Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0608-10038. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The final report began editorial review in May 2015 and was accepted for publication in January 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peter Brocklehurst reports personal fees from Oxford Analytica, grants from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, grants and personal fees from the Medical Research Council (MRC), grants from the MRC, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme, NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, and Wellcome Trust outside the submitted work; and that he is chairperson of the NIHR HTA Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health Panel.

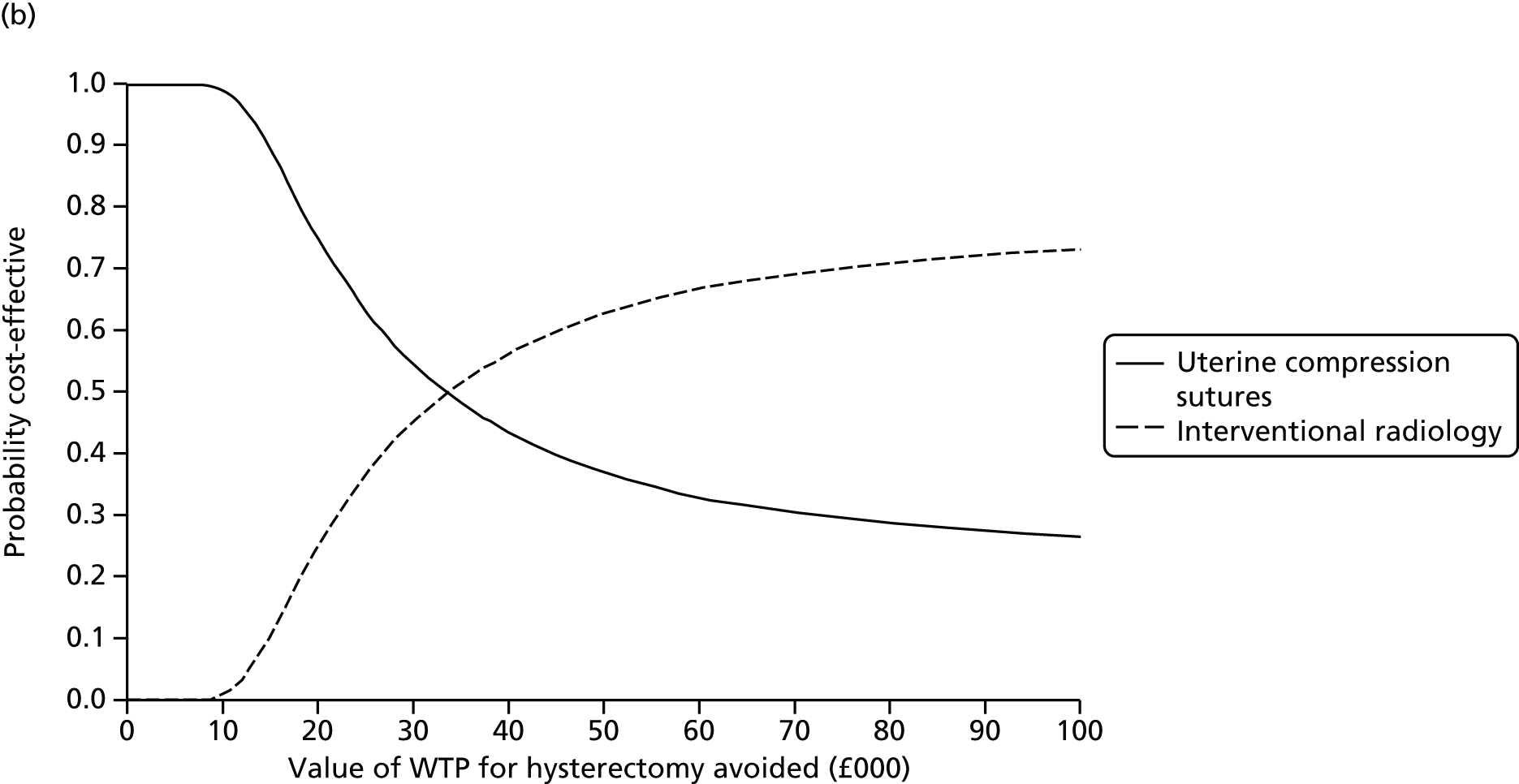

Permissions

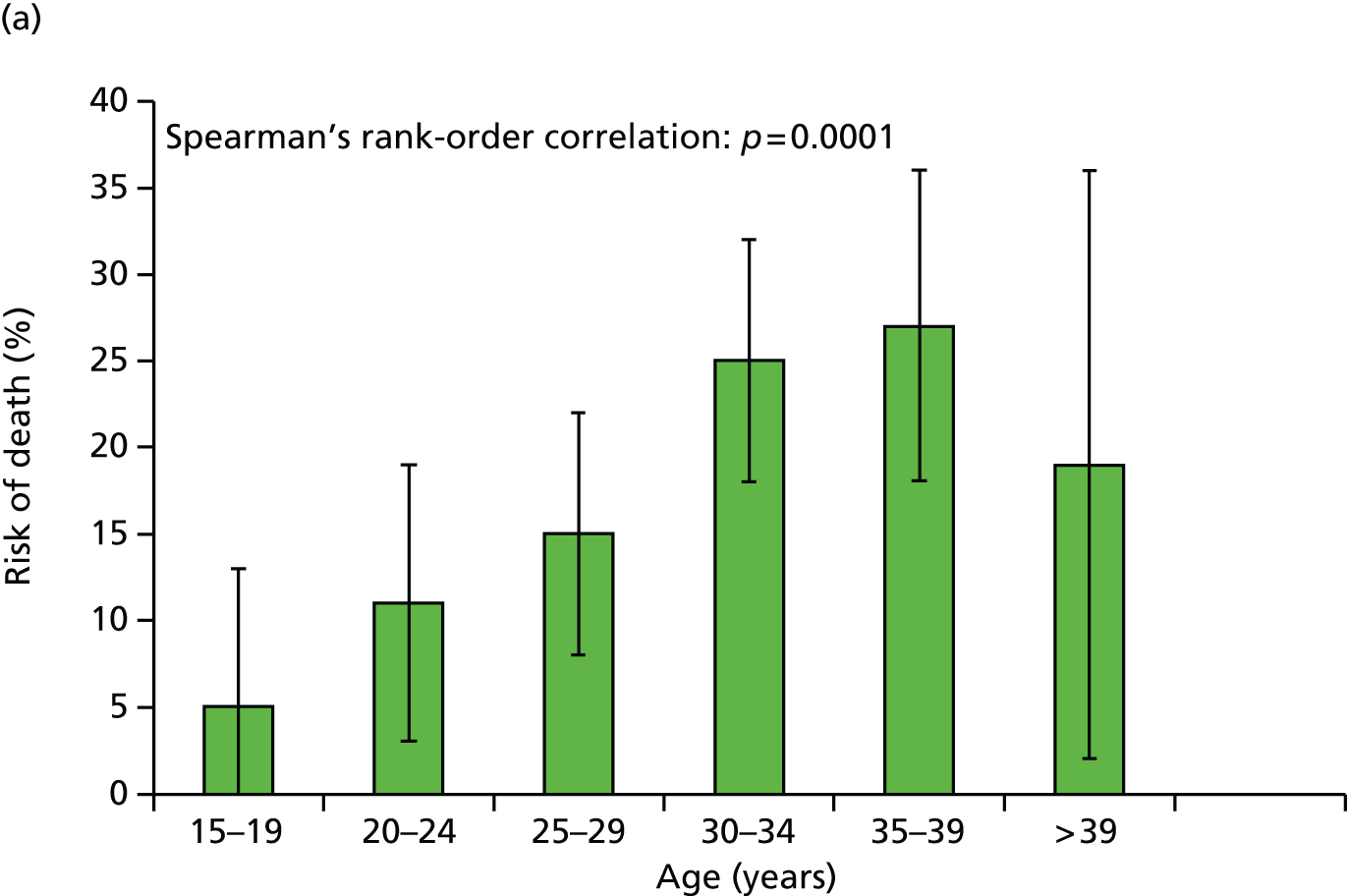

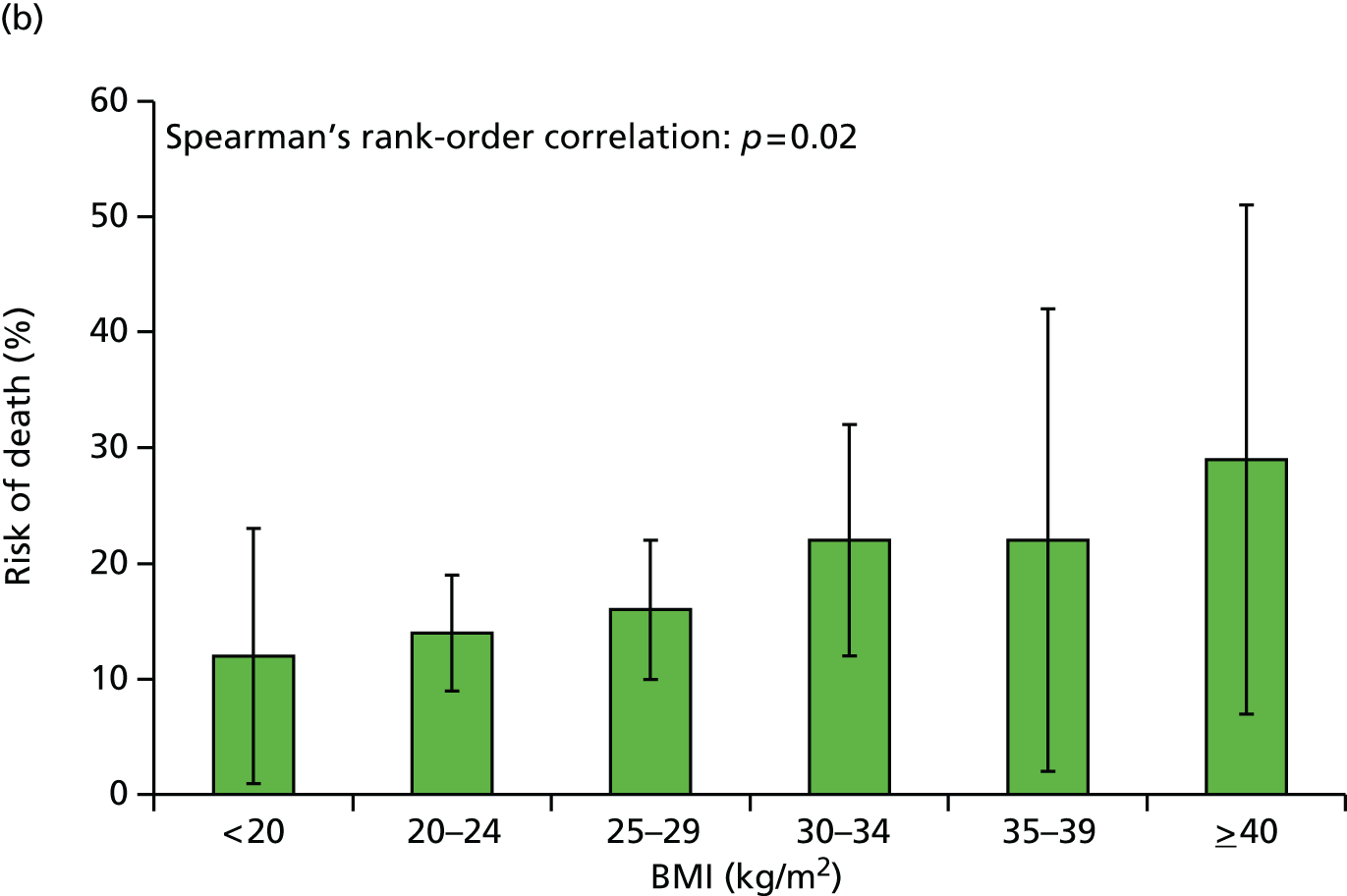

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Knight et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

A comprehensive programme of study of maternal deaths has been undertaken in the UK for > 50 years,1,2 including confidential external review. This has contributed to major improvements in the quality of maternity care and a dramatic reduction in the maternal mortality rate,2,3 such that maternal deaths are now very rare. The latest figures from the confidential enquiry into maternal deaths show that only three women died from causes directly related to pregnancy for every 100,000 women giving birth,2 equating to fewer than 30 deaths per year. This rate has not changed significantly for more than 20 years, but this does not mean that pregnancy can be regarded as ‘safe’. Waterstone et al. 4 demonstrated in 1997–8 that 1200 cases of near-miss severe maternal morbidity occurred per 100,000 births in the South East Thames region, with a ratio of near-miss morbidity to death of more than 100 : 1. 4 It is now increasingly being recognised that in countries such as the UK, where maternal deaths are rare, the study of near-miss severe maternal morbidity (defined as a ‘severe life-threatening obstetric complication necessitating urgent medical intervention in order to prevent likely death of the mother’5) provides additional important information to aid disease prevention, treatment and service provision. 6,7

The advantages of an additional study of near-miss morbidity are several. Near-miss morbidity occurs more frequently, allowing for more rapid study completion and reporting of results owing to the larger number of cases identified. 6 The higher case numbers give studies of near-miss morbidity greater power to identify factors associated with disease incidence and hence generate recommendations to impact on disease prevention. 8 In addition, morbidity studies allow for the investigation of factors associated with poor disease outcomes. When information about fatal and non-fatal cases is compared, factors associated with progression from severe disease to death can be identified and management guidelines produced to help improve outcomes. 9 A further advantage of a national programme of study of near-miss morbidity is the ability to examine the quality of care of specific rare diseases10 and hence impact on patient safety. 11 The national collaboration of clinicians contributing to the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS)10 provided a unique opportunity to undertake such a programme of study of near-miss severe maternal morbidity.

The only population-based study of near-miss maternal morbidity previously undertaken in England4 suggested that 1% of births are complicated by near-miss maternal morbidity. This illustrates the high burden of disease underlying maternal deaths in the UK, with an estimated 8000 women in the UK experiencing near-miss maternal morbidity each year compared with only approximately 80 who die from direct or indirect causes during pregnancy or in the first 6 weeks after the end of pregnancy. 2 Changes to the characteristics of women giving birth in the UK, including older age at childbirth,12 rising levels of obesity,13 more births to ethnic minority women14 and greater numbers of women with multiple pregnancies,15 each a reported risk factor for near-miss maternal morbidity, suggest that this rate is likely to rise.

