Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10384. The contractual start date was in July 2008. The final report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in April 2017. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

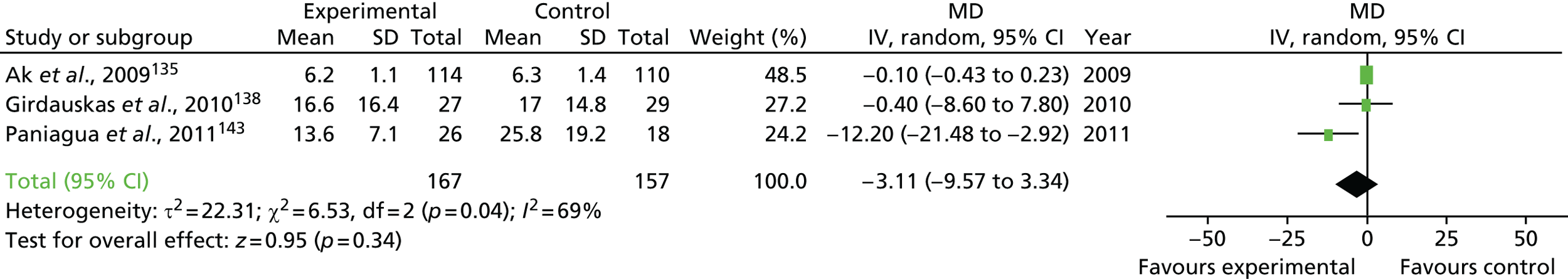

Gavin J Murphy reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the British Heart Foundation and Zimmer Biomet during the conduct of the study. He also received consultancy fees from AbbVie and Thrasos Inc. with respect to the conduct of trials of organ protection interventions in cardiac surgery. Andrew D Mumford reports grants from the NIHR and the British Heart Foundation during the conduct of the study. Chris A Rogers reports grants from the NIHR and the British Heart Foundation during the conduct of the study. Sarah Wordsworth reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of the study. Elizabeth A Stokes reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of the study. Tracy Kumar reports grants from Zimmer Biomet during the conduct of the study. Marcin Wozniak reports grants from the British Heart Foundation and Zimmer Biomet during the conduct of the study. Jonathan A Sterne reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of the study. Gianni D Angelini reports grants from the NIHR and the British Heart Foundation during the conduct of the study. Barnaby C Reeves reports grants from the NIHR during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Murphy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The clinical problem

Organ failure in cardiac surgery

Cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) results in a complex inflammatory response attributable to haematological activation (coagulation and protease cascades, platelets, leucocytes) by the extracorporeal circuit. 1 This often results in activation of vascular endothelium, tissue hypoxia and organ injury, particularly in those with pre-existing organ dysfunction. 2 In addition, cardioplegic arrest results in a myocardial-specific ischaemia–reperfusion injury. This can result in low cardiac output post surgery that compounds the tissue hypoxia, inflammation and organ injury attributable to CPB. 3 Organ injury is an important cause of morbidity and mortality and results in an increased use of hospital resources. In a study by Murphy et al. ,4 clinically significant kidney, lung and myocardial injury occurred in 34%, 16% and 11% of patients respectively, contributing to 41%, 36% and 24% of all deaths respectively. Every year, cardiac surgery is performed in > 35,000 UK patients and > 1 million patients worldwide. The number of elderly patients with pre-existing organ dysfunction referred for cardiac surgery increases year on year. 5 Reducing perioperative organ failure therefore presents an ever-increasing challenge for clinicians and health services.

Blood management

The safe and effective management of perioperative anaemia and coagulopathic bleeding is a key determinant of outcome following cardiac surgery. 6 Anaemia and coagulopathic bleeding are common, often require multiple blood management interventions and are associated with increases in the rates of organ failure, sepsis and death. However, there is clinical uncertainty as to how these conditions should be managed clinically because of our limited understanding of the underlying mechanisms and the lack of clinical efficacy for most blood management interventions that have been evaluated in clinical trials. 7 This has led to significant variability in care.

Coagulopathic bleeding is a potential complication of every cardiac operation. Death as a direct consequence of bleeding is rare; in the Blood Conservation Using Antifibrinolytics in a Randomised Trial (BART) study, 23 of 2330 patients (1%) died of uncontrolled blood loss. 8 However, emergency sternotomy for life-threatening bleeding and large-volume blood transfusion (LVBT; > 4 units of red cells) are common and are associated with significant increased risks of organ failure, sepsis and death. LVBT occurs in 22% of UK cardiac surgery patients. 9 This has been associated with an eightfold increase in the risk of death. 10 Emergency re-sternotomy for life-threatening bleeding or tamponade occurs in 4% of UK cardiac surgery patients and increases the risk of death two- to fivefold. 11–13

The causes of coagulopathy are complex and poorly understood but they relate to the activation of platelets and serum proteases by the extracorporeal bypass circuit. These are discussed in detail in Chapter 2. Summaries of interventions in common clinical use to prevent or reverse coagulopathy are described in Table 1. The most effective of these is tranexamic acid, a lysine analogue that inhibits the serum protease plasmin, thereby reducing fibrinolysis and promoting clot stability. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss, transfusion rates and, most importantly, death in cardiac surgery patients. 16–18 Other interventions to prevent or reverse coagulopathic haemorrhage reduce blood loss and transfusion but lack the clinical efficacy of tranexamic acid (see Table 1) and their use has declined. 22 Transfusion of non-red cell blood components [pooled platelets, fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) and cryoprecipitate] remains the primary treatment for coagulopathic haemorrhage. However, their use is empirical, their risks and benefits are poorly defined and the frequency of their use is highly variable (described in more detail in Chapter 2).

| Intervention | Reference | n studies/n participants | Effect on transfusion, risk ratio (95% CI) | Effect on clinical outcome, risk ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimise loss of autologous red cells | ||||

| Preoperative autologous donation | Henry et al.14 | 14/1506 | 0.32 (0.22 to 0.47) | Infection: 0.70 (0.34 to 1.43) |

| Thrombosis: 0.82 (0.21 to 3.13) | ||||

| Any transfusion: 1.24 (1.02 to 1.51) | ||||

| Acute normovolaemic haemodilution | Davies et al.15 | 11/1423 | 0.36 (0.25 to 0.51) | Infection: 0.70 (0.34 to 1.43) |

| Thrombosis: 0.82 (0.21 to 3.13) | ||||

| Mechanical cell salvage (high-risk patients) | Murphy et al.16 | 4/223 | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.93) | Death: 0.97 (0.64 to 1.47) |

| Thrombosis: not estimable | ||||

| Infection: 0.4 (0.18 to 0.87) | ||||

| Mechanical cell salvage (medium-risk patients) | Murphy et al.16 | 3/384 | 0.74 (0.5 to 1.12) | Death, thrombosis and infection: not reported |

| Stimulate erythropoiesis | ||||

| Intravenous iron vs. placebo or no intravenous iron (surgery) | Murphy et al.16 | 5/467 | 0.77 (0.59 to 0.99) | Death: 1.1 (0.49 to 2.47) |

| Thrombosis: – | ||||

| Infection: 1.23 (0.63 to 2.42) | ||||

| Oral iron vs. intravenous iron | Murphy et al.16 | 6/699 | 1.2 (0.56 to 2.61) | Death: 1.22 (0.58 to 2.56) |

| Thrombosis: – | ||||

| Infection: – | ||||

| Erythropoietin vs. placebo (surgery) | Murphy et al.16 | 12/1663 | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.67) | Death: 1.55 (0.79 to 3.07) |

| Thrombosis: 1.37 (0.73 to 2.56) | ||||

| Infection: not estimable | ||||

| Erythropoietin plus intravenous iron vs. placebo | Murphy et al.16 | 2/283 | 0.51 (0.39 to 0.67) | Death: 0.33 (0.01 to 7.93) |

| Thrombosis: not estimable | ||||

| Infection: not estimable | ||||

| Erythropoietin plus oral iron vs. oral iron | Murphy et al.16 | 2/880 | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.25) | Death: 0.88 (0.39 to 1.96) |

| Thrombosis: 1.71 (0.68 to 4.3) | ||||

| Infection: 0.5 (0.05 to 4.98) | ||||

| Reverse coagulopathy | ||||

| Tranexamic acid vs. placebo (high-risk surgery) | Murphy et al.16 | 38/4105 | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.81) | Death: 0.73 (0.15 to 3.66) |

| Thrombosis: 0.69 (0.44 to 1.07) | ||||

| Infection: 0.93 (0.22 to 3.93) | ||||

| Tranexamic acid vs. placebo (moderate-risk surgery) | Murphy et al.16 | 25/4577 | 0.45 (0.38 to 0.52) | Death: 0.73 (0.15 to 3.66) |

| Thrombosis: 0.69 (0.44 to 1.07) | ||||

| Infection: 0.93 (0.22 to 3.93) | ||||

| Tranexamic acid high dose vs. tranexamic acid low dose (surgery) | Ker et al.17 | 129/10,488 | 0.62 (0.58 to 0.65) | Death: 0.61 (0.38 to 0.98) |

| Myocardial infarction: 0.68 (0.43 to 1.09) | ||||

| Pulmonary embolism: 1.14 (0.65 to 2.00) | ||||

| Tranexamic acid vs. placebo (trauma) | Ker et al.18 | 2/20,367 | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) | Death: 0.90 (0.85 to 0.96) |

| Myocardial infarction: 0.61 (0.40 to 0.92) | ||||

| Tranexamic acid plus cell salvage vs. cell salvage (high-risk surgical patients) | Murphy et al.16 | 5/514 | 0.71 (0.6 to 0.85) | Death: 1.04 (0.07 to 16.41) |

| Tranexamic acid plus cell salvage vs. tranexamic acid (high-risk surgical patients) | Murphy et al.16 | 1/63 | 0.79 (0.43 to 1.45) | Death: 7.71 (0.43 to 137.53) |

| Aprotinin vs. placebo | Henry et al.19 | 108/1172 | 0.66 (0.60 to 0.72) | Death: 0.81 (0.63 to 1.06) |

| Myocardial infarction: 0.87 (0.69 to 1.11) | ||||

| Renal failure: 1.10 (0.79 to 1.54) | ||||

| Aprotinin vs. tranexamic acid | Henry et al.19 | 21/4185 | 0.90 (0.81 to 1.01) | Death: 1.35 (0.94 to 1.93) |

| Myocardial infarction: 1.00 (0.71 to 1.42) | ||||

| Renal failure: 1.02 (0.79 to 1.31) | ||||

| Desmopressin | Carless et al.20 | 19/1387 | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.06) | Death: 1.72 (0.68 to 4.33) |

| Thrombosis: 1.46 (0.64 to 3.35) | ||||

| Hypotension: 2.81 (1.50 to 5.27) | ||||

| Recombinant activated factor VII | Simpson et al.21 | 8/868 | 0.85 (0.72 to 1.01) | Death: 1.04 (0.55 to 1.97) |

| Arterial thromboembolic events: 1.45 (1.02 to 2.05) | ||||

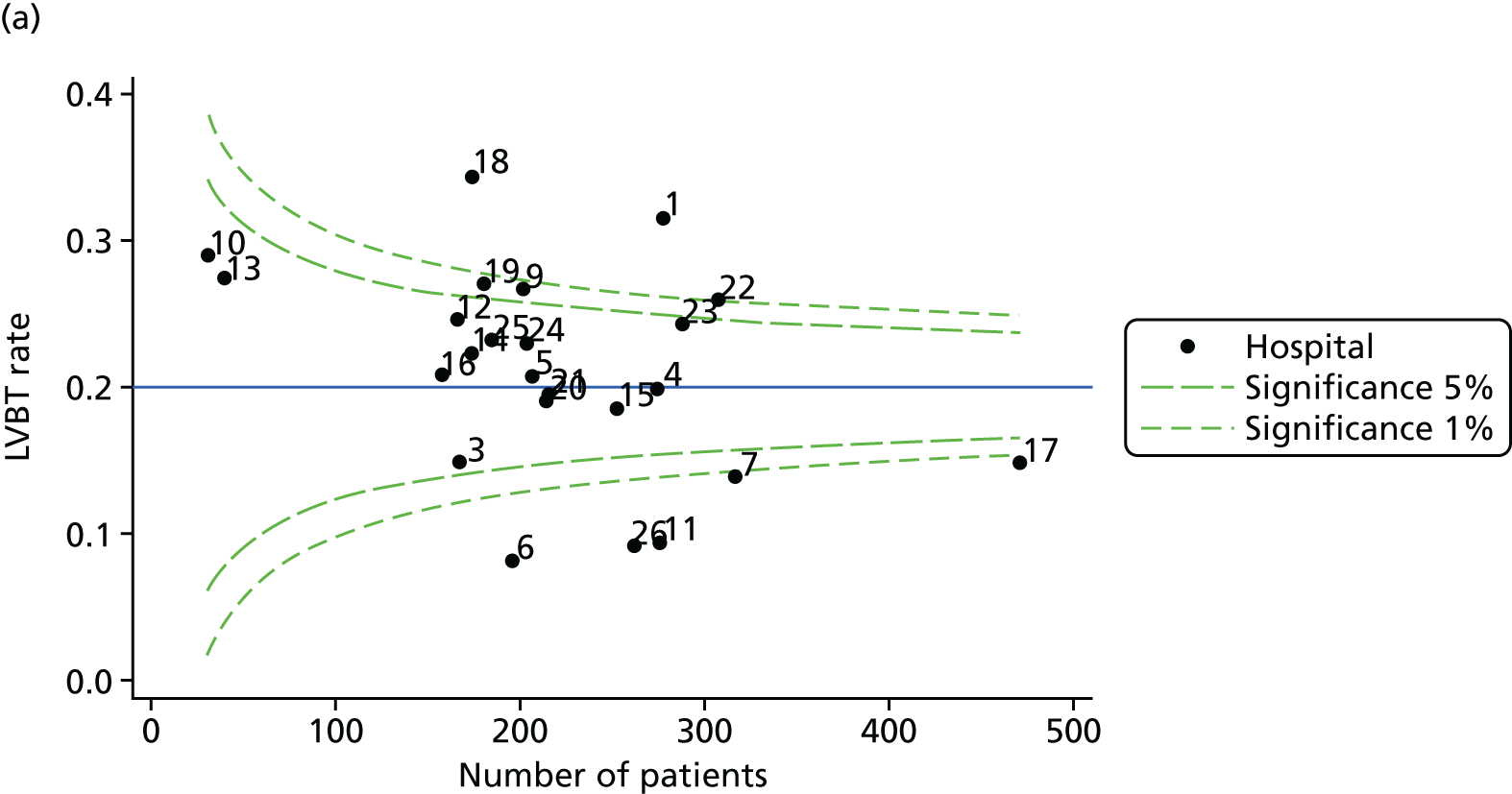

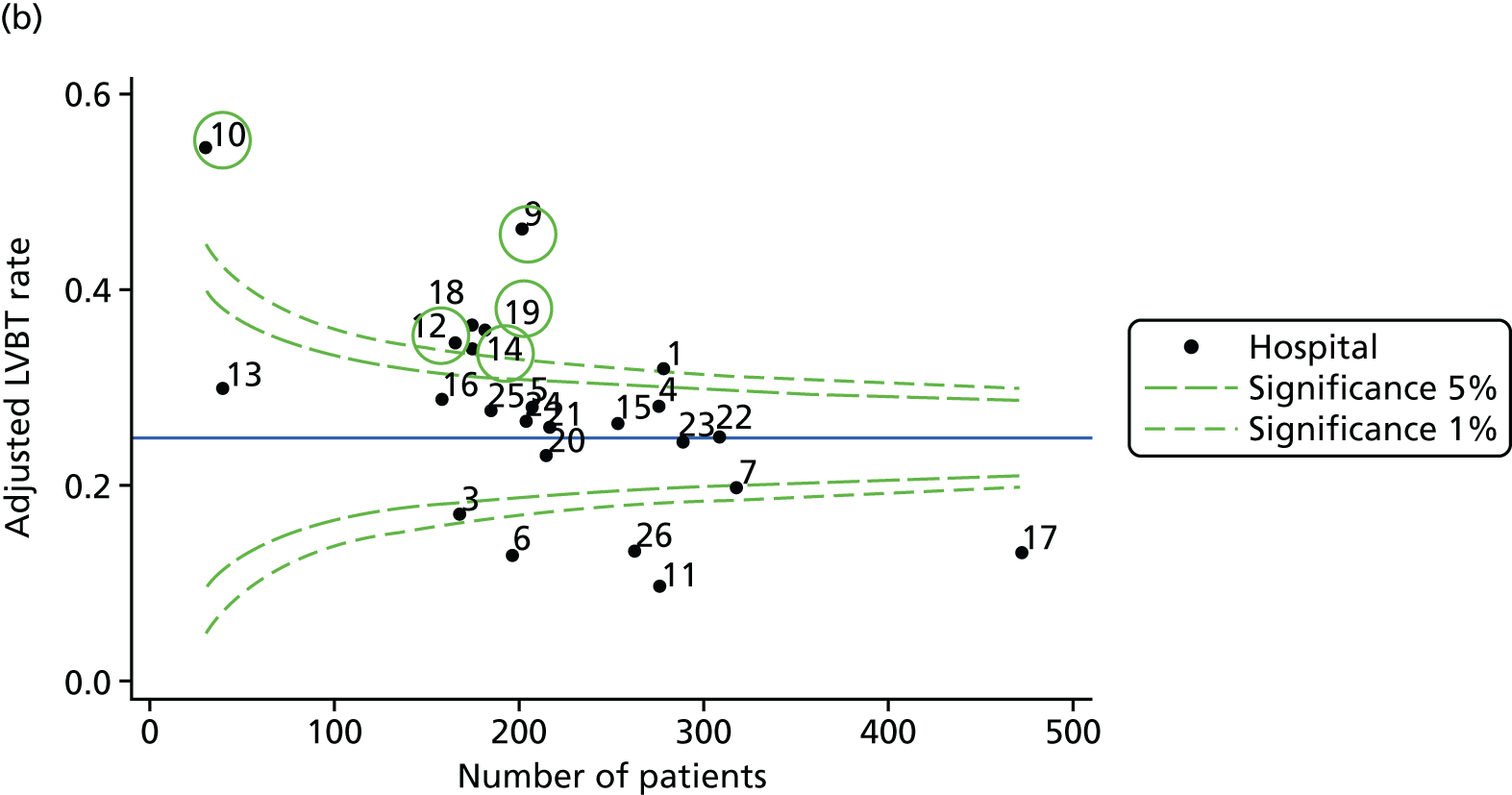

Identifying those most likely to bleed may benefit patients by allowing preoperative optimisation or the use of targeted blood management interventions such as the reversal of the effects of antiplatelet agents or the reversal of specific coagulation defects identified by laboratory tests or preferably point-of-care (POC) diagnostic tests for coagulopathy. Current guidance recommends that patients undergo careful risk assessment prior to surgery, in combination with POC haemostasis testing to direct therapy in bleeding patients. 23,24 Existing bleeding risk scores have significant limitations, however (reviewed in Chapter 3), and are not widely used. Moreover, the evidence to support the use of POC tests is of low quality. 25,26 These limitations are reflected by wide variability in the assessment and management of bleeding patients. In a UK audit, 12% of units reported that they did not use POC tests for coagulopathy, 24% reported that they were used in < 25% of cases, LVBT rates ranged from 8% to 35% and emergency re-sternotomy rates ranged from 0.3% to 12%. 9 To better define the roles of preoperative clinical assessment and near-patient platelet and viscoelastometry testing for the prediction of severe bleeding, we undertook the COagulation and Platelet laboratory Testing in Cardiac surgery (COPTIC) study in a large cohort of adult cardiac surgery patients (see Chapter 2). We hypothesised that the use of near-patient testing would improve the prediction of severe bleeding beyond the use of clinical risk factors alone. We also critically reviewed the limitations of previously published clinical risk scores and developed two new risk scores for preoperative risk assessment (see Chapter 3).

Anaemia, defined as a blood haemoglobin concentration of < 12 g/dl, can be identified in approximately 30% of cardiac surgery patients presenting for surgery in the UK. 9 A significant number also develop intraoperative or postoperative anaemia. The most common cause of anaemia is chronic disease (45%), with relatively small proportions of patients presenting with diagnosable and reversible causes of anaemia such as iron deficiency (7%) or vitamin B12 deficiency (11%). 27 Additional aetiological factors for intra- and postoperative anaemia are haemodilution, haemorrhage or impaired erythropoiesis. It is hypothesised that anaemia contributes to organ failure and death by reducing tissue oxygen delivery during CPB, resulting in hypoxic cellular injury and organ dysfunction. 28 Organs with high metabolic demands are considered more susceptible to injury in the presence of anaemia and there are strong associations between perioperative anaemia and kidney, myocardial and brain injury. 29,30

Preoperative interventions for the treatment or reversal of anaemia have limited clinical benefit (see Table 1) and the preferred treatment for acute perioperative anaemia is red cell transfusion. The severity of anaemia, or haemoglobin threshold, that triggers a red cell transfusion differs between clinicians and units. As a result, red cell transfusion rates vary widely. In the UK, red cell transfusion rates range from 32% to 75% in different centres. 9 In the USA, rates range from 45% to 92%. 31 This is potentially important as red cell transfusion is strongly associated with increased rates of postoperative organ failure and death (see Table 1). Transfusion is also associated with an increased frequency of sepsis. 32 It has been hypothesised that these complications are the result of pathological changes that occur in red cells during storage, termed ‘the storage lesion’, which result in inflammation and organ injury in recipients. 33

Differentiating the cause and effect of anaemia on adverse outcomes from those of transfusion is not possible from existing epidemiological analyses because these variables are so strongly linked. Furthermore, in complete contrast to observational studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing restrictive haemoglobin transfusion thresholds (6.5–8 g/dl) with more liberal thresholds (8–10 g/dl) suggest that the reversal of anaemia with red cell transfusion may benefit patients. The Transfusion Indication Threshold Reduction (TITRe2) trial4 demonstrated higher mortality in patients randomised to more restrictive thresholds, that is, with more severe anaemia. These observations were supported by the results of a systematic review of this and four similar trials,32 with more liberal transfusion thresholds found to reduce mortality [risk ratio (RR) 0.7, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49 to 1.02]. In trials that included only patients with severe symptomatic cardiovascular disease, the reduction in mortality was statistically significant (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.95; Table 2). This suggests that conditions predisposing to anaemia are the principal contributors to organ failure and death observed in epidemiological analyses, rather than red cell transfusion.

| Outcome | Observational analyses | RCTs of liberal vs. restrictive thresholds in cardiac surgery | RCTs of liberal vs. restrictive thresholds in symptomatic cardiovascular disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n studies/n participants | Odds ratio (95% CI) | n studies/n participants | RR (95% CI) | n studies/n participants | RR (95% CI) | |

| Death | 19/138,357 | 1.48 (1.42 to 1.53) | 5/3304 | 0.70 (0.49 to 1.02) | 7/3439 | 0.67 (0.47 to 0.95) |

| Myocardial infarction | 8/35,763 | 1.55 (1.48 to 1.62) | 1/2003 | 1.34 (0.30 to 6.02) | – | – (–) |

| Stroke | 7/43,649 | 1.41 (1.34 to 1.48) | 1/2003 | 1.14 (0.57 to 2.30) | – | – (–) |

| Acute kidney injury | 14/59,003 | 1.73 (1.65 to 1.83) | 5/3304 | 0.86 (0.68 to 1.09) | – | – (–) |

| Pulmonary injury | 7/43,431 | 1.68 (1.63 to 1.74) | 6/3357 | 0.94 (0.76 to 1.17) | – | – (–) |

| Infection | 11/88,025 | 1.81 (1.73 to 1.89) | 4/2802 | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.19) | – | – (–) |

The evidence from randomised trials notwithstanding, clinical uncertainty as to the indications for red cell transfusion in anaemic patients remains. Transfusion guidelines published by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)16 recommend more liberal transfusion thresholds in patients with severe cardiovascular disease; however, many other guidelines recommend restrictive thresholds, including those published by the American Association of Blood Banks,34 the Society of Thoracic Surgeons24 and the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM). 35 In addition, a limitation of existing ‘transfusion trigger’ trials is that they compare protocolised transfusion thresholds. It has been hypothesised that the critical haemoglobin level, that is, the threshold below which oxygen delivery becomes impaired, is different both between patients and in individual patients during their perioperative course. 36,37 Changes in tissue oxygen requirements are not reflected by protocolised transfusion thresholds and recent commentaries have stressed the importance of more personalised measures of the need for transfusion. 38 We evaluate a personalised red cell transfusion algorithm in the PAtient-SPecific Oxygen monitoring to Reduce blood Transfusion during heart surgery (PASPORT) trial in Chapter 4.

Safer red cells may move the balance of risks and benefits to favour the more aggressive treatment of anaemia. The Red Cell Storage Duration Study (RECESS)39 randomised participants to red cells that had been stored for longer (> 21 days) or shorter (< 10 days) periods of time to test the hypothesis that the storage lesion directly contributed to organ injury. There was no difference between the groups in this trial for the primary outcome of multiple organ dysfunction [95% CI for the mean difference (MD) –0.6 to 0.3; p = 0.44]. This study was limited in that the difference in severity of the storage lesion between day 10 and day 21 red cells is small. Furthermore, epidemiological analysis that compared organ injury and death in many thousands of patients receiving younger red cells or older red cells did not suggest important differences between red cells stored for these different time periods. 40 The clinical importance of the storage lesion in transfused patients remains uncertain. In Chapter 5 we consider the effects of an intervention to modify the storage lesion in the REDWASH trial.

Medical devices

A medical device may be defined as any instrument, apparatus, appliance, software, material or other article used specifically for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes. CPB circuits, prosthetic heart valves and other implants, monitoring equipment and web-based mortality risk scores are examples of devices used in cardiac surgery. The most common devices in clinical use as blood management adjuncts are cell salvage devices that collect shed mediastinal blood for autotransfusion. These have been used in cardiac surgery for decades. However, despite their widespread use, the evidence of clinical benefit to patients from these devices is limited. Cell salvage devices reduce red cell transfusion rates and infections when used in isolation in patients at high risk for bleeding and red cell transfusion. 16 This benefit is not observed when patients are also administered tranexamic acid (see Table 1). This apparent lack of clinical benefit has emerged only in recent analyses,16 prompted by the evidence of effectiveness for tranexamic acid from a high-quality RCT in trauma41 and a subsequent systematic review in surgical patients. 17 This reflects a common criticism of the levels of evidence required for approval of medical devices compared with that required to introduce a medicinal product into clinical care. 42 Unlike pharmacological interventions, medical devices do not require evidence of efficacy from RCTs. Rather, in Europe, manufacturers are required to submit a dossier of supporting evidence to a notified body. Notified bodies are private companies that specialise in evaluating many products, including medical devices, for European Conformity (CE) marks. Notified bodies are designated by a national competent authority, such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the UK, to cover certain types of devices. If the notified body deems that a device meets the standards for performance and reliability testing linked to the risks of its intended use, it verifies a Certificate of Conformity and the device may enter clinical use. This process has been criticised for lack of transparency, and variable quality, as well as the fact that CE marks may be obtained in the absence of evidence of clinical efficacy. 43 On the one hand the flexibility of the process promotes innovation, but on the other it may lead to widespread use of ineffective or even harmful medical devices.

We identified multiple devices in common use as blood management adjuncts in our own clinical practice, for which there was uncertainty as to their clinical efficacy. Principal among these were POC haemostasis tests for the management of coagulopathic bleeding. These devices are of uncertain utility as existing studies show only limited predictive accuracy for coagulopathic bleeding and clinical efficacy, in terms of the benefit to patients from their use. 25,26 We also identified a knowledge gap with respect to clinical risk assessment. Importantly, there was no available published risk calculator available for clinical use. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), a device for measuring regional tissue oxygenation in the forebrain, is also widely used in cardiac surgery. It has been suggested that these devices may be used to personalise transfusion decisions by identifying the critical haematocrit below which tissues become hypoxic. 44,45 Finally, we noted that mechanical cell salvage devices are used in some clinical situations to wash allogenic red cells prior to transfusion, with the intention of removing harmful metabolites of red cell storage and attenuating inflammation and organ injury in recipients. 46,47

Structure of this report

The overarching aim of this programme was to provide high-quality evidence on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of devices in common clinical use as blood management adjuncts. A common theme of all of the workstreams was to design trials that would address the bias and limitations that were identified in our reviews of existing data.

Our work was divided into three workstreams, summarised in the following sections.

Workstream 1: diagnosis of coagulopathy and assessment of bleeding and transfusion risk

Our objectives were to:

-

evaluate the predictive accuracy of clinical risk assessment using data available at baseline for bleeding, organ injury, sepsis and death following cardiac surgery

-

evaluate the additional clinical value of routine POC tests of platelet function, coagulation and fibrinolysis

-

evaluate the additional clinical value of pre- and postoperative laboratory reference tests (LRTs) of coagulation

-

evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the routine introduction of POC tests into clinical practice

-

review the evidence supporting the clinical use of POC haemostasis tests in a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs

-

develop two new clinical risk prediction scores for red cell transfusion and bleeding.

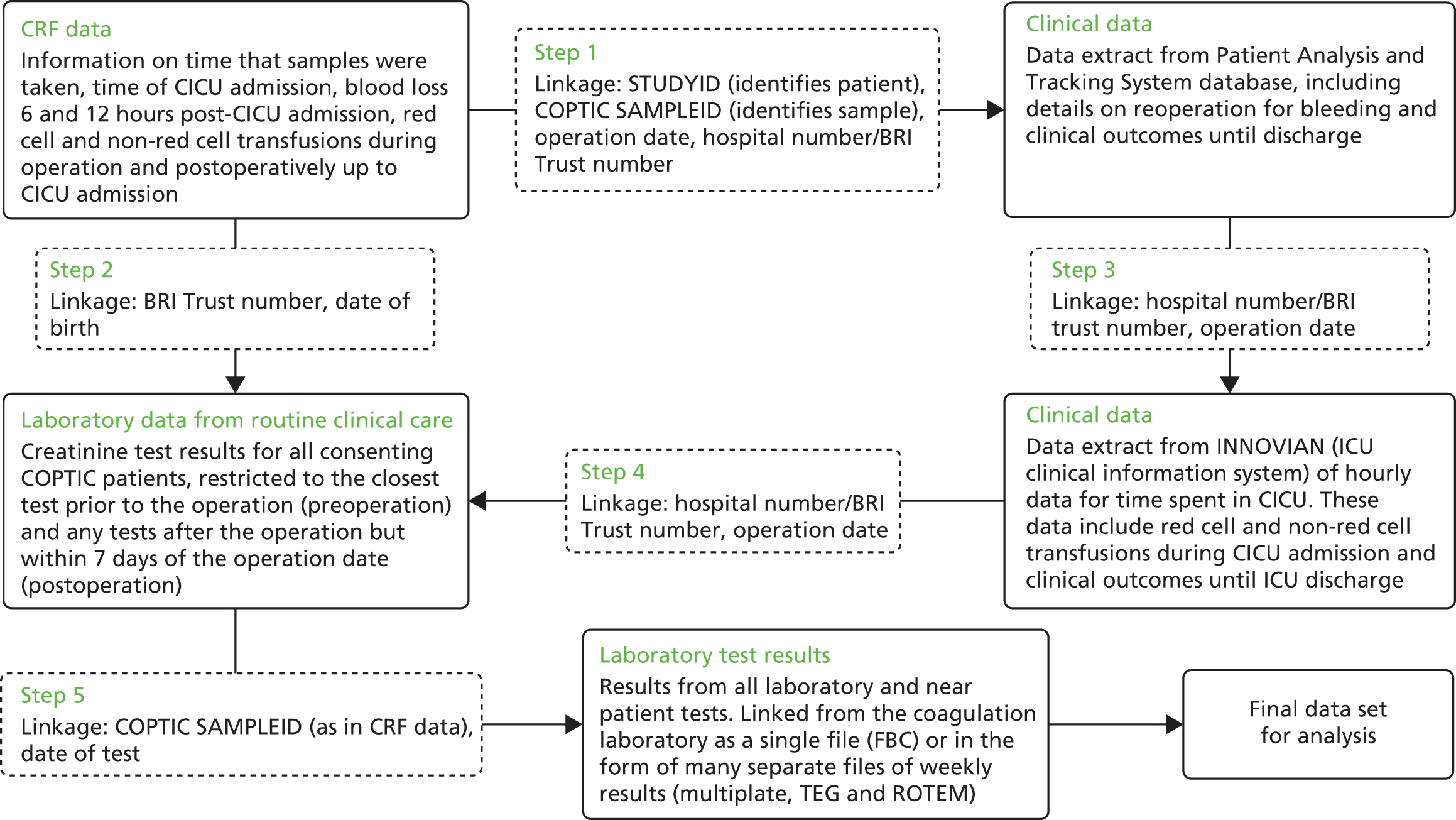

Our plan of investigation to address these objectives was as follows.

-

A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs comparing POC haemostasis test-based algorithms for the prevention of post-cardiac surgery bleeding and organ injury (reported in Chapter 2).

-

A prospective diagnostic accuracy study evaluating the benefits of pre- and postoperative POC tests for the prediction of bleeding and adverse outcome over those achieved using routinely measured baseline factors (the COPTIC study; reported in Chapter 2).

-

A prospective diagnostic accuracy study evaluating the benefits of pre- and post-LRTs for the prediction of bleeding and adverse outcome over those achieved using routinely measured baseline factors (the COPTIC study; reported in Chapter 2).

-

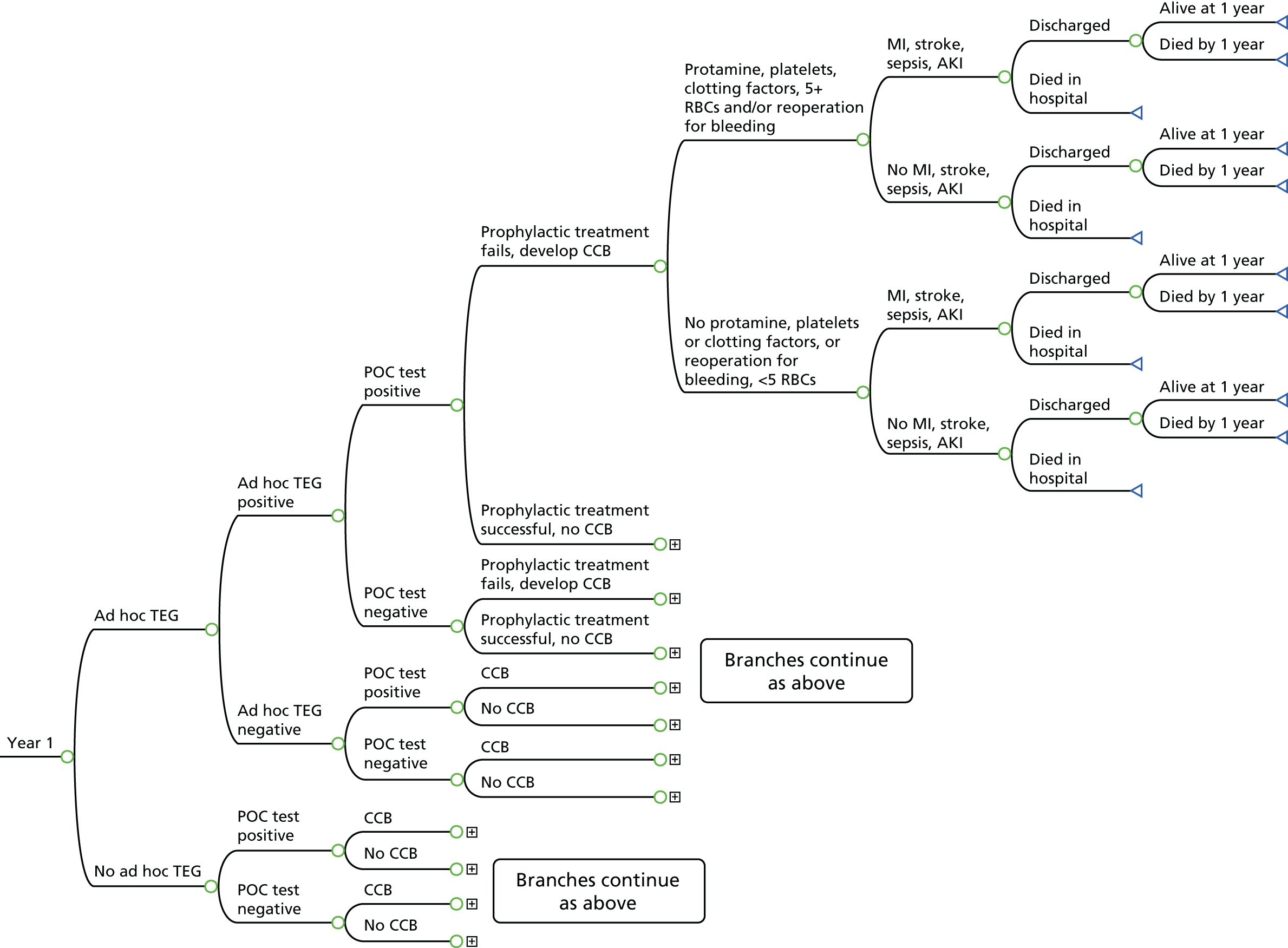

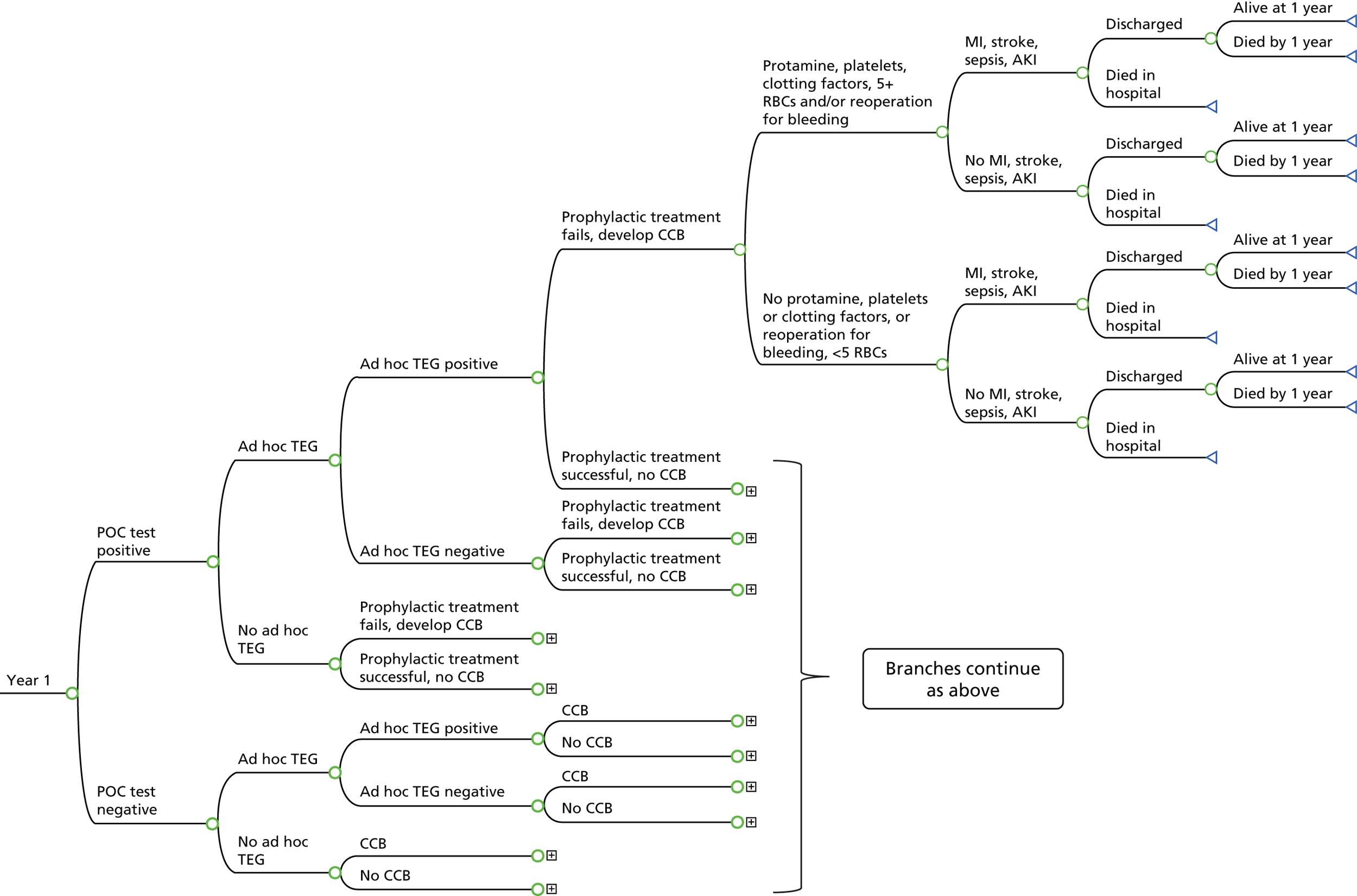

A health economic analysis to assess the cost-effectiveness of introducing POC tests into routine clinical care (reported in Chapter 2).

-

A narrative review of existing risk prediction scores for bleeding and transfusion in cardiac surgery (reported in Chapter 3).

-

The development and validation of novel web-based risk scores for preoperative clinical risk assessment (reported in Chapter 3).

Workstream 2: the use of near-infrared spectroscopy as a patient-specific indicator of regional tissue oxygenation and the need for red cell transfusion in cardiac surgery

Our objectives were to:

-

evaluate the efficacy of a personalised NIRS-based algorithm that incorporated a restrictive red cell transfusion threshold compared with standard care during CPB in a multicentre RCT

-

estimate the cost-effectiveness of introducing into clinical practice a NIRS-based algorithm to guide the conduct of CPB and red cell transfusion

-

review the evidence to support the clinical use of cerebral NIRS monitors and NIRS-based algorithms during CPB in a systematic review and meta-analysis of the PASPORT trial and other similar trials.

Our plan of investigation to address these objectives was as follows.

-

A multicentre randomised controlled efficacy trial comparing a patient-specific NIRS-based algorithm with standard care (the PASPORT trial; reported in Chapter 4).

-

A health economic analysis of the cost-effectiveness of introducing a NIRS-based algorithm into routine clinical care (reported in Chapter 4).

-

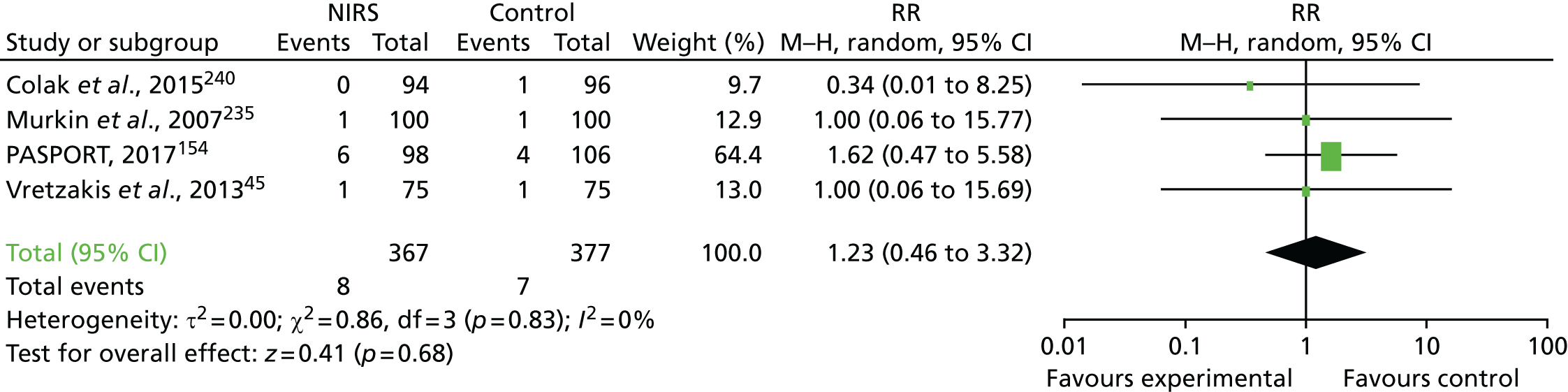

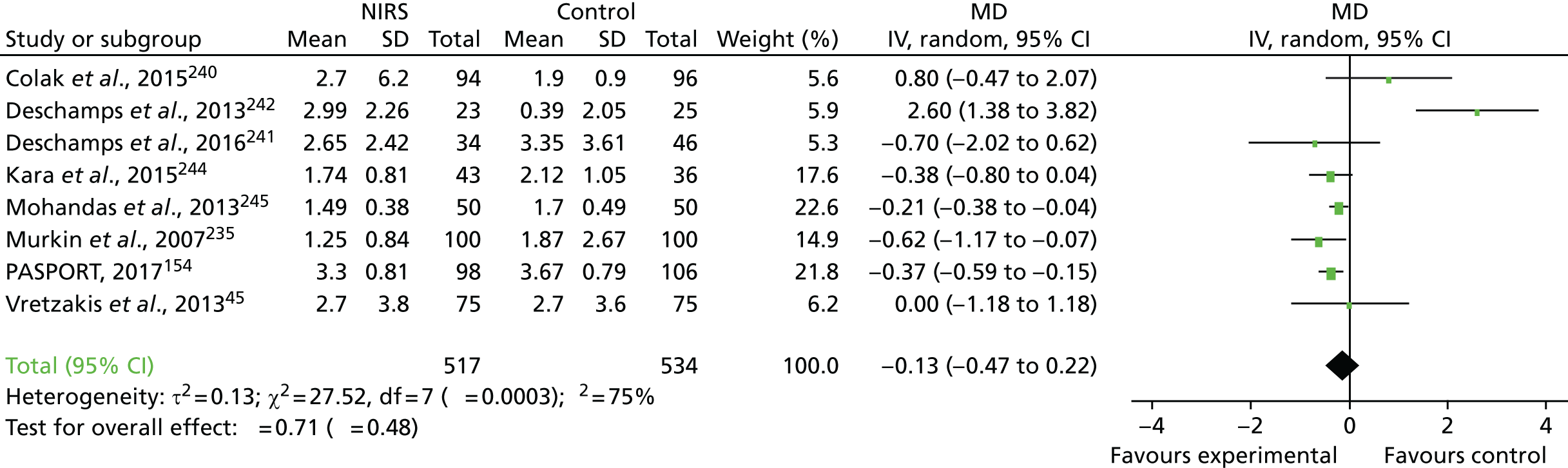

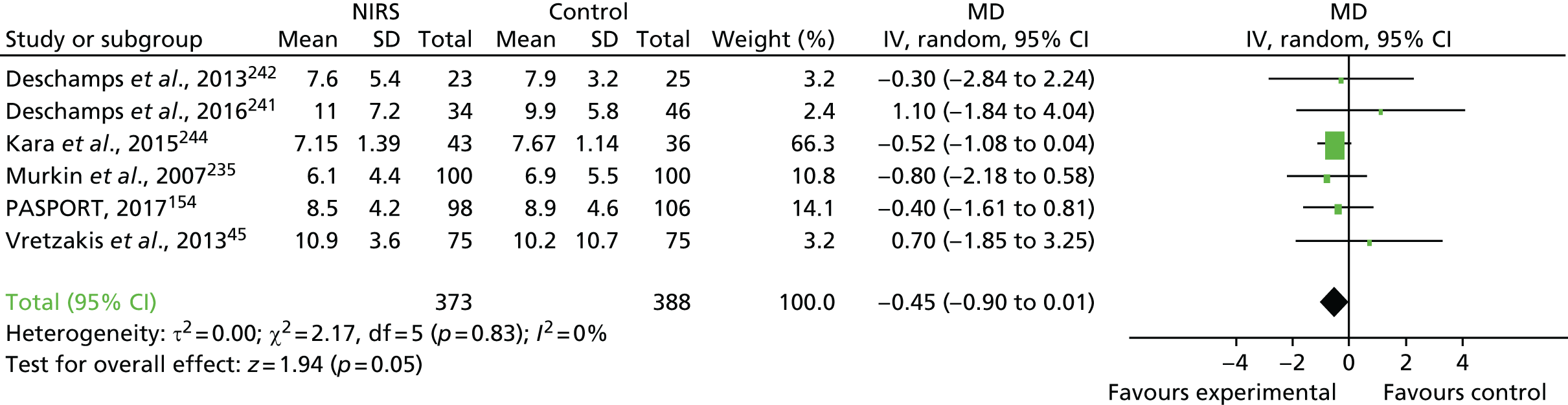

A systematic review of RCTs that have assessed the effectiveness of NIRS-based algorithms for the reduction of red cell transfusion and organ injury in cardiac surgery (reported in Chapter 4).

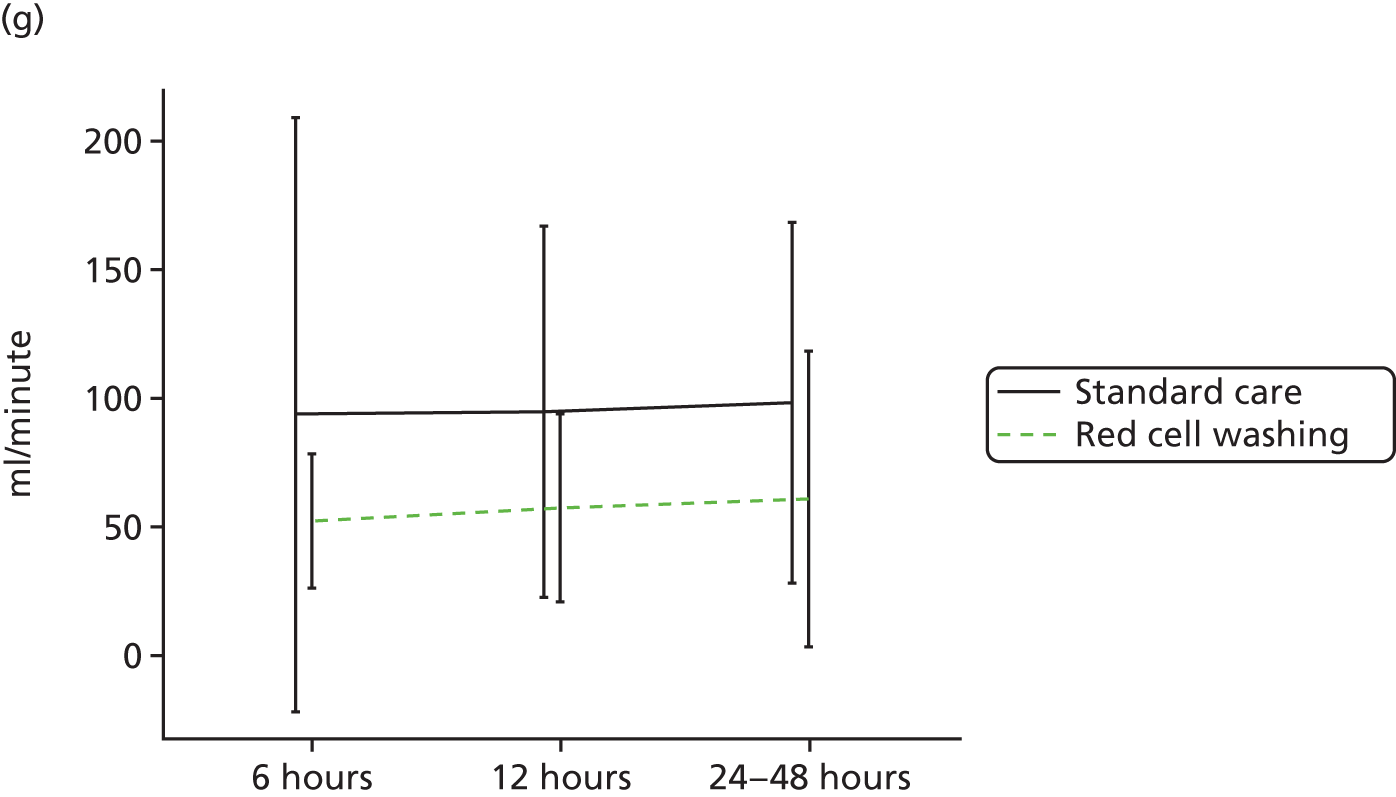

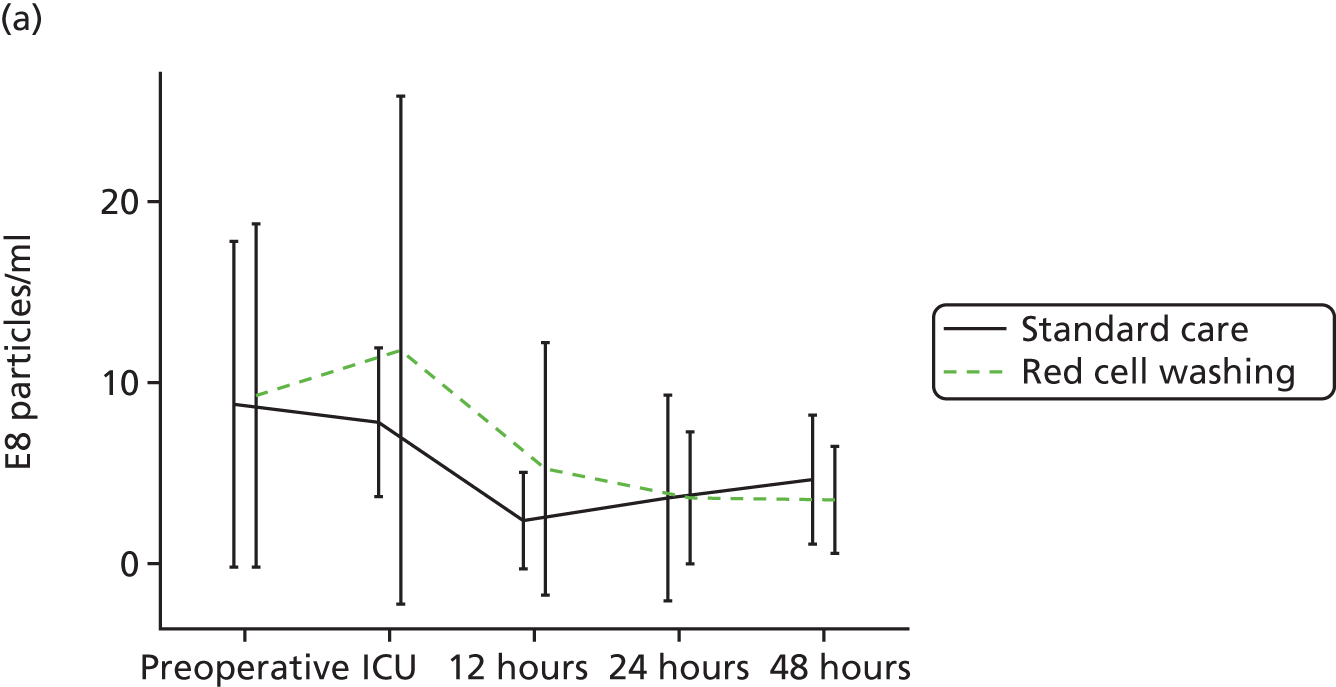

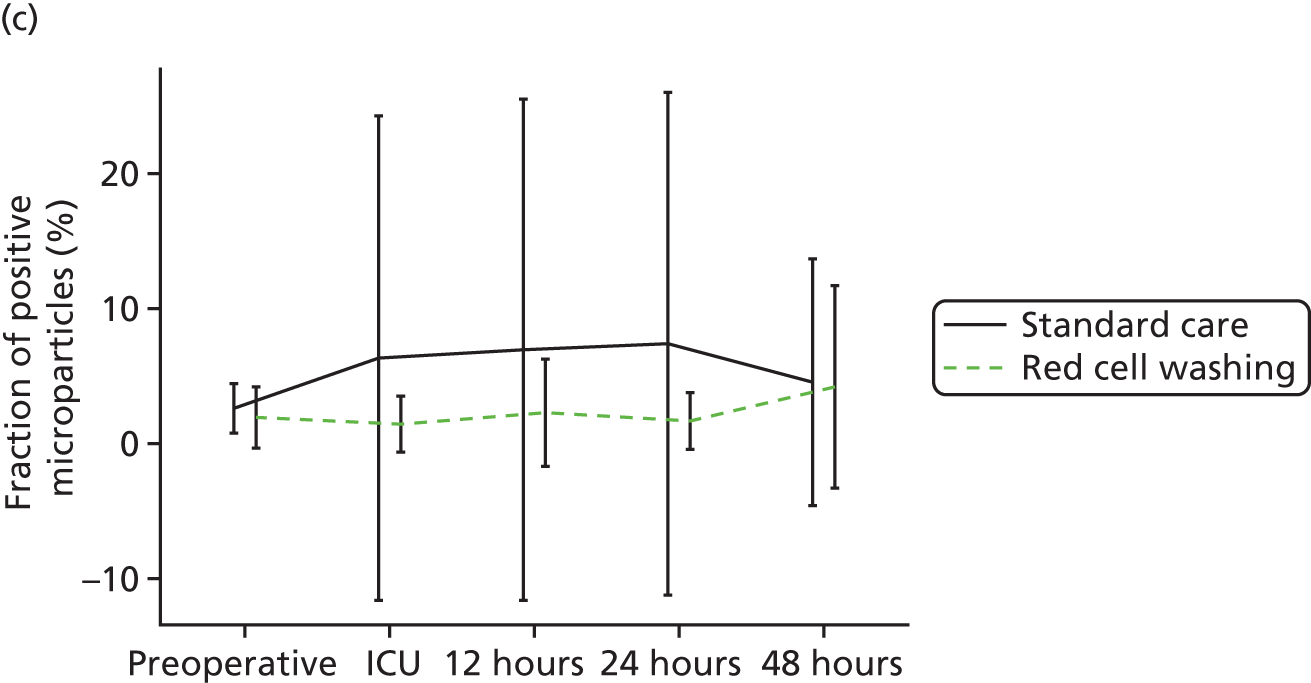

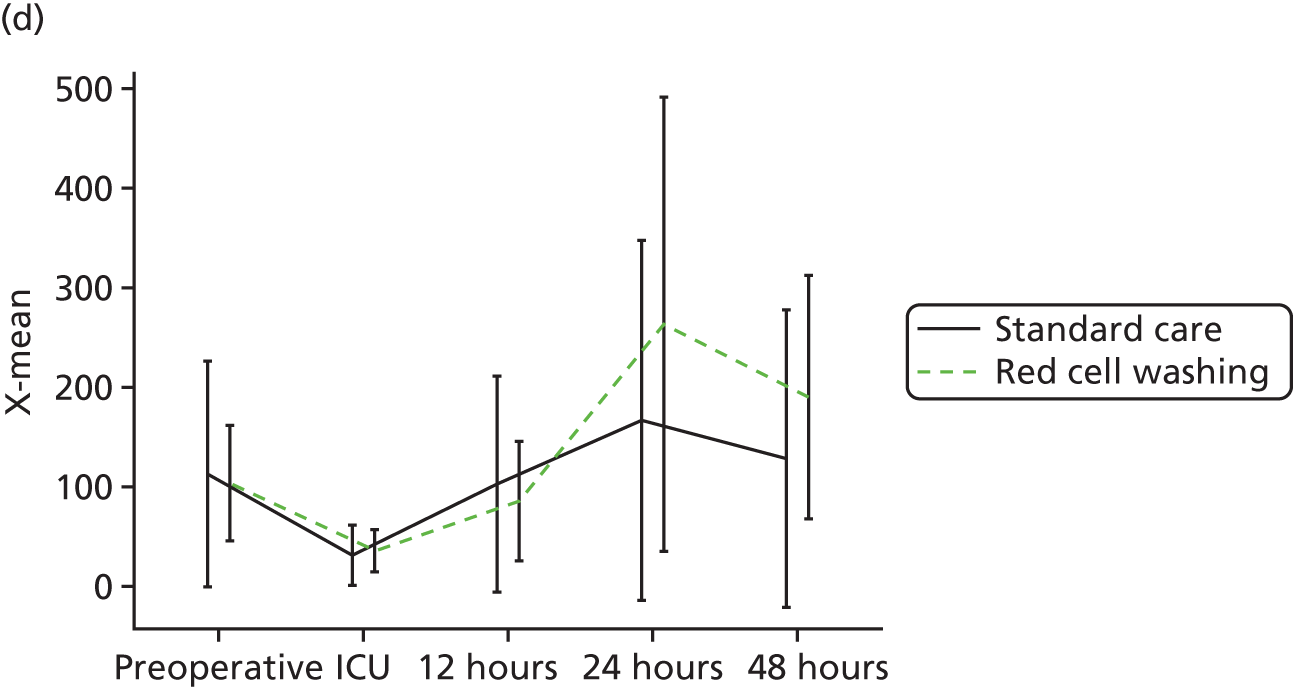

Workstream 3: the use of mechanical red cell washing devices to remove the red cell supernatant from stored red cells, thereby reducing inflammation and organ injury attributable to the storage lesion

Our objectives were to:

-

compare clinical outcomes including inflammation, organ injury and sepsis in participants randomised to receive mechanically washed allogenic red cells compared with standard care

-

evaluate the effects of mechanical washing on the structure, function and inflammatory properties of allogenic red cells in vitro and in participants in vivo

-

evaluate the cost-effectiveness of introducing red cell washing into clinical care.

Our plan of investigation to address these objectives was as follows.

-

A multicentre RCT to assess the efficacy of allogenic red cell washing compared with standard care for the prevention of past cardiac surgery inflammation and organ injury (reported in Chapter 5).

-

A substudy to explore the mechanisms underlying the results of our clinical trial (reported in Chapter 5).

Trial registration

Studies in the programme were prospectively registered as follows:

-

ISRCTN20778544 – coagulation and platelet laboratory testing in cardiac surgery (the COPTIC study)

-

PROSPERO CRD42016033831 – the routine use of point-of-care tests for the diagnosis and treatment of coagulopathic bleeding in cardiac surgery: a systematic review

-

ISRCTN 23557269 – a randomised controlled trial of patient-specific oxygen monitoring to reduce blood transfusion during heart surgery (the PASPORT trial)

-

PROSPERO CRD42015027696 – efficacy of near-infrared spectroscopy on the outcome of patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review

-

ISRCTN 27076315 – a randomised controlled trial of red cell washing for the attenuation of transfusion associated organ injury in cardiac surgery (the REDWASH trial).

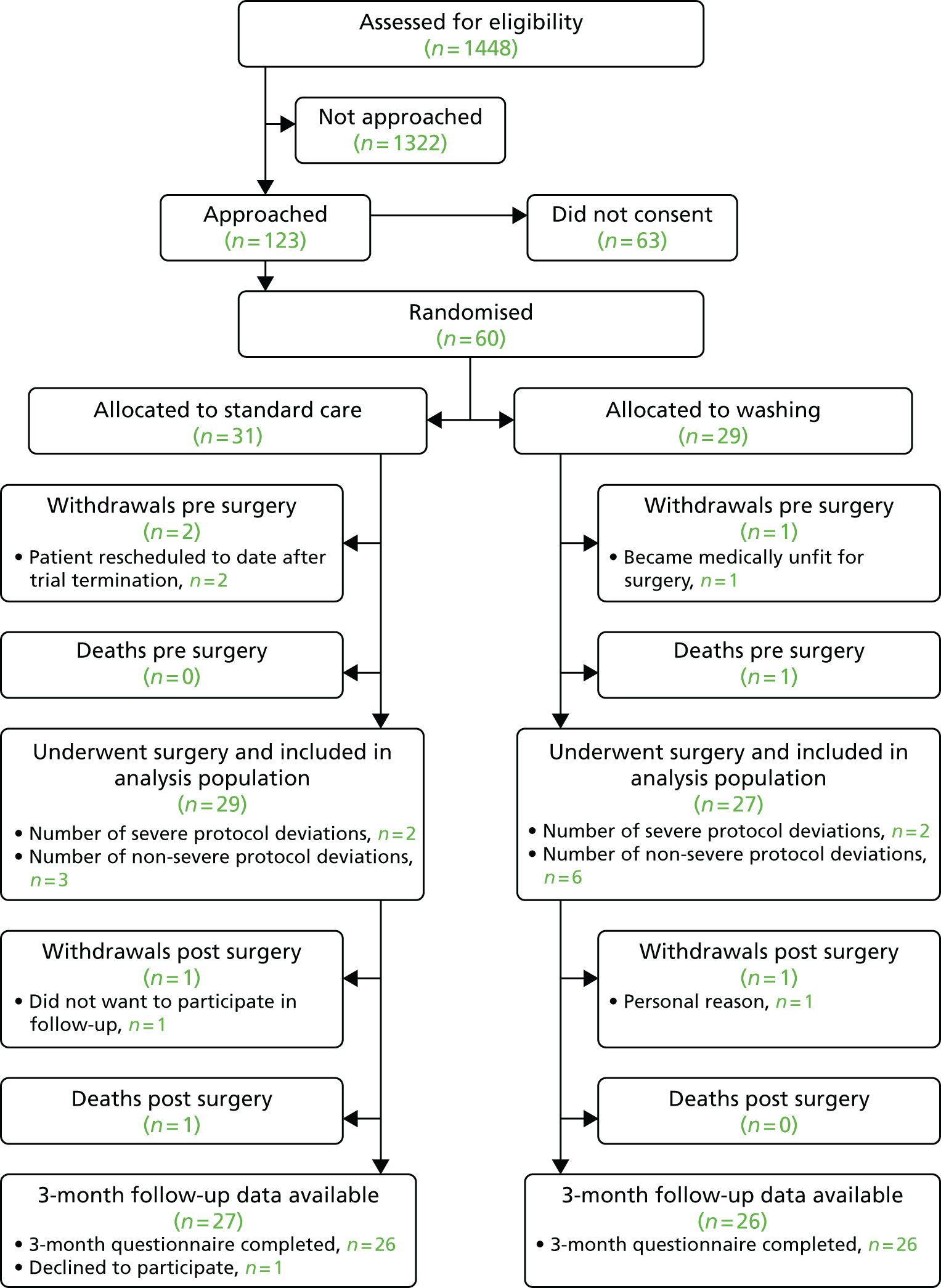

Changes to the original programme of work described in the grant application

The original programme of work was completed in its entirety, with the exception of the REDWASH study, which was terminated prematurely because of poor recruitment. For this reason no cost-effectiveness analysis was performed in the REDWASH trial as originally planned. In addition, two systematic reviews are included (see Chapters 2 and 4) and a mechanisms substudy was performed alongside the REDWASH trial (see Chapter 5).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) groups in Bristol and Leicester were involved in the development, governance, conduct and dissemination of this programme. The groups were composed of cardiac surgery patients, some of whom had participated in clinical trials, and members of the public, many of whom had PPI clinical research experience in local and national organisations. Of these, the Leicester Cardiac Surgery PPI group was the most developed, with specific subgroups dealing with consultation in respect of research protocols and materials, research activity including the development of recruitment strategies, trial governance and the enhanced patient visitor role, raising awareness about research in the public forum and disseminating research findings in partnership with the research team. The activities of this group have ensured that patient needs have remained at the centre of the research programme throughout.

Transparency declaration

The lead author (GJM) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the studies being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Chapter 2 Point-of-care coagulation and platelet laboratory testing in cardiac surgery: a predictive accuracy study with linked health economic analysis and parallel systematic review of efficacy trials of viscoelastometry

Abstract

Background: Coagulopathic bleeding is a common and severe complication of cardiac surgery.

Objective: To assess the benefits of introducing routine POC tests or an expanded range of laboratory diagnostic tests for coagulopathy compared with the current standard of care (clinical risk assessment) for the management of cardiac surgery patients with severe bleeding.

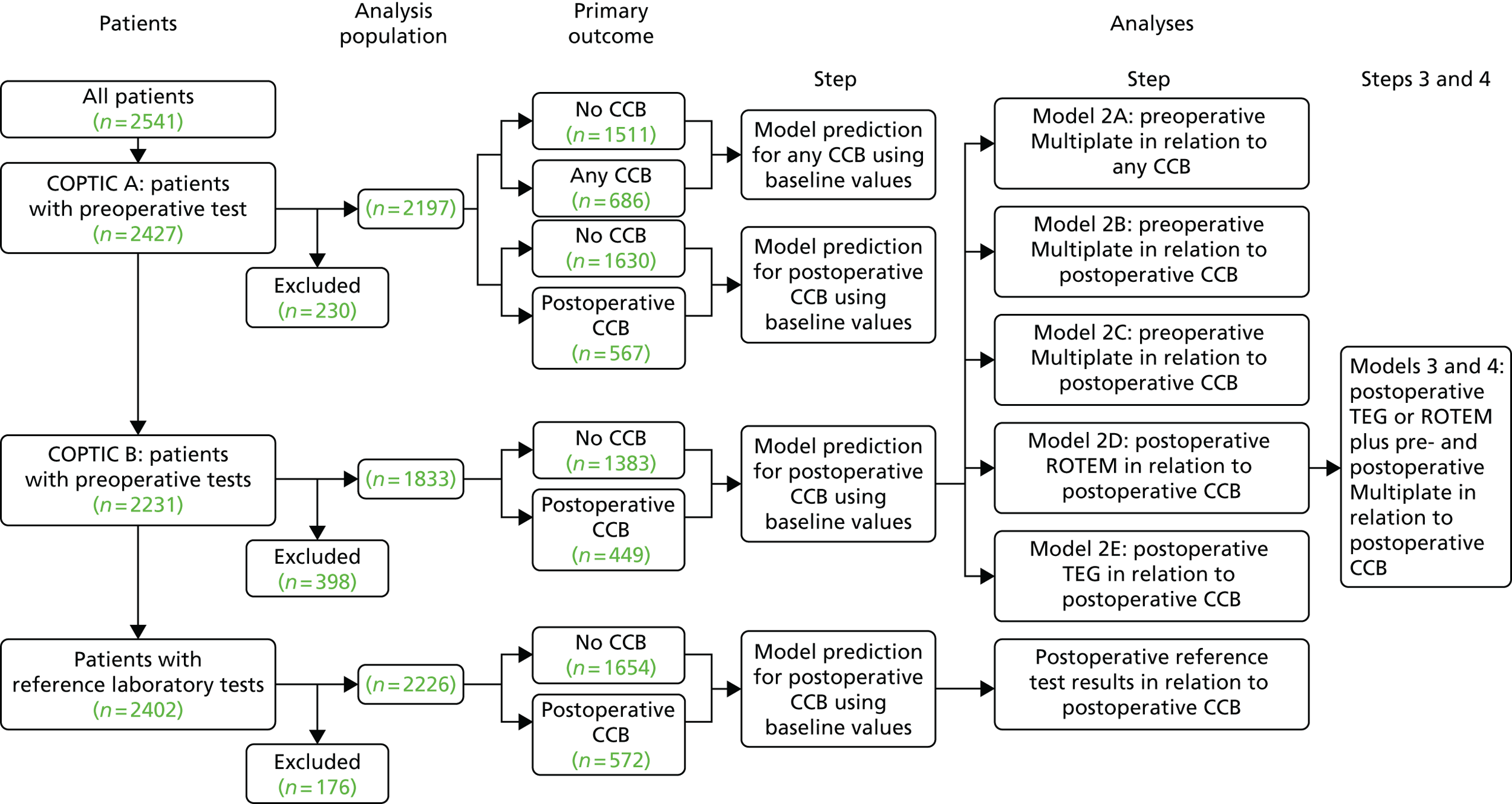

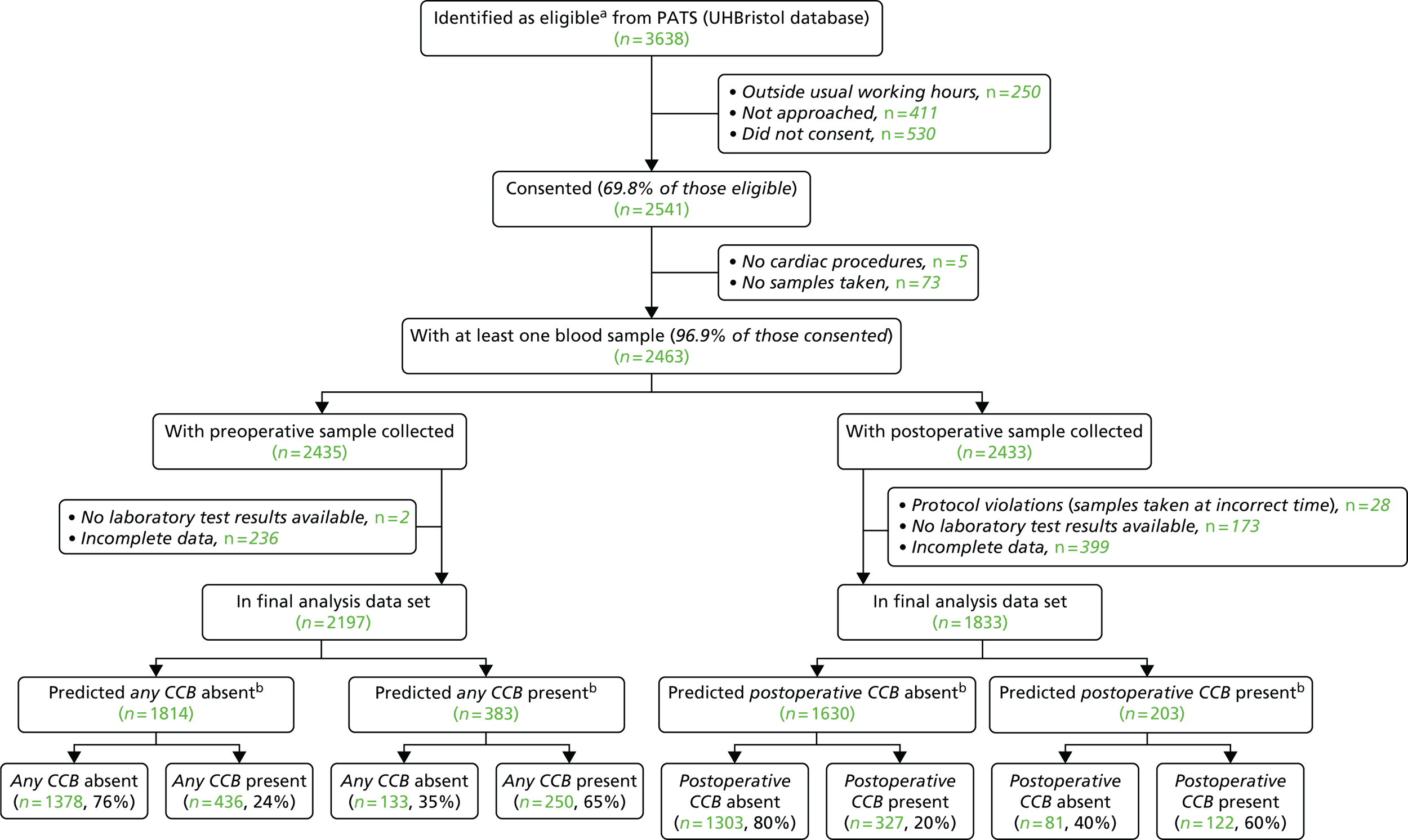

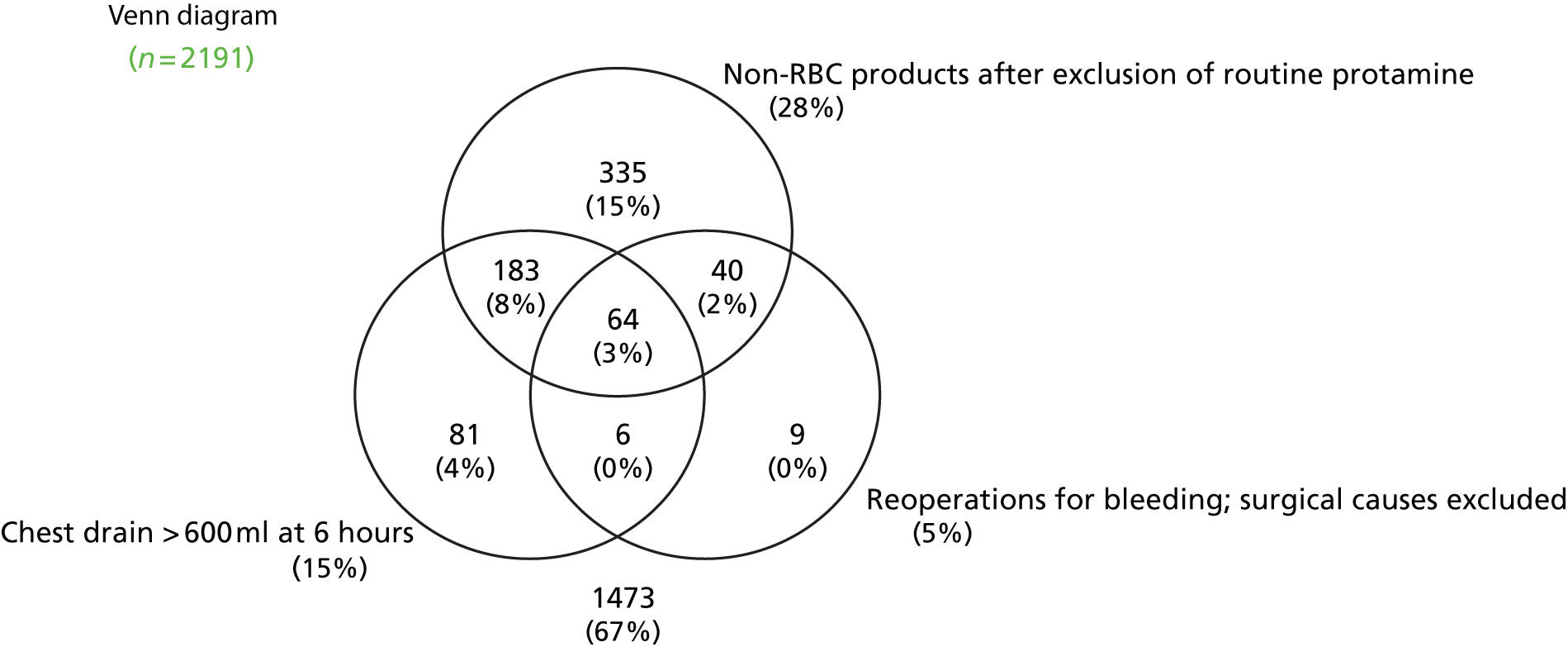

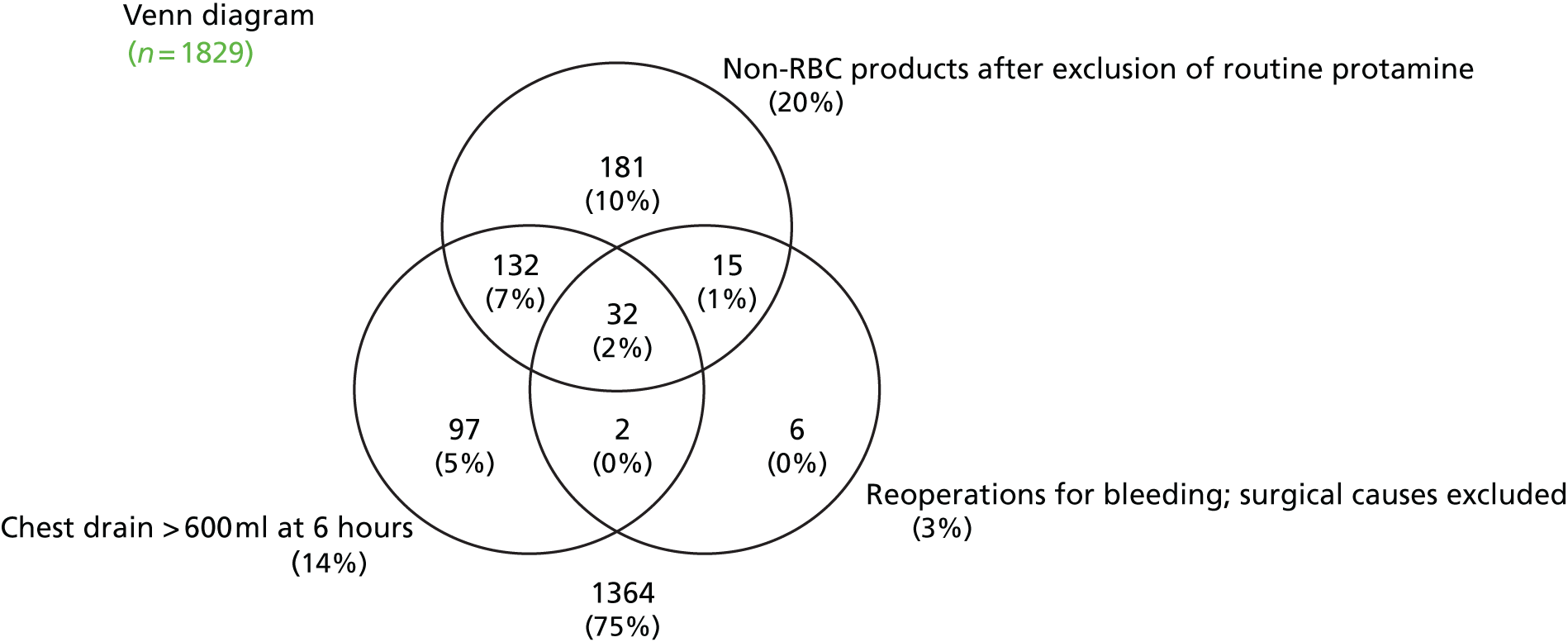

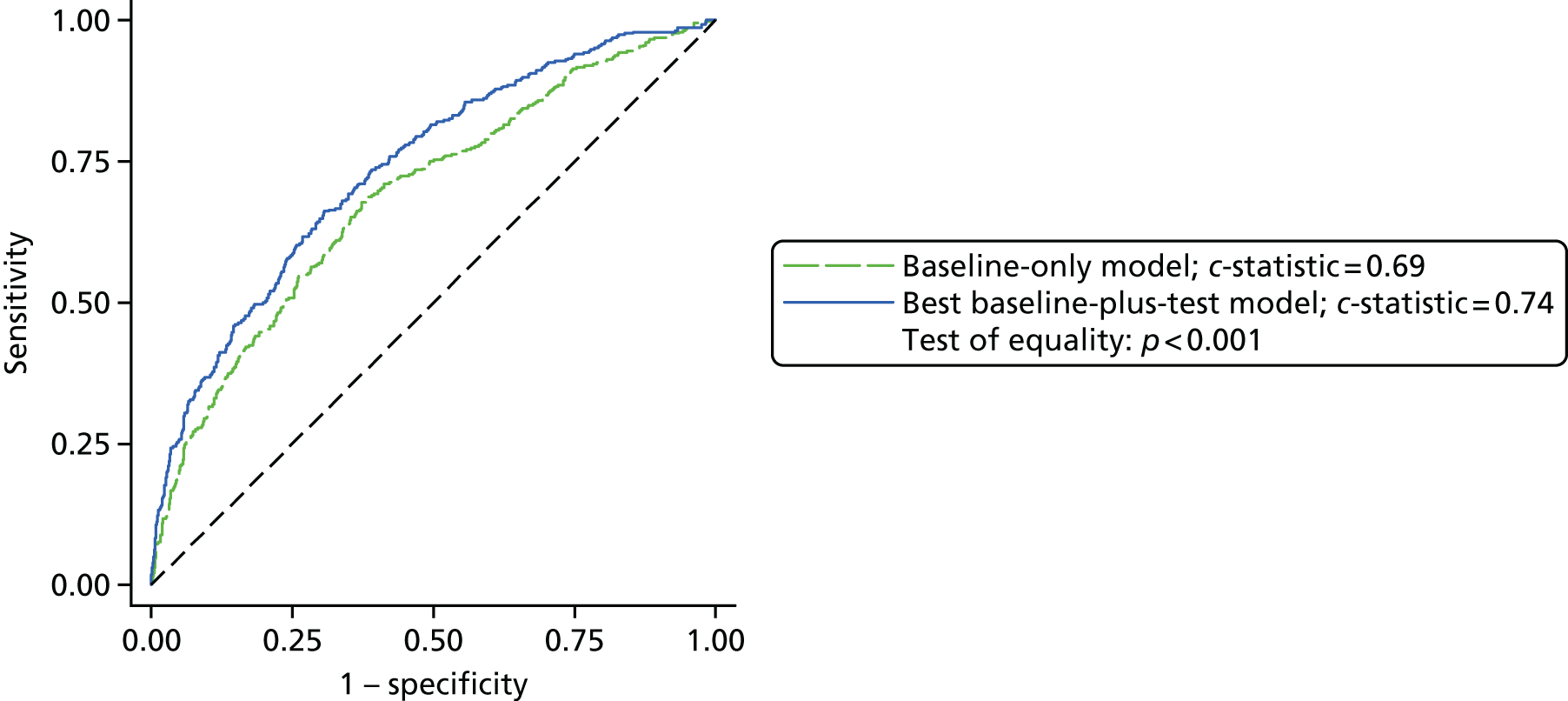

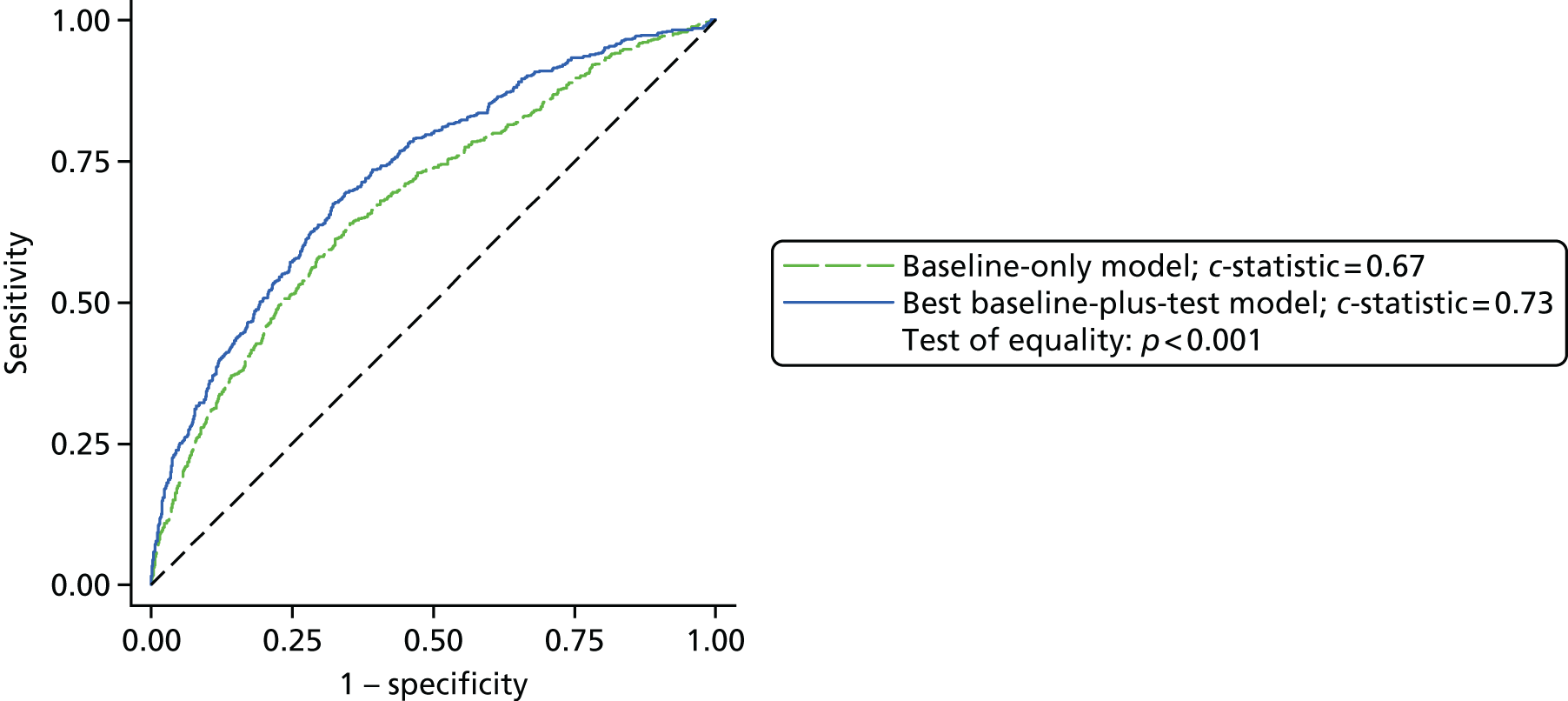

Methods: A diagnostic accuracy study and linked cost-effectiveness analysis compared POC platforms in current use for the prediction of post-surgery haemorrhage [rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) (ROTEM® Delta; TEM International GmbH, Munich, Germany), thromboelastography (TEG) (TEG® 5000 Thromboelastograph® Haemostasis Analyzer; Haemonetics Corporation, Niles, IL, USA) and Multiplate® analyzer (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland)], as well as alternative LRTs of coagulopathy, with standard care. The clinical effectiveness of POC testing in cardiac surgery was evaluated in a systematic review of RCTs.

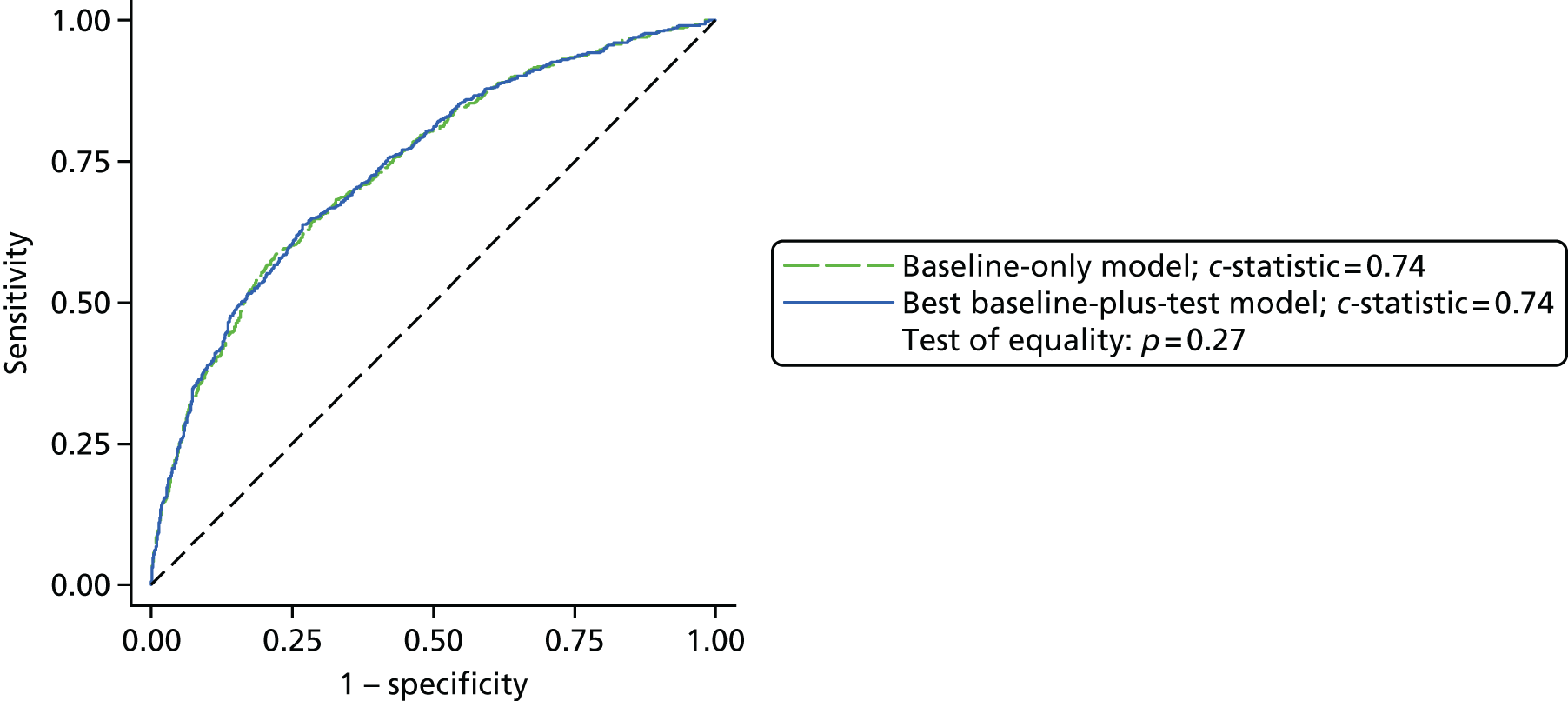

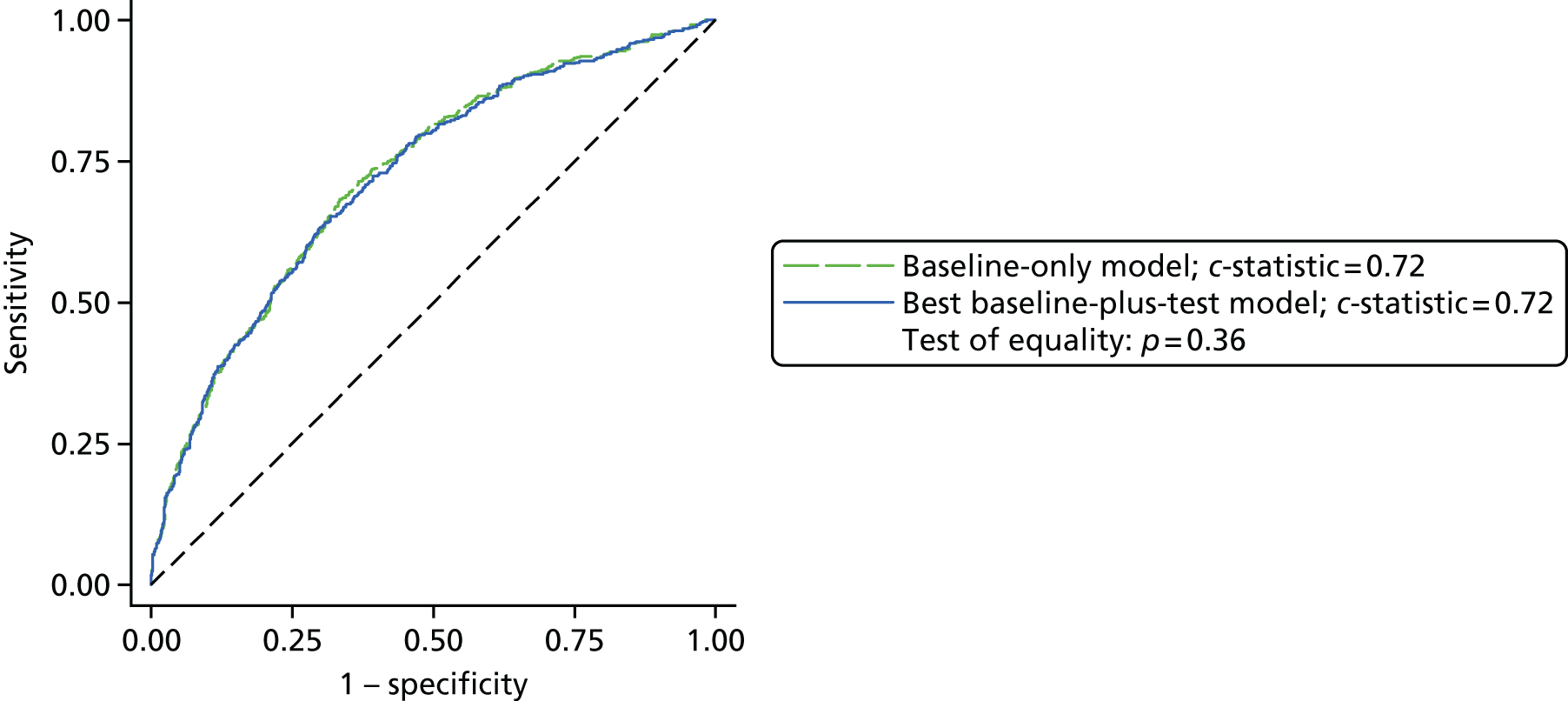

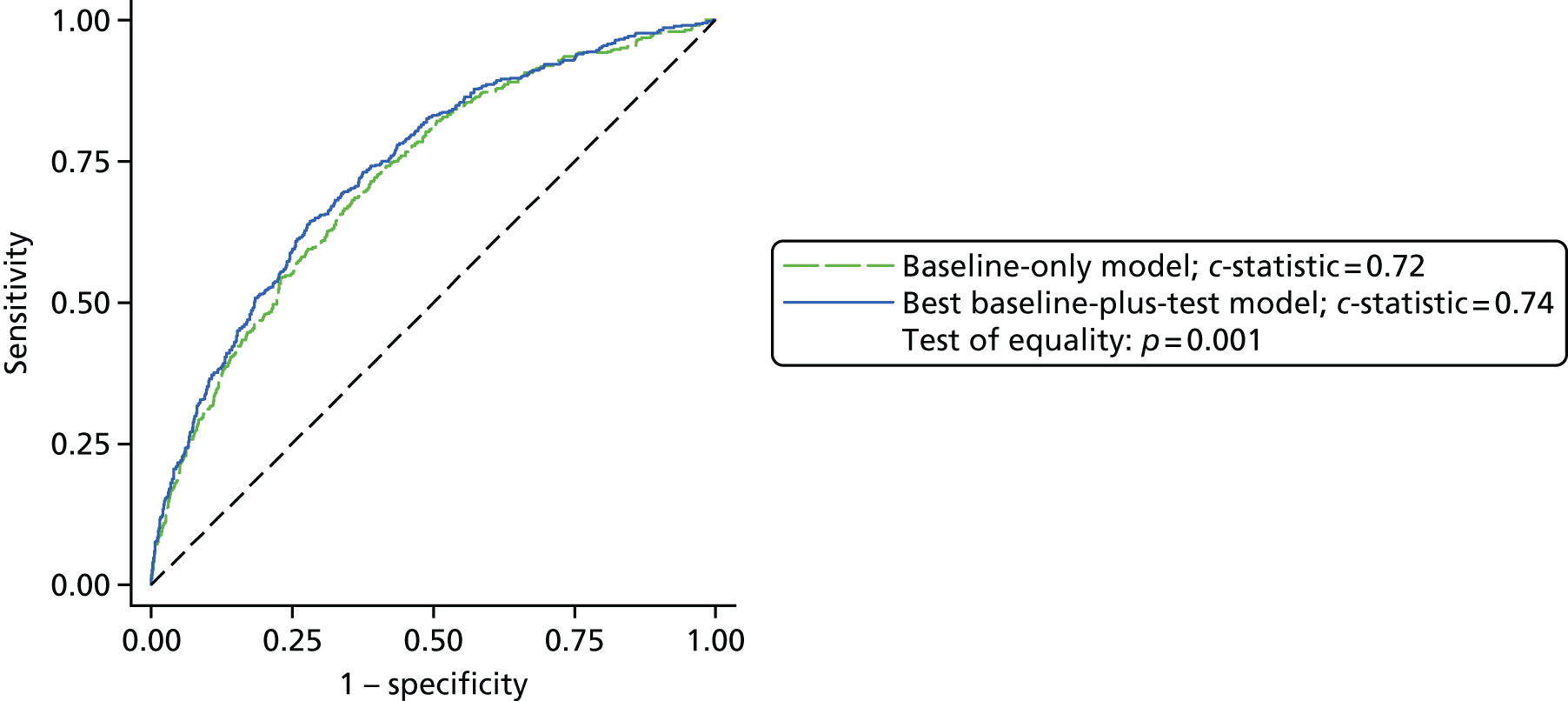

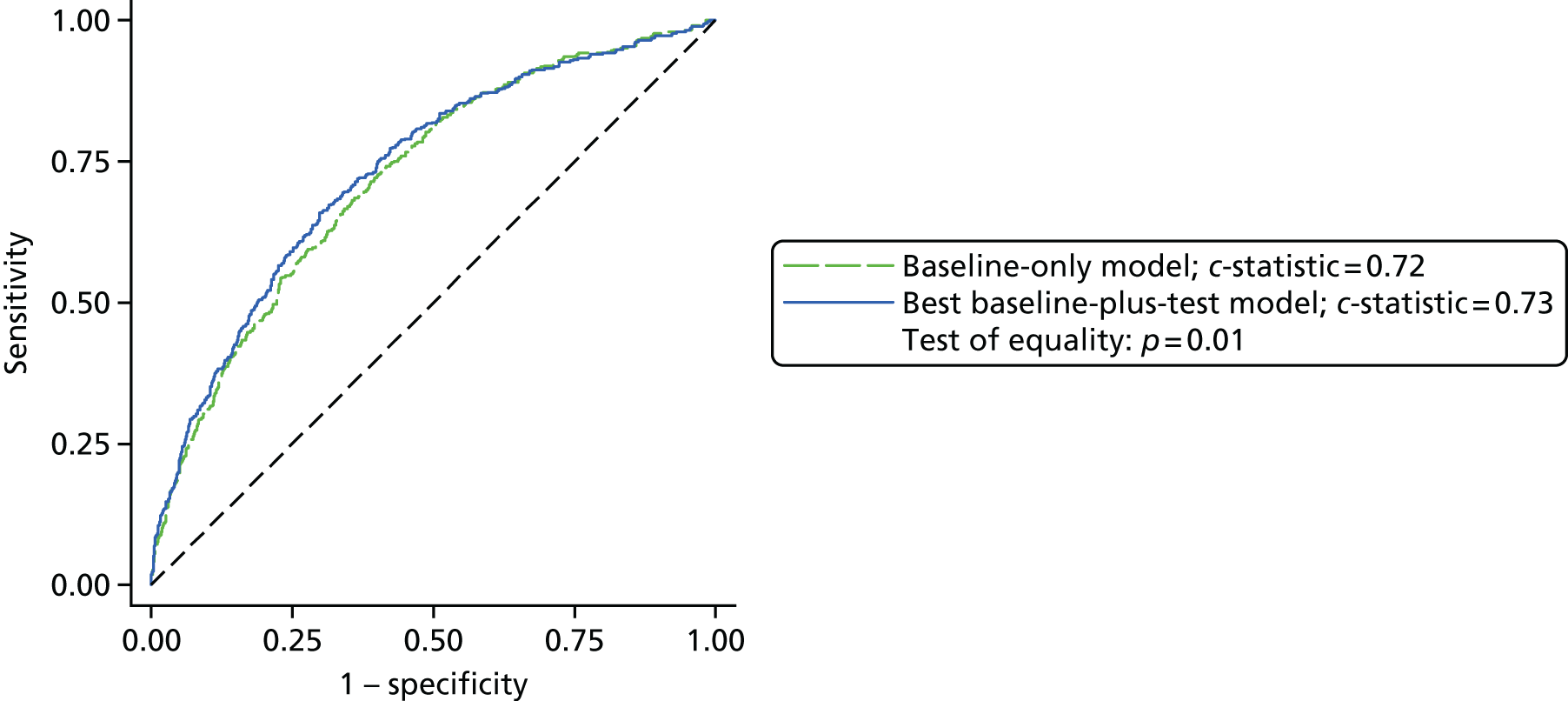

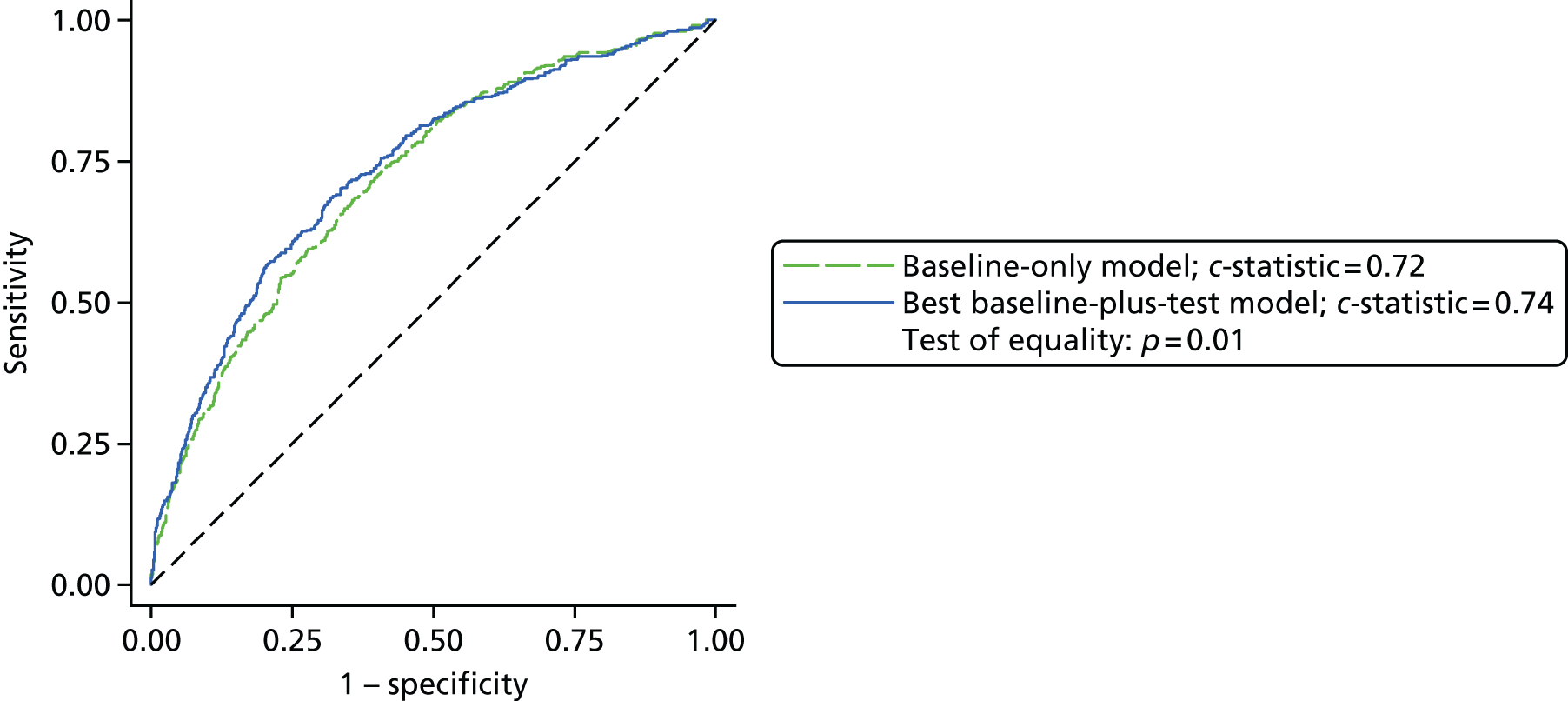

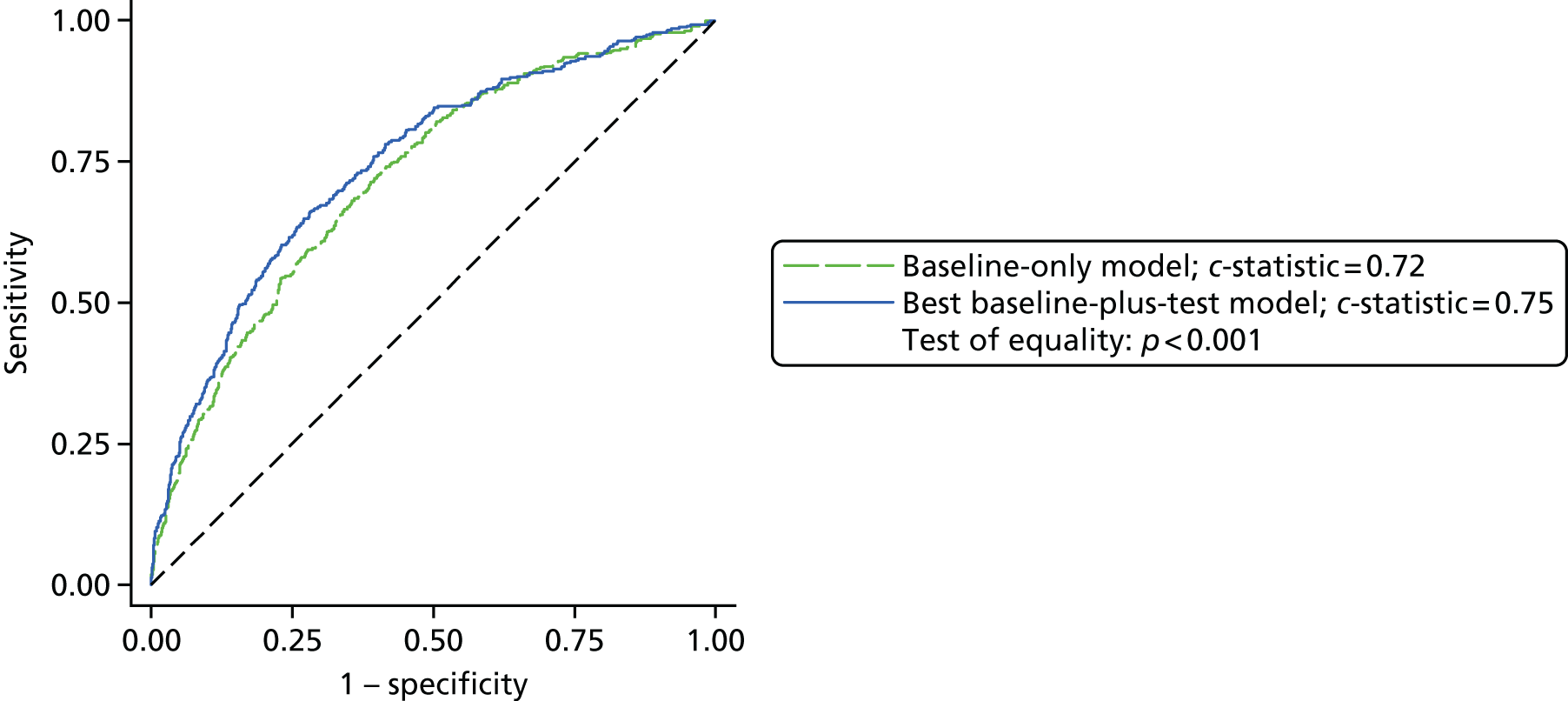

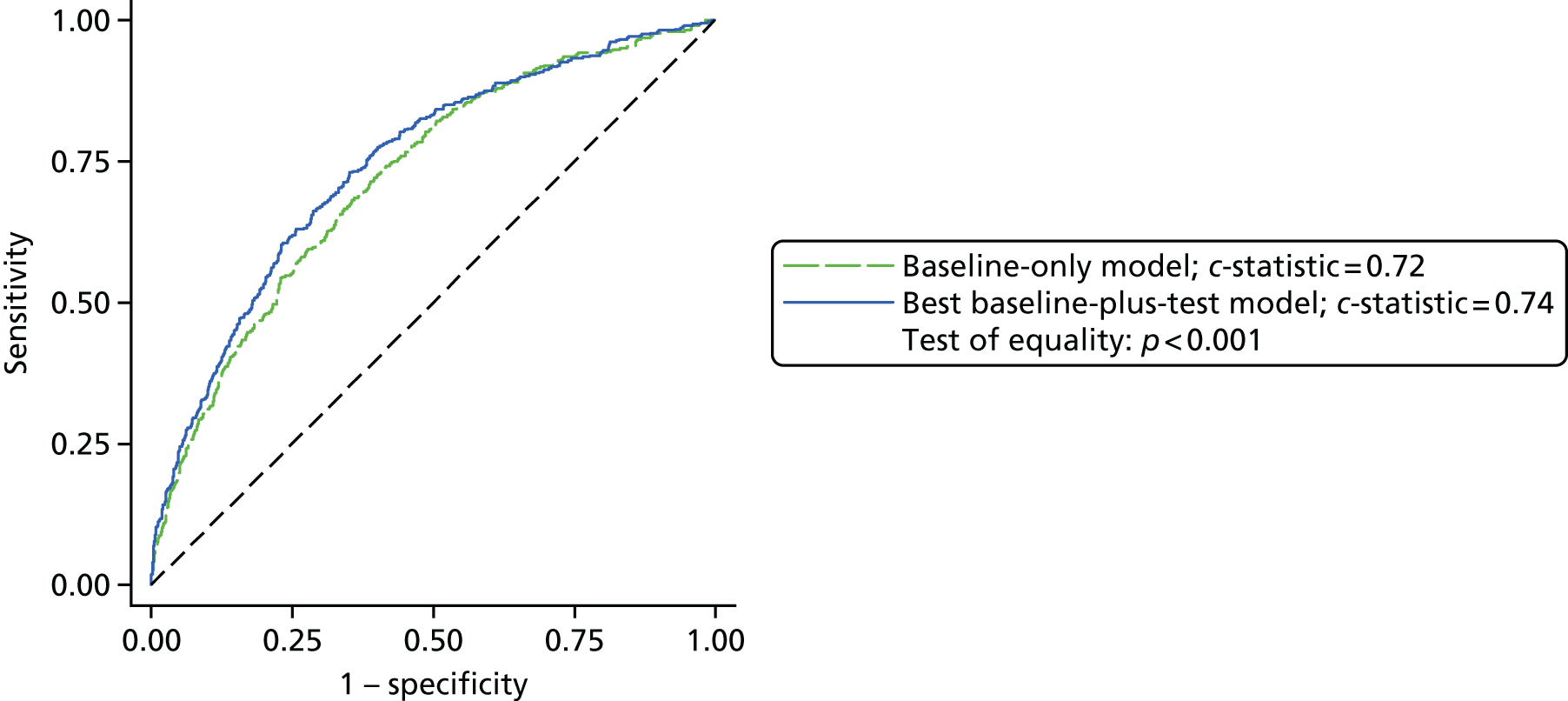

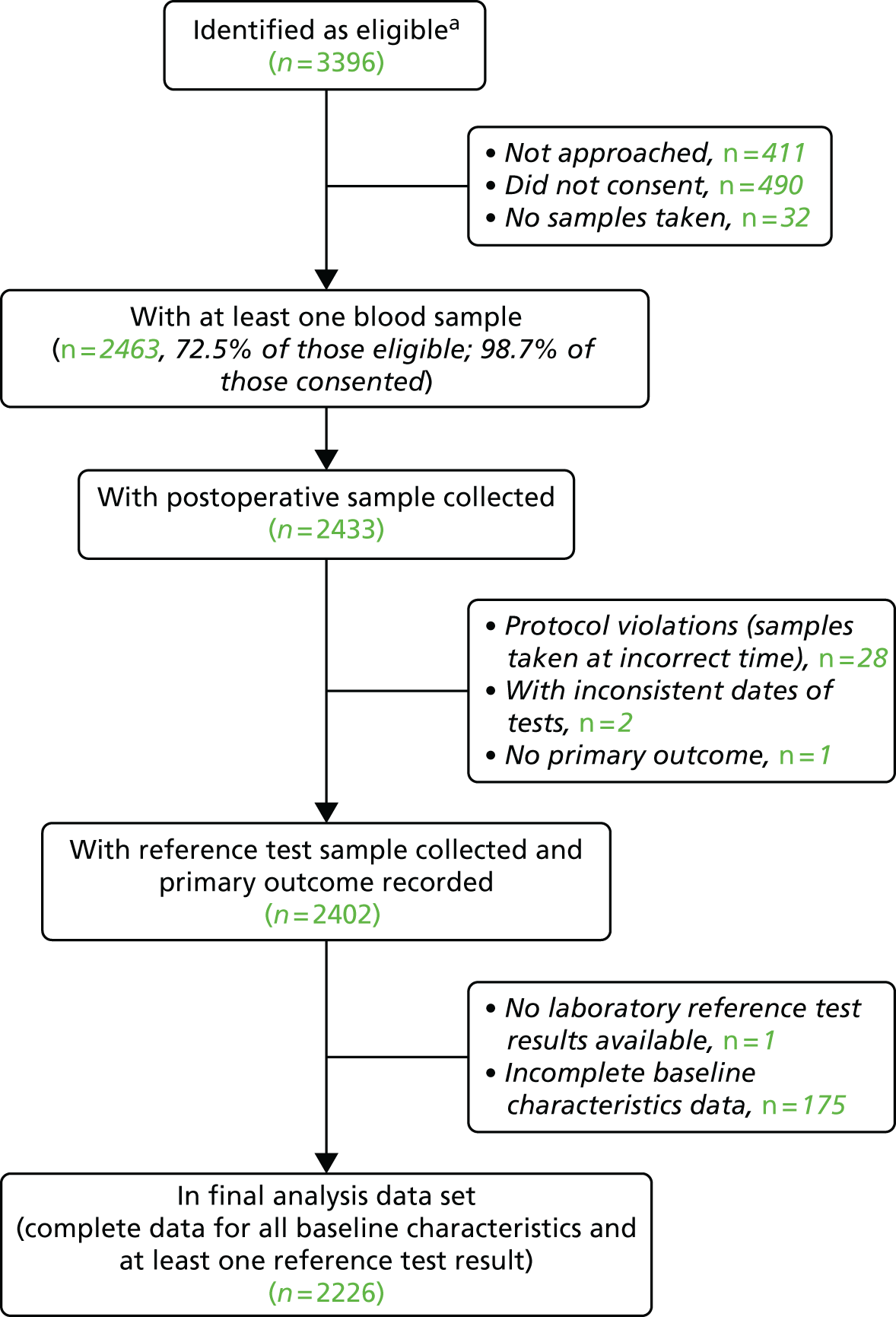

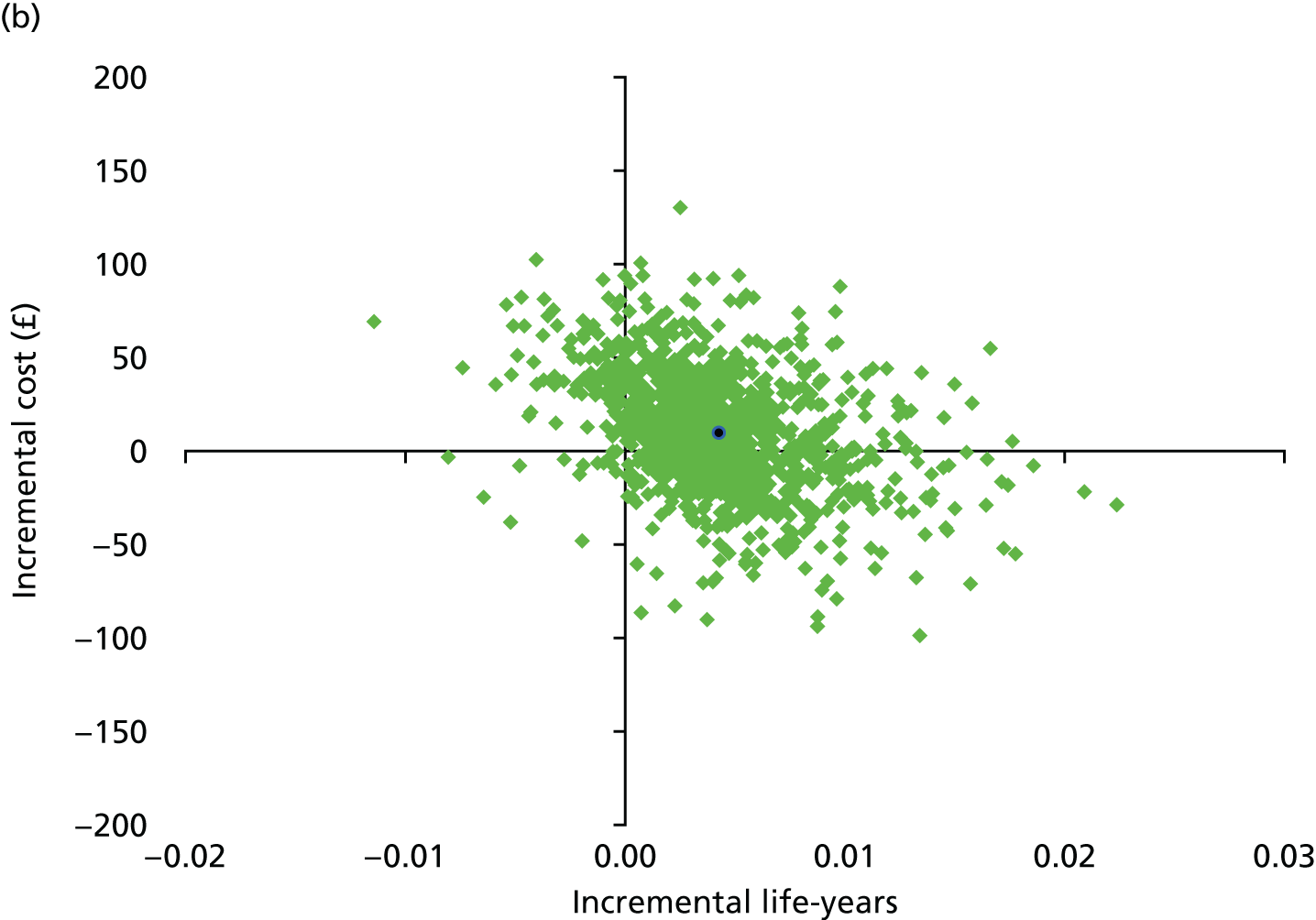

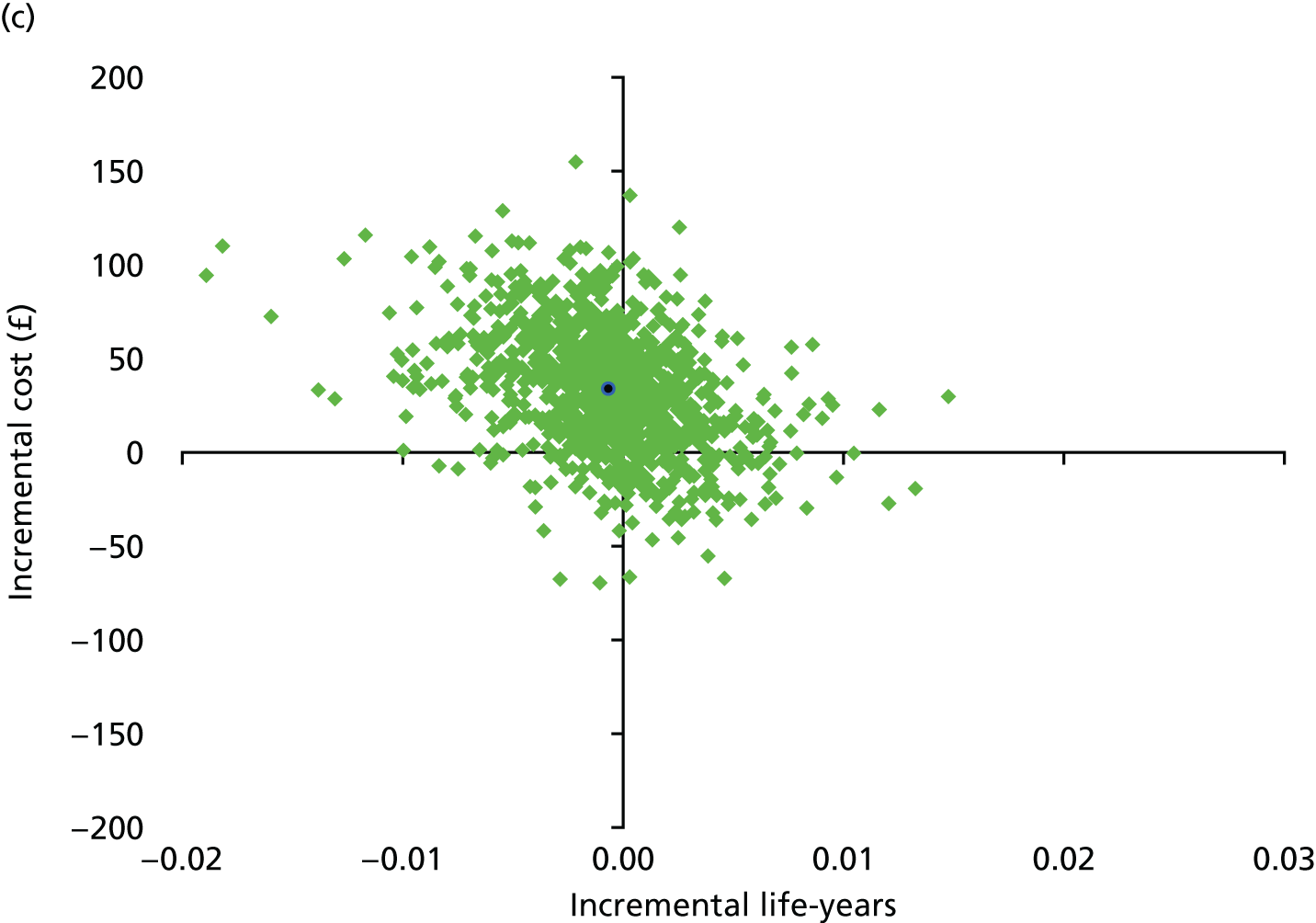

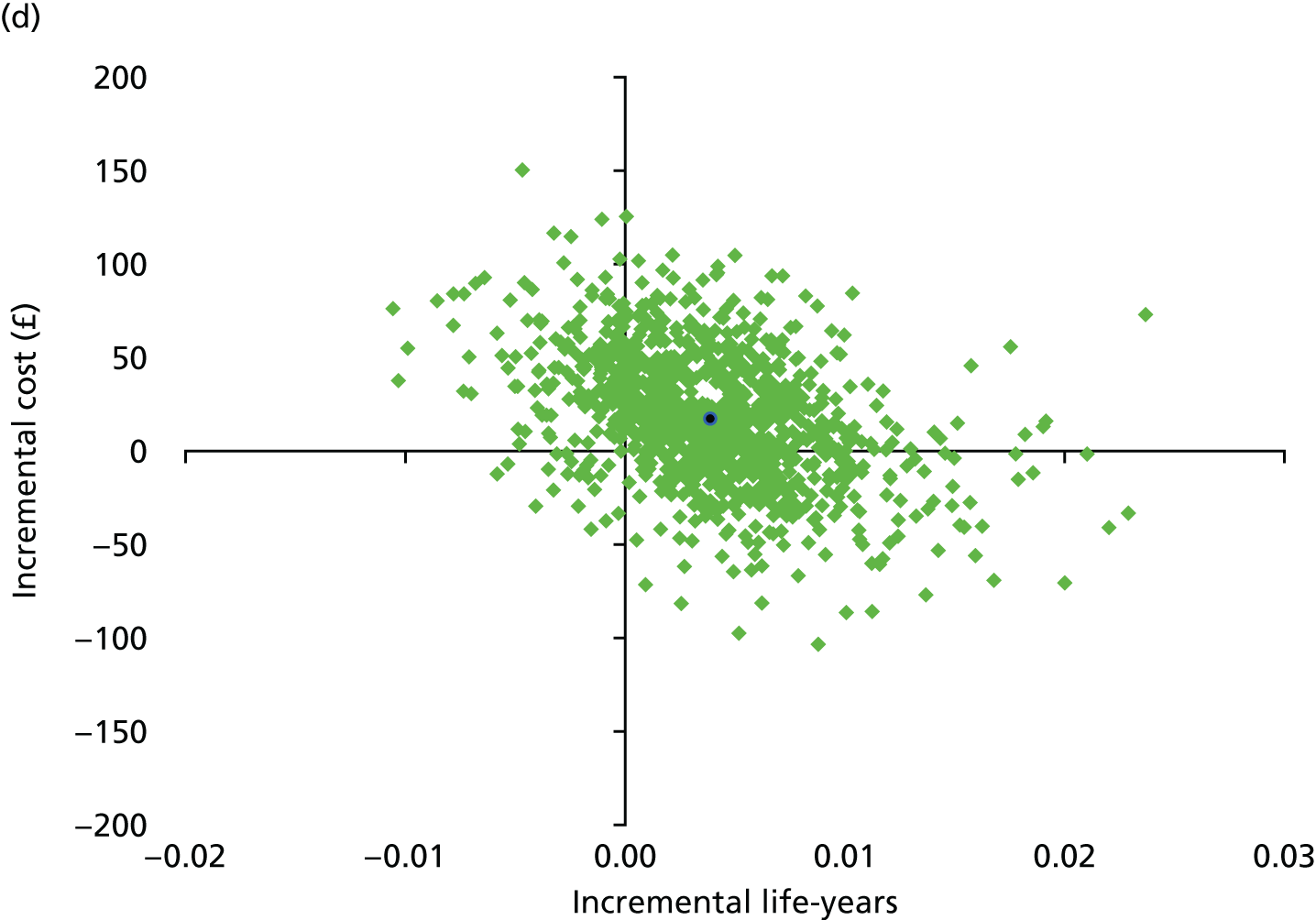

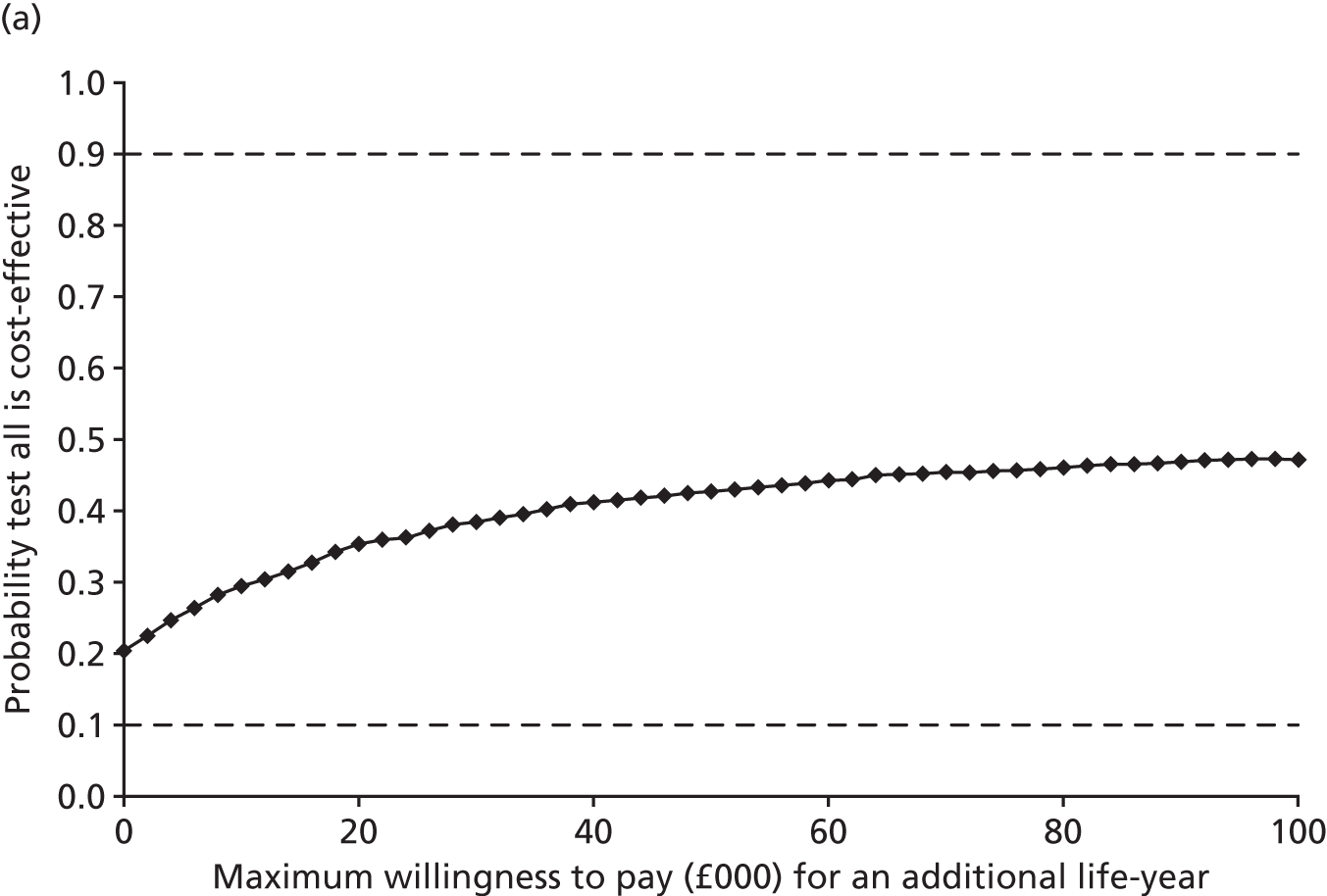

Results: In the predictive accuracy study 2541 participants were recruited between March 2010 and September 2012. Perioperative POC and LRT results did not result in clinically important improvements in predictive accuracy beyond that achieved using clinical risk prediction alone. The cost-effectiveness analysis demonstrated very little difference between any of the POC tests and current practice in either costs or life-years saved. The systematic review demonstrated that the routine use of POC tests did not improve clinical outcomes.

Conclusions: Existing diagnostic tests for coagulopathy have limited additional value for the diagnosis and treatment of coagulopathic bleeding in cardiac surgery beyond the current standard of care.

Study registration: Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN20778544 and PROSPERO CRD42016033831.

Background

The clinical problem

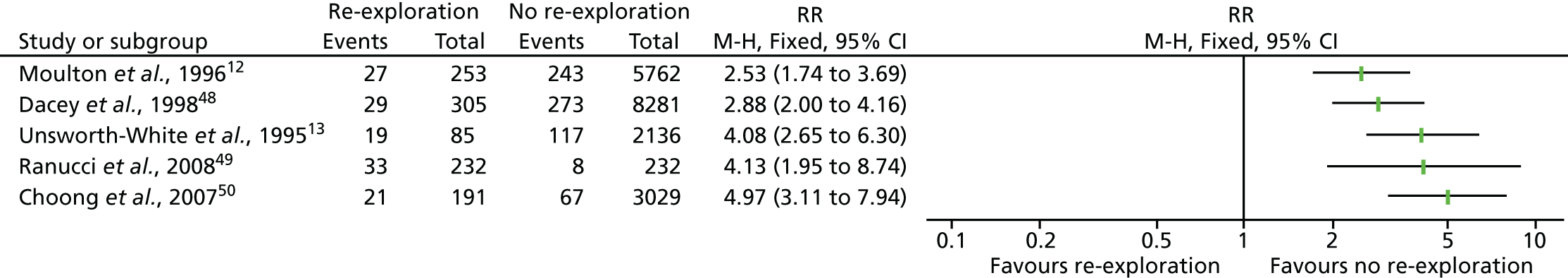

Coagulopathic bleeding is a common and severe complication of cardiac surgery. In the UK up to 5% of all patients require emergency re-exploration for bleeding in the immediate postoperative period. 9 This is associated with a fourfold increase in mortality and resource use (Figure 1). Adverse events associated with severe bleeding may be attributable to the severity of the underlying illness and the complexity of surgery, which contribute to coagulopathy, as well as the consequences of significant haemorrhage and shock. The adverse effects of coagulopathic bleeding may also be attributable in part to the side effects of treatment. Large-volume red cell transfusions or the administration of pro-haemostatic therapies such as platelet and FFP transfusion and recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) have well-documented risks. 7 These risks, although offset by the risks of ongoing bleeding in coagulopathic patients, may be clinically significant in those without coagulopathy or when administered to those who are not actively bleeding.

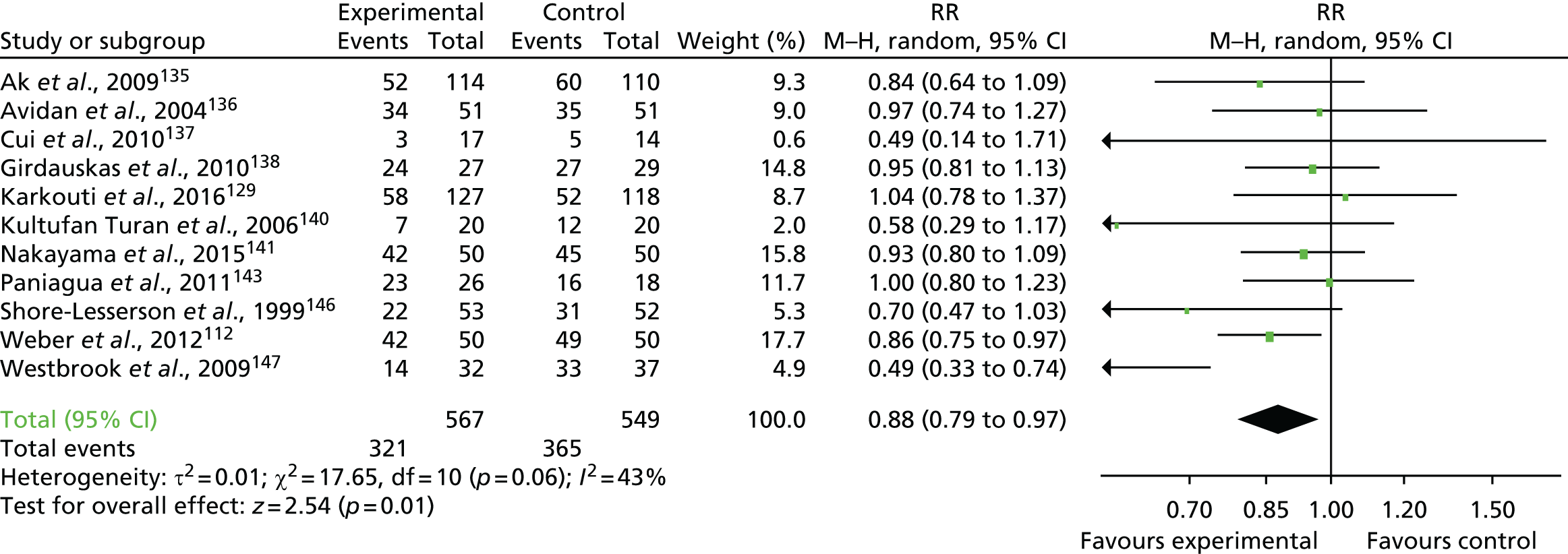

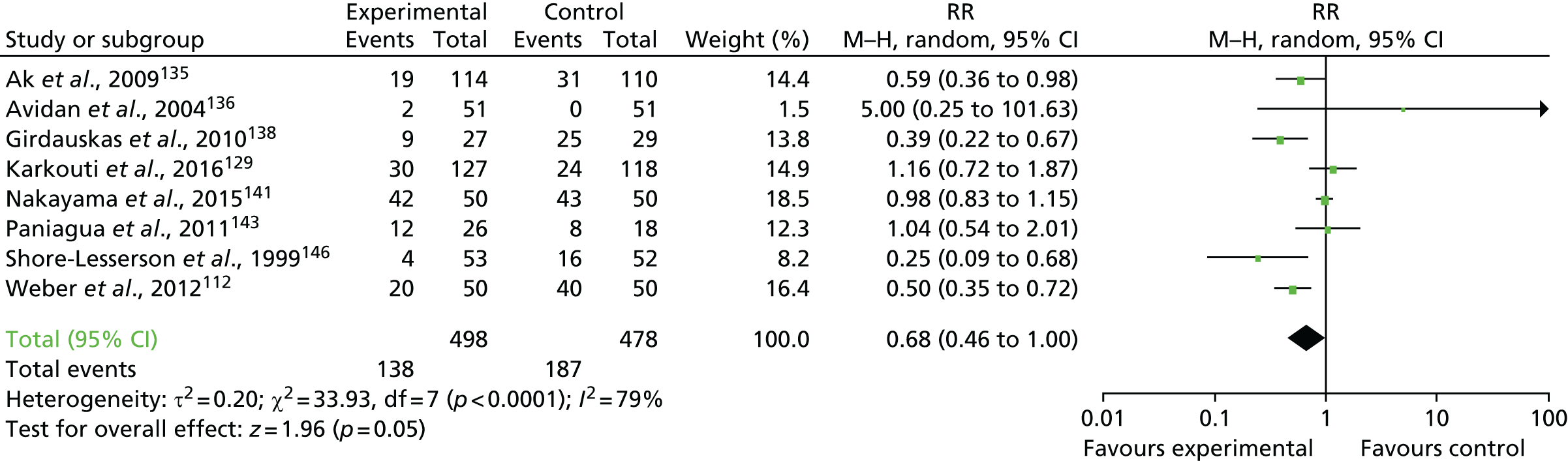

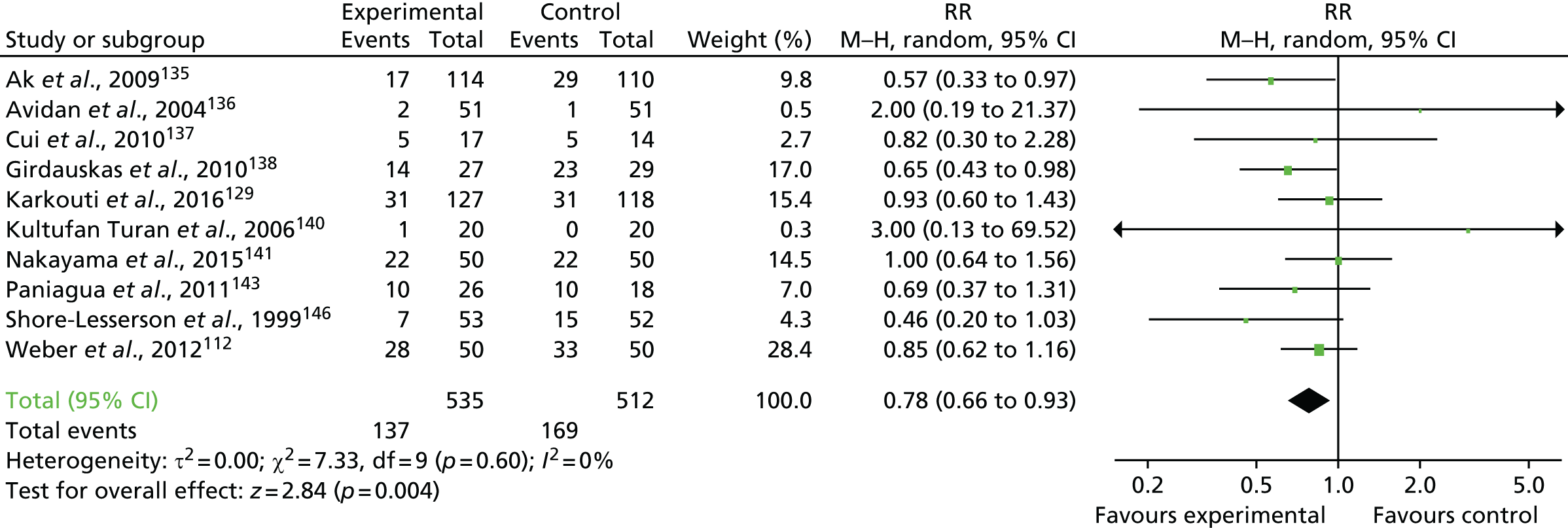

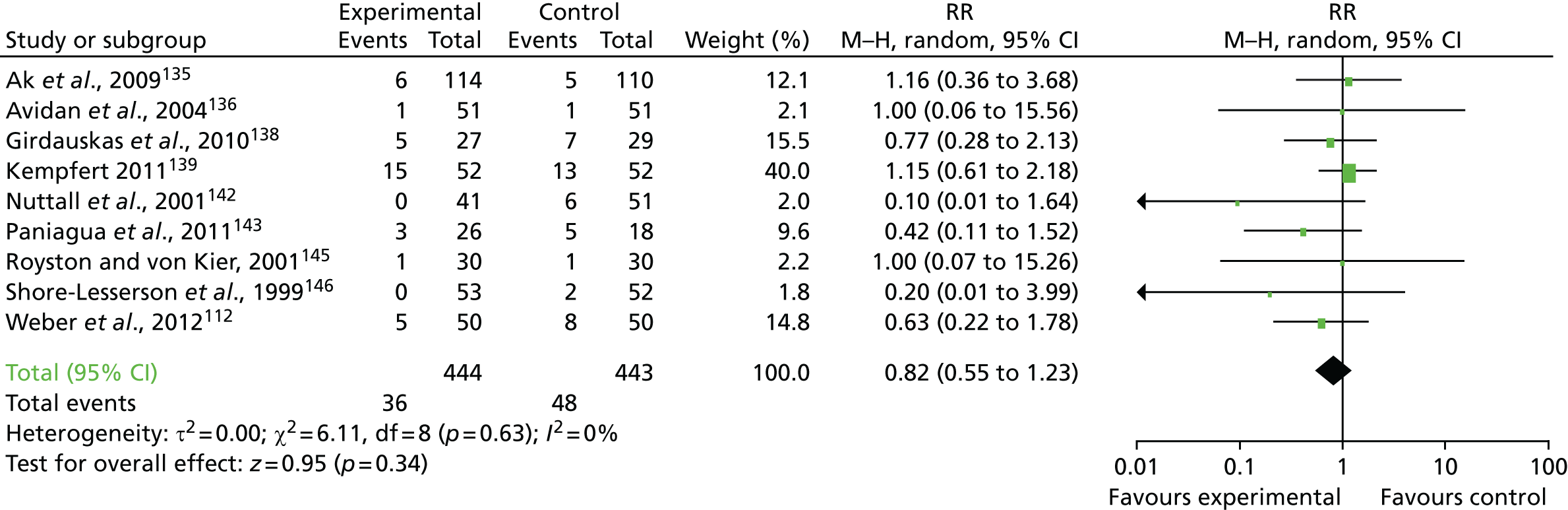

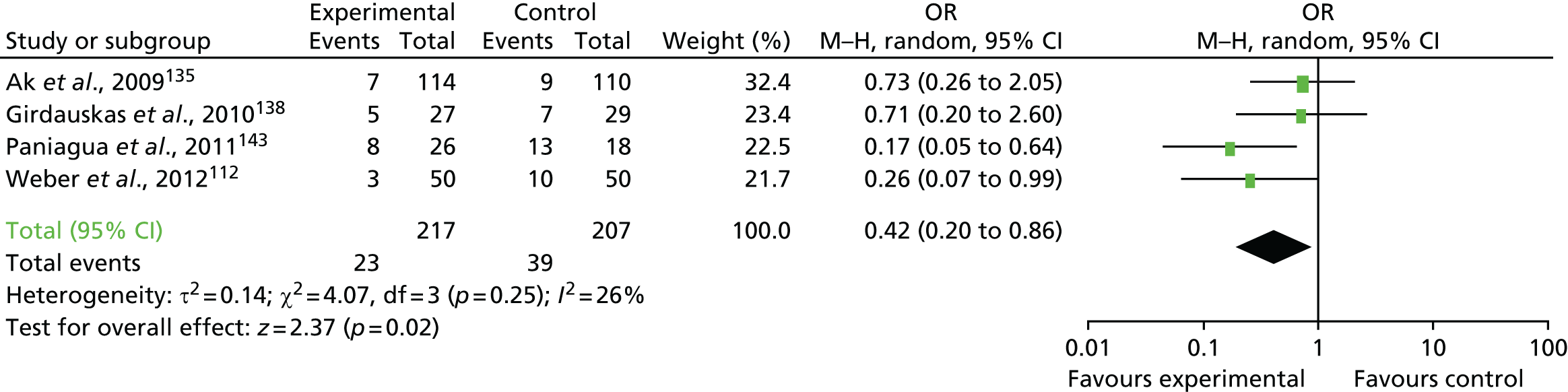

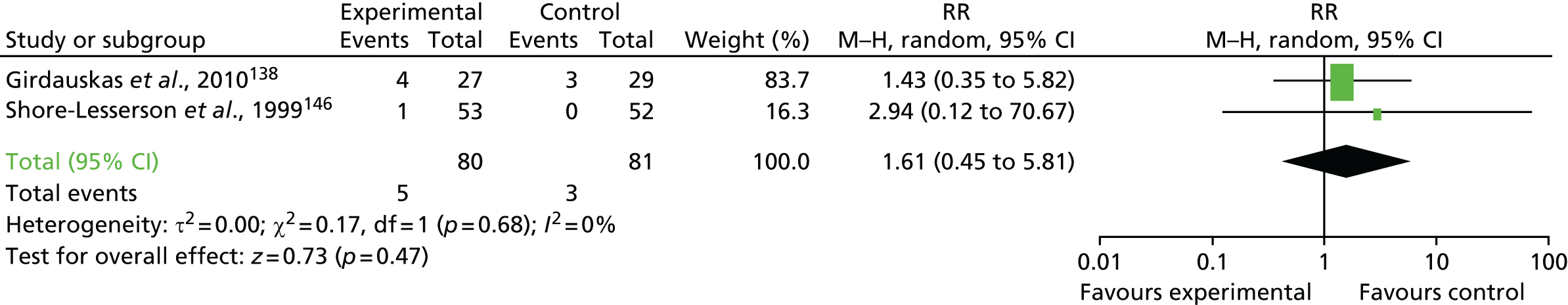

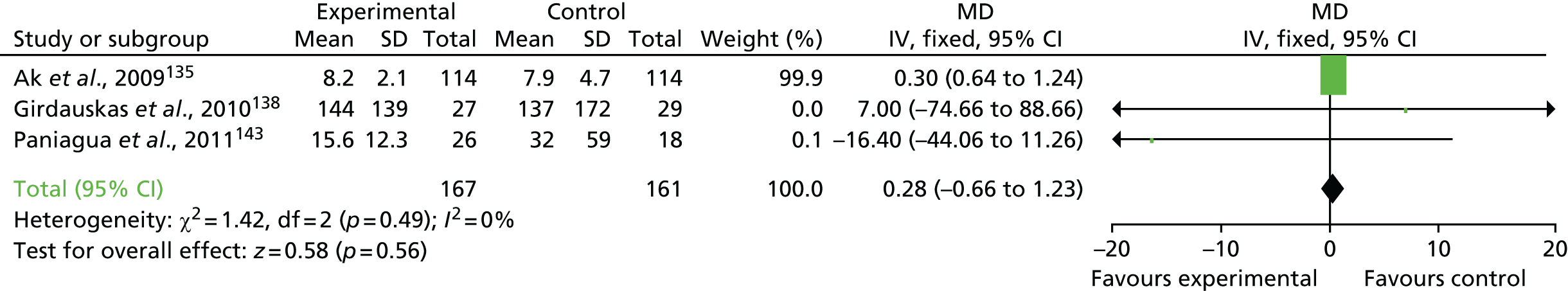

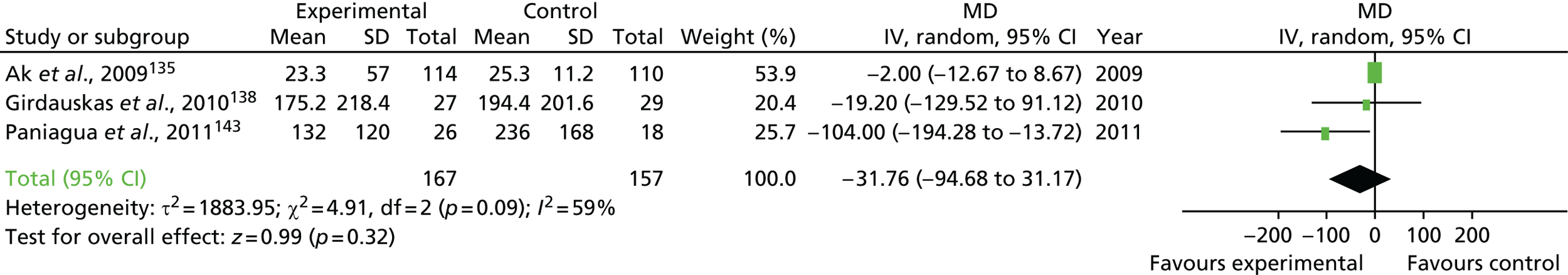

FIGURE 1.

Forest plots summarising effect estimates from observational studies that have considered the effects of emergency reternotomy for bleeding on mortality. M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

A range of medical devices are in common use as POC diagnostic tests for the prediction of severe bleeding in patients and its treatment; however, the evidence to support their use is inconsistent and this is reflected by wide variation in their use. 9 This chapter will establish whether commonly used POC testing devices have good predictive accuracy for coagulopathic bleeding when used routinely and consider whether the introduction of POC testing algorithms for the diagnosis and management of bleeding is cost-effective. It will also consider whether the introduction of additional diagnostic tests improves predictive accuracy and effectiveness.

Coagulopathic bleeding

Coagulopathic haemorrhage is poorly defined. The current consensus definition of coagulopathy is a prolonged prothrombin time (PT) of > 1.2 times normal. 51 However, prolonged PT and abnormalities in other standard laboratory tests (SLTs) have not been found to have predictive accuracy for coagulopathic haemorrhage in cardiac or non-cardiac surgery. 52,53 Many patients with abnormal standard laboratory coagulation tests do not develop bleeding and coagulopathic bleeding may occur when these tests are normal. This reflects the limitations of the tests and the complex aetiology of coagulopathy. This means, however, that it is often difficult to distinguish coagulopathic bleeding from non-coagulopathic bleeding. Defining excessive bleeding is also problematic in situations in which bleeding occurs to some degree in all patients. The efficacy of haemostatic interventions is also unclear. The lack of a clear definition of coagulopathic bleeding complicates epidemiological analyses and the development of accurate diagnostic tests and treatments. Excessive bleeding in cardiac surgery may be defined clinically as:

-

Emergency re-sternotomy for life-threatening haemorrhage or cardiac tamponade within hours of surgery. This definition includes patients with very severe coagulopathic haemorrhage in which conventional pro-haemostatic therapies have failed to control bleeding. This has limitations as a definition because emergency re-sternotomy may be required for ‘surgical’ bleeding in the absence of coagulopathy. There are also important institutional differences in how patients with haemorrhage are managed and how readily patients are re-explored when tamponade is suspected. This is reflected by emergency re-sternotomy rates that range from 0.3% to 12% between UK units. 9 This definition may therefore underestimate the proportion of patients with coagulopathic haemorrhage.

-

Large-volume red cell transfusion. Massive blood transfusion (MBT) defined as ≥ 10 units of red cells within 24 hours, or 4 units within 1 hour, is rare in cardiac surgery. Large-volume red cell transfusion (≥ 4 units of red cells) is common, however. In the UK 22% of patients receive a LVBT perioperatively. 9 This equates to approximately 1000 ml of packed red cells or 20% of the circulating blood volume of a 70-kg adult. Transfusion of ≥ 4 units has been shown to be associated with significant increases in perioperative morbidity and mortality in cardiac surgery. 10 A limitation of this definition is that red cells are also commonly administered for the treatment of anaemia and this may therefore overestimate the frequency of coagulopathic haemorrhage. Late transfusions, for example after 24 hours postoperatively, are also unlikely to represent treatment for bleeding.

-

Transfusion of allogenic non-red cell components to promote haemostasis. In the UK up to 25% of cardiac surgery patients receive FFP or platelets to arrest or prevent coagulopathic bleeding. 9 The limitation of this definition is that currently non-red cell transfusions are often administered empirically based on subjective assessments by clinical staff. As a consequence there is variation in the frequency of non-red cell component transfusion across UK units. 9 This reflects differences in case mix and institutional practices; however, it also suggests that many patients receive unnecessary transfusions. This definition would therefore overestimate the frequency of coagulopathic bleeding.

-

Excessive blood loss. The volume of blood loss in the drains is routinely measured. Excessive bleeding has been defined as > 10 ml/kg/hour. 54 This has limitations as an indicator of coagulopathic bleeding because (1) patients with coagulopathic bleeding who receive effective pro-haemostatic treatment may not have excessive blood loss, (2) excessive blood loss may be masked by blocked chest drains and this may present as tamponade or late pleural and pericardial collections, (3) excessive blood loss may have a surgical as opposed to a coagulopathic cause and (4) drain losses may not represent active bleeding and may consist of pleural or pericardial collections and effusions.

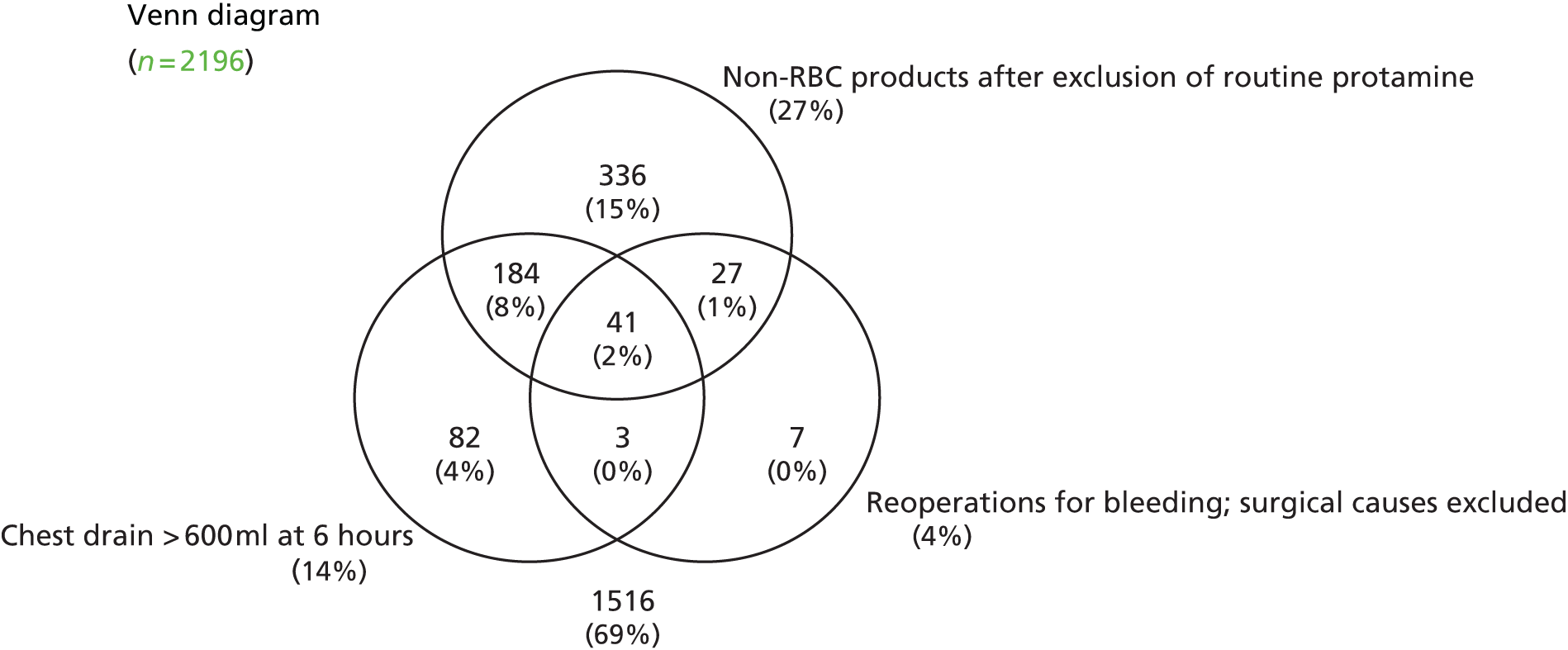

In summary, existing consensus definitions of coagulopathy or coagulopathic haemorrhage in cardiac surgery have important limitations. Clinical studies must anticipate these limitations by, for example, excluding patients with clear ‘surgical’ causes of bleeding; by careful assessment of adherence to blood management protocols for transfusion and the use of therapeutic adjuncts such as cell salvage or antifibrinolytic use; and by using definitions of drain losses that are most likely to reflect active bleeding. Assessment of predictive accuracy should also consider alternative definitions of coagulopathic haemorrhage within analyses to obtain a balanced assessment of utility. These are features of the COPTIC study.

Clinical risk factors for coagulopathic bleeding

Careful clinical assessment can be used to identify patients at risk of coagulopathic haemorrhage and this is recommended as part of standard care. 24 Diagnostic tests for coagulopathy should be interpreted, and pro-haemostatic treatments should be administered, only in the context of known clinical characteristics.

Preoperative factors

Heritable coagulopathy

Mild heritable coagulation factor defects are prevalent in the general population and are associated with increased bleeding during surgery. 55 These may be detected by routine screening SLTs or by clinical assessment and a history of bleeding after surgical procedures. These require further detailed investigation by a haematologist.

Antiplatelet agents

Most patients with symptomatic cardiovascular disease receive aspirin. In addition, patients with acute coronary syndromes or those who have received coronary stents receive dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with the addition of the P2Y12 receptor antagonists clopidogrel, prasugrel (Efient®; Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN, USA) or ticagrelor (Brilique®; AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK), because of the proven benefit of DAPT in these settings. 56–58 Platelet inhibition increases blood loss during surgery,59 but, although desirable, early withdrawal of antiplatelet therapy increases the risk of preoperative acute cardiovascular events and death in those at greatest risk. Current guidelines recommend that aspirin be continued until the time of surgery as RCTs have indicated that, although this increases blood loss marginally, there are no serious adverse events attributable to this blood loss and there are clear benefits in terms of fewer adverse cardiovascular events prior to surgery. 60 Observational analyses demonstrate more severe bleeding and adverse events attributable to platelet inhibition with DAPT relative to aspirin alone61,62 and current guidelines (class I recommendation, evidence level B) recommend that P2Y12 receptor antagonists be stopped 3–5 days prior to surgery. 24 This empirical approach is not without risk; many patients may be left at increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events prior to surgery and this is not detected by observational studies that commonly analyse events from surgery, a form of lead time bias. Conversely, other patients may have significant residual platelet inhibition at operation. This variability in responsiveness is more commonly observed with clopidogrel than with the newer agents such as ticagrelor and prasugrel, for which pharmacokinetics are more predictable.

Preoperative morbidity

Clinical risk prediction scores have been developed that allow objective assessment of bleeding risk. These identify age, female sex, low body mass index (BMI), preoperative anaemia, chronic kidney disease, poor left ventricular function and recent myocardial ischaemia as predictive of excessive bleeding or MBT. 63,64 The mechanism by which these factors contribute to bleeding is poorly understood. Existing scores are not widely used because of the limited generalisability of risk models developed in single centres or subpopulations of patients. This is considered in detail in Chapter 3.

Intra- and postoperative factors

Protease activation/clotting factor consumption/fibrinolysis

Direct activation of the contact system of proteases (kallikrein, kininogen) by the negatively charged surface of the CPB circuit results in the generation of factor XIIa and activation of the intrinsic clotting cascade (Figure 2). In addition, release of tissue factor by surgical trauma and the activation of inflammatory cells will activate the extrinsic coagulation pathway. Both result in activation of the common coagulation pathway and the uncontrolled generation of thrombin during CPB. Thrombin and activated contact proteases also promote fibrinolysis through the activation of tissue plasminogen activator. High levels of thrombin formation and fibrinolysis ultimately result in factor depletion and deranged haemostasis, which is most evident after prolonged CPB duration. 66 This is further impaired by haemodilution with circuit prime, platelet dysfunction and depletion.

FIGURE 2.

Intrinsic, extrinsic and common coagulation protease cascades. TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons. 65 This material is distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/.

Platelet dysfunction

The circulation of blood through the CPB circuit directly activates circulating platelets, as do thrombin and contact proteases, which then adhere to the circuit or activated endothelium and leucocytes. This may lead to depletion of platelets, whose number may be further reduced by haemodilution. Non-adherent activated platelets become desensitised to further stimuli and the degree of platelet dysfunction correlates well with CPB duration. 67 Post-cardiac surgery platelet dysfunction is common and is enhanced by the administration of antiplatelet agents such as aspirin or P2Y12 receptor antagonists preoperatively. Administration of more potent antiplatelet agents such as P2Y12 receptor antagonists up to the time of surgery may be associated with severe bleeding. 61

Acidosis, hypothermia and haemodilution

These factors serve to reduce coagulation factor and platelet activity through direct suppression of enzyme activity. They also promote inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and organ injury. 68

Inflammation and organ dysfunction

Protease and platelet activation during CPB lead to oxidative stress, leucocyte and endothelial activation, leucocyte extravasation, endothelial dysfunction, refractory tissue hypoxia and ultimately organ injury. 2 The contribution of these factors to coagulopathy is poorly understood; however, there are strong associations between coagulopathy and post-cardiac surgery organ failure in observational studies. 69

Heparin

Heparin is used in almost every patient undergoing cardiac surgery to provide systemic anticoagulation and prevent fibrin formation and thrombosis within the patient or activated CPB circuit. Heparin is reversed by the administration of protamine once the patient has been weaned from bypass successfully. Heparin is a small highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan and can accumulate in the extravascular compartment during CPB, where protamine may be less effective at reversal. Subsequent re-entry of heparin to the intravascular space may lead to residual heparin activity or ‘heparin rebound’ and contribute to bleeding. 70

Blood management adjuncts

Evidence from RCTs indicates that the administration of antifibrinolytics such as tranexamic acid reduces bleeding and improves survival in cardiac surgery. 17 Concomitant use of blood management adjuncts is an important consideration when determining the effectiveness of blood management interventions being evaluated in clinical trials.

Diagnosis of coagulopathy

Standard laboratory tests

Prothrombin time is a measure of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. The PT is the time that plasma takes to clot after the addition of tissue factor. PT is often expressed as the international normalised ratio, which is the ratio of a patient’s PT to a normal (control sample) referenced against the international sensitivity index value for the analytical system used and corrects for differences in assay responses to different sources of tissue factor.

The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) measures the ‘intrinsic’ or contact activation pathway and the common coagulation pathway. An activated matrix (e.g. silica, celite, kaolin) and calcium are mixed into the plasma sample and the time that the sample takes to clot is measured.

Fibrinogen (factor I) is a soluble plasma protein that is cleaved by thrombin to generate insoluble fibrin polymers, a principal component of the primary haemostatic response. Fibrinogen levels are commonly measured using the Clauss assay, with the time taken for plasma to clot in the presence of high thrombin concentrations compared with that of reference plasma with a known level of fibrinogen calibrated against a known international standard. Low preoperative fibrinogen levels or depletion of fibrinogen during prolonged CPB have been associated with excessive blood loss and adverse clinical events in observational studies. 71,72

Cross-linked fibrin is cleaved in the presence of plasma into fibrin degradation products, the largest of which is the D-dimer. Levels of the D-dimer are therefore considered as markers of thrombus (fibrin) formation and lysis.

Standard laboratory tests are considered to have limited utility in the setting of acute haemorrhage and coagulopathy. These limitations include the following:

-

There is a slow turnaround time for results of 40 minutes on average, which precludes their use in unstable bleeding patients.

-

These tests (aPTT, PT, fibrinogen) evaluate time to clot formation in platelet-poor plasma at 37 °C in standardised conditions and were developed to screen for clotting factor deficiencies or to monitor anticoagulant therapy. They were not designed to diagnose coagulopathy in the acutely bleeding surgical patient. 73 Moreover, the effects of important factors such as the patient’s temperature, acidosis or platelet function are not reflected in these tests.

-

The tests lack specificity with regard to the specific defect in the coagulation pathway responsible for prolonged PT or aPTT values and do not reflect platelet dysfunction.

-

Platelet counts in whole blood do not account for alterations in platelet function or clinical status (antiplatelet therapy), which limits their utility in cardiac surgery.

As a consequence of these limitations, SLTs have poor predictive and prognostic utility in cardiac surgery. 52,53 Despite this, they are routinely performed pre- and postoperatively in all patients.

Laboratory reference tests

Reference assays have important advantages compared with SLTs. They can measure specific components of the coagulation pathway, as well as provide quantitative measures of pathway activity. They have important disadvantages, however, in that they are expensive and time-consuming to perform and this limits clinical utility. However, they may be used to accurately define specific phenotypes of coagulopathy that other tests may be compared against and have a valuable role as reference tests in studies of coagulopathy.

Factor XIII or fibrin-stabilising factor is a circulating transglutaminase that is cleaved by thrombin to form activated factor XIII. This acts on fibrin to form cross-links between fibrin molecules to form an insoluble clot. Factor XIII becomes depleted during CPB and has been implicated in post-cardiac surgery coagulopathy. 74 Factor XIII activity can be assessed using the Berichrom® XIII assay (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan), which measures ammonia release (transglutaminase activity) by activated factor XIII in soluble fibrin.

Incomplete reversal of heparin leads to anticoagulation and bleeding. There is no accurate SLT for incomplete reversal or ‘heparin rebound’ and it is common for this to be evaluated using the activated clotting/coagulation time (ACT), a measure of global clotting activity in whole blood. However, the ACT may be affected by non-heparin factors and can be normal in the presence of residual heparin activity or coagulopathy. 75 Heparin acts by binding to antithrombin (see Figure 2). This inhibits both thrombin (factor II) and factor Xa. Anti-Xa activity is less sensitive to the effects of non-heparin factors than ACT or aPTT and is considered a more accurate measure of residual heparin activity. 76 Anti-Xa activity may be measured accurately in automated laboratory analysers using a commercial assay (anti-Xa kit; HYPHEN BioMed, Neuville-sur-Oise, France).

The endogenous thrombin potential (ETP) is a test of global coagulation pathway function, similar to the PT and aPTT, performed using a thrombinoscope. Unlike SLTs, the output of this assay is presented as a thrombin generation curve, rather than simply the time to clot formation. This curve reflects all three phases of coagulation: initiation, which corresponds to the PT or aPTT depending on the activator, followed by propagation and termination, which are quantitative measures of thrombin activity. It has been hypothesised that this is a measure of the thrombin burst, a functional, rather than a static, measure of common coagulation pathway activity. The propagation and termination phases of the curve can be quantified as the area under the curve (AUC), which is termed the ETP. In one study the ETP was shown to discriminate between cardiac surgery patients who developed severe blood loss and those who did not. 77

Von Willebrand factor (vWF) is a multimeric adhesive glycoprotein that mediates the adhesion of platelets to injured subendothelium (collagen) and to the platelet surface receptor GPIb. It is required for the formation of the initial platelet plug that achieves primary haemostasis following vascular injury. It also serves as the specific carrier protein for coagulation factor VIII in plasma, preventing proteolytic degradation. vWF, as a large multimeric protein, is subject to shear and fragmentation during CPB. Depletion of multimeric vWF has been implicated in post-CPB bleeding. 78 vWF activity can be measured using the collagen binding assay, which detects the ability of multimeric forms of vWF to bind collagen.

In addition to data from specific LRTs, routinely recorded data obtained from automated cell counters used as part of standard clinical care may be able to provide information that will discriminate between patients who are likely to bleed and those who are not. Automated cell counters that measure the standard platelet count can detect thrombocytopenia, a risk factor for bleeding. In addition, they also measure the immature platelet count. This is a measure of thrombopoiesis that reflects the accelerated reduction of immature platelets in the setting of accelerated platelet consumption, as seen, for example, following prolonged CPB. High levels of immature platelets would implicate low platelet function as a cause of associated coagulopathy. Conversely, an elevated mean platelet volume (MPV) is associated with increased platelet activation and thrombosis. A low platelet volume may reflect reduced platelet activity. As no additional tests are performed beyond existing care, these data are available at no additional cost as they are obtained routinely as part of usual care. The predictive accuracy of these measures for bleeding has not previously been reported.

Point-of-care tests

Near-patient tests allow clinical teams to undertake rapid, reproducible and repeated assays of coagulation with short turnaround times at the POC. These offer more personalised and effective management in bleeding patients, whose clinical status may be unstable. The two most common POC testing platforms in clinical use are the viscoelastic tests ROTEM and TEG.

These devices have limited ability to discriminate between platelet dysfunction and defects in fibrin generation and are often complemented by platforms that can detect specific defects in platelet function. 79 A commonly used platelet function testing platform in the UK is the Multiplate analyzer.

Rotational thromboelastometry

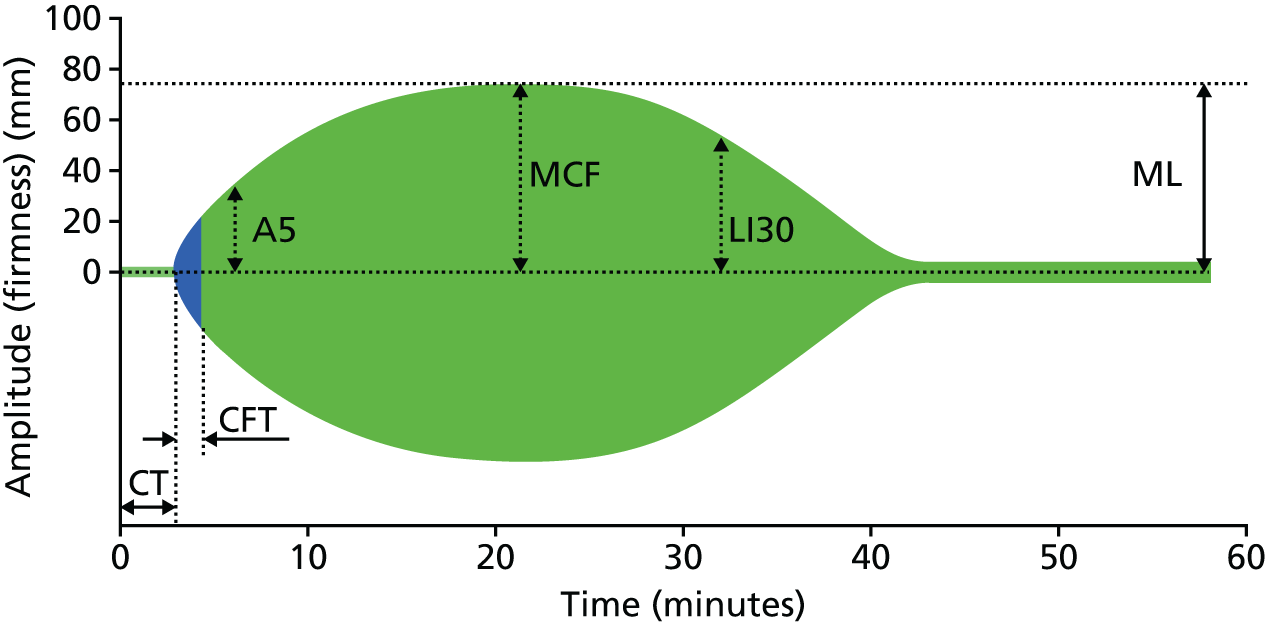

Previously known as rotational TEG, the ROTEM assays are based on the oscillation of a disposable sensor pin suspended within a citrated whole blood sample (340 µl) placed within a disposable cuvette (sample cup). Coagulation is activated by a range of assays and as the clot forms the resistance to the rotation of the pin is increased to provide a measure of clot firmness. This is detected by an optical sensor and translated into the ROTEM output (Figure 3). By using different activators discrete components of clot formation can be assessed within a single integrated platform. The individual assays are as follows:

-

INTEM. Uses an activator of the contact (kallikrein) proteases and measures the intrinsic clotting pathway.

-

EXTEM. Uses tissue factor as an activator and is a measure of the extrinsic pathway. This assay is not affected by heparin.

-

HEPTEM. Uses an activator of the contact proteases along with heparinise (effectively the INTEM assay in the presence of heparinase) and indicates the presence of residual heparin activity.

-

FIBTEM. Uses tissue factor as an activator along with an inhibitor of platelet activation (effectively the EXTEM pathway in the absence of platelet function). The output of this assay denotes fibrin formation and is considered a measure of fibrinogen concentration.

FIGURE 3.

Diagrammatic representation of ROTEM output. Reproduced with permission from ROTEM® (TEM International GmbH, Munich, Germany; www.rotem.de). A5, amplitude 5 minutes after CT; CFT, clot formation time; CT, clotting time; MCF, maximum clot firmness; LI30, lysis index at 30 minutes (percentage decrease in MCF 30 minutes after maximum amplitude is reached).

Each test generates multiple values that reflect dynamic clot formation and lysis. A separate graphical output of results is produced for each assay. A representative output is displayed in Figure 3. Output definitions are listed in Box 1.

Clotting time (CT). Time from activation until initial fibrin formation; represents activation of the intrinsic and common (INTEM) and extrinsic and common (EXTEM) pathways respectively. Prolongation of the CT in INTEM and EXTEM assays denotes coagulation factor deficiencies or residual heparin activity (INTEM only). Prolongation of the INTEM CT relative to the HEPTEM CT specifically denotes residual heparin activity.

Clot formation time (CFT). Time from the start of fibrin formation until a clot firmness of 20 mm has been achieved. These values reflect primarily platelet function and fibrinogen concentration, along with other clotting factors.

Amplitude 10 minutes after CT (A10). A predictive indicator of maximum clot firmness (MCF) at 10 minutes, a global measure of clotting factor and platelet function. This result is available earlier than MCF. Initial results for coagulation factor activity, platelet function and fibrin formation are therefore available within 10 minutes of assay commencement.

Maximum clot firmness. The greatest vertical amplitude of the ROTEM trace. Low MCF values denote deficiencies in platelet function, fibrinogen levels or clot stabilisation (factor XIII). The difference between the MCF for EXTEM and FIBTEM denotes the contribution of platelets to clot formation. The absolute MCF value for FIBTEM reflects fibrinogen levels.

Lysis index at 30 minutes (LY30). The percentage decrease in MCF at 30 minutes post clot activation. This is a measure of clot lysis. The time taken to obtain this result means that is has limited clinical utility in the setting of severe haemorrhage.

Thromboelastography

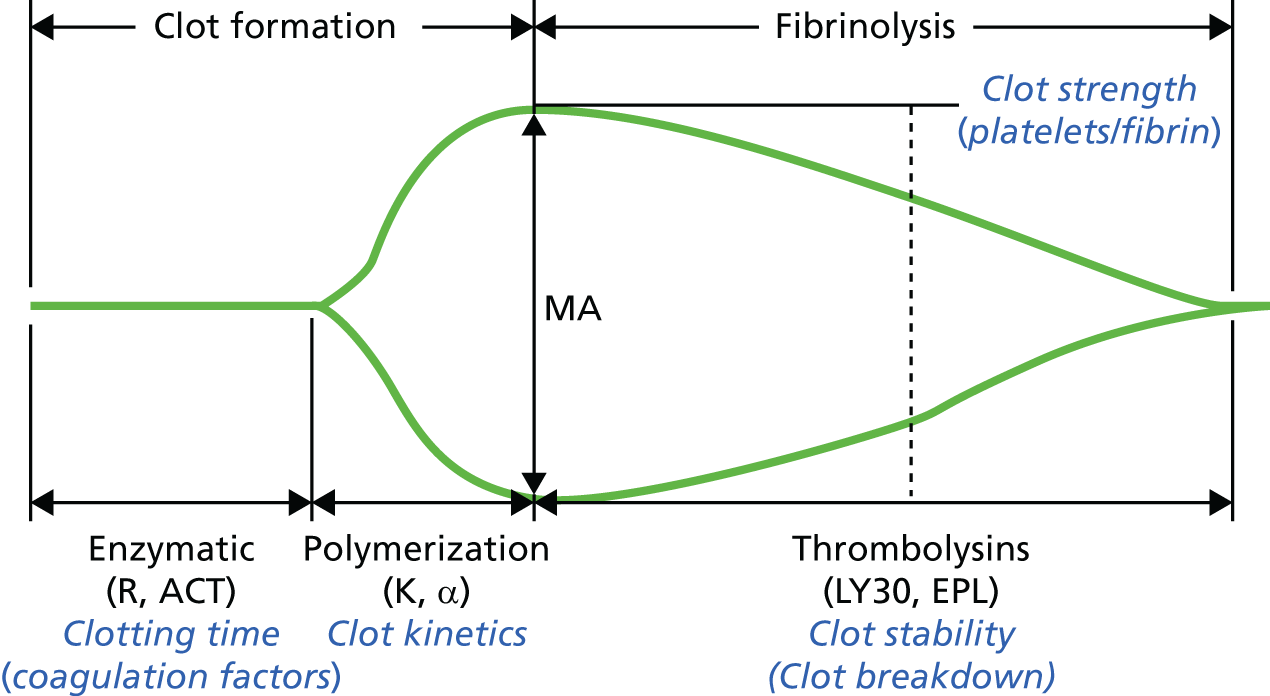

The TEG system is also based on a viscoelastic test, with some differences between this system and ROTEM. In this system 340 µl of citrated whole blood is placed in a cuvette. A disposable pin is then lowered into the fluid blood and the cuvette is rotated. As the first fibrin strands are formed the pin becomes tethered to the cup and starts to follow its motion. When maximum clot firmness (MCF) is achieved, the cup and pin move in unison. The motion of the pin is detected by a torsion wire linked to a transducer that is interpreted as a graphical trace by computer software. As with ROTEM, different activators may be used to evaluate different components of clot formation:

-

kaolin is used as an activator of the intrinsic pathway – analogous to the INTEM assay

-

heparinase is used along with kaolin – analogous to the HEPTEM assay.

Other activators and assays have been described, including a functional fibrinogen assay and platelet mapping; however, these are not in common use and are associated with additional and significant costs relative to the two principal assays. As with ROTEM, the graphical output provides visual information related to dynamic clot formation and also provides information that reflect specific stages of clot formation (Figure 4). Definitions of TEG outputs are listed in Box 2.

FIGURE 4.

Diagrammatic representation of TEG output. (TEG® Haemostasis Analyzer tracing images presented by permission of Haemonetics Corporation, Niles, IL, USA; www.haemonetics.com. TEG® and Thromboelastograph® are registered trademarks of Haemonetics Corporation in the US, other countries or both.) α, α-angle; EPL, estimated per cent lysis (estimated rate of change in amplitude after the MA is reached); K, K time; LY30, lysis index at 30 minutes (percentage decrease in MCF 30 minutes after maximum amplitude is reached); MA, maximum amplitude; R, R time.

R time. Time from assay activation until fibrin formation. Prolongation of this value denotes deficiency in coagulation factor concentrations from the intrinsic and common pathways or residual heparin activity. Prolongation of the R time from the kaolin assay relative to the R time from the kaolin and heparinase assay specifically denotes residual heparin activity.

K time or α-angle. The K time is the time from fibrin/clot formation until clot amplitude reaches 20 mm. The α-angle is the angle of the slope between the R time and the point on the TEG output that corresponds to time K. These are measures of fibrin clot formation. Prolongation of the K time or the α-angle, or reduction of the maximum amplitude (MA), reflects fibrinogen concentrations, platelet function or clotting factor activity (factor XIII).

Maximum amplitude. A measure of the maximum strength of the clot. Low MA values indicate deficiencies in fibrinogen concentrations, platelet function and clotting factor activity (factor XIII).

Lysis index at 30 minutes (LY30). Percentage decrease in MCF 30 minutes after MA is reached. This is a measure of clot lysis.

Multiplate

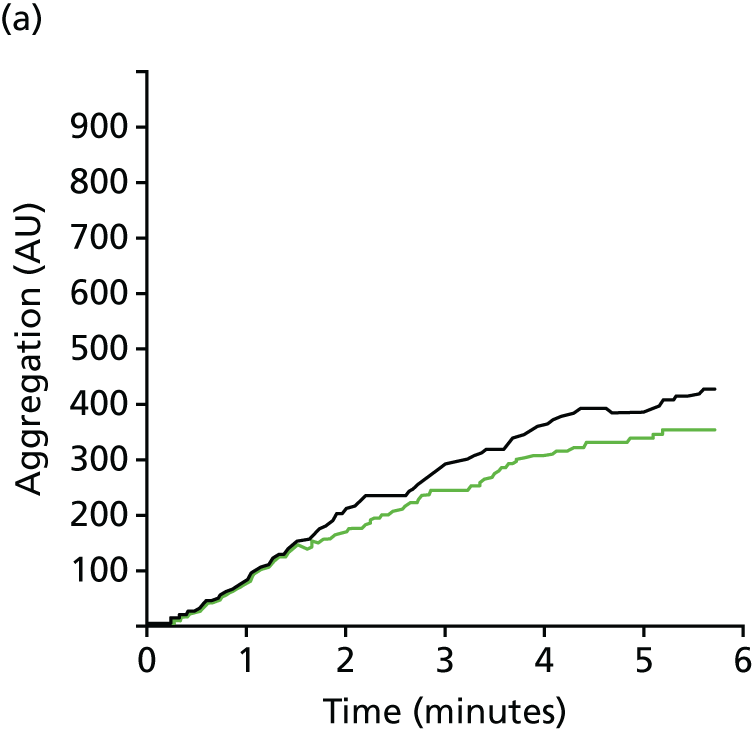

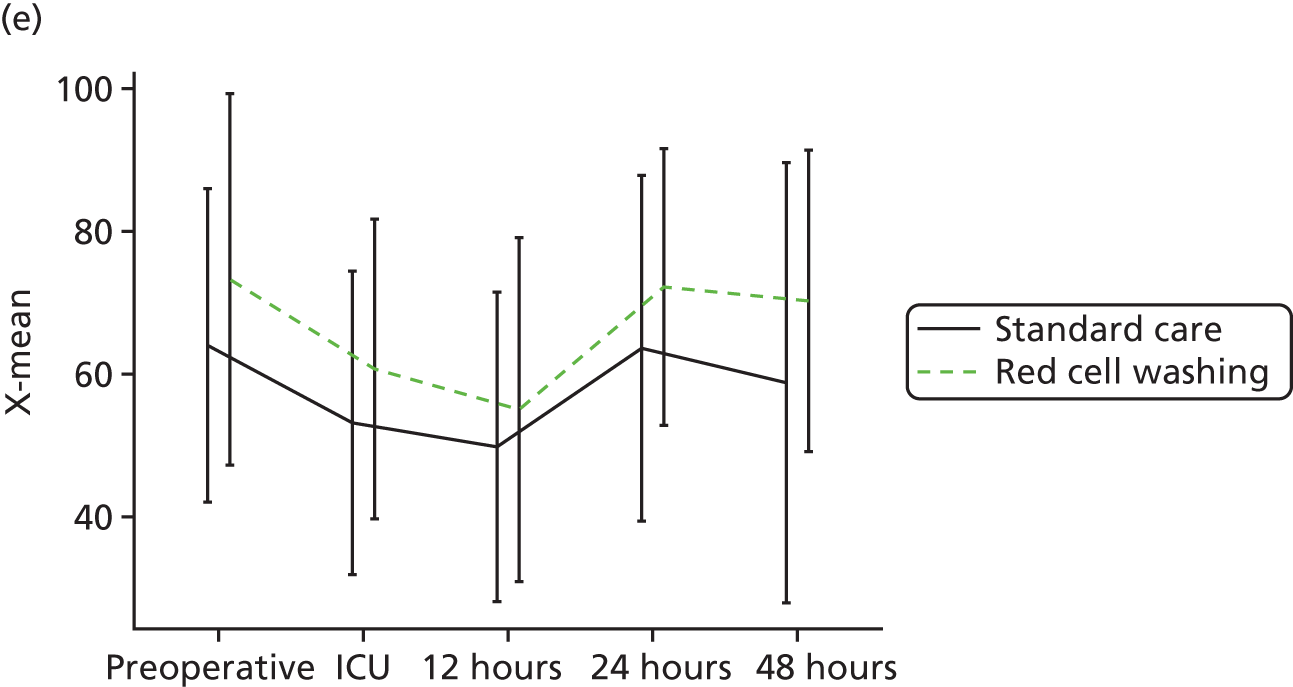

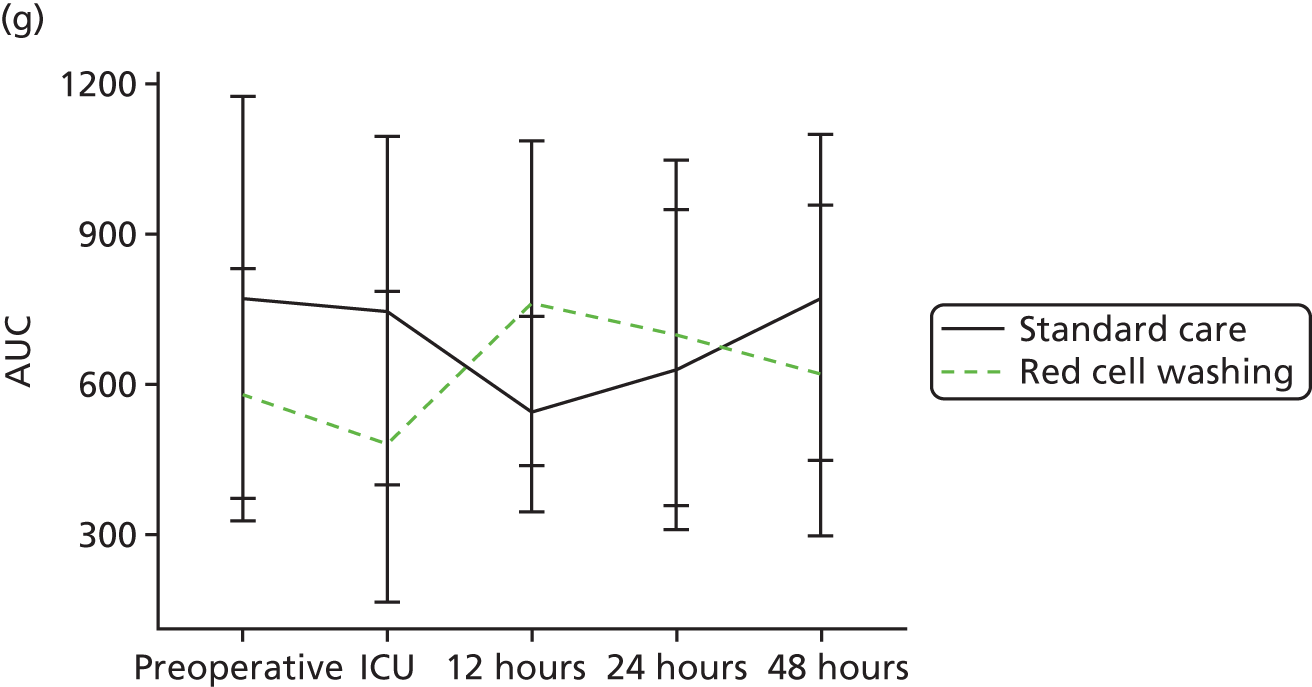

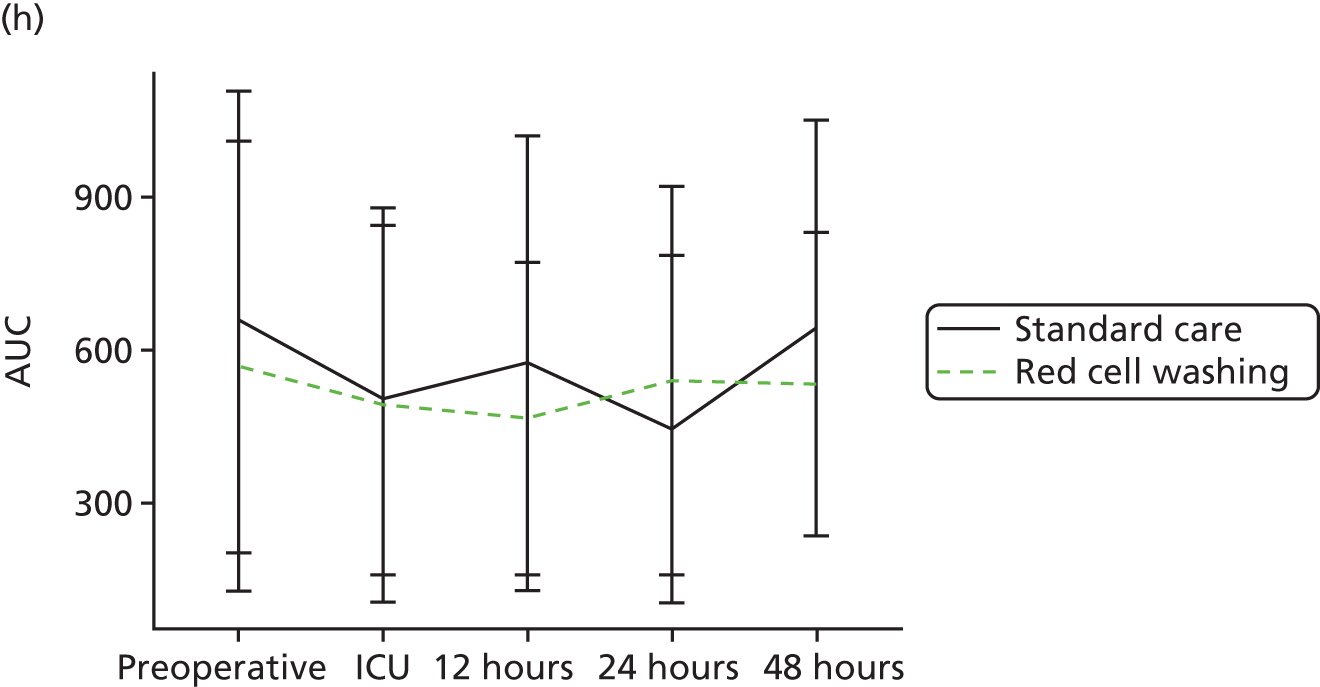

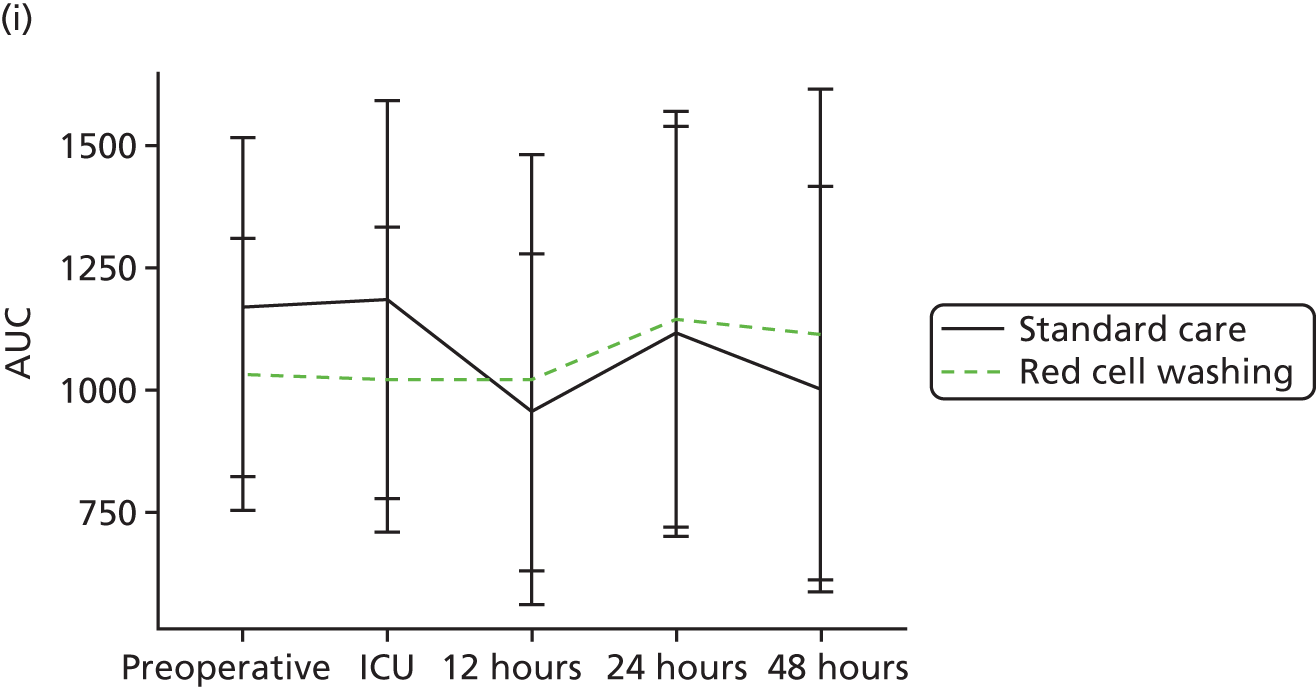

Platelets are activated by a wide array of stimuli that include thrombin, tissue factor, adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and arachidonic acid metabolites such as thromboxane. Activation is accompanied by aggregation and adhesion to other platelets via fibrin strands and to exposed extravascular matrix through interaction with vWF. Aggregation can be measured in small volumes of whole blood (1.2 ml) by multiple electrode aggregometry (MEA) using the Multiplate device. The instrument performs the analysis by employing two independent sensor units for every test cell, representing an internal control of the reaction. Each unit consists of two silver-coated, highly conductive copper wires on which the platelets adhere on specific activation. The aggregation function is measured in terms of increasing electrical impedance between the metallic electrodes of the sensor as platelets aggregate on the electrodes in the presence of an activator. The results are displayed graphically (Figure 5) within minutes. Up to four activators may be assessed in a single assay. The cyclo-oxygenase pathway is activated with 0.5 mM of arachidonic acid (ASPI) (ASPItest®), the P2Y12 receptor pathway with 6.5 µM of ADP (ADPtest®) and the thrombin receptor with a thrombin receptor-activating peptide (TRAP) (TRAPtest®). By comparing these results with those for maximal platelet activation using high adrenaline (epinephrine) concentrations (20 mg/ml) (ADRENtest®), the degree of inhibition of specific activation pathways can be assessed. Outcomes are expressed as the AUC [in aggregation units (AUs)*min] or the maximum amplitude (in AUs). The test results can be assessed more rapidly using the test velocity, expressed as dAU/dt, within minutes of activation (see Figure 5). A limitation of the Multiplate is that platelet counts must ideally be > 100 × 109/l to obtain reproducible results.

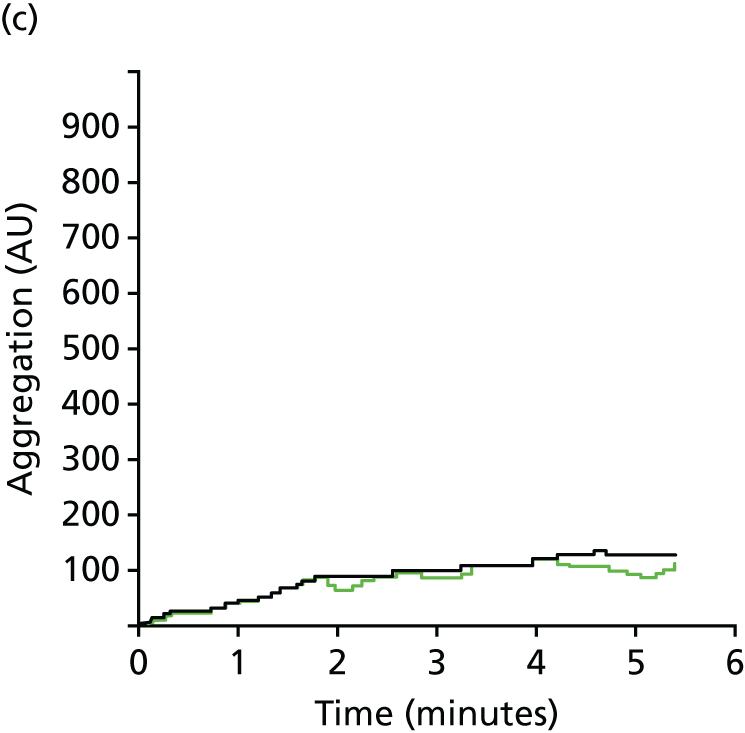

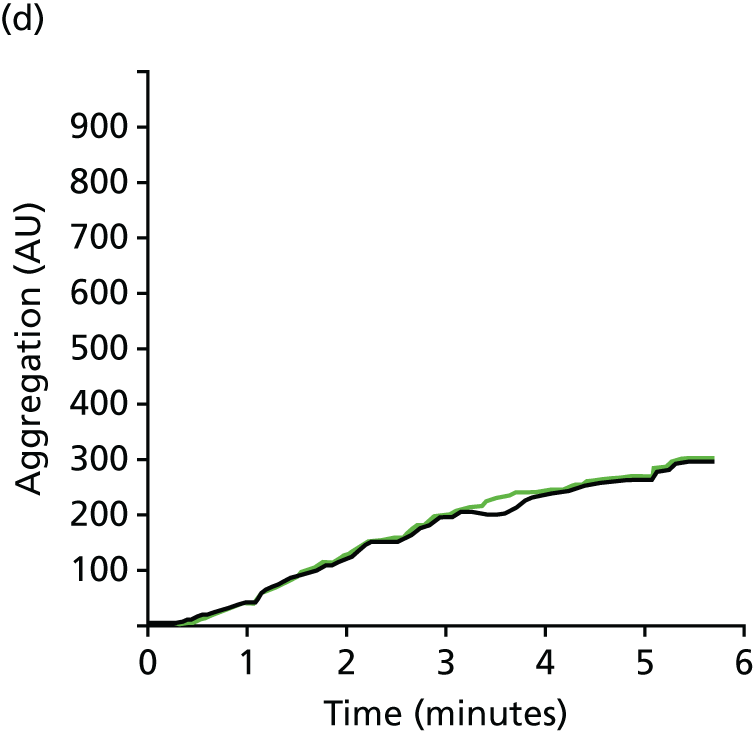

FIGURE 5.

Representative MEA graphs for (a) ADPtest; (b) ASPItest; (c) TRAPtest; and (d) ADRENtest. Outputs may be expressed as the AUC (AU*min), maximum amplitude (AU) or test velocity (dAU/dt). This result in a post CPB patient demonstrates diminished platelet responsiveness in response to ADP, TRAP and adrenaline (epinephrine), but not arachidonic acid.

Treatment

Without accurate diagnostic tests to identify specific defects in the coagulation pathway, which if treated or reversed can improve clinical outcomes, the management of coagulopathy is often empirical, non-specific and based on the assumption that reversal of coagulopathy is beneficial.

Fresh-frozen plasma

One unit of FFP is derived from a single unit of donated red cells and contains variable concentrations of the coagulation factors I (fibrinogen), II, V, VII, VIII, IX, X and XI. It also contains anticoagulants such as protein C, protein S and antithrombin along with a large number of proteins such as immunoglobulins, albumin and acute-phase proteins. A standard dose of FFP is 2 units and there is uncertainty whether this significantly increases coagulation factor concentrations in recipients. Uncertainty over the risks and benefits of FFP80,81 is reflected by the variability in its use, with use ranging from 9% to 59% of patients between centres (mean 25%). 9 Cardiac surgery uses up to 12% of all FFP produced by NHS Blood and Transplant. 82

Platelets

In the UK a standard unit of platelets contains the pooled platelet component of up to six donors. There is very little evidence to guide platelet transfusion in the setting of coagulopathic haemorrhage. A recent RCT reported that empirical transfusion of higher platelet ratios, in combination with higher plasma ratios, improves haemostasis and leads to fewer deaths from bleeding at 24 hours in trauma patients. 83 Evidence on the risks and benefits of platelet transfusion in cardiac surgery comes from observational analyses and shows conflicting results. 84,85 The rate of platelet transfusion in cardiac surgery is variable, ranging from 10% to 56% (mean 28%) of patients between UK cardiac surgery units. Cardiac surgery is one of the largest single consumers of platelets (17%) produced by NHS Blood and Transplant. 82

Fibrinogen

UK guidelines recommend that fibrinogen is replaced during major blood loss or as part of the management of disseminated intravascular coagulation once the Clauss fibrinogen value falls below 1.5 g/l, although this recommendation is based on weak evidence. 86 Cryoprecipitate is the first-line treatment in the UK for acquired hypofibrinogenaemia and a standard adult dose (two pools) raises the plasma fibrinogen level by 1 g/l. A Cochrane review of predominantly cardiac surgical RCTs found that fibrinogen reduced transfusion requirements (very low-quality evidence), but there was insufficient evidence to evaluate differences in important clinical end points, including mortality. 87

Recombinant activated factor VII

Recombinant activated factor VII is a potent pharmacological pro-haemostatic agent licensed for use in patients with haemophilia. This has led to the off-label use of rFVIIa for the treatment of severe coagulopathic bleeding in trauma and surgical settings as an adjunct to conventional non-red cell blood components.

Prothrombin complex concentrates

Prothrombin complex concentrates are plasma-derived coagulation factor concentrates that contain three or four vitamin K-dependent factors at high concentration, typically factors II, VII, IX and X, as well as variable amounts of anticoagulants and heparin. These are increasingly used off-licence in cardiac surgery in the setting of coagulopathic haemorrhage; however, this is not supported by evidence.

Current compared with proposed new standards of care for the diagnosis and treatment of coagulopathy

As both preoperative and operative variables may contribute to coagulopathy and bleeding in cardiac surgery, we considered how improved testing of coagulopathy both before and after surgery would benefit patients when used in conjunction with careful clinical assessment.

Preoperative testing

Current standard of care

Patients undergoing cardiac surgery undergo preoperative screening with SLTs including tests of PT and aPTT. In some centres preoperative fibrinogen is also measured routinely. Platelet counts are measured on standard haematology analysers. Abnormal screening tests or a clinical history of excessive blood loss following previous dental extractions or minor surgical procedures may lead to further haematological investigations on an individual basis. In addition to standard care, current blood management guidelines recommend (class 1, level of evidence C24) that patients undergo a formal assessment and documentation of bleeding risk. Risk scores that may accurately predict the risk of bleeding and red cell transfusion exist;63,64,88,89 however, these are not widely used. The predictive accuracy of any new diagnostic test should therefore complement appropriate clinical assessment and the benefits of additional testing should be assessed beyond those attributable to clinical assessment combined with standard testing.

Proposed new standard of care

Our proposed new standard of care includes routine preoperative platelet function testing in addition to current standard care. We suggest that this may have clinical benefits by allowing targeted interventions to be given to patients with pre-existing platelet dysfunction that will reduce the risk of severe bleeding and its complications, particularly in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy preoperatively. Currently, it is recommended that aspirin be continued until surgery but that P2Y12 receptor antagonists be discontinued 3–5 days prior to surgery. 24 This reflects the reversal characteristics of current P2Y12 receptor antagonists and clinical outcomes in observational studies in which patients on recent DAPT have undergone cardiac surgery. There is marked variation in the implementation of these guidelines. Specifically, increases in the numbers of non-elective surgeries for patients with unstable cardiovascular disease or recent coronary stenting in the setting of myocardial infarction (MI) mean that patients frequently present to surgery within 3–5 days of taking DAPT or require DAPT because of the risk of acute stent thrombosis. 90 In these patients preoperative platelet function testing may allow more informed decision-making as to the risks of surgery and bleeding and the need for pre-emptive platelet transfusion or deferment of surgery.

What evidence supports this change in the current standard of care for preoperative testing?

Corredor et al. 25 recently reviewed clinical studies that have evaluated the predictive accuracy of POC platelet function tests to detect platelet dysfunction and predict postoperative bleeding in cardiac surgery (Table 3). They identified 16 studies in which platelet function tests had been used in isolation to predict postoperative haemorrhage. The studies included in the systematic review were at high risk of bias and only five of 15 studies reported test discrimination for bleeding or transfusion. Overall, the Multiplate was evaluated in the largest number of patients and showed modest discrimination. Test results were more likely to accurately predict bleeding in patients receiving P2Y12 receptor antagonists prior to surgery. The authors concluded that there was inconsistent evidence that routine preoperative platelet function testing had predictive accuracy for bleeding, particularly in patients receiving DAPT. This uncertainty is reflected in current treatment guidelines. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons clinical practice guidelines (updated in 2012) state that ‘For patients on dual antiplatelet therapy, it is reasonable to make decisions about surgical delay based on tests of platelet inhibition rather than arbitrary use of a specified period of surgical delay (Class Iia, Level of Evidence B)’. 91 Conversely, a recent position statement has recommended routine Multiplate use in patients receiving P2Y12 receptor antagonists. 92 To address this uncertainty we assessed the predictive accuracy of routine preoperative platelet function tests in the COPTIC A study.

| Study | Patient population | Number of patients | POC assay | Timing of POC test | SIGNa | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet function testing | ||||||

| Lasne et al. (20) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 146 | PFA-100 | Preoperatively and 5 minutes and 5 hours post protamine | + | No correlation between blood loss and pre- or postoperative PFA-100 values |

| Slaughter et al. (21) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 76 | PFA-100 | Preoperatively, intraoperatively and postoperatively | + | Low positive predictive value (18%) for post-bypass collagen/ADP closure times. Negative predictive value 96% |

| Forestier et al. (22) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 45 | PFA-100/haemostatus | Postoperatively | + | No correlation between POC testing and chest drain output |

| Fattorutto et al. (24) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 70 | PFA-100 | Pre and post bypass | + | Weak correlation between pre-bypass collagen/adrenaline (epinephrine) closure time and 2-hour mediastinal blood loss (r = 0.34; p = 0.01) |

| Chen et al. (27) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 90 | PFA-100 | Preoperatively | + | ADP aggregometry was a better predictor of blood loss and platelet and/or red cell transfusion than PFA-100 |

| Gerrah et al. (28) | Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting | 18 | Cone and platelet analyser | Preoperatively and perioperatively | + | Preoperative average size and surface coverage values correlated with postoperative bleeding (r = 0.7; p = 0.01) |

| Dalen et al. (41) | Coronary artery bypass grafting, receiving DAPT | 50 | Plateletworks | Preoperatively | + | Correlation between ADP-induced aggregation and postoperative blood loss (r = 0.83; p < 0.01) |

| Orlov et al. (45) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 100 | Plateletworks | Pre bypass and postoperatively | ++ | Functional platelet count increase associated with high blood loss. Rewarming RR 0.89 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.97; p = 0.006). Post-protamine RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.98; p = 0.02) |

| Lennon et al. (26) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 50 | Plateletworks | Preoperatively | + | Poor correlation with postoperative blood loss (r = 0.14; p = 0.34) |

| Ranucci et al. (40) | Cardiac surgery, exposed to thienopyridines | 87 | Multiplate | Preoperatively | + | Multiplate ADP (cut-off value 31 U) predicts postoperative bleeding risk. Sensitivity 72%, specificity 66% |

| Rahe-Meyer et al. (34) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 60 | Multiplate | Preoperatively and postoperatively | + | Pre- and postoperative ADP test predicts risk of platelet transfusion (AUC 0.74; p = 0.001). No relationship between decreased platelet aggregation and postoperative blood loss |

| Velik-Salchner et al. (35) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 70 | Multiplate, LTA | Preoperatively and 15 minutes and 3 hours post protamine | ++ | Multiplate and LTA detect bypass-induced platelet dysfunction but do not predict blood loss |

| Reece et al. (39) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 44 | Multiplate | Pre and post bypass | ++ | Patients requiring blood transfusion had significantly reduced platelet aggregation compared with non-transfused patients. ADP: 18 U vs. 29 U (p = 0.01); thrombin receptor agonist peptide-6: 65 U vs. 88 U (p = 0.01) |

| Schimmer et al. (43) | Mixed cardiac surgery with bypass | 223 | Multiplate | Preoperatively and postoperatively | + | Abnormal ADP test and thrombin receptor agonist peptide test significantly predict postoperative blood transfusion requirements |

| Petricevic et al. (44) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 211 | Multiplate | Preoperatively, post bypass and post protamine | + | Multiple values correlated with 24-hour chest tube output. Arachidonic acid < 20 AU and ADP < 73 AU were ‘bleeder’ determinants |

| Ranucci et al. (46) | Cardiac surgery, exposed to P2Y12 receptor inhibitors | 361 | Multiplate | Preoperatively | ++ | ADP test and thrombin receptor agonist peptide-6 test significantly associated with postoperative bleeding (p = 0.001) |

| Combined platelet function testing and viscoelastic tests | ||||||

| Wahba et al. (18) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 40 | Hepcon Haemostasis Management System, PFA-100 | Preoperatively | + | Significant correlation between preoperative PFA-100 and blood loss (r = 0.41; p = 0.022). No correlation with Hepcon Haemostasis Management System |

| Dietrich et al. (19) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 16 | TEG, impedence aggregometry, PFA-100 | Preoperatively, intraoperatively and postoperatively | + | None of the methods predicted postoperative blood loss |

| Cammerer et al. (25) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 255 | TEG, PFA-100 | Pre, during and post bypass | + | High negative predictive value for bleeding post bypass. ROTEG α-angle 82%, PFA-100-ADP 76% |

| Ostrowsky et al. (29) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 35 | Plateletworks/TEG | Preoperatively, post protamine and 24 hours postoperatively | + | Plateletworks collagen tubes correlated with postoperative bleeding (r = 0.324; p = 0.048). No correlation with TEG |

| Kotake et al. (30) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 26 | Whole-blood aggregometry, Sonoclot | Pre and post bypass | + | No correlation between postoperative blood loss and reduced platelet aggregation |

| Hertfelder et al. (31) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 49 | PFA-100, impedence aggregometry, TEG | Pre and post bypass | + | PFA-100 and impedence aggregometry do not predict postoperative blood loss |

| Alstrom et al. (36) | Coronary artery bypass grafting, receiving DAPT | 60 | VerifyNow/TEG 5000, platelet mapping | Preoperatively and postoperatively | + | Weak correlation between preoperative platelet inhibition measured by VerifyNow and postoperative blood loss (r = 0.29; p = 0.03). No significant correlation observed with TEG 5000 |

| Kwak et al. (37) | Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting, receiving clopidogrel | 100 | TEG, platelet mapping | Preoperatively | + | Association between 70% platelet inhibition and postoperative transfusion requirements (AUC = 0.77, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.87; p < 0.001) |

| Preisman et al. (38) | Coronary artery bypass grafting, receiving DAPT | 59 | TEG, platelet mapping | Preoperatively | ++ | Only maximum amplitude ADP predicts excessive postoperative blood loss. Sensitivity 78%, specificity 84% |

| Viscoelastic tests | ||||||

| Dorman et al. (17) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 60 | TEG | Preoperatively | + | TEG failed to predict blood loss (r < 0.25; p = 0.78) |

| Lee et al. (42) | Cardiac surgery with bypass | 321 | ROTEM | Preoperatively and postoperatively | + | ROTEM did not improve performance of statistical model predicting blood loss |

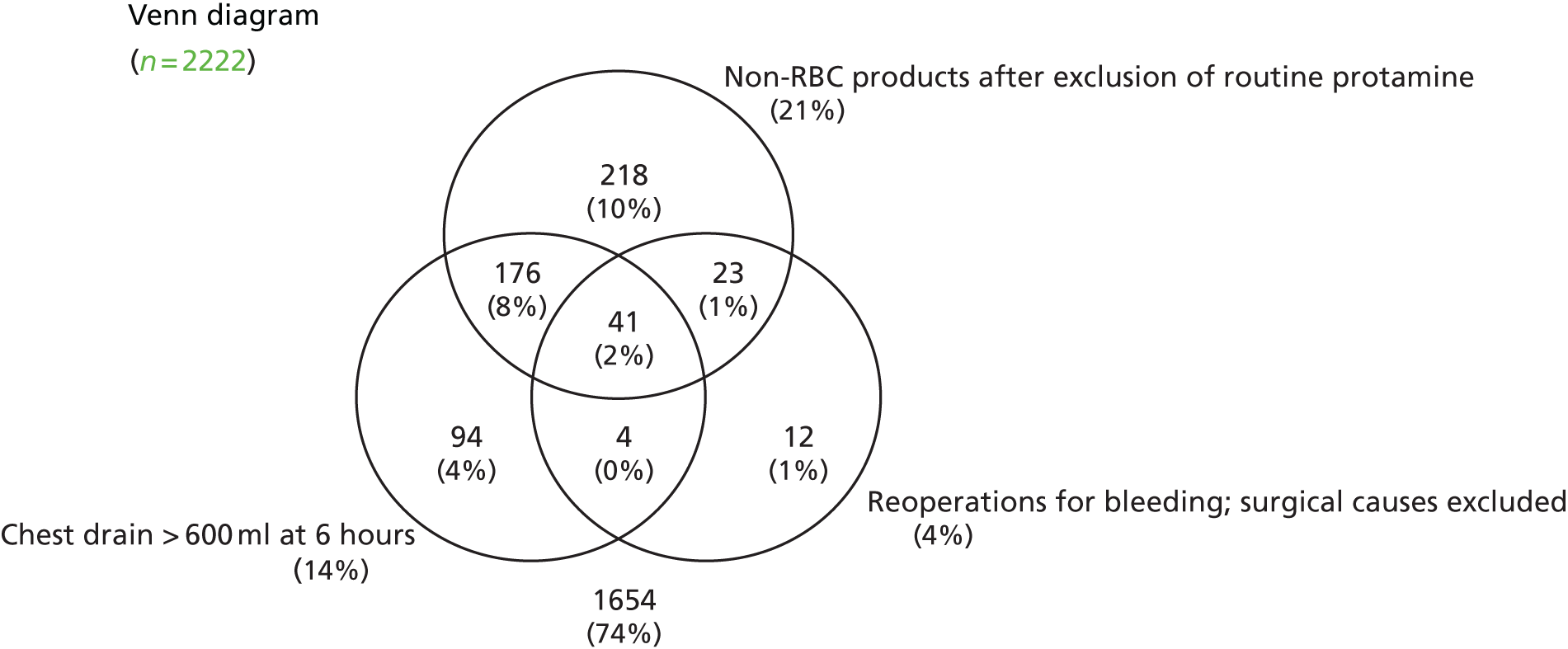

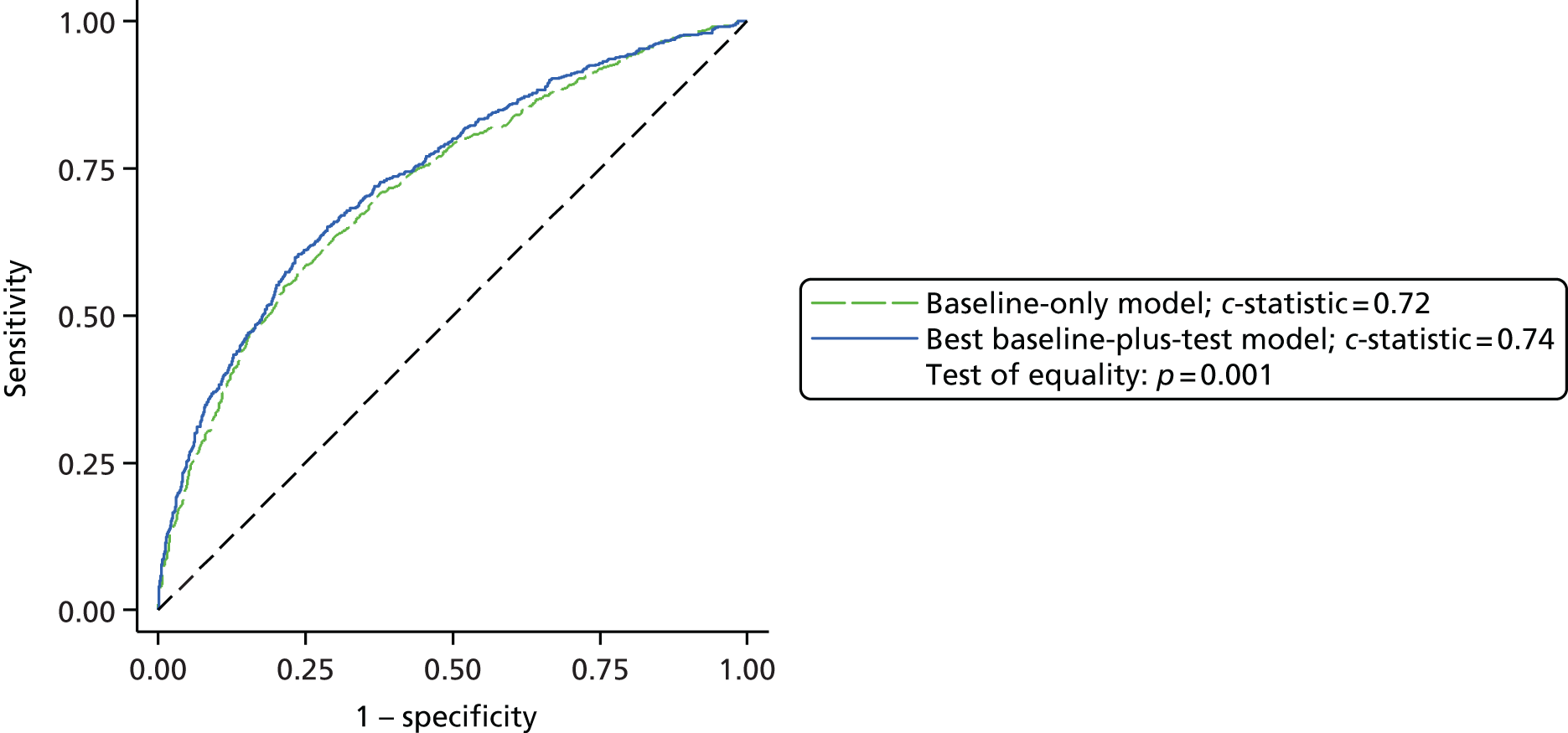

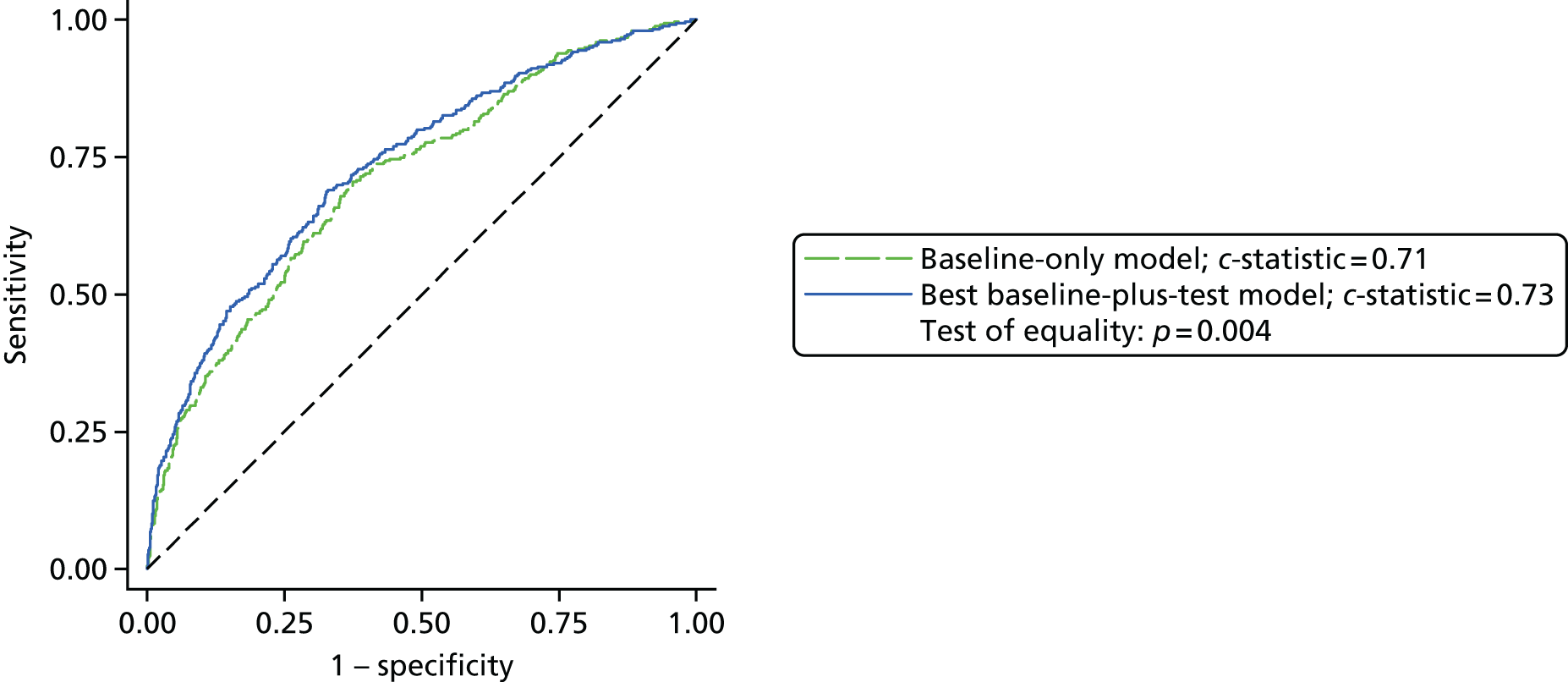

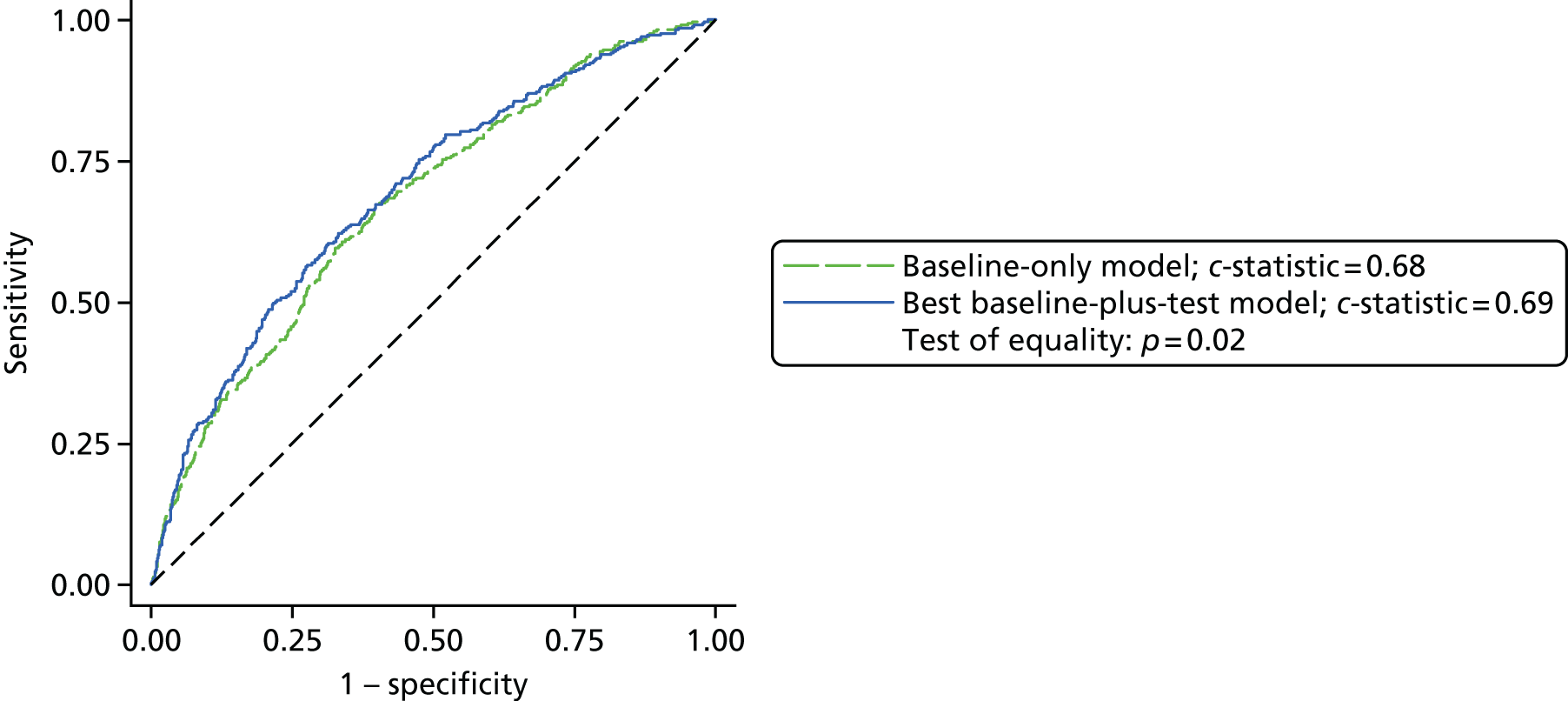

| Ti et al. (23) | Coronary artery bypass grafting | 40 | TEG | 10 and 60 minutes post protamine | + | Limited predictive ability. Positive predictive value 58% at 10 minutes and 55% at 60 minutes |