Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10500. The contractual start date was in July 2008. The final report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in June 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Coid et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Violence-related morbidity is a key public health problem1 resulting in major concern among the public and policy-makers in the UK. Interventions to prevent violence are no longer the sole responsibility of criminal justice agencies2 and mental health services have become increasingly involved in initiatives to reduce violence. However, prevention in the field of mental health is underdeveloped and almost exclusively operates at secondary and tertiary levels. This means that mental health professionals are restricted to secondary preventative measures, such as early detection of violence risk with the aim of prompt intervention to prevent violence occurring among service users, or tertiary prevention, including measures aimed to reduce the impact on the public of future violence from those who have already been identified as a potential risk on the basis of their previous behaviour. At present, tertiary-level strategies focus on reducing the impact of identified risk factors, including psychiatric morbidity, usually after violence has occurred.

Violence prevention is not recognised as a primary function in all mental health services. Furthermore, it tends to be just one of several goals even within secure mental health services. This means that the primary prevention of violence (which consists of actions and measures aimed at inhibiting the emergence of environmental, economic, social and behavioural conditions, cultural patterns of living, etc., known to increase the risk of violence) is not yet perceived as a core focus of mental health services. Public mental health equivalents of primary prevention through personal and communal efforts, such as enhancing nutritional status, immunising against communicable diseases and eliminating environmental risks, have not yet been developed. Risk assessment, which is designed to facilitate risk management in mental health and the criminal justice system, is of increasing importance but represents the equivalent of secondary and tertiary levels of prevention. By implication, risk management by mental health professionals for violence involves targeted, rather than population, interventions with individuals who are recognised as being of high risk. 3

Compton et al. 4 have argued that the population approach to prevention can be applied in mental health. Universal preventative interventions or population interventions target a whole population or the general public. 5 Such interventions benefit everyone in the population, regardless of their risk for violence. These might include public service announcements or media campaigns to prevent substance abuse, legislation to increase the legal drinking age or more serious penalties for violent behaviour and carrying weapons. Selective preventative interventions target individuals or subgroups of the population whose risk of violence is significantly higher than average. A high-risk group may be identified by psychological, biological or social risk factors. An intervention can include lifestyle modification to avoid situations in which individuals encounter or become involved in violence or, as indicated by our programme, an intervention for boys who witness violence in the family home (see Chapter 7, Study 1).

Indicated preventative interventions target particularly high-risk individuals – those with risk factors, or a condition, that identify them as being at high risk of future violence. At the present time, much of the debate around risk assessment in mental health and the criminal justice system has focused on the accuracy of identifying high-risk individuals. This is primarily because of the implications for these individuals if judged to be at high risk. Interventions available for those who are considered to be at exceptionally high risk, for example psychopathy, are often very limited. Interventions can include prolonged detention, more severe sentencing in court and detention and treatment in hospital against an individual’s will.

Development of risk assessment has been led primarily by clinical psychologists over the past 30 years. As the law has turned to behavioural and medical sciences to improve accuracy in the assessment and management of violence, specialist instruments (or ‘tools’) have been developed for the prediction and management of certain kinds of serious violence and criminal offending. 6 It has been estimated that > 120 risk assessment instruments have been developed and promoted for use in mental health services and the criminal justice system, with competing claims of superiority with regard to accuracy. 7 However, our programme has questioned the superiority of the predictive accuracy of any one tool over another. 8 Furthermore, few of these instruments lead easily to the second and essential component of a risk assessment – a plan of risk management. Bridging to risk management is described as the key component. 9 However, few currently available risk assessment tools either link to or incorporate risk management strategies.

Changes to the original aims of the programme

The theoretical basis of the research programme underwent major changes over the 5-year period. Unexpected findings conflicted with established views of how risk should be assessed, as described in the international literature. These had determined the basis of the original application and its aims. By the time the programme began, risk assessment for violence had become divided into two main approaches: actuarial risk assessment (ARA) and structured professional judgement (SPJ). Adherents to these approaches had become increasingly in opposition to each other. Our original application was largely committed to the actuarial approach to develop our new instruments during the programme. ARA instruments provide numerical probabilities of future violence, at different subsequent time intervals from a baseline measurement. This is a predictive method. Adherents to the alternative approach, SPJ, have argued that an actuarial approach is inappropriate for risk assessment because probabilities based on the group average method do not apply to the individual being assessed. 10 Assessors are encouraged instead to rate individual risk items according to their presence or absence and then formulate their risk-level rating according to a global, clinical understanding of the risk posed by the individual, followed by possible scenarios that could result in violence that might occur in the future.

By the time the programme started, the UK criminal justice system and the NHS mental health systems had proceeded in opposite directions. Risk assessment within the criminal justice system is currently based on a series of actuarial measures developed from large data sets of offenders. Ratings typically determine level of security and intensity of supervision and are provided to sentencers in courts to assist with sentencing or to parole boards to help determine parole. These are administered by offender managers (probation and prison staff). This method provides a highly efficient and economic method of assessing risk and can be carried out with minimal training. Probabilities of an individual’s future offending can be determined using computerised data derived from routine ratings by Ministry of Justice staff. However, our programme increasingly began to question the accuracy of these measures, corresponding to doubt expressed by previous investigators,10,11 particularly the high percentage of individuals incorrectly classified as at risk of further offending or not at risk.

Mental health services had meanwhile adopted SPJ, specifically the use of the Historical, Clinical, Risk Management-20 (HCR-20). 12 The authors of this instrument are Canadian. Over the time span of the programme, intensive training for NHS staff as well as staff in other European countries had begun. Local initiatives for risk assessment previously introduced by NHS trusts were replaced by SPJ, which became the risk assessment of choice in mental health services. For some NHS services, completion of the HCR-20 for each patient had become essential to receive funding from commissioners.

To carry out a risk assessment such as the HCR-20, staff require intensive training. Completion of the instrument can take over an hour. Clinical teams in mental health services typically complete the assessment together, with a member of the team filling in the forms. These are then filed as a hard copy in case notes or entered in electronic format. Different services have opted for different time spans over which the SPJ should be repeated, although in most cases this is on a single occasion during hospital admission. There is little indication that SPJ continues routinely after discharge. This is when service users are most likely to encounter new or previously demonstrated risk factors and when intervention is most urgently required if there is an indication of impending violence.

Structured professional judgement also provides no clinical advice on how, when or indeed whether or not to intervene; instead, it considers whether or not the service user is a risk and encourages the rater to imagine what situations might occur to increase risk. The strategy of management is then for the clinician to determine.

The costs of using SPJ methods include fees for training. European trainers now increasingly run courses, with less reliance on employing North American teachers. More recently, however, new versions of SPJ have become increasingly expensive and it is necessary to buy manuals from North America. Trainers in North America and Europe have also developed their own commercial interests. There is therefore a need for the NHS to develop new approaches to risk assessment and develop its own products. This became a key aim of our research by the end of the programme with our development of new Bayesian networks.

The programme of research therefore progressed through a series of phases. It initially became necessary to ‘deconstruct’ earlier approaches to risk assessment that had been applied within the actuarial approach, but also within SPJ. At an early stage we discovered that the statistical model that we had chosen to develop our risk assessment instrument, and which had appeared to show considerable promise before we started, conveyed no benefits whatsoever. Furthermore, it was likely to result in an instrument with poorer accuracy than if we had used conventional statistical methods. This corresponded to the disappointing findings from the US MacArthur risk study,13–15 the largest and most expensive ever conducted, which had used a similar statistical method. This US programme had ultimately failed in its aim to develop a new method of risk assessment with superior accuracy for patients discharged from psychiatric hospitals in the USA. 13–15 We had intended to develop a similar method of risk assessment in our programme and compare it with the McArthur Classification of Violence Risk (COVR) instrument. 13

The reasons for this failure are now entirely clear from our research. As we learned more about the shortcomings of risk assessment, particularly the actuarial approach, it became necessary to substantially revise our approach. Our original aims and objectives for the programme therefore changed. At the same time, we also became increasingly sceptical about the SPJ approach. SPJ had evolved during the early stages of our programme, exemplified in the change from the HCR-20 version 2 (HCR-20v2)16 to the HCR-20 version 3 (HCR-20v3),17 which we had agreed to validate in our programme with the authors of the instrument. Whereas proponents of the SPJ approach were highly critical of the rival actuarial method of adding scores from risk items, this method had previously been widely used in the rating of the HCR-20v2. It was now prohibited for clinical use in the new third version and assessors were instructed to make overall correlations of ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ future risk based on their global perception following the assessment. Nevertheless, all empirical research using SPJ continues to rely on producing numerical scores of risk based on individual items. Validation of SPJ instruments therefore continues to depend on actuarial prediction methods, most commonly using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) statistic, to determine their accuracy of prediction of future violence. Although we have applied this method in our programme, we have also investigated its considerable limitations and proposed alternatives.

One additional limitation became apparent from our research: the HCR-20 and other SPJ instruments are ‘checklists’. They do not allow for the multidimensional approach that is necessary for a comprehensive risk assessment. They depend on a ‘compartmentalised’ assessment of a predetermined number of areas. These are fixed and not determined by an individual’s previous longitudinal history. The HCR-20v3 has been improved and considerably expanded in an attempt to incorporate more information on risk and encourages assessors to use their own judgement and identify additional risks. However, the included items are not covered in a manner similar to clinical history taking in mental health services. For a clinical assessment, individual components such as criminal history require a greater depth of understanding if the links are to be made between a previous history of antisocial behaviour and associated risk and predictive factors. The HCR-20 does not capture the potential synergistic effects of these different components and ultimately relies on clinical experience and the expertise of the clinician rater. Finally, SPJ does not impel the rater to intervene when a risk factor is clearly present or indicate which factors should be targeted for intervention on the basis of an established causal link between the factor and violent outcome, and these limitations are the motives for moving from a risk assessment to effective risk management. They became our primary aim by the end of our programme.

Finally, and most importantly, there is currently no evidence that SPJ can predict violence more accurately than an ARA instrument. 8 Furthermore, there is currently no evidence that either an ARA instrument or an assessment based on SPJ can prevent violence. The only randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a SPJ instrument, the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START), failed to demonstrate any improvement in clinical outcome or violence reduction compared with management as usual. 18 Although our programme provides a third alternative to ARA instruments and SPJ, a RCT is clearly the next phase of research required; it will be necessary to test our Bayesian models in the future against current clinical practice.

