Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0608-10147. The contractual start date was in February 2010. The final report began editorial review in August 2015 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sue Ziebland declares that she is deputy chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship Panel, is a Policy Research Panel Committee Member and is a NIHR Senior Investigator. Louise Locock declares current membership of the Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board. John Powell declares current membership of the Health Technology Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Ziebland et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Overview of the programme

Health-care decisions are made at every stage of an illness from the point at which we first experience a symptom and try to identify what it might mean. The dilemmas that people face include a lot of ‘whether, how and for how long’ questions about self-management, seeking professional help, using treatments and minimising the disruptive effects of illness on daily life, work, and relationships. The programme of work reported in this monograph grew from the awareness that the public and patients need reliable health information to support these decisions and the recognition that the relatively new ability to find other patients’ experiences online could be transforming the health information landscape and the information that patients seek, find and use.

When the programme began in 2010, it was already becoming routine for people in the UK to seek health information online. There was also an evident growth in online ‘patient experience’ (PEx) in many formats, including social networking, reputation systems (an approach borrowed from e-commerce and now widespread in health), peer-to-peer forums, chat rooms, blogs and personal experience sections on health and voluntary sector websites. However, there were also many concerns being voiced about whether or not the internet was too overwhelming and confusing (especially for people with low heath literacy), whether patients would misinform or alarm themselves, and how all of this might affect their choices and communication with NHS staff, in particular during the brief consultation in primary care.

We therefore proposed a 5-year programme to examine the phenomenon of the online experiences of patients, to understand its potential for both benefit and harm and identify whether, when and how the NHS might recommend incorporating people’s health and care experiences (hereafter referred to as PEx) into online health information.

When we began this work, the role of online PEx was a new field with no agreed theoretical and methodological basis: almost all of the research had been exploratory or descriptive. It has long been recognised that people seek knowledge about their health from others who have been through the same experiences. 1,2 What was unknown was how the online environment might be transforming this behaviour, perhaps opening up opportunities for support, information and new forms of connection. Our own work had indicated that exposure to online PEx had the potential to both improve health and do harm. 3 We were aware that PEx might be of greater or lesser value depending on how it is presented, the type of condition involved, the stage in the patient journey and individual preference.

Aim

The aim of the programme was to find out whether, when and how the NHS should incorporate PEx into online health information.

To achieve the aim of the programme, we needed to understand the mechanisms through which PEx may influence health, develop the tools to measure the effects, explore how PEx is used and test prototype websites in exemplar patient groups: (1) people who wanted to stop smoking, (2) people with asthma and (3) carers of people with multiple sclerosis (MS). The programme was delivered through three work packages (WPs) which used mixed methods comprising a conceptual literature review, a qualitative secondary analysis, the development and testing of a new questionnaire, an online ethnography, observational and experimental studies in an internet café environment and, last, some exploratory feasibility trials.

Our WPs were designed and implemented by a multidisciplinary team led by a medical sociologist and including health psychologists, a public health doctor, academic general practitioners (GPs), experts in questionnaire design, statistics and website design, and clinical trialists, with coinvestigators from health policy and a service user perspective.

We summarise below the full programme and the relevance of each of the WPs.

Note: we acknowledge that there are many different ways of referring to people who are interviewed about their health, who contribute to or seek health-related information, or who publish their own material about their health experiences online. These terms include ‘patients’, ‘the public’, ‘people’, ‘consumers’ and ‘health service users’. For the sake of brevity and to conform with other NHS and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) documents, we use PEx or ‘patient experience’ to encompass the various roles of the public and patients in this field.

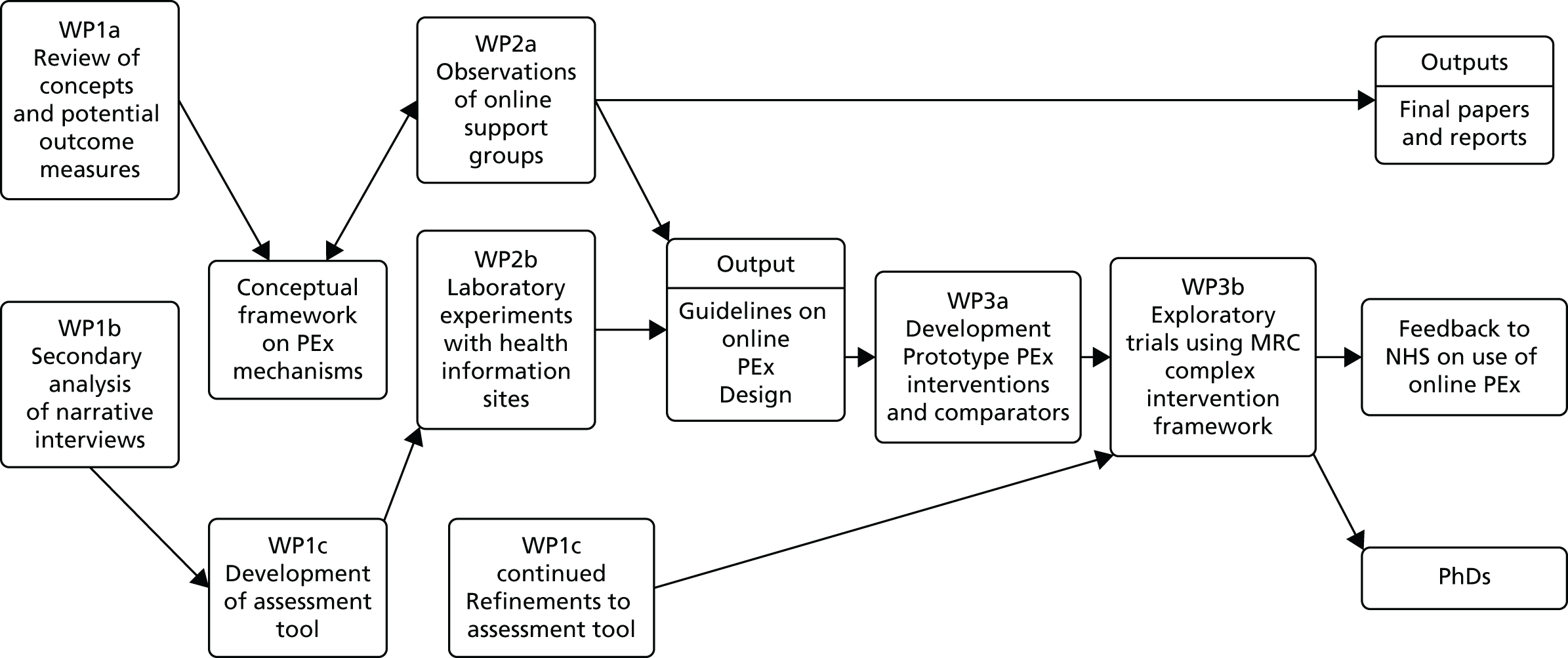

Figure 1 shows the connections between the elements of the programme and the main outputs.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the programme.

Work package 1

Conceptual and literature review

We used reviews and secondary analysis to clarify the theoretical mechanisms and the domains of health that we expected to be affected by exposure to online PEx. An approach drawing on ‘realist’ literature review methods was conducted to identify theories, mechanisms of action and the potential impact of PEx and to establish the conceptual and theoretical framework for the whole programme. The review identified seven domains through which access to other people’s experiences of a health condition could affect health; these comprised finding information, feeling supported, maintaining relationships, using health services, changing behaviours, learning to tell the story and visualising illness.

Secondary analysis of narrative interviews

Interviews from a unique Oxford archive of interviews, held by the Health Experiences Research Group (HERG), were used for a qualitative secondary analysis. At the time of the study, the archive included over 60 health conditions, which were sampled to (1) gather evidence through thematic analysis about how and why information based on real experience is sought and used, and (2) select quotations from interview transcripts which illustrate participants’ views on their use of the internet for health information, to inform the item pool for a questionnaire tool.

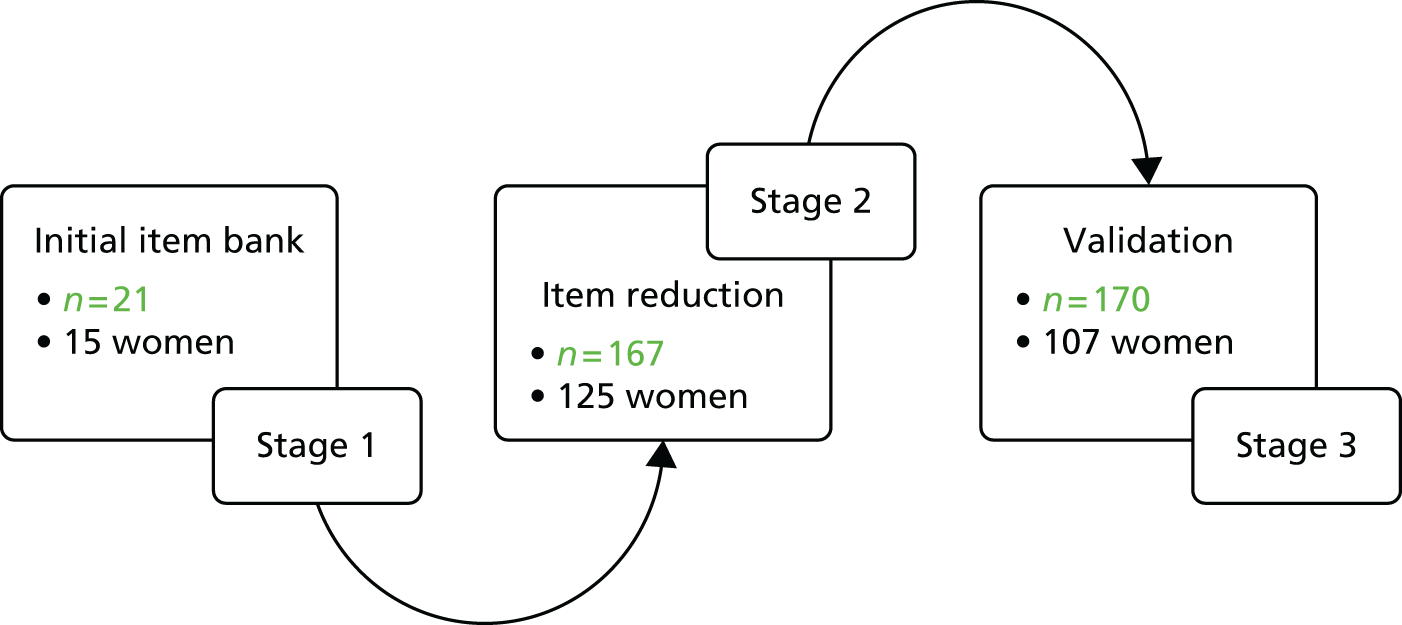

Development and piloting of the e-Health Impact Questionnaire

Trials to evaluate the impact of online PEx need to identify the most appropriate outcomes to be measured. The range of outcomes is potentially large and may be addressed, in part, by existing measures. However, as research on online patient experiential information was in its infancy at the time this WP commenced, there was no valid and reliable assessment tool to capture the health effects of using websites which contain PEx. We therefore developed the e-Health Impact Questionnaire (eHIQ) to assess health-related websites which contain either experiential or factual information. The tool was developed and tested for use across a range of health groups (e.g. people with long-term conditions, carers and those viewing websites aimed at changing health behaviour) and can also be used for websites that include different styles of online information (e.g. factual or experiential information and discussion forums). This WP was written up by LK as her doctorate (awarded in 2014, supervised by CJ and SZ).

Work package 2

Online ethnographic observations

In this WP, we explored internet behaviour using in-depth observational research methods to establish how different types and formats of online PEx are used and how online PEx material might be optimised. We studied how and why people share experiences of health and illness on the internet in the context of MS. Through a content analysis of online settings, ethnographic observation of online activity and telephone interviews, we studied how people living with MS and those who care for them seek out others’ experiences, how they share their own experiences, and how this affects their understanding of MS, their relationship with health-care practitioners, their health-care decision-making and their general well-being.

Observations and experimental studies

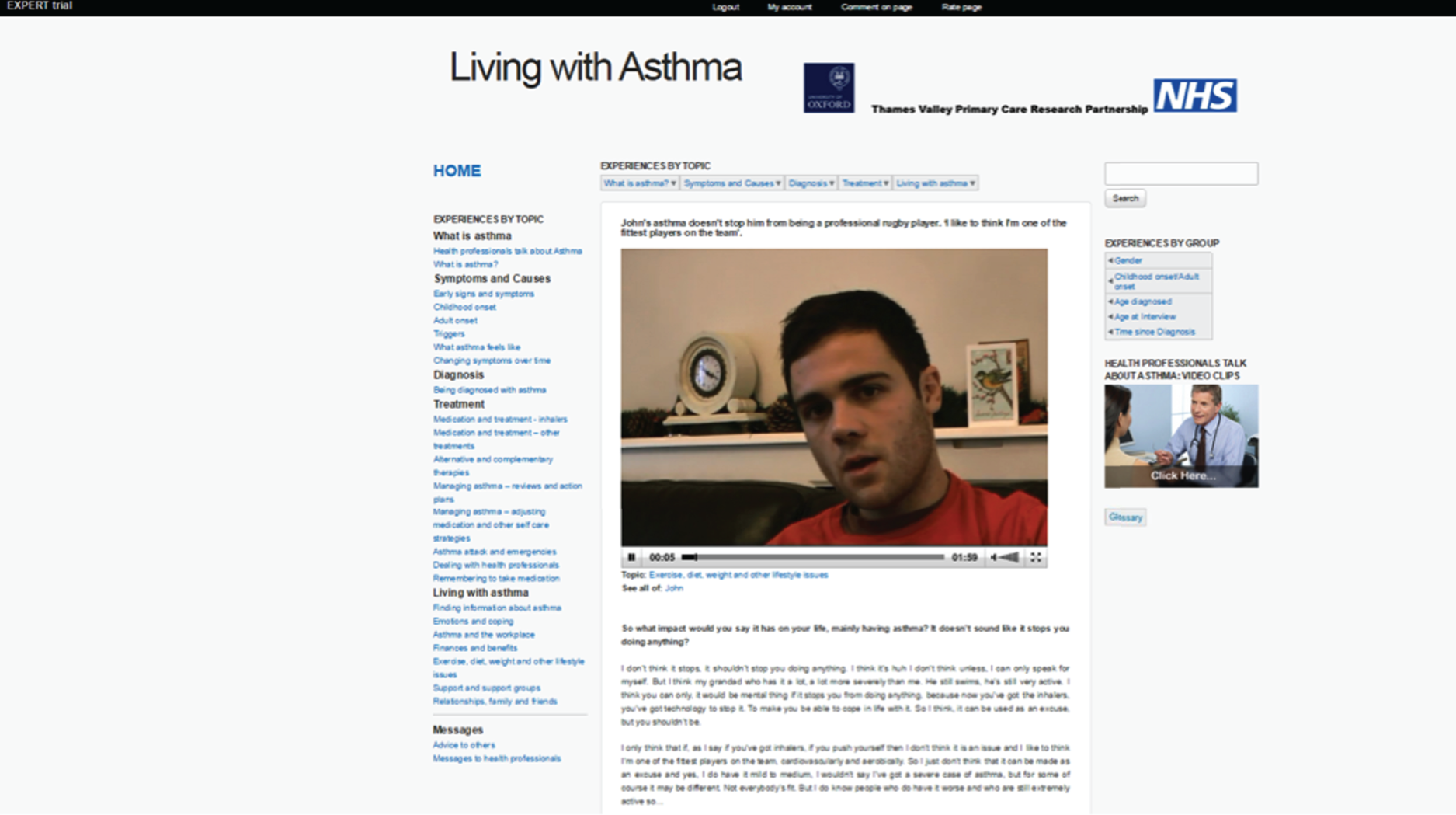

Acknowledging the diverse quality of online PEx, we conducted three studies using observational and internet laboratory café methods to discover how patients find and use PEx to inform health and lifestyle choices. The first study was expanded from that stipulated in the proposal and included, in addition to the asthma and MS carers elements, two further elements with people who wished to stop smoking. The second study, which focused on people with asthma and MS carers, involved the collection of eye-tracking data, to identify where people spend time, what holds their attention and how they organise their searches, and a comprehensive interview. From these studies, we developed a model of patients’ peer-to-peer engagement online, which was used to develop the prototype PEx websites that were used in the feasibility trials in the final WP.

