance, erectile dysfunction is a common problem that is not addressed routinely despite clinician awareness that this can contribute to depression and that if people with CHD become housebound, they are unlikely to receive any help for depression.

Strengths and limitations

Through the inclusion of only recent studies conducted in the UK, we ensured that our metasynthesis produced findings relevant to current practice within the NHS; findings may be less relevant to those wishing to develop interventions in other health-care systems. The aim of our review was to identify broad themes concerning depression management in order to inform our qualitative study focusing on managing depression when it is comorbid with CHD and hence we excluded studies focusing on specific aspects of the management of major depression such as antidepressant use. These more specific aspects of management were, however, addressed in our qualitative study focusing on their relevance to people with comorbid CHD. As is the case with all metasyntheses, we had to make decisions concerning which studies to include; we have detailed our methods clearly but others conducting the same review may have selected different studies. The findings of our review and qualitative study were, however, concordant, indicating that our choices were appropriate and that we produced robust findings to inform our intervention.

The findings of our metasynthesis were extremely useful in ensuring that our qualitative interviews were focused on known barriers and facilitators to managing depression in the UK; this information was essential in ensuring that our intervention would be feasible to deliver in primary care. However, we also used an iterative process of data collection and analysis so that new topics could be explored in subsequent interviews. For instance, the idea that depression in some people with CHD may be compounded by erectile dysfunction or by being housebound had not been identified in our review. Such findings emphasised the need for a future intervention to be personalised in order to address the varying needs of individuals. A potential weakness is that our participants were all practising within south-east London; however, we were careful to recruit from areas of contrasting deprivation and affluence in order to elicit a range of experiences.

It should also be noted that, as in the case of all qualitative research, it is possible that our positionality influenced our final findings. For instance, the UPBEAT-UK programme was funded to consider the ‘problem’ of depression comorbid with CHD and this informed our methodology. Had we conducted a study about the impact of illness on well-being and health as a resource for daily living, our findings may have been different.

Finally, since we conducted our study, guidelines for the management of depression with a chronic physical health problem have been issued;18 these may impact on attitudes and practice in the future.

Conclusion

Our systematic review of existing literature describing GPs’ and PNs’ experience of managing depression in UK primary care identified a range of barriers and facilitators to delivering care that need to be considered when designing future interventions for depression. We were then able to determine whether or not similar barriers and facilitators were experienced by GPs and PNs when managing depression in patients who also have CHD by conducting our own qualitative study. This work addressed a gap in the literature highlighted by our review and helped us to determine GPs’ and PNs’ views concerning what an intervention for people with sCHD and comorbid depression should consist of. By seeking clinicians’ views directly, we were able to identify elements (such as the need for a flexible, personalised intervention which allowed clinicians to use both their clinical judgement and existing tools and resources) of a future intervention, which would make it not only effective (in terms of addressing care needs identified as unaddressed in these patients) but, importantly, feasible to deliver in current practice.

The following chapter describes how we also sought the views of patients with CHD and comorbid depression to inform our intervention. How this work was synthesised to develop an intervention to test is then detailed in Chapter 4.