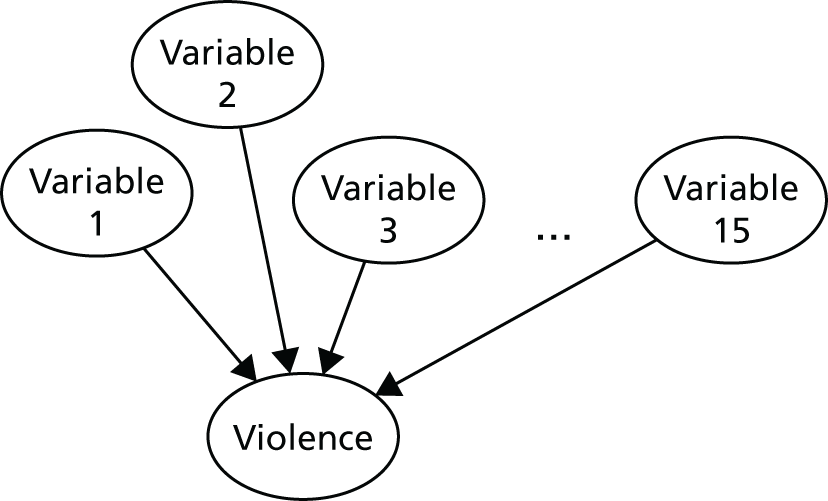

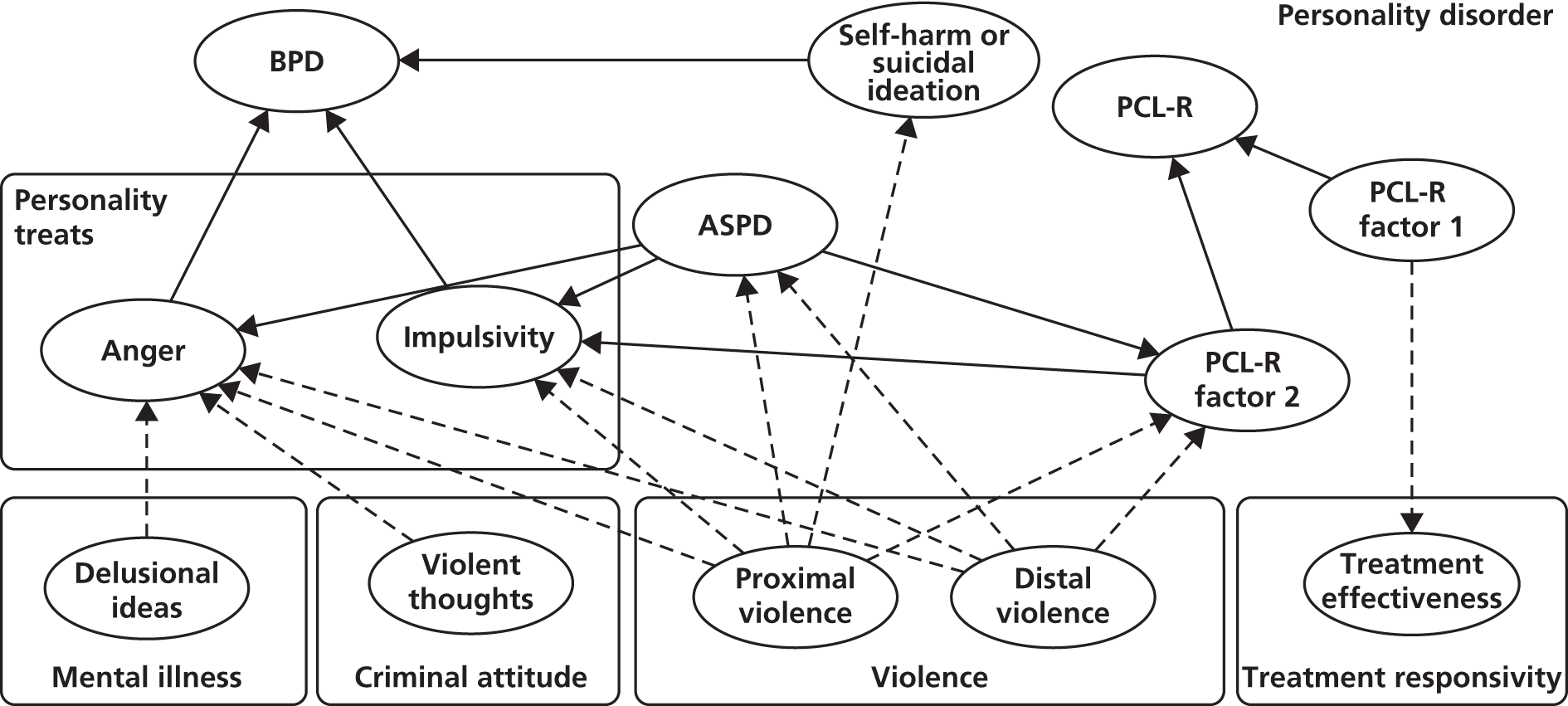

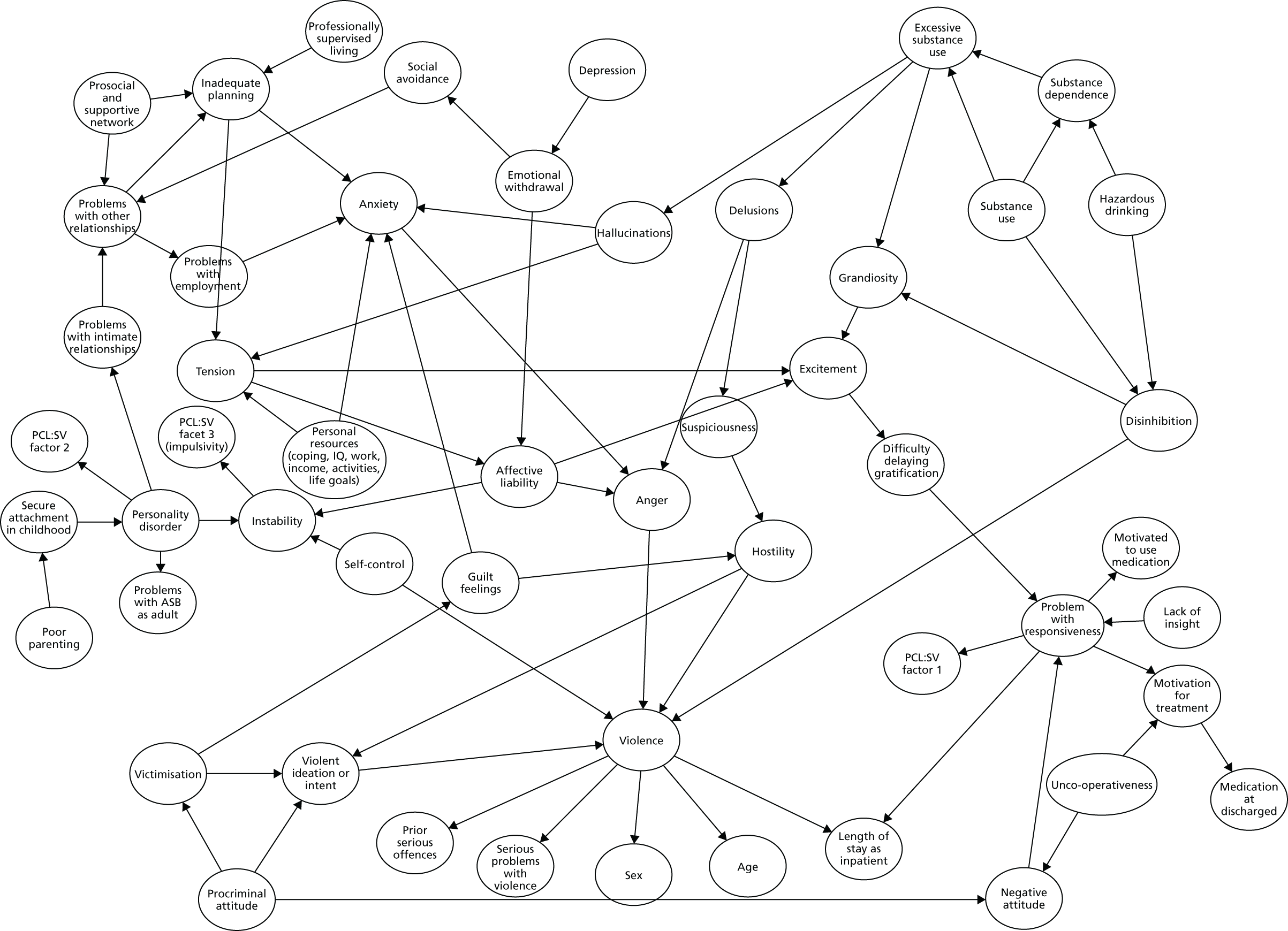

A theoretical model of risk pathway to violence

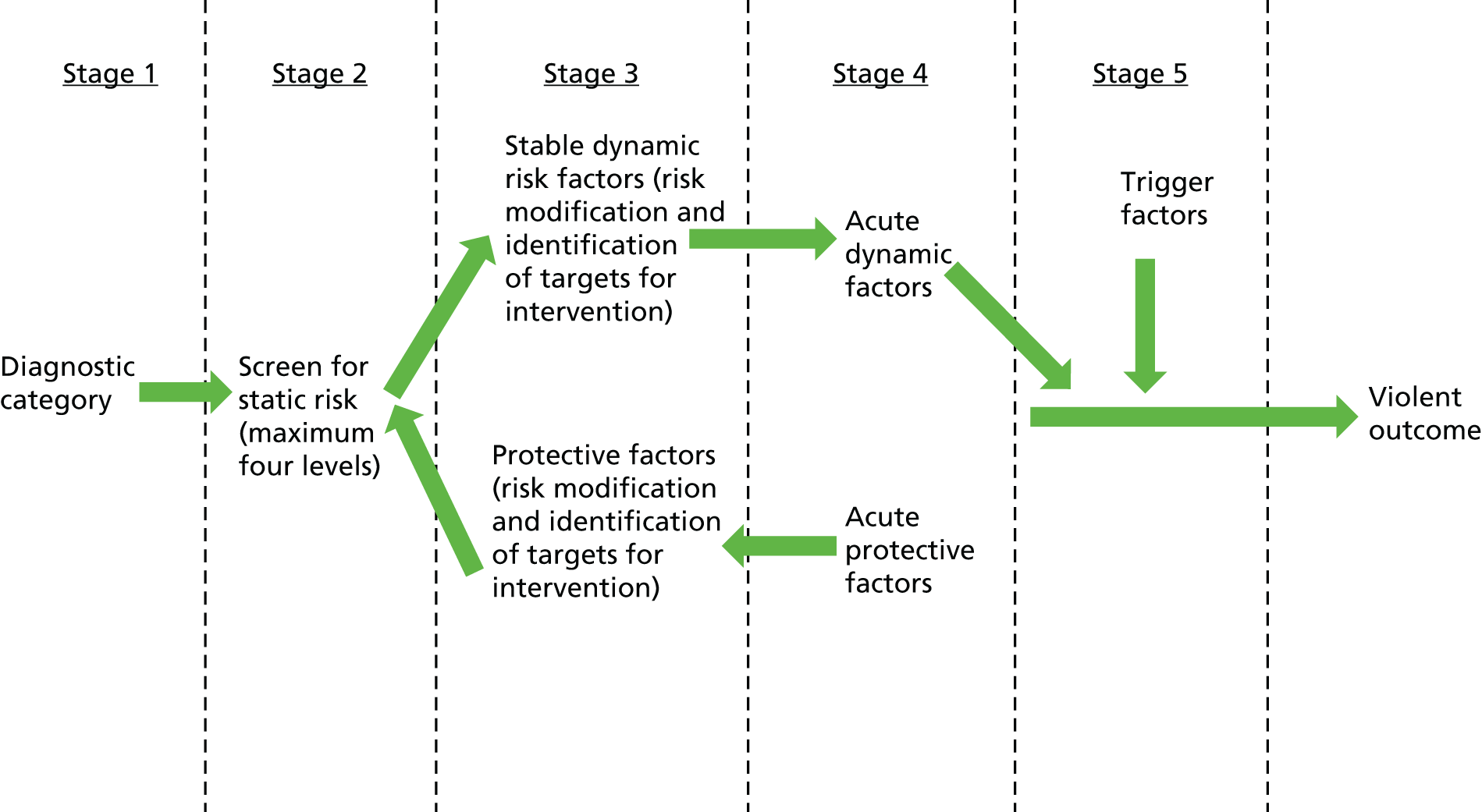

This report presents a new approach to risk assessment and risk management (Figure 1) that could be incorporated into clinical practice. It is based on a model of assessment that we have empirically tested, but is also derived from clinical experience. It is based on a longitudinal approach that aims to capture the evolution of risk over time when an offender is released from custody or a service user is discharged from hospital. Clinical risk assessment of an individual would proceed through each of the five stages in Figure 1. This would be based on previous behaviour and a full assessment of an individual’s previous history, including current circumstances and reason for the assessment, detailed assessment of previous and more recent violent and criminal behaviour, family history and developmental history from childhood to the present day. Although Figure 1 shows that the first stage of the assessment is to make a diagnosis, clinicians would point out that this is usually completed towards the end of a clinical assessment. It would include assessment of current and previous mental state to attain a formal diagnosis of mental disorder, including personality disorder and history of substance misuse. Figure 1 is therefore the basis of a risk formulation. This would follow a full clinical assessment. It also forms the basis of our programme of research.

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical model of risk pathway to violence.

Figure 1 therefore begins with the establishment of a psychiatric diagnosis at the outset together with the level of static risk for future violence, based on actuarial measures. We have already referred to the limitations of the actuarial approach but it is necessary to demonstrate these in this programme report in coming to this conclusion. We believe that an actuarial measure of risk has some value but this is limited. We shall explain the limits and the importance of combining actuarial measures with dynamic risk assessment. A clinician may wish to know the score of risk based on previous offending and this may result in a more in-depth profiling of an individual’s criminal history, but should not be the basis of major decisions such as release from hospital or prison. It is also of some limited value when screening offenders to indicate when an in-depth clinical assessment is required. However, when combined with dynamic factors, a static or actuarial measure of risk can provide a more accurate assessment and indicate dynamic risk factors that will be targeted for intervention.

Stage 3 requires an assessment of ongoing dynamic risk factors, which are changeable and should be identified as targets for future intervention. In our previous research we identified the importance of protective factors and the interaction that can occur between protective factors and risk factors. 19 However, protective factors were not an aim of the programme and are not described in detail in this report.

In stage 4, the individual may encounter acute risk factors that have a direct influence on subsequent behaviour, for example acute intoxication or involvement in a group or gang, which have a more immediate bearing on violent outcome.

At stage 5, certain trigger factors, which have an immediate and causal effect on the violent outcome, may be encountered. Alternatively, the violence may have been planned for some time, although a sudden triggering factor can occur in certain cases when planning has been present.

In developing this model we have shifted considerably from our original goal, which was to develop predictive measures. Our programme of research changed to the identification of causal risk factors because only causal factors should be targets for intervention. A risk factor may be highly predictive of future violence but, if it is not causal, attempts to modify it will not prevent future violence from occurring. In contrast, we have observed that causal risk factors may have no predictive ability in estimating the probability of future violence. This is particularly the case for a dynamic risk factor that shows fluctuations of intensity, such as the presence of anger as a result of delusions. 20,21

Aim

Our overall aim was to carry out a programme of linked research studies aimed at improving the quality of clinical risk management of individuals identified as being at high risk of harm to the public.

Section A of our report examines both static risk factors and psychiatric diagnosis (relating to stages 1 and 2 of our theoretical model in Figure 1). We shall show that risk of violence in terms of cross-sectional associations at the population level differs according to both diagnostic category and demographic factors.

Section B of our report describes the development of a risk assessment tool for patients presenting to general psychiatric services based on a first-episode cohort of patients with psychoses. This section describes a model based on multilevel modelling, a sophisticated statistical approach to multiple measures over a prolonged period. This is a prototype for further development. Section B covers stages 1–4 of the model.

Section C of our report describes the Validation of new Risk Assessment Instruments for Use with Patients Discharged from Medium Secure Services (VoRAMSS) study, a prospective follow-up of patients discharged from medium secure units (MSUs) across England. In this section, which covers stages 1–4 of the model, we test the accuracy of prediction of violent behaviour of standardised risk assessment instruments, ARA instruments and SPJ over the 12 months following discharge. We also validate the Medium Security Recidivism Assessment Guide (MSRAG),22 an actuarial instrument that we developed previously. We shall demonstrate that all ARA instruments and SPJ have shortcomings if validated using predictive methods and that dynamic factors are essential measures because they directly influence the violent behaviour. Nevertheless, we describe a new way of using ARA instruments in conjunction with dynamic measures that can improve accuracy.

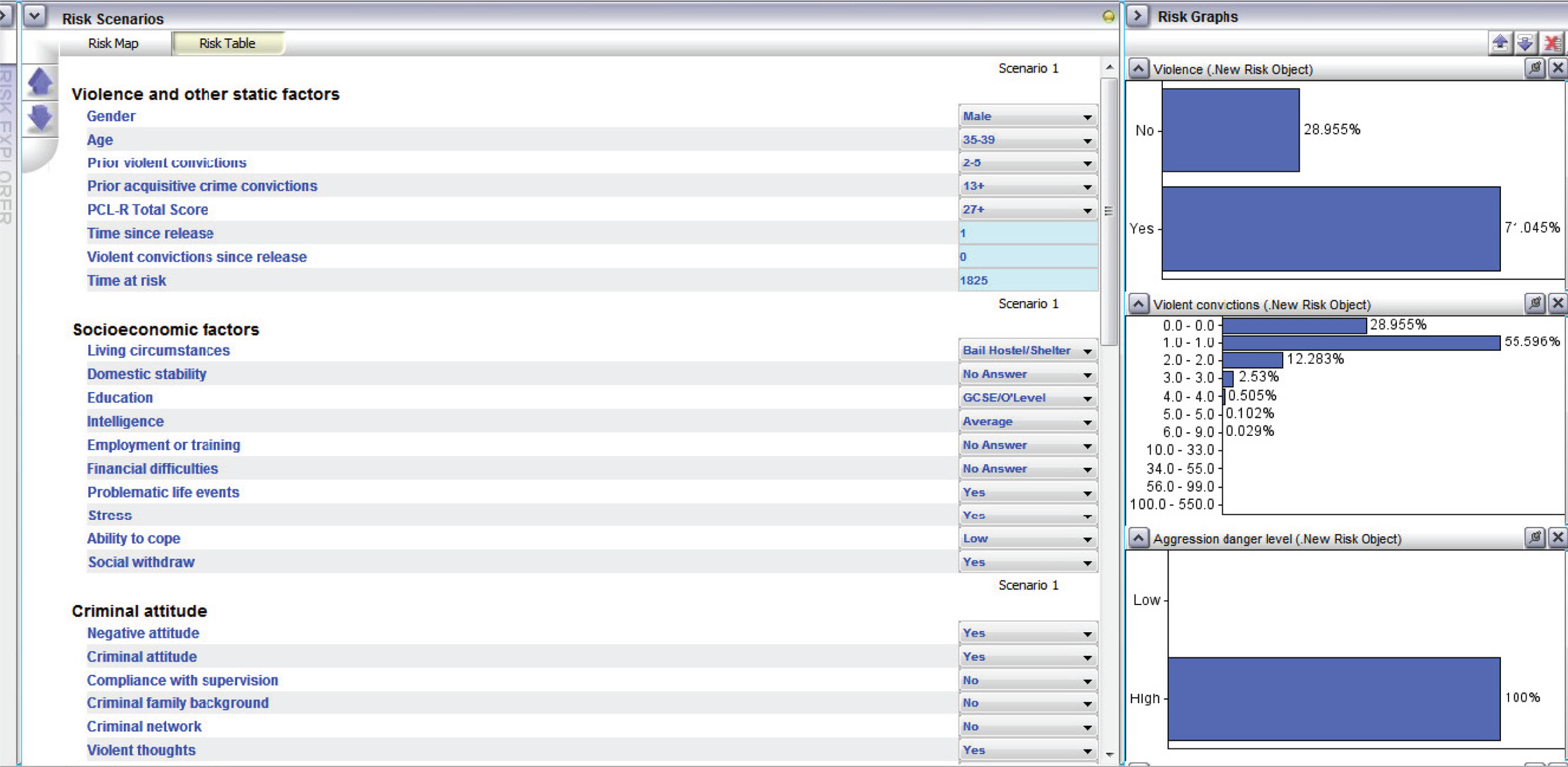

Section D describes the development of four new ARA instruments for violent, robbery, drug-related and acquisitive offending. We have developed a computerised version of each as well as a version that can be used by clinicians with pencil and paper. Although ARA instruments clearly have their limitations, we show that combining them with dynamic factors shows a highly promising method that can be adapted and used in clinical practice. We then developed a dynamic risk assessment instrument to combine with these ARA instruments and validated it using a very large data set provided to us by the National Offender Management Service (NOMS). In the criminal justice system, offender managers use ARA instruments because they are economical, are less time-consuming and do not require intensive training. It is not possible to routinely use SPJ because of the number of offenders who must be assessed and the consequent size of caseloads. The instruments that we have developed are therefore of primary usefulness to the work of criminal justice personnel, especially probation officers. Because probation officers routinely complete Offender Assessment System (OASys) ratings on their clients that are computerised, our model can now be adapted for routine use for improved risk assessment, with important implications for risk management.

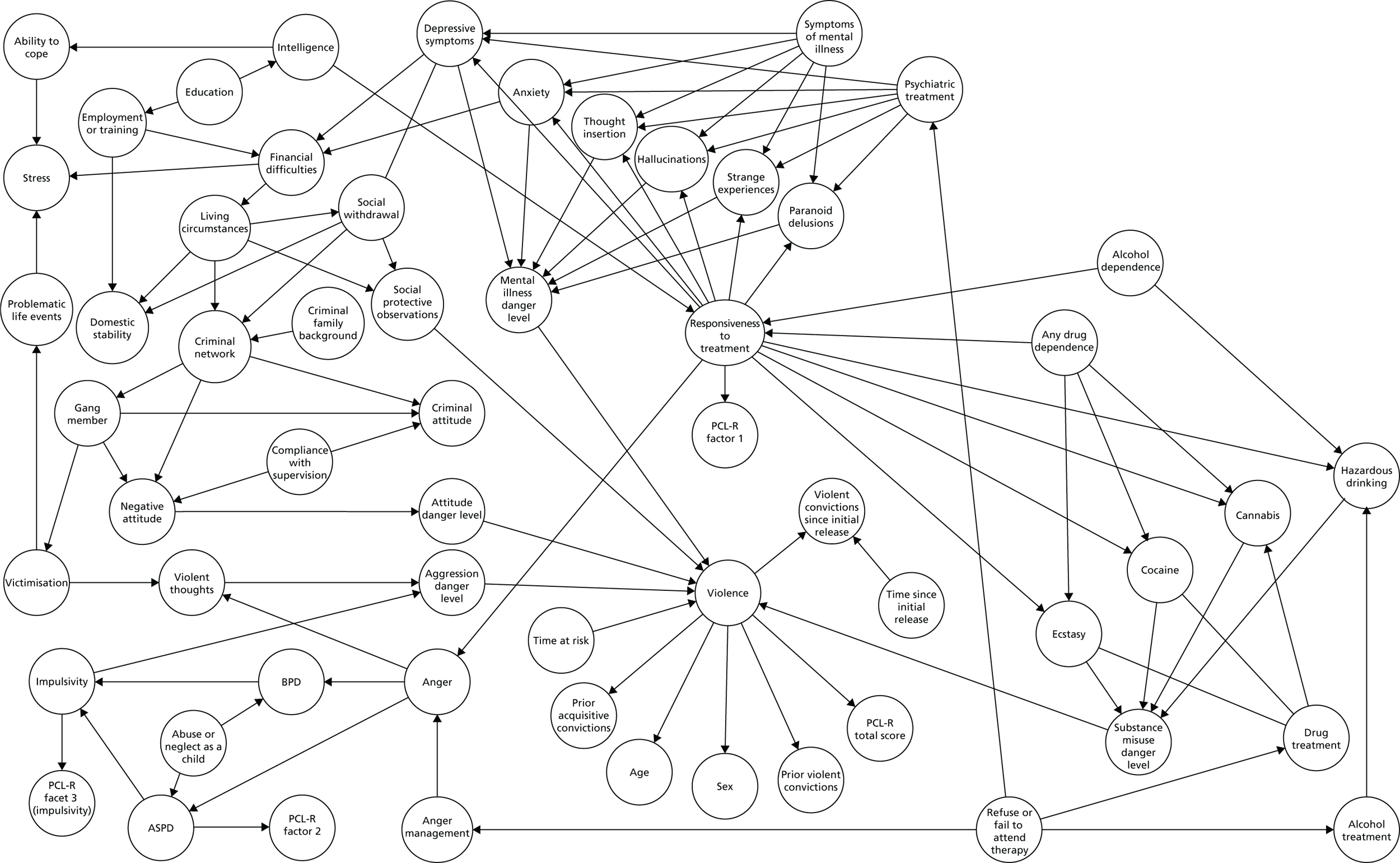

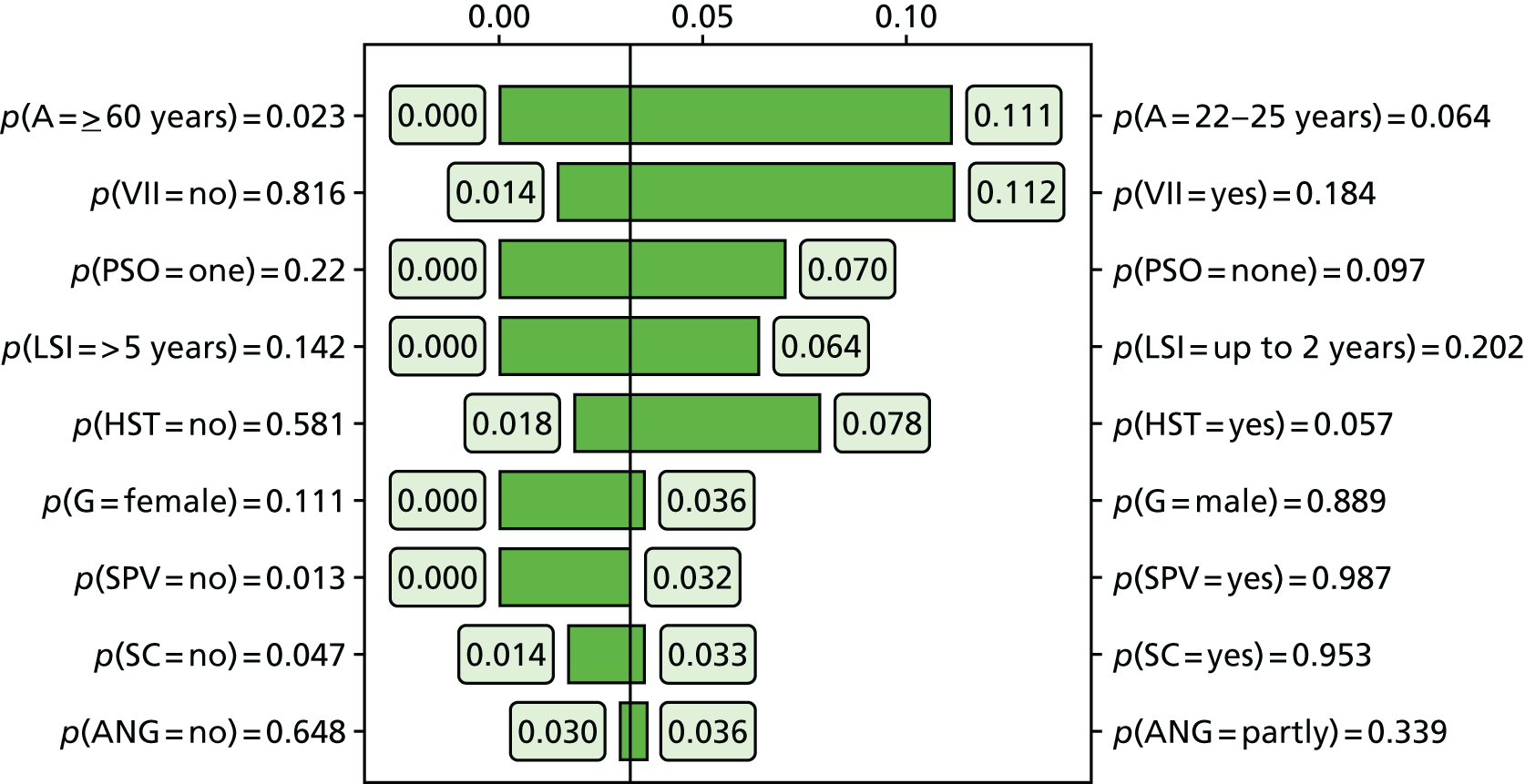

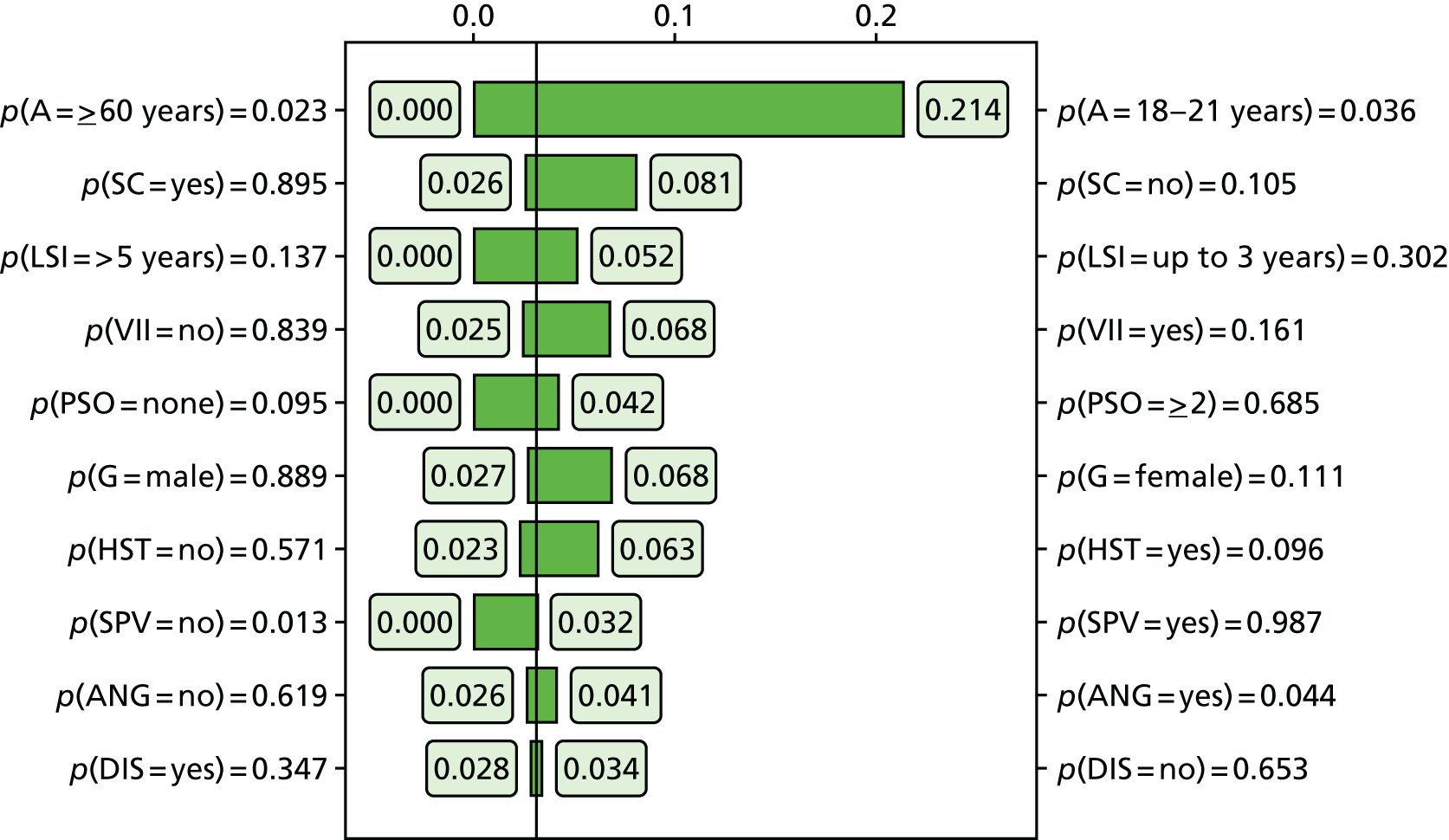

Section E describes the development of a Bayesian network to assess risk and identify the key dynamic risk factors for preventative interventions to guide risk management. Bayesian networks were chosen for this section of the programme because they are used to identify factors that are causal. They can provide actuarial measures of risk as well, but are better suited to our main aim of establishing causal associations. This final and most important part of our programme has established the basis for further development in the field of risk assessment and management. We have developed models that have operated successfully and have been used in their preliminary prototypic form by clinicians. They are at the stage of development before programming of a computerised application (app) for use by a clinician on a tablet in the field. Following this stage, the models will be ready for comparison with standard SPJ in a RCT to assess their effectiveness for violence prevention.

Table 1 summarises the studies, populations and outcomes presented in this report.

| General population | Adult psychiatric population | Adult forensic population | Prisoners | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households in England, Wales and Scotland (n = 8880) | First-episode psychosis: baseline (n = 409), follow-up (n = 389) | VoRAMSS study: baseline (n = 409), 6-month follow-up (n = 387), 12-month follow-up (n = 344) | PCS: pre release (n = 1717), post release (n = 1004) |

| APMS (n = 7403) | ||||

| Men’s Modern Lifestyle Survey: main (n = 3247), ethnic minority booster (n = 1540), low social class booster (n = 1002), Hackney, London, booster (n = 883), Glasgow East booster (n = 789) | NOMS (n = 53,800) | |||

| Location in report | Section A | Section B | Sections C and E | Section D |

| Outcome | Identification of risk factors for violence in the general population | Development of sex-specific static and dynamic instruments for the assessment and management of violence risk | Validation of static and dynamic risk instruments for violence; development of a Bayesian model for the assessment and management of offending behaviour | Development and validation of static and dynamic risk assessment instruments; development of a Bayesian model for the assessment and management of offending behaviour |

Section A Epidemiology of risk factors for violence in Great Britain

Chapter 2 Demography and typology of violence

Background

The public health impact of mental health on violence depends on the base rate of violence in the general population. This may ultimately influence whether targeted ‘high-risk’ or large-scale ‘population’ strategies are chosen for violence prevention. 3 In geographical locations with low violence rates, the proportion of violence attributed to mentally disordered people may appear high and efforts to contain their violence will achieve public health and political prominence. However, in locations with high base rates, more relevant risk factors may include weapon availability, substance misuse and gang violence, and being young, male, single and of low social class are the strongest risk factors for violence, irrespective of psychiatric morbidity. Demographic and social factors are prominent in most risk assessment instruments for violence and criminality. Factors such as younger age and criminological variables are contained in most tools and these, together with childhood factors indicating early onset of violence behaviour and substance misuse, appear to be the most predictive individual items for future violence. For some instruments, these are the only predictive items and clinical factors may have little predictive ability. 23 Nevertheless, there is a consensus that mental disorder is related to violence24–31 and that it increases the risk of violence over the lifespan. 32–36 Questions remain, however, over the size of the contribution from those with mental disorder to the overall level of violence within the general population and also over which disorders make the greatest contribution. The predictive ability of mental health variables to determine future violence will be dealt with in subsequent chapters. This current chapter will outline the association between mental health and violence at the population level in Great Britain, the size of the problem and whether or not the public health approach to violence is appropriate.

The public health problem of violence has generated less interest here than in the USA. 37,38 The UK has a relatively low rate of homicide. However, the high annual medical and social costs of injury from deliberate harm are highlighted by investigations in accident and emergency (A&E) departments in the UK. 39 Violence is a major public health problem that affects millions of people across the UK. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW)40 estimated that just over 2 million violent incidents were committed against adults in 2011/12. Over the same period, police recorded around 762,500 violence against the person offences in England and Wales. 41 A further 53,665 sexual offences were recorded. Just under half of violent incidents recorded by the police resulted in injury, as did half of those reported by adults to the CSEW. The difference between the number of violent incidents reported through the CSEW and the number of offences recorded by police shows that many incidents of violence are not recorded in the criminal justice system. Nevertheless, violence resulting in injury often requires treatment and there were 34,713 emergency hospital admissions for violence in England and Wales in 2010/11. 42 Rates were highest among young males and among those with increasing levels of socioeconomic deprivation. 43 For every hospital admission for violence it is estimated that a further 10 assault victims require treatment in A&E. A&E assault attendances peak at night over the weekend and are often related to alcohol. There were large increases in the levels of violence across England in the 1990s and early 2000s. However, more recent data suggest that the trend has reversed and that violence is decreasing. 44

Study 1: the demography of violence among adults in Great Britain

Objectives

The objectives of study 1 were to:

-

investigate the demographic characteristics of adults in the UK general population who report violence

-

construct a typology of violence among men and women based on behavioural characteristics, including victims and the location of the violence.

Methods

Data from two national cross-sectional surveys and the commissioned second Men’s Modern Lifestyle Survey (MMLS) were used to identify high-risk behaviours, including violence, and demographic, psychiatric, lifestyle and service use correlates.

National surveys of psychiatric morbidity in the UK

People aged 16–74 years were sampled in the National Household Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (NHPMS) in 2000, details of which have been described previously. 45 This was a two-phase survey. 46 Computer-assisted interviews in person were carried out by Office for National Statistics interviewers. The small users Postcode Address File (www.poweredbypaf.com) was used as the sampling frame and the Kish grid method47 was applied to systematically select one person in each household. A total of 8886 adults completed the first-phase interview reported here, a response rate of 69.5%, and 8397 (94.5%) of these completed all sections of the questionnaire. Among non-respondents, 24% refused and 6.5% were non-contacts in the household. There was no information on psychiatric status of non-respondents to enable analysis of whether or not their omission resulted in biased estimates of the prevalence of violence. However, weighting procedures that were applied throughout the analyses took into account the proportions of non-respondents according to age, sex and region. This was to ensure a sample that was representative of the national population, compensating for sampling design and non-respondents in the standard error (SE) of the prevalence, and to control for the effects of selecting an individual per household.