At the time of commencement of this programme, the aim of health reform in England was ‘to develop a patient-led NHS that uses available resources as effectively and fairly as possible to promote health, reduce health inequalities and deliver the best and safest healthcare’. 16 Guidance for commissioners of maternity services stated that ‘this means providing high quality, safe and accessible services’. 17 Reducing the gap in infant mortality between socioeconomic groups was one of the key measures of the national Public Service Agreement health inequalities target18 and, as part of interventions to address this, the Department of Health also called for specific action to improve the quality of antenatal care. 19 Maternity care, safety and quality of maternity services remains a priority area in the NHS as recognised by the recent report on maternity services in a group of hospitals in the north of England20 and a recently announced review of maternity services by NHS England. 21

The aim of this programme of research into near-miss maternal morbidity was to address these priorities by providing evidence to underpin the development of preventative and management strategies for near-miss maternal morbidity, hence leading to improved quality of maternity care. Basic information, such as method and timing of diagnosis, use of specific interventions at the right time and in the right order, appropriate transfer to secondary care, seniority and discipline of carer and the impact of these factors on the outcomes for women and their babies, is largely lacking in this field. Exploring the role of these modifiable events yields important information to improve the quality and safety of maternity care.

Rationale

Although individually rare, when considered together, near-miss maternal morbidities represent a considerable burden to women, their families and health-care systems. Studies of rare disorders, such as specific near-miss maternal morbidities, require large collaborations to identify even a small number of cases. High-quality research is thus rarely undertaken, with studies frequently limited to retrospective hospital-based case series. Hence, clinical practice is rarely based on robust evidence and evidence-based guidelines for management are frequently lacking. We established the UKOSS in 2005 to enable the study of rare disorders of pregnancy, including near-miss maternal morbidity,10 and have shown that national data collection is feasible with the participation of all UK consultant-led maternity units in the UKOSS programme and clear identification of messages to improve patient outcomes. 11 However, in order to conduct a comprehensive programme of study to improve the care of women with near-miss maternal morbidity, this work needed to be expanded to address additional research questions through different methodologies.

Studies in other developed countries have investigated near-miss maternal morbidity through routine sources of data,22–25 but these studies are limited in their scope to identify risk factors by incomplete information on potential confounders. 26 In addition, the use of routine data means that these studies are unable to investigate diagnosis and management and hence provide evidence to improve clinical care. Only one population-based study has been conducted in England,4 although the small number of cases meant that the authors were unable to address research questions specific to individual morbidities and the impact of maternal characteristics, diagnosis and management on outcomes. This study only conducted follow-up to a maximum of 1 year following the event27 and did not explore women’s experiences. Surveillance studies of specific near-miss morbidities in the UK have been conducted through UKOSS,8,28–32 but further expanded work was required to conduct a comprehensive programme covering all the main causes of direct maternal death.