The third study involved a sample of smokers. We sought to examine the effect of (1) message type (i.e. PEx vs. information only), (2) the palatability of material in terms of pre-existing beliefs (attitude towards quitting by using or not using aids and support) and (3) perceived similarity (based on gender) between the reader and the author of the PEx on a participant’s readiness to accept the message. The study adopted a longitudinal approach to examine the potential impact of these variables on behavioural intentions and actions 2 weeks and 3 months after exposure.

Work package 3

Development and testing of patient experience web interventions for exploratory trials

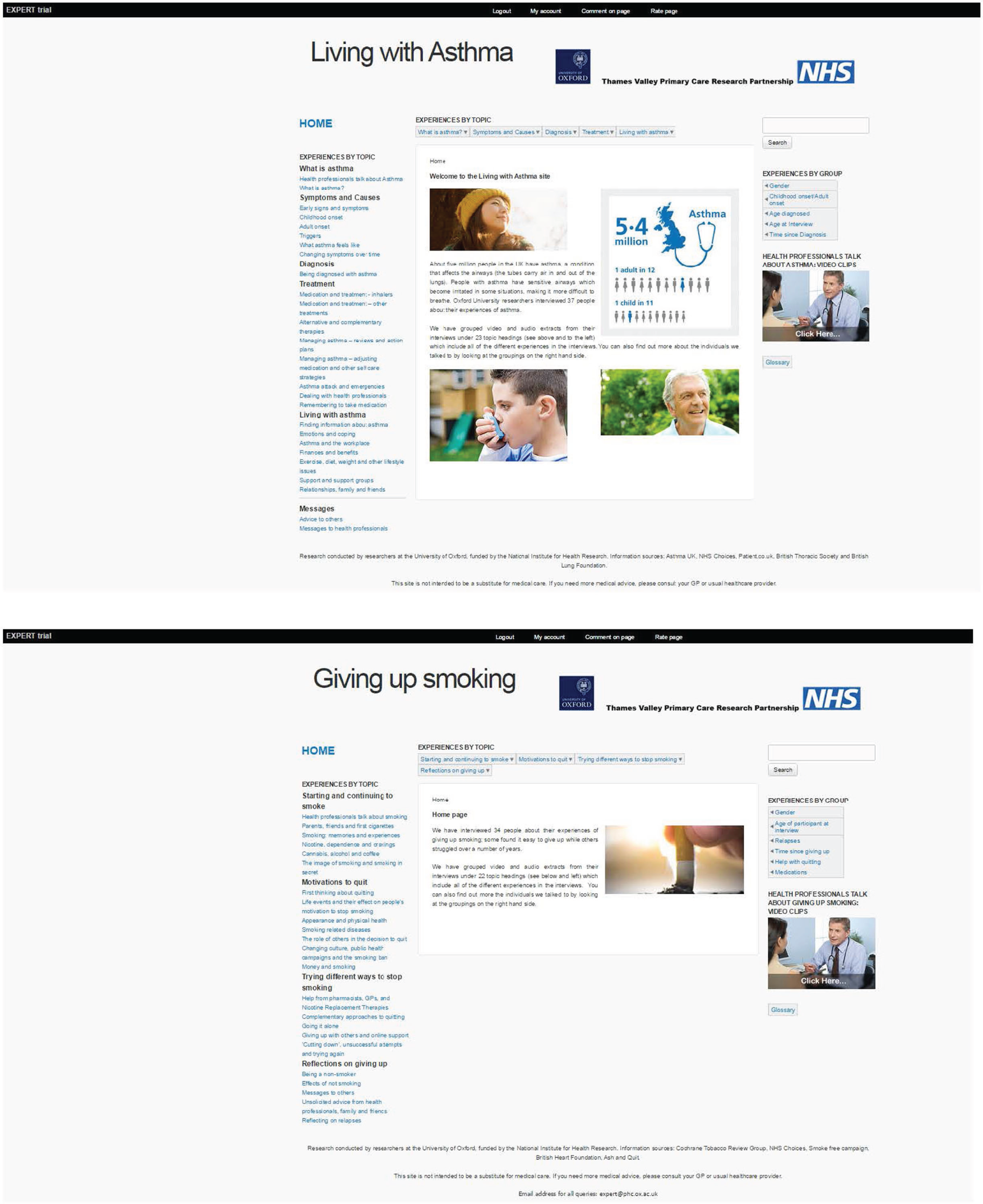

We developed six prototype multimedia websites featuring either PEx information (intervention) or non-PEx factual information (comparator) for each of three exemplar health issues (adults with asthma, carers of people with MS and people considering giving up smoking cigarettes). We used established qualitative research methods, led by experienced qualitative social scientists based in the Oxford team, to collect unstructured, narrative interviews about the experiences, information and support needs of people in each of the three exemplar groups. The design and presentation of PEx information on the websites were developed in accord with the guidelines developed in WP2. The comparator websites were based on non-PEx material from NHS Choices and were presented in a similar design to that of the intervention sites.

