Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10177. The contractual start date was in September 2008. The final report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Hywel Williams reports membership of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board and NIHR Journals Library Board. Hywel Williams is Deputy Director of the NIHR programme and chairperson of the HTA Commissioning Board. On 1 January 2016 he became Programme Director for the HTA programme. Sandra Lawton reports personal fees from Genus Pharmaceuticals and Almirall Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Jo Leonardi-Bee reports grants from F. Hoffmann-La Roche outside the submitted work. Anthony D Ormerod reports personal fees from Amgen, grants from Abbvie, Jansen, Merck, Novartis and Pfizer and non-financial support from Jansen outside the submitted work. Jochen Schmitt reports personal fees from AbbVie and Novartis and grants from Novartis, Pfizer, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd and ALK-Abelló outside the submitted work. Eric Simpson reports grants from National Institutes of Health K23 (National Institutes of Health Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award) during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. James Mason has been involved as a university-employed health economist on several other funded dermatological studies, but none presents a conflict with the content or findings presented in this report. Lester Firkins reports membership of NIHR Journals Library Board, James Lind Alliance and patient and public involvement reference group. Sally Crowe reports personal fees from the University of Nottingham during the conduct of the study. Nicholas Evans reports being a trustee of the Psoriasis Association. John Norrie reports grants from University of Aberdeen and from University of Glasgow during the conduct of the study, and is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group.

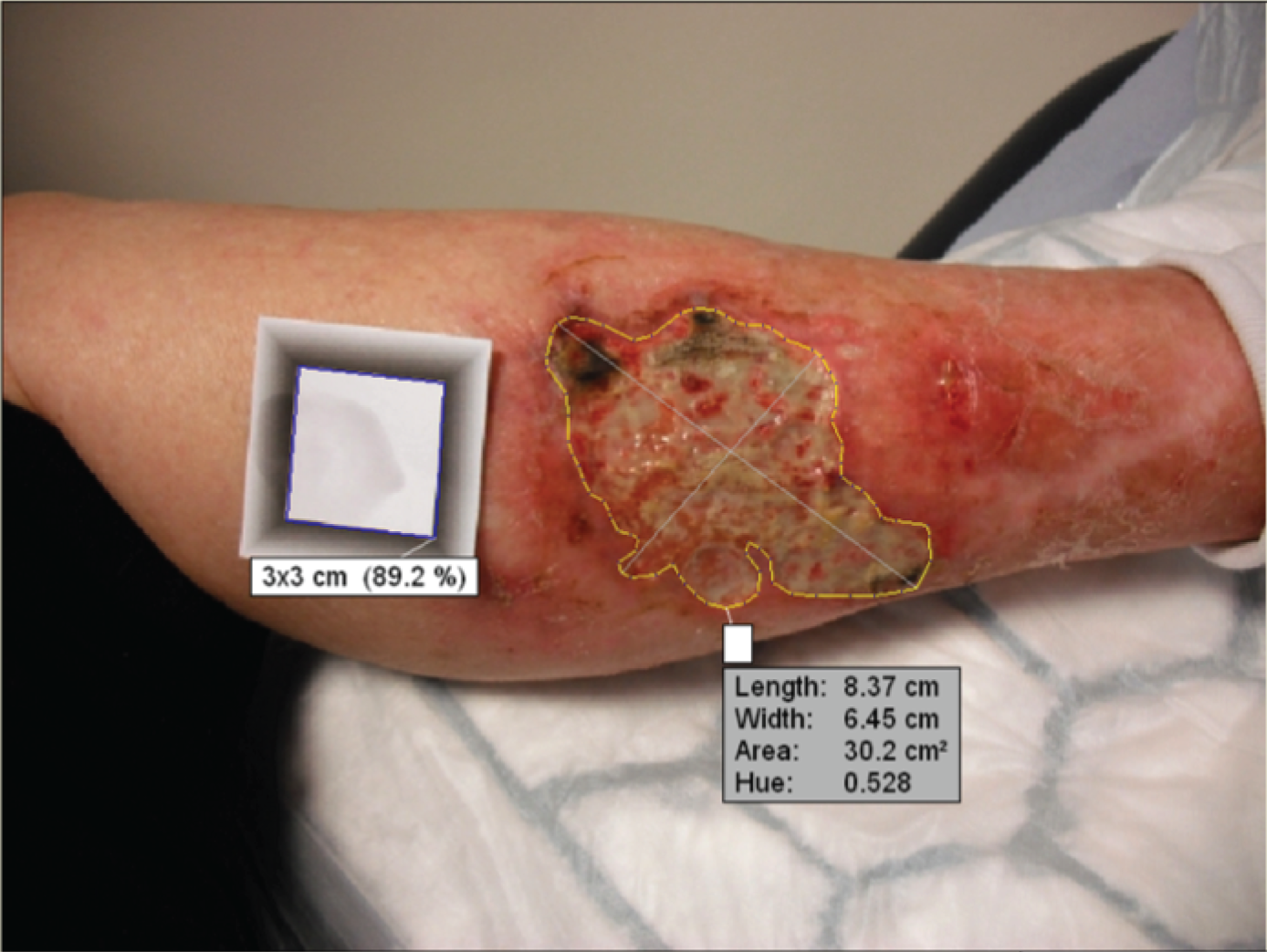

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Thomas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Navigating this report

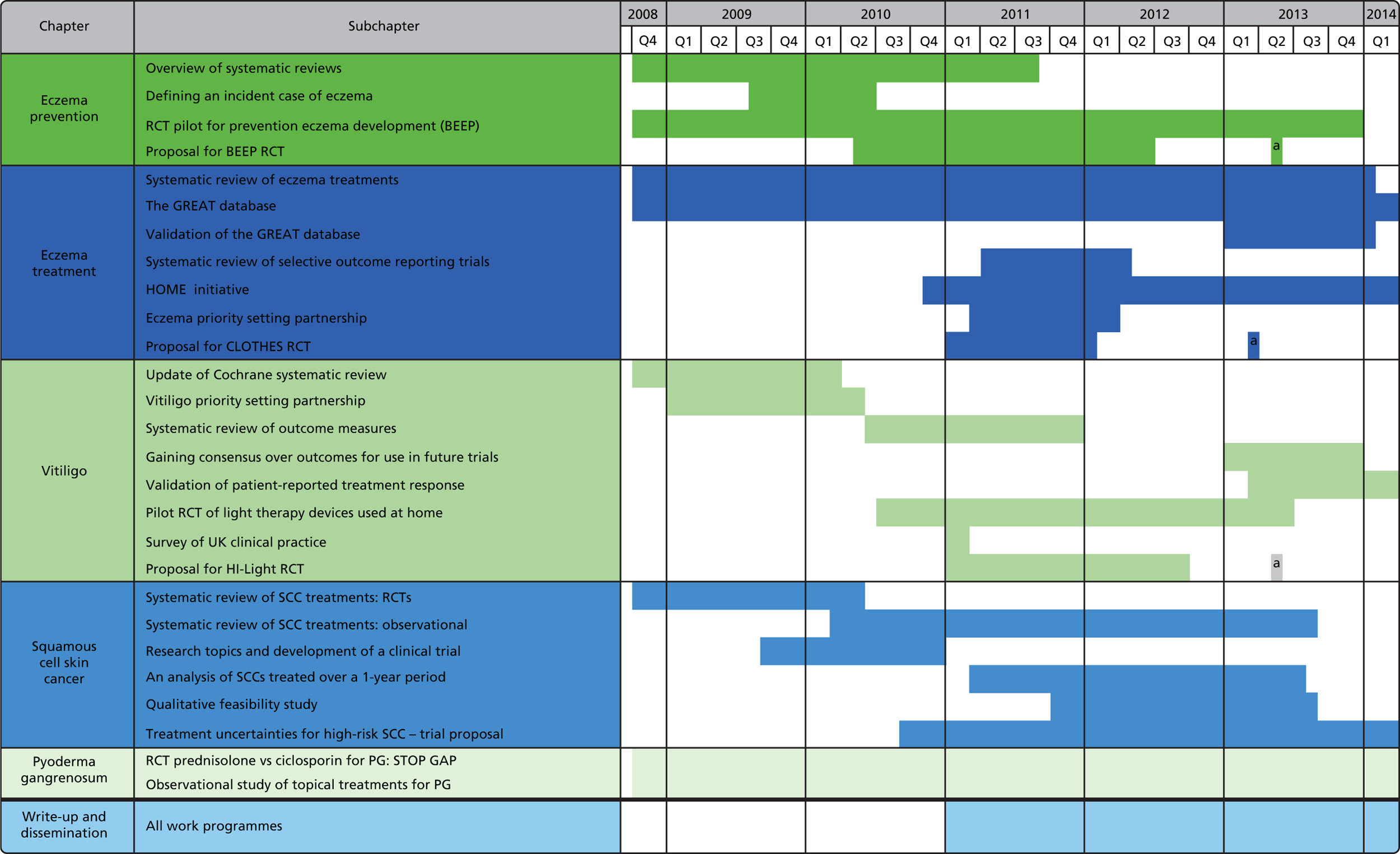

This report is a broad programme of related activities looking at the prevention and treatment of skin disease. It covers five distinct topic areas (Table a and Figure a).

Key milestones for each work programme are outlined, along with a summary of additional activities that were incorporated into the programme of activities during the funding period.

All amendments and additions to the programme award were approved by NIHR prior to implementation.

| Key outputs | Included in original plan | Amendments/additions to original plan |

|---|---|---|

| Eczema prevention work programme (see Chapter 1) | ||

| Overview of systematic reviews | ✓ | None |

| Defining a new case of eczema | Additional | Additional systematic review conducted to establish how to capture the primary outcome of eczema incidence in the BEEP trial |

| Pilot work | ✓ | Follow-up extended from 6 months to 2 years and additional mechanistic and patient preference work included |

| Proposal for a RCT to determine whether or not emollients can prevent eczema development | ✓ | The BEEP trial funded by NIHR HTA |

| Patient resources/guidelines updated | ✓ | Information used to inform existing guidelines and patient information resources rather than creating new ones |

| Eczema treatment work programme (see Chapter 2) | ||

| Scoping systematic review of eczema treatments | ✓ | Published as separate NIHR report |

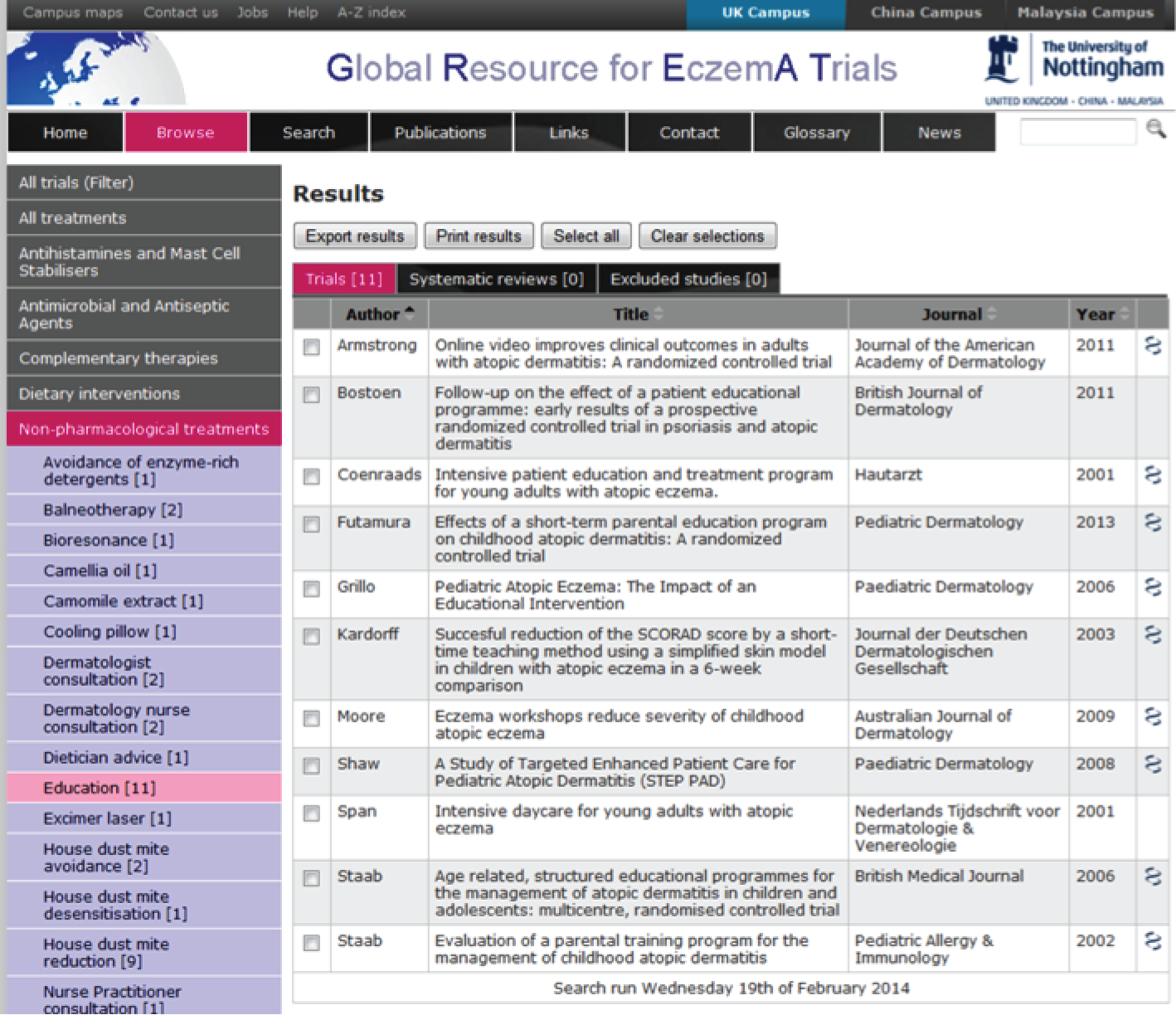

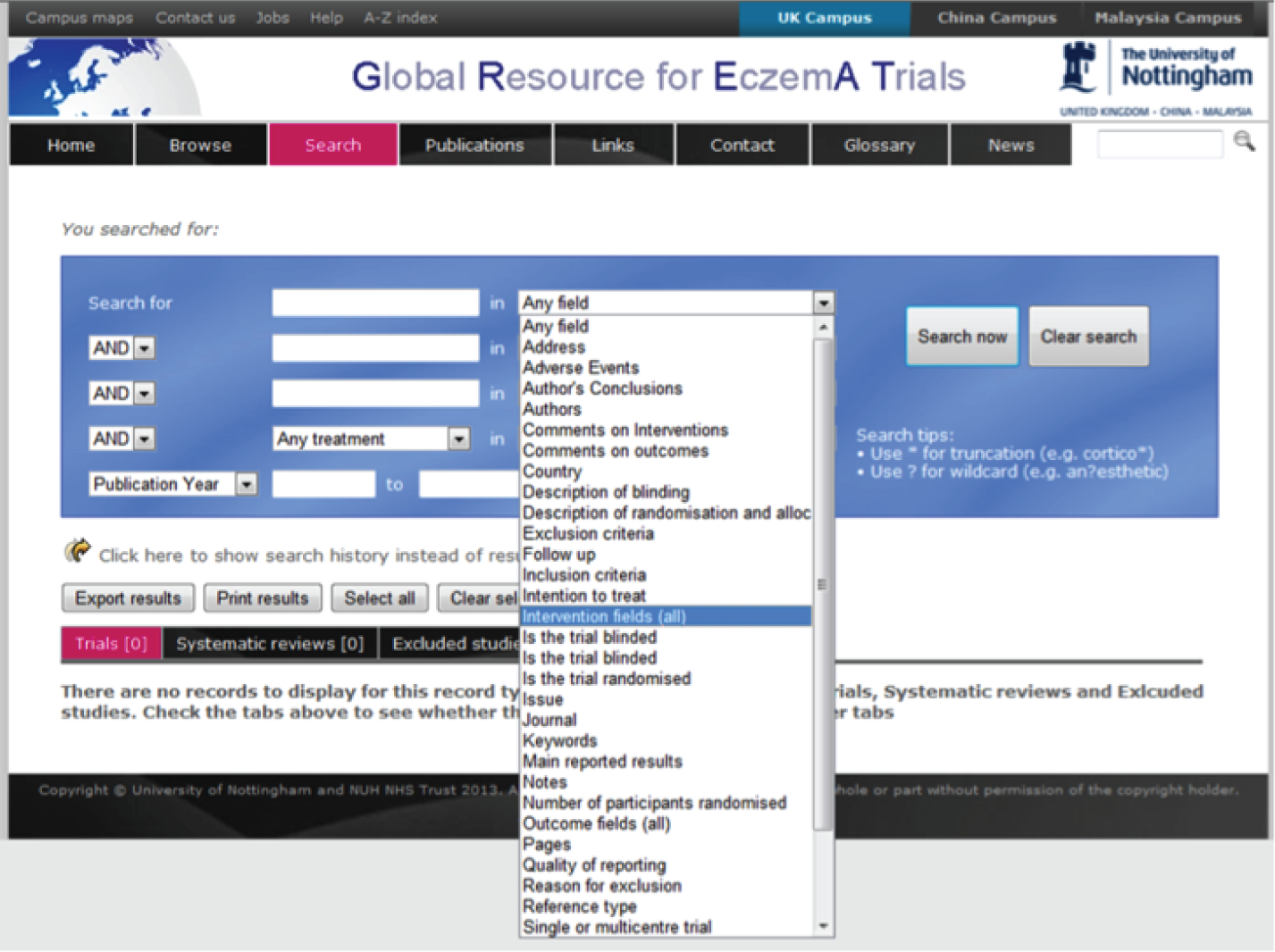

| The GREAT database | ✓ | Expanded to include RCTs published prior to 2000 and systematic reviews published since 2000 |

