Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10231. The contractual start date was in April 2009. The final report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in February 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elaine McColl is a subpanel member for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) journal, but in that capacity has already declared a conflict of interest in respect of this grant and has not been involved in any discussions or decisions thereon. Elaine McColl was a NIHR journal editor for the NIHR PGfAR journal at the time that this report was written and has a declared conflict of interest in respect of this report and will not participate in any discussions, work or decisions thereon. The Keeping Children Safe programme received Flexibility and Sustainability Funding from Nottinghamshire County Teaching Primary Care Trust, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and Norfolk and Suffolk Comprehensive Local Research Network and Research Capability Funding from Nottinghamshire County Teaching Primary Care Trust and Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust to support NIHR Faculty members’ salaries.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Kendrick et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction to the Keeping Children Safe programme of research

Why are child injuries important?

Unintentional injuries are a major public health challenge facing children in England today. Injuries are a particular problem in young children, with death and hospital admission rates being higher in the under-fives than at other ages in childhood. Unintentional injuries resulted in 311 deaths in the under-fives in England between 2008 and 2012, making injuries the most common cause of death in the 1–4 years age group. 1 More than 45,000 children aged < 5 years were admitted to hospital in England in 2012/13,2 and approximately 450,000 under-fives attended an emergency department (ED) in the UK following an unintentional injury in 20023 (the latest year for which detailed national data on unintentional injuries were collected in the UK). Childhood injuries, especially severe injuries, can also have long-term health, educational, social and occupational consequences. These include physical disability,4–6 psychological morbidity,7,8 cognitive or social impairment,9 lower educational achievement9,10 and poorer employment prospects. 9 In addition, injuries also impact psychologically on those caring for children. 7

Unintentional injuries do not just result in death and injury. They also place burdens on the NHS and other care agencies and on injured children and their families. The Chief Medical Officer (CMO)’s report for England in 2012 highlighted the high cost of injuries to the NHS and the potential for prevention. 11 The annual cost of ED attendances was estimated to be £9M, and the cost of hospital admissions was estimated to be £16–87M, depending on injury mechanism.

Unintentional injuries disproportionately affect children living in socioeconomic disadvantage. The socioeconomic gradient in unintentional injury deaths is steeper than for any other cause of death in childhood,12 with children living in the most disadvantaged households having a death rate that is 13 times higher than that for children living in the most advantaged households. 13

Child injury prevention policy in England

Child injury prevention has had varying prominence in government policy in England over the past 25 years. The Health of the Nation White Paper14 formed the central health policy in England between 1992 and 1997. It was the first attempt by a government in England to strategically improve the health of the population. Reduction in accidental injury was identified as one of five national targets for health improvement.

This was replaced by Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation (1999)15 under the Labour administration’s health policy, which included accidental injury as one of its four key public health priorities. It set a target to reduce death rates from accidents by at least one-fifth and to reduce the rate of serious injury from accidents by at least one-tenth by 2010, describing this as a ‘tough but attainable target’. It also recognised that injury was a leading cause of childhood admissions to hospital. The White Paper announced that an interdepartmental and expert task force would be set up to advise on how the targets should be achieved.

The Accidental Injury Task Force published a report for the CMO in 2002 to identify steps that would have the greatest impact on injury prevention. 16 One working group focused on child injury. Recommendations included cross-governmental co-ordination of initiatives, data collection and integration, developing the workforce for delivery and leadership, and research and dissemination of evidence. It highlighted the significance of deprivation in childhood injury. The task force recommended that a series of headline interventions should form the core of local implementation plans, giving focus and clarity to the somewhat fragmented approach to injury prevention at the time. It also advised targeting of interventions at areas of health inequality.

The Every Child Matters17 policy arose with the Children Act 2004. 18 There were five outcomes that the policy sought to achieve for all children, one of which was ‘stay safe’, which included safety from unintentional injury.

A joint study by the Audit Commission and the Healthcare Commission, Better Safe Than Sorry, in 200719 examined the deployment of resources, arrangements for working in partnership and activities to prevent unintentional injury to children, especially the under-fives. The report contained a series of recommendations for the government, including re-emphasising the recommendations and strategy from the Accidental Injury Task Force and encouraging local organisations to take up and follow the evidence-based guidance contained within the report and commissioning the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to develop guidance on the prevention of unintentional injury for children aged < 15 years.

The Staying Safe: Action Plan was launched in 2008,20 setting out the government’s priorities for the period 2008–11. These included establishing the National Home Safety Equipment Scheme Safe at Home. 21 A review examining prevention practice at the time and making recommendations also arose from the action plan and led to the publication of Accident Prevention Amongst Children and Young People: a Priority Review. 22 The government also set a Public Service Agreement target (PSA 13) to improve children’s and young people’s safety that included four indicators, including one on a reduction in hospital admissions caused by unintentional and deliberate harm.

In 2010, the coalition government published the Healthy Lives, Healthy People White Paper,23 setting out plans for a comprehensive reform of the public health system. The plans revolved around decentralising public health and giving local authorities more power over public health budgets in their area. The new system took effect from April 2013, when Public Health England was established and public health services formally transferred from the NHS to local authorities. The new system focuses on outcomes rather than targets, which are set out in the Public Health Outcomes Framework,24 including one indicator to reduce hospital admissions from unintentional and deliberate injuries for the 0–4 years age group, with support from other partners in the public health system. Other indicators relate to reducing health inequalities.

In 2013, the CMO for England highlighted the issue of child accident prevention and has made a powerful economic case for preventing childhood injuries. 11

Other major national health-related initiatives included the development by NICE of a series of guidance documents on the prevention of unintentional injuries in children aged < 15 years. NICE published public health guidance, Strategies to Prevent Unintentional Injuries among Children and Young People Aged under 15 [public health guidance (PH) 29] in 2010. 25 Evidence published since the development of PH29 was reviewed in 2013 but did not result in any changes to the recommendations. 26 A further document, Preventing Unintentional Injuries in the Home among Children and Young People Aged under 15 (PH30) was also published in 2010. 27 PH29 recommends that local and national plans and strategies for children and young people’s health and well-being include a commitment to preventing unintentional injuries. Emphasis is also given to targeting injury prevention towards the most vulnerable groups to reduce inequalities in health.

Despite the policies described above, Better Safe Than Sorry also highlighted that there was little evidence of a systematic strategic approach to develop, implement and monitor programmes to prevent unintentional injuries in children within the NHS. 19 A report in 2012 from the European Child Safety Alliance and EuroSafe, the European Association for Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion, assessed evidence-based national-level child injury prevention policy measures in 31 European Union (EU) member states. 28 The report concluded that there was much scope for improvement in implementing child injury prevention measures in England, stating that if England had the unintentional injury death rate in 2010 of the EU country with the lowest rate (the Netherlands), 198 deaths in children and young people would have been avoided. It identified some progress in addressing the issue of child injury, but also that stronger government leadership was needed to produce and implement a national evidence-based child injury prevention strategy including funding for injury prevention measures, co-ordination of child injury prevention activities, infrastructure and capacity building. Recommendations included the integration of evidence-based good practice strategies into national public health programmes, the adoption and implementation of evidence-based injury prevention strategies at national and local levels and capacity building for stakeholders working at all levels. 29

The report also highlighted unintentional injuries as the leading cause of inequality in childhood deaths and acknowledged that the English government had supported studies examining inequities and provided time-limited funding for a home safety equipment scheme targeting disadvantaged families. However, it concluded that ‘vacillating government support for the injury issue and related programmes has not resulted in a comprehensive coordinated approach that would ensure equitable coverage of children on safety issues’ (p. 3). 29

The Keeping Children Safe (KCS) programme of research was, therefore, undertaken over a period of time in which there was an increasing acceptance of the need for evidence-based injury prevention, development of national guidelines to facilitate this and the use of indicators to reduce admissions for injuries in children and young people. However, during this period of time there was no national strategy or widespread adoption and implementation of co-ordinated evidence-based child injury prevention.

The most important injuries to focus on

The KCS programme of research focused on the prevention of thermal injuries, falls and poisonings. In terms of injury-related deaths in the under-fives in England, deaths from falls are the third most common, deaths from smoke, fire and flames are the fourth most common and deaths from poisoning are the sixth most common. 1 Thermal injuries, falls and poisonings are three of the four most common types of injury resulting in hospital admission in the under-fives in England. 2 In 2012/13, > 18,300 under-fives were admitted to hospital in England following a fall, > 5100 were admitted with poisoning and > 2210 were admitted following a thermal injury, 1420 of which were scalds. Emergency admissions for falls, poisonings and scalds in the under-fives cost the NHS in England £19.1M in 2012/13. 30 There are no recent data available on ED attendances, but data from 2002 show that approximately 280,000 under-fives attended an ED following a thermal injury, fall or poisoning in the UK. 3 The cost of these visits to the NHS converted to 2012/13 prices is nearly £32M. 31 In total, 80% of all admissions in children aged 0–14 years for thermal injuries occur in the under-fives, as do 73% of all poisonings and 45% of all scalds, highlighting the importance of focusing on this age group. The majority of injuries in the under-fives occur at home,32 hence the KCS programme focused on thermal injuries, falls and poisonings occurring at home in the under-fives.

The need to develop the evidence base for preventing thermal injuries, falls and poisonings

The NHS needs to be able to make evidence-based decisions about which interventions to fund to prevent home injury in childhood, but the lack of evidence on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions hampers decision-making. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses33–42 show that home safety interventions increase safety behaviours and use of safety equipment, but also highlight the lack of evidence about whether these interventions reduce injury occurrence or are cost-effective. In addition, there is a lack of data on the cost of injuries to children, families and the NHS and on how to implement effective child injury prevention interventions within the NHS. The KCS programme, therefore, aimed to increase evidence-based thermal injury, falls and poisoning prevention by assessing risk and protective factors for these injuries, evaluating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to prevent these injuries, developing injury prevention briefings (IPBs) for effective and cost-effective interventions and evaluating the implementation of one IPB in children’s centres. We have considered thermal injuries in two categories in this research programme – scalds and fire-related burns – because although the tissue injury and pathophysiology are similar, the mechanisms and potential safety measures are very different. Some work streams (e.g. work streams 1, 2 and 6) focus on specific types of thermal injuries (e.g. scalds or fire-related injuries) whereas others focus on all thermal injuries, depending on the existing evidence base. The programme of work to achieve the aims is outlined below.

The Keeping Children Safe programme of research

Research questions

The research questions addressed within six work streams in the KCS programme are outlined in the following sections and shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The Keeping Children Safe programme of research.

Work stream 1

This work stream addressed the question, ‘What are the associations between modifiable risk and protective factors and medically attended injuries resulting from five common injury mechanisms in children under the age of 5 years?’ This question was answered by a series of five case–control studies exploring risk and protective factors for each of the three most common types of medically attended falls (falls from furniture, stair falls and falls on one level), poisonings and scalds. These five studies are collectively referred to as study A. In addition, a study to validate the self-reported exposures was nested within the case–control studies in study A, and this is referred to as study B.

Work stream 2

This work stream addressed the question, ‘What are the NHS and child and family costs of falls, poisonings and scalds?’ This was answered by a cohort study measuring costs and injury outcomes nested within the case–control studies in study A. In addition, as there were no validated tools to measure health-related quality of life (HRQL) in the short term following a range of injuries in the under-fives, this study also validated the toddler version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL™)43 for this purpose. These two studies are referred to as study C, with the costs study referred to as the study C costs substudy and the validation of the PedsQL study referred to as the study C HRQL substudy.

Work stream 3

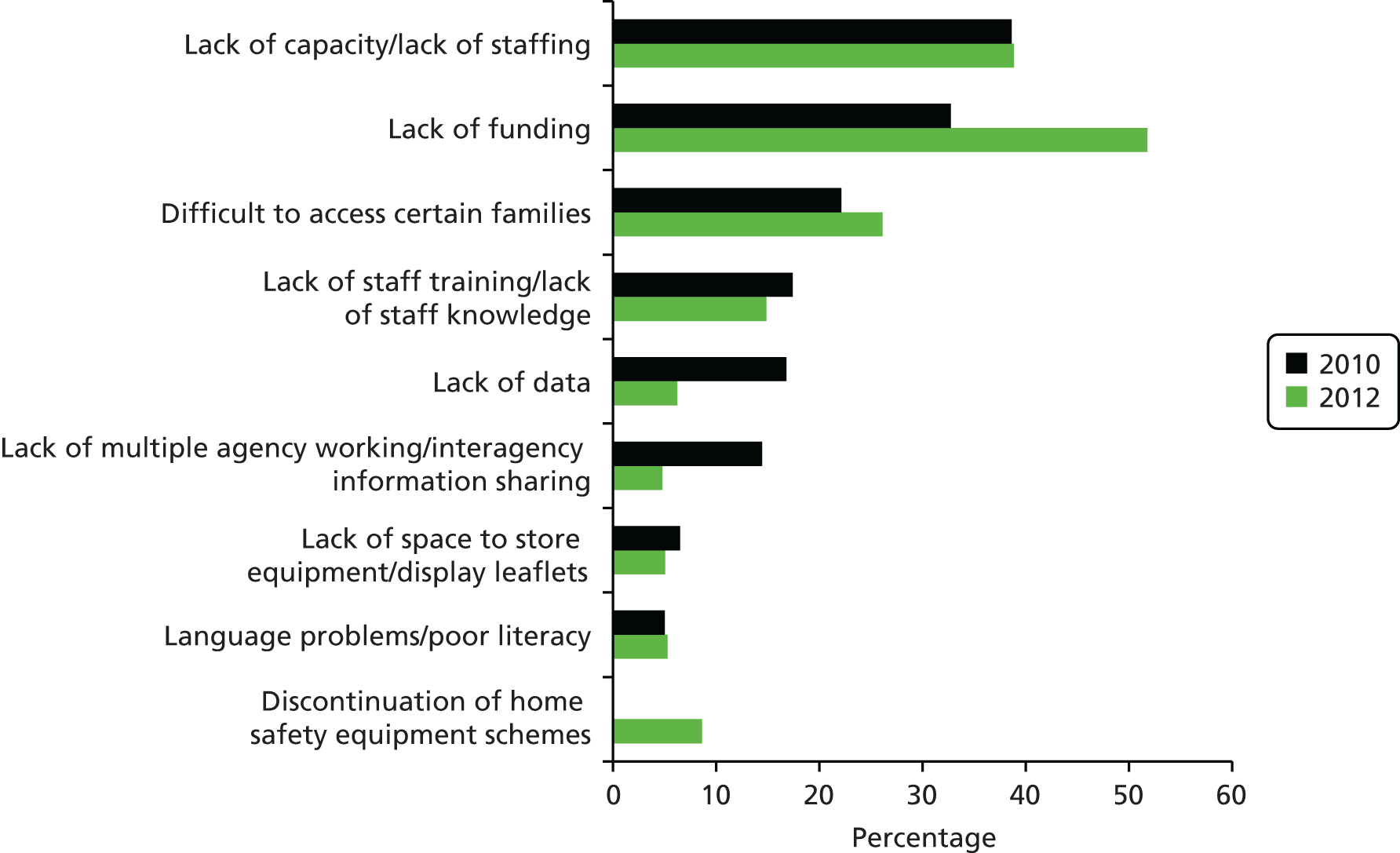

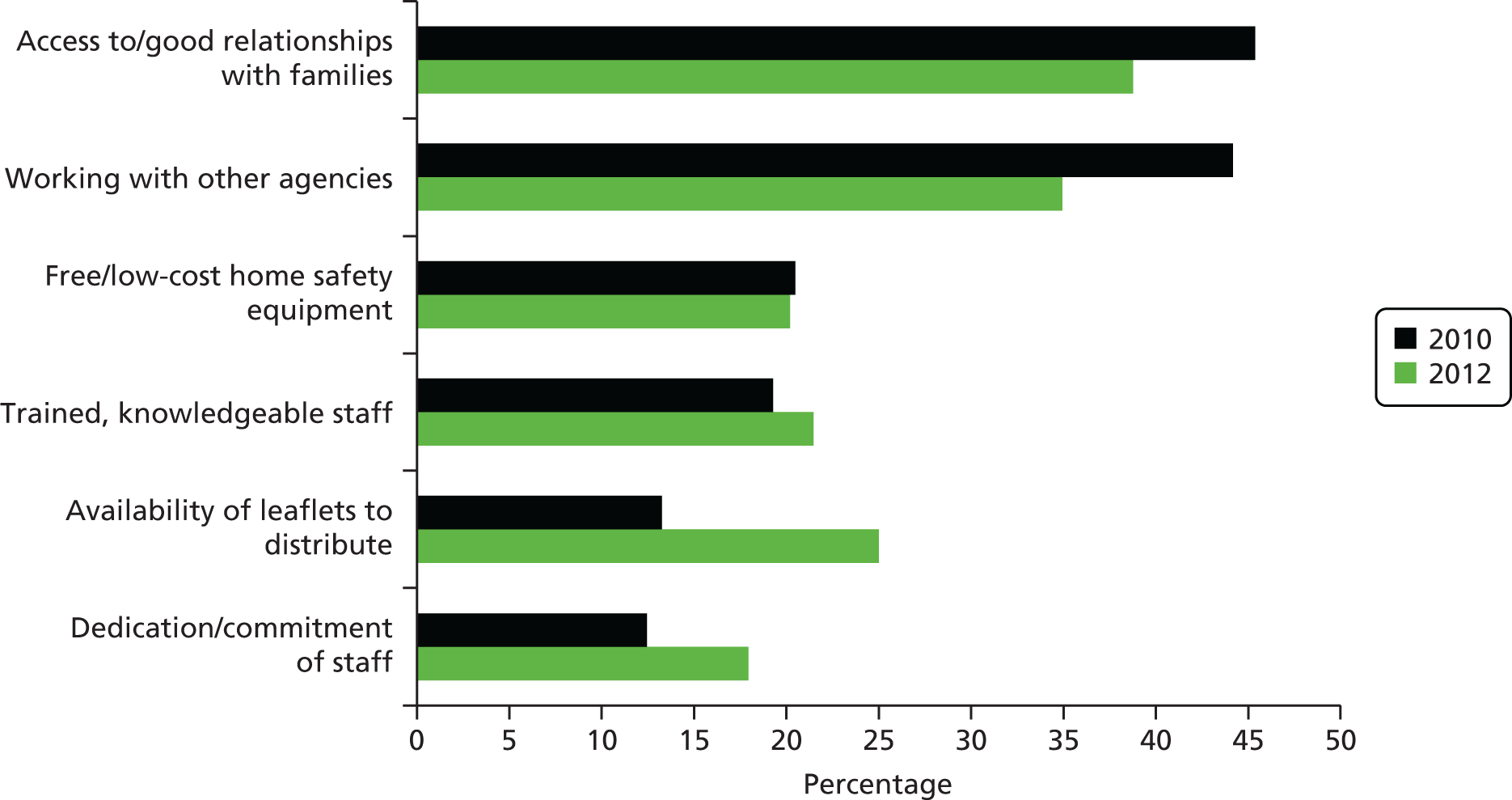

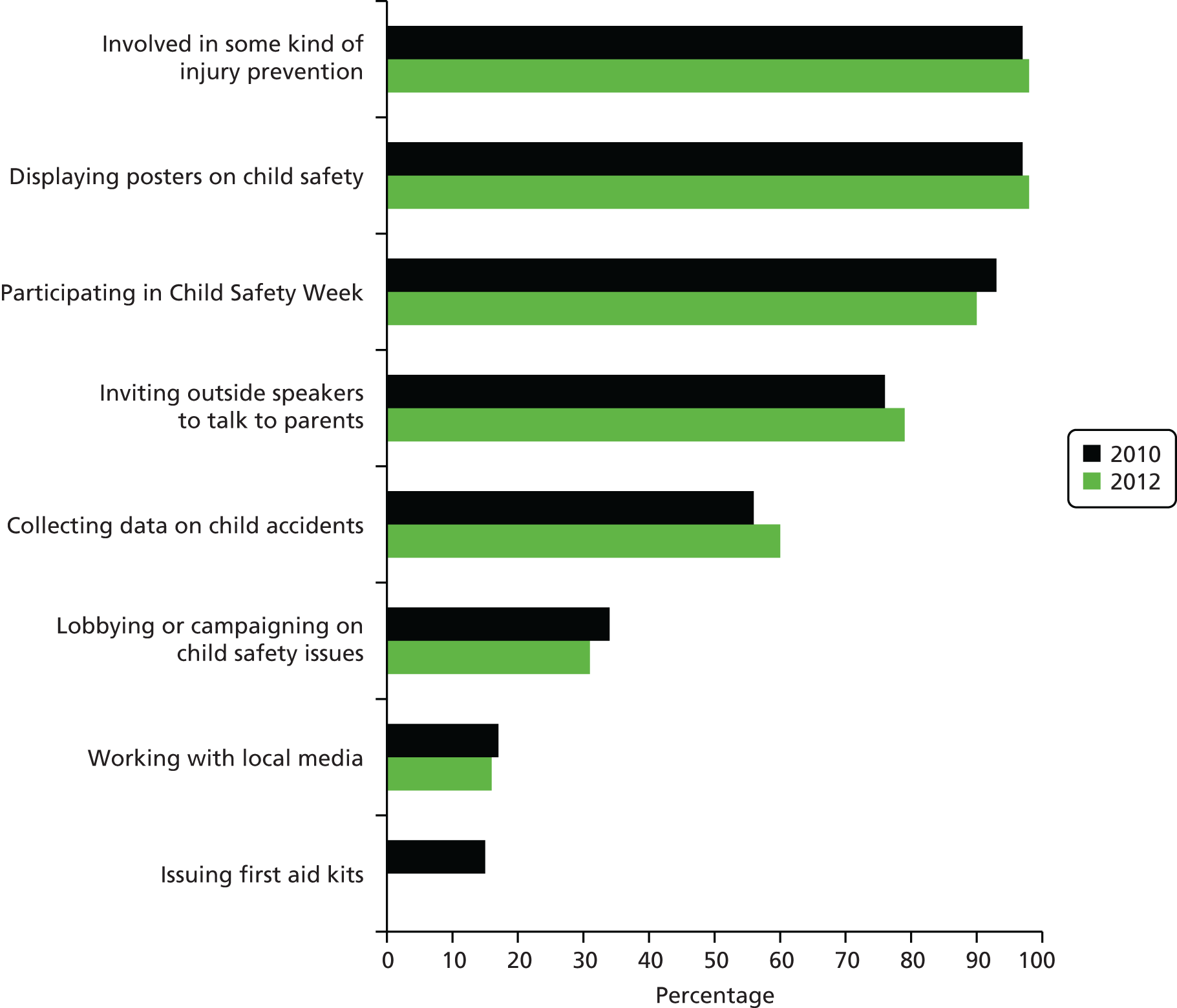

This work stream addressed the question, ‘What interventions are being undertaken by children’s centres to prevent thermal injuries, falls and poisonings?’. This question was answered by two national surveys of children’s centre managers and staff. These studies are referred to as study D.

Work stream 4

This work stream addressed the question, ‘What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, implementing thermal injuries, falls and poisoning prevention interventions among children’s’ centres, professionals and community members?’. This question was answered by three studies: first, a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence on barriers to, and facilitators of, injury prevention (study E); second, a qualitative study consisting of interviews with children’s centres managers and staff to explore their views on barriers to, and facilitators of, implementing injury prevention interventions in children’s centres (study F); and, third, a qualitative study of parents of injured and uninjured children to explore views on barriers to, and facilitators of, implementing home injury prevention nested in the case–control studies in study A (study G).