Exploratory trials

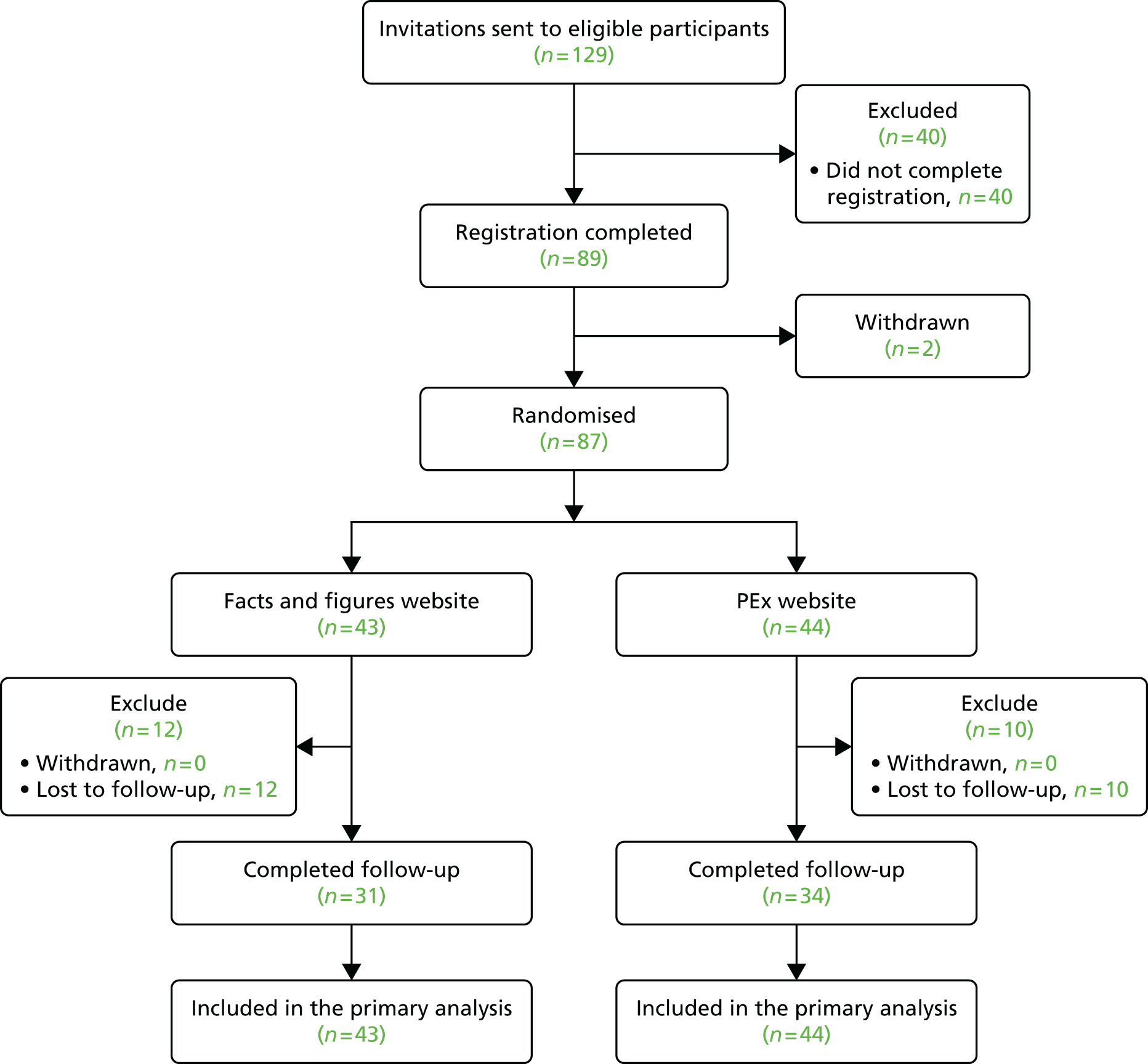

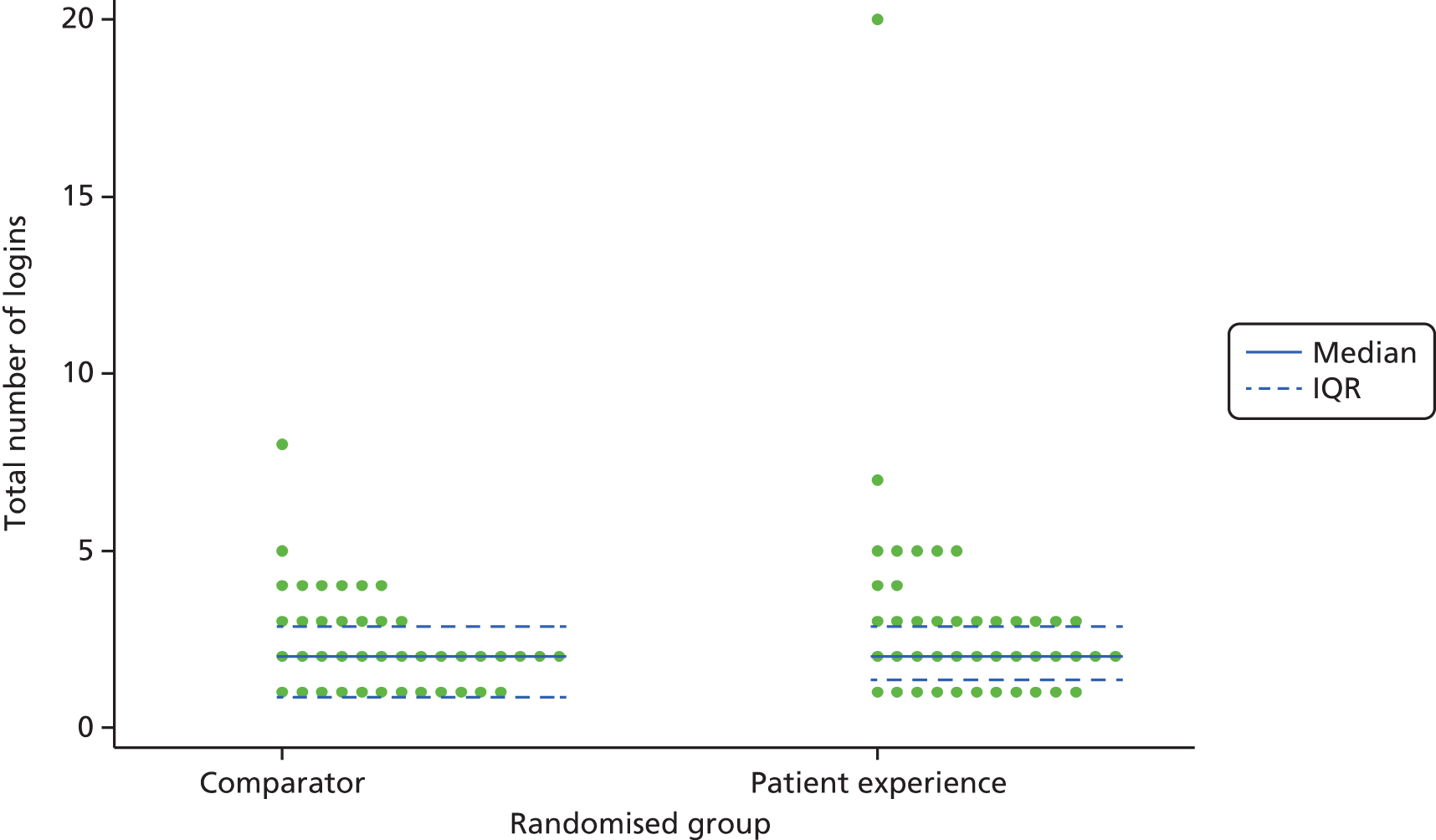

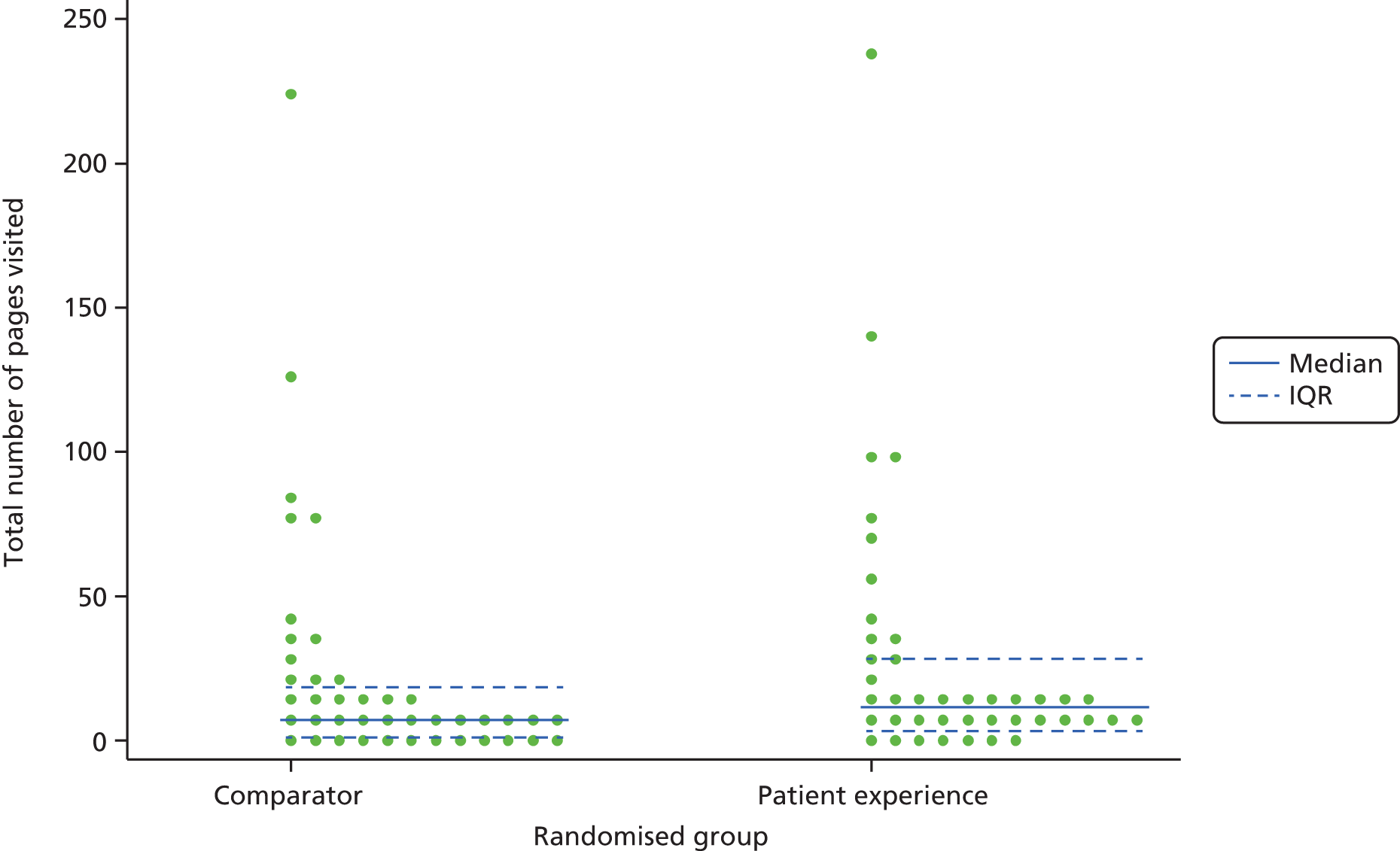

As originally proposed, we conducted a phase II pilot randomised single-blind trial, in which eligible participants were randomly allocated to a condition-specific PEx-based health information website or to a comparator website which contained no PEx information, stratified by one of three health conditions. The original application described three separate pilot randomised trials, one for each health condition. For operational efficiency, the three trials were run under the governance of a single trial protocol and analysed by condition (smoking cessation, asthma or caring for someone with MS). As this was an exploratory study, our main aim was to establish the feasibility of undertaking this research and to identify any emergent evidence of efficacy or harm. We measured recruitment and retention rates, usage of the intervention and comparator, and any adverse events. We measured the impact of all six websites on health status, and we assessed attitudes towards the websites using the new instrument, the eHIQ. We also included some condition-specific measures as secondary outcomes (such as self-efficacy measures). We also undertook qualitative interviews with 30 purposively selected trial participants to explore why and how they took part and used the websites (or did not).

Chapter 2 Work package 1a: how might sharing experiences on the internet affect people’s health? A conceptual overview

Abstract

Introduction: the role of information based on online PEx is a new field with no agreed theoretical and methodological basis. As a first step to improving the scientific base and policy guidance, we aimed to provide an overview, or conceptual map, of the potential health effects of online PEx in health and health care.

Methods: we drew on realist review methods in three stages: (1) a wide-ranging review of literature in social and health sciences distilled in a matrix that covered potential positive and negative impacts (we continued reading until we reached data saturation); (2) further refinement of the results with reference to a public panel; and (3) even further refinement after testing with expert colleagues.

Findings: seven domains characterise how online PEx could affect health, each with the potential for positive and negative impacts. The domains are finding information, feeling supported, maintaining relationships with others, affecting behaviour, experiencing health services, learning to tell the story and visualising disease.

Conclusions: the value of first-person accounts, the appeal and memorability of stories, and the need to make contact with peers all suggest that reading and hearing others’ accounts of their own experiences of health and illnesss will remain a key feature of e-health.

Introduction

As we have seen, the role of information based on online PEx is a new field with no agreed theoretical and methodological basis. As a first step to improving the scientific base and policy guidance on the provision of information based on people’s experiences, we drew on a wide literature in the social and health sciences to provide an overview, or conceptual map, of the potential health effects of online PEx in health and health care. The below contains extracts from and represents an abridged version of material first published in the Milbank Quarterly © (2012) The Milbank Memorial Fund. 4

We identified seven domains of the online PEx terrain. In this section of the report, we describe the methods we used to develop this conceptual map before going on to describe the seven domains of the terrain in turn.

Methods

We conducted the overview in three stages: a literature review, a public panel, and a final review and revision after we presented our initial findings at a specialists’ workshop.

Literature review

Our approach was informed by realist review, a method for synthesising research evidence regarding complex interventions. 5,6 It is based on the idea that research should pass on collective wisdom about the successes and failures of previous initiatives in particular policy domains ‘before the leap into policy and practice’. 5 Its main purpose is to identify explanations through which complex social programmes might operate so that policy-makers can learn how to introduce or adapt programmes based on a good understanding of why and how they might work.

This approach was suited to our task because the science of the role of information based on online PEx is epistemologically complex and methodologically diverse. 6 However, in our case, there was no set of theories or even defined social or health programmes to identify and evaluate: the field is too new. We therefore adapted the approach to allow us to identify and describe the domains of the territory rather than to develop programme theories of how it may work. Our approach was iterative and collaborative; SZ and SW worked intensively face to face, through e-mails and by telephone over 6 months in 2010. Box 1 summarises the review’s five overlapping steps.

-

Settled the review question: ‘what is written in peer-reviewed journals and scholarly books about the health effects of access to and use of online patients’ experiences?’.

-

Refined the purpose of our review: to provide ‘a conceptual map’ of what is known about the health effects of access to and use of online PEx about health and illness.

-

Articulated the key ideas to be explored in a multidisciplinary project meeting in which we developed our initial matrix.

-

Exploratory background reading gave ‘a feel’ for the literature based on our own and colleagues’ bibliographic databases (concurrent with steps 1a and 1b).

-

Pragmatic and wide-ranging search (with assistance from a librarian at the Oxford Knowledge Centre) sought to identify any studies that had tested the effects of exposure to online PEx or that described theories or ideas about the potential effects of exposure to online PEx.

-

Both authors scanned all resulting titles and abstracts and, after discussion, chose potentially promising papers that could inform our thinking.

-

Sought more papers and books by ‘snowballing’ from reference lists as promising ideas emerged.

-

Our final search for additional studies came when we had nearly completed our review or when we came across them in the course of our professional lives, for example through discussions and seminars.

-

At least one of us read full papers. Although we used no formal quality appraisal tools, we considered papers in relation to their:

-

relevance – does the research address the topic and enable us to add to, adapt, or amend the initial matrix developed in step 1c?

-

rigour – does the research support the conclusions drawn from it by the researchers or the reviewers?

-

-

Both of us identified papers containing important ideas, explained them, and discussed their relevance during a period of intensive working together.

-

We added categories and specific instances to the initial matrix, which became our main data extraction framework.

-

We developed our initial ‘map’ or overview in a tabular form, identifying potential effects of access to and use of personal experiences of health and illness on the internet, the potential negatives and the potential mechanisms through which it might work.

-

A constant comparison between our reading and the working table identified the point at which no new ideas were emerging and we were confident that we had achieved data saturation.

-

We drew up a glossary of terms defining, recording and explaining key concepts; our understanding of them; and their application in this overview.

-

We presented and discussed the table and glossary at a full team meeting and made some modifications and clarifications regarding how the table should be presented.

-

We discussed the table in a workshop with 30 members of a health service public panel, who suggested the emphasis and importance of topics.

-

A final search and discussions at a conference identified the importance of visual as well as written and read presentations of experiences.

-

We identified and described seven domains.

Public panel of health website users

To check our interpretation of the literature, we convened a public panel which consisted of 30 participants primarily recruited through an invitation from Oxfordshire Primary Care Trust sent to a list of people who had previously agreed to help with research (see Chapter 11). We selected the respondents to ensure that they were representative of a cross-section of the community (gender, age, occupation and ethnic group) and included those who had used the internet for heath information in a variety of ways (websites, forums, blogs) and for a variety of health conditions (either for themselves or on behalf of family and friends).

We first showed examples of health information with and without the inclusion of ‘personal experiences of health and illness’. The panel was divided into four groups, each with a rapporteur, and asked to think about how people might be positively and negatively affected by experiential information. The rapporteurs delivered the feedback to the whole group. In a final plenary session, we summarised the results of the conceptual review and discussed how they compared with the results of the group discussions. A final questionnaire asked participants what, in their view, were the most important ways in which experiences might affect people, both positively and negatively, from the perspective of someone with a condition and that of a caregiver of someone with a condition. A report was circulated and feedback was sought.

Final review and revision

During our final search for relevant papers we presented our findings at a specialists’ workshop at the 25th British Computing Society conference on Human–Computer Interaction, July 2011, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, as part of the workshop ‘Online patient experience (PEx) and its role in e-health’, organised by the authors. During discussion, we identified the importance of the visual presentations of online PEx. We had not identified this topic in our reading but on realising its importance we included it in our matrix. Finally, we agreed on the seven ‘domains’ of our conceptual map of the potential health effects of online PEx.

Results

The potential health effects of seeing and sharing experiences online: seven domains

Our approach allowed us to identify seven domains which broadly map the role of online PEx:

-

finding information

-

feeling supported

-

maintaining relationships with others

-

experiencing health services

-

learning to tell the story

-

visualising disease

-

affecting behaviour.

For each of these we considered the potential for both positive and negative effects.

Finding information

Other people’s experiences of illness can provide information that is valued in its own right. They can make information more relevant,7,8 provide contextual information about causes and consequences, and help people to understand what may happen. 9,10 Hearing about how others have coped may change one’s orientation to the illness11 and offer a framework for managing the uncertainties. Simple, practical tips on how to manage problems encountered in everyday life, coping strategies that others use, and advice based on what has worked for others are highly valued for their pragmatism12,13 and because they are easy to understand. 14

In making decisions, people draw on many sources of information. They discuss using their own and others’ experiences as well as more traditional ‘factual’ information for decisions,15 and they often say that they prefer not to base their health decisions solely on other people’s experiences. 16 However, hearing about other people’s decisions can help them to recognise that a decision must be made, understand what the range of options might be and clarify the alternatives (e.g. in relation to treatment, lifestyle and attitude). 16,17

Learning through other people’s accounts of their experiences can be memorable because the accounts are vivid,18,19 but if the experiences presented are not typical,16 are inaccurate and biased, or if the sites are sponsored by vested interests or open to commercial exploitation,16 the information may be distorted, which could lead to worse decisions if people are not aware of this. 1,20 Our public panel emphasised that the internet’s unregulated nature means that all sources of information might be seen as having equivalent status, regardless of their trustworthiness. The panel also raised the issue of information overload. Descriptions of negative or dramatic outcomes might mean that more numerous but unremarkable experiences remain unwritten or unnoticed. The difficulty of providing ‘balanced’ information has been previously addressed21 but no clear solutions are yet available.

Feeling supported

Having an illness, facing a health issue or being a family caregiver can challenge one’s personal identity, and some people may feel embarrassed or even stigmatised by their condition. Knowing that others are tackling similar problems and learning how they deal with difficult issues can reduce these feelings of isolation, bringing a sense of belonging to a group and reassurance that one’s experiences and reactions are ‘normal’22 so that one feels more supported.

People who have joined an online peer-to-peer group may also benefit from feeling that they are connected by helping and supporting others. 23,24 Online contacts can provide a safe environment for ‘emotional labour’. 25,26 Hearing about others’ experiences can induce feelings of compassion, so that one becomes less self-absorbed and gains a better perspective. 27 In their study of participation in online support groups, van Uden-Kraan et al. 13 describe ‘emotional empowerment’ as the process through which information is exchanged, emotional support is encountered, and recognition is gained through sharing experiences. Cohen28 calls this ‘emotional support’ and suggests that it can make people simply feel better. Our public panel considered this process important, saying that it meant that you knew you ‘were not alone’ because hearing about other people’s experiences gave you a sense of ‘being supported’. For people who have rare conditions, who are undergoing unusual treatments or who are geographically isolated, the internet may be their only source of this type of support and, therefore, be especially important. 29,30

In contrast, depending on their content, others’ experiences may arouse feelings of anxiety and lead to unrealistic expectations, false hopes or even despair, fear, guilt, anger and inadequacy if others seem to be managing better. Patients’ feelings of despair at their own condition may become worse if they find out that peers have fared badly;31 internet-based support groups are sometimes dominated by a single viewpoint. How one responds to other people’s experiences depends greatly on one’s mood at the time of the encounter, and, if that goes badly, it can reinforce one’s vulnerability or feelings of inferiority. The public panel were particularly concerned that people with mental illness might be adversely affected by negative postings, especially from those they described as the ‘trolls and fruitcakes’.

Maintaining relationships with others

The internet raises the possibility of having a distinct set of ‘online’ and ‘offline’ relationships that can be helpful when it is hard to maintain both an illness identity and an everyday identity. Online and offline relationships need not, of course, be mutually exclusive; many people keep in touch with friends via the internet and people who meet on the internet can become real-life friends. 32 There are, however, big differences in the way that people communicate and establish relationships online and offline. In an online forum, the usual requirement for conversational give-and-take need not apply: although a person may choose to write in extensive detail about their experiences, their audience can quickly browse through the account, break off at any point, or go back and review a section in more detail. Needless to say, such actions might be difficult to achieve in real-world interactions without causing offence.

Learning about how others cope may help patients become socialised into a new role in relationships (e.g. as a patient or as the spouse or parent of a patient). Finding that other people are facing similar problems may help one to feel more ‘normal’ and confident in managing one’s health condition in other contexts, including family, work, relationships and travel. Thus, online support may even help to sustain ‘real-world’ relationships by providing another sounding board and emotional outlet for health concerns, thereby ‘saving’ real-world relationships from that role.

Paradoxically, isolation in the real world could increase if people feel that only those who have been through exactly the same thing can understand them. For example, Hinton et al. ,31 writing about the use of online infertility support groups, drew attention to the possibility that web support could increase real-world isolation by reinforcing the notion that only those who have dealt with infertility themselves could possibly understand what it is like. A related idea, drawing on the work of Nicholas Negroponte,33 is that by enabling people to refine and personalise all of the information they receive (characterised as ‘The Daily Me’), they will rarely be exposed to any ideas that challenge their own. In this way the internet could reinforce entrenched interests and misunderstandings. Our public panel endorsed the idea that over-reliance on ‘virtual support’ can lead to ‘wasted time’ browsing and posting on the web, which could be to the detriment of face-to-face social contact in their own locality.

Experiencing health services

Finding out about other people’s experiences of care can affect the use of health services. In health systems that encourage patients to make choices about health-care providers, feedback and commentary about others’ experiences of providers can often be found either on ‘reputation’ sites (designed to present public ratings) or on patients’ chat rooms, forums or social networking sites. Accessing this information can contribute to decisions about which clinic to attend, which professionals to consult or which treatment to request or avoid17,34 and may even help to raise and address safety issues for patients. 35

Health consultations may be more efficient and patient centered if patients pick up useful ideas about the questions to ask, the best terms to use, and the symptoms or side effects to mention to their doctor. 36 Learning through other people’s experiences of symptoms and consultations may reassure the ‘worried well’ that they do not have the health problem they feared, thereby preventing unnecessary consultations. Our public panel expressed concern about ‘hypochondria heaven’, in which the unnecessary use of health services might be encouraged by seeing other people’s experiences online. People often look online to ‘follow up’ on the advice given by health professionals or to seek validation for their own interpretations or feelings. 37–39 Responses may spur them to seek a second opinion or further clarification from their health-care team. 40

At a macro level, by finding out how stigmatized conditions affect others or through restricted access to care and support, people can become more aware of inequalities and injustices which might foster changes in social attitudes or a more equitable provision of care. 41 It may also stimulate advocacy and campaigns. In some cases, shared experiences have been used to challenge not only the provision of services but the very parameters of what counts as an illness, particularly for contested illnesses such as fibromyalgia and contested treatments such as vascular surgery for MS. 42 Patients who compare what ‘counts’ as an illness or a recognised treatment in different health systems find ample examples of inconsistency, which are used to fuel campaigns for either better evidence or more treatment options.