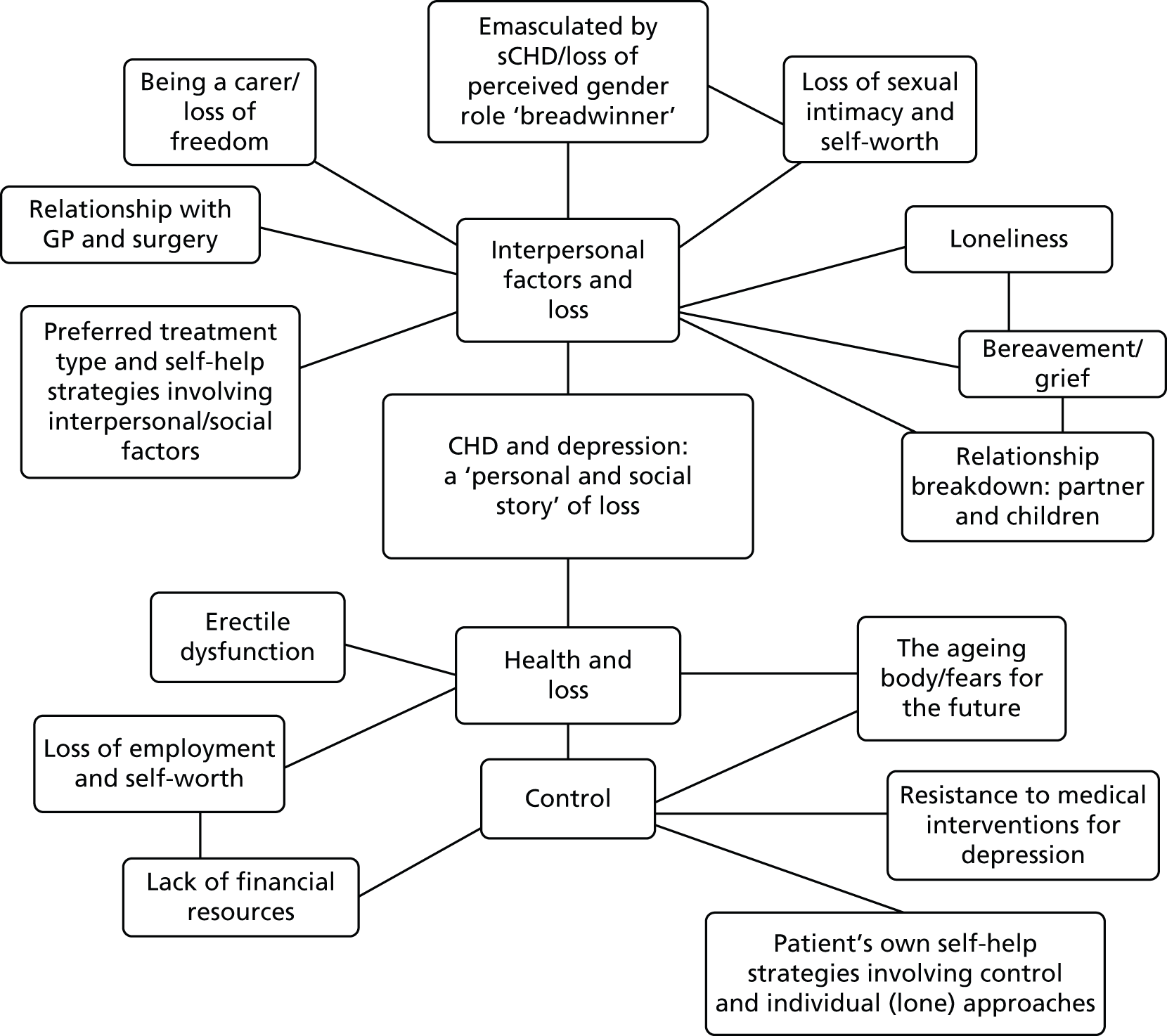

Chapter 3 Perceptions of distress and depression in patients with symptomatic coronary heart disease: a qualitative study (work package 1)

Introduction

In the introductory chapter, we described how CHD and depression are both common health problems worldwide and are predicted to be the two top causes of global health burden and disability by 2020. We have described how depression has previously been associated with worse cardiac prognosis and an increased cardiac mortality. We described a need to better understand the relationship between the two disorders and a pressing global public health need to improve integrated primary care for people with both disorders.

Although the prevalence of depression in patients with CHD is high, little is known about how people with CHD and comorbid depression perceive these conditions and the relationship between them. Treatment trials for patients with CHD and depression have included antidepressant medication with some success in reducing mortality. 78,79 However, it is currently unclear whether or not patients with CHD would opt for other interventions recommended by NICE for depression, such as supervised exercise, guided self-help, problem-solving, group or individual CBT or interpersonal therapy. It is also unclear whether or not NICE guidelines for depression need modification for patients with concurrent CHD and depression.