Work stream 5

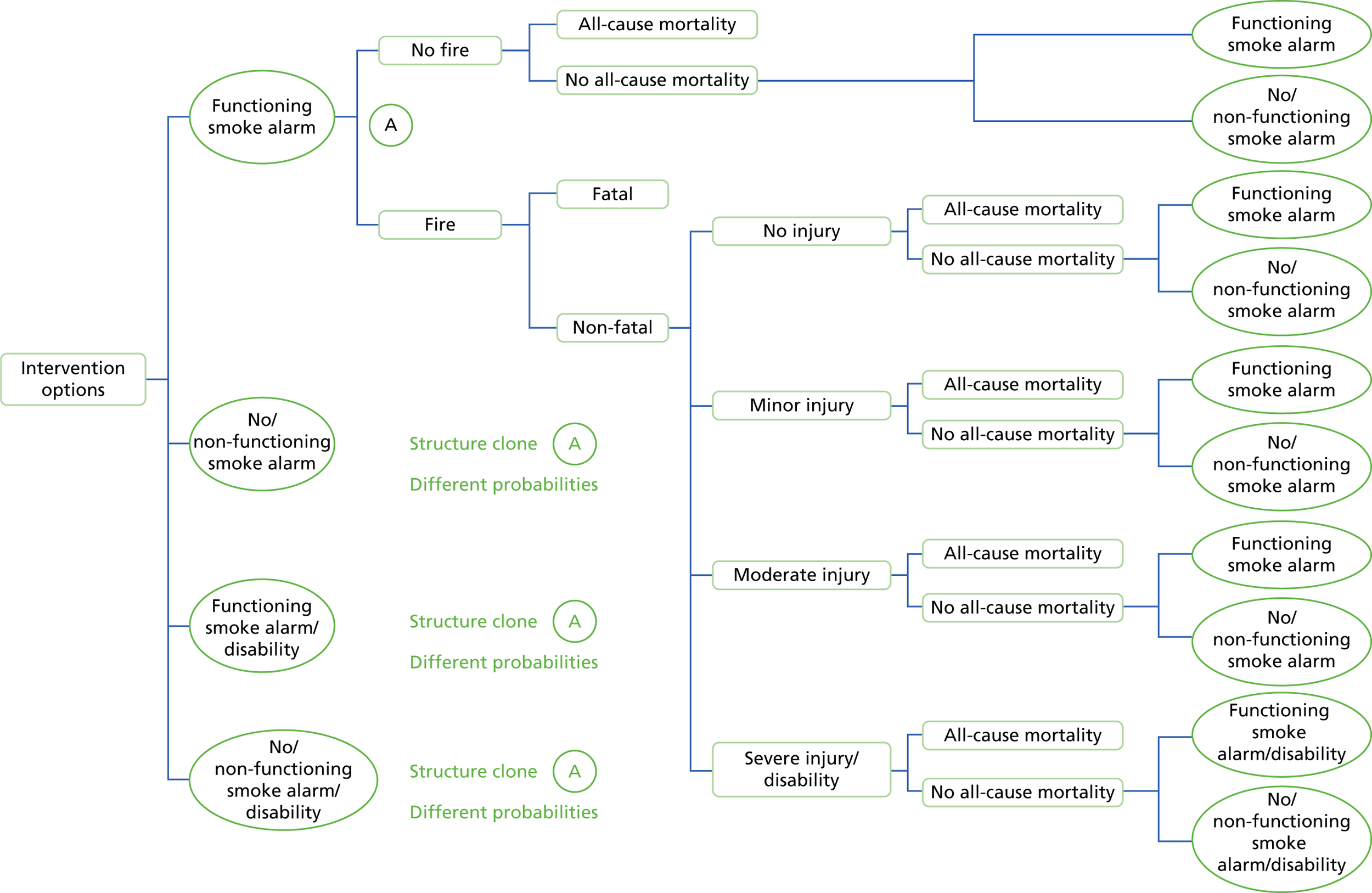

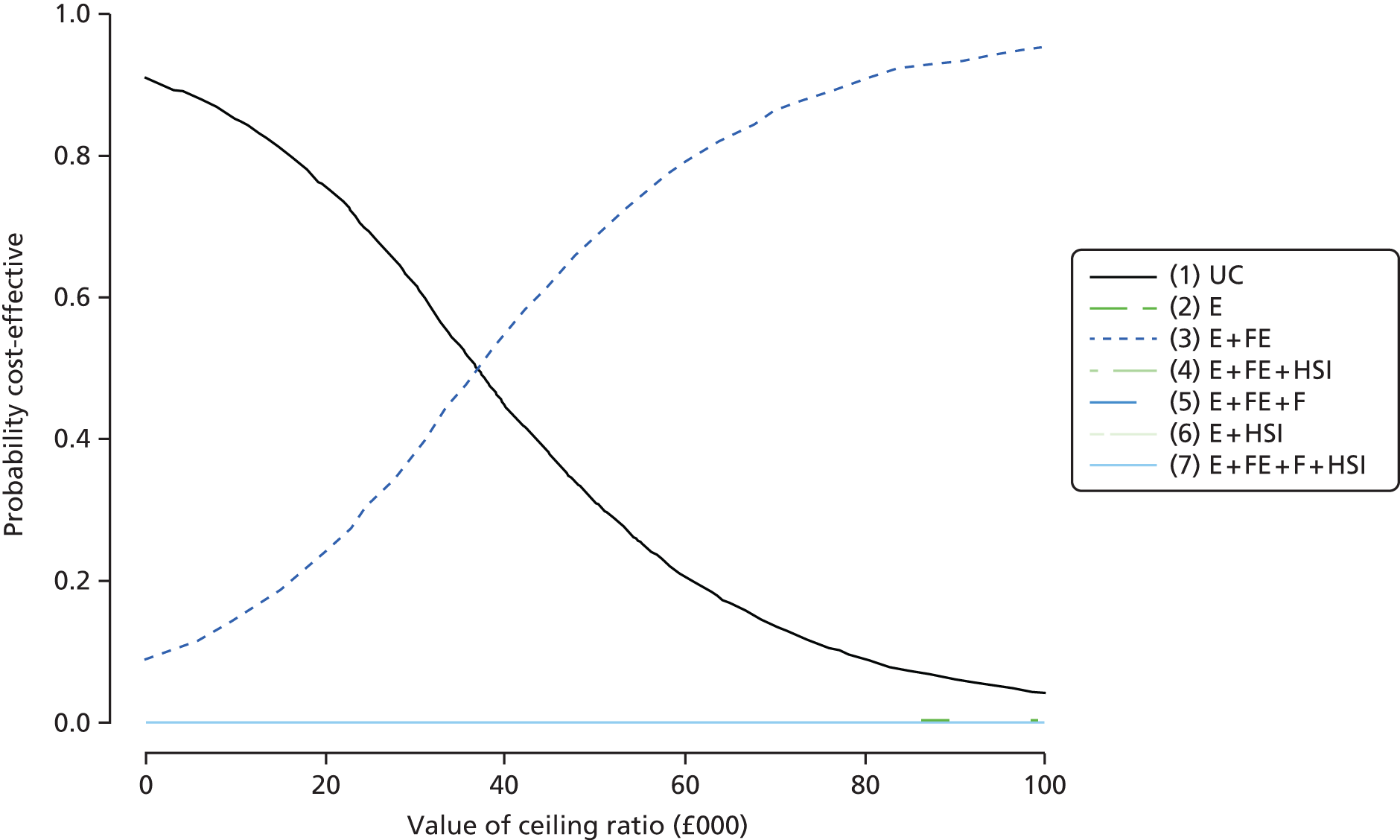

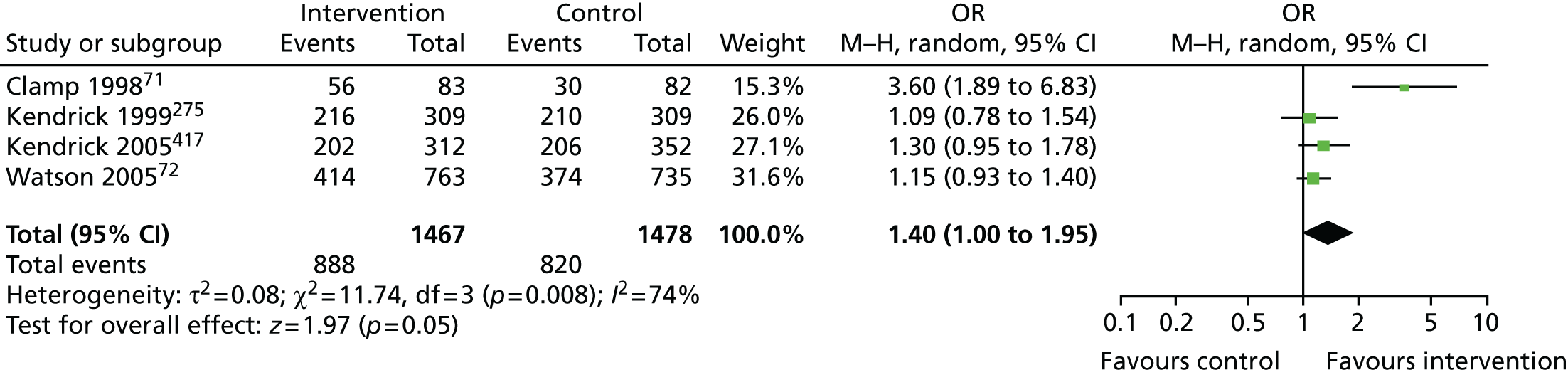

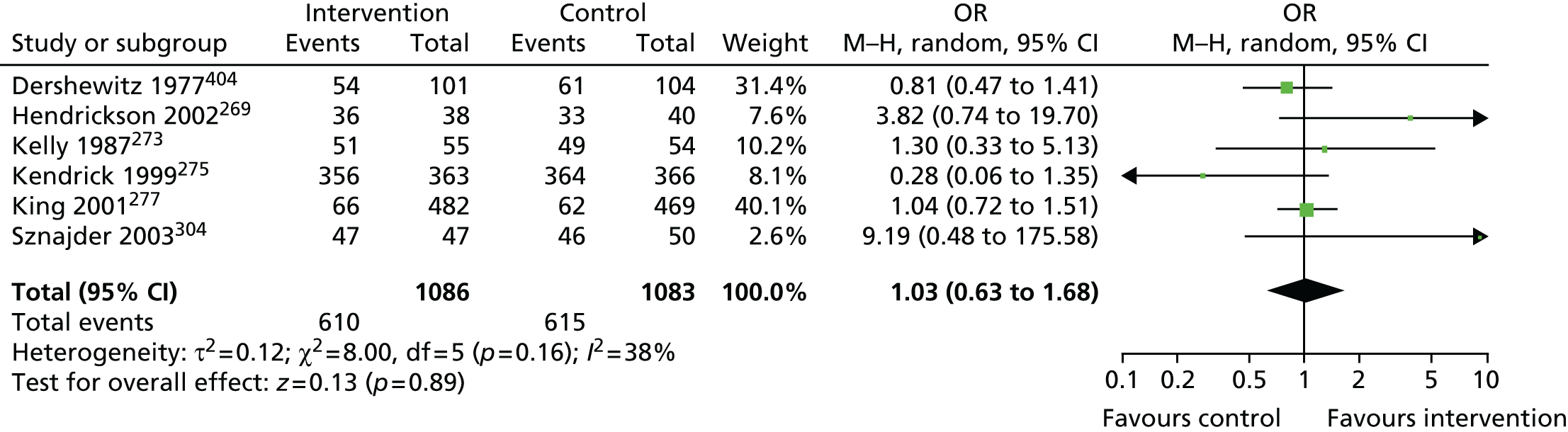

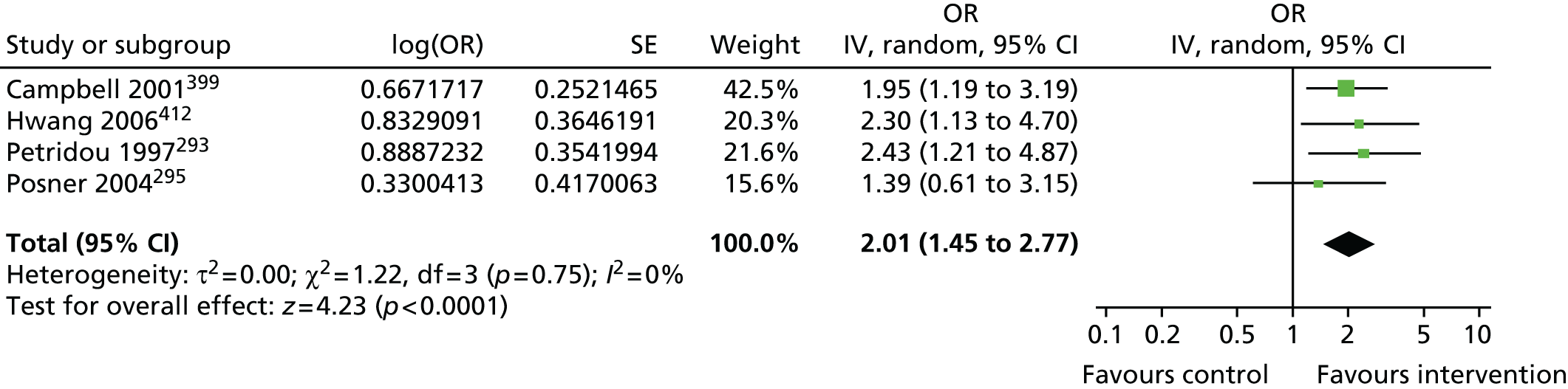

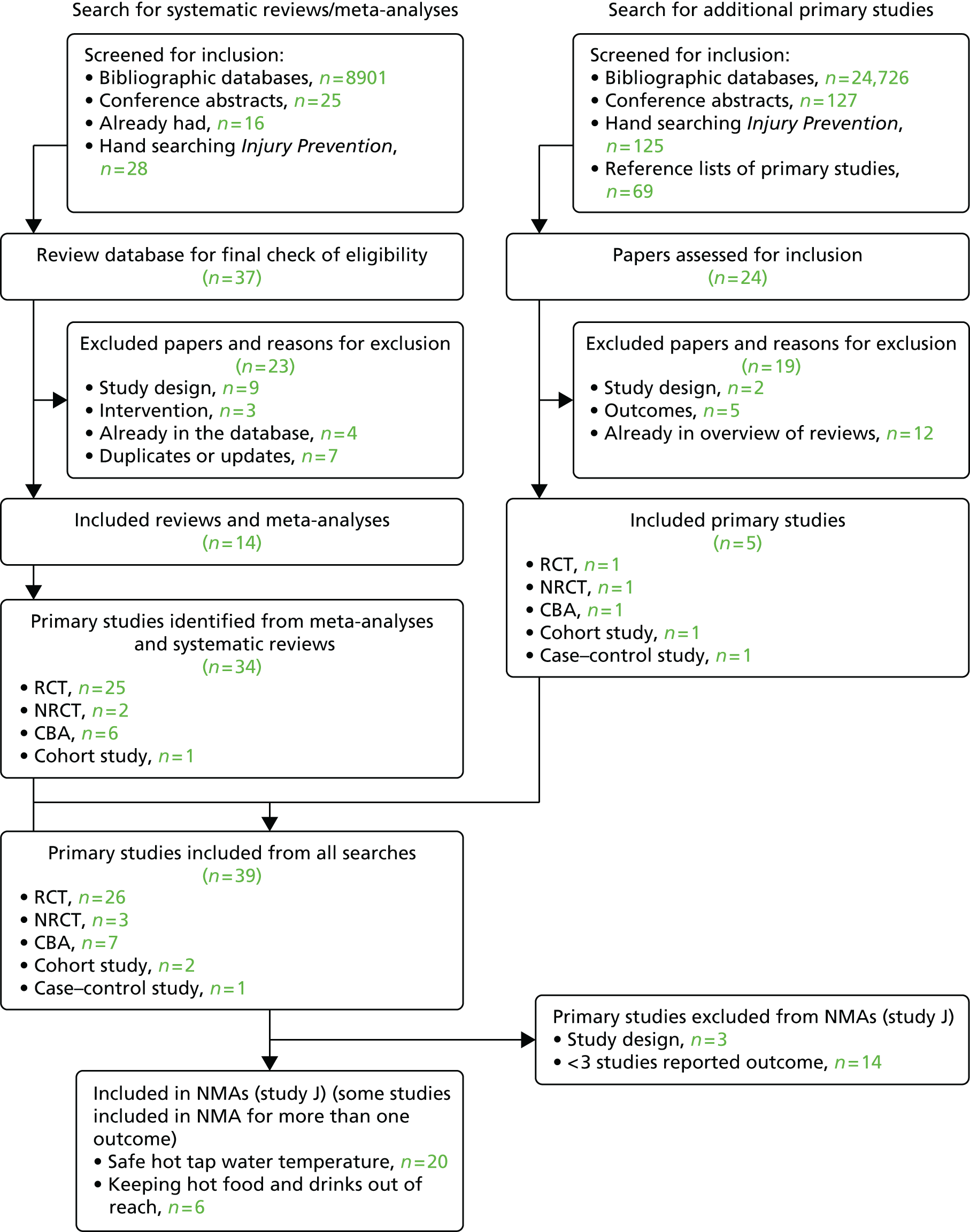

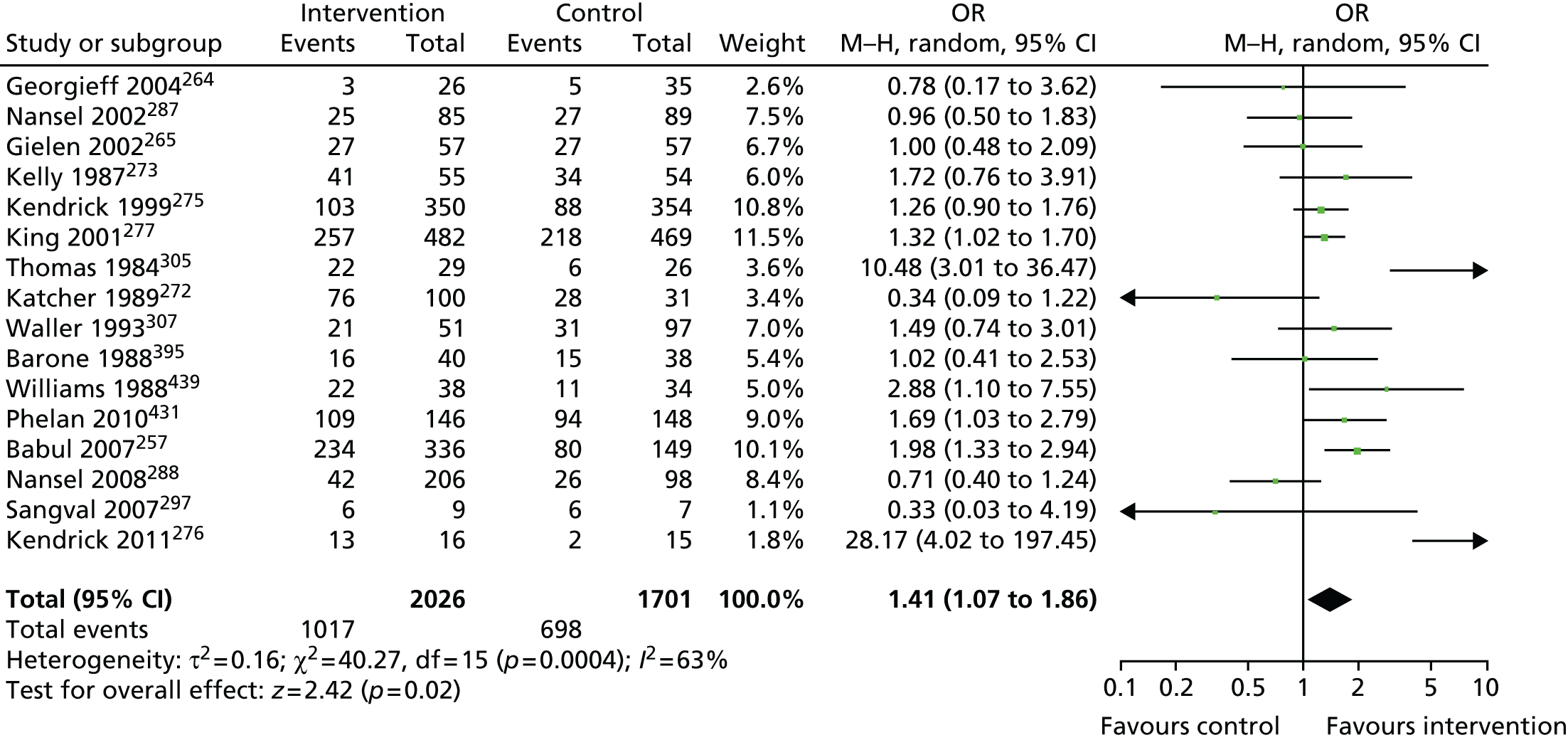

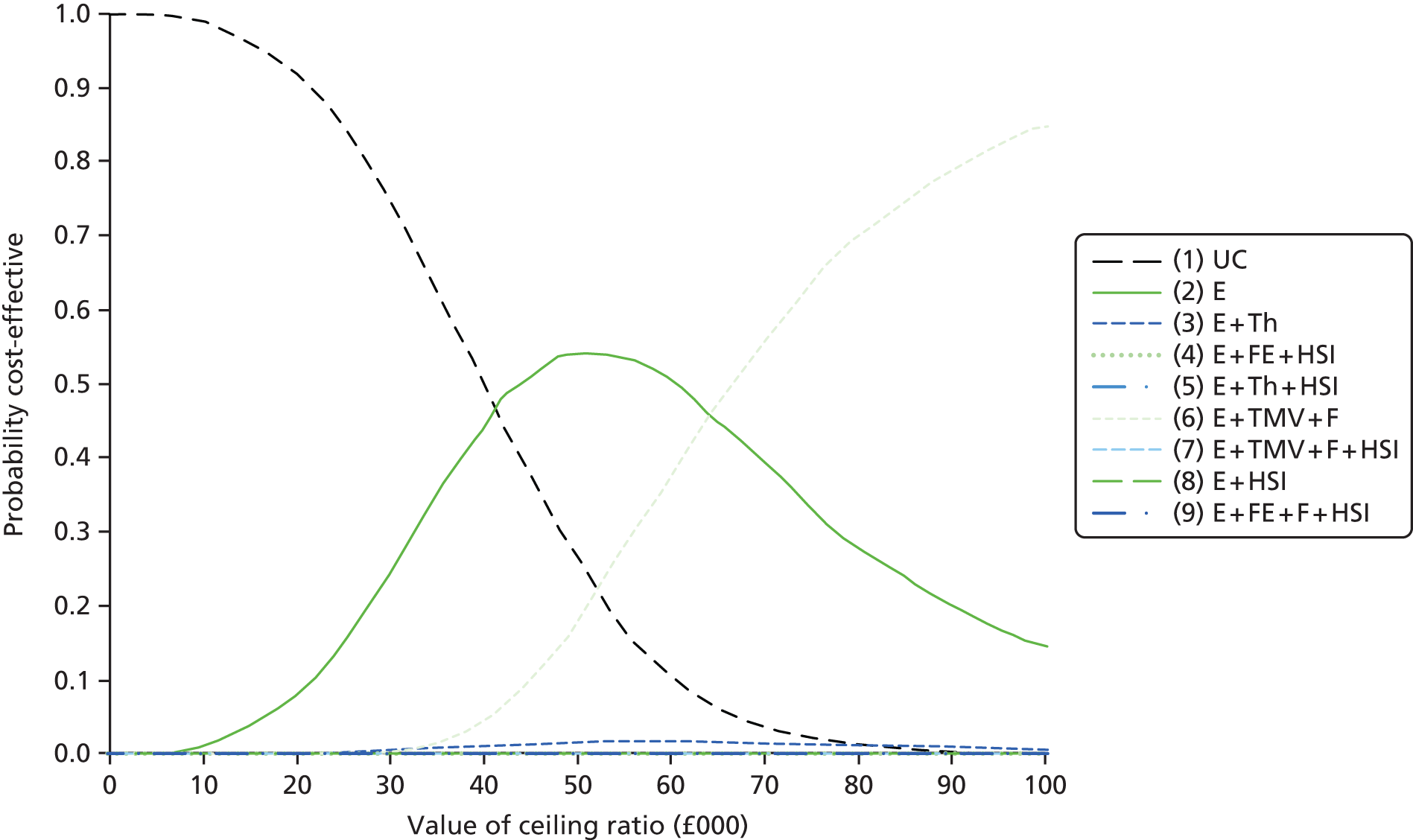

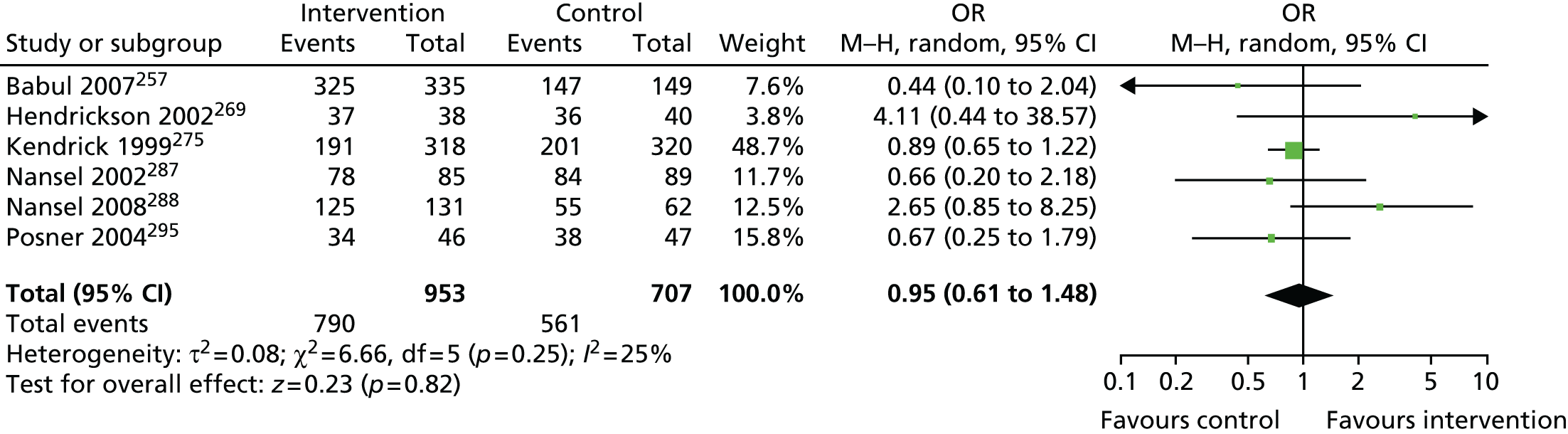

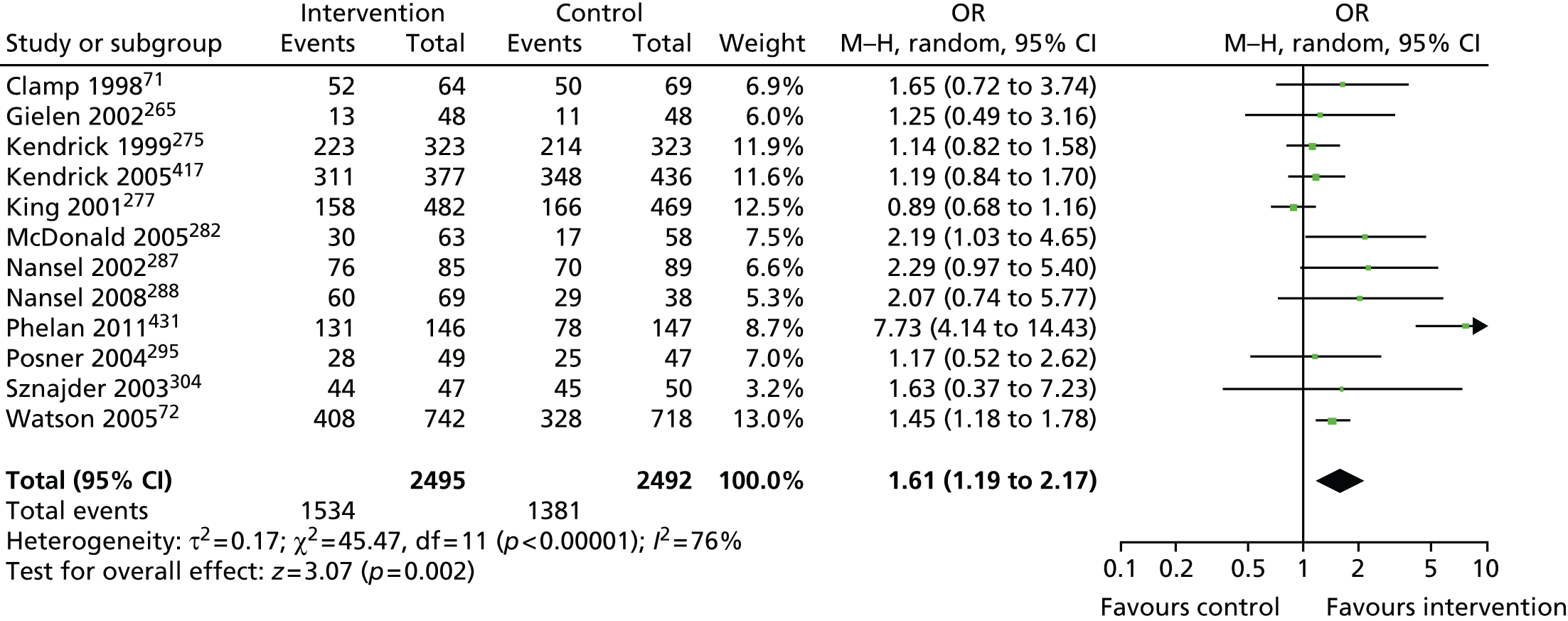

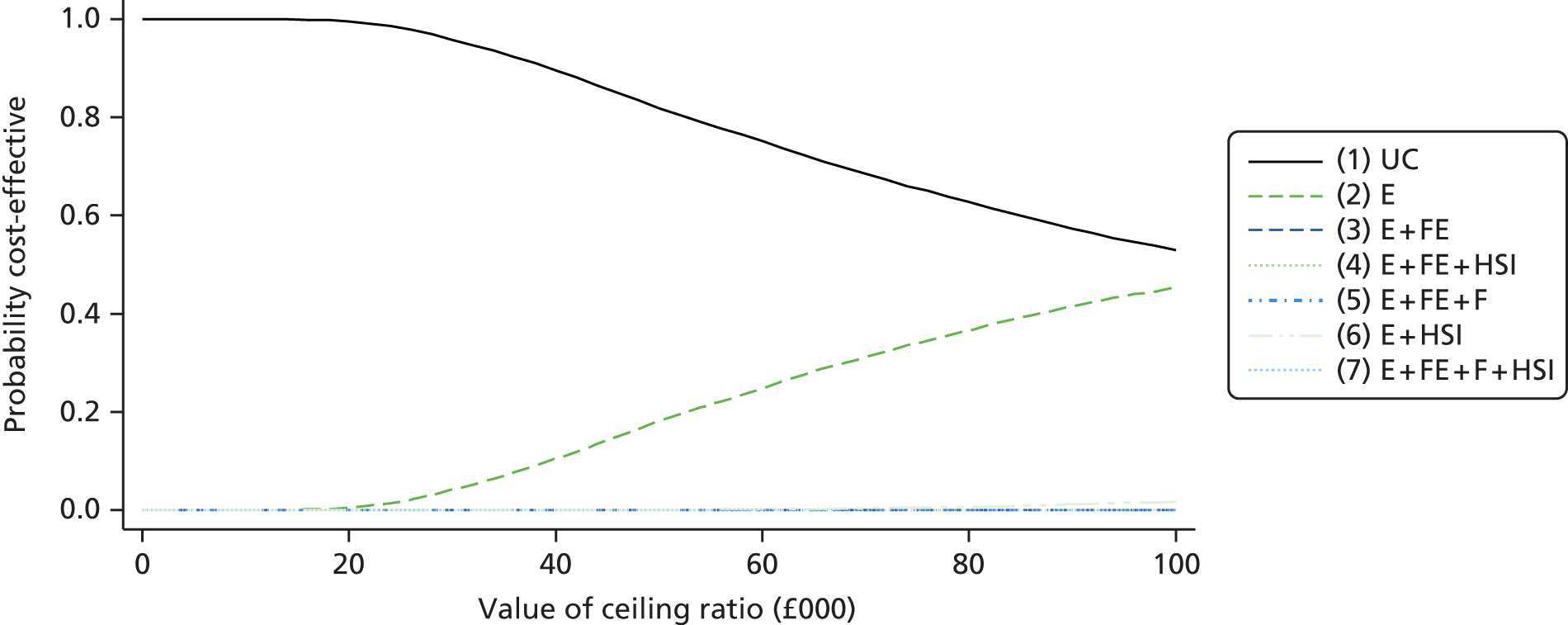

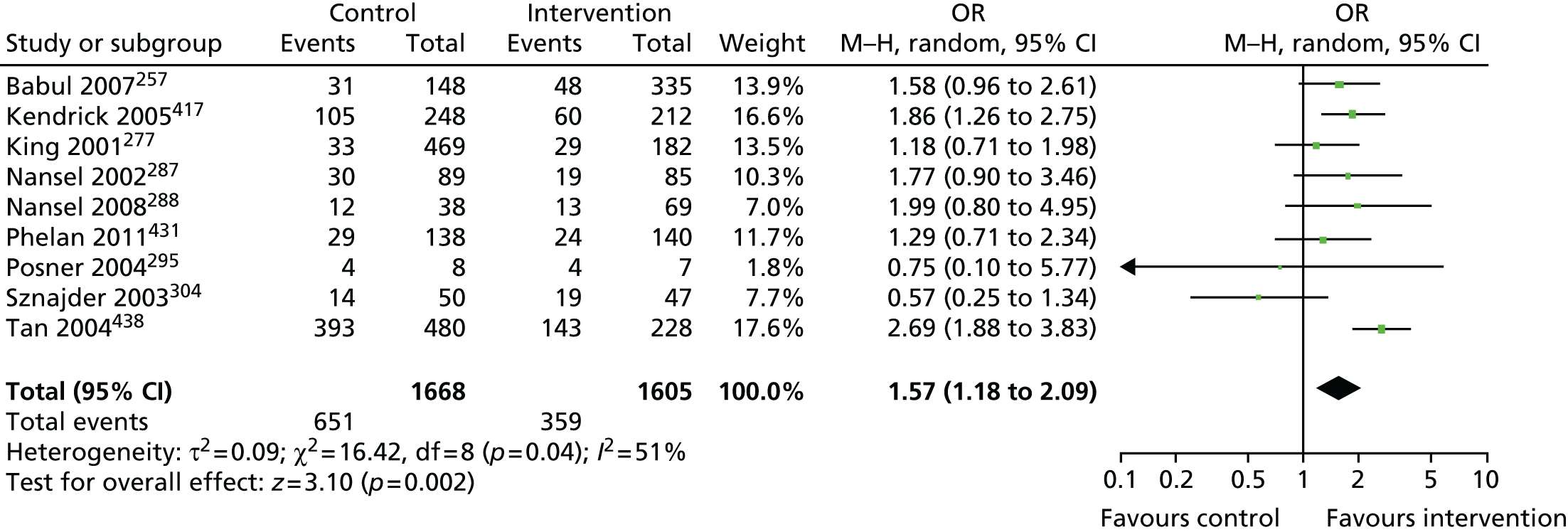

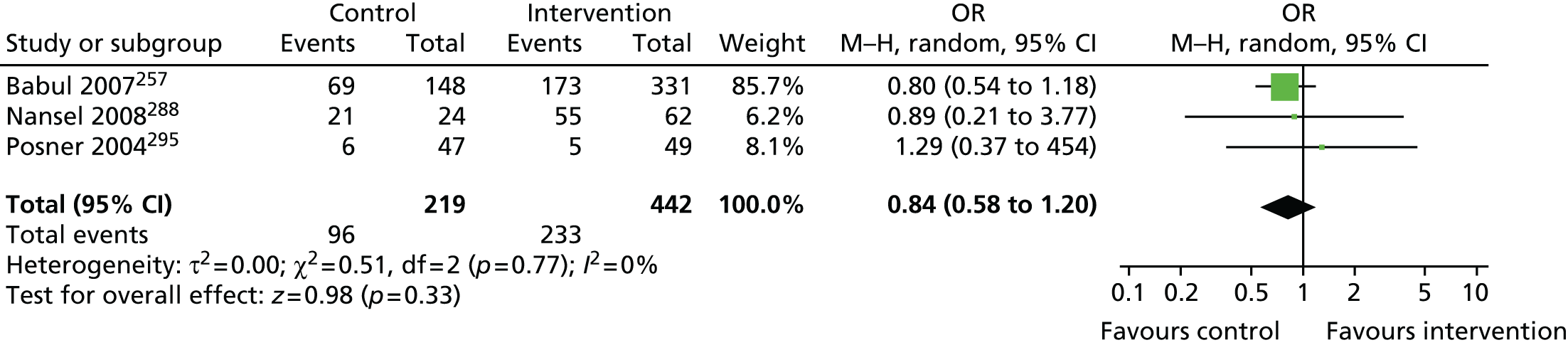

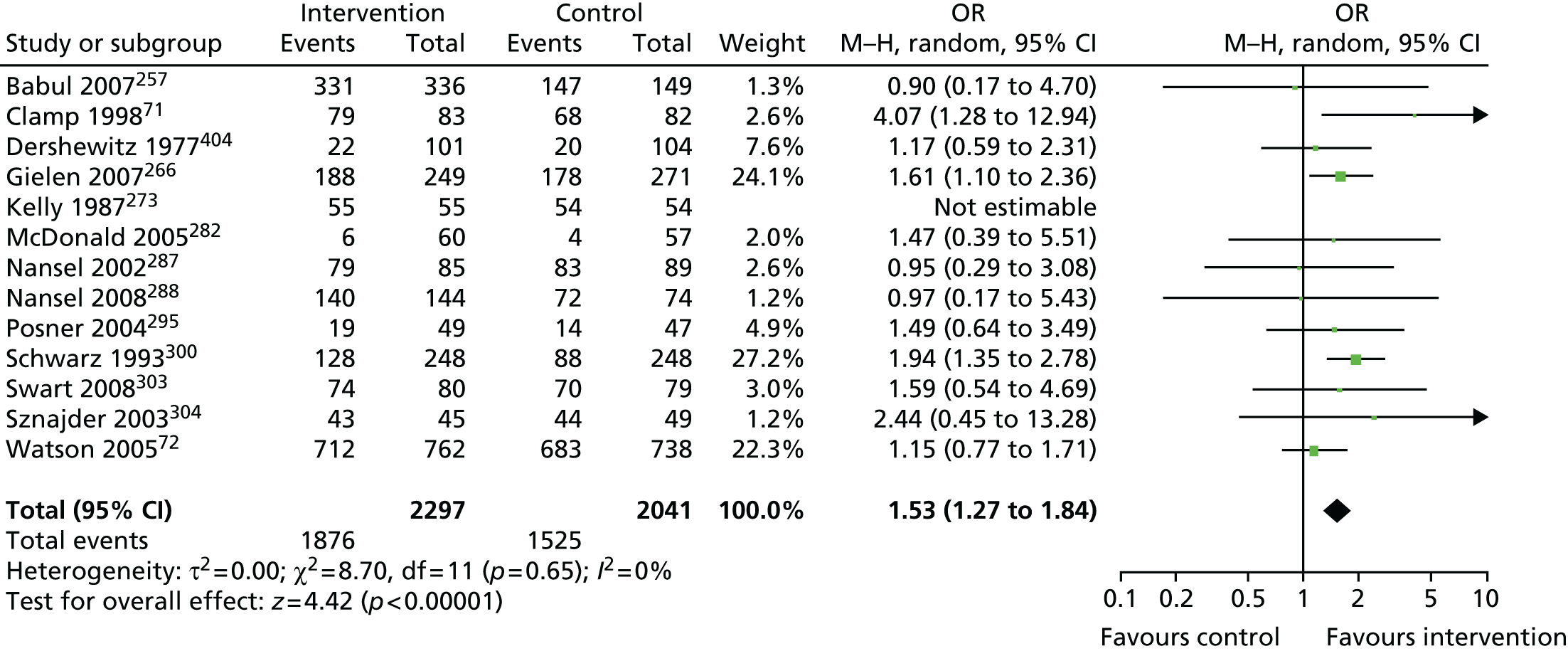

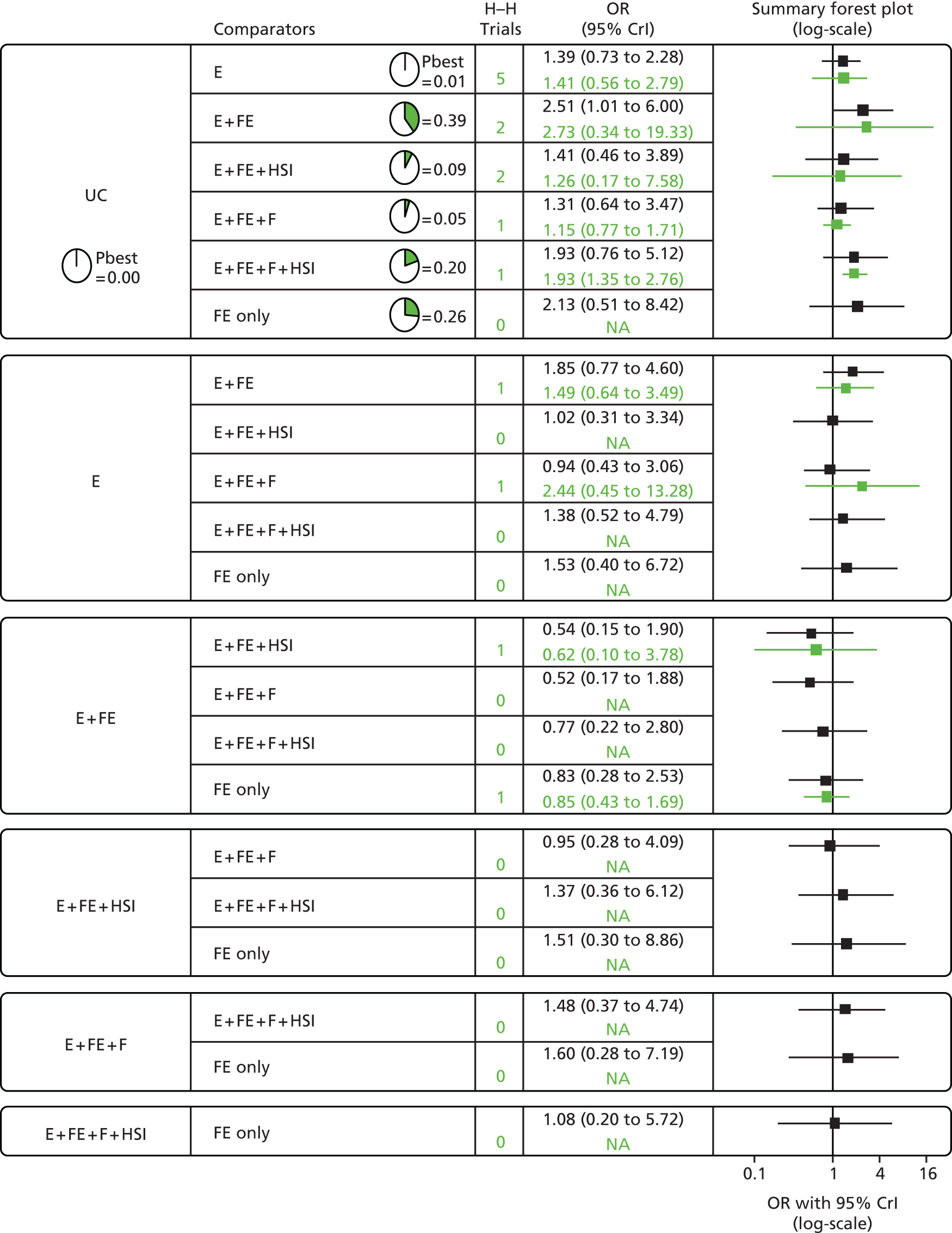

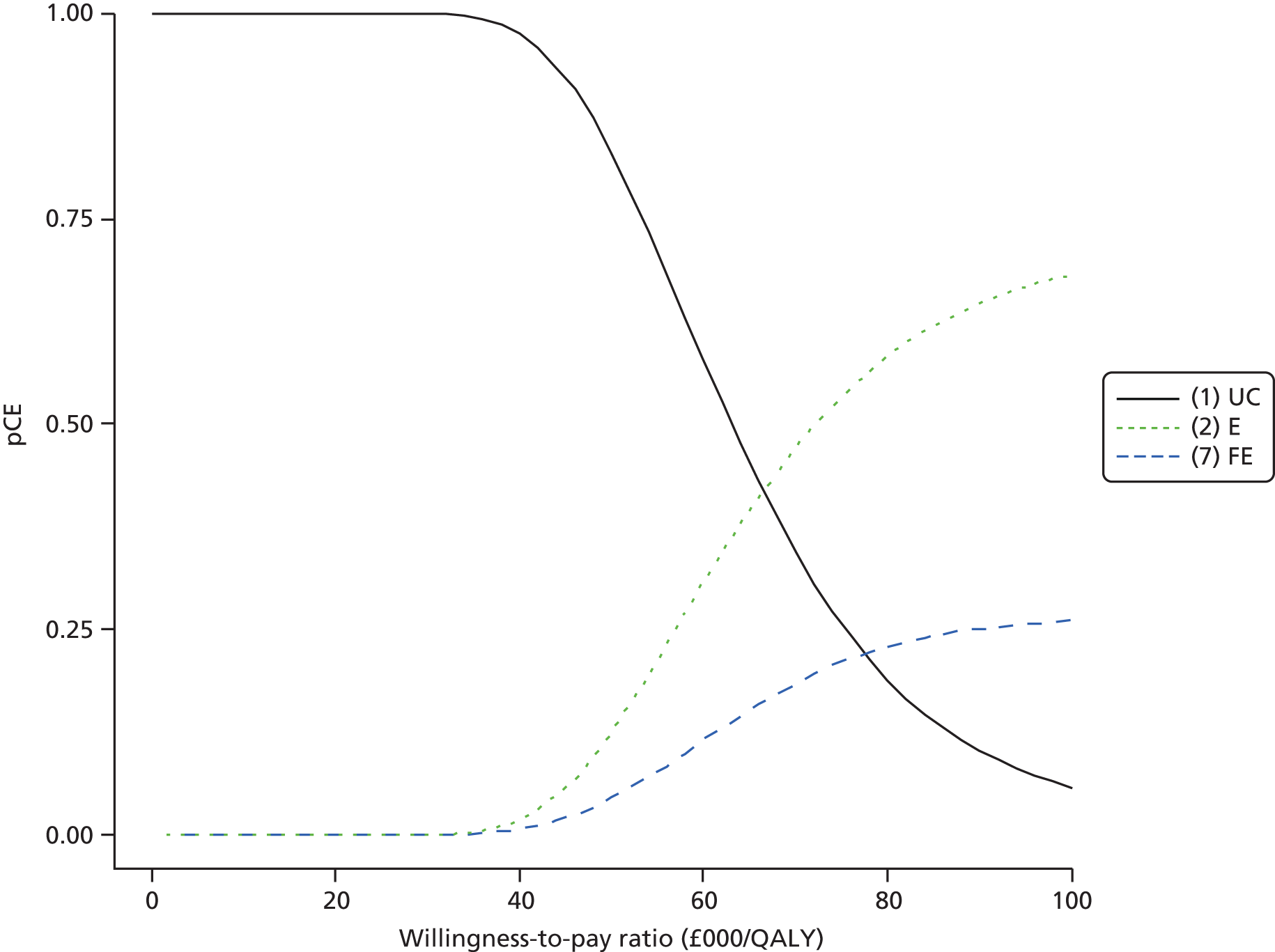

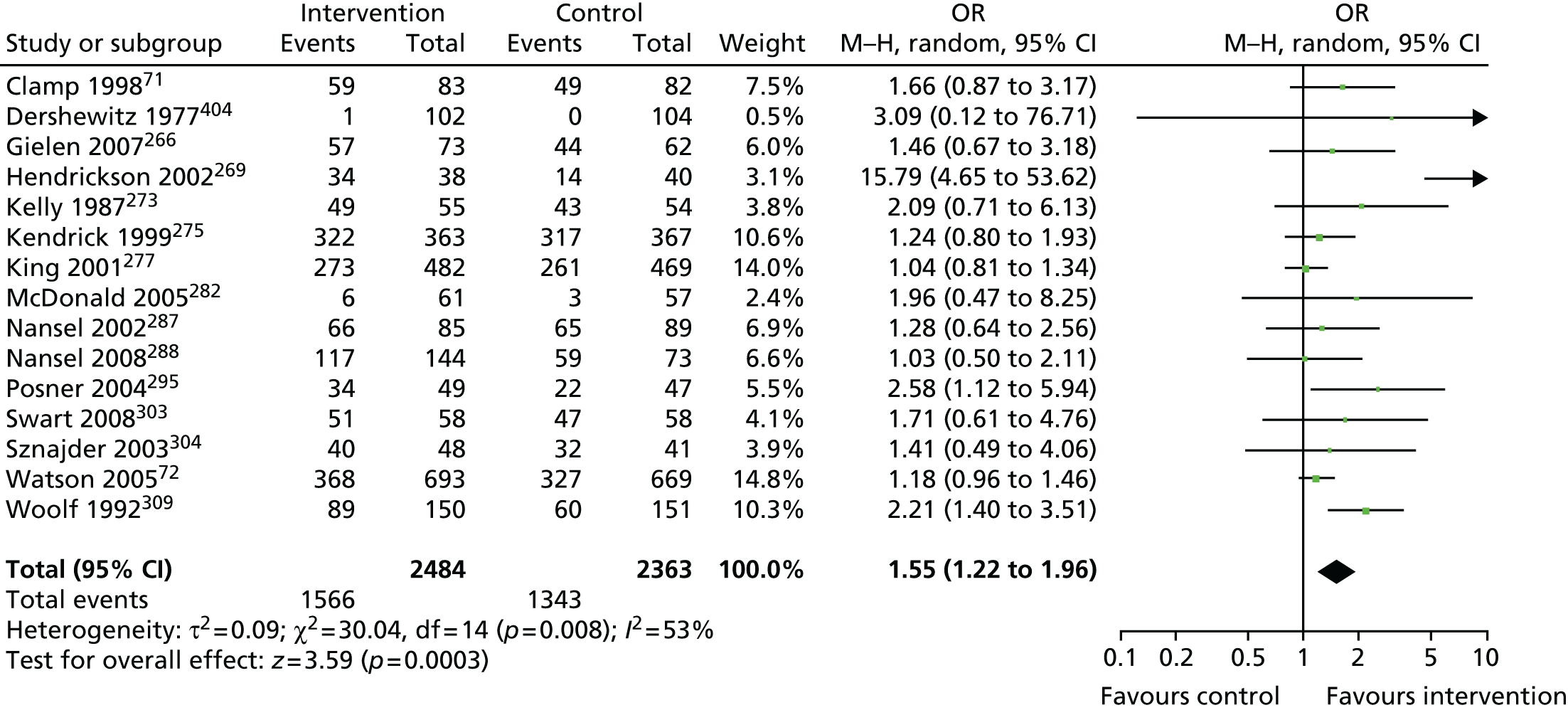

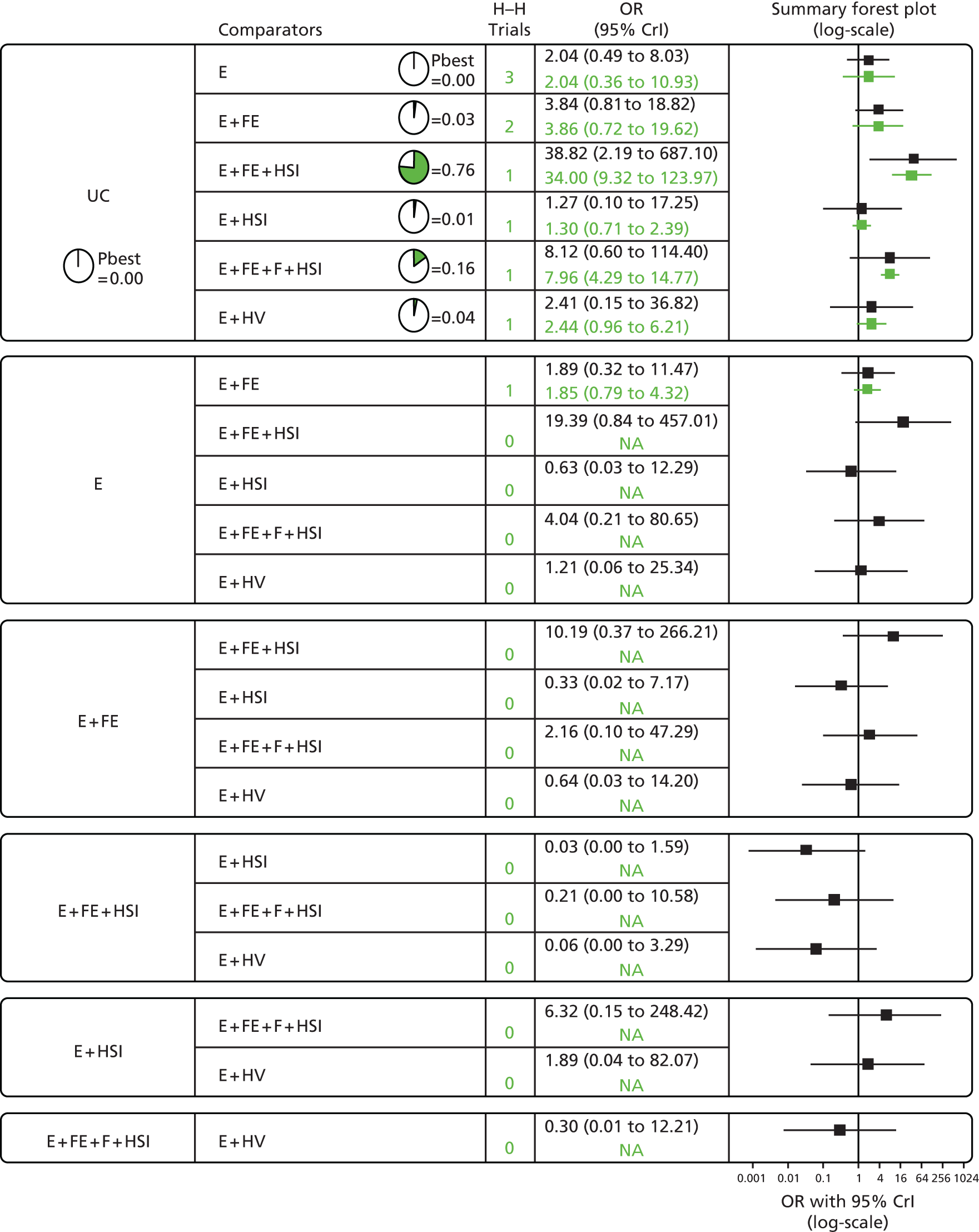

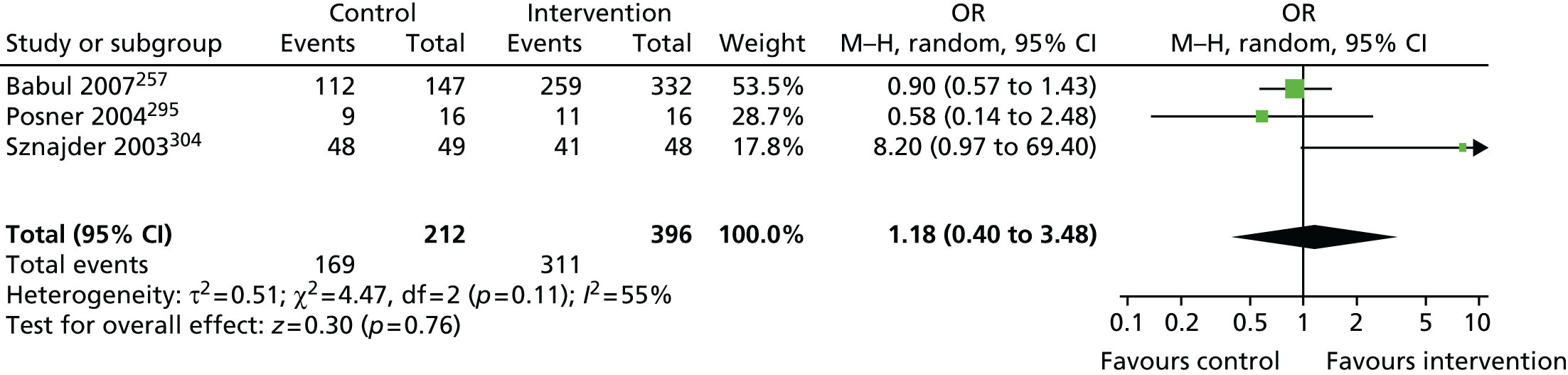

This work stream addressed the question, ‘How cost-effective are strategies for preventing thermal injuries, falls and poisonings?’. This question was answered by systematic overviews and systematic reviews of the literature on preventing falls, poisonings, fire-related injuries and scalds (study H), a systematic review and pairwise meta-analysis (PMA) of home safety interventions (study I), network meta-analyses (NMAs) of interventions to promote smoke alarm use and promote falls prevention practices, poison prevention practices and scalds prevention practices (study J) and decision analyses of interventions found to be effective in the NMAs (study K).

Work stream 6

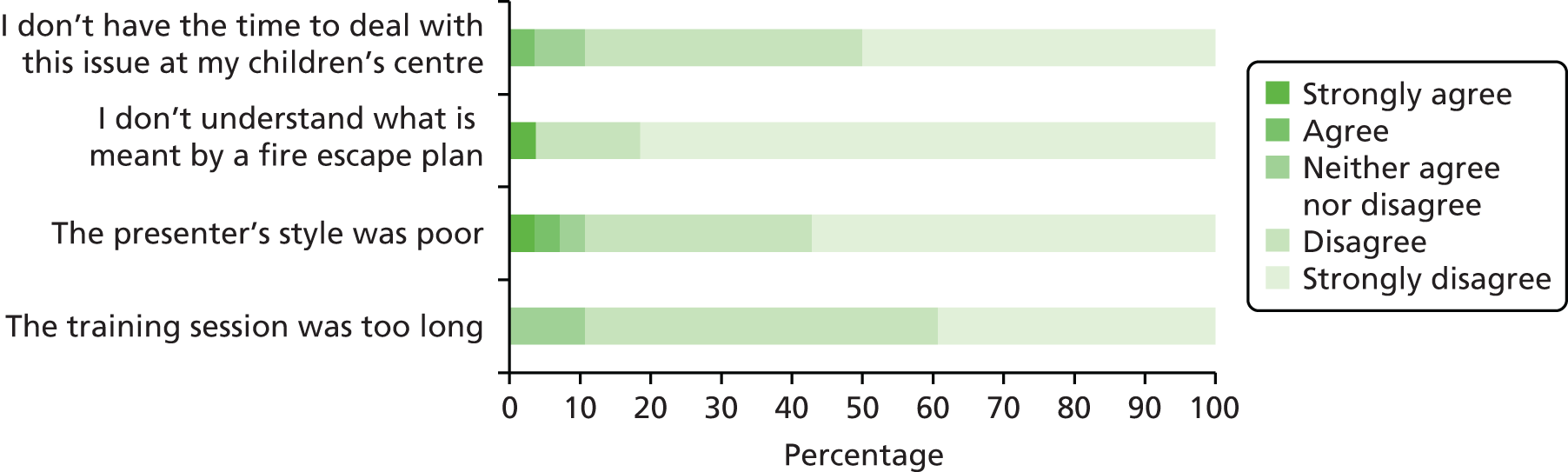

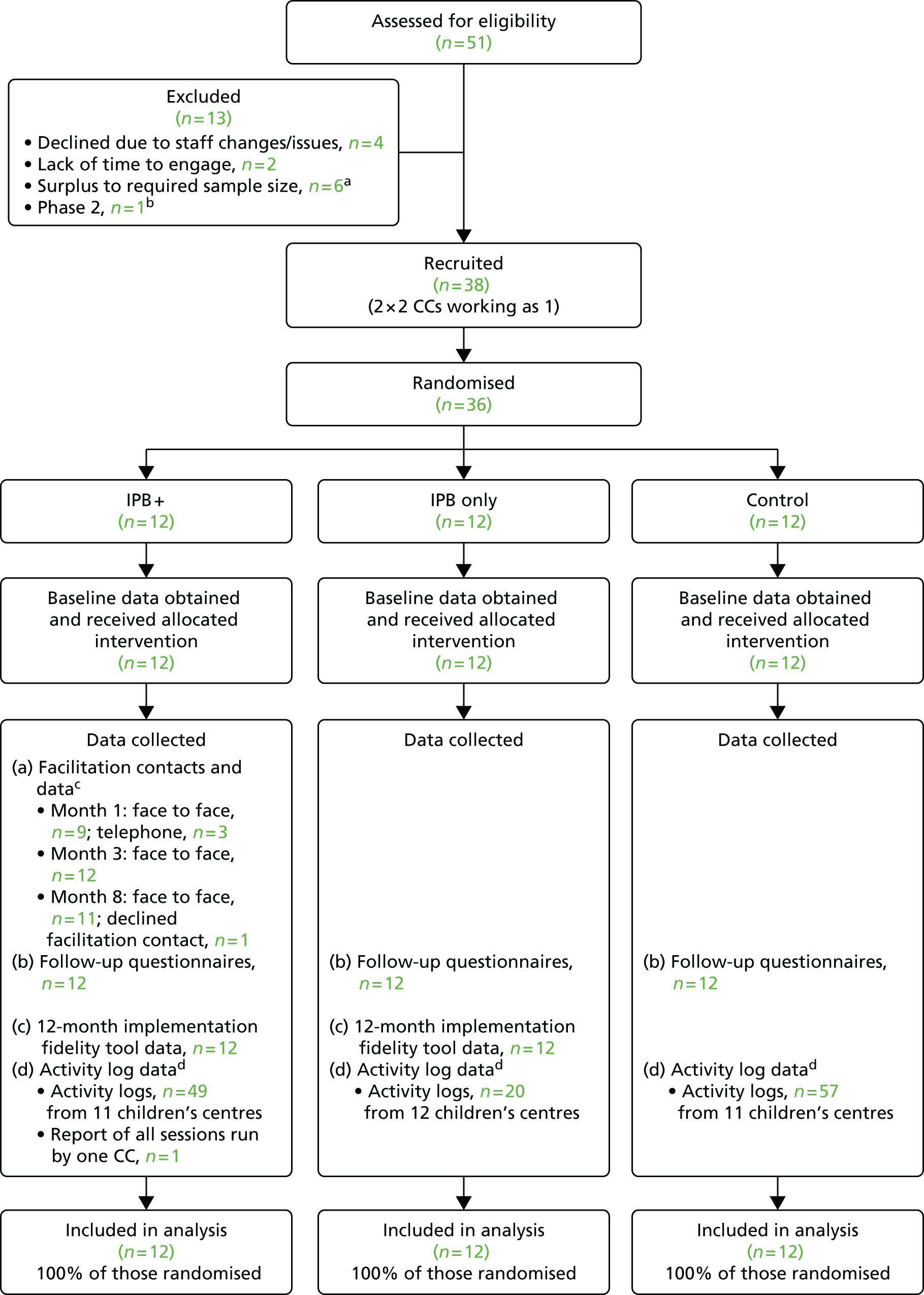

This work stream addressed the question, ‘How effective and cost-effective is implementing an IPB for one exemplar injury prevention intervention?’. This question was answered by a randomised controlled trial (RCT), set in children’s centres, which evaluated the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an IPB for the prevention of fire-related injury (study M). The trial was preceded by a review of the literature on the implementation and facilitation of health promotion interventions (study L) to inform the design of the intervention. Evidence from the trial was then incorporated into the development of a second IPB. This covered the prevention of fire-related injury, falls, poisonings and scalds, based on findings from studies A and D–M.

Structure of this report

Each work stream is reported in a separate chapter in the report. Each of these chapters includes the following sections: abstract, introduction, methods, results and discussion. This is followed by a chapter reporting the contribution of the lay research adviser who collaborated with the KCS programme from its inception to its completion. The report ends with three chapters drawing together the conclusions, implications and recommendations for research from the programme.

Chapter 2 What are the associations between modifiable risk and protective factors and medically attended injuries resulting from five common injury mechanisms in children under the age of 5 years? (Work stream 1)

Abstract

Research question

What are the associations between modifiable risk and protective factors and medically attended injuries resulting from five common injury mechanisms in children under the age of 5 years?

Methods

Five multicentre case–control studies were undertaken (study A). Cases were children aged < 5 years attending secondary care with a fall (three types: fall from furniture, fall on one level or a stair fall), poisoning or a scald. Control subjects (controls) were matched to cases on age, sex and calendar time, and were recruited from the register of the cases’ general practice (or neighbouring general practice). Exposures (safety equipment use, safety behaviours and hazards) were measured using parent-completed questionnaires and were validated by home observations in a sample of cases and controls (study B). Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated using conditional logistic regression adjusted for confounding factors.

Results

Validation of exposures

In total, 162 home observations were conducted. Sensitivities of ≥ 70% were found for eight out of 12 exposures for falls, for eight out of 15 exposures for poisoning and for three out of three exposures for scalds. Specificities of ≥ 70% were found for 10 out of 12 exposures for falls, for eight out of 15 exposures for poisoning and for two out of three exposures for scalds.

Falls from furniture

In total, 672 cases and 2648 controls participated. Parents of cases were more likely not to use a safety gate [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.65, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.29 to 2.12], to leave children on raised surfaces (AOR 1.66, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.06) and not to have taught their children rules about climbing on objects in the kitchen (AOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.15), and their children were less likely to climb or play on garden furniture (AOR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.97)*. For children aged 0–12 months, parents of cases were more likely to leave children on raised surfaces (AOR 5.62, 95% CI 3.62 to 8.72), change nappies on raised surfaces (AOR 1.89, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.88) and put children in car/bouncing seats on raised surfaces (AOR 2.05, 95% CI 1.29 to 3.27) than parents of controls. In the 13–36 months age group, parents of cases were less likely to put car or bouncing seats on raised surfaces than parents of controls (AOR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.94)*. In children aged > 36 months, cases were more likely to climb or play on furniture (AOR 9.25, 95% CI 1.22 to 70.07) than controls.

Falls on one level

In total, 582 cases and 2460 controls participated. Parents of cases were less likely not to use furniture corner covers (AOR 0.72, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.94)* and not to have rugs/carpets firmly fixed to the floor (AOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.99)* than parents of controls.

Stair falls

In total, 610 cases and 2658 controls participated. Compared with controls, parents of cases were more likely not to use safety gates on their stairs (AOR 2.50, 95% CI 1.90 to 3.29) or to leave them open (AOR 3.09, 95% CI 2.39 to 4.00) than to keep gates closed. Parents of cases were more likely not to have carpeted stairs (AOR 1.52, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.10) or not to have a landing part-way up their stairs (AOR 1.34, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.65). They were also more likely to consider their stairs not safe to use (AOR 1.46, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.99) or in need of repair (AOR 1.71, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.50). Case households were less likely than control households to have tripping hazards on their stairs (AOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.97)* or to not have handrails on all stairs (AOR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.86)*.

Poisonings

In total, 567 cases and 2320 controls participated. Parents of cases were more likely not to store all medicines at adult eye level or above (AOR 1.59, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.09) and not to store all medicines safely (locked away or at adult eye level or above) (AOR 1.83, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.42). They were more likely not to put medicines (AOR 2.11, 95% CI 1.54 to 2.90) or household products (AOR 1.79, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.48) away immediately. Parents of cases were less likely not to store all household products safely (AOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.99)* and not to have taught children rules about what to do if medicines were left on the worktop (AOR 0.66, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.96)*.

Scalds

In total, 338 cases and 1438 controls participated. Parents of cases were more likely than parents of controls not to have taught their child rules about not climbing on things in the kitchen (AOR 1.66, 95% CI 1.12, 2.47), what to do or not do when parents are cooking on the cooker top (AOR 1.95, 95% CI 1.33, 2.85) or about hot things in the kitchen (AOR 1.89, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.75). They were also more likely than control parents to have left hot drinks within reach of their child (AOR 2.33, 95% CI 1.63 to 3.31). Cases were less likely than controls to have played or climbed on furniture (AOR 0.62, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.96)* or to have been left alone in the bath (AOR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.75)*.

Conclusions

Despite a small number of apparently counterintuitive findings (indicated with an asterisk), a range of modifiable risk factors were associated with falls from furniture, falls on stairs, poisonings and scalds in children aged 0–4 years. These results provide evidence on which to base safety advice and recommendations.

Work stream 1 consisted of five case–control studies (study A) quantifying associations between modifiable risk factors and falls from furniture, falls on one level, falls on steps or stairs, poisonings and scalds. Work stream 1 also included a study to validate self-reported exposures in the case–control studies (study B). The findings from work stream 1 informed:

-

the decision analyses undertaken in work stream 5

-

the development of an IPB for the prevention of fire-related injuries, falls, poisonings and scalds undertaken in work stream 6 (see Chapter 7).

Introduction

The case–control studies focused on falls, poisonings and scalds as these are among the most common types of injury resulting in hospital admission and ED attendance in children aged 0–4 years in England and the UK. In 2012/13, > 26,000 children aged 0–4 years were admitted to hospital in England following a fall, poisoning or scald,2 as described in more detail below. There are no recent data available on ED attendances, but data from 2002 show that approximately 280,000 children aged 0–4 years attended an ED following a fall, poisoning or thermal injury (burns and scalds) in the UK. 3

Falls resulted in 19,569 hospital admissions in children aged 0–4 years in England in 2012/13. Of these, 18% were falls from furniture, 11% were falls down stairs or steps and 23% were falls on one level. 2 Falls also result in a large number of ED attendances in the UK; in 2002, there were 229,600 attendances in children aged 0–4 years following a fall. Of these, 18% were falls down stairs or steps and 31% were falls on one level. 3 Falls from furniture most commonly involve beds, chairs,2,44 baby walkers, bouncers, changing tables and high chairs. 45,46

Poisonings resulted in 5286 hospital admissions in children aged 0–4 years in England in 2012/3. The majority (74%) were medicinal poisonings, with 26% being non-medicinal poisonings. 2 Poisonings also result in a substantial number of ED attendances in the UK; in 2002, there were 24,887 attendances in children aged 0–4 years following a poisoning. 3

Scalds accounted for 1811 hospital admissions in children aged 0–4 years in England in 2012/13. 2 Most (61%) were caused by drinks, food, fats and cooking oils, 13% were caused by hot tap water and 26% were caused by other hot fluids. The number of ED attendances for scalds is not routinely available, but there were 26,015 attendances for all thermal injuries in children aged 0–4 years in the UK in 2002. 3 A recent UK study found that 67% of thermal injuries in children aged 0–4 years attending six hospitals in the UK and Ireland resulted from scalds;47 hence, it can be estimated that approximately 17,000 ED attendances occurred as a result of a scald in the UK in 2002.