| Validation of the GREAT database | Additional | Validation study to establish the sensitivity and specificity of the GREAT database in identifying all published RCT evidence |

| Systematic review of selective outcome reporting in eczema trials | Additional | Spin-off methodological paper demonstrating the utility of the GREAT database for informing methodological projects |

| HOME initiative | Additional | International consensus initiative to establish a core outcome set for future eczema trials |

| Eczema PSP | ✓ | None |

| CLOTHing for the relief of Eczema Symptoms – a study proposal | ✓ | CLOTHES trial funded by NIHR HTA |

| Scoping systematic review of eczema treatments | ✓ | Information used to inform existing guidelines and patient information resources rather than creating new ones |

| Vitiligo work programme (see Chapter 3) | ||

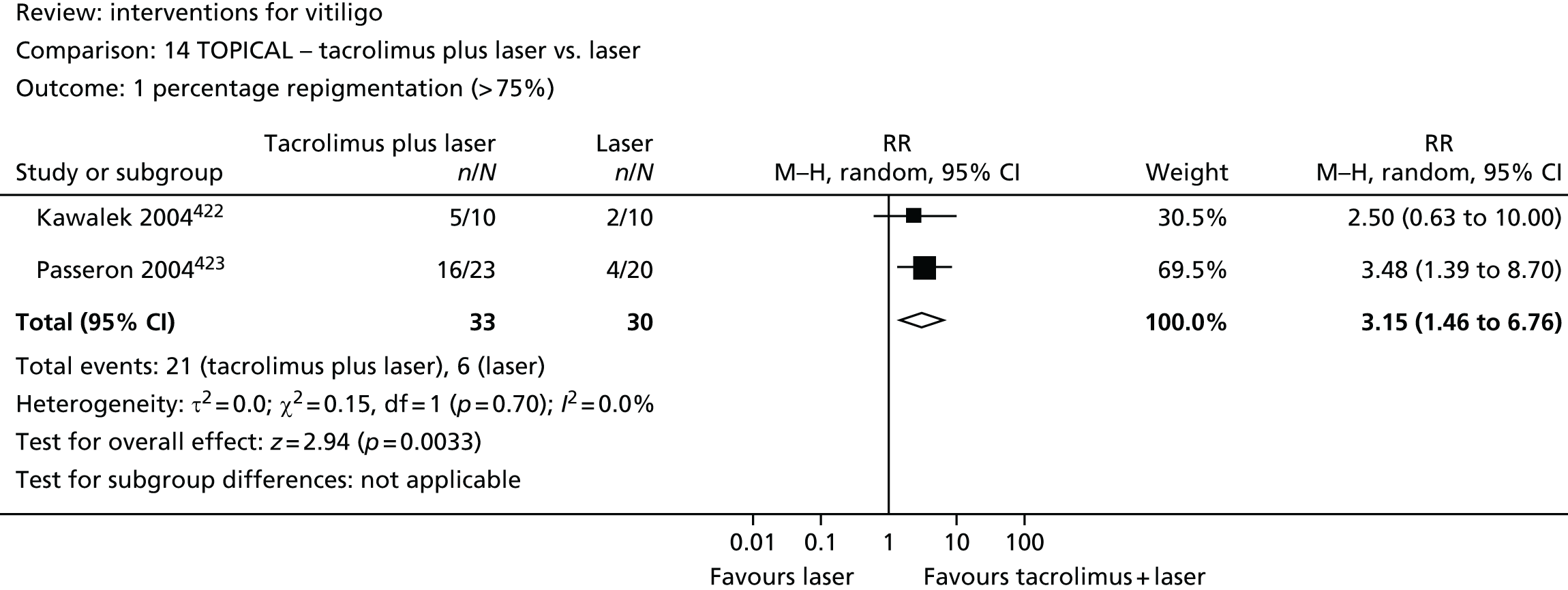

| Update of Cochrane systematic review | ✓ | Updated in 2010 and 2014 |

| Vitiligo PSP | ✓ | None |

| Systematic review of outcome measures | Additional | Systematic review of outcome measures used in published vitiligo RCTs and online survey to establish what is important for patients and clinicians |

| Gaining consensus over outcomes for use in future vitiligo trials | Additional | An international activity designed to established core outcome domains to be included in future vitiligo trials |

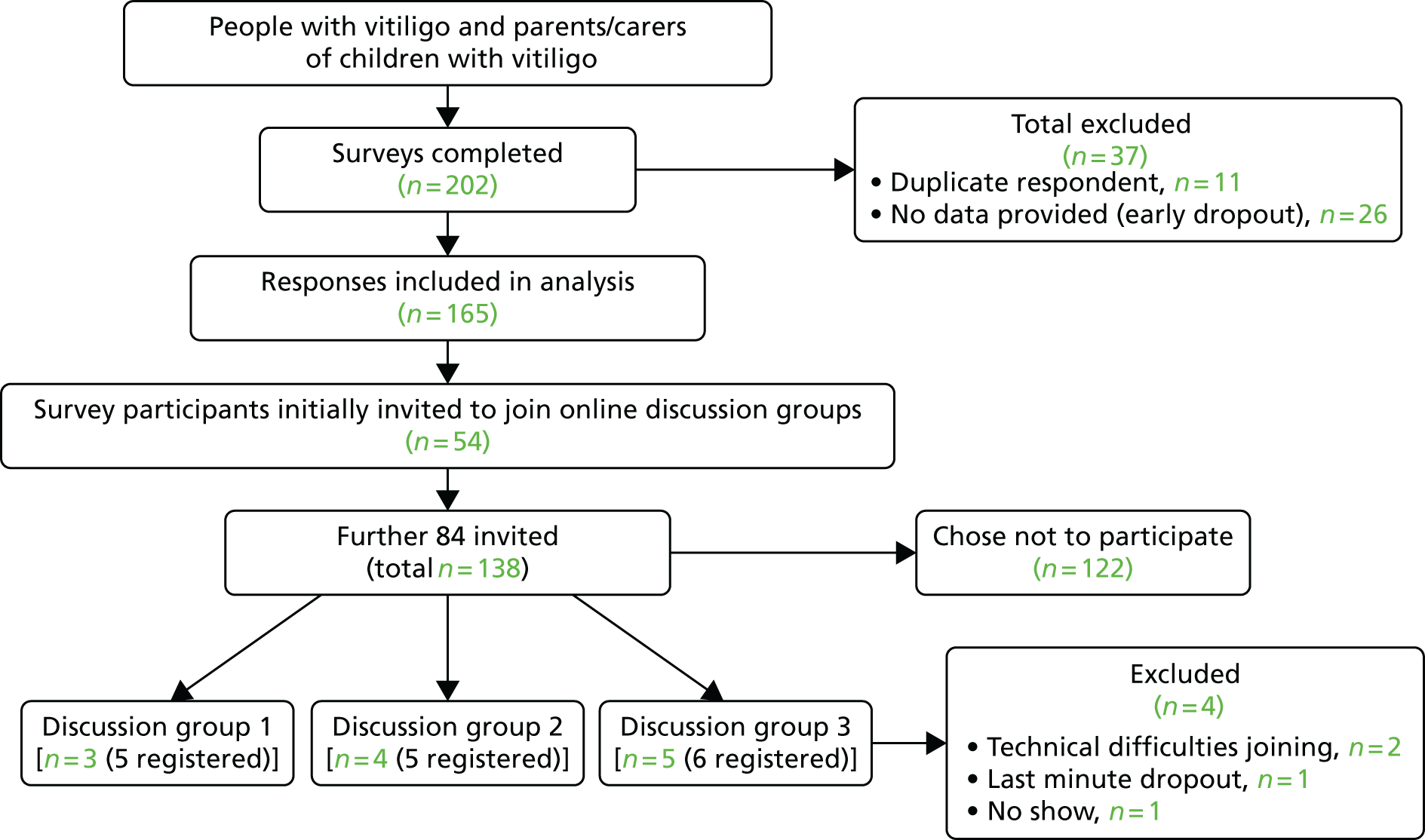

| Validation of patient-reported treatment response | Additional | Patient survey and online discussion groups to establish face validity of patient-report definition of treatment success |

| Pilot RCT of light-therapy devices used at home | ✓ | None |

| Survey of UK clinical practice | ✓ | None |

| Proposal for a trial light therapy and topical corticosteroids for the treatment of vitiligo (HI-Light) | ✓ | HI-Light trial funded by NIHR HTA as a result of prioritisation setting partnership |

| Patient resources/guidelines updated | ✓ | Information used to inform existing guidelines and patient information resources rather than creating new ones |