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) in 200748 sampled adults aged ≥ 16 years living in private households in England. In this survey, data were obtained from English adults only. The survey was commissioned by the NHS Health & Social Care Information Centre and was carried out by the National Centre for Social Research in collaboration with the University of Leicester. Field work was carried out between October 2006 and December 2007. A multistage stratified probability sampling design was adopted based on the small user Postcode Address File. One adult aged ≥ 16 years was selected from each household for interview using the Kish grid method. 47 Phase 1 data were collected by lay interviewers. A total of 7403 adults completed first-phase interviews, representing 57% of those eligible and originally approached. There is no information regarding the mental health status of non-respondents. However, data were again weighted to account for non-response. Sample weights were also assigned to take into account different probabilities in household selection. All models were corrected for area clusters based on postcodes. Of the 7403 participants, 7369 completed the violence self-report questions.

Men’s Modern Lifestyle Survey

Violence and high-risk behaviour at the population level disproportionately involves young men. However, young men are the least likely demographic group to voluntarily access health services, especially when confronted with emotional and social problems. 49,50 To investigate in more detail violence and use of services by young men, together with implications for risk management, we commissioned our own survey for the programme. This was carried out by ICM Research (www.icmunlimited.com).

The second MMLS was carried out in 2011. The MMLS was based on random location methodology, an advanced form of quota sampling shown to reduce the biases introduced when interviewers choose a location to sample from. Individual sampling units (census areas of 150 households each) were randomly selected within British regions, in proportion to their population. The basic survey derived a representative sample of young men (aged 18–34 years) from England, Scotland and Wales (n = 3247). In addition, there were four boost surveys. First, young black and minority ethnic men were selected from output areas with a minimum of 5% black and minority ethnic inhabitants (n = 1540) and young men from lower social grade D or E were selected from output areas with a minimum of 30 men aged 18–64 years in these social grades (n = 1002); The final boost surveys were based on output areas in two locations characterised by high levels of deprivation, the London borough of Hackney (n = 883) and Glasgow East (n = 789). The same sampling principles applied to each survey type.

Topics in the survey not included in the NHPMS or APMS included leisure activities, weight and exercise, use of pornography, enhanced information on antisocial and criminal behaviours and attitudes, including violence, harassment and stalking, gang membership and attitudes to accessing health-care services. Respondents completed the pencil and paper questionnaire in privacy and were paid £5 for participation.

Violence module

Participants in all surveys answered questions about the presence of violent behaviour. An affirmative answer to the question ‘Have you ever been in a physical fight, assaulted or deliberately hit anyone in the past 5 years?’ was followed by questions that qualified the violent events, including frequency, whether there were injuries or whether the act was committed while intoxicated. Additional questions assessed the identity of victims and the locations of the incidents.

Measurement of psychiatric morbidity

The Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (PSQ)51 was used to screen participants for psychosis, with a positive screening being one in which three or more criteria were met. Questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) screening questionnaire52,53 identified antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) in all surveys.

In the MMLS, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)54 was used to define anxiety and depression, based on a score of ≥ 11 in the past week. In the NHPMS and APMS, the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised Version (CIS-R)55 was used to obtain the prevalence of common mental disorders in the week preceding the interview. These were combined into two categories of anxiety disorder and depressive disorder.

The principal instrument used to assess alcohol misuse was the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),56,57 which defines hazardous drinking (a score of ≥ 8), alcohol misuse (a score of ≥ 16) and alcohol dependence (a score of ≥ 20). A number of questions designed to measure drug use were included in the NHPMS and APMS. Positive responses to any of five questions measuring drug dependence for a series of different substances over the previous year were combined to produce categories of drug dependence according to drug type. 45 Scores of ≥ 6 on the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT)58 were used to identify drug misuse and scores of ≥ 20 were used to identify drug dependence in the MMLS.

Analysis of data

Outcome data, including self-reported violent behaviour towards others and violent and sexual victimisation, including domestic violence, were examined in relation to measures of demography, general health, service use, common mental disorders, personality disorder, psychosis screen, adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use, among others. Weighted analyses were used to account for the sampling procedure. Risks were measured by odds ratios (ORs) in all cross-sectional data. Multivariate statistical models were used to handle covariates among multiple outcomes of lifestyle and behaviour. Random-effects models were employed when area variation was thought to have a substantial effect on the outcome of interest.

Results

The weighted prevalence of severity and type, victims and location of violence in the three UK surveys (NHPMS 2000, APMS 2007 and MMLS 2011) is summarised in Table 2.

| Violence outcomes | NHPMS 2000, n (%) | APMS 2007, n (%) | MMLS 2011, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants, Na | 8382 | 7393 | 5240 |

| Any violence | 982 (11.7) | 614 (8.3) | 1681 (32.1) |

| Violence when intoxicated | 422 (5.0) | 263 (3.6) | 765 (14.9) |

| Repeated violence (five or more incidents) | 237 (2.8) | 98 (1.3) | 255 (5.0) |

| Victim injured | 333 (4.0) | 172 (2.3) | 720 (13.8) |

| Perpetrator injured | 310 (3.7) | 204 (2.8) | 713 (13.7) |

| Police involved | 254 (3.0) | 177 (2.4) | 410 (7.9) |

| Minor violence | 408 (4.9) | 247 (3.3) | 374 (7.2) |

| Gang fights | NA | NA | 266 (5.3) |

| Victim of violence | |||

| Intimate partner | 137 (1.6) | 115 (1.6) | 201 (3.9) |

| Family member | 63 (0.8) | 91 (1.2) | 223 (4.3) |

| Friend | 180 (2.1) | 132 (1.8) | 437 (8.4) |

| Someone known | 316 (3.8) | 195 (2.6) | 483 (9.3) |

| Stranger | 484 (5.8) | 300 (4.1) | 737 (14.1) |

| Police | 53 (0.6) | NA | 131 (2.5) |

| Location of violent incident | |||

| Own home | 168 (2.0) | 123 (1.7) | 235 (4.5) |

| Someone else’s home | 76 (0.9) | 61 (0.8) | 281 (5.4) |

| Street/outdoors | 555 (6.6) | 354 (4.8) | 855 (16.4) |

| Bar/pub | 358 (4.3) | 183 (2.5) | 622 (11.9) |

| Workplace | 81 (1.0) | 21 (0.3) | 60 (1.2) |

| At sporting event | NA | NA | 360 (7.2) |

The MMLS survey, which was restricted to men aged 18–34 years, reported the highest prevalence of violence in all categories, including violence when intoxicated, victim and perpetrator injured and violence repetition (i.e. five or more incidents). However, Table 2 also shows that, when the NHPMS and APMS are compared, the prevalence of all levels of severity and types of violence, victims and violence in specific locations was lower in the 2007 survey than in the 2000 survey among both men and women (except for violence against intimate partners and family members).

In terms of victims, violence towards strangers was the most prevalent category in the NHPMS, AMPS and MMLS. The rate of intimate partner violence (IPV) was similar in both household surveys and was higher among young men.

In each survey the most common location of violent incidents was in the street or outdoors. This was followed by violence in a pub or bar and violence in the respondent’s own home.

Age

Age was subsequently included as an adjustment in all models of association with violence in our studies. The mean age of violent men was 31.0 [standard deviation (SD) 11.6] years in the NHPMS, 32.0 (SD 12.7) years in the AMPS and 24.6 (SD 5.0) years in the MMLS, compared with 47.4 (SD 14.9) years, 52.7 (SD 17.7) years and 25.7 (SD 5.1) years, respectively, for non-violent men. Violent men were significantly younger than non-violent men in each survey (p < 0.001). The mean age of violent women was 30.1 (SD 9.9) years in the NHPMS and 31.4 (SD 11.8) years in the AMPS whereas the mean age of non-violent women was 46.3 (SD 15.4) years and 52.2 (18.5) years respectively. Violent women were significantly younger than non-violent women in each survey (p < 0.001).

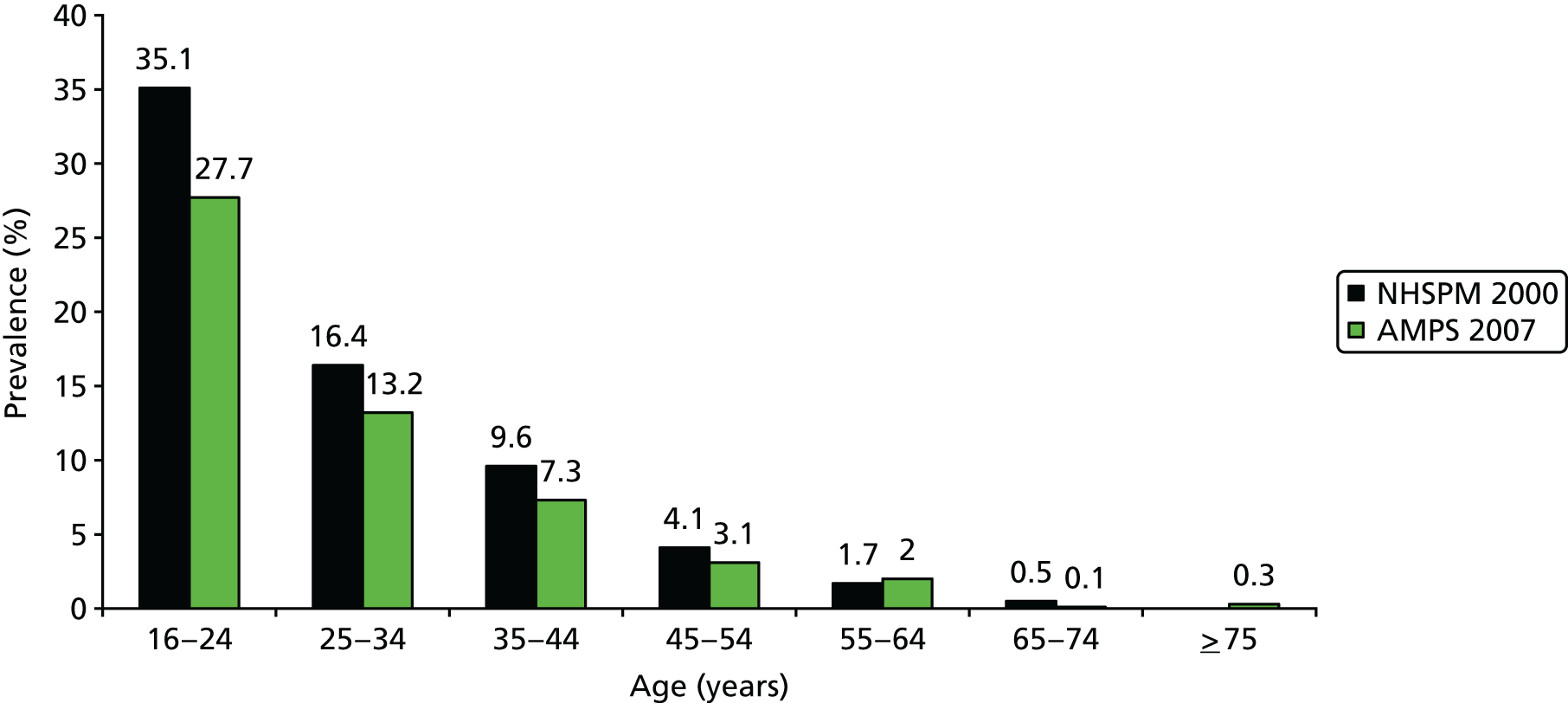

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of self-reported violence in the last 5 years by age group (10-year age bands) for the two household surveys. In both surveys the prevalence of violence decreased with increasing age. This linear decrease was significant for both surveys (p < 0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of any violence in the past 5 years in the UK by age group and survey.