Although there are clearly several potential benefits for the way in which people use health services and influence the development of care services,43 clinical relationships may be strained if unrealistic expectations are raised or if alarming stories from other patients damage people’s confidence in professionals and adherence to treatment. Those who take the time to provide feedback on services may feel frustrated if this does not lead to improvements. Finding out about other people’s experiences of poor care could increase anxiety in situations in which they have little choice or control.

Learning to tell the story

From childhood onward, stories provide a powerful, palatable and memorable way of learning about the world. 44 An engaging narrative can immerse the audience in the account and thereby transfer information in a particularly effective manner. 45,46 When a story is well told and encountered at an opportune moment, it can reassure and ground the reader or listener. It can also help her make sense of her own situation by suggesting a practical and emotional frame for her response. 12–14 We can see stories as a conduit for memorable and meaningful information and support.

Another relatively neglected aspect of stories, which we believe is important and distinct, concerns the very language, including the terms of reference and the figures of speech, that is used to construct an account. Hearing how others describe what has happened to them (as well as what has happened) adds to the richness of the vocabulary and can help to construct our own account. Although it is well understood that we learn through stories, the effect of hearing about other people’s experiences on our ability to relate our own narrative is less well understood. The consequences of gaining an enriched and more powerful vocabulary, being able to tell their story well, may help people to develop an appropriate professional interest by giving a concise and relevant account in a clinical setting, help them explain salient points to professionals11 and elicit understanding, support and affirmation from friends, family and wider audiences via the media and web blogs. We therefore see ‘learning to tell the story’ as distinct from other aspects of the exchange of information and support because it focuses on the ‘how’ rather than the ‘what’ of the accounts that we are able to relate.

Frank47 and Pennebaker and Seagal48 suggested that even the very process of constructing a coherent story may help the healing process. Narrative construction (and reconstruction) may also help people make sense of what has happened to them and thus support emotional recovery. 49 The internet allows those who want to share their stories with others to do so by adding a posting on a forum or chat room or perhaps setting up a site or blog of their own. Such sharing can feel empowering, especially if it attracts many followers or elicits approving commentary. 24

The question of verification cannot be ignored: how can we know whether or not accounts of people’s health experiences are true? ‘Telling’ or ‘spinning’ stories is sometimes used as a synonym for telling lies, but Bury50 recommends that we view people’s accounts of their illness as ‘factions’, a meld of facts and fiction that weave interpretation and presentation into the account of what actually happened. As Entwistle et al. 16 observed, people rarely present themselves as naive users of any information, yet we know relatively little about the effects (which could include incoherence and confusion) of exposure to numerous, and sometimes conflicting, accounts of health experiences on the web. Schwartz51 proposes that, far from helping, a plethora of options may prevent one from being able to make (and live with) a choice. Those who post their own stories online may be harmed if their account is misappropriated, criticised, ridiculed or even just corrected for facts. A mental health service user on our panel pointed out that a person posting a story when he or she is in the ‘wrong’ frame of mind may later regret their action. Internet posts can expose people to ‘flaming’ criticism from others. Yet if no-one comments on a heartfelt posting, the writer may feel even more isolated and ignored precisely because the potential audience was so vast. It may also be intimidating for some people to encounter a highly articulate account of an experience similar to their own.

Visualising disease

Many health-related websites include images; even some that were originally intended to be based on text now link to video clips on sites such as YouTube (YouTube LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA). The incorporation of photographs and videos on health websites has been treated mainly as a design issue rather than considered in terms of the potential consequences for the way in which people deal with their health problems. Williams and Cameron52 argued that images – in a variety of forms – are increasingly used in health-care communication and can be powerful ways of communicating important messages. The internet is inherently visual and the ability to post and access images of people dealing with health issues may be another important, albeit rarely explored, feature of health experiences and the internet.

How do people use images of PEx online? Dermatological conditions are undeniably visual; photographs can help people to compare and evaluate the effects of different treatments ‘with their own eyes’. Hardey (University of York, 2011, personal communication) reviewed video postings of eczema on YouTube and found more than 1000 clips, some of which had more than 2 million viewers. Some types of behaviour change are documented online through repeated images. Weight loss blogs, for example, often include a visual chronicle (a series of before, during and after photographs) of a person’s changing body shape. Sometimes these blogs feature a weekly picture of feet standing on a set of bathroom scales, adding ‘objective’ evidence to the bloggers’ claims about their progress. 53 There also is evidence that adding imagery to text-based website information about the risk of cardiovascular disease can work better than text alone in increasing the perception of risk and motivating protective behaviour. 54

Among the thousands of YouTube films of people with different health conditions, some capture a single moment, some record progress by following treatment and some are undoubtedly positioned to promote a particular treatment (although the presentation may or may not make this explicit). Like stories, imagery can be powerful and memorable; like stories, this has both positive and negative consequences. Illness can dramatically change a person’s appearance. People with serious progressive conditions, such as motor neurone disease (MND) (also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), may choose to avoid looking at images of other people whose appearance may grimly foreshadow their own future. 55

Affecting behaviour

Advertising has long recognised the persuasive power of testimonials in changing behaviour. The field of health education and health promotion was quick to see the potential of the internet to deliver efficient, tailored advice56 to help people lose weight, do more exercise, give up smoking, tackle depression, control diabetes or high blood pressure and practise safe sex. 57 Some behaviour change sites have evident commercial backing, and others are funded through government or health insurance and promoted in self-management programmes. Testimonials and stories may be used to advertise a particular product, but they also may be intended as illustrations or for general encouragement and inspiration.

In her study of weight loss bloggers, Oostveen53 suggests that, through public blogging, people may feel accountable to an audience, and that by being aware that their progress is being watched, they may feel motivated to adhere to their programme. Reflecting on what they have posted may make people feel proud and in control, or embarrassed and regretful. For some health behaviours, such as cigarette smoking, people acknowledge that health professionals now are unlikely ever to have been smokers themselves, so advice from those who have ‘been there’ may have greater weight (through empathy and resonance) with those trying to make changes. Hearing about how others deal with a problem or a concern can also build confidence and self-efficacy. 58

Narratives or stories hold people’s attention by melding imagery and feeling. De Wit et al. 45 studied the effect of statistical and narrative evidence on the perceived threat of hepatitis B infection among men who have sex with men. They found that the intention to be vaccinated was higher among those who were presented with a personal narrative, and they believe that this is because narratives are less susceptible to the defensive processing through which people distance themselves from health education messages. In their study in South Wales, Davison et al. 59 noted that people use a ‘lay epidemiology’ (e.g. the popular image of an elderly relative who lived into his nineties despite smoking and drinking) to resist acknowledging that health education messages apply to them. This tendency to distance oneself from an unwelcome message (e.g. about susceptibility to a smoking-related disease or a sexually transmitted infection) may be strongly challenged by a resonant account from someone else who had held the same belief that they would not be affected yet was shown to be mistaken in their optimism.

In some circumstances, hearing about other people’s experiences may reinforce unhealthy behaviours. Some sites contain messages that contradict or challenge medical advice and suggest or reinforce unhealthy behaviours. Several studies have examined the content of online pro-anorexia support groups;60 people with diabetes can learn from forums about non-prescribed ways to use (misuse) their insulin for weight loss. Some online forums promote unsafe sexual practices and even provide advice on how to most effectively contract human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At the extreme end of harm, those who are inclined toward suicide can even find forums that offer advice (and possibly encouragement) about how to end their life.

Conclusions

The profusion of patients’ experiences online has dramatically influenced the health information field. Health choices cannot be made without information,61 and the importance of internet health information is not disputed. Yet our conceptual review demonstrates that the full gamut of effects (for both the ‘poster’ and the ‘consumer’) of websites that cite patients’ experiences go far beyond the provision of ‘information’or ‘support’, at least as they are conventionally conceived. Our conceptual review shows that we are unlikely to identify the effects of exposure to online PEx simply by measuring outcomes such as knowledge acquisition, coping or decisional quality alone.

We were careful to consider the potential for harm as well as benefit, trying to avoid the temptation to be either pessimists and optimists. 62 Online PEx may help people make better health-care choices and alert them to health issues, improve their health literacy and understanding of susceptibility to illness, compare their situation with that of others, improve their own illness narration, access more appropriate services and develop better relationships. Yet we cannot assume that the effects of exposure to online PEx are always benign. They may raise anxiety. They may be disadvantageous if they feature only a small number of unrepresentative patients’ stories. A single story with strong emotional content can distort decisions. 1,20 Overengagement with online communities can be detrimental to life ‘offline’. The powerful and memorable delivery of a personal experience could be used for a deliberately misleading or exploitative message. The benefits and disadvantages are unlikely to be evenly distributed across socioeconomic, age and gender groups, yet little is known about these patterns, and, as the digital ground shifts again, new applications may encourage new types of use and users.

Guided by realist review methods,6 we considered the processes through which PEx may operate. The literature suggests that the processes may differ depending on, for example, whether people are reading about others’ experiences or writing about their own. Those who help to create health content may be participating in a different way from those who consume rather than post their own contributions, yet the widespread use of social media and blogs is already blurring these boundaries. Some of the outcomes or consequences (e.g. the ability to make sense of what has happened and construct a coherent account) may be similar, whether one has learned from other people’s stories or from constructing a coherent account of one’s own.

The extent to which patients and members of the public have turned to other people’s experiences on the internet has provoked both surprise and, in some quarters, concern, although with the rise of social media and access from multiple platforms it is becoming the norm across health systems. Our review sheds some light on the features that make first-hand accounts compelling and the processes through which they operate. The value of first-person accounts, the appeal and memorability of stories, and the need to make contact with peers all strongly suggest that reading and hearing others’ accounts of personal experiences of health and illness will remain a key feature of e-health.

Chapter 3 Work package 1b: how, why and with what effect do people seek out and share health information online? Secondary analysis of the Oxford Health Experiences Group archive

Abstract

Introduction: the HERG archive contained almost 3000 interviews on over 60 health conditions. We conducted a secondary analysis on a subset of interviews to gain insight into how, why and with what effect people seek out and share health information online.

Methods: information relating to internet use and/or PEx was extracted from 276 interviews. First, 95 interviews were analysed in depth with a focus on seeking and sharing PEx. Second, statements relating to the use of health-related websites were extracted, recast as questionnaire items and reviewed by an expert panel for the eHIQ.

Findings: perceptions and experiences of online PEx differ between individuals and across conditions. Factors influencing people’s desire for and response to PEx include personal characteristics and preferences; condition and stage of illness; health-care environment; source and type of PEx; and the format and medium through which PEx is communicated. Eighty-two items relevant to the impact of health-related websites were identified for use in the eHIQ.

Conclusions: online PEx is widely available, diverse and hard to control. Reasons for, practices of and the health effects of seeking and sharing PEx are complex and relationally contingent. A secondary analysis of the HERG archive enabled us to explore key aspects of this complexity across multiple conditions and develop new questionnaire items suitable for use across health conditions.

Introduction

At the time of this study, the Oxford HERG archive contained almost 3000 qualitative interviews covering more than 60 different conditions. It is ethically approved for secondary analysis and is an invaluable resource for health-related research. As interviewees are routinely asked about their experiences of seeking and receiving information, internet use, professional and peer support, it was thought that the archive would contain a great deal of information of relevance to the iPEx (Internet Patient Experiences) programme grant. To benefit from these data, a secondary analysis, or more accurately, a series of iterative secondary analyses, was conducted on the material. 63 The aims of this process were (1) to inform the design and implementation of subsequent WPs (especially WP1c and WP2b; see Chapters 4 and 6); (2) to contribute to extant knowledge on how, why and in what ways seeking and sharing PEx online affects people’s health and well-being; and (3) to identify the main reasons that people use online health information in order to construct a set of items for an assessment tool that measures the impact of using health-related websites to be used later in the programme (WP1c; see Chapter 4).

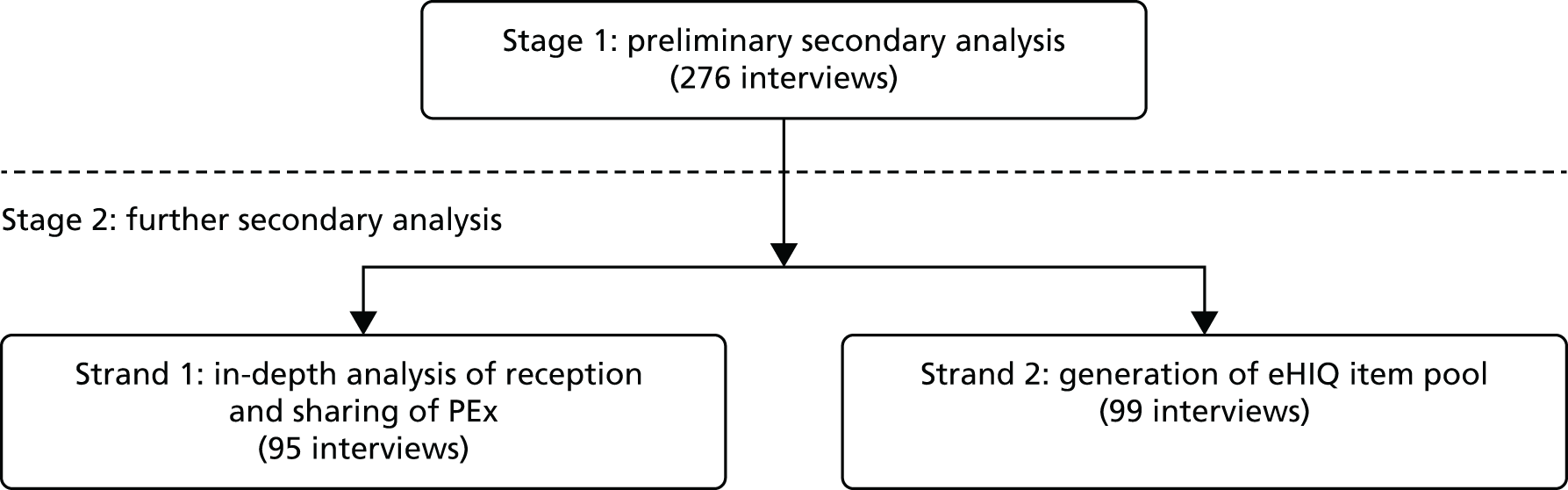

The analysis was conducted in two stages (Figure 2). In stage 1, two researchers (FM and LK) conducted a high-level thematic analysis on a subset of 276 strategically selected interviews. The aim of this preliminary stage was to familiarise ourselves with the data, develop appropriate sampling approaches and forms of analysis for subsequent work, generate a high-level list of themes relating to people’s perceptions and experiences of online PEx and select key topics and questions for further analysis. To ensure that a range of experiences, practices and perceptions of online health information was included, we aimed for breadth rather than depth of coverage.

FIGURE 2.

Work package 1b: high-level overview of the secondary analysis process.