Systematic overviews (study H)48 and a systematic review and PMA (study I)49 undertaken as part of the KCS programme of research found that home safety interventions providing education, some of which also provided safety equipment, can increase safety gate use and reduce baby walker use, increase safe storage of medicines and household products and availability of poison control centre (PCC) numbers and increase the proportion of families with a safe hot tap water temperature. However, little evidence was found showing whether such interventions reduced fall-related injuries, poisonings or scalds. These reviews highlighted the lack of adequately powered RCTs of interventions to prevent falls, poisoning or scalds that measured injury outcomes. One of the challenges is that, although on a population level injuries are a major public health problem, for individual children, specific injuries are relatively rare events. Hence, trials frequently require prohibitively large sample sizes and are extremely expensive and logistically difficult. Therefore, the best available evidence for effective interventions in the field of injury prevention often comes from rigorous case–control studies, for example those for smoke alarms50 and cycle helmets. 51 Such evidence has had a major impact on policy and legislation. The NHS, local authorities and other organisations need to be able to make decisions about which home safety interventions to commission or provide, but at present such decisions lack an evidence base. We have therefore undertaken these case–control studies to quantify associations between modifiable risk factors and falls, poisonings and scalds in young children.

Methods

The methods for these studies are described in full in the published protocols. 52–54

Objectives

The primary objectives of study A were to estimate associations between modifiable risk and protective factors and medically attended injuries resulting from five injury mechanisms in children aged < 5 years:

-

falls from furniture

-

falls on one level

-

stair falls

-

poisoning

-

scalds.

Our secondary objectives were to explore whether or not associations between risk and protective factors and injuries varied by child age, sex, ethnicity, single parenthood, housing tenure and unemployment and injury severity. 49

Study design

We used five multicentre matched case–control studies [one for each of the injury mechanisms (a)–(e)].

Setting

We recruited participants from EDs, minor injury units (MIUs) and hospital wards from acute NHS trusts in Nottingham, Bristol, Newcastle upon Tyne, Norwich, Gateshead, Derby, Great Yarmouth and Lincoln, UK. Recruitment of cases commenced on 14 June 2010 for all studies and finished on (a) 15 November 2011 for the falls from furniture study, (b) 15 November 2011 for the falls on one level study, (c) 30 September 2012 for the stair falls study, (d) 18 January 2013 for the poisoning study and (e) 18 January 2013 for the scalds study. Recruitment of controls commenced with recruitment of the first case to each study and controls were recruited within 4 months of recruitment of cases.

Participants

Cases were children aged 0–4 years with:

-

a fall from furniture

-

a fall on one level

-

a stair fall

-

a poisoning or suspected poisoning from a medicinal or other household product or

-

a scald, resulting in hospital admission or ED or MIU attendance.

Injuries had to have occurred at the address at which the child was registered with a general practitioner (GP) (hereafter referred to as the child’s home). Intentional and fatal injuries were excluded, as were children living in residential care. Cases were eligible to be recruited only once to the study.

We used two sources of controls; community controls and hospital controls. For clarity and simplicity the findings relating to community controls (hereafter referred to as controls) are presented in the main text of the report. Findings relating to hospital controls are summarised in Appendix 1. Children living in residential care were excluded. Controls were children aged 0–4 years without a medically attended injury of the same mechanism as the case on the date of the case’s injury. Controls were eligible to be recruited as a case or as a further control if their second recruitment occurred at least 12 months after their first recruitment. They were not eligible to be recruited more than twice to the study. We aimed to recruit an average of four controls per case, individually matched on age (within 4 months of age of case), sex and calendar time (within 4 months of case injury). To increase the study power and make the most efficient use of controls, when we recruited more than four controls per case (or when cases were later excluded), the extra controls were eligible to be matched to other cases who did not have four matched controls. These were matched on age (within 4 months of age of case), sex and calendar time (within 4 months of the case injury) and study centre, and were eligible to be used only once as an extra matched control.

The eligibility of putative cases to take part in the study was assessed from medical records by clinical staff prior to study invitations being issued. Research staff also assessed eligibility on receipt of completed study questionnaires. Potentially eligible cases were approached by clinical staff face to face during their medical attendance or by telephone or post within 72 hours of their attendance. Controls were recruited by post by general practice or primary care trust (PCT) staff, from the practice register of the case’s GP or, when the case’s practice was unable to participate, from that of a neighbouring practice. To minimise age differences between cases and controls resulting from the time taken to recruit practices and then recruit controls, study invites were sent to children born up to 4 months before and 2 months after the case’s date of birth. Ten children were invited to participate for each case. One reminder was sent to case and control non-respondents 2 weeks after the original mailing.

Variables

Data on injuries

We collected data from parents of cases and hospital controls on the type of injury sustained and the treatment received. We did not seek consent to access medical records to assess injury severity as we considered that this might discourage study participation. We therefore used parent-reported data on treatment as a proxy for injury severity. This is described in more detail below.

Definition of exposures

The exposures of interest were safety equipment use and home hazards measured for the 24 hours prior to the injury for cases and for the 24 hours prior to completing the questionnaire for controls. Safety behaviours were measured over the week prior to the injury for cases and the week prior to completing the questionnaire for controls.

The exposures measured for each study were:

-

falls from furniture – use of baby walkers, playpens (or travel cots while child awake) or stationary activity centres; use of safety gates anywhere in the house; use of harnesses in high chairs; changing nappies on a raised surface; leaving child unattended on a raised surface; placing car seats or bouncing cradles on a raised surface; having objects that children could climb on to reach high surfaces; frequency of children climbing or playing on furniture; and teaching children safety rules about falls

-

falls on one level – use of baby walkers, playpens (or travel cots while child awake) or stationary activity centres; use of safety gates anywhere in the house; rugs/carpets firmly fixed to the floor; electric wires or cables trailing across floors; floors clear of tripping hazards; use of furniture corner covers; locking back doors to prevent access to the garden; unsupervised playing in the garden; and teaching children safety rules about falls

-

stair falls – use of any safety gates; use of safety gates on stairs; leaving safety gate on stairs open; use of baby walkers, playpens (or travel cots while child awake) or stationary activity centres; presence of banisters and width of banister gaps; presence of handrails and tripping hazards on stairs; stairway characteristics (carpeted steps, lighting, steepness, width, landing part-way, winding stairs and steps, stair covering or handrails/banisters in need of repair); and teaching children safety rules about stairs

-

poisonings – storage of medicinal and household products (analgesics, iron/vitamins, cough medicine, antidepressants/hypnotics and any other medicines, bleach, dishwasher products, oven cleaner, toilet cleaner, turpentine/white spirit and rat/ant killer, garden chemicals and other household products)55,56 at adult eye level or above; storage of products in locked cupboards, drawers, fridges or cabinets; frequency of returning products to usual storage place immediately after use; use of child-resistant caps (CRCs) or blister packs on products; storage of medicines in a locked medicine box; not transferring products to other containers; use of a safety gate to prevent access to the kitchen; presence of things that child may climb on to reach high surfaces; use of baby walkers; and teaching children safety rules about poisonings.

-

Scalds – use of safety gates; presence of things that child may climb on to reach high surfaces; drinking hot drinks while holding a child; holding child while using cooker; passing hot drinks over a child; keeping hot drinks out of reach of children; use of curly/short kettle flexes; storing kettles at back of worksurface; use of back rings on cooker; turning saucepan handles away from edge of cooker; use of tablecloths; hot tap water/thermostat temperature; using cold water first when running a bath; measuring bathwater temperature; checking bath water temperature with elbow/hand; leaving child without an adult in the bath or bathroom; children running baths; frequency of child climbing or playing on furniture; use of baby walkers, playpens (or travel cots while child awake) or stationary activity centres; and teaching children safety rules about hot liquids in the kitchen and bathroom.

Definition of potential confounding variables

The potential confounding variables that were measured consisted of sociodemographic and economic characteristics, out-of-home child care and validated measures of child behaviour and temperament [Infant Behaviour Questionnaire (IBQ),57 Early Child Behaviour Questionnaire (ECBQ)58 and Child Behaviour Questionnaire (CBQ)59 activity and high-intensity pleasure subscales], safety rules,60 Parenting Daily Hassles (PDH) scale (parenting tasks subscale),61,62 parental mental health [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)63] and proxy-reported child’s HRQL [PedsQL and a general health visual analogue scale (VAS)64]. Eight questions, each with three-point Likert scale responses from ‘not likely’ to ‘very likely’, assessed perceptions of children’s ability to climb; these were analysed as a categorical variable grouping responses into (1) all not likely, (2) at least one quite likely but none very likely and (3) at least one very likely. In addition, where plausible, some of the exposures listed above were also considered as potential confounders, for example use of a playpen may confound the relationship between use of a safety gate on stairs (as parents may be less likely to use a safety gate if they have a playpen) and the occurrence of a stair fall (as children may have less exposure to stairs if they spend time in a playpen).

As we were not able to recruit all controls from the same general practice as cases, area-level deprivation and distance from hopsital were included in all models as a priori confounders. Deprivation was measured using the 2010 version of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). 65 IMD scores for lower super output areas were matched to postcode using GeoConvert. 66 Distance from hospital was calculated based on postcodes and calculating straight line distances between two postcodes. 67 For cases we used the postcodes of the home address and the hospital that they attended. For controls we used the postcode of the home address and that of the hospital that the matched case attended. The choice of other confounders to include in multivariable models was determined through the use of causal directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), as described in Statistical methods.

Measurement of exposures and confounding variables

We developed age-specific questionnaires (0–12 months, 13–36 months and 37–59 months) for completion by parents or guardians using previously validated measures of exposure when possible68 (see Appendix 1, Case–control questionnaires). Questionnaires, study information leaflets and study invitation letters were pre-piloted on families from local children’s centres to assess face validity, comprehension, ease of completion and time taken to complete and were then piloted on 11 families of children who had attended EDs at participating NHS trusts and on 29 families from children’s centres in study centres.

Validation of exposure measurement (study B)

We assessed the agreement between exposures reported by parents on study questionnaires and those observed on home observations in a sample of cases and controls. Parents of participants in all case–control studies were asked to express interest in other child safety research projects (studies B, C and G) nested within study A. Home observations were undertaken as soon as possible after parents agreed to participate to miminise the time between questionnaire completion and home observation. Observations were undertaken by trained researchers, blind to parents’ responses on the study questionnaire, using a checklist of observations (see Appendix 1, Home observation checklist for study B). To assess whether or not recent changes to the home may account for differences between reported and observed exposures, participants were asked if changes to safety behaviours, safety equipment use or home hazards had been made in the preceeding 3 months and what the changes were, if any. We chose 3 months as the time period to allow for the time taken to recruit cases and controls to the home observation study (time between receipt of questionnaire and date of home visit: median 29 days, range 1–92 days). Participants were provided with a £5 gift voucher for use in local stores to thank them for their time.

Bias

We used several strategies to try to minimise bias. We aimed to minimise recall bias by inviting cases to participate in the study within 72 hours of the injury attendance and measured exposures over a short time period prior to the injury attendance (ranging from 24 hours to 1 week); for controls we measured exposures over the same time period prior to completing the study questionnaire. When possible, we validated the accuracy of self-reported exposures in cases and controls by home observations. To minimise non-response bias, we used methods shown in systematic reviews to increase response rates, including providing a small monetary incentive (£5) for the return of completed questionnaires, using personalised letters, sending mail by first class post, providing Freepost reply envelopes, using reminders including the provision of further questionnaires, keeping the questionnaire as short as possible and using university logos on study documentation. 69,70

Study size

Validation of exposures

For a sensitivity of 80%, assuming that a minimum of 20% of participants displayed the safety behaviour, used the safety equipment or had the hazard of interest, and a CI of ± 20%, 80 home visits were required. As it was plausible that sensitivity could vary between cases and controls, we aimed to recruit 80 cases and 80 controls.

Case–control studies

For the case–control studies, all sample size estimations were based on 80% power, a 5% significance level and a correlation between exposures in cases and controls of 0.1. Sample sizes were estimated to detect protective associations [i.e. an odds ratio (OR) of 0.7 for the falls studies and an OR of 0.63 for the poisoning and scalds studies]. These reductions were chosen as they were considered to be clinically important and required sample sizes that were feasible to achieve. For ease of interpretation of our results, we have presented ORs for risk factors for injury (i.e. not using safety equipment, not having a safety behaviour or having a hazard). The sample size estimations in the following sections therefore use the inverse of the protective ORs given above.

Falls

To detect an OR of 1.43, each case–control study would require 496 cases and 1984 controls for each type of fall (falls from furniture, falls on one level and stair falls), based on the exposure prevalence from previous studies71,72 [not using safety gates on stairs (55%) or across doorways (70%), not using a playpen (58%), not using a stationary activity centre (76%), rugs not firmly fixed to floors (46%), floors not clear of tripping hazards (57%%), using a baby walker (36%) and leaving a child unattended on raised surfaces (35%)]. We chose the exposure prevalence from this list that required the largest sample size.

Poisoning

To detect an OR of 1.59, 266 cases and 1064 controls would be required. This is based on the exposure prevalence estimated from the first 428 controls recruited to the study, taking account of missing data on exposures and choosing the exposure prevalence that required the largest sample size from not storing all medicines safely (27%), all cleaning products safely (55%) or all products safely (65%), not putting medicines away immediately after use (23%), not putting cleaning products away immediately after use (21%) or not putting all products away immediately after use (29%).

Scalds

To detect an OR of 1.59, 259 cases and 1036 controls would be required. This is based on the exposure prevalance estimated from the first 428 controls recruited to the study, taking account of missing data on exposures and choosing the exposure prevalence that required the largest sample size from drinking hot drinks while holding a child (27%) and not using kettles with curly/short flexes (22%).

Quantitative variables

All exposures were categorical variables. For confounders measured on a continuous scale, we assessed the linearity of their relationship with outcome measures by adding higher-order terms to regression models and tested significance using likelihood ratio tests with a p-value of < 0.05 taken as significant. When the relationship between age and the outcome of interest was non-linear we grouped age into the three age groups consistent with the age groups for which we had developed age-specific questionnaires (0–12 months, 13–36 months, ≥ 37 months). When other relationships were non-linear, we examined distributions of the confounders and grouped values based on cut-off points that separated the distribution into groups of similar values while ensuring sufficient numbers in each group for analysis. When standard groupings had been used in previous research, for example quintiles of deprivation scores, we grouped values similarly to allow comparisons with previous research. The cut-off points for groupings are given in the results tables.

We devised a score representing parents’ perceptions of their child’s ability to climb by combining responses across eight questions asking about perceptions of ability to climb or reach a range of hazards. Each question had a three-point Likert scale response from ‘not likely’ to ‘very likely’, with a ‘don’t know’ option. The score was created by categorising responses into (1) all not likely, (2) at least one quite likely but none very likely and (3) at least one very likely. Those with missing or ‘don’t know’ responses to individual items were categorised as missing an overall score unless respondents had at least one ‘very likely’ response. We also devised a composite categorical variable describing parents’ perceptions of their stair characteristics by combining responses across seven questions with a three-point Likert response from ‘agree’ to ‘disagree’ (stairs too steep, stairs too narrow, stairs poorly lit, steps in need of repair, banister/handrail in need of repair, stair covering in need of repair and stairs being safe to use). The categories of the composite variable were ‘unsafe’ (answered agree to any of the first six questions or disagree to last question), ‘moderately safe’ (answered combinations of agree, disagree and neither agree nor disagree) and ‘safe’ (answered disagree to all first six questions and agree to last question). Those with missing responses to individual items were categorised as missing a response on the composite variable unless they agreed with any of the first six questions or disagreed with the last question.

When the relationship between distance from hospital and the outcome of interest was non-linear, distance was grouped into quintiles. When the relationship between IMD and the outcome of interest was non-linear IMD was grouped into quintiles.

We used the treatment received as a proxy for injury severity. We created two categories: those who were seen and examined but who did not require any treatment and those requiring treatment in the ED, admitted to hospital or discharged with outpatient or primary care follow-up. We chose these groupings based on the number of cases in each group and combined hospital admissions, those treated in the ED and those discharged with outpatient or primary care follow-up as the numbers admitted to hospital and discharged with outpatient or primary care follow-up were small.

Statistical methods

We calculated kappa coefficients, sensitivities, specificities and predictive values (and 95% CIs) comparing each reported exposure with the observed exposure, with observations used as the ‘gold standard’.

Characteristics of cases and controls have been described using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means [standard deviations (SDs)] or medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs)] for continuous variables dependent on their distributions. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate unadjusted ORs and AORs and 95% CIs for the matched analysis. Analyses were adjusted for area-level deprivation65 and distance from hospital and for confounders identified from DAGs. We developed separate DAGs for each exposure–outcome analysis. All variables that we considered as potential confounders were included in the DAG, and we used Dagitty software [see www.dagitty.net/ (accessed 2 October 2016)] to create a causal diagram for each exposure–outcome analysis and to identify the minimum adjustment set of variables. The regression model for each analysis was adjusted for the variables belonging to the minimum adjustment set for that exposure–outcome analysis by entering them on one step into the model. They were retained in the model regardless of statistical significance or effect on the OR for the exposure. Potential differential effects by child age, sex, ethnicity, single parenthood, housing tenure and unemployment were assessed by adding interaction terms to models. Significance was assessed using likelihood ratio tests with a p-value of < 0.01 taken as significant. When significant interactions were found, the results are presented stratified by socioeconomic variables. Differential effects by injury severity were assessed by stratifying analyses into those who were seen and examined but who did not require any further treatment and those who received treatment or who were admitted to hospital. For the unmatched analyses using hospital controls, unconditional logistic regression was used to estimate unadjusted ORs and AORs and 95% CIs. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, area-level deprivation65 and distance from hospital, in addition to other confounders identified from DAGs. The population attributable fraction (PAF) per cent was calculated for exposures with statistically significantly raised AORs using a published formula. 73

We followed standard guidance on missing data for the PedsQL score and did not compute mean scale scores when > 50% of the individual scale score responses were missing. When > 50% of questions were answered, mean scale scores were generated with imputation of missing values using the mean of the answered questions. 74 For the HADS score we imputed single missing item values for each subscale using the mean of the remaining six items. When more than one item was missing, subscale scores were not computed. 75 The IBQ, ECBQ and CBQ allowed missing values and were scored as the total score divided by the number of questions answered. 76 We were unable to find guidance for dealing with missing values for the PDH scale so we used the same approach as for the HADS. The main analyses are complete-case analyses, excluding cases and controls with missing data for the exposure or confounding variables. Complete-case analysis gives unbiased estimates when people with missing data are a completely random subset of the individuals in a particular study; the missing data are then called missing completely at random. If, however, missingness is related to other observed or participant data, for example age or sex, this is called missing at random. We undertook multiple imputation, which assumes that missing data are missing at random, to create 20 imputed data sets. These were combined using Rubin’s rules. 77 The multiple imputation models included all sociodemographic characteristics, exposures and confounding variables considered in the analysis models, along with case–control status. The imputation models included interaction terms identified in the complete-case analyses when possible, but in some cases the imputation models would not converge when interaction terms were included so these were omitted. When exposures had > 5% of ‘not applicable’ responses, analyses were repeated coding these as a separate category.

For the validation of exposure measures, to assess whether differences between reported and observed practices may have arisen because of changes made to the home by families after completing questionnaires, we incorporated any changes made in the last 3 months as reported at the home visit to derive a modified value for each exposure. For any cell within the tables comparing reported and observed values, when the percentage of people reporting a change in the previous 3 months was > 20%, the numbers were adjusted to accommodate an assumed change from ‘yes’ to ‘no’ and vice versa, and positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs) were recalculated.

Ethics

Approval for the case–control studies and the validation of exposures study was granted by Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 1 (reference number 09/H0407/14).

Results

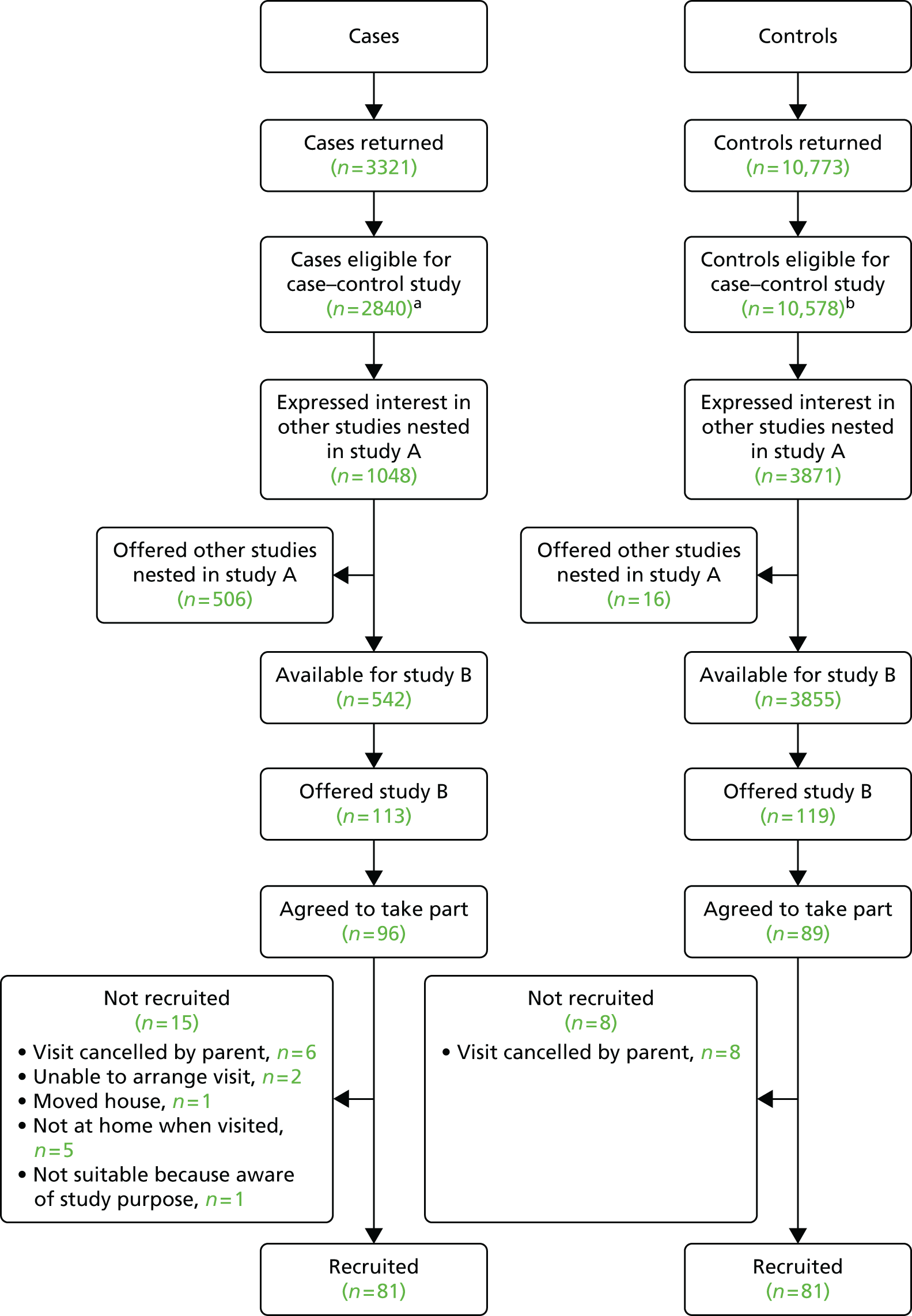

Validation of exposures study (study B)

