Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1067. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in January 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Moniz-Cook et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Understanding does not only help find solutions, but it can generate tolerance as the behaviour loses its mystery. With tolerance comes the potential to cope, even with situations that are basically unchanged.

Stokes G. Behavioural, Ecobehavioural and Functional Analysis. In Stokes G, editor. Challenging Behaviour in Dementia: A Person-Centred Approach. pp. 142–541

Chapter overview

In this chapter we describe the background to our programme of assisting mental health practitioners and care home staff to respond effectively to challenging behaviour (CB) from people with dementia living at home and in care homes. First, we provide a conceptual overview and definitional rationale for CB in dementia care. This includes the layers of complexity that need to be considered in the management of CB in dementia within the ‘real world’ of family life and care home settings. Next, we summarise the development of functional analysis, as an approach to systematic assessment and associated management; the findings of our literature review of interventions based on this method; and a second review of the range of psychological and emotional needs of family carers that are associated with caring for people with dementia with CB. The conceptual overview and review findings provide a theoretical and empirically informed grounding for this approach to systematic assessment and the tailoring interventions to individual needs, in the management of CB in dementia care. Finally, we outline and discuss the studies we conducted in the chapters that follow.

Definition of challenging behaviour in dementia

Challenging behaviour associated with dementia includes a wide range of behaviours such as violent resistance to help with personal care and other aggressive responses, repetitive questioning, yelling or screaming, sexual disinhibition and apathy. It causes significant distress to caregivers. Often it is itself a manifestation of distress experienced by the person with dementia, whose cognitive impairment increasingly limits their ability to carry out desired actions, or to express their needs or to inhibit their own behaviour – as would be ‘normal’ for them within their interpersonal and social context. Two influential theories that partially, but far from comprehensively, account for these phenomena are the ‘unmet needs’ hypothesis2 and the ‘progressively lowered stress threshold’ hypothesis. 3

Together with incontinence, CB is the most common reason why family members pass over care responsibilities to residential facilities such as care homes. 4 This may be because the person’s behaviour has passed a threshold of intolerability or is deemed unmanageable at home. In care homes these behaviours then have to be managed by care staff,5–7 many of whom are poorly paid, are accorded low status and are insufficiently resourced and supported. 8,9 Behaviours can become more ‘florid’ (e.g. screaming or violent aggression) and frequent after a move to a care home. Increased frequency of these behaviours in care homes may be attributable to heightened distress, as the person is away from ‘home’ and familiar faces or routines, and does not have the cognitive capacity to adjust to the care home, or possibly because of deficiencies in care.

Phenomena or symptoms associated with CB in dementia are sometimes referred to as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPSs) or behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), which are defined as ‘signs and symptoms of disturbed perception, thought content, mood or behaviour that frequently occur in patients with dementia’. 10 This definition has the advantage of acknowledging the strong component of psychological suffering by the person and that there can be comorbid or accompanying mental illness, such as mood disorders, hallucinations and delusions. The definition is less satisfactory, in that it roots the phenomena solidly in the dementia, when this may not necessarily be the case,11 and it mixes up a diverse range of behaviours and mood states. However, its most serious disadvantage is that it takes no account of the context in which the behaviour occurs.

The importance of context in the management of CB in dementia was recognised within the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE)’s Dementia Practice Guideline Number 42, in the term ‘behaviour that challenges’ (p. 210). 12 This includes the wide-ranging ways in which people with dementia and others in their environment respond to the phenomena of BPSD. Some of these responses can exacerbate distress for the person and/or their family or staff carers, or others in their environment. In line with these understandings, CB in dementia has been defined as a manifestation of distress or suffering for the person with dementia and/or distress in a carer’ (p. 573),13 and in this programme we extend this definition to describe a person’s behaviour as challenging when it causes distress to the person or the carer or others, thus threatening the quality of life of one or both parties.

There are no good data comparing the level of distress between family members and care home staff, but there is reason to believe that some family members may be more distressed by the unfamiliar and often embarrassing or threatening behaviour of a family member they thought they knew well. In contrast, disturbed behaviour may be seen as part of the job for care home staff, as they can at least look forward to relief at the end of their shift. However, the difficulties14 or ‘occupational disruption’ experienced by care workers faced with CB, regardless of whether or not they actually go on to become distressed later, remains a key factor in them seeking help from specialist services, admissions to hospital, accident and emergency (A&E) use, or transfer to another care home for the person with dementia. This in turn potentially results in increased levels of ‘excess disability’, meaning that functional abilities of people with dementia decline more quickly than can be accounted for by reducing cognition alone over the same period. We use the term CB here because its key component is that, for behaviour to become a clinical problem in need of treatment, it has to challenge the capacity of those exposed to it (usually family or staff carers) to cope.

There are no precise prevalence data because of widely differing perceptions of what is ‘challenging’ among those exposed to it; differences in how symptoms are ascertained and variable thresholds of severity and setting where behaviour problems are said to be ubiquitous. 15,16 Nonetheless, the cost of CB in dementia should not be underestimated, as 35.6 million people and families worldwide live with dementia,17 with an estimated cost of care of US$604B in 2010. 18 Breakdown of care at home becomes an inevitable extra cost if the public purse has to meet the costs of a proportion of the one-third of people with dementia who live in care homes. Although prevalence is hard to estimate, over 80% of people who move to nursing homes can have at least two or more of these behaviours. 19 The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) is a commonly used measure20 of NPSs and the incremental cost of just a one-point increase in score in a family care setting has been estimated, in the context of the USA, at US$30 per month on average, resulting in urgent calls for targeted intervention to reduce this significant cost. 21

Management of challenging behaviour in dementia

Treatment is problematic. There is extensive evidence of over-reliance on psychotropic medication, in particular antipsychotics,22 despite meta-analyses from 1990 to date showing modest efficacy at best, as well as frequent problematic side effects. 23–25 A rough measure of ineffectiveness is that half to two-thirds of participants referred to intervention studies because of unresolved problem behaviour will already be taking antipsychotic medication. 26,27 Because of the mounting evidence of harm from antipsychotic use in older people with dementia, there are occasional surges of interest in other compounds, in particular anticonvulsants (mood stabilisers), but the evidence is that they are equally ineffective and have equally harmful side effects. 28,29 The dangers of benzodiazepines for older people have long been known30,31 and their use for CB has declined, though a substantial number of medical practitioners are reported as remaining unaware of the literature. 32 The inadequacies of psychotropic drugs mean that there are frequent recommendations to make non-pharmacological interventions the routine first-line treatment. 29 Such calls are honoured more in the breach than the observance but, in any case, the evidence for standard psychosocial approaches is at least as weak as that for psychopharmacology. Systematic reviews of various discrete approaches, such as aromatherapy, light therapy or activity programmes, describe them as showing promise, but most studies lack the methodological rigour required to determine whether or not they are truly effective. 33 In 2005, in one of the most comprehensive meta-analyses of drug trials, Sink et al. 29 concluded that there was ‘no magic pill for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia’. This applies equally to standardised psychosocial interventions.

It should be no surprise that where the main clinical target is the suppression of behaviour, standardised pharmacological or psychosocial interventions are only intermittently effective. Interventions often appear to be based on a ‘one syndrome standard treatment’ paradigm. 13 The syndrome is the behaviour or, mostly, a cluster of behaviours and other phenomena usually labelled BPSD or agitation, and treatments applied include interventions for multisensory stimulation such as snoezelen,34 antipsychotics such as risperidone,29 and analgesics. 35 The primary problem is that the behaviour alone is the wrong target for intervention, as the syndrome-standard treatment model takes little or no account of the multifaceted context of the behaviour and its effects. This includes causal or exacerbating factors for the behaviour, why it becomes a clinical or care problem in any one case, and the characteristics and capabilities of those involved. The syndrome is actually very elusive because each of these contextual matters varies widely from case to case and over time. This has profound implications for the nature of clinical interventions, how they are delivered and their utility, as well as for measurement and methodology in intervention research.

Elusiveness of the syndrome: aetiology and other contextual factors

Many current guidelines, including the International Psychogeriatric Association’s Complete Guide to Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia36 and Dementia: A NICE–SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care (p. 210),12 acknowledge multiple aetiologies for CB, including genetic, neurobiological, psychosocial, medical and physical factors. Given such a complex causal mix, it follows that there will be wide variability between individuals, even if the behaviour is the same, and that a case-specific approach will often be required. Genetic and neurobiological variables are not currently adjustable, but many psychosocial and physical/medical factors are actually or potentially treatable. For example, many treatable or modifiable factors, often in interaction, can contribute to screaming or yelling in dementia, including pain or depression,37 the way care is carried out,38 sensory loss,39 overstimulation40 or loneliness. 41 Similarly, the cause of sleep disturbance or night-wandering can be staff noise or active waking of residents;42 too much sleep/dozing or inactivity during the day;43 inability to find the toilet or the way back to a room at night;44 previous night-time regimes;13 or any combination of these. 45 Addressing potentially treatable case-specific aetiological factors such as these is an obvious first step, and some studies do acknowledge and treat common conditions underlying CB, such as delirium or, in particular, pain, which is grossly undertreated in dementia. 35 However, in the main, trials of standard psychosocial or pharmacological treatments aimed at the behaviour do not typically address causal factors. At best, this is poor practice, but it is also pernicious, leading to non-treatment or wrong treatment of causes of suffering. For example, several studies have shown that, by contrast with cognitively intact older people, people with dementia who are in pain are more likely to be given antipsychotics than analgesics. 46

The elusiveness of the syndrome is not just because of idiosyncratic causes of behaviour. It applies equally to distress among family carers or care staff, and in care homes there may also be distress caused to other residents. Hence, distress in others or the potential for injury to the person and others is what defines the behaviour as ‘challenging’. For example, in family care settings, frequent behaviours are not necessarily the most challenging for carers;47 the carer’s own characteristics (independent of dementia severity) and their sense of a declining relationship with their relative can contribute to the development or maintenance of CB. 48,49 Emotional responses to, and perception of, the behaviour vary widely,26,50 from extreme distress to regarding the behaviour as ‘no problem’. Most people are distressed by behaviours such as screaming, repetitive questions, violence or behaviour of great intensity. Nevertheless, in many cases, individual characteristics of family carers51,52 or care staff are often as important as severity of behaviour in determining whether or not, or to what degree, the behaviour is perceived as challenging. These factors include limited understanding of the changes associated with dementia; lack of support; limited skills; pejorative attitudes to people with dementia or older people; and mood disorders in caregivers. 53,54 In an early example, Hinchliffe et al. 55 found that treating depressed family carers changed their perception of the behaviour, from ‘intolerable’ to ‘no problem’. Thus, in a significant number of cases, though far from all, CB can be described as being in ‘the eye of the beholder’, and a successful intervention can be one that does not change the behaviour but leads to carers no longer perceiving that behaviour as a problem, or at least as not so great a problem.

In residential care, the characteristics of the home contribute to the elusiveness of the syndrome in much the same way. It tends not to depend on the formal classification of the home and nature of funding (subsidised or non-subsidised), but more on individual differences between homes. 56 Even if residents have much the same profiles, in relatively stable facilities where the culture fosters a high level of dementia literacy, empathy and skills, and strong support, disturbed behaviour is less likely to occur, or, where it does occur, it is less likely to be perceived as challenging. 53,57 This means that it is not only the syndrome that is elusive, but also any sense of a standard treatment, because the nature of the intervention and how it is delivered will depend on the existing skill set and culture. However, not even here can stability be assumed. The residential care sector is often in flux; organisational changes, including takeovers and loss of staff, are common, even during intervention studies. 9 Accordingly, attention must be paid to how to engage sufficient staff to make a sustained difference. 58

In summary, because of the multiple interacting contextual factors surrounding BPSD, many of which may have nothing to do with dementia per se, and some of which have little to do with the person with dementia or the objective severity of the behaviour, standardised pharmacological or psychosocial treatments are always going to have strictly limited effectiveness. This is exactly what the literature shows. Treatment should vary in each individual case depending on the aetiology and/or the context in which it occurs, including characteristics of carers, practitioners and the person with dementia – which will determine what is possible in any given case. Thus, the identified focus may be the person with dementia and/or family and/or staff members and/or a whole facility, and treatment may include pharmacological and/or psychosocial methods. Injunctions to use psychosocial methods first are incorrect. If the cause of someone being violent in personal care is painful joints, pharmacological pain relief is likely to be the front-line treatment adjunct with empathic support during personal care. If the cause is poor staff skills, treatment is likely to be psychosocial. If the cause is a combination of both, for example where a care worker with low skills is also insensitive to the fact that the resident is in pain, then the treatment is likely to be both analgesics and training with supportive supervision of the staff member. Where the behaviour is simply dangerous (to self or others), the first line of treatment will often involve psychotropic medication, including antipsychotics, if there is no other alternative (p. 261),12 but usually there are alternatives. 59

Implications for methodology

As there is no standard syndrome based on the behaviour and, therefore, no standard treatment, a range of measures must cover multiple domains in intervention studies. By definition, CB involves both an individual’s behaviour and another’s response to this; therefore, measures of both are needed, and the response must be linked to the referred behaviour. Measures of behaviour must include the actual behaviours that are distressing carers or practitioners, but also generic behaviour measures so that change over time can be aggregated across a diverse range of behaviours of widely varying frequency. Given that severity of behaviour often predicts carer distress, measures of severity as well as frequency are required; for example, the effects of a very low-frequency behaviour, such as physical aggression, can be much more serious than, for example, high-frequency pacing or walking up and down. This often leads to problems in determining what constitutes ‘caseness’, that is, the threshold for offering a clinical intervention, and, equally, what constitutes a successful intervention. In residential care, because of variability between staff and the influence of care culture in determining the quality of care, as well as receptivity to interventions, there must be more general measures (e.g. staff morale, knowledge, skill levels, whether or not organisational change occurs), to enable an analysis of staff and care home factors likely to predict benefit from an intervention. Because of large differences between care homes’ organisation and facilities, there must be a representative sample of them rather than just one or two and, because of the effect of culture, the facility or specific unit rather than individual residents must be the unit of randomisation.

Rationale for current study

A number of trials have delivered education to family carers or care staff as the sole or an important component of interventions, variously covering generic and client-specific skills and knowledge, and/or providing emotional support. That is, they recognise the case- and context-specific nature of CB by attempting to enhance the emotional, attitudinal and practical skills of care providers such that they can flexibly adapt to each new case or change care practices to prevent or minimise CB occurring. Few of these trials have had adequate methodology (for reviews see McCabe et al. 58 and Spector et al. 60), but there have been encouraging, though not conclusive, results in trials of adequate rigour. Changes in behaviour or family carer or staff distress are more likely to occur in programmes that are more case or client specific, that is, education that is person centred or more explicitly links interventions to the specific environment. 60

Examples of outcomes for people with dementia living in residential care have been reductions in frequency and perceived severity of the target behaviour and general practitioner (GP) call-outs,50 reductions in antipsychotic use,27 reductions in agitated behaviour and increases in observed participant pleasure,61 reductions in behaviour frequency and perceived severity, hospitalisations, antipsychotic use, and drug side effects;26,62 and for staff, reductions in stress and short-term improvements in the perception of how challenging staff found the behaviour. 63 Systematic interventions of this type, targeting a variety of outcomes within family care settings, are less common, but they can be found, including within NHS settings in England, where they have demonstrated reductions in CB and improvements in carer mental health. 55,64,65

Many of these studies, especially those involving supervision, required expert clinicians to work with family carers or with residential care facilities. However, Bird et al. 26 showed that the individualised formulaic ‘case-specific’ approach was no more time consuming when compared with ‘usual care’ practice in residential care settings, but it still required a mean of 5.5 clinical visits per case. Applying a similar approach to ‘treatment-resistant cases’, in care homes, Davison et al. 50 required a median of 3 months per case, spread over three visits, to achieve improvements in some, but not necessarily in more complex or treatment-resistant cases. This necessitates significant time/resource investment, namely addressing the shortage of clinicians with the requisite skills to provide the necessary assessment and subsequent intervention to the large and growing number of older people with dementia and CB, and those who care for them. Such ‘expert’ interventions are expensive, so alternative models of service provision are required. In residential care, where the most florid behaviour occurs, there seems to be the potential for staff, if given enough sustained support, to gain and retain these skills for themselves. Furthermore, most of the information required to assess CB, from the resident’s health status to the way intimate personal care is carried out, is already available in the care home, and care staff members are often the primary source of the information that is required by visiting professionals. Support for CB in family care settings in the UK has traditionally been provided by community mental health nurses (CMHNs) working within community mental health teams for older people (CMHTsOP). By providing these practitioners with specialist supervision to target their interventions, reductions in CB and improvements in carer mental health have been demonstrated. 65

Given the elusiveness of the syndrome, our first challenge was to devise a method to assist care home staff and community practitioners themselves to gather and analyse information required for CB interventions in a sufficiently standardised manner to be taught in a generic way, but which also takes as much account as possible of the idiosyncratic biomedical, social, environmental and other contextual factors of each case where behaviour is perceived as challenging. The closest approximation is a well-established range of techniques known as ‘functional analysis’ (see Functional analysis-based interventions), which has been used in a number of single case studies or case series. 66–69 Our second challenge was to devise a means to engage staff in a way that they perceive as relevant to their working experience and with sufficient power to change or expand the way they perceive and respond to behaviour they find challenging. There are preliminary studies of successful interactive online programs using actors to simulate common behaviours in context followed by demonstration of how effective responses can be achieved. 70–73 There is also increasing interest in online education. 72–75 Furthermore, emerging approaches towards personalised electronic decision support systems for targeting dementia care in community settings are being developed. 76 However, these are at an early stage and are yet to be considered for CB.

Functional analysis-based interventions

Functional analysis is a systematic framework for assessment that takes into account potential factors that may cause or contribute to a given behaviour (i.e. the function of the behaviour) for an individual at a given time and within a given social interaction or environmental setting. Following a functional analysis that has fully considered the potential cause(s) or contributory factors underlying the person’s behaviour in their interpersonal situation, the practitioner can then generate ideas of ways of intervening and then test these out in the individual case. If the challenge has not been resolved in an acceptable way, the practitioner can return to other creative ways of addressing the cause and associated challenge. If the challenge has not been resolved in a satisfactory way or if the practitioner wants to consider the function of the same behaviour in a different context or another behaviour, s/he can continue to use the information from the comprehensive assessment, together with observations in the relevant interpersonal setting, to consider other potential ways of intervening. The approach is essentially one of systematic ‘hypothesis generation’, akin to an iterative ‘detective’-like approach to CB in dementia, and overcomes the aforementioned pitfalls of the search for a magic psychosocial or medical ‘pill’ to overcome the challenges that face individual and groups of carers in dementia care. The interventions that arise from a functional analysis are referred to here as functional analysis-based interventions and can include factors, such as pain or infection, that cause discomfort, as well as psychological or social need. Next we outline the development of functional analysis as a means of managing CB in dementia in the UK.

Firmly nested in the tradition of applied behaviour analysis, the functional analytic perspective came to prominence initially in the field of intellectual (learning) disability where, from the early 1980s, conceptualisation and research gradually moved away from the reductionist ‘behaviour modification’ approach to a perspective that encompasses a more person-centred functional analytic perspective. Thus, the term ‘challenging behaviour’ – used in the USA in 1988 by The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, replaced that of ‘problem’ or ‘disruptive’ behaviour. 77 This change of terminology signalled an important relocation of responsibility from the individuals displaying the behaviour to the systems around them. A significant body of research emerged over the subsequent two decades attesting to the importance of functional analysis in the field of CB. 78 Although the emerging literature on functional analysis from the USA emphasised the importance of tightly controlled hypotheses-driven behavioural experiments, the literature from the UK also included analysis of the wider context of the person’s life and variables that were closer to the concept of function, where the ‘meaning’ or ‘purpose’ of behaviour was also considered. Thus, the British conceptualisation of functional analysis combined the rigours of experimental analysis with a more anthropological and contextual emphasis on function,79 and some professional societies in the UK provided associated guidance for practitioners. 80,81

In 2000, Stokes1 (see chapter 8) provided an overview of the translation of applied behaviour analysis and the growth of functional analytical approaches to dementia care from around the mid-1980s in the UK. By the mid-1990s a parallel movement associated with the person-centred model of dementia strengthened the potential for application of applied behavioural analysis by allowing researchers to identify the functional significance of many ‘bizarre’ CBs. The challenge was now for services, professionals and carers to find more effective methods of understanding the origins and meaning of a person’s behaviour. This person-centred approach also saw the growth of attempts to find creative ways of responding to the challenges to services. 1 However, although modelling and testing of functional analysis through single case studies exist,1,65–69 these tend to be located in the care home setting. Systematic attempts by professionals and researchers alike to reduce the need of a person with dementia to engage in ‘behaviour that challenges’, where the guideline outlines the same considerations that we have also described previously within a functional analytical assessment framework (see Dementia: A NICE–SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care, p. 210),12 have been, on the whole, anecdotal and intuitive. This may be because making systematic choices about the most appropriate and often multicomponent interventions in a given case can be difficult for the practitioner. This is also the case when the practitioner requires to assist a professional or family carer to respond, through understanding of the sometimes ‘idiosyncratic’ meaning of the ‘behaviour that challenges’ in an individual who may be communicating an unmet need and/or distress through their behaviour.

Challenge Demcare

The programme of work reported here sought to use the wider conceptualisation of functional analysis as the basis of its methodology and associated technology, using the internet to expand availability of the method as widely as possible. In order to apply our theoretical stance to a functional analysis-based framework for CB interventions in dementia, we conducted two literature reviews, which will be outlined next.

Literature reviews on the management of challenging behaviour in dementia

First, we conducted a systematic Cochrane review of functional analysis-based interventions for the management of CB in dementia in 2009–10 (updated and published in 2012). 82 This integrated a number of features taken from the conceptual overview described above, including the growth of functional analysis in dementia care and the importance of including the context of CB in the analysis. Thus, although a central tenet of the approach was to teach staff and practitioners to carefully observe the person and their immediate environment before making assumptions about the function of the behaviour, the analysis of function moved beyond the mere completion of antecedent–behaviour–consequence charts and the reductionist assumption that behaviour is a function of its consequences. The review therefore also focused on interventions that included identifying the function of behaviour for an individual, based on knowledge of the person’s life story, to understanding the ‘unmet need’ that was being communicated by the distressed person. Finally, the review included interventions that incorporated training and specialist support of staff in care homes, and trained community practitioners who provided care to families, to apply, monitor, evaluate and adjust individually tailored interventions to reduce CB in dementia. Our primary outcome measure was CB, including the behaviour and responses or reactions to this.

All randomised controlled studies that included functional analysis-based interventions for dementia compared with a control condition were included if they had a valid outcome measure of reported occurrence, in terms of frequency or incidence of CB. Participants included those living at home or in care homes or those cared for in hospital or other dementia facilities, such as assisted living units. The primary outcome was change in reported behaviour or mood on standardised measures, and secondary measures included changes in the caregiver, that is, their reaction, distress, perceived management difficulty and well-being (mood, morale efficacy and burden). The searches located 3335 references, from which 144 abstracts were retrieved. One hundred and twenty-six papers were excluded following our quality ratings and checks for duplication, and 18 were selected for review (see Moniz Cook et al. ,82 table 2), with a baseline total of 2558 care recipients. The majority of these (n = 13) were within family care settings and just three were conducted in care homes. Of these, only two family care studies were conducted in England, in Kent64 and Hull,65 and only one care home study, in Manchester. 83 The review concluded that functional analysis within multicomponent interventions that are geared to the context of either the family or the care home shows promise. A striking finding from the studies reviewed in family settings was the importance of providing support to meet the psychological needs of the family carer. This was consistent with our conceptual understanding of CB that was described earlier, that is, attending to context within the family system is an important target for interventions to reduce CB in dementia. The relatively few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in care home settings made it hard to properly evaluate the importance of intervening in the system or context of the care home. However, one of these three studies from England,27 in which person-centred care was offered to reduce the use of antipsychotic medication (but did not show change on behaviour outcomes), has been recently upscaled in an implementation study. The authors achieved reductions in antipsychotics equivalent to the original study in some cases, but conclude by outlining contextual barriers to implementation; they recommend revisions to the intervention to address these barriers. 84

Second, given the findings from the Cochrane review on the functional analysis-based interventions,82 that effective interventions usually involve a component of psychotherapy or counselling directed at the family carer, we conducted a second review to gain an in-depth understanding of the potentially ‘hidden’ needs of families living with dementia and CB. This was thought to be important as a focus for the content of a multicomponent intervention for the management of CB in dementia in family settings, as two-thirds of families that receive professional support report an unmet need associated with behaviour management in dementia. 85 A meta-ethnographic approach was chosen to review studies that employed qualitative and quantitative methods of family carer experiences of dementia and CB. Our wide-ranging search strategy identified 10,375 references, of which 70 studies met our initial inclusion criteria and 25 high-quality studies were finally included in the review. Reasons for CB were associated with changes in communication and misunderstandings about the meaning of the relative’s behavior, which was seen by some carers as ‘antisocial’. 86

Our conceptual overview and review findings together provide a theoretical and empirically informed grounding for a functional analysis-based framework for choosing interventions for the management of CB. Thus, we conceived case-specific functional analysis-based interventions for CB to include the health and psychological needs of the person with dementia at a given time, as well as attention to the physical and social environment and the caregiving context. This then included the support needs of staff within a given care home or, for example, the psychological needs of families. In the design of an interactive online intervention for CB in dementia, we created algorithms for intervention within each of these three domains, ensuring that the third domain differed for people living at home or in a care home.

Outline of studies within Challenge Demcare: Chapters 2–6

Our interactive online intervention aimed to provide easy access for care home staff and community practitioners to training and support to meet the needs of people with dementia and CB (see Chapter 2). The ‘e-intervention’ consisted of an e-learning course for staff that was graded across three modules and a decision support system consisting of two e-tools that followed the e-learning course. These e-tools were context specific and tailored for use by staff supporting people with dementia either at home or in a care home. Our aim, in keeping with the applied behaviour analysis roots of functional analysis, was to help care home staff to alter their interactions with the person through an understanding of the basic principles of functional analysis. But we hoped to go beyond behaviour change alone, by changing attitudes as well as behaviour. We anticipated that by paying more attention to the functions of a person’s behaviour, staff would go beyond a ‘rule-governed’ approach that assumed function (‘He’s just doing it to get attention’) and develop a shared sense of humanity and affinity with the person. In this way, we hoped to build a higher tolerance to those CBs that were unlikely to change. For community practitioners, such as CMHNs working in CMHTsOP across England, who provide support to family carers, we expected the training to provide the background and tools for functional analysis-based interventions. Thus, the e-learning course and decision support e-tool were structured in the same way to facilitate the production of a targeted action plan, referred to as functional analysis-based interventions for the management of CB in dementia. Application of the interactive e-learning course for staff from the intervention arm of our care home study, ResCare, and experiences with the decision support e-tool in our family care study, FamCare, are outlined in Chapter 2.

Following adjustments to the procedure of delivery of functional analysis-based interventions in care homes, the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the web-assisted intervention were evaluated within a cluster randomised trial (CRT) (see Chapter 3).

We then conducted a comprehensive process evaluation to throw light on the mechanisms responsible for our findings in the ResCare trial (see Chapter 4).

Chapter 5 describes the FamCare observational study, our study of specialist community mental health services for people with dementia and CB living in family care settings in England.

Finally, we conclude by reflecting on our programme across care home and family care settings. We summarise key findings, and, on the basis of observed limitations to our care home intervention, important implications for the design of future research of this type are outlined. We also consider the implications for future research and practice in the delivery of support for CB in dementia care, in the light of changing policies and services for people with dementia and CB (see Chapter 6).

Chapter 2 Development and testing of an online application of functional analysis approaches to intervention for challenging behaviour in dementia

Abstract

Aim

To describe the development and field testing of an interactive online training and decision support intervention, using functional analysis approaches for the management of CB in dementia.

Method

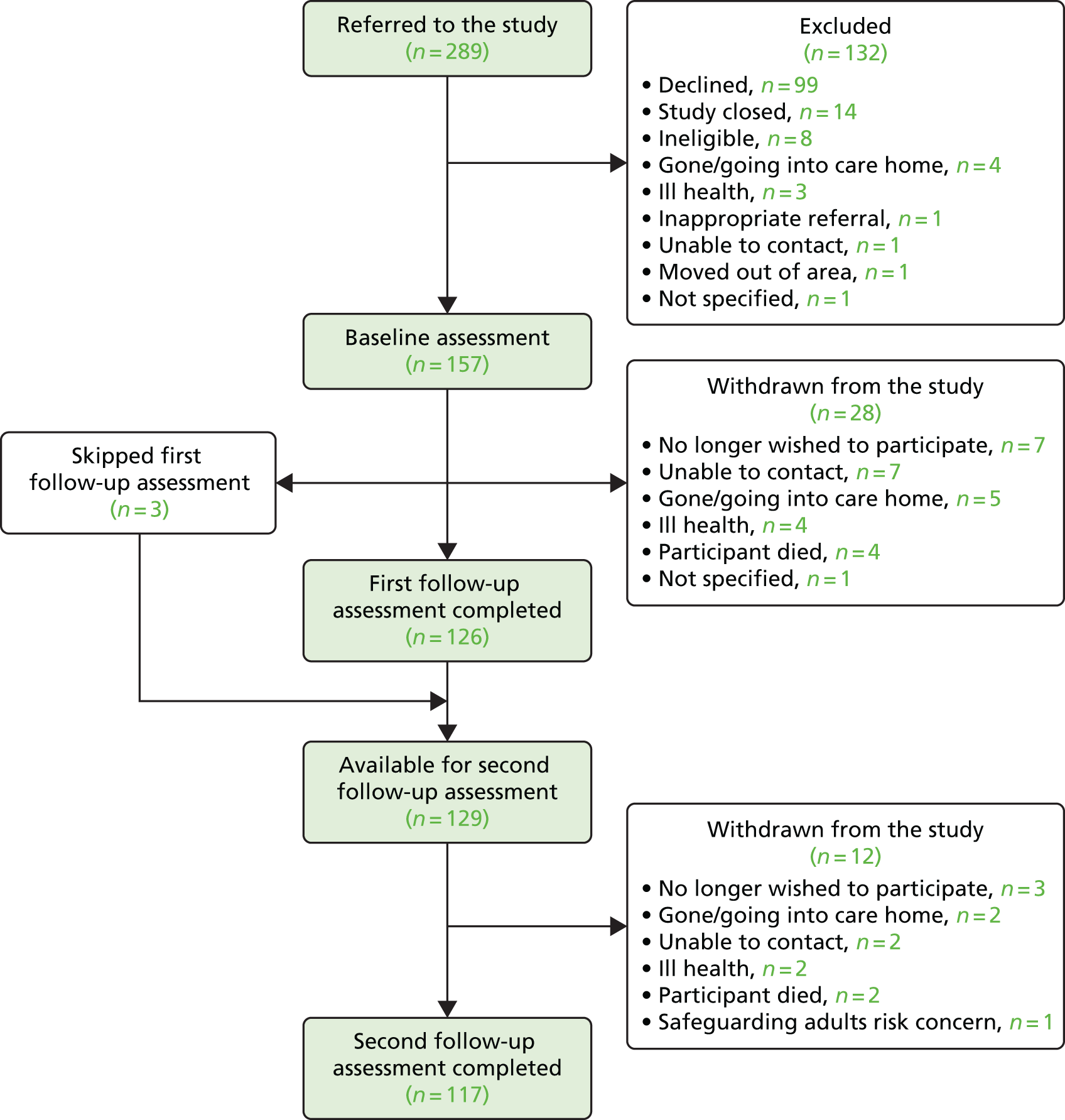

An e-learning course and two decision support e-tools were developed to help staff to use functional analysis-based interventions for up to 25 commonly reported CBs in dementia. The intervention was tested (2011–12) with 92 nominated ‘staff champions’ from 27 care homes and 26 community mental health practitioners from six NHS organisations across England.

Results

The course was well received and strongly recommended by care home staff champions who completed an evaluation sheet (n = 92), but only when this occurred at an external venue, with opportunity for facilitated discussion and practice. Although freely available within homes, e-learning take-up by other staff was limited. Staff selected as champions by their managers were, on average, younger [t(606) = 2.12; p = 0.032], had higher educational attainment (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.0448) and were more likely to have had dementia training (χ2 = 4.38; p = 0.036) than others working in the care homes. E-tool-assisted action plans were developed for 199 residents with CB. Aggression was mostly selected by staff where 58 action plans (29%) were delivered. Immediately after training, staff appeared to have expanded the way in which they viewed some behaviour. They were less likely to perceive behaviour as challenging, with a significant reduction in ratings of CB following training [t(178) = 7.4; p < 0.001]. Community mental health practitioners, who tested the community decision support system for their patients with CB, valued its logical assessment framework and the ‘if–then’ algorithmic method for choosing potentially helpful case-specific interventions.

Conclusions

Worksite-based e-learning opportunities are not at present readily taken up by staff working in care homes in England. Computerised decision support for interventions for CB appears premature in care homes, but shows promise for training community dementia practitioners. However, usability will depend on successful collaboration between clinical experts, information technology (IT) advisors within NHS organisations and software engineers.

Introduction

The concept for the design of the intervention is outlined in Chapter 1. Our aim was to devise a means to engage staff in a way that they perceived as relevant to their working experiences and that had sufficient power to change or expand the way in which they responded to behaviours they found challenging. The intention was to provide an easily available and sustained resource in care homes for staff to learn about behaviours seen as challenging, common contextual reasons why they occur and effective ways to respond, that is, to make them aware that the syndrome is elusive and that, as a consequence, standard responses based only on the nature of the behaviour will be ineffective. By providing a structured framework for capturing the syndrome, with some examples from family and care home settings, we considered this resource to also be relevant for community mental health practitioners working with family carers, in the management of CB in the home setting. Second, when CB does occur, our intervention was designed to enable care home staff and community mental health practitioners to use functional analysis to assess all the parameters of the case sufficiently comprehensively and thus apply systematic support to reduce the impact of CB in dementia care.

Development of the intervention

We conceived a multimedia interactive functional analysis-based intervention for CB in dementia. This comprised a training programme, together with two suites of decision support systems (one for staff in care homes and the other for staff supporting family carers in the community) for the targeting of individualised or person-centred interventions for CB in dementia. A range of options for the platform was considered, including our original plan to develop DVD and CD materials. We explored the potential strengths of an online solution, which were as follows: increased accessibility to information, where content could be standardised, easily updated and revised (see Ruiz et al. 87 for an overview of e-learning in education); options for self-pacing to overcome time pressures;88 immediate feedback with options for improvement, which is an important approach for adult learners;89 and fidelity of presentation with automated documentation, such as tracking and reporting of the learner’s activity,73 to allow monitoring of usage and problems with the program itself and thus facilitate improvements to meet the needs of the learner. In addition, feasibility studies in the USA have noted that direct care workers in nursing homes respond positively to internet-based multimedia training, including the management of aggression. 70,71,73 In family care settings, information and communication technology (ICT)-based solutions have been piloted74 and are also described as important uncharted territory in supporting families to cope with CB at home. 90 Given the huge growth of internet use in recent years, we considered that the online option would offer greater flexibility for those, including care home workers and community practitioners, who may wish to access the e-learning aspect of the resource from other venues, including potentially their own home.

The e-learning course was a multimedia, interactive, skills-based method, to encourage comprehensive assessment, such that knowledge about the person with dementia’s behaviour in their environment could be understood in order to provide solutions. These could include signposting or referral to other professionals when needed. Its aim was to encourage staff to systematically consider variables such as the person’s medical status, life story, communication and a host of other ‘unobservables’ that may give clues about the function of the behaviour. The information management systems (IMSs) for the two decision support e-tools were designed to follow on from a ‘functional analysis’ of the behaviour, in selecting approaches that were likely to ameliorate the behaviour, the emotional response to it or both. Three e-learning modules (outlined below) were developed, using actors to simulate common behaviours seen in people with dementia in context. 70,73,91 The learner is required to observe the potential function of the behaviour from observations and knowledge provided about the person’s past and present circumstances and then consider supportive actions within three domains (i.e. health, psychological and caregiving context) to meet their needs. The e-learning course was underpinned by a learning management system that allowed users to manage their learning and user input to be recorded and potentially assessed and used for targeted feedback. The e-tools that followed led to an assessment summary and algorithms for developing an action plan, in each of the three domains, with the third domain being relevant to the context of either a care home or family care setting. These were structured in line with the third e-learning module, to provide functional analysis-based interventions for up to 25 CBs in dementia. The three e-learning modules are as follows:

-

Module 1: an introductory module, introducing person-centred approaches in which CB is seen as a response to a frightening environment or unmet need. This introduced the notion of a shared sense of humanity and affinity with the person, in line with the philosophy underlying person-centred care. 92

-

Module 2: a skill development module, using interactive video-clips to practise observation and interviewing. This allowed staff to move away from the traditional ‘antecedent–behaviour–consequence’ observational approach to that of observing the relationship between emotion and communication through the behaviour,93 in order to enhance emotion-orientated care94 where relevant. The intention was to enable staff to appreciate the ‘language of behaviour’,95 that is, the feelings and intentions of the person with dementia that were being communicated by the behaviour, using observation of real-life practice in the care setting and thus recognise triggers and early warning signs that can then be acted on to prevent escalation of the behaviour into full-blown CB. 96

-

Module 3: this comprised nine case examples of graded complexity, incorporating video-clips, and an interactive procedure for accessing information about the person, relevant to a functional analysis of the behaviour. This was followed by a case-specific intervention summarised in an ‘action plan’ to address unmet need97 and thus reduce CB. Cases were derived from the clinical situation in which some cases have been documented in the literature. 1,13,68,69,98 Learners were guided through interactive video-clips, resources that are relevant to the person with dementia, such as life story information or case notes, audio-clips on views of others within the care context, and then provided with structured feedback to set their observations of the person’s CB in the context of ‘causation’. 49 The learning focused on guiding staff to use ‘why’ questions63 to consider the potentially multiple causes for what they had observed about the person and the behaviour in the vignette. 13 Through using information about the person’s current health and functional status, their life story and how others respond to the person with dementia during an episode of CB, key concepts for managing CB13,99 were systematically covered to address causation and possible methods of remediation. Three groups of ‘actions’ or interventions were designed and tested in the clinical situation, including those to address unmet somatic and psychological need97,100 in the person with dementia, as well as the caregiving environment, in which consideration of the particular needs of the staff group or family carer were considered. 86,101 These we refer to as functional analysis-based interventions for the management of CB in dementia. These groups were (1) ‘actions to support health needs’, for example signposting for help by the GP, to alleviate pain or discomfort due to constipation, or review of medications, such as antipsychotics or sedatives that may have been overlooked;100 (2) ‘actions to meet the psychological need of the person, such as how to support the person who may be surrounded by a sense of ‘disorder’, perhaps trying to escape from this, or feeling ‘trapped’ or ‘set aside’;102 and (3) ‘actions to support the caregiving context, environment or system’,101 such as accessing support for care home staff or psychological therapy for the family carer. Thus, in addition to the commonly advocated biopsychosocial approach for the management of CB in dementia care,103 our system included interventions to address contextual needs such as those of people providing care, which can be associated with CB,49,86 and are often overlooked (see Chapter 1).

The decision support e-tools were based on clinical practice guidelines76,104 with our assessment questions firmly set within Dementia: A NICE–SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care for ‘behaviours that challenge’ in dementia. 12,105 The questions that were used to provide the ‘assessment summary’ are found in Appendix 1. We used case-based reasoning,106 in which information collected about the person with dementia and their setting is stored and can be used as a knowledge source to develop personalised interventions for particular problems. The case-based reasoning method then flows into the action-planning part, in which the individual’s assessment is collated and ‘if–then’ logic is applied to generate choices for the practitioner to consider. The stored information can be used to work on different problems, as a setting-specific (care homes and family care settings) CB checklist is supplied at the beginning. The information source can also be updated; for example, if the person has a change in their health or if they have recently experienced a bereavement or if new knowledge of a person’s life story or personal ways of managing life is discovered. Our e-tool started with the 25-item Challenging Behaviour Scale (CBS) of commonly reported behaviours in care homes107 for staff to select a behaviour to work on. This scale has been recommended as a helpful measure for use in care homes across the UK (see Appendix 2 in Brechin et al. 108). For community settings, we used the Problem Checklist,109 as this was based on the concerns of UK family carers and had been used effectively in our previous study. 65,109 This was seen as important, as many guidelines for the management of aggression, for example, have poor representation of some of the important individualised and contextual characteristics necessary for management. 110 Having chosen the person’s behaviour to work on, the staff member or practitioner is then asked to input selective information about the person with dementia and CB, as they had discovered was necessary in module 3 of the e-learning course. They are guided through the assessment process (see Appendix 1 for a detailed description), concluding with a printable summary of the individual’s assessment. This summary includes documentation of the potential cause(s) or function(s) of the behaviour that was based on the staff member’s or practitioner’s responses (see Appendix 1, Box 7). 65,109 The practitioner is thus provided with a systematic assessment framework where questions they considered covered important aspects of the person’s life story, health status and other factors13 (see also Appendix 1). The next part of the decision support system is the ‘algorithmic’ flow of the information into considering what interventions can be tried. The IMS was conceived to use algorithms (which we tested in the clinical situation using a paper workbook), using the aforementioned ‘if–then’ logic to provide options for treatment – in this case functional analysis-based interventions for given behaviour that is seen as challenging. The interventions in our system are structured within the three action groups that had been used in module 3. These are (1) support for health need, such as considering the effects of commonly encountered medical conditions or the effects and side effects of psychotropic and other medication; (2) support for psychological need, such as needs for reassurance, privacy, comfort and occupation or activity; and (3) support for contextual needs, such as advice on how to optimise the environment or system around the person. For each suggested action, tailored information is provided on what staff can do themselves and when and whom to access for further help. Many of the options for intervention for the first two groups of interventions are outlined in Dementia: A NICE–SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care. 12 However, a structured approach to making decisions about treatment based on the particular cause(s) underlying CB (functional analysis) has been absent to date. The algorithms used for the decision support enable the care home staff or community mental health practitioner to apply a structured methodology to choose a set of actions that are possible for them to try within the resources available to them in their routine practice settings. The logic for the case-based reasoning, using tailored assessments, and the algorithms for action plans was developed by the co-chief investigator (BW). It was tested by the chief investigator (EM-C) using a paper workbook with 19 residents who had a score of 4 or more (eight residents) or 10 or more (11 residents) on the CBS. 107 These residents were drawn from eight care homes that were not involved in the CRT (see Chapter 3) and one inpatient dementia unit. All of the 25 items of CB were covered when testing the logic, and actions were refined at this stage. A separate paper workbook for family settings was tested with 15 cases of clinically significant CB determined by a score of 5 and above on a widely used research tool – the Revised Memory and Behaviour Problems Checklist (RMBPC). 111 The practitioner was provided with the Problem Checklist,109 as this was based on the concerns of UK family carers. Action suggestions were further refined to add opportunities that were available in NHS contexts, during our feasibility test with 26 community practitioners from six NHS organisations. The software engineers who were employed to develop the IMS were required to design the system to allow clinical experts (such as physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists and pharmacists) to add content for the functional analysis-based interventions, described within three action plan groupings. Thus, the utility of the action-planning component was that of flexibility for new actions that could be added on an ongoing basis to the system, as experience with the system grew.

Summary of the Challenge Demcare intervention

We used three modules of e-learning to introduce care staff to observational skills and the algorithmic approach to interventions comprising the first two components of the decision support e-tool. This required the practitioner, working with the care staff and the family, to collect important information on key contributory factors associated with CB (see Dementia: A NICE–SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care, section 8.6.1.1 on p. 260 and section 8.6.3.1 on pp. 262–312), such as the person’s current health and functional status, their life story, interpersonal and communication style and how others respond to the person during an episode of CB. The decision support system comprised relevant assessment tools and systems to collect this information with algorithms to provide two sets of biopsychosocial groups of ‘action plans’ where practitioners could choose the most relevant way to meet the person’s health or psychosocial need. These are referred to as functional analysis-based interventions, as the approach was to assist practitioners to assess, analyse and then choose the most appropriate set of interventions (‘actions’) for a given episode of CB. Actions for these two components were extracted from the literature, including our overview in Chapter 1, the Cochrane review,82 guidance from the International Psychogeriatric Association (see Complete Guide to Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia),36 the range of interventions for CB from Dementia: A NICE–SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care12 and policy initiatives to reduce the use of antipsychotics in dementia. 112

Interventions included in the third component of the decision support tool were not related to the person’s unmet need, but arose from a new concept derived from our overview (see Chapter 1), relating to the needs of the caregiving system. These reflected, for example, the needs of the family carer for those living at home (such as counselling or skills training) and those of staff or the environment (such as training, skills enhancement or altering lighting or sound in a room). Algorithms for this component of the interventions were therefore bespoke to the care home or family care setting, where the focus was the need of the caregiving environment or system.

Methods

The e-learning course in care homes

The training, consisting of the three e-learning modules, was planned to occur within the care home, to facilitate ease of access by all staff who wished to engage with this. As noted by researchers in Canada113 and the Netherlands,104 we too found very early on in the process that the majority of the care homes did not have adequate computer equipment to offer online training. For example, most had just one or two computers in the home for sole use by the manager and/or administrator. Therefore, a lengthy process of installing the necessary additional equipment to enable access to the internet ensued. We supplied and installed computers in 19 of the 27 experimental homes (14 laptops and five desktop computers), and provided 16 printers. As noted by researchers in the USA when implementing internet-based training for nursing assistants, buildings were also not always designed to accommodate computers and the internet, in terms of either wiring or space. 73 We arranged for broadband installation in three homes and new telephone lines for broadband in two homes. On one occasion, a wireless internet booster had to be installed in a resident’s bedroom and, to activate the wireless access, the router (located underneath the manager’s desk) had to be switched on each time the staff required to access training. In some homes we provided memory upgrades to the existing computer, wireless access points, power extension cables and headphones to allow staff to access the interactive program without disturbing others. Apart from access to equipment and the internet, organisational obstacles had to be overcome to facilitate staff access to the e-learning. These included support from the research team when home managers were unable to ascertain whether or not they had internet access, obtaining permissions from organisation head offices where their policies would not allow for internet use in the home and negotiating with IT departments where technical support for care homes was outsourced.