In stage 2, two distinct strands of work were conducted. In the first strand, FM, JP and LL investigated two areas of interest that emerged during the first stage of analysis, and were new contributions to research in this area. The first, focused on issues around the reception of PEx, was an exploration into how processes of identification and visualisation mediated the ways in which people with serious neurological conditions (MND and Parkinson’s disease) communicated and responded to PEx. 55,64 The second, focused on issues around the sharing of PEx, explored the ‘value’ that people who actively shared their experiences attributed to doing so. 65 In the second strand, drawing on the theoretical framework outlined in the previous chapter (WP1a), LK conducted further analysis to generate an item pool for the development of the eHIQ. This secondary analysis enabled the incorporation of internet users’ actual words as a basis for questionnaire items and helped enhance content validity of the assessment tool.

In this chapter, we provide a high-level overview of the methods used for the secondary analyses and present overarching findings. Much of the research discussed here has been published elsewhere. 55,64–66 To avoid duplication, we do not go into the details of published work, but rather (1) provide a high-level overview of the findings from stage 1 of the secondary analyses that have not been published elsewhere and (2) summarise and contextualise key findings from both strands of stage 2 (which have been published) in relation to this wider secondary analysis. 55,64–66

Methods

Secondary analysis, broadly defined as the use of an existing data set to answer questions not posed in the original research,67 has long been conducted on quantitative data. In qualitative research, where the need for contextual sensitivity and specificity is seen as paramount, secondary analysis is less well established. More recently, as evidenced by the creation of the Economic and Social Research Council Qualitative Archival Research Data Centre (QUALIDATA) in the mid-1990s and its incorporation into the UK Data Service, there has been an increased interest in the value of conducting secondary analyses on qualitative data. In spite of this acceptance and, indeed, in some cases, active encouragement (e.g. from funding bodies) of the secondary analysis of qualitative data, persistent concerns remain. According to Heaton,63 these can be broken down into three main areas: (1) the ‘fit’ between the data and the questions posed in the secondary analysis; (2) the position of the researcher and their relationship with the data; and (3) verification of the data and findings generated from it. All three of these concerns were taken into consideration and addressed during the course of our secondary analysis.

The interviews collected by the HERG are in-depth narrative ones, conducted with a view to soliciting as wide a range of experiences of illness as possible, which makes them particularly suitable for secondary analysis. 68 In the first half of the interview, participants are invited to tell their story for as long as they want with as little interruption as possible. In the second half, a semistructured interviewing approach is adopted to enquire after topics of interest that have not already been raised and to explore key topics in more depth, including questions on information seeking, internet use and peer support. The interviews are collected using maximum variation sampling, with variation across demographic variables and type of experience. 69 Ethics approval for secondary data sharing and analysis was received from the Eastern Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (reference 03/05/016) and the interviews have been successfully used for secondary analysis in extant studies on health-related use of the internet. 10,15 Further information about the methods used to collect and conduct the interviews is available elsewhere. 70,71

Stage 1: preliminary analysis

Given the range of conditions contained in the archive, it was not possible to undertake an exhaustive analysis of all available interviews. Key findings of HERG interview collections are published as online resources (www.healthtalk.org). These website sections were explored to gain an insight into the topics that the primary researchers had identified in each interview collection and to help select which interviews to use in the secondary analysis. We decided, in the first instance, to focus our analysis on those deemed to have closest relevance to the three exemplar conditions being investigated by the iPEx programme (smoking cessation, asthma and carers of people with MS). To maximise the chances of finding information about internet technologies, only interviews published from 2005 onwards were included. Based on this, seven complete collections and a further nine ‘pilot’ interviews with people affected by MS were included in the first round of analysis (Table 1). These were selected through discussions with key members of the project team, including those who were very familiar with the content of the HERG archive.

| Title of collection | Date | Number of interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Carers of people with dementia | 2005 | 31 |

| MS | N/A | 9 |

| MND | 2008 | 47 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 2008 | 40 |

| Young people with type 1 diabetes | 2006 | 39 |

| Young people with epilepsy | 2008 | 41 |

| Young people with depression and low mood | 2009 | 39 |

| Young people with long-term health conditions | 2007 | 30 |

| Total | 276 |

With the exception of the MS-related interviews, thematic summaries and interview extracts are available online for all of these conditions (see www.healthtalk.org). The summaries contain sections of direct relevance to the secondary analysis (e.g. ‘information and support’, ‘support and support groups’). The interviews were read (by FM or LK and in many cases by both) and all information relating to internet use and/or sharing or seeking experiences (online and off) was extracted. Scoping summary reports were compiled to identify the extent to which the collections had content relating to using the internet for health. A list of key emergent themes and associated statements (examples of the exact wording and language used by interviewees) was created for each condition. This list was subjected to an additional round of constant comparison coding, and key cross-cutting themes and areas for further investigation were summarised. This summary was not intended to be an exhaustive assessment of all the interviews. Instead, alongside the conceptual review (WP1a; see Chapter 2), it was used to highlight areas of interest for more in-depth secondary analysis and to index interviews and excerpts for the development of the assessment tool (WP1c; see Chapter 4).

The sample design and suitability of the data was further informed by consulting the original researchers of the selected interview collections. The researchers (most of whom are still employed in the HERG) provided input and advice based on their experiences of the collections they had created and their expertise in terms of online PEx more generally, which was incorporated into the analysis. Following discussions about the suitability of an interview collection for the research purpose, the original researchers provided coding reports [generated at the time of their own research using either the NUD*IST or NVivo (both QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative analysis software] that they believed would be particularly relevant to the topic. Coding reports took the form of electronic reports of sections of interview transcripts which related to a specific topic and were subsequently reviewed to inform the sample selection. Examples of coding reports were entitled ‘Web forums’, ‘Information’, ‘Support groups’ and ‘Information carer’.

The steps outlined above aided familiarisation with the data sets and helped us to assess the suitability of particular interview collections for further analysis. Sampling and selection of interview transcripts were not finalised at the outset, but, as is usual in qualitative analysis, remained continuous throughout the process.

Stage 2: further secondary analysis

Strand 1: secondary analysis to explore the sharing and receiving of patient experience in more depth

Numerous topics of interest emerged from the first round of analysis, and it was not possible to explore all of them in depth. We decided to focus on areas that have been underexplored in the extant literature and had wider implications for our understanding of online PEx. Based on this and in discussion with the project team, two areas were chosen for further analysis. The first was an exploration into the ways in which people articulated and responded to different types of PEx in relation to neurological conditions. Here, we performed a secondary analysis on 87 interviews conducted between 2006 and 2008 in the UK with people (patients and carers) affected by MND (46 interviews) and Parkinson’s disease (41 interviews). The second was an examination of people’s self-reported reasons why they shared their experiences through the internet and other mediums. We were interested not in psychological motivations, but in using these data to develop a nuanced understanding of the value(s) associated with sharing PEx. Here, we selected and analysed a strategic sample of 37 interviews conducted with people affected by 15 different conditions who had reflected on why they chose to share their experiences (Table 2).

| Condition | Number of interviews |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1 |

| Autism spectrum disorders | 2 |

| Cervical abnormalities | 6 |

| Colorectal cancer | 2 |

| HIV | 2 |

| Leukaemia | 1 |

| Ethnic minority experiences of mental health | 2 |

| Organ donation | 1 |

| Osteoporosis | 5 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1 |

| Experiences of psychosis | 2 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 |

| Testicular cancer | 1 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 7 |

| MND | 2 |

| Total | 37 |

In both cases, a supra-analysis (analysis of existing data from a new theoretical perspective)63 was conducted using a modified grounded theory approach. 72 All of the interviews were read in their entirety, online summaries were, once again, consulted and discussions were held with primary researchers. One of the authors (LL) was the original researcher for the MND module and hence was able to contribute to the analysis with contextual knowledge. Constant comparison coding was used, with discussions held among FM, LL and JP at regular intervals to validate and further conceptualise key themes. Throughout the course of the analysis, we presented the work in progress at programme grant meetings and conferences, receiving useful feedback that assisted with the development of key ideas. For more detail on the methods used please refer to Mazanderani et al. ,55 Locock et al. 64 and Mazanderani et al. 65

Strand 2: secondary analysis for the development of the e-Health Impact Questionnaire

Following the preliminary analysis in stage 1, interview collections were reviewed which were likely to be rich in data regarding the use of online health information. Of the 203 interviews reviewed, relevant extracts from 99 transcripts were identified and analysed using a modified version of the framework method73 (Table 3). Framework analysis allows a researcher to look at the data and conduct analysis in a systematic and comprehensive manner. 74 The framework method involves five stages: (1) familiarisation with the data gathered; (2) identification of a thematic framework which allows emerging issues, concepts and themes to be listed; (3) indexing the transcripts according to the thematic framework; (4) charting the data through extracting and synthesising it in a manner which allows within-case and between-case comparison; and (5) mapping and interpretation of the data. 75,76 Many of the themes that were expected to be raised during analysis had been identified in the WP1a review of the literature (see Chapter 2). This stage of the secondary analysis sought to gain a deeper understanding of existing (‘anticipated’) themes found in the literature while being mindful of any new (‘emergent’) ones that arose.

| Condition group | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long term condition (younger people) | 3 | 12 | 15 |

| Diabetes (younger people) | 5 | 14 | 19 |

| Depression (younger people) | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Parkinson’s disease (carers) | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Motor neuron disease (carers) | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Dementia (carers) | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Antenatal screening | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Fetal abnormality | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Menopause | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Mental health: BME (carers) | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 28 | 71 | 99 |

Two further sources of data were used to corroborate the themes identified for inclusion in the item pool: (1) focus group transcripts (n = 16) from research carried out on trust and online health information at Northumbria University76 and (2) comment forms (n = 29) completed by members of the programme’s public panel (WP1a; see Chapter 2) consisting of lay persons using local primary health-care services. Using more than one data source served as a method of ‘data triangulation’, enhancing rigour in the research. 77

This process contributed to the development of an item pool relating to the impact of using health-related websites which would be subsequently entered into psychometric testing (see Chapter 4). The assessment tool needed to be suitable for use in the WP3b Phase II pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT). Therefore, for each theme identified, candidate items were developed and checked for applicability to people viewing a website containing scientific information only and a website containing scientific information plus experiential health information. Emphasis was also placed on checking the suitability of the items among the WP3 exemplar condition groups (i.e. smoking cessation, asthma and carers of people with MS). Candidate items were circulated among colleagues in the project team for review and the feedback received was incorporated into the development of the final questionnaire.

Results and discussion

Key findings from the preliminary secondary analysis (stage 1)

The conceptual review presented in Chapter 2 drew attention to how practices of seeking and sharing PEx can have numerous and often profound (both positive and negative) consequences for people affected by different conditions. 4 Our secondary analysis of patient interviews reinforced and supported the findings of the review.

The first five domains of how online PEx could affect health (‘information’, ‘feeling supported’, ‘relationships with others’, ‘experiencing health services’ and ‘affecting behaviour’) identified in the review were evident across all the modules analysed. The sixth (‘learning to tell your story’) emerged in interviews with people who had actively shared their experiences online or in other forums. As many more people seek out others’ experiences rather than share their own, this domain was less prevalent than the first five. Interestingly, the seventh domain (‘visualising disease’), although not common across the corpus of interviews, was evident in certain conditions with visible and highly variable symptoms (namely MND and Parkinson’s disease). Given their importance in both our secondary analysis and the extant literature, the first five domains were used as a key structuring device for the development of the assessment tool for measuring the impact of health-related websites. 66 Owing to the lack of research on the sixth and seventh domains, they were selected for further secondary analysis. 55,64,65

In our secondary analysis we found both variations and similarities between how people affected by different conditions used the internet and responded to PEx. This is significant, as a great deal of current research on health-related use of the internet is condition specific and hence unlikely to pick up on wider cross-condition trends and differences. Although it is not possible to provide an exhaustive list of all the factors that influence how people respond to online PEx, we list some particularly notable ones that emerged from our high-level analysis.

The first is the condition in question and, linked to this, the age of the people affected by it. This was especially striking in relation to carers of people with dementia, where, despite the fact that interviewees spoke about benefiting from sharing PEx in face-to-face environments, there was very little evidence of them using online PEx. This may be because interviewees tended to be older and used the internet less, but it may also be related to the nature of the condition and the types of PEx available about dementia. In contrast, young people are particularly active online, seeking and sharing PEx across a variety of technologies and platforms [e.g. patient forums, Facebook (Facebook Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), YouTube]. However, in the case of young people with serious chronic conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, interviewees spoke of being upset by and in some cases actively avoiding ‘negative’ or distressing information, including PEx.

It has long been recognised that PEx can be a highly ambivalent source of information with the potential to bring about feelings of both hope and fear, provide support and increase isolation, and be perceived as ‘true’ knowledge or discarded as irrelevant. 31,78 In our secondary analysis we found that this was most definitely the case, with interviewees speaking of having had both ‘positive’ (e.g. feeling ‘supported’, ‘empowered’, ‘inspired’) and ‘negative’ (e.g. feeling ‘depressed’, ‘upset’, ‘devastated’) responses to online PEx. In relation to the former, interviewees said that PEx was an extremely valuable source of information that was simply not available elsewhere. Key areas of information provided by PEx discussed across interviews were practical hints and tips about actually living with a condition, information about diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, side effects, family and personal relations, finances, jokes and humour. Furthermore, PEx affected the health and well-being of interviewees not only by virtue of its informational content (important as this was), but from the sense of support and mutual understanding that was gained from speaking to, sharing with and identifying with other people affected by the same condition. In terms of ‘negative’ responses to PEx, the two most common concerns were fears about the danger of misinformation and the emotional difficulties of dealing with PEx. Interestingly, we found that people with serious chronic or terminal conditions tended to respond especially strongly to PEx, seeing it as an extremely valuable source of information and support, but at the same time often finding others’ experiences very distressing.

It is important to note that what were perceived as ‘negative’ versus ‘positive’ experiences of PEx were not static but, as with other forms of health information, changed over time, sometimes radically. For many people diagnosis was a crucial time for seeking out PEx, while others preferred to wait and seek out PEx once they had adjusted to their new diagnosis. The fact that for many people the internet is available at any time and can be customised to filter and select different PEx was seen as an important feature of the technology. Indeed, interviewees were selective about the source of the PEx they found online (who and where was it coming from), as well as the format and medium through which it was communicated (e.g. text written on a patient forum or a video on YouTube). Thus, the value and, crucially, evaluation of PEx as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ was highly relational and contingent not only across interviews, but over time, and in relation to different modes of communication. For example, in the case of MND and Parkinson’s disease, a number of interviewees expressed a strong preference for PEx communicated in writing rather than face to face to avoid seeing physical symptoms of the disease that they found upsetting.

Moreover, when interviewees spoke of how online PEx had affected their health and well-being they situated it in relation to their wider health-care environment and informational landscape (both online and offline). In some rare cases health-care practitioners had encouraged patients to look up PEx, occasionally suggesting websites and other sources; in others (again often in relation to more severe conditions), the use of the internet was actively discouraged by medical practitioners. Either way, across all of the collections we analysed, interviewees interpreted and used PEx in conjunction with information they received from numerous different sources, including the information they received from their health-care practitioner(s), NHS services, charitable organisations, the media, family and friends.

Key findings from the further secondary analysis (stage 2, strand 1)

Identification, mediation and visualisation in online patient experience

In our secondary analysis of the HERG interviews, interviewees regularly stated that PEx was a valuable source of ‘experiential knowledge’: ‘truth based on personal experience with a phenomenon’. 79 However, not all PEx was considered equally useful or relevant. Interviewees often spoke about how they were particularly interested in and affected by PEx from people they could relate to. Although the importance of relationships has been discussed in the sociological literature on ‘experiential knowledge’,18,80,81 little explicit attention has been given to examining the different forms of relationality at play in whether or not PEx is deemed as a valid source of ‘knowledge’. We explored this question in more depth through a secondary analysis on the MND and Parkinson’s disease collections. The main findings have been published55 and are summarised here.