Studies of near-miss maternal morbidity using other methodologies, beyond hospital-based case series and surveillance using routine hospital data, are even more limited. The impact of basic factors on outcomes, such as pregnancy-related factors (e.g. multiple pregnancy following assisted reproduction), maternal characteristics (such as obesity), method of diagnosis (e.g. antenatal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of placenta accreta), timing of diagnosis [e.g. of acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) or haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome], interventions (such as induction or augmentation of labour in women with uterine rupture) or other management techniques (e.g. brace sutures or arterial embolisation in severe peripartum haemorrhage), have not been systematically assessed for any of these conditions in national studies. All these factors are potentially modifiable and, hence, this programme sought to provide important information, currently lacking, to guide clinical practice and service provision and improve outcomes for women and their babies.

Aims and objectives

Aims

-

To implement a national programme of study of near-miss maternal morbidity to complement confidential enquiries into maternal deaths.

-

To use mixed methodologies to improve the evidence base for disease prevention and treatment and to inform commissioning of maternity services.

-

To use the data to develop recommendations for best practice to prevent and manage near-miss maternal morbidities.

Objectives

-

To determine the incidence of the specific morbidities most commonly leading to maternal death in the UK.

-

To assess the contribution of existing risk factors to disease incidence and identify steps that may be taken in clinical practice to address these factors to reduce incidence.

-

To describe how the conditions are managed and describe any variations in management, exploring the impact that different management strategies or interventions have on outcomes and costs, in order to make recommendations for best practice to improve outcomes for all women.

-

To describe the outcomes of the conditions for mother and infant and identify any groups in which outcomes differ.

-

To investigate which factors influence the risk of death and how these might be addressed to prevent death.

-

To explore whether an external confidential enquiry or a local review approach can be used to investigate and improve the quality of care for affected women.

-

To assess the longer-term impacts of near-miss maternal morbidity for women, their babies and families.

Workstreams

The aims and objectives were addressed in six workstreams.

Workstream 1: incidence, risk factors, management and outcomes of near-miss maternal morbidity, described in Chapters 3 and 4.

Workstream 2: factors contributing to case fatality, described in Chapter 6.

Workstream 3: addressing inequalities – focusing services for near-miss maternal morbidity, described in Chapter 7.

Workstream 4: working with hospitals to maximise the benefits of studies of near-miss maternal morbidity, described in Chapter 8.

Workstream 5: exploring the use of UKOSS data to conduct economic evaluation of treatments for near-miss morbidities, described in Chapter 5.

Workstream 6: long-term follow-up of women and their infants affected by near-miss morbidity, described in Chapters 2, 9 and 10.

Patient and public involvement

We set up an Advisory Group, consisting of women who had experienced severe morbidities in pregnancy, their partners and representatives of voluntary groups working in the maternity area. We held an annual face-to-face meeting, with e-mail discussion in the intervening periods. The first meeting took place in September 2010. The group, chaired by a public member, advised on developing the different component studies in a manner appropriate for women and so that they would provide most benefit in terms of improving maternity care. Members also helped recruit participants for the studies and publicised them through their networks when appropriate. Study progress and interim results of all studies were discussed with the group, who advised on additional analyses, interpretation and presentation prior to publication. The Advisory Group also suggested future research priorities based on their experiences and priorities and the findings of the programme. The activities of this group thus contributed throughout the component workstreams and their contribution was invaluable to the success of the programme.

Chapter 2 Unheard voices: women’s and their partners’ experiences of severe pregnancy complications

Background

Facts and figures are essential, but insufficient, to translate the data and promote the acceptance of evidence-based practices and policies . . . narratives, when compared with reporting statistical evidence alone, can have uniquely persuasive effects in overcoming preconceived beliefs and cognitive biases.

Meisel and Karlawish33

Up to 8000 women and their families each year have to cope with a life-threatening pregnancy complication and its aftermath. The causes of these ‘near-miss’ maternal morbidities are varied but include pre-eclampsia, haemorrhage, thrombosis and sepsis, and may in some cases require an emergency hysterectomy and/or result in pre-term delivery. 4 Mother and newborn are often separated, as women may have to spend time in intensive care or a high-dependency unit (HDU). Their babies may be born prematurely and require the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Recent studies draw attention to the potential for long-term psychological and emotional impact on women of maternal morbidities. 34–38 In addition to their physical recovery, women can experience anxiety, isolation and flashbacks in the aftermath. Birth trauma can have lasting consequences that impact negatively on maternal, infant and family well-being. 39 Medically complicated pregnancies can also impact negatively on breastfeeding rates. 35,40

Women may be discharged from hospital having had major surgery and emergency treatment or time in intensive care, and follow-up is variable. Some may have lost their baby as a result of their illness. Babies delivered pre-term may need to spend long periods in NICU. These experiences are a long way away from normal birth.

Qualitative research allows a detailed exploration of the range of different reactions, emotions and experiences of care women encounter and the significance of the ‘near-miss’ in their life and their wider family. It may suggest avenues for service improvement that are not apparent from quantitative survey findings. The aim of this workstream was to explore the impacts of experiencing a near-miss obstetric emergency, in order to inform development of subsequent workstreams, provide a resource for women who have had a severe maternal morbidity and develop teaching and learning materials for NHS staff in order to help improve future care.

Research questions

-

What are the experiences of women who have near-miss maternal morbidity in the UK?

-

How does this experience impact on their social and family relationships and future childbearing plans?

-

Are there any aspects of the care experience that were particularly good or bad or could be improved?

Methods

The study was conducted using the standard methodology developed by the Health Experiences Research Group at the University of Oxford. 41 Interviews were conducted by a professional qualitative researcher.

Women who experienced a life-threatening complication in pregnancy (defined as ‘severe maternal illnesses which, without urgent medical attention, would lead to a mother’s death’5) were invited to take part in an interview study. We also invited the women’s partners to participate.

The sample

We aimed for a maximum variation sample of women living in the UK42,43 covering a wide range of conditions, based on the principal causes of direct maternal deaths identified in recent maternal death enquiry reports. 2 We sought to include women with a range of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds and at varying times after their ‘near-miss’ event. Interviews continued until thematic saturation was reached. Our overall sample included 36 women, 10 male partners and one lesbian partner (Table 1). The majority of partners were interviewed together.

| Characteristic | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Age at the time of interview (years) | |

| 21–30 | 3 |

| 31–40 | 31 |

| 41+ | 13 |

| Age at time of near miss event (years) | |

| 21–30 | 11 |

| 31–40 | 31 |

| 41+ | 5 |

| Sex | |

| Women/mothers | 36 |

| Fathers/partners | 11 (10 men, one lesbian partner) |

| Occupation | |

| Professional | 21 |

| Other non-manual | 13 |

| Skilled manual | 4 |

| Unskilled manual | 2 |

| Other (such as housewife or student) | 7 |

| Ethnic group | |

| White British | 42 |

| British Pakistani | 1 |

| White other | 3 |

| British Somali | 1 |

| Time since near miss | |

| < 1 year | 9 |

| > 1 to < 2 years | 16 |

| 2–4 years | 16 |

| 5–9 years | 4 |

| 10+ years | 2 |

Recruitment packs were distributed through a number of routes to ensure a wide, varied sample. Routes included support groups, the National Childbirth Trust, social network forums [Mumsnet (www.mumsnet.com) and Netmums (www.netmums.com)], newspaper advertisement, intensive care clinicians contacted through the Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC), an advertisement in the UKOSS newsletter and word of mouth. To try and reach a wider ethnic minority population, we had the recruitment packs translated into Bengali and distributed through a consultant in an east London hospital. Note, however, that the final sample had limited ethnic diversity (see Table 1). We sought to include as broad a range of conditions and time distance from the event as possible as we were keen to understand the longer-term effects of a near-miss maternal morbidity. All women had experienced a severe life-threatening complication in pregnancy [thrombosis or thromboembolism, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, haemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) or sepsis]. Our sample included broad socioeconomic diversity. Interviews took place between 2010 and 2014.

After obtaining informed consent, one of the authors (LH) interviewed participants in the setting of their choice (usually their home). Participants were asked about their or their partner’s experiences of pregnancy and life-threatening illness. The interview started with an open ended narrative section during which respondents described what had happened, followed by a semistructured section with prompts to explore any relevant issues that had not already emerged, including their recovery and family life since their near-miss. The interviews were all audio- or video-taped and transcribed verbatim.

The analysis reported here focuses on the implications that emerged from the data for quality improvement, commissioning and clinical practice across the care pathway for women and their families. Verbatim quotations are used to illustrate themes that emerged from the data.

Analysis

The transcripts were read and reread, a coding frame was constructed and the data coded. Anticipated and emergent themes were then examined across the whole data set as well as in the context of each person’s interview. A qualitative interpretive approach was taken, combining thematic analysis with constant comparison. 44,45 NVivo 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to facilitate the analysis.

Results

Implications for quality improvement, commissioning and clinical practice

This section pulls together all the implications for quality improvement, commissioning and clinical practice that have been identified from analysis of the data. Implications were identified across the care pathway:

-

the emergency

-

experiences of intensive care

-

transfer from intensive care

-

contact with the baby

-

communication

-

the aftermath

-

follow-up

-

support in the community

-

emotional recovery

-

counselling

-

impact on the family – partners

-

impact on the family – family and family life

-

information and support

-

good practice.

The emergency

-

Symptoms that lead to an unexpected or traumatic event in childbirth are varied; some have early warning signs but others are an emergency (to the mother or baby) that develops rapidly, out of the blue. However, both groups of women may find it difficult to adjust emotionally to their unexpected childbirth experience.

-

Some women may be hospitalised during their pregnancy for monitoring, which can be challenging but provides an opportunity for good communication and understanding of their condition.

-

If the baby suddenly arrives early, mothers may be especially emotionally unprepared for the arrival of their newborn:Kirsty, first baby

-

You know, I wasn’t ready. I wasn’t mentally prepared. I certainly wasn’t emotionally prepared. [Um] Luckily I’d had some time to sort out a Moses basket and [um] some clothes and nappies, but that was what the last 4 weeks were for. For reading the books. For doing some research. For decorating the nursery, you know, getting it all set up. That was going to be the joyous moment of preparing. And that was all taken away from me, I suppose. Well from us.

-

-

Women are reassured by calm professionalism from staff during their emergency.

Experiences of intensive care

-

Some mothers (or babies) may need to be in intensive care for a while. For a mother, waking up in intensive care can be very shocking. As new mothers they are often distressed at being separated from their baby. It would be helpful to develop protocols for women who require high dependency or intensive care to facilitate the baby being taken to visit their mother or vice versa. Rachel, third baby

-

You’re not as I would thought, in a place where may be there’s other people who have been through pregnancy related or birth related issues. I was in this, some old man ranting, there was a man ranting and pulling out his drips on one side. There was a man who’d had an accident opposite me. They brought in somebody who they discovered had E. coli [Escherichia coli] next to me and then she died next to me, and they were busy cleaning up.

-

-

Separation from their newborn baby can be very hard as mothers feel they are missing vital first steps. If it is not possible for women to see or be with their baby, they appreciate being kept in touch with the baby’s progress through photos, updates or contact with the paediatrician.

-

Many find it helpful to piece together what has happened to them, filling in the blanks, with the help of discussion with both staff and family and friends.

-

Being in an intensive therapy unit (ITU) can be very distressing; women often experience fear, humiliation and difficulties communicating.

Experiences of transfer from intensive care

-

Women who have suffered an unexpected event feel different from other new mothers. They feel more supported when information about what has happened has been handed over between staff and the team in the new setting shows that they are fully aware of what they have experienced.

-

Transfer from intensive care, although a positive step, can be difficult. Although there appears no ideal solution to step-down care:

-

Women who go to a high-dependency area alongside a labour ward find this helpful.

-

If women are in high-dependency care for an extended period, policies that allow visits from the wider family (e.g. grandparents) are appreciated.

-

-

Similarly, women can find transfer to the postnatal ward challenging:

-

If possible, a side room is the most comfortable place for women who have experienced a near-miss to be cared for.

-

If side rooms are not available or not appropriate in view of a woman’s clinical condition and potential safety concerns, a clear explanation of the reason for this is helpful.

-

Some women will experience significant problems with caring for themselves and their new baby in a side-room and will need extra help. Clara, first baby

-

And then through the night, I actually had what I kind of look back on, I felt like I was in a survival mode through that first night because I was left on my own with the baby. Now bearing in mind the baby had been looked after by the nurses at night. This is my first night out of intensive care. And my first night with the baby, all on my own, with no support whatsoever.

-

-

Personal support and empathy from individual staff members makes a real difference to how women cope with transfer and recovery.

-

Contact with the baby

-

Even when very ill, women want to be a mother to their new baby.

-

Sometimes babies will be in intensive care for days or weeks.

-

Many women face challenges in seeing their new baby and it would be helpful to develop protocols ahead of time for women who require high dependency or intensive care to facilitate the baby being taken to visit their mother or vice versa. Amy, first babyKirsty, first baby

-

You have this idealistic picture in your head, what it’s like when you’ve got a baby, that you’ll spend all the time cuddling them, and I didn’t feel I could do that, because just holding him to start with was just exhausting. So that was a really difficult sort of emotional battle really.

-

And obviously I didn’t see my son for 4 days. Such an odd feeling. I mean [not] expecting to have the baby so early and then I wasn’t a mother. I was just some useless person lying there.

-

-

When it is not possible for women to see or be with their baby, they appreciate being kept in touch with the baby’s progress through:

-

photos

-

regular verbal or written updates such as a diary of the baby’s day

-

direct contact with the paediatrician when the baby is ill.

-

-

Missing a baby’s ‘firsts’ is something women particularly notice; if at all possible they want to be there for important milestones such as the first feed.

-

Breastfeeding is very important for some women, particularly in the context where they may feel they have failed at normal childbirth.

-

Having a baby in a neonatal unit, after a severe obstetric emergency, is often challenging for women as they recover from their own illness. Sometimes they need to focus on getting well themselves, as well as being with their baby.

Communication

-

Women and their partners appreciate staff giving clear explanations in non-medical language at all stages before, during and after the emergency (Box 1):

-

When conditions are diagnosed in the non-emergency situation antenatally, being aware of what might happen helps women and their partners prepare and cope better afterwards.

-

During the emergency, repeated reassurance is appreciated.

-

Being listened to and being able to ask questions after the emergency is important for women to come to terms with what has happened. Naomi, first baby

I do vaguely recall someone sitting next to me holding my hand, and just saying, ‘It’s all right, you know, it’s going to fine. Just they need to get some blood into you’. And I don’t actually remember all of what she said. It’s more a memory present of there being somebody next to me, kind of trying to reassure me. So there was after that initial flurry of activity, I’m fairly certain that there was someone with me, trying to keep me calm. Which I greatly appreciated.

-

-

Partners/fathers can feel forgotten during and after the emergency:

-

Frequent updates from any member of staff can help them to feel less anxious and isolated.

-

Having another family member with them for support can help.

-

-

Knowing that staff have learned from a woman’s near-miss is reassuring for her.

Kerry and Sarah were both diagnosed with placenta praevia and didn’t feel doctors explained to them the severity of their condition. In contrast, Alex, who had the same condition, described excellent communication with her doctors who explained to her clearly why she needed to stay in hospital until her baby was born.

Kerry felt that doctors did not fully explain to her the risks of her placenta praevia. She wished they had sat her down and explained to her what a haemorrhage was and what to expect.

I would rather they had sat down and said are you aware of what haemorrhage is? What it means. Expect, this is how much … I just thought I haemorrhage was when you was bleeding and it just trickled slowly out of you, but didn’t stop. That to me was what a haemorrhage was. I didn’t expect it to be the biggest gush. I felt like, to look at the blood, I can see it now, I felt like every pint of blood in my body was on the floor it was that bad.

Kerry, second baby

Alex was told she was a walking time bomb. Doctors explained very well how serious her situation was in a way that allowed her to process little things at a time.

They did it very well. They explained the gravity of the situation but not in a way that would have complete…. I mean every time, it was almost like a drip feeding process. And I mean, it might not work for everyone, but it worked well for me, because it enabled me to process little things at a time.

Alex, second baby

The aftermath

-

What physical shape women are in when they get home will vary greatly; some will be recovering from major abdominal surgery, others from severe blood loss. Women find general practitioner (GP) support once they are discharged, and recognition of their particular childbirth experience, valuable to help them return to normal life.

-

Many women experience longer postnatal recovery periods than normal, although, on the whole, women did make a good recovery.

-

Women felt frustration at not being able to look after their new baby properly on their own.

-

Scars left over from the surgery caused distress for some women.

-

Women may face difficulties settling back into their previous social relationships with family, friends and their local community. Emma, second baby

-

But it is hard you know, when I left hospital people, people just stopped bothering and . . . I felt I really struggled with friends. I really struggled with people that made false promises, and I’ve still got a lot of upset towards them people that were all round and all there, when I was in hospital. But as soon as I came out they didn’t care. That’s when I really needed my friends. That’s when I really needed people to be there for me.

