Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1043. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in October 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ulrike Schmidt, Sabine Landau and Janet Treasure received salary support from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust’s Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre. Savani Bartholdy reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Council outside the submitted work. Charlotte Rhind reports grants from the Psychiatry Research Trust during the conduct of the study. Janet Treasure reports personal fees from Routledge (publishers) outside the submitted work. Rebecca Hibbs reports grants from the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit Programme (PB-PG-0609-19025) during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Schmidt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and structure of the report

Introduction

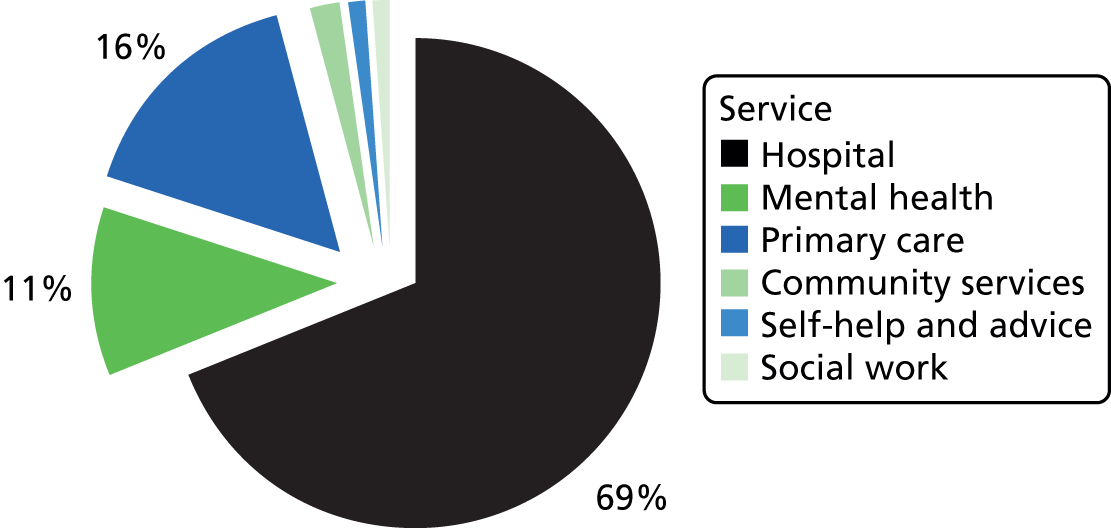

Anorexia nervosa (AN) has existed throughout different epochs and cultures. 1 Key symptoms are restricted food intake, weight loss, hyperactivity, and in some cases bingeing and purging. Psychological features include morbid fear of fatness and body image disturbance. AN typically affects young females, although it also affects some men. 2 AN usually starts in adolescence, when brain development is incomplete. 3 Starvation can impair brain function in a lasting way. 4 Early intervention is essential in producing good outcomes. 5 Treatments in the later stages of illness are much less successful. AN is highly heritable but environmental factors are aetiologically important. 6,7 Progress has been made in identifying risk factors for AN (e.g. premorbid feeding problems, obsessive compulsive and anxious traits, high levels of exercising and overinvolved parenting). 6,7 Research on the genetic, epigenetic and neurobiological underpinnings of eating disorder (ED) psychopathology8–13 has identified neurocognitive and social cognitive biomarkers, such as impaired set-shifting, poor central coherence or emotion processing impairments, including poor theory of mind,14–18 which have the potential to inform predictions of treatment outcome and prognosis. A key challenge is to utilise all this knowledge to develop targeted treatments. To this end, we have developed a model of how AN arises and is maintained, informed by these and other clinical neuroscience findings and with the aim of guiding treatment. 19,20

People with AN consult their general practitioner (GP) significantly more than others in the 5 years prior to diagnosis. 21 A single consultation about eating or weight/shape concerns strongly predicts the subsequent emergence of AN. 22 Although GPs exclusively treat 20% of cases with AN,23 they are often not confident at managing AN,24 and there is usually a considerable delay between a diagnosis being made in primary care and the point when more specialist help becomes available. 25

Many parts of the UK lack NHS provision of specialist services for AN. 26,27 Treatment by non-specialists is problematic as many patients are admitted unnecessarily and for lengthy periods,28 with extra costs to the NHS. 29 For example, 35% of people with AN seen in non-specialist Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) are admitted to hospital, contrasting with only 10% of those seen in specialist ED services. 30 More child and adolescent psychiatric beds (20%) are occupied by young people with AN than any other diagnostic group. 31 Weight gain32 and longer-term outcomes33 are poor in non-specialist units and the mortality is higher. 34,35 Thus, there is a need to disseminate specialist knowledge of this illness. Transitions between services (e.g. from child to adult services, home to university health services, inpatient to follow-up care) are common and can result in fragmented care, thus putting patients at risk. 36,37

Lifetime prevalence rates for AN are 1.6% in women and 0.3% in men. 7 The median duration of illness is 6 years. 38 Physical complications affect all organs39 and the risk of death is the highest of any psychiatric disorder. 40 If they become pregnant the pregnancy is considered high risk and they experience difficulties feeding and playing with their children. 41 Severe psychiatric comorbidity is common. 42 Quality of life is severely impaired,43 more so than in depression. 44 The cost per case of AN is at least that of schizophrenia. 45,46 AN accounts for the highest proportion of admissions of duration > 90 days (26.8%) and the longest median length of stay (36 days). 28 Eating disorders are one of the leading causes of disease burden in terms of years of life lost through death or disability in young women. 47 The family are usually the main carers. They report similar difficulties to carers of people with psychosis, but are more distressed. 25,48 The burden of caregiving and other societal costs have never been examined in economic terms.

This report presents the results of seven independent but integrated work packages (WPs), which form the Applied Research into Anorexia Nervosa and Not Otherwise Specified Eating Disorders (ARIADNE) programme. These WPs focus on optimal disease management for people with AN at all stages of illness, from prevention and detection through to treatment and preventing relapse. The studies focus on a range of populations, including samples from the community, those drawn from inpatient and outpatient settings, as well as specialist groups, such as mothers with an ED and carers of those with an ED. The majority of our WPs focus on building evidence on the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions for these populations, grounded in our clinical neuroscience model of AN. We report on findings from six independent interventions that have been developed and tested by the ARIADNE group during this programme. In addition, we present analyses of the economic and clinical implications of existing care pathways and patterns of service use.

Aims and objectives of the ARIADNE programme

Broad aims

Responding to the need for high-quality research into the management of AN, the overarching aims of the ARIADNE programme were to:

-

produce, validate and disseminate improved evidence-based interventions for AN

-

collaborate with patients and carers throughout the project

-

improve clinical outcomes in AN, by early detection and intervention, by reducing chronicity and relapse, and by improving carer outcomes

-

improve acceptability and cost-effectiveness of AN treatments

-

deliver standardised, trainable and disseminable AN treatments

-

assess service utilisation and NHS costs of AN and implications of changes in clinical practice for patient care and resources.

Objectives

Our objectives were: WP1a, to develop a training programme for school staff to enable them to detect and manage EDs; WP1b, to develop and test a school-based prevention programme for risk factors for EDs; WP2a, to develop an improved treatment for adults with AN that targets disease-maintaining factors, is matched to symptoms, personality and neuropsychological profile and which can be used as a first-line treatment in outpatient settings, and to evaluate the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of this treatment; WP2b, to test and validate components of this treatment, designed as intensive modules for inpatients with AN (i.e. those with severe, chronic or treatment-resistant AN); WP3, to evaluate the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a carer skills training intervention, and to assess its impact on carer outcomes (e.g. distress, caregiving efficacy) and patient outcomes; WP4, to improve understanding of the nature of a debilitating core symptom of AN (i.e. hyperactivity); WP5, to develop and test a relapse prevention programme for inpatients with AN; WP6, to obtain information on the needs of mothers of children with an ED and the risks of the maternal ED for their offspring and to use this information to inform the development of an intervention for mothers with an ED to minimise the impact of their ED on their children; WP7a, to study existing care pathways for AN, with a focus on the impact of having access to specialist ED services; and WP7b, to study service utilisation and cost of illness in EDs.

Patient and public involvement in the ARIADNE programme

Patient, carer and public involvement has been central to the research in the ARIADNE programme. Mrs Susan Ringwood, the Chief Executive Officer of Beat (the main UK patient carer organisation for EDs) was a co-applicant on the programme. As such, she was involved in the development of the overall programme aims, ensuring that the research questions were aligned with patients’ and carers’ needs. Patients and carers were also part of the Programme Steering Group.

Examples of patient and public involvement (PPI) in specific WPs are as follows.

Example 1: early intervention in schools

Wok package 1a involved the development and pilot testing of a teacher training programme for EDs (see Chapter 2). This research was devised and led by a former ED service user. It involved an extensive period of public consultation, which was used to assess the needs of both school staff and school students in this area. Thorough consultation was achieved through online surveys reaching over 800 school staff and over 500 students. Intervention materials for the training programme were then developed using an iterative process in which two panels of school staff (six members per panel) reviewed draft materials and their feedback was incorporated. PPI ensured that the training materials being developed were responding to a genuine need and were aligned with the needs of the school staff that would be using them.

Example 2: prevention

The intervention development in WP1b for the prevention programme (see Chapter 3) was informed by focus groups with 22 adolescent girls, who provided their experiences of body dissatisfaction, disordered eating and their recommendations for a preventative intervention. The intervention materials were then developed in conjunction with a panel of key stakeholders, which included a young person with a history of an ED, two young people without a history of an ED, and three secondary school teachers. Feedback provided by this panel was incorporated into the materials in an iterative process.

Example 3: carers interventions

Work package 3 evaluated an intervention for carers of people with AN, which was used as an adjunct to inpatient treatment (see Chapter 6). It included extensive PPI, with several members of the research team having personal experiences of an ED. The self-help materials (Experienced Carers Helping Others; ECHO) were developed in collaboration with patients and carers. 49 In addition, the majority of telephone coaching sessions offered during the intervention were provided by trained individuals with personal experience of an ED (either having recovered from the disorder themselves or as a carer). The findings from this trial are being disseminated to the public through a website dedicated to carers of those with an ED [URL: www.thenewmaudsleyapproach.co.uk (accessed 3 July 2017)], a newsletter, the database of ED volunteers and the annual carer’s conference which we run with Beat – the main national organisation for people with EDs and their families.

From the above, it is clear that patients and carers were involved in designing the programme, implementing the WPs and disseminating findings. Such collaboration between researchers and service user representatives has been highlighted as exemplifying good practice in service user involvement by the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN). 50

Report structure

The overarching aims of the ARIADNE programme were realised through seven independent, but integrated, WPs which are presented in detail in this report. An outline of the chapters is as follows:

Work package 1: prevention and early intervention

Chapters 2 and 3 focus on prevention, detection and early intervention of EDs. In Chapter 2, we present the development and evaluation of a learning package for school staff on how to recognise symptoms of EDs, how to communicate about EDs sensitively and how to assess risk. Chapter 3 outlines the development of a teacher-delivered prevention programme for EDs, and the results of a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating its efficacy.

Work package 2: treatment

Chapters 4 and 5 focus on treatment of AN. In Chapter 4 we present the evaluation of the Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA) using a large RCT with individuals in an outpatient setting. Chapter 5 explores the use of components of this treatment in an inpatient setting, designed as intensive modules for severe, chronic or treatment-resistant AN. Here, we evaluate this approach through case report, qualitative evaluation and a pilot trial comparing it to treatment as usual (TAU).

Work package 3: carers interventions

Chapter 6 presents an intervention for those caring for individuals with AN. We present findings from a large RCT assessing the impact of a guided self-help intervention for carers of individuals with AN (ECHO), in addition to standard inpatient care. We report on outcomes for both carers and for patients up to 12 months post discharge from inpatient care.

Work package 4: physical activity in anorexia nervosa

Chapter 7 focuses on the assessment of activity levels and endocrine changes in individuals with AN. We present data from an observational study. Individuals with AN (inpatients and outpatients) are compared with individuals with anxiety and healthy controls (HCs) using a range of methods, including body composition, endocrine measurements, self-report and actimetry.

Work package 5: relapse prevention

Chapter 8 focuses on relapse prevention. Here, we present a feasibility RCT on a novel e-mail-guided manual-based intervention to be used in the post-hospitalisation aftercare of patients with AN.

Work package 6: mothers with an eating disorder

In Chapter 9, we present research on mothers with an ED, a special population that may need tailored services. We report findings regarding fertility difficulties in women with an ED, and associations between maternal EDs and their children’s diet and growth trajectories.

Work package 7: care pathways and economic evaluations

Chapter 10 presents results regarding service use, focusing on how access to specialist services affects rates of referrals, admissions for inpatient treatment, continuity of care and service user experiences. Chapter 11 uses data from ARIADNE WPs (WPs 2, 3, 5 and 7a), plus the British Cohort Study (1970) (BCS-70), to identify the costs of services and treatments used by people with AN and to estimate its annual costs for England.

General discussion

Chapter 12 draws together the findings from the seven WPs and highlights clinical implications and recommendations for future research based on this programme.

Chapter 2 The development and feasibility testing of an eating disorders training programme for UK school staff (work package 1a)

Abstract

Work package 1a composed of four studies.

Study 1: 511 school students aged 11–19 years completed an online questionnaire exploring their experiences of EDs at school. Respondents provided actionable recommendations about improvements that could be made.

Study 2: 826 school staff completed an online questionnaire exploring their ED experiences. Participants highlighted a lack of understanding and knowledge within their schools and a willingness to access training and support.

Study 3: 63 members of staff from 29 UK schools participated in focus groups to further develop the themes explored in study 2. Five salient themes emerged from the focus group discussions.

-

There was little general knowledge about EDs among staff.

-

Mental health issues, including EDs, were not openly talked about among staff.

-

School staff do not feel confident or comfortable teaching students about EDs.

-

When they exist, positive relationships with parents contribute to ED recovery, but sometimes relationships with parents are very negative.

-

More support is needed for school staff involved in the care of students undergoing ED recovery.

Study 4: a 1-day training programme for UK school staff aimed at improving attitudes towards, confidence in supporting and knowledge about EDs was tested for feasibility and acceptability, and was found to have a positive, significant impact with medium and large effect sizes (ESs) that were maintained after 3 months.

Introduction

Eating disorders have a high rate of onset during adolescence,51,52 the period during which young people attend secondary/high school. Research indicates that up to 1.5% of secondary school students suffer from a diagnosable eating disorder53–55 and up to 15% experience subclinical eating disturbance. 56 However, many of these cases go undetected and untreated. 57

As students spend an average of 40 hours a week attending school,58 school staff are in a good position to pick up on the physical and behavioural symptoms that are present during the early stages of eating disorders. 59 Furthermore, school staff are well placed to offer ongoing support as young people have indicated that they are up to nine times more likely to talk to a teacher than a parent about food-related difficulties. 60

Work package 1a is a series of interlinked studies designed to understand the current context of EDs in school and use this understanding alongside school staff and student recommendations in the development of a face-to-face training programme. The WP culminated in the training programme being feasibility tested.

Study 1: student experiences of eating disorders within the school setting – an online survey

Methods

First- and second-hand student experiences of suffering with an ED at school were explored using an online questionnaire (see Appendix 1, Student questionnaire), completed by 511 students aged 11–19 years [mean = 15.4 years, standard deviation (SD) = 2.3 years, 72% female]. Note that n varies by question as not all participants responded to all questions.

The questionnaire included free-text responses, which were coded using content analysis. 61,62 A categorisation system was developed by analysing responses and classifying them into categories ,with care being taken to ensure that the coding system was comprehensive, while avoiding overlapping of categories. A second researcher independently applied the categories, blind to the original researcher’s decisions. An inter-rater reliability of 94% was achieved.

Results

Students’ experiences and recommendations

Thirty-eight per cent (n = 195) reported a current or previous ED, although 49% (n = 96) of these students had not received a diagnosis which confirms this. In total, 53% (n = 115) reported being friends with a student suffering with an ED.

Quantitative data are summarised in Table 1. Qualitative data are summarised in Table 2. Below, both forms of data are considered together under three salient themes which emerged during data analysis:

-

recognition of early symptoms

-

encouraging and supporting sufferer help-seeking

-

providing a supportive school environment for recovery.

| Topic | Response | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Could you spot eating disorder warning signs in a friend? (n = 458) | Yes – I have done so before | Yes – I would know the signs | I’m not sure | No | ||

| 257 (56%) | 104 (23%) | 64 (14%) | 33 (7%) | |||

| Have you learnt about eating disorders at school? Was it helpful? (n = 499) | Taught – it was helpful | Taught – it was not helpful | I’ve not been taught | I’m not sure | ||

| 27 (5%) | 124 (25%) | 332 (67%) | 16 (3%) | |||

| What would you do if you spotted eating disorder warning signs in a friend? (n = 505) | I’d help my friend if they came to me | I’d proactively offer my friend my help | I would tell a teacher | I would anonymously tell a teacher | I would talk to a trusted adult outside school | I would watch and wait |

| 137 (27%) | 263 (52%) | 33 (7%) | 15 (3%) | 29 (6%) | 28 (6%) | |

| If you shared your concerns with a teacher, what would you want them to do? (n = 479) | Speak with my friend | Support me in helping my friend | Talk to my friend’s parents | Arrange for support from a counsellor or doctor | Listen | |

| 122 (25%) | 216 (45%) | 11 (2%) | 78 (16%) | 52 (11%) | ||

| If you shared your concerns with a teacher, what would you expect them to actually do? (n = 474) | Speak with my friend | Support me in helping my friend | Talk to my friend’s parents | Arrange for support from a counsellor or doctor | Listen | |

| 106 (22%) | 24 (5%) | 229 (48%) | 50 (11%) | 65 (14%) | ||

| What would be your preferred way of communicating your concerns to a member of school staff? (n = 461) | In person | By telephone | Text/SMS/IM | E-mail/in writing | ||

| 337 (73%) | 5 (1%) | 17 (4%) | 102 (22%) | |||

| Do you consider your school to be a supportive place for someone recovering from an eating disorder? (n = 504) | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

| 12 (2%) | 41 (8%) | 81 (16%) | 133 (26%) | 237 (47%) | ||

| Topic | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How could your school help students understand more about eating disorders? (n = 351) | Psychoeducation | Better services available at school | Talk more openly about eating disorders | Improve teacher knowledge | Be less judgemental |

| 185 (59%) | 68 (22%) | 22 (7%) | 19 (14%) | 18 (7%) | |

| Teachers take more caring approach | School cannot help | Improve access to services in school | Better resources | ||

| 16 (6%) | 10 (4%) | 9 (3%) | 4 (1%) | ||

| How could your school be more supportive to students during eating disorder recovery? (n = 342) | Reduced stigma about eating disorders | Bespoke support | Specialist support | Nothing | Support groups |

| 133 (43%) | 72 (23%) | 46 (15%) | 27 (9%) | 25 (8%) | |

| Confidentiality | Peer mentors | Promote school services | |||

| 20 (6%) | 12 (4%) | 7 (2%) | |||

| How has the school helped you or a friend in response to an eating disorder? (n = 169) | They referred the case to a specialist | Staff were supportive | They spoke to parents | They were flexible re schooling | They provided on-going support |

| 67 (22%) | 63 (20%) | 19 (6%) | 10 (3%) | 10 (3%) | |

| Have you had any negative school-based experiences in response to an eating disorder? (n = 321) | No one noticed | I was punished | I was not appropriately consulted | I did not get the specialist help I needed | Staff broke my confidence |

| 89 (27%) | 31 (10%) | 31 (10%) | 27 (8%) | 21 (6%) | |

| Judgemental | Lack of knowledge | Problems with the services | Negative experience not expanded upon | ||

| 12 (4%) | 10 (3%) | 8 (2%) | 92 (28%) | ||

Recognition of early symptoms

Seventy-nine per cent (n = 361) of students surveyed were confident that they would recognise the symptoms of an ED in a friend. Thirty per cent of students had been taught about EDs as part of a planned programme of study at school, but this was not generally well received, with 82% (n = 124) reporting that these lessons could have been better.

Fifty-nine per cent (n = 185) of students surveyed recommendeded that ED education be improved for both students and their teachers. In free-text responses, 16% (n = 46) of students stated that school staff had minimal or no knowledge about EDs. Reducing stigma and enabling friends to recognise and respond to early symptoms were the key motivators outlined in responses.

Encouraging and supporting sufferer help-seeking

Students expressed a reluctance to highlight ED concerns about a friend with a teacher, with only 7% (n = 33) of students stating they would be happy to do so. Several barriers for this type of help seeking emerged including:

-

fear a teacher would dismiss their concerns

-

fear a teacher would over-react to their concerns

-

fear that a teacher would not treat their concerns in confidence.

When school staff help was sought, students shared a clear preference for face-to-face discussions (73%; n = 337) above writing/e-mail (22%; n = 102), or sharing concerns via telephone/text (5%; n = 22).

The positive impact of school staff on student outcomes was shared by 49 respondents. Four students claimed that the support provided by school staff was instrumental in preventing them from dying as a consequence of their ED.

Providing a supportive school environment for recovery

Seventy-three per cent of respondents (n = 370) did not view their schools as a supportive environment for facilitating recovery from an ED. Key reasons cited were:

-

bullying from peers

-

poor reintegration into school

-

staff uncertainty about how to support.

Students whose experiences had been more positive outlined the important role of the school and school staff in their recovery. When asked to describe the ideal approach from school staff, respondents highlighted their desire for honesty (n = 71), openness (n = 19), a non-judgemental approach (n = 23) and someone who felt approachable (n = 29).

Discussion

This was the first UK study of student experiences of EDs. Respondents provided valuable insight into the experiences of UK school students with EDs and, further, provided actionable recommendations about improvements that could be made.

A strength of the study was that both male and female students were surveyed, which has not previously been the norm. 64 Future work could explore moderators (e.g. gender, school type) of student experiences.

The opportunity for students to recognise and respond to early ED symptoms in their friends, and for schools to provide a safe and supportive recovery environment, was clearly highlighted by respondents. However, it is clear that more work needs to be done if this potential is to be realised in UK schools. Psychoeducation and training for students and teachers was suggested by respondents as a key method for addressing this.

Study 2: school staff experiences of eating disorders within the school setting – an online survey

Methods

A total of 1250 UK school staff were invited to respond to an anonymous online survey exploring their experiences of EDs within the school setting (see Appendix 1, Staff questionnaire). A total of 826 (66%) of the convenience sample chose to participate.

Free-text responses were analysed using content analysis. 61,62 A categorisation system was developed by analysing responses and classifying them into categories, with care being taken to ensure that the coding system was comprehensive while avoiding overlapping of categories. A second researcher independently applied the categories, blind to the original researcher’s decisions. An inter-rater reliability of 89% was achieved (κ = 0.471; p < 0.001).

Results

Multiple-choice questions generated quantitative data, which have been summed and recorded in Table 3. Content analysis was used to interrogate the large amount of qualitative data produced in the form of free-text responses to open questions. This is summarised in Table 4.

| Topic | Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is there an eating disorders policy at your school? (n = 774) | No | Yes – within another policy | I’m not sure | Yes – we have a specific policy |

| 320 (41%) | 208 (27%) | 205 (26%) | 41 (5%) | |

| Do you think eating disorders policies are effective? (n = 519) | Very effective | Effective | Ineffective | Very ineffective |

| 42 (8%) | 317 (61%) | 148 (29%) | 12 (2%) | |

| Have you been offered eating disorders training at school? (n = 791) | No | Yes | ||

| 583 (74%) | 208 (26%) | |||

| Who was the training for? (n = 147) | Specialist staff members (three or fewer) | All school staff | All pastoral staff | All senior and middle leaders |

| 82 (56%) | 43 (29%) | 19 (13%) | 3 (2%) | |

| How was the training delivered? (n = 161) | Seminar | Lecture | Written materials | |

| 107 (66%) | 37 (23%) | 17 (11%) | ||

| If you have not received any training, do you think you would find eating disorders training useful? (n = 346) | Very useful | Quite useful | Not very useful | Not at all useful |

| 160 (46%) | 156 (45%) | 30 (9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Are there any current or past eating disorders cases in your school? (n = 530) | Yes, I am directly involved with at least one case | Yes, but I am not directly involved | No | |

| 266 (50%) | 181 (34%) | 83 (16%) | ||

| At your school, what should a student do if they are worried a friend may have an eating disorder? (n = 781) | They can talk to any member of the school’s staff | This is something that has never been discussed/agreed | There is a specific member of staff they should speak to | There is a system in place for anonymously raising concerns |

| 364 (47%) | 287 (37%) | 112 (14%) | 18 (2%) | |

| How comfortable would you feel teaching students about eating disorders? (n = 785) | I would feel very uncomfortable | I would feel uncomfortable | I would feel comfortable | I would feel very comfortable |

| 419 (54%) | 273 (35%) | 84 (11%) | 9 (1%) | |

| Has your school ever had to reintegrate a student after a period of absence caused by an eating disorder? (n = 487) | Yes we have | No we have not | ||

| 329 (68%) | 158 (32%) | |||

| Did you receive any guidance about how to support students returning following a period of absence? (n = 317) | Yes we did | No we did not | ||

| 240 (76%) | 77 (24%) | |||

| Topic | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived benefits of eating disorders training that had been completed (n = 142) | An increase in confidence supporting eating disorders | I learned how I can support someone with an eating disorder | I now know what warning signs to look out for | It was good to share ideas with other people | Nothing specific just generally useful |

| 39 (27%) | 31 (22%) | 21 (15%) | 15 (11%) | 14 (10%) | |

| Learned about referral processes | Raised awareness of ED | Not useful | |||

| 12 (8%) | 7 (5%) | 3 (2%) | |||

| How could the training have been improved (n = 96) | If it was more in depth | If it had been available to more staff | Booster sessions | The use of real case studies | Nothing the training was comprehensive |

| 24 (25%) | 17 (18%) | 10 (10%) | 10 (10%) | 7 (7%) | |

| More practical suggestions about how to support | If it was more tailored to a student causing concern | A better teacher | Information about developing policies or making referrals | Being taught in a smaller group | |

| 7 (7%) | 6 (6%) | 6 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 4 (4%) | |

| What staff would do next if worried that a student might have an eating disorder (n = 782) | I’m not sure | I’d refer to my school’s policy | I would ask a more experienced colleague | I would speak with the pupil | I would talk to the pupil’s parents |

| 316 (40%) | 168 (21%) | 146 (19%) | 107 (14%) | 25 (3%) | |

| I would make an external referral | I would watch and wait | ||||

| 13 (2%) | 7 (1%) | ||||

| Reasons given for feeling uncomfortable teaching students about eating disorders (n = 546) | Too little knowledge of the topic | Fear of iatrogenic effects | It’s not necessary as students have a good understanding | I would not know how to manage disclosures | |

| 312 (57%) | 109 (20%) | 64 (12%) | 61 (11%) | ||

| How parents have responded to being told their child has an eating disorder (n = 781) | Parent has responded with denial or refusal to speak to us | Both positive and negative reactions | Difficult at first but relations improved | Parents have been angry accusing us of criticising their parenting | |

| 364 (47%) | 287 (37%) | 112 (14%) | 18 (2%) | ||

| Support that staff suggested would be helpful during the reintegration of a student with an eating disorder into school (n = 105) | Tailored information based on the specific student’s needs | More or better training than is currently provided | More people should be involved in training (including e.g. parents, students) | Training should be provided for all relevant staff | Specialist support and advice on an ongoing basis |

| 30 (29%) | 25 (24%) | 17 (16%) | 13 (12%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Students need to be supported in the run up to their friend’s return | Other | ||||

| 8 (8%) | 4 (4%) | ||||

Below, both forms of data are considered together under four salient themes which emerged during data analysis:

-

supporting students with EDs

-

ED training and policies

-

teaching about EDs

-

reintegrating students who were absent as the result of an ED.

Supporting students with eating disorders

Only 40% (n = 316) of respondents stated that they would feel confident following up ED-related concerns in a student.

Eating disorders training and policies

Sixty-one per cent (n = 317) of respondents found policies to be an effective tool within schools. Despite this, only 32% (249) of respondents reported that their school had a policy that made any reference to EDs and, of these, only 5% (n = 41) were specific ED policies.

Thirty-one per cent (n = 160) of respondents found school policies to be ineffective in most cases. This was attributed to a lack of understanding of the role of frontline staff by senior leaders who developed policies.

The majority of respondents (74%; n = 583) reported that their school had never provided training about EDs. Ninety-one per cent (n = 316) of respondents who had not been trained said that they would welcome the opportunity.

Twenty-six per cent (n = 208) of respondents reported that their school had provided training. In most instances (56%; n = 82) this was for specialised groups of three or fewer staff.

Those staff who had received training outlined a range of benefits, including:

-

an increase in confidence (27%; n = 39)

-

practical strategies (22%; n = 31)

-

awareness of early symptoms (11%; n = 15).

They also outlined suggestions for improvement, including:

-

greater depth (25%; n = 24)

-

more widely available (18%; n = 17)

-

booster sessions (10%; n = 10).

Teaching about eating disorders

Eighty-nine per cent (n = 692) of respondents reported that they would not feel comfortable teaching their students about EDs. Reasons given for this included:

-

they lacked the appropriate knowledge (57%; n = 312)

-

fear of iatrogenic effects (20%; n = 109)

-

students’ knowledge exceeded teacher knowledge (n = 64; 12%)

-

uncertainty about how to manage resulting disclosures (n = 61; 11%).

Reintegrating students who were absent as the result of an eating disorder

Sixty-eight per cent (n = 329) of respondents reported that their school had reintegrated one or more students following absence caused by an ED. Twenty-four per cent (n = 77) of these reported receiving no training, support or advice about how best to manage this transition.

Those who had received support outlined suggestions for improvement including:

-

training more heavily tailored to the needs of the specific returning student (24%; n = 25)

-

training for a wider range of people including parents and students as well as the teachers (16%; n = 17).

Discussion

This was the first UK study of school experiences of EDs. Respondents provided valuable insight into the experiences of UK school staff with EDs and, further, provided actionable recommendations about improvements that could be made.

Study 3: recommendations from school staff about spotting and supporting eating disorders

Methods

Participants for study 3 were recruited from those in study 2. Of 826 respondents in study 2, there were 109 expressions of interest in participating in further studies. Sixty-three of these went on to take part in the focus groups conducted in study 3.

A total of eight focus groups were held with 63 members of school staff from 29 schools in the UK. Topic guides were developed to explore school staff experience and opinion with relation to:

-

school culture

-

knowledge of school staff about EDs

-

understanding of school staff about EDs

-

communication with students

-

support strategies

-

working with parents

-

working with external agencies.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Following initial familiarisation with the transcripts, a categorisation system was developed using content analysis. 61,62 Transcripts were analysed and classified into categories, with care being taken to ensure the categorisation system was comprehensive while avoiding overlapping of categories. The transcripts were independently catergorised by two researchers and inter-rater reliability was 87%, with a few minor discrepancies caused by one researcher applying more categories to some items than the other. There were no instances of the two researchers failing to agree on the primary category for a transcript section.

Results

Five salient themes emerged from the focus group discussions:

-

There was little general knowledge about EDs among staff.

-

Mental health issues, including EDs, were not openly talked about among staff.

-

School staff do not feel confident or comfortable teaching students about EDs.

-

When they exist, positive relationships with parents contribute to ED recovery, but sometimes relationships with parents are very negative.

-

More support is needed for school staff involved in the care of students undergoing ED recovery.

These themes are outlined briefly below. An extended discussion, including supporting quotes, is provided by Knightsmith et al. 65

There was little general knowledge about eating disorders among staff

In general, the staff attending the focus groups stated that their own knowledge of EDs was relatively good, but that this was not reflected in colleagues throughout the staff body. Staff reported a lack of knowledge of the major types of EDs and their symptomology.

Staff also reported a lack of misunderstanding of EDs, with many colleagues belieivng that EDs are a teenage phase students will grow out of. Colleagues were reported not to realise that EDs are mental health issues that frequently require specialist medical and psychological intervention.

Mental health issues, including eating disorders, were not openly talked about among staff

Participants frequently reported a lack of open discusion about mental health issues, including EDs, at their schools. Many cited a fear of iatrogenic effects of discussing EDs either among staff or with students, whereas others shared senior management concern that being seen to be focusing on EDs would result in potential students and parents gaining a negative impression of the school.

School staff do not feel confident or comfortable teaching students about eating disorders

Staff expressed a lack of confidence and knowledge about how to talk safely to students about EDs, both in the context of speaking directly to sufferers and in the context of teaching students about EDs as part of a structured curriculum. Staff feared saying or doing the wrong thing and in so doing promoting ED behaviours either in students during their recovery or among the general student population.

When they exist, positive relationships with parents contribute to eating disorder recovery, but sometimes relationships with parents are very negative

Participants highlighted the importance of the role of the parent during recovery and the need for schools and parents to work closely together during the period of recovery. However, many staff also outlined incidents that illustrated very negative school–parent relationships. Negative responses were reported most often as a result of the initial disclosure from school to parents about a child’s ED and negative reactions from parents included:

-

parents seeing the school as interfering unnecssarily

-

parents believing that the school was accusing them of poor parenting

-

parents suggesting that the school was over-reacting.

Focus group participants highlighted the importance of the initial conversation with parents as a key time for setting the tone for the school–parent relationship.

More support is needed for school staff involved in the care of students undergoing eating disorder recovery

Focus group participants highlighted the need for further support for school staff during the recovery period. They expressed a need for practical guidance on a range of topics including:

-

student participation in sports, exercise or physical education lessons

-

supporting mealtimes

-

academic expectations including expectations around homework.

Discussion

Focus group participants provided detailed, actionable insights into the current of confidence, understanding, knowledge and attititudes of UK school staff from a range of geographically and socioeconomically diverse schools.

Although the group reported themselves to be more than usually interested in and informed about EDs and other mental health issues, they drew widely on the knowledge, experience and attitudes of colleagues during the course of the focus groups.

Development of content and outcome measures

A day-long training programme for school staff on the topic of EDs was developed in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Behaviour Change: The Principles for Effective Interventions. 66 Data from studies 1–3 were drawn on significantly during programme development. Furthermore, school staff and clinicians were heavily involved in the authoring and piloting of training materials to ensure that the resulting training programme was relevant and practical for use within a UK school setting, while also drawing on the most recent evidence-based practice.

Content outline

Based on school staff feedback about what is feasible in terms of in-service training days, the intervention was designed to be delivered in four 90-minute sessions, which could be delivered within the space of 1 day.

Each 90-minute session had clearly designed objectives and focus. These were:

-

session 1 – EDs introduction

-

session 2 – when and how to talk to students causing concern

-

session 3 – working with parents, staff and students

-

session 4 – providing a supportive environment during recovery.

Outcome measures

An outcome measure of school staff ED attitude, confidence and knowledge was developed for use during the current study as there was no existing tool. The new tool drew on existing measures of GP attitudes,67 and the feedback of school staff and students shared in studies 1–3.

A self-report style tool was developed which captured attitudes, confidence and knowledge about EDs. A copy of the self-report measure is included in Appendix 1, Eating disorders attitudes and knowledge questionnaire.

Study 4: feasibility study of a 1-day eating disorders training programme for UK secondary school staff

Methods

Forty-five members of UK school staff completed a 1-day face-to-face training programme designed to improve their knowledge about, attitudes towards and confidence in managing EDs. Participants completed self-report measures of knowledge, attitudes and confidence at the beginning of the day, before training commenced (T1, baseline), at the end of the day, once training was completed (T2, post intervention) and again 3 months later (T3, follow-up).

The significance of intragroup changes was determined using generalised estimating equation models.

Results

The full results of the statistical analyses are shown in Tables 5 and 6. There was a statistically significant improvement (all p-values < 0.001) in participants’ self-reported knowledge, attitude and confidence scores post intervention (T2) compared with baseline (T1), with a large ES on all three comparisons. 68 These differences were maintained at the 3-month follow-up (T3) and there was no significant difference between the knowledge, attitude or confidence scores measured post intervention (T2) and at the 3-month follow-up (T3).

| Measure | Time point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (T1) | Post intervention (T2) | Follow-up (T3) | ||||

| n | Mean (SE) | n | Mean (SE) | n | Mean (SE) | |

| Knowledge | 45 | 17.1 (0.76) | 45 | 29.9 (0.78) | 45 | 29.3 (0.76) |

| Attitude | 45 | 29.9 (0.17) | 45 | 37.9 (0.56) | 45 | 37.2 (0.53) |

| Confidence | 45 | 24.9 (1.44) | 45 | 48.7 (1.40) | 45 | 47.0 (1.38) |

| Measure | β | ES | 95% CI | Hypothesis test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Sig. | |||

| Baseline (T1) to post intervention (T2) | |||||

| Knowledge | 12.8 | 0.8 | 11.3 | 14.4 | < 0.001 |

| Attitude | 8.1 | 0.8 | 7.0 | 9.1 | < 0.001 |

| Confidence | 23.8 | 0.8 | 21.2 | 26.4 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline (T1) to follow-up (T3) | |||||

| Knowledge | 12.2 | 0.7 | 9.9 | 14.5 | < 0.001 |

| Attitude | 7.4 | 0.8 | 6.3 | 8.4 | < 0.001 |

| Confidence | 22.1 | 0.8 | 17.9 | 26.3 | < 0.001 |

Participants all completed a post-course evaluation form designed to assess the acceptability of the intervention. All delegates (n = 45) considered the course either good (16%) or very good (84%) in terms of course content, course materials and for providing practical strategies they could use at school.

Discussion

A 1-day training programme for UK school staff aimed at improving attitudes towards, confidence in supporting, and knowledge about EDs was tested for feasibility and acceptability and was found to have a positive, significant impact with medium and large ESs, which were maintained after 3 months. However, the study was limited by the use of outcome measures, which were entirely subjective/self-reported and in the lack of a longer-term measure of maintenance of positive outcomes.

General discussion

Strengths

All four studies conducted as part of this WP were the first of their type within the UK setting. The contribution of male viewpoints is a significant strength of the current work as this has not previously been the norm. 64 A further strength of the studies was the large number of participants for studies of this type (511 student survey responses in study 1 and 826 school staff responses in study 2), and the depth of responses provided by these participants. A key strength of study 4 was the immediate and lasting impact of the intervention on participant attitudes, confidence and knowledge about EDs despite its brevity. A programme that took longer to deliver or the effects of which were not lasting would not be feasible or relevant for use in UK schools. Data collection at baseline, post intervention and 12 weeks post intervention is recommended, but not widely practised. 69,70

Limitations of the studies

It was not feasible to include both experimental and control groups within each school participating in study 4 owing to the possibility of trial arm contamination resulting from sharing of information between school staff, especially post intervention. In future studies, a stepped-wedge design could be employed to overcome this, with every participant completing both the control and intervention conditions.

The positive outcomes reported from study 4 in terms of an improvement in staff attitudes, confidence and knowledge were based entirely on self-report measures. Future studies could include some additional objective measures.

Study 4 looked only at school staff outcomes; the impact of the intervention was not extrapolated to explore the impact on student outcomes. Similar studies have similarly failed to provide such evidence,69,70 but appropriate measures should be considered for inclusion in future studies.

Future directions

The implementation of a fully powered stepped-wedge design in order to fully test the training programme developed in study 4 is a key future direction. Another possibility for exploration is the development of online training materials that could be accessed remotely in order to increase the reach and cost-effectiveness of the programme.

Conclusions

The aim of the current WP was to develop and feasibility test an ED training programme for school staff aimed at improving attitudes, confidence and knowledge.

This aim was achieved through a series of studies that drew extensively on the experiences and understanding of UK school staff and students in relation to EDs.

The work of all four studies was unique within the UK setting and the outcomes were promising and provide clear pathways for future research.

Chapter 3 Body image in the classroom: developing and testing a teacher-delivered eating disorder prevention programme using a clustered randomised controlled trial (work package 1b)

An abbreviated version of this chapter has been published in the British Journal of Psychiatry. 71

Abstract

Objectives

To design and evaluate a universal prevention programme for EDs in secondary schools.

Trial design

Clustered RCT comparing intervention lessons with curriculum-as-usual control.

Participants

Students in years 8 and 9.

Intervention

Six-session Me, You & Us programme delivered by teachers.

Outcomes

Questionnaires at baseline, post intervention and at the 3-month follow-up, assessing body esteem (primary outcome), eating pathology, thin-ideal internalisation, appearance conversations, peer support, depressive symptoms and self-esteem.

Randomisation

Unrestricted randomisation of intact classes using random number generator.

Blinding

Teachers, students and researchers were not blinded to group assignment.

Numbers randomised

Sixteen classes were allocated to the intervention (nine classes, 261 students) or control group (seven classes, 187 students). No participants dropped out.

Results

There were significant between-group differences in body esteem favouring the intervention group at post intervention (d = 0.12) and 3-month follow-up (d = 0.19). There were also significant between-group differences in thin-ideal internalisation (d = 0.17, maintained at follow-up, d = 0.16) and self-esteem (d = 0.20, not maintained at follow-up). There were no between-group differences for the other outcomes. Fidelity to intervention material and acceptability of the programme varied across the three schools.

Harms

There was no evidence of reduction in body esteem.

Conclusions

The Me, You & Us programme improved body esteem, thin-ideal internalisation and self-esteem, but no other outcomes. Further work to increase efficacy across the range of outcomes and improve fidelity would be valuable.

Trial registration

Current Controlled Trials International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) 42594993.

Introduction

Eating disorders are valuable targets for prevention because they are linked with poor outcomes, elevated mortality rates and associated personal and financial costs. 72–77 Universal prevention programmes are a useful element of the prevention portfolio as they allow us to tackle elements of the social environment that are known to be risk factors for EDs, such as perceived pressure from peers towards thinness. 78,79 Universal interventions also do not face some of the difficulties of selective programmes, namely the stigma associated with participating and the low uptake of those identified as being at risk. 80

Secondary school teachers are in a unique position to deliver prevention material widely and with minimal costs, as they have regular contact with almost all of the adolescent population. However, given the difficulties of achieving randomisation in the school setting, very few teacher-delivered interventions have been evaluated by means of a RCT,81–86 and none have done so within the UK. In addition, several of these trials have small sample sizes making them underpowered. 82,85,86 The current state of evidence regarding the efficacy of teacher-delivered interventions for eating disorders is therefore very poor. Given the potential scope for these universal interventions, this lack of high quality evidence is problematic.

In 2012, the UK All Party Parliamentary Group on Body Image recommended that all schools (primary and secondary) include mandatory lessons on body image in response to the high levels of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in the adolescent population. 87 However, the lack of evidence base in this field means that teachers and school staff are unable to make evidence-based decisions about how best to implement this recommendation. This has resulted in some programmes, such as Media Smart [developed by the Advertising Standards Agency, URL: www.mediasmart.org.uk/resources/bodyimage (accessed 3 July 2017)] being widely disseminated without any evidence for their efficacy. This is problematic as, aside from the potential for wasted resources, some trials of interventions for eating disorders88 and depression89 in schools have found evidence of detrimental effects. There is therefore a need for safe and effective, evidence-based eating disorder prevention programmes that are deliverable by school teachers.

This study describes the evaluation of a universal teacher-delivered eating disorder prevention programme called ‘Me, You & Us’. The intervention material was based on identified risk factors for EDs and body dissatisfaction:6,90,91 thin-ideal internalisation, appearance conversations with friends, negative affect and low self-esteem. Intervention development was supported by a panel of experts and stakeholders, including PPI representatives; clinicians and researchers specialising in EDs; teachers and school nurses; and young people with and without a history of EDs.

In addition, three focus groups with 21 adolescent girls were used to determine young people’s experiences of body dissatisfaction and eating pathology, their understanding of the aetiology of these problems, and their recommendations for preventative strategies. These groups revealed that young people largely endorse a sociocultural approach to body dissatisfaction and EDs, in which media literacy and building networks of support are seen as helpful. These recommendations informed intervention development with the aim of improving the acceptability of the material produced.

Based on this review of empirical literature, including previous universal interventions, and the consultation period, a facilitator’s guide and student workbook were developed (Sharpe H, Treasure J, Schmidt U. King’s College London, London. Me, You & Us: Facilitator’s Guide. Unpublished manual; 2011). There were six interactive 50-minute lessons, with the following topics.

Lessons 1 and 2: media literacy

The aim of the first two lessons was to help participants to critique media presentations of ideal beauty through exploring how conceptions of beauty have varied over time and place, what messages are hidden in media images and how to take action.

Lessons 3 and 4: fat talking

Lessons 3 and 4 focused on perceived peer pressure towards thinness, introducing the concept of fat talking, and examining why we might fat talk as well as possible consequences. The lessons went on to challenge negative appearance-related commentary through exploring the giving and receiving of compliments.

Lessons 5 and 6: personal strengths and well-being

The remaining lessons focused on tackling negative affect and low self-esteem, through learning about personal strengths and how to use them. Simple exercises to promote well-being were explored in the final lesson, including writing a gratitude letter and carrying out small acts of kindness.

Aims and hypotheses

The aims of this study were to assess the efficacy, feasibility and acceptability of Me, You & Us, a teacher-delivered universal prevention programme for EDs. The following hypotheses were generated.

Main hypothesis

-

Students receiving the intervention will show significant improvements in body esteem, internalisation, peer support, appearance conversations, depressive symptoms, self-esteem and eating pathology compared with students in the control group at post intervention and at a 3-month follow-up.

Subsidiary hypotheses

-

Students will find the material in the intervention acceptable, in that they will report enjoying the lessons and perceive them as useful.

-

It will be feasible to train secondary school teachers to deliver an ED prevention programme from a manual and student workbook with high fidelity.

The aims of the trial were to determine the acceptability, feasibility and efficacy of this universal prevention programme for EDs.

Methods

Trial design

The study used a cluster RCT design with intact classes of students allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio to intervention or control arms (trial registration: ISRCTN42594993, including protocol).

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Participants were adolescents in years 8 and 9 in a secondary school in the UK. Secondary schools provided the point of access to participants. Schools were eligible to take part if they:

-

were based in the UK

-

had classes of students in years 8 and/or 9

-

had a sufficiently flexible timetable to manage random allocation of lessons to participating classes.

Participants were eligible to take part if they:

-

attended years 8 or 9 in a participating secondary school

-

were deemed by a member of school staff (head teacher, form teacher, school nurse) to have sufficient English language reading ability to be able to comprehend consent procedures and manage written questionnaires.

Settings and location of data collection

All data were collected within the school setting. School staff administered questionnaires within regular school hours, based on protocols provided by the researcher. Data collection took place between September 2011 and May 2012.

Intervention

The programme involved six 50-minute lessons which teachers delivered to existing classes. The intervention content was described in a Facilitators’ Manual and Student Workbook, both of which are available from the first author (HS). As discussed above, the material targeted risk factors for EDs and body dissatisfaction, namely thin-ideal internalisation, peer factors, depression and low self-esteem. 6,91 Participating teachers received a standardised 2-hour session, involving education about EDs and introduction to the Me, You & Us manual.

The control group received their usual curriculum. The content of these lessons was not determined by the research team.

Outcomes

Age, ethnicity and parental education were provided by participant self-report 1 week before the intervention began (‘pre-intervention’). Participants also completed an ED screening tool, the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale,92 which identifies Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for AN, bulimic nervosa and binge ED.

All primary and secondary outcome measures were administered at pre-intervention, 1 week following the intervention period (‘post intervention’) and at approximately 3 months following the intervention period (‘3-month follow-up’).

Primary outcome

Body esteem

Body esteem was assessed using the Body Esteem Scale for Adults and Adolescents,93 a 23-item self-report measure in which participants have to rate the frequency with which they agree with statements about confidence with their appearance on a five-point Likert scale. Note, that higher scores represent greater body esteem (i.e. lower body dissatisfaction).

Secondary outcomes

Presence of binge eating

The presence of binge eating was assessed using the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale92 and was defined as self-reported binge eating with loss of control at least once a week for 3 months.

Presence of compensatory behaviours

Compensatory behaviours were also assessed using the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale92 and were defined as self-reporting of at least one of the following behaviours at least once per week for 3 months: vomiting, laxative/diuretic use, meal skipping or excessive exercise.

Thin-ideal internalisation

The extent to which participants adhered to the media portrayal of the ideals of thinness was assessed using the General Internalisation subscale of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearances Scale-3. 94 The General Internalisation subscale consists of nine items about appearances and the media (TV, magazines, films), such as ‘I would like my body to look like the models who appear in magazines’, with which participants have to agree or disagree on a five-point Likert scale. Higher scores represented greater thin-ideal internalisation.

Appearance conversations with peers

The frequency with which participants engaged with friends on the topic of appearances was measured using the Appearance Conversations with Friends Scale. 95 The five items are designed to assess ‘how often students talked with their friends about expectations for their bodies and for appearance enhancements’,95 and take the form of statements such as ‘my friends and I talk about the size and shape of our bodies’, with which participants have to agree or disagree on a five-point Likert scale. Higher scores represent more frequent appearance conversations.

Peer support

Perceived social support was measured using the Friend subscale of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. 96 This four-item scale assesses perceived support from friends through responses on a seven-point Likert scale to items such as ‘My friends really try to help me’. Higher scores represented greater perceived social support.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Depression subscale of the short version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21). 97 The DASS-21 Depression subscale is a seven-item scale in which participants are required to state how often particular statements, for example ‘I felt that I had nothing to look forward to’, applied to them over the past week. Higher scores represent greater depressive symptoms.

Self-esteem

A single item – ‘How positive do you feel about yourself?’ – was used to assess self-esteem. Participants were required to respond on a five-point Likert scale from ‘Not at all positive’ to ‘Very positive’. Higher scores represent higher self-esteem.

Acceptability

The programme’s acceptability was assessed using two five-point Likert scales. The first asked ‘How much did you enjoy Me, You & Us?’, and the second asked ‘How useful did you find Me, You & Us?’. The Likert scales ranged from ‘Not at all’ to ‘Very much’. Higher scores represent greater acceptability.

Fidelity to intervention guide

In order to determine fidelity to the intervention manual, two lessons were observed and rated in each school against adherence to planned content. Each activity in the Facilitator’s Guide was scored as ‘completed’ or ‘not completed’. Free text was used to note whether or not any additional material was covered.

Sample size

To account for clustering, the sample size calculation was increased by an inflation factor [1 + (average cluster size – 1) intracluster correlation (ICC)]. The inflation factor for this trial was based on a small ICC (ICC = 0.05). 98 With an average class size of 28 students the estimated inflation factor was 2.35.

G*Power 3 (University of Düsseldorf) was used for sample size calculations. 99 Assuming a 1 : 1 ratio, a small ES (d = 0.20)100 and power set to 0.80, the basic sample size requirement was 394 participants per group, which increased to 926 per group when the estimated inflation factor was taken into account.

Randomisation and blinding

Intact classes were randomly allocated to intervention and control arms. As classes were enrolled into the trial, an unrestricted random allocation was generated by an online random number generator. 101 One researcher (HS) carried out the enrolment of classes, the generation of the random allocation sequence and the allocation of classes to conditions. Participants’ allocation in trial arm was based on their class membership. Informed consent for participants was obtained from all participants’ parents/carers following randomisation. In addition, participants provided written assent post randomisation, when completing the pre-intervention questionnaire measures.

The trial design precluded blinding of school staff or students participants as intervention materials, such as the student workbooks, would have been identifiable to staff and students as being distinct from their usual curriculum. Researchers were also unblinded.

Statistical analyses

Full details of statistical analyses, including managing of missing data, are reported by Sharpe et al. 71 All analyses were based on originally assigned groups. The main hypothesis was tested using linear and logistic mixed-effects models. Two continuous outcomes that were not normally distributed (depression, peer support) were dichotomised for all analyses.

In addition to significance testing, ESs (d) for continuous outcomes were calculated using the differences in adjusted means at each time point. Reliable and clinically significant changes were also computed102 using reliability data and clinical cut-off points from previous work. 103

Results

Participant flow and characteristics

Three schools agreed to participate in the trial. One additional school refused participation because it did not want to trial previously untested resources. Each of the schools was state maintained and had 100% female intake. The three schools varied in their average level of deprivation (free school meal eligibility ranged from 2% to 24%), and in the ethnic background of their students (the percentage of students from black and ethnic minority backgrounds ranged from 28% to 77%). Random allocation of 16 intact classes from year 8 or 9 in these schools resulted in nine classes allocated to the intervention arm and seven classes allocated to the control arm. Of the 479 students from these classes, 31 were excluded because of lack of parental consent. This resulted in 261 students in the intervention arm and 187 students in the control arm. Between 92% and 98% of students provided data at each data collection point. All missing data were due to school absence. No participants withdrew from the trial.

There were no significant differences between the two trial arms at the beginning of the trial. Participants had a mean age of 13.06 (SD = 0.59) years in the intervention group and 12.99 (SD = 0.54) years in the control group. Equal proportions of participants came from ethnic minority backgrounds (intervention = 47%, control = 53%), and had parents with university-level education (intervention = 76%, control = 78%). There was also no difference on reports of body esteem (intervention: mean = 2.30, SD = 0.75; control: mean = 2.27, SD = 0.70), or across any of the other clinical outcomes for the trial. Eight participants scored above the cut-off point in the ED screening tool and so were excluded from analyses on the grounds that the aim of the programme was prevention of future difficulties.

Acceptability and feasibility

Students in the intervention arm were asked to rate how useful and enjoyable they found the lessons in the intervention. The results are shown in Table 7. Looking across both ratings of lessons being enjoyable and useful, the acceptability are notably higher in two schools (A and C) compared with the third school (B). Whereas few students (3–16%) in schools A and C rated the programme negatively, this figure was nearer 50% for school B.

| Acceptability | School, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 31) | B (n = 79) | C (n = 80) | |

| Enjoyable | |||

| Negative | 3 | 48 | 9 |

| Neutral | 34 | 36 | 48 |

| Positive | 63 | 16 | 43 |

| Useful | |||

| Negative | 10 | 51 | 16 |

| Neutral | 39 | 30 | 41 |

| Positive | 51 | 19 | 43 |

These findings mirror the results of the feasibility assessment, in which the teachers’ fidelity to the intervention manual was assessed. A greater amount of intervention content was delivered in schools A and C than in school B (78% activities rated as ‘completed’ in schools A and C compared with 50% in school B). School B did not deliver material outside the programme, but instead took longer to complete each activity, meaning that fewer activities were completed within the set lesson time.

Body esteem

Results from the mixed-effects models showed an overall marginal effect of the intervention on improvements in body esteem [β = 0.09, standard error (SE) = 0.05; p = 0.08]. Post hoc analyses at each time point showed a marginal difference between the groups post intervention (intervention: mean = 2.31, SE = 0.32; control: mean = 22.2, SE = 0.39; p = 0.07) and a significant difference between the groups at the 3-month follow-up (intervention: mean = 2.37, SE = 0.32; control: mean = 2.22, SE = 0.39; p = 0.006). In each case the results favoured the intervention over the control condition. The ESs for these group differences were small (d = 0.12–0.19).

Reliable and clinically significant change from baseline to post intervention was calculated separately for those above and below the clinical cut-off point at baseline. As this was a community sample, few participants were above the clinical cut-off point at baseline (n = 60). Of those above the cut-off point initially, 50% (n = 17) of participants in the intervention group showed clinically significant improvement, compared with 38% (n = 10) in the control group. However, this difference was not statistically significant [χ2(1) = 0.79; p = 0.37]. When considering reliable change, 32% (n = 11) of participants in the intervention group showed reliable improvement, compared with 8% (n = 2) in the control group. This difference was statistically significant [χ2(1) = 5.97; p = 0.02].

Considering those participants that began the trial in the normal range for body esteem, it was notable that there were no participants that experienced clinically significant worsening of symptoms. Some participants did, however, show reliable improvements in body esteem. In the intervention group, 12% participants (n = 20) experienced reliable improvement compared with 4% in the control group (n = 4). This difference was statistically significant [χ2(1) = 6.58; p = 0.01].

Secondary outcomes

A linear mixed-effects model for continuous secondary outcomes showed that there was a main effect of group for thin-ideal internalisation (β = –1.53, SE = 0.74; p = 0.04) and self-esteem (β = 0.19, SE = 0.09; p = 0.04). There was no significant main effect for appearance conversations (β = –0.04, SE = 0.32; p = 0.90). For thin-ideal internalisation, looking separately at each time point showed significant differences between the groups both post intervention (intervention: mean = 21.94, SE = 0.47; control: mean = 23.47, SE = 0.57; p = 0.04) and at the 3-month follow-up period [χ2(1) = 3.84; p = 0.05]. At each time point the results favoured the intervention. For self-esteem, the comparisons between the groups at each of the time points revealed a significant difference post intervention (intervention: mean = 3.52, SE = 0.06; control: mean = 3.33, SE = 0.07; p = 0.04), but no difference by the 3-month follow-up (intervention: mean = 3.47, SE = 0.06; control: mean = 3.34, SE = 0.07; p = 0.15).

Logistic mixed-effects models were used to explore intervention effects for binary outcomes. There were no main effects of group for binge eating [odds ratio (OR) = 4.44, 95% CI 0.39 to 51.22; p = 0.23], compensatory behaviours [OR = 1.69, 95% CI 0.74 to 3.89; p = 0.22], peer support [OR = 1.40, 95% CI 0.64 to 3.06; p = 0.40] or depressive symptoms [OR = 1.49, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.78; p = 0.50]. Rates of each of these outcomes at each time point are reported in detail elsewhere. 71

Discussion

This study described the design of a teacher-delivered ED-prevention programme and its first rigorous evaluation in UK secondary schools. The results suggest that the approach is feasible and that a programme of this kind can have benefits for adolescents’ mental health.

The programme produced significant improvements in participants’ body esteem compared with their peers who received their usual school curriculum, and this impact was maintained through the 3-month follow-up period. The programme also improved several of the secondary outcomes. First, thin-ideal internalisation was reduced, meaning that the participants were less likely to endorse social ideals associated with thinness. Second, self-esteem was greater in those who received the intervention, although the effects were not maintained at the post-intervention assessment. In contrast to these findings, there were no effects for eating pathology, appearance conversations, peer support or depressive symptoms. There was also clear evidence that intervention delivery and reception varied substantially between the three schools. This suggests that understanding the best way to support delivery of materials such as these in a wide range of schools is a key aspect to take forward from this research.

It is difficult to compare these results with previous work, difficult because most body image interventions in schools have been delivered not by teachers but rather by external expert facilitators. 100,104 The small ESs found in this trial are in line with work outside the UK in which teacher-delivered interventions have been tested. 81,105 Existing work has also reported similar null findings for the broader impact of ED-prevention programmes. For example, other work has found like effect on depressive symptoms despite some content dedicated to this factor. 81,85 Given that interventions focusing specifically on depression are more intensive, it may be that the problem is one of dosage. 106 Similarly, few teacher-delivered prevention programmes have successfully impacted on eating pathology,84,85 although one study with considerably more intensive teacher training has shown promise in this area. 82

Strengths and limitations

A number of factors limit the conclusions of this trial. First, there was a risk of control group contamination, due to random allocation of classes within the same school. Second, we did not use an active control condition. Potentials for sham interventions that have been used in previous similar trials include activities such as expressive writing,107 educational brochures108 and healthy eating programmes. 109 Third, the sample size recruited was below that required for desired statistical power. Post hoc estimates of achieved power using the ES for the primary outcome at the 3-month follow-up (d = 0.19) show that the trial only had 49% power to detect group differences. Fourth, the assessment of intervention fidelity was coarse (two lesson observations per school). Ideally, the trial would have involved recording all sessions and having these rated by independent researchers. Finally, the follow-up period in this trial was limited to 3 months. Valuable information about whether or not effects are maintained in the medium to long term would be gained from longer follow-up.

The generalisability of the results was bolstered by the fact that the schools involved represented a wide range of different participants, including many from ethnic minority backgrounds as well as a range of economic backgrounds. It is also of significance that the trial was conducted in state-funded schools, and was not delivered by specialist school staff. However, it should be pointed out that the reliance on girls’ schools does limit the generalisability of these findings, as typical state-maintained schools in the UK are coeducational. Replication of these findings in coeducational schools is a priority going forwards with this work.

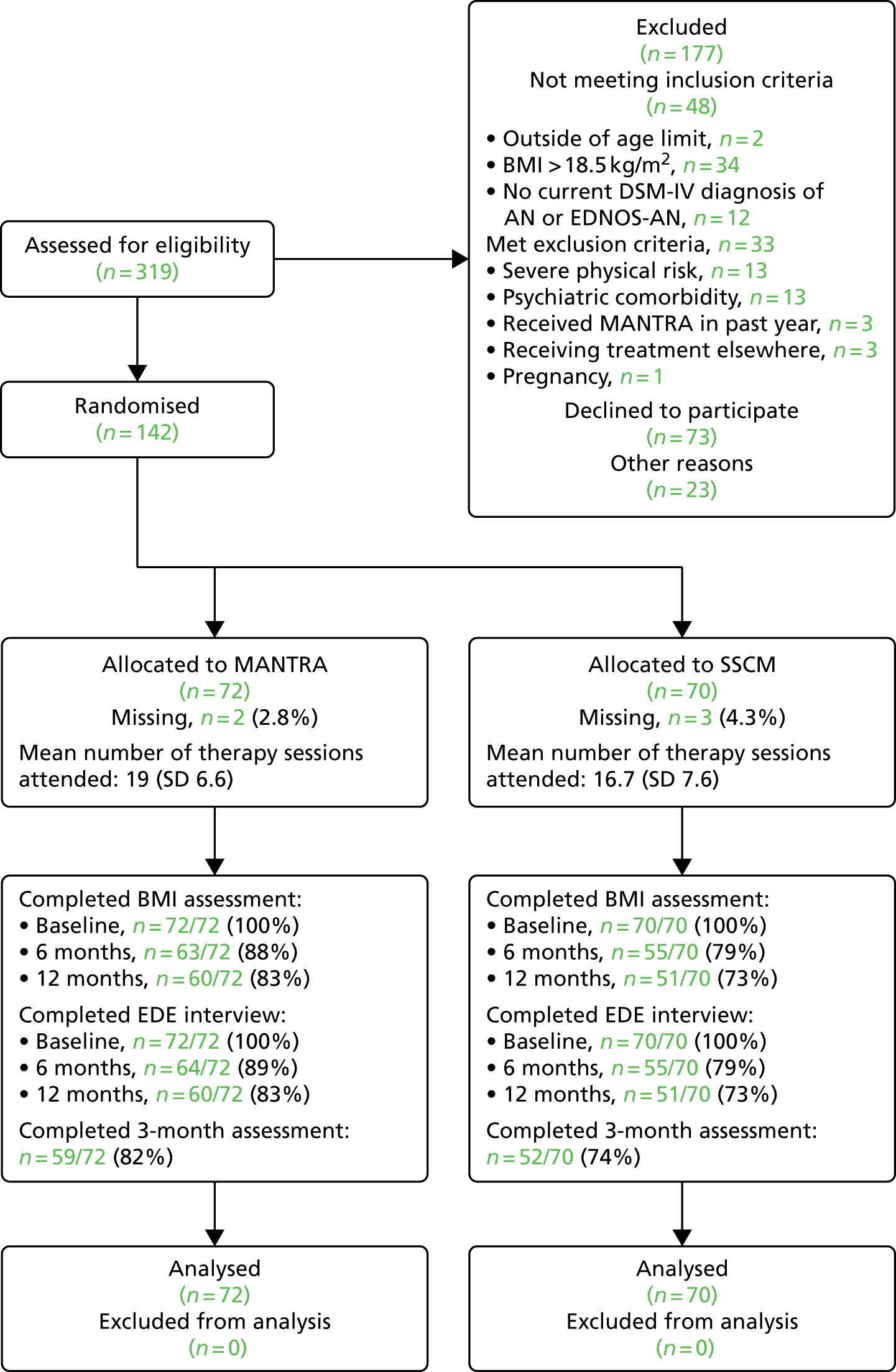

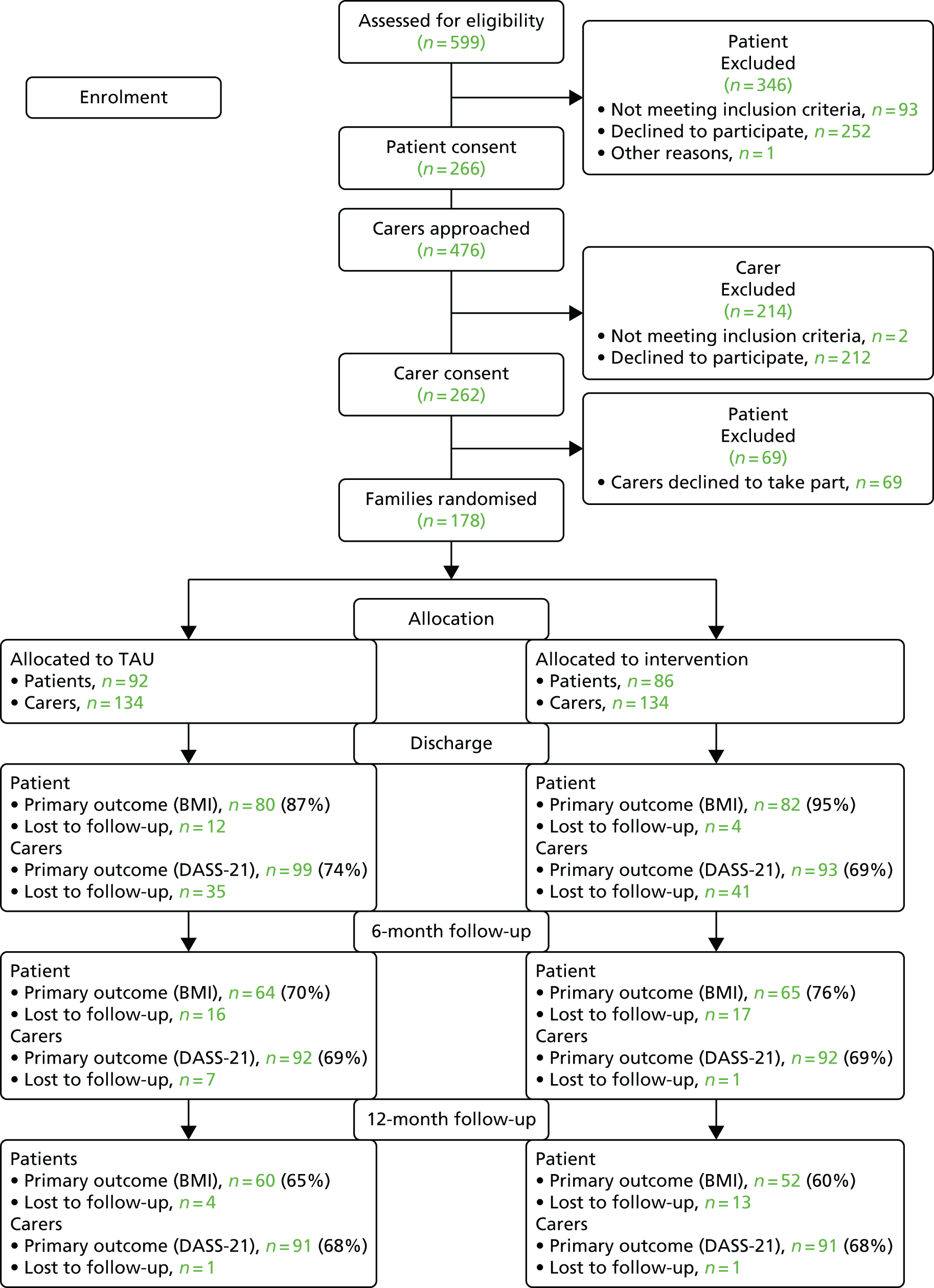

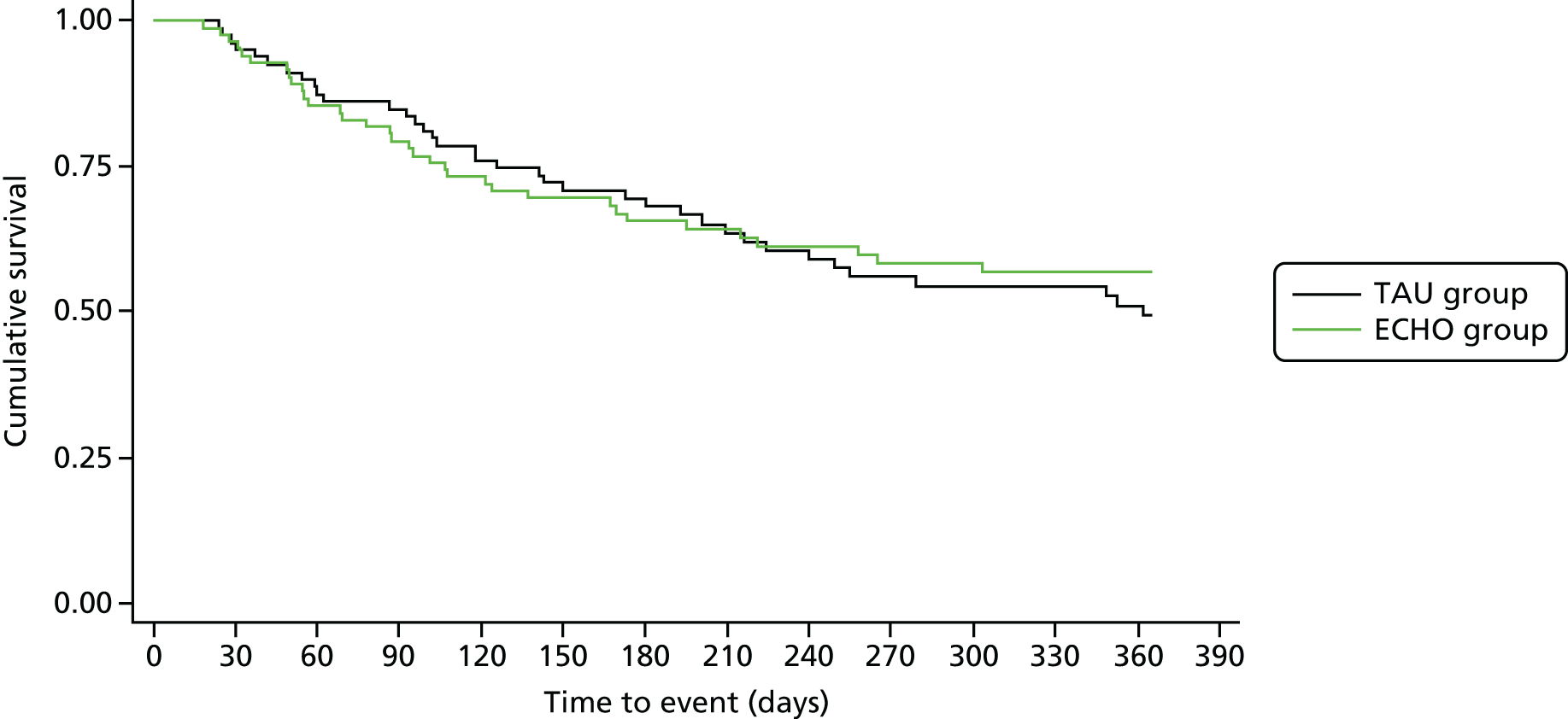

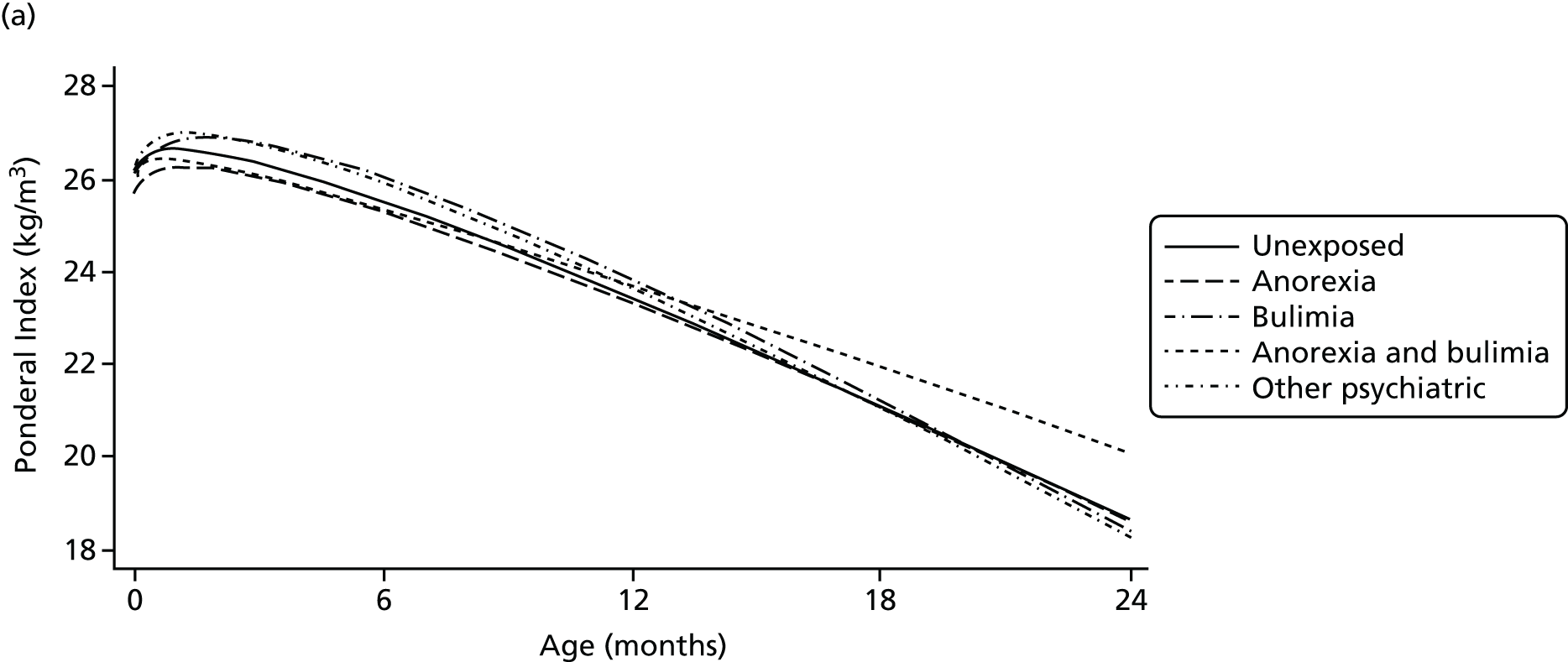

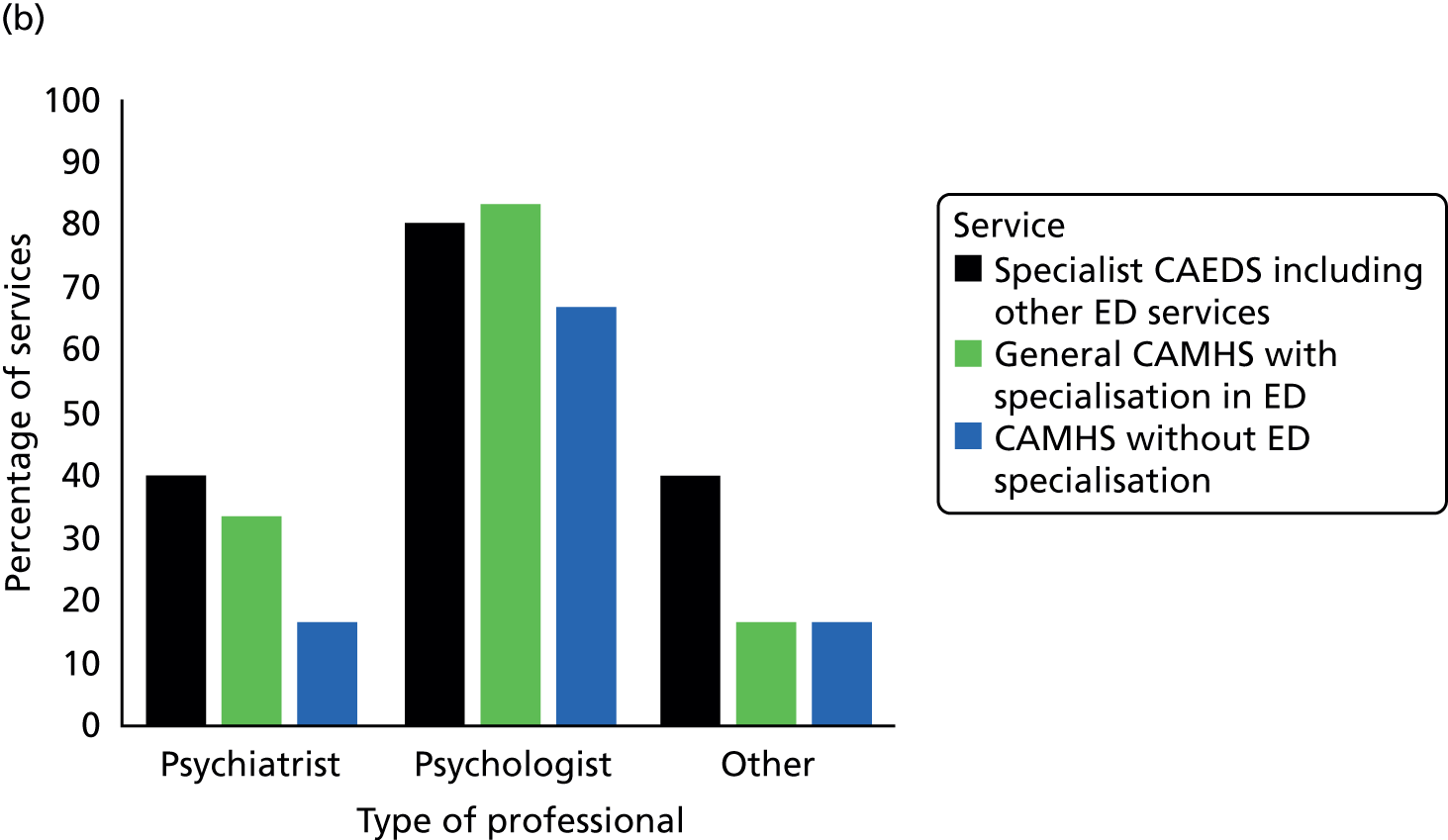

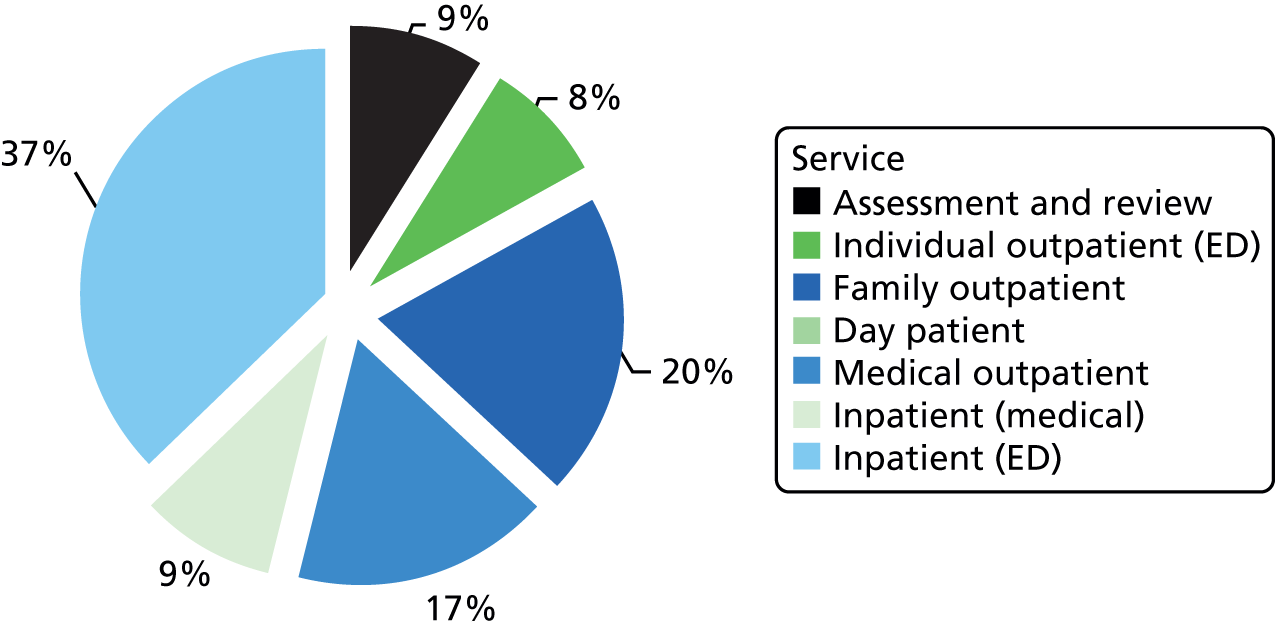

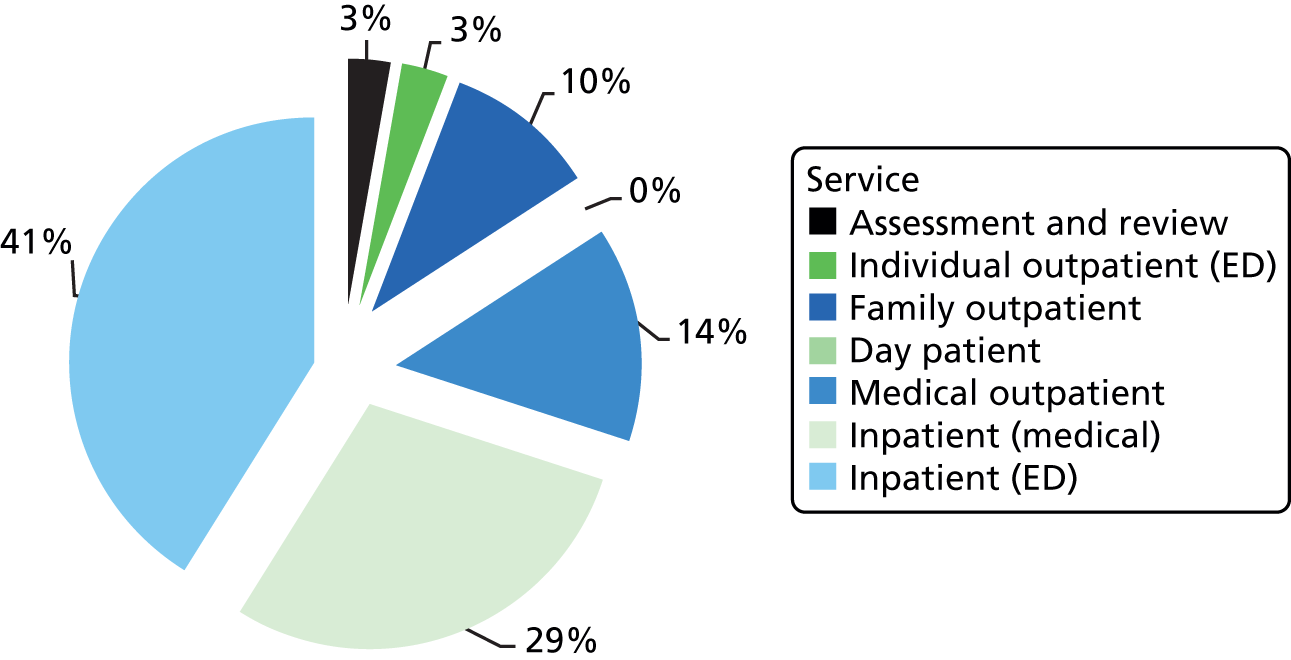

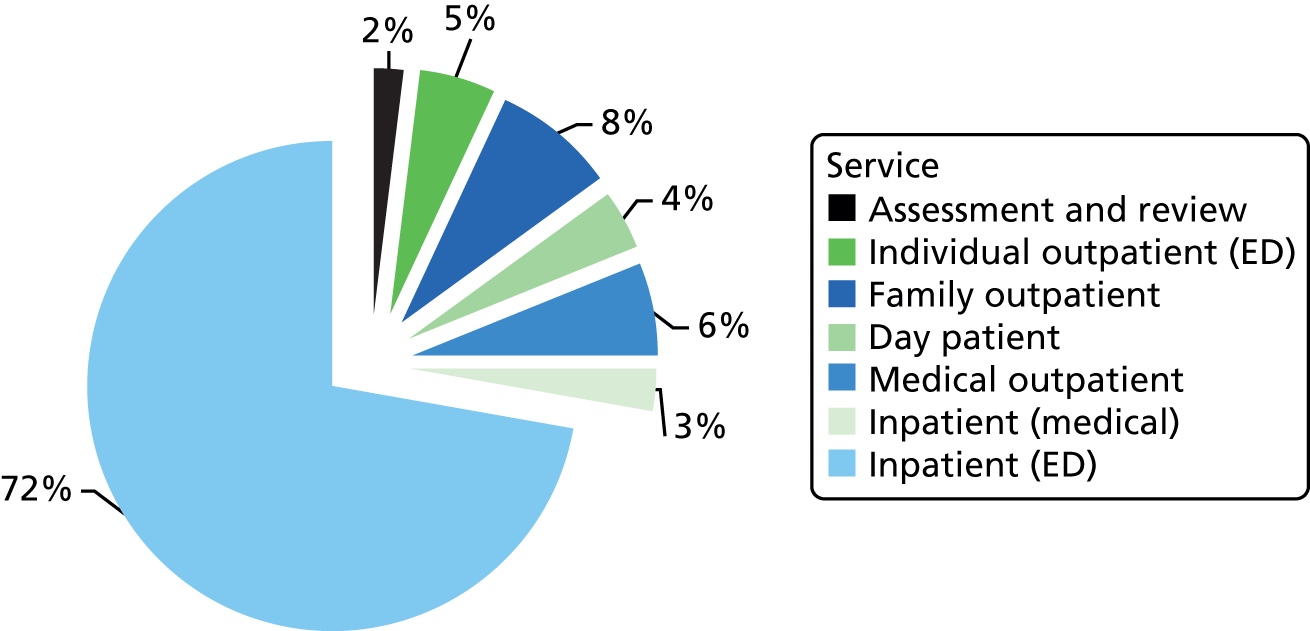

Conclusions