Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1006. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in March 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Burns et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Part 1 Introduction to the programme

Chapter 1 Overview

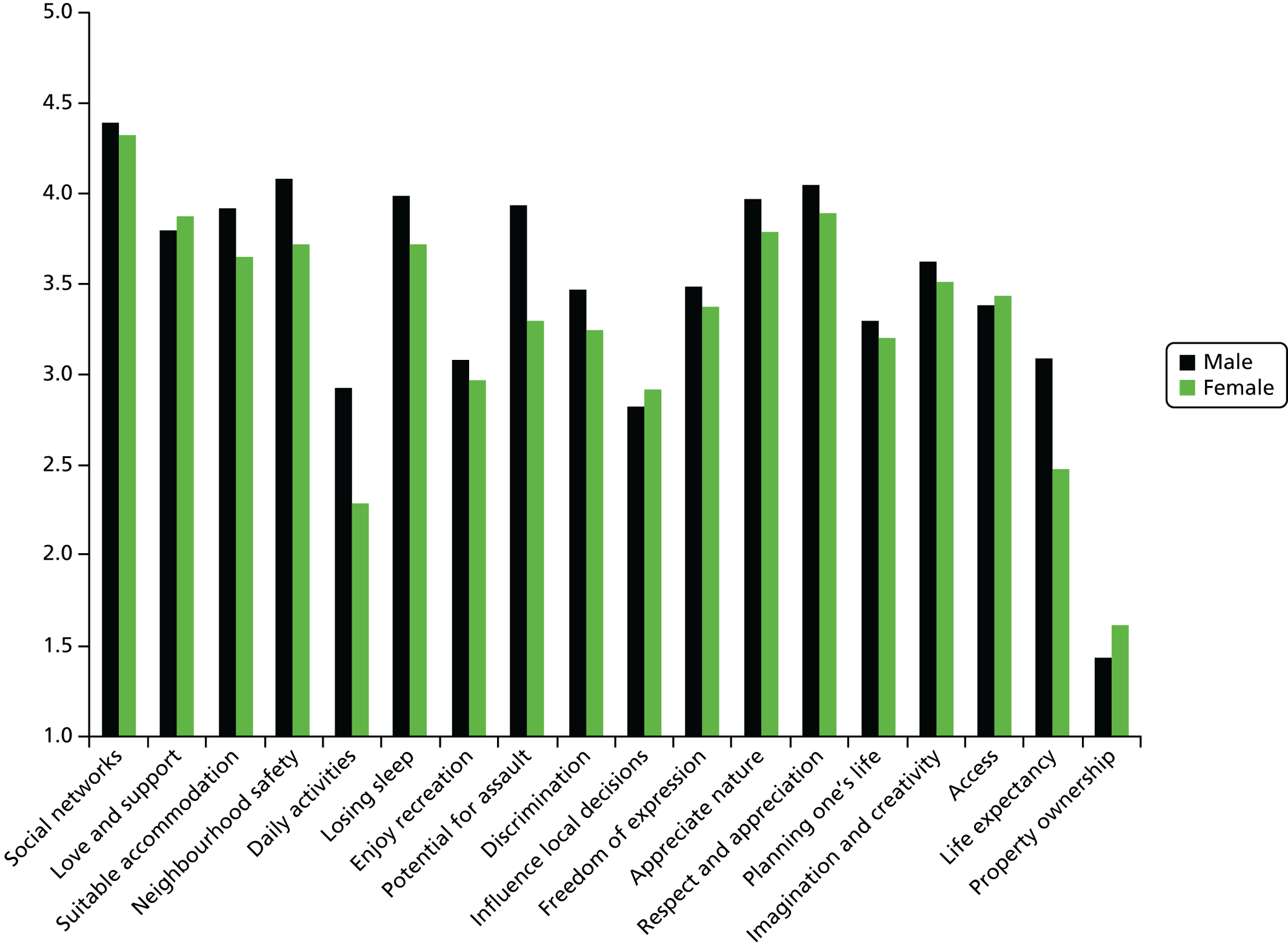

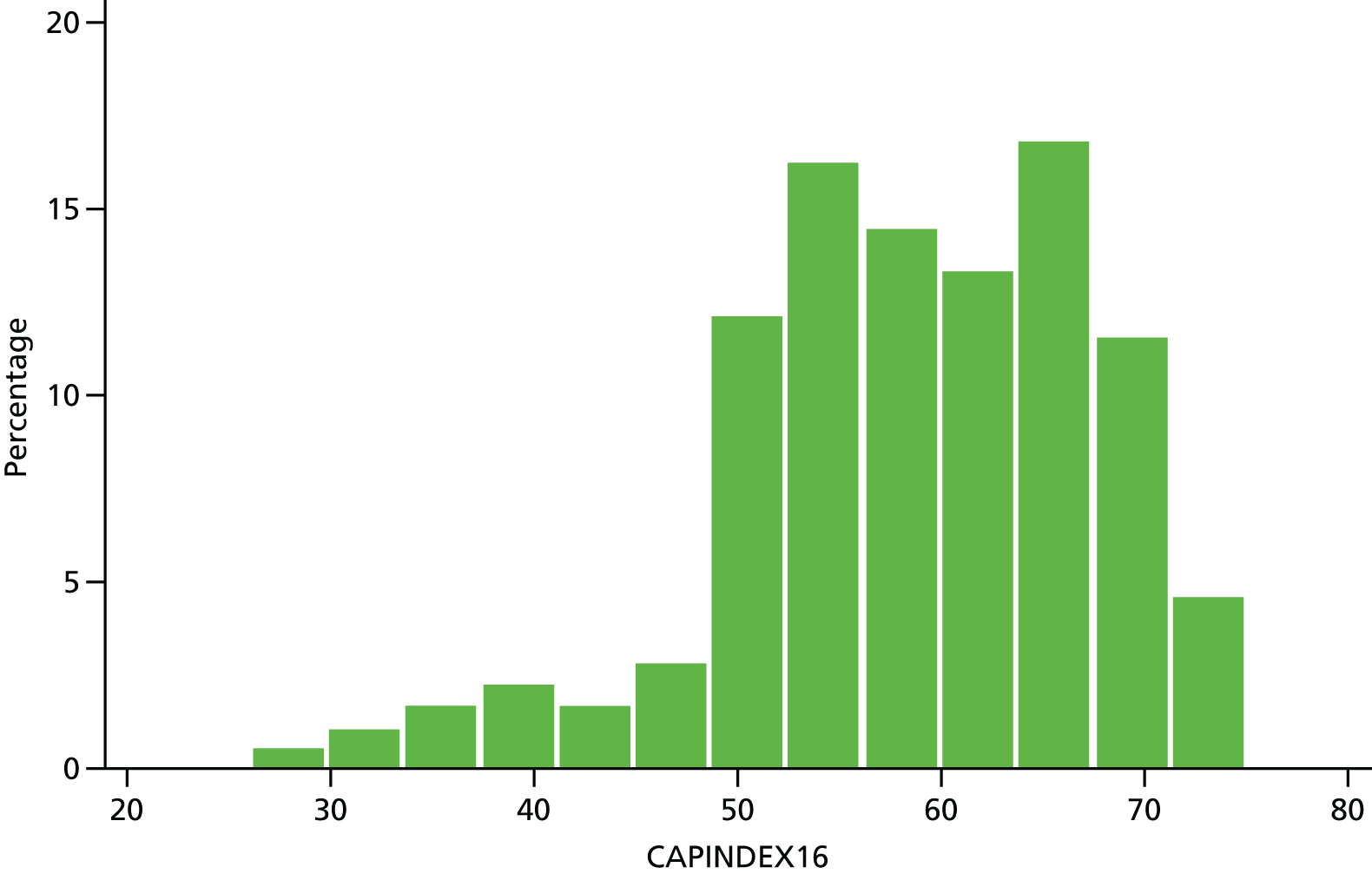

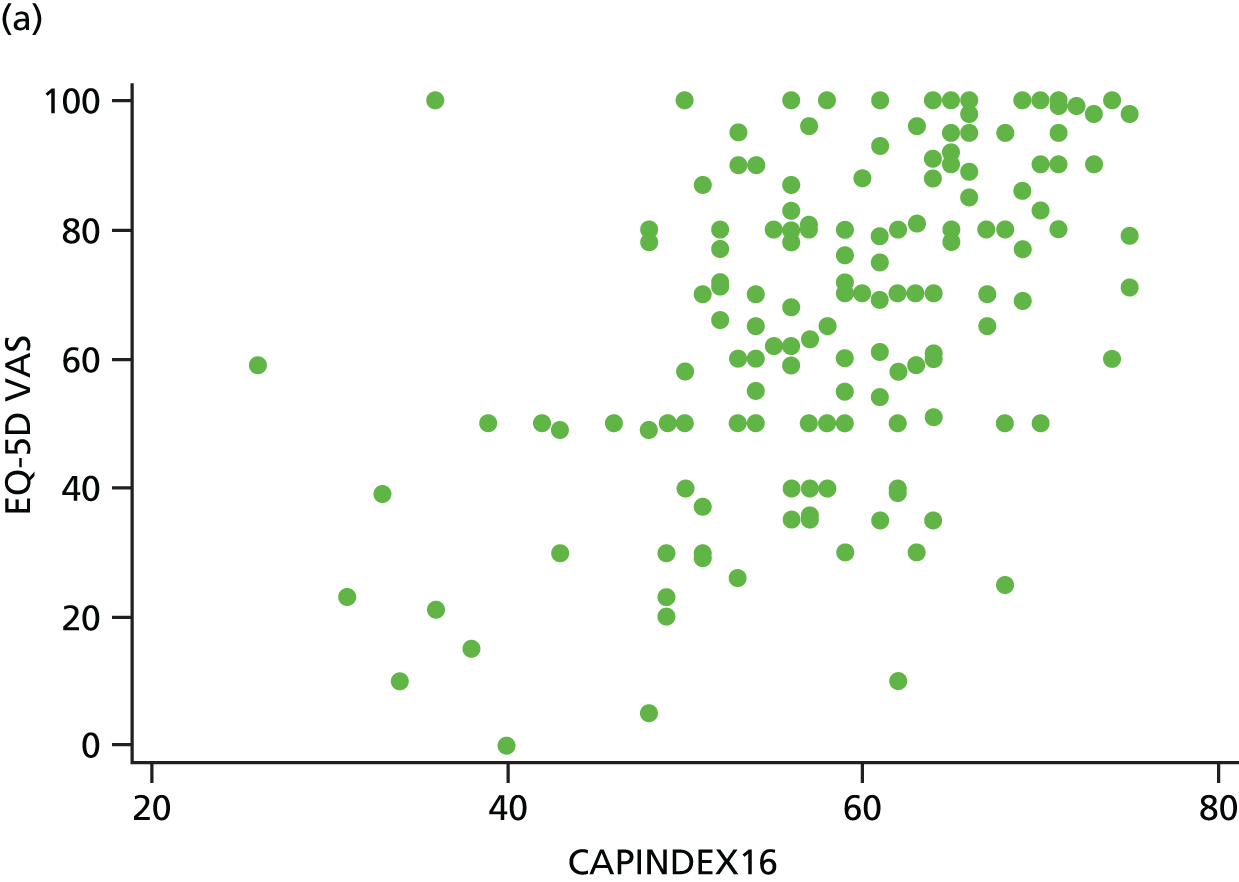

The Oxford Mental Health Coercion Programme focused on two key areas: formal and informal coercion. Formal coercion, hereafter referred to as compulsion, is authorised in mental health legislation. Within community mental health care, this takes the form of outpatient compulsion: community treatment orders (CTOs) in England and Wales. Informal coercion comprises a range of treatment pressures that mental health professionals may use with patients, including but not limited to leverage, defined as the use of an explicit and specific treatment lever.

The Oxford Mental Health Coercion Programme, which took place from 2007 to 2014, comprised three studies: the Oxford Community Treatment Order Evaluation Trial (OCTET) and the OCTET Follow-up Study, evaluating and exploring compulsion in the form of CTOs, and the Use of Leverage Tools to Improve Adherence in community Mental Health care (ULTIMA) Study, evaluating and exploring informal coercion, including leverage.

The OCTET Study was built around the OCTET Trial, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the effectiveness of CTOs, but also encompassed a number of substudies, including an economic evaluation; a qualitative study of patients’, family carers’ and professionals’ perspectives; a substudy developing and testing a measure of capabilities; an ethical analysis of the implications of CTOs; and an analysis of the lawfulness of an RCT of CTOs leading to the development of the OCTET Trial design. The OCTET Follow-up Study determined long-term outcomes of CTO use, focused on disengagement and continuity of care, through a follow-up study of the cohort from the OCTET Trial at 36 months after randomisation. The ULTIMA Study assessed patients’ experiences and perceptions of informal coercion in community mental health care in a cross-sectional quantitative study, and investigated patients’ and mental health professionals’ views in a qualitative study.

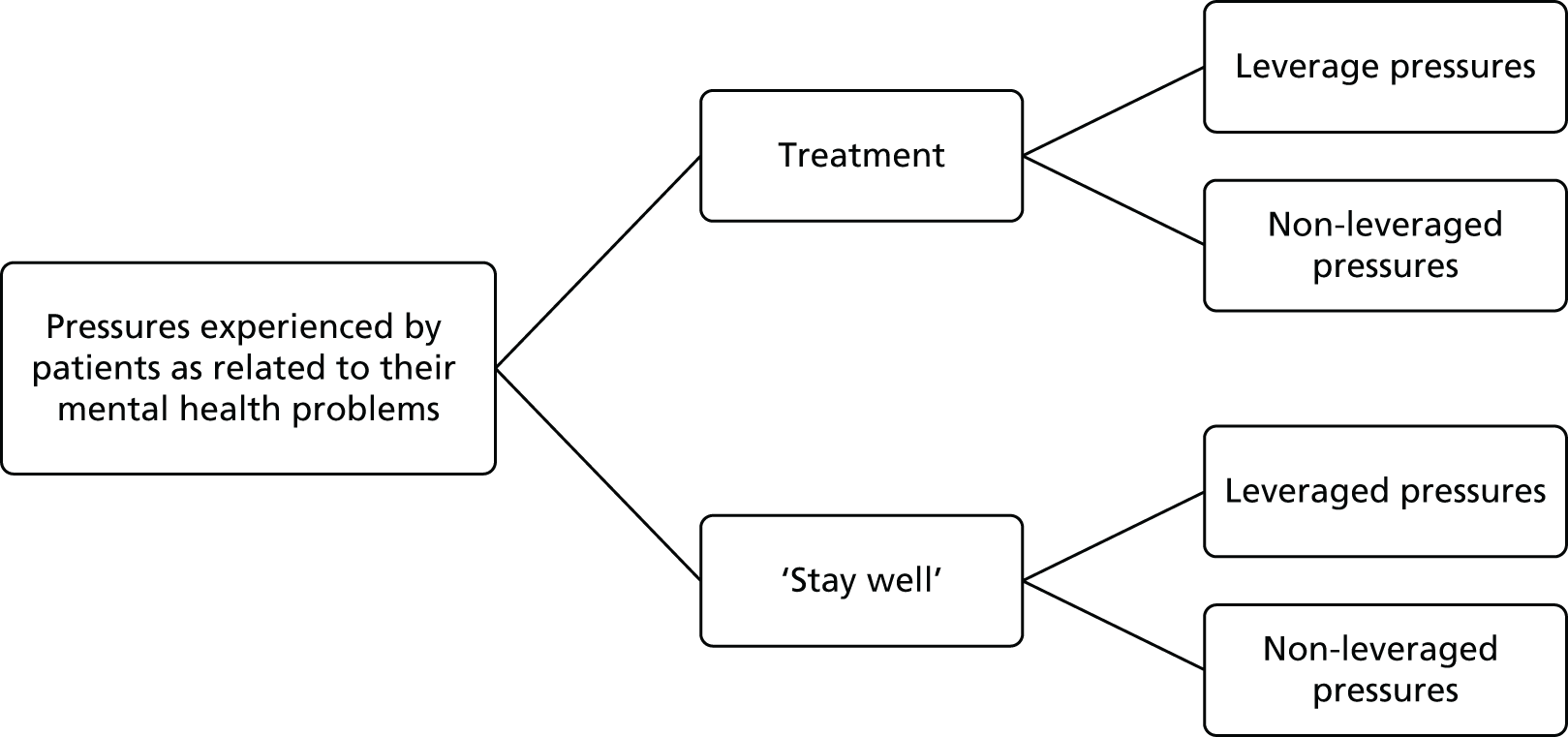

Although the literature uses a range of terminology (see Part 2, Chapter 5 and Part 4, Chapter 17), we use the terms described above throughout this report. Thus we use the term compulsion to indicate formal or statutory coercion through mental health legislation; our focus is on compulsion within community mental health care, but other types of compulsion are discussed when this is relevant to understand CTO legislation or the procedures of our trial. We use informal coercion to cover the range of treatment pressures mental health professionals may exert over patients, and reserve leverage for those in which a particular explicit treatment lever is utilised. We use the term perceived coercion to indicate patients’ assessments of coercion in their care (Figure 1). For clarity, the term discharge is used to indicate discharge from inpatient care rather than from an involuntary to a voluntary legal status; for the latter, we use discharge from section (referring to a section of the mental health legislation).

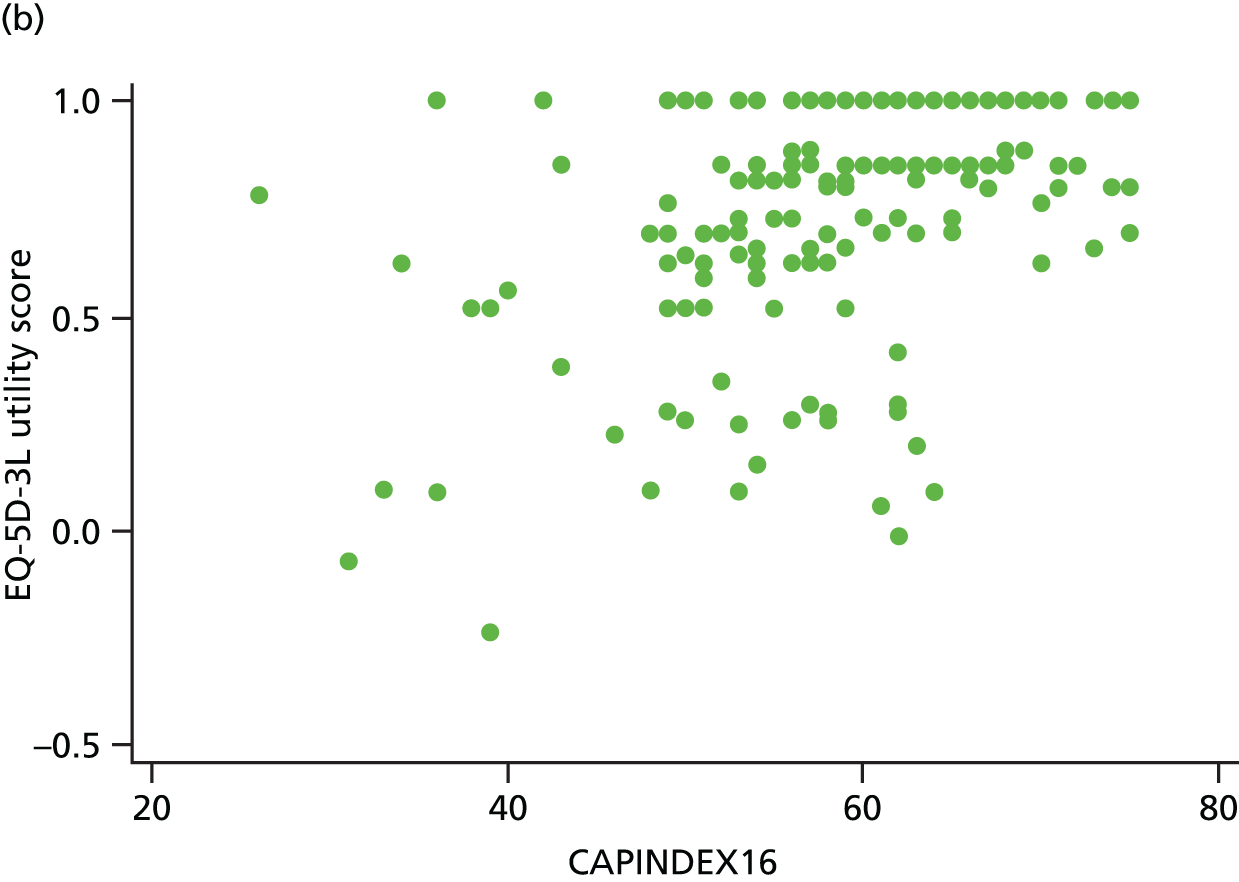

FIGURE 1.

Coercion in community mental health care.

Each study reported here – the OCTET Study, the OCTET Follow-up Study and the ULTIMA Study – appears in a separate section of the report (see Parts 2–4, respectively). Each has its own introduction, including the background to the study, and its own discussion section. Individual chapters within these three parts then report the main study and the related substudies, such as the OCTET Trial within the OCTET Study.

The OCTET Study, and in particular the OCTET Trial, was a tremendous undertaking in its scope and complexity, as well as in its international importance. We describe the development of the OCTET Trial design, including extensive consultation with stakeholders and legal experts, in an introductory section to the OCTET Study (see Part 2, Chapter 6, Introduction), along with the complicated logistics involved in the trial’s execution.

The OCTET Trial had a tremendous impact when its findings were first published, and international interest in it has been extensive. We have given 109 presentations on the whole programme to date, of which 67 were on the findings of the OCTET Trial, across 22 countries. The OCTET Trial also generated considerable controversy. We describe these aspects in the final section of the report (see Part 5) and here we also detail the dissemination of the studies in the Oxford Mental Health Coercion Programme (henceforth referred to as the OCTET Coercion Programme). We also describe the range of additional research generated through the programme’s capacity building. This is also where we discuss the findings of the entire programme and give recommendations for future research.

In the remainder of Part 1, we describe the rationale for the OCTET Coercion Programme, its objectives and how the three studies met these objectives, and its overall governance structures.

Chapter 2 Rationale

We designed the OCTET Coercion Programme to fill significant gaps in the evidence base concerning compulsion and informal coercion by conducting a series of high-quality linked studies. Our aim was to improve understanding of the care of severely unwell patients experiencing multiple admissions, particularly patients with psychosis, and to guide the targeting of the new powers conferred by CTO legislation. We also designed the programme to form the basis of effective evidence-based practice guidance for both this group and a wider group of patients whose treatment is not subject to compulsion but who, nevertheless, experience high degrees of dependency on mental health services. It was designed to address public, professional and policy concerns,1,2 with the aim of facilitating a more balanced, less stigmatising, public engagement with the issues.

The management of people with severe mental illness in the community (and, in particular, failures to achieve it) has been the yardstick used by the public to judge mental health services. There is a pressing need to understand better and improve how professionals succeed in maintaining contact and support treatment adherence with these patients.

The introduction of compulsory treatment in the community has been intensely controversial, and has remained so, sustained by the absence of convincing scientific evidence for its effects (despite its widespread adoption internationally) (see Part 2, Chapter 5). Providing such evidence is particularly necessary because of the complex ethical balance of personal autonomy against the need for care and public safety, and because there are strongly held conflicting opinions. There is also a pressing need to determine whether or not a reduction in personal autonomy resulting from being on a CTO is sufficiently justified by concomitant clinical improvements.

As we describe below (see Part 2, Chapter 5), there is a substantial gap in the evidence base for supervised community treatment. 3,4 There is thus a compelling need to provide the most robust evidence possible, for both clinical and ethical reasons. To conduct such research in the form of an RCT, the accepted gold standard for evidence of the effectiveness of interventions, is hugely important both for patients and for the clinicians who have responsibility for making decisions about their care. Without such a study, a clear estimate of the effects of CTOs cannot be acquired, and understanding of their target patient group and implementation would accrue only slowly and unsystematically.

We therefore designed the most extensive of the studies in this programme, the OCTET Trial, to provide robust evidence of the effectiveness for patients with psychosis of CTOs, which had just been introduced in England and Wales at the time of the study’s inception, and to give a clear and early indication of the specific clinical groups that might or might not benefit from them. The trial included a rigorous economic analysis in order to inform policy and resource planning. It was anticipated that the OCTET Study might identify a trade-off between improved outcomes and the duration of compulsion. We investigated this by developing and testing a new instrument to measure capabilities.

In the OCTET Follow-up Study, the longer-term implications of CTO use for these patients were investigated through a follow-up of the original OCTET Trial cohort focusing on disengagement, hospitalisation, discontinuity and the use of involuntary treatment at 36 months after randomisation. Until now, no empirical study has been published about persisting effects of CTOs. Serious concerns about CTO use motivated this study, particularly that the compulsion involved might be excessively prolonged5,6 and might lead to disengagement from services. We thus designed the study to determine whether or not CTOs might drive patients away from services.

Establishing the extent and form of informal coercion, including leverage, and its variation across different clinical groups is an essential precursor to an informed debate on its place in modern community mental health care. Such a debate would also inform the inclusion of discussions of what informal coercion is and how patients experience it in mental health training. The ULTIMA Study represents the largest systematic study of patient-reported informal coercion and leverage in European mental health services to date. We designed this study to identify the frequency and pattern of leverage and replicate the methods of a key study from the USA,7 thus providing both the first English data and an international comparison. The ULTIMA Study also expanded on the previous research by examining patterns of leverage and informal coercion more widely across different patient populations, and investigating the association of leverage with important clinical characteristics.

Both the OCTET Study and the ULTIMA Study included qualitative substudies conducted with patients and mental health professionals and, in the OCTET Study, family carers, in order to access insights beyond those which would be achievable by quantitative and experimental means. 8 Qualitative methods are recognised as an excellent way of exploring areas for which there is a paucity of data. They are flexible and adaptable and can allow for changes or refinement of instruments during the course of the research. They commonly encourage discussion of issues deemed important by research participants. We designed the qualitative substudies in OCTET and ULTIMA to access perspectives on CTO use and informal coercion, respectively, which might be key to understanding their mechanisms of action and guiding policy decisions. 9,10 They included close attention to patients’ and professionals’ understanding of the use of compulsion and informal coercion within therapeutic relationships. Given the central role of therapeutic relationships in current mental health policy,11 investigating the conceptualisations of these relationships by those involved in them has the potential to shed light on how such policy is implemented in practice.

The programme also included an extensive exploration of the ethical issues surrounding the use of community coercion. The two qualitative substudies provided an opportunity to identify dilemmas and ethical aspects of compulsion and informal coercion. The ethical substudies were designed to break new ground in informing development of training in good practice, relate findings to the wider context and promote a more nuanced public discourse.

Chapter 3 Aims, objectives and programme design

The overall aim of the OCTET Coercion Programme was to obtain a detailed understanding of the compulsion and informal coercion experienced by patients with mental health problems, including testing the effectiveness of CTOs following their introduction into English and Welsh mental health legislation in 2008.

This aim was to be achieved by six overarching objectives [as expressed in the original National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) grant application]. We follow each objective listed here by a brief description of how it was met by different studies or substudies within the OCTET Coercion Programme (Table 1).

| Objective | Study/substudy | Part/chapter |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Informal coercion | ULTIMA | Part 4 |

| ULTIMA Quantitative Study | Chapter 18 | |

| 2. Obstacles, ethical, legal, clinical and practical | OCTET | Part 2 |

| Legal Analysis | Chapter 11 | |

| 3. CTO trial | OCTET | Part 2 |

| OCTET Trial | Chapter 6 | |

| 4. Experiences of patients, carers and staff, including ethical dilemmas | ULTIMA | Part 4 |

| ULTIMA Qualitative Study | Chapter 19 | |

| ULTIMA Ethical Analysis | Chapter 20 | |

| OCTET | Part 2 | |

| OCTET Qualitative Study | Chapter 8 | |

| OCTET Ethical Analysis | Chapter 9 | |

| 5. Economic evaluation | OCTET | Part 2 |

| Economic Evaluation | Chapter 7 | |

| Capabilities Project | Chapter 10 | |

| 6. Disengagement and readmission at 36 months | OCTET Follow-up | Part 3 |

Objective 1

To investigate levels of informal coercion (‘leverage’) in differing UK clinical populations and investigate their sociodemographic and clinical correlates.

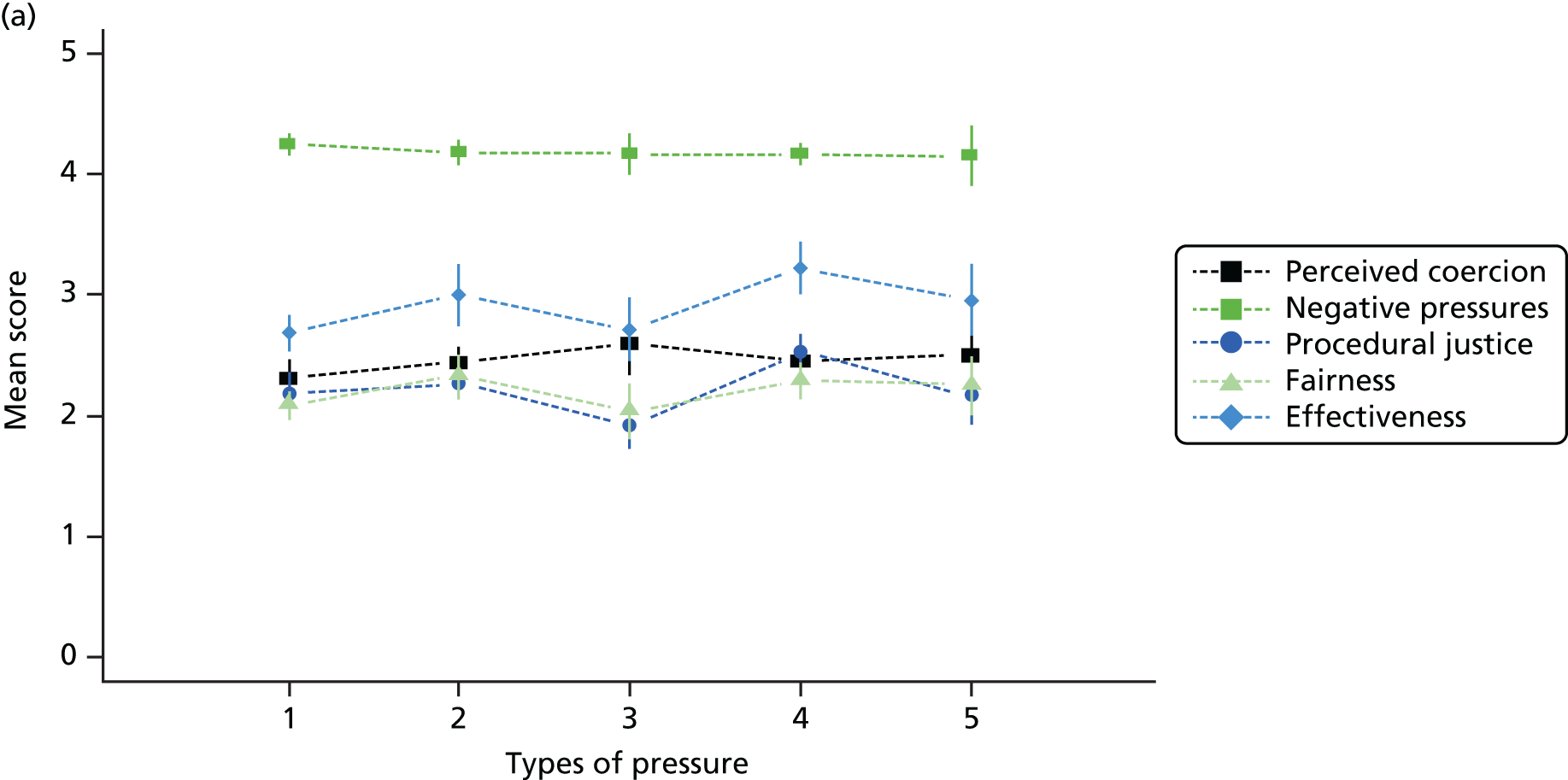

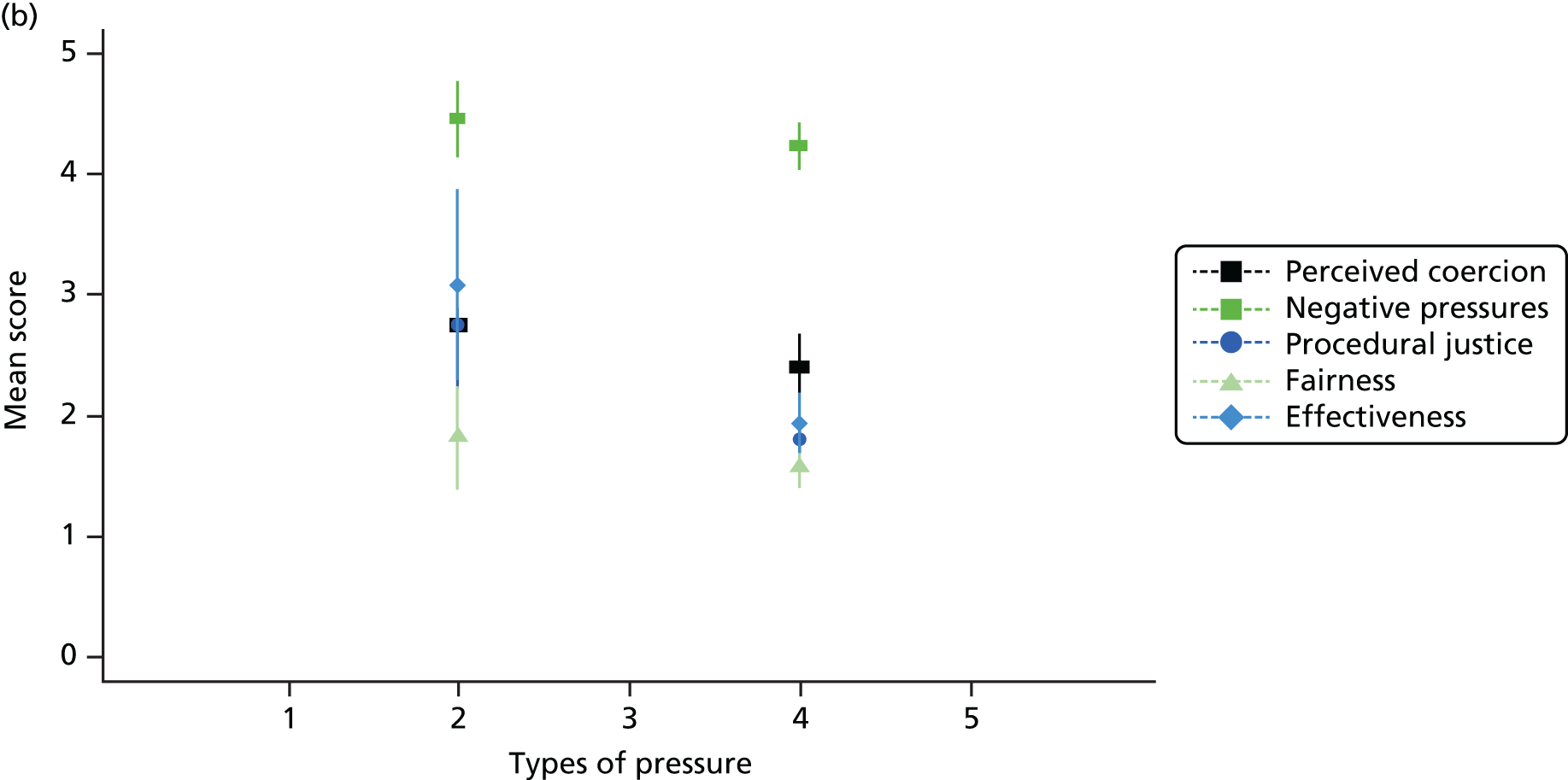

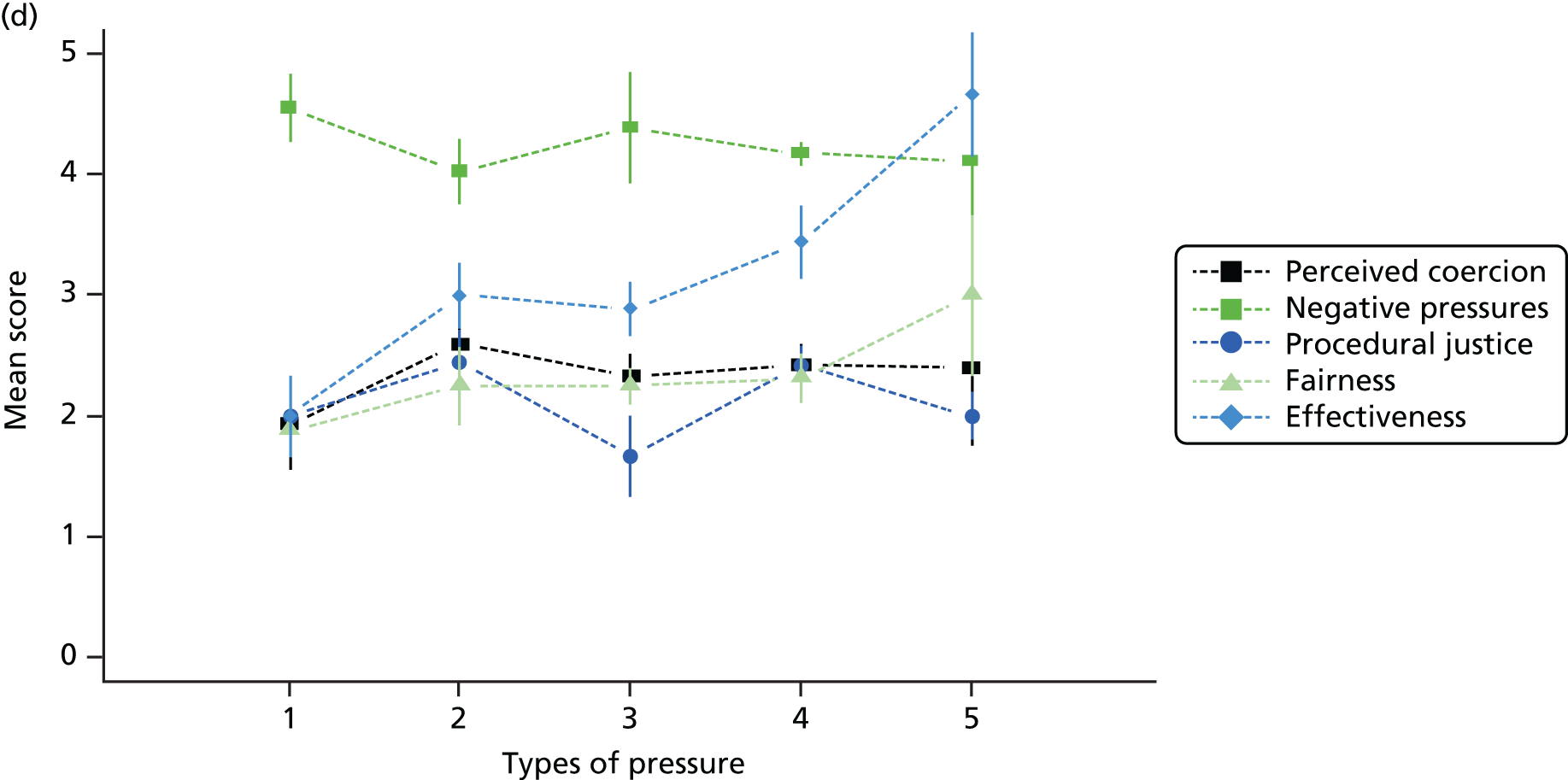

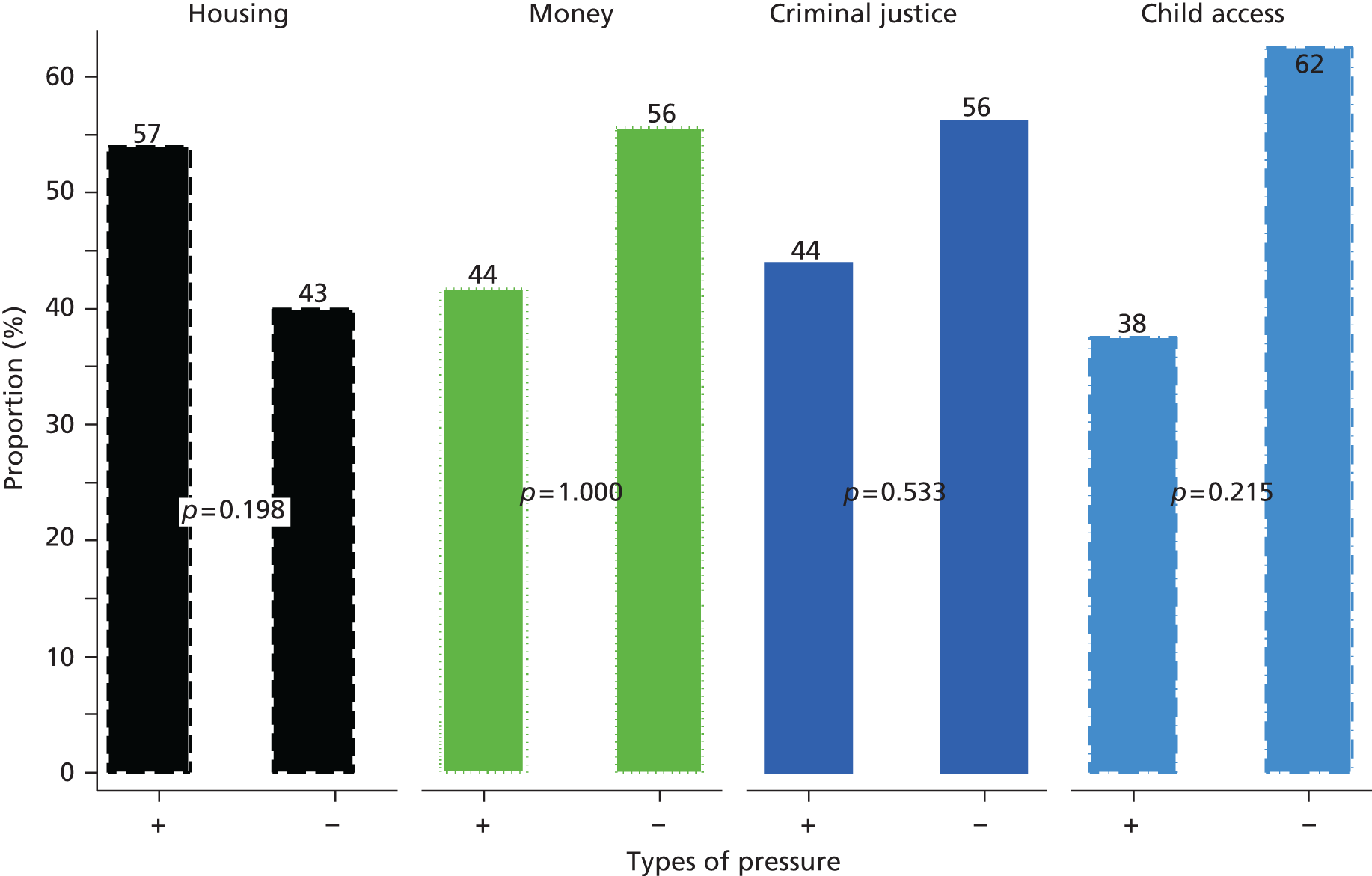

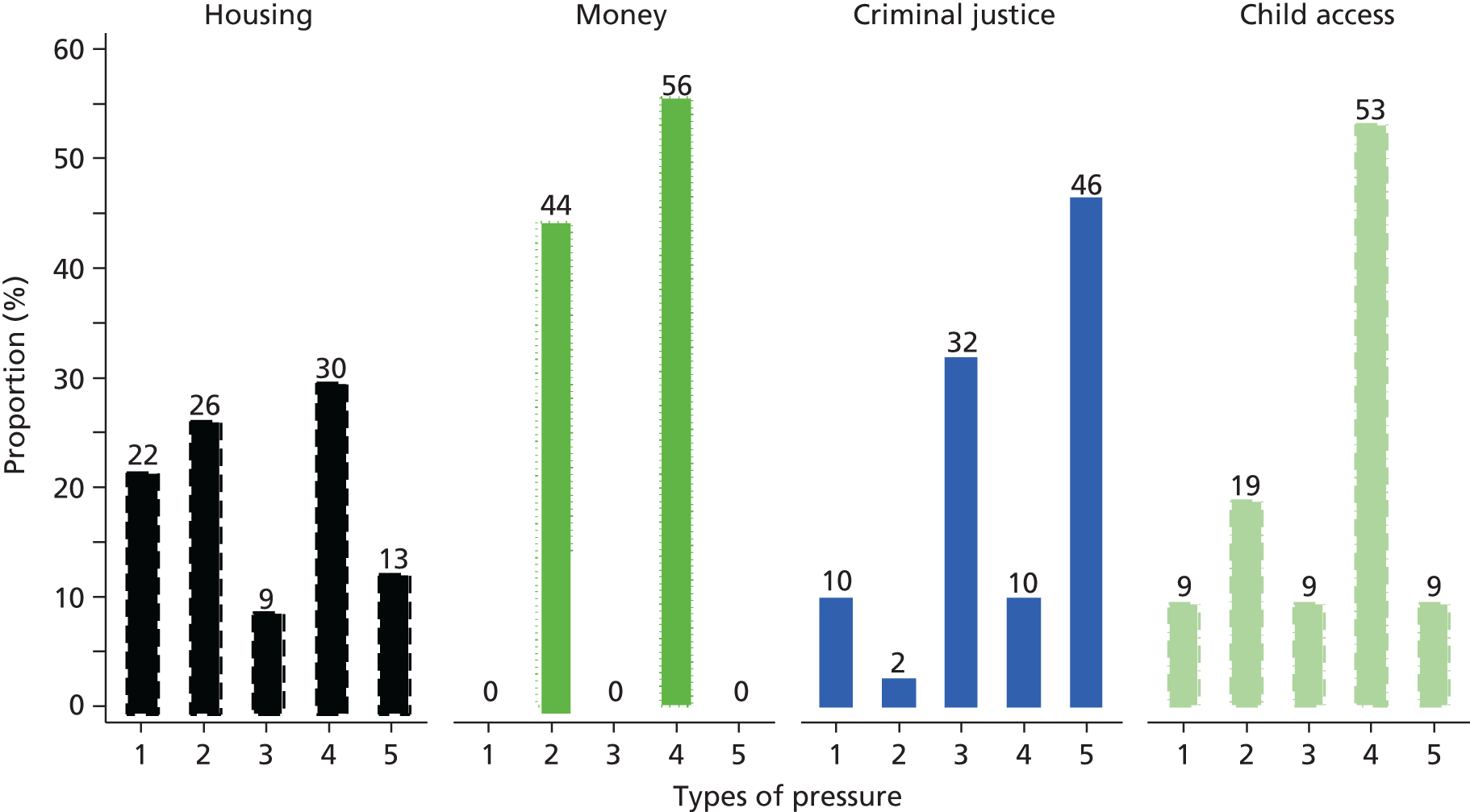

We addressed this objective by conducting the ULTIMA Quantitative Study of informal coercion (see Part 4, Chapter 19). We interviewed four distinct samples [psychosis patients in Assertive Outreach Teams (AOTs), psychosis and non-psychosis patients in Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) and substance misuse patients] about their lifetime experiences of four forms of leverage (housing, finance, avoidance of criminal sanction and child access). We also explored associations between these leverages and patient and treatment characteristics and perceived coercion.

Objective 2

To explore and address the ethical, legal, clinical and practical obstacles to designing and conducting the most powerful study possible for testing the efficacy of community treatment orders, which will maximise the power of the conclusions for policy and practice.

We addressed this objective in a preliminary substudy within the OCTET Study conducted as a means of designing the most appropriate and most powerful RCT possible. The aim was to establish the feasibility of, and obtain agreement about and support for, the strongest test of the intervention, in order to produce a detailed study brief. We held a series of meetings with clinicians and legal, policy and ethical groups in order to carry out a detailed investigation of ethical, legal and practical issues of methodologies to test the impact of CTOs (see Part 2, Chapter 5). The need for a detailed legal analysis emerged through this process and we report this in detail in a separate chapter (see Part 2, Chapter 11).

Objective 3

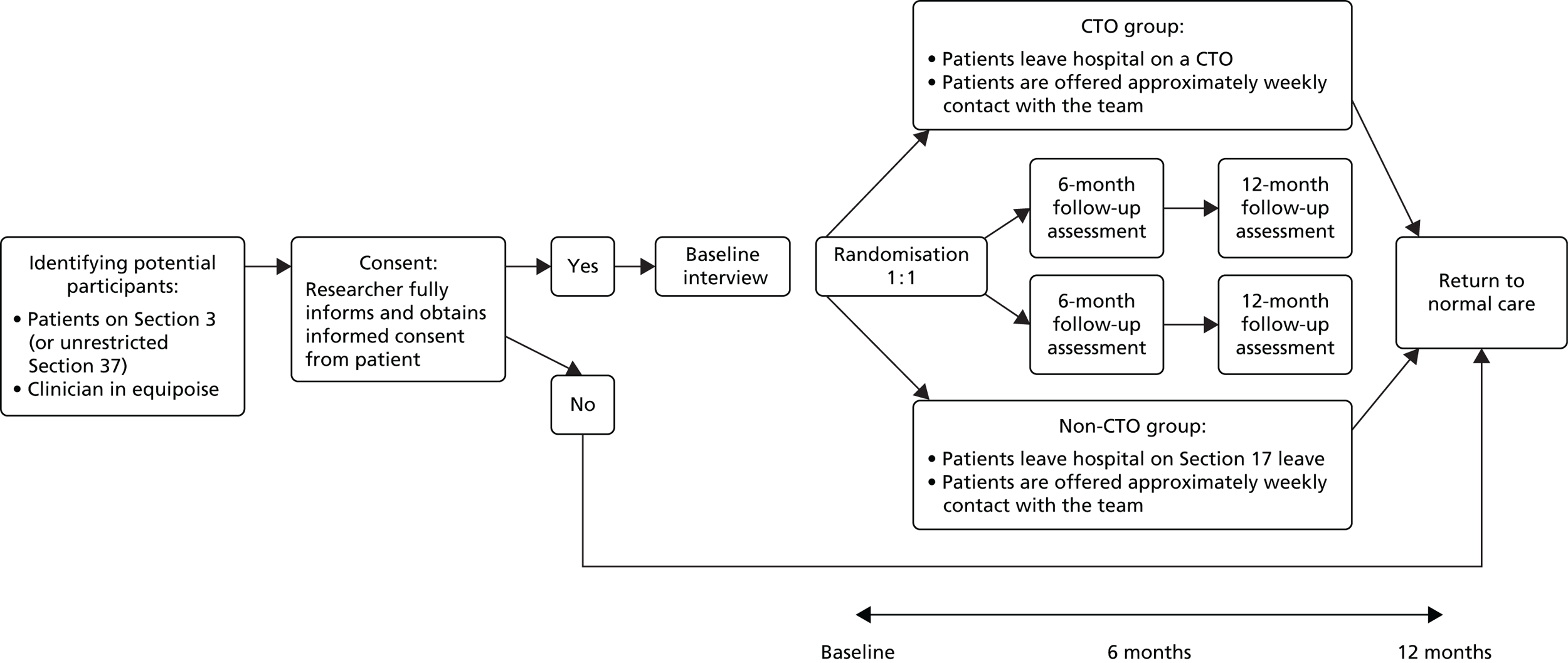

To conduct the most rigorous trial possible of community treatment orders, with prolonged, high-quality care incorporating a broad range of outcomes, and identify patient and service predictors of response.

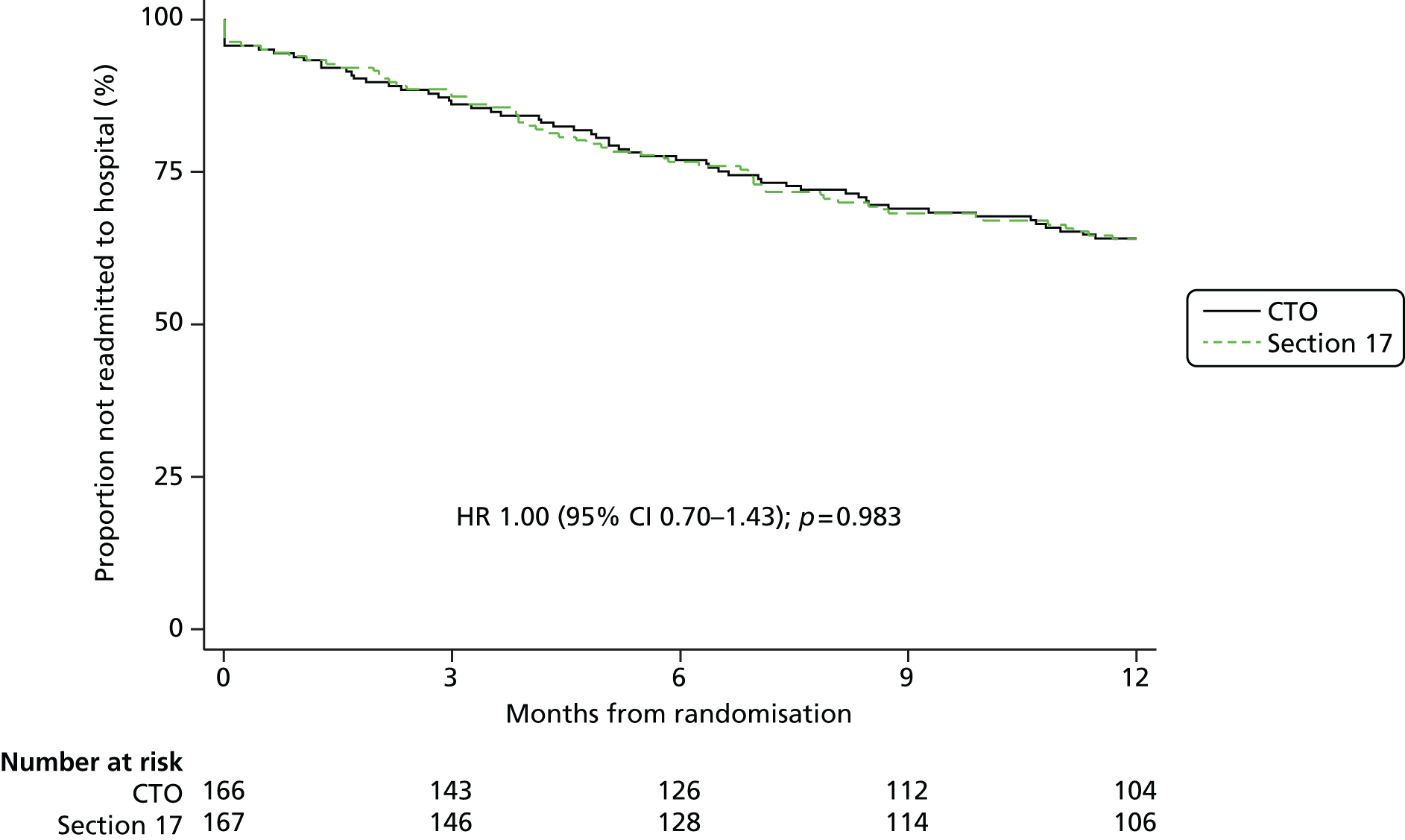

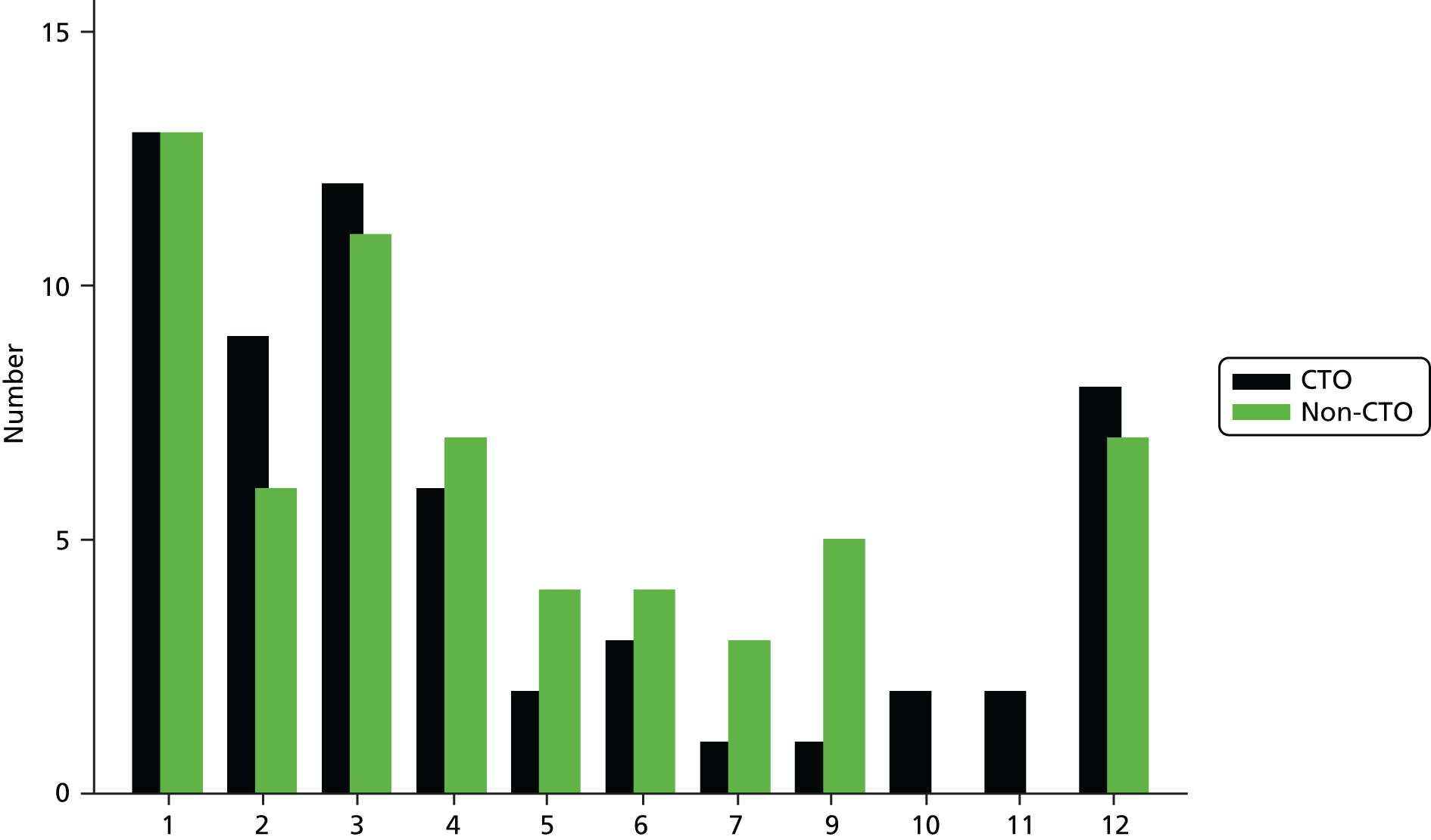

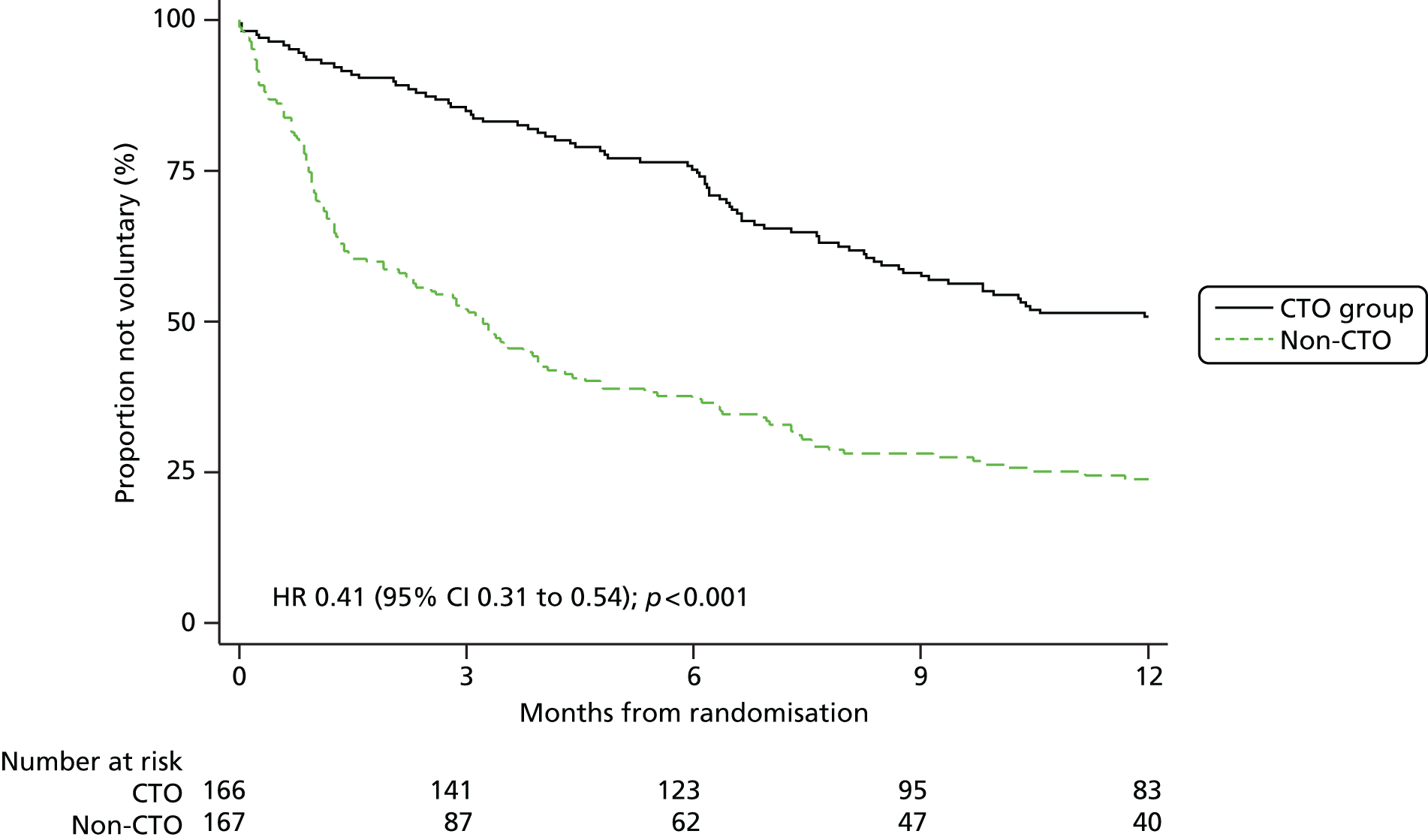

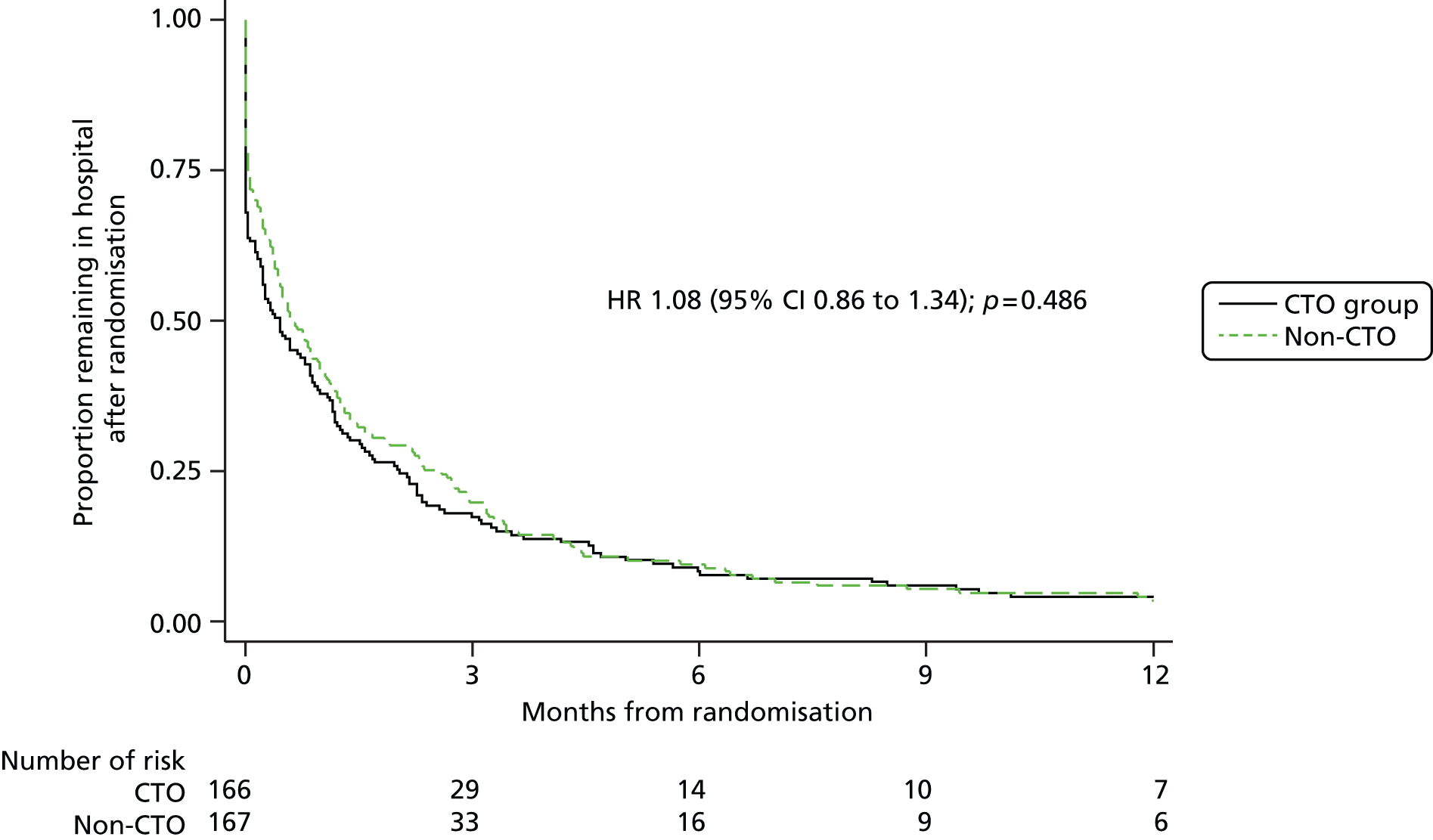

Following the successful completion of the analysis of obstacles meeting objective 2, we met objective 3 by conducting the OCTET Trial (see Part 2, Chapter 6). The objective was to compare CTO use with voluntary outpatient care, although legal advice required that patients be randomised to leave hospital either on a CTO or via Section 17 Leave. Independent researchers conducted interviews with patients at baseline and at 6 and 12 months, and examined case notes. The primary outcome was rate of readmission. Other outcomes included Mental Health Act (MHA)12 use and patterns of care and social and quality of life outcomes. We also explored patient and treatment characteristics that were associated with outcomes.

Objective 4

To conduct a detailed qualitative assessment of the experiences (including ethical dilemmas) of patients, staff and carers in both studies.

We met this objective by conducting two qualitative substudies: the ULTIMA Qualitative Study (see Part 4, Chapter 19) and the OCTET Qualitative Study (see Part 2, Chapter 8), each of which conducted a qualitative exploration of the experiences and perceptions of patients in the study and other key groups. We sampled from each study in order to conduct a series of semistructured, in-depth interviews with a subsample. For mental health professionals in the ULTIMA Study, we used focus group methods. We did not seek the experiences of family carers in the ULTIMA Qualitative Study, for reasons given below (see Part 4, Chapter 19), but we included their experiences of informal coercion as well as CTOs in the OCTET Qualitative Study. In both substudies, we analysed the qualitative data in two ways: first, to explore experiences and perceptions of CTOs (OCTET) and informal coercion (ULTIMA), and, second, to address ethical questions raised by the use of CTOs (OCTET) and informal coercion (ULTIMA). We report the Ethical Analyses arising from this secondary aim of the two substudies separately (see Part 2, Chapter 9 and Part 4, Chapter 20, respectively).

Objective 5

To conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis of community treatment orders and model the costs of their national introduction.

We met this objective by conducting an economic evaluation as part of the OCTET Trial (see Part 2, Chapter 7). This comprised a detailed cost analysis of health, social care and other broader societal costs, and an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis. We also developed a capabilities and well-being index13 from the capabilities framework. 14 We report the development of this index separately (see Part 2, Chapter 10).

We later added an additional objective, to be met by a further study, as agreed by the funder.

Objective 6

To compare disengagement and clinical outcomes between those randomised to community treatment order and those randomised to non-community treatment order treatment at 36 months after randomisation.

We met this objective by conducting the OCTET Follow-up Study (see Part 3). It aimed to establish whether or not CTO use had a significant effect on rates and duration of readmission, engagement with services and service use at 36 months after randomisation. This was based on medical records and a follow-up to patients to measure longer-term outcomes.

The original proposal also included a further objective: ‘to develop a training package for best clinical and ethical practice in CTOs and use of leverage’. We subsequently omitted this, by agreement with the funder, as Department of Health training programmes in CTO use had already been initiated by this time. The OCTET team held an annual conference involving clinicians involved in the trial and other interested clinicians, attended by up to 90 people each time (see Appendix 4). The contribution towards training was also indirectly met by the considerable amount of discussion and debate generated by the study, along with dissemination conferences, associated studies and replication studies (see Part 5, Chapter 22).

Chapter 4 Ethical approval, registrations, user involvement and data

The Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee A gave ethical approval for the ULTIMA Study (22/02/2006, reference no. 05/Q1604/180).

The Staffordshire NHS Research Ethics Committee gave ethical approval for the OCTET Study (30/10/2008, reference no. 08/H1204/131). An amendment to the ethical approval (20/07/2011) covered the additional work required for the OCTET Follow-up Study, which was funded by a supplementary grant held from 2012 to 2014.

The OCTET Trial is registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (reference: ISRCTN73110773). All three studies were part of the UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio.

We performed all three studies in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. 15 Some changes to the original research protocols were agreed with the funder and the relevant ethics committees during the course of the research, as we describe below (see Part 2, Chapter 6, Methods and Part 4, Chapter 19, Methods).

We held a number of meetings with service user and carer representatives during the course of the programme to discuss the procedures for the studies. (We give details about governance for the OCTET Study in more detail below; see Part 2, Chapter 5, Governance.) The service user and carer representatives on the OCTET Steering Group formed part of the OCTET Follow-up Study’s governance structure. We designed the OCTET Follow-up Study partly to meet concerns raised by service users and service user representatives in the consultation phase of the OCTET Trial.

Part 2 The OCTET Study

Abstract

Background

Community treatment orders were introduced in England and Wales in 2008, despite equivocal evidence of effectiveness.

Design

The study comprised an RCT (OCTET Trial) comparing treatment on CTO to voluntary treatment via Section 17 Leave, over 12 months; an Economic Evaluation; a Qualitative Study and an Ethical Analysis. A new measure of capabilities was developed.

Methods

Trial participants were patients with psychosis diagnoses currently admitted involuntarily and considered for ongoing community treatment under supervision. The trial primary outcome was psychiatric readmission. Secondary and tertiary outcomes included hospitalisation and a range of clinical and social measures. A subsample of patients, carers and mental health professionals was interviewed in depth.

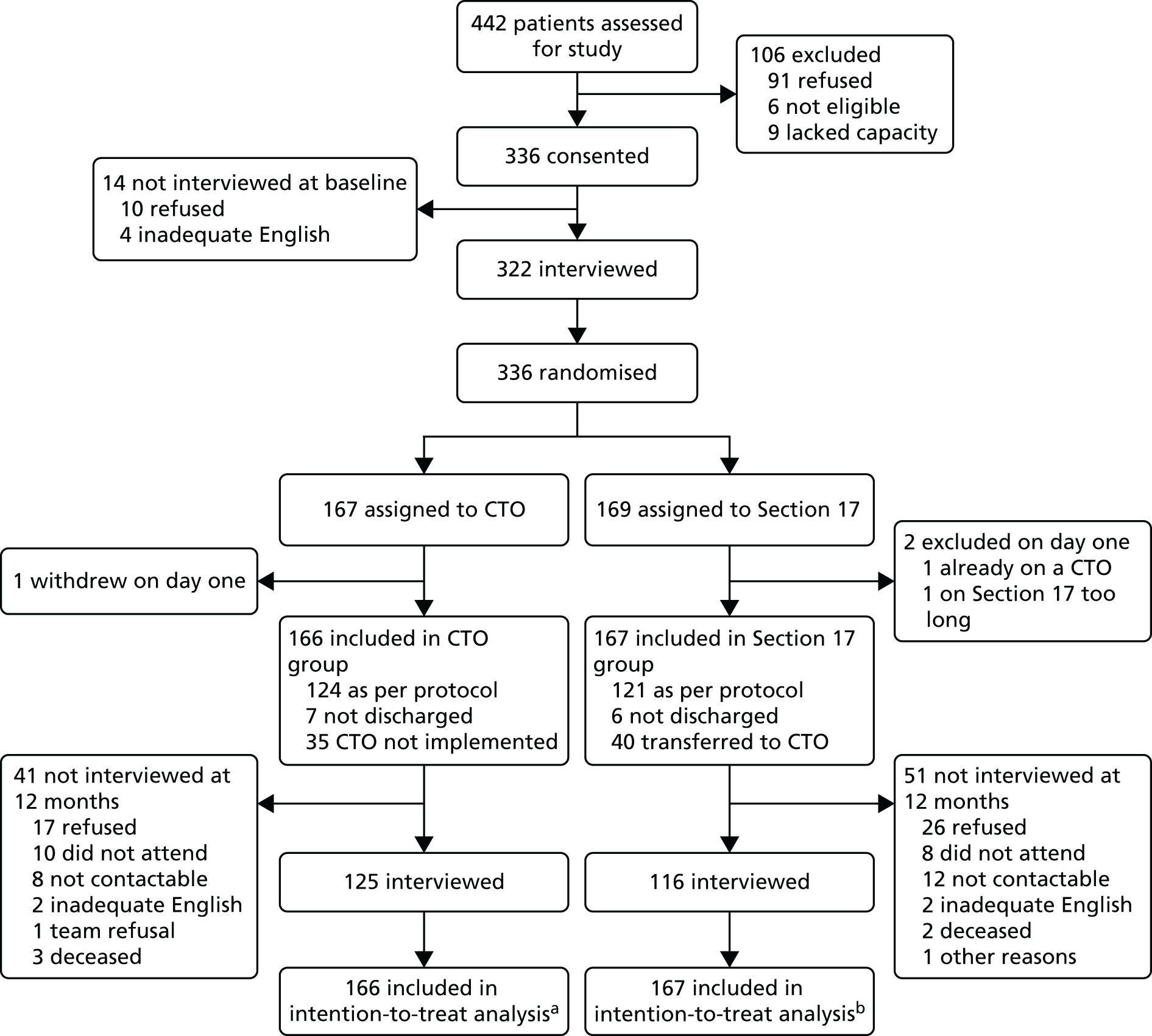

Results

A total of 336 patients were randomised. CTO use did not reduce rates of readmissions to hospital {[59/166 (36%)] of patients in the CTO group vs. 60/167 (36%) of patients in the non-CTO group; adjusted relative risk 1.0 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.33)} or any other secondary or tertiary outcome. There were no differences for any subgroups. It did not reduce hospitalisation costs and there was no evidence that it might be cost-effective. The results from in-depth interviews about CTO experiences with 26 patients, 24 family carers and 25 psychiatrists showed divergent views and that CTOs’ (perceived) focus on medication adherence may influence how they are experienced. No general ethical justification was found for the use of a CTO regime.

Conclusions

Community treatment orders do not confer early patient benefits despite substantial curtailment of individual freedoms.

Chapter 5 Introduction to the OCTET Study

Overview

The OCTET Study was built around the OCTET Trial. It comprised the following:

-

OCTET Trial An RCT evaluating the effectiveness of CTO use.

-

OCTET Economic Evaluation A detailed cost analysis of health, social care and other broader societal costs and an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis.

-

OCTET Qualitative Study An in-depth investigation of patient, carer and professional views and experiences of CTOs, utilising interviews with a subgroup from the OCTET Trial cohort and recruited groups of carers and mental health professionals.

-

OCTET Ethical Analysis A detailed empirical ethical analysis drawing on the OCTET Trial and qualitative data from the Qualitative Study.

-

OCTET Capabilities Project A study of the operationalisation of the capability model for outcome measurement in mental health studies, tested in the OCTET cohort.

-

OCTET Legal Analysis An investigation of the legal implications of designing an RCT of CTO use which preceded and informed the design of the trial.

The rigorous RCT design of the OCTET Trial (see Chapter 6) was designed to test the use of CTOs in the target group considered by most clinicians to be likely to benefit from the new regime. It included an economic evaluation (see Chapter 7), which also applied the newly developed multidimensional capabilities instrument and the resulting capability index, developed and tested in the trial cohort (see Chapter 10).

The OCTET Qualitative Study (see Chapter 8) was designed to complement and extend the trial results. Rather than testing a predetermined hypothesis, the objective here was to explore personal experiences of and perspectives on CTOs that might turn out to be the key to understanding their mechanism of action. This was particularly important given that CTOs were new at the time of the study’s inception, and it was impossible to anticipate all of the potential relevant outcomes in the trial. It was also important to explore the reasoning of psychiatrists, patients and family carers about their perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of CTOs.

The OCTET Qualitative Study also provided an opportunity to identify the dilemmas and ethical aspects of using compulsion in community mental health care. We conducted a detailed ethical analysis in the context of the relevant empirical data and the ethics literature: the OCTET Ethical Analysis (see Chapter 9). A thorough exploration of ethical, legal, clinical and practical obstacles to developing the OCTET Trial preceded the finalisation of the OCTET protocol. The consultation exercise undertaken to this end is summarised below (see Chapter 6, Introduction), whereas the OCTET Legal Analysis is given in full in Chapter 11.

Background

This section draws substantially on papers by members of the OCTET Coercion Programme Group (Burns et al. ,16 with permission from Elsevier; Molodynski et al. ,17 with permission from Oxford Journals; and Rugkåsa et al. ,18 with permission from Springer Publishing Company).

Mental health care in the community

Mental health care is an international priority. 19 In the UK, expenditure on mental health care accounts for between 3% and 4% of gross domestic product. 20 Mental ill health is the leading cause of invalidity benefit in the UK21 and mental disorders are set to become the major causes of disability worldwide. 22

Psychiatry is the only area of medicine in which adult, competent patients can be treated against their will. This is governed by specific mental health legislation (in the UK, the MHA). Compulsory treatment is integral to mental health care and was originally restricted to inpatient settings. 23 Over the last 50 years or so, however, a policy focus on deinstitutionalisation has gradually moved psychiatric services from hospital settings into the community. The psychiatric inpatient population has fallen drastically in developed countries since its peak in the mid-1950s. 24 In England and Wales, for example, although there were 154,000 psychiatric beds in 1954, this had been reduced to 33,000 by 2005,25 despite the overall increase in the population. This has placed new demands on practices, policies and legislation for managing individuals with mental illness and their associated complex vulnerabilities.

Community psychiatry creates difficulties for professionals in terms of how to encourage and monitor patients to ensure both their safety and well-being and that of others. Community services may subject patients to intense levels of supervision, restrictions on their behaviour and elements of compulsion. 26 In fact, it is now commonly accepted that coercive treatment is provided outside hospitals. 27 This has been reflected in several amendments and challenges to mental health legislation over the last 30 years, as new models for more assertive treatment in the community have emerged, often monitoring patients closely while seeking to assist them to achieve stability, insight and independence. 28–30

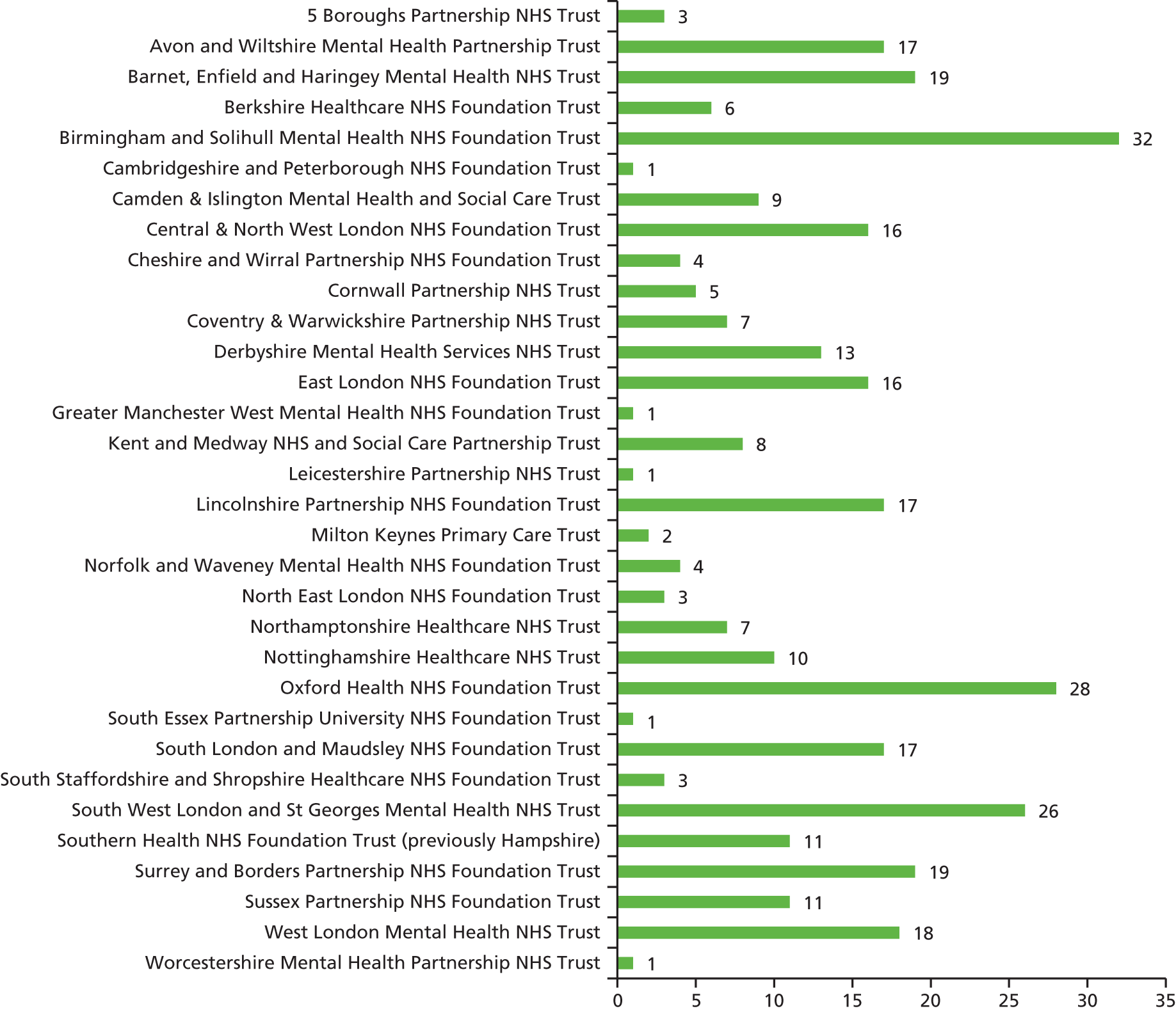

Various provisions to maintain contact with outpatients are used where required, at differing levels of intensity and regularity as appropriate. Mental health services are increasingly delivered via case management approaches by multidisciplinary teams consisting of psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, social workers, support workers and occasionally other professionals such as occupational therapists. 28,31,32 Such case management may be provided by the CMHT, a multidisciplinary team with diagnostically mixed caseloads (usually 1 : 25) and some provision of outreach. An alternative model, the AOT, was introduced in England from 1999,20 modelled closely on Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams as developed in the USA. 33 AOT teams target hard-to-engage patients with psychosis and provide much more intensive multidisciplinary outreach with small caseloads (1 : 12). These services operate within policy frameworks such as the Care Programme Approach20 and, less often, within legal frameworks provided by mental health legislation. The terms and implications of these provisions tend to vary by jurisdiction. 34,35 In England, specialist mental health services are provided by area-based UK NHS mental health trusts, each divided into catchment areas where, at the start of the OCTET Trial, community teams provided both community and inpatient care. As we discuss below (see Chapter 6, Introduction), during the recruitment phase of the trial, many trusts separated their inpatient from their community services, and CTOs were then increasingly initiated by specialist inpatient psychiatrists. 36

Community care37 has been a success for the majority of patients who have been discharged from long-term inpatient care to more dignified and rewarding lives in the community. It increasingly provides for severely disabled patients requiring complex and expensive care. 38 Despite these efforts, a substantial minority of patients are subject to repeated compulsory admissions (‘the revolving-door syndrome’39). The absolute rate of these involuntary admissions has increased following deinstitutionalisation. 40

At the same time as community mental health services have evolved, public confidence in community care has, in many countries, been profoundly undermined by a series of high-profile violent offences: usually by individuals with psychosis who, although known to mental health services, were not effectively engaged in treatment. 41 This has given rise to significant public concern about the ability of services to manage severely ill patients in the community, possibly contributing to recent trends of increasing compulsion and institutional care, with its attendant high costs. Policy-makers and clinicians have long been concerned to address such concerns about the safe management of severely ill patients. 42 In the UK, however, a number of alterations to the MHA such as Supervision Registers43 and Supervised Discharge44 are widely regarded as having achieved only limited results. The introduction of CTOs in 2008,45 described in Community treatment orders: the legislation, was designed to ensure that this group of very ill patients could be more successfully monitored and treated.

Detailed accounts of the literature on CTOs also appear in papers by members of the OCTET Coercion Programme Group. 17,18

Compulsion in community mental health care

In attempting to increase patients’ adherence to treatment and thereby improve their outcomes, mental health professionals use a range of formal and informal techniques. (We discuss informal techniques, or informal coercion, in Part 4, Chapter 17.) At the formal end of the spectrum, legislation for compulsory outpatient psychiatric treatment (compulsion) has been introduced in around 75 jurisdictions worldwide, across the USA, Australasia, some Canadian provinces, the UK and several other European countries. 4

Community treatment orders were designed with the aim of helping so-called revolving-door patients: those who have a long history of psychotic illness and experience multiple hospital admissions. They were principally aimed at preventing this revolving-door scenario by helping patients experience a period of stability after leaving hospital.

Community treatment orders were introduced in England and Wales in November 2008. 45 CTOs require patients to accept treatment and clinical monitoring, and allow rapid recall to hospital when necessary, as is described more fully in Community treatment orders: the legislation. This provision had been sought for at least 15 years by some professionals,46 but it was heavily debated and resisted during the build-up to its introduction by a coalition of 32 professional and patient organisations. 47

Mental health legislation in England and Wales

Patients in England and Wales who meet the legal criteria can be treated in hospital against their will under Section 3 of the MHA. While on Section 3, they can be given leave of absence for some hours or days, or even – exceptionally – weeks, for instance to spend time with family or engage in other social activities. This is called Section 17 Leave. Its purpose is to assess recovery before granting voluntary status. Section 17 Leave is a well-established rehabilitation practice used for brief periods to assess the stability of a patient’s recovery after or during a period of involuntary hospital treatment. Under Section 17 Leave, the treatment order (Section 3) remains active and the patient can be immediately readmitted without additional legal process. Section 17 Leave is extensively used but, as it is a continuation of Section 3, no routine national data on its use are collated. Its frequency and duration are therefore unknown, but both are believed to be highly variable, with some clinicians using it for extended periods and others hardly at all. The use of this extended leave of absence from involuntary hospital admission under Section 3 of the MHA has been shaped by several legal challenges. 25 It is generally agreed, however, that such leave has a place in mental health services. Indeed, the Code of Practice that accompanies the 1983 MHA48 states that such leave may constitute an important part of a patient’s treatment plan.

Prior to the introduction of CTOs, a series of attempts was made to introduce outpatient compulsion. Guardianship (Section 7) had been available since 1983 and remains unchanged today. It can require a patient to attend medical appointments and can direct where he or she should reside. 49 It has never really been used for patients other than those with learning disability and dementia. Since 1983, Section 117 has required that aftercare be provided for those treated under section (e.g. Section 3) following their discharge from hospital. To meet the needs of those who rejected their right to this aftercare provision, aftercare under supervision (known as Supervised Discharge or Section 25) was introduced in 1996. 25 This required the patient to attend for treatment, live where directed and make themselves available for assessments. It was widely perceived to be ineffective because it could not insist on medication adherence and it was removed from the legislation in 2008.

Community treatment orders: the legislation

The introduction of CTOs in England and Wales in 2008, as part of the amended MHA 2007,45 marked the next step in this evolution of forms of compulsory treatment in the community. This regime authorises compulsory treatment for patients in the community following a period of involuntary hospital treatment. Enforcement is provided via the power of recall, which permits patients to be returned to hospital for treatment or assessment without conducting a formal MHA assessment. The intention is to prevent relapse or harm (to self or others), help maintain a period of stability and provide a least restrictive alternative to hospital (i.e. one in which the intervention given restricts the patient’s freedom the least). 48

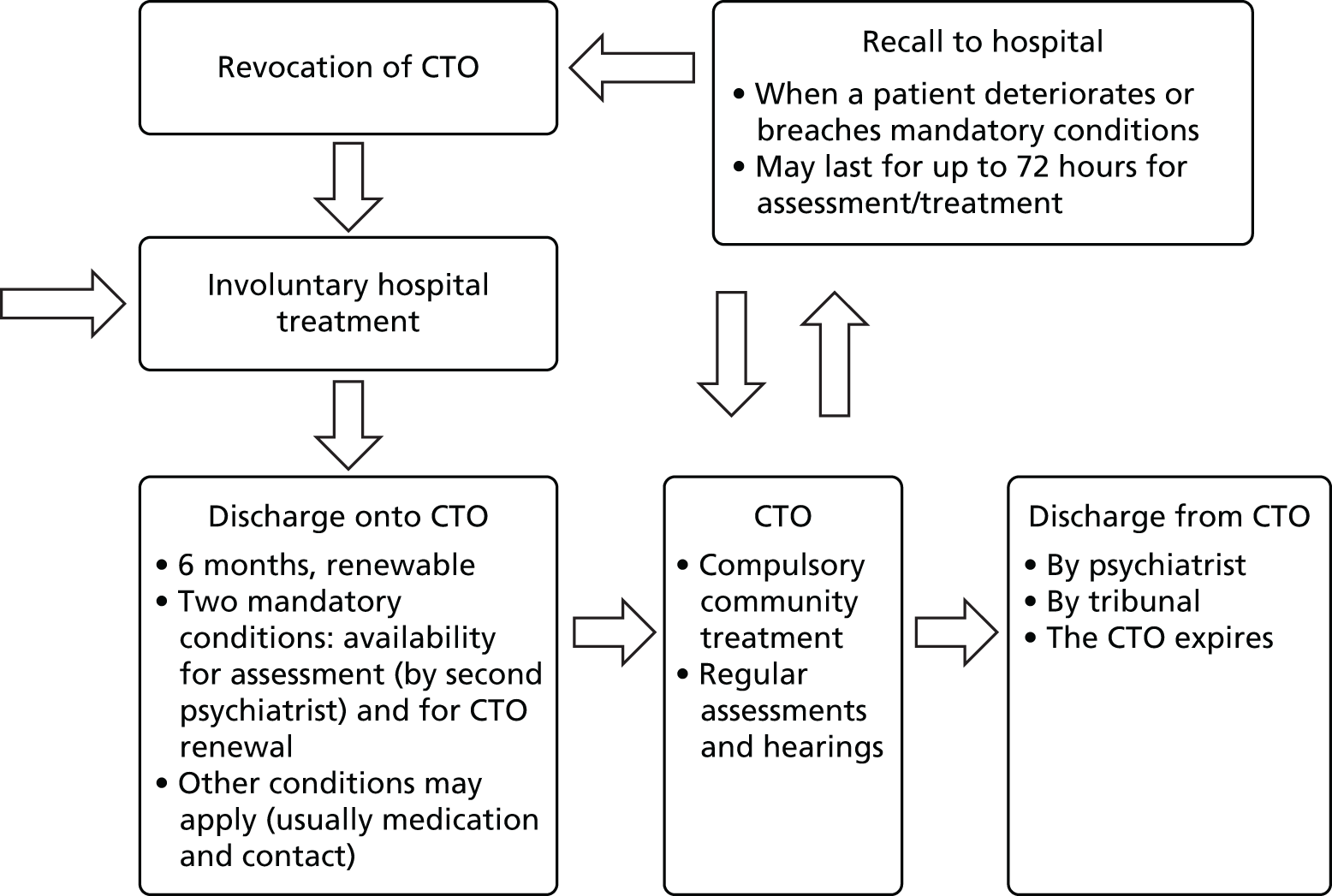

A CTO can be imposed when the responsible clinician (RC) (usually a consultant psychiatrist) and an approved mental health professional (AMHP) (usually a social worker) deem that a patient needs supervision after a period of involuntary hospital treatment and that, without it, he or she is highly likely to relapse and be readmitted involuntarily. The AMHP is required to consult with the patient and with family carers. The formal process is intentionally time-consuming to ensure that the CTO is not used for clinical convenience. Several days, sometimes more, elapse between the clinical decision and CTO activation. Alternatively, RCs may choose to use Section 17 Leave (described above). Unlike with Section 25, CTOs can insist on medication. Medication cannot be given by force in the community, however, regardless of whether or not a CTO or Section 17 Leave is used. Forceful administration is permitted only if the patient has been recalled to a ‘safe place’. Patients can be discharged directly from Section 3 without the need for either Section 17 Leave or a CTO, and most are. (Such patients would not be eligible for recruitment to this trial.)

The CTO requires the patient to comply with treatment and he or she can be recalled to hospital without delay if necessary. The regime in England and Wales specifies two mandatory conditions that apply to all CTOs. 48 First, a second opinion appointed doctor (SOAD) must assess patients who refuse medication or who lack capacity, to confirm that the treatment specified is appropriate. 50 Second, all patients must make themselves available for assessment for renewal of the CTO. The RC and AMHP who initiate the CTO may also specify discretionary conditions based on their knowledge of an individual patient. The most frequently stipulated conditions are to take prescribed treatment and remain in contact with the mental health team. 51–53 The power of recall can be used when the patient:

-

requires treatment in hospital and in the absence of recall there would be a risk of harm to self or others, or

-

does not comply with one of the mandatory conditions.

Recall can be used for the purpose of giving treatment or for assessment for up to 72 hours, after which the patient returns to the community under the CTO or the CTO is revoked and the patient remains in hospital for involuntary treatment under Section 3 of the MHA. The MHA Code of Practice states that patients and their families should be consulted about the CTO, its conditions and the need to recall, not least because family carers are likely to hold information of importance. 48

A CTO is imposed for up to 6 months in the first instance and is then renewable for a further 6 months and subsequently for 1-year terms; frequent clinical monitoring was anticipated in the Code. 48 It can be discharged at any time by the RC or by a Mental Health Review Tribunal (MHRT) if the patient’s mental state or circumstances change. During the period covered by the CTO, the hospital treatment order (Section 3) remains in place but is inactive; it is reactivated if the CTO is revoked after a recall to hospital (Box 1 and Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The CTO process.

Community treatment orders were introduced via a 2007 amendment to the MHA for England and Wales, with effect from 3 November 2008. They are referred to in the Act under the heading of supervised community treatment.

To be placed on a CTO, a patient must fulfil all the following criteria:

-

suffering from a mental disorder of a nature or degree which makes it appropriate for them to receive medical treatment

-

it is necessary for that person’s health or safety or for the protection of others that the person should receive treatment

-

treatment can continue in the community without the person being detained in hospital

-

it is necessary that it be possible to recall that person swiftly to hospital if needed

-

appropriate medical treatment is available.

The order is made by a responsible clinician (usually a psychiatrist) and an approved mental health professional (usually a social worker). The order lasts for 6 months initially, can be renewed for another 6 months and thereafter for 12-month periods. The responsible clinician can end the order when clinically indicated, and it may also be ended by the managers of the treating hospital or the MHRT.

The order includes two mandatory conditions. Patients on CTOs must make themselves available:

-

to be assessed by a second psychiatrist to complete the mandatory peer review process concerning treatment without consent, when required

-

for assessment concerning renewal of the CTO.

The RC and AMHP may also specify discretionary conditions that are needed to ensure the patient receives medical treatment, or to prevent risks of harm to the patient or others, based on their knowledge of an individual patient. These may subsequently be varied by the RC.

Patients on CTOs may be recalled to hospital for up to 72 hours when they:

-

breach the mandatory conditions, or

-

require further treatment in hospital and there would be a risk of harm to self or others if they were not recalled.

Recall can be used for assessment or to provide treatment without consent. When 72 hours have elapsed, the patient returns to the community under the CTO, remains in hospital for involuntary treatment under Section 3 of the MHA or is discharged from involuntary care under the MHA.

Section 17 Leave remains an available option under the new law, but since the amendment to the MHA, clinicians must consider using a CTO instead if they are granting leave for more than seven consecutive days, as is stated in the Code. This change, along with the removal of supervised discharge, signalled that the government saw CTOs as the primary means of providing involuntary supervision in the community.

Controversy surrounding community treatment orders in England and Wales

The introduction of supervised community treatment was highly controversial and was preceded by a heated debate lasting for at least 15 years. In other countries there had been similar levels of debate and controversy,54 but when the orders were made available, they were incorporated into practice swiftly. Initial proposals in England and Wales were met with broad opposition from service users, psychiatrists and mental health charities. The amended proposals, once enshrined in law, continued to provoke vigorous debate and to divide the psychiatric profession. Some viewed CTOs as ethically unacceptable because of the infringement of rights and freedoms. 55 Others believed they were potentially beneficial to patients and their families4,56 or argued that they constituted only a minor amendment to current law or practice. 25

The arguments emphasising individual human rights and people’s rights to make lawful decisions about their own lives were particularly forceful. This position provided powerful arguments against coercive treatment6 but was vulnerable to the criticism that such a purely rights-based approach could leave revolving-door patients in unacceptable circumstances, preventing them from improving their lives. Not to pursue compulsory interventions could be seen as conflicting with mental health practitioners’ primary obligation to help. 6

Much of the debate centred on issues of an individual’s capacity to make decisions about his or her treatment. Such competence might, of course, be compromised or even absent in those with severe mental illness. Others might have to make decisions on their behalf. This would require good knowledge about the person’s values and opinions based on when he or she had full capacity. It is commonly viewed as appropriate that when the patient’s views are not available, ‘best-interest’ standards should be applied. 6

It has been argued that although politicians sought to introduce CTOs in order to address the public’s fear of crimes committed by people with mental health problems, the protection of society is an insufficient reason to justify detention. 57 This is particularly the case given the difficulty in predicting serious violence by those with mental health problems. 58 The ‘principle of reciprocity’ requires that restrictions of civil liberties must be matched by the provision of adequate and high-quality services. 27,57 This was one of the underpinning principles of the amended MHA in Scotland, which introduced compulsory powers in the community in 2005. 59 Some have suggested that the use of compulsion may be enabling and consistent with the recovery model if adequately resourced and accompanied by clear goals for treatment and progress. 3

The change in the law in England and Wales was thus highly controversial. A fierce debate continued about how it impacts on patients’ lives and mental health services. It was argued, for instance, that even if compulsion in the community may be necessary in itself, CTOs in the form introduced in the 2007 MHA may not be in patients’ best interests. In particular, the following issues were identified that needed to be resolved:

-

whether or not capacity should have been a fundamental principle of the new MHA

-

whether or not having CTOs would increase the overall level of coercion

-

whether or not CTOs would contribute to better outcomes

-

which patient groups might benefit from CTOs and in what ways

-

whether or not it might be relatively easy to be placed on a CTO but harder to get off one (a lobster pot effect), leading to an inexorable rise in numbers over time

-

whether or not potential benefits would justify the restrictions in civil liberties. 17

Evidence base for community treatment orders

Although early opposition to CTOs focused on civil liberties6 or lack of improvement on the existing leave regime,25 more recent opposition has emphasised the absence of experimental evidence. 3,60

Around 40 published non-randomised studies have investigated CTO effectiveness by measuring outcomes, particularly in Australia, New Zealand, the USA and Canada,3,4,61,62 but prior to the OCTET Trial there had been only two published RCTs. 63,64 Most of the studies have methodological limitations. 65 It is therefore problematic to generalise from these findings. Generalisability is also problematic because of significant differences between the contexts into which CTOs have been introduced, such as the mental health systems and legal procedures. Neither of the two RCTs demonstrated a difference in the primary outcome measure of readmission rates, as detailed below.

The most common research designs used in studies of CTOs conducted prior to the OCTET Trial (which have been reviewed in detail by Dawson,4 Churchill et al. 3 and by the OCTET Coercion Programme Group18,66,67) have been controlled before-and-after (CBA) studies and uncontrolled before-and-after (UBA) studies, in which patient outcomes are compared before and after the intervention. Some epidemiological studies have also been conducted in which CTO and non-CTO populations have been observed but not matched. Studies using routine administrative data in this way have the advantage of including data on all CTO patients in whole areas or jurisdictions, avoiding selection bias following from excluding, for instance, violent or non-consenting patients.

Observational studies

Numerous studies describe local CTO patient cohort characteristics or stakeholder views. Overall, these studies suggest that clinicians prefer to work in systems where CTOs are available,68 views among psychiatrists may become more positive over time,69 and many believe CTOs to have positive clinical outcomes. 70,71 Many of these studies report perceptions of reduced readmission rates or that positive change occurs after many months on a CTO. Study designs preclude conclusions being drawn, and observed effects could be influenced by regression to the mean and rater bias.

A review by Dawson4 points out that after an initial ‘bedding in’ period, the use of CTOs often increases, particularly when there is a reduction in hospital beds and build-up of community teams. Some studies report therapeutic benefits for patients, such as greater compliance with outpatient treatment (particularly medication) and reduced rates of hospital admission. Some studies show better relationships between patients and their families, enhanced social contact, reduced levels of violence or self-harm and earlier identification of relapse. Dawson’s review4 also identifies some potentially negative effects of CTOs, such as a strong focus on medication (particularly depot medication) as opposed to other treatments, and that they are often used for the maximum time allowed and possibly overused.

The literature on personal experience of CTOs is very limited and derived from surveys and qualitative studies. It suggests that patients hold ambivalent, and sometimes contradictory, views about CTOs; for instance that they appreciate the sense of security and attribute health improvements to CTO use, but do not appreciate the restriction of their choices, particularly about residence, travel and medication. 72,73 Similarly, patients may appreciate a sense of safety,74 but dislike the sense of external control,75,76 and they may feel coerced but believe the CTOs provide a necessary structure in their lives. 77 Family carers generally find them helpful,77 albeit with similar misgivings,75 and regard them as providing relief and a supportive structure for the patient’s care. 78 They tend to consider the community services offered to be inadequate. 77,79 When professionals have been studied, they generally report finding CTOs useful,77 particularly for engaging the patient in a therapeutic relationship and increasing adherence to medication,78 although some also report disliking the sense of external control. 75 The main expressed concern of all three stakeholder groups is usually to avoid hospital admissions. 80

Controlled before-and-after studies

A handful of studies from the 1980s and early 1990s, mainly from the USA with UBA designs, led to initial optimism about positive effects of CTOs on hospital outcomes. 3 Since then, however, studies from a number of jurisdictions have reported discrepant findings. 3,81 Eight out of 12 studies published since 2006 and measuring readmission18 reported reductions under CTOs, but several of these were uncontrolled studies. Some reported reductions for subgroups of CTO patients. Four studies reported increased readmissions. The picture is equally complex for duration of admissions and community service use, with some studies reporting no difference and some reporting benefits for subgroups. There is considerable variability in outcome measurement and it is not always clear whether reported measures are considered part of the CTO intervention or as an outcome of it. 81

A number of studies analyse outcomes at different time periods under the CTO, frequently the first 6 months and then periods beyond that. These studies commonly report benefits from the second 6-month period on the CTO onwards. This might be a result of long-term benefits from CTOs,64 but an alternative interpretation would be that those on the CTO over a longer period were kept on it because things were going well clinically and the CTO was presumed to be responsible. 82 The latter interpretation would be supported by the evidence that psychiatrists are reluctant to change treatment in long-term conditions when the patient is stable. 83,84

These studies do not always include all available CTO patients, which affects generalisability. Many analyse CTOs in conjunction with other interventions, such as ACT. Many utilise routine administrative registers providing data on large numbers of patients over time. The two most frequently used registers are the Victoria register in Australia and the New York State register in the USA. There is a trend for the Victoria register studies to report increases in admission, whereas those using the New York State register report reductions. 67 This may be due to prioritisation of CTO patients for enhanced community services in the USA, whereas such services form part of standard care in the Australian context. Improved patient outcomes may thus be an effect of the services rather than compulsion.

Studies with non-randomised designs may be confounded by methodological limitations. Their results are vulnerable to changes being made over time. 67 CBA studies may be confounded by problems in adequate matching of patient characteristics, particularly lack of insight or adherence. UBA studies eliminate the problem of matching using patients as their own controls, but may be confounded by regression to the mean, that is, patients may improve as part of the natural fluctuation of their illness after they are placed on the CTO, which is often initiated at a time of maximal instability in their condition.

Overall, the evidence from these studies shows no strong or consistent effect for CTOs in any direction. These conflicting findings are complicated by the variation in study designs including the lack of standardised outcome measures.

Randomised controlled trials

By randomising the treatment condition, RCTs reduce the risk of sample and observer bias and the effects of regression to the mean.

The New York RCT63 recruited patients referred to the outpatient commitment programme at an acute hospital in New York City. It randomised 142 patients to either treatment under court-ordered CTO or voluntary status. It was not possible to randomise patients with a history of violence. No difference was found in the primary outcome of readmission or any of the other outcomes measured at 11-month follow-up. Both groups received case management and close follow-up during the trial (which was not standard care) and both had significantly fewer admissions in the trial period than in the preceding 12 months. The trial took place within a pilot CTO project and no police pick-up procedures were in place in case of non-adherence, so there was no systematic enforcement of the CTOs. The trial also experienced considerable problems, including lack of adherence to the protocol and an apparent confusion among staff and patients that some in the control arm were in fact on CTOs. A smaller than expected sample size and high attrition rates (45% at 11 months) could mean that the trial lacked statistical power to detect differences. 63 The New York data are therefore usually treated with caution.

The North Carolina trial64 was more rigorously conducted and has been highly influential. It recruited 264 patients from one state hospital and three public inpatient services, and randomised them between court-ordered CTO and voluntary status. All received case management, which went beyond standard care. The control group was ‘immunised’ from being on a CTO for 1 year. Attrition was low (18%) and equally distributed between the two groups. The primary outcome of readmission to hospital showed no difference between the two groups at 12 months. 64 No difference was found in treatment adherence, quality of life, service intensity, arrests, homelessness, quality of life or perceived coercion. A significant difference was detected in victimisation (being a victim of crime) with those in the CTO group less likely to report this. Outcomes for both groups improved during follow-up.

A secondary analysis showed significant reductions in readmissions for patients who were on a CTO for > 6 months while also receiving frequent service contacts (three or more per month). This analysis has been criticised for potentially introducing a selection bias if only patients who were considered to do well on the CTO were kept on the order long term. Several other outcomes (adherence, violence, arrest, quality of life) also reached statistical significance when dividing up patients according to duration of the CTO or including the non-randomised violent patient group, but this does not represent RCT-level evidence. 3,81

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

A Cochrane review of these two RCTs61 found no advantage to CTO for readmission, service use, social functioning, mental state, homelessness, satisfaction with services or perceived coercion. There was some evidence that CTOs reduced the risk of victimisation. The authors suggested that the generalisability of the USA trials may be limited by the exclusion of violent patients and the court-initiated nature of the CTOs. 81 They subsequently reviewed non-randomised studies to identify those that measured relevant outcomes and were of sufficient quality to be pooled with the RCT data. Three further studies were included, bringing the number of patients to 1108, including those with a history of violence and those on clinician-initiated CTOs. No outcome reached statistical significance, including admissions, duration of admissions, total days in hospital and treatment adherence. 81

Churchill et al. 3 conducted a systematic review including 72 papers published up until 2006. Most reported descriptive or observational studies. They found the quality of the evidence base to be poor, with studies showing discrepant results, and concluded that there was no robust evidence of positive or negative outcomes of CTOs. They also found that various stakeholder groups hold very different views about CTOs. Avoiding involuntary hospitalisation was, however, the shared top priority for patients, family members, clinicians and members of the general public alike.

Churchill et al. 3 found, however, that when CTOs are implemented, they are used for the same patient group, usually men around 40 years of age, in the middle phase of their illness, with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, several prior hospital admissions and a history of non-compliance with outpatient care: features characterising the revolving-door stereotype. Many had problems with substance misuse and had experienced imprisonment or forensic care. Most were single and living in rented accommodation alone or, less often, with their family.

As the Cochrane review61 concluded, there is clearly an urgent need for high-quality RCTs in this field, particularly to establish whether or not it is the intensity of treatment or the compulsion in itself that is responsible for any outcomes achieved by CTOs. This is consistent with Churchill et al. ’s3 conclusion that:

Research in this area has been beset by conceptual, practical and methodological problems, and the general quality of the empirical evidence is poor . . . [T]here is currently no robust evidence about either the positive or negative effects of CTOs on key outcomes, including hospital readmission, length of hospital stay, improved medication compliance, or patients’ quality of life. 3

How to measure relevant outcomes

There have been different opinions on what constitutes the best measure to assess the outcome of CTOs. This relates to whether the chief purpose of CTOs is considered to be prevention of relapse or the provision of a least restrictive alternative. Readmission to hospital has been the most widely used outcome measure of success in preventing relapse in patients with psychosis. The term relapse has different meanings in the literature and no unambiguous measure of it has emerged. Readmission is the measure that has been the most consistently used, not only as the primary outcome of the two RCTs, but also in most of the non-randomised studies. It has also been widely used as the primary outcome measure in most antipsychotic maintenance trials. 85 Measures obtained directly from patients have been vulnerable to attrition and difficult to standardise. Despite criticism of it as being a crude proxy for relapse, readmission is a measure for which data are obtainable. A binary measure of readmission, excluding brief recall or breach admissions, where they are permitted, may be least sensitive to particularities of service organisation and other contextual issues. (This was the primary outcome measure we used in our trial; see Chapter 6, Methods.) When recall admissions are not routinely distinguished, it may be difficult to ascertain the effect of CTOs. Similarly, frequent contact with the community team may indicate that the CTO is working, whereas contact with a crisis team may suggest relapse, and these situations must be carefully distinguished. 67

Some have argued that the duration of admission should be the preferred measure because shorter admissions may reduce the overall restrictiveness of CTOs. Duration of admission does measure relapse, but it also measures the clinical response to that relapse. Although duration of admission conveys important information, it does not measure the effectiveness of CTOs in their purpose of stabilising patients in the community and reducing or preventing relapse. It may therefore be more suitable as a secondary measure (as we used it in our trial; see Chapter 6, Methods). It is of obvious importance in cost-effectiveness studies.

The outcomes most frequently measured in the existing literature include readmission rates, time to readmission, duration of admissions and use of community services. The ways in which these outcomes have been measured has varied. Duration of admission, for example, has been measured by the number of days from admission to release from hospital for each episode,86 and as the patient’s mean number of days in hospital during months in which a hospitalisation occurred, compared across 6-month periods. 87 Other outcomes, such as medication possession, adherence, victimisation, arrest, mortality and quality of life, have been measured in some studies. 3,81 This means that the total number of outcome measures applied has been rather large for a relatively small body of research.

The clinical ambition of a CTO is to foster longer-term changes in patient well-being and insight as a result of a protracted period of treatment. Churchill et al. 3 argue that ‘if CTOs are intended to improve outcomes for patients, then . . . patient relevant outcomes should be prioritised in future research.’ Their review reveals the paucity of data on such patient-level outcomes as symptoms, social functioning, quality of life and satisfaction. Churchill et al. 3 also argue for the inclusion of measures of perceived coercion, found to be associated with CTO use in the literature, which they argue may be mediated by factors such as treatment adherence and therapeutic relationship. In fact, measuring perceptions of the therapeutic relationship and the patient’s experience of the service may be particularly important given the indications in the literature that the use of CTOs may threaten the patient–professional relationship, although Churchill et al. 3 note that ‘the impact and duration of such problems have not yet been properly investigated’.

The literature on CTOs suggests that any effect of CTOs on admission to hospital may be achieved by improving treatment compliance. Although, as noted above, there is no robust evidence to support either contention, it is clearly important to understand the factors that might affect treatment compliance or engagement. Churchill et al. 3 note the emphasis in the literature on insight, or awareness of the need for treatment, along with other factors such as previous experience of the mental health system (including coercion) or poor access to services.

In designing the most robust possible study of CTOs, there is thus a clear need to include data on patient-level outcomes such as these. As well as the hospitalisation outcomes described above, the OCTET Trial used well-established measures of clinical and social outcomes, attitudes to medication and experiences of services and of coercion, including measures of insight and therapeutic relationship (see Chapter 6, Methods). We also identified a need to develop a measure capable of capturing quality of life for people with severe mental illness, in particular one that would capture their capabilities (things that they are free to do or be). We therefore developed and tested such a measure as part of the OCTET Study (see Chapter 10) and it was utilised as part of the Economic Evaluation (see Chapter 7).

Ethical implications of community treatment orders

Ethicists studying CTOs have largely been critical of what has been taken to be a new paternalistic approach to the delivery of community-based mental health services. Instigating involuntary outpatient treatment into patients’ care regimens outside of hospital has been argued to constitute an unjustified restriction of patients’ personal freedoms and autonomy, undermining the principles of respect for liberty and self-determination. 6,88,89 These ethical arguments have moved beyond the use of catch-all normative concepts such as coercion, and have been accompanied by a more general recognition of, and concern about, the use of a range of pressures to influence patients’ adherence to treatment within community mental health settings, as investigated in the ULTIMA Study.

In response to these principle-led attacks on the justification of CTOs, other commentators have offered spirited defences of the new legal powers by highlighting the difficult realities of the lives of those patients who have severe illnesses that undermine treatment adherence and frequently require readmission to hospital. Established to support these so-called revolving-door patients in ways that could secure the longer-term positive outcomes associated with continued treatment and prompt intervention in the face of crisis, CTOs have been claimed to be liberty enhancing and potentially beneficial to those in receipt of them. 90,91

Although the ethical discussion has begun to take seriously the realities of the treatment settings within which CTOs are used, the academic psychiatric literature continues to scrutinise whether or not the ethical considerations identified can be balanced in such a way as to defend the use of CTO regimes in different jurisdictions. Moreover, little is known about how these considerations translate into practice, given the complex and varied mental health and social support needs of the patients who will be subject to these powers. The empirical studies that have explored the experiences of mental health professionals and patients have highlighted positive and negative views about the use of CTOs in practice,73,77,92 but the authors of these studies have not sought to explicate their findings in ways that directly address the ethical questions that concern the use of this new legal power. These complex ethical considerations provided the starting point for the ethical analyses conducted in the OCTET Coercion Programme.

Governance

We established a clear governance framework for the OCTET Study, which covered all its substudies as well as the OCTET Trial.

Host/sponsor

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the research and development (R&D) office of the then Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire NHS Mental Health Foundation Trust (from March 2011, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust). The trust accepted its role as study sponsor and issued the necessary indemnity documentation.

Ethical approval

Details of ethical approval are given above (see Part I, Chapter 4). During the course of the study, seven amendments to the original protocol were sought and approved (see Appendix 1). All were communicated to all participating trusts.

Steering group and data monitoring committee

The OCTET Study Steering Group consisted of an independent clinician, a service user, a service user organisation representative, a carer representative and a mental health lawyer. Its function was to advise on the implementation process and on how to translate our findings into policy and practice.

The OCTET Trial also had a data monitoring committee (DMC) as part of its governance structure, as is a prerequisite for all high-quality RCTs. The purpose of a DMC is to judge at agreed intervals whether or not it is ethical and desirable to continue with the trial, by examining reports of interim data. The DMC is asked to assess on the basis of these reports whether or not the trial should be stopped because:

-

there are unanticipated adverse outcomes clustered in one arm, or

-

the result is already clear (i.e. there is a statistically clear advantage to one arm because of a very large effect size).

It was anticipated in the OCTET Trial protocol that the first report could be delivered for the committee’s consideration 12 months after the study’s inception. Recruitment was delayed, however, by delays in obtaining R&D approval and negotiating researcher access in the participating NHS Trusts, so at 12 months we had follow-up data for only about 30 patients. This was deemed insufficient to give any meaningful indication as to the trial’s progress. With the agreement of the DMC, we therefore decided to postpone the first report to 18 months and the second to 24 months after the study’s inception. The statistical data were prepared by a statistician who was independent from all data collection. Although the OCTET research team assisted in her work, in particular by preparing the background information, they were kept blind from all calculations of outcome data. The committee reviewed the project at the agreed time points and saw no reason to stop the trial.

The composition of the OCTET Steering Group and DMC is given in Appendix 5.

Chapter 6 OCTET Trial

Introduction

The need for a randomised controlled trial of community treatment orders

As the Introduction to this study made clear, CTOs were highly controversial when they were introduced and have remained so (see Chapter 5). The key issues of contention in the period before their implementation included:

-

ethics – whether or not CTOs ought to be enacted

-

legality – whether or not CTOs would comply with constitutional and/or human rights

-

empirical issues – whether or not established CTO schemes had the intended beneficial outcomes.

The only methodology which could convincingly address concerns about the effectiveness of CTOs was an RCT. We therefore designed the OCTET Trial to:

-

provide rigorous evidence to inform the debate about CTOs

-

demonstrate whether or not adding CTOs to community care reduced readmission rates and affected a range of other outcomes

-

identify patient characteristics and care patterns associated with positive and negative outcomes

-

inform an economic evaluation.

This chapter draws substantially on papers by members of the OCTET Coercion Programme Group: the trial protocol summarised in The Lancet (Burns et al. ,93 with permission from Elsevier); its primary and secondary outcome findings as published in The Lancet (Burns et al. ,16 with permission from Elsevier) and the tertiary outcome and subgroup findings (Rugkåsa et al. ,94 with permission from John Wiley & Sons).

Development of the Trial design: consultation exercise

The aim of the OCTET Trial was to compare CTO use to voluntary outpatient treatment. A number of ethical, legal and practical issues rendered this a complex undertaking.

In view of concerns being raised about the ethical, legal and practical issues of methodologies to test the impact of CTOs, we conducted a consultation exercise with clinicians and legal, policy and ethical groups in the spring and summer of 2008, before finalising the protocol for the OCTET Trial. As is reported below, the exploratory work on the legal constraints involved led to our seeking a detailed legal opinion; we report this separately (see Chapter 11).

This detailed consultation exercise involved numerous opportunistic discussions and a series of more structured meetings to explore the ethical, legal, clinical and practical aspects to the proposed study methodology and to obtain agreement about, and support for, the strongest test of the intervention, in order to produce a detailed study protocol. The consultation exercise involved > 50 people from the full range of stakeholders from the following groups:

-

patients and carer organisations and mental health voluntary organisations

-

MHA practitioners

-

mental health lawyers

-

academic legal experts

-

the MHRT

-

approved social workers

-

clinicians in inpatient and outpatient services

-

ethicists.

There were some differences between the different groups of stakeholders, in particular between those working with patients in a clinical capacity and those who practised mental health law as solicitors or as representatives of the MHRT. Here we summarise the views expressed by each group, in turn. The summaries represent the breadth of views in each group and the main points, from across the groups, which were of relevance to the trial’s feasibility and design. It should be noted that this consultation was conducted after the legislation had been passed by Parliament in 2007 but prior to the actual introduction of CTOs on 3 November 2008, so none of the consultees had any practical experience of the new regime.

Clinicians and approved social workers

The long and heated debate preceding the introduction of CTOs nationally was reflected in the views raised during our consultations. Some were concerned that CTOs constituted ‘incarceration in the community’ and that CTOs might lead to a lowering of the threshold for compulsion so that a larger proportion of people at relatively low risk might be subject to compulsion. Others commented that, in practice, the new provision did not represent much change and that ‘we are doing it anyway with Section 17 as a long leash: at least a CTO is honest’.

Clinicians noted that attitudes to CTO use had changed since the new legislation had been passed by Parliament. Much of the opposition had dissolved and CTOs were rapidly becoming accepted as part of the provision that was soon to be implemented. This was expressed in concerns or even fear associated with not complying with the new legislation: ‘As a clinician, I will opt for a CTO because of the new law [when it takes effect]. We would be frightened what will happen if we do not.’ They were also concerned about public harm and liabilities in the event that tribunals would discharge patients in the non-CTO group who subsequently committed crimes. As such, CTOs were considered the more restrictive option, with more control remaining with the clinician.

At the time of the consultation, few mental health professionals had received training on the amended MHA and how it would impact on services. There was considerable uncertainty about how CTOs would work in practice and whether or how Section 17 Leave would change. Prolonging Section 17 Leave was seen as being likely to be challenged by tribunals, as the new Code of Practice indicated that this would not constitute ‘good practice’. Psychiatrists were concerned that mental health lawyers might be eager to test the amended MHA, and worries were expressed about how to explain to tribunals why an RC had repeated Section 17 Leave instead of placing the person on a CTO. Several psychiatrists stated ‘I don’t want to be involved in the first judicial review’.

Mental health lawyers

Lawyers representing patients in tribunals emphasised the right of patients to make decisions about their treatment, including taking part in trials; they suggested that legal representatives would be obliged to take a client’s participation in any study into account when representing them at a hearing. They strongly emphasised that patients must be fully informed about the trial and that the different mechanisms for treatment following from randomisation should be made clear to patients prior to enrolment in the study.

The legal representatives we spoke to expressed surprise at the degree of fear of the MHRT among clinicians. Their view was that a tribunal only recommends treatment and that it is a matter for clinicians to ‘stick to their guns’ regarding what they consider an appropriate course of action.

Academic legal experts

Unlike many clinicians, who believed that the clinical effectiveness of CTOs needed to be tested, some of the academic legal experts we consulted saw the overall research question as being of limited interest to the law, since the amended MHA had already been passed by Parliament and CTOs were soon to become part of the MHA.

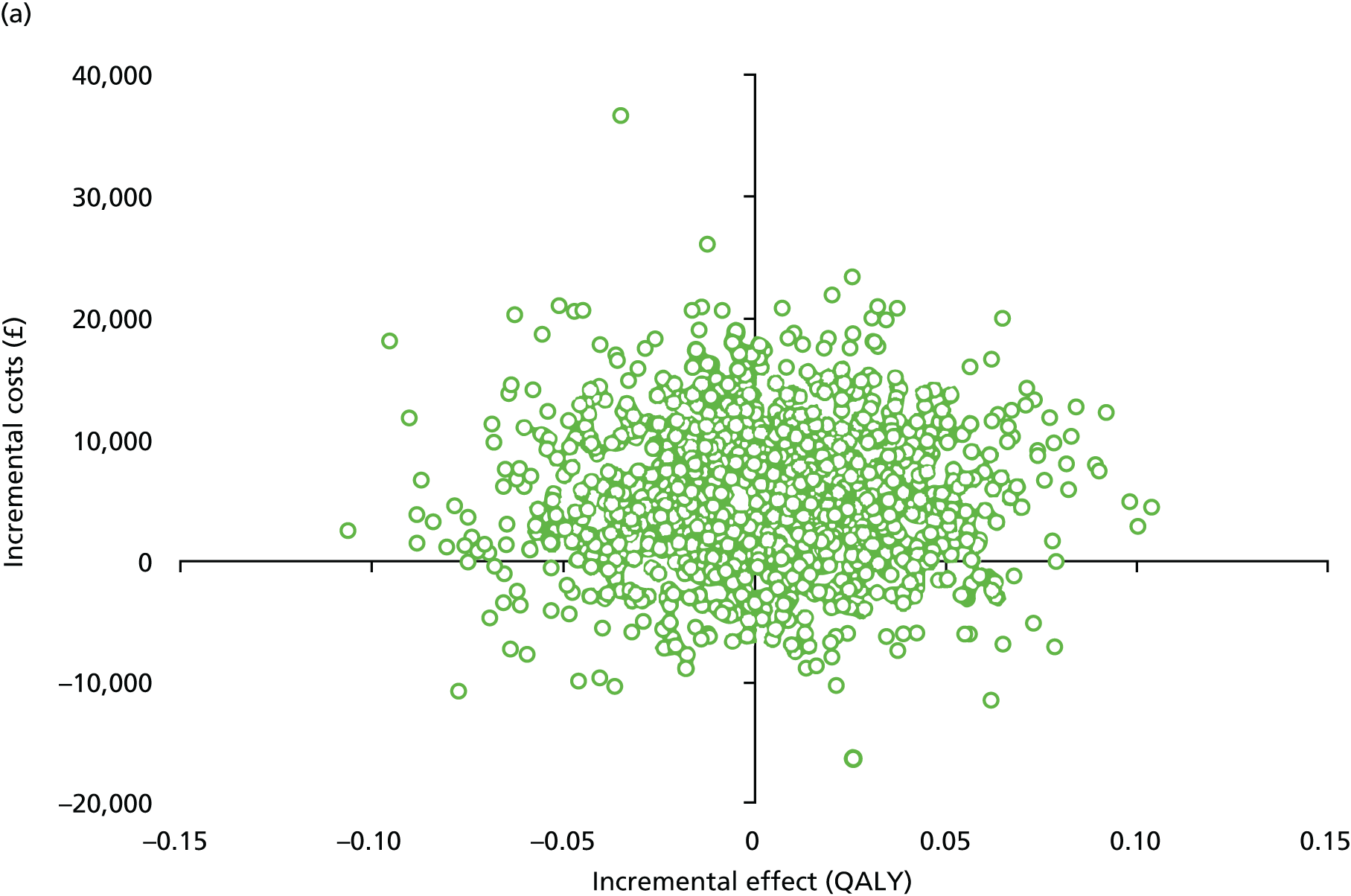

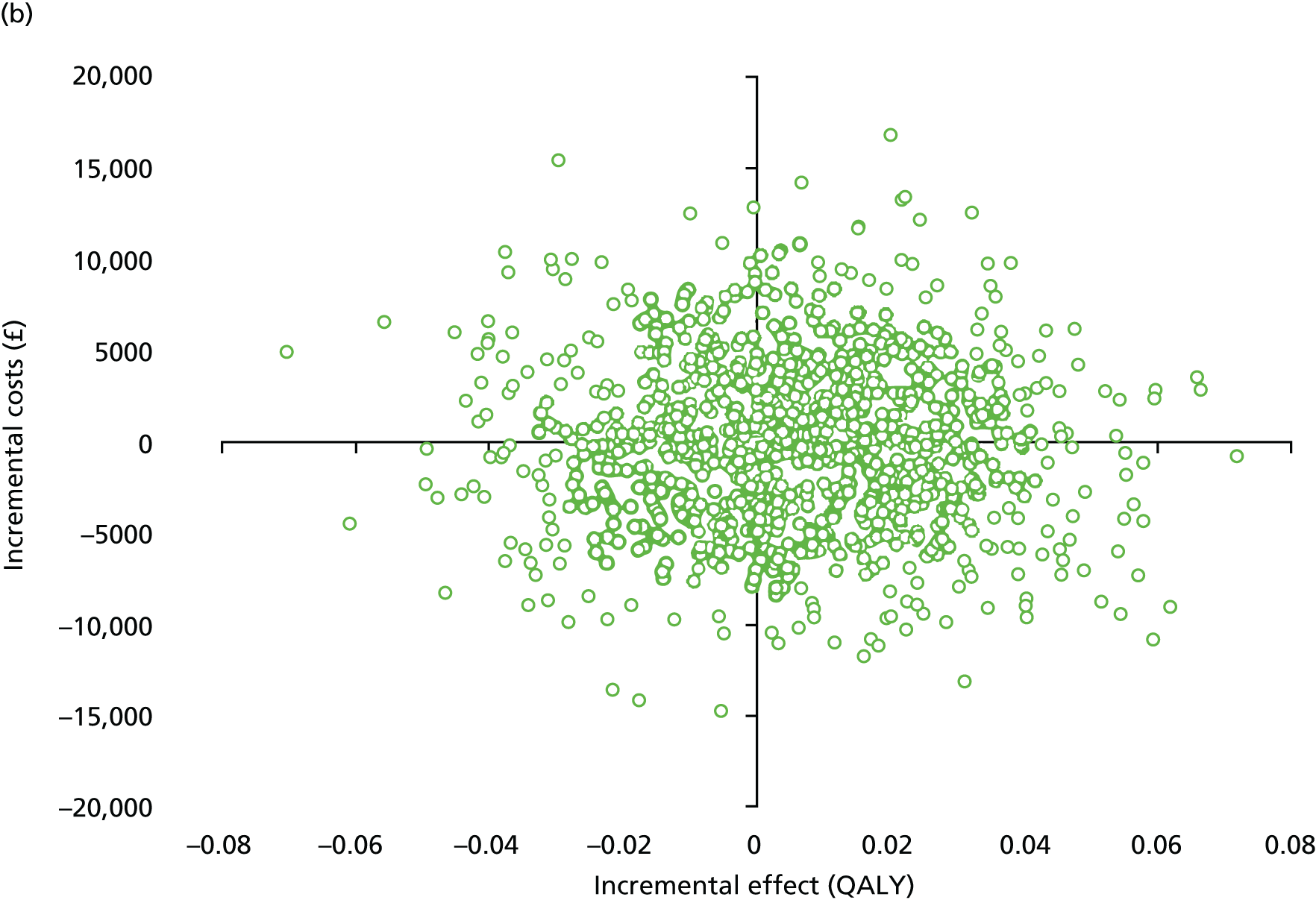

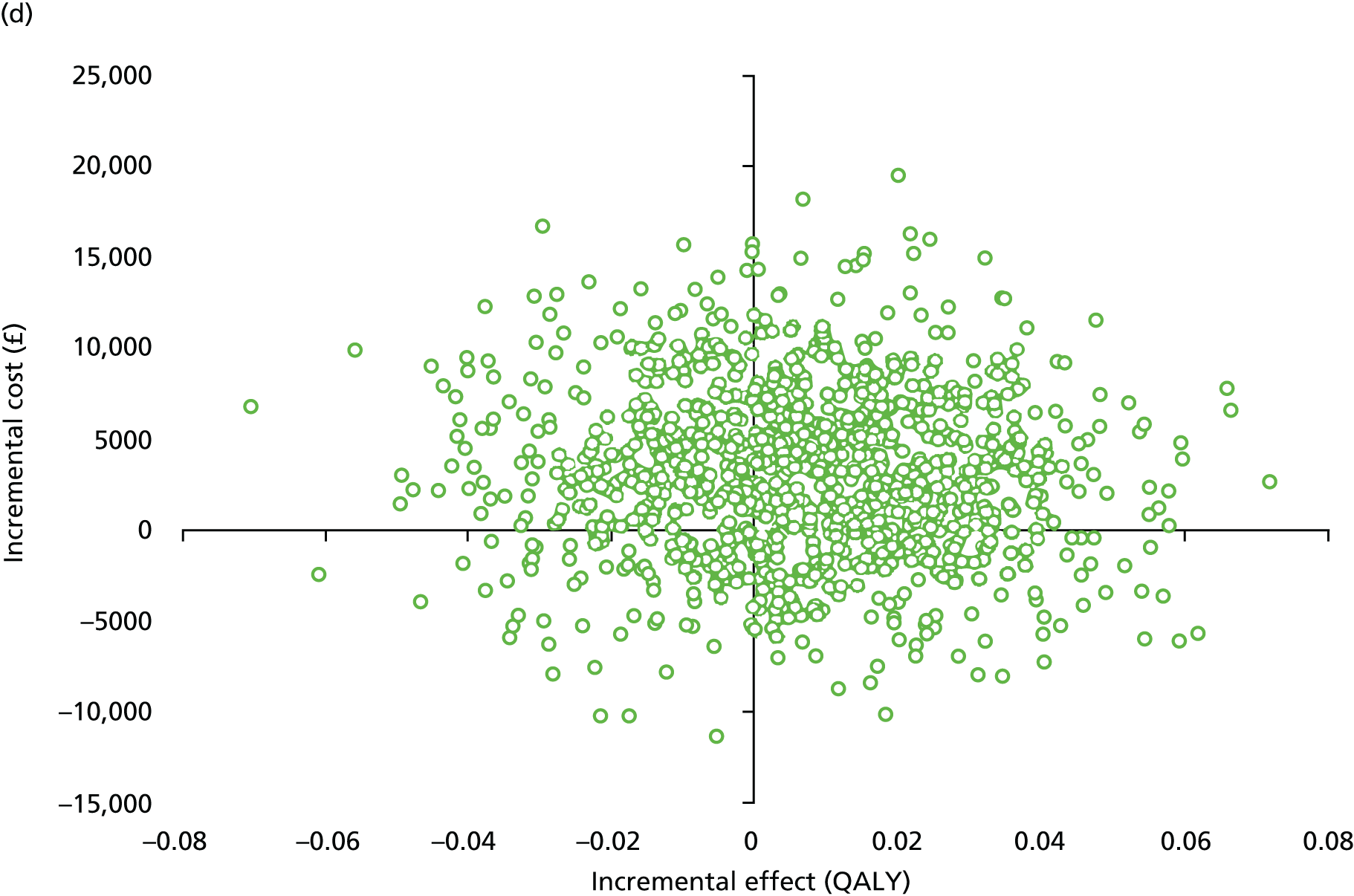

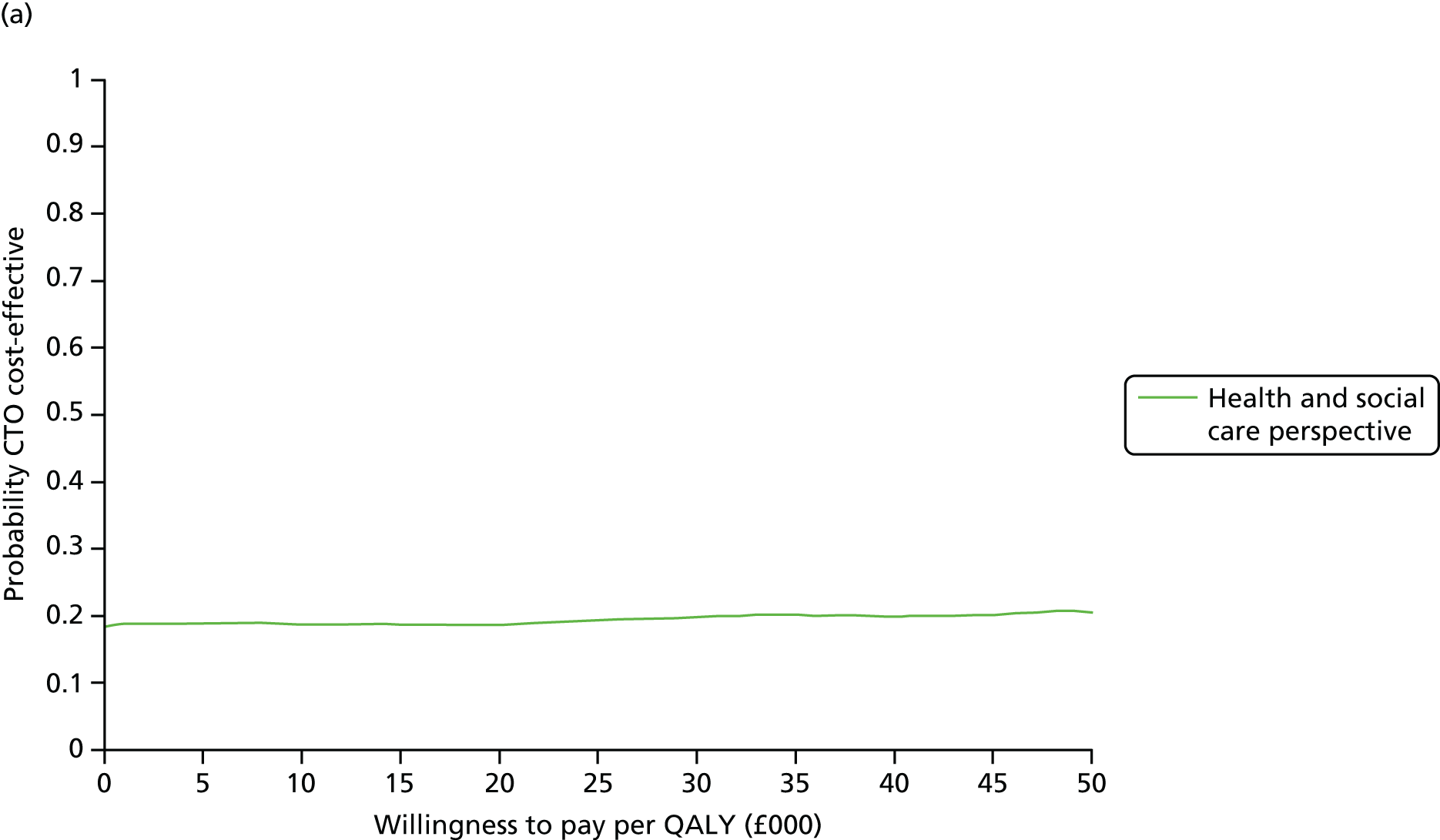

Some legal experts expressed uncertainty whether or not the new Act presented the option of using Section 17 Leave as the control arm of the trial, given the directions in the Code of Practice; they anticipated that MHRT hearings would insist on the Code being followed. They thus saw the MHRT, despite its inability to go beyond recommending treatment, as potentially exerting influence over the trial.