A key factor that influenced whether or not interviewees considered someone else’s experience to be relevant to them was based on the recipient’s identification with the person sharing their experience. In the case of health-related PEx, this sense of identification was premised, in the first instance, on a shared diagnosis. Interviewees regularly said that only someone else living with the same condition as them could understand what they were going through and, therefore, be able to provide them with appropriate advice and support. However, a shared medical condition was not the only factor that affected whose experiences were considered relevant and useful. Interviewees sought out and responded most strongly to PEx provided by people they felt were ‘the same’ or similar to them. The key factors that informed whether or not someone was deemed similar, and hence that their experience was relevant, can be broadly classified as medical (e.g. stage and severity of illness, medication and symptoms) or personal and/or social (e.g. age, gender, lifestyle, family situation, education or job).

However, although the subtle processes of identification play key roles in underpinning how people respond to PEx, identifying with a ‘disease’ and with people living with it can be a source of emotional distress that is particularly acute in people with serious, stigmatised and/or degenerative conditions. 31 This results in a tension. To learn from PEx and consider it relevant to his or her own situation, the recipient of the PEx needs to identify with the person sharing it. At the same time, to minimise the negative associations and emotional distress that results from this identification, the recipient seeks out ways to distance him- or herself from the sharer. A key way people manage this tension is through emphasising both the similarities and the differences between their experiences and those of others: what, drawing on Ricoeur’s work on metaphor,82 we have conceptualised as ‘being differently the same’. 55

The tension between making someone else’s experience relevant and, at the same time, avoiding becoming upset by the more ‘negative’ or distressing aspects of the experience was also managed through mediating the way in which that experience was communicated. This is expressed in the excerpt below from an interview with a woman with MND:

You like the support you have helping one another but you’re scared that, I think, well I’m personally scared that if I met up with someone face-to-face and we started meeting up that if they needed to become reliant on me or to talk to me about their problems with MND that I wouldn’t be strong enough for that. I mean it might not be the case that they would do that but you don’t know. So I think too. I like having the e-mail contact but I don’t think I would want personal contact with someone else with MND because I think it gets too involved then.

MND collection, interview 10

It was precisely in contexts like the one described above, seeing other people with the same condition as them experiencing poor health or visible disability, that interviewees said the internet could be very helpful. Indeed, the ability to control seeing people and being seen was a key reason interviewees gave for using internet technologies for seeking out PEx and meeting people, rather than going to face-to-face support groups. This is illustrated in a quotation below, which was taken from an interview with a woman living with Parkinson’s disease:

[. . .] whilst I’m happy to go onto the web forum and communicate with people who’ve, with, who have had Parkinson’s for twenty years. I’m anxious about meeting people in the flesh, I don’t want to, I don’t want to see my future.

Parkinson’s disease collection, interview 17

When people speak about their experiences of illness, they often use extremely vivid imagery and metaphors that can have a powerful impact on others. 64 The articulation of PEx through written and verbal language, especially in the form of narratives and stories,14,47,50,83 has received a considerable amount of academic attention. In contrast, the visual dimensions of PEx through images and video has been relatively under-researched. We explored this topic further in WP2a, as discussed in Chapter 5. 84

Exploring the multiple ‘values’ of patient experience in contemporary health care

Patient experience has become an increasingly central part of contemporary health care. Patients’ experiential accounts are used for many different purposes, ranging from artistic expression through to fundraising for biomedical research and lobbying for changes to health-care policy. Yet relatively little is known about why people choose to share their personal experiences of illness.

Everyone who took part in the HERG interviews knew that text, audio and/or video clips of their interviews would be made available on a publicly accessible website with the specific aim of making their experience available to others. In addition, some interviewees had already shared their experiences in other mediums (e.g. blogs, support groups, face to face, books, documentaries, etc.). This meant that the archive contained a considerable number of data on this rarely discussed topic. In the first round of secondary analysis, we noted a number of cases in which interviewees reflected on why they had chosen to share their experiences and what they thought the effects of this had been on themselves and on others. To explore this topic, we selected additional interviews where this had been elaborated on in more depth and subjected them to a further round of analysis (for more detail on our sampling approach see the full account of this research, published elsewhere65). A significant portion of what we found related to the emotional and therapeutic benefits of peer support. As this has already been discussed in depth elsewhere,25,84 we chose to focus on other aspects of why interviewees share their experiences, especially in more public forums.