Before designing a new primary care-based intervention by nurses for patients with CHD and concurrent depression we undertook qualitative research to explore patients’ perceptions of their depression in the context of CHD, their health-care preferences and own self-help strategies for coping with depression.

In this chapter we report on qualitative findings from a pilot study of five unstructured interviews with UPBEAT-UK cohort study patients with sCHD (chiefly chest pain) and symptoms of depression, as well as qualitative findings from a semistructured interview study with 30 UPBEAT-UK cohort study patients presenting with sCHD and symptoms of depression.

Aims

The study aimed to explore (1) primary care patients’ perceptions of links between their physical condition and mental health; (2) their experiences of living with depression and CHD; and (3) their own self-help strategies and attitudes to current personalised care (PC) interventions for depression.

Methods

The sampling frame was the UPBEAT-UK cohort study database of primary care patients with CHD. At the time of recruitment (November 2008–January 2009) this numbered 376. On recruitment to the cohort, study participants were given the option of being interviewed in depth about their experiences of CHD and how this affected them emotionally. From participants who agreed to be contacted, we purposively sampled for positive scores on the PHQ-9,80 which indicates symptoms of depression. We also sampled for maximum variation on sociodemographic factors: age, sex, ethnicity and occupational status.

At the time of sampling, 42 patients screened positive for symptoms of depression and of these, five were included in the pilot interview study. Of the remaining 37, one patient declined and three could not be contacted or had died. Of the remaining 33 patients, 30 were interviewed, at which point interviewing was stopped as data saturation had been reached.

We conducted five individual unstructured pilot interviews and 30 semistructured interviews. Topic guides were informed by the aims of the research, review of the literature, discussion with coauthors and findings from the pilot interview study. We audio-recorded all interviews and transcribed them verbatim following written informed consent. Transcribed interviews were entered into NVivo 8 qualitative software for analysis and data management.

All transcripts were analysed using a thematic approach81 involving a process of constant comparison between cases. 82 Analysis began alongside data collection, with ideas from early analysis informing later data collection in an iterative process. Analysis of individual transcripts commenced with open coding grounded in the data. This generated an initial coding framework, which was added to and refined, with material regrouped and recoded as new data were gathered. Codes were gradually built into broader categories through comparison across transcripts and higher-level recurring themes were developed. Data were scrutinised for disconfirming and confirming views across the range of participants. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion at regular UPBEAT-UK research meetings to ensure consistency.

