Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10314. The contractual start date was in January 2009. The final report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in April 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Hemingway et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Linked electronic health records and learning health systems

The global political importance of data

People increasingly leave digital ‘traces’ relevant to health in multiple different information systems as they interact with health and other services and go about their everyday lives. The potential for such data to inform, and potentially transform, our understanding of health and disease has been recognised by world leaders. For example, George Osborne, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2010 to 2016, said in a Science Speech to the Royal Society in November 2013 that the UK has ‘some of the world’s best and most complete data-sets in healthcare’ (© Crown copyright; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 1 Following the 2015 State of the Union address, the White House signalled an initiative that would ‘catalyse a new era of data-based and more precise medical treatment’ (reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License). 2

Data tapestry

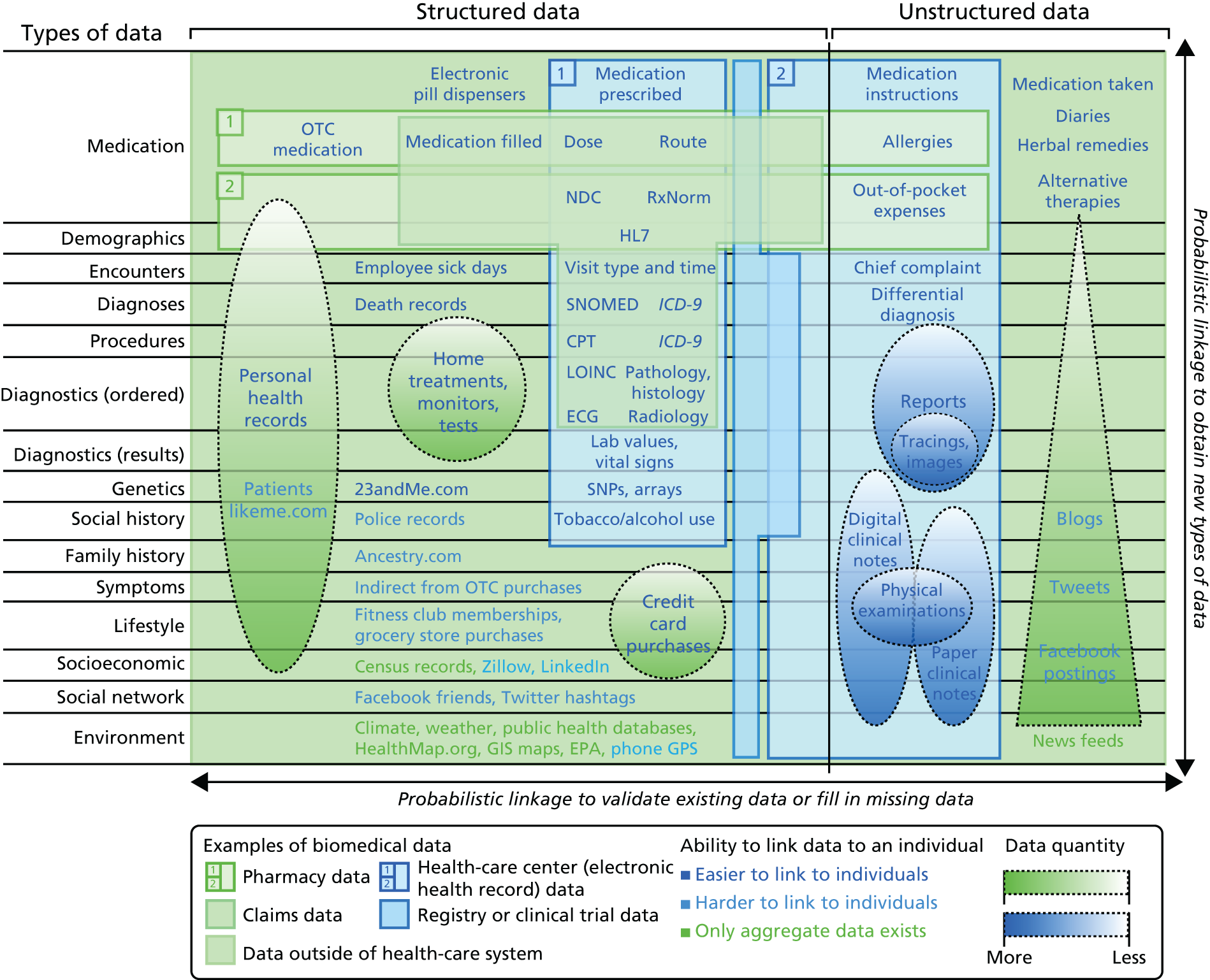

The electronic record relevant to health is diverse. This ‘data tapestry’ of information (Figure 1) spans records in primary care and in hospitals, structured data (codes, values) and unstructured data (text). It includes information on genomics, through to social media, the sensed self and wider social determinants of disease. Deriving information and knowledge from one or more sources of these rapidly developing sources of health-relevant data might be of great benefit to inform improvements in care and outcomes of disease.

FIGURE 1.

The tapestry of potentially high-value information sources that may be linked to an individual for use in health care. CPT, current procedural terminology; ECG, electrocardiogram; EPA, US Environmental Protection Agency; GIS, geographic information system; GPS, global positioning system; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition; LOINC, Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes; NDC, National Drug Code; OTC, over the counter; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism. Reproduced with permission from Weber et al. Finding the missing link for big biomedical data. JAMA 2014;311:2479–80. 3 Copyright © 2014 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

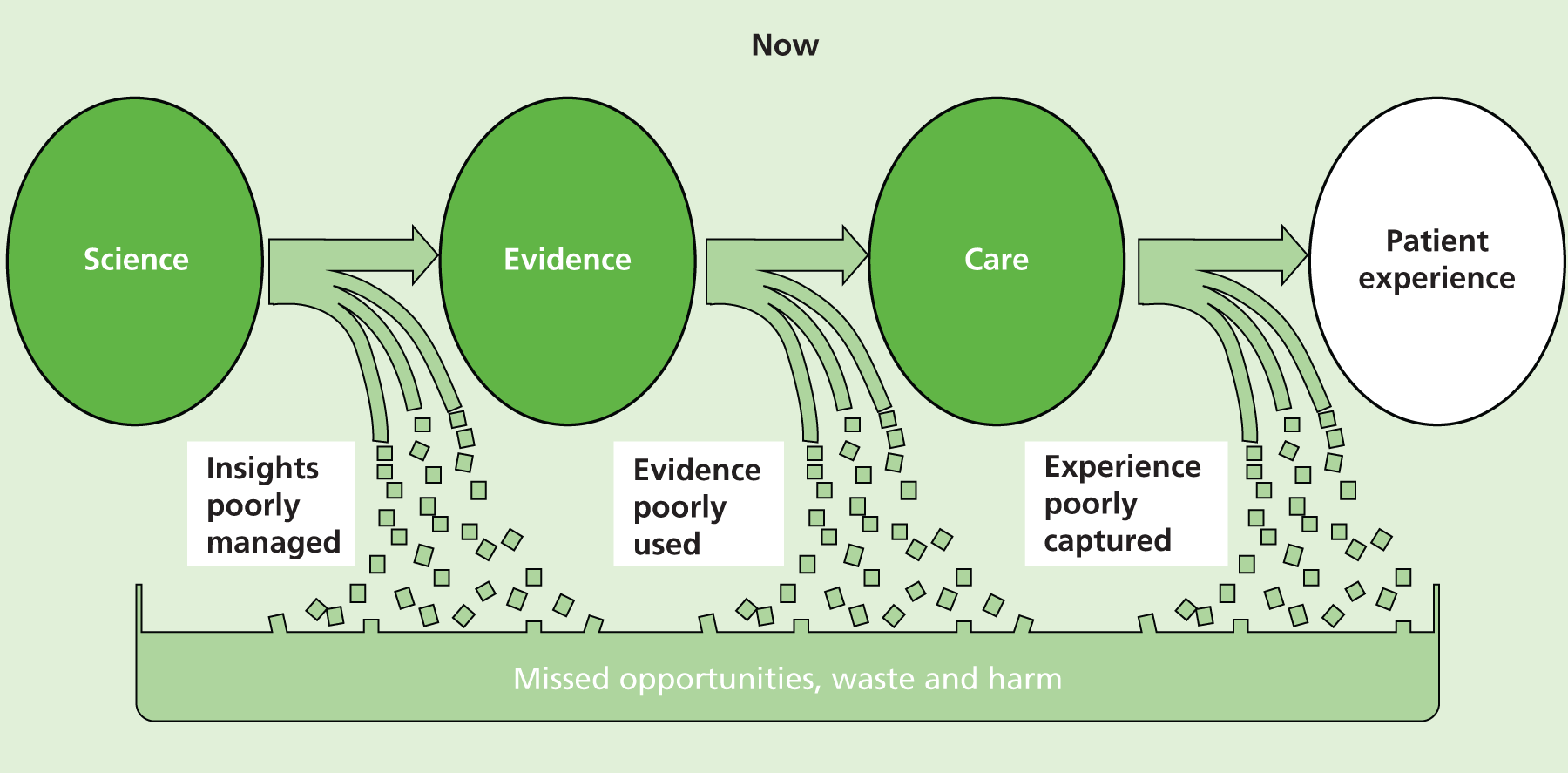

Translational gap

One model that links the process of science and improvements in health care and that has attracted considerable attention in the UK is the translational model, as laid out, for example, in the Cooksey Review. 4 This identified two gaps in the translation of biomedical science to health care, construed as an essentially linear process. The first translational gap is the generation of new therapies to improve health care based on biomedical science. Epidemiological research using electronic health records (EHRs) can help to close the first translational gap by enabling researchers to quantify the need for new therapies, identify risk factors and (with genomic data) suggest potential new drug targets. Randomised clinical trials with follow-up through EHRs can be cheaper and simpler than conventional investigator-led trials and may be particularly helpful for increasing the evidence base for non-drug interventions.

However, it is in the second translational gap, that is, the introduction of new therapies into clinical practice, on which EHR-based research programmes may have the greatest impact.

For example, new prognostic risk scores may help interventions to be targeted most appropriately, decision support tools embedded in clinical systems may help to improve clinical decision-making and health economic analyses can ensure that treatments are managed in a cost-effective way.

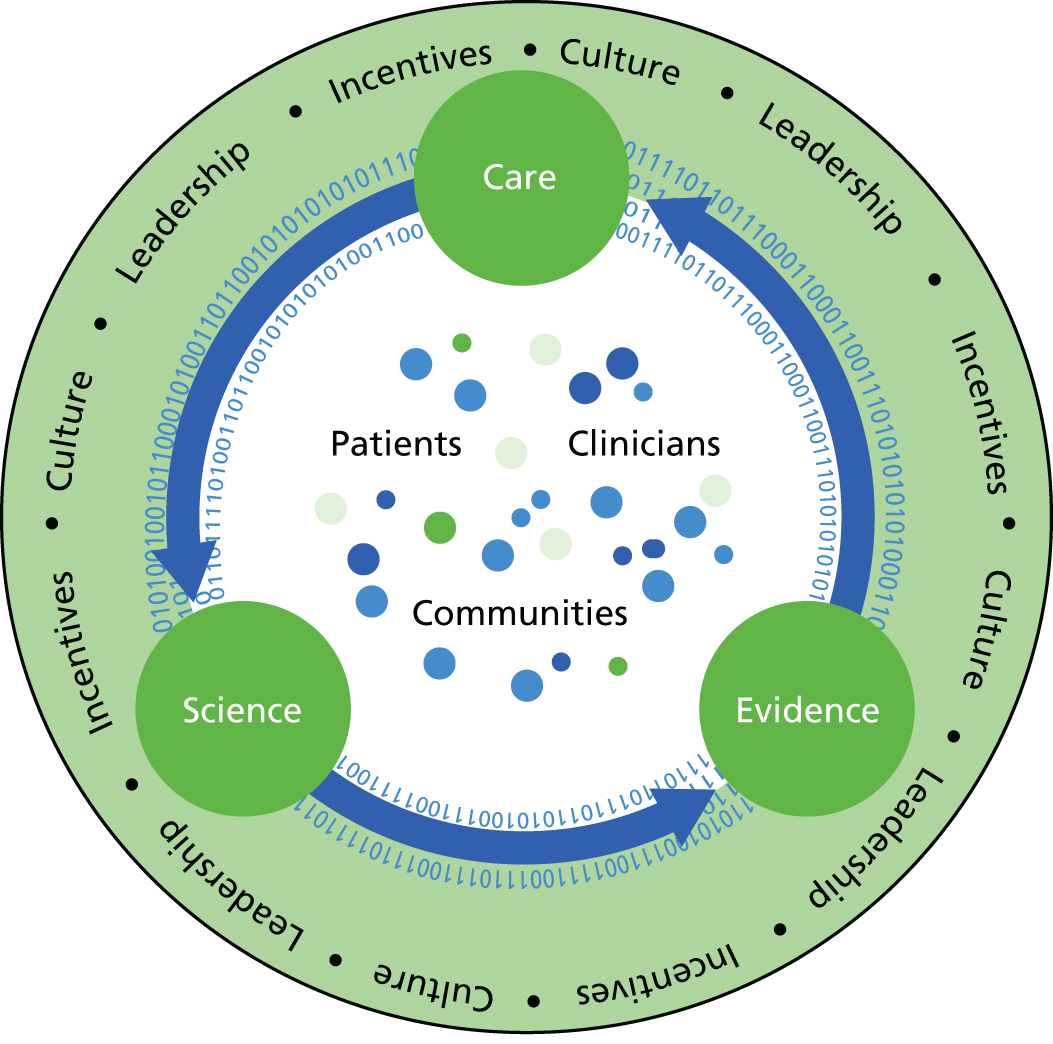

Learning health systems

A second, more recent, model linking data, information and knowledge to improvements in health care comes from the concept of a learning health system5 in which science and informatics, involving the real-time access to knowledge and digital capture of the care and outcomes, are a central component.

Electronic health records: what does the UK contribute?

Although there may be a strong scientific and health system case for making much better use of the diversity of the ‘data tapestry’, in reality, existing research efforts have been largely focused on structured data collected as part of an interaction with one or more components of the health system.

The UK is one of the few countries in the world in which a picture of the patient journey can be traced through EHRs spanning primary care, hospitals and, ultimately, death registries. The UK has the potential to address research questions that would currently not be possible in Denmark and Sweden (Table 1), countries that do have outstanding national registries but that have not brought national primary care records to research in the same way as is possible in the UK.

| Country | National or regional | Primary and ambulatory care data available for research linkages |

|---|---|---|

| UK | National | CPRD,6 accessed through Academic Health Sciences Networks |

| Sweden | National | Primary care is organised regionally; national initiatives in SwedeHeart7 and the National Registry of Secondary Prevention |

| Denmark | National | Register of Medicinal Product Statistics8,9 |

| Canada | Regional | Ontario, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences10 |

| Regional | Ontario Health Insurance Plan Physician claims database | |

| USA | National | Medicare (for people aged ≥ 65 years) (see www.medicare.gov/) |

| National | Million Veteran Program (see www.research.va.gov/mvp/veterans.cfm) | |

| Regional | Mayo Clinic11 | |

| Regional | Rochester Epidemiology Project, Olmsted County (see http://rochesterproject.org/) | |

| Regional | Kaiser Permanente California Research Program on Genes, Environment, and Health12 | |

| Regional | Intermountain Healthcare13 | |

| Republic of Korea | National | National health insurance claims database from the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service14 |

A combination of features in the UK underpin the potential of EHRs:

Free at point of use

+

unique health identifier

+

≈ every citizen registered with a general practitioner (GP)

+

≈ every general practice uses EHRs

+

wide range of linkage possibilities, including to the national heart attack registry [Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP)].

Linkage of EHR and registry data, which are commonly held separately across multiple sources, with bespoke phenotypic and genetic information can generate a unique platform to explore why diseases occur and progress, to investigate quality of care and to identify opportunities to improve health outcomes. This new data revolution has attracted substantial investment and promotion with initiatives to improve access to and use of linked EHR data, which will serve to decrease the burden of obtaining data in a research-ready format and encourage research collaboration.

In what senses are linked electronic health records ‘big data’?

One widely used definition of big data concerns the 4 Vs: volume, variety, veracity and velocity. EHR data are potentially ‘big data’ in every sense; not only do they cover a large number of people (entire populations) with a large amount of information [e.g. 2 million patients, 5 billion rows of data in our ClinicAl disease research using LInked Bespoke studies and Electronic health Records (CALIBER) data platform, which forms the foundation of this programme] per patient, but the data are highly varied and complex, with different ways of coding information (e.g. by means of International Classification of Diseases and Read codes). The data validity (‘veracity’) is simultaneously a concern for clinical care and for research. Clearly, having data in real time (‘velocity’) can be crucial for clinical decision support. Harnessing EHR data for research requires a deep understanding of the health-care system from which the data originated, as well as the statistical and computing skills to analyse large data sets.

In 2011 the UK government published a Strategy for UK Life Sciences,16 which placed EHR research as a central part of the strategy to accelerate health research in the UK. The UK is unique in being the only country with national cardiovascular disease (CVD) registries and primary care data (including important information on cardiovascular risk factors and their management in the community) available at a scale for research. The recent report on personalised health care by the National Information Board and Genomics England17 urged the NHS to transform its use of information in order to provide better care as well as to enable better research. This will require a substantial increase in the maturity of EHRs in the UK as well as a framework to make these data available for research.

Current state of electronic health records in UK hospitals relevant to quality and outcomes research

Although UK general practices have, via the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD)6 and other initiatives, contributed EHR data that have led to > 1000 peer-reviewed publications, the use of data within hospitals beyond the simple Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) returns to generate useful knowledge has led to very few publications. One of the reasons for this is that UK hospitals, like those in Europe, have been at a low level of maturity, according, for example, to the Healthcare Information Management Systems Society classification (Table 2). This is changing rapidly in the UK in light of the emerging strategy from the National Information Board and NHS Transformation programmes such as the Genomics England-led 100,000 Genomes Project. 19

| Stage | Cumulative capabilities | Percentage of hospitals |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 7 | Complete electronic medical record; continuity of care documents to share data; data warehousing feeding outcomes reports, quality assurance and business intelligence; data continuity with emergency department, ambulatory and outpatient | 0.3 |

| Stage 6 | Physician documentation interaction with full clinical decision support and closed loop medication administration | 2.5 |

| Stage 5 | Full complement of picture archiving and communication systems displaces film-based images | 29.5 |

| Stage 4 | Computerised physician order entry in at least one clinical service area or for medication (ePrescribing) | 6.7 |

| Stage 3 | Nursing/clinical documentation (flow sheets) | 5.3 |

| Stage 2 | Clinical data repository | 34.5 |

| Stage 1 | Laboratory, radiology and pharmacy information systems | 7.9 |

| Stage 0 | No laboratory, radiology or pharmacy information systems | 13.3 |

However, part of the government’s plan for making health-care information available for research, the care.data programme,20 aroused national anxieties about patient confidentiality and had to be suspended pending further public consultation. This illustrates the sensitivities that must be respected in EHR research. Technical solutions such as data pseudonymisation and secure computer workspaces (‘safe havens’) can enable sensitive patient data to be safely used for research, but it is vital to involve patients and the public in balancing privacy concerns against the benefits of research.

Cardiovascular disease

People at risk of, or with, CVDs increasingly leave digital ‘traces’ relevant to health in multiple different information systems in different parts of the health-care and health systems. The potential for such data to inform, and potentially transform, our understanding of cardiovascular health and disease is the focus of this programme.

Cardiovascular diseases: current public health impact

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of premature death in the UK and the developed world. 21 Between 1990 and 2010 there were only minor improvements (3% decrease) in years lived with disability from coronary heart disease (CHD),22 and CVD is estimated to cost the NHS about £15.7B a year – 21% of the total NHS budget. 23 Preventing the onset or progression of CVDs remains an important national priority. Interventions can be targeted at different time points along the patient journey: before disease manifests (by risk factor modification), during initial presentation of disease (with prompt and accurate diagnosis, delivery of effective care on referral and admission to hospital) and after discharge from hospital and beyond (optimising secondary prevention). Temporal changes in CVD management have been driven by the availability of new treatment targets [e.g. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance and Joint British Societies recommendations on the prevention of CVD guidance] and availability and use of effective treatments for CVDs. 24 Increases in the number of prescriptions of lipid-lowering drugs and number of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) carried out in the UK, together with changes in CVD risk assessment and prevalence, have contributed towards decreases in CVD mortality over the past decade, although the extent to which improved mortality can be attributed to changes in major risk factors, such as smoking, blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol, or specific CVD treatments, remains unclear.

Concerns of a ‘broken pipeline’ in cardiovascular research

There is widespread concern that current models of discovering new interventions, evaluation in trials and implementation in clinical practice take too long (an average of 17 years), are too costly (US$5–11B for each new licensed drug) and are too risky for investors. There is a major need for new research models in general and trial models in particular in cardiovascular research, for several reasons. First, because major unmet needs remain [e.g. acute myocardial infarction (AMI) 1-year mortality is still 20% despite five proven secondary preventative medications]. Second, because late drug failures occurring within Phase III trials (each costing US$50M–100M) are particularly problematic and have been recently seen for drugs that raise high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and for heart rate-lowering agents [ivabradine (Procoralan®, Servier, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France)]. Third, non-drug interventions, based on clinical algorithms and decision support, are of growing importance in CVD but are rarely trialled at all. Fourth, growing use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs is associated with major side effects (bleeding is the second most common cause of iatrogenic hospital admission). Fifth, rare CVDs are undertrialled, partly owing to difficulties in recruitment. Finally, the observational evidence that leads to trials often comes from primary prevention settings; however, the populations in which drugs are first trialled are often in secondary preventative and high-risk settings. Planning a trial can be complex because of the lack of suitable populations from which to estimate accurate event rates and select the most appropriate end points. It is too slow and costly to evaluate feasibility, and opportunities are frequently missed to collect valuable data that will adequately inform late-phase trials. It is inefficient to collect clinical data separately for trials and for clinical care, and the process of randomisation and outcome ascertainment is not integrated into the pathway of clinical care. Trial participants are highly selected, which may limit the generalisability of the trial results, and clinical outcomes in clinical care may not be as promising as suggested by the trials.

Electronic health records data opportunities in coronary disease

It is precisely because hospital information systems have historically been unfit for any purpose relating to understanding the quality and outcomes of care that professional societies have organised themselves and established post hoc collections of data that populate disease registries.

There are very few countries (possibly only the UK and Sweden) that have national mandatory ongoing heart attack registries in which every hospital in the country returns data on care and outcome. MINAP is one of the only national registries recording continuous data from every hospital that manages acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients. The information it provides about clinical phenotypes is unavailable from any other national source and has shown that the reduced rates of heart attack in the early part of this century have been largely confined to ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI), whereas rates of non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) have remained static. 25 This detailed epidemiology is less easily available for other manifestations of CVD, such as abdominal aortic aneurysm and ischaemic stroke, because disease-specific registries either have not been developed or have become nationwide (all hospitals) only in the past 5 years. 26 This represents an important gap in our knowledge, and it is not clear whether or not the risk factors and changing epidemiology for CHD can be generalised to other manifestations of CVD.

In the UK, rates of hospitalised AMI (heart attack) and coronary death can be extracted from national data sets such as HES and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) death registry. Richer data on CVDs and procedures are available from national cardiovascular registries. The national registry of percutaneous intervention was originally managed by the British Cardiovascular Interventional Society, and the British Cardiovascular Society and the Royal College of Physicians originally managed the MINAP heart attack registry. In 2010, the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership handed responsibility for the six cardiovascular registries to the newly established National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR), which now not only has responsibility for the annual audit reports but also makes the registry data available to research groups. 27

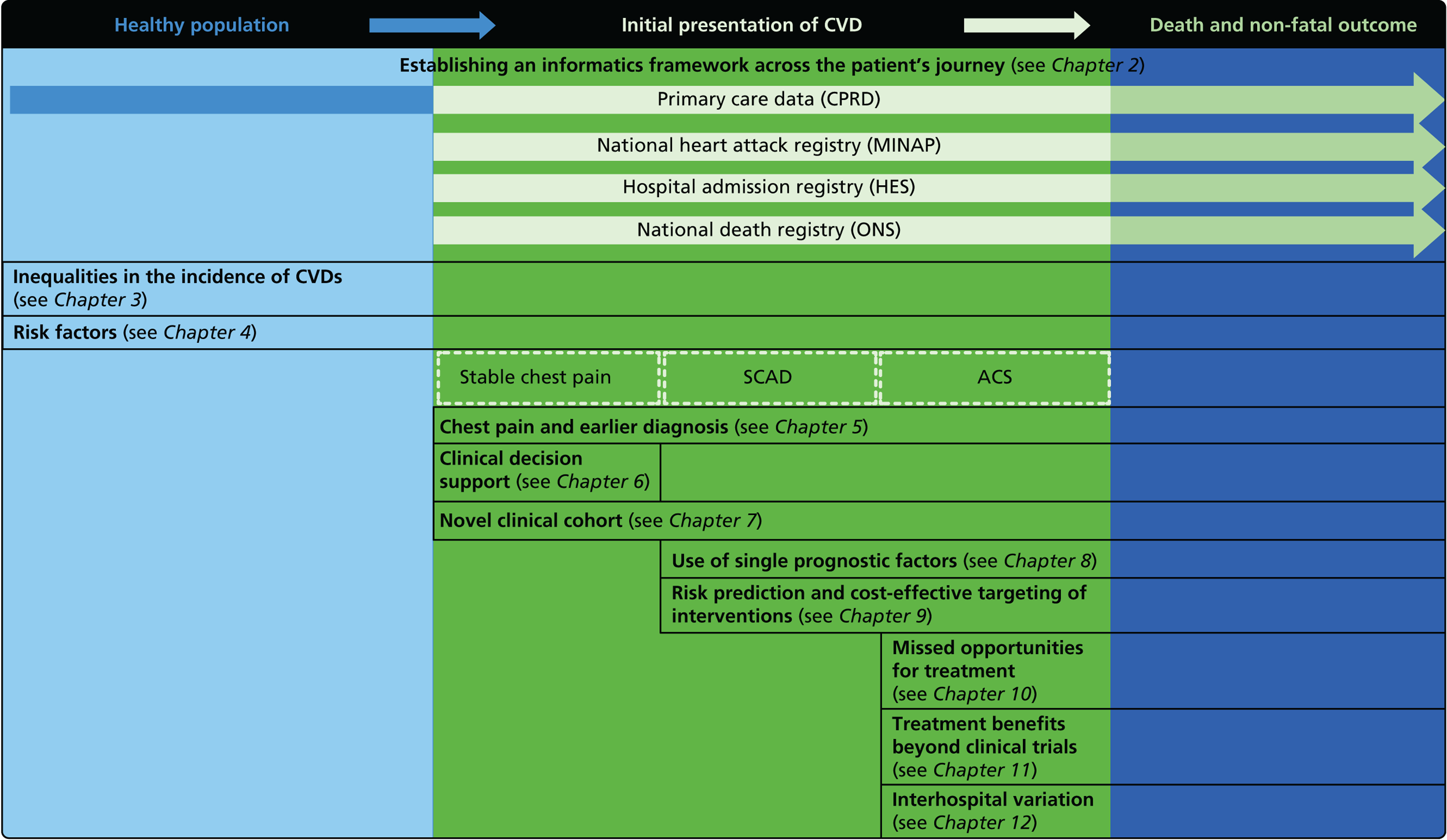

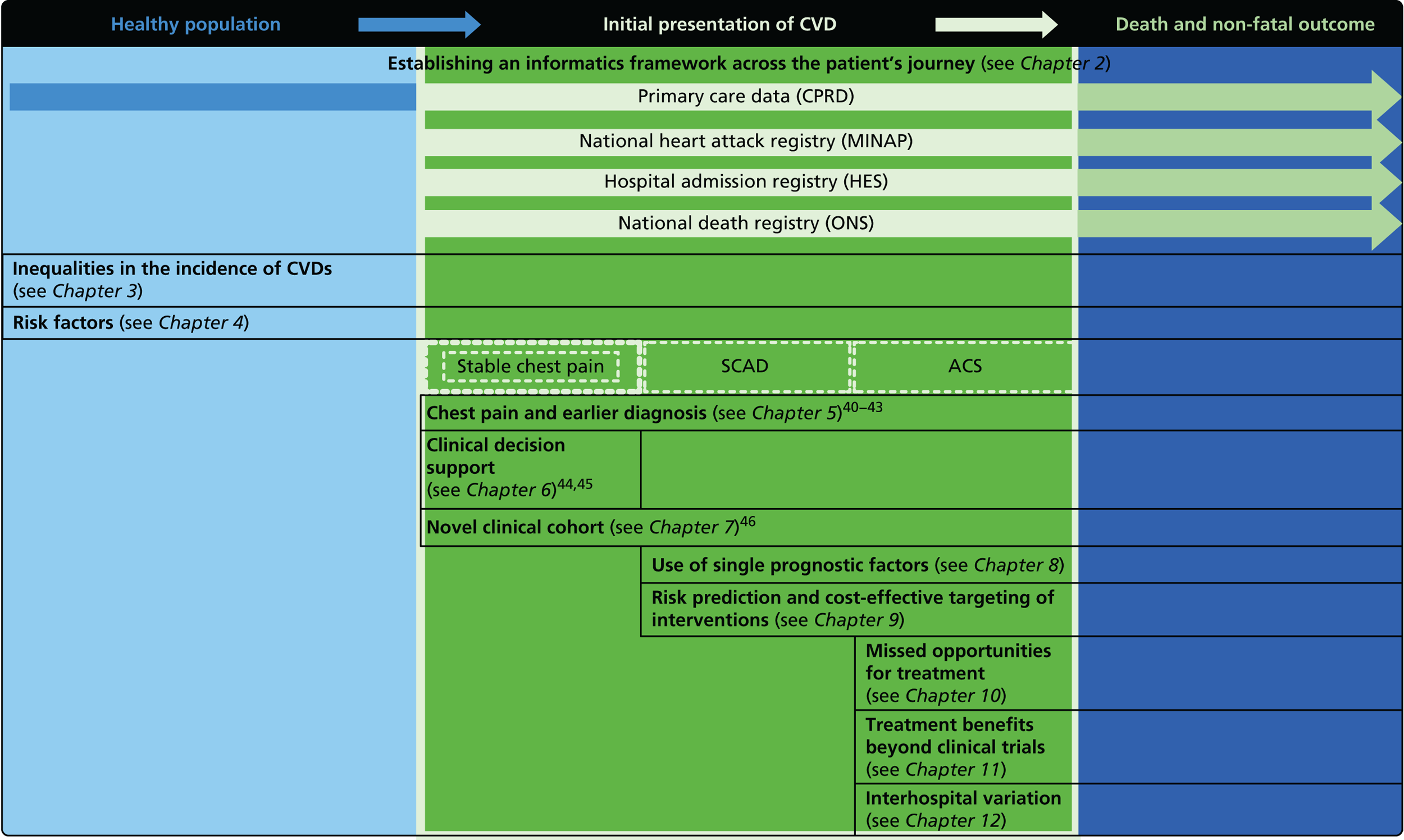

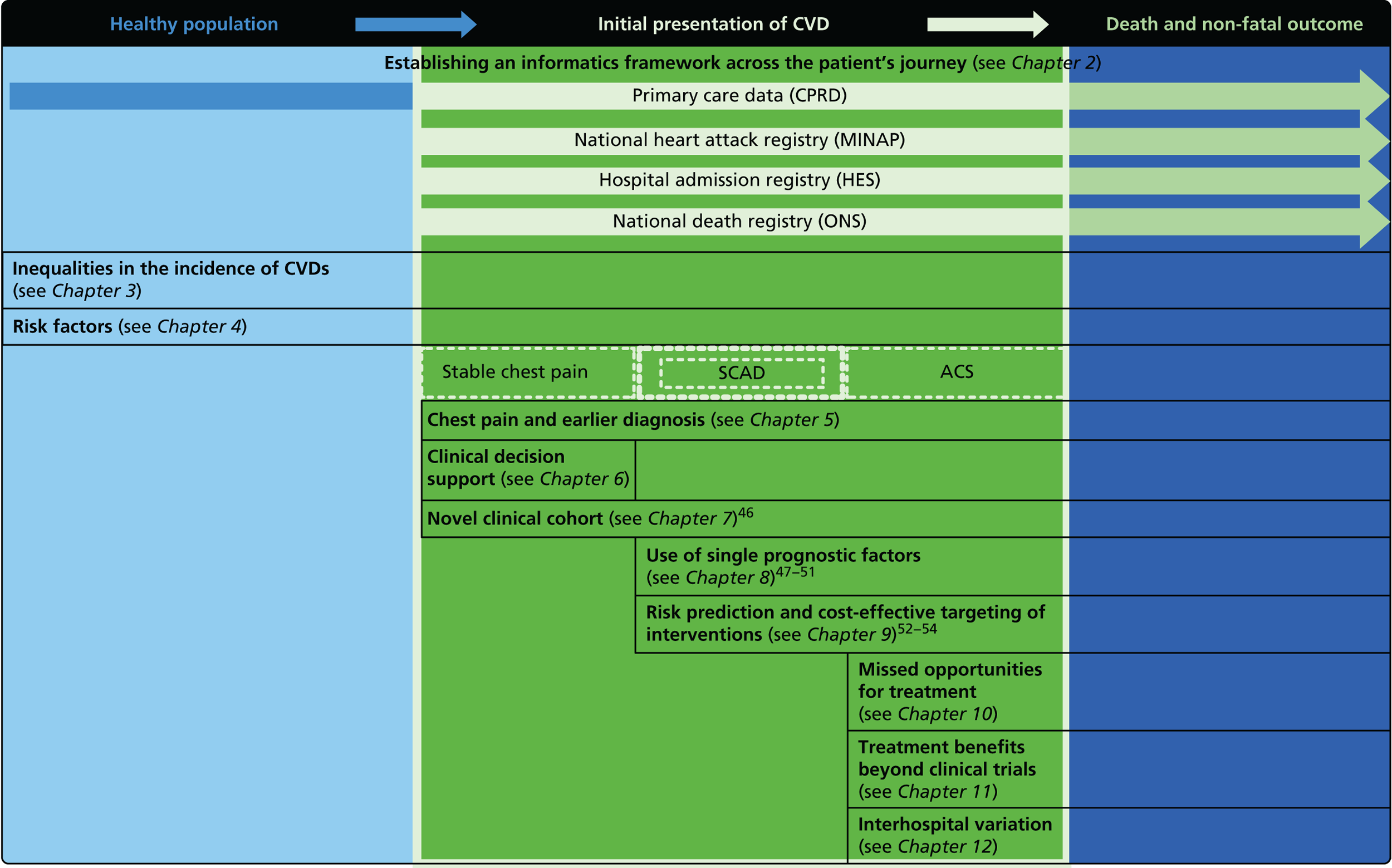

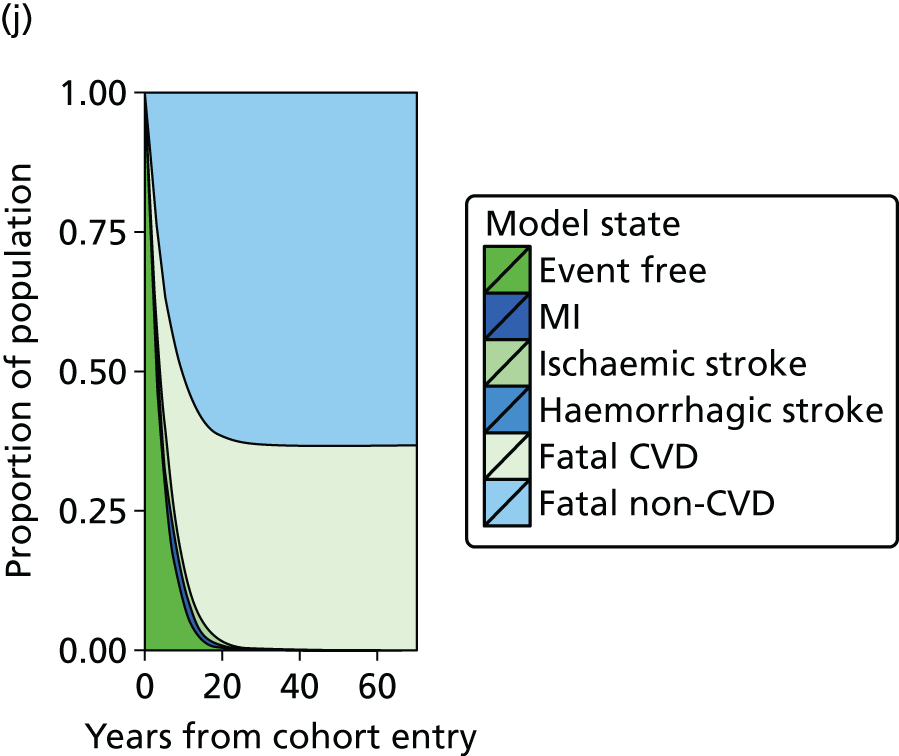

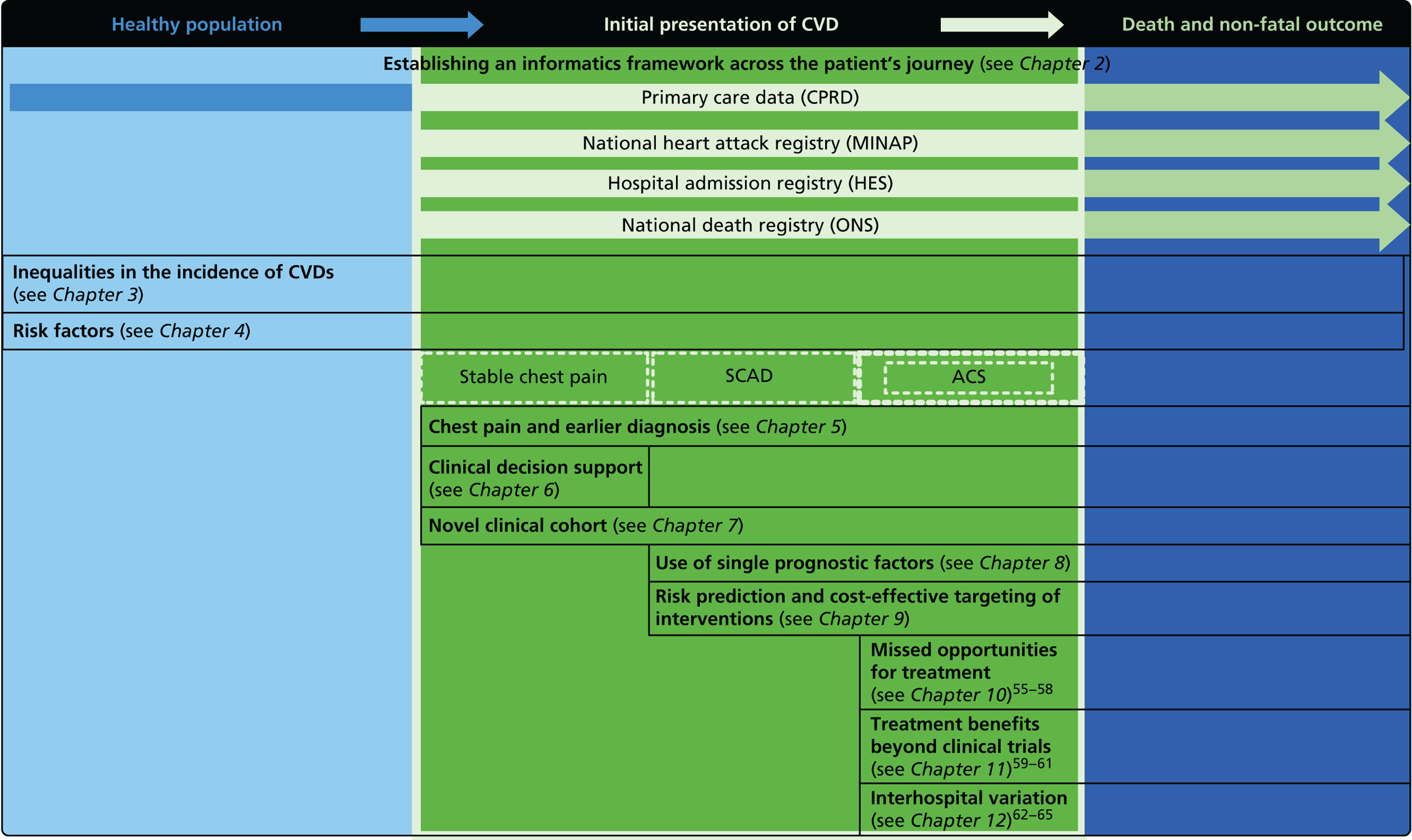

The overarching aim of CALIBER is to harness diverse data sources to undertake novel research in CVDs, including opportunities improving care. Our research programme adopted the ‘patient journey’ concept to explore missed opportunities in primary prevention, diagnosis, acute care and secondary prevention (Figure 2). By harnessing the potential of linked EHRs, we seek to provide valuable information to guide clinical decision-making and health policy-making, with the potential to improve quality of care and outcomes for patients.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of the 33 studies in our programme: the patient journey. SCAD, stable coronary artery disease.

Owing to the evolution of coronary atherosclerosis and symptomatic manifestations (angina, heart attack), which can be viewed as chronic, long-term conditions, our research programme adopted the ‘patient journey’ concept to explore missed opportunities in primary prevention, diagnosis, acute care and secondary prevention. In particular, we have attempted to exploit the potential offered by linked EHRs spanning the patient journey through primary care, the hospital system and ultimately to death. By identifying the nature and scale of such missed opportunities over time, we seek to provide valuable information to guide clinical decision-making and health policy-making, with the potential to improve quality of care and outcomes for patients. A summary of our main findings and research recommendations for 33 studies included in our programme can be found in Table 3.

| Main research findings | Research recommendations |

|---|---|

| Chapter 2 | |

| Study 1: we established the CALIBER data resource. We successfully built tools to link coded data on diagnoses, symptoms, drugs and procedures, and clinically recorded biomarkers across primary care, secondary care and disease registries for almost 2 million people and curated ≈ 600 EHR disease and risk factor phenotyping algorithms based on linked EHR data15 |

|

| Study 2: we assessed the completeness and diagnostic validity of recording AMI events in primary care, hospital care, disease registry and national mortality records. Across CALIBER’s four linked sources, we found that each source misses a substantial proportion of events; therefore, linking multiple sources is important. AMI recorded in these sources, in terms of risk factor profiles and mortality at 1 year was found to be valid28 | Further research is required to:

|

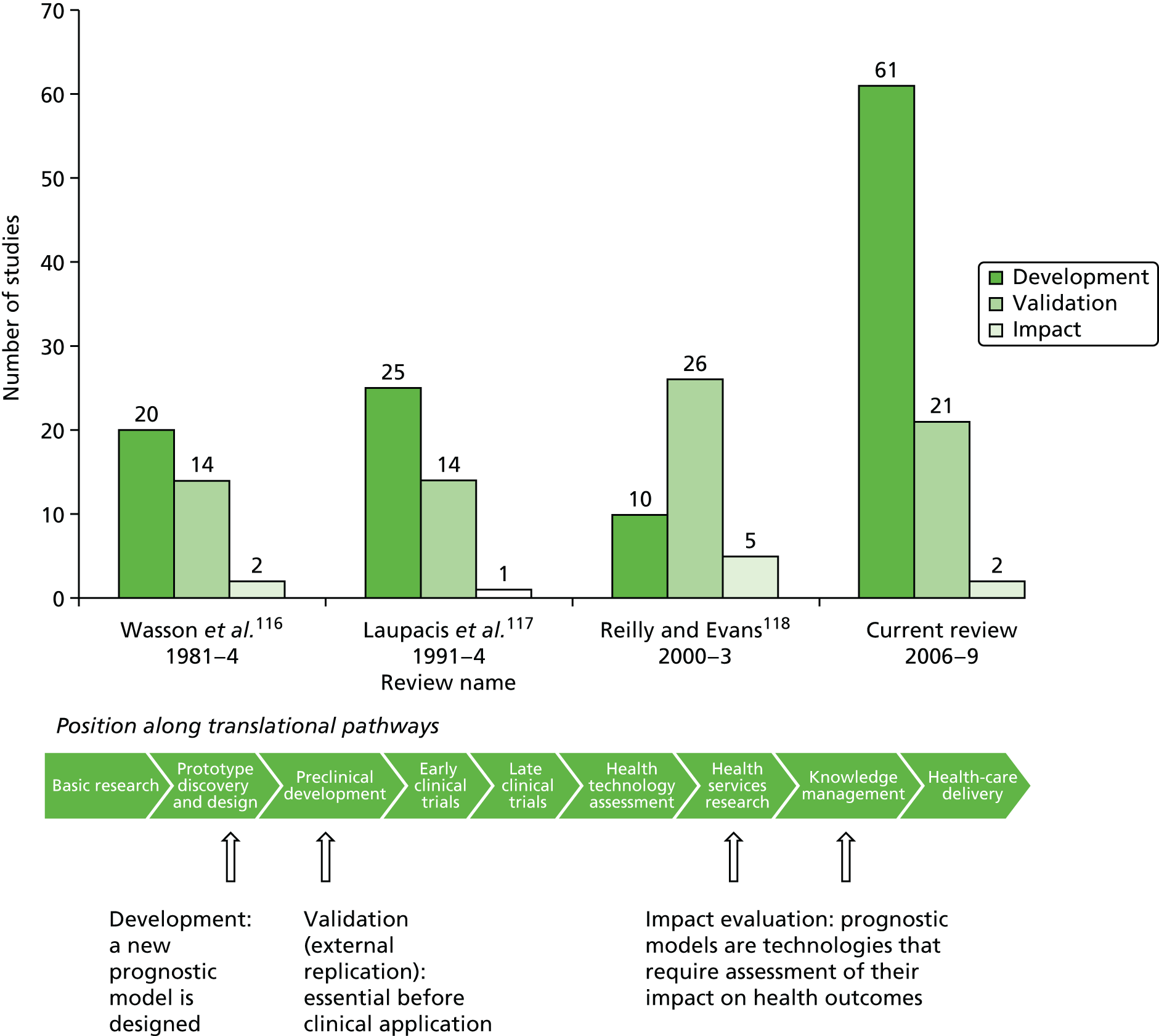

| Study 3: we established the PROGRESS partnership to promote high-quality prognostic research leading to patient benefit. We highlighted opportunities to improve the design, conduct, analysis and reporting of prognosis research in 24 recommendations29–33 | The PROGRESS recommendations include:

|

| Chapter 3 | |

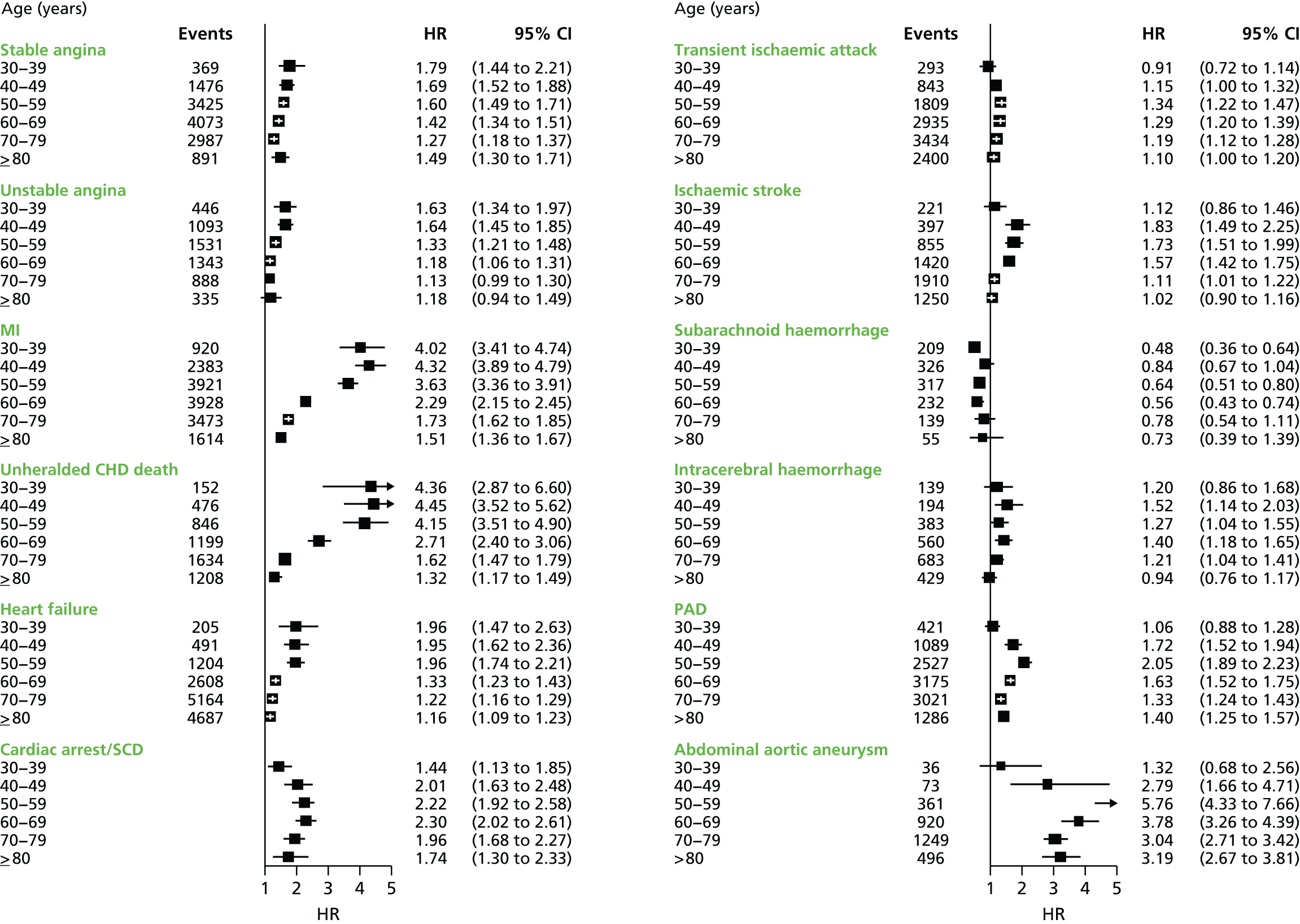

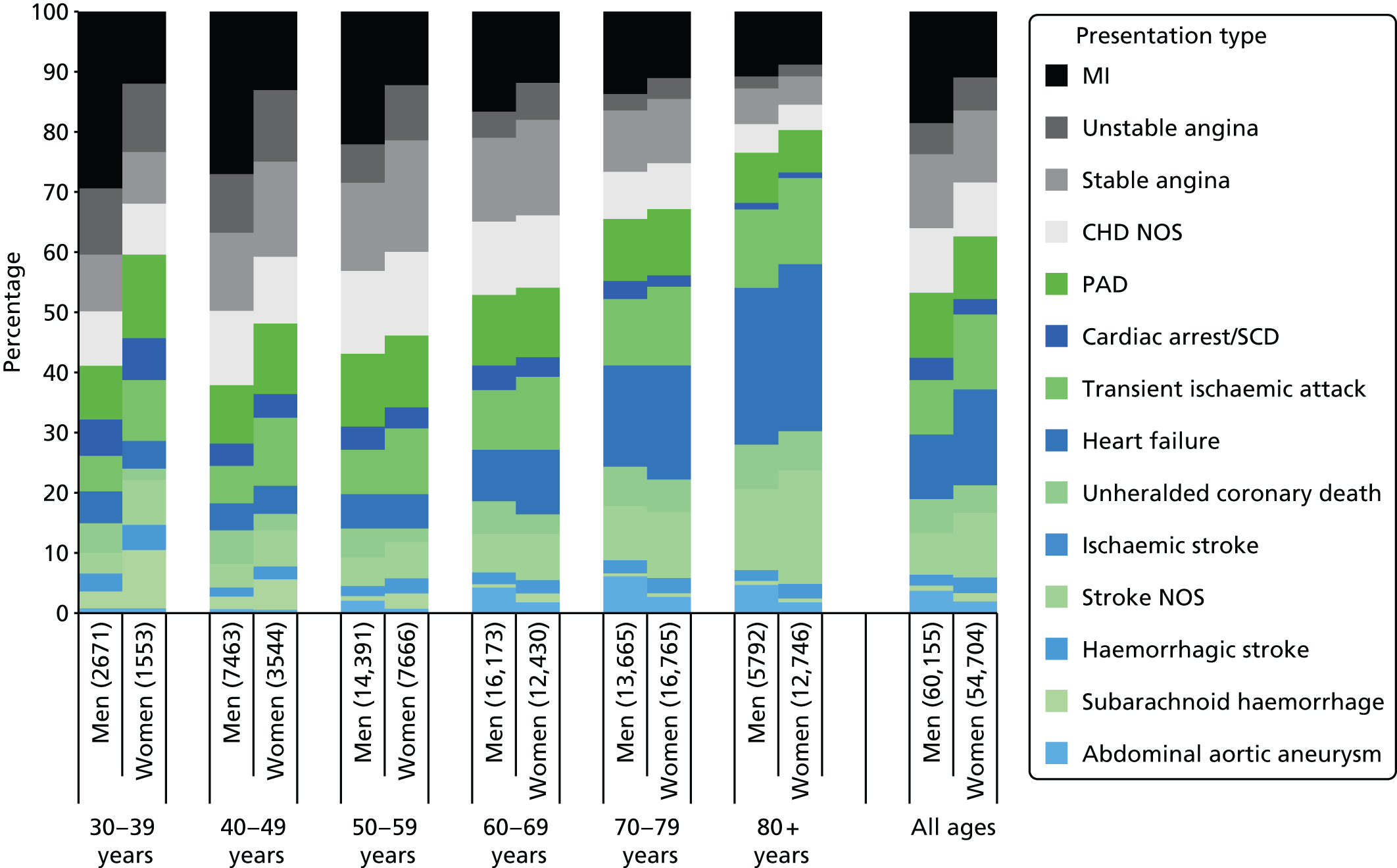

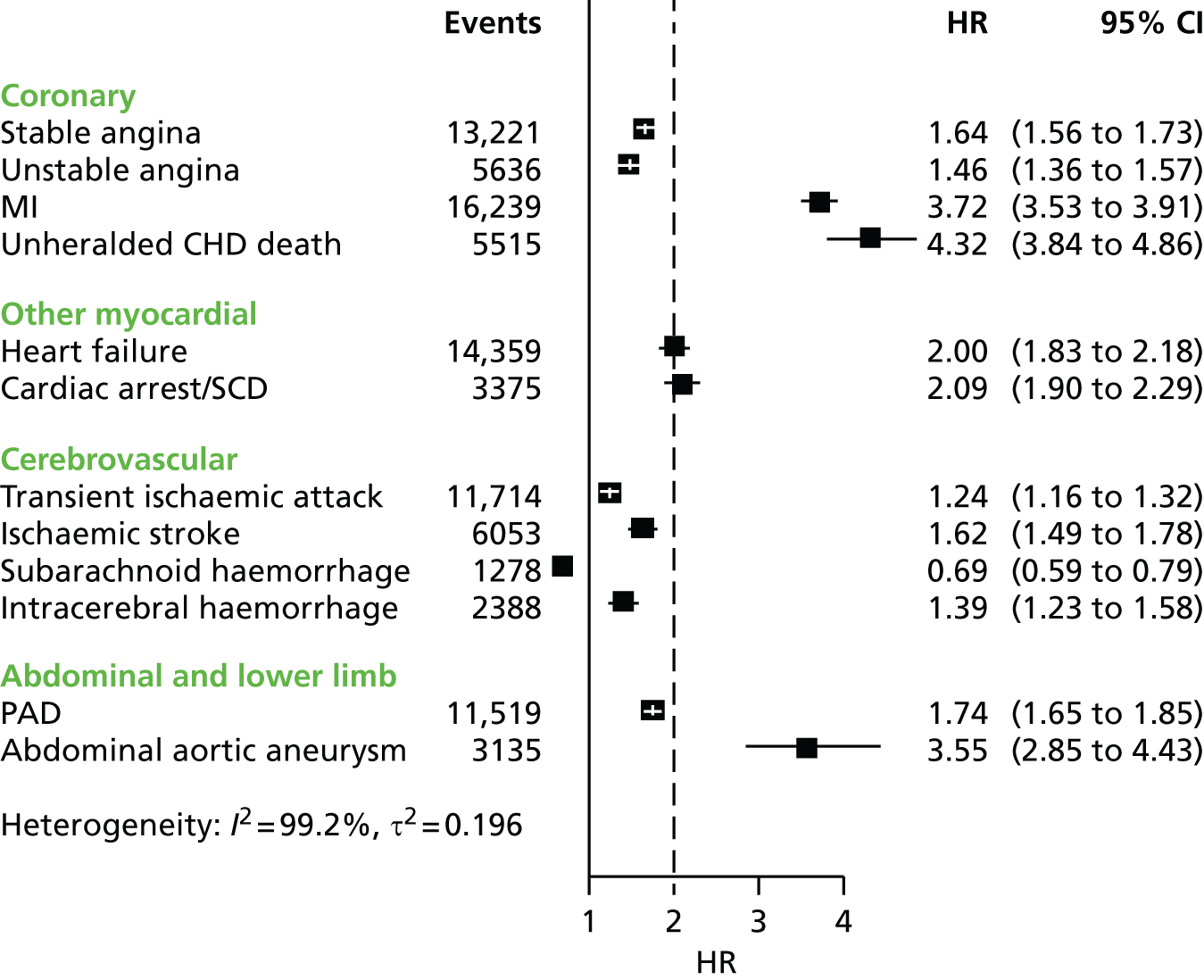

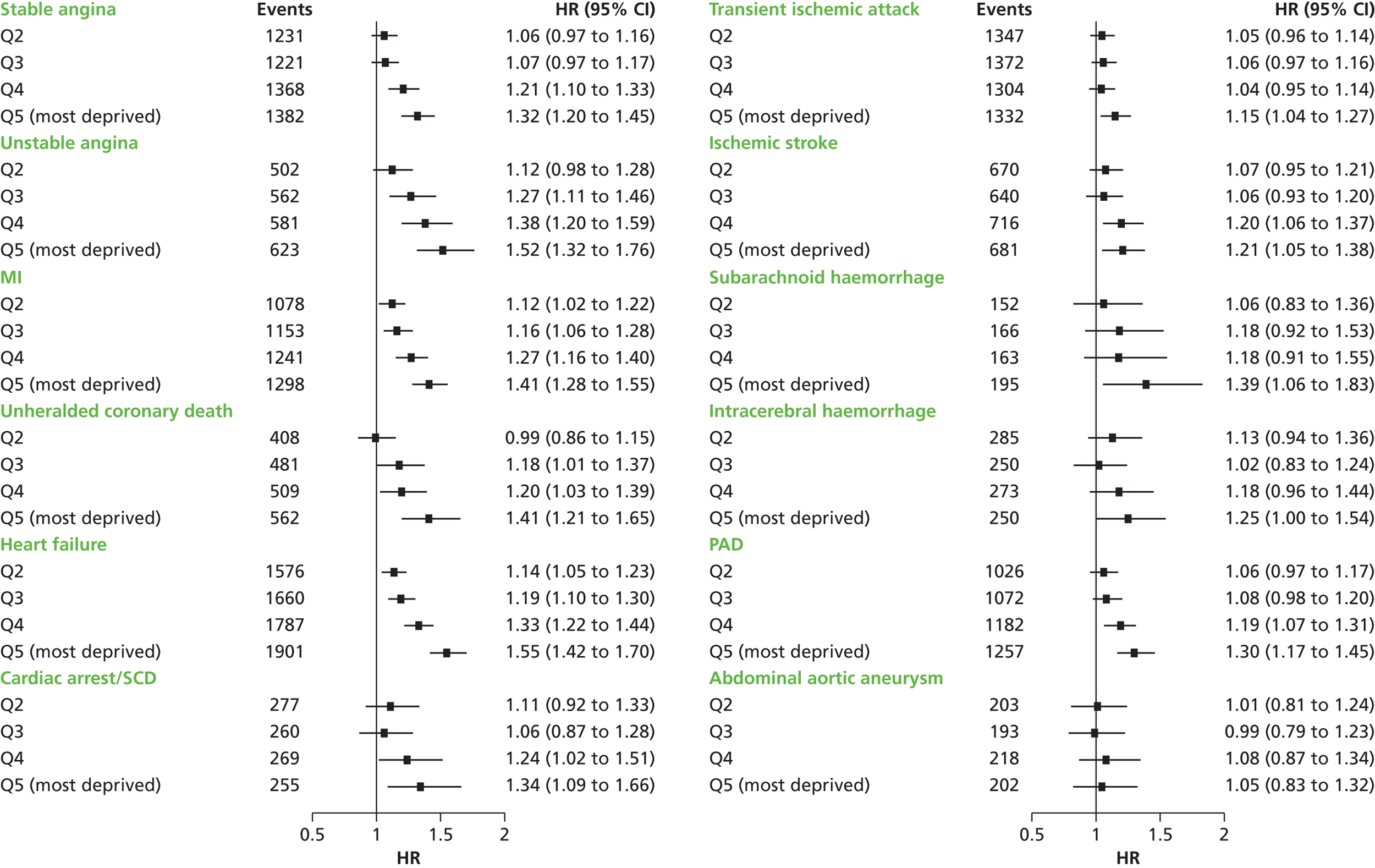

| Study 4: we investigated a central question in CVD – what is the first CVD to present across different ages, sexes, ethnicities and levels of deprivation? We found important differences that conventional epidemiological approaches based on small consented studies have eluded. These include that heart attack and stroke account for the minority of presentations, that women are less likely to get some CVDs than men (e.g. subarachnoid haemorrhage), the strength and shape of association of age with many CVDs varies substantially, and those of South Asian ethnicity experience substantially increased hazard of stable and unstable coronary presentations compared with white people34,35 | Estimates of national and global burden of CVDs need to take account of the modern epidemic in which heart failure, PAD and other chronic diseases are becoming more common than AMI and stroke. Male sex, older age, South Asian ethnicity and low social deprivation, although associated with many CVDs, are not associated with all, and this heterogeneity has implications for research into risk prediction, aetiology and prognosis |

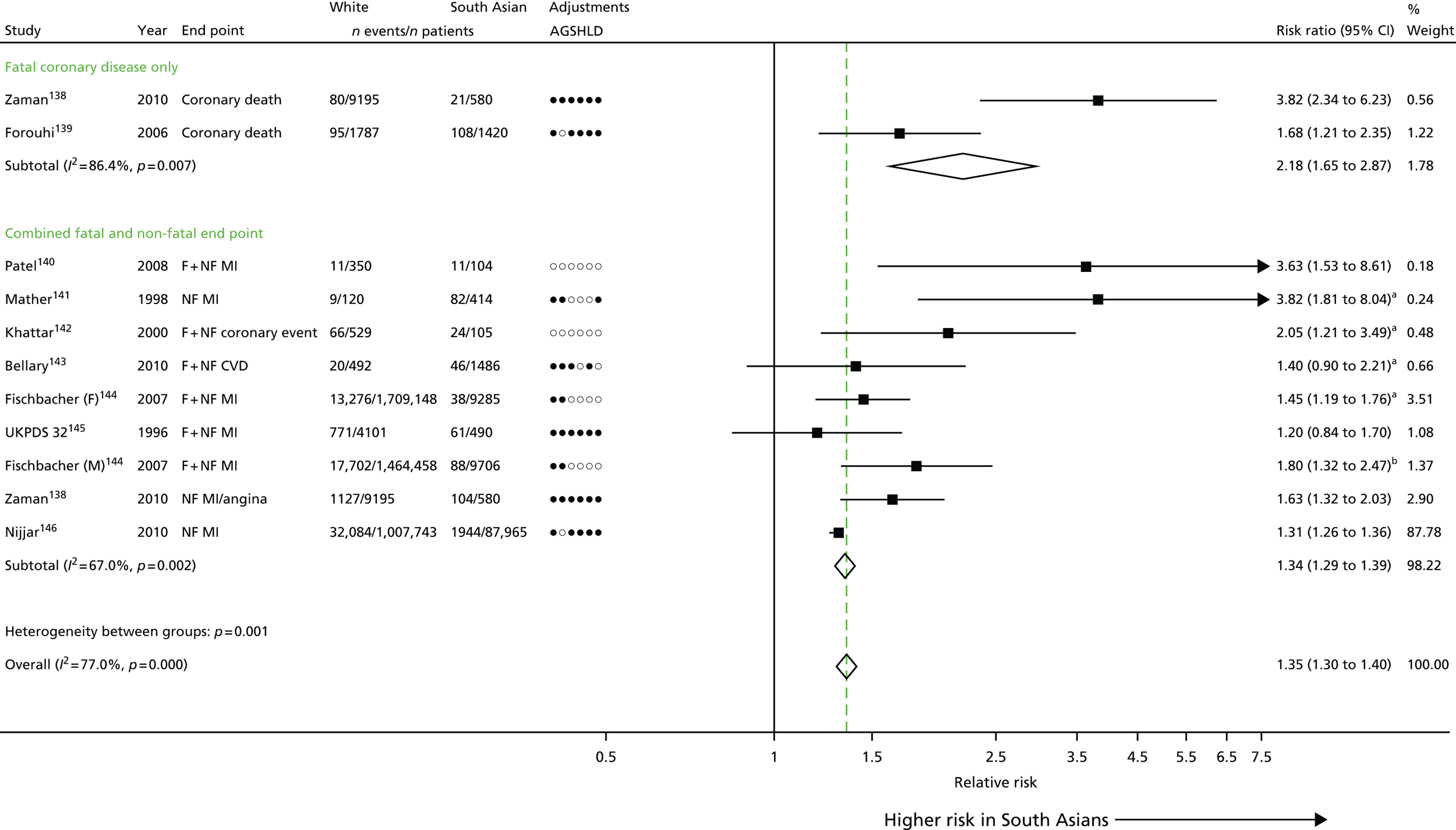

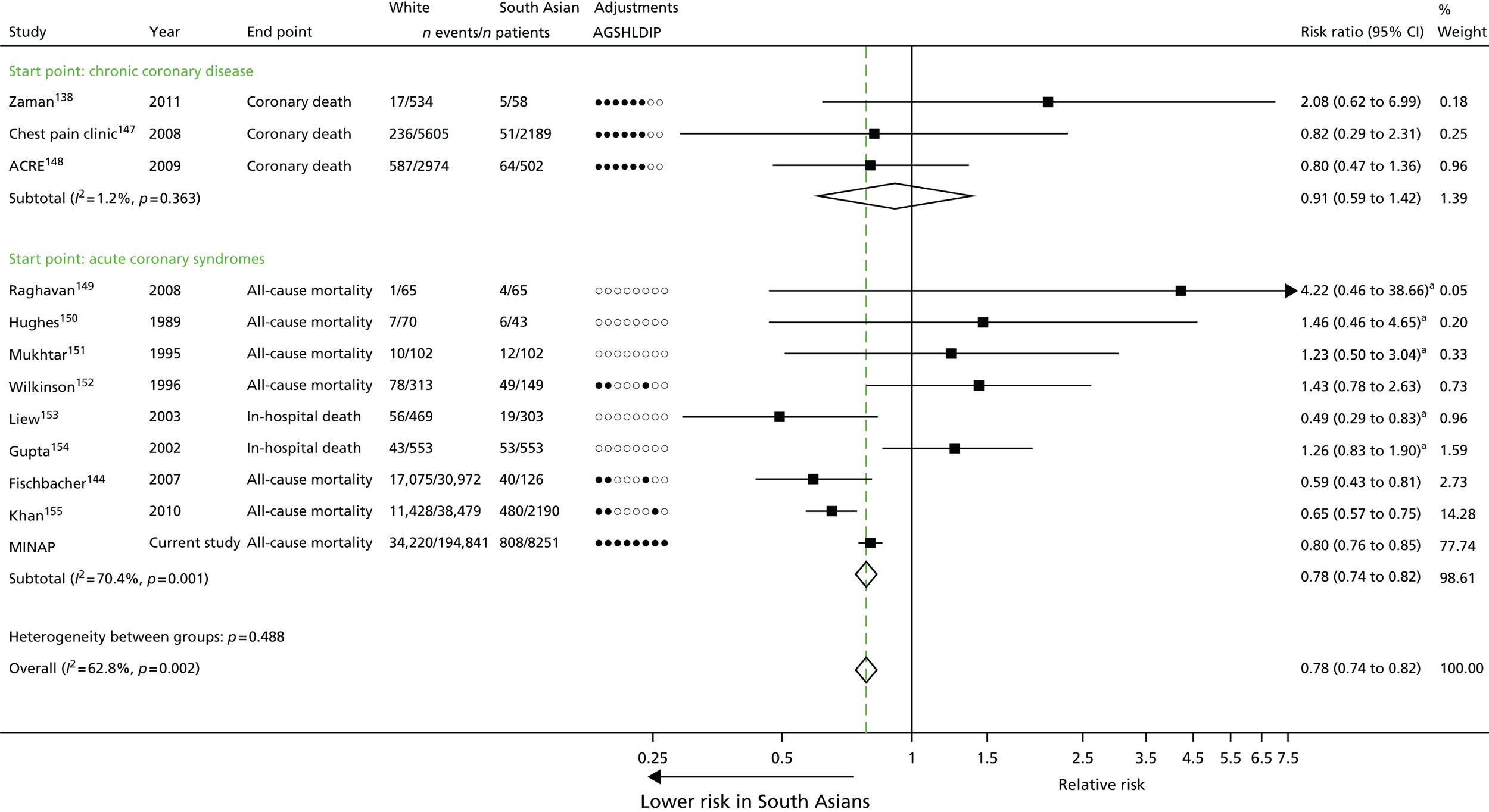

| Study 5: there was a discordance between incidence of SCAD, which was markedly higher among those of South Asian ethnicity than for those of white ethnicity, and prognosis which was significantly better in South Asians36 | Large-scale EHR cohort studies with detailed measures over time of clinical risk, and patient care identified through linkage of primary care, ACS registry, hospitalisation and cause-specific death data are warranted to better understand how South Asian ethnicity influences the onset and progression of coronary and other CVDs. Such studies will allow longitudinal patterns of risk and missed opportunities to lower risk before admission and after discharge to be evaluated |

| Chapter 4 | |

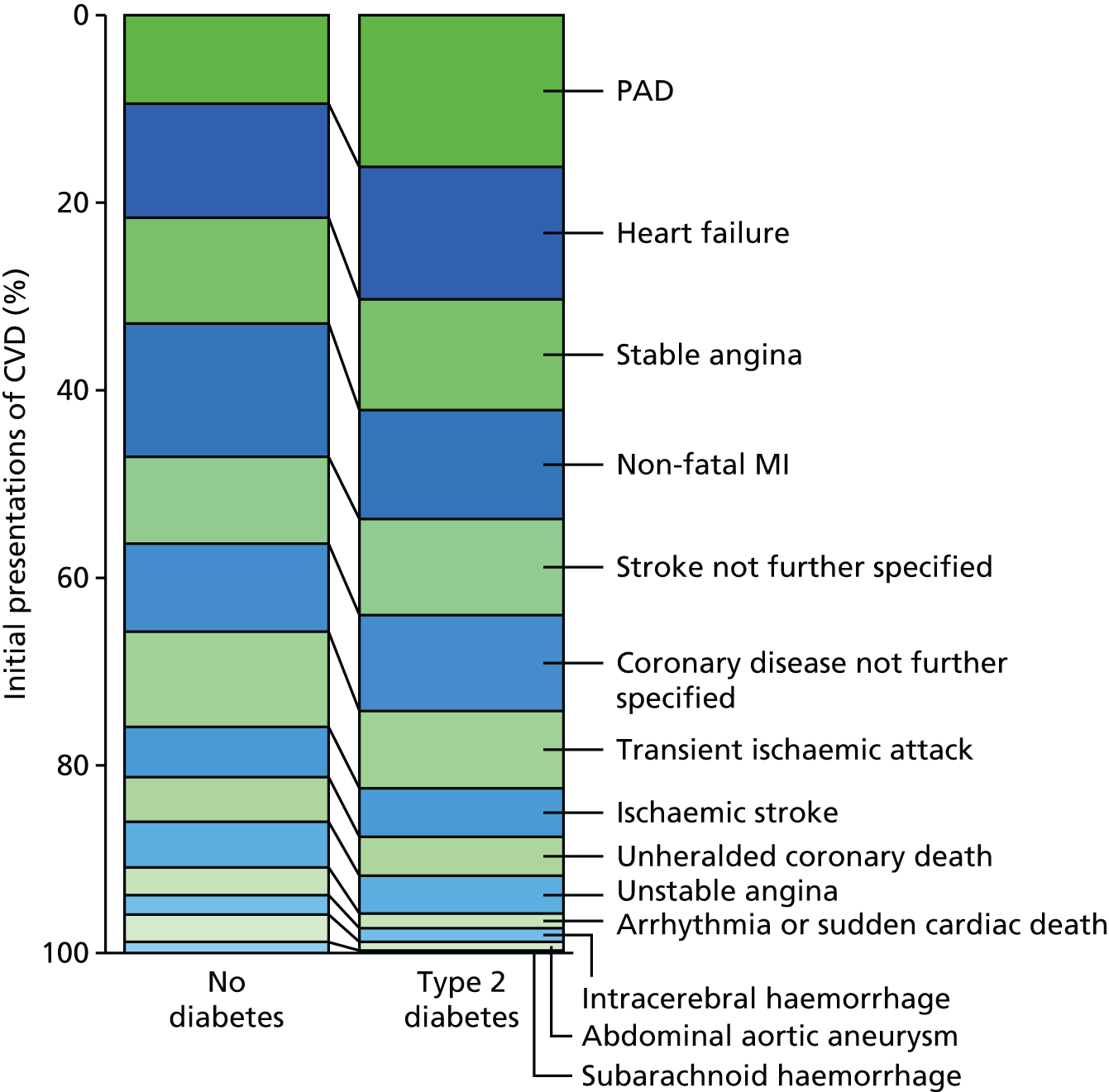

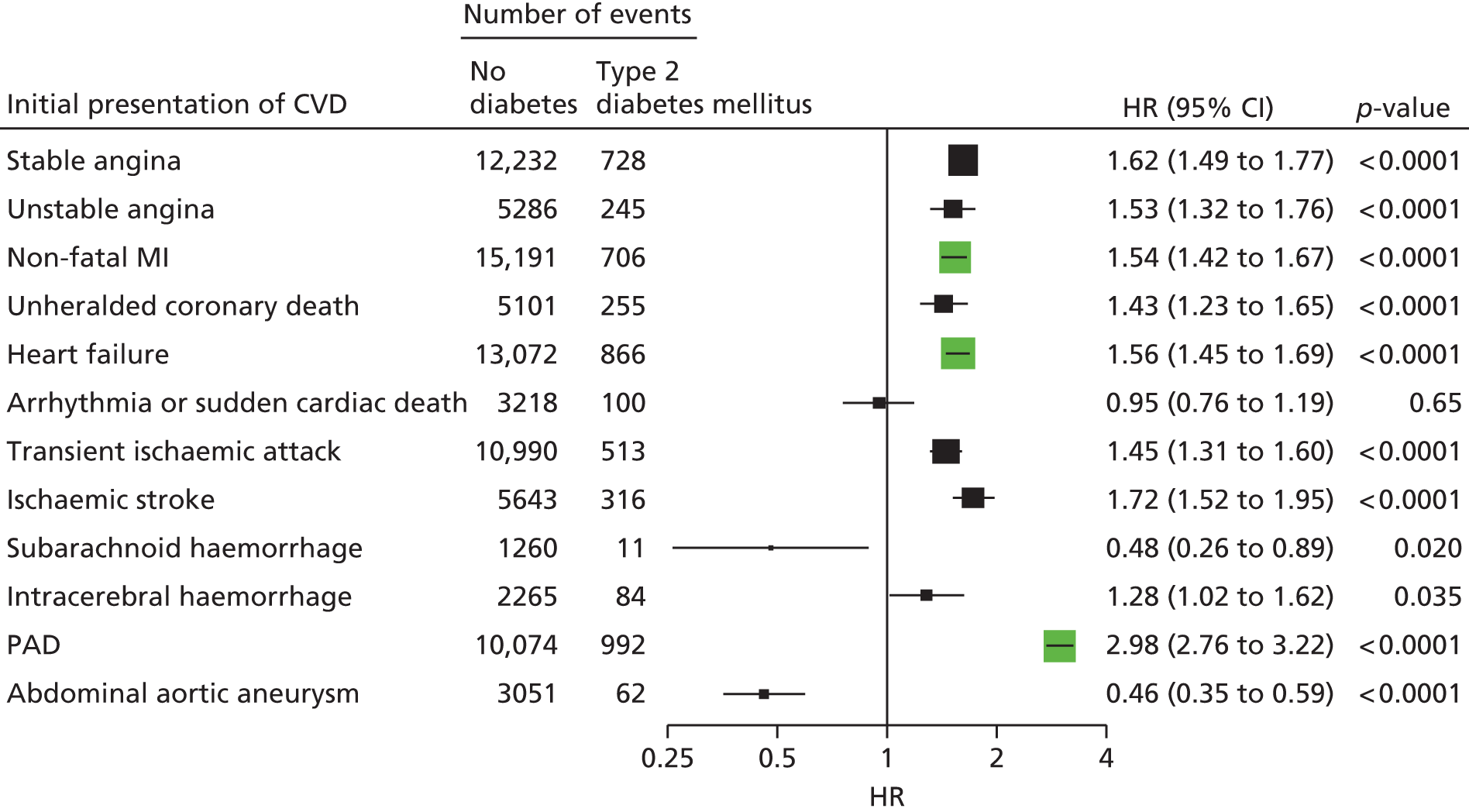

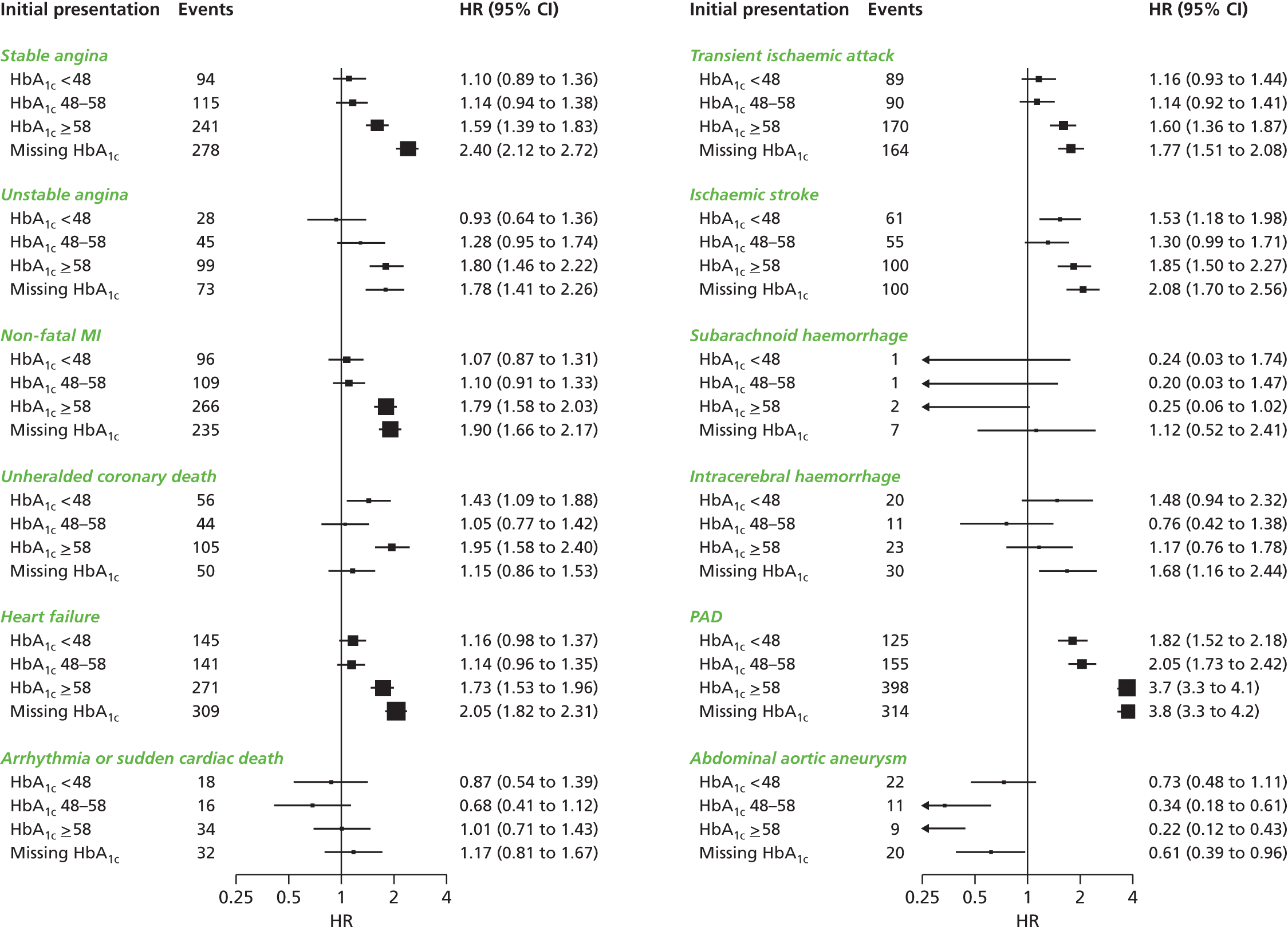

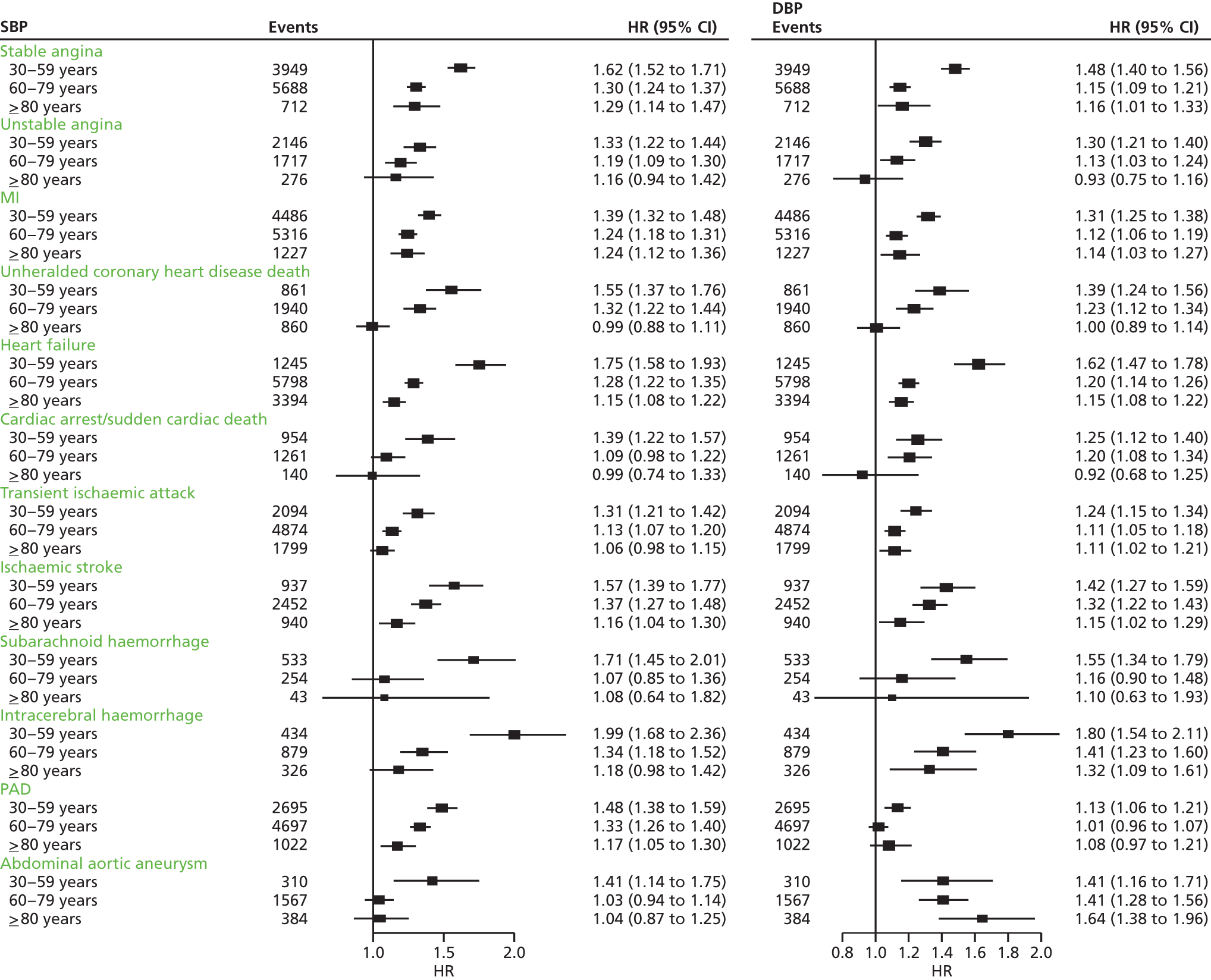

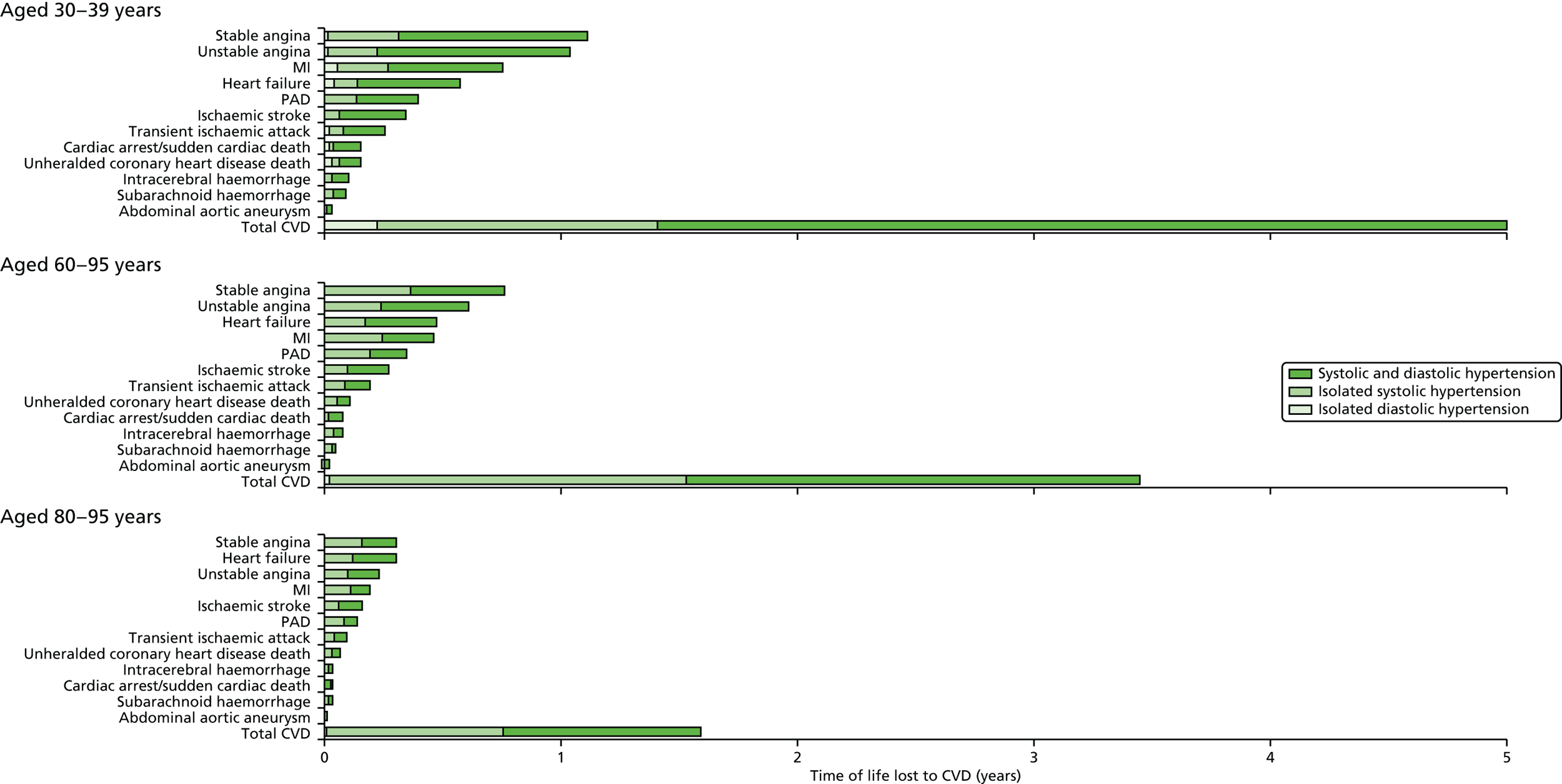

| Study 6: among 34,198 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, we found that type 2 diabetes differs in its associations with 12 CVDs, with its greatest impact on PAD and heart failure, but type 2 diabetes was protective against abdominal aortic aneurysm37 | In clinical trial design, selection of primary end points is crucial and should reflect the mechanism of action of the intervention and, where appropriate, the public health burden of CVDs in the 21st century. This would suggest a growing importance of trials with end points of heart failure and PAD |

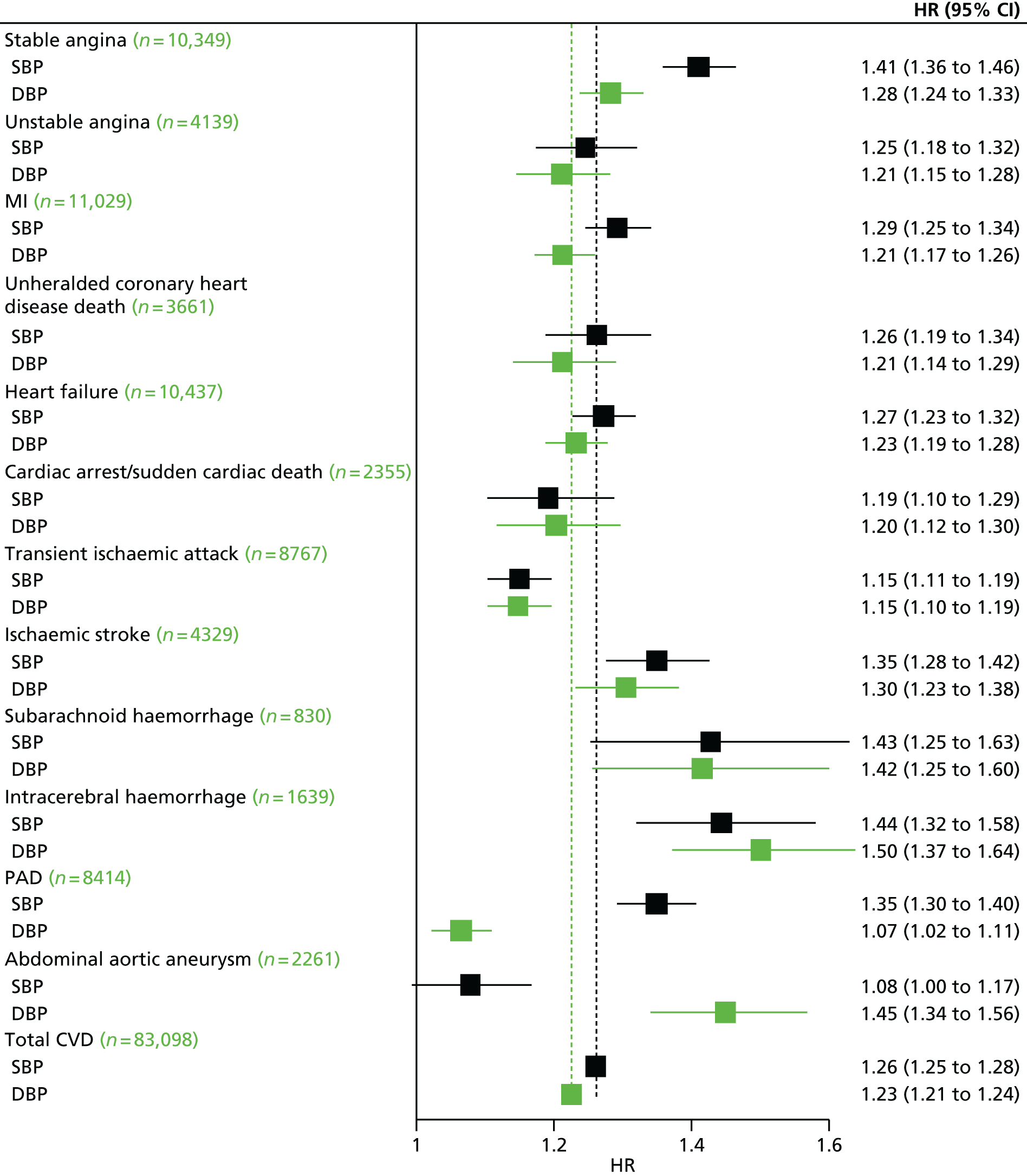

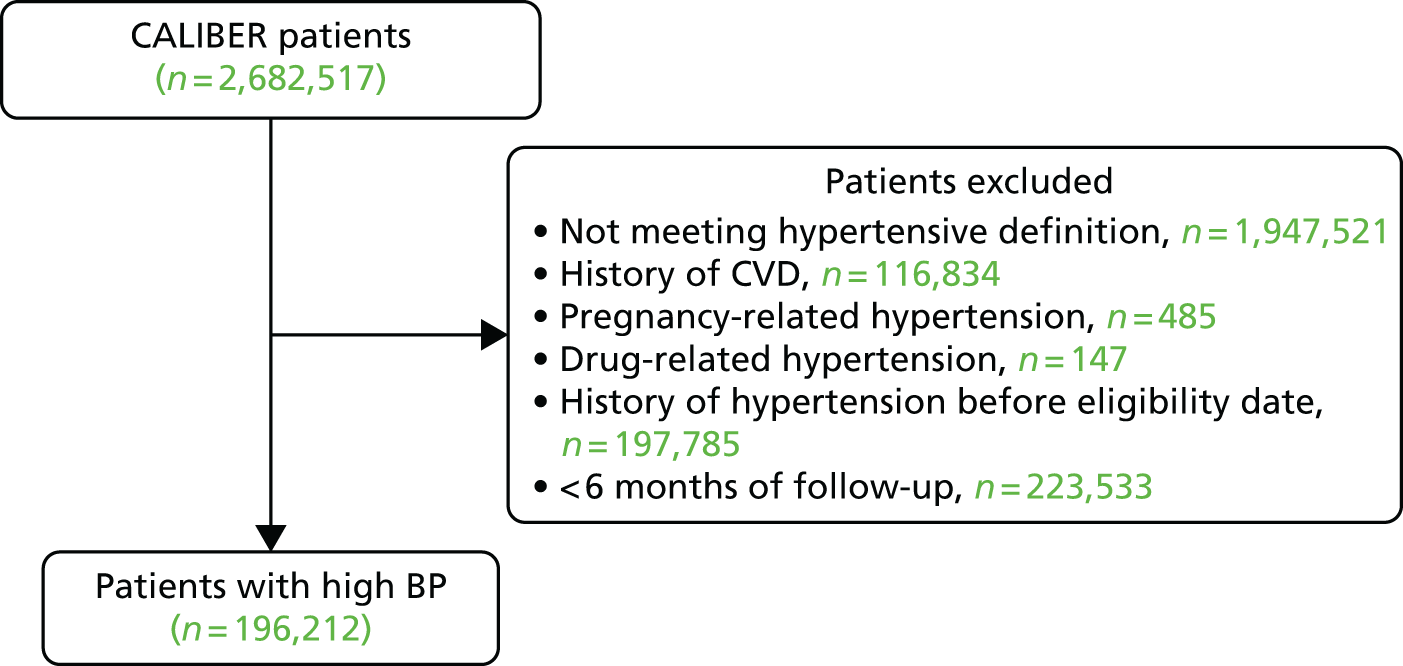

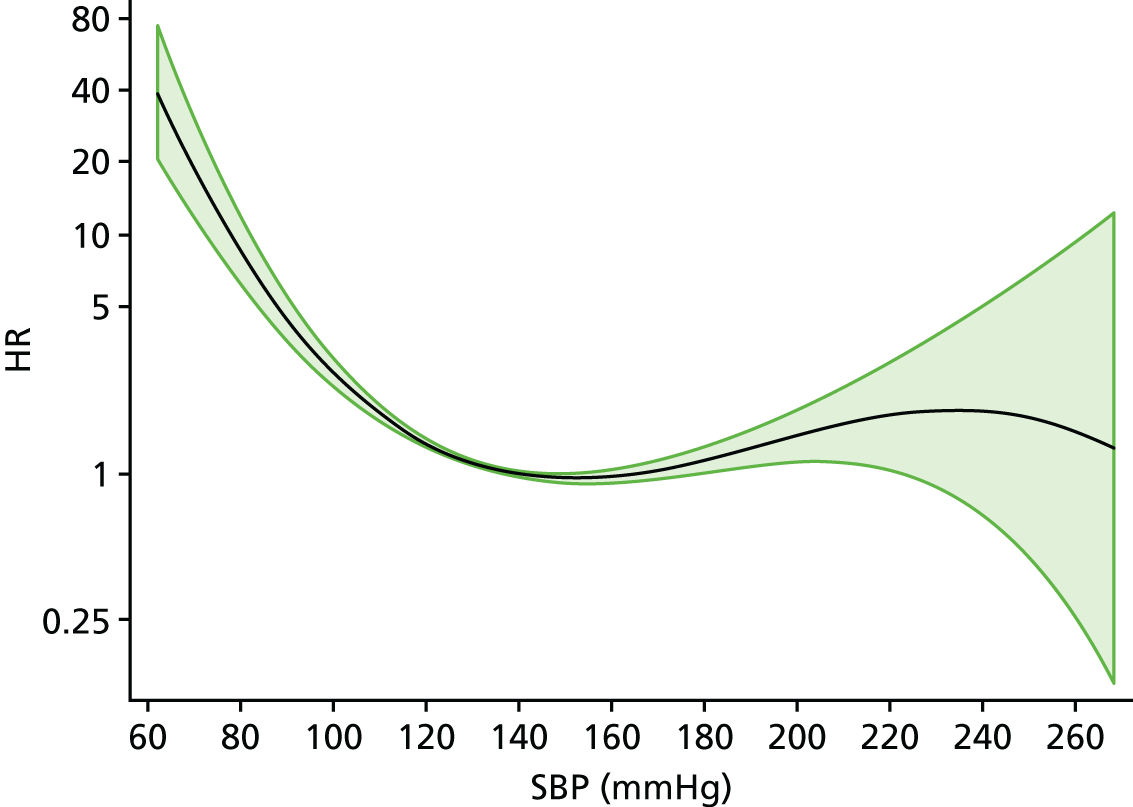

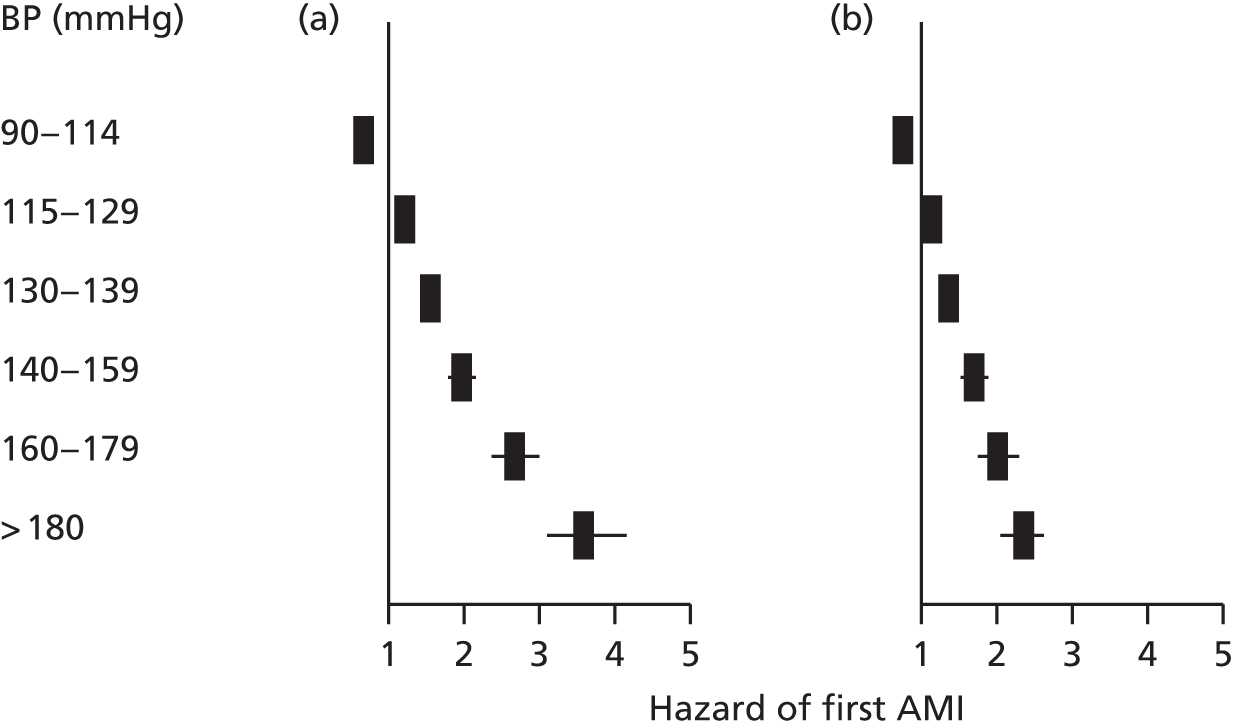

| Study 7: in this contemporary study of 1.25 million adults, we found that despite the availability of modern preventative medication, the lifetime burden of hypertension on incidence of subsequent CVDs remains considerable. Notably, SBP and DBP were found to differ in their associations with 12 CVDs and at different ages38 | New approaches are required to mitigate the excess CVD risk that remains despite modern BP-lowering therapy combinations. New and existing clinical trials investigating the effectiveness of BP-lowering strategies should include other common initial CVD presentations as the primary outcome |

| Study 8: in a cohort of individuals with newly diagnosed hypertension, we identified high levels of undertreatment among hypertensives. Consultation rates were significantly lower among those whose BP was not reduced to target (manuscript in preparation)39 | New approaches are required to close the second translational gap in BP lowering. This may include research on clinical decisions support for multiple drug classes to achieve target BP levels and other interventions, as well as understanding how best to lower absolute cardiovascular risk |

| Chapter 5 | |

| Study 9: we identified high levels of failure to diagnose angina at first presentation with chest pain, which led to poor prognosis among this group (manuscript in preparation)40 | Contemporary prognostic models should be developed and validated based on the characteristics of patients presenting with unspecified chest pain so those at risk of cardiovascular events can be more accurately identified |

| Study 10: we found that first AMI, especially with STEMI, was heralded by previous symptomatic atherosclerotic disease, one or more cardiovascular risk factors, or chest pain41 | Further research is warranted to better characterise the phenotypes, causes and prognosis of unheralded STEMI and NSTEMIs to improve the usability of EHR for research. Analyses comparing AMI patients with a control group without AMI, including a comparison of missed opportunities for care in measuring and controlling elevated risk are warranted |

| Study 11: we developed an open source free-text data mining tool (the FMA) for extracting diagnoses and causes of death from unstructured text in EHRs, which showed high precision and recall on a test data set from CPRD, and can be used to extract uncoded diagnosis or symptom information for EHR research. The tool may be useful in aiding early identification of CVD42 | Machine learning and NLP approaches to examining the large corpus of unstructured (free-text) data that exists in primary care and hospital records should be developed in order to identify opportunities for earlier diagnosis, add phenotypic information and safety signals |

| Study 12: we developed a data mining tool (the S3CM algorithm) to extract diagnoses and investigation results from unstructured text in EHRs by semisupervised machine learning, which outperformed comparator programs on data-mining tasks43 | Further testing of our semisupervised machine learning tool should be conducted using other EHR data sets, such as discharge letters and electronic hospital notes |

| Chapter 6 | |

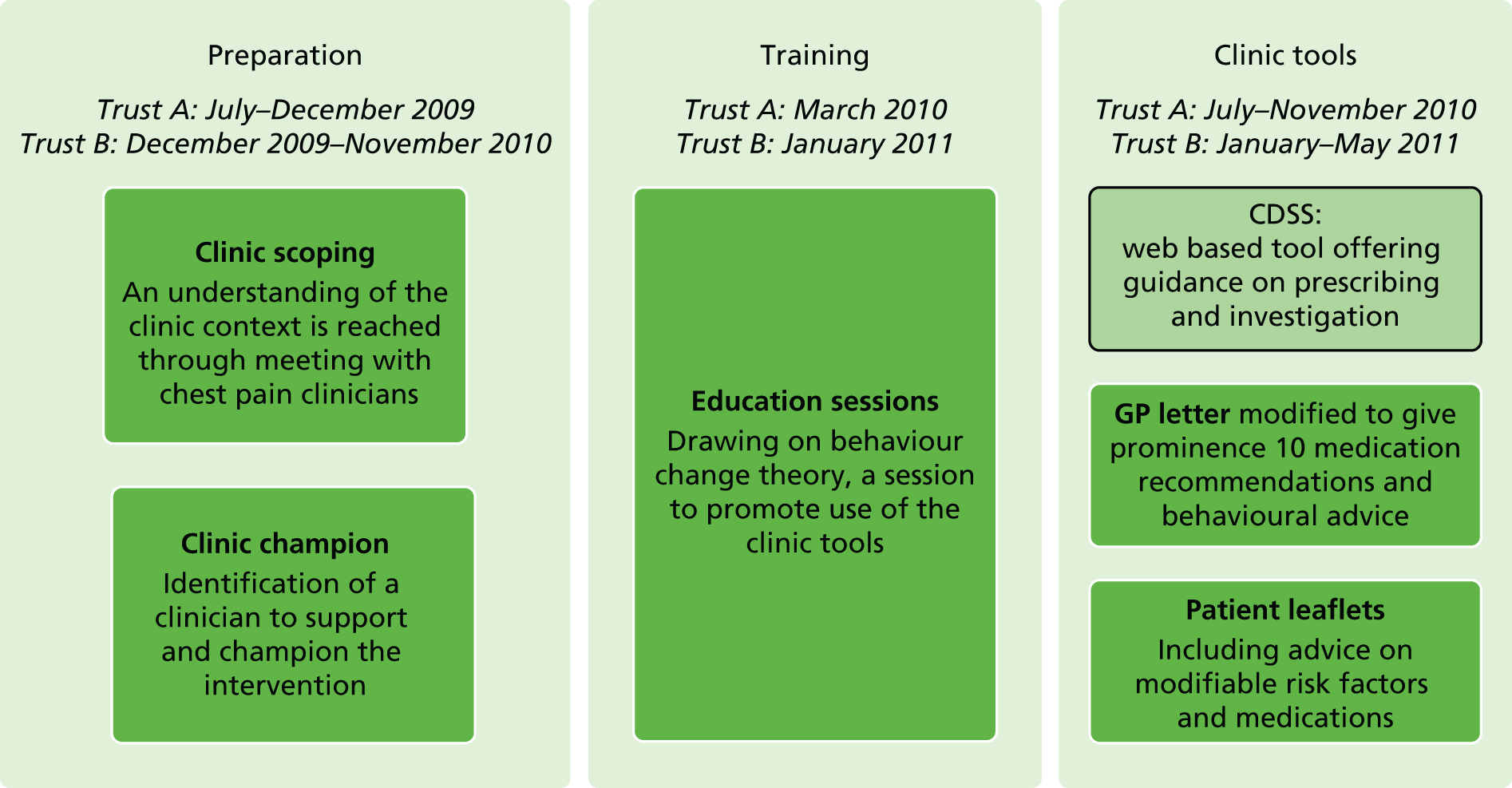

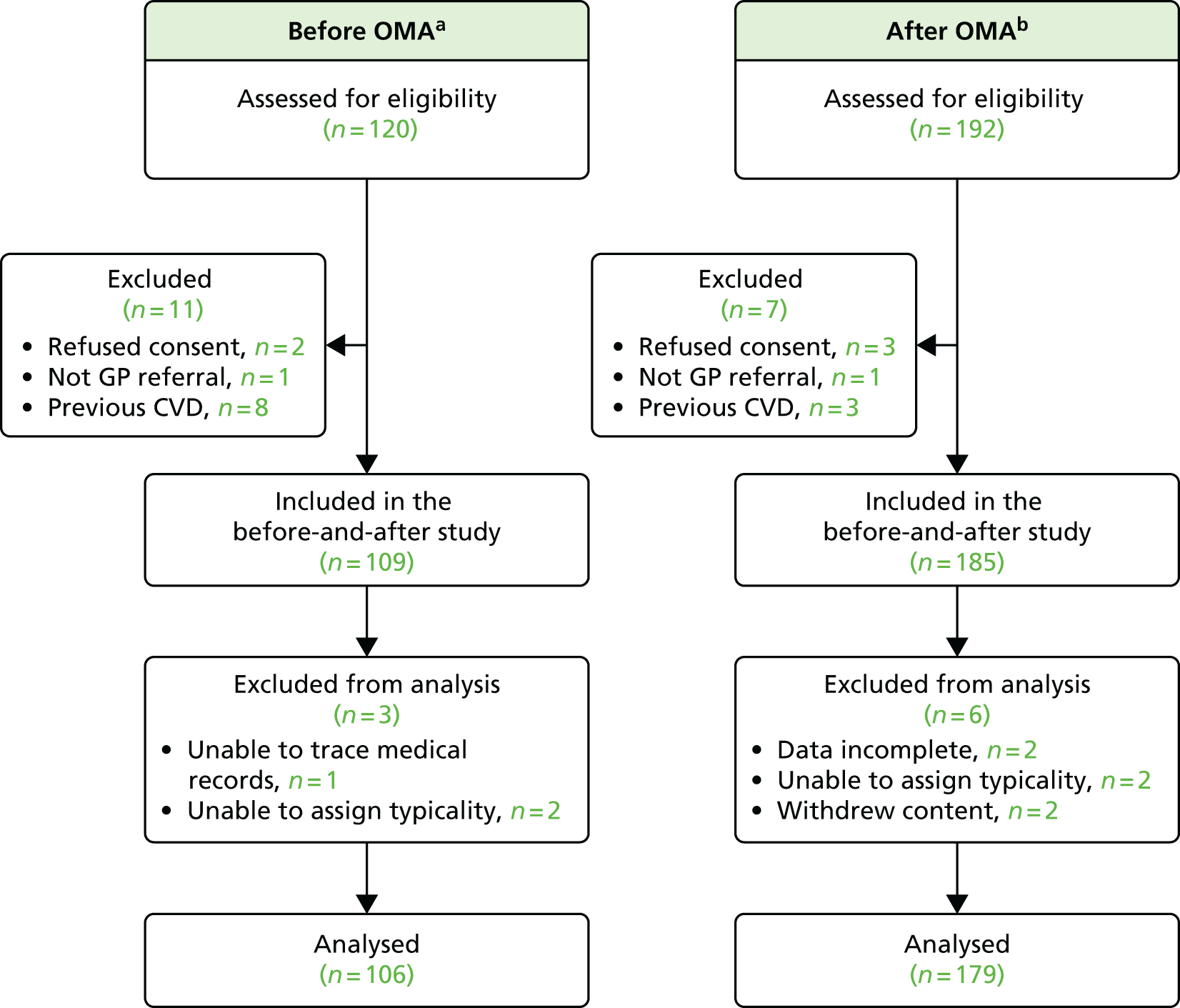

| Study 13: the OMA CDSS was used in 84% of RACPC consultations. OMA was found to have a negligible impact on decision-making in the hospital chest pain clinic, with qualitative data suggesting that clinicians found OMA useful in confirming their decision-making44,45 | Based on our understanding of the ways in which clinicians interacted with a computerised CDSS, there is a need to develop new tools to aid clinical decision-making with a greater likelihood of being adopted in practice |

| Chapter 7 | |

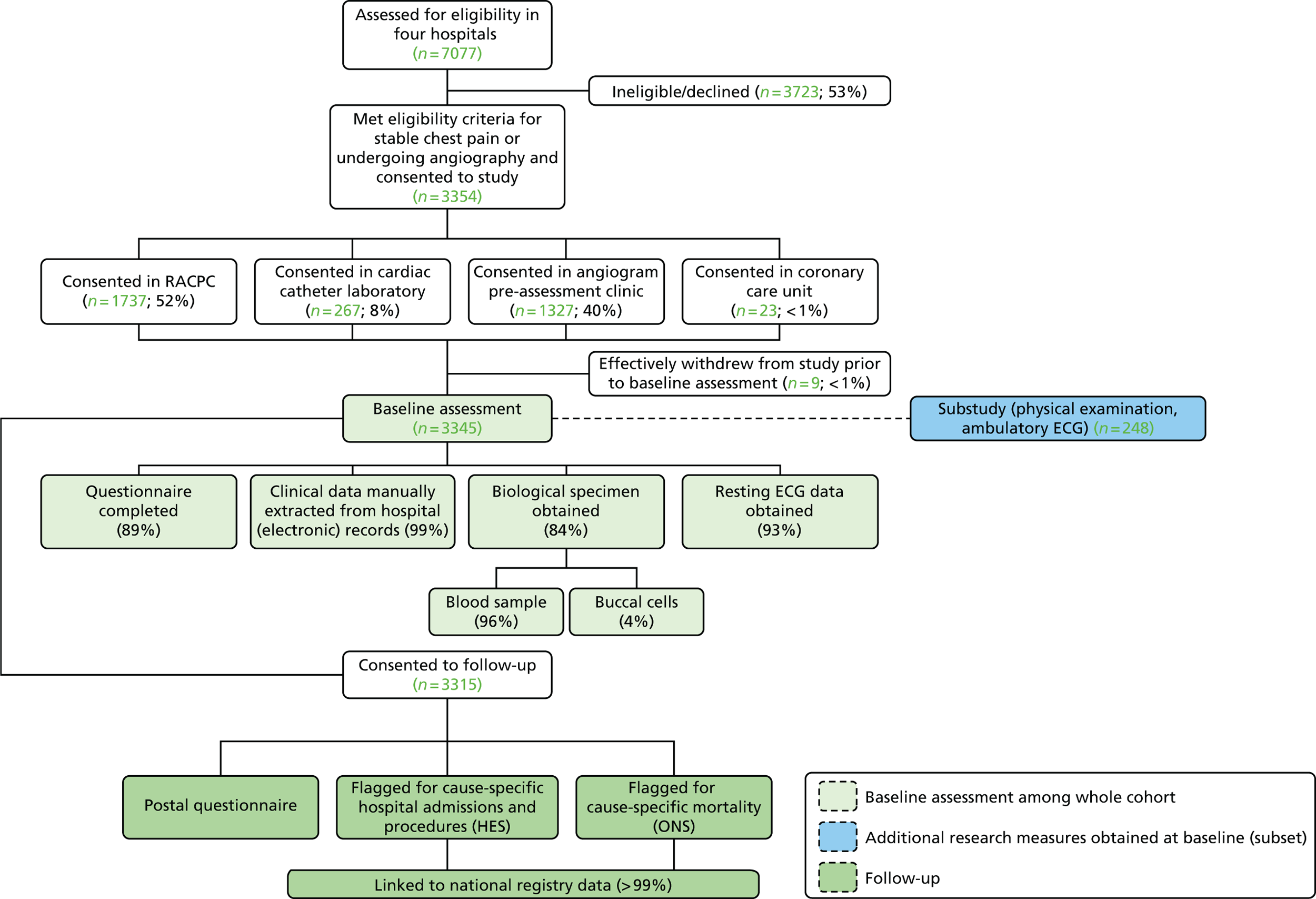

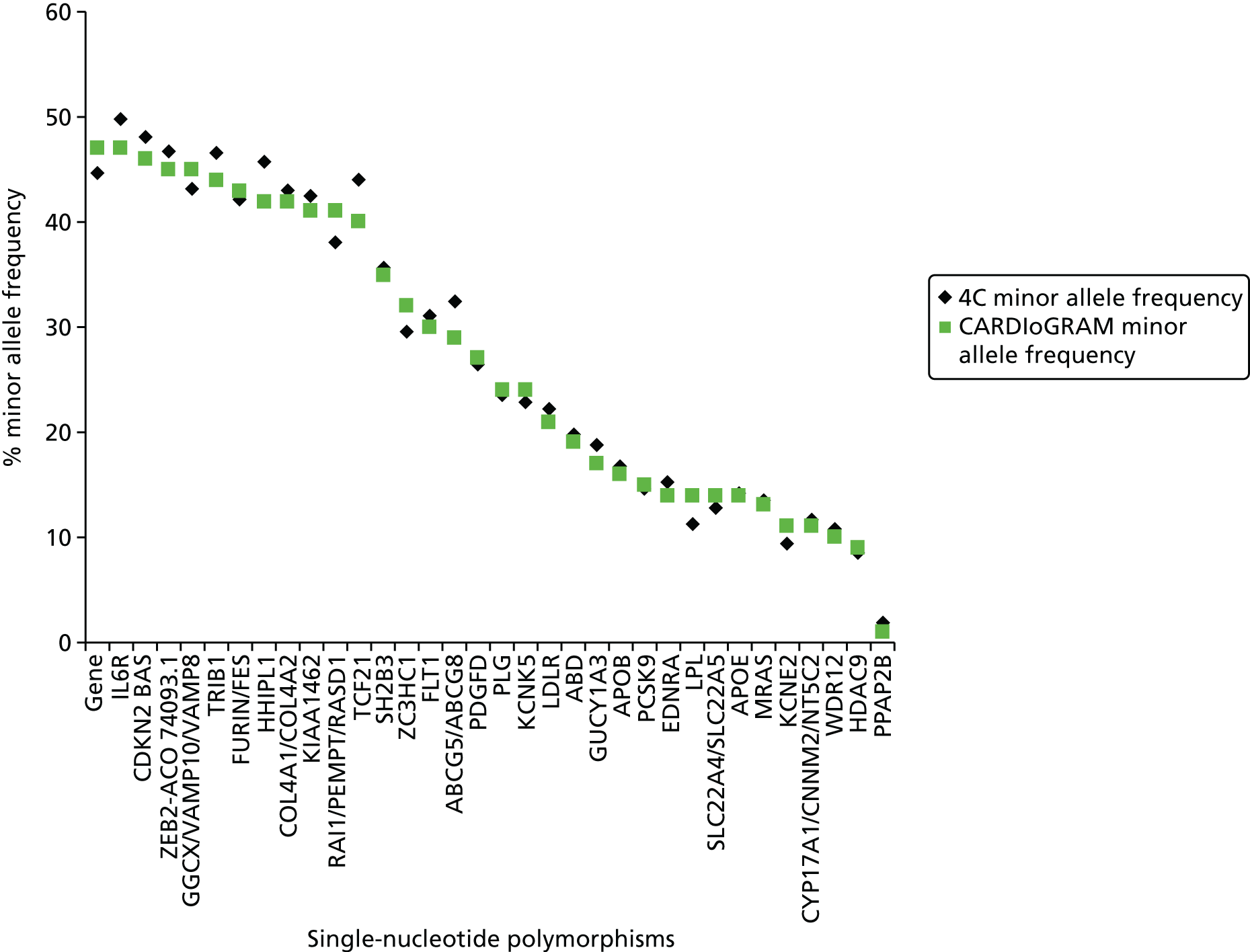

| Study 14: we established a novel consented clinical cohort of 3345 patients being investigated for new-onset chest pain with linked phenotypic, genetic and biomarker data. 4C is a resource for researchers investigating onset of SCAD and its progression to CVD events (manuscript in preparation)46 | There is a need for embedding genetic information in hospital EHR at scale in order to carry out a wide range of translational research, from discovery efforts, through drug repurposing and embedded pharmacogenetics for patient safety. Collaborative research based on individual patient data should be encouraged to strengthen prognostic model development and external validation of models |

| Chapter 8 | |

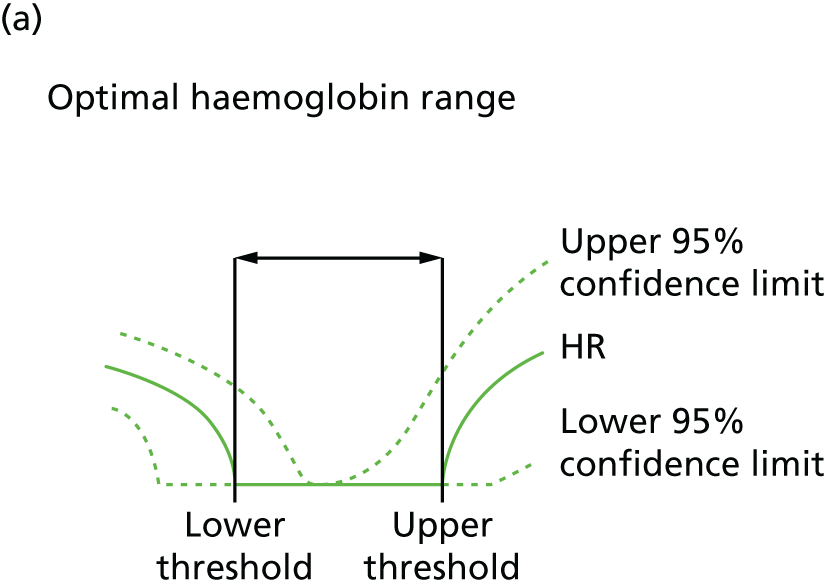

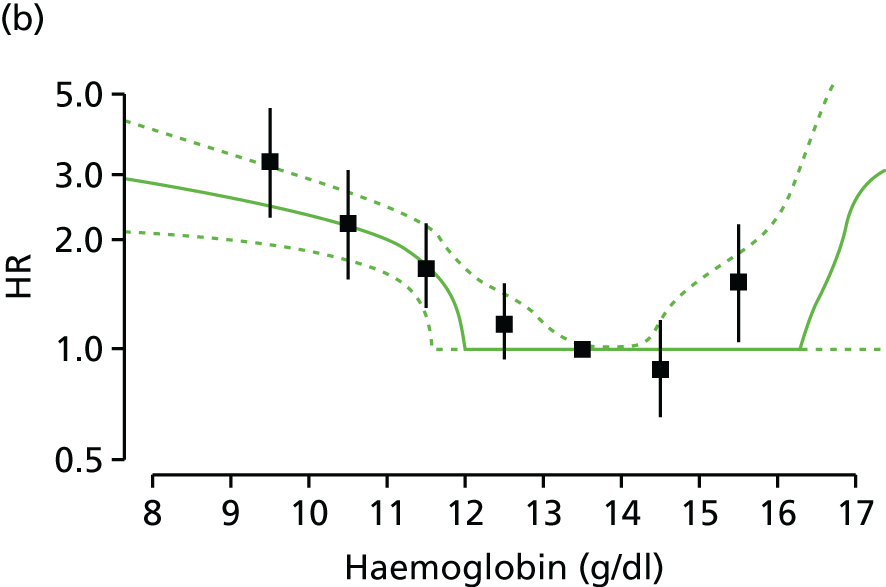

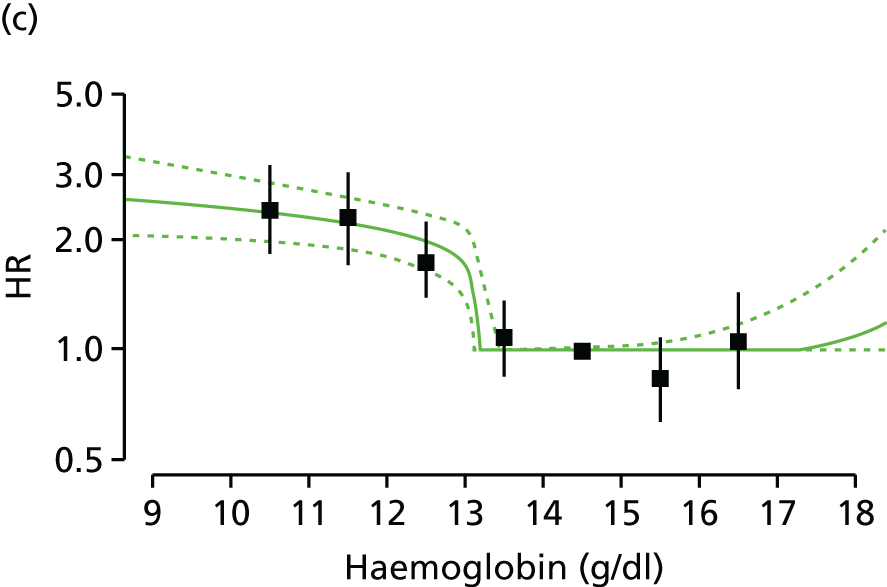

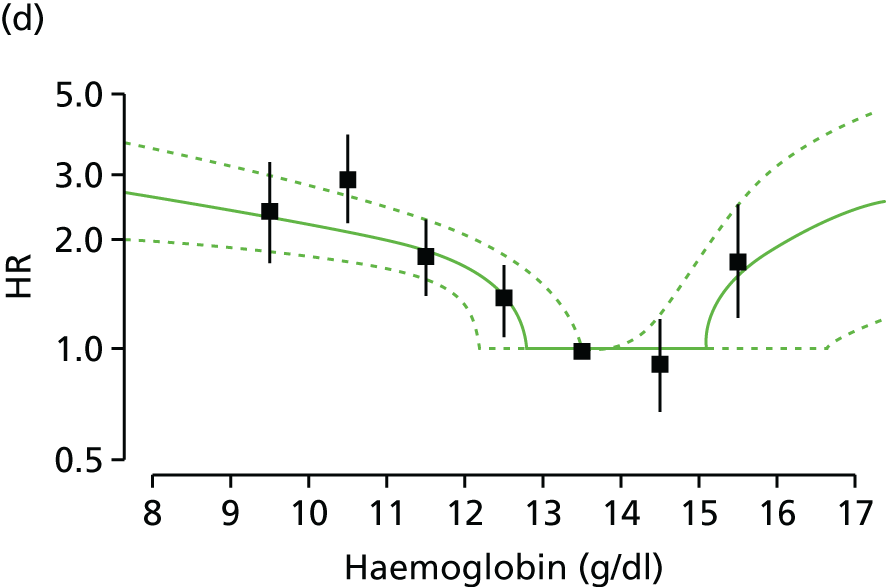

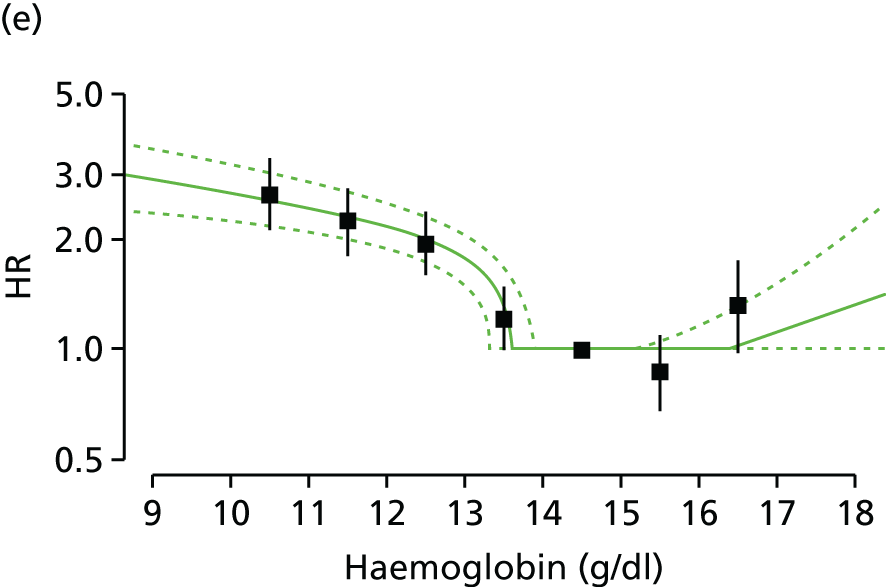

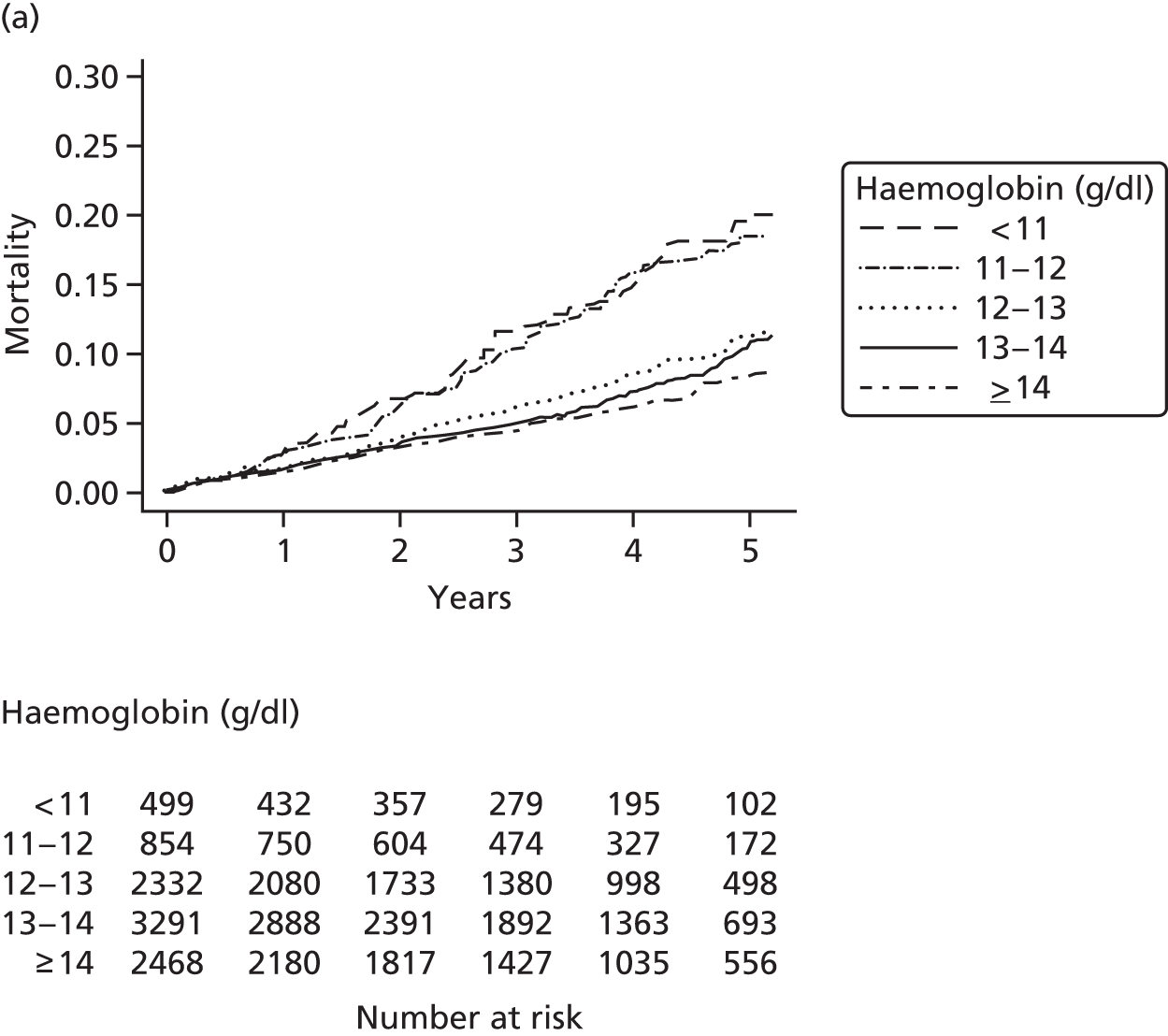

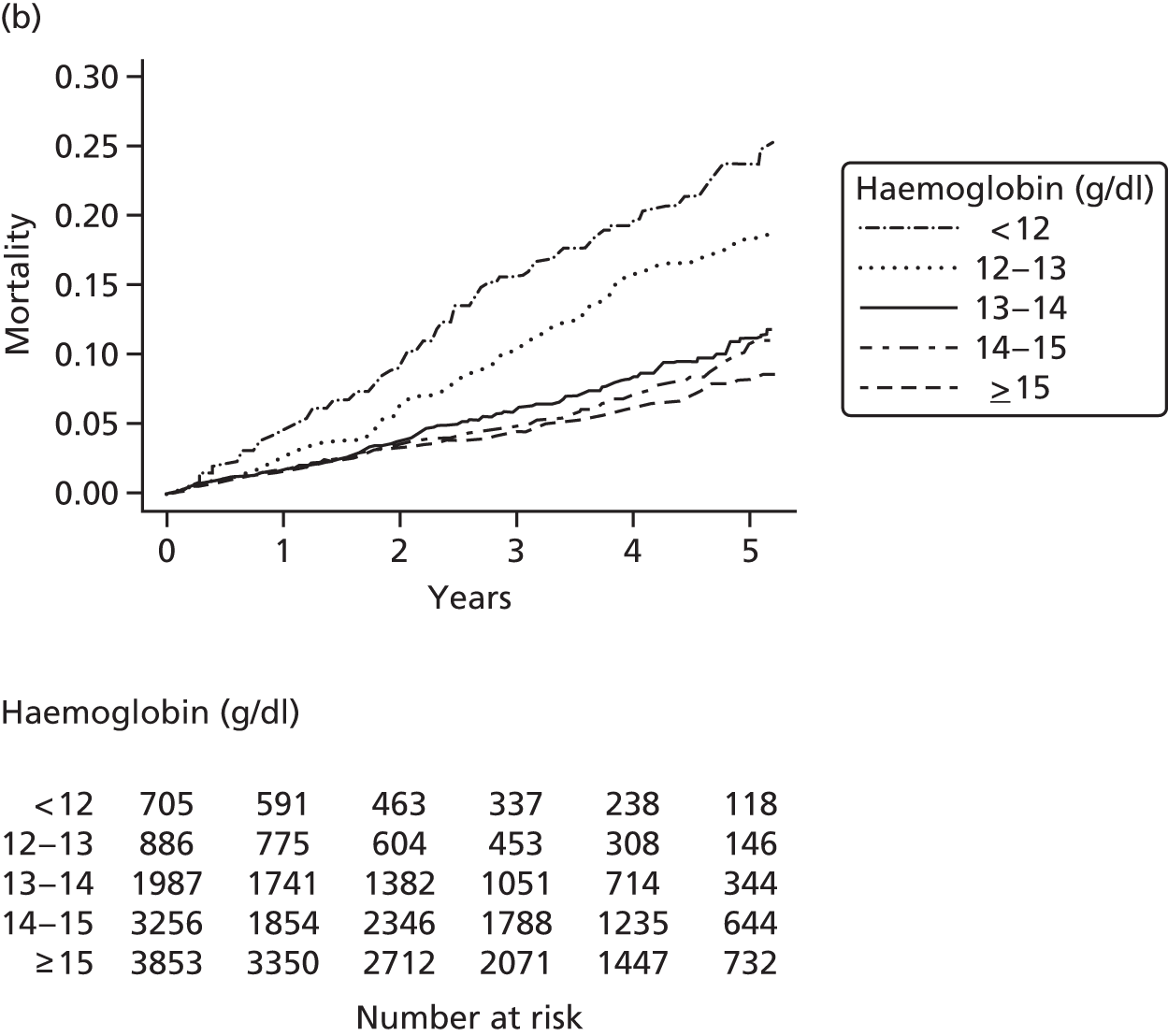

| Study 15: among two study populations (patients with new-onset stable angina and no previous ACS and patients with a first AMI) thresholds in both men and women were identified below which the clinically available biomarker haemoglobin showed a linear inverse relationship with increased mortality47 | New clinical trials are warranted to assess whether or not haemoglobin levels are causal and whether or not clinicians should intervene to increase haemoglobin levels |

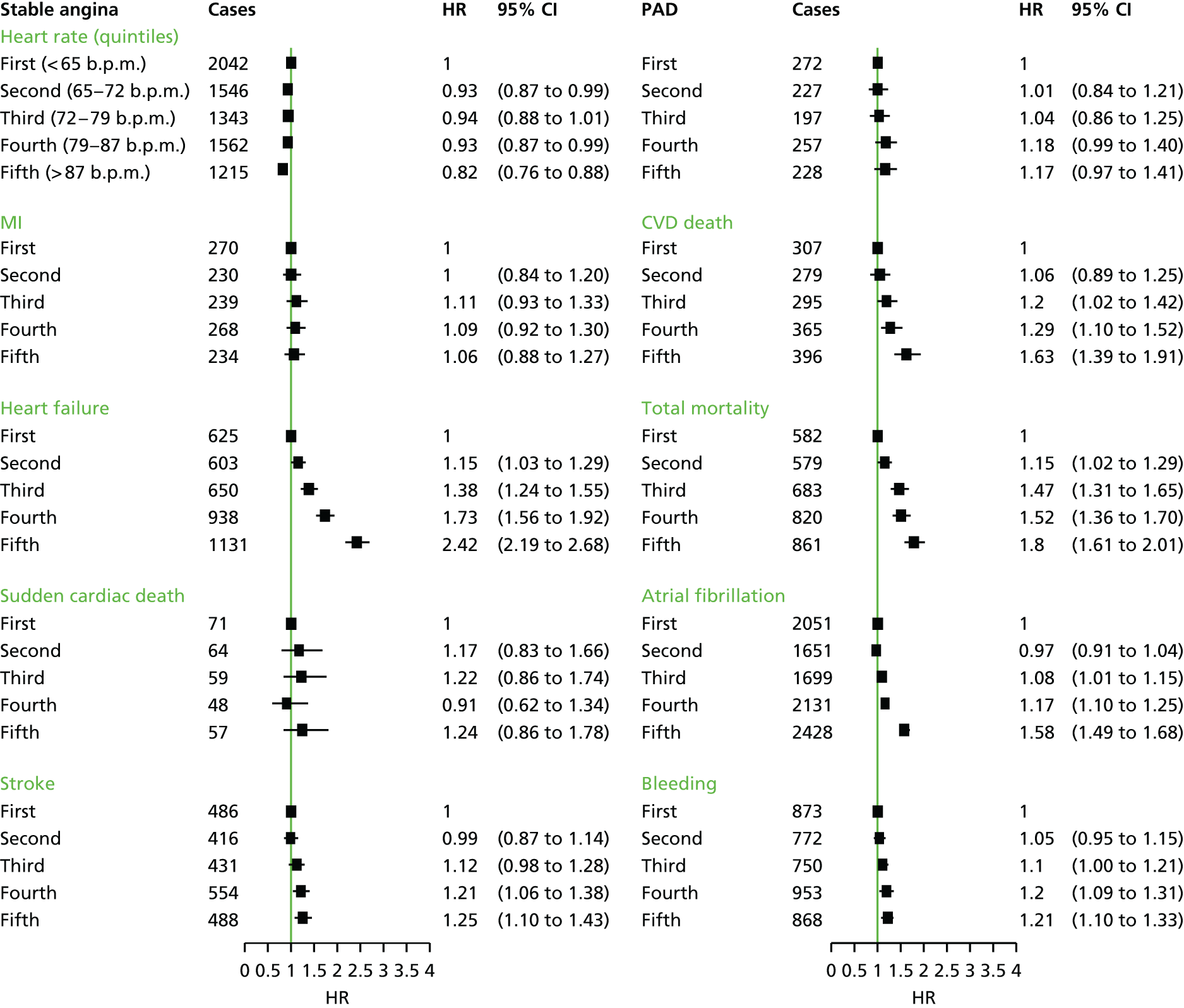

| Study 16: elevated heart rate was associated with increased risk of heart failure and cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality in patients with SCAD (manuscript in preparation)48 | In designing randomised trials, the target population, the choice of composition of the primary end point and the likely rate at which the end point accrues can all be informed by the examination of linked EHRs |

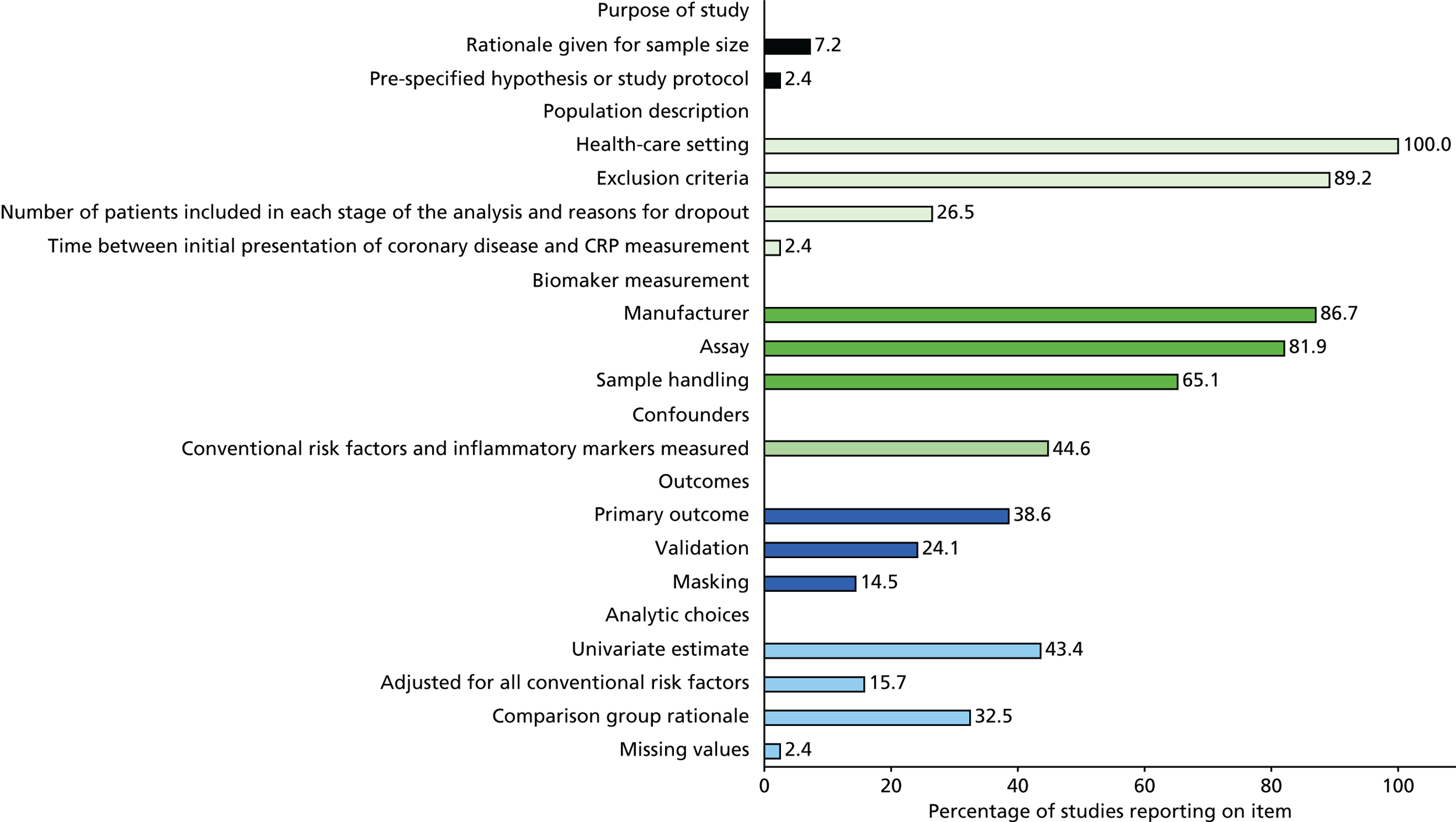

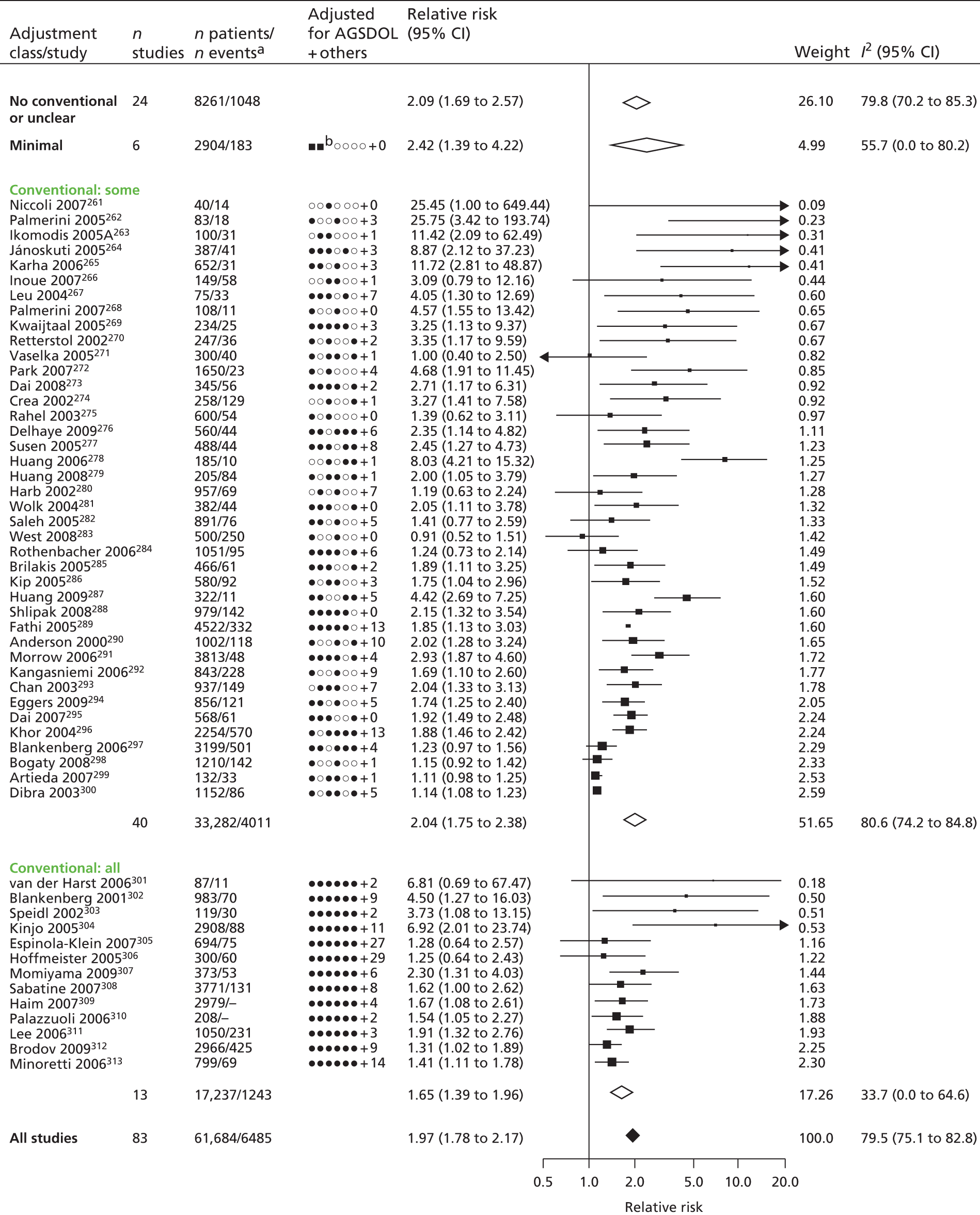

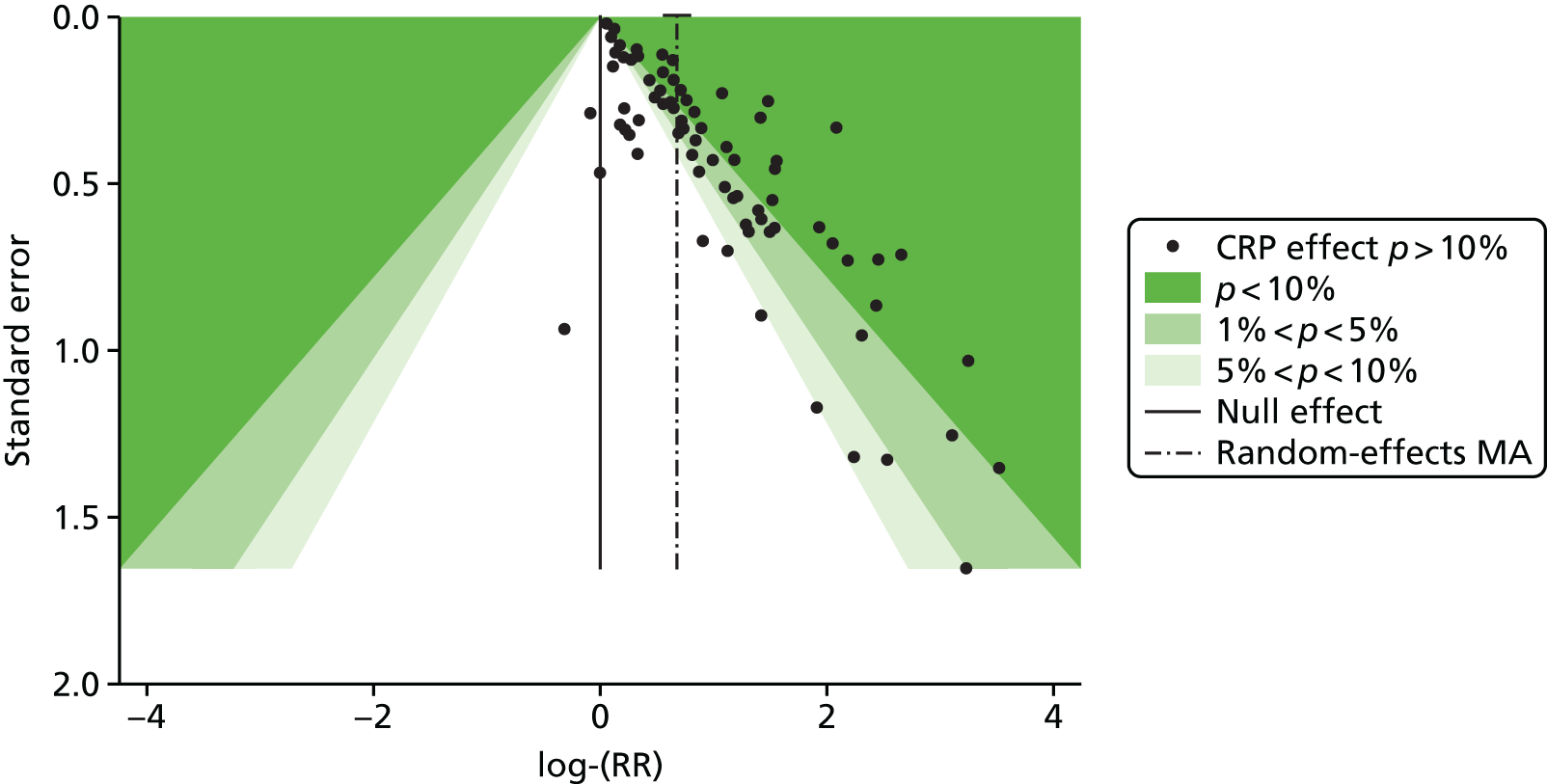

| Study 17: published evidence of associations between levels of the novel circulating marker of inflammation CRP levels and risk of cardiovascular events was of variable quality, and our data suggest that the degree of association may have been overstated49 | New clinical cohorts are needed with published pre-specified statistical analytic protocols and prospective registration of studies, which can be pooled to evaluate the true usefulness of the role of CRP in prognosis in SCAD |

| Study 18: our systematic review and meta-analysis from > 190,000 individuals experiencing 20,000 events showed that Ch9p21, a novel genetic factor, was associated with increased risk of first but not subsequent cardiovascular events50 | More work should be carried out to determine the effect of mechanistic differences for the differential genetic effect, to enhance understanding of the underlying reasons. Our findings argue for a consortium of studies set in individuals with established CHD to better understand the genomic susceptibility to subsequent CHD events and also to perform detailed analysis, including assessment for selection biases, which is not possible with literature-based meta-analyses |

| Study 19: we found that changes in BP in people with diabetes and SCAD predict risk. SBP in type 2 diabetes patients with stable angina declined over time. Lower values of SBP significantly increased risk of CVD outcomes (manuscript in preparation)51 | Methods for dynamic risk prediction in which the patterns of change of clinically measured biomarkers can be incorporated into clinical decision support models in clinical practice are required |

| Chapter 9 | |

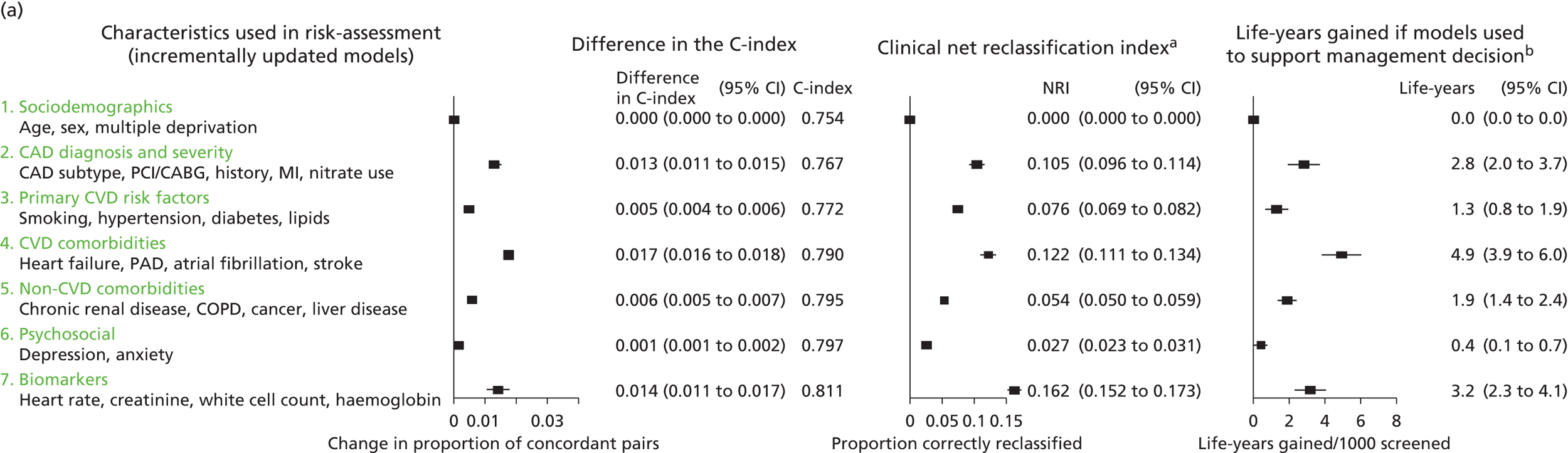

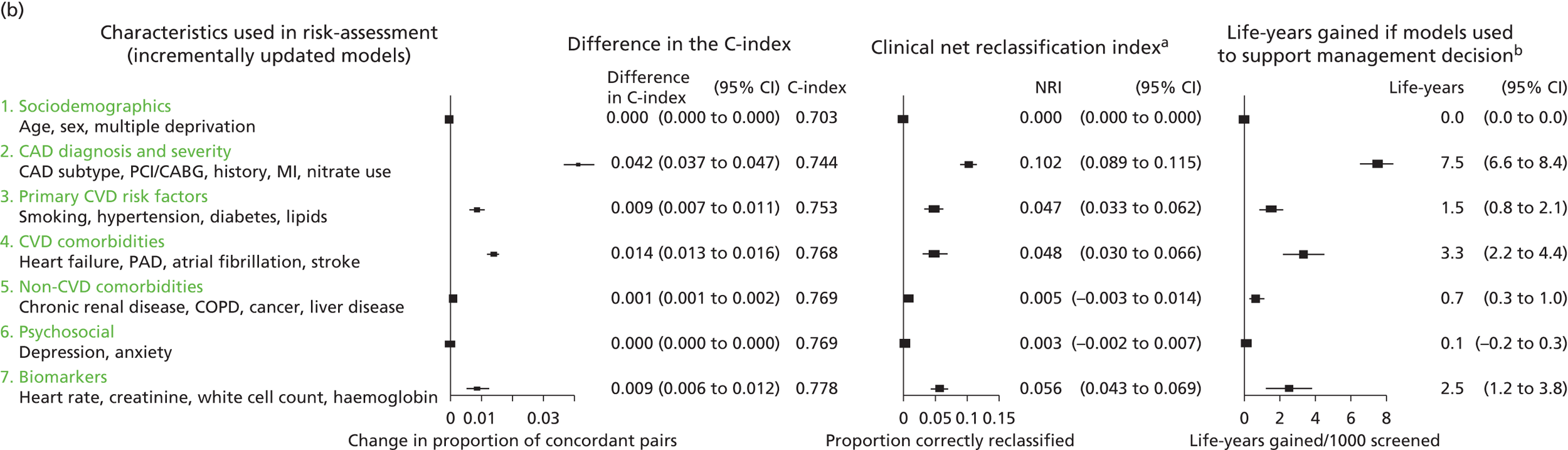

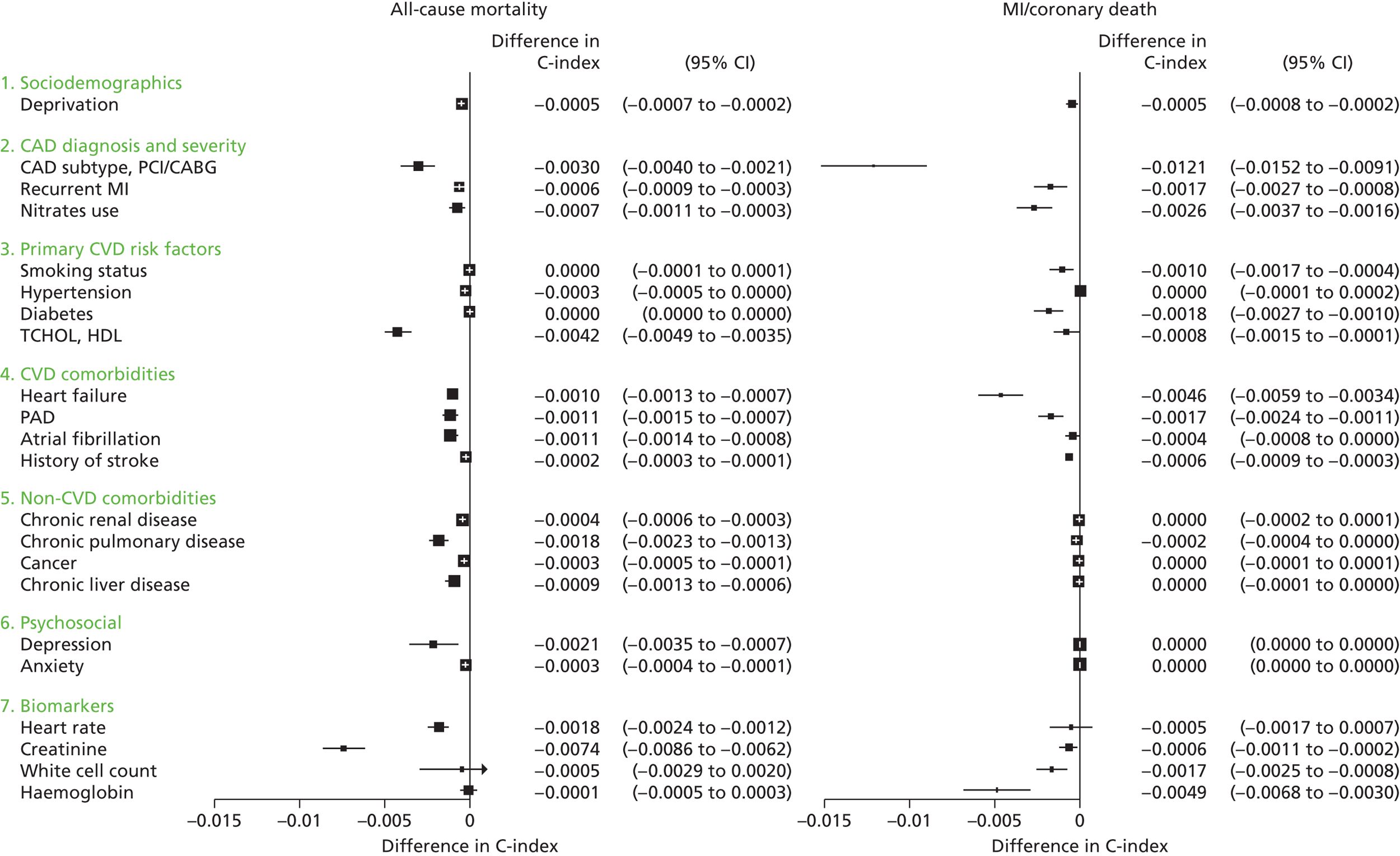

| Study 20: we present validated prognostic models developed with 5-year risk predictions for estimating risk of all-cause mortality and coronary outcomes based on clinical parameters that are commonly available in all people with SCAD52 | Further external validation in external data sets and recalibration for different populations and time periods is required. Economic evaluation is needed to establish the appropriateness of using the prognostic model in practice |

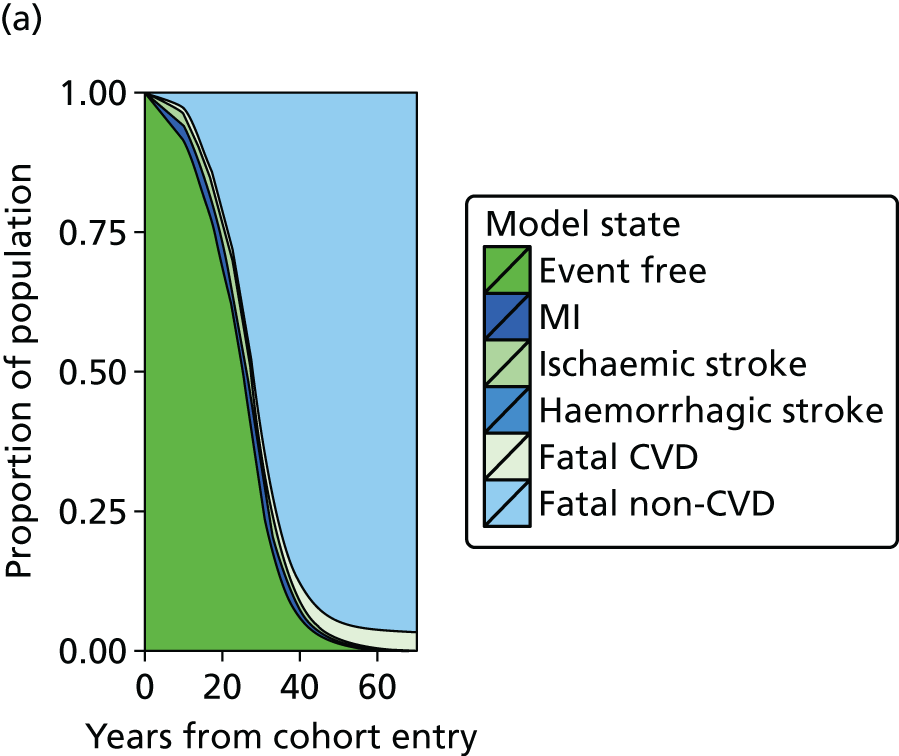

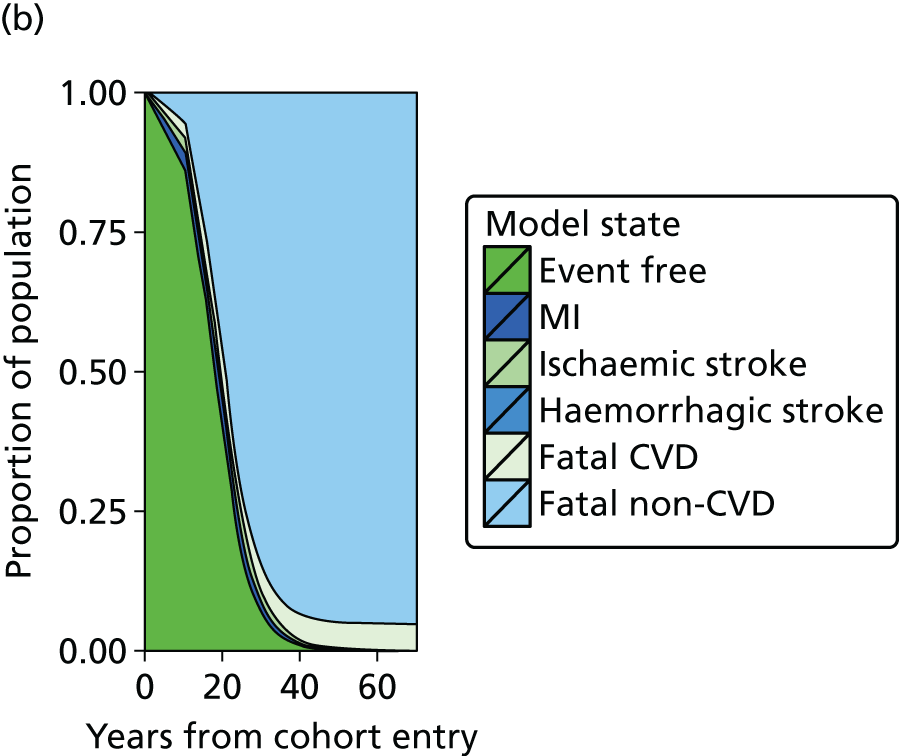

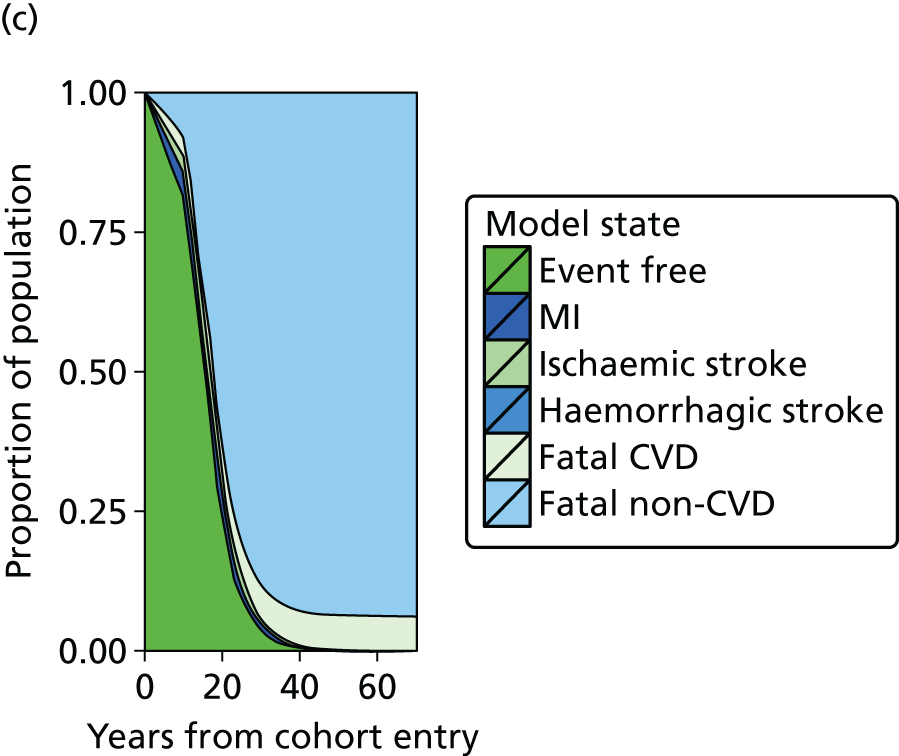

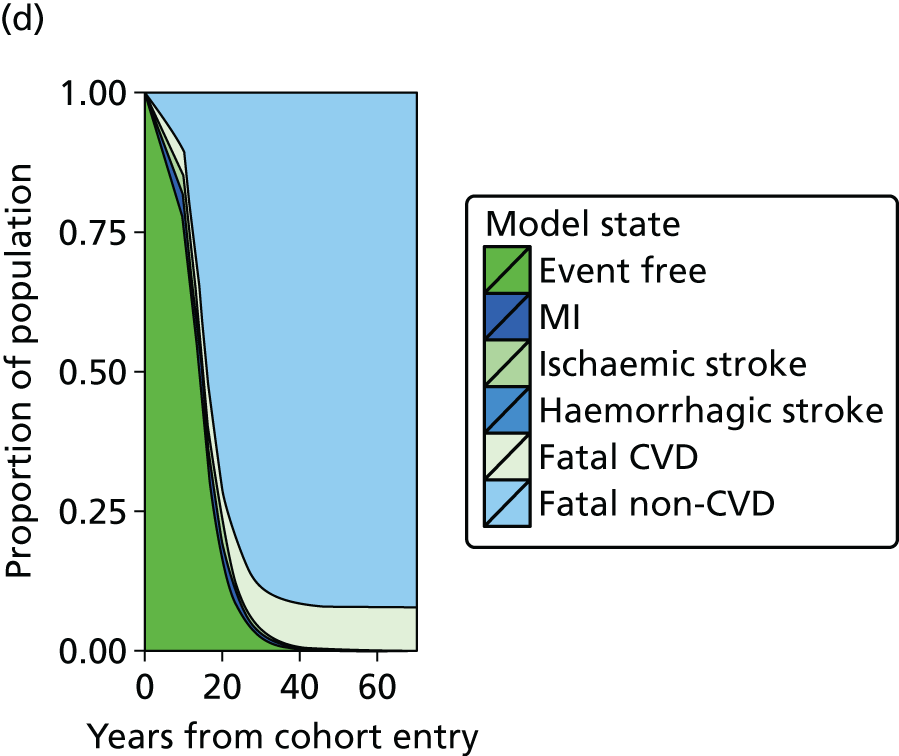

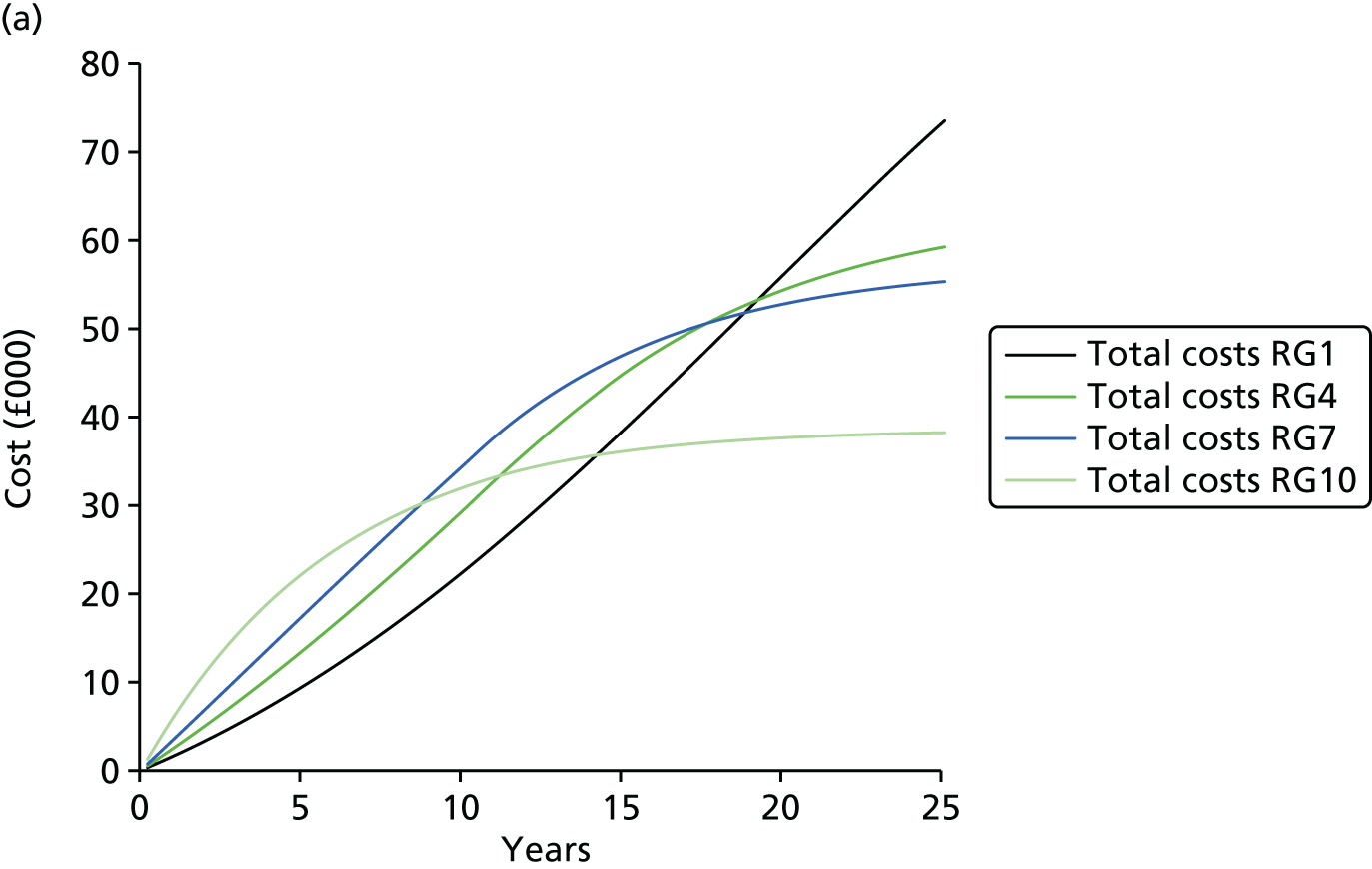

| Study 21: our cost-effectiveness studies using linked EHR data showed high use of primary care and frequent hospitalisations in patients with SCAD, who incurred considerable ongoing costs. Five-year and lifetime costs varied according to CVD risk, which may be predicted from baseline patient-level data. Based on published data53,54 | Extend models such as the model presented here to explicitly capture the trajectory of prognostic risk factors over time, to address broader questions around the cost-effectiveness of interventions that target underlying risk factors |

| Chapter 10 | |

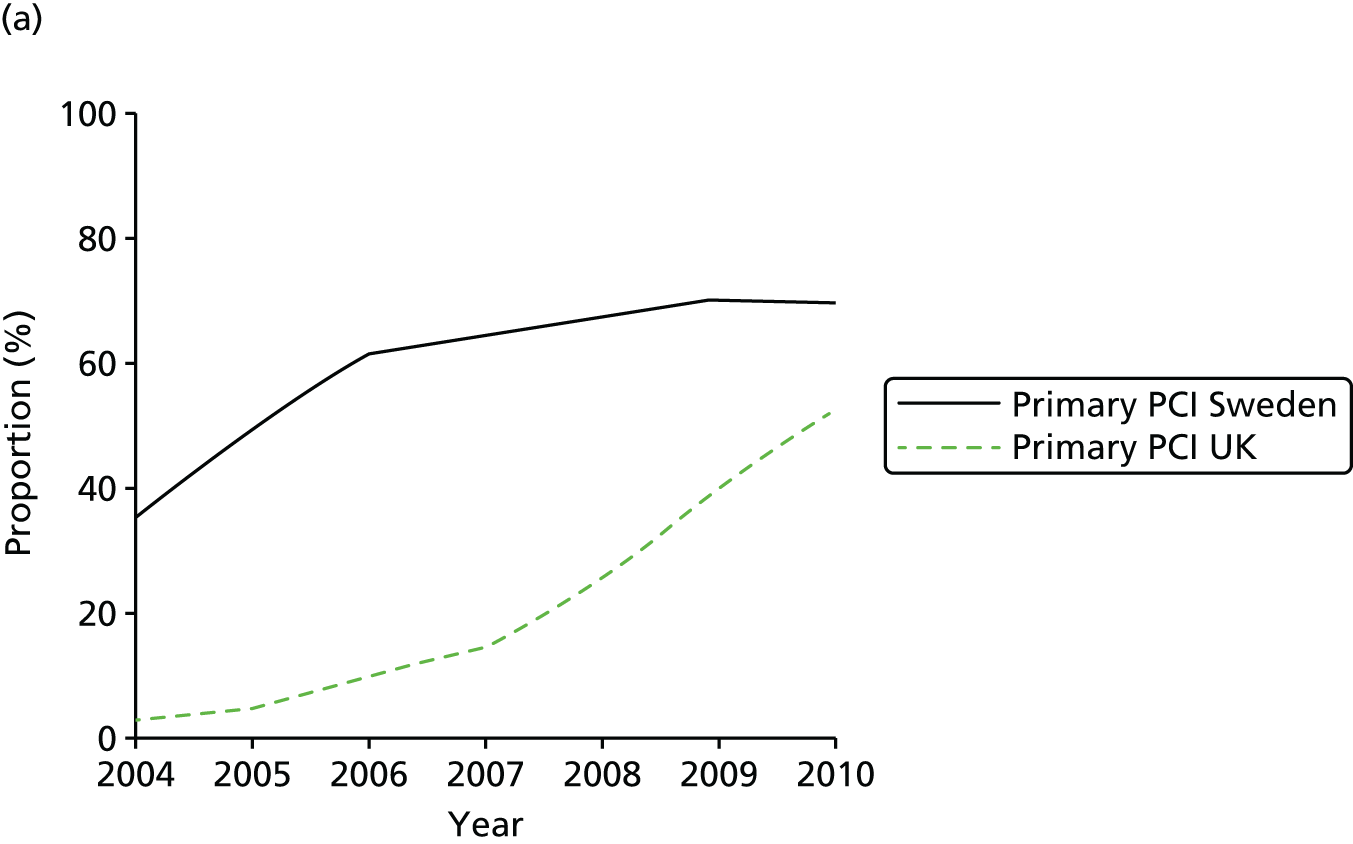

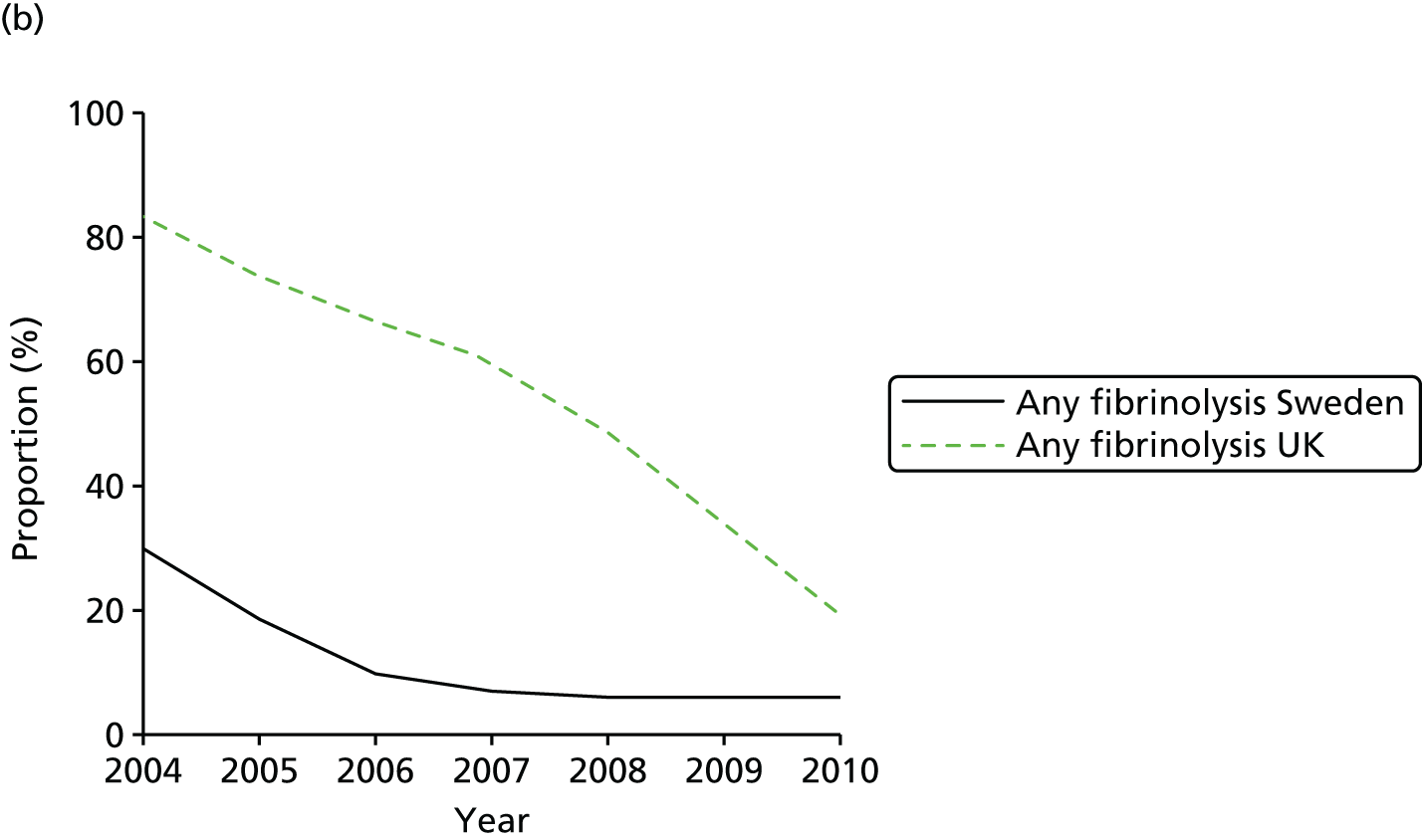

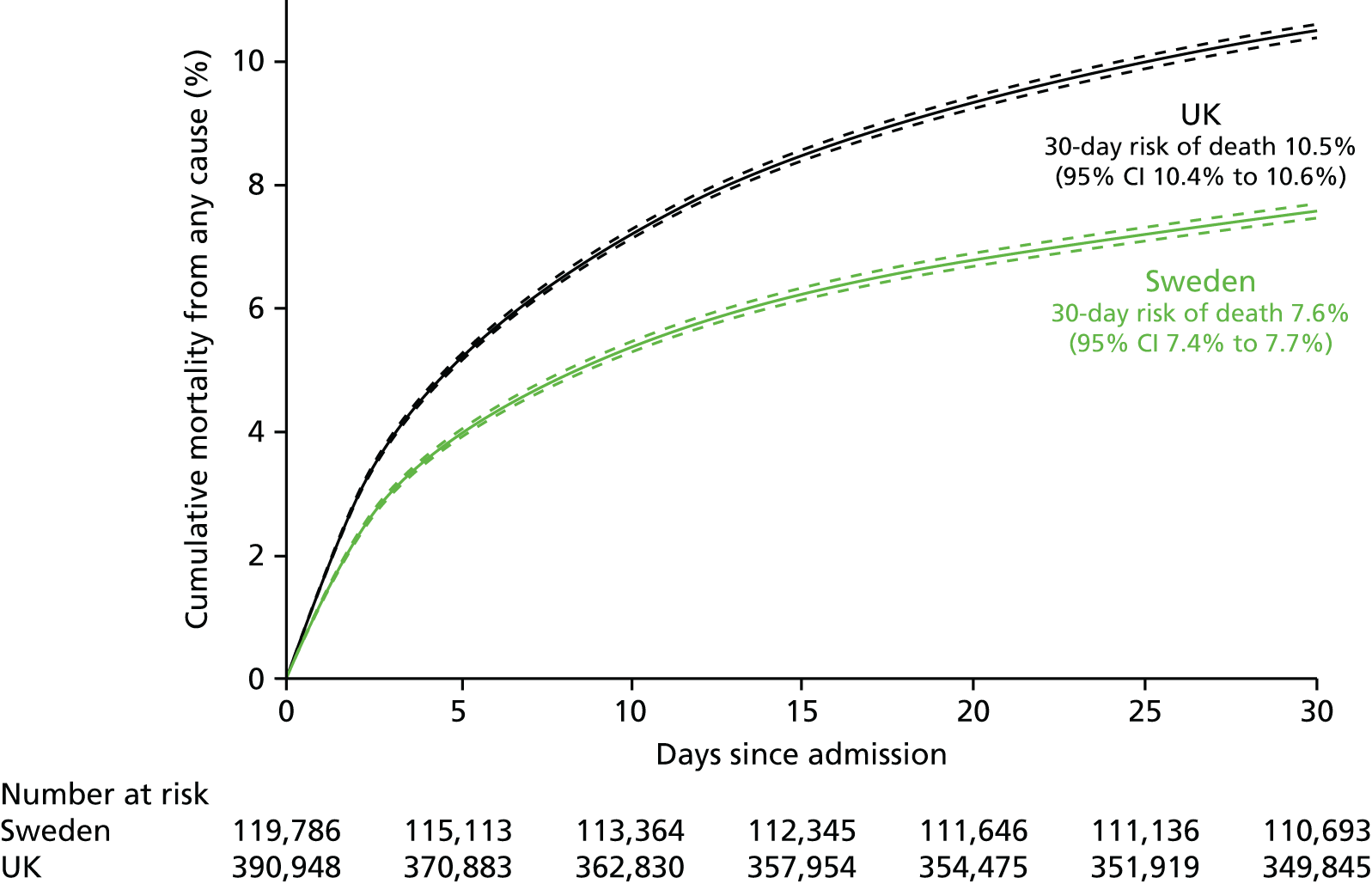

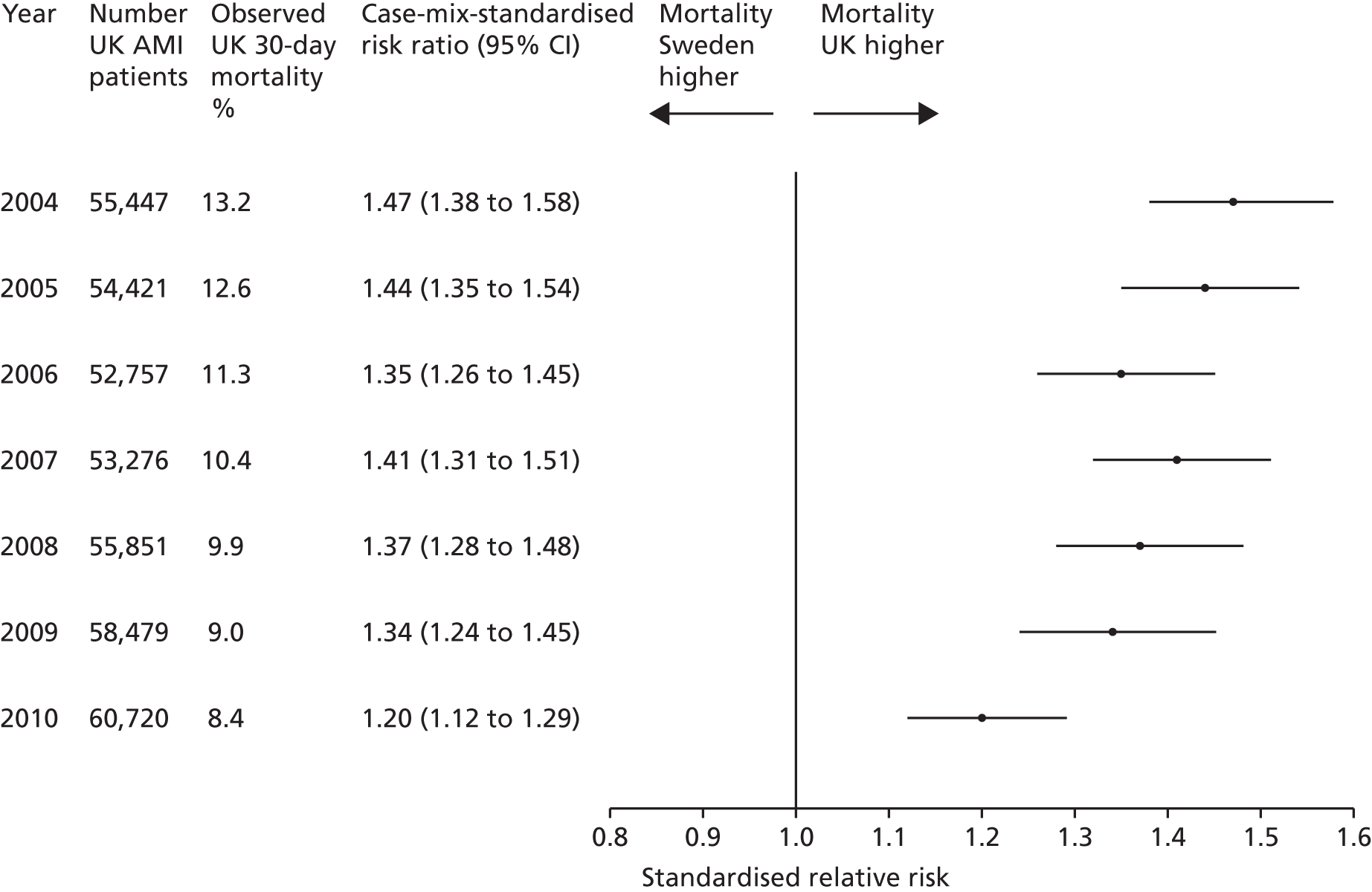

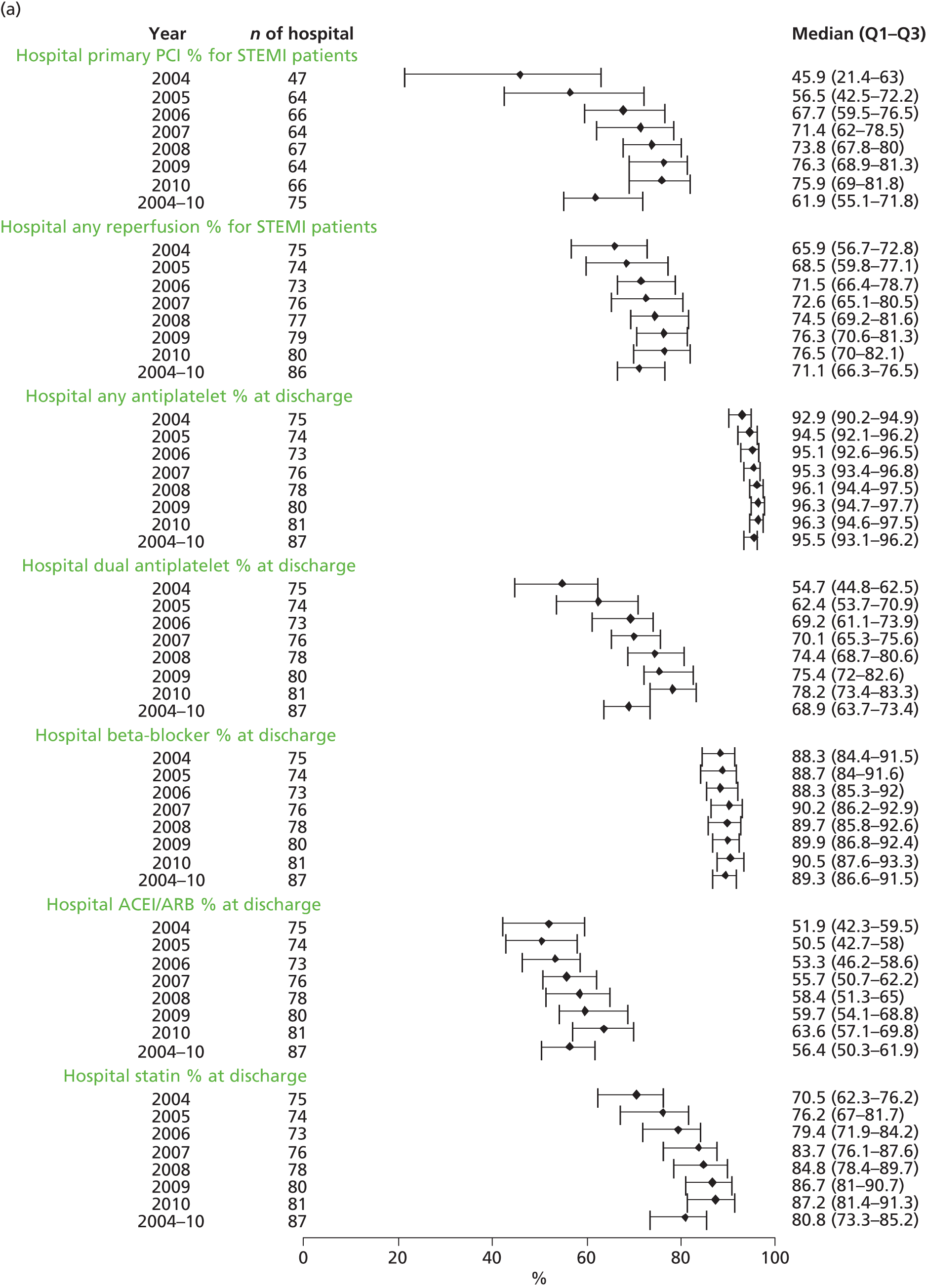

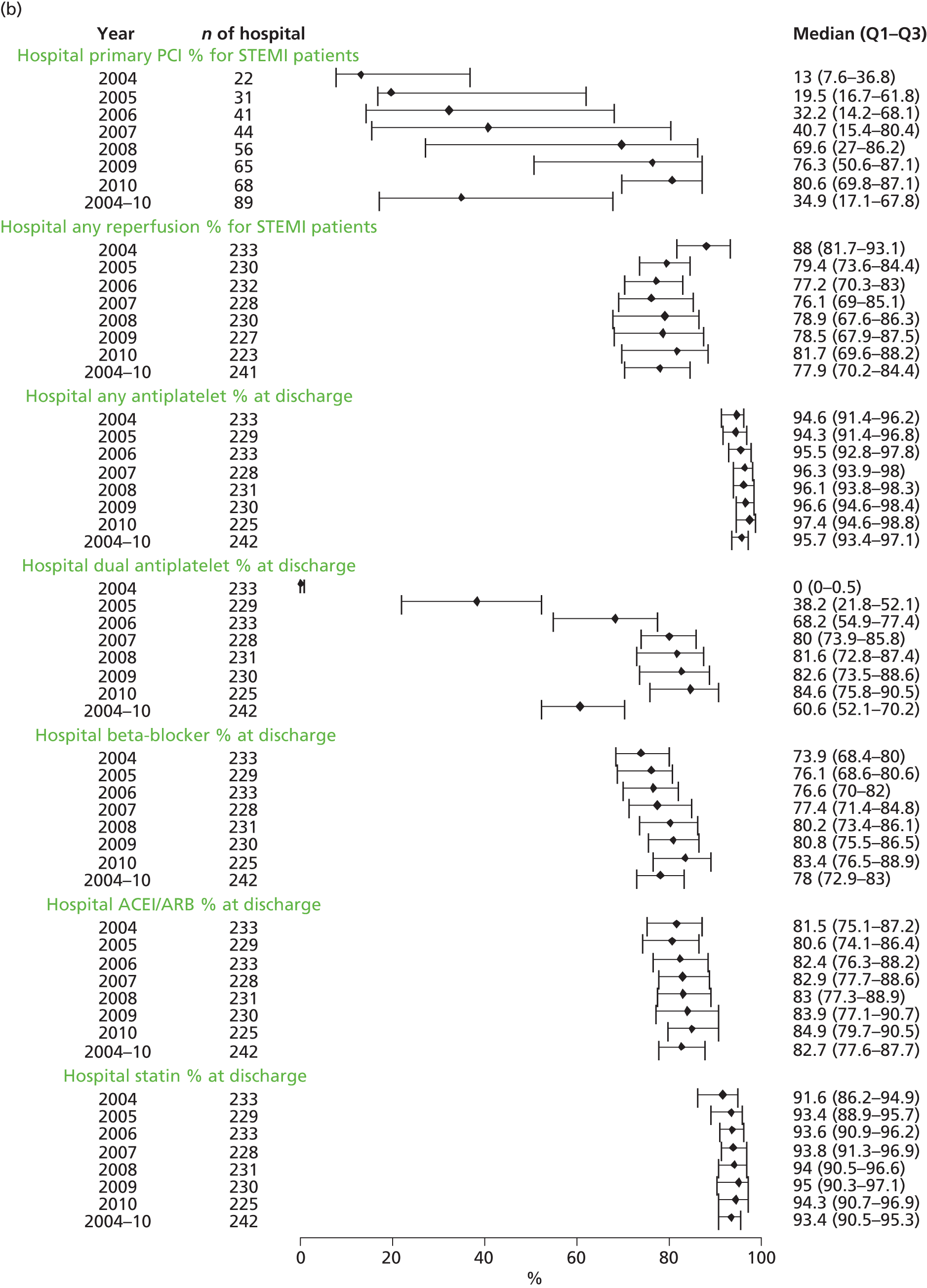

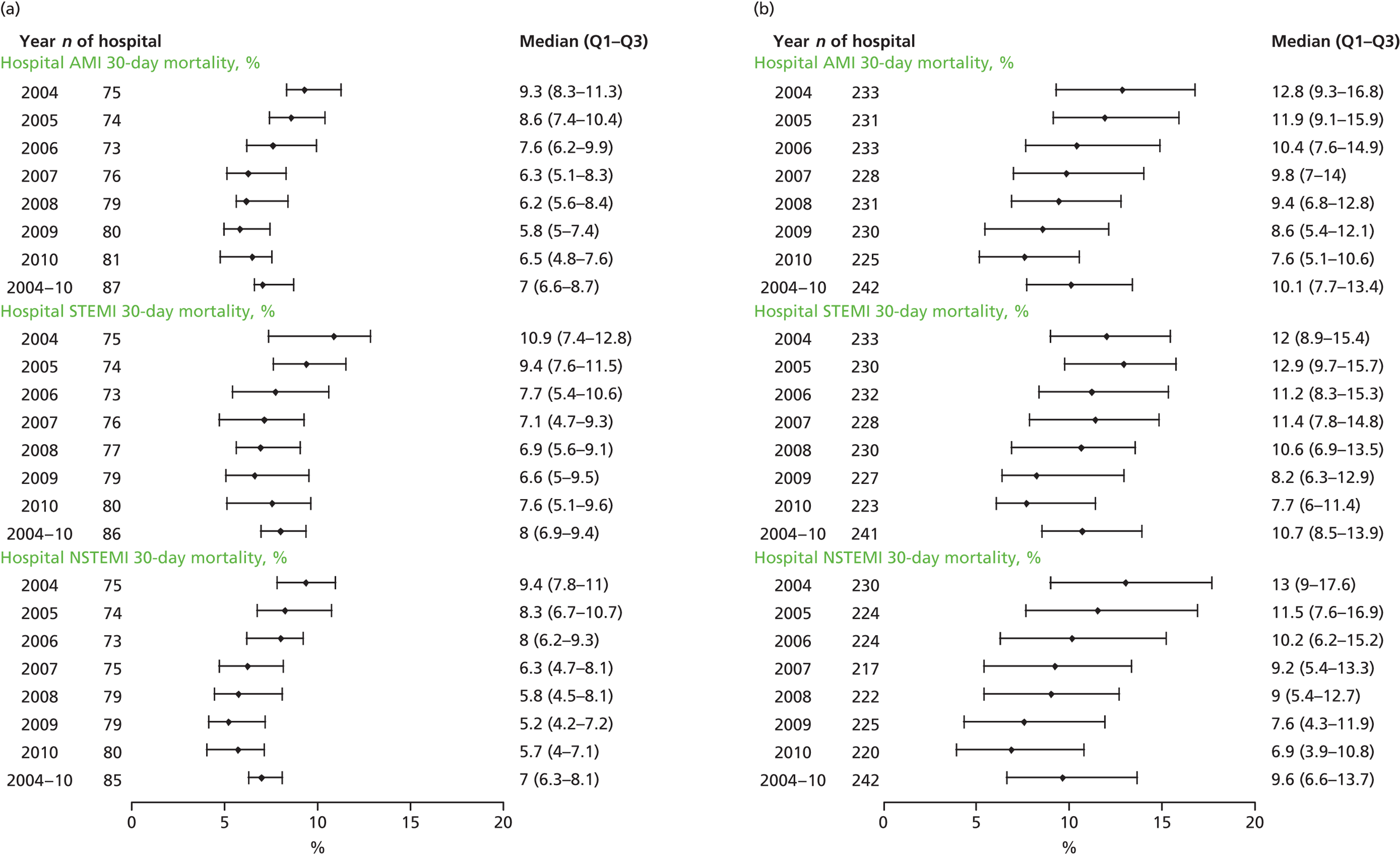

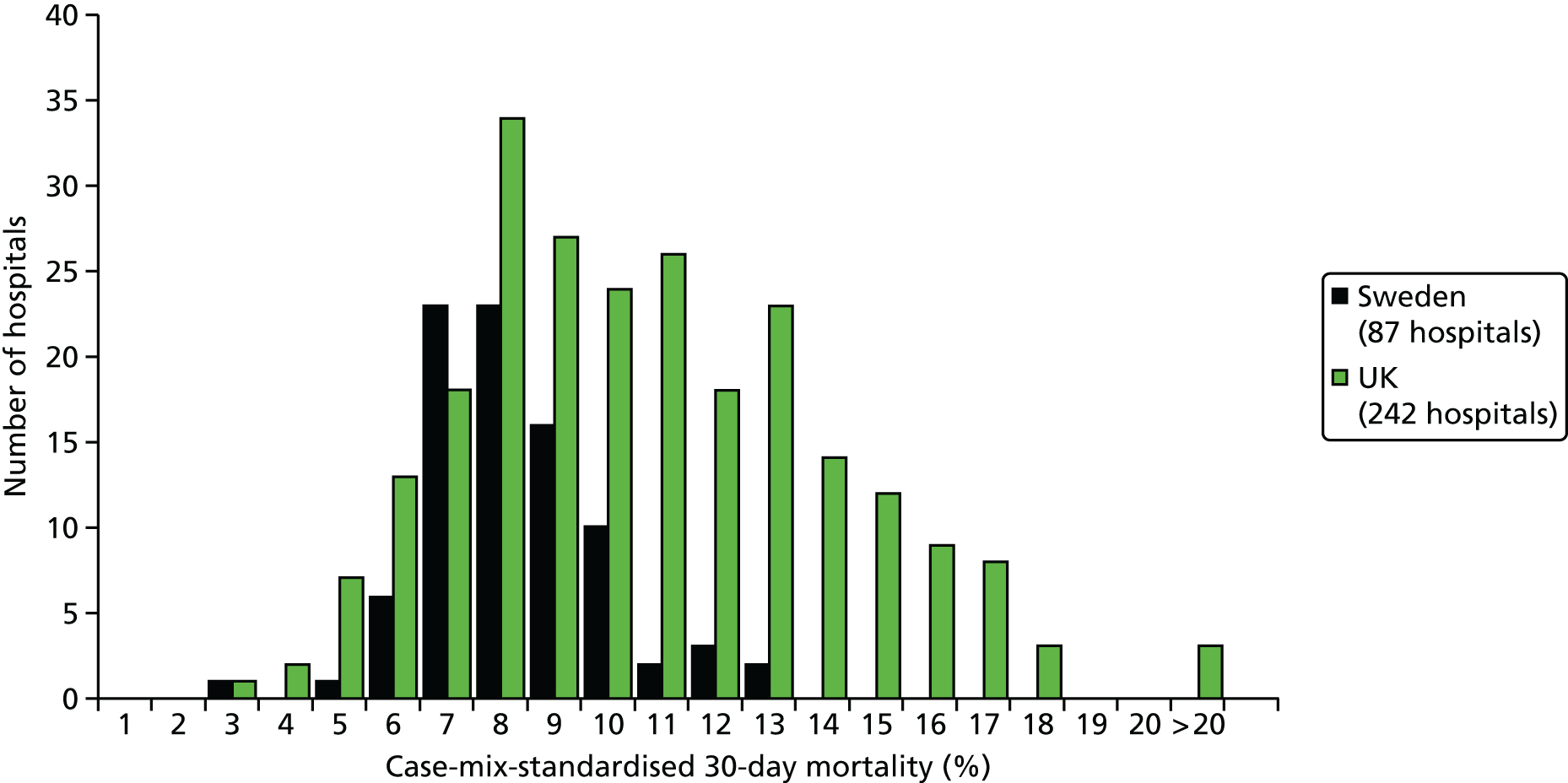

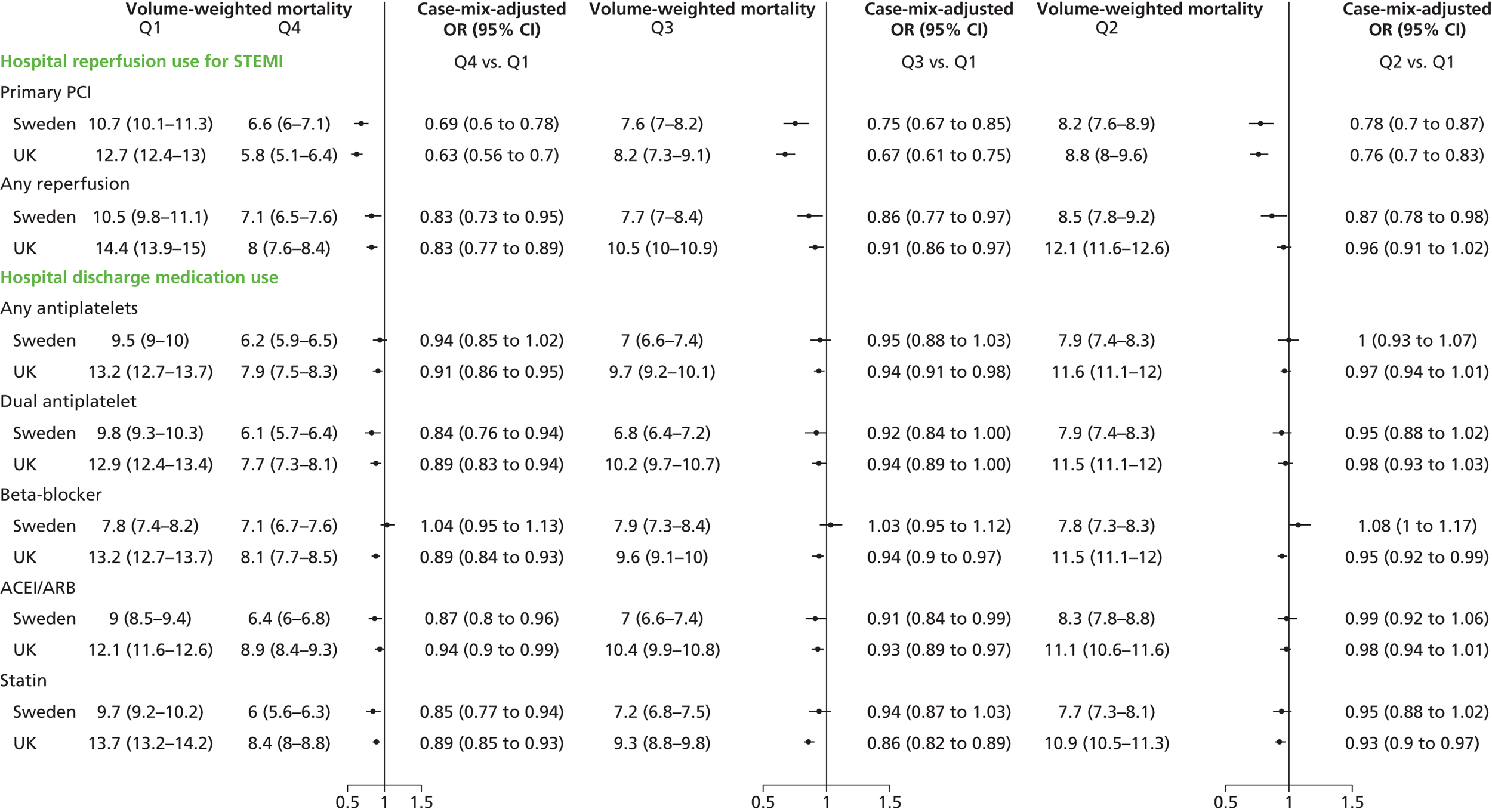

| Study 22: we compared short-term mortality outcomes among patients with a first AMI admission using nationwide outcome registries in Sweden and the UK. Our findings, which took into account measures of case-mix and in-hospital treatment measures, showed that short-term mortality after AMI was markedly higher in the UK than in Sweden and suggest that > 10,000 early deaths would have been prevented or delayed had UK patients experienced the care of their Swedish counterparts55 | International harmonisation of detailed measures of quality of care in clinical registries, such as pathways of care, is needed to identify and evaluate additional patient-level health-care factors that are not measured here and which might explain differences between countries. Outcomes should be compared with those in other countries, such as France, Hungary, Poland and the USA, through assessment of national registries. Linkage to national EHRs will extend comparisons to include ambulatory care before and after admission for heart attack, non-fatal events and longer-term outcome |

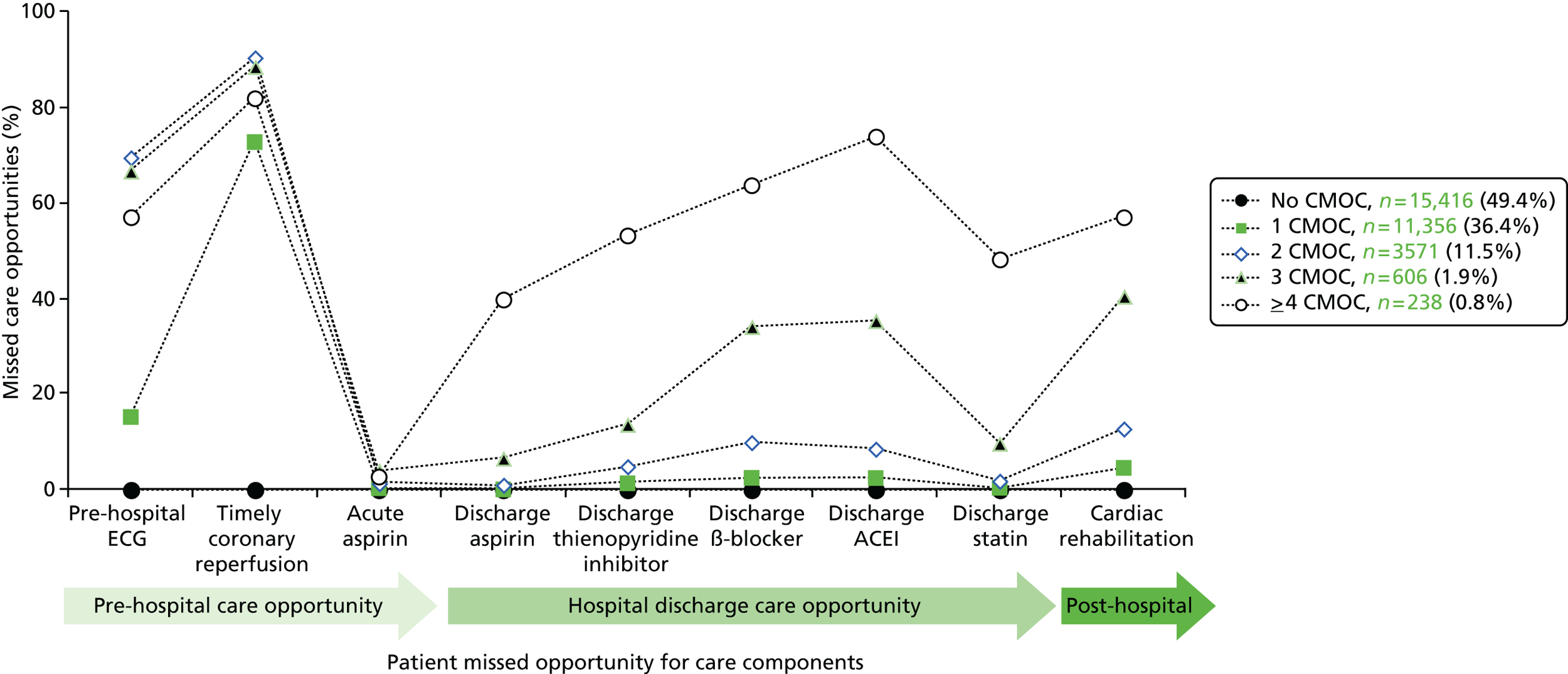

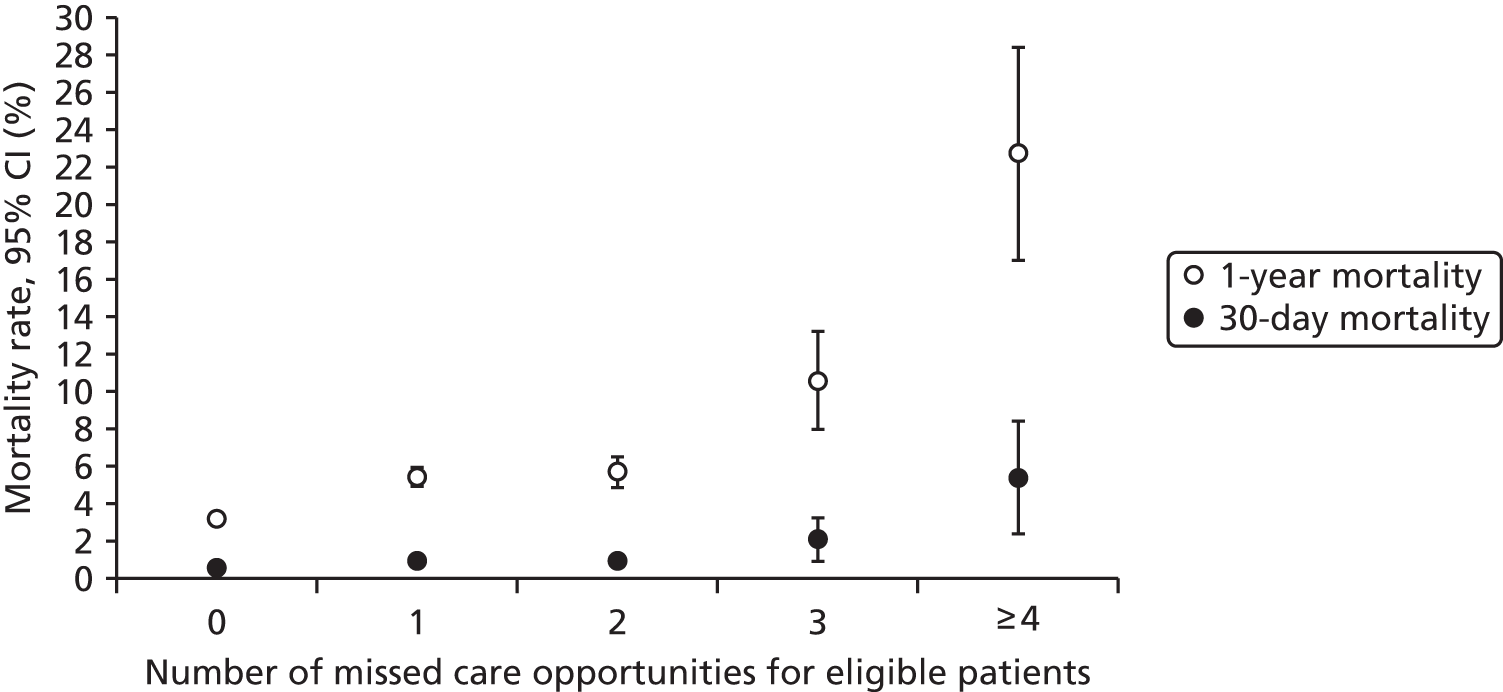

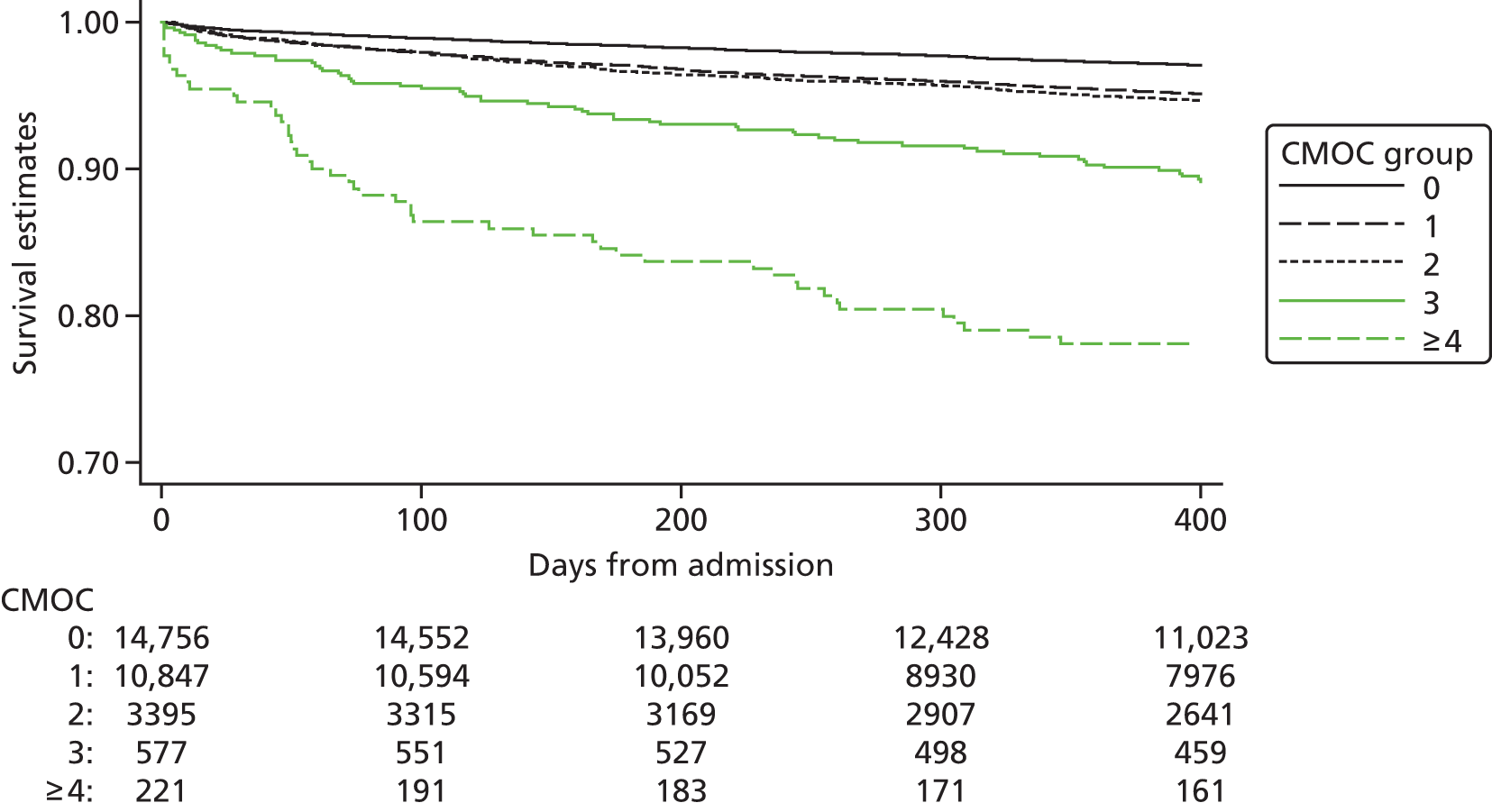

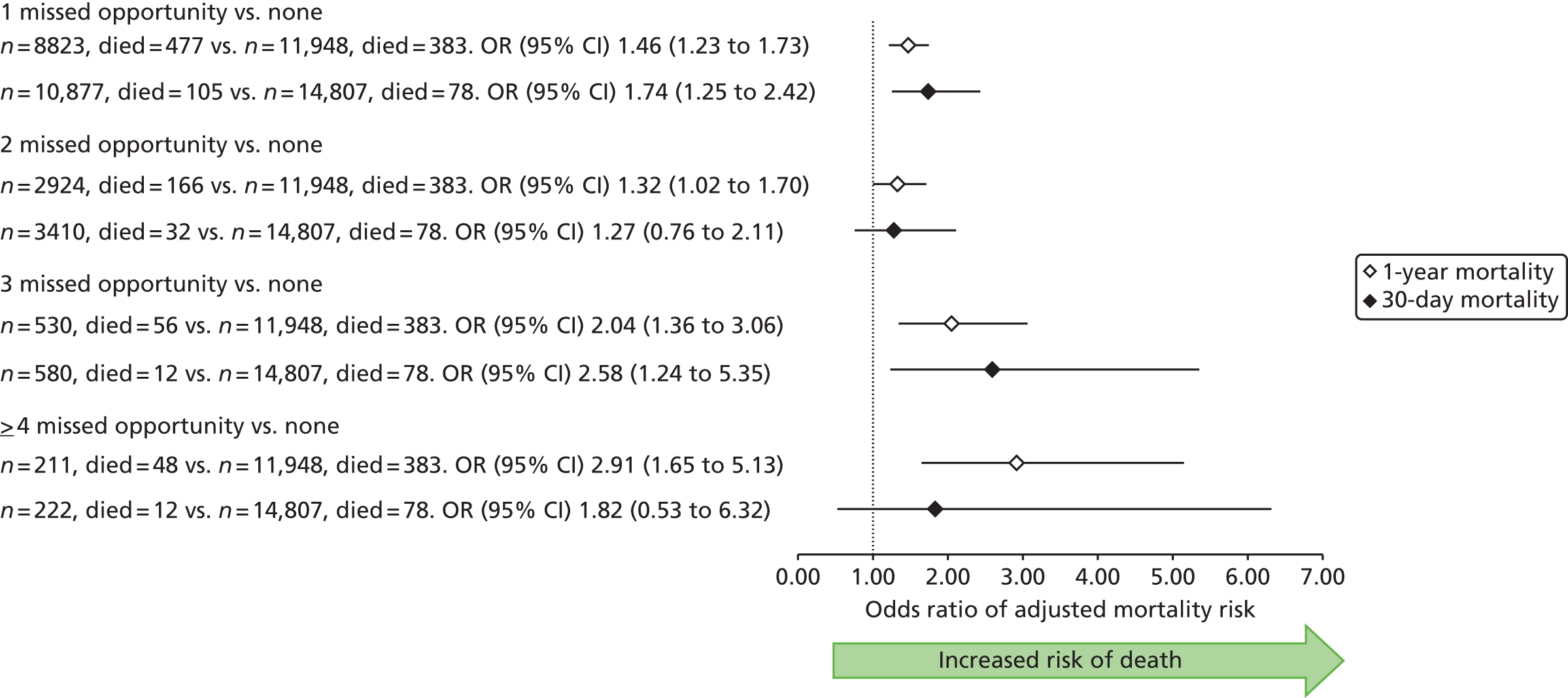

| Study 23: we identified that high numbers of patients hospitalised with STEMI who were eligible for nine evidence-based care components did not receive all components, and that these patients went on to experience higher rates of mortality56 | Outcomes research specifically designed to follow care into the primary care setting is warranted to quantify the full implication of CMOCs |

| Study 24: we carried out analyses of data from national registries in the UK, Sweden and the USA. International comparisons identified significant differences in use of surgical interventions and use of some secondary prevention medications in the UK57 | Further studies are needed to better explain patterns of clinical practice within and outside the UK, such as rates of coronary angiography and PCI |

| Study 25: in a study to determine the extent to which GPs offer recommended smoking cessation advice and pharmacological interventions to smokers after discharge from hospital with ACS, we found that fewer than one-quarter of smokers received smoking cessation interventions in the 3 months following discharge. Those who quit experienced fewer cardiac events than those who continued smoking58 | Future research, both in larger prospective epidemiological studies and in RCTs, of the promotion of general practice smoking cessation interventions, the association between interventions and cessation and the effects on long-term clinical outcomes is warranted |

| Chapter 11 | |

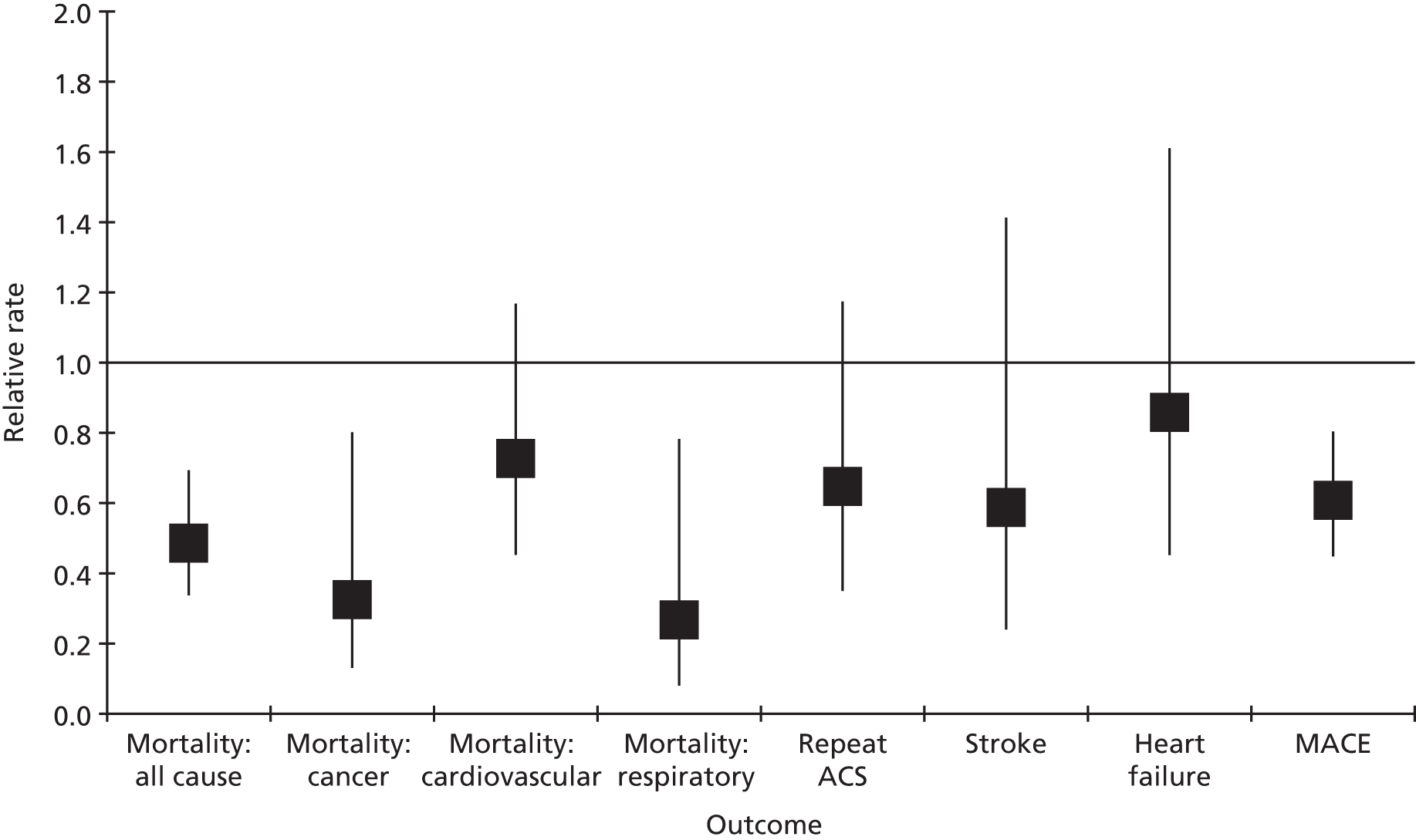

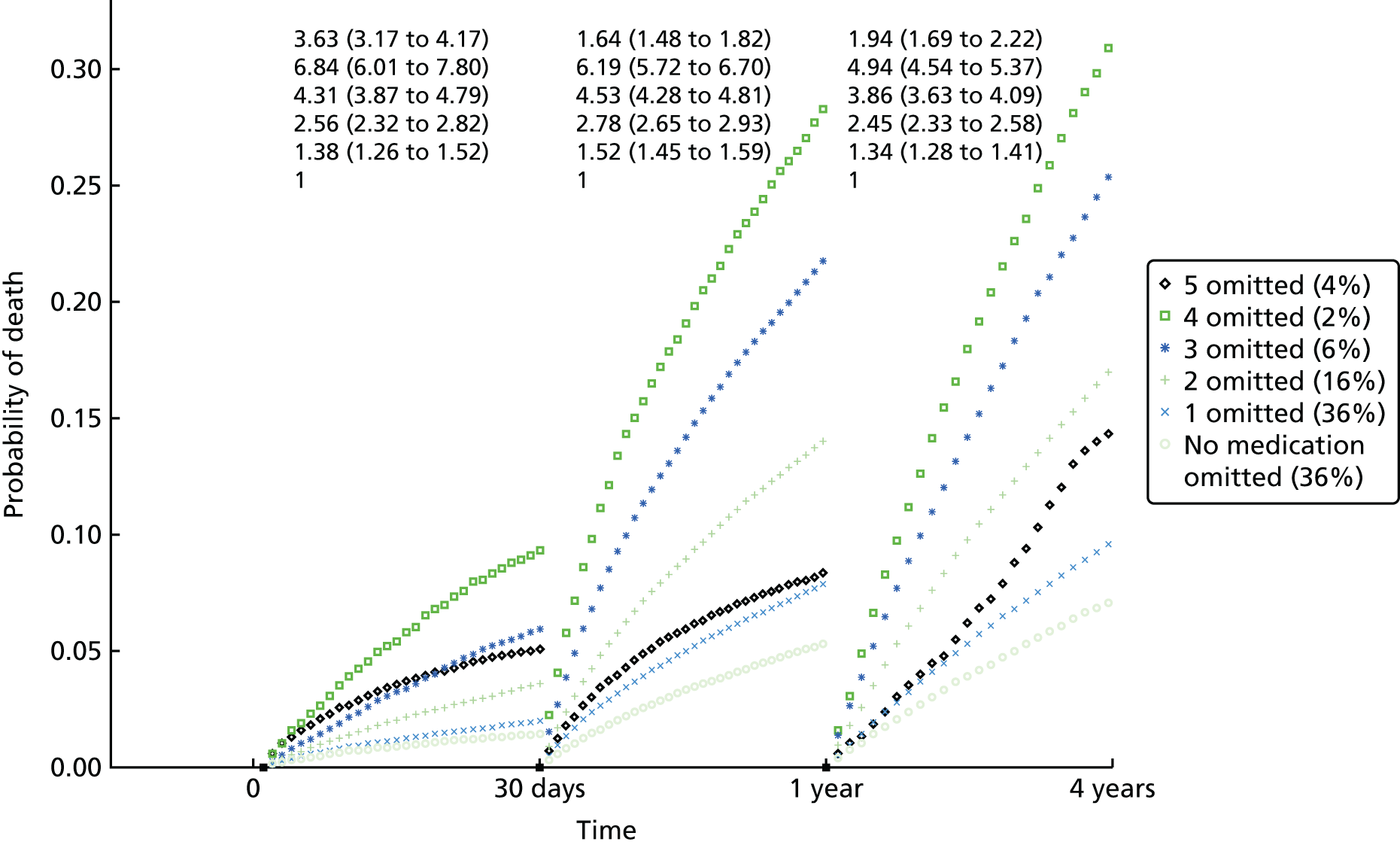

| Study 26: our study using linked CALIBER data to compare the effectiveness of drugs used for secondary prevention of CVD after AMI showed that use of fewer than five classes of secondary prevention drugs was associated with increased mortality. Omission of beta-blockers or statins from the discharge prescription was associated with a marked increase in the hazard of death in the first 30 days, with only minor reductions in the effect size during the first year and beyond (based on unpublished data) | Combinations of drugs that are recommended lifelong but have not been evaluated in RCTs should be investigated in observational studies for associations with fatal and non-fatal outcomes over the remaining life expectancy |

| Study 27: we found that use of a beta-blocker after AMI in adults with COPD was associated with lower subsequent mortality. Improved survival was observed for use of beta-blockers started either at the time of hospital admission for AMI or before an AMI59 | A RCT is justified to examine the effectiveness of beta-blockers after AMI in patients with COPD |

| Study 28: we used linked CALIBER data and a self-controlled case series design to measure the association between use of PPIs and a range of harmful outcomes in patients using clopidogrel and aspirin. Our findings suggest that drug interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel does not result in clinical harm60 | Methods are required by which a learning health system can interrogate the safety of drugs and drug–drug interactions in a more timely and more scaled fashion |

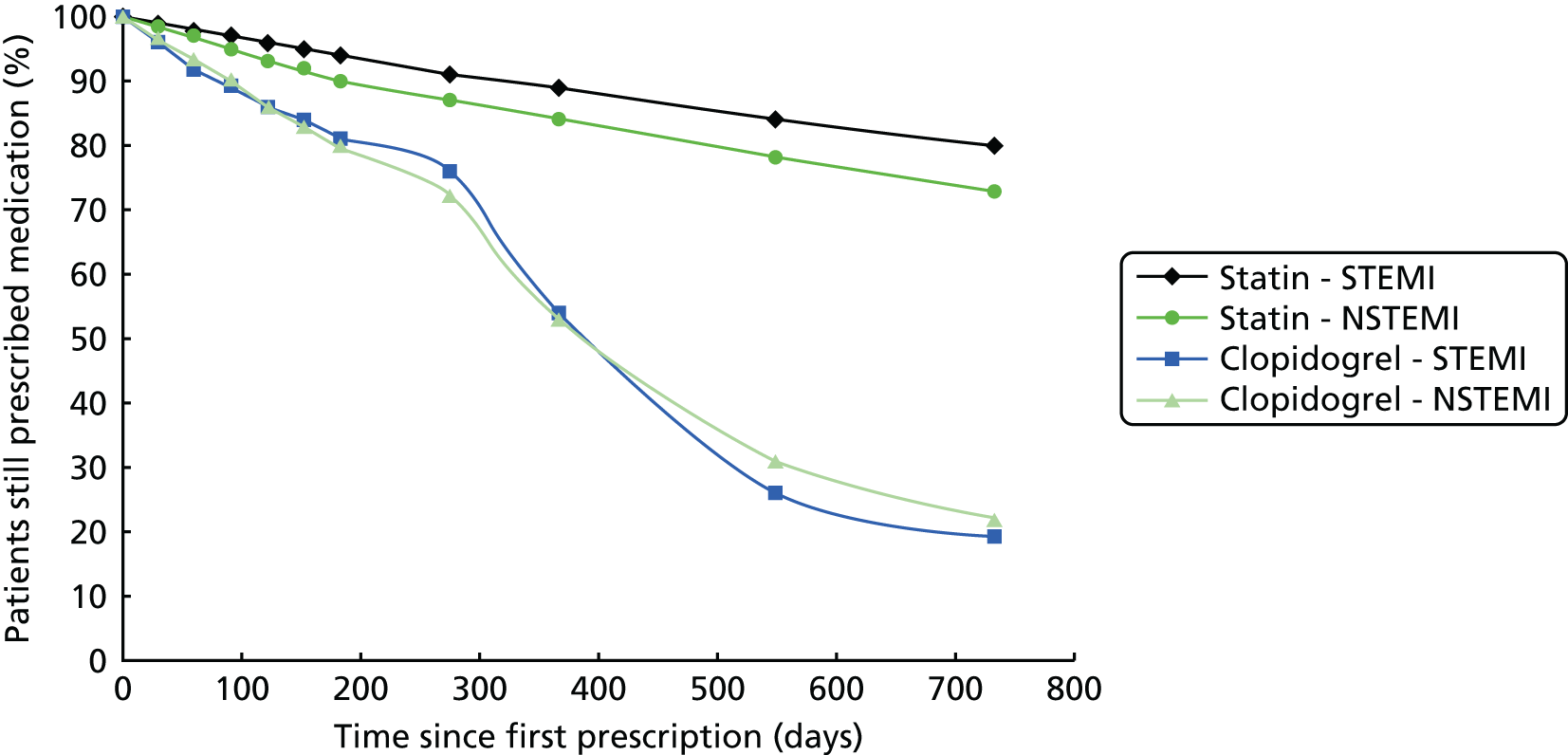

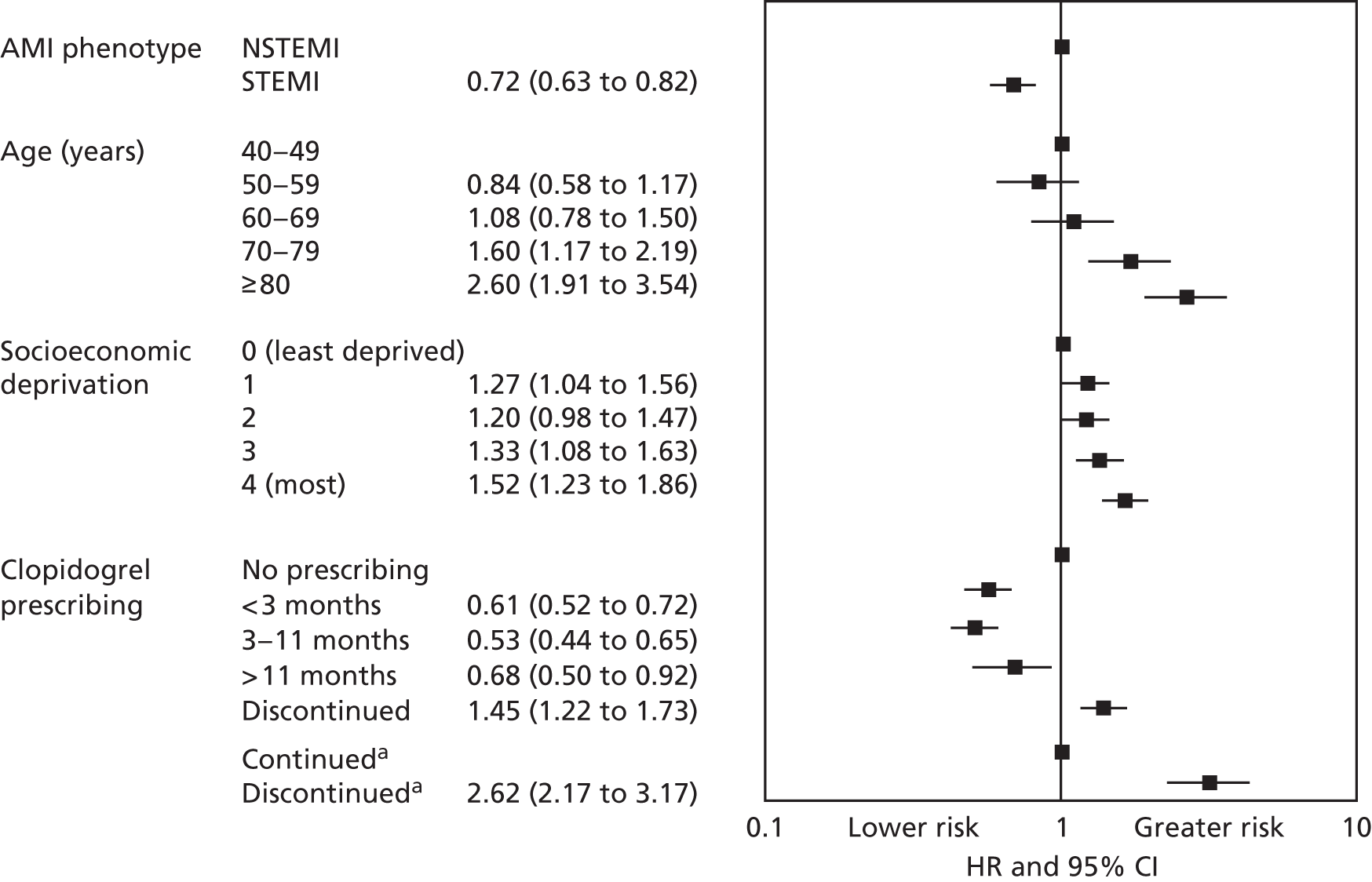

| Study 29: in this first study to use linked registries to determine persistence of clopidogrel treatment after AMI in primary care, we found that discontinuation of clopidogrel after AMI is common and is associated with adverse outcomes61 | Further research, incorporating methods of causal inference, is required to fully investigate the extent to which the association between clopidogrel discontinuation and adverse events we identified was causal or was confounded by the influence of unrecorded comorbidities or bleeding events |

| Chapter 12 | |

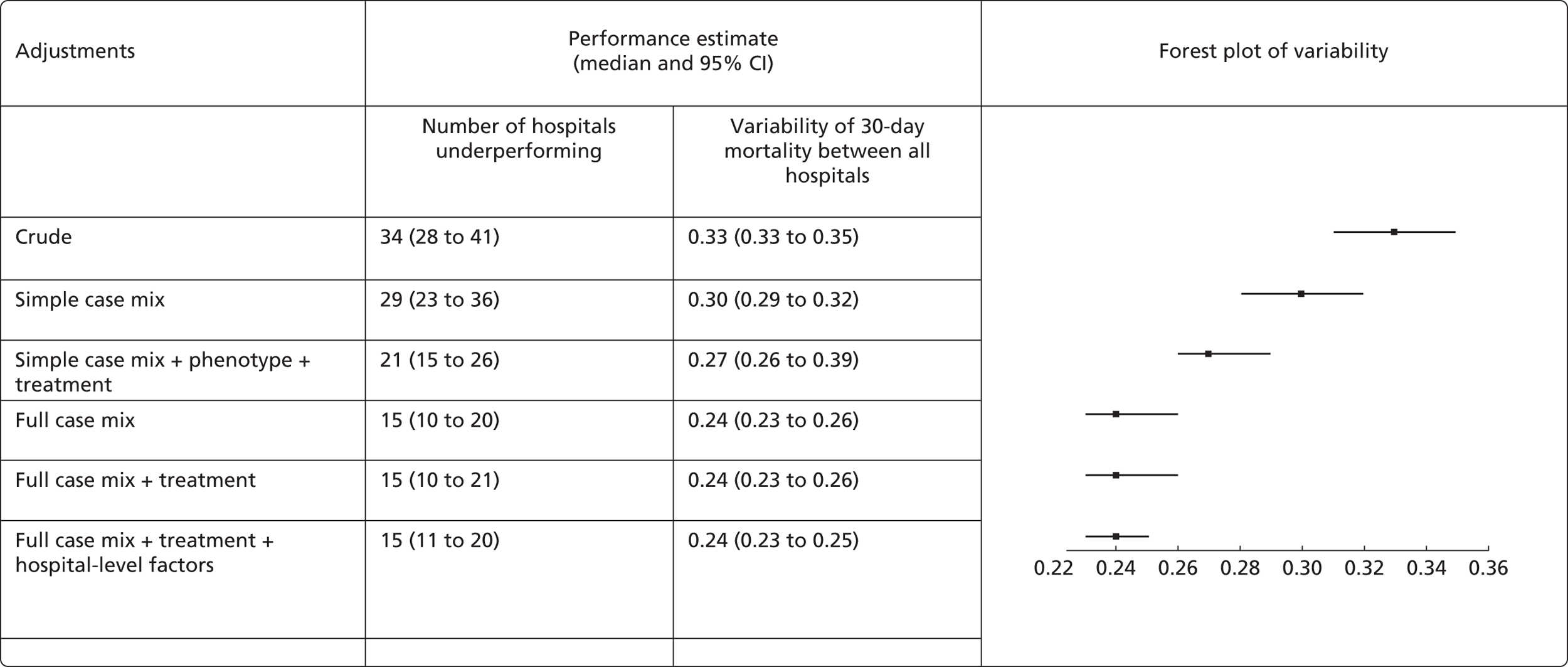

| Study 30: in this study comparing mortality among hospitals in the UK, we observed that short-term mortality varied substantially between hospitals. Up to four severely underperforming hospitals were identified with high confidence but there was considerable uncertainty in adjusted mortality rates (based on unpublished data) | Further research is required to obtain real-time risk-adjusted, treatment-adjusted estimates of between-hospital variation in mortality and a wider range of non-fatal outcomes |

| Study 31: we carried out a preliminary volume–outcome analysis of patients with AMI admitted to all hospitals in England and Wales. We found no clear relationship between the number of patients admitted to individual hospitals or the quality of BP management in primary care and 30-day mortality rates (based on unpublished data) | Further work is necessary to assess the distribution of AMI patients across hospitals and other hospital characteristics that contribute to patient outcomes |

| Study 32: international comparisons using AMI disease registry data in Sweden and the UK showed that hospital-level treatment varied between the two countries. Short-term mortality was greater in the UK than in Sweden (9.7% vs. 8.4%, respectively)62 | Opportunities for more ambitious comparisons along the care pathway should be exploited by linkage to national EHRs, that would permit analysis of non-fatal events before and after hospital admission and longer-term outcomes |

| Study 33: our qualitative study in 10 hospitals identified five processes that appeared to facilitate good care for NSTEMI patients: (1) early specialist assessment; (2) active patient monitoring and appropriate action; (3) cross-disciplinary communication; (4) co-ordinated discharge and initiation of secondary prevention prior to discharge; and (5) visible cardiology leadership63–65 | Mixed-methods research is required to inform actions to reduce hospital variations in care and outcomes |

Public and user group involvement

Electronic health records are increasingly considered to belong to individual patients. The National Information Board recommended online access to the full primary care record by April 2015. 17 In CALIBER we have had an active public and user involvement group which has had biannual meetings since 2006. Following the INVOLVE guidelines,66 this group represents a high level of user and lay participation in research, which includes contributing to the design and conduct of research. The group includes people relatively new to the ‘patient journey’ and others with many years’ experience of being cared for within the UK NHS. Our programme has benefited greatly from the group’s engagement, which has informed the development of studies from inception through to analysis and interpretation of findings. Central to the vision of the Farr Institute of Health Informatics Research is the need to transform the relationship between the patient, their health record and its uses for clinical care and translational research. The Farr Patient and Public Working Group meets biannually and is actively involved in national health informatics research network projects, research and events which are also open to lay members of the public.

Introduction to chapters

Chapter 2 (studies 1–3): the ClinicAl disease research using LInked Bespoke studies and Electronic health Records platform

We have established a framework for studying CVD across the patient journey, introducing novel approaches and scrutinising underlying methodology.

-

Linked EHRs: to map the patient journey, we exploited the previously untapped resource of the EHR for research purposes and, for the first time, linked data across primary care (CPRD), hospital admission (HES), a disease-specific registry (MINAP) and the national death registry (ONS). The resulting CALIBER data set comprises > 2 million patient records. The governance and analytic challenges were considerable, requiring a series of permissions, a contractual relationship with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, engagement of a trusted third party to perform the linkage, safe storage of the linked data sets, development of detailed algorithms to define clinical phenotypes of interest and, finally, application of complex analytic strategies to take account of the volume of data, missing data and hidden confounders.

-

Promoting high-quality prognostic research leading to patient benefit: in order to establish a high-quality framework for prognosis research, we created the international PROGnosis RESearch Strategy (PROGRESS) partnership, with representatives from academia and medical journal editors, to evaluate the field of prognosis research and make specific recommendations on improving the quality and impact of prognosis research.

Clinical context of diagnosis, risk prediction and treatment of coronary diseases: synopses of studies

The studies in the chapters that follow are a combination of synopses of previously published (n = 26) and currently unpublished (n = 15) studies and are summarised in Table 3 and Figure 2. We have included more detail for the unpublished studies. A summary of the published papers relating to individual studies is presented in Appendix 1.

Primary prevention of disease

In principle, CHD is largely preventable with behaviour change (including smoking cessation, increasing physical activity and lowering saturated fat intake) and, in some cases, pharmaceutical intervention to lower BP or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. 67 In the landmark INTERHEART study conducted in 52 countries, just nine potentially modifiable risk factors were found to account for > 90% of the population attributable risk of AMI in all regions of the world. 68

Primary prevention is thus an important public health priority in the UK. National public smoke-free legislation introduced in 2006 saw an almost immediate decline in rates of STEMI,69 and the NHS Health Check Programme introduced 2 years later identifies individuals at risk of disease development for whom preventative strategies are deemed appropriate. 70 The contemporary focus on disease prevention is reflected in the 2014 NICE guideline,71 which has now dramatically widened its recommendations for statin therapy to include all people with a 10-year risk of heart attack or stroke that is ≥ 10%. 71 The Joint British Societies 2014 guideline,24 which also emphasises lifetime risk assessment, further widens access to risk-lowering strategies to many young people at risk of disease in later life. 24 In practice, there are many missed opportunities for primary prevention; this is the focus of studies in Chapters 3 and 4 of this report.

Chapter 3 (studies 4–5): inequalities in health care by demographic determinants of cardiovascular disease

In this chapter we present a novel analysis of inequalities and their associations with age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation across these 12 CVD conditions. We also unravel the complex relationships between incidence and prognosis of CHD among people of South Asian ethnicity living in the UK and analyse factors driving the excess coronary mortality among South Asian groups.

Chapter 4 (studies 6–8): prevention

Reported failures to meet national guideline targets and treatment opportunities to optimise risk reduction among people without established disease represent an important missed opportunity for protecting patients against CVD. We have investigated risk factor modification among healthy populations and people at risk of coronary disease, specifically evaluating if guideline targets for BP reduction are being achieved in clinical practice, as well as opportunities for risk reduction in people with diabetes mellitus. We also investigate the association between two major risk factors (BP and type 2 diabetes) and 12 different presentations of CVD.

Importance of studying first presentation of cardiovascular disease

The Department of Health’s 2013 Cardiovascular Outcomes strategy72 has recommended management of CVD as a single family of diseases. An initial CVD event affecting head (stroke), abdomen (aneurysm) or legs [peripheral arterial disease (PAD)] shows some common risk factors and usually leads to initiation of lifelong secondary prevention medication. The pattern of initial presentation of CVD is changing, with a decrease in relative frequency of AMI and stroke. The study of the initial presentation of other CVDs has been difficult because of the need for large cohorts with detailed clinical follow-up, covering hospital and ambulatory care. However, linked EHR data provide the statistical scale and clinical resolution necessary to carry out this research. 73

Initial presentation with stable chest pain

Securing a firm diagnosis of coronary artery disease (CAD) is important to reduce the number of unnecessary invasive tests on the one hand and inappropriate discharges on the other hand. Early diagnosis of patients is a high priority for policy-makers, as evidenced by the widespread introduction of rapid access chest pain clinics (RACPCs) for patients with suspected coronary disease. A central requirement for early diagnosis is that primary care physicians are able to recognise early symptoms and signs of disease and respond appropriately with prompt referral for specialist assessment. However, there is considerable diagnostic uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of chest pain and we investigate this in Chapters 5 and 6. RACPCs are effective at identifying patients with angina74 but, in study 9, we found that during follow-up nearly one-third of cardiac events occurred in patients who had not been given a diagnosis of angina. As well as becoming more common, there are substantial uncertainties in how to manage such patients, including how to identify them and stratify them according to risk. Development of new-onset chest pain is a crucial intervention point, and identification of those at risk is a major clinical and research challenge.

Chapter 5 (studies 9–12): diagnosis and first presentation

These studies identify important missed opportunities at the point of initial presentation of disease and opportunities for early diagnosis.

-

Incidence of chest pain and heralding of AMI. We have investigated missed opportunities for diagnosis of chest pain in RACPCs, as well as the extent and nature of STEMI and NSTEMI heralding and its impact on primary and secondary prevention of ACS.

-

Mining free text in clinical notes to improve research on symptoms. Primary care EHRs contain clinician-entered records of patient symptoms as well as formal diagnoses. It is important to study these symptoms in order to be able to improve primary care decision and early diagnosis, but many of the symptoms are entered as free text rather than using medical terminology codes. We have developed tools that may help to extract information from unstructured free text in EHRs.

Chapter 6 (study 13): tools to improve assessment

We conducted a pilot evaluation of a clinical decision support system (CDSS) aimed at optimising use of angiography (and thereby revascularisation), secondary preventative medication, lifestyle interventions and referral to cardiac rehabilitation in RACPCs, to determine whether or not a large trial was justified. The study built on our earlier simulation showing that a tool incorporating contemporary appropriateness criteria could contribute positively to clinical judgement in guiding investigation of patients with suspected angina.

-

Piloting a CDSS in a RACPC. We developed a patient-specific computerised CDSS, piloting its use in four RACPCs, to model the effectiveness of the intervention and determine the need for a definitive trial powered on CVD events.

-

Qualitative ethnographic study. To determine the utility of the tool in day-to-day practice, we conducted an ethnographic study based on interviews with clinicians and observation of clinical practice.

Consented cohorts recruited in clinical settings make important contributions towards addressing translational research questions in prognosis research.

Chapter 7 (study 14): clinical cohort

We have established a new cohort of patients with suspected stable coronary artery disease (SCAD), the Clinical Cohorts in Coronary disease Collaboration (4C), consisting of genetic, biomarker, clinical and phenotypic data, linked to outcome data from national registries. The cohort was established as a resource to encourage collaboration among researchers through sharing of individual patient data, to strengthen prognostic model development and external validation of data.

Stable coronary artery disease

Better diagnosis and improved survival is leading to growing numbers of patients with SCAD, spanning two patient populations: those who have survived an AMI and are in the early very high-risk period, arbitrarily defined as the first 6 months after an AMI event, and patients who have never had an AMI but who have been diagnosed with coronary disease after coronary angiography or documented with myocardial ischaemia; the latter patients usually present initially as having ‘chronic stable angina’. SCAD is of growing importance for several reasons. Investigation of SCAD, independently of AMI, is important because the distinction of CAD phenotypes may yield causal mechanistic insights relevant to public health;75,76 angina pectoris is one of the most common initial presentations of coronary disease, yet it is commonly excluded from such aggregates, and little is known about factors determining disease progression. Furthermore, compared with ACS, there has been much less research on outcomes and quality of care for SCAD.

Among patients with SCAD, RACPCs now provide prompt patient access to specialist consultation and prescription of antiplatelet and statin therapy to stabilise atherothrombotic disease and protect against coronary events. Meanwhile, the options for correcting symptoms have been extended by the recent introduction of novel antianginal drugs such as ivabradine and ranolazine (Ranexa®, Menarini, Florence, Italy) which, together with rapidly changing drug-eluting stent technology, allow many patients with coronary disease to lead an active life free from ischaemic symptoms. 77,78

Chapter 8 (studies 15–19): biomarkers and prognostic indicators

Single biomarkers have traditionally lacked incremental predictive value to be considered for clinical use. We have evaluated the use of biomarkers as prognostic indicators to improve targeting of clinical interventions in SCAD. Using evidence syntheses and analyses of linked CALIBER data, we have examined the strength of the evidence base supporting the use of established and novel prognostic factors in SCAD, and evaluated the general quality of evidence being generated in prognostic factor research.

Chapter 9 (studies 20–21): prognostic and economic modelling

Improved survival after ACS and an ageing population have resulted in a large population of SCAD patients, with high health-care resource use. Validated prognostic tools and information on resource use and costs based on data collected as part of usual clinical care could assist in clinical management of SCAD patients and policy-making. We have developed and validated prognostic models, which we have used to examine health-care resource utilisation and costs, and to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of treatments.

-

Development, validation and impact of a risk prediction model. We have used linked CALIBER data sets to develop a prognostic model for SCAD, and validated the model using data from an independent study.

-

Health-care costs, resource use and decision models using a risk prediction model. We have combined resource use estimates derived from CALIBER data and prognostic models to model the outcomes and lifetime health-care costs of patients with SCAD.

Acute myocardial infarction treatments

The decline in the population burden of CHD has been driven partly by novel drug and device therapies, for which clinical efficacy has been established in randomised trials. 79 Thus, reperfusion strategies in AMI have moved away from thrombolytic therapy towards percutaneous intervention, together with potent dual antiplatelet regimens that now include adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonists such as clopidogrel and ticagrelor (Brilique®, AstraZeneca plc, London, UK). 80 This has seen UK hospital mortality rates for AMI drop to 9%,47 and ongoing antiplatelet therapy, statins and inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system provide protection against recurrent coronary events and left ventricular remodelling. Nevertheless, AMI 1-year mortality is still 20% despite five proven secondary preventative medications (study 26 in this report) and patients remain at high risk of further CVD events and death. In Chapter 10, we examine the extent of missed opportunities for treatment after hospitalisation for AMI, and go on in Chapter 11 to investigate further opportunities to improve outcomes after AMI.

Chapter 10 (studies 22–25): hospital and post-discharge care

A key aim of our research programme was to determine the cumulative impact of missed opportunities for improving patient outcomes after hospitalisation for AMI, across a spectrum of the most common symptomatic cardiovascular presentations. We anticipated the evolving interest in outcomes research and recognised that the management of CVD is an ongoing commitment for clinicians that spans the patient journey from initial presentation through hospitalisations to death.

-

Missed opportunities in hospital. We used linked CALIBER data to evaluate the impact of missed opportunities in hospital for patients with ACS. We also report, for the first time, international treatment and outcome comparisons in collaboration with investigators in the USA and Sweden.

-

Missed opportunities after discharge from hospital. We examined opportunities for smoking cessation, which substantially reduces the risk of recurrent AMI and coronary death, in the community after discharge from hospital, recognising that sustained lifestyle modification and secondary prevention treatment is a key guideline recommendation in patients who have experienced AMI.

Chapter 11 (studies 26–29): ‘real-world’ evidence

We have used EHR data to explore treatment benefits beyond clinical trials, examining the efficacy of specific drug combinations for secondary prevention, the safety and effectiveness of beta-blockers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and the clinical consequences of clopidogrel’s interaction with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Hospital and clinician performance

The importance of applying evidence-based treatments equitably has been recognised through the development of regularly updated guidelines published in the national society journals of Europe and the USA. In the UK these have been complemented by landmark policy initiatives such as the National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease in 2000,81 which focused on disease management in the hospital sector, and the Quality and Outcomes Framework in 2004, which introduced an incentive programme to enhance treatment in primary care. 82

Recognition that a major purpose of treatment is to improve patient outcomes has led policy-makers to shift their attention towards the monitoring of performance not only of hospitals but also of individual clinicians. 72 Methods of evaluating hospital performance have been the subject of debate but the need was brought into sharp focus by the Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust scandal in 2009, when it became clear that mortality rates in preceding years had been higher than expected yet no action had been taken by those charged with the supervision and regulation of the hospital. 83 One of the main recommendations of the 2013 Francis Report83 was that the ‘Department of Health should set up a working group to review the use of comparative hospital mortality statistics’ for identifying underperformance (© Crown copyright 2013; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). We await the working group’s report but, meanwhile, individual clinicians are increasingly being held accountable for the outcomes of patients under their care, particularly clinicians engaged in surgical and interventional procedures (e.g. http://scts.org/modules/surgeons/default.aspx and www.bcis.org.uk/).

This focus on performance is central to the UK Government’s 2013 transparency in health-care agenda, which not only includes commitments to publish more clinician-level data but also to link clinical data from primary care to hospital data systems in order ‘to allow new insights into the quality of services and better understanding of the way services interact’. 84 These commitments relate directly to some of the achievements of our research programme.

International comparisons can provide additional insight into performance, and have highlighted poor performance within the UK health system. 22 The extent to which this applies to CVD is not yet clear. Variation in outcomes between hospitals for ACS patients is the subject of our studies in Chapter 12.

Chapter 12 (studies 30–33): hospital variation

Using EHR data and in-depth qualitative studies, we have examined the impact of individual hospitals on the outcomes of AMI patients.

-

Hospital-level variation in outcomes after AMI. For the first time, we have analysed interhospital variation in 30-day mortality adjusted for case-mix and hospital treatment, and examined its potential to identify and rank underperforming hospitals. In collaboration with Swedish investigators, we have compared interhospital mortality variations in the UK and Sweden.

-

Qualitative analysis of hospital processes of care. We carried out qualitative studies examining processes of care potentially associated with favourable outcomes.

Chapter 2 Establishing a framework to study cardiovascular diseases across the patient journey: underlying methodology and approaches

Abstract

Background

Electronic health records are generated at an unprecedented scale during patients’ interactions with the NHS. The UK is unique in being able to trace a complete patient journey through coded EHRs spanning primary care, hospitals, disease registries and, ultimately, death registries. Large-scale linkage of EHRs in CVD has major challenges, and the quality of prognosis research, which provides crucial evidence for translating research findings into clinical practice, is poor.

Objectives

(1) To establish an EHR-based research platform and data resource in CVD (CALIBER) and (2) to develop a framework for exemplary prognosis research.

Methods

(1) We linked coded EHR data from four sources spanning primary care (CPRD), secondary care (HES) and national registry databases (MINAP and the ONS death registry). (2) We established the international PROGRESS partnership.

Results

(1) Through CALIBER, we linked and curated data covering almost 2 million people, and curated ≈ 600 EHR disease and risk factor phenotyping algorithms based on linked EHR data. (2) We made 24 recommendations to address challenges and opportunities across four prognosis research themes.

Conclusions

The CALIBER platform promotes the transparent and scalable use of EHR data, enabling the wealth of information in UK EHRs to be exploited for research purposes. Our CALIBER data resource and recommendations for improving the quality of prognosis research provide a framework for high-quality CVD research.

Development, feasibility and validation of our data linkage platform: ClinicAl disease research using LInked Bespoke studies and Electronic health Records

Patients’ interactions with the health-care system generate unprecedented amounts of structured and unstructured EHR data that are stored in disparate clinical information systems. There, rich national EHR data sources are increasingly being linked for translational research in the USA and Europe with the potential to have a positive impact on medical care and research. In the UK, a unique 10-digit identifier is assigned to each patient on their interaction with the NHS, allowing the complete patient journey to be traced through EHRs spanning primary care, hospitals, disease registries and, ultimately, death registries.

These features have provided a platform for the CALIBER programme, led from the Farr Institute (London, UK, under the directorship of Harry Hemingway), which has linked EHRs from four key sources: the CPRD, HES, MINAP and the ONS death registry. CALIBER is a research platform that aims to meet the need for a structured approach to EHR phenotyping algorithm development for epidemiological research using national linked data, while also providing a central online repository for the storage and distribution of algorithms, documentation (flow charts, free-text description, pseudocode) and metadata. The platform contains EHR data on 2 million people and provides a unique platform for investigating a range of important issues in CVD diagnosis, management and prevention, and health system performance. Our findings have important implications for clinicians and clinical decision-making, for health policy and for shaping future research.

Study 1: establishing the ClinicAl disease research using LInked Bespoke studies and Electronic health Records data resource

This study is based on the peer-reviewed paper by Denaxas et al. 15

Surprisingly little is known about the initial presentation of CVD in general practice and its long-term management through to death. However, the UK is the only country in the world where all the components of this patient journey are recorded electronically at national scale in primary care, hospital and death registries. Moreover, all patients in the UK are uniquely identified by a 10-digit NHS number, providing a reliable and robust identifier for record linkage and data sharing while preserving patient confidentiality. This has provided the opportunity to develop a programme of CVD research using linked bespoke studies and EHRs (CALIBER) led from the Farr Institute. 15 The linkage was carried out in October 2010 by a trusted third party, using a deterministic match between NHS number, date of birth and sex. Overall, 96% of patients with a valid NHS number were successfully matched.

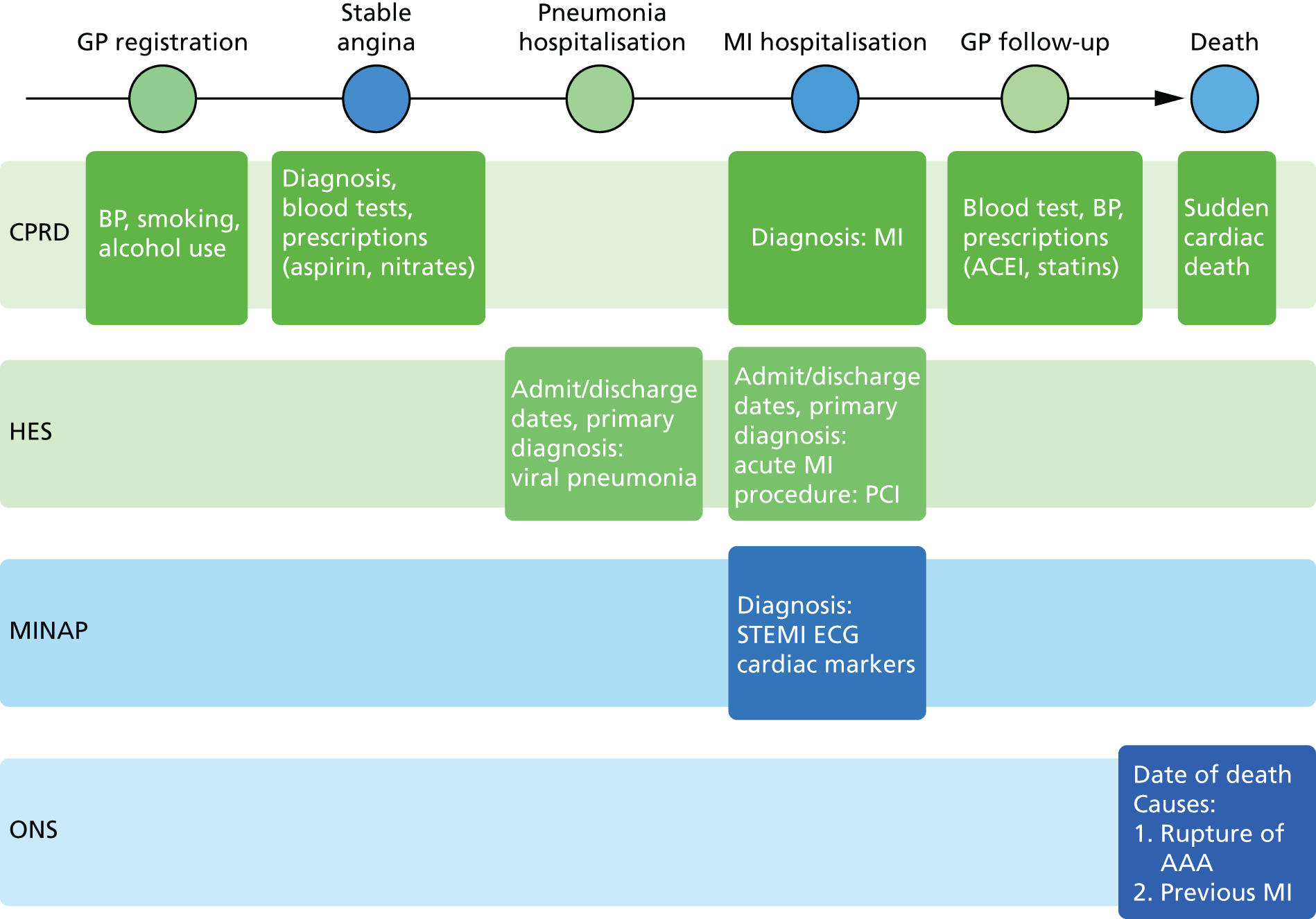

Linked data sources

The four linked data sets that we used are shown in Figure 3, which illustrates the longitudinal, population-based nature of CALIBER data sets. Each source captures a different aspect of the patient journey:

-

CPRD contains longitudinal primary care coded data on symptoms, diagnosis, prescriptions, investigations, referrals and vaccinations. 85 Data are recorded prospectively as part of clinical care and are not subject to recall bias or differential bias related to outcome. Diagnostic data are coded using Read codes, which map to Systematic Nomenclature of Medicine – Clinical Terms. Of the 684 primary care practices in CPRD (13.6 million patients), 226 consented to data linkage across the CALIBER data sources. These practices contained 3.9% of the population of England in 2006.

-

HES is a national data set of all admissions to NHS hospitals in the UK (see www.hscic.gov.uk/hes). Diagnoses are recorded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) and procedures using the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys’ Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4.

-

MINAP is a national registry of patients admitted to all acute hospitals in England and Wales with ACS events (n = 230). For each admission, MINAP records patient demographic characteristics, limited medical history, clinical features and investigations, drug treatment (pre, during and post admission) and final diagnosis, including differentiation into STEMI, NSTEMI and unstable angina. Data undergo annual quality assessments. A descriptive review of the MINAP registry has been published. 86

-

The ONS provides data on cause-specific mortality for all residents of the UK. 87 Cause-specific mortality data are extracted from death certificates and recorded using ICD-10. Small-area measures of social deprivation are recorded using the 2007 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)88 and Townsend scores.

FIGURE 3.

Longitudinal nature of four linked primary care and disease registry data sources in the CALIBER data resource. AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ECG, electrocardiogram; MI, myocardial infarction. Reproduced from Denaxas et al. 15 Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Epidemiological Association. © The Author 2012. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits non-commercial reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Converting raw data to research-ready data: curated common data model

Important challenges remain in relation to converting raw EHR data into research-ready variables. The manner and reason for the generation, capture and recording of EHR data vary substantially between health-care settings. In addition, different medical classification systems are often used for different data sources and, consequently, clinical information may be recorded in multiple sources but at different levels of clinical detail. Integrating data from these different sources is therefore complex, but doing so is advantageous for research and consequently for clinical purposes. For example, our research illustrated how linkage of EHR data sources substantially improves the identification of AMI cases.

The complexities of EHR data mean that a structured method for combining diverse data sources and creating EHR ‘phenotypes’ is needed, but no internationally recognised framework currently exists. An EHR phenotyping algorithm translates these clinical requirements into queries that leverage multiple linked EHR sources, identify relevant patients and extract disease onset, severity and subphenotype information. Defining phenotyping algorithms for a study (disease end points, disease start points, exclusions, covariates and risk factors) consists of identifying relevant codes for diagnosis (e.g. diagnosis of cancer) or risk factors (e.g. recording of smoking status) and defining how they should be combined. However, these definitions, on which research findings are based, are poorly described in published literature, with the exception of cases in which the curation of phenotyping algorithms occurs upstream by the data provider [e.g. electronic medical records and genomics network (eMERGE)].

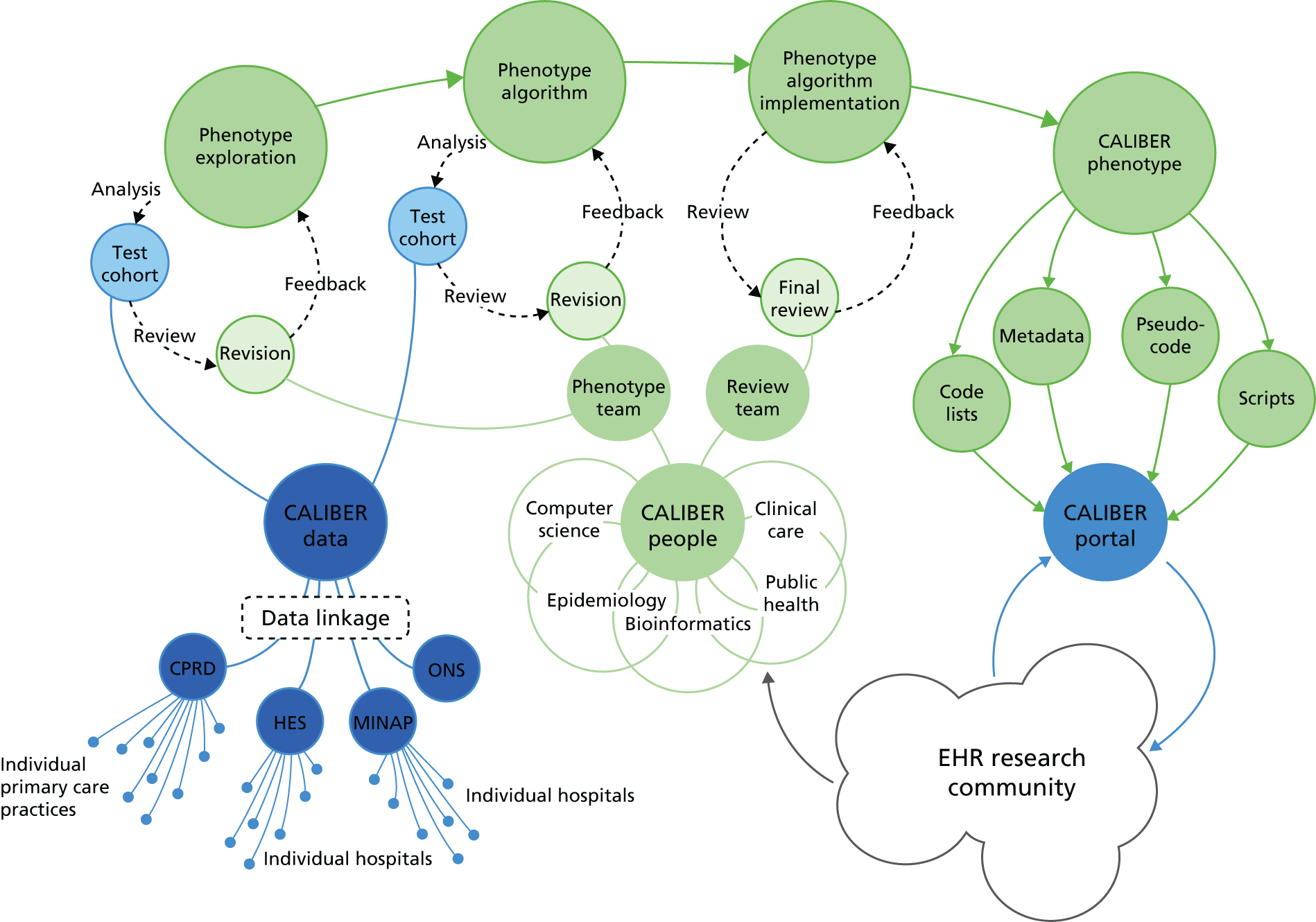

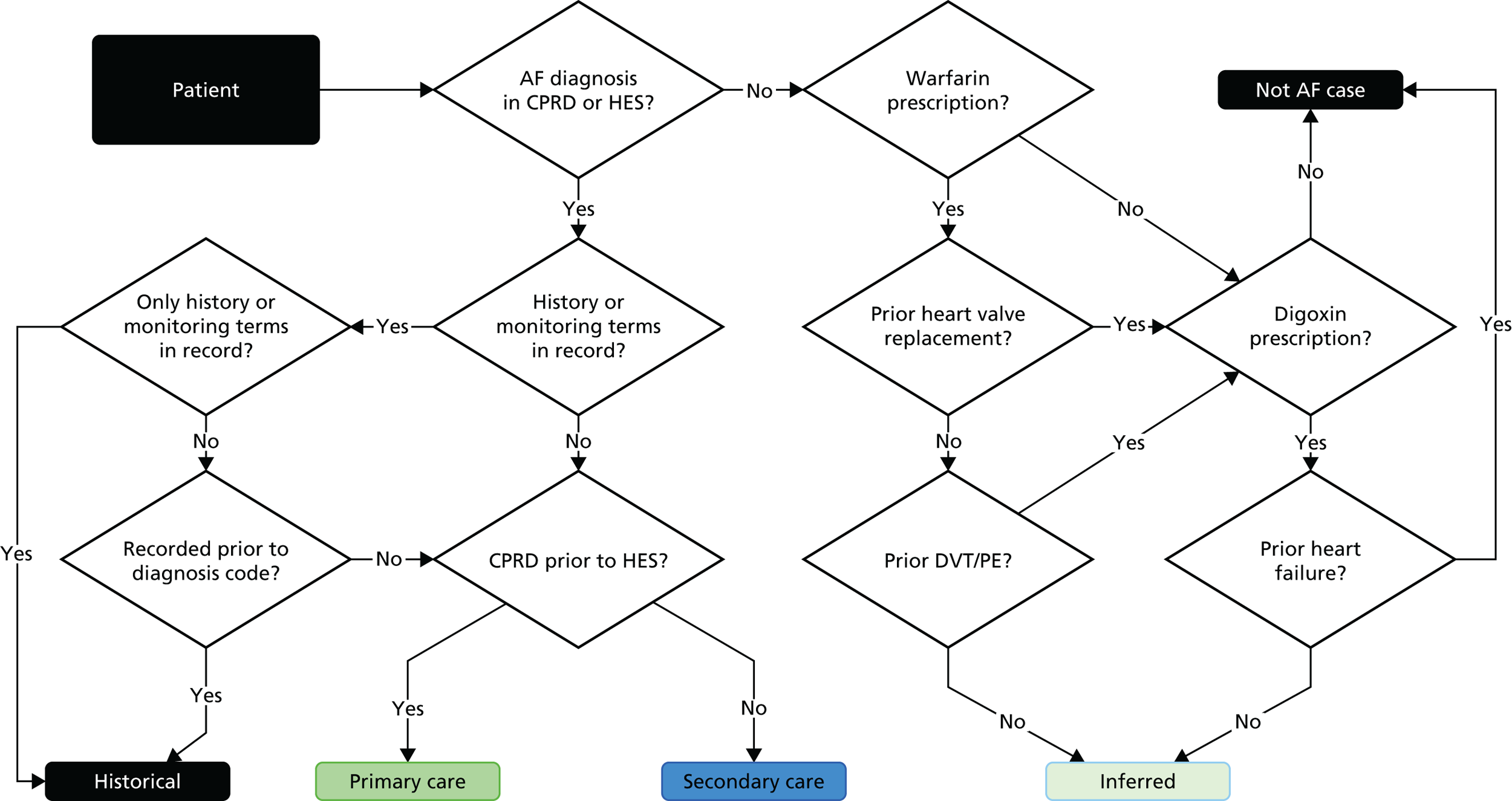

We created and evaluated a framework (Figure 4) for transforming raw EHR data into research-ready phenotypes in a collaborative and transparent manner by involving domain experts across disciplines (epidemiology, computer science, public health, health informatics) and using a centralised repository for their distribution and curation. Here, we illustrate the steps involved in creating a phenotype using the example of atrial fibrillation (Figure 5). The framework consists of multiple iterative steps from initial phenotype definition with domain experts to algorithm implementation, validation and distribution to the scientific community. All CALIBER studies are registered in the public domain on Clinicaltrials.gov, and their analytic protocol is made available for download.

FIGURE 4.

Development of a phenotype algorithm using the CALIBER programme. Reproduced from Morley et al. 89 © 2014 Morley et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

FIGURE 5.

Flow diagram illustrating the CALIBER phenotype for atrial fibrillation. AF, atrial fibrillation; DVT, deep-vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. Reproduced from Morley et al. 89 © 2014 Morley et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

To aid the process of creating, validating and disseminating EHR phenotyping algorithms for epidemiological research, we created the CALIBER data portal (www.caliberresearch.org/portal), an interactive online repository of phenotyping algorithms. All algorithms are displayed on the portal, where registered external researchers can view and comment on them. A number of metadata fields is recorded for each algorithm and is made available. The data portal contains phenotyping algorithms that leverage multiple EHR data sources in order to define > 90 diseases and related risk factors. The data portal also facilitates the transportability of the developed algorithms on national EHR data from different countries where subtle differences might exist in the manner clinical information is recorded. Algorithms available through the data portal can be utilised for performing international comparisons between health systems (e.g. England and the USA) or act as the base on which phenotyping algorithms reflecting the local health system are created.

The CALIBER portal operates a collaboration-driven data-sharing model and prioritises collaborations based on scientific-added value, capacity development and sustainable funding. Details on CALIBER and how to access CALIBER resources are available at www.ucl.ac.uk/health-informatics/caliber.

Strengths and limitations of the data platform

The CALIBER portal spans ambulatory and hospitalised care in large population samples, permitting a ‘higher resolution’ approach to cardiovascular epidemiology in three respects:

-

resolution of broad CVD aggregates (e.g. CVD, CHD) into distinct disease phenotypes in different vascular beds:

-

cerebral circulation – transient ischaemic attack, ischaemic stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage, intracerebral haemorrhage

-

peripheral circulation – PAD, abdominal aortic aneurysm

-

coronary circulation – stable angina, unstable angina, AMI (STEMI and NSTEMI), unheralded CHD death, heart failure, cardiac arrest/sudden coronary death

-

-

sufficient temporal resolution to distinguish whether a first event (e.g. heart attack or stroke) was the first manifestation of CVD or if it was preceded by any of a range of non-fatal events

-

sufficient number of events and patients to generate accurate estimates of risk.

The main limitations of any EHR research platform relate to data quality:

-

Missing data. Data completeness is variable [e.g. 82.6% of people have ≥ 1 body mass index (BMI) measurement but only 44.9% have ≥ 1 cholesterol measurement]. Developments in imputation within longitudinal cohorts may offer a partial solution. 90

-

CALIBER makes use of coded data from multiple national EHR sources. A plethora of unstructured data exist in secondary care that are recorded within hospital information systems but remain inaccessible for research. This is mainly due to the lack of a centralised manner in which these data can be extracted, linked and utilised at scale. Significant national initiatives such as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Informatics Collaborative (HIC) aim to create informatics infrastructure that will provide means for accessing these phenotypically rich data sources.

-

An important aspect of EHR phenotype development is validation, preferably against a ‘gold standard’ (such as a manual review of case notes). We could not validate the developed phenotypes in this manner as, for the CALIBER programme, the initiation and funding of a separate study is required for recontacting participants or clinicians to confirm diagnoses or review records. Previous studies, however, have shown the high degree of reliability of the data. 91

-

Currently, restrictive confidentiality legislation and information governance constraints in England prevent the use of anonymised clinical text on a large scale. Electronic free text in secondary care does not get captured or extracted in any form by HES and is thus not available for research. In primary care, free text from GPs contributing to CPRD is downloaded and held on government servers at CPRD, and is not readily available at scale to researchers based in universities (researchers can get access to very small corpora of text which has to be manually anonymised, a process that requires substantial resources and does not scale). Consequently, our approach to developing phenotyping algorithms has limited ability to fully utilise data elements extracted from clinical text as others have done.

Study 2: completeness and diagnostic validity of recording acute myocardial infarction events in primary care, hospital care, disease registry and national mortality records

This study is based on the peer-reviewed paper by Herrett et al. 28 Sections of the text have been reproduced/adapted from the original article; Copyright © Herrett et al. 28 2013. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

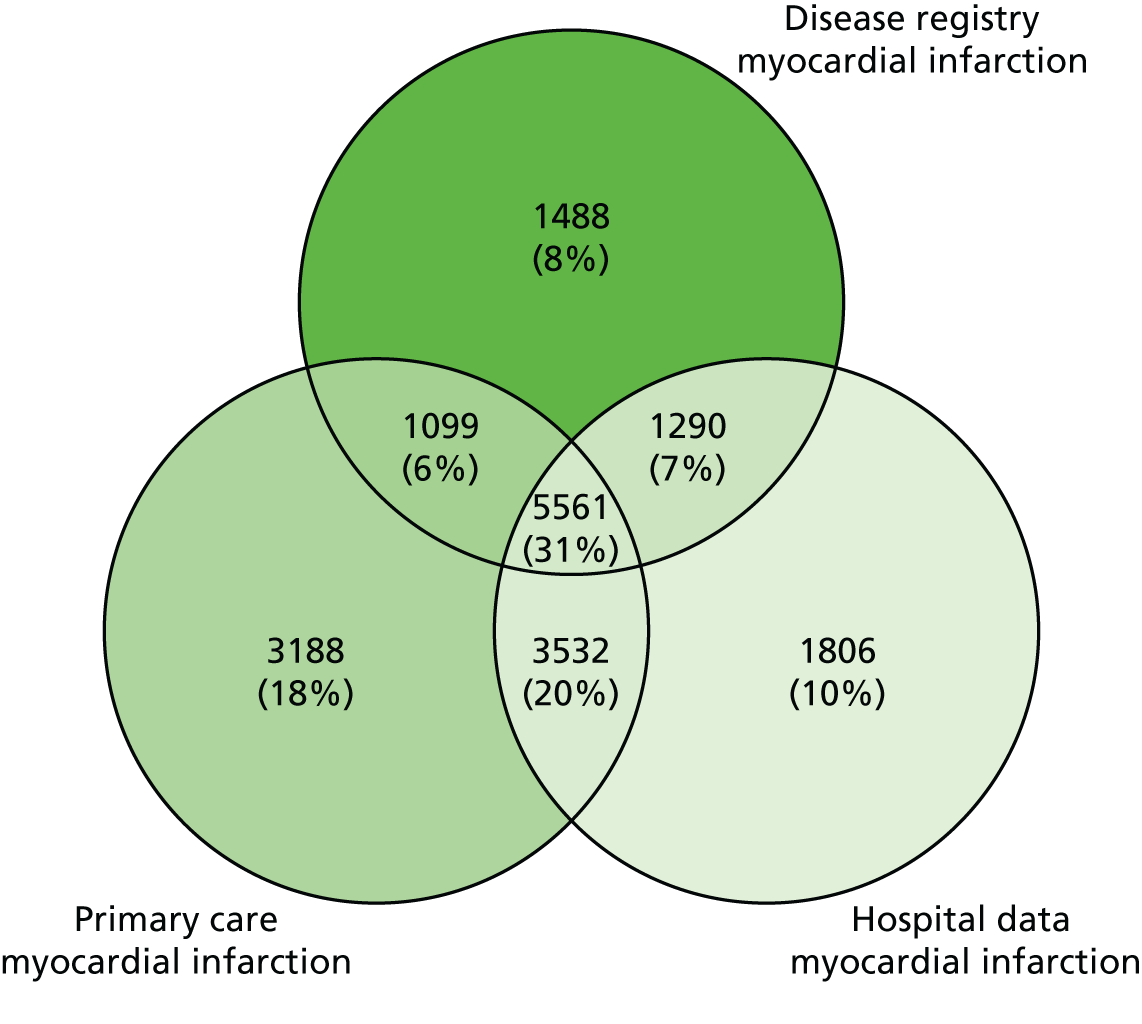

Introduction

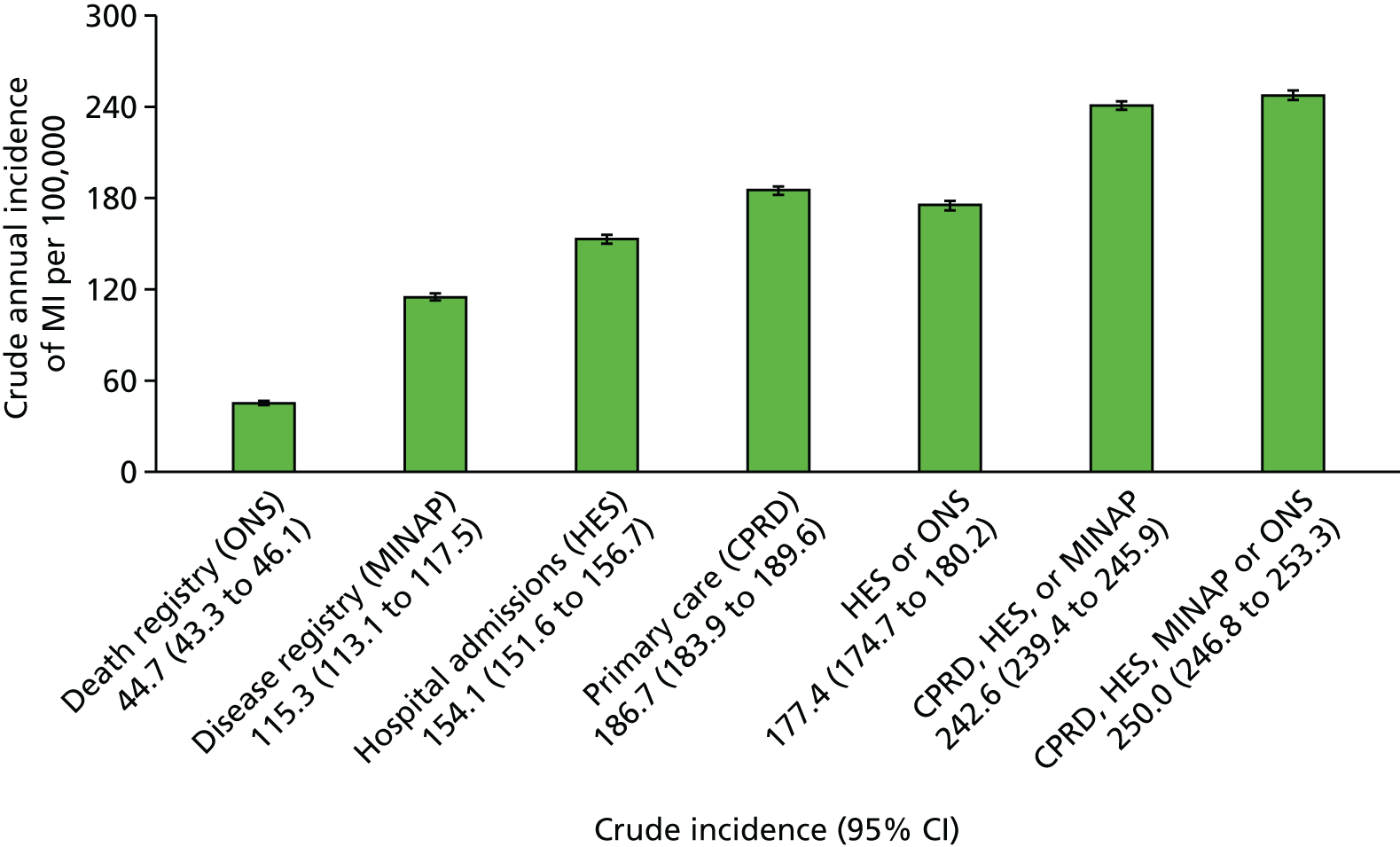

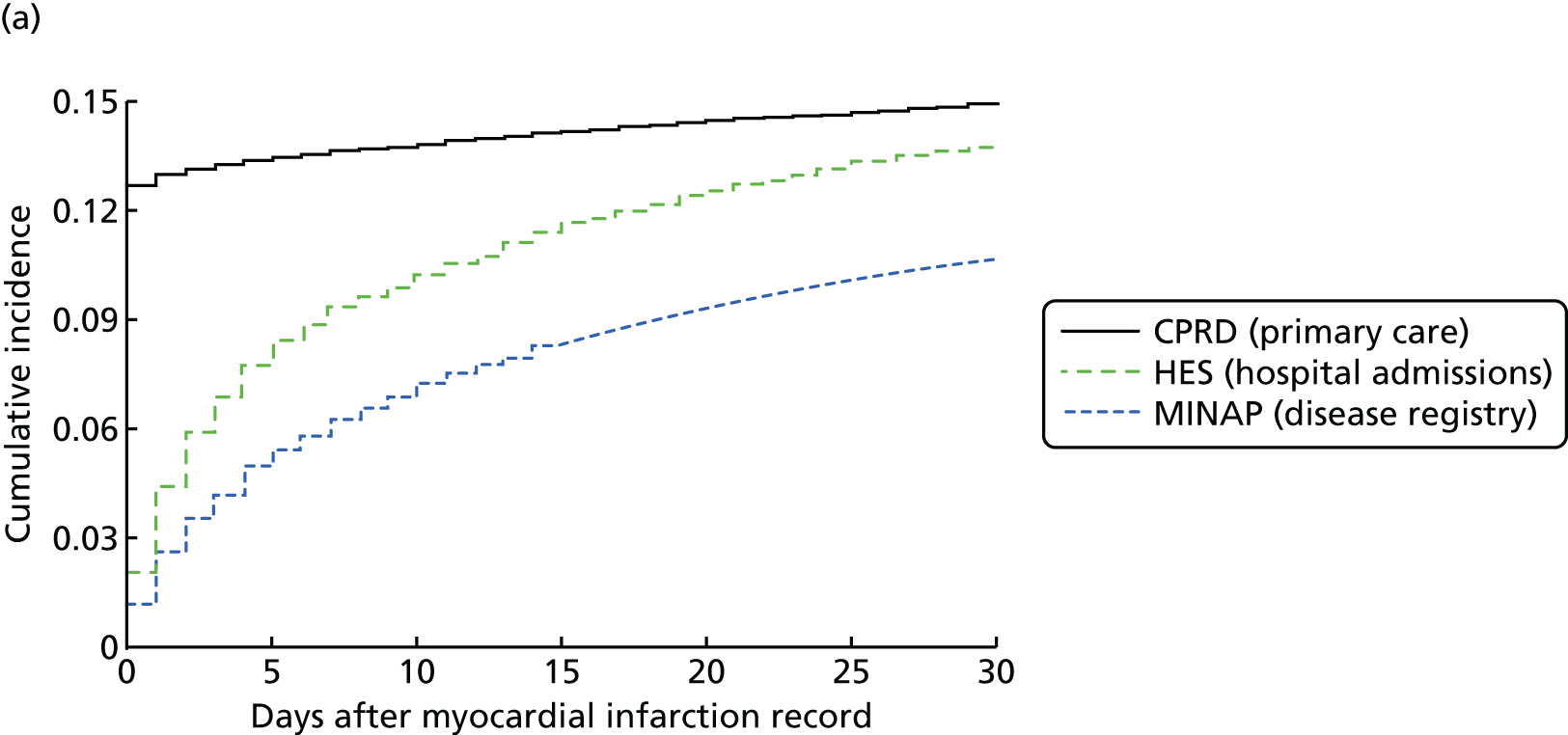

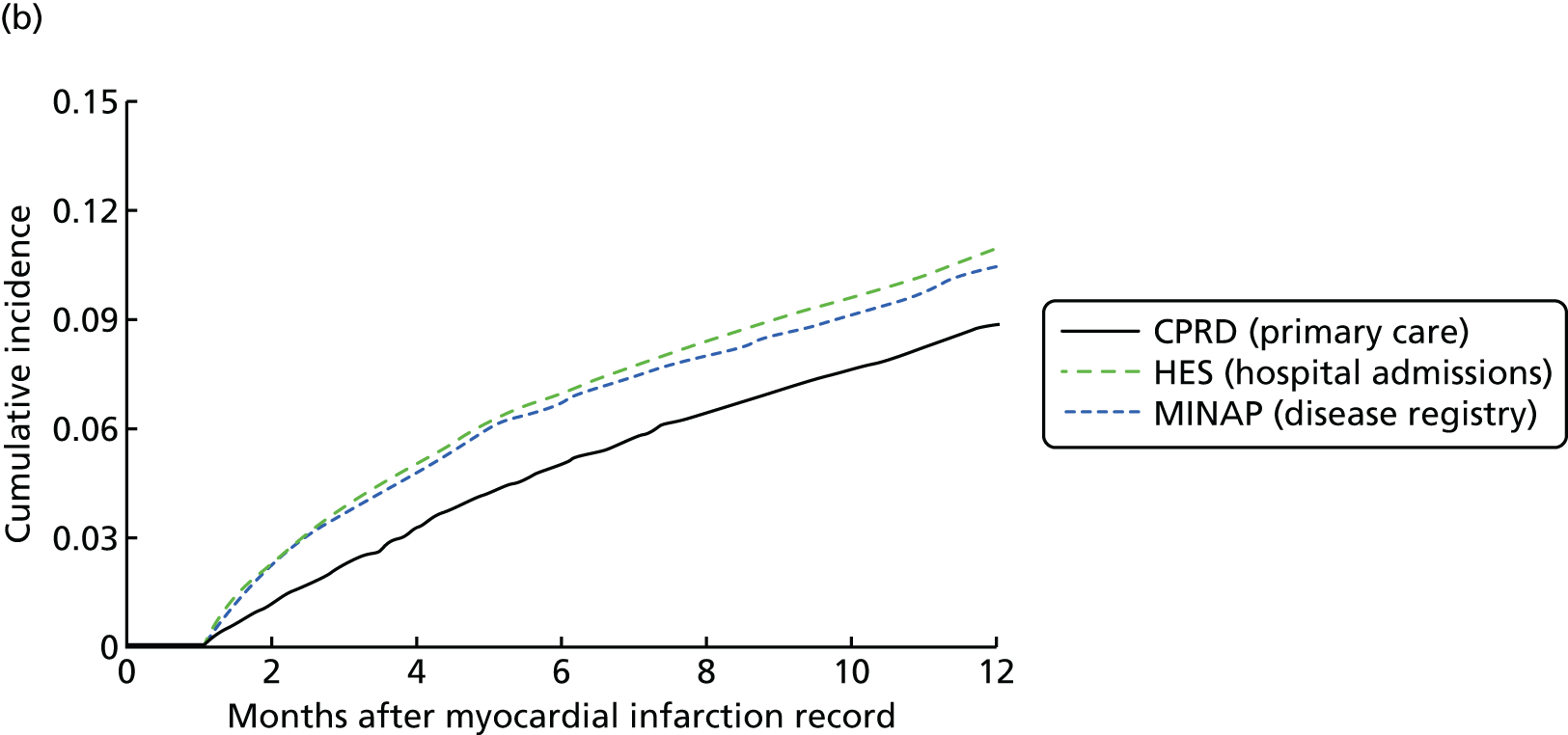

We assessed the concordance, completeness and diagnostic validity of AMI recording across CPRD, HES, MINAP and ONS in order to ensure the robustness of the data linkage. Our specific aims in this study were to compare the incidence, recording, agreement of dates and codes, risk factors and all-cause mortality of AMI.

Methods

Study population and follow-up

We identified records of AMI in CPRD, HES and ONS. In MINAP, STEMI and NSTEMI were identified using hospital discharge diagnosis, markers of myocardial necrosis and coded electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, in accordance with the international definition of AMI. 92 The study period was 1 January 2003 to 31 March 2009 (when all record sources were concurrent) and confined to patients who had been registered with their general practice for at least 1 year. We selected the first record of AMI during the patient’s study period as the index event and considered AMI records in the other data sources as representing the same event if they were dated within 30 days of the index event. Follow-up after a record of AMI was for death as recorded in the ONS death registry. We categorised patients as having fatal or non-fatal AMI according to whether or not they died of any cause within 7 days of AMI.

Agreement in recording

If the time difference between the earliest date of AMI in different sources was ≤ 30 days we considered that the records of AMI in the different sources agreed. An AMI recorded > 30 days after the earliest date was considered a new event and was not included, ensuring that each patient appeared only once in the analysis.

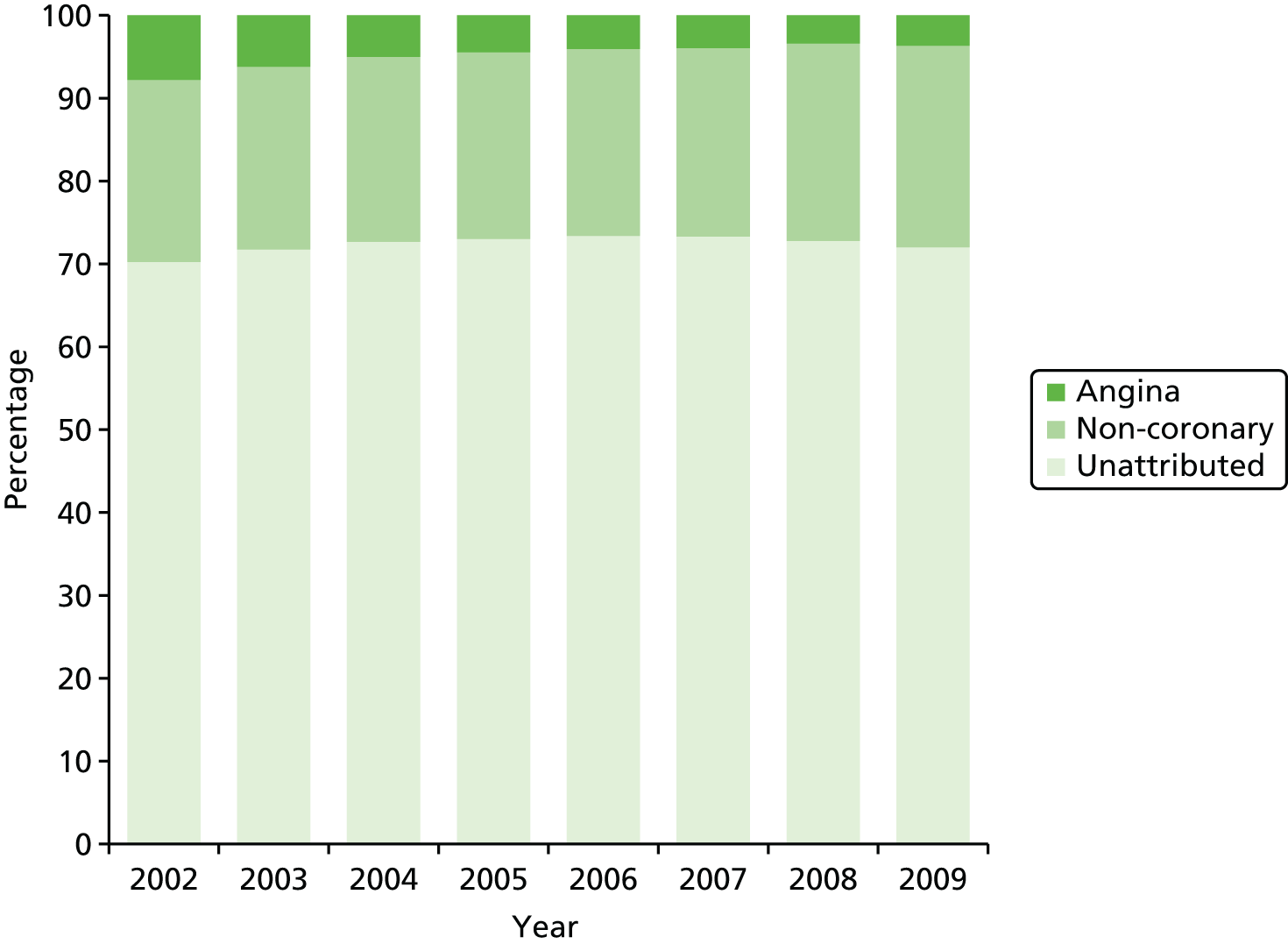

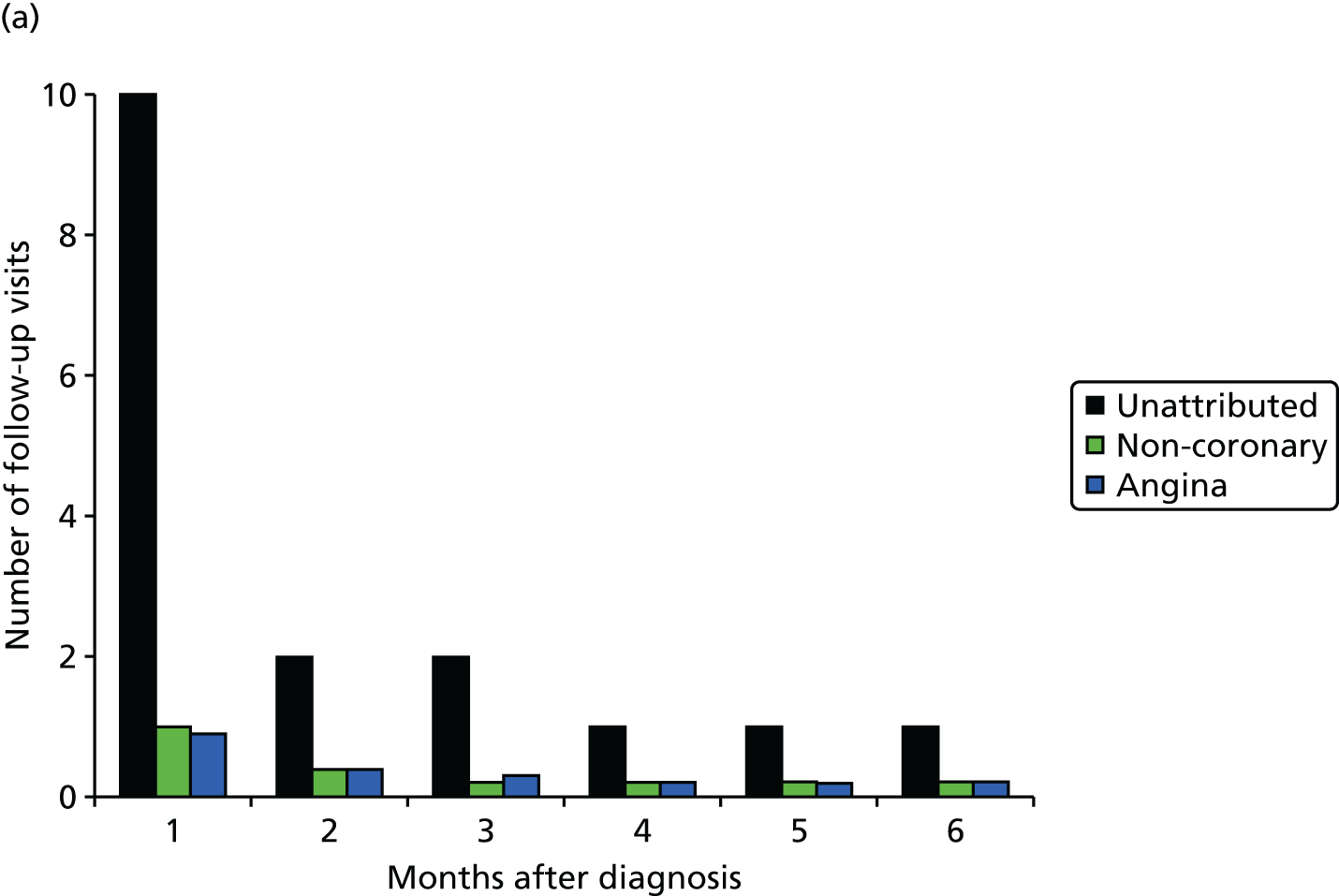

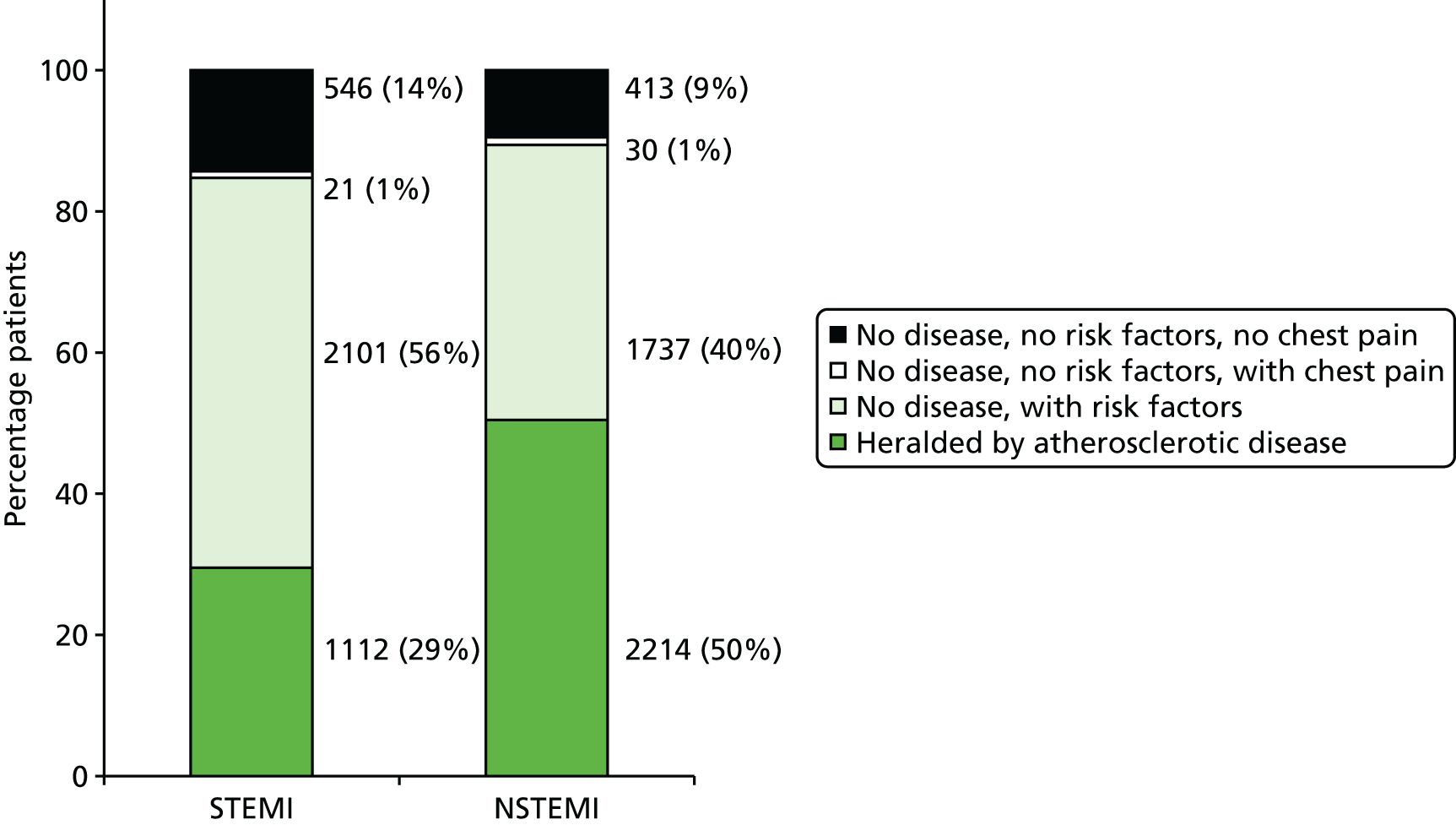

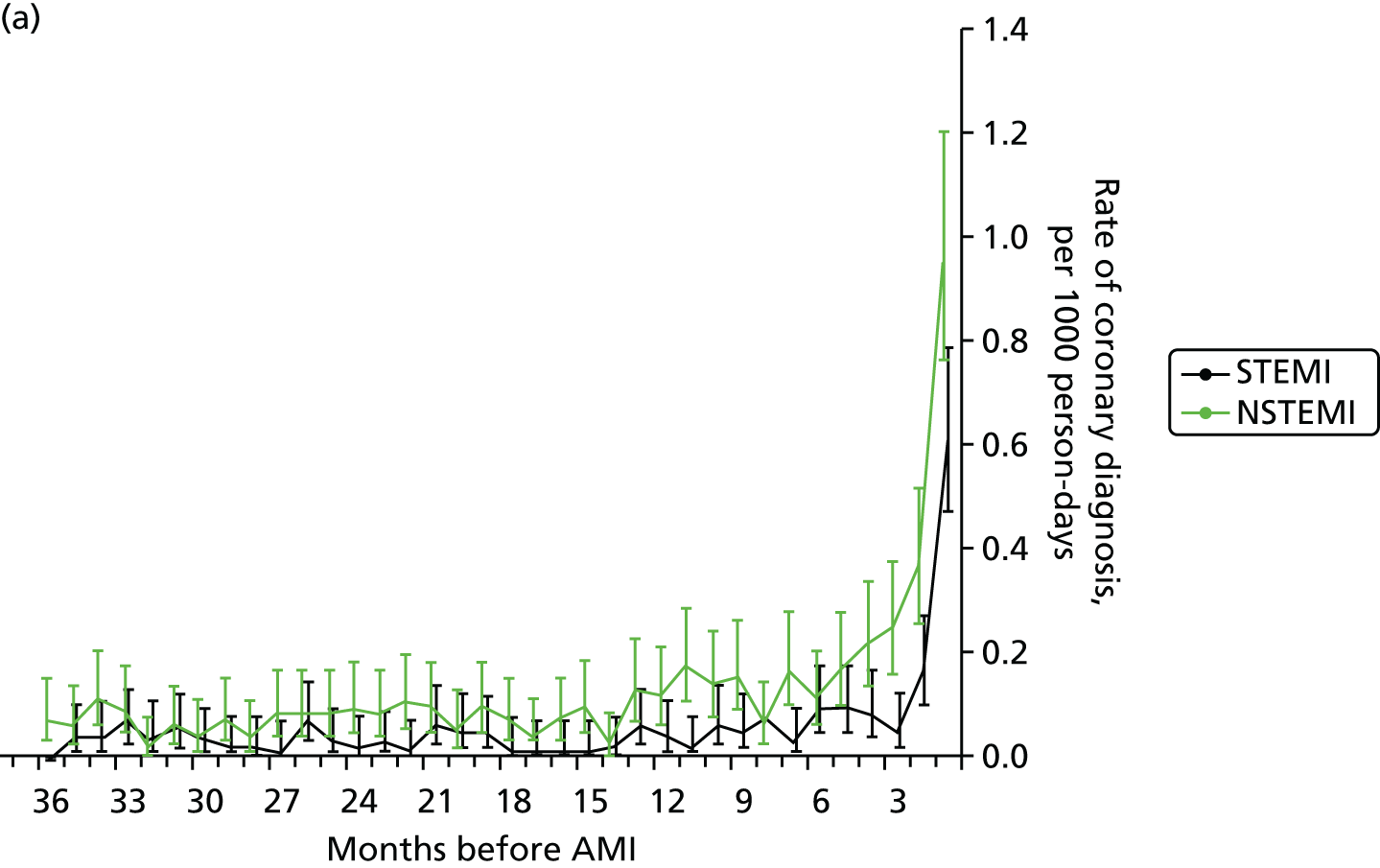

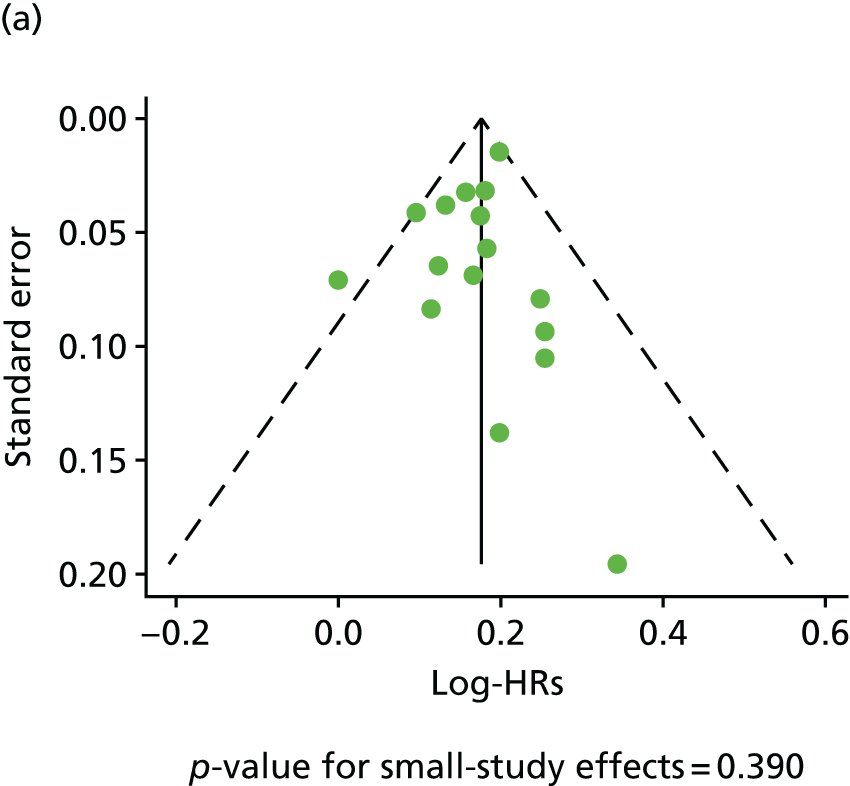

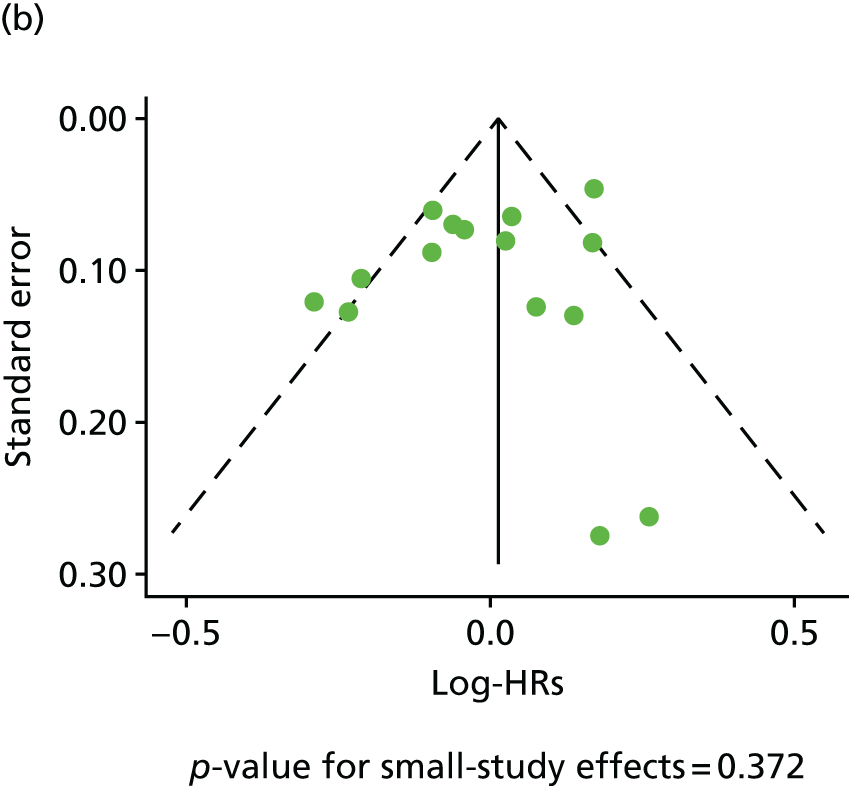

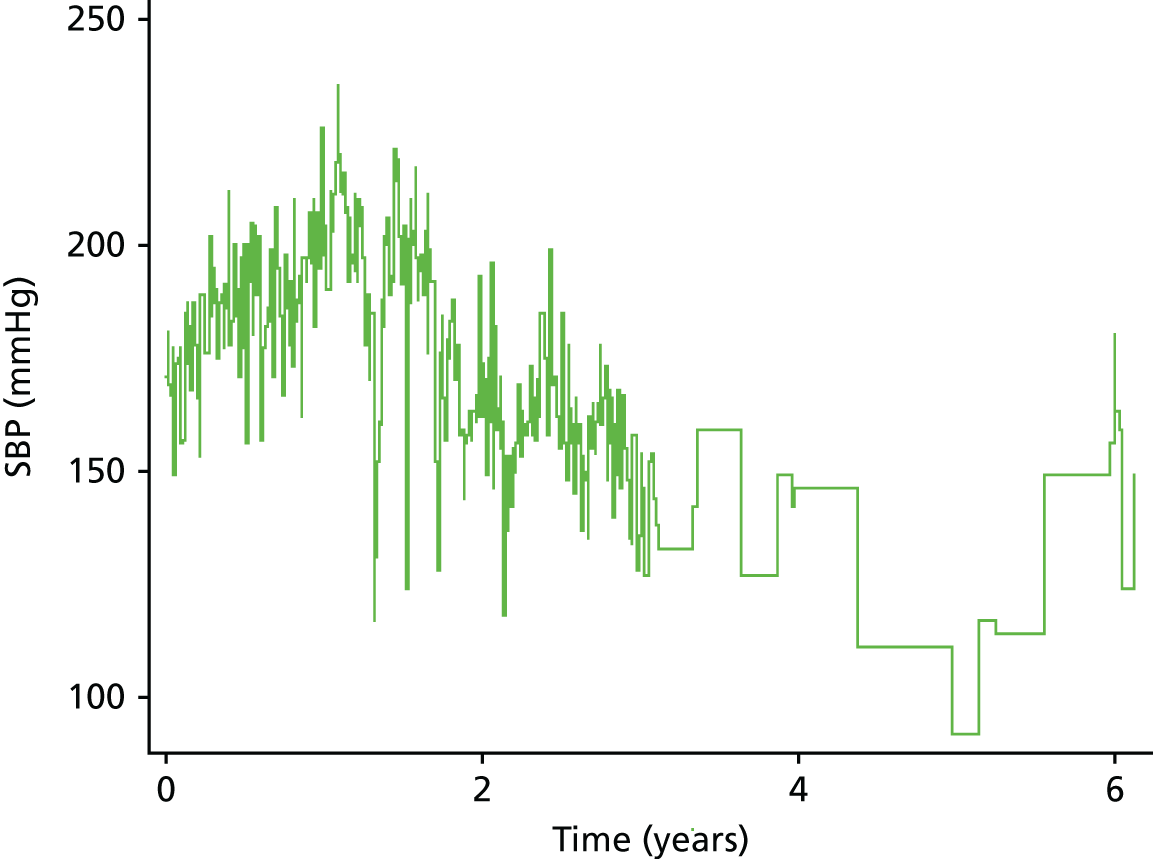

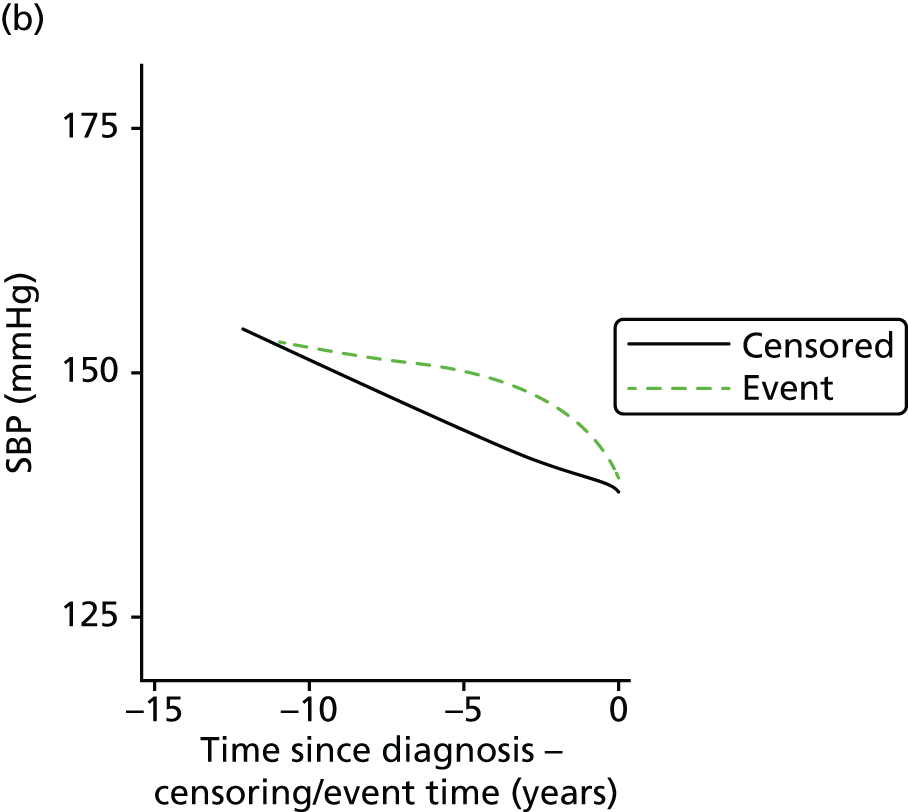

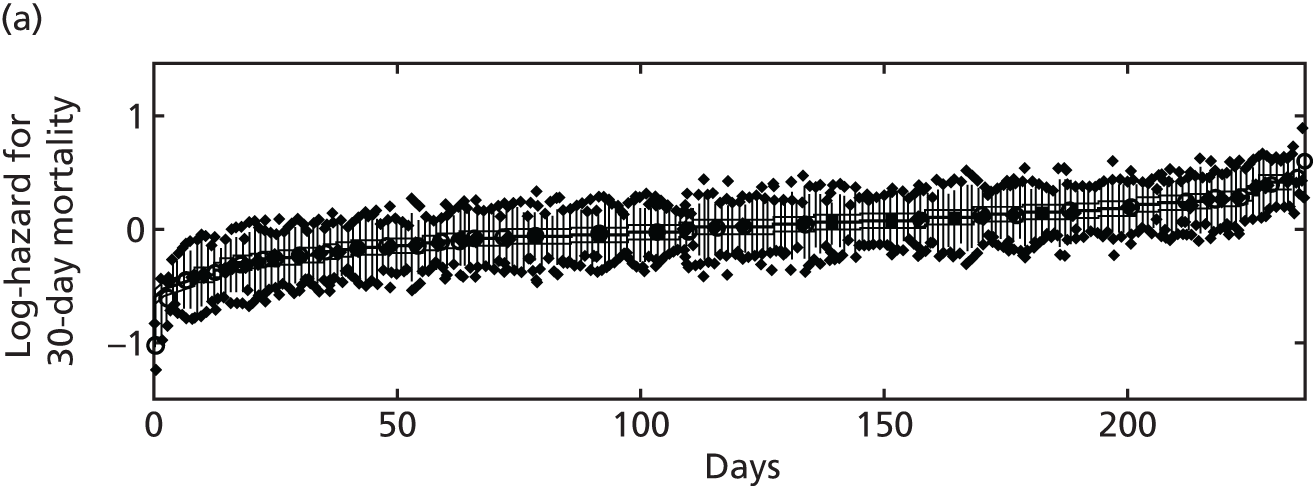

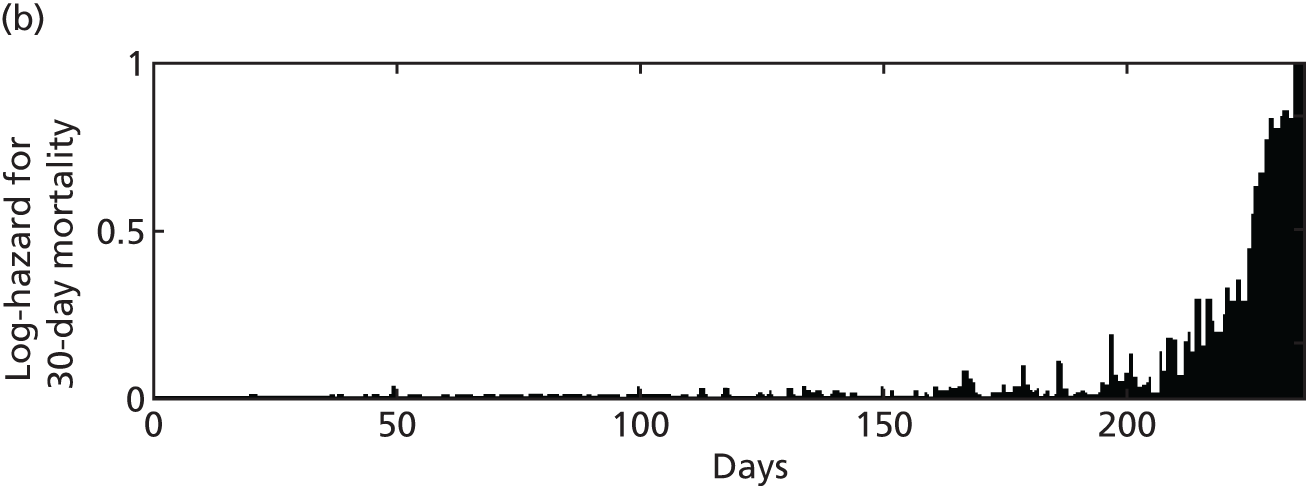

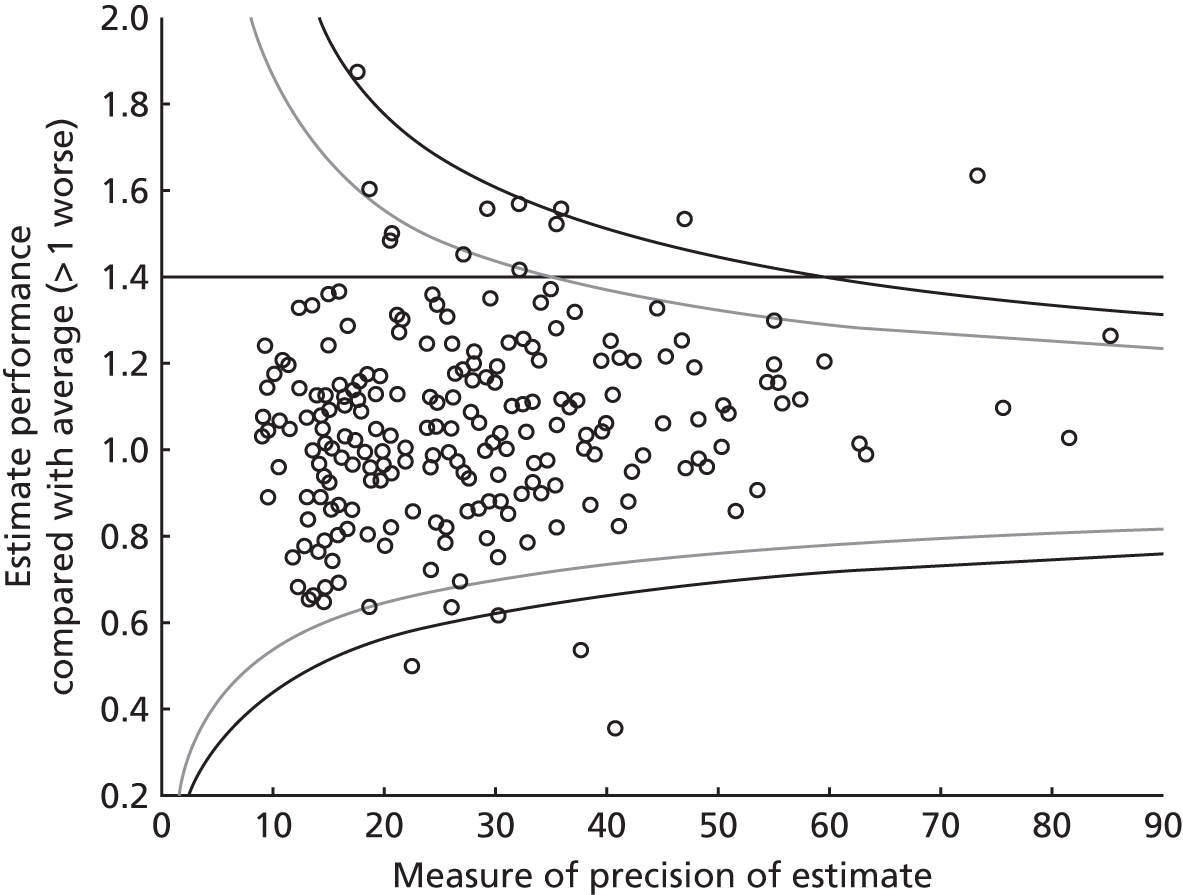

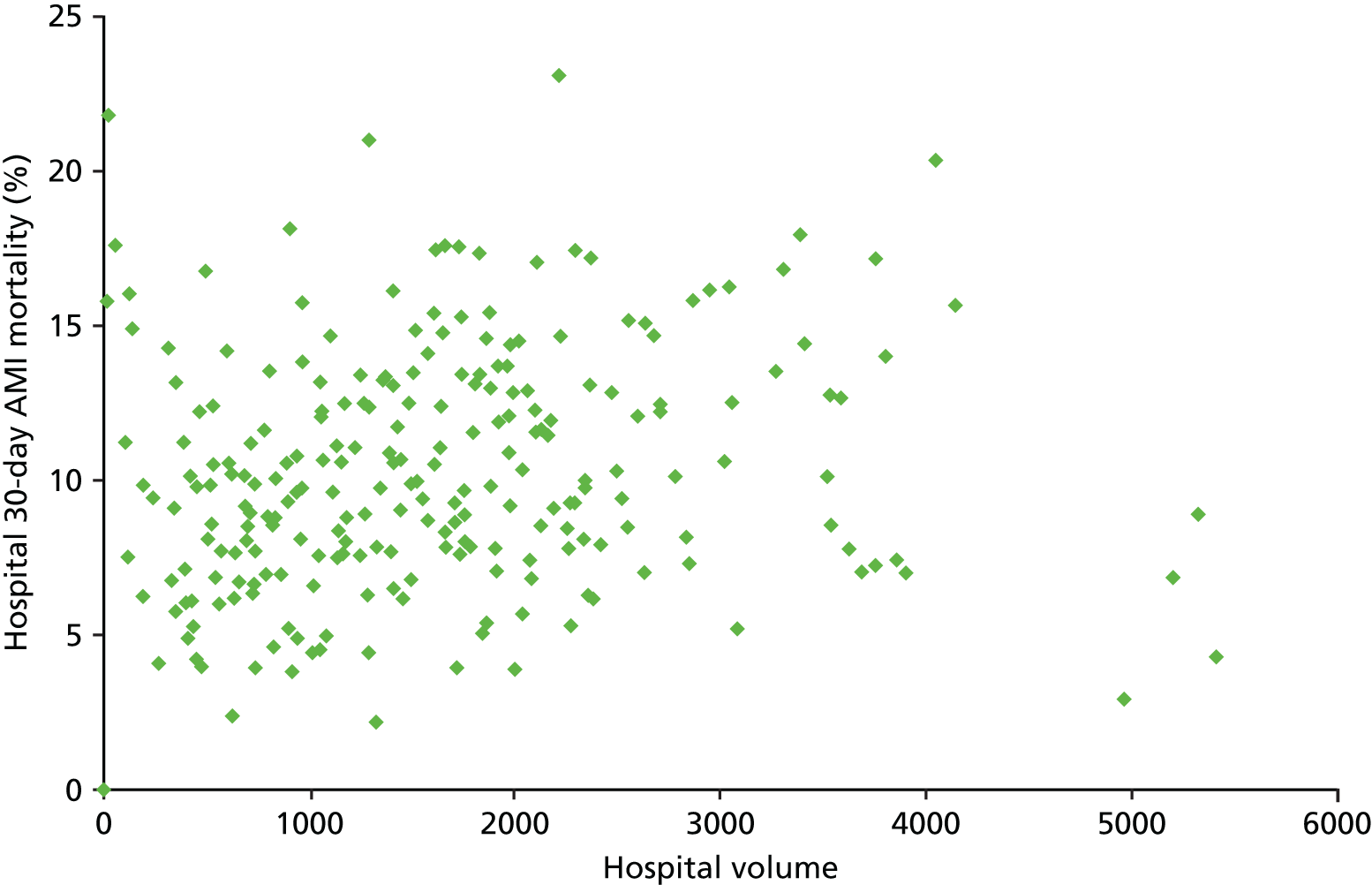

Statistical analysis