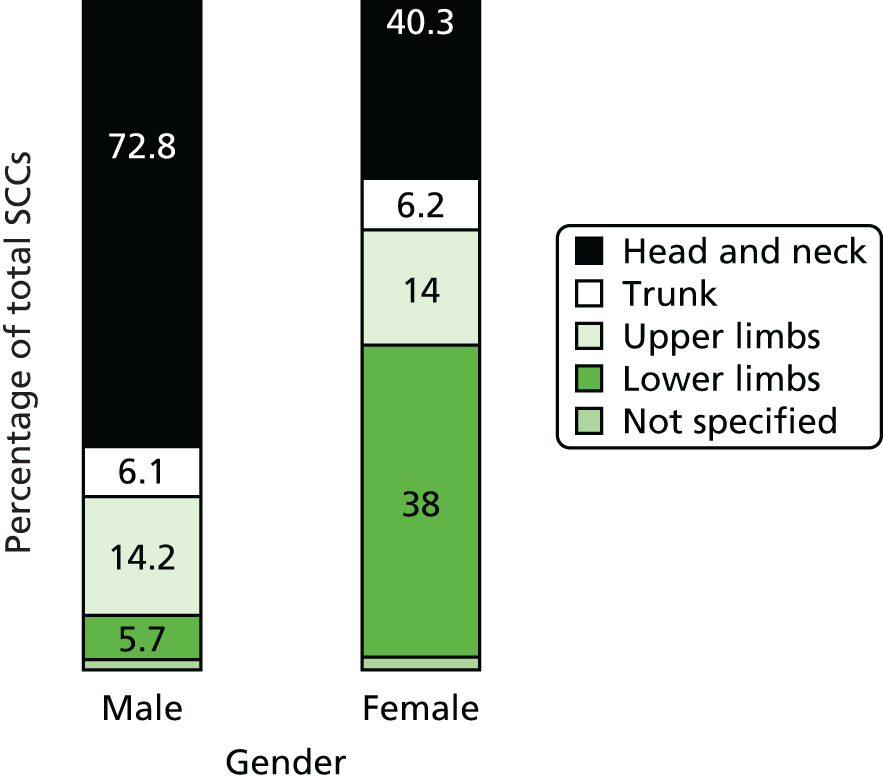

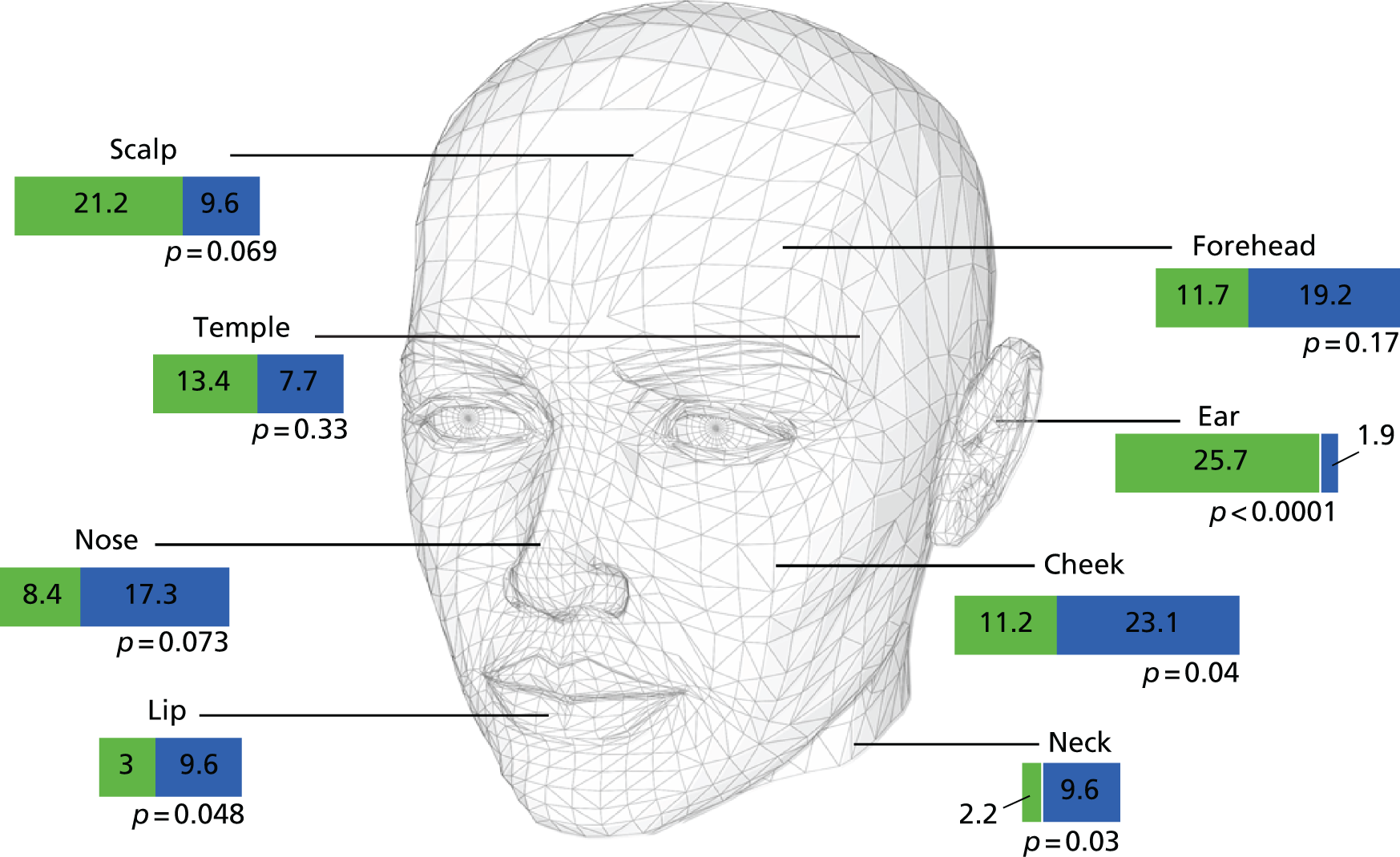

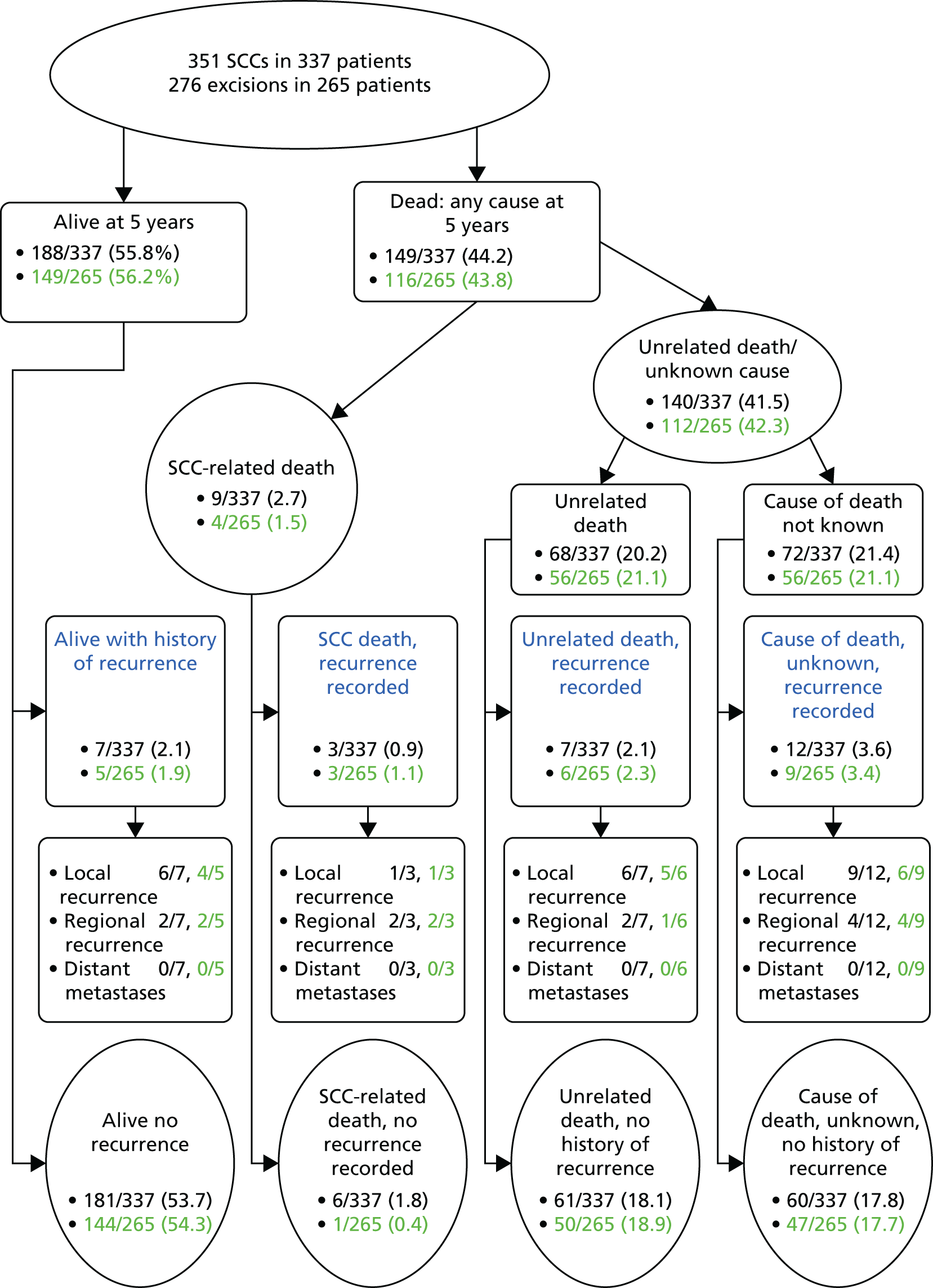

| Squamous cell skin cancer work programme (see Chapter 4) | ||

| Systematic review of SCC treatments: RCTs | ✓ | None |

| Systematic review of SCC treatments: observational studies | Additional | Additional review of observational studies added to the programme since the Cochrane review of RCTs found just one RCT on the topic |

| Identification of potential research topics and development of a clinical trial scenario | Additional | Survey of dermatologists, plastic surgeons, radiologists and other clinicians involved in SCC management to establish the most important treatment uncertainties to be addressed by research |

| An analysis of SCC treated over a 1-year period | ✓ | None |

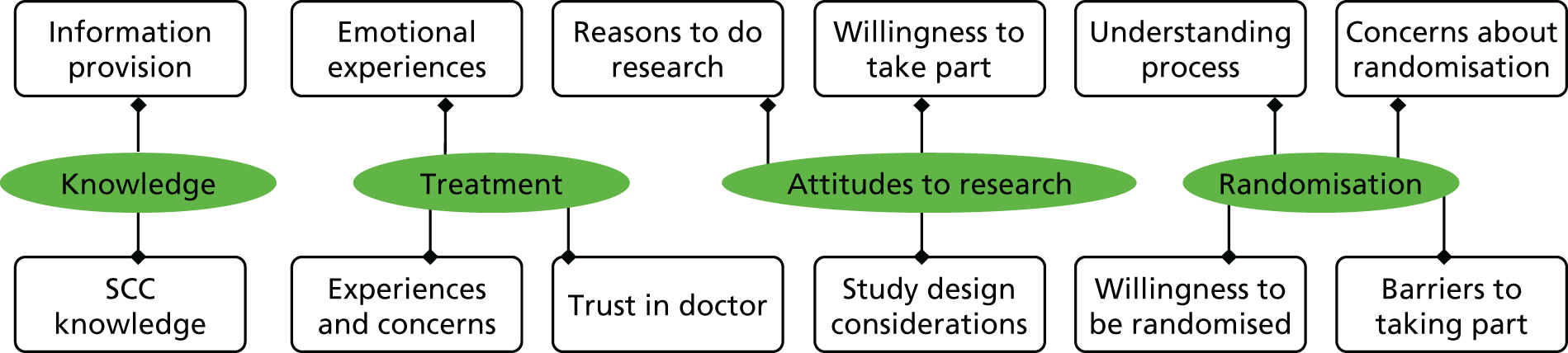

| Qualitative feasibility study | ✓ | None |

| Treatment uncertainties for high risk SCC – a trial proposal | ✓ | None |

| Patient resources/guidelines updated (decision aids removed from planned activities) | ✓ | Information used to inform existing guidelines and patient information resources rather than creating new ones |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum work programme (see Chapter 5) | ||