Once access to the technology required was in place, as with the US and Canadian research teams,73,113 a specialist dementia care therapist needed to work with individual staff in the first three care homes to assist them with logging in and troubleshooting user errors or computer problems. We additionally offered homes money to backfill staff in order that others could complete the training. Thus, we overcame some of the impeding factors to e-learning in the care home setting, that is, a lack of ready access to computer equipment or internet services and low-speed connections that could detract from the utility of the programs, and staff confidence and motivation to use the training in their work environment. However, despite everyone’s best efforts, our strategy for in-home access to training was not successful because of interruptions, when staff felt that they were needed to help with care tasks or when they felt guilty because they thought that their colleagues might be busy or struggling. An alternative strategy was then used following discussion with care home managers, who nominated staff champions to undertake training, with the intention that they would then support other staff in delivery of support to residents with CB. As noted by others in this field,70,73 we needed to arrange training at an external venue where computer suites were available, to allow staff protected time to complete training within small facilitated group sessions. Funding for travel and time for backfill at the care home was made available. However, training facilities within small groups were still not used to capacity, as it was difficult at times for some homes to release staff to participate. Nonetheless, this worked much better than our attempts at offering in-home access to e-learning, as staff champions had their own uninterrupted learning time, with access to the specialist dementia care therapist and the opportunity to share and discuss with staff from other homes.

The decision support e-tool in care homes

The technological underpinning for, and functionality of, the decision support software proved unreliable, because of what may have been computer coding and software design problems with the IMS. The case-based aspect of the system was mostly, but not always, successful in producing case-specific assessment summaries, although these required some editing for presentation. The rule-based aspect was less successful and the range of actions built into the system remained smaller than desirable. Moreover, the IMS did not allow clinical experts to add management content on an ongoing basis. It had always been envisaged that input from a specialist dementia care therapist, such as a CMHN or a psychologist, would be required to assist with the care home intervention and support the action plans. With the limited range of actions available from the decision support e-tool, this was indeed the case. Therefore, a specialist dementia care therapist checked and, when necessary, edited the assessment summaries produced by the system using the rule-based logic we developed, and worked with staff champions to provide an action plan that the champions considered feasible to deliver in their home.

The decision support e-tool in the community

A second software company was employed to work on the community decision support e-tool. Community practitioners from six NHS organisations were selected by their managers to deliver the intervention. They had access to the e-learning course and were additionally trained in a small group setting by clinical experts from the research team, using relevant cases from module 3 of the e-learning course. This was supplemented by education about the rationale for case-specific functional analysis-based intervention, use of a training manual comprising tools and resources necessary for functional analysis in people with dementia and CB living at home (see Appendix 1, Box 9), and ‘hands-on’ practice with the community e-tool. For this case practice they used the e-tool, with anonymised cases from their own experiences, and engaged in facilitated group discussion with the clinical expert team and each other. These discussions focused on how to use the functional analysis for the anonymised case to develop action plans that were feasible to deliver in their own NHS context and its local resources.

Unlike the care home staff, all community mental health practitioners had access to computers and IT facilities within their NHS organisations. For them, the use of computers was a routine part of their job. Overall, the case-specific aspect leading to the assessment summary was superior to that of the care home e-tool, in terms of functionality, presentation and navigation; that is, the assessment summary was of the quality that was envisaged by the clinical expert research team. However, the software engineers did not deliver a system that was fully populated with actions or one that allowed flexibility for new actions to be added by the clinical experts. Therefore, the community mental health practitioners were provided with our manualised resources, including validated tools to assess common CBs in family settings, and other relevant contributory factors such as pain or discomfort in people with dementia or other family concerns (see Appendix 1, Box 9). This provided them with a workbook, to assist them in adopting a systematic functional analysis-based approach to individualised interventions for clinically significant CB in dementia within family care settings.

Results

The e-learning course in care homes

Ninety-two staff champions across 27 care homes that constituted the experimental arm of the ResCare trial (see Chapter 3) were trained on the e-learning course: 10 managers/deputy managers, 36 senior care assistants, 45 care assistants and one administrator. Of these, seven staff completed the online training within their care home setting and 85 attended sessions over 1.5 days. These occurred at a training centre with a large computer suite. As with e-learning at the care home, this was facilitated by the specialist dementia care therapist, but it additionally offered staff the opportunity for group discussion and demonstration of the e-tool using anonymous cases of residents with dementia and CB from their own care home. In total, 11 training sessions were held outside the home over a 12-month time period (June 2011–June 2012). Attendance ranged from 5 to 10 staff for each cohort (average of eight staff per group).

In all homes the manager agreed to select at least two staff champions for training. Two of the homes were unable to meet this requirement. The number of staff who attended training from the homes varied, ranging from one to nine. Managers were asked to select ‘appropriate’ staff for the training, that is, staff who were involved in care planning for residents with CB and dementia and, to the best of the manager’s knowledge, were likely to be working in that home regularly for the foreseeable future. However, those who ultimately attended the training were not always the most appropriate, as was the case of an administrator who had no involvement in resident care and was not sure why they had been selected by the care home manager.

Characteristics of staff champions

The majority of participating care home staff across both arms of the ResCare trial were female (89.7%), and those designated as champions showed a similar gender balance to the overall pattern, with 89.1% being female. However, staff champions were slightly younger in age [mean 36.3 years, standard deviation (SD) 11.8 years] than other staff (mean 39.6 years, SD 13.3 years), that is, those not trained in experimental homes and all the staff in control homes. The difference in age was statistically significant [t(606) = 2.12; p = 0.032].

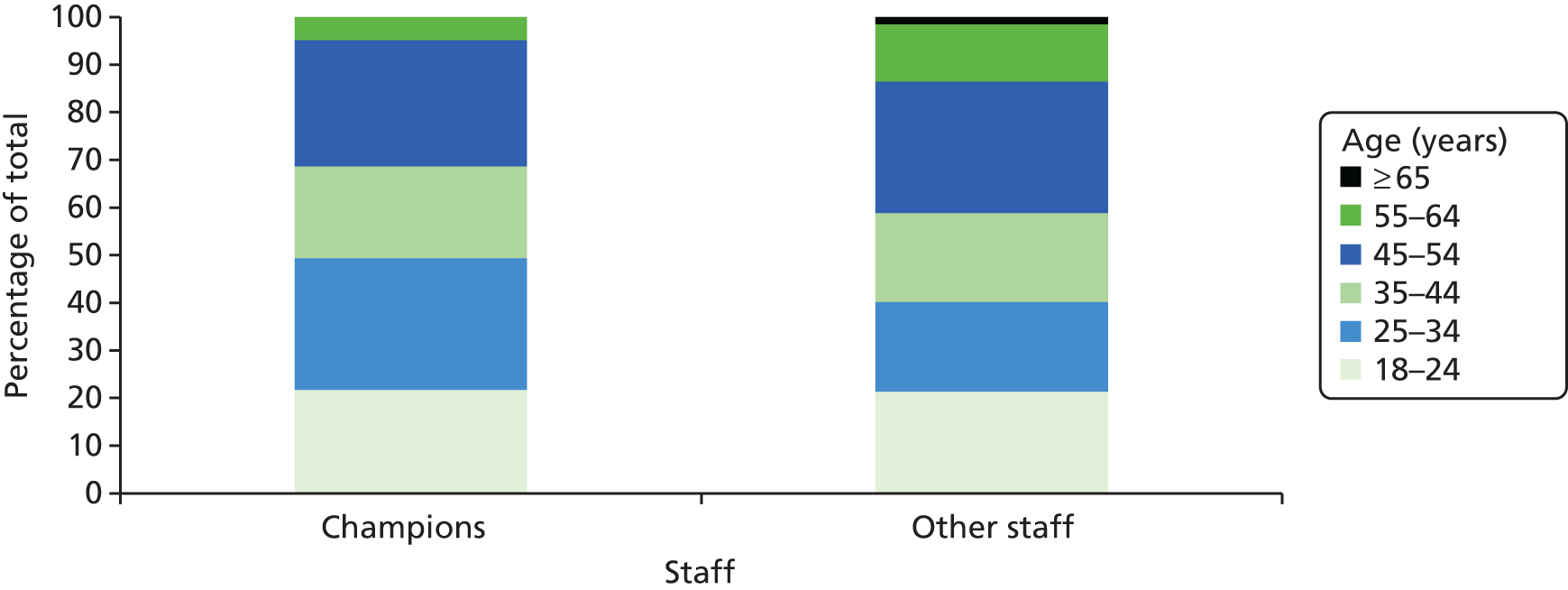

Figure 1 shows the age groups of the champions compared with the ‘other’ non-champion staff members in the ResCare trial, with differences particularly evident in the proportion of people aged ≥ 55 years and between 25 years and 34 years.

FIGURE 1.

Age distribution of care home staff selected as champions (n = 92) compared with other staff working in the homes.

All staff reported whether or not they had received previous training in dementia care or in the use of computers and provided details of their highest qualification. Tables 1 and 2 summarise these data, comparing staff selected as champions with the rest in the ResCare trial. The majority (n = 585) provided most of the details requested.

| Previous training | Staff | Chi-squared test | p-value | All staff (N = 564) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Champions (N = 77) | Other (N = 487) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Previous dementia training | ||||||||

| Yes | 62 | 80.5 | 331 | 68.0 | 4.38 | 0.036 | 393 | 69.7 |

| No | 15 | 19.5 | 156 | 32.0 | 171 | 30.3 | ||

| Previous computer training | ||||||||

| Yes | 32 | 41.6 | 171 | 35.1 | 0.94 | 0.333 | 203 | 36.0 |

| No | 45 | 58.4 | 316 | 64.9 | 361 | 64.0 | ||

| Qualification level | Staff | All staff (N = 557) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Champions (N = 76) | Other (N = 481) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| No qualifications | 3 | 3.9 | 25 | 5.2 | 28 | 5.0 |

| One to four O Levels/CSEs/GCSEs (any grades), entry level, Foundation Diploma, NVQ level 1, Foundation GNVQ, basic skills | 6 | 7.9 | 68 | 14.1 | 74 | 13.3 |

| Five or more O Levels (passes)/CSEs (grade 1)/GCSEs (grades A*–C), School Certificate, one A Level/two or three AS Levels/VCEs, Higher Diploma, NVQ level 2, Intermediate GNVQ, City & Guilds Craft, BTEC First/General Diploma, RSA Diploma | 24 | 31.6 | 175 | 36.4 | 199 | 35.7 |

| Apprenticeship, two or more A Levels/VCEs, four or more AS Levels, Higher School Certificate, Progression/Advanced Diploma, NVQ level 3, Advanced GNVQ, City & Guilds Advanced Craft, ONC, OND, BTEC National, RSA Advanced Diploma | 29 | 38.2 | 139 | 28.9 | 168 | 30.2 |

| Degree (e.g. BA, BSc), higher degree (e.g. MA, PhD, PGCE), NVQ level 4 or 5, HNC, HND, RSA Higher Diploma, BTEC Higher Level | 10 | 13.2 | 36 | 7.5 | 46 | 8.3 |

| Professional qualifications (e.g. teaching, nursing, accountancy) | 3 | 3.9 | 26 | 5.4 | 29 | 5.2 |

| Other | 1 | 1.3 | 12 | 2.5 | 13 | 2.3 |

Champions were significantly more likely to have had previous dementia training (χ2 = 4.38; p = 0.036), but were no more likely to have had computer training. As seen in Table 2, champions were more likely to have reached a higher educational level than other staff. Over half the champions (55.3%) had the equivalent of two Advanced (A) Levels or a National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) of level 3 or above, compared with 41.8% of the non-champions. This difference (higher vs. lower educational attainment) is statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0448).

It may be that some managers’ decisions in selecting staff to receive training and to oversee the management of residents with CB may have been influenced by their perceptions of strengthening capability for future leaders within the home, by selecting younger staff, with higher educational qualifications and previous dementia care training.

Staff champion feedback

Following the e-learning course, staff champions were asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire using a set of study-specific open and closed questions, to access their views on the training, including how it might be improved in the future. Eighty-five of the 92 care staff who received training completed the evaluation questionnaire.

Only four participants identified aspects for improvement. The majority found the modules interesting, understandable and easy to navigate. Ease of use was reported as follows: module 1, 95%; module 2, 82%; and module 3, 69%. Apart from one participant, the staff rated the modules as manageable to navigate. In a few cases learners had difficulties with the system crashing but, generally, they reported that this was overcome with help from the specialist dementia care therapist, who assisted with restoring connectivity. The majority of participants reported that the additional information provided by the system (such as a glossary and specific help/information boxes, particularly those relating to medication) had been very useful.

Most responses on aspects of the three individual modules were positive (Box 1). Only five people stated that they found parts of the individual modules difficult. The few negative comments were mainly regarding some aspects of the commentary, which was described as repetitive, and when suggestions for improvement ‘to vary the narrators’ were made.

-

People with dementia act the same as other people (36%).

-

I learnt something about myself (25%).

-

Greater awareness about behaviour in general (16%).

-

We are all individuals (13%).

-

A mixture of the first two responses (5%).

-

Strategies for coping with CB (4%).

-

Videos and strategies to manage CB (30%).

-

Similar behaviour may be for different reasons (28%).

-

A basic grasp of functional analysis (i.e. look for reasons behind the behaviour) (17%).

-

Generalised comments about what they had observed and the use of videos of real situations that helped them become more aware of resident ‘communication’ (14%).

-

Greater awareness of self-stimulation for pleasure (8%).

-

Comments about self-development (3%).

-

Each person is unique and this impacts on their behaviour (38%).

-

Comments about usefulness of videos of their situations and strategies to manage CB (29%).

-

Stressed the need for effective care planning (18%).

-

Greater understanding about behaviour in general (10%).

-

Ill health as a causal factor (3%).

All those completing the evaluation form stated they would recommend the e-learning to other colleagues working in similar care roles. Examples of comments taken from the questionnaires from those completing the e-learning course were as follows:

I enjoyed the training because I could listen and watch at the same time – this was important because I have dyslexia.

I liked everything about it. I really enjoyed the course and found it very helpful and have learned a lot . . . would recommend all my work colleagues to take the course.

I would like the lecturer to bring the computer to my residential home so everybody could do the training.

Liked it all – I wish I had this teacher when I was at school.

It’s so lifelike.

The video clips showed just how it can really can be.

I learnt that the same type of behaviour can mean lots of different things.

Some answers were a bit tricky and really made me think.

It was very realistic and well planned out.

Learnt how to manage situations better – and also how to interact with the residents.

To look at the whole person, not just one problem . . . that’s what I learned.

The computer training and the teacher information was helpful and helped me to ask questions and share my ideas. I would like the tutor to come to the home.

That I could do it at my own pace but could ask the teacher questions.

I found this tool very insightful and look forward to putting it into practice.

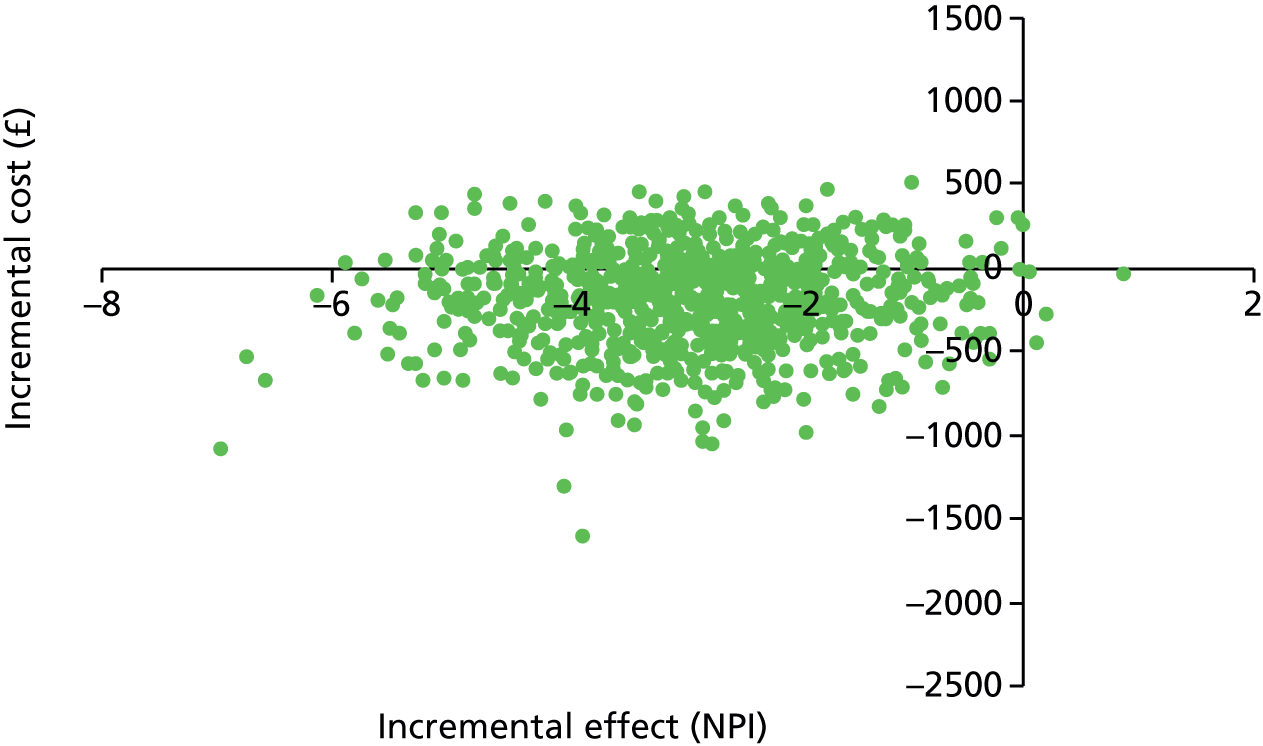

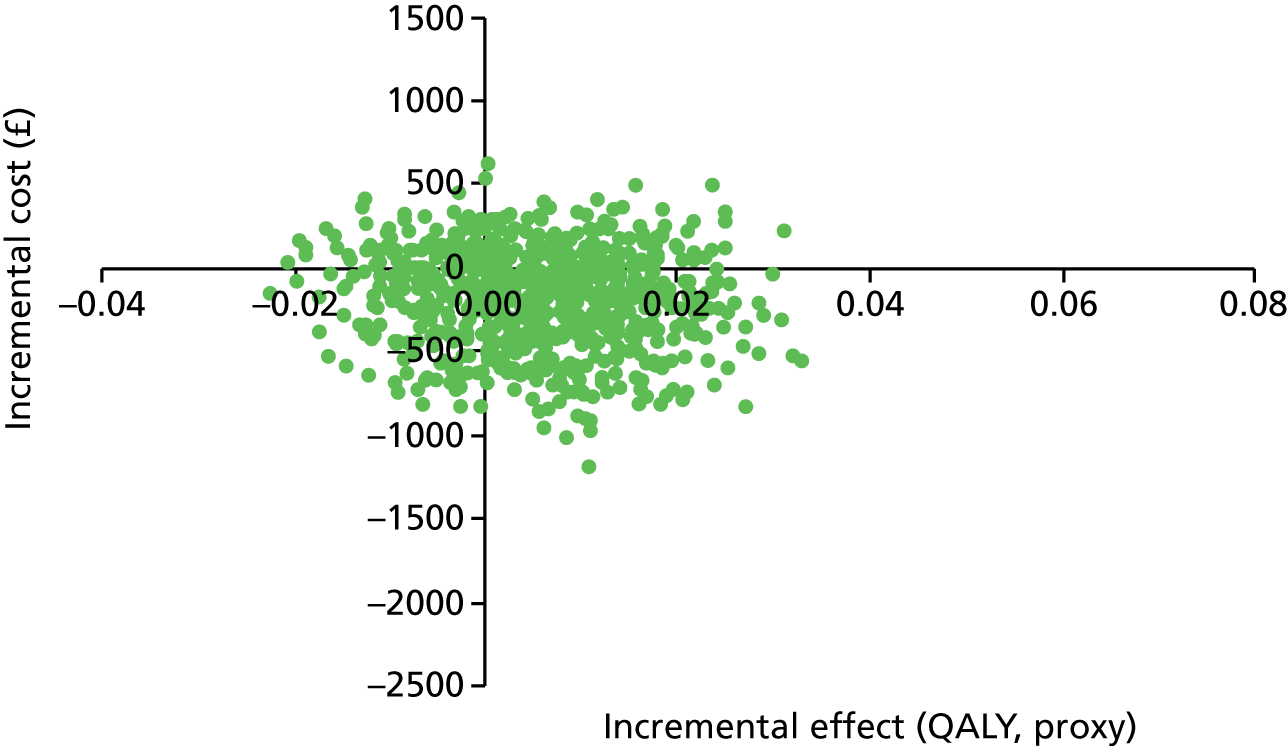

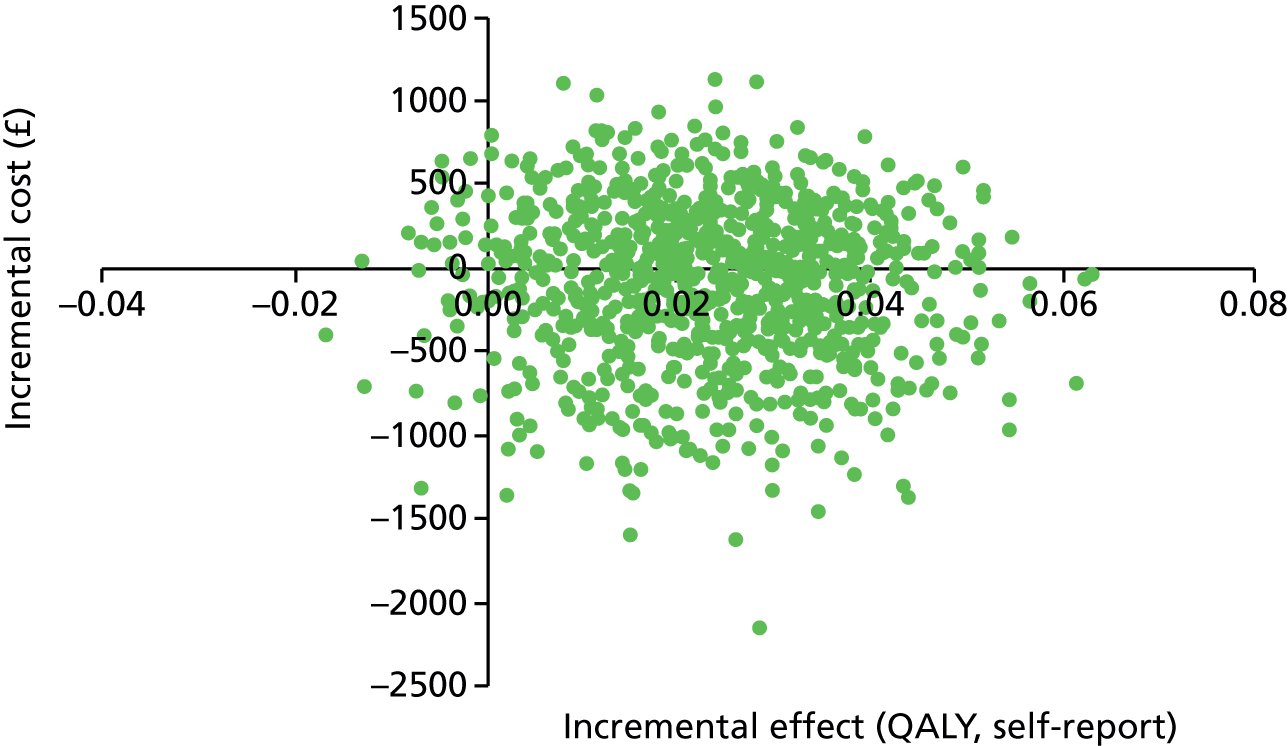

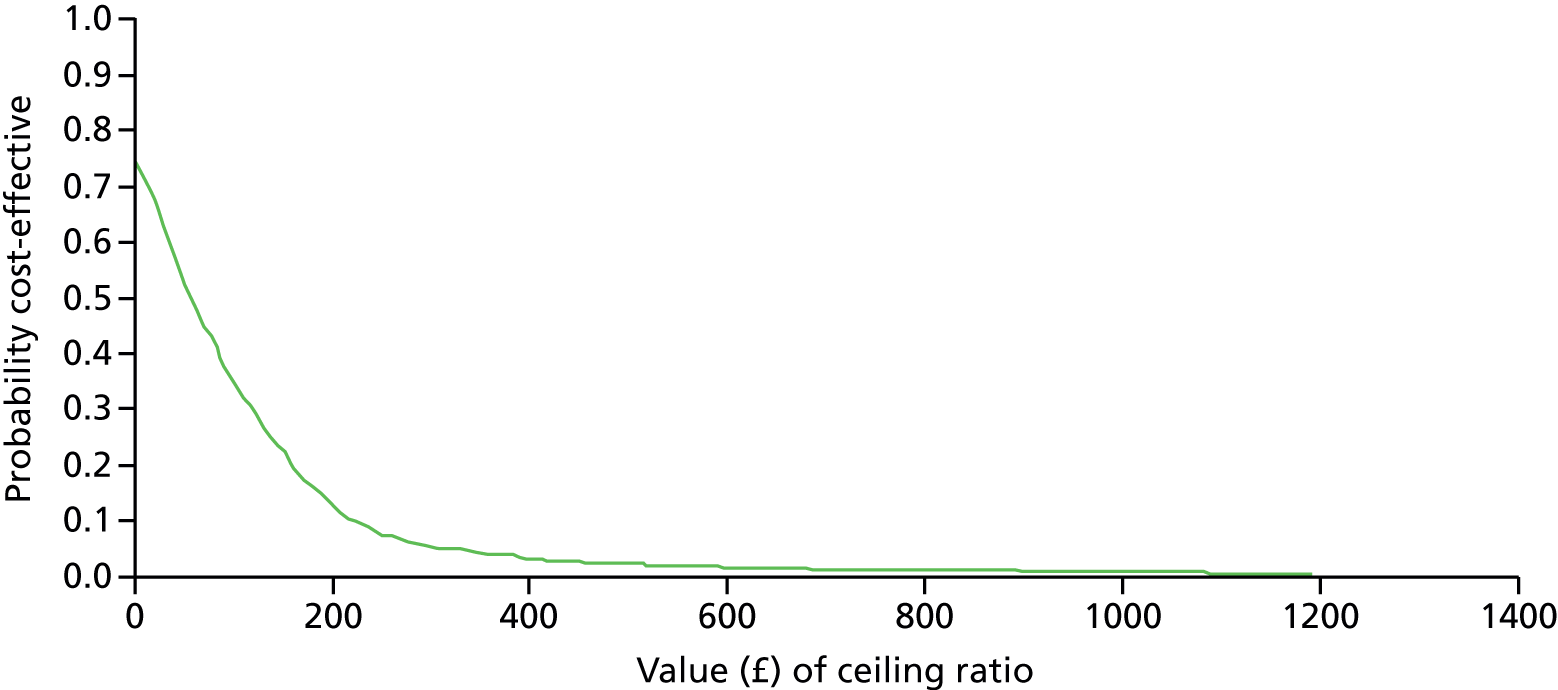

Staff learning styles