Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10136. The contractual start date was in July 2008. The final report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Thompson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction to the programme

The programme of research reported here derives from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research project number 11/77/82.

The original aims and objectives were:

-

project 1 – to take an evidence-based self-management support model [Whole system Informing Self-management Engagement (WISE)] for established chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) in primary care and to test clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness when translated from research settings into routine care

-

project 2 – to determine how well the WISE model prevented patients with new-onset functional gastrointestinal problems from developing chronic ill-health.

Issues related to the delivery of project 2 were identified following NIHR monitoring visits, which acknowledged that recruitment and data quality issues rendered the original plan for project 2 unviable. The focus on project 2 was therefore modified in discussion with the funder to a focus on identification and risk assessment.

The description of the research actually conducted in relation to project 2 is provided in Chapter 7.

Chronic gastrointestinal disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and FGID, account for approximately 8% of the general practice workload in the UK, at an estimated cost of £1B per year. 1,2 Around 50% of these consultations are for FGID. 2,3

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the most prevalent FGID, comprises chronic physical symptoms [abdominal pain (AP) and bloating, erratic bowel habit], which remain unexplained after medical exploration. 4

Improving management of functional gastrointestinal disorder

Over the last decade, members of the research team have developed therapies for these conditions, using patient education and self-management. 5–15 These have been combined with patient-centred psychological approaches, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and hypnotherapy. 16,17

These findings suggested that:

-

information can be improved to incorporate patient experience and expertise alongside medical information about management and treatment

-

clinician training in patient-centred consultation skills and shared decision-making with patients is acceptable and appropriate and leads to positive outcomes

-

health systems that are better aligned to self-management are well received

-

an integrated approach leads to reduced health service utilisation and costs without adverse clinical effect

-

defining the boundaries of care in professional support for self-management is necessary for success.

The results of these studies led us to propose a new integrated WISE model. The WISE model is designed to enhance well-being by improving patient information, drawing on patients’ existing skills in living with long-term conditions, training health professionals to support self-management and improving access to further care. The system is applicable to chronic FGID, such as IBS, and commonalities in the management of conditions suggest that it may be applicable to other long-term conditions.

Although existing evidence shows that the WISE model was effective, we also identified two key issues that required further study:

-

Although results have been demonstrated in research trials, there has been no demonstration that the results could be achieved when translated from research settings into routine care.

-

Psychological ill-health can adversely influence the chronicity and burden of chronic FGID. Psychological therapies could be added to the original WISE model to increase effectiveness, but their uptake, acceptability and cost need to be assessed.

Project 1 research questions

-

What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intervention to enhance self-management support for patients with chronic conditions when translated from research settings into routine care? [Phase IV randomised controlled trial (RCT) and economic evaluation.]

-

What are the barriers and facilitators that affect the implementation of the WISE model among patients, clinicians and organisations? (Process evaluation.)

Patient and public involvement

Our patient and public contributors are named in the Acknowledgements. They guided project delivery through attendance at Study Steering Group meetings and provided particular assistance around the challenges of recruiting patients to the project.

Chapter 2 The WISE model of self-management support

Introduction

Long-term conditions are important determinants of quality of life and health-care costs worldwide. 18 Increasing focus has been placed on self-management, defined as:

The care taken by individuals towards their own health and well-being: it comprises the actions they take to lead a healthy lifestyle; to meet their social, emotional and psychological needs; to care for their long-term condition; and to prevent further illness or accidents.

The Wanless report, Securing our Future Health: Taking a Long-term View, suggested that the future costs of health care were very much dependent on:

How well people become fully engaged with their own health. 20

However, realising the potential of self-management requires effective ways of encouraging appropriate behaviour change in patients and professionals. There are a number of factors influencing self-management, including patient factors (e.g. lay epidemiology and health beliefs, self-efficacy, emotional responses to long-term conditions, identity and pre-existing adaptations), and wider influences (such as the organisation of the health-care system and access to material and community resources). 21 A number of models of self-management have been proposed in the literature, including increasing access to health information5 and deployment of assistive technologies. 22 Patient skills training (through the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program and its derivatives) can be used to encourage patients to enhance their individual self-management skills. 23,24 There is evidence for the effectiveness of the programme on some outcomes,25 but there are significant limitations. Intervention ‘reach’ is defined as the:

. . . percentage and risk characteristics of persons who receive or are affected by a policy or program.

Interventions with limited ‘reach’ are unable to translate the effectiveness of an intervention at the individual level to that of the wider population. In the case of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program, requirements for self-referral or referral from health-care professionals means that levels of uptake can be low, and biased towards certain patient groups, threatening reach and equity.

Models of self-management support

Health policy in the UK has worked with a model that organises care for long-term conditions around three tiers: (1) self-management support for low-risk patients, (2) disease management for patients at some risk and (3) case management for patients with multiple, complex conditions. 27 In the UK, the bulk of disease management is already delivered through primary care. Primary care is generally defined in terms of attributes such as a gatekeeping function and first contact care,28–30 but other attributes also make it an excellent platform for self-management support. Primary care offers open access between the health service and the population, can deliver continuity of care through an extended personal relationship or through informational continuity,28–30 and has a role in helping patients achieve care that balances compliance with clinical guidelines and consistency with patient needs and preferences. Delivering self-management support through primary care also maximises reach.

However, there are major barriers to achieving effective self-management support in primary care. Self-management is only one priority among many facing primary care professionals31 and there is evidence that many primary care professionals do not see self-management as a core part of their remit. 32,33 This is especially true when incentives (financial and otherwise) are focused on specific clinical tasks and biomedical parameters. 34

Achieving the potential of primary care in delivering self-management support

Our research team has engaged in a programme of research over a number of years that has explored the barriers to, and facilitators of, effective self-management support. On the basis of this work, we argue that self-management support requires the following.

-

A whole-systems perspective that involves interventions at the patient, practitioner and service organisation levels in the delivery of self-management support. Many self-management interventions have focused on patient behaviour change or professional training only, but we argue that each level has a different function in encouraging and supporting self-management behaviour, and that effects are maximised when interventions occur at all levels and include attention to patient actions outside the context of contacts with the health service. 13,14,35

-

Widening the evidence base to acknowledge a range of disciplinary perspectives on the way in which patients and professionals respond to, and manage, their long-term conditions. Although psychology has dominated the design of many interventions for self-management support through models such as self-efficacy theory, there are a wide range of applied social science theories that can inform an understanding of the way that patients and professionals understand, respond to and manage long-term conditions. 36–38

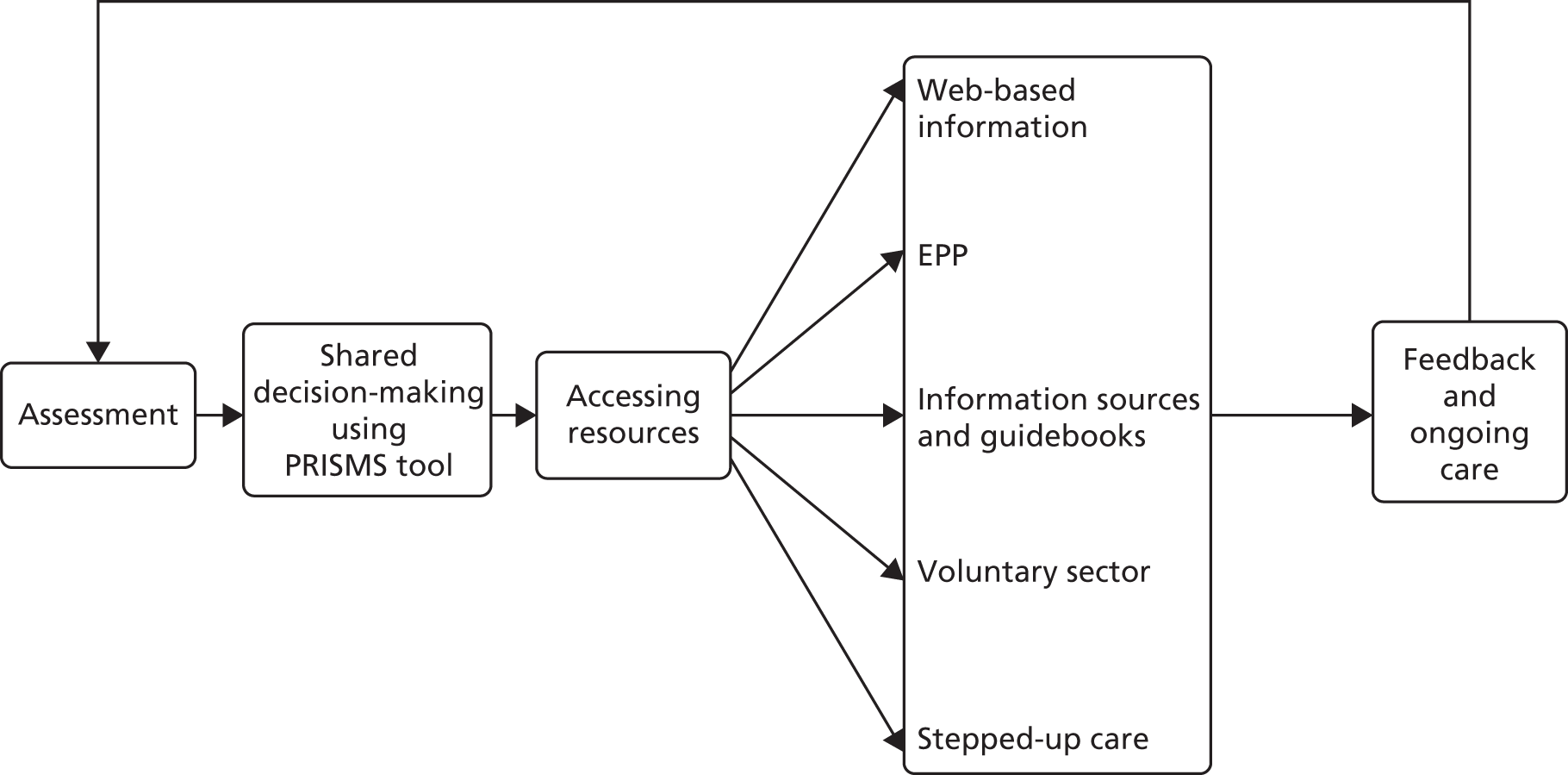

The model has been designed to reflect these findings and provide a feasible and effective model of self-management support. The model (Figure 1) aims to support patients to receive guidance from trained practitioners working within a health-care system geared up to be responsive to patient need.

FIGURE 1.

The WISE model. PRISMS, Patient Report Informing Self-Management Support.

Our approach broadly follows the phased development and evaluation framework outlined for complex interventions by the Medical Research Council (MRC). 39,40 We have developed an evidence base for the elements of the WISE approach using mixed methodology: a combination of RCTs, nested qualitative studies and economic evaluation. In summary, the evidence shows that:

-

information can be effectively improved to incorporate patient experience and expertise alongside medical information about management and treatment5,7,41

-

clinician training in patient-centred consultation skills and shared decision-making with patients to guide and support self-management is acceptable and appropriate, and leads to positive outcomes5

-

health systems that are better aligned to patient practices of self-management are generally well received. 14,35,42

The WISE model as a complex intervention

Complex interventions are defined as those that:

. . . comprise a number of separate elements which seem essential to the proper functioning of the intervention although the ‘active ingredient’ of the intervention that is effective is difficult to specify.

The WISE model, as applied to primary care, met this definition. The intervention was designed to impact on the patient, professional and system levels (see Figure 1). The primary target of the intervention was the practice. The overall aim of the intervention was to encourage practices to adopt a structured and patient-centred approach to the routine management of long-term conditions through providing skills, resources and motivation to make changes to service delivery in line with the principles of the WISE model (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Process of care in the WISE model. PRISMS, Patient Report Informing Self-Management Support. EPP, Expert Patients Programme.

The development, and evaluation, of the training intervention took place prior to this trial, and details have been published elsewhere. 43 The planned approach to training combines evidence-based approaches to changing professional behaviour with approaches to ‘normalise’ those behaviours in current practice. The intervention involved the whole practice and there were also ‘system’ links to the local health organisation, which provided access to additional resources (including a dedicated website of local groups and organisations providing self-management support).

The components of the WISE training intervention include the following:

-

Priority and agenda setting: an intervention, aimed to promote active patient participation in sharing their priorities and management preferences, was developed from the existing published literature and refined in a ‘think aloud’ and qualitative interview study. 44 The Patient Report Informing Self-Management Support (PRISMS) tool was based on a combination of patient-reported outcome measures and a values clarification exercise, intended to encourage patients to clarify and share values and priorities of personal importance. 45,46 The PRISMS tool is intended as a starting point for discussion of patient priorities.

-

Patient-centred information: information can be effective when it incorporates patient experience and expertise alongside medical information about management and treatment, and when it is given in a supportive and timely manner. 10

-

Shared decision-making: shared decision-making about the appropriate type of self-management support, supported by PRISMS and by the use of appropriate ‘explanatory models’. Patients’ explanations and understanding of a condition often differ from the medical model. Explanatory models are ways to make sense of problems and encourage discussion about the causes and consequences of their condition.

-

Referral to community groups: to promote a whole-system approach to self-management, it is essential to engage with relevant community resources. Referral to third-sector providers (i.e. voluntary and community organisations) from primary care has clinically relevant benefits. 47 These groups provide services that are embedded within local community settings to help normalise health-related activities into everyday life. Despite the potential benefits of referral to third-sector providers, there remains an underutilisation of these services by primary care as practitioners report lack of knowledge of the services available. To promote the system change necessary between primary care and relevant third-sector providers, an online database of local self-management support options was developed.

Practice-based training sought to teach the following core skills to primary care staff:

-

Assessment of the individual patient’s self-management support needs, in terms of their current capabilities and current illness trajectory.

-

Shared decision-making about the appropriate type of self-management support based on that assessment (e.g. support from primary care, written information sources, long-term condition support groups or condition-specific education), facilitated by the PRISMS tool and the use of explanatory models.

-

Facilitating patient access to support. This may involve signposting patients to various resources depending on the outcomes of the assessment and shared decision-making processes. These may include access to the Expert Patients Programme, disease-specific courses (such as pulmonary rehabilitation) or generic support (such as befriending). The training encompasses ways that health professionals can negotiate with patients about the more appropriate use of health care.

-

In the case of IBS, this may also involve referral to psychological treatment services (CBT and hypnotherapy) for eligible patients (so-called ‘stepped-up care’). Patients with IBS were informed of the possibility of referral to such services through information leaflets.

As part of the training, primary care professionals received specific assistance in development of the core WISE skills, followed by integration of techniques through role play (with individualised performance feedback based on that role play). 48 The intervention was delivered over two sessions. All relevant staff within the practice were invited to the first session, including general practitioners (GPs), nurses, practice managers and reception staff. Clinical staff were invited to the second session (Box 1). A short intermediate meeting was held between the two main sessions to review progress, and involved the nominated practice lead only.

The first session is delivered to the whole practice by two trainers employed by the PCT who are familiar with primary care. The session involves clinicians, the practice manager and administrative staff and has the following structure:

-

brief introduction to the WISE model

-

team-building exercise

-

exercise on care pathways for patients with long-term conditions

-

WISE tools – PRISMS, explanatory models and menu of local support

-

interactive discussion

-

nomination of practice member to lead on implementation.

This session is a short meeting between the trainers and the nominated practice lead to discuss progress with the WISE approach since session 1.

Session 2This session is delivered by two trainers to all clinicians in the practice team. Through the use of role play and clinical discussion, the training focuses on embedding the three core skills: (1) assessment of self-management needs and capabilities, (2) shared decision-making and (3) facilitating patient access to support into primary care consultations. The session has the following structure:

-

introduction and provision of manual

-

reflection on competencies

-

demonstration of skills to support self-management

-

skills practice

-

discussion on how to ensure sustainability of the WISE model.

PCT, primary care trust.

A training manual was given to all of those who participated in the training for use within the training session and to support practice (see Appendix 1). The training was piloted and modified on the basis of the pilot. The intervention was conducted by trained facilitators working alongside the research team, rather than the research team itself, to test a model of delivery that would be feasible in routine practice and wider implementation.

Enhancement of the WISE model with psychological therapies

Our previous studies had identified a residual group (up to 20%) who fail to benefit and who show high levels of psychological ill-health despite the use of the WISE model.

Evidence demonstrates that physical and psychological factors have an impact on symptom chronicity in patients with chronic gastrointestinal disorders, not only in patients with FGID49 but also in patients with IBD. 50 Such psychological components, particularly anxiety and depression, are important determinants of clinical outcome and health resource use. Although there are limited studies investigating effectiveness of psychological interventions for all FGID, the most common of these disorders (IBS) has been subject to a number of trials. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of psychological treatment for IBS, there was a 50% reduction in symptoms. 51 Our own studies have shown that psychological treatments are of value in chronic gastrointestinal problems. 52 Given the clear evidence of the clinical efficacy of CBT in common mental health problems,53 current best evidence would suggest that either CBT or hypnotherapy would be of utility. We therefore offered both in addition to treatment by the GP.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

We developed a 12-week CBT intervention comprising an initial assessment of between 60 and 90 minutes, followed by up to 11 weekly, individual, face-to-face sessions of between 45 and 60 minutes. Session 1 consisted of a patient-centred assessment for problem identification, risk assessment and development of a shared problem formulation. The following sessions involved education about the condition and specific CBT techniques (pacing, behavioural activation, diary keeping, identifying and challenging negative and unhelpful thinking patterns, and the development of a longer-term management plan). Participants received a self-management manual with information about IBS, CBT and ‘patient stories’ typical of people’s experience of IBS and how to manage their symptoms.

Hypnotherapy

Gut-focused hypnotherapy consists of giving patients ideas about how the gastrointestinal system works and then using hypnosis to try and control abnormalities of gut function as well as dealing with any other factors that might exacerbate their condition. All sessions last 45–60 minutes on a weekly basis for up to 12 weeks, with the first consisting of an assessment of the patient and their symptom profile, followed by an ‘educational’ tutorial on simple gut physiology and how it might be controlled. Subsequent sessions involve the introduction of relaxation and hypnosis in general, followed by progressively more emphasis being placed on control of gut symptoms by the use of imagery or tactile techniques. All patients are given a compact disc to practise on a regular, preferably daily, basis.

The CBT therapist was an experienced and accredited therapist with the British Association for Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapies. A 2-day training workshop, provided by the trial team, consisted of a range of presentations about IBS and applying CBT interventions for people with IBS, with a focus on skills practice. The training was accompanied by a training handbook. The hypnotherapist had been previously fully trained and had been working for 2 years in the local hypnotherapy unit. CBT supervision was provided to the therapist on a fortnightly basis by applicant Karina Lovell (an experienced and accredited CBT therapist). Supervision for the hypnotherapist was provided on a regular basis by applicant Peter Whorwell (an experienced hypnotherapist).

Procedure

Initial and follow-up sessions

Following GP referral, the therapist contacted the participant to arrange the initial session at a convenient time. Each potential patient was given an information sheet prior to the first meeting, and those who agreed to take part signed a consent form to allow access to the self-reported measures (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7). Treatment sessions were delivered in a range of primary care settings, including practices.

The low-intensity aspects of WISE were rolled out from April 2009 and patients with a history of IBS who did not benefit from the WISE low-intensity intervention after 3 months were then given information about different step-up options by their GP or practice nurse. Following discussion with their GP, patients were directly referred to a therapy.

Recruitment

At the start of the project, both therapists identified the need to introduce themselves to the practices that could potentially refer to step-up, and, when possible, this took place. The aim of these meetings was to educate the practice team about the CBT and hypnotherapy treatments and to reiterate the referral protocol.

However, as a result of the low uptake of step-up via this route, alternative recruitment strategies were developed. This included building a relationship with the local primary care mental health teams in Salford that sought to promote the step-up with the relevant GP practices and facilitated a number of referrals. In addition, an individual letter to every GP in a WISE-trained practice was sent in March 2010, advising GPs about the availability of step-up for their IBS patients. In May 2010, in recognition that the referral rate to step-up remained very low, a leaflet describing the CBT/hypnotherapy options was produced in conjunction with NHS Salford Primary Care Trust (PCT); > 200 leaflets were then directly mailed to patients known to the trial. The step-up treatments were regularly advertised in WISE communications (e-mails and newsletters), and a poster advertising the availability of CBT or hypnotherapy for IBS sufferers was also displayed in patient waiting areas in WISE-trained surgeries.

Chapter 3 Design of the randomised controlled trial

The research question was:

What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intervention to enhance self-management support for patients with chronic conditions when translated from research settings into routine care? (Phase IV RCT and economic evaluation.)

The initial iteration of the MRC framework for the development of complex interventions suggested five phases: preclinical and Phases I–IV. Phase III involves comparing ‘a fully defined intervention with an appropriate alternative’ in the context of an appropriately powered RCT. The RCTs completed in the development and initial testing of the WISE model can be considered to be Phase III.

Phase IV has received the least attention of all aspects of the framework. 54 The initial guidance suggested that it concerns replication of Phase III outcomes ‘in uncontrolled settings’. Recent exploration of the differences between Phase III and IV studies suggest other important differences, including:

-

Phase IV RCTs being based on Phase III evidence

-

broad patient inclusion criteria based on those for the clinical service

-

randomisation at the service level

-

outcomes often collected using routine data

-

uptake of the intervention is a crucial variable

-

the implementation of the service is an important part of reporting.

Many of these were present in the study, although not all. For example, measures of self-management and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) are not available in routine data and had to be collected.

Methods

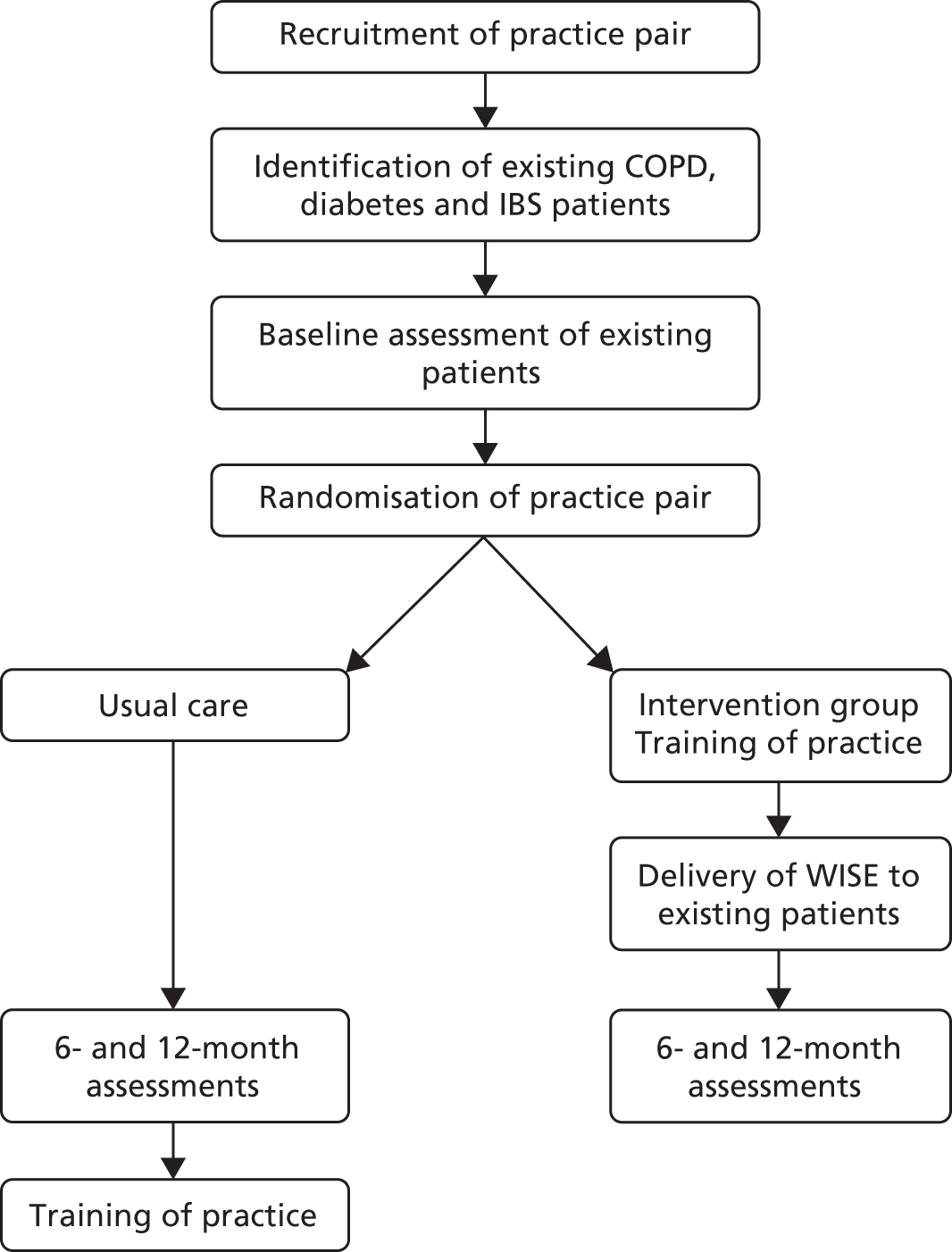

The trial was a pragmatic, two-arm, practice-level cluster Phase IV RCT evaluating outcomes and costs associated with the WISE model (Figure 3). The study was approved by the Salford and Trafford local Research Ethics Committee (reference number 09/H1004/6). We include a summary of the main outcomes of the RCT in this report. A full publication is available elsewhere. 55 The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist is provided in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 3.

Planned trial design. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Research question

What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intervention to enhance self-management support for patients with chronic conditions when translated from research settings into routine care? (Phase IV RCT and economic evaluation.)

Population

The general practice was the cluster and, in line with the Phase IV study design, we aimed to involve all practices in a local ‘health economy’ in the UK. The context was a PCT in Salford, in north-west England. The organisation had a strong commitment to supporting self-management, viewing this as part of a strategic approach to improving the health and well-being of the population. This study took place between 2009 and 2012.

The WISE model is designed to be robust and adaptable enough to use with the vast majority of patients with a long-term condition. We recruited patients with three long-term conditions: diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and IBS. The particular conditions to be included were chosen on the basis of a number of theoretical, policy and practical criteria, and they have important similarities and differences. Each condition is amenable to self-management interventions, and there is already a significant evidence base that will facilitate comparison of the effects of the WISE model with alternatives. The conditions are also of sufficiently high prevalence within practices to meet the sample size needs of the proposed trial. The conditions also have important differences in symptoms, experience and management. IBS is a more ‘contested’ condition with greater disagreement about diagnosis and appropriate management. The management of both diabetes and COPD is also incentivised in the UK under the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), whereas IBS is not.

As a Phase IV RCT, the inclusion criteria were simple and broad to enhance the external validity of the study.

-

Patients had a clinical diagnosis of COPD, diabetes or IBS, identified from existing primary care systems using appropriate clinical registers (for COPD and diabetes) and Read Codes (for IBS), and verified by primary care professionals.

-

Patients also had to demonstrate sufficient English to be able to complete questionnaires.

-

The practice had to agree that the patient was appropriate for research assessment.

Exclusion criteria included patients in the palliative care stage of condition or the presence of mental health problems that reduced capacity to consent and participate.

Patients who had two or more of our index conditions, or a single index condition and another long-term condition, were still included in the trial. Where a patient was identified as having two or more of the three conditions, clinical staff in the practice were asked to determine the main condition, in order to assist with appropriate outcome measurement (see Outcomes).

Intervention

The intervention was described in detail in Chapter 2.

Intervention practices received training as soon as possible after baseline data collection and subsequent allocation; control practices received training 1 year later. Training was undertaken in two sessions, with the second session approximately 1 month after the first. Practices were asked to select two WISE champions (a health-care professional and a member of the administration team) to help embed the WISE approach in the practice (a short mid-training session for them with the trainers was made available).

Outcomes

All outcomes were at the level of the individual patient. Each practice sent eligible patients a questionnaire at baseline, to be returned directly to the research team. Follow-up questionnaires were sent at 6 and 12 months.

The primary end point was the 12-month follow-up of patient health outcomes and costs.

The trial had three primary outcomes, all at 12 months:

-

shared decision-making (short-form Health Care Climate Questionnaire)56

-

self-efficacy (confidence to undertake chronic disease management)57

These outcomes represent core measures along the ‘causal pathway’ from intervention to health outcomes.

The study also collected a number of secondary outcomes, including disease-specific quality of life, self-management behaviours, service utilisation, empowerment, general health, social/role limitations, well-being and vitality. These are all detailed at URL: www.bmj.com/content/bmj/suppl/2013/05/13/bmj.f2882.DC1/kena009790.ww2_default.pdf (accessed 26 October 2017).

There was no blinding of patients or outcome assessors, although all outcomes were self-report. The analyst remained blind to allocation.

Design

The study was a pragmatic cluster RCT using a waiting list control (see Figure 3). The intervention was designed to impact on all primary care staff in a practice, thus randomisation was at the level of the practice to avoid contamination.

Practice recruitment and randomisation

Practices were recruited via practice visits and asked to identify their preferred time during the year for training. Practices were paired as closely as possible according to their preferred times, and using a minimisation procedure, one practice in each pair was allocated to training in the first year, with the other practice allocated to training at the same time the following year. Research staff recruiting practices were unaware of the next allocation in the sequence at the time of recruitment. Baseline (and subsequent follow-up) data collection then took place at both practices in a pair at the same time. This ensured a balance between the intervention and control groups, to avoid potential bias from changes to care delivery outside the trial context (e.g. new government policy or local system changes on the management of long-term conditions).

The practice (cluster) pairs were allocated – one to the intervention group and the other to the control group – using a minimisation algorithm by the trial statistician. Minimisation variables were practice size, practice deprivation [as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)] and practice contractual arrangements (i.e. general medical services or personal medical services). This ensured that, barring attrition, the two arms of the trial would have equal numbers of practices and be balanced on the minimisation variables and data collection timeline.

After practice pairing and allocation, potentially eligible patients at each intervention and control group practice were identified from the computer systems and checked for eligibility to be contacted by practice clinical staff.

Sample size

Sample size calculations were made on the basis of data collected from the national evaluation of the Expert Patients Programme. Although all three patient groups were combined in the primary analysis (see Analysis), we powered the trial to detect a fairly small effect of the intervention on diabetes, COPD and IBS separately. Data on outcomes from the national evaluation of the Expert Patients Programme had a range of intraclass correlation coefficients from 0.01 to 0.07. For the power calculations, we assumed an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.05. Baseline follow-up correlations were taken to be 0.6, that is, towards the lower end of those found in the Expert Patients Programme. On these assumptions, each arm of the trial required 18 practices and 36 patients per condition per practice, to achieve 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.21 per condition. To allow for attrition of practices (estimated to be around 10%), we aimed to recruit 20 practices into each arm of the trial. Questionnaires were to be sent to 80 patients per practice with each condition. For each of the three conditions, this aimed to provide, on average, 48 patients per practice at baseline, reducing to 36 patients at 12 months. We recognised that smaller practices might not have 80 patients with COPD, in which case we compensated by recruiting additional patients from larger practices. On the basis of the above, we aimed to recruit totals of 1728 patients with diabetes, 1728 with COPD and 1728 with IBS.

Analysis

Analysis followed a prespecified analysis plan. Each outcome was subjected to analysis of covariance within a multilevel (patients within practices) regression framework, following intention-to-treat principles and with the analyst (applicant DR) blind to practice allocation. Although we powered the study to detect effects for separate conditions, we maximised power and minimised multiple testing in the analysis by testing for a treatment effect across all three condition groups combined, and for an interaction between trial arm and condition group (controlled for the main effects of condition group). This analysis also controlled for baseline values of each outcome, design factors (practice list size, deprivation and contractual type), and additional covariates (see Process evaluation).

In the case of a statistically non-significant (p > 0.05) interaction between trial arm and condition group, no further condition-specific analyses would be conducted; if the interaction term were significant, this would imply that the effect varied by condition and further analyses would be conducted for each separate condition group.

We applied multiple imputation (five imputed data sets) to baseline variables with missing values (all < 5%), using chained equations and all variables in the model. We did not impute missing follow-up data, but used multivariate logistic regression to identify baseline covariates predictive of missing data and included these (disease condition, age, general health, deprivation index and home ownership) as covariates. Additional prespecified covariates included gender, comorbid conditions count, education and primary care visits 6 months prior to baseline.

Sensitivity analyses assessed the stability of the results to the model specification. All analyses used Stata® v12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and an alpha value of 5%. For outcome variables with skewness or kurtosis values of ≥ 1.0, confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values were derived using standard errors based on 100 bootstrapped samples.

The trial included an economic analysis to compare the costs and outcomes for the trial arms (see Chapter 5 for details of the health economic analysis).

Process evaluation

A process evaluation was designed to complement and provide additional information concerning the trial. 60 Details about the process evaluation and accompanying qualitative study are included in Chapter 6.

Changes to original protocol

The size and complexity of the evaluation meant that it was extremely challenging to implement, and initial delivery of the intervention and research components faced a number of barriers that led to a number of minor changes to the original protocol. We detail these changes and their potential threats to internal and external validity in the following sections.

Single health economy

Our aim was to deliver the proposed intervention across all practices in a single PCT to assess an intervention effect across a complete health economy. Although we were able to recruit 32 practices in Salford (73% response rate), this did not give us the desired level of statistical power. We therefore spread our recruitment to a neighbouring PCT (Bury). This area has a similar socioeconomic profile and the overall spread of IMD scores across practices is quite similar to Salford (4.5–65.5 compared with 6.6–77.2). In addition, the two trusts shared the same chief executive and both are part of a north-west self-management initiative.

However, some aspects of the whole-system intervention detailed previously were not available, such as existence of a dedicated self-management education team and availability of certain community-based support schemes. Differences in the financial arrangements between trusts also meant that we were unable to offer the intervention to control group practices in Bury PCT after 12 months.

Selection of patients before practice allocation

One of the threats to the validity of a cluster randomised trial is recruitment bias, where professionals allocated to different trial arms recruit differently depending on their allocation, leading to selection bias and baseline incomparability. 61 It is preferable in these cases to recruit patients prior to allocation. Although this was our intention, in the event we found that practices required adequate advance notice of their training date; hence it became necessary to inform them of their group allocation prior to patient selection. This does raise the possibility of bias, but we are confident that such bias was small. Initial patient selection was via existing disease registers and Read Codes; therefore, the only way practices could influence recruitment was to request exclusion of a patient after they had been identified through these methods. These exclusions represented a relatively small proportion of patients (11% control and 15% intervention with COPD, 10% and 11%, respectively, for diabetes and 18% and 11%, respectively, for IBS).

Baseline sampling and assessment

Response rates from patients at the practices first to enter the trial were considerably lower than originally expected. In view of this, we made a number of adjustments to improve response. To ensure the patient numbers required for our target level of statistical power, we increased the number of patients surveyed to include all eligible patients at each practice, up to a maximum of 200 per condition (selected at random where this applied). Very few practices had > 200 patients for any condition; hence the study became, in effect, a total population survey. In addition, we introduced a financial incentive to patients for returning a completed questionnaire. We also took the decision to change the baseline questionnaire to focus on a smaller number of core variables. The main effect on the trial of the shortened baseline questionnaire is to reduce our scope for analysis of baseline moderators of treatment effect. However, such analyses are always secondary to the primary intention-to-treat analysis.

Long-term follow-up

Although the original protocol planned for implementation of the model in usual-care practices and a further follow-up at 24 months to assess long-term effects, delays to the project and the lack of effect demonstrated (see Chapter 4) meant that a longer-term follow-up was not possible or appropriate.

Chapter 4 Results

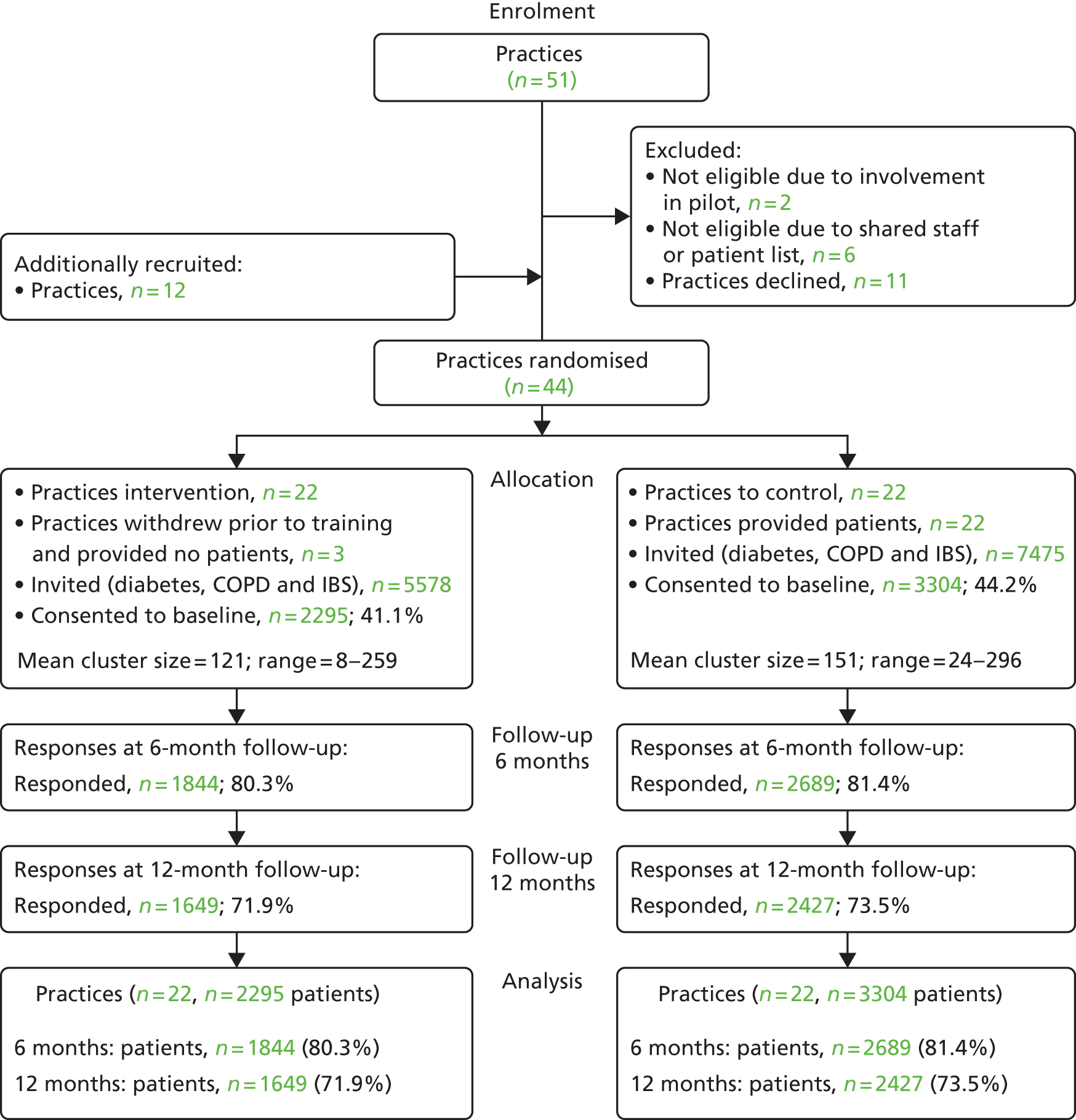

Figure 4 presents the trial CONSORT flow diagram. Practice recruitment from the main PCT (32 practices) fell short of the 40 required to ensure full power. We therefore included additional practices from an adjoining PCT with a very similar demographic profile, resulting in a final total of 44 practices randomised. Three practices randomised to the intervention group withdrew prior to data collection, leaving 19 intervention and 22 control practices.

FIGURE 4.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the trial.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

A total of 5599 patients (n = 2546 diabetes, n = 1634 COPD and n = 1419 IBS) were recruited, representing 43% of the eligible population. Just over half the sample were female (53.5%) and around half (50.8%) were aged ≥ 65 years (Table 1). Very few (3.4%) were non-white. The great majority (72.5%) had more than one long-term condition, and 23% had visited their GP five times or more in the 6 months prior to the study.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | Total (N = 5599) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 3304) | WISE model (N = 2295) | ||

| Main chronic condition, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 1486 (45.0) | 1060 (46.2) | 2546 (45.5) |

| COPD | 1009 (30.5) | 625 (27.2) | 1634 (29.2) |

| IBS | 809 (24.5) | 610 (26.6) | 1419 (25.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 1728 (52.4) | 1262 (55.1) | 2990 (53.5) |

| Male | 1573 (47.7) | 1030 (44.9) | 2603 (46.5) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | |||

| < 50 | 540 (16.4) | 431 (18.9) | 971 (17.5) |

| 50–64 | 1039 (31.6) | 730 (32.0) | 1769 (31.8) |

| 65–74 | 948 (28.9) | 627 (27.5) | 1575 (28.3) |

| ≥ 75 | 757 (23.1) | 492 (21.6) | 1249 (22.5) |

| Number of chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| None or one | 909 (27.5) | 628 (27.4) | 1537 (27.5) |

| Two | 999 (30.3) | 709 (30.9) | 1708 (30.5) |

| Three | 780 (23.6) | 532 (23.2) | 1312 (23.4) |

| Four or more | 615 (18.6) | 426 (18.6) | 1041 (18.6) |

| Accommodation, n (%) | |||

| Owner–occupier | 2164 (66.2) | 1498 (66.2) | 3662 (66.2) |

| Renting | 1106 (33.8) | 765 (33.8) | 1871 (33.8) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 1044 (31.6) | 699 (30.5) | 1743 (31.1) |

| School-level qualifications | 362 (11.0) | 250 (11.0) | 612 (10.9) |

| Professional or vocational | 949 (28.7) | 649 (28.3) | 1598 (28.5) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 198 (6.0) | 157 (6.84) | 355 (6.3) |

| Missing | 751 (22.7) | 540 (23.5) | 1291 (23.1) |

| IMD, mean ± SD | 30.7 ± 20.0 | 28.9 ± 18.1 | 30.0 ± 19.3 |

| GP visits in prior 6 months, n (%) | |||

| None | 407 (12.9) | 265 (12.1) | 672 (12.6) |

| 1 or 2 | 1215 (38.4) | 881 (40.3) | 2096 (39.2) |

| 3 or 4 | 808 (25.5) | 545 (24.9) | 1353 (25.3) |

| 5 or 6 | 448 (14.2) | 264 (12.1) | 712 (13.3) |

| ≥ 7 | 287 (9.1) | 233 (10.7) | 520 (9.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 3167 (96.4) | 2207 (97.0) | 5374 (96.7) |

| Not white | 117 (3.6) | 69 (3.0) | 186 (3.4) |

| Shared decision-making, mean ± SD | 76.7 ± 24.0 | 75.7 ± 24.4 | 76.3 ± 24.1 |

| Self-efficacy score, mean ± SD | 71.1 ± 23.0 | 70.5 ± 23.5 | 70.8 ± 23.2 |

| HRQoL, mean ± SD | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| General health, mean ± SD | 41.4 ± 23.7 | 41.2 ± 24.2 | 41.3 ± 23.9 |

| Practice variables | |||

| Number of practices | 22 | 19 | 41 |

| Practice list size, mean ± SD | 4528 ± 2591 | 4003 ± 2211 | 4285 ± 2407 |

| Practice IMD, mean ± SD | 37.9 ± 21.9 | 40.6 ± 19.6 | 39.1 ± 20.6 |

| Contract type, n (%) | |||

| General medical services | 14 (63.6) | 11 (57.9) | 25 (61.0) |

| Personal medical services | 8 (36.4) | 8 (42.1) | 16 (39.0) |

The two trial arms were well balanced on all variables at the patient level, although practices in the intervention group were, on average, slightly smaller (mean list size of n = 4003 patients compared with n = 4528).

Engagement with training

Practice staff attendance rates at the training sessions were generally high: 90% of eligible staff attended session 1 (n = 179) and 82% (n = 85) attended session 2. Training was rated positively (mean score of > 2.5 on a 5-point scale) by 76% of session 1 participants and by 89% of session 2 participants.

Implementation of training

This is detailed in Chapter 6.

Implementation of step-up therapies

Generally, implementation was limited. In total, 94 referrals were received for step-up therapies, 36 referrals for CBT and 58 referrals for hypnotherapy.

Analysis

With one exception, no statistically significant differences were found between patients attending WISE-trained practices and those attending control practices on any primary or secondary outcome (Table 2). The exception was shared decision-making at the 6-month follow-up (p = 0.05), and the difference favoured the control group.

| Outcomea | Trial arm, unadjusted analyses (mean ± SD; n) | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI)b | Effect size (95% CI)c | p-value | p-value for interaction with condition groupd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | WISE model | |||||

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Shared decision-making | 69.1 ± 26.3; 2379 | 67.7 ± 27.7; 1626 | –0.47 (–2.55 to 1.61) | –0.02 (–0.11 to 0.07) | 0.657 | 0.696 |

| Self-efficacy score | 71.2 ± 22.5; 2394 | 70.4 ± 22.8; 1611 | –0.35 (–1.42 to 0.71) | –0.02 (–0.06 to 0.03) | 0.519 | 0.205 |

| HRQoL | 0.6 ± 0.3; 2382 | 0.6 ± 0.3; 1609 | –0.00 (–0.02 to 0.01) | –0.01 (–0.05 to 0.04) | 0.724 | 0.305 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| General health | 41.7 ± 24.8; 2413 | 42.2 ± 25.8; 1643 | 0.28 (–1.37 to 0.82) | 0.01 (–0.03 to 0.06) | 0.621 | 0.884 |

| Social/role limitations | 63.3 ± 31.1; 2408 | 62.8 ± 32.3; 1638 | –0.49 (–1.95 to 0.96) | –0.02 (–0.06 to 0.03) | 0.505e | 0.436e |

| Energy/vitality | 46.8 ± 20.9; 2411 | 46.2 ± 21.8; 1638 | –0.42 (–1.53 to 0.69) | –0.02 (–0.07 to 0.03) | 0.456 | 0.332 |

| Self-care activity | 42.4 ± 14.6; 2382 | 42.5 ± 14.9; 1613 | 0.01 (–0.95 to 0.97) | 0.00 (–0.06 to 0.07) | 0.977 | 0.960 |

| Psychological well-being | 64.7 ± 21.9; 2412 | 64.7 ± 22.2; 1640 | 0.49 (–0.75 to 1.73) | 0.02 (–0.03 to 0.08) | 0.436 | 0.303 |

| Enablement | 78.6 ± 28.8; 2365 | 80.7 ± 28.3; 1624 | 0.85 (–1.36 to 3.06) | 0.03 (–0.05 to 0.11) | 0.450e | 0.948e |

| Shared decision-making (6 months) | 70.3 ± 26.1; 2658 | 68.3 ± 27.3; 1818 | –1.77 (–3.53 to 0.0) | –0.07 (–0.15 to 0.0) | 0.050f | 0.065g |

| Self-efficacy (6 months) | 71.1 ± 22.5; 2659 | 70.4 ± 23.1; 1816 | –0.70 (–1.69 to 0.29) | –0.03 (–0.07 to 0.01) | 0.168 | 0.316 |

| HRQoL (6 months) | 0.6 ± 0.3; 2646 | 0.6 ± 0.3; 1803 | 0.00 (–0.01 to 0.01) | 0.00 (–0.04 to 0.05) | 0.862 | 0.824 |

| Self-care activity (6 months) | 42.5 ± 14.6; 2645 | 42.7 ± 15.0; 1813 | 0.03 (–0.88 to 0.93) | 0.00 (–0.06 to 0.06) | 0.955 | 0.776 |

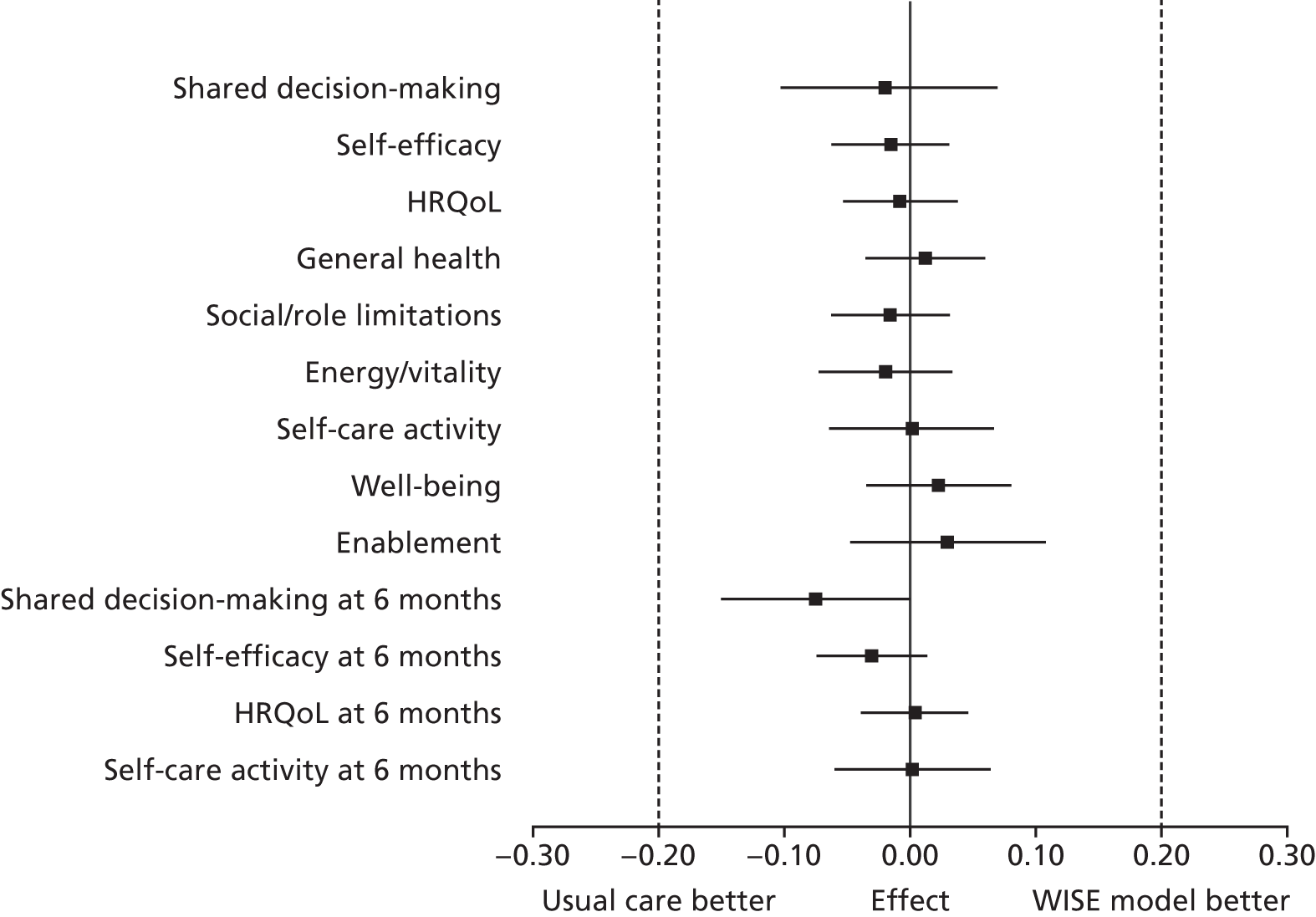

All effect size estimates were very small with narrow 95% CIs and well below the minimally important difference of 0.2 that the trial was powered to detect (Figure 5). The lack of effect applied equally to the intermediate outcomes of shared decision-making, self-efficacy, enablement and self-care activity – which might reasonably be expected to be most directly affected by increased support for self-management – as it did to health-related outcomes. Furthermore, none of the interactions between intervention group and condition group was significant; therefore, we conducted no condition-specific analyses in accordance with the analytic plan. Sensitivity analyses provided no evidence that the results were substantively influenced by model assumptions.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of standardised effect sizes (vertical bars indicate minimally important differences).

We repeated the analysis for the IBS sample of 1419 patients, of whom 1119 (79%) completed 6-month follow-up and 1004 (71%) completed 12-month follow-up. Table 3 gives the baseline characteristics for the IBS participants. The analysis, again, found no statistically significant differences between groups on any primary or secondary outcome (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Trial arm | Total (N = 1419) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 809) | WISE model (N = 610) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 626 (77.4) | 478 (78.5) | 1104 (77.9) |

| Male | 183 (22.6) | 131 (21.5) | 314 (22.1) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | |||

| < 50 | 333 (41.2) | 295 (48.6) | 628 (44.4) |

| 50–64 | 264 (32.7) | 195 (32.1) | 459 (32.4) |

| 65–74 years | 130 (16.1) | 81 (13.3) | 211 (14.9) |

| ≥ 75 | 81 (10.0) | 36 (5.9) | 117 (8.3) |

| Number of chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| None or one | 323 (39.9) | 251 (41.2) | 574 (40.5) |

| Two | 237 (29.3) | 198 (32.5) | 435 (30.7) |

| Three | 164 (20.3) | 93 (15.3) | 257 (18.1) |

| Four or more | 85 (10.5) | 68 (11.2) | 153 (10.8) |

| Accommodation, n (%) | |||

| Owner–occupier | 561 (69.6) | 456 (75.9) | 1017 (72.3) |

| Renting | 245 (30.4) | 145 (24.1) | 390 (27.7) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| No qualifications | 142 (17.6) | 99 (16.2) | 241 (17.0) |

| School-level qualifications | 115 (14.2) | 99 (16.2) | 214 (15.1) |

| Professional or vocational | 276 (34.1) | 208 (34.1) | 484 (34.1) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 86 (10.6) | 65 (10.7) | 151 (10.6) |

| Missing | 190 (23.5) | 139 (22.8) | 329 (23.2) |

| IMD, mean ± SD | 27.7 ± 19.2 | 25.3 ± 16.1 | 26.7 ± 17.9 |

| GP visits in prior 6 months, n (%) | |||

| None | 91 (11.7) | 81 (13.8) | 172 (12.6) |

| 1 or 2 | 303 (38.9) | 237 (40.4) | 540 (39.6) |

| 3 or 4 | 217 (27.9) | 134 (22.9) | 351 (25.7) |

| 5 or 6 | 98 (12.6) | 77 (13.1) | 175 (12.8) |

| ≥ 7 | 70 (9.0) | 57 (9.7) | 127 (9.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 776 (96.4) | 593 (97.9) | 1369 (97.0) |

| Not white | 29 (3.6) | 13 (2.2) | 42 (3.0) |

| Shared decision-making, mean ± SD | 71.9 ± 25.9 | 71.9 ± 24.6 | 71.9 ± 25.3 |

| Self-efficacy score, mean ± SD | 70.2 ± 22.8 | 70.8 ± 22.3 | 70.4 ± 22.6 |

| HRQoL, mean ± SD | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| General health, mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 1.0 |

| Practice variables | |||

| Number of practices | 21 | 19 | 40 |

| Practice list size, mean ± SD | 4654 ± 2586 | 4003 ± 2211 | 4345 ± 2407 |

| Practice IMD, mean ± SD | 36.1 ± 20.7 | 40.6 ± 19.6 | 38.2 ± 20.1 |

| Contract type, n (%) | |||

| General medical services | 14 (66.7) | 11 (57.9) | 25 (62.5) |

| Personal medical services | 7 (33.3) | 8 (42.1) | 15 (37.5) |

| Outcomea | Trial arm, unadjusted analyses (mean ± SD; n) | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI)b | Effect size (95% CI)c | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | WISE model | ||||

| Primary outcomes | |||||

| Shared decision-making | 66.0 ± 27.7; 560 | 64.5 ± 27.7; 431 | 0.60 (–3.17 to 4.38) | 0.03 (–0.13 to 0.19) | 0.755 |

| Self-efficacy score | 70.6 ± 20.9; 563 | 71.9 ± 21.0; 420 | 0.96 (–0.88 to 2.80) | 0.04 (–0.04 to 0.12) | 0.305 |

| HRQoL | 0.7 ± 0.3; 564 | 0.7 ± 0.3; 423 | 0.01 (–0.02 to 0.04) | 0.03 (–0.06 to 0.12) | 0.521 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| IBS-specific quality of life | 80.3 ± 22.4; 536 | 81.8 ± 21.9; 403 | 2.07 (–0.46 to 4.59) | 0.07 (–0.02 to 0.16) | 0.109d |

| General health | 3.0 ± 1.0; 570 | 3.0 ± 1.0; 432 | 0.02 (–0.06 to 0.11) | 0.02 (–0.06 to 0.11) | 0.588 |

| Social/role limitations | 68.1 ± 29.6; 569 | 69.2 ± 29.7; 428 | 1.14 (–1.76 to 4.04) | 0.04 (–0.06 to 0.13) | 0.441d |

| Energy/vitality | 47.6 ± 20.0; 568 | 47.3 ± 21.5; 431 | 0.40 (–1.73 to 2.53) | 0.02 (–0.08 to 0.12) | 0.714 |

| Self-care activity | 42.4 ± 15.8; 558 | 42.1 ± 16.1; 423 | 0.02 (–1.97 to 2.02) | 0.00 (–0.13 to 0.14) | 0.983 |

| Psychological well-being | 61.1 ± 22.4; 569 | 61.3 ± 22.0; 432 | 1.21 (–1.22 to 3.65) | 0.06 (–0.06 to 0.17) | 0.329 |

| Enablement | 81.0 ± 28.2; 556 | 82.8 ± 26.4; 426 | 1.06 (–2.23 to 4.36) | 0.04 (–0.08 to 0.15) | 0.528d |

| IBS-specific quality of life (6 months) | 80.7 ± 22.4; 598 | 82.3 ± 22.5; 454 | 1.66 (–0.61 to 3.93) | 0.06 (–0.02 to 0.14) | 0.151d |

| HRQoL (6 months) | 0.7 ± 0.3; 626 | 0.7 ± 0.3; 476 | 0.00 (–0.03 to 0.02) | –0.01 (–0.08 to 0.07) | 0.871 |

| Shared decision-making (6 months) | 68.3 ± 26.4; 634 | 64.5 ± 27.4; 479 | –2.87 (–5.81 to 0.06) | –0.12 (–0.25 to 0.00) | 0.055e |

| Self-efficacy (6 months) | 72.4 ± 20.6; 627 | 70.8 ± 22.2; 477 | –1.89 (–3.66 to –0.12) | –0.08 (–0.16 to –0.01) | 0.036f |

| Self-care activity (6 months) | 42.4 ± 15.8; 624 | 41.7 ± 16.1; 478 | –0.37 (–2.25 to 1.50) | –0.03 (–0.15 to 0.10) | 0.697 |

Discussion

This chapter reports one of the largest trials of self-management support in primary care. The WISE model had no significant effects on patient outcomes or on service use. This chapter focuses on trial results, but a separate process evaluation will explore barriers to implementation (see Chapter 6).

Strengths of the study included a very large practice and patient sample size, an intervention based on previous published trials and delivered at an intensity feasible in primary care. A patient recruitment rate of 43% is relatively high for a community-based trial in UK primary care and we achieved excellent levels of follow-up. We also achieved high levels of practice participation. Although it might be argued that effects may have been demonstrated in different long-term conditions or outcomes, our inclusion of a range of conditions and our comprehensive outcome assessment gives us confidence that the lack of effect is robust.

The key threat to trial validity is recruitment bias, which occurs when professionals recruit differently depending on the trial arm to which they are allocated. 61 We intended to recruit patients prior to allocation, but this proved logistically impracticable. Recruitment was via electronic health records rather than professional invitation, but practitioners could exclude patients after identification. 62

A common complaint in health services research is that effective interventions are often not feasible, and feasible interventions are often not effective. Many published self-management trials are conducted in atypical contexts with selected, volunteer samples. Our study took proven components of self-management support and tested whether or not we could implement these as a comprehensive package in routine primary care practice using existing educational structures and applied to an entire local health economy. We sought to sensitise our intervention to the particular nature of primary care, providing a structure and tools to allow practitioners to introduce self-management support into time-limited consultations, to enhance partnerships with patients, and to encourage behaviour change.

The local context included indicators of institutional commitment from the host organisation. This was reflected in the relatively high level of practice engagement. Data from practice staff (see Chapter 6) suggest that training facilitation was successful in parts, with relatively high levels of attendance and acceptability. Limited time was available for training. However, time provided for training was based on our pilot studies and negotiations with practices, and was judged the maximum acceptable to clinical staff, given time demands and the high costs of providing staff cover. Staff self-report data suggest that implementation was variable. We allowed practices flexibility in how they implemented self-management support at the practice level and flexibility can lead to attenuated outcomes. Although a more standardised approach may have enhanced effectiveness, this may have equally jeopardised recruitment and engagement.

In addition, despite our best efforts and the full support of the PCT, no practice was prepared to free up further staff time for reinforcement sessions or fuller engagement of the ‘WISE champions,’ and only one practice allowed access for fidelity checks.

A fuller discussion of the results of the RCT will be presented following the economic analyses and the results of the process evaluation.

Chapter 5 Health economic analysis

In this chapter we assess the cost-effectiveness of the WISE approach to provide useful information for decision-makers. The Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist is provided in Appendix 3.

Methods

Design

The trial was a two-arm, practice-level cluster RCT evaluating outcomes and costs associated with adoption of the WISE approach in primary care to manage three conditions. The intervention and comparator have been described in Chapter 3, as has the trial design.

Decision problem

To assess the cost-effectiveness of the WISE model in the management of long-term conditions, compared with routine primary care services, and to assess the cost-effectiveness of the model in IBS separately.

Parameter estimates

The following parameter estimates were generated as part of the RCT.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life was measured in the trial using quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). QALYs were generated as the product of the health state of each individual and the time spent in that state. The health state of each individual in the study was assessed at entry to the trial (baseline), and at 6- and 12-month follow-up using the EQ-5D descriptive system.

Quality-adjusted life-years were estimated using the area under the curve approach,63 with linear interpolation between EQ-5D scores at each follow-up point. The QALY estimates are presented adjusted for baseline EQ-5D score,64 but also without the adjustment.

Resource use and unit costs

At each follow-up (6 and 12 months post randomisation), patients were asked to recall their use in the last 6 months of hospital services (including inpatient stays and outpatient attendances), visits to GP surgery (GP or practice nurse), home visits (from GP, physiotherapist, or occupational therapist) and other health/social sector resource use.

The unit costs of health services, for example the cost of a visit to a GP, were estimated using the published literature and are presented in Table 5. The unit costs were then applied to the appropriate resource use item.

| Description | Mean (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per elective bed-day | 341.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| Outpatient attendance | 105.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| A&E | 119.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| Physiotherapist | 47.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| Occupational therapist | 74.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| District nurse | 38.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| GP | 25.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| Practice nurse | 11.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| GP home visit | 82.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| Nurse specialist (community) | 44.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| NHS Direct | 25.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| NHS walk-in centre | 99.00 | Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust |

| Home help | 9.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| Meals on Wheels | 3.50 | Variable |

| Respite care | 500.00 | PSSRU 199867 (inflated to 2010/11) |

| Counsellor | 60.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

| Other | 9.00 | Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010/1165,66 |

Missing data

All data were available at baseline. There were missing data when follow-up questionnaires were incomplete or patients missed one or more follow-up interviews. In the main analysis missing data were imputed by multiple imputation. Complete-case analysis was conducted as a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of results to imputation assumptions.

Where data were missing, the relevant item (e.g. EQ-5D index and/or health-care costs) was imputed by multiple imputation with the Stata v11 program. The ‘mi impute chained (pmm)’ command was employed to generate values for missing data at each follow-up using a predictive mean matching method. Multiple imputation generates several (in this instance, five) data sets rather than a single imputed data set. Each data set contains different imputed values and analysis is then conducted on each of the imputed data sets. The multiple analyses are then combined to yield a single set of results. The major advantage of multiple imputation over single imputation is that it produces standard errors that reflect the degree of uncertainty as a result of the imputation of missing values. In general, multiple imputation techniques require that missing observations are missing at random. This means that, given the observed data, the reason for the observation being missing does not depend on the unobserved data. So, for example, a missing HRQoL observation might be predicted by previous HRQoL, but does not depend on current HRQoL.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions index scores were imputed rather than missing responses to individual EQ-5D domains. Thus, an individual who responded to three of the five EQ-5D domains would have an index score imputed that would reflect their age, gender and other characteristics, but not their responses to the non-missing EQ-5D domains. However, EQ-5D index scores from other time periods were included in the predictive mean matching imputation.

Similarly, because of the complexity of imputing missing resource use by each item, costs were aggregated to levels of primary care, secondary care and community care. Missing data were then imputed at these levels (i.e. primary care costs, secondary care costs or community care costs).

Sensitivity analyses were carried out by excluding patients with missing data. Although complete case can be a useful sensitivity analysis, only a small proportion of individuals completed every question at every follow-up. Therefore, available case data are presented as a sensitivity analysis. The difference between groups was then assessed on this subset of available data.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

A NHS and Personal Social Services perspective was considered. All costs and outcomes fell within a 12-month period and, therefore, discounting was not conducted. The analysis presented is a ‘within-trial’ analysis. Thus, only costs and effects observed within the period of the trial were analysed and presented. Where any substantial differences were demonstrated between groups, we intended to investigate the consequences of extending the period of analysis to a longer, more appropriate time horizon.

The mean cost and mean QALYs per patient were calculated for both groups over the period of the trial. The difference in mean costs and mean effects between groups was estimated, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated where appropriate. Currently, NHS treatments in England are considered cost-effective by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) if the ICER is < £20,000 per QALY. For interventions that are associated with an ICER between £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY gained, there needs to be evidence that the intervention is innovative and/or that HRQoL is not captured adequately and/or that there is considerable uncertainty around the ICER. As the ICER goes above £30,000 per QALY gained, this evidence needs to be stronger.

Cost-effectiveness analysis is conducted under uncertainty. Uncertainty around the adoption decision is presented graphically using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. 68,69 Uncertainty in the choice of analysis (e.g. the form of imputation) is addressed using sensitivity analysis.

Results

The results are presented initially for the three conditions combined. The subsequent analysis considers the cost-effectiveness of the WISE model in individuals whose primary condition was IBS only.

The unit costs of the health-related resource use in the trial are presented in Table 5.

The resource use for each item recorded is presented, by trial group, in Table 6. These figures are based on the available cases and will therefore differ from those presented in later tables, which are based on imputed values.

| Resource use | Trial arm, mean resource use | Difference in mean (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WISE model | Usual care | ||

| Length of stay | 1.589 | 1.322 | 0.268 (–0.343 to 0.879) |

| Outpatient attendances | 2.912 | 2.887 | 0.024 (–0.366 to 0.415) |

| A&E attendances | 0.298 | 0.290 | 0.009 (–0.050 to 0.068) |

| GP surgery visits | 4.429 | 4.505 | –0.077 (–0.371 to 0.218) |

| GP home visits | 0.155 | 0.227 | –0.072 (–0.009 to –0.135) |

| GP other | 0.208 | 0.280 | –0.072 (–0.157 to 0.012) |

| Practice nurse visits | 2.783 | 2.893 | –0.110 (–0.307 to 0.086) |

| Community nurse visits | 1.141 | 0.615 | 0.525 (0.129 to 0.922) |

| OT visits | 0.136 | 0.081 | 0.055 (–0.057 to 0.166) |

| Home care worker | 1.156 | 2.290 | –1.133 (–4.405 to 2.139) |

| Meals on Wheels | 0.028 | 0.181 | –0.153 (–0.402 to 0.095) |

| Physiotherapist | 0.104 | 0.090 | 0.014 (–0.041 to 0.070) |

| NHS Direct | 0.172 | 0.136 | 0.036 (–0.030 to 0.101) |

| Walk-in centre | 0.534 | 0.357 | 0.178 (0.034 to 0.321) |

| Respite care | 0.077 | 0.039 | 0.038 (–0.031 to 0.107) |

| Counsellor | 0.252 | 0.281 | –0.029 (–0.156 to 0.098) |

| Other | 0.865 | 0.528 | 0.337 (0.045 to 0.630) |

Table 6 shows that there are few substantial and/or statistically significant differences in resource use between the two trial groups. Although the analysis above describes available cases, these results are completely consistent with the complete-case analysis.

Health-related quality of life

Table 7 shows the percentage of each patient group in each EQ-5D domain by follow-up for those who completed the EQ-5D at the relevant follow-up time point. An examination of the table indicates that there was very little movement between dimensions for either the WISE model or the usual-care group over the 12-month period.

| Intervention and EQ-5D dimension | Time point, % of patients in health state at | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| WISE model | |||||||||

| Mobility | 47.2 | 52.3 | 0.4 | 46.6 | 53.1 | 0.2 | 46.9 | 52.6 | 0.5 |

| Self-care | 76.9 | 22.1 | 1.1 | 76.1 | 22.9 | 1.1 | 76.8 | 22.3 | 1.0 |

| Usual activities | 46.1 | 46.3 | 7.6 | 46.9 | 46.5 | 6.7 | 46.4 | 46.9 | 6.7 |

| Pain/discomfort | 28.8 | 56.3 | 15.0 | 27.2 | 59.0 | 13.9 | 28.4 | 56.9 | 14.7 |

| Anxiety/depression | 55.0 | 39.2 | 5.8 | 54.0 | 39.8 | 6.1 | 54.7 | 38.8 | 6.5 |

| Usual care | |||||||||

| Mobility | 45.0 | 54.8 | 0.2 | 43.8 | 55.9 | 0.3 | 44.7 | 55.0 | 0.3 |

| Self-care | 77.7 | 21.6 | 0.7 | 76.9 | 22.2 | 0.9 | 78.3 | 20.7 | 1.0 |

| Usual activities | 44.8 | 48.8 | 6.4 | 44.9 | 48.8 | 6.3 | 45.6 | 47.6 | 6.8 |

| Pain/discomfort | 27.5 | 59.6 | 12.9 | 26.9 | 59.9 | 13.3 | 28.0 | 59.2 | 12.8 |

| Anxiety/depression | 56.3 | 37.9 | 5.7 | 54.9 | 39.6 | 5.5 | 55.8 | 38.7 | 5.5 |

Imputation of missing data

There were a considerable number of missing resource use data at each follow-up point, although the response rate was > 70% for each resource use variable and > 80% for inpatient stays at 6 months. Thus, the analysis based on multiple imputation is considered as the primary analysis, with the available and complete cases conducted as secondary/sensitivity analyses.

Cost-effectiveness

The mean QALYs for both the WISE model and usual care group are presented in Table 8, together with the CIs around the difference. Unadjusted QALY differences are presented, followed by the adjustment for EQ-5D baseline score, as recommended in the literature. 64 Whether the adjusted or unadjusted analysis is considered, the QALY differences are not substantial. The change in direction of effect that occurs after allowing for baseline differences in EQ-5D score is attributable to the small absolute difference in effectiveness. The mean costs by group are presented in Table 9 and are based on the imputed data.

| Group | Mean QALY | Difference (95% CI) | Difference allowing for baseline characteristics (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WISE model | 0.6871 | –0.0029 (–0.0176 to 0.0117) | 0.0044 (–0.0052 to 0.01385) |

| Usual care | 0.6900 |

| Group | Mean total cost (£) | Difference in mean total cost (£) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| WISE model | 1264 | 144 (–99 to 387) |

| Usual care | 1120 |

The difference in cost between the two trial arms is, again, insubstantial. Combining the difference in costs and effects generates the ICER. This statistic is presented in Table 10 with and without adjustment for baseline EQ-5D scores (although the latter is the preferred statistic).

| Cost difference (£) (95% CI) | QALY | ICER (£) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | Difference allowing for baseline characteristics (95% CI) | Unadjusted QALY | Adjusted QALY | |

| 144 (–98.9 to 386.7) | –0.0029 (–0.0176 to 0.0117) | 0.0044 (–0.0052 to 0.01385) | Dominated | 32,695 per QALY |

There is a considerable amount of uncertainty around the adoption decision, driven by uncertainty in whether the intervention is less or more effective, and less or more costly. This is reflected in the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (Figure 6), which shows that, at commonly used threshold values of a QALY, we are unsure whether or not the intervention is cost-effective. For example, at a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000, there is approximately 30% chance that the WISE model is cost-effective, whereas at £30,000 this rises to almost 50%. The ICER of around £33,000 would not be considered cost-effective at commonly used thresholds. Therefore, the choice of analysis does not affect the adoption decision and the WISE model would not be implemented based on these data.

FIGURE 6.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, controlling for baseline utility.

Sensitivity analysis

To test the robustness of the multiple imputation assumption, costs and effects were estimated for the groups based on the responses received at each follow-up and including the adjustments for zero values described earlier. The results are very similar in magnitude, and direction, for all estimates, thereby adding weight to the conclusion that the WISE model has little impact on either costs or effects on these patient groups (Table 11).

| Cost difference (£) (95% CI) | QALY | ICER (£) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | Difference allowing for baseline characteristics (95% CI) | Unadjusted QALY | Adjusted QALY | |

| 172 (–27.5 to 372.1) | –0.0025 (–0.0175 to 0.0125) | 0.0050 (–0.0046 to 0.01499) | Dominated | 34,400 per QALY |

Subgroup analysis of irritable bowel syndrome patients

Costs

Based on imputed data for those individuals whose primary condition was IBS, the WISE model was associated with an increased cost of £387 per patient over the duration of the trial. Although this may appear substantial, it would not be considered statistically significant, with a 95% CI of –£133 to £907.

Health-related quality of life

Again, based on imputed data for IBS patients, the WISE model was associated with a small increase in HRQoL. This difference of 0.0015 QALYs is not statistically significant (95% CI –0.0163 to 0.0193 QALYs).

Cost-effectiveness

In the IBS population, the WISE model was associated with small increases in HRQoL observed together with some increases in cost. Thus, it is appropriate to generate an ICER. With an ICER of > £260,000 per QALY for IBS patients, the WISE model would not be considered cost-effective at commonly considered thresholds.

Comparison with other conditions in trial

The three conditions combined yielded a very small improvement in QALYs at an increased cost. The analysis of IBS patients generates very similar results, suggesting that the conclusion that the WISE model has little impact on costs or QALYs over the duration of the trial in any of the conditions considered.

Discussion

The WISE model had little impact on either costs or effects within the time period of the trial. In addition, there is no evidence to suggest that there were any longer-term implications that may not have been captured within the time period of the trial. The results were robust to alternative assumptions about missing data and did not differ between conditions included in the trial. The results of the cost-effectiveness analysis are therefore consistent with the results of the effectiveness analyses.

The strengths of this study are clearly that it is a large RCT so that any demonstration of a treatment effect on costs or outcomes is likely to be reliable. The variety of sensitivity analyses performed also suggests that this result is robust.

A potential weakness of the economic analysis is the time horizon. This assumes that there are no differences between groups after the end of the trial. However, given the lack of movement within EQ-5D dimensions (and single index scores) over the trial period, it is considered a justifiable assumption. Similarly, the trajectory of the EQ-5D scores between follow-up periods is unknown. We have assumed a linear interpolation in the absence of evidence to the contrary. It is feasible that if EQ-5D scores were collected more frequently, differences may have been observed. However, again because of the lack of movement in individuals across dimensions, this is considered unlikely.

Chapter 6 Process evaluation

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Kennedy et al. 70 Copyright © 2013 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Primary care potentially provides ready access and continuity of care for patients and, therefore, an appropriate location for guideline-based disease management programmes for patients and, more recently, as a key provider of self-management support. 14 In UK primary care, long-term condition management operates through an increasingly biomedical framework, partly as a result of the QOF, a system of payment to practices for activities done and outcomes achieved.

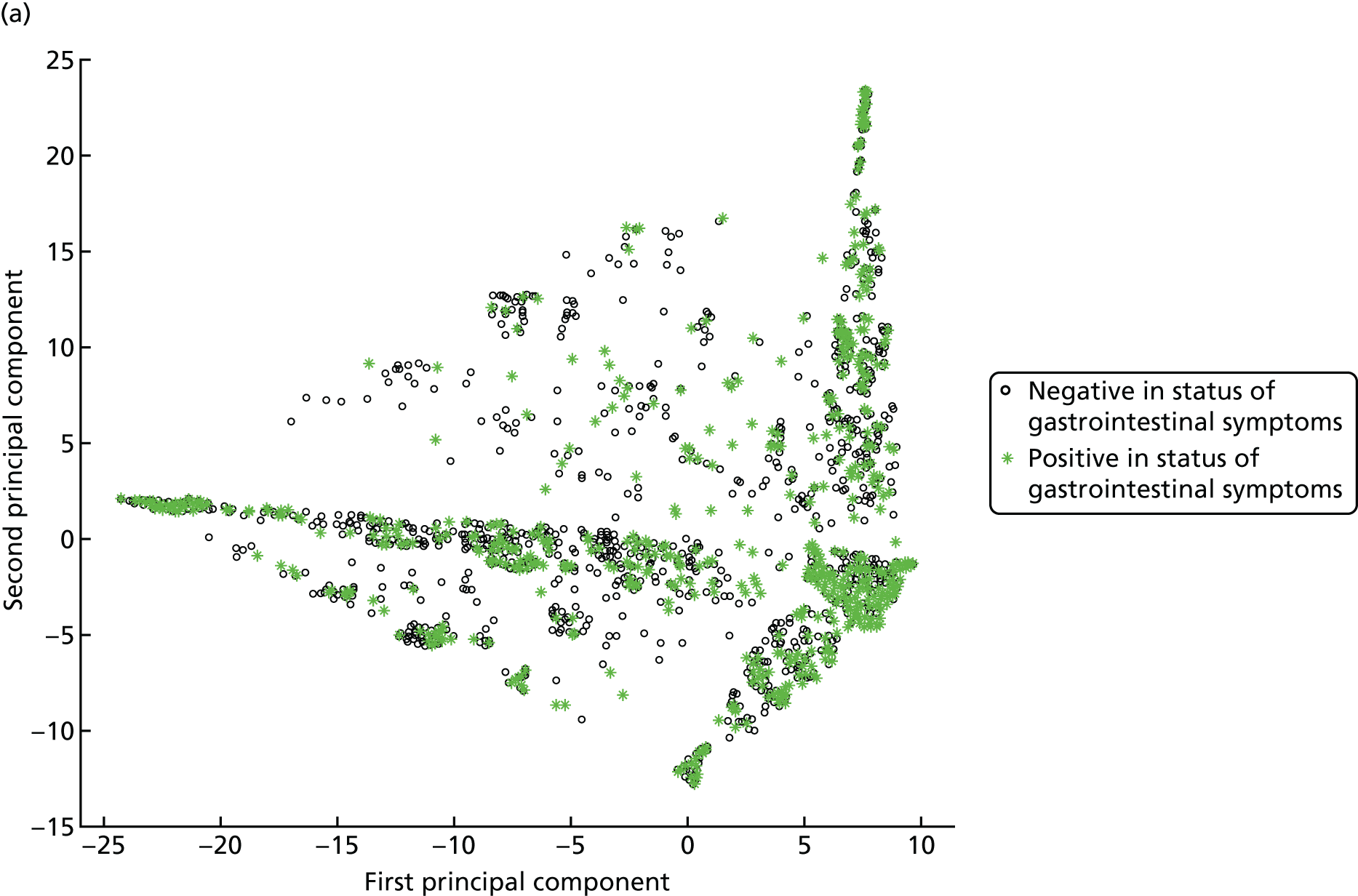

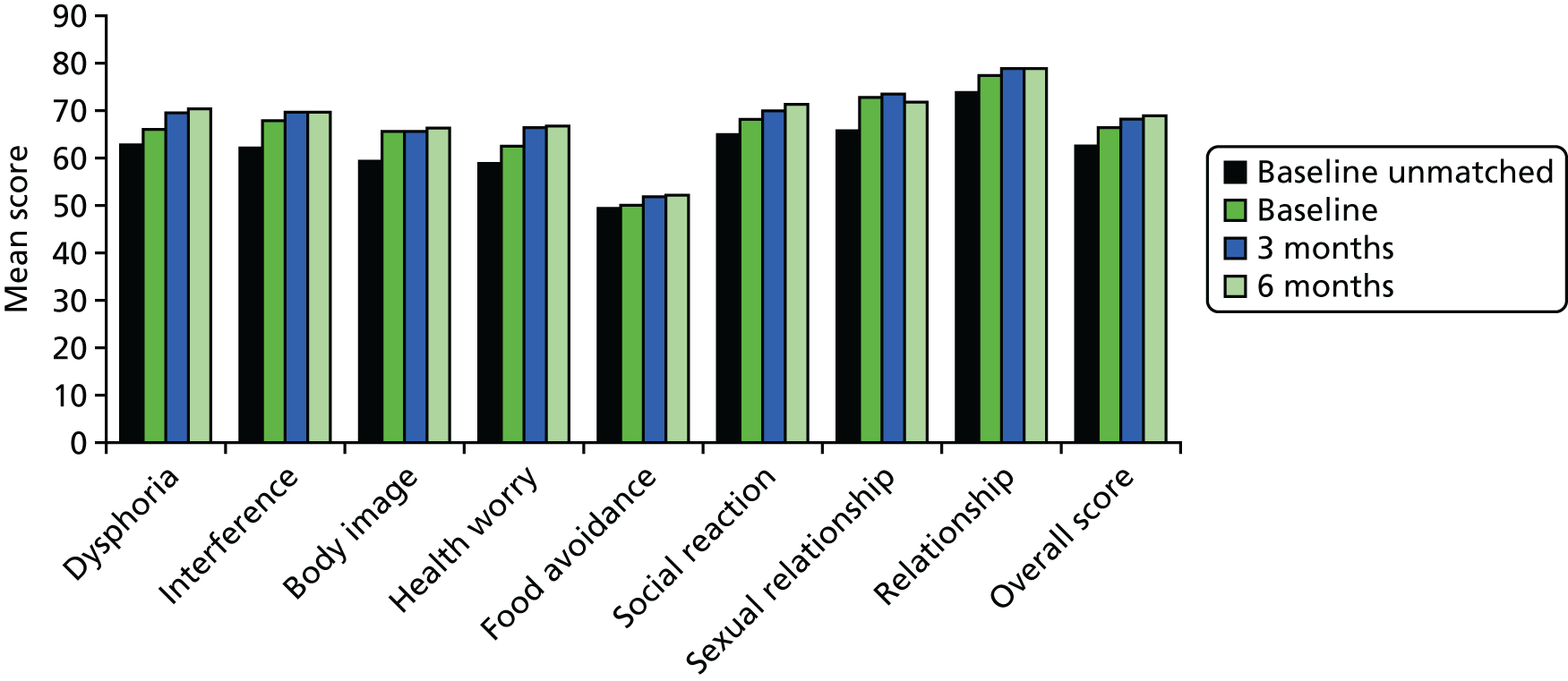

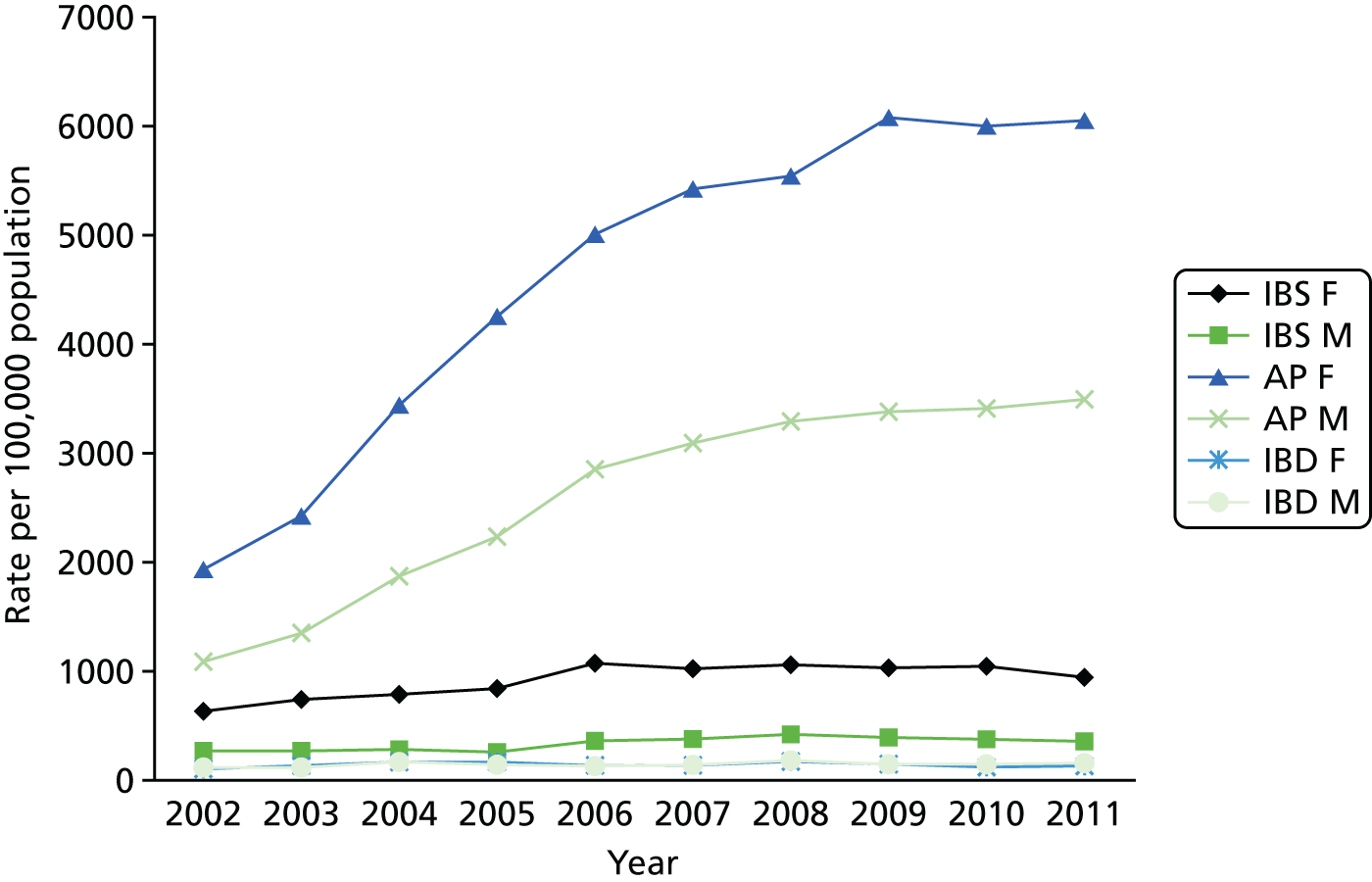

The organisation of care for people with long-term conditions is in transition and self-management support policies are seen as important to enhance peoples’ self-management capabilities and thus improve health outcomes and reduce the fiscal burden on health-care systems. 71