Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0707-10162. The contractual start date was in December 2013. The final report began editorial review in May 2015 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon de Lusignan has received funding from Eli Lilly and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologicals. Funding has also been received from the Department of Health for the National Evaluation of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT). Elspeth Guthrie reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study. Karina Lovell reports grants from NIHR, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and Arthritis Research UK during the conduct of the study. Chris Dickens reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Linda Davies reports grants from the NIHR, Medical Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Macmillan, Cancer Research UK, Arthritis Research UK and Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (CMFT) during the conduct of this study. Peter Salmon reports grants from Marie Curie Cancer Care, the Liverpool Institute of Health Inequalities Research, Merseycare NHS Trust, Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen Hospitals NHS Trust, the Economic and Social Research Council, and the Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study. Navneet Kapur reports other research funding from NIHR, the Department of Health and the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership during the conduct of the study. He was not in receipt of any industry funding. He was involved in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines and Department of Health (England) advisory groups on suicidal behaviour unrelated to the conduct of the current study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme or the Department of Health.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Guthrie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Unscheduled care is defined as any unplanned contact with the health service by a person requiring or seeking help, care or advice. 1 It includes a wide range of service contacts from specialised hospital support, emergency hospital admissions (EHAs), attendances at emergency departments (EDs), attendances at minor injury units, unplanned primary care call-outs and, finally, self-care. 2 Unscheduled care also includes both urgent care, which refers to conditions that require assessment and treatment within 7 days, and emergency care, which needs assessment and intervention within 24 hours. 2

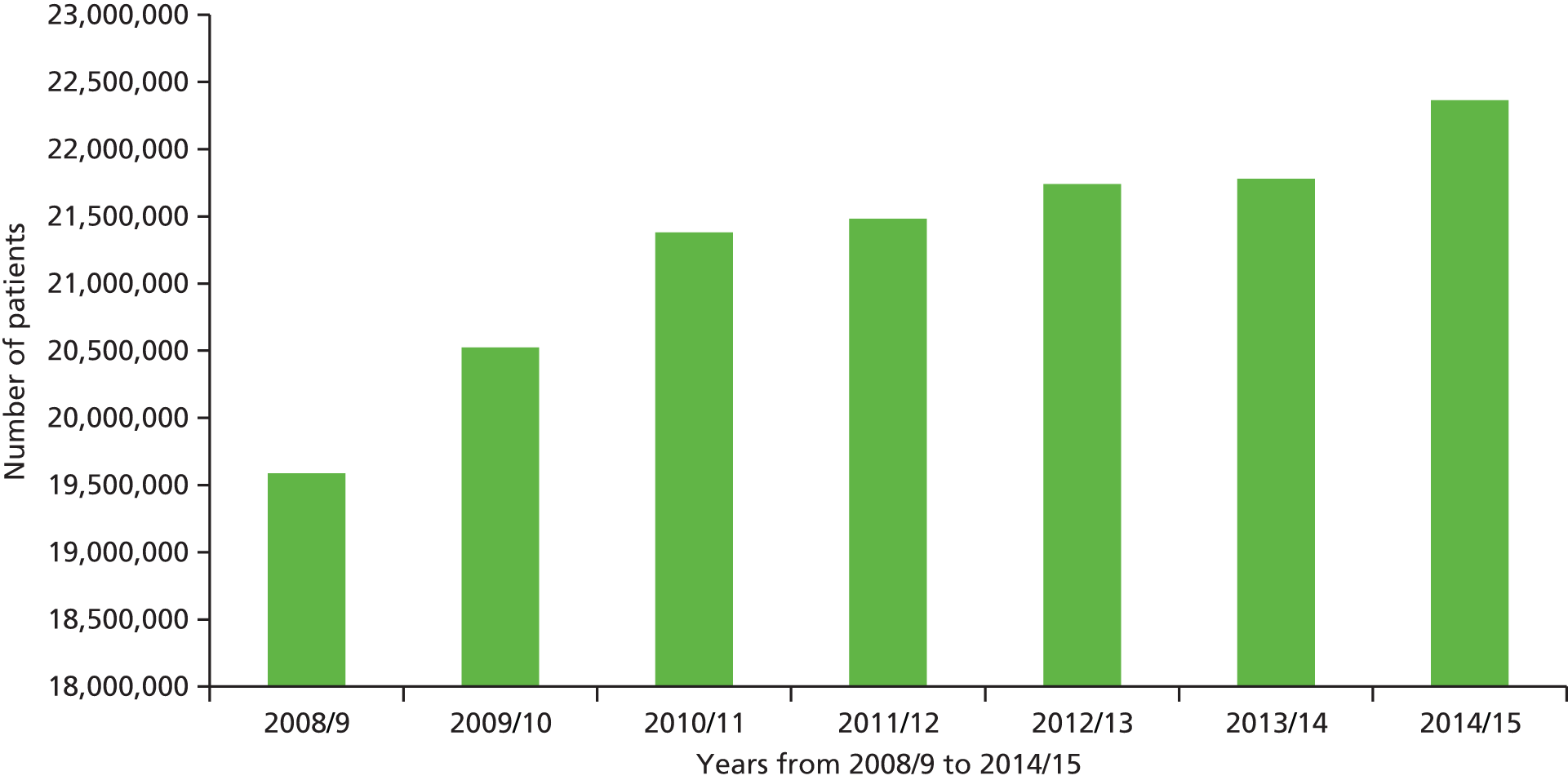

Use of urgent or unscheduled services is high. Sixteen per cent of the general population access unscheduled care over any 4-week period,3 and attendances at EDs in England have been increasing year on year (Figure 1). The total number of ED attendances in England has risen from 13.9 million in the year 1987–8 to 14.4 million in 1997–8, 19.1 million in 2007–8 and 22.4 million in 2013–14. 4

According to a report published by the Department of Health (DH) in 2013, in 2012–13, there were 5.3 million emergency admissions to hospital, costing approximately £12.5B. 5 In 2014–15, the total number of EHAs had risen to 5.5 million. 4 Reducing unscheduled care has become a DH priority. 6

The increase in EHAs has largely resulted from an increase in short-stay admissions of patients presenting to EDs. These ‘short-stay’ admissions (< 2 days) have increased by 124% over the last 15 years; in comparison, longer admissions have increased by 14%. 5

Avoiding unnecessary EHAs is a major concern for the NHS not only because of the costs associated with these admissions, but also because of the pressure and disruption caused to elective health care and to the people admitted. In a recent report from The King’s Fund, it was suggested that emergency admissions of people with long-term conditions (LTCs) that could have been managed in primary care cost the NHS £1.42B annually and that this could be reduced by 8–18% through investment in primary care- and community-based services. 7

It is estimated that 17.5 million adults in the UK have at least one LTC, by which is meant a chronic physical or mental health condition. 8,9 Over 70% of the health-care budget in England is spent on the care of people with LTCs,10 and many people live with multiple conditions. LTCs account for 50% of general practice consultations and 70% of inpatient bed-days per year in the UK. 11

During this programme of research, there was a growing awareness at a national level of the importance of improving the mental health of people with LTCs. 12 There was also a recognition of the need to better integrate physical and social health care, particularly for the elderly. 13–15 The national mental health strategy for England calls for patient-centred management together with joined-up personalised pathways and systems. The strategy states that interventions must be as efficient as possible at delivering outcomes that are effective, cost-effective and safe. 16 There is the expectation that better joined-up care will reduce costs, particularly the burden on emergency services. A recent report from The King’s Fund, entitled Bringing Together Physical and Mental Health: A New Frontier for Integrated Care, makes a strong case for change to the current ways in which services are organised. 17

There are major challenges to ensure that patients’ needs are met holistically, effectively and efficiently. Importantly, the evidence base underpinning many current recommendations is limited or patchy.

This programme of research addressed several of the key areas described above and its findings are both informative and timely for those involved in policy, practice and research. Instead of focusing on one LTC, the programme included four common exemplar LTCs. This allowed us to compare people with different LTCs but also to study the effects of multimorbidity on use of unscheduled care.

The use of unscheduled care is common in people with LTCs, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 18–20 It is argued that, in the case of certain long-term physical conditions, more effective management and treatment in primary care could reduce ED attendance and EHAs, and there has been, and remains, a drive from the DH to reduce urgent care and emergency readmissions to hospitals of those people with long-term physical conditions who could be managed in the community. 11

It is difficult to determine whether or not the use of unscheduled care by an individual is appropriate, as it depends on a value judgement made by a clinician at the point of contact, and the criteria for determining inappropriate contact vary considerably. 21 Although, undoubtedly, some use of unscheduled care is unjustified, it is recognised that, for many people, the use of unscheduled care is entirely appropriate and necessary at the time they access services. An important question, however, is whether or not such contacts could be prevented, in certain groups of patients, by improved management and treatment of their physical health problems, so that crises are avoided.

The provision of unscheduled care is complex, and the relationship between different components of unscheduled care and scheduled care is difficult to disentangle. For example, increased use of general practitioner (GP) out-of-hours (OOH) services, or seeing the same GP on a regular basis, may result in a reduced need to attend the ED. So an increase in one aspect of unscheduled care or scheduled care may result in a decrease in another aspect of unscheduled care. 22 With this in mind, many of the analyses in this programme focus on secondary care aspects of unscheduled care, namely ED attendance and EHAs. These are the two most costly aspects of unscheduled care and the two that government has identified as a priority area to reduce. 11 Where relevant, however, and where possible in the programme, we also comment on other kinds of unscheduled care use.

Several factors have been identified as being associated with increased unscheduled care use in people with LTCs. Higher levels of multimorbidity and greater illness severity are associated with higher rates of EHAs and readmission following discharge. 20,23–25

Organisational factors include proximity to EDs or other kinds of emergency provision, and the availability of scheduled services. 26 Like all health-care decisions, unscheduled care use occurs in a clinical, social and cultural context, which may differ in different countries and health-care settings. There has been relatively little work which has addressed the influence of family and providers of routine care, and the cultural norms which underlie people’s beliefs and their behaviours in relation to unscheduled care use.

Psychosocial factors have also been recognised as increasing the risk of unscheduled care use in people with physical LTCs. Depression and anxiety are associated with higher rates of unscheduled care use in people with a variety of different LTCs. 27–30 Poorer quality of life (QoL) and perceived control of illness are also associated with greater health-care utilisation and increased ED attendances for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 31–35 The reasons for these associations are unclear. Psychological factors may influence people’s decisions about when to use unscheduled care, or reduce their ability to cope in health emergencies, or may just be markers of greater morbidity.

There are major initiatives to improve the quality of care for people with LTCs11 and primary care is seen as the optimal context to deliver care. 36,37 One of the main drivers for the focus on primary care is to attempt to reduce the use of unscheduled secondary care use, by improved provision of scheduled or routine care.

In this context, the primary purpose of this programme of research was to ‘develop effective psychosocial strategies to reduce the need for unscheduled care in patients with LTCs’. The programme of work began in 2009 and its findings are therefore highly relevant to current health-care initiatives. The programme has become known as the ‘CHOICE’ programme, and this term will be used throughout this document in preference to its longer official title (Choosing Health Options in Chronic Care Emergencies). For the purposes of the programme, we focused on people with physical chronic health conditions, and the term ‘LTC’ will be used throughout this report to refer to physical long-term health conditions.

We chose to study four exemplar LTCs: asthma, COPD, coronary heart disease (CHD) and diabetes. We chose these conditions because (a) they are common; (b) they are all in the leading 15 discharge diagnoses of EDs;38 (c) they are associated with EHAs;39 (d) they are all recognised as ambulatory care-sensitive conditions for which effective care can prevent flare-ups and the need to use secondary care emergency services;40 and (e) GPs in England have a requirement under the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)41 to review people with these conditions at least once per year. Therefore, all primary care practices in England keep electronic databases that enable people with these conditions to be identified.

In a recent European study, unscheduled care accounted for 56% of total health-care costs in adults with asthma,18 regardless of the severity of patients’ symptoms. In the USA, over 12 months, 8.3% of patients with asthma made at least one visit to the ED19 and 13% of COPD patients made six or more visits. 20 Over 300,000 people attend an ED in England and Wales each year because of chest pain. 42

The rate of EHAs for people with LTCs varies considerably across England, and is much higher in socially deprived areas than in the least deprived areas of the country, varying from 38 to 207 admissions per 1000 registered patients. 7 Differences are also apparent in the way people are assessed and treated in an emergency facility, with large variability in services that facilitate discharge. 43

Many of the GP practices participating in the programme are located in areas of high deprivation. Although it could be argued that the findings of the programme may not be representative of the most affluent areas of the UK, it is generally the more deprived and highly populated areas where there is high use of unscheduled care. 26

We chose to focus on psychosocial factors (e.g. depression, anxiety, life stress) that may contribute to unscheduled care use, as these factors (particularly mental health problems) are often hidden in clinical practice, under-reported, and under-researched. A recent systematic review, which examined features of primary care that impact on use of unscheduled care, identified several organisational factors and people-related factors of relevance. 26 Although social deprivation, social isolation, older age and having multiple conditions were identified as potential drivers, mental health did not feature in the studies included in the review.

The inclusion in this programme of four exemplar conditions enabled us to study not only each individual condition, but the effects of one or more of our exemplar conditions (i.e. comorbidity) on use of unscheduled care.

The focus for the programme was the potential relationship between psychosocial factors, LTCs and unscheduled care (primarily ED attendance and EHAs) and the possibility that a tailored psychosocial intervention may reduce the requirement to use unscheduled care in people with LTCs.

Six key factors underpinned the research programme.

High psychological morbidity associated with long-term conditions

Psychological morbidity is two to three times higher in people with LTCs than in those who do not have a LTC,44,45 and people with two or more LTCs are seven times more likely to have depression. 46

Each of the four conditions we chose to study is associated with high psychological morbidity. For example, rates of depression in patients with COPD are 2.5 times higher than in control subjects,47 and the presence of diabetes doubles the odds of comorbid depression compared with no diabetes. 48 There is similar evidence for high psychological morbidity in asthma and CHD. 49,50

Poor health outcomes associated with psychological symptoms

The presence of psychological symptoms in LTCs is associated with poor health outcomes in all four conditions. Depression has an adverse effect on QoL in asthma,49 COPD,51 diabetes52 and CHD. 53 Depression has been linked to adverse morbidity and mortality in CHD53,54 and COPD. 55 Those with CHD who are also depressed have higher rates of complications and are more likely to undergo invasive procedures. 56,57 Depression has also been linked to poorer self-care in asthma49 and in diabetes. 58 Recent work also suggests that depression in diabetes is associated with an increased risk of dementia. 59,60

Increased health expenditure associated with psychological morbidity

The presence of psychological symptoms is associated with increased health-care use and expenditure in LTCs, and those with depressive disorder are twice as likely to use EDs as those without depression. 61 Total health-care expenditure on patients with diabetes is 4.5 times higher for individuals with depression than for those without depression. 27

Perception of illness is associated with outcome

Knowledge about and perceptions of illness are critical factors for optimal medication adherence in patients with LTCs. 62

Treatment of depression improves outcome

In patients with diabetes, treatment of depression produces an improvement in symptoms at no additional overall cost, as savings are made by reductions from inpatient medical costs and other forms of medical care. 63 Improved self-care of diabetes also reduces health-care costs. 64 CHD patients who respond to treatment for depression have fewer cardiac events and associated costs. 65

Psychological morbidity is a known, but little researched, predictor of unscheduled care use

A variety of risk-modelling approaches have been utilised in the NHS to identify people at risk of using secondary forms of unscheduled care, predominantly EHAs. The most common models in use at the time the CHOICE programme began, such as the Patients at Risk of Re-Hospitalisation algorithm,66,67 employed data about prior health-care use, plus certain physical parameters, but did not include data on mental health. There is, however, preliminary evidence, from a small number of studies, that psychological factors are independent predictors of the use of unscheduled care in people with LTCs. 30,55,57,68