Pilot interview study

Study results

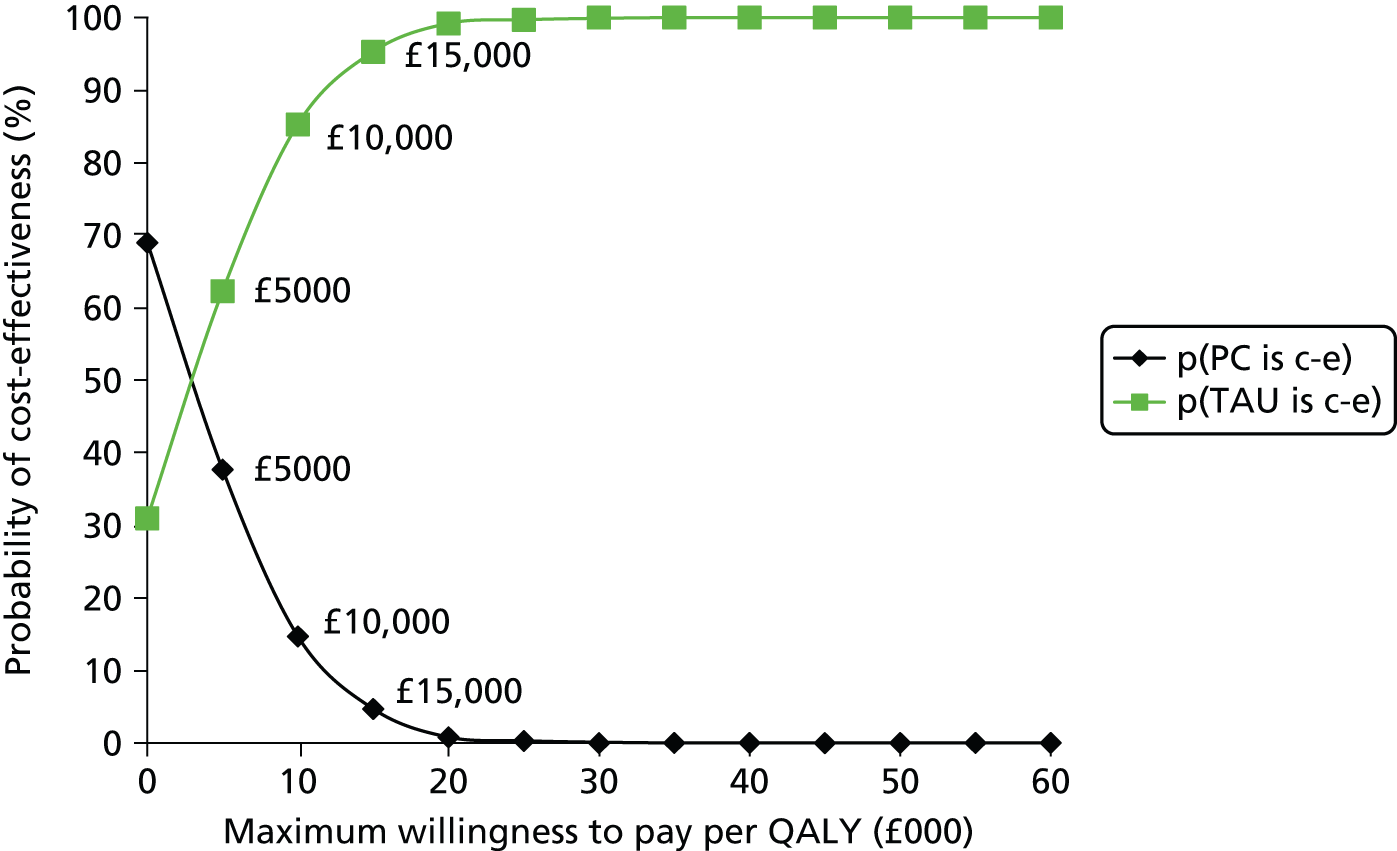

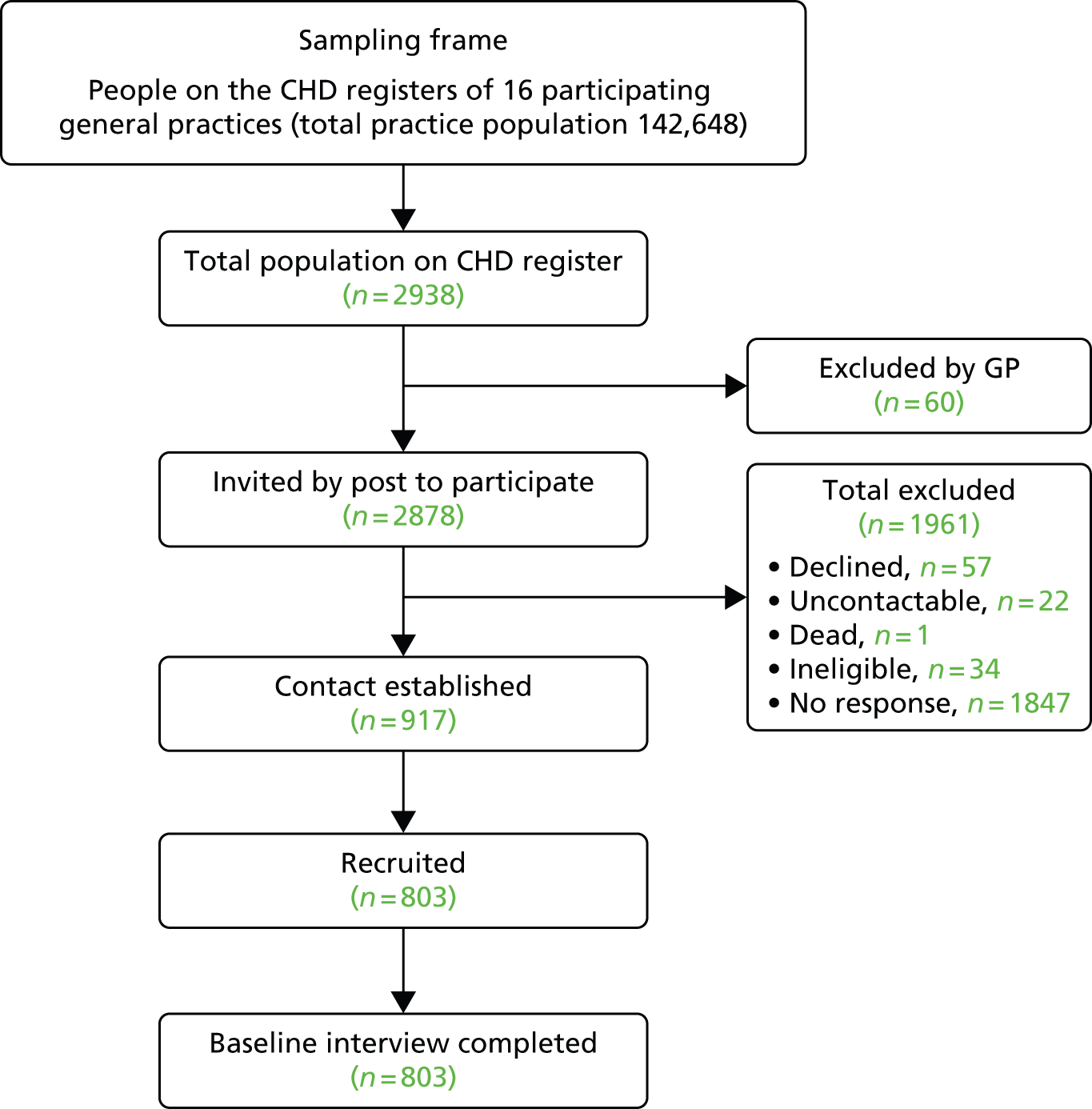

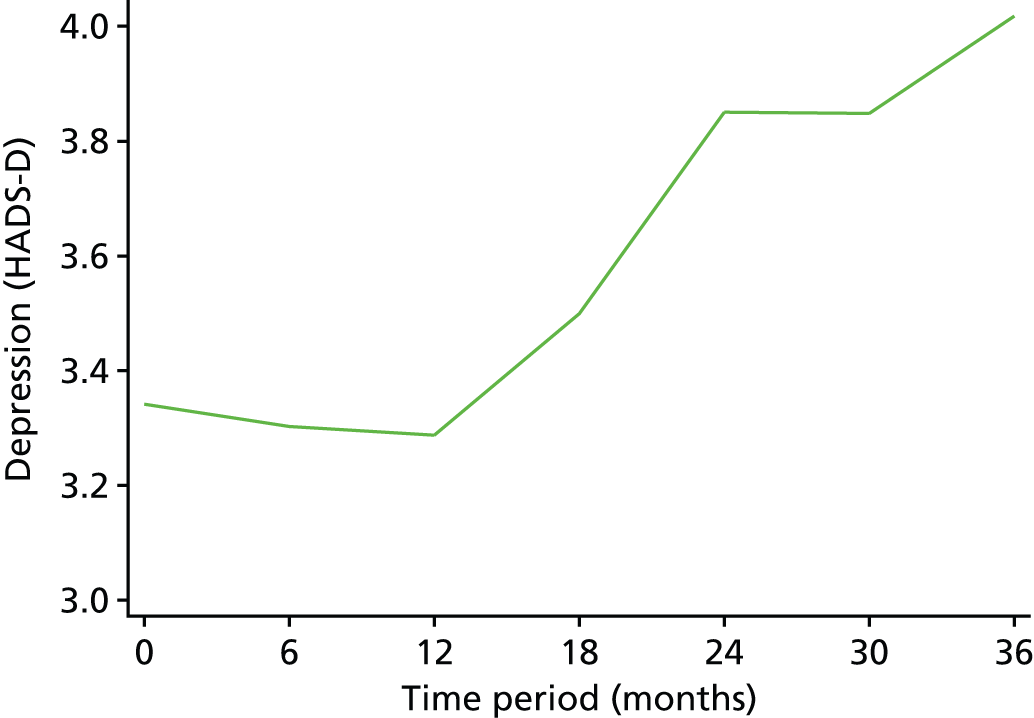