-

-

Women often feel isolated (physically and emotionally) when they first come out of hospital, unable to relate to others who have not experienced their trauma.

-

They feel that it is a taboo subject to raise at postnatal support groups, an experience which can be particularly isolating for first-time mothers.

-

Given the rarity of the conditions that lead to a near miss, or unexpected event, women can struggle to find anyone to talk to about it. Online support groups can be particularly valuable in providing access to other patient experiences.

Follow-up

-

Women who had a follow-up review at the hospital found this a positive experience to help their understanding of their emergency and their recovery.

-

When follow-up was not offered, women felt abandoned and were left with questions.

-

Women noted a number of things that were particularly helpful elements of the follow-up review:

-

Seeing and talking through their notes.

-

Answering questions about future pregnancies.

-

Sensitivity about the place where the review was conducted – returning to the antenatal clinic or labour ward or even hospital could be upsetting.

-

Flexible timing of the follow-up review – some women were not ready for this until several months or even years after the event.

-

An offer of counselling was helpful to some.

-

-

The follow-up programme with intensive care unit (ICU) staff that some women were involved with was considered a good model. Catherine, second baby

-

Huge, hugely helpful, because it made you feel, because after about 6 weeks I felt that everybody had kind of not forgotten about it, but moved on. You know, you’re alive you made it through it, you know, it’s time to put it behind you and everybody has moved on with their life and you’re just left with this yuk you know. And so to be able to be actually go into hospital and talk to people who knew, because even if you talk to some people who weren’t related to ICU, they still couldn’t really understand the trauma of what your body had gone through, having lost so much blood and what an impact that had on you.

-

Support in the community

-

Support from their GP and health visitors was highly valued by women who received it. It helped their physical and mental recovery. Kathryn, second baby

-

He’s seen me every 4 weeks. He put me in touch with support groups and things like that. And he was really patient, because I did keep going back. I thought I had illness after illness.

-

-

Those who did not receive support felt they could have done with:

-

practical help coping with their physical recovery and new babies or young children

-

emotional support as they came to terms with their emergency experience and its implications

-

help overcoming isolation from peers

-

early discussions around fears about future pregnancies/fertility

-

an awareness of how their emergency experience could impact on other family members.

-

Emotional recovery

-

Finding out what happened to them, and coming to terms with the seriousness of their illness and what a narrow escape they had had, was often very emotionally difficult for women.

-

Realising the severity of what they have been through can take time.

-

Understanding what had happened was very important; it helped mothers fill in the gaps in their memories and start to come to terms with their illness. Sally, third baby

-

I know from hearing through the grape vine that there was some kind of debrief that happened. That my case was kind of obviously looked into and sort of, they kind of had a look at what had went wrong. And I would have liked to have been involved in that. I would have liked to have had, not even a say I would have just liked to have known what had happened, because I still don’t know to this, to this day, quite what happened. I just kind of know just kind of bits and pieces.

-

-

Talking through events with clinicians at follow-up meetings, or going through their notes, can be valuable in helping women understand what has happened to them.

-

Coming to terms with their emergency experience can be difficult and take time. Anniversaries could stir up strong emotions. Emma, second baby

-

Before the [year] anniversary, that’s when I really panicked, because I just thought, well what am I going to do? I don’t know what I’m . . . It’s weird, it’s like I was in, in prison in my head . . . It was like I put on a front every day, and I don’t think many people saw past it, but my boyfriend did. And I know he worried for me, and he would just say to me, ‘You know, we need to get over this’. But not because he was like, oh get over it. It was because he could see how much underneath everything it was sort of eating me up and that was really hard.

-

Counselling

-

Women felt the need for counselling at different times after their emergency and there was great variation in when women felt ready to talk. Penny, first baby

-

The aftermath was so kind of overwhelming really, that at the time you just work through it, and its only afterwards you kind of think, you know, you stamp your foot a bit and say that was really unfair, that happened to me. You know, and so I was able to do all of that with, with the counsellor then, just at the time I needed it.

-

-

Many found counselling very helpful, in particular cognitive–behavioural therapy.

-

Others who had not received counselling said they wish they had received it as it would have helped them make sense of what they had been through.

-

Help may not be sought for long-term mental health issues; therefore, actively offering help may be beneficial.

Impact on the family

Partners

-

All of the partners/fathers we spoke to have been deeply affected by their partner’s life-threatening experiences; for some it has had a profound impact on their long-term mental health.

-

In situations for which an emergency delivery might be anticipated, such as when a woman has placenta praevia, explanation of what might happen helps partners prepare and cope subsequently.

-

Frequent updates during the emergency help partners/fathers feel less isolated and anxious. Joe, first baby

-

So there was this massive rush, alarms going everywhere, rush, shooting off and everything and they said, ‘Well you stay there’. And I’m thinking, what’s going on, you know, no one was telling me. And this is the bit I don’t like telling [my partner], is I was left there with blood everywhere, all over me, all over the floor, and they left me there for about 3 to 4 hours.

-

-

Personal touches of support from individual staff make a real difference to how partners cope.

-

Partners remember more about events than the woman who is ill, but still appreciate repeated explanations.

-

Partners/fathers can find seeing their partner in high dependency or intensive care very traumatic and may need support from staff and family members to:

-

enable them to visit their partner

-

understand that the situation is not hopeless – their partner may recover

-

come to terms with what has happened.

-

-

Long-term mental health problems in partners/fathers after a near-miss experience may have a big impact financially, practically and emotionally, and families may need additional support in this event.

-

Partners/fathers who experience mental health symptoms do not necessarily seek help, although they do feel that counselling, if offered, could be beneficial.

Family and family life

-

Women’s relationships with their partners are often put under severe strain and additional support may be required in this context.

-

Parenting advice can be important because:

-

Existing children can be severely affected by nearly losing a parent.

-

Building a relationship with the new baby following a near-miss event can be challenging even when the baby does not require neonatal unit care.

-

-

Issues around future fertility and family size can be complex:

-

Some women require support to come to terms with a loss of future fertility.

-

For others, the worry about the possibility of a near-miss event in a future pregnancy leads to a decision not to have further children and robust contraceptive advice can be important in these circumstances.

-

-

Mental health impacts for both mothers and fathers may require long-term management. Justin, third baby

-

And so, yes, it’s not nice. I get flashbacks every now and again. They used to be really bad, really, really bad, because visions are, meant to be a happy time picking your baby up. I get . . . it is visions of her being whizzed passed me, my wife. Doctors and nurses running and all of a sudden me baby is whizzed straight past and she’s going to special care baby unit, you know, in an incubator. It’s not nice. And that’s what visions come back all the time and haunt me.

-

-

Mental health and other impacts can lead to significant changes in career or life paths, which places an additional burden on parents.

-

Many women reported that they would have welcomed more support in the community, in particular access to mother and toddler or other parent’s groups where other women had similarly ‘abnormal’ birth experiences.

Information and support

-

Women and their families often needed a great deal of practical support as they recovered from their emergency.

-

Because of the rarity of these conditions, women often felt isolated when they came home and found it hard to access information.

-

Women wanted further information for various reasons and at various stages:

-

if possible, before the baby was born – to understand more about the condition they had been diagnosed with, and the risks to them and their baby

-

while in hospital – clear, jargon-free explanations of what has happened to them

-

after the emergency – practical information about what to expect during recovery.

-

-

Information tailored to new mothers, particularly in the case of hysterectomy, was highly valued.

-

Specialist online support was described as invaluable. Catherine, second baby

-

An oasis of somewhere that I could talk to women who’d been through exactly what I’d been through and to be able to pour out your grief feelings without being judged. It was like having a huge family of sisters . . . It is just a place to go that you can absolutely unload.

-

Good practice

-

Personal touches from individual staff can make a real difference to how women and their partners cope with the emergency and recovery.

-

Transfers within the hospital can be difficult and are made easier for women by:

-

considering both their critical care needs and their needs as a new mother

-

use of a single room if possible.

-

-

Reviewing their notes and/or a discussion with their consultant after an event can help women make sense of what happened.

-

Women find GP support once they are discharged valuable to help them return to normal life.

-

Explanations, often repeated, of what is happening are helpful to women and their partners at all stages of the emergency and recovery.

Teaching and learning points

The themes identified in the interviews were summarised as a series of teaching and learning resources. They are intended as a resource for clinicians across the care pathways of these women and their families, including midwives, obstetricians, nurses, anaesthetists, intensive care specialists, health visitors and GPs. Below are the key learning points from each of the summaries. A fuller description and clips are available on www.healthtalk.org. 46 Note that themes relevant to both analyses are repeated.

Good practice that makes a big difference

-

Personal touches from individual staff can make a real difference to how women and their partners cope with the emergency and recovery.