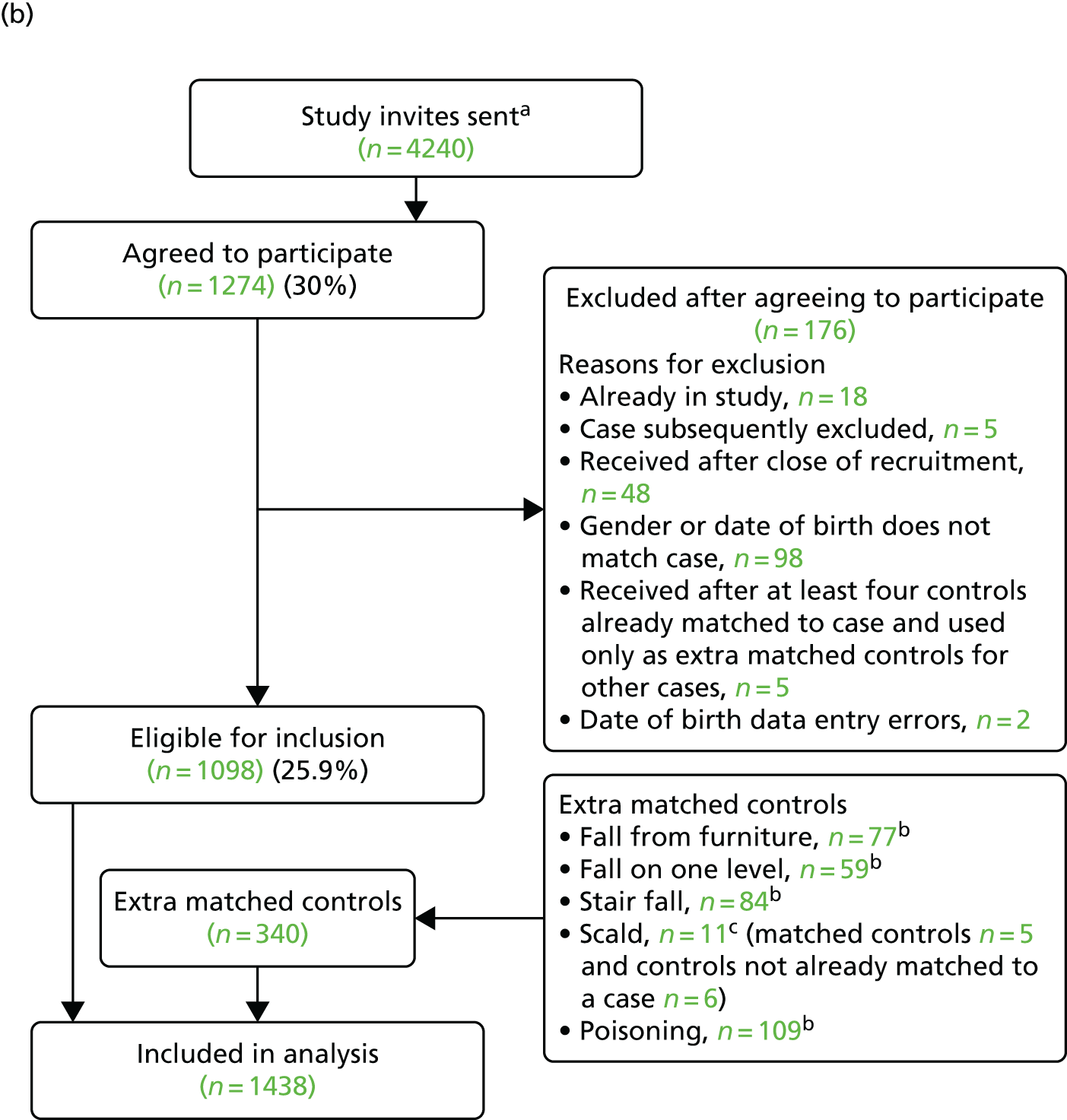

The process of recruitment to study B is shown in Figure 2. In total, 113 cases and 119 controls were contacted by the research team, of whom 81 (72%) and 81 (68%), respectively, received a home visit. This represents 3% of cases and 1% of controls eligible for study A. The period of time between receipt of questionnaire and the visit being carried out varied between 1 and 92 days, with a median of 29 days.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment to the validation of exposures study (study B). a, Includes eight cases subsequently found not to be eligible for study A (study C, n = 7; study G, n = 1). These eight were not used to compare characteristics of participants in study B. b, Includes 37 controls subsequently found not to be eligible for study A.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of families participating in the home observations and those returning completed questionnaires who were eligible to participate in any of the five case–control studies but who did not have a home observation. For most characteristics, there was no significant difference between families who participated and those who did not. Families for whom the questionnaire respondent was female or the participating child was male were more likely to participate; this was also the case for single-parent families or households with more adults out of work.

| Characteristic | Home observation (n = 162) | Cases/controls not observed at home (n = 13,248) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of child (months) | 0.15 | ||

| 0–12 | 20 (12.3) | 2329 (17.6) | |

| 13–36 | 107 (66.0) | 7883 (59.5) | |

| 37–62 | 35 (21.6) | 3036 (22.9) | |

| Sex of child: male | 103 (63.6) | 7232 (54.6) | 0.022 |

| Ethnic origin: white | 150 (92.6) | 11,860 (91.1) [225] | 0.50 |

| Number of children aged < 5 years in family | [204] | 0.81 | |

| 0 | 0 | 122 (0.9) | |

| 1 | 91 (56.2) | 7843 (60.1) | |

| 2 | 64 (39.5) | 4571 (35.0) | |

| ≥ 3 | 7 (4.3) | 508 (3.9) | |

| Case or control is first child | 67 (43.2) [7] | 5317 (43.9) [1136] | 0.87 |

| Sex of respondent: female | 156 (96.3) | 12,189 (92.0) | 0.045 |

| Maternal age ≤ 19 years at birth of first childa | 21 (13.6) [1] | 1328 (11.0) [112] | 0.31 |

| Single adult household | 29 (17.9) | 1505 (11.6) [313] | 0.014 |

| Adults out of work | [240] | < 0.001 | |

| 0 | 77 (47.5) | 7193 (55.3) | |

| 1 | 44 (27.2) | 4132 (31.8) | |

| ≥ 2 | 41 (25.3) | 1683 (12.9) | |

| Receipt of state benefits | 63 (39.4) [2] | 4754 (36.8) [331] | 0.50 |

| Overcrowding (more than one person per room) | 10 (6.4) [6] | 1004 (8.0) [775] | 0.45 |

| Non-owner occupier | 64 (39.5) | 4565 (35.2) [261] | 0.25 |

| Household has no car | 26 (16.0) | 1479 (11.3) [207] | 0.061 |

| Median IMD score (IQR) | 17.1 (9.5–34.0) [1] | 15.6 (9.3–27.6) [160] | 0.18 |

Table 2 shows the sensitivities, specificities and predictive values for exposures related to falls. NPVs were high (≥ 70%) for all 12 exposures relating to risk of falls. However, the PPV was ≥ 70% for only five of the fall exposures: safety gates at the top of the stairs; safety gates at the bottom of the stairs; use of safety gates elsewhere in the house; carpeted stairs; and the presence of a landing half-way up the stairs. The sensitivity for eight of the exposures was ≥ 70%. Exposures for which the sensitivity was < 70% were the presence of safety gates other than on the stairs and use of baby walkers, use of stationary play centres and use of travel cots as play pens. The specificity was ≥ 70% for 10 of the 12 exposures, being below this for banisters on stairs and handrails on stairs. Kappa coefficients ranged from 0.2 for use of baby walkers (slight agreement)79 to 0.74 for carpeted stairs (substantial agreement). 79 There was no significant difference [t = 1.77, degrees of freedom (df) = 1.42, p = 0.08] in measured stair steepness (stair height-to-depth ratio) between those reporting that their stairs were too steep (n = 23; mean 0.87, SD 0.21) and those not reporting that their stairs were too steep (n = 121; mean 0.82, SD 0.09). Observed banister gaps were significantly larger than reported gaps (n = 55; Z = 3.12, p = 0.002). The median reported gap was 3.0 inches (IQR 2.0–4.0 inches) whereas the median observed gap was 3.8 inches (IQR 3.5–4.3 inches).

| Practice | Number (%) observed to have practice | Sensitivity (95% CI) (%) | Specificity (95% CI) (%) | PPV (95% CI) (%) | NPV (95% CI) (%) | Kappa coefficienta (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has stair gate at top of stairsb [3] | 83 (52.2) | 90.4 (81.9 to 95.7) | 73.8 (61.5 to 84.0) | 81.5 (72.1 to 88.9) | 85.7 (73.8 to 93.6) | 0.65 (0.53 to 0.78) |

| Has stair gate at bottom of stairsb [6] | 59 (37.8) | 91.5 (81.3 to 97.2) | 82.6 (72.9 to 89.9) | 78.3 (66.7 to 87.3) | 93.4 (85.3 to 97.8) | 0.72 (0.61 to 0.83) |

| Has other safety gates in the houseb [0] | 57 (35.2) | 42.1 (29.1 to 55.9) | 95.7 (89.5 to 98.8) | 85.7 (67.3 to 96.0) | 73.2 (64.4 to 80.8) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.56) |

| Stairs are carpetedb [1] | 142 (88.2) | 98.6 (95.0 to 99.8) | 75.0 (34.9 to 96.8) | 98.6 (95.0 to 99.8) | 75.0 (34.9 to 96.8) | 0.74 (0.49 to 0.98) |

| Presence of landing part-way up stairsb [2] | 75 (46.9) | 73.3 (61.9 to 82.9) | 85.1 (75.0 to 92.3) | 83.3 (72.1 to 91.4) | 75.9 (65.3 to 84.6) | 0.58 (0.46 to 0.71) |

| Presence of banisters on all stairsb [8] | 78 (50.6) | 91.0 (82.4 to 96.3) | 36.9 (25.3 to 49.8) | 63.4 (53.8 to 72.3) | 77.4 (58.9 to 90.4) | 0.29 (0.15 to 0.43) |

| Presence of handrails on all stairsb [6] | 57 (36.5) | 87.7 (76.3 to 94.9) | 51.1 (40.2 to 61.9) | 53.8 (43.1 to 64.2) | 86.5 (74.2 to 94.4) | 0.35 (0.22 to 0.48) |

| Use of corner covers on any furniture [0] | 17 (10.5) | 70.6 (44.0 to 89.7) | 85.5 (78.7 to 90.8) | 36.4 (20.4 to 54.9) | 96.1 (91.2 to 98.7) | 0.40 (0.21 to 0.58) |

| Use of baby walkerc [1] | 14 (8.7) | 57.1 (28.9 to 82.3) | 76.3 (67.4 to 83.8) | 22.9 (10.4 to 40.1) | 93.5 (86.5 to 97.6) | 0.20 (0.03 to 0.38) |

| Use of stationary play centrec [2] | 15 (9.4) | 60.0 (32.3 to 83.7) | 82.1 (73.8 to 88.7) | 31.0 (15.3 to 50.8) | 93.9 (87.1 to 97.7) | 0.30 (0.10 to 0.50) |

| Use of play penc [2] | 5 (3.1) | 80.0 (28.4 to 99.5) | 95.9 (90.7 to 98.7) | 44.4 (13.7 to 78.8) | 99.2 (95.4 to 100) | 0.55 (0.23 to 0.87) |

| Use of travel cot instead of a playpenc [1] | 10 (6.2) | 50.0 (18.7 to 81.3) | 93.2 (87.1 to 97.0) | 38.5 (13.9 to 68.4) | 95.7 (90.1 to 98.6) | 0.38 (0.11 to 0.65) |

Table 3 shows the sensitivities, specificities, predictive values and percentage agreement for 16 exposures relating to poisoning. All PPVs were low, the highest being 68% for all medicines having CRCs or blister packs. For 11 of the exposures, the NPV was > 70%, whereas sensitivity was > 70% for eight exposures. Kappa coefficients varied from –0.03 for all medicines stored in locked cupboard, cabinet, drawer or fridge (poor agreement)79 to 0.54 for medicines kept in fridge (moderate agreement). 79

| Practice | Number (%) observed to have practice | Sensitivity (95% CI) (%) | Specificity (95% CI) (%) | PPV (95% CI) (%) | NPV (95% CI) (%) | Kappa coefficienta (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All medicines stored safelyb [23] | 68 (48.9) | 83.8 (72.9 to 91.6) | 31.0 (20.5 to 43.1) | 53.8 (43.8 to 63.5) | 66.7 (48.2 to 82.0) | 0.15 (0.01 to 0.28) |

| All household products stored safelyb [18] | 29 (20.1) | 75.9 (56.5 to 89.7) | 60.9 (51.3 to 69.8) | 32.8 (21.8 to 45.4) | 90.9 (82.2 to 96.3) | 0.25 (0.11 to 0.38) |

| All medicines and household products stored safelyb [22] | 16 (11.4) | 68.8 (41.3 to 89.0) | 68.5 (59.6 to 76.6) | 22.0 (11.5 to 36.0) | 94.4 (87.5 to 98.2) | 0.19 (0.05 to 0.34) |

| All medicines stored in locked cupboard, cabinet, drawer or fridge [5] | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0 to 70.8) | 87.7 (81.4 to 92.4) | 0 (0.0 to 17.6) | 97.8 (93.8 to 99.5) | –0.03 (–0.07 to 0.00) |

| All household products stored in locked cupboard, cabinet, drawer or fridge [8] | 11 (7.1) | 54.5 (23.4 to 83.3) | 79.0 (71.4 to 85.4) | 16.7 (6.4 to 32.8) | 95.8 (90.4 to 98.6) | 0.16 (0.00 to 0.33) |

| All medicines and household products stored in locked cupboard, cabinet, drawer or fridge [3] | 0 (0.0) | Unable to calculate because of frequencies of 0 in some cells | ||||

| All medicines stored at adult eye level or above [27] | 64 (47.4) | 78.1 (66.0 to 87.5) | 42.3 (30.6 to 54.6) | 54.9 (44.2 to 65.4) | 68.2 (52.4 to 81.4) | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.35) |

| All household products stored at adult eye level or above [22] | 10 (7.1) | 90.0 (55.5 to 99.7) | 88.5 (81.7 to 93.4) | 37.5 (18.8 to 59.4) | 99.1 (95.3 to 100) | 0.48 (0.27 to 0.69) |

| All medicines and household products stored at adult eye level or above [18] | 5 (3.5) | 80.0 (28.4 to 99.5) | 87.1 (80.3 to 92.1) | 18.2 (5.2 to 40.3) | 99.2 (95.5 to 100) | 0.25 (0.04 to 0.47) |

| All medicines have CRCs or blister packs [1] | 105 (65.2) | 93.3 (86.7 to 97.3) | 17.9 (8.9 to 30.4) | 68.1 (59.8 to 75.6) | 58.8 (32.9 to 81.6) | 0.13 (0.00 to 0.27) |

| Any medicines put in a container different from the one they came in [1] | 9 (5.6) | 33.3 (7.5 to 70.1) | 98.0 (94.3 to 99.6) | 50.0 (11.8 to 88.2) | 96.1 (91.8 to 98.6) | 0.37 (0.05 to 0.69) |

| All medicines kept in a locked medicine box [1] | 4 (2.5) | 50.0 (6.8 to 93.2) | 82.8 (76.0 to 88.4) | 6.9 (0.8 to 22.8) | 98.5 (94.6 to 99.8) | 0.08 (–0.06 to 0.22) |

| Medicines kept in the fridge [1] | 36 (22.4) | 61.1 (43.5 to 76.9) | 91.2 (84.8 to 95.5) | 66.7 (48.2 to 82.0) | 89.1 (82.3 to 93.9) | 0.54 (0.38 to 0.70) |

| All household products have CRCs [1] | 57 (35.4) | 71.9 (58.5 to 83.0) | 35.6 (26.4 to 45.6) | 38.0 (28.8 to 47.8) | 69.8 (55.7 to 81.7) | 0.06 (–0.06 to 0.19) |

| Any household products put in a container different from the one they came in [0] | 16 (9.9) | 6.3 (0.2 to 30.2) | 97.9 (94.1 to 99.6) | 25.0 (0.6 to 80.6) | 90.5 (84.8 to 94.6) | 0.06 (–0.12 to 0.24) |

| Safety catch/lock on fridgec [1] | 1 (0.6) | 100 (2.5 to 100) | 67.7 (48.6 to 83.3) | 9.1 (0.2 to 41.3) | 100 (83.9 to 100) | 0.12 (–0.10 to 0.33) |

Table 4 shows the sensitivities, specificities, predictive values and percentage agreement for exposures relating to scalds. Sensitivity was > 70% for all three scald-related exposures. The PPV was high for two exposures (a kettle with a curly flex and kettle kept at the back of the kitchen surface), whereas the NPV was high for having a safety gate across the kitchen doorway and for having a kettle kept at the back of the kitchen surface. Kappa coefficients ranged from 0.13 (slight agreement) to 0.57 (moderate agreement). 79

| Practice | Number (%) observed to have practice | Sensitivity (95% CI) (%) | Specificity (95% CI) (%) | PPV (95% CI) (%) | NPV (95% CI) (%) | Kappa coefficienta (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has cordless kettle or curly flex [2] | 156 (97.5) | 82.1 (75.1 to 87.7) | 75.0 (19.4 to 99.4) | 99.2 (95.8 to 100) | 9.7 (2.0 to 25.8) | 0.13 (– 0.02 to 0.28) |

| Kettle kept at back of kitchen surface [1] | 121 (75.2) | 94.2 (88.4 to 97.6) | 42.5 (27.0 to 59.1) | 83.2 (75.9 to 89.0) | 70.8 (48.9 to 87.4) | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.59) |

| Safety gate across kitchen doorway [0] | 34 (21.0) | 79.4 (62.1 to 91.3) | 85.2 (77.8 to 90.8) | 58.7 (43.2 to 73.0) | 94.0 (88.0 to 97.5) | 0.57 (0.43 to 0.72) |

Over-reporting of safety practices was more common than under-reporting. We were able to calculate predictive values for 30 safety practices and found that, for 24 of these, more families over-reported than under-reported (NPV exceeds PPV) and, for the remaining six practices, more families under-reported than over-reported (PPV exceeds NPV).

We explored whether or not differences between reported and observed safety practices could be accounted for by families changing safety practices between completing the questionnaire and the home observation. This did not appear to explain the differences between reported and observed practices, as the findings were similar to those from the main analysis when using the adjusted figures. 78 The results are available from the authors on request.

Associations between observations and self-reports differed significantly between cases and controls for only one exposure, which was storage of household products in containers that were different from the ones in which they came (χ2 = 4.91, p = 0.03). The results are available from the authors on request.

Case–control study of risk and protective factors for falls from furniture (study A)