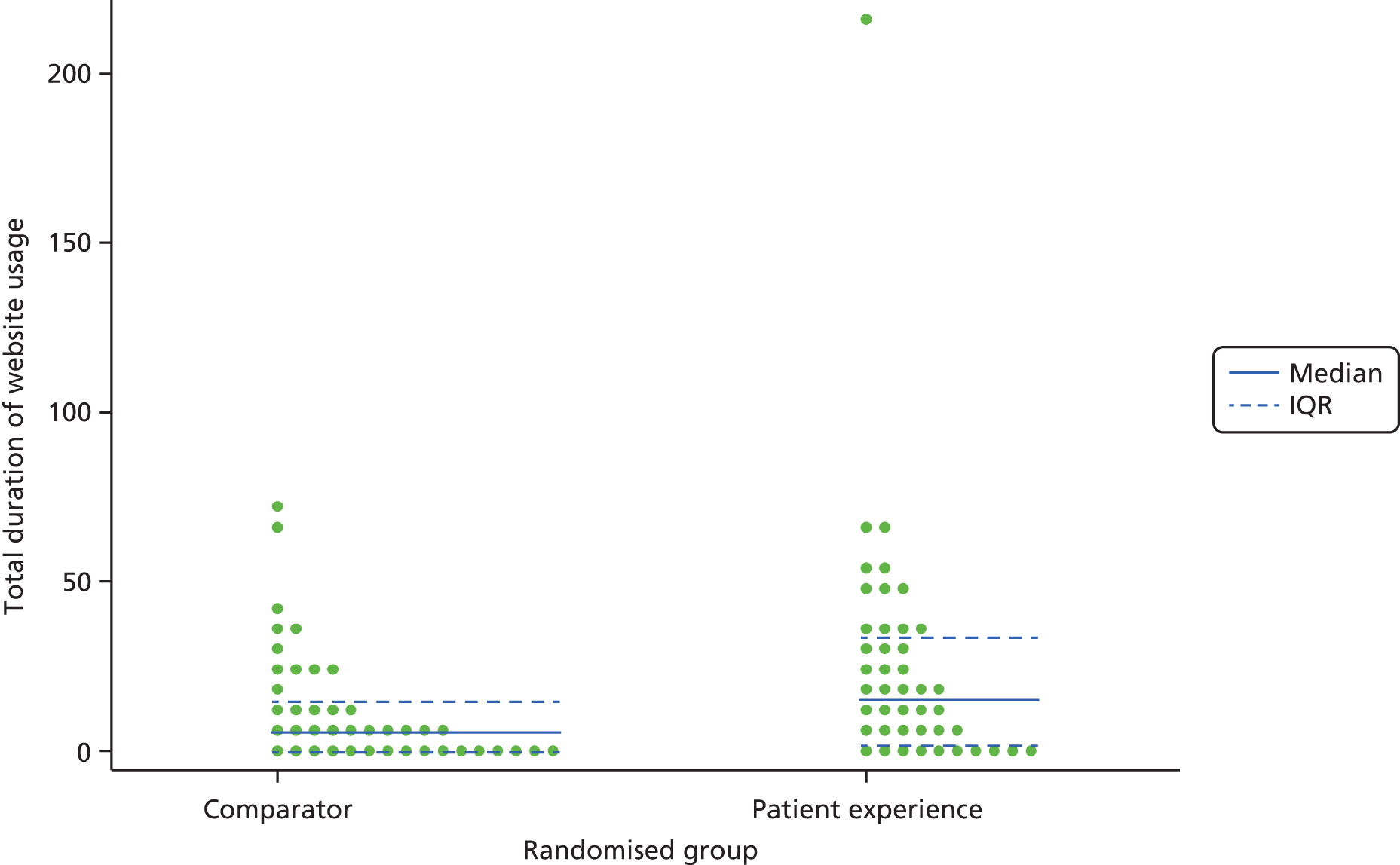

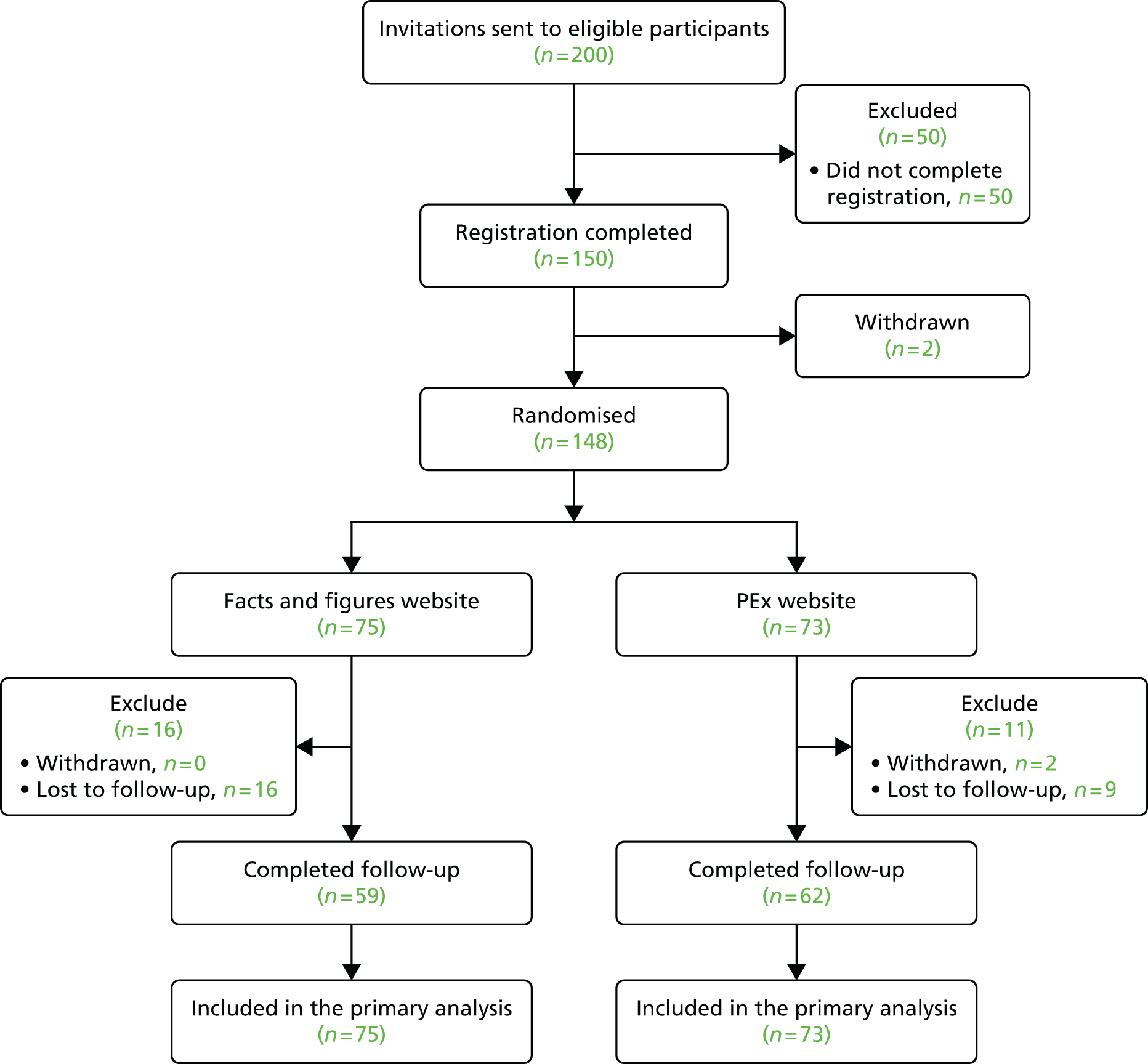

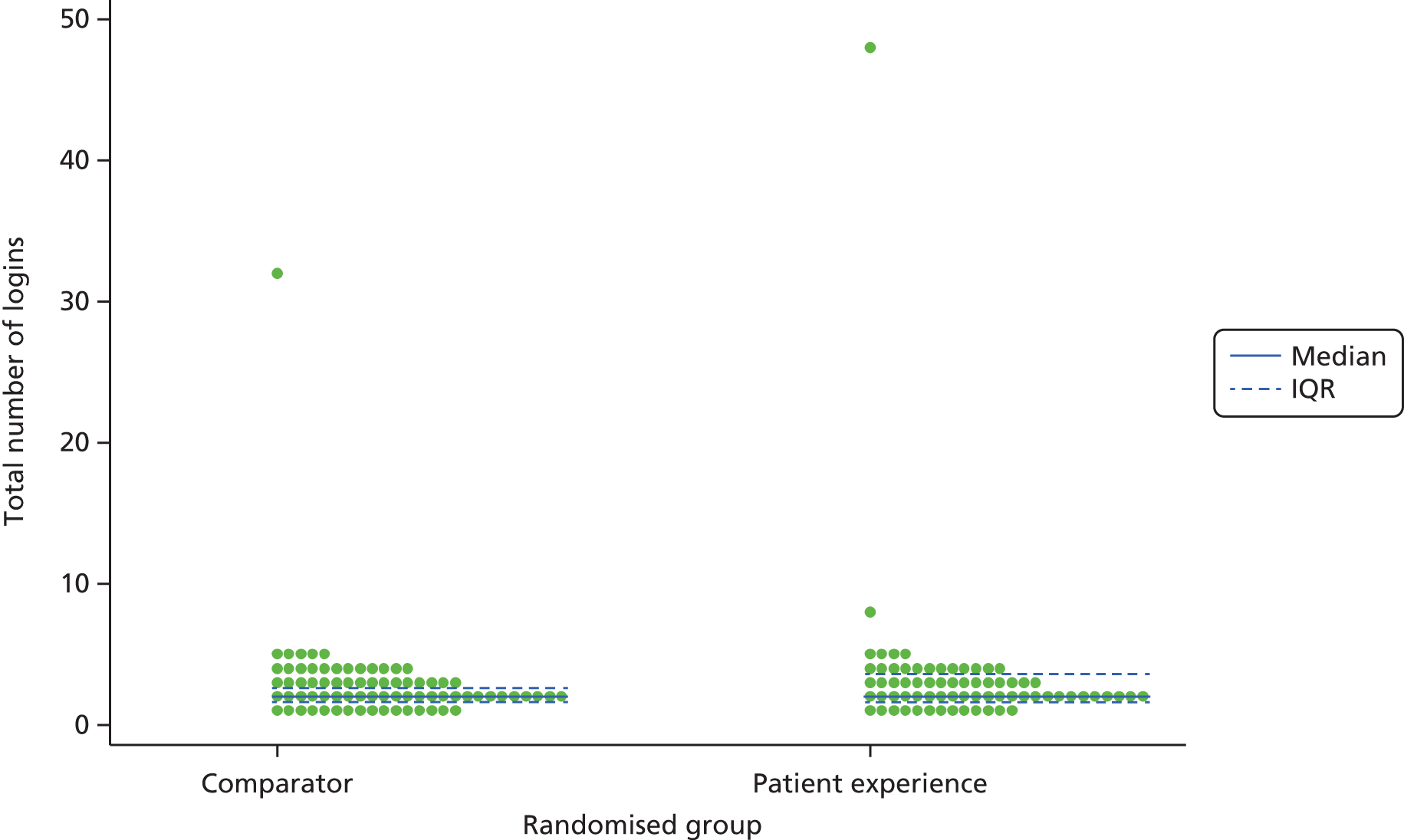

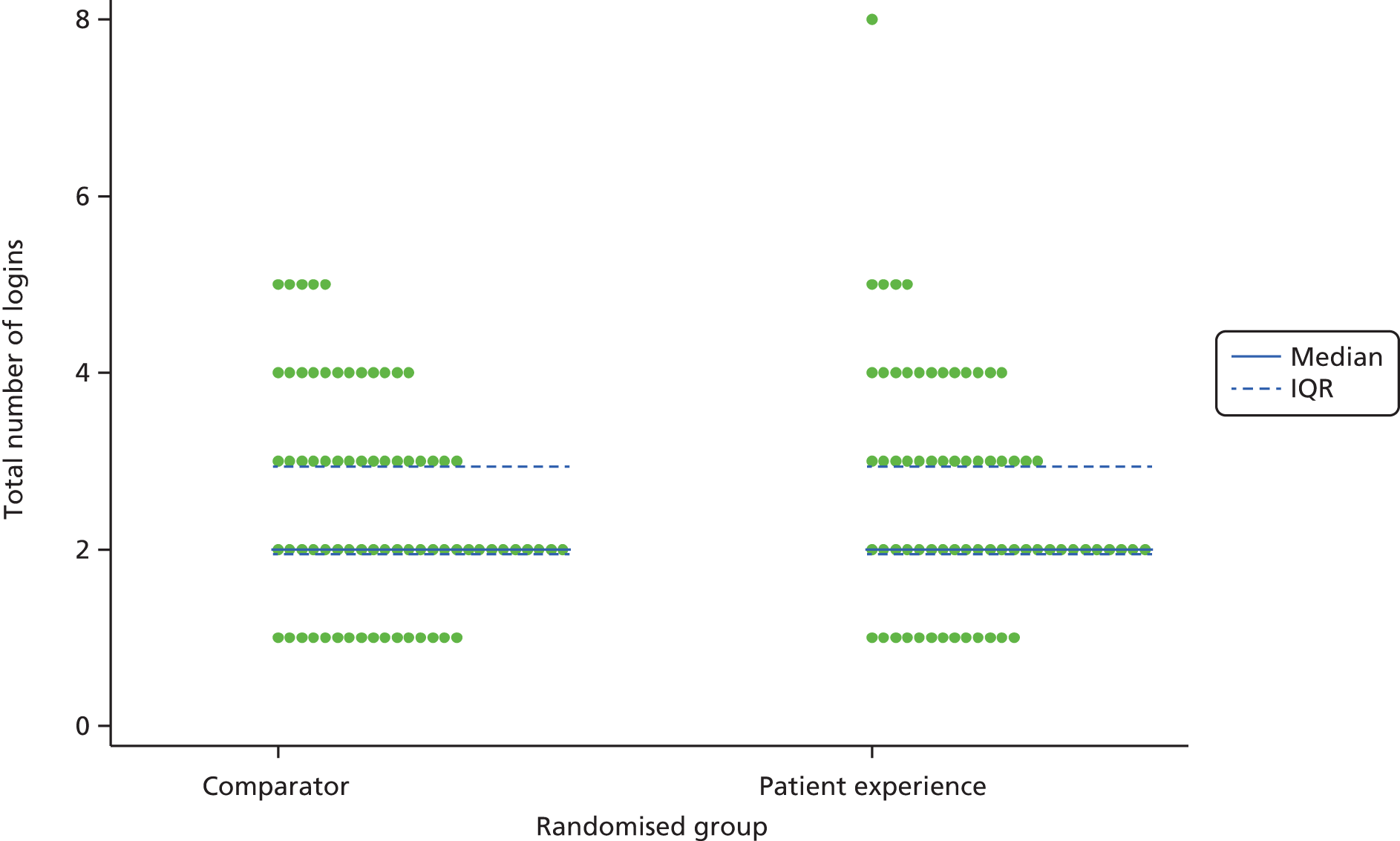

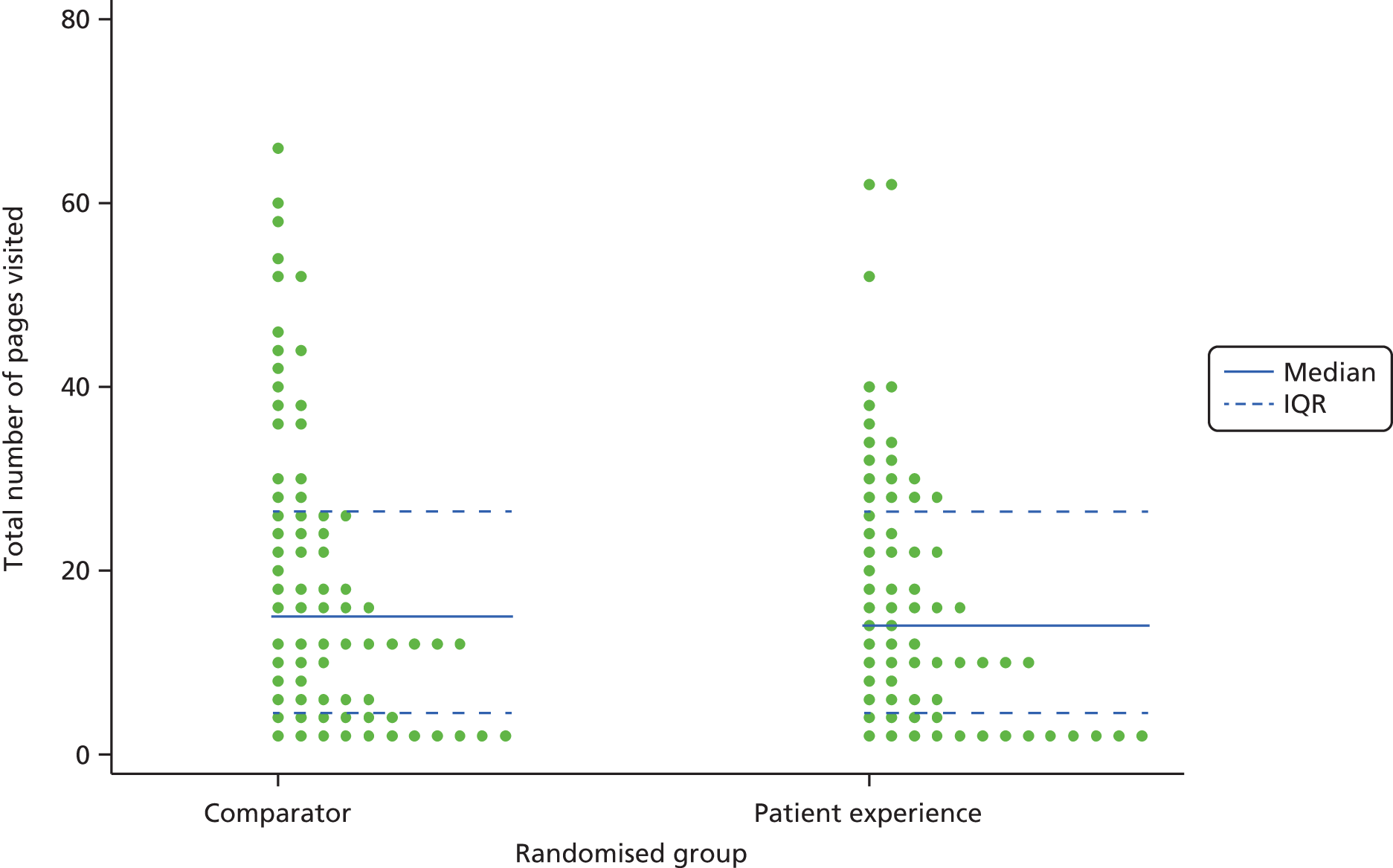

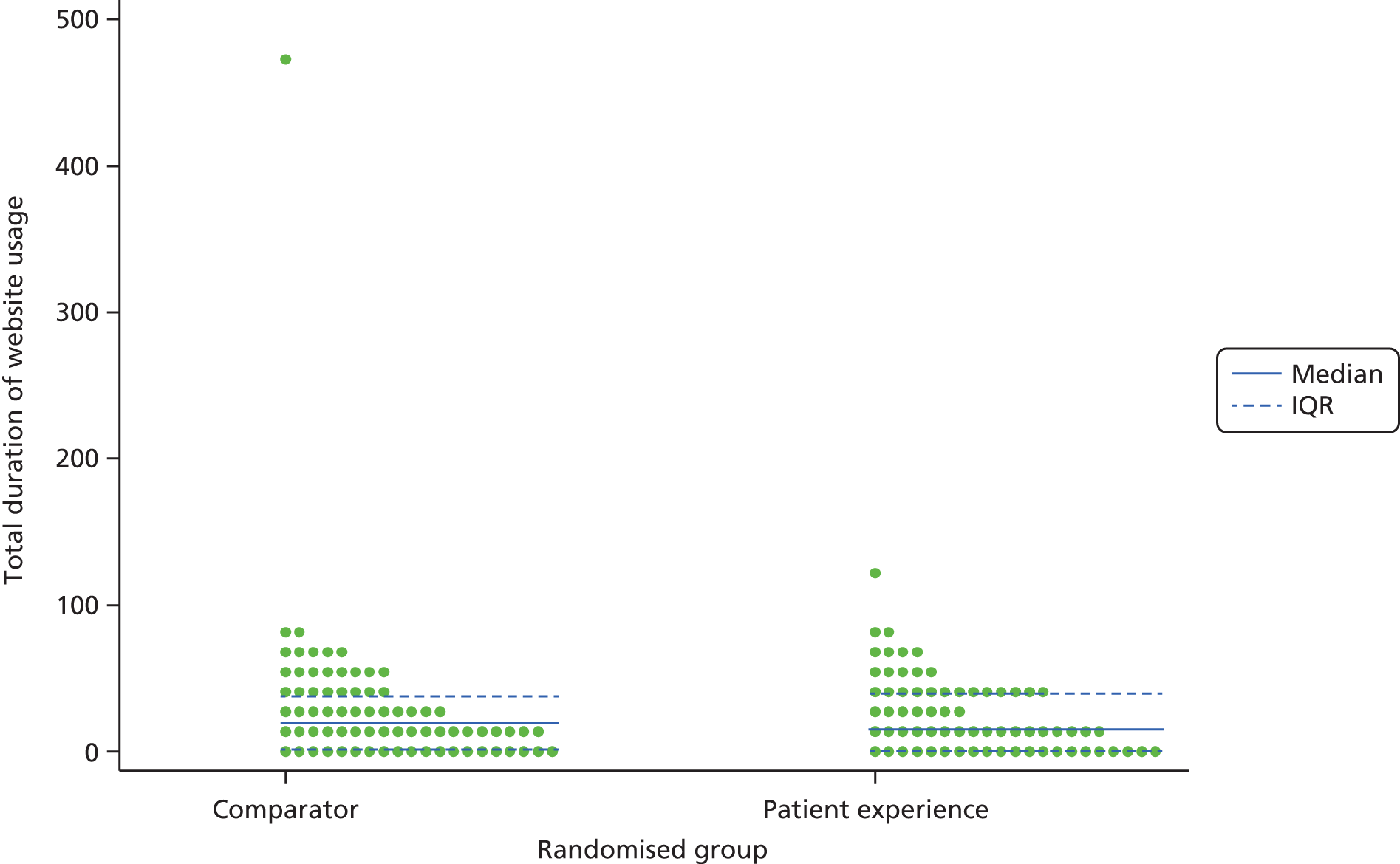

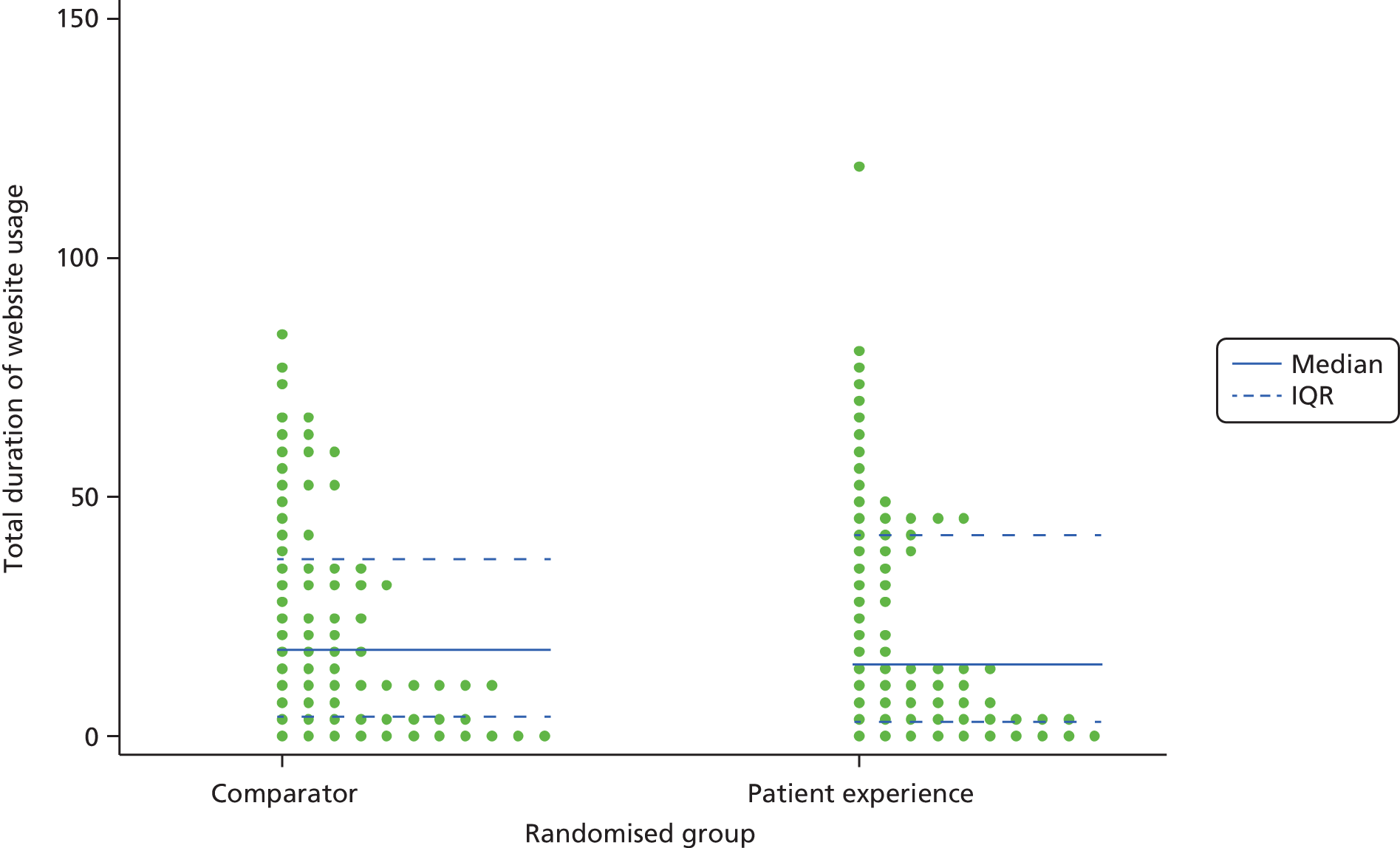

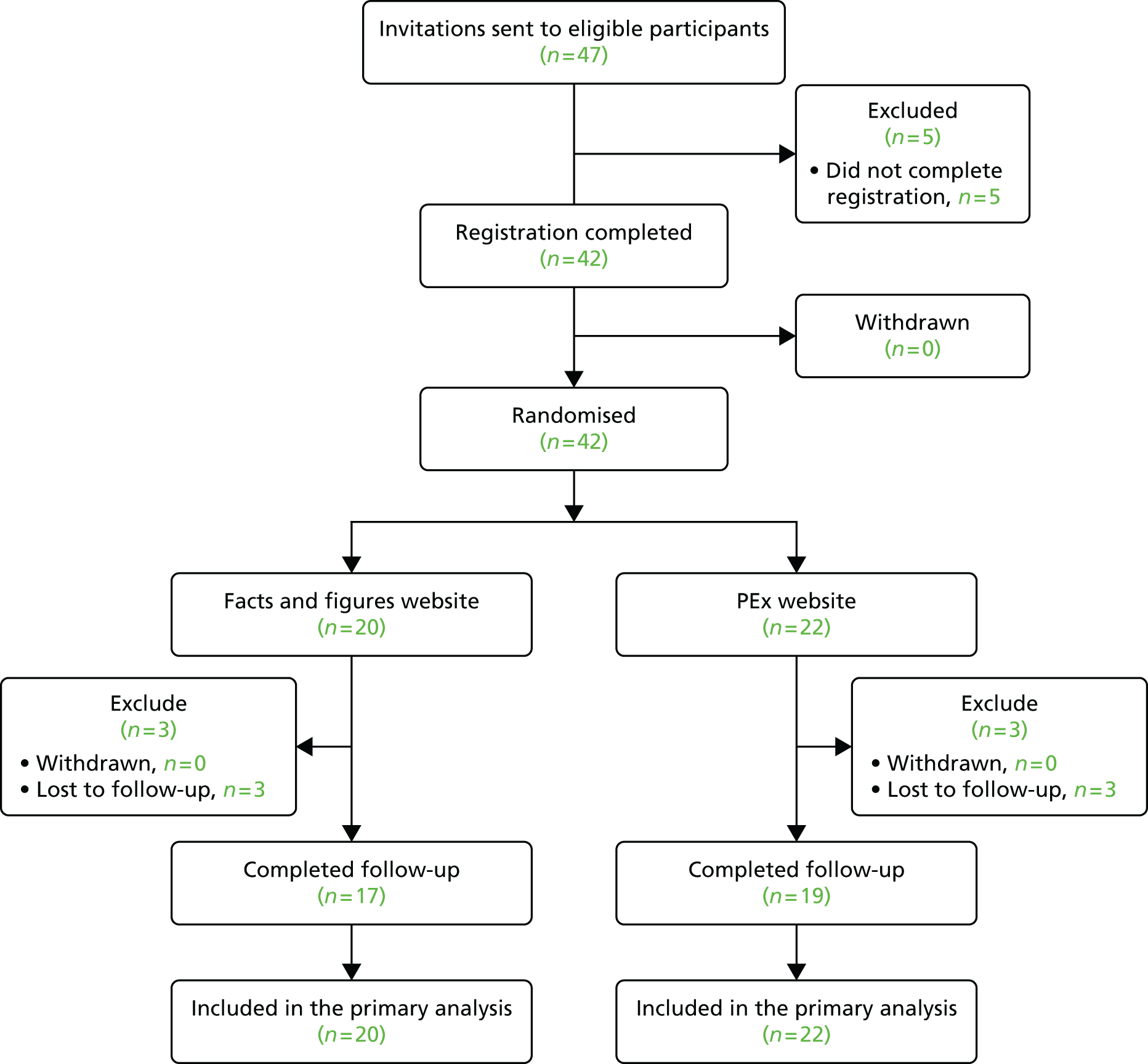

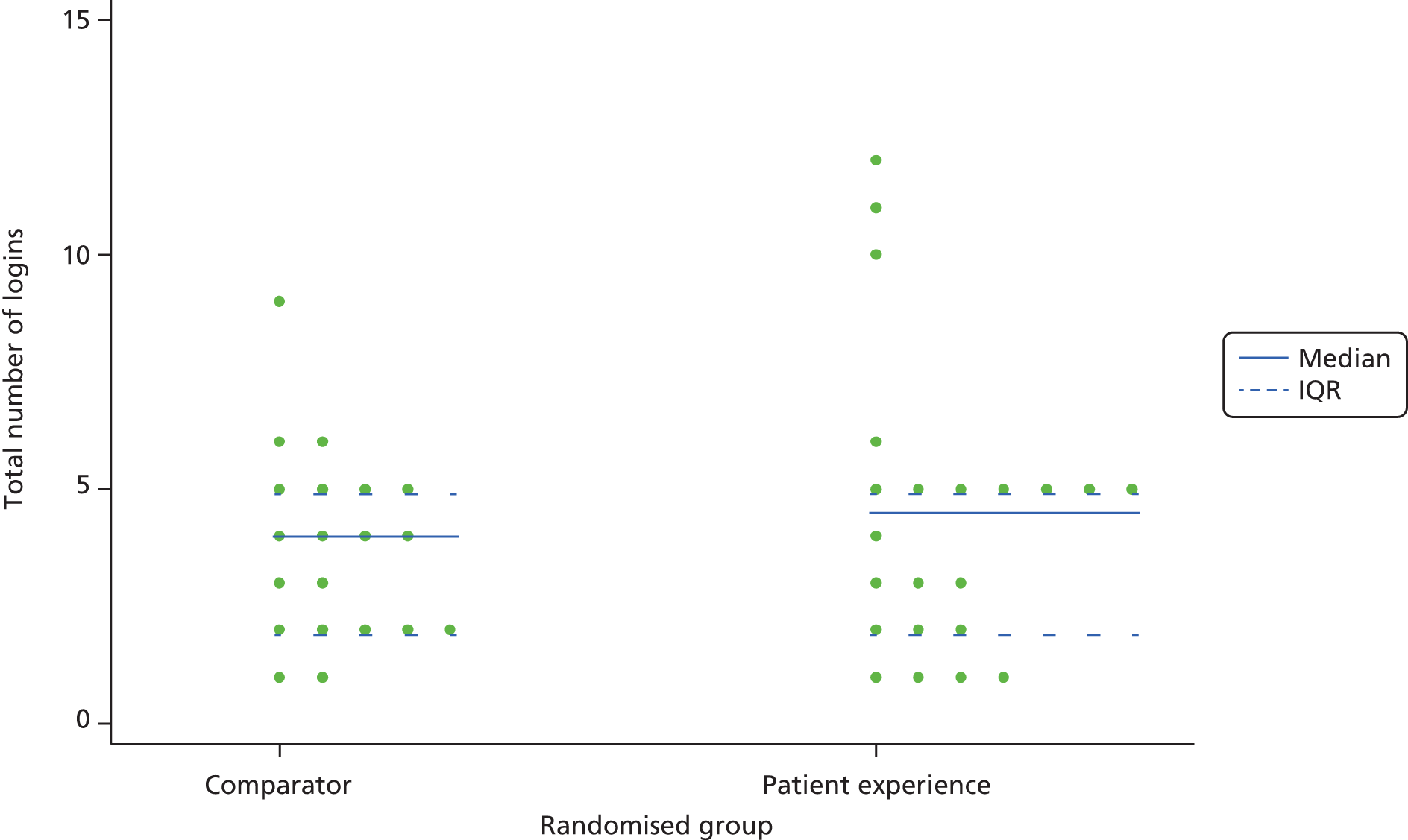

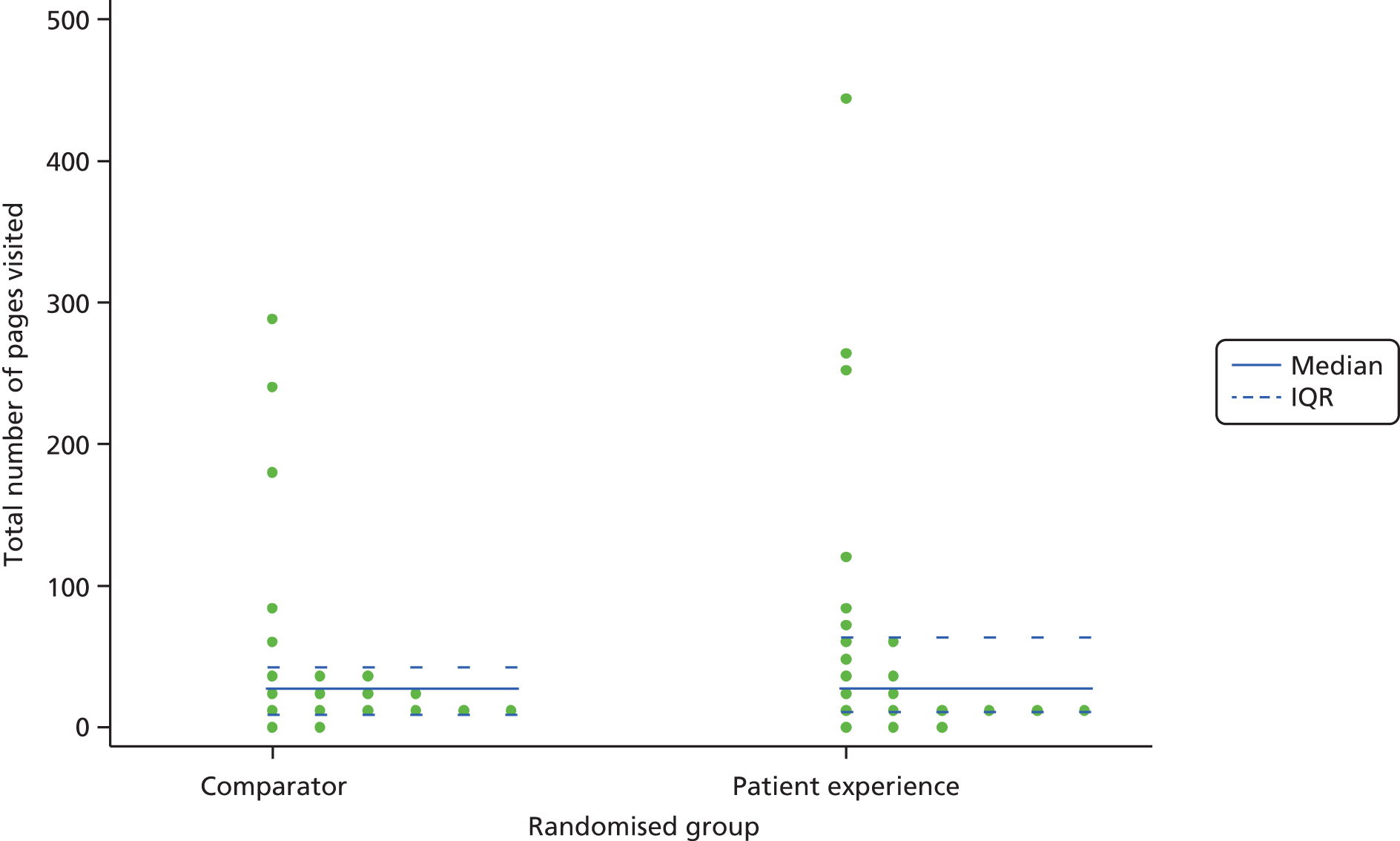

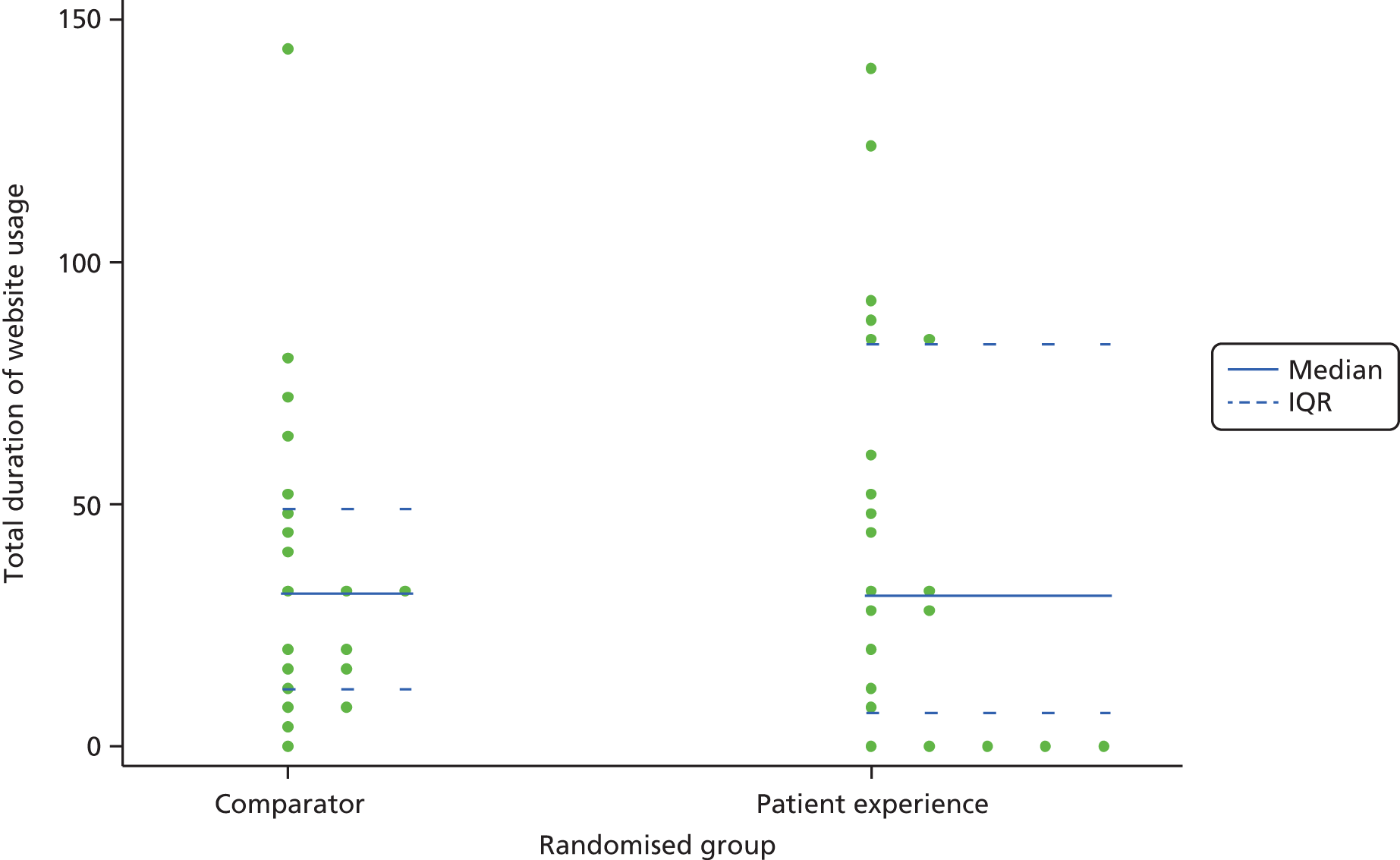

In summary, interviewees said that they shared their experiences because they believed that living with a condition on a daily basis meant that they had unique insights, which could be of value to others. They explicitly distinguished the type of knowledge and ways of knowing that came about as a result of embodied experiences of illness from both fictional accounts of illness and medical knowledge. This is illustrated in the quotation below taken from an interview with a man with colorectal cancer: