Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10452. The contractual start date was in August 2008. The final report began editorial review in December 2015 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Lucilla Poston has received payment from International Life Sciences Institute Europe as reimbursement of expenses incurred in attending a workshop on obese pregnancy and long-term outcomes and was paid as a member of the Tate and Lyle Research Advisory Group 2007–10, before submission of this work. Lucilla Poston also reports a research grant from Abbott Nutrition, outside the submitted work. Thomas AB Sanders reports personal consultancy fees from the Natural Hydration Council, Heinz Foods, Archer Daniels Midland, the Global Dairy Platform and GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work, and is a trustee and scientific governor for the British Nutrition Foundation, outside the submitted work. Keith M Godfrey reports reimbursement of travel and accommodation expenses from the Nestlé Nutrition Institute, outside the submitted work; research grants from Abbott Nutrition and Nestec, outside the submitted work; and patents pending for phenotype prediction, predictive use of 5‘-C-phosphate-G-3’ (CPG) methylation and maternal nutrition composition, outside the submitted work. During the period of research reported here, Jane Sandall was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research core group of methodological experts (2011–15), and of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Programme Commissioning Board (2012–15) and Stephen C Robson was a Medical Research Council/NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation board member (2012–15).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Poston et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 The UK Pregnancies Better Eating and Activity Trial phase 1 – development phase: involvement of patients and providers in development of the UK Pregnancies Better Eating and Activity Trial intervention

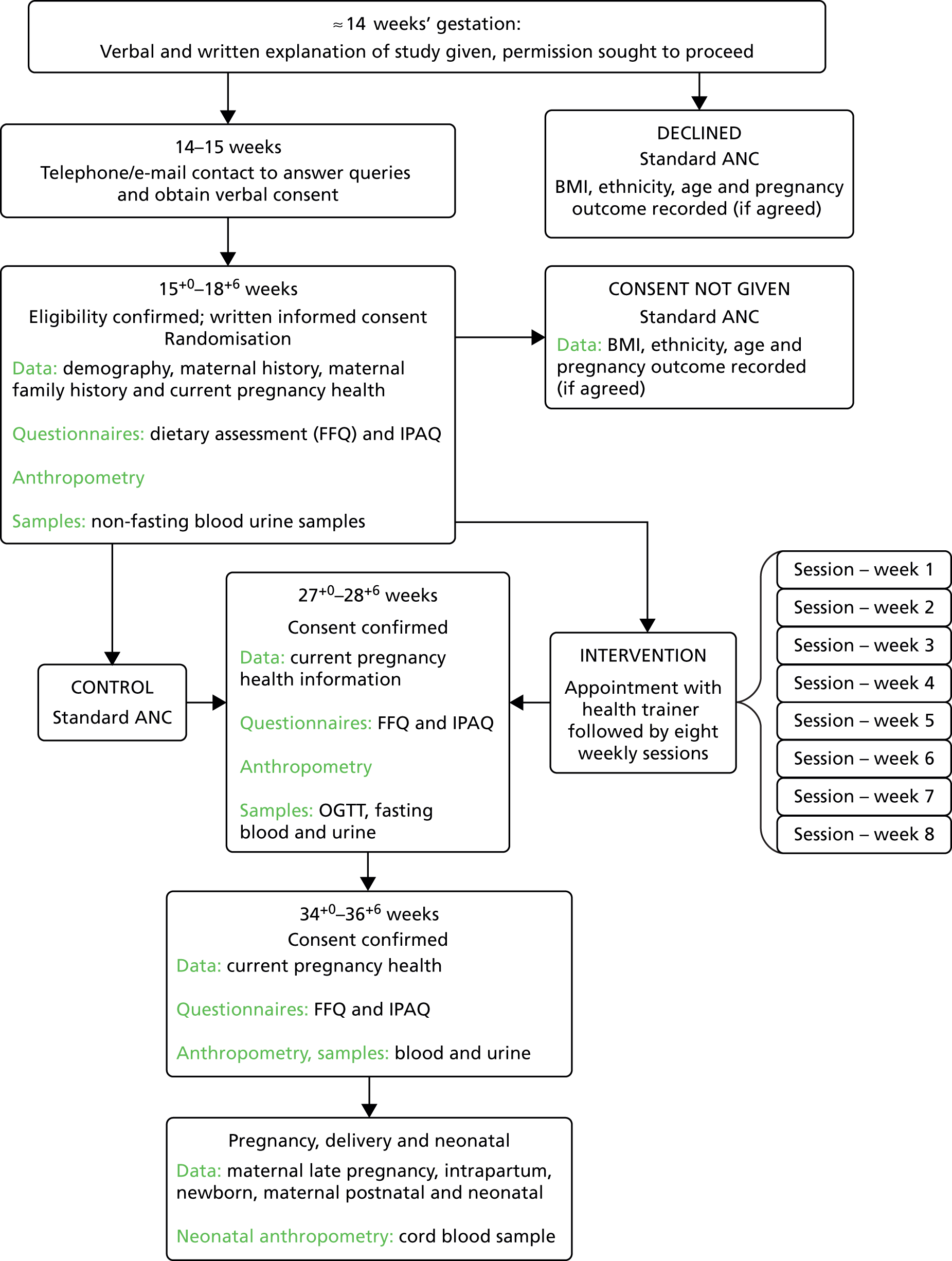

This programme of work was designed to develop a behavioural intervention combining dietary and physical activity (PA) advice to improve insulin sensitivity, and thereby reduce gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and large-for-gestational age (LGA) deliveries, in obese pregnant women. The programme followed the UK’s Medical Research Council framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, which is delineated by three phases. 1

-

Development phase: to determine, following a review of the relevant literature, the best approach and method of delivery of the proposed intervention, develop and standardise the content and delivery method, and assess feasibility and acceptability to women and providers with a view to optimising the intervention for use in a pilot trial.

-

Pilot: to undertake a pilot trial to establish the efficacy of the intervention in changing dietary and PA behaviours, and to evaluate all practical aspects of delivering the intervention.

-

Randomised controlled trial (RCT): to undertake a RCT to determine whether or not the intervention reduces GDM and LGA deliveries in obese pregnant women.

The aim of phase 1 was to determine the best approach and method of delivery for the proposed intervention, develop and standardise content and delivery method, and assess feasibility and acceptability to women and providers with a view to optimising the intervention for use in a pilot trial (phase 2).

Objectives and design

To assess appropriateness, acceptability and delivery of the intervention in target groups

To understand likely motivations for, and barriers to, changes in diet and activity in pregnancy by developing a quantitative measure of knowledge and attitudes about healthy eating and activity.

At the onset of this programme there were no pre-existing validated instruments to assess attitudes towards diet and PA in obese pregnant women. Initial work was undertaken to explore the relative clinical effectiveness of different behaviour change strategies used in previous studies of healthy lifestyle interventions for pregnant women. All relevant studies had focused on the reduction of gestational weight gain (GWG) as the primary end point. None was targeting insulin resistance, which was the focus of this programme. Ten controlled trials of interventions that aimed to reduce GWG through changes in diet or PA were reviewed. Meta-analysis showed that, overall, diet and PA change was effective in reducing GWG, but there was considerable heterogeneity in outcomes. 2 The analysis showed that sample characteristics and aspects of intervention design, content, delivery and evaluation differed between studies, and that these were likely to explain the variation between studies in effectiveness. A common issue was the failure to evaluate changes in behaviour or its psychological determinants, as well as inadequate detail of the intervention content. These were likely to have contributed to difficulty in identification of the processes by which weight change was effected. Because of this, it was difficult to discern active intervention ingredients. The study concluded that behaviour-based GWG reduction interventions should be more systematically designed, evaluated and reported to build on insights from behavioural science. This important conclusion reinforced our intention to systematically develop an evidenced-based intervention based on known theory, and our decision to pilot the intervention to evaluate all aspects of the intervention, particularly to evaluate change in behaviour, acceptability and its psychological determinants.

A questionnaire to measure attitudes towards diet and PA in pregnancy was then developed, based on psychological models of determinants of health behaviour, previous literature in pregnant women and interviews conducted with pregnant women (see Appendix 1). The questionnaire comprised the following constructs: attitudes to healthy behaviours, social norms, intention to change behaviour, knowledge regarding nutritional and PA recommendations and motivations for food choices. The outcomes of a study using this questionnaire were published as below by Gardner B, Croker H, Barr S, Briley A, Poston L, Wardle J; UPBEAT Trial. Psychological predictors of dietary intentions in pregnancy. J Hum Nutr Diet 2012;4:345–53. 3 Minor formatting edits have been made to the published text, which is reproduced with permission.

Psychological predictors of dietary intentions in pregnancy

Abstract

Background: Consuming a healthy diet in pregnancy has the potential to improve obstetric outcome, including minimising the risk of macrosomia. Effective promotion of dietary change depends on identifying and targeting determinants of gestational diet. The present study aimed to model psychological predictors of intentions to reduce the intake of high-fat and high-sugar foods, and increase fruit and vegetable (F&V) consumption, among pregnant women.

Methods: One hundred and three pregnant women completed questionnaire measures of intentions to modify the consumption of the target foods, current intake, perceived vulnerability to, and severity of, adverse outcomes of non-healthful consumption of these foods (i.e. ‘threat’), benefits of dietary change to mother and baby, barriers to dietary changes and social approval for dietary change (‘subjective norms’). A cross-sectional design was used. Logistic regression analyses were undertaken to model dietary change intentions.

Results: Participants who reported excessive current intake of high-fat and high-sugar foods were more likely to commit to reducing the intake of these foods. The perceived benefits for mother and baby enhanced the mothers’ intentions to eat more F&V and fewer high-fat foods and marginally significantly increased their intentions to reduce the consumption of high-sugar foods. There were no effects of threat, barriers or subjective norms.

Conclusions: Lack of effects for barriers, threat and subjective norms may indicate that pregnant women discount barriers to health-promoting behaviour, understand the threat posed by unhealthy eating and perceive social approval from others. Dietary change interventions for pregnant women should emphasise likely positive outcomes for both mother and child.

Introduction

Research in gestational diet and nutrition has traditionally focused on preventing nutritional deficiencies in the maternal diet and ensuring adequate neonatal growth. 4 There is, however, growing interest in the potential for dietary changes among pregnant women with GDM or obesity to minimise the risk of macrosomia and associated adverse outcomes, including the risk of obesity in the child in later life. 4–6 Maternal glucose is the main substrate for the growing fetus and, consequently, maternal hyperglycaemia may result in fetal hyperinsulinaemia, thereby increasing growth rate and thus the risk of macrosomia. 7 Maternal insulin sensitivity reduces with advancing pregnancy. 8 Certain dietary interventions might, theoretically, reduce insulin resistance among pregnant women. 9 Reducing the consumption of foods rich in carbohydrates that release glucose rapidly into the bloodstream [i.e. high-glycaemic index (GI) foods] can promote glycaemic control and improve insulin sensitivity by manipulating the type of carbohydrate-rich foods and drinks consumed rather than necessarily restricting the quantity of carbohydrates per se. 7,10 A recent review found some evidence to support the use of low-GI diets, defined by the consumption of carbohydrates that release glucose gradually, in women with GDM, although it is less clear whether or not they could also benefit non-diabetic women. 7 Two intervention trials in non-diabetic women have yielded promising results, with reduced delivery rates of babies who are LGA (i.e. > 90th birthweight percentile) being observed among women who ate a low-GI diet relative to those consuming a usual diet. 11,12 Notably, both studies included women with a range of body weights, suggesting that dietary glycaemic control may benefit both normal and overweight women, although there are some concerns over ensuring adequate fetal growth, particularly in normal-weight women. 13 Another study investigating overweight and obese pregnant women found that a low-glycaemic load (GL) diet (i.e. foods with low values on an index that accounts for both GI value and carbohydrate content) improved cardiovascular risk factors, lengthened pregnancy duration and increased infant head circumference. 14 Further clinical trials are planned or are under way that aim to explore the impact of such diets on pregnancy outcome in obese women, these include the UK Pregnancies: Better Eating and Activity Trial [UPBEAT; International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) 89971375], described in this programme, and another in women who have had a previous macrosomic pregnancy. 15

Reducing the GI relies on changing dietary behaviour in pregnant women. Changing pregnant women’s food choices will be aided by identifying and targeting the determinants of diet in pregnancy. Behaviour change is often portrayed as a consequence of changes in psychological variables: modifying knowledge, attitudes and beliefs in turn influences intentions16 and ultimately alters behaviour. 17 However, interventions designed to improve diet in pregnancy, including those designed specifically to lower the GI or GL,12,14 have neglected psychological changes. 2,18 Identifying psychological determinants of dietary decisions in pregnancy would assist intervention development in two respects. First, psychological variables represent potential targets for intervention. Second, assessing changes on these variables can aid our understanding of why diet has or has not changed in response to an intervention. 17 However, little empirical evidence is available regarding the psychological determinants of dietary behaviour in pregnancy.

Pregnancy has been portrayed as a transitional life event that is psychologically characterised by heightened awareness of (and responsiveness to) threats to the health of either mother or child. 19 Risk perceptions may therefore underpin motivation to take health-protective action in pregnancy. The health belief model (HBM)20 proposes that responses to risk are underpinned by two psychological dimensions: threat perception and behavioural evaluation. 21 Threat perceptions are a function of perceived susceptibility to, and perceived severity of, a threat (e.g. GWG or its associated health complications), and behavioural evaluations refer to the expected benefits of, and barriers to, taking action (e.g. consuming a nutritionally balanced diet) to avert the threat. The HBM predicts that protective behaviour will be elicited where the individual perceives themselves as vulnerable to a serious threat, the action is deemed beneficial and there are few barriers to taking action. Although originally proposed as direct determinants of health behaviour, subsequent research has indicated that the HBM constructs largely influence action indirectly via the formation of intentions, which subsequently determine behavioural responses. 16

As determinants of intention, the threat perceptions and cost–benefit analyses proposed by the HBM compete with social influences in guiding health motivation in pregnancy. 22 For example, intentions to consume a healthy diet in pregnancy are likely to be a function not only of the subjective utility of a nutritionally balanced diet for averting health threats, but also expected (dis)approval from relevant others for consuming such a diet. 22 Expectations of friends, family and health-care professionals may therefore contribute to dietary decisions in pregnancy independently of a subjective threat and behaviour evaluations.

Dietary change focused on a reduced intake of saturated fat and high-sugar foods, as well as increased F&V consumption, has been proposed as an approach for reducing insulin resistance in pregnancy,9 and is consistent with the UK national guidance for healthy eating in pregnancy. 23 The present study assessed pregnant women’s attitudes and motivations concerning these food types, and examined which psychological variables predicted intentions to consume healthier quantities of these foods over the remainder of the pregnancy term. Our analysis draws on variables from the HBM,20 augmented by a measure of perceived social approval (i.e. ‘subjective norms’). 22 To isolate the unique influence of psychological variables on behaviour change intentions, we controlled for the current intake of each of the three foods, as well as the pregnancy-related personal characteristics that may influence dietary intentions or behaviour [pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), gestational age and parity]. 24,25

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were approached, in person, by a researcher at antenatal clinics and given a paper questionnaire (together with a prepaid envelope) for return (see Appendix 1). One hundred and three pregnant women returned completed questionnaires. Data were collected from one hospital outpatient clinic and five community clinics in south-east England (n = 92) and one hospital outpatient clinic in north-east England (n = 11). Response rate data were not available. A cross-sectional design was used. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from a NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference number 09/H0802/5).

Measures

Personal characteristics

Participants completed self-report measures of parity, gestational age (in weeks), height (m/cm or ft/in) and pre-pregnancy weight (kg or st). Height and weight measures were used to compute pre-pregnancy BMI values. For sample description purposes, participants also indicated their ethnicity and highest educational qualification.

Psychological variables

Unless otherwise indicated, psychological variables were measured using single items in the form of statements with which participants indicated (dis)agreement on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Scores on multi-item scales represented the mean of all component items. Measures related to three dietary behaviours in pregnancy: eating (more) F&V, eating (less) high-fat food and eating (less) high-sugar food.

Current behaviour was estimated based on the perceived adequacy of current dietary intake [‘Do you think the amount of (F&V/high-fat food/high-sugar food) you eat is much too little/too little/about right/too much/much too much?’]. Participants who reported eating ‘too much’ F&V or ‘too little’ high-fat or high-sugar food were excluded from analyses; this removed nine participants (7%) from the high-fat and high-sugar food analyses, respectively, and four participants (3%) from the F&V analyses. Remaining values were dichotomised to denote deficient current health behaviour (‘much too little’ or ‘too little’ F&V, ‘too much’ or ‘much too much’ high-fat or high-sugar foods, coded as 0), or adequate current behaviour (‘about right’, coded 1).

Intention items followed a stem: ‘Over the rest of your pregnancy, do you intend to eat much less/eat a little less/ not change/eat a little more/eat much more [F&V, high-sugar foods, high-fat foods]?’. Participants intending to eat less healthily (i.e. less F&V, more high-sugar food or more high-fat food, one participant per behaviour, 1%) were excluded from respective analyses. Intention scores were transformed into binary values to represent no intended change (coded 0) or an intention to consume a healthier diet (coded 1, i.e. more F&V, less high-fat food and less high-sugar food).

Perceived vulnerability and perceived severity were each measured using two items. Items related to adverse health outcomes for mother and baby separately [e.g. vulnerability, ‘Eating too few F&V could cause problems for (me/my baby)’; severity, ‘I would worry about (my health/my baby’s health) if I ate too few F&V’]. For each behaviour, all four items were consistently highly intercorrelated (minimum a = 0.91) and so were combined into a composite threat measure.

Perceived benefits related to positive outcomes for mother [e.g. ‘Eating (more F&V/less high-fat foods/less high-sugar foods) than I do now would . . . make me look better/make me feel better/prevent me putting on too much extra weight’] and baby (‘. . . be good for my baby/reduce my chances of having a baby that is too big’). Items were adapted from previous research. 26,27 For each behaviour, the five items were combined into a reliable composite index (minimum a = 0.82).

Perceived barriers items were combined into behaviour-specific indices. Barriers to consuming F&V related to difficulty of access and preparation, and cost (e.g. ‘It costs too much to eat more F&V’). Barriers to reducing fat consumption related to high-fat foods being easy to cook, satisfying cravings and helping deal with stress. Barriers to reducing sugar consumption related to using high-sugar foods to satisfy cravings and helping deal with stress.

For each behaviour, subjective norm items, which focused on expected approval from family and health-care professionals, respectively (e.g. ‘My family would approve of me eating fewer high-fat foods during pregnancy’), were combined because of strong inter-item correlations (minimum, r = 0.66; minimum, a = 0.80).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using predictive analytics software (PASW Statistics version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Multiple logistic regressions were run to explore psychological predictors of intentions to consume a healthier diet, controlling for personal characteristics (pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational age, parity) and current behaviour. For ease of interpretation, psychological variables (threat, benefits, barriers, subjective norms) were dichotomised, using a median split to separate lower (below the median value) and higher scores (at or above the median).

Cases with missing intention values were excluded from the analyses to ensure that dependent variable scores were observed rather than estimated. This removed four cases relating to F&V consumption, 12 for high-fat consumption and 11 for high-sugar consumption, thereby reducing the sample size to n = 99 for analyses of F&V consumption intentions, n = 91 for high-fat foods and n = 92 for high-sugar foods.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants were aged from 20 to 45 years (mean age 33 years), and between 8 and 40 weeks pregnant (mean 27 weeks). The majority (n = 49; 48%) were in the second trimester (13–28 weeks) or third trimester (29 weeks to birth; n = 47; 46%), with seven participants (7%) in the first trimester (up to 12 weeks) of pregnancy. Most participants (n = 68; 66%) were nulliparous. Pre-pregnancy BMI was in the range 14.8–45.8 kg/m2 (mean 24.9 kg/m2). Twenty-two participants (21%) were overweight (BMI of ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 < 30.0 kg/m2) and a further 17 participants (17%) were obese (BMI of ≥ 30.0 kg/m2).

Participants were predominantly of white ethnic origin (n = 72; 70%). Eleven participants (11%) were of black or black British ethnicity, eight were Asian or Asian British (8%), nine were of mixed (n = 6; 6%) or other ethnicity (n = 3; 3%) and three participants did not indicate their ethnicity. Most had a university education (n = 74; 72%). Ten participants (10%) had an A-level education, 15 participants (15%) had National Vocational Qualifications or General Certificate of Secondary Education qualifications, and one participant had no formal qualifications (1%). Three participants (3%) did not report qualifications.

Descriptive statistics

Most participants intended to increase their F&V consumption (n = 66, 67%) or decrease their high sugar intake (n = 54, 57%) during their pregnancy, although fewer than half of the participants intended to reduce their fat consumption (n = 41, 45%). Only a minority felt that they ate too few F&V (n = 21, 21%), too much high-sugar food (n = 31, 34%) or too much high-fat food (n = 26%), with most participants viewing their current intake of these foods as ‘about right’.

Current behaviour and intentions were negatively correlated for each behaviour: participants who felt they ate ‘too little’ F&V had stronger intentions to increase F&V consumption (r = –0.26; p = 0.009) and those who felt they consumed ‘too much’ high-sugar or high-fat foods were more likely to want to decrease their intake (r = –0.41 and –0.42; p < 0.001, respectively).

Correlations were observed between high-fat and high-sugar consumption intentions (r = 0.69; p < 0.001) and between current intake of high-fat and high-sugar foods (r = 0.57; p < 0.001), indicating similar beliefs and behaviour surrounding these two foods. Weaker correlations were observed between F&V intentions and high-fat or high-sugar intentions (maximum r = 0.35; p < 0.001). Correlations between perceived adequacy of F&V consumption and of high-fat or high-sugar foods (maximum r = 0.22; p = 0.03) were moderate in size.

Participants tended to be aware of the potential health threat associated with unhealthy dietary consumption in pregnancy (mean score 4.25), although the perceived benefits of healthy eating for mother and baby were more modest (mean score 3.66; Table 1). Average barrier scores were consistently below the scale mid-point, implying that participants felt relatively unhindered in changing their diet, although participants tended to expect even fewer barriers to consuming more F&V (mean score 1.81) than to reducing high-fat (mean score 2.78) or high-sugar foods (mean score 2.85). Social approval from family and health-care professionals was seen as supportive for all three behaviours (mean score 3.91) and strong intergroup correlations for each behaviour reflected perceived agreement between family and health-care professionals in this respect.

| Variables | Food type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| F&V (n = 99) | High-fat food (n = 91) | High-sugar food (n = 92) | |

| Perceived adequacy of current behaviour, n (%) | About right: 78 (78%) | About right: 67 (74%) | About right: 61 (66%) |

| Too few F&V: 21 (21%) | Too much high-fat food: 24 (26%) | Too much high-sugar food: 31 (34%) | |

| Intention to engage in health behaviour, n (%) | Do not intend to change: 33 (33%) | Do not intend to change: 50 (55%) | Do not intend to change: 38 (41%) |

| Intend to increase: 66 (67%) | Intend to decrease: 41 (45%) | Intend to decrease: 54 (59%) | |

| Threat (posed by inaction), mean (SD), median | 4.25 (0.78), 4.25 | 4.39 (0.53), 4.25 | 4.43 (0.55), 4.38 |

| Benefits of healthy behaviour for mother and baby, mean (SD), median | 3.66 (0.67), 3.80 | 3.67 (0.81), 3.80 | 3.65 (0.84), 3.60 |

| Barriers to healthy behaviour, mean (SD), median | 1.81 (0.82), 1.67 | 2.78 (0.72), 2.67 | 2.85 (1.02), 3.00 |

| Subjective norms (family, health professionals), mean (SD), median | 4.07 (0.89), 4.00 | 3.91 (0.96), 4.00 | 3.89 (0.98), 4.00 |

Predicting dietary consumption intentions

For each of the three food types, a model comprising demographic variables, current behaviour and psychological variables was significantly predictive of intentions to eat more healthily (minimum model χ2 = 25.37; p = 0.001).

As shown in Table 2, participants who perceived their current intake to be excessive were significantly more likely to intend to eat less high-fat foods [odds ratio (OR) 5.28; p = 0.02] and high-sugar foods (OR 5.65; p = 0.01) than those who believed their intake to be adequate. A tendency for participants who perceived that they ate ‘too few’ F&V to intend to increase their F&V intake (OR 3.36) was not statistically significant (p = 0.15).

| Variables | Intention to eat | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More F&V (n = 99) | Less high-fat foods (n = 91) | Less high-sugar foods (n = 92) | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value for trend | OR (95% CI) | p-value for trend | OR (95% CI) | p-value for trend | |

| Current engagement in health behaviour | About right: 1.00 reference | 0.15 | About right: 1.00 reference | 0.02 | About right: 1.00 reference | 0.01 |

| Too few F&V: 3.36 (0.64 to 17.60) | Too much high-fat food: 5.28 (1.38 to 20.19) | Too much high-sugar food: 5.65 (1.50 to 21.22) | ||||

| Threat | Lower threat: 1.00 reference | 0.83 | Lower threat: 1.00 reference | 0.68 | Lower threat: 1.00 reference | 0.18 |

| Higher threat: 0.89 (0.31 to 2.55) | Higher threat: 1.27 (0.41 to 3.89) | Higher threat: 2.05 (0.72 to 5.89) | ||||

| Benefits for mother and baby | Lower benefits: 1.00 reference | 0.02 | Lower benefits: 1.00 reference | 0.003 | Lower benefits: 1.00 reference | 0.10 |

| Higher benefits: 6.59 (1.28 to 10.11) | Higher benefits: 5.70 (1.78 to 18.21) | Higher benefits: 2.66 (0.82 to 8.66) | ||||

| Barriers | Higher barriers: 1.00 reference | 0.27 | Higher barriers: 1.00 reference | 0.86 | Higher barriers: 1.00 reference | 0.21 |

| Lower barriers: 0.56 (0.20 to 1.57) | Lower barriers: 1.12 (0.33 to 3.80) | Lower barriers: 0.50 (0.17 to 1.49) | ||||

| Subjective norms | Lower norms: 1.00 reference | 0.22 | Lower norms: 1.00 reference | 0.29 | Lower norms: 1.00 reference | 0.21 |

| Higher norms: 1.98 (0.66 to 5.91) | Higher norms: 1.93 (0.57 to 6.57) | Higher norms: 2.24 (0.64 to 7.85) | ||||

| R2 (Cox and Shell) | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.32 | |||

| R2 (Nagelkerke) | 0.31 | 0.45 | 0.43 | |||

| Model χ2 | 25.38*** | 36.84*** | 34.93*** | |||

There was no effect of threat on intentions for any of the three food types (maximum OR 2.05; p = 0.18). However, strong effects were found for perceived benefits of action for mother and baby, with participants who expected greater benefits being more likely to intend to eat more F&V (OR 3.59; p = 0.02) and fewer high-fat foods (OR 5.70, p = 0.003). A similar tendency was found for intention to eat fewer high-sugar foods (OR 2.66), although this was only marginally significant (p = 0.10). There were no effects of perceived barriers (minimum p = 0.21) or of subjective norms (minimum p = 0.21) on dietary intentions.

Discussion

A low-GI diet in pregnancy has the potential to improve obstetric outcome. 12,14 The design of diet-based interventions in pregnancy may be aided by identifying the psychological determinants of dietary choices because modifying these variables should translate into dietary change. 17 The present study examined appraisals of benefits and barriers, threat perceptions, evaluations of current behaviour and perceived social pressures (subjective norms) as potential influences on intentions to improve three aspects of diet linked to insulin resistance (increased F&V consumption, decreased high fat and high sugar consumption19) in a community sample of pregnant women. Perceived levels of current behaviour predicted intentions to eat fewer high-fat and high-sugar foods, with participants who felt that they ate too many high-sugar or high-fat foods being more likely to intend to reduce their consumption. Perceived benefits of action for mother and baby were associated with the intention to eat more F&V and less high-fat food, with participants who perceived greater benefits of adopting more healthy eating patterns being more likely to intend to do so. A similar association, which was only marginally significant, was observed between perceived benefits and intention to eat less high-sugar food. There were no associations between perceived barriers, threat perceptions and subjective norms and intentions.

Our analysis drew on variables derived from the HBM,20 which proposes that health behaviour arises from deliberation over the threat posed by health risks, as well as the benefits of, and barriers to, taking action recommended to minimise these threats. We observed consistently high levels of perceived threat among our sample and, perhaps as a result of minimal variation in threat levels, there was no association between threat and dietary intentions. As predicted by the HBM, perceived benefits for mother and baby were associated with healthy eating intentions, although, in contrast to theoretical predictions,16 perceived barriers had no impact. Although further evidence from larger samples is needed, these results suggest that, when making the cost–benefit analyses that underpin evaluations of health-related behaviours,28 pregnant women may weigh barriers to behaviour less heavily than do the general population. Perhaps this may be understood in the light of the immediacy with which health threats faced by pregnant women can be realised. Perceived health benefits of diet outside pregnancy may be typically distal and orientated towards the prevention of later morbidity or mortality, whereas barriers relate to immediate short-term obstacles (e.g. missing out on tasty foods, choosing less favoured options). By contrast, the benefits of healthy eating in pregnancy, such as the prevention of macrosomia and the reduced likelihood of delivery complications, are typically more proximal, becoming apparent at or shortly after birth. Consequently, these benefits may be easier to foresee or are perceived to be more real than the distal benefits associated with health behaviours outside pregnancy. To support this hypothesis, further exploration is needed of the health decision processes in pregnancy and other conditions when the health effects are more immediate than the decision processes in non-pregnant community samples. However, the stronger effects of perceived benefits than perceived barriers in our sample, coupled with raised threat perceptions, support the conceptualisation of pregnancy as a period of heightened responsiveness to potential health risks and a greater appreciation of the value of health-protective action. Pregnancy may therefore represent ‘an opportune time to initiate (behavior) change’.

Several behaviourally based pregnancy interventions have been described based on the provision of dietary ‘counselling’. 29–33 However, the term ‘counselling’ can refer to a variety of behaviour change techniques. 34 Although some interventions have focused primarily on identification of barriers to healthy eating,30,32 the results of the present study indicate that bolstering expectations of positive outcomes for both mother and child associated with adopting a healthier diet may have more impact. The under emphasis of the benefits of healthy diet in interventions tested to date may reflect an assumption that pregnant women are aware of the implications of gestational diet. 2 Changing dietary choices in pregnancy may require efforts to ensure that pregnant women consistently prioritise the benefits of healthy eating over beliefs that support consumption of unhealthy foods. No relationship was observed between perceived social approval from family or health-care professionals and healthy eating intentions. However, the high mean scores, coupled with the strong positive correlation between family and health-care professional expectations, suggest that our sample perceived strong and consistent approval for healthier dietary choices. The absence of an association between norms and intentions may therefore be the result of a lack of variation, although more work is needed to establish the generalisability of the normative beliefs of our sample.

The findings of the present study are limited in several respects. The survey was cross-sectional, and so we could not observe ‘prediction’ of intentions in a temporal sense or assess the effects of intentions on subsequent consumption of each of the three foods types. Although further longitudinal research is needed, there is considerable theoretical and empirical evidence to support the temporal relationships that we have inferred, as well as the assumption that modifying dietary intentions will change dietary behaviour. 35 The data were also based on self-report, which is susceptible to responses biased by participants’ motivations to portray themselves positively. 36 Retrospective self-reports may underestimate true pre-pregnancy weight especially in obese women,37 although objective weight data were not available to validate our BMI measure. Participants were not informed by us of weight gain or gestational diet recommendations or of the potential consequences of healthy and unhealthy eating in pregnancy, and the accuracy of their perceptions was not tested and cannot be estimated. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that modifying such perceptions may boost healthy eating intentions over the remainder of pregnancy. The representativeness of our sample is questionable; for example, participants were mostly white and well educated, and more than two-thirds were educated to university level. This may reflect a systematic participation bias within our pool of potential participants, although we cannot test this because no data were available from those who declined participation. However, our sample encompassed a wide distribution of participant BMI scores and gestational age. Most participants were in the second or third trimester of pregnancy, and more work is needed to explore beliefs and behaviour earlier in pregnancy because dietary changes achieved in early pregnancy and maintained over the remaining gestational period may be most beneficial. Our sample was also modest in size and, therefore, unable to identify small effects, neither could we reliably explore differences in the beliefs, intentions and behaviour of demographic subgroups of pregnant women. Further research, using larger samples, is needed into whether or not nutrition beliefs, intentions and behaviour differ systematically by, for example, parity, age, socioeconomic status or ethnicity. Such differences may have implications for the design and delivery of effective dietary interventions in pregnancy.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our results offer some insight into the health beliefs and dietary choices of pregnant women. Best practice for diet modification in pregnancy is likely to require the adoption of health promotion strategies to target the underlying psychological determinants of gestational diet.

Implications for intervention development

This study provided important insights into optimising delivery of the intervention, the results indicating that pregnant women are likely to respond to bolstering their expectations of positive outcomes for both mother and child through focus on a healthier diet, rather than an emphasis on overcoming perceived barriers to behavioural change.

To assess delivery style, mode and method of delivery and acceptability to recipients

Exploratory study: interviews with obese pregnant women to inform the development of a pilot randomised controlled trial intervention and protocol

This pre-trial exploratory interview study aimed to examine the sociocultural context within which women made decisions about pregnancy, diet and lifestyle, body image, health beliefs and their readiness to engage with the type of health interventions that the trial team was in the process of developing.

A total of 30 women were approached, and semistructured qualitative interviews were undertaken with 13 pregnant women with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2. Maximum variation sampling was used, selecting by maternal age, family composition (e.g. lone parent, first baby) and sociodemographic characteristics (employment, education level, ethnicity). The interviews aimed to explore pregnant women’s existing beliefs about diet and activity in pregnancy, their receptiveness to dietary change, perceived economic and time implications, increased activity levels and other views on acceptability. We explored obese women’s preferred approaches to intervention delivery (e.g. individual or group contacts, inclusion of family members, frequency of contacts, setting for intervention delivery, etc.) and barriers and constraints to change, including the impact of family circumstances and need for childcare. We investigated what types of activity obese pregnant women perceive to be feasible and what they believe to be the key features of a healthy diet in pregnancy. The interview schedule is provided in Appendix 2. Interviews were taped, transcribed and analysed using a framework approach geared to producing policy- and practice-relevant findings. The interviews were undertaken at either Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, or the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle. The qualitative studies were given ethics approval [Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) reference number 09/H0802/05].

Sample characteristics

The mean age of the women was 35 years (range 25–41 years). The mean gestational age at the time of the interview was 30 weeks (range 15–39 weeks). The mean BMI was 38 kg/m2 (range 32–58 kg/m2). Eight of the women were self-defined as white and five were black. Five women were multiparous and the others were primiparous. Eight women were employed at the time of the interview. Four women were managing pre-existing chronic health conditions.

Findings

Comparative thematic analysis of the interview data led to the identification of themes and subthemes that contributed to an overall category, ‘willingness to engage with diet and lifestyle changes during pregnancy’. This category included two first-order themes (meaning that they are drawn directly from interview text): ‘feeling ill, pregnancy symptoms, and complex obstetric histories’ and ‘experience of stigma’. Each had the potential to impact upon women’s engagement with the proposed RCT and willingness to engage in lifestyle change was also mediated (either facilitated or reduced) by the relative complexity of the women’s lives.

Theme 1: feeling ill, pregnancy symptoms and complex obstetric histories

Interviewees reported feeling ill during pregnancy or described experiencing pregnancy in the context of past pregnancy loss, including miscarriage and stillbirth. Four out of 10 of the interviewees were affected by GDM in their current pregnancies (note that women with known GDM were excluded from recruitment in phase 3, UPBEAT, but approximately one in four developed GDM, see Chapter 5). Common pregnancy-related symptoms, particularly nausea, tiredness and pelvic or back pain, also interfered substantially with women’s eating patterns and ability to undertake PA.

Some women interviewed had worked hard to address their weight and activity before pregnancy or as part of treatment for infertility. These activities involved notable cost and effort: some interviewees had attended diet groups such as Weight Watchers® (New York City, NY, USA) or Slimming World (Alfreton, UK) or bought diet plan foods; others paid to attend gyms or fitness classes or took up exercise activities with their partners. However, once pregnant, they were advised to stop dieting by commercial weight loss group leaders. Others were advised against exercise by clinicians, particularly after they had experienced past miscarriages:

I know that I was overweight before I was pregnant, but I was quite conscious of the fact and I was doing something about it, I was exercising loads, but then as soon as I fell pregnant I was like, I’m not doing any exercise, because I was scared in case anything happened.

White English ethnicity, aged 27 years, married, a BMI of 36 kg/m2 and interviewed at 29 weeks’ gestation

The tiredness and nausea of early pregnancy, combined with busy lives looking after other children, doing household chores and working, all decreased likelihood of additional physical exercise. Pelvic pain was a significant problem for 6 out of 10 interviewees, and others reported back pain. The combination of pain and illness symptoms as pregnancy progressed meant that many led increasingly sedentary lives:

I mean I was quite keen to like stay quite fit, and I go for long walks and stuff, just because I thought it’s better for me long term, but with this [pelvic] pain I’ve had I’ve been literally like, the physio who I see at the hospital, she’s just literally said, ‘You’ve got to treat it like a sprained ankle and rest it.’ And I’m saying, ‘Yeah but then you just sit, it’s not good for us just sitting all the time either.’ So that was kind of a goal, I think I wanted to like do more exercise but I haven’t been able to.

White English ethnicity, aged 27 years, married, a BMI of 36 kg/m2 and interviewed at 29 weeks’ gestation

At thirty-five I first got pregnant and I had . . . a miscarriage at 13 weeks. It was quite traumatic . . . And then I had three more [miscarriages], in the December I got pregnant again . . . I had a 7-week scan and there was no heart beat . . . then I lost it. So I thought to myself, well, it could be stress, maybe I should change my lifestyle . . . I didn’t feel that fit, I felt overweight . . . I actually stopped exercising because with my other pregnancies the doctor had said, ‘Don’t exercise, we don’t really know why you’re miscarrying’. And I really missed the exercise. I missed that feel-good factor. I’ve managed my expectations, I’m hoping to breastfeed successfully and the doctors have said that can help shift the weight. I’m definitely going to be eating an extremely healthy diet, in fact my mother would be proud of me.

White English ethnicity, aged 41 years, married, a BMI of 32 kg/m2 and interviewed at 39 weeks’ gestation

Do you have any specific goals for yourself during this pregnancy?

No. Just to get to the end of it.

White English ethnicity, aged 35 years, single, a BMI of 34 kg/m2 and interviewed at 38 weeks’ gestation

Interviewees rarely envisaged their pregnancies as ‘normal’ or healthy, and some had been informed by health professionals that the induction of labour at, or before, term was a possibility, either because a diagnosis of GDM meant they were being screened for elective induction to reduce complications of birth with a LGA baby or for other reasons, such as pre-eclampsia. However, this perspective was not universal: at least one interviewee who had GDM felt more positive about her physical health during pregnancy. She reported substantial weight loss prior to pregnancy, and felt confident that she was managing her diet and blood sugars well and could lose weight again following birth.

Theme 2: experience of stigma

Linked to the notion that their pregnancies were not experienced as healthy or ‘normal’, some interviewees recounted occasions when they felt stigmatised, singled out or labelled, with assumptions made about their intelligence and life skills on the basis of their body size. They felt that they did not receive the positive public reinforcement that other pregnant women experience as their ‘bumps’ were often assumed to be body fat. However, some interviewees challenged the stereotype of overweight women as lazy, uneducated consumers of fast food. Others felt happy with their size because, having struggled with being larger all their lives, they had come to terms with this, or because they had already lost substantial weight. Given the difficulties that openly discussing weight during pregnancy posed for women, the medical language used to discuss weight generated controversy. The term ‘obese’ was often problematic because it did not equate to women’s own views of their bodies. Some felt that even the term ‘BMI’, while perhaps more neutral than ‘overweight’ or ‘obese’, was still not useful, because failed to reflect their overall weight trajectories, especially if they had achieved pre-pregnancy weight loss:

I think the term ‘obese’ or ‘morbidly obese’ is absolutely horrendous. I think it’s really awful, even if you were a hundred stone or 12 stone, it’s a really, really awful word. Um . . . it’s just an awful kind of terminology. I just think if you’re overweight just say they’re overweight, you know, there’s no need to kind of say ‘morbidly’, it sounds like you’re some sort monstrous disgusting person type thing.

White English ethnicity, aged 27 years, married, a BMI of 36 kg/m2 and interviewed at 29 weeks’ gestation

Several interviewees recalled being told their BMI was raised or high, and that they found it painful and offensive to be described in this way (they described being ‘singled out’ or ‘pounced on’) and felt that health professionals addressed the subject in ways which were rude and insensitive. Other interviewees had not heard the term ‘BMI’, and said that their doctors or midwives had not mentioned their weight but focused instead on other issues, such as smoking or pregnancy complications.

Theme 3: willingness to engage with diet or lifestyle changes during pregnancy

Although interviews were undertaken with pregnant women who were known to have a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above, and whose routine care during pregnancy included information about weight gain, diet and lifestyle from health professionals, most mentioned broad public health messages about diet (such as the need to eat ‘five-a-day’), rather than identifying implications of raised BMI for their individual pregnancy outcomes.

In the interviews, women volunteered information about their age, blood sugar control and smoking, but did not talk about whether or not altering their own behaviour might change pregnancy outcomes for themselves or their babies. Despite their awareness of broad public health dietary advice, women did not volunteer more specific information about fat or carbohydrate intake during pregnancy. Interviewees also questioned dietary advice during pregnancy, reasoning that health advice varies over time and should be taken with ‘a pinch of salt’, citing too much focus on food ‘scares’ and too little effort towards individualised education.

Many women felt they needed to suspend their attempts to manage their diet or exercise while they were pregnant; pregnancy was seen as time when weight gain was inevitable, dieting contraindicated and when metabolic demands and nausea altered food preference and appetite. Instead, their efforts were focused upon ‘getting through’ this pregnancy, with a view to addressing diet and exercise goals during the postnatal period:

I don’t have any problems with [pregnancy body changes] because when I had [my daughter] I lost all the weight I gained quite quickly, . . . so it’s not been a problem for me to worry about. And I’ve actually gained less weight now than I did when I was having her, so I haven’t really had any negative thoughts or worries about that. So that’s been good. [Laughs] That’s been good.

Black African ethnicity, aged 32 years, married, a BMI of 35 kg/m2 and interviewed at 36 weeks’ gestation

When the proposed pilot RCT diet and PA intervention was described to interviewees, responses were mixed. Most supported the idea of an educational approach to diet and cooking, but fewer thought that advice about PA would be valuable. The suggestion of a group-based intervention engendered a polarised response; about half welcomed this idea and thought they would benefit from sharing their experiences and social support. The remainder said they would not participate in a group intervention, either because this would pose difficulties in the contexts of their work commitments and family lives or because the intention to single women out on this basis was patronising and grew from a perceived assumption that they needed to be educated about issues that they understood only too well:

If [the health trainer (HT) group] was happening now, would that be something you’d be interested in?

Yes, I would. Because sometimes, especially about food, I don’t know what to eat and maybe they can give me ideas what I can do. Or maybe they can encourage me to go to the classes.

Black African ethnicity, aged 38 years, has partner, a BMI of 34 kg/m2 and interviewed at 15 weeks’ gestation

I would feel very belittled. [Laughs] I wouldn’t . . . no, I wouldn’t like that at all. Yes, fair enough, they could offer it. I know what’s healthy . . . well yes, I do know, even though I can understand some people say it and they don’t, but I do know! And, yes, I wouldn’t like someone telling me.

White English ethnicity, married, a BMI of 36 kg/m2 and interviewed at 27 weeks’ gestation

Me personally, no. Because of the fact of the family I’ve got. A new time mum it would be good for, somebody that can devote more time to it.

White English ethnicity, aged 41 years, lives with partner, a BMI of 37 kg/m2 and interviewed at 37 weeks’ gestation

Conclusions

The phase 1 exploratory study, undertaken with pregnant women with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 who matched criteria for inclusion in the proposed UPBEAT pilot RCT other than gestational age at recruitment and concurrent underlying health problems (see Implications for intervention development and limitations) but were not involved in the subsequent pilot RCT, suggested that willingness to change lifestyle was diminished by pregnancy illness and symptoms and by the demands placed upon women’s time by their family and work responsibilities. A lack of concrete knowledge about the effect of changing diet or increasing PA on pregnancy or birth complications also appeared to reduce the perceived value of the intervention. Previous experience of being stigmatised by peers or health professionals affected some women’s willingness to participate. Although most of these findings were also identified during the pilot trial process evaluation, the influence of stigma was less apparent. It is unclear whether or not this is because women who felt stigmatised were less likely to participate in the pilot RCT or whether modifications to the recruitment approach reduced the experience of stigma.

Implications for intervention development and limitations

Important information was provided by these interviews that contributed to the delivery of the intervention, notably the need to avoid stigmatisation of women with a higher than normal BMI and the care required to approach the subject. This became a topic of continued discussion and learning throughout the trial development and the trial itself. In addition, these interviews led us to appreciate that some pregnant women who are obese may suffer considerable physical discomfort, which is likely to impact upon their motivation to undertake PA.

There were several important limitations to this study. These included many of the interviews being carried out towards term rather than at the proposed time of recruitment, and that several of the women were already affected by health complications, including existing diagnosis of GDM. Relevance to women approached to join the trial at 15–18 weeks of pregnancy was therefore limited.

To produce a combined diet and activity intervention for use in obese pregnant women

An intervention was developed based on goal-setting and review, to be delivered over a period of 8 weeks from recruitment by study-specific health trainers (HTs). Full details are provided in Chapters 2 and 4.

-

Dietary intervention: a dietary intervention was developed by a postdoctoral nutritionist (Dr S Barr) and, principal investigator (PI), Professor T Sanders based on the intention of reducing insulin resistance and improving maternal glucose homeostasis; the dietary component of the intervention included a low dietary GI, reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and reduced saturated fat intake.

-

PA intervention: PA advice was developed by a postdoctoral researcher (Dr Kinnunen) and PI (Dr Ruth Bell) based on the available literature and the intention of improving maternal glucose homeostasis and on Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guidelines. This component of the intervention was designed to encourage obese pregnant women to increase their daily activity incrementally over the period of delivery of the intervention and to maintain the achieved activity level as long as possible as their pregnancy progressed. Pedometers would be provided as a self-motivational tool and women would set individual step targets weekly.

-

Behavioural intervention: the behavioural theory on which to base the intervention was developed from control theory with elements from social cognitive theory. Strategies used included graded goals, behavioural goal-setting, monitoring behaviours, providing feedback regarding goal attainment, identification and problem-solving of barriers, enlisting social support and providing opportunities for social comparison. This approach also supported the building of self-efficacy. HTs delivered the intervention, following training that included the information gained during the development phase. Training of the HTs and midwifery staff who recruited the women continued during the 5-year programme.

To develop patient information leaflets, a provisional treatment manual and a training package to support intervention

The following were developed: patient information leaflets and consent forms, goal-setting and monitoring logbook, a PA ‘work-out’ digital versatile disc (DVD), a HT manual (standard operating procedures) (see Appendix 3) and a handbook for women in the intervention arm of the trial (see Appendix 4). All the trial literature was read, approved and amended with the help of obese women attending antenatal clinics at Guys and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, and approved by the King’s College London division of women’s health patient and public involvement group.

To assess feasibility, acceptability, validity and reliability of outcome measures

Physical Activity Measurement Study

The measurement of PA in a large number of subjects within a trial setting presents practical and financial issues. Accurate objective assessment would be the ideal, and at the time of study validation studies had shown that certain accelerometers could provide reasonably accurate objective measures. However, expense and collection and download of the accelerometer data were preclusive for the purposes of the main trial. A study was therefore designed to determine whether or not pedometers could be used instead of accelerometers in the pilot trial and the main RCT. This has been published as Kinnunen TI, Tennant PW, McParlin C, Poston L, Robson SC, Bell R. Agreement between pedometer and accelerometer in measuring physical activity in overweight and obese pregnant women. BMC Public Health 2011;11:501. 38 © Kinnunen et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd 2011. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For the purposes of this report minor formatting edits have been made to the original text.

Agreement between pedometers and accelerometers in measuring physical activity in overweight and obese pregnant women

Abstract

Background: Inexpensive, reliable objective methods are needed to measure PA in large-scale trials. This study compared the number of pedometer step counts with accelerometer data in pregnant women in free-living conditions to assess agreement between these measures.

Methods: Pregnant women (n = 58) with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 at a median of 13 weeks’ gestation wore a GT1M (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL, USA) accelerometer and a CW701 Digi-Walker™ Pedometer (Yamax, Bridgnorth, UK) for four consecutive days. The Spearman rank correlation coefficients were determined between pedometer step counts and various accelerometer measures of PA. Total agreement between accelerometer and pedometer step counts was evaluated by determining the 95% limits of agreement estimated using a regression-based method. Agreement between the monitors in categorising participants as active or inactive was assessed by determining kappa.

Results: Pedometer step counts correlated moderately (r = 0.36–0.54) with most of the accelerometer measures of PA. Overall step counts recorded by the pedometer and the accelerometer were not significantly different (medians 5961 vs. 5687 steps/day; p = 0.37). However, the 95% limits of agreement ranged from –2690 to 2656 steps/day for the mean step count value (6026 steps/day) and changed substantially over the range of values. Agreement between the monitors in categorising participants to active and inactive varied from moderate to good depending on the criteria adopted.

Conclusions: Despite statistically significant correlations and similar median step counts, the overall agreement between the pedometer and accelerometer step counts was poor and varied with activity level. Pedometer and accelerometer steps cannot be used interchangeably in overweight and obese pregnant women.

Background

Current recommendations emphasise that regular moderate-intensity leisure-time PA during an uncomplicated pregnancy may have benefits such as reducing fatigue, back pain, stress and depression and improving glycaemic control but has no known harmful effects on the health of the mother or the fetus. 39,40 However, the available evidence is limited, and larger and better-quality trials are needed to define the potential role for PA promotion in preventing pregnancy complications such as GDM and pre-eclampsia. 41 Most previous studies assessing PA in relation to pregnancy outcome have used questionnaires or other self-reported measurements of PA, as these are cheap to administer in large-scale studies. 42 Although some of the questionnaires have been validated in pregnant women either against accelerometer,43–45 a portable activity monitor46 or pedometer and a PA logbook,47 their validity has usually been low or moderate, especially with regard to the low-intensity activity that is common among pregnant women. 48 These limitations are also observed for PA questionnaires in other populations. 49,50 Therefore, inexpensive, objective PA measurement methods are needed for large-scale studies to obtain more accurate information on PA levels during pregnancy. Accelerometers and pedometers are the most commonly used objective methods of assessing PA in epidemiological studies, and have been used in a number of previous studies of pregnant women. 43,44,48,51–54 Although accelerometers provide more detailed information on PA than pedometers, pedometers are much less expensive and, therefore, more economically feasible for larger studies. 55 It is unclear whether or not pedometers and accelerometers provide comparable estimates of PA in pregnant women. This issue was recently explored in two small studies (n = 30 in both cases) examining pregnant women in free-living conditions56 and on a treadmill. 57 Similar comparisons have also been reported in healthy adults58,59 infected with human immunodeficiency virus60 and older people61 in free-living conditions. These studies suggest that pedometer and accelerometer step counts are highly correlated, but large individual differences in step counts exist. Nevertheless, pedometer step counts for assessing overall PA were advocated in most of these studies. 56,59–61

This study was designed as a preliminary investigation to determine appropriate PA measurement methods for a large RCT (UPBEAT) of a lifestyle intervention in obese pregnant women. Overweight and obese women have a higher risk of several pregnancy complications and may benefit from increasing their PA levels during pregnancy. 62,63 The aim of this study was to compare pedometer step counts with several accelerometer-derived measures of PA in overweight and obese pregnant women in free-living conditions.

Methods

Study participants

Participants were overweight and obese pregnant women with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2 based on self-reported height and measured weight at the first visit to antenatal care, usually before 12 weeks’ gestation. The exclusion criteria were a BMI of < 25 kg/m2, age < 16 years, multiple pregnancy, abnormal ultrasound scan result, complicated medical problems, inadequate language skills in English or inability to give written informed consent. A research midwife recruited the participants when they attended for their routine ultrasound scan at either 11–14 or ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation at the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, between July and December 2009. The participants were recruited in early pregnancy because information on the appropriate PA measurement methods for the intervention study starting in early pregnancy was needed.

A total of 286 women were eligible for the study and 93 (33%) agreed to participate. All participants signed a written informed consent for participation. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from St Thomas’s Hospital Research Ethics Committee, London, UK (National Research Ethics Service, Research Ethics Committee reference number 09/H0802/5).

Data collection

This study was a cross-sectional comparison of two objective PA measurement methods. The research midwife asked participants to wear an accelerometer and a pedometer for four consecutive days, including one weekend day. In adults, 3–5 days of monitoring by accelerometer usually provides a reliable estimate of PA. 64 The participants kept a diary to record when the monitors were put on and when they were taken off. Data on participants’ demographic details were collected using a short structured questionnaire. An appointment for returning the monitors was arranged after the 4-day period.

Accelerometer

The GT1M accelerometer used in this study was a small uniaxial monitor, which detects vertical accelerations over a user-specific time interval (epochs). 65 The former version of the ActiGraph accelerometer [Computer Science and Applications (CSA) 7164 model; ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL, USA] is one of the most extensively validated accelerometers and its activity counts correlate reasonably with double-labelled water-derived energy expenditure in non-pregnant populations. 66

Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on the right hip during waking hours except while swimming or having a shower or bath. They were given the choice of belt or waistband attachment and information was recorded on which they found to be the most comfortable. Most participants (n = 40, 69%) wore the accelerometer using a belt, whereas 14 (24%) clipped it on to the waistband of their clothing; in four participants (7%) the status was unknown. A 60-second epoch length was used in this study. The raw data were processed using the MAHUffe program [Medical Research Council (MRC) Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK] (www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/physical-activity-downloads). Periods of at least 60 minutes with no counts and days with < 500 minutes of total valid recording time were excluded.

The following cut-off points were used to assess time spent at different intensity levels: sedentary < 100 counts per minute (cpm),67 light activity 100–1951 cpm, moderate activity 1952–5724 cpm and vigorous activity > 5724 cpm. 68 These cut-off points were originally developed for CSA Model 7164 accelerometer. Currently, there is no consensus on the best cut-off points to be used and these may vary in different populations. The Freedson cut-off points, derived from treadmill conditions, were selected because leisure time PA in our population mainly consisted of walking and because these cut-off points have been used in previous studies comparing pedometers to accelerometers. 56,58–60

Pedometer

The CW701 Digi-Walker™ pedometer was used to measure daily step counts. Yamax Digi-Walker models have been shown to be among the most accurate models in measuring step counts. 69,70 The participants were asked to wear this device during the same time period as the accelerometer. The participants clipped the pedometer either to the accelerometer belt or to the waistband of their clothing depending on how the accelerometer was attached.

Categorising participants as active or inactive

Three different criteria were used to categorise participants as active: (1) ≥ 30 minutes moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA)/day (for accelerometer data only, as this information could not be derived from the pedometer data), (2) ≥ 10,000 steps/day and (3) ≥ 8000 steps/day. The first criterion was based on current PA recommendations. The second criterion is a commonly used step target in health promotion and has been shown to be associated with health benefits. 71,72 The third criterion was chosen as there is some evidence to suggest that 8000 steps/day corresponds to 30 minutes of MVPA/day measured by accelerometer when using similar intensity cut-off points as in the present study. 58,59,72

Statistical analyses

All activity data were averaged over the valid days of recording. The majority of variables were not normally distributed and, therefore, non-parametric methods were employed for all analyses. Continuous variables were described using the median and interquartile range. Differences in background characteristics of included (n = 58) and excluded (n = 35) participants were tested using Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorised variables.

Agreement between the accelerometer and the pedometer was assessed in several ways. Absolute step count measurements were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The relative agreement between pedometer-derived step counts and various accelerometer measures of PA was examined by determination of the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r).

Total agreement between accelerometer-derived and pedometer-derived step counts was evaluated by determination of the 95% limits of agreement. The difference between both measures of step counts was plotted against the mean of both measures. As there was a statistically significant negative correlation between these variables, which was not resolved by transformation, the limits of agreement were estimated by a regression-based method. To test whether or not the limits of agreement varied by baseline BMI (25.0–29.9 kg/m2 vs. ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) or gestational age (11–14 vs. ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation), interactions terms were added to regression models, and absolute residuals were compared by Student’s t-tests.

The classification of participants according to whether or not they recorded a daily mean of at least 8000 or 10,000 steps/day was compared between pedometer and accelerometer by calculating Cohen’s kappa over 2 × 2 contingency tables. Kappa was also determined to assess the agreement between those reaching 8000 pedometer steps/day and those achieving 30 minutes MVPA, as measured by accelerometer. Kappa values of 0.81–1.00 were regarded as indicating almost perfect agreement, while values of 0.61–0.80 indicated good agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement and 0.0–0.20 slight agreement. 73

Confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values for r were estimated by bootstrapping over 5000 iterations. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The majority of statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA); however, bootstrapping methods used Stata® version 10.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Of the 93 women recruited, 32 (34%) had valid accelerometer data for fewer than three days, 17 (18%) had valid data for 3 days and 44 (47%) had valid data for 4 days. All valid days from women with valid data for at least 3 days (n = 61) were included in further analyses, excluding three women who did not have pedometer data. The final study sample consisted of 58 women (62% of those recruited). The excluded women (n = 35) were younger (median age 28 vs. 32 years; p = 0.018) and more often smokers during the previous year (46% vs. 13%; p = 0.002) than the included women, and fewer of them were highly educated (5% vs. 59%; p < 0.001), but gestational age, BMI, parity, ethnicity, marital status and employment status were similar to those of the included women. The background characteristics of the included women are described in Table 3. The median age was 32 years and the median BMI was 29.3 kg/m2 (range 25.3–46.2 kg/m2).

| Background characteristics | Participants |

|---|---|

| Continuous variables, median (interquartile range)a | |

| Age (years) | 32 (27–36) |

| Weeks’ gestation | 13 (12–20) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3 (27.5–33.8) |

| Categorised variables, number (%) | |

| Weeks’ gestation category | |

| 11–14 | 32 (55.2) |

| ≥ 20 | 26 (44.8) |

| BMI category | |

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 35 (60.3) |

| ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 | 22 (39.7) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 27 (46.6) |

| 1 | 21 (36.2) |

| ≥ 2 | 10 (17.2) |

| Education (highest qualification)b | |

| GCSE or equivalent (at age ≥ 16 years) | 9 (17.0) |

| A-level or equivalent (at age ≥ 18 years) | 13 (24.5) |

| Degree or higher postgraduate qualification | 31 (58.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 48 (88.9) |

| Other | 6 (11.1) |

| Smoked during the last year | |

| Yes | 7 (12.7) |

| No | 48 (87.3) |

| Employed at the beginning of pregnancy | |

| Yes | 48 (84.2) |

| No | 9 (15.8) |

| Hours of employmentc | |

| Full time (≥ 37 hour/week) | 30 (63.8) |

| Part time (< 37 hour/week) | 17 (36.2) |

| Living with a partner/husband | |

| Yes | 55 (96.5) |

| No | 2 (3.5) |

Descriptive activity data

The median wear time of the accelerometer was 13 hours 40 minutes/day (Table 4). The women were sedentary for most of that time and total active time (median 4 hours 50 minutes/day) mainly comprised light-intensity activity. The median time spent in MVPA was 18 minutes/day.

| PA measure | Median (interquartile range) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer | ||

| Total included wear timeb | 821.8 (754.0–869.3) | 608.0–1111.0 |

| Sedentary timeb | 514.0 (464.3–583.1) | 255.7–849.8 |

| Total activity timeb | 290.9 (245.8–340.1) | 127.7–473.5 |

| Light activityb | 271.3 (218.8–315.4) | 99.3–429.3 |

| Moderate activity | 18.0 (11.4–29.1) | 5.3–70.0 |

| Vigorous activity | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0–4.3 |

| Moderate or vigorous activity | 18.0 (11.7–30.1) | 5.3–70.0 |

| Total counts/day | 202,680 (166,951–248,348) | 92,131–429,497 |

| Average cpm | 256.3 (209.5–323.7) | 131.0–615.5 |

| Steps, counts/day | 5687 (4452–7086) | 1545–11,453 |

| Pedometer | ||

| Steps, counts/dayb | 5961 (3727–8510) | 267–12,833 |

Agreement between continuous pedometer and accelerometer measures of PA

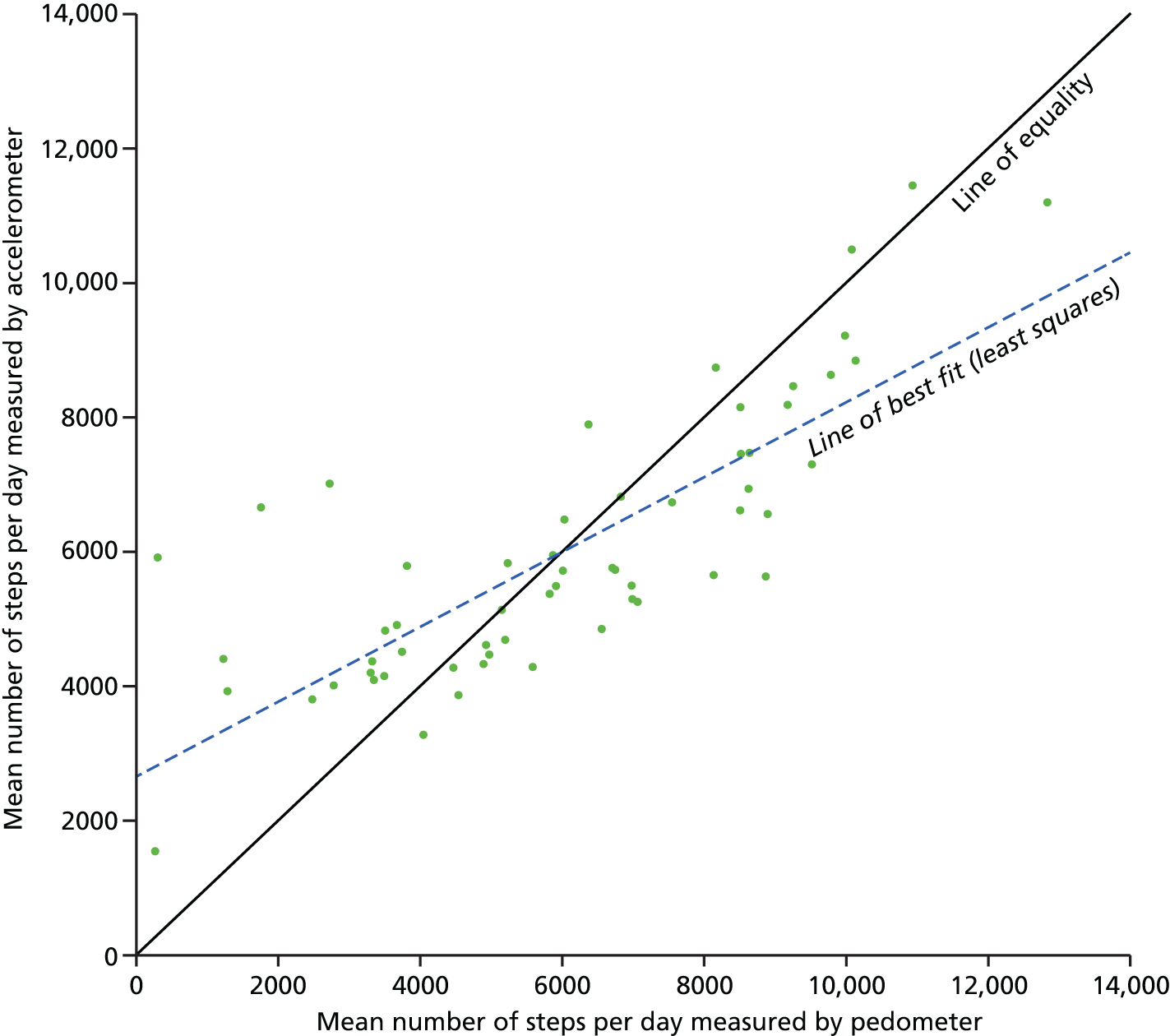

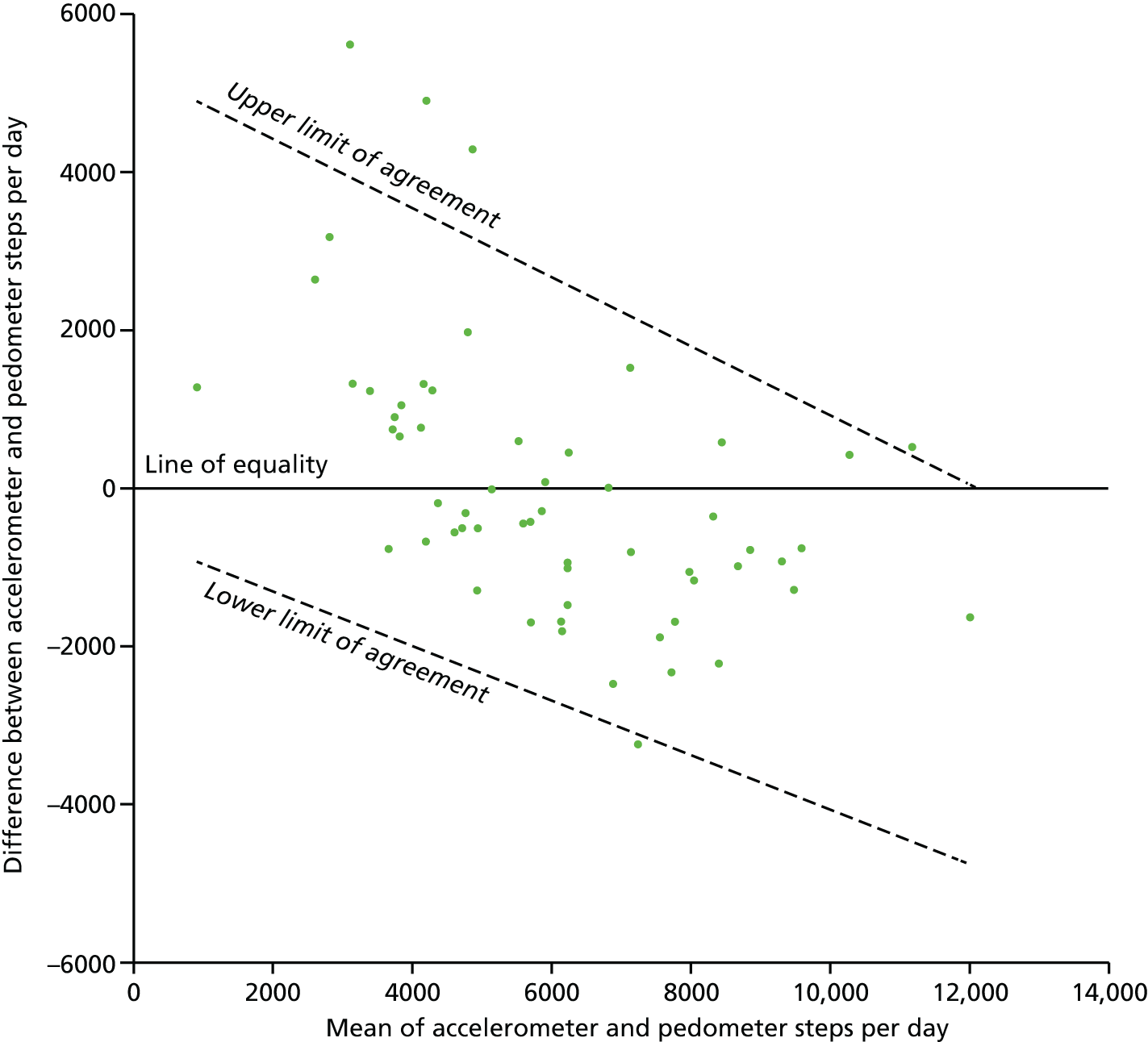

There was no significant difference between the overall step counts recorded by the pedometer and the accelerometer (median 5961 vs. 5687 steps/day, respectively; p = 0.37; see Table 4). Pedometer step counts were significantly correlated with all accelerometer measures of PA except for sedentary time (Table 5). The correlation was good for accelerometer step counts (r = 0.78) and moderate (r = 0.36 to 0.54) for all other measures of PA. Pedometer step counts are plotted against accelerometer step counts in Figure 1. Despite these statistically significant correlations, the 95% limits of agreement were very broad, ranging between –2690 and 2656 steps/day for the mean value (mean of accelerometer and pedometer steps/day = 6026) (Figure 2). The limits of agreement also varied substantially over the range of values, indicating a differential bias. At the lowest recorded step count (mean of accelerometer and pedometer steps/day = 906), the limits were –927 to 4897 steps/day (a range of 5824), indicating that the accelerometer was on average recording more steps/day than the pedometer. In contrast, at the highest step count value (mean of accelerometer and pedometer steps/day = 12,018) the limits were –4753 to 33 steps/day (a range of 4786) indicating that, while the level of random disagreement had decreased, the direction of bias had reversed, with the accelerometer recording less steps/day than the pedometer on average. BMI and gestational age did not modify the limits of agreement as there were no statistically significant differences in the slope of the regression line (p = 0.28 for BMI; p = 0.68 for gestational age) or in the absolute spread from the regression line (p = 0.64 for BMI; p = 0.35 for gestational age).

| Variable measured | Correlation coefficient | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary time (minutes/day) | –0.30 | 0.51 to 0.05 | 0.023 |

| Total activity time (minutes/day) | 0.40 | 0.13 to 0.63 | 0.002 |

| Light activity (minutes/day) | 0.36 | 0.10 to 0.58 | 0.006 |

| Moderate or vigorous (minutes/day) | 0.47 | 0.18 to 0.69 | < 0.001 |

| Activity (minutes/day) | 0.51 | 0.24 to 0.72 | < 0.001 |

| Total counts/day | 0.54 | 0.28 to 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| Average | 0.78 | 0.59 to 0.90 | < 0.001 |

FIGURE 1.

Daily step counts as measured by accelerometers and pedometers. The figure also shows the line of equality and least-squares line.

FIGURE 2.

Differences in step counts/day between accelerometers and pedometers, plotted against the mean of both (n = 58). The limits of agreement were calculated using a regression method previously described by Bland and Altman. 74

Agreement between categorised pedometer and accelerometer measures of physical activity

Based on the accelerometer data, 15 (26%) of these women recorded ≥ 30 minutes MVPA/day, 12 (19%) recorded ≥ 8000 steps/day and three (5%) recorded ≥ 10,000 steps/day. The pedometer data showed that 18 (29%) of the women recorded ≥ 8000 pedometer steps/day and four (7%) recorded ≥ 10,000 steps/day.

There was moderate agreement between those achieving ≥ 8000 pedometer steps/day and those achieving ≥ 30 minutes MVPA/day (kappa 0.45, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.67) (Table 6). Agreement between the pedometer and the accelerometer in categorising women to < 8000 or ≥ 8000 steps/day was good (kappa 0.63, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.83). Very few women achieved ≥ 10,000 steps/day with either of the monitors (n = 3 for accelerometers and n = 4 for pedometers), thus the agreement between these was artificially high (results not shown).

| Accelerometer dataa | Kappa (accelerometer data vs. ≥ 8000 pedometer steps counts/day)b | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 30 minutes MVPA/day | 0.45 | 0.24 to 0.67 |

| ≥ 8000 steps/day | 0.63 | 0.43 to 0.83 |

Discussion