-

Transfers within the hospital can be difficult and are made easier for women by:

-

considering both their critical care needs and their needs as a new parent

-

use of a single room if possible.

-

-

Reviewing their notes and/or a discussion with their consultant after an event can help women make sense of what happened.

-

Women find GP support once they are discharged valuable to help them return to normal life.

-

Explanations, often repeated, of what is happening are helpful to women and their partners at all stages of the emergency and recovery.

Access to the baby after the emergency

-

Even when very ill, women want to be a mother to their new baby.

-

Many women face challenges in seeing their new baby and it would be helpful to develop protocols ahead of time for women who require high dependency or intensive care to facilitate the baby being taken to visit their mother or vice versa.

-

If it is not possible for women to see or be with their baby, they appreciate being kept in touch with the baby’s progress through:

-

photos

-

regular verbal or written updates such as a diary of the baby’s day

-

direct contact with the paediatrician when the baby is ill.

-

-

Missing a baby’s ‘firsts’ is something women particularly notice; if at all possible they want to be there for important milestones such as the first feed.

Transfer from critical care

-

Women who have suffered a near-miss feel different from other new mothers. They feel more supported when information about their condition has been handed over between staff and the team in the new setting show that they are fully aware of what they have experienced.

-

Transfer from intensive care, while a positive step, can be difficult. Although there appears no ideal solution to step-down care:

-

Women who go to a high-dependency area alongside a labour ward find this helpful.

-

If women are in high-dependency care for an extended period, policies that allow visits from the wider family (e.g. grandparents) are appreciated.

-

-

Similarly, women can find transfer to the postnatal ward challenging:

-

If possible, a side room is the most comfortable place for women who have experienced a near-miss to be cared for.

-

If side rooms are not available, a clear explanation of the reason for this is helpful.

-

Some women will experience significant problems with caring for themselves and their new baby in a side room and will need extra help.

-

-

Personal support and empathy from individual staff members makes a real difference to how women cope with transfer and recovery.

Information and understanding

-

Women and their partners appreciate staff giving clear explanations in non-medical language at all stages before, during and after the emergency:

-

When conditions are diagnosed in the non-emergency situation antenatally, being aware of what might happen helps women and their partners prepare and cope better afterwards.

-

During the emergency, repeated reassurance is appreciated.

-

Being listened to and being able to ask questions after the emergency is important for women to come to terms with what has happened.

-

-

Partners/fathers can feel forgotten during and after the emergency:

-

Frequent updates from any member of staff can help them to feel less anxious and isolated.

-

Having another family member with them for support can help.

-

-

Knowing that staff have learned from a woman’s near-miss is reassuring for her.

Support for partners/fathers

-

All the partners/fathers we spoke to have been deeply affected by their partner’s life-threatening experiences, for some it has had a profound impact on their long-term mental health.

-

In situations for which an emergency delivery might be anticipated, such as when a women has placenta praevia, explanation of what might happen helps partners prepare and cope subsequently.

-

Frequent updates during the emergency help partners/fathers feel less isolated and anxious.

-

Personal touches of support from individual staff make a real difference to how partners cope.

-

Partners remember more about events than the woman who is ill, but still appreciate repeated explanations.

-

Partners/fathers can find seeing their partner in high dependency or intensive care very traumatic and may need support from staff and family members to:

-

enable them to visit their partner

-

understand that the situation is not hopeless – their partner may recover

-

come to terms with what has happened.

-

-

Long-term mental health problems in partners/fathers after a near-miss experience may have a big impact financially, practically and emotionally, and families may need additional support in this event.

-

Partners/fathers who experience mental health symptoms do not necessarily seek help, although they do feel that counselling, if offered, could be beneficial.

Follow-up and counselling

-

Women who had a follow-up review at the hospital found this a positive experience to help their understanding and recovery.

-

When follow-up was not offered, women felt abandoned and were left with questions.

-

Women noted a number of things that were particularly helpful elements of the follow-up review:

-

Seeing and talking through their notes.

-

Answering questions about future pregnancies.

-

Sensitivity about the place where the review was conducted – returning to the antenatal clinic or labour ward or even hospital could be upsetting.

-

Flexible timing of the follow-up review – some women were not ready for this until several months or even years after the event.

-

An offer of counselling was helpful to some.

-

-

The follow-up programme with ICU staff that some women were involved with was considered a good model.

Long-term effects

-

Women’s relationships with their partners are often put under severe strain and additional support may be required in this context.

-

Parenting advice can be important because:

-

Existing children can be severely affected by nearly losing a parent.

-

Building a relationship with the new baby following a near-miss event can be challenging even when the baby does not require neonatal unit care.

-

-

Issues around future fertility and family size can be complex:

-

Some women require support to come to terms with a loss of future fertility.

-

For others, the worry about the possibility of a near-miss event in a future pregnancy leads to a decision not to have further children and robust contraceptive advice can be important in these circumstances.

-

-

Mental health impacts for both mothers and fathers may require long-term management.

-

Help may not be sought for long-term mental health issues; therefore, actively offering counselling may be beneficial.

-

Mental health and other impacts can lead to significant changes in career or life paths, which place an additional burden on parents.

-

Many women reported that they would have welcomed more support in the community. In particular:

-

access to mother and toddler or other parent’s groups where other women had similarly ‘abnormal’ birth experiences

-

GP and health visitor support for first-time mothers to help with feelings of isolation.

-

Conclusions

There has been little research about the long-term impact of traumatic birth and how best to help women. There is inconclusive evidence on the impact of debriefing programmes. However, we know that those who are most likely to be well after childbirth are women who had no complications, no worries about their labour and birth and information about their choices for care. 47 Women who experience a near-miss maternal morbidity have had none of these. For them, there is often no follow-up from hospital obstetric or midwifery staff. Primary care teams should routinely be made aware if a woman has had a near-miss event so they can offer the support these women may need and be aware these new mothers may be isolated from their peers. Therefore, potential support networks, GPs and health visitors need to be alert for mental health problems developing and mindful of the impact that the near-miss experience can have on the whole family (including partner and other children) and be prepared to offer advice about future pregnancies.

Although critical illness may be uncommon, it is a potentially devastating complication in pregnancy. 48 The obstetric population is changing, increasingly presenting clinicians with older mothers with pre-existing disorders and advanced chronic medical conditions. The 2011 report by the Maternal Critical Care Working Group49 acknowledged the many challenges of caring for critically ill obstetric patients. Multidisciplinary approaches are essential for these women and require urgent attention. 50 However, there is minimal guidance for nursing management of critically ill obstetric patients in the ITU. Critical care nurses report concerns about their competence and confidence in managing obstetric patients in the ICU, finding it hard to meet their needs. Special issues arise in terms of lactation support, emotional impact and communication with family members. 51,52 Midwives express anxiety about caring for critically ill pregnant women53 and further research is still needed into how to provide optimum care for critically ill pregnant and postpartum women.

All the partners/fathers we spoke to had been deeply affected by their partner’s life-threatening experiences. For some, it had a profound impact on their long-term mental health. In situations for which an emergency delivery might be anticipated, such as when a woman has placenta praevia, an explanation of what might happen helped partners prepare and cope subsequently. Staff might consider that frequent updates during the emergency help partners/fathers feel less isolated and anxious. Our study demonstrates that (often small) personal touches of support from individual staff can make a real difference to how partners cope. Although partners may remember more about events than the woman who is ill, they still appreciate repeated explanations. Partners/fathers can find seeing their partner in high dependency or intensive care very traumatic and may need support from staff and family members to enable them to visit their partner, understand that the situation is not hopeless and that their partner may recover, and to come to terms with what has happened.

Long-term mental health problems in partners/fathers after a near-miss experience may have a big impact financially, practically and emotionally, and families may need additional support in this event. They often felt that counselling could have been beneficial, if it had been offered. However, clinicians should take into account that partners/fathers who experience mental health symptoms do not necessarily seek help.

