Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1083. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in February 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Bob Woods reports that Bangor University has received royalties from the sale of therapy manuals in the UK and the USA. Ian Russell reports that Swansea University has received funds from University College London for lectures and staff mentoring.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Orrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Dementia is very common in old age and the frequency of dementia increases with age, from around 5% in those aged > 65 years to around 20% in those aged > 85 years. 1,2 In the UK there are 850,000 people living with dementia3 which leads to progressive intellectual deterioration, increasing disability and social exclusion. 4 This has an enormous social and economic impact on health and social care services, and on family carers. There is little high-quality research on the effectiveness of psychological and social interventions, and there is an urgent need to find more useful interventions to help reduce the impact of dementia on people with dementia, carers and society. Drug treatments have an important role in dementia care, but in the UK they are limited to people with Alzheimer’s disease, with mild to moderately severe dementia, have a limited impact on the illness, are not suitable for all patients and cost approximately £1000 per year. 5 There is increasing recognition that psychological and social interventions may have comparable value6 and may be preferable (e.g. when medication may have intolerable side effects). 7

In the UK there is recognition that psychological therapies for older people should be more widely available, and the National Service Framework for Older People4 states that ‘treatment for dementia always involves using non-pharmacological management strategies such as mental stimulation’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). However, the delivery of such therapies has been generally unstandardised, and many evaluations of psychological treatments have been either small or of poor methodological quality, or both. A number of systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions are now available,8–10 as well as a number of Cochrane reviews on interventions with a cognitive focus. 11,12 Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) is an evidence-based approach which has been shown to be beneficial to cognitive function and quality of life, and also cost-effective. 6,13 Indeed, the recent draft National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on dementia14 recommend that all people with mild to moderate dementia should be ‘given the opportunity to participate in a structured group cognitive stimulation programme’.

In the UK, reminiscence work with people with dementia has an extensive history;15,16 it involves enjoyable activities that tap into early memories and encourage communication and well-being. However, its popularity has not led to a corresponding body of evidence on its effects. The Remembering Yesterday, Caring Today (RYCT) trial platform suggested that it was useful to involve family carers in reminiscence groups with people with dementia, and a recent meta-analysis of outcomes for family caregivers confirms that involving people with dementia and their carers together is more effective than working with carers only. 10 Over the last decade, the needs of carers have remained a high priority, with a national strategy published in 1999. 17 Being a family carer is stressful and a recent study showed that one in three carers had a mental illness. 18 The carers of people with dementia experience greater strain and distress than the carers of other older people. 19 The Expert Patients Programme for people with long-term conditions aims to increase their confidence, improve their quality of life and better manage their conditions. 20 In a 2006 White Paper21 the government pledged funding for the creation of an Expert Carer Programme, which would include training to develop carers’ skills in addition to self-care skills of people with dementia. The progressive decline and the changing nature of dementia over time mean that family carers’ needs will change. 22 There is an evidence base for cognitive–behavioural packages being the predominant approach for psychoeducation, stress and behaviour management, with principles and basic components that could be disseminated for use by non-therapists. For example, in caring for a person with dementia, sessions may include coping with the psychological and behavioural symptoms of dementia.

In the last few years there has also been an increasing emphasis on maintaining older people with dementia at home, rather than admitting them to hospital, to help to maintain their independence and quality of life. The document Everybody’s Business: Integrated Mental Health Services for Older Adults23 advised that community mental health teams (CMHTs) for older people needed to have some provision for 24-hour home-based crisis support, and Raising the Standard: Specialist Services for Older People with Mental Illness24 highlighted the need for alternatives to inpatient care. A 2005 review25 noted the lack of evidence for alternatives to acute psychiatric admissions for older people and another study from the same year indicated that home treatment teams (HTTs)/crisis teams are effective at reducing admissions for those aged < 65 years. 26 There are suggestions that this approach may also reduce admissions for those aged > 65 years with mental health problems,27,28 including people with dementia.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this research programme is to prevent excess disability, promote social inclusion, improve health outcomes and enhance the quality of life of people with dementia and their carers. The aim was achieved by a rigorous 5-year programme of psychosocial research building on our existing work in cognitive stimulation, reminiscence work and carer support, and also by a new initiative developing intensive home support to manage crises at home and prevent admission to hospital for people with dementia.

Cognitive stimulation therapy is an evidence-based approach which has been shown to be beneficial to cognitive function and quality of life, and also cost-effective. As the degree of cognitive benefit from CST is similar to that from cholinesterase inhibitors, longer-term CST may have an impact on long-term care.

Reminiscence work with people with dementia taps into early memories and encourages communication and well-being, and a recent meta-analysis indicated that involving people with dementia and their carers is more effective than working with carers only. Our trial platform successfully developed a manual for joint reminiscence, RYCT, and suggests that RYCT improves the caring relationship and benefits both people with dementia and carers. Our experience from the Befriending and Costs of Caring (BECCA) programme29 showed that many ex-carers are motivated to support others at an earlier stage in their role as a family carer, through mentoring and teaching.

There is some evidence that HTTs may reduce admissions for people with dementia; however, better evidence for their effectiveness is required before wider implementation is considered.

This research programme provides essential evidence to clarify the role of each of these interventions in helping to support people at home, reducing hospital and care home admissions, and improving the quality of life of people with dementia and their carers.

The three projects are (1) cognitive stimulation groups for people with dementia to improve their cognition and quality of life, (2) a new initiative called the Expert Carer Programme, which trains ex-carers to help new carers of people with dementia and was undertaken alongside reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their carers which help to maintain quality of life and improve their relationships, and (3) the development of intensive home support to help manage crises at home and prevent admission to hospital for people with dementia.

Each of the three projects completed a number of components of the pathway through development of theory, modelling, feasibility and evaluation to dissemination and implementation, as illustrated in the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for complex interventions. 30

All of these approaches were carefully evaluated to look at their potential benefits to people with dementia and their carers. We have also produced training manuals which will be made widely available to help other services implement the same approaches.

Objectives

-

To develop a model to identify the most promising interventions and components for an effective home treatment package (HTP) for dementia.

-

To carry out systematic reviews in the areas of home treatment for dementia and to update the Cochrane review on reality orientation/CST for dementia.

-

To develop a HTP for dementia and a package for carer supporters.

-

To carry out a pilot study for (a) the reminiscence and carer programmes separately and in combination, and (b) the effectiveness of maintenance CST (MCST) with donepezil.

-

To provide definitive randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for MCST, RYCT and the Carer Supporter Programme (CSP).

-

To conduct in-depth field testing of the HTP for dementia.

-

To conduct a post-RCT surveillance study of MCST in practice, including minimal outcome measures and qualitative approaches.

-

To provide economic evaluations for the MCST and CSP/RYCT interventions.

-

To involve users, carers and the voluntary sector, and to develop a model of user/carer involvement that can be widely used.

-

To develop training and manuals for all three interventions.

-

To disseminate service models, training programmes, tools and outcomes.

This report outlines the work undertaken for each project and individual aims and objectives for each study are given in their respective chapters. The development of the interventions focuses on the involvement of service users and key stakeholders.

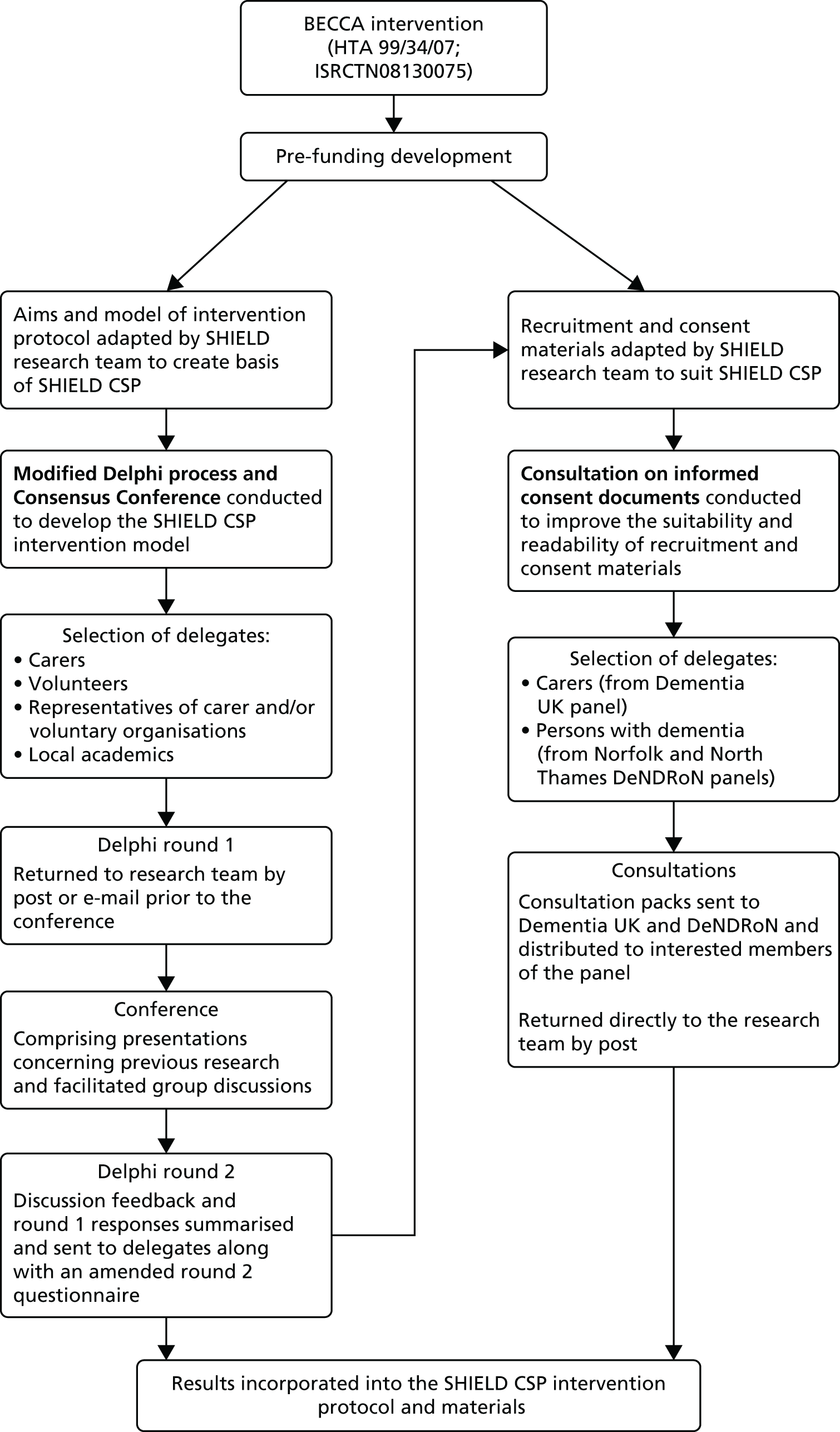

User and carer involvement

User and carer involvement is now central to research and development (R&D) strategy in health and social care nationally, and their involvement is required as a condition of funding. 31 User involvement and collaboration has been found to improve the quality, depth and utility of research. 32,33 We developed a strategy for user and carer involvement as part of the SHIELD (Support At Home – Interventions to Enhance Life in Dementia) research programme. 34 The strategy encompassed principles of good involvement practice (i.e. clarity and transparency, respect, diversity, flexibility and accessibility) and meaningful involvement. 35 Service users and carers were involved in consensus workshops, focus groups and consultation processes for developing interventions to ensure their relevance and acceptability. User involvement can help develop more theoretically coherent and evidence-based interventions, which are more likely to be practical, generalisable and meaningful for potential users. 36 Carers were also involved in the recruitment of staff and provision of training and as part of the SHIELD research programme steering and monitoring committees.

Ethics arrangements and research governance for the SHIELD research programme

All projects obtained ethics approval from a NHS Research Ethics Committee and local R&D approvals for all sites involved in the research. Amendments to protocols were made and approvals were sought from ethics committees as needed throughout the research programme. The trial was sponsored by University College London and North East London Foundation Trust (NELFT). Our Programme Steering Committee consisted of an independent chairperson and external committee members comprised interested clinicians, academics, voluntary sector staff and service users, as well as the grantholders and key individuals from the research programme (see Acknowledgements). 37 A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee was created as a subcommittee of the Programme Steering Committee. This group consisted of an independent academic as chairperson, an independent statistician and a family carer37 (see Acknowledgements).

Consent

Informed consent was sought whenever appropriate. Participants were at various stages of dementia ranging from mild to moderate, to severe. Some participants were competent to give informed consent for participation, provided that appropriate care was taken in explaining the research and sufficient time was allowed for them to reach a decision. However, those people with more advanced dementia were also included and, in these situations, the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act were followed. 38,39 It was helpful for a family member or other supporter to be involved, and we aimed to ensure that this was done whenever possible. It was made clear to all that no disadvantage would accrue if they chose not to participate. In seeking consent, we followed current guidance from the British Psychological Society40 on the evaluation of capacity; thus, consent was regarded as a continuing process rather than a definitive, and willingness to participate was continually checked through discussion with participants during the assessments. When a participant’s level of impairment was more severe or increased so that they were no longer able to provide informed consent, the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act were followed. 38,39 The initial giving of informed consent provided a clear indication of the person’s likely perspective on continuing at this point, and the family caregiver was consulted in this regard. If a participant with dementia became distressed during the assessments, the assessments were discontinued.

Adverse events

Prospective participants were fully informed of the potential risks and benefits of the projects they were recruited to. A reporting procedure was in place to ensure that serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported to the chief investigator (MO). 41 On becoming aware of an adverse event involving a participant or carer, the research programme co-ordinator (JH) assessed its seriousness. A SAE was defined in the trial as an untoward occurrence experienced by either a participant or a carer which resulted in death; was life-threatening; required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation; resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator; or was within the scope of the Protection of Vulnerable Adults protocol. 41 A reporting form was submitted to the chief investigator, who assessed whether or not the SAE was related to the conduct of the trial and was unexpected. If SAEs were judged to be related and unexpected, they were reported to the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and the trial Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.

Changes from the planned protocol

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funding for SHIELD was received in August 2007 and the research programme commenced in February 2008. The original scope of the programme was to undertake four trials examining the effectiveness of MCST programmes, the implementation of MCST in practice, RYCT and the CSP, and a HTP for dementia. Time and budgetary constraints meant that we were advised by the NIHR review team not to complete a trial of the home treatment intervention. This will now be tested in a further NIHR-funded trial. All studies followed the MRC guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions. 30

Chapter 2 Maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy

Background

Cognitive ‘training’, cognitive ‘stimulation’ and cognitive ‘rehabilitation’ have on occasion been used almost interchangeably, but Clare and Woods42 have proposed clear definitions for all of these terms. Cognitive stimulation has been defined as the engagement in a range of activities and discussions (usually in a group) aimed at the general enhancement of cognitive and social functioning. 42 CST6 is a therapeutic non-pharmacological treatment for dementia that aims to optimise cognitive function based on the notion of cerebral plasticity. A large multicentre RCT of CST found that it improved cognition and quality of life,6 and was cost-effective. 13 Indeed, the 2007 draft NICE/Social Care Institute for Excellence guideline on dementia14 recommended that all people with mild-to-moderate dementia should have the opportunity to take part in a structured programme of cognitive stimulation groups.

As CST is only a brief intervention (a 14-session programme over 7 weeks), it is necessary to investigate if its benefits can be extended over a longer period of time. This has been investigated as a pilot study43 in which the 16 additional weekly sessions led to a significant improvement in cognitive function for those receiving MCST, compared with those receiving CST only. The programme grant funded a full-scale trial of MCST over 24 weeks.

The MSCT programme included an update of the Cochrane review on reality orientation/cognitive stimulation, explored the long-term effects of a MCST programme versus CST for dementia and compared the effectiveness of two different training approaches with care staff from a range of dementia care settings. The cognitive stimulation groups for people with dementia aimed to improve cognition and quality of life. The training package comprises a workbook, a digital versatile disc (DVD) and training seminars.

Work package 1: update of the Cochrane review on cognitive stimulation therapy

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness and impact of cognitive stimulation in dementia

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness and impact of cognitive stimulation in dementia was conducted with the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG), based in Oxford, UK. 44 The review followed the Specialised Register of the CDCIG, called ALOIS (Action in Language, Organisations and Information Systems). This yielded 94 studies, of which 15 were RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria. The analysis included 718 participants (407 receiving cognitive stimulation and 311 in control groups).

Objectives

-

To evaluate the effectiveness and impact of cognitive stimulation interventions aimed at improving cognition for people with dementia, including any negative effects.

-

To indicate the nature and quality of the evidence available on this topic.

-

To assist in establishing the appropriateness of offering cognitive stimulation interventions to people with dementia and identifying the factors associated with their efficacy.

Review methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol was registered with The Cochrane Library and can be found online at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub2/pdf.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

We selected RCTs examining the effect of cognitive stimulation for dementia if they had been published and written in English, peer reviewed and presented in a journal article. Authors were contacted for missing data, such as details of randomisation, means and standard deviations (SDs).

Search methods for identification of studies

The search methods included a combination of the search terms cognitive stimulation, reality orientation, memory therapy, memory groups, memory support, memory stimulation, global stimulation and cognitive psychostimulation, which were used to search ALOIS on 6 December 2011. The studies were identified from the following databases:

-

health-care databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS)

-

trial registers: metaRegister of Controlled Trials, Umin (University Hospital Medical Information Network) Japan Trial Register and World Health Organization portal [which covers ClinicalTrials.gov, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN), Chinese Clinical Trials Register, German Clinical Trials Register, Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others]

-

The Cochrane Library’s Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

a number of grey literature sources: ISI Web of Knowledge Conference Proceedings, Index to Theses, Australasian Digital Theses.

Additional searches in each of the sources listed above to cover the time frame from the last searches performed for the Specialised Register to December 2011 were run to ensure that the search for the review was as up to date as possible. A total of 670 references were retrieved from the December 2011 update search. After deduplication and a first assessment, authors were left with 94 references to further assess for inclusion, exclusion or discarding.

Participants

Participants were any age with a diagnosis of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia or mixed Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, other types of dementia), including all severity levels of dementia, indicated through group mean scores, range of scores or individual scores on a standardised scale, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)45 or Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). 46 The participants could receive the intervention in a variety of settings (own home, outpatient setting, day care setting or residential setting). We documented when participants were receiving concurrent treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs).

Interventions

Participants attended regular therapy sessions (involving a group or family caregiver) for a minimum period of 4 weeks. The intervention needed to describe a cognitive stimulation intervention targeting cognitive and social functioning, offering generalised cognitive practice. These may also be described as reality orientation groups, sessions or classes. The intervention needed to be compared with ‘no treatment’, ‘standard treatment’ or placebo.

Outcome measures

These assessed the short- (immediately after the intervention) and medium-term (follow-up 1 month to 1 year after the intervention finished) impact on the intervention on the person with dementia, the family caregiver or both. For the person with dementia, outcome measures needed to evaluate performance on at least one cognitive measure and/or include the assessment of any of the following variables: mood, well-being, activities of daily living (ADLs), behaviour, neuropsychiatric symptoms and social engagement. Rates of attrition and reasons for withdrawal were noted. Family caregiver outcomes, such as self-reported well-being, depression and anxiety, burden, strain and coping, and satisfaction with the intervention, were considered.

Data collection and analysis

Searches were conducted as detailed above to identify all relevant published studies. The date and time of each search, together with details of the version of the database used, were recorded. Additional information was sought, as outlined above, and hard copies of articles were obtained.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently screened the identified RCTs for inclusion and the final list of included studies was reached by consensus. Trials not meeting the criteria were excluded. The studies were assessed against a checklist of quality requirements using the Cochrane approach:

-

grade A – ‘low risk’: adequate concealment (randomisation; concealed allocation)

-

grade B – ‘unclear risk’: ‘randomised’, but methods uncertain

-

grade C – ‘high risk’: inadequate concealment of allocation or no randomisation, or both.

Only trials with a grade A or B ranking were included in the review. Again, the reviewers worked independently to ascertain which studies met the quality criteria, and consensus was reached through discussion. Attempts were made to obtain additional information from the study authors when needed.

Data extraction

Descriptive characteristics (such as quality of randomisation and blinding) and study results were extracted, recorded and entered into RevMan 5.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Additionally, letters and e-mails were sent to some authors of controlled trials asking for essential and additional information (statistics, sources of bias and details of randomisation). The summary statistics required for each trial and each outcome for continuous data were the mean change from baseline, the standard error (SE) of the mean change and the number of patients for each treatment group at each assessment. When changes from baseline were not reported, we extracted the mean, SD and number of patients for each treatment group at each time point, if available. We calculated the required summary statistics from the baseline and assessment time treatment group means and SDs, assuming in this case a zero correlation between the measurements at baseline and assessment time. This conservative approach was chosen, as it is preferable in a meta-analysis. For binary data, the numbers in each treatment group and the numbers experiencing the outcome of interest were sought. The baseline assessment was defined as the latest available assessment prior to randomisation, but no longer than 2 months prior. For each outcome measure, data were sought on every patient randomised. To allow an intention-to-treat analysis, the data were sought irrespective of compliance, or whether or not the patient was subsequently deemed ineligible or otherwise excluded from treatment or follow-up. Discussion between the two reviewers and the other authors was used to resolve any queries.

Data analyses

RevMan 5.1 was used for the meta-analysis. Analyses were adjusted to the random-effects model, owing to the heterogeneity of trials. Because trials used different tests to measure the same outcomes, the measure of the treatment difference for any outcome that we used was the weighted mean difference when the pooled trials used the same rating scale or test, and the standardised mean difference (SMD) (the absolute mean difference divided by the SD) when different rating scales or tests were used. For binary outcomes, such as clinical improvement or no clinical improvement, the odds ratio was used to measure treatment effect. A weighted estimate of the typical treatment effect across trials was calculated. Overall estimates of the treatment difference were employed, presenting the overall estimate from a fixed-effects model and performing a test for heterogeneity using a standard chi-squared statistic. The reviewers achieved consensus on the interpretation of the statistical analyses, seeking specialist statistical advice from the CDCIG as required. Non-randomised studies were described in tabular form and the reviewers discussed and reached consensus on the presentation of the findings in the background to the review.

Results

Studies included in the review

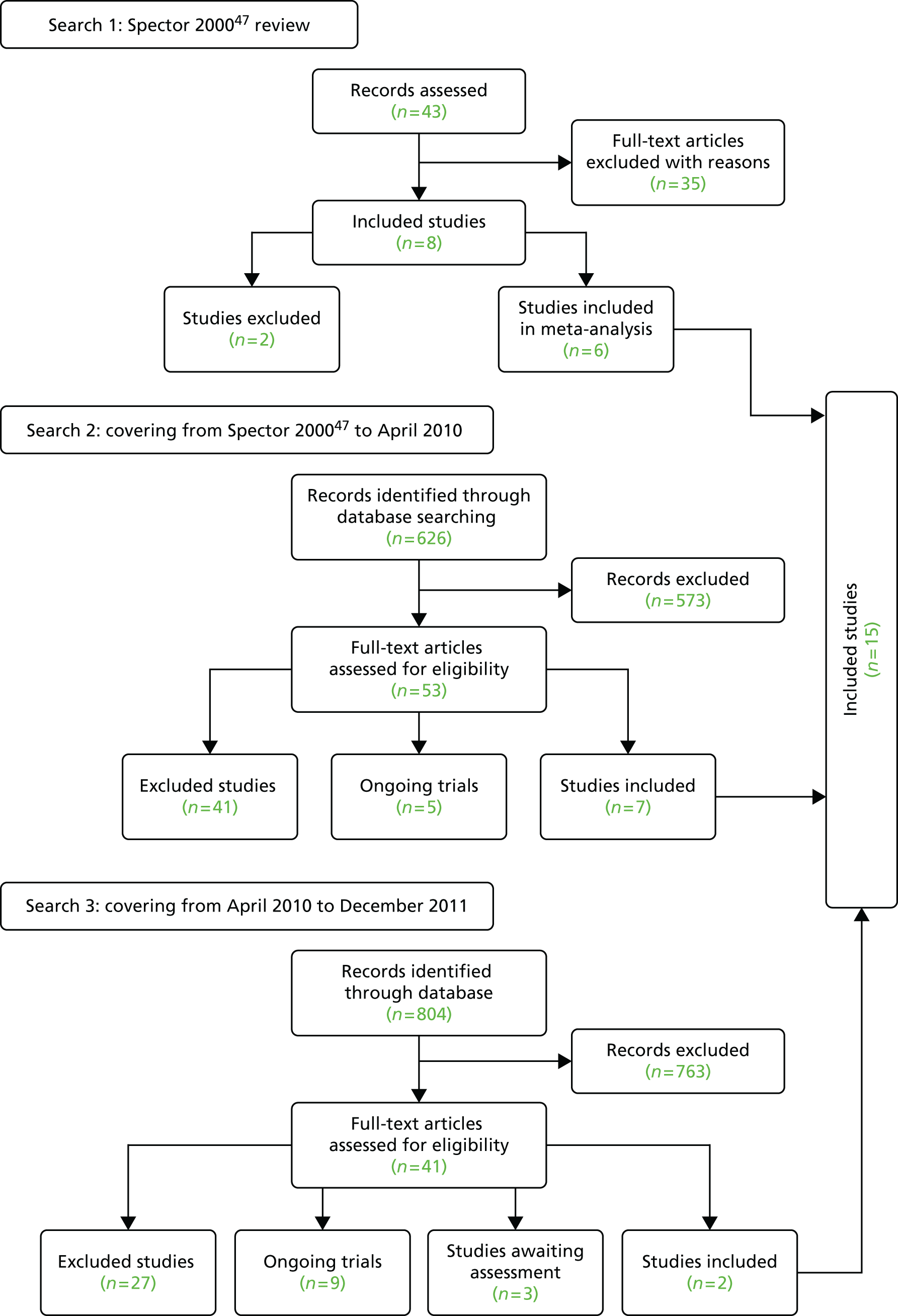

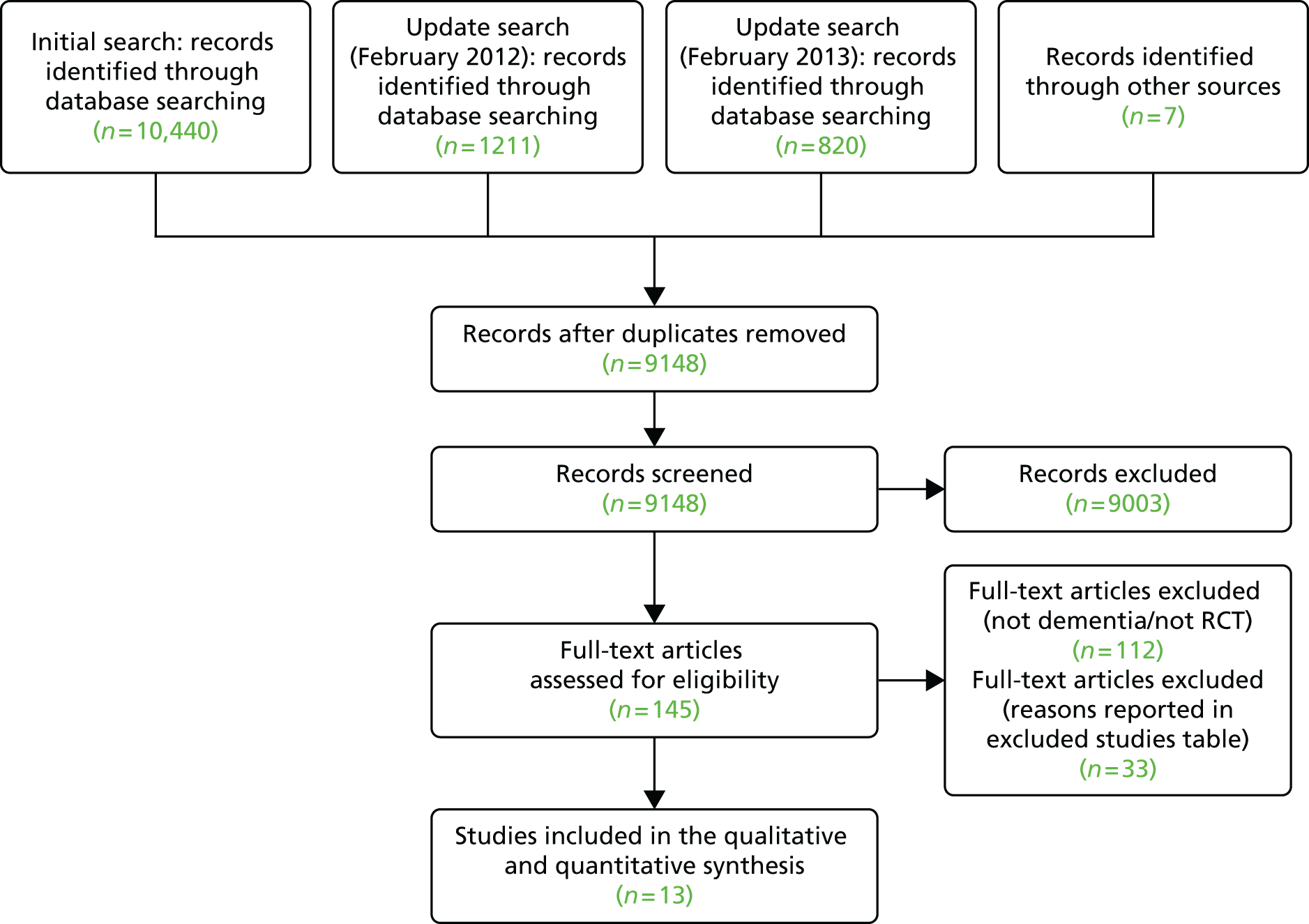

Ninety-four studies were identified since the last review through the literature search. 47 Two reviewers independently assessed eligibility. Of the 94 references, nine studies met the inclusion criteria48–55 and were included in the analysis. Three recent studies were left awaiting classification. 56–58 Our previous review47 included eight studies in the meta-analysis and six of these met the criteria for inclusion in this updated review. 59–64 Two studies from our previous review were excluded this time, as the data needed for the meta analysis were not available. 65,66 Therefore, a total of 15 studies was included in the analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart of the review and selection process of studies.

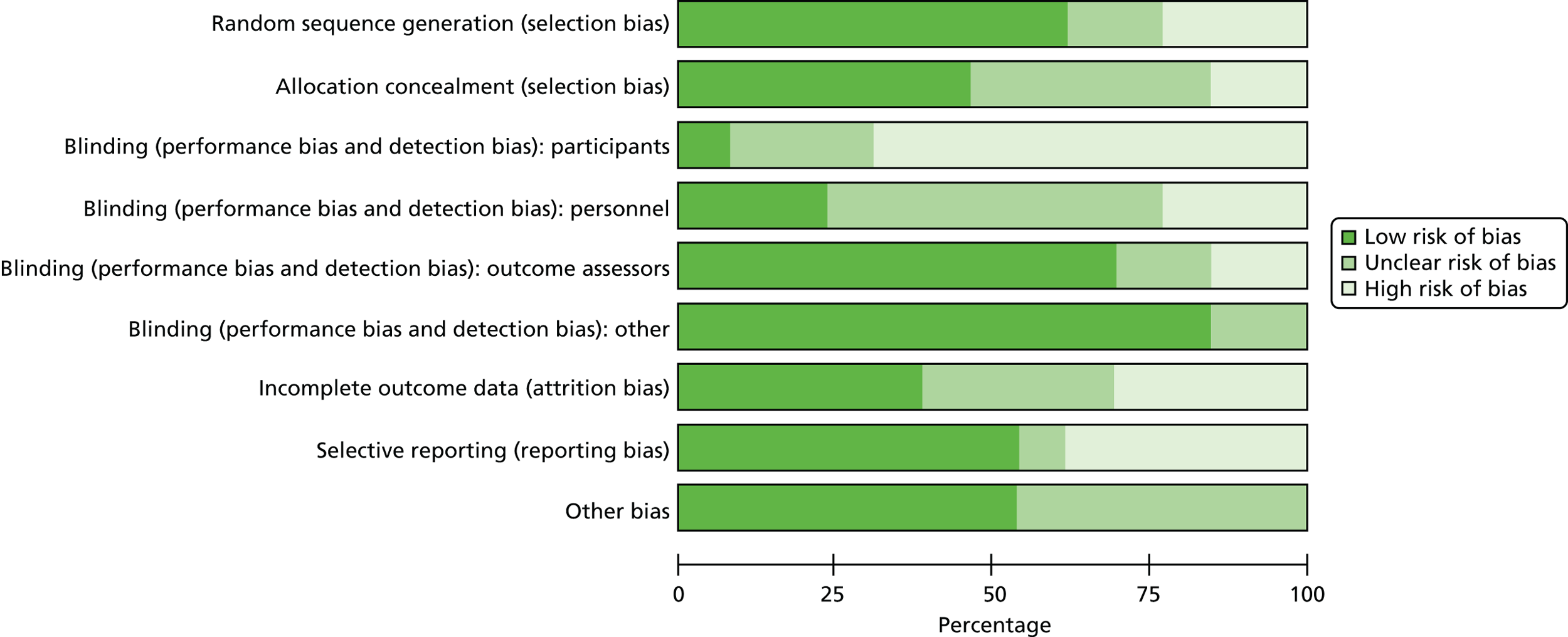

Quality of included studies

The quality of each study was assessed according to the four criteria outlined in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook:67 selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias and detection bias. The details of biases and descriptions of studies can be seen in Table 1. Performance bias was difficult to evaluate. With psychological interventions, unlike drug trials, it is impossible to totally blind patients and staff to treatment. Patients are often aware that they are being treated preferentially, staff involved may have different expectations of treatment groups and independent assessors may be given clues from patients during the assessments. There may also be ‘contamination’ between groups, in terms of groups not being held in separate rooms and staff bringing ideas from one group to another.

| Study ID | Intervention | Content of therapy | Alternative activity | Allocation concealment | Attrition bias (dropouts) | Detection bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baines et al.,59 1987 | 30 minutes, five times per week for 4 weeks | RO board, multisensory stimulation | Reminiscence therapy/no treatment | No details | 0/15 dropouts | Assessment by independent psychologist and staff not involved in therapy No details of assessors |

| Baldelli et al.,60 1993 | 60 minutes, three times per week for 3 months | No details | No treatment (TAU) | No details | 0/23 | No details of assessors |

| Baldelli et al.,48 2002 | 60 minutes, five times per week for 1 month | No details | Physical therapy programme | No details | 0/87 | No details of assessors |

| Bottino et al.,49 2005 | 90 minutes, once per week for 5 months | Temporal and spatial orientation, discussion of interesting themes, reminiscence activities, naming people, daily activities, planning use of calendars and clocks | AChEIs only | Randomised blocks design | 0/13 | Assessment by a blind and independent assessor |

| Breuil et al.,61 1994 | 60 minutes, twice per week for 5 weeks | Drawing, associated words, object naming, categorising objects | No treatment | No details | 5/61 dropouts | Assessment by a psychologist unaware of group allocation |

| Buschert et al.,50 2011 | 120 minutes, once per week for 6 months | Multicomponent cognitive group intervention: for Alzheimer’s disease group emphasis on cognitive stimulation (for mild cognitive impairment group more emphasis on cognitive training) | Pencil-and-paper exercises for self-study and monthly meetings | Blocked randomisation procedure | No attrition n = 35 | Cognitive assessments made by an assessor blind to group allocation |

| Chapman et al.,51 2004 | 90 minutes, once per week for 8 weeks | Current events; discussion of hobbies and activities; education regarding Alzheimer’s disease; life story work; links with daily life encouraged | AChEIs only | SAS procedure | 6/54 | Assessment by a psychologist unaware of group allocation |

| Coen et al.,52 2011 | 45 minutes, twice per week for 7 weeks | Cognitive stimulation | No treatment | Computerised randomisation and random number tables were used | No attrition n = 27 | Tests administered by staff blind to group membership. Not clear if staff ratings were made by staff who were blinded |

| Ferrario et al.,62 1991 | 60 minutes, five times per week for 21 weeks | No details | No treatment | No details | 2/21 dropouts | No details of assessors |

| Onder et al.,53 2005 | 30 minutes, three times per week for 25 weeks | Current information, topics of general interest, historical events and famous people, attention, memory and visuospatial | AChEIs only | Computerised block randomisation procedure | 19/156 | Assessment by a psychologist unaware of group allocation |

| Requena et al.,54 2006 | 45 minutes, five times per week for 24 months | Orientation, body awareness, family and society, caring for oneself, reminiscing, household tips, animals, people and objects | AChEIs only No treatment |

Registration order procedure | 10/50 | Assessment by a psychologist unaware of group allocation |

| Spector et al.,55 2001 | 45 minutes, two/three times per week for 7 weeks | Orientation, categorising objects, sounds, number, physical and word games, current events | No treatment | Drawing names from a sealed container | 8/35 | Assessment by a researcher blinded to group allocation |

| Spector et al.,47 2000 | 45 minutes, twice per week for 7 weeks (14 sessions) | Orientation, categorising objects, sounds, number, physical and word games, current events | No treatment | Drawing names from a sealed container | 34/201 | Assessment by a researcher blinded to group allocation |

| Wallis et al.,63 1983 | 30 minutes, five times per week for 3 months | Repetition of orientation information (e.g. time, place, weather), charts, pictures, touching objects and material | Diversional occupational therapy (group and individual activities) | Drawing from a hat, consecutive allocation | 22/60 dropouts | Assessment by a senior nurse or occupational therapist unaware of group allocation |

| Woods, 197964 | 30 minutes, five times per week for 20 weeks | Daily personal diary, group activities (dominoes, spelling, bingo), naming objects, reading RO board | ‘Social therapy’ (various group activities) | Drawing from a hat | 4/18 dropouts | Mixture: some assessments blind, some others not |

The latter effect would be reduced with clear therapeutic protocols, the existence of which was not mentioned in any of the studies, although during a face-to-face meeting with Professor Woods he stated that ‘Checks were made to ensure compliance with the therapeutic protocol’ (Bangor University, 2008, personal communication).

In relation to contamination, Wallis et al. 63 and Baines et al. 59 both stated that staff were unaware of the allocation of patients to groups, as they were removed from the setting for treatment, and several other studies described the groups being run in a separate or specific room. 6,55,62,64 Most studies took steps to ensure that at least part of the assessment of outcomes was carried out by assessors blinded to treatment allocation. Only three studies48,60,62 did not report the blinding of assessors. Of course, even independent assessors may be given clues from participants during the assessments, but this was not reported as an issue in the studies reviewed here. Using independent assessors works well for evaluating change in cognition or self-reported mood, well-being and quality of life. Ratings of day-to-day behaviour and function are typically carried out by care staff, who may be more difficult to keep blind to group allocation, unless the group sessions are carried out in a separate location to which all participants are taken. Whether or not the patients were blind to treatment is a controversial issue, depending on how much information was given to them and their level of comprehension.

Several studies reported48,62–64 that the reality orientation groups were held in separate areas, reducing the chance of contamination. Spector et al. 6,55 said that the groups were run in a separate and specific room for the programme. The other studies did not provide information regarding where groups were held. 49,51,53

All of the studies reported on attrition to the programme, although the intention-to-treat analysis plan was described in only two. 6,51 Given the nature of the condition and the age of the participants, attrition in several studies was remarkably small, with zero attrition recorded in six studies48–50,52,59,60 out of 180 participants. The largest attrition rate was reported in the study by Wallis et al. ,63 in which there was 39% attrition in the group of participants with dementia. In this study, patients who attended < 20% of the group sessions were eliminated from the study. Requena et al. 54 reported 32% attrition, but this was over a 2-year period. The two largest studies had rates of 19%59 and 17%6 over periods of 6 and 2 months, respectively.

Detailed treatment protocols were hard to find from the authors of the included studies, so the extent to which the cognitive stimulation was delivered as intended could be questioned. Some recent studies described that staff received training and/or supervision in running the groups. Chapman et al. 51 described weekly meetings held to ensure that their treatment programme was implemented as designed:

Sub-groups were led by a licensed speech-language pathologist and three masters level speech-language pathology students; all underwent two hour training before the groups started; weekly meetings to ensure the programme was implemented as designed.

Onder et al. 53 described how family caregivers were trained by a multidisciplinary team and given a manual and specific schedule for each session. No records were made, however, of how often caregivers delivered the sessions or how closely the manual was followed. The only available data from an early study came from Professor Woods, who stated during a face-to-face meeting that ‘A sample of sessions were tape-recorded and rated to ensure compliance with the therapeutic protocol’ (Bangor University, 2008, personal communication).

Meta-analysis

Data from the included studies were entered into ‘Metaview’ (the Cochrane term for meta-analysis). Data were identified, included and pooled from the 15 included RCTs,6,48–55,59–64 with a total of 718 participants (407 in experimental groups and 311 in control groups). Analyses were adjusted to the random-effects model, owing to the heterogeneity of trials, and SMDs, because trials used different measures to assess the same outcomes.

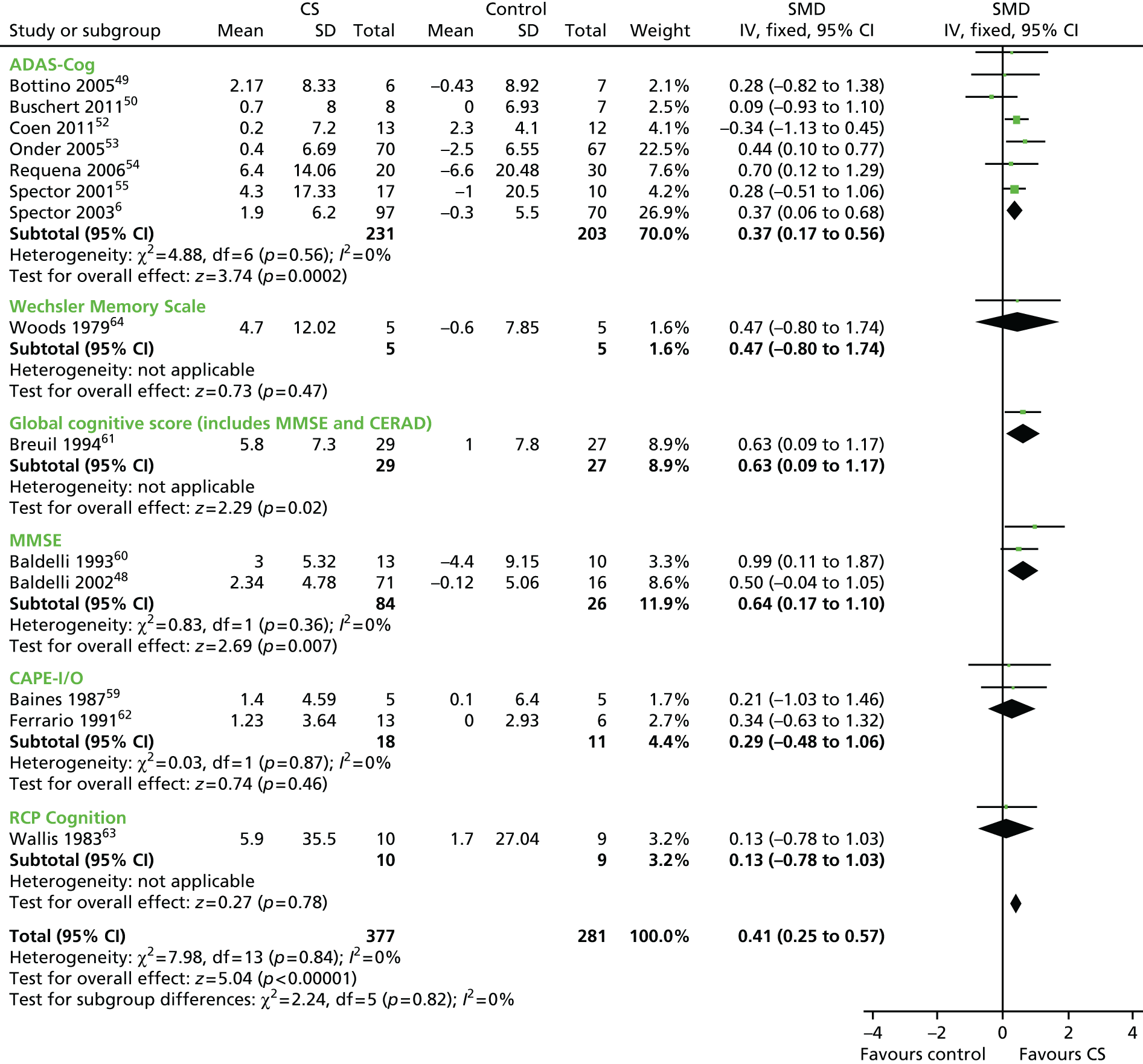

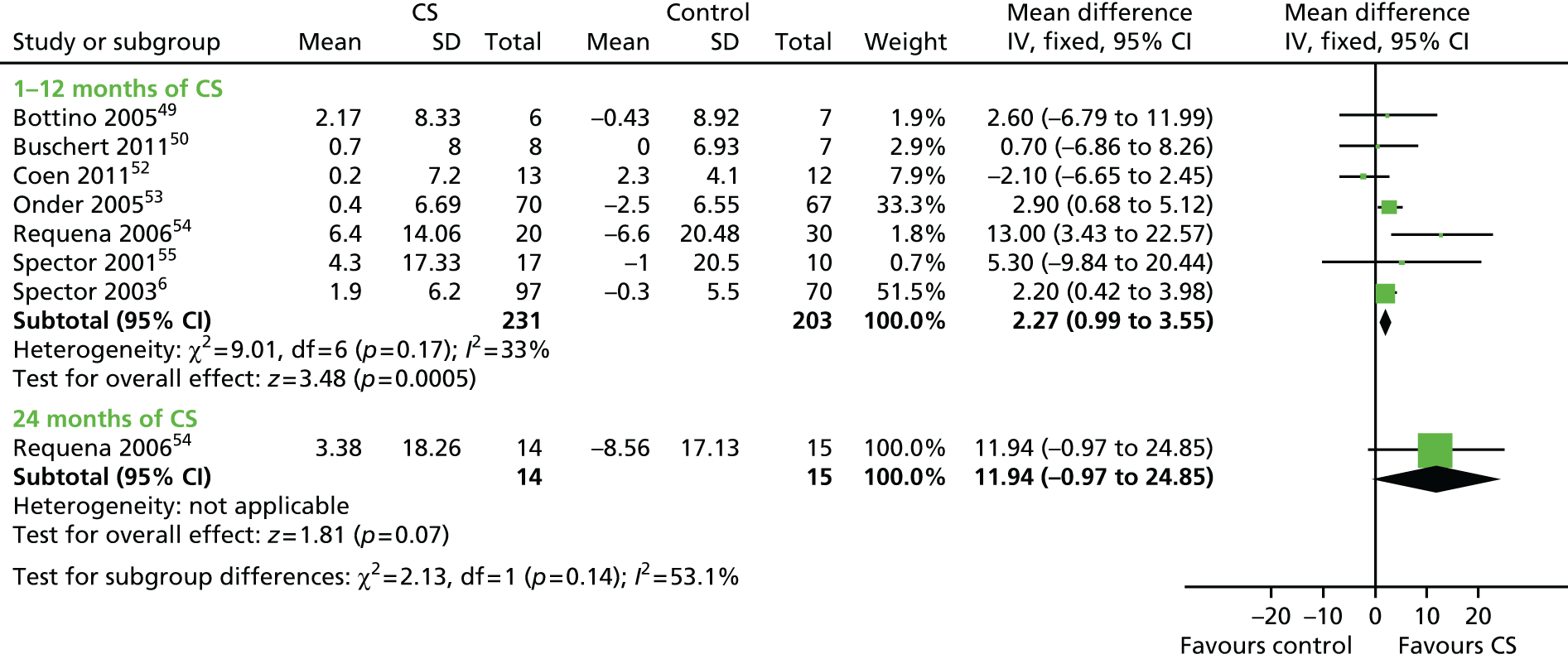

In order to evaluate the effect of cognitive stimulation on cognitive function, 14 RCTs that included useable data were included in the analysis (n = 658; 377 received treatment and 281 received no treatment or placebo). In comparison with the control groups at the post-treatment assessment, cognitive stimulation was associated with significant improvements on all measures of cognition. The overall results in the cognitive section were significantly in favour of treatment (Figure 2). The overall effect size (SMD) was 0.41 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25 to 0.57]. The results were strongly weighted by Breuil et al. 61 (n = 61), Onder et al. 53 (n = 137) and Spector et al. 6 (n = 201), the largest studies. The largest effect sizes can be seen at the 12-month point in Requena’s et al. 54 study [SMD 0.70 on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog)] and the Baldelli et al. 60 study (SMD 0.99 on the MMSE), both of which offered above-average duration of exposure to cognitive stimulation. Other studies with longer exposure62 had below-average effect size and other studies which offer only 10 hours of exposure had above-average effect size (0.63), showing that these effects require replication, as the CIs are broad and cross zero.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: outcome – cognition. ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Co-Operative Study–Cognitive Subscale; CAPE I/O, Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly – Information/Orientation scale; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; CI, confidence interval; CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; RCP, Royal College of Physicians.

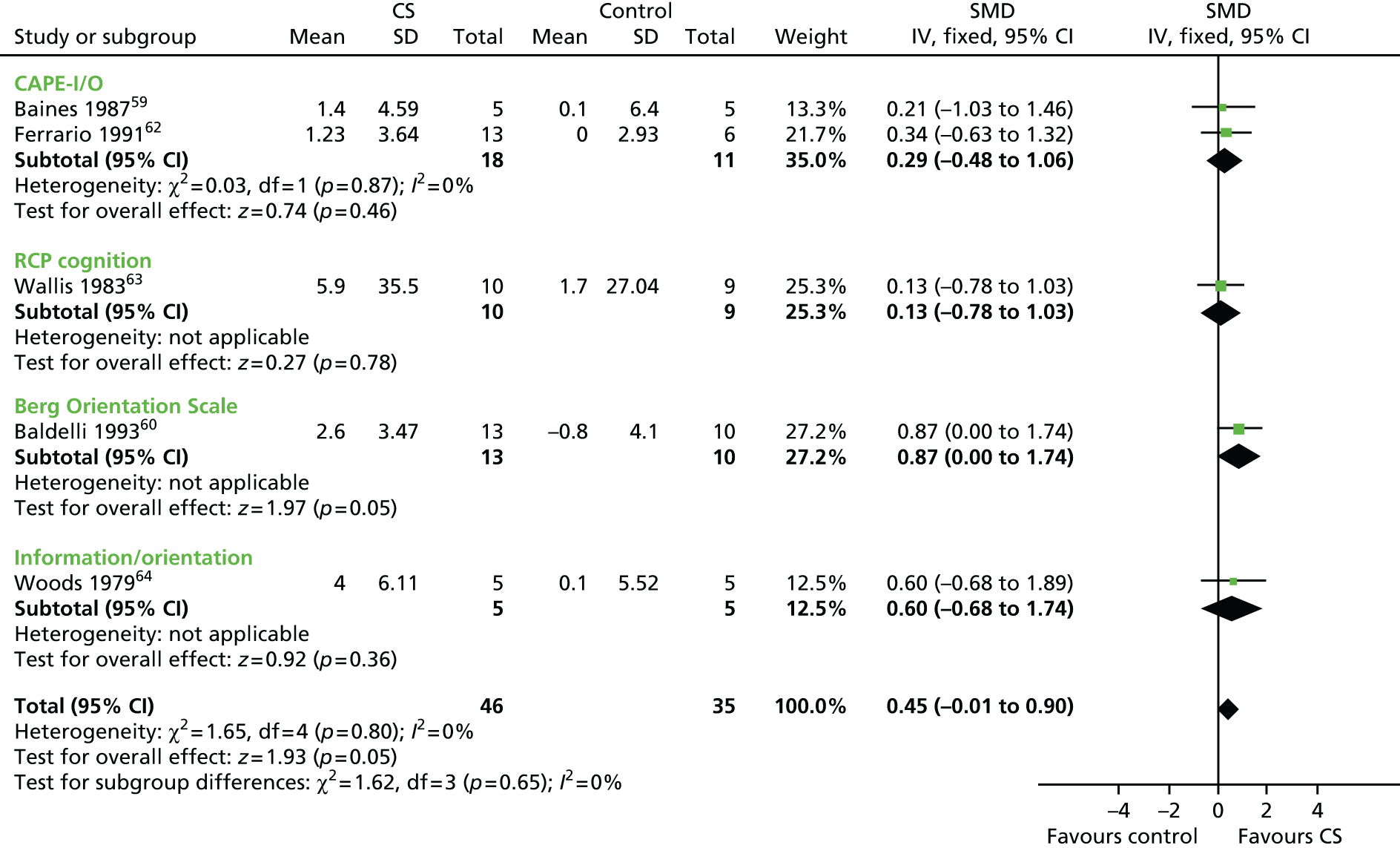

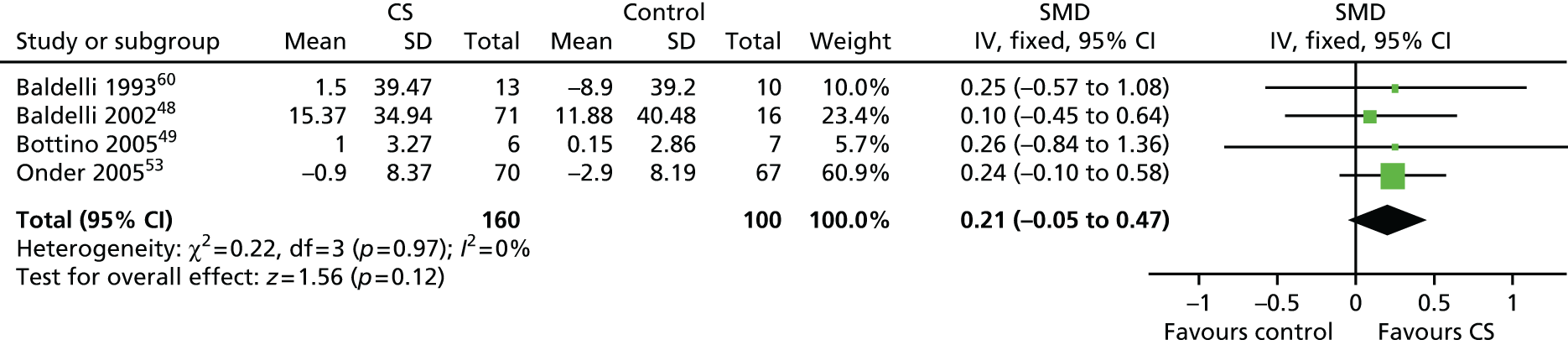

To evaluate the effectiveness of cognitive stimulation on behaviour, three separate meta-analyses were conducted. One focused on outcome measures seen as a problem, the second focused on ADLs and the third focused on general behaviour outcomes. Three studies used behavioural outcome measures seen as a problem (Figure 3) including 166 participants, showing that no difference was apparent related to cognitive stimulation (SMD –0.14, 95% CI –0.44 to 0.17; z = 0.86; p = 0.39). The ADL measure results also did not achieve significance (Figure 4), including four studies, involving 260 participants. There was no benefit identified associated with cognitive stimulation (SMD 0.21, 95% CI –0.05 to 0.47; z = 1.56; p = 0.12). The third behaviour analysis (Figure 5) (general behaviour) showed a similar picture, with no difference emerging. Eight studies reported data on relevant scales, including 416 participants (SMD 0.13, 95% CI –0.07 to 0.32; z = 1.30; p = 0.20).

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: outcome – ADAS-Cog. CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: outcome – MMSE. CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: outcome – other cognitive measure (information/orientation). CAPE-I/O, Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly – Information/Orientation scale; CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; RCP, Royal College of Physicians.

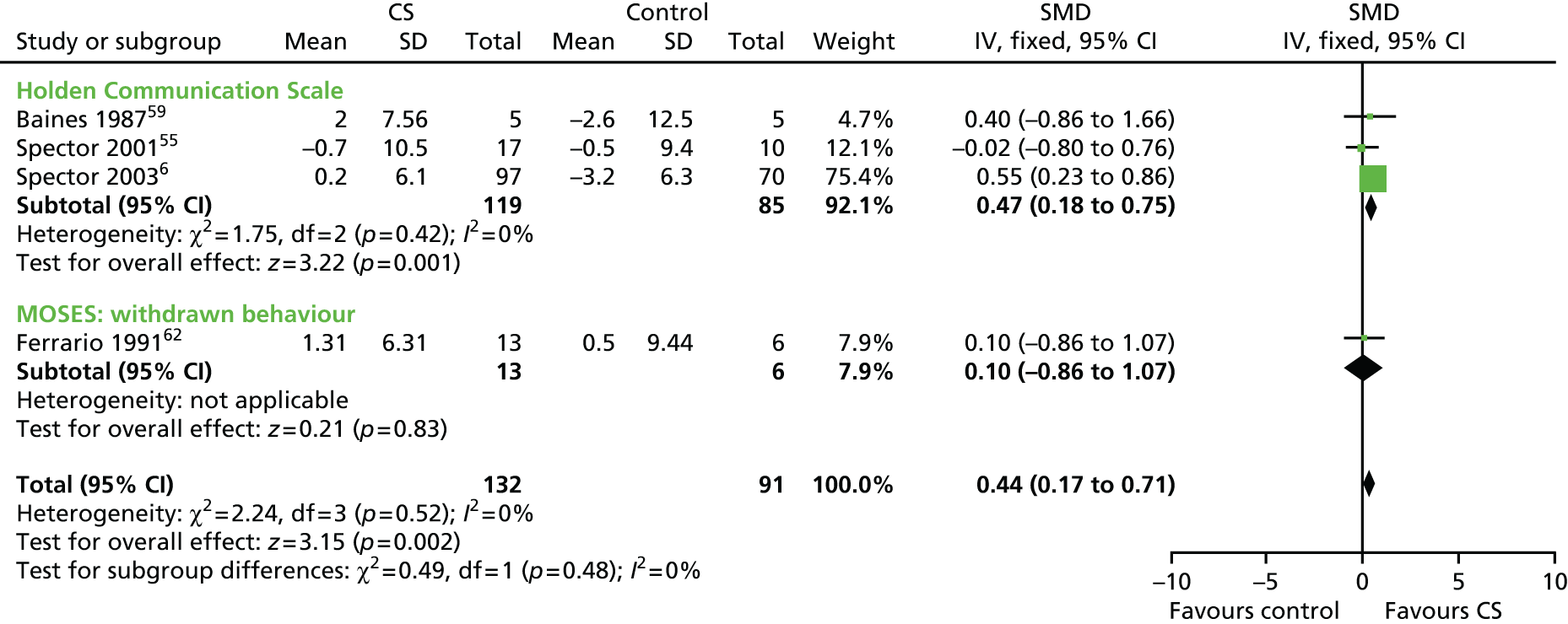

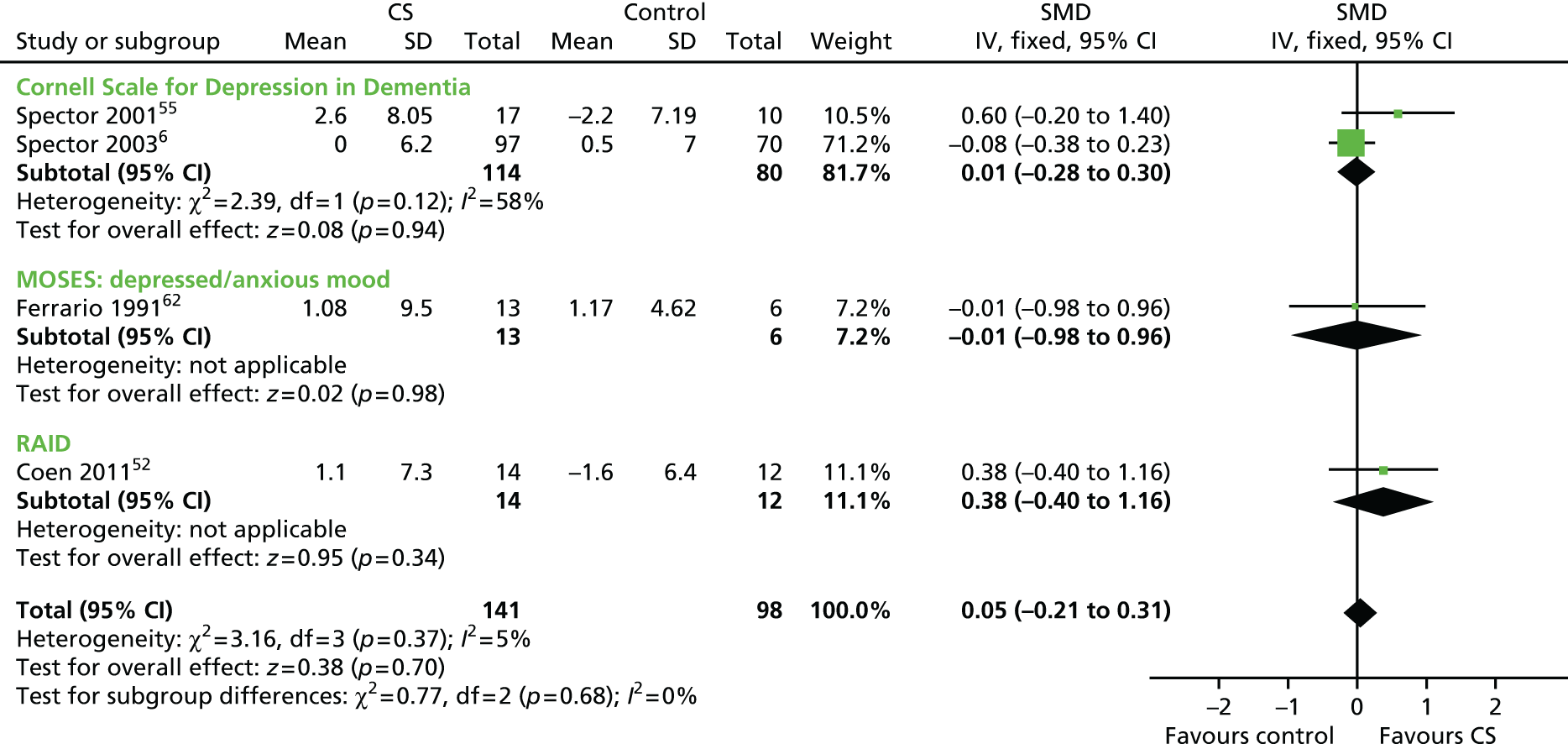

Five studies, involving 201 participants, used a self-report measure of mood (the Geriatric Depression Scale or the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale) (Figure 6). Cognitive stimulation is not associated with a clear improvement in mood (SMD 0.22, 95% CI –0.09 to 0.53; z = 1.42; p = 0.16). This is of similar magnitude to the finding of proxy report of mood and anxiety, where the SMD is close to zero (SMD 0.05, 95% CI –0.21 to 0.31) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: post treatment, outcome – communication and social interaction. CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; MOSES, Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects.

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: outcome – GDS. CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance.

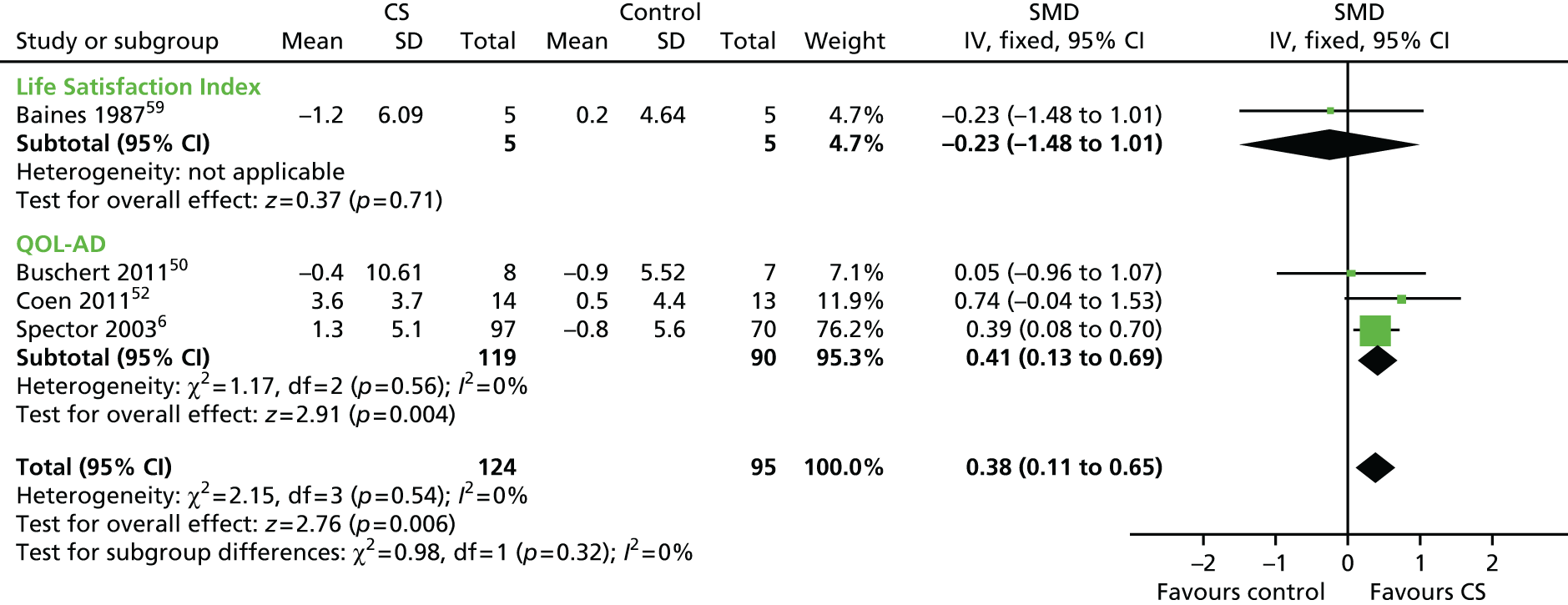

Four studies included self report well-being and quality-of-life measures (n = 219) (Figure 8). The analysis showed a significant improvement on this outcome measures following treatment, compared with control groups. The SMD was 0.38 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.65; z = 2.76; p = 0.006).

FIGURE 8.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: outcome – quality of life. CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; QOL-AD, Quality of Life – Alzheimer’s Disease.

Follow-up

Owing to the great variety in follow-up data, the analyses were divided in two sections: short- and long-term follow-up. Short-term follow-up analysis included Baines et al. 59 and Wallis et al. ,63 who had a 1-month follow-up, and Baldelli et al. ,60 who reported data from a 3-month follow-up. Long-term follow-up data included Chapman et al. ,51 who reported useable data only from a 10-month follow-up, a much longer period in the context of the progression of dementia. For cognitive measures (Figure 9), the three studies with short-term follow-up reported data for 52 participants. The significant advantage for cognitive stimulation on cognitive measures seen immediately post treatment remained at this point (SMD 0.57, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.14; z = 2.00; p = 0.05). For the 54 participants included by Chapman et al. 51 (Figure 10), there was no significant effect on either the MMSE (SMD 0.18) or the ADAS-Cog (SMD 0.12) at the 10-month follow-up. No other significant results were found in the other outcome measures at either the short- or the long-term follow-up analysis.

FIGURE 9.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: post treatment, outcome – mood, staff-reported. CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; RAID, Rating of Anxiety in Dementia.

FIGURE 10.

Forest plot of comparison for CS vs. no CS: outcome – ADLs. CS, cognitive stimulation; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance.

Discussion

The results of this updated meta-analysis of 15 studies with a total of 718 participants (407 receiving treatment and 311 controls) provide strong evidence of the benefits of cognitive stimulation for dementia on cognitive function. Moreover, they provide positive evidence that benefits can be extended to quality of life and self-reported well-being outcome measures. This review did not show a clear relationship between either the amount/frequency or the length of intervention and benefits to cognition, and the studies that showed most benefit were both shorter (Spector et al. 6 and Breuil et al. 61 having 7 and 5 weeks, respectively) and longer (Onder et al. ,53 with 25 weeks). The MMSE was of a similar size to the SMD (1.30) of the Spector et al. 6 and Onder et al. 53 studies. Because MMSE scores decline, on average, by 2 to 4 points per year on the MMSE for dementia,68 the benefits of cognitive stimulation might equate to a 6-month delay in the usual cognitive deterioration.

Recent reviews of psychosocial interventions for dementia are in line with the findings of this review and give strong recommendation for the use of cognitive stimulation for dementia. 8,69 Moreover, the 2011 World Alzheimer’s Report1 offered some evidence in relation to the benefits of AChEI medication and cognitive stimulation. This review also offered some evidence in relation to AChEI medication. Five out of the 15 included studies report data whereby all of the participants were prescribed AChEI medication in combination with cognitive stimulation. The additional effect of cognitive stimulation, over and above the medication (in four studies providing post-treatment data), was 3.18 points on the ADAS-Cog, compared with the overall finding (from seven RCTs) of 2.27 points. This supports the proposition that cognitive stimulation is effective irrespective of whether or not AChEIs are prescribed, and any effects are in addition to those associated with the medication.

Conclusions

Our review consolidates the growing evidence that cognitive stimulation improves cognitive function in people with dementia. It also indicates that cognitive stimulation benefits not only cognition but also self-reported well-being and quality of life, as has been reported by qualitative studies and people with dementia for a long time. 70 These benefits are over and above any antidementia medication effects.

Work package 2: development of the maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy programme

This section reports the development of the MCST programme manual. We followed the MRC guidelines for the development and evaluation of complex interventions30 using a systematic review of the literature44 and the original CST trial programme6 to produce a full draft of a manual for a MCST programme. As in the main CST programme, maintenance sessions focus on ‘themes’, with a primary emphasis on cognitive stimulation, while incorporating the process of reminiscence therapy and multisensory stimulation. Group names and songs, a ‘reality orientation board’ and introductory exercises provided continuity between sessions.

Objectives

-

To identify, from the Cochrane review studies, the interventions that have shown to be effective and have had an impact at improving cognition and quality of life of people with dementia, including any negative effects.

-

To indicate the nature and quality of the interventions and identify key themes and elements.

-

To develop, from the analysed interventions and current CST training manual, 24 weekly sessions of MCST.

-

To develop a MCST training package for care staff based on the existing CST manual. This comprised a manual workbook, a DVD and training seminars.

Development of maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy sessions and workbook

We selected all relevant and effective interventions from the CST Cochrane review. We contacted study authors with the aim of obtaining additional information, hard copies of the intervention programme manuals and the manuals translated into English. The research team developed a database identifying key themes from the initial CST manual71 guiding principles and sessions, and included the 16 sessions developed for the MCST pilot project. A draft manual (version I) was produced based on the results.

The results from the analysis of the cognitive stimulation manuals, including the original papers, manuals and table database, were presented in a consensus workshop (comprising key academics, research staff and clinical staff involved in CST practice) and used to validate and review a subsequent draft of the MCST manual (version II), which included 24 maintenance sessions and was produced using the results of the consensus workshop. The MCST manual (version II) was discussed in focus groups with care staff (three groups), carers (three groups) and people with dementia (three groups) to review key themes, feasibility and potential modifications. The revised MCST manual was further modified in consultation with the attendees of the consensus workshop and key contributors to other aspects of process (e.g. a sample of care staff, carers, clinical staff and leading experts on CST).

The next draft of the MCST manual (version III) was produced to publication quality and was used in the development of a revised version of the CST training package compromising the revised manual, a CST/DVD including extra maintenance sessions, a PowerPoint® 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentation, methods of evaluation and adherence. We developed the training package in consultation with trainers from Dementia UK.

Focus groups: a comparison of the views of people with dementia, staff and family carers

We included qualitative testing of the intervention through focus groups, developing a consultation process with people with dementia, family carers and staff. The aim was to identify improvements for the draft version of the MCST manual. Focus groups were the natural choice, as the aim was to gain comprehensive views of the key stakeholders with regard to the MCST programme. A key strength of focus groups is their ability to ‘tune in’ to the attitudes and perceptions of users regarding services.

Method

Sample

Focus groups were undertaken separately with three user groups that consisted of key stakeholders in the project. Three focus groups were carried out with people with dementia, three groups were carried out with staff and three groups were carried out with family carers of people with dementia. In total, 17 people with dementia, 13 staff and 18 family carers took part in separate focus groups. In the people with dementia groups, there were eight men (47%) and nine women (53%). Their mean age was 78 years, they all scored mild to moderate on the CDR scale46 and were able and willing to consent to participate in the focus groups. The staff groups consisted of three men (23%) and 10 women (77%), with a mean age of 36 years. All were permanent, paid staff, with at least 1 month’s employment, from residential homes, day centres or day hospitals. Their main duties involved caring for people with dementia. The family carers consisted of six men (33%) and 12 women (67%), with a mean age of 53 years. All were former or current carers of a person with dementia and had at least monthly contact during their time as a family carer.

Purposive sampling, for example sex, length of caring experience and dementia type, was used to ensure a wide range of participants. The centres selected were typical in size, organisational structure and management of others in the area. When people were recruited via local carers’ organisations (Uniting Carers for Dementia and Alzheimer’s Society), permission was also obtained from the management committees of these groups.

Procedure

We used the Noticeable Problems Checklist72 to screen potential participants who were then approached for their consent and further screening using the CDR scale. Participants with a CDR score of mild to moderate were included, provided that they did not meet the exclusion criteria (diagnosis of severe learning disability and/or diagnosis of depression, anxiety or other mental or physical illness adversely affecting their ability to participate in focus groups) and were willing to take part in the discussion groups. Seventeen participants met the inclusion criteria and agreed to take part. Members of staff who were working directly with people with dementia in the different centres approached were invited to take part in the groups. Eighteen family caregivers were recruited through Uniting Carers, Dementia UK and the Alzheimer’s Society. Participants were reminded that they could leave the group at any time.

Two researchers conducted self-contained, hourly focus groups. The sessions included a brief presentation about the overall project. One facilitator led the interview, with the second person actively listening and seeking clarification, to ensure the adequacy and accuracy of content as appropriate. 73 The second facilitator also took substantive and methodological field notes during and immediately after the focus groups, as recommended by Burgess. 74 A semistructured interview schedule based on the CST empirical literature was used as cues for open questions. The groups focused on the 24 themes developed for the MCST programme and the cognitive stimulation definition by Clare et al. 11

Design

Focus groups were chosen in preference to individual interviews, as they are useful for stimulating discussion, generating ideas to explore topics in depth, gaining insight and obtaining rich data. 75 A focus group interview schedule was constructed and developed to provide a framework for the discussions, which was piloted and adapted. The participants were encouraged to express their opinions and discuss issues through a series of open questions, which covered various aspects of mental stimulation activities, beginning with a presentation of the programme on a DVD and followed by open questions designed to elicit the activities and themes that participants particularly enjoyed and factors that contributed to the programme activities being stimulating and meaningful. Questions included ‘what do you think about use it or lose it/mental stimulation?’ and ‘could you tell us a bit about what sort of things you do that you find as being mental stimulating for you and you enjoy doing them?’. Pictures and materials used in the different themes and activities were used to help stimulate discussion in the participant groups. All groups used the same schedule, and participants were asked their opinions of what activities/themes they thought would be successful among people with dementia.

Analyses

The focus group interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. The facilitators then reviewed the transcripts. The notes taken by the second facilitator were consulted to clarify the context of the discussion (e.g. benefits of being part of a group that was expressed by people with dementia focus groups). We used an inductive (data driven) thematic analysis approach76 to code and analyse the data. Inductive analysis allows themes to emerge from the data and is useful when the intent is exploratory and descriptive, as in our case. Consistent with various qualitative research methods, the focus group inquiry allows participants the freedom to provide information that does not necessarily fit with any expectation/hypotheses going into the research. This openness to new and unexpected information allows measurement designers to more fully ‘ground’ the content of new patient-reported outcomes in the concerns and issues that participants think are relevant. 77

To develop a thematic codebook, researchers immersed themselves in the transcripts and rereading to gain deeper understanding of and familiarity with the content. One transcript was revisited and analysed into exclusive in vivo categories; that is, one theme was applied to one unit of meaning and the words used by the participant were adopted as the label of the theme. These themes were then applied to the remaining transcripts using a method of constant comparison to refine themes within the coding manual. During this process themes became more conceptual, with some original themes split into subthemes and others linked under one category depending on the emphasis placed on each theme within the transcripts. The resulting coding manual provided a meaningful way of understanding the views of the participants and assessing similarities and differences across the different groups (people with dementia, staff and family caregivers). Using the final codebook, all transcripts were coded independently by both researchers and then compared to reach 100% consensus.

Results

Thematic analysis revealed themes relating to perceptions and opinions of ‘mental stimulation/use it or lose it’, ‘examples of mental stimulating activities of daily life‘, ‘factors influencing successfulness and unsuccessfulness of a mental stimulation activity’ and ‘opinions and perceptions of specific themes of the presented maintenance CST programme’. Patterns of themes were found among the different groups (people with dementia, family caregivers and members of staff).

In the quotations below, PWD refers to the group ‘people with dementia’, FC refers to the group ‘family caregivers’, SC refers to the group ‘staff caregivers’, FG1 and FG2 refer to the focus group numbers and the digits refer to the line numbers in the transcript.

Mental stimulation: ‘use it or lose it’

This included discussing their opinions regarding mentally stimulating activities, ‘use it or lose it’, in terms of their views and beliefs about the effects of keeping the brain active. All participants showed general agreement about the usefulness of keeping the brain active.

People with dementia expressed the view that keeping the brain active was very important and a way of relieving frustration. They thought that it was essential for a healthy life and preserving their mental abilities, and that engaging in activities would keep the brain going. Some family carers expressed the view that the need for mental stimulation was universal and could bring neurological (building connections in the brain) and mental (helping with mood, anxiety, depression) benefits to everyone, and was important for promoting a healthy lifestyle and well-being. Staff and family carers also thought that there were added benefits to people with dementia in terms of increasing confidence, giving a sense of achievement, satisfaction, retaining skills and enjoyment.

No participants with dementia expressed negative views about the value of ‘use it or lose it’; however, there were concerns about the importance of keeping the brain active from members of staff and family carers groups who gave examples of individuals for whom the idea of ‘use it or lose it’ did not apply. Famous writers and politicians were given as examples of people who maintained a mentally stimulating, active lifestyle but nevertheless developed dementia. Some family caregivers expressed concerns that mental stimulation programmes may result in people with dementia losing confidence, experiencing anxiety or a sense of inferiority if confronted with their own cognitive deficits and difficulties as a result of undertaking a challenging mental activity.

Perceived stimulation in everyday life

Listening to music, singing and dancing, reading, painting, drawing, cooking and knitting were highlighted as being important for people with dementia. Factors that made an activity important included being interesting, being enjoyable, having a relaxing effect and helping to pass the time. Reading was a popular activity for most people with dementia as it raised their confidence and helped to increase interaction and participation when part of a group. In particular, talking and listening to others appeared enjoyable and were highly valued among people with dementia. They thought that talking to another person, to a pet or to the TV maintained their links with important current and past relationships and helped to reduce feelings of isolation.

Being part of a group helps considerably. I think being left on your own is not as effective as being part of a group. I belong to an African Caribbean group and I find that very stimulating. We talk on a number of things what we have done and why we did it. I think talking is very important.

PWD: FG1; 175–179

Family caregivers perceived that activities involving music (e.g. listening to music, singing, tapping and clapping) were those that people with dementia enjoyed the most.

Sounds and music are very important to stimulate something that’s there already so they recognise . . .

FC: FG2; 183–184

Those in the family caregivers group also spoke of having the opportunity to enjoy dinner together and to reminisce together by looking at photographs or sharing memories.

They learned a lot about others, everyone was telling their old past stories of how they went to school in shared shoes and things like this as a family. And we got so much information and it really stimulated them.

FC: FG2; 232–238

Staff caregivers thought that their planned activities were the most valuable stimulating activities for people with dementia. Staff participants identified reminiscence as an activity people with dementia enjoyed and often engaged in. However, there appeared to be little understanding of its value, and concern that it did not relate to the present.

I think we have to be careful with reminiscence, for me one of the best bits of this therapy is the variety of activities that you are going to do, otherwise it can get very repetitive as you tend to do things that you know work well, like reminiscence. You have to set goals within every session . . .

SC: FG1; 60–66

Factors influencing success of a cognitive stimulation programme

The perceptions of what made a CST programme successful were based on the person’s values and beliefs, with their interests and routines reinforcing a sense of identity and sense of belonging. Staff and family caregivers appreciated that the philosophy of the programme should be person centred and that enjoyment was a measure of what made programme activities successful.

People with dementia stated that basic human courtesies were important: being kind, trying to make others happy and not underestimating participants’ abilities.

Nothing that involves cruelty. As long as there’s kindness you can’t fault it.

PWD: FG1; 366

Being able to discuss, learn and make contributions was also mentioned.

I think it is very important to learn new things, you don’t stop learning ‘till you die.

PWD; FG1; 669–672

Other factors highly valued in the groups were activities that included reminiscence as an aid to orientation and activities that were provided in a multisensory way. Activities involving discussion and sharing opinions among the group were highly valued, as were challenging activities and quizzes requiring right or wrong answers.

Some people will remember more things than others you know. But it’s good for the brain . . .

PWD: FG1; 576–579

In contrast, family caregivers and staff participant groups stated that activities in the programme should not be based on right or wrong answers, so that people with dementia did not feel under pressure. ‘Playing it safe’ was perceived as being very important and this helped people feel more secure.

You have to adapt to the person and never ask them to do anything they can’t do because they have a sense of self and it will give them a sense of inferiority or inadequacy.

FC: FG2; 90–94

Most staff acknowledged that it was important to identify participants’ individual preferences, skills and abilities, as this affected their level of engagement in activities, whereas some recognised the need to adapt activities to a participant’s capabilities as a way of providing choice and contributing to their well-being. Some family carers stressed the importance of providing this programme to people only in the mild-to-moderate stages of dementia, as they thought that it would not be appropriate for people in more advanced stages.

The group participants should be of [a] similar level of dementia.

SC; FG2; 176

They also thought that group participants should be chosen based on having similar abilities and interests so that the group could run successfully and be stimulating and enjoyable. Both staff and family carer groups noted that attention needed to be paid to each participant’s level of hearing and vision, as they thought that high levels of impairment in either would limit a person’s participation.

You have to think about the personality dynamics within each group.

SC: FG2; 109

Staff and family caregivers also indicated that the group facilitator’s skills, knowledge, understanding of dementia and attitudes towards participants was also key to running the group effectively. The need for several facilitators was mentioned, as was limiting the number of group participants. Appropriate equipment was identified as another key factor to the success of this programme.

I think the size of the group has to be pretty small as an important factor.

FC: FG2; 388–391

Presented themes

A total of 19 themes was presented to the focus groups of people with dementia, family caregivers and staff. Fourteen themes were from the existing CST programme. Five new themes were developed from the literature review and the pilot MCST study (Table 2).

| Maintenance session | Version 2 | Version 3 | People with dementia | Staff | Family carers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New session themes | |||||

| Useful tips | 11 24 | 11 24 | Excellent: discussion (learn and teach) and reminiscence | Excellent: discussion (learn and teach) and reminiscence | Good: some concerns about healthy tips |

| Visual clips | 13 | 13 | Not interested | Good theme | Very good, discussion, reminiscence and multisensorial |

| Thinking cards | 12 22 | 12 | Very good | Mixed opinions, down on list | Mixed opinions |

| Art discussion | 14 | 14 | Mixed emotions | Mixed emotions: will generate discussion | Very good, discussion |

| Using objects | 10 | 10 22 | Very good | Excellent theme: discussion and reminiscence | Excellent theme: discussion and reminiscence |

| CST session themes | |||||

| Physical games | 8 | 8 | Very good | Very good | Very good |

| Sounds | 7 | 7 | Very good | Very good, music and multisensorial | Very good, music and multisensorial |

| Childhood | 1 23 | 1 23 | Good, enjoyable | Very good: multisensorial and reminiscence | Very good: multisensorial and reminiscence |

| Food | 3 17 | 3 17 | Very good | Very good: multisensorial | Very good: multisensorial |

| Current affairs | 2 21 | 2 | Very interesting | Mixed emotions: needs to include reminiscence | Mixed emotions, not for everyone. Needs to include reminiscence |

| Faces/scenes | 15 | 15 | Very successful (discussion and reminisce) | Very good theme: discussion | Very good theme: discussion, recognition |

| Associated words | 18 | 18 | Very good | Very good at the right level | Very good |

| Being creative | 4 | 4 | Fun | Good theme, some dangers (not for everyone) | Very good: multisensorial |

| Categorising objects | 9 | 9 | Mixed emotions | Very successful (discussion and reminisce) | Very successful (discussion and reminisce) group cohesiveness |

| Orientation | 19 | 19 | Very good | Very good: discussion and reminiscence | Very good: discussion and reminiscence |

| Using money | 20 | 20 | Very good | Mixed emotions, sensitive topic | No good topic |

| Number games | 5 | 5 | Not popular | Mixed opinions, some dangers (not for everyone) | Mixed emotions |

| Word games | 16 | 16 21 | Excellent activities | Very popular, good | Good activity, pay attention to presentation |

| Quiz | 6 | 6 | Excellent theme | Very popular, good | Good |

The five new themes

People with dementia rated useful tips, thinking cards and using objects as very positive themes. They stated that these themes were good for learning, hearing other people’s opinions and giving their own opinions in the group. They thought that the themes could help the group cohesiveness and would trigger conversation. Family caregivers and staff groups also thought that useful tips and using objects were good themes for the session and highly valued the involvement of reminiscence in the activities as an aid to orientation. Some staff expressed concern that the thinking cards theme would not work but others challenged that it would. Some family caregivers thought that the proposed activities for this theme would not be appropriate, as some people did not like ‘closing your eyes and imagining’ and might feel uncomfortable with this. Other carers liked this theme and thought that the questions were a good way of stimulating conversation and possibly helping group cohesion.

People with dementia rated visual clips discussion and art discussion as neutral. Although they liked the idea of group discussion, they did not feel enthusiastic about the topics presented. Staff and family caregivers groups rated these themes positively, as visual prompts were highly valued and they liked the idea of promoting discussion. Some staff had successfully run these types of activities previously with people with dementia and advised that materials be chosen appropriately.

Existing cognitive stimulation therapy themes

Participants were asked to rate and organise the presented themes as very positive, neutral or negative, and to rank them in order of those themes perceived as most and least successful. My life (childhood and occupations), food and orientation were perceived as positive themes; they were applicable to everyone, helped people to keep in touch with themselves and were multisensorial. Quizzes and word games were rated highly among people with dementia, who thought that they were very stimulating and helped the brain to keep working and ‘ticking together’. Family caregivers and staff also rated these two themes very highly. Physical games, sounds, faces and scenes, categorising objects, associated words and being creative were also rated positively by all groups, as these were good for stimulating recognition, reminiscence and discussion, offered multisensorial stimulation and promoted keeping healthy and active.

Number games was the only theme rated very low by people with dementia, who said that, as numbers were not something they related to very well and were a bit meaningless to them, this was not their preferred choice of activity. Family caregivers and staff shared similar views, as their previous experience indicated that number games required more one-to-one work with people with dementia, and were frustrating and pointless unless the numbers were related to pricing.

Using money and current affairs were rated very low by the family caregivers and staff groups but rated highly by people with dementia. Some family caregiver and staff participants stated that people with dementia did not often relate to current affairs (owing to the disease) and it would be meaningless to present topics about news unless reminiscence was used as a context for the information. However, people with dementia expressed a great interest in current affairs and stated that they loved reading newspapers. People with dementia also stated that they would enjoy talking about the value of money, and there were spontaneous comments about the value of money and the cost of bus journeys in the past and the present. In contrast, family caregivers and staff thought that money was too complicated and not a good theme, as it could be a very sensitive topic for some people with dementia.

Discussion

We used a novel approach to refine an existing psychological intervention programme that investigated the opinions, types of activities and qualities which make a cognitive stimulation programme more successful for people with dementia. An advantage of using focus groups with people with dementia is that sharing experiences may trigger recall. A possible disadvantage is that they rely on verbal communication and short-term memory, both of which are often impaired in people with the condition. 78

Opinions about mental stimulation programme and key factors for success

People with dementia thought that keeping the brain active was essential and they acknowledged that this helped with their memory losses and difficulties. This finding supports Barnett’s79 statement that bereavement with memory losses is a major theme for people with dementia, who value the opportunity to be listened to. They also value being in a group. As indicated in other studies, socialising is an important activity for older people in care. 80–82 People with dementia valued quality social interactions, especially when being part of a group, and feeling a sense of belonging, reflecting Kitwood’s83 theory, which claims that positive interactions reinforce the personhood of those with dementia.

Conversely, staff and family carers expressed mixed opinions about the effectiveness of keeping the brain active; they cited examples of public figures who had developed dementia and said that the focus should be on the factors that would make a programme successful or unsuccessful for people with dementia. The main factors to consider when planning a CST group were grouped into participant characteristics (level of dementia, sensory impairments, personality, interests, life history), facilitator characteristics (knowledge about dementia, group skill and personality), group size and materials (multisensorial prompts, age appropriate).

Limitations

Staff focus groups included managers or senior carers, the presence of whom may have affected the opinions expressed by other staff members. Participants sometimes appeared reluctant to give personal examples, perhaps inhibited by the stigma of sharing information in a group, and this may be a disadvantage of using focus groups. We selected a thematic analysis, as it is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. Although thematic analysis is used widely, there is a lack of consensus regarding its precise methodology. 84

Conclusion

Findings from the user focus groups regarding MCST programmes support the 2006 NICE guidelines on dementia85 that state that all people with mild to moderate dementia should be ‘given the opportunity to participate in a structured group cognitive stimulation programme’. Positive agreement was found among 14 themes and suggestions were made for the five remaining themes. These results were used to revise the manual for the MCST programme.

Work package 3: maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia – a single-blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial of maintenance cognitive stimulation therapy versus cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia

Introduction

This section describes the study protocol for a pragmatic RCT of CST versus CST followed by a 24-week MCST programme undertaken with people experiencing mild to moderate dementia. This research programme aims to provide essential evidence to clarify the role of long-term CST interventions alone and in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors, and to assess the cost-effectiveness of this long-term vision.

Methods

Design

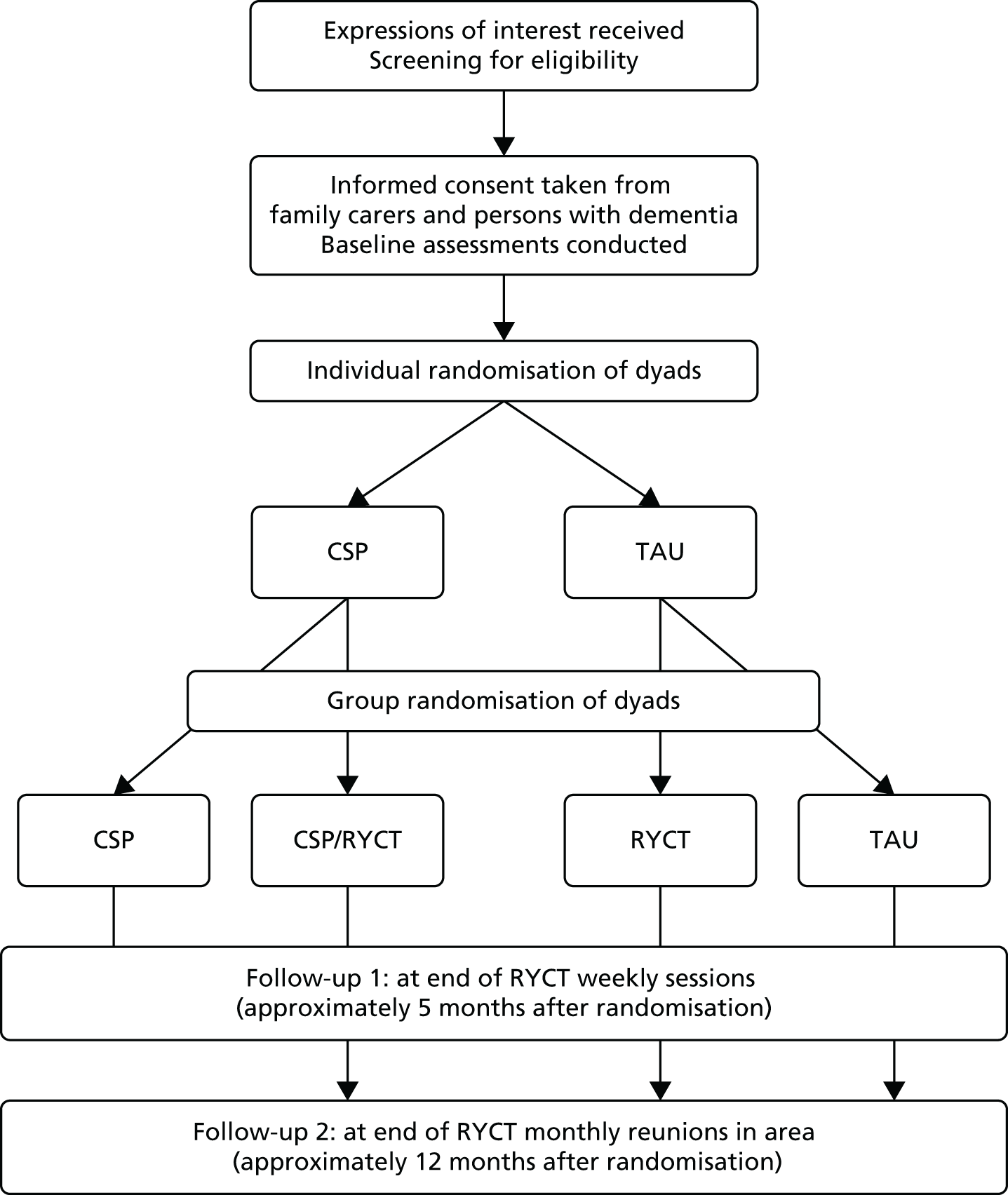

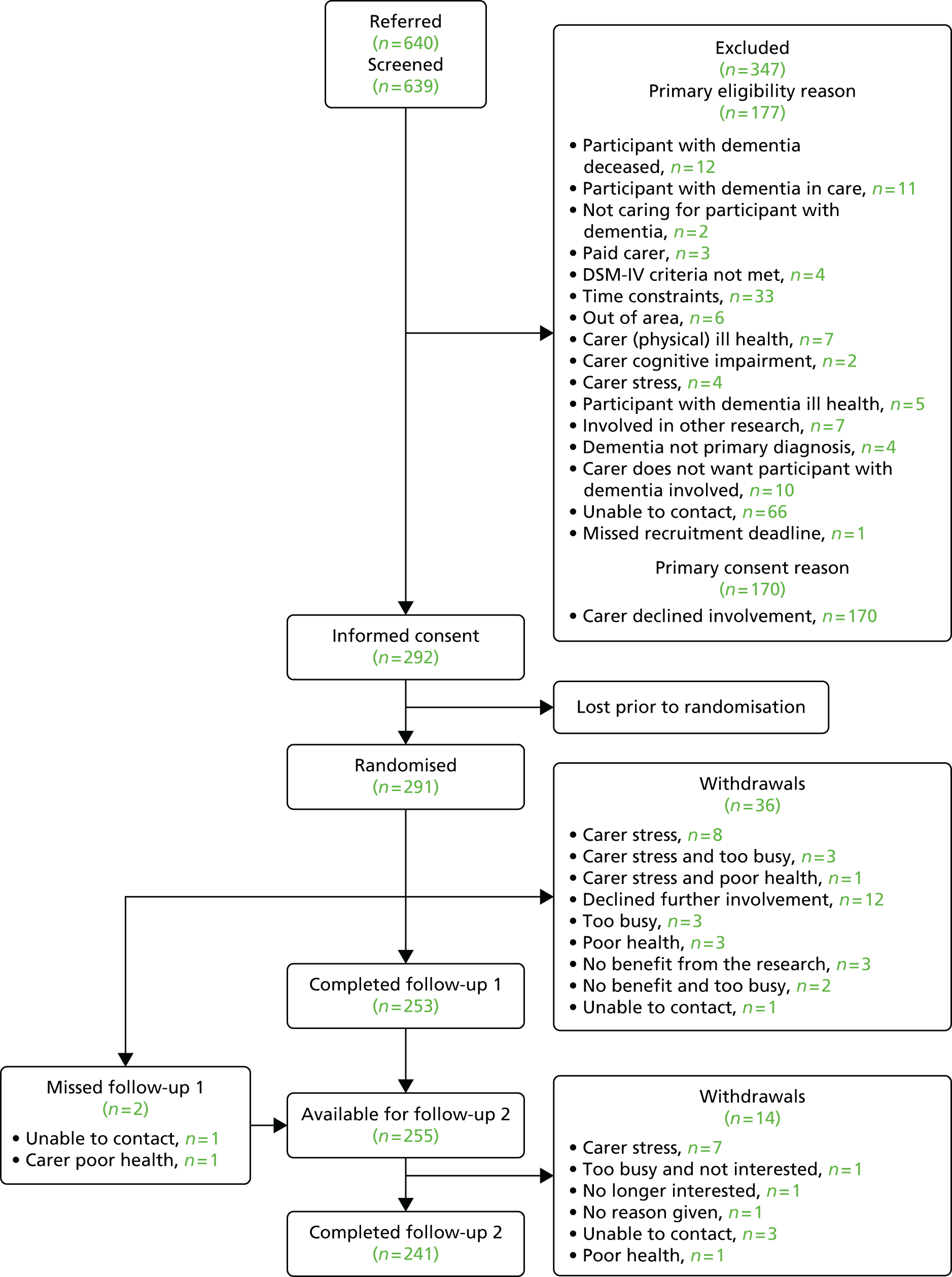

The design was a single-blind, multicentre RCT of CST groups for dementia versus MCST groups (Figure 11). After the completion of the initial CST programme (twice-weekly 45-minute sessions for 7 weeks), participants were randomly allocated to the treatment group (maintenance sessions weekly for 24 weeks) or the control group (usual care). Data were collected at baseline (baseline 0), after completion of the 7-week CST programme (baseline 1), and at 3- (follow-up 1) and 6-month follow-ups (follow-up 2). It was calculated that a sample size of 230 participants was needed at baseline 1 to detect an effect size of 0.39 on the ADAS-Cog,86 with power of 80% using a 5% significance level. Ethics approval was obtained through the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (reference number 08/H0702/68). The clinical trial was registered as ISRCTN26286067.

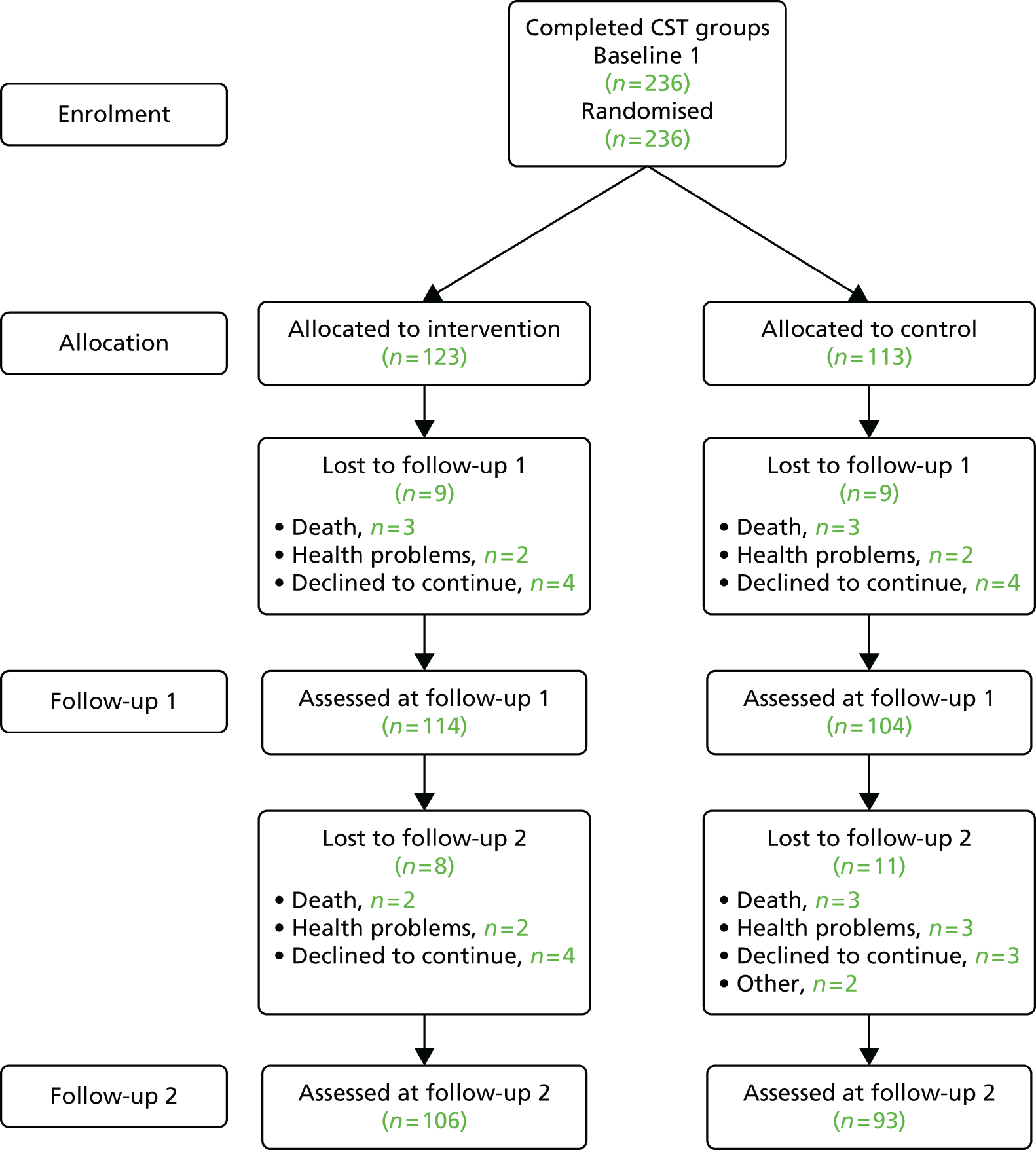

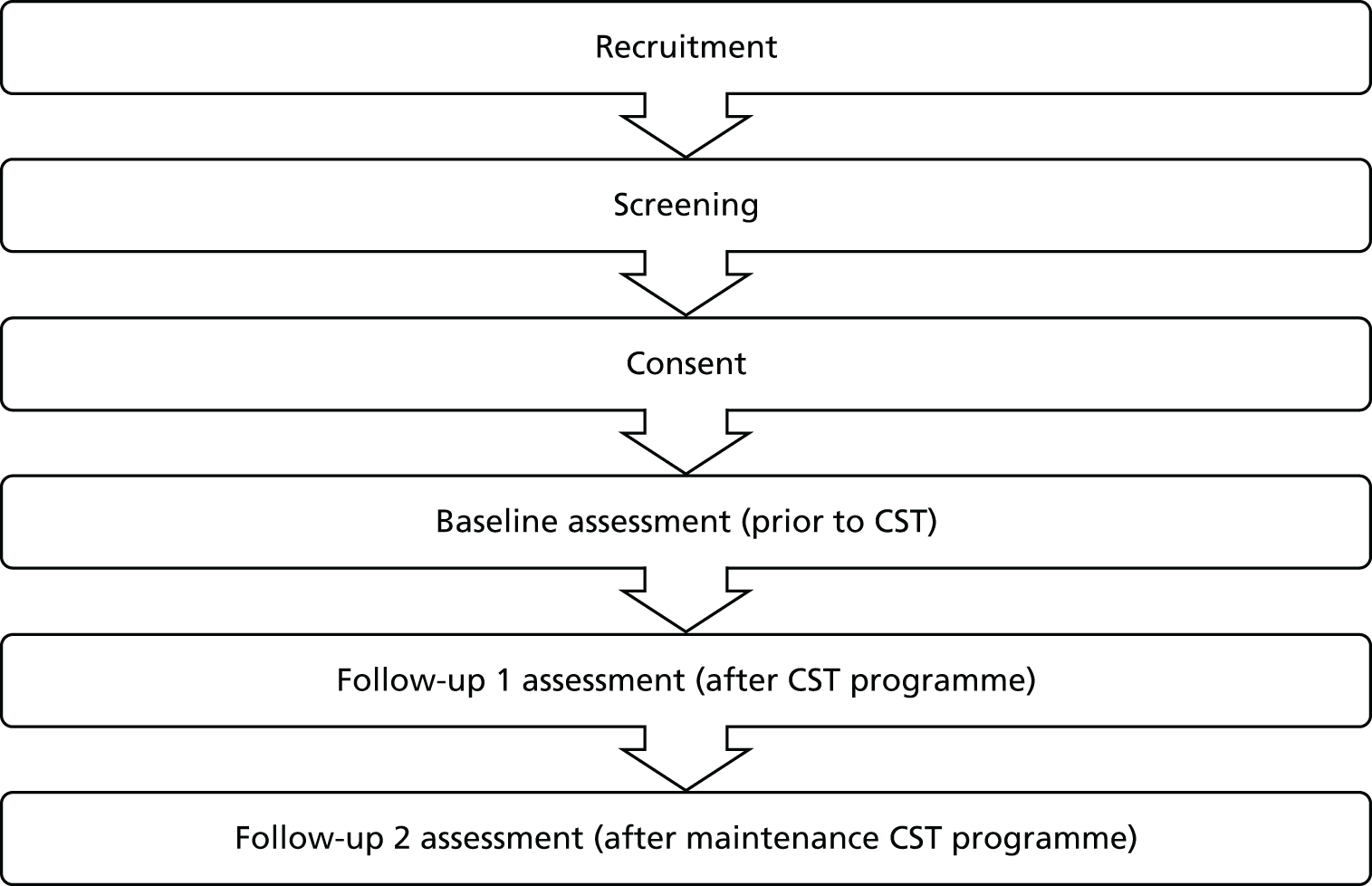

FIGURE 11.

Flow diagram of the trial: trial and randomisation stages.

Participants

The participants were people meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)87 criteria for dementia graded as mild to moderate on the CDR scale,46 with the ability to communicate, hear and see well enough to participate in the group, with no major physical illness or disability, and without a learning disability. Half of the sample was recruited from care homes and half was recruited from community settings, including CMHTs, day centres and voluntary organisations in London, Essex and Bedfordshire. Of the 21 centres initially contacted, one refused to participate and two were excluded owing to a lack of participants.

Randomisation

The randomisation process in this trial was undertaken in two stages: randomisation 1 and randomisation 2. Figure 11 sets out the two-stage randomisation process. The allocation ratio at randomisation 1 stage was 1 : 1; into either group A or group B, with both groups receiving 7 weeks of CST.