The MMLS has a more restricted age range (18–34 years), which was divided into four age groups. Among those aged 18–20 years the prevalence of violence was 39.4%, among those aged 22–25 years prevalence was 34.8%, among those aged 26–29 years it was 28.5% and among the oldest age group of 30–34 years it was 27.3%. The linear trend for the effect of age on the prevalence of violence was highly significant (p < 0.001). Age was inversely associated with violence in all three surveys. Adjusted associations between age and any violence (Table 3) indicate that, compared with the youngest age group, increasing age exerts a protective effect on violence.

| Demographic characteristics | NHPMS 2000 | APMS 2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 3.74 (3.12 to 4.49)*** | 4.23 (3.39 to 5.27)*** | 2.94 (2.36 to 3.66)*** | 2.87 (2.22 to 3.71)*** |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 16–34 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 35–54 | 0.24 (0.20 to 0.29)*** | 0.32 (0.26 to 0.40)*** | 0.23 (0.18 to 0.29)*** | 0.29 (0.22 to 0.38)*** |

| 55–74 | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.06)*** | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08)*** | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.08)*** | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.09)*** |

| ≥ 75 | No data | No data | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.05)*** | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.07)*** |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/widowed/cohabiting | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Single | 6.60 (5.46 to 7.97)*** | 2.27 (1.83 to 2.83)*** | 5.34 (4.24 to 6.72)*** | 1.78 (1.35 to 2.35)*** |

| Separated/divorced | 2.53 (1.96 to 3.26)*** | 2.66 (2.03 to 3.49)*** | 1.63 (1.16 to 2.28)** | 2.03 (1.38 to 3.00)*** |

| Social class | ||||

| I | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| II | 1.37 (0.78 to 2.41) | 2.11 (1.15 to 3.87)* | 1.38 (0.57 to 3.32) | 1.73 (0.66 to 4.51) |

| IIIM | 2.10 (1.19 to 3.70)* | 3.87 (2.10 to 7.13)*** | 2.26 (0.94 to 5.41) | 2.93 (1.12 to 7.66)* |

| IIINM | 3.34 (1.93 to 5.78)*** | 4.22 (2.31 to 7.70)*** | 4.10 (1.75 to 9.63)** | 4.57 (1.81 to 11.54)** |

| IV | 3.13 (1.81 to 5.43)*** | 5.05 (2.78 to 9.14)*** | 3.26 (1.36 to 7.84)** | 3.64 (1.39 to 9.52)** |

| V | 2.60 (1.37 to 4.94)** | 4.65 (2.35 to 9.21)*** | 4.21 (1.67 to 10.62)** | 6.15 (2.22 to 17.03)*** |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 1.38 (0.85 to 2.26) | 0.82 (0.44 to 1.50) | 1.13 (0.58 to 2.18) | 0.86 (0.43 to 1.69) |

| South Asian | 0.59 (0.29 to 1.20) | 0.33 (0.14 to 0.76)** | 0.81 (0.42 to 1.57) | 0.45 (0.21 to 0.97)* |

| Other | 1.30 (0.72 to 2.37) | 1.18 (0.61 to 2.30) | 1.05 (0.58 to 2.18) | 0.77 (0.38 to 1.57) |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unemployed | 2.60 (1.84 to 3.66)*** | 1.20 (0.78 to 1.84) | 3.08 (1.90 to 5.00)*** | 0.99 (0.57 to 1.74) |

Sex

Just over half of the participants in the NHPM 2000 and APMS 2007 surveys were women. Table 4 provides the frequencies and proportions of all violent outcomes by sex. Among men, the most prevalent violent outcome in 2000 was violence when intoxicated, towards strangers and taking place in the streets or outdoors and in bars/pubs. The same pattern was observed in 2007, but with a lower prevalence.

| Violence outcomes | NHPMS 2000 | APMS 2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Any violence | 749 (18.0) | 233 (5.5) | 441 (12.3) | 173 (4.6) |

| Violence when intoxicated | 361 (8.7) | 61 (1.4) | 194 (5.4) | 69 (1.8) |

| Repeated violence (five or more incidents) | 193 (4.6) | 44 (1.0) | 82 (2.3) | 16 (0.4) |

| Victim injured | 287 (6.9) | 46 (1.1) | 132 (3.7) | 40 (1.0) |

| Perpetrator injured | 245 (5.9) | 65 (1.5) | 149 (4.2) | 55 (1.4) |

| Police involved | 202 (4.8) | 52 (1.2) | 129 (3.6) | 48 (1.3) |

| Minor violence | 282 (6.8) | 126 (3.0) | 174 (4.8) | 73 (1.9) |

| Victim of violence | ||||

| Intimate partner | 47 (1.1) | 90 (2.1) | 39 (1.1) | 76 (2.0) |

| Family member | 31 (0.7) | 32 (0.8) | 56 (1.6) | 35 (0.9) |

| Friend | 144 (3.5) | 36 (0.9) | 92 (2.6) | 41 (1.1) |

| Someone known | 252 (6.1) | 64 (1.5) | 144 (4.0) | 51 (1.4) |

| Stranger | 435 (10.4) | 48 (1.1) | 249 (6.9) | 51 (1.3) |

| Police | 47 (1.1) | 6 (0.1) | 26 (0.7) | 9 (0.2) |

| Location of violent incident | ||||

| Own home | 65 (1.6) | 104 (2.5) | 53 (1.5) | 70 (1.8) |

| Someone else’s home | 54 (1.3) | 22 (0.5) | 40 (1.1) | 21 (0.6) |

| Street/outdoors | 455 (10.9) | 100 (2.4) | 262 (7.3) | 92 (2.4) |

| Bar/pub | 307 (7.4) | 51 (1.2) | 136 (3.8) | 47 (1.2) |

| Workplace | 71 (1.7) | 9 (0.2) | 15 (0.4) | 6 (0.2) |

| Other | 123 (3.0) | 22 (0.5) | 78 (2.2) | 17 (0.5) |

The highest prevalence among women was for minor violence, IPV and violence taking place in the home. The prevalence of self-reported IPV was higher among women than among men. However, men were overall three times more likely to have engaged in any violence than women in both the NHPMS and the APMS (see Table 4).

Marital status

Marital status was coded according to three combined categories: (1) married, widowed or cohabiting, (2) single and (3) separated or divorced. In all statistical models category (1) was the reference group against which other categories were contrasted to estimate risk for violence. The prevalence of violence in the NHPMS was 4.9% among those who were married/cohabiting/widowed, 25.4% among those who were single and 11.6% among those who were separated or divorced. The prevalence of violence in the AMPS was 4.6% among those who were married/cohabiting/widowed, 20.4% among those who were single and 7.2% among those who were separated or divorced. The prevalence of violence in the MMLS was 26.6% among those who were married/cohabiting/widowed, 35.0% among those who were single and 36.1% among those who were separated or divorced. Tables 2 and 4 show the unadjusted and adjusted findings of the effects of marital status on violence, respectively.

Being single or separated/divorced was associated with a higher prevalence of violence throughout. In the household surveys, the likelihood of violence was approximately twofold among single and separated/divorced respondents. The odds of violence increased by approximately 50% among single and divorced young men in the MMLS.

Ethnicity

Ethnic groups recorded in the surveys were reclassified as white, black (originating from Africa or the West Indies), South Asian and ‘other’. In the NHSPM the prevalence of violence was 11.7% among white participants, 15.5% among black participants, 7.3% among South Asian participants and 14.7% among participants from other ethnic groups. In the AMPS the prevalence of violence was 8.3% among white participants, 9.3% among black participants, 6.9% among South Asian participants and 8.7% among participants from other ethnic groups. In the MMLS the prevalence of violence was 36.9% among white participants, 31.1% among black participants, 19.2% among South Asian participants and 21.1% among participants from other ethnic groups. The adjusted demographic models indicate that the South Asian ethnicity group was protective for any violence compared with white respondents in both household surveys (see Table 3). All black and minority ethnic groups in the MMLS were less likely to report violence than white respondents (Table 5).

| Demographic characteristics | MMLS 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) | |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 18–24 | Reference | Reference |

| 25–34 | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.73)*** | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.82)*** |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/cohabiting | Reference | Reference |

| Single | 1.48 (1.30 to 1.69)*** | 1.27 (1.09 to 1.47)** |

| Separated/divorced | 1.56 (1.15 to 2.12)** | 1.50 (1.09 to 2.07)* |

| Social class | ||

| I and II | Reference | Reference |

| IIIM/IIINM | 1.06 (0.86 to 1.31) | 0.97 (0.78 to 1.21) |

| IV and V | 1.30 (1.05 to 1.61)* | 1.19 (0.95 to 1.48) |

| Unemployed | 1.53 (1.25 to 1.87)*** | 1.21 (0.97 to 1.50) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.91)** | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.92)** |

| South Asian | 0.41 (0.34 to 0.48)** | 0.41 (0.34 to 0.49)*** |

| Other | 0.46 (0.27 to 0.78)** | 0.49 (0.28 to 0.86)* |

Immigration

Among the young men in the MMLS, 740 (14.0%) reported being born outside the UK. Of these, 99 (13.4%) reported any violence in the past 5 years; this compared with 1346 (30.6%) of those who were born in the UK. Those who were not born in the UK were significantly less likely to report any violence in a univariate model [OR 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.36 to 0.58; p < 0.001] and after adjusting for all other demographic characteristics (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.69; p < 0.001).

Social class and unemployment

Social class was based on the UK Registrar General’s classification,59 which was chosen because it uses the most recent occupation of head of household: I – professional, II – managerial, IIINM – skilled non-manual, IIIM – skilled manual, IV – partly skilled and V – unskilled. This classification provides an indicator of various domains including income, education and level of responsibility at work. 60,61

Table 6 shows the results for each category of social class (with class I as the reference) by sex. Among men in the NHPMS, all other categories of lower social class increased the risk for violence compared with class I. Participants from social classes IIINM and below were four times as likely to report violence in the past 5 years and social class V was associated with a fivefold increase in violence. However, among women, only social classes IIIM and V were associated with an increase in reported violence.

| Social class | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | AORa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHPMS 2000 | |||

| Men | |||

| I | 22 (5.3) | Reference | Reference |

| II | 126 (10.2) | 1.71 (1.04 to 2.81)* | 1.94 (1.16 to 3.24)* |

| IIINM | 136 (27.5) | 5.71 (3.46 to 9.43)*** | 4.62 (2.74 to 7.79)*** |

| IIIM | 214 (18.1) | 3.32 (2.05 to 5.38)*** | 4.02 (2.43 to 6.64)*** |

| IV | 127 (22.3) | 4.31 (2.61 to 7.12)*** | 4.40 (2.61 to 7.42)*** |

| V | 45 (27.7) | 5.76 (3.24 to 10.23)*** | 5.08 (2.75 to 9.36)*** |

| Women | |||

| I | 22 (5.3) | Reference | Reference |

| II | 40 (3.6) | 1.58 (0.41 to 6.06) | 3.06 (0.68 to 13.74) |

| IIINM | 71 (4.8) | 2.14 (0.57 to 8.06) | 3.74 (0.84 to 16.57) |

| IIIM | 22 (6.8) | 3.11 (0.79 to 12.27) | 5.79 (1.25 to 26.92)* |

| IV | 66 (9.0) | 4.22 (1.12 to 15.93)* | 7.22 (1.62 to 32.14)** |

| V | 11 (4.0) | 1.76 (0.42 to 7.37) | 4.65 (0.94 to 22.95) |

| All | |||

| I | 21 (5.3) | Reference | Reference |

| II | 166 (7.1) | 1.37 (0.86 to 2.17) | 2.11 (1.30 to 3.42)** |

| IIINM | 207 (10.4) | 2.10 (1.33 to 3.31)** | 3.87 (2.38 to 6.28)*** |

| IIIM | 236 (15.6) | 3.34 (2.12 to 5.26)*** | 4.22 (2.62 to 6.81)*** |

| IV | 192 (14.8) | 3.13 (1.98 to 4.96)*** | 5.05 (3.10 to 8.21)*** |

| V | 56 (12.6) | 2.60 (1.55 to 4.35)*** | 4.65 (2.66 to 8.12)*** |

| APMS 2007 | |||

| Men | |||

| I | 8 (3.2) | Reference | Reference |

| II | 66 (6.0) | 1.96 (0.93 to 4.12) | 2.03 (0.92 to 4.50) |

| IIINM | 61 (14.8) | 5.34 (2.51 to 11.36)*** | 3.96 (1.77 to 8.86)** |

| IIIM | 142 (14.3) | 5.13 (2.48 to 10.60)*** | 6.16 (2.84 to 13.37)*** |

| IV | 73 (15.5) | 5.65 (2.68 to 11.92)*** | 4.72 (2.12 to 10.48)*** |

| V | 32 (26.2) | 10.92 (4.86 to 24.54)*** | 10.77 (4.45 to 26.07)*** |

| Women | |||

| I | 4 (3.6) | Reference | Reference |

| II | 36 (3.1) | 0.84 (0.29 to 2.43) | 0.99 (0.34 to 2.90) |

| IIINM | 47 (4.3) | 1.19 (0.42 to 3.38) | 1.33 (0.46 to 3.87) |

| IIIM | 14 (4.9) | 1.39 (0.44 to 4.33) | 1.56 (0.49 to 5.03) |

| IV | 38 (5.9) | 1.68 (0.58 to 4.82) | 1.69 (0.57 to 4.97) |

| V | 6 (3.3) | 0.91 (0.25 to 3.31) | 1.45 (0.36 to 5.79) |

| All | |||

| I | 12 (3.3) | Reference | Reference |

| II | 102 (4.5) | 1.38 (0.75 to 2.53) | 1.73 (0.91 to 3.29) |

| IIINM | 108 (7.1) | 2.26 (1.23 to 4.15)** | 2.93 (1.54 to 5.60)** |

| IIIM | 156 (12.2) | 4.10 (2.25 to 7.47)*** | 4.57 (2.42 to 8.63)*** |

| IV | 111 (10.0) | 3.26 (1.77 to 5.99)*** | 3.64 (1.91 to 6.95)*** |

| V | 38 (12.5) | 4.21 (2.16 to 8.22)*** | 6.15 (2.98 to 12.73)*** |

Certain differences were observed in the APMS. Social class was not significantly associated with violence among women; however, among men in social class V, the risk associated with violence was increased 10-fold.