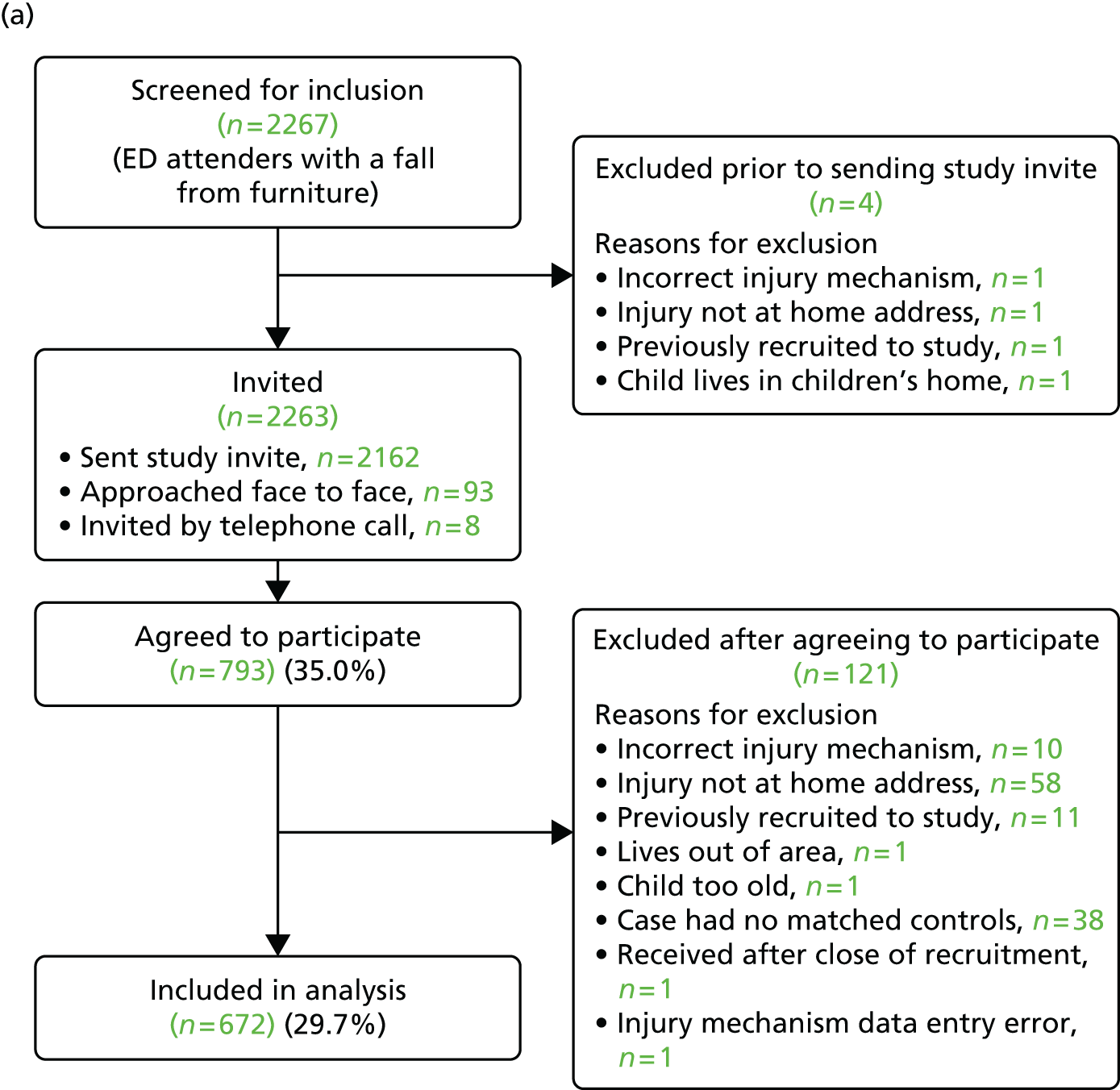

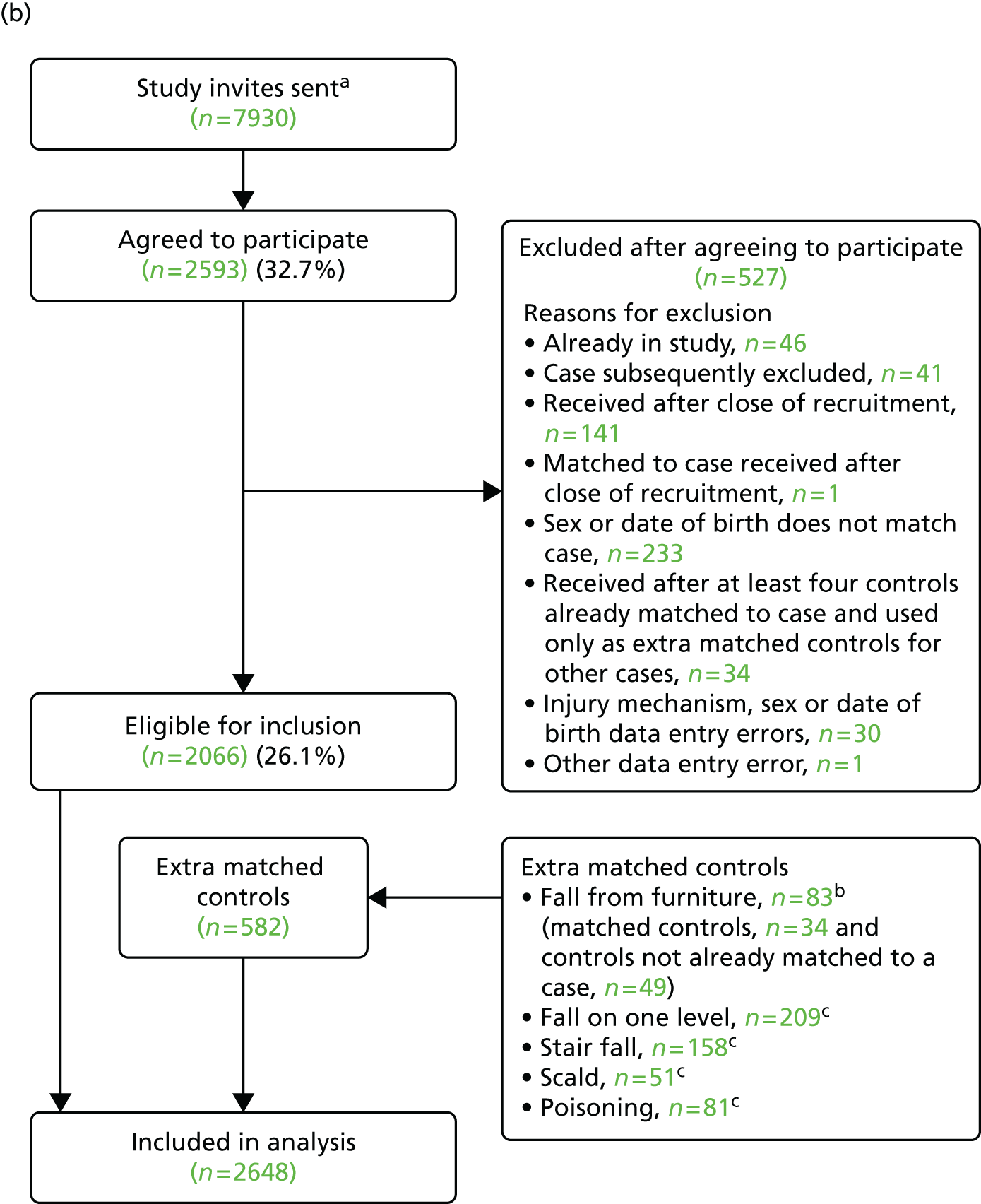

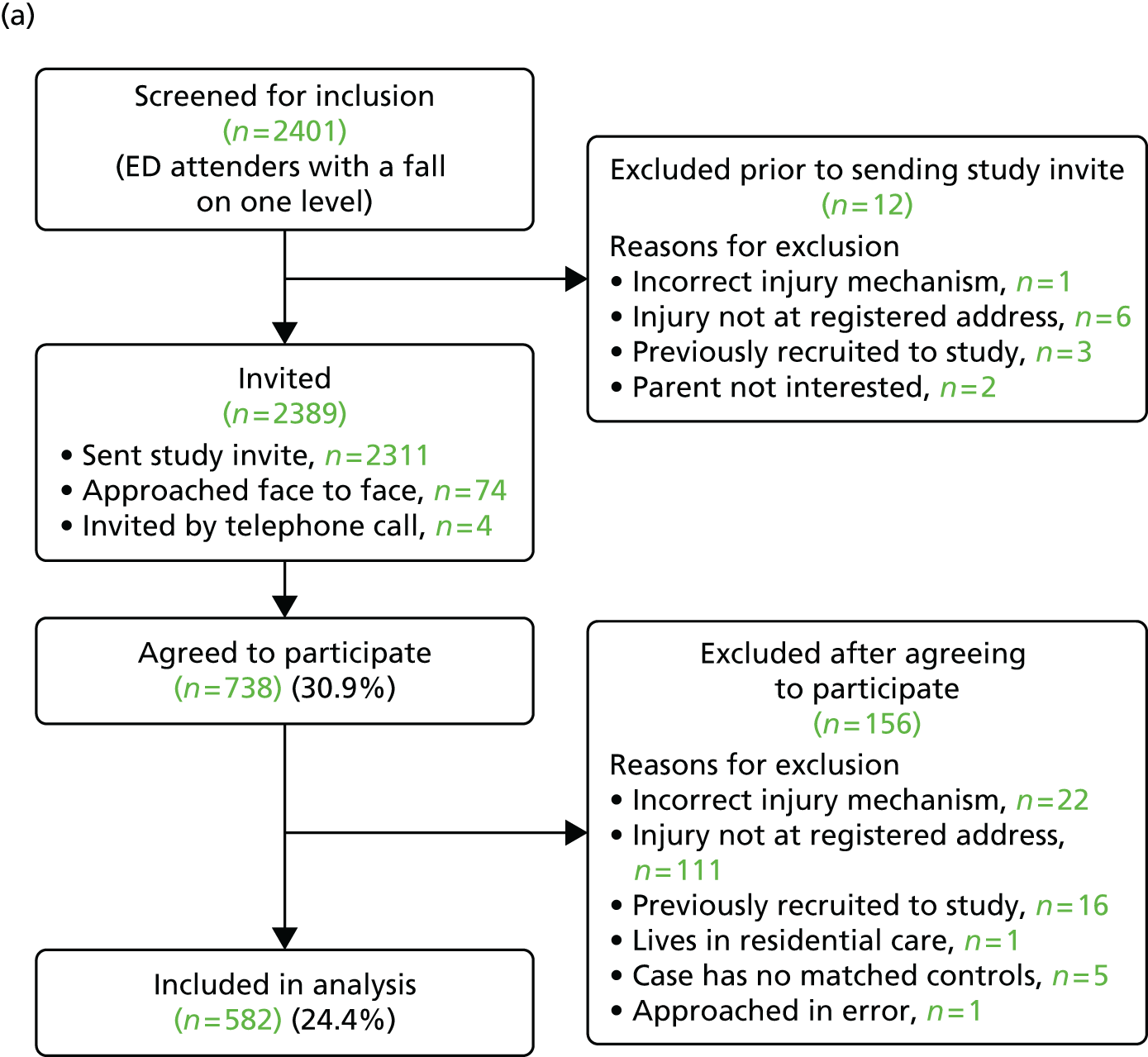

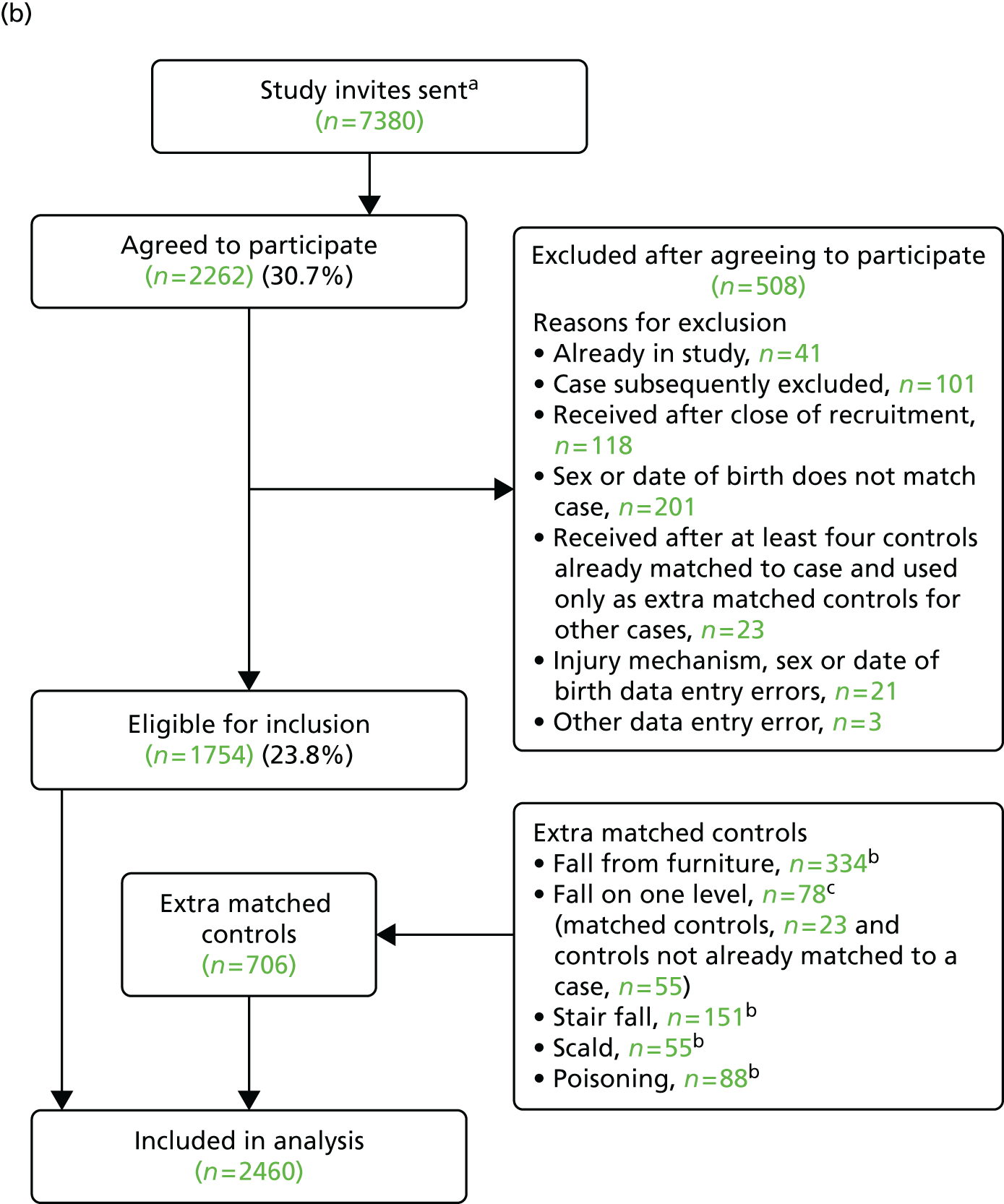

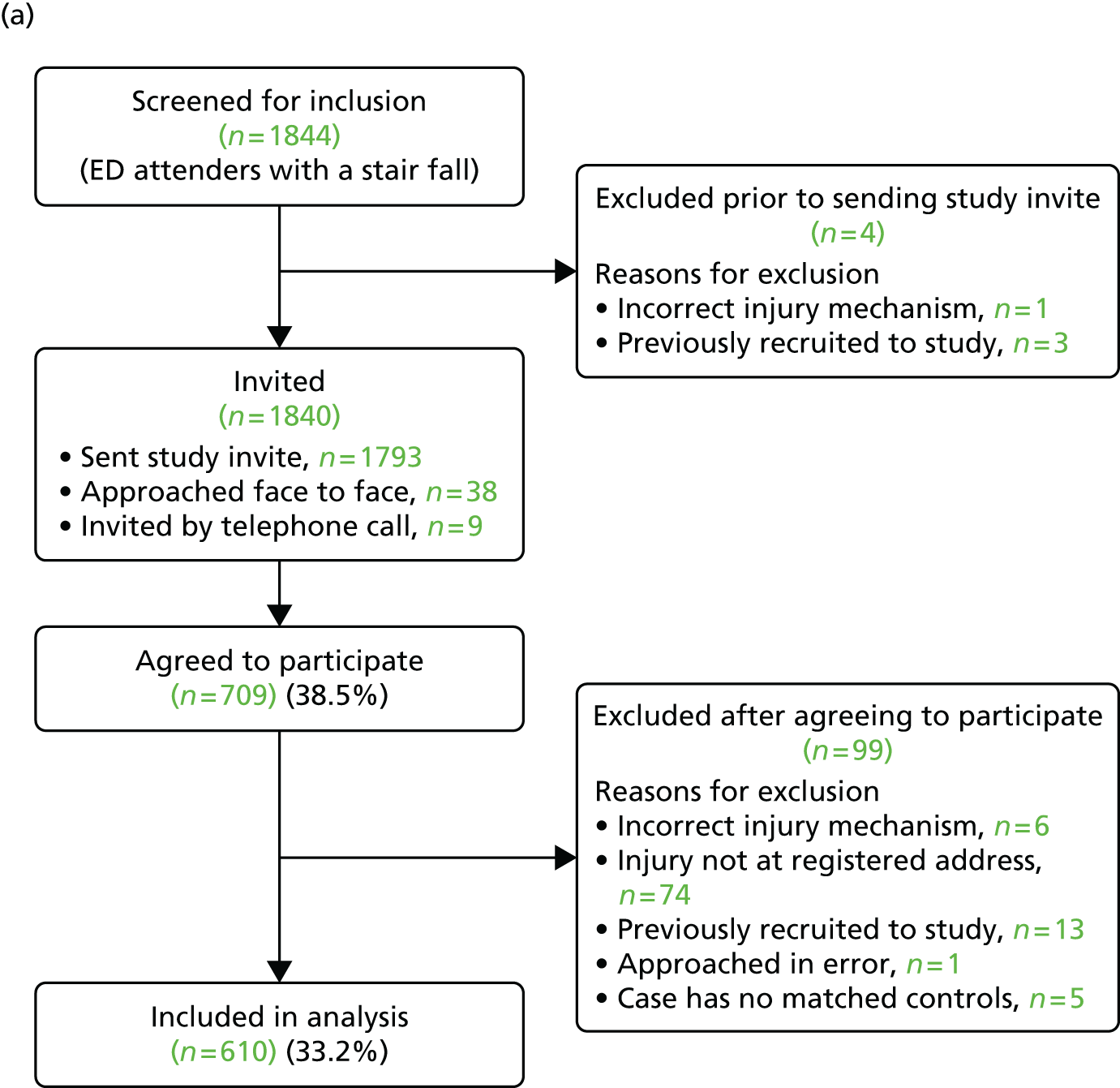

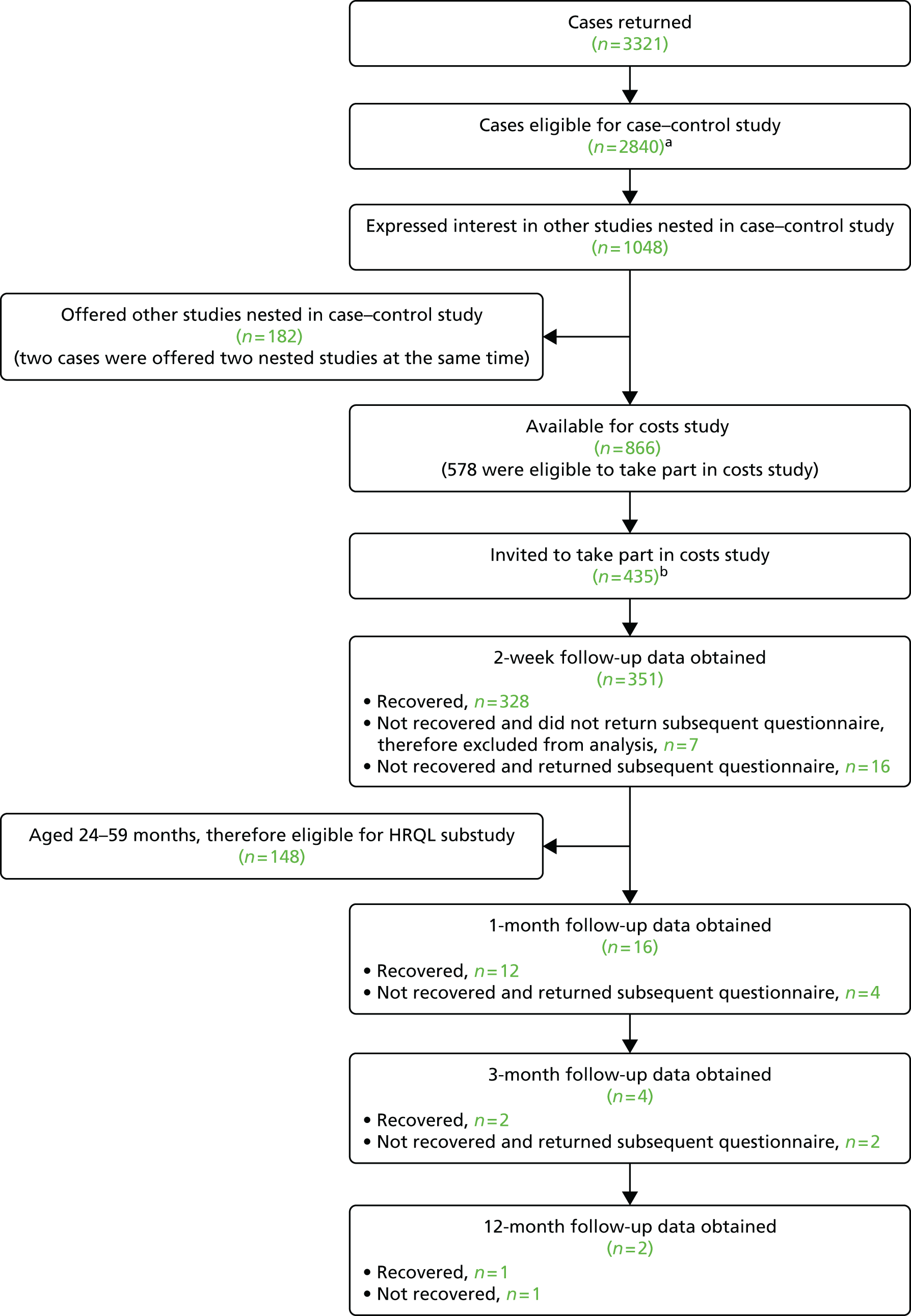

A total of 672 cases and 2648 controls participated in the study. The process of recruitment to the study is shown in Figure 3. In total, 35% of cases and 33% of controls agreed to participate. The age and sex of participants and non-participants in the falls from furniture study were similar, as shown in Table 5.