Chapter 3 Incidence, risk factors, management and outcomes of severe maternal morbidities

This chapter includes excerpts from Fitzpatrick KE, Hinshaw K, Kurunczuk JJ, Knight M, Risk factors, management, and outcomes of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome and elevated liver ezymes, low platelets syndrome, Obstetrics and Gynecology, 123, 3, 618–27, reproduced with permission. 54

Background

Rare obstetric events are, by virtue of their rarity, difficult to study. Each clinician will see less than one affected woman per year, and perhaps only one in a clinical lifetime. As noted in Chapter 1, any study beyond a small case-series requires a large collaboration and thus management is rarely evidence based, and information for women and their families about the likely outcome and long-term prognosis of their condition is lacking. Hospital-based studies of these conditions require retrospective review of many years of data and are not necessarily representative of the condition in the current population as a whole because of changes over time and social and demographic differences in the populations served by individual hospital units as well as local differences in clinical practice. Fundamental questions, therefore, remain unanswered and the potential remains for significant improvements in the outcomes of these conditions for women and their babies by the collection of detailed national information. This workstream included a rolling programme of studies, thus enabling the study of risk factors, diagnosis and management, and relating these to outcomes of a range of near-miss maternal morbidities on a national basis. This co-ordinated programme of parallel studies had the additional advantage of preventing clinicians being burdened with multiple requests for information from different researchers. National studies of the following near-miss morbidities were conducted: AFE, placenta accreta/increta/percreta, HELLP/elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (ELLP) syndrome, and uterine rupture.

Amniotic fluid embolism

Amniotic fluid embolism although rare, remains one of the leading causes of direct maternal mortality in high-income countries,2,55,56 characterised by sudden unexplained cardiovascular collapse, respiratory distress and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The rarity of AFE together with the fact that clinical diagnosis of the condition is one of exclusion makes it difficult to obtain reliable information concerning incidence, risk factors, management and outcomes. Previous reviews56,57 suggest that the reported total incidence of AFE varies from 1.9 per 100,000 to 7.7 per 100,000 maternities; the reported incidence of fatal AFE cases varies from 0.4 per 100,000 to 1.7 per 100,000 while the case fatality rate owing to AFE ranges from 11% to 43%. There is little consistency in the factors reported to be associated with the occurrence of AFE and very limited data available regarding factors associated with serious maternal outcomes.

Placenta accreta/increta/percreta

Three variants of abnormally invasive placentation are recognised: placenta accreta, in which placental villi invade the surface of the myometrium; placenta increta, in which placental villi extend into the myometrium; and placenta percreta, in which the villi penetrate through the myometrium to the uterine serosa and may invade adjacent organs, such as the bladder. Placenta accreta, increta or percreta are associated with major pregnancy complications58 and are thought to be becoming more common59 owing to a number of factors including rising maternal age at delivery and an increasing proportion of deliveries by caesarean. 60,61 This finding is of particular concern in the context of increasing rates of caesarean delivery and older maternal age at childbirth. 62,63 However, the risk associated with these factors has not been quantified on a population basis in studies using robust clinical and pathological definitions. There is also limited information to guide the optimal management of this condition.

HELLP/ELLP syndrome

Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets syndrome is a serious complication of pregnancy that usually occurs in women who have signs of pre-eclampsia. 64 In the absence of haemolysis, the condition has been called ELLP syndrome. 65,66 Incidence estimates vary widely and there has been no comprehensive study of the risk factors for this complication. There is also debate over the optimal management of the syndrome, particularly with regard to women who develop the condition remote from term. 66,67

Uterine rupture

Uterine rupture is a complication of pregnancy associated with severe maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. In high-income countries it most commonly occurs in women who have previously delivered by caesarean section. 68 This observation has led to debate about the optimal management of labour and delivery in women who have delivered by caesarean section in previous pregnancies. Women with a previous caesarean delivery have generally been encouraged to attempt a trial of labour in subsequent pregnancies,69 but recent reports of an increased risk of morbidity, particularly owing to uterine rupture, are thought to have contributed to a marked decrease in some countries in the number of women attempting vaginal birth after caesarean section. 70

Research questions

The following questions were addressed in all studies:

-

What is the incidence of the condition?

-

Are any factors (e.g. age, parity, obesity, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, multiple pregnancy, late or poor attendance for antenatal care) associated with an increased risk of developing the condition?

-

How is the condition managed in the UK?

-

What are the outcomes of the condition for women and their babies?

In addition, the following condition-specific questions were addressed.

Amniotic fluid embolism

-

What are the presenting features of the condition?

-

Are there any temporal trends in the incidence of the condition?

-

Are there specific factors, including timing of involvement of medical personnel and management strategies used, that are associated with adverse maternal outcomes?

Placenta accreta/increta/percreta

-

What are the risks associated with previous caesarean delivery and older maternal age?

-

What proportion of cases are diagnosed antenatally by ultrasound or MRI? Is antenatal diagnosis related to outcomes?

-

What proportion of cases have no attempt to remove their placenta, in an attempt to conserve their uterus or prior to hysterectomy? Do cases managed in this way have different outcomes?

HELLP/ELLP syndrome

-

What are the presenting features of the condition?

-

What proportion of antenatally diagnosed cases have a planned management of immediate delivery, delivery within 48 hours or expectant/conservative management? Are there any differences in outcomes according to planned management?

-

How are corticosteroids used to manage the syndrome in the UK?

-

Are there any differences in the characteristics, diagnostic features, presenting symptoms/signs, management and outcomes of women diagnosed with HELLP syndrome compared with women diagnosed with ELLP syndrome?

Uterine rupture

-

What are the common symptoms and signs noted prior to diagnosis of uterine rupture?

-

What proportion of ruptures occur in women who have previously delivered by caesarean section?

-

What are the risks associated with planned mode of delivery and labour induction and/or augmentation among women with a prior delivery by caesarean section?

-

What are the characteristics of the women who experience uterine rupture in the absence of a previous caesarean delivery?

UK Obstetric Surveillance System methodology

Case and control definitions

The case and control definitions used for each of the studies were as follows:

Amniotic fluid embolism

Cases were all women in the UK identified as having AFE defined as follows:

In the absence of any other clear cause:

EITHER

acute maternal collapse with one or more of the following features: acute fetal compromise, cardiac arrest, cardiac rhythm problems, coagulopathy, hypotension, maternal haemorrhage, premonitory symptoms (e.g. restlessness, numbness, agitation, tingling), seizure and shortness of breath, excluding women with maternal haemorrhage as the first presenting feature in whom there was no evidence of early coagulopathy or cardiorespiratory compromise

OR

women in whom the diagnosis was made at postmortem examination with the finding of fetal squames or hair in the lungs.

Controls were defined as the two women who did not have AFE and delivered immediately before other UKOSS study cases. 8,28,29,71–74

Placenta accreta/increta/percreta

Cases were all women in the UK identified as having placenta accreta/increta/percreta defined as either placenta accreta/increta/percreta diagnosed histologically following hysterectomy or postmortem, or an abnormally adherent placenta, requiring active management, including conservative approaches where the placenta is left in situ.

Controls were defined as the two women who did not have placenta accreta/increta/percreta and delivered immediately before each case in the same hospital.

HELLP/ELLP syndrome

Cases were any pregnant women in the UK identified as having new onset of the following:

elevated liver enzymes (serum aspartate aminotransferase ≥ 70 IU/l or gamma-glutamyl transferase ≥ 70 IU/l or alanine aminotransferase ≥ 70 IU/l)

AND

low platelets (platelet count < 100 × 109/l)

AND EITHER

haemolysis [abnormal (fragmented or contracted red cells) peripheral blood smear or serum lactate dehydrogenase levels ≥ 600 IU/l or total bilirubin ≥ 20.5 µmol/l)

OR

hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg) OR proteinuria [1 + (0.3 g/l) or more on dipstick testing, a protein : creatinine ratio of ≥ 30 mg/mmol on a random sample, or a urine protein excretion of ≥ 300 mg per 24 hours].

Cases with haemolysis were classified as HELLP syndrome and those without haemolysis were classified as ELLP syndrome.

Controls were defined as the two women who did not have HELLP or ELLP syndrome and delivered immediately before each case in the same hospital.

Uterine rupture

Cases were all women in the UK identified as having a uterine rupture defined as a complete separation of the wall of the pregnant uterus, with or without expulsion of the fetus, involving rupture of membranes at the site of the uterine rupture or extension of the complete separation of the wall of the uterus into uterine muscle separate from any previous scar and endangering the life of the mother or fetus. Any asymptomatic palpable or visualised defect, noted incidentally at caesarean delivery for example, was excluded.

Controls were defined as any woman delivering a fetus or infant who had not had a uterine rupture and who had delivered by caesarean section in any previous pregnancy regardless of the mode of delivery of the current pregnancy.

Data collection

Cases of the specific near-miss morbidities were notified through the monthly card mailing of UKOSS from all hospitals with obstetrician-led maternity units in the UK. On reporting a case, clinicians were sent a data collection form requesting further details to confirm the case definition and ascertain information regarding potential risk factors, diagnosis, management and outcomes. AFE cases were identified between 1 February 2005 and 31 January 2014; placenta accreta/increta/percreta cases were identified between 1 May 2010 and 30 April 2011; HELLP/ELLP syndrome cases were identified between 1 June 2011 and 31 May 2012; and uterine rupture cases were identified between 1 April 2009 and 30 April 2010.