There was a statistically significant trend in prevalence of violence according to lower social class for men (p < 0.001) and women (p < 0.001). However, in the NHPMS, we observed an unexpected 17.3% increase in the prevalence of violence among men from social class II to social class IIINM. This increase was statistically significant (10.2% vs. 27.5% respectively; p < 0.001). This contrasted with a 1.2% non-significant increase in self-reported violence among women from social class II to social class IIINM (3.6% vs. 4.8% respectively; p = 0.14). Compared with other categories, those men in social classes II and IIINM were younger (82.9% were aged 16–34 years vs. 67.1%; p < 0.008), more were single (81.1% vs. 56.6%; p < 0.001) and more were living with their parents (34.0% vs. 11.8%, p < 0.001). In addition, fewer lived in rented accommodation (25.0% vs. 40.1%, p < 0.01) and as a couple (21.9% vs. 51.7%, p < 0.001). Violent men in social class IIINM were approximately three times more likely to be single and living with their parents than violent men in other social classes.

Discussion

Sex and age differences in violent behaviour identified in our study are in accordance with a previous meta-analysis. 62 Physical aggression is more common among men than women at all ages and this is consistent across cultures, appearing from early childhood onwards and showing a peak between 20 and 30 years of age. However, studies that have measured anger did not show sex differences. Higher levels of indirect aggression among females, such as expressions of anger, are limited to later childhood and adolescence, but tend to vary according to the methods of measurement and were not included in this study.

Sexual selection theory hypothesises that the origin of greater male physical aggression in human evolutionary history is a consequence of unequal parental investment, leading to greater male than female reproductive competition and, therefore, overt aggression. 63 This is thought to be the psychological accompaniment of physical sex differences such as size, strength and longevity. 62 Evolutionary analyses have identified different degrees of risk that an individual is prepared to take during a conflict as a crucial difference between the sexes. Greater variation in male and female reproductive success among mammals leads to more intense male competition. Selection favours high-risk strategies (even when mortality rates are high) if the reward of victory is high and the consequence of losing is little or no chance of reproducing. 64 This theoretical approach suggests that sex differences and physical aggression will be largest when reproductive competition is highest, for example during young adulthood, and can include higher risk and escalated forms of aggression, such as those involving death or severe injury. Our findings are in agreement with this theory in demonstrating that men in early adulthood were more likely to engage in severe violence against strangers and people known to them. Weissfeld65 has argued that boys compete in this way to form dominance orders or hierarchies. This has been compared with the behaviour of other primates and is thought to be important for providing access to resources, including reproductive success in social animals. Hierarchies are based on dominance and the use of aggression, which is stable over time, together with high dominance. This appears to rank with certain other attributes, including personality.

All levels of severity of violence and all victim types were more prevalent among men than women, except violence against intimate partners and family. Women were approximately twice as likely to report an intimate partner as a victim than men. However, national surveys have shown that women who are married or cohabiting are more likely to report fear of bodily injury, actual injuries and the use of medical, mental health and criminal justice system services as a result of IPV than men. 66 Similarly, substantially more women report that they have experienced sexual violence from an intimate partner,67 which was not included in this study. Nevertheless, Dutton and Nicholls68 have argued that the sex disparity in injuries from domestic violence is less than originally portrayed by feminist theory. In a review of studies,69 high levels of unilateral intimate violence by women towards both men and women have been observed. Furthermore, men report their own victimisation less often than women and do not view female violence against them as a crime. As a result, male victimisation by female partners is under-reported in crime victim surveys.

Married men are less likely to commit crimes, including violence. However, there are questions of selection and confounding when studying this relationship. Samson et al. 70 carried out a study of high-risk boys followed up prospectively from adolescence to age 32 years. They found that being married was associated with an average reduction of approximately 35% in the odds of committing a crime compared with not being married. Previous research has also indicated that marriage is a key turning point in desistance from crime. 71 The establishment of a good relationship is thought to facilitate this. Correspondingly, Bersani et al. 72 found that marriage reduced offending, including violent offending, for both men and women in the Netherlands. Laub et al. 73 argue that a close relationship acts protectively on crime and violence by the formation of social bonds and an investment process in the relationship. It is the quality of the marital bond that affects this. However, the influence is gradual and is cumulative over time. Our finding that divorce and separation were strongly associated with violence in this study corresponds to this. However, the processes leading to the breakdown of a relationship are likely to be complex and could reflect an individual’s tendency to violence or even be the result of violence towards the intimate partner.

The association between violent crime and single marital status could be explained by social factors in the lives of young people and was independent of age. The move to social independence among young men is important. Although many young men now remain in the parental home, this was not found to have a protective effect among young men in Great Britain. 74 Furthermore, violence when intoxicated observed among young men (see Chapter 6, Study 2) and fighting with strangers can be construed as one example among a series of hedonistic and negative social behaviours (including hazardous drinking, drug misuse, sexual risk taking and non-violent antisocial behaviour) exhibited by single young men without the responsibilities of providing their own accommodation or supporting dependent children or the ameliorating effects on their behaviour of living with a female partner. It has been questioned whether or not this lifestyle has become more prevalent among some men within the context of increasing prolongation of early adulthood and when it now takes longer to obtain a full-time job that pays sufficiently to support a family. 75 US research has indicated that many young people in their early 20s have not become fully adult according to their own subjective assessment and do not perceive themselves as either ready or able to perform these roles. A comparison of census data in the USA from the years 1960 and 200076 demonstrated that fewer men aged 40 years in 2000 than in 1960 had completed all the major transitions of leaving home, finishing school, becoming financially independent, getting married and having a child. Furthermore, young people remaining at home now receive more substantial financial aid from their parents than previous generations. 75 Not having to provide accommodation or support dependents means a relatively higher disposable income and more leisure time, possibly associated with higher-risk activities, including violence.

We did not find differences in self-reported violence in our surveys between black and minority ethnic subgroups and white study participants. Being of South Asian origin appeared to convey a protective effect. This was before adjusting for other demographic factors, most importantly social class. This finding is in marked contrast to the number of stop and search encounters and convictions for violent crime in black and minority ethnic populations and proportions of people imprisoned from a black and minority ethnic origin in the UK. Similarly, the lack of an association between immigration and violence in this study is consistent with the lack of an association between immigration and crime in the UK. 77 The continuous reduction in the number of overall property crimes in England and Wales since 2002 has occurred in the face of an increasing foreign-born population, but there is no evidence to suggest that rising migration causes a decline in crime rates. The foreign-born proportion of the population is also unrelated to violent crime according to most recent research findings. 78

It has long been established that the strength of the relationship between social class and violence varies significantly, but depends primarily on the measure of social class. 79 Our finding that in 2000 there was a higher than expected prevalence of violence among men from social classes II and IIINM is most likely explained by the characteristics of the men in these two social groups. For example, an unexpectedly large number of men still living in the parental home, not having children or not being involved in a relationship contributed substantially to the association between social class IIINM and violent behaviour.

It is thought that unemployment has a key part to play in violence and that lack of routine activity and the economic effects of being unemployed increase the risk of crime. However, research has indicated that violent crime, as opposed to burglary and theft, is pro-cyclical: higher in good times when unemployment is lower. It has been argued that alcohol consumption, which is higher in good times and more strongly related to violence, is a key determinant. 80 Nevertheless, the association between violence and unemployment is highly complex and other associated factors are highly relevant. Lack of finances is important because labour markets are important sources of status and the focus of struggles over norms of fairness and a validated identity. Unemployment can be relevant to violence when it intersects with collective identities: masculinity, race or ethnicity or religion. When there are no structured institutional mechanisms for unemployed people to express complaints and press for improvement, the chances are increased that there may be one or other type of violence. This may also apply to IPV. At the international level, the contribution of the labour market structure and opportunities and relations to violent conflicts cannot be understood in isolation from the broader structural and policy features of a society. 81

Study 2: a typology of violent persons in the population

Aims and objective

The aims of study 2 were to:

-

Identify groups, or subtypes, of people in the population of Great Britain according to their patterns of self-reported violent behaviour. We included measures of severity and frequency, their victims and the location of their violence to determine subtypes.

-

Validate these subtypes according to their differing demographic characteristics.

The overall objective was to create a typology for investigating the associations with psychiatric morbidity in subsequent studies in this section of the report.

Methods

Participants

We used a combined sample of men and women drawn from the first phase of the NHPMS 2000 and the APMS 2007 (see Study 1). Design and sampling procedures have previously been described. 45,82 As each of the surveys employed the same measures of demography and violence outcomes, we conducted joint analyses of individual-level data. All analyses on violence typologies were carried out separately by sex.

Measures

We used the self-reported measures of violence described in study 1. Social class was based on the UK Registrar General’s classification,59 which uses the most recent occupation of the head of the household. Sociodemographic covariates included age in 20-year bands, marital status, ethnicity and employment.

Latent class analysis

We used latent class analysis (LCA) to explore whether or not individuals could be classified into a set of latent variables based on their endorsement of the violence indicators. Membership of these subgroups, often called latent classes, is defined by the specific set of responses to a series of observed characteristics. This approach allowed us to describe the relationships of the variables as they combined into classes that defined groups of people within a sample or population.

Latent class analysis was used to empirically define participant groups based on their violent behaviours profile and explore the existence of typologies of violence. Decisions regarding the most appropriate model were led by statistical indicators and clinical considerations. The default estimator was the robust maximum likelihood (MLR). However, MLR may lead to the presence of a problem called local maxima. To fully avoid this, all LCA models were estimated with different random starting values: we used 2000 random starts at the initial stage and 200 optimisations at the final stage. Models were inspected to ensure that the log-likelihood value for each model was successfully replicated several times (an indication of low probability of local maxima). We gave priority to this rule in selecting our final latent class model.

After selecting the classes that fitted best by sex, we described them in terms of the aforementioned demographic characteristics.

All analyses were performed using Mplus software (Muthéu and Muthéu, Los Angeles, CA, USA) for Windows OS version 7.11.