Aims and objectives

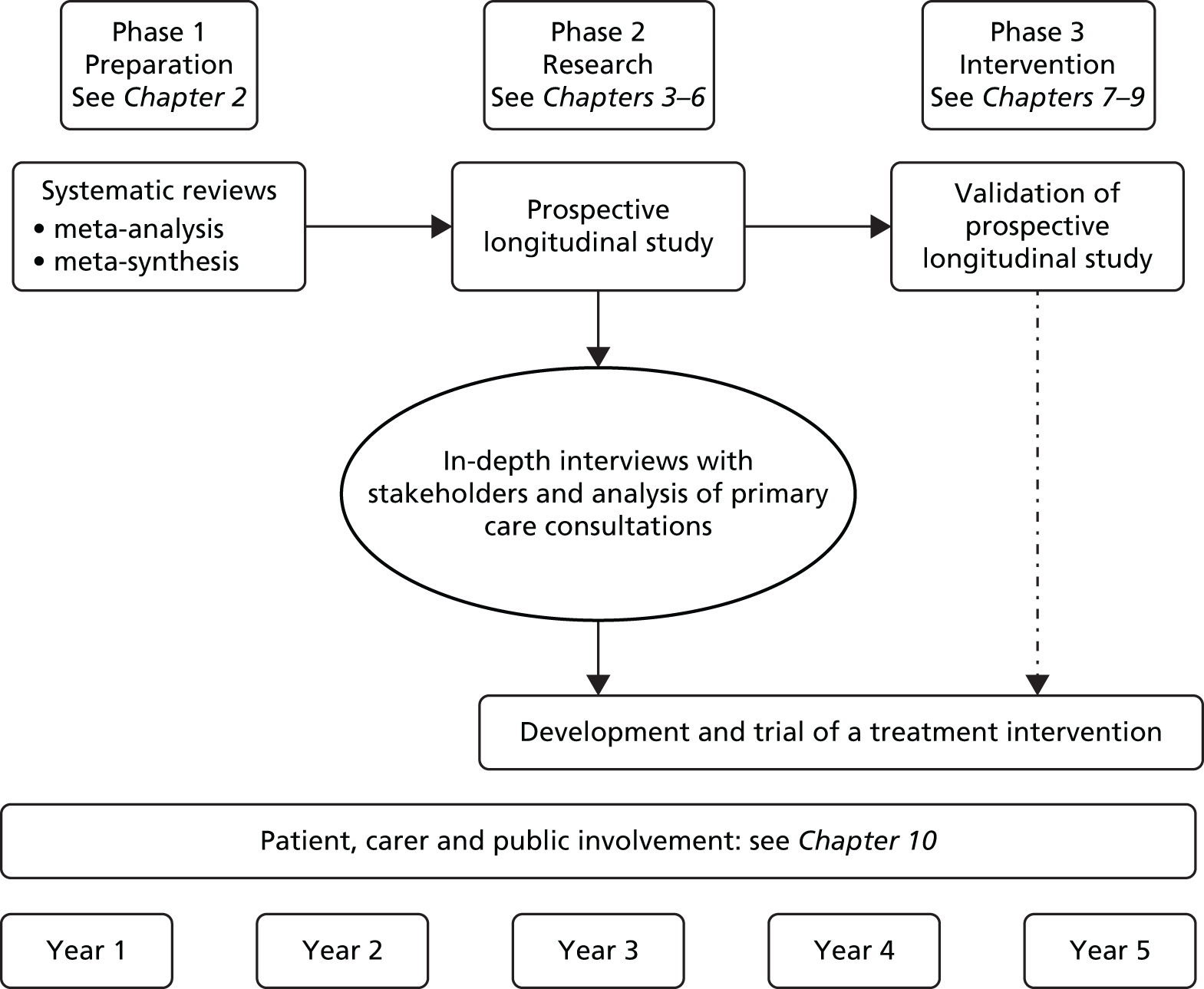

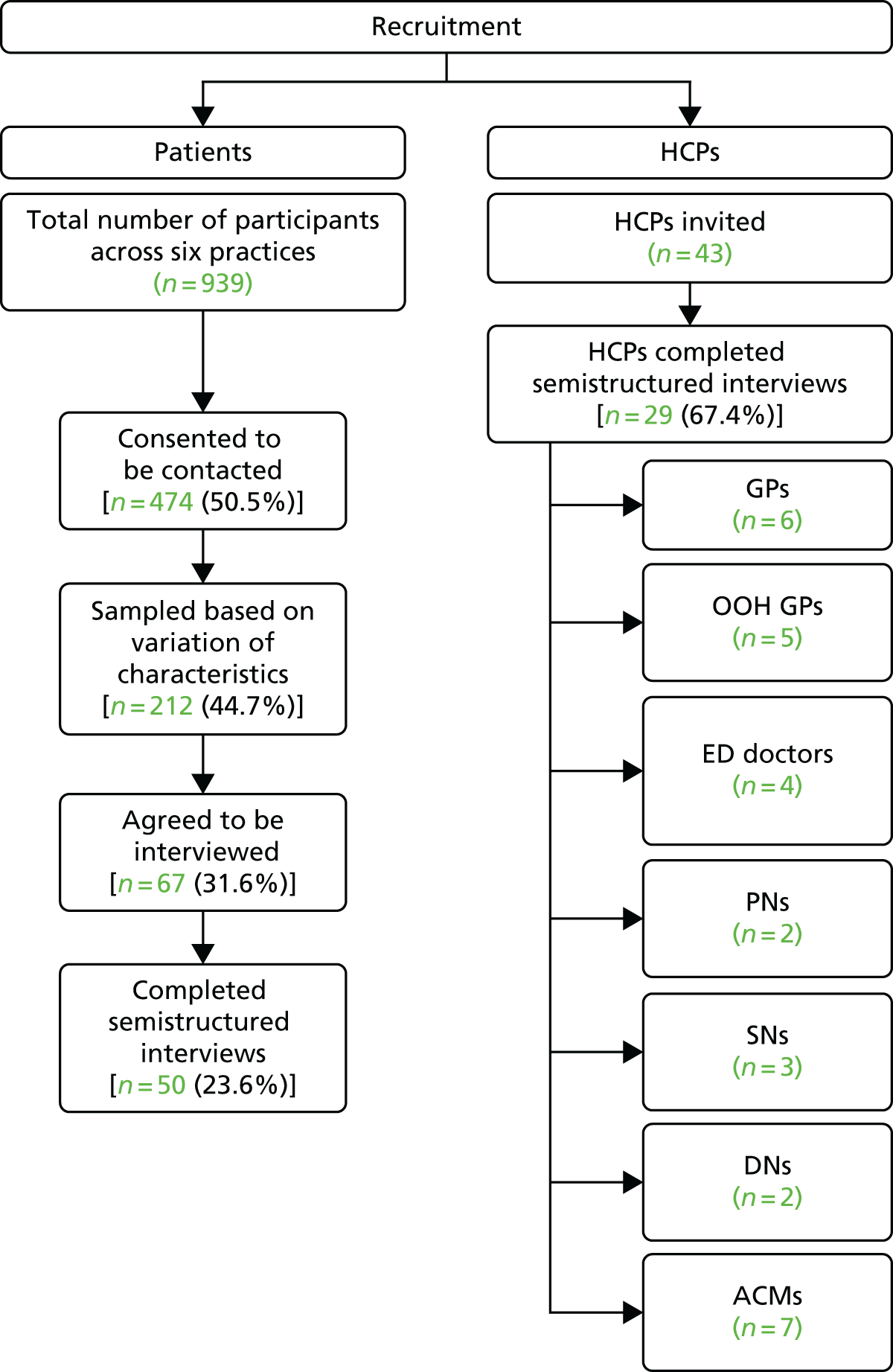

The programme was given the acronym CHOICE and was divided into three phases of work (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The three phases of the CHOICE programme.

The overall aim was to better understand psychosocial drivers of unscheduled care in people with physical LTCs and develop an intervention to reduce unscheduled care.

Phase 1 involved understanding the problem in greater depth using systematic review methods to identify psychosocial factors that act as drivers for unscheduled care in LTCs, and to identify interventions or strategies to reduce the frequency of unscheduled care.

Phase 2 involved mapping the frequency and pattern of unscheduled care in patients with the four exemplar LTCs (asthma, CHD, COPD and diabetes) over a 12-month period, and the development of a red flag marker to identify patients at risk of becoming high users of unscheduled care.

Phase 3 involved developing and testing the validity and utility of the red flag marker using current NHS databases. We also developed and evaluated a low-intensity psychosocial intervention for use in primary care, with the intention of reducing use of unscheduled care in people with LTCs.

Qualitative methods and analyses were embedded within the programme to provide rich personalised accounts, which were used to:

-

triangulate findings with the quantitative methods

-

identify mechanisms accounting for the quantitative findings

-

evaluate the acceptability and inform the implementation of the intervention.

Our objectives were to:

-

Systematically synthesise the current evidence about psychosocial drivers of unscheduled care, and about interventions or strategies to reduce the frequency of unscheduled care use in patients with LTCs (phase 1).

-

Derive estimates of the frequency and pattern of unscheduled care use in patients with asthma, CHD, COPD and diabetes, as examples of common LTCs (phase 2).

-

Develop and validate a ‘red flag’ system that will identify patients with LTCs who are at risk of becoming frequent users of unscheduled care (phases 2 and 3).

-

Identify personal reasons for unscheduled care use, including barriers to access for routine care, patients’ motivations, expectations and decision-making processes, influences from families and relevant health-care workers, and factors in consultations with active case managers (ACMs) (phase 2). This objective was modified during the life of the programme as ACMs were phased out, so the focus of study was switched to routine health-care reviews in primary care for people with LTCs.

-

Develop and evaluate an intervention that will reduce/prevent unscheduled care use, while maintaining or improving patient benefit (phase 3).

-

Use statistical and health economic modelling to evaluate the costs and benefits associated with a treatment intervention (phase 3). This objective was modified over the life of the programme (there were unavoidable delays in phase 2). These and the findings from phases 1 and 2 meant that the planned decision analyses were unlikely to further inform the development of a red flag system and development of the intervention to reduce/prevent the use of unscheduled care. Accordingly, this objective was adapted to focus on statistical analysis of the costs of scheduled and unscheduled hospital care in phase 2 and exploratory sensitivity analyses of the trial data generated in phase 3.

Patient and public engagement and involvement

During the lifetime of the programme, we involved service users and user-led organisations in workshops/groups/stakeholder meetings to help us evaluate our findings, and to develop appropriate and practical interventions. Our service users were involved in all aspects of the programme and this work was led by our co-applicant, Mrs Jackie Macklin.

The work of the programme is described in this report in a sequential fashion, except for our patient and public engagement and involvement (PPE&I), which we have presented in a separate chapter (see Chapter 10), in order to capture the depth and quality of this important contribution that ran across all areas of our programme.

Terminology

We have used the term ‘unscheduled care’ to refer to all aspects of unplanned health-seeking, in both primary and secondary care. We use the term ‘ED attendance’ to refer to attendances at EDs and the term ‘EHA’ to refer to EHAs that do not included planned admissions to hospital. In this programme, the term ‘LTCs’ is used to refer to long-term physical conditions and does not include long-term mental health conditions. The term ‘scheduled care’ refers to all planned contacts with health care including GP appointments, reviews, outpatient appointments and planned hospital admissions.

Chapter 2 Evidence synthesis (phase 1)

Abstract

Background

Our objectives for evidence synthesis were to identify the psychosocial drivers of unscheduled care use in patients with LTCs; to identify existing evidence about psychosocial interventions to reduce unscheduled care use; and to understand patients’ reasons for using unscheduled care.

Method

We carried out systematic searches of prospective cohort studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and qualitative studies in patients with asthma, diabetes, COPD and CHD, and conducted five systematic reviews.

Results

We found that depression predicts unscheduled care use in asthma, COPD, CHD and diabetes. Psychosocial interventions can reduce unscheduled care use in COPD and asthma by 32% and 21% respectively.

The value that patients with LTCs place on both unscheduled and routine health care depends on their previous health-care experiences and their personal circumstances. Patients report that unscheduled care is easily accessible, available and complements routine health care, but should only be used for pressing health-care needs. Patients do not talk about psychosocial factors as drivers for unscheduled care use.

Discussion

We conducted five systematic reviews that show that depression predicts unscheduled care use in LTCs; unscheduled care use can be reduced using psychosocial interventions in patients with COPD and asthma; and patients use unscheduled care when they feel they have a pressing health-care need. We were not able to control for the severity of LTCs in our quantitative analysis of the existing evidence; therefore, future work should aim to identify the relationship between depression, severity of LTC and unscheduled care use.

Overview

In this chapter we report the results from phase 1 of the CHOICE programme of research, which was principally involved with evidence synthesis. The aim was to systematically synthesise current evidence about psychosocial drivers of unscheduled care use and about interventions or strategies, which may reduce the frequency of unscheduled care use in patients with LTCs. As throughout the whole programme, we focused on four exemplar conditions: asthma, CHD, COPD and diabetes.

We carried out five major reviews: two focused on potential psychosocial drivers of use of unscheduled care and two focused on evidence concerning treatment interventions to reduce unscheduled care use. The final review synthesised evidence from studies that had used qualitative research methods to understand why people with LTCs use unscheduled care.

Psychosocial predictors of unscheduled health-care use

For the purpose of the first two reviews, we focused on the two most commonly identified psychosocial predictors of unscheduled care use: depression and anxiety. 55,68 Both are common in people with LTCs69,70 and are associated with poor health outcomes. 71,72 Evidence as to their role in the use of unscheduled care, however, is unclear.

Several studies have shown that depression increases ED attendances or EHAs in patients with LTCs. 63,73–75 However, other studies have found no significant impact of depression on unscheduled care use. 55 The relationship between anxiety and use of unscheduled care in patients with LTCs is also unclear. 68,76,77

Review 1 focused on the relationship between depression and use of unscheduled care, whereas review 2 focused on the role of anxiety and its effect on the use of unscheduled care. Both systematic reviews have been published and will be summarised in this chapter. 78,79 The findings from the review concerning the role of depression as a predictor of unscheduled care (i.e. Dickens et al. 78) are reproduced with the permission from Elsevier. 78

Aims of studies 1 and 2

The aim of the first review (study 1) was to conduct a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis to determine if depression is a predictor of unscheduled care use in patients with any of four exemplar LTCs (asthma, CHD, COPD and diabetes).

The aim of the second review (study 2) was to conduct a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis to identify if anxiety predicts the use of unscheduled care in patients with any of four exemplar LTCs (asthma, CHD, COPD and diabetes).

Method

The methods for both reviews are summarised below. Full descriptions of the methods are available in the published papers. 78,79

Studies were eligible for inclusion in these reviews if they met the following criteria:

-

employed a prospective cohort design

-

included adults with one or more of the following LTCs: asthma, CHD [myocardial infarction (MI), stable or unstable angina], COPD and diabetes

-

used a standardised measure of depression or anxiety at baseline

-

assessed the use of unscheduled health care prospectively, defined for the purposes of the reviews as urgent GP visits, attendance at EDs, urgent or EHAs.

Studies of children were not included. Search strategies (see Appendix 1) were developed and searches conducted in the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the British Nursing Index (BNI), PsycINFO and Cochrane database. Searches for both reviews were first conducted on 19 August 2008 and then updated on 22 June 2012 for depression studies and again on 1 April 2013 for anxiety studies. For eligible papers, reference lists were searched and citations of eligible papers were screened for relevance using the Social Sciences Citation Index.

The titles and abstracts of the identified papers were screened by one of three researchers [AB, Angee Khara (AK), CB] and the full text of studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria were then screened by two out of three researchers (AB, AK, CB). Any disagreements about eligible papers were discussed with another member of the team (CD, EG). Data extraction was completed by two out of three researchers (AB, AK, CB). Data were extracted on the characteristics of participants; measures of depression or anxiety used; methodological characteristics of the study; measure of unscheduled care use; and the strength of the association between depression or anxiety and unscheduled care use.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. 80,81

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were extracted or calculated for each study in which number of subjects using unscheduled care with and without depression, or with and without anxiety, and the total number of subjects in each group were presented. Where data were presented in alternative formats (e.g. where studies presented results as continuous data, as p-values for comparisons across groups with group sizes, or as a correlation between depression or anxiety, and unscheduled health-care use), appropriate transformations were made using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (version 2.2.048, 7 November 2008; Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). An OR of > 1 indicated that depression or anxiety was associated with increased use of unscheduled care. Where follow-up data were collected at multiple time points, data collected nearest to 1 year were used. Where studies included two measures of unscheduled care, ORs for each measure were averaged so that each independent study contributed a single effect to the meta-analysis. 81 ORs for depression and anxiety across independent studies were combined using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method. 82 Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochrane’s Q and I2 statistics. 83,84 Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot, Egger’s regression method, Peters’ regression method, and fail-safe N (i.e. the number of additional negative studies that would be required to make the results of our meta-analysis non-significant). 85–88 We used Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure to correct for the effects of studies missing due to publication bias. 89 Meta-analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (version 2.2.048) and Stata (version 11; StataCorp LP, TX, USA).

Study 1: does depression predict the use of unscheduled care in patients with long-term conditions?

Results

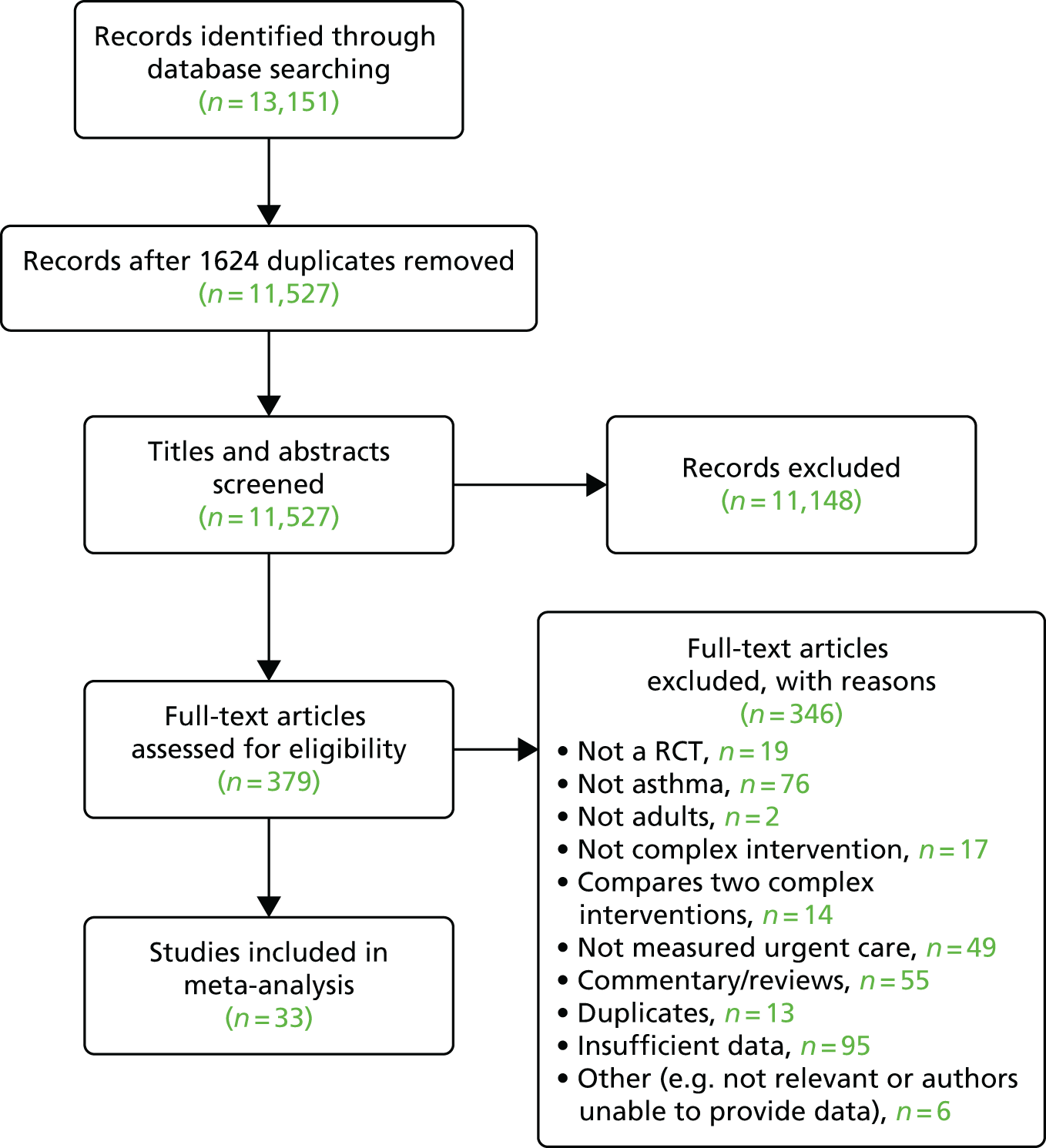

Figure 3 shows the flow chart for the search strategy used in this review. Sixteen independent prospective studies were identified that had investigated whether or not depression predicted unscheduled care use in patients with either asthma, CHD, COPD or diabetes. 23,24,28–30,55,57,68,90–97 From the 16 studies, there were data for 8477 patients with LTCs (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 flow chart for longitudinal cohort studies of patients with LTCs (asthma, CHD, COPD and diabetes), which included a measure of depression at baseline and a measure of unscheduled care at follow-up. Reprinted from Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 73, Dickens C, Katon W, Blakemore A, Khara A, McGowan L, Tomenson B, et al. Does depression predict the use of urgent and unscheduled care by people with long term conditions? A systematic review with meta-analysis, pp. 334–42. © 2012, with permission from Elsevier. 78

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of each of the included studies and is adapted from data in the published paper by Dickens et al. 78 There were eight studies of COPD,23,29,30,55,90,94–96 five of CHD,28,57,91–93 two of asthma24,68 and only one of diabetes. 98 There were no studies from the UK and only two were based in primary care. 68,98 Most studies involved following a cohort of hospital inpatients admitted for an acute episode of illness, or exacerbation of illness, after their discharge to determine readmission rates or ED visits. Depression was assessed in all of the studies using a self-rated measure, and in most as a categorical construct (case or non-case).

| First author and date | Condition of study | Sample size | Mean age | Males | Sample | Depression measure | Urgent health-care utilisation measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan et al., 200755 | COPD | 603 | 66.5 years | 64.1% | 603/611 eligible patients with moderate to severe emphysema self-referred or were referred by a clinician at U.S. clinics to control arm of a lung surgery trial (NETT) | BDI (scores ≥ 10 vs. < 10) | Hospital records for COPD-related inpatient admissions and (ED visits for 1 year |

| Eisner et al., 200524 | Asthma | 756 | 59.9 years | 29.8% | All adults admitted to ITU with asthma plus sample of all patients hospitalised (without ITU) | CES-D (≥ 16 = depressed) | ED visits and hospitalisations recorded from hospital computerised records for 12 months |

| Schneider et al., 200868 | Asthma | 256 | 56.3 years | 38.3% | Consecutive patients with asthma consulting GPs, Germany | Validated German version of PHQ, from which derive DSM-IV depressive disorder | Patients’ self report of urgent hospitalisations and emergency hospital visits over 1 year |

| Ng et al., 200723 | COPD | 376 | 72.2 years | 85.1% | Eligible consecutive inpatients hospitalised for COPD exacerbation in Singapore | Chinese HADS (≥ 8 vs. < 8 on Depression Score) | Patient self-reported on urgent hospitalisation at 6 and 12 months after discharge |

| Almagro et al., 200630 | COPD | 141 | 72.0 years | 93% | Eligible, consecutive patients on inpatient ward for acute exacerbation of COPD over 7 months | Yesavage Depression Scale (continuous) | Clinical records checked for readmissions of 24 hours or more over 1 year |

| Gudmundsson et al., 200690 | COPD | 416 | 69.2 years | 48.8% | Patients hospitalised with COPD exacerbation | HADS depression score (continuous) | Self reported hospitalisations for acute exacerbations of COPD 1 year after discharge, checked via hospital records |

| Lauzon et al., 200357 | CHD | 550 | 60.0 years | 78.9% | Consecutive patients approached after admission in 10 Coronary Care Units | BDI (≥ 10 vs. < 10) | Hospital admissions recorded after 30 days, 6 months and 1 year by self report (postal questionnaire) and chart review |

| Frasure-Smith et al., 200091 | CHD | 848 | 59.3 years | 69.0% | Subjects were recruited to 2 separate studies – 1 prospective cohort study and 1 control arm of RCT. All patients were post MI | BDI (≥ 10 vs. < 10) | ED visits (all cause) and associated costs for 1 year post discharge for MI |

| Kurdyak et al., 200893 | CHD | 1941 | 64.0 years | 30.4% | MI in-patients from 53 hospitals across Ontario Canada | Depression questionnaire, based on Brief Carroll Depression Rating Scale (5 or more vs. < 5) | ED visits (all cause) |

| Xu et al., 200829 | COPD | 491 | 65.6 years | 68.8% | Patients with physician diagnosed COPD, attending 10 general hospitals in Beijing China | Mandarin Chinese HADS (≥ 8 vs. < 8 on Depression scale) | Medical interventions were monitored by a telephone-administered questionnaire over 12 months. Hospitalisations confirmed by chart review |

| Shiotani et al., 200292 | CHD | 1086 | 63.6 years | 80.4% | Eligible consecutive patients with AMI, directly admitted or transferred to 25 collaborating hospitals eligible | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale. Non-depressed – scores < 40: depressed – scores ≥ 40 | Data on cardiac events 12 months following discharge from hospital records and telephone interviews with patients and family 12 months after baseline |

| Ciechanowski et al., 200098 | Diabetes | 350 | 61.3 years | 44% | Patients from a diabetes register of 2 primary care clinics | SCL-90-R – scores divided into tertiles (low/medium/high) – low vs. others used for meta analysis | ED visits for 6 months following questionnaire assessments collected using General Health Cooperative automated data |

| Ghanei et al., 200796 | COPD | 157 | 58.3 years | 63% | Patients attending chest clinic | HADS depression subscale used as continuous measure | Acute hospitalisation resulting from COPD exacerbation |

| Carneiro et al., 201095 | COPD | 45 | 68 years | 84.4% | Inpatients admitted due to exacerbation of COPD | BDI used as continuous scale | Hospitalisation resulting from exacerbation of COPD |

| Farkas et al., 201094 | COPD | 127 | 66 years | 79% | Hospital outpatients with COPD | CES-D scale used as continuous measure | Hospitalisation resulting from exacerbation of COPD |

| Pishgoo 201128 | CHD | 334 | 57.5 years | 67.8% | Cardiology outpatients with ≥ 50% stenosis in at least 1 major coronary artery | HADS depression scale – (Persian translated and validated | Al cause ED visits |

Table 2 summarises the results of each individual study, and includes univariate and multivariate analyses where they were reported. Eight of the 16 studies reported significant effects of depression on unscheduled care use (either EHAs or ED attendances)29,30,57,68,91–94 and two showed near-significant effects. 24,96

| Author and date | Univariate findings | Factors controlled | Multivariate findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan et al., 200755 | Patients hospitalised or that had ED visit for COPD were slightly more likely to be depressed at baseline (29.9% vs. 24.8% in non-depressed, p = 0.16) | Adjusted for sex, COPD severity, previous admissions, comorbidity score | States BDI score > 10 not associated with hospitalisation in adjusted analyses |

| Eisner et al., 200524 | Depression did not predict ED visits (HR = 1.36, p = 0.12) Trend for depression to predict hospitalisation (HR = 1.34, p = 0.06) |

Age, sex, race, education and smoking | Depression did not predict ED visits (HR, 1.20; p = 0.36) Depression did not predict hospitalisation (HR, 1.34; p = 0.06) |

| Schneider et al., 200868 | Depression predicted hospitalisation (OR, 6.1, p = 0.011) but not emergency GP visits (OR = 1.7, p = 0.30) | Medication guideline adherence, smoking, age and sex | Depressive disorder predicted hospitalisation (p = 0.009) |

| Ng et al., 200723 | 61% depressed patients had ≥ 1 urgent hospitalisation 57.8% non-depressed had ≥ 1 urgent hospitalisation, p = 0.31 | Age, sex, FVC, previous admissions SGRQ | Depression did not predict hospitalisation [HR = 0.93 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.28)] |

| Almagro et al., 200630 | Readmitted patients showed higher baseline depression scores (5 vs. 3.7, p ≤ 0.05) than those who were not readmitted | Age, sex, FEV1, comorbidity, social support | Depression not independent predictor of readmission |

| Gudmundsson et al., 200690 | Hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients had similar baseline depression scores (5.6 vs. 5.4, p = 0.63) | Age, smoking status, FEV1 | Depression HR = 1.09 (95% CI 0.8 to 1.51) |

| Lauzon et al., 200357 | Patients depressed at baseline had higher rates of hospitalisation because of any cardiac complication (30.9% vs. 17.5%) | Age, previous MI, anterior MI, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, sex, previous angina | Readmission due to cardiac complications higher in depressed patients [HR = 1.4 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.86)] |

| Frasure-Smith et al., 200091 | Authors unable to confirm all hospitalisations were urgent Depressed patients had greater mean ED visits (1.3 vs. 0.9, p < 0.0001) |

– | Findings of multivariate analysis not presented for urgent health-care utilisation |

| Kurdyak et al., 200893 | Author unable to confirm that all hospital admissions were urgent Depressed patients had significantly more ED visits (mean = 1.7 vs. 1.3, p < 0.001) |

Age, sex, income, comorbidity, GRACE score, drugs at discharge, cardiac interventions and symptom burden | Adjusted risk for ED visits not presented. Approx adjusted risk for depression predicting ED visits read from figure = 1.1 |

| Xu et al., 200829 | More depressed patients were hospitalised for COPD exacerbations (29.5% vs. 19.8%) | Age, sex, marital, educational and employment status, smoking, FEV1, dyspnea, 6-minute walk, social support, self efficacy, comorbidities, hospital type, drug and O2 use, previous hospitalisations | Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio for probable depression predicting hospitalisation = 1.72 (95% CI 1.04 to 2.85) |

| Shiotani et al., 200292 | Incidence of cardiac event-related readmission was significantly higher in depressed patients (7.8% vs. 4.3%, p = 0.018) | – | Multivariate results not presented for cardiac event-related readmissions |

| Ciechanowski et al., 200098 | ED visit costs-mean and SD Low depression group = 81 (375) Medium depression group = 128 (479) High depression group = 185 (548) |

– | Not reported for urgent health-care utilisation |

| Ghanei et al., 200796 | Rehospitalised patients had higher depression scores than those not rehospitalised (12 vs. 11, p = 0.039) | Monthly income and medical comorbidities | Depression is an independent predictor of urgent readmission (risk ratio = 0.31, p = 0.012) after controlling for monthly income and medical comorbidities |

| Carneiro et al., 201095 | Number of readmission correlated with depression score (p = 0.09) | – | Not reported |

| Farkas et al., 201094 | Depression score was higher for hospitalised compared to non-hospitalised [15 (SD = 11) vs. 11 (SD = 9)] | – | Depression not entered into the multivariate analyses |

| Pishgoo 201128 | Baseline depression score 5.7 among those with ED visits vs. 5.1 in those without, p = 0.22 | Sex, angina grade, anxiety and somatic comorbidity score contributed entered into final model | Sex, angina grade, anxiety and somatic comorbidity score contributed significantly to the final model. Depression wasn’t entered into the model as univariate findings were non-significant |

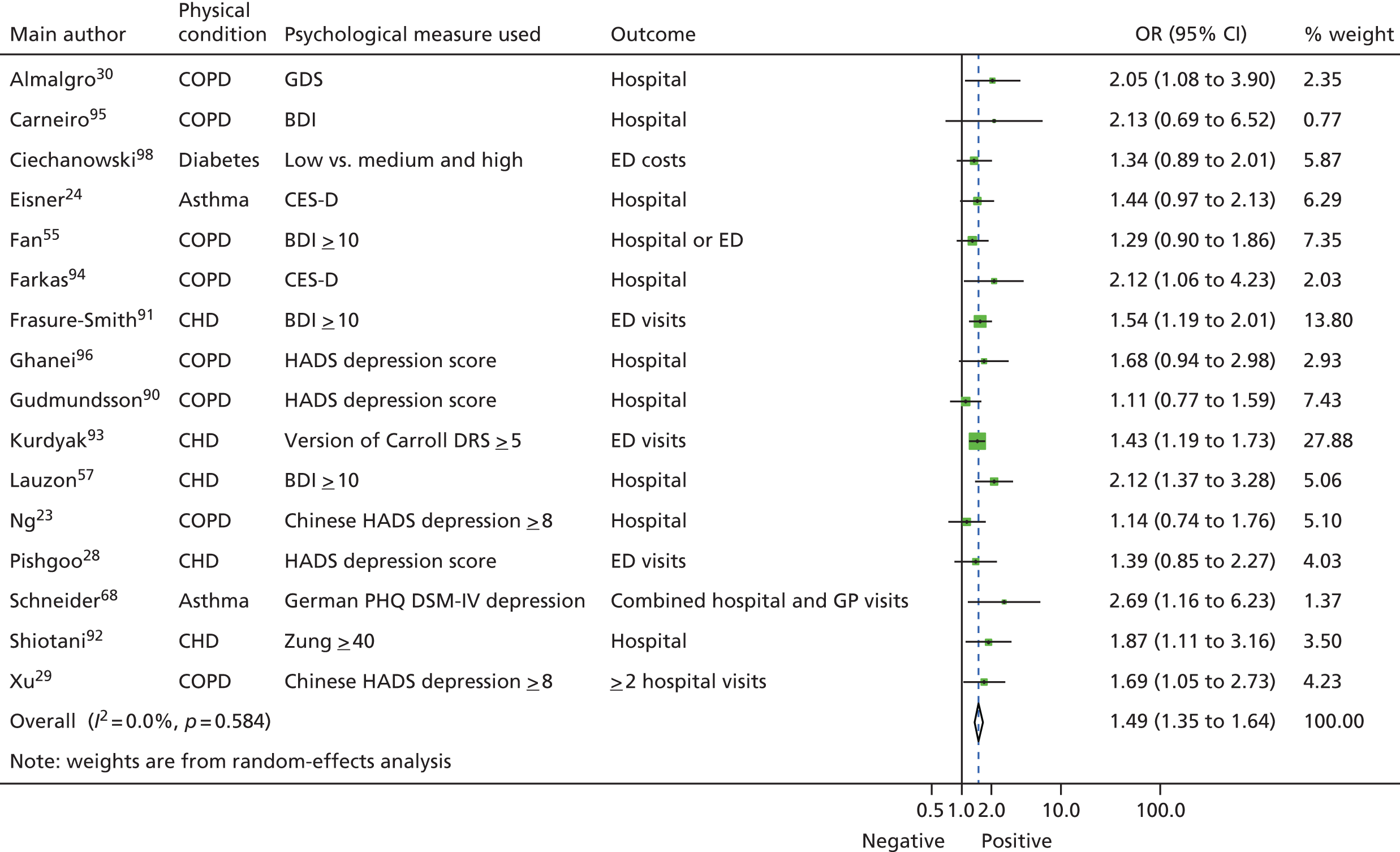

The results of the meta-analysis are shown in Figure 4. There is a combined OR for depression across all the studies of 1.49 (95% CI 1.35 to 1.64; p < 0.0005). Effects of individual studies were very homogeneous (Q = 13.2, I2 = 0.0, 95% CI 0 to 52; p = 0.58).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot for associations between depression and subsequent use of unscheduled health care in patients with one of four exemplar LTCs (N = 16; OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.35 to 1.64; p < 0.001; Q = 13.2, I2 = 0.0%; 95% CI 0 to 52; p = 0.58). BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DRS, Depression Rating Scale; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; Zung, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale. Reprinted from Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 73, Dickens C, Katon W, Blakemore A, Khara A, McGowan L, Tomenson B, et al. Does depression predict the use of urgent and unscheduled care by people with long term conditions? A systematic review with meta-analysis, pp. 334–42. © 2012, with permission from Elsevier. 78

Effects varied with different types of unscheduled care. The combined OR for ED attendances was 1.45 (n = 4; 95% CI 1.26 to 1.66; p < 0.0005), for urgent hospitalisations it was 1.56 (n = 10; 95% CI 1.32 to 1.84; p < 0.0005), for combined urgent hospitalisations or ED visits it was 1.29 (n = 1; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.86; p = 0.17) and for combined urgent hospitalisation and urgent GP visits it was 2.69 (n = 1; 95% CI 1.16 to 6.23; p = 0.021). Comparison across groups using the analogue to analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that these differences across different types of unscheduled care were not statistically significant [Q = 2.9, degrees of freedom (df) = 3; p = 0.41].

Effects also varied across the different LTCs, but these were not statistically significant. Only eight of the studies included a measure of severity of illness. 23,28–30,55,57,90,93 In six of these,23,29,30,55,90,93 the independent effects of depression were not significant.

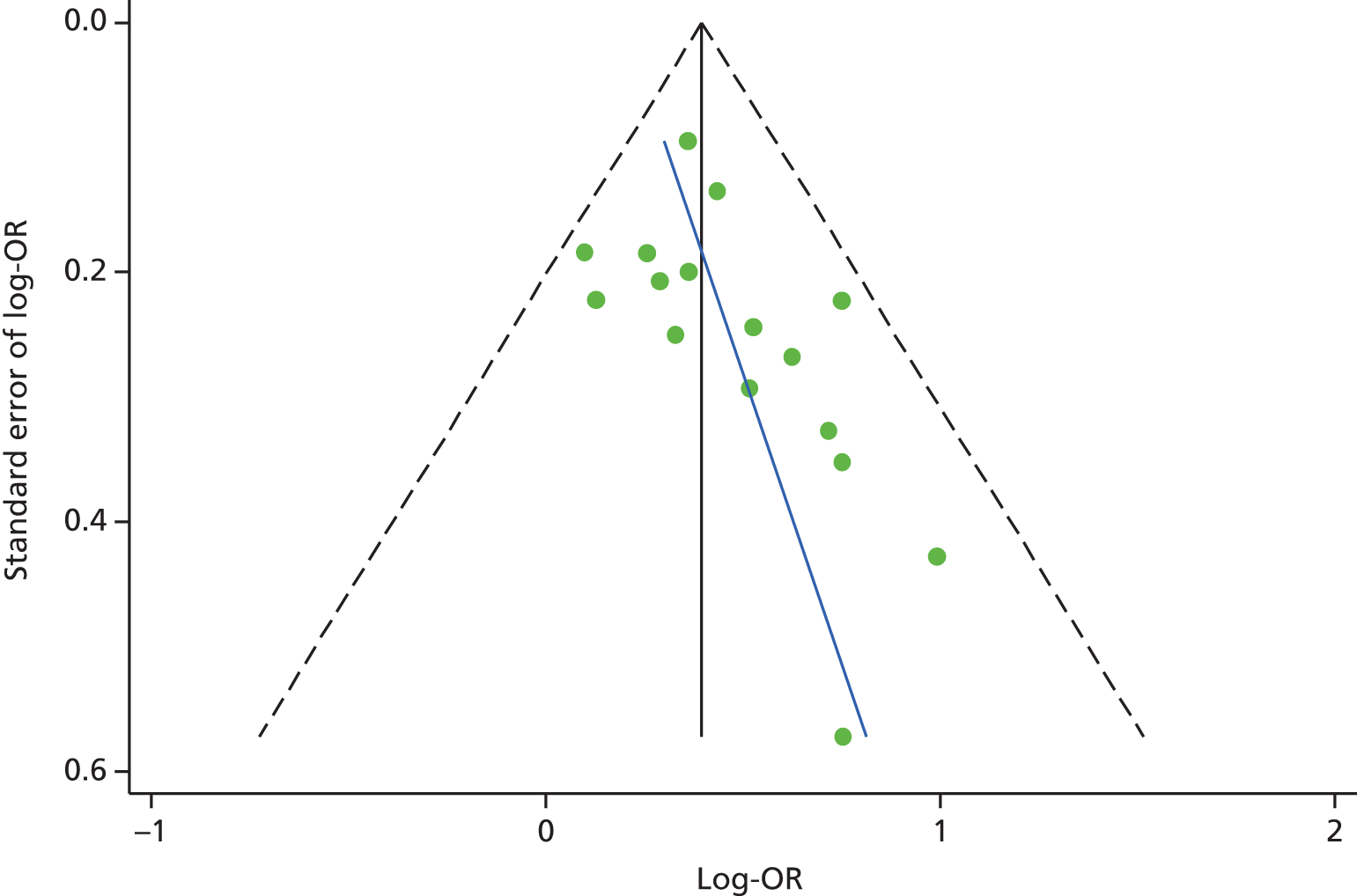

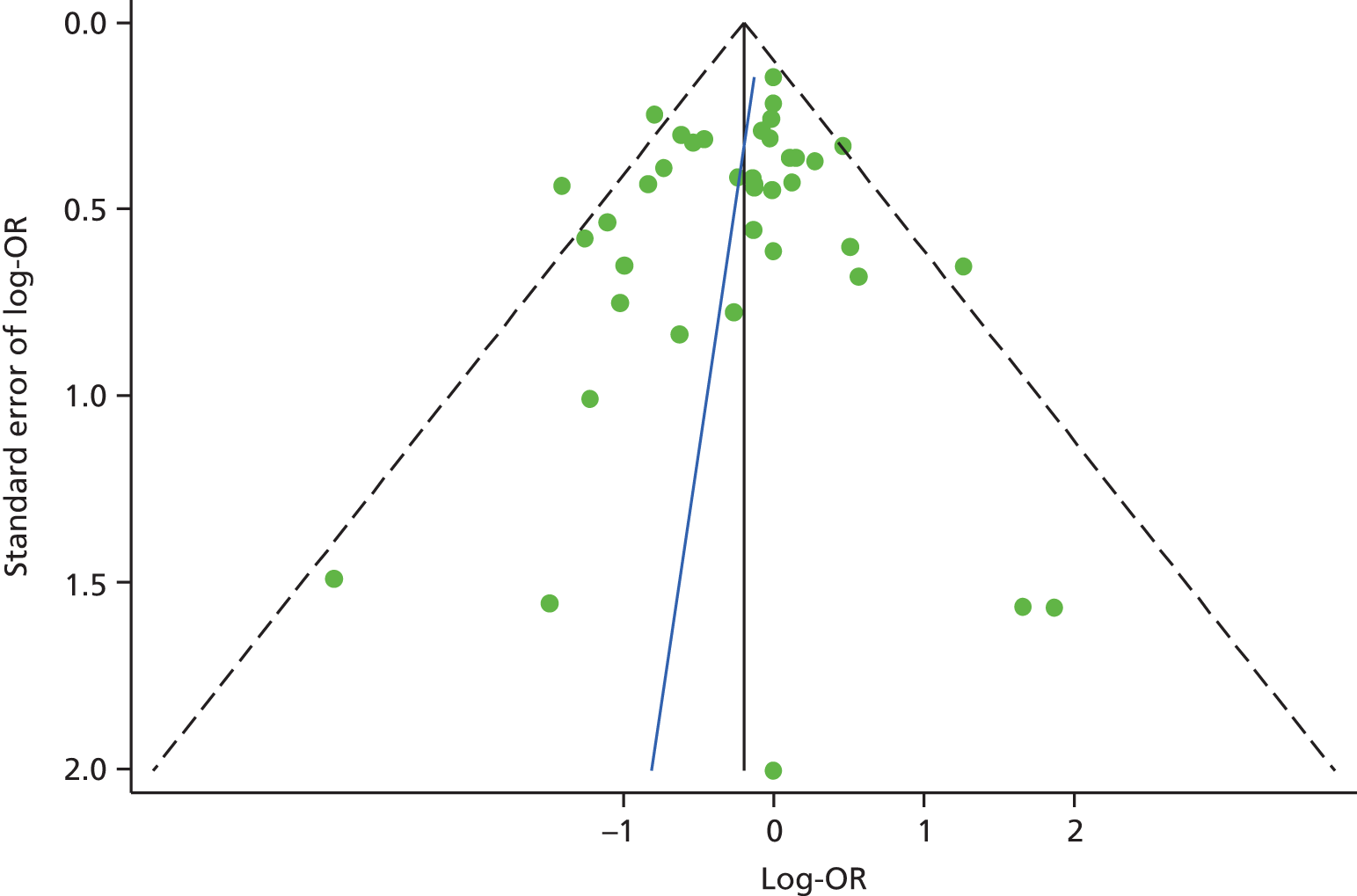

The funnel plot for depression studies appeared asymmetrical, with a relative absence of small negative studies (Figure 5). Egger’s regression method confirmed an association between log-OR and standard error of log-OR (Egger’s intercept = 1.98, 95% CI 0.22 to 3.74; p = 0.03). This suggested that there may be some publication bias in the papers included in our review.

FIGURE 5.

Funnel plot for studies of depression and subsequent use of unscheduled health care in patients with LTCs (Egger’s intercept = 1.98; 95% CI 0.22 to 3.74; p = 0.03). Reprinted from Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 73, Dickens C, Katon W, Blakemore A, Khara A, McGowan L, Tomenson B, et al. Does depression predict the use of urgent and unscheduled care by people with long term conditions? A systematic review with meta-analysis, pp. 334–42. © 2012, with permission from Elsevier. 78

Table 3 shows the results of the quality review for studies that assessed the impact of depression on unscheduled care. Meta-analysis was repeated for the studies subgrouped according to methodological quality (strong, moderate or weak). There was no apparent association between study quality and effect size. There were two studies that were rated as methodologically strong,23,30 which, when combined, produced an OR of 1.46 (95% CI 0.82 to 2.58; p = 0.20). There were six studies that were rated as methodologically moderate, which resulted in a combined OR of 1.53 (95% CI 1.31 to 1.77; p < 0.0005). 24,29,55,57,68,93 Eight studies were rated as methodologically weak with a combined OR of 1.47 (95% CI 1.26 to 1.72; p < 0.0005). 28,90–92,94–96,98

| Author and date | Selection bias | Design | Confounding | Blinding | Data collection | Dropouts | Global rating | Discrepancy between reviewers | Reasons for discrepancy | Final rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almagro et al., 200630 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No | 1 | |

| Carneiro et al., 201095 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | No | 3 | |

| Ciechanowski et al., 200098 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | Yes | Oversight | 3 |

| Eisner et al., 200524 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | No | 2 | |

| Fan et al., 200755 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Yes | Oversight, differences in interpretation | 2 |

| Farkas et al., 201094 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | No | 3 | |

| Frasure-Smith et al., 200091 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | No | 3 | |

| Ghanei et al., 200796 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | Yes | Differences in interpretation | 3 |

| Gudmundsson et al., 200690 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | No | 3 | |

| Kurdyak et al., 200893 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Yes | Differences in interpretation | 2 |

| Lauzon et al., 200357 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Yes | Oversight | 2 |

| Ng et al., 200723 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | No | 1 | |

| Pishgoo 201128 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | No | 3 | |

| Schneider et al., 200868 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | No | 2 | |

| Shiotani et al., 200292 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Yes | Differences in interpretation | 3 |

| Xu et al., 200829 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | No | 2 |

Conclusions

Our main conclusion from this systematic review was that depression was associated with a 49% increase in the odds of using subsequent unscheduled care among people with LTCs. The effects for depression were not significantly different across different types of unscheduled care (EHAs or ED attendances) or across different LTCs. However, only eight of studies included attempts to control for the severity of illness, and this appeared to be an important confounder. 23,28–30,55,57,90,93

Limitations

There are several limitations of this review of the relationship between depression and unscheduled care use. First, none of the studies that we identified had been carried out in the UK, so it is unclear how translatable the results are to the UK health-care system. The delivery and organisation of health care varies across countries and the same factors that drive attendance at an emergency room; for example, the factors that drive attendance in the USA may not be the same as those that drive health-care-seeking in the UK. Second, we were able to identify only one study on diabetes98 and two on asthma,24,68 which limits the generalisability of the results to these conditions and other LTCs. Third, only two of the studies were based in primary care,68,98 with most studies focusing on hospital populations, so the results may not be generalisable to patients in primary care with LTCs. Fourth, the methodological quality of the studies identified varied considerably, though this does not appear to have distorted our results. Fifth, we found evidence of a potential publication bias, which may have inflated the observed association between depression and unscheduled care. Finally, a wide variety of different measures of depression were utilised across the studies, as shown in Table 1. Although there is generally good agreement between measures of depression, there will have been some variability between the studies because of the different measures that were employed. Of note, only three of the studies used a depression measure specifically developed for use in populations with physical illness. 28,90,96

Study 2: does anxiety predict the use of unscheduled care in patients with long-term conditions?

Results

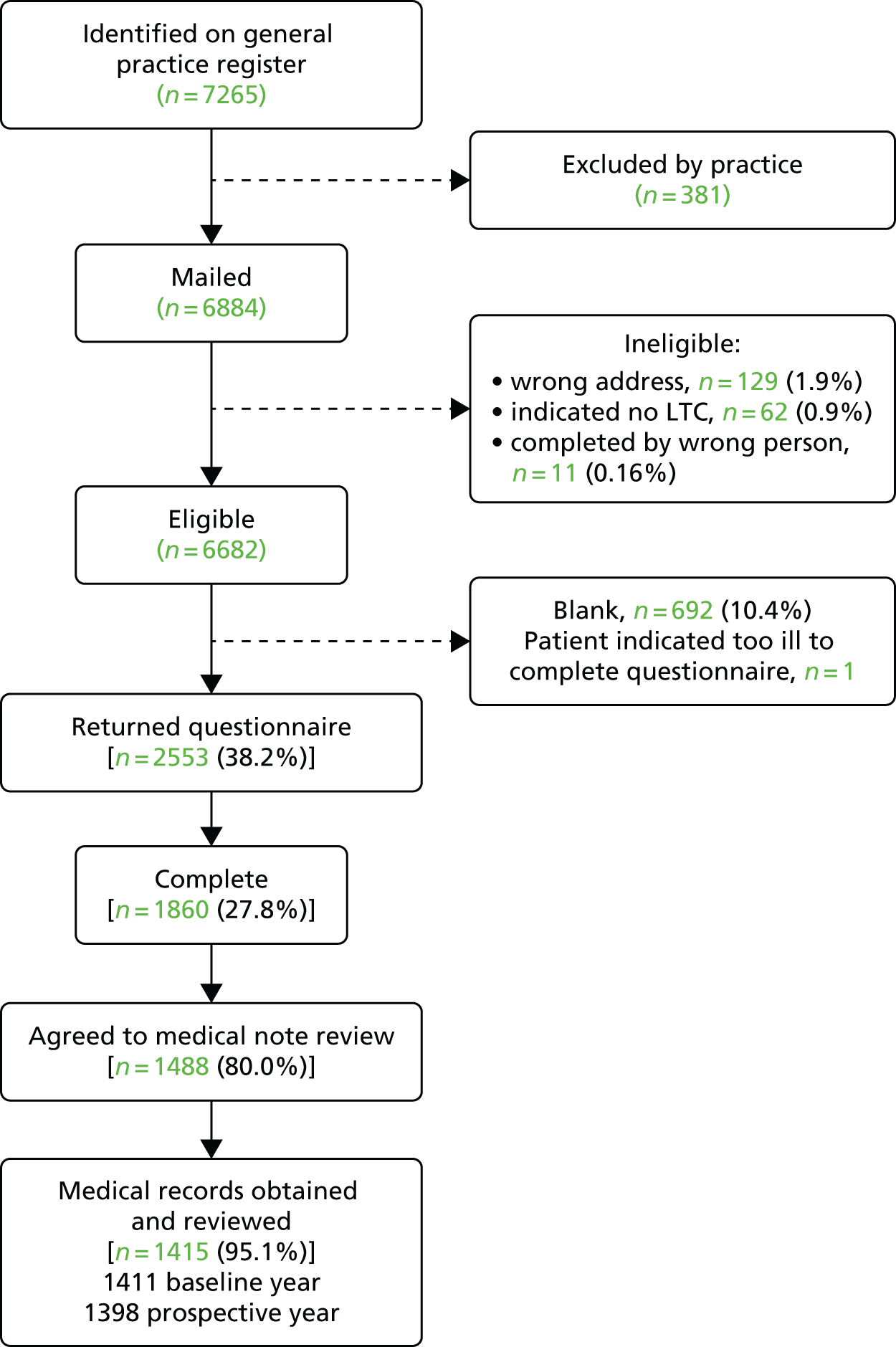

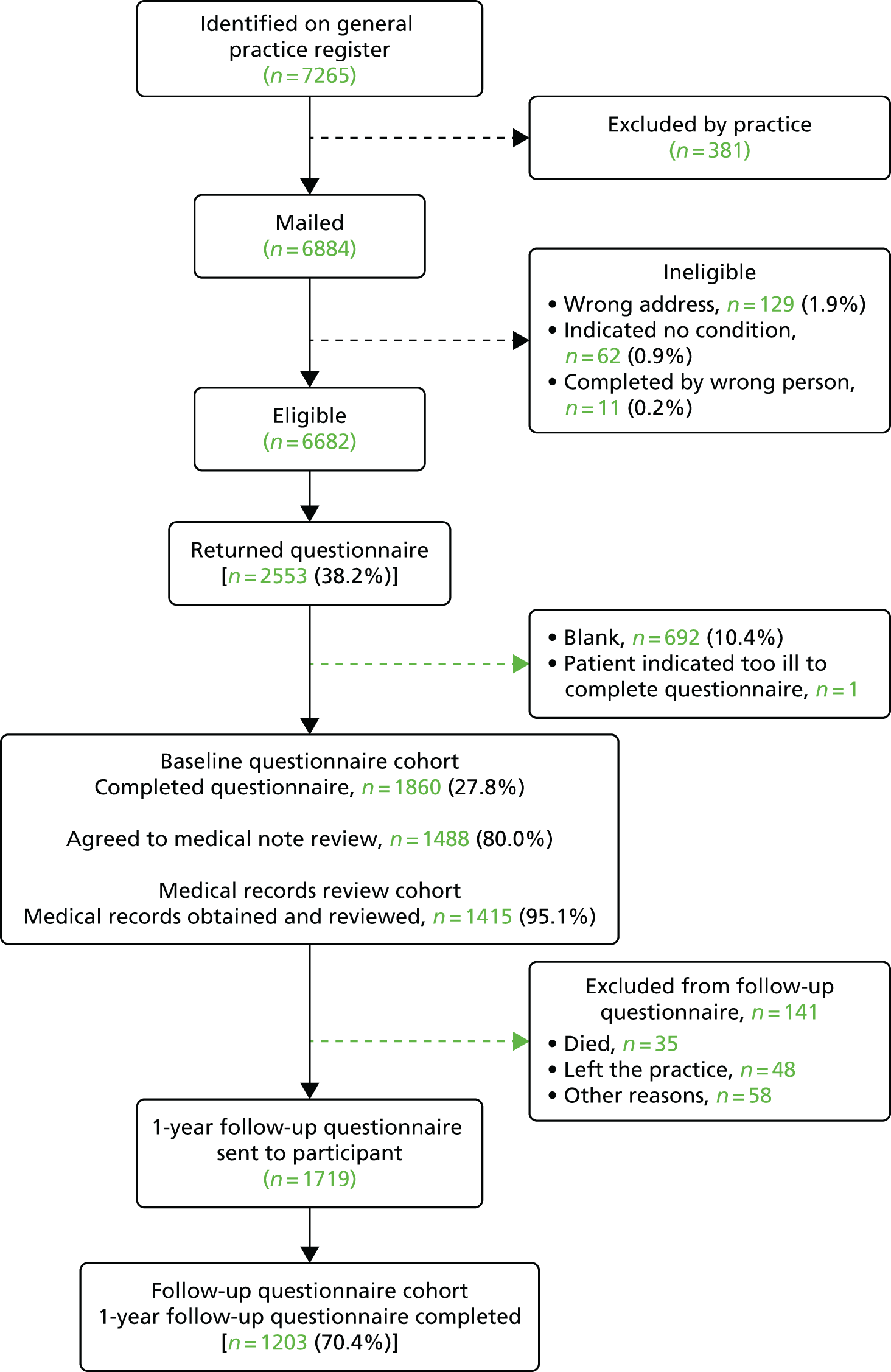

The results of the second systematic review we conducted will now be presented. Figure 6 shows the flow chart for this study. Eight independent studies with a prospective design and which included a measure of anxiety at baseline and a measure of unscheduled care at outcome were identified. 29,68,76,77,97,99–101 From the eight studies we identified, there were data for 28,823 participants. The details of the characteristics of each of the included studies can be found in the published paper by Blakeley et al. 79 and are summarised in Table 4.

FIGURE 6.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for prospective longitudinal studies of patients with LTCs, which included a measure of anxiety at baseline and a measure of unscheduled care at follow-up. Adapted from Blakeley et al. 79

| Author, date, LTC and country of origin | Sample and size | Measure of | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Unscheduled care | ||

| Abrams et al., 2011;77 COPD, USA | Veterans with COPD exacerbation, acute or chronic bronchitis admitted to hospital (n = 26,591) | ICD-9 | 30-day readmission records |

| Schneider et al., 2008;68 asthma, Germany | Patients from 43 primary care practices (n = 256) | Validated German PHQ | Patient self-reported ED attendances and EHAs over 1 year |

| Greaves et al., 2002;97 asthma, UK | Community subjects with asthma, one group stable, one group who had suffered recent asthma attack (n = 74) | Seven-item panic fear scale of Asthma Symptom Checklist | Practice records ED attendance and hospital attendance over 1 year |

| Grace et al., 2004;99 CHD, Canada | Patients with unstable angina and MI admitted to CCUs (n = 913) | Phobic anxiety subscale of Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire Anxiety subscale of PRIME-MD |

Self-reported cardiac events over 6 months and 1 year |

| Kaptein, 1982;100 asthma, the Netherlands | Patients with acute, severe asthma hospitalised for condition (n = 40) | State–Trait Anxiety Inventory plus panic–fear personality scale | Rehospitalisation within 6-month period |

| Xu et al., 2008;29 COPD, China | COPD patients attending hospitals in Beijing (n = 491) | Mandarin HADS | EHAs confirmed by chart review over 1 year |

| Gudmundsson et al., 2006;90 COPD, Iceland | Patients hospitalised for COPD (n = 416) | HADS (cut-off point of ≥ 8) | Self-reported readmissions over 1 year |

| Coventry et al., 2011;76 COPD, UK | Patients admitted to hospital with COPD (n = 79) | HADS | Readmissions over 1 year |

Four of the studies involved patients with COPD,29,76,77,90 three involved patients with asthma68,97,100 and one involved patients with CHD. 99 There were no studies on diabetes. Two of the studies were based in the UK. 76,97

The main, multivariate results for each individual study are shown in Table 5. None of the eight studies included in this review found that anxiety had a significant effect on the use of unscheduled health care. One study found near significant effects for anxiety on unscheduled health-care use for patients with asthma (see Table 5). 68

| Author and date | Univariate findings | Factors controlled for | Multivariate findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abrams et al., 201177 | Patients with anxiety were not more significantly likely to be readmitted than those without anxiety [11.3% vs. 11.5% (NS)] | Smoking status | No significant difference in risk of admission regardless of smoking status. Smoking present (HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.44) and smoking absent (HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.43) |

| Schneider et al., 200868 | Panic disorder did not predict hospitalisation (OR 3.5, 95% CI 0.7 to 18.3; p = 0.145), but did predict emergency visits (OR 4.8, 95% CI 1.3 to 17.7; p = 0.019) | ||

| Greaves et al., 200297 | There was no main effect of panic (p > 0.05) | ||

| Grace et al., 200499 | Anxious patients (mean 1.11, SD 1.57) reported more visits to the ED than non-anxious (mean 0.83, SD 1.18) patients (t = –1.37; p = 0.17). However, this was NS | Age, family history of CVD, depression, Killip class, sex, family income, smoking status, diabetes and phobic anxiety | Age (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.05; p = 0.05), family history of CVD (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.54; p = 0.03), depression (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.12; p ≤ 0.01) and PRIME-MD anxiety score at 6 months (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.65; p < 0.01), were all significant predictors of self-reported recurrent cardiac events. All other factors NS |

| Kaptein, 1982100 | State and trait anxiety not associated with increased length of hospitalisations State anxiety not significantly associated with readmission; however, trait anxiety had slight effect (one-tailed t-test: t = 1.72; p = 0.048) |

||

| Xu et al., 200829 | Anxiety not associated with increased risk of EHA (p = 0.11); however, length of exacerbation in days was longer for patients with anxiety than for those without (p = 0.03) | Age, sex, smoking, marital status, education, employment, living situation, FEV1, dyspnoea score, 6-minute walk distance, social support, COPD-specific self-efficacy, significant comorbidities, hospital type, use of long-acting bronchodilator and inhaled corticosteroid, long-term oxygen therapy and past hospitalisation | Anxiety was not associated with hospitalisation: IRR 1.63 (95% CI 0.88 to 3.03) for HADS anxiety score of ≥ 11; or with length of hospitalisation for those readmitted: IRR 1.99 (95% CI 0.59 to 6.72) |

| Gudmundsson et al., 200690 | Anxiety had no significant effect on rehospitalisation (p = 0.61). No significant difference between HADS anxiety scores for those who were readmitted [mean 7.1 (SD 4.3)] and those who were not [mean 6.7 (SD 4.0); p = 0.28] | Age smoking status, FEV1, SGRQ | Significant association between the HADS anxiety score and the risk of readmission in patients with a low health status (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.04). In the same group, anxiety (HADS score of ≥ 8) was related to increased risk of rehospitalisation (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.74) |

| Coventry et al., 201176 | No significant difference between HADS anxiety scores for those who were readmitted (8.53 ± 4.2) and those who were not (9.47 ± 4.6; p = 0.407) | Age, race, sex, individual medical comorbidities and laboratory values | Depression (OR 1.300, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.60; p = 0.013), FEV1 score (OR 0.962, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.99; p = 0.021), and age (OR 1.092, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.18; p = 0.026) were the only significant predictors of readmission. Anxiety was insignificant |

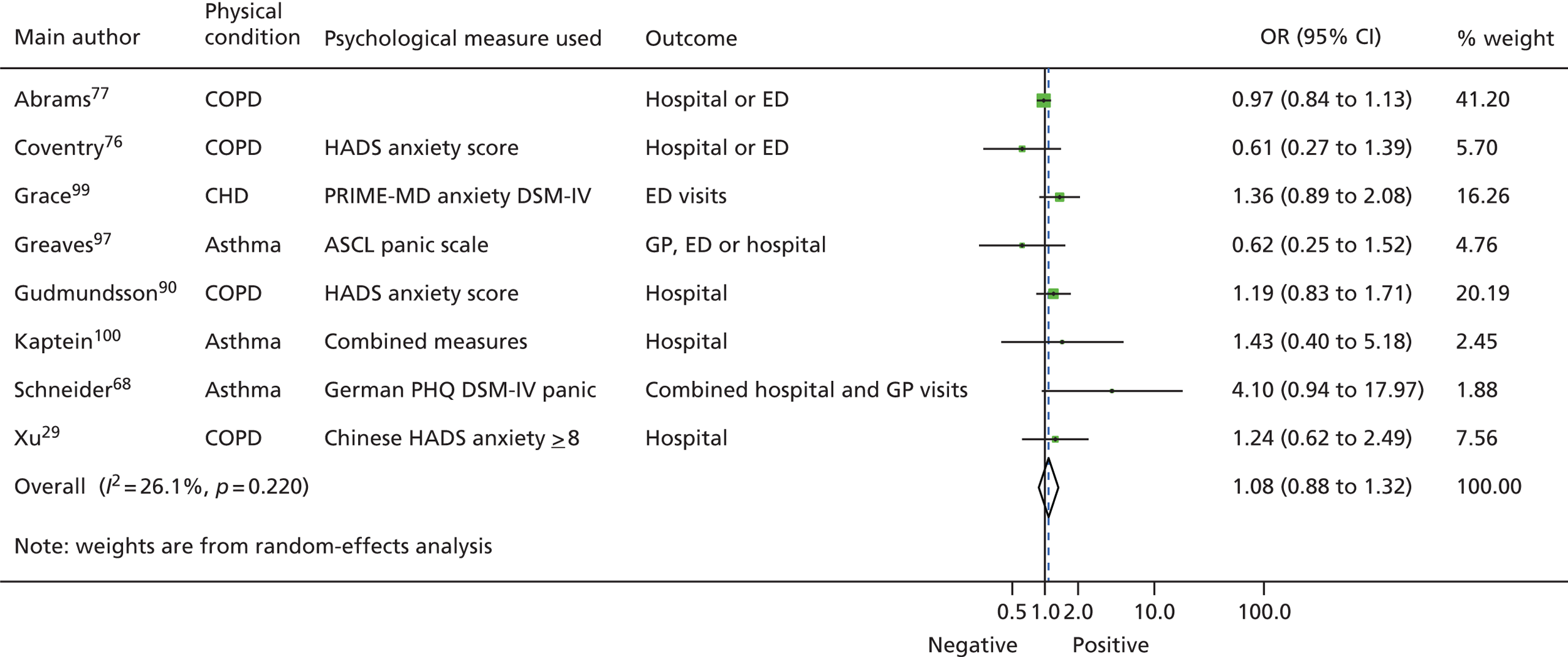

Figure 7 shows a forest plot of the eight studies. 29,68,76,77,90,97,99,100 There was a combined OR for anxiety across all studies of 1.078 (95% CI 0.877 to 1.325; p = 0.476). Effects of individual studies showed a low level of heterogeneity (Q = 9.5, df = 7, I2 = 26.07%; p = 0.221).

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot for associations between anxiety and subsequent use of unscheduled health care. ASCL, Asthma Symptom Checklist; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders screening questionnaire. From Blakeley et al. 79

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding the largest study, as this had the largest sample size (n = 26,591) of whom 97% were male. 77 The combined effect in random-effects meta-analysis for the studies excluding Abrams et al. 77 was 1.238 (95% CI 0.969 to 1.551; p = 0.087). Again, the effects of these studies showed low heterogeneity (Q = 5.116, df = 5, I2 = 2.27%; p = 0.402).

We investigated whether or not the effects of anxiety varied across the different types of unscheduled care used between studies and the different types of LTCs. The effect of anxiety varied across the different types of unscheduled health-care use and across the four LTCs, but none of the differences was significant.

Four studies conducted multivariate analysis that controlled for the severity of the LTC studied. 76,77,99,101 One out of four studies found that, when severity of the LTC was controlled for, anxiety was significantly related to hospital readmission rates for a subgroup of patients with COPD and poor health status. 101

Meta-analysis was repeated for the studies subgrouped according to methodological quality (strong, moderate or weak). Study quality did not change the results: anxiety had no significant impact on unscheduled care use across studies that were rated as methodologically strong (n = 2; OR 0.927, 95% CI 0.872 to 1.143; p = 0.978), moderate (n = 4; OR 1.243, 95% CI 0.650 to 2.375; p = 0.511) or weak (n = 2; OR 1.258, 95% CI 0.955 to 1.656; p = 0.102).

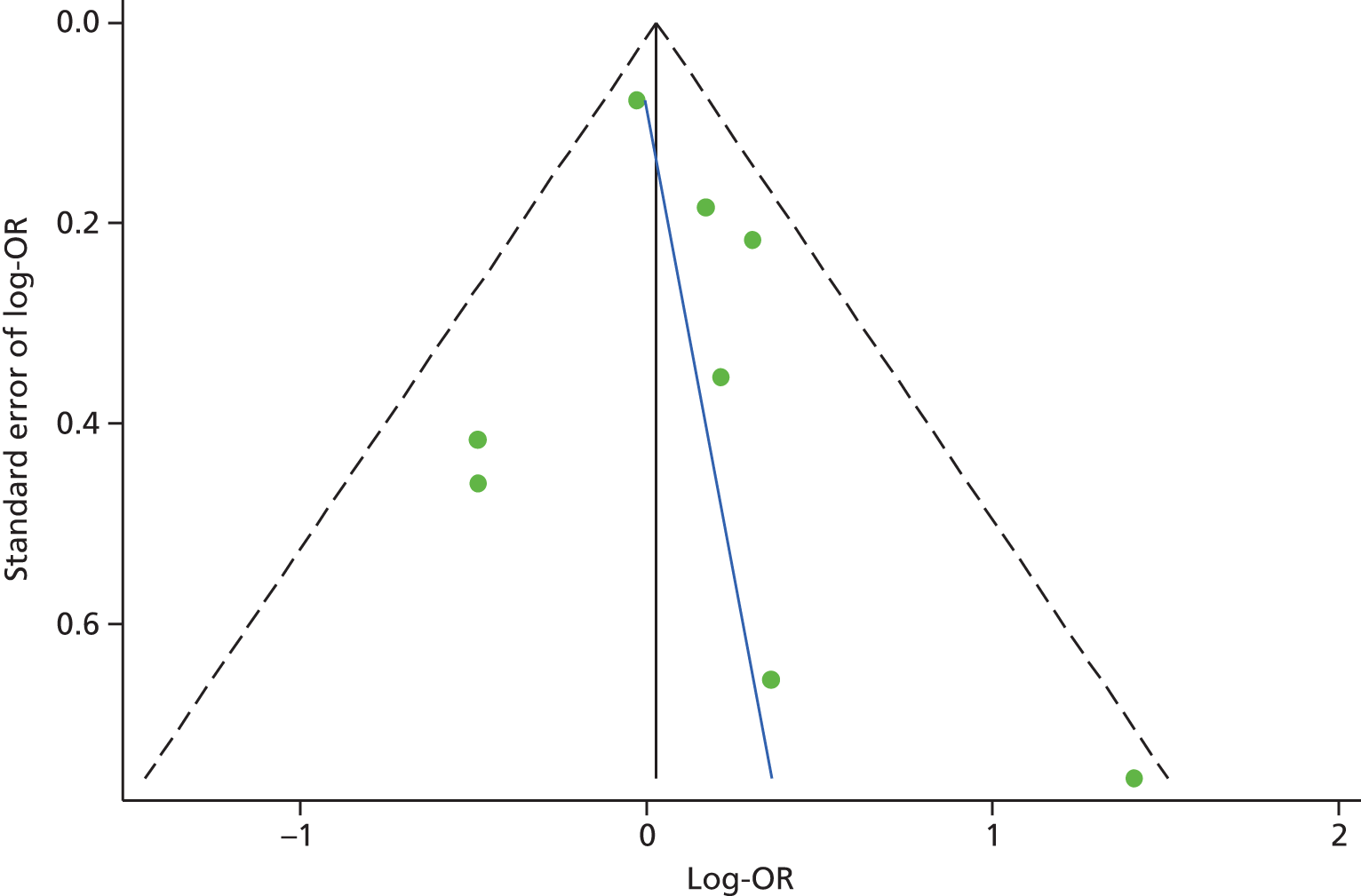

Publication bias was investigated using a funnel plot. The plot for anxiety studies did not appear to be asymmetrical, except for one small negative study (Figure 8). Egger’s regression method confirmed the lack of association between the loge-OR and standard error of loge-OR (Egger’s bias = 1.24, 95% CI –1.01 to 3.48; p = 0.23). The Duval and Tweedie trim and fill procedure created just one imputed study, giving a revised random-effects-combined OR for anxiety across all studies of 1.05 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.33; p = 0.69). The heterogeneity between studies was increased slightly, and was still significant (Q = 12.9, df = 8; p = 0.040).

FIGURE 8.

Funnel plot with pseudo-95% confidence limits for studies of anxiety and subsequent use of unscheduled health care (Egger’s test: bias = 1.24, 95% CI –1.01 to 3.48; p = 0.23). Adapted from Blakeley et al. 79

Conclusions

Our main conclusion from this systematic review was that anxiety does not appear to be associated with an increase in using unscheduled care in patients with LTCs. This is in contrast to our findings from the first systematic review, which showed a relationship between depression and use of unscheduled care.

The number of studies in the anxiety review was small and we did not focus specifically on panic or other forms of anxiety-related symptoms and disorders, which have been shown to be involved in care-seeking. 102,103 However, the findings for our review suggest anxiety does not appear to be an important psychosocial driver of unscheduled care in patients with asthma, CHD, COPD and diabetes.

Discussion for systematic reviews to determine whether depression or anxiety predicts unscheduled care use

The findings from our two first systematic reviews were puzzling. Why should depression, but not anxiety, be associated with unscheduled care use? Both are common in patients with LTCs and both are associated with adverse outcomes in LTCs. 10,69,104,105

One of the reasons for the difference we found between depression and anxiety may be methodological problems with the included studies, which are detailed below, and the relative paucity of studies that have examined the effects of anxiety at all. In addition, depression and anxiety often coexist, particularly in primary care,105 and it may be somewhat of an artificial distinction to separate them in the context of comorbid physical illness. However, as they have been analysed and reported separately in the included studies, it would not have been possible to combine them in a meaningful way for the purposes of the systematic reviews.

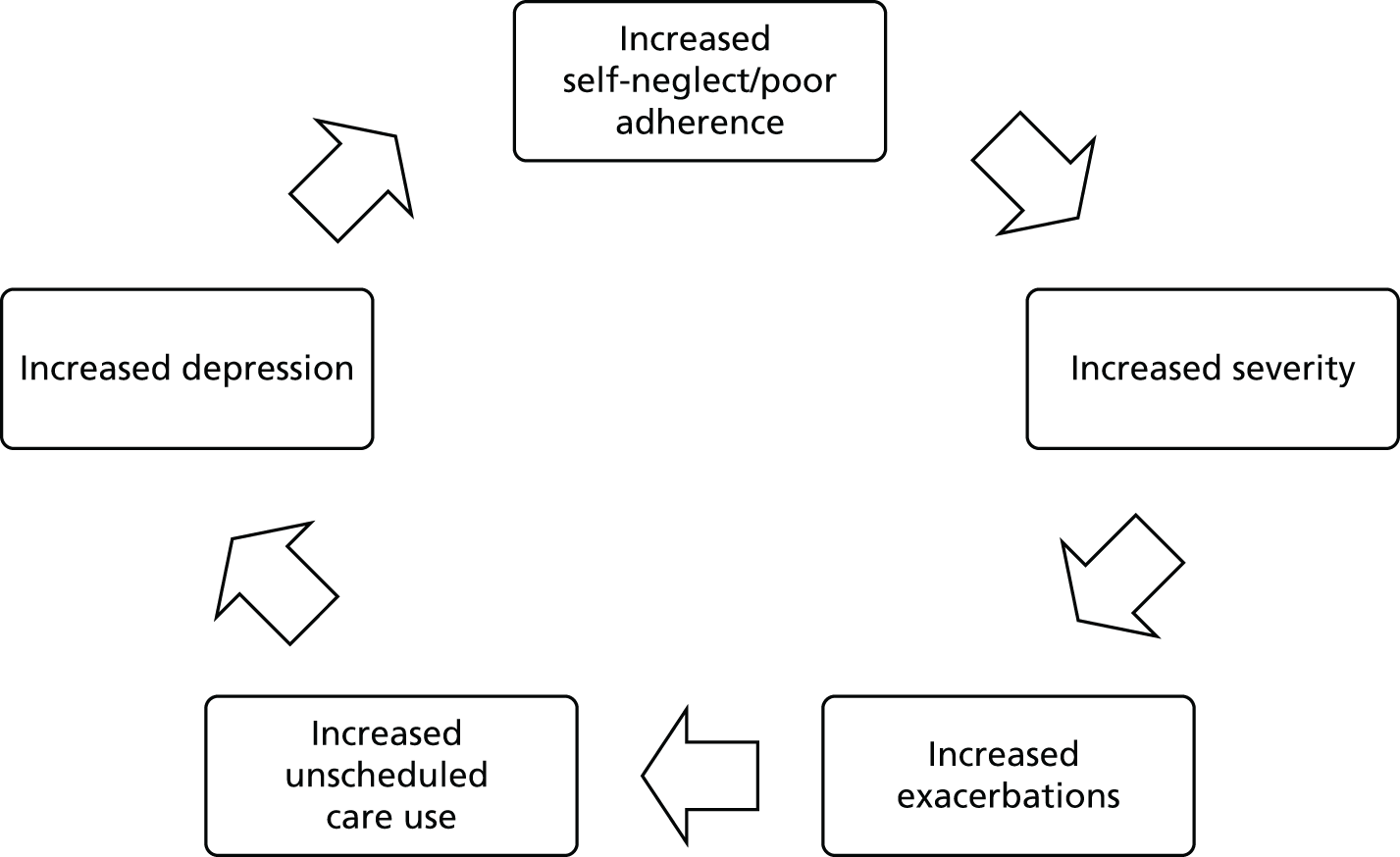

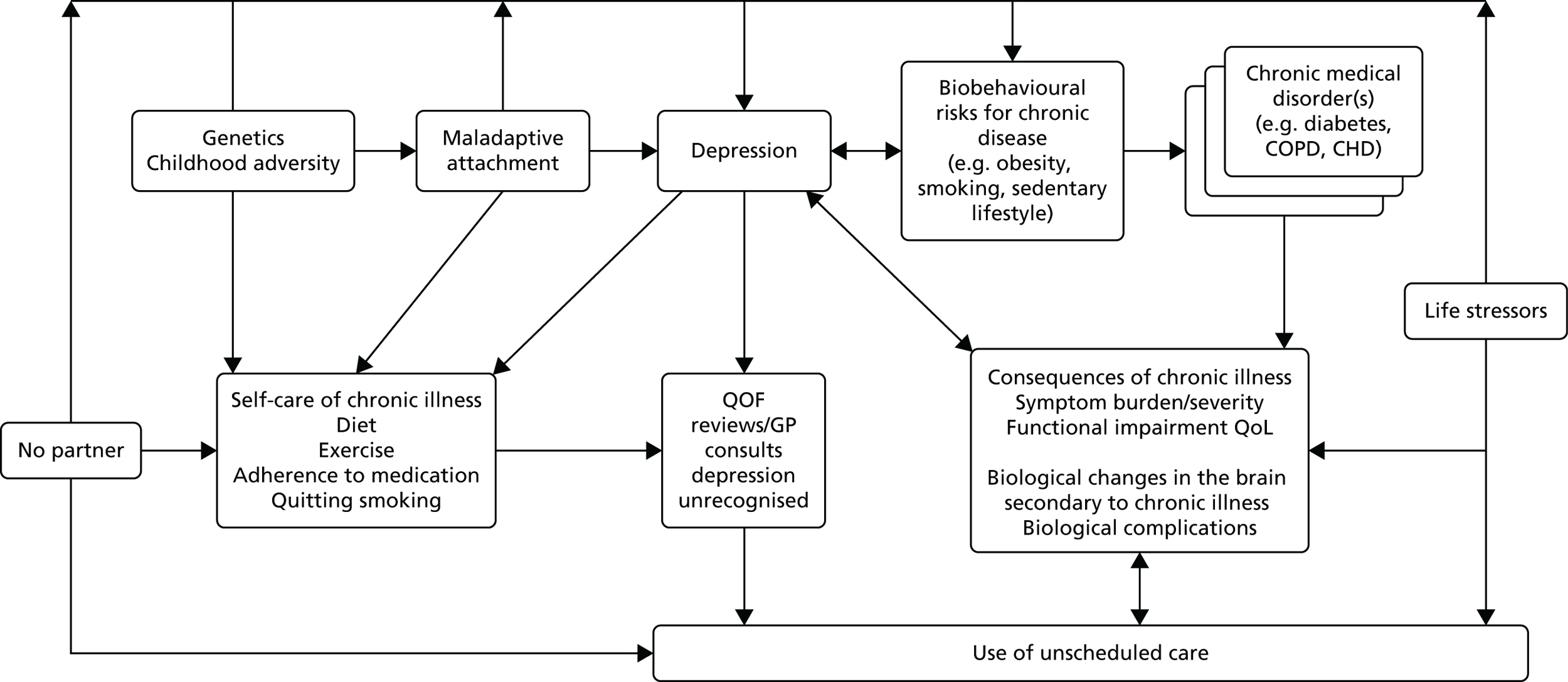

Our findings give support to a model of depression in relation to unscheduled care use in people with LTCs. Depression results in greater self-neglect106,107 and less adherence to routine treatment. 108 This in turn results in more symptoms, or more severe symptoms or exacerbations, which may increase the risk of unscheduled care.

This model is illustrated in Figure 9. A similar model has been put forward by Pooler and Beech in relation to COPD and increased hospital admissions,109 although that model also includes a role for anxiety, which is not supported by our findings.

FIGURE 9.

A model illustrating the potential mechanism whereby depression may affect unscheduled care use. Adapted from Pooler and Beech. 109

Anxiety is clearly associated with a variety of poor outcomes in people with LTCs, and is reported from the qualitative literature to be associated with acute exacerbations of illness. 110 It is possible that, once an acute exacerbation of illness is triggered, this is then associated with an increase in worry and anxiety, which heightens the focus on bodily symptoms, resulting in some cases, in fear of death and panic, which necessitates the need to seek immediate health care. Thus, anxiety may not be a long-term predictor of unscheduled care but may play an important role in the immediacy of treatment-seeking which would not be captured by studies employing a prospective longitudinal design, but may be captured by other methods (e.g. qualitative work). This potential mechanism is illustrated in Figure 10.

FIGURE 10.

A model illustrating the potential mechanism whereby depression and anxiety may affect unscheduled care use. Adapted from Pooler and Beech. 109

Limitations

By limiting the two systematic reviews to our four exemplar LTCs, our findings may not be generalisable to all people with LTCs. The studies in the two reviews were diverse and focused on different patient populations at different points in the care pathway, in different countries, with different health-care systems, and with different times to follow-up. In some countries, health care would not be free at the point of delivery, and this is likely to have an impact on health-care-seeking behaviour. There were very few UK studies, so it is difficult to determine whether or not the findings are relevant to the NHS.

We included only studies in which a prospective longitudinal cohort design had been employed and, particularly in relation to anxiety, there were very few published studies. We chose not to include cross-sectional studies because of the difficulty interpreting casual links with such designs; however, this limited the number of studies that were available to include.

Very few of the studies had been specifically designed to test the relationship between baseline depression or anxiety and unscheduled care, and in many cases the findings we used were the result of secondary analyses. There were also differences in the types of unscheduled care that were examined in the studies, including hospital readmission rates following discharge, acute admissions and ED attendances. The results of the systematic review focusing on depression were also potentially subject to publication bias, and only half the studies took account of the severity of patients’ physical symptoms.

Complex interventions that reduce unscheduled health-care use

The second aim of this section of the research programme was to systematically synthesise the evidence for existing complex interventions which have been used to reduce the frequency of unscheduled care use in patients with LTCs. Our initial search in 2008 identified that there were over 30 relevant studies for COPD and asthma, but only six studies that examined the effect of complex interventions on unscheduled care use in diabetes and four studies in CHD. We chose to focus on two of our four exemplar conditions [COPD (study 3) and asthma (study 4)], as there was a large number of studies, 32 and 33, respectively, for each condition, which had looked at the effect of complex interventions to reduce unscheduled care use.

Aims

The aim of our third review (study 3) was to identify the characteristics of complex interventions that reduce the unscheduled health-care use in adults with COPD. 111

The aim of our fourth review (study 4) was to identify the characteristics of complex interventions that reduce the unscheduled health-care use in adults with asthma. 112

Methods

The methods for studies 3 and 4 are summarised here. Full descriptions of the methods are available in the published papers. 111,112

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the reviews if they met the following criteria:

-

Included adults with COPD or asthma (aged ≥ 16 years).

-

Assessed the efficacy/effectiveness of a complex intervention. A complex intervention is defined as an intervention that involves multiple components and/or multiple professionals. The interventions can be delivered on an individual or a group basis, face to face, over the telephone, or on a computer. Interventions could include any of the following: education, rehabilitation, psychological therapy, social intervention (e.g. social support or support group), organisational intervention (e.g. collaborative care or case management) and drug trials that targeted a psychological problem (e.g. anxiety or depression).

-

Assessed unscheduled health-care use as an outcome. This could include ED visits, EHAs or unscheduled GP visits.

-

RCT design.

Search strategies (see Appendix 1) were developed and searches conducted in the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, BNI, PsycINFO and Cochrane databases. Searches for both reviews were first conducted on 19 August 2008 and then updated on 25 January 2013. Each eligible paper identified from searching the databases was also checked for relevant citations using the Social Science Citation Index to identify more papers.

We were not able to develop a search strategy that was sensitive and reliable enough to detect studies investigating unscheduled health care specifically. Therefore, searches were developed that more broadly identified studies that had measured all health-care use and further restriction to relevant papers that had looked at unscheduled care was specifically achieved by hand-searching. Additional papers were identified by screening reference lists and citations of eligible papers.

The titles and abstracts of all identified papers were screened by one of three researchers [AB, Angee Khara (AK), RA] and the full text of studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria were then screened by two out of three researchers (AB, AK, RA). Any disagreements about eligible papers were discussed with another member of the team (CD, EG).

Data extraction was completed by two out of three researchers (AB, AK, RA) using standardised electronic data extraction sheets that were developed by the team and modified after piloting the first five papers. Data were extracted on the characteristics of participants; the characteristics of the intervention; methodological characteristics of the study; and the effects of the intervention on the use of unscheduled health care.

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using a component approach as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0113 to assess whether or not:

-

allocation sequence was adequately generated

-

treatment allocation was adequately concealed

-

knowledge of the allocated intervention was adequately prevented

-

incomplete outcome data were adequately dealt with

-

reports were free from selective outcome reporting

-

the study was free of other problems that may cause bias.

Each study was rated as low, medium or high risk for each of the components listed. Where the rating was not certain, studies were rated as unclear. 113

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios and 95% CIs were extracted or calculated for each study. An OR of < 1 indicated that the intervention reduced the use of unscheduled health care. 114 Where data were presented in alternative formats, appropriate transformations were made. 81 Where follow-up data were collected at multiple time points, data collected nearest to 1 year were used. Where studies included more than one measure of unscheduled care, ORs for each measure were averaged so that each independent study contributed a single effect to the meta-analysis. 81 For studies that included more than one intervention group, data for each intervention were entered as separate records and the sample size for the control group was halved for the comparison. ORs for interventions across independent studies were combined using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method. 82 Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Cochrane’s Q and I2 statistics. 83 Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger’s regression method. 86

Differences in effect across the methodological characteristics of the trials were tested using the analogue to ANOVA for categorical variables and univariate meta-regression for continuous variables. 81 Random-effects multivariate meta-regression was used to identify which components of the interventions were independently associated with reductions in unscheduled health care. 115,116

Study 3: complex interventions that reduce unscheduled health-care use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Results

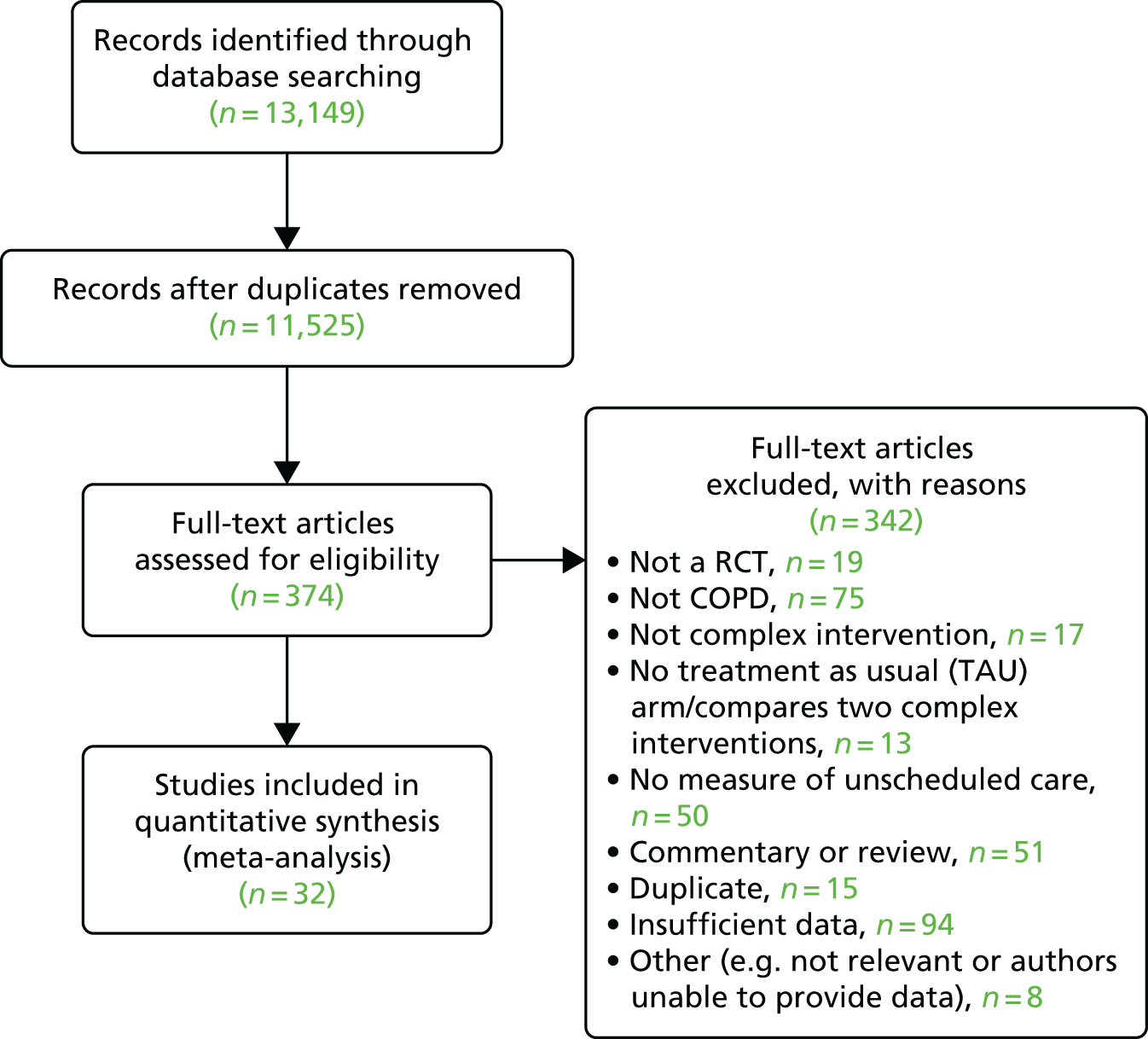

The flow chart for this study is shown in Figure 11. Thirty-two independent studies were eligible for inclusion in this review, which included the comparison of 33 independent interventions. 114,117–148

FIGURE 11.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for studies of the effectiveness of complex interventions in the reduction of unscheduled care use in COPD. Reprinted from Respiratory Medicine, Vol. 108, Dickens C, Katon W, Blakemore A, Khara A, Tomenson B, Woodcock A, et al. Complex interventions that reduce urgent care use in COPD: a systematic review with meta-regression, pp. 426–37. © 2014, with permission from Elsevier. 111

The details of the characteristics of each included study are summarised in Table 6. In the majority of studies, patients with COPD were recruited from secondary care settings, and either ED attendances and/or EHAs were the measure of unscheduled care use.

| Authors | Year of publication | Sample size | Where recruited | Assessment of urgent health-care use | Method of urgent health-care assessment | Duration of follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergner et al.119 | 1988 | 244 | Secondary | ED visits | Records | 12 |

| Bourbeau et al.118 | 2003 | 191 | Secondary | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation | Self-reported | 12 |

| Boxall et al.120 | 2005 | 46 | Combined | Urgent hospitalisations | Self-reported | 6 |

| Casas et al.114 | 2006 | 155 | Secondary | Urgent hospitalisations | Combined | 12 |

| Eaton et al.121 | 2009 | 97 | Secondary | Unscheduled emergency visits to primary or secondary care | Combined | 3 |

| Farrero et al.122 | 2001 | 94 | Primary | ED visits | Records | 12 |

| Gadoury et al.123 | 2005 | 191 | Secondary | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation | Records | 24 |

| Gallefoss and Bakke124 | 2000 | 71 | Secondary | Urgent hospitalisation | Combined | 12 |

| Güell et al.125 | 2000 | 60 | Secondary | Urgent hospitalisation | Unclear | 24 |

| Hermiz et al.126 | 2002 | 147 | Secondary | ED visits | Records | 3 |

| Hernandez et al.127 | 2003 | 209 | Secondary | ED visits | Combined | 2 |

| Jarab et al.128 | 2012 | 127 | Secondary | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation | Unclear | 6 |

| Khdour et al.129 | 2009 | 173 | Secondary | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation/urgent doctor visits | Combined | 12 |

| Ko et al.130 | 2011 | 60 | Secondary | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation | Combined | 12 |

| Koff et al.131 | 2009 | 40 | Secondary | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation | Combined | 3 |

| Lee et al.132 | 2002 | 89 | Secondary | ED visits | Unclear | 6 |

| Díaz Lobato et al.133 | 2005 | 40 | Secondary | Urgent ICU admission | Unclear | 1 |

| Man et al.148 | 2004 | 34 | Secondary | ED visits | Combined | 3 |

| Martin et al.134 | 2004 | 89 | Primary | Ambulance calls | Unclear | 12 |

| McGeoch et al.135 | 2006 | 154 | Primary | ED visits | Unclear | 12 |

| Rea et al.117 | 2004 | 135 | Combined | ED visits | Records | 12 |

| Rice et al.137 | 2010 | 554 | Primary | ED visits | Records | 12 |

| Ries et al.138 | 2003 | 137 | Secondary | ED visits | Self-reported | 12 |

| Seymour et al.139 | 2010 | 60 | Secondary | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation | Combined | 3 |

| Smith et al.140 | 1999 | 92 | Combined | ED visits | Records | 12 |

| Soler et al.141 | 2006 | 26 | Secondary | ED visits | Records | 12 |

| Sridhar et al.142 | 2008 | 104 | Secondary | Urgent doctor visits | Combined | 24 |

| Tougaard et al.143 | 1992 | 82 | Secondary | General practice emergency care | Records | 12 |

| Trappenburg et al.144 | 2011 | 216 | Combined | ED visits/urgent hospitalisation | Combined | 6 |

| Wakabayashi et al.145 | 2011 | 85 | Secondary | ED visits | Unclear | 12 |

| Wong et al.146 | 2005 | 60 | Secondary | ED visits | Self-reported | 3 |

| Wood-Baker et al.147 | 2006 | 112 | Primary | ED visits/urgent doctor visits | Self-reported | 12 |

Table 7 summarises the type of interventions that were employed in the studies included in the review of complex interventions in COPD, and the duration of the intervention.

| Study | Intervention | No. sessions | Who delivered the intervention? | Delivery method | Where delivered | Unidisciplinary or multidisciplinary | Intervention components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergner et al.119 | Respiratory home care vs. TAU and standard home care vs. TAU | Unclear | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Home | Multidisciplinary | 12 |

| Bourbeau et al.118 | Education and case manager vs. TAU | 18 | Non-mental health practitioner | Combination | Home | Multidisciplinary | 1, 3, 4, 6, 10 |

| Boxall et al.120 | Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation vs. waiting list | 11 | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Home | Multidisciplinary | 1, 3, 4 |

| Casas et al.114 | Integrated care vs. TAU | 1 comprehensive education session | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face, telephone and online | Home, hospital, online | Multidisciplinary | 1, 12 |

| Eaton et al.121 | Early pulmonary rehabilitation | Unclear | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Combination | Multidisciplinary | 1, 4, 6, 10, 12 |

| Farrero et al.122 | Hospital-based home care vs. TAU | 4.8 | Non-mental health practitioner | Combination | Combination | Multidisciplinary | 12 |

| Gadoury et al.123 | COPD self-management vs. TAU | 18 | Unclear | Combination | Home | Unclear | 1, 4, 12 |

| Gallefoss and Bakke124 | Self-management education vs. TAU | 4 | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Unclear | Multidisciplinary | 1, 3, 6, 12 |

| Güell et al.125 | Rehabilitation vs. TAU | 31 | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Hospital | Unclear | 1, 3, 4, 10 |

| Hermiz et al.126 | Home-based self-management education and support vs. TAU | 2 | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Home | Multidisciplinary | 1, 12 |

| Hernandez et al.127 | Home hospitalisation vs. TAU | Unclear | Non-mental health practitioner | Combination | Home | Unclear | 1, 3, 6 |

| Jarab et al.128 | Pharmaceutical care programme with emphasis on self-management vs. TAU | Unclear | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Unclear | Unidisciplinary | 1, 3 |

| Khdour et al.129 | Clinical pharmacy-led; disease and medicine; management programme vs. TAU | 1 initial education session, reinforcement at outpatient visit every 6 months plus telephone calls at 3 and 9 months | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face and telephone | Clinic | Unidisciplinary | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12 |

| Ko et al.130 | Outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programme vs. TAU | 24 | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Hospital | Unidisciplinary | 1, 3, 4 |

| Koff et al.131 | Proactive integrated care vs. TAU | Unclear | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face and telephone | Clinic and home | Unidisciplinary | 1, 3, 12 |

| Lee et al.132 | Treatment guideline implementation vs. TAU | 9 | Non-mental health practitioner | Combination | Home | Unidisciplinary | 1, 2, 3, 6, 12 |

| Díaz Lobato et al.133 | Home hospital vs. conventional hospital | Unclear | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Home | Multidisciplinary | 1, 12 |

| Man et al.148 | Community rehabilitation vs. TAU | 16 | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Hospital | Multidisciplinary | 1, 4 |

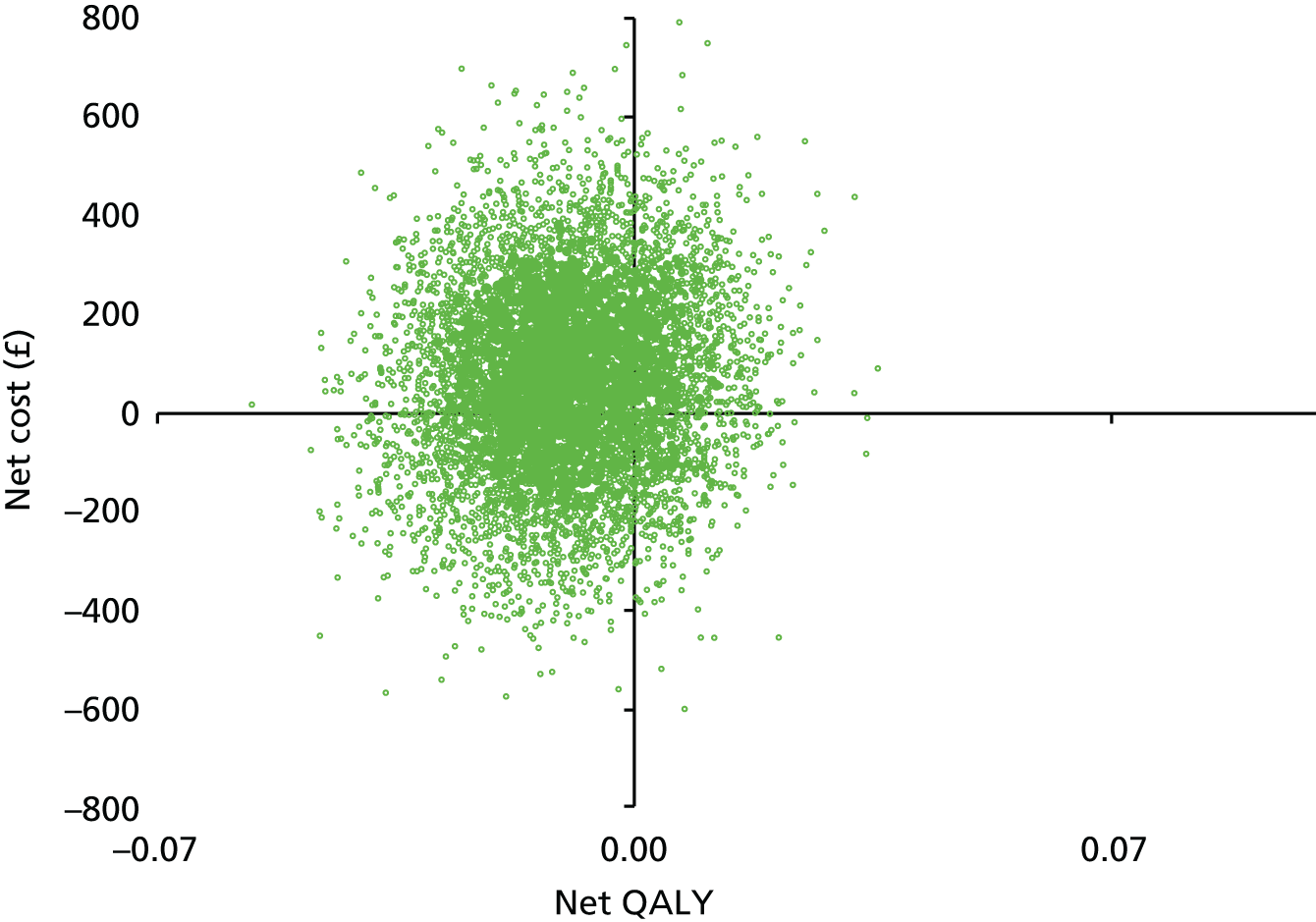

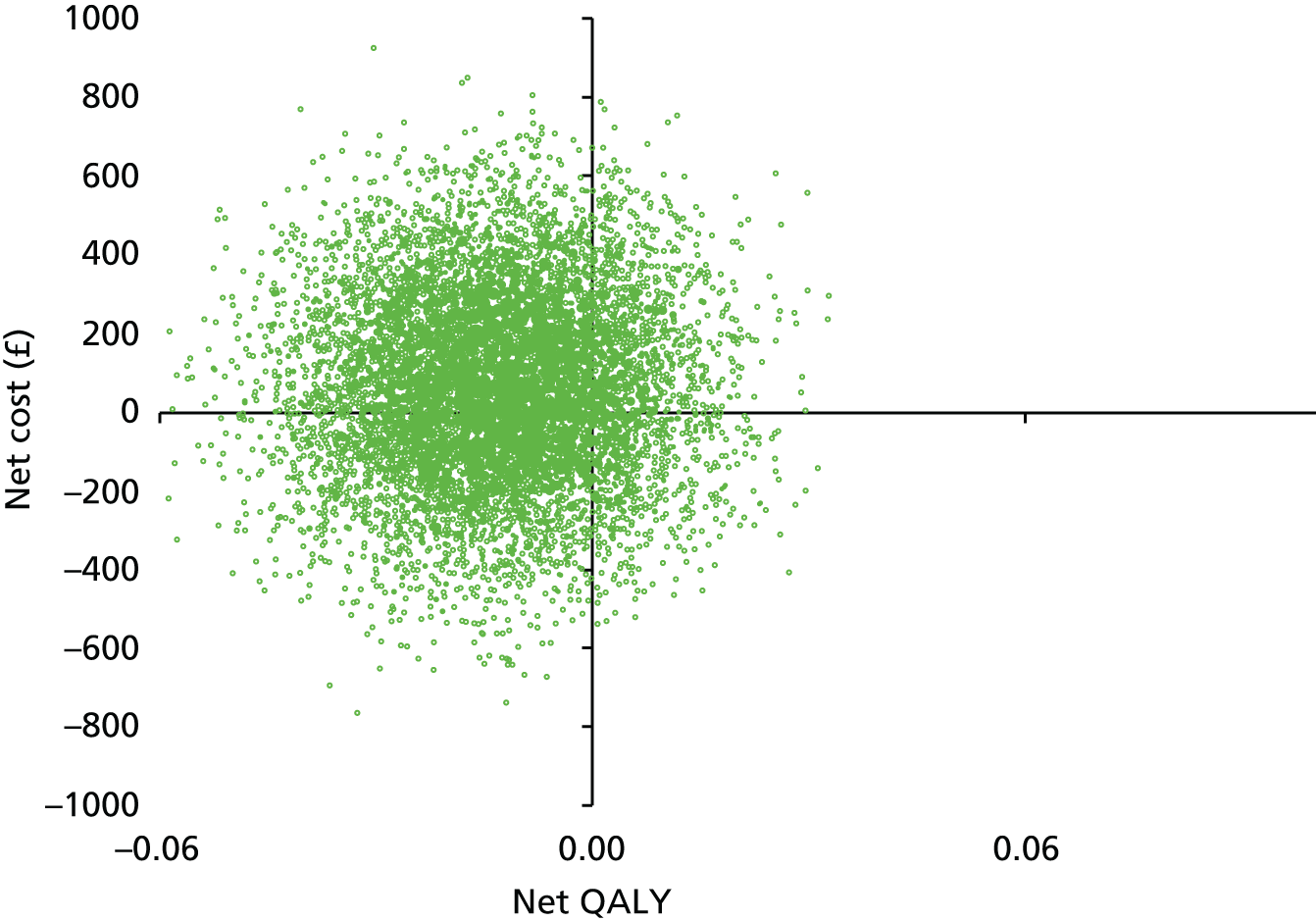

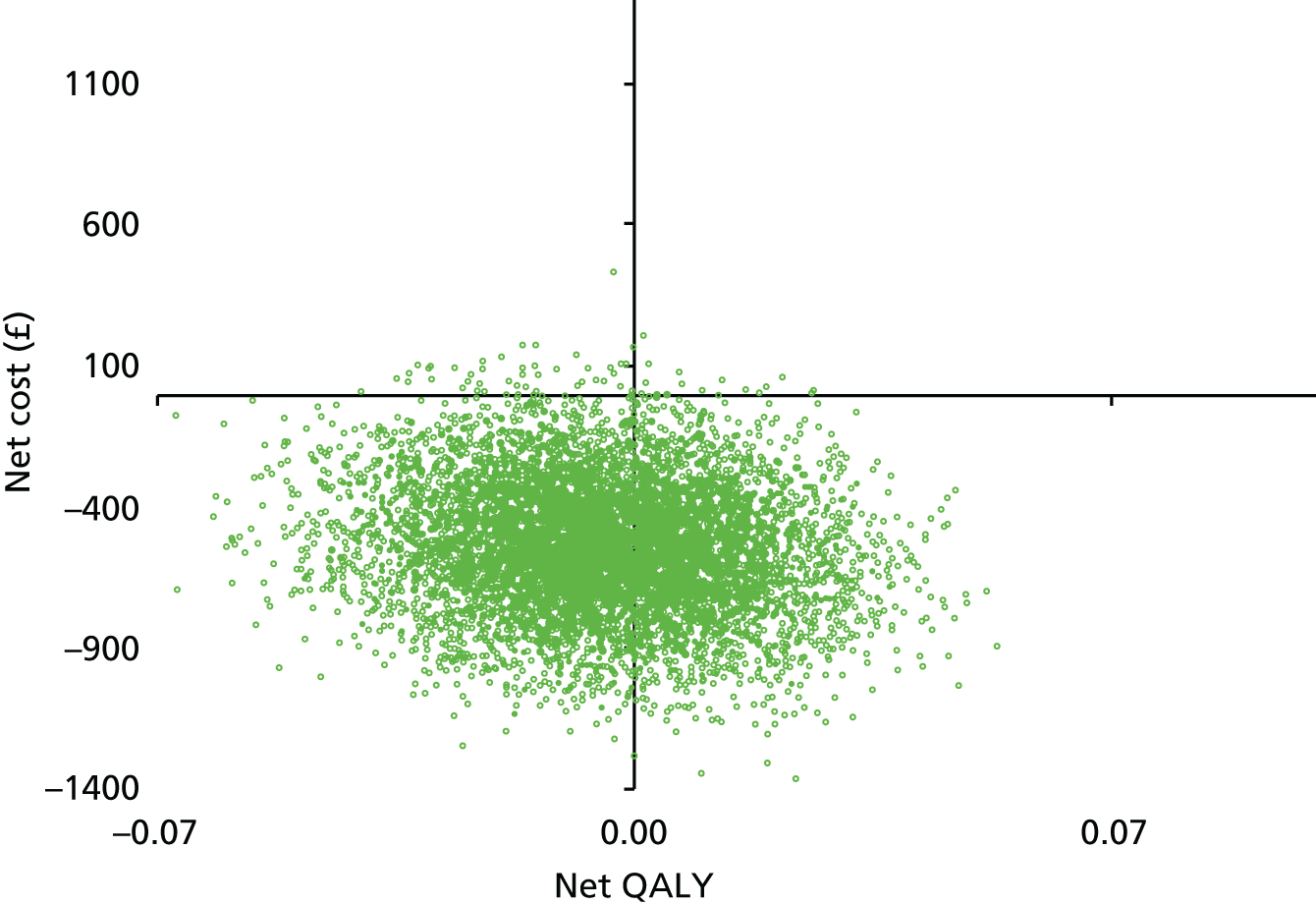

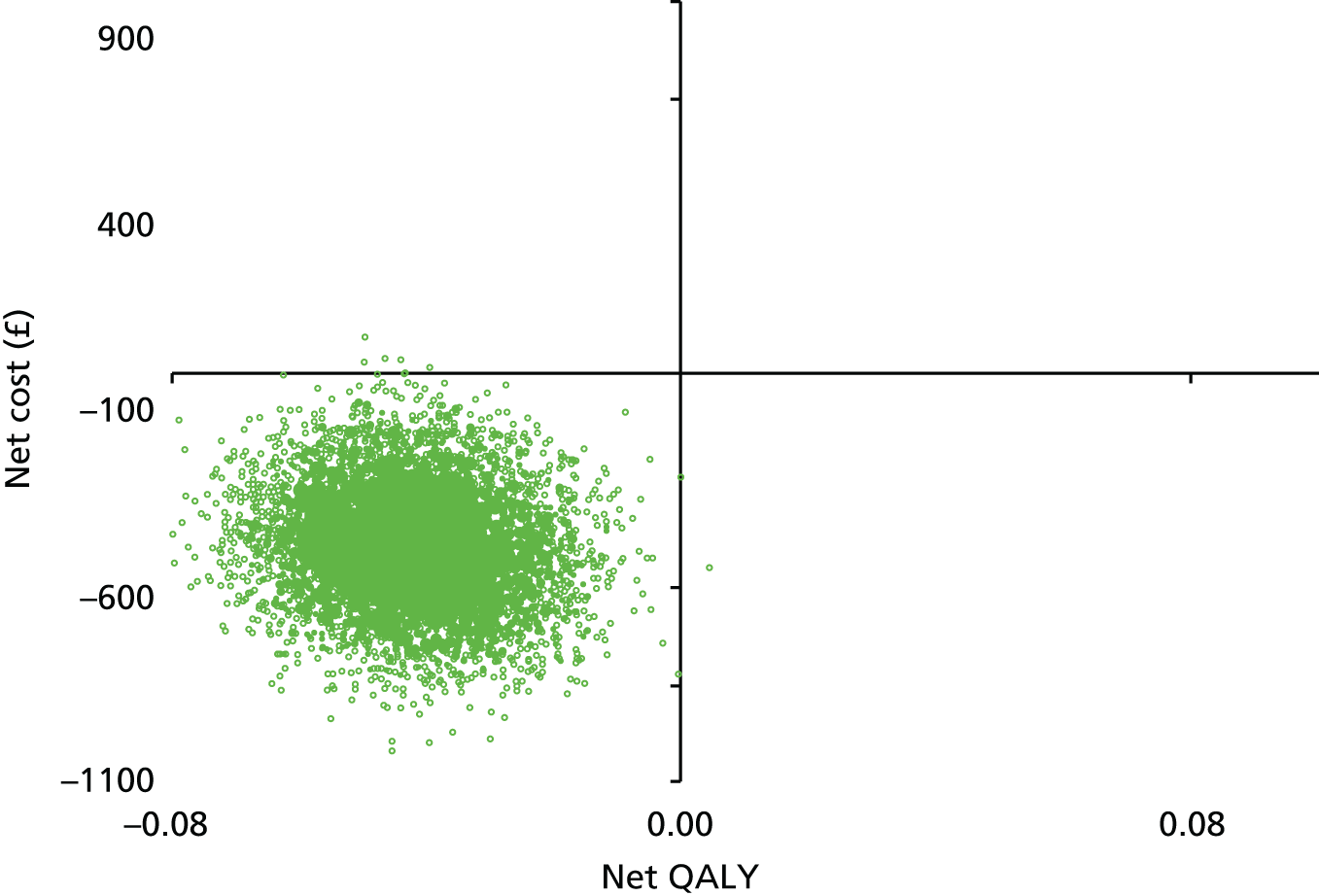

| Martin et al.134 | Care plan vs. TAU | Unclear | Non-mental health practitioner | Face to face | Combination | Multidisciplinary | 1, 3, 12 |