For the uterine rupture study, controls were obtained from a random sample of obstetrician-led maternity units in the UK in month 4 and month 12 of the study, weighted by the total number of births. The time and day on which reporting clinicians were asked to select controls were randomly identified using data on birth date and time from one county of England (Leicestershire) to try and provide a representative sample of women delivering during each 24-hour period and on different days of the week. Clinicians were then asked to complete a data collection form for these controls. For the placenta accreta/increta/percreta and HELLP/ELLP syndrome studies, clinicians who reported a case were asked to select and complete a data collection form for two controls, identified as the two women meeting the control definition.

All data requested were anonymous and obtained from the woman’s medical records. If complete forms were not returned, up to five reminders were sent. The data were double entered into a customised database. Duplicate reports were identified using information on the woman’s year of birth and expected date of delivery. Cases were checked to ensure that they met the case definition and controls were checked to confirm they had been selected correctly. When data were missing or a data validity check highlighted a problem, the reporting clinicians were contacted to provide or check the information.

Study power

Amniotic fluid embolism: the analysis had 80% power at the 5% level of statistical significance to detect odds ratios (ORs) of ≥ 1.7 and ≥ 2.6, assuming putative risk factors have a prevalence of 40% and 5%, respectively.

Placenta accreta/increta/percreta: the actual number of cases and controls identified during the study gave an estimated power of 80% at the 5% level of significance to detect ORs between 1.9 and 3.3, assuming a prevalence range for potential risk factors of between 5% and 40% in the control women.

HELLP/ELLP syndrome: the actual number of HELLP cases and controls identified gave an estimated power of 80% at the 5% level of significance to detect ORs between 1.8 and 2.9, assuming a prevalence range for potential risk factors of between 5% and 40% in the control women.

Uterine rupture: over the 13-month study period, we anticipated identifying 200 cases (based on an estimated incidence of 1 in 4000 maternities4) and 600 controls. A ratio of three controls per case was planned in the study proposal to maximise the power of the study given that uterine rupture is a rare condition and the number of cases would be limited by disease incidence. Assuming that 10% of women with a previous caesarean section delivering in the UK are induced with prostaglandin and/or receive oxytocin in their labour, and with a 3 : 1 ratio of controls to cases, 106 cases and 316 controls would give an estimated power of 80% at the 5% level of statistical significance to detect a 2.5-fold increase in the odds of uterine rupture in women with a previous caesarean section who have prostaglandin labour induction and/or oxytocin used in labour.

Analysis

The overall incidence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of each condition was calculated using the most recently available national birth data that corresponded most closely with the particular study period, as a proxy denominator for the number of maternities during the study period. Denominator data to calculate the incidence and 95% CIs of placenta accreta/increta/percreta in women with and without a previous caesarean delivery and in women with and without placenta praevia diagnosed prior to delivery were estimated using the proportions of women in these various categories observed in the control women together with the most recently available birth data. To calculate the incidence and 95% CIs of placenta accreta/increta/percreta in women with a previous caesarean with and without placenta praevia diagnosed prior to delivery, we used an estimate of the incidence of placenta praevia in women with a previous caesarean delivery (1.2%), derived from a 2010 systematic review. 75 To calculate the incidence with 95% CIs of uterine rupture in women with and without a previous caesarean section, the most recently available birth data were used together with an estimate of the proportion of women in the UK who had previously delivered by caesarean section (15%), derived from the rate in a group of population-based controls comprising women giving birth in the UK in 2005–6. 8 Information on the proportion of women with a previous caesarean delivery planning a vaginal or caesarean section delivery in their current pregnancy, estimated from that observed in the control women, was used to estimate the denominator for calculation of the incidence and 95% CI of uterine rupture according to planned mode of delivery in women with a previous caesarean section. Denominator data to allow calculation of the incidence and 95% CI of uterine rupture in women with a prior caesarean delivery planning a vaginal delivery according to whether labour was induced with or without prostaglandin and/or oxytocin were also estimated using the proportions observed in the control women.

Potential risk factors for each condition were investigated using unconditional logistic regression to estimate ORs and 95% CIs. A full regression model was developed by including both explanatory and potential confounding factors in a core model if there was a pre-existing hypothesis or evidence to suggest they were related to the condition in question; the findings are reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs. Continuous variables were tested for departure from linearity by the addition of first-order fractional polynomials to the model and subsequent likelihood ratio testing. When there was evidence for non-linearity, continuous variables were presented and treated as categorical in the analysis. When there was no evidence of departure from linearity, continuous variables were presented as categorical for ease of interpretation, but have been treated as continuous linear terms when adjusting for them in the analysis. Plausible interactions were tested in the full regression model by the addition of interaction terms and subsequent likelihood ratio testing on removal, with a p-value of 0.01 considered evidence of significant interaction to account for multiple testing. The chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate, were used to compare groups. Logistic regression using robust standard errors (SEs) to allow for the non-independence of infants from multiple births was used when comparing infant outcomes. All analyses were carried out using Stata statistical software version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Amniotic fluid embolism

Incidence

There was a total of 120 confirmed cases of AFE, 23 of which were fatal (case fatality rate 19%, 95% CI 12% to 29%), in an estimated 7,001,438 maternities. 76–89 This represents a total incidence of 1.7 per 100,000 maternities (95% CI 1.4 to 2.1) and a fatal incidence of 0.3 per 100,000 maternities (95% CI 0.2 to 0.5).

Presentation

Amniotic fluid embolism presented at or before delivery in 53% (62/117) of women, at a median gestation of 39 weeks (range 28–42 weeks); the remaining women (n = 55) presented with AFE a median of 19 minutes after delivery (range 1 minute to 6 hours and 27 minutes) having delivered at a median gestation of 39 weeks (range 28–42 weeks). Diagnosis of AFE, including both antenatal and postnatal cases, was first considered a median of 33 minutes (range 0 minutes to 2 days) after presentation. Women with AFE who died were also significantly more likely than those who survived to present with cardiac arrest (87% vs. 36%; p < 0.001) and exhibit this feature as the first recognised symptom or sign of AFE (26% vs. 5%; p = 0.006); no other significant differences in presentation were found between these groups. The majority of women (91%, 108/119) had ruptured membranes at or before AFE presentation.

Risk factors

The characteristics of the women with AFE compared with the control women are shown in Table 2. Women aged ≥ 35 years had significantly raised odds of having AFE. The odds of having AFE were also significantly increased in women who had a multiple pregnancy, placenta praevia and induction of labour using any method.

| Risk factor | Number (%) of cases (N = 120) | Number (%) of controls (N = 3834) | uOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI)a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <35 | 74 (62) | 3062 (80) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 35 | 46 (38) | 766 (20) | 2.48 (1.71 to 3.62) | < 0.0001 | 2.15 (1.43 to 3.23) | 0.0002 |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 6 (0) | ||||

| Ethnic group | ||||||

| White | 92 (77) | 3064 (80) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black or other minority ethnic group | 25 (21) | 699 (18) | 1.19 (0.76 to 1.87) | 0.4458 | 1.17 (0.72 to 1.91) | 0.5183 |

| Missing | 3 (3) | 71 (2) | ||||

| Socioeconomic group | ||||||

| Managerial and professional occupations | 42 (35) | 977 (25) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other | 60 (50) | 2075 (54) | 0.67 (0.45 to 1.01) | 0.0529 | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.24) | 0.3306 |

| Missing | 18 (15) | 782 (20) | ||||

| BMI at booking (kg/m2) | ||||||

| < 30 | 90 (75) | 2797 (73) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 30 | 22 (18) | 674 (18) | 1.01 (0.63 to 1.63) | 0.9528 | 0.99 (0.60 to 1.62) | 0.9559 |

| Missing | 8 (7) | 363 (9) | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never/ex-smoker | 99 (83) | 3045 (79) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Smoked during pregnancy | 20 (17) | 732 (19) | 0.84 (0.52 to 1.37) | 0.4842 | 1.12 (0.66 to 1.89) | 0.6829 |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 57 (1) | ||||

| Previous obstetric factors | ||||||

| Parity | ||||||

| 0 | 48 (40) | 1669 (44) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 1 | 72 (60) | 2160 (56) | 1.16 (0.80 to 1.68) | 0.4353 | 1.07 (0.72 to 1.60) | 0.7336 |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 5 (0) | ||||

| Current pregnancy factors | ||||||

| Multiple pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 106 (88) | 3786 (99) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 14 (12) | 48 (1) | 10.42 (5.57 to 19.48) | < 0.0001 | 7.75 (3.60 to 16.69) | < 0.0001 |