Results

Typology of violence among men

To identify the constructs in each class (classification) included in Table 7, we established indicators with probabilities of < 0.29 (low probability), from 0.30 to 0.59 (moderate probability) and > 0.60 (high probability). We classified men into the following classes: class 1 – ‘no violence’; class 2 – ‘minor violence’, characterised by fights with strangers, persons known and friends, in the street or in bars, with few incidents or only one incident and in which no-one is injured; class 3 – ‘violence towards known persons/family’, characterised by more serious violence resulting in injuries to the victim and perpetrator, involving a range of different victims but mainly persons known, friends, family members and intimate partners and in a range of locations, mainly in the street or in bars but also in their own or another’s home; class 4 – ‘fighting with strangers’, characterised by fights almost exclusively with strangers taking place in the street or in bars, often when intoxicated and leading to injury to the victim or perpetrator (one in five men in class 4 had been involved in multiple violent incidents with strangers); and class 5 – ‘serious repetitive violence’, characterised by multiple incidents of violence, usually when intoxicated, resulting in injuries to multiple victims and in multiple locations and including family and intimate partners (see Table 7).

| Violence indicators | Class 1 (N = 6583; 84.8%), n (%) | Class 2 (N = 453; 5.8%), n (%) | Class 3 (N = 296; 3.8%), n (%) | Class 4 (N = 308; 4.0%), n (%) | Class 5 (N = 121; 1.6%), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated violence (five or more incidents) | 1 (0.0) | 66 (14.6) | 43 (14.5) | 63 (20.6) | 102 (84.5) |

| Violent when intoxicated | 0 (0.0) | 155 (34.2) | 142 (47.8) | 158 (51.3) | 100 (83.5) |

| Victim injured | 4 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 138 (46.4) | 157 (51.1) | 121 (100.0) |

| Perpetrator injured | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 172 (58.0) | 137 (44.6) | 85 (70.4) |

| Minor violence | 0 (0.0) | 453 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.7) |

| IPV | 0 (0.0) | 25 (5.6) | 37 (12.6) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (19.2) |

| Towards a family member | 0 (0.0) | 31 (6.8) | 39 (13.3) | 3 (0.9) | 14 (11.7) |

| Towards a friend | 0 (0.0) | 86 (19.0) | 84 (28.5) | 16 (5.3) | 49 (40.9) |

| Towards someone known | 0 (0.0) | 134 (29.5) | 177 (59.8) | 2 (0.7) | 83 (68.7) |

| Towards a stranger | 0 (0.0) | 237 (52.3) | 31 (10.6) | 308 (100.0) | 108 (89.2) |

| In the home | 0 (0.0) | 34 (7.4) | 58 (19.5) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (22.2) |

| In someone else’s home | 0 (0.0) | 26 (5.7) | 33 (11.3) | 13 (4.1) | 22 (18.3) |

| In the street/outdoors | 5 (0.1) | 206 (45.5) | 182 (61.4) | 212 (68.8) | 111 (92.2) |

| In a bar/pub | 0 (0.0) | 144 (31.9) | 76 (25.7) | 112 (36.5) | 110 (91.2) |

| In the workplace | 2 (0.0) | 30 (6.7) | 15 (5.0) | 15 (4.8) | 25 (20.7) |

Several models of latent subgroups defined by violence indicators were estimated for men and women. Complex sampling and weights were considered in the development of the latent class models. Model fit and information criteria for LCA model selection are included in Table 8 for men and Table 9 for women. Model fit indices favoured the five-class model in men. A three-class model provided the best fit to the data in women.

| Model | Log-likelihood | Replicated log-likelihood | AIC | BIC | aBIC | VLMR-LRT p-value | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | 17590.6 | Yes | 35211.3 | 35313.9 | 35266.3 | NA | NA |

| Class 2 | 11163.4 | Yes | 22388.8 | 22601.0 | 22502.5 | < 0.0001 | 0.99 |

| Class 3 | 10638.0 | Yes | 21370.1 | 21691.8 | 21542.4 | < 0.0001 | 0.99 |

| Class 4 | 10484.1 | Yes | 21094.2 | 21525.4 | 21325.2 | < 0.0001 | 0.99 |

| Class 5 | 10392.1 | Yes | 20816.1 | 21356.8 | 21105.8 | 0.0002 | 0.98 |

| Model | Log-likelihood | Replicated log-likelihood | AIC | BIC | aBIC | VLMR-LRT p-value | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | 9320.7 | Yes | 18671.3 | 18777.6 | 18729.9 | NA | NA |

| Class 2 | 5360.1 | Yes | 10782.2 | 11001.9 | 10903.4 | < 0.0001 | 0.99 |

| Class 3 | 5145.5 | Yes | 10385.1 | 10718.1 | 10568.8 | < 0.0001 | 0.99 |

Table 10 shows that members of class 5 (‘serious repetitive violence’) were younger than members of the other classes, with no men in the older age group (55–74 years), no black men and predominantly white and single men. Most were employed in occupations from social classes IIIM and IIINM. Class 4 showed similar demographic characteristics, with significantly fewer Asian men and fewer separated or divorced men. Class 3 had the largest proportion of separated or divorced men and one-quarter were economically inactive. Class 2 showed few differences from class 1 (non-violent men), except that more were younger and single.

| Demographic characteristics | Violence typologies (latent classes) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (%) (reference) | Class 2 (%) | Class 3 (%) | Class 4 (%) | Class 5 (%) | |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 16–34 (reference) | 27.3 | 75.3 | 70.9 | 69.2 | 82.7 |

| 35–54 | 40.4 | 21.9a | 24.0a | 26.6a | 17.3a |

| 55–74 | 32.3 | 2.8a | 5.1a | 4.2a | 0.0a |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White (reference) | 90.8 | 88.6 | 93.4 | 95.7 | 96.7 |

| Black | 2.7 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.0a |

| South Asian | 4.0 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 1.0a | 2.3 |

| Other | 2.5 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Social class | |||||

| I and II (reference) | 42.8 | 23.4 | 17.9 | 23.6 | 10.6 |

| IIIM and IIINM | 40.5 | 49.0b | 54.7b | 48.9b | 70.3b |

| IV and V | 16.7 | 27.6b | 27.4b | 27.6b | 19.1b |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married or cohabiting (reference) | 67.9 | 27.0 | 36.3 | 35.8 | 26.7 |

| Single | 24.3 | 66.9b | 54.6 | 57.2b | 67.4b |

| Separated/divorced | 7.8 | 6.1b | 9.0b | 7.0b | 6.0 |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed (reference) | 70.2 | 74.8 | 66.2 | 81.8 | 73.5 |

| Unemployed | 3.1 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 4.6 |

| Inactive economically | 26.7 | 16.7 | 25.3b | 11.7 | 22.0 |

We carried out a further investigation to see to what extent IPV had determined the classes. We found that only 24 (3.1%) men reported that they were uniquely violent towards their intimate partner, indicating that IPV had little effect in determining the classes among men.

Typology of violence among women

As with men, we established that indicators with a probability < 0.29 as low, from 0.30 to 0.59 as moderate probability and above 0.60 as high probability among women. Table 11 shows that class 1 was characterised by ‘no violence’ and had a prevalence of 94.9%. Class 2 (‘general violence’) was characterised by a range of different victims, mainly persons known and strangers, but also family members, intimate partners and friends, with violence occurring usually in the street or in a bar, but also in the perpetrator’s own or someone else’s home. This class resembled class 3 in men. Class 3 (‘intimate family violence’) was characterised by violence occurring exclusively in the home and involving intimate partners and family members. It usually involved minor violence and if a participant was injured it was usually the female perpetrator. Class 2 included the highest proportion of women of young age (16–34 years) (83%) followed by class 3 (58.3%). Ethnic composition was similar across the classes. Class 2 had significantly higher proportions of women in lower social classes. Women in classes 2 and 3 were mainly single, with more women in class 3 separated or divorced. There was no association with employment status (Table 12).

| Violence indicators | Class 1 (N = 7608; 94.9%), n (%) | Class 2 (N = 282; 3.5%), n (%) | Class 3 (N = 124; 1.5%), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated violence (five or more incidents) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (12.4) | 25 (20.0) |

| Violent when intoxicated | 0 (0.0) | 108 (38.2) | 22 (18.2) |

| Victim injured | 0 (0.0) | 76 (27.1) | 9 (7.5) |

| Perpetrator injured | 0 (0.0) | 88 (31.2) | 32 (25.7) |

| Minor violence | 0 (0.0) | 119 (42.4) | 79 (64.3) |

| IPV | 0 (0.0) | 35 (12.6) | 98 (79.3) |

| Towards a family member | 0 (0.0) | 68 (24.2) | 31 (25.1) |

| Towards a friend | 0 (0.0) | 76 (27.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Towards someone known | 0 (0.0) | 115 (40.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Towards a stranger | 0 (0.0) | 99 (35.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| In the home | 0 (0.0) | 50 (17.6) | 124 (100.0) |

| In someone else’s home | 0 (0.0) | 36 (12.9) | 7 (5.9) |

| In the street/outdoors | 0 (0.0) | 176 (62.4) | 17 (13.6) |

| In a bar/pub | 0 (0.0) | 93 (33.1) | 5 (3.9) |

| In the workplace | 0 (0.0) | 14 (5.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Demographic characteristics | Violence typologies (latent classes) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (%) (reference) | Class 2 (%) | Class 3 (%) | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 16–34 (reference) | 30.2 | 83.0 | 58.3 |

| 35–54 | 37.8 | 15.9a | 36.1a |

| 55–74 | 32.0 | 1.1a | 5.6a |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White (reference) | 92.8 | 90.4 | 93.1 |

| Black | 2.4 | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| South Asian | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Other | 2.1 | 4.7 | 1.4 |

| Social class | |||

| I and II (reference) | 33.6 | 18.9 | 31.5 |

| IIIM and IIINM | 42.5 | 44.8b | 39.6 |

| IV and V | 23.9 | 36.4b | 29.0 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or cohabiting (reference) | 68.4 | 20.3 | 35.7 |

| Single | 21.1 | 68.7b | 42.1b |

| Separated/divorced | 10.5 | 11.0b | 22.1b |

| Employment | |||

| Employed (reference) | 57.4 | 62.5 | 70.6 |

| Unemployed | 2.1 | 5.2 | 1.5 |

| Inactive economically | 40.6 | 32.3 | 27.8 |

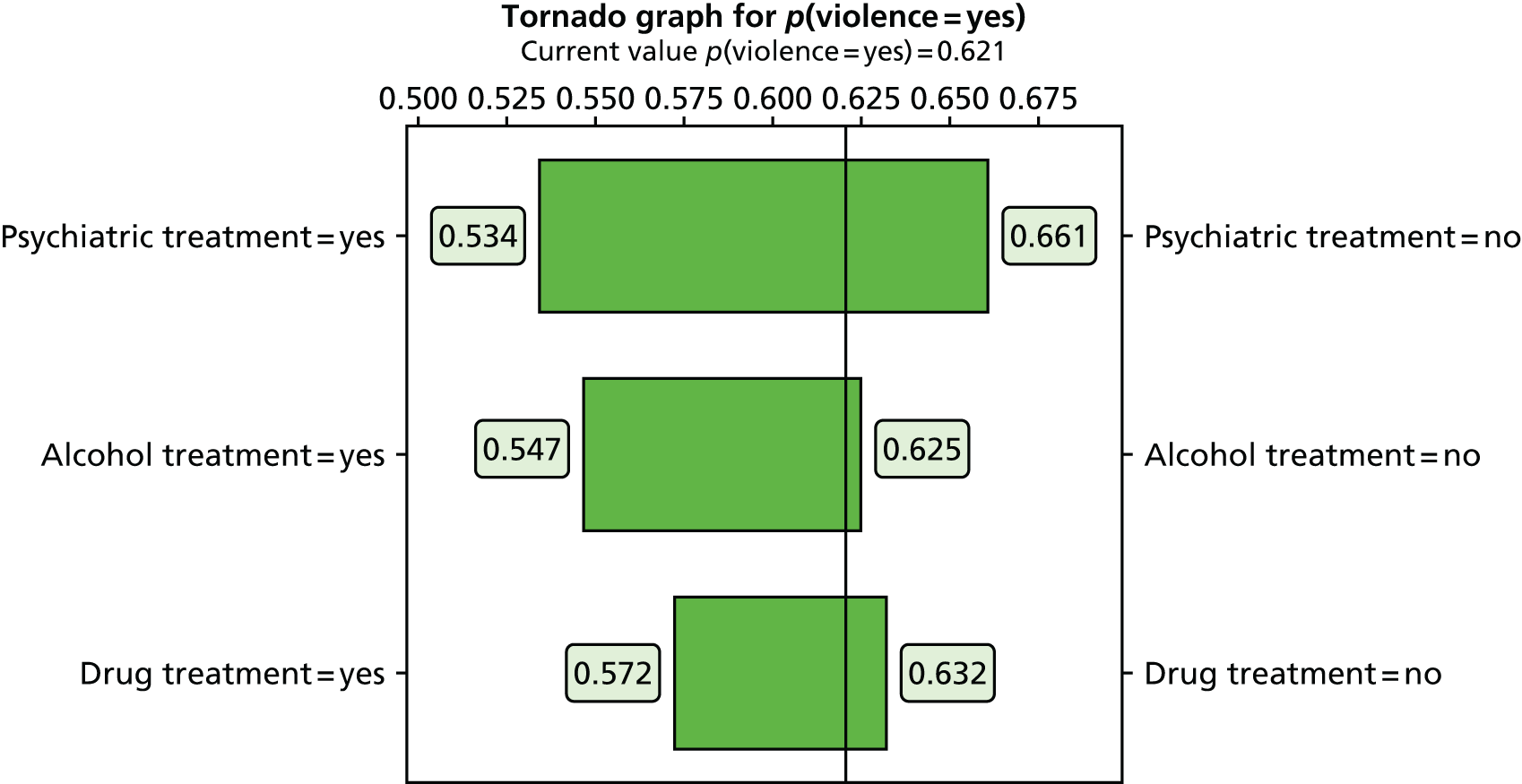

Discussion