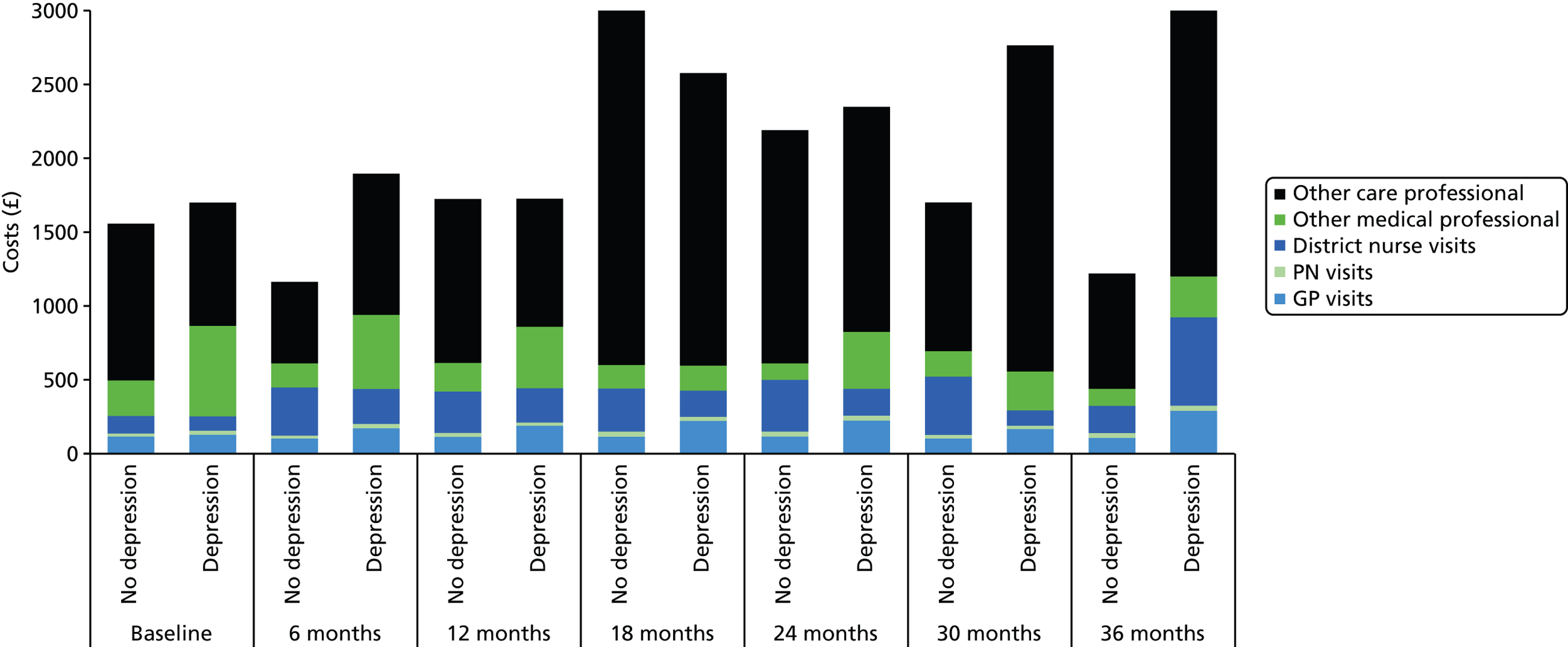

Participants