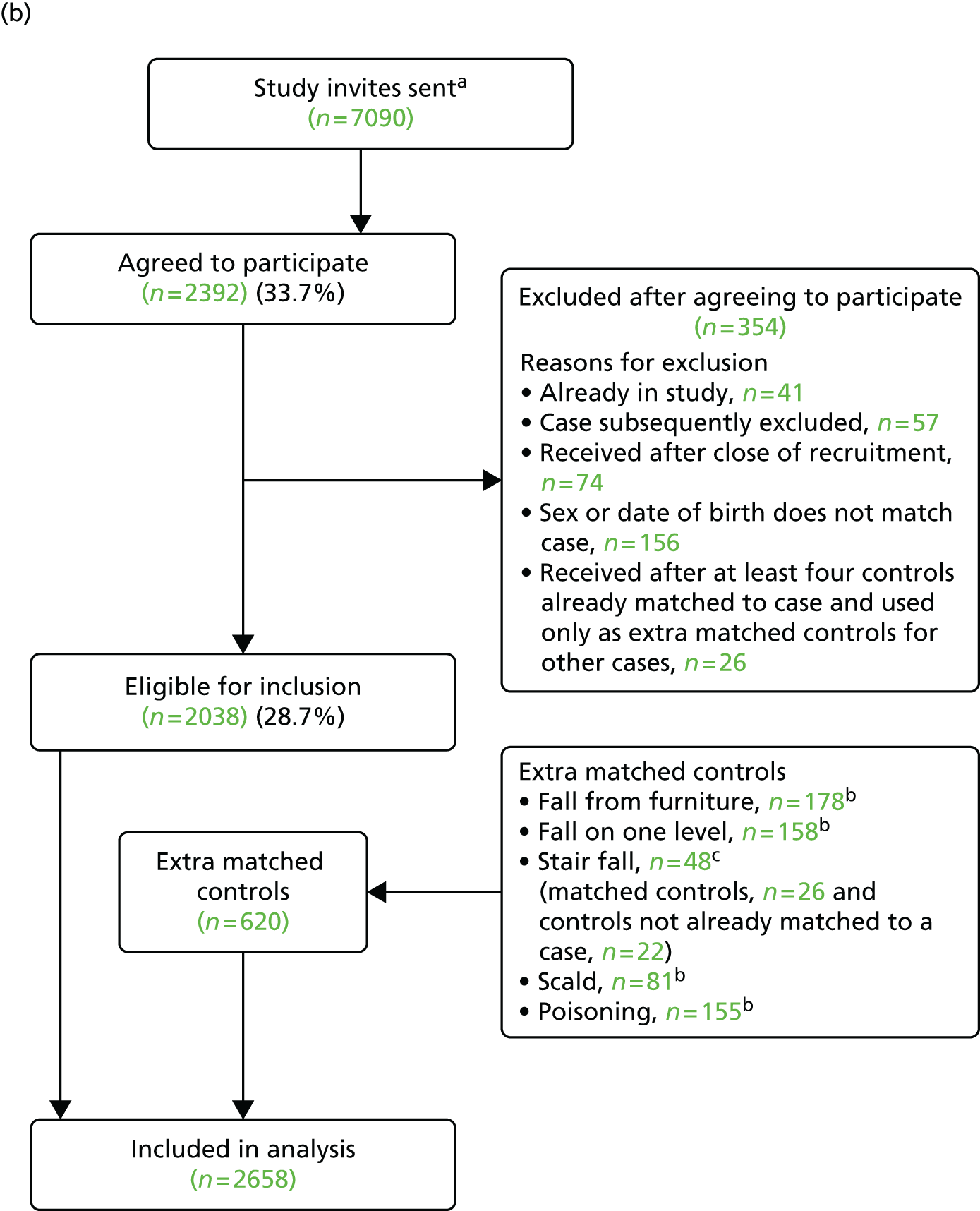

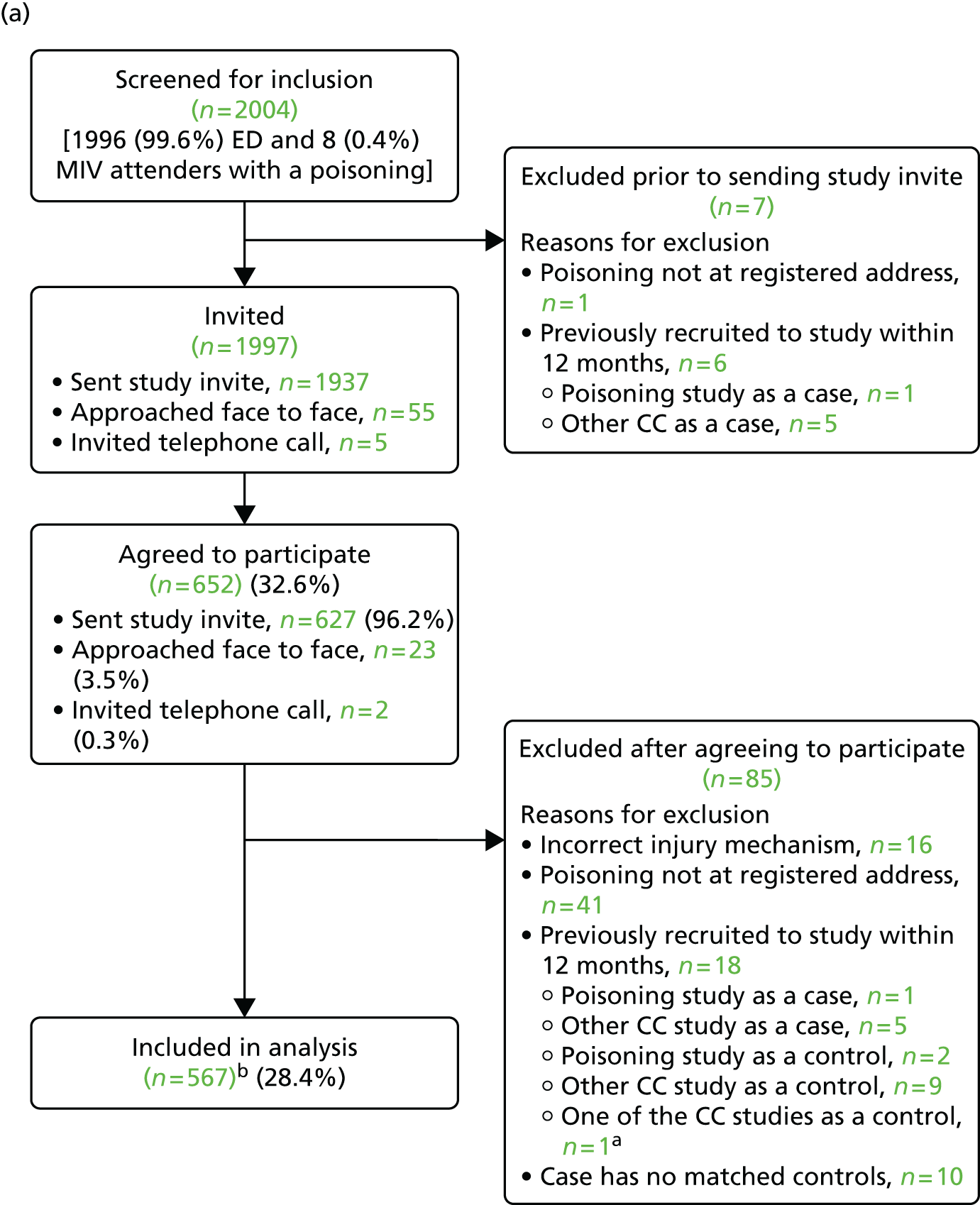

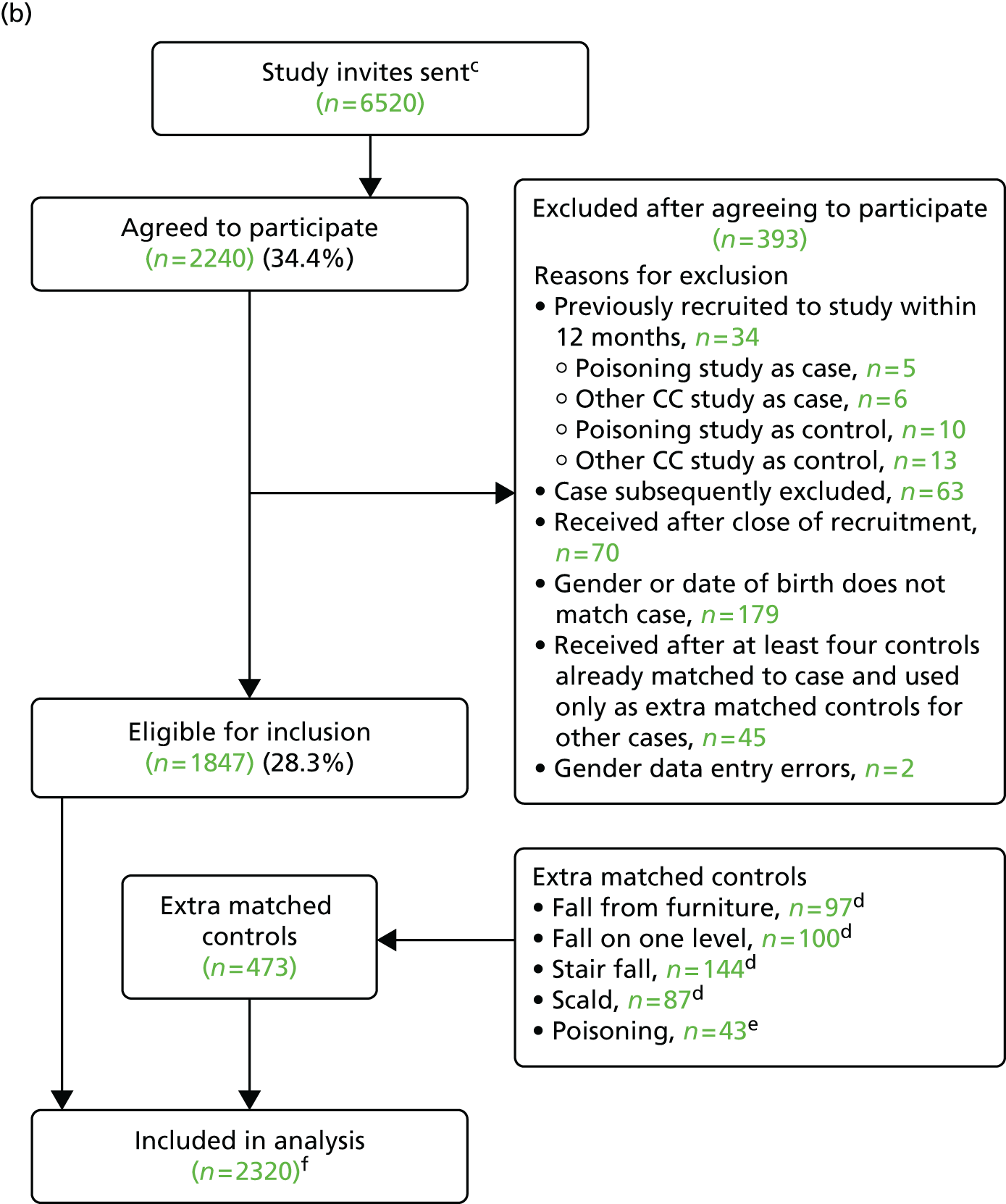

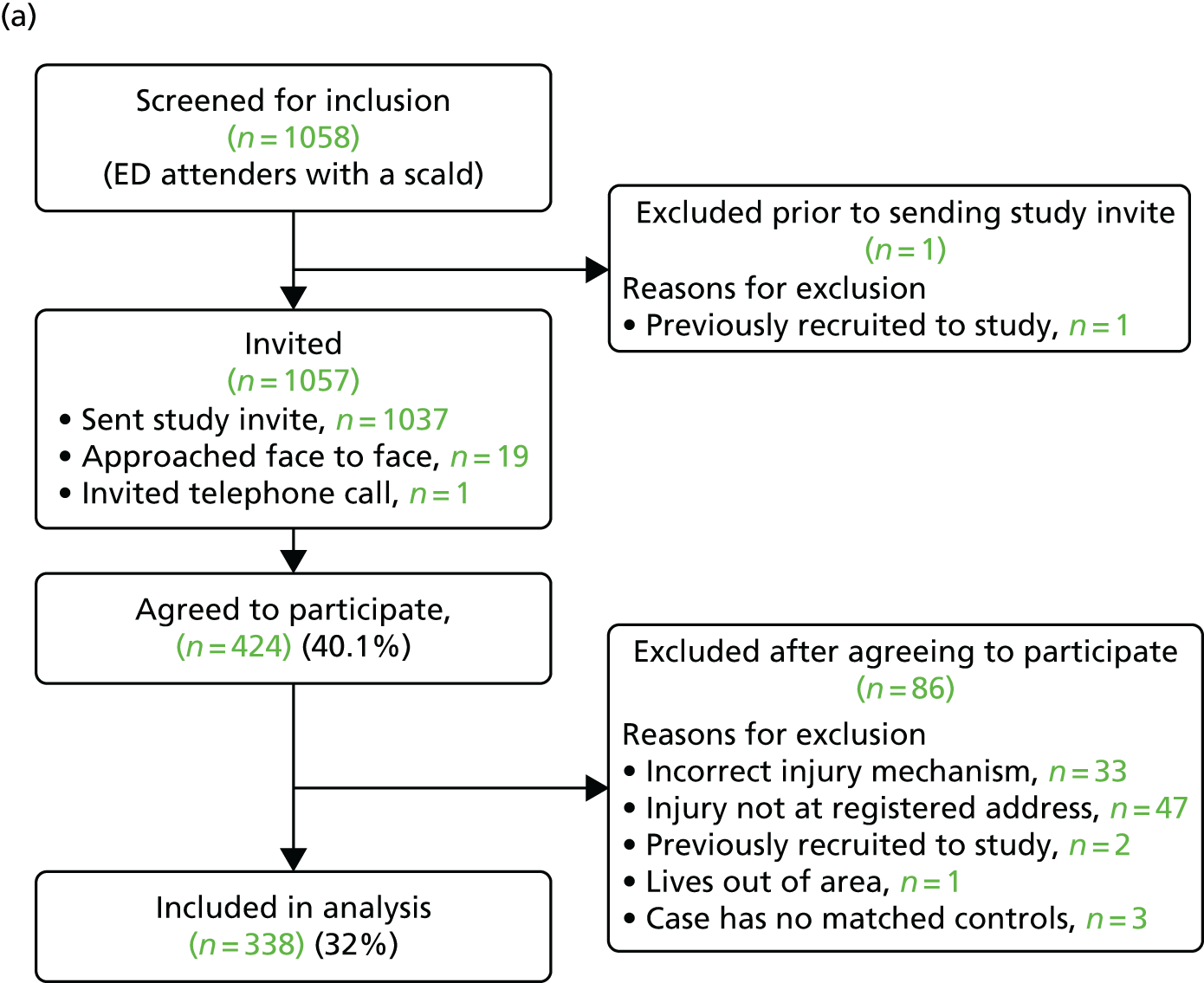

FIGURE 3.

Flow of cases and controls through the falls from furniture study: (a) recruitment of cases; and (b) recruitment of controls. a, Assumed to be 10 times the number of cases as practices were asked to invite 10 controls for each case; b, controls for cases from the falls from furniture study for whom there were more than four controls and controls for fall from furniture cases who were not matched to the case (e.g. because the case was excluded); c, controls for cases from the other four ongoing case–control studies. Reproduced with permission of JAMA Pediatrics 2015;169(2):145–153. 80 Copyright 2015 American Medical Association.

| Characteristic | Participants (N = 672), n (%) | Non-participants (N = 1470), n (%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (months) | |||

| 0–12 | 223 (33.2) | 451 (30.7) | χ2(2) = 4.05, p = 0.13 |

| 13–36 | 296 (44.0) | 716 (48.7) | |

| ≥ 37 | 153 (22.8) | 303 (20.6) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 365 (54.3) | 788 (53.6) | χ2(1) = 0.09, p = 0.76 |

| Female | 307 (45.7) | 682 (46.4) | |

The mean number of controls per case was 3.94. The median time from date of injury to date of questionnaire completion for cases was 10 days (IQR 6–20 days).

Most cases sustained single injuries (86%), most commonly a bang on the head (59%), cuts/grazes not requiring stitches (19%) and fractures (14%). Most cases (60%) were seen and examined but did not require treatment, with 29% treated in the ED, 4% were admitted to hospital and 7% treated and discharged with a follow-up appointment.

Table 6 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of cases and controls. As expected, because controls were recruited after the matched cases, they were slightly older than cases (median age 1.91 vs. 1.74 years). Cases were slightly more likely than controls to live in a household with no adults in paid work (17.7% vs. 12.6%), in a household receiving state benefits (43.0% vs. 35.9%) and in non-owner-occupied housing (39.5% vs. 32.2%).

| Characteristic | Cases (n = 672) | Controls (n = 2648) |

|---|---|---|

| Study centre | ||

| Nottingham | 246 (36.6) | 966 (36.5) |

| Bristol | 215 (32.0) | 832 (31.4) |

| Norwich | 146 (21.7) | 644 (24.3) |

| Newcastle | 65 (9.7) | 206 (7.8) |

| Age (years), median (IQR)a | 1.74 (0.84–2.86) | 1.91 (1.00–3.01) |

| Age group (months) | ||

| 0–12 | 223 (33.2) | 741 (28.0) |

| 13–36 | 296 (44.0) | 1270 (48.0) |

| 37–62 | 153 (22.8) | 637 (24.1) |

| Male | 365 (54.3) | 1478 (55.8) |

| Ethnic origin: white | 583 (88.9) [16] | 2403 (92.2) [41] |

| Children aged 0–4 years in family | [6] | [40] |

| 0 | 9 (1.4) | 20 (0.8) |

| 1 | 391 (58.7) | 1563 (59.9) |

| 2 | 231 (34.7) | 927 (35.5) |

| ≥ 3 | 35 (5.3) | 98 (3.8) |

| First child | 285 (45.4) [44] | 1093 (44.9) [212] |

| Maternal age ≤ 19 years at birth of first childb | 77 (12.5) [4] | 219 (9.0) [19] |

| Single adult household | 95 (14.5) [15] | 263 (10.2) [61] |

| Weekly out-of-home child care (hours), median (IQR) | 7.5 (0.0–18.0) [46] | 12.0 (1.0–22.0) [179] |

| Adults in paid employment | [16] | [45] |

| ≥ 2 | 319 (48.6) | 1481 (56.9) |

| 1 | 221 (33.7) | 795 (30.5) |

| 0 | 116 (17.7) | 327 (12.6) |

| Household receives state benefits | 280 (43.0) [21] | 928 (35.9) [65] |

| Overcrowding (more than one person per room) | 56 (8.8) [32] | 173 (6.9) [146] |

| Non-owner occupier | 262 (39.5) [9] | 838 (32.2) [49] |

| Household has no car | 95 (14.4) [10] | 288 (11.0) [40] |

| IMD score, median (IQR)c | 16.8 (10.0–31.9) | 14.9 (9.0–26.8) [28] |

| Distance from hospital (km), median (IQR) | 3.4 (1.9 to 5.4) | 3.9 (2.4 to 7.4) [29] |

| CBQ score, mean (SD)c | 4.68 (0.92) [45] | 4.67 (0.88) [234] |

| Long-term health condition | 60 (9.0) [5] | 185 (7.0) [14] |

| Child health VAS score (range 0–10), median (IQR)c | 9.9 (9.3–10.0) [6] | 9.7 (8.5–10.0) [22] |

| HRQL in children aged ≥ 2 years (PedsQL score), median (IQR)c,d | 93.1 (86.9 to 97.6), n = 287 [4] | 90.0 (82.9 to 94.4), n = 1270 [21] |

| Parental assessment of child’s ability to climb | [18] | [57] |

| All scenarios ‘not likely’ | 166 (25.4) | 536 (20.7) |

| One or more scenarios ‘quite likely’ and none ‘very likely’ | 85 (13.0) | 235 (9.1) |

| One or more scenarios ‘very likely’ | 403 (61.6) | 1820 (70.2) |

| PDH tasks subscale score, median (IQR)c,e | 13 (10 to 17) [65] | 14 (11 to 18) [168] |

| HADS score, mean (SD)c,e | 10.7 (6.0) [8] | 10.8 (6.0) [39] |

Table 7 shows the frequency of exposures among cases and controls and unadjusted ORs, and Table 8 shows ORs adjusted for a range of confounding variables. Adjusting for confounders had relatively little impact on most ORs; only one out of 13 ORs changed by > 10% after adjustment (had things child could climb on to reach high surfaces – OR 0.85, AOR 0.94). Compared with parents of controls, in the adjusted analyses parents of cases were more likely not to use a safety gate (AOR 1.65, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.12; PAF 15%), more likely to leave children on raised surfaces (AOR 1.66, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.06, PAF 23%) and more likely not to have taught their children rules about climbing on objects in the kitchen (AOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.15, PAF 16%) and their children were less likely to climb or play on garden furniture (AOR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.97). Most of the ORs for the remaining nine exposures were close to 1, with seven being > 1 (ranging from 1.01 to 1.35) and two being < 1 (0.77 and 0.94). All had CIs indicating that associations could have occurred by chance.

| Exposure | Cases (n = 672) | Controls (n = 2648) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not use any safety gatesa | 227 (36.9) [56] | 688 (27.7) [160] | 1.68 (1.36 to 2.07) |

| Used high chair without harness at least some daysb,c | 118 (26.3) [11] ((213)) | 522 (29.6) [34] ((853)) | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.05) |

| Had things child could climb on to reach high surfacesa | 248 (37.6) [12] | 1075 (40.9) [22] | 0.85 (0.70 to 1.04) |

| Left child on a raised surface at least some daysb,c | 357 (57.7) [13] ((40)) | 1221 (49.0) [33] ((121)) | 1.56 (1.29 to 1.88) |

| Changed nappy on raised surface at least some daysb,c | 297 (56.0) [10] ((132)) | 1106 (53.9) [30] ((565)) | 1.09 (0.89 to 1.33) |

| Put child in car/bouncing seat on raised surface at least some daysb,c | 59 (11.4) [11] ((142)) | 176 (8.8) [30] ((626)) | 1.33 (0.95 to 1.87) |

| Child climbed or played on furniture at least some daysb,c | 472 (78.1) [7] ((61)) | 1909 (77.9) [27] ((169)) | 0.95 (0.73 to 1.26) |

| Child climbed or played on garden furniture at least some daysb,c | 181 (34.4) [10] ((136)) | 816 (39.1) [28] ((532)) | 0.74 (0.62 to 0.98) |

| Had not taught child rules about climbing in kitchen | 282 (44.5) [39] | 1026 (40.0) [82] | 1.52 (1.15 to 2.00) |

| Had not taught child rules about jumping on bed/furniture | 283 (44.5) [36] | 1079 (42.0) [80] | 1.30 (0.97 to 1.73) |

| Cases (n = 519) | Controls (n = 2011) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Exposures measured only in children aged 0–36 months | |||

| Did not use baby walkera | 372 (73.5) [13] | 1359 (68.8) [36] | 1.27 (1.01 to 1.60) |

| Did not use playpen or travel cota | 411 (81.9) [17] | 1628 (82.6) [41] | 0.95 (0.73 to 1.23) |

| Did not use stationary activity centrea | 375 (74.6) [16] | 1469 (74.5) [39] | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.24) |

| Exposure | AOR (95% CI) | Confounders adjusted fora |

|---|---|---|

| Did not use any safety gatesb | 1.65 (1.29 to 2.12) | PDH score, HADS score, hours of out-of-home care, ability to climb, first child |

| Used high chair without harness at least some daysc | 0.77 (0.57 to 1.03) | CBQ score, hours of out-of-home care |

| Had things child could climb on to reach high surfacesb | 0.94 (0.75 to 1.24) | Hours of out-of-home care, ability to climb, first child, safety gate, safety rules on climbing in kitchen and jumping on furniture |

| Left child on a raised surface at least some daysc | 1.66 (1.34 to 2.06)d | CBQ score, hours of out-of-home care |

| Changed nappy on raised surface at least some daysc | 1.10 (0.87 to 1.40)d | CBQ score, hours of out-of-home care |

| Put child in car/bouncing seat on raised surface at least some daysc | 1.35 (0.91 to 2.01)d | CBQ score, hours of out-of-home care |

| Child climbed or played on furniture at least some daysc | 1.03 (0.73 to 1.44)d | CBQ score, hours of out-of-home care, things child could climb on to reach high surfaces |

| Child climbed or played on garden furniture at least some daysc | 0.74 (0.56 to 0.97) | CBQ score, hours of out-of-home care, things child could climb on to reach high surfaces |

| Had not taught child rules about climbing in kitchen | 1.58 (1.16 to 2.15) | HADS score, PDH score, first child, things child could climb on to reach high surfaces |

| Had not taught child rules about jumping on bed/furniture | 1.21 (0.87 to 1.68) | HADS score, PDH score, first child, things child could climb on to reach high surfaces |

| Did not use baby walkerb | 1.22 (0.90 to 1.65) | HADS score, PDH score, hours of out-of-home care, ability to climb, first child, uses safety gate, uses playpen/travel cot, uses activity centre |

| Did not use playpen or travel cotb | 1.01 (0.71 to 1.46) | HADS score, PDH score, hours of out-of-home care, ability to climb, first child, uses baby walker, uses safety gate, uses activity centre |

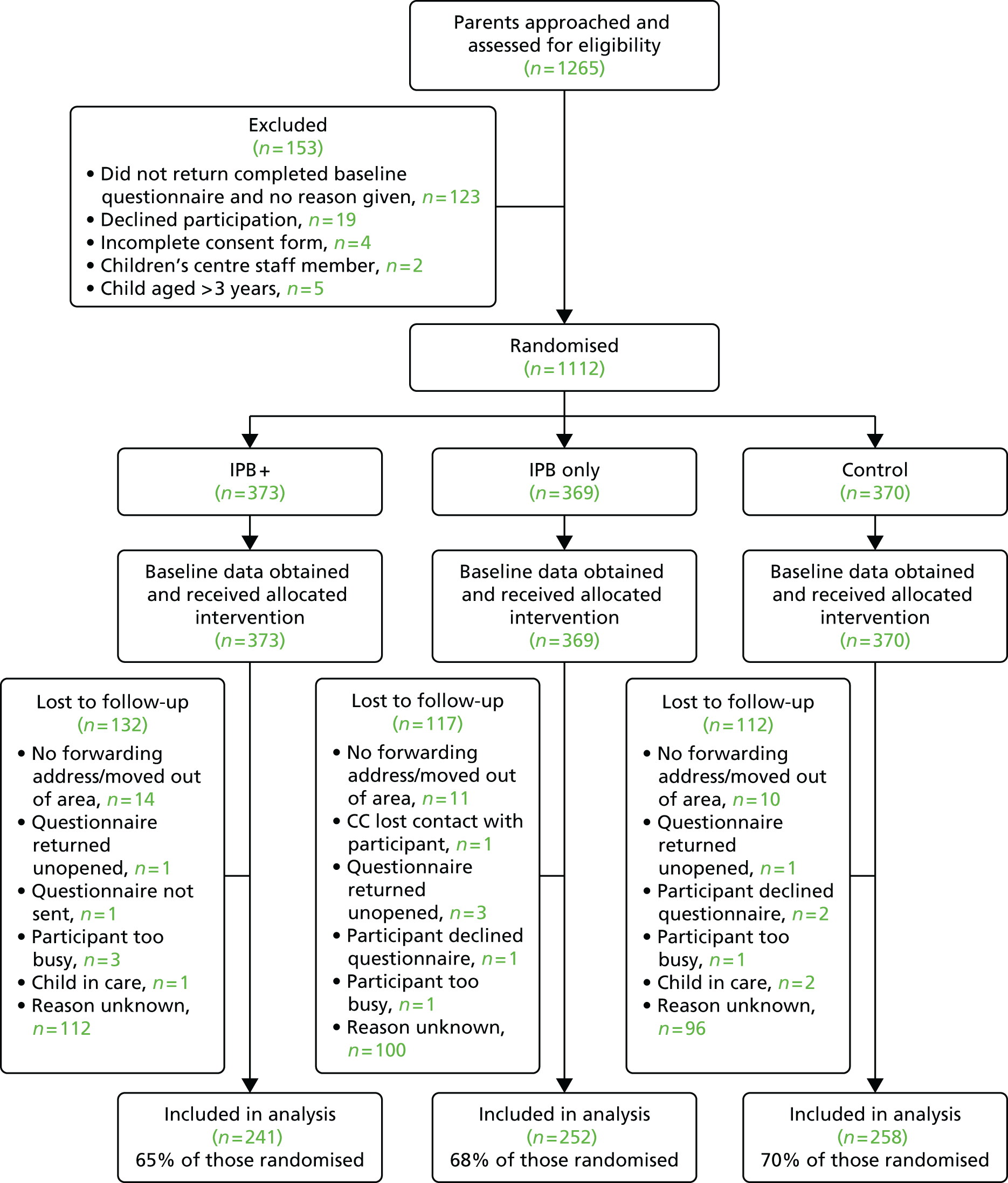

| Did not use stationary activity centreb | 0.94 (0.69 to 1.27) | HADS score, PDH score, hours of out-of-home care, ability to climb, first child, uses baby walker, uses playpen/travel cot, uses safety gate |