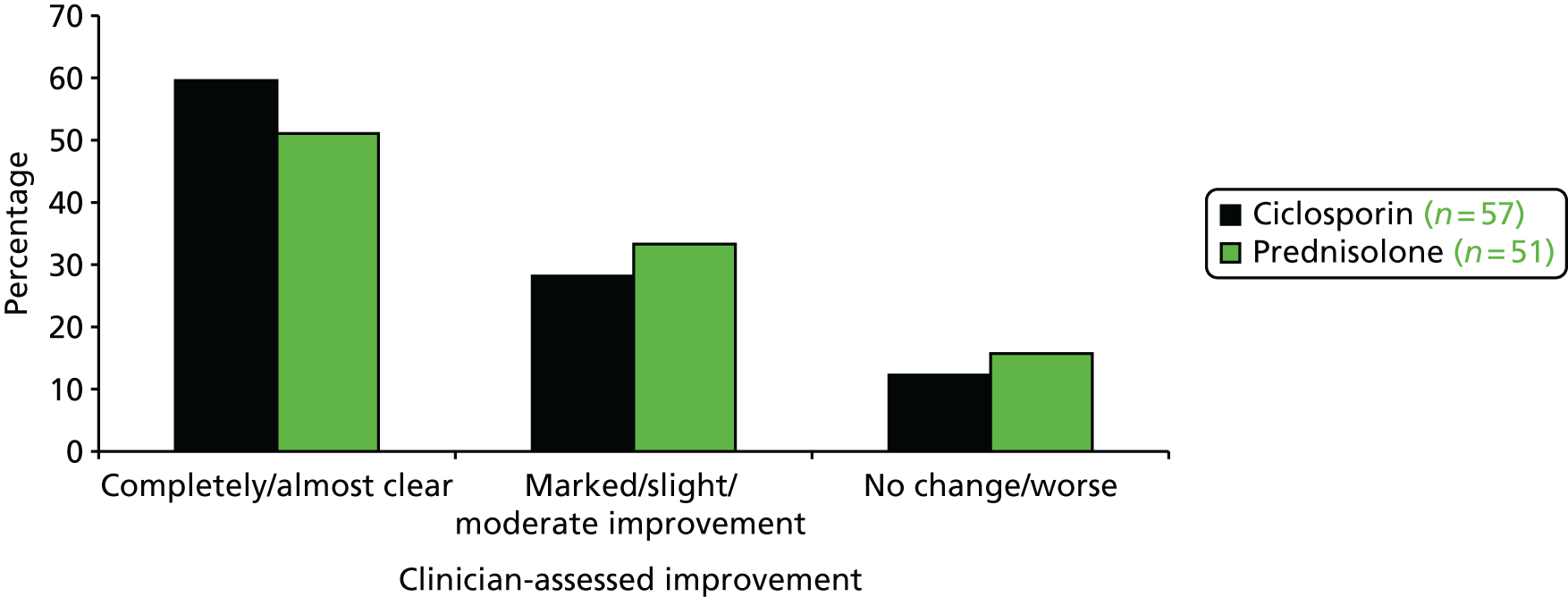

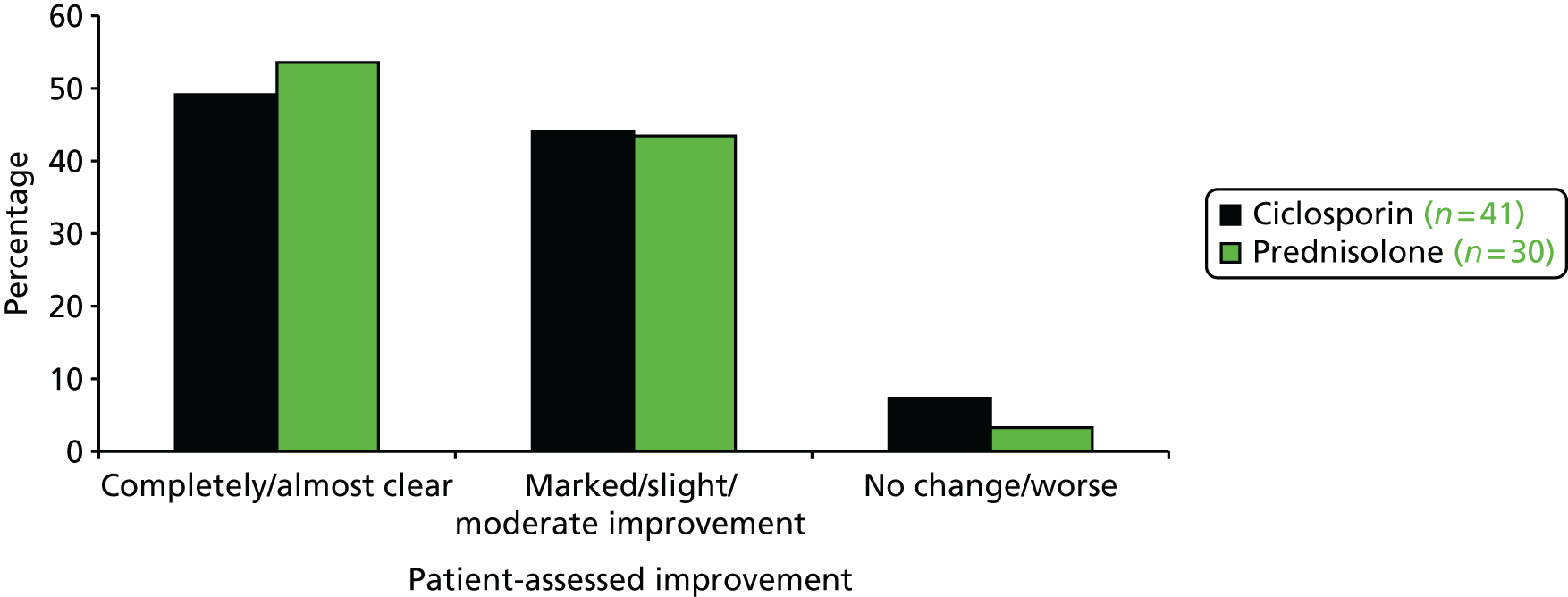

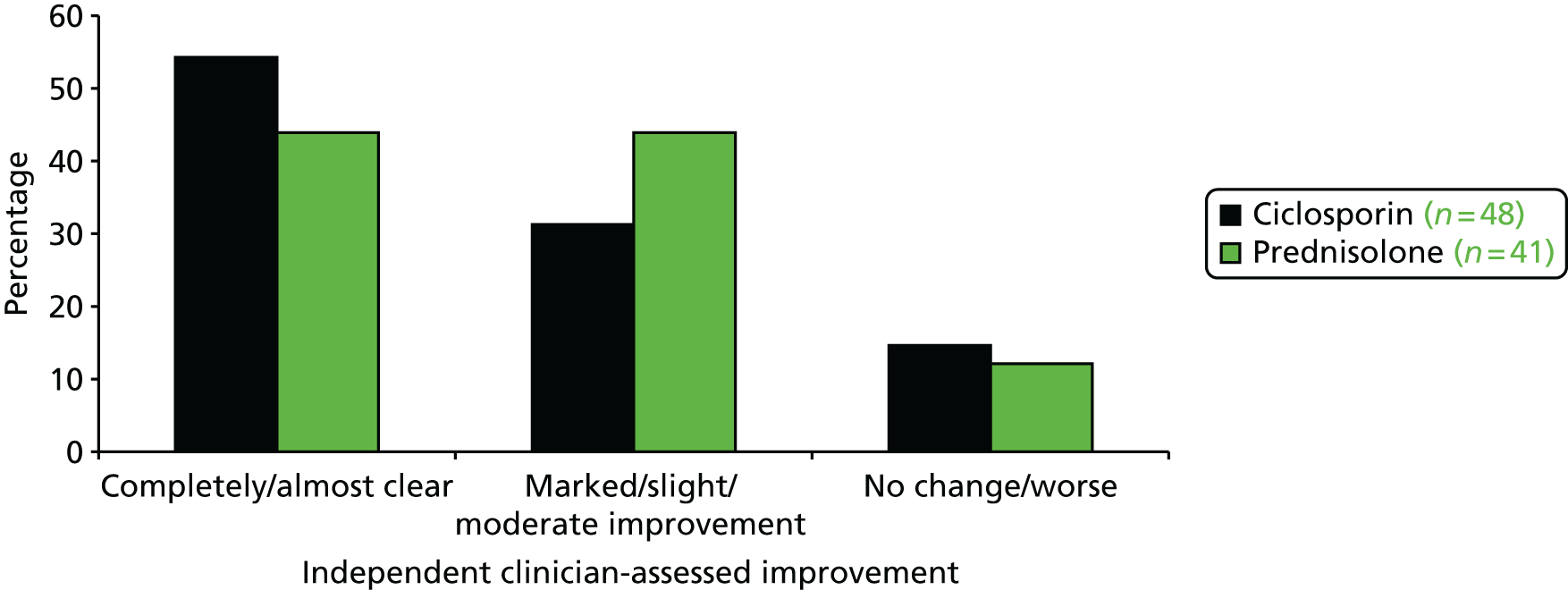

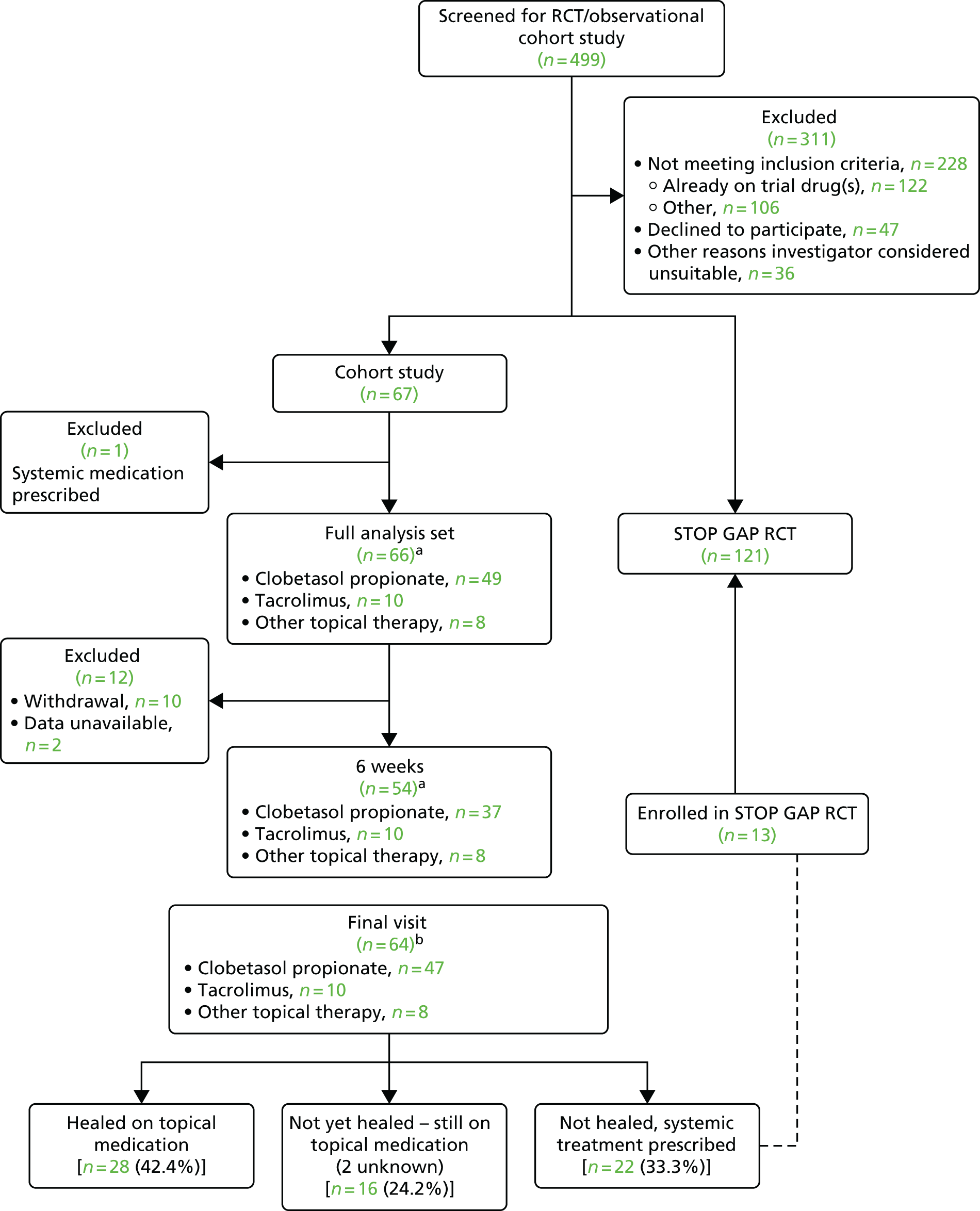

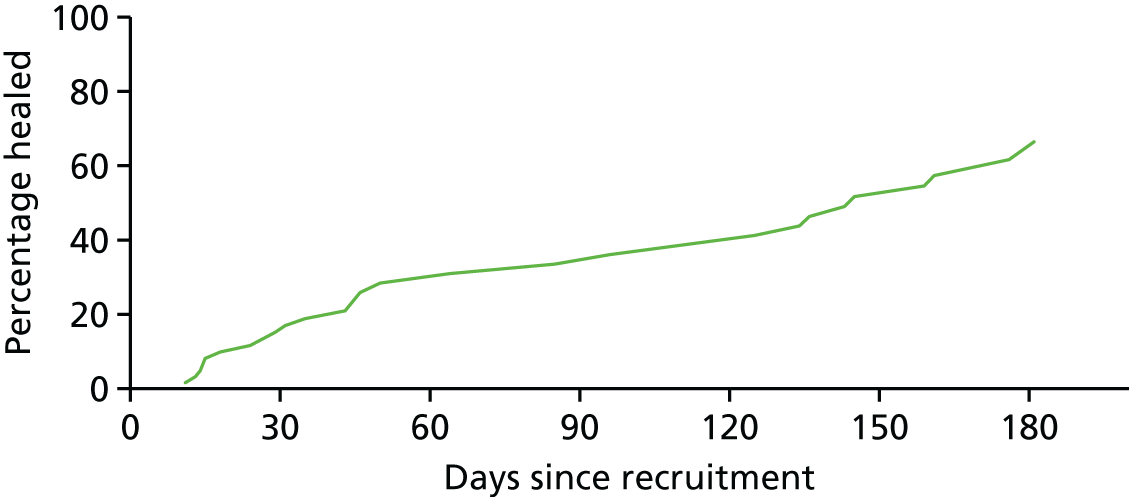

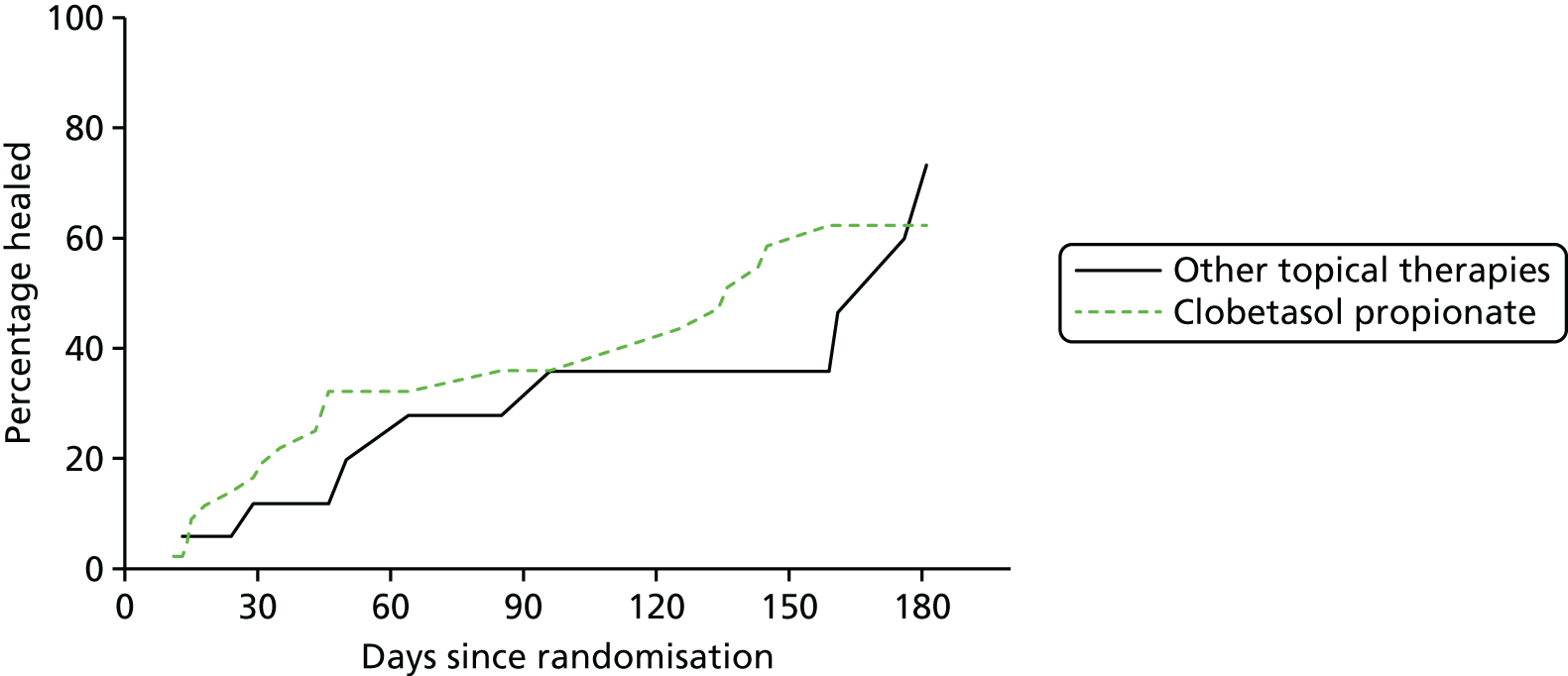

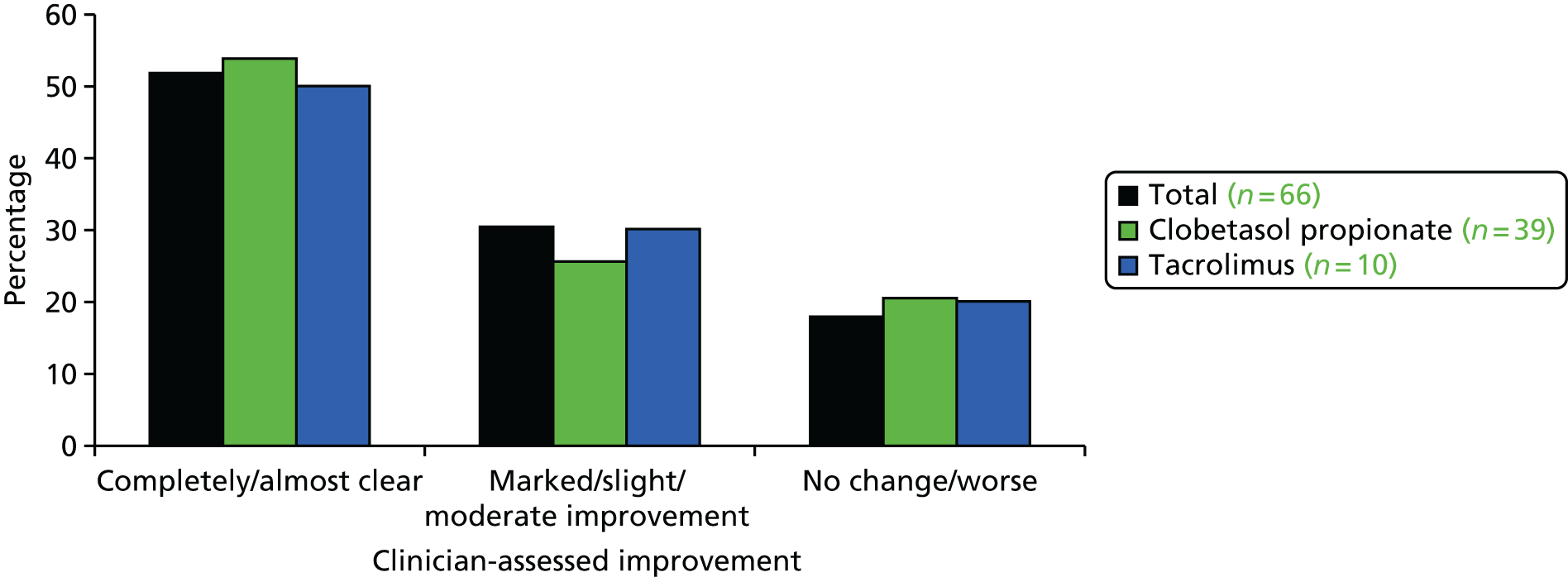

| A RCT of prednisolone vs. ciclosporin in the treatment of PG: STOP GAP trial | ✓ | None |

| Treatment response of patients receiving topical treatments for PG: a prospective cohort observational study | ✓ | None |

| Capacity development | ||

| Dermatology patient panel established and trained | ✓ | None |

| Industry liaison project | ✓ | Removed from programme as this aspect is now provided by NIHR Clinical Research Networks |

| Three researchers trained to PhD level | ✓ | |

| Training fellowships for Specialist Registrars and Dermatology nurses supported by UKDCTN | ✓ | Additional fellowships developed for staff and associate specialist and GPs |

FIGURE a.

Gantt chart showing delivery of the work packages. Time range: September 2008 to March 2014. a, Awarded funding for proposed RCT. CLOTHES, CLOTHing for the relief of Eczema Symptoms.

Chapter 1 Eczema prevention work programme

Abstract

Introduction

Although eczema is a very common condition and its prevalence is on the increase, its prevention has received little attention. We sought to pull together various strands of best evidence to provide the building blocks to inform the design of primary research in this area.

Methods

The approaches used were as follows.

-

An overview of systematic reviews of interventions for primary prevention of eczema.

-

A systematic review of how new cases of eczema have been defined in previous primary prevention studies.

-

A pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test the feasibility of conducting a trial of emollients to prevent eczema.

-

A parent survey to determine emollient preferences, together with biophysical studies, to make sure that the chosen emollients improve barrier function.

-

An application for a full-scale RCT of emollients for eczema prevention.

Results

-

Our overview of seven systematic reviews (comprising 39 RCTs and 11,897 participants) failed to find clear evidence that any of the commonly perceived strategies for eczema prevention work.

-

The review of how new cases of eczema are defined in trials found that many definitions rely on the presence of signs or symptoms over a long period of time (up to 1 year), which is not appropriate for defining new cases of eczema.

-

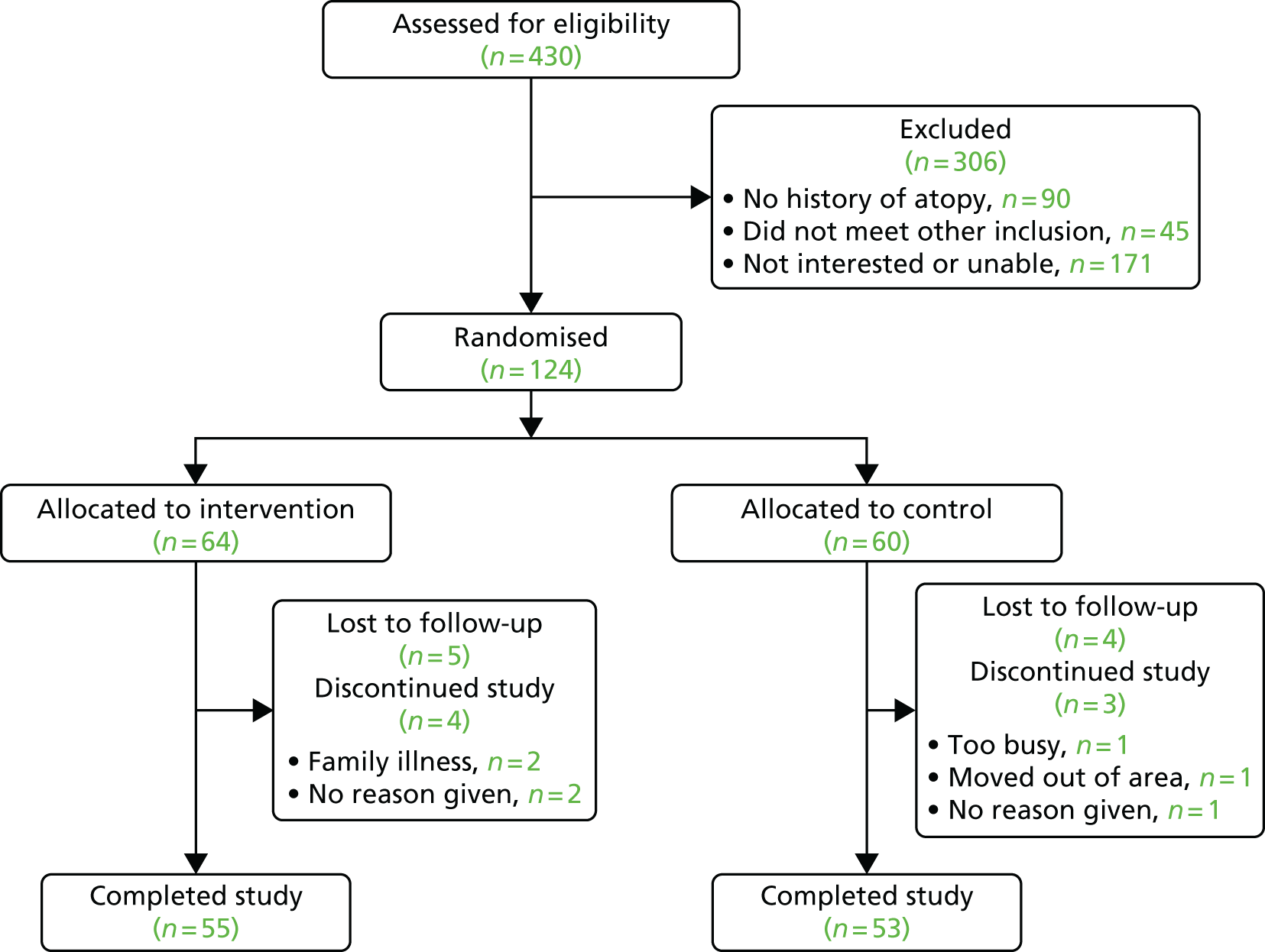

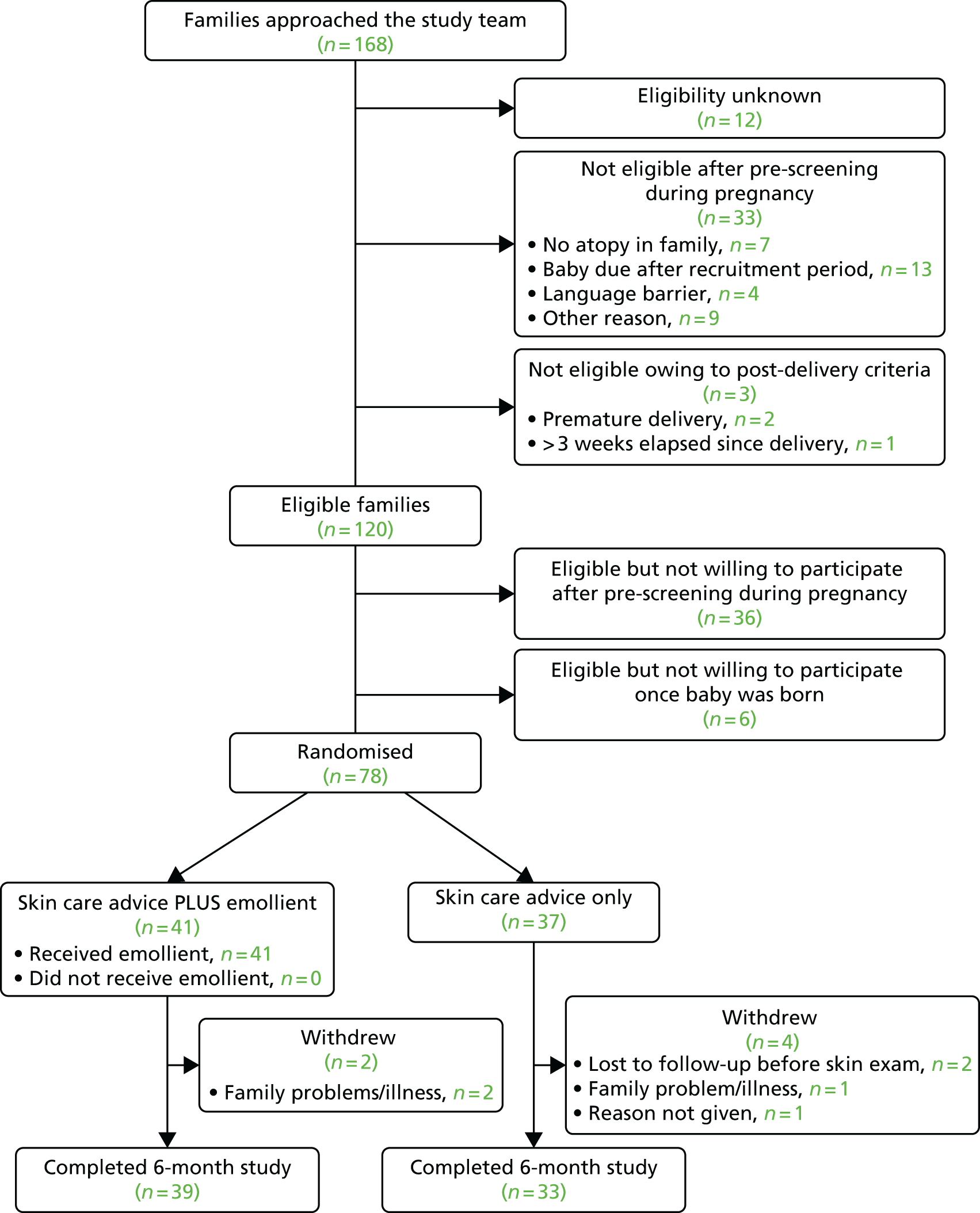

Our pilot RCT included 124 families and confirmed that recruitment and retention was feasible and that contamination was minimal.

-

Our surveys and biophysical studies identified two emollients as being acceptable to parents and effective in skin barrier protection.

Conclusion

This work has provided the key building blocks for justifying and refining the design of a new approach to eczema prevention by enhancing the skin barrier from birth. Our application to the National Institute Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme for a full-scale trial has been successful. 1

Content

| Details | Comment |

|---|---|

| Introduction | Briefly summarises eczema epidemiology and pathology |

| Overview of systematic reviews | An analysis of all the studies which have tried different methods to prevent eczema developing |

| Defining a new case of eczema: a systematic review | A review of how previous studies have diagnosed new cases of eczema in infants given that guidelines usually require signs or symptoms to be present for long time periods |

| Pilot work for a randomised controlled trial to determine whether or not emollients can prevent eczema development (BEEP) | A trial to assess how feasible a study examining skin barrier enhancement (using an emollient) would be to perform and how best to perform it |

| Proposal for a randomised controlled trial to determine whether emollients can prevent eczema development | A proposal for a large scale trial assessing whether emollients can prevent eczema development. A funding application to the NIHR HTA funding stream |

| Patient and public involvement | A summary of the contributions made by patients and how this influenced the work |

| Summary and conclusions |

Introduction

Terminology

The World Allergy Organization (WAO) suggests that the phenotype of atopic eczema (AE) should be referred to as ‘eczema’ unless specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies are demonstrated. Furthermore, the terms ‘eczema’ and ‘dermatitis’ are synonymous, thus ‘eczema’ is typically used in this report.

Characteristics and burden of eczema

Eczema2 is a very common skin problem affecting 16–30% of children in the UK and around 20% of children worldwide. 3,4 Global surveys have shown that eczema is on the increase but it is not clear why. 5 Eczema usually starts in infancy and around 40% of cases persist into adulthood, especially those with early and widespread disease. 6 Although all skin areas can be affected, eczema often starts on the cheeks and limbs and then settles in the skin creases. Reliable diagnostic criteria have been developed that emphasise flexural involvement, early onset and dry skin. 7 Constant scratching results in skin damage and causes a vicious itch–scratch cycle. Scratching can result in bleeding, secondary bacterial infection and sleep loss to the child and family. Damage from scratching may lead to autoreactivity developing against skin components, which can lead to disease chronicity. 8 Eczema is also associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, perhaps as a consequence of severe disease in early life. 9 The stigma associated with a visible skin disease adversely affects the quality of life (QoL) of the child and family, yet it is often trivialised as ‘only a skin disease’. The family impact of caring for a child with moderate or severe eczema is greater than that caring for children with type 1 diabetes mellitus, mainly owing to sleep deprivation, employment loss, time to care for eczema and financial costs. 10 In the World Health Organization 2010 Global Burden of Disease survey,11 eczema was the most common reason for disability-adjusted life-years. 11 Eczema results in a high economic burden,12 with overall costs comparable to asthma. 13 Families often incur additional costs for special clothing and creams. 10,14 A systematic review of 59 studies estimated that direct costs of eczema treatment in the USA could be as high as $3.8B per year. 14 Eczema is a chronic condition accounting for the highest number of new general practitioner (GP) consultations in England for a skin complaint. 15 Moderate to severe eczema often requires referral to secondary care. Guidelines for children with eczema were produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2007. 16

Relationship of eczema to other allergic diseases

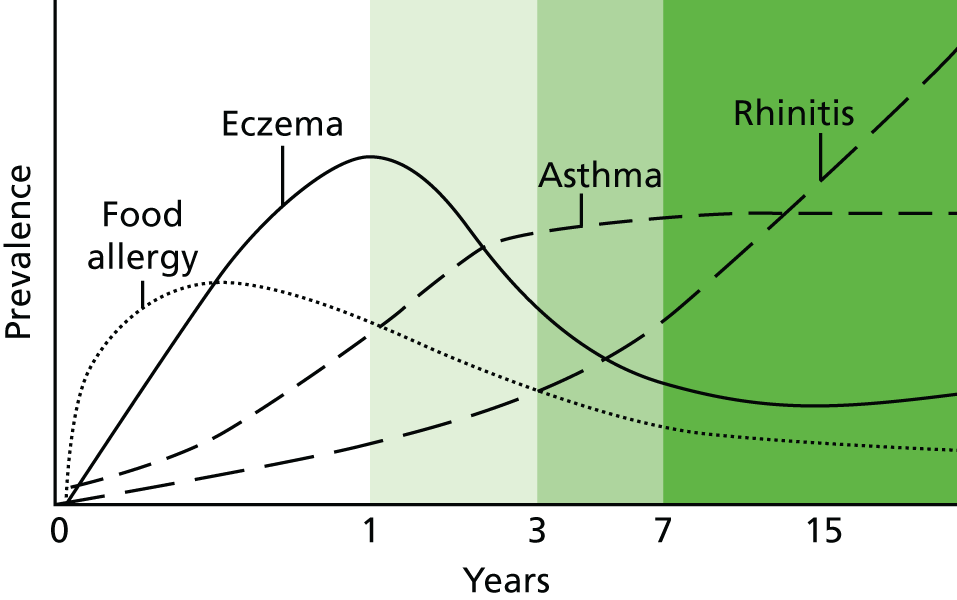

Children with eczema, especially severe eczema, are at increased risk of also developing other allergic IgE-mediated diseases including food allergies, allergic asthma and allergic rhinitis (hay fever). Together, these are the most common chronic diseases of childhood and represent a major financial burden to the NHS, with direct costs estimated at over £1B per annum in 2004. 17 Eczema is often the first manifestation of the so-called ‘atopic march’, in which a child progresses from eczema to asthma and allergic rhinitis later in life (Figure 1). 18,19 Eczema is strongly associated with peanut allergy and sensitisation to other foods such as milk, eggs, soy, wheat and fish. 20 Population-based cohort studies reveal that around one in three children with eczema go on to develop asthma, especially allergic asthma, in later life. 21 Allergic rhinitis is usually the last of the allergic diseases to appear and is about three times more common in children with eczema in early life. 22 Around half of UK school children with eczema also suffer from allergic rhinitis. 23

FIGURE 1.

Atopic march: allergic diseases tend to develop in a specific order.

Causes of eczema

Eczema is a complex disease caused by the interplay of multiple genetic and environmental factors. The early onset of disease, the rising prevalence and increased incidence of eczema in smaller families,24 as well as in those from a higher socioeconomic background and in those migrating to Western countries from countries with a low prevalence of eczema, suggest that environmental factors operating early in life play a critical role in determining disease expression. 5,25 The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ has been proposed to explain why allergic diseases are more prevalent in developed societies. This hypothesis suggests that a lack of stimulation of the developing immune system by microbes prevents its full maturation. However, experimental evidence for this hypothesis is still conflicting. 26,27 Environmental risk factor studies have also shown conflicting results and have not, to date, led to useful preventative strategies. 28–31 Eczema is highly heritable and shows strong familial clustering. 32

Although genetically determined variation in cutaneous and systemic inflammation are important in eczema predisposition,33 common mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin, a key skin barrier protein, represent the strongest known genetic risk factor for eczema. 34,35 A meta-analysis of 24 studies demonstrated that loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene are found in approximately 9% of the white European population; these individuals have a measurable reduction in their skin barrier function and a striking threefold increased risk of AE. 36

Overview of systematic reviews

The following text is adapted with permission from John Wiley & Sons Ltd from Foisy M, Boyle RJ, Chalmers JR, Simpson EL, Williams HC. Overview of reviews. The prevention of eczema in infants and children: an overview of Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews. Evid Based Child Health 2011;6:1322–39. 37

Summary

What was already known about this topic?

-

Many published studies have evaluated different interventions aimed at preventing eczema. Often, these have been incorporated into systematic reviews on the topic.

-

However, there is no single source of information that compares all of the different interventions; thus, it is difficult to make comparisons and clinical recommendations.

What did this study add?

-

This overview of systematic reviews presented the available evidence from Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews on seven interventions for preventing eczema.

-

There was no clear evidence that any of the interventions reviewed can reduce the incidence of eczema.

-

In a subgroup of high-risk infants, there was a significant reduction in the incidence of eczema in those given prebiotics compared with no prebiotics.

-

A similar reduction in eczema incidence was seen in high-risk infants who were exclusively breastfed for 6 months compared with those given non-breast milk liquids and/or solid food at 3–6 months, but this effect was not sustained past the age of 2 years.

-

There were very few published data on the prevention of truly AE, that is, eczema associated with IgE sensitisation; data on probiotics versus no probiotics showed no significant difference.

-

Adverse event data were available for infants only. The only adverse event to emerge from the review was that more infants receiving probiotics were spitting up (reflux/regurgitation) at 1 and 2 months of age than those not receiving probiotics.

-

We were not able compare breastfeeding versus infant formula alone or the avoidance of pets and other aeroallergens from birth owing to an absence of published systematic reviews dealing with these topics that met the inclusion criteria.

Introduction

Successful prevention of eczema may be possible by either modifying environmental risk factor(s) or compensating for genetic variations that lead to eczema development. Many systematic reviews have been published that have assessed interventions for eczema prevention but, more often than not, these examine prevention of all allergies including asthma and seasonal allergic rhinitis. Although some systematic reviews have dealt with eczema alone, these tend to cover just one intervention, making it difficult to draw any comparative data or conclusions across all of the commonly tried prevention strategies. The purpose of this overview is to present the most up-to-date evidence from Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews on pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for preventing eczema in infants and children in order to ensure that any attempts at devising new preventative strategies build on previous work rather than inadvertently duplicating it. 38

Several interventions to prevent eczema have been proposed and tested, primarily based on allergen avoidance, but despite this there are no clear, evidence-based guidelines for eczema prevention. 39 To date, interventions to modify the infant’s exposure to dietary antigens pre- or postnatally have been the major focus of eczema prevention research on the basis that these might prevent food sensitisation and, thereby, promote intestinal and skin health. Such interventions include the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding for a defined period of time, maternal dietary antigen avoidance and the use of hydrolysed protein formula (in which the allergenic properties of cow’s milk are reduced by breaking down the proteins in the milk) or soy formula for those infants who are not exclusively breastfed.

More recent studies have attempted to capitalise on the theoretical link between eczema and intestinal health, such as differences in intestinal microbiota composition and possible altered intestinal permeability and inflammatory markers in people with eczema. 40,41 The presence of an altered intestinal milieu in infants at risk for developing eczema has been shown in many, but not all, studies, and is therefore an area of ongoing controversy and research. 42,43 Dietary interventions such as prebiotic and probiotic supplementation may modify early intestinal microbiota development. 41,44 Some studies have also demonstrated that maternal supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy may decrease the risk of infant eczema. 45

Other approaches for eczema prevention have focussed on T helper cell type 1 (Th1) or regulatory T cell type immune responses, which have been found to be altered in eczema. 46 The close association between eczema and allergic sensitisation has also led some investigators to test the effects of avoiding specific aeroallergens such as pet allergens and house dust mites.

Promotion of skin barrier function by use of emollients in early life is another approach that has been suggested,47 based on the observations that skin barrier dysfunction may play a role in initiating eczema. In 2006, Palmer et al. 34 showed an association between genetic mutations in the gene encoding the skin barrier protein filaggrin and the development of eczema, a finding that has now been replicated in > 20 studies. 36 Several lines of evidence support a skin barrier approach to eczema prevention including data showing that barrier dysfunction precedes presentation of eczema in infants with a filaggrin gene mutation48 and an early case–control study found an association between use of petroleum ointment and the development of eczema. 49 It is also possible that protecting the barrier from birth may reduce IgE sensitisation and the subsequent development of other allergic disease. 50

Methods

Systematic reviews were identified using the 2010 UK NHS Evidence Skin Disorders Annual Evidence Updates Mapping Exercise on Atopic Eczema, which had previously identified all systematic reviews on eczema prevention published between January 2000 and August 2010.

To ensure trials were only counted once, only one review on each topic was included. The criteria for inclusion were:

-

data on participants between 0 and 18 years of age available separately from any adult data presented

-

search date for the review had been conducted no more than 5 years ago

-

contained RCTs only (with the exception of breastfeeding and pet avoidance because RCTs are not ethical)

-

contained data to enable calculation of a risk ratio (RR) and confidence interval (CI).

If a Cochrane review was published that met the inclusion criteria, this was automatically selected. If no Cochrane review was published for an intervention, then the most up-to-date non-Cochrane review that met the inclusion criteria was included instead.

Two reviewers (MF, JRC) independently assessed the eligibility of each potential review based on the inclusion criteria listed above. Both reviewers agreed on the final set of included reviews.

Two reviewers (ELS, JRC) independently assessed the methodological quality of each included review using the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool. 51 Both reviewers evaluated whether or not each review satisfied the eleven different criteria of the AMSTAR tool. In addition to recording which AMSTAR criteria were fulfilled, the reviewers also made a subjective assessment of overall quality of each review by assigning an overall rating of ‘good’, ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ based on their global evaluation of the review and informed by the AMSTAR criteria. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (MF).

The primary outcome measures were pre-specified as:52

-

development of eczema (clinical phenotype)

-

development of AE (IgE sensitisation).

Secondary outcomes were pre-specified as:

-

any atopy/IgE sensitisation

-

eczema severity

-

time to development of eczema

-

QoL

-

health-care utilisation

-

adverse events.

The main analysis included all ages and all risk levels of developing eczema. Two subgroup analyses were also pre-specified:

-

infants (≤ 2 years of age) and children (> 2 to 18 years of age)

-

high-risk participants (family history of allergic disease) and participants not selected for risk.

One reviewer (MF) extracted the following information from each of the included reviews: inclusion criteria (including population, intervention, comparisons and outcomes), methodological quality of included trials and numeric results. Numeric results were extracted for aggregate data (all ages and risk levels combined) as well as for our pre-specified subgroups examining different ages and risk levels. When trials or reviews documented outcomes for the same patients at both infancy and childhood, we included only the childhood data in the aggregate data. Numeric results were extracted from the published reviews, and RevMan5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for all statistical analyses. A second reviewer (JRC) independently verified accuracy of numeric results and discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

All data contained in the included reviews were dichotomous; therefore, all data in this overview were summarised using RRs with 95% CIs. RRs describe the probability of the event in the treatment group compared with the probability of the event in the control group, and are interpreted as statistically significant if the 95% CIs do not touch unity. A random-effects model was used for all outcomes in order to provide the most conservative estimate.

For all pooled effect estimates, the accompanying I2-values were reported and represent the degree of statistical heterogeneity between the trials. An I2-value close to 0% indicates minimal or no heterogeneity of trials, whereas an I2-value of ≥ 50% indicates substantial heterogeneity. 53

Results

Results of the search

Seven systematic reviews were included, containing 39 relevant trials (11,897 participants) (see Appendix 1). Six were Cochrane reviews covering the following interventions for preventing eczema: maternal dietary antigen avoidance,54 optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding,55 hydrolysed protein formula,56 prebiotics,57 probiotics58 and soy formula. 59 One non-Cochrane review on omega-3 and -6 fatty acid supplementation was also included. 60 The included Cochrane review on optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding compared prolonged exclusive breastfeeding with the introduction of complementary solid or liquid foods following a short period of exclusive breastfeeding. It did not compare breastfeeding with infant formula alone. Therefore, we sought to include a review on this topic, but none met our inclusion criteria. Similarly, none of the non-Cochrane reviews examining the avoidance of pets or other aeroallergens satisfied the inclusion criteria, so we were unable to assess these interventions.

Eczema

There was no strong evidence that any of the seven interventions reviewed can prevent the development of eczema (Table 1). However, there was weak evidence that some of the interventions may reduce the risk of developing eczema in some subgroups.

| Comparison | Participants (trials) | RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months vs. introduction of solids at 3–6 months | 3731 (2) | 0.75 (0.42 to 1.32) | 61 |

| Hydrolysed formula vs. cow’s milk formula (prolonged feeding) | 1478 (8) | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.08) | 0 |

| Extensively hydrolysed formula vs. cow’s milk formula (prolonged feeding) | 912 (3) | 0.84 (0.58 to 1.23) | 19 |

| Partially hydrolysed formula vs. cow’s milk formula (prolonged feeding) | 823 (7) | 0.92 (0.72 to 1.17) | 0 |

| Extensively hydrolysed formula vs. partially hydrolysed formula (prolonged feeding) | 1061 (4) | 0.88 (0.73 to 1.05) | 0 |

| Hydrolysed formula vs. human milk (early short-term feeding) | 09 (1) | 0.48 (0.05 to 4.41) | – |

| Hydrolysed formula vs. cow’s milk formula (early short-term feeding) | 77 (1) | 0.34 (0.04 to 3.15) | – |

| Soy formula vs. cow’s milk formula | 744 (3) | 1.23 (0.99 to 1.53) | 0 |

| Maternal antigen avoidance vs. standard diet | 360 (3) | 0.95 (0.63 to 1.44) | 21 |

| Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation vs. placebo | 664 (3) | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.54) | 45 |

| Omega-6 fatty acid supplementation vs. placebo | 259 (2) | 0.80 (0.56 to 1.16) | 0 |

| Prebiotic vs. no prebiotic | 432 (2) | 0.79 (0.21 to 2.94) | 80 |

| Prebiotic vs. other prebiotica | 150 (1) | 0.22 (0.07 to 0.76)b | – |

| Probiotic vs. no probioticc | 1492 (6) | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.08) | 46 |

Exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months compared with introduction of non-breast milk liquids and/or solid food at 3–6 months did not significantly decrease the overall incidence of eczema. However, in a subgroup analysis of high-risk infants, exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months significantly decreased the risk of developing eczema by 60% (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.78), an effect that was not significant beyond 2 years of age or in infants not selected for risk of developing allergic disease.

When prebiotics were compared with no prebiotics in infants not selected for risk, there was no overall effect on eczema prevention. However, in high-risk infants, use of prebiotics was found to significantly decrease risk of developing eczema by 58% (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.84). One trial61 comparing different types of prebiotics found that a combination of polydextrose, galacto-oligosaccharide and lactulose compared with polydextrose and galacto-oligosaccharide alone significantly decreased the incidence of eczema by 78% in infants not selected for risk of developing allergic disease (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.76).

Compared with cow’s milk formula, there was no clear benefit of prolonged feeding of hydrolysed milk formula (all types) or subgroup analyses of partially or extensively hydrolysed milk formula. Prolonged feeding with extensively versus partially hydrolysed milk formula showed no significant difference. Early short-term feeding of hydrolysed milk formula (all types) showed no benefit over human milk or cow’s milk formula. Soy milk formula versus cow’s milk formula also showed no significant benefit. Maternal antigen avoidance was no better than standard diet, omega-3 or -6 fatty acid supplementation was no better than placebo, and there was also no effect of probiotics compared with no probiotics. None of the above subgroup analyses was significant based on either age or risk level.

Atopic eczema

Although we pre-specified AE associated with IgE sensitisation as one of our two primary outcomes, only one comparison – probiotics versus no probiotics – provided data examining this outcome. There was no significant difference in the overall incidence of AE, nor in subgroup analyses of high-risk infants and infants not selected for risk.

Atopy

Data were available for three different comparisons that measured atopic sensitisation using skin prick tests to various allergens: exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months versus introduction of solids at 3–6 months, maternal dietary antigen avoidance versus standard diet and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation versus placebo. No significant differences were identified.

Adverse events

The only data available on adverse events were from infants, based on nine different comparisons of interventions. The only significant difference identified in adverse events was in the comparison of probiotics versus no probiotics. Parents reported that significantly more infants receiving probiotics were spitting up (reflux/regurgitation) at 1 and 2 months of age (RR 1.88, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.45, and RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.80); however, premature infants receiving probiotics experienced a 65% reduction in necrotising enterocolitis and/or death (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.83).

Discussion

Quality of the evidence

Significant numbers of trials and participants have been included in this overview, allowing reasonably robust conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness of different interventions. A particular problem in some included reviews was the heterogeneity in the nature of the interventions (e.g. partially vs. extensively hydrolysed formula, and whey vs. casein formula) and population (e.g. early, late and prolonged formula feeding; exclusively breastfed, mixed breastfed or exclusively formula-fed; and high or normal risk for allergic disease) which makes it difficult to perform meta-analyses in such populations. Trials of prebiotic and probiotic interventions also suffered from large heterogeneity in the interventions and it should be noted that several probiotic trials have been published since the last systematic review on this subject,62–70 warranting an updated review.

The quality of the systematic reviews included in this overview was high: six reviews were Cochrane reviews and all seven reviews in this overview addressed most of the AMSTAR51 systematic review quality criteria and received overall ratings of ‘good’ (all included reviews are detailed in Appendix 1).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Many of the interventions of interest that we identified prior to conducting this overview were captured in Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews. Comparisons examining exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months, hydrolysed formula, omega-3 fatty acids and probiotics contained significant numbers of trials and participants and were thus powered to detect important treatment effects. However, analyses of soy formula, maternal antigen avoidance and prebiotics included smaller numbers of participants and studies, so may have missed important treatment effects on the incidence of eczema.

Other areas for which more systematic reviews and trials are needed are interventions to promote normal immune development and interventions to correct skin barrier dysfunction. The latter is particularly important in view of the growing body of evidence for abnormalities of skin barrier function in eczema. Common loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for eczema34 and skin barrier dysfunction can be detected prior to eczema development. 48

There is a need for more complete reporting of adverse events within systematic reviews of interventions for eczema prevention. In addition, greater numbers of trials must report the effects of these interventions on eczema prevalence beyond infancy, particularly in normal-risk infants.

Limitations

This overview was undertaken using a consensus-based process informed by The Cochrane Collaboration expertise in preventing bias and provides a thorough review of several interventions for eczema prevention. A particular strength of the overview was collaboration with the authors of the 2010 NHS Evidence Skin Disorders Annual Evidence Update on Atopic Eczema, which ensured a thorough literature search and access to all published systematic reviews of interventions for preventing eczema. All analyses were defined a priori, such as the inclusion of reviews of non-randomised studies for two interventions (breastfeeding and pet avoidance) where RCTs are ethically difficult to perform.

The strength of some conclusions was limited by small numbers of trials or participants included in the relevant reviews and the analysis of probiotic effects was limited by the recent publication of many relevant trials62–70 that have not yet been incorporated into a Cochrane systematic review. A more recent meta-analysis incorporating many of these trials71 found that probiotic supplementation significantly reduces risk of developing eczema in infancy (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.92), a finding supported by subsequent reviews. 72

It was not possible to extract data from the published systematic reviews on breastfeeding versus no breastfeeding and pet exposure in a form that could be incorporated in this overview. The systematic review of breastfeeding versus no breastfeeding73 did find a significant protective effect against eczema [odds ratio (OR) 0.70, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.99]; however, when one controversial trial was excluded from the analysis, this comparison became non-significant (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.09). The review on pet exposure74 found that, in longitudinal studies, exposure to cats (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.92), dogs (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.87), or ‘any furry pets’ (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.84) was associated with reduced risk of developing eczema. However, one trial noted that when adjustments were made for avoidance behaviour in participants allergic to pets, the protective effect of cats became non-significant.

We identified only one review which reported specifically on ‘atopic eczema’ as defined by the WAO recommendations as an outcome rather than ‘all eczema’. 2 Additionally, although we pre-specified AE associated with IgE sensitisation as one of our two primary outcomes, only one comparison – probiotics versus no probiotics – provided data examining this outcome. There was no significant difference in the overall incidence of AE, nor in subgroup analyses of high-risk infants and infants not selected for risk.

It is worth noting that very few of the systematic reviews evaluated atopy/allergic sensitisation as an outcome, despite it being reported in many of the included RCTs. Although this may be justified because atopy/allergic sensitisation is not a widely recognised disease entity, the primary prevention of atopy/allergic sensitisation may be associated with prevention of later onset allergic disease and is therefore worth including in future systematic reviews in this area. In addition, no data were identified for four of our pre-specified secondary outcomes: eczema severity, time to development of eczema, QoL and health-care utilisation. All are important parameters to measure in future trials and systematic reviews; for example, there is little gain in preventing eczema incidence if the absolute number of severe cases (which disproportionately account for most health-care costs) remains unchanged.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this overview are broadly consistent with those of other published trials and reviews of RCTs, but are less in agreement with reviews and practice guidelines that include ‘all allergic disease’ or ‘allergy’ as primary outcomes or that include significant numbers of non-randomised trials. For example, a recent German taskforce on allergy prevention recommended exclusive breastfeeding for 4 months or, if not possible, the use of a hydrolysed formula for high-risk infants and general avoidance of pets. 75 These differences might stem from the inclusion of other allergy outcomes and a large number of non-randomised studies in the German taskforce recommendations. A recent RCT of hydrolysed formula for preventing allergic disease in high-risk infants supports our conclusion that further research is needed before recommending this intervention to prevent eczema. 76

Implications for clinical practice

This overview of systematic reviews on eczema prevention has not found any clear evidence that any of the main interventions reviewed can reduce the incidence of eczema. That does not mean to say that some interventions do not work; new, larger, well-conducted trials may indeed show a modest benefit in time. However, the current evidence is simply not strong enough to influence practice recommendations. Some interventions, such as the use of soy instead of cow’s milk, are unlikely to show a clinically useful benefit based on the lower 95% CIs and the pooled effect estimates. It may be considered that some of the interventions are unlikely to do much harm; however, it should be considered that adverse events were poorly reported in many of the included trials.

It is also worth noting that we have not been able to address some of the most commonly asked questions by parents (e.g. whether or not exclusive breastfeeding or owning a pet prevents eczema) owing to lack of appropriate data. This may partially reflect the ethical difficulties of conducting trials in these areas. Furthermore, some interventions such as ‘probiotics’ are simply too heterogeneous to consider as one intervention – some may work but some may be completely ineffective. This overview has found that the possible benefit of some interventions (such as exclusive breastfeeding or prebiotics) may only be present in infants born to families at high risk for allergic disease and that the magnitude of risk reduction is larger than the RRs from unselected populations. Again, caution has to be expressed as these results were based on only one trial each with significant limitations.

Implications for research

These findings indicate that there is little justification for further study of some proposed interventions for eczema prevention, such as omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and use of soy milk instead of cow’s milk. Other interventions, such as hydrolysed formula, prebiotics and probiotics, have shown inconclusive results and are worthy of further study. New interventions designed to enhance skin barrier function, such as intensive use of emollients, water softeners or avoidance of alkaline soaps, should also be explored and a separate overview of reviews examining interventions for preventing asthma and other allergic diseases is warranted.

Defining a new case of eczema: a systematic review

The following text is adapted from J Allergy Clin Immunol, vol. 130, iss. 1, Simpson EL, Keck LE, Chalmers JR, Williams HC, How should an incident case of atopic dermatitis be defined? A systematic review of primary prevention studies; pp. 137–44 (see www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091674912002680),77 copyright 2012 with permission from Elsevier.

Summary

What was already known about this topic?

-

There are many published definitions for the diagnosis of AE. Many require the presence of signs or symptoms over a long period of time as a diagnostic criterion, but this is not appropriate for defining new cases.

-

Interventions that delay rather than prevent the onset of eczema could still have a significant public health impact. Identification of such interventions requires more precise determination of the date of onset of eczema than is offered by cumulative incidence rates.

What did this study add?

-

This study was a systematic review of how incident cases of eczema have been defined in previous primary prevention studies.

-

Many different definitions have been used to define a new case of AE, with the Hanifin and Rajka criteria the most commonly applied. Many trials used a definition that was unique to that particular study.

-

The Hanifin and Rajka criteria include presence of signs or symptoms over a long period of time as one of the major criteria, but only two studies stated how they dealt with this in relation to definition a new cases.

-

We propose a minor modification to the UK Working Party Criteria to define an incident case to reduce the timescale from 1 year to 4 weeks for the presence for the presence of an itchy skin condition.

Introduction

Research into the prevention of eczema has been hampered by inconsistency in study methodology, especially with regard to methods for defining high-risk populations and disease outcomes. 78–80 In addition, although there are well-established validated definitions for diagnosing established eczema, there are no standardised definitions for defining an incident case, as is needed for longitudinal birth cohort studies or interventional prevention studies.

The problem is not easy to resolve as many definitions of eczema include having signs or symptoms over a long period of time as a diagnostic criterion, which is clearly unsuitable for defining an incident case. Although some prevention studies measure cumulative incidence rates at 1 or 2 years, a more precise determination of the date of onset of eczema is especially important when evaluating prevention strategies that may only delay the onset of disease. Identifying strategies that delay, rather than prevent, the disease onset would still have a significant public health impact, given the high prevalence of eczema and the finding that the earlier onset disease predicts a more severe disease course. 81 We sought to conduct a systematic review of how new cases of eczema have been defined in previous primary prevention studies of eczema, using systematic review methodology.

Methods

Included studies

Prospective, interventional, prevention trials published after 1980, which specified eczema as an outcome, were eligible. Studies whose primary outcome was not eczema, such as asthma prevention trials, but had eczema as a secondary outcome, were included. There were no age or language restrictions. Observational cohort studies were excluded as these studies most often use cumulative incidence as an outcome. Current validated definitions for the diagnosis of eczema are suitable for the measurement of cumulative incidence with a maximum precision of 1 year. We aimed to investigate incident case definitions that would capture cases as they occur in a primary prevention trial, enabling a time of disease onset to be determined.

Information sources

Studies were identified by searching electronic databases, scanning reference lists of articles and eczema reviews, and consultation with experts in the field. The search was applied to MEDLINE (1980–2012), Cochrane (1980–2012) and the last database search was run on 5 January 2011 (see Appendix 2). Multiple articles were identified through hand-searching, predominantly of reviews identified in search results, reviewing the literature and from the NHS Evidence mapping exercise of systematic reviews for eczema prevention. 82

Study selection

All database search results were entered into RefWorks (ProQuest LLC, MI, USA) in which duplicates were removed. Screening for eligibility was performed independently in a standardised manner by two reviewers (ELS and LEK) based on titles and abstracts. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by consensus. Full-text articles for all studies past screening were obtained. Full-text copies of studies with seemingly eligible titles but without abstracts were automatically included and scrutinised further for eligibility. All full-text articles were assessed for eligibility by one reviewer prior to data collection. Of note, if multiple publications of a larger longitudinal trial were identified, they were counted as only one definition unless the definitions significantly differed between publications, in which case they were kept separate.

Data collection process/items

Data collection was performed by one reviewer using a data extraction database created for the study. Information extracted from each trial included the type of intervention and the eczema definition used. One author (LEK) extracted the above data from the included studies and a second reviewer (ELS) double-checked all verbatim definitions that were considered to lack a true definition of eczema. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and consultation with a third arbitrating author.

Summary measures

The primary outcome measured was the presence of any specified definition for eczema.

Results

Study selection

The study selection procedure is summarised in the flow chart in Figure 2. A total of 108 articles met the criteria for inclusion. Seven of these were multiple publications from the same longitudinal study, so this definition was counted only once, resulting in 102 distinct studies for inclusion in the analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Study flow chart for showing screening process for screening studies related to defining new cases of eczema. AD, atopic dermatitis.

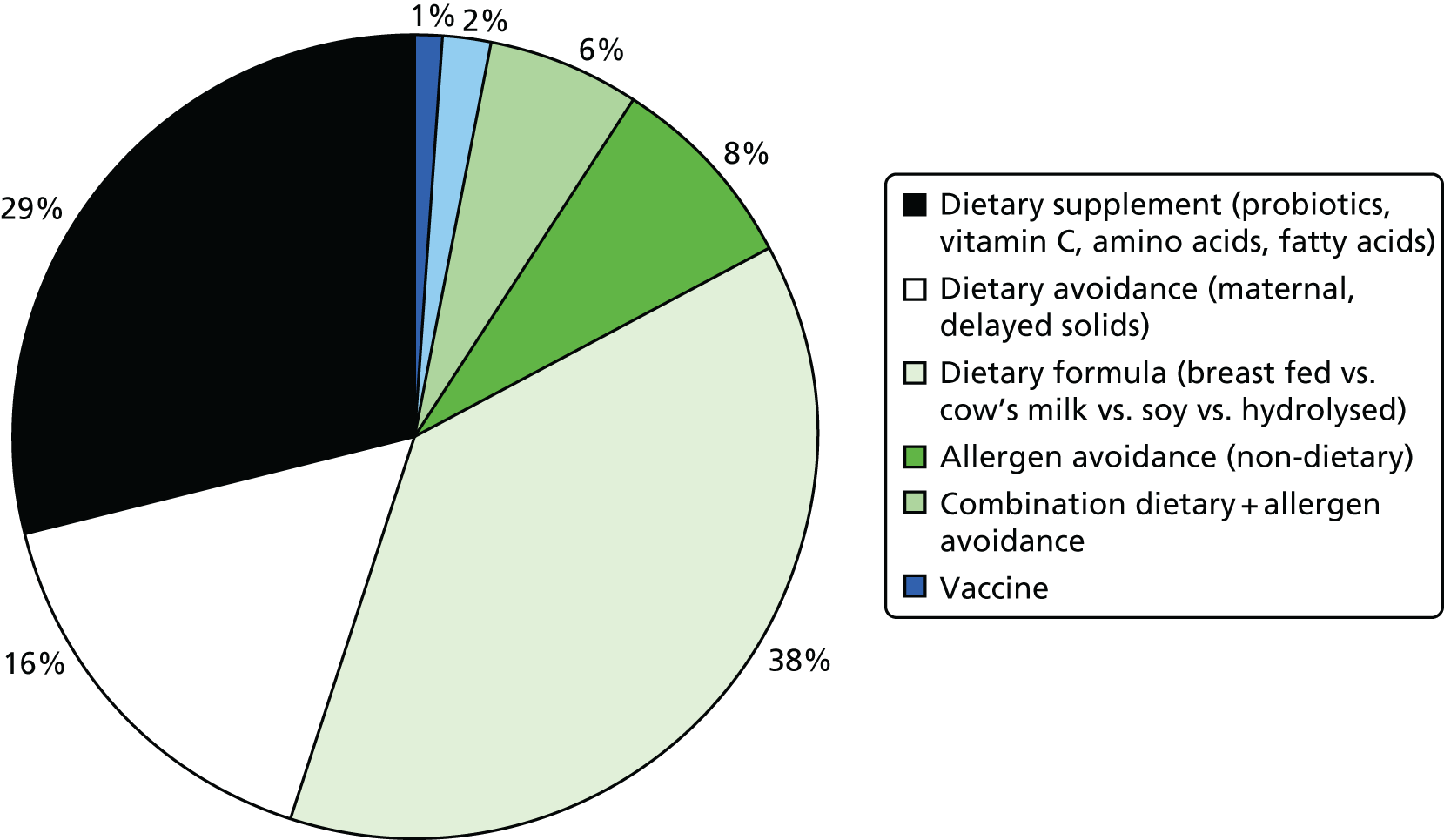

More than 80% of the included 102 studies evaluated a dietary intervention on either the mother or the infant, with infant formula as the most common eczema prevention strategy used. The other interventions were non-dietary allergen avoidance, vaccination and an emollient intervention (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Interventions assessed in the 102 included studies relating to defining new cases of eczema.

Definitions of eczema

Of the 102 studies selected for further analysis of eczema definition, only 75 (73.5%) included some form of a description of the criteria used to diagnose eczema. The other 27 articles mentioned either a diagnosis made by a questionnaire that was unavailable for review (one study), a general morphological description of eczema (four studies), a physician or investigator diagnosis of ‘eczema’ without further elaboration of specified criteria (20 studies), or no description at all (two studies). 77

Of the 75 studies with reported disease criteria, the Hanifin and Rajka criteria were the most commonly used disease criteria (28 studies; Table 2). Of those studies that used the Hanifin and Rajka criteria (which includes chronic or chronically relapsing dermatitis as one of its four major diagnostic criteria), only two studies specified how they dealt with the anomaly of disease chronicity in relation to definition a new case. 84,85 The study by Laitinen et al. 85 required visible eczema to be present for at least 4 weeks at the 6- and 12-month visits and for at least 8 weeks at the 24- and 48-month visits. Arslanoglu et al. 84 required ‘symptoms’ to be present for at least 4 weeks to meet criteria for eczema.

| Name of definition | Studies, n (%) | Definition | Reference number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hanifin–Rajka | 28 (27) | Must have three or more basic features: pruritus, typical morphology and distribution, chronic or chronically relapsing, personal or family history of atopy plus three minor criteria. See source for full definition83 | 45,47,64,65,67,68,84–106 |

| Unique | 21 (21) | Variable | 54,107–125 |

| ISAAC | 4 (4) | Has your child had this itchy rash at any time in the last 12 months? Has this itchy rash at any time affected any of the following: the folds of the elbows, behind the knees, in front of the ankles, under the buttocks or around the neck, ears or eyes?126 | 127–130 |

| UK Working Party | 7 (7) | Must have an itchy skin condition in the last 12 months. Plus three or more of onset below age 2,a history of flexural involvement, history of generally dry skin, personal history of other atopic disease,b visible flexural dermatitis as per photographic protocol131 | 63,66,69,132–134 |

| Hanifin and Lobitz | 5 (5) | Must have each of the following: pruritus, typical morphology and distribution, tendency towards chronic or chronically relapsing dermatitis. Plus two or more of the following features: personal or family history of atopic disease, immediate skin test reactivity, white dermographism and/or delayed blanch to cholinergic agents, anterior subcapsular cataracts; or four or more features listed in the reference Hanifin and Lobitz135 | 136–140 |

| Seymour | 4 (4) | The criteria used in selecting infants with atopic dermatitis were the presence of at least two major, or one major and one minor, feature from the following lists. Major features included family history of atopic disease (asthma, seasonal rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis), evidence of pruritic dermatitis, typical facial or extensor, eczematous or lichenified dermatitis. Minor features included xerosis/ichthyosis/hyperlinear palms, perifollicular accentuation, chronic scalp scaling, periauricular fissures141 | 70,142–144 |

| Halken | 4 (4) | AE was diagnosed if physical examination revealed areas of scaly, erythematous and itchy eczematous rash, primarily of the face, scalp and flexural folds. Only eczema with at least two locations in typical areas relapsing with a duration of at least 3 months was recorded145 | 145–148 |

| Moore | 2 (2) | Eczematous skin lesions were classified as 0 (normal skin); 1 (dry skin, cradle cap, mild perioral erythema); 2 (some or all of these features with, in addition, an area of skin, usually on the face or behind the ears, that was red, scaly, cracked, or weeping); 3 (as 2 but more extensive lesions, usually on the face, trunk, and limbs). Grades 2 and 3 were regarded as eczema149 | 149,150 |

| None | 27 (26) | 106,151–174 |

Disease definitions cited in eczema prevention studies

A disease definition that was unique to that particular study (21 studies) was the second most commonly used disease definition. These reports did not cite a specific source and none described a scientific method or even more detailed empirical reasoning for justifying the choice of a novel definition of an incident case.

On closer examination of the 21 definitions that were unique to an individual study, most definitions included pruritus, the presence of visible eczema, and disease distribution requirements. Only 50% of these definitions had a time requirement, which ranged from requiring ‘chronic disease’ to 4 weeks of eczema needing to be present (data not shown).

Discussion

Main findings

We found a large degree of variability in the methods used to define an incident case of eczema in relevant prevention studies, with one-quarter of studies failing to report any form of definition whatsoever. Of the studies reporting some form of definition of an incident case, many used a definition that was unique to that particular study, rendering comparisons between studies very difficult. In addition, most studies used eczema incident case definitions without strict time requirements. Combined, these findings demonstrate an urgent need for a standardised, valid and repeatable definition of an incident case of eczema in order to improve the ability to compare outcomes between studies and to allow more informative meta-analyses of prevention studies. Although no previous studies have examined incident case definitions for eczema, our results are consistent with the larger problem of the lack of standardised disease outcome measures in eczema research. For example, Schmitt et al. 175 found 20 different scoring systems for measuring the severity of eczema. Chamlin et al. 78 found 30 different definitions for defining an individual as high risk for developing eczema. In 2010 an international group called the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative (see Chapter 2, Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema initiative) began the process of creating an accepted core group of outcome measures for eczema research. 176

Problems with existing definitions

The two most commonly used validated criteria found in our review were the Hanifin and Rajka criteria and the UK Working Party refinement of the Hanifin and Rajka criteria. Despite the potential usefulness of these criteria in reliably identifying cases of established eczema, as would be used for determining cumulative incidence over time in cohort studies,177 they were not designed for defining an incident case in prospective prevention studies. By defining an incident case in prevention trials, as opposed to a cumulative incidence, incidence rates can be more accurately calculated and a more accurate date of disease onset can be established. In order to qualify as a case of eczema using the Hanifin and Rajka criteria, at least three out of four of the following major criteria need to be fulfilled:

-

the presence of eczema

-

typical distribution

-

pruritus

-

a relapsing and remitting course.

The definition of ‘relapsing and remitting’ is not further defined and is left to the discretion of the investigator. The UK criteria state that a child must have an itchy skin condition in the past 12 months. These time requirements, although appropriate for diagnosing established cases of eczema, become problematic when diagnosing new onset eczema during the course of a prospective study.

Defining an incident case of eczema is not simply a question of noting the first time an eczematous rash appears in an infant because previous studies have shown that many forms of transient eczematous rashes occur often in infants, even in those children who do not eventually develop true eczema. 178 Thus, there is an urgent need for a standardised definition of an incident case of eczema that offers a satisfactory trade-off between overinclusion of transient eczematous eruptions of irritant and other aetiologies and overexclusion of genuine milder short-lived forms of eczema that still represent a health-care problem.

Proposed solution

Until more sophisticated validation studies can be performed, we suggest a modification of the UK Working Party criteria for eczema, adapted for prospective observational or interventional studies. This modification specifies a time frame that the eczema must be present in order to be considered as a case of eczema and allows for a diagnosis to be made even if the rash is treated early in its course. We propose the following definition, based on empirical reasoning considering the requirements of such a definition, and informed by previous studies that signal the best markers of true eczema. 178

A history of an itchy skin condition, which is either continuous or intermittent, lasting at least 4 weeks, plus three or more of the following:

-

a history of a rash in the skin creases (folds of elbows, behind the knees, fronts of ankles or around the neck), or on the extensor aspects of the forearms or lower legs

-

a personal history of asthma or hay fever or a history of atopic disease in a first-degree relative

-

a history of generally dry skin since birth

-

visible flexural dermatitis and/or visible dermatitis on the forearms or lower legs with absence of axillary involvement as defined by our online photographic protocol. 179,180

Visual confirmation of eczema diagnosis by a clinician, dermatology nurse or a research nurse suitably trained in recognising the symptoms of eczema is recommended. Clearly it is important to add the proviso that any infant fulfilling these criteria but who, on examination by a suitably trained health professional, is deemed to have a different skin disease, will be classified as not having eczema.

There are several benefits of our proposed definition, the strongest being that it is based on a current eczema definition that has undergone extensive scientific development assessing validity, repeatability and applicability. The only change added to the UK Working Party definition is the addition of a specified time requirement of 4 weeks. This time requirement should exclude most transient eczematous rashes that are typically irritant in nature and usually of little medical consequence. The use of an established eczema definition for incident eczema that is derived from one used for prevalent eczema allows for consistency in defining the public health burden of disease when assessed using different study designs. Another benefit of this proposed definition is that it does not allow a definition of eczema to be made based on the presence of facial eczema alone. Halkjaer et al. 178 found that 40% of children with facial eczema do not eventuate into chronic eczema. Finally, this definition allows for early treatment intervention during the course of a prospective study and does not require the disease to be untreated for a full 4 weeks if anti-inflammatory therapy is needed. Therefore, if a child develops significant eczema in the classic locations, it would be unethical to withhold treatment. Treatment can begin immediately if needed and, provided some degree of symptoms last for a 4-week period, a diagnosis of eczema will still be captured using this definition.

Very mild cases of new eczema treated immediately resulting in complete clearance will not be captured by such an approach, although it is debatable how many of these case are true eczema and it is probably wise to treat such new very mild cases with emollients alone until the disease declares itself. This approach is consistent with the recommendation to avoid diagnosing asthma in an infant based on a single episode of wheezing.

Particular strengths of this study include its systematic approach to the review of the literature and extensive searching of reference lists for prevention studies not found on the initial search. The findings are particularly relevant given the renewed interest in eczema prevention research and prevention by the National Eczema Association in the United States. 181

With regard to limitations, it is possible that other unpublished definitions of incident cases exist but these would not be detected by our search. In addition, the proposed eczema definition has not yet undergone extensive validity testing in prospective studies in the field. However, this limitation has to be tempered with the alternative practice to date, which has been to use unsuitable definitions or an array of poorly defined or completely undefined definitions. Our proposed definition is meant to be a starting point and we encourage those undertaking or designing new prospective studies of eczema to include it along with their preferred definitions so that knowledge of its utility and validity can be built up.

Pilot work for a randomised controlled trial to determine whether or not emollients can prevent eczema development (BEEP)

The following text is adapted from Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, Thomas KS, Cork MJ, McLean WH, Brown SJ, Chen Z, Chen Y, Williams HC. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2014;134:818–23. 182 Crown Copyright © 2014 Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Summary

What was already known about this topic?

-

Studies showing an association between loss-of-function filaggrin gene mutations and AE have generated interest in the potential for enhancing the skin barrier to prevent the development of eczema.

-

Emollients can reduce the incidence of flares of existing eczema and there is some evidence from small pilot studies that emollients may have a preventative effect against development of eczema.

-

A definitive RCT is needed but pilot work is required before this can go ahead.

What did this study add?

-

Parents appear to be willing to participate in an emollient prevention trial. Those in the intervention group adhered to the emollient regimen and those in the control group were prepared to refrain from using emollients.

-

We were able to establish that the liquid-paraffin based emollients, Doublebase® gel (Dermal Laboratories Ltd) and Diprobase® cream (Bayer Plc) are popular with parents and do not have any detrimental effects on skin barrier function.

-

This pilot RCT provides the first signal from a RCT that daily full body emollient application from birth can prevent eczema.

-

Caution should be shown in reading too much into the finding of reduced eczema at 6 months in this study because it might simply represent suppression of very mild eczema by the continued use of emollients.

-

The results of the pilot study and emollient studies were used to support a successful bid to the NIHR HTA to conduct a definitive RCT of emollients for the prevention of eczema.

Introduction

Importance of the skin barrier

Although previous eczema research has focused on the role of the immune system in atopic inflammation, the strong association between filaggrin mutations and AE (as well as atopic asthma and allergic rhinitis) has generated interest in the potential role of the skin barrier as the key early event leading to eczema development.

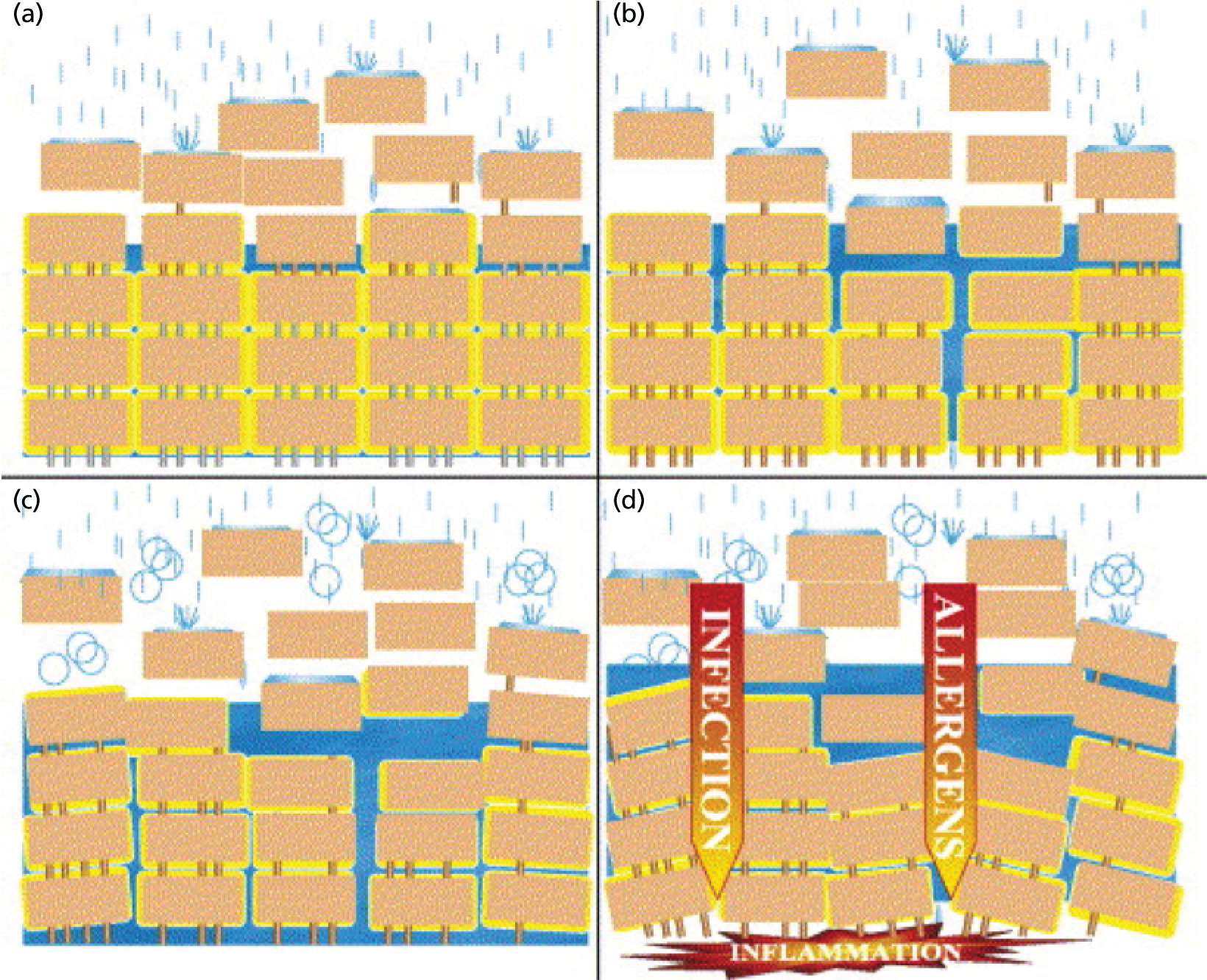

Dry skin is very common in eczema,183 even in the absence of known filaggrin loss-of-function mutations. A defective skin barrier allows water to be lost from the skin, resulting in a generally dry skin – one of the first abnormalities to be noticed in babies who eventually develop eczema, which supports the notion that the primary event in the development of eczema and atopy is a dysfunctional skin barrier. The skin barrier not only keeps useful things like water in, but also helps to keep out potentially harmful things such as irritants, bacteria and allergens. The use of harsh soap and detergents can raise the pH of the outer layers of the skin and disturb the fine balance of enzymes, proteins, lipids and micro-organisms on the skin surface. 184 A rise in pH leads to further breakdown of the skin barrier and is therefore a common pathway through which genetic and environmental factors influence skin barrier function. 184–186 Skin irritation from soaps and other wash products is worse in children with a pre-existing skin barrier defect (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Model of skin barrier function. In healthy skin, the corneodesmosomes (iron rods) are intact throughout the stratum corneum. At the surface, the corneodesmosomes start to break down as part of the normal desquamation process, analogous to iron rods rusting (a). In an individual who is genetically predisposed to eczema, premature breakdown of the corneodesmosomes leads to enhanced desquamation, analogous to having rusty iron rods all the way down through the brick wall (b). If the iron rods are already weakened, an environmental agent, such as soap, can corrode them much more easily. The brick wall starts falling apart (c) and allows the penetration of allergens (d). Reprinted from J Allergy Clin Immunol, vol. 118, iss. 1, Cork MJ, Robinson DA, Vasilopoulos Y, Ferguson A, Moustafa M, MacGowan A, et al. New perspectives on epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis: gene–environment interactions, pp. 3–21, copyright 2006 with permission from Elsevier. 187

It is also possible that the skin is the primary organ for development of allergic sensitisation. Animal studies have suggested that IgE sensitisation may occur via the skin. 188 Even though allergens are too large to penetrate the skin directly, the defective skin barrier makes it easier for allergens to interact with skin cells such as Langerhans cells, which are responsible for initiating sensitisation. 189 The observation that mutations in the gene coding for the skin barrier protein filaggrin are associated with peanut allergy independently of eczema,190 and that the use of creams containing peanut oil on the skin during the first 6 months of life may be a linked to developing a peanut allergy,191 further support the notion that the skin might be a primary route of sensitisation for food allergies. If true, then the skin barrier is a target for prevention of not only eczema, but also for food allergy and progression to asthma and allergic rhinitis in the atopic march.

This evidence provides the basis for our proposal, to perform a primary prevention trial designed to enhance the skin barrier, by using emollients from birth, in an effort to prevent eczema and associated allergic diseases. It is unclear how long skin barrier enhancement needs to occur in order to produce possible lifelong benefits, but as allergic diseases occur in the first few months of life, and most sensitisation occurs in the first year of life, we have opted for a 12-month emollient intervention period.

Emollients and the skin barrier

Emollient (moisturiser) therapy improves the skin barrier function. An emollient improves skin hydration by trapping in water. Emollients have also been shown to play a role in preventing irritant occupational hand eczema. 192 Emollients have been shown in premature babies to reduce the incidence of skin inflammation,193 to reduce flares of eczema (secondary prevention) and to decrease the need for topical steroids. 194 Not all emollients are the same, as they vary in their consistency from greasy paraffin derivatives to lighter, water-based, creams.

Primary prevention and the NHS

Primary prevention is a highly desirable goal in a chronic disease such as eczema with no cure. Parents with experience of eczema are often anxious to know whether or not their future children will develop eczema and what they can do minimise the risk. 195 If primary prevention of eczema using a strategy of early skin barrier enhancement with simple low-cost emollients works, it would represent a significant cost saving for the NHS through reduced treatment and appointment costs, especially in those cases persisting into adulthood. Further cost savings would result if early skin barrier enhancement prevents sensitisation and associated food allergy, asthma or allergic rhinitis. Even if the frequency of eczema cannot be significantly reduced, a reduction in the severity distribution of eczema could reduce the distress to patients, the number of consultations in primary care and subsequent referrals to secondary care.

Other emollient prevention studies

An early case–control study conducted in Kenya and published in 1991 suggested that petroleum had a protective effect against the development of eczema,49 but this study has not been followed up with a definitive RCT. One RCT from Bangladesh has shown that barrier enhancement from sunflower oil and Aquaphor ointment may reduce serious infections in preterm babies. 196 A small Japanese pilot study197 [International Clinical Trials Registry Platform study identifier (ID): UMIN000004544] of 70 patients looking at emollients as a prevention strategy for eczema reported a significant difference between eczema onset between the proactive and reactive groups, and that this demonstrated that emollient use in early life can protect high-risk babies from developing eczema. Another small, short-term pilot study conducted in Japan randomised 71 babies at high risk of atopic disease to skin care instructions (including emollients) versus no instructions and found no difference in diagnosed eczema at 6 months. However, the group did show that positive reaction to skin prick tests was lower in the intervention group. 198 An open-label pilot study of emollient therapy from birth showed only 15% of high-risk infants developed eczema against an expected rate of 30–50%. 47 This study also showed that emollient therapy was a safe and acceptable intervention.

We are not aware of any other definitive trials under way to evaluate the prevention of eczema through barrier enhancement after searching trial registries (World Health Organization meta-register from inception to 18 December 2013). We did find one commercial study (n = 400) taking place in the USA and Canada (NCT01577628) that is evaluating a cosmetic moisturiser containing shea butter, paraffin, waxes and vegetable oils (Lipikar Balm AP, Cosmétique Active International) for the prevention of eczema. 199

This section describes the pilot work that has been conducted in order to design a large definitive RCT of emollient therapy from birth as an eczema prevention strategy. A pilot RCT was carried out to determine the feasibility of a large RCT, followed by a parent preference ranking exercise of emollients and mechanistic studies to look at the effects of emollients on the skin barrier to inform the choice of emollient(s) in the main RCT.

Pilot randomised controlled trial

Methods

The full protocol is available. 200

Study design

This was a multicentre, multinational (UK and USA) two-arm parallel group, assessor-blind, randomised, controlled, pilot trial of 6 months’ duration. The intervention started within the first 3 weeks of birth.

Participants

Infants at high risk of developing eczema, defined as having a parent or full sibling that has (or had) doctor-diagnosed eczema, asthma or allergic rhinitis, were included. Infants needed to be in overall good health and the mother at least 16 years of age at delivery and capable of giving informed consent. If the mother had taken Lactobacillus rhamnosus supplements during pregnancy, they were excluded. Babies were excluded if they were born prior to 37 weeks’ gestation, or if they had a major congenital anomaly, hydrops fetalis, any immunodeficiency, a severe genetic skin disorder or a serious skin condition that would make the use of emollients inadvisable.

Intervention

Skin care advice

Both the intervention and the control groups were given an infant skin care advice booklet that reflected current guidelines. 201 The guidance advises parents to (1) to avoid soap and bubble bath, (2) use a mild, fragrance-free synthetic cleanser that has been designed specifically for babies, (3) avoid bath oils and additives, (4) use a mild, fragrance-free shampoo designed specifically for babies and avoid washing the suds over the baby’s body and (5) avoid using baby wipes when possible (see Appendix 3).

Emollients

Parents in the intervention group were offered a choice of three different emollients of different viscosities: an oil, a gel/cream and an ointment.

In the UK, the choices were sunflower seed oil (William Hodgson and Co.), Doublebase gel, which contains liquid paraffin and isopropyl myristate, or 50 : 50 white soft paraffin/liquid paraffin (commonly known as ’50 : 50’ ointment).

In the USA, Cetaphil® Cream (Galderma Laboratories) was offered instead of Doublebase gel and Aquaphor® Healing Ointment (Eucerin®) instead of 50 : 50 ointment (Table 3). Research nurses provided samples to help parents make their choice and changing emollient was permitted during the study. Sunflower seed oil offered parents a ‘natural’ product and was chosen over olive oil because of evidence that olive oil can harm the skin barrier owing to the high levels of oleic acid. 202 Therefore, a sunflower seed oil with low oleic acid content (25%) and high linoleic acid content (64%) was used in this study. Doublebase gel or Cetaphil cream were offered because they are popular with parents in eczema clinics. The 50 : 50 ointment or Aquaphor Healing Ointment were offered because some parents prefer a heavier emollient. None of the emollients offered contain sodium lauryl sulfate because this emulsifier has been shown to adversely affect the skin barrier. 203

| Emollient type | UK | USA |

|---|---|---|

| Oil | Sunflower seed oil | |

| Cream/gel | Doublebase gel | Cetaphil cream |

| Ointment | 50 : 50 ointment | Aquaphor Healing Ointment |

Parents were asked to apply the emollient to the baby’s entire body surface, with the exception of the scalp and nappy area if preferred, starting as soon as possible after birth (within a maximum of 3 weeks) and continuing until the infant was 6 months of age. Instructions were to apply the emollient in gentle downwards strokes in the direction of the hair growth at least once a day and always after a bath. The concomitant use of probiotic supplements containing L. rhamnosus was discouraged during the study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this pilot study was the proportion of eligible families who approached the study team who were willing to be randomised.

Secondary outcomes were:

-

proportion of families eligible for the trial

-

proportion of families accepting the initial invitation to participate

-

percentage of early withdrawals

-

cumulative incidence of eczema at 6 months

-

age at onset of eczema and the proportion which are transient cases

-

incidence of emollient-related adverse events

-

proportion of families who found the interventions acceptable

-

reported adherence with intervention

-

amount of contamination in the control group as a result of increased awareness

-

success of blinding of the assessor to the allocation status.

Filaggrin gene mutation testing was performed by the laboratory of Irwin McLean evaluating for the four most common mutations (R501X, R2447X, 2282del4, S3247X) using Taqman® allelic discrimination assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), as described previously. 204

An adaptation of the validated UK Working Party Criteria131 was used to measure new cases of eczema (see Defining a new case of eczema: a systematic review). These adaptations were a reduction in the duration of presence of symptoms from 1 year to 4 weeks and reflect the distribution pattern of the signs and symptoms of